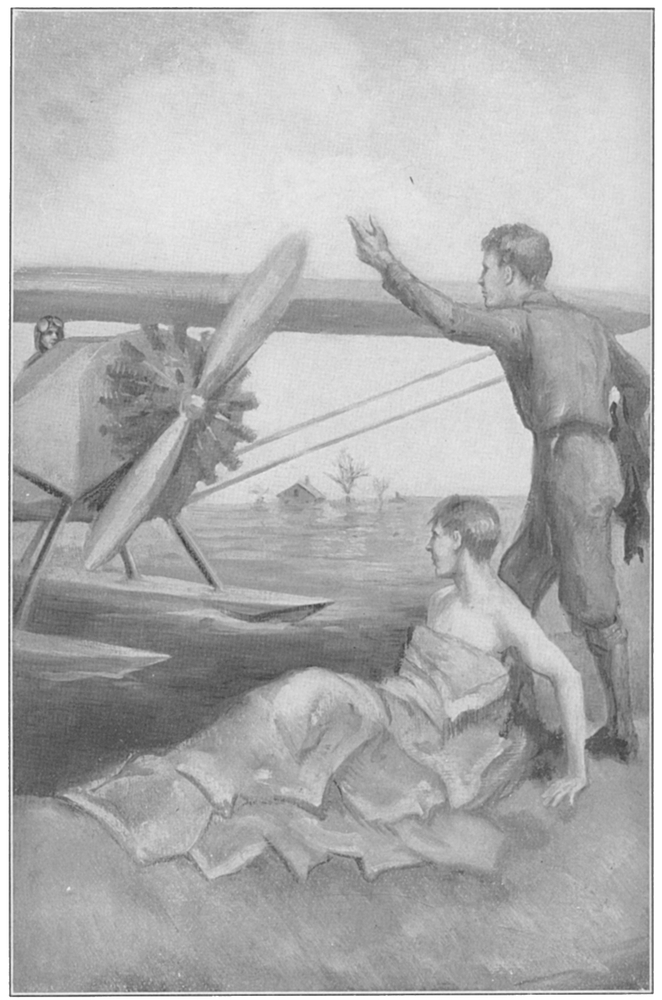

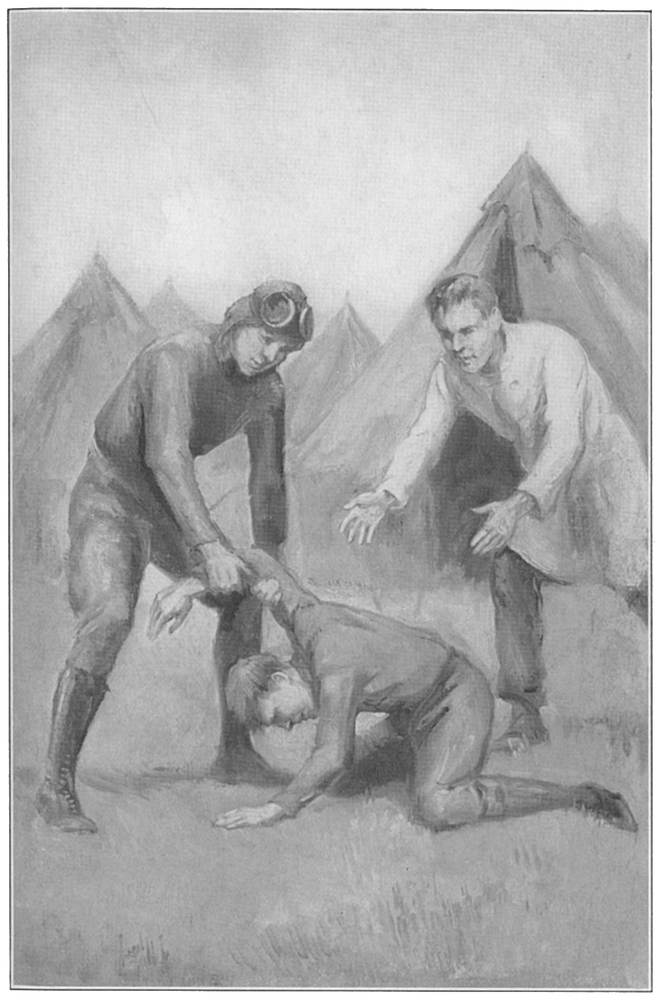

THE SEAPLANE STOPPED WITHIN TWENTY-FIVE FEET OF THE BEWILDERED, OVERJOYED WESTY.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Westy Martin on the Mississippi

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: May 15, 2020

Date last updated: May 15, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200541

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

WESTY MARTIN ON THE MISSISSIPPI

THE SEAPLANE STOPPED WITHIN TWENTY-FIVE FEET OF THE BEWILDERED, OVERJOYED WESTY.

WESTY MARTIN

ON THE

MISSISSIPPI

By

PERCY K. FITZHUGH

Author of

THE TOM SLADE BOOKS

THE ROY BLAKELEY BOOKS

THE PEE-WEE HARRIS BOOKS

THE WESTY MARTIN BOOKS

ILLUSTRATED BY

HOWARD L. HASTINGS

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1930, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Made in the United States of America

CONTENTS

| I | Aftermath |

| II | Norris Cole |

| III | Advice from Trick |

| IV | Just Talk |

| V | Circumstantial Evidence |

| VI | An Invitation |

| VII | A Familiar Face |

| VIII | Information |

| IX | A Promise |

| X | Jake Miller |

| XI | A Discovery |

| XII | It’s a Go! |

| XIII | Followed |

| XIV | A Helping Hand |

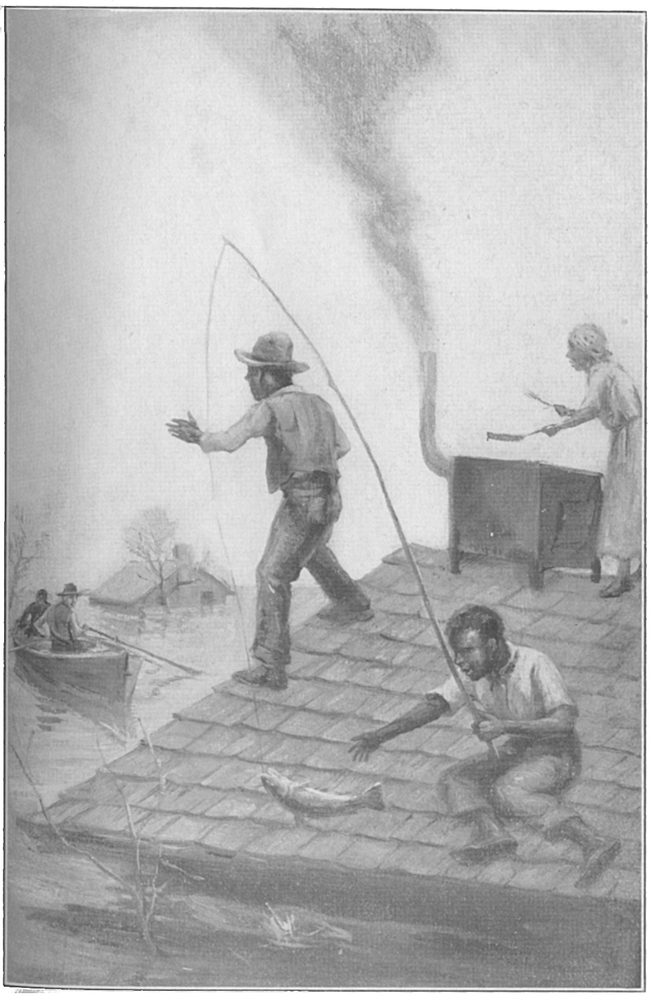

| XV | Flood Scenes |

| XVI | Refuge? |

| XVII | Buzzards |

| XVIII | Rescued |

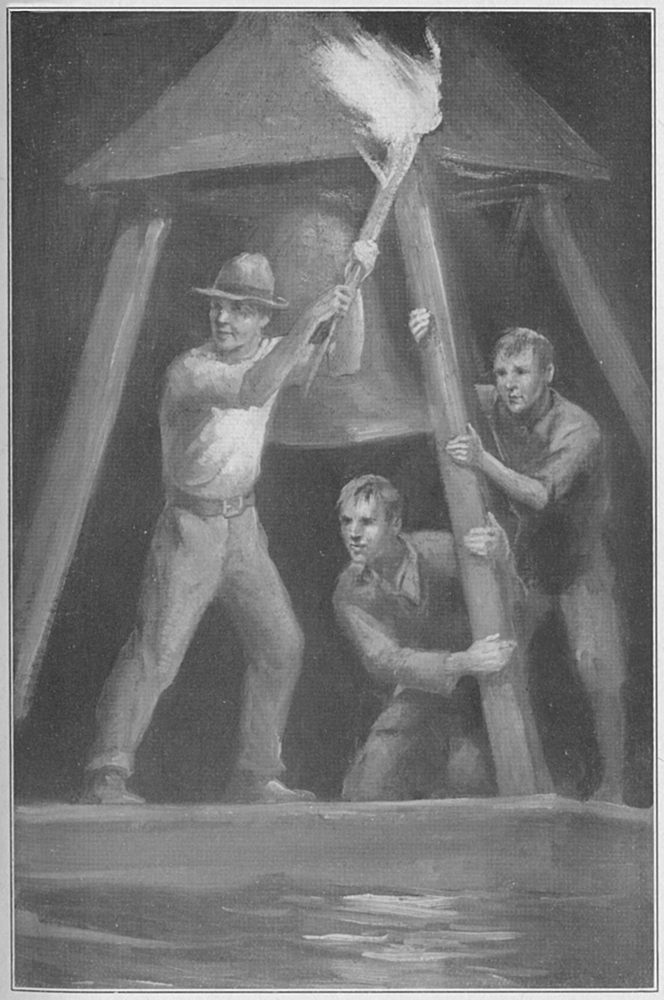

| XIX | The Torch |

| XX | Hanging On |

| XXI | A Boat! |

| XXII | Hunger and Thirst and— |

| XXIII | Fear |

| XXIV | Vigil |

| XXV | And Then— |

| XXVI | Disheartening News |

| XXVII | Discouraged |

| XXVIII | A Letter |

| XXIX | A Request |

| XXX | A Happy Ending |

WESTY MARTIN ON THE MISSISSIPPI

“Norris Cole is under a cloud,” said Mr. Martin decisively, as he entered the living room with the Sunday papers tucked under his arm. “And as for you, my son—well, Mr. Cole thinks you’ve been a party to the whole affair.”

