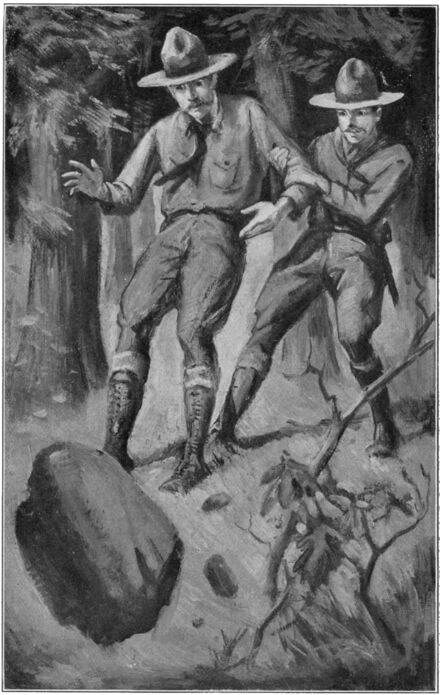

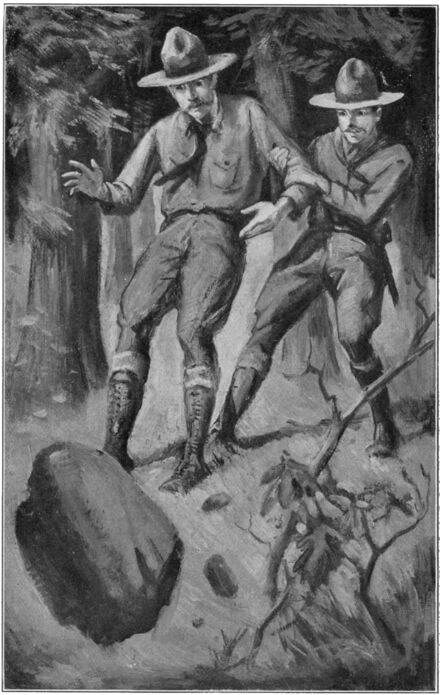

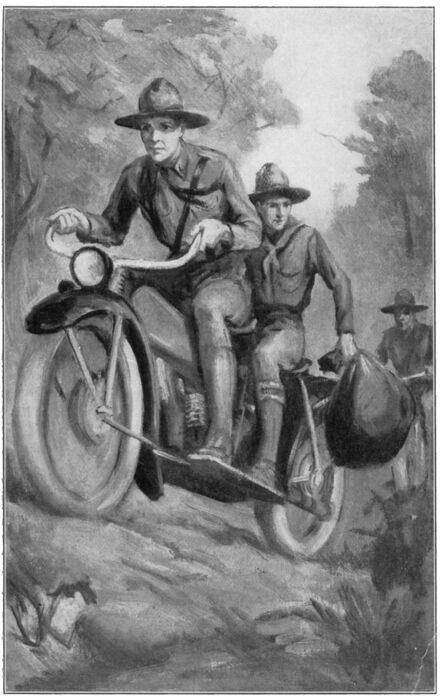

SPIFFY GRABBED TOM AND PULLED HIM BACK JUST IN TIME.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Spiffy Henshaw

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Feb. 1, 2020

Date last updated: Feb. 1, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20200161

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

SPIFFY GRABBED TOM AND PULLED HIM BACK JUST IN TIME.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | THE WAY OF THE TRANSGRESSOR |

| II | COMMON SENSE |

| III | RESOLVED |

| IV | WHERE CREDIT IS DUE |

| V | AN ERRAND |

| VI | THE STORM |

| VII | DUTY |

| VIII | A SORT OF SCOUT |

| IX | SCOUT TALK |

| X | PICKING A WINNER? |

| XI | SPIFFY AND TOM |

| XII | WITH THE NIGHT |

| XIII | CAPTAIN |

| XIV | THE CACHE |

| XV | LOYALTY |

| XVI | LOOKING FORWARD |

| XVII | ADDISON UPP |

| XVIII | A THREAT? |

| XIX | SHADOW |

| XX | LIES |

| XXI | SUSPICION |

| XXII | DISCOVERY |

| XXIII | SELF-PUNISHMENT |

| XXIV | THE RACE |

| XXV | A TURN OF THE PAGE |

| XXVI | DOWN JEB’S TRAIL |

| XXVII | A SMILING AWARD |

Spiffy Henshaw had been washing dishes for two whole weeks. That is, it seemed to him as if it had been two weeks but in reality it was only three times a day for fourteen days.

In answer to his numerous complaints, his scoutmaster had told him that the way of the transgressor was hard and though Spiffy agreed with him the words slipped off his shoulders as lightly as the summer rain.

There had been a new transgression each day of his protracted sentence, until at the end of the week it seemed quite likely that his superiors would inflict another fortnight’s penance upon him. That was to be in the form of peeling potatoes in the large kitchen at Kanawauke.

Therefore, Spiffy immediately sought to retaliate this imminent penalty and succeeded in capturing a muskrat and hiding it between the snow-white sheets of his scoutmaster’s cot. This appeased his hunger for vengeance but added to his duties in the kitchen. He was commanded to sweep it up after every meal.

This long term of punishment was the result of one of Spiffy’s major transgressions. He swam the lake one night in defiance of the camp rules and was sentenced next morning for kitchen duty. This order was to take effect immediately after breakfast but instead, Spiffy had left the waters of Kanawauke far behind him and was intent on reaching his parents’ home in Jersey City rather than expiate his folly in such ignoble pursuits.

His purpose was thwarted however, by Tom Slade, the young camp assistant of Temple Camp at Black Lake, who was on a little adventure that summer in the foothills of Bear Mountain. Spiffy walked into the cabin early in the evening and gave a frank account of himself.

Before ten minutes had passed, Tom had succeeded in making the runaway believe that he wasn’t a quitter and that he would go back to his camp and take what was coming to him. Also he had given up his beloved flashy stickpin that had earned him the famous cognomen that would cling to him for life. Tom had told him that it was a signal for HELP. That brought him to his senses and sent him scurrying back to Kanawauke.

The next morning he was commended for his fine conscience and remanded for sentence, and hardly was the breakfast over before he was standing at the big sink, toiling away at a job that was thoroughly loathsome to him. It was only the thoughts of Tom Slade that kept his impish desires in check.

“Gee, he’s one swell guy,” he said as he rattled the heavy dishes. “He’s not like the scouts around here—gee, I haven’t any use for scouts. None of them, ’cepting that Slade. I liked him right off. Said he came from Bridgeboro. That’s the place where my aunt and uncle live—I’d like to go there some day.”

The chef who was busy at the stove looked questioningly at the mumbling boy and decided that he was just another queer kid. But there was nothing queer about Spiffy at all. He was wilful and stubborn to an alarming degree and when mischief stalked his keen young brain, nothing could stop him. And until his meeting with Tom Slade nothing had.

He was destined not to see Tom again for a long time but he never forgot the little bits of common sense that that young man had imparted to him during their short meeting. His desire to create havoc in the peaceful camp was as strong as ever but he knew that never again would he be a quitter.

And so he started his acquaintance with potatoes after his adventure with the muskrat. When he was at this occupation the thought occurred to him that his superiors might reconsider their sentence upon him if he put a good quantity of dry mustard in with the potatoes. The innocent looking can stood on a line with his sparkling black eyes just under the cupboard and the chef had stepped out of the kitchen for a few minutes.

The peace of Kanawauke camp was indeed threatened that luncheon hour by Spiffy’s latest prank. His scoutmaster and camp manager were at a loss to know just what could be done about him. Punishment seemed to be only another form of mischief, and they at last decided to inform his parents that they might write and order him home.

Their wish was soon realized as Mr. Henshaw sent his son a peremptory note demanding his return home at once. Also a letter of apology was dispatched to the powers that be in Kanawauke, on behalf of this same mischief maker and some money for his carfare was enclosed in care of the scoutmaster to insure his return home.

Spiffy accepted this money humbly and seemed indeed repentant at that moment. He asked permission to stay until the morrow and that same afternoon took a trip into the nearest village and bought a scout suit for a poor member of his patrol. Thus he was without the wherewithal to return home and when his scoutmaster upbraided him for his rash act he simply stood by, innocent looking and smiling. No matter what else was said of Spiffy in those days, no one could do other than admit the power of his smile. And never was he lacking in respect to his elders.

“That’s one scout rule you never break,” said the scoutmaster. “You never fail to be courteous and you never fail to smile. I wish you obeyed the other laws as well. You’d make an A-l scout, Arnold.”

“I don’t want to be an A-1 scout,” Spiffy returned frankly. “I don’t want to be a scout at all—I never wanted to be one but my father made me. I’ll never do things I’m made to do because I don’t like rules. And that’s all the scouts have—rules!”

The scoutmaster frowned. “That’s nonsense, Arnold. Even a baby must obey some law—where would the world be without laws? We’d be like a lot of savages.”

“I’d like to be a savage,” Spiffy said wilfully, “then my father couldn’t make me go home when I didn’t want to go.”

