* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

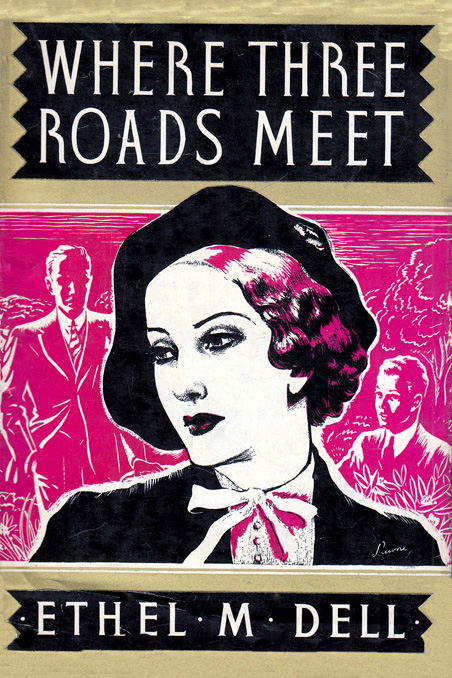

Title: Where Three Roads Meet

Date of first publication: 1935

Author: Ethel M. Dell (1881-1939)

Date first posted: Oct. 8, 2020

Date last updated: Oct. 8, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20201019

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Jen Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Electric Torch

The Prison Wall

The Way of an Eagle

The Knave of Diamonds

The Rocks of Valpre

The Keeper of the Door

The Bars of Iron

The Hundredth Chance

Greatheart

The Lamp in the Desert

The Top of the World

The Obstacle Race

Charles Rex

Tetherstones

A Man Under Authority

The Unknown Quantity

The Black Knight

By Request

The Gate Marked Private

The Altar of Honour

Storm Drift

The Silver Wedding

Dona Celestis

WHERE THREE

ROADS MEET

By

ETHEL M. DELL

RYERSON PRESS

Corner Queen and John Streets

Toronto 2, Ontario, Canada

First published 1935

Printed in Great Britain by

Greycaine Limited, Watford, Herts

F200.935

| CONTENTS | ||

| PROLOGUE | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | A Birthday | 3 |

| II. | The Mutual Benefit | 15 |

| III. | The Last Of The Line | 28 |

| IV. | The Birthday Night | 35 |

| V. | The Bosom of the Family | 42 |

| VI. | Nightmare | 49 |

| VII. | The Wheel of Life | 60 |

| PART I | ||

| 1. | The Heir | 69 |

| 2. | The Second Event | 76 |

| 3. | Travellers | 83 |

| 4. | The Mask-maker | 91 |

| 5. | The New Motto | 100 |

| 6. | The Human Wreck | 106 |

| 7. | The Summons | 114 |

| 8. | The Stables | 124 |

| 9. | The Message | 131 |

| INTERLUDE | ||

| The Ivory Mask | 141 | |

| PART II | ||

| 1. | The House of Aubreystone | 151 |

| 2. | Bedtime | 158 |

| 3. | The Lesson | 167 |

| 4. | The Stranger | 174 |

| 5. | The Gauntlet | 182 |

| 6. | The Off-chance | 191 |

| PART III | ||

| 1. | His Father’s Son | 209 |

| 2. | The Knotty Point | 223 |

| 3. | Ivor | 233 |

| 4. | The Arrival | 245 |

| 5. | Craven Ferrars | 253 |

| 6. | The Test | 262 |

| 7. | The Chance of a Lifetime | 271 |

| 8. | An Old Friend | 279 |

| 9. | A Memory | 289 |

| 10. | The Bargain | 298 |

| PART IV | ||

| 1. | The Journey | 309 |

| 2. | The Vision | 318 |

| 3. | The Meeting | 325 |

| 4. | Discovery | 336 |

| 5. | The Impossible | 343 |

| 6. | The Ordeal | 354 |

| 7. | The Choice | 365 |

| 8. | An Act of Grace | 377 |

| 9. | The Guest Night | 384 |

| 10. | The Open Grave | 394 |

| 11. | The Oasis | 402 |

| 12. | Midnight | 408 |

| EPILOGUE | ||

| Dawn | 415 | |

It was the twentieth anniversary of Molly’s birthday—a June day of most entrancing beauty—and she sat on the lower step of a stile that led into a deep green wood that was decked with coral patches of campion, and watched over a small round boy of two who sprawled in infant slumber at her feet. Only a few yards away a nightingale was pouring liquid music into the leafy glade—flute-like, elusive as the pipes of Pan—an invisible singer with the gift of a ventriloquist.

It was such music as had awakened her heart to wildest rapture three years ago, but to-day, though something within her stirred with a vague pain in response, she was not even listening to the tender, love-inspired notes. They floated past her almost unheeded. She was hearing something very different, something which had nothing to do with the splendour of June in a Kentish woodland, something which was more like a throbbing in the air than sound, something which now and then sent a swift shudder through her light frame.

Only twenty—and already a widow of nearly three years’ standing! Only twenty, and stricken to the very soul of her by that far, far rumble that was throbbing rather than sound!

The baby boy slept and heard it not; the bird sang its pure and heaven-sent song in utter disregard; but far away the earth rocked and the tremors spread like waves from the heart of the tempest. Many miles distant, the guns were roaring like giant fiends let loose, and in the fairy beauty of the June evening the still air pulsed with the message of Death. And the girl who was just twenty gripped her thin brown hands together round her knees to still the quiver of anguish that from time to time assailed her. Life was so terrible when there was time to think.

Rollo did not often fall asleep during the day-time. It was only when it was hot and sultry that his usually abounding energy ever flagged. She stooped to whisk away a fly from his rosy cheek, and looking down upon his relaxed form some of the tension went out of her own. He was so lovely in repose, perfectly shaped, like a tiny woodland faun, she told herself; and though the burning blue eyes were shut, the beauty of the black thick lashes against the apricot-shaded skin made up for their invisibility. She thought him the most exquisite thing that she had ever looked upon, not realizing that had she retained her own youthful plumpness he would have been an almost exact replica of herself.

Her eyes were blue also, but their colour was of a still bluebell intensity rather than the fire of molten spirit which was Rollo’s. Her features were straight and fair save for the warm browning of the June sun, but they were sharpened out of all childish roundness, the nose was thin, the mouth somewhat anxious; the delicate chin, very dainty in its poise, was more pointed than the chin of a girl of twenty should have been. Her brown neck was thin also, and the collar-bones stood up in strong relief. Her whole personality seemed to betoken an amount of nervous strain which was pathetic in one so young. For she still retained the look of youth—youth that had been cheated, youth that had lost its spring.

Sitting there, all a-quiver with the muttering of that hell in her ears, she looked like a lost fairy waiting on the edge of the wood for some guardian sprite to take her by the hand and give her refuge in its depths. She was indeed in sore need of refuge, but the sleeping child at her feet was the barrier that kept her where she was. The far-off thunder behind her and the green sweet glade before were mingled in the one great ache that possessed her spirit. She would fain have taken advantage of the boy’s slumber to marshal and compose her thoughts, but the pain was too present and too overwhelming. She could not crush out memory—that poignant, disturbing essence of the soul. She could not annihilate the past with those booming guns as a perpetual background, and give herself to a steady contemplation of the future. Neither could she blot out the haunting sweetness of that springtime wood that tugged perpetually at her very heartstrings.

It was impossible. A great sigh broke from her, and she stooped again over the chubby body of her little son, trying—as she had tried many myriads of times before—to stifle the heavy pain within her with the sight and touch of the beloved being who, while greatly complicating the issues thereof, alone made life worth living.

But for Rollo, she would have been across the sea in that war-tortured country where the guns were roaring, working with the zeal that smothers heartbreak to ease the sufferings of the men who stood as a living wall between England and the foe. But for Rollo, the gaping wound within her might by now almost have begun to close, lulled into some sort of dormancy by the perpetual urge of self-forgetting activity. But for Rollo, she could have hewn her own way, independent and untrammelled, and the problem which now confronted her—the ghastly problem which must be dealt with however persistently her bewildered brain might shirk the task—would never have arisen.

