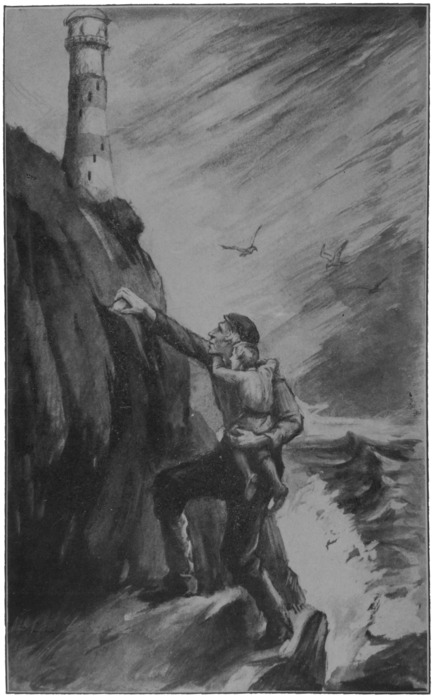

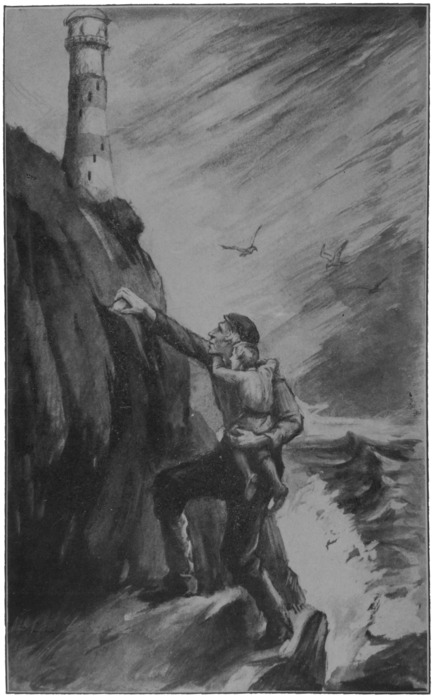

“MY GRANDPAP HAD ME IN HIS ARMS.”

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Tom Slade at Shadow Isle

Date of first publication: 1928

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Dec. 27, 2019

Date last updated: Dec. 27, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20191253

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

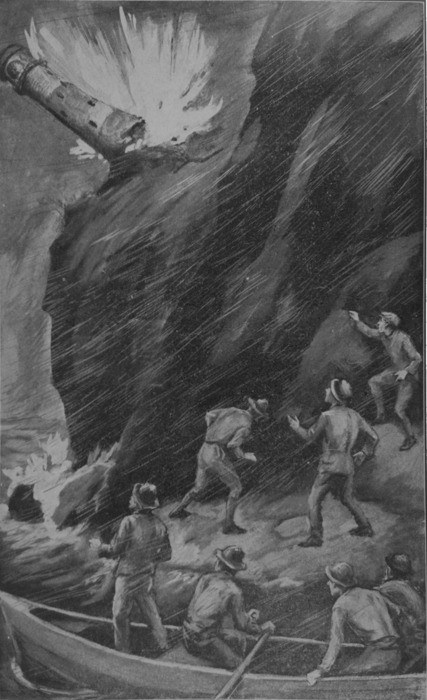

“MY GRANDPAP HAD ME IN HIS ARMS.”

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I | Peter Pearson |

| II | A Turn of the Dial |

| III | Preparedness |

| IV | And Again |

| V | Rhodes |

| VI | A Price |

| VII | Old Jones |

| VIII | Off Watch |

| IX | That Man |

| X | The Web |

| XI | Gathering Clouds |

| XII | Storm and Suspicion |

| XIII | The Eyes Have Seen |

| XIV | A Night |

| XV | Driftwood |

| XVI | Seth Blucher Talks |

| XVII | Along the Way |

| XVIII | Discovery |

| XIX | Pearson’s Ghost? |

| XX | Mr. Blucher Drops In |

| XXI | Old Jones’ Views |

| XXII | And With the Tide |

| XXIII | Hidden Fires |

| XXIV | Peter’s Future |

| XXV | Something to Ponder |

| XXVI | Storm Clouds Gather |

| XXVII | Out of the Dusk |

| XXVIII | A Little Surprise |

| XXIX | Peter Comes Into His Own |

| XXX | And Pearson Knows |

| XXXI | Oliver’s Ghost |

| XXXII | The Dead Man Speaks |

| XXXIII | The Ghost of the Bell |

There was something about Peter Pearson that struck a responsive chord in Tom Slade. He felt it the very first time he saw the little pioneer scout sitting quite alone outside the “eats” shack at Leatherstocking Camp.

Peter’s attention was fixed upon the lake. A certain wistful expression shadowed his tanned face and crinkled the skin about his temples. His mouth was puckered as if in thought and his two small hands were clasped about his drawn up knees.

Tom watched him through the window just over his desk. No one was in the Lodge and he had time to ponder over many reasons that could have brought about Peter’s self-imposed exile.

Tom had lived and worked with boys so long that he could tell at first glance why and when a boy didn’t fit in. And he had only to glance at Peter’s misty eyes to know that he wasn’t fitting in at all.

The corners of Tom’s generous mouth smiled understandingly. He had seen so many kids at the end of their first day in camp, sitting in that same pensive attitude. They all sat apart from the bustling camp life after supper just as Peter was doing. But unlike Peter they all looked wistfully down toward the wagon trail that led out to the main road and thence to Harkness and the railroad station—to home. That is, all except the happy-go-lucky ones. To them, home was a place to go to when they couldn’t go anywhere else. Tom knew that type well.

Certainly Peter did not fit under that category. Neither did he add his name to the list of those who watched the wagon trail. He was simply in a class by himself, Tom thought. For never before in the short history of Leatherstocking Camp had any scout gazed so steadily upon the sombre waters of Weir Lake after the supper hour. It was a record worth noting.

With the sun going down, the lake presents more or less of a depressing picture. No last lingering scarlet ray of sunset ever skims its leaden surface. Old Hogback, like the perverse, towering giant it is, shuts out Weir’s full measure of daylight and sunlight, and casts great, black misty shadows full upon it in a premature twilight. It is a scene to turn away from.

Still Peter stared on.

Tom’s curiosity was aroused. He rose determinedly and strode quickly out of the Lodge. He just had to find out the why of Peter Pearson.

At Peter’s side, he stopped short and turned, facing the lake. He said not a word, hoping the scout would voluntarily enlighten him as to the mist’s evident allure.

Peter glanced sideways without moving his head. He said nothing and looked confused. Tom felt disappointed but decided on another course.

He leaned over and gave Peter a cordial smack on the shoulder. “What’s so interesting out there?” he asked. “Are you wondering whether you’ll get trout for breakfast?”

Peter grinned sheepishly. Tom gave him a friendly shove and sat down beside him on the bench. “Come on,” he urged gaily, “what is it all about? I’m here to hear all that’s to be heard. Don’t you like our Camp?”

Peter chuckled audibly. “S-u-ure,” he answered falteringly. “I like it fine, Mr. Slade.”

“But you don’t like the kids. Is that it?” Tom queried.

“Oh, honest—” Peter began.

“That’s understood,” Tom laughed. “The main thing is to unload all your difficulties before bedtime. You’ll sleep better. Are you getting enough to eat?”

“Uh huh,” Peter answered. “I even had more than I could eat.”

“Well that’s better than not enough, isn’t it?” Tom smiled.

Peter nodded.

“Outside of being homesick, there’s no other difficulty that I can think of just now. Perhaps you could tell me a new one.”

Peter’s face brightened and he moved closer to Tom. “I like the scouts here, Mr. Slade,” he confessed in a low voice. “I do like them. Only I never met any scouts before I came here. I never even talked to boys, except big fellers. That’s the trouble—I don’t know what to talk about.”

“Explain all that,” Tom said, kindly.

“It’s funny,” Peter said softly, “about me, I mean. I can see I’m funny, just since I came here today.”

Tom looked down at him inquiringly. “How do you mean?” he asked.

Peter flushed. “I mean I can see I’m different from other boys,” he answered. “I spose it’s ’cause Grandpap never lets me have any friends or nothing. He taught me how to read and write and everything. I’ve never been inside a school even. I guess that’s what made me different, don’t you think so?”

There was a sort of appeal in Peter’s question. Tom sensed it. He put his hand over on the boy’s knee. “That’s not such a difficulty to get over, kid,” he said, consolingly. “You’ll know every boy here by next week and you won’t have time to feel different. Get the idea?”

Peter smiled. “Sure,” he answered. “Only you can’t understand what it is to be me, Mr. Slade. Even if I do get to know the scouts here I’ll have to be careful not to be like them so I might as well stay alone by myself. Grandpap’d be mad if I came home acting and talking like other boys—I had to promise him I wouldn’t before I could even come here. He hates everybody in the world he says and that’s the reason he doesn’t want me to be like everybody else.”

“Your grandfather must be an odd number,” Tom said half aloud.

“He is,” Peter agreed. “Everybody over at Rhodes (that’s the mainland), they say he’s queer and that he’s trying to make me queer too. No one is friendly with him, not even old Jones. He’s Grandpap’s helper and he lives with us. Sometimes he’s nice to me.”

Tom looked puzzled. “Where do you live, Peter?” he asked.

“At Shadow Isle, Maine. It’s a mile from the mainland.”

“How is it,” Tom spoke at length, “that your grandfather allowed you to come here? How is it he will recognize scouting if he hates all the rest of our civilization?”