“I thought you didn’t like the scouts?” asked the scoutmaster.

“I don’t, but it’s better than going home to Jersey City and having my father lecture me every day for a week or more,” he admitted. “Gee, the scouts are better than that.”

The scoutmaster smiled patiently. “It’s comforting to hear you admit that much, Arnold. I’m afraid you’ve never been honest with yourself about scouting—you’ve never so much as tried to understand us. Perhaps some day you will, eh?”

“I will when they stop having rules,” smiled Spiffy.

“You will when you learn to respect rules as you do your parents,” the man prompted him.

“Parents are like the scouts,” Spiffy insisted. “Mine are anyway. They’re always making me do things I don’t want to do.”

The scoutmaster shook his head hopelessly. “You’ve a lot to learn, Arnold, but that is neither here nor there just now. Pack up your things. I’m going to buy your ticket and see you safely on the train for Jersey City.”

Spiffy turned obediently and went straight to his patrol cabin. He whistled merrily and packed his bag and when a member of his patrol asked him where he was going, he winked mischievously.

“Are you sorry that you’re leaving us?” asked the scoutmaster as they walked around on the platform waiting for the train to come in.

“Nope,” smiled Spiffy, “I’m never sorry for anything I do. I’m sorry for what other people do to me.”

“That’s your creed, eh? Well, my boy, perhaps you’ll have to do otherwise some day. Here’s your train—I wish you luck and plenty of common sense.”

Spiffy returned the proffered hand clasp, boarded the waiting train and went merrily on his way. In five minutes he had completely forgotten the best wishes of his scoutmaster and the thought of ever having common sense seemed tragic to him. It made him wonder if he could stand on the bottom step of the railroad coach for five minutes without being thrown off.

This idea was quickly dismissed by the appearance of a news butcher who entered his coach bearing a tray full of tempting looking candies. He called the man and bought some imported Swiss milk chocolate, a package of lemon drops and a five cent bag of salted peanuts. Also he inquired as to whether or not the business of the news butcher was a lucrative one.

Having received an affirmative answer he made a wager with the man that he could carry the tray the length of the train and sell more goods than he did.

“I’ll go you one,” laughed the news butcher, who was richly endowed with sporting blood. “If you can make a good showing I’ll give you what you ask for—providin’ it’s reasonable.”

Spiffy immediately took him up and started through the train, the tray adorning his khaki-clad figure quite imposingly. He cried his wares appealingly and looked pensively into the faces of the fair sex, both young and old.

“Help a scout who is earning his way home, lady?” he pleaded. “Buy a bar of chocolate or some lemon drops and you’ll be helping me.”

It was a hard hearted traveler who could resist the naive, Arnold Henshaw, alias Spiffy. Few did resist him and before the train entered Jersey City he handed the news butcher an empty tray. He had won his wager.

“Will a dollar do?” asked the genial news butcher.

“Sure,” answered Spiffy. “That ain’t bad for a half hour’s work. Gee, it was easy—I’m going to be a news butcher too after I quit school.”

Spiffy left the train at Weehawken and took a bus to the Erie Railroad Station at Jersey City. There he bought a ticket for Bridgeboro and after an hour’s wait was embarked once more upon another adventure.

The spotless looking town of Bridgeboro made quite a favorable impression upon him and after he had roamed its streets for a delightful hour he decided to call upon his aunt and uncle who lived up in the suburb of North Bridgeboro. It was his first visit there as his uncle was not kindly looked upon in the Henshaw family. His aunt Kate was pitied because of her marriage to a ne’er do well and while she had often visited Jersey City, Spiffy had never been allowed to mention his Uncle William Riker or to ask the privilege of visiting that household.

“I’ll see what my uncle’s like,” he said aloud as he waited for a bus to take him uptown. “I’m just going to find out because Ma and Pop told me never to go. I want to see why they don’t like him.”

Spiffy was not long in finding out for in ten minutes he alighted from the bus in front of his aunt’s humble looking cottage. He walked up the path between rows of overgrown weeds and as he stepped upon the porch he noticed that it was badly in need of repair.

His Aunt Kate opened the door and admitted him with a pained expression upon her tired, careworn features. Once inside, however, she put her arms around him and smiled affectionately. “I’m put out about you coming here,” she said in hushed tones. “Your father and mother will be angry, Arnold.”

“I know,” he admitted indifferently, “but ain’t you glad to see me, Aunt Kate?”

“Course I am, silly,” she said, glancing uneasily toward the stairs. “Your uncle’s upstairs, asleep. I don’t know how he’s likely to treat you—he has a chip on his shoulder on account of the way your Ma and Pop won’t recognize him.”

“Well, that ain’t my fault, is it?” Spiffy asked. “I never did nothing to him . . .”

“Is that your nephew Arnold?” asked a wheezy voice from the stairway.

They looked up to see the tall, spare frame of Mr. Riker bending over the worn balustrade. “You heard me!” he shouted to his startled wife. “Don’t stand there as if you was dead!”

“Yeh, it’s him, Bill,” she said, as if in a trance.

“Sure, it’s me,” Spiffy spoke up. “I came because I met a dandy scout feller by the name of Tom Slade and he works for a man named Temple and he owns a big scout camp in the Catskills. I bet it’s a better scout camp than the one I just got put out of.”

“Put out!” said his aunt, horrified.

“Sure,” said Spiffy boastfully. “Not many scouts can say that. Gee, they were glad to get rid of me and believe me, I was glad to get rid of them.”

“It serves your mother and father right,” said Mr. Riker still depending on the flimsy balustrade for support. “You wouldn’t ketch me lettin’ any youngster o’ mine wastin’ his time like that. Yuh wouldn’t git the chance to go in the first place. They’re a no good bunch!”

Spiffy looked up at his uncle, wonderingly. This was a different person he was encountering. Everyone that had any interest in him at all had continually urged him to be a good scout and here his uncle was denouncing them the same as he had been doing. He wasn’t quite sure that he liked to hear it.

“Aw, they ain’t so bad,” he said with all trace of bravado gone. “Gee, I did a lot of things to them and all I got was to be put in the kitchen to wash dishes and peel potatoes. They ought to ’ve given me a good sock for the way I treated them and the way I broke rules.”

“Yeh, that’s just it,” said Mr. Riker shuffling downstairs and into the living room. “They handle boys like they were made of silk instead o’ makin’ them rustle aroun’ and work and givin’ them a good beatin’ once in a while.”

“Well, it’s good you’re not the scouts,” said Spiffy bravely, “that’s all I’ve got to say! I was the only one that made any trouble up there and gee whiz, there’s hundreds of guys in that camp so that doesn’t prove it hurts scouts to be treated like they were silk, does it?”

Mr. Riker glared at his nephew and seated himself in a large, worn rocker. “I got no use for anything that gives boys time to do mischief. I had to work hard when I was a boy and now . . .”

“You let Aunt Kate do it,” Spiffy interposed with a smile.

Mrs. Riker put out a detaining hand, for her husband leaned forward in his amazement. “Well, you impudent pup, you,” he said to Spiffy. “What’s it your business if your Aunt Kate does work a little bit to help me out! I ain’t a well man, but I’d learn yuh to hold your tongue if you was under this roof.”

Mrs. Riker smiled feebly. “There now, Bill,” she said, trying to bring about a truce, “I’m sure Arnold didn’t mean to be impudent—he just repeated what he hears at home most likely.”

Mr. Riker scowled, got up from the chair and sought seclusion upstairs once more. “I’d learn him different if he was here,” he mumbled angrily as he left the top step. “I’d take some of it out o’ him.”

“I bet he would,” Spiffy said when his uncle was well out of earshot. “Gee, he’s a bear, ain’t he Aunt Kate?”

“Hush, Arnold,” said the patient woman, “don’t let him hear you. He’s always ready to pick everything up.”

“Gee, I wouldn’t want to live with him,” Spiffy admitted frankly. “If I had a father like that—gee, I just now realized that Pop ain’t half bad. He lets me do everything. Gee, I guess I’ll go right back home and apologize.”

“I’m glad to hear you say that, Arnold,” said his aunt. “You’ve given your father a lot of worry with your pranks and he’s a good man. He’s trying hard every day to earn a lot of money so’s you can have a good education and grow up to be a fine young man. And your mother too, think how she worries.”

Spiffy was all contrition. “Come on home with me, too,” he urged her. “Tell them how I said I was sorry—otherwise they’ll think I’m joking again.”

Mrs. Riker went over and hugged him. “I will, Arnold,” she said, sweetly. “I will, because at last you seem to have sense.”

Spiffy strolled out around the back of the Riker cottage while he was waiting for his aunt to dress. This shabby home stood at the top of the hill on a little knoll of rocky ground and down below the river wound its way between grassy banks and sweet-smelling woods.

“I’d like to live here on account of the river,” he said enviously gazing at the placid looking stream. “Boy, I sure would swim—night and day.”

