* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

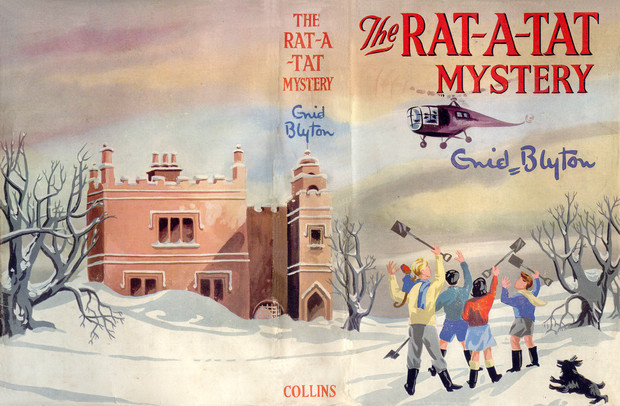

Title: The Rat-a-Tat Mystery

Date of first publication: 1956

Author: Enid Blyton (1897-1968)

Date first posted: Dec. 23, 2019

Date last updated: Dec. 23, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20191244

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE RAT-A-TAT

MYSTERY

Enid Blyton

First published in 1956 by

William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., London and Glasgow.

Text of this edition from the 1976 Collins reprint.

This is the fifth book about Roger, Diana, Snubby and his dog Loony, and Barney and his monkey Miranda.

The other books in this series are:

The Rockingdown Mystery

The Rilloby Fair Mystery

The Ring O’ Bells Mystery

The Rubadub Mystery

The Ragamuffin Mystery

All these books are about the same characters as this one, but each book is complete in itself. The dog Loony, is based on my own dog, Laddie.

I must say a few words about the circus-boy, Barney, in this foreword. In the first four books above, Barney was a circus-boy, but only knew his mother, who was in the circus. When she died she told him that his father was alive and asked him to try and find him. As Barney was now all alone in the world, he longed to find his father—and set out to look for him. On his travels he met Roger, Diana, Snubby and the spaniel, Loony, who all became his firm friends. In the fourth book, The Rubadub Mystery, he at last finds his father.

This present book, The Rat-a-Tat Mystery, is the first one in which he is with his father and family, and no longer a circus-boy. I hope you will like it.

Best wishes from

Enid Blyton

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| 1. | Christmas Holidays | 7 |

| 2. | Barney | 13 |

| 3. | An Exciting Invitation | 19 |

| 4. | At Barney’s Home | 25 |

| 5. | Rat-a-Tat House | 31 |

| 6. | Settling In | 36 |

| 7. | Knock-Knock-Knock! | 42 |

| 8. | What Fun! | 49 |

| 9. | A Happy Day | 55 |

| 10. | Whose Glove? | 62 |

| 11. | Noise in the Night | 70 |

| 12. | The Footprints | 75 |

| 13. | A Few Interesting Things | 81 |

| 14. | Another Mystery | 88 |

| 15. | Look Out, Snubby! | 94 |

| 16. | Down in the Cellar | 100 |

| 17. | Barney Thinks Things Out | 106 |

| 18. | On the Trail | 112 |

| 19. | Rather Disappointing | 118 |

| 20. | The Telephone at Last! | 124 |

| 21. | Diana has an Idea | 129 |

| 22. | Here Comes the Helicopter | 135 |

| 23. | Snubby Stubs his Toe | 142 |

| 24. | The End of the Mystery | 147 |

“How long do these Christmas holidays last?” said Mr. Lynton, putting his newspaper down as a loud crash came from upstairs. “I sometimes think I’m living in a madhouse—what are those children doing upstairs? Are they practising high jumps or something?”

“I expect it’s Snubby as usual,” said Mrs. Lynton. “He’s supposed to be making his bed. Oh, dear—there he goes again!”

She went to the door and called up the stairs. “Snubby—what in the world are you doing? You are making your uncle very angry.”

“Oh—sorry!” shouted back Snubby. “I was only moving things round a bit—and the dressing-table fell over. I forgot you were underneath. Hey, look out—Loony’s coming down the stairs, and he’s a bit mad this morning.”

A black spaniel came hurtling down the stairs at top speed and Mrs. Lynton hurriedly got out of the way. Loony slid all the way along the hall and in at the sitting-room door almost to Mr. Lynton’s feet. He was most surprised to receive a smart slap on the head from Mr. Lynton’s folded newspaper. He shot out of the door almost as fast as he had come in.

“What a house!” groaned Mr. Lynton, as his wife came back. “As soon as Snubby arrives peace and quiet vanish. He makes Diana and Roger three times as bad, too—as for that dog Loony, he’s even more of a lunatic than usual.”

“Never mind, dear—after all, Christmas only comes once a year,” said Mrs. Lynton. “And poor old Snubby must have somewhere to go in the holidays—you forget he has no father or mother.”

“Well, I wish he wasn’t my nephew,” said Mr. Lynton. “And WHY must we have his dog Loony every time we have Snubby?”

“Oh, Richard—you know Snubby wouldn’t come here if we didn’t have Loony—he adores Loony,” said his wife.

“Ha!” said Mr. Lynton, opening his newspaper again. “So Snubby won’t go anywhere without Loony—well, tell him next holidays we won’t have that dog here—then perhaps Snubby won’t inflict himself on us!”

“Oh, you don’t really mean that, dear,” said Mrs. Lynton. “Snubby just gets on your nerves when you’re home for a few days. You’ll be back at the office soon.”

Upstairs Snubby was sitting on his unmade bed, talking to his cousins, Diana and Roger, and fondling Loony’s long silky ears. They had come to see what the terrific crashes were.

“You’ll get into a row with Dad,” said Roger. “You never will remember that your room is over the sitting-room. Whatever do you want to go and lug the furniture about for?”

“Well, I didn’t really mean to move it,” said Snubby. “But a sixpence went under the chest-of-drawers, and when I moved it out I thought it would look better where the dressing-table is, but the beastly thing went over with a crash.”

“You’re going to get a whacking from Dad pretty soon,” said Diana. “I heard him say you were working up for one. You really are an ass, Snubby. Dad goes back to the office soon. Why can’t you behave till then?”

“I do behave!” said Snubby indignantly. “Anyway, who spilt the coffee all over the breakfast-table this morning? Not me!”

Roger and Diana stared at their red-haired freckle-faced cousin, and he stared back at them out of his green eyes. They were both fond of the irrepressible Snubby, but, really, he could be very irritating at times. Diana gave an impatient exclamation.

“Well, I don’t wonder Dad gets tired of you, Snubby! You and Loony rush about the house like a hurricane—and WHY can’t you teach Loony to stop taking shoes and brushes from people’s bedrooms? Did you know he’s taken Dad’s clothes-brush this morning? Goodness knows how he got it off the dressing-table.”

“Oh, golly! Has he really?” said Snubby, getting off the bed in a hurry. “There’ll be another explosion from Uncle Richard when he discovers that. I’ll go and find it.”

Christmas had been a mad and merry time in the Lynton’s house. All the children had come home from school in high spirits, looking forward to plenty of good food, presents and jollifications. Snubby had been a little subdued at first, because he was afraid that his school report might be even worse than usual, and his uncle and aunt had been pleasantly surprised to find him most polite and helpful.

But this wore off after a few days, and Snubby had now become his usual riotous, ridiculous self, aided in every way by his black spaniel, Loony. His uncle had quickly become very tired of him, especially since Snubby had forgotten to turn off the tap in the bathroom and flooded the floor. If it hadn’t been Christmas time Snubby would certainly have got a first-class whacking!

All the same, everyone had enjoyed Christmas, though the children wished there had been snow.

“It doesn’t seem like Christmas without snow,” complained Snubby.

“Oh, we’ll get plenty as soon as Christmas is gone,” said Mrs. Lynton. “We always do. Then you can go out the whole day long, and snowball and toboggan and skate—and I shall be rid of you for a little while!”

But there had been no snow yet, only a drizzling rain that kept the children indoors for most of the time, much to Mr. Lynton’s annoyance. “Why must they always talk at the tops of their voices?” he said, in exasperation. “And is there any need to have the radio on so loudly? And will someone tell that dog Loony that if I fall over him again he can go and live out of doors in the shed?”

But it wasn’t really any good telling Loony things like that. If he wanted to sit down and scratch himself, he sat down, no matter whether someone was coming along to trip over him or not. Even Snubby couldn’t make him stop. Loony just looked up with his melting spaniel eyes, thumped his little tail, and then went on scratching.

“I don’t know why you scratch!” said Snubby, in exasperation. “Pretending you’ve got fleas! You know you haven’t, Loony. Oh, get up, do!”

One rainy morning Diana was mooning about, getting in her busy mother’s way. “Oh, Diana, dear—do get something to do!” said Mrs. Lynton. “Have you done all your morning jobs—made your bed, dusted your room, done the——”

“Yes, Mother—everything,” said Diana. “I really have. Do you want me to help you?”

“Well, will you take down all the Christmas cards?” said her mother. “It’s time they were down. Stack them neatly in a big cardboard box, so that we can send them to Aunt Lucy—she makes scrap-books of them for children in hospital.”

