* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Ringed by Fire

Date of first publication: 1936

Author: Percy F. Westerman (1876-1959)

Date first posted: July 29, 2020

Date last updated: July 29, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200742

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Jen Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

RINGED BY FIRE

BY

PERCY F. WESTERMAN

Author of “The Black Hawk” &c.

Illustrated by W. Edward Wigfull

BLACKIE & SON LIMITED

LONDON AND GLASGOW

By Percy F. Westerman

Captain Flick.

Tireless Wings.

His First Ship.

The Red Pirate.

The Call of the Sea.

Standish of the Air Police.

Sleuths of the Air.

The Black Hawk.

Andy All-Alone.

The Westow Talisman.

The White Arab.

The Buccaneers of Boya.

Rounding up the Raider.

Captain Fosdyke’s Gold.

In Defiance of the Ban.

The Senior Cadet.

The Amir’s Ruby.

The Secret of the Plateau.

Leslie Dexter, Cadet.

All Hands to the Boats.

A Mystery of the Broads.

Rivals of the Reel.

Captain Starlight.

The Sea-Girt Fortress.

On the Wings of the Wind.

Captain Blundell’s Treasure.

The Third Officer.

Unconquered Wings.

The Riddle of the Air.

Pat Stobart In the “Golden Dawn”.

Ringed by Fire.

Midshipman Raxworthy.

Chums of the “Golden Vanity”.

Clipped Wings.

Rocks Ahead!

King for a Month.

The Disappearing Dhow.

The Luck of the “Golden Dawn”.

The Salving of the “Fusi Yama”.

Winning his Wings.

The Good Ship “Golden Effort”.

East in the “Golden Gain”.

The Quest of the “Golden Hope”.

Sea Scouts Abroad.

Sea Scouts Up-Channel.

The Wireless Officer.

A Lad of Grit.

The Submarine Hunters.

Sea Scouts All.

The Thick of the Fray at Zeebrugge.

A Sub and a Submarine.

Under the White Ensign.

With Beatty off Jutland.

The Dispatch Riders.

A Cadet of the Mercantile Marine.

Printed in Great Britain by Blackie & Son, Ltd., Glasgow

Contents

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | A Soft Job or——? | 9 |

| II. | Forced Down | 19 |

| III. | Threatened | 30 |

| IV. | The Maudlin Manager | 39 |

| V. | The Wrecked Monoplane | 48 |

| VI. | An Awkward Mistake | 59 |

| VII. | The Conspirators | 75 |

| VIII. | What the Boy Revealed | 81 |

| IX. | The End of the Vigil | 91 |

| X. | Caught | 101 |

| XI. | In Captivity | 111 |

| XII. | A Check | 120 |

| XIII. | Ringed in by Fire | 129 |

| XIV. | Inspiration | 140 |

| XV. | The Inner Cave | 149 |

| XVI. | The Intercepted Lorry | 160 |

| XVII. | An Unlucky Joy-ride | 169 |

| XVIII. | Doped! | 181 |

| XIX. | Through the Race | 191 |

| XX. | A Scrap and a Rescue | 199 |

| XXI. | Rounded Up | 210 |

| XXII. | Duty Calls | 218 |

Illustrations

| Facing | |

| Page | |

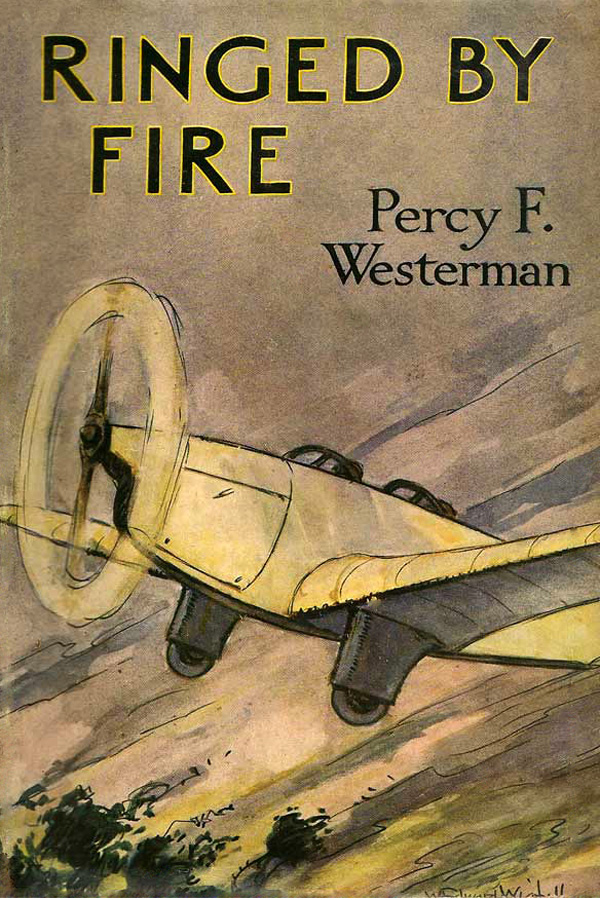

| A Slender Chance | Frontispiece |

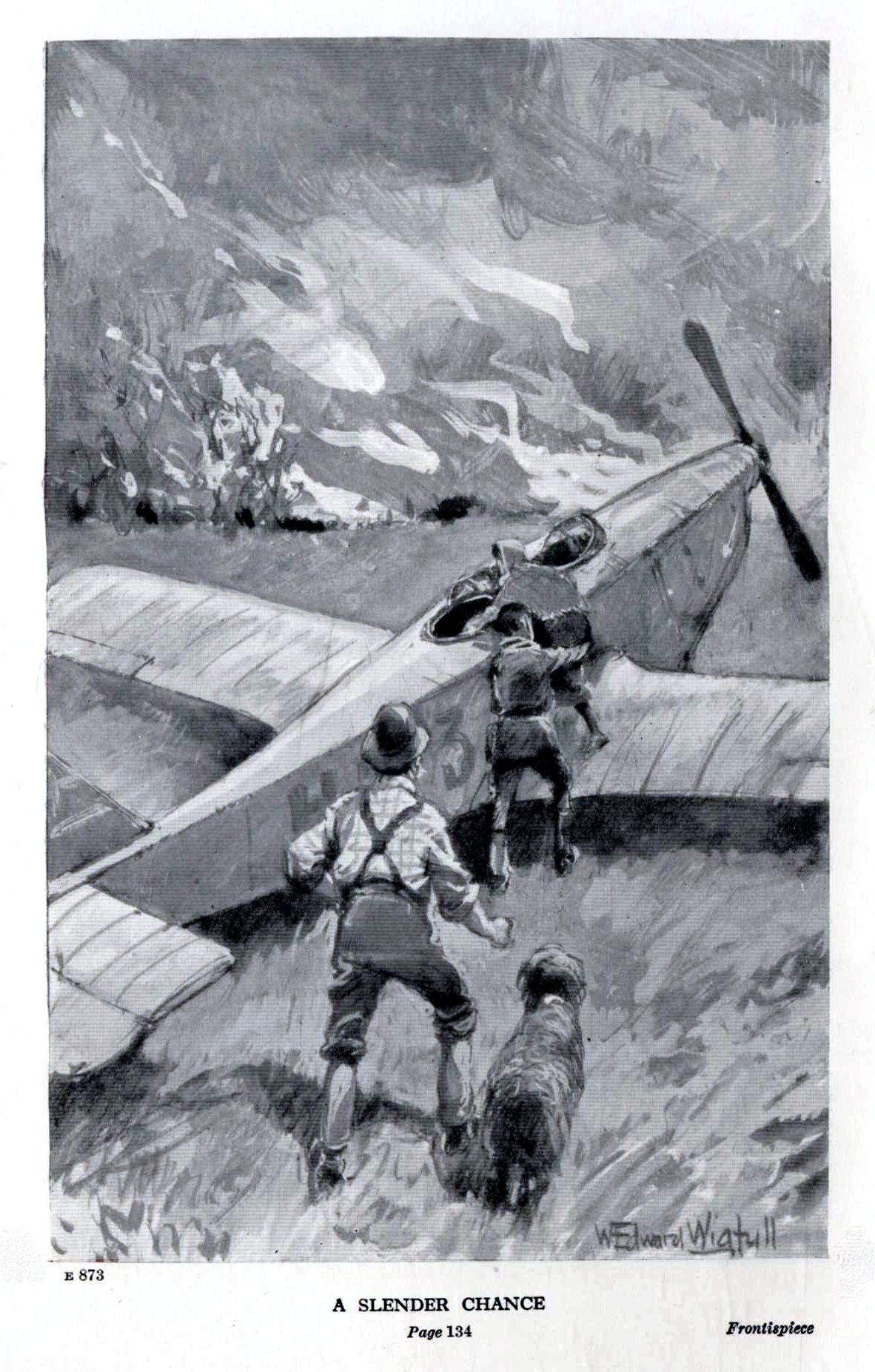

| Standish heaved and hauled | 48 |

| Wild Work at Tilly Whim | 96 |

| Almost Lost! | 192 |

“I’m having you transferred at once, Standish,” announced Colonel Robartes, Superintendent of the North-Eastern Division of the Royal Air Constabulary.

