* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Woodmyth & Fable

Date of first publication: 1905

Author: Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946)

Date first posted: Apr. 14, 2020

Date last updated: Apr. 14, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200427

This eBook was produced by: Alex White, David Edwards, David T. Jones, Chuck Greif & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

TEXT & DRAWINGS BY

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON

PUBLISHED by THE CENTURY CO. NEW YORK 1905

Copyright, 1903, 1904, by

The Century Co.

Copyright, 1905, by

Ernest Thompson Seton

——

Published April, 1905

——

First

Impression

April

15,

1905

THE DE VINNE PRESS

{3}

| Page | |

| List of Full-page Drawings | 7 |

| Foreword | 11 |

| The Collector of Lies | 13 |

| The Land-crab | 16 |

| The Cure of the Gulper | 18 |

| How the Giraffe Became | 23 |

| Three Lords and a Little Lord | 30 |

| The Ten Trails | 36 |

| Where Truth Lives | 39 |

| The Twin Stars | 40 |

| The Two Log-rollers | 41 |

| The Converted Soap-boiler | 42 |

| The Wise Woodchuck | 46 |

| The Fairy Lamps | 48 |

| The Scatterationist | 53 |

| The Point of View | 57 |

| The Origin of the Bluebird | 60 |

| |

| The Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo | 64 |

| The Sunken Rock | 67 |

| Dogwood | 68 |

| The Three Phœbes of Wyndygoul | 70 |

| The Road to Fairyland | 78 |

| Comfort | 79 |

| Kalendar of the Seton Indians | 80 |

| Kalendar of the Seton Indians | 81 |

| The Seasons on Chaska-water | |

| The Awakening Days | 83 |

| The Thunder-bird | 91 |

| The Smoking-days | 101 |

| The Demon Dance | 109 |

| The Indian and the Angel of Commerce | 118 |

| A Recipe | 121 |

| The Big Rough Statue | 122 |

| Appetite and Food | 125 |

| The Fairy Ponies | 126 |

| Witches’ Luck | 127 |

| The Fable of the Yankee Crab | 128 |

| The Bullfrog fills his little throat | 130 |

| Up to Date | 131 |

| The Grasshopper that Made the Missimo Valley | 134 |

| A Knotty Problem | 137 |

| The Single Way | 138 |

| A Fable for Architects | 140 |

| The Feather and the Frump | 142 |

| Familiar Sayings | 143 |

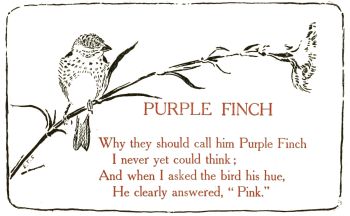

| Purple Finch | 144 |

| Veery and Solomon’s Seal | 145 |

| The Fretful Porcupine | 146 |

| How the Chestnut Burrs Became | 147 |

| An Explanation | 149 |

| The Heaven-sent Skunk | 150 |

| The Doings of a Little Fib | 152 |

| The Wendigo | 161 |

| The Saving Warmth | 162 |

| The Myth of the Song-sparrow | 164 |

| The Pack-rat | 166 |

| The Hunters | 170 |

| The Great Stag | 173 |

Most boys gather in the woods pretty and odd bits of moss, fungus, and other treasures that have no price. They bring them home and store them in that universal receptacle, the Tackle-box. Some boys, like myself, never outgrow the habit. One day a friend observed that my Tackle-box was full and suggested that a selection be given to the public.

Most of this booty I gathered in the woods myself, but an Indian gave me fragments of “The Recipe” and “Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo,” and a Chinaman told me where to find “The Frog in the Well.{13}{12}”

VENERABLE old man with a pen behind his ear, and ink on his fingers,

went up the main street of Humantown, calling out as he went:

VENERABLE old man with a pen behind his ear, and ink on his fingers,

went up the main street of Humantown, calling out as he went:

“Lies! Any old lies to-day? Biscuits for lies to-day!”

He had a basket of sweet wafers, or biscuits, on one arm, and they were shaped like a human ear. These he was exchanging for the lies, that were very abundant in this town.

Most of the inhabitants freely gave them to the man; some even pressed them on him: but a few had to be repaid with at least a wafer. Very soon the old man’s bag was full.

It was a new thing to collect lies, and{14} many jokes were bandied at the expense of the old man and his odd occupation. The strange merchant left the main street, and a little child had the curiosity to follow him. The venerable one turned aside through a door into a beautiful garden in the very heart of the town and yet quite unknown. He closed the door, but the child peeped through the keyhole, and saw the old man take the bag of lies and give it a good shake. There was a commotion and rattling inside for a time, and the mass seemed to be smaller.

“Ah, hear them eating each other up!” chuckled the old man.

Another shake was followed by more commotion and another shrinkage. The collector’s face beamed.

A few more shakes, and the bag seemed actually empty; but the old man opened{15} it carefully, and there in the far corner was a pinch of pure gold.

The child reported all these things, and the next time they saw the old man, the people demanded who he was. He answered:

“I am the Historian.{16}”

AM absolutely unchangeable. Nothing can turn me aside one

hair’s-breadth from my purpose,” said the little Land-crab, as he left

his winter quarters in the hills and began his regular spring journey to

the Sea. But during the winter a line of telegraph poles had been placed

along his track. The Land-crab came to the first pole. He would not turn

aside one inch. He spent all day climbing up the side of the pole, and

all the next day climbing down the other side, then on till he came to

the next pole, where he had another frightful climb up and over and down

again. Thus he went on day after day, and when the summer was gone they

found the body of the poor{17} little Land-crab dead at the bottom of one

of the poles only half-way to the Sea, which he might have reached

easily in half a day had he been contented to deviate six inches from

his usual line of travel.

AM absolutely unchangeable. Nothing can turn me aside one

hair’s-breadth from my purpose,” said the little Land-crab, as he left

his winter quarters in the hills and began his regular spring journey to

the Sea. But during the winter a line of telegraph poles had been placed

along his track. The Land-crab came to the first pole. He would not turn

aside one inch. He spent all day climbing up the side of the pole, and

all the next day climbing down the other side, then on till he came to

the next pole, where he had another frightful climb up and over and down

again. Thus he went on day after day, and when the summer was gone they

found the body of the poor{17} little Land-crab dead at the bottom of one

of the poles only half-way to the Sea, which he might have reached

easily in half a day had he been contented to deviate six inches from

his usual line of travel.

Moral: A good substitute for Wisdom has not yet been discovered.

O, my child; the dragons and monsters are not all gone. There are just

as many as ever there were, and they are just as powerful and wicked,

only we fight them differently now. We do not send for a good fairy, but

for some other kind of dragon.

O, my child; the dragons and monsters are not all gone. There are just

as many as ever there were, and they are just as powerful and wicked,

only we fight them differently now. We do not send for a good fairy, but

for some other kind of dragon.

“Not long ago, and not far away, there was a farming country of great thrift and prosperity, but much handicapped by the smallness of its horses,—the best of these could carry only a small load,—so every one was surprised, and later on delighted, when a philosopher brought them a wonderful monster that was stronger than a thousand horses. This was called a Gulper, and it drew the heaviest loads as{19} though they were nothing. Large numbers were bred, and soon each community had at least one. Before long, however, the new beasts developed an unpleasant nature. Their original meekness began to disappear. They became surly, then dangerous; at last they had to be pampered and pacified on all occasions. They still did a great deal of the heaviest work, but became so tyrannical and outrageous in their demands that each community was reduced to a state of slavery, and its monster terrorized all and owned everything, quickly destroying those who resisted him. There was never a more downtrodden people. Things were as bad as possible, when a naturalist, one day, as he walked in the woods and pondered this terrible condition, said:

“‘In my world every beast has his foe{20} that tames him when he outrages the bounds. If I only could find the Bugaboo of the Gulper!’

“So he sought and sought and sought; then he came to the country whence they had brought the Gulper, and there he found the Gulper’s Bugaboo. It was nothing but an ordinary monoculous Angletail. It was a slim yellow thing with very short legs, one immense red eye at each end of its body, and a long thin tail that grew out of the middle of its back and was carried stiffly raised and pointing behind. The Angletail could go backward or forward equally well, but one could always tell beforehand which way it was going, because the tail would switch over and point backward, and the eye at the end which now became the rear would lose its light and would go sleepy, while{21} the other fairly blazed with fire. The Angletail was much smaller than the Gulper, but its activity was wonderful. The Gulper was swift, but the Angletail could climb hills and dodge in a way that was far beyond the ablest Gulper, and once it got after the monster it never stopped running alongside till it had sucked his life-blood. Not that Gulpers were its only food, but the farmers did all they could to urge on the Angletail, and it was very ready to respond. Finally all a man had to do to tame a rebellious Gulper was to put up his mouth as though about to whistle for the monoculous one, and at once the monster was cowed and glad to make any kind of terms, and they all lived happy ever after.