“Right!” said Diana. “Oh, there’s Snubby with his mouth-organ. Mother, doesn’t he play it well?”

“No, he doesn’t,” said her mother. “He makes a simply horrible noise with it. Let him do the cards with you, then perhaps he’ll put it down and forget it. I really do believe your father will go mad if Snubby wanders round the house playing his mouth-organ.”

“Snubby, come and help with the Christmas cards,” called Diana. “Look out, Mother—Loony’s coming down the stairs.”

“Christmas cards? What do you mean?” said Snubby, coming into the room. “Oh—take them down? Right oh! It’s always fun to look at them again. Let’s put all the funny ones into a pile.”

He and Diana were soon happily taking down the gay cards. They read each one and laughed at the funny ones, stacking them all neatly into a box.

“Oh, here’s the one Barney sent us!” said Diana. “Look—isn’t it marvellous! Just like old Barney too.”

She held up a big card, on the front of which was a picture of a fair ground. Drawn neatly in one corner was a boy with a monkey on his shoulder.

“Barney’s drawn himself and Miranda on the card,” said Diana. “Snubby, I wonder how he enjoyed Christmas-time with his family for the very first time in his life!”

Roger came into the room just then, and took up Barney’s card too. “Good old Barney!” he said. “I wish we could see him these hols. I say—wasn’t it MARVELLOUS how he found his father—and discovered that he had a whole family of his own?”

“Yes,” said Diana, remembering. “He spent all his life in a circus with his mother, and thought his father was dead. And when his mother died, she told him his father was still alive, and he must find him. . . .”

“And he went out to seek for his father, and hunted everywhere,” said Roger. “And do you remember how at last he met him—last hols, it was, at Rubadub, that dear little seaside place where we were holidaying—and what an awfully nice man he was, exactly like Barney . . .”

“Oh, yes,” said Diana, remembering it all clearly. “And then dear old Barney discovered that he hadn’t only a father, but a grandfather and grandmother and an uncle and aunts. . . .”

“And cousins!” finished Snubby. “Gosh, what a wonderful Christmas Barney must have had. I bet he’s forgotten all about us now!”

“I bet he hasn’t!” said Diana at once. “I say—I’ve got a smashing idea! Let’s ask Mother if we can have Barney to stay for a few days! Then we’ll hear all his news.”

“And we’ll see Miranda, his pet monkey, again,” said Snubby, thrilled. “Do you hear that, Loony? We’ll see Miranda!”

“Come on—let’s go and ask Mother this very minute!” said Diana, and flew out of the room. “Mother! Mother! Where are you?”

The three children raced upstairs to find Mrs. Lynton. Loony went with them, almost tripping them up, he was so anxious to get to the top of the stairs first. He barked as he went, sensing the children’s excitement and wanting to join in.

Mr. Lynton, trying to write letters in his room, groaned loudly. “That dog! I really will have him kept out of doors if he goes on like this!”

“Mother! We’ve got such a good idea!” said Diana, finding her mother putting clean towels into the bathroom.

“Have you, dear?” said her mother. “Snubby, could you tell me HOW you get your towel as black as this? You haven’t been climbing chimneys by any chance, have you?”

“Ha-ha! Funny joke!” said Snubby, politely.

“Oh, Mother, do listen. We’ve got a splendid idea!” said Diana again.

“Yes! Can we have Barney to stay for a few days, Mother?” said Roger, going straight to the point. “Do say yes! You like Barney, don’t you?”

“And we haven’t seen him since the summer holidays,” said Diana. “Not since he found his father and all his new family, and went to live with them.”

“And we simply MUST see him,” said Snubby, snatching the bathmat away from Loony, who was shaking it as if it were a rat.

“Well, dears,” began Mrs. Lynton, looking most uncertain. “Well . . . I really don’t know what to say.”

“Oh, why? Why can’t we ask Barney—and Miranda too, of course?” said Diana, astonished. “You always liked him, Mother, you know you did.”

“Yes, dear, and I do still,” said her mother. “But I don’t feel that Daddy will welcome anyone else here while you are all three turning the house upside-down, and——”

“Oh, we don’t turn it upside-down!” cried Diana. “Haven’t I been tidying things all the morning? Oh, Mother, we’ll be as quiet and tidy as anything if you’ll let Barney come. We simply must hear his news before we go back to school again.”

“Well, you must ask Daddy, Diana,” said her mother. “If he says yes, Barney shall certainly come. I’ll leave it entirely to him.”

“Oh,” said Diana, looking gloomy. “Can’t you ask him, Mother?”

“No,” said her mother. “Stop turning on the taps, Snubby. I said stop. And take Loony out of the bathroom please. He’ll have that sponge next, out of the bath-rack.”

“Come on, Loony,” said Snubby, in a sorrowful voice. “We’re not wanted here. We’ll go and have a game together in the garage.”

“No, you won’t,” said Roger firmly. “You’ll come and back us up when we ask Daddy if we can have Barney.”

“I can’t,” said Snubby. “Uncle said he didn’t want to set eyes on me again this morning. Or Loony either.”

“Oh, well—you come, Di, and we’ll tackle Dad together,” said Roger. “And for goodness’ sake, Snubby, don’t start playing your mouth-organ outside the study door just when we’re inside.”

Loony shot down the stairs at top speed as usual, followed by Snubby three steps at a time. Mrs. Lynton shook her head and smiled to herself—nobody, NOBODY would ever teach Snubby and Loony not to hurl themselves downstairs.

Mr. Lynton heard a discreet knock on his study door and raised his head from his letters. “Come in!” he said, and in came Diana and Roger.

“What is it?” asked their father. “Surely you don’t want any pocket-money yet, after all the money you had given to you at Christmas?”

“No, Dad, no,” said Roger hurriedly. “We shouldn’t dream of asking you for any yet. Er—we just wondered if—er—well, we thought it would be nice if——”

“Nice, and kind too,” said Diana. “If we—er—if Barney could——”

“What is all this?” said her father impatiently. “Can’t you ask a straight question?”

“Well, we wondered if Barney could come to stay for a few days,” said Diana, bringing it all out in a rush. “You remember Barney, don’t you, Dad? The circus-boy we got to know so well.”

“Yes, I remember him,” said Mr. Lynton. “Nice boy—very blue eyes—and didn’t he have a monkey?”

“Yes, Dad!” said Roger eagerly. “Miranda—a perfect darling. Could we have them to stay?”

“Ask your mother,” said her father.

“We have,” said Roger, “and she says we’re to ask you.”

“Then I say No,” said Mr. Lynton firmly. “And I’m pretty certain your mother really wants to say No as well—you’re all wearing her out these holidays! Also, I’ve got your Great-Uncle Robert coming for three days, and I’ve really been wondering if I can’t send Snubby and Loony off to Aunt Agatha while Great-Uncle is here—I don’t feel that the old gentleman will be able to cope with the three of you—and that mad dog Loony too.”

“Oh, Dad! You didn’t ask Great-Uncle in the Christmas holidays, surely!” cried Diana. “He talks and talks and talks, and we daren’t say a word, and——”

“Perhaps that’s why I asked him!” said her father, a sudden twinkle in his eye. “No—actually the old fellow asked himself. He hasn’t been well—which is why I’m sure he can’t cope with Snubby and Loony—and the mouth-organ.”

“Oh,” said Diana sadly. “Well, it’s no good asking Barney then—there wouldn’t be room, for one thing. Oh, and I did so want to see him these hols—and now we shan’t see him for ages. Couldn’t you possibly put Great-Uncle off, Dad?”

“No, I couldn’t,” said her father. “And even if I did, I wouldn’t have Barney here—one more to add to the madhouse! And you might warn Snubby he may have to go to his Aunt Agatha’s soon.”

Snubby was horrified at this news. “But I don’t like being there!” he said. “Loony has to live in a kennel—and I have to wash at least twenty times a day! I say, I won’t play my mouth-organ any more. And I’ll stop whistling. And I’ll tiptoe down the stairs, and——”

“Ass!” said Roger. “That would only make Mother think you were ill, or sickening for something! Blow! All our plans made for nothing!”

“And we shan’t see Barney now,” said Diana. “Or that darling little Miranda.”

“I say,” said Snubby suddenly, “look—it’s snowing!”

They ran to the window and looked out. Yes, big snowflakes were falling steadily down. Diana looked up at the sky, but the snowflakes were already so thick that they hid it completely.

“If it goes on like this, we’ll have some fun,” said Roger, feeling more cheerful. “And when Great-Uncle comes to stay we can keep out of his way all day long—we’ll be out in the snow, tobogganing!”

“And skating, if there’s any ice,” said Diana, thrilled.

“But I shan’t be here!” said Snubby, in such a desperate voice that the others laughed. “I shall be with my Aunt Agatha and Uncle Horace, with poor old Loony howling by himself out in his kennel.”

“Poor Snubby. Never mind. Perhaps Great-Uncle won’t come,” said Diana.

