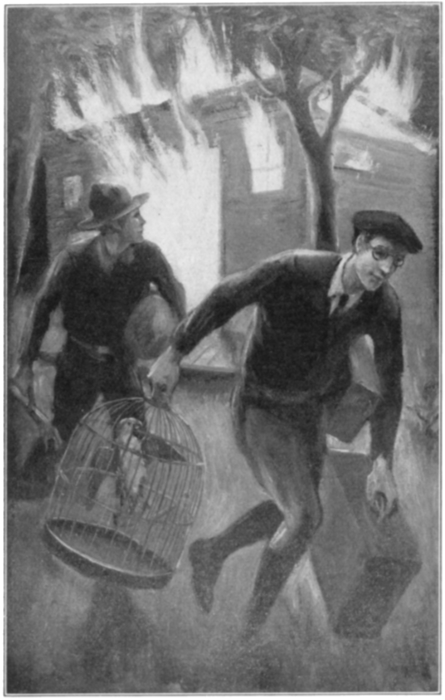

“DON’T LET GO OF ME!” TOM SHRIEKED.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Tom Slade in the Haunted Cavern

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Dec. 30, 2019

Date last updated: Dec. 30, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20191258

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

“DON’T LET GO OF ME!” TOM SHRIEKED.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | Before the River Moved |

| II | A New Job |

| III | Established |

| IV | A Light in the Darkness |

| V | “Who’s There?” |

| VI | The Old Boat House |

| VII | The Wreck |

| VIII | Brent’s Vigil |

| IX | “Lost, Strayed or—” |

| X | A Shock |

| XI | What Tom Overheard |

| XII | Camouflage |

| XIII | A Day’s Diversion |

| XIV | Accidents Will Happen |

| XV | The Unfortunate Stranger |

| XVI | A Poor Excuse |

| XVII | A Discussion of Talents |

| XVIII | Wally Ryder Departs |

| XIX | Trouble |

| XX | Old Tightheart |

| XXI | The Boardman Tragedy |

| XXII | Mascot |

| XXIII | The Letter |

| XXIV | On the Trail |

| XXV | A Night Prowler |

| XXVI | A Night in the Open |

| XXVII | Something Unlooked For |

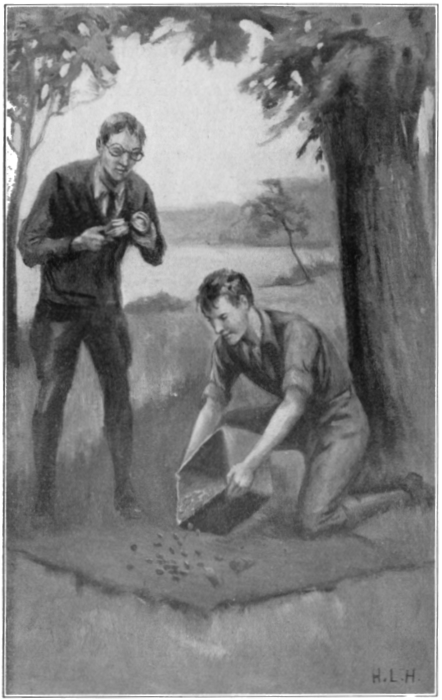

| XXVIII | Buried Treasure |

| XXIX | The Old Bridge-Tender |

| XXX | All’s Well |

I have only myself to blame for the task which is now before me. I went up Old River for a day’s holiday with Tom Slade upon his enthusiastic representation that the stream was full of fish. We caught just exactly two eels and three bullheads; or, to be exact, two eels, three bullheads and a tin can which cut my hand when I tried to disentangle it from my fish line. This was the first blood of the great adventure.

Somebody had told Tom that there were perch, “yes and bass,” up the old stream; “thousands, millions of them waiting to be caught. And nobody ever thinks of going up there.”

There you have Tom Slade all over. Sometimes I could choke him. Yet again and again I fall a willing victim to his enterprises. And on that day he did get on the track of an adventure—an adventure which has occupied his time for these several weeks past and postponed poor Brent Gaylong’s vacation at the seashore. Such a rumpus I never heard.

And now I must write out the whole queer business. “It will make a rattling story,” enthused my young friend. “Tell it just the way it happened; how if we hadn’t gone up there fishing....”

And so on, and so on.

“You don’t have to figure much in the story,” he said.

“Thank you, I don’t intend to,” I answered. “I shall gracefully withdraw after the fishing trip.”

“You know how everything happened,” he encouraged, “and you know how Brent and I talk—you can put in the talk, all right. Just the way you did in the Bear Mountain yarn.”

“I will depict both of you to perfection,” I observed.

“Brent’s drawling way, you know—”

“And your adventurous blundering,” I added. “Leave everything to me. Even the parrot will see all his winsome human traits reflected. Kindly don’t come up to see me till the task is finished.”

It was only last week that the astonishing climax of Tom’s adventure caused no small sensation in this quiet town of ours. And now I notice that our local newspaper is running a series of very interesting articles about the Bridgeboro River in its golden age when coastwise vessels poked their noses up its winding course bringing sugar and molasses from the tropics and sailed away again with their holds full of lumber from our Jersey forests.

I remember as a very small boy playing about old Squire Van Gelder’s crate mill where thousands upon thousands of crates were made to be sent to the Indies and there packed with oranges and bananas. I suppose they make their own crates down there nowadays. Some of these old-time articles are full of blunders, as for instance the statement that old Mammy Shannon’s hovel in the marsh was washed away when the river changed its course and took a hop, skip and a jump to another bed some three or four miles east of Old River.

But it is true that the old witch predicted the flood. No matter. Her old hovel on the marsh was moved up to the drawbridge in the woods and placed there for the bridge-tender. Mammy Shannon died in the county poorhouse when I was still quite young. Still, for all, I like these reminiscent articles which the recent adventure of Tom and Brent has inspired.

And here I am committed to the task of writing out the whole strange business about the old schooner, Carrie C. Boardman. There is an old crayon of that ship hanging in the Public Library now, and no one ever looks at it. She was built in these parts, down at White’s Crossing, and my own uncle riveted some of the planks that are now rotting in a muddy grave.

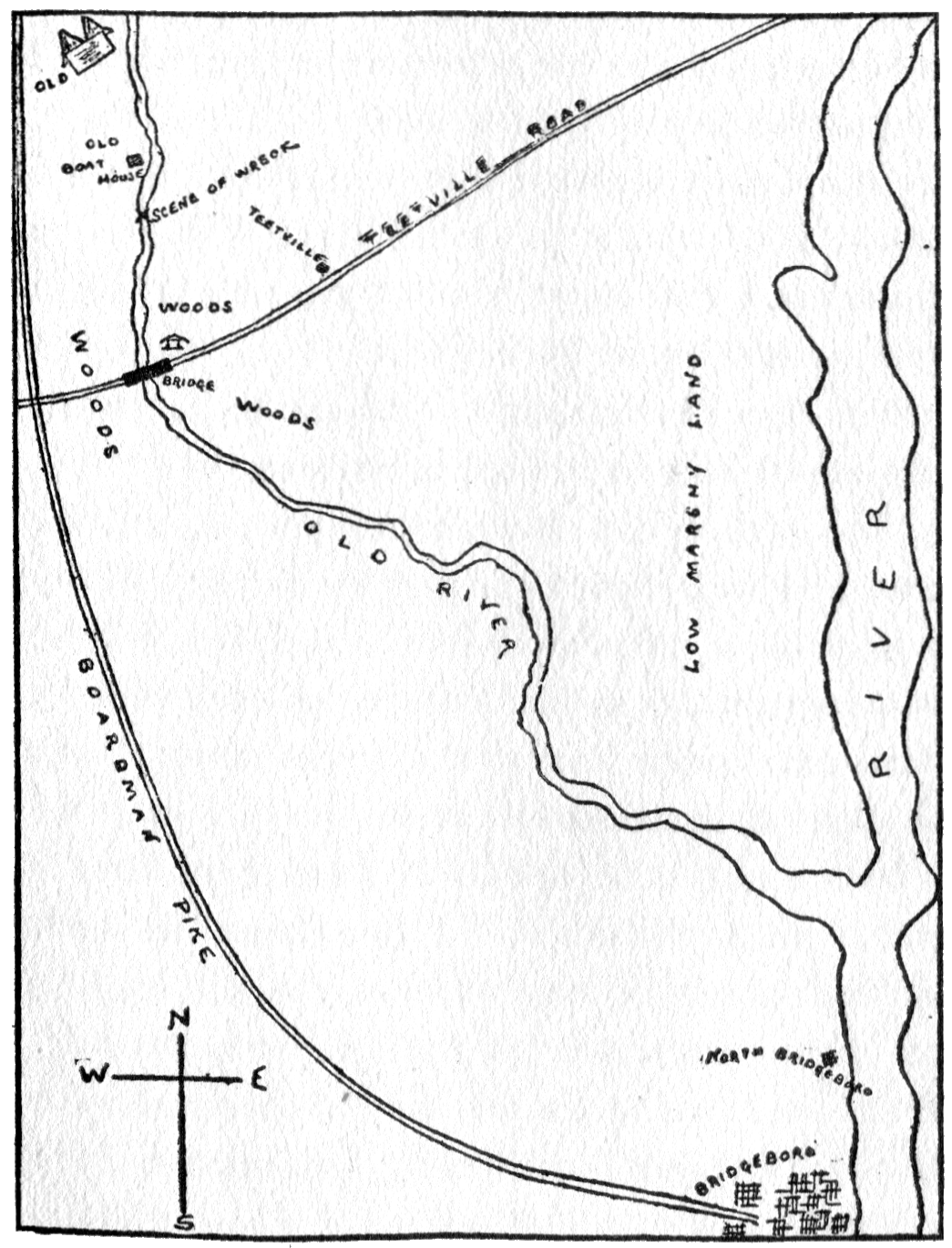

Well, as I said, Tom asked me to go fishing with him up Old River. I have begun my task by making a crude map of this region which many be helpful to you in reading this winter’s tale. And I must tell you something of the locality.

