* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Poppy Ott and the Prancing Pancake

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Edward Edson Lee

Date first posted: Nov. 4, 2020

Date last updated: Nov. 4, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20201107

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutchseon & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

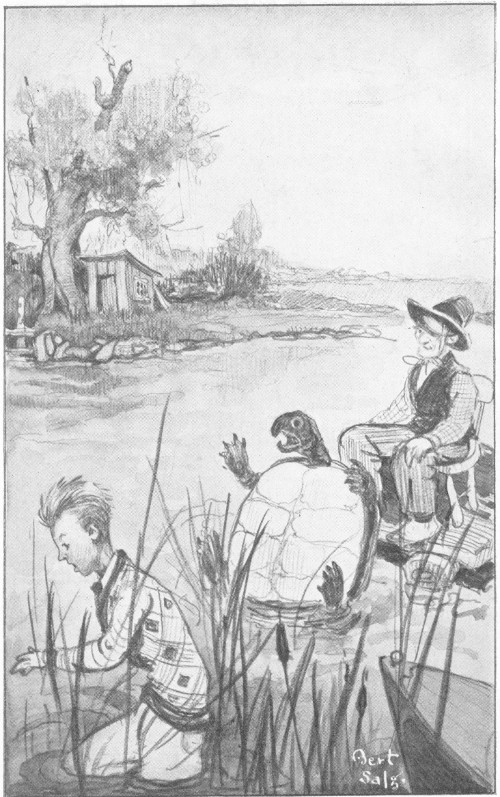

THE OLD GEEZER WAS FEEDING RAW LIVER TO THE BIGGEST TURTLE THAT I EVER SET EYES ON. Frontispiece (Page 24)

BY

LEO EDWARDS

AUTHOR OF

THE POPPY OTT BOOKS

THE JERRY TODD BOOKS

THE ANDY BLAKE BOOKS

THE TRIGGER BERG BOOKS

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1930, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Made in the United States of America

TO

MY PAL

JOHN VAN WAGNER

Always, I suppose, in preparing the copy for my books (this is Leo Edwards speaking), it will be necessary for me to explain, at the beginning of this department—“Our Chatter-Box”—what it is and why it’s here. For new readers are constantly joining our friendly circle. And it is at these fine young chaps, now lined up on Jerry’s and Poppy’s side, that these opening informative paragraphs are directed.

Boys reading my books find in them an intended atmosphere of friendliness. The books are more than mere entertainment. They are the message of a grown-up boy to boys—the message of a man who dearly loves boys, who wants to fill their lives with clean, skylarking fun and watch them grow up into strong-bodied, capable, useful men.

You can’t fool boys. If you’re their friend, they know it. And if you just pretend friendship, they know that, too. So, it isn’t surprising that my daily mail is jammed with letters from boys everywhere, which open-hearted communications are the answer to the friendly appeal built into my books.

And what bully good letters they are! They thrill me, so frank are they. They amaze me, too, for I find that countless boys (Jerry Todd fans, I call them) remember every little detail that I put into my books. If I state in one volume that Jerry has a pet toad, and fail to mention the toad in the next book of the series, dozens of boys hasten to inquire what became of the toad.

Of great interest to me, and of great help, too, I felt that the readers of my books in general would be interested in these letters. So, not long ago, I picked out the best of them, incorporating them in our first “Chatter-Box,” which appeared in Poppy Ott and the Tittering Totem. Since then similar “Chatter-Boxes” have appeared in the order given in Jerry Todd and the Bob-Tailed Elephant, Andy Blake’s Secret Service, Trigger Berg and the Treasure Tree and Trigger Berg and His 700 Mouse Traps. Hence this is our sixth “Chatter-Box.”

If you have written me a letter, be sure and read these preceding “Chatter-Boxes.” For your letter may have been used. Then, too, if you want inside information on Jerry, Poppy, Scoop, Peg, Red and Leo himself—if you want to know if the story characters and places that I write about are real—by all means turn to these earlier books. There’s a treat in store for you.

This is your department, boys. For “Chatter-Box” means a lot of gab from everybody. So, if you want to be represented, write me an interesting letter. If it is interesting—if it contains something of undoubted interest to our readers in general—I’ll try and use a part of the letter in a future “Chatter-Box.” The published letters of other fans will give you an idea of what we like best. Letters of criticism are just as welcome as letters of praise. For the right kind of criticism points the way to bigger and better things.

Or, if you wish to dip into poetry, do your best—or your worst! Read the poems in this issue. These young poets each received, as a reward, an autographed copy of this particular book. Such will be your reward, too, if your submitted poem is published, only, of course, you will receive a copy of the book in which your masterpiece appears.

We can’t use drawings, but will consider any brief practical contribution of interest to boys. Writers of accepted letters do not receive awards. The publication of such letters is sufficient reward in itself.

And now let us see what some of the boys have to say.

“I know how Jerry must have felt when his scow sank in the canal, as related in the Whispering Cave book,” writes Philip Colwell of Yonkers, N. Y., “because in Pittsfield, Mass., where I used to live, we had an old leaky rowboat that sank with us.”

And what a fine piece of journalistic work is this hand-lettered, nine-page newspaper, The Exeter Meteor, sent to me by Bob Rathbone of Exeter, Vt. Each page contains three columns of news, editorials and advertisements. Also Bob has produced two of his own original stories. It took time and patience to create this newspaper, for each word is printed neatly by hand and the whole contains many beautiful decorations in colors. Bob evidently has the “urge” of both a journalist and an artist. I predict that he will go far.

“Every time I have an ache or a pain,” writes Buddy Savage of Fredericksburg, Va., “my father buys me an Ott or Todd book. I now have two Otts and five Todds.”

From which we are to assume that Buddy has had only seven pains. This makes my twenty-first book. So, Buddy, why not have fourteen more pains and thus secure the complete file, including the new “Trigger Bergs?”

“During my summer vacation,” writes Donald Pitman of Wilkes-Barre, Pa., “I went to a place called ‘Promised Land Lake.’ One night I started out alone to get a mess of catfish. There is a channel for the boats, easily seen in the daytime but not at night. The lake was quite low and the stumps of trees and bushes made the place quite dangerous for anyone who did not know the channel. I fished around for two or three hours and then it began to get dark. I was reminded of Jerry in the Pirate book. The bullfrogs tuned up for their evening concert, and believe me there were plenty of frogs. I started for home in the dark. And now comes the funny part: I got lost. I bet I rowed around that blamed lake ’steen times before I gave it up. Every ten feet or so I’d get hung up on a sunken log. Finally I came upon another fishing party, who told me to stick around with them and later they’d show me the way home. I stuck. I fished, too, and in about three minutes I pulled in a big catfish. Got eight all together. Next morning I told the story that the fish were so plentiful that I had to sock them with an oar to keep them from climbing up my line and upsetting the boat.”

And here’s a letter from John Van Wagner of Shelby, Ohio, the boy pal of mine to whom this volume is dedicated. I worked with John’s fine dad in advertising. That was several years ago. John then was a very small boy. Since then he has grown into a fine, manly (and mighty good-looking) boy of sixteen, now an Eagle Scout. For which attainments I am very proud of him and have a very deep affection for him. Twice during his “growing-up” process he has visited me at Lake Ripley, where I have a summer home, and the last time he was here we enjoyed a memorable trip up the Dells of the Wisconsin River. It is this trip that John has reference to in his letter. We were in a small boat, propelled by an outboard motor. The waves from a passing big boat filled our craft half full of water. Bob Billings and my boy Beanie were seated on the bottom. So you can imagine how wet they got. John and I, on seats, got only our feet wet. Landing on a sandy beach (regular Robinson Crusoe stuff), we built a fire. Bob and Beanie stripped to the skin—ducking behind trees when a passing boat came along, which was often. It took us an hour to dry out. Nor did we get back to the hotel, where the four of us were staying, without other hazardous adventures. So I was glad when we landed safely at the hotel dock. And now let us read John’s letter.

“Dear Uncle Leo: I wish I were still in Wisconsin. I miss the fun we had there. And the most fun was where we had the boat swamped and had to build a fire and dry out in the Dells. I suppose you are working on your new books. I loaned the books I brought home with me and also some of the others you gave me. Most of the boys, including myself, prefer your Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott books to your Andy Blake books. Your Todd and Ott books are different from most books, but your Blake books aren’t. Therefore most boys prefer the former.

“I am working only part time now. I am doing a lot of swimming so as to pass the Red Cross Life-saving test, which will pass me for Boy Scout Life-saving merit badge. And then I will be an Eagle!

“Have the Cambridge Boy Scouts taken their trip yet? I hope they have a good time and I am sure they will, because we had a fine time when we went on that trip.

“Well, I hope you are all feeling good. None of our family are sick except my sister Alice, who has a bad cold. By the way, to-day is Alice’s birthday. She is twelve and will now have to pay full-price admission at the shows. Since I came home I have spent two dollars and thirty-five cents going to shows.