“He says most of scouting is sensible,” Peter answered. “He says it isn’t like other modern things—a lot of trash where you don’t learn anything. He just let me have this one vacation he says because I’ll soon have to learn to tend the light.”

Tom whistled low. “Oh,” he said, “so you’re a lighthouse scout, eh?”

“Yep,” Peter answered. “I’d rather do other things though. I like the land better than the ocean all the time. That’s why I got the idea of selling fish over at the mainland. I go in the spring and summer twice a week and I earned enough money to come here. A man I sold some fish to gave me a scout handbook. Grandpap wouldn’t let me read it for a long while.”

“But then he finally did,” Tom interposed.

“Yes, all of a sudden,” Peter went on. “He never was so nice to me before. He gave it to me and he said I should write to the scout headquarters and find out what camps there were and that I could pay my way with the money I had saved. Gee, I was surprised because he’s always been so cranky about me talking to anybody.”

“So that’s how you come to pick on the Adirondacks and Leatherstocking Camp, eh?”

“Yes,” Peter admitted. “It’s fine here I think, especially that great big cabin you call the Lodge.”

Tom smiled. “It is pretty nice,” he said. “This was once owned by a very rich man and he lived in the Lodge in the summer. We built all the cabins since the Scouts took it over. It was intended for a scoutmaster’s training camp but afterward they decided to use it for all purposes. That’s the reason I’m here—to take charge of you kids.”

Peter grinned. “Well I’m glad it’s you, Mr. Slade,” he said, naively. “It’s nice to have an older person treat me like I was grown up. Grandpap don’t do that. He’s most always mad at me.”

“Except when he decided you could come here,” Tom said. “He couldn’t have been mad then, I guess.”

“Oh no, he wasn’t,” Peter admitted proudly. “Gee, he acted like I wasn’t going away fast enough. Even old Jones noticed it because he asked me one night what had come over Grandpap to get so kind hearted all of a sudden. But I couldn’t tell him. I was only too glad to come here and see what the rest of the world was like.”

“You poor kid,” Tom said sympathetically. “Is it the first time you were ever away?”

“Sure,” Peter answered. “That is, as far back as I can remember. Grandpap said my father and mother died when I was a baby. He said I was born at the lighthouse and afterward they took me away for a couple of years.”

“Do you remember any of it?” Tom queried with interest.

“Well, a little,” Peter answered. “It’s sort of like a dream. I remember a nice tall lady—I guess she was my mother. And I remember a great big man that I called Father and we were out on the ocean like, because the waves were high just like I’ve seen them at the light in a storm. After that I sort of got sleepy and the next thing I knew my Grandpap had me in his arms and was climbing up the rocks to the lighthouse. That’s all I know.”

“That’s strange,” Tom said, aroused. “How do you know that it wasn’t all a dream?”

“I’ve always been sure it wasn’t a dream, Mr. Slade,” Peter said. “But Grandpap says it was a dream and if I tell it to anybody he’ll give me a licking. So don’t you ever tell on me, will you?”

“I should say not, Peter,” Tom promised. “You can depend upon that.”

Tom watched closely over Peter during the following week. He did all he could to encourage his participation in the numerous activities that the big camp offered to its scouts. And on several occasions he paired him off with a boy his own age and sent them off on hikes through the mountains. But Tom’s every attempt proved futile.

In the games, Peter would either miss his turn or make some blunder and it wasn’t long before he was quietly frozen out of everything. On the hikes, he would almost always return alone, sad and despairing looking. He wasn’t fitting in.

One sunny morning, Tom made a final attempt to pair Peter off with a scout from Connecticut. There was to be a hike down to Harkness village. The scout looked rather disdainfully at the young camp manager for a moment, then stepped up close to him. “Say,” he said in an undertone, “can’t you pick out somebody else for me? Gee, that Pearson kid’s a flat tire. He never says a word and he looks as if he’s afraid to laugh half the time. He’s as good on a hike as a dummy.”

That was almost too much for Tom. He felt the scout’s criticism of Peter as much as if it directly affected himself. He wanted so much to make the short summer weeks a memorable time in the little scout’s uneventful life. Yet Peter’s fear of his grandfather would put to rout the noblest effort. Tom realized that.

The knowledge made him angry. What right had that fanatical old man to instill such fear, such a creed of life, into that wistful young boy? He felt it would soon destroy all that was fine and upright in him.

Tom recalled what Peter had told him of the opinion of Rhodes. Perhaps those people knew what they were talking about. Perhaps they suspected the reason why the grandfather was pinning the boy down.

He felt sure there was a motive in it. And about Peter’s dream—why did he forbid him to tell of a simple thing like that? There was something more or something less than fanaticism underlying Pearson’s rigid discipline of his grandson.

The more he thought about it the more aroused Tom was to protect the boy from the kind of life that seemed to be threatening. He felt a strong desire to go up to Maine and teach Pearson some of the fundamental principles of scouting and show him that his grandson was a very part of the fine old world that he professed to hate.

Now that Peter had been discarded by his brother scouts, Tom’s sense of injustice had received its final blow. Pearson had gone a little too far when his discipline had prevented Peter from laughing and talking like a normal young boy.

He swung around in his desk chair considering a letter to Shadow Isle when Peter’s voice broke in upon his thoughts. Tom looked up to see him standing outside the window. He motioned him to come in.

Peter ran in breathlessly, holding an opened letter in his hand. “It’s from home, Mr. Slade,” he said. “From Grandpap. He says he has to go away on business after the first of the month and that he’d like to get a helper for Old Jones without anyone in Rhodes knowing about it.”

“Why,” Tom said, “I should think the government would take care of that. Don’t they usually send one in cases like that?”

“Yes, they do,” Peter admitted. “That’s what I can’t understand. Grandpap writes that he doesn’t want the government to know nor anybody else because it’s a secret. He’s not even going to tell Old Jones until the day he goes.”

“I wonder why?” Tom asked.

“Gee, I don’t know,” Peter answered. “All I know is, he asked me if there was anyone down here who could keep his mouth shut. He said most people down here will do that for a little money and he’d pay well whoever would come.”

“What an admirable thought,” Tom said, drily. “Still it’s no more than I expected somehow. This would be an agreeable situation for Brent Gaylong,” he added more to himself than to his listener.

Peter looked at Tom inquiringly.

“Brent’s my best friend, Peter kid,” Tom said, answering the look. “You’d like him. He lives in my town, Bridgeboro.”

Peter smiled. “If he’s your friend I’d like him, no matter what,” he said, sincerely. “Do you mean you’d want Mr. Gaylong to go to Shadow Isle?”

“Indeed,” Tom answered. “I intend to go too. I have a hunch that the trip will be worth the trouble. And I don’t think your grandfather will mind there being two of us—not in his present evident need for secrecy. As long as we remember to keep our mouths shut. That’s the main thing, eh? Brent looks harmless and he doesn’t say much but he can think an awful lot.”

Peter looked plainly puzzled. “You really mean you’re going, Mr. Slade?” he asked, incredulously. “How can you get away from this camp?”

“Oh, they can spare me, I guess,” Tom laughed. “There’s always someone around to look after things. I don’t very often take a vacation during the season. Camp closes in four weeks anyhow so that will only make three I miss if we get off next week. And the week after that you’ll be heading for Maine too.”

“I’ll miss you, honest I will,” Peter said, keenly disappointed. Then he brightened up again. “Anyhow, maybe Grandpap wouldn’t be so cranky after he talks to you and Mr. Gaylong. Maybe he’ll even be nicer to me when he comes back from his business.”

“That’s what I’m hoping for, Pete,” Tom said, feelingly. “I’ll miss you too, but you’re better off with the kids just as long as you can stay here.”

Peter smiled.

“One thing though,” Tom continued, “you won’t be better off if you keep on sitting in front of the ‘eats’ shack and staring at the lake. You’ll just have to forget your grandfather’s hating this and that. Think of yourself and what fun you can have with the rest of these nice kids. Laugh when they laugh and talk when they talk. Your grandfather can’t hear you. Get the idea?”

Peter laughed happily. “I’m going to try, Mr. Slade, honest I am,” he said. “And when I get back home if I’m talking and acting like all the other boys here, why Grandpap won’t be there anyhow. You will.”

“That’s it,” Tom applauded. “Now let me have your grandfather’s letter so I can answer accordingly. There’s only one way for me to find out why he’s so queer. That’s to go there.”

Peter laid the letter down and looked at Tom appealingly. “You won’t tell him I talked about him to you?” he pleaded.

“There you are back at it again,” Tom said, reprovingly, yet kindly. “My name’s Tom Slade. That doesn’t mean much to you but it means a lot to some of the scouts down in Bridgeboro, New Jersey, where I come from. I was brought up in the slums there and then the scouts caught hold of me and took the stones out of my hands and taught me not to lie. They did everything for me that was good and kind so that in turn I’d be fit to do that same for other kids—for you.

“Read your handbook over again. A scout is trustworthy and a scout is loyal. I’m out to help you, Peter kid. Not make things worse. Now run along so I can write to Brent and your old grandfather.”

Peter beamed at Tom. He walked to the doorway and lingered there just a second. “I bet you’re going to Shadow Isle on account of me,” he said smilingly. “I bet you’re going to help me with Grandpap.”

Tom looked up and winked fraternally. “I bet I am!” he said.

A week later Tom was on the train bound for New York. Brent and he were to meet there at the railroad station and journey on to Maine together.