And yet Rollo was her whole world now, and slipping to her knees beside him she gathered him passionately close, cooing softly into his ear to soothe his frowning murmur at being disturbed. It was better to provoke a complaint from him than to continue to listen in immobility to the dumb rolling of those terrible guns.

The nightingale sang on, spreading the illusion of peace in a war-racked world, and the girl who knelt at the edge of the charmed wood heard its rhapsody with a kind of quailing amazement. There was something almost awful in its unconscious sweetness. She wondered if any man hanging from a gallows at a cross-roads had ever heard the singing of a bird close by ere his soul had escaped from his agonized body. Beauty and destruction dwelling side by side—love and death forever mingled!

She hid her face against her baby’s soft round body and prayed a broken prayer. “O God, deliver us—from evil! O God,—deliver us—deliver us!” . . .

A long time passed before she looked up—not until the nightingale, grown tired, had dropped into silence.

Her face when she did so was strangely composed; it even had a fateful look. There was a baby’s chair on wheels on the other side of the stile. With the child in her arms, she got to her feet and climbed carefully over.

He was very sleepy and complained again as she did so, but she hushed him tenderly and laid him for a moment in the grass while she returned for the rug. This she spread in the chair, arranging it as far as possible to accommodate his relaxed figure. It was growing late, and she told herself reproachfully that he ought to have been put to bed long ago. Just because it was her birthday she had come to this enchanted wood, and it had been foolish as well as selfish of her to have done so. For the place was haunted by ghosts of the past.

It was here—it was here—only deep in the green shade of the trees—that Ronald Fordringham had first thrown his eager arms about her and held her against his breast. The memory of that first overwhelming kiss went through her like a stab, transfixing her heart. It was sheer anguish, yet she clung to it with closed eyes for a few moments.

“Roy!” she whispered. “Roy! My Roy!”

Then again the shuddering vibration in the air that was scarcely sound came to her. She set her lips resolutely and looked up.

A shadow had fallen over the quiet woodland. The nightingale had ceased to sing, and all was still. Only the throbbing of the guns remained.

She drew a long, hard breath and, stooping, lifted little Rollo from the grass. He opened his eyes as she did so, and, smiling, stroked her face. Something in the action pierced her composure, catching her unawares. She gave a quick sob, but in a moment, seeing his round face begin to crumple, she turned it into a laugh, shaky but determined.

“Little darling! And you’re so tired!” she said. “We’ll go home quick—quick—and you shall have your lovely milk and biscuits and go to bed.”

She settled him in the chair, softly kissing him, and laughing again when he tried to clasp his fat arms round her neck.

“Mum—Mum—Mum!” he crooned.

“We must go home, Rollo,” she said, and strapped him in with tender care. “What will poor Granddad say?”

Rollo had no suggestions to make on this point, but, having now quite recovered from his drowsiness, he said a great deal in a language of his own about nothing in particular. He could be very talkative when the spirit moved him, and his mother’s smiling encouragement always spurred him to fresh effort. She was ever an appreciative listener.

The hay was lying in the fields through which they returned. They had some distance to traverse, but there were no more stiles to negotiate, and dark clouds had rolled up to obscure the sun, so that the heat, though still oppressive, was less intense.

Molly moved quickly, as if hastening to leave the haunted wood far behind her, and the elasticity of youth was in her gait if the fire of it no longer quickened her veins. A lovely warm flush bloomed on her sun-tanned face. She gave soft crowing answers to her baby boy in response to his unintelligible speech. They had almost developed a language of their own with which he at least was hugely content.

It took nearly half an hour of quick walking to reach the road that led to the village, but it was a relief to be moving after the emptiness and pain of that strange birthday-treat of hers.

“I mustn’t go again,” she told herself, as she opened the last gate that led out on to the highway. “I won’t—ever—go again.” But somehow it hurt her to say it, as though it had been a disloyalty to Ronald—that dearly loved and adoring lover who would never come to her again.

Out on the road the journey became both physically and spiritually easier. There was no traffic, and she was able to increase her pace. Rollo ought to have been in his bath nearly an hour ago. No wonder he had become sleepy in the wood! She would be busy now for the rest of the evening, and she was glad. She would be more glad still when her birthday was past. She was getting too old for birthdays, she decided. The ordinary humdrum days were much easier to cope with.

So, with Rollo’s funny broken chatter in her ears, she came at length within sight of the first cottage of Little Bradholt—her native village. It was a picturesque spot—typical of the English by-ways. Practically all its houses were ancient, and it had a green with a pond in the middle. There were also two yew-trees of great antiquity which once might have helped to point the way of pilgrims to the saintly shrine of Canterbury; for these yew-trees were continued at uneven intervals beyond the park gates of Aubreystone Castle where the lords of the manor had reigned from time immemorial, possessing and governing Little Bradholt in a long line of succession which claimed direct descent from a baron who had arrived with William the Conqueror.

Molly had always regarded the Aubreystone family with a certain amount of awe. They had always done their duty unfailingly by the village which they owned. It was a model place in every respect. Old Lady Aubreystone was a terrible person, firm of lip and strong of will. No one ever smiled in her presence without her permission. She had known many sorrows, but they had left no apparent mark upon her. Her husband had been killed years before in the hunting-field. People believed that she had been deeply attached to him, but they had no means of knowing it. She had borne him four sons, of whom one only—the present Lord Aubreystone—remained. He was the youngest of them. The two above him had been killed, one in France and one at sea, and his eldest brother and immediate predecessor, with his wife, had fallen victims to one of those mysterious diseases manifesting themselves in England at that time which were commonly regarded as having their origin in the trenches and battlefields of Europe. They had died childless. Lord Aubreystone himself at the age of thirty-eight was unmarried, and for the first time almost in history the fate of the family succession hung in the balance. He also was in the Army and had seen Staff service in Egypt, but—it was whispered, through desperate efforts on his mother’s part—he was now employed in a responsible position at the War Office, and likely to remain there until the War was over.

If indomitable human will could be held as a deciding factor in the destiny of any single being at that time, then this youngest son, who had never expected to enter upon any sort of heritage, was safe until such time as he should marry and beget a son. His mother had never greatly cared for him before, but now her whole soul was centred upon the achievement of this end. It had become almost an obsession with her, and nothing else counted in the whole of her existence. He was the only thing left in a world of complete desolation, and if she entertained but slight affection for the man himself, her whole being was wrapped up in the accomplishment of her end, and he was the only means remaining.

Besides her four sons, she had given birth to three daughters, the eldest of whom—the Honourable Caroline—had never married, and, at the age of fifty-six, was her mother’s right hand, or perhaps it would be fairer to describe her as an auxiliary, had such been required. The two younger daughters had married, possibly to escape the stringency of the maternal rule. But Caroline was understood to scorn all men, and only to her mother did she accord any sort of deference. Treading in her father’s footsteps, she led a sporting life, following the hounds every season with unfailing regularity and very often leading the field. In many ways she closely resembled Lady Aubreystone, being hard of feature and gruff of speech, and they were generally regarded as a redoubtable pair. But in Molly’s opinion the daughter was almost more formidable than the mother, and she often marvelled that two people of such pronounced character could continue to live together. But if they ever quarrelled, it was behind closed doors, and not even the servants of Aubreystone Castle knew it. Lady Aubreystone often made very crushing remarks to this single daughter of hers, but she never provoked any reply in the hearing of anyone else beyond a somewhat raucous and sarcastic laugh. Caroline had never been beloved by her mother on account of her sex, but she was by no means downtrodden on that account. In fact, some people were uncharitable enough to say that she was merely biding her time till old age should incapacitate the tyrant of the family. There was no doubt that so long as Caroline lived, a tyrant in the house of Aubreystone would not be lacking.

All this Molly knew and appreciated to the full with a somewhat quailing apprehension. Her thoughts dwelt upon it as she wheeled little Rollo past the village green towards her father’s tumbledown abode next door to the village inn. But though she quailed, she braced herself with resolution to meet the future which somehow—for Rollo’s sake—seemed inevitable. Her vigil in the wood was over, and Ronald—her lover—was gone from her. Hope was long since dead within her so far as he was concerned. Rollo alone was left. And for him there could be no future at all unless she embraced the destiny held out to her.