Colin Standish tried not to show his disappointment. He had been very happy at Hawkscar. It was not pleasant to think of parting from his brother officers, staunch comrades all in peril and stout adventures, especially his chum—Don Grey.

“I shall be sorry to leave Hawkscar, sir.”

“No doubt,” rejoined Colonel Robartes drily. He, too, knew that comradeship, especially comradeship of the air, is a bond not easily broken. “No doubt; but duty before everything, Standish!”

“Exactly, sir.”

“Glad to hear you say that, Standish,” continued the superintendent briskly. “However, you won’t be sent very far away, and if you have your usual luck you’ll be back here within a month or so. You know Dorset pretty well?”

Of course Standish did. He had spent most of his boyhood days in that county. He had commenced his air career at the Far Eastern Airways’ principal aerodrome at Bere Regis. From there he had flown on his two adventurous missions—that of the Amir’s Ruby and the affair of the Westow Talisman.

“Yes, sir.”

“Of course. You were at Bere Regis Aerodrome. Shows I haven’t refreshed my memory by studying your dossier. You start your next job with the great advantage of knowing the district in which your work lies. It may not sound very exciting; but, as often happens, there may be a lot behind it. You’ve heard about all these heath fires in Dorset?”

“Seventeen last week, I understand, sir.”

“Seventeen if not more. Now, even taking into consideration the prolonged dry spell, that number of fires—serious all of them—cannot owe their origin to natural conditions. The heat of the sun and spontaneous combustion of peaty ground can be safely ruled out. Sparks from a railway engine might account for three of the conflagrations, but in other cases the scene of the outbreak is remote from railways and roads. Hikers have been blamed; but people of that sort appreciate the countryside too much to destroy its beauties, even through carelessness.”

“Is anyone suspected, sir?”

“I should certainly think so, but so far the county police have nothing to go on. They’ve applied for Royal Air Constabulary co-operation. That’s why I’m sending you.”

If the truth be told, Standish did not feel particularly keen about the job. It seemed a dull sort of business flying aimlessly over miles of desolate heathland looking for—in all probability—a half-witted youth or a man of unsound mind whose amusement it was to set fire to patches of gorse and heather. Yet it would be pleasant to be down in Dorset again—his boyhood’s home county. A sort of mild relaxation after his wild adventures with gangs of desperate international crooks.

“Do you wish me to take one of the H machines, sir?”

“One of the H machines, and advertise the fact that you’re a member of the Force to anyone who chances to lift up his eyes and gaze into the sky? That would be a deterrent to the incendiary, but he’d just lie low until the air patrol was withdrawn and then start his merry game all over again. What I want you to do, and what you must do, is to surprise the fellow in the act, keep him under observation while you wireless the nearest police station, and see that they get him. That’s simple enough, isn’t it?”

“No, sir.”

“Eh?” The superintendent raised his bushy eyebrows and glanced sharply at his subordinate. He wasn’t used to having his judgment criticized. “What do you mean, eh?”

“You imply that I am to fly solo, sir, in a bus that is indistinguishable from private light aeroplanes.”

Colonel Robartes waggled his forefinger accusingly.

“Now, I know what you’re angling for, young man!” he exclaimed. “You want me to send your chum Grey with you?”

Colin Standish was too honest to deny this implication. At the same time, any other member of the flying police would serve his purpose.

“I’d like to take Grey, sir,” he replied. “We sort of understand each other. And for observation purposes, sending out wireless reports, and——”

“And what?” inquired the superintendent, noticing the other’s hesitation. “Carry on, I’m listening.”

“Well, sir, supposing the fires are being started by a gang operating in a car——”

He paused again. It seemed rather absurd to suggest that a gang would have nothing better to do than to roam a certain district and set fire to heathland. There seemed to be no object in it, and yet—he remembered that there was a vast naval cordite factory at Holton Heath, surrounded by acres of highly inflammable gorse.

“That probability cannot be overlooked, Standish.”

“What then, sir? With an H machine we could bring the magneto-cutout apparatus into action and hold the car up while some of our crew could land to effect an arrest.”

“Too obvious, employing a service machine, as I said before,” objected Colonel Robartes. “I’ll spare Grey to go with you. I had meant him to investigate that fish-poaching case off Whitby, but I’ll detail Willis for that. You’ll take a two-seater observation bus—I’ll leave you to make your own arrangements with the Air Ministry concerning the identification markings—but you’d better take the spraying apparatus. You may find that handy. By the by, I shall not require any reports from you until the business is settled one way or other.”

“Very good, sir.”

“And another thing. When you get south it would be as well to pay a call at the customs office at Poole. They’re a bit worried about something that may or may not be connected with the fire-raising business. That’s all, I think. I’ll see that Murchison gets your papers through by midday and then you can start off immediately. Good luck!”

Crossing the parade-ground on his way to the officers’ mess, Colin caught sight of his chum Don, who, in civilian garb, was carrying a small suitcase.

“Hallo!” exclaimed Standish. “What’s up?”

“Off for the week-end,” replied the other. “Had to apply for special leave. I meant to look you up and tell you before I went.”

“Very urgent?”

“Very.”

There was a pause—a sort of uncomfortable silence.

Grey, usually so communicative, had made no effort to give explanations.

“Well, I’m sorry,” observed Standish.

“You needn’t be.”

“But I am.”

Curiosity got the better of Don’s reticence.

“Why?”

“Because I’m off on special duty. Just had instructions from Colonel Robartes. I wangled it that you should breeze along too.”

“Right-o. I’m on it!” declared Grey.

“But your urgent leave?”

“Can wait,” replied Don crisply. “Come along. I’ll tell the taxi fellow I shan’t want him. Now, what’s the latest stunt?”

Standish explained.

“Doesn’t look as if we’re going to add to the ‘hurt aggregate’,” observed Don. “Pretty tame business, I think.”

In referring to the “hurt aggregate” he implied that he did not consider the undertaking a risky one. In the orderly-room a record is kept of the number of days lost in that branch of the Royal Air Constabulary owing to officers and men incapacitated through “hurts” and sickness. This record showed how hazardous was their work in combating crime and how healthy the life was in other respects. During the first year of its existence, Hawkscar showed nearly two thousand days “hurts” and ninety-four days on the sick list.

“Well, if it is, then it will be a sort of rest-cure,” said Colin. “We can both do with that after the Down ’em Gang set-to. If it isn’t—and Robartes hinted at something behind it—then all I hope is that we have our usual luck.”

By two o’clock in the afternoon the chums were ready to take off. Their machine, a two-seater single-engined monoplane, had been given a distinguishing letter and number, as in the case of privately owned buses. It was otherwise indistinguishable from thousands of its type; but there was a difference.

In the floor of the after-cockpit was a small box-like arrangement on a swivelled mounting and with a nozzle projecting downwards through a slot. This was what Colonel Robartes had referred to as the “spraying apparatus”. Actually it was a modified form of a quick-firing gun—the propellent being compressed air. But instead of discharging metal shells it fired circular missiles made of celluloid. These contained strong aniline dye which, spreading upon impact, covered their object with an indelible stain.

Underneath the deck and close to the observer’s seat was a small but efficient wireless set capable of sending out and receiving messages over a radius of two hundred miles by day. Ready to hand were a pair of earphones, while in the coaming in front of the bucket seat was a small lamp that showed a red light whenever a message intended for the occupants was sent out on this particular wave-length.

Stowing their personal belongings under the deck, the two chums, both of whom were now in plain clothes, made a brief but comprehensive test of the engine and controls, boarded their bus and, giving their confrères a cheery farewell, took off into the blue.

Or, rather, into the clouds, for the sky was obscured by a flat layer of fleecy vapour in suspension, which was just what Standish wanted.

Outside the unclimbable iron fence enclosing the aerodrome there were at least fifty people watching the proceedings. Quite possibly most of them were there out of pure curiosity. On the other hand, there might be some with other intentions. They might take more than ordinary interest in the monoplane that differed from the huge H-type aircraft that formed part of the standard equipment of the Royal Air Constabulary.

So, climbing steeply, Standish headed his bus northwards until she was well above the bank of clouds. Then, secure from earthly observation, he swung her round and headed southwards.

Half an hour later, in a now cloudless sky, the two chums noticed that they were over a large river. They knew exactly where they were. The river was the Trent; they had flown over it several times.

“We’re out of the North-eastern Area now,” said Don, speaking through the voice-tube. “Not doing so badly.”

There were at least a dozen aircraft within sight—a liner bound from Croydon to Edinburgh and Aberdeen, a Post Office plane conveying letters and parcels from South Wales to Lincoln and Hull, and the rest seemed to be private machines.

