* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Grandeur and Misery of Victory

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929)

Date first posted: Apr. 28, 2020

Date last updated: Apr. 28, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200449

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

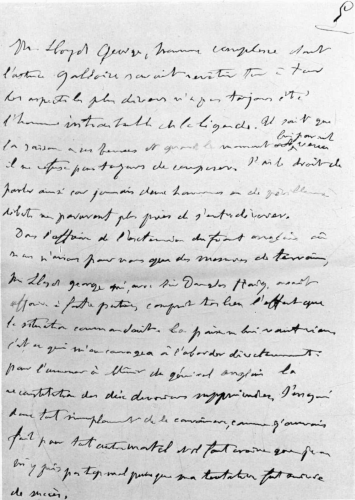

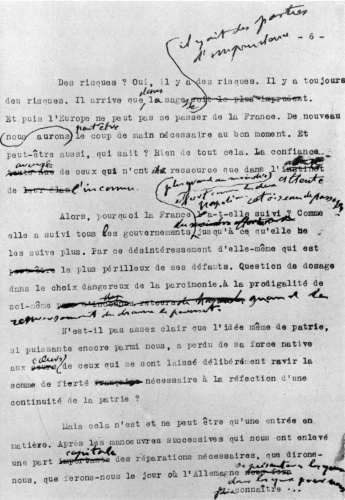

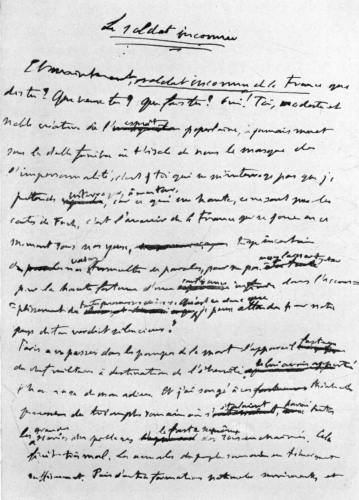

EVENING IN VENDÉE

At the table under the window Clemenceau wrote much of his book.

Looking up from his manuscript, he would see his rose-trees and,

beyond, the ocean.

From a photograph by H. Martin

GRANDEUR AND MISERY

OF VICTORY

BY

GEORGES CLEMENCEAU

THE RYERSON PRESS

TORONTO

Printed in Great Britain at The Ballantyne Press by

Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co. Ltd.

Colchester, London & Eton

FOREWORD

The Parthian, as he fled at full gallop, loosed yet one more shaft behind. At the moment when he was swallowed up in the perpetual night of the tomb Marshal Foch seems to have left a whole quiverful of stray arrows to the uncertain bow of a chance archer.

The present hour is not one for suggestions of silence. On every side there is nothing but talkers talking futile words, the sound of which perhaps charms crowds of the deaf. Perhaps that is why I have myself yielded to the universal impulse, with the excuse of preventing the absence of a reply from appearing to mean confirmation. Not that this matters to me so much as might be imagined. When a man has placed the whole interest of his life in action he is little likely to pause over unnecessary trifles.

When I saw this impudent farrago of troopers’ tales in which, in the cosy privacy of the barrack-room, the soldier is unconsciously seeking his revenge for conflicts with authority that did not always end in his favour, I might perhaps have been incapable of turning my back on my duty had not the breath of the great days magically fanned to new life the old, ever-burning flame of the emotions of the past.

What, my gallant Marshal, are you so insensible to the thrill of the great hours that you took ten years of cool and deliberate meditation to assail me for no other reason than a stale mess of military grousings? What is more, you sent another to the field of honour in your place—which is not done. Were you so much afraid of my counter-thrust? Or had it occurred to you that if, as was probable, I died before you, I should for ever have remained, post mortem, under the weighty burden of your accusations? My gallant Marshal, that would not have been like a soldier.

Ah, Foch! Foch! my good Foch! have you then forgotten everything? For my part, I see you in all the triumphant assurance of that commanding voice of yours, which was not the least of your accomplishments. We did not always agree. But the tilts we had at one another left no ill-feeling behind, and when tea-time came round you would give me a nudge and utter these words that were innocent of either strategy or tactics, “Come along! Time to wet our whistles.”

Yes, we used to laugh sometimes. There is not much laughing to-day. Who would have thought that for us those were, in a way, good times? We were living when the agony was at its worst. We had not always time to grumble. Or, if there were occasional grumblings, the arrival of tea put an end to them. There were displays of temper; but there was one common hope, one common purpose. The enemy was there to make us friends. Foch, the enemy is still there. And that is why I bear you a grudge for laying your belated petard at the gates of history to wound me in the back—an insult to the days that are gone.

I am sure that you did not remember my farewell to you. It was at the Paris Hôtel de Ville, and about a memorial tablet on which three of us were inscribed as having served our country well—a crying injustice to so many others. As we went away I laid my hand, as a friend might, on your breast, and, tapping your heart under the uniform, said, “Through it all, there’s something good in there.”

You found no answer, and it so happened that I was never to see you again except as you lay in state. What a stain on your memory that you had to wait so many years to give vent to childish recriminations against me through the agency of another, who, whatever his merits, knew not the War as you and I lived it! Worse still: when I went to America to take up the cudgels for France, accused of militarism, you allowed the New York Tribune to publish an interview in your name full of gross abuse of me, an interview which the writer of your Mémorial did not dare to print, but which I shall lay before the reader side by side with the letter in which you express your overflowing gratitude to me for having given you your Marshal’s staff. Our country will judge us.

As for myself, I am the man I have always been: with my virtues and failings, wholeheartedly at the service of my country, caring naught for the honours or for the steps in rank, with their appropriate emoluments, that weigh so heavily in the scales of success. Never has there been anyone who had power to confer a reward upon me. There is a strength in looking to no one but oneself for anything.

You have to your credit the Marne, the Yser, Doullens, and, of a surety, other battles besides. I forgave you a flagrant disobedience which, under anyone but me, would have brought your military career to an end. I saved you from Parliament in that bad business of the Chemin des Dames, which even now has not been altogether cleared up. Suppose I had sat still and said nothing; where would you be to-day?

Yet, when you had reached the highest honours, after a ten years’ silence, to wait till you had disappeared from the scene and then have me pelted out of your window with roadside pebbles—I tell you frankly it does not redound to your glory. How different were my feelings when I went to meditate beside you as you lay in state! Why must you, of your own accord and without the slightest provocation, strike this blow at your own renown?

It will not be gainsaid that it is my right, nay, my duty, to reply to an inquisitor who begins by establishing himself in a position aloof, remote, and under cover. I once had, and still have, a considerable reserve of silence at the service of my country. But, since the public could hardly fail to impute to faint-heartedness my failure to reply, I cannot remain speechless. You challenge me. Here I am.

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory | 13 |

| II. | The Unity of Command | 24 |

| III. | The Chemin des Dames | 43 |

| IV. | The Employment of the American Contingents | 58 |

| V. | The Man-power Problem in England | 89 |

| VI. | The Armistice | 98 |

| VII. | Military Insubordination | 115 |

| VIII. | The Belgian Incident | 128 |

| IX. | The Peace Conference | 134 |

| X. | The Treaty: The Work of President Wilson | 156 |

| XI. | The Treaty: A Europe founded upon Right | 170 |

| XII. | The Treaty: An Independent Rhineland | 193 |

| XIII. | The Treaty: The Guarantee Pact | 218 |

| XIV. | Critics after the Event | 235 |

| XV. | German Sensibility | 255 |

| XVI. | The Mutilations of the Treaty of Versailles: Mutilation by America—Separate Peace | 277 |

| XVII. | The Mutilations of the Treaty of Versailles: Financial Mutilations | 286 |

| XVIII. | The Mutilations of the Treaty of Versailles: Locarno | 300 |

| XIX. | The Mutilations of the Treaty of Versailles: Germany arms. France disarms | 317 |

| XX. | The Mutilations of the Treaty of Versailles: The Organization of the Frontiers | 334 |

| XXI. | The Mutilations of the Treaty of Versailles: Defeatism | 340 |

| XXII. | The Retrograde Peace | 355 |

| XXIII. | The Unknown Warrior | 368 |

| Appendix I: The Unity of Command: March 1918. Memorandum to the Cabinet by Lord Milner on his Visit to France, including the Conference at Doullens, March 26, 1918. | 380 | |

| Appendix II: The Problem of the Inter-Allied Debts. Open Letter from M. Clemenceau to President Coolidge | 392 | |

| Index | 395 | |

Grandeur and Misery of Victory

Ambitions and falterings—they belong to humanity in every age.