“Here’s hoping you can get something out of this for your ‘Chatter-Box.’ With best wishes, I am your loving pal, John.”

“I was run down and had a terribly bored thinking apparatus,” writes Bingham Soph (alias Hambone Soap-suds) of Tulsa, Okla. “A friend said: ‘Use some of Dr. Leo Edwards’ Jerry Todd Laugh Medicine.’ I have taken nine bookfuls. It is a wonderful cure.”

“I carved a totem pole as near like the one in the frontispiece of the Tittering Totem book as I could,” writes Scott Boylan of Portsmouth, Va. “I painted it, too.”

“It was a thrill to meet the author of my favorite books and to ride with him in his fast motor boat on Lake Ripley,” writes Bill Jones of Beloit, Wisc. “But to have an autographed copy of one of his books is a pleasure I cannot express. I will not be satisfied now till I have read the rest of the Jerry Todd books.”

“After reading Jerry Todd, Pirate,” writes Rodney Courant of Oakland, Calif., “I organized a club of my own. We mounted a regular ‘Big Bertha’ in front of our clubhouse. Some boys living on another street thought they would like to have a little ‘talk’ with mud balls. Sweet sardines! Did we ever paste them? I think your ‘Chatter-Box’ idea is swell.”

It might surprise the big army of Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott fans to learn how many thousands of girls are reading my books. I never have tried to make these books of special interest to girls. Yet the required manly conduct of my heroes seems to strike the fancy of girls of a type—I might say the tomboy type.

I get a big kick out of the letters that girls write to me. Recently one girl in the South told me that her nickname was “Jackie.” And whoever dared to call her by her real name, she said, would get a “poke in the face.”

However, I hasten to add, out of justice to girls in general, that very few of my feminine correspondents express themselves so forcibly. For all girls, even girls who read boys’ books, aren’t tomboys.

This book will be of particular interest to my girl readers. For one of the story’s chief characters is a most fascinating girl. And how other true-hearted girls will thrill over Bobs’ splendid triumph!

Quite probably I made a feature character of Bobs to please the many known girl readers of my books. Which prompts me to add that no girl who wants to become a Freckled Goldfish is ever denied membership. Girls, too, if they wish, may start Local Chapters. We show no partiality.

“Your idea of poems for books is very good, I think,” writes Robert Bash, 628 E. 8th St., Oklahoma City, Okla. “You will undoubtedly go down in history as the first author to think of theme songs for books. All talking movies now have theme songs, so why not books? And here’s a poem of my own:

Poppy Ott and Jerry Todd

Set out to make some money.

Poppy had a fine idea,

But Jerry thought it funny.

Poppy had a nifty scheme

To make stilts, strong and high,

To advertise the merchants’ wares

And make the people buy.

The “Seven League Stilts” were painted red,

They really looked immense.

They made all other homemade stilts

Look like eleven cents.

A smart rich kid butted in

And tried to kick them out,

But Jerry and Poppy locked him up

And let the young snob shout.

Though started on a smaller scale,

The business grew so large,

They had to start a factory

With Mr. Ott in charge.”

Which, I think, is a dandy good poem. And it gives me great pleasure to award Bob an autographed copy of this book.

And now let us see what happens to “The Galloping Snail” when Thomas Broderick of 63 Leamington Rd., Brighton, Boston, Mass, breaks into poetry.

Lawyer Chew bit off more than he could swallow

When he undertook to follow

Poppy and Jerry in the Galloping Snail,

With sweet young Eggbert hot on the trail.

Chatter-box Ma Doane

Was afraid when alone,

But when facing Fatty Chew,

Oh, boy! What couldn’t she do?

Poor Goliath had to have another bed,

One for his feet and one for his head.

Dr. Madden was the key

To the puzzling mystery.

Miss Ruth was not fair

In not relieving Ma of her despair.

And maybe Jerry didn’t go

When the gander bit his toe.

But Jerry was like slow-motion

When a hornet took a notion

And landed square on Eggbert’s pants.

Boy! You should have seen him dance.

Very good, Tom. And I hope you’ll treasure the book I’m sending to you.

Here’s one from George Butler, 819 North State St., Jackson, Miss.

My name is Jerry Todd,

I live in good old Tutter.

I like to eat ice cream and cake

And jam and bread and butter.

Scoop Ellery and I are chums,

Peg Shaw and also Red.

It makes me sad to say good-by

To them and go to bed.

We always have a lot of fun

When we go out together.

We’re seldom very far apart

In any kind of weather.

Mysteries are our meat.

Detectives gay are we.

The easiest thing for us to do

Is solve a mystery.

So you, too, George, are going to be awarded an autographed book. And may you become as famous as Longfellow himself.

Jack Reed of Liberty, Mo., contributes this one:

The show in Red’s barn was a big success,

But he paid for it at home with a scolding (more or less).

Red got huffy and when his folks went away

He packed up his stuff and skinned out that day.

He got on the turnpike near Mrs. Bibbler’s farm,

When he fell down a bank and nearly broke his arm.

When he looked in the water he felt very meek

For he had lost a thirty-buck mattress in the creek.

A chum of Jerry’s disappeared one day.

It seemed as if into the air he had vanished away.

They hunted for him, but all in vain,

Then, about two months later, he turned up again.

Nothing has been said of the elephant,

For I want you to read the book,

And see how much trouble,

The elephant took.

When you’ve read the book,

Please let me know

What you think of the elephant

And the show.

Good work, Jack. And, of course, you get a book, too.

Here’s a snappy one, contributed by Hubert J. Bernhard, 218-22 36 Ave., Bayside, L. I.

Aunt Pansy’s parrot

Started to roam.

Red Meyers’ job was to

Bring it home.

He brought it home—

A messy mess.

And did he catch Hail Columbia?

I guess yes!

Thanks, Hubert. I’ll see that you, too, get the promised award.

And this one comes from Gordon Mann, 62 N. Robinson St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Oh, Jerry Todd lives in Tutter.

One day Bid Stricker pushed him in the gutter.

But who should come along but trusty Peg Shaw,

And Bid went home with a broken jaw.

One day the gang went to explore

The wilds of Oak Island galore.

They thought they had some secret caves to discover.

But to their dismay they found Bid under cover.

Jerry Todd grabbed him by the neck.

And Bid went home a nervous wreck.

I suppose we should have had two more lines in that last verse, Gordon. But you get an award just the same.

And we’ll close with this one, contributed by Ralph Mohat, 538 N. Prospect St., Marion, Ohio.

Jerry Todd, Scoop and Peg

Slept in Jerry’s yard.

The tent was big and had a floor,

But, gee, the cots were hard!

They met a mysterious yellow man,

Also a yellow cat.

What was the connection between the two?

Boy! You’ll wonder about that.

Cap’n Tinkertop got a bath

With paint so very red.

To fool a fat lady they pretended

That he was sick in bed.

What about that peculiar hen

That so beautifully did waltz?

Was it the Cap’n’s transmigration?

Or was that stuff all false?

These are stories for older boys, for Andy himself is a young man in his early twenties. Having picked out advertising and merchandising as his life’s work, these books written around him contain that specific business atmosphere—something I know considerable about, for I, too, spent many productive and happy years in advertising work.

Four titles are now listed:

Andy Blake

Andy Blake’s Comet Coaster

Andy Blake’s Secret Service

Andy Blake and the Pot of Gold

Please remember, boys as you grow older, that Andy, with his big business ideas and the courage to put these ideas into effect, is a book pal worth having. His is a warm, loyal, lovable nature. Now that we have “Trigger Berg” at the foot of the class, as you might say, you can start in reading my books (or having them read to you) at the age of eight and keep on reading them until you are in college.

Thousands of you boys, I dare say, have already seen and read my two “Trigger Berg” books, the first of a new series. Trigger is very dear to me. I enjoy writing about him. Fair and square all the way through—that’s the kind of a little lad he is. It would seem, though, that there’s nothing within a radius of fifty miles of his home that he doesn’t get into. As a result of this unsuppressed energy he frequently finds himself in hot water, all of which helps imbue the books with clean boyish fun.

Yes, Trigger (the baby of the family!) is one of my most beloved story characters. And I hope that you Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott fans will give him a place in your friendly hearts. You’ll find him a pal worth having. And his buddies, Slats, Friday and Tail Light, are of the same stamp.

To better introduce Trigger to you I have, with my publisher’s permission, incorporated a chapter from one of his skylarking books in the conclusion of this volume. For really, fellows—and I say this in utmost earnestness—I don’t want you to miss the jolly good fun that these books provide. Written in diary form, each book, from start to finish, fairly sparkles with fun and natural boyish activities and accomplishments.