But the next day there was a letter from Great-Uncle announcing that he was arriving in two days’ time. Snubby looked at his aunt in despair. Would he be sent away? He was ready to promise anything rather than that. Especially as the snow was now beautifully thick and deep, and the ponds had begun to freeze. There would be no tobogganing or skating at his Aunt Agatha’s, he knew that.

But Mrs. Lynton was quite firm. If Great-Uncle Robert was not very well, then the worst thing in the world for him would be a dose of Snubby and Loony. He might even have a heart-attack at some of the things Loony did.

“I must telephone to your Aunt Agatha at once,” she said. “Don’t look like that, Snubby—the world isn’t coming to an end.”

She went into the hall to telephone—and almost as she touched the receiver, the shrill bell rang out. Ring-ring! Ring-ring! Ring-ring!

“I hope it’s to say Great-Uncle can’t come!” cried Snubby. But it wasn’t. Mrs. Lynton turned round, smiling. “Who do you think wants to speak to you?” she said. “It’s Barney!”

“Barney!” cried everyone, and they all rushed to the telephone. Roger grabbed the receiver first. “Barney! Is it really you! Did you have a good Christmas?”

Then he listened to Barney’s reply—and suddenly a look of utter delight came over his face. “Oh, BARNEY! What a wonderful idea! Yes, I’ll ask Mother—hold on. I’ll ask her straight away!”

Snubby and Diana could hardly wait for him to ask his mother whatever it was that Barney wanted to know.

“Mother!” said Roger, “Barney and one of his cousins are going to stay at a house his grandmother owns, by a little lake surrounded by hills—the lake is frozen and the hills are covered with snow—so there will be tobogganing and skating. And he says, can we go too?”

There were shrieks of delight from Diana and Snubby. “Of course we’ll go, of course!”

“Barney says, if you say yes, his grandmother will telephone all the arrangements to you,” said Roger, his eyes shining. “Oh, Mother—it’s all right, isn’t it? We can go to stay with Barney, instead of him coming here—and Snubby won’t have to go to his Aunt Agatha’s—and Great-Uncle Robert can come here in peace, without any of us to worry him. Oh, Mother—we can go, can’t we?”

Mrs. Lynton looked at the three eager children, and nodded her head, smiling round at them.

“Yes. I don’t see why you shouldn’t. In fact, I think it’s an excellent way of solving all our difficulties. Oh, Snubby, dear, DON’T!”

Snubby had caught hold of his aunt and was waltzing her round and round in delight, shouting, “Hip-hip-hip, hurray, it’s a hap-hap-happy day!”

Mr. Lynton came out into the hall in surprise, and was told what the excitement was about. He listened with approval.

“Ha! That will give your Great-Uncle a little peace and quiet—and us too,” he said. “I hope you’re not going to leave Loony behind. I really should like to see the back of that dog for a little while.”

“You will, you will!” shouted Snubby, approaching his uncle to give him a waltz-round too, he was so very relieved. But fortunately he thought better of this—his uncle did not take kindly to such idiotic manners.

Roger was already telling Barney of his parents’ consent, and getting a few more details. Diana snatched the receiver from him after a minute or two, longing to have a word with dear old Barney. A little chattering noise greeted her.

“Oh, is that you, Miranda!” she cried, enchanted to hear the familiar monkey-chatter once more. “We’ll be seeing you soon, Miranda, soon, soon, soon.”

“Woof, woof!” said Loony, not understanding what was going on at all, and quite amazed at all the excitement. He tried to tug the mat from Mr. Lynton’s feet and run off with it, but Snubby stopped him just in time.

Everyone was thrilled to hear from Barney. After Snubby had had a few words on the telephone with him too, the receiver was put down and they all trooped into the sitting-room to talk over the exciting news.

“Fancy—a house in the middle of the snowy hills—and by a frozen lake too—it couldn’t be better!” said Roger exultantly. “I must look out my skates. You’re lucky, Snubby, you had new ones for Christmas.”

“What about our toboggan?” said Diana. “I don’t believe it’s any good for us now—too small. We haven’t used it for about three years. Blow!”

“I’ll buy a new one with my Christmas money,” boasted Snubby. “Oh, I say—I wish I could buy skates for Loony!”

Roger laughed. “I wish you could. Loony would look priceless on skates—he wouldn’t know which skate to use first!”

“Oh, it’s too good to be true!” said Diana, sinking into a chair. “Mother, you don’t mind us going, do you? You won’t be lonely, will you?”

“Dear me, no,” said her mother. “I shall be glad to have time to devote to your Great-Uncle. Thank goodness Loony won’t be here. When is Barney’s grandmother going to telephone about the day and time and other arrangements, Roger. Did Barney say?”

“Yes. She’ll phone to-night,” said Roger. He turned to the others. “Barney sounded exactly the same, didn’t he?” he said.

“Exactly,” agreed the others.

“But why shouldn’t he?” said Mrs. Lynton, surprised.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Roger. “After being a circus-boy so long—with ragged clothes and often hardly enough to eat—and no schooling to speak of—and then finding a whole new family, and having to have lessons—and decent clothes and table-meals instead of camping out—well, somehow I thought he might have changed.”

“Barney will never change,” said Snubby. “Never. I say—think of toboganning down steep hills—whoooooosh!” He slid at top speed over the polished floor, and stopped when he saw his aunt’s face. “And skating round and round—and in and out. . . .”

He skated into a little table and Diana just caught it as it fell. “Don’t be more of an idiot than you can help!” she said. “I bet you’ll fall down a thousand times before you can skate even half a dozen steps. Ha—I’m looking forward to seeing you sitting down bump on the ice!”

Barney’s grandmother telephoned to Mrs. Lynton that evening. She had a kind, very soft voice, and Mrs. Lynton thought how lucky Barney was to have a grandmother who sounded so nice. She told the waiting children what the old lady had arranged.

“She says that this house in the hills has been shut up for some time,” said Mrs. Lynton. “Her sons and daughters used to use it for winter sports when they were young. She is sending someone to clean it up and air it, and it should be ready for you to go to in two days’ time.”

“Is any grown-up going with them?” asked Mr. Lynton. “They must have someone sensible there.”

“Barney’s very sensible,” said Snubby, at once.

“Mrs. Martin—that’s Barney’s grandmother—says she is sending her cook’s sister to look after them,” said Mrs. Lynton. “She will cook for them, and dry their clothes, and see that they don’t do anything too idiotic. But I hope Roger will see to that, as well. He’s quite old enough to take charge, with Barney.”

“We’ll be all right,” said Roger. “You needn’t worry, Mother. My word—only two days and we’ll be down at this little house!”

“It doesn’t sound very little,” said his mother. “There are five or six bedrooms, and a big old kitchen, and two or three other rooms. You’ll have to help to keep it tidy, or the cook’s sister will walk off and leave you!”

“I’ll help her,” promised Diana. “And we can all make our beds—though all Snubby does is simply to get out of his in the morning and pull the sheets and blankets up again.”

“Tell-tale,” said Snubby at once. “It’s my bed, isn’t it?”

“I think to-morrow we’d better look into the question of skates and boots and clothes,” said Mrs. Lynton. “And you will all need good wellingtons, of course. I hope you’ve brought yours back from school, Snubby. You forgot them last term.”

“Yes, I brought them back. Anyhow, I quite well remember bringing one back,” said Snubby, helpfully.

“What’s the house called?” asked Diana.

“Well—I think I must have heard it wrongly over the telephone,” said her mother; “but it sounded like Rat-a-Tat House.”

Everyone laughed. “How lovely!” said Diana. “I hope that is its name. Rat-a-Tat House—why ever was it called that, I wonder?”

Next day was a busy one. Boots, socks, gloves, sweaters, skates—all were pulled out and carefully examined. The weather remained very cold and frosty, and snow fell again in the night. The forecast was cold weather, much snow, and hard frost—just right for winter sports, as Snubby kept announcing. He produced his mouth-organ once more, and nearly drove everyone mad by trying to learn a new tune. In the end Mrs. Lynton took it away and packed it at the very bottom of one of the suit-cases that were going with them.

But, not to be outdone, Snubby then went about pretending to strum on a banjo, and made a peculiar twanging noise with his mouth half-closed as he strummed an imaginary banjo with his fingers and thumb. This was really worse than the mouth-organ, and unfortunately, as the banjo was purely imaginary, it could not be taken away from him.

“Can’t that boy be sent to Rat-a-Tat House to-day?” demanded Mr. Lynton, hearing the banjo passing his door for the twentieth time that morning. “My word, it’s a good thing he won’t be here when Great-Uncle Robert comes.”

At last the suit-cases were all packed, the skates strung together, and clothes set out fresh for the next morning, when they were to join Barney. Loony rushed about eagerly all the time, trying to help, and making off with shoes and bundles of socks whenever they were put ready to pack. Even Snubby got a bit tired of him when he met Loony rushing up the stairs, just as he, Snubby, was rushing down, and both arrived in a bruised and tangled heap at the bottom.

