* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Up Eel River

Date of first publication: 1928

Author: Margaret Prescott Montague (1878-1955)

Date first posted: Nov. 18, 2019

Date last updated: Nov. 18, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20191136

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

First Published 1928

Reprinted 1971

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER:

0-8369-3849-6

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER:

77-150552

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To West Virginia

To its flowing mountains and golden valleys; to its tall trees, hickory, white oak, and pine; to its laurel and rhododendron, wild ginger, arbutus, and hepaticas, and to its forest streams; to its beneficent days, Indian summer in November, and corn-planting weather in May; to all its gay company of wild life, rabbits, squirrels, and ground-hogs, birds and butterflies, crickets and katydids; and to its mountaineers, with love for their expressive and beautiful vernacular, and delight in their whimsical humor; to all these aspects of West Virginia, these stories of “Tony Beaver,” that distinguished son of the State, who has his log camp “up Eel River,” are affectionately dedicated, hoping that they may serve to portray, however inadequately, that spirit of laughter and extravagance which is at the heart of nature and human nature, and may at the same time voice the author’s gratitude to her native State.

All over the United States there appears the legend of a super-lumberman who performs impossible feats. This legend is said to be the only genuine bit of folklore which America has as yet produced. In New England and the North West this mythical character appears under the name of “Paul Bunyan,” and as “Paul” has figured in several books, and even been honored in a poem, “Paul’s Wife,” by Robert Frost. The present writer stumbled upon the same myth among the lumbermen of West Virginia, only in this locality the hero is known as “Tony Beaver,” and has his lumber camp “Up Eel River.” There is no real Eel River in West Virginia, and in local fantasy it is the place where all the impossible things happen, so that here if one doubts some statement it is not necessary to apply to it the short and ugly word, but merely to say with a shrug, “Aw, that must er happened up Eel River.” I may remark also in passing that “Eel River” has sometimes been used as a boundary mark for locating fictitious coal lands in West Virginia, which were sold to trusting capitalists of the North. Therefore let me warn any would-be purchaser to beware of property in West Virginia in any way connected with “Eel River,” for however respectable a river of that name may be in other parts of the country, with us it is as slippery in its habits as the snake-like fish for which it is named.

Until I began taking liberties with him, “Tony Beaver,” as far as I know, had never figured in print, his exploits merely being passed from mouth to mouth—losing nothing, one may be sure, between mouths; for which reason it would seem that stories about him should not be dressed up in formal English, but should be appareled rather in the free and easy speech of Tony’s own mountains. Moreover, I agree with Mr. George Moore that country speech is more alive, and therefore more beautiful and effective than city speech, and that localities should treasure their own vernacular.

Thanks are due to The Atlantic Monthly for permission to reprint four of these stories, and to The Forum for the same courtesy in regard to “Big Music” and “Hog’s Eye and Human.” I am also indebted to Mr. James Stephens for information in regard to “Paul Bunyan,” and to Mr. Edward O’Reilly for having introduced me to “Pecos Bill.” Lastly, and most especially, I am grateful to Messrs. W. B. Hines, Henry Casto, and Jack Ridgeway, for having given me news of Eel River and Tony Beaver.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Preface | ix | |

| I. | From Somewheres to Nowheres | 1 |

| II. | The To-day To-morrer | 35 |

| III. | Owning the Earth | 68 |

| IV. | Big Music | 92 |

| V. | Miss Betsy Beaver | 123 |

| VI. | Hog’s Eye and Human | 153 |

| VII. | The World’s Funny Bone | 185 |

| VIII. | Far’ You Well | 219 |

Howdy, strangers, I sure am pleased to meet you-all. My name’s Jerry Dan Doolittle, but up Eel River in Tony Beaver’s log camp, they all calls me Truth-Teller. Sure, make yerself at home, step right inside the kivers, set a spell, and take a chaw of this book.

Mebbe you think that’s a right funny way to commence, but I ain’t never written no book afore, and it looks like to me that this tale, what’s got me and Tony Beaver in it, along with Preacher Moses Mutters, and his ole partner, Ain’t-That-So, Big Henry, and Jack Sullivan and all the tother hands from the Eel River crew—not to say nothing of Miss Betsy Beaver, and that little boy, what’s sech a great buddy of Tony’s—is going to pass out into the world, travel around, and meet up with a heap of folks we don’t even know, so me and the tother hands is aiming to be polite and make any feller that steps inside these kivers feel at home right from the jump. Yes, sure! Help yerself to these tales! Take one of ’em—take two of ’em—Why, take darned nigh all of ’em if you crave to.

Now then, seeing as we’re kind of acquainted, I’ll git on with the job.