It would make me exceedingly happy if you would write a letter telling me what you think of Trigger. If you share my affection for him, tell me what inspires the corresponding warmth in your own heart. Or, if he bores you, tell me what’s wrong with him, according to your ideas. For I want these books to stand out. I want them to be my best. So you can see why I value your opinion.

Two titles are listed:

Trigger Berg and the Treasure Tree

Trigger Berg and His 700 Mouse Traps

And coming soon is Trigger Berg and The Sacred Pig. Nor will the odd little pig featured in this promising story be the only one who “squeals” when you get the story into your hands. You’ll very probably do considerable squealing yourself, along with your chuckling and giggling.

“Maybe you don’t know it,” writes Harris Fant of Anderson, S. C., “but I am the seventeen-year-old author of the famous ‘Stiletto Murder Case,’ which has been successfully produced in Greenville, S. C., as a three-act play.”

Congrats, Harris. To judge from the title your play must be nice and gooey—ketchup to the right of us, ketchup to the left of us, etc., etc.

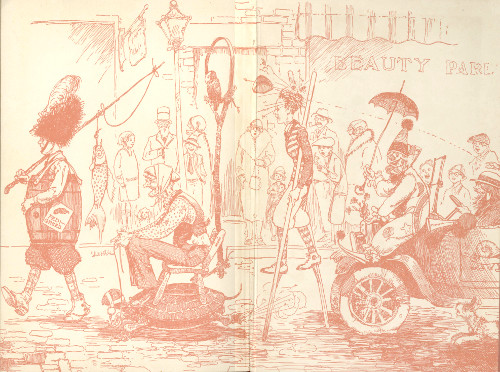

And what do you know if Markle Sparks (alias Freckled Perch) of Oklahoma City, Okla., hasn’t sent in a complete map of Tutter and surrounding country, showing the location of Oak Island, the lock, Mr. Arnoldsmith’s house, the Stricker clubhouse, the Weir house, the Chinese laundry, the Elite beauty parlor, etc. In all, twenty-two points of interest to Jerry Todd fans are mentioned. A splendid piece of work.

“In one of our English tests,” writes Jack Cunningham of Nutlay, N. J., “we were required to write about some book that we had read. Practically every boy in the class wrote about a Jerry Todd or Poppy Ott book. I wrote about a battle between Bid Stricker’s gang and Jerry’s gang. Here’s a poem that a friend of mine made up about Red:

Red mixed his beans with honey—

He did it all his life.

Not because he liked the taste,

But because they stuck on his knife.”

“My mother,” writes Marshall Clagett of Los Angeles, Calif., “enjoys your books and always looks forward to the evenings when she can read aloud. Also, I would suggest that you have Jerry’s whole gang in the Poppy Ott books.”

“I am striving to be an author,” writes fourteen-year-old Charles Herman Pounders, Jr., of Florence, Ala., “and would like to have a lot of friendly advice from you. So please write me a big long letter.”

Such letters frequently reach me. So earlier I was tempted to give these aspiring young authors some helpful advice. My comments and suggestions were published in our first “Chatter-Box.”

And again and again boys ask me the question: “Is Jerry Todd a real boy?” In the same “Chatter-Box” in which I gave my comments on writing, as mentioned in the preceding paragraph, I told boys the truth about Jerry and his gang, who they are and all about them. So, if you want the “low-down” on Jerry, turn to Poppy Ott and the Tittering Totem and read the complete “Chatter-Box.”

“I read Poppy Ott and the Stuttering Parrot at school,” writes William J. Weichlein of Maywood, Ill., “and the story went over big.”

You’re luckier than another boy pal of mine, Bill. He took the same book to school for the teacher to read aloud. And when she came to the part where the parrot says: “B-b-blood! B-b-blood! Gu-give me a bucket of b-b-blood!” she snapped the covers of the book together, calling it rubbish, threatening the boy if he ever brought another book like it to school she’d use a switch on him.

“I call you ‘Dear Leo,’” writes Don Gallagher of Chicago, Ill., “because you are a good fellow and want your readers to be familiar with you.”

You’re right, Don. Boys who feel they should be “on their dignity” around me, either in person or in correspondence, sure are wasting a lot of energy. The other evening (in July), some boys who dropped in to spend a few hours with me took me down, stood me on my head (or, rather, on the back of my neck), and then pulled off my shoes and socks, hanging the latter (in knots) on a light fixture.

“I believe,” further writes Don, “that if Poppy, Jerry, Scoop, Peg, Red and Rory started a circus and had freckled goldfish, a rose-colored cat, a waltzing hen, a bob-tailed elephant, with Red to complete the menagerie, the circus would be a humdinger.”

“When I was in camp,” writes Harvey Travis of Endicott, N. Y., “the Boy Scouts all went over to Warren Center one day to help the little burg celebrate ‘Old Home Day.’ Boy, did we ever have fun marching up and down the one and only main street. I wish you could have been there, and Jerry, too. The village band was out; so was the fire department, consisting of four men and a two-wheeled hose cart from which dangled a lot of buckets. I thought of Tutter. And in a picture show we saw a fellow, a sort of goofy detective, who was a dead-ringer for Bill Hadley.”

Just as my Jerry Todd, Poppy Ott and Trigger Berg books are written primarily to fill the lives of boys with clean, natural fun, so also would I like to have my young readers share this book fun of theirs with others. Which can be done individually if you will prevail upon your teacher to read one of my Todd, Ott or Berg books aloud. That will be fun for the whole room.

If your teacher, through your personal efforts, reads one of my books to the school (or if you read the book) you automatically become a member of our “School Club,” and should so notify me. Your name will be published in a future “Chatter-Box.” Also, at the end of the year the names of all members will be put “into the hat.” Twenty names will be drawn at random. And each of these twenty boys or girls (the first year we drew ten names and next year we will draw thirty) will receive an autographed copy of my latest book. The names of club members once receiving awards will not be included in later drawings. After the third year we may want to make some changes in the club, probably retiring the older members.

You’ve all heard the old saying about making hay while the sun shines. Well, to judge from appearances that is what is being done in this picture before me of Edward Derzius of Worchester, Mass. Ed is thirteen, a stocky lad; and not so hard on the eyes, either.

In sending me his photo, Wolfram Stenzel of Long Island City, N. Y., asks that in return I send him a photo of Jerry, Peg, Scoop and Red. “Is Peg really such a fighter?” inquired Wolfram. “And is Scoop such a thinker as to make Jerry the ghost of the hermit in the Oak Island story? Also, has Red freckles? Is Al Moore, in the Pirate story, in the Bob-Tailed Elephant book? If not, what became of him?”

And my answer is—you bet Red has freckles. Oodles of ’em. And Peg (a character taken from life) is as liberally supplied with grit. Al is not in the Elephant book—as I understand it, he’s away at boarding school. Yah, Scoop has brains, all right, and how!

And just to prove to me that Wisconsin, my home state, produces just as many real he-boys as our neighboring states, Irving Bremman of Waukesha accompanies his Goldfish application with a snapshot of himself. He says he’s a great reader, and he looks it. I wish, Irv, you’d drive over and see me some time. You’re only about forty miles away. And I sure love to have the boys drop in on me.

Evidently George Frantz of Coatesville, Pa., sells papers. For having sent me his picture, in boxing position (boy, I’d hate to have him sock me!), he asks me to write a book about Jerry boxing and selling papers.

And who’s this round-faced, good-looking chap whose picture bobs up in front of me? Oh, yes—Nathaniel Friedman of Beachmont, Mass. And you say, Nat, that you haven’t read a Poppy Ott book? Suffering cats! You sure are missing a lot of fun. For surely you know that Jerry Todd is in these books, too. Jerry, in fact, tells the story.

Nor must I overlook this picture of Margaret Truhar of Paterson, N. J. “This is me when I’m not in knickers,” Margaret writes. And is she a Freckled Goldfish? Yes, indeed.

Some boys think it’s a task to write by hand. But here’s the picture of a good-looking, bathing-suited boy—Wilbur Bogart of Westfield, N. J.—who claims that he can write with his feet. “Also,” confides Wilbur (he doesn’t state whether his letter was written by his uppers or lowers), “I can pick up small objects with my toes, such as spools and thimbles. When writing in the sand I use a pointed stick.”

And here’s the picture of another girl—Lucy Marie Geraghty of San Francisco, Calif.—all togged up in pirate clothes, which costume, I am given to understand, was inspired by Jerry Todd, Pirate. There is a second picture of Lucy and her girl friend and still another of two swell-looking boys in uniform. “They are my two favorite cousins, Owen and Jim McCoy,” writes Lucy, “and they attend St. John’s Military Academy.”

And in final, here’s a snapshot of Carlyle Dunaway of Norfolk, Va., His letter is very interesting; and he’s a mighty bright-looking lad.

