* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Knights of the Round Table

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Enid Blyton (1897-1968)

Date first posted: May 24, 2020

Date last updated: May 24, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200551

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

John o’ London’s Children’s Library

THE

KNIGHTS OF THE

ROUND TABLE

THE KNIGHTS OF THE

ROUND TABLE

BY

ENID BLYTON

LONDON

GEORGE NEWNES, LIMITED

SOUTHAMPTON ST., STRAND, W.C.2

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

MORRISON AND GIBB LTD., LONDON AND EDINBURGH

The Knights of the Round Table

| PAGE | |

| The Enchanted Sword | 7 |

| The Round Table | 15 |

| The Finding of the Sword Excalibur | 18 |

| Balin, the Knight of the Two Swords | 24 |

| Prince Geraint and the Sparrowhawk | 33 |

| The Further Adventures of Geraint and Enid | 43 |

| Gareth, the Knight of the Kitchen | 57 |

| Sir Gareth Goes Adventuring | 64 |

| The Bold Sir Peredur | 78 |

| The Quest of the Holy Grail | 86 |

| The Adventures of Sir Galahad | 91 |

| Sir Mordred’s Plot | 102 |

| Sir Gawaine meets Sir Lancelot | 110 |

| The Passing of Arthur | 117 |

| Arthur pulled at the sword fiercely | |||

| (Colour plate) | Frontispiece | ||

| PAGE | |||

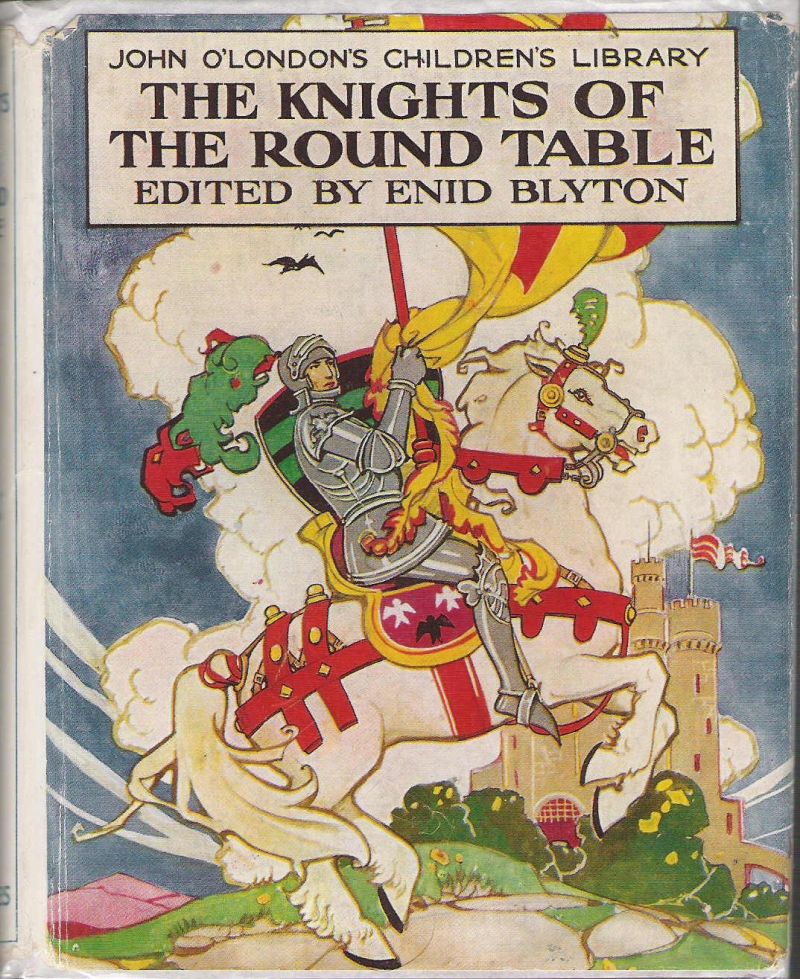

| When the King came to the hand, he reached out and took the sword from it | 23 | ||

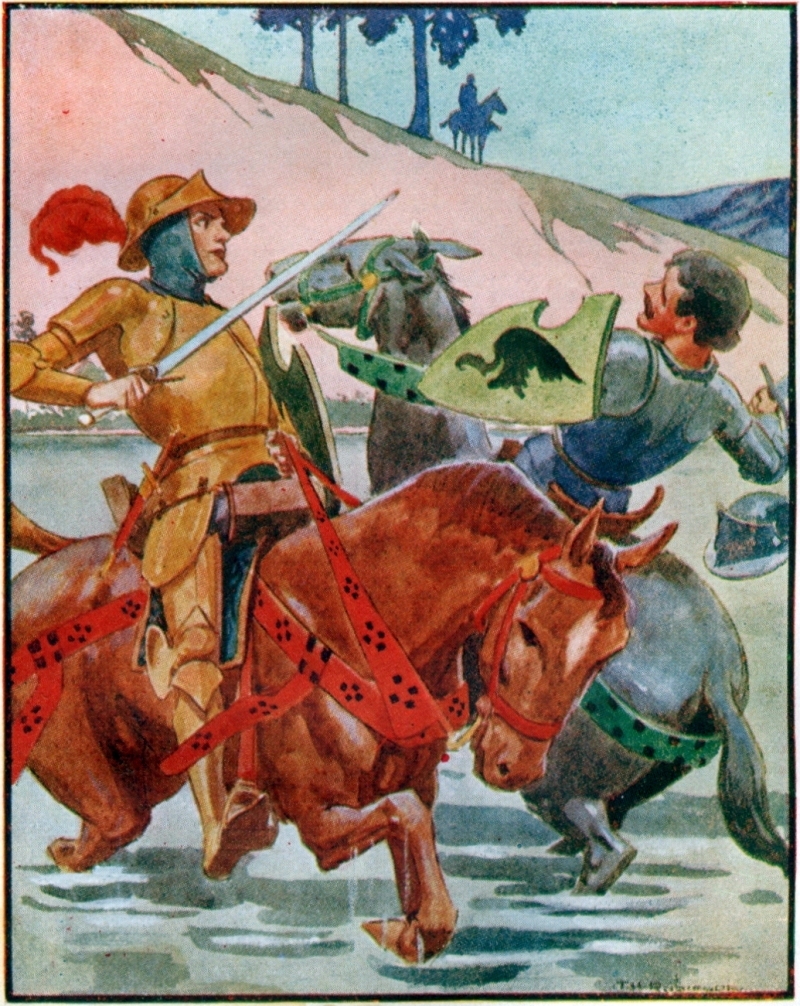

| Next day Geraint donned the rusty armour | |||

| (Colour plate) | facing | 40 | |

| The sound awoke Geraint from his swoon, and with sudden strength he leapt from his couch | 55 | ||

| Gareth struck the knight from his horse | |||

| (Colour plate) | facing | 66 | |

| “Damsel, I obey you,” said Gareth, and he lowered his sword | 71 | ||

| The maiden bade Galahad enter the ship | |||

| (Colour plate) | facing | 96 | |

| He swung her up on his horse, and, sword in hand, galloped away again | 109 | ||

There once lived a King called Uther Pendragon, who loved the fair Igraine of Cornwall. She did not return his love, and Uther fell ill with grief.

As he lay on his bed, Merlin the Magician appeared before him.

“I know what sorrow is in your heart,” he said to the King. “If you will promise what I ask, I will, by my magic art, give you Igraine for your wife.”

“I will grant you all you ask,” said Uther. “What do you wish?”

“As soon as you and Igraine have a baby son, will you give him to me?” asked Merlin. “Nothing but good shall come to the child, I promise you.”

“So be it,” said the King. “Give me Igraine for wife, and you shall have my first son.”

It came to pass as Merlin promised. The fair Igraine became Uther Pendragon’s wife, and made him very happy. One night a baby son was born to her and the King, and Uther looked upon the child’s face, and was grieved when he remembered his promise to Merlin.

He named the tiny boy Arthur, and then commanded that he should be taken down to the postern gate, wrapped in a cloth of gold.

“At the gate you will see an old man. Give the child to him,” said the King to two of his knights. The knights did as they were commanded, and delivered the baby to Merlin, who was waiting at the postern gate.

The magician took the child to a good knight called Sir Ector, and the knight’s wife welcomed the baby, and tended him lovingly, bringing him up as if he were her own dear son.

Not very long after this King Uther fell ill and died. Then many mighty lords wished to be king, and fought one another, so that the kingdom was divided against itself, and could not stand against any foe.

There came a day when Merlin the Magician rode to the Archbishop of Canterbury, and bade him command all the great lords of the land to come to London by Christmas, and worship in the church there.

“Then shall you know who is to be King of this country,” said Merlin, “for a great marvel shall be shown you.”

So the Archbishop sent for all the lords and knights, commanding them to come to the church in London by Christmas, and they obeyed.

When the people came out of church, a cry of wonder was heard—for there, in the churchyard, was a great stone, and in the middle of it was an anvil of steel a foot high. In the anvil was thrust a beautiful sword, and round it, written in letters of gold upon the stone, were these words:

“Whoso pulleth out this sword from this stone and anvil is rightwise king born of all England.”

Lords and knights pressed round the sword and marvelled to see it thrust into the stone, for neither sword nor stone had been there when they went into the church.

Then many men caught hold of the sword and tried to pull it forth, but could not. Try as they would, they could not move it an inch. It was held fast, and not even the strongest knight there could draw it forth.

“The man is not here that shall be king of this realm,” said the Archbishop. “Set ten men to guard the stone day and night. Then, when New Year’s Day is come, we will hold a tournament, and the bravest and strongest in the kingdom shall joust one with another. Mayhap by that time there shall come the one who will draw forth the sword, and be hailed as king of this fair land.”

