* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Abbey Girls Win Through

Date of first publication: 1928

Author: Elsie Jeanette Dunkerley (as Elsie J. Oxenham) (1880-1960)

Date first posted: June 17, 2020

Date last updated: June 17, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200619

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

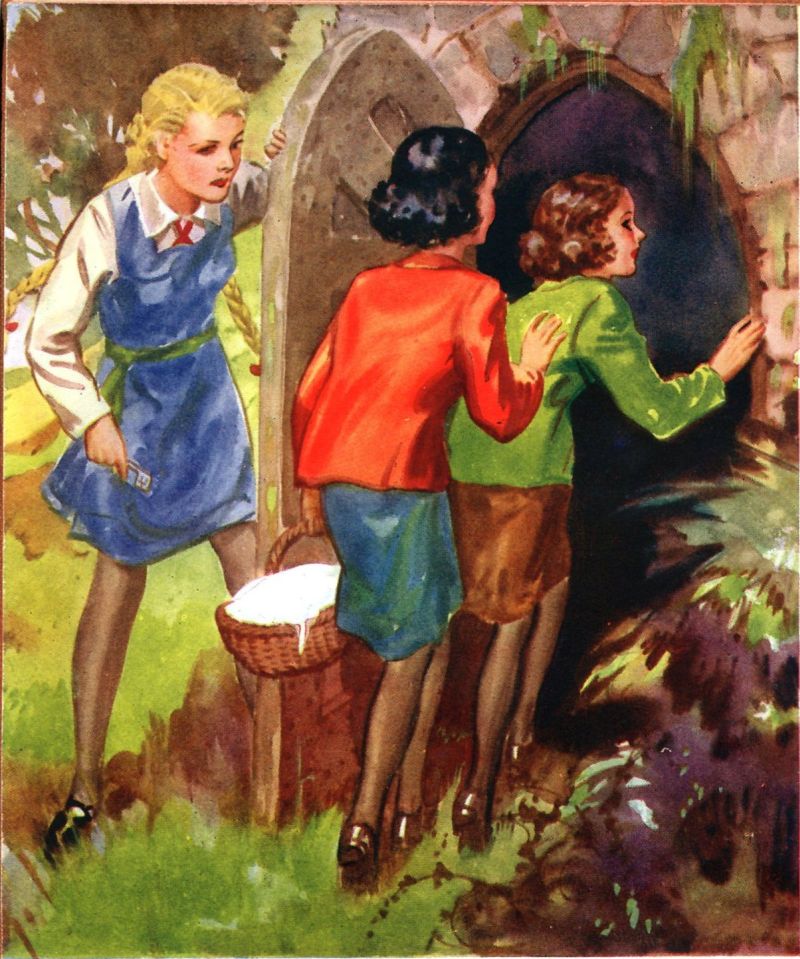

The girls entered quickly.

THE ABBEY GIRLS

WIN THROUGH

by

ELSIE J. OXENHAM

LONDON AND GLASGOW

COLLINS CLEAR-TYPE PRESS

The three girls in the corners of the railway carriage stopped talking, as the train drew up in Wycombe station, and a fourth girl got in and took the vacant corner.

The first three had talked excitedly as they passed through the London suburbs; then for a time Ann had fallen silent, gazing out at the spring meadows and hills of Buckinghamshire and the endless marvellous shades of young green in the woods. The other two were old friends, who shared rooms together in town; they did not know her very well yet, as it was only two months since she had been taken on in the typing office, where Norah had worked for two years. The office girls had found Ann pleasant and friendly, but she was still “Miss Rowney” to them, and nobody knew very much about her.

Norah and Connie were different. They were a recognised couple. Con, who sold gloves in a big West-End establishment, was the wife and homemaker; Norah, the typist, was the husband, who planned little pleasure trips and kept the accounts and took Con to the pictures.

The stranger girl, who had taken the fourth corner and stopped the Con-and-Norah chatter, had a big shopping-basket full of parcels. The three Londoners eyed her for a moment or two, as the train set off towards Aylesbury; she was fair, with pretty delicate colouring, and she wore navy blue—a long coat and a little bonnet—which looked like some sort of nurse’s uniform.

Then the chatter broke out again, and this time Ann Rowney joined in. They were getting near their destination, and she was as much excited as the other two; perhaps more so. She showed it more often by a lapse into thoughtfulness; but now her feelings grew too much for her, and she had to talk.

“What do you all want to do most? Pick primroses? Or wander along those little wood paths—have you noticed them?—winding among the trees. Or sit in those red fallen leaves under the bare trees with the gray trunks? I don’t know one tree from another, do you? But I can see the differences. I like the white-stemmed ones, with tiny green leaves hanging down like hair. Do you know trees by their names, Norah? I’ve always lived in town.”

“I never knew they were so different,” Norah said helplessly. “I’ve just thought of them as trees, all alike, you know.”

“I never knew there were so many shades of green before,” Ann said reflectively. “I thought trees were merely green! But these are all green and yet all different. I’ll have to make somebody tell me the names.”

“I want to pick violets till I’m tired,” said Con. “I’ve never picked violets in my life. I want to send boxes of them to everybody. Mrs. White would love to have some, Norah. She’s our landlady,” she explained to Ann.

“I want to walk for miles on those hills,” said Norah hungrily. “I’ve never had room to walk as far as I liked. It’s no fun in streets; and if you go out for the day—we do try to, on Bank Holidays—you always have to catch a train or bus, and to fight to get in, and it spoils the end of the day.”

“I know. And a journey home when you’re tired; and town at the end of it,” Ann assented. “Think of living among all this for a fortnight! It’s too wonderful for words. I want to do all those things; but most of all I want to see the people who could have such kind thoughts for girls they’ve never even heard of. I can’t believe it’s true, even now.”

“Neither can I,” Con said, in heartfelt tones. “I can’t see why I should be here at all. You are in the office Miss Devine used to work in, even if she never knew you. But I’ve nothing to do with the office; I’m only Norah’s friend. But Miss Devine not only asks you and Norah, from the office, to come for a fortnight into the country, but sends word that we could bring a friend! I don’t see why she should, somehow.”

“It makes it far jollier. I wouldn’t have gone without you, old chap,” said Norah.

“Perhaps Miss Devine remembers that girls often live in twos,” Ann remarked. “She used to be in the office herself; she’ll know girls don’t like to go and leave their other half alone. I do hope we’ll see her! I’ve heard about her so often. I’ve promised my little sister to tell her exactly what Mary Dorothy Devine is like; she’s read her book, of course.”

The girl in blue, in the fourth corner, had put down her library book and was listening, amusement in her face. The other three had forgotten her, however.

“I expect we’ll see Miss Devine,” Norah said. “I want to see her again. It’s only a year since she left the office in such a hurry. But it’s Lady Marchwood I want to see most. It’s her house, and her idea, really. Mary Devine is only carrying on for her while she’s abroad. I’m dying to see Lady Marchwood; but I’m afraid we shan’t have any such luck. She isn’t home from Africa yet.”

“She’s expected any day now,” said the girl in the fourth corner.

The London girls whirled round to stare at her, all taken utterly aback.

“Oh, I say!” Norah cried in dismay. “We—we forgot! We oughtn’t to have been talking like that before anybody.”

“We’d had the carriage to ourselves all the way,” Connie faltered.

“Did we say anything very awful?” Ann’s eyes danced in response to the twinkle in the stranger’s eyes. “I don’t think we could! We feel too grateful. But we should have thought. Please tell us what we said? It was chiefly about trees and flowers, I’m sure!” she pleaded.

“Do you come from the Abbey?” Norah asked eagerly, since their new friend looked neither shocked nor reproachful, but merely amused. “Oh, will you tell us more about it all? And is Lady Marchwood really coming home? Is there any chance that she’ll come while we’re here? Oh, what topping luck! Isn’t everything turning out well?”

The girl in blue laughed. “You said very nice things. I couldn’t be sure you were our three new visitors until you began to talk about Miss Mary. I was hoping I’d meet you if I came by this train; I’ve been shopping for Matron. I’m Nelly Bell; I came down a year ago, as you are doing now, for a holiday, and stayed some time, as I wasn’t well and I’d lost my job in town; then Miss Mary asked me to help Matron with the babies in Miss Joy’s children’s home. Miss Joy is Lady Marchwood; but I hear her called Miss Joy all the time, and I forget she’s married. I stayed for a while, and liked it so much that I stayed altogether.”

“Lucky beggar!” said Con. “Fancy living in the country always!”

“Oh, I don’t know!” said Norah. “I’d miss town. You’d have to give up heaps of things.” She explained matters to Nell Bell. “Miss Rowney and I—the little dark one is Miss Rowney—come from the office Miss Devine used to work in, before she wrote her book and came to live here. This is my friend, Con Parsons, who lives with me.”

Ann leaned forward from her corner. “I think you might drop the ‘Miss’ now,” she said reproachfully. “Miss Bell, I’m Ann; but sometimes nice people call me Nancy. I really like Ann best, because it’s dignified, and there’s so little of me that I have to make the most of it.”