For Lord Aubreystone, urged by his mother, had at last begun to look around him for a wife, and—to Molly’s vast amazement—he had decided that she was the only one who could occupy that high position to his satisfaction and to the comfortable fulfilment of his ambition to perpetuate the succession.

That his choice should have fallen upon her seemed to be mainly due to the fact that she alone was always to be found in the same place and available when wanted. All other women were occupied in some national work that called them in all directions. Molly only—so it seemed—had home duties to occupy her, a house to run, a father to care for, a baby to tend. She was always on the spot whenever he had time to spare to visit his ancestral home, and at first idly, but now seriously, his fancy had been caught. She seemed somehow to be planted there in readiness for his requirements, the very thing he needed; too gentle and unsophisticated to clash in any way with his redoubtable mother and sister—probably quite useless from a hostess point of view, but who wanted hostesses in these hard days of war? And doubtless, being young, she would prove adaptable and easy to train if ever the necessity should arise. Caroline could teach her. Caroline knew everything; even if his mother should fail, which in itself was almost unthinkable. He fully recognized that something ought to be done towards providing an heir, and this girl was already the mother of a bouncing baby-boy, whom he would have given a good deal to have called his own. Of course her father was a drawback—a man who had never been a success in life, trained for a schoolmaster, but without the ability to teach, and now stricken with heart-disease. But his days were so obviously numbered that he was hardly worthy of consideration.

Molly was the thing that mattered and upon which he had set his heart. Matrimony had never appealed to him before. A fourth son, without prospects, could hardly expect to please himself in such matters; but now that matrimony was practically forced upon him, and with Molly Fordringham all ready to his hand, so to speak, he was quite prepared to approach the matter in a proper spirit, prepared even to adopt her son and educate him as he hoped to educate his own.

It was this—and this alone—which held any attraction for Molly. Her husband had possessed genius, or so she imagined, but his career had been cut off at its very beginning, and when he had met his fate in the trenches he had been merely a private in the British Army. Her father was even now living on the little he had been able to save and when that was gone, there would be only her widow’s pension left. She might work. She was willing to work; but she could never hope to make enough to give Rollo a fair start in life. And Rollo too had genius. She was certain of it. His astuteness and inventive powers often astonished her even at this stage. He would make his mark some day, but if she threw away this one great chance he would be hopelessly handicapped by poverty.

She had no right to throw it away. She owed it to him—and even in a sense to Ronald—that greatly beloved one who had never even known of his son’s coming—to enlarge the scope of his opportunities to the utmost limit.

Ivor was not deeply in love with her. She had sensed that already, she to whom love meant so much. So, if she brought herself to accept him, she would be doing him no wrong. For she knew within herself that she could never love again. Soul and body shrank together from the prospect of re-marriage—true union it could never be. But for that very reason she would be giving more than she received. To her personally it would be as the burnt offering of her very self. To Ivor—Lord Aubreystone—it would be quite possibly the most enjoyable episode of his life, and probably the accomplishment of what had become the main ambition of himself as well as of his mother.

No, he would not be a loser. She would play an honest game with him, even though she did violence to every instinct of her being. He was coming to her to-night for her answer, from his castle on the hill to her humble dwelling-place in the little village below. And she felt—albeit with a shrinking perception—that she knew already what that answer was going to be—though something closely imprisoned within her was crying out wildly through its confining bars that it was wrong—wrong—wholly and most horribly wrong.

Her father was out when she reached the cottage. He often went forth for his slow walk in the cool of the evening. He would probably linger about in the scented lanes until supper-time.

She had put everything in readiness for that simple meal before leaving the house, and there remained only Rollo’s milk to warm up. She carried him into the kitchen with her and there let him toddle about while she prepared it. He took the keenest interest in everything, and she had to keep a sharp eye upon him to save him from the pitfall of the coal-scuttle which possessed an irresistible attraction for him. He was perfectly good-humoured over this frustration, for he knew already that she would never refuse him anything within reason, and he had a baby adoration for his mother which was greater even than his spirit of adventure. His faith in her judgment was absolute, and on the very rare occasions when she was obliged to rebuke him he invariably wept inconsolably, not as a spoilt child weeps, but from sheer heartbreak. Molly was his whole world, and he had a shrewd suspicion that he was hers—poor old Granddad coming in a very bad second. As a matter of fact, Granddad counted for so little in his life that he was apt to regard him with something of contempt. He was not even as interesting as the aforesaid coal-scuttle, and there was one fact in relation to him which Rollo resented acutely. He was never allowed to make a noise in his vicinity, and as making noises was at that time one of his chief joys, perhaps he was hardly to be blamed for trying to scamper in the opposite direction whenever he heard the slow and rather shuffling step approaching.

He was extremely pleased on that June evening that he and Molly had the cottage to themselves. After his nap in the wood, he was by no means anxious to have his energies quenched a moment sooner than was necessary. It was such fun to potter round and hammer things just as the fancy took him, and—except in the matter of the coal-scuttle—Molly was very tolerant. She even laughed at him once or twice, showing her pearly teeth in a fashion which Rollo found quite entrancing. He would have paid her a great many compliments had he possessed the vocabulary. Certainly she would never lack an admirer while the breath remained in his sturdy young body. She would always be exquisite in his sight—as he would be in hers.

The heating of the milk was not a lengthy operation, not nearly lengthy enough for Rollo. Armed with a saucepan-lid he was beating everything with which he came into contact with uproarious enthusiasm, and it was hard to be deprived, however gently, of this fascinating weapon.

But Molly was firm. It was already past bedtime, and the undressing and bathing process had still to be accomplished. Tenderly silencing his protests, she led him up the old rickety stairs that emerged rather disconcertingly into the tiny little room in which he slept. There was a gate at the top which she was careful to close. So much a rule of the household was this that Rollo himself always closed it if Granddad, who was inclined to be absent-minded, failed to do so.

A door out of Rollo’s chamber which was perpetually open led into Molly’s, and another which was kept shut and through which Rollo was never allowed to wander led from hers to that of her father. The rooms were low, and it was very hot. Rollo’s little tub, poured out in the early morning, was quite tepid by evening, a device which in summer saved a considerable amount of trouble. In the winter months he took his bath in the kitchen.

He played his usual joke of trying to get into it without undressing, and received the usual phantom slapping from Molly with shrieks of delight. She had a most satisfying sense of humour where he was concerned. That little farce over, he submitted with a good grace to being divested of his few garments, and then proceeded to wallow in his bath with great contentment.

He splashed rather more than usual that evening, but Molly uttered no reproof. When Rollo was not making a definite bid for her notice, she was inclined to be abstracted. Behind his back her brow was puckered in deep thought. When at length he was ready for supper and bed she held him closely in her arms for several silent moments. Then, when he was in his cot at last, she set about putting everything in order in a mechanical fashion, and finally drew the curtain and left him to sleep while she went downstairs to lay the supper.

It was very quiet in the little oak-beamed parlour. Only the gruff voices of a few old men in the bar of The Plough next door were audible now and again. The lattice-windows were wide open, but no air was stirring. It would be a hot night up under the slanting roof.

She was tired after her walk in the fields, but she scarcely knew it. She was conscious only of a dreary sense of being pushed forward—a helpless pawn in the game of life—whither she had no desire to go.

When she had finished she dropped down upon the window-seat and leaned her head against the woodwork with a sigh. Evidently Rollo had fallen asleep. The drone of bees in the old-fashioned pinks outside gave an illusion of restfulness. She tried to marshal her thoughts for a final review of the situation before her father should return.

But weariness tricked her, and before she had even realized that she was drowsy she had dropped into a doze. It was scarcely sleep, but rather that floating state of consciousness between slumber and waking in which visions sometimes take shape. And for the first time in all the long aching period of loss and bereavement, in a dream that did not seem to be a dream, she saw her husband. He was very far away from her. She might have been looking through the wrong end of a telescope; but his figure, his attitude, were quite unmistakable. His face, owing, apparently, to some flaw in the medium through which she looked, was as though veiled. She felt, rather than saw, his eyes. And in the same fashion she sensed—rather than heard—his voice.