“You don’t understand? Well, my child, the Gulper is the greedy, grinding{22} railroad company, and its Bugaboo is the trolley-car. Let us hope that there will always be deadly enmity between the monopolous Gulper and the monoculous Angletail.”

Moral: Every bug has its bugaboo.

AGES ago in the deserts of Africa there lived a little brown Antelope. He was not strong like the Lion, nor big like the Elephant, nor had he horns like the Koodoo, nor claws like the Leopard. He could not swim, nor could he climb or fly. When danger came he could do nothing but run away, and this he did very well.

But he was not satisfied.

One day he saw a Man, and he walked quietly up to look more closely at the strange creature of whom he had often heard. As he watched he saw a Lion crawling to spring on the Man. Now the Antelope’s mother had taught him that when he saw a Lion trying to{24} kill some creature he must warn that creature; this is desert etiquette. So he gave a great start, and snorting out, “Lion! Lion!” he bounded past the Man, spreading the little white danger-flag that some writers call his tail. The Man heard the warning and got into a tree in time to escape the Lion. After the Lion had gone the Man called the Antelope and said:

“Little Antelope, I am a prophet of Allah; you have saved my life from that ill-informed Lion, and therefore you shall have whatever you ask.”

Then the Antelope said: “When Allah made the beasts it seems he forgot me, for he gave me no claws, teeth, horns, nor tail to flap the flies, nor strength nor power to fly, climb, or swim. Please, good Prophet, tell him that he left me{25} out and ask him to give me the things I need.”

“But,” said the Prophet, “you cannot have all: if you have size you cannot climb a tree; if strength, you need not be swift.”

But all the Prophet’s talk was in vain; the little Antelope wanted at least horns, size, strength, a long fly-flapper tail. “Then,” said he, “I shall be content.” To this the Prophet said: “So be it, little Antelope; go to the long slope of Mount Epoch, and there roll in the Dust of Ages.”

The Antelope did so, and was overjoyed to find himself of great size and strength, with a beautiful fly-flapper tail, and two long horns on his head.

After some time, however, he found that there was yet much needed to{26} complete his happiness. His great size called for so much more food that he had to live in the rank bushes, where he could not see the lurking dangers; and, besides, it cost him his speed, so that his troubles were increased. Therefore he again sought the Prophet and said:

“Good Prophet, it was clearly your intention to make me happy for saving your life at great risk to myself. Now, surely you are not going to make a failure of any of your good plans. Please ask Allah to complete my equipment by giving me a long neck so I can overlook the bushes where I must feed, and also increase my speed, for I need it.”

“Very good,” said the Prophet. “Now go and bathe in the Long Reach of the{27} River called the Wear-of-Time.” The Antelope did so, and when he came out he had a long neck and legs, as he had wished.

But his long neck made grazing troublesome, and his great weight made marshy ground dangerous, so he was driven to seek his food among the bushes as tall as himself, where the ground was firm.

At length there came a very dry year when all the low foliage died, and the Antelope had eaten all he could reach and was like to die of hunger. So he sought the Prophet as before, and begged his aid to make his neck yet longer, that he might reach the topmost foliage. “As a matter of fact,” said the Antelope, “I would gladly give up these stupid horns for a few more inches of neck.”

“Very good,” said the Prophet. “Go{28} and pass through the Burning Valley called the Tribulator of Selection.”

The Antelope did so, and found himself as he had wished, with a neck that would reach the tallest trees, but with the useless horns burnt off where the hair of his head ended.

Before long the Antelope was back with a new request. His long yellow neck was too easily seen afar; he wanted it painted like a tree-trunk; and the four hoofs he still had on each foot were a positive handicap—he knew he could get around faster if they were reduced to two on each foot. “Then,” said he, “I know I should really and truly be content.”

But in all his asking the Antelope never once asked for a change of heart, and the Prophet, out of all patience, said: “These last requests shall be granted when you{29} have eaten of the tree called Environal Response; but to prevent you making any more you shall henceforth forever be mute.” And it was so.

There he is to-day, of vast stature, the tallest in the world, only two hoofs on each foot, no horns, voiceless—a huge creature, truly; but his heart is still the heart of the timid little Antelope, and the days of his kind are numbered.

While those of his race who were content as Allah meant them to be—nothing but swift—still dwell in safety on their wild, free deserts in the Land of the Sun.

Moral: Any fool can improve on creation.

HERE were three Lords and a little Lord in the forest where Manitou

made them.

HERE were three Lords and a little Lord in the forest where Manitou

made them.

The first was Mi-in-gan. He was swift as the spotted Redfin and tireless as the Kamanistiquia where it leaps from Kakabeka Rock to the boiling gorge of the Gitche Nanka. His voice was like the moan of a far looming whirlwind—not loud nor rough, but soft, and yet with a tone to freeze the stoutest heart. His weapons were twenty-four white arrows that pierced the foe, then leaped back again to their quiver; and his cunning was like that of the Wa-wa of many snows.{31} In this was his power—in this and in his tireless feet.

The second great Lord was Mūs-wa, of mighty strength and great stature. None could equal him. When he went to war, he brandished four war-clubs and a hundred spears that always returned to his hand after throwing. His voice was like the rending of ice in the Hunger Moon. He was swiftest of them all and strongest of them all, and in his great strength he put all his trust.

The third was Mai-kwa, the silent. He was strong, but less so than Mūs-wa. He was cunning, but less so than Mi-in-gan. He carried two great clubs and had twelve white arrows which pierced and returned to the quiver.

There was yet another, a little Lord in{32} the Forest, Wee-nusk. He was weak and small, and he knew it. He had two little axes for wood-cutting. He had no great strength, and he knew it, and knowing his weakness, he had wisdom.

Now Manitou, when he had made them and the Forest, spake thus:

“Behold, I have made you and given you the Forest to live in. Go now and live according to the law of the Forest; but remember this, ye children of Mother Earth: to all the Earth-born there comes a day of dire extremity, of peril beyond all power to save but one—the power of Mother Earth. Therefore, be ready to seek her. Keep open and clear the trail to her abode. Make plain the way in Sunshine of prosperity, for no trail opens in the hour of dreadful stress.”

But Mūs-wa trusted in his might.

He said: “I am the strongest in the Wood.” And Mi-in-gan trusted in his cunning. He said: “I am the wisest in the Wood.” And Mai-kwa said: “I am wise as fearless Mi-in-gan, and strong as fearless Mūs-wa. Why should I fear?”

Only Wee-nusk remembered the warning. He was not cunning, but he spent part of each spring and fall making plain the trail to Mother Earth. So when the Far-Killing Mystery reached the Forest, the first to go down was the strong Mūs-wa, and the second the tireless, cunning Mi-in-gan, and the third was Mai-kwa. Their strength was as a burnt grass-blade; their cunning was silly. There was no help for them, for they knew no trail of escape.

But Wee-nusk ran to Mother Earth, and the Far-Killing Mystery could in no wise do him harm.{35}

So to-day he alone remains in the Land of the Pequot. Mūs-wa, the great Moose, is gone; Mi-in-gan, the cunning Wolf, is gone; Mai-kwa, the strong and cunning Bear, is gone.

They forgot the road to Mother Earth, and the Rifle wiped them out.

But Wee-nusk, the weak and unintelligent Woodchuck, is left, the only Lord of the Forest; for he trusts not to himself but flies for refuge to the Earth.

Moral: Get back, ye Earth-born, back to Mother Earth.

NCE there were two Indians who went out together to hunt. Hapeda was

very strong and swift and a wonderful bowman. Chatun was much weaker and

carried a weaker bow; but he was very patient.

NCE there were two Indians who went out together to hunt. Hapeda was

very strong and swift and a wonderful bowman. Chatun was much weaker and

carried a weaker bow; but he was very patient.

As they went through the hills they came on the fresh track of a small Deer. Chatun said: “My brother, I shall follow that.”

But Hapeda said: “You may if you like, but a mighty hunter like me wants bigger game.”

So they parted.