Old River, as I have said, was once a more pretentious stream—it was the river proper. Those were the days when it bore the ships of commerce on its wider bosom. Sometimes nowadays when the stream is at low tide, you may see a slimy thing sticking a foot or so out of the river like a ghastly finger. This is the bowsprit of the old schooner Carrie Boardman, and the fact that the authorities do not remove this submerged peril indicates how little Old River is frequented in these latter days.

But a more eloquent sign of neglect is the old drawbridge which spans the stream up in the woods and the deserted shack close by it where the bridge-tender once lived. They keep the bridge closed in deference to the rather infrequent passing of cars on the old country road.

We have a new state highway now, running east and west above the region included in my rough map. You will see how the crossing where the bridge is, is embosomed in dense woods. The old bridge and the adjacent shanty look strange enough now in this solemn and deserted wilderness. A couple of miles upstream from the road you will see the old Boardman mansion, falling to pieces, one of those dismal looking places which are commonly alleged to be haunted. If so, it must be by the shades of a patrician family, for the Boardmans in their remote home were lordly aristocrats in those old days and had grown rich in the West Indian trade.

I have often heard my parents tell how old Roscoe Boardman used to drive down to Bridgeboro with his team and tally-ho when such ostentatious turnouts were even then things of the past. They were veritable “lords of the manor”—these Boardmans. The feature of their palatial establishment which appealed most vividly to my boyish mind was the group of alligators which passed a drowsy existence in the sparkling fountain bed on the spacious lawns. I suppose they had been brought from the West Indies.

One other member of that household was also brought from the West Indies, and still lives in honored old age, after the Boardmans have long since gone the way of all flesh. And this sole survivor is not human. He has triumphed over Time and only lately played his part in a great adventure. Dignified and aloof, he sits in solitary glory, with no heroic ostentation. You shall meet him in good time.

It is odd, when you come to think of it, that the most intensely interesting episode of those old river days, and one which was connected with this old house of Boardman, was never known to me till very lately, when Tom and Brent brought it to light. And that is the real story of the schooner, Carrie C. Boardman.

“Well, you’ve wasted another day for me,” I said to Tom. He always understands my complaining to be conceived in good humor. “There is nothing up here, not even fish. But you’ve had a look at the old country. It’s a deserted region, Tommy. Even the river has gone away. This, you see, is only the ghost of the old river, haunting forgotten scenes. Pretty desolate, huh?”

“And the house is haunted, eh?” he commented, as we reeled in our lines just below the old mansion.

“Positively, guaranteed,” I said.

“Golly—funny I’ve never been up here, right around here,” he said with an inclusive sweep of his arm, “why, it might be a thousand miles away from town.”

“Right,” I observed. “You perceive that your adventurous nature hasn’t taken you everywhere.”

We rowed down, pausing just north of the bridge. The tide, moving ever as of yore, had risen to within a couple of feet of the bridge, and our old skiff would not pass under.

“Now we’re in a pickle,” I said. “Marooned in the wilderness. I never gave two thoughts about the tide, did you? That’s something that an ex-boy scout ought to have thought about.”

Puzzled at our predicament I glanced about. The scene was dismal enough in the mellowing glow of the twilight. Close to either shore the rusted girders and broken railings of the old bridge were partly covered by woodbine, suggesting long disuse. So also the little shack near by was almost buried in these embracing vines which softened its dilapidated appearance. There was a chill solemnity about the dim woods. Every ripple of the steadying oar with which we held our boat was strangely audible in the solitude.

“Such a place to live!” I said. “I wonder what the poor bridge-tender found to do up here in those old days?”

“Well, there were boats passing up and down then,” said Tom. “He had to open and close the bridge, and I suppose they spoke with him as they passed.”

“A lonesome life it must have been even then,” I mused.

“It’s lonesome enough now,” he added, glancing into the deep woods. “There’s one thing I don’t like here.”

“The place won’t change, Tommy, whether you like it or not,” I said.

“That house ought to be occupied,” said he, in his boisterous way. “Why, look at that old bridge—closed up and the vines growing on it. This stream is a public waterway—it’s open to boating and they can’t obstruct it—that’s the law!”

“Don’t make me laugh,” I said. “Who ever comes up here?”

“That doesn’t make any difference,” said he in that decided way he has. “Not a bit of difference. This is a tidal stream and cannot be obstructed. That’s what drawbridges are for. Why, here we are now and we can’t get by—waiting for the tide to drop. Where there’s a drawbridge, that means that the stream can’t be obstructed. There’s got to be someone to open and close the bridge. Why, take the big drawbridge down at Berry’s Crossing—I’ve seen them swing that great big thing around just to let a canoe pass by. They’ve got to do it!”

“Tommy,” I laughed, “look at the vines growing over the ends of the bridge. Why, it hasn’t been opened in years. Don’t be such a stickler for the law! I doubt if you’re right, anyway!”

“How do you know nobody ever wanted to come up here?” he snapped. “Why, motor boats could pass up this river, even tugs.”

“For why, Tommy? No,” I laughed, “there are no tugs.”

“You can’t close up a river for good and all any more than you can close up a street,” he persisted. “Some poor cripple needs that job and he ought to have it. Why, don’t you know anything about the public waterways law?”

“You and your public waterways!” I laughed.

“If a boat comes up here once a month, that’s enough,” he jerked out. “They can’t obstruct a stream. And that’s what they’re doing now. Why did they have to build a drawbridge—why not just an ordinary bridge? Because this is a tidal stream. That—gol blame it! That’s what makes me mad.”

“Well, I think we can just about make out to squeeze underneath now, Tommy,” I said.

And so we did, by lying almost flat in the boat, but my precious fishing rod was broken against the low metal framework. Tom did all the rowing by reason of my cut hand, and all the way down to Bridgeboro he was stewing away about the “obstructed waterway.” He said that if a cabin launch should sail up the river it would have to turn around and go back. And so forth and so on.

In truth, the matter did not much trouble me. And I don’t think it troubled many people. Doubtless, from time to time, boats had ascended Old River for no reason at all, their pleasure-seeking owners being willing enough to turn about at the first obstacle.

In the old days of river traffic the draw was necessary. But you see the traffic has been dead these many years and even the river proper (that is our Bridgeboro River) pursues its placid course two or three miles east of these lonesome scenes. Once upon a time the marsh was flooded and when the waters subsided, there was the Bridgeboro River flowing in a new channel.

It was thus that the old river became nothing but a minor stream. It had jumped its banks above the region shown on my map and ploughed across the low country up there with devastating loss to the farmers. Government engineers came to take note of this boisterous prank of the river, but couldn’t do anything. Old Nature had her own way.

And why on earth Tom Slade was lashing himself into a fine heroic frenzy of public spirit about the old bridge was beyond my comprehension. But that is Tom all over. He knows all about the game laws and I have seen him reprove a motorist for throwing a cigarette away on a woods road. He got that training in the Scouts and he thinks he is guardian of all outdoors.

Of course, I thought he would soon forget about this matter for his mind is as fickle as it is active (he will wince when he reads this) and you will therefore understand my astonishment when, several days later, I received the following letter from him addressed to me. “Dear Knight of the Fountain Pen” (a gentle crack at my unadventurous spirit, which originated not with him but with Brent Gaylong).

Well, you see I’m right, I was in touch with the State Waterways Commission and they as much as admit that there has to be a bridge tender where there’s a drawbridge. Why there’s even an appropriation for this particular one—eighteen fifty-two a month—in cold cash.

I saw Harley of the County Freeholders and he said O.K.—that was right. You can’t close up a public waterway. He says no one would take the job—that’s the trouble! They usually have a lame man or a war veteran for that kind of a job. But no one could be got to go up there since the old tender died up there years ago—he was a kind of a Spaniard or something or other, I heard.

Do you know what I am going to do? I bet you’d laugh. That’s some lonely spot—you said so yourself. Camping—yes? Leave it to me! I’m going up there for the summer if I can get Brent to go along. The eighteen fifty-two will buy all the grub—maybe! Anyway it’ll help. Any boats that want to pass up—Johnny on the spot. Always ready. Service and roughing it all mixed up together.

