* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Exploits of Peter

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Sydney Horler (1888-1954)

Date first posted: July 20, 2020

Date last updated: July 20, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200726

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

EXPLOITS OF PETER

SYDNEY HORLER

LONDON AND GLASGOW

COLLINS’ CLEAR-TYPE PRESS

Printed in Great Britain

| CONTENTS |

| A McTAVITY STUNT |

| MAKING ALLOWANCES |

| SAVING HIS BACON |

| CIRCULATING IT |

| A MATTER FOR McTAVITY |

The Exploits of Peter

Some of you, with such very old heads on such very young shoulders, may scoff at this and say that I do not know the things of which I write. To all of which I would fire a volcanic counter-volley from my typewriter and say: But you did not know McTavity!

In those words lies the essence of my tale. Those who were fortunate enough to have met that amazing prodigy during the four years he was at St. Colston’s, before passing to another place, came to discredit the ordinary, and believe the frankly impossible, the bizarre, and the weirdly humorous in connection with this shock-headed youth in whose head burned the lamp of genius.

I find it difficult to describe Peter McTavity, as splendid a character as ever author wove fictional romances about, in a few words. If I had to sum him up in a single line, I should call him a boy with a man’s brain.

There could be no question about his being abnormal; every one admitted that, none more sorrowingly than the Rev. Joseph Baxter, the benign Head of the famous school, which he ruled with a Bible in one hand, and a birch-rod in the other.

McTavity’s father was the most phenomenally successful newspaper proprietor in the country, and to those sage souls who believe in the strain of heredity, the fact may be worthy of note. But the historic “stunts,” by means of which Sir Robert Angus McTavity had built up the colossal circulation of the Daily Miracle, glowed wanly when compared with the superb eccentricities which his only son “put over” from time to time, and when the fancy seized him.

* * * * *

The Big Hall was crowded. There was a tense air of expectancy, and the whole school, which had been summoned from the morning classes at the Head’s decree, was on the tiptoe of excitement. A suppressed buzz of sensation, like the humming of a thousand bees, piano, filled the building. The Rev. Joseph Baxter was a martinet so far as erudition went; it was only on the gravest and most serious occasions that he forced studies to be wasted by calling the whole school together in Big Hall.

Of course, the wildest yarns were going round. Some said that a couple of kids had been discovered breaking out of “Dom.”; another theory was that some one had caught measles or the mumps and the whole crowd would be sent home. (This was received with a certain reserve, it being felt that it was far too good to be true). Yet a third supposition was that, for some highly mysterious reason, the Head was going to declare the town of Stapleford out of bounds.

When the revelation came, it proved to be a shock equal in intensity to any of these dire forebodings.

“I always said the young blighters would get caught sooner or later!” commented Bridges, the footer captain, to Jenkins, his crony and fellow Sixth Former.

Loudly and menacingly the Head’s voice rang out. The chilled tones sent a dreadful shudder down the entire backbone of St. Colston’s; while the plight of the two boys who were occupying the empty space in front of the Rev. Baxter’s desk was pitiable to witness. They were the Awful Warnings, and indeed they looked awful enough to warn the most valiant.

“I had always considered St. Colston’s, unlike some of its contemporaries, to be an establishment of young gentlemen; to my regret I discover it is the home of young blackguards!”

That was the opening spasm of the Head’s thunder, and there were many to agree with Mike Beavis, McTavity’s aide-de-camp, that it was “some snort.” Certainly, it promised interesting developments. When the Rev. Joseph Baxter once got the bit between his teeth, as he appeared to have now, there was no saying to what length he would not go in his mad gallop. Of course, he wasn’t to be taken seriously; at least, that was the considered consensus of opinion at St. Colston’s. Once he had got the bad air out of his system he wasn’t intolerable; but until he had he was frankly impossible. I quote again the weighed and pondered view of St. Colston’s.

After such a start, it was not surprising that every eye was bent on the Head and the luckless wights who were even now trembling under his spiritual wrath, as they were destined shortly to bend beneath the physical tornado which was the Rev. Joseph Baxter when he had a swishing cane in his hand.

“I am informed—and I am afraid there can be no question about it, seeing that the culprits have themselves confessed to the crime—that these two boys, Johnson Minor and Davey, were yesterday afternoon seen coming out of a public-house in Stapleford!” He waited for the dramatic announcement to have its full weight before repeating “public-house” in much the same tone as the Devil is supposed to say “Holy Water.”

“It does not concern me minutely why they went to this place, abusing alike the pass, which I had given them for an afternoon’s enjoyment of the fresh air, and my confidence; it is sufficient for the purpose I have in hand to know that they did go, setting my authority at naught and bringing a terrible disgrace upon the school. In case there is any one present this morning who desires to follow the example set by these two misguided youths, I would ask him to note the measures I shall take to put a stop to this scandal!”

It is true enough to say that the inclination to visit public-houses, either at Stapleford or any other place, showed a marked decrease in popular favour after the despairing wails of the flogged boys died away.

“Smite the heathen!

Smite them hip and thigh!”

was the motto which carried the Rev. Joseph Baxter through life, and the vigour with which he now carried out its teachings filled the Big Hall with dreadful sound.

When the quivering forms of his victims had been led away, and he had resumed his official composure once more, the Head spoke again. And it was this wise: “This has been a very regrettable incident, but I was forced to take strong measures. It is to be deplored—I have thought so before to-day—in some ways that there isn’t an outlet in Stapleford for legitimate amusement. In such a day of progressive competition as this, it is to my mind surprising, to say the least, that some enterprising individual has not erected the ubiquitous ‘picture palace.’ Perhaps if something of the sort existed, we should not have the degrading spectacle of ill-balanced youths wandering into dens of vice and iniquity in search of amusement. Ah, well! it doesn’t rest with me. I need only add that, if another case of this description is brought to my notice, the punishment I shall inflict will be—expulsion! The School will now dismiss!”

“And that’s that!” murmured Peter McTavity, as he rode in solemn state to the dining-room on the shoulders of his admiring disciple, Mike Beavis, who beamed with as much pride as he would have done if the King of England had expressed a fervent desire to look through his collection of postage-stamps.

There was no other topic of discussion throughout the day. Crowds that rivalled each other in size gathered round both Johnson Minor and Davey, who were besieged with questions varying from “What would the Pater say?” to “Do they hurt now?”

It appeared from the statements of both delinquents that they had gone into the Spotted Cow to play, or rather, to essay to play a game of billiards.

That evening Mike Beavis, hearing McTavity thoughtfully but loudly playing his banjo, and knowing that this was a sign of spiritual exaltation on the part of the genius of St. Colston’s, burst open the door. Sitting on the table, McTavity was enrapturedly composing a march of triumph in praise of one of his own ideas!

On account of an auriflame of luxuriant growth, which was of a nicely burnished copper tinge, a few of his intimates styled McTavity “Ginger,” and it was by the affectionate abbreviation of this that Beavis now called upon him.

“I say!” he declared in wondering awe; “you make it noisier every day, Ging.; is that a new thing you’re playing?”

“Quite new—brand new! Never been out of my shop, sir! This is the best article at the price that can be bought!”

“What’s all the excitement?” cut in Mike, and reading with a shrewd eye the mood of the boy he knew so well.

“And why shouldn’t I be excited?” cried the other, flinging the banjo on the table, and jumping down to catch Beavis by the shoulders. “Have I not suddenly resolved to save the school we love and upon whose playing-fields the battle of Trafalgar was won?”

“What on earth are you rottin’ about?” cried Beavis, puzzled out of his depth, used as he was to the other’s eccentricities.

McTavity frowned so realistically that Mike started back alarmed.

“Your greatest fault to my mind has always been your ill-timed levity in moments of the gravest national importance,” was the rebuke that was hurled at his defenceless head. “How can you laugh when I was about to save St. Colston’s from the awful degradation which threatens to engulf it?”

“I wasn’t laughing, Ging.; but what do you mean?”

“Can you have so soon forgotten the burning words of your head master? Did he not tell you only this morning that the school is faced with moral degeneration unless some public-spirited man can come forward and provide legitimate and healthful amusement at our doors? And lo! the need brings forth the hour, and the hour the man. Behold! the man!”

So saying, McTavity thrust his hand inside his waistcoat, à la Napoleon Bonaparte, and beamed as though he had just been presented with the freedom of the city.

The look of blank amazement still persisting on Beavis’s face, he pushed Mike gravely and sadly into a chair, and talked animatedly to him for several minutes. During the recital, Mike struggled convulsively with the merriment that threatened to choke him, and when at length McTavity finished, he gave one long, piercing howl of delight that threatened to burst his lungs.

That night McTavity got on the London telephone to his father, and the next morning he was stopped by his form master, who said,—

“The Head has given you permission to go to London for two days, McTavity, I understand.”