My relations with General Foch go back to a period long before the war that brought us together, different as we were, in common action in our country’s service. The newspapers have told how I appointed him Commandant of the École de Guerre, looking to his known capabilities without taking any notice of his relations with the Society of Jesus. As it chanced, matters really happened pretty much as the popular tale relates. Which is not usual. So I confirm the story of the two speeches we exchanged.

“I have a brother a Jesuit.”

“I don’t give a ——.”

I might have chosen a politer expression. But I was speaking to a soldier, and I meant to be understood. If it had no other merit my phrase had the advantage of being clear. Which might be taken as sufficient. General Picquart, the Minister of War, had very warmly recommended General Foch to me, to start a course in strategy, which the Minister, with the General specifically in mind, wished to set up. I asked nothing further. In similar circumstances I am not at all certain that some of my opponents would have been capable of following my example.[1]

Naturally I claim no particular merit for such a simple act of French patriotism. I belonged to the generation that saw the loss of Alsace-Lorraine, and never could I be consoled for that loss. And I here recall, with pardonable pride, that in 1908 I stood up against Germany in the Casablanca crisis, and that the Government of William II, after demanding apologies from us, was forced by my calm resistance to be satisfied with mere arbitration, as in any other dispute. We had not yet come to the days of the humiliating cession of an arbitrary slice of our Congo to Germany by M. Caillaux and his successor, M. Poincaré.

I will not try to hide the fact that I had one or two nights of uneasy slumbers. I was running a very formidable risk. The weak, who are usually the majority, were already quite prepared to repudiate me. Nevertheless, my country’s honour remained safe and intact in my hands.

If I had any relations with General Foch between those far-off days and the War I have kept no memory of them. He was not in politics, and had no need of me.

At Bordeaux, after the battle of the Marne, I received a letter from my brother Albert, who had enlisted, telling me that General Foch, who had never met him, had sent for him to whisper confidentially in his ear, “The War is now virtually ended.” That was perhaps going a little fast. No one assuredly felt that better than the General himself when once he had the military responsibility in his own hands. But the happy forecast was none the less justified by the event. It did honour to the soldier’s swift intuition.

It was impossible for me to feel better disposed toward the military chief who already held that the tide had definitely turned in the direction of victory. And so I was not surprised in evil days—at the close of 1914, when my thankless task kept me in severe opposition to the authorities—to receive a request from General Foch, again through my brother, for a private interview in the prefecture of Beauvais, then occupied by my friend M. Raux, who was later Prefect of Police.

In my simplicity I had thought that some important revelation would prove the justification for this unlooked-for step. So I came to the interview warm and expectant, to be chilled by the discovery that it was merely that I might be questioned, in war-time, by the head of an army, as to the more or less favourable attitude of the political world toward a recasting of the High Command, which interested my interlocutor in direct personal fashion.[2]

My general attitude was friendly but reserved. I was most certainly willing to trust the professional capabilities of the former Professor of Strategy at the École Supérieure de Guerre, but none the less I regretted his preoccupation with his purely personal interests. Thus I came away rather disappointed, and so ended this mysterious colloquy, without really beginning.

Later on, in 1916, another surprise was in store for me. For one day there arrived my Parliamentary colleague, M. Meunier-Surcouf, orderly officer to General Foch, bringing me a bust (in imitation terra-cotta) of his chief, with the latter’s compliments. I was astounded. What was I supposed to do in return? Questioned on this point, M. Meunier-Surcouf told me that a sculptor had been summoned to headquarters and given a commission to produce from a larger model fifteen copies of reduced size meant for various persons supposed to be influential. This was doing things in a big way. The whole affair may give rise to a smile. Still, the fact remains that such a proceeding might seem strange at the height of a war in which the very life of France was at stake. I had heard that kings used to send photographs to visitors with whom they were pleased. General Foch went as far as a bust, and I can aver that, for a man who never intrigues either with soldiers or civilians, it was a very embarrassing article.

More outspokenly candid than his chief, the orderly officer did not conceal from me that he was of the opinion that General Foch should be placed at the head of the French armies. I was far from being opposed to this. M. Meunier-Surcouf visited me again and again to confirm me in his views. He has been kind enough to make up from his notes a report from which I shall quote a few passages:

At 10 A.M. on April 15, 1916, I presented myself at M. Clemenceau’s house in the Rue Franklin; I had never had occasion to approach him previously.

What was it prompted me to pay him this visit?

It was because underneath the often violent polemics of the Homme Enchaîné there could be discerned in him an unmistakable love of France and an uncompromising desire for victory.

“I am old,” he said, “I don’t set much value on life, but I have sworn that my old carcase should hold out until victory is complete, for we shall have the victory, Monsieur Charles Meunier, we shall.”

In turn I put my interlocutor in possession of the military situation as it appeared to me from an examination of the facts. . . .

“I have seen around me,” I told him, “only one general who believes wholly and absolutely in our military victory, and that is General Foch: since to this indispensable belief he adds the qualities that make him one of the highest in his profession, he seems to me marked out to lead our armies, and the Government will find in him the firmest prop, and the most loyal too, in the difficult months that are approaching.

“I do not want you to believe merely that I am speaking of him as a devoted officer of his, a friend who has become attached to him during the eighteen months he has been by his side. I wish to base myself on facts.”

And I gave him my own account of the handling of the battle of the Marne, when Foch was in command of the Ninth Army, to which I was attached as officer in an artillery group of the 60th Reserve Division, and of the race to the sea that ended in the arrest of the German offensive in the north on November 15, 1914.

In these two actions there were revealed such qualities of the offensive spirit, for using and economizing reserves, of moral energy, and even of diplomacy, that it might be confidently affirmed that, while many of our generals had excellent qualities, General Foch seemed to stand in a superior category.

“In any case,” I added, “come and see him. You came twice close to us—I saw you—without stopping at our headquarters. I am of the firm belief that if you are working together, you at home and he in the Army, we shall be in the best position for achieving success in the end.

“The General’s talents for attack make him capable of gaining the victory, but he might lose a battle; it is indispensable that he should have by him some one able to shield him, to uphold him in such a contingency before the Chambers of Parliament,[3] before the country, of whose sensitiveness you are fully aware, and I think you are the very man needed for this purpose. It is time for you two to come to an understanding.”

I confess that the distribution of those busts gave me certain misgivings about the candidate for the post of Commander-in-Chief. A reminiscence of General Boulanger?

As he left me General Foch’s orderly said:

“It’s a promise, isn’t it?”

“I make no promises to anyone whatever,” I replied. “But I am well disposed. In any case, I shall not be consulted.”

Time goes on. A fresh surprise! One morning, at the end of 1916, I see General Foch himself enter my house in a state of great excitement.

“I have come straight from my headquarters,” he said, “where I have just had a visit from General Joffre. This is what he said to me:

“ ‘I am a most unhappy man. I am coming to entreat you to forgive a meanness I have just been guilty of. M. Poincaré sent for me, and gave me an order to relieve you of your command; I ought never to have consented. I gave way. I have come to beg your pardon.’ ”

And General Foch wound up with:

“And now I have come to ask your advice. What do you think I ought to do?”

Not a word of the cause of the calamity. That was a bad sign. I refrained from asking questions. Yet that was the real vital point of the business. But I thought I must spare the nerves of the general torn away from his soldiers.

