Frontispiece: Private Simmons

* A Distributed Proofreaders US Ebook *Thanks to A Celebration of Women Writers http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/ for providing the source text.

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Three Times and Out

Author: McClung, Nellie Letitia

Date of first publication: 1918

Date first posted: July 11, 2004

Date last updated: October 29, 2020

Faded Page ebook#20201064

When a young man whom I had not seen until that day came to see me in Edmonton, and told me he had a story which he thought was worth writing, and which he wanted me to write for him, I told him I could not undertake to do it for I was writing a story of my own, but that I could no doubt find some one who would do it for him.

Then he mentioned that he was a returned soldier, and had been for sixteen months a prisoner in Germany, and had made his escape—

That changed everything!

I asked him to come right in and tell me all about it—for like every one else I have friends in the prison-camps of Germany, boys whom I remember as little chaps in knickers playing with my children, boys I taught in country schools in Manitoba, boys whose parents are my friends. There are many of these whom we know to be prisoners, and there are some who have been listed as "missing," who we are still hoping against long odds may be prisoners!

I asked him many questions. How were they treated? Did they get enough to eat? Did they get their parcels? Were they very lonely? Did he by any chance know a boy from Vancouver called Wallen Gordon, who had been "Missing" since the 2d of June, 1916? Or Reg Black from Manitou? or Garnet Stewart from Winnipeg?

Unfortunately, he did not.

Then he began his story. Before he had gone far, I had determined to do all I could to get his story into print, for it seemed to me to be a story that should be written. It gives at least a partial answer to the anxious questionings that are in so many hearts. It tells us something of the fate of the brave fellows who have, temporarily, lost their freedom—to make our freedom secure!

Private Simmons is a close and accurate observer who sees clearly and talks well. He tells a straightforward, unadorned tale, every sentence of which is true, and convincing. I venture to hope that the reader may have as much pleasure in the reading of it as I had in the writing.

NELLIE L. McCLUNG

Edmonton, October 24, 1918

Contents

CHAPTER VIII. OFF FOR SWITZERLAND!

CHAPTER XI. THE STRAFE-BARRACK

CHAPTER XVI. THE INVISIBLE BROTHERHOOD

CHAPTER XVII. THE CELLS AT OLDENBUBG

CHAPTER XVIII. PARNEWINKEL CAMP

CHAPTER XIX. THE BLACKEST CHAPTER OF ALL

CHAPTER XXI. TRAVELLERS OF THE NIGHT

CHAPTER XXII. THE LONG ROAD TO FREEDOM

List of Illustrations

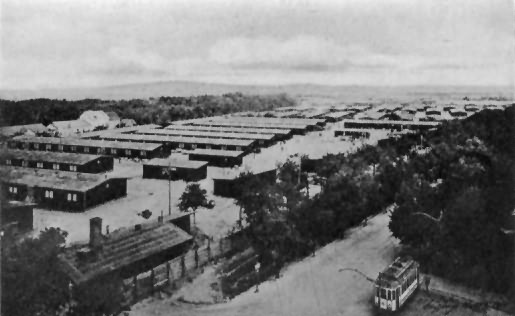

Officers' Quarters in a German Military Prison

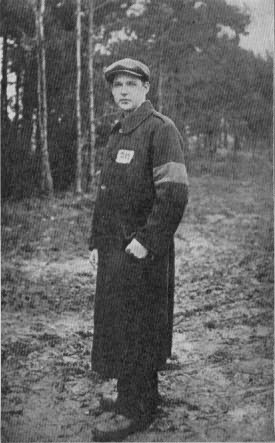

Tom Bromley / in Red Cross Overcoat With Prison Number And Marked Sleeve

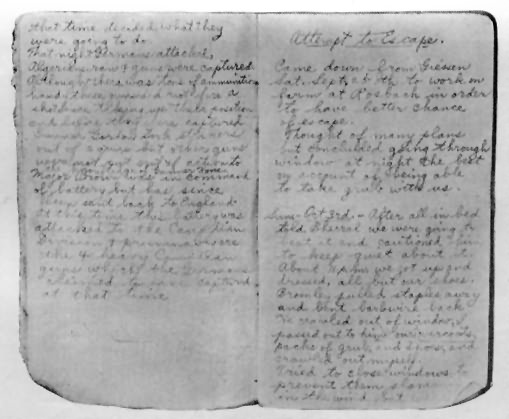

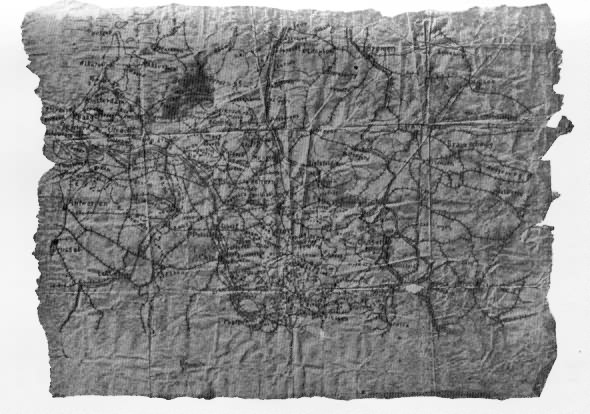

Two Pages from Private Simmons's Diary

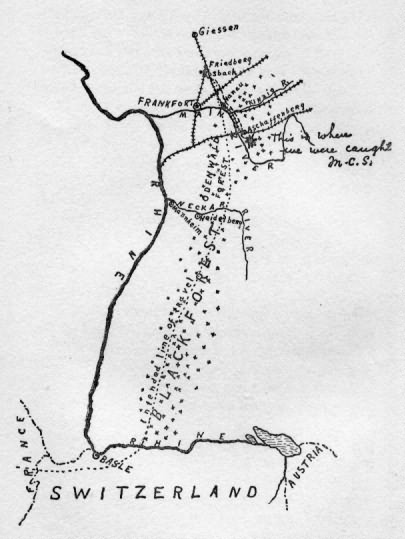

Map Made by Private Simmons of the First Attempt

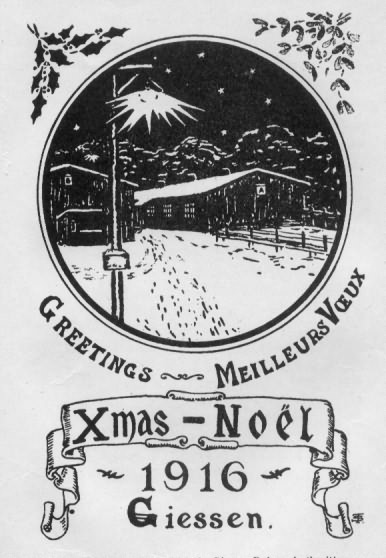

The Christmas Card Which the Giessen Prison Authorities Supplied to the Prisoners

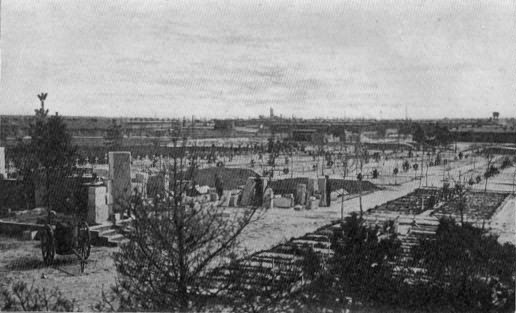

Friedrichsfeld Prison-camp in Winter

Friedrichsfeld Prison-camp in Summer

"England has declared war on Germany!"

We were working on a pumphouse, on the Columbia River, at Trail, British Columbia, when these words were shouted at us from the door by the boss carpenter, who had come down from the smelter to tell us that the news had just come over the wire.

Every one stopped work, and for a full minute not a word was spoken. Then Hill, a British reservist who was my work-mate, laid down his hammer and put on his coat. There was neither haste nor excitement in his movements, but a settled conviction that gave me a queer feeling. I began to argue just where we had left off, for the prospect of war had been threshed out for the last two days with great thoroughness. "It will be settled," I said. "Nations cannot go to war now. It would be suicide, with all the modern methods of destruction. It will be settled by a war council—and all forgotten in a month."

Hill, who had argued so well a few minutes ago and told us all the reasons he had for expecting war with Germany, would not waste a word on me now. England was at war—and he was part of England's war machine.