Westy was dumbfounded and looked it. He hunched his body up in the big chair, then frowned. “Gosh, he’s got a nerve. What’s the big idea?”

Mr. Martin leisurely seated himself upon the long divan and looked searchingly at his son’s face. “Something has been discovered since Mrs. Cole called us this morning to tell us that Norris hadn’t been home all night.”

“What?” queried Westy, cold with an unnamed fear.

“There’s five thousand dollars missing from Mr. Cole’s safe,” he answered quietly. “Five thousand dollars in twenty dollar bills. Old Brower had counted it and put it in an envelope. The safe was open while you boys were in the store, but he didn’t discover the loss until he was ready to close up. Then he called up Mr. Cole about it but nothing was said to Mrs. Cole until about an hour ago.”

Westy was indignant. “Gosh, that’s going some—do they mean to say that I had anything to do with that money?” he shouted.

“Calm down,” said his father. “Nothing of the kind was implied about you. Mr. Cole merely said that Brower had remembered the safe being open while you and Trainor and his friends were in the store. That was after Norris had left for the movies.”

“Then why is Norrie under a cloud if he wasn’t there?” Westy demanded to know. “Mr. Cole has some nerve to....”

“Hold on, son,” said Mr. Martin patiently. “Mr. Cole is taking facts and summing them up in just the same way that you or I would sum them up under the circumstances. Now wait until you hear what he told me: First, Norris demanded that his father give him permission to go to the movies, thereby leaving them shorthanded in the store. And Saturday night, as you know, is their busiest time.”

“Oh, I know all that,” said Westy, restlessly. “I was there when he asked his father and I heard all the argument that went on. Does Mr. Cole think I put him up to do that?”

Mr. Martin shook his head. “Not exactly, but he does think that you made Norris restless with your talk of adventure on the Mississippi. He said that Norris never before demanded anything—he always asked.”

“Hmph!” said Westy, with utter disgust “Norrie’s not a baby. He’s seventeen. I’d have a swell chance of leading him into something he didn’t want to do—anyway, it wasn’t any crime for me to tell him what fun he could have if he went down the Mississippi.”

“I should say it wasn’t,” smiled Mr. Martin patiently. “But you can’t blame Mr. Cole for feeling that this thing wouldn’t have happened if you hadn’t come back with your vivid word pictures of flood times on the Mississippi.”

Westy shrugged his shoulders. “He’d have gone away, anyhow,” he said, sullenly. “He told me the first day I met him that he was getting sick of working for his father and not getting anything. Gosh, he never went anywhere.”

“Perhaps that is so,” said Mr. Martin, thoughtfully, “but I do wish he had arranged his disappearance before you got back to Bridgeboro. Now it appears that you are the logical one to blame it on since Trainor has also disappeared. His father and mother haven’t seen him since dinner-time yesterday.”

Westy whistled with surprise. “And the money—do they think he has anything to do with it?”

“They think Trainor and Norris planned this together.”

“I don’t believe it—not about Norris anyway.”

“Well, the police believe it. They’ve handled a good many cases where a loafing boy like Trainor can lure an adventure-seeking boy like Norris into just such predicaments. And the missing money seems to be the crux of the whole affair. Mr. Cole seems to think that Trainor would be capable of planning that and Norris knowing Brower’s movements on Saturday nights seems to bear out the theory that it was a premeditated disappearance.”

Westy scoffed that idea silently. “It’s a coincidence, that’s what it is,” he insisted.

“I’d say it was anything but that,” smiled Mr. Martin. “I’ve saved the last apple out of the bag to shatter that notion, son, for the police have found out that Norris and Trainor met on the ten o’clock bus bound for New York. The driver knows them and remembers well that he let them out in front of the Pennsylvania station. Now you can see why Mr. Cole resented you setting the Mississippi bee buzzing in Norris’ ears.”

Westy was silent, but none the less amazed at this latest revelation. “How about Trick’s friends—do they know anything about it?” he asked at length.

“Oh, they’ve maintained a discreet silence through all the questioning they’ve had,” said Mr. Martin, opening up his papers. “A couple of detectives have been giving them quite a grilling, I heard downtown. Chief Hobert said they had told him that they didn’t think the boys had anything to do with it. Their opinion is that Trick Trainor used them as lookouts and had them keep Brower in the front of the store until he got what he was after. They only admitted that Trainor walked back where the safe was a few times.”

“Well, I saw him do that too,” said Westy calmly. “But that doesn’t prove anything. He never sits still or stands still, Trick doesn’t. I don’t like him any more than Mr. Cole but I wouldn’t accuse him of stealing five thousand dollars just because he was walking around the open safe.”

“No, but on the other hand he hasn’t come back to defend this accusation and neither has Norris,” Mr. Martin said, with an air of finality. He read his paper in earnest.

“I wish I had gone with Norrie to the movies now,” said Westy, regretfully. “He wanted me to but I didn’t like the picture. That shows he wasn’t planning anything then when he asked me to go, doesn’t it?”

Mr. Martin appeared not to have heard. He had said all he knew about the matter and apparently had enough of it. But Westy was persistent He rambled on in an abused tone and finally his mother tactfully hurried into the living room, having left her dinner preparations half completed.

“Don’t take on so, Westy,” she said, consolingly, and hurried over to smooth out a wrinkle in the east window curtain. “Facts do not lie and it’s just what one would expect when a nice boy like Norris is swayed by Trick Trainor’s influence.”

“Oh, gosh,” said Westy, despairingly, “you too? Anyone would think that Trick was a gangster or something. Just because he’s been out of High a year and hasn’t worked....”

“Don’t forget how hard he’s worked standing around in front of Pellett’s drug store,” his mother smilingly interposed.

“All right,” Westy admitted freely. “Maybe he has, but there isn’t anyone in Bridgeboro can say that he’s done anything else. Gosh, I’ve sometimes felt pretty sore at Trick with that swaggerish way he has and trying to make other guys feel that they aren’t worth two cents, but I wouldn’t hint that he was crooked unless I knew it—then I’d say it right out.”

“Mrs. Trainor told me that she didn’t ever give him more than two dollars a week for spending money,” said Mrs. Martin. “And of course you realize, Westy, that one can’t travel far on that, much less two.”

Westy was going to answer that they could get as far as New York where they probably were now, but he thought it useless. “You’re all dead set on it that Norrie’s guilty,” he said, angrily, “and I’m dead set on it that he isn’t. Trick’s friends were there as well as me. Why don’t they say that I did it? But no, just because it’s a coincidence that Norrie and Trick decided at the last minute to beat it away together they’re supposed to be thieves too.”

At this thundering statement, Mr. Martin looked up from his paper and frowned. “I think,” he said sternly, “that from this moment on, we’ll leave the troubles of the Cole family to the Coles.”

Westy was duly silenced but not squelched and as his mother hurried back to the kitchen to resume her duties, he arose and sauntered out on the front porch. It was a likely place to regain his usual good temper for there was a brisk March wind blowing and a hint of spring in the air.

He perched himself on the porch railing and tried thinking over the events of the past four days since he had come back from Arizona. “Gosh, it sure looks black enough for them,” he said reflectively. “If Norrie only hadn’t lost his head last night and beat it away so sneaky. But I know him and—why, I can go right back and think of all we talked about Let’s see now....”

He shut his eyes and let his mind drift back to the day, his first day in Bridgeboro in over a year, when he had been standing on that very porch. He had been looking up and down the street in hopes of seeing someone he knew, some familiar face when....

It was the hatless figure of Norris Cole that suddenly emerged from the side street and came hurrying past his house. Westy leaped down the porch steps and out to the sidewalk.

“Whoa, boy,” he shouted. “What’s the idea of passing me up, Norrie?”

Norris turned quickly and, seeing Westy, smiled. “Oh, Wes,” he cried joyfully. “I didn’t think of looking for you. When did you get back?”

“This morning—hard luck. Gosh, I liked it. But my mother and father are going to California in the car and they wanted me to come home before they started. Did you quit military school, Norrie?”

“Nope,” smiled Norris. “I graduated, boy—in February. I’m working for Pop while I’m waiting for the fall sem at the Institute.”

“Good,” smiled Westy. “That’s where I’m headed for myself. I’m trying to make Dad let me go down the Mississippi with Major Winton. He’s invited me to go along with a party of engineers and himself on an inspection tour of the big levees. Gosh, I hope I can make him say yes but he thinks I’ve had enough time with the major in Arizona.”

“Boy, I wish I had a chance like that,” said Norris, enviously.

“That’s what I’m trying to put across in the house,” said Westy seriously. “It’s only for a few months and I’ll probably be back long before September but no. Dad keeps harping on rest. Gosh, I can’t make him see that I won’t do anything else but, if I go along with the major. He says I’d sort of be his guest, because I don’t know anything about that kind of work—it’s much different than what I was doing in Arizona.”