“I’m not dead, Molly,” he said. “I can’t come back to you. I can never come back. But I’m not dead.”

She clasped her hands fast together. The words seemed to go through her, setting every pulse and nerve a-quiver. “Sweetheart!” she said. “Sweetheart, I’ve never thought you dead. No one like you could die.”

“No—not dead,” he said again. “Only—gone away. Think of me—like that, dearest—and love me still!”

“Love you!” she cried, and suddenly speech and breathing were alike choked with sobs. “My darling, as long as I live I shall love you—first—and best—and always.”

“Ah!” he said, and there was a pause.

Into it she cried with a wild and piteous entreaty. “Ronald—Roy—darling—don’t go away! Tell me you love me too! Tell me—tell me!”

The vision was fading like a shadow from a screen. Her very agony was defeating her, bringing her out of her trance. But ere her full physical consciousness claimed her again, she caught—or thought she caught—a wandering echo from the eternal spaces: “Only God knows—how much.”

Sobbing she awoke and started up between anguish and ecstasy. That his spirit had for those few fleeting seconds found hers, she had no shadow of doubt. It had been soul-communion of an unfathomable description. Most people would have called it a dream, but Molly knew otherwise with that deep conviction which defies all reasoning. Somehow the gulf between them had been bridged; she did not ask how. She only knew that it was so. His body might lie in a nameless grave among all those myriads in the land where the guns were thundering, but his spirit was alive and able to call to hers. It filled her soul with awe and longing. She had a wild yearning to cry out to him again, but something held her back. Something told her that the means of communication had been cut off and she would cry in vain.

Dazed and strangely bewildered, she put her hand to her head and stood listening. It was then that other sounds, purely of earth, came to her—the quiet and purposeful tread of a man’s feet on the narrow flagged path outside. Someone was coming up to the door, and she knew who that someone was. Her heart gave a hard, sickening throb that seemed to constrict her throat. She waited without breathing for a knock upon the panels.

But it did not come. There was a moment’s pause, and then a voice spoke instead, and she remembered that the door was open.

“Can I come in?”

The voice had breeding and a semi-conscious note of superiority which yet was free from intentional condescension. Molly freed herself with a violent effort from the invisible bonds which seemed to be holding her. “Of course! Come in!” she said.

He entered, bending his tall frame to do so. He was a fine man, well-proportioned, self-possessed. All the Aubreystone family were thus distinguished. His hair was brown and rather sparse, his eyes a calm mid-grey.

“Well, Mary!” he said. “I am a little early, but I thought I should find you in. Are you alone?”

He held out his hand to her—a cool, steady hand that closed upon hers before she even realized that she had moved in response.

“There has been an air-raid warning,” he continued with the utmost composure. “They probably will not pay us a visit or waste any bombs upon us if they do. But I thought I would come all the same.”

“My father’s out,” said Molly somewhat breathlessly. “Do you think——”

“He is quite as safe out as in,” said Lord Aubreystone. “There is no need for anxiety. As I said, a place like Little Bradholt is quite unworthy of their notice. They probably will not even pass over it.”

“Oh, I hope not,” murmured Molly. “I think I will run up and fetch Rollo.”

“My dear child—ridiculous!” protested Lord Aubreystone. “This cottage is no more likely to be struck by a bomb than by a flash of lightning. The chances are infinitesimal. We must allow ourselves a little commonsense. Leave the poor child in peace!”

He smiled at her with the words, and, though nervous still, Molly felt reassured. His deductions were so abundantly obvious, and she did not want to startle Rollo unnecessarily now that he had settled down to his night’s rest.

“Won’t you sit down?” she suggested.

“May I?” said Lord Aubreystone.

He had kept her hand in his, and he drew her down beside him on the couch, as if to give her confidence.

“You know what I have come for, don’t you?” he said.

“Oh!” said Molly.

She made a little movement to draw her hand away, but he detained it in a quiet but slightly imperious grasp.

“We are going to be very sensible,” he said, and there was a hint of admonition in his voice, “and treat the matter as, in my opinion, these matters always should be treated, in a frank and business-like spirit. Believe me, I am not pretending that in offering you marriage, I am proposing to place you irretrievably in my debt. It is true that in my position I have a good deal to give, but you will give in return. It will be a mutual benefit. So you need not feel overwhelmed from that point of view.”

“Oh, I haven’t—I don’t,” began Molly tremulously.

He swept her scarcely heard rejoinder aside.

“There are many ways of giving,” he said, “just as there are many ways of withholding, as I am sure you realize. I am prepared to give a considerable amount myself. In fact, there is nothing in reason which I would deny you. I think that is the sort of spirit at which we ought to aim, in order that the foundations of our mutual happiness may be well and truly laid.” He smiled a little and pressed her hand more closely. “Don’t you agree with me?” he asked.

Molly snatched at her ebbing courage, aware that she was being borne down by superior weight and wisdom before she had been given a chance to express her own point of view. She quivered with embarrassment as she made her stand, but her voice was resolute and her look unwavering.

“I am very sorry,” she said, “if I have let you understand that everything is settled. I’m afraid it isn’t. I think I ought to have said ‘No’ from the very beginning. You see, Lord Aubreystone, there are some things which it isn’t in my power to give. I ought to have told you that—only you wanted me to take time to consider.” She paused in distress.

“Come—come!” he said. “We’re not going over all the old ground again, are we? I’m not proposing to be a very exacting husband. I haven’t asked you to fall deeply in love with me, for instance.”

Molly shivered. “I am sorry,” she said again. “That’s just it. I’m afraid I am the sort of person that only does that once.”

“Well?” he queried. “And does that make it impossible for you ever to have any sort of affection for anyone else again?”

“No,” said Molly. She paused, but her steadiness was returning and she faced him unflinchingly. “It only makes it impossible for me ever to forget that once.”

“I understand,” said Lord Aubreystone. He made a large and tolerant gesture with his free hand. “You want to keep your little garden of memories undisturbed. Well, my dear, you are quite at liberty to do so. I fully realize that every nature must have its reserves, and I should be the last to wish to trespass upon ground which I have no doubt you regard as sacred. You have had your day of happiness and it has been all too short. You think you can never be happy again. At twenty years of age, one does,—and I must not forget that it is your birthday. I have not forgotten it. But you must forgive me if I fail to recognize in your objection a serious obstacle to our marriage. In my opinion it merely constitutes a further reason for urging it upon you.”

He stopped, looking at her with kindly temperate eyes that somehow made her feel that she was being childishly unreasonable. She turned away from them with that desperate sense of being overborne.

“Don’t persuade me too hard!” she begged in a low voice, “There are some things it’s impossible to explain which make it very difficult for me.”

“That I can quite understand,” he said. “You have had a very tragic experience, but I don’t think you are quite justified in letting it spoil your whole life. Remember, it is not only yourself that you have to consider!”

“Oh, I know—I know!” Molly said, and released her hand almost forcibly to rise to her feet. “That’s what is troubling me so. Little Rollo! But he is his child. It seems like an act of treachery.”

She began to pace the uneven floor, while he stood punctiliously attentive, watching her, still in a fashion controlling her, or so she fancied.

“My dear,” he said after a moment, “I think you’re taking rather a morbid point of view. There can be no talk of treachery to one who is dead.”

She turned round, her face curiously convulsed. “Dead to you!” she said. “To me—never—never!” She stopped a second or two to steady herself; then: “He is as much alive to me,” she told him, “as if he were upstairs at this very moment with Rollo. In fact—I don’t know—he may be. He was with me—only just before you came in.”

“My dear Mary!” said Lord Aubreystone.

She advanced towards him, her hands clasped tightly over her breast. Her eyes were strangely bright; she seemed to be looking beyond him. “I know it sounds absurd to you,” she said, speaking rapidly but very clearly. “And I admit it is purely a spiritual connection. But it is there, and nothing will ever alter it. You must understand that, if you really want to marry me. There may be times when he will be so close to me that nothing else will count—times when I must walk in my secret garden and be alone with him.”