I’m not going to take up the space here to tell you in detail about our Freckled Goldfish Club. That growing club has been given extensive mention in all of my recent books. But I will tell you a lot about the club in my next book, Jerry Todd, Editor-in-Grief.

Which is all for this time. Remember, fellows, the more letters you write to me the happier it makes me.

Leo Edwards,

Cambridge,

Wisconsin.

Here is a list of Leo Edwards’ published books:

If you think that Red Meyers isn’t a big monkey (and what reader of my books doesn’t remember him, freckle-faced, red-headed, gabby little runt that he is), you should have been in school the day we organized our band. For what do you know if he didn’t get up with his mouth full of gumdrops and tell the organizer that his ma wanted him to study the accordion so that he could play solos when she entertained the Tutter Stitch and Chatter Club.

Good grief! I thought I’d bust. For he let on that he was in dead earnest. He wanted to study some of the compositions of the old masters, he said, such as “The Mocking Bird” and “Who Put the Overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s Chowder?” The kids, of course, almost laughed their heads off. For Red is well liked.

Later, he bought a trombone. And then he and Rory Ringer, his new pal, who also has a trombone, got up a set of signals. Red would roost on the peak of his pa’s barn and toot, a long agonizing toot representing “a,” a long and a short “b,” and so on. And Rory, a block away, would correspondingly toot through an attic window. The neighbors got kind of huffy about it, especially when the hard-working tooters took to imitating various kinds of farm animals. Gee! First one would bellow like a bull with red-hot tweezers on its tail. Then the other would squeal like a stuck pig. They could imitate dogs, too, and fighting roosters. At times it got real exciting. And did I ever laugh the day they were putting on a special rehearsal in the gooseberry bushes in Red’s back yard? Old Mrs. Higgins, who now lives next door to Red, threw a pan of dishwater on them, thinking, I guess, that they were a couple of squabbling tomcats. Red has had it in for the old lady ever since, claiming darkly that she put some kind of bug powder into the dirty dishwater that made his back break out terrible.

Mr. Mear, our band director, lives in Ashton, the county seat, where he has taught music in the public schools for more than ten years. He also has charge of other school bands throughout the county. Late getting started in this new work, we were eager to catch up with the neighboring bands so that we could take part in the annual spring tournament. And as though to encourage us the district organization, which included several counties, voted to hold the coming two-day tournament in Tutter.

When told that the visiting bands would probably number more than two thousand players, all boys and girls, the Tutter people generously offered to throw open their homes, thus providing the visitors with free lodging. And the various churches agreed to serve inexpensive meals.

Our band was entered in class “C.” But we knew we’d never get a prize if Red Meyers played with us. For his only purpose in buying a trombone, we learned, was to show off and make a noise. Unlike Rory and the rest of us he didn’t even try to learn his notes. Boy, his playing was awful. Talk about sour notes! So we very tactfully got together (having talked the matter over on the sly) and elected him drum major.

Poppy Ott had charge of the meeting.

“If we’re going to march,” says he, in good leadership, “we’ve got to have a drum major. For every marching band requires a drum major. . . . Have you any suggestions, Jerry Todd?” he called on me.

I then inquired innocently, mainly for Red’s benefit, what a drum major was supposed to do.

“He leads the band,” says Poppy.

I let my face light up.

“Oh! . . .” says I. “You mean the guy who wears the classy uniform and beats time?”

Classy uniform! Red’s ears were as big as pieplant leaves.

“Exactly,” says Poppy. Then he gravely looked around the room, letting his eyes rest on freckle face, who, of course, was tickled pink (like his hair!) when we finally elected him to the important job. For he dearly loves to show off.

Our new uniforms came the following Wednesday. There was a baton, too, about three feet long, with a big silver-plated knob. A sort of cane. Instructed how to beat time with it, Red further conceived the clever idea of doing juggling tricks with it.

Naturally, he would!

The tournament was to be held the last week in May. And the preceding Saturday morning I meandered over to the drum major’s house where I found him leading an imaginary band in and out among the bushes.

But did I ever leap for cover when he sent the shiny, tasseled baton whirling into the air, it being his clever intention, of course, to catch it nimbly when it came down. And it is well for me, let me tell you, that I did jump. For he missed the whirling stick by at least three feet.

I jiggled my handkerchief through the barn door.

“Is it safe to come out?” I inquired cautiously, when he recognized my peace signal.

“You aren’t funny, Jerry Todd,” he scowled.

“How’d it be,” I suggested brightly, referring to the tricky baton, “if you tied a halter on it? Then you could kind of lead it around, cow fashion, without any danger of it jumping out of the pasture.”

“What pasture?” says he, still scowling.

“Any pasture,” says I liberally.

Here our old enemy, Bid Stricker, stuck his homely mug over the alley fence.

“Haw! haw! haw!” jeered the newcomer, who, it seems, had been watching the practicing drum major through a convenient knot hole. “What you need, butter fingers, is a big basket.”

Another mug then came into sight.

“Yah,” says Jimmy Stricker, Bid’s mean cousin, “I guess you could catch it, all right, if you had a basket as big as the town.”

If you are a regular reader of my books, you’ll need no lengthy introduction to the Stricker gang, of which Bid and Jimmy are the leaders. Other members of the crummy gang, all from Zulutown, which is the name that the Tutter people have for the tough west-side section, are Hib and Chet Milden, brothers, and Jum Prater.

Except for Red and Chet the members of the rival gangs are all about the same age. And do we ever have some hot battles! Oh, baby! We’ve come to expect interference from Bid every time we start anything new. For it seems to be his chief ambition to want to smash up our stuff. That’s why we have such a general dislike for him.

“Some drum major,” sneered Hib, lining up his mug beside the two Strickers.

Then up bobbed Chet and Jum.

“Are those freckles on his face,” says Jum, poking fun at the sweating drum major, “or dirt pimples?”

“Maybe it’s clay pimples,” says Jimmy.

“There is such a thing as red clay,” nodded Chet.

“Is that what makes his hair red, too?” says Jum, kind of innocent-like.

“All baboons have red hair,” says Bid learnedly.

“And freckles,” put in Chet.

“Boy, I’m glad it isn’t me,” says Jimmy. “I sure would hate to look like that.”

“Yah,” says Bid, “imagine having to look at that face in a mirror.”

“Suffering cats!” squeaked Jum. “Did you see him open his mouth? It looked like a trapdoor.”

“Maybe he’s a human fly catcher,” says Bid.

Red, of course, was madder than heck. For he hates above all else to be called a baboon. But instead of rushing at them in his usual hot-headed way, he darted into the bushes. And did I ever yip with joy when he came back dragging a basket of rotten apples that his father had earlier lugged out of the cellar.

Sweet essence of sauerkraut! Bid surely would get his now.

It was no easy matter, though, for us to sock the jeering Strickers with our decayed fruit. For every time we fired a broadside they ducked, the soft apples either going over the fence or squashing harmlessly against the weathered boards. And did they ever smell sour!—meaning the rotten apples, of course, and not the fence boards. Wough! Later Mrs. Higgins bawled us out to beat the cars, telling us that her whole house, as it was swept by the summer breezes, smelled like a vinegar factory.

“Ya, ya, ya,” Bid guardedly poked his mug into sight. “You guys couldn’t hit the broad side of a bloated alligator.”

Under his directions they then showered us with tin cans. But by watching our chance, and pretending fake throws, we finally put Jum out of business.

Boy, he spit apple seeds clear over the barn.

“Apple butter,” shrieked Red, next socking Jimmy Stricker in the bread basket. Then, to our good fortune, I got a crack at Bid through a big knot hole. After which the whole gang took to its heels.

Following them down the alley, and screeching at the top of our voices, so excited were we over our victory, we cracked Hib a hot one in the seat of his pants. Then Chet got an equally warm one in the same tender spot.

The day had started with bright sunshine. But now, as is the way with May weather, black clouds came suddenly into sight. And when the expected rain came tumbling down Red and I legged it into the barn where we were shortly joined by Peg Shaw and Rory Ringer, the latter of whom had come over to teach us how to play an old English card game called “Sir Hinkle Funnyduster.”

Peg Shaw, you will remember, is one of the original members of our gang, of which, for a long time, Scoop Ellery was the sole leader. But lately the leadership has been divided between Scoop and Poppy Ott. A big guy for his age, Peg is one of the town’s peachiest scrappers, which doesn’t mean, though, that he goes around picking scraps. I guess not. He’s everybody’s friend until someone starts shoving him around. And then—oh, baby, how he can make the fur fly! As we told him, when he joined us in the barn, on the roof of which the raindrops were dancing a crazy jig, it was too bad he hadn’t arrived a few minutes sooner.

Born in England, and recently transplanted to this country, Rory Ringer has a lingo consisting mainly of subtracted and added “H’s” that would make a cow laugh. Sir Hinkle Funnyduster, he told us (only he called it “Sir ’Inkle Funnyduster”), was a very popular game with the boys in England. And I could very well believe it. For a funnier game I never played in all my life.