“It’s a crool worl’, Wes,” said Norris, laughingly. Suddenly he became serious, then: “You’d know something if you had a father like I have. Gee, he sure believes in all work and no play, believe me. I had a tough enough time for four years away at school and he won’t even stand for me having a little vacation now.”

“Maybe I can put in a good word for you,” said Westy, thoughtfully. “Your father liked me better than the rest of the kids in our bunch, remember?”

“That’s not saying much, Wes,” said Norris, bitterly. “Pop doesn’t see anything outside of work. He’ll even have something to say when he hears that you’re going to loaf until fall.”

“I should worry. I’ll compromise and follow you around the store then. That won’t be loafing.”

“A feller’s a fool not to loaf when he has the chance,” said Norris. “I sure would like to have you with me in the store after not seeing you all this time, but it won’t be any pink tea, Wes. I’m getting so I even dream about hardware. Gee, Pop has me going all the time. I’m getting sick of it.”

Westy had heard this plaintive cry from his friend many times in their scouting days and he recalled how difficult it had been for Norris even then to get away on hikes. Mr. Cole never wanted for some excuse to detain Norris in the store and had it not been for the maternal ingenuity of Mrs. Cole, Norris would have seldom found time to mingle with his brother scouts and friends.

“Try and stick it out, Norrie,” he said, sympathetically. “You’re not a baby any more—you’ll soon be able to do what you like.”

“Bet your life I will,” said Norris with a flash of strong looking teeth, “I’ll do it before that, if he keeps pushing me the way he has been. Gee, I don’t even get off long enough to go to the movies, but I’m going to fix him this Saturday, you can bet I’m all set to ask him to let me go to the movies and just let him refuse me—just let him!”

Westy tried to coax him out of his mood. “Atta boy,” he laughed. “Don’t get mad, Norrie, you can go down the Mississippi if you can’t go anywhere else. There’s lots of young college fellers working on the levees down there—Major Winton told me that. Gosh, you’re good and strong and it would be a nice vacation for you.”

Norris’ blue eyes sparkled with lively interest. “Are you on the level, Wes?” he queried.

Westy nodded smilingly. “The levees aren’t on the level though—they’re high and dry.”

“Gee,” Norris said, obviously captured by the suggestion, “what do they do on levees, huh? How does a guy know what levee to go to, huh?”

Westy laughed heartily at his friend’s enthusiasm.

“You’ll have to find the Hotel Malone in St. Louis and get Major Winton to answer those questions. He’ll tell you where to go and what you’ll do.”

By this time, they were seated on the top step of the porch. The necessity of getting back to sell hardware for his father did not occur to Norris now. “Does Major Winton have charge of the men who work on the levees?” he asked seriously.

“No,” Westy answered, “the main line levee system runs from Cairo, Illinois to New Orleans. He only inspects the big levees but I guess he could tell anyone where the best place would be to get work. Why, Norrie?”

“Nothing,” said Norris thoughtfully. “I’m glad to know those things though, Wes, in case I ever did get enough money to go there. But a swell chance I have of getting any further than New York. Pop pays me a big salary—a dollar a week. Sometimes when he feels generous he makes it a dollar and a half. Gee, that kind of treatment makes a guy feel that he doesn’t care about what happens.”

There was considerable bitterness in his tones and Westy watched him sympathetically. “Have you ever asked your father to let you go on a vacation—I mean since you’ve been home from school?”

Norris laughed sardonically. “Gee, have you forgotten Pop as much as that?” he returned. “If he thought for a minute I was going to ask he’d start telling me how poor business has been and how it is he can’t give me a regular salary. But I know better, Wes. I know he keeps piling his money up in the safe—he’s even scared to trust it to the bank. Trick Trainor said he’s a fool to do that, because sooner or later someone will get on to it.”

“Trick out of High?” asked Westy.

“Yep. One year. Hasn’t done anything but loaf, though. Boy, my father sure hates him but I stick up for him. He’s kept me company since I’ve been home. Comes in the store every day.”

“It’s easy to be friendly when you haven’t anything to do, Norrie,” Westy reminded him. “My father and mother never liked the way he’s always had of hanging around Pellett’s but I never saw him do anything. The one thing about him that gets my goat is his sneering way.”

“He doesn’t mean a thing by it,” Norris said. “Take my word for it—I know. It’s just his way.”

“Well, he ought to work anyhow. Maybe I ought to tell him about the Mississippi too,” laughed Westy. “That’s going pretty far for a job but it might be the only way Trick would care to work.”

“That’s only one thing about him, Wes,” Norris confided. “He doesn’t like to overdo himself but he’d like the idea of traveling. Anyway, I like it all around and I’m going to spring it on Pop tonight. I’ll tell him what you’ve said.”

“He’ll have my life tomorrow,” Westy laughed.

“You should worry if he does. Oh, he wouldn’t mind me going there to make money if I could get the carfare to go.” Norris sighed and stirred preparatory to leaving.

“Well,” said Westy, in an effort to be consoling, “you can do as you like when you get through at the Institute. That’s one thing.”

Norris shook his head. “Don’t kid yourself, Wes,” he said. “Pop thinks he has me chained for life to that store.”

Westy glanced at him wonderingly. “Do you mean your father’s going to make you work in the store after you’re finished with school?”

Norris leaned back in the rocker and laughed heartily. Suddenly he stopped, his mouth drawn tightly and his eyes hard and determined looking.

“That’s just one of life’s little jokes, Wes—that idea of Pop’s,” he said, vehemently. “He thinks he’s going to make me.”

Westy strolled down to Cole’s Hardware Store later that same day. It was his first visit there in perhaps three years. He had little occasion to go when Norris was away at school and his own absence of a year had seen many changes in Bridgeboro’s Main Street shops. But not so Cole’s—they prospered but never progressed.

As he approached the old store and looked up at the rickety sign precariously waving in the high wind, he did not wonder at Norris’ evident rebellion against his father’s antiquated methods and ideas. Mr. Cole was still living in the year eighteen hundred and ninety nine.

Perhaps there was no one in Bridgeboro who knew the adamantine qualities of Mr. Cole any better than did Westy. And, too, he knew that his thriftiness was taking on a parsimonious look. In truth, he felt that Norris was entirely justified in wanting to get away from it. He sauntered in through the street door and encountered Brower, Mr. Cole’s faithful old clerk who had served the establishment since eighteen hundred and ninety. He had shriveled up in those years of devoted service and looked as dry and uninteresting as the carton of wire nails he was unpacking.

He nodded distantly in answer to West’s friendly greeting and went on with his task. Hearing his friend’s voice, Norris called gaily from a distant aisle where he was perched high on a gaunt, rolling ladder and surrounded by a formidable looking array of stock boxes.

“I’ll be down in a minute, Wes,” he said brightly. “Grab a stool for yourself and get out of the dust. We have enough of it here to fill Main Street.”

Westy laughed, but he shuddered at the thought of happy, carefree Norris spending his life in that desolate, dusty store. “Gosh, I don’t know why I should mind it so,” he whispered to himself as he swung around on one of the aged oak stools that were ranged along in front of the counter. “It oughtn’t to be my funeral what happens to Norrie, but somehow I feel it is.”

That was Westy all over—a creature of sunlight and adventure and he pitied anyone who could not have it in the measure that he had it, especially Norris.

In a few moments, Norris descended the ladder and taking a graceful leap, landed on the worn, gray counter. He sprawled his long, slim body across the counter and sighed, restlessly. “That’s the way it is in this business, Wes. You’re either rushed to death or there’s nothing to do. It’s dead on Friday afternoons but we make up for it tomorrow and tomorrow night.” He grinned mischievously.

“What’s the big joke?” Westy asked, taking another swift revolution on the creaking stool.

“I’m thinking about tomorrow night,” Norris answered in an undertone. “Pop doesn’t know that I’m going to get off yet. I’m going to spring it to him after dinner tomorrow night. Be here and watch the fireworks.”

“I will,” laughed Westy. “Where are you going?”

“Movies,” Norris answered with sparkling eyes. “Trick and I are going—that is, he’s going to meet me later. Want to come?”

“I don’t like the talkies much, Norrie, else I’d come.”

The store door opened at that juncture and a young fellow of their own age strolled leisurely in. His small, light blue eyes glittered at sight of Westy. “Well, if it ain’t our little Arizona cowboy!” he exclaimed jovially.

“It’s me all right,” said Westy, frowning at Trainor’s indolent swagger and sleek, small town elegance. “What are you doing now, Trick, studying your brains away or working yourself to death?”

Trick Trainor bent forward and with his thumb and forefinger, smoothed down the already knife-like crease in his wide-bottomed trousers. Then he glanced at Westy and smiled. “Neither, is the answer to your question,” he said hoarsely. “I’m just having a hard time spending my spending money.”

“I was just asking Wes if he wanted to go to the movies tomorrow night,” Norris interposed.

“I’d rather see real adventure than go to the movies and watch the make-believe,” said Westy, modestly. “Gosh, when a feller’s had a taste of it like I did in Arizona you can’t be satisfied with watching it in the movies.”

“Gee, I don’t blame you,” Norris agreed. Then to the smiling Trainor he said: “Westy may go along on an inspection tour of the big levees with that Major Winton. He’ll go in every big town on the Mississippi. Boy, wouldn’t you like that, Trick?”

“I’ll say,” Trick condescended. “Anything’s better than this berg.”

Norris’ eyes were alight with some inner enthusiasm. “If we had the carfare we could go down,” he said in hushed tones. “Wes says that they’ll give jobs to strong fellers on any of the big levees—even college fellers are working there now.”