“Yes, sir, I have some business that requires seeing to!” was the reply which flabbergasted the master, and sent him staggering away.

Calvey took the surprising retort straight to the Head, who looked up from his papers with a puzzled frown.

“It is most surprising, I agree, Calvey; but Sir Robert sent me a telegram to say that he wished to see his son on an urgent matter, and that he couldn’t spare the time to come down to Stapleford. So I gave my permission. But the boy’s head is full of extraordinary ideas—I really do not know what he will develop into when he gets out into the world—and so I dare say we need not attach any undue importance to the matter. I will see him when he returns.”

But—and perhaps it was a freakish Fate who decided it—the multifarious duties of the Head prevented him from interviewing the boy on whose youthful shoulders the cares of business pressed so heavily. Instead of taking war into the enemy’s camp, the enemy actually brought war—or something which at first threatened to be akin to it—into the sacred precincts of his own study.

It happened this way: in the interval between tea and Prep, the Rev. Joseph Baxter placidly reading Greek verse in the original—his one luxury—was informed that a boy wished to have a private interview with him. It was a time-honoured custom, that, if a boy followed the correct procedure, the Head was accessible to him in case of need. Somewhat wearily then, the Head gave permission for the boy to enter.

The visitor proved to be McTavity—a serenely-confident McTavity, oozing goodwill and benevolence to the world at every pore.

The Head straightened himself up, scenting mischief.

“And what do you want to see me about, my boy?” he asked sharply.

“I have come to know, sir, if you would lend your kind support to a scheme which has as its object the providing of wholesome amusement for the boys of the school; and which, I have every reason to believe, would do away with the lamentable tendency of some of the more ill-balanced minds for seeking relaxation in unhealthy atmospheres, and the consequent degrading scenes which were witnessed a few days ago in the Big Hall!”

“What in thun”—the Head nearly said “thunder,” but stopped himself on the brink of the precipice—“the name of all that’s intelligible do you mean?” cried the Rev. Joseph Baxter. “Are you trying to make a fool of me?”

“Sir!” was the shocked reply, “you pain me! I am sorry if I have vexed you in any way, or if you question the objects which have prompted me to undertake this work. You said in your speech the other morning that you deplored the fact that there wasn’t an outlet in Stapleford for legitimate amusement; well, sir, it is my sincere and honest endeavour to supply that long-felt want. I counted on your support, sir.” This last with a look of mute reproach that was calculated to move the heart of a dyspeptic rhinoceros.

The Head was cornered—pushed into a situation by a quotation from his own oration. He felt himself in the power of an agency that was seeking to overthrow him by nefarious means, and yet against which he knew he was helpless.

He did the best he could for himself in the circumstances.

“If you are arranging some form of entertainment for the school—an entertainment which will prove helpful and wholesome—I shall be pleased to lend my support to the scheme,” he replied, “but, remember, I must have the scheme laid before me. You can go.”

McTavity went—grinning from ear to ear—to be embraced, bear-fashion, by a highly expectant and inordinately delighted Mike Beavis, who had been fretfully waiting in the corridor.

* * * * *

Three days later, and the bombshell fell. Although made of paper, it created as much commotion at the breakfast table of the Rev. Joseph Baxter as a 5.9 might have done.

Amongst the Head’s correspondence was a large envelope, highly ornamental, on the top of which was printed in flaming scarlet letters:

THE STAPLEFORD COLOSSEUM

Bewildered, the eminent pedagogue tore open the envelope: a large card dropped to the floor.

At first, the Rev. Joseph Baxter thought he must be dreaming, but a second scrutiny through his pince-nez assured him that he could no longer harbour any illusions on that score.

This is what he read:—

UNDER THE DISTINGUISHED PATRONAGE OF

THE REV. JOSEPH BAXTER, HEADMASTER OF ST. COLSTON’S,

SIR ROBERT ANGUS McTAVITY, AND OTHER NOTABILITIES.

The charming Picture Play House to be known as

THE STAPLEFORD COLOSSEUM

will be opened with great éclat on Saturday next at

2.30 p.m. sharp. Doors Open at 2.15 p.m.

MONSTER PROGRAMME OF STARS!

FORGET DULL CARE! COME AND LAUGH!

Come Early to Avoid the Crush

Come and shake hands with Peter McTavity, the world’s

youngest manager, who lives only to see you happy!

POPULAR PRICES!

The Rev. Joseph Baxter had led an uneventful and sequestered life; his heart wasn’t equal to the tremendous strain which suddenly had been put upon it. With a faint, despairing cry like unto that of a wounded bird in fright, his head fell forward.

And it was thus that Sir Robert McTavity, who, a proverbial early riser, had come down by the first train from London, found him when, to use his own terse phrase, he dropped in for a bite.

On the eventful Saturday, the quiet rural town of Stapleford was roused as it had never been awakened since the days of Noah. McTavity had sworn to make it realise that progress was marching through its mildewed streets with iron-clad feet and a rushing of mighty wings; and he had pursued his determination with such indomitable purpose that the sedate Staplefordians were scarcely aware if they stood on their heads or on their heels.

They did not recognise their own town, with the hoardings plastered with the striking designs that the printers, acting on McTavity’s instructions, had turned out. The walls were simply plastered with them; there was no escaping them; they met the eye at every turn.

McTavity was a great strategist; he invariably covered his retreat. That was why he had persuaded his father, who was one of the school’s most liberal patrons, to stay on at Stapleford over the eventful Saturday. The millionaire, who, although he would have been the last one to admit it, was really led by the nose by the son he idolised, had to persuade himself in turn that he could do with a short holiday. Anyway, there he was on hand in case Trouble raised a disturbing finger.

The excitement throughout the school was unparalleled in its intensity.

At length Saturday came—a peerless, sunny day that held the sweet graciousness of September. In any other case, the footer field would have claimed its devotees; but this afternoon the playing-grounds were practically empty.

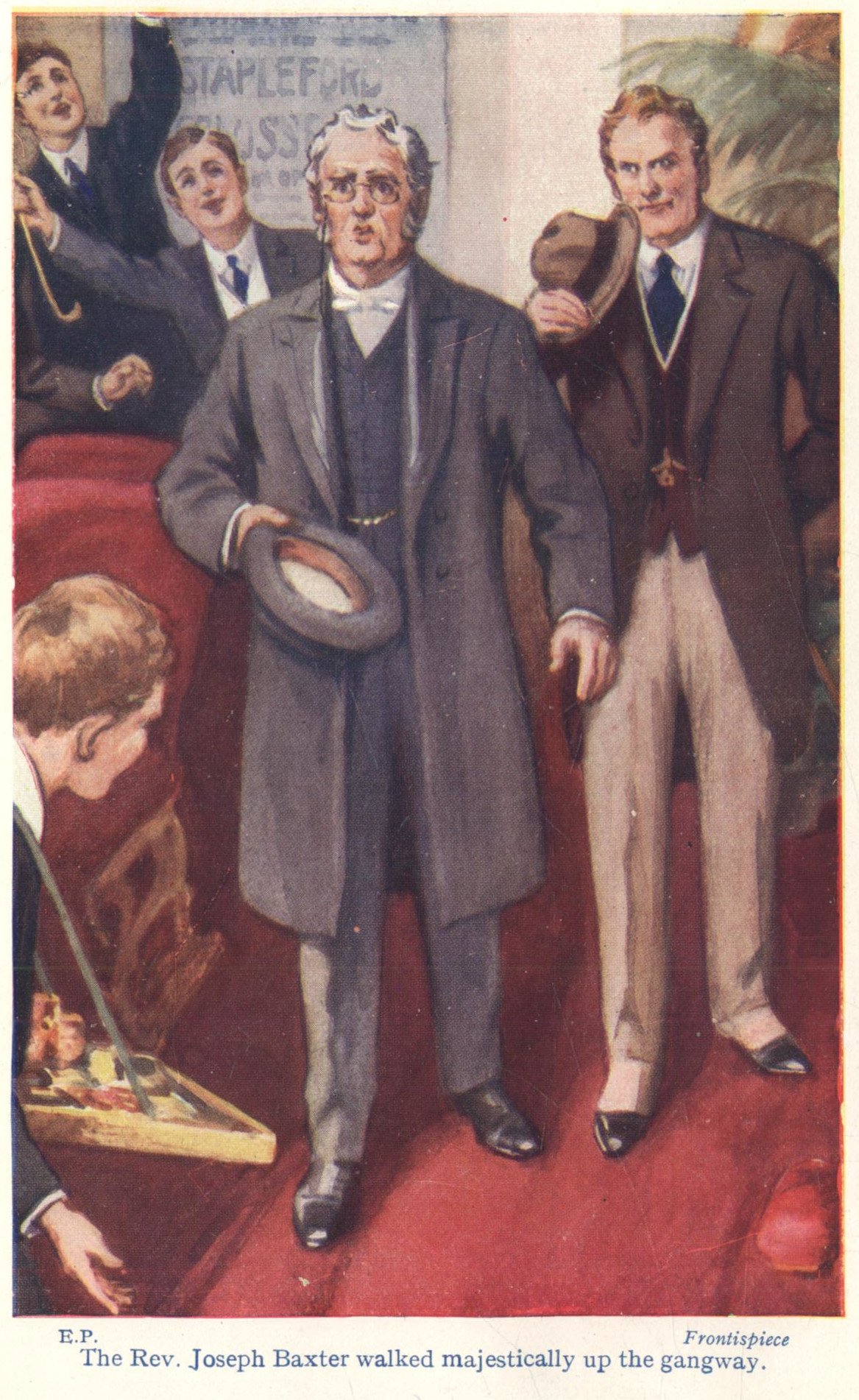

Sir Robert called for the Head himself. As he—or rather his son—put it, they couldn’t let the opening notices down!