Brent’s reply to Tom’s letter had been brief but enthusiastic over the contemplated venture at Shadow Isle. And as for keeping his mouth shut, he wrote Tom that he would promise faithfully not to say a word after they reached Maine.

Tom smiled at the thought. It sounded just like Brent. And it would be comforting to have him along. Especially now that he had heard from Lightkeeper Pearson. His reply had been very interesting.

Evidently he was a very shrewd man. He reiterated the need for secrecy and courteously warned Tom and his friend against talking of their plans. He told them to inform whoever might ask that they were merely on a few weeks’ visit to the lighthouse at Shadow Isle, and concluded by saying he would meet them at Rhodes in a dory.

This thoroughly aroused Tom. He was positive now that there was something underlying Pearson’s business venture. He couldn’t wait for the train to get in so that he might ask Brent his opinion.

That long, lanky person strolled leisurely up the platform to greet Tom. As usual, his spectacles were perched halfway down his nose and he gave one the impression of being made for his clothes, rather than his clothes being made for him.

“Well, Tomasso!” he drawled. “I’m here on the stroke of the hour you see.”

“I see,” Tom returned and clasped his hand feelingly. “It’s good to see you, Old Scout! All set for Shadow Isle?”

“All set,” Brent answered in that droll way of his. “My microscope is in the bag.”

Tom laughed. “Is that all?” he queried.

“No,” said Brent, “I haven’t overlooked a single necessity. I stopped in the five and ten too, before I left and bought a pair of canvas gloves.”

“What for?” Tom asked.

“Fingerprints, old dear,” Brent drawled. “Suppose I should confuse my own with someone else’s? The trusty canvas gloves will prevent any such catastrophe. One can’t be too careful.”

“Still the same old Brent,” Tom laughed. “You may need them at that. From the tone of Pearson’s letter he has something more than business in his head.”

“Didn’t I tell you!” Brent said in that funny, drawling way. “I shall put them on the moment we reach the place.”

“I’d wait till I was seated in the dory if I were you,” Tom advised.

“Safety first,” Brent said, solemnly. “I take no chances with old geezers who are willing to pay big money to people just because they promise not to talk.”

“There’s something in that,” Tom agreed. “But seriously, Brent, what do you think we ought to do first?”

“Get our tickets, Tommy,” said Brent. “It’ll be a load off my mind to set down this bag and take a nap in the Pullman. I’m not fond of manual labor you know. It just tires me out.”

“I know,” Tom grinned.

They pushed their way laboriously through the late August vacation crowd. The station fairly hummed with activity and heat. Finally Tom espied their ticket window. A long line stood waiting to be accommodated, moving forward at a snail’s pace.

“Do we have to wait behind that?” Brent asked, pointing a despairing finger at the line.

“You don’t,” Tom said, affably. “You can hold the bags, if that will suit you better, and I’ll get the tickets.”

“I’ll wait on the line, Tommy,” said Brent, promptly. “You hold the bags.”

Tom laughed. “Just as you say, Brent,” he said. “Only make it snappy before the line gets longer.”

Brent had never hurried in his life. He strolled. And by the time he reached the line there were a half-dozen people or more ahead of him, perspiring and excited. Not so Brent. He took his place, cool and calm looking, and motioned Tom to come nearer and move along beside him.

Tom shook his head in answer. He had already found a place to deposit the bags a little out of the crowd and was sitting contentedly on top of them. Brent stared at this picture of comfort, then pulled a wry face in mock disgust.

Ten minutes later Brent found himself facing the ticket seller. He also faced the fact that he had forgotten the name of the place that the train would take them to.

He turned and shouted at the top of his voice to Tom. “Before Shadow Isle,” he yelled, “where to?”

“Rhodes!” Tom roared back above the din of the crowd.

In his anxiety not to miss Tom’s answer, Brent unconsciously stepped backwards. He felt his rubber heels pressing down on someone’s toes. Quickly he turned, all apologies, to a dark, straw-hatted man behind him, upon whose toes he had trodden.

The man whisked away the offense with a half-grin. He looked curiously at Brent but said nothing. And the tall, lanky adventurer proceeded with his business of ticket buying.

As Brent turned away from the window he felt the man still watching him. He instinctively looked up and their eyes met. Then the man took his place at the window.

Brent was still thinking of the man’s curious look when he approached Tom. “Did you see the way that chap gazed at me?” he asked.

“No,” Tom answered. “What did you do to him?”

“Not enough to warrant him staring, that’s sure,” said Brent. “My rubber heels might have caused a little pressure on his pet bunions but that’s all.”

“Isn’t that enough!” Tom exclaimed. “Be thankful you didn’t get more than a look.”

“But I apologized,” Brent exclaimed. “And the man grinned and started staring at me as if I ought to be quarantined or something worse.”

Just then the dark haired subject of their discussion walked past. He was busily stuffing his railroad tickets into a bulging, green leather wallet and did not seem to be aware of either Tom’s or Brent’s presence.

“Some fancy blue band he has around his hat,” Tom commented as the man disappeared through the revolving door. “He didn’t give you a tumble that time, Brent.”

“It’s fortunate for him that he didn’t,” Brent said.

“Why?” Tom queried. “What would you have done?”

“I’d have said, Tag, you’re it,” answered Brent. “No other words could express my feelings more effectively, Tommy.”

“Maybe he senses that you’ve a Sherlock Holmes complex,” Tom laughed.

“In that case,” drawled Brent, “I’d reverse my opinion of the brute. One must make allowances for him if his staring was prompted by noble impulses. He’s evidently recognized the genius that’s in me.”

“Oh, don’t we love ourselves,” Tom said in sing-song tones and picking up his bag.

“It’s my one means of encouragement,” said Brent in his droll way. He took up his bag and followed Tom out to the train.

“It’ll be a toss-up who’s worse,” said Tom as they climbed the short steps into the Pullman, “you or Lightkeeper Pearson.”

“Now I feel normal,” Brent said, as he stretched his legs out the full length of their Pullman section.

“And I feel uncomfortable,” Tom said. “I’d like at least a quarter of the seat to sit on. What do you think I am, a fly?”

“Pardon the oversight, Tommy boy,” Brent drawled. He hugged his long legs closer to the window. “I do love comfort.”

“As if that’s news to my young ears,” Tom laughed. “Were you ever exhausted from working too hard, Brent?”

“No,” Brent admitted solemnly. “I’ve kept all my surplus effort in reserve. Stored it away, so to speak, for some momentous occasion.”

“When will that be?” Tom queried.

“Perhaps at Shadow Isle,” answered Brent. “Who knows! Maybe old boy Pearson will set me to work sweeping the ocean off the rocks every morning.”

The train started off for Boston and Brent and Tom lapsed into the silence that seems so usual at the beginning of a journey. Tom’s head drooped after a little while and Brent’s right leg rudely slipped off its resting place on the opposite cushion. He made no effort to restore it to its former position. He seemed not to have a care in the world.

An hour passed by in this manner when Brent was startled out of his lethargy by the train’s coming to a stop. Sleepily he raised a heavy eyelid nearest the aisle only to find a man in the next forward section staring curiously at him.

Brent roused himself and sat up straight. The man, evidently embarrassed, quickly turned and reached for his straw hat hanging on the upper hook. He placed it on his head and strode out toward the smoking room.

Astonished, Brent watched him. Then he shook Tom roughly and woke him out of a nice, peaceful nap. “Hey, Tomasso,” he said, “there’s something suspicious about that bird.”

“What bird?” Tom asked drowsily, trying to pull himself together.

“The fellow that came under my heels in the station,” answered Brent.

“Gosh,” Tom said with a sigh, “are you still thinking about him?”

“Certainly,” said Brent. “Why wouldn’t I? He has the next section to ours and I woke up to find him still staring at me. Why wouldn’t I think about him? He hasn’t given me a chance to think about anything else.”

“I told you a couple of hours ago,” Tom said, “that maybe you interest him. Anyway, he has as much right to be riding on this train as you or I. So where’s the kick?”

“None,” drawled Brent, “as long as he keeps his eyes to himself. It makes me feel like a flapper.”

“If I were you, I’d go and question him,” Tom suggested. “He might tell you a different way to knot your necktie.”

“Not a bad suggestion, Tommy,” said Brent. “I’ll act upon it at once.” He rose lazily out of the seat and strolled in the direction of the smoking room. Tom snuggled back into his unfinished slumber.

Brent entered the smoke filled room. A number of men were lolling about on the black leather seats, their knees and shoes flecked with cigar ashes, and the man he had come in to see was sitting on the divan at the end nearest the window.

He seemed not to be taking any part in the conversation; rather he seemed quite out of it, for he kept his face averted, looking out at the passing scenes.

There was the usual smoking room talk and, bored, Brent walked to the wash basin, took up the cake of soap and indifferently rubbed it on his palms. Meanwhile he glanced through the haze at the buzzing group.

Suddenly a bald-headed man removed a cigar from his mouth with a flourish. “I’ll leave it to that young man washing his hands there, if it ain’t so,” he said.

Brent stopped and looked at the man inquiringly. “I beg your pardon,” he said. “Did you speak to me?”

The bald one threw his stub to one side and looked up at Brent. “I was just trying to tell this thick article here that Bangor’s the capital of Maine. And I just happened to see you standing there and wanted you to back me up on it. I leave it to you, young man. Now ain’t Bangor the capital?”