“My dear friend,” I replied, “your duty is all clearly marked out for you. Rivalries that I know nothing about may have caused this momentary reverse. They cannot do without you. No fuss. Obey without arguing or recrimination. Go back quietly to your own home. Lie low. Perhaps you will be called back inside a fortnight.”

My forecast was a long way out, for the General remained limogé for several months.

Several months kicking his heels in meditation is a great deal for a gallant soldier who sees his comrades falling on the battlefield. Foch endured this trial without uttering a word. That was a feat which I appreciate at its full value.

In later years I told this story to Poincaré, who shrugged up his shoulders laughing, with the sole comment, “These generals! They are always the same.”

I was not greatly enlightened by that.

In November 1917 I found General Foch in Paris, as Chief of the General Staff; in a word, not in any active command. From Picquart’s report of him I had expected some dazzling display of military talents. Perhaps the last word had not been spoken.

M. Poincaré and Marshal Joffre certainly know all the details of this affair. There has been talk of an intrigue carried on by a politician general who put himself forward openly as a competitor of Foch, and who was at that time a frequent visitor to the Élysée. M. Painlevé has written that Foch was relieved of his command by Joffre for purely military reasons. And for his part Commandant Bugnet declares expressly that it was a question of the Somme offensive, a marked failure that it was later tried to pass off as a mere attempt to “ease Verdun.”

Unprovided with transport adequate for exploiting the break-through, the Somme offensive presents itself as an operation that failed. Certain leaders, when everything is over, too often have an explanation all cut and dried to justify a failure. In this way it is easy to get out of an awkward situation cheaply. There is nothing to be astonished at in those who pretended to have relieved Verdun none the less thinking themselves bound to ‘limoger’ Foch “for the sake of example.” Some day or other the affair will be cleared up. But it may be believed that there must have been very serious reasons to make M. Poincaré, who was very careful about questions of responsibility, withdraw the soldier of the Marne and the Yser from the fighting. In the end the two men understood each other, at which history will not be astonished.

For my part, as soon as I came to the Ministry, I naturally resumed my good relations with the new Chief of the General Staff. I still counted upon the effect of his strategic talents. As for him, with or without a bust, he had succeeded his old rival in the intimacy of the head of the State. Each henceforth played his part on the card of mutual confidence that he thought safest.

Before going further I make a point of expressly declaring that this book is not to be regarded as a series of memoirs. I have been called upon to reply upon certain points. I am replying, but without losing sight of the broad considerations that are essentially imposed in such a subject. During more than ten years I have preserved silence at all costs, despite the attacks that were never spared me, and it was most certainly not any fear of the fray that held me back.

I had simply considered that, in the anxious and dangerous situation into which our country had been brought, the utmost restraint and reserve was laid upon me—and to the last word of this book I shall regret departing from it. After the terrible loss of blood France has suffered it appears that she has reacted less virilely in peace than in the great days of her military trial. Her ‘rulers’ seem to have forgotten, all nearly in the same degree, that no less resolution is needed to live through peace than war. Perhaps even more, at certain moments. Some know as much who talk of action instead of acting. Whether in the Government, in Parliament, or in public opinion, I see everywhere nothing but faltering and flinching.

Our allies, dis-allied, have contributed largely to this result, and we have never done anything to deter them. England in various guises has gone back to her old policy of strife on the Continent, and America, prodigiously enriched by the War, is presenting us with a tradesman’s account that does more honour to her greed than to her self-respect.

Engrossed in her endeavours for economic reconstruction—alas! all too sorely needed—France is seeking in the graveyards of politics for human left-overs to make a pale shadow of what used to be. The vital spark is gone. An old, done man myself, here I find myself at grips with a soldier of the bygone days, who brings against me arguments within the comprehension of simple minds—now, when I had changed my workshop and meant to end my days in philosophy.

With far less wisdom, after ten years of reflection he chooses to hurl at me the ancient shell of a long-delayed attack, sparing himself, by deliberately and intentionally keeping under cover, all anxiety as to the inevitable reply. Thus, like a good strategist, he secured his rear before giving free vent to old grievances of the most virulent nature against me. To one who now seeks only rest this is of no great importance, but for a leader in war to let his battle lie dormant for ten years and then give a casual passer-by the task of stirring it into life, that is not the mark of a spirit sure of itself, nor of a magnanimous heart.

[1] In the case of a university appointment, in circumstances less serious, though still delicate enough, I fixed my choice in the same way on M. Brunetière, because he seemed to me the best-qualified candidate, although he was in declared opposition to my ideas. I take pride in this kind of behaviour, which is due to entire and perfect confidence in the ultimate emergence of truth through the free play of the human mind.

[2] A string of commonplaces about the War—our chances of success, what might be done. My interlocutor seemed to me short of ideas.

[3] My italics. M. Meunier-Surcouf had a premonition of the Chemin des Dames.

What was it that determined me to appoint General Foch to the Supreme Command? General Mordacq’s notes allow me to follow the battles of the future chief of the Allies.

After the battles in Lorraine, on August 29, 1914, General Foch relinquished the command of the Twentieth Army Corps, in order to take up that of an army detachment intended to cover the left of the Fourth Army more effectively, and to link it up with the Fifth. . . .

This detachment before long became the Ninth Army, at the head of which General Foch was to play an important part in the battle of the Marne. . . .

General Joffre, deeming “the strategical situation excellent and in accord with the dispositions aimed at,” issued orders, on the evening of September 4, to resume the offensive on the morning of the 6th, and to concentrate upon the German First Army the efforts of the Allied armies on the left wing. . . .

September the 6th sees the general launching of the attack. The Ninth Army is in the centre. It is precisely at this point the Germans are making their main effort. In reply to the manœuvre of Maunoury’s army on the German right, von Moltke orders Bulow’s army, which includes the Guard and the best German troops, to drive home the attack upon the French centre—that is to say, upon the Ninth Army. . . .

This army is stopped, and that at the height of its attack. Impossible for it to reach its objective, the district to the north of the Marais de Saint-Gond. At the end of the day it has barely struggled up to the southern fringe of the marshes. . . .

Its left wing, violently assailed, is fighting desperately at Mondement (the Moroccan division). The 42nd Division succeeds in driving the Guard back into the Marais de Saint-Gond. The Eleventh Army Corps, on the right, is holding out against the German attacks with difficulty.[1] . . .

September 9. The situation is becoming grave: the Prussian Guard have carried Fère-Champenoise by storm; the Ninth and Eleventh Army Corps are falling back. General Foch, unperturbed by the situation, sends a report to G.Q.G. which concludes, “I am giving fresh orders to resume the offensive.”[2]

And so, reinforced by the Tenth Army Corps, he launches a fresh counter-attack on Fère-Champenoise. . . .

September 10. He resumes the offensive along his whole front; after desperate fighting Fère-Champenoise is retaken. In the evening the Germans retreat, and are pressed back north of the Marais de Saint-Gond. . . .

September 11. Helped by a cavalry corps (under General de l’Espée), which General Joffre has placed at the disposal of General Foch, the pursuit begins in the direction of the Marne, which is reached by the Ninth Army on September 12, between Épernay and Châlons. Large numbers of prisoners are captured, and considerable quantities of stores and provisions.

The German High Command had ordered a general retreat on the evening of September 10.

After the battle of the Marne the German Staff had at once prepared a new enveloping movement against the French left wing. On its side the French High Command was trying to outflank the German right, which brought about the battles of Picardy and Artois and the “race to the sea.”

In the early days of October 1914 the situation was serious for the Allies: Lille threatened by the German cavalry, Flanders lying open, while the whole of the enemy forces were moving up more and more to the north, and threatening to break through the front at any moment.

It was at this juncture that General Joffre, on October 4, entrusted General Foch (whose Ninth Army had been broken up) with the task of co-ordinating all the forces engaged between the Oise and the sea—Castelnau’s and Maud’huy’s armies, a group of territorial divisions under General Brugère, and the Dunkirk garrison.

At the same time the English Army was transferred to Flanders (the Hazebrouck-Ypres region).