Suddenly—for neither of the two sub-inspectors had glanced astern—a huge triple-engined biplane overtook them at at least one hundred and eighty miles an hour.

Colin recognized it as one of the Royal Air Constabulary machines belonging to the Midland Area, and which differed considerably in design from the H’s of his division.

He waved. There was no response. Swiftly and majestically the other machine drew ahead, swerved slightly, and took up a position less than fifty yards ahead.

From the tail of the fuselage a green light, clearly visible in the strong sunshine, suddenly flashed. It was a signal known to every airman.

It meant: “Stop, land immediately!”

“Got a bee in his bonnet, that speed cop!” exclaimed Grey. “What are you going to do about it, old son?”

Under other conditions Standish might have felt inclined to “lead the Midland Air Constabulary a dance”; but it was imperative that he should be in Dorset well before sunset.

He touched a button on the dashboard. Above the centre of the wing-span a small oval disc appeared displaying the Royal Coat of Arms and the letters R.A.C. This was the identification disc used only between Royal Air Constabulary machines.

The green light ahead was switched off, only to reappear five seconds later. It was an acknowledgment that the disc had been observed; but it also meant that the biplane’s crew were not satisfied, for some reason.

Standish held on. He felt peeved. The action of the Royal Air Constabulary’s crew seemed inexplicable. Had they wanted to communicate any information they could have done so by wireless, without ordering him to volplane to earth as if he had been a suspect.

His blood boiled when a few seconds later his engine konked out. The other machine had released a ray that had polarized the magneto of his engine. Until that numbing influence was removed the monoplane was not even as efficient as a mere sailplane.

The only thing to be done was to dive steeply, alight, and get the exasperating business over. He tried to think of the blistering remark he would make to that unknown sub-inspector when they met.

Swooping swiftly earthwards, Standish kept his eyes skinned for a suitable landing-ground. Fortunately he was over the rich grazing district of the Trent valley, where it was easy to descend. In the distance he could see the factory chimneys of Leicester and the surrounding industrial hamlets. The way the smoke was blowing enabled him to land head to wind.

He swung his bus eastwards. So did the pilot of the monoplane. Below was a large, gently sloping field, surrounded by hedges and with a row of tall trees and a wide ditch dead to wind’ard.

“I’ll make ’em sit up!” he muttered. “The bone-heads!”

He reckoned that if he could prolong the volplane and time his descent to enable his bus to stop within a few feet of those trees the biplane would have to zoom, clear the tree tops, and come to earth at least two hundred yards away. He pictured the wrathful indignation of the sub-inspector and his men at having to wade through what was probably a muddy ditch and force their way through a thick-set hedge before they could get to him.

Apparently the pilot of the biplane divined his purpose. Banking steeply, he swung round until he was almost on Standish’s tail. The paralysing rays held Colin’s bus in their inexorable grip.

The monoplane bumped gently, taxied for about fifty yards, and came to a standstill with her nose almost touching the hedge. For taking off Standish could hardly have chosen a worse place.

Indignantly Standish and Grey alighted. In the event of an argument a person sitting down is at a disadvantage. They saw the biplane descend and a uniformed sub-inspector and five constables alight.

“What does this mean?” demanded the sub-inspector, a big, beefy-faced individual who struck Standish as being a blusterer. “You saw the stop signal. Why didn’t you obey at once?”

“You saw our identity disc,” rejoined Colin. “If you had anything to communicate, why didn’t you do so by wireless?”

“None of your lip, my fine fellow,” exclaimed the other. “You claim to be Royal Air Constabulary officers. Where are your warrant cards? I’m too old a bird to be caught by chaff!”

“You certainly look an old bird,” retorted Standish coolly. “Here you are; now are you satisfied?”

The sub-inspector looked at both Standish’s and Grey’s warrant cards, the constables peering over his shoulder as he did so.

“H’m: Inspector Colin Standish and Sub-Inspector Donald Grey—perhaps,” he remarked with a sneer. “I’m placing both of you under arrest. Get the bracelets on ’em, men!”

This was wholly illegal. It was not even the usual police procedure of making an arrest, since the charge was not stated.

“One moment!” exclaimed Colin authoritatively. “Where’s your warrant card?”

“Here!” snapped the fellow, pointing to a pair of handcuffs held by one of his subordinates. “Come on, now; no nonsense!”

If either Standish or Grey had had their doubts they were now convinced. Their would-be arresters were not members of the Royal Air Constabulary. For some reason—and the thought flashed through Colin’s mind that there were several—they were attempting to kidnap two genuine officers.

“They’ve streaked after us all the way from Hawkscar,” he thought. Then aloud:

“Stand back! Put your hands up!”

He whipped his automatic from the side pocket of his flying-coat. Don did the same.

The five men drew back but made no attempt to obey the second of Colin’s orders.

They knew perfectly well that an air constable is not entitled to use firearms except in self-defence, and then only if he has reasonable ground for suspecting that his life is in danger.

Probably the would-be kidnappers were armed too. Either they were afraid to shoot or else afraid to draw, covered as they were by the pistols of two now cool and determined men.

“You’ll hear more about this!” snapped the bogus sub-inspector. “Come along, you men!”

He swung on his heel and walked back to the waiting biplane, his companions following his example. There was no chance of their being shot in the back.

Colin was thinking hard.

Since this country differs very considerably from the “wild and woolly west”, it is not within the right of the civil law to round up criminals at the point of the pistol. Physically he and Don were strong, but not capable of tackling eight desperate men; since those who had remained in the biplane would almost certainly come to their friends’ assistance.

Yet for the honour of the Royal Air Constabulary something must be done.

“Come on, Don!” he exclaimed in a low voice. “We’ve got to cripple that bus.”

The would-be kidnappers retired in good order and climbed into the biplane. Their trouble in taking off, if they succeeded in so doing, would be similar to Standish’s. They must turn, taxi down-wind to the other side of the field, turn again and gather sufficient ground speed for the take-off.

The question was, how to stop them? Damaging the rudder and tail fins might do; on the other hand, a triple-engined bus can steer by throttle control. Several instances occurred during the War of pilots bringing their machines down in safety even with the tail of the bus shot away.

The vulnerable part of the biplane was her petrol tanks. These, in order to economize space, were built into the metal wings of the upper plane—of strong, though light, rustless steel. Was the metal stout enough to stop a ·230 nickle-coated bullet?

Keeping “well from under”, Colin fired. A stream of petrol gushed through the bullet hole. Then he ought to have left well alone and directed his attention to the other wing tank. Possibly it was excitement, probably the determination to do the business thoroughly. At all events he fired a second shot.

The result exceeded his expectations. A spurt of reddish flame issued from both bullet holes, rapidly increasing in intensity until the petrol-fed tongues of fire soared twenty feet or more into the air.

“Get your fire-extinguishers to work!” shouted Standish to the crew.

He had disabled the bus right enough. There was no need to turn it into a huge bonfire. Technically, he had committed the crime of arson.

His exhortation fell upon deaf ears; or, if the crew did hear, they were too astounded to take action. Their whole desire seemed to be to get clear away.

They jumped and took to their heels across the field, with Standish and Don in hot pursuit.

Now, at last, was the chance to make an arrest or two by pouncing on the stragglers at the tail-end of the fugitives.

Standish in the course of his duty had been one of several constables in pursuit of a gang. Invariably the fugitives had scattered. In this case there was no attempt to disperse. The rascals could run. They outstripped their pursuers even though the two chums had hastily thrown off their flying-coats; and they kept together in a pretty solid group so that there were no laggards who could be overtaken and captured.

Through the first hedge the fugitives forced their way with only a slight loss of lead. They had more than regained it by the time they were across the next field.

Their pursuers stuck it grimly. It looked like a losing game for them, but something might happen to enable them to overtake their quarry.

This went on for over a mile.

Colin and his chum were getting their “second wind” when, to their dismay, they saw that the eight men had gained a high road. Actually it was in the Fosse Way running between the outskirts of Leicester to Newark in an almost straight line and with hardly a village on it for nearly the whole of that distance.

Usually there was a large amount of motor traffic on it. Now it was almost deserted except for a lorry proceeding towards Newark.

From a distance of about two hundred yards Standish and Grey saw the end of the pursuit, as far as they were directly concerned.

The gang stopped the lorry, jumped in and compelled the scared driver to make it travel far in excess of the legal speed limit. By the time the two sub-inspectors had gained the tarmac the lorry and their quarry were out of sight.

About a minute later a saloon car came along in the same direction. Standish signalled it to stop. The driver accelerated. How was he to know that these two civilians were Royal Air Constabulary officers?

The next car was a sports model driven by a bare-headed youth of about eighteen. He pulled up and grinned cheerfully at the two perspiring, panting chums.

“Too warm for a marathon, eh?” he remarked. “What’s the bright idea? Want a lift?”

Briefly Colin explained the situation.

The youth’s eyes gleamed.

“Hop in,” he exclaimed. “Hang on tight—she’ll do seventy easily.”