“Not since I went to school,” Brent drawled. “Augusta’s the capital. I could always remember it because a fellow in my class named Gus came from there.”

They all laughed, all except the man at the window. He had not yet turned his face. Brent wondered why he hadn’t turned and stared then.

The bald one jarred him out of his thoughts. “Hey, young fella,” he said, “how about it? You seem to know your little geography of Maine. Do you know a good up-and-comin’ fishin’ village where we could get good accommodations?”

Brent shook his head. “Sorry,” he drawled, “but I don’t. The only fishing village I know of is the one I’m bound for and I know nothing of it except that its name is Rhodes.”

“Humph!” the bald one said. “What accommodations you gettin’ there?”

“None,” Brent answered. “I go further on to a lighthouse about a half-mile from the mainland, I believe.”

The man at the window turned quickly, glanced at Brent a second, then averted his face again. It really didn’t signify anything—that look. It was just a curious glance. Yet somehow it left in Brent a rather dissatisfied feeling. He wished the fellow had said something.

He hung around for a few minutes more until the talk switched to reminiscences. He decided that was his cue to move on. Staring people annoyed him but reminiscences were worse.

He found Tom quite wide awake and expectant looking. “Well, is everything O.K. now?” he asked Brent.

“I know less than I did before,” Brent admitted, trying to infuse sadness into his tones.

“Didn’t he talk to you at all?” Tom queried.

“No,” Brent answered. “I’m beginning to think he just doesn’t care about my looks. Or it might be as you say, Tommy, he doesn’t like the way I knot my tie.”

They tumbled sleepily out of one car at Boston and into another one. And when they alighted upon the platform at Rhodes, Brent was not fully awake.

He stood blinking his eyes while Tom inquired of the wizened looking station agent the way to Rhodes Beach. Then a Ford taxi wheeled around into the driveway, Tom hailed the driver, they piled in with their bags.

After they were settled comfortably the taxi started away and swung them unceremoniously around as it turned into a rut filled road. Brent commented upon it and mumbled that it was worse than any Jersey detour.

“After this then,” Tom said, “I hope you’ll never make another mean remark about my flivver.”

“Bring your flivver out here first, Tommy,” Brent said. “Drive her along a road like this and then I’ll give you my honest opinion.”

A man carrying a small bag was walking the road just ahead of them. Brent noticed him indifferently at first, but the nearer they came to him the more familiar did he appear.

He grasped Tom’s arm. “Look, Tommy!” he exclaimed. “As I live, it’s that bird again!”

“What bird?” Tom asked, looking around. All he could see was the man’s back about fifty yards away.

“The bird with the hat band,” said Brent. “The fancy blue one.”

“Well, what of it?” asked easy-going Tom. “Why the excitement? Can’t he come to Rhodes too?”

“Sure,” Brent answered in that droll way of his, “as long as he stays in Rhodes. But he can’t follow us out to Shadow Isle and stare at me there. I won’t let him.”

“What’ll you do to him?” Tom laughed.

“I’ll throw him out in the ocean,” said Brent.

At that juncture their cab whizzed by the man, raising a cloud of dust that obstructed any further view of him. Then they turned again, leaving him in full possession of the road.

“He probably came up here for fishing,” Tom said.

“He ought to make a good catch,” Brent said. “He has patience enough, that’s certain.”

Then the vast expanse of ocean spread before them. A small sandy beach rolled down to meet it. To the left, a large pier jutted its nose far out into the white foam.

The cab stopped in front of a little, white painted building. A huge gilt-lettered sign hung dejectedly from its porch bearing the inscription:

At odd times it was used as a bulletin board as was evidenced by numerous thumb tacks and bits of faded paper stuck fast under its ornate lettering.

Brent scrutinized it while Tom was paying the driver. Then he turned his attention to the farther side of the street where a yellow painted building stood imposingly in the early sunlight. A hitching post outside in the road added to its old-fashioned atmosphere.

A number of small shacks dotted both sides of the road. The curtains were all drawn and from the backyards came the crowing of the busy roosters. Nothing else stirred, not even in the White House Hotel. Only the ocean pounded below on the beach, like many distant drums.

The cab turned and rattled its way back to the station. “Where are we to meet Old Man Fearful?” Brent asked.

“Right here,” Tom answered. “He said he’d be watching for us.”

“We might as well look the village over while we’re waiting,” Brent said. “It’s too early to see the populace, I guess. Evidently they don’t get up with the chickens in these fishing villages.”

“That ought to suit you, Brent,” Tom laughed. “Want to walk around?”

“Me?” Brent asked, indignantly. “I should say not. I’m tired out. I think I’ll go up on the White House porch and rest my weary bones. I can see all of the village from up there.”

“Some thriving village,” Tom commented, looking around. “I wonder if this is all that comprises Rhodes.”

“There might be some houses holding out on us,” drawled Brent. “They’ll probably come out of their hiding places when we’re not looking.”

Tom smiled, then his features grew serious. “You can just imagine why that little Peter kid ducks the crowd at camp. This crowded metropolis probably boasts of at least twenty-five families.”

“I wonder if the White House man will give us breakfast before we sail the high seas,” Brent mused.

“I’m hoping so,” Tom said. “Still, an empty stomach might be better to ride the waves on.”

They both looked toward the deserted beach. It was high tide and the waves dashed swiftly up on the shore. They saw no sign of a boat upon the horizon. Nothing but sunlight, sky and water.

To the east a stretch of rocky land abutted upon the ocean. Sharply it swerved, making a decided turn away from the little village. From that point the rocks piled high, stretching along as far as the eye could see. Thick growths of stubby pines hung tenaciously from the cliffs.

“I imagine the lighthouse must be off there, east,” Tom said. “It’s all woodland to the west so it can’t be there. Little Pete said the lighthouse had lots of rocks about it so I guess the island is just a good sized reef.”

Even as he talked, Tom could see a moving figure out at the pier’s edge. Brent, too, saw it and they watched in silence. Then they discerned that it was the figure of a man walking landward.

“Tommy,” Brent drawled from his easy chair on the porch. “I’ve a sneaking feeling that it’s Old Man Fearful himself.”

“So have I,” Tom said. “Think I ought to wave to him?”

“You can run on down and kiss him if you want to,” Brent answered. “But I’ll sit here and wait until he comes. I have my reputation to think of.”

Tom laughed. “I hope he understands you,” he said. “He’s likely to think you’re kidding him half the time.”

“There’s an even chance I will be,” Brent said whimsically.

The man drew nearer and nearer. As he left the pier he walked over toward the beach and his figure loomed larger with each step.

He was a little over six feet tall, a trifle bent and wore a small black cap atop his white, straggling hair. One could see even at that distance that his frame was spare, but powerful.

“Heavens, Tommy!” Brent exclaimed. “I think he’s Jack the Giant Killer in disguise!”

He hailed Tom with a sort of snort, giving neither hand nor smile in greeting. “Reckon yore Slade and that’s yore friend Gaylong settin’ up there,” he grumbled in a deep, hoarse voice.

“And you’re Mr. Pearson, I believe,” Tom said, smiling pleasantly.

“Jonah Pearson. Old Lightkeeper Pearson,” he snapped. “That’s what the nosey ones call me in this here cursed place. Yer kin call me what ye like, long as yer don’t speak out o’ yore turn. Talk little. That’s what I say.”

“Are you any relation to the first Jonah?” Brent asked innocently and dragging himself unwillingly out of his chair.

“Don’t b’long ter nobody,” Pearson answered tersely. “Glad I don’t. Relations never was comfortin’.”

Brent studied him intently as he spoke. He had watery blue eyes that were almost hidden beneath shaggy white lashes. His nose was long and pointed and his lips resembled two straight purplish lines, so thin and compressed were they. The chin was pointed in keeping with his nose and his ears were remarkably small for so tall a man.

“We haven’t had our breakfast, Mr. Pearson,” Tom spoke up. “We thought perhaps the hotel would open soon.”

Jonah Pearson looked from Tom to the hotel and back again. His features instantly became distorted in a contemptuous sneer. Then he made a sweeping gesture with his clawlike hands. “Pity the sea wouldn’t sweep ’em all away. The whole pack o’ ’em. Breakfast—hmph! Like as not ye’d git pizened by his food. Yer kin have breakfast soon’s we git ter the light.”

With that he turned and started back toward the beach. “I suppose that means he’s ready to go right now,” Tom said in an undertone and picking up his bag.

“Without a shade of a doubt,” said Brent falling into step beside Tom. “One thing, he’s right to the point. No ceremony with him.”

Tom smiled. “Are your canvas gloves ready, Brent?” he asked in a low voice.

“Leave it to me,” Brent answered. “I intend to take note of the smallest detail. And further, I’m convinced that no whale will ever swallow this Jonah. He’s too mean to die.”

“Sh-sh!” warned Tom. Then in a loud voice, “I think it’s going to be a nice day.”

If Jonah Pearson thought so too he did not say so. He just slouched along ahead of them, his ill-fitting clothes flapping against his bony frame. And his little black cap looked quite absurd upon his large head.

Tom and Brent exchanged significant glances but said no more. They followed Pearson up on the pier and out to the end. He stood there waiting until they came up to him.

“I’ll git in first,” he said tersely. “Yer kin give me yore junk one at a time. Got ter take it easy. Sea’s heavy.”

He proceeded down the ladder and into a dory that bobbed gaily upon the swell. Tom followed and Brent handed him the bags which in turn he passed into Pearson’s grasping looking hands.