October 9. The fortress of Antwerp capitulates, and the Belgian field army which was surrounded there succeeds in reaching the coast, and, on October 11, occupies the region between Ypres and the sea. King Albert intimates that he will be happy to give his entire support to the co-ordination of the efforts of all the Allied forces which General Foch had been delegated to bring about.

The German Plan. After the fall of Antwerp the Germans, following their original plan, aimed at turning the position of the Allies by proceeding if necessary as far as the sea, and took Dunkirk, Boulogne, and Calais for their objective.

After the march to Paris came—as the German Press announced—the march to Calais. To attain their goal, the Germans concentrated no fewer than 600,000 men in Belgium and Flanders.

The French, warned of this huge manœuvre, brought up all their available reserves into Belgium.

October 20. The transport of the English Army has been achieved under favourable conditions. It is grouped entirely in the Ypres region.

The Belgian Army established the line of the Yser.

All these movements of the Belgian and English Armies were covered by the two French cavalry corps.

It may be said, then, that on October 20 the “race to the sea” was at an end, and the barrier established. It remained to hold it, and this was what brought on the battle of the Yser.

October 21. The situation of the Allies is as follows:

On the right, the English (three army corps).

In the centre, the French (three divisions, the marines, a Belgian brigade).

On the left, the Belgians (six divisions).

On the extreme left, the French 42nd Division.

Against which the Germans have at their disposal:

Six army corps belonging to the Fourth Army,

Five army corps belonging to the Sixth Army.

October 22. To frustrate the German plan, General Foch, in conjunction with Field-Marshal Sir John French and King Albert, gives the order to attack. The battle of the Yser begins.

In the north the Belgians and French make a vigorous attack, but a violent German counter-attack, supported by a formidable weight of heavy artillery, cuts short their offensive, and they have speedily to resort to flooding the district in order to stay the onrush of the Germans. The lock-gates at Nieuport are opened, and the water covers the whole valley of the Yser between Nieuport and Dixmude.

October 30. The Germans, nevertheless, are still pressing on the attack; but they are brought to a stop, and on November 2 are forced to recross the Yser, abandoning part of their artillery.

Farther south, in the Ypres region, the English in turn have taken the offensive on October 23, making Courtrai their general objective. From the 23rd to the 28th of October the attack develops favourably, but on the latter date the Germans make a vigorous counter-attack with six army corps, and drive in the English front.

At this point General Foch puts the equivalent of three corps of French troops at the disposal of Field-Marshal Sir John French, but again the Germans attack in force and compel the Allies to fall back. Field-Marshal Sir John French now contemplates a withdrawal to the west of Ypres. General Foch succeeds in making him give up this idea—an act of capital importance which was the deciding factor of the battle. The Allies counter-attack and stop the German advance.

From the 1st to the 6th of November the battle rages along the whole front: but, despite the superhuman efforts of the Germans, they fail to break through. The fighting continues, but it may be said that the great battle of the Yser was at an end on November 15. The Germans have failed to get through and attain their objective—the sea. Their losses are enormous. The Guard has been decimated, and more than 250,000 men are gone. On the Allied side, too, casualties are heavy. Both sides are exhausted, but set about reorganizing.

This huge battle of the Yser was the end of the “race to the sea.” The Germans, after trying in vain to turn the Allies’ left, had undertaken this march nach Calais, which might, indeed, have procured them considerable advantages from a strategical point of view. On November 15, 1914, they were obliged to give up the attempt. This battle of Ypres, if not a victory for the Allies, who with their depleted ranks were unable to exploit it, was, beyond a shadow of doubt, a decided defeat for the Germans.

The success was definitely and distinctly due to General Foch, who, though without official status, had known how to impose his will upon the Allies in the conduct of operations by his energy, his tenacity, and his unfailing confidence. To sum up, it was he who at all points DIRECTED the gigantic battle of the Yser and won it. Had it been lost, it was he who would certainly have borne the responsibility.

It is not my intention here to picture the gloomy realities of our pre-War military position. We know that the first effect of our unpreparedness was to lay French territory open to the enemy. Up to the present nobody has come forward to accept responsibility for our lack of quick-firing heavy artillery, or for the scandalous shortage of machine-guns, mistakes so grave that, but for the rally on the Marne, our territories from the frontier to Paris would have been in the grip of the enemy. Admirable as was this recovery from our defeat, it could not exhaust the impetus of the enemy offensive. The result of the first battle was to determine that the War was to be fought out on French soil, where the hostile armies applied themselves to the systematic ravaging of our industrial towns and of our country districts, along with the enslavement of the people.

Who then was responsible for this initial blunder? Is it impossible to tell us, or, at any rate, to pretend to make inquiry? If the historian ever thinks of timidly putting this question I will take advantage of the fact and put another to him. Was it forbidden to forecast that Germany might dishonour her own signature by violating the neutrality of Belgium? And what could prevent her from taking certain military steps to that end? And who did not know the German state of mind? And who could believe that a moral obstacle was the kind that could stop men or rulers for a single moment? I have looked through Colonel Foch’s work on the principles of war. I saw with utter dismay that there was not a single word in it on the question of armaments. A metaphysical treatise on war! And yet it is not without importance to know if an attack with catapults or with quick-firing guns may call upon us to vary our means of defence. Questions of this nature really deserve some consideration.

What a difference in mentality on the two sides of the Rhine! In Germany every tightening up of authority to machine-drill men with a view to the most violent offensive; with us all the dislocations of easygoing slackness and fatuous reliance on big words.

The letters exchanged between the King of England and M. Poincaré at the moment of the declaration of war bear sufficient witness to the common distress of the peoples concerned. Skilful and discreetly worded, M. Poincaré’s letter was in substance a request for help. Friendly but evasive. King George’s reply amounted to a refusal for the moment. England, still less prepared than ourselves, was slow to understand that she was to play her part. Had she had but one hour of flinching, all might well have been lost. The violation of Belgian neutrality was to put an end to her hesitations.

There was a certain incoherence and confusion about the preliminary arranging of alliances for a war that could no longer be avoided. It could not be otherwise, seeing that the advantage of organized anticipation was altogether on the side of Germany, in whose hands lay the offensive. So the first impulse of the Allies in the critical hours was in the direction of a universal demand for one supreme military authority. But every army is the highest expression of nationality in action, and the heads of the national power it represents did not easily yield on this point, nay, it was even the American people, the least military of all, that raised the greatest difficulties at the decisive moment.

From the outset of the War popular feeling in France had placed the hope of success in unity of command; and when once experience and the logic of theory were both agreed on this point, nothing was left but to agree upon the choice of the Generalissimo.[3] There never was the shadow of a discussion, to my knowledge, as to the principle, any more than there was about the person to whom that high post could be entrusted.[4] There were no competitors. Only the name of Foch was uttered. The main point was that Foch had displayed qualities of the highest kind in desperate circumstances which, above everything, called for miracles of resistance, while Mangin, with his vehement temperament, had been able to work miracles in the offensive. Both had, by logical sequence, the grave defect of being unable to endure the civil power—when they did not need its support.

Pétain, who is no less great a soldier, has brilliant days, and is always steady. In perilous battles I found him tranquilly heroic—that is to say, master of himself. Perhaps without illusions, but certainly without recriminations, he was always ready for self-sacrifice. I have great pleasure in paying him this tribute. He has been greatly blamed for the pessimistic utterances of his headquarters staff. The truth was, I verily believe, that the very worst could not frighten him and that he had no difficulty in facing it with unshakable serenity. But his entourage were too prone to open their ears to croakings. A few embusqués on the Staff flourished these abroad, with deductions and conclusions that were not those of their chief—who remained unshakably a great soldier.

This frightful War brought us out good generals, and many of those who have the right to risk an opinion will perhaps tell us that Foch was the most complete of them all. Simple minds, which are the majority, love to judge men in the lump, by an approximate description that they like to think final and clinching. But human nature is too complex, too variable, to lend itself readily to these summary methods, which do not always enable the most earnest sincerity to discover the true formula to describe a living force. Did General Foch, who was by no means rich in subtleties of character, possess along with his strategic talents the diplomatic aptitudes essential to an international chief? But we must not anticipate.