“Nobody calls me ‘Miss Bell,’ ” Nell said promptly. “It isn’t done. I’m just Nell Bell. The bare gray trees with the red leaves underneath are beeches; and the white ones with little green leaves like hair hanging down are silver birches. Miss Mary taught me trees. You see so much more when you know things.”

Ann produced a notebook and gravely put down this information. “Thanks awfully, Nell Bell! That’s a good beginning. I mean to learn all about the country in these two weeks!”

“Good luck to you! You’ll have a busy time,” Connie mocked. “I’m just going to enjoy it, and not think about learning names and things.”

“It’s more fun if you know things,” said Ann.

“That’s like her,” Norah remarked. “We’re used to that notebook in the office. She’s always putting down things. Won’t you tell us more about everything?” she asked Nell Bell. “Where does Mary Devine live now? At the Abbey? When she left us, she said she was going to live in an old ruined Abbey.”

“That was only for a week or two, this time last year,” Nell explained. “When Miss Joy married and went to Africa, Miss Mary went to live at the Hall. It’s Miss Joy’s house, close to the Abbey;—but I must remember to say Lady Marchwood! Nobody does, you know; she’s still Miss Joy to everyone. Her old aunt, Mrs. Shirley, lives at the Hall, and the two girls Miss Joy adopted, Rosamund and Maidlin; they’re still at school. Miss Mary takes care of them all and of the house and the Abbey, and looks after all the village work Miss Joy has started.”

“When does she find time to write her books?” Ann inquired. “Her hands must be fairly full, I should say.”

“Miss Jen is at the Hall now, too,” Nell added. “She’s Miss Joy’s great friend. She was away at her own home all through the summer and autumn, but she lost her father, and then she came back to the Hall, before Christmas. That’s all the family at present—Miss Jen, and Mrs. Shirley, and the girls, and Miss Mary. But they expect Lady Marchwood quite soon. We have to change here,” as the train drew up at Princes Risborough. “That little motor train is waiting for us.”

“I’m glad we met you! We understand things ever so much better now!” Ann said exuberantly, as the little train carried them along by the foot of the hills.

Nell pointed out the big white chalk cross above Whiteleaf village, and the smaller one at Bledlow. Then, presently, she was able to show the gray tower of the Hall, among the green-tinted woods; and half a mile off, along the hillside, the white walls and turrets of Marchwood Manor.

“That’s Sir Andrew’s house, where his mother lives. It ought to be Miss Joy’s home, now that she’s married him, but they say she wants to come back to her own house, for a time, at least. Miss Jen has just got engaged to Sir Andrew’s younger brother, so perhaps she’ll be going out to Africa next,” Nell explained. “Mr. Marchwood’s at home for a visit; he lives in Kenya, so I suppose Miss Jen will go back with him.”

“What a family business! Is she any relation to the Abbey people?” Norah asked.

“Just a very great friend. She seems to have lived here a great deal; everybody knows her. But she’ll be Miss Joy’s sister-in-law when she marries Mr. Marchwood, of course. Here’s our station; and the wagonette’s waiting. Miss Mary always comes to meet people herself, if she possibly can. She says they ought to be welcomed, not just allowed to arrive anyhow.”

“How topping of her!” Con and Norah spoke together, eager for a first sight of their deputy-hostess.

“It’s a very kind idea,” Ann said warmly. She had heard so much during her two months in the office, and from her hero-worshipping little sister, of Mary-Dorothy Devine that she was even more eager to see her than Norah, who had worked with her, or Con, who had never met her. “Oh! But I thought you told me Miss Devine was small and dark?”

“It’s somebody else,” said Norah disappointedly.

“But isn’t she jolly pretty?” murmured Con.

Nell Bell had paused to speak to the porter about the luggage. She came hurrying up, just as the tall girl sitting by the driver of the wagonette leaned down and called to Norah.

“Are you the three new girls for the Abbey? Didn’t you meet Nell Bell? Oh, yes, there she is! Then hop in, all of you, and we’ll take you home. You caught that train so that you’d get a lift, didn’t you, Nell Bell? Very smart of you!”

“It’s Miss Jen,” Nell said in an undertone, in answer to the inquiring, almost accusing, looks turned on her by the strangers.

Jen, on the box seat, heard and laughed, and turned. “Were you expecting Mary? Some of you were in the office with her, weren’t you? She’ll come to see you, or you must come to see her. But she’s in the middle of a rush of work—proofs that are late and are wanted in a hurry; and she really hadn’t time to come to the station. So as I’m doing nothing much for my living at present, I came instead. I’ll come in with you; then we can talk. I must make you feel at home! Did you have an easy journey?”

She had climbed down from her perch, and was coming round to the back of the wagonette to join them. She was bareheaded, with waving yellow bobbed curls, and she wore a springlike frock of lavender linen and a green sports’ coat. The newcomers felt suddenly very travel-stained and Londonish, and longed to get rid of their own hats and gloves and big coats.

Ann remarked, “I feel like a dirty little town sparrow beside a country——”

“Maypole is the usual word,” Jen said gravely, disposing of her long legs with difficulty. “There is rather much of me, I know. Mary-Dorothy would have fitted into this thing much better. That’s why I rode outside; so that bits of me could hang over the edge. Sure you’ve all got room? Right-o! Then let’s get home. You must be dying for some tea. Did you get us nice library books, Nell Bell? Oh, cheers! I was wanting that. And all the shopping? Any difficulties? Were you able to get Maidie’s songs? And Mary’s pencils? She vows she can’t write a word with any we can get in the village. You’re a benefactress to the whole household, Nell.”

As they drove up through the lanes to the village, the London girls eyed her continually. She was so fresh and full of life; as joyous as the thrushes calling overhead. The opal engagement ring on her finger told its own story, and gave the clue to her happiness; there was no trace of mourning for the father she had lost six months before, but this was not forgetfulness, but was rather a sign of her whole attitude to life. She rejoiced for him, and knew no rebellion.

The lane opened on to the village green, a wide triangular lawn, kept in beautiful condition. In the middle stood a flagstaff, which on occasion could become a maypole, as a centre for country-dancing. The parish church, the village hall, a few small general shops, and the Abinger Arms, lay around the green, beyond a wide roadway. There were also two or three old houses, behind high walls, and at the gate of one of these the wagonette drew up.

“If I remove myself, you’ll get out more easily,” and Jen uncoiled her long legs and jumped out into the road. “Do you see our maypole? We put leaves on the top when we want to dance round it; the whole village knows ‘Sellenger’s Round’ and a few more dances, and now and then we have festive little occasions of our own. Mary teaches in the hall over there, and so do I, when I’m here. We’re all keen folk-dancers. Now we’ll introduce you to Mrs. Colmar, and then I must—oh, well! I must go home now, evidently! Nell Bell, take them in and make them feel at home!” she said laughing.

A big car had come whirling round the corner of the green and was drawing up beside them. Jen waved her hand, and jumped in to take the seat beside the tall young man who was driving, and who had opened the door for her. She threw a laughing look back at the girls, who were just climbing down from the wagonette.

“Wasn’t that neatly done? I didn’t think he knew where I’d gone. But somehow he always does know. It’s a sort of instinct, or—or intuition, or secret sympathy, or telepathy. He always knows; I can’t escape. I’ll see you all again soon. Good-bye! I’m glad you’ve come!” and then the car whirled her away.

“Is that——?” began Ann Rowney eagerly.

“Yes, that’s Mr. Marchwood. She doesn’t want to escape,” Nell remarked. “Did you ever see anybody more radiantly happy? They all call her Jenny-Wren; or Queen Brownie, because her colour, as the school May Queen, was brown. I sometimes think Miss Jen is the real spirit of this whole place; its good fairy. Miss Joy—Lady Marchwood—is the mistress; and Miss Mary is her second, and takes care of everything for her. But Queen Jen is something different; something very special. It didn’t seem itself without her while she was away all autumn.”

“And now she’s going to Africa,” Norah suggested. “What will you do without her?”

“We daren’t think about it,” Nell said briefly. “Come into the house. I’ll take you to Mrs. Colmar; then I must go on to the babies’ house, farther up the road.”

“We’ve been beautifully welcomed, between you and Queen Jenny-Wren,” Ann said fervently.

“It’s an old farmhouse,” the Matron explained, as she led the girls upstairs. She was a good hostess, gray-haired and kind-faced, and her welcome had made them feel at home at once. “We have four other girls here this week-end, but two have to leave very early on Monday morning. I have one double room, with two beds, and one little room. So sort yourselves out as you wish.”

That matter solved itself at once, of course. Ann was by nature a hermit, so far as bedrooms were concerned, and would not have been really happy if she had had to share; and the “married couple” did not want to be parted, even on holiday. So Ann joyfully took the tiny room, and hung out of the window and cheered, to find herself overlooking an orchard, where cherry-trees were white, and the air was scented, and thrushes and blackbirds shouted all day long.

“Couldn’t be better!” she said to herself rapturously. “And it’s a lattice-window, under a gable! Perfect! Oh, there’s the cuckoo! What do I do? Turn my money and wish; where is my money? I’ve nothing left to wish for, I do believe!”