Hapeda went on for an hour or more and found the track of ten large Elk going{37} different ways. He took the trail of the largest and followed for a long way, but not coming up with it, he said: “That one is evidently traveling. I should have taken one of the others.”

So he went back to the place where he first found it, and took up the trail of another. After a hunt of over an hour in which he failed to get a shot, he said: “I have followed another traveler. I’ll go back and take up the trail of one that is feeding.”

But again, after a short pursuit, he gave up that one to go back and try another that seemed more promising. Thus he spent a whole day trying each of the trails for a short time, and at night came back to camp with nothing, to find that Chatun, though his inferior in all other{38} ways, had proved wiser. He had stuck doggedly to the trail of the one little Deer, and now had its carcass safely in camp.

Moral: The Prize is always at the end of the trail.

It’s my opinion,” said the Frog in the well, “that the size of the ocean is greatly overrated.”

CERTAIN good man loved things old because they were quaint. He said he

would gladly give up locomotives and printing-presses to have “the”

spelled “ye,” as of old. It gave him a spasm of joy to see a building

called a “bvilding,” and he was filled with gloats whenever he could get

a newspaper to spell “gospel” as “gofpel,” or “honor” as “honoure”—it

was “so qvaint, so Shakespearian!”

CERTAIN good man loved things old because they were quaint. He said he

would gladly give up locomotives and printing-presses to have “the”

spelled “ye,” as of old. It gave him a spasm of joy to see a building

called a “bvilding,” and he was filled with gloats whenever he could get

a newspaper to spell “gospel” as “gofpel,” or “honor” as “honoure”—it

was “so qvaint, so Shakespearian!”

A friend, who was making a fortune boiling soap by day, and spending it in gathering a library by night, took him to task one day, thus: “There was a time in the evolution of the alphabet when u and v, d and t, p and b, w and v, etc., were imper{43}fectly differentiated, and used somewhat indiscriminately; but to revive this thing now is to breed confusion, to step backward and downward. It is as bad as restoring the useless tags that the horse once had on each side of his feet where formerly there were other toes. In their day these oddities of spelling reflected their time; to import them into our present day is not only opposed to common sense, it is as dishonest as if we were to stamp a modern product ‘Anno Dom. CC.’ Suppose, now, one of these spurious imitative inscriptions to be dug up five hundred years hence. Though only five hundred years old, the internal evidence makes it double that age, thus lending itself to a lie and building up an abominable deceit.”

“Thou art all wronge,” said the antiquary. “Ye delycious quaintnesse of ye{44} antient masters waye did breede yem an atmosphere of sweetnesse and joyaunce yat was verily ye mother of theire greatnesse. Shakespeare never could have written had he been yforced to a type-writer, neither could Spenser have sung had he been compelled to spell ‘faerie’ as ‘fairy.’ Ye atmosphere which bred yem was bred of ye quaintnesse of yr spelling.”

The soap-boiler was touched, for he loved books. He pondered all these things for long, and then he wrote to his friend:

“Verily mine eyen are oped. I have seen a greate lichte and have a newe hearte withinne me. Odzooks! I have lost much time, pardee, but I will this atmosphere of quaintnesse in mine owne kingdomme, for I have charged mine hirelings that they call me ‘ye master.’ Be{45}shrew me, but I am minded to oust mine—my—type-writer—is it not so called?—and hie me to ye holy goose-quille of mine fathers. I have, moreover, inscribed a newe tablet for ye gabel that is ye ende of mine workes wherein I do boyle mine soap. By my halidome, methinks it lilteth right merrilie and smacketh of much and comelie quaintnesse.”

F all the beasts that roamed the woods in their primeval state,

F all the beasts that roamed the woods in their primeval state,

HERE was once a little bare-legged, brown-limbed boy who spent all his

time in the woods. He loved the woods and all that was in them. He used

to look, not at the flowers, but deep down into them, and not at the

singing bird, but into its eyes, to its little heart; and so he got an

insight better than most others, and he quite gave up collecting birds’

eggs.

HERE was once a little bare-legged, brown-limbed boy who spent all his

time in the woods. He loved the woods and all that was in them. He used

to look, not at the flowers, but deep down into them, and not at the

singing bird, but into its eyes, to its little heart; and so he got an

insight better than most others, and he quite gave up collecting birds’

eggs.

But the woods were full of mysteries. He used to hear little bursts of song, and when he came to the place he could find no bird there. Noises and move{49}ments would just escape him. In the woods he saw strange tracks, and one day, at length, he saw a wonderful bird making these very tracks. He had never seen the bird before, and would have thought it a great rarity had he not seen its tracks everywhere. So he learned that the woods were full of beautiful creatures that were skilful and quick to avoid him.

One day, as he passed by a spot for the hundredth time, he found a bird’s nest. It must have been there for long, and yet he had not seen it; and so he learned how blind he was, and he exclaimed: “Oh, if only I could see, then I might understand these things! If only I knew! If I could see but for once how many there are and how near! If only every bird would wear over its nest this evening a little lamp to show me!{50}”

The sun was down now; but all at once there was a soft light on the path, and in the middle of it the brown boy saw a Little Brown Lady in a long robe, and in her hand a rod.

She smiled pleasantly and said: “Little boy, I am the Fairy of the Woods. I have been watching you for long. I like you. You seem to be different from other boys. Your request shall be granted.”

Then she faded away. But at once the whole landscape twinkled over with wonderful little lamps—long lamps, short lamps, red, blue, and green, high and low, doubles, singles, and groups: wherever he looked were lamps—twinkle, twinkle, twinkle, here and everywhere, until the forest shone like the starry sky. He ran to the nearest, and there, surely, was a bird’s nest. He ran to the next; yes,{51} another nest. And here and there each different kind of lamp stood for another kind of nest. A beautiful purple blaze in a low tangle caught his eye. He ran there, and found a nest he had never seen before. It was full of purple eggs, and there was the rare bird he had seen but once. It was chanting the weird song he had often heard, but never traced. But the eggs were the marvelous things. His old egg-collecting instinct broke out. He reached forth to clutch the wonderful prize, and—in an instant all the lights went out. There was nothing but the black woods about him. Then on the pathway shone again the soft light. It grew brighter, till in the middle of it he saw the Little Brown Lady—the Fairy of the Woods. But she was not smiling now. Her face was stern and sad as she said: “I fear I{52} set you over-high. I thought you better than the rest. Keep this in mind:

IMS settlement was beginning to feel itself a place of importance. The

chief road had a fence on both sides of it for over a mile, and a blaze

on a large tree was already ordered with the official inscription “Main

street.” There had been talk of the possibility of a store, and local

pride broke forth in noble eruption when a meeting was called to

petition for a post-office. The wisdom, worth, and wealth of the place

were represented by old Sims. He was a man of advanced ideas, the

natural leader of the community; and after all the questions had been

duly discussed, the store and post-office resolved upon, the question of

who was{54} to run them came up. There were several aspirants, but old Sims

led the meeting, expressing the majority and crushing the minority in a

brief but satisfactory speech:

IMS settlement was beginning to feel itself a place of importance. The

chief road had a fence on both sides of it for over a mile, and a blaze

on a large tree was already ordered with the official inscription “Main

street.” There had been talk of the possibility of a store, and local

pride broke forth in noble eruption when a meeting was called to

petition for a post-office. The wisdom, worth, and wealth of the place

were represented by old Sims. He was a man of advanced ideas, the

natural leader of the community; and after all the questions had been

duly discussed, the store and post-office resolved upon, the question of

who was{54} to run them came up. There were several aspirants, but old Sims

led the meeting, expressing the majority and crushing the minority in a

brief but satisfactory speech:

“Fust of all, boys, I’m opposed to this yer centerin’ of everything in one place. Now that’s jest what hez been the rooin of England; that is why London ain’t never amounted to nothin’—everything at London. London is England; England is London. If London’s took, England’s took, says I, an’ that hez been her rooin.

“The idee of House o’ Lords an’ House o’ Commons in the same town! It ain’t fair, I tell ye; it’s a hog trick. Why didn’t they give some little place a chance instead o’ buildin’ up a blastin’ monopoly like that? Same thing hez{55} rooined New York, an’ I don’t propose to hev our town rooined at the start.