The difficulty came mainly from the British side, where our military influence was all the greater, inasmuch as we made no parade of it. I remained very moderate in conversations on the matter, knowing, in any case, through our constant friend Lord Milner, that the problem was moving slowly but surely toward the happy solution.

There was a long way to go. We had had too many wars with the British for them readily to fall in with the idea of placing their soldiers under the command of a Frenchman.

The day[5] I first broached the subject to General Sir Douglas Haig, as I was breakfasting at his headquarters, the soldier jumped up like a jack-in-the-box, and, with both hands shot up to heaven, exclaimed:

“Monsieur Clemenceau, I have only one chief, and I can have no other. My King.”

A bad beginning. Conversations followed without result, until that day at Doullens, when under the pressure of events Lord Milner, after a short colloquy with Field-Marshal Haig, informed me that the opposition to the unity of command had been dropped.

The rest followed. But several stages more were needed to arrive at a formula that should approximately secure all the necessary conditions for increased efficiency through the single command. Resistance in England came not so much from the Army as from Parliament, and, most of all, from the ‘man in the street.’ The idea of seeing a French general commanding British generals was for a long time unendurable. The argument seemed more to the point when our joint failure of 1917, under the temporary command of General Nivelle, was pointed out. But that was nothing more than the outward semblance of an argument that held good because no one ventured to go absolutely to the bottom of it.

It was at Doullens that Foch, without anyone’s permission, laid hold of the command. For that minute I shall remain grateful to him until my last breath. We were in the courtyard of the mairie, under the eyes of a public stricken with stupefaction, which on every side was putting the question to us, “Will the Germans be coming to Doullens? Try to keep them from coming.” Among us there was silence, suddenly broken by an exclamation from a French general, who, pointing to Haig close by us, said to me in a low voice:

“There is a man who will be obliged to capitulate in open field within a fortnight, and very lucky if we are not obliged to do the same.”

From the mouth of an expert this speech was by no means calculated to confirm the confidence we wanted to hold on to at all costs.

There was a bustle, and Foch arrived, surrounded by officers, and dominating everything with his cutting voice.

“You aren’t fighting? I would fight without a break. I would fight in front of Amiens. I would fight in Amiens. I would fight behind Amiens. I would fight all the time.”[6]

No commentary is needed on that speech. I confess that for my own part I could hardly refrain from throwing myself into the arms of this admirable chief in the name of France in deadly peril.

At the moment when we had found Foch out of favour in the post of Chief of the General Staff he already had to his credit two great defensive actions of the utmost brilliance.

On the Marne and on the Yser he had reached the heights in the desperate resistance that, by the power of his word, had fixed Field-Marshal French on the field of battle, and by his mere example he had maintained his troops invincible under the terrific onslaught of the enemy. The Germans had determined to win at all costs. Immovable in this extremity of peril, Foch had flung in his men to the very limit of the wild gallantry that carries the fighting soldier beyond the demands of duty. On that day they all entered together into the glory of the heroes of antiquity.

At length, in the Doullens conference—March 26, 1918—the varying phases of which have been many times related,[7] in the end the following text was agreed upon:

General Foch is charged by the British and French Governments with co-ordinating the action of the Allied armies on the Western Front. For this purpose he will come to an understanding with the Generals-in-Chief, who are invited to furnish him with all necessary information.

This was merely a first step, but it was decisive. The title of Commander-in-Chief was not yet accepted by the English. At Beauvais[8] I proposed to entrust Foch with “the strategic command,” and the formula was accepted. The text of the new agreement was as follows:

General Foch is charged by the British, French, and American Governments with the duty of co-ordinating the action of the Allied armies on the Western Front, and with this object in view there is conferred upon him all the powers necessary for its effective accomplishment. For this purpose the British, French, and American Governments entrust to General Foch the strategic direction of military operations.

At the request of the English the following phrase was added:

The Commanders-in-Chief of the British, French, and American Armies shall exercise in full the tactical conduct of their Armies. Each Commander-in-Chief shall have the right to appeal to his Government if, in his opinion, his Army finds itself placed in danger by any instruction received from General Foch.

In order to define the advantages attached to the title that was finally obtained, I asked General Foch to write to the Allied Governments. In his letter he laid stress on this argument, “I have to PERSUADE, instead of DIRECTING. Power of supreme control seems to me indispensable for achieving success.”

All that took time. At last, after continual pressing on my part, I obtained an answer from Mr Lloyd George: the British Government, he said, had no longer any objection to General Foch taking the title of Commander-in-Chief of the Allied armies in France.[9] On the same day our excellent General Bliss, after a conversation with General Mordacq at Versailles, sent me this message in the name of the President of the United States: “I guarantee that our Government will see nothing but advantage in the unity of command.”

For me it was less a matter of formulas than of the acts depending on them. Already at Clermont (Oise)[10] General Pershing had come to place himself at the disposal of his new chief in a moving speech, the memory of which has remained fresh and vivid in our hearts. At the same time Pétain too had come to take General Foch’s orders. On every side there was full harmony. We were on the threshold of decisive action.

What use was made of this higher command is a question that military history will have the task of clearing up. For many reasons I am not convinced that it actually played the decisive part public opinion is inclined to attribute to it. That history will have to be written by others than those who lived it. We must be told what amount of obedience was asked for and obtained, and in what circumstances, and for what results. We have not got so far as that yet.

It must indeed be said that in his exercise of the single command the Generalissimo at times gave way to hesitancies, to temperings of authority calculated to leave the desired and expected results in uncertainty. On the other hand, I think I can say that the commander of the British Army never submitted wholly to the instructions of General Foch, who was perhaps over-anxious to have no difficulty with the two great chiefs theoretically his subordinates.

Then came the evil day of the Chemin des Dames. To procure fresh effectives and to confirm General Foch’s authority[11] I had the following sentence inserted into the message sent by the heads of the Allied Governments to Mr Wilson:[12] “We consider that General Foch, who is conducting the present campaign with consummate skill, AND WHOSE MILITARY JUDGMENT INSPIRES US WITH THE UTMOST CONFIDENCE, DOES NOT EXAGGERATE THE NECESSITIES OF THE MOMENT.”

The chief trouble at this moment[13] came from Sir Douglas Haig, who, as usual, was unwilling to allow the Generalissimo to remove reserves from the English Army to use them on the French front.[14] The English desired first and foremost to protect the Channel ports. Nothing could be more natural. General Foch, who had French divisions in Flanders, did not wish to bring them away, because that was where he was expecting the German attack before and after the Chemin des Dames collapse. He informed me of the position. I had made it a fixed rule to abstain from all discussions of a purely military nature, but I had the right—it was even my duty—to make inquiries to discover whether the Supreme Command was functioning properly.

[1] September 7 and 8.

[2] These simple words at this critical moment display the character of the soldier.

[3] In an excellent article in the Revue des Deux Mondes (April 15, 1929) general Mordacq has elucidated this question in a remarkable manner. Subsequently he expanded this work in a volume in which General Foch is treated with the honour that is his due. Everybody knows that General Mordacq, one of our best generals of division, was the head of my military secretariat. I know those who have never forgiven him yet for that.

[4] Lord Milner had had the idea, in order to soothe the susceptibilities of the British soldier, of giving the title to me, so that the function might devolve upon Foch as Chief of the General Staff. It was never broached to me. Need I say that I should never have fallen in with this curious scheme?

[5] January 1918.

[6] I did not fail to report these words to the President of the Republic, who quoted them in his address to the great soldier when handing him the bâton of Maréchal de France, which I myself proposed for him.

[7] “. . . The meeting was fixed for eleven o’clock at Doullens, which was sensibly situated half-way between the English and French headquarters. At eleven o’clock precisely M. Clemenceau and I arrived at the Place de la Mairie, a square thenceforth historic. Shortly after came M. Poincaré, accompanied by General Duparge. . . . Field-Marshal Haig was there already, in conference in the mairie with his army commanders, Generals Home, Plumer, and Byng.