Of course, I don’t care two cents about the job. I mean as jobs go. But there’s the place for camping all right. Primitive abode and all that stuff, hey? And we may catch some fish at that—I think you were the hoodoo. Anyway there are beavers in those marshy ponds, I’m dead sure of it. So I’m taking my Kodak. You know—pictures of beavers at work—why they’re worth money.

What I want to know is, will you let us have your rowboat? The steward at the Boat Club tells me you never use it. Otherwise I suppose I can buy one. I’ve still got my flivver but thought I’d give her a rest for the summer. Anyway the rowboat is what we need for that place—and of course we’ll want you to come up some week end and have hunter’s stew. I’m going to try and see you in couple of days—I just wanted to let you know.

Good we went up there, hey?

It was amusing how his jealousy for the public interest was all but swamped by his quest for adventure. He was not going to be a useful bridge-tender at all. He was going to be a camper at one of those quaint, remote spots that he loves.

He was going to fish and cook hunter’s stew! And I must come up for a weekend! Tom Slade has not the spirit of a bridge-tender. He has the spirit of a pioneer.

It was in my presence that Tom drafted Brent into the public service. I went down to the Boat Club with him to get the oars and rudder out of my locker and turn over the boat to him, for he intended to paint it. And there was long, lanky Brent Gaylong sitting on the veranda, his chair tilted back against the building, his feet up on the rail. He was reading a magazine and his spectacles were half-way down his nose giving him that funny old man and professor look which is comical in one so young.

“You’re just the one I want to see,” said Tom boisterously, and straightway poured out the whole story about the bridge and the shack and his plans.

“What am I supposed to do up there?” drawled Brent. “Turn the bridge around?”

“If a boat comes up at high tide, yes,” said Tom.

“Why don’t they come up at low tide?” was Brent’s leisurely query.

“I don’t know,” said Tom, a trifle nettled as he sometimes is with Brent. “Maybe none will come up at all.”

“Then why go there?” asked Brent.

“Will you please lay down your magazine and listen?” Tom snapped at him. “Don’t you want to go camping? Didn’t we have a peach of a summer up at that forest lookout station?”

“Every time I dropped my glasses I had to go down fourteen flights of stairs,” said Brent. “There wasn’t a hook to hang my bathrobe on, I hung it on a jackknife jabbed in the wall and the jackknife fell out when the wind blew and my bathrobe sailed out of the window. I found it in Cornville at the foot of the mountain—three days later.”

“Well, I guess the walk did you good,” said Tom.

“How far is it to a drug store up there?” Brent drawled.

I couldn’t blame Tom for being nettled.

“Do you want to go or don’t you?” he snapped. “It’s in the wilds and there are no improvements. You can bring your cards for you’ll have plenty of time to play solitaire.” Then turning to me he added aloud: “I’m blamed if I know why I like to have him with me—he ought to be in an old lady’s home—but he’s good company.”

“Thanks,” said Brent, reading his magazine. “And you’ll go?”

“I’ll make the sacrifice. What is there to do on a rainy Sunday?”

“Just what we did up at Long Gulch on a rainy Sunday,” said Tom.

“That was to rip my pajamas chasing a garter snake. Nevertheless I will go,” said Brent in the voice of a martyr. “When do we start and if so, why not a couple of weeks later?”

“We’re going next Saturday, that’s the Fourth of July,” Tom said.

“We go off on the Fourth,” said Brent still reading his magazine.

“Today we paint the boat,” continued Tom, “and tomorrow we go shopping for provisions—we’ll hit up the chain stores for bacon and sugar and coffee and—here, I’ve got a list.”

“Couldn’t we call up the stores?” asked Brent. “Let’s go to stores that deliver, then we won’t have to carry any bundles. My mother’s way is good enough for me. Shall we take some Eskimo pies?”

“How about brown sugar?” asked Tom, adding it to his growing list.

“Sure, brown is my favorite color,” said Brent. “We should have a bottle of olives, and buy a pickle fork at Woolworth’s to get them out with. Nothing like having a true pioneer along with you, Tommy. Put down animal crackers and, let’s see—how ’bout ginger snaps?”

“Come on, get up and work!” said Tom.

“I thought you said we were going to loaf—and meditate?” asked Brent.

“Not here!” Tom shouted at him. “Up there!”

“Pardon—my error,” said Brent, letting down his lanky legs from the veranda rail and rising lazily. It is funny to see him. He is so indolent and casual in all his movements. He has a figure like Ichabod Crane in Irving’s story. Sometimes I think his legs will fall off. I think he enjoys Tom’s annoyance at his exasperating slowness. “Is there any detective work to do up there, Tommy? Remember Leatherstocking Camp, how I—”

“Come on, help me pull that boat out of the water,” said Tom impatiently.

I left them drying off the boat preparatory to painting it. Little I thought as I went away that there was indeed detective work to do up there and that lazy, lanky Brent Gaylong would acquit himself gloriously in those silent wilds. He has a humorous but keen mind and is seldom aroused. To see those two together is as good as a circus, Tom bubbling with energy, and Brent whimsical, lazy and observant. Yet I think he enjoys Tom and likes him quite as much as I do.

The next I heard, they were up at the shack. I think they must have been up there a week or so when I received a letter from Brent (he is a rare correspondent) and I include this in my narrative notwithstanding its irrelevant playfulness. It gives you what you will wish to have, and that is a familiar glimpse of the shack which was to be the scene of startling adventures. The letter was mailed at Teetville, a tiny hamlet on the old road three or four miles east of the river.

Dear Professor:1

Well, here we are close to nature’s heart. The place is not as melancholy as I was made to believe. There is a turtle here; also several frogs who broadcast most every night.

I am mailing this in Teetville, which is four thousand miles through the woods—I walked it and I know. The principal exports are postage stamps. They don’t keep two cent stamps, only ones—strictly retail. There is a dog there—I think he must be lost.

Ours is a model home with all inconveniences. You will not be able to visit us comfortably for there are only two chairs and one of them has hip disease. But do not despair—we have three cots—two army cots and a collapsible one—it collapses in an emergency. I mean we have it for an emergency. That may mean you—who knows! Also we have a lamp and I got some oil in Teetville. That’s why I went there.

And now about the layout of our love nest. As you come in from the bridge (you can also fall in as there is no doorstep—it’s level with the ground) you step into our dining-room, living-room and bedroom—all at once. We sleep, eat and sit there and I play solitaire under the glaring light of the lamp. It stands on what was once an oak table but it looks as if it’s full of pine knots now. Anyway I have to hold my knee up under it and Tommy follows suit when we’re eating to keep the dishes from rolling off. It’s quite a trick. Last but not least is our kitchette—it’s about two by two and is sort of built on the shack. There’s a wood stove in it, a small dish cupboard and a garbage pail that I keep in the corner. The latter won’t have to be utilized when you come to visit us. That’s all there is in the kitchette—it lives up to its name.

Yesterday I washed the window so we could see through it. It faces the north and we can look up the river. I tried to boil an eel but he escaped from the can when the water got hot. He is still somewhere around. Did you ever try to hold an eel?

The well is in the shack and I am in constant fear that the shack will fall into the well. But there is no water in the well and we get our supply from a spring—a crystal spring I suppose you would call it. I go up there with a colander and have to hurry back while the water runs out of it. I wonder if you’d mind stopping in the ten cent store on your way up and get us a pail?

There is a lot of truck in the bottom of the well. I fished up an old rotten burlap bag with a fish line. You open an old closet or locker just before you step out into the kitchette—well, it isn’t any locker anyway—it’s just a well. The old oaken bucket is down there all in pieces. I think the eel is hiding down there and that’s the reason I don’t like to climb down.

Nobody has been up the river. A soap box floated up last night at high tide and I tried to open the bridge for it but couldn’t. The crowbar, or whatever you call it, is missing. Tom says it must be around somewhere.

I guess that’s about all. We play cards and checkers and go fishing. I know there’s a perch in the river because I caught him and put him back.

It was my intention to get Bill Scolley to chug me up with his outboard kicker at the next weekend, but I didn’t get around to it, and before I did go there were great doings up there.

From this point on I must tell you the story as I heard it long afterward from Tom and Brent and others concerned. But I have heard it so many times and in such detail that I think I can tell it almost as well as if I had been there. To be sure, some of the talk is imagined, but heaven knows I have listened so much to Tom’s account of what he said to Brent, and Brent’s account of what he said to Tom, that I fancy I can give a pretty accurate picture, not only of their great adventure, but of their character and personalities as well.

At all events, they have both cordially waived any cause they might have in a suit for libel. As for the other main character, the venerable Mascot, all he can do is to scream at me and I don’t mind that at all.

| 1 | I am not a professor. |

Tom admits that their life for just ten days was a blissful round of eating, sleeping and loafing. Brent, of course, forced that admission from him in the light of later events, because he (to quote his exact statement) didn’t want the public hoodwinked into thinking that he’d be so foolish as to break the spell of their Elysian existence.

Brent also claims that Tom began weakening the threads by wanting to cut down the weeds and trim the vines that were twining so enchantingly around the bridge and even up to the door of the shack. “Why, that’s the very thing that makes this place so charming, Tommy,” he said in his delightful, drawling way. “Cut down the weeds and I’ll no longer feel as if I’m a vagabond.”