“Now I say no man hez any right to live on the public. ‘Live an’ let live,’ says I; an’ if we let one man run this yer store, it’s tantamount to makin’ the others the slaves of a monopoly. Every man hez as much right as another to sell goods, an’ there is only one fair way to do it, an’ that is give all a chance; an’ sence it falls to me to make a suggestion, I says, let Bill Jones thar sell the tea; let Ike Yates hev the sugar; Smithers kin handle the salt; Deacon Blight seems naturally adapted for the vinegar; and the other claims kin be considered later. I’ll take the post-office meself down to my own farm. Now that’s fair to all.”

There was no flaw in the logic; it was most convincing. Those who would fight{56} found themselves without a weapon, and Scatteration Flat became a model of decentralization.

Work? Oh, yes, it works. Things get badly mixed at times, and it takes a man all day to buy his week’s groceries; but old Sims says it works.

Moral: The hen goes chickless that scatters its eggs.

QUIET country home among fruit-trees and shrubbery; the gray-bearded

Master, a famous vegetarian, in the porch reading a paper; a rolling

meadow; a flock of well-fed sheep.

QUIET country home among fruit-trees and shrubbery; the gray-bearded

Master, a famous vegetarian, in the porch reading a paper; a rolling

meadow; a flock of well-fed sheep.

Scene I. In the Master’s House. The Graybeard looking over the meadow.

“How can human beings be so bestial as to prey on their flocks? For me there is no greater pleasure than to know I can make their lives happy. Their annual wool is ample payment for their keep. But I see by the paper that this awful sheep pestilence has broken out on the coast. I must waste no time; nothing but inoculation can save them. Poor things, how I{58} wish I could spare them this pain!” So the Graybeard, with his man, caught the terrified sheep one by one, while a butcher in a blue blouse sat on the fence and grinned. Each sheep suffered a sharp pang when the inoculator pierced its skin. Each was more or less ill afterward. But all recovered, and the plague which swept the country a month later left only them alive of all the countless flocks.

Scene II. Among the sheep.

First Sheep: “Ah, how happy we should be but for that treacherous gray-bearded monster! Sometimes and for long he feeds us and seems kind, and then without any just cause there is a change, as the other day, when he came with his accomplice and ran us down one by one and stabbed us with some devilish in{59}strument of torture, so that we all were very ill afterward. How we hate the brute!”

Second Sheep: “If only we could come into the power of that gentle creature in the blue blouse!”

Chorus: “Ah, that would be joy! Bah—bah—bah!”

Moral: The more we know the less we grumble.{60}

INNA-BO-JOU, the Sun-god, was sleeping his winter’s sleep on the big

island just above the thunder-dam that men call Niagara. Four moons had

waned, but still he slept. The frost draperies of his couch were gone;

his white blanket was burned into holes; he turned over a little. Then

the ice on the river cracked like near thunder. When he turned again it

began to slip over the big beaver-dam of Niagara, but still he did not

awake.

INNA-BO-JOU, the Sun-god, was sleeping his winter’s sleep on the big

island just above the thunder-dam that men call Niagara. Four moons had

waned, but still he slept. The frost draperies of his couch were gone;

his white blanket was burned into holes; he turned over a little. Then

the ice on the river cracked like near thunder. When he turned again it

began to slip over the big beaver-dam of Niagara, but still he did not

awake.

The great Er-Beaver in his pond flapped his tail, and the waves rolled away to the shore and set the ice heaving, cracking, and groaning; but Ninna-bo-jou slept.{61}

Then the Ice-demons pounded the shore of the island with their clubs. They pushed back the whole river-flood till the channel was dry, then let it rush down like the end of all things, and they shouted together:

“Ninna-bo-jou! Ninna-bo-jou! Ninna-bo-jou!”

But still he slept calmly on. Then came a soft, sweet voice, more gentle than the mating turtle of Miami. It was in the air, but it was nowhere, and yet it was in the trees, in the water, and it was in Ninna-bo-jou too. He felt it, and it awoke him. He sat up and looked about. His white blanket was gone; only a few tatters of it were to be seen in the shady places. In the snowy spots the shreds of the fringe with its beads had taken root and were growing into little{62} flowers with beady eyes. The small voice kept crying: “Awake; the Spring is coming!”

Ninna-bo-jou said: “Little voice, where are you? Come here.”

But the little voice, being everywhere, was nowhere, and could not come at the hero’s call.

So he said: “Little voice, you are nowhere because you have no place to live in; I will make you a house.”

So Ninna-bo-jou took a curl of Birch bark and made a little wigwam, and because the voice came from the skies he painted the wigwam with blue mud, and to show that it came from the Sunland he painted a red sun on it. On the floor he spread a scrap of his own white blanket, then for a fire he breathed into it a spark of life, and said: “Here, little voice,{63} is your wigwam.” The little voice entered and took possession, but Ninna-bo-jou had breathed the spark of life into it. The smoke-vent wings began to move and to flap, and the little wigwam turned into a beautiful Bluebird with a red sun on its breast and a shirt of white. Away it flew, but every Spring it comes, the Bluebird of the Spring. The voice still dwells in it, and we feel that it has lost nothing of its earliest power when we hear it cry: “Awake; the Spring is coming!”

FTER the Great Spirit had made the world and the creatures in it, he

made the Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo. This was like an Owl, but bigger than

anything else alive, and his voice was like a river plunging over a

rocky ledge. He was so big that he thought he did it all himself, and

was puffed up.

FTER the Great Spirit had made the world and the creatures in it, he

made the Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo. This was like an Owl, but bigger than

anything else alive, and his voice was like a river plunging over a

rocky ledge. He was so big that he thought he did it all himself, and

was puffed up.

The Blue Jay is the mischief-maker of the woods. He is very smart and impudent; so one day when the Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo was making thunder in his throat, the Blue Jay said: “Pooh, Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo, you don’t call that a big noise! You should hear Niagara; then you would never twitter again.”

Now Niagara was the last thing the{65} Manitou had made; it never ceases to utter the last word of the Great Spirit in creating it: “Forever! forever! forever!”

But Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo was nettled at hearing his song called a “twitter,” and he said: “Niagara, Niagara! I’m sick of hearing about Niagara. I will go and silence Niagara for always.” So he flew to Niagara, and the Blue Jay snickered and followed to see the fun.

When they came to Niagara where it thundered down, the Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo began bawling to drown the noise of it, but could not make himself heard.

“Wa-wa-wa,” said the Gitch-e O-kok-o-hoo, with great effort and only for a minute.

“WA-WA-WA-WA,” said the river, steadily, easily, and forever.

“Wa-wa-wa!” shrieked Gitch-e O-{66}kok-o-hoo; but it was so utterly lost that he could not hear it himself, and he began to feel small; and he felt smaller and got smaller and smaller, until he was no bigger than a Sparrow, and his voice, instead of being like a great cataract, became like the dropping of water, just a little

And this is why the Indians give to this smallest of the Owls the name of “the water-dropping bird.”

When the top is wider than the root, the tree goes down.

POSITIVELY decline to have that young Clippercut in my house again.

His influence on my son is most dangerous.”

POSITIVELY decline to have that young Clippercut in my house again.

His influence on my son is most dangerous.”

“Why, my friend, he is far from being a bad fellow. He has his follies, I admit, but how unlike such really vicious men as Grogster, Cardflip, and Ponyback!”

“Sir, the only danger of a sunken rock is that it is not sunk deep enough.”

HEN Adam was in Eden, his choicest plant of all

HEN Adam was in Eden, his choicest plant of all

HREE little Phœbes came to Wyndygoul in the month of March, and sang

their song in the trees by the water till it was time to set about

nesting.

HREE little Phœbes came to Wyndygoul in the month of March, and sang

their song in the trees by the water till it was time to set about

nesting.

The first one was a Wise Little Bird,—even he suspected that,—and after thinking it all out he said: “I shall build high on the rock that is above the Lake of Wyndygoul, and the deep water shall be the moat of my castle.”

Then the second one thought it all out, and he was the Wisest of all the Phœbes. He simply knew it all, and he knew that he knew. So he said: “The rock has its advantages, but it is very ex{71}posed to the enemies above. I shall build under this low root on the bank. It shelters all sides, my nest will be concealed, and the rushing water of the River of Wyndygoul shall be the protecting moat of my castle.”

But the third little Phœbe was a Little Fool, and he knew it. And he said to his wife: “We are so foolish we cannot foresee all the dangers—we do not even know what they are; but we do know this: that there is a Blue Devil called the Blue Jay, and a Brown Devil called the Hawk, and a Night Devil called the Weasel, and we know that they are not the biggest things on earth. There is some one here bigger than they. Let us put our trust in him. We will build our nest between the sticks of his nest: perhaps he will protect us.”