“First time I’ve heard the cuckoo this year,” said Mrs. Colmar, with interest.

Con and Norah were equally delighted with their big low attic room, which had a wide view over the green. “I wish they’d dance out there while we’re here!” Con said wistfully. “If they do, we’ll invite you in to sit at our window, Miss—I mean Nancy!”

“I hope you do mean Nancy. Nobody could go on being stiff and proper in this friendly place. But if they dance, perhaps I’ll be dancing too,” Ann retorted. “Come and look out at my cherry-trees! And the red buds on the apples—Mrs. Colmar says the red buds are apples—are the most marvellous colour in the world.”

“We’ve got wallflowers under our window,” Norah boasted, sniffing with enjoyment.

“I’ve got bluebells under my apple-trees,” Ann said haughtily.

“I love attic roofs. They feel so countrified,” and Con rose rashly from the suitcase she had been unstrapping, and knocked her head on the sloping whitewashed ceiling. “But you need to get used to them,” she added ruefully.

Ann laughed, and retired to her tiny room, to smooth her neat, dark, shingled head, and to change her shoes.

“What is the bit of gray roof that sticks up above the cherry-orchard? I can just see it from my window,” she asked at tea time, when they had met the four girls already in residence, in the long low pleasant dining-room.

“That’s the Abbey. What you see is part of the refectory roof,” Mrs. Colmar explained. “The refectory is the highest building left. The rest is mostly in ruins.”

“Oh!” Ann’s eyes lit up. “Can we see the ruins? I think I want that almost most of all; except perhaps one other thing!”

That one other still greater wish was to be gratified that same evening, which was usual with Ann’s wishes, for she saw to it that they should be fulfilled whenever possible. The Abbey was closed to the public at six, Mrs. Colmar explained, but would be open again at twelve next day. Ann thanked her, and perforce postponed her visit to the ruins; and presently went for a walk alone, looking thoughtful.

“To explore,” she said to Con and Norah, and added that she would prefer to go alone; but that they would compare notes at supper time.

The two chums had already made friends with the girls in the house, and in their company they wandered off to the woods in search of primroses and violets, and to look up at the smooth round hills on which Norah intended to roam all the next day.

Ann, with thoughtful eyes full of secrets—of eager resolve with just a hint of shyness and of dread of a possible rebuff—turned the other way, up the Abbey lane. She passed along by its low wall, with a wondering glance across the lawn to the great stone gateway, standing all alone and apart from the other buildings—a high arched entrance, leading nowhere now, but she supposed it had once had some real purpose.

Passing the Abbey, she came very soon to the gate of the Hall, and stood there, actually hesitating for several moments, though it was not her way to hesitate. Then, with heightened colour and bright, nervous eyes, she went bravely up the long drive.

She met no one on the way. If she had heard a car coming down, she would have fled or have hidden among the trees. But they were beeches, bare of stem and with great rugged roots; there was no undergrowth to hide an intruder, though she was slim enough to have slipped out of sight behind one of the massive boles. She saw and heard no one, and kept steadily on her way.

The great stone house stood on a wide terrace, overlooking a lawn kept like a bowling-green. All around were flowering trees, prunus of every kind in full bloom, lilacs and laburnums just breaking into flower; the gray Abbey buildings rose above the trees at one side, beyond an ancient wall.

There was no one to be seen. Ann, her heart thumping in a most unusual way, went to the big door and pulled the bell; and jumped, as it clanged.

“It feels such cheek!” she murmured. “I hope she won’t mind!”

“Can I see Miss Devine?” she asked of the maid. And, on being asked her name, “She won’t know me. But I’m one of the new girls from London; at Mrs. Colmar’s, you know.”

Almost too nervous and shy to think, and yet, by the laws of her own nature, unconsciously taking in everything, to be remembered clearly afterwards, Ann looked round the great hall as she waited. Dark oak-panelled walls, windows of stained glass, with coats of arms wrought into them in colours, family portraits in heavy frames, polished wood floor, dark oak settles, and tables and chairs with solid twisted legs; big dark wood staircase rising from the hall—these were one side of the picture. Windows wide open to the lawn, the sunset streaming in, white and yellow flowers in delicate glass jars wherever these could stand—narcissi, late daffodils, primroses—these were the other side, and gave lightness and beauty to the stately sombre entrance.

As the maid opened a door, a stream of clear high music came drifting out, sweet piping notes in a gay little tune. Then it stopped very abruptly, and there was a chorus of exclamations of surprise.

Then at the door Jen appeared, in a white frock, as white and yellow as the flowers; a wooden pipe in her left hand explained the music. “Which of them is it? Oh, it’s the little dark one! I told Mary-Dorothy there were two tall fair ones and one little dark one, and that I was sure she was shingled, because she’d got such a tiny head. What’s the matter? Can we do anything for you? Is there anything wrong? Or are you just in such a hurry to see more of us that you simply couldn’t wait——”

“Jenny-Wren, don’t be absurd,” Mary Devine pushed Jen gently aside. She was smaller, darker, and ten years older than Jen; she wore a handwoven dress of shades of amethyst and blue, and her hair had stray threads of gray. “Come in,” she said to Ann. “We’re all in here together. I ought to have come to meet you; I was coming round to-morrow morning. I hope you’ll be comfortable; Mrs. Colmar is very kind.”

“Oh, she’s kindness itself, and everything’s beautiful,” Ann began breathlessly. “I just had to say thank you, or I couldn’t have gone to sleep. We love every bit of it, and I think my room’s the most perfect of all. I had to come.”

“How very nice of you!” Mary began in surprise, for such immediate gratitude was unusual.

Ann’s quick eyes had taken in everything; the little oak-panelled library, the tea-tray on a low table pushed to one side, the old lady seated in a big chair, the two schoolgirls on the window-seat, one with two long yellow plaits, the other with black plaits and great dark eyes, both gazing at her in astonished questioning.

“I know you think it’s funny of me to come so soon,” she began desperately. “But—well, I had to, that’s all. It’s to please my little sister.”

“Your little sister?” Jen and Mary spoke together, bewildered and unbelieving; and all five people stared at her blankly.

Ann, scarlet, but with dancing eyes, went on bravely, “Oh, please, I’m not a mental case, really. I must write home to say I’m safely here, and I had to see you first. I daren’t tell Sybil I hadn’t seen you. It would have been such a blow to her.”

“That you hadn’t seen us?” Mary asked doubtfully, quite bewildered still and almost frightened.

“No, not the rest; you,” Ann explained carefully. “She’s dying to hear about you. She’s read your book; I gave it to her last Christmas; and she’s crazy to know everything about you. She gave me a letter for you.”

Mary shrank back, confused and overwhelmed. “Oh, I never thought——”

With a bound, Jen was upon Ann, shaking her warmly by both hands; while Rosamund, on the window-seat, set up a delighted cheer.

“You dear! Oh, how I love you and your little sister!” Jen cried excitedly. “I’ve been longing for this to happen. You’re the first, the very first, outsider to make Mary feel she’s a celebrity! It’s no use our saying anything, of course; she just says we’re prejudiced and not able to judge. She says she thinks a lot of my opinion, but she doesn’t really pay a scrap of attention to it. I’ve told her again and again how good that book is; and the new one’s better still. But it doesn’t have any effect; she doesn’t believe me. But she’ll believe you. She can’t help it; and we won’t let her forget it. Mary-Dorothy Devine, stand up and be looked at! You’re a famous author; don’t funk! Now that people have begun coming to look at you, I expect there’ll be streams of them. Look at her, Miss—Ann, isn’t it? Look at her hard; and then tell your darling little sister all about every inch of her!”

“Jen, do be quiet!” cried poor Mary, scarlet, and shy, and embarrassed; and she looked as if she would like to run and hide.

Rosamund sprang to the door and barred the way. “Oh, no, you don’t! Stay and be looked at,” she mocked. “How does it feel to be on show? It’s a jolly good book, Mary-Dorothy; but I don’t know that I’d have been as much excited about it as the little sister seems to have been.”

“Sybil’s only twelve,” Ann explained, amused but rather dismayed by the uproar she had called forth. She was not yet used to Jen’s tempestuous methods. “She’s my step-sister really. I hope you’ll forgive me, Miss Devine. But you do understand, don’t you? I must write to Syb to-night; and she’s dying to hear what her beloved Miss Devine is like. She says she adores you, and all that sort of thing, you know.”

Rosamund gave a shout, at sight of Mary’s face. “Send her a photo, Mary-Dorothy! That hideous snap Jen took of you in the Abbey! That would cool her off!”

“Don’t be an ass, Ros!” Jen said sharply. Her first excitement had cooled down, and she knew that if they went too far Mary might be really hurt. “It’s not funny; it’s the jolliest thing that’s happened here this year. Sybil has jolly good sense, and I shall write and tell her so. After all,”—haughtily—“the book was dedicated to me! I’m sure she’d like to have a letter from me.”

“She’d love it,” Ann said earnestly. “She’ll be thrilled to hear you’re real, and that I’ve met you.”