There were twenty illustrated cards, divided into four groups. The first group consisted of Sir Hinkle Funnyduster, his wife, son, daughter and pet turtle. The second group consisted of Bottles the butler, his wife, son, daughter and pet cat. The third group consisted of Spade the gardener, his wife, son, daughter and spade. And the fourth group consisted of Whip the horseman, his wife, son, daughter and whip.

“Hi’ll take Sir ’Inkle Funnyduster from Red,” says Rory, when the cards had been dealt around, each of us having five to start with.

Red, though, didn’t have “Sir ’Inkle.” And when it came his turn to call for a card he asked Rory for Sir Hinkle’s wife. But I was the one who had the “wife” card, together with the one picturing the odd turtle. So, knowing that Red hadn’t Sir Hinkle, the wife or the turtle, it wasn’t hard for me to call the name of the card that he did have, after which I called on Rory for the fifth card, thus completing a “book.”

From which you’ll see that the game is played somewhat like “Authors.” We had to say “Thank you,” though, each time we accepted a requested card. And if a player called “Duster” on us, because of some error that had been made, the player who was caught had to give up all his cards to the one “Dustering” him. He, in turn, watched his chance to “Duster” another player. And it was these “Thank yous” (that were frequently overlooked) and “Dusters” that made the game exciting.

“I’ll take Bottles the butler from Jerry,” says Peg, when the cards had been dealt around for a new game. And having the requested card I gave it up.

Red almost jumped over the box that we were using for a table.

“Duster!” he yelled at the top of his voice.

“How do you get that way?” scowled Peg, shoving his cards out of the smaller one’s reach.

“You forgot to say, ‘Thank you.’”

Then did we ever yip when Red, in accepting Peg’s cards, made the same error.

“Duster!” yelled Rory.

And there he was with all of his own cards, all of Red’s and all of Peg’s. But he didn’t keep them long. For Red soon “Dustered” him.

“I want Sir Hinkle Funnyfuster from Jerry,” says Red.

“Sir Hinkle Funnyfuster!” I jeered.

“I mean Sir Hinkle Honeyfuster.”

“You big nut!”

“Oh, shucks, you know what I mean.”

“Well, say it.”

“I want——”

“Sir Pinkle Pennyfister,” prompted Peg, with twinkling eyes.

“No, I don’t want Sir Penny Picklefister. I want——”

“Sir Dinkle Donkeyduster,” next suggested old hefty.

“Oh, shut up,” Red tore his hair. “You’ve got me rattled.”

Then it came Peg’s turn.

“I want Sir Hinkle Funnyduffer’s— What’s he got, anyway?”

“Whiskers,” says I.

“Sure thing,” laughed Red. “Somebody cough up Sir Hinkle’s whiskers for Peg.”

“Don’t forget,” put in Rory, with further reference to old Funnyduster’s anatomy, “that ’e’s got ’air.”

“How about his ’eart,” says I, “and his hears?”

“Haw! haw! haw!” boomed Red. “Somebody else is getting razzed now.”

You may wonder why I’m telling you so much about this new game of ours. But, as you will learn later on, it has an important bearing on my story. At the moment, Sir Hinkle Funnyduster was merely a pictured card to us. Strangely, though, we were soon to have the name given to us by a queer old man who claimed the title as his own.

Poppy Ott came in when the fun was at its height. And sharing my seat with him (for he and I are bosom pals), I explained how the game was played, after which we tried it five-handed.

The shower having passed over, we then went outside, Red making the boast that he could catch the flying baton six times out of seven. But even better than that (to our amazement) he caught it eight times in succession.

“But whatever put that idea into your head?” quizzed Poppy, when the chesty drum major explained how he was going to perform these juggling tricks at the head of the procession.

“Oh, I saw it done in a movie.”

“Kid,” says Poppy soberly, patting the smaller one on the back, “I’m proud of you. We may never win a prize for playing tunes. But it’s a cinch our drum major ought to win a prize.”

“He’s all right,” Peg put in generously, “if he keeps his face covered up.”

“Go lay an egg,” scowled Red. “If anybody happens to ask you I’m as good looking as you are.”

Peg turned up his nose.

“Red hair,” he jeered, “and freckles.”

“Sure thing,” Red pushed out his mug in that scrappy way of his. “And I’m glad that I am red-headed and freckled.” His voice changed. “I don’t suppose you ever heard of Wesley Barry.”

“Who’s he?” grinned Peg. “Some poor relation of yours?”

“He’s a movie actor. And his freckles have earned a fortune for him. Besides,” Red kind of stepped around, “everybody knows that Clara Bow is red-headed.”

“Clara Bow!” jeered Peg, who dearly loves to get Red’s goat. “A lot you know about her.”

A kind of mysterious look crept into the freckled one’s eyes. Wondering at it, I afterwards remembered it.

“I could tell you things that would surprise you,” he spoke in riddles.

“Meaning which?” Peg urged curiously.

But the freckled one’s only answer was a tantalizing laugh.

Here our attention was drawn to Eva Ringer, Rory’s spunky little sister, who, it seems, was the true owner of the “Sir Hinky-dink” cards, as we jokingly called them. But, strangely, the “turtle” card had disappeared. At Rory’s request we turned our pockets inside out. And then, thinking that the missing card might have fallen through a crack in the floor, we crawled under the barn. But to no success. If a magician had used his magic wand on the card it couldn’t have disappeared more completely.

Had some thief made off with it? I wondered. But why, I asked myself, should a thief take only the one card? And who was the unknown thief? Certainly, not Bid Stricker. For if given the chance he would have taken the whole pack.

Quite unknown to us a mystery was creeping in on us. And we were soon to learn amazing things.

To see Poppy Ott to-day, so tall and straight and manly-looking—and to my notion there isn’t a finer-looking or smarter kid in the whole world—you’d never suspect that a short time ago he and his father were common tramps.

But such is the case. And long will I remember the day I met Poppy in the big willow patch in Happy Hollow, where he and his father were camping in a rickety covered wagon. There was an old horse, too, named Julius Cæsar, whose hip joints stood out of its skinny frame like scrawny chair knobs. On top of being a rover by nature, Mr. Ott had a lot of silly detective notions. Poppy, though, having a great deal more sense than his shiftless father, wanted to settle down and be somebody. And in the end he won out, even prevailing upon his father to give up his silly detecting and go to work in Dad’s brick yard.

To-day Mr. Ott, a changed man, is the bustling general manager of the stilt business that Poppy and I started in the old carriage factory on Water Street. Of course, in the beginning it was a very small business, as any business naturally would be that was gotten up by boys. But Poppy (who, I might add here, got his odd nickname from peddling popcorn) had a lot of good ideas. And he put these ideas to work, to the result, as I say, that the stilt business is now a paying proposition.

It’s fun to go to Poppy’s house. For he and his father are all wrapped up in each other. And while Mr. Ott never admits it, or even talks about it, I dare say that he is ashamed of his earlier shiftless life as it probably helped to bring about his wife’s death. For it’s a fact that he and Poppy, as they wandered here and there, first in one state and then in another, frequently went without food. As for clothing, Poppy in particular when I first met him had barely enough ragged garments to cover his bare skin.

Through my close association with him (and a better chum no boy ever had), a lot of added fun has come into my life, as the books that I have written about him testify. Not only do I think the world and all of him, but it makes me happy to know that he has the same warm feeling for me. Once we went on a hitch-hike. Boy, that was some adventure! Spooks, creepy noises in a haunted house and other queer truck. Then we got tangled up in separate “Freckled Goldfish” and “Tittering Totem” mysteries, though, as I say, we little dreamed that we were now rubbing noses with a brand new mystery.

Another shower having driven Eva home, with the final spiteful threat (directed at Rory) that “’e’d catch hit for losin’ one of ’er nice cards,” we later applauded Red in the yard as he tossed the whirling baton higher and higher into the air with scarcely a miss.

Say, he was hot!

Then, banging on tin pans and the like, we marched around the yard single file, pretending that we were a band of musicians (the neighbors thought we were a band of hoodlums, I guess) which gave the drum major an added chance to exercise his juggling talents. Instead of gumming things up for us, as usual, I could see now that he was going to be our band’s biggest attraction.

“And to think,” Poppy whispered to me on the sly, as we melodiously sashayed in and out among the gooseberry bushes, “that we shoved him into this job to get rid of him.”

“Don’t ever let him find it out,” I whispered back uneasily. “For you know how touchy he is.”

Striking a projecting limb, the baton suddenly swerved and fell kerplunk! on the outside of the alley fence. At the same instant we heard a kind of gurgling groan. And when we ran to the fence, hoping, of course, that it was Bid Stricker, there lay an old man on the ground.