“Ass of a dog!” said Snubby fiercely to the surprised Loony. “I’ll leave you behind if you do that again. I nearly broke my leg. Grrrrrrr! Bad dog!”

Loony put his tail down and crept under the hall chest. There was a smell of mouse there, and he had a wonderful time scrabbling round and round to find it, snuffling loudly all the time, much to Mr. Lynton’s amazement.

“We’re to go to Barney’s home first, and then go on with him and his cousin to Rat-a-Tat House,” said Roger to the others. “I wish to-morrow would come. I say—I wonder what the cousin’s like. Mother, how long can we stay away?”

“Till the snow’s gone, I should think,” said his mother. “That’s what Barney’s grandmother said. But, of course, if it lasts more than a week or so, you’ll have to come back because of getting ready for school again.”

Roger groaned. “Don’t mention the word! Snubby, STOP that noise. Or play another instrument for a change. That imaginary banjo of yours is getting boring.”

Snubby obligingly changed over to a zither, which was certainly much pleasanter. He really was a marvel at imitating sounds. Mrs. Lynton hoped he wouldn’t start on a drum next!

The morning came at last—a brilliant morning, with a clear blue sky and pale yellow sun—and the snow underfoot as crisp as sugar. “Heavenly!” said Diana. “Just exactly right for us!”

Off they went in a taxi to catch the train to Barney’s town, Loony too, so excited that he had to be put on the lead. Now for a good time—now for some sport—hurrah for the winter holidays!

Barney’s home was at Little Wendleman, and a car was at Wendleman station to meet them—a nice big utility van with plenty of room for luggage. Best of all, Barney was there to meet them too, with Miranda sitting excitedly on his shoulder.

“Barney! Old Barney! And Miranda; hey, Miranda!” shouted Snubby, hanging out of the compartment window as the train drew in. He opened the door and he and Loony fell out together. Barney ran up in delight, his brilliant blue eyes shining as brightly as ever. Miranda, the little monkey, leapt up and down on his shoulder and chattered at the top of her voice. She knew everyone immediately.

“Barney! Dear old Barney!” said Diana, and gave him a hug. Roger clapped him on the back, and Snubby grinned all over his freckled, snub-nosed face. As for Loony, he went completely mad, lay on his back, and did one of his bicycling acts at top speed, barking loudly.

“Hallo!” said Barney, his brown face glowing with pleasure at seeing the children who had befriended him when he was a down-at-heel circus-boy. “Gosh—it’s grand to see you all again. Isn’t it, Miranda?”

The little monkey leapt on to Diana’s shoulder and whispered in her ear, holding the lobe in her paw the way she often did. Diana laughed. “Darling Miranda—you haven’t changed a bit, not a bit. And you do look smart in your little red coat and bonnet and skirt!”

Barney looked different. He was no taller and no fatter, and his face was as brown as ever. But now he was dressed well, his hair was cut properly, and he wore a tie, which he had rarely done when he had been a circus-boy. In fact, he looked extremely nice, and Diana gazed at him in admiration.

Barney laughed, as he saw the eyes of all three on him. “Do I look different?” he said, in the voice they knew so well, with the slight American twang he had picked up in his circus travels. “I’m not a circus-boy any more—I’m a gentleman—whew—think of that! Me, Barney the hoop-la boy, the boy who took any job he could, who never wore anything but canvas shoes, dirty old trousers, and a ragged shirt. . . .”

He paused and twinkled round at the three listening children. “Yes, I’m a gentleman now—but I’m still the same, see? I’m just Barney—aren’t I, Miranda?”

Miranda leapt on to his shoulder again and jigged up and down, chattering in monkey-language. What did she care how Barney was dressed, or where he lived, or whether he was a circus-boy or a gentleman? It was all the same to her. He was just Barney.

“Yes, you’re still just Barney,” said Diana, and gave a little sigh of relief. She had wondered just a little if having a family, and a fine house and money to spend would have changed Barney—but no, it hadn’t.

“Come on,” said Barney. “The car’s here, see, and there’s my father driving it.” He said the words “my father” in a very proud voice. Diana felt touched. How very, very glad Barney must be to have a father of his own, and to have found him after so many years of thinking he was dead!

Barney’s father, Mr. Martin, was sitting at the wheel of the car. The children marvelled at the likeness between the two—bright blue, wide-set eyes, corn-coloured hair, a wide mouth, ready to smile. Yes, they were certainly father and son. The only real difference between their faces was that Barney’s was so much browner than his father’s.

“Hallo, kids!” said Mr. Martin, and smiled, looking more like Barney than ever. “Nice of you to come all this way to see Barnabas—or Barney, as you call him. Hop in! We’re to have lunch at his grandmother’s, and then I’ll take you to Rat-a-Tat House.”

“Thank you very much, sir,” said Roger politely. “It’s good of you to meet us like this—and jolly good of Barney’s grandmother to invite us to stay with him at Rat-a-Tat House. We’re thrilled.”

The boys piled the suit-cases into the utility van. Loony clambered in, and sat up in a corner so that he could look out of the window. He loved hanging his head out of a car, his long ears flapping in the breeze. He was delighted to see Barney again, though he wasn’t so sure about Miranda the monkey. He had suddenly remembered how she used to ride on his back, jigging up and down in a most aggravating manner. He looked at her out of the corner of his eye. Would she try that old trick again?

The car drew up in the drive of a pleasant-looking house, timbered, with white walls, tall chimneys and wide casement windows. As they drew up, the front door flew open, and a little old lady stood there, as brown-eyed as the monkey that sat on her shoulder.

“Ah, here you are!” she cried. “Welcome, welcome! I’ve longed to meet dear Barney’s friends. Come along in, come along in!”

The children liked Barney’s grandmother at once. She had curly white hair, a very pink, soft-cheeked face, brown eyes, and a lively smile. They smiled to see the monkey on her shoulder as they shook hands.

“Ah—you see I have a monkey just like Barnabas!” she said in a merry, bird-like voice. “Monkeys run in our family—my mother kept two. Jinny, here are good friends!”

Jinny, the little monkey, was not dressed like Miranda. She wore a little yellow cape round her thin shoulders. She held out a tiny, wizened paw in a very solemn manner and shook hands with each of them. Loony stared in astonishment at her. What—another monkey—or was he seeing double?

Soon they were all sitting in a cosy room, with a blazing fire, gay curtains and a lovely meal laid ready on a round table. Snubby looked at it approvingly. Hot tomato soup to begin with—now that was just what he felt like! He took his place at once and beamed round. This was the kind of thing Snubby enjoyed.

“What comes next?” he asked Barney, in a loud whisper.

“Ah—Barnabas has told me what you like,” said the old lady, who had very sharp ears. “Sausages—plenty of them—and fried onions and tomatoes—and potatoes and peas. Barnabas has had many a meal with you, I know—and now I am proud you should have a meal with him.”

Snubby thought this sounded fine. What a nice old lady. Barney was certainly lucky to have such a splendid family belonging to him. For a second Snubby was just a little jealous when he looked at Barney’s handsome, smiling father. He would have liked a father like that—but he had no parents at all, worse luck. Snubby simply couldn’t understand children who grumbled at their parents—they didn’t know how lucky they were to have them!

It was a very pleasant meal. Barney told them all about the lessons he had had during the last term. He had never been to school, and his father had thought he must have plenty of private coaching before he sent him anywhere. The boy was very intelligent, and enjoyed his lessons immensely.

“He’s as good at them as he is at walking the tight-rope or turning cart wheels!” said his father, with a laugh.

“How marvellous!” said Snubby, enviously. “I’m no good at either! Barney—do you ever miss the circuses and fairs and shows you used to belong to?”

“Sometimes,” said Barney. “Not often. But just at times I think of what fun it was sleeping out under the stars—or having a tasty meal out of some cook-pot in a fair when I was very hungry—and I miss the show people a bit.”

“You can always go off for a taste of that life again, whenever you want to, Barney,” said his father, smiling at him.

“I know,” said Barney. “But I shall always come back home—come back here to you and Granny. I like the freedom of the show-life—but I like putting out roots too, as I can here. That feeling of belonging somewhere—to a place or a family—that’s what I’ve missed all my life, and now I’ve got it, I’m going to keep it.”

The talk went on during the meal, happy, jolly talk, friendly and intimate. Loony lay beneath the table, amazed at the variety of titbits that came down to him from Snubby, Roger and Barney. Miranda, curious to see why Loony was so peaceful, slid down a table leg to investigate, and joined in Loony’s little feast, much to his annoyance. Jinny, the other monkey, seldom left her mistress’s shoulder, and gravely took little titbits in her tiny paw. Sometimes she patted the soft old cheek near to her, and often did what Miranda did to Barney—slid a small paw down her mistress’s neck to warm her tiny fingers.

“Now, after lunch, the car will take you all to Rat-a-Tat House,” said Barney’s grandmother. “Mrs. Tickle, the cook’s sister, is already there.”

“Mrs. Tickle—is that really her name?” asked Snubby. “Is she ticklish?”

“I have no idea,” said Mrs. Martin. “And if I were you I wouldn’t try to find out.”