Jen curtseyed, then drew herself up to her full height. “I’m a celebrity too! Nobody wants to see you, Rosamunda. Sybil’s a very sensible child.”

“She’s very easily thrilled, if a letter from you will do it; a scrawl, I should say,” Rosamund retorted. “I should get Mary to type it, if I were you, Brownie.”

Jen turned away from her to Ann again. “I’m really very grateful to you. I’ve been trying for a year to make Mary-Dorothy believe she has done something worth while by writing that book; but nobody has backed me up. The Press notices helped; but she’s forgotten all about them now. She needs a lot of encouraging. I’ve had serious thoughts of writing dozens of letters, all from make-believe children, and having them posted in different parts of the country, begging her to write a sequel. I thought it was rather a brilliant idea. Unfortunately I was so pleased with the thought that I went and told her all about it, in my first wild excitement, and so it was no good. But you’re far better than made-up letters. She can’t have any doubts about you. You’ve really come to look at her! That’s fame, I’m sure. And your little sister adores her and is thrilled by her book! Now, Mary-Dorothy! Isn’t that something to have lived for? Never mind Rosamunda! She’s a mere infant, we all know that. What do you think about it, Maidlin?”

The black-eyed girl of sixteen, a year younger than Rosamund, had been listening and watching. “I’m glad,” she said briefly. “I liked Mary’s book. If I hadn’t known her, and somebody I knew was going to see her, I’d have wanted to hear what she was like too. I like Sybil.”

“Right you are, Madalena; so do I! But I want to know her name, so that I can write to her; and yours, the whole of it,” Jen said to Ann. “I’ll always remember you as the first person who came to the Abbey, not to see us, but to look at Mary! You’re Ann—what?”

“Ann Rowney; often called Nancy,” Ann said promptly.

“Nancy Rowney, I shall thank you for ever, because you’ve been the first to make Mary-Dorothy realise her importance!” Jen proclaimed.

“The trouble is,” Mary said, very quietly, “that whoever comes here, and no matter whom they’ve come to see, Jenny-Wren always does all the talking.”

Jen collapsed into a big chair. “Mary, you brute! And I was thanking her so nicely, to cover your blushes!”

Rosamund gave an ironical cheer. “Go it, Mary! Hit her again! Get a bit of your own back!”

Maidlin, her chin in her hand as she gazed at them, broke into a slow smile. “Jen’s so big. She always does fill up the picture; a large sort of thing in the foreground, isn’t she?”

“Blot on the landscape, sometimes,” Rosamund said darkly.

Jen’s dancing eyes met Ann’s. “Did you say you had brought a letter from your nice little sister, Nancy?”

“Red herring! Change the subject when you’re getting the worst of it! Funker!” jeered Rosamund.

Ann handed the letter to Mary. “If you would give Sybil your autograph, she’d be happy for ever.”

Mary reddened again, and laughed. “Of course I will. It’s sweet of her to care.”

“It’s a very plain ordinary one,” Rosamund observed. “You’d better cultivate something more impressive, with flourishes in it, Mary. We’ll invent a posh one for her, shall we, Maidie? Give her a dozen, Mary. She’ll sell them at school for five shillings each.”

“What you’d do, evidently, Ros dear,” and Mary sat down to read Sybil’s letter.

“Oh, read it out!” Rosamund urged. “I’ve never heard an adoring letter to an authoress! I might want to write one some day.”

But the child’s letter, which brought the colour into Mary’s cheeks again, was not for Rosamund to see, though it would be shown to Jen in private later.

“I’ll tell you all about the new book for next Christmas, Nancy,” Jen said kindly. “It’s even better than the first one. We’re just correcting the proofs, all of us. We try to help; but Ros can’t spell ‘disappoint’ or ‘disapprove,’ or any other word where you double one consonant and not the other; she got muddled over ‘desiccated,’ and it went to her head, and now she spells ‘disappointment’ on the same plan. And Maidie always gets lost over anything with ‘ie’ in it. So we aren’t a very useful crowd. My stumbling-block is ‘accommodation’; I double everything I can, and trust to luck. I’ll tell you the story, and you can tell Sybil; but you’ll have to buy the book; I shan’t give away the whole plot. You aren’t anything connected with the Press, by any chance? An interviewer in disguise, or anything like that?”

Ann, flushing hotly at the very idea, laughed and denied it warmly. “I’m certainly not an interviewer. I’m sure we’ll buy the book. Whom is it dedicated to this time?”

“Oh, Joy, of course; I mean, Lady Marchwood. As Mary says, it was thought of in Joy’s woods, and written in Joy’s house. Would you like to see the Abbey? There’ll be light enough for half an hour yet. I could take you; I love showing it to people.”

“Jen shows the Abbey better than any one else,” Mary said. “Will you give Sybil my love, and thanks for her letter, if you write to-night, Miss Rowney, and say——”

“Nancy!” Jen said reprovingly. “I’ve adopted her, because I’m so grateful to her for coming to look at you.”

Mary and Ann laughed. “Say I’ll write to her in a day or two,” said Mary.

Ann walked soberly back through the beechwoods to the village, after an enthralling hour in the Abbey with Mary Devine and Jen.

All had gone well beyond her wildest dreams; so well that she should have been dancing down the woodland path. And yet she went gravely, almost as though burdened by some new anxiety.

To be shown over the ruins by Jen was a privilege she had never dared to hope for. Jen’s love for the Abbey was so intense that she was an ideal guide, and her stories and legends, and descriptions of the life of the white-robed Cistercian brothers, had a vivid reality which any caretaker’s must have lacked, however carefully learned. Ann had a lively imagination also, and she had enjoyed the recital as much as Mary had done, when she had heard it first from Jen, two years ago. Ann had also had the advantage of enjoying the reciter, who had not been a new friend to Mary when she heard the story; and she had been studying Jen, and delighting in her animated face and vivid life, while she listened to the tales of the Lady Jehane and Brother Ambrose, and of the spoiling of the monastery; or, coming to more modern times, of the finding of the buried jewels and the Abbey books, by Jen herself, of the hermit’s well and the buried crypt. To be told stories such as these by Jen Robins and not by a mere caretaker in charge of a party, was indeed a piece of good fortune for which Ann would always be grateful. Her introduction to new places or persons was apt to colour her feelings towards them for some time; and her first visit to the Abbey and to the girls at the Hall could not have been happier.

Her sober face, as she walked home through the woods, carrying her hat and a bunch of wallflowers from the Abbey walls, was not due to any dissatisfaction with her surroundings, nor to the fact that she had undoubtedly gone one better than her travelling companions, and would presently have to confess where she had been. The cause lay in herself, in a sense of discomfort beginning to make itself felt; she thrust it down, but knew it would have to be faced in time.

At supper, when Norah and Con told of their walk and showed their flowers, Ann owned up. “I’ve been to the Hall to see Miss Devine and Miss Jen. Yes, I know I might have waited to go with you to-morrow; but I’d promised my small sister not to lose a moment if I could possibly help it; so I thought I might as well walk that way as any other.”

“You haven’t half got cheek,” Norah observed. “It isn’t as if you’d known Mary Devine, as I did. There’d have been some reason in my going in a hurry. If you’d told us, we’d have come too.”

“Were they nice?” Con asked curiously. “Did you walk up to that great house and say you’d come to see Miss Devine? I couldn’t have done it!”

“They were topping, all of them. I had a letter for her from my sister; that made a sort of introduction. She was pleased; and Miss Jen was more pleased still,” and Ann told a little about her visit and described the hour in the Abbey, to the envy of the other two.

“If you have cheek enough, you always get the best,” Con sighed. “I simply couldn’t have done it!”

“I don’t think they felt it was cheek,” Ann said stoutly. “They may be saying awful things about me now; but somehow I don’t think they are.”

She wrote her letter to Sybil, sitting under the lamp in the pleasant dining-room; then went up to her attic, but blew out her candle before she undressed, and sat by the low window above the shadowy orchard, where the white-draped pear and cherry trees looked like dim ghosts, and the mingled scents drifted about on the night breeze. The Abbey wallflowers stood in a pot on the sill; Ann fingered them wistfully as she sat down on a stool, to come to terms with that disturbing thought.

“Couldn’t be better! I’ve nothing left to wish for!” she had said, when she first saw that lattice window under the gable.

Now, reluctantly but deliberately, she said to herself, “I can’t do it! I can’t. I know I can’t. They’ve made it out of the question, just by being such perfect dears. They’ve disarmed me. I can have a jolly holiday, and enjoy every minute of it. But—no, I can’t do the other thing. Not after the way they’ve made me welcome. And what’s more, I’m beginning to think I shall have to confess. Won’t I perhaps feel bad if I go away without telling them? I’ll have to see about that later. But I never dreamt they’d be so friendly. It takes the wind right out of my sails! And it leaves me rather stranded. If I can’t use all this”—she pursed her lips and frowned down at the invisible bluebells—“I’m wasting my time here, in one way. I must just do what, after all, they’re expecting me to do; what they think I’ve come for! And that is, have a thorough rest and a very good time, and enjoy it all to the limit. Everything else must wait.”