“Don’t you know that’s what draws the mosquitoes?” Tom demanded, standing with a sickle in his hand.

“Nonsense,” Brent answered. “We’d get them from the marsh in any case. In point of fact, I don’t mind them so much—it makes me feel more vagabondish to fight off the pests. Poor defenseless wretch at the mercy of the denizens of the swamp and all that stuff—you know! Contracts a deadly fever as a result and is nursed back to health by his true comrade, Tomasso Slade! I like the sound of that, don’t you, Tommy?”

“You sound as if you weren’t quite sound in mind. That’s how you sound,” Tom laughed. “You’d soon cry for a truce with the pests if we had a spell of some nice, sticky weather. Believe me, you wouldn’t feel very pretty if they got a good hold on you some night. You’d wake up looking like a natural map of the Rockies—bump upon bump. Do I cut down the weeds or not?”

Brent heaved a sigh of relief. “Just as you say, Tommy,” he drawled. “Do I have any part in the labor?”

“Only to gather it up after it’s cut,” Tom laughed. “That’s the easiest part of it. You can pile it up on the bank and when it dries out we’ll burn it up.”

“We’ll?”

“I will,” Tom laughed. “I’ll have this place looking civilized if it takes me all day long to do it in.”

“Take your time, Tommy,” Brent drawled languidly. “It won’t matter if I gather it up tomorrow, will it?”

“Oh, I suppose it will end up in me doing the whole thing,” Tom grinned.

“You would have only yourself to blame if you do,” Brent said. “And I don’t like the idea of making this place look civilized—we came up here to get away from civilization. You said yourself that it was the ideal place for roughing it—wild and deserted.”

Tom’s back shook from laughter as he bent over the sickle. “Do you ever stop to realize the time you spend in arguing? Think of the energy you could use!”

“Think of the energy I save—that’s the point,” Brent returned. “But I’m afraid I’ll have no peace from now on. When you get restless it sounds the death knell to all my slumbering proclivities.”

“Good,” said Tom. “Now you can put them to good use.”

Brent sighed and dragged his long, lanky frame around gathering up the fruits of Tom’s toil. He had to take it up by the handful and it was well along toward evening before the patch just down off the bridge was cleared. It was evident that it would take another day before they could clear it up to the shack.

At any rate Tom announced that he was hungry—an announcement that caused Brent no end of relief. Indeed, he immediately offered to quit and get the supper so that Tom could work on uninterruptedly. “We’ll do the dishes together afterward,” he suggested, “and then we’ll both be able to rest in the twilight.”

“You will, you mean,” Tom laughed. “Anyway, let’s eat.”

Twilight was indeed upon them before the dishes were done and they were glad enough to get out of the stuffy little shack. It had grown considerably warmer within the last hour and the humidity was oppressive. Not a blade of grass moved and except for the sound of the water lapping against the river banks the silence was deadly.

“I’d give the world to see a traffic signal now,” drawled Brent as he came out of the shack into the gathering darkness. “Do you think the county would appropriate an arc light for the bridge if we asked them, Tommy?”

“Like fun they would,” Tom laughed. “Anyway, you’d be wishing it out of the way if we had one because then we’d have skeenteen kinds of night bugs and bats flying around us when we wanted to enjoy the night breeze.”

“I never thought of that,” Brent said. “But on a dark night like this a little light wouldn’t go bad. Lighting the way to happiness and all that sort of stuff.”

“Talking about lights,” Tom said seriously, “I’m not so sure but what you are getting your wish.” He was looking intently up the river and his arms rested on the broken bridge rail.

“What do you mean, Tommy?” Brent said strolling over to his side.

“Look for yourself and see,” answered Tom, pointing.

Brent looked up along the bank where a tiny light cast its cheery glow out upon the river. By all the laws of human nature it should have symbolized friendliness and hospitality in that lonely place but somehow it did not. Not to Tom, at any rate. It had rather a hostile effect instead, and that meant that it puzzled him.

Brent was not aware of any such feeling. He was merely indifferent about it. Perhaps the afternoon’s work was responsible. At any rate he blinked his eyes lazily at the little glow and let his long arms support the weight of his body heavily resting upon the broken bridge rail.

“A light is a light, Tommy,” he said at length. “The longer I watch it the more I’m convinced that it’s a light!”

Tom was too interested, too curious, to take notice of Brent’s banter. Something had challenged his adventurous spirit and he was on the alert at once. “It’s funny,” he said, squinting so that he might see farther in the dark. “I can’t make out where that light is. Maybe it’s a camper though, huh?”

“Not necessarily, Tommy,” Brent answered, quizzically. “It might be a lightning bug.”

“A lightning bug isn’t stationary,” Tom said in his boisterous way. “Not this long anyhow.”

“Now that’s a question for science,” Brent said, soberly. “It’s something I’ve often wanted to find out. A lightning bug must certainly rest at some time or other. But when? Or where? Yes, Tommy, it’s the ambition of my young life to find out about the life, death and Christian sufferings of the little lightning bug.”

Tom suppressed a smile with difficulty. “You’re crazy as usual. But we’ll talk about that later. The lightning bug theory is disposed of right now. For one thing, the light we’re after is at least a quarter of a mile from here. Don’t you think so?”

“Whatever you say,” Brent answered complacently.

“But I want your opinion,” Tom persisted. “What do you think about the light?”

“I think it’s fine just where it is,” Brent drawled whimsically. “I wouldn’t have it any nearer.”

Tom stood with his arms akimbo. “Say, will you be serious for a minute? I’m just curious about it because we haven’t seen a soul around here daytimes. It’s been dead as far as civilization goes....”

“Until you got the idea of cutting down the weeds,” Brent interposed languidly. “Now all we’ve got is dead weeds.”

“There you go,” Tom said a little nettled. “Listen to what I’m saying, will you?”

“I’m all ears, Tommy. I have nothing else.”

“All right, then. We’ve been here a week and there hasn’t been a human being pass up this river and except for about three or four cars that whizzed along over this bridge we might as well have been in the desert as far as we knew. That is, where neighbors were concerned. Now all of a sudden we see a light spring up out of the darkness—in this comparative wilderness!”

“Well, it must be campers then,” said Brent. “We’ll arrive unanimously at that decision because I want to go to bed in peace.”

“All right,” said Tom laughingly. “It’s settled—they’re campers. But we’ll go and take a look up around there tomorrow, huh? Give them a friendly, neighborly call. What do you say?”

“I have no say in the matter, Tommy,” Brent said, in weary tones. “You’ve decided to go up there so that ends it. I was afraid that our nice, quiet week would get you going. Now you’re set to go on the rampage so I suppose I must make the best of it.”

That next day, however, there was much to be done. Brent had to go into Teetville for some supplies and Tom decided to go with him. When they got back they were busy about the shack and they had quite forgotten about calling on their strange neighbor or neighbors up the river.

Before they were aware of it another sun had set, and another twilight wrapped the river and neighboring woods in its protecting shadows. A solemn peace pervaded all. Then suddenly, night, black and starless, shut off the world from the two outside the bridge-tender’s shack.

Brent was sprawling rather than sitting in a camp chair, which he had purchased in Teetville that day. His long, lanky legs were crossed in a nonchalant attitude and his bespectacled head was tilted in such a manner that it rested lightly against the side of the shack and afforded him an unobstructed view of the inky heavens—if indeed one can get a view on such a night.

Tom was pacing back and forth across the rickety little bridge in that nervous way he sometimes has when he gets restless and has nothing to do. Each time he walked off the western end of it he stepped on some loose boards that rattled audibly in the quiet night. And coming back the noise would be repeated.

“Can’t you jump across those loose boards, Tommy?” queried Brent.

“If I could I wouldn’t be here,” he answered. “I’d be over at the Olympic games doing my stuff. There’s about twenty feet of planking to jump—you ought to be able to do it with your height and you could too, with a little practice!”

“Not at my age,” Brent drawled. “I’m long on height and short on wind. That’s the sad part of it. Otherwise I feel that would have been my calling.”

Tom laughed, then stopped suddenly and looked up the river. “Brent!” he called in guarded tones. “Brent, if it isn’t that light again!”

“Again or yet?” queried Brent complacently. He did not move a muscle.

“How do I know?” Tom returned. “We didn’t stay up all last night to watch it. Maybe it is the same light still burning. Anyway, it’s a light and we should have gone up there sometime today. We should have!”

“Never do today what you can put off until tomorrow,” Brent drawled. “I’ve always found that a delightful rule to go by. If we had gone up there today we would know tonight what and where that light is.”

“Well, isn’t that what we want to know?” Tom demanded.

“Certainly,” Brent answered leisurely. “But by having put it off today we have another night to wonder and speculate in. In other words, it gives us something to look at and think of tonight. Get my point, Tommy?”