That done they entered the dory carefully. Tom looked around the little boat in wonderment that such a frail structure could ride the heavy waves with so much buoyancy. “Wouldn’t you think it would get swamped!” he remarked to Brent.

“Not with such light spirits aboard,” Brent said, dryly.

Pearson was untying the little craft from the pier. He looked Brent’s way, puzzled, but said nothing. Then he leaned down and brought up a pair of oars which he handed to Tom. Brent, comfortably seated in the stern, nodded smilingly to Tom.

As the lightkeeper seated himself at the prow he scowled toward Brent. “You Gaylong,” he snapped gruffly, “get the rudder. Take her easy.”

It was really Tom’s turn to smile at Brent but he had to concentrate on helping to guide the boat away from the pier. They were instantly swung around by the mountainous waves and he had all he could do to keep the oars fast in his hands. His eyes and his face smarted keenly from the salt spray.

“Take her easy,” Jonah Pearson shouted. “Let her go with the tide. Jest hold her steady.”

Tom did as he was told. He felt soaked to the skin and wondered if Brent was too. The thought made him smile. “We should have put on our bathing suits or our raincoats,” he laughed.

“If I could let go of this thing I’d get out my folding umbrella,” Brent said. “I packed it in right on top.”

“Little thing like water won’t hurt yer,” Pearson grumbled. “Yer’ll git wetter ’n that before yer go back to the city.”

After they passed around the bend the swell seemed to calm down. Tom felt relieved. He released an oar to dash away the spray trickling from his forehead. Brent looked at him and winked slyly, then looked interestedly over his shoulder.

“What do you see?” Tom asked curiously.

“The lighthouse,” Brent answered. “Quite a skyscraper.”

“Be there in ten minutes,” Jonah Pearson called quite humanly. “Git along faster when there’s three on the job.”

Tom felt quite encouraged at that. “I should think so,” he said cheerfully. “I can’t understand how you come over all alone. Especially near that pier. It sure is rough.”

“Don’t mind a’tall,” Pearson called gruffly. “Sooner be alone any time. Don’t like folks nowheres.”

“So agreeable,” Brent drawled between his teeth. “We’re in for a jolly time, Tommy!”

Tom moved his eyes frantically for Brent to be cautious about his remarks. But he could have spared himself that worry as Jonah Pearson was not aware of anything but his own thoughts. His brows were drawn up into many little lines and his mouth worked convulsively as if he were talking to himself. Brent watched him.

Suddenly he looked up. “Give yer a hundred dollars apiece,” he said quickly. “If yer willin’ ter do as I tell yer.”

Brent glanced at Tom.

“What,” Tom asked, “do you want us to do?”

Jonah Pearson rowed on for a few seconds in silence. Then he leaned forward confidentially, as if to even exclude the ocean from his secret. “There’s a man comin’. He’ll come next week ter see me. But I won’t be there. I won’t talk ter nobody if I kin help it. Leastways a smart aleck city chap like him. Most all of ’em’s trash.”

“Oh,” Tom said, ignoring the sarcasm, “you want us to interview him for you. Is that it, Mr. Pearson?”

“Yes,” Pearson grunted. “Old Jones hain’t got sense enough ter do it. You’re ter keep him up in the tower till after the city feller goes. Old Jones, he’s kind o’ deaf. He hain’t got no license ter know my business anyway.”

“You know best,” Tom said. “Could you tell us beforehand what the city chap is coming for?”

Tom could almost feel Pearson’s watery blue eyes boring through his back. He sensed the man was floundering about for a logical reason to give.

Finally he coughed. “He’ll ask yer questions ’bout me. ’N ’bout Peter. But you and Gaylong don’t know nothin’. ’Cept ye were jest knockin’ ’round nosin’ in lighthouses. Understand?”

Tom nodded. “Of course,” he answered. “Naturally, Mr. Pearson, you do not want to tell every stranger your business. I can understand that perfectly.”

Just then Brent caught a crafty smile passing across Jonah Pearson’s face. He looked off in the distance before he spoke again. “One thing,” he snapped, “no matter what he asks you there’s only one answer.”

“What’s that?” Tom queried, interestedly.

“Yer tell him Peter Pearson hain’t never lived here. Yer tell him he jest came vacations and he was no relation. And yer tell him he hain’t a-comin’ here no more, either—that he’s dead!”

Tom’s hands instinctively pressed down firmly upon the oars. And Brent’s long sensitive fingers clenched the rudder rope tightly.

No further word was spoken. Jonah Pearson’s face seemed to indicate that he didn’t want to hear any. And Tom felt a tenseness that he had not experienced before. Every swing of his muscular arms seemed a blow in defense of little Peter.

He could not explain to himself why he should feel so. But there seemed to be an undercurrent, some evil spirit emanating from Jonah Pearson that threatened Peter’s happiness.

He tried to argue himself out of his morbid deductions. After all, old Pearson’s words did not have to be taken literally. Filled with portent though they were, it did not necessarily mean that Peter really was going to die or that he wouldn’t be at Shadow Isle again.

Pearson might merely want those words conveyed to the city chap in order to cover up his real motive. And the real motive? In some subtle way Peter was concerned in it. That much was evident now.

Pearson called to Brent to guide the dory around. “Have ter drift in a piece,” he said. “Tide’s goin’ out.”

Tom was struck with his first view of the light as the little craft turned around. It stood so imposingly upon the little rocky isle, vividly painted in bands of black and white with its gallery and tower of steel high up in the billowy clouds and dazzling sunshine.

The isle itself rose gradually but determinedly out of the sea with the lighthouse like some tall, graceful guardian of the dangerous rocky reefs. It spread around the edge of the ocean for a distance of about one city block. And the booming surf hurling itself mercilessly against its shore line formed a continuous screen of transparent spray about the isle.

Pearson nosed the dory up to the lowest level. Two other good sized boats stood well out of range of the surf. Farther up nearer the lighthouse was a lifeboat sunning itself upon the warm rocks. Tom couldn’t help wondering how many dark nights and stormy seas that mute looking craft had battled with.

Pearson grasped a jagged rock tightly and held the boat steady while Tom and Brent climbed out with their luggage. After they were high and dry the lightkeeper directed a watery eye at Tom. “Yer tell Old Jones yer a couple o’ city fellers what wants ter study lighthouses. Understand? Yer go on up while I run her up on the rocks.”

“Can’t we help you?” Tom asked as pleasantly as he could.

“Yer just do as I tell yer,” Pearson grunted. “That’s all the help I want.”

Tom nodded for want of something to say and he and Brent went on. As they glanced up at the tower a figure moved upon the gallery, then disappeared.

“Must be Old Jones,” Tom commented. “He’s been watching us coming in.”

“I expect, Tommy,” Brent drawled, “if we come out of this adventure unharmed that we too will be fit subjects for the Old Men’s Home. Everything around here seems to be decrepit and old. I feel my hair getting white already and I’m darned if I’m sure of my step. I have a premonition that we’re walking into an ancient trap of some kind. Old Gaylong and Old Slade—how does that strike you?”

“Seriously, Brent,” Tom said, “what do you make of him, anyway?”

“I think,” Brent answered, “that Old Fearful has more up his sleeves than his elbows.”

“I’m afraid so,” Tom agreed. “Don’t you think there’s something off color, criminal, about it?”

“Well, it isn’t any Hallowe’en party that the old duck is planning. You can be sure of that. And did you notice he didn’t answer your question as to why that city bird is coming! That excuse of his about not wanting to talk to city trash is a lot of bunk. He’s hiding something all around, that’s what’s the matter.”

“It’s a good thing little Peter kid is safe in camp. Gosh, that old man gives me the creeps all right. He sure is gloomy,” Tom mused.

“Well, I wouldn’t enjoy spending a rainy Saturday night with him, I know that,” Brent drawled. “It’s a good thing I brought my crossword puzzles along or I’d have visions of throwing myself off the rocks into the sea.”

They climbed the long, iron stairway and stood at last before the stout looking door. “Shall we go in?” Tom queried.

“Might as well,” answered Brent. “If Old Jones is in there you can knock after we get in. He won’t hear you anyway.” Tom pulled at the knob and the door swung out with great force.

No one was about as they walked in. “Old Jones probably sticks to the tower,” Tom commented as he gazed about the little, circular room.

“I would too,” said Brent, “if I had to live with that mean old geezer Pearson.” He strode over to a mahogany rocker that stood under the tall, narrow west window. True to himself he thumped down wearily and stretched out his long, lanky legs.

“What’s the matter?” Tom asked. “Pulling the rudder rope was too much for you, I guess.”

“Too much,” Brent sighed, adjusting his spectacles as his eye lighted upon the little bookcase standing opposite. “We can read here and everything.”

“Yes,” Tom said. “And we cook and eat here too. Just like a modern one-room New York apartment.” He walked over to the east window and inspected the trim looking little stove with its cupboards adjacent. Then he strolled back to the center of the room where the little dining table stood with its clean red cloth spread carefully.

“That looks like Grandma’s time, doesn’t it?” Brent remarked to Tom. “And they’ve even pushed up the four chairs in readiness for the banquet in our honor. One for Old Jones, one for Old Pearson and the other two for Old Gaylong and Old Slade. What a hilarious party we’re going to have!”

Tom laughed and tripped over the faded green carpet, landing almost plunk against the iron stairway that wound itself around by the inner wall. “Gosh,” he said, breathlessly, “I wouldn’t want to come down that thing in the dark. Sh-sh, Brent! I think I hear someone’s footsteps now!”