And she drew the patterned chintz curtains and lit the candle and began to prepare for bed.

Con and Norah clamoured for a visit to the Abbey next morning. But Mrs. Colmar warned them that twelve o’clock was the earliest they could be admitted, so they prowled in the woods for a while with the other girl visitors, and went along to the Babies’ Home to call on Nelly Bell. Ann, original always, and solitary in her tastes, while the others preferred to go about in a big merry party, begged to be given something useful to do, so long as it was out of doors.

“I’m very domesticated,” she informed the Matron, “and if you really need help, or if there’s a wet day, I’ll enjoy a morning’s housework more than anything. It would be a real treat, after office life in town; I mean it, honestly. I live with friends, who board me, and I never have a chance to do any kitchen work; but I love it. So do make use of me, if you can. There must be heaps to do, with so many of us to feed! But while this sunshine lasts, I do want to be out. Let me peel the potatoes! I’ll sit on that bench in the yard.”

She carried off the pan and the potatoes, and was sitting near the pump, humming and working, wearing a big overall of Mrs. Colmar’s over her frock, when Mary Devine pushed open the garden gate.

“Oh!” said Mary, and began to laugh. “Have they made you work already? But why? Mrs. Colmar isn’t shorthanded at present.”

Ann dropped a potato into the pan. “I just wanted to. I’m very fond of cooking, and I never get the chance at home. We’re all going up to the Abbey when it’s open; Norah and Con are mad with me because they say I sneaked in ahead of them last night.”

“They’ll find it still there this morning. I came to see them. Have they gone out?”

“They’re seeing Nell Bell,” said Ann. “She told us to come and see the babies. I thought I’d go along when I’d done a job or two.”

Mary sat down on the wall of the old well, and looked at her closely. “Why are you so keen to do something to help? It’s very kind of you. But it isn’t usual. As a rule, girls don’t think about it.”

Ann flushed suddenly. She had accepted the invitation—had begged for it, in fact—with a secret motive of her own; the friendly welcome at the Hall had forced the hidden reason up into the light, and she had been ashamed of it; and her half-conscious feeling in the morning had been to do something to atone for it. To offer to help had seemed obvious and necessary. But if Mary Devine were going to give her undeserved credit for a kind and unusual thought, Ann knew she would feel very uncomfortable. She wished Mary had not come just at that time.

“I really do like housework,” she said evasively.

Mary saw her embarrassment, and changed the subject at once. Ann knew she was being given credit for modesty and delicate feeling, and grew still more unhappy. She kept her eyes on the potatoes, but peeled wildly and extravagantly; and Mary, seeing it with amusement, said no more, but helped her to forget herself.

“We’re going to have a country-dance party on the village green this afternoon,” she said. “The dry days have made the grass in such beautiful condition that Jenny-Wren is pining to dance on it. But, as she says, she can’t be a party all by herself; and there’s no time to call together the school dancing club, of which she and Rosamund are May Queens. So we thought we’d just have a little village party. I think it will be quite pretty. You’ll like to watch, won’t you?”

“I’d heaps sooner dance,” Ann said promptly. “Mayn’t I join in? You won’t have all super-advanced dances, if it’s a village party, will you?”

“Oh, do you dance?” Mary’s face lit up. “Oh, that’s splendid! Of course, you must join in! Oh, we have dances like ‘Butterfly’ and ‘Peascods’ and ‘Rufty.’ ”

“And ‘Newcastle’!” Ann pleaded. “I’ve been to classes in town. I’ll simply love a party; I brought my shoes, because Norah told me you were all country-dance mad. I am, too; so I hoped you’d have an attack of madness while I was here.”

Mary laughed. “What fun to have invited a folk-dancer! I had no idea. It has never happened before, though we’ve converted a good many people. Give me a dance, won’t you? You’ll have heaps of partners. Then it was ‘Boatman’ you were singing as I came in! I couldn’t believe my ears!”

“Miss Jen was piping it last night, when I walked in on you,” Ann said simply. “It’s been in my head ever since. Did you mind the way I barged in? The rest think it was frightful cheek; they’ve been ragging me ever since.”

“I think it was very kind of you,” Mary said warmly. “Sybil’s little letter was a great joy, and it was nice of you to bring it instead of posting it. I’ve written to her, in spite of Rosamund’s mockery.”

“Syb will be awfully bucked to have a letter from you,” Ann remarked.

When the potatoes were finished and Mary had had her talk with Mrs. Colmar, Ann and she walked along together to the Babies’ Home, on another side of the green. Mary had come through the lanes from the Hall bareheaded, wearing a morning frock of blue linen; and Ann joyfully fell in with the usual custom and left her hat behind. Her dark shingled head was very neat, and Mary admired its curve and poise, though she made no comment.

Norah and Con had done no country-dancing and were too shy to try; so they had to be content to form part of the audience that afternoon, when the village children and girls, and many of the older women, and a few boys and men, gathered round the maypole and the friend who had brought her fiddle. Jen and Mary, Rosamund and Maidlin, came from the Hall, and proved energetic stewards, as they directed the crowd into lines of couples, radiating from the pole. Jen, with a village lad, went to the head of one line, and Mary led Ann to another.

“It’s ‘Bonnets So Blue,’ ” she said.

“Doesn’t Mr. Marchwood dance?” Ann asked, as they waited for the fiddler to tune up. “I thought he’d be here.”

Mary laughed. “Oh, he dances! Jen insisted on it, and taught him herself. But he’s in town for the week-end; his mother had to visit friends, and he had to look after her. She’s very frail now.”

“Will Miss Jen be married soon?” Ann asked curiously, as they made the first star in the dance and then Mary led her down the middle.

“He wants to go out to Kenya again. He’s getting restive; he hasn’t enough to do here. But Jen’s mother doesn’t want her to go so far. Mrs. Robins is living in Scotland with her married son, and their home in Yorkshire is shut up for the time being. Jen has begged her mother to do without her until Joy has come home; she’s desperately anxious to be here to greet Joy. They’re all waiting till she comes before deciding anything; it depends partly on her arrangements, and Sir Andrew’s.”

“I wish she’d come while we’re here!” Ann said wistfully. “I would love to see her!”

“She’s on her way home,” said Mary.

They talked at intervals during the dance, when they were together. When it was over, and rings were forming for ‘If All the World were Paper,’ Jen came up to offer to be ‘man,’ and led Ann into a set.

“I’m always man, except when I dance with Kenneth, because I’m bigger than any one else,” she explained. “I’d feel silly, and I’m sure I’d look absurd, with you or Mary as my man. We want you to come up to tea at the house afterwards, and tell us what town classes you’ve been to, and whom you’ve had to teach you, and what you think of her! It’s always thrilling to gossip. Have you been to any of the Hyde Park parties? Or any big demonstrations? Don’t tell me now; save it up for tea time.”

Ann danced through the party in a state of blissful anticipation. The common interest of their enthusiasm for folk-dancing had lifted her at one step from the position of temporary visitor-in-the-village-guest-house to that of personal friend; she realised her good fortune to the full, and rejoiced in the excitement of the moment, without allowing any awkward or disturbing thoughts to trouble her. She had never dared to hope she would go to tea at the Hall; she was sure business girls on holiday were not usually admitted to the family on terms of friendship. Con and Norah would be envious, but she could not very well ask that they might go too.

The village had taken its cue from its leaders, and the girls and lads were friendly and always welcomed strangers generously. Joy and Jen were their idols, and had taught them by example never to let any one feel an outsider. Ann had plenty of partners; Rosamund came up to romp through “Brighton Camp” with her, and Maidlin, more reserved, said little but smiled and led her into “Rufty Tufty.” Nell Bell was dancing, and came to claim her twice, and brought others to be introduced; Ann was never allowed to sit out, or to feel friendless for a moment.

“You’ve had to work hard!” Jen said laughing; when, after “Sellenger’s Round” in one big ring round the maypole, they walked off up the lane, shoes in hand. “Our girls are always like that. They never let you rest for half a minute.”

“It’s been a lovely party,” Ann said warmly. “I do think this is the friendliest place! I can’t believe I’d never seen it this time yesterday. It feels as if I’d known it always.”

“What a jolly compliment! I shall tell Joy. She’ll feel Mary has done her work well while she’s been away.”

“Mary! Isn’t it a good deal you?” Ann suggested.

“Oh, I haven’t been here much! I was in Yorkshire for months. I think it’s Mary-Dorothy’s influence. She’s only carrying out Joy’s ideas, of course; but she has done it well.”

“Mrs. Shirley’s having tea up in her own room to-day,” Mary explained, waiting for them on the terrace before the house. She had slipped away as the last dance began, waiting only to watch the first two figures from the end of the lane, and then going ahead of the rest up to the house. She explained more fully to Ann. “Mrs. Shirley isn’t fit for very much, and we persuade her to take a day’s rest upstairs now and then. The quiet is good for her. We’re so very anxious she should be well when Joy comes; Joy adores her aunt. We’ll have tea out here in the sunshine. Sit down and rest! You must be tired.”