“Then came General Foch, calmer than ever, nevertheless not succeeding in hiding his ardent desire to see the Allies at last come to certain logical decisions. . . .

“Lastly, General Pétain arrived in his turn, anxious enough. . . .

“It was rather cold, and to keep ourselves warm we walked about in little groups in the square in front of the mairie, these little groups halting every now and then to talk together.

“The scene was not lacking in impressiveness and unusualness. Upon the highway, which runs along the square itself, there might be seen English troops retiring sedately, in perfect order, without showing the least trace of any emotion of any kind—the British imperturbability in the fullest acceptation of the word; then, seemingly nearer every moment, a violent cannonade: the German guns, which were, in fact, a few kilometres away, calling us back to reality and making us think of ‘the great game that was being played.’

“All those men in that modest little square, all those Frenchmen who fully understood the situation, were well aware of the importance of this day. That is why under a calm exterior the pangs of anxiety gnawed at every heart.

“But time was going on, and still the English did not arrive.

“Noon. . . . Still nobody. . . .

“At length, at five minutes after twelve, Lord Milner’s cars rolled up. General Wilson was with him.

“The Anglo-French conference then began, the time being twenty minutes past twelve.

“M. Clemenceau at once brought up the question of Amiens. Field-Marshal Haig declared that there had been a misunderstanding on the matter, that not only had he never thought of evacuating Amiens, but that it was his firm intention to bring together every division at his disposal to reinforce his right, which was obviously his weak spot, and consequently that of the Allies. His line would hold north of the Somme, that he guaranteed absolutely; but to the south of the river he could do nothing more; and besides he had placed all the remaining elements of the Fifth Army under General Pétain’s orders. . . . To which General Pétain replied, ‘There is very little of it left, and in strict truth we may say that the Fifth Army no longer exists.’ Field-Marshal Haig added further that he might perhaps be obliged to rectify his line before Arras, but that this was not yet certain: he even hoped it need not come to that. Those were the resources at his disposal; in his turn he asked the French to disclose theirs.

“General Pétain was then called upon. He explained the situation as he saw it, and as it really was—in other words, gloomy enough—and stressed all the difficulties he had been forced up against since March 21. He added that since the previous day, and the Compiègne interview, he had looked for all possible resources to cope with the situation, and that he was happy to be able to say that he would perhaps manage to throw twenty-four divisions into the battle, though, of course, these divisions were far from fresh, and most of them had just been fighting. In any case, he felt that in a situation of this kind it was essential not to be deceived by illusions, but to look realities in the face, and accordingly it must be realized that a fairly considerable time was necessary to get these units ready to take part in operations. At all events, he had done everything possible to send all available troops to the Amiens region, not hesitating even to strip the French front in the centre and east—even beyond what was prudent. He therefore asked that Field-Marshal Haig would be good enough to do the same on his side.

“Field-Marshal Haig replied that he would ask nothing better than to ‘do the same, but that unfortunately he had absolutely no reserves and that in England itself there were no men left capable of going into the line immediately.’

“At this a distinct chill fell upon the meeting, and for some moments no one said a word. General Pétain’s straightforward account of the position had naturally made a profound impression upon everybody, and especially on the English. This can be traced from Lord Milner’s report [see Appendix I for the official text of this report made by Lord Milner to his Government on his journey to France].

“General Pétain, he says, ‘gave a certain impression of coldness and caution, as of a man playing for safety. None of his listeners seemed very happy or convinced. Wilson and Haig evidently were not; indeed, Wilson made an interjection which almost amounted to a protest. Foch, who had been so eloquent the day before, said not a word. But, looking at his face he sat just opposite me—I could see he was still dissatisfied, very impatient, and evidently thinking that things could and must be done more quickly.’ This interval of silence and embarrassment could not continue for long. M. Clemenceau signed to Lord Milner, and taking him into a corner put this question to him at once, ‘We must make an end of this. . . . What do you propose?’ As a matter of fact, he felt that this time the thing had come to a head, and, like a clever manœuvrer, he meant to leave it to the English to make the request for what France had been preaching for months past, but always without obtaining any satisfaction. Lord Milner was very clear and definite: he proposed to entrust General Foch with the general control of the French and the English Armies, the one logical solution of the problem, in his opinion, as matters then stood. M. Clemenceau forthwith called General Pétain over, and informed him of Lord Milner’s proposal. Nobly the General replied that he was ready to accept whatever might be decided in the interest of his country and of the Allies. Lord Milner was in the meantime putting the same thing to Field-Marshal Haig, who, with an eye only to the general interest, likewise immediately accepted the proposed solution.

“M. Clemenceau forthwith drew up the following note: ‘General Foch is charged,’ ” etc.—Le Commandement unique, by General Mordacq (pp. 77-88).

[8] April 3, 1918.

[9] April 14, 1918.

[10] March 28, 1918.

[11] June 2, 1918.

[12] It was only at the express request of Mr Balfour that General Foch’s declaration was communicated to President Wilson in the name of the French Government, as well as of the British.

[13] June 1918.

[14] I know nothing of the relations between Sir Douglas Haig and Foch. I think I can say that the British commander never gave his complete obedience. It may readily be supposed that I never put too definite questions to the military chiefs in regard to this.

Foch, then, was unwilling to withdraw troops from Flanders, where he expected the German attack. It took place on the Aisne, but that did not deter the Commander-in-Chief from keeping his reserves in the north and on the Somme, as in his opinion the Germans could get no results from the attack on the Aisne. Three rivers crossed within five days nevertheless brought the German artillery to Château-Thierry—that is to say, within eighty kilometres of Paris. Will anyone maintain that that is not an important result? Anybody can make a mistake, but there is no real reason for clinging to an opinion in the teeth of the evidence. The man who knows he can go wrong himself might very well grow lenient. When the Marshal lectured his comrades because they had not won the War in 1917, they might have hit back with the failure of the Somme offensive in 1916 and the Chemin des Dames collapse in 1918. We might just as well say that if Marshal Joffre had won the battle of Charleroi the War might have stopped at that.

To avoid all contradiction, the Chemin des Dames affair has been dealt with in the Mémorial by way of judicious selection. It would really be too plain sailing if it was possible to avoid discussion by this simple device.

The Commander-in-Chief may have made a mistake, a mistake of the worst kind, with regard to the point of the enemy’s attack, but his first duty was to guard himself to the best of his power, and the Chemin des Dames, our most important field fortification, was badly—indeed, very badly—guarded. The event proved this only too well.

In reply to my first inquiries I was briefly told that such things are inevitable in war, that anyone, soldier and civilian alike, may be found at fault, and that it was no good dwelling upon the fact. After this opening Foch changed the conversation. When he saw me insisting with my questions he wanted to know if I intended to court-martial him, to which I replied that there could be no question of that.

However, personal responsibilities were involved, and we had first of all to find some temporary settlement of the case, at the same time taking every care not to shake what confidence remained in the minds of the public. To-day this all seems elementary, but in such an emergency, when the very life of the country was at stake, a head of the Government had to have the power of making up his mind promptly and of finding the happy medium between severity and moderation.

As was natural, Parliament, spurred on by public opinion, was greatly excited and did not spare the military leaders, but this did not alter the fact that I should have aggravated the situation considerably, had I begun, in the midst of this grievous confusion, replacing them by others who, after all, were perhaps less prepared. Above all, it was necessary to hold one’s own against the currents of public opinion clamouring for penalties without knowing on whom they were to fall.

I was thoroughly resolved not to stake the final success on a random chance. I complied unhesitatingly with all the demands for information that came from Parliament. I appeared before the commissions, where I met with the keenest hostility. But there was a speedy return of confidence when it became clear that I meant to hide nothing. Meanwhile I was continually up and down the country to see the leaders at their fighting-posts, to comfort and encourage them if necessary, and to maintain confidence, as much as lay in my power. In such emergencies a chief, with uniform or without, who keeps the stubborn will to win has plenty to do.