"I am quitting, George," he said to the boss carpenter, as he pulled his cap down on his head and started up the bank.

That night he began to drill us in the skating-rink.

I worked on for about a week, but from the first I determined to go if any one went from Canada. I don't suppose it was all patriotism. Part of it was the love of adventure, and a desire to see the world; for though I was a steady-going carpenter chap, I had many dreams as I worked with hammer and saw, and one of them was that I would travel far and see how people lived in other countries. The thought of war had always been repellent to me, and many an argument I had had with the German baker in whose house I roomed, on the subject of compulsory military training for boys. He often pointed out a stoop-shouldered, hollow-chested boy who lived on the same street, and told me that if this boy had lived in Germany he would have walked straighter and developed a chest, instead of slouching through life the way he was doing. He and his wife and the grown-up daughter were devoted to their country, and often told us of how well the working-people were housed in Germany and the affairs of the country conducted.

But I think the war was as great a surprise to them as to us, and although the two women told us we were foolish to go to fight—it was no business of ours if England wanted to get into a row—it made no difference in our friendly relations, and the day we left Clara came to the station with a box of candy. I suppose if we had known as much then as we do now about German diplomacy, we shouldn't have eaten it, but we only knew then that Clara's candy was the best going, and so we ate it, and often wished for more.

I have since heard, however, of other Germans in Canada who knew more of their country's plans, and openly spoke of them. One of these, employed by the Government, told the people in the office where he worked that when Germany got hold of Canada, she would straighten out the crooked streets in our towns and not allow shacks to be built on the good streets, and would see to it that houses were not crowded together; and the strangest part of it is that the people to whom he spoke attached no importance whatever to his words until the war came and the German mysteriously disappeared.

I never really enlisted, for we had no recruiting meetings in Trail before I left. We went to the skating-rink the first night, about fifteen of us, and began to drill. Mr. Schofield, Member of the Provincial Parliament, and Hill were in charge, and tested our marksmanship as well. They graded us according to physical tests, marksmanship, and ability to pick up the drill, and I was quite pleased to find I was Number "One" on the list.

There was a young Italian boy named Adolph Milachi, whom we called "Joe," who came to drill the first night, and although he could not speak much English, he was determined to be a soldier. I do not know what grudge little Joe had against the Germans, whether it was just the love of adventure which urged him on, but he overruled all objections to his going and left with the others of us, on the last day of August.

I remember that trip through the mountains in that soft, hazy, beautiful August weather; the mountain-tops, white with snow, were wrapped about with purple mist which twisted and shifted as if never satisfied with their draping. The sheer rocks in the mountain-sides, washed by a recent rain, were streaked with dull reds and blues and yellows, like the old-fashioned rag carpet. The rivers whose banks we followed ran blue and green, and icy cold, darting sometimes so sharply under the track that it jerked one's neck to follow them; and then the stately evergreens marched always with us, like endless companies of soldiers or pilgrims wending their way to a favorite shrine.

When we awakened the second morning, and found ourselves on the wide prairie of Alberta, with its many harvest scenes and herds of cattle, and the gardens all in bloom, one of the boys said, waving his hand at a particularly handsome house set in a field of ripe wheat, "No wonder the Germans want it!"

My story really begins April 24, 1915. Up to that time it had been the usual one—the training in England, with all the excitement of week-end leave; the great kindness of English families whose friends in Canada had written to them about us, and who had forthwith sent us their invitations to visit them, which we did with the greatest pleasure, enjoying every minute spent in their beautiful houses; and then the greatest thrill of all—when we were ordered to France.

The 24th of April was a beautiful spring day of quivering sunshine, which made the soggy ground in the part of Belgium where I was fairly steam. The grass was green as plush, and along the front of the trenches, where it had not been trodden down, there were yellow buttercups and other little spring flowers whose names I did not know.

We had dug the trenches the day before, and the ground was so marshy and wet that water began to ooze in before we had dug more than three feet. Then we had gone on the other side and thrown up more dirt, to make a better parapet, and had carried sand-bags from an old artillery dug-out. Four strands of barbed wire were also put up in front of our trenches, as a sort of suggestion of barbed-wire entanglements, but we knew we had very little protection.

Early in the morning of the 24th, a German aeroplane flew low over our trench, so low that I could see the man quite plainly, and could easily have shot him, but we had orders not to fire—the object of these orders being that we must not give away our position.

The airman saw us, of course, for he looked right down at us, and dropped down white pencils of smoke to show the gunners where we were. That big gray beetle sailing serenely over us, boring us with his sharp eyes, and spying out our pitiful attempts at protection, is one of the most unpleasant feelings I have ever had. It gives me the shivers yet! And to think we had orders not to fire!

Being a sniper, I had a rifle fixed up with a telescopic sight, which gave me a fine view of what was going on, and in order not to lose the benefit of it, I cleaned out a place in a hedge, which was just in front of the part of the trench I was in, and in this way I could see what was happening, at least in my immediate vicinity.

We knew that the Algerians who were holding a trench to our left had given way and stampeded, as a result of a German gas attack on the night of April 22d. Not only had the front line broken, but, the panic spreading, all of them ran, in many cases leaving their rifles behind them. Three companies of our battalion had been hastily sent in to the gap caused by the flight of the Algerians. Afterwards I heard that our artillery had been hurriedly withdrawn so that it might not fall into the hands of the enemy; but we did not know that at the time, though we wondered, as the day went on, why we got no artillery support.

Before us, and about fifty yards away, were deserted farm buildings, through whose windows I had instructions to send shots at intervals, to discourage the enemy from putting in machine guns. To our right there were other farm buildings where the Colonel and Adjutant were stationed, and in the early morning I was sent there with a message from Captain Scudamore, to see why our ammunition had not come up.

I found there Colonel Hart McHarg, Major Odlum (now Brigadier-General Odlum), and the Adjutant in consultation, and thought they looked worried and anxious. However, they gave me a cheerful message for Captain Scudamore. It was very soon after that that Colonel Hart McHarg was killed.

The bombardment began at about nine o'clock in the morning, almost immediately after the airman's visit, and I could see the heavy shells bursting in the village at the cross-roads behind us. They were throwing the big shells there to prevent reinforcements from coming up. They evidently did not know, any more than we did, that there were none to come, the artillery having been withdrawn the night before.

Some of the big shells threw the dirt as high as the highest trees. When the shells began to fall in our part of the trench, I crouched as low as I could in the soggy earth, to escape the shrapnel bullets. Soon I got to know the sound of the battery that was dropping the shells on us, and so knew when to take cover. One of our boys to my left was hit by a pebble on the cheek, and, thinking he was wounded, he fell on the ground and called for a stretcher-bearer. When the stretcher-bearer came, he could find nothing but a scratch on his cheek, and all of us who were not too scared had a laugh, including the boy himself.

I think it was about one o'clock in the afternoon that the Germans broke through the trench on our right, where Major Bing-Hall was in command; and some of the survivors from that trench came over to ours. One of them ran right to where I was, and pushed through the hole I had made in the hedge, to get a shot at the enemy. I called to him to be careful, but some sniper evidently saw him, for in less than half a minute he was shot dead, and fell at my side.

An order to "retreat if necessary" had been received before this, but for some reason, which I have never been able to understand, was not put into effect until quite a while after being received. When the order came, we began to move down the trench as fast as we could, but as the trench was narrow and there were wounded and dead men in it, our progress was slow.

Soon I saw Robinson, Smith, and Ward climbing out of the trench and cutting across the field. This was, of course, dangerous, for we were in full view of the enemy, but it was becoming more and more evident that we were in a tight corner. So I climbed out, too, and ran across the open as fast as I could go with my equipment. I got just past the hedge when I was hit through the pocket of my coat. I thought I was wounded, for the blow was severe, but found out afterwards the bullet had just passed through my coat pocket.

I kept on going, but in a few seconds I got a bullet right through my shoulder. It entered below my arm at the back, and came out just below the shoulder-bone, making a clean hole right through.

I fell into a shallow shell-hole, which was just the size to take me in, and as I lay there, the possibility of capture first came to me. Up to that time I had never thought of it as a possible contingency; but now, as I lay wounded, the grave likelihood came home to me.