“I always think ‘Sellenger’s’ will kill me, but I dance it every time,” and Ann sank into a chair gladly.

“I funk it,” Mary said seriously. “I like to watch, but I do think it’s about the most tiring dance there is. There’s a letter for you, Jenny-Wren.”

“From Joy?” Jen went eagerly towards the house.

“No. From Scotland,” Mary was busily arranging the tea table. “Bring out more chairs, Ros. Maidie, fetch those photos Jen has looked out for Ann to see.”

“Oh, she’s Nancy, not Ann,” Jen said absently, standing in the doorway to read her letter. “Sounds so much jollier.”

“I like to be Nancy—here!” Ann said enthusiastically.

“Mary!” Jen’s voice rang out, sharp and terrified.

They all turned to stare at her. She stood in the doorway, her face whiter than her dress, the letter falling from her hand.

Ann and Mary sprang towards her, sure she would fall. “Jenny-Wren dear, what is it?” cried Mary, aghast.

“Brownie, what’s the matter? You look like a ghost!” cried Rosamund.

Maidlin, sensitive and highly-strung, had no reserve for emergencies. She dropped the photos she was carrying, and leant against the wall—as white as Jen, shaking all over. “Is anything wrong with Joy?” she whispered.

“It’s mother,” Jen, dazed, groped for the letter. “Harry says—oh, it can’t be! Mary, we’d have had some warning! He says—he says——”

Ann thrust the letter into her hands. “Bring a chair!” she commanded, her arm round Jen.

Rosamund sprang to help. “Sit down, Jen, old chap! Here you are; Mary can’t hold you, you know.”

“I’m not going to faint,” Jen said breathlessly. “Only—I’ve heard of such things happening—but I never thought—so far as we knew she was quite well—I hadn’t seen her for months. Oh, why didn’t I go? Why wasn’t there time? It’s cruel! She—she wasn’t ill at all, Mary,” half sobbing, she tried to tell them the story, reading the details as she went on. “It was last night. They found her; she’d felt tired and had gone to lie down. She’d been out for a walk, with Alison and the baby; and it was very cold; they think it had perhaps affected her heart. Harry says she wasn’t ill at all; she never knew. There was nothing they could do. Oh, if I’d only been there! I ought to have been with her!”

Mary and Ann looked at one another, their hearts aching for her. Mary, in helpless dismay, was conscious of deep relief that the other girl was there. She could not have borne to be the only one to comfort Jen at this moment. She did not know what to say.

She put her arms round Jen. “Dear! Oh, Jenny-Wren, we’re all so sorry!”

“I can’t believe it,” Jen quivered, and clung to her. “Mother! I can’t believe she’s gone. I won’t see her again. Oh, Mary, help me to bear it!”

Mary’s arms tightened round her. She tried to speak, but could think of nothing to say that would not seem a mockery.

The comfort came from Ann. “Of course you’ll see her again! Don’t you believe anything, Jen Robins? And aren’t you glad for her? She’s gone to be with your father; she’s only had to do without him for a few months. Now they’re together again. Can’t you be glad for them? Can’t you see past yourself?”

Jen raised her head and stared at her. Slowly a new look dawned in her eyes. “I hadn’t thought of that. I hadn’t had time,” she said eagerly. “It knocked me silly for a moment. Say that again, Nancy! Go on saying it till I take it in! It’s going to help me a lot. Father—yes, of course. And mother meant so much to him. They were everything to one another; they’d been married forty years. Mother didn’t know how to live without him at first.”

“Forty years,” Ann said sharply. “And how long has he had to wait for her to come? Five months, is it? Five months, only, for her to be lonely here. Nobody could make up to her for him. She had you, and her sons, and the grandchildren; but she’d always have missed him. Can’t you be glad for them, Jen Robins?”

“I am,” Jen spoke with bent head, tears in her voice. “I shall be, more and more. I hadn’t thought; just at first I couldn’t, Nancy. I do see that it’s better. When I get used to the idea, I think I shall be glad, for both of them. But—but it was such a shock. She was quite well. I had a jolly letter from her this morning,” her voice shook.

“Brownie, dear, it’s been a dreadful shock,” Mary said pitifully.

Ann withered her with a look of scorn. “But aren’t you glad she had no illness, Jenny-Wren?”—the pet name came unthinking, in response to Jen’s “Nancy.” “When you think, won’t you be glad of that too? Did you really want her to be ill, and perhaps have pain, and to know she was getting weaker, and to feel more helpless? My mother went as yours has done; and I’ve thanked God for it ever since. Not to have pain, not to know, not to feel helpless; what are you sorry about?”

Jen looked up, her face brave, new resolve in her eyes. “Only about myself, Nancy. And that’s a very little bit of it. Yes, I see; it’s better for her, in every way. And she won’t be lonely; father would meet her.”

“Lonely!” said Ann. “No one is ever lonely, who goes ahead. There’s always somebody to meet every one who goes. We’re lonely, who are left behind; but we usually have friends. Think of the friends you have!”

“You’re the very newest one; and you’ve helped me most of all,” Jen said thoughtfully. “I suppose that’s because you’ve been through it yourself.”

Mary turned away, as if resigning her to Ann. Jen would never know—Mary would take care to shield her from the knowledge—the blow she had dealt in those words; Ann, the newest friend, had helped her most of all.

Mary would have given her life to be able to help. But here was the truth, and it gripped her and left no way of escape—Jen had turned to her for comfort, and she had had none to give. She had not known what to say.

Ann realised something of her trouble. “Miss Mary, couldn’t we have the tea brought in?” she asked gently. “It would help us all.”

“I’ll go!” Rosamund sprang forward eagerly, and ran off to give the order. She, too, was longing to help, but had shrunk back, afraid and awkward and shy.

Maidlin, with no words, but urged by a wise impulse, dropped on the ground beside Jen and put her arms round her. “I wish Joy was here. She’d be so sorry,” she whispered.

Jen kissed her. “You must tell her, if I’m not here when she arrives, Maidie. I’ll try to come back; I can’t quite say when. Oh, of course, I shall have to go,” as Maidlin looked up at her in quick distress. “Mary! I must go. You see that, don’t you? I—I must see her once more, Mary.”

Mary had been aimlessly moving the chairs and tea-cups about, her lips trembling in the dawning realisation of what had happened. She pulled herself together with a tremendous effort, and banished that haunting thought. Here was something to do for Jen; if she could not comfort, she could still serve.

“Yes, you’ll want to go at once, Jenny-Wren. I’ll get some things together for you, shall I? What would be best? Mr. Marchwood must meet you in town. Shall I ’phone and tell him when you’ll arrive?”

“Yes, do, please. You’ll have to look up the trains. I could take the car to Wycombe, and pick up a quick train there; that would be best,” Jen was thinking clearly now. “Ken will meet me at Paddington. Tell him I want to go straight through; if he could take me across to Euston, I could catch a night train there.”

“He’ll go with you, I’m sure,” Mary took the time-table from Rosamund, who had heard Jen’s words.

“I’ll love to have him, of course,” Jen said wistfully. “I’m glad I’ve got him! You’ll tell him—all about it, Mary-Dorothy? So that he’ll understand?”

“I’ll ring him up at once,” and Mary gave the book to Rosamund, who was much quicker in looking out trains, and went into the house.

“He sends his love, and he’ll meet the eight-thirty, and go on with you after he’s given you some dinner somewhere, Brownie,” she came back presently, to find Rosamund pouring out the tea and Maidlin waiting on Jen and Ann. “He’ll see you safely to Glasgow, so you’ll be all right. Shall I go and pack for you, Jenny-Wren? I’ve told Mrs. Shirley. She’s badly upset for your sake. So go in to speak to her before you pack, Brownie.”

“Of course.” Jen glanced at her anxiously. “This has been a shock to you too, Mary-Dorothy. I’m so sorry! Don’t do anything more till you’ve had tea. Make her sit down, Nancy; she was tired before this happened.”

“Oh, don’t worry about me!” Mary caught her breath. “I only want to help—to be of use, somehow.”

“You’re doing everything,” Jen said gratefully. “You shall pack for me presently. I shan’t want much. It’s no use taking clothes from here; I shall have to get new things up there.”

They looked at her quickly, for she had not worn mourning for her father, at his special request. She said quietly,—

“It isn’t a question of what I like. Harry and Alison have been very good to mother all these months, and her home has been with them. I can’t hurt their feelings. Alison is a dear, but she likes everything to be proper and usual. I can’t possibly go among her friends wearing colours at such a time, whatever I may feel myself.”

That was obvious. Rosamund nodded agreement. Maidlin said, “Of course, you must please them. But not when you come back here, Brownie?”

“I’ll see how I feel and decide by that,” Jen said quietly. “I’ll take almost nothing with me, Mary-Dorothy.”

Mary was restless and eager to be doing something to help, afraid to sit still because of the misery within her. She rose to go upstairs, to find Jen’s suit-case and to begin packing, and Jen rose wearily to go too, but turned for a word with Ann first.