Now, when New Year’s Day came, many lords and knights rode to the fields to take part in the tournament. With them went the good knight Sir Ector, to whom Merlin had given the baby Arthur some years before.

Sir Ector had brought up the boy with his own son, Sir Kay, and had taught him all the arts of knighthood, so that he grew up brave and courteous. He loved Sir Ector and his wife, and called them Father and Mother, for he thought that they were truly his parents. Sir Kay he thought was his brother, and he was glad and proud that Kay, who had been made knight only a few months before, should be going to joust at the tournament.

Sir Ector, Sir Kay, and Arthur set off to go to the lists. On the way there Sir Kay found that his sword, which he had unbuckled the night before, had been left at the house. He had forgotten it!

“I pray you, Arthur, ride back to the house and fetch me my sword,” he said to the boy beside him.

“Willingly!” answered Arthur, and turning his horse’s head round, he rode swiftly back to fetch Kay’s sword. But when he got to the house, he found the door locked, for all the women had gone to see the tournament.

Then Arthur was angry and dismayed, for he knew how disappointed his brother would be if he returned without his sword.

“I will ride to the churchyard, and take the sword from the stone there,” he said to himself. “My brother Kay shall not be without a sword this day!”

So when he came to the churchyard Arthur leapt off his horse, and tied it to a post. Then he went to ask the men who guarded the sword if he might take it. But they were not there, for they, too, had gone to the tournament.

Then the boy ran to the stone, and took hold of the handle of the sword. He pulled at it fiercely, and lo and behold! it came forth from the steel anvil, and shone brightly in the sunshine.

Arthur leapt on to his horse once again, and rode to Kay.

“Here is a sword for you, brother,” he said.

Sir Kay took the beautiful weapon, and looked at it in amaze, for he knew at once that it was the sword from the stone. He ran to his father and showed it to him.

“Where did you get it?” asked Sir Ector, in astonishment and awe.

“My brother Arthur brought it to me,” answered Sir Kay.

“Sir, I will tell you all,” said Arthur, fearing that he had done wrong. “When I went back for Kay’s sword I found the door locked. So, lest my brother should be without a weapon this day, I rode to the churchyard and took the sword from the great stone there.”

“Then you must be King of this land,” said Sir Ector, “for so say the letters around the anvil. Come with me to the churchyard, and you shall put the sword in the stone again, and I will see you draw it forth.”

The three rode to the church, and Arthur thrust the sword into the anvil, then drew it forth again easily and lightly. Then he put it back, and Sir Ector strove to draw it forth and could not. After him Sir Kay tried, but he could not so much as stir it an inch.

Then once again Arthur pulled it forth, and at that both Sir Ector and Sir Kay fell down upon their knees before him.

“Why do you kneel to me?” asked the boy. “My father and my brother, why is this?”

“Nay, nay,” said Sir Ector. “We are not your father and your brother. Long years ago the magician Merlin brought you to us as a baby, and we took you and nursed you, not knowing who you were.”

Then Arthur began to weep, for he was sad to hear that the man and woman he loved so much were not his parents, and that Kay was not his brother. But Sir Ector comforted him, and took him to the Archbishop, bidding him tell how he had drawn forth the enchanted sword.

Then once again Arthur was bidden to ride to the churchyard, this time accompanied by all the lords and knights. He thrust the sword into the stone, and then pulled it forth. At that many lords came round the stone, shouting that what a mere boy could do could be done by a man with ease.

But when they tried to draw forth the sword, they could not. Each man had his turn, and failed. Then, before all the watching people, Arthur lightly drew out the sword, and flourished it round his head.

“We will have Arthur for our King!” shouted the people. “Let us crown him! He is our King, and we will have none other!”

Then they all knelt before him, and begged the Archbishop to anoint him as king.

So, when the right time came, Arthur was crowned, and swore to be a true king, and to rule with justice all the days of his life.

After Arthur had been made King, many of his lords would not come to do him homage, and made war against him. The King fought bravely against them, and soon the kingdom was his from north to south, from east to west.

Then he set about making the country safe for honest men to live in. He captured robbers, slew wild beasts, and made wide paths through the gloomy forests so that men might journey here and there in peace and safety.

There was a king called Leodegrance whom Arthur helped greatly. This king had a fair daughter, Guinevere, and Arthur loved her as soon as he saw her. He sent to Leodegrance and asked him for his daughter’s hand, which that king was pleased to grant.

Then in great pomp and ceremony the two were wed, and the lovely Guinevere became Arthur’s queen. Leodegrance sent Arthur a wonderful wedding present—the famous Round Table.

This had been made for King Uther Pendragon by Merlin the Magician. When Uther died, the table went to King Leodegrance, and he in his turn sent it to Arthur, who was full of joy to receive it.

It was a very large table, for it would seat one hundred and fifty knights. Leodegrance sent Arthur a hundred knights, and the King called Merlin to him, and bade him go forth into his kingdom and seek for fifty more true knights, worthy to sit at the Table.

Merlin set out, but he could find only twenty-eight, and these he brought back with him. Thus the Table was not full, and there was always room for new knights. These were ordained at every Feast of Pentecost, and very proud were men or youths when there came for them the great day on which they sat for the first time at the Round Table.

Merlin made the seats for the knights, and as soon as a new knight had sat at the table, his name appeared in golden letters on his seat. Thus the knights always knew their places, and each man took his own.

Soon all the seats were full save only one, called the Siege Perilous, which no knight might take unless he was without any stain of sin. This was not filled until Sir Galahad came, for none dared sit there save him.

The greatest day in a knight’s life was when he took upon himself the vows of true knighthood, and sat at the Table Round in the company of all the other noble knights. Then he had to swear many things.

He must promise to obey the King; to show mercy to all who asked for it; to fight for the weak; to be kind, courteous, and gentle to all; and to do only those deeds which would bring honour and glory to knighthood.

So began the famous company of the Round Table, whose names have come down to us in many a brave and marvellous adventure. Any man or woman who was distressed could come to Arthur’s court, sure of finding a knight who would ride forth and right their wrongs.

King Arthur took horse one morning, and set out to seek adventure. As he rode through the forest, he came to a fountain, and by it was a rich tent. A knight in full armour sat near by. He was tall, and very broad and strong. Never yet had he met a man who could defeat him in battle.

King Arthur made as if he would ride by, but the knight commanded him to stop.

“No knight passes here unless he first jousts with me,” said the strange knight, Sir Pellinore.

“That is a bad custom,” said Arthur. “No more must you joust here, Sir Knight.”

“I take my commands from no man,” answered the tall knight angrily. “If you would that I forswear this custom, then you must defeat me.”

“I will do so!” said the King, and forthwith Sir Pellinore mounted his horse and the two rode at one another.

They met with such a shock that both their spears were shivered to pieces on one another’s shields. Then Arthur pulled out his sword.

“Nay, not so,” said the knight. “We will fight once again with spears.”

“I would do so, but I have no more,” answered Arthur.

Then Sir Pellinore called his squire and bade him bring two more spears. Arthur chose one and he took the other. Then once again they rode at one another, and for the second time they broke their spears. Then Arthur set hand on his sword, but the knight stopped him.

“You are a passing good jouster,” he said. “For the love of the high order of knighthood, let us joust once again.”

The squire brought out two great spears, and each knight took one. Then they rode hard at one another, and once more Arthur’s spear was broken. But Sir Pellinore hit him so hard in the middle of his shield that he brought both man and horse to earth.

Then Arthur leapt to his feet, and drew his sword.

“I will now fight you on foot, Sir Knight!” he cried, “for I have lost the honour on horseback.”

So Sir Pellinore alighted, and the two set about one another with their swords. That was a great battle, and mighty were the strokes that each gave the other. Soon both were wounded, but they would not stop for that.

Then Arthur smote at Sir Pellinore just as the knight was smiting at him, and the two swords met together with a crash. Pellinore’s was the heavier sword, and it broke the King’s weapon into two pieces.

Arthur leapt straight at the knight, and taking him by the waist, threw him down to the ground. The knight, who was exceedingly strong, rolled over on top of the King. Then he undid Arthur’s helmet, and raised his sword to smite off his head.

But at that moment Merlin the Magician appeared, and cried out in a stern voice to Sir Pellinore:

“Hold your hand, Sir Knight, for he whom you are about to kill is a greater man than you know.”

“Who is he?” asked the knight.

“He is King Arthur,” answered Merlin.

“Then I must kill him for fear of his great wrath,” cried Pellinore. He lifted up his sword, and was about to hew off the King’s head, when Merlin cast an enchantment about him. His hand fell to his side, and he sank to the ground in a deep sleep. Then Merlin bade Arthur come with him, and the King, mounting on his horse, obeyed.

“You have not slain that knight by your enchantments?” asked Arthur anxiously. “He was a great knight, and a strong, and his only fault was his discourtesy.”

“He will be quite whole again in three hours,” said Merlin. “He is but cast into a sleep. There is not another knight in the kingdom so big and strong as he is. If he comes to crave your pardon, grant it, for he will do you right good service.”

Then Merlin took the King to a hermit, and the wise man tended Arthur’s wounds, so that in three days he was ready to depart.

As they rode forth, Arthur glanced down at his side.

“I have no sword,” he said. “Sir Pellinore broke mine in our battle.”

“No matter,” said Merlin. “You shall soon have another.”

They rode on and came to a broad lake. In the midst a strange sight was to be seen; for out of the water came a hand and arm clothed in rich white silk, and in the hand was a beautiful sword that gleamed brightly.

“There is a sword for you,” said Merlin. “See, it glitters yonder in the lake. Below the water is a wonderful palace, belonging to the Lady of the Lake, and it is she who has wrought this sword for you. Go, fetch it.”