The Head, too dazed to speak, walked down the street hanging on the arm of the millionaire.

Outside a gaily decorated building, hung with flags and emblazoned with lurid pictures of the “World’s Most Famous Films,” a huge crowd was struggling to get inside.

“Seems as though it was going to be a success,” commented the newspaper owner.

“But this used to be a disused barn!” replied the Head of St. Colston’s in a bewildered tone. “I cannot understand!—how has all this been done in so short a time?”

“Perhaps I ought not to say it,” said the millionaire, “but hustle is in our family! But wait until you get inside! You will get a further surprise!”

“Surprise” was the right word, judging by the perfectly blank expression which was on the Head’s face when, heralded by an outburst of cheering that threatened to lift the roof off, he walked majestically up the gangway to the front-row seat which had been reserved for him. This was a strange world to the Rev. Joseph Baxter; a world in which he could not find his bearings.

He looked around him. There was a band—if a violinist and a pianist could be termed a band. There were carpets on the floor, and serried row after row of well-upholstered chairs. There were also a corps of programme-sellers, with trays of chocolate and cigarettes. These he recognised, with a fear that the worst was yet to come, as his own pupils.

Presently the hall was packed to the point of suffocation; any doubt that the affair wasn’t a huge commercial success was speedily dissipated. Everything was managed in splendid fashion; no hitch in any of the arrangements could be discovered. Looking round after a time, the Head was agreeably surprised to find that several of the leading residents of Stapleford were present.

He turned again when a chorus of amused tittering broke on his ears. And if he had not been the Rev. Joseph Baxter, and responsible head of St. Colston’s, it is possible that he, too, might have laughed.

For, walking down the gangway, with a gravely responsible air, was a diminutive figure clad in an immaculate evening dress suit, talking earnestly to a fellow in overalls who looked like an electrician—and smoking a cigar!

He looked again, adjusting his pince-nez the better to view this phenomenon!

There could be no mistake: the diminutive figure in evening dress who bore himself with all the assurance of a famous entrepreneur was—McTAVITY!

A shrill-throated roar of welcome came from the cheaper seats, where the boys from the school were safely entrenched, to which the young manager graciously bowed his acknowledgments as he retired.

Turning to Sir Robert McTavity, the Head found that an intelligible conversation with the newspaper owner was impracticable. The millionaire was shaking with uncontrollable mirth.

But now the lights were lowered, and the audience, on good terms with itself, settled itself to enjoy the programme.

And if there is one fact which stands out more than another in the vivid and pulsating events of that afternoon, it is that this unsophisticated yet thoroughly genteel audience did enjoy itself.

McTavity had chosen the different items with care and discrimination. In this, his judgment had fought a duel with his heart. He would have liked to have thrown in one or two thrilling murder films—and in this it is safe to say he would have had the whole-hearted support of the St. Colston’s section of the audience—but, curbing these desires of the Higher Art, he put on the screen a nice, soothing-syrup sort of show which would have suited a Congress of Baptist Ministers!

Stapleford was delighted! It showed its delight by the frequent genteel hand-pattings with which picture after picture was greeted.

After an hour and a half had run its course, there was a break. “Interval” was flung on the screen.

The programme-sellers now put down their trays and busied themselves with fresh burdens—cups of tea and neatly cut bread-and-butter, with a small slice of cake to round the whole thing off!

“How awfully nice! If I could see that sweet little man in the evening dress I would thank him!” was the general opinion of the female recipients, while the men ate, silently thankful.

But the “sweet little man” was busy; he had a job on hand.

While the audience was blissfully munching their bread-and-butter, and seedcake, a diminutive figure, looking very debonair in the severe black and white in which he was dressed, stepped on to the platform. The cigar was gone—but an ineffable smile had taken its place.

Simultaneously, a tornado of sound came from the cheaper seats. The fragmentary teas had long since been disposed of in this quarter, leaving mouths open for no other purpose than acclamation.

When the applause, and the concomitant cries of “Good old Ging.” had died down, a small hand was put up for attention, and, after seeing that the reporter for the local paper was quite ready, the manager of the Stapleford Colosseum delivered the following address:—

“Ladies and Gentlemen, it gives me very great pleasure to welcome you all here this afternoon. I wish you to believe me when I say that my one wish is to give you satisfaction—and value for your money! I hope you will think that you have had value for your money this afternoon.” (Cheers, and a voice: “The cake was worth it!”)

“Upon me has fallen the honour of bringing the marvels of the cinematograph to Stapleford. It is a novel, but a worthy handmaiden of Art.

“Some of you may have been in the habit of going into public-houses for your amusement; in future I hope you will come to the Colosseum. You will get better value for your tan—er, money!” (Looks of horror amongst the front-seaters accompanied these devastating words, but, without the slightest hesitation, the speaker plunged on).

“But perhaps it is to my young friends—I trust they will not mind my calling them my young friends, for once I was a boy myself, heigho! how long ago it seems!—that the opening of the Colosseum will come as the greatest boon and blessing. They are on the threshold of that knowledge which we call Life. Many temptations are open to their untrained minds; many erring finger-posts are put up for them to follow. At the Colosseum, where I shall always be pleased to take their grimy sixpences, they will be able to obtain an afternoon’s healthy entertainment; and it is to meet their needs that I am arranging a special juvenile’s matinee every Saturday afternoon!”

“He—ah, he—ah!” cried a shrill voice, which tried to be deep, from the back of the hall, and which McTavity had no difficulty in recognising as belonging to Mike Beavis.

“I shall now have great pleasure,” announced the speaker, “in calling upon the Rev. Joseph Baxter, the well-known and revered headmaster of St. Colston’s School, by whose kindness the juvenile members of the audience are present this afternoon, to say a few words.”

A fresh round of frantic applause in the midst of which the Rev. Joseph Baxter, looking something like a bewildered owl, was seen to rise to his feet, a proceeding in which he was assisted by Sir Robert McTavity.

Like a man dazed, he stepped on the platform, and from there to the stage, to be greeted most kindly by the manager of the Stapleford Colosseum, who seized his hand and shook it cordially—to the delight of the spectators!

Truth has ever guided the faltering hand of the present author, and Truth compels him to put it on record that the speech of the Head of St. Colston’s was not a pronounced success. The first essential of a speaker is to make himself heard, but only fragmentary portions of what the Rev. Joseph Baxter actually said could be heard. From the back of the hall, where Mike Beavis sat gloating fiendishly on the scene, the speech sounded something like this:—“. . . delighted . . . exercise good influence. . . cannot say too much. . . in praise. . . most enjoyable. . . er. . . er. . . er.”

Not too good—but good enough to put the finishing touch to what the local reporter, writing better than he knew, truthfully described as a “memorable afternoon.”

* * * * *

“But this is monstrous—monstrous!” declared the Rev. Joseph Baxter, striding up and down his study, in a white rage. “To be made appear ridiculous before my own school; why, it is intolerable! You must think so, if you do not say so, yourself!”

“My dear sir,” replied Sir Robert McTavity, “if I were in your place I should laugh! The boy—drat him!—gave you actually no cause for complaint. You said Stapleford wanted a picture palace, or words to that effect; well, he supplied one! He asked for your support in his scheme, and you appear to have given it. His asking you to speak was a stroke of genius—really I’m proud of the young rascal, although he’s my own boy!—but there was nothing disrespectful in it! If you ask me, I’m more injured than you are over the business!”

“You are—why?”

“Why, he made me promise I would double any sum he could prove to me he could earn by honest means! Now, he’s done the spade work he’ll put in a real manager, for of course you wouldn’t allow him to carry on that farce, and draw a nice little weekly sum out of the proceeds!