Below I quote as far as I can from the notebook of General Mordacq, whose tireless devotion never flagged for as much as a single hour.

On May 27, 1918, the Chemin des Dames, which was supposed to be an impregnable fortress, falls at the first onslaught of the German attack without offering any resistance. The bridges of the Aisne are carried, and to this day nobody has attempted to tell us how. The enemy crosses three rivers in succession without any trouble. He reaches Château-Thierry, where he blows up the bridge.

The next day, May 28, a journey to Sarcus, General Foch’s H.Q. He does not believe in an attack on a large scale, as it is quite certain that it could not have important strategical results for the Germans. So he does not think he ought to move his strategical reserves, which at the moment are in Flanders and in the Amiens district.[1]

May 26, 1918. The French tactical situation on May 26, on the Aisne front (Chemin des Dames):

This front, which stretched over a length of ninety kilometres, was very weakly held: three army corps (eleven divisions) with a thousand guns. . . .

The German tactical situation on the same front (between Noyon and Rheims):

Nine divisions between Noyon and Juvincourt.

Three divisions between Juvincourt and Courcy.

For the attack on May 27 the Germans increased these forces, first of all to thirty divisions, and then, between May 27 and May 30, to forty-two divisions, supported by four thousand guns.

Thus the Germans were going to attack with four times the strength of the Allies in both men and artillery.

The German Plan. The attack in Flanders having failed to obtain the results hoped for (namely, to separate the Belgian and English Armies, to use up the English reserves, and to reach the coast), Ludendorff decides to attack the Allies on the Aisne, a sector that he knows is weakly defended and without strategical reserves. His intention is to draw the Allies’ reserves to that region, and then to reopen the main attack in Flanders and make an end of the British Army.[2] . . .

The Attack, May 27. The infantry attack is launched at 4 A.M. after an artillery preparation lasting four hours. . . .

The Germans, thanks to their numerical superiority, advance rapidly. At 8 A.M. they cross the Chemin des Dames.[3] At twelve they are over the Aisne and reach the Vesle in the evening. . . .

May 28. Their progress continues. By 11 A.M. Fismes has fallen, and at close of day they are outside Soissons, having taken a considerable number of prisoners. . . .

Paris is in a high state of excitement. The French G.H.Q. has to-day ordered nine divisions to the Soissons district, but without paying sufficient attention to the organization of the command.

May 29 and 30. The Germans continue their victorious march: they capture Soissons, cross the Arlette on the 30th, and this same day reach the Marne at Jaulgonne.

The French reserves continue to arrive.[4] The Tenth Army is recalled from the Doullens district.

May 31 and June 1. The Germans lie along the banks of the Marne between Dormans and Château-Thierry. Everywhere else they can only advance with the greatest difficulty, continually coming up against the French reinforcements, which are arriving in ever-increasing numbers. They try, in vain, to get round the thickly wooded massif of Villers-Cotterets; they cannot penetrate into the forest itself, which is strongly held by our troops. . . .

June 2. It may be said that by the 2nd of June the German attack is definitely stopped. The Germans now have thirty-seven divisions facing them, divided into three armies (Maistre, Duchesne, and Michelet), while another fifteen divisions are on their way to reinforce these. So the enemy’s onrush will not be able to make much further headway.

June 2 to June 8. And, in fact, from the 2nd to the 8th of June all the German efforts are broken against the organized resistance of the Allies.

In this battle of the Chemin des Dames the Allies lost more than sixty thousand prisoners, seven hundred guns, two thousand machine-guns, a considerable amount of flying and artillery material, large depots of munitions, provisions, and stores of all kinds, important medical organizations, etc. . . .

The Paris-Châlons railway, so necessary for bringing up supplies, was no longer usable.

Thus it was a real disaster.[5]

This attack was quickly followed by that of Compiègne (June 9 to June 12).

May 28. Go to Belleu, H.Q. of General Duchesne, in command of the Sixth Army; he has fallen back to Oulchy-le-Château. We go there. He explains the situation to us, which is by no means bright; the German advance continues, and we have nothing but ‘sweepings’ to pit against them. He complains that since the attack began he has not seen a single chief belonging to the High Command.

We spend the night at Provins, General Pétain’s H.Q. He complains of Foch’s sending the reserves up north and to the Somme. He had opposed it. Sends troops to stop the gap, but they are not used to advantage. There is a shortage of artillery.

May 29. The next day, May 29, we go to Fère-en-Tardenois, which we reach just as the Germans arrive. We escape. Thence to Fresnes, General Degoutte’s fighting-post. His part in the fight: he tells us of divisions being flung into the battle one after another, without artillery. A tragic sight to see the General silently weeping over a tattered remnant of a map, and all the while a continuous stream of motor-cyclists arriving with reports of the enemy’s approach. I left him with no hope of ever seeing him again. For me this is one of the most poignant memories of the War.

Lunch at Oulchy-le-Château with General Duchesne, to cheer him up, and try to get precise information about the battle.

Visit General Maud’huy at Longpont. His impressions—his anger against Duchesne. Then to Ambreny, General Chrétien’s H.Q.

We return to Paris. State of confusion.

Panic in the Chamber.

May 30. Go to Trilport (General Duchesne’s fighting-post), to Coupru (General Degoutte’s fighting-post), to Longpont (General de Maud’huy).

The hole is stopped up, but there is a great lack of artillery.

Popular agitations at Paris demanding the heads of Duchesne, Franchet d’Esperey, Pétain, and Foch.

Interview at Trilport. Discussion on the journey. Foch, Pétain, and Duchesne severely criticized. Weakness of the subordinate command. Necessity of cutting out the dead wood.

Paris very nervous, especially over the abandoning of the bridges on the Aisne.

In spite of the animosity of the Allies against Foch, M. Clemenceau has these words inserted in a telegram to the Allied Governments: “We consider that General Foch, who is conducting the present campaign with consummate skill, and whose military judgment inspires us with the utmost confidence, does not exaggerate the necessities of the moment.[6] . . .”

June 3, evening. Sitting of the Commission de l’Armée. M. Clemenceau says, “We must have confidence in Foch and Pétain, those two great chiefs who are so happily complementary of each other. . . .”

June 4. My interview with Foch at Mouchy-le-Châtel. The necessity of removing the incompetent Divisional Commanders. Foch must speak about this to Pétain.

Better news from the Front.

I had to make things right with Parliament. I am always and unvaryingly a staunch Parliamentarian. I must admit that the Parliamentary system as we know it is not always a school for stout-heartedness. All the conversations before that formidable meeting were full to bursting with evil auguries for the High Command. I never wavered. I took everybody under my shield, to the great astonishment of those who had told me that by throwing all the responsibility on the Commander-in-Chief I should regain the authority belonging to my position.

Obviously, the more Foch’s power had been increased, the greater was his military responsibility. No one knew it better than he did. By nature he was not a great talker. I did not try (for I had not the time) to form a personal opinion as to the military responsibility taken as a whole, and later I was given no opportunity to get to know. So I only exchanged a few vague remarks with the Generalissimo, and went to the Parliamentary battle without telling anyone what I proposed to do. I won a signal victory, and at the same time shielded all my subordinates; but nobody can seriously doubt that, had I faltered for a single moment, the High Command would have been swept away. Foch never said a word to me about this sitting, at which it is no mere boast for me to say that I saved him. You must admit that this silence on Foch’s part might well lend itself to comment. We had not yet come to our great disputes over the American Army and the annexation of the Rhineland. No harsh words had or have ever passed between us. Nothing more, perhaps, than the inevitable clash of military and civil power. But I took great pains never to press the discussion too far, and for my part I never took a very marked stand against him until the day he tried to maintain to me that he was not my subordinate, going on to open insubordination in the matter of the Nudant telegram.

Meeting of the Chamber, June 4, 1918[7]

The Chemin des Dames Affair. Questions.