“I thought a cousin of Barney’s was coming too,” said Roger. “Where is he? Are we going to pick him up somewhere?”

“No. He has started a cold,” said Mrs. Martin. “He may be along in a day or two, but not to-day. You’ll have to settle in without him.”

This pleased everyone very much. They badly wanted to have a long, friendly talk with old Barney, and a strange cousin would have embarrassed them.

They piled into the utility van, and waved good-bye to Barney’s grandmother and little Jinny, the monkey. Then away they drove over the snowy roads towards the white-clad hills.

“Wake me up at Rat-a-Tat House,” said Snubby, suddenly feeling sleepy after his enormous lunch. “What fun we’re going to have there!”

You’re right, Snubby—you just wait and see!

The car had to go slowly along some of the roads because they were already slippery. It took about an hour to reach the little village of Boffame, which was two or three miles from Rat-a-Tat House.

“Now we shall soon be there,” said Barney’s father, who was at the wheel. “My word, we had some fun at Rat-a-Tat House when I was a boy, and played there with my brother and sisters and cousins. You’ll have fun too, Barnabas, with your friends.”

They went through the little village, and then up a small, very steep hill. The car stopped half-way up, and would not go on. Its wheels slid round and round in the same slippery place.

“Get the sacks out and the spade, children,” said Mr. Martin. “I thought this might happen, so we’ve come prepared!”

They got the spade and dug away the snow under the wheels, slipping the sacks beneath them instead. Then Mr. Martin started up the car again, the wheels gripped the sacks instead of the slippery snow, and the car slowly reached the top of the hill. It stopped and Mr. Martin waited for the children to come along to the car with the sacks and spade.

“It’s a good thing I took all the goods yesterday that you’ll need at Rat-a-Tat House,” he said. “I doubt if a car will be able to get through if we have any more snow.”

“Perhaps we shall be cut off from everywhere!” said Snubby in delight. “Lost in the snowy hills. Marooned in Rat-a-Tat House. We shan’t be able to go back to school. Hurrah!”

Loony barked joyfully. If anyone said “hurrah” it meant they were happy, so he had to join in too. Miranda leaned across the car and tweaked one of his long ears, and there was a scrimmage immediately. Mr. Martin looked round for a moment. “I don’t know what’s happening at the back, but it’s most disturbing to the driver,” he remarked, and Loony at once got a smack from Snubby, and yelped in surprise.

The car went slowly on. They came to another hill—would the car stick half-way up this time? No, it went up steadily and everyone gave a sigh of relief.

The countryside looked enchanting in its thick blanket of dazzling white snow. Every little twig was outlined in white, and every sharp outline of fence or roof was softened by the snow. Diana looked out of the window and thought how beautiful it was.

“We’ll have marvellous tobogganing,” said Roger. “Best we’ve ever had. And plenty of skating if the frost holds.”

“It’s sure to,” said Barney’s father, driving the car down into a little valley surrounded by snow-clad hills on every side. “Now we’re nearly there—you’ll see Rat-a-Tat House in a minute—it’s round this corner. Ah, there’s the frozen lake, look.”

“Oh, it’s quite a big lake!” said Diana, surprised. “What a pity we can’t go boating and swimming, as well as skating.”

Everyone laughed. “Rather impossible,” said Barney’s father. “Perhaps you can come again in the summer and have some fun here with Barney and his cousins then.”

“So this is the house,” said Snubby, in approval, as they swung in at a small drive. “Ha—I like it! It’s—it’s rather odd looking, isn’t it? All those turrets and towers and tucked-in windows and things.”

“It’s old,” said Mr. Martin; “but was so very sturdily built that it has lasted well for a great many years. It’s seen a bit of history too. Oliver Cromwell once stayed here, and it is said that a celebrated Spaniard, who was taken prisoner, was brought here and hidden—and what is more, was never heard of again.”

“Gosh!” said Snubby, thrilled. “I hope he isn’t still there. I can’t speak a word of Spanish. I like the look of Rat-a-Tat House. I feel as if plenty of exciting things have happened here.”

As they swung slowly up the drive, the front door opened, and someone stood there smiling at them—a very small woman with plaits of dark hair wound round her head, and merry dark eyes. She wore a flowered overall, and over it a spotless white apron. The children liked her at once.

“Is that Mrs. Tickle?” asked Snubby, leaping out of the car before anyone else.

“Yes,” said Barney. “But don’t ask her if she’s ticklish, because hundreds of people have asked that already and she’s tired of it. Hallo, Mrs. Tickle! I hope you haven’t been lonely.”

“Not a bit, I’ve been too busy!” said the little woman, coming to help with the suit-cases. “Are you cold? Come away in, then, I’ve a fine fire for you. Good afternoon, Mr. Martin, sir—I’m right down glad to see you all, I was afeard you’d not get through the snow.”

“We were only stuck once,” said Mr. Martin. “I’ll just see the children in safely, Mrs. Tickle, and then I must go, because I want to get away before more snow falls. It looks as if the sky is full of it again.”

“That’s right, sir, you get home before it’s dark,” said little Mrs. Tickle. “Oh, my word, who’s this?”

It was Loony, prancing round in the snow, getting into everyone’s way as usual.

“I didn’t know you were bringing a dog,” said Mrs. Tickle. “I’ve got no dog biscuits for him.”

“Oh, he doesn’t mind having what we have,” Snubby assured her. “He loves a slice off the joint or a chop.”

Mrs. Tickle looked quite horrified. “He won’t get anything like that while I’m in charge!” she said, leading them all indoors. “I like dogs to be kept in their place. And monkeys too,” she said, with a look at Miranda sitting on Barney’s shoulder. “Well, here you are—sit down and warm yourselves!”

She led them into a big, panelled room, at one end of which was an enormous fireplace with a fire of logs, crackling and blazing.

“Oh, it’s lovely!” said Diana, glancing all round. “It’s like a house in a story book. And how light the room is!”

“That’s the reflection of the snow outside,” said Mrs. Tickle. “Bless us all, what’s the matter with that dog?”

Loony was growling in a most peculiar manner, and backing away from the fireplace, towards which he had run for warmth. Barney gave a bellow of laughter.

“He’s just seen the bearskin rug in front of the fire! It’s got a bear’s head at one end and he thinks it’s real!”

Certainly poor Loony had had a terrible shock! He had run towards the fire, and had suddenly seen the bear’s head at the end of the rug, its two glass eyes shining balefully at him. Loony imagined that the bear was crouching down ready to spring, and had backed away at once, producing his fiercest growls.

“Idiot,” said Snubby. “Look at Miranda—she’s braver than you are, Loony!”

Miranda had also seen the bear—but she had seen bearskin rugs before and was not at all worried. She leapt down and sat on the bear’s head, chattering away at Loony, and jigging up and down.

“She’s telling you not to be such a coward, Loony,” said Snubby, severely. “Really, I’m ashamed of you!”

“Well, children, Mrs. Tickle will take you all round the house and show you your rooms,” said Barney’s father, looking at his watch. “And no doubt she has a fine tea waiting. Help her all you can, please. Barney, you are in charge here, remember, and if anything goes wrong, let me know at once.”

“Yes, sir,” said Barney. “I suppose Rat-a-Tat House is on the telephone?”

“Yes,” said his father. “So you’ll be quite all right. Mrs. Tickle knows where the toboggans are, and your skates—we brought them here when we drove her over with all the food and bedclothes and so on. Well, have a good time. Mrs. Tickle, keep them in order—and don’t stand any nonsense.”

“I’ll keep them in order all right, sir,” said little Mrs. Tickle, looking quite fierce. Then she smiled. “I’ll enjoy having them round me,” she said. “Mine are all grown up now, and it will be like old times to have them rampaging round. I hope you get back all right, sir.”

They all went to see Mr. Martin off in the car. It was getting dark already, though the gleaming snow threw its white light everywhere. “Good-bye!” shouted everyone, and waved till the car had crawled out of the gate.

They all went back into the fire-lit sitting-room, with its wide window-seats, its enormous fireplace, and gleaming old furniture. Snubby stood by the fire, rubbing his hands in glee.

“Isn’t this smashing?” he said. “I wish we could go out into the snow now, and toboggan. Fancy sliding down those hills at top speed. Loony, do you think you’ll like tobogganing?”

Loony had no idea what tobogganing was, but he was sure he would like anything that Snubby liked. He felt the general excitement and decided to show off. He rushed round the room at top speed, barking, then suddenly lost his footing on the highly polished floor, rolled over and finished by sliding along swiftly on his back. Everyone roared.

“Is that how you’re going to slide over the snow?” said Snubby. “You’ll get along fine like that, Loony.”

“Would you like to come and unpack?” said Mrs. Tickle’s voice at the door. “And by that time, you’ll be ready for tea, I’ve no doubt!”

She was right—they certainly would!

A wide staircase led up to the first floor of Rat-a-Tat House, and many rooms opened off the upstairs landing. Everywhere there was panelling, and Snubby went along knocking at the walls, rat-a-tat-tat!

“Snubby, must you do that?” said Diana. “What’s the idea?”