“Work!” Trick repeated scornfully. “That doesn’t mean anything to me. And you ought to be the last one in the world to get fussed up over it, Norrie. Your old man doesn’t give you anything but work in this dump. If you said vacation I might listen.”

Norris colored faintly. “Oh, Pop doesn’t mean to be the way he is—he just won’t listen to reason,” he said bravely. “If I could only make him see that I’d like a little fun once in a while.”

“Fun,” laughed Trick, sardonically. “What you need is a lot of spending money and a year’s vacation like I’ve had.”

“You’ll soon be going into your second year, won’t you, Trick?” Westy asked mockingly.

“That’s my funeral,” Trick answered. He jerked his splashy blue tie and patted his tight-fitting collar. “As long as my old man ain’t worrying, why should you?”

Brower, passing at that moment, glared at Trainor. “It’d be better for you if your father did worry some,” he grumbled. “Boys nowadays ain’t got enough on their minds, that’s the trouble.”

Trick smoothed his shining blond hair and laughed. “That’s enough from you, old horse-feathers,” he said with a sneer.

Brower pretended not to hear that retort and went about his duties. Norris frowned and bit his lip. “Be careful, Trick,” he said softly. “I know Brower’s a cranky old duffer, but he’s gotten just like Pop. They’re both rusty and in a rut, that’s all. I wouldn’t want....”

“Cut out the lecture,” Trick interposed lightly. “You’d be a swell guy with me to guide you.”

“It’s my turn to laugh,” said Westy mockingly. Trick turned to say something but voices from the street boisterously claimed his attention. They were the voices of his friends—three counterparts of himself and at their insistent beckoning he swaggered off to join them.

“S’long,” he called over his shoulder. “See you again.”

Norris watched until he and his friends disappeared in Main Street’s throngs. Westy frowned. “Gosh, Norrie,” he said, “there’s something about Trick—I don’t know—he’s in with the wrong bunch of fellers or something. He’s worse than when I saw him last. The way he talked to Brower and all—gosh, I’d be careful of him. I know I’ve talked to you about going away but I really wouldn’t want you to do it. That is, I wouldn’t want you to sneak about anything. I’d tell your father first and if he refuses why then it’s up to you.”

“And have a fine rumpus,” said Norris tersely. “Don’t you worry about me, Wes. I’m not a baby. Gee, I can look out for myself.”

Westy sensed that Norris resented his advice. “Boy, I didn’t mean to preach,” he said apologetically, “but I’m just afraid that you’ll get into trouble through Trick. You heard him laugh about working. He wants easy money and my father says a feller like that always gets into trouble sooner or later. Gosh, I wouldn’t say anything if you weren’t a friend of mine. We were scouts together....”

“Do you think I’d ever forget that!” Norris said with vehemence. “But I’ve got to stick up for Trick, Wes. He’s been friendly ever since I’ve been home and I can’t forget that he’s a lot of noise and he doesn’t mean a bit of harm. My mother says he’ll get over his loafing one of these days and work as hard as any of us.”

“Maybe you’re right,” said Westy thoughtfully. “Gosh, I’m a fine ex-scout to talk about a feller like that, huh? I’ll take it back, Norrie, and believe me I’ll never say a word against Trick until I know it’s the truth.”

“Atta boy, Wes,” smiled Norris. “There’s lots of things Trick does and says that I don’t like exactly but when I’m a friend, I’m a friend.”

Westy had much cause to ponder on the weight of that statement during the coming weeks, but innocently he asked: “Does that include me too, Norrie?”

“I’ll prove it to you,” answered Norris stoutly.

“You can wait until Christmas, huh?” Westy laughed.

By chance, Westy happened in Cole’s Hardware Store that next evening after dinner. Trick Trainor and his friends were there and Norris stood behind the counter with his father. One could feel the tense atmosphere.

“You’re just in time to referee this argument,” Trick Trainor laughed loudly. “Norrie’s threatening to strike unless he gets tonight off.”

Norris frowned at Trainor’s tactlessness and Mr. Cole scowled angrily. “Let him strike then,” he said, without glancing at his son. “’Tain’t any of your business if he does or not, Trainor.”

Trick merely smiled and walked toward the back of the store with that indolent swagger he affected. He stood for a few seconds and watched Brower who was busy at the open safe, then turned and came back. Westy wondered why he didn’t have sense enough to take his friends and leave.

Norris looked at Westy and smiled. “Would you want to stay and help Pop for an hour, Wes?” he asked. “The worst of the rush will be over then—I’m leaving in ten minutes.”

Faint patches of color showed in Mr. Cole’s pinched looking features. “I don’t want none of your friend’s help, Norrie,” he said harshly. “If you want to go—go, but don’t think you can smooth things over by asking him to stay. Ain’t it bad enough that he’s got you dead set on goin’ down the Mississippi on some fool adventure?”

Westy opened his lips to protest but Mr. Cole would have none of it. “Don’t say you didn’t tell him, ’cause you did. Maybe you didn’t mean no harm but it’s made him dissatisfied with his home and even working for his own father. He’d sooner work like them niggers on the levees than do nice, easy respectable chores in his father’s store,” he said, breathlessly.

Norris reddened perceptibly and without a word walked from behind the counter and out of the store. Westy felt decidedly uncomfortable and did not know whether or not to stay. It was evident that Trainor and his friends were not perturbed by that little family scene for they retreated to one end of the counter and were soon engrossed in their usual flippant conversation.

Mr. Cole went about the store silently and after a few moments approached Westy. “Anyhow, I can rely on you more than that fool bunch,” he said, with a jerk of his thumb toward Trainor and his friends. “I’m going to slip out to the lunch room and get a bite before we get busy so I’ll just let you sit here and watch ’till Brower gets through with the safe. I’m not asking you to wait on anybody, just call Brower if someone comes in.” He coughed as if he had already regretted asking that small favor and reached back of the counter for his worn-looking derby hat.

He had only been gone a minute when a customer came in and Brower was called. Trainor’s friends came forward also, spoke to Westy for a few moments while Trick paced around the store restlessly, then left. Mr. Cole hurried in a few minutes afterward.

“Too many in there,” he explained to Westy curtly. “They’re going to bring me in some sandwiches so you needn’t wait.” He bowed distantly.

Westy moved toward the door gladly and Trainor joined him. “Guess I’ll blow too,” he said casually. “Have a date before I go to the movies.”

They walked to the corner together but Westy found nothing to say. The scene between Norris and his father had thoroughly depressed him and he felt that Trainor was in some way responsible for it.

“I s’pose you’re making for home and mother, huh?” queried Trainor, laughingly, as Westy made a move to cross the street.

“I suppose I am,” answered Westy drily. “Why?”

“Nothing,” Trainor returned with his eyes averted. “I’m going up this way to keep my date. S’long—see you in church.” He swaggered away up Bond Street without looking to right or left.

Westy watched him for a swift second then went straight home and to bed. Midnight found him still awake wide-eyed and beset with strange premonitions. They were vague, yet haunting enough to make him restless and sleepless. “Aw, I’m crazy,” he said half-aloud as the big clock in the hall struck the half hour. “Why should I worry myself to death over what Norrie’s going to do or Trick either, for that matter?”

But even as he asked himself that question he knew. He knew that in some vague way he was concerned about Norris, he always had been. “And like a fool I’ve been gassing about the Mississippi to him and set him off,” he rambled on. “Gosh, there was something queer about that store tonight—Norrie sure didn’t care what his father said. Anyhow, he’s not a baby, but I wish he’d cut Trick out.”

Thought after thought flashed through his mind until sleep came to him and then his dreams were wild and terrifying. He awoke at eight o’clock next morning at the insistent ringing of the telephone and jumped out of bed as his mother answered.

“Yes,” her voice echoed up the stairway and into his room. There was something in that word that aroused Westy’s interest and he tiptoed silently out into the hall and leaned his arms upon the broad balustrade.

“Why, no, I don’t know, Mrs. Trainor,” Mrs. Martin continued. “I’m awfully sorry.” There was a pause. “You’re right, they’re no longer babies.” Another pause. “I hope so. Goodbye.”

“What’s up?” asked Mr. Martin in the midst of his breakfast.

“Trick hasn’t been home all night and the queer part of it is, neither has Norris Cole,” Mrs. Martin answered, replacing the receiver. “Mrs. Trainor said that Trick had passed the remark yesterday that Westy told them they could get work on the Mississippi levees and that he and Norris would think it over. I suppose they’re going to try and ride freights there. Well, they won’t get very far.”

“I wish Westy’d keep his adventurous ideas to himself,” said Mr. Martin from the recesses of the breakfast nook beyond the kitchen. “Mr. Cole and Mr. Trainor won’t thank him for that.”

“Well, Mrs. Trainor said herself that they were no longer babies,” Mrs. Martin said as she hurried back to the kitchen. “She says if they want to leave nice, comfortable homes for a rough and tumble life like that, why it’s up to them. They’ve spoiled Trick terribly though, it’s a wonder he isn’t worse. But I can’t understand Norris.”

“I can,” Mr. Martin called out. “Old Cole’s been hard with that boy—I’ve often wondered if he’d ever break away. It’s all right if he doesn’t encounter worse difficulties away from home. There’s worse things in the world than skinflint fathers.”

Westy could hear no more after that. His mother had probably joined his father in the breakfast nook and all the sound that reached him was the monotonous hum of their distant voices speaking in ordinary conversational tones. Shrugging his shoulders, he went back to his room and dressed.

“I guess I knew that’s what was going to happen—I guess I knew it last night,” he said, pulling on his shoes. “Anyway, Norrie would have gone whether I came or not. I haven’t anything to do with it.”