It was a tight squeeze—three in that little sports model, but it was a job after the youthful owner’s heart.

How that car moved! Even Standish, accustomed to speed up to two hundred miles an hour, hung on tightly and shut his eyes as the road appeared to move past them at breakneck speed. At the crown of a low bridge she leapt with all four wheels clear of the ground. A gentle curve she took with the off-side wheels a foot in the air. Other cars she simply left standing.

Thought Standish: “Now, if a tyre bursts——”

Although they didn’t overtake the lorry or even get a glimpse of her, Standish and Grey found themselves in the police station at Newark, having accomplished the twenty-three mile run in nineteen and a half minutes. They had to harden their hearts and firmly refuse to let their young amateur chauffeur accompany them into the station. There were things to be said that were not for his ears, even though he had played no mean part in the interests of Law and Order.

The telephone and wireless telegraphy got to work. Police cordons were thrown out; mobile police patrols searched a wide area.

All to no purpose.

The lorry in which the gang had made their escape was soon discovered. The pale and agitated driver told how he had been compelled to turn off the main road into a lane leading to Farndon Ferry. There they had left him with a blood-curdling threat as to what would happen to him if he dared to move or raise an alarm within the next twenty minutes. Actually he waited five; then he made his way towards Newark, only to be challenged by a mobile police officer.

Police were immediately dispatched to scour both banks of the River Trent, but, meanwhile, after a brief consultation with the Chief Constable, Colin and Don returned by car to the spot where they had left the fields.

They were feeling rather down in the mouth over the whole business. Not only had they been greatly delayed—it was now close on six o’clock—but an unpleasant fact was evident; some gang, probably in touch with other similar organizations who use aircraft for the maturing of their nefarious schemes, had made a determined attempt to kidnap them. The attempt had failed; the miscreants had got clear—and they were in possession of the fact that Inspector Standish and Sub-Inspector Grey, in civilian clothes and flying a disguised machine, were on their way southwards.

The audacity of the rogues had been astonishing. They had gained possession of a machine that could not readily be distinguished from a Royal Air Constabulary patrol plane; they had contrived to acquire or else construct a magneto neutralizer—a contrivance hitherto sacred to the fighting and police air forces of the Realm.

Apparently they had gone to all this length merely in an attempt to capture Standish and Grey. For what reason? Revenge, or did they regard these two as a positive menace to their activities?

It looked as if from now onwards Colin and Don were marked men.

Not that Standish and his chum worried very much about that. They had been threatened over and over again. Like most of their brother officers, they had received several anonymous letters which, on the principle that “threatened men live longest”, they had treated with indifference. Their successful efforts in laying the Down ’Em and the Moss gangs by the heels had resulted in several attempts against their lives.

Up to within recent years the habitual criminal in this country was unique in this respect: he rarely, if ever, harboured resentment or revenge against the policeman who had effected his arrest. He regarded it all as part of a game—desperate, it is true. It was a contest between the cunning of the law-breaker on the one hand and the protector of Law and Order on the other. Should the former lose he “took his medicine” more or less cheerfully, and in many instances the ’tecs who had been responsible for his arrest also made themselves responsible for looking after his family while he did his “stretch”.

Latterly criminals have changed both their character and their methods. They enlist the latest scientific discoveries in their aid. They are no longer an almost wholly British type. Criminals from the States, from the Continent and from the farthermost regions of the earth have flocked into the country—men who do not hesitate to resort to violence both in the commission of their crimes and in their efforts, successful or otherwise, to effect their escape.

The motor-car was found to be a valuable ally, and latterly that means of locomotion has been largely superseded by the aeroplane, especially in the execution of schemes planned on the Continent by international crooks.

“I have an idea,” observed Don, as they tramped across the fields towards the place where they had left their monoplane. “Those fellows weren’t really after us.”

“Weren’t they?” queried his chum. “Then who in the name of goodness were they after?”

“It seems to me as if they were after someone else,” continued Colin. “I’ll have to make inquiries from Divisional Headquarters. As likely as not they disguised themselves as R.A.C. men in order to stop and rob someone in a bus resembling ours. They’d hardly go to all that trouble merely to kidnap us.”

“They’ve found out who we are, though.”

“Yes, worse luck. . . . Hallo! What a gallery!”

The biplane that Standish had set on fire (grimly he recollected that his task was to attempt to stamp out arson and he himself had committed that offence) was by this time nothing but a mass of twisted metal and a pile of white embers from which smoke was still rising. Two or three Leicestershire County Constabulary policemen were examining the wreckage, their actions being watched with deep interest by a crowd. It seemed strange where all that number of people could have come from considering that the district was a sparsely populated rural one.

Fortunately the flames had been confined to the would-be kidnapper machine and a small circle of grass. The chums’ monoplane was untouched by fire; but it was certainly being touched by a crowd of yokels. Three or four urchins were dancing about in the cockpit and fiddling with the controls, to the evident satisfaction both of themselves and their parents.

Fortunately the crowd appeared honest, for no one had “pinched” the chums’ leather flying-coats, which they had thrown off at the commencement of the pursuit.

Seeing the two airmen approach, the urchins hurriedly abandoned their new plaything. One of the constables strolled up, produced a notebook and assumed an inquisitorial air.

“Which of you two is in charge of this machine?” he demanded.

“Neither,” replied Standish. “I always understood that the police take charge of abandoned property. You’ve neglected your duty by allowing those children to jump all over this machine instead of——”

“Do you think you’re going to teach me my duty?” interrupted the policeman angrily.

“I really think I am,” rejoined Colin coolly. “Just cast your eye on this.”

For the third time that day he produced his warrant card.

The policeman wilted.

“Very sorry indeed, sir.”

“That’s all right,” said Standish. “We all make mistakes sometimes. Ask the other constables to come here.”

He questioned the trio and discovered that they knew nothing about the affair except that they had been informed by a neighbouring farmer that an aeroplane was on fire.

Standish told them of what had occurred, suggested that they should get into communication with their Chief Constable, and that they’d better get an aeronautical expert to examine the wreckage.

He and Grey then overhauled their monoplane. Hardly any damage had been done, although the youthful intruders had been monkeying with the wireless apparatus. Fortunately the spraying gadget had been overlooked, while the controls, although they had been tampered with, were intact.

With the help of some of the onlookers they swung the bus round, started up and taxied across the field. Then, after a short run, the monoplane resumed its interrupted journey.

Without further incident the monoplane hurried southwards, crossed the Thames just below Oxford and, skirting Salisbury, entered upon the last phase of its flight.

The prolonged spell of hot, dry weather looked like breaking up. In fact, a few miles from the Dorset boundary they encountered a heavy hailstorm.

Standish regretted the change, for two reasons. He hated rain like a cat, even though he had known what thirst means in more than one arid desert. He revelled in the exceptionally fine weather with which Great Britain had been favoured. The second reason was that a heavy downpour would effectually put a stop to the heath fires. That, of course, would relieve a great many people from anxiety, but it would also deprive Standish of any possible chance of arresting the suspected incendiary.

He had previously telephoned to Far Eastern Airways Aerodrome at Bere Regis asking the manager to reserve a private hangar for him for at least a fortnight.

Just before sunset—and an angry looking sun was visible through a rift in the dark wind-torn clouds—the monoplane skimmed the summit of Woodbury and came to earth on the well-known stretch of tarmac from which Colin and Don had taken off on their memorable flight to Bakhistan and to the Egypto-Sudanese frontier.

“Back again, then, Mr. Standish!” exclaimed Symes, the veteran ground foreman. “Don’t say you’ve chucked the Royal Air Constabulary and are coming here to sign on again?”

“Hardly,” replied Colin. “We’re having a sort of spot of leave. I suppose there are some of the old pilots still here. Where’s Mr. Truscott?”

Symes informed him that the managing director was in town and would probably return by car that evening. The curious fact about Mr. Truscott was that he’d never go anywhere by air, preferring the older method of locomotion.

“All right,” continued Standish; “you’ve reserved the hangar? Good; we’ll trundle the bus in. I don’t think we’ll want her to-morrow, do you, Don?”

Grey, glancing up at the rain-teeming clouds, opined that it didn’t look like it.

The monoplane was housed, the chums removed their suitcases, the door of the hangar was locked with a Yale. Standish was given one key, the other Symes retained, and in no circumstances, except in a case of danger from fire, would he open those doors without Standish’s permission—not even at the request of the resident managing director.

“Who’s in the mess?” asked Standish.

“Only Mr. Evans and Mr. Brown,” replied Symes. “You’ll not be knowing them. They joined after you left.”

“Then we’ll push straight on to the Bear,” decided Standish. “You might get a taxi.”

In choosing to stop at an hotel at Wareham—a distance of eight miles from the aerodrome, Colin knew that he and Grey would not be recognized as former pilots in the Far Eastern Airways or as officers of the Royal Air Constabulary. The little town was in the centre of the heath on which a series of mysterious fires had occurred. They stood a good chance of picking up information without their informants knowing that they were on official duties. For the present they would be two tourists exploring the district.