“Ha—secret passages of course!” said Snubby at once. “You never know! This place might be riddled with them!”

“Well, I hope you’re not going to knock on the walls every time you pass them,” said Diana.

“It’s Rat-a-Tat House, isn’t it?” said Snubby, with a grin, and knocked again on some wooden panelling—rat-a-tat-tat! “I say, I wonder why it’s got such a peculiar name? Do you know, Barney?”

“No,” said Barney. “But maybe Mrs. Tickle does. We’ll ask her sometime.”

Mrs. Tickle was away along the landing opening doors as she went. “You can choose your own rooms!” she called. “Barney has one to himself, and so has Diana, but you other two boys are to share. The dog can sleep down in the kitchen.”

“Well, he can’t,” muttered Snubby under his breath. “And what’s more, he won’t! He’ll be sleeping on my bed as usual.”

The rooms were rather exciting. They all had panelled walls, which Snubby proceeded to knock on smartly with his knuckles, cushioned window-seats, old-fashioned wash-stands, and cupboards that opened out of the panelling.

“You can hardly tell they’re cupboards!” said Diana, opening hers. “They look just like part of the oak walls. I never had a room like this before. I feel as if I’ve slipped a few hundred years back in history!”

“Our room’s smashing too,” announced Snubby. “Where’s Mrs. Tickle? Oh, she’s gone. Good. I just wanted to say something she’s not to hear. I am not going to let her shut Loony up in the kitchen to-night, so I shall think of some way to prevent it—and then he can come on my bed as usual. He’d be miserable if he had to sleep in the kitchen.”

Diana opened her suit-case and unpacked and put her things away neatly, while the boys explored the other part of the house. Mrs. Tickle called up the stairs. “Tea will be ready in five minutes—and the scones are hot, so don’t be too long.”

Diana shouted for the others. “Roger—Barney—Snubby! Tea’s almost ready, so buck up and unpack!”

Roger and Barney came along and put their things away in the great old chests and dark cupboards. Snubby rushed up with Loony at the very last minute, covered with dust and cobwebs.

“Where in the world have you been?” said Diana, looking at him in disgust. “Don’t come near me, please! You’re so cobwebby that you’ve probably got spiders crawling all over you!”

“Am I?” said Snubby, surprised, and brushed himself down so vigorously that dust flew everywhere. “I found a little attic place—rather exciting, with old boxes and trunks in it. Hey, what’s that!”

It was the booming sound of the old gong in the hall. Mrs. Tickle was tired of waiting for them to come down and had suddenly remembered the gong. How it made them jump! Miranda leapt to the top of the curtains at once, and Loony ran under the bed.

“That’s calling us for tea, I expect,” said Diana. “Snubby, you’ve got to undo your suit-case and put your things away before you come down. Go on, now—buck up!”

“All right, all right, teacher,” said Snubby. “Don’t start trying to boss me! It won’t take me long to unpack.”

It didn’t. He simply undid his suit-case, opened his cupboard door, and emptied everything into it, pell-mell. He shoved the suit-case in at the back and then shot downstairs at top speed, Loony just in front of him. The staircase ended in a wide, polished hall, and Loony was able to slide all the way to the front door with the greatest ease.

“Jolly good, Loony,” said Snubby admiringly, and walked sedately into the sitting-room, where the others were just about to sit down. Diana stared at him accusingly.

“You haven’t had time to unpack. You go back and do it!”

“Everything is safely in my cupboard,” said Snubby. “And the suit-case is empty, teacher!”

“Don’t keep calling me that,” said Diana, exasperated, but Snubby didn’t even hear. His attention had been caught by the meal on the tea-table. On a spotless white cloth were six different plates of food. Where Diana was sitting was a very large brown teapot, a large blue milk jug, and a large basin of sugar lumps. Two dishes of jam were on the table and one pot of fish-paste.

Snubby looked in awe at the six plates of food. “Stacks of new bread-and-butter—hot buttered scones, at least three each—gingerbread squares, all brown and sticky—a giant of a chocolate cake—a jam sponge twice as large as usual—and home-made macaroons! Macaroons—my very favourite goody. Hey, Mrs. Tickle, Mrs. Tickle!”

And the delighted Snubby with Loony at his heels went rushing out into the kitchen to the surprised Mrs. Tickle to tell her what he thought of the tea. He debated whether to give her a hug but decided that he didn’t know her well enough yet.

Mrs. Tickle was very pleased with his admiration of the first meal she had provided. “Go along with you,” she said, beaming. “You’re a caution, you are! You’d better be careful that the others haven’t eaten everything by the time you get back to the table!”

That made Snubby rush off in a panic, but to his relief there was still plenty left. He had to gobble to catch up with them, but Snubby never minded that.

“Your table manners haven’t improved at all,” said Diana primly. She felt quite like her mother, sitting in state behind the big brown teapot.

“Sorry, teacher,” said Snubby, in such a humble voice that everyone laughed. “I’ll stay in and write out ‘I must please dear Diana, I must please dear Diana’ one hundred times!”

“I shall throw something at you in a minute,” said Diana. “Probably the teapot.”

“Right,” said Snubby. “But wait till it’s empty. I may want another cup of tea. I say, look at Miranda, Barney—she’s dipping her fingers into the strawberry jam and then licking them.”

“Miranda—how can you?” said Barney, reprovingly, and the little monkey hid her face in his neck as if she was ashamed—but the next minute, down went her little paw into the jam dish again!

It was a happy, merry tea, and Barney enjoyed it more than any of them. He had been a lonely boy for so many years, longing for the companionship, the teasing, the family talk that he had never had. Now he was quite at home in the fun, and entered into all the teasing with delight. But nobody ever had a readier answer than the cheeky, irrepressible Snubby—he was never at a loss as to what to say or do!

They all helped to clear away tea. By this time, of course, Mrs. Tickle had had to light the lamps. These were old-fashioned oil-lamps, because there was no electricity in Rat-a-Tat House.

“You be careful of these lamps,” she warned them. “And if you want to rush about with that mad dog of yours, Snubby, don’t knock them over or you’ll have the place afire.”

“I’ll be careful,” promised Snubby.

“There are candles upstairs on the landing,” went on Mrs. Tickle, “and candles waiting in the hall for when you all go up to bed. And if you want wood for the fire, it’s in that cupboard there, by the fireplace. I’ll bring you more from outside if you want it.”

“No, you won’t,” said Roger at once. “I’ll do that—and just tell us whatever jobs you want done, Mrs. Tickle, and we’ll do them straight away.”

“That’s what I like to hear!” said the little woman, pleased, and went out smiling.

Soon they were all sitting round the fire. “Let’s have a game,” said Snubby. “I brought some cards. I’ll go and fetch them.” He went off upstairs, knocking on the panelling all the way—knock-knock-knock—rat-a-tat-tat, rat-a-tat-tat!

“I wish he wouldn’t,” said Diana. “Why does Snubby always have to make some kind of noise?”

Snubby came back with the cards, and the children heard his knock-knock-knock on the panelling again. Loony listened with his head on one side and so did Miranda. It was rather an eerie sound, hollow and irritating.

“Let’s put some more wood on the fire before we begin,” said Roger, and opened the door of the little cupboard beside the fireplace, where logs were kept. He hauled one out, threw it on the fire and shut the cupboard door. Then he went with the others to the table and they all sat down to play cards.

But they hadn’t dealt more than one hand when something made them jump. It was a hollow, knocking sound—knock-knock-knock—rat-a-tat-tat! Knock-knock-knock—rat-a-tat-tat!

Loony growled, and that made them all jump, too. It wasn’t Snubby knocking this time—he was there at the table with them, listening, half-scared.

“Pooh—it must be Mrs. Tickle knocking or hammering something in the kitchen!” said Roger, seeing that Diana looked frightened.

“It isn’t,” said his sister in a low voice. “It’s in this room. But there’s nobody here but us!”

Knock-knock-knock—rat-a-tat-tat! It was exactly the same knocking as Snubby had drummed on the panelling when he went up and down the stairs.

“It is in this room,” said Barney, starting up. “Whatever can it be? Who is it? I don’t like it.”

“Let’s get Mrs. Tickle,” said Roger, and shouted for her. “Mrs. Tickle! We want you. Quickly!”

In came Mrs. Tickle, most surprised. “Whatever is the matter?” she said, seeing their startled faces.

“Listen,” said Roger, as the soft knock-knock-knock came again. “That knocking, Mrs. Tickle . . . what can it be?”

Mrs. Tickle stood in the middle of the room, listening. She looked alarmed. “The knocking!” she said. “The knocking! It’s come again after all these years!”

“Whatever do you mean, Mrs. Tickle?” said Barney. “My father didn’t tell me about any knocking—and he knows all about this house.”

“Maybe he doesn’t know about the knocking, though,” said Mrs. Tickle, looking relieved as the noise stopped. “I heard the tale in the village of Boffame yesterday. It’s because of the knocking that this house got its name.”