The King saw a little boat by the side of the lake, and he untied it, and rowed on the water. When he came to the hand, he reached out and took the sword from it. As soon as he had done so the hand and arm disappeared under the water.

Arthur rowed back to land, and then, taking the sword from its scabbard, he looked at it closely. It was very beautiful, and the King was proud to have such a noble weapon. On each side were written mystic words that Arthur did not understand.

“What mean these writings?” he asked.

“On this side is written, ‘Keep me,’ and on the other, ‘Throw me away,’ ” said Merlin. “But the time is far distant when you must throw it away. Look well at the scabbard. Do you like it or the sword the better of the two?”

WHEN THE KING CAME TO THE HAND, HE REACHED OUT AND TOOK THE SWORD FROM IT.

“The sword,” answered the King.

“You are unwise,” said Merlin. “The scabbard is worth ten of the sword, for while you have the scabbard you will never lose blood, however sorely you may be wounded. So guard the scabbard well. The sword is called Excalibur, and is the best in the world.”

Arthur rode back to his court with Merlin, glad to have such a fine weapon at his side. Joyfully his knights welcomed him into their company again, and once more they sat down together at the Round Table.

Before long Sir Pellinore came to crave pardon of the King for his discourtesy. Freely Arthur forgave him, and henceforth the great knight served the King well and faithfully, doing brave deeds in his service.

King Rience of North Wales once sent an insolent message to King Arthur:

“Eleven kings have I defeated, and their beards make a fringe for my mantle. There is yet a space for a twelfth, so with all speed send me yours, or I will lay waste your land from east to west.”

The listening knights clapped their hands to their swords in anger, eager to slay the messenger, but the King forbade them.

“Get you gone!” he commanded the man sternly.

Now there was a knight there called Balin, he who wore two swords. He was very wrath when he heard the wicked message sent by King Rience, and he vowed to avenge the insult done to Arthur.

For eighteen months Balin had been in prison for slaying a knight of Arthur’s court, and he longed to do some deed that would win him the King’s favour once more. So he left the hall and went to don his armour, eager to fight against King Rience.

Whilst he was arming himself, a false lady came to the hall, and reminded the King that she had once done him a service.

“In return for the good I did you, I beg you to grant me a favour,” she said.

“Speak on,” said the King.

“Give me the head of the knight Balin,” said the lady.

“That I cannot do with honour,” answered Arthur. “I pray you, madam, ask some other thing.”

But the lady would not, and departed from the hall, speaking bitterly against the King. At the door she met the knight Balin, who was returning, fully armed.

As soon as he saw her, he rode straight at her and cut off her head, for he knew her to be a witch-woman and very wicked. She had caused his mother’s death, and for three years he had sought for her in vain.

Then he rode forth to go against King Rience. But when Arthur found that he had cut off the lady’s head, he was very angry.

“No matter what cause for anger he had against her, he should not have done such a thing in my court,” said the King. “Balin has shamed us all. Sir Lanceor, ride after him and bring him back again.”

Lanceor at once armed himself, and rode after Balin. He galloped his horse hard, and when he came up to Balin he shouted loudly—for he was an insolent knight—well pleased at the thought that Balin must needs go back with him to court.

“Stay, knight! You must stop whether you will or no, and I warrant your shield will not protect you if you turn to do battle with me!” he cried.

“What do you wish?” asked Balin fiercely, reining in his horse. “Would you joust with me, insolent knight? Have a care to yourself then!”

They rushed at one another with their spears held ready, and the two horses met with a crash. Lanceor’s spear struck sideways on Balin’s shield, and shivered to pieces, but Balin’s spear ran right through the insolent knight’s shield and slew him.

Balin looked sorrowfully at the knight, for he was sad to see a brave man fallen. He buried him, and went on his way grieving.

Soon he saw a knight riding towards him in the forest, and by the arms he bore he knew him to be his well-loved brother, Balan. They rode eagerly to meet one another, and greeted each other with joy.

“Now am I right glad to see you,” said Balan. “A man told me that you had been freed from your imprisonment, and I came to see you at the court.”

“I go to avenge my lord Arthur,” said Balin. “King Rience has done him an insult. Come with me, my brother, and together we will follow this adventure.”

The two knights rode on side by side, and presently they met the magician Merlin.

“You ride to find King Rience,” said Merlin, who knew the thoughts of all men. “Let me give you good counsel, and you shall meet with him and overcome him.”

“We will do as you say,” said Balin, and he and his brother followed the magician to a hiding-place in the wood, just beside a pathway.

“The King will come this way shortly with sixty knights,” said Merlin.

It came to pass as the magician had said. King Rience rode by with his knights, and, when he came near, Balin and Balan rose up and attacked the company.

First they unhorsed King Rience, and struck him to the ground, where he lay wounded sorely. Then they rode at the rest of the knights, and so fiercely did the two brothers fight that soon forty of the King’s men were vanquished, and the rest fled.

Then Balin returned to Rience, and would have slain him, but he begged for mercy. So his life was spared, and Balin and Balan took him to Arthur’s court, and there delivered him to the King to do with as he thought best.

Then the two brothers parted, and each went on his way alone.

Balin met with strange adventures, and fought many hard battles. Then one day as he rode onward, he came to a cross, and on it, written in letters of gold, were these words:

“It is perilous for a knight to ride alone towards this castle.”

As he was reading this, Balin saw an old man coming towards him, and heard him speak to him in warning.

“Balin of the Two Swords,” he said, “do not pass this way. Turn back, or you will ride into great peril.”

When he had finished speaking he vanished. Then Balin heard a horn blow as if some beast had been killed in the hunt, and his blood turned cold within him.

“That blast was blown for me,” said the knight. “I am the beast who shall die—but I am still alive, and I will go forward as befits a brave knight.”

So he rode onwards past the cross, and soon came to the castle. There he was welcomed by many fair ladies and knights, who led him into the castle and feasted him royally.

Then the chief lady of the castle came to him and said:

“Sir Knight of the Two Swords, know that all knights who pass this way must joust with one nearby who guards an island. No man may pass without so doing.”

“That is an unhappy custom,” said Balin; “but though my horse is weary my heart is not, and I will joust with this knight.”

Then a man came up to Balin, and took his shield.

“Sir,” he said, “your shield is not whole. Let me lend you mine, I pray you.”

Balin agreed, and took the strange knight’s shield instead of his own, which had his arms blazoned on. Then he mounted his horse and rode to where a great boat waited to take him and his charger to the island.

When he arrived at the island he met a maiden, and she spoke to him in dolorous tones.

“O Knight Balin, why have you left your own shield behind? You have put yourself in great danger by so doing.”

“That I cannot help,” said Balin, “for it is too late now to turn back. I must face what lies before me, for I am a knight of Arthur’s court.”

Then Balin heard the sound of hoofs, and saw a knight come riding out of a castle, clad in red armour, and his horse in trappings of the same colour. When this knight saw Balin he thought that surely it must be his brother Balin, because he carried two swords—for the Red Knight was no other than Balan, who had been forced by a foe to keep the castle against all comers.

But when Balan looked upon his enemy’s shield, he saw that it did not bear his brother’s arms, and he therefore galloped straight at him, deeming him to be a stranger.

The two knights met with a fearful shock, and the spear of each smote the other down. They lay in a swoon upon the ground, and for some time they could not rise.

Then Balan leapt up, and went towards Balin, who arose to meet him. But Balan struck first, and his sword went right through his brother’s shield, and smote his helmet. Then Balin struck back and felled his brother to the ground.

So they fought together till they had no more strength left, and each had seven great wounds. Then Balan laid himself down for a little, and Balin spoke to him.

“What knight are you?” he said. “Never till now did I meet a knight that was my match.”

“My name is Balan,” answered the knight. “And I am brother to the good knight Balin of the Two Swords.”

“Alas, that ever I should see this day!” cried Balin, in grief and dismay, for he loved his brother better than any one else on earth. Then he fell in a faint.

Balan went to him and raised his helmet so that he might look upon his face. And when he saw that it was his own well-loved brother, he wept bitterly.

“Now when I saw your two swords I did indeed think you were my brother,” he said, “but when I looked upon your shield and saw that it was not yours, I did not know you.”

“A knight bade me take his in exchange for mine that was not whole,” said Balin. “Great woe has he brought us this day, for we have slain one another, and the world will speak ill of us both for that!”

Then came the lady of the castle and her men. She wept to hear their tale, and when the two brothers begged her to bury them in the same grave, she promised with tears that she would do so.

So died Balin and Balan, and were buried in the same place. The lady knew Balan’s name, but not Balin’s, and she put above their grave how that the knight Balan was slain by his brother.

Then the next day came Merlin the Magician, and sorrowfully, in letters of gold, he wrote Balin’s name there too. Then below he put the story of their deaths, that all men might know how it came to pass that the two brothers had each killed the other.

One morning the King and all his court went hunting. As soon as dawn came, there arose a great noise of baying hounds, of tramping feet, and thudding hoofs—the knights were getting to horse.

Queen Guinevere meant to ride with the huntsmen, but she slept late, and when she arose the sun was already high. She went with one of her ladies to a little hill from where she could see the hunt passing by.

As she waited there, Prince Geraint came riding to greet her. He too had slept late. He was not dressed for the hunt, but was clad in a surcoat of white satin, hung with a purple scarf.

He greeted the Queen, and together they waited for the hunt to pass by. As they sat there on their horses, they saw some strangers riding near. There was a knight, fully armed, a lady with him, and behind them a mis-shapen, evil-faced dwarf.

“Who is yonder knight?” wondered the Queen. She turned to her maiden, and bade her go and ask. The lady rode off, and prayed the dwarf to tell her his master’s name.