“Not if your Uncle Bill had anything to do with it,” said Mrs. Riker emerging from the cottage, dressed for the little journey. “I’m afraid the river wouldn’t do you much good as long as he was around. It ain’t done me a bit o’ good, I know that. And how I could swim when I was a young girl.”

Spiffy looked at her pityingly and made a solemn resolution that he was going to be better to her and to everyone. The world had been kind to him and he had done nothing in return and in this frame of mind he walked lightly out to the road, helping his aunt over all the rough places.

“That’s a scout rule—to be chivalrous,” he told her. “Funny that when I was a scout I never thought about it and now that I’ve been put out I start living up to it.”

“You haven’t been put out exactly, have you, Arnold?” Mrs. Riker asked anxiously.

“Maybe not,” he answered. “But I’d have a nerve to go back now after all I did.”

“Oh, they ain’t that kind to hold it against you if they see you’re sorry,” she said.

“I know it,” he admitted, “but I’m—aw, I’m ashamed now.”

“Well, that ain’t a bad sign,” she said, pleased. It was indeed a delight to her to see her favorite nephew so penitent and humble.

And Spiffy was humbled. The transformation had been so swift that he was himself amazed and he wondered all the way back to Jersey City whether Tom Slade had caused the change or whether it was his uncle’s denunciation of the scouts that set off the spark of his slumbering loyalty. At any rate, he pressed his face against the dusty windowpane of the old railroad coach and silently planned how he was going to win his way back into the scouts upon his own merits.

“I’ll start first by being kind to Mom and Pop,” he resolved in a half-whisper.

“What did you say, Arnold?” asked his aunt who just caught his lips moving.

He told her. “They won’t be so pleased to hear that I was just kicked out but when they know I got some sense on account of it, they’ll be glad.”

He walked expectantly beside his aunt all the way up the tree shaded street and poured forth upon her listening ears, the virtues that he hoped to live up to during the rest of his natural life. It was all very new and exhilarating to him.

The Henshaw home was located in the center of the block and as they approached it, they noticed a small group of women standing on its porch, talking and seemingly agitated. Mrs. Riker hurried a few steps and Spiffy ran ahead.

When the ladies espied Spiffy they ceased talking instantly and each one looked at him with grim and troubled features. Mrs. Riker was aware of this and mounted the porch steps with pounding heart. Was this an evil sign of her nephew’s home-coming or was . . .

“I’m awfully glad your Aunt Kate’s with you,” spoke one of the ladies to the wondering boy. “I’m glad because—well, oh . . .”

“I’ll tell him and Mrs. Riker,” interposed another neighbor. “I—oh, it’s hard to begin.”

“What is it?” Mrs. Riker demanded. “What’s the matter?”

At that juncture, a big burly policeman came out of the Henshaw’s front door and surveyed the tense group. Mrs. Riker saw the look of appeal that the ladies gave him and her heart seemed to forsake her. She knew then that some terrible thing had invaded that home.

“This is the Henshaw boy, officer,” an elderly lady said. “This is his aunt too—Mrs. Henshaw’s sister. You—you better tell them.”

The officer nodded and a look of pain crossed his genial looking features. “Someone’s got to do it,” he said quietly, “so it might as well be me.” He tried to smile at Spiffy and his aunt—a smile that told much.

Mrs. Riker spared him further, however. She nodded slowly and set her mouth as if to get ready for the threatening pain. “We’re ready, officer,” she said bravely. “Arnold and me.”

“It’s Mr. and Mrs. Henshaw, ma’am,” the man said dully. “They’ve just been killed in their car. A truck ran into ’em down the street and did for ’em. They’re a-waitin’ identification. Youse better go down.”

Spiffy never got over that shock exactly. Time softened it of course, but he always remembered that the world had seemed to slip out from under his feet. And that night when he sat with his aunt in the deserted home he was still too dazed to cry.

“All I can think of is that I didn’t get chance to tell them that I . . . Well, anyhow Aunt Kate, I spose I’ll go live with you, huh?”

Mrs. Riker nodded. “I’ll be good to you, Arnold,” she said softly.

“Yeh, I know it. But Uncle Bill—he don’t like the scouts, does he?”

“No, he doesn’t like the scouts.”

“And I do,” said the boy mechanically. “It serves me right that I like them when its too late.”

Two years passed.

Spiffy stood outside of his back door contemplating the river in its devious course from the bridge. Particularly was he interested in its flowing path after it left the reedy banks just below his uncle’s house.

It was not ten minutes since he had heard gay voices and carefree shouts echoing up the hill, causing him to immediately abandon his wood chopping and join in the shouting. Perhaps he did not abandon himself to the shouting as thoroughly as he had abandoned chopping wood but then he had his uncle to consider. That gentleman was a hard task master and Spiffy had long since learned to keep that knowledge uppermost in his young mind.

Two canoes loaded with scouts had hailed him, urging him to join them on that bright, warm morning. But Spiffy was only able to shout that Saturday was a busy day for him. He wanted to add that every day was a busy day but the slamming of a door from somewhere in the cottage prevented him.

Unwillingly he turned his back upon the river and upon the scouts and took up the axe. The door opened and someone stepped out of the kitchen. Spiffy did not look up but knew by the shiftless swish of the footfalls that it was his uncle.

“’S ’at you a-hollerin’ just before, Arnold?” the man asked in short, wheezy tones.

Spiffy let the axe rise and fall twice before he answered. “Yep,” he said, slowly. “Some of the fellers—scouts—were going up the river for all day. They wanted me to come. That’s about all.”

Bill Riker, as all North Bridgeboro called him, stared lazily at the axe glittering in the sunshine. He turned his head around without moving his tall, spare frame one inch and selected a soap box out of an accumulation of various other boxes standing piled up against the back of the little frame cottage.

“Fetch me that soap box, Arnold!” he rasped at the busy boy. “I’m tired out.”

Spiffy laid down his axe and went over. He dragged out the box from under the rest and pushed it toward his uncle. “I’m tired too,” he said, surprised at his own temerity. “All yesterday afternoon and since seven o’clock this morning I been chopping up this log. I got pains in my back even.”

Bill Riker flopped down onto the box and crossed his long legs. He watched his nephew for a few minutes then shook his head. “I declare you’re the laziest kid I ever did see. You ain’t got the slightest notion to be grateful for what your aunt and me is doin’ for you. Maybe you’d like to be traipsin’ around with them good-for-nothin’ scouts, eh?”

Spiffy stopped and faced him. “I once said they were good for nothing—I said it when my father and mother was alive and when I was up to a lake with them one summer. They were always nice to me even when I didn’t really belong to them. I didn’t know what I was talking about that time I guess—I even ran away and I disobeyed so many rules that they had to let me go back home. Gee, I was an awful sap when I think of it because I had a chance then. Now I haven’t any because you and Aunt Kate are too poor to let me join.”

Bill Riker disliked any pointed reference to his impecuniousness. He scowled. “Just as if I couldn’t afford to let you join if I wanted to,” he sneered. “But if I was a good deal richer than I am I wouldn’t let you join—they’re a lazy lot, they are, and they’d have you as bad as them in no time. You’re bad enough now,” he added as an afterthought. “You better hurry up with that choppin’ ’fore it rains. That wood’s got to get down celler ’fore night or your Aunt Kate won’t have no fire to cook your meals with. You’re glad enough to eat from us, ain’t you?”

Spiffy grasped the axe again with trembling fingers. He wondered how any boy could feel grateful to a man like his Uncle Bill. He wondered why relatives gave orphaned nephews a home and then spent the rest of their lives in making them feel miserable about it.

In the midst of these thoughts, his good but timid Aunt Kate opened the back door and looked out rather fearfully. “Bill,” she called in frightened tones. “Bill, Mr. Temple’s just stopped in front of the house in that grand car of his. I ’spect he’s come after the rent.”

An uneasy look crossed Bill Riker’s face and he stood up. “It’s blame easy for him to come pesterin’ me for money!” he wheezed and shook his fist in Spiffy’s direction. “All he’s got to do is to ride up here in a swell car and fill up his pockets and then go give it to them scouts what you want to traipse around with so bad. Yeh, give it to a lot of rascals what has nothin’ to do but go up on the river Saturdays and raise Cain. And you want to join ’em, eh? Hmph! Not while I got my senses you won’t.”

Spiffy could see nothing but his aunt’s work worn fingers tremulously holding the door open. His eyes blazed with anger. “Anyhow, they’ve been nice to me, the scouts have. I never forget when people are nice to me, even Mr. Temple,” he said bravely.

Bill Riker wheeled around as if to strike the boy. “Please!” his wife pleaded from the doorway. “Mr. Temple’s here, Bill. He’s a-knockin’ on the front door now.”

The mist of righteous indignation that blurred Spiffy’s vision did not clear away until long after the door closed behind his uncle. He threw his axe to the ground and walked a few feet, then stopped.

The voices of the shouting scouts had died away but the trail of the canoes was still visible in the sparkling water. Spiffy followed it with his shining black eyes and smiled. He could almost feel what it was like to be with them—just by looking and thinking.