So they did. They put the nest right in the porch of his house. It was not high, and it was not hidden, nor was there any moat to their castle. Its only protection was an “influence,” and that was invisible; but it was felt all about the porch that is on the lawn that is above the Lake of Wyndygoul.

And there they all sat on a warm April morning when the nests were made, the Wise One on the rock singing “Phœ-bee,” and the Very Wise One under the root singing “Phœ-be,” and the Foolish One on the porch singing “Phœbe-e.”

They sang so loudly that a Hawk, passing by, thought, “Something is up,” and he looked for the nests; but the one on the rock he could not reach, the one{73} under the root he could not find, and the one on the porch he dared not go near.

And the Weasel heard them and thought, “Oh, ho! I shall investigate this to-night.” But the chilly water kept him from the two nests, and there was an uncomfortable feeling about the porch that he preferred to avoid.

But there came at length the Blue Devil called the Jay. When he heard the singing he said: “Where there are songs there are nests.” And he found where the nests were, by watching their owners. So he flew to the rock and looked in that nest. It was finished, but empty. “Very good,” said the Blue Jay; “I can wait.”

Then he flew to the root and looked into that nest, and there was one egg.{74}

“Oh, ho!” said the Jay, “this is good luck, but not enough. I know that Phœbes lay more than one egg. I can wait.” So, though his beak watered a little, he let it alone and went—but no; he did not go to the porch, because the man had made an “influence” there, and it was repugnant to the Blue Jay.

And the three little Phoebes sang merrily their morning-song in the trees by the Lake of Wyndygoul.

Next morning the Blue Jay went over to the rock nest, and there was one egg in it, and he said: “Very good as far as it goes, but I can wait. I’ll see you later.”

Then he went to the nest under the root,—a very hard nest to find it had been,—and there were two eggs. The Blue Jay turned his wicked head on one side and counted them with his right eye, then on the other side and counted them with{75} his left eye, and said: “This is better, but I know that a Phœbe lays more than two eggs. I can wait.”

He did not go to the porch. He had his own reasons. And next morning the three little Phœbes sang their three little songs in the trees by the Lake of Wyndygoul.

But the Blue Jay came as before, and he looked at the nest in the rock, and said: “Oh, ho! there are two eggs now. Keep on, my friends, keep on; this is true charity. You are going to feed the hungry. I think I will wait a little longer.”

Then he went to the root above the water, and in that nest were three eggs. “Very good,” said the Blue Jay. “A Phœbe-bird may lay four or even five eggs, but give me a sure thing.” So he swallowed the three eggs in the root nest.

And next morning there were only two{76} little Phœbes singing happily in the trees by the Lake of Wyndygoul.

But the Blue Jay came around again two days later, and he called only at the rock nest. He looked out of his right eye, and then out of his left. Yes, there were four eggs in it now. “I know when a nest is ripe,” said he, and he swallowed them all and tore down the nest. Then the little Wise Phœbe came and saw it, and was so heart-broken with sorrow that he tumbled into the lake and was drowned.

Next morning there was only one little Phœbe that merrily sang in the trees by the Lake of Wyndygoul.

But the Very Wisest Phœbe began to say to himself: “I made a mistake. I built too high up. My nest was all right, it was perfect, but a little too high.”

So he began a new nest low down, close to the water, under the same black root,{77} by the River of Wyndygoul, and the Blue Jay could not reach it then; he only got wet in trying.

But one night, when there were three more eggs, and the Wisest Phœbe was sitting on them, a great Mink put his head out of the water and gobbled up Phœbe, eggs, and all.

And the next morning there was only one little Phœbe-bird with his nest, and that was the Foolish One that knew he was foolish, and that built in the porch of the house that stood on the hill that is close by the Lake of Wyndygoul. And he sang all that spring, and his nest was soon filled with growing little ones. And they got bigger and bigger, till they were too big for the nest; and at length they all fledged and flew, and lived happily ever after in the trees by the Lake of Wyndygoul.

Moral: Wisdom is its own reward.{78}

HITER than death was Chaska-water, paler than fear. Well had the

Ice-demons worked; swift and sure had their arrows sped. Only the waste

of snow was there. Nothing was left that moved or cried or rustled on

Chaska-water.

HITER than death was Chaska-water, paler than fear. Well had the

Ice-demons worked; swift and sure had their arrows sped. Only the waste

of snow was there. Nothing was left that moved or cried or rustled on

Chaska-water.

Oh, Moon that swung in the silent sky, knew ye ever so fearful a stillness?

Oh, black cloud blocking the blacker sky, was there ever so awful a deadness?

Tense—tenser—snap!

The breaking had come—not a sound, not a move, but a feeling. Up from the south came a gentle breath, a fanning too faint{85} for a south wind; only a feeling bearing a voice that reached not ears, but our being, and told of a coming—a coming.

A snow-lump fell from a fir-tree and ruffled the white on the water. “Coming, coming!” it sang.

A drop of water rolled from a sandbank and dimpled the white on the water, with a “Coming, coming!”

Trronk—trronk—trronk, in the sky to the southward.

Trronk—trronk—trronk, the flying buglers come.

TRRONK—TRRONK—TRRONK, and louder. An arrow, a broad-headed arrow, appears.

TRONK—TRONK—TRONK, and a whirring of pinions, and the broad arrow grows to an army—an army of buglers.{86}

Hark how they shake all the fir-trees! See how they stir the small snow-slides!

Tronk—trónk—tronk, and the ice on the lake is a-shiver.

Trónk—tronk—trónk, and the rill that was dead is a-running.

Tronk—trónk—tronk, and the stars are lost.

TRÓNK—TRONK—TRÓNK, and the sun comes up to blaze on the Chaska-water. Red and gold and bright is the sun, silver the bugles blowing.

Tronk, coming, coming, coming, and the clamor is lost in the northlands. The heralds have sped with the tidings.

“Coming, coming!” the Cranes are crying.

“Coming, coming!” the Woodpecker drums.

“Coming, coming!” the Reeds whisper, rejoicing and rasping together. Only the{87} snow-drifts weep, and their tears in a thousand rills run down, melting the snow and sawing the ice as they trickle on Chaska-water.

Open the stretches of water now; Gulls and Terns and Ducks are there, Divers and Butterflies, Midges and Gnats, singing and shouting, even while silent—“Coming, coming, coming!”

But loudest of all is the calm, clear sky of warmest blue, with a golden sun, a golden ball in the great over-bowl.

“Coming, coming, coming!” It booms in silence, and still looks down, and all is expectant—awaiting.

“Coming, coming!” And the myriad heralds’ cries have melted and softened to a world-wide gentle murmur, almost a hush—the hush in the pageant that follows the heralds’ announcement.

It came at last: not from the south or{88} the east or the west, not from the skies of promise, but from the sand at the edge of a dwindling snow-drift, up from the earth it came. Up to the light of the golden sun in a warm blue sky, raised and gazed a golden star in a warm blue bowl—the Sun-god flower, the Sand-hill bloom.

It sprang, and it spread like a fire on the plains, and it heaved and it drifted like opal snow—like lilacs all sprinkled with golden dust.

And this is the Sand-bloom born of the Spring; this is the Spring-bloom born of the Sand. This is the darling the heralds announced; and Spring is on Chaska-water.

EAD was the wind on Chaska-water.

EAD was the wind on Chaska-water.

Gone were the living breezes.

Long had the winter been banished, and the sheen of the blue on the hills of the brown was lost in the screening of leafage.

Life there was in the pool, in the bush, in the marsh and the wood: life, life in a precious abundance, but life that was heavy with heat-sleep.

Heavy hung the reeds and the cattails; heavy and limp the leather-soft leaves of the aspen.

Heavy and hot and dry were the Wolf-willows thick on the ridges.{93}

Hot and dry and listless the Snake; dusty and hot was the Redtail.

A day and a week, and the air grew hotter and deadlier—fiercer than heat in the sweat-lodge; and muffled was every face, like the dead, in blankets—invisible blankets.

Instead of a sky was a coppery bowl, that fitted tight down at the world-rim.

The song of the birds had faded and died; there was no sound in the branches.

There was no song but the hot-weather bug, that chirrred as he added his torment.

“Better far was the onset of Peboan, for he gave a warning. Better, for we could escape to the south, but now we are buried and helpless.”

Baked in their shells were the unhatched birds; roasted the feet of the downlings; and when, in the morning, the{94} mother Grouse clucked hoarsely to her brood, there was no answer, for dead were they lying around her.