“He’s unconscious,” cried Poppy, leaping the fence. “The baton must have struck him on the head!”

Which indeed was the case. But imagine our surprise, when we removed the battered derby, to find that the baton’s victim had a pancake tied on his bald head.

“Get some water,” Poppy instructed quickly, loosening the stranger’s shirt collar.

The breast, thus exposed, was covered with thick black hair, a peculiar contrast, I thought at the time, though kind of scattered-like, to the smooth bald head.

“Who is he?” Peg inquired, in a queer voice.

“Search me,” says Poppy shortly. And again I caught him looking at the pancake with an expression on his face I can’t describe. As you can imagine, the sight of the pancake, which was held in place by a knotted handkerchief, had amazed all of us. But even more than being amazed, the leader, I saw, was plainly puzzled.

“A pancake,” I heard him mutter to himself. “A buckwheat pancake. Well, I’ll be jiggered.”

One time when we were camping the kids fooled me with a rubber “weenie.” But I saw right off that this was no rubber pancake.

Anyway, why should a man (unless he was cuckoo) wear a rubber pancake on his bald head? Or, to the same point, why should a man wear any kind of pancake on his bald head, rubber or otherwise?

“He must be a nut,” I told Poppy.

“Even more than that, Jerry,” was the leader’s peculiar reply, “he’s a mystery.”

“Then you think he was spying on us through the fence?” I inquired eagerly.

“There can be no doubt of that. And I suspect, too, that he’s the fellow who wrote the ‘pancake’ letter.”

“Pancake letter!” I repeated, eager to get the details. “What pancake letter do you mean?”

But Poppy had no time just then to explain his queer words. For Red, the clumsy boob, having climbed the fence, upset the contents of a water pail in the grizzled face, which, as you can imagine, brought the prostrate one to his senses in short order.

“Did—did I git ketched in the rain?” he inquired vaguely, looking at us with dizzy blue eyes.

Then, as his memory returned with a rush, he jerked the battered derby down on his ears and scrambled quickly to his feet.

“Um . . .” he scowled at us. “What business have you b’ys got a-peekin’ at my pancake?”

“You were knocked senseless,” explained Poppy. “And we were trying to help you.”

“Yes, and it was you who did it, too,” the old man turned a pair of baleful eyes on the drum major, which proved, all right, that he had been watching us through the fence, as we suspected.

He then went off down the alley, kind of stiff-like in his legs, turning occasionally in the stooped way so common with old people to look back at us. And once I thought I heard him chuckle.

Red had to mow the lawn that afternoon. And having coaxed Peg and Rory to help him (like the lazy little runt that he is), Poppy and I, thus left to our own devices, resurrected a pair of cane fishing poles and set out for the old mill pond in Pirate’s Bend, which is the odd name that the Tutter people have for the upper end of Happy Hollow where the big Piginsorgum Creek (I guess that name will hold you for a while!) joins Clark’s Creek.

It was here, years and years ago, that a man by the name of Amasa Gimp built a mill, which in time became known as Gimp’s pancake mill. For the old miller (the story goes that he turned from piracy to milling) made a specialty of buckwheat flour. He had a secret formula, or whatever you call it, and so delicious were the pancakes made of his compounded flour that the farmers within driving distance would have no other. Even the Indians came on their spotted ponies to barter trinkets of their own manufacture for bags of the coveted flour; and it was one of these friendly Indians who told the miller about the hidden lead mine, now called the lost lead mine.[1]

Inheriting the mill from his father, Peter Gimp, the eldest son, now a white-haired old man, let the promising business go to rack and ruin. The shingled roof of the stone building, with its accompanying stone dam, is covered with moss, as is also the miller’s near-by cottage, both buildings having the appearance of being hundreds of years old.

In sharp contrast of his brother’s known poverty, Sylvester Gimp has made a fortune out of the hinge factory that he started on the east bank of the mill pond. In the beginning it was understood that he and his older brother were to share the water power between them. But everybody in Tutter now knows that the wealthy hinge manufacturer controls the water power to suit himself. His factory is a barn-like building of many cheap additions, these representing the business’ steady growth. And the men who work for him, in dirty, dingy rooms, are poorly paid. Dad, who is a manufacturer himself (he runs a brick yard) says it’s a crying shame that such factories should be permitted to operate. But old Gimlet, as many people call the miserly hinge manufacturer (and I’ll tell you frankly that I, for one, have not the slightest respect for him), keeps on year after year, crowding the workmen into greater speed and cutting down their wages, which, of course, all adds greatly to his profits.

There was still another son in the miller’s family, the youngest of the three. Having quarreled with his brother Sylvester, Rufus Gimp, the father’s known favorite, and, as I have been told, a dancing-eyed, reckless youth, ran away to sea, where, so the report goes, he, too, sailed under a “Jolly Roger” flag. But buccaneering wasn’t so soft in those later days, and instead of retiring to some secluded corner of the earth in pattern of his father (granting that the stories of the miller’s early life are true), he ended up in an English prison where the official hangsman put him out of the way. The letter telling of his favorite son’s dishonorable death literally killed the old miller, following whose funeral the fortunes of the crafty middle brother began to rise and those of the elder brother to fall.

And how do I know all this? Well, I’ve heard Dad talk about it. Then, too, old Cap’n Tinkertop, who grew up with Rufus Gimp, has told me the story time and time again. In fact, it’s the kind of a story, with its background of piracy and mystery—for it isn’t to be doubted that the old miller had secrets that died with him, including the probable location of the lost lead mine—that a boy likes to remember.

Overtaken by another passing shower, Poppy and I started on the run for the bridge that spans the creek below the aged stone dam, figuring that we could find shelter in the old mill, near the worn water wheel of which we planned to do our fishing. Nor did I suspect at the moment that the leader, deep kid that he is in many respects, had a secret object in coming here. I was soon to learn, though, that he was a great deal better informed on the present miller’s circumstances, and the general layout of things at Pirate’s Bend, than I imagined.

Just before we came within sight of the dam, at the opposite ends of which, as I have described, are the two separate water wheels, one of which seldom turns and the other of which churns constantly, an ever-active money-making machine for its grasping owner, young Sylvester Gimp, III, or, as we call him at school, Silly Gimp, came up behind us in his grandfather’s high-powered automobile. The road was narrow here and full of puddles. So, to escape a splashing, I jumped into the weeds on one side of the road and Poppy on the other.

Imagine my amazement when I tumbled over the old pancake geezer, who, hidden in the weeds, was feeding bits of raw liver to the biggest turtle that I ever set eyes on.

The turtle evidently didn’t like my looks. For it made a lunge at me. And I actually believe it would have bit a hunk out of my seat-a-ma-ritis if the old man hadn’t stopped it.

“Back, Davey,” came the sharp nasal command. “Back, I tell you.”

And as though it understood, the huge turtle kind of drew in its long legs, thus lowering itself to the ground, after which it slowly backed into the weeds until only its head showed.

“Davey ordinarily has purty good manners,” the old man told me, sort of talkative-like. “But you kind of surprised him. An’ bein’ jest a turtle, after all, we’ll have to kind of excuse him.”

And again, as though it understood what was being said, the turtle, whose shell was as big as a washtub, crawled out of the weeds and held up one of its front flappers to me, which, the beaming owner explained, was its way of indicating to me that it wanted to be friends.

“No,” the old man seemed to read my mind, “you needn’t be a-feered of him—not when I’m around. For he’s bin brought up to mind, he has, an’ he knows from experience that if he don’t mind I’ll take a stick to him. By cracky! I don’t stand fur no monkey work from him. No, I don’t.”

“What would have happened,” I inquired, still kind of shaky-like, “if you hadn’t called him off?”

There was a short silence.

“Wa-al,” came the indirect and somewhat evasive reply, “he’s got a whoppin’ big mouth, as you kin plainly see. An’ the power in them jaws of his’n, I might say, hain’t nothin’ to monkey with.”

My curiosity overcame my uneasiness.

“What is he?” I further inquired. “A snapping turtle?”

“Partly. Scientists call him a Galapagos turtle.”

Galapagos! That, I recalled, was the name of a tropical island famed for its big turtles.

“His complete name,” the old man told me, “is Davey Jones. An’ so fur as I know to the contrary he’s the only eddicated turtle in the world.”

Nor did I doubt that!

“Me an’ him,” the old man then went on, sort of reminiscent-like, “has bin travelin’ companions fur more’n forty years, prior to which time he lived a somewhat monotonous life on Boot Island, boots an’ shoes, I might add, bein’ the one thing he won’t eat. But when they put me on the island, expectin’ Davey, of course, to gobble me up jest as he had gobbled up dozens of other unfortunate seafarin’ men whose empty boots was the only thing left on the beach to tell of their terrible fate, he right off took a fancy to me an’ me to him, which friendship, as I say, me an’ him havin’ escaped from the island on a raft, me ridin’ an’ him towin’, has endured to this day.”