It was a weird drive through the darkness and the rain across the heath. For miles the undulating country had been devastated. The air was thick with the reek of burnt gorse. Here and there the peaty soil was emitting dense smoke in spite of the downpour.

Next morning the rain had cleared away and the sun shone from an unclouded sky.

“Ground’s too damp yet for a heath fire,” remarked Don.

“So we can take a holiday,” rejoined Colin. “We’ll run up to Bere Regis and have a yarn with Truscott; then we may as well go on to Poole and see the customs people there. Colonel Robartes wouldn’t have suggested our doing so unless there’s something in the wind.”

Arriving at the aerodrome they learnt that Mr. Truscott had not returned. He had telephoned from London stating that he had been detained and would probably arrive just before noon.

“May as well hang on,” decided Colin. “There’s no violent hurry. Look here, Don! While we’re waiting I think I’ll have a go at the throttle control. It seemed a bit on the coarse side. Perhaps those kids stretched it.”

They went to the lock-up hangars, threw open both doors to admit plenty of light and ventilation.

Standish swung himself on board.

His chum heard him give a little gasp of astonishment.

“What’s up?” asked Don.

“Look here,” said Colin, pointing to the instrument-board.

Pinned to it was a piece of paper on which was written in red ink and in block capitals:

“WE KNOW WHAT YOU ARE AFTER, INSPECTOR STANDISH. UNLESS YOU WANT A BROKEN NECK YOU HAD BETTER TRANSFER YOUR ACTIVITIES ELSEWHERE. YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!”

It was not the threat that had given Standish a nasty jolt. He was used to receiving anonymous letters couched in lurid terms.

What did astonish him was the fact that the missive had been affixed to the instrument-board of the monoplane after the machine had been placed behind locked doors. There were, he felt sure, only two keys to the Yale lock. He held one; Symes the other. Symes was a veritable Cerberus, vigilant, impeccable and above suspicion.

Carefully withdrawing the pin and handling the rectangular piece of paper by its edges, Colin examined the writing. The block letters had been deliberately made—no hurried scrawl. The fact that they were in red ink pointed to the suggestion that the person who had penned the threatening notice had done so at his leisure, and in some place where he had not been liable to interruption. A pencilled scrawl could have been made on the spot. An intruder would not carry red ink about with him. The writing had not been blotted—another fact that showed that the writer had been deliberate.

Probably a microscopic examination might reveal finger-prints. On the other hand, the writer might have worn gloves in order to prevent such incriminating evidence.

Without creasing the paper, Colin placed it carefully in his pocket-book.

“What do you make of it, old son?” he asked.

“Do you remember when we took a stowaway from this very aerodrome?” rejoined Grey. “Some other blighter might have concealed himself when we left the bus yesterday. You didn’t notice her dipping by the stern, did you?”

“No; she was in perfect trim. Your theory won’t hold, though. If there were someone stowed away we must have locked him in here. The lock’s intact.”

“Well, someone’s been in and out; that’s certain,” declared Grey. “Pretty cool customer, too. There doesn’t seem any place where he could have broken in or out.”

They made a careful examination of the hangar. The floor was of concrete, the walls of breeze brick with three small louvre ventilators fifteen feet from the ground, and a few air bricks an inch or so above the floor. The roof was of curved galvanized iron on steel trusses. The whole building was fireproof and without means of egress or ingress except by the door, unless a hole had been made in either the walls or the roof. There was no hole, nor any signs of one having been made.

Surrounding the aerodrome was a so-called unclimbable fence—a metal spiked barrier sufficient to deter most people who had any regard for their skins or their clothes; but one that would present little difficulty to the average cat-burglar. All the same, unless the intruder had entered the main gate under some pretext and had concealed himself until after midnight, he would have not only to scale the fence but to find his way into the hangar by some means that at present was an unsolved mystery. In so doing the chances were that he would have creased the paper. There were no creases. The paper was as fresh as if it had just been taken from a packet.

Throwing off his coat, Standish tackled the job he had in mind—the adjustment of the throttle control.

Then they relocked the hangar doors and made their way to the mess-room.

There were now half a dozen pilots, four of whom Colin and Don knew. They greeted the newcomers boisterously, chaffing them at being so bored stiff with a flying policeman’s job that they were only too glad to re-engage with Far Eastern Airways and see life.

“You haven’t met these two birds,” said Dixon. “Bright lads both of them—this is Evans, this is Brown. Standish and Grey were pilots here when you were being licked into shape at school.”

“Of course we know of you,” said Evans smilingly. “I’m glad to make your acquaintance.”

Conversation became general. Presently, without any leading question by either Standish or Grey, the subject of the recent heath fire was brought up.

“No joke making for the ’drome a few days ago,” declared Dixon. “I was bringing a crowd from the south of France. You couldn’t see Bere Regis a mile away. Smoke from acres of burning heath rising a thousand feet up. You mayn’t believe it, but there were bits of burning wood thrown up into the air well above the smoke cloud.”

“Windy?” asked Standish laconically.

“Rather. Burning embers drifting into the cockpit make you wonder what might happen if there’s any leaking petrol pipe union. A few weeks ago I had the job of flying over the crater of Vesuvius. London press photographer’s stunt. By Jove! It was child’s play compared to dashing through that smoke cloud.”

“Worse than a sandstorm, then,” remarked Colin. “Any chance of another fire?”

“We’ve had quite enough around here, thank you,” replied Dixon. “ ’Sides, the ground’s pretty sodden with last night’s rain. All the same, if there should be one I’d advise you to keep clear, even if you have a gas-mask, which I bet you haven’t. But when there was a big blaze at Sandford the other day—there were three quite distinct heath fires that afternoon—there were half a dozen buses buzzing around.”

“What for?” asked Grey.

“Aerial photographs for the press, of course,” replied Dixon. “What do you think they were—a fire brigade?”

“What do you think is the cause of all these outbreaks?” asked Standish.

“Dunno: seems too big a thing to be accidental every time.”

“I know for a fact that someone’s been starting them,” declared Evans.

“What do you mean?”

“Last Monday week I was coming back from Wool in my car. I was alone,” explained the young pilot. “On the bend near the top of Gallow’s Hill I surprised a fellow deliberately firing the gorse. He’d got down from a car to do it.”

“And what then?”

“He hopped back into his car and drove off like mad.”

“And you chased him. Didn’t you get the number of the car?” asked someone.

“I did neither,” explained Evans. “I thought it was the best thing to stamp the fire out. Wouldn’t you?”

“You informed the police, I suppose?” asked Standish.

Evans grinned.

“I don’t mind admitting that you’re the first policeman I’ve mentioned it to,” he answered. “You see, I’d forgotten my driving licence. I should have been asked for it, and as I didn’t feel like being touched for ten bob by the local beaks, I gave the police a wide berth. . . . Hallo! Here’s the boss! Looks as if he’s had a night of it.”

Through one of the windows Standish caught sight of his former employer. Mr. Truscott had just returned from town in his saloon car. His face was flushed. He walked somewhat unsteadily. Somehow he looked different from the pompous, self-confident resident managing director of the days when Colin and Don were under his orders.

“He’s taken to bending his elbow a lot recently,” explained Dixon. “Bad example to pilots, only none of us has imitated him so far.”

“I suppose we’d better see him,” said Standish, picking up his cap. “Come along, Don; cheerio, you fellows. We must try to arrange an evening in Bournemouth before my leave’s up.”

On their way across the tarmac to Truscott’s private office Standish remarked:

“Dixon was right. Our old boss has been imbibing a bit too freely. It’s a pity; he used to be very abstemious in the old days.”

“He certainly surprised me,” admitted Grey.

“I meant to take him into our confidence and to tell him why we’re here,” continued Colin. “It wouldn’t be safe to do that now. ‘When wine’s in wit’s out’, you know. We’ll have to pitch the same yarn as we told the others.”

There was a strange messenger-boy in the lobby. The chums gave their names.

“Appointment? ’Cause Mr. Truscott won’t see anyone except by appointment.”

“Loyal lad,” thought Standish. “Trying to boom off visitors while the boss is like that.”

“Yes, appointment,” he replied.

The resident general manager was sitting in a low armchair. He made an effort to rise, but gave it up.

“My word, you two!” he exclaimed. “Until I got your telephone message yesterday I didn’t expect to see you here again. ’Scuse my not rising; touch of lumbago or something. Take a chair, each of you. Spot?”

The chums sat down, but declined the offer of a drink. There was an awkward silence.

“Well; sorry you left the company and became Air cops?” inquired Truscott. “Not thinking of asking for re-engagements, eh?”

“No; sort of holiday,” replied Colin.

“Sort of holiday? Does that mean you’ve what they call a case on down this way?”

It was a point-blank question. Standish hesitated and wondered whether the manager in his present slightly bibulous state would notice it.