Distinctly they could hear the click of hard leather striking the metal stairs. Nearer and nearer it came. “It’s Old Santy Claus Jones,” Brent drawled languidly as he tried another easy chair near the door. “I wonder who’ll get here first—Jonah or Jones? That’d make a good team name in vaudeville, eh Tommy?”

Tom laughed outright just as two feet appeared on the stairway descending from the room above. Both he and Brent looked up expectantly.

Old Jones descended into the room, a short rounded bit of body and tiny bald head. His clear gray eyes looked curiously at Brent and Tom. Then his gray-fringed eyebrows drew up and his full, red lips parted in a friendly smile.

Tom stepped forward and smiled, shouting in his ear an introduction of themselves and the nature of their stay. He hated using a subterfuge, even though he knew it was not a permanent one. There was something so frank and honest looking about Old Jones that he felt mean in deceiving him.

Jones studied both young men thoughtfully. Then he patted down the bosom of his faded shirt and looked toward the half-opened door. Suddenly he raised his hand and motioned. “Old Jonah,” he said, trying to speak low, “yer can’t tell ’bout him.”

Tom nodded understandingly.

“Alius he wuz queer,” he went on, shaking his round head tragically. “But now fer a long spell he’s like crazy. All of a sudden he’s goin’ ter git wealthy. I’ll show yer.”

Brent and Tom were not aware of it at first. Neither was Old Jones. Then suddenly the realization came leaving in them a curious chilled feeling as of some awful impending calamity. They all looked up.

Jonah Pearson stood framed in the doorway. His hands were clenched tightly at his sides and his mouth had sucked his cheeks into great hollows. The bell in the gallery boomed the hour.

Old Jones backed away nearer to Tom. But Jonah Pearson merely turned and quietly shut the door. “’Spose yer want breakfast,” he said hoarsely, and walked toward the stove.

The silence was so tense that Tom strolled over toward the window. Brent never stirred but keenly observed Pearson’s furtive glances toward his old helper as he shuffled up the stairs back to the tower.

The coffee soon bubbled in the pot and Pearson stood silently frying some bacon and eggs. Brent wondered just how much he had heard of Old Jones’ remarks. It was hard to tell as Pearson scowled whether he was ill-tempered or pleased.

“Yer’ll know where ter git things after this,” he said quite pleasantly. “Dishes, pots and food’s in these here cupboards. Old Jones and me mostly git our meals separate. Yer kin do the same if yer want. Wash ’em up when yer git through. And sweep up. That’s a rule with me.”

“I like that idea, Mr. Pearson,” Tom said for want of something to talk about. “When do we start at the light?”

Pearson was busily setting the plates on the table. He walked to the stove and fetched the hot food, putting some on each plate. Then he poured the coffee.

He looked at Tom, paused, coffee pot in hand. “Gaylong’ll sleep bedroom ’bove here. You next, ’bove him. I sleep ’bove you and Old Jones, he’s next ter the tower.”

“All right,” Tom said as pleasantly as he knew how. “We’ll unpack our bags and get ready for business soon as the dishes are washed.”

Pearson walked back to the stove and set the coffee pot down. Then he walked to the stairway. When he was halfway up he paused and looked back down. “Yer kin start polishin’ lenses,” he snapped. “Old Jones, he’ll show yer. I’ll be up in the tower too. Goin’ up now.” With that he went on.

Brent and Tom listened until the sound of his footfalls died away. “Whew!” Tom exclaimed. “A wet firecracker would explode in this place.”

“If poor Old Jones talks out of his turn again today there’ll be no light in the lighthouse tonight,” Brent said. “Can you imagine the loving words that old geezer is pouring into the ears of Santy Claus Jones?”

“Well, one thing,” Tom answered, “unless Pearson shouts he won’t get a tumble from Old Jones. It’s a good thing he’s deaf.”

“What you say is very true, Tomasso,” Brent drawled. “But one look at Old Fearful when he’s mad is very convincing indeed. He doesn’t have to say a word to tell you what he’s thinking about.”

Tom laughed. “Perhaps things will quiet down after we get on the job.”

“It’s the working part of this job that doesn’t attract me,” Brent drawled. “I’d much rather sit out there on the rocks and hear what the wild waves are saying.”

Fifteen minutes later they mounted the steps to Brent’s room. A small rug covered the center of the floor, a trim white bedstead faced the stairs and alongside of the long, narrow window stood the tiny dresser. “It’s all in the handling,” murmured Brent, as he laid himself down leisurely upon the bed.

Tom laughed and went on upstairs. Brent raised himself up on his elbow and gazed through the window out to sea. At some distance off toward Rhodes, a lone dory bobbed up and down on the tide.

Brent unwillingly parted from the bed and went up to Tom’s room. “We’re twins, Tommy,” he said critically looking around the room. “Your dugout’s the same as mine.”

“I guess the other rooms are too,” Tom said. “They do that in lighthouses way out like this one. They strike a simple keynote.”

“They struck a simple keynote for the chappie that loses his collar button,” Brent drawled. “These turret rooms are good for that purpose. There’s no corners that hide in the dark.”

Tom shut his bureau drawer. “Now for work, Brent,” he said, cheerfully.

“Don’t mention it, Tommy,” Brent said in mock despair. “I was watching a lone dory out of my window a minute ago and envying its lone occupant. All he has to do is sit and catch fish in the sunshine and I have to go up and polish glass in a dark tower.”

Tom laughed and walked to his window. He stopped, leaning forward. “That dory’s heading for here, Brent. Sure as you live.”

“Hurrah!” said Brent. “I don’t have to polish glass. We’re going to have company!”

Tom walked to the stairs and smiled. “Come on, Ambitious, on to the tower for us. That’s probably some hick from Rhodes dropping in to see Pearson. We can’t entertain his company.” Tom went on up the winding stairway and Brent followed resignedly.

Past Pearson’s room they climbed and then past Old Jones’. The metal floor containing the huge, circular base of the great light looked dim and spooky. “There’s lots of places to play hide and seek in this tower,” Brent commented.

“Are you picking out a place to hide already?” Tom asked, laughing.

“I think I told you, Tommy,” Brent whispered, “that I intended to take note of the smallest detail. And we may have occasion some dark night to want a place to hide from Old Fearful if he gets running around after Old Jones with a gun. You can never tell.”

Tom was still smiling when they came upon Old Jones diligently polishing his lenses in the tower. Pearson sat by on a stool watching and incidentally enjoying the breeze from the gallery.

“Here we are,” Tom said, almost gaily.

Pearson snorted. “Yer jest watch Old Jones fer today. See how he does it. He’s almost through.” He rose abruptly and went out on the gallery.

In a few minutes he came hurrying in and passed them by without speaking, going straight on down the stairway. Brent stepped out on the gallery and looked. The man in the dory was now walking up toward the lighthouse. He called Tom and told him.

Old Jones stopped in his labors and looked questioningly at Tom. Brent came in then and shouted the reason for Pearson’s hasty descent.

The little old fellow hurried to the stairway to make sure of Pearson’s being well out of the way. Then he came back giving his tiny round head its usual tragic shake. He stepped out on the gallery with the boys and watched the man, slowly but steadily climbing the rocks below.

“There’s queer goin’s on in this here light, Mr. Slade,” he said again, trying to subdue his voice to a whisper. “Since he’s got jewelry crazy and money crazy, there’s queer goin’s on.”

“In what way?” Tom queried, close to his ear.

Old Jones looked almost sad. “I can’t tell ’zactly,” he answered. “It’s jest that I found letters of his’n. He’s been gittin’ letters from some place in Noo York and once they sent him a big check. I saw it. ’N I don’t think it wuz an honest check neither.”

Tom opened his mouth in astonishment. Old Jones looked encouraged to tell more. “’Nother letter I found,” he confided, “was ’bout a man comin’ ter see him ’bout some joolry he had sent them ter sell. I know where that letter is too. I kin lay my hands on it when he’s on watch ternight.”

“What makes you think it’s queer?” Tom asked him.

Old Jones leaned close to him. “He’s hid ten thousand dollars in his old boots for one piece of joolry he sent to that joolry place in Noo York. That’s what the letter said they would send him for it and they did. I found the money one night when he was on watch.”

“Where,” Tom asked in amazement, “did he ever get such a valuable piece of jewelry?”

“That’s what’s queer,” Old Jones answered. “That’s what’s queer. He thinks I don’t know nuthin’ but I do. He let little Peter go ’way on purpose. He didn’t want him ’roun’ ’count of the goin’s on. I know.”

“And you think Peter’s concerned in it then?” Tom asked.

Old Jones shook his head mournfully. “All I say is, time’ll tell. That’s all I say.”

The stranger was close enough to observe that he was being watched from the tower. He waved cordially and they waved back.

“That’s why I know things is queer,” Old Jones said close to Tom’s ear. “No one ever comes ter visit Jonah. Not in years. So it must be the man the letter said would come. And Jonah wuz plannin’ ter go way ’fore that man showed up. He didn’t want ter see him and talk ter him fer some reason. I know it.”

“I wonder why?” Tom asked, thoroughly aroused.

Old Jones looked at Tom; then went over to the stairs and looked down once more. He came back, a far off look in his eyes. “It’s jest since he got that letter,” he said more to himself than to his listeners. “He’s skeered o’ somethin’. Jest plain skeered!”

“Let me help you finish up,” Tom said to Old Jones. “It’s better than standing around waiting for things to happen.”