He reached the breakfast nook just as his father was getting ready to leave the house in pursuit of the Sunday paper. “Well, I heard all you were talking about,” he announced, frankly. “I kind of felt last night that it was going to happen. Norrie’s been talking about it ever since I’ve been home but I thought it was just talk. I didn’t think he’d have the nerve to do it.”

Mr. Martin stopped at the threshold. “It will be a good experience for him if he keeps the scout laws in mind, Westy,” he said kindly. “What I don’t quite like, is his going with Trainor. There’s something about that boy that makes me suspicious. Maybe it’s just an idea, but....”

“Norrie said there’s no harm in him,” Westy spoke up stoutly. “He said he’s just a lot of talk.”

“I’ve heard of talk that did a lot of harm, son,” smiled Mr. Martin. “I’m going down Main Street now and I’ll stop at Cole’s and hear what’s to be heard.” He closed the door lightly and was gone.

The words of his father rang in his ears: “Norris Cole is under a cloud.” Westy shifted his position on the porch railing and aimlessly scanned some feathery-looking wind clouds overhead. Cloud, clouds; he thought of the simile and realized that Norris had certainly enveloped himself in some pretty black ones by his first act of independence.

Too, he thought of Norris’ words to him in the store saying: “When I’m a friend, I’m a friend.” Well, that was enough for him to know. He wouldn’t believe any of these incriminating details against either of the absent pair. He’d have to hear it from them, first.

“The only thing—I wish he had told me,” said Westy, moving away from the railing. “That’s all. It would seem as if he meant what he said about friends, then. This way I have to stick up for them and tell people everything when I don’t know anything.”

And Westy had a good deal of “sticking up” to do during the next forty-eight hours. He was interviewed by newspaper reporters and by the chief of police, until on Tuesday morning he began to feel that perhaps it was all his fault. People that he had been familiar with all his young life looked at him curiously (or so he thought), and he wished heartily that he was miles away.

On Wednesday, Bridgeboro was united in condemning Norris and the other conspirators (as the paper called them), and Trainor was listed as the brains of the whole affair. Old Brower, the headline of the afternoon edition said, had dropped dead in the store as a result of the shock. He had had charge of Mr. Cole’s safe for fifteen years and had told one of the reporters just the day before that he felt responsible for the loss of the money. It was said he actually brooded over it all Tuesday night At any rate, he was too old to bear up under it.

“Boy, but Mr. Cole’s all het up now,” said Vic Norris, a friend of Westy’s whom he met on Main Street. “They say he’s sworn out a warrant for Trick and Norrie. He was fond of old Brower and he told my mother that it was almost like murder. Gee, he won’t listen to reason—he won’t give Norrie any quarter.”

Westy walked on and was still a-tingle from the injustice of that news when he saw Mr. Cole coming down Main Street. It almost seemed that Fate had planned the meeting.

“I won’t keep you a minute, Mr. Cole,” said Westy, stopping directly in the man’s path. “I—I just want to tell you that I’m sorry for what’s happened, but I don’t think it’s right to kick Norrie when he’s down and can’t defend himself.”

Mr. Cole sniffled through his thin, pinched nose, drew himself up and stopped, aghast. “Kick him! Defend himself!” he repeated. “What do you mean, young man?”

“I mean about you making charges against him,” Westy answered bravely. “You can’t prove he’s taken the money until you see him with it. Another thing, when a feller’s father goes back on him the whole world will too,” he said, breathless at his own temerity.

Mr. Cole frowned. “He’s got to be taught a lesson, young man,” he said hoarsely. “Yes, sir! And what’s more—if he didn’t have the money he’d be back before this! Didn’t that scamp Trainor tell his friends that my own son told him about all the money I kept in that safe and that Brower always counted it between six-thirty and seven on Saturday nights? Yes, sir, that’s what he told ’em and you can’t tell me they didn’t mean anything by that. Why were they so particular to be in the store at that time and why was Norrie so crazy to get out to the movies before poor old Brower shut the safe? Answer me that!”

“A court wouldn’t listen to that kind of evidence,” said Westy with blazing eyes. “That’s circumstantial. And anyhow, Mr. Cole, if you don’t stick up for your own son, I will. I’ve been doing it right along and I’ll go on doing it till he tells me differently. Trick too—I don’t like him any more than you do but I wouldn’t call him a thief until the law proves that he’s one. Gosh....”

“I guess you know where you can find Norrie and that Trainor to tell you, too,” interposed Mr. Cole ambiguously. “You’re pretty cocksure about their innocence, ain’t you? Well, time’ll tell, that’s all I say. I don’t forget that you started Norrie off about this Mississippi thing—he was crazy for me to pay his carfare there. Now I’m paying his carfare and that scamp’s twenty times over, I guess.” He started moving away.

“It’s not fair!” Westy shouted at the man’s back. “You’re not giving him a chance—you never did give him a chance and now you see what happens!”

Mr. Cole swung around, more puzzled than angry. “I never gave him a chance, eh?” he asked.

“No, you didn’t,” answered Westy firmly. “You never gave him a chance to have fun; you’ve always kept him in that store vacation times when all the other fellers were away or having a little recreation. Gosh, Norrie’s only human and he’s not an old man and he’s crazy about adventure.”

Mr. Cole looked wide-eyed at his breathless accuser. “He’s crazy, all right,” he said grumblingly, “he’s crazy to do what he’s done. I’m through with him—he needn’t come back. We don’t want him!” With that he turned and went on his way.

Westy stared after him as if he could not even then believe what the man had said.

“Gosh, it sure is funny the way things happen,” Westy said quite vehemently as he flung his hat into the hall closet.

“Why, funny?” queried Mr. Martin, just taking his place at the dining-room table.

Westy told him in a few words of his conversation with Mr. Cole. “He didn’t mention about old Brower but I know that was on his mind,” he said, thoughtfully. “Do you know, Dad, I’d give anything if I knew where I could find Norrie and tell him what people are saying about him here. Gosh, it’s terrible now, with Brower dead. To hear Mr. Cole talk, you’d think that Norrie and Trainor had murdered him—anyway, you’d think that Norrie was a criminal. It isn’t right!”

“Don’t you suppose that Norris can read the papers,” Mr. Martin reminded him. “He must know it all by this time, wherever they are.”

“Thank goodness, we’re leaving Friday,” sighed Mrs. Martin as they began the meal. “I’m really getting tired of hearing it, sorry as I feel for the boys’ mothers. I think it’s affected Westy worse than anyone. He actually looks haggard.”

“Why wouldn’t I?” Westy asked. “I blame myself, sort of—no, I don’t either—not now. Not after I talked to Mr. Cole. Gosh, with a father like that I wouldn’t blame Norrie for doing anything—outside of stealing. Anyway, I wish I could leave Bridgeboro miles behind until summer.”

“Maybe you can,” smiled Mrs. Martin significantly. “Peek under your plate, Westy. There’s a letter in Major Winton’s handwriting.”

Westy’s face beamed as he shoved the plate aside and saw the familiar handwriting on the white envelope. “It’s from St. Louis,” he said happily. “I bet—I bet....” He tore it open and spread it out.

“Go on,” laughed Mr. Martin, “let’s hear the worst.”

Westy smiled at his father and read aloud:

Dear Young Martin:

This is the last chance I’ll have to write for quite some time as we’re starting down the big stream on that inspection tour I told you of. We’re scheduled to steam off Monday next.

Now, read this carefully and see what your father thinks about letting you come. Following lines are written merely for inducement.

A Mr. C. J. Curran of St. Louis who has just left for a year’s vacation in Italy, has offered his graceful looking yacht, the Atlantis, for any service the government sees fit during this flood period along the river. Incidentally, Uncle Sam has ordered me to use it for our tour.

There will be a small company of us and room enough for you as my guest. You can follow me around and keep your eyes open and any young chap with as strong an engineering kink as you have ought to get a heap of experience and useful knowledge out of the trip. Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Am still at the Malone and will still be here until Monday at dawn. Now then, send me a brief wire and I’ll be watching out for you. Also tell your father that I’ll send you home in plenty of time to rest up before school opens.

Best wishes to your parents and hoping to see you on Sunday—

Winton.

Westy whistled with delight and read the letter again to himself. When he looked up it was to see his parents exchanging favorable glances and his heart leaped expectantly. Was this to be his chance to get away?

His mother nodded. “That’s nice of the major, Westy,” she said. “He surely takes an interest in you.”

“He’s pretty keen about having you go along, isn’t he, son,” Mr. Martin said.

Westy did not miss the softness of his father’s tones. He raised his head, his eyes shining expectantly. “Gosh, and if he says he’ll send me home in time, he’ll send me home! May I—gosh, will you?”

Mr. Martin put down his knife and fork and smiled. “I suppose there’s no real reason why I shouldn’t say yes, son. And now that this other affair’s cut you up so, why, I guess it will do you good to get away.”

“Boy, you’re great!” Westy’s eyes glistened. “If Mr. Cole was like you—well, Norrie would be here now to go with me. Major Winton would even make room for him, I bet.”

“I bet,” said Mr. Martin.

“And Norris could have gone with you if we had known the way things were with him,” said Mrs. Martin. “I would have even been willing to pay his carfare out there myself rather than have happen what has happened. Somehow we always think of those things when it’s too late.”

“It’s just as I said before,” Westy said, “it’s funny the way things happen. I sure didn’t think that Major Winton liked me enough to write me an invitation. Gosh, when he asked me about going just before I left for home and I told him I thought Dad wouldn’t like it—well, I just decided; he wouldn’t ask again. If I got out there, all right and if I didn’t all right—that’s the way he is with most everybody. But he must like me to write me, huh?”

“He likes you because you generally accomplish what you set out to do,” said Mr. Martin. “That’s what he told me, so keep up your reputation with him, son.”

“Leave it to me, Dad,” Westy said determinedly. “Leave it to me.”