She ceased to speak, her face still strained and unnatural, her whole attitude one of tense aloofness.

But her companion betrayed neither resentment nor discouragement. He merely smiled at her compassionately.

“My dear,” he said, “I quite understand. All this is quite comprehensible—almost inevitable to any but a superficial nature. But I assure you, it does not count with me. The world is full of grief, especially at the present moment, and it behoves us to make the best we can of the unfortunate circumstances in which we find ourselves. You are young and, whether you realize it or not, your trouble is partly physical. That is the part which I shall hope to heal. I have no desire to intrude upon any spiritual territory. I am merely asking you to place your physical well-being in my hands. I am quite willing to leave anything beyond that to take its ordinary course.”

“You want me to bear you children,” she said in a voice that sounded too weary to express active repugnance.

He made a slightly deprecatory gesture. “I think it would make for your own happiness as well as mine that you should do so,” he said. “You are too young to live alone. And it would make for Rollo’s happiness also. An only child is always handicapped, and, as I have already promised, though I could not make him my heir, he would share all educational advantages with any children of my own.”

Her lower lip twisted as if from some sudden pain. She turned from him with an almost fierce movement. “Oh, I know it’s only the body,” she said, “but I don’t think I can—I don’t think I—possibly—can.”

It was at that moment that through the summer stillness there came a sound—a humming as of a swarm of bees high up in the air—a disturbance of the atmosphere that seemed to drift down as it were from another planet.

Lord Aubreystone heard it and sharply turned his head towards the window.

In the little inn next door a dead silence had fallen, but almost immediately, as the sound swelled, a voice cried out, “That’s them! They’re coming! They’ll be over us in another minute!”

It was the voice that reached Molly rather than the sound to which it alluded. Her expression changed to swift alarm.

“Oh!” she gasped. “An air-raid!” and sprang to the door.

In a moment her light feet were running up the steep stairs, and the man was left alone.

He leaned from the window and listened. The sound was approaching very rapidly. It no longer resembled the humming of bees, but was obviously the roar of machinery overhead. The heavy foliage of some chestnut trees obstructed his view, but he judged that the advancing horror was at no great distance.

And then suddenly—like a thunderbolt—it came. Something swift, piercing, appalling, fell from the heavens. A thunderous crash and a roar in the village street—a fearful smell of explosive—flame and smoke and shrieks—all intermingled like a ghastly nightmare! And after it the running to and fro of many figures, and the cracking and smashing of falling masonry—while the terrible death-machine sped on in search of its objective a few miles beyond.

There came a child’s frightened crying from the room above, but it was swiftly drowned in the general commotion outside.

“It’s the church!” shouted a man’s voice, and another, “No, it’s the school!”

And then suddenly the little garden gate was pushed open, and a scurrying, dishevelled countrywoman tore up the path. She was calling out hysterically at the top of her voice.

Lord Aubreystone went to meet her, gripped her and held her up as she stumbled at the step. She practically fell into his arms in the doorway.

“Steady! Steady!” he said. “It’s no good panicking. You’re as safe here as anywhere.”

“Safe!” she screamed. “Safe! There’s a whole crowd more of ’em up there. I seen ’em as I run along the street. And I’ve come to tell Mrs. Fordringham as ‘er poor father is lying dead in the road.”

Old Lady Aubreystone sat in her boudoir, very upright, unbendingly self-assured, facing her son who, somewhat stiff and ill at ease, sat opposite and smoked a cigarette.

They had been talking for some minutes, but a silence had fallen, and the mother was better at silences than the son. She conducted the present one with an air of magisterial equanimity which was weightier than any speech. She had very nearly—though not quite—said all that she had to say.

Of this Ivor Aubreystone was aware, but he knew better than to attempt to hurry her. Given plenty of time she would probably express herself with less acerbity.

She spoke, and he stirred in his seat as if he had found a thorn.

“I am sorry,” she said, “that your ambitions have not led you to look any higher than the daughter of an out-at-elbows pedagogue, but I suppose I should be grateful that your fancy has not directed you in any less desirable direction. I do think, however, that I might have been consulted before you actually brought this girl and her child on to the premises.”

Her son shifted his position again and cleared his throat. “As to that,” he said, “I should quite agree with you, Mother, if the circumstances were normal, but they are not. The poor girl was left with a choice of sleeping in a tiny cottage with her dead father lying in the sitting-room, or finding a lodging next door at a cheap and by no means commodious village inn. I could not have allowed that, for, as I have already told you, it is my full intention to make her my wife within the next week if possible; and in consideration of that, I thought it the most natural thing to do to bring her here to you for shelter.”

Lady Aubreystone bent her head slightly. “I can appreciate that, but as I scarcely know her, perhaps you also can appreciate that I am hardly in a position to receive her with enthusiasm. Of her antecedents—and of her previous marriage—I know nothing whatever. I hope that you have taken some steps to satisfy yourself upon these points.”

Ivor made another small movement and brought his grey eyes directly to hers. “I knew her father,” he said. “He was a gentleman of the old school—the scholarly type. I did not know her husband, as he did not live here. He was, I understand, the son of an old friend of her father’s, now dead. But the child is obviously of decent birth, and I only hope that I may some day possess a son as presentable.”

A quick gleam shone in his mother’s eyes at the words. He had sounded the right note. “In that respect,” she said, “I entirely agree with you. And for that reason alone I do not altogether condemn your idea of a hasty marriage. The matter is one of great urgency, and in these days of battle and murder, etc., it seems almost criminal to count upon the future. Even to-night, for instance, you might have been caught by that bomb—and you are the last of the line.”

“Quite so!” Ivor’s mouth twitched a little, but he had deliberately conducted the conversation into this channel and he could hardly take exception to a remark which he himself had intended to utter, had the necessity arisen. “I am glad you realize that,” he said. “We don’t want to risk a complete wipe-out like that. By the way, the bomb itself did no actual damage beyond knocking down the churchyard-wall. Mary’s father died of shock, not injury. But there is no knowing what might happen next time. As you say, we can’t count on anything. I am going to make that clear to Mary herself, for she is rather inclined to try to delay matters.”

“Indeed!” Lady Aubreystone suddenly became more upright. Her black brows met. “D’you mean to tell me that this girl—this little village nobody upon whom your choice has fallen—considers herself to be in a position to dictate terms—to you?”

Ivor smiled, and the tension went out of his attitude as he rose. “No, Mother, no! She will be most reasonable, and I am sure most grateful. But she is a faithful little soul, and still worships the memory of her dead husband—probably more than she would his actual presence if she had it. She will get over all that as soon as she has other things to think about. She would probably have forgotten it long ago if she had not been cooped up in such a narrow space and thrown back on herself at every turn. Her father was a dreamer and no help to her whatever, and the child is only just beginning to be old enough to be interesting. She must have other children—plenty of them. That will take her mind off back numbers.”

Lady Aubreystone smiled somewhat grimly. “I hope you are right,” she said, “and that she will at least be prepared to do her duty in that respect. For, frankly, Ivor, to my mind the situation is desperate. I could never give my consent to your marrying such a girl were it not that she would probably have greater health and strength for the production of children than anyone of your own standing. One puny heir is not enough. I should like to see you with at least four sturdy sons to your credit, and even they”—her voice trembled a little—“might not be enough.”

He came across to her and patted her shoulder. “That’ll be all right, Mother. Don’t fret or be anxious on that score! Mary knows my wishes, and I have no fear that she will not be able to supply them. But you will be kind to her, Mother, won’t you? She is shy and unused to grandeur. I had great difficulty in persuading her to come here. In fact, I almost brought her by force.”

“She will have to do as she is told,” said Lady Aubreystone with firmness.

“Yes, of course,” agreed her son patiently. “I know you will find her very amenable and get very fond of her. But please be kind to her now, for she is in very great trouble! And I think a good deal depends upon your attitude in getting her to agree to the immediate marriage which we both think desirable. She wants to stop and think. But, Mother, there is no time for that. She must take life as it is and make the best of it. Everyone has to now.”

“But of course!” said Lady Aubreystone. “And she ought to consider herself very lucky into the bargain. Surely she realizes that you are doing her a very great honour!”