“No, Head, I don’t think you can kick, if you will pardon the vulgarism; you see, you put the idea in his head!”

“Evidently something will have to be done!” quoth Peter McTavity; “such barbarism as this flings one straight back into the Middle Ages!”

“In the Middle Ages,” replied Matthew Ord, “one could go out and kill your grub. Nowadays you have to buy it—and I ask you, how can you buy it if your beastly allowance is cut off?”

“That is the exact problem which is causing my forehead to bulge right now!” remarked the Thinker of St. Colston’s. . . “Ah! gold—rich, yellow gold!”

Fishing out a penknife, he “retrieved” an ancient piece of toffee, which had stuck to the bottom of a desk drawer, and after wiping the “find” in an incredibly mouldy handkerchief, divided it into two parts.

“Pard,” he said, offering Ord one piece; “this may be our last meal together for many moons—don’t gobble it all up at once.”

The two chewed and sucked gloomily.

There was undoubtedly a crisis in the affairs of Peter McTavity and his chief henchman. A day or so before, in answer to a very strong attack of Up-and-Do-ism, McTavity and Ord had sallied forth one dewy eve and had placed a derelict topper (bought at an old clothes shop in Stapleton especially for the event) on the august head of Nathaniel Morley, Stapleton’s one celebrity, whose statue stood in a commanding position in the local market-place. The worthy Nat had represented Stapleton in Parliament for upwards of twenty years, and he was in every way to be respected. But the sculptor had depicted him bareheaded, and, the weather being somewhat inclement just about then, McTavity had said it was up to him as a humanitarian to provide the old boy with headgear—suitable if possible, unsuitable if not; anyway headgear!

He had advanced this plea to the Head, the Rev. Joseph Baxter, but the latter knew his McTavity.

“Across that chair, sir!” he had thundered—and the heavy swishing sound that followed told its own sad story to the watching and waiting Ord.

It was not the switching each had received, however, that had caused a crisis in the affairs of Messrs. McTavity and Ord. It appeared that the Head must have written to the father in each case telling of the disgraceful escapade.

It was the answers to these letters that had caused War Loan to drop so low.

In both instances Messrs. McTavity and Ord, Senior, had backed up the Head’s plea for substantial support by cutting off their offspring’s allowance. That was one of the darkest days at St. Colston’s within local living memory.

The toffee finished, McTavity relapsed into thought, and Ord stood in too much awe of that great brain to dare to interrupt once he saw the knob on each end of his friend’s forehead begin to throb. . . . Besides, being totally incapable of thinking for himself, he had to leave it to McTavity.

“The situation,” said the latter after a while, “is serious, but not hopeless. It would serve your guv’nor right, Ord, if we never smoked any of his rotten fags again! By Jove!” with a joyous cry, “we won’t! we won’t!”

“I say,” protested the lesser mind, who was incapable of following the other’s gorgeous nights of fancy, “I can’t stop smoking as well as eating! That’s too thick!”

“In the interests of humanity I am afraid you will have to!” replied McTavity sternly. “And now I must leave you—I have business to attend to. . . . I don’t know whether there is any more toffee in that drawer, but you might have a look—I shan’t be long!”

Having said so much McTavity made his way to the office of the local newspaper, the Stapleton Mercury, and spent some time there.

In the ordinary way a good many copies of the local newspaper found their way into St. Colston’s, but on the day following the events narrated in the first chapter, the demand for the Stapleton Mercury was unprecedented. And for a sufficiently reasonable cause.

SCHOOLBOY REFORMER

ST. COLSTON’S SCHOLAR SETS A PATTERN

PLEDGES HIMSELF TO LEAD CAMPAIGN IN FAMOUS SCHOOL

“NO CIGARETTES!” BUT WHAT WILL HIS FATHER SAY?

The job really had been beyond the local sub-editor, but he had done his best. Personally, he had thought the last headline rather too flippant and sensational, but the boy from St. Colston’s who had supplied him with the astonishing “story” had threatened that if it didn’t go in the Mercury should not have the privilege of printing the article, which would be sent instead to a London newspaper. So he had yielded in the interests of his journal, if not for the ease of his soul.

Below these streaming legends was the following:—

“Many leading thinkers of to-day agree that cigarette smoking is pernicious. To these reformers the name of Matthew Ord, a schoolboy at the famous local school, St. Colston’s, will be blessed, and of the best possible repute. For Matthew Ord has started a reform where it is most urgently required, i.e., amongst the rising generation. Hygienists and eugenists of a future age will in all probability canonise Matthew Ord.

“The latter, who, it is interesting to note, is the son of the well-known tobacco magnate, Mr. Adrian Ord, the maker of the world-famous ‘Glory’ cigarette, has started a ‘No-Cigarette League’ at St. Colston’s, among his schoolfellows, of which he is President. Active propaganda is being done amongst the scholars, and good results are already being reported. Amongst the notable recruits already secured may be mentioned Peter McTavity, the son of the millionaire newspaper owner, who has sworn off smoking and has signed a certificate to that effect.

“Matthew Ord, a serious-looking, thoughtful boy, is allowing no personal ties to bias his considered judgment; even his father’s cigarette, famous as it is, is to be tabooed. Of course, officially no smoking is allowed at St. Colston’s, as at other famous schools, but unofficially——! Anyway, Matthew Ord is determined to root out the evil.

“In these circumstances it would be interesting to learn his father’s views.”

Pretty nearly every one who read the article had something to say about it, but every one else’s comment was drowned by Matthew Ord’s.

“I’ll shoot the fellow who wrote that bunkum,” he said, quivering; “it makes me look the biggest kind of fool!”

“Ord, old sausage!” blithely replied McTavity, to whom the white-hot words had been addressed; “speak not so hastily. Think of your name being inscribed on the Roll of Fame along with George Washington and—er—other great non-smokers! Think of your grandchildren clustering round your knobbly knees and asking you what you did in the year following the Great Peace. Think of your—father—” went on McTavity, reverentially lowering his voice.

“Holy Joe!” cried the tortured President of the St. Colston’s “No-Smoking League,” “that’s who I am thinking about! What he’ll say when he reads this, I don’t know——”

“Perhaps he will reflect on his former inhuman conduct, my worthy President. At least, that was my intention in writing it!”

“You wrote it?” cried Ord.

“Of course I did. You surely don’t imagine that any one else would have had the intelligence to do it, do you? Why don’t you think, Ord?”

“I can’t,” weakly confessed the Cigarette Maker’s Romance.

“Sit down, and I will unfold the whole works,” went on McTavity, warming to his subject by this time. “Some people may call this scheme gentlemanly blackmail, but I prefer to term it ‘intelligent persuasion.’ There’s no doubt that when our respected and respective guv’nors wrote those letters cutting off the Ready, they meant what they said. Now it was up to us—or rather to me, as representing the Brain of the Business, to get them to change their minds. I think they will do so. Having set the machinery in motion, all we have to do is to watch and wait—especially wait. Situated as we are, waiting may fittingly be called one of the Exact Sciences. . . .”

“But ‘Andy Andy,’ ” said Ord, referring thus cavalierly to the Head, “what about him?”

“What can he do?” beamed McTavity; “he surely cannot rebuke us for being on the side of the angels—for trying to stamp out the pernicious cigarette habit among the growing generation. Pull your socks up, Ord, and leave the estimable Joseph to me.”

The whole school, and not merely Ord and McTavity, watched and waited. By this time St. Colston’s knew that it was another “McTavity stunt.” The watchers included the Rev. Joseph Baxter. In spite of his beard (or, if you like, because of it) “Andy Andy” was not nearly such a fool as he looked. He traced the fine, Italian hand of McTavity in this business, and past experience as well as discretion told him to keep well in the background—for the present at any rate. What possible objection could he reasonably make to the laudable project which the President of the St. Colston’s “No-Smoking League” and his principal convert had in mind? None at all—but “Andy Andy” often fondled a cane lovingly. . . .

The Rev. Joseph Baxter, as befitted one learned in the classics, pinned much faith to the tag: “Everything comes to him who waits,” and one morning he received a letter which caused a look of satisfaction to play over his stern features.

After morning school, Ord, in a bath of perspiration, raced up to his evil genius.

“I say, what are you going to do now?” he almost screamed; “ ‘Andy Andy’ lugged me into his den this morning. I thought I was going over a chair, but it wasn’t that. He started grinning like an ass, and then he said something about me being only the poor tool—whatever that meant——”

“I am suspected—ah!” interrupted McTavity, striking a tragic attitude—“and yet curfew shall ring to-night! Carry on, Macduff!”