It was a lighthearted, carefree Westy that smiled as the train left New York. He had left his troubles and perplexities in Bridgeboro and determined that they should stay there. Nothing, he promised himself, should disturb his peace of mind, and the enjoyment of this trip.

He sauntered into the club car just after they left Chicago and sank luxuriously into one of the comfortable chairs. Directly opposite, he noticed at once, was a bulk of a man with florid complexion and shrewd, black eyes. And as he stared the eyes immediately centered their attention upon the passing landscape.

Westy swung himself around and also gazed at the snow-covered country through which they were passing. But his thoughts were upon the man opposite. There was something familiar about the florid face and shrewd, black eyes. He tried to think what it was.

After five minutes of contemplation he decided that the man reminded him of Bridgeboro. That was it—he had seen him some time, some place, there. It came to him in a flash and mentally he saw that human bulk peering at him in the passing throngs of Main Street.

“Maybe I’m wrong,” he murmured as they rattled over a grade crossing, “and then again, maybe I’m not. Anyway, it wouldn’t hurt to ask him. It’d be nice having someone from home to talk to all the way to St. Louis.”

Westy glanced over his shoulder but the man had gone. He looked up and down the car but there was no sign of him. “Probably gone back to the Pullman,” he said, disappointed. “I’ll see him again, though—I’ll look for him if I don’t.”

He sat watching people coming in and going out at each end of the car until the first call for luncheon pierced through his abstraction. Automatically, he arose and followed the tall, gaunt crier of these good tidings, for to Westy food came before all else.

He was the first one seated in the dining car and all through the meal he kept his eyes upon the door. It wasn’t until he went back into the Pullman, however, that he saw the man again, sitting two sections back of his own. He walked straight up to him.

“Say-a,” he began, a little confused, “haven’t I seen your face somewhere before?”

The man frowned slightly and shook his head.

“In Bridgeboro?” Westy queried.

The frown and shake were more pronounced this time and when the man yawned rudely Westy felt so embarrassed that he retreated awkwardly to the privacy of his own section. While he was trying to regain his composure he espied the man leisurely making his way to the dining car.

“He needn’t have been so grouchy about it,” Westy mumbled and drummed his knuckles upon the narrow sill. “Gosh, it wouldn’t have cost him anything to smile or even say no. He just didn’t want to talk to me—that’s all.”

“What’s a-matter, boy,” said a soft, friendly voice at his side, “did Mistah Silent give yo’ de air too?”

Westy looked up to see the smiling countenance of the colored porter. He smiled in return. “Won’t he talk to you either?”

The porter shook his black head profoundly and seated himself upon the arm of the seat. “Ah cain’t get a word out o’ dat man but yes and no. ’Ceptin’ fo’ dat, ah’d o’ swore he wuz deaf ’n dumb. Yes suh!”

“You should worry about him,” Westy said, delighted at the chance to talk to someone. “I wouldn’t speak to him again—no matter what. Gosh, I only wanted to be friendly. I thought I saw his face somewhere before.”

“Ah saw him give yuh de cold shoulder,” said the porter with a chuckle. “And ah says to m’self—what kin yuh expec’ o’ such a man! S’pose yu’ wuz jes’ lonesome, boy, huh?”

“You bet,” answered Westy, brightly. “I thought it would be nice to have him to talk to all the way to St. Louis and I couldn’t get it out of my head but that I knew him. I can’t get it out of my head yet! I’m sure I’ve seen him in Bridgeboro—that’s where I live.”

“Whar ’bouts is dis place you live, boy?” the porter inquired with evident interest.

“New Jersey. Ever been there?”

“No suh. Ah cain’t ever remember anythin’ east o’ Chicago.”

“Well, Bridgeboro’s a nice town anyway. It’s not a city, of course, but it’s big enough to remember people. And no one can make me believe that I didn’t see that guy on Main Street—I know it.”

“Did yuh ask him?”

“Sure. That’s what makes me sore. All he did was shake his head when I asked him. I think he thought I was too much of a kid to be bothered with. I should worry.”

“Absolutely, boy,” the porter agreed, abstractedly.

“Aw, I don’t care now,” Westy said indifferently. “I’ve got too much else to think about anyway. I’m going all the way down the Mississippi on a private yacht called the Atlantis.”

“Yo’ is?”

“Yep. A man in St. Louis is letting the government use it for an inspection tour of the big levees and a government engineer named Major Winton has asked me to go along on it.”

“Boy, yo’ sho’ am lucky. Is dis here Major goin’ to meet yuh?”

“Yep,” answered Westy, proudly. “He’s been at the Hotel Malone—do you know where it is?” The porter nodded and chuckled amiably as he shuffled off in answer to the insistent ringing of a bell.

After a few seconds the man strolled leisurely back into the Pullman, passed Westy without even a glance and kept on through the aisle in the direction of the club car. Presently, the porter reappeared, still chuckling.

“Heah I is,” he announced pleasantly and seated himself as before. “Ah’m sho’ interested ’bout yuh goin’ down the river, boy. They say de flood wuz never so bad befo’. In some places, I heerd, de water am reachin’ right up on a level with de levee top.”

“I bet I’ll see some excitement there, huh?” Westy asked, thrilled.

“Yes suh,” answered the porter. “But ah’d rather it be you den me, boy. I likes to do all mah travelin’ on dry lan’ ’n I can’t see no excitement where de people am drownin’ ’n de homes floatin’ away. No suh.”

The smile left Westy’s face and his eyes grew serious. “No kiddin’—is it going to be as bad as that?”

“Ah dunno, boy, but dat’s what de river’s done many times ’fo’ dis and de water ain’t been racin’ ’long as bad as ’tis now,” he said seriously. Then: “Ain’t yuh never been down this way befo’?”

“Nope.”

The porter shook his head. “Yo’ don’ know what yo’ is in fo’ den,” he said ominously. “If yuh ain’t seen a Mississippi flood befo’ den yo’ ain’t seen nuffin’ yet. Jes’ take a look out dat window, boy, ’n if yuh can multiply dat water by one hundred yuh’ll git an idea what dat country down thar looks like in a flood.”

Westy’s eyes roved over the lowlands of Missouri and he saw that he did not have to stop and multiply the scenes they were passing in order to get an idea of what destruction the water could do in the Mississippi valley. This landscape before him was a vast stretch of forlorn looking shanties and stunted trees and the water in some places had crept up to the very doorstep of these makeshift homes.

“De po’ whites,” the porter commented. Then: “Say boy, ah got somethin’ to tell yuh.” He looked rather furtively up and down the aisle.

Westy sat up straight. “What is it, a dark secret?” he laughed.

The porter smiled but his eyes were serious. “Take it or leave it,” he said in hushed tones, “it may be a secret an’ then again, maybe no. But jes’ the same ah’m passin’ the word on to yuh that Mistah Silent am a ’tective, sho’ as anything.”

“Detective—is that what you mean?” asked Westy, interested at once.

“Absolutely, absolutely.”

“How do you know?”

“Ah saw his badge wif mah own two eyes. It fell out-a his pocket when he wuz washin’ dis mawnin’. Yes suh.”

“How is it you didn’t tell me that before when we were first talking about him?” Westy asked, interested.

“Fo’ sev-erial reasons,” answered the porter, promptly. “Ah didn’t know who yo-all were at first and den when yo’ told me ’bout thinkin’ yuh knowed him ’n was sho’ yuh saw him befo’, I was suspicious.”

“Suspicious?”

“De very same. Ah thought maybe yo-all was de one he was travelin’ after. Then ah got thinkin’ how yuh said this army man asked yuh to go ’long and ah knew ah was wrong in my first impression. Yes suh—ah knew den dat you wasn’t de one he’s trailin’. An’ he’s after someone on dis heah train, boy—sho’ nuff.”

Westy turned his face toward the window and frowned. Then quickly he looked up. “You mean—you mean he’s watching someone on this very train—this very car?”

“De very same,” the porter answered complacently. “Den again maybe he’s goin’ after someone in St. Louis. Yuh jes’ cain’t tell ’bout dem ’tectives sometimes. Dey sho’ is like ghosts.”

Westy agreed with a mechanical nod. “I knew I saw him somewheres,” he said in monotones. “Now that you say detective, I’m almost sure.”

“Yes suh, he am a ’tective.” Then confidentially, “If ah find out mo’ ’bout him, boy, ah’ll pass yo-all de word.”

“Thanks,” said Westy listlessly. “I’d like to know all right. I sure would.”

The porter departed upon his duties once more and Westy leaned back against the cushioned headrest. For some reason his heart was thumping wildly and each time the porter’s words recurred to him, his mind seemed deluged with threatening voices and vague fears.

“What’s the matter with me?” he said, by way of restraining those tormenting voices within. “What have I got to do with him? Why should I care who he’s following or who he’s after, huh? I should worry if he’s watching everyone in this train.”

The train was picking up speed and rushing him nearer and nearer to St. Louis. He felt that he couldn’t get there quick enough now. The knowledge of the man’s identity had somehow spoiled his trip and yet when he reasoned the thing out he asked himself what a detective could possibly want with him.

At intervals, above the clamor of the wheels just beneath, Westy could faintly hear the engine’s siren screeching its right of way and he pressed his burning face against the cool window-pane to hear it better. Anything was better to listen to than the clamor and turmoil of his thoughts.

But he soon found that he could not bar those insistent voices within. They were asking, why, suspicion? And he answered that it was a lot of rot. In the fraction of a second his own voice was saying, “Rot? Very well, but here’s the detective on the train and right in your own car. Incidentally, he’s from Bridgeboro—your own town. What do you make of that?”