“Anyway,” he said aloud, “the scouts saved me a good biff just then. Uncle Bill would have let one go at me if it hadn’t been for Mr. Temple that time. And Mr. Temple’s the scouts so I might as well give the credit to them.”

The day continued warm—too warm almost for early June—and toward mid-afternoon the sun took on a lead-colored hue. The still air became oppressive and Spiffy stopped for a moment to mop his perspiring face.

His aunt Kate, watching him from the kitchen window, shook her head pityingly and hurried out to him. “Arnold,” she said softly, “I ain’t a-goin’ to let you slave at that any longer. It’s a burnin’ shame, that’s what it is, to make a boy your age do such hard work the whole live-long day. And such a day!”

Spiffy turned his head away and looked toward Bridgeboro. Like a great mist the humidity was rising out of the valley and slowly up the hill to them. He pointed to it. “You can see for yourself, Aunt Kate,” he said wearily. “It does look as if it were going to rain before night, just like Uncle Bill said.”

“I don’t care what your Uncle Bill said,” she whispered. “You’ve got enough chopped to last us for a week or more and if the rest of it gets wet it can dry out ’fore then, can’t it? ’Nother thing, Arnold, I’m gettin’ right tired of your uncle making out he’s always tired so that he don’t have to work. I have to work and you have to work and go to school too and even now he’s inside sleeping away because he says he can’t stand the heat!

“Just as if any of us can stand it when it comes to that! But the difference between him and you and me is that we have to stand it!” She reached in her dress pocket and pulled out a coin and offered it to the boy. “Here, take this and see a movie, Arnold. You’ll cool off for a change as well as him!”

Spiffy could not keep the tears back. There had been very few movie shows that he had attended since his parents died. He knew his aunt worked hard with her sewing and that every penny counted while his uncle would not work. It was hard to refuse the money but he shook his head. “You’ll have to do without something else if you give it to me,” he said. “’Nother thing, what about Mr. Temple and the rent?”

“You can imagine, Arnold,” she answered. “He’s always so nice about it, Mr. Temple is, but your uncle has tried him to the limit—it’s four months or more he owes and Mr. Temple said he’ll have to take steps or somethin’ like that.”

“Does that mean we’ll be put out?”

Mrs. Riker nodded. “But don’t worry, Arnold. I think he knows we have nothin’ to do with it. He heard you choppin’, Mr. Temple did, and he looked out at you and said to me what a fine, ambitious boy you were, workin’ so hard on such a terrible day.

“I guess your uncle took the hint because after Mr. Temple went he started goin’ on about rich men and such. Anyway, he got himself so worked up he had to take a nap. A queer man, Mr. Riker is,” she said musingly. “He ain’t got no use for folks what he owes money to.”

Spiffy leaned up against the cottage in sheer fatigue. His face looked worn and white. “Maybe I could go and speak to Mr. Temple so he wouldn’t put us out,” he said thoughtfully. “Maybe I could ask him to let me do some work so’s we could pay him that way.”

“And encourage your uncle in more laziness?” she asked him. “You’ll do nothin’ o’ the kind, Arnold. Just run along now and get out o’ sight before he wakes up. I want to have a talk with him when you’re not around, anyway. I’ll tell him I sent you on an errand to Bridgeboro ’cause I was too tired to go.”

The movies would have been incentive enough for any boy and it is not to be denied that Spiffy was moved by so tempting an offer. But he had something else in mind. His plans concerned the immediate present and he felt sure that if they worked out everything else would too.

He smiled gratefully at the woman who had tried to make up for his uncle’s treatment of him. Never once had she ever thrown up to him what she was doing so that he might sleep and eat after a fashion. It all flashed across his mind as he saw her outstretched hand with the quarter offered to him. He took it, humbly.

“Maybe I won’t have to use it, Aunt Kate,” he said mysteriously. “I’ll only take it in case it storms and I have to ride home on the bus. Anyway, I’m not going to the movies—that’s settled. I got to find out somethin’ in Bridgeboro and I won’t have time maybe.”

Mrs. Riker shook her head. “Don’t be foolish, Arnold,” she said in a tone of warning. “If you’re thinking about Mr. Temple—please don’t! Your uncle won’t never work if he finds it out and it’ll make me . . .”

“Not that I say I’m going to Mr. Temple’s,” Spiffy interposed, “but do you say it wouldn’t help you if I spoke to him and told him how Uncle Bill treats us and how he won’t work and all?”

Mrs. Riker conceded that it would. “If you just went and said that, it would be all right, Arnold,” she said. “He’d know then that you and I were honest and that we wasn’t upholdin’ your uncle in makin’ him wait for his money.”

“That’s what I mean,” said Spiffy.

At that juncture a sound, like the falling of some heavy object inside the cottage, made itself heard to them. Plainly startled, Mrs. Riker pushed Spiffy around the side of the tiny building and out of sight of any windows. “Run, Arnold,” she said timorously, “it’s him, I bet, like as not. Get out o’ sight, quick as you can!”

Spiffy lost no time in slinking along through the high weeds surrounding the Riker cottage. It had always annoyed him—this jungle growth, but now he was glad that his uncle had complacently allowed it free rein even up to their very windows. It hid him sufficiently until he reached the road.

When he emerged onto the hot pavement a small, ramshackle Ford drew up and stopped not two feet from him. Its lone occupant spied him instantly and hailed him in gruff, impatient tones. “Say, your uncle in?” he snapped, getting out a small black book.

Spiffy nodded.

“He better be!” the man said. “What’s he think I am, anyway?”

Spiffy shrugged his shoulders and ran pell-mell down the road. He knew from past experiences who the man was and the nature of his business at the Riker cottage. He was just another collector, a little more impatient than the rest.

Spiffy breathed more freely when he rounded the curve of the highway into lower North Bridgeboro. No longer could he see his uncle’s house standing almost precariously on that ridiculous little knoll. It often seemed to him that he lived on two hills really. Certainly they got the full benefit of the elements there, without shade or protection of any kind.

And so when he came within the city limits and on to the sidewalks he slowed down a little, thankful to feel the shade-cooled flagging under his worn soles. The river too seemed to send a little breeze just at that point. He hated leaving it for the hot unshaded spaces of Main Street.

For a moment he stopped and wondered what new argument his uncle would give the gruff collector. Then his eyes strayed toward the river. The tide was on the ebb and several rowboats were on their way downstream. Familiar voices again echoed in the still, humid air. Spiffy peered through the trees and made out the two scout canoes being swiftly paddled on their homeward way. It gave him the loneliest feeling that he had ever experienced in his life and he turned away from the scene with a little ache in his heart.

In the distant east some thunder rumbled ominously. He looked up to see a great mass of black clouds moving toward the sun.

He had not gone more than two blocks when the world seemed suddenly in the grip of a portentous calm. The black storm clouds had merged into one vast heavenly pall that threatened the silent earth.

Spiffy shrunk inwardly from the fearful scene and wished that he had stayed at home until the storm was over. A little nervous quiver ran down his spine whenever he thought of the freshly chopped wood that his uncle would have to carry “down cellar.” He dreaded the scene that such a procedure would bring about when he got back.

He did not have much time to linger on such terrifying thoughts, however. A great gust of wind whirled him roughly against a tree but luckily did no more than scare him out of his wits. Ear-splitting thunder crashed right above his head and in its wake flashed a blinding streak of lightning.

Spiffy had been endowed with a good deal of moral courage by his Creator but never before had it been put to such a test. He was stunned by the suddenness of his impact with the tree and it was some few seconds before he was able to think clearly.

The vast pall was swiftly moving toward upper North Bridgeboro, he judged. It seemed to be gathering itself into a great ball almost the shape of a huge balloon. He had never seen anything like it before and when another onslaught of wind accompanied by a slash of rain struck him full in the face he decided that the bravest thing to do was to run.

With difficulty he managed to keep himself balanced in the driving wind and rain and took to the middle of the street for safety. Heavy branches were blowing down onto the sidewalks like wisps of moss. Just after he passed the huge elm in front of the Stanton mansion it bent under the fury of the wind and was borne to the street like a piece of cardboard. Spiffy heard a sputter and noticed that it had taken the high tension wires in its downward course.

He looked cautiously after that to left and right and sped along as fast as it was possible. No living being could he see in the length or breadth of Main Street. Everyone but himself seemed safely sheltered from that wanton wind and rain.

He reached the beautiful Temple Mansion, dripping with water, and as he ran up the long, flower-bordered foot-path the storm ceased as quickly as it had begun. Spiffy smiled ironically. “That’s just my luck,” he said half-aloud. “As if my clothes didn’t look bad enough dry, comin’ into this swell dump!”

But he made up his mind that he wouldn’t turn back then. He had plans and he meant to carry them out despite his forlorn appearance. And what he had learned of Mr. Temple’s “charity toward all” attitude was sufficient to give him the courage to carry on in the face of everything.

Quite bravely then did he stuff his drenched knicker cuffs more securely in under his hose.