I scrambled to my feet, resolved to take any chances rather than be captured. I have an indistinct recollection of what happened for the next few minutes. I know I ran from shell-hole to shell-hole, obsessed with the one great fear—of being captured—and at last reached the reserve trench, in front. I fell over the parapet, among and indeed right on top of the men who were there, for the trench was packed full of soldiers, and then quickly gathered myself together and climbed out of the trench and crawled along on my stomach to the left, following the trench to avoid the bullets, which I knew were flying over me.

Soon I saw, looking down into the trench, some of the boys I knew, and I dropped in beside them. Then everything went from me. A great darkness arose up from somewhere and swallowed me! Then I had a delightful sensation of peace and warmth and general comfort. Darkness, the blackest, inkiest darkness, rolled over me in waves and hid me so well no Jack Johnson or Big Bertha could ever find me. I hadn't a care or a thought in the world. I was light as a feather, and these great strong waves of darkness carried me farther and farther away.

But they didn't carry me quite far enough, for a cry shot through me like a knife, and I was wide awake, looking up from the bottom of a muddy trench. And the cry that wakened me was sounding up and down the trench, "The Germans are coming!"

Sergeant Reid, who did not seem to realize how desperate the situation was, was asking Major Bing-Hall what he was going to do. But before any more could be said, the Germans were swarming over the trench. The officer in charge of them gave us a chance to surrender, which we did, and then it seemed like a hundred voices—harsh, horrible voices—called to us to come out of the trench. "Raus" is the word they use, pronounced "rouse."

This was the first German word I had heard, and I hated it. It is the word they use to a dog when they want him to go out, or to cattle they are chasing out of a field. It is used to mean either "Come out!"—or "Get out!" I hated it that day, and I hated it still more afterward.

There were about twenty of us altogether, and we climbed out of the trench without speaking. There was nothing to be said. It was all up with us.

It is strange how people act in a crisis. I mean, it is strange how quiet they are, and composed. We stood there on the top of the trench, without speaking, although I knew what had happened to us was bitterer far than to be shot. But there was not a word spoken. I remember noticing Fred McKelvey, when the German who stood in front of him told him to take off his equipment. Fred's manner was halting, and reluctant, and he said, as he laid down his rifle and unbuckled his cartridge bag, "This is the thing my father told me never to let happen."

Just then the German who stood by me said something to me, and pointed to my equipment, but I couldn't unfasten a buckle with my useless arm, so I asked him if he couldn't see I was wounded. He seemed to understand what I meant, and unbuckled my straps and took everything off me, very gently, too, and whipped out my bandage and was putting it on my shoulder with considerable skill, I thought, and certainly with a gentle hand—when the order came from their officer to move us on, for the shells were falling all around us.

Unfortunately for me, my guard did not come with us, nor did I ever see him again. One of the others reached over and took my knife, cutting the string as unconcernedly as if I wanted him to have it, and I remember that this one had a saw-bayonet on his gun, as murderous and cruel-looking a weapon as any one could imagine, and he had a face to match it, too. So in the first five minutes I saw the two kinds of Germans.

When we were out of the worst of the shell-fire, we stopped to rest, and, a great dizziness coming over me, I sat down with my head against a tree, and looked up at the trailing rags of clouds that drifted across the sky. It was then about four o'clock of as pleasant an afternoon as I can ever remember. But the calmness of the sky, with its deep blue distance, seemed to shrivel me up into nothing. The world was so bright, and blue, and—uncaring!

I may have fallen asleep for a few minutes, for I thought I heard McKelvey saying, "Dad always told me not to let this happen." Over and over again, I could hear this, but I don't know whether McKelvey had repeated it. My brain was like a phonograph that sticks at one word and says it over and over again until some one stops it.

I think it was Mudge, of Grand Forks, who came over to see how I was. His voice sounded thin and far away, and I didn't answer him. Then I felt him taking off my overcoat and finishing the bandaging that the German boy had begun.

Little Joe, the Italian boy, often told me afterwards how I looked at that time. "All same dead chicken not killed right and kep' long time."

Here those who were not so badly wounded were marched on, but there were ten of us so badly hit we had to go very slowly. Percy Weller, one of the boys from Trail who enlisted when I did, was with us, and when we began the march I was behind him and noticed three holes in the back of his coat; the middle one was a horrible one made by shrapnel. He staggered painfully, poor chap, and his left eye was gone!

We passed a dead Canadian Highlander, whose kilt had pitched forward when he fell, and seemed to be covering his face.

In the first village we came to, they halted us, and we saw it was a dressing-station. The village was in ruins—even the town pump had had its head blown off!—and broken glass, pieces of brick, and plaster littered the one narrow street. The dressing was done in a two-room building which may have been a store. The walls were discolored and cracked, and the windows broken.

On a stretcher in the corner there lay a Canadian Highlander, from whose wounds the blood dripped horribly and gathered in a red pool on the dusty floor. His eyes were glazed and his face was drawn with pain. He talked unceasingly, but without meaning. The only thing I remember hearing him say was, "It's no use, mother—it's no use!"

Weller was attended to before I was, and marched on. While I sat there on an old tin pail which I had turned up for this purpose, two German officers came in, whistling. They looked for a minute at the dying Highlander in the corner, and one of them went over to him. He saw at once that his case was hopeless, and gave a short whistle as you do when blowing away a thistledown, indicating that he would soon be gone. I remember thinking that this was the German estimate of human life.

He came to me and said, "Well, what have you got?"

I thought he referred to my wound, and said, "A shoulder wound." At which he laughed pleasantly and said, "I am not interested in your wound; that's the doctor's business." Then I saw what he meant; it was souvenirs he was after. So I gave him my collar badge, and in return he gave me a German coin, and went over to the doctor and said something about me, for he flipped his finger toward me.

My turn came at last. The doctor examined my pay-book as well as my wound. I had forty-five francs in it, and when he took it out, I thought it was gone for sure. However, he carefully counted it before me, drawing my attention to the amount, and then returned it to me.

After my wound had been examined and a tag put on me stating what sort of treatment I was to have, I was taken away with half a dozen others and led down a narrow stone stair to a basement. Here on the cement floor were piles of straw, and the place was heated. The walls were dirty and discolored. One of the few pleasant recollections of my life in Germany has been the feeling of drowsy content that wrapped me about when I lay down on a pile of straw in that dirty, rat-infested basement. I forgot that I was a prisoner, that I was badly winged, that I was hungry, thirsty, dirty, and tired. I forgot all about my wounded companions and the Canadian Highlander, and all the suffering of the world, and drifted sweetly out into the wide ocean of sleep.

Some time during the night—for it was still dark—I felt some one kicking my feet and calling me to get up, and all my trouble and misery came back with a rush. My shoulder began to ache just where it left off, but I was so hungry that the thought of getting something to eat sustained me. Surely, I thought, they are going to feed us!

We were herded along the narrow street, out into a wide road, where we found an open car which ran on light rails in the centre of the road. It was like the picnic trolley cars which run in our cities in the warm weather. There were wounded German soldiers huddled together, and we sat down among them, wherever we could find the room, but not a word was spoken. I don't know whether they noticed who we were or not—they had enough to think about, not to be concerned with us, for most of them were terribly wounded. The one I sat beside leaned his head against my good shoulder and sobbed as he breathed. I could not help but think of the irony of war that had brought us together. For all I knew, he may have been the machine gunner who had been the means of ripping my shoulder to pieces—and it may have been a bullet from my rifle which had torn its way along his leg which now hung useless. Even so, there was no hard feeling between us, and he was welcome to the support of my good shoulder!

Some time through the night—my watch was broken and I couldn't tell the time exactly—we came to another village and got off the car. A guard came and carried off my companion, but as I could walk, I was left to unload myself. The step was high, and as my shoulder was very stiff and sore, I hesitated about jumping down. A big German soldier saw me, understood what was wrong, and lifted me gently down.

It was then nearly morning, for the dawn was beginning to show in the sky, and we were taken to an old church, where we were told to lie down and go to sleep. It was miserably cold in the church, and my shoulder ached fearfully. I tried hard to sleep, but couldn't manage it, and walked up and down to keep warm. I couldn't help but think of the strange use the church—which had been the scene of so many pleasant gatherings—was being put to, and as I leaned against the wall and looked out of the window, I seemed to see the gay and light-hearted Belgian people who so recently had gathered there. Right here, I thought, the bashful boys had stood, waiting to walk home with the girls... just the way we did in British Columbia, where one church I know well stands almost covered with the fragrant pines...