O Wabung! the Wind of the Morning, O Mudjeekeewis, the West Wind! are ye dead? Are ye dead?

O Master of Life! art thou sleeping?

Mes-cha-cha-gan-is! thou swiftest of runners, take word.

Pai-hung! thou trumpet-voiced herald away.

Chewusson! best loved of singers, proclaim to the Master our fearful condition.

But Mes-cha-cha-gan-is was lying as dead. Pai-hung was feeble, and Chewusson silent as Pauguk. Only the Hot-weather Bug, the Cicada, was heard as he sang, as though glad of our torment, “B-z-z-z-z-z.”

And louder in glee he sang and thrilled{95} and rejoiced in his moment—“B-z-z-z-z-z-z.”

And louder—till Anee-mee-ki was awaked; not the Master, but he of the Wings and the Thunder.

“What stifles the Chaska-land? What murders the Middle-folk? The big bronze Over-bowl,—the lid of the Evil One,—killing the air, killing the rain.”

And he flew down on it like a Nighthawk, stooping and booming—flew so it rumbled beneath him.

But it moved not.

Then he struck with his mountain-splitter, so it rumbled and rang; and again, so it split.

And the Evil One rushed hot-breathed to attack him.

Bang! thunder! he smote on the Death-bowl—so it crashed, but the red arrows flamed and rebounded.{96}

The Evil One tore up an oak for a club.

Bang! Baim-wa—again, so the sky was dark with clouds of dust, the gloom and the heat were dreadful, and frightful the swishing of pinions, the eye-flashing glances were fearful, and the fighters were hot-breathed and cold-breathed, as they rumbled and pounded.

Crack! bang! and the bowl was a-shiver. Swish, flash, ha-roo! Roll! Roll! Baim-wa, battler, warrior, fighter!

Bang! Baim-wa, again and again, and the rain of a month withheld came roaring in rivers downward.

Crack! arrows of light; crash! war-clubs of power, as the two were a-swirl, in the battle, on the hills of the Chaska-water—tossing, dashing, bending the groves; pelting with arrows {97} {98} and spears and a sky full of hail; wrecking the trees and flowers, smashing the birds, jarring the hills, tilting the lake from end to end so its waters went foaming and racing. Flying coppery fragments in the sky; cold wind pursuing the hot wind; a broad and trampled pathway across all the Chaska-land where the two had united in battle.

Down, down on all sides fall the shards of the bowl. The blue sky is appearing. Down, down to the margin they fall—and are lost.

The pent-up rain has been emptied: only the gentle shower of last night is now falling. The frightened lake looks pleasantly blue and rippling. The cool breeze is abroad; and out of a thicket all trampled and smashed by the fighters{99} comes the voice of the gentlest and simplest of singers—the green-leaf singer—the Vireo.

The spirit bird, so frail that an unkind breath, a falling flower, might kill him, without a puissant guardian, what could he do?

But there is no fear in his voice, no broken plume in his wing; he is unwounded and fearless as he softly sings:

A song of the bluest sky he sings, of the greenest leaf, of the freshest airs and the rippling lake; a song of the sweetest days, for now is the calm summer weather abroad—aglow on the Chaska-water.{100}

HE Red moon waned over Chaska-water, the Red and the Hunting and

Leaf-falling moons.

HE Red moon waned over Chaska-water, the Red and the Hunting and

Leaf-falling moons.

Signal-fires rose on the hills by the lake.

Signals to all: “Come to council.”

Teepees were seen on the hills—painted and beautiful teepees, red and orange and brown, the tents of the tribes now assembling.

A herald outcries:

“The days grow short and the Mad moon comes. Old Peboan’s scouts have spied out our camp. Oh, blacken your faces for Chaska-water.”

That night came the hostile spies{103} again. There was fear on the camp in the morning.

The spruce-spires made uneasy sounds. A going there was in the tree-tops; a shivering sound in the aspens. And the hard white clouds above bumped together like ice-chunks in the spring flood of Assiniboinisipi.

The loud trumpeters crossed the sky; the squawkers were squawking; the rumblers were rumbling; a thousand added to the clamor born of the fear that was born of the clamor.

“The White foe comes; we are as the brood of Shesheep when Wah-gush finds them afoot and a mile from the water. We are caught unready.”

There was confusion and panic—till Ninna-bo-jou was apprised, and, vexed at their fear, proclaimed: “I alone plan{104} for the future; take ye what I send ye”; and he blew a blast that shook down all the painted teepee covers; only the poles were left, standing in rows, on the banks of the Chaska-water.

“Hear, now, ye trembling Teepee-folk! War there is coming, but Truce for ten days there shall be, while I smoke my peace-pipe; Peace while its smoke is up-curling. Prepare ye, prepare for your trial of hardship.”

Down on the bank of the Chaska-water sat he a-smoking; and the Teepee-folk, hastening, made ready.

The Bluejay began another hoard of acorns.

The Beaver added two span to his dam.

The Muskrat piled on one more layer of rushes to his hut-thatch.

The Partridge dusted his plumage, so it might fluff out more fully.{105}

The Spruce-borer went his length more deep into the solid tree.

The Fox shook and licked his tail into shape for a muffler.

The Red Squirrel chewed ten more bundles of bark for his blanketing.

The Chipmunk stuffed another handful of earth into his alleyway.

The Gopher rushed forth for a final load of grass, took one look backward at the sun, and hid below.

The Trumpeter Cranes, the Swans, and the Geese went sailing away to the offing.

The last Red Rose dropped her petals five—the last of the race of the prairie.

Still Ninna-bo-jou sat a-smoking. Over the tree-tops circled the smoke,—for calm and bright and warm was the weather,—over the hills and the lake, till the landscape{106} was veiled in a haze. A mystical haze and a splendor, a dreamy calm, was over all, for this was the Peace of the Smoking-days. This was the Indian Summer.

For ten fair days the Peace was smoked. The Fliers had gone and the Dwellers made ready. Then Ninna-bo-jou arose, and departing, he shook the ash from his pipe. A rising wind drifted its whiteness over the hills, blew all the smoke from the landscape. Now another feeling spreads abroad. The moon of the Falling leaves has waned, the Mad moon comes, awesome and chilling and dark. At morn there are spears of white on the ponds, there are tracks and signs—the signs of an on-coming enemy, of a foe irresistible. For this is the death of the Red Rose days; this is the dawn of the Mad moon gloom. This is the end of the joy and the light—the coming of Kabibonokka.{107}

LUE in its tawny hills is Chaska-water. Black are the spruce-trees that

raise their spires on its banks. Ducks and Gulls in myriads are here,

and the shallows are dotted with Rat-houses. The Loon and the Grebe find

harvest in its darker reaches. The Blue Heron and the Rail stalk and

skulk on its sedgy margin. Fish swarm in its depths, Deer and Rabbits on

its banks, Birds in its trees abound. For Chaska-water, rippling bright

or darkling blue, is a summer home of the Sun-god. Ninna-bo-jou is its

guardian and its indwellers are his special care. All through the summer

he taught them and led them{111}—showed them the way of their living,

taught them the rights of the hunter; all through the autumn he led

them.

LUE in its tawny hills is Chaska-water. Black are the spruce-trees that

raise their spires on its banks. Ducks and Gulls in myriads are here,

and the shallows are dotted with Rat-houses. The Loon and the Grebe find

harvest in its darker reaches. The Blue Heron and the Rail stalk and

skulk on its sedgy margin. Fish swarm in its depths, Deer and Rabbits on

its banks, Birds in its trees abound. For Chaska-water, rippling bright

or darkling blue, is a summer home of the Sun-god. Ninna-bo-jou is its

guardian and its indwellers are his special care. All through the summer

he taught them and led them{111}—showed them the way of their living,

taught them the rights of the hunter; all through the autumn he led

them.

Then came the cold.

Down from the north it came riding—riding with wicked old Peboan; and the Red Linnets swept before it like sparks in the van of a prairie fire, and the White Owl followed after like ash in the wake of a prairie fire.

Down from the sky there fell a white blanket, the Sun-god’s blanket, and Ninna-bo-jou cried: “Now I sleep. Let all my creatures sleep and be at peace, even as Chaska-water sleeps.”

The Ducks and Geese flew far to the south, the Woodchuck went to his couch, the Bear and the Snake and the Bullfrog, the Tree-bugs, slept; and the blanket covered them all.{112}

But some were rebellious.