M. Aristide Jobert. I wish to ask the Government what steps they intend to take in order to provide our heroic and magnificent French Army with the leaders it deserves, and also what penalties they propose to inflict upon those who are found to be incompetent. . . .

M. Frédéric Brunet. . . . Mr Prime Minister, it does not appear to us that in the recent fighting sufficient foresight has been shown in taking all the precautionary measures necessary for safeguarding the lives of the men and for employing their heroism to the best advantage. When we saw the first onrush of the Germans on the Somme not a soul faltered in the whole country; we all said with you, “They shall not get through.” But when we have seen this Chemin des Dames, along which so many of our men have fallen in order to keep it in French hands, we could not but feel a momentary pang, and asked ourselves if those in command had really done their whole duty, . . . and if the law comes down with crushing force upon the soldier who fails to do his duty it ought to deal still more drastically with the leader who through negligence or lack of foresight may well be the cause of irretrievable defeats.

M. Clemenceau addresses the House:

If, to win the approbation of certain persons who judge in rash haste, I must abandon chiefs who have deserved well of their country, that is a piece of contemptible baseness of which I am incapable, and it must not be expected of me.

If we are to raise doubts in the minds of the troops as to the competence of certain of their leaders, perhaps among the best, that would be a crime for which I should never accept responsibility. . . .

These soldiers, these great soldiers, have leaders, good leaders, great leaders, leaders in every way worthy of them.

. . . Does that mean that nowhere there have been mistakes? That I cannot maintain; I know the truth full well. It is my place and duty to find out those mistakes and to correct them. That is what I am devoting my energies to. And in that task I have the support of two great soldiers whose names are General Foch and General Pétain.

Our allies have such high confidence in General Foch that yesterday, at the Conference of Versailles, it was their wish that the communiqué given to the Press should contain a reference to that confidence.

(A deputy: It was you that made them.)

These men are at this very moment waging the hardest battle of the War, and they are waging it with a heroism for which I can find no words equal to the task of describing it. And is it for us, because of some mistake that occurred in this place or that, or even never occurred, to ask for, to extort explanations before we know the facts, while the battle is still raging, from a man exhausted with fatigue, whose head droops over his maps, as I have seen with my own eyes in hours of dreadful stress? Is this the man we are going to ask to tell us whether on such and such a day he did thus or thus?

Turn me out of the tribune, if that is what you want, for I will never do it.

. . . I said that the Army had surpassed all we could have expected of it, and when I say “the Army” I mean the men of all ranks and of all grades under fire. That is one of the factors in our confidence, the chief factor. Faith in a cause is indeed a fine thing, but it does not bring victory; for the victory to be assured men must die for their faith, and our men are dying now.

We have an Army made up of our children, our brothers, of all our own people. What could we have to say against it?

The leaders too have sprung from among ourselves; they too are our kinsmen; they too are good soldiers. They come back to us covered with wounds, or remain for ever on the field of battle. What have you to say against them?

. . . We have allies who are pledged with us to carry on the War to the end, to the ultimate success that is within our grasp, that we are on the very eve of grasping if only we have enough tenacity. I know full well that the majority of this House will have that tenacity. But I should have rejoiced had it been unanimous.

I maintain—and these must be my closing words—that victory depends on us . . . so long as the civil powers are equal to their task, for this exhortation would be superfluous to the soldiers.

Dismiss me if I have been a bad servant, drive me out, condemn me, but at least first take the trouble to put your criticisms into plain words.

For my part I claim that up till now the French people, and every section of it, has done its duty to the full. Those who have fallen have not fallen in vain, for they have found a way to add to the greatness of French history.

It remains for the living to finish the glorious work of the dead.

Foch was saved.

I quote again from General Mordacq’s notes:

June 5. Parliamentary intrigues proceed. M. Clemenceau is obliged to stay in Paris, and sends me on June 5 to Bombon (Marshal Foch’s H.Q.) and to Provins (General Pétain). We must have done with the incompetent leaders. On the other hand, the need for energetic and competent chiefs is felt more than ever. M. Clemenceau decides to recall Guillaumat from Salonica, and to relieve Franchet d’Esperey of his command and send him to Salonica. Foch and Pétain both agree.

This resolution was taken without consulting Lloyd George, who had declared himself against Foch and Pétain.

June 7. Meeting at the War Ministry: Lord Milner, Haig, Foch, Wilson. Use of English divisions on the French front. Foch’s dilatory answer.

June 8. Visit Third Army, General Humbert (Oise). Warning of impending German attack. Everything prepared to receive it.

June 9. The attack is launched.

Night and day since the vote of confidence had I been going up and down visiting the fighting-posts. Everywhere I was brought back to the everlasting question of the lapses of subordinate commanders. This lamentable rout, upon which some day we shall have to make up our minds to shed the light of day, was no doubt attributable in the first place to the High Command, which was not sufficiently in touch with the actual fighting units. But had the secondary commands been strongly welded together, we should have been able to hold out, in spite of the absence of the reserves whom Foch was keeping up in Flanders doing nothing.

Finally I told the Generalissimo that new duties had been imposed upon us by reason of our victory in Parliament, and I appealed to him on his military conscience as supreme commander to tell me if he had no urgent reforms in the personnel to suggest. Without hesitating he replied that the chief fault was the inadequacy of his Staff,[8] but that it was very difficult to reorganize, because it meant breaking up General Pétain’s Staff.

I replied that General Pétain was the most disinterested of men, and that it would be sufficient to give him the explanation to which he was entitled. At the same time I drew from my pocket a fairly long list of older generals whom I had decided to replace.

I had defended the High Command in the House, but I knew very well, from having seen it close to on my visits to the Front, that an important group of leaders had grown old and ought to be replaced. Foch certainly knew it as well as I did, perhaps even better, but, as with many chiefs, the phrase ‘old comrade’ was a very potent charm with him.

I must say that the Commander-in-Chief offered no resistance to my determination. Without losing a moment we went to General Pétain, and I laid before him as well as I could the conversation I had just had with his chief. With his customary placidity General Pétain, Commander-in-Chief of the French Army, heard me through without uttering a word. Then he said:

“Monsieur le Président, I give you my word that if you leave me an army corps to lead I shall deem myself greatly honoured, and that I shall rest content in carrying out my duties properly.”

It was one of those high moments that can never be forgotten.

I then returned to my list of generals to be relieved of their commands, which the Generalissimo did not challenge in one single instance; he knew too well each one’s deficiencies. At certain names I saw him shrug his shoulders with the murmur, “An old friend!” The sacrifice was consummated with but few exceptions. As a matter of fact, Foch asked me to spare those of his “old comrades” who were on parts of the Front where there was no fighting, and promised that if the occasion called for it he would rigorously apply the same standard.

My duty should have been to resist this appeal to normal human weaknesses, for the battle might break out at any moment in those places where it was temporarily dormant. If a disaster occurred the blame would have only too justly been laid at my door. I took that chance to win my way into the good graces of the Generalissimo, who himself only retained his post thanks to my intervention in the Chamber. On what grounds does he accuse me of persecuting him? Where would you be to-day, my dear Marshal, had I not interposed my breast between you and your judges? I have to remind you of this because you never thought of it yourself.

In accordance with my promise, a Parliamentary commission was set up, and had placed before them all the documents, which, owing to other more pressing occupations, I have never seen. When they had declared themselves unable to discover where the various responsibilities lay my only remaining opponent was Marshal Foch, and the reason for the silence in which the Mémorial is entrenched is only too well understood to-day.

[1] I am inclined to think that a great deal might be said on the passages I have italicized.

We must look at our losses in men and artillery, and in ground too, before agreeing with Foch that the Chemin des Dames affair “was not an attack on a large scale.” On what sort of scale is an attack that enables the Germans to get within eighty kilometres of Paris?

The Germans had the advantage in numbers, but that was because they had managed to deceive Foch—which cannot possibly be considered a feather in his cap. They taught me at school that the first thing in the art of war is to meet the enemy in force.