“If there had been anything of that sort you would have heard of it,” he rejoined. “I suppose you are of the opinion that the local heath fires are the work of an incendiary?”

“I’m not,” replied Truscott, raising his voice. “And supposing they were, you’d better transfer your activities elsewhere. We don’t want the aerodrome set on fire as a protest because we’re harbouring two Royal Air Constabulary officers.”

He broke off and then uttered a cackling laugh.

“He, he! Can’t help pulling your leg, Standish. As if such a thing would happen. The cause is simple enough. Ground dry as tinder for weeks. A broken bottle acting as a sort of burning-glass would easily account for a fire. But proceed with your duty, only I hope you won’t spray me with aniline dye by mistake.”

Aniline dye! How did Truscott get to hear of the spraying apparatus? Of course it was standard equipment of certain types of R.A.C. machines; but Truscott was in London when their monoplane arrived. He had only just returned. He had had no time to have the hangar unlocked even if Symes had made a special concession—which was most unlikely.

“How did you know about the spraying apparatus?” asked Colin pointedly.

Truscott grinned fatuously and waggled his fat forefinger.

“Little bird told me,” he replied, and hurriedly changed the topic of conversation.

This unsatisfactory interview lasted about ten minutes, and the chums left the aerodrome in order to have lunch at one of the village inns.

“Silly old josser,” remarked Grey. “Trying to be funny. Of course that was a chance shot of his, mentioning the dye.”

“Of course,” rejoined Standish.

And that was all that was said about it for the present; but Colin Standish was doing some very hard thinking.

“We’ll carry out our programme and run into Poole this afternoon,” said Colin, after lunch. “The waiter told me that there’s a bus at one-fifty.”

“What’s the idea?” asked Grey.

“Dunno, beyond Colonel Robartes’ suggestion. If there is anything we’ll soon hear.”

Their bus route lay to the north of the fire-devastated area. Although the flames had not succeeded in crossing the highway they had destroyed the hedges in several places, particularly towards a cluster of artificial mounds which, although some distance away, the chums knew to be the Royal Naval Cordite Factory at Holton.

Arriving at Poole, they made their way down the High Street to the quay, close to which was an eighteenth-century brick building with two semicircular flights of stone steps each leading to a doorway on the first storey.

This was Poole’s custom-house, the scene of many a stirring episode in the old days when smuggling was conducted with crude cunning and brute force.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Standish; good afternoon, Mr. Grey!” was the greeting given them by a big, red-faced, blue-eyed, clean-shaven individual in the inner office. “So you’ve arrived.”

Seeing that the chums had not given their names, it was somewhat surprising to be thus addressed. If secrecy were to be one of the factors of success their errand looked like being foredoomed to failure.

They tried to look impassive, but the effort was not a success.

The customs officer smiled broadly.

“Not so much of a mystery,” he explained. “We’ve had a communication from—let me see. Ah, yes—Colonel Robartes, stating that you would pay us a visit. He enclosed your photographs; that’s how I recognized you.”

“But the superintendent of our area did not give us definite instructions to report here,” said Standish.

“I know nothing about that. All I know is that we applied to the North-Eastern Area for the services of two R.A.C. officers.”

“Then what’s the trouble?”

“Smugglers,” replied the other laconically.

“Strange are the workings of the official mind,” thought Colin. “We were sent down here to investigate supposed cases of arson; now it seems we’re switched on to a contraband problem.”

“Smugglers?” he echoed.

“Yes. We’ve every reason to believe that a considerable amount of smuggling occurs on this part of the coast between Swanage and Weymouth. The stuff may be landed from motor-boats at such isolated places as Arishmell Gap, Warborough or Chapman’s Pool; or it may be brought over in aeroplanes and dumped somewhere on the heath until it’s picked up by a car.”

“If it’s brought by air surely it’s a job for the Southern Area Air Constabulary?” observed Don.

“They’ve had a good try,” replied the customs officer. “But they’re too well known about here. That’s why it was suggested that assistance should be obtained from a different area. Fresh blood, so to speak, and you’ve made a very successful capture up north, so I understand.”

“All these yachts,” remarked Standish, indicating a line of trim motor-cruisers lying alongside the quay. “What’s to prevent them nipping across Channel and bringing stuff back with them?”

The customs officer smiled tolerantly.

“We know them all and where they come from,” he explained. “Besides, yacht owners don’t do that sort of thing. We had one instance some years ago, though. A yacht landed several cases of spirits at the mouth of the harbour during the night, and then came up alongside the quay and reported she’d come foreign and had nothing to declare. We took the owner’s word for it, as we generally do.”

“Then how——?”

“Ah; you may well ask how. It was quite a fluke. Months afterwards some of the owner’s friends talked about it in a London restaurant. There was a customs man sitting at the next table.”

A chart of Poole Harbour and another of the coast from Portland Bill to Christchurch Head were produced, and the customs officer pointed out the districts over which he would like the two air officers to fly.

“We can’t do much at night,” expostulated Grey.

“I know. It’s about dawn when there’s a good chance of swooping down over a suspicious craft.”

“It looks as if we’re going to be deprived of our beauty-sleep, old son,” remarked Colin to his chum. “All in a good cause. It isn’t the first time that we’ve been called upon to do night duty.”

They discussed matters for some time and then the chums suggested that they’d better be going.

“Where shall we be able to get in touch with you?” asked the customs officer. “You’re based upon Bere Regis aerodrome, you say. How are you getting back? By bus? Well, look here; I’m sending two of my men to Wareham by motor-boat. Would you like a trip up the harbour with them? You can easily get back to Bere Regis from there.”

It was an inviting prospect. The afternoon was warm, the sea was as smooth as glass. It wanted about an hour to second high-water—Poole is remarkable in having four tides a day.

Standish quite expected the customs boat to be a smart motor-launch capable of doing at least twenty-five knots. He was somewhat disappointed to find that she was a lubberly old tub of about twenty feet in length propelled by an ancient outboard motor.

“She’s good for about six knots,” explained one of the boatmen. “With the tide we’ll be at Wareham quay in about an hour. . . . Start her up, George.”

After three attempts George succeeded in getting the engine to fire. The boat gathered way, glided past the line of moored yachts and small coasters alongside the quays, and gained the expansive land-locked harbour.

Presently Standish found himself peering into the dazzling rays of the late afternoon sun and wondering how the helmsman could see his way.

“It is a bit tricky, sir,” explained the man. “It’s a mile from shore to shore; but if we went twenty yards on either side of our present course we’d be hard on the mud.”

“Seems an ideal spot to run a cargo ashore in a small boat,” remarked Colin. “And how do you know you’re on your correct course?”

The customs man pointed to a small black pole that had just become visible in that patch of dazzling sunlit water.

“That’s one of the booms, sir. Easy enough to pick up when you know somewhere where they are. Hello, what’s that?”

Above the tinny noise of the outboard motor could be heard the noise of an aero engine. An aeroplane over Poole Harbour was quite a common sight; but both Colin and Don, with their trained ears, had heard something that had escaped their companions in the boat.

About five hundred feet up was a small monoplane suffering from engine trouble. The engine was missing badly. Although the pilot could have glided down on the sandy shore, for some reason he preferred to nurse his failing engine and circle above the boat.

“What’s the idea?” asked Don. “She’s not a seaplane.”

“If she were she’d come a nasty cropper on the mudflats,” declared the boatman at the helm.

Just then the monoplane’s motor sounded as if it had picked up. The pilot banked steeply, sidestepped, and came down with a resounding smack and a terrific cloud of spray.

He had stalled his machine in about six inches of water over liquid mud that was probably thirty feet deep. The propeller blades had broken off short, but the prop boss was still revolving at high speed, the jagged fragments of the built-up blades churning up mud and water. The machine, with crumpled wings, was rapidly sinking into the ooze.

There was no sign of the pilot. Probably the impact had hurled him against the instrument-board and had rendered him senseless even if he had not broken his spinal column.

“There may be enough water to float us, sir,” declared one of the boat’s crew. “Do you mind coming for’ard? She won’t squat so much.”

The outboard engine boat dashed to the rescue. About twenty feet from the wrecked plane she smelt the mud. The steersman tilted the engine and allowed the boat to come to a standstill within six feet of the now silent monoplane. The boat’s forefoot was actually resting on one of the partly submerged wings.

“No chance of her blowing up, is there, sir?” asked one of the customs boatmen apprehensively.

“I think not. Her engine’s stopped,” replied Colin. “Stand by, we’ll jump for it.”

He leapt and landed on the deck of the fuselage. Don followed. As he did so the boat, relieved of the combined weight, slithered on the mud. In consequence Grey leapt short and landed up to his waist in black slime.

Under different circumstances his sudden misadventure might well have been greeted with roars of laughter from his companions; but this was no occasion for mirth.

Gripping his chum by the wrists, Standish heaved and hauled. Gradually he extricated Don from the tenacious embrace of the mud. There was a gurgling sound and both men subsided across the deck of the monoplane. Before the suction had been overcome Don had left both shoes irretrievably lost in the clinging mud.