Tom turned away from the rail and glanced despairingly in Brent’s direction. “I get your point,” he said, shaking his head. “But the question looms larger tonight than it did last night. Why, if they are campers, haven’t we seen their smoke today? And why haven’t we seen some sign of them bathing or fishing? No one camps at the river’s edge just to sit and look—they come to a place like this to fish and swim. We do anyhow! We ought to have seen some sign of them today. Heaven knows they would be near enough for us to see. The light is just about where the fountain-pen adventurer and myself cast our lines on our way up the first day I saw this place. There’s an old boathouse there and the landing’s rotted away. Nothing but a few sticks of wood left. Up above it, a mile maybe, is the old Boardman place. But we couldn’t see a light from there anyway. The woods are in between.”

“I’m glad of that,” Brent sighed, “and I’m sorry that there was ever a day when you and the professor cast your lines.”

Tom chuckled. “That’s what he said. But it’s a fact, Brent, and it makes me wonder. Why, we sat right under that decrepit old boathouse for four hours. That’s where we caught the bullheads. Gosh, I counted every board nailed up against those windows. The one window facing this way had a couple of loose boards that looked as if they had been sort of forced into that position. And that’s why I’m curious about it—it looks just as if the light was shining through a sort of chink.”

Even as he spoke the light was suddenly extinguished. It happened so quickly that Tom could not be sure but what it was some trick that the darkness had played upon his concentrated vision. He snapped his eyes shut thinking it might have been strain, but when he opened them again he was convinced that the little yellow gleam was indeed gone.

“Well, it’s out, all right,” he observed.

“Thank goodness for that,” Brent remarked, rising. “Now there’s nothing to prevent us having a peaceful game of checkers, is there, Tommy?”

“No, you lazy bird!” Tom laughed. “But I won’t feel contented until I look that up tomorrow.”

“Neither will I,” drawled Brent, carefully folding his camp chair. He stopped for a moment and sniffed the heavy, warm air. “Tide must be going out, Tommy. I smell mud and feel mosquitoes.”

“Right you are, Brent. She’ll be dead low by midnight, I guess.”

Brent walked inside and was lighting the oil lamp as Tom entered. The tiny glow cast weird shadows about the dark, dingy walls, but gradually as the flames spread through the wick the place seemed suddenly transformed and became instantly cozy and cheerful looking.

Tom drew two chairs up to their little oak table and Brent went over to his cot and pulled out from under it a checker board. “That’s one thing I don’t like about this place,” he said as he spread it out on the table. “The architect made no provision whatsoever for closet room. Here we have to keep our clothes in our bags and the rest of the dustproof articles under our cots. What kind of a way is that to build a shack?”

Tom laughed. “You ought to complain to him, Brent, not me.”

“He’s dead probably,” Brent said. “And if he isn’t he ought to be. That was a silly idea of his in making that fake locker. What good is it to us?”

“He might have meant it to be a locker or cupboard or whatever you want to call it,” said Tom, taking the checkers out of their box. “But I suppose the owner suddenly decided to dig a well there instead.”

“Well, I hope he fell into it,” Brent drawled. “Maybe that’s the reason it dried up. Anyway, I’m going to climb down there some day before the summer’s over. I hope I find his skeleton or that eel—it doesn’t make any difference.” For the next half hour there was little sound, save for the soft scrape of the checkers being moved back and forth upon the board. The players were annoyed by the occasional buzz of a mosquito picking out its prey. As it landed there it would pause, then a resounding swat—and the game would proceed.

It was on one of these occasions when Brent was the victim that he slapped his head heartily in quest of the pesky creature and in his distraction lost the game to Tom.

“That means we better call quits for tonight,” he said, stretching his long arms lazily. “When there’s a bunch of those things around I can’t keep my mind on my knitting. I can only do one thing at a time. What do you say we turn in.”

“Righto,” said Tom cheerfully. “If I thought there was any chance of us coming up here next summer I’d get a screen door for this shebang.”

“Ask the county to appropriate us one,” Brent suggested.

“Yes, and catch them doing it too,” Tom said as he blew out the light.

Suddenly they were both aware of a sound other than that of their own voices. They stood still and listened and they could hear distinctly the lap, lap of water quite near.

“Raining, I wonder?” Tom queried as he poked his head outside of the door. Then: “No,” he whispered back into the darkened room. “C’m here, Brent!”

They went outside the door and the lapping of the water continued. But now it seemed to be going away from them—up the river.

“It’s a boat—a canoe being paddled!” Tom whispered. “Can’t you hear it?” Then aloud: “Who’s there?”

No answer came. Nothing but the lapping water and the faint swish that Tom had detected. Then a frog lustily broke the spell for a few moments and suddenly stopped.

“Who goes there? Friend or foe?” Brent called whimsically.

There was no answer save that of his own echo. And indeed one would almost say that was answer enough in the deadly stillness of Old River.

The darkness seemed to increase the tenseness of the situation. At all events they could not see more than three feet ahead of them and whoever the canoeist was, he had gotten well out of range of their inquiring eyes.

“Whoever it was,” said Tom after a few minutes, “I bet they thought you were fooling.”

“I was,” said Brent. “I must have my little joke. But where’s your flashlight, Tommy?”

“I thought of it and the lamp too, but neither would do much good, I guess. My light’s too small and the lamp’s too rickety. We ought to be better equipped than that. I’ll go home tomorrow sometime and get that big one you gave me for Christmas last year. I was saving it for an emergency.”

“That’s why I gave it to you,” Brent said. “I was hoping it would help you throw light on some mystery.”

Tom chuckled but quickly stopped and nudged Brent meaningly. “How do you know but what that bird can hear what we’re saying?” he whispered.

“Well, he’ll hardly know it’s himself that’s being talked about,” drawled Brent. “We won’t say anything flattering about him unless he tells us who he is.”

Tom literally dragged Brent inside the shack. “Now, no fooling,” he said pleadingly. “We gave that fellow chance enough to answer and he didn’t. He’s got a reason for disregarding our friendly salutes so there’s only one construction to put on such actions.”

“Monkey business, I suppose,” drawled Brent.

“You said it,” Tom agreed. “It would be risky for us to try and hunt him in the dark but I’ll tell you one thing—I think he has some connection with that light up there.”

“I was afraid it would end up this way,” Brent drawled complainingly. “You’ve hatched up a mystery out of a dinky little light and a canoeist that was too stuck up to answer you. But while we’re on the subject—if I have to go hunting in the dark I want to know where I’m hunting. And as long as you show a disposition to go night prowling for mysterious canoeists you might give me a day at least to study the lay of the land around here. Just now I can’t tell the marsh from the river, except by the smell.”

Tom laughed. “It’s a go,” he said. “We’ll see what we can see tomorrow.”

Brent began getting ready for bed. “You’re making a lot of fuss over nothing, Tommy,” he said. “You can’t accuse a chap of monkey business just because he doesn’t answer you.”

“Perhaps not,” Tom admitted. “But still if he was bent on honest pursuits, you’d think he’d have no cause to do other than answer me.”

“I can think of only one cause, Tommy,” Brent drawled as he settled himself in his cot. It creaked audibly.

“What’s that?” Tom asked, straightening out his own pillow.

“Maybe he was deaf and dumb,” answered Brent.

Tom turned, pillow in hand. “If I hadn’t this pillow shaken up so nicely I’d throw it at you,” he laughed.

Nothing more disturbed them that night. They slept soundly until the sun was well up out of the east. The river had been at flood tide during that time and dead low more than an hour past when Tom stepped outside the shack.

“Come on, Brent,” he called inside. “It’s a swell morning. We can get up the river and down to Bridgeboro by noontime or a little later. I’ll promise you that we won’t walk much.”

“Can I depend upon that?”

“Absolutely. I’m only going to walk up to the house for my flashlight and I think I can dig up enough stuff to make a screen door.”

“Well, that’s an incentive,” Brent drawled, dressing leisurely. It was a half hour later when they stepped down into the rowboat and they had some difficulty in pushing themselves out of the mud.

Tom’s theories and anxiety of the night were dispelled in the warm morning sunshine. It seemed incredible that only a few hours ago they could not see farther than the broken rail and yet had distinctly heard the steady swish of the canoeist’s paddle.

Brent watched Tom rowing with quiet amusement. “Do you think the county would dock on the eighteen fifty-two if they knew you were off your job?” he asked at length.

“Don’t be foolish,” Tom answered. “We won’t see a boat up here all summer, I’d like to bet. Not if we haven’t seen any so far.”

“The professor ought to hear you make that admission,” Brent smiled. “He’d kid the life out of you about public waterways.”

“Well, if a boat did come we’d be there,” Tom protested. “And that’s what I was arguing with him about. Another thing, the county would excuse us from going off the job on a hunt like this. We have the liberty of seeing that no one evades the law or violates it, haven’t we?”

“Well, we’re almost there,” said Brent, propping his legs on either side of the boat. “You have about twenty more strokes, Tommy, before you solve the mystery.”

“How does it look?” asked Tom, not bothering to turn around. “Any signs of camping around?”

“No.”

“Can you tell if anyone is inside that old place?”

“Not from here, I can’t. My eyesight isn’t that good. But if you want me to, I’ll call yoo-hoo.”

“You’ll call nothing,” Tom laughed. “We’ll wait till we get there.”