“Yes, yes, I am sure she does. But she is scared. Goodness knows she has had enough to frighten her, poor child! I want you to guide her, Mother, to help her and advise her. When we are married, it will all be very much easier, but until then—oh, don’t you see she may be frightened away altogether?” Ivor’s voice had a note of urgency.

His mother looked sardonic. “Very unlikely, I should say!” she remarked. “But I see your point. If it must be this girl, and you certainly haven’t been in a hurry to marry till now, I will see what I can do to further your wishes. Heaven alone knows what is going to happen to us all, but it is no good thinking of that. We can only act for the best.”

“And quickly,” said Ivor with emphasis. “Thank you, Mother. I am very grateful to you.”

He turned to the window and stood looking out over the valley and winding river below the Castle garden, his brows slightly drawn as though the situation had not developed entirely in the direction he desired.

His mother’s voice came after a pause from behind him. “Well, there’s no more to be said, except that I remain the mistress here—which seems superfluous.”

Ivor barely turned his head. “My dear Mother, of course! No one ever suggested anything else. You will find her most unassuming. All she has ever done hitherto has been to run her father’s cottage and look after her baby.”

Lady Aubreystone sniffed a little. “She sounds an absolute rustic, but we may be able to make something of her if she is willing to learn. Have her in if you like, and I will speak to her!”

He turned round. “Mother, don’t—please—treat her like that, or I shall have to take her away! I intend to marry her, and I also intend that she shall be happy. But if I can’t count upon your helping me to make her so——”

“And have I refused to do so?” His mother’s voice was stiff with righteous indignation. “Have I done anything whatever to obstruct your wishes? You have expressed your desires—or should I say your intentions?—and I have so far done my best to fall in with them. But, my dear Ivor, there are limits, and you are very nearly approaching them. I may remind you that, but for the absolutely exceptional circumstances, nothing would have induced me to agree to the type of alliance which you are about to make. It is wholly against the principles which I have observed throughout my life.”

“I quite understand,” said Ivor, and he also spoke stiffly though with a certain wariness. “But we are agreed that circumstances have altered this particular case, so there is no need to go into it again. All I do say is that in her present frame of mind it would take very little to scare her away entirely, and I must beg you to consider her feelings and to treat her as a guest and not an interloper.”

“As to that,” said his mother, “I reserve to myself the right to treat her exactly as I choose. I have never been dictated to by any of my children before, and I am not going to submit to such a state of affairs now.”

Ivor swallowed back all rejoinder with an obvious effort. There was a note in Lady Aubreystone’s voice that warned him that he could not afford to lose any further ground. He had never loved her, having always been aware that her feeling for him was of a very tepid description. It was only of late that he had entered into her scheme of life at all. Who could have foreseen that a fourth son would ever inherit the family title and honours? He had been a mere adjunct for the greater part of his existence. But he could not afford to quarrel with her, nor had he any wish to do so. He was not naturally aggressive, and he liked a quiet life.

So after a few moments he walked quietly to the door with the remark, “I will see if I can find her.”

And Lady Aubreystone was left to contemplate her approaching dowagerhood in solitude.

That birthday of Molly’s was destined to be branded upon her as it were in letters of fire for the rest of her life.

The awful shock of her father’s death and the masterly removal of herself and her child from the old tumbledown cottage which they called home, bereft her for the time of the power to think coherently, and when her full faculties returned she found herself an inmate of the Castle and almost, it seemed, a prisoner. How it had come about she hardly knew, but a will that was stronger than hers now encompassed her, and her own fate as well as that of little Rollo had passed out of her control. Circumstances had combined to defeat her, and she was no longer capable of resistance. As one borne upon an irresistible current she was swept forward towards an unknown goal, and however she might fear the issue she lacked the strength to hold back.

When Ivor came to her that evening, she was crouched in a low chair beside the bed in which Rollo lay asleep, and the look she turned upon her visitor was one of pathetic resignation. He knew before he spoke to her that the battle was over. The sight of her great eyes gazing up at him like the eyes of a lost child moved him to compassion.

“You’re very tired,” he said. “Why don’t you go to bed yourself?”

“I couldn’t possibly sleep,” she answered. “Besides, I must be ready—in case the aeroplanes come back.”

“There’s no fear of that now,” he said. “And, anyway, I shall be at hand. Have they brought you anything to eat?”

“Oh, yes,” said Molly with a sigh. “They were very kind, and it was very good of you to bring me here. I don’t know what I should have done.” She repressed a sharp shudder. “I haven’t really grasped it yet,” she added apologetically.

He bent over her. “You must have a rest,” he said. “You’ll be ill if you don’t. Try to realize that you are in safe keeping! I will arrange everything for you. There will be nothing for you to worry about.”

Her look went to the round dark head on the pillow. “I couldn’t leave Rollo,” she said somewhat irrelevantly.

“My dear, I haven’t the faintest desire to separate you from him,” he assured her. “But you couldn’t go on living alone with him now that your father has gone. You are much too young. Besides, what have you got to live on?”

She shook her head. “I really don’t know. Life is difficult. One never has long enough to decide.”

He laid a quiet hand upon her. “I think you will have to let me decide for you,” he said. “I am older than you are, and I have had more experience of life. You may rely upon me not to let you make a mistake.”

She leaned her head against his arm almost involuntarily while a deep sigh broke from her. “It’s Rollo I think of,” she said with a weary sort of iteration of the thought. “Things happen so suddenly. I might die too. And then—what would become of him?”

“As my stepson, I should naturally provide for him,” said Ivor. “I am quite ready to accept responsibility in that direction, as I have already told you. I cannot make him my heir, but I can do everything else that is necessary to fit him for the life of an English gentleman.” He stooped a little lower over her. “Do you think you are quite justified in holding back?” he asked in a tone of gentle reasoning. “Doesn’t the very uncertainty of which you speak make you feel that there is no time to be lost? I assure you that thought has been in my mind a great deal lately. We are bound to make quick decisions in times such as these. It is only those who do so who can hope for any kind of security.”

He paused. She had made no attempt to respond, but her head still lay in utter weariness against his arm. Save for a certain throbbing which seemed to denote some hidden agitation, he could have almost believed her to be sleeping.

He tried to look into her downcast face, but could only do so by deliberately turning it up to his own. This, after a few moments, he did with quiet compulsion; and then, as she made no resistance, merely suffering his action with closed eyes, he stooped and kissed her.

Her lips quivered under his own, but she remained quite passive in his hold.

“I think that decides it, doesn’t it?” he said. “You have made up your mind to marry me at last.”

“Have I?” she murmured weakly.

His arms closed about her, strongly yet restrainingly. “Yes,” he said with steady emphasis. “The matter is settled. And, now that you are left alone, I am going to take everything into my own hands. There is nothing to prevent our immediate marriage. In fact everything is in favour of it. And then you will be able to stay quietly here in my mother’s care until the end of the War. You agree with me, my dear?”

Her trembling lips moved in answer. “Yes, if you wish it. I agree.”

“Good!” he said, and kissed her again as one who had earned the right. “I shall arrange for our marriage to take place within a week. No, hush!” For she had made a faint sound of protest. “I know what is best, and delay is only painful. I could never allow you to go back to the cottage after the funeral. We will put all that is morbid and sorrowful behind us. It is far better that you should enter upon your new life at once. Believe me, you will never regret it.”

She made no further effort at remonstrance, but sank again into quivering passivity. The steady pressure of his lips upon her own again deprived her of the power of speech, and when he released her at length the will to act and free herself had somehow been subdued. He had taken her at a moment when her strength was at a very low ebb, and in making the decision irrevocable he firmly believed that he was acting in her interests as much as his own.

He remained with her for a little while, but not for long, for after all she had undergone she was plainly worn out, and his caresses—though they served to strengthen his own proprietary attitude—seemed almost too much for her tottering strength.

“I will leave you now,” he said finally. “I think there is no need for me to press my sympathy upon you. But before I go, I should just like to give you my birthday gift, and then you must go to bed.”