I fell into a pleasant reverie then of sunny afternoons and dewy moonlit nights, when the sun had gone over the mountains, and the stars came out in hundreds. My dream then began to have in it the brightest-eyed girl in the world, who gave me such a smile one Sunday when she came out of church... that I just naturally found myself walking beside her.... She had on a pink suit and white shoes, and wore a long string of black beads...

Then somebody spoke to me, and a sudden chill seized me and sent me into a spasm of coughing, and the pain of my shoulder shot up into my head like a knife... and I was back—all right—to the ruined church in Belgium, a prisoner of war in the hands of the Germans!

The person who spoke to me was a German cavalry officer, who quite politely bade me good-morning and asked me how I felt. I told him I felt rotten. I was both hungry and thirsty—and dirty and homesick. He laughed at that, as if it were funny, and asked me where I came from. When I told him, he said, "You Canadians are terrible fools to fight with us when you don't have to. You'll be sick of it before you are through. Canada is a nice country, though," he went on; "I've been in British Columbia, too, in the Government employ there—they treated me fine—and my brother is there now, engineer in the Dunsmuir Collieries at Ladysmith. Great people—the Canadians!"

And he laughed again and said something in German to the officer who was with him.

When the sun came up and poured into the church, warming up its cold dreariness, I lay down and slept, for I had not nearly finished the sleep so comfortably begun in the basement the night before.

But in what seemed like three minutes, some one kicked my feet and called to me to get up. I got to my feet, still spurred by the hope of getting something to eat. Outside, all those who could walk were falling in, and I hastened to do the same. Our guards were mounted this time, and I noticed that their horses were small and in poor condition. We were soon out of the village and marching along a splendid road.

The day was bright and sunny, but a searching wind blew straight in our faces and made travelling difficult. It seemed to beat unmercifully on my sore shoulder, and I held my right wrist with my left hand, to keep the weight off my shoulder all I could.

I had not gone far when I began to grow weak and dizzy. The thirst was the worst; my tongue was dry and swollen, and it felt like a cocoa doormat. I could see rings of light wherever I looked, and the ground seemed to come up in waves. A guard who rode near me had a water-bottle beside him which dripped water. The cork was not in tight as it should have been, and the sight of these drops of water seemed to madden me. I begged him for a drink, and pointed to my parched tongue; but he refused, and rode ahead as if the sight of me annoyed him!

Ahead of us I could see the smoke of a large town, and I told myself over and over again that there would be lots of water there, and food and clean clothes, and in this way I kept myself alive until we reached Roulers.

Roulers is a good-sized town in West Flanders, of about thirty thousand population, much noted for its linen manufacture; and has a great church of St. Michael with a very high tower, which we could see for miles. But I do not remember much about the look of the town, for I could hardly drag my feet. It seemed as if every step would be my last. But I held on some way, until we reached the stopping-place, which happened to be an unused school. The men who had not been wounded had arrived several hours ahead of us.

When, at last, I sat down on one of the benches, the whole place seemed to float by me. Nothing would stand still. The sensation was like the water dizziness which makes one feel he is being rapidly propelled upstream. But after sitting awhile, it passed, and I began to recognize some of our fellows. Frost, of my own battalion, was there, and when I told him I had had nothing to eat since the early morning of the day before, he immediately produced a hardtack biscuit and scraped out the bottom of his jam tin. They had been served with a ration of war-bread, and several of the boys offered me a share of their scanty allowance, but the first mouthful was all I could take. It was sour, heavy, and stale.

The school pump had escaped the fate of the last pump I had seen, and was in good working order, and its asthmatic creaking as it brought up the stream of water was music in my ears. We went out in turns and drank like thirsty cattle. I drank until my jaws were stiff as if with mumps, and my ears ached, and in a few minutes my legs were tied in cramps.

While I was vainly trying to rub them out with my one good hand, Fred McKelvey came up and told me a sure cure for leg-cramp. It is to turn the toes up as far as possible, and straighten out the legs, and it worked a cure for me. He said he had taken the cramps out of his legs this way when he was in the water.

I remember some of the British Columbia boys who were there. Sergeants Potentier, George Fitz, and Mudge, of Grand Forks; Reid, Diplock, and Johnson, of Vancouver; Munroe and Wildblood, of Rossland; Keith, Palmer, Larkins, Scott, and Croak. Captain Scudamore, my Company Captain, came over to where I sat, and kindly inquired about my wounds. He wrote down my father's address, too, and said he would try to get a letter to him.

There was a house next door—quite a fine house with a neat paling and long, shuttered windows, at which the vines were beginning to grow. It looked to be in good condition, except that part of the verandah had been torn away. The shutters were closed on its long, graceful windows, giving it the appearance of a tall, stately woman in heavy mourning.

When we were at the pump, we heard a gentle tapping, and, looking up, we saw a very handsome dark-eyed Belgian woman at one of the windows. Instinctively we saluted, and quick as a flash she held a Union Jack against the pane!

A cheer broke from us involuntarily, and the guards sprang to attention, suspecting trouble. But the flag was gone as quickly as it came, and when we looked again, the shutters were closed and the deep, waiting silence had settled down once more on the stately house of shutters.

But to us it had become suddenly possessed of a living soul! The flash of those sad black eyes, as well as the glimpse of the flag, seemed to call to us to carry on! They typified to us exactly what we were fighting for!

After the little incident of the flag, it was wonderful how bright and happy we felt. Of course, I know, the ministrations of the pump helped, for we not only drank all we wanted, but most of the boys had a wash, too; but we just needed to be reminded once in awhile of what the real issues of the war were.

Later in the day, after we had been examined by another medical man, who dressed our wounds very skillfully, and gently, too, we came back to the school, and found there two heavily veiled Belgian women. They had bars of chocolate for us, for which we were very grateful. They were both in deep mourning, and seemed to have been women of high social position, but their faces were very pale and sad, and when they spoke their voices were reedy and broken, and their eyes were black pools of misery. Some of the boys afterwards told me that their daughters had been carried off by the Germans, and their husbands shot before their eyes.

I noticed the absence of children and young girls on the streets. There were only old men and women, it seemed, and the faces of these were sad beyond expression. There were no outbursts of grief; they seemed like people whose eyes were cried dry, but whose spirits were still unbroken.

Later in the day we were taken to the station, to take the train for the prison-camp at Giessen. Of course, they did not tell us where we were going. They did not squander information on us or satisfy our curiosity, if they could help it.

The station was full of people when we got there, and there seemed to be a great deal of eating done at the stations. This was more noticeable still in German stations, as I saw afterwards.

Our mode of travelling was by the regular prisoner train which had lately—quite lately—been occupied by horses. It had two small, dirty windows, and the floor was bare of everything but dirt. We were dumped into it—not like sardines, for they fit comfortably together, but more like cordwood that is thrown together without being piled. If we had not had arms or legs or heads, there would have been just room for our bodies, but as it was, everybody was in everybody's way, and as many of us were wounded, and all of us were tired and hungry, we were not very amiable with each other.

I tried to stand up, but the jolting of the car made me dizzy, and so I doubled up on the floor, and I don't know how many people sat on me. I remember one of the boys I knew, who was beside me on the floor, Fairy Strachan. He had a bad wound in his chest, given him by a dog of a German guard, who prodded him with a bayonet after he was captured, for no reason at all. Fortunately the bayonet struck a rib, and so the wound was not deep, but not having been dressed, it was very painful.

I could not sleep at all that night, for the air was stifling, and somebody's arm or foot or head was always bumping into me. I wonder if Robinson Crusoe ever remembered to be thankful for fresh air and room to stretch himself! We asked the guards for water, for we soon grew very thirsty, and when we stopped at a station, one of the boys, looking out, saw the guard coming with a pail of water, and cried out, "Here's water—boys!" The thought of a drink put new life in us, and we scrambled to our feet. It was water, all right, and plenty of it, but it was boiling hot and we could not drink it; and we could not tell from the look of opaque stupidity on the face of the guard whether he did it intentionally or not. He may have been a boiling-water-before-meals advocate. He looked balmy enough for anything!