Better to let them drip down his legs and into his shoes than to spoil the high polish on Mr. Temple’s floor. He slicked back his tightly waved hair with two sweeps of his thin, calloused hands and strode up to the high, imposing door. Then he rang the bell with a long, determined ring.

A little thin Japanese butler opened the door and seemed not at all surprised at the unusual appearance of the caller. Instead he smiled suavely and bowed quite low. Spiffy felt encouraged.

“Mr. Temple in?” he asked timidly.

The butler smiled more brightly than ever. “I tink not—but maybe so,” he said. “Come in. I shall see very soon.”

Spiffy hesitated. “Gee, I’m pretty wet, mister,” he said lingering on the threshold. “I might get the place all mussed up.”

The butler smiled amusedly. “It is not-ting, young man. Come in!”

Spiffy stepped in and the door closed behind him. The butler left him and soon disappeared through a swinging door at the end of a long hall. There was a distant medley of voices and presently the door swung open again admitting a large, round-faced woman.

It was Mrs. Pearson, Mr. Temple’s trusted housekeeper, and Spiffy had long known her through his aunt. Mrs. Riker had occasionally done sewing for the genial soul and she had often visited the humble cottage that the boy called home.

Mrs. Pearson threw up her chubby arms above her head in a gesture of surprise when she saw him. “Land sakes alive, Arnold Henshaw!” she exclaimed in her soft, kindly way. “What in all creation are you doing out in such weather?”

Spiffy smiled to cover his embarrassment. “I started out when it wasn’t such weather,” he answered frankly. “Gee, I never thought it was going to be so bad.”

Mrs. Pearson smiled sympathetically. “It’s good you weren’t hurt, anyway,” she said. “You’re lucky because they called Mr. Temple from up near your way I guess it was, and they told him to come right up and see what damage the storm did to his property. So that’s where he’s gone, Arnold. I ’spect he won’t be back for a while.”

“Did whoever call say where the damage was?” Spiffy asked, startled. “Do you think it could o’ been Aunt Kate’s or anything?”

“Shucks, don’t get excited!” Mrs. Pearson answered. “I don’t think anything of the kind. Whoever called was one of that kind that loses their head, I guess. Ten chances to one Mr. Temple had his trouble for nothing already. The storm was terrible bad, I guess, but not enough to take him on a fool’s errand up there. Anyway, what did you want of him, Arnold?”

Spiffy rested his right foot over his left. He felt decidedly uncomfortable. “I—I—came on account of I wanted to speak to him about the rent,” he stammered. “On account of Uncle Bill.”

“Is that good-for-nothing loafer still out of work?” she asked incredulously. “Do you mean to tell me you’ve had to come to plead for him?”

“Well, I—I thought maybe for Aunt Kate’s sake he could let me work or something,” Spiffy answered. “I thought that would make it all right.”

A maternally anxious look came into Mrs. Pearson’s misty eyes. “You poor boy,” she said soothingly. “Come on into the kitchen and dry your wet feet and clothes!” Then: “I’d just like the chance to tell Bill Riker what I think of him now! It’s little enough that he’s done for you and your poor aunt but he’s made you work and now he’d see you do more!”

The good woman led the boy down the long, dim hall and through the swinging door. A rush of sweet, warm air greeted him as he stepped into the big kitchen. From the gas range emanated that delicious smell of baking cake. Spiffy sniffed the air hungrily.

“Smell good, Arnold?” Mrs. Pearson smiled. “Take a chair and get up close to the oven. Put your shoes on the warming shelf—they’ll dry without burning.”

Spiffy did as he was told and was grateful for Mrs. Pearson’s motherly attentions. She busied herself with odd tasks that were concerned with Saturday baking and the butler passed noiselessly to and from the kitchen through another swinging door on the other side of the house.

Once when he was carrying a tray full of silverware from the kitchen he braced himself against the door long enough to give Spiffy a peek into the Temple dining-room. An austere looking buffet gleaming with a gold and silver service gave the orphaned boy a delicious insight into the lives of those whom he had always read and heard about. He determined to keep his eye on that door in order to get another look at such a royal display of wealth.

Mrs. Pearson turned to him from her tasks. “What are you thinking about, Arnold?” she asked, aware of his thoughtfulness.

“I was thinking about that silver and gold stuff in that room, there,” he answered pointing toward the door. “I was thinking how nice it must be to have things like that and not have to worry about rent or anything. Gee, you’d think Mr. Temple would be afraid to leave it around on account of burglars.”

Mrs. Pearson laughed. “Mr. Temple ain’t afraid of burglars, Arnold,” she said. “He always says that he’s been charitable to all the burglars in Bridgeboro and now they don’t have to steal any more. No one would think of stealing from Mr. Temple—he’s too kind!”

Spiffy kept his eyes on the door. “Gee, I bet that stuff’s worth a lot of money. I bet if a feller was hard up so that he was starving or something I bet he’d forget how kind Mr. Temple was,” he said musingly.

“They’d have to be mighty ungrateful if they did,” Mrs. Pearson said loyally. “I can’t imagine anybody doing a mean thing to that man, no, I can’t.”

The butler came out once more and Spiffy got a longer, better look. He was captivated. “Ain’t no one home here but you and him?” he asked her.

“You mean the butler?” she asked.

Spiffy nodded.

“Mrs. Temple and Mary are gone for the summer and the cook’s away on her vacation,” explained Mrs. Pearson. “There’s just the butler and me looking out for Mr. Temple and he’s away half the time too. Why did you want to know, Arnold?”

“Aw, I don’t know,” Spiffy answered. “It’s such a big house with only a few people and I never been inside a place like this before so I guess I get to thinking about burglars all the time just because Mr. Temple’s so rich.”

Mrs. Pearson laughed. “You always were a queer little duck. I’ve told your Aunt Kate that many’s the time.”

The fire siren screeched boldly into their conversation and cut it short. Mrs. Pearson stopped her work and audibly counted the shrieks one by one. “It’s forty-two,” she said at the first pause. “That’s right up at the limits. S’pose we got the storm to thank for that.”

“Lightning, I bet,” said Spiffy, feeling the comfort of his drying clothes.

“Maybe,” Mrs. Pearson said.

The siren kept up its horrible din and presently the agile little butler came running into the kitchen, waving his hands excitedly.

“What’s the matter, Kato?” she asked.

“Gardener just tell me up there there’s fire from storm!” he panted breathlessly. “Terrible fire!”

Mrs. Pearson smiled. “Kato does love a good fire,” she told Spiffy. “And the fun of it is he likes me to enjoy it with him. We’ll go out in the back yard and see if we can see any of it. Want to come, Arnold?”

Spiffy stood up and felt his shoes. “They’re not dry,” he announced. “But you go ahead because I like it in here—it’s so nice I don’t mind not seeing one fire.”

“That’s good,” Mrs. Pearson said, taking off her apron. “It’s pretty wet out there still so I guess it’s just as well that you don’t try getting your feet wet too often.” She hurried out close on Kato’s heels, the screen door slamming noisily behind her.

Spiffy turned at that moment and noticed that the swinging door into the hall swung along with the draught and seemed to stick there. He pushed back the chair he had been sitting on and went over to it and saw that the front hall door was also standing open.

His first impulse was to go and shut it but the thought occurred to him that perhaps Kato had left it that way purposely and that he better let it alone. In point of fact, he felt too awed by the solemn grandeur of that fine old home to tread its stately halls in his stocking feet. Instead he pulled the door to in the kitchen and padded his way to the window where he could watch Mrs. Pearson and Kato.

He saw them hurrying toward the river bank with the gardener and as the trees were in full bloom and the land sloping gradually it was only a few moments before they were out of his sight. He called after Mrs. Pearson and told her to let him know how bad it was and she answered him cheerfully.

Spiffy felt singularly happy. He walked around and around the kitchen drinking in its clean, wholesome atmosphere. Everything was so spic—he wished heartily that his Aunt Kate could have things one half as nice. It must be nice not to have to worry about wood being chopped so that one may have the fuel to cook with. Gas was an unknown luxury in the Riker cottage.

As he made his seventh round he stopped near the dining-room door—near enough to push it open. He looked longingly at the wide mahogany panels that stood between him and that wondrous room and wondered if he might just take another peek at the gold and silver. But Spiffy was nothing if not thoroughly honest and he remembered that Mrs. Pearson had made no offer to let him look while she was there. Consequently he told himself that it would be sneaking to do it now and with firm resolve he shuffled his way back to the window, whistling a tune.

As he stood there idly waiting, one of the doors creaked eerily behind him. He did not bother turning but told himself it was the wind. The door creaked again and he roused himself out of his comfortable reverie in time to see that it was the dining-room door closing ever so slowly—almost too slowly to be caused by a mere gust of wind.

The fact struck him forcibly and he walked across the floor. He stopped mid-way and laughed. “Gee, I’m crazy—seeing things or somethin’, I guess. Anyhow, I got no business going in there and I bet it was something in me that shouldn’t be there telling me I should go in because it wasn’t the wind when all the time I knew it was. That’s what Aunt Kate calls an evil spirit and I bet anything it was.”