“I will not tell you,” answered the dwarf rudely.

“Then I will ask your master himself,” said the maiden.

“You shall not!” cried the dwarf in anger, and struck the maiden across the face with his whip. She rode back to the Queen in dismay and told her what had happened.

“This dwarf has insulted your maiden and you!” cried Prince Geraint in rage. “I will do your errand myself!”

He rode after the dwarf, and demanded his master’s name. The ugly little creature refused to tell him, and when Geraint would have ridden to the knight himself to ask, the dwarf struck the Prince such a blow across the mouth that the blood spurted forth, and stained his scarf.

Geraint clapped his hand to his sword, thinking to have slain him, but then, seeing that he was but a poor mis-shapen creature, he stayed his anger. He rode swiftly back to the Queen, and told her that he would ride after the knight, demand his name, and ask for redress for the wrong done to the Queen and her maiden.

“I have no armour,” he said, “but that I will perchance get at the next town. Farewell, madam. I go to ride after the churlish knight.”

Geraint galloped after the knight, the lady, and the dwarf, and followed them closely all that day. Up hill and down they went, and towards evening they came to a town. They rode through the streets, and Geraint saw that all the people ran to watch them pass by, leaning out of windows to see them, and peering out of doorways.

The three travellers rode to a castle at the farther end of the town, and entered the gates, which closed behind them.

“They will ride no farther to-night,” said Geraint. “I will find a lodging for myself, and buy armour so that I may challenge the knight on the morrow.”

But no matter where Geraint went, people seemed too busy even to answer his questions. To his request for arms, he could only get the reply, “The Sparrowhawk, the Sparrowhawk,” and this strange name seemed to be on the lips of every one.

The town was full of people, and everywhere the smiths were polishing armour and sharpening swords. But for all the wealth of arms, there were none for Geraint.

“The Sparrowhawk,” answered an old man, who was busy polishing a shield, when Geraint asked him for help. “Have you forgotten the Sparrowhawk? You will get no arms in this town to-night because of the Sparrowhawk.”

“Who is this Sparrowhawk?” demanded Geraint impatiently, but no one could find time to answer him. He rode through the town, and at last, despairing of finding a lodging, came to a marble bridge that led to a half-ruined castle. On the bridge sat an old man, in rags that had once been rich clothing. He greeted Geraint courteously.

“Sir,” said the Prince, “can you tell me where I may get shelter for the night?”

“Come with me, and you shall have the best that my castle can offer,” said the old man. He led Geraint to his castle, which the Prince saw had been half burnt down. He took him inside, and seated by the fire Geraint saw the old man’s wife and his daughter, Enid, the fairest maiden that the Prince had ever seen. She was dressed in old and faded garments, but even these could not hide her loveliness.

“Enid,” said the old man, “take the knight’s horse to the stable, and then go into the town to buy bread and meat.”

Geraint did not wish the maiden to do this errand for him, but she obeyed her father, and went. Soon she came back again, and set the supper for her father and his guest. She waited on them as they ate, and Geraint thought he had never before seen such a sweet and modest maiden.

“Why is your castle ruined like this?” the knight asked the old man.

“It is because of my nephew, the knight called the Sparrowhawk,” said his host. “Three years ago he burnt my castle down because I would not give him my daughter Enid for wife. I am Earl Yniol, and once all this broad earldom was mine; but now I have barely enough left of my great wealth to show kindness to strangers like yourself. The Sparrowhawk lives in the big castle yonder, and, as you saw, the whole town is in a ferment about him.”

“Why is that?” asked Geraint. “I could not get arms as I rode through, for every one murmured ‘The Sparrowhawk! Have you forgotten the Sparrowhawk?’ ”

“He holds his yearly tournament to-morrow,” said the Earl. “On the field is set up a silver rod, on which is placed a silver sparrowhawk. My nephew challenges all knights to win this prize from him. Two years has he won it, and when he wins it the third time, as he will, I fear, it becomes his for always, and all men will know him as the Sparrowhawk.”

“This Sparrowhawk must be the knight who this morning insulted the Queen and her maiden,” said Geraint. “I will challenge him to-morrow, if only I can get some arms.”

“I have arms,” said Earl Yniol. “But they are old and rusty. Even so, Sir Knight, you cannot enter the lists to-morrow, for only they that have ladies to fight for, and proclaim them to be the fairest there, may enter the tournament.”

“Lord Yniol,” cried Geraint, “let me fight for your daughter Enid, for surely she is the fairest maiden in the land! If I win, I will marry her, and she shall be my true wife.”

The Earl was proud to think that such a famous knight as Geraint should ask for his daughter’s hand.

“If Enid consents, you shall have your wish,” he said. “Now we must seek our beds, for to-morrow you must arise early if you would enter the tournament.”

Next day Geraint donned the rusty armour that the Earl found for him, and rode to the lists. Yniol, his wife, and their daughter Enid went to watch the tournament, praying that the brave Prince would be the victor.

The Sparrowhawk rode proudly on to the field, whilst all the heralds blew loudly on their trumpets. He called to his lady, and pointed to the silver sparrowhawk on the rod.

“Take it, lady,” he said. “It is yours, for no maiden here is fairer than you.”

“Stay!” cried Geraint, galloping up. “Here is a lovelier maiden, and for her I claim the silver sparrowhawk!”

The surprised knight looked at Geraint, and then, seeing his old and rusty armour, laughed mockingly.

“Do battle for it!” he cried.

Then he and the Prince rode at one another with their lances in rest. So fiercely did they come together that each broke his spear. Again and again they galloped on one another, and then Geraint rode at the Sparrowhawk with such fury that he smote him from his horse, and he fell to the ground, saddle and all.

Then the two set upon one another with their swords, and the sparks flew as the hard steel met.

NEXT DAY GERAINT DONNED THE RUSTY ARMOUR.

They fought fiercely, till Geraint raised his sword, and smote the other on the helmet. The sharp weapon cleft right through it, and cut to the bone. The Sparrowhawk dropped his sword and fell to the ground.

“I surrender,” he said weakly.

“Tell me your name,” demanded Geraint.

“Edyrn, son of Nudd,” replied the vanquished knight. “Spare my life, I pray you.”

“On this condition,” said Geraint sternly. “You shall return to the Earl all that you robbed him of, and you shall go to Arthur’s court, and there crave pardon for your sins.”

“I will do this,” promised the Sparrowhawk. “Let me go now, I beg you, for my wounds are heavy.”

Geraint dragged him to his feet, and he went to have his wounds dressed. Then proudly the Prince took the silver sparrowhawk from its rod, and gave it to Enid. Bitter were the real Sparrowhawk’s thoughts, as he saw Geraint place it in the hands of the maiden he would dearly love to have married.

“To-morrow, fair Enid, you shall ride with me to Arthur’s court, and there we will be wed,” said Geraint.

That night there was merry feasting in Earl Yniol’s castle, for Edyrn, his nephew, had returned to him his wealth, and many of the townspeople had brought back to the castle treasure that had been taken three years before.

The next day the Earl brought Enid to the Prince, dressed in a lovely gown that her mother had found for her. But Geraint wanted her in her old faded dress.

“Go, I pray you, and put on the gown you wore when first I saw you,” he said. “I would bring you to the Queen in that robe, and she shall dress you in garments bright as the sun for your wedding.”

Enid obeyed, for she wished to wear the dress in which Geraint loved her best. Then happily they set off for Caerleon, and soon arrived at the court.

Queen Guinevere kissed the shy and lovely maiden, and with her own fair hands she dressed her for her wedding. Every one loved her, and Geraint most of all.

When they were married they lived for many months at the court, and were as happy as prince and lady could be. Soon there came riding Edyrn, the Sparrowhawk, coming to crave pardon for his evil deeds. Freely Arthur forgave him, and sent him forth to do battle for him against wicked and pestilent men.

In time he became a good and true knight, and won for himself a great name in fighting for the King.

For a year Geraint and Enid lived at Arthur’s court. Enid was loved by all, for she was gentle and kind, and Geraint was the foremost knight in every tournament, brave, handsome, and strong.

But soon there came news to Geraint of robbers in his own land of Devon. He went to Arthur and begged leave to return to his home, to fight the robbers and put them all to flight, so that once again honest men might travel without fear.

The King gave his consent, and Geraint and Enid set forth. When he came to Devon, Geraint rode out to destroy the bands of robbers. Soon he had driven them forth, and once more his country was at peace.

But when he had done that, Geraint seemed to forget that there were such things as hunts and tournaments. He loved Enid so much that he wished always to be with her, and would never leave her side. He would not go hunting, and he would no longer ride to tournaments, so that the nobles spoke his name mockingly, and the common people called him coward.

Enid heard of this, and she was grieved, for she could not bear to think that because of her Geraint was called coward. She did not dare to tell him what she had heard, but daily she grew sadder, and at last the Prince became uneasy, not knowing the reason for her pale, unhappy face.

One summer morning Enid awoke early and gazed upon Geraint as he lay sleeping. So huge he looked, and so strong, that Enid wept to think that because of her he had become weak, and would not play the part of a man.

“Alas, alas!” she said, “how grievous it is that I should be the cause of my lord’s shame! If I were a true wife to him, I should tell him all that is in my heart.”

At that moment Geraint awoke, and heard her words. He thought that she was reproaching herself because she no longer loved him, and was weary of being with him. He wondered, too, if she scorned him for proving himself so poor a knight of late. He asked her nothing, but in anger he called to his squire, and ordered him to get ready his horse and Enid’s palfrey.

“Put on your oldest clothes,” he said to the astonished girl. “You shall ride with me into the wilderness. I will show you that I am still as brave a knight as when I fought the Sparrowhawk, and won the prize for you.”

“Why do you say this?” asked Enid.