At some of the stations the civilians standing on the platform filled our water-bottles for us, but it wasn't enough. We had only two water-bottles in the whole car. However, at Cologne, a boy came quickly to the car window at our call, and filled our water-bottles from a tap, over and over again. He would run as fast as he could from the tap to the window, and left a bottle filling at the tap while he made the trip. In this way every man in the car got enough to drink, and this blue-eyed, shock-headed lad will ever live in grateful memory.

The following night after midnight we reached Giessen, and were unloaded and marched through dark streets to the prison-camp, which is on the outskirts of the city. We were put into a dimly lighted hut, stale and foul-smelling, too, and when we put up the windows, some of our own Sergeants objected on account of the cold, and shut them down. Well, at least we had room if we hadn't air, and we huddled together and slept, trying to forget what we used to believe about the need of fresh air.

As soon as the morning came, I went outside and watched a dull red, angry sky flushing toward sunrise. Red in the morning sky denotes wind, it is said, but we didn't need signs that morning to proclaim a windy day, for the wind already swept the courtyard, and whipped the green branches of the handsome trees which marked the driveway. My spirits rose at once when I filled my lungs with air and looked up at the scudding clouds which were being dogged across the sky by the wind.

A few straggling prisoners came out to wash at the tap in the courtyard, and I went over to join them, for I was grimy, too, with the long and horrible ride. With one hand I could make but little progress, and was spreading the dirt rather than removing it, until a friendly Belgian, seeing my difficulty, took his cake of soap and his towel, and washed me well.

We were then given a ration of bread about two inches thick, and a drink of something that tasted like water boiled in a coffee-pot, and after this we were divided into ten groups. Those of us who knew each other tried hard to stay together, but we soon learned to be careful not to appear to be too anxious, for the guards evidently had instructions to break up previous acquaintanceships.

The wounded were marched across the compound to the "Revier," a dull, gray, solid-looking building, where again we were examined and graded. Those seriously wounded were sent to the lazaret, or hospital proper. I, being one of the more serious cases, was marched farther on to the lazaret, and we were all taken to a sort of waiting-room, and taken off in groups to the general bathroom to have a bath, before getting into the hospital clothes.

With me was a young bugler of the Fifth Royal Highlanders, Montreal, a little chap not more than fifteen, whose pink cheeks and curly hair would have made an appeal to any human being: he looked so small and lonesome and far from home. A smart young military doctor jostled against the boy's shattered arm, eliciting from him a cry of pain, whereupon he began to make fun of the little bugler, by marching around him, making faces. It gave me a queer feeling to see a grown-up man indulging in the tactics of a spoiled child, but I have heard many people express the opinion, in which I now heartily agree, that the Germans are a childish sort of people. They are stupidly boastful, inordinately fond of adulation and attention, and peevish and sulky when they cannot have their own way. I tried to imagine how a young German boy would have been treated by one of our doctors, and laughed to myself at the absurdity of the thought that they would make faces at him!

The young bugler was examined before I was, and as he was marched out of the room, the doctor who had made the faces grabbed at his kilt with an insulting gesture, at which the lad attempted to kick him. The doctor dodged the kick, and the Germans who were in the room roared with laughter. I hated them more that minute than I had up to that time.

The Belgian attendants who looked after the bathing of us were kind and polite. One of them could speak a little English, and he tried hard to get information regarding his country from us.

"Is it well?" he asked us eagerly. "My country—is it well?"

We thought of the shell-scarred country, with its piles of smouldering ashes, its pallid women with their haunted faces, the deathlike silence of the ruined streets. We thought of these things, but we didn't tell him of them. We told him the war was going on in great shape: the Allies were advancing all along the line, and were going to be in Berlin by Christmas. It was worth the effort to see his little pinched face brighten. He fairly danced at his work after that, and when I saw him afterwards, he eagerly asked—"My country—is it well?" I do not know why he thought I knew, or maybe he didn't think so. But, anyway, I did my best. I gave him a glowing account of the Allied successes, and painted a gloomy future for the Kaiser, and I again had my reward, in his glowing face.

Everything we had was taken from us except shoes, socks, cap, and handkerchief, and we did not see them again: neither did we get another bath, although I was six weeks in the hospital.

The hospital clothes consisted of a pajama suit of much-faded flannelette, but I was glad to get into it, and doubly glad to get rid of my shirt and tunic, which were stiff on one side with dried blood. From the lazaret, where I had my bath, I could see the gun platform with its machine guns, commanding every part of the Giessen Prison. The guard pointed it out to me, to quiet my nerves, I suppose, and to scare me out of any thought of insubordination. However, he need not have worried—I was not thinking of escaping just then or starting an insurrection either. I was quite content to lie down on the hard straw bed and pull the quilt over me and take a good long rest.

The lazaret in which I was put was called "M.G.K.," which is to say Machine Gun Company, and it was exactly like the other hospital huts. There were some empty beds, and the doctor seemed to have plenty of time to attend to us. For a few days, before my appetite began to make itself felt, I enjoyed the rest and quiet, and slept most of the time. But at the end of a week I began to get restless.

The Frenchman whose bed was next to mine fascinated me with his piercing black eyes, unnaturally bright and glittering. I knew the look in his eyes; I had seen it—after the battle—when the wounded were coming in, and looked at us as they were carried by on stretchers. Some had this look—some hadn't. Those who had it never came back.

And sometimes before the fighting, when the boys were writing home, the farewell letter that would not be mailed unless—"something happened"—I've seen that look in their faces, and I knew... just as they did... the letter would be mailed!

Emile, the Frenchman, had the look!

He was young, and had been strong and handsome, although his face was now thin and pinched and bloodless, like a slum child's; but he hung on to life pitifully. He hated to die—I knew that by the way he fought for breath, and raged when he knew for sure that it was going from him.

In the middle of his raging, he would lean over his bed and peer into my face, crying "L'Anglaise—l'Anglaise," with his black eyes snapping like dagger points. I often had to turn away and put my pillow over my eyes.

But one afternoon, in the middle of it, the great silence fell on him, and Emile's struggles were over.

Our days were all the same. Nobody came to see us; we had no books. There was a newspaper which was brought to us every two weeks, printed in English, but published in German, with all the German fine disregard for the truth. It said it was "printed for Americans in Europe." The name of it was "The Continental Times," but I never heard it called anything but "The Continental Liar." Still, it was print, and we read it; I remember some of the sentences. It spoke of an uneasy feeling in England "which the presence of turbaned Hindoos and Canadian cowboys has failed to dispel." Another one said, "The Turks are operating the Suez Canal in the interests of neutral shipping." "Fleet-footed Canadians" was an expression frequently used, and the insinuation was that the Canadians often owed their liberty to their speed.

But we managed to make good use of this paper. I got one of the attendants, Ivan, a good-natured, flat-footed Russian, to bring me a pair of scissors, and the boy in the cot next to mine had a stub of pencil, and between us we made a deck of cards out of the white spaces of the paper, and then we played solitaire, time about, on our quilts.

I got my first parcel about the end of May, from a Mrs. Andrews whose son I knew in Trail and who had entertained me while I was in London. I had sent a card to her as soon as I was taken. The box was like a visit from Santa Claus. I remember the "Digestive Biscuits," and how good they tasted after being for a month on the horrible diet of acorn coffee, black bread, and the soup which no word that is fit for publication could describe.

I also received a card from my sister, Mrs. Meredith, of Edmonton, about this time. I was listed "Missing" on April 29th, and she sent a card addressed to me with "Canadian Prisoner of War, Germany," on it, on the chance that I was a prisoner. We were allowed to write a card once a week and two letters a month; and we paid for these. My people in Canada heard from me on June 9th.

I cannot complain of the treatment I received in the lazaret. The doctor took a professional interest in me, and one day brought in two other doctors, and proudly exhibited how well I could move my arm. However, I still think if he had massaged my upper arm, it would be of more use to me now than it is.

Chloroform was not used in this hospital; at least I never saw any of it. One young Englishman, who had a bullet in his thigh, cried out in pain when the surgeon was probing for it. The German doctor sarcastically remarked, "Oh, I thought the English were brave."

To which the young fellow, lifting his tortured face, proudly answered, "The English are brave—and merciful—and they use chloroform for painful operations, and do this for the German prisoners, too."

But there was no chloroform used for him, though the operation was a horrible one.

There was another young English boy named Jellis, who came in after the fight of May 8th, who seemed to be in great pain the first few days. Then suddenly he became quiet, and we hoped his pain had lessened; but we soon found out he had lock-jaw, and in a few days he died.