Still harder did he press his face against the pane and he clenched his teeth. But soon he was shouting within himself, “He’s crazy if he’s following me! They’re all crazy! I’m crazy! Why should I worry, huh? Why should I be afraid? From now on, I won’t be. I’ll make up my mind that I won’t!”

Westy was not a coward, but he was human enough to fear the presence of the law.

They were two hours late getting into St Louis and, much to his relief, Westy saw nothing of the ponderous Mr. Silent. The porter, however, managed to whisper a word of reassurance when he handed him his bag on the broad platform.

“Ah thinks Mistah Silent am gwan right on traveling boy,” he whispered. “He done give me orders tuh get him off first one, cuz he said he had tuh make connections. Yes suh, he am now on his way. G’bye ’n g’luck, boy.”

Westy returned this parting shot and looked around but could see no sign of Major Winton. He had hardly expected that he would for he knew that the major wouldn’t waste five minutes, much less two hours, waiting. His time was too valuable. After he had made sure that the major wasn’t in the vast waiting room, he turned and pushed his way out of the crowds and into the dark street. A rush of soft spring air filled his nostrils and he hailed a passing taxi with a feeling of exultation. There were no more fears to disturb his peace of mind and the annoying presence of Mr. Silent was a closed chapter. Adventure seemed to beckon him forward and as he stepped into the cab he had a delightful vision of that tawny river lying somewhere below the murky streets, waiting, just waiting for him.

Travel weary as he was, he jumped briskly out at the Malone and swung eagerly through the big, revolving door. In the lobby a bellhop approached him and deftly claimed his bag.

“Yo’ name Martin?” he inquired with a polite smile.

Westy nodded, surprised.

The boy chuckled. “Major Winton’s had me watching fo’ yuh an hour and more. Train’s been late, huh?”

“I’ll say,” Westy answered, genuinely pleased. “How’d you know me?”

They stepped into the elevator and the boy smiled pleasantly. “Major Winton described yuh,” he admitted, then laughed. “He said yuh had a great habit o’ swingin’ yuh right hand way out when yuh walked so I watched fo’ that and it turned out right.”

Westy laughed. “That’s a hot one. Who’d ever think Major Winton noticed that.”

“He don’t miss nothin’,” said the boy, as they stopped at the fourth floor and got out. “But I like him.”

That was a subject dear to Westy’s heart and he would have liked very much to discuss it further had it not been that Major Winton flung open the door in response to the bellhop’s knocking. And to quote a certain young man whose acquaintance Westy had made out in Arizona, “There’s never any use in praising the major when the major’s right there.”

For all that, Westy silently agreed with the bellhop and was secretly pleased when Major Winton gave him a friendly push into a big chair. He tipped the smiling boy, sent him on his way, then surveyed his guest thoughtfully.

“Well, young Martin,” he smiled, “I guess you’re pretty tired, eh?”

“I was when I first got off the train,” Westy admitted, “but I don’t feel it now. It’s so nice and warm here compared to Chicago and Bridgeboro.”

Major Winton nodded and sat down on the arm of a chair opposite. “Talking of Bridgeboro, reminds me. I received a special delivery letter from your father today. He thanked me for being bothered with you.” There was a soft chuckle, then: “He also told me of a rather unfortunate happening in your town involving you more or less indirectly.”

Westy nodded, feeling not quite pleased that his father had mentioned it in the letter.

“He said you were quite upset by it as one of your best friends figured chiefly. Tell me about it,” he said casually.

Westy sighed at the thought of reviving Bridgeboro troubles way out in St. Louis. But the major was waiting and wanted to know—given facts he was eager for details. “Norrie Cole was my best friend before he went away to military school,” he said at length. “He would have been my best friend again if this thing hadn’t happened.”

Major Winton walked over to a desk and procured a cigarette. He lighted it and went back to the chair listening intently the while to Westy’s short narration of the clouds that had gathered on Norris Cole’s horizon.

They were frequently interrupted by telephone calls and from the major’s answers one gathered that they were all pertaining to the imminent departure of this brilliant army engineer. After the fourth call was finished he apologized.

“There’ll be no more tonight, thank goodness,” he laughed. “They’re all in on our little tour—those four—Wade, Grimes, Jones and Roberts. You’ll see them all tomorrow. Wade and Grimes are my right hand men. This is a big job we’re going on, Martin. That’s why I’m taking you—it’ll be a big help if you ever go in for engineering seriously.”

Westy felt elated that a man of the major’s standing should take such an interest in him. He wanted to hear all about what they were going to do and just where they were going and hoped that he would hear more engineering talk. But he was disappointed.

“Where do you think this young Cole is now?” queried Major Winton, obviously more interested in human matters at that time. He settled himself in the chair and flung a trim, khaki clad leg over the arm.

Westy was intensely disappointed but cleverly concealed it. Would he ever get away from hearing about that affair? Finally he answered, “Gosh, I don’t know where he is, Major Winton. And if they’re together, I don’t know either. Neither of them ever had much money at a time so I can’t see how they’d get very far.”

“You believe they didn’t take the money, then?”

“Well, I promised Norrie once that I wouldn’t say anything against Trick until I could prove it and I’m going to stick to my promise. I can think as I like about him, but I won’t say anything. Anyway, I can almost swear to it that Norrie wouldn’t touch a cent of anybody’s money.”

“You’re quite sure then that he didn’t confide in you that this Trainor had even suggested robbing Mr. Cole?” Major Winton asked him pointedly.

Westy flushed at the directness of this question. For a second he felt as if he were floundering, mentally. “Why—why,” he stammered, “how could Norrie confide in me about something he didn’t even know was going to happen? I tell you, Major Winton, I believe in Norrie.”

“And what makes you so cocksure about him?”

“Just something tells me, that’s all,” Westy answered, wonderingly. “We had a couple of talks—just like I told you. He was mad at his father for keeping him down and he talked to me about it but I noticed when Trick made any remarks about Mr. Cole or Old Brower, why, Norrie stuck up for them right away. That shows what he was made of, doesn’t it?”

Major Winton conceded that it did and puffed leisurely away on his cigarette. He stared hard across the room and the smoke rose from between his long, thin fingers and enveloped his tanned face. Suddenly he leaned forward and dropped the stub into an ash tray on his desk. There was something almost deliberate in his gesture.

“And you say they were last seen getting off that New York bus together?” he queried, interlacing his fingers thoughtfully.

“Yes,” said Westy, aroused by this veritable barrage of questioning. “But it could have been a coincidence that they met on that bus, couldn’t it?”

“Yes.” The major smiled pleasantly and looked directly at his guest, “but whether or not it was, is another matter. I’m not so interested in that, Martin. Indeed, I was only curious about the affair just so far as it concerned you. All I wanted to hear from you was that you knew nothing of the affair until after it happened and that you have no idea even now as to what has become of your friend, Cole, and his friend, Trainor.”

“I don’t know where Norrie or Trick are,” Westy said, vehemently. “As true as anything. Major Winton, I was as surprised as anyone else to hear that Mr. Cole had been robbed.”

“I believe you, Martin,” Major Winton said, smiling. “I have great faith in you concerning this little affair and it means a whole lot to me that you don’t fail me in my belief.”

“Well, I never failed you yet, and I guess I never will,” said Westy stoutly.

Westy slept that night in a room adjoining Major Winton’s. That is, he slept until two o’clock in the morning and spent the remainder of the night in contemplating his life, past, present and future. Perhaps that is going pretty strong for one of his age, but at any rate he was certainly contemplating himself.

The major’s talk recurred to him at intervals and each time he went over it in detail just for the delight of repeating his words before they had said goodnight. But suddenly he paused and asked himself a question. Why had Major Winton pressed him so about his knowledge of Trick and Norrie’s whereabouts?

He puzzled and frowned over it in the dark room, then smiled sleepily. “It’s because he’s taken an interest in me,” he answered himself, “gosh, I suppose he just wanted to make sure I wouldn’t be mixed up in an affair like that—that’s all. After all, I can’t blame him because it’d make him look like a monkey if I turned out to be something he didn’t expect.”

He turned over on his right side and vainly tried counting sheep. The stars blinked themselves into nothingness in the heavens above his window and soon that vast realm seemed but a yawning black abyss. It was approaching dawn.

Suddenly the door opened and Major Winton called him and made apologies for having to start off so early. The Atlantis was scheduled to start at dawn, he said, in order to make their first stop that evening. He hurried into his room to complete his packing and left Westy to dress.

A few minutes later they were being jounced around with their baggage in a taxi along the dark streets. Westy got a glimpse of dismal looking houses and as they swerved around a corner a shabby negro lounging against a lamp post stared idly as they passed.

“Gosh, I wouldn’t mind stopping and taking a peep at St. Louis,” he remarked.

“Maybe there’ll be more time for that on your way back,” the major said. “But if all you want is the stops, why you’ll have plenty of them from tomorrow on. You may even get tired of stopping.”

“Not me,” laughed Westy. “I like to keep on going, and in this case to stop means to keep on going, huh?”

“I guess so,” Major Winton smiled. “At any rate, just act as if the Atlantis belonged to you—this is your vacation.”

Westy was a little disappointed with his first glimpse of the great river. It looked anything but great to him—more like some huge mud puddle as he viewed it in the gray light of morning. True, its waves lapped greedily about the rope ladder of the shining, white yacht as they ascended to the deck, but they were not the dancing blue waves of his anticipation.

He spoke of this to Captain Earl after they had been introduced and were seated at breakfast in the luxurious dining-room. “When it comes to looks the Hudson has it beat forty ways,” he concluded proudly.

The white-haired, blue-eyed captain winked across the table at Major Winton. “That may be true, son,” he said jovially, “but your lordly Hudson isn’t the magician that our muddy Mississippi is.”