“Ask me no questions,” answered Geraint sternly.

Enid went to find her meanest clothes, and remembered the old, faded dress in which Geraint had first seen and loved her. She clad herself in it, thinking that perhaps, when the Prince saw her thus gowned, he would remember too, and be gentle to her.

Soon the squire brought their horses, and they mounted.

“Ride before me,” said Geraint to Enid. “And do not turn back nor speak to me, no matter what you see or hear, for I would have no speech with you this day.”

So Enid rode sadly in front. Soon they came to a vast and lonely forest, and there, as she rode, Enid saw four armed men hiding some way ahead.

“See,” said one; “here comes a doleful knight. We shall find it easy to overcome him, and then we will take his arms and his lady.”

Enid heard these words, and was fearful, for she did not know if Geraint would see the men. Yet she was afraid to ride back and tell him, for she thought he would be angry with her.

“Still, I would rather he stormed at me, or even killed me, than that he should be set upon and slain by these robbers,” she thought.

So she waited until Geraint came up to her, and then she told him of the men ahead.

“Did I not say that you were to speak no word to me?” said Geraint in anger. Then he rode furiously at the four robbers, who came to meet him. He used such force that his spear entered the body of the first robber, and went right through it. He did the same to the second, but the third and the fourth, seeing his great strength, turned their horses aside, and fled for their lives.

But they could not escape Geraint. He rode after them, and slew them both. Then he stripped all the dead robbers of their armour, tied it upon their horses, and knotted the bridle reins together. He gave the reins to Enid, and bade her drive the four horses in front of her.

“And speak to me again at your peril!” he said sternly.

Enid took the reins, and went forward as she was bidden, happy that her lord was safe. After some while her ears caught the sound of hoofs, and through the trees she saw three horsemen riding. Their voices came to her clearly.

“Good fortune is ours to-day!” said one. “See, here come four horses with armour tied upon them, and only one knight to guard them.”

“And he is a coward, surely,” said another. “See how he hangs his craven head!”

Enid knew that Geraint was weary with his last fight, and she resolved to warn him, even though he might punish her for speaking. So again she waited until he came up to her, and then spoke.

“I see three men, lord,” she said. “They mean to take your booty for themselves.”

“I would rather be set upon by three men than have your disobedience!” cried Geraint wrathfully. Then, seeing that the horsemen were almost upon him, he rode fiercely at the foremost and smote him straight from his horse. Then he slew the other two with mighty strokes, and dismounting, he stripped them of their armour in the same manner as before, and tied it upon the horses.

Now Enid had seven horses to drive before her, and she found her task difficult. Geraint was sad at heart to see his lady labour so, but he was stubborn of temper, and said nothing. They passed out from the gloomy forest, and came to open hills and fields, where reapers were at work.

Seeing that Enid was faint with hunger, Geraint beckoned to a boy who was taking dinner to the reapers. He carried bread and meat, and gaped to see such a fine knight, with a lady driving seven horses laden with armour.

“Give the lady some of the food you carry,” commanded Geraint. “She is faint.”

“Gladly, Sir Knight!” said the boy. “See, I will spread all I have before you, for I can go back to the town and fetch more for the reapers.”

So he spread out the bread and meat, and watched Geraint and Enid eat. When they had finished he took up the remains, and put them into his basket, saying that he would now return to the town for fresh food.

“Do so,” said Geraint, “and find a fair lodging there for myself and the lady. In return for your service, you may take a horse and armour for yourself. Choose which you will from among the seven.”

The boy was beside himself with joy. He chose a horse and armour, and leapt up on his steed. Then, thinking himself already a knight, he rode off to the town.

Geraint and Enid followed. They came to an inn, in which the biggest room was set ready for them. Suddenly there arose the sound of loud voices and tramping hoofs. Then into the inn strode the lord of that country, the Earl of Doom, with twelve of his followers.

Geraint greeted him, and he Geraint. Then they ordered the host of the inn to set out a fine meal, and all of them sat down to feast. Geraint took no notice of Enid, who sat in the farthest corner, hoping that no one would notice her. But the Earl saw her, and thought she was very lovely.

After the feast was over, he went to Enid and spoke to her.

“Why do you go with your knight?” he asked. “He is churlish to you, and treats you shamefully. Why does he let you travel without page or maiden to wait upon you? He is truly a discourteous knight.”

“Not so,” answered Enid loyally. “He is my lord, and I go willingly with him wheresoever he wishes.”

“Say but the word, and I will have him slain,” said the Earl. “We are many, and he is but one. Then you shall come with me, and share my fair lands and my great riches.”

“No,” said Enid. “That I cannot do, for I love my lord, and will not leave him.”

“What if I kill him, and take you with me, whether you will or no!” said the wicked knight.

Enid was filled with terror, for she saw that the Earl would do what he said. So she answered guilefully:

“Nay, take me not by force. Come to-morrow, for I am too weary now to ride with you. Then you shall slay my lord, and I will come with you willingly.”

The Earl promised to come the next day, and rode off with his followers. Geraint flung himself down on a couch, and fell fast asleep, but Enid stayed awake, watching fearfully, dreading lest the Earl should come during the night.

When dawn was near she put ready Geraint’s armour, and awoke him.

“Arm yourself, my lord,” she said, “for you must save both yourself and me also.”

Then she told him what the wicked Earl had said to her, and though Geraint reproached her angrily for speaking to him again, he hastily armed himself, and called for their horses. In payment for his night’s lodging, he left the six horses and armour, and the host of the inn could hardly believe in his great good fortune.

They had not been gone from the inn very long when the wicked Earl of Doorn came hammering at the door with forty men at his back. When he heard that Geraint had gone, he was very angry, and at once galloped down the road that the Prince had taken.

Soon Enid’s quick ears caught the sound of pursuing hoofs, and she turned.

“My lord,” she cried to Geraint, “do you not see the Earl and his men riding down upon us?”

“Yes, I see them,” replied Geraint in wrath; “and I see also that you will never obey me!”

The Prince turned his horse, and rode straight at the Earl. So violently did he meet him that his foe was flung right off his horse, and lay on the ground as if dead. Then Geraint rode at the men behind, unhorsed many, and wounded others so badly that the rest fled in fear, terrified at their master’s overthrow.

Seeing that his enemies were all slain or fled, Geraint signed to Enid to ride on. For about an hour they travelled forward in the hot summer sun. Then suddenly, without warning, Geraint pitched forward on his horse, and fell heavily to the ground. He had received a sore wound in his last fight, and it had bled under his armour. The knight had fainted, and now lay prone in the highway.

In alarm Enid dismounted and ran to him. She loosened his armour and tried to stop the wound with her veil. She took his head on her lap, and, leaning over him, sheltered him from the burning sun, for she was not strong enough to drag him into the shade.

Presently a troop of horsemen came that way, with the Earl Limours at their head.

The Earl stopped and looked at Enid as she sat weeping.

“Is your knight slain?” he asked. “Do not weep for him, fair lady, but come with me, and I will treat you well.”

“He is not dead!” said Enid, weeping still more bitterly. “Oh, Sir Knight, help me to take him to some place of shelter, where I may tend him well.”

“He is surely dead,” said the Earl. “But for the sake of your fair face, I will carry him to my castle.”

Two servants picked Geraint up. Enid mounted her palfrey, and the troop moved off once more. Soon they reached the Earl’s castle. Geraint was placed on a couch, and Enid knelt by him, trying to bring him back to life by all the means in her power.

And soon Geraint recovered a little, for he was not dead. But he still lay in a kind of swoon, hearing what passed around him, but thinking it to be part of a dream.

The Earl commanded a feast to be set ready, for he was hungry. Presently the table was spread with food of all kinds, and the Earl and his men sat down to the meal. After a while the Earl remembered the fair lady whose knight he had brought to the castle, and he looked round for her.

“Leave your dead knight!” he called. “Come and sit by me, and you shall be my lady!”

“I will neither eat nor drink till my lord eats with me,” said Enid.

“You speak rashly,” said Earl Limours. “You shall obey me, and drink.”

He filled a goblet with wine, and went to where poor Enid crouched in terror.

“Drink!” he commanded.

“Be pitiful!” begged Enid. “Leave me to my sick lord.”

Then the Earl, full of rage, struck her across the face with his hand. Enid, thinking that her lord must indeed be dead, or the Earl would never dare to do such a cruel thing, gave a loud and grievous cry.

THE SOUND AWOKE GERAINT FROM HIS SWOON, AND WITH SUDDEN STRENGTH HE LEAPT FROM HIS COUCH.

The sound awoke Geraint from his swoon, and with sudden strength he leapt from his couch. He threw himself upon the Earl Limours, and with one blow cut his head clean off. All the rest of the people fled screaming from the hall, for they thought that a dead man had come to life.

Then Geraint turned to Enid, and looked with love and sorrow upon her.

“I had thought that you did not love me,” he said, “but I did you great wrong, and I crave your pardon.”

They kissed one another, but Enid was full of fear lest the Earl’s men should return.

“Let us fly while there is yet time, my lord,” she begged. “Your charger is outside. Let us go quickly.”

She took Geraint to where his horse stood by the gate, and he mounted it, with Enid set behind him. Then together they rode off to Geraint’s castle, happy once again.

And never more did Geraint doubt his lady, nor did Enid have cause to sigh that men spoke mockingly of her lord—for Geraint was ever foremost in hunt, battle, and tournament, and all men spoke his name with love and honour.

It was Arthur’s custom at the Feast of Pentecost not to sit down to meat until he had seen some strange sight. There came a year when he held the feast at Kin-Kenadonne, and before he went to eat he looked about for some strange thing.