Tom let the boat drift in to where the bank sloped gradually down to the water’s edge. A few sticks stuck out on either side of where the landing had once been. The slimy indentation spoke eloquently of the footsteps that had worn it down to its present condition. But one could see that years had passed since it had felt the trample of many feet. The dank luxuriance growing all around gave silent evidence of that.

A large spider was busily spinning her web around an enormous weed but Tom’s oars made short work of that as he pulled the boat up against the bank and it sent the spider scurrying away to parts unknown. Brent fished around the bottom of the boat for the anchor and pretty soon they were fast.

“It’s kind of damp here, Brent,” Tom said, gazing critically from the embankment up toward the old boathouse. “The land’s low and the earth is soggy. We’re likely to get our feet a little wet.”

“Don’t worry about me, Tommy,” drawled Brent. “I’m prepared. I put my rubbers in my back pocket. You see I know these mysterious excursions of yours—I know what they lead to most times.”

Tom laughed and helped Brent out of the boat. They scrambled up the slippery bank, Brent adjusting his spectacles deliberately and glancing around in that comical way he has. Then he looked over them at the soggy ground.

“Someone’s been walking here, all right,” he said. “Maybe it was that frog we heard last night.”

Tom shook his head and with an inclusive sweep of his arm drew Brent’s attention to where a long stretch of the high grass had been dragged down almost to a level with the ground. “Doesn’t that look as if someone’s been dragging a boat up here lately—last night?”

Brent shrugged his shoulders and continued to snoop around as they made their way up to the old boathouse. Some birds from the neighboring woods trilled a charming roundelay, a few insects hummed drowsily in the damp, warm weeds but they heard no human step or voice save their own.

Tom walked up to the rickety door and gave it a resounding knock. They waited quite breathlessly (that is, Tom did) but no answering voice greeted them. The place seemed utterly deserted.

Tom walked around and cautiously peeked in the window where the boards had been loosened. But his efforts were rewarded with nothing more than a vague glimpse of something shiny inside. All the rest was a muddle of darkness compared to the bright sunlight outside.

He could have pulled off the boards with one swift wrench of his tanned, muscular hands. But he dared not. It was someone’s property and he respected it. He walked around and joined Brent, feeling quite disappointed.

“Nothing doing, eh?” Brent queried.

“Nah, I guess we scared him away last night. Looks so, anyway.”

“Well we won’t be bothered tonight then,” Brent said, with something like a thankful sigh. “We ought to sleep blissfully now.”

Tom could only shake his head.

They rowed back through the late afternoon and reached the shack at suppertime. Tom was now in possession of the powerful searchlight and it gave him a feeling of security. “Even if we never use it,” he said, “we’ll keep it handy. A fellow needs an aid on a job like this. You can never tell....”

“When the oil lamp’ll give out,” Brent interposed.

Tom smiled and went out to the bridge. He had done this many times since their return. He said he had a feeling that each time he went there he would see something up the river. But he did not. And he walked back again thinking the whole thing quite strange.

“No matter when I’ve looked up there,” he said to Brent, “I haven’t seen a soul. I don’t know why I look—that padlock on the boathouse door is proof enough that whoever it was went away. But somehow I have a feeling about the place—I don’t know—as if I will see something if I keep on looking.”

“It’s the air on Old River, Tommy,” Brent drawled. “It’s having an effect on you.”

“I don’t know,” Tom said seriously, ignoring Brent’s banter. “One thing, that old Boardman wreck sticking out there at low tide gives me the creeps. You’d think they would have removed it long ago. If there was much river traffic, a stranger would get an awful spill there at high tide. Anyway, I don’t like the looks of it.”

Brent managed to rouse himself and walked to the window. He gazed rather indifferently up the river at the bit of wreck poking itself up out of the mud. It looked to be no more than a foot high and on a cloudy day reminded one of a long, gray ghostly hand pointing heavenward.

“What do you know about that wreck, Tommy?” he asked at length.

“Nothing much,” Tom answered, “except that it went down maybe thirty or thirty-five years ago—maybe more. None of the Boardmans are left—I guess there isn’t even an heir to the ruins of the old Mansion. It’s about two miles up from here. There’s nothing below and above the old place but swamp and woods. Too bad the river played such a trick—the property would be worth something now.”

“Yes,” said Brent musingly. “It’s interesting. Old family and an old schooner. Did you say you knew the name of the barge, Tommy?”

“Schooner,” Tom corrected smilingly. “Our fountain pen adventurer told me it was called the Carrie C. Boardman and was named after old Roscoe Boardman’s only daughter. I heard somewhere once something about a son who was killed in the West Indies, I think. Anyway, the old man died a little while after the schooner sank and his daughter didn’t live long after that. She must have been kind of young when she died.”

“Maybe Carrie Boardman haunts her own schooner, eh?” Brent asked whimsically.

“Maybe,” answered Tom with a shudder. “I don’t like to think of it or look at it.”

“Well, I’ll do it for you,” Brent said complacently. “Why do you suppose that one part sticks up and not the rest?”

“The professor and I argued about that the day we were up here,” Tom answered. “He finally convinced me that some of it struck a sand pile and the rest is rocky bed. Sounds plausible, huh? Anyway, it’s too rotten to salvage if that’s what you’re wondering.”

Brent made no comment about that. He just stood musing and frequently tapped the window sill with his bony knuckles. “I suppose the papers were full of it for a few days?” he queried leisurely.

“The wreck, you mean? Oh, I suppose so,” Tom answered. “Naturally, it was a big thing for a little Bridgeboro paper. And Bridgeboro must have been pretty small in the days when the river was so big. I know the professor said the Boardmans were considered quite high society then. That’s about all he knows, too.”

“Well, I rather like what I’ve heard,” Brent drawled. “And I won’t mind seeing that little bit of Carrie every day. In fact, I shall look forward to it with extreme pleasure.”

“And the pleasure’s all yours,” Tom laughed. “Let’s talk of cheerful things.”

Twilight came once more. The tide rose and fell and the evening wore away before they knew it. The sun had gone under a cloud late in the afternoon and the evening had been too humid and damp to sit out of doors.

“I wish we’d have a long night of nice, cool rain,” said Tom, poking his head out of doors to inspect the heavens. “The mosquitoes are thick and ... Brent!”

“Eh?”

“It’s the light—again!”

Brent shuffled out to Tom’s side and together they stared at the little yellow glow upon the misty water. There was something weird and ghostly about its steady flicker.

“Now’s our chance, Brent!” Tom said impulsively. “Let’s go!”

“Now I’m in for it,” Brent said wearily. “Just when I was ready for a good night’s sleep too. But no, you must be dragging me out on that black river chasing up a glowworm. Well, come on, let’s get it over with.”

They got into the boat and were soon skimming noiselessly up the river. “I’m glad it’s misty,” Tom whispered.

“So am I,” Brent answered. “We might run plunk into your mysterious friend on the river. I hope we do. It would save us the trouble of going all the way up to that boathouse.”

“I don’t hope any such thing,” Tom said. “I’d like to see what he’s up to first.”

“I hope we catch him playing checkers,” Brent drawled.

They reached the landing place without much difficulty and cautiously made their way up the embankment toward the boathouse. Just short of it, Tom stopped and pointed to where the door was padlocked. The light trickling out from the unboarded window cast an odd reflection upon the worn red paint of the old building.

Tom held his breath and knocked. “Anyone in there?” he called loudly.

The silence was depressing until the still air itself seemed to become sound. Suddenly from quite near them they could hear the unmistakable purr of an engine.

“It’s a car!” whispered Tom. “Do you think it’s near?”

But even as he asked the question the purring became fainter and fainter. Finally it ceased altogether and the dismal, ghostly place lapsed back into its uncanny silence.

They stood staring at each other for a while, then Brent smiled. “What do you suggest doing next, Tommy—calling the police or the fire department?” he queried.

“You have to admit that bird is up to something!” Tom declared boisterously. “But we can’t call the police until we have something to work on—a clue. I have a hunch that he’s a counterfeiter.”

“I hope he is,” drawled Brent. “I’ve always wanted to meet a nice, jolly counterfeiter. Say it with money, eh?”

“This would be a likely place,” said Tom, ignoring Brent’s banter. “I suppose he’s counted ten to one that no one would ever bother him up here. Let’s walk up a little way and see where that car was parked.”

“It sounded rather flivverish to me,” Brent observed.

“Well, he got away in it, anyhow,” Tom said walking slowly ahead. He flashed his light over the mist-covered path and here and there they could see a man’s footprint in the soggy earth.

In a few moments they reached a wider path where the weeds had been carefully cut down. Farther on was a clump of trees and the tracks of the departed car could be plainly seen. Just beyond was a narrow country road running north and south.

“Do you suppose that crosses the Teetville Highway?” Tom asked.

“You’re not going to suggest that we walk it to find out, are you?” Brent asked, alarmed.

“No,” Tom laughed. “I’m not going to ask you but I’m going to find out myself tonight! You can go back in the boat and I’ll see you safely off. Then I’ll see where this road brings me out. I bet I’ll get back to the shack long before you.”

“I don’t envy you, Tomasso, not at all,” Brent said, as they started back toward the river. “Only be careful that you don’t step in a swamp or worse.”