“That’s a good idea, Tomasso,” Brent drawled. “You get the idea of the work first and I’ll sit out on the gallery and report to you each development in our little mystery.”

“Has that fellow gone in down below, Brent?” Tom asked nervously.

“Yes,” Brent answered lazily, stretching his long legs luxuriously before him. “All’s as quiet as a tomb, Tommy.”

Tom instinctively shuddered. He took the polishing cloths from Old Jones and set to work polishing the topmost lenses. As the minutes passed, he found himself staring into the hyper-radiant ribbons of glass and trying to visualize all that was taking place below. But he succeeded only in puzzling himself more. The whole affair was far too steeped in mystery.

“Polish the clock case, Mr. Slade,” Old Jones said courteously. “I likes everythin’ ter shine when I’m on the job.”

“I bet you do,” Tom returned smilingly. “What’s this clock for anyway?” he asked, standing before the clock-like contrivance that was snugly sheltered in a glass case.

“Yer have ter wind that a coupla times a night,” Old Jones explained willingly. “That’s ter keep the lenses swingin’ roun’ so the light’ll shine far out ter sea. If that gits busted yer have ter turn her by hand and that hain’t so easy.”

Tom looked at the intricate mechanism of the great beacon with interest. “I’d like to sit up with you on your watch tonight,” he said to Jones.

“Jest as yer say,” Old Jones returned. “Jest as yer say. Yuh’d be a heap o’ company with things so queer aroun’.”

Tom was wondering if Old Jones knew more than he had already told when his musings were interrupted by the clang of a heavy gong from below. He started. So did Brent.

Old Jones smiled. “It’s Jonah,” he explained. “That means he’s went and got dinner ready fer all of us. He hain’t cooked a meal fer me in years.”

“Maybe that’s in honor of the company,” Brent shouted at him.

“Mebbe,” Old Jones returned, “but yer kin never tell ’bout him though. He’s either got conscience stricken or he’s schemin’ somethin’ else. I know him.”

“As long as he doesn’t put poison in my soup I don’t care,” drawled Brent. “That’s one thing I’d object to strenuously.”

“Can’t you think of something a little less fatal?” Tom queried smilingly.

“Not where that old geezer’s concerned, Tommy,” said Brent. “I can’t picture him not being tempted to put a dash of something in the pot after he opens up a can of soup. Don’t you think he looks as playful as that?”

“Oh, very,” Tom said soberly. “You certainly aren’t encouraging my appetite, Brent. I’ll be thinking over your cheerful words with every mouthful of food.”

Old Jones motioned them to come on. Tom followed him and Brent was last. Each one eagerly listened for telltale sounds from below. But none came. Only the savory odor of cooking drifted up to greet them.

Pearson was at the stove when they descended into the living room. He looked up and greeted them a little more pleasantly than usual. “Everythin’s ready,” he announced. “We have comp’ny fer dinner. Yes sir, we have comp’ny.”

Tom looked up in time to meet his eyes. He smiled vividly. It came almost as a shock—that smile. And Tom knew not which he liked less, Pearson’s contemptuous scowl or his vivid smile.

He noticed that the iron door was propped open. “Your company out looking at the rocks?” he ventured.

Pearson smiled again. “Yep,” he answered. “Likes it roun’ here jest fine. Says he’d like ter stay here allus. I told him he cud.” He ended his words with an unpleasant cackle.

Brent looked at Tom questioningly. Old Jones shuffled over into the further end of the room and stood in front of the bookcase. Idly he took down a book and looked curiously at it.

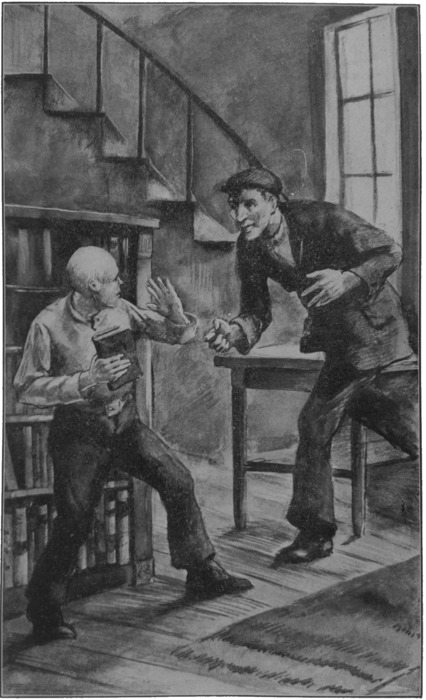

Without warning, Jonah Pearson made a sudden, almost superhuman leap across the room, landing at Old Jones’ side. “What yer nosin’ fer now, eh?” he rasped in guttural tones. His face was dark with temper.

“WHAT YER NOSIN’ FER NOW, EH?” HE RASPED.

Poor Old Jones raised a deprecative hand and replaced the book without a word. Pearson looked at Tom and Brent rather sheepishly, then walked back to the stove, a purplish tinge coloring the back of his tanned neck.

“Come on!” he snapped out. “Pour out the coffee, yer old fool! I’ve got ter fetch that feller in.” With three great strides he stepped out of the room and kicked the prop away from the door. It slammed behind him with a resounding bang.

Old Jones went to the stove and took off the coffee pot with trembling hands. After he had filled each cup he set it down and looked up appealingly.

“Yer see,” he said, “it’s jest as I said. The man’s gone plumb crazy. Yuh’d think them books wuz gold. The idea—makin’ all that fuss. He don’t even own ’em. The government does.”

“Never you mind,” Tom said sympathetically, “there comes an end to everything, Jones.”

“It’ll be an end ter me,” he said tragically, “if I stay here. It’s cuz he’s tryin’ ter hide things frum me. He doesn’t want me ter know nothin’ ’n’ all the time he’s afraid I do. And he’s right.”

Brent glanced at the bookcase a moment, then strolled slowly to the window and looked out thoughtfully. Then he gave a little start when he saw Pearson and his visitor coming up the long, outside stairway.

Tom walked over to him. “What’s wrong? Seen a ghost or something?” he asked curiously.

Brent pointed to the man. “Look, Tommy! He’s with us again. Our friend with the fancy blue band. That man!”

In another second the door swung out and the two men entered. Pearson, seemingly, was feeling quite genial. He wore the vivid smile that Tom was beginning to dislike and his attitude was one of cordiality.

He introduced Tom and Brent. “Meet Mr. J. P. Oliver of Noo York,” he said. “Mr. Oliver and me have some important business ter talk over after we eat. Hain’t we, Mr. Oliver?”

Mr. Oliver smiled pleasantly and bowed to Brent and Tom. “I believe I met you gents somewhere before,” he said with a sort of humorous twinkle in his dark eyes.

“Many times, Mr. Oliver,” Brent drawled, smiling back. “My friend Slade here thought maybe you didn’t like the knot in my necktie.”

Mr. Oliver laughed heartily. “No,” he said apologetically, “I was just puzzled as to what you were going to do after you arrived here. I heard you shout where you were going on the ticket line, remember.”

“Yes,” said Brent, “I remember. No wonder you were curious about us when you were coming here yourself.”

Jonah Pearson stood listening to the conversation and watched all three furtively. Tom thought he acted uneasy as though he were afraid something might be said that he didn’t want to hear. And now and again he shifted from one foot to the other. “I told Mr. Oliver how yer aimin’ ter study lighthouses,” he said abruptly. “Come on now, yore suppers are cold.”

Their talk at the table was general. Before they were quite finished, Old Jones rose from the table and silently mounted the stairs to the tower. After his heavy footsteps died away Pearson said, “Hmph! Old Jones, he sleeps from now till five. He has first watch.”

“Don’t you get tired of this life year in and year out?” Tom asked impulsively.

“No,” Pearson snapped, quite his unpleasant self again. “Git tired o’ nosey people. That’s all.” Then he caught himself up, looked at Oliver and smiled.

His smile was getting on Tom’s nerves. He knew that it was forced for Oliver’s benefit—that it wasn’t sincere. In point of fact, Pearson’s show of temper with Old Jones about the book was proof enough of what lay under the smiling countenance.

After a little pause, Mr. Oliver smiled across the table to Tom. “What is your line, young man?” he asked pleasantly.

Pearson’s brows gathered a trifle. Then he brightened. “Slade’s jest out o’ school, Mr. Oliver,” he lied. “Jest out o’ school ’n’ he hain’t nothin’ better ter do than ter traipse aroun’ lookin’ at lighthouses.”

Tom reddened with consternation. Mr. Oliver saw it and glanced toward Pearson. Long afterward, observant Brent remembered the understanding gleam that lighted his eye.

Oliver looked steadily at Pearson, then back to Tom again. “I’m from Hedley’s Incorporated, Jewelers, New York,” he said quietly. “I’m a detective. How about it, Mr. Pearson?” His voice was vibrant with meaning. It told Pearson that he had caught him.

A glow of deep red slowly mounted Pearson’s throat and suffused his cheeks. His anger and confusion seemed to conflict within him. After an embarrassing silence he burst out with, “Hmph! Yes, yes!” He then rose and hurried with some dishes over to the cupboard.

Brent looked after him and as his eyes roved back to the table he felt Oliver looking too. Their eyes met in a look of understanding. Then a faint smile lighted Oliver’s face and he winked.

Tom too had caught that wink and yawned audibly to suppress a smile. “We didn’t get much sleep last night,” he said to Oliver. “That is, I didn’t. I don’t know about Brent.”