Then Sir Gawaine glanced through a window, and saw three men on horseback, and a dwarf afoot. The men alighted, and one of them was higher than the others by a foot and a half. They walked towards the King’s hall, and the tall young man leaned heavily on the shoulders of the others as if he would hide his great stature and strength.

He was very handsome, and very broad of shoulder. His hands were fair and large, and very strong. When he saw King Arthur sitting on his throne he went up to him, and stood up straight and tall.

“King Arthur,” said the youth, “God bless you and all your fair fellowship of the Round Table. I am come hither to ask three boons of you. The first I will ask now, and the second and third a year hence.”

“Ask, and you shall have your wish,” said Arthur, liking the youth greatly.

“Grant that I may have food and drink for a twelve-month,” said the youth.

“Ask something better,” said Arthur. “You may have it for the asking.”

“I want nothing more,” said the youth.

“So be it,” said the King. “You shall have the food and drink you want. Now tell me your name.”

“I cannot tell you that,” said the youth.

“That is strange!” said Arthur. “You are the goodliest young man that ever I saw, and yet you cannot tell your name! Ho, Sir Kay! Where is Sir Kay, my steward? Bid him see that this youth has good food and drink, and is treated like a lord’s son, for I like his looks very well.”

“Like a lord’s son!” said the churlish Sir Kay. “That were folly indeed! If he had been of high birth, then would he have asked for a horse and armour, and not for food and drink. He is a common serving-boy, and none other! He shall live in the kitchen with the other serving-lads, and eat with them. And since he cannot tell his name, I will give him one. He shall be called Fairhands, for never did I see a serving-boy with such white hands as his!”

Sir Gawaine and Sir Lancelot were angry at Sir Kay’s mockery, and bade him cease his jibes. But Sir Kay took no heed of them.

“Come with me to the kitchen, Fairhands!” he commanded. “There shall you have fat broth every day, and in a year’s time you will be as fat as a pork-hog!”

The youth went to the kitchen, and sat with the kitchen-lads, who jeered at him. But when they saw his angry strength, they grew afraid. Only Sir Kay mocked at him openly, and gave him the worst and the dirtiest work to do.

Fairhands did not complain, but did as he was bid. Sir Gawaine and Sir Lancelot would have had him come to their rooms for meat and drink, but he would not. He stayed with the kitchen-lads, ate with them, and slept on the kitchen floor with them at night.

But whenever there was any jousting among the knights, Fairhands was there, looking on eagerly; and when there were games of skill between the kitchen-boys, he always beat the rest with ease; and often Sir Lancelot would look at him, and wonder who and what he was.

At last the year was up, and the Feast of Pentecost came again. As the King was sitting at meat, there came a damsel into the hall, asking to speak with him.

“Sir,” she said, “I am the Lady Lynette, and I come to your court for help.”

“What is your trouble?” asked the King.

“I come to beg your help on behalf of a great lady,” said the damsel. “She is besieged in her castle by a tyrant knight, who will not let her go forth. Will you send one of your noble knights to rescue her?”

“What is the lady’s name?” asked the King. “Where does she dwell, and who is the knight that besieges her?”

“The wicked knight is called the Red Knight of the Red Lands,” answered the damsel. “As for the lady’s name, that may I not tell you.”

“None of my knights can go with you if you cannot tell the lady’s name, nor where she dwells,” said Arthur.

But as he spoke, Fairhands came forward and stood before the King.

“Sir King,” he said, “I have been for twelve months in your kitchen, and I thank you for my food and drink. Now I crave leave to ask my two further boons.”

“Speak on,” said Arthur.

“Sir,” said the youth, “I pray you to let me have the adventure of this damsel. My second boon is that you will let Sir Lancelot ride after me and make me knight, if he thinks I am worthy.”

“Your boons are granted,” said the King.

But the damsel was very angry when she heard that Fairhands was to be her knight.

“Fie, fie!” she cried. “Am I to have none but a kitchen-page?”

She ran to her horse and mounted in rage. Then she rode away swiftly, but Fairhands saw the way she went.

At that moment a messenger came to the youth, and told him that his horse and armour had come for him. At that every one was astonished, and went to see what manner of arms the kitchen-boy had. Outside they saw a dwarf, and with him he had a goodly horse and a fine suit of armour.

Then Fairhands armed himself quickly, and when he came into the hall to bid the King farewell, there was hardly a knight there that looked as noble as he. He took leave of the King, and then rode swiftly to join the damsel.

Every one looked after him, and Sir Kay was angry to think that his kitchen-boy was gone.

“I will ride after him and see if he knows his kitchen-master!” he cried. So he leapt to horse, and rode up to Fairhands, crying to him to stop.

“Do you not know me, your master?” he said.

Fairhands turned and saw him.

“Yes, I know you well,” he answered. “You are the most ungentle knight of all the court!”

With that he rode straight at Sir Kay and unhorsed him, giving him a sore wound as he did so. Sir Kay fell to the ground and lay as if he were dead. Then up rode Sir Lancelot, and Fairhands called upon him to joust with him.

So the two rode at one another fiercely, and met with such a shock that each fell to earth. Then they fought together with swords, and Sir Lancelot marvelled at the youth, for he was so big and strong that he fought more like a giant than a man. At last Sir Lancelot began to feel that Fairhands might press him too hard, and he cried out to him:

“Fairhands, do not fight so hard, for we have no quarrel, as you know. We are but jousting.”

“That is true,” said Fairhands. “But, my lord, it is good to feel my strength against yours. Tell me, am I worthy yet to be made knight?”

“You are right worthy,” said Sir Lancelot. “Kneel before me, and tell me your name, and I will knight you here and now.”

“Keep my secret, I pray you,” said Fairhands, kneeling down. “My name is Gareth, and I am a son of King Lot of Orkney. Sir Gawaine is my brother.”

“I am glad of that,” said Sir Lancelot. “I guessed that you were of princely birth.”

Then he knighted Gareth, and bade him keep well the order of knighthood. Sir Gareth rose up, mounted his horse, and with a heart full of gladness rode after the damsel.

When the Lady Lynette saw him coming, she turned to him angrily.

“Why do you come after me?” she said. “You smell of the kitchen! You are but a serving-lad and a dish-washer!”

“Say what you will,” said Gareth. “I go with you, for so I have promised King Arthur, and I must follow this adventure to the end.”

Now as they rode, a man came running out from the trees, and sped to Gareth’s side.

“Lord, lord, help me!” he cried. “My master has been captured by six thieves, and they have bound him. I fear he will be slain.”

“Take me to him,” commanded Gareth.

He followed the man, and soon came to where the six robbers were. Gareth rode straight into them, struck the first one dead, and then the second. Then he turned upon the third and slew him also. The others fled, but Gareth rode after them and smote them down. Then he returned to the bound knight and unloosed him.

“I give you great thanks,” said the knight. “Now as night is coming fast, I pray you bring your lady to my castle hard by, and you shall sup with me and rest there till the morrow.”

So Lynette and Gareth went to the castle, and there the knight commanded food and drink to be brought. But when he would have set the damsel and Gareth together at the table with him, Lynette was angry.

“Fie on you for a discourteous knight!” she said. “Would you have us sit at table with a kitchen-boy that smells of grease? He knows better how to kill a pig than to eat with a lady!”

Then the knight of the castle was ashamed to hear her unkind words. He bade his servants set a table apart, and to it he took Gareth and sat with him, talking merrily all the night through. But as for Lynette, she supped alone.

The next day Gareth and Lynette set out once more. Soon they came to a river, and there was but one place where it might be crossed. On the other side of the ford sat two knights, and they would let no one pass over the river.

“You had better turn back, kitchen-boy,” said Lynette. “You are no match for two knights.”

“If they were six I should still ride onward,” answered Gareth. He rushed into the water, and one of the knights came to meet him. They broke their spears, and then drew their swords. Gareth smote the knight upon his head, and he fell into the water and was drowned.

Then Gareth spurred his horse up the bank on the farther side, where the second knight awaited him. Fiercely he fought him, and it was not long before he had cleft the other’s helmet, and slain him straightly.

But Lynette had no word of praise.

“Alas!” she said, “that two good knights should take their death from the hands of a common serving-lad! You did not fight fairly. The horse of the first knight stumbled, and threw him into the water, and you went behind the second knight and struck him a false blow.”

“Say what you will, damsel, I follow this adventure,” said Gareth.