The Partridge safe under the snow, the Hare safe under the brush, and the Muskrat safe under the ice, said: “Why should we fear old Peboan?” Then the Marten and the Fox and the Mink said: “While the Partridge and the Hare and the Muskrat are stirring abroad, we will not fail to hunt them.” So they all broke the truce of the Sun-god, war-waging when peace was established.

But they reckoned not with the Ice-demons, the sons of the Lake and the Winter, whose kingdom they now were invading, and vengeance was hot on their warring.

The sun sank lower each day; the North Wind reigned, and the Ice-demons, born of the Lake and the Winter, grew bigger and stronger, and nightly danced, in the air and on the ice.{113}

Deep in the darkest part of the dark month, in the Moon of the darkest days, they met in their wildest revel; for this was their season of sovereignty. Then did they hold their war-dance on the ice of the Chaska-water, dancing in air like flashes of rosy lightning—in a great circle they danced. And they shot their shining deadly arrows in the air, frost-arrows that pierced all things like a death; they pounded the ice with their war-clubs as they danced, and set the snow a-swirling louder, harder, faster.

There were sounds in the air of going, sounds in the earth of grinding, and of groaning in Chaska-water.

“I am not afraid,” said the Partridge, as fear filled her breast: “I can hide in the kindly snow-drift.” “I have no fear,” said the trembling Marten: “my home is a hol{114}low, immovable oak.” “What care I?” cried the unhappy Muskrat: “for the thick ice of Chaska-water is my roof-guard.”

Faster danced the Demons, louder they sang in their war-dance; glinting, their arrows flew, splitting, impaling, glancing.

Fear was over the lake, was over the woods.

The Mink forgot to slay the Muskrat, and, terror-tamed, groveled beside him. The Fox left the Partridge unharmed, and the Lynx and the Rabbit were brothers. Tamed by the Fear were they who had scoffed at the Peace of the Sun-god, and trembling they hid in the snow-drift, in the tree-trunk, in the ice—trembling, but inly defiant.

Whoop! went the Ice-demons, dancing louder and higher. A mile in the air went their hurtling spears.{115}

Wah! whoop! crack! and they pounded the ice.

Wah! hy-ya! louder and faster, with war-arrows glancing, they whirled in the war-dance, Wah! hy-ya! and snow-drifts went curling like smoke, betraying the Partridge and Rabbit.

Flash! went the frost-arrows and pierced them.

WHOOP! hy-ya! crack! poom! rang the Ice-demons’ clubs, and the oak-tree was riven asunder. Bared were the Marten, the Fisher.

Flash! ping! and the frost-arrows pierced them.

Whoop! clang! on the ice they circled, and louder, still louder. Poom whoooop! and the ice-field was riven; from margin to margin the frost-crack went skirling.

Wah! baim! and it zigzagged in branches,{116} so the Mink and the Muskrat in hiding were thrust into view. Ping! zip! and the frost-arrows pierced them.

Whoop-a-hy-a! whoop-a-hy-a! round and round in swirling snow and splintered trees and riven ice, with hurtling spears and glancing shafts; up from the ice a mile on high and away, A TRAMPLING, A GLANCING, a trampling, a glancing, a twinkling; and fainter, a glancing, a glinting, a stillness—a stillness most awful; for this is the Peace of the Sun-god. This is the Peace in the dark of the darkest Moon. I have seen it; you may see it, away on the Chaska-water.{117}

HERE

is a stately Angel with a marble brow and a sword that strikes

straight down. There is no Angel more calm and strong or more

relentless. His pathway is straight; no pity ever turned that sword—it

always strikes straight down.

HERE

is a stately Angel with a marble brow and a sword that strikes

straight down. There is no Angel more calm and strong or more

relentless. His pathway is straight; no pity ever turned that sword—it

always strikes straight down.

There be wrongs that he heeds not; there be rights that he helps not. There is no anger in his heart—only immutability, intention, directness, progression, and preterpotency.

There hath never yet been human{119} purpose that lasted without his aid. Imperial Rome at length forgot his power, essayed to turn his trail, and the ready sword struck down.

Small Holland, led by him, faced all the world, and England followed this calm guide to lasting power and greatness.

Napoleon prospered while his path was in the Angel’s train; but when he tried to lead, and gave that mad, rebellious order to the world, the Angel struck him down.

There is no problem we need fear; the future has no dread for me. Statesmen are filled with high dismay—South America, China, the Turk, the Trusts, the Negro at home, are dreadful names to men in power who have not marked the Angel’s track—who have not learned the lesson that the Jew learned ages{120} back: that those who follow have the vanguard of his matchless power, and those who face him must go down.

“What,” cried the Red-man’s friends—“what shall save the Indian, with his noble lesson of simple life and unavarice?”

Nothing! He was doomed; he was dying; for he stood in the Angel’s way. But we, his friends, learned wisdom. We moved him from the pathway and set him in the train of the cold, resistless one whose path is straight, and thus we saved him.

He shall not die. His lesson—of the highest in our time—shall live and grow, preserved by the awful Angel, upheld by the pitiless Angel: the one with the changeless, angerless front, and the sword that strikes straight down.

When the Oak-leaf is the size of a Squirrel’s foot, take a stick like a Crow’s bill and make holes as big as a Coon’s ear and as wide apart as Fox tracks. Then plant your corn, that it may ripen before the Chestnut splits and the Woodchuck begins his winter’s sleep.

HERE was once a burly, big-chested Peasant Boy who had an idea. He was

full of it, mad to express it; but he did not know how. He went to a

rugged mountain-side one night when his work was finished, and he saw a

great crag standing out by itself. Then a plan came. He went every night

and worked at this mass of living rock till he had shaped his idea in

stone. It was rough and chisel-grooved, unskilfully worked, for he was

no mason, but the main thought was there—the lines of a superb and

colossal human form. The pose, the expression, the grandeur of the

conception, were noble, as it loomed against the sky, and the message of

the maker was big—big{123} in every part and thought. But his people would

none of it. They laughed at the Rugged Boy who was unlike themselves,

and he died in obscurity.

HERE was once a burly, big-chested Peasant Boy who had an idea. He was

full of it, mad to express it; but he did not know how. He went to a

rugged mountain-side one night when his work was finished, and he saw a

great crag standing out by itself. Then a plan came. He went every night

and worked at this mass of living rock till he had shaped his idea in

stone. It was rough and chisel-grooved, unskilfully worked, for he was

no mason, but the main thought was there—the lines of a superb and

colossal human form. The pose, the expression, the grandeur of the

conception, were noble, as it loomed against the sky, and the message of

the maker was big—big{123} in every part and thought. But his people would

none of it. They laughed at the Rugged Boy who was unlike themselves,

and he died in obscurity.

Long after, a Stranger came from a far country and discovered this great statue of living rock in its native hills. He said, “This is the work of a Giant,” and he sent others to see, till all the world knew and some understood, and others wrote learnedly about the colossal masterpiece.

One day there came a Critic who was kindly disposed toward the great statue. He said it was “good, quite good,” but he regretted its clumsy workmanship, its poor technic. So he set himself a life-task. He began on one of the huge rugged bumps that stood for the statue’s fingers, and he filed and he polished, and{124} he polished and he filed, for half his lifetime, till he had carried out the exact form of the finger-tip and the nail and the wrinkles on the joint. He even suggested the grain of the skin and implanted some scattering hairs. Last of all, he painted it flesh-color and placed dirt under the nail, for he was a Realist.

Now the people came, and when they saw how like a finger-tip the lump of stone had become and how very real the dirt was, they all fell down and worshiped. They said, “This is a great Master,” and they loaded the Realist with honors and riches.

It was many years before kind nature restored the rugged surface of the colossus.

Moral: It’s the acid of Time that proves the gold.{125}

ROSY boy once dreamed a dream

ROSY boy once dreamed a dream

AMA, mama,” cried the little Crab, “see, there is a fine fat Clam

taking a sunbath as wide open as can be. I must go. He is too good to

lose.”

AMA, mama,” cried the little Crab, “see, there is a fine fat Clam

taking a sunbath as wide open as can be. I must go. He is too good to

lose.”

“My child,” said the old Crab, turning greenish, “that Clam would close with a snap and cut off both your pincers if you did but get near enough to touch him.”

“But, mama, I should take—”

“That will do, my child: you are not to go near the dangerous monster.”