As he got to the window again he saw Kato running up from the river, obviously under the stress of great excitement. Coming nearer, Spiffy could see that he was frantically trying to make him hear.

The boy stepped quickly to the screen door and out onto the back porch. Kato spied him and shouted, “M’s Pearson, she say you should come. Terrible fire up by hill and she tink it where you live. She want you to come down with us and see.”

Spiffy stood like one in a trance and nodded his head mechanically. Kato interpreted it as an assent and, being very much interested in the march of events, turned quickly and ran back. He could not know what an announcement of that kind meant to the orphaned boy—his chief interest was in the glow and intensity of the fire, not what kindled it.

But Spiffy knew only too well. He knew that a disaster of that kind would blight his aunt’s life—she had endured too much already. “Funny how I’m always thinking what things mean to her,” he said aloud as he ran to the stove and got his shoes. “Anyhow, she’s been the one that’s helped me and never told me about it either,” he added defiantly.

For a moment he stopped, thinking of Kato’s message. Then he shrugged his shoulders. “Anyhow,” he said, “if the fire’s up on the hill I belong up on the hill. There’s no use of me going down to see first—gee whiz! And anyhow, if Aunt Kate’s afraid or anything I got to be there—she’s been good to me.”

Blindly he ran out the back way and around out to Main Street. One picture he held firmly in his mind and as he waited for a bus or a chance lift it seemed to stand out as clear as crystal. It was the memory of his aunt standing before him with the quarter held tremblingly in her weary hand.

Spiffy, that deserter of scouts, as Tom Slade had once called him, had changed considerably. He had thought himself worthy when he was entirely unworthy. Loyalty and gratitude were entirely foreign to his active mind. But happily, Fate (or whatever you wish to call that mistress of our fortunes and misfortunes) had taught him those very virtues in that hard school of poverty. And now that he had proven himself worthy he was blissfully unaware of it.

Certainly Spiffy mended every scout law that he had broken.

Who shall say what Spiffy’s feelings were on that memorable day as a kindly driver raced him homeward? The man had told him of the disaster that laid waste almost the entire section of upper North Bridgeboro. He told to the fearful boy of the terrific cyclone that had leaped out of the black skies and crushed everything in its path—houses, trees and people.

“I heard down Main Street,” said the man, “that people living on the hill were blown right down into the river. Just think of that—in the river!”

Spiffy sat mute. He had only one thought—that of his aunt. But, on the other hand, it did not seem conceivable that any such disaster would harm her like that. He had been orphaned once—it just wasn’t possible again.

And so Spiffy reached upper North Bridgeboro fearful that he no longer had a home but optimistic as to his aunt’s safety. Even as they drove around the bend and came face to face with the appalling scene of desolation everywhere he would not give up hope.

Someone’s roof was leisurely floating down the river and household furnishings cluttered up the road and neighboring fields. Wearing apparel dangled from the limbs of trees as if it had been hung there. Then Spiffy looked up toward the little knoll knowing that what he wished for wouldn’t be there.

It wasn’t and he winced for a moment. “It’s gone,” he said spiritlessly to the man at the wheel.

“Gosh, that’s tough luck!” the man said sympathetically and stepped on the gas. “What are you going to do, huh?”

Spiffy stared at him as if in a trance. “Just let me out there—I’ll find my Aunt Kate among those people. Gee, there’s so many you can’t tell who’s there,” he mumbled hopefully.

There was line after line of fire hose and the engines were busy moving from one ruin to the other making sure that nothing was smoldering. People stood about in dazed silence, utterly incapable of thinking what they were going to do. Also there was the usual crowd of onlookers and before the man was able to get Spiffy in front of his home they were stopped by the police.

The boy got out of the flivver and thanked the man, leaving him to talk to the police. He saw from where he was standing that nothing was left of the Riker cottage except the props that had held up the front porch. There wasn’t a sign of his aunt or uncle anywhere around the ruined place so he started for the crowds that were assembled in the fields.

In and out among the people he went eagerly searching each face and listening for the voice that he so wanted to hear. He went the full length of one field and spied some neighbors of his aunt. Almost joyfully he ran up to them and asked them the question that trembled on his lips but they just stared in answer as if to say they knew nothing but that they themselves were safe.

Spiffy left them and sought the crowd on the other side of the road. A few gave him an answering glance of great sympathy but it only tended to lower his spirits the more. And in this aimless, hopeful, fearful fashion he wandered around until the little pink glow in the west became a purple streak.

No one paid the least attention to the stunned boy. The survivors were too interested in salvaging what was left of their personal and household effects to be concerned with his futile search. He felt utterly alone.

Without giving much thought to his wanderings he trudged up the hill and to the knoll. The weeds had been trampled down and as he reached the crumbled foundation wall that had once supported his home he felt his eyes smarting with tears. The cellar was flooded with water and little familiar things that he had associated with his aunt were now floating upon its surface.

With a shudder he wondered if she was buried under any of those things. In the fullness of his emotion he was able to think kindly of his uncle also and entirely forgot the mean, petty acts and lazy traits that he had so long despised in him.

He stared down and gradually he became aware of a bit of khaki bobbing its way around in the water. It was his scout suit—the suit that he wore when he wasn’t fit to be a scout. He had long outgrown it and it had been hanging for a couple of years on a peg in the attic.

There was something prophetic in its coming to that ignominious end. With one sweep it had been buried with the past and in a sense Spiffy felt exhilarated by the thought that if he ever joined the scouts again it would be in a suit that had no past. The knowledge kept him from sobbing aloud.

He turned and watched the river flowing easily below as if nothing had happened to change the hearts or minds of humanity. Everything went on, he realized—went along the same as before. Nothing waited for him or cared, not even the river. He shuddered at that thought—it made him wonder if the ebb tide could reveal the secret of his aunt and uncle.

He shuffled listlessly back to where the props were standing. He sat down on one and hunching his knees up under his chin, clasped his hands tightly around them. Then he poked his nose through the little gap in the leg of his knickers and let the tears fall as they would.

He abandoned himself to this for five minutes or more and didn’t look up until he felt utterly exhausted. He was glad it was over—he knew that it wouldn’t happen again for a long while, perhaps never. But he felt certain that the world had turned its back on him entirely.

He did not see Warde Hollister trudging up from the river bank and hastening toward him. He saw nothing but a leaden colored sky and great piles of ruined homes. Suddenly the cheery voice called from behind.

“I’ve been looking all over for you, Spiff!” Warde said feelingly. “Jiminy, I’m glad I found you!”

Spiffy jumped down from the prop and faced Warde with red-rimmed eyes. He tried to smile but his heart seemed to break in his throat. “I—I—been looking around for my aunt and uncle,” he said in a quivering tone. “I—I can’t seem to find out anything and I was down in Mr. Temple’s . . .”

“I know all about it, Spiff, old kid,” Warde interposed kindly. “We’ve got all the dope—we meaning the Silver Foxes of our own First Bridgeboro Troop. Anyhow, we’re all on the job to see what we can do—even Kid Harris himself. He can’t do much but shout orders but he kids himself he’s the whole works just the same. It was a pretty mean trick that cyclone played on you, Spiff——”

“You said it,” Spiffy answered mechanically. “Have you heard anything about my aunt and uncle?” he repeated.

Warde shook his head slowly, unwillingly. “I just asked a cop down there, Spiff,” he said. “They all knew your uncle, you know.”

Spiff nodded sadly.

“I mean they were all used to seeing him around town and all,” Warde said apologetically. “Anyway, the cops said that one of your neighbors told him that she saw your uncle out in the back yard a few minutes before the crash came. No one seems to know anything more than that. I asked the minute I spied you sitting up here alone. I knew you hadn’t found out yet.”

“I guess then they were blown into the river like that man told me,” Spiffy said in measured tones. “He said there were lots of them.”

Warde was filled with pity for the poor, unfortunate boy. “Gee, I know, Spiff,” he said striving to say the suitable thing. “It certainly is awful but gee, if you could only feel that way—my mother says sometimes things like this happen for the best. Your aunt worked hard and all, didn’t she?”

Spiffy was too choked to speak.

“Come on,” said Warde trying to smile. “Maybe you’ll like my mother—maybe it won’t seem so bad after tonight.”

Spiffy gazed at him questioningly.

Warde nodded. “Gee whiz, you don’t think we’d let you stay here and starve, do you?” he asked. “No siree, we’re dividing up—not only the scouts but everybody in Bridgeboro. And somehow on account of you being a sort of scout—we thought of you right away. I asked first thing if I could have you and my mother says to bring you straight there as soon as I found you.”

Spiffy wriggled his toes inside of his wet shoes. He could not talk just then because there was a queer little voice ringing inside of him, repeating over and over that he had once been a sort of a scout.

Spiffy was carried away from the desolate scene on a vertiable avalanche of scouting hospitality. He wasn’t given a chance to think of anything but the immediate present. Roy Blakely saw to that with, of course, Pee-wee’s gentle aid.