“Then he showed me a letter,” went on the violently-agitated Ord. “At first I couldn’t make top nor tail of it—I was in such an unholy stew, you see. But after reading it through about four times I found that it was written by some blighter who is connected with a real No-Smoking League! He is coming down here to see us——!”

“Good egg!” said the undisturbed McTavity; “let us hope he’ll bring some trusty coin of the realm with him to help on the good cause. . . . By the way, Ord, got a fag on you?”

“Do listen to what I’m saying!” replied the tormented Ord; “you know what I am—the fellow will double me all up! The Head’s going to be there, too—‘Andy Andy’ told me he should enjoy being present at the interview——”

“Beast!” snorted Ord’s red-headed assistant in reforming the masses. “But,” brightening, “that will mean that, in my official capacity of Honorary Secretary to the ‘St. Colston’s No-Smoking League,’ I shall have to be present also! To show that we’re little willing workers we’ll get everybody in the shop to sign to-night. When’s this joker coming?”

“To-morrow.”

“Well, we’ll be ready for him!” said McTavity.

It was not an idle boast, as events were to prove.

It really was not surprising that the National No-Smoking League of Great Britain and Ireland should have decided to send a representative to interview (with the kind consent of the Head Master) the courageous lad who had declared so spectacularly for the Right at a leading public school.

The Press had “eaten” the story originally published by the Stapleton Mercury. The situation of the son of a prominent tobacco manufacturer declaring that his own father’s cigarettes were works of the evil one was piquant, to say the least, and Fleet Street made the most of this blessing.

Even Sir Robert McTavity himself had been moved. His great metropolitan daily, the Daily Miracle, was the apple of his eye, and he had telegraphed to his son who was at the seat of operations:

“Wire full facts about No-Smoking League at once. Be funny if possible.—McTavity.”

He was doomed to disappointment, for this was the reply he received:—

“Regret cannot accede to your request. No fun here, only deadly seriousness.—McTavity.”

“Fathers must learn!” said McTavity cryptically, as he handed in this telegram at the Stapleton Post Office.

This, then, was the situation when Ord, closely followed by McTavity, presented himself as President of the “St. Colston’s No-Smoking League” at the door of the Rev. Joseph Baxter’s study at eleven o’clock in the following morning.

“What do you want?” boomed “Andy Andy,” glaring at Ord’s companion.

McTavity made a graceful inclination of his small body.

“I attend the President of the ‘St. Colston’s No-Smoking League’ in my official capacity of Honorary Secretary to the above organisation,” was the grave reply. “Both the President and myself regard this morning’s meeting of such importance that I have brought the minute book so that our deliberations may be rightfully transcribed and placed on record. Has our distinguished co-worker in the Cause arrived yet, sir?”

The Rev. Joseph Baxter choked—it was the only thing he could do—and led the way into his study.

Much might be written about the interview which followed. Whatever the dried-up little man who represented the National Association thought of the President of the St. Colston’s branch, there was no doubt he was impressed by the St. Colston’s Secretary. Indeed, he said as much.

“You seem to have your work thoroughly at heart, young man!” he said.

“When one can see all around one the evidence of the havoc done by the vice of smoking, it is the duty of every right-thinking man—and boy—to do what he can, sir,” was the confirmatory reply.

“Indeed, yes. And now tell me what induced you to start this organisation, what aims you have in mind, and what progress you have accomplished?”

McTavity told him. It was a wonderful earful. He told him that whilst the vice of smoking was not dragging the youth of St. Colston’s down to an early grave, as was the case at so many other public schools, the President and himself had decided to nip the danger in the bud.

“In this book, sir,” said McTavity, “are the names of those boys who have supported the movement by signing their names for all the world to see!” He held up the small exercise book impressively, and then passed it over to his co-worker on the National Association.

“Very creditable! Very creditable indeed—if a little extraordinary!” the latter commented, turning to the Head Master.

“Very extraordinary!” remarked “Andy Andy” in a particularly dry tone.

McTavity scented the danger and launched a counterattack at once.

“I agree,” he said earnestly, “that the success which up till now has attended our efforts is extraordinary! And if I may say so without egotism, it is the fact that I have been known myself in days gone by to indulge in the pernicious vice of secret smoking that has caused so many boys to be persuaded that tobacco is a deadly poison. Practical example—that has been our working principle, sir.”

“Excellent! Excellent!” said the Man Who Ought Not To Have Been Out Alone dreamily. “Now, I have a message to deliver to you—a message, and something else.”

At the words “and something else,” two boys and a man leaned well forward in their seats. They were, in the order named, McTavity, Ord, and the Rev. Joseph Baxter.

“I have to say,” went on the dreamy, sing-song voice, “that the National Association most heartily appreciate the noble efforts which you, two mere boys, are putting forward for the moral welfare of your fellow scholars. It is a wonderful work and deserves all the publicity which it appears to have gained. And I am also authorised to hand over to you the sum of £2, the said money to be devoted to enlarging the work which you have in hand.”

While the President of the “St. Colston’s No-Smoking League” made queer, babbling noises, McTavity smiled his irresistible smile.

“I accept the generous gift with gratitude,” he said, extending his hand, “and can but say in reply——”

“That the money will be disbursed under the personal direction of myself,” put in the threatening voice of the Rev. Joseph Baxter.

This was a staggering blow, and the President of the local branch was distinctly heard to groan.

“Quite respectfully, sir, seeing that you are a smoker yourself, I submit that our principles might clash. I put it to you, sir. As we have started this work ourselves and entirely of our own initiative, don’t you think that we can be trusted to enlarge our scope with the aid of this grant ourselves?”

“Quite so—quite so!” replied the Dreamy One, and “Andy Andy” was routed. Like the heathen, he “raged furiously,” but he was helpless; his authority was an empty mockery.

Even the worst-hated of Heads must be human beings—in that moment of defeat the Rev. Joseph Baxter kept his mouth shut. Perhaps he had read aright the little dried-up man.

It was the latter who banished the sun out of the heavens.

“You will have pamphlets setting out the virtues of abstaining from the objectionable and dangerous habit of smoking printed locally,” he said, as he rose. “These pamphlets you will distribute amongst the school, with the kind permission of the Head Master—and—er—you will send me the receipt for the money from the printer!”

“And that rotten beast, ‘Andy Andy,’ laughed!” said Ord.

“I always thought the fellow had a low mind!” replied McTavity; “yes, sergeant?” This to the school sergeant who had hurried up to the pair, consternation written on his honest, if homely features.

“Your father, Sir Robert, has come, Mr. McTavity—and yours along wi’ ’im!” turning to Matthew Ord. “They seemed angry as I let ’em in through the lodge gates. I thought I ought to tell you!” concluded this sworn ally of the St. Colston’s meteor.

“Quite right, Sampson,” graciously replied McTavity; “and if I had the wherewithal to reward you, I would even do so. But see me to-night; methinks I shall have sundry Pieces of Eight at that time. The visit of my father is auspicious!”

“Suspicious, you mean!” cried Ord, after Sampson had wound his heavy feet away; “my guv’nor will be dancing mad, I feel sure of it!”

“Compose yourself, faithless one,” was the crushing retort; “you may not think it, but this visit is going to be a blessing in disguise. Prepare yourself for a summons to the parlour—I don’t know, but I think we may as well wash ourselves, now that we are engaged on national work. . . .”

Twenty minutes later they stood in the presence of their sires.

“I have taken the trouble to come down,” started Mr. Adrian Ord in a thick, throaty voice, “to stop this ridiculous idea of yours at all costs! I didn’t think you had enough intelligence to say your alphabet let alone——”

“He hasn’t!” interrupted a crisp young voice; “and what about you, guv’nor?”

Sir Robert McTavity smiled—he couldn’t help it.

“Pained as I was to see an old friend”—he nodded towards the glaring tobacco manufacturer—“made to appear ridiculous, I wanted to get the real facts of the case for my paper, the Searchlight. You refused to send them to me, you young rascal!”

His son made no immediate reply to this accusation. Instead, he held up his hand for silence.

“Apart from poor Ord—your son, I mean, sir—we are all business men here. It’s a simple business proposition which I have to put up to you,” he continued. “We—Ord and myself—thought it was a beastly trick of yours to cut off supplies. Money we had to get from somewhere and somehow. Now, yesterday we had a visit—the Head Master will confirm it—from a very interesting individual. He happened to be an official of the National No-Smoking League, and, after praising the efforts which we have put forward to date, he gave us the sum of £2. Personally, I believe that we have done as much good as is possible in the way of telling the local young that they will probably be sick if they start smoking too early, but it is for you to say, gentlemen. It is for you—especially Mr. Ord Senior—to say whether we shall spend that £2 on further propaganda work.”

“I have lost thousands of pounds over this business already!” raved the cigarette manufacturer; “and every one is joking me about it.”