But this little Crab was of Yankee stock. He had a scheme. He waited till his mother’s eyes were pulled in, and then slipped softly behind the Clam that{129} lay spread open like a rat-trap. He had brought a large pebble, and now dropped it neatly into the open Clam, close up to the hinge. In vain then the powerful muscles tried to close the shell. The Crab found ample room to insert one pincer, and when last seen he was comfortably seated, one arm around the helpless Clam, and with the other pulling out its delicious fatness bit by bit, and cramming it into his mouth.

Moral: Mother does not know it all.

HE Bullfrog fills his little throat

HE Bullfrog fills his little throat H, brothers, look at that fine big Culex coming to our pond!” cried

Stethorynchus, a lively little Stickleback that lived in a marshy place

near Yorkadelphia.

H, brothers, look at that fine big Culex coming to our pond!” cried

Stethorynchus, a lively little Stickleback that lived in a marshy place

near Yorkadelphia.

“Keep quiet, you fool!” cried Cataphractus (who, though he had but two sticklers, had a broad, intelligent forehead, and was highly respected among the Gasterosteidæ). “Can’t you see she is coming to lay her eggs?”

“It is not a Culex at all, you microcephalous idiot; don’t you see by the straight line of her back that that is an Anopheles? said Polyplectron, with characteristic rudeness.

“So much the better,” returned Cata{132}phractus. “Culex certainly lays twice as many eggs as Anopheles, but she is more suspicious.”

“I never saw an Anopheles with spotted thoracic segments,” whispered Pegrozila, peevishly, for he had a touch of malaria.

“Well, Dr. Howard has,” retorted Cataphractus, with crushing sarcasm. “Hush—sh—sh—”

So each of the little Sticklebacks hid behind a grass-seed, hushed, and held his gills until the Anopheles had laid over one hundred lovely pink eggs with a sweet little baby Anopheles in each. Then, in blissful ignorance of the awful fate awaiting her beloved offspring, the Mosquito floated away with a lightsome ping!

The little Sticklebacks made a rush. It was who could get there first. In a trice the floating eggs were rent to pieces{133} and devoured. Then the seventeen little Sticklebacks fluffed their gills in glee, and for two hours afterward were full of eggs and happiness and congratulations that their pond had not been kerosened.

Moral: Lives should be weighed, not counted.

HE vast low Jurassic Island had been raised above the level of the sea,

where now the great continent stands. A Matriarchal Dinosaur was leading

her ponderous troop in single file across the upheaved marshy plain. A

dry season had blighted the lower pastures and forced them to travel,

and as she was about to turn northerly, a Jurassic Grasshopper said

Bizz! under her nose. The insect is quite harmless, but it protects

itself by imitating the fearful bizz of the ancestral Rattlesnake. The

old Dinosaur wheeled to one side and raised her head. Her little

twinkling eyes fell on a rank green{135} marsh to the eastward, and she now

turned and led her troop to that. Each day they came to the

feeding-ground along their first discovered trail, until it was worn

deeply.

HE vast low Jurassic Island had been raised above the level of the sea,

where now the great continent stands. A Matriarchal Dinosaur was leading

her ponderous troop in single file across the upheaved marshy plain. A

dry season had blighted the lower pastures and forced them to travel,

and as she was about to turn northerly, a Jurassic Grasshopper said

Bizz! under her nose. The insect is quite harmless, but it protects

itself by imitating the fearful bizz of the ancestral Rattlesnake. The

old Dinosaur wheeled to one side and raised her head. Her little

twinkling eyes fell on a rank green{135} marsh to the eastward, and she now

turned and led her troop to that. Each day they came to the

feeding-ground along their first discovered trail, until it was worn

deeply.

Time went by. A wet season made the upland marsh a brimming lake. It would have overflowed to the westward, for this was its lower side, but the deep-worn trail of the Dinosaurs offered an outlet that enlarged with the yearly rains faster than the slowly rising lands could tilt the other way; and so it became a stream.

Ages went by. The great upheaval went on. The Rocky Mountains arose. The former trail was now a crooked river flowing eastward, growing larger, carrying into the shallow sea millions of tons of clay, till that shallow sea became{136} the Missouri and Mississippi Valley, which might never have existed had the Dinosaur been allowed to follow her original course—a course that would have left these vast, turbid, land-creative waters free to seek the Western Sea: and the bizz of the harmless Grasshopper did it all.

“The line between business and robbery has never yet been clearly defined,” said the Blue Jay, as he swallowed the egg of the Robin, who was off hunting for worms.

FAR up on the Continental Divide the Mother Raincloud gave birth to two

little Rills. They were close together, but had different paths. “I

shall be a great River and do great things, for I believe in breadth; a

hundred valleys and all the plains shall know me,” said one, as he

turned eastward.

FAR up on the Continental Divide the Mother Raincloud gave birth to two

little Rills. They were close together, but had different paths. “I

shall be a great River and do great things, for I believe in breadth; a

hundred valleys and all the plains shall know me,” said one, as he

turned eastward.

“I shall be a River in one valley. You will think me narrow, but one interest is all I can attend to,” said the other, as he turned westward.

So they went their divers ways. The one to the east chopped and changed its course. It ran all over the plains, each year in a new channel. It has not yet begun to scoop out a valley. It is of no{139} account, a scorn and reproach; its scattered waters have no power. It is not even a feature of the big landscape. Men call it the Platte.

The other, with no more water, stuck to one channel and sawed and sawed till it made the mightiest gash in all the globe; for this is the Colorado River, and the Grand Cañon is the channel it made.

Moral: A Bull can paw more earth than an Ant, but he leaves no monument.{140}

NCE upon a time a savage race came into possession of a great island

which had formerly been the home of a people far advanced in

civilization. There were traces of their occupancy everywhere. In

particular, the country was marked with tall chimneys, all that remained

of the great factories once used by the bygone race. The savages had no

knowledge of building, but they found that by putting a few floors and

ladders in these chimneys, puncturing a few holes through the walls for

doors and windows, and finally knocking off the upper half of the

smoke-stack, they could make for themselves a house, very strong, very

inconvenient, but still a possible dwelling.

NCE upon a time a savage race came into possession of a great island

which had formerly been the home of a people far advanced in

civilization. There were traces of their occupancy everywhere. In

particular, the country was marked with tall chimneys, all that remained

of the great factories once used by the bygone race. The savages had no

knowledge of building, but they found that by putting a few floors and

ladders in these chimneys, puncturing a few holes through the walls for

doors and windows, and finally knocking off the upper half of the

smoke-stack, they could make for themselves a house, very strong, very

inconvenient, but still a possible dwelling.

In time these savages developed a crude civilization of their own. They acquired something of the art of building, and when they set about making a new dwelling they had always for models those that had been their fathers’ guides. Accordingly, each new dwelling was made as an immense factory chimney; a few holes were punctured in its sides for light and air, floors were bungled in, the upper half of the chimney was pulled down, and lo! a dwelling expensive, inconvenient, and absurd, but on the line of the “grand old classics” that had been preserved by their “innate nobleness and hallowed by tradition.”

This fable is especially commended to those architects who try to turn everything into a Greek temple.{142}

Pa Porky: “It hurts me far more than it hurts you.{144}”

HE wise men say each growing thing in nature has a sound:

HE wise men say each growing thing in nature has a sound:

In the woods of Poconic there once roamed a very discontented Porcupine. He was forever fretting. He complained that everything was wrong, till it was perfectly scandalous, and the Great Spirit, getting tired of his grumbling, said:

“You and the world I have made don’t seem to fit. One or the other must be wrong. It is easier to change you. You don’t like the trees, you are unhappy on the ground and think everything is upside down, so I’ll turn you inside out and put you in the water.”

This was the origin of the Shad.{147}

FTER Manitou had turned the old Porcupine into a Shad the young ones

missed their mother and crawled up into a high tree to look for her

coming. Manitou happened to pass that way, and they all chattered their

teeth at him, thinking themselves safe. They were not wicked, only

ill-trained; some of them, indeed, were at heart quite good, but, oh, so

ill-trained, and they chattered and groaned as Manitou came nearer.

Remembering then that he had taken their mother from them, he said: “You

look very well up there, you little Porkys, so you had better stay there

for always, and be part of the tree.{148}”

FTER Manitou had turned the old Porcupine into a Shad the young ones

missed their mother and crawled up into a high tree to look for her

coming. Manitou happened to pass that way, and they all chattered their

teeth at him, thinking themselves safe. They were not wicked, only

ill-trained; some of them, indeed, were at heart quite good, but, oh, so

ill-trained, and they chattered and groaned as Manitou came nearer.