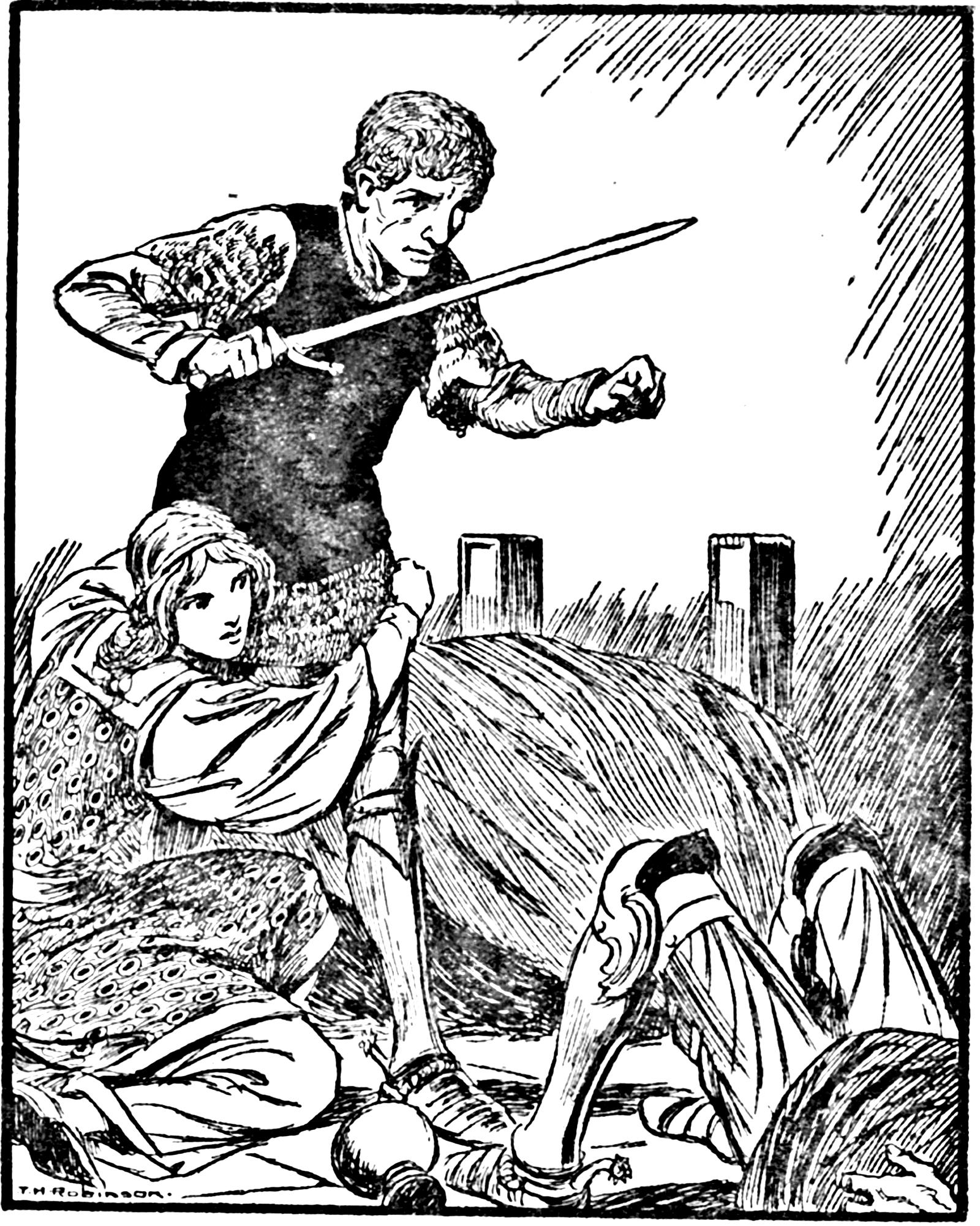

GARETH STRUCK THE KNIGHT FROM HIS HORSE.

Then on they rode again until they came to a black and desolate land. In front of them they saw a black hawthorn tree, and on it hung a black banner and a black shield. By it stood a black spear and a black horse, and on a black stone there sat a knight, armed all in black harness, who was the Knight of the Black Lands.

“Run whilst there is time!” said Lynette to Gareth mockingly. “See, here before us is a knight who will slay you with ease.”

“Damsel,” said the Black Knight, greeting her, “is this knight your champion?”

“Nay; he is not a knight,” said Lynette. “He is but a common serving-boy from King Arthur’s kitchen.”

“Then I will not fight him,” said the Black Knight. “I will take his horse and harness from him, and make him go afoot. It were shame to fight a poor kitchen-boy.”

“You speak freely of my horse and harness,” said Gareth wrathfully. “You must fight me for them before you get them! Look to yourself now!”

With that he rode headlong at the Black Knight, and the two horses met with a sound like thunder. The Black Knight’s spear broke, and they drew their swords. They hacked at one another fiercely, and each gave the other sore wounds. But after an hour and a half the Black Knight fell from his horse in a swoon and so died.

Then Gareth stripped the knight of his fine black harness, and took it for himself, for it was better than his own. Then he mounted the knight’s horse, and rode after the damsel.

But still she would have none of him, and pushed him away from her, holding her nose daintily.

“Away, kitchen-knight, away!” she cried. “The smell of your clothes comes to me on the wind, and they smell strong of the kitchen. Alas, that such a fine knight should be slain by you! Soon you will meet one that shall punish you well, so I bid you flee away whilst yet there is time.”

“I may be beaten or slain,” said Gareth, “but I will never flee away.”

As they rode on another knight came towards them. He was all in green, both his horse and his harness. He rode up to the damsel and greeted her.

“Is that my brother, the Black Knight, who is with you?” he asked.

“Nay, nay,” she answered; “this is but a kitchen knave, who has falsely slain your brother, and taken his horse and armour.”

“Ah, traitor!” cried the Green Knight, turning fiercely on Gareth. “You shall die for slaying my brother!”

“I defy you!” said Gareth. “I did not slay your brother shamefully, but in fair fight.”

Then they rode at one another, and both their spears broke. They drew their swords and began to fight furiously. Gareth’s horse swerved into the Green Knight’s horse, so that it fell, whereupon the knight slid lightly off, and attacked Gareth on foot. The youth at once leapt off his horse, and fought on foot also.

Suddenly the Green Knight smote such a mighty blow upon Gareth’s shield that it cleft it right asunder. Then was Gareth ashamed, and he in turn gave him a buffet upon the helm. So fierce a blow it was that the knight fell to the ground, and straightway begged for mercy.

“I will spare your life only if my damsel asks me,” said Gareth, resolved to make Lynette crave something from him.

“False kitchen-page, I will never beg anything from you!” said Lynette.

“Then he shall die,” said Gareth, and unlaced the Green Knight’s helm as if he would slay him.

“Nay, spare me!” pleaded the Green Knight in fear. “If you will grant me my life, I and my thirty men will be yours, and will follow you gladly, for you are a fierce and lusty fighter.”

“Shame that a kitchen-boy should have you and your thirty good men for his followers!” cried Lynette in a rage.

“Damsel, speak a word for me,” begged the Green Knight.

“Unless the lady prays me to spare your life, you shall die,” said Gareth, and he raised his sword.

“Let be,” said Lynette hastily. “You miserable kitchen-knave, let be.”

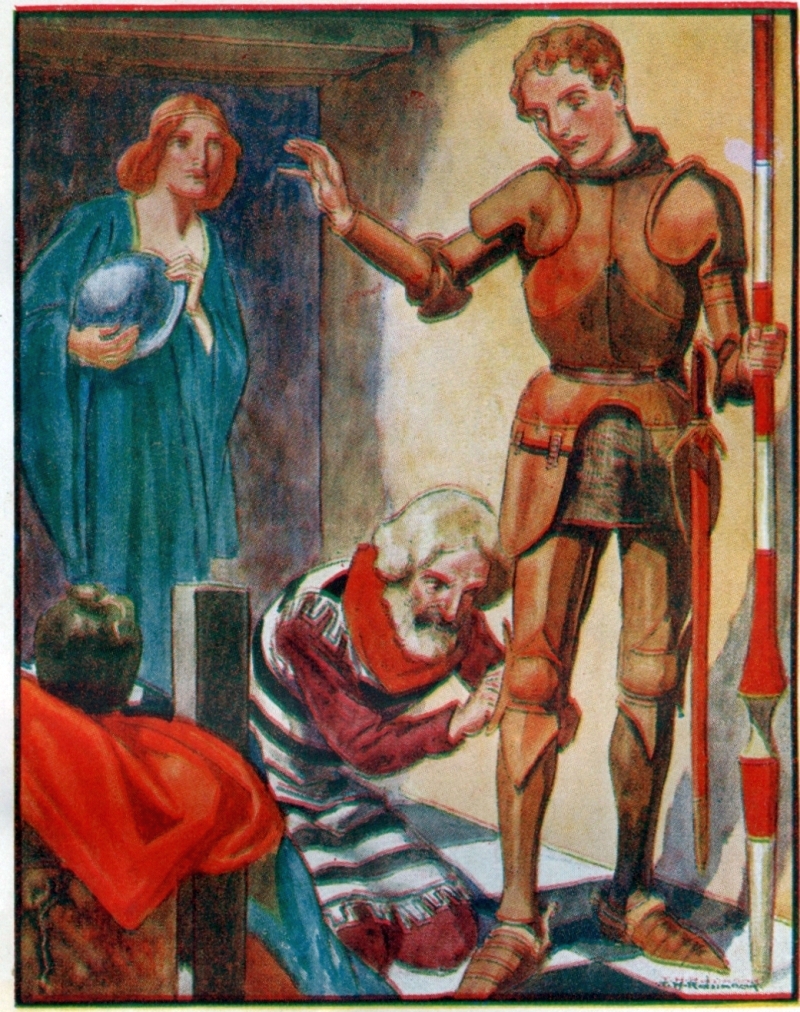

“Damsel, I obey you,” said Gareth, and he lowered his sword. “Sir Knight, I give you your life at this lady’s request. Rise up.”

Then the Green Knight kneeled himself at Gareth’s feet and did him homage.

“DAMSEL, I OBEY YOU,” SAID GARETH, AND HE LOWERED HIS SWORD.

“Come to my castle, where I can do you honour,” he said. “You shall feast with me, and rest there for the night.”

So Lynette and Gareth followed him to his castle. But the damsel ever reproached Gareth, and would not sit at table with him. So the Green Knight took him to a table apart, and sat with him gladly.

“You do wrong, maiden, to reproach this noble knight in such manner,” said he. “He is no kitchen-boy, but a fair and courteous knight.”

Then for the first time Lynette was ashamed of the harsh words she spoke, for she knew well that Gareth had behaved in a true and knightly manner, and had never once answered her reproaches with angry words.

She turned to Gareth and begged his forgiveness.

“Pardon me, I pray you, for all I have said or done to you,” she said.

“With all my heart I pardon you,” said Gareth. “It gladdens me to hear you speak pleasant words, and now there is no knight living that is too strong for me, so happy am I in your pleasure.”