“Unfortunate—but you have your remedy, Mr. Ord. Cutting off supplies was not quite sporting, I submit (I speak for self and friend in this connection). Now then, gentlemen—any advance on two pounds?”

“You infernal young scoundrel!” choked Sir Robert McTavity. Then turning to Adrian Ord, he added: “But I suppose we must make allowances, Ord?”

“Yes, jolly big ones!” Peter McTavity, as usual, had the last word.

In the avalanche of wealth that descended on them, Ord and McTavity evidently despised the paltry two pounds given them by the National No-Smoking Association. The latter organisation received the money back, with the intimation (in McTavity’s handwriting) that “as all the printers in Stapleton were smokers no one could be got to do the required printing.”

That remarkable product of modernity, Peter McTavity, the bright light of the scholastic life of St. Colston’s, puckered his brows.

“My respected parent,” he said, bowing ceremoniously to a portrait of a strong-jawed man which stood on the mantelpiece of the ornately-furnished study, “has laid it down as one of the soundest maxims of the business career that when a thing doesn’t come to you of its own accord, you should go out and get it for yourself. Now that, Mike, applies equally well to the present case. Having become possessors of something which is registered at the General Post Office as a newspaper, it is up to us to see that it becomes a paying proposition. For the good red gold is the very basis of existence. I hope you follow me?”

Mike Beavis, a bullet-headed, freckled youth, and McTavity’s admiring disciple, looked with a vacant expression.

“Ginger! you are a one!” he said ecstatically. “Why, you’re better than a book! But what do you actually mean, old bean, by all this gush?”

For reply, McTavity did his celebrated imitation of Napoleon, and frowned.

“For sheer, unadulterated idiocy, you take the bag of buns, Mike!” he said. “Listen, and I will try to mould my language in form more fitting for your undeveloped mind. I’ve bought the Staplefield Gazette, haven’t I?” (A nod.) “A newspaper is no use unless you have some news to put into it, is it?” (A shake.) “There’s nothing stirring in the district now, is there?” (A nod, but not so brisk. Then: “What about the visit of those old buffers on Thursday?”)

“That’s not news in itself!” promptly retorted McTavity; “but, with a little effort on our part, it may very well become news!” he added, with one of those seraphic smiles which Beavis knew always boded dire mischief for some one.

“What do you mean, Ginger?” eagerly inquired his disciple.

“Call for me in an hour’s time, and we will even sally forth!” McTavity, still smiling, waved his hand towards the door. From experience, Beavis knew that he must obey the command; casting furtive glances behind him, he left the boy who bore such a striking resemblance to a youthful Napoleon—except that his hair was red—to his labours.

The giant brain was working on a scheme. Peter had long since made it a rule that he never allowed a wrong to remain long unrighted. The thousand lines which the Rev. Joseph Baxter, the Head of St. Colston’s, had lately administered to our young hero had promptly been placed under the heading of “Wrongs—Grievous,” by McTavity. His soul yearned for vengeance. With hand placed on throbbing forehead, he waited for an idea. As usual, it was not long in coming.

The scheme happened to fit in admirably with his latest business venture. But this last sentence requires in itself a little explanation. Be it known, then, that McTavity from time to time varied the monotony of school life by embarking upon various business adventures whereby he augmented the exceedingly handsome allowance made him by his millionaire father. For instance, he had once become the school agent for a well-known firm of athletic outfitters. On every order he had taken from his fellow-scholars he had received a liberal commission (he had stipulated the exact percentage before he took on the job), and the result was that at the end of the cricket season he was over sixty pounds to the good.

His latest stunt was something near and dear to his heart. The flair for newspaper work had been handed down to him by his father; the love for running a newspaper was in his blood. When he had heard that the local newspaper, the Stapleford Gazette, which had been run at a loss for years, and had always been a hopeless failure, could be bought for a song, Peter wired to his father for the necessary cash—and bought it! He installed one of his father’s bright young men from the Daily Miracle in as Editor, and then started to think out some original “stories.” Whether these were based on facts or not did not worry him in the least; if there was a dearth of legitimate news, McTavity was quite prepared to “make” some. Indeed, as he had a little earlier that day stated to his disciple, Mike Beavis, he considered it to be his duty to do so!

By the time that Beavis returned McTavity was beaming with satisfaction.

“We will go for a little country walk, Mike!” he said enigmatically; and because Beavis knew by all the signs that mischief of some sort or other was afoot, he smiled too. They might have been a pair of choirboys. They might have been——!

A country walk on a beautiful afternoon in summer would seem, on the face of it, a simple enough pleasure, but that this one was not entirely innocuous was proved when, arriving on the outskirts of some farm buildings, McTavity held up his hand, partly in warning and partly to halt his disciple’s hurrying footsteps.

“Hist!” he enjoined.

“What do you want to hist for, Ging.?” inquired the unimaginative Beavis.

“Know, O ignorant one, whose head is wholly composed of solid wood, that beyond that dip there is a barn. In that barn are many pigs. I would seize one of those pigs and carry it away with me, for it is necessary unto me. That was why I said ‘Hist!’ you ass!”

Beavis chuckled. This was a stunt after his own heart. He wasted no further energy in speech, but blithely followed his leader.

“You keep a lookout,” said McTavity, and, darting round the side of the wall, suddenly disappeared inside the barn.

The next moment the most frightful bedlam of sound that had ever smote upon the watcher’s ears rent the air. In the midst of it, as it were, Beavis saw the slim but beloved figure of his mentor hastening towards him. In his arms McTavity carried a small but particularly active piglet, which squealed unceasingly.

“Hop it!” swiftly commanded the leader of the expedition. “Fortunately, this barn is some distance from the farm-house, but they must have heard that unholy racket back at St. Colston’s, so we will hustle along!”

They both slipped into their best stride, and, as they were in fair training, it was not long before they had set a considerable portion of the earth’s surface between them and the scene of the outrage. In spite of the fact that McTavity was still carrying the juvenile pig, he made capital time.

St. Colston’s was eventually reached safely. At the lodge gates Beavis went on ahead to borrow a sack from Mulligan, the porter, who was a sworn but secret ally of McTavity. It was in this that Clarence—as Peter had christened his hostage—was conveyed to the seclusion of McTavity’s study. Here, fed on bread and milk, he became quite docile, and, as his new proud owner stated, “a credit to any decent middle-class home!”

After tea had been satisfactorily disposed of—and the door locked in case of any inquisitive callers—Beavis put the question which he had been too busy to ask before.

“Don’t think it a cheek, Ging., old bean—but what are you going to do with the little chap? Teach it to sing?” He pointed to Clarence, who, his animal wants satisfied, had now coiled himself up and gone to sleep on the hearthrug.

“I am keeping him for a very special occasion; for the annual visit of the governors of the School, to be exact. Joey always likes these visits to go off successfully; if he were here, I think I could promise him that this one will! Mike, get me some vaseline; we shall have to keep that by us!”

The momentous Thursday broke clear and fine. The weather gods had been propitious, and everything pointed to a most successful function. Peter McTavity looked out of the window and permitted himself a slight smile. Mike Beavis, on the other hand, was grinning from ear to ear.

“It is ten o’clock now,” said McTavity. “In half an hour the whole school will be paraded and marched into Big Hall for the usual weary, dreary speeches. Mike, my son, we haven’t got much time; where’s that vaseline?”

Clarence, good-tempered through good feeding and the loving care which its eccentric master had bestowed upon it, did not pay much attention to the curious grooming which Mike and McTavity now proceeded to give him. The feel of the vaseline was soothing to him; but for the friction he would have been perfectly contented to sleep.

“There!” said McTavity, ten minutes later, “I think Clarence can be relied upon to defy capture at any hands. We will wash our maulers and repair to the scene of the festival!”

The pair of conspirators remained in the study till the very last moment, however, for the sight of the great crowd of immaculately dressed scholars of St. Colston’s assembling beneath fascinated them.

“When we go we will leave the door slightly ajar. Some one will be bound to come in to clear up very soon afterwards, and that will probably start the ball rolling. Whoever it is will not be prepared to see Clarence—and a greasy Clarence at that; while Clarence himself has led such a retired existence lately that the slightest excitement is likely to upset him. And when Clarence gets upset, the fun is likely to begin!” Thus McTavity, as the pair sped away to join the rest of the school assembled beneath.

Ten minutes later: the march into Big Hall was proceeding with all the pomp and circumstance attendant on, and appertaining to, the annual visit of the School Governors, when the calm, monastic air of the quadrangle was shattered into a thousand quivering fragments. The eyes of the whole school were turned suddenly and unanimously in the direction in which the uproar proceeded—and then delirium broke loose.