Picking themselves up, the chums devoted their attention to the unfortunate pilot. He was unconscious and breathed stertorously. There was a severe gash across his forehead which was bleeding profusely. His left arm had been fractured at the wrist and there were indications that his left leg had been broken below the knee.

Within the limited space at their disposal the chums quickly set to work to render first-aid. It was a fairly straightforward task to cut strips from the wreckage to make into splints and to apply iodine and bandages to the nasty wound in the pilot’s forehead; but the difficult part of the business came when they had to transfer him from the wrecked monoplane to the waiting boat.

Meanwhile, since the tide was still on the flood, the two boatmen had succeeded in getting her close alongside. By taking up the bottom-boards and using them as a rough-and-ready stretcher, the four men succeeded, not without a good deal of effort, in getting the patient into the boat without further risk of injury to the fractured limbs.

“The sooner we get him to hospital the better,” declared Grey.

“Well, there’s not one in Wareham,” rejoined one of the boatmen. “We’d better make for Poole as fast as we jolly well can. The tide’ll turn soon and that will help us.”

Then, with the proverbial cussedness of outboard engines, the motor obstinately refused to fire. Her crew, hampered by the presence of the injured and unconscious pilot, were faced with the possibility of having to row the cumbersome craft for six miles—unless they were lucky enough to get the offer of a tow.

Just as they pushed off the mud into navigable water they noticed a speed-boat approaching at high speed.

She slowed down as she drew near.

One of the customs boatmen signalled to the crew to bring her alongside.

“A crash, I see,” remarked one of the speed-boat’s crew of three. “Anyone hurt? Can we do anything to help?”

“If you’ll tow us to Poole, sir,” suggested the boatman.

“We’re unmanageable at low speed,” explained the other, shaking his head. “The load on the engine would soon make her stop. I tell you what: we’ll take the injured man. We’ll be at Poole quay in less than fifteen minutes.”

It seemed a sound proposition.

“Thank you, sir,” agreed the boatman. “George! You’d better go with them. These gentlemen here will come in to Wareham with me and you’d better come up by the first train and help take our boat back.”

“That will hardly do,” objected the owner of the speed-boat. “We’ve a full complement already. We can only just manage to accommodate the injured man.”

“It’ll have to do, sir,” exclaimed the boatman firmly—and unreasonably, Standish thought. “My mate here must be in charge of the patient until he’s in the doctor’s hands.”

To Colin’s astonishment the owner of the speed-boat raised no further objections.

Yet again the unconscious pilot was transferred. George, the customs boatman, boarded the speed-boat and, for lack of other seating accommodation, perched himself on the after-deck with his feet in the narrow well.

The speed-boat’s engines were restarted. She leapt ahead and rapidly gained pace. One of her crew, seated in the after-cockpit, touched George on the shoulder and pointed in the direction of the wrecked monoplane.

George, naturally, looked; as he did so the other deftly gripped him by the ankles and toppled him neatly over the transom into the creamy wake of the swiftly moving speed-boat.

Standish showed no signs of surprise at George’s unexpected bath. He was getting used to sudden developments. His mission, which had promised to be a humdrum affair, was rapidly showing signs of becoming “something big”.

Seizing one of the heavy ash oars, he helped the customs man urge the boat towards the latter’s jettisoned confrère, while Grey assisted by tilting the now useless motor in order that the propeller should not act as a drag.

Fortunately swimming is compulsory with the sea-service branch of H.M. Customs and Excise, so George, although encumbered by his heavy boots, was in no immediate danger.

Nevertheless, by the time they hauled him over the gunwale, he was considerably puffed and not a little indignant.

“I’ll bet a pound note that yon speed-boat won’t be seen in Poole again,” he declared, as he proceeded to wring the water out of his clothes. “It’s a put-up job. I don’t mean to say he mistook us for that blinking speed-boat and didn’t find out his mistake until it was too late.”

“What do you think he meant to do?” asked Standish.

“You’ll find the answer in that wreck, sir,” replied George, pointing to the monoplane that was slowly yet surely being swallowed up by the mud.

“I guess you’re right there, George,” agreed his mate. “Supposing we have a look-see before it’s too late.”

Again they made their way towards the wreck, Colin and the other boatman rowing, while Don scraped the thick deposits of mud from his nether garments and George removed his uniform and wrung the sodden articles out.

It was on the top of high water when the boat made fast alongside the monoplane.

Assisted by Standish, the two customs men made a systematic search of what remained of the interior of the fuselage above water. Abaft the cockpit they found two leather suitcases and a large package wrapped up in oiled silk.

“Enough to pay for your ducking, George,” declared his companion with a chuckle of satisfaction. “We’d better be getting along before the tide leaves us, unless we want to make a night of it sitting in an open boat in the mud and with nothing to eat and drink.”

“Do you think she’ll quite disappear?” asked Grey.

“May not for a tide or two. I’ll ’phone the harbour-master and see if he can send a salvage craft along. Keep her on the move, sir, and I’ll try my luck with the engine again.”

Standish and Grey were contemplating the possibility of having to row the heavy craft for the rest of the way to Wareham when, either by good luck or good management, the boatman contrived to get the outboard running.

Presently they entered the River Frome, following its meandering course between reed-fringed banks until, skirting a tall yellow sandstone cliff, they came in sight of a number of moored motor-yachts, most of which displayed an orange and yellow burgee.

“Now, supposing that speed-boat came from here?” asked Standish.

“Not she,” replied George. “We know all these boats. They belong here. There’s no harm in asking.”

He hailed one of the cruisers.

“Seen a speed-boat passing here this afternoon, sir?”

“No,” was the reply. “There’s been nothing up here to-day.”

“Then that speed-boat must have been lying doggo either in Murmer’s Cove or behind Gigger’s Island,” suggested George’s mate.

“Or else up North River.”

“May be. Well, here we are, gentlemen. It hasn’t been a dull trip, has it?”

The boat ran alongside a landing stage almost under the shadow of a church tower. The customs men tied her up and went off—one to borrow some dry clothes and the other to pursue the business that had brought them to Wareham. What it was Standish hadn’t discovered; they hadn’t volunteered the information and he had not inquired.

It was not until the chums were in their room at the Bear that Colin drew a small metal case from his pocket.

“This does not contain contraband goods, old son,” he remarked. “Otherwise I would have handed it over to our worthy George and his fellow officer. But it does concern what we’re after, and therefore I’ve taken possession of it without pangs of conscience.”

He snapped open the lid and disclosed several sealed glass tubes divided by a thin disc. On each side of the disc each tube was filled with powder of different kinds.

“Snow?” asked Don.

Standish shook his head.

“Nothing of that nature,” he replied. “If it were, it would have been a job for the customs. As it isn’t, I’ll take the liberty of experimenting with its contents.”

He extracted the cork and poured half the contents upon a metal ash tray. Then, with the aid of the blade of his penknife, he punctured the celluloid disc and released the remainder of the powder. This he poured upon the heap already on the tray.

Almost immediately the combined chemicals burst into a vivid white flame.

“Pretty dangerous stuff to carry in a plane,” remarked Grey.

“Harmless enough provided it doesn’t mix,” explained his chum. “Unless I’m much mistaken, these chemicals are phosphorus and potassium chloride. The two, kept separate, are harmless. Mix them and, as you saw, there’s a big flame. That fellow who crashed this afternoon had a supply of these. If he dropped one from a height and the glass splintered there would be an immediate flash.”

“But how would that account for a heath fire supposing the tube dropped into a patch of heather and wasn’t broken?” asked Grey.

“It wouldn’t ignite until, in the rays of the sun, the disc separating the chemicals became melted,” explained his chum. “It may take hours, days, or even weeks.”

“What’s your opinion about this business, old son?” asked Grey. “Hanged if I can see why a drug smuggler should want to weigh in with arson.”

Standish gave it.

“But I’m dashed if I’m going to be the early bird to get a worm in order to please the Poole customs,” he added. “This afternoon’s crash will have dislocated the air-smugglers’ plans.”

However, just before noon, the chums left their hotel and motored to Bere Regis aerodrome.

When the doors of the hangar were unlocked they hastened to see if there were another mysteriously placed warning pinned to the instrument-board.

There was none. A piece of silk thread that Standish had stretched across the forward cockpit had not been disturbed.

They manhandled their plane into the open, saw that there was petrol enough and that the controls were in order. As far as they could ascertain, no attempt at sabotage had been made.

“May as well take her up,” decided Colin.

Symes, the ground foreman, came up holding his well-known log-book.

“Going to log us, Symes?” inquired Standish. “We aren’t Far Eastern pilots now, you know.”

“Routine, sir,” replied Symes imperturbably. “I’ll have to know your destination and probable time of return.”

“Oh, just pottering round,” explained Colin. “We may be an hour or we mayn’t return before dusk.”