It was as if he spoke to a child, his voice kindly, compassionate, slightly condescending. But Molly did not even raise her eyes in answer. She was tired to the soul.

He took a little paper packet from his pocket and unwrapped it. The glint of diamonds shone in the shaded light.

“Just a token!” he said. “Let me have your hand—yes, the left one. Ah, splendid! It may be a little loose, but I expect you will grow to it—as to everything else.” He began to slip the ring on to her third finger, but paused. “I think the old wedding-ring must come off,” he said. “You may wear it on your right hand till we are married, if you like.”

She uttered a sudden hard sob and drew her hand away. “It—has never been off,” she said in a choked voice. “I couldn’t—I couldn’t!”

He caught her hand back again and firmly held it. “Oh, come! This is nonsense!” he said with a touch of austerity. “I can’t allow it. Morbid sentiment, my dear Mary,—nothing else! Perhaps, however, I am the most suitable person to take it off.”

Her fingers clenched. “No!” she said. “No!”

He opened them out with quiet force and drew the gold band, which was loose enough, from her finger. She gave a low cry as she felt it go.

“It is best,” he said. “It is far best. There! You shall have the engagement one instead. I will take this one away. It will only give rise to sad memories.”

“No!” she cried. “No! Give it to me!”

But he withheld it, faintly smiling, fully determined. “I know what is best for you,” he said. “You are very young and impressionable. What I do is for your good. You will realize that later. I want to help you over the bad places and make you happy.”

“Happy!” she repeated in a wrung whisper. “Happy!”

“I know,” he said. “It seems impossible to you now. That is because you are young, poor child, and have been through so much trouble. But very soon things will be quite different. You will learn to look forward and leave your sorrows behind. Good night, Mary, my dear! By this time next week you will be wearing—another wedding-ring.”

She moaned in answer; words seemed to have failed her.

“Go to bed,” he said, “at once! You are worn out: but you will feel better in the morning.”

He drew her to him, kissed her once again on lips and forehead, paused a moment, and then—as she still found no words—patted her hand and turned away.

He was gone. She was alone with her child. But for the first time in the whole of her widowhood she was unaware of him there beside her. A great passion of feeling shook her, such a tempest as her slender frame was scarcely able to endure. Her hands were clenched. She dared not throw away the alien ring. Yet it seemed to be searing her flesh like a hot iron. She had suffered it, she had accepted it, she was powerless. But her agony of soul was such as even in her deepest sorrow she had never known before.

Softly, with a subdued violence, like a caged creature, she paced the room—the sumptuous prison to which she had been brought—driven, despite all weariness, by the fire within.

Wild thoughts and impulses rushed through her brain in a confused medley. At one moment she was terrified, at another desperately brave. And all the time within her the dreadful yearning gnawed—too deep for words or any physical expression, the longing that must go for ever unsatisfied for Roy—Roy, her husband, most precious, most beloved—to whose memory a bitter fate compelled her to be false.

How long she wandered through that terrible wilderness of despair and anguish she never knew. It was as a blackness that pressed upon her, shutting out all sight and sound, even smothering the thought of her father lying alone in death in their little cottage in the village. So cruelly was her spirit rent that all power of concentration was gone from her, and only the agony remained.

Later it seemed to her that all night long she wandered piteously crying for Roy, and receiving no answer because by her own action she had placed him beyond her reach. But when morning broke with the singing of many birds she was lying exhausted and sleeping on the bed with little Rollo in her arms.

Molly’s first interview with Lady Aubreystone was not as alarming as might have been anticipated. In the first place she was too weary and too bewildered to be aware of any acute embarrassment, and in the second her appearance with its youth and pathos made a more favourable impression upon the old lady than that hard critic had deemed possible.

Her greeting was in fact wholly different from what she had intended it to be. “Heavens, child! You look like a ghost!” she said. “Why didn’t you stay in bed?”

Molly’s smile was one of pure courtesy. “I’m not ill, thank you,” she said. “I always get up early.”

“Then you’d better go back again,” said Lady Aubreystone gruffly.

Molly shook her head. “I couldn’t, thank you very much. I have my little Rollo to see to.”

“Rollo? Who’s that? The child? Sounds like a dog,” was Lady Aubreystone’s comment.

Molly flushed rather painfully. “It’s only a pet name,” she explained. “His real name is Ronald—after his father.”

Lady Aubreystone frowned; but in a moment softened and drew the girl to her. “Well, well, I suppose that’s natural. So you’re going to marry again, I hear, and make my son happy!”

Molly’s flush faded so completely that the old woman, watching, thought that she would faint. But she answered with a composure that reassured her. “He says I must, so I expect I shall. But it’s difficult for anyone to be happy now, isn’t it?”

Lady Aubreystone made a brief sound of sympathy. “I know what you mean. When you get to my age, you’ll expect it. But it’s hard at yours. I don’t suppose you’ll believe me when I tell you that you’ll get over it, but you will for all that. Unless I’m much mistaken, the happiest time of your life is in front of you.”

Molly’s lips compressed themselves, but she uttered no contradiction.

“Oh yes, it is,” asserted Lady Aubreystone, still watching her. “You wait till you’re married! It’s a pity to keep all your eggs in one basket. You’ll be happier when there are more of them.”

Molly spoke in a low voice. “I’m not thinking about happiness any more. Perhaps I’ve had my share. Anyhow, I suppose one can do one’s best without it.”

Old Lady Aubreystone gave her a shrewd look. “You’re a queer girl,” she said. “But for goodness’, sake, don’t cultivate sadness! I must have cheery faces round me. I don’t want to hear anything about your troubles, any more than I ever want to talk about my own. You certainly can’t do your best for anyone if you’re being miserable. And it takes time to be unhappy, remember that! No busy people ever are.”

“I am sure you are right,” said Molly humbly. “Only sometimes I can’t help feeling that it would be a help if only one had a little time to think.”

“Not a bit of it!” rejoined Lady Aubreystone with a kindling of the eyes that denoted her determination to crush every vestige of an opinion that differed from her own. “Absurd nonsense! Girls never stop to think, and a good thing too! They’d never get married if they did. There are too many of them nowadays.”

Molly regarded the indomitable old lady with steady blue eyes that were not wanting in courage. “Yes,” she said. “It seems rather mean for any of us to marry twice, don’t you think?”

Lady Aubreystone frowned upon her, then laughed—a raucous laugh that was like the croaking of a raven. “Oh, you and your theories!” she said. “You’re one of the lucky ones. Just you realize that! I believe I can get rather fond of you, if you behave yourself. But mind—you’ve got to make a study of it! Being a good wife is a whole-time job, and you must give your mind to it.”

“Being a good mother is the same,” said Molly, almost under her breath.

“Yes, and you’re going to be that too.” Lady Aubreystone put an arm suddenly about the slender figure. “Heavens, child! How scraggy you are! Who would give you credit for producing that bouncing boy of yours? I must take you in hand and feed you up before any more come along. How old are you? Twenty? Well, well, plenty of time—if only this miserable War will stop! But not much to be wasted till it does. You’re going to be a good girl and do your duty as my son’s wife, eh?”

She looked up at Molly with a gleam of persuasion in her hectoring old eyes, but her arm held like a vice.

Molly hesitated a moment, and then she stooped and quietly kissed the withered face. “Yes, I’ll try hard—to do my duty,” she said.

She did not expect to be caught closer in that steely embrace, and she was startled the next moment to find herself drawn irresistibly downwards, and pressed against Lady Aubreystone’s breast. It was a novel and not wholly pleasant sensation, for she could not have checked the gesture had she desired to do so. But she sought to smother her discomfiture by surrendering completely to the old woman’s whim.

“That’s right,” said the harsh voice. “I’m pleased with you. I think my son has shown some good sense, and the sooner you’re married the better. You leave everything to me, and don’t fret! Your own child shall be looked after. I’ll see to that.”

“You’re very kind,” whispered Molly, hoping to escape.

“Kind!” said Lady Aubreystone. “I’m sensible, that’s all. Now don’t you go and disappoint me! I can’t endure much more at my age.”

“I will try to be everything you want,” Molly said.