The sight of Pudgy, the elderly and obese maths. master, trying desperately but unsuccessfully to grasp a young but singularly active pig, whose coat shone with a brilliancy that dazzled the eyes, proved too much for the noble sportsmen of St. Colston’s. With one accord they went to the pedagogue’s assistance, breaking ranks and dispersing in the wildest confusion en route!

What one moment had been an orderly procession had now degenerated into the maddest scramble. Clarence, alarmed at the gestures of the stout gentleman, who was a perfect stranger to him, put on speed, and scampered headlong into the quadrangle.

He had no sooner shown himself than he realised that he had made a mistake. What seemed thousands of black-coated assassins made at him with outstretched hands. Enraged, he charged direct at one of these young good-for-nothings, and Clarence had the pleasure of seeing one of his tormentors go down in a heap.

If Clarence didn’t like this new game, St. Colston’s did. This pig-hunt was not nearly so prosy as the speechmaking in Big Hall; and it, moreover, possessed a sporting side which was quite inspiriting. Having heard the uproar and ascertained what it was all about, hundreds of other youths who had been content to stand by up till now joined forces with those who were already trying to place captive hands upon Clarence.

It was not the laying of hands upon Clarence that was the difficulty. Mike and McTavity had applied the vaseline with no niggardly hand, and the result was that Clarence held the trumps; at least, as long as the supply of vaseline on his round body held out!

It was noteworthy that no one stopped to ask where the pig had come from. Sufficient unto the day was the joy thereof, and St. Colston’s was far too excited to want to stop to ask any foolish, unnecessary questions. The sight of the gleaming Clarence was sufficient: in less time than it takes to tell, the quadrangle was the scene of the most memorable event in the history of St. Colston’s. This usually dignified portion of the scholastic buildings had become a bedlam of riot.

Needless to say that forerunners in the chase were Mike and Peter. By a pre-conceived arrangement, when they drew near Clarence—who, in the general confusion caused by his inexplicable change in life was not able to exchange greetings with his friends—they hustled the pig in the direction of Big Hall. Much of the savour of the thing would be lost if Clarence did not make the acquaintance of the day’s guests of honour.

Neither of our young friends need have feared. The tumult was so bewildering, and so inexplicable, let it be added, that suddenly looking up, the School found the steps of Big Hall black with personages. They looked angry personages.

By this time, Clarence, a pacifist usually, was seeing red. He had been forced into Bolshevism under extreme provocation. Caring little for anything but to run amok, he charged up the steps of Big Hall like a mountain battery.

At the precise moment that he charged, Mr. Alexander Tweetie, the chairman of the Governors of St. Colston’s, adjusted his nose-glasses. Mr. Tweetie was a great believer in his own personal dignity, and he performed the operation with a certain air.

That is to say, he endeavoured to perform the said operation with a certain air. But we are all the victims of Fate. Fate, in the case of Mr. Alexander Tweetie, took the form of Clarence, the runaway pig.

Before Mr. Tweetie was scarcely aware of the existence of Clarence as a concrete fact, Clarence had caught him a resounding biff in the shins with his snout. Alarmed and dismayed, Mr. Tweetie fell precipitately backwards.

Here again Fate was unkind, for Mr. Tweetie retired on to a nail hidden in the door of Big Hall. There was a gasping tear, and when the dust had cleared, the highly dignified Chairman of the School Governors could be seen regarding a large rent in his immaculately-creased trousers with sorrow-stricken eyes.

This was the final straw—this, and the beautiful sight of Clarence slipping through the fingers of the Rev. Joseph Baxter. With heart and voice, as the psalmist says, St. Colston’s gave itself up to laughter.

In vain the Head thundered for silence; the sight of Mr. Tweetie (familiarly known as “Nuts” on account of his vegetarian tendencies) doing his best with a safety-pin hastily borrowed from one of the servants was too much. Howl after howl of hysterical laughter went up from the assembled scholars. It is noticeable in this connection that throughout this unseemly exhibition of hilarity, a red-haired youth named Peter McTavity maintained the utmost composure. Indeed, if he had any expression at all it appeared as though he was deeply shocked at the thoughtless behaviour of his compatriots.

“Will you listen, or shall I punish the whole school so severely that you will never forget it?” roared the Rev. Joseph Baxter, taking advantage of a temporary lull. “The meeting in the Big Hall to celebrate the annual visit of the Governors of the School will be held this afternoon instead of this morning in consequence of—er—unseemly circumstances.”

“What old Joey really meant, Ging!” said Mike Beavis a few minutes later, “was that ‘Nuts’ wanted a chance to change his trousers. I’ll bet you anything that he’ll be wearing a pair of old Joey’s this afternoon!”

“I am chiefly worried about Clarence,” replied McTavity. “A little pig with the sensitive nature that our dear Clarence is known to possess will feel the events of this morning very keenly. Let us haste to his relief!”

The Annual Visit of the Governors was a thing of the past. It had been held, as the Head had stated it would be held, in the afternoon of the day appointed, instead of in the forenoon as originally arranged. Every one tried their best, but the affair could not be styled a success. The sight of Mr. Tweetie attired in a pair of pepper and salt trousers, which every boy in the school knew belonged to the Rev. Joseph Baxter, prevented the audience from having that concentration which is so essential in meetings of this dignified character.

With the best will in the world, a section of the audience would every now and then break into a shriek of merriment that had been suppressed until it had become uncontrollable. Every time this fierce merriment broke loose, the distinguished company on the platform would cast hasty and anguished glances into the body of the hall, as though expecting any moment the gleaming form of Clarence, the vaselined pig, to emerge from the ruck of figures.

No, the meeting could not by the most perfervid optimist have been called a success—a fact which led the Rev. Joseph Baxter to remark at the close of the proceedings, no doubt, that he was going to start the strictest inquiry into the cause of the disgraceful scenes that had marred a day which should have been dignified and harmonious. “And when I have found the culprit—if, as I fear, there is a culprit,” he wound up, “it will go very hard with him; I can promise him that!”

The threat left St. Colston’s cold, but mildly excited. This excitement was increased when, on the following day, it was discovered that the week’s issue of the Stapleford Gazette contained a full account of the hunt for Clarence.

Stretching right across the front page were the staring headlines:—

TRAGEDY OF A PAIR OF TROUSERS!

_____

How a Pig Marred the Solemn Splendour of St.

Colston’s Important Day!

_____

“Clarence” and the Governors!

_____

Special Photographs

By some apparently magic means or other it was all there; and St. Colston’s not only read it themselves, but recited it to each other!

Safe in the privacy of his study, McTavity reviewed the situation with his disciple.

“This will make Joey tear pieces out of himself!” he said, with a certain brooding air; “but the circulation of the Gazette must have gone up by several hundred. If——”

“Mr. McTavity, the Head, wishes you to see him at once!” broke in a gloom-laden voice from the door.

Resolutely, McTavity strode down the passage after the school sergeant, while Mike Beavis wondered whether his master had left a will behind him.

* * * * *

“I have traced this abominable outrage of yesterday to you, McTavity!” said the Head Master of St. Colston’s in a voice of terror. “I understand that for a couple of days past you had a pig in your study; and that it was this same pig which caused that lamentable consternation yesterday. What have you to say?”

“Nothing, except that I am very fond of animals, sir; and I did not know it was against the rules of the school to have a household pet.” The cherubic face was uplifted in a look of pure inquiry.

“You are trifling with me!” thundered the Rev. Joseph Baxter. “Get over that chair!”

“One moment!” replied Peter McTavity. “I do not want you to do anything which you will afterwards regret, sir. If you thrash me, I shall feel it to be my duty to state the full circumstances of the case in the local newspaper, of which I am now proprietor! Perhaps you have seen this week’s number; it contains a very full account of the Annual Visit of the Governors of the School yesterday!”

The Rev. Joseph Baxter paused before making a reply. He had seen the newspaper, and had been filled with a wrath that could not possibly be put into words at the sight. But this was not the first skirmish he had had with that master of tactics, Peter McTavity. He knew that the boy was capable of anything, providing it was diabolically clever enough to warrant his interest. But for the fact that the millionaire newspaper proprietor was lavish with a cheque whenever a call was made upon him, the Rev. Baxter would long since have seen to it that his life was no longer burdened, and his flesh plagued, by the continued presence at St. Colston’s of Peter McTavity. As it was—— Well, like many a bigger and greater man, the Head of St. Colston’s compromised.

“What have you done with that wretched animal?” he asked.

“That’s a better tone, sir. Well, I don’t mind informing you that kind friends—outside the school—are looking after Clarence. But he will always be procurable in case—well, let us say in case I am given the task of writing out one thousand lines. If you will pardon the mild joke, sir, I believe in saving my bacon! That is vulgar, but expressive, and I feel sure that you will understand.”