“Sit down, Mrs. Tickle, and tell us,” said Barney, and the little woman sat down at once, on the very edge of a chair. She began to speak again in a low voice.

“I’m only telling you what’s said,” she said. “A tale that’s handed down through the years, you understand. I heard it from old John Hurdie, in the post office, and he got it from his great-granny, so he said.”

“Go on, go on,” said Roger, as she stopped for breath. A piece of wood broke in the flames of the fire and the burning log fell to the bottom of the hearth, making them all jump.

“Well,” said Mrs. Tickle, “it’s said that the house was called Boffame House after the lake and the village—but soon after people came to live here, there were strange knockings on the front door. . . .”

“On the front door?” said Roger. “Do you mean someone hammered there with their fists?”

“No. They used the great knocker there,” said Mrs. Tickle. “Didn’t you see it when you came in this afternoon?”

“The door was wide open, so we didn’t notice,” said Diana, trying to remember. “Is it a very big knocker?”

“Enormous,” said Mrs. Tickle. “And you wouldn’t believe the sound it makes—thunderous, Mr. Hurdie at the post office told me. But when the footman went to answer the door all those years ago and see who was there—there was nobody.”

“The one who knocked might have run away,” said Snubby, hopefully. “Lots of people do knock at doors or ring bells, and then run away. They think it’s funny.”

“Well, it isn’t, it’s stupid,” said Mrs. Tickle. “We’ve got a boy in our village who does that—but he did it once too often to me. Aha—I put glue all round the knocker—and what a mess he was in!”

Everyone laughed. “But why didn’t the person who knocked all those years ago stay till the door was opened?” asked Snubby. “And who was he?”

“Nobody ever saw him, though often he came knocking day or night,” said Mrs. Tickle, enjoying the telling of such a dramatic story. “And what was more, that knocking went on for a hundred and fifty years, so the old story goes!”

“Ha—then it couldn’t have been the same person knocking all that time,” said Snubby. “But what did the knocking mean—anything at all?”

“Yes, it was said to give warning that there was a traitor in the house!” said Mrs. Tickle. “So there must have been a good many traitors then, it seems to me! And old Mr. Hurdie, he says that when the knocking came, there was always a searching of the old place to see if anyone was hiding there—and the servants were always questioned to find out if one of them was untrustworthy. Oh, there were some goings-on in those old days, you mark my words.”

“How long ago did the knocking stop?” asked Barney. “You said it only lasted a hundred and fifty years—but this house is much older than that.”

“It’s more than a hundred years ago now since Mr. No-One hammered at the door with that knocker!” said Mrs. Tickle. “It’s so old now that I reckon it would fall off the door if anyone touched it!”

Mrs. Tickle’s story was so very interesting that the children had quite forgotten about the mysterious knocking they themselves had heard a little while back—but they soon remembered it when it suddenly came again!

Knock-knock-knock . . . rat-a-tat-tat! There it was again, soft and hollow and mysterious—and somewhere in the room! There wasn’t a doubt of it.

Barney sprang up at once. “We’ve got to find what it is!” he said.

“Oh, dear!” said Mrs. Tickle, beginning to tremble at the knees. “Oh, dear—I’ve gone and scared myself with that old story. I’m all of a shake. It’s the knocker back again—Mr. No-One after all these years. But what’s he knocking for? There’s no traitor here!”

“Cheer up!” said Roger. “He’s not knocking at the front door, Mrs. Tickle. Come on, Barney—let’s trace where the knocking is!”

They waited for it to come again—and it did, as soon as they were quite silent. Knock-knock-knock . . . rat-a-tat-tat!

“It’s over there—in that corner of the room!” said Barney, and ran towards the corner. The knocking stopped and then began again. Knock-knock-knock.

“It’s coming from the wood cupboard!” cried Mrs. Tickle. “Bless us all, that’s where it’s coming from. But there’s only logs there, that I do know.”

“We’ll soon see,” said Barney grimly, and flung open the little door of the wood cupboard.

And out sprang a very indignant and rather frightened Miranda! The little monkey ran chattering to Barney and leapt straight up to his shoulder, burying her little furry head in his neck.

“Miranda! MIRANDA! Why—it was only you in the cupboard after all,” said Barney. “You little pest—you gave us such a fright! But why did you knock like that?”

“She was imitating Snubby!” cried Diana. “She heard him keep on knocking on the panelling as he went up and downstairs—and you know how she loves to copy what we do—so when she got shut in the cupboard, she did what Snubby did—and knocked on the wooden door in exactly the same way—knock-knock-knock . . . rat-a-tat-tat!”

“That’s it,” said Roger, most relieved. “Phew—I didn’t like it much. When did Miranda get shut in?”

“When you opened the wood cupboard door to put more logs on the fire,” said Barney. “She must have slipped in without your noticing it, and you shut the door on her. Funny little thing—knocking like that!”

“Well, I hope she doesn’t do anything else to give us such a scare,” said Mrs. Tickle, getting up, and looking herself again. “Right down feared I was! And don’t you start thinking about that big old knocker on the front door—Mr. No-One hasn’t been at it for a hundred years, and it’s not likely he’ll start now.”

“Anyway—there are no traitors in this house now,” said Barney. “Only four kids, you, Mrs. Tickle, and a monkey and a dog. Miranda, don’t do such an idiotic thing again. I’m surprised we didn’t miss you, but I quite thought you were asleep in that rug on the sofa.”

“Why didn’t Loony go to the cupboard and scratch at it as he usually does when he hears a noise coming from somewhere?” wondered Diana.

“Easy,” said Snubby, with a grin. “He’s not awfully keen on getting Miranda out of trouble! I bet he thought she could jolly well stay there as long as possible!”

“Yes. I believe you’re right,” said Barney, looking at Loony, who was busy scratching himself. “Bad dog, Loony—to let poor little Miranda stay in the dark cupboard without lifting a paw to help her.”

“Wuff,” said Loony politely, and went on scratching. Snubby poked him with his foot.

“Stop it!” he said. “Sit up and listen when you’re spoken to.”

Loony wagged his tail, and it thumped on the floor—knock-knock-knock!

“Oh, my goodness—don’t you start rat-a-tatting now!” said Snubby, and Diana giggled. She was very relieved to find that their scare had been groundless—and she half-wished that Mrs. Tickle hadn’t told them that queer old story.

“Let’s get on with our game,” said Snubby. “Let me see—we’d better deal again. Come on!”

They dealt again and Snubby looked at his cards. “Ha!” he said. “Couldn’t be better! I can tell you this—even if Mr. No-One comes and hammers at that knocker now, I shall go on with this game—I’ve got a smashing hand!”

Fortunately for him, there was no hammering at the front door, and he won the game easily, looking very pleased with himself.

It was cosy and warm in the sitting-room, with the log fire blazing away. The children felt very happy, thinking of the next day and all the fun they would have. Diana drew the curtains after a while, shutting out the starry night and the white snow.

Later on Mrs. Tickle came in with a tray. “Supper!” she said, beaming. “Will you lay it for me, Diana, while I go and see to the poached eggs?”

“Poached eggs! Mrs. Tickle, how did you know I was simply longing for one?” said Snubby at once.

“Well, I had a feeling you were longing for two, not one,” said Mrs. Tickle, who had taken quite a liking to the snub-nosed, freckle-faced “imp” as she called him to herself. Snubby grinned in delight.

“Two! How well you know me already!” he said. “Loony—salute Mrs. Tickle, please—your very best salute!”

And Loony, proud to show off his very newest trick, sat up and saluted quite smartly, much to Miranda’s interest.

“There now—he’s as sharp as his master!” said Mrs. Tickle, putting down her tray and laughing. “You’re cautions, both of you. I’ll be back with the poached eggs in a minute.” And off she went, chuckling over Snubby and Loony. Really—what a pair!

Supper was a very pleasant meal, a simple one of poached eggs, hot cocoa, and biscuits and butter. Diana began to yawn before she was half-way through it. Miranda immediately copied her, yawning delicately, showing her tiny white teeth, and patting her mouth as she did so, just like Diana.

Both Miranda and Loony were enjoying a buttered biscuit. Each of them licked off the butter first, Loony with his large pink tongue and Miranda very daintily with her tiny, curling one.

“Not very good manners,” said Roger, lazily. “My word, I’m sleepy. It’s this big fire, I suppose. Snubby, how are you going to prevent Loony having to sleep down in the kitchen? I bet Mrs. Tickle will insist on it.”

She did, of course. She appeared at nine o’clock, carrying her candle to go up to bed.

“Time for you all to go up,” she announced firmly. “And I’ll take that dog to the kitchen now, Snubby.”

“You won’t mind if he chews up the rug there, and the cushion on the chair, and any slippers or towels you’ve left out, will you, Mrs. Tickle?” said Snubby solemnly. “I’ll pay for them all, of course, if he does much damage—but it’s very, very hard on my pocket.”

Mrs. Tickle was taken aback. She looked at Loony who stared back at her unwinkingly.

“He can’t help being a nibbly, chewy dog,” said Snubby earnestly. “It’s his nature, you see. The funny thing is, he NEVER chews anything when he sleeps with me. Never.”