Probably the old man knew what he was talking about. But this scattered gab didn’t make sense to me.

“Wasn’t that the Gimp b’y who jest drove by here in a red autymobile?” he then inquired, with a sharper look in his faded blue eyes.

“Yes, sir,” I nodded.

“Friend of your’n?” came the added inquiry.

I laughed.

“No,” I shook my head, “Sylvester Gimp is no friend of mine.”

People hate a tattler. So I didn’t tell the old man in detail what a smart aleck Silly was, and how he tried to lord it over the other kids of his age (which is the reason I detest him), it being his notion, I guess, that his grandfather’s money gives him power. But somehow, from the odd look on the old man’s face—and not until this moment did I wonder if he still had the buckwheat pancake on his bald head!—I had the feeling that he was reading my thoughts.

He asked me then in a quiet voice about the two brothers who had inherited the water power from their father. And a kind of hard look came into his wrinkled face when I told him about Sylvester Gimp’s great business success and the older brother’s failure.

Then, getting a call from Poppy, who was waiting for me down the road, I started to go, but stopped when the old man got slowly to his feet.

“My name is Funnyduster,” he said, gravely offering me his gnarled hand. “Sir Hinkle Funnyduster. And this,” he pointed, “is my pet turtle.”

Sir Hinkle Funnyduster! Well, say! You could have knocked me over with a feather.

I was further reminded of Amasa Gimp, the pioneer miller, as I hurried down the bumpy, weed-bordered stone road that connects the old mill and its neighboring hinge factory with the highway. For like the old mill itself this stone road, I had been told, was the early miller’s work. Those following him, though, had been too indifferent and too miserly to keep it up. In places the flat stones, so helpful to the early farmers, had completely disappeared into the black earth, leaving holes that the recent showers, as mentioned, had turned into small lakes. A few loads of gravel would have nicely repaired the private right of way, used principally by the hinge manufacturer and his trudging workmen. But old Gimlet was too fond of his growing wealth to spend even a small part of it for gravel or other public improvements. Nor did he care a rap whether his poorer brother, who also used the road, approved of its condition or not. I guess, though, that Peter Gimp was too deeply wrapped up in his silly inventions to worry about roads.

Eager to overtake Poppy, to tell him about my startling experience with the big turtle and its undoubtedly mysterious owner, I made another flying leap into the weeds when a second automobile overtook me. But this time the car stopped.

“Oh! . . .” cried Majorie Van Ness, recognizing me. “Here you are now.”

“Hi,” I grinned.

Marjorie is all right, I guess, only I’d like her better if she hadn’t so many grown-up ideas. And what she can see in Silly Gimp is beyond me. But I’ve been told that she’s kind of crazy over him. Girls sure are funny. I could understand perfectly why any girl with sense should fall for old Poppy. But that goofy Gimp kid! Good night! If a sister of mine took a shine to him I’d feel tempted to wring her neck.

“I have something for you, Jerry,” Marjorie smiled brightly.

“What is it?” I inquired, when she handed me a neat white envelope.

“An invitation to my birthday party.”

“Thanks,” says I politely.

“And here’s one for Poppy.”

I thanked her again.

“I was told,” says she, looking down the road, “that I’d find Sylvester Gimp at his grandfather’s factory.”

“Sure thing,” I nodded. “He just passed here.”

I could see that she felt pretty big sitting behind the steering wheel of her father’s car. She looked nice, too. A swell little kid, all right.

“So long,” she waved, starting off. “Don’t forget that I’ll be expecting you to dance with me the night of my party.”

Gosh! It would be some dance, I thought, grinning sheepish-like to myself, if I had anything to do with it. For when it comes to dancing I’m about as graceful as the bird they call the cow.

Opening my invitation I studied it as I walked slowly down the winding road. Later, having joined Poppy near the dam, he and I studied the corresponding invitations together.

“Queer,” says I finally.

“What’s queer?” says be.

“That Marjorie should send you a separate invitation. For you could have gone with me just as well as not.”

He saw what I meant.

“Don’t be dumb, Jerry. She never expected you to bring me.”

“But everybody around here knows that we’re bosom pals,” says I earnestly.

“Of course,” says he warmly.

“And the invitation reads: ‘Yourself and friend.’”

“Jerry,” he laughed, “you seem to forget that you’re growing up.”

“I’m reminded of it,” I grinned, sharing his mood, “every time Dad buys me a new suit.”

“Marjorie expects you to bring a girl.”

I stared at him. A girl! Gee-miny crickets! Me take a girl to a party. I began to sweat. For I saw, all right, smart kid that he is, that he had hit the nail on the head.

Some more of Marjorie’s grown-up ideas!

“Are you going to the party, Jerry?”

“To tell the truth I’m not crazy about it. For Lawyer Van Ness and his wife put on too many airs to suit me. Besides, I’ve never had any practice rushing girls around. Doesn’t the thought of it scare you, Poppy?”

He pushed out his chest manfully.

“Me?” he kind of strutted around. “I should say not.”

“Who are you going to take?” I quizzed curiously.

“Oh, give me time,” he hedged.

“What does R.S.V.P. mean?” I then inquired, studying the quartet of capital letters in the lower left-hand corner of the neat invitation.

“Marjorie’s ma wants you to bring a pie,” he grinned.

“A pie?” says I, searching his face.

“Sure thing. The ‘P’ stands for ‘pie.’ And the first of the four letters stands for ‘raspberry.’ A ‘raspberry pie.’ See?”

He was kidding me.

“And the ‘S.V.’, turned around, stands for ‘veal sandwiches,’ I suppose.”

“Correct,” he further grinned, like the big monkey that he is.

“Honest, Poppy,” says I, “what does it stand for, anyway?”

“It means that you’ve to ‘respond if you please.’ It’s French.”

“Some class,” says I. “I wonder where Marjorie found out about it.”

He laughed.

“You’ll have to borrow your pa’s dress suit, Jerry.”

“Yah, watch me. . . . I think I’ll stay at home with Red Meyers and eat licorice.”

At this time of the year the Gimp mill pond is usually full to the brim. For the frequent seasonable showers swell the two streams that empty into it. Clark’s Creek, named after an early owner, extends into the hilly northern country for more than two miles, having its source above a waterfall of the same name. Piginsorgum Creek, too, stretching in a westernly direction, is of considerable length. So the stone dam that Amasa Gimp built, with its accompanying pond, supplies considerable power. Fed by springs, Clark’s Creek never has been known to go dry. And if you think Clark’s Falls isn’t a beautiful sight I wish you’d drop around there sometime, preferably after a heavy shower, and take a look at it. Boy, I sure do love the country around here, with its hills and hollows.

We found old Cap’n Tinkertop working on the bridge below the dam. And when I stopped to speak to him about his new job it seemed to me that he acted kind of queer. Anyway, if I must tell you the truth, it was a big surprise to me to find him jiggling a crowbar around. For usually he sits in his bird store and takes life easy, perfectly satisfied if he has a peck of spuds on hand or a doughnut or two. Of course, I wouldn’t want to say outright that he’s lazy. For he and I are the best of friends. On the other hand I could think of a dozen things that were more liable to take him off than overwork. Still, why shouldn’t he loaf, if he wants to? For he’s an old man. And with his peg-leg it isn’t easy for him to get around.

“No wonder,” says I, “that I found your store locked up yesterday afternoon.”

“Yep,” he spit on his hands. “I’m workin’ here now. But if you’ll come around this evenin’ you’ll find the store open as usual. I never did do much business durin’ the day, anyway.”

“What do you call yourself?” I grinned, referring to his work. “A bridge builder?”

“I hain’t a-doin’ no buildin’ on it, Jerry,” he replied. “I’m jest tearin’ it down.”

“Tearing it down?” Poppy spoke up quickly. “Do you mean you’re going to discontinue it altogether?”

“Them’s ol’ Gimlet’s orders.”

“You hadn’t better call him that to his face,” I grinned. “Or you’ll be looking for another new job.”

Up went his warty nose.

“Humph! I wouldn’t lose much if I lost this job. They hain’t no pay in it to speak of, nor satisfaction nor nothin’ else. Fur what satisfaction could a man git workin’ fur an old skinflint like him?”

Poppy, I noticed, looked troubled.

“But if you tear the bridge down,” says he, “how can the miller get across the creek?”

“You go put that question to ol’ Gimlet,” replied the Cap’n. “He’s the boss. Oh-hum! The best part about this job is when the six o’clock whistle blows. . . . Got anything to eat in your pockets?”

I gave him a couple of soiled gumdrops.

“Souvenirs?” says he dryly, spitting out a tack that had lodged in one of the soft pieces.

“Beggars shouldn’t be choosers,” I grinned.

Then who should heave into sight but old Gimlet, himself.