Well, of course I don’t have to tell none of you-all that if you go into the tall timbers, you’ll sure run up erginst some tall tales, and jest about the tallest tales a person kin find anywheres air right here in West Virginia about Tony Beaver and that big log camp of hisn up Eel River. Why, some of them tales is so tall that if you was to up-end ’em they’d look right over the tops of the white oak trees—a fact I’m telling you.

Yes, sir! You’ll hear every kinder tale about that Tony Beaver, but, if you want the truth about the feller, you’ll jest have to come to me, for I’m the onliest hand in all these woods what’s ever been up Eel River and met Tony right face to face, and Tony hisself handed me out a trick for telling the truth from the tother thing. More’n that he named me the Truth-Teller, and ast me please to write a kind of a history of all his big doings—and that’s what I’m aiming at right this minute.

It sure was funny how I happened to go up Eel River. The thing come to pass sorter by chance, but more by me allus being sech a great hand to git to the truth of a thing—Yes, sirs! I’m jest a hog for truth.

Course I’d heared every kinder tale about Tony Beaver and all the fellers in his crew, but I jest passed ’em all up as nothing in this world but a whole parcel of lies, twill one time when ole man Wiley and me was out working in the woods together. Mebbe you know that ole feller? He’s got a great bush of whiskers, and his years is so large, and sets out so from his head, that folks ’lows he needn’t to mind sleeping out nights, for he kin jest lay down on one year, and kiver up with the tother—yes, that’s the feller I mean. Well, him and me was out in the woods one day, like I said. We’d jest felled a right tough ole hickory, and when the thing was down, jest to show it who’s boss, ole man Wiley spits on his hands and jumps acrost the stump of the thing. Then he sets down on the trunk, and bites him off a great chaw of terbacker—and if you’ll notice, strangers—I mean you-all what’s reading this book—the bigger the chaw, the bigger the lie—and says, “Tony Beaver, now, he kin jump acrost Eel River and back ergin, and never tech ground on the tother side. And more’n that he’s got him a yoke of steers up yonder in his camp, so big it takes a crow a week to fly betwixt the horns of one of ’em.”

“Yes, that sounds jest like the Gospel truth to me,” I says right sarcastic.

“ ’Tis the truth, Jerry Dan! Take it or leave it!” says the ole feller, kinder miffed.

“I’ll take the truth, and leave the tother thing,” I says, not wanting to stir him up too much, seeing’s as he ain’t so very old and has got him a right stout fist at the end of his arm.

“You’ll take the whole of it then,” the ole feller says, squinting down his nose and gitting ready for another big one. “It was up Eel River too, Tony growed him that powerful big watermelon, what was so large it tuck the whole of a freight flat to ride it down the river. Tony he had the hands to load it onto the flat, and then he clomb up atop of it, and the train started out. But it’s mighty rough up Eel River, the grades is steep, and the railroad makes a heap of hairpin bends, and being a watermelon, I reckon that melon jest natcherly tuck to the water. Anyhow, that ole freight was hitting the rails jest lickety split on a down grade, and Tony was setting up a-straddle of his melon, with the dust and cinders flying through his hair, the wind whistling in his years, and all the tother hands swinging onto the back cars for dear life, when whoo—pee! the freight hit a sudden bend, and dogged if it didn’t switch Tony and the melon both right off the flat, down the bank, and into Eel River itself!

“Well, sirs! The hands they was all skeered to death for fear pore Tony’d be drowned: but when they got the train checked up, and run back to look, hold and below! The melon had done busted all to pieces, and here come Tony riding down the river on one of its seeds jest like he was riding a saw-log. He hollers to the tothers to get ’em seeds too, and come on jine the drive, and it wa’n’t hardly no time ’fore the water it was right full of hands, whooping and hollering, buck-jumping down the river on them black watermelon seeds, all in the wildest kind of a jamboree. It sure muster been somepen to see, and I know doggoned well it ’ud only be up Eel River you’d run acrost a melon with seeds that big, but you know the saying—

“That’s the way they do

In the Eel River crew!”

“Well!” I says, all fired up, “where in the H—” Aw-oh! Excuse me, strangers! I didn’t go to let fly no kinder rough word like that—jest at the start too! “Where in the heavens is Eel River!” I says.

“That’s it!” says the ole feller, which of course wa’n’t saying nothing at all.

“All right,” I says. “I’ll jest go on over to the schoolhouse, and hunt me up the place in a geography.”

“Aw no, Jerry Dan, you’ll not locate Tony Beaver’s Eel River in no school book!”

“Well, I’m a gonna locate it somewhere, and locate the truth of all these here tales at the same time!” I busts out.