“I guess there isn’t anything to worry about. And I don’t believe there’s any quicksand,” Tom said gaily. “Don’t get fussed up, Brent. I’ll be as safe as if I were walking on Broadway.”

“It would have been just as well to leave our calling cards for the counterfeiter or whatever he is, when he returns,” Brent said. “If you’d only wait we’d hear from him and you wouldn’t have to go to so much trouble. Maybe we could have induced him to talk terms with us if we had used more persuasive methods upon our arrival. By now we might have had a share in the business. Who knows!”

Tom’s laughter rang out over the misty river. “You row back leisurely, old man,” he said. “And I bet before you get back on the bridge, I’ll be there!”

He pushed the boat off with Brent still protesting. Tom stood on the bank watching and was considerably amused at his slow progress with the oars. “You’re a little bit out of practice, aren’t you?” he laughed.

“I’d rather do it than walk,” Brent answered. “It’s not such a tax on the brain. Hurry along now, Tommy.”

Tom turned his light back on the path and Brent was soon enveloped in the mist and darkness of the river. But the little yellow glow from the boathouse followed him along that black, watery path and the frowning woodland that lined either shore now looked like huge spectral cloaks, dipping their frayed ends into the silent stream.

Brent was never the nervous sort nor was he very imaginative. But he did love companionship and without it he was lonely. Consequently he was tempted once or twice to call to Tom just for the sake of breaking the chill solemnity of the misty night. But he thought that his friend must, by now, be pretty well along the dark road. Tom was a swift hiker.

Finally he came abreast of the old Boardman wreck. It could be seen quite plainly in the little light from the boathouse. He rested his oars and stared, fascinated by the gray, ghostly thing sticking there out of the mud. That gleam of yellow seemed strangely concentrated upon this relic of the dim past. Indeed, it even lighted up the little area surrounding the rotting hulk, giving one the impression that the wreck must have some magnetic power of drawing the light.

Brent could see that at low tide one could stand in the mud and touch the ghastly looking object. And the tide was going out now quite fast. By twelve o’clock one could do it with ease. He wondered if it would fall apart with handling.

But in the midst of these musings he yawned audibly, took up the oars again and started more vigorously this time for the bridge. When it came to choosing between his love for ghostly wrecks and his love for sleep, Brent always chose the latter.

And so he tied the boat up under the bridge and climbed the bank. There was no light in the shack and he straightway walked to the farther end of the wooden structure and peered down the road. There wasn’t a sound, not even in the distance.

“Oh, Tom-my!” he called cheerily. “I beat you to it!”

There was no answer from Tom and the air was so heavy that he did not hear even an echo of his own voice. “I knew he couldn’t make it in that short time,” Brent said aloud. “That road must stretch out quite some before it meets this one.”

He walked to the shack, groped his way through the dark interior and finally found the table and lamp. He lighted it carefully and then went back and shut the door to keep out the mosquitoes. After that he drew a chair up to the table and settled himself for a quiet game of solitaire while he waited.

Those who have indulged themselves in this solitary pastime can readily testify as to its amazing disposal of time. An hour can be easily spent in waiting for the decisive card to appear out of a capricious pack. And so it was that night with Brent. An hour and a half had gone by before he won a game.

He got up and went to the door and opened it. His features became fixed as he listened. Rather indifferently, he noticed that the mist was lifting and straight above his head a star was shining bravely through the clouds. After a few minutes he went back to the table and his cards.

“It can’t be that he’d get lost,” he mused aloud as he set a queen of hearts under a king. “But of course, that’s impossible with Tommy! He’s found out it’s a longer route than he thought. That’s about it.”

Another half hour had gone. Brent looked at his watch. Twelve o’clock. A worried look crept in under his spectacles and he piled the cards neatly into their box. Then he rose and went outdoors again.

He walked to the far end of the bridge and peered eagerly down the road. The mist had gone completely and he could see along the dusty highway for quite a distance. But no sign of Tom could he see; no sound he could hear.

“I wonder if he got on the track of that fellow and tried to trail him?” he asked himself aloud. “It’s like Tommy to do it. Just like him to do it!” Then: “I shouldn’t wonder but that’s what he’s up to.”

He felt better after that decision and hunted for a place on the old drawbridge where he might sit and watch. But it was quite damp from the recent mist and the under railing was broken so that he couldn’t rest his feet on it. He decided to go back in the shack and wait.

“There’s really nothing to worry about,” he tried to comfort himself. “Tommy wouldn’t do anything that was foolhardy. No, there’s really nothing to worry about!”

He fussed at the oil lamp, turning the wick up and down a half dozen times or more. Then he went over to his cot and took a half reclining position on it, leaning heavily on one elbow. But always he was listening.

After another half-hour’s vigil his eyes refused to stay open. His elbow kept slipping from under him and gradually his head reached the pillow. He was sound asleep.

He awoke suddenly and was sitting up before his eyes were fully opened. Yes, he told himself, he had been sleeping. The light was still burning and.... He looked at Tom’s cot—empty.

No, he hadn’t come. Of course he hadn’t! Everything was just the same as before. All except Tom. He looked at his watch nervously. It was half-past three.

He went outdoors—walked over the bridge and onto the hard, dusty road. The air was clear, a cool breeze blew and it revived him—gave him new hope that perhaps it was just another exploration of Tom’s into the realm of adventure. He had done things of that nature before. At Leatherstocking Camp that time when he was gone so long and they thought he had been killed.

“But it wasn’t exactly like this affair,” Brent mused as he strode along. “He didn’t promise us any special time to return. And he distinctly told me this time that he would be at the bridge before I was! It was a sort of promise.”

After a few steps further: “I don’t like the looks of it! I should have gone with him—I should have!”

In this mood he stepped lightly over the rutty highway. He looked eagerly for some road that would take him up the river. And all the while he kept muttering worriedly to himself.

“Maybe it doesn’t come out on this road at all,” he argued with himself. “If it does, it must be an awfully long way down.”

In his anxiety, he did not take into consideration that distance seems an eternity when one is in a hurry. For, to be exact, he had been walking just six minutes and thirty seconds when he espied the break in the road. He timed himself sometime later.

It was the first time he remembered having taken a running step since he was at school. He fairly raced around the bend, bareheaded and breathless. When he got a few feet farther he had to stop and rest.

He was startled suddenly by a strange voice. “Where are you going?” he was asked harshly.

He quickly regained his composure and stood on guard. “Who wants to know?” he returned in his usual leisurely way.

Just then he caught a gleam of metal from under the trees. Naturally he was frightened, but nevertheless he stood his ground. Then a man emerged pushing a motorcycle before him. Brent felt an almost hysterical relief at the welcome sight.

It was a state trooper.

“I’m the one who wants to know,” the man said, a little less harshly. “Now how about an answer to my question? It’s a pretty fancy hour for a young guy like you to be runnin’ bareheaded in this neck o’ the woods!”

“I know it,” Brent smiled. “But you couldn’t hardly expect me to answer such a question unless I knew to whom I would be talking.”

“Righto,” agreed the trooper. He scrutinized Brent keenly. “So....”

“I’m staying up at the drawbridge with a friend of mine—Tom Slade, bridge-tender,” he said in his drawling way.

The man nodded. “Yeh, I’ve heard about a couple of young guys taking that. So you’re one o’ them—just for the summer, eh?”

“Yes,” Brent answered. “Business and pleasure combined. You know. But mostly pleasure. We’ve been there over a week now and there hasn’t been a boat come up yet.”

“And there won’t be,” said the man. “Things are deader than dead on Old River. I ought to know. In fact all around here. To tell you the truth, I was trying to get forty winks under that tree myself. Been helping out one of the boys that’s been sick and fifteen hours of riding makes a guy pretty fagged—believe me!”

“I bet,” Brent said pleasantly. He was turning over and over in his mind how much he would tell the officer of their quest at the old boathouse. But he realized that after all they had nothing definite to tell of the man in the car. He had a perfect right not to answer if he so wished. They had proved nothing.

Somehow Brent had the amateur sleuth’s dread of telling a policeman of his suspicions and vague clues. He decided finally to keep that part of the story to himself. Consequently, the officer was given to understand that the two bridge-tenders had been merely nosing around in the mist and Tom, he told the man, had decided to walk back and see where the road came out.

“So, you see,” Brent said, “I got back all right but when he didn’t come, I started worrying, naturally. And now I’m rather upset about it. I can’t understand it!”

“Aw, I guess nothing’s happened to him, young feller,” the trooper said pleasantly. “It’s a long hike from the place you describe. At least three miles—and some parts I’ve been knee deep in water too! Terrible marshy, but not dangerous. I bet he gave up the idea when he saw that marsh. He probably went hiking back to that old boathouse to bunk there for the night.”

“He couldn’t. It’s padlocked,” said Brent.

“Well, then he’s found some other dry place to bunk,” said the man, hearteningly. “They are to be found—I find ’em!”

Brent smiled. “I wish I could believe that. But Tom knows what an old lady I am—he’d hardly keep me on the anxious seat all night.”

The officer smiled. “Now, I’ll tell you what,” he said. “I’ll scoot up there for you and look him up. Then I’ll whizz up to the bridge and let you know. I won’t take you with me because I couldn’t have three coming back on my Fierce-Sparrow. I’d be likely to dump one of you in the marsh. Anyway, I’ll be off.”