A group of pilots and groundsmen watched them take off. Assistance was not necessary as in the case of the huge Condor biplanes used in the company’s service for long-distance flights. They did not have to depend upon petrol, and, remembering that some intruder had been alone with their monoplane, Standish found himself wishing that his bus was not dependent upon highly inflammable spirit.

Grey took charge of the controls, while Standish, armed with a pair of low-powered binoculars, which, giving a wide field, were preferable to the high-powered prism glasses for his task, occupied the bucket seat in the after-cockpit.

Quickly the monoplane climbed to an altitude of two thousand feet. The air was inclined to be misty, so that the Isle of Wight, which, when visible from this part of Dorset, was a sure indication of stormy weather, was hidden in the heat haze.

Following the coastline of the extensive harbour of Poole, Standish scanned the numerous indentations where a hundred small craft could lie hidden from ground observation in the esparto grass. It was now nearly high tide and the whole extent of the harbour resembled a large lake. There were hundreds of craft, large and small, towards the eastern side; but to the westward of the island and in the Wareham Channel the number of vessels under way could be counted on the fingers of one hand. One of the latter craft was a lighter with a crane from which hung a crumpled shape that Standish knew to be the wrecked monoplane. The harbour-master had not lost much time in getting the suspicious machine away from the tenacious grip of the mud.

Except for that, there was little to attract attention.

“Swing her out to sea, Don.”

“Aye, aye, skipper!”

They crossed the coast in the neighbourhood of the famous Old Harry Rock; then, turning westwards, passed over Swanage, St. Alban’s Head, Kimmeridge and Warbarrow. Several flying-boats proceeding from Portland to Portsmouth and a Far Eastern Airway biplane heading south were the only aircraft sighted.

High over Lulworth Cove the monoplane turned and headed inland towards Wareham. Soon they were over a part of the great heath that had suffered considerably from a recent fire. Gaunt barrows, previously hidden in masses of gorse, were now revealed—blackened rounded mounds that were in existence long before England had a written history, and, perhaps even now, held the gold and silver funeral trappings of more than one long-forgotten chieftain.

Presently, not far from an expanse of trees that he recognized on his map as Holme Woods, Standish caught sight of a stationary saloon car. He focused his glasses on it, not out of mere idle curiosity but because he fancied——

He was not mistaken. A man had alighted and was setting fire to something by the side of the road.

A thin wisp of bluish smoke, visible even to the naked eye, rose into the still air. The man, satisfied that a fire had been well and truly started, jumped into his car and made off.

“There’s one of the blighters, Don!” shouted Colin through the voice-tube. “Shut off your engine and plane down. We’ll mark him, right enough.”

Grey, his eyes fixed upon the comparatively slowly moving car—actually it had already attained a speed of about forty miles an hour—followed his chum’s instructions while Colin, releasing the safety-catch of the spraying gun, awaited the chance of “marking” his man in more senses than one.

Smart as he had been in swooping earthwards, Grey was not in time. The car, swinging round a corner, disappeared under the trees from his sight. The pilot had to zoom to avoid a crash into the tree tops.

“Sorry, old son!” exclaimed Don.

“Couldn’t be helped,” replied Colin. “We’ve got the fellow cold all the same. He’s got to come out by one of these three roads. Circle over the wood and keep a sharp look-out while I wireless the police.”

The monoplane regained altitude; Standish unwound the aerial and proceeded to call up the Wareham police.

The signals were quickly answered. Then Colin sent out the following message:

“From Air Constabulary patrol. Car driver seen setting fire to heath half-mile south of East Holme. Is hiding in Holme Woods.”

“Right! Sending motor-police to close each exit, and police to scour woods,” came the reply.

Standish had only just switched off, when Don exclaimed:

“There he is!”

Glancing downward, Standish saw the car proceeding at a much slower speed towards the village of Stoborough by the eastern exit from the woods; but instead of proceeding in that direction the driver swung the car to the right along an unfrequented road in the direction of Creech Barrow. That meant that the mobile police would not be able to intercept him. It would mean a stern chase and only after Standish had informed them by wireless of the suspect’s unforeseen ruse.

The only thing to be done for the present was to swoop down and spray the car with aniline dye.

Again Standish prepared the spraying-gun. He realized that the car was speeding against a fairly stiff breeze and consequently the celluloid shells would be considerably deflected. He’d have to aim several yards ahead of the moving target in order to score a direct hit.

The occupant of the car was obviously ignorant of the fact that the monoplane with engine shut off was swooping down and rapidly overtaking him. The saloon roof prevented him looking upwards and, unless he thrust his head out of the window, he would be unable to see the aeroplane even if he knew he was being pursued.

The car descended a dip in the road and ran under a railway bridge. Beyond that point the road was unimpeded for a mile or so.

Watching his opportunity, Colin fired three “shells” in quick succession, while Don, having overshot their quarry, promptly restarted the engine, zoomed, and then banked in order to see the effect of his chum’s marksmanship.

The celluloid cylinders had done their work well. One had hit the roof fairly and squarely, another had shattered itself on the bonnet, liberally spraying both wings and the wind-screen. The third had struck the ground in front of the car and had left a big splash of violet fluid upon the road.

Then, to both chums’ surprise the car wobbled and came to a standstill with the near side wings on the verge of the road. The off-side door was flung open and the driver emerged, wiping his face with a handkerchief that had been white but was now of a violet hue.

The aniline dye, blowing back through the partly opened wind-screen, had done its work only too well. It had very efficiently marked not only the car but its occupant.

He looked up and shook his fist defiantly at the monoplane. No doubt he shouted angrily as well, but if he did his voice was drowned by the roar of the machine.

“Bring her down, Don!” exclaimed Standish. “I didn’t expect to make an arrest, but we may as well make a thorough job of it.”

They landed on a rough grassy track about a hundred yards from the car. Both alighted and made their way towards the suspect, who, however, made no attempt to escape.

“Poor specimen of a criminal, that,” thought Standish contemptuously, for an easy capture never appealed to him. “Unless, of course, the dye has blinded him. Then the fat will be in the fire with a vengeance!”

“What do you mean, sir, by this unwarrantable outrage?” demanded the motorist. “I say, what do you mean by it?”

Colin, however, had heard that sort of greeting before. Suspects often try to bluff their captors by such words.

“It’s my duty to arrest you!” exclaimed Standish.

“What, what, what!” spluttered the other furiously. “Arrest me? What the deuce d’ye mean? Look what you’ve done! It’s an atrocious act. You don’t even attempt to apologize for a mistake, which it isn’t. Arrest me? Who are you? I’d like to have your name and address!”

“We are police officers,” replied Standish. “If you insist on seeing our warrant cards. . . . You’re under arrest. Any statement you may make may be used in evidence against you.”

“Arrest be hanged!” stormed the other, dabbing his face, and transferring more dye from his handkerchief to his nose and cheek. “Call yourselves police officers and you don’t know who I am? I’m a Justice of the Peace, sir, and—Ha! That’s better. Here’s someone with grey matter under his cap instead of batter pudding.”

A constable riding a motor-bicycle arrived upon the scene, glanced at Standish and, before the latter could say a word, at his prisoner.

Then, to the chagrin of the two chums, the policeman, successfully suppressing a grin, saluted the owner of the car.

“Quite evidently a mistake, Sir Gregory,” he exclaimed.

“Mistake? Of course it’s a mistake or worse,” rejoined the other heatedly. “Ruined my car, made me look a perfect guy, and then the fellow talks of arresting me. He says he’s a policeman, too. I doubt it.”

Was the man still bluffing? Since the constable had unhesitatingly recognized and saluted him, he was evidently someone of standing. But even persons in the higher walks of life had been known, through some inexplicable mental kink, to commit utterly senseless crimes.

Producing his warrant card, Colin showed it to the constable.

“We sighted this person in the act of deliberately firing the heath,” said Standish. “In the circumstances we are justified in arresting him.”

“Setting fire to the heath?” echoed the motorist, either with well-feigned indignation or genuine surprise. “Where, might I ask, did you see me doing that?”

“On the Lulworth Road about half a mile south of East Holme, about twenty minutes ago.”

“Haven’t been within a mile of the place,” declared the suspect. “To satisfy you, I’ll give an account of my movements. Half an hour ago I was talking to your superintendent outside the town hall at Wareham. I left there, paid a call at the house of a friend and found no one at home, and then drove along this road.”

“Apparently it’s a case of mistaken identity, sir,” observed the constable, addressing Colin. “I saw Sir Gregory Wyatt talking to our super at the time he mentioned. That was four minutes before we got your radio message.”

“In that case, Sir Gregory, I must most deeply apologize,” said Standish. “But the fact remains that we did spot a car similar to yours from which a man alighted to set fire to the gorse. He drove under cover into Holme Lane woods.”

“Then go and find him,” rejoined the J.P. “Don’t waste time here. Look here! Hop into my car and I’ll drive you there. The constable had better ride off as hard as he can and warn the others.”