“Haw! Haw! Haw! You’ll never locate Eel River somewheres!” old man Wiley hollers out like I’d hit the biggest kinder joke—I had, but didn’t know it. “If you do locate the place, mebbe you’ll locate the truth, and mebbe you won’t—but you’ll not git there at all, lessen Tony sends that there path of hisn out for you.”

“Tony’s path—what’s that? I never heared nothing about him having a path afore,” I says.

“Well, spread yer years then, and I’ll pour the tale into ’em,” says the ole feller. “That path now, it sure is a handy little trick! Tony he happened up on it all by chance one day when he was coming along through the woods. First off it looked to be jest a common enough little trail going about its business, not paying no ’tention to nobody, with ferns and moss hanging onto its edge, and little gray rocks poked up through its middle, but the minute Tony set foot on it, whoop—ee! the thing squirmed right out from under his feets and pitched him over in the bresh.

“ ‘Hey! Doggone you! What in the thunder air you up to!’ Tony bawls at it mighty mad, for where Tony Beaver sets his foot thare he aims to have it stay. With that he jumps back ergin on the path good and hard with both feet. But ergin she humped up and bucked him off. Well, sirs! Tony he set back in the bresh and studied that frisky little trick for quite a spell, and when he done that he seen it wa’n’t struck down to the ground like most trails, but was kinder loose and free. So then he went to one end of it and ripping it away from the ground, rolled it up mighty keerful and tuck it on back to camp, jest like it was, with the moss and ferns and little gray rocks swinging onto it. There he tamed the critter, and now whenever he wants a person to visit him up Eel River, all he has to do is to send out that there little path, and dogged if the thing won’t fetch anybody into camp jest for all the world like a cat fetching in a mouse.”

“Well, I sure did have to spread my years—large as they is—to take in that tale!” I says. “And how does a person git the word to Tony that he’s wanting to see him?”

“Send it by a jay bird, Jerry Dan,” says the ole feller, kinder laffing. With that he picks up his saw, and went moseying off to camp.

“Jay bird nothing!” I says out loud to myself kinder mad, and “Jay! Jay!” a blue jay says right back at me outer a sumac bush.

“Here, bird! Who you sassing? You git on back up Eel River where you belong, and tell yer boss I’m a-wanting to see him!” I says, and along with the words I throwed a rock at the critter.

The jay give a right funny flirt to his tail and flew off, and I didn’t think nothing more of the thing, but Great Day in the Morning! It was jest that very evening when I was coming through the woods along ’bout sundown, that I run up on a little path laying out there on the ground, looking jest as innocent as you please, and like it wa’n’t doing a thing in this world but warming up its back ’fore the sun went down. “Hey!” I says to myself. “This must be a short cut to camp I’ve never seen afore—b’lieve I’ll take it!” I says.

With that, never thinking nothing, I steps out on the thing. Well, sirs! It had jest been a-laying there waiting for me! The minute I teched foot to it, it busted itself loose from the ground, and went a-t’aring and a-r’aring out through the woods like a black snake racer!

“Aw my soul! What’s got you now, Jerry Dan!” I hollers out, flinging both arms right tight round the thing’s neck, swinging on for all I was worth to keep from being bucked off and fatally busted.

“Hole on! Hole on! Jest—jest—jest—wait a second if you please, sir!” I bellers at the thing, so skeered my words was shaking all up and down, and the goose flesh was right stiff up the spine of my back.

But it never broke its stride, and yonder we went out through the woods, wriggling and wrastling, t’aring up the hills, sliding down the hollers, and diving acrost the cricks and little runs, with the water splashing up, the wind zooning in my years, and my logger boots, heavy as they is, stripped right offen my feet by the pace—a fact I’m telling you.

I shet up both eyes, and give up all for lost, and splash! We split a river wide open, and swee—eeeeesh! we went up the bank on the tother side. “Aw my lands! I wished I’d said good-bye to my folks ’fore ever I tromped on this thing!” I says to myself.

The path had got itself going good by now, and when we hit the top of the next ridge, dogged if it didn’t spread itself right out in the air and jest sail acrost to the next ridge, never teching ground in between. Strangers, I wouldn’t like to tell you-all what a turrible feeling it give me in the stomick when the thing done that.

After that, it never bothered about the hollers no more, but jest went hop-skip, skip-hop, from ridge to ridge, for all the world like a young un hopping acrost a crick on stepping stones, with me swinging onto its neck and wishing I was mo’ ready for a exchange of worlds. “Aw my soul! We’re a-heading straight for the Atlantic ocean, an’—an’—an’ then what?” I says, trying to keep the chatter outer