From the pasteboard box in which my first parcel came, I made a checker-board, and my next-door neighbor and I had many a game.

In about three weeks I was allowed to go out in the afternoons, and I walked all I could in the narrow space, to try to get back all my strength, for one great hope sustained me—I would make a dash for liberty the first chance I got, and I knew that the better I felt, the better my chances would be. I still had my compass, and I guarded it carefully. Everything of this nature was supposed to be taken from us at the lazaret, but I managed, through the carelessness of the guard, to retain the compass.

The little corral in which we were allowed to walk had a barbed-wire fence around it—a good one, too, eight strands, and close together. One side of the corral was a high wall, and in the enclosure on the other side of the wall were the lung patients.

One afternoon I saw a young Canadian boy looking wistfully through the gate, and I went over and spoke to him. He was the only one who could speak English among the "lungers." The others were Russians, French, and Belgians. The boy was dying of loneliness as well as consumption. He came from Ontario, though I forget the name of the town.

"Do you think it will be over soon?" he asked me eagerly. "Gee, I'm sick of it—and wish I could get home. Last night I dreamed about going home. I walked right in on them—dirt and all—with this tattered old tunic—and a dirty face. Say, it didn't matter—my mother just grabbed me—and it was dinner-time—they were eating turkey—a great big gobbler, all brown—and steaming hot—and I sat down in my old place—it was ready for me—and just began on a leg of turkey..."

A spasm of coughing seized him, and he held to the bars of the gate until it passed.

Then he went on: "Gee, it was great—it was all so clear. I can't believe that I am not going! I think the war must be nearly over—"

Then the cough came again—that horrible, strangling cough—and I knew that it would be only in his dreams that he would ever see his home! For to him, at least, the war was nearly over, and the day of peace at hand.

Before I left the lazaret, the smart-Alec young German doctor who had made faces at the little bugler blew gaily in one day and breezed around our beds, making pert remarks to all of us. I knew him the minute he came in the door, and was ready for him when he passed my bed.

He stopped and looked at me, and made some insulting remark about my beard, which was, I suppose, quite a sight, after a month of uninterrupted growth. Then he began to make faces at me.

I raised myself on my elbow, and regarded him with the icy composure of an English butler. Scorn and contempt were in my glance, as much as I could put in; for I realized that it was hard for me to look dignified and imposing, in a hospital pajama suit of dirt-colored flannelette, with long wisps of amber-colored hair falling around my face, and a thick red beard long enough now to curl back like a drake's tail.

I knew I looked like a valentine, but my stony British stare did the trick in spite of all handicaps, and he turned abruptly and went out.

The first week of June, I was considered able to go back to the regular prison-camp. A German guard came for me, and I stepped out in my pajamas to the outer room where our uniforms were kept. There were many uniforms there—smelling of the disinfectants—with the owners' names on them, but mine was missing. The guard tried to make me take one which was far too short for me, but I refused. I knew I looked bad enough, without having elbow sleeves and short pants; and it began to look as if I should have to go to bed until some good-sized patient came in.

But my guard suddenly remembered something, and went into another hut, bringing back the uniform of "D. Smith, Vancouver." The name was written on the band of the trousers. D. Smith had died the day before, from lung trouble. The uniform had been disinfected, and hung in wrinkles. My face had the hospital pallor, and, with my long hair and beard, I know I looked "snaggy" like a potato that has been forgotten in a dark corner of the cellar.

When we came out of the lazaret, the few people we met on the road to the prison-camp broke into broad grins; some even turned and looked after us.

The guard took me to Camp 6, Barrack A, where I found some of the boys I knew. They were in good spirits, and had fared in the matter of food much the same as I had. We agreed exactly in our diagnosis of the soup.

I was shown my mattress and given two blankets; also a metal bowl, knife, and fork.

Outside the hut, on the shady side, I went and sat down with some of the boys who, like myself, were excused from labor. Dent, of Toronto, was one of the party, and he was engaged in the occupation known as "reading his shirt"—and on account of the number of shirts being limited to one for each man, while the "reading" was going on, he sat in a boxer's uniform, wrapped only in deep thought.

Now, it happened that I did not acquire any "cooties" while I was in the army, and of course in the lazaret we were kept clean, so this was my first close acquaintanceship with them. My time of exemption was over, though, for by night I had them a-plenty.

I soon found out that insect powder was no good. I think it just made them sneeze, and annoyed them a little. We washed our solitary shirts regularly, but as we had only cold water, it did not kill the eggs, and when we hung the shirt out in the sun, the eggs came out in full strength, young, hearty, and hungry. It was a new generation we had to deal with, and they had all the objectionable qualities of their ancestors, and a few of their own.

Before long, the Canadian Red Cross parcels began to come, and I got another shirt—a good one, too, only the sleeves were too long. I carefully put in a tuck, for they came well over my hands. But I soon found that these tucks became a regular rendezvous for the "cooties," and I had to let them out. The Red Cross parcels also contained towels, toothbrushes, socks, and soap, and all these were very useful.

After a few weeks, with the lice increasing every day, we raised such a row about them that the guards took us to the fumigator. This was a building of three rooms, which stood by itself in the compound. In the first room we undressed and hung all our clothes, and our blankets too, on huge hooks which were placed on a sliding framework. This framework was then pushed into the oven and the clothes were thoroughly baked. We did not let our boots, belts, or braces go, as the heat would spoil the leather. We then walked out into the next room and had a shower bath, and after that went into the third room at the other side of the oven, and waited until the framework was pushed through to us, when we took our clothes from the hooks and dressed.

This was a sure cure for the "cooties," and for a few days, at least, we enjoyed perfect freedom from them. Every week after this we had a bath, and it was compulsory, too.

As prison-camps go, Giessen is a good one. The place is well drained; the water is excellent; the sanitary conditions are good, too; the sleeping accommodations are ample, there being no upper berths such as exist in all the other camps I have seen. It is the "Show-Camp," to which visitors are brought, who then, not having had to eat the food, write newspaper articles telling how well Germany treats her prisoners. If these people could see some of the other camps that I have seen, the articles would have to be modified.

News of the trouble in Ireland sifted through to us in the prison-camp. The first I heard of it was a letter in the "Continental Times," by Roger Casement's sister, who had been in Germany and had visited some of the prison-camps, and was so pleased with the generous treatment Germany was according her prisoners. She was especially charmed with the soup!!! And the letter went on to tell of the Irish Brigade that was being formed in Germany to fight the tyrant England. Every Irish prisoner who would join was to be given the privilege of fighting against England. Some British prisoners who came from Limburg, a camp about thirty miles from Giessen, told us more about it. Roger Casement, himself, had gone there to gather recruits, and several Irishmen had joined and were given special privileges accordingly. However, there were many Irishmen who did not join, and who kept a list of the recruits—for future reference, when the war was over!

The Irishmen in our camp were approached, but they remained loyal.

The routine of the camp was as follows: Reveille sounded at six. We got up and dressed and were given a bowl of coffee. Those who were wise saved their issue of bread from the night before, and ate it with the coffee. There was a roll-call right after the coffee, when every one was given a chance to volunteer for work. At noon there was soup, and another roll-call. We answered the roll-call, either with the French word "Présent" or the German word "Hier," pronounced the same as our word. Then at five o'clock there was an issue of black bread made mostly from potato flour.

I was given a light job of keeping the space between A Barrack and B Barrack clean, and I made a fine pretense of being busy, for it let me out of "drill," which I detested, for they gave the commands in German, and it went hard with us to have to salute their officers.

On Sundays there was a special roll-call, when every one had to give a full account of himself. The prisoners then had the privilege of asking for any work they wanted, and if the Germans could supply it, it was given.

None of us were keen on working; not but what we would much rather work than be idle, but for the uncomfortable thought that we were helping the enemy. There were iron-works near by, where Todd, Whittaker, Dent, little Joe, and some others were working, and it happened that one day Todd and one of the others, when going to have teeth pulled at the dentist's, saw shells being shipped away, and upon inquiry found the steel came from the iron mines where they were working. When this became known, the boys refused to work! Every sort of bullying was tried on them for two days at the mines, but they still refused. They were then sent back to Giessen and sentenced to eighteen months' punishment at Butzbach—all but Dent, who managed some way to fool the doctor pretending he was sick!