“Get back to your studies!” snapped the Rev. Joseph Baxter, understanding only too well.

Peter McTavity went—as usual, a victor!

Funds were low. Financially speaking, there was something very rotten in the state of Denmark. Peter McTavity, presiding over a hurriedly-convened meeting of the “Hearts of Oak” at the well-known school of St. Colston’s, that illustrious academy of Dead Languages and other things that were very much alive, acknowledged the fact in characteristic fashion. But he was all for action was McTavity.

“Money,” stated the Chairman, Peter McTavity, “was meant to be circulated. That is the first law in regard to money; the thing’s first duty. As it has not circulated in our quarter lately, we must remind it of its duty. I have a plan whereby we can force this sorry knave to fulfil its obligations to worthy citizens——”

“Chuck it, Ginger!” quoth a rude if friendly voice; “when you once get on the jaw it’s like a barrel organ! Besides, some of us don’t understand the meaning of all the jawbreakers you trot out. Let’s have it in plain language: what’s the Great Idea?”

“In olden times, Mike Beavis!” said the chairman, in heavy remonstrance, “I’d have thrown you into a dungeon for that insolence: as it is, you will have to clean my footer boots to-night. Haven’t you sufficient respect for the Greatest Brain in the County to listen respectfully until I have finished?”

“There you are—off again!” groaned Beavis. “Holy Joe! get it off your chest, Peter!”

Controlling himself with an obvious effort, McTavity curtailed the flow of language which was one of his chief assets.

In commendably few words he outlined the scheme whereby he hoped to raise some cash, the shortage of which every boy in the room was beginning to feel acutely.

“We will organise a concert and give it in the Village Schoolroom. We will do the complete programme on our own; that fact will cause not a little excitement in the neighbourhood; mothers’ hearts will be touched, while we in turn will touch their pockets. In brief, we shall be local heroes, and attached to the heroic business will be much hard oof. If there isn’t I shall be disappointed, that is all!”

Whereas before there had been silence, now the air fairly vibrated with noise.

“Good old Ginger!” shouted a number of voices; “top-hole scheme! Very sound!”

After the enthusiasm came the comments of the cold-blooded.

“Yes—but how do you know Joey will let us do it? Besides, the Johnnies who have the letting of the schoolroom might think you were up to some lark—setting the place on fire or something! And what a programme—pretty rotten, what?”

McTavity listened with the attitude of an Olympian (or a Senior Wrangler) to all these doubting Thomases, and then demolished all the arguments of the Opposition in one clear-cut, ringing sentence.

“I will pledge myself that this will turn out a success!”

So might Napoleon have gone amongst his troops when they were heavy with want of sleep and dispirited because the rum ration had gone astray with the Army Service Corps.

The determined words rallied the forces. Memories came to the doubters of McTavity’s proud boast that never once had he fallen down on a stunt. Hope was born again; visions of illimitable sausage-rolls and oceans of gingerade filled the minds of the once despondent.

“All right, Ging., if you say so!” said a voice, and then the whole company of penury-stricken boys burst into an inspiriting yell—“Good old Ginger!”

Like Homer, McTavity nodded—just a brief inclination of the head; nothing more. The doubt which had been cast on him had wounded his spirit, and he was not in the mood yet to forgive.

“Mike, Vowles, you, Harty, will stop behind and discuss the necessary details!” he ordered, before turning to the other four boys and adding curtly, “The conference is at an end!”

* * * * *

It was due more to Mr. Smingles, the music master at St. Colston’s, than any one else that the proposed concert for the restoration of the languishing funds of certain St. Colston’s scholars became an accomplished fact. Stephen Smingles was a true artist in that his head was for the greater part of each day in the clouds. He was a new-comer at the school, and had only accepted the post of music master because it would provide him not only with sufficient sustenance but also leisure to enable him to complete his epochal work (at least, he intimated it would be epochal) which he had entitled “Creation.”

There was no shrewder reader of character than Peter McTavity within a forty-mile radius, and it was to Mr. Smingles that he took his programme when it had been drawn up.

“Dear me! What is this?” exclaimed the music master, when what looked a musical programme was thrust beneath his nose by a boy who gave every appearance of trembling with nervousness.

“This, Mr. Smingles,” said Peter, “is the proposed programme of a concert I want to give in the village—at the Schoolroom. You see, Mr. Smingles,” the promoter went on quickly, “I thought this would be a good advertisement for the musical tuition at St. Colston’s. This programme is made up of items all rendered by boys at the school. As you see, it is very varied—there are soprano solos, flute solos, banjo solos, bone solos——”

“I do not know that you can safely say that a bone solo is a musical item!” mildly interspersed Mr. Smingles.

“Very well, sir!” quickly retorted McTavity. “That bone solo of Dunster’s can forthwith consider itself done in. But look at the rest, sir!”

Even a man who was not musically crazed—as was Mr. Smingles—could scarcely have resisted the earnest pleading that was in the boy’s voice.

After examining the sheet of paper carefully for a few moments, the music master beamed at his visitor.

“Very creditable, I’m sure!” he said; “now, tell me exactly how I can help you—er——”

“McTavity, sir!” put in Peter. “What I was rather hoping, sir, was that you would get the Head Master’s permission for us to give this concert out of school. The proposition is, sir, that we hold it for the—er—edification of the villagers in the Village Schoolroom. The sooner the better, sir!” The last words were uttered so earnestly that Mr. Smingles instinctively turned.

“Why this feverish haste?” he asked.

McTavity had temporarily forgotten himself, but he was not to be caught napping a second time.

“Er—I believe that the musical education of Stapleford has been sadly neglected, sir!” replied the boy.

Now, if Mr. Smingles had not been a new-comer to St. Colston’s, that extraordinary phrase of McTavity’s would have made the music master suspicious, to say the least. But, being a somewhat peculiar character himself, he saw nothing unusual in this boy who spoke as his own grandfather might have spoken.

“I will speak to the Head and let you know,” said Mr. Smingles.

Now it chanced that on the very morning that the music master broached the subject of the proposed concert in the Stapleford Village Schoolroom, the Rev. Joseph Baxter, Head Master of St. Colston’s, had received a very handsome cheque from Peter McTavity’s father towards the new Physics Laboratory. Whereat the Rev. Joseph Baxter was—for a change—at peace with the world. Even then, however, it is very doubtful if he would have given such a ready acquiescence to the proposition if the music master had not quite unconsciously given his superior the impression that he (Stephen Smingles) was the leading mover in the business. As it was, “Joey” was affable—for him.

“Leave it all to you, Smingles!” he said, and turned once more to his correspondence.

* * * * *

Having once obtained the official sanction, preparations went ahead at a pace that would have given apoplexy to a Government Department. The end of the term was still several weeks ahead, but the official purse-strings had closed down for one and all of the promoters. Fathers in each case—even in the instance of that Crœsus, Sir Robert McTavity—had sternly refused to allow another shilling to be wasted. The need was urgent: “Ma” Lake, the keeper of the school tuck-shop, in common with the rest of the trading world, had put up her prices, but even at the old tariff little if any business could have been done by the melancholy band who assembled under Peter McTavity’s banner. Why, when Mike Beavis unexpectedly came upon half-a-crown hidden away in the lining of an old pair of footer shorts there was almost a riot!

Practically all the organisation fell upon Peter McTavity. But then, in view of the fact that he had expected to do the work, and was, moreover, confident that no one else could, Peter did not hang out any signs of distress at this fact. But still it was rather wearing, as witness the following conversation which ensued one night in his study with his lieutenant, Mike Beavis.

Beavis (excitedly): I say, Ging., we ought to get posters out, didn’t we?

McTavity: It is done!

Beavis: Where’s the money come from?

McTavity: It hasn’t come; they trusted my sweet angel face!

Beavis: More mugs they! But, I say, Ging., do you really think the programme is strong enough? I mean, is it honestly worth a tanner for the chairs and a bob for the front rows?

McTavity: Since you press me, Mike—no! But the originality of the thing will carry us through. Here is the idea: A party of musical-inclined schoolboys are out to please the villagers amongst whom they live. Is that not a worthy object? Is it not a fit cause for charity?

Beavis: If any one should want to know what becomes of the admission money, what would you say?

McTavity: Is not the labourer worthy of his hire? If the seeker after knowledge was too pressing I should say that it was being spent on band parts.

Beavis: Isn’t it robbery?

From the foregoing it will be seen that the job of organiser was not a birthday party in itself. Any less stout soul than Peter McTavity might well have quailed. Yet a worse hour was to come.

The night before the concert the Ways and Means (not that there were any of the latter) Committee met in Peter’s study. The items on the Agenda included the disposal of free tickets.

Peter burrowed amidst the figures.