Ben Maxwell drove them into Bridgeboro just before dusk and the noisy flivver rattled through the street just as carefree and gay as if they were all returning from a picnic. Spiffy sat listening to their talk—to everything as if it were all a dream. Presently Warde gave him a friendly tap on the arm.

“We’re home, Spiff,” he smiled. “Jiminy, I’m hungry.”

“And how!” roared Pee-wee.

“You surround me, Kid Harris,” Roy said. “Didn’t I see you chewing on a burned potato up there just a little while ago?”

“You’re crazy,” Pee-wee answered. “That was an orange I found and it had a little mud on it that I wiped off and it was just as good so you must have seen it before the mud got wiped off.”

“Exactly,” said Roy. “I misunderstand you perfectly.”

Spiff found himself smiling as he and Warde reached the sidewalk. They said goodbye to the gang and the flivver leaped forward like a rocking-horse. “Some crowd,” said Warde as they walked up onto the porch. “One thing, they’ve always liked you and been anxious to get you back again.”

Spiffy longed to find words for an answer but his mind seemed utterly blank.

Understandingly, Warde rambled on. “Maybe you heard that when you were going to meetings,” he said. “But anyhow Mr. Ellsworth, he’s our scoutmaster—he likes to keep reminding us of it all the time and now I can see it’s a good thing. He says, once a scout always a scout.”

Spiffy gulped. “If I ever join again—that’s if, I don’t want to be the scout I was once. I wouldn’t go back into it that way,” he seemed to sigh with effort when the words had been spoken.

“Atta boy!” Warde said as he opened the door. “Jiminy, you’ll be all right when you feel like that about it—don’t worry.”

If ever people tried to open up their hearts to a lonely boy, the Hollisters did just that to Spiffy. He was taken in, as it were, from the time he entered the hall until Mrs. Hollister insisted that he better sleep under a light blanket after all his exposure that day.

He was fed royally and bathed so that when the door shut softly behind Mrs. Hollister he was too exhausted and sleepy to wonder about the uncertainties of his existence. And of his aunt he thought very tenderly, particularly of Warde’s gentle reminder that she had worked hard. If she was spared that now and could rest for all time then he was willing that things had happened as they did. Sleep wrested his perplexities from him.

Morning dawned bright and clear and Spiffy descended to the Hollister dining room arrayed in Warde’s clothes. Mr. Hollister beamed upon him and winked fraternally. “You and I have a date for a little talk after breakfast,” he smiled. “We’re going to dope out the whys and wherefores of all your troubles so don’t have any fears. Eat your breakfast as if the world owed it to you, Arnold.”

“Call him Spiff,” said Warde looking up from his grapefruit. “Gee, I think that’s a swell nickname. It’d sound dandy in our patrol.”

Spiffy smiled and his heart warmed to his benefactor. “I don’t care what you call me, Mr. Hollister,” he said timidly. “Some fellers called me that when I lived in Jersey City—my mother and father were alive then. I used to like to dress up all the time and I was always buying spiffy looking stick pins and things in the five and ten. Even after I couldn’t dress up and all the name stuck to me.”

Mrs. Hollister smiled. “Well, you look spiffy now,” she said. “Warde’s grown out of a lot of good clothes and I’m very glad that you fit into them so well.”

“I bet Arnold would look spiffy in a scout suit—what do you think, Warde?” Mr. Hollister said significantly.

“I bet you he would!” Warde said vehemently.

Spiffy flushed with embarrassment. “I used to feel swell in one,” he admitted. “I honestly did, Mr. Hollister.”

“Well, we’ll see if we can’t fix you up,” Mr. Hollister said. “It’s pretty near camping time too, isn’t it, Warde?”

“A month yet,” Warde said joyously. “And will Spiff be able to come?”

“I don’t see what’s going to stop him,” answered Mr. Hollister genially.

Spiffy looked up and almost choked in his amazement. “I got to go to work, Mr. Hollister,” he struggled nervously. “It ain’t right for anyone to do anything for me when I can work.”

“Calm down, Arnold,” Mr. Hollister smiled. “We’ll talk it all over in the library. Come in as soon as you finish.”

A few minutes after, Spiffy sat down in a comfortable chair facing the man who had been an utter stranger to him only twenty-four hours before. He could not comprehend the swift change of events and looked it, drawing his brows up into a hundred tiny lines.

“You’re wondering why we sent Warde up for you yesterday and why we’re willing to share and share alike with you—isn’t that it, Arnold?” Mr. Hollister said with a kind smile playing about the corners of his mouth.

Spiffy nodded emphatically and smiled. “That’s a fact, Mr. Hollister, because nobody ever paid much attention to me before—nobody except the scouts. Tom Slade told them about me, I suppose, and they sort of always watched for me when they’d pass our house on hikes or going up the river. They always made me feel that they wanted to make friends with me and I would have only that I never had time after school or on Saturdays. My uncle wouldn’t let me mention scouts even so I couldn’t have made friends with them anyway.”

Mr. Hollister nodded understandingly. “Warde has often said that too, Arnold, and of course your uncle had a way of speaking his mind in public,” he said. “On several occasions he has done odd jobs for me—I suppose you know?”

“He didn’t talk about his business much in front of me,” Spiffy said frankly. “He always whispered things as if he was afraid I’d tattle.”

There came to Spiffy’s mind just then one occasion when his secretive uncle had spoken disparagingly of generous Mr. Hollister. He had muttered something about the latter’s failing to fully recompense him for a certain job and that he had gotten even. Just what form that reprisal had taken, Spiffy never knew.

But Mr. Hollister was well aware of what it was. A certain quantity of silverware had disappeared after Bill Riker had walked away from a half-finished job, refusing to return and complete it. The Hollisters were positive of his guilt but did not try to prove it. They had in mind a certain tired and much tried woman—Spiffy’s Aunt Kate.

Mr. Hollister sat thinking it over. He was willing to let the dead past bury its dead, as it were. He had done that long ago but his feeling for Bill Riker had always been one of contempt—the contempt for the strong, ambitious man for the weak and lazy one. But all that was changed—he could try and talk charitably of the misguided man now that death had closed in upon his weaknesses.

“I’m not going to be hypocritical and extol your uncle just because he is dead,” said Mr. Hollister, seriously. “If in life, a man is not worthy of extolment, then neither is he when dead. And your uncle was not worthy.”

Spiffy nodded vehemently. “He was mean to Aunt Kate,” the boy said bravely.

“All Bridgeboro knew that, Arnold,” said Mr. Hollister. “And that is why we’re going to try and be charitable in our thoughts and speech about your uncle. Because of his sudden death we are going to try and convince ourselves that he might have proved worthy after all. We will say that death snatched that chance away from him and that hereafter we will give him the full benefit of the doubt. What do you say to that kind of scouting?”

“You mean I ought to think good of him and all?” Spiffy asked.

“Yes.”

Spiffy looked out of the window idly musing as some children strolled along the quiet street in their Sunday clothes. Then he turned to Mr. Hollister. “I get you all right,” he said in his naive way. “I’ve got to be loyal on account of the quick way he was killed and that’s why you sent Warde for me and all that, huh?”

“In a measure; yes,” Mr. Hollister answered. “Mrs. Pearson saw Warde hurrying by and of course everyone knew of the horror then so she told him how worried she was about you because the reports were that your cottage had been blown right into the river with your aunt and uncle in it.

“She told him in what condition you came to the Temples’ in search for work—work to make up for your uncle’s deficiencies, and she was greatly excited over your future in case your aunt and uncle could not be found. Warde, of course, came running home to us with the story, as much excited and equally as concerned as Mrs. Pearson was.”

Spiffy’s heart thumped just from sheer gratitude.

“Mrs. Hollister, being the mother of Warde,” Mr. Hollister continued smilingly, “would not be satisfied until you were found and brought to her to be clothed properly and sufficiently fed. Now she is satisfied and happy and I hope you are too.”

Spiffy was plainly overcome. “Gee, gee whiz,” he mumbled. “I couldn’t tell you how I feel—not in a thousand years!”

“I’ll wait,” Mr. Hollister laughed. “But one thing, Arnold, you’re not fit to plunge into work just yet. You’re undernourished and you need to make up for some of the healthy exercise that you’ve lost.”

“But . . .” Spiffy began.

“I know what you want to say,” Mr. Hollister interposed. “I know too what an ambitious, independent boy you are and I think it’s good for a healthy boy to work. But you’re not well enough now—anyone can see that. You’re not sixteen yet, are you?”

Spiffy shook his head. “Not till September,” he admitted.

“Well, that settles it,” said Mr. Hollister. “You go up to Temple Camp with Warde just as if you were a Hollister. Don’t think of anything but play the whole summer long, and when you come back in the fall we’ll see how you look and act. If you want to do something light that would keep your mind at rest as to obligations, why, all right. I wouldn’t discourage that in any boy. But you can go to night school and fool them anyway, can’t you?”