That they fared badly there, I found out afterwards, though I never saw any of them.

Some of the boys from our hut worked on the railroad, and some went to work in the chemical works at Griesheim, which have since been destroyed by bombs dropped by British airmen.

John Keith, who was working on the railroad,—one of the best-natured and inoffensive boys in our hut,—came in one night with his face badly swollen and bruised. He had laughed, it seemed, at something which struck him as being funny, and the guard had beaten him over the head with the butt of his rifle. One of our guards, a fine old, brown-eyed man called "Sank," told the guard who had done this what he thought of him. "Sank" was the "other" kind of German, and did all he could to make our lives pleasant. I knew that "Sank" was calling down the guard, by his expression and his gestures, and his frequent use of the word "blödsinnig."

Another time one of the fellows from our hut, who was a member of a working party, was shot through the legs by the guard, who claimed he was trying to escape, and after that there were no more working parties allowed for a while.

Each company had its own interpreter, Russian, French, or English. Our interpreter was a man named Scott from British Columbia, an Englishman who had received part of his education at Heidelberg. From him I learned a good deal about the country through which I hoped to travel. Heidelberg is situated between Giessen and the Swiss boundary, and so was of special interest to me. I made a good-sized map, and marked in all the information I could dig out of Scott.

The matter of escaping was in my mind all the time, but I was careful to whom I spoke, for some fellows' plans had been frustrated by their unwise confidences.

The possession of a compass is an indication that the subject of "escaping" has been thought of, and the question, "Have you a compass?" is the prison-camp way of saying, "What do you think of making a try?"

One day, a fellow called Bromley who came from Toronto, and who was captured at the same time that I was, asked me if I had a compass. He was a fine big fellow, with a strong, attractive face, and I liked him, from the first. He was a fair-minded, reasonable chap, and we soon became friends. We began to lay plans, and when we could get together, talked over the prospects, keeping a sharp lookout for eavesdroppers.

There were difficulties!

The camp was surrounded by a high board fence, and above the boards, barbed wire was tightly drawn, to make it uncomfortable for reaching hands. Inside of this was an ordinary barbed-wire fence through which we were not allowed to go, with a few feet of "No Man's Land" in between.

There were sentry-boxes ever so often, so high that the sentry could easily look over the camp. Each company was divided from the others by two barbed-wire fences, and besides this there were the sentries who walked up and down, armed, of course.

There were also the guns commanding every bit of the camp, and occasionally, to drive from us all thought of insurrection, the Regular Infantry marched through with fixed bayonets. At these times we were always lined up so we should not miss the gentle little lesson!

One day, a Zeppelin passed over the camp, and we all hurried out to look at it. It was the first one I had seen, and as it rode majestically over us, I couldn't help but think of the terrible use that had been made of man's mastery of the air. We wondered if it carried bombs. Many a wish for its destruction was expressed—and unexpressed. Before it got out of sight, it began to show signs of distress, as if the wishes were taking effect, and after considerable wheeling and turning it came back.

Ropes were lowered and the men came down. It was secured to the ground, and floated serenely beside the wood adjoining the camp.... The wishes were continued....

During the afternoon, a sudden storm swept across the camp—rain and wind with such violence that we were all driven indoors....

When we came out after a few minutes—probably half an hour—the Zeppelin had disappeared. We found out afterwards that it had broken away from its moorings, and, dashing against the high trees, had been smashed to kindling wood; and this news cheered us wonderfully!

A visitor came to the camp one day, and, accompanied by three or four officers, made the rounds. He spoke to a group of us who were outside of the hut, asking us how many Canadians there were in Giessen. He said he thought there were about nine hundred Canadians in Germany altogether. He had no opportunity for private conversation with us, for the German officers did not leave him for a second; and although he made it clear that he would like to speak to us alone this privilege was not granted. Later we found out it was Ambassador James W. Gerard.

It soon became evident that there were spies in the camp. Of course, we might have known that no German institution could get along without spies. Spies are the bulwark of the German nation; so in the Giessen camp there were German spies of all nationalities, including Canadian.

But we soon saw, too, that the spies were not working overtime on their job; they just brought in a little gossip once in a while—just enough to save their faces and secure a soft snap for themselves.

One of these, a Frenchman named George Clerque, a Sergeant Major in the French Army, was convinced that he could do better work if he had a suit of civilian clothes; and as he had the confidence of the prison authorities, the suit was given him. He wore it around for a few days, wormed a little harmless confidence out of some of his countrymen, and then one day quietly walked out of the front gate—and was gone!

Being in civilian dress, it seemed quite likely that he would reach his destination, and as days went on, and there was no word of him, we began to hope that he had arrived in France.

The following notice was put up regarding his escape:

NOTICE!

Owing to the evasions recently done, we beg to inform the prisoners of war of the following facts. Until present time, all the prisoners who were evased, have been catched. The French Sergt. Major George Clerque, speaking a good German and being in connection in Germany with some people being able to favorise his evasion, has been retaken. The Company says again, in the personal interests of the prisoners, that any evasion give place to serious punition (minima) fortnight of rigourous imprisonment after that they go in the "Strafbaracke" for an indeterminate time.

GIESSEN, den 19th July, 1915.

Although the notice said he had been captured we held to the hope that he had not, for we knew the German way of using the truth only when it suits better than anything they can frame themselves. They have no prejudice against the truth. It stands entirely on its own merits. If it suits them, they will use it, but the truth must not expect any favors.

The German guards told us quite often that no one ever got out of Germany alive, and we were anxious to convince them that they were wrong. One day when the mail came in, a friend of George Clerque told us he had written from France, and there was great, but, of necessity, quiet rejoicing.

That night Bromley and I decided that we would volunteer for farm service, if we could get taken to Rossbach, where some of the other boys had been working, for Rossbach was eighteen miles south of Giessen—on the way to Switzerland. We began to save food from our parcels, and figure out distances on the map which I had made.

The day came when we were going to volunteer—Sunday at roll-call. Of course, we did not wish to appear eager, and were careful not to be seen together too much. Suddenly we were called to attention, and a stalwart German soldier marched solemnly into the camp. Behind him came two more, with somebody between them, and another soldier brought up the rear. The soldiers carried their rifles and full equipment, and marched by in front of the huts.

We pressed forward, full of curiosity, and there beheld the tiredest, dustiest, most woe-begone figure of a man, whose clothes were in rags, and whose boots were so full of holes they seemed ready to drop off him. He was handcuffed and walked wearily, with downcast eyes—

It was George Clerque!

It was September 25th that we left the prison-camp and came to Rossbach—eighteen miles south on the railway. The six of us, with the German guard, had a compartment to ourselves, and as there was a map on the wall which showed the country south of Rossbach, over which we hoped to travel, I studied it as hard as I could without attracting the attention of the guard, and afterwards entered on my map the information I had gained.

It was rather a pretty country we travelled through, with small farms and fairly comfortable-looking buildings. The new houses are built of frame or brick, and are just like our own, but the presence of the old stone buildings, gray and dilapidated, and old enough to belong to the time of the Crusaders, kept us reminded that we were far from home.

However, we were in great humor that morning. Before us was a Great Adventure; there were dangers and difficulties in the way, but at the end of the road was Liberty! And that made us forget how rough the going was likely to be. Besides, at the present time we were travelling south—toward Switzerland. We were on our way.

At Wetzlar, one of the stations near Giessen, a kind-faced old German came to the window and talked to us in splendid English.

"I would like to give you something, boys," he said, "but"—he shrugged his shoulders—"you know—I daren't."

The guard pretended not to hear a word, and at that moment was waving his hand to a group of girls—just the regular station-goers, who meet the trains in Canada. This was, I think, the only place I saw them, for the women of Germany, young and old, are not encouraged to be idle or frivolous.

"I just wish I could give you something," the old man repeated, feeling in his pocket as if looking for a cigar.

Then Clarke, one of our boys, leaned out of the window and said, "I'll tell you what we would like best of all, old man—if you happen to have half a dozen of them on you—we'll take tickets to Canada—six will do—if you happen to have them right with you! And we're ready to start right now, too!"

The German laughed and said, "You'd better try to forget about Canada, boys."

The guards who brought us to Rossbach went straight back to Giessen, after handing us over to the guards there, and getting, no doubt, an official receipt for us, properly stamped and signed.