“Yer kin take a nap now,” Pearson called out rather eagerly. “Yer’ll prob’ly need it if yer goin’ ter stay up on watch ternight.”

“And what about these dishes, Mr. Pearson?” Tom asked.

“Never yer mind ’bout them,” Pearson answered. “I’ll tend ’em while me and Oliver’s talkin’ business. Then we’re a-goin’ ter take a walk ’roun’ while I show him the island.” He chuckled.

“Just as you say,” said Tom. “We’ll have to take a walk around too. Some time before the day is over.”

“Yes, yes,” Pearson said tersely.

Tom and Brent rose and made their way to the stairway. Before they started up they smiled farewell to Oliver, who in turn gave them a friendly nod. “I’ll see you later, boys,” he said significantly.

“Sure thing!” they answered.

Brent stretched himself out on his bed. “Well, Tommy,” he said with a yawn, “the gods have played right into our hands. We got out of doing the dishes. And I got out of polishing the glass. I say we give three cheers for Mr. Oliver’s timely presence and Old Fearful’s crooked business!”

“Sh-sh!” warned Tom. “We’re right above them. Do you realize that?”

“Sound always goes up, Tomasso,” Brent answered indifferently. “I have an idea that young Oliver Goldsmith has Jonah’s number.”

“Whatever that is,” Tom said. Then he lowered his voice perceptibly. “There is a number to him, Brent, and I’d like to know what it is. Darn it all, he’s a pretty crafty individual.”

Just then loud voices were distinctly heard from below. It was Oliver’s voice that they distinguished first. “What my employers want to know, Mr. Pearson,” he was saying, “is how you acquired this jewelry. It’s worth a fortune and having been the former property of their client they are naturally interested to know.”

Tom and Brent sneaked on tiptoe to the stairway and listened eagerly. But Pearson’s answer was a hoarse whisper and impossible to understand.

Then Oliver’s voice came up to them once more. “But that is impossible, Mr. Pearson,” he went on. “No metal box, however airtight, would float on the surface of the water. With all that jewelry in it, it would sink at once to the bottom.”

Brent and Tom stared at each other in astonishment. Jonah Pearson’s hoarse whispering sounded like a rusty buzz-saw below. Then all became quiet.

The iron door banged shut.

Tom rushed to Brent’s window and looked out. Oliver and Pearson were going down the stairway. The lightkeeper’s pointed features were set in a smile.

They turned to walk back of the lighthouse. Oliver paused just a moment to watch a lone gull flying high above the sea. Suddenly the sun became blotted out by a passing cloud and the winged creature loomed against the sky like a dark, fluttering shadow.

“Pearson’s taking him for the promised walk,” said Brent looking over Tom’s shoulder at the scene below.

“Why is it, Brent, that I feel like shouting to Oliver not to go?” Tom said.

“Go ahead and shout,” Brent said. “Oliver would be glad to get rid of Pearson, I bet. I know I wouldn’t relish exploring this lonely place with that suspicious old duffer.”

“That’s it,” said sensitive Tom. “It’s him. He gets on my nerves with that smile since Oliver came here at noon. It means something.”

“Sure it does,” Brent agreed soberly. “It’s the face he puts on for company. The scowl he justs keeps for week days and Sundays.”

“You’ll get on my nerves, Brent,” Tom said quickly, “if you don’t quit your nonsense. Things look too serious, somehow. I feel that way about it if you don’t.”

Pearson and Oliver passed out of their sight toward the back of the island. A few slate-colored clouds were gathering in the east, spreading ever so slowly. The sun seemed loath to show its cheerful face again and from the sea, a heavy damp breeze was blowing. Tom withdrew from the window, slowly, thoughtfully.

“Well, Tommy,” Brent said, “while the cat’s away this mouse will play. The mouse meaning me.”

“Now what are you getting at?” Tom asked, rather irritably.

“I mean that it’s our turn to play at Old Jones’ game of hide and seek,” drawled Brent.

“I wish you’d stop beating around the bush and explain what you mean!” Tom demanded.

“Everything comes to him who watches,” Brent said enigmatically. “Follow me downstairs, Tomasso, and I’ll see if I can find who’s it.”

Tom looked searchingly at Brent’s face, but no trace did he find of his usual dry humor. “All right,” he said. “Let’s see what you’re up to.”

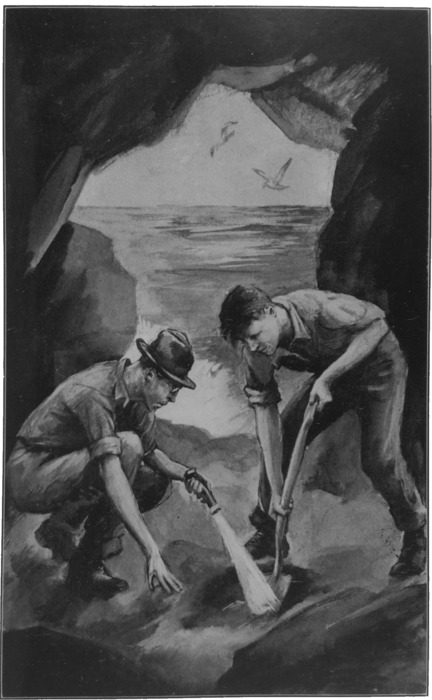

In the living room, Brent strolled at once to the bookcase. He stood in front of it studying it thoughtfully. “Wasn’t it about center front on the second shelf that Old Jones took out the book, Tommy?” he asked.

“Yes,” Tom answered with evident interest. “Why?”

“I’ll tell you better when I know myself,” Brent drawled. “This is just a hunch I’m acting upon. Nevertheless it’s a strong one. Keep a watchful eye on the stairway, Tommy. We don’t want a repeater of the Old Jones episode this morning.”

Tom hurried to the window overlooking the stairway. Brent began taking books out one by one and looking through them carefully. As he finished with each one he put it back exactly as he found it.

Finally he brought forth a large, red leather volume of Stevenson’s Treasure Island. “I supposed I would find a copy here,” he said, holding it up for Tom to see. “One couldn’t picture a lighthouse not possessing Treasure Island, eh Tommy?”

“Hardly,” Tom answered smilingly. “I’m curious, Brent, to know what you’re up to.”

“So am I,” Brent said as he dropped into the rocker and opened the book. He turned page after page with a precision that thoroughly aroused Tom.

About in the center of the book, from between the leaves he drew forth a medium sized white envelope and held it up. “Here is the cause of the old geezer losing his temper before. He thought old Jones would come across it.”

Tom looked to the stairway and seeing no one in sight, took the envelope from Brent’s hand. “Why, it’s the one Old Jones told us of,” he said. “The letter from Hedley’s.”

Brent nodded. “See what’s inside, Tommy,” he said.

Tom puffed open the envelope. “It’s in pieces,” he said. “He’s torn the letter in pieces.” He stepped over and shook the contents out into the open book resting on Brent’s knees.

“He’s torn that up quickly,” said Brent. “Then he’s heard someone coming before there was time to dispose of it.”

“And he’s just thrust it in there as the likeliest hiding place,” Tom interposed. “Most likely when he came to meet us. I suppose he’d be wild if he knew Old Jones has already seen it.”

“Yes, I suppose. Still, Old Jones didn’t remember half that he read,” said Brent. “It’s quite a coincidence that he should thrust it in Treasure Island, eh?”

“It is,” Tom agreed. “Old Jones must never read. That’s what Pearson counted on when he put it there.”

“Well, he didn’t count on us, that’s certain,” said Brent, studying the pieces thoughtfully. “Some crossword puzzle putting them together.” He gathered them up and put them carefully into the envelope.

“Aren’t you going to piece them together?” Tom asked.

“And have Old Fearful walk in at the crucial moment? Not me,” said Brent. “No one with true sleuthing ability like mine would commit such a gross error.”

“I beg your pardon,” Tom said solemnly. “When is this great piece of detective work to take place?”

“Just before the midnight hour,” Brent answered.

“Oh,” said Tom. “Then you’re going to sit up on watch with Old Jones and me, eh?”

“Correct,” said Brent. “You’ll do yet, Tommy. I’ll need you and Old Santy Claus to keep a watchful ear at the stairway, won’t I? I demand privacy and protection on an important clue like this.”

“Well, you’ll get it,” Tom laughed. “What’s worrying me is how you’ll keep awake long enough to do it.”

“I’ll take care of that now,” said Brent. “I’m going to take a nap. You might as well too. Old Jones must be snoring by now.”

“Not a bad idea,” Tom agreed.

Brent found a stray safety pin hiding in the corner of his dresser drawer. He took possession of it and pinned the envelope fast to his undershirt. Then he went to bed.

Tom’s shoes thumped twice upon the floor over Brent’s head. He smiled at the thought of Tom taking a nap in the daytime—ambitious, nervous, active Tom.

Brent’s eyelids closed. In his drowsy state he could hear the ocean as if from a distance. The surf, ceaselessly pounding away at the rocks and the spray making a slight, swishing noise as it rose and fell. The wind was coming up—a whistling summer gale. A black pall seemed to be hanging over the sea and island. A storm was coming on, Brent thought, unable to fight off the sleep that was weighting down his lids.

Above the din and roar of the storm-tossed ocean, the bell in the gallery dolefully boomed the hour.

In a daze, Brent saw Pearson standing alongside his bed and watching him. “Don’t git up,” the lightkeeper said to him. “I jest looked in ter see if ye were asleep.”

“I was,” Brent answered.