“Magician?” Westy queried.

“Exactly,” answered the captain with a broad smile upon his benign face. “This stream of mud can play the durndest tricks on a feller that you could think of. I’ve known it for twenty-five years now and it ain’t never behaved the same twice in succession. It’s what them writing fellers call a dual personality, I guess.”

Westy thought the captain was teasing him but when he looked around the table at the interested faces of their party he changed his mind and ventured to ask, “How?”

Captain Earl leisurely bit off a piece of toast and chewed it complacently. “In threatening flood times like now,” he answered slowly, “the river’ll flow along under a warm spring sun as lazy and harmless looking as a country brook. But all the time, mind you, it keeps rising and the further on down we get the higher it’ll be. Then finally in some places you’ll see it squirming against a weak levee. Even when it flows in through a crevasse and down the streets of a town it doesn’t seem to be in a rush but all the same it is. It can fill up a whole village the quickest I ever did see. A poet feller I knew one time said ‘it slays with a caress’ and I guess he was pretty near right.”

Major Winton had turned and was looking out of the wide window at his elbow. They were now under full steam and the city of St. Louis was fast becoming a blur on the horizon. At length he shook his head, doubtfully.

“I guess it’s higher now than it has been for years, eh?” he asked.

Captain Earl nodded. “Some say it’s no worse, but I say it is worse,” he said emphatically. “’Tain’t no use to be pessimistic, I s’pose, but when you see a thing you see it and when the Mississippi Valley has to face the facts of a flood they might as well admit it and get to work fightin’ it as best they can.”

“I agree with you,” said Major Winton, his eyes still fixed on the passing landscape. “There’s been a pile of erosion since I was last here. Too bad they don’t plant more trees.”

A discussion started then between the major and his assistants. Or rather, there started a friendly argument among that little group as to which was the simplest means of curbing this great river. Westy listened with interest until he saw Captain Earl rise and walk out on deck and, seeing that he would not be missed, he went also.

He followed the captain aft and gained his side just as he stopped at the rail. “I was interested in what you said about the river, Captain Earl,” he said, eagerly. “I—I hope you didn’t feel offended at what I said about it because I only meant that I was surprised to see how funny and muddy it was after all I’d heard about it.”

Captain Earl tousled Westy’s curly head and laughed. “Offended!” he said. “Why, son, folks down here never get offended at anything strangers say about their river. They know it’s muddy and they know it’s treacherous so you can’t hurt their feelings none by telling them. They love it just the same.”

“And you don’t get offended either?” queried Westy.

“If you mean, would I, if I were a southerner, I’d answer no, too,” he smiled.

Westy looked at him, puzzled.

The captain laughed heartily. “I’m only a southerner when I’m on the Mississippi, son. And when I take a four months’ vacation every winter at my home in Connecticut I s’pose you’d call me a northerner. Anything else troubling you, lad?”

Westy liked him, “Sure,” he answered, encouraged. “Have you ever been down on our river—the Bridgeboro River? Why I ask you is because it curves and bends like the Mississippi even if it isn’t very long.”

Captain Earl’s sparkling blue eyes took on a puzzled expression. “Bridgeboro River, eh?” he asked. “Is that where you live—Bridgeboro?”

“Yep,” answered Westy. “Ever been there?”

“No,” answered the captain, thoughtfully. “I was just wondering—Major Winton must have a weakness for Bridgeboro people, eh?”

“Weakness? I don’t know—why?”

“Nothing, ’cept that I took on an extra deck hand at the major’s special request and he told me the feller was from Bridgeboro, too. But then I s’pose you know all about it, eh?”

Westy shook his head, puzzled.

Captain Earl smiled. “Well, I s’pose Winton’s been so busy he hasn’t thought about telling you. And maybe it’s just a coincidence that you both come from Bridgeboro. Maybe you know the feller, eh—Jake Miller?”

Westy shook his head again.

“Then it is a coincidence,” said the captain genially. “Maybe it’s another Bridgeboro he’s from, eh? There could be more than one Bridgeboro in the country just the same as there’s a dozen or more Hicksvilles and Cold Springs.”

“Maybe,” said Westy, not very convincingly.

“Anyway, there’s only one Mississippi,” laughed the captain, his hands firmly clasping the shining rail. “Just look at it, son, wouldn’t it make you think of a sleeping tiger with its claws sheathed?”

Westy looked over the side, his eyes dark and thoughtful. Indeed, the lazy, tawny stream reminded one of just that, and its placid lapping against the speeding yacht seemed to mock his whirling thoughts. Captain Earl’s splendid simile had struck a responsive chord in him.

Why hadn’t Major Winton mentioned about this Jake Miller from Bridgeboro? Who was he?

“I’ll ask him, I will!” he exclaimed, after the captain had left him to go about his duties. “Gosh, it’s darn funny—anyway, I’ll go ask him right now.” He hurried back to the dining-room, or the mess room as Major Winton called it, and the only person he found there was a negro waiter who was clearing away the remains of their breakfast. “De major and de other gen’lemen am in de liberry on de fo’ward deck,” that person informed him politely. “I heerd de major say dat dey would be in conference if anyone should ask.”

“That means me, too,” said Westy irritably, as he left the mess room. “That means he doesn’t want to be bothered by anyone.”

He knew the major well enough to respect his wishes on that score, but he dared pushing a deck chair along to the forward deck and adjacent to the door that opened into the library. “I’ll be right here when he comes out,” he told himself, and proceeded to read a magazine that he had found in the empty chair.

For the next two hours he heard the low murmur of their voices and eagerly waited for the door to open. But it did not open and he grew tired of sitting and reading and went up to pass away some more time with the captain.

At intervals he would see a deck hand passing below and he anxiously scanned each face trying to seek out this other protege of the major’s. For some unknown reason he did not want to ask Captain Earl’s aid in identifying this extra deck hand that he had mentioned.

Luncheon was announced and when Westy entered the room they were all seated at the long table. He felt terribly disappointed that he couldn’t get the major’s ear alone, for even then he was occupied in a lengthy discussion with his right hand men, Wade and Grimes.

Westy tried making the best of it and spoke occasionally to Roberts and Jones, both serious-looking young men. They, on their part, did not seem very sociably inclined, obviously preferring to keep an attentive ear upon the remarks of their superior.

“They think I’m just a kid—eighteen,” said Westy, disgruntled. He attacked his lunch almost fiercely and finished it in record time. “Anyway, Major Winton doesn’t think I’m too young to learn things or he wouldn’t have asked me to go along,” he said, after he had repaired to the deck once more.

Shortly afterward he learned that the major had retired to his stateroom for the afternoon as he was suffering with a headache. They were scheduled to stop at Cairo sometime between six and seven o’clock of that evening, where the engineers were to have an important conference with the levee board.

All this Westy learned from the yacht’s engineer, with whom he became quite friendly. The afternoon passed rapidly and at five-fifteen o’clock he had dinner with Wade and Grimes and Captain Earl. Jones and Roberts were still busy and the major wouldn’t be getting up till they came into Cairo, he was informed.

He experienced a twinge of homesickness after the meal was over and attributed it to the major’s absence. “I hope I find more to do,” he murmured. “Gosh, nobody to talk to—gosh!”

He sought a comfortable chair on the deck where the last rays of the sun were playing and lazily watched the water swirling out of the yacht’s path. A drowsiness stole over him and he did not try to fight it. Instead he welcomed it—it brought thoughts of what adventure he might have.

Might have? He smilingly asked himself that question. “I better have,” he mumbled, drowsily, “or I’ll be wishing I’d gone to California.” With that in mind he fell asleep.

Someone put a covering of some kind over him but he was too sleepy to open his eyes and look. He was content to feel the warmth and snuggled in it like a child. Dreams, wild and terrifying, tossed his mind about and he seemed to be struggling to awaken but could not. Suddenly he felt a tugging at the covering about him and heard a voice call his name.

He awoke, staring into darkness. The yacht seemed to be standing perfectly still and there was a great profusion of lights glowing somewhere in the darkness. He threw aside the covering and looked up.

Major Winton and the four engineers were standing around him, laughing. “You’re some sleeper, young Martin,” the major said pleasantly. “I thought I’d better wake you and let you spend the rest of the night in your stateroom. It’s pretty cold out here.”

Westy blinked his heavy lids. “Huh?” he asked, astonished. “What’s—what time is it?”

“Ten o’clock,” answered Wade, looking at his wrist watch in the light from the library.

“I wanted to take you along,” said the major, “but you looked too peaceful to disturb. Wade covered you over before we left.”

Disappointment was evident in Westy’s brown eyes. “You mean you’ve been—we’ve been in Cairo?”

“We’re there now,” laughed the major.

“And you’ve been at that conference while I was asleep?” he asked.

Major Winton nodded. “I’d have wakened you if I’d known you wanted to go that badly,” he said. “There really wasn’t anything so interesting for you though and you looked all in. I thought you needed the sleep more. But never mind, you won’t get left again—we’ll stay at our next stop for a week perhaps.”

Westy got up and stretched his cramped legs. “Gosh, that won’t make me mad,” he said. “I’d like to have something to do, all right.” Then: “One thing, I’d like to talk to you Major Winton—I want to ask you something.”

“Do you think it will keep until morning?” the major asked, pleasantly.

Westy nodded. “It’ll have to if you say so,” he answered.

“That’s settled then,” said the major. “We have some reports to go over and then I’m going to turn in. My headache isn’t quite gone, and I’ll feel more like answering questions in the morning.”

The big yacht was again under way and after the little group had entered the library Westy strolled around the decks. He poked his nose inside his stateroom door in passing and decided that it was more pleasant outside. His long nap had rested him too thoroughly, and he went below to chat with the engineer.