Rossbach has a new town and an old, and, the station being in the new town, we were led along the road to the old town, where the farming people live. It is an old village, with the houses, pig-pens, and cow-stables all together, and built so close that it would be quite possible to look out of the parlor window and see how the pigs are enjoying their evening meal or whether the cow has enough bedding.

There have been no improvements there for a hundred years, except that they have electric lighting everywhere, even in the pig-pens. There were no lights in the streets, though, I noticed, and I saw afterwards that a street light would be a foolish extravagance, for the people go to bed at dark. They have the real idea of daylight-saving, and do not let any of it escape them.

The guards took us around to the houses, and we created considerable interest, for strangers are a sensation at Rossbach; and, besides, prisoners are cheap laborers, and the thrifty German farmer does not like to miss a bargain.

The little fellows were the first choice, for they looked easier to manage than those of us who were bigger. Clarke was taken by a woman whose husband was at the front, and who had five of as dirty children as I ever saw at one time. We asked one little boy his age, which he said was "fünf," but we thought he must be older—no child could get as dirty as that in five years!

I was left until almost the last, and when a pleasant-looking old gentleman appeared upon the scene, I decided I would take a hand in the choosing, so I said, "I'll go with you."

I was afraid there might be another large family, all with colds in their heads, like the five which Clarke had drawn, waiting for me, so that prompted me to choose this benevolent-looking old grandfather.

The old man took me home with him to one of the best houses in the village, although there was not much difference between them. His house was made of plaster which had been whitewashed, and had in it a good-sized kitchen, where the family really lived, and an inner room which contained a large picture of the Royal Family, all in uniform, and very gorgeous uniforms, too. Even the young daughter had a uniform which looked warlike enough for a Lieutenant-Colonel's. There was also a desk in this room, where the father of the family—for the old man who brought me in was the grandfather—conducted his business. He was some sort of a clerk, probably the reeve of the municipality, and did not work on the farm at all. There was a fine home-made carpet on the floor, but the room was bare and cheerless, with low ceiling, and inclined to be dark.

When we entered the kitchen, the family greeted me cordially, and I sat down to dinner with them. There were three girls and one brother, who was a soldier and home on leave.

Bromley went to work for a farmer on the other side of the village, but I saw him each night, for we all went back to a large three-storied building, which may once have been a boarding-house, to sleep each night, the guard escorting us solemnly both to and from work each day. This was a very good arrangement for us, too, for we had to be through work and have our supper over by eight o'clock each night.

After our prison diet, the meals we had here were ample and almost epicurean. We had soup—the real thing—made from meat, with plenty of vegetables; coffee with milk, but no sugar; cheese, homemade but very good; meat, both beef and pork; eggs in abundance; but never any pastry; and lots of potatoes, boiled in their skins, and fried.

There were plenty of fruit-trees, too, in Rossbach, growing along the road, and, strange to say, unmolested by the youngsters. The trees appear to belong to the municipality, and the crop is sold by auction each year to the highest bidder. They are quite ornamental, too, standing in a straight row on each side of the road.

The farmers who lived in this village followed the oldest methods of farming I had ever seen, though I saw still more primitive methods in Hanover. Vegetables, particularly potatoes and mangels, were grown in abundance, and I saw small fields of stubble, though what the grain was I do not know. I saw a threshing-machine drawn by a tractor going along the road, and one of the girls told me it was made in England. The woman who had the farm next to the one I was on was a widow, her husband having been killed in the war, and she had no horses at all, and cultivated her tiny acres with a team of cows. It seems particularly consistent with German character to make cows work! They hate to see anything idle, and particularly of the female sex.

Each morning we rode out to the field, for the farms are scattered over a wide area, and three-acre and five-acre fields are the average size. The field where we went to work digging potatoes was about a mile distant from the house, and when I say we rode, I mean the brother and I—the girls walked. I remonstrated at this arrangement, but the girls themselves seemed to be surprised that it should be questioned, and the surly young brother growled something at me which I knew was a reflection on my intelligence.

When we got into the field and began to dig potatoes, good, clear-skinned yellow ones, Lena Schmidt, one of the girls, who was a friend of the family, though not a relation, I think, began to ask me questions about Canada (they put the accent on the third syllable). Lena had been to Sweden, so she told me proudly, and had picked up quite a few English words. She was a good-looking German girl, with a great head of yellow hair, done in braids around her head. The girls were all fairly good-looking though much tanned from outdoor work. Lena had heard women worked in the house, and not outside, in Canada—was it true?

I assured her it was true.

"But," said Lena, "what do they do in house—when bread is made and dish-wash?"

I told her our women read books and played the piano and made themselves pretty clothes and went visiting and had parties, and sometimes played cards.

Of course it was not all told as easily as this sounds.

I could see that Lena was deeply impressed, and so were the two others when she passed it on. Then she began to question me again.

"Are there many women in Canada—women in every house—like here?"

I told her there were not nearly so many women in Canada as here; indeed, there were not enough to go around, and there were lots of men who could not get married for that reason.

When Lena passed that on, excitement reigned, and German questions were hurled at me! I think the three girls were ready to leave home! I gently reminded them of the war and the complications it had caused in the matter of travelling. They threw out their hands with a gesture of despair—there could be no Canada for them. "Fertig," they said—which is the word they use to mean "no chance," "no use to try further."

Lena, however, having travelled as far as Sweden, and knowing, therefore, something of the world's ways, was not altogether without hope.

"The war—will be some day done!" she said—and we let it go at that.

Lena began to teach me German, and used current events as the basis of instruction. Before the end of the first day I was handling sentences like this—"Herr Schmidt expects to have his young child christened in the church next Sunday at 2 o'clock, God willing."

Helene Romisch, the daughter of the house, had a mania for knowing every one's age, and put the question to me in the first ten minutes of our acquaintance. She had evidently remembered every answer she had ever received to her questions, for she told me the age of every one who passed by on the road, and when there was no one passing she gave me a list of the family connections of those who had gone, or those who were likely to go, with full details as to birthdays.

I think it was Eliza, the other girl, who could speak no English and had to use Lena as interpreter, who first broached the tender subject of matrimony.

Was I married?

I said, "No."

Then, after a few minutes' conference—

Had I a girl?

"No—I hadn't," I told them.

Then came a long and heated discussion, and Lena was hard put to it, with her scanty store of English words, and my recently acquired German, to frame such a delicate question. I thought I knew what it was going to be—but I did not raise a hand to help.

Why hadn't I a girl? Did I not like girls? or what?

I said I did like girls; that was not the reason. Then all three talked at once, and I knew a further explanation was going to be demanded if Lena's English could frame it. This is the form in which the question came:

"You have no girl, but you say you like girls; isn't it all right to have a girl?"

Then I told them it was quite a proper thing to have a girl; I had no objections at all; in fact, I might some day have a girl myself.

Then Lena opened her heart, seeing that I was not a woman-hater, and told me she had a beau in Sweden; but I gathered from her manner of telling it that his intentions were somewhat vague yet. Eliza had already admitted that she had a "fellow," and had shown me his picture. Helene made a bluff at having one, too, though she did not seem able to give names or dates. Then Lena, being the spokeswoman, told me she could get a girl for me, and that the young lady was going to come out to the potato digging. "She see you carry water—she like you," declared Lena. This was interesting, too, and I remembered that when I was carrying water from the town pump the first day I was there, I had seen a black-eyed young lady of about sixteen standing in the road, and when I passed she had bade me "Good-day" in splendid English.

On Saturday, Fanny Hummel, for that was the black-eyed one's name, did come out. The three girls had a bad attack of giggles all the time Fanny and I were talking, for Fanny could speak a little English, having studied a year at Friedberg. She had a brother in the army who was an officer, and she told me he could speak English "perfect." As far as her English would go, she told me about Friedberg and her studies there, but when I tried to find out what she thought about the war, I found that Fanny was a properly trained German girl, and didn't think in matters of this kind.

When the day's work was over, Fanny and I walked back to town with the three girls following us in a state of partial collapse from giggles. That night, Lena wanted to know how things stood. Was Fanny my girl? I was sorry to break up such a pleasant little romance, but was compelled to state with brutal frankness that Fanny was not my girl!

I do not know how Fanny received this report, which I presumed would be given to her the next day, for the next day was the one we had selected for our departure.