“What’s the meaning of this, Cap’n?” boomed the big-bodied newcomer in his important blustering way. “Why aren’t you at work? I can’t afford to have this job drag along forever. And be careful, as I told you, about dropping those boards in the creek. For we can use every bit of this old lumber in the boiler room.”

“An’ how about the ol’ nails?” drawled the Cap’n, sort of winking at us on the sly. “Is it your plan to have me save ’em so that you kin use ’em when you go fishin’?”

“Um. . . . What do you mean?” came sharply.

“You-all could use ’em fur sinkers, couldn’t you?”

Instead of snickering, like me, Poppy stepped out in front of the red-faced manufacturer as sober as you please.

“Is it true, Mr. Gimp, that you’re planning to discontinue this bridge?”

“Um . . .” the grunt was accompanied by a dark unfriendly scowl. “Who wants to know?”

“I do,” says Poppy quietly.

“And who are you?” the words were snapped out sharply.

“The guy who socked your grandson on the nose last month,” was Poppy’s unexpected reply.

Well, say! I thought old Gimlet would keel over into the creek.

“Get out of here,” he thundered. “This is private property. So move before I move you with the toe of my boot.”

He was four times as big as us. In fact he was one of the biggest men in town, with a huge red face, a hammock-like chin and broad shoulders. His hands were like hams. But did we cower? Not so you could notice it.

“And in addition to being the guy who gently socked your grandson,” Poppy added, in a peculiarly steady voice, “I’m the guy who’s going to help your brother run his pancake mill. So, as we need this bridge, you better think twice before you wreck it. For it’s just as much ours as yours.”

Old Gimlet had to work his huge jaws several seconds before he could find his voice.

“You insolent young puppy,” he thundered. “If you go messing into my affairs I’ll wring your blasted neck. I’ve heard about you and your confounded Pedigreed Pickles. You may have gotten the best of that Pennykorn bunch. But you can’t get the best of me.”

“The point is,” says Poppy quietly, “do you leave the bridge stand as it is, or don’t you?”

There was a short silence.

“Have you been talking with my brother?” old Gimlet then inquired.

“How could he have hired me to help him run the mill,” says Poppy, “if we hadn’t talked it over?”

“Then he has hired you?”

“I think he showed mighty good judgment if he did. Don’t you think so, Mr. Gimp?”

The Cap’n had been resting on his crowbar.

“Wa-al,” he put in, very well pleased with the situation, “do I further wreck it, or don’t I?”

“Let the job rest,” says old Gimlet, “until I find out from my brother how much of this boy’s story is true.”

We watched him stomp across the sagging bridge and disappear into the mill.

“The ol’ skunk,” scowled the Cap’n. “How men kin git that mean is beyond me.”

Evidently the irritated hinge manufacturer found the mill deserted. For he shortly reappeared in the mill yard. Nor did he arouse anybody in the adjacent cottage.

I looked at Poppy curiously.

“Were you telling him the truth?” I inquired.

“Partly,” was my chum’s reply.

“And are you really going to work for the miller?”

“Sure thing.”

“When did he hire you?”

“He hasn’t hired me yet.”

I knew that kid!

“Poppy,” says I, “tell me the unvarnished truth: Have you said anything to the miller about working for him?”

The other grinned. And if there’s anything in this world any sweller than one of Poppy’s ear-to-ear grins, when he’s in a mood like that, I’d like to have you trot it out. Boy, I sure love that kid. Solid gold all the way through—that’s him, all right.

Evidently he had found out that the miller was in trouble. In the same big-hearted way he had found out that old Patsy Corbin, as featured in the Tittering Totem book, was in trouble, and others. And just as he had helped them, even cranking up his sturdy young fists and fighting for them, he was now planning to help old Peter, as the miller was affectionately spoken of by his neighbors.

“Well,” says I, “I’m waiting.”

“For what?” the leader further grinned.

“For an answer to my question.”

“What was it?”

“I asked you if you really had said anything to the miller about working for him.”

“No.”

“What are you going to do?” says I. “Work for him whether he wants you to or not?”

“Oh,” the word was accompanied by a free-and-easy laugh, “he’ll want me to, all right, when I tell him what a swell scheme I have for popularizing his pancake flour. There’s millions in it, Jerry.”

“And what is your scheme?” I inquired eagerly.

“I haven’t given it any thought yet.”

I looked at him steadily.

“You’re cuckoo,” I told him.

But I didn’t mean it. There was a time, as written down in my earlier book, when I doubted him. I thought he was acting too big for his shoes. The idea of boys trying to run stilt and pickle factories! But I have unlimited confidence in him now. A born business man. That’s what he is.

And I was kind of glad that he had chipped in on the miller’s side. For it was plain to be seen that old Gimlet, arrogant, blustering slave driver that he was, and a power in the community because of his great wealth (thank heaven there are few like him in this world), had no regard for his brother’s rights at all.

Gee! Wouldn’t it be bully, I thought, the blood jumping through my veins, if Poppy could put new life into the old pancake mill. Half of the water power was the miller’s. And I, for one, was ready to stand back of him and see that he got it.

There’d be a battle, of course. That was to be expected. But I was ready to fight both with my fists and my wits. So was Poppy. He had started out to land a fish or two (we still had our cane fishing poles). But instead he had landed a partnership in a run-down pancake mill. Of course, a few little details had to be worked out, such as informing the miller that he had a new partner. But details such as that were mere pie and ice cream to old Poppy.

Poppy got his eyes on something.

“Look!” he cried, pointing excitedly to the mill pond. “There’s the old pancake geezer riding on a raft.”

“Yah,” says I, as a red speed boat shot into sight from a boathouse on the east shore near the hinge factory, “and there’s Silly Gimp hot on the trespasser’s trail, too.”

I had heard about Silly’s new racer, and how he had ordered all the other boats off the big pond so that he could have it entirely to himself, selfish snob that he is. But this was the first time that I had seen the expensive boat perform. With its high-powered out-board motor it sure was a nifty little outfit. I kind of wished that I had one just like it. Still I wouldn’t have traded places with that kid for all the motor boats in the world. Money isn’t everything. Nor is the stuff that money buys everything. Character, I’ve found, and the right kind of thoughts in a fellow’s head, are what counts.

Cutting through the water at high speed Silly stopped with a grand flourish beside the slow-moving raft.

“Git that junk out of here,” he ordered in his overbearing way. “And see that you keep it out of here, too. For this is a private pond.”

It hadn’t occurred to him, I guess, to wonder what made the raft move. But I knew! And was I ever excited! Gee-miny crickets!

“It’s Davey Jones!” I cried, clutching my chum’s arm. “There! He just stuck up his head. Do you see?”

That didn’t make sense to Poppy.

“What are you talking about?” says he, shoving a curious look at me.

“The big turtle,” says I, in continued excitement. “See? He’s towing the raft.”

“What big turtle?” Poppy further inquired.

I told him then about my strange adventure in the weed patch. I had met old Sir Hinkle Funnyduster himself, I said. And he had a pet turtle with a shell as big as a washtub.

“Which reminds me,” says Poppy pleasantly, “of the time I met Sir Christopher Columbus. Would you care to hear about it, and how I helped him trim the corns of his pet rattlesnake?”

“Honest, Poppy,” I waggled, “I really tumbled over the old man in the weeds. And, as I say, he was feeding hunks of raw liver to the biggest turtle that I ever set eyes on. It’s an educated turtle too. It minds him just like a kid.”

Convinced now that I was telling the truth the other searched my face.

“And he gave you the name of Sir Hinkle Funnyduster?”

I nodded.

“Which proves plainly enough,” the leader put his ready wits to work, “where the missing card went to. This old geezer was hiding in the barn. See? During the game he heard us talking about a ‘turtle’ card. And having a turtle of his own, curiously, he was attracted to the cards when we dropped them and left the barn. Sir Hinkle Funnyduster! Just the name he needed. And to remember it he pocketed the card. . . . Did he talk like Rory?”

“No,” I shook my head.

“There you are!” Poppy spoke with conviction. “He’s no more Sir Hinkle Funnyduster than you or I. For Englishmen all talk alike.”

“But who is he?” says I, bewildered-like.

“That,” says Poppy, kind of shutting his teeth down hard on the word, “is what we’re going to find out.”

“Detective stuff, huh?” says I happily, recalling other mysteries that we had solved.

“Nothing else but,” says he.

I fell into thought.

“He must have had an object,” says I, “in giving me that particular name, and an added object in hiding in the barn.”

“Even queerer,” says Poppy, with a puzzled look, “is his ‘pancake’ letter—granting that he is the one who wrote the odd letter. . . . Did you ever hear of anybody using buckwheat pancakes to restore hair to bald heads?”

I stared at him.

“It sounds cuckoo, all right. But the old miller has a letter from a man who claims that Gimp’s Fancy Mixture did that very thing for him, believe me.”