“You do believe that, Nancy? You really believe it’s true? It’s the only thing I’m hanging on to just now. I mean, that mother would find father waiting for her, and that now they’re together somewhere, wherever it is? You’re sure they’d know one another? I believe in Heaven, of course; but—but it seems so big. Everybody there! How can I be sure they’d ever meet? Mary, how can we ever feel sure?”

“Oh, I’m sure; I’m certain of it!” Mary said hurriedly. “But I don’t know how, Jenny-Wren. I just feel that it must be so.”

“That’s all any one can ever say. But we all feel it, Jen,” Ann said earnestly. “It’s the one thing everybody in the world wants to be certain about. I can’t believe there could be such a craving all through the world unless it was to be satisfied. It would be too cruel. Do you believe God is like that? Would you make people, and put that craving into them—the longing that we’ll know our friends again—and not mean to satisfy it? Would you make a world like that?”

“No. No, I wouldn’t,” Jen said slowly. “Then God couldn’t. I see. Thank you, Nancy!”

“Don’t you think God knows your mother will want your father, far better than you do?” Ann asked quietly.

Jen gave her a startled look. “Of course! I quite forgot that! Then it’s all right. He’ll take care of her, won’t He?”

“He’ll know what’s best for them both, and for you. All we have to do, when we’re left behind, is to remember that, and believe it hard, and then be brave when we feel lonely,” Ann said bracingly.

“I’m going to believe it hard, very hard!” and Jen, with new courage in her face, ran off upstairs to pack.

Mary followed more slowly, one great question surging up in her heart till she almost heard the words. Why had she had no help to give Jen in this time of need? What if Ann Rowney had not been there?

“I say, Mary-Dorothy!” Jen was hauling down her case from a high shelf. “Keep Nancy here till I come back, by fair means or foul! I like her. I want to talk to her some more. If it’s time for her to go back to town, do something to keep her here. Break her leg, or give her mumps, or find her a job in the village, or something! She’s got a jolly lot in her. She’s thought things out for herself; I never have. That’s the trouble; I’ve just drifted along and been happy, and felt thankful I was alive and the world was so beautiful. I’ve tried to be good, and to be nice to people, and to see that the ones I met had a good time; and to play the game, you know. But beyond that I’ve never thought much about anything. Nancy has; that’s evident. I want to ask her things. So keep her here, if you can, there’s a dear. If she really has to go, get her address in town, and I’ll get hold of her again later.”

“I’ll keep in touch with her, Jenny-Wren. Perhaps you’ll be back before she goes. You won’t want to stay there very long, will you?”

“Don’t want to stay at all. Want to come back as soon as I can, and if poss., before Joy comes,” Jen said briefly. “But I can’t say. I’ll have to stay at least a week, I should think, between Glasgow and home. We’ll have to go home, you know. Mother would want that,” and she set her case on the floor and began quickly packing the things Mary brought to her.

“Come back as soon as you can, Brownie. We’ll be missing you here,” Mary said wistfully. “And if Joy comes, she’ll want to see you.”

“I’ll come the first moment I can,” Jen promised.

“Shall we come with you to Wycombe?” Mary asked, as she folded garments. “Choose whom you’ll have for company, Jenny-Wren. I’d love to come, and so would the children. But you won’t want a crowd. It’s for you to say.”

Jen looked up. “Do you think Nancy would come? Perhaps she’d like the drive. It might be a treat to her.”

“If that’s the only reason, I’ll see that she has a drive on Monday,” Mary began, cold fear at her heart again.

Jen, wrapped up in her trouble, was unconscious of it. “But I’d like her to come with me, if she would. I believe she’d say things that would help me, Mary-Dorothy. I don’t want cheering up exactly; I know you and the dear kids would do all that. But I do want something, and I believe Nancy can give it to me. You don’t mind, do you?”

“Mind?” said Mary, a catch in her breath. “I want you to have what’s best for you, the very best. Nothing else matters. I’ll tell her, and I’ll fetch my big coat for her to wear. Of course she’ll go with you.”

She fled from the room, and for one moment took refuge in her own study, because, to her utter dismay and fright, she had turned sick and almost faint. She locked the door, and dropped into a chair.

“Oh, idiot! Idiot! What do you matter just now? Can’t you think only of Jen? Nothing else matters. . . . I don’t know what’s wrong with me, but I daren’t think till she’s gone. . . . Don’t be such a baby! Buck up and help her, do!”

She drank a glass of water and rubbed her white cheeks roughly to bring back their colour; and went downstairs, the big coat on her arm, to ask Ann Rowney if she would go to Wycombe.

Rosamund, all ready in hat and coat, set up a wail. “I want to go with Brownie! I’m going, Mary! I’m all ready!”

“Are you going if Brownie doesn’t want you?” Mary turned on her, and the sharpness of her tone betrayed her own heartbreak.

“Oh!” said Rosamund, and stared at her blankly. “N-no, Mary-Dorothy,” and she began to unbutton her coat, her lips trembling.

Ann looked at them. Mary had turned away, unable to face any one for a moment.

Maidlin, sheltered by the dreams in which she lived from clear realisation of all this meant, said with a sob, “We’re only kids, Ros. We can’t say the proper things. I wish Joy was here! Brownie wants somebody really grown-up just now.”

Rosamund’s unhappy eyes went from Ann to Mary, an unspoken question in them. But a fine intuition held it back, and she said nothing. She took off her hat and hung it up in the little cloakroom by the garden door, and turned to Mary. “Isn’t there anything I can do, Mary-Dorothy?”

Mary was idly turning the pages of the time-table, struggling for self-control. This crisis had hurt Rosamund’s awakening sensibilities deeply, but it had just about broken Mary’s heart. She shook her head, unable to speak.

Ann said quickly, “Couldn’t you put down those trains for Jen, so that she won’t have to remember when she’s due in town? She’ll get thinking, once she’s in the train, and she won’t want to be bothered with things like trains.”

Rosamund gratefully seized the book. “Find me a pencil, Maidie! And come and help.”

“Has Jen got rugs for the night journey?” Ann asked of Mary.

Mary had not thought of that. “I’ll get some; and straps,” she said, and began to hurry about.

Ann’s understanding eyes had seen all the tragedy. These three, Mary, Ros, and Maidie, would have done anything to help Jen in this crisis; the two younger girls loved her, Mary worshipped her. It was all obvious. And yet none of them knew what to do, how to say the things she was needing to hear; not one of them had the right word for her in her trouble.

“Pity I was here!” Ann thought. “And yet I don’t know. Jen has to be thought of first. She needed somebody, and they just went all to pieces. I wonder why? With their love for her, they ought to have been able to help. One can forgive the children; but what about Miss Devine? She knows she’s failed; it’s breaking her heart. I don’t understand her. She’s felt it more because I was here; it’s been worse for her, though better for Jen. I wonder if she’ll talk to me about it afterwards? I don’t think I’ll dare to ask her!”

Then Jen came down, dressed for the journey, after a few minutes in Mrs. Shirley’s room, and Rosamund called that the car was at the door.

Ann turned away, and was very busy putting on Mary’s big coat and the leather hood which belonged to it, while the farewells were being said.

Rosamund carried out the rugs and suitcase and stowed them away under the seat. “Well, good-bye, Brownie, and good luck to you!” she said, a lump in her throat.

Mary tucked the rug round Jen, quite forgetting that Ann was still to come. “Come back soon, Jenny-Wren! And wire us from Glasgow.”

“Ring us up from Paddington,” Rosamund amended. “Ken will see to that.”

Maidlin, wordless and in tears, clung to Jen and had to be dragged away gently by Mary.

“Take care of Maidie, Mary-Dorothy,” said Jen, and made room for Ann beside her. “Good-bye, all! Give my love to Joy when she comes.”

Then the car whirled away and she was gone.

Mary turned to Rosamund. “Ros, comfort Maidie somehow. I’ll come presently. I’m not well; you must do without me,” and, on the verge of a breakdown, she fled to her own room.

Rosamund looked frightened. “I say, Maidie, do buck up, old girl! Did you see Mary’s face? She looked ghastly. This has knocked her all to bits. She’s awfully keen on Jen, you know.”

“We all are,” Maidlin steadied herself with an effort. “It’s cruel that Jen should have such things happen to her. She’s good to everybody, always, and yet things always go wrong with her. It was bad enough about her father, but she did have time to think about that. But this is cruel, Ros!”

“I don’t believe Nancy would let you say that.” Rosamund slipped an arm round her waist, and they wandered down the bank of the terrace and across the lawn together. “She’d have some good reason why it isn’t. But I don’t know what it would be. But I’m bothered about Mary-Dorothy, Maidie. It would be horrid if she were ill; and she looked ill.”

“But why should she be ill? We’re all sorry for Jen, but it doesn’t make us ill,” Maidlin argued.

“No, but Mary cares such a thumping lot about Jen, and she takes things so badly. Biddy told me that. Before she went to France, a year ago, she said to me that something had once gone wrong between Mary and Joy; I don’t know the story. But she said Mary had cried till she was almost ill, because she cared so much about Joy. And then she said, ‘And she cares even more about Jen. If ever she should have trouble with her—but I can’t imagine it.’ Neither could I, so I didn’t bother. But it looks as if it had happened.”