Spiffy nodded. “Gee, I do want an education because I want to learn things and not be lazy like my . . .”

Mr. Hollister smiled. “Don’t worry about that, my boy,” he said. “You couldn’t be lazy if you tried. And now we’ll bring our little conference to an end and call the bargain square, eh?”

He got up and strode over to the boy and grasped his thin hand. Spiffy returned the pressure as well as he was able and they smiled into each other’s faces.

It was a scout handclasp.

Mr. Hollister smacked Spiffy fraternally upon the shoulder. “That wasn’t doing so bad for an old scout like me, was it, Arnold?”

“Yes sir—I mean no sir,” Spiffy answered, stumblingly exultant. “I’ll say it wasn’t.”

“You know why I did it, Arnold?” he asked.

Spiffy smiled. “Yes sir,” he answered happily. “A scout’s a brother to every other scout.”

“Good!” Mr. Hollister applauded.

Late that afternoon the Hollisters had a call from Mr. Temple. Spiffy was out with Warde, being shown off to other members of the fraternity, and it wasn’t until they returned in time for supper that they learned of the great philanthropist’s visit.

Mr. Hollister did not have anything to say about it until they were all gathered around the tea table that evening. He looked down the length of snowy table cloth and smiled at Spiffy. “A very unusual thing happened in Mr. Temple’s house yesterday afternoon,” he said. “It occurred either during Arnold’s visit there or immediately after. Mrs. Pearson discovered it just after her talk with Warde.”

Spiffy watched his host, puzzled.

“What was it?” Warde asked eagerly.

“Mr. Temple’s silver service was stolen,” Mr. Hollister said quietly.

Spiffy felt almost sick. “Gee, and me being there and everything! Would Mr. Temple think I did . . .”

“Wait, Arnold!” Mr. Hollister interposed, smilingly. “That’s precisely what he doesn’t think. That’s why he came to see you!”

“Me?” asked Spiffy incredulously.

“Exactly,” smiled Mr. Hollister. “But don’t get excited about it, Arnold. Mr. Temple just wondered if you noticed anything unusual while you were there.”

Spiffy thought of the front door being open. He told them about it in short, nervous accents. “Maybe that’s how they got in, whoever it was,” he said. “I wanted to close the door but then I thought it was none of my business.”

“Well, you go over and tell him about that,” Mr. Hollister said. “It might help them find some clue. Mr. Temple asked me if I would have you come after tea.”

If Spiffy had had time to recover from the shock of grief of the day before, perhaps that revelation would not have affected him. But coming at the time it did, it took another little toll from his physical resistance.

He rang the Temples’ bell with trembling fingers and when Mrs. Pearson opened the door, serious and troubled looking, he felt as if he were already condemned. She put her arm around his shoulder almost patronizingly he thought and led him straight into Mr. Temple’s library.

Mr. Temple rose and came toward him, smiling. “What makes you look so scared, son?” he said heartily. “Do you think I’m going to accuse a frail little youngster like yourself of carrying away that huge service?”

Spiffy’s heart bounded in one leap. Mrs. Pearson too was smiling. “I really think that’s what he was thinking of, Mr. Temple,” she said. “As if such a thing were possible!”

Mr. Temple reached down and took Spiffy’s hand. “When life makes a boy as sensitive and timid as you are now, Arnold,” he said kindly, “it’s time things did change. I’m glad to see the interest that Mr. Hollister has taken in you.”

Spiffy felt overwhelmed by all that kindness. And Mr. Temple had called him Arnold! He looked up and tried to smile his brightest at the great man. “I—gee, everybody’s been nice to me—you too! I only thought you might think I did it because I was here in the house and all,” he panted breathlessly. “I even didn’t go in the dining-room to peek at that nice stuff because Mrs. Pearson didn’t tell me I could before she went out so I wouldn’t do it afterward. And I wanted to see it too!”

Mr. Temple laughed. “I bet you did,” he said. “And I believe you, so we won’t speak of that any more. But just one word: I know that a boy who comes seeking work in the manner that you did, doesn’t come to steal.”

Spiffy felt relieved for a moment but in the next second looked troubled. “Anyway, it’s kind of my fault, Mr. Temple,” he said. “I should have gone and closed the front door when I saw it open. I should have known that it wouldn’t be a crime to walk through your hall just to close the door. Gee whiz, if I’d have done that it wouldn’t have happened maybe.”

Mr. Temple waved his hand. “No vain regrets, Arnold. If is a vain word. You’ve had no more to do with it than I had. All I wanted to know was if you noticed the front hall door standing open. Now I’m satisfied that the thief came in that way—having taken advantage of Mrs. Pearson’s and Kato’s absence during all the excitement.”

Mrs. Pearson nodded to Spiffy. “You see we’re partly to blame too, Arnold,” she said seriously. “Kato and I have something to think of also.”

Mr. Temple smiled. “No one has anything to do with it,” he said. “No one but the thief, and even he has some excuse—I could forgive one almost anything under the stress of yesterday’s horror.”

“Tell him about tonight’s discovery,” Mrs. Pearson said.

“Oh yes,” Mr. Temple said. “We’ve recovered part of it—or rather the gardener found part of the service just before dark. It was hidden under the rose bushes right back of the house.”

“Gee, that’s fine,” Spiffy said. “Then is it much more that was stolen?”

“Quite a little, yes,” answered Mr. Temple. “The thief evidently meant to come back for the rest of it tonight. He couldn’t carry any of it away in broad daylight when it was first stolen so he got the idea of hiding it there and last night he must have taken a part of it. You see, I didn’t notify the police until this afternoon.”

“Whoever it was,” said Mrs. Pearson, “they certainly knew something of what Kato and I were doing. I can’t conceive of a thief doing such a thing in broad daylight unless he was sure of himself.”

“Well, he won’t get much for what he’s taken,” Mr. Temple said complacently. “Monogrammed, the way the pieces are, they’re not very salable—not in the places that stolen articles are sold. I doubt if he gets more than fifty dollars for the entire lot.”

That ended the conference concerning the stolen silver but it did not end Mr. Temple’s interest in Spiffy. He had the boy sit down and relate his life even up to the morning’s talk with Mr. Hollister.

“Mr. Hollister is a very fine man, Arnold,” Mr. Temple said. “He won’t regret sharing with you, I’m sure. He told me he picked a winner in you and I thoroughly agree with him—so much so that I’m going to make him let me share some of the winnings too. Your little camp vacation this summer is going to be my affair.”

Spiffy felt that things were coming thick and fast. “Gee whiz, Mr. Temple, gee whiz!” he stammered. “I don’t know how I’m going to pay you and Mr. Hollister back for everything—I honestly don’t. It’ll take years because I won’t be able to make much when I first go to work but I won’t care as long as I can pay back!”

“I like that kind of talk,” Mr. Temple said seriously. “That’s why I’m going to enjoy doing things for you—that’s why Mr. Hollister enjoys doing things for you. But for now, we’re not going to talk about the future—we’ll let it take care of itself. We’re going to think of today and this summer.”

“That’s just what Mr. Hollister said,” Spiffy said, enjoying the new order of things. “And if he said he picked a winner I’m going to show him (and you, too) that I am. I’ll win no matter what and I’ll be loyal—even I’ll be kind of loyal to my uncle because he’s dead and Mr. Hollister said it wasn’t fair if I didn’t on account of he didn’t have a chance to show what he could have done if he had lived!”

“You talk like an Eagle Scout right now!” Mr. Temple laughed.

“I feel like one,” Spiffy said frankly. “Honest I do!”

He left the Temple Mansion fully resolved “to show people.” He glowed inwardly when he thought that he had been picked as a winner. That knowledge swept away all his fears and doubts and the future seemed to shine as brightly as the stars that sparkled gaily above his head.

He jumped the steps and landed on the Hollister porch as lightly as a cat. And he whistled joyously. Mr. Hollister heard him and smiled. “Are you home so soon, Son Arnold?” the kind man asked feelingly.

Spiffy gulped in sheer joy. “Yep, I’m home,” he answered.

A month later Spiffy left Bridgeboro for Temple camp a full fledged member of the hilarious Silver Fox Patrol. Pee-wee Harris having scouted on a large scale in a little town called Hickson’s Crossroads made that membership possible.

Roy said that Pee-wee’s desertion of their famous patrol was a bit of luck for them for it gave to them Spiffy. “The only thing I miss about the kid’s leaving us,” Roy said as the train rumbled on up through New York State, “is Ben Maxwell’s flivver. Wherever Pee-wee goes the flivver goes and if he’d stuck to us—I mean the kid, why we all could have piled into the flivver and had a nice uncomfortable ride up to Camp.”

“Not saying when we’d get there,” Warde added. “After the way that Lizzie behaved when it brought us home from Hickson’s Crossroads, why, I wouldn’t trust it through any mountain roads. We’d have to walk and push the flivver besides.”

“That’s nothing to the way you’re going to walk this summer,” Roy said. “We’re going to have one hike after the other and more besides.”