When morning came, Gareth and Lynette set forth once more, riding together happily for the first time. They rode through a fair forest, and came to a plain on which was set a beautiful castle.

As they rode towards it Gareth saw a strange and dreadful sight, for upon great trees hung goodly armed knights, their shields about their necks. Gareth counted forty, and with a sad countenance he turned to Lynette and asked her how all the knights had met their death.

“Well may you look sad,” said the damsel. “These forty knights are they that came to rescue my sister, Dame Lyonors. The Knight of the Red Lands, who now besieges the castle, defeated each one, and put them to the shameful death you see. Now haste you away whilst there is time, for the knight will treat you in the same manner.”

But Gareth had no thought of turning back. He rode onwards with Lynette, and soon they came to the castle.

By it stood a great sycamore tree, and on a branch was hung a mighty horn of elephant’s tusk.

“Any knight that comes hither to rescue my sister, Dame Lyonors, must blow this horn, and then the Knight of the Red Lands makes him ready for battle,” said Lynette.

Gareth spurred his horse eagerly, and rode up to the tree. He blew the horn so loudly that the sound echoed for miles around.

The Red Knight of the Red Lands armed himself hastily, and rode out to meet Gareth. He was harnessed all in blood red, and he rode a red horse and carried a red spear.

“Yonder is your deadly enemy,” said the damsel, turning pale. “And see, yonder too is my lovely sister, the Lady Lyonors, looking down on us from the castle.”

Gareth looked up to see the lady, and as soon as he saw her sweet face, he felt his heart warm with love.

“She is the fairest lady ever I looked upon,” he said. “She shall be my love, and for her will I gladly fight.”

Then the Red Knight called out in a loud voice:

“Cease your looking, Sir Knight, for she is my lady.”

“That is a lie,” said Gareth. “If she were your lady, I should not have come to rescue her from you. She loves you not. She shall be my lady, so make you ready to do battle for her.”

Then the two rode at each other, with their spears in rest, and came together with such a mighty shock that both fell to the ground and lay there stunned. Those that looked on thought that each had broken his neck. But in a short time the two knights leapt up, put their shields before them, and ran one another with their swords.

Then began a terrible battle, and soon each knight was sorely wounded, but neither would give in. For hours they hacked at one another, and then, when each was panting for breath, they lay down to rest.

Once again they ran together, hurtling forward as if they had been two rams. In places their armour was all hewn off, and their wounds bled sorely.

So the battle went on, until Gareth, glancing up to the castle, saw the Lady Lyonors smiling down upon him with love in her eyes. Then he leapt to the fight with greater strength.

Suddenly the Red Knight struck him such a mighty blow that Gareth’s sword flew from his hand, and he fell to earth. The Red Knight fell on top of him and held him down, striving to deal the death-blow.

Then loudly cried the maiden Lynette:

“Oh, kitchen-knight, where is your courage? My sister weeps to see you so.”

Her words stirred Gareth’s heart, and with a great effort he rose up, leapt to his sword, and then turned once more upon the Red Knight. This time he struck his foe’s sword from his hand, and when he saw the Red Knight lying on the ground, he leapt on him, and began to unlace his helm to slay him.

“I yield me, I yield me!” cried the knight in a loud voice.

“You do not deserve your life,” said Gareth sternly, “for you have put many good knights to a shameful death.”

“I yield me to your mercy!” cried the Red Knight again.

“I will release you on one condition,” said Gareth at last. “You must go to the castle, and crave pardon of the Lady Lyonors for all your wrongdoing. If she forgives you, you may go free. After that you must go to King Arthur’s court, and there humbly recite your evil deeds, and crave pardon of him too.”

The Red Knight promised to do this, and Gareth freed him. When the Lady Lynette saw that the fight was over she hastened to Gareth and dressed his wounds. Then she had him carried into the castle, where the Lady Lyonors tended him lovingly.

Soon Gareth had won her promise to marry him, and when he returned to Arthur’s court, she went with him to be wed. Then was King Arthur glad to know that the one-time kitchen-boy was no other than Prince Gareth, his own nephew. Proudly he listened to the many tales that his knights told him of Gareth’s prowess and bravery.

Then the Lady Lyonors and Sir Gareth were wed with great pomp and honour, and happily did they live together at Arthur’s court. As for the damsel Lynette, she came again to the court, and married Sir Gaheris, Gareth’s younger brother. Then were they all happy, and lived at peace one with another.

There was once a great Earl who had seven sons. Six of them went to tournaments with him, but the seventh was too young. Then one day there came news that the Earl and his six strong sons had all been killed.

The poor mother was filled with grief. She had only one boy left now—Peredur, the youngest. She took him away to a lonely place, where dwelt only women and old men, and where he would never hear of knights and tournaments, arms and battle.

Peredur grew up straight and strong. He was happy among the hills and woods, and knew nothing of the world of knights and lords. Then one day Sir Owain, one of Arthur’s own knights, came riding by. Peredur saw him, and stood still in the greatest amazement. What was this fine stranger, sitting grandly on a horse more beautiful than Peredur had ever seen before?

Sir Owain reined in his steed, and spoke to the boy.

“Have you seen a knight pass by this way?” he asked.

“A knight?” said Peredur. “I pray you, tell me what a knight may be.”

“One like myself!” said Sir Owain, laughing.

Then Peredur felt the saddle with his strong fingers.

“What is this?” he asked, and the knight told him. Then the youth took hold of Sir Owain’s sword and spear, and asked their names too, and what they were used for. The knight told him all he wanted to know, and then Peredur bade him farewell and ran off.

He went to where the horses were kept—gaunt, bony creatures used for carrying firewood—and picked the strongest out for himself. He placed a pack on the horse’s back for a saddle, and then picked some supple twigs from which to make himself trappings such as he had seen upon Sir Owain’s steed.

Then he went to say farewell to his mother, for he had resolved to be a knight like the man he had spoken to. The poor woman was full of distress, but she did not keep him back. Instead, she gave him some good advice.

“Ride to Arthur’s court,” she said, “for there you will find the noblest company of knights in the kingdom.”

Peredur proudly rode off. He was a queer figure on his bony old horse. He held a long, sharp-pointed stick in his hand for a spear, and he thought gladly of the day when he would indeed be a knight.

After many days he came to Arthur’s court. At the same moment there rode up an insolent knight, so vain of his strength and skill that he was resolved to fight with any one of the King’s knights, and, by overthrowing him, gain glory and honour for himself.

This knight entered the hall in front of Peredur, and snatching up a goblet, threw the wine it contained straight into the face of Queen Guinevere.

“Does any knight here dare to avenge the insult I do the Queen?” cried the arrogant knight. “If any one of you is bold enough to do battle with me, let him follow me to the meadow, where I will speedily overcome him!”

With that he strode out, mounted horse, and rode to the field. All the knights in the hall were dumb with amazement at the insult to the Queen, and not one moved, so much were they astonished.

But Peredur, who was just behind the stranger knight, was stirred with anger.

“I will do vengeance upon this evil fellow!” he cried. Then he turned, and, swiftly mounting his horse, rode after the insolent knight.

But when the knight saw him coming on his bony horse, he laughed loudly. “Tell me, boy,” he said, “is any knight coming to do battle with me from the court?”

“I will do battle with you,” answered Peredur fiercely.

“I will not fight with such a scullion as you!” cried the knight in scorn. “Go back to Arthur’s court, and tell the knights they are cowards, and I have shamed them all!”

“You shall fight with me!” said Peredur grimly. “You shall give me that goblet whose wine you dashed into the Queen’s face, and you shall give me your horse and armour also!”

Then in anger the knight rode at Peredur, and struck him a fierce blow in the shoulder with the butt-end of his spear.

“Would you play with me?” said Peredur. “Then I will play too.”

He rode at the insolent knight and drove his sharp-pointed stick at him. It entered his eye, and straightway the knight fell from his horse and died.

Peredur leapt down, and ran to him, eager to take his armour and his horse, so that he might be dressed like a knight. But he did not know how to undo the fastenings of the armour, and he could not drag it off, try how he would.

Then Sir Owain galloped up, hot from Arthur’s court, and stopped in amaze to see the arrogant knight slain by an unskilled youth, whose only weapon was a stick.

“What are you trying to do with his armour?” he asked.

“I want it for myself,” said Peredur, “but I cannot undo the fastenings.”

“Leave the dead knight his arms,” said Sir Owain. “I will gladly give you my own horse and armour. But first come with me to Arthur and he will knight you, for you have proved yourself well worthy of the honour.”

“I accept your gift,” said Peredur, rising. “But I will not come to Arthur’s court until I have proved myself in other adventures.”

Sir Owain helped the youth to put his armour on, and then gave him his own fine horse. He bade the bold boy farewell, and watched him ride off to seek further adventures.

Peredur, rejoicing in his new arms and steed, rode on gaily. Many a knight he met on his way, and jousted with them. He overthrew each one, but spared every man’s life, only bidding him go to Arthur’s court and say that Peredur had sent him.

Then one night he arrived at a castle, and begged for food and shelter till the morning. He gained admittance, and a meal was set for him at the table of the lady who owned the castle. But sadness and gloom hung over the Countess, and the meal was poor, for two nuns brought in six loaves and a decanter of wine, and that was all the food there was.

“Pardon the poor fare,” said the Countess, blushing, “but I am in great trouble.”

“Tell me your distress, and I will help you,” said Peredur.

“There is a wicked baron near here, who wishes to marry me,” said the lady. “I refused his offer, and because of this he has taken all my lands from me, and left me only this castle. All my servants are fled, and there is no food left save the loaves and wine which some kind nuns have brought me.”

“To-morrow I will do battle with this robber!” said Peredur eagerly. “I will overthrow him, and force him to return to you all those things that he has stolen.”