“Good! That’s a promise.” The grim arms tightened. “I’ve borne seven children in my time. I thought it was enough, but it wasn’t. Nearly half of them were girls. Ah, here’s Caroline! I suppose I mustn’t say that in front of her. Here Caroline! Come and look at this child! She is going to be your very younger sister. No, you stay as you are, child! You’re all right.”

The door had opened to admit Caroline Aubreystone who entered with an athletic swing and stopped short to stare.

Molly, greatly disconcerted, managed to lift her head and turn a scarlet and apologetic face in her direction. She had never even spoken to the Honourable Caroline, and the situation embarrassed her beyond words.

But Lady Aubreystone only laughed—her raven croak. “Come on in, Caroline! She can’t get up to drop you a curtsey. You’ll have to take her as you find her—my adopted daughter—your adopted sister.”

Caroline spoke briefly as she advanced. Her look was somehow scathing. “My prospective sister-in-law, I suppose?” she said in a voice that was extraordinarily like her mother’s. “I didn’t expect to find you quite so literally clasped to the family bosom, I admit. Well, I suppose it’s all in a good cause. You may be interested to hear”—her hard-featured face suddenly twisted in a mirthless smile—“that I have just interviewed your charming infant, who is still shrieking himself blue in the face over the ordeal.”

That was more than enough for Molly. All scruples were scattered, and she accomplished her release with a swift and violent effort that admitted of no further restraint. “Oh, I’m sorry. Forgive me! I must go!” she panted, and fled through the open door before either mother or daughter could attempt to check her.

They looked at each other—the older woman with an expression of semi-angry frustration, the younger with open contempt.

It was the latter who spoke. “It’ll be a case of weaning the mother from the child with a vengeance. Ivor will have his work cut out.”

“But he will succeed.” Lady Aubreystone spoke in an undertone but her words were fateful. “I can conquer that slip of a thing single-handed, and amongst us all we shall manage to break her in to the Aubreystone traditions. She’s young and fairly plastic yet. Anyhow, I have accepted her.”

“So I perceive,” said Caroline drily. “Well, I never expected to be consulted, but I wouldn’t have chosen a bereaved widow with a child if I’d been Ivor. They are not plastic as a rule. However—we shall see. It’s three to one, as you say.”

“If she fails to give us an heir——” said Lady Aubreystone in a voice that shook too much to continue the sentence.

Her daughter snapped her fingers in the air. “That’ll be her look-out. It’ll be for us to find some cause or impediment for terminating the contract. But she’s young enough. She’ll probably have a dozen.”

“But she’s got a will of her own,” said Lady Aubreystone. “I can sense it. And girls are beginning to get so headstrong. That’s why I say she must be broken in.”

Caroline swung to the window with her man’s gait and looked out. It was a day of perfect June. The green world that stretched below her was like a peaceful dream.

She made an abrupt scornful sound and swung back again. “Well, she shall be—if Ivor doesn’t go soft over her. He’s well on the way.”

“Oh—Ivor! I can manage him,” said Lady Aubreystone with sweeping self-confidence. “There’s not one of my children who can say he has ever had the better of me.”

Caroline laughed sardonically. “You put that very tactfully, but I quite realize that the feminine gender doesn’t count in your estimation—except as a means to an end. What a comic world we live in! The brainless male forced into a position of authority which he is totally unfitted to occupy! It’s a good thing there are a few brainless women left—from his point of view.”

“Oh, my dear Caroline!” her mother protested irritably. “What nonsense are you talking now?”

Caroline laughed. “Not nonsense, my dear Mother; heresy is a better word. You used to punish me for it as a child, but you never managed to exterminate it. I probably inherited it from you.”

“I don’t understand you,” said Lady Aubreystone testily. “But it doesn’t matter. I’m not interested. All I care about now is to get Ivor married as soon as possible. I’ve given my consent, so there’s nothing to wait for.”

“Really an ideal romance!” commented her daughter. “Well, I’m off to the stables to do some gingering up. I’ll march the bride to the altar if she requires an escort. But I don’t think on the whole you’ll find that the prospect of becoming Lady Aubreystone is one which she will desire to postpone indefinitely—unless she’s a bigger fool than she looks.”

With which caustic surmise she tramped to the door, paused to light a cigarette, and then swung it open and went away, leaving a draught behind her.

Afterwards, when it was all over, Molly used to wonder by what mystic means she was rendered so submissive. Up to her birthday she had been mistress of herself; after it, she became a mere puppet in the hands of others, forced into subjection by wills so dominating that her own gave way with scarcely a struggle. Always in her heart was the knowledge that she did not want to marry again, but she lacked the strength to act upon it. Somehow everything was taken for granted in such an irrevocable fashion that there seemed no possibility of turning back. She was as much a prisoner as if she had been kept under lock and key, and even if panic had urged her to flee from the situation, there was always Rollo to keep her where she was. For his sake she never dared to make the attempt.

As one in a dreadful dream she went through the ceremony of her father’s funeral, while yet she could not bring herself to realize his death. They had never been very close companions. He had led his life apart from her, immersed in his books, but he had constituted home to her, and without the familiar figure she felt lost and outcast.

When Ivor told her that he had made arrangements for their marriage two days later, she felt too stunned to protest. It had got to be. Like a slave sold in the market, she had no choice. There was no one to whom she could turn for deliverance, and there was Rollo—always Rollo—to provide for and protect.

Had she been even a little older, she might have held her own; but, worn down as she was, by a long struggle against pitiless odds, there was nothing left for her but to go the way she was driven. Her father’s small savings were gone, and she and Rollo were practically destitute. So, without further remonstrance, she accepted her lot and made ready for the sacrifice.

Ivor was very kind to her—but always from the possessive standpoint. He never let her lose sight of the fact that she was to be at his complete disposal, and without words he managed to convey to her that she was very fortunate to find so safe a harbourage. She began to suppose that she must be, and anyhow—shrink as she might from the life that lay before her—it was bound to be better for Rollo.

But she would not have him at her wedding. There for once, strangely, her wounded spirit asserted itself. She would go through it without raising the faintest difficulty, but it must be alone. Upon this point her resolution concentrated, and they let her have her way.

After all, as Caroline humorously put it, who wanted a squealing brat in church at a wedding which was supposed to be conspicuously quiet?

It was a quiet ceremony enough, but the old men and women of the village thronged to see it, and thoroughly enjoyed themselves. It was an event not likely to be forgotten in the village where the pathetic bride was so familiar a figure, and they were unanimous in congratulating her upon her good luck. Some there were who were surprised that Lord Aubreystone did not look higher and wondered at the reason for his choice, but to most of them his motive was fairly obvious. Molly was already the mother of one robust child, and he needed an heir. The dwindling of the ancient line had caused something approaching to panic in the family. If he were to die childless the title would lapse. So upon mature consideration he had probably chosen wisely. It was no time for taking risks. No one could afford to do that, the Aubreystones least of all.

Yet it was generally conceded that he seemed very pleased with his bargain. It was only Molly with her strained smile and rather scared eyes who showed any lack of confidence. But this was as it should be in one so young scaling the social ladder with such unexpected rapidity.

“Poor dear! She’ll feel out of place up at the Castle,” was one woman’s verdict. “And the old lady and her daughter won’t make it any easier for her neither.”

“Well, she’s done better for herself than she did last time,” snapped back a neighbour. “That young man she married first time wasn’t nothing to boast about—and no money.”

“Money isn’t everything,” said gentle Miss Mason the postmistress. “I hope she hasn’t been induced to marry for it this time.”

The two other women smiled at one another. Miss Mason was known to be on the romantic side, but even she surely could scarcely have been proof against rank and money combined. Was there any woman living who could—especially now when times were so hard?

“Well, she won’t have to wait for her meat rations outside the butcher’s any more,” was their envious verdict, with which, at least, Miss Mason was obliged to agree.

And Molly went through it all as one lost. No further message had come to her out of the unknown, nor ever could again; for she had locked the door. She and Rollo had been left to fend for themselves, and she had taken the only possible course open to her. Her widow’s pension was totally inadequate to educate him as he must be educated; and for herself, what did anything matter now?