Mrs. Tickle made up her mind at once. “Well, you let him sleep with you then,” she said, “if you can abide a smelly dog in your bedroom. I won’t have him chewing up my kitchen, and that’s flat.”

“I’ll do anything to please you,” said Snubby, rather overdoing it now. “Anything. I’ll even have a smelly dog in my bedroom. Won’t I, Loony?”

Loony thumped his tail on the floor and Miranda at once pounced on it. Loony swung round at her and she leapt on to his back, hanging on to his silky fur for all she was worth.

Loony raced round the room with her on his back, trying hard to remember how to unseat her. “Roll on the floor, ass!” cried Snubby. “Roll on the floor!”

But, as soon as Loony rolled over, Miranda was off like a bird, springing here and there till she came back to Barney’s shoulder.

“Good as a play they are!” said Mrs. Tickle, laughing. “Now—are you all coming up or not? I’m not leaving you down here—not with an oil-lamp to upset and cause a fire! Mr. Martin did leave strict instructions about that.”

“Right,” said Barney, getting up. “Come on, everyone. Light your candles!”

He waited till they were all in the hall, lighting their candles, then put out the oil-lamp in the sitting-room. Miranda was annoying everyone by blowing out their candles as soon as they lighted them.

“Hey, Barney!” called Snubby indignantly. “Come and stop this fat-headed monkey from blowing out our candles! She must be dotty!”

Barney gave one of his uproarious laughs. “Oh, Miranda!” he said. “Do you still remember Grandmother’s birthday cake?” He turned to the others and explained.

“You see, my grandmother had her seventieth birthday a little while ago, and our cook actually put seventy little candles on it—and Miranda helped Granny to blow them all out. She loved it!”

“So I suppose she’ll blow out any candle she sees now,” groaned Roger. “Stop it, Miranda. Gosh, she’s blown mine out again! Barney, get hold of her. We’ll never get to bed.”

Miranda was safely captured, and then the little procession made its way up the wide staircase, Loony tearing on ahead as usual, and Miranda firmly tucked in Barney’s right arm, well away from his candle.

“Good night!” he said. “Sleep well. We’re all near one another, so if anyone’s scared in the night, give a yell!”

But they were all far too sleepy to be scared by anything. The beds were very comfortable, and there were plenty of blankets to keep out the cold, for the rooms were none too warm. Snubby decided that the water in his jug was really far too cold to wash in—he would tackle that in the morning. He decided too, that he would tidy his belongings in the morning; it would take him so long now to sort them out from the heap he had thrown on the floor of his cupboard!

Loony was already asleep on the middle of the bed. Snubby pushed him firmly down to the end and then got into bed himself, quite pleased at the warm patch Loony had made in the middle. He lay for half a minute, wondering at the utter quiet and stillness of the old house—not a sound to be heard, not one!

How awful if the great old knocker began to knock as in the olden days! Snubby was giving himself quite a pleasant thrill about this when he suddenly fell sound asleep—so sound that he didn’t even feel Loony creeping up the bed and lying heavily on his middle.

The morning was bright and clear and the sun shone so brilliantly that the snow on the pond began to melt fast. “That’s good,” said Roger, looking out of his window as he dressed. “If the snow melts on the pond and we get no more, it will freeze again to-night and we can skate to-morrow, because the ice will be free of snow. To-day we’ll go tobogganing.”

After what Snubby called a “super-smashing” breakfast of porridge, bacon, eggs and toast, they went to see what jobs they could do for Mrs. Tickle. Her kitchen was enormous, and had a pump at one end to pump water for her sink. At the other was a large old kitchen range, but beside it was a new oil-cooker on which she managed to cook everything.

She had the fire going in the range to heat the kitchen, and it all looked very cheerful. She looked up as the children came in carrying the breakfast things, and smiled all over her pleasant face.

“What else can we do for you?” asked Diana. “I’ll help you with the washing-up.”

“Well, you don’t need to do that,” said Mrs. Tickle. “But if you could see that you each make your bed—and get some wood in for me—and clean the lamps—that would be fine. I’ll be able to get on well then.”

“Upstairs everyone,” ordered Diana, taking charge. “Roger, you get Snubby to help you with your bed, then you help him with his—or he’ll just leave it as it is. Do you hear, Snubby?”

“No, teacher,” said Snubby, and skipped out of the way of a slap from Diana.

Everything was soon done, and well done too. Snubby’s bed was as well made as the others—the lamps were cleaned and ready for the night—and so much wood was got in that Mrs. Tickle said she had almost enough for a week! She was very pleased. Snubby decided that he now knew her well enough to give her a hug.

“Now then, get away with you,” she said, surprised. “Squeezing all the breath out of me like that. You’re a caution, that’s what you are. Oh, bless us all, there’s that dog got my brush again. I’ll give him such a larruping if I catch him.”

But she never could catch the artful Loony. He enjoyed himself running off with her brush, her duster, and her mop—till she took to keeping a big broom at hand and chasing him every time he appeared.

“Let’s go and get our things on now,” said Roger, when all the jobs were done. “I’m longing to get out into the snow. Let’s toboggan first of all, before we have a snowball fight or anything.”

It wasn’t long before they were all in their outdoor things—Wellington boots, scarves, gloves, thick jerseys. It was bitterly cold out of the sun, but they soon got warm.

They had two toboggans—each big enough to take two or three of them at once. They set off up the nearest hill, dragging the toboggans behind them. Loony tried to gallop off at a furious speed as usual, but to his dismay found that his legs sank right into this soft white stuff that so mysteriously covered the ground—and for once in a way he had to get along very slowly indeed.

Miranda wouldn’t leave Barney’s shoulder. She didn’t like the snow, though it did occur to her that it would be fun to put some down Barney’s neck. She kept her little paws under his collar to warm them. Barney liked feeling them there.

The hill was steep enough to give the children a very thrilling run down to the bottom. There they all tumbled off into the soft snow, roaring with laughter. Loony soon learnt to sit on the toboggan with Roger and Snubby, his long ears flying backwards in the wind. He loved it, and barked all the way down.

Miranda went with Barney and Diana. She was a bit scared of the sudden rush down the hill and cuddled under Barney’s coat, her tiny head just peeping out. “You’re scared, Miranda!” said Barney. But when he tried to make her stay behind on the top of the hill, she wouldn’t. No, she wanted to be with Barney every minute of the time.

They had races on their toboggans—two on each toboggan, and then one on each. Barney won easily. His brilliant blue eyes were bluer than ever on this dazzling snowy day, and he looked very happy. In fact, they were all very happy. It was Snubby, as usual, who was the first to feel the pangs of hunger.

“You can’t be hungry already,” said Roger. “Not after that colossal breakfast, Snubby. Why, you had six pieces of toast on top of everything else. It can’t possibly be lunch-time yet.” He undid his glove to look at his watch.

But at that moment a bell sounded clearly through the frosty air—Mrs. Tickle ringing to tell them lunch was ready.

“What did I tell you?” said Snubby, triumphantly. “I don’t need to look at the time to know when a meal’s due. Come on, Loony—race you to Rat-a-Tat House!”

“What a lovely smell,” said Snubby as soon as he reached Rat-a-Tat House. “What is it?”

“Stew!” said Roger, sniffing. And stew it was, full of carrots and onions and turnips and parsnips. Loony almost pulled everything off the table in his anxiety to see what it was that smelt so good.

“Now you stop that!” ordered Mrs. Tickle, pushing him away just in time. “If you come out to the kitchen with me you’ll see I’ve got some delicious stew-bones for you. Paws off the tablecloth, please.”

“I’m quite tired,” said Diana, sitting down with a flop. “Aren’t you, Barney?”

“No, not really,” said Barney. “But I’m used to a strenuous sort of life and you’re not. I remember the days when I was a hoop-la boy and got up at half-past five to help to get the fair ready—worked all the morning—took charge of the hoop-la stall in the afternoon, and after that worked as gate-boy, taking the money—and then helped the fellow on the swing-boats.”

“Oh, Barney—your life must seem so different now,” said Diana, beginning to eat her stew. “Barney, didn’t you feel queer when your father first found you and took you home to a family you didn’t know?”

“Yes, I did,” said Barney. “I was shy for the first time in my life, I reckon. I couldn’t seem to shake hands properly, or say how-do-you-do, or even look them in the face—except my grandmother. I wasn’t shy of her. But I guess that was partly because she had a monkey on her shoulder like me—and the two monkeys took to one another from the first. They even shook paws.”

“Are your cousins nice?” asked Snubby, holding out his plate for a second helping of stew.

“Yes. Very,” said Barney. “You know—it was queer—I’ve never been ashamed of being a circus-boy, or of any of the jobs I’ve ever done in my life, but when I met my clean and tidy cousins—they even had clean nails—and saw their fine manners—well, I sort of felt ashamed, and wished I could sink into the ground.”

“You didn’t!” said Snubby, surprised. “I bet you’re worth six of any of your cousins. Why, you’re even worth six of me and Roger. I think you’re a marvel.”