“What kind of trouble?” Maidlin asked doubtfully. “You don’t mean that she could quarrel with either of them? Nobody could, Ros.”

“There are other things besides quarrelling,” Rosamund said, with the wisdom of seventeen instructing sixteen. “I don’t know what it was with Joy; Biddy wouldn’t say a word. It wasn’t quarrelling, for you know how much Joy thinks of Mary, and how fond Mary is of Joy. I can’t imagine what happened. But now——” she sat on the edge of a garden seat and reviewed the situation, with her own experience to help her—“don’t you think perhaps Mary wanted to go to Wycombe with Jen? I did. If she knew Jen would rather have Nancy, that might upset Mary quite a lot, don’t you think so? That’s how I felt. I see now it was better for Nancy to go. She’s older, and she could say things that would help, and that’s what Jen needed. But for a minute or two I felt awfully bad, to know Jen didn’t want me. Perhaps it’s the same with Mary, only worse. For Mary does worry so over things. You know how we’ve ragged her and said it was her artistic temperament coming out!”

“She needs it to help her write her lovely books. That’s what Jen always says,” said Maidlin.

“I know. But it makes things extra bad for her when any trouble happens,” Rosamund said wisely.

She sat swinging her legs and pondering, while Maidlin, with a wistful, “I do wish Joy would come!” lapsed into a dream of a happy future, when Joy was living at home, and Jen had come back and was happy again, and every one had everything and was content.

“There’s Mrs. Pennell from the village!” Rosamund said suddenly, as a young woman came through the Abbey gate and towards the house. “I wonder what’s up?” and she went flying across the lawn.

Maidlin woke from her dream with a sigh, and followed.

Rosamund met her, dismay in her face. “The Institute class! It’s at seven. You know, Jen meant to have tea and then hurry back; she wouldn’t put it off. They’re all waiting for her down there.”

“They’ll have to go home. They’ll understand,” Maidlin faltered. “Or shall we tell Mary-Dorothy?”

Rosamund was the type who could rise to an occasion. “We can’t worry her. She’s ill. But Jen wouldn’t like the class put off. We’ll take them, Maidie. It will be something to do for Mary and Jen.”

“We couldn’t, Ros!” Maidlin shrank back, aghast at the thought.

“Of course we can. Haven’t we been to Chelsea? We know reams more than they do. Come on, old chap, and back me up! Don’t funk!”

Mrs. Pennell’s face lit up. “If you would, Miss! Everybody’ll be pleased.”

“I’m game,” Rosamund said briefly. “Maidie, run to the house and say we’ve gone to the village. Then come after me; you don’t want to be left out, do you?”

Not to be left out was one of Maidlin’s ruling passions in life. Her power of initiative was quite unawakened, but she could follow, and her desire to follow Rosamund carried her on many a time when she would have stood still if left to herself.

She went to give the message, then took the path through the Abbey ruins to the village. Shyness overtook her as she reached the Institute, but she went in bravely, and a group of women in the doorway smiled and made way for her to pass.

Rosamund, with heightened colour and very bright eyes, stood on a chair addressing the class of girls, and young men, and older women. She was telling of Jen’s trouble and sudden departure; and a sympathetic murmur arose.

“It wasn’t possible for Miss Devine to get away,” Rosamund explained. “So if you’ll put up with me, and if you don’t mind too much, I’ll do my best to help you through, just for to-night. I hear you’re learning ‘Oaken Leaves.’ I know it, so that’s all right. Make up sets of eight, and we’ll see how much you remember.”

“I thought that was a good way to start,” she murmured to Maidlin, as the class clapped, and laughed, and began to arrange itself in sets. “It sounds kind; I’m sure it’s tactful! Of course, they won’t remember any, but we’ll pretend not to notice that.”

Maidlin watched with admiration and deep envy as Rosamund, who had never taught in her life before, took command, watched critically, made pointed yet kindly comments at the end, and demanded the dance over again. But Rosamund had watched Jen teaching many a time, and she had not a trace of shyness. She had not been twice a May Queen in a big school for nothing, and her slight diffidence vanished as she gained confidence.

The hour that followed was enjoyable to all. Maidlin forgot herself enough to join in and make up a set for “Hey, Boys,” so that three girls should not have to sit out; and Rosamund watched her dancing with much satisfaction. Maidie was always less dreamy after dancing; in dancing, in her singing lessons and practice, or in dreams of Joy’s return, she forgot herself entirely; but while the first two were healthy for her, the last was not so good, and Rosamund had private orders from Jen to “keep Maidie from mooning about and going inside herself.” Just what that meant Rosamund did not know; she was not in the habit of “going inside herself.” But she did know the signs of it in Maidlin, and she understood it was not to be allowed.

“You’re a sport, Maidie!” she said warmly, as they walked home through the Abbey together. “It helped tremendously to have you joining in. Your dancing’s jolly good; you’re so light, and so full of music; and they all try to play up to you. You bucked up that whole set.”

“How can dancing be full of music?” Maidlin asked doubtfully, always distrustful of herself.

“Yours is,” Rosamund said briefly.

“It’s just by chance, then. I love the way you teach, Ros. You should take them again for Mary.”

“It was rather fun,” Rosamund admitted. “I say, Maidie! You know what all the girls want! Won’t you rise to the occasion?”

Maidlin flushed and shrank. The suggestion that she should be the new May Queen, to follow Jen, had startled and dismayed her. She did not know that the proposal had been made to the Club by Rosamund at Jen’s suggestion, and had been accepted by the girls only on Rosamund’s promise to prompt in the background and to keep Maidie up to her duties; for the girls quite frankly felt it would be undesirable to have a dreamy Queen. But Jen had felt that here might be a cure for Maidlin’s growing tendency to withdrawal into an inner world of her own, and had urged her election on Rosamund and on the Club with energy. The invitation had been given at the Club’s last meeting, a few days before, and Maidlin was supposed to be considering it, and to be about to make her gracious acceptance of the honour known very shortly. Actually she was trying, nervously and desperately, to find some way of escape which would not disappoint Jen and Rosamund too deeply.

“I’m not good enough, Ros,” she pleaded. “You know I couldn’t do it. It’s awful for anybody to have to come after you and Jen; you’ve been such ripping Queens. It’s simply silly to think of me.”

Rosamund looked at her with amusement. “Maidie, you are funny! I was in the seventh heaven when they asked me.”

“I’m not,” Maidlin said unhappily. “We’re different.”

“Well, I should say we are,” Rosamund chuckled. Then she said more earnestly, “Think how pleased Joy would be, Maidie!”

“Oh, shut up!” blazed Maidlin, and fled to hide herself in a corner of the garden.

Rosamund started in pursuit, then checked herself, and laughed. “Poor Maidie! That’s the one thing that upsets her. She knows Joy would like it. I don’t understand her a scrap. If it comes to that, I don’t understand Mary-Dorothy either. I don’t know why she’s so fearfully upset. It’s awfully jolly for me, with Mary on one side and Maidie on the other! I’m glad I don’t have feelings; at least . . . well, I do! But I do think I’ve got them in better order! Maidie can’t manage hers at all; and it seems as if Mary-Dorothy sits on hers, but now and then they get on top of her. I suppose she and Maidie have ‘temperaments.’ Thanks be, I’m just plain and ordinary!—All the same, ordinary people are useful. What would happen if we were all like Maidie and Mary? Mary’s books would happen, of course, and Maidie’s singing; but things like those wouldn’t run the house or keep Joy’s clubs going! I guess both kinds of people are needed—I and Maidie! I won’t tease her now; she’ll come along presently, and it will be all right. I won’t plague Mary-Dorothy either. She’ll come down when she wants to.”

Rosamund stood in the hall, hesitating. “I’ll begin a letter to Jen, telling her I took the club for her. But I’ll go and talk to Mrs. Shirley first; she’ll be feeling left out of everything. Perhaps Mary has been with her.”

She went hopefully upstairs, but found the old lady alone and waiting anxiously for some one to talk to. The maids had told her the girls had gone to the village, but had not been able to give the reason, and she had wondered, and fidgeted, and had grown anxious at last.

Rosamund put aside the thought of her letter and sat down on a stool at Mrs. Shirley’s feet, to tell the story of the evening’s class.

Rosamund’s estimate of Mary had been accidentally correct. Mary’s feelings, once roused, stirred her to her depths; she was afraid of them, and never, if she could help it, allowed them free play. Now and then they broke loose and swept her off her feet.

To-night the revelation of her powerlessness to help Jen in her need had almost broken her heart. She loved Jen better than her life; but in Jen’s direst need she had been unable to help her. She had failed her friend at her biggest crisis.

It all came back on her, as she lay broken on her bed, in a torrent of realisation under which she went down; and she lay and cried till she felt sick again.

“Brownie wants somebody really grown-up just now,” Maidlin had said. “We can’t say the proper things.”

“You’re the newest friend,” Jen had said to Ann Rowney. “But you’ve helped me most of all. Thank you, Nancy!”