In a moment he was gone and Brent reluctantly made his way back to the shack. He got his camp chair and brought it outside. Tilting himself against the side of the building he prepared to wait, patiently, hopefully.

Dawn crept slowly up on the distant horizon and soon the whole eastern sky was flecked with tiny points of light. It seemed to Brent that he had been waiting for hours before he heard that welcome, familiar chug of the motorcycle.

He stood up and looked eagerly down the road until the trooper came into sight. Then he pushed his spectacles more firmly on his nose and stared hard as the officer steered his machine over the loose boards of the drawbridge.

Tom was not with him.

The man came abreast of Brent and precipitately swung the motorcycle around. “Got to get right back,” he explained breathlessly above the roar of the motor. “I’m due on the pike at four-twenty so I’ll have to skip some. No sign of your friend around that old boathouse. Everything was as dark as pitch. I looked a little further up by the old Boardman Mansion, too. Guess he found himself a nice, dry bunk for the night. Don’t worry—you’ll see him in a couple o’ hours, I bet. So long!”

The motorcycle rattled off the drawbridge as noisily as it had come. Then it was gone. Brent stood staring after it, unable to think or move.

“I should have told him!” Brent muttered after a little while. “I should have told him the whole thing. He’s never realized how serious it is.”

He felt foolishly helpless as he stood there. And he looked it. It hardly seemed to be the same indifferent, easy-going Brent. The change was incongruous somehow. In place of the twinkling, bespectacled eyes, there was a gray, worried expression. It would have inspired mirth even in Tom.

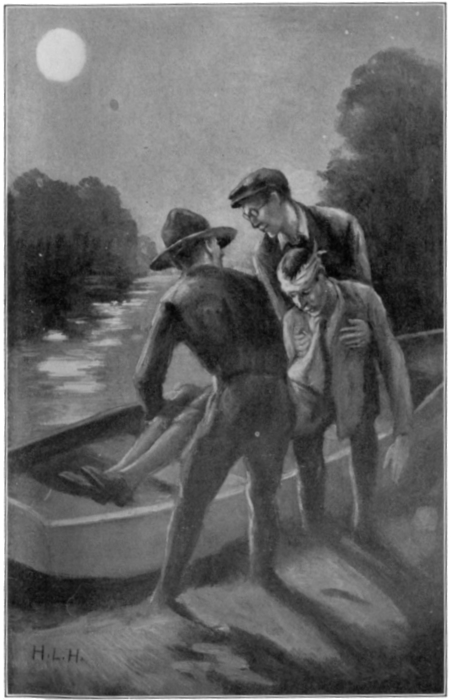

After a time he entered the shack and made himself some coffee, black and hot. It pulled his nerves together enough so that he was able to think out some concerted plan of action. Then he hurried out, got into the rowboat and pushed into midstream.

He had seldom, if ever in his life, exerted himself to the point of perspiring. But that morning he came as near to it as he ever had. He rowed with effort against the tide and finally reached the landing place under the old boathouse.

The trooper was right, he realized as he climbed up the bank. “The light is out there, all right,” he whispered. “Now I’ve got to be careful, cautious. Maybe Tommy wasn’t!” The thought chilled him.

He walked noiselessly through the high weeds in the old path. A good deal of it had been trampled considerably and the growth to his left, that he had noticed the day before, looked still more broken and bent in the early light of morning.

The padlock was still in place and it was hard for him to realize that everything did look the same around the place. All except the light. He centered his attention then upon the soft, soggy ground and tried to pick out his own and Tom’s footprints from that of the third party. But it was a futile task.

“Tom might be able to do it,” he murmured rather hopelessly, “but I can’t.”

He stopped just under the boathouse window and thought it over. He decided to walk up to the road and go back to the bridge the same way that Tom had promised to go. Marsh or no marsh, he resolved to make it. Just then a mischievous little breeze slightly rattled the loose boards above his head and he glanced at them casually.

He wondered why he hadn’t thought of it before—why Tom hadn’t thought of it last night. He had not the slightest trouble in looking through the window and he shaded his eyes from the light so that he might see more clearly for it seemed to be quite dark beyond the window sill.

After a few seconds the blur passed away and his eyes got used to the dark interior. He could see something in there—a little away from the window; perhaps a distance of about six feet. He pressed his face closer to the dusty pane.

Soon the object took form—he could see it clearly now. It was—yes, it was a human being! He moved a little to let the daylight aid him. It was just enough to throw that face and its features into bold relief against the dark background.

He pressed closer and saw to his horror that something red seemed to be covering the hands and lower part of the body. The eyes were closed....

There wasn’t any doubt of it. It was Tom.

For the moment, Brent almost lost his head. He was too shocked to utter a sound and was all for breaking the window. But when reason reasserted itself in his mind he knew that such a movement would not get him anywhere. The window was too small and narrow to allow more than his head to go through.

Next, he thought of the door and he went around and fumbled with the padlock. But it was useless. He hunted around for a stout stick to see if he could wrench it loose.

This search took him up almost as far as the pike but all he could find was rotten wood. Nothing could stay dry very long in that soggy earth. He returned to the old boathouse, disheartened and disgusted.

Again he tried the door and touched it here and there to see if any part of it was soft. But the whole place seemed to have stood the ravages of time remarkably well. It was firm and gave not the slightest under his persistent pressure.

Finally he gave it up and hurried around to the window again. There he pressed his face close to the pane, hopefully and then despairingly. Tom was still in the same position.

There was almost a deathly stillness about him, Brent thought. He walked away from the tragic sight and decided that his only salvation would be to get help. But all that would take time, and time might mean life to his best friend.

He would not admit the worst. He thought of it but would not consent to it. He would not believe Tommy dead until he had to believe it. Until then....

There was a crowbar down at the shack—the one he and Tom had fooled about opening the drawbridge with. He thought of it with rising spirits and was positive that if he went down and got it he could wrench the padlock off with that. And if that availed him nothing, he would then break down the door with it.

It seemed the best and quickest plan to him and he resolved to act upon it at once. He strode down the embankment in all haste and got into the boat. He couldn’t help wondering what Tom would think if he could see the speed with which he pushed the boat off.

Perhaps he had gone twelve yards, perhaps more. At any rate, he heard a muffled cry and a loud pounding as if on glass. His heart seemed to leap up into his throat as he rested the oars and listened.

But it came louder—a sort of stifled shouting and in its wake, a vigorous bang. Brent looked up at the boathouse, perplexed. Then he fairly shoved the boat back against the bank and jumped on to shore again.

The sound was not coming from the door. He knew that. Breathlessly, he reached the window and looked. What he saw shocked him, leaving him trembling and unstrung. But it was true and as real as life itself.

Tom’s face was there, pressed hard against the window-pane.

Was it his ghost or was it actually he? The question flashed through Brent’s mind as he continued to stare. But no, Tom was speaking, almost shouting at him.

“Gosh, I’m glad you came, Brent,” he was saying, with a ring of feeling in his voice. “I’ve been here all night—I’m locked in! Can you get me out? I’m suffocating with the heat.”

“Then—then you’re not hurt—not bleeding or anything?” Brent asked incredulously.

Tom shook his head and really smiled. “Hurt? Bleeding? You look as if you’ve been dreaming or seen a ghost,” he called with a laugh. “I’m O.K. except that I’d give my kingdom for one breath of fresh air.”

“Want me to break the window, Tommy?” Brent asked feelingly.

“Oh, no-o!” Tom exclaimed vehemently. “Not that—no matter how much I want the air! For a good reason, I don’t want you to, Brent. I’ll tell you later.”

Brent nodded. “Then I’ll wrench the padlock off,” he said. “That’s what I was starting back for when I heard you calling. I was going to get the crowbar.”

Tom laughed. “It’s going to be useful for something after all, huh?” Then he looked thoughtful, and: “But I don’t want that bird to know we’ve been monkeying around here. He doesn’t know I’ve been in here even and I saw and heard enough of him last night to convince me he’s up to something.”

“Leave it to you, Tommy,” Brent said.

“How can you get me out without making it appear that we wrenched the lock?” Tom queried. “He knows we’re down at the bridge but he doesn’t think we have anything but a neighborly curiosity in him. That’s straight!”

“All right,” Brent answered. “That’s easy, Tommy. You just leave it to me. I’ll get down and back as soon as possible.”

Tom smiled joyfully. “You bet I’ll leave it to you!” he shouted.

Brent was as good as his word. He hurried down to the shack and secured the crowbar. Then he grabbed four bananas, and out of a box where they kept the bread he managed to get a lot of crumbs which he put in a paper bag. A stale piece of cake was thrown in and he wrapped the whole thing together. Lastly, he got a good-sized piece of chalk out of the inner recesses of his traveling bag.

“I’ve been carrying this around for no apparent reason,” he drawled aloud as he put the chalk in his pocket. “I got it—let’s see ... Oh, I got it before Tommy and I blazed that trail through Old Hogback Mountain. Now I remember—I bought it just to get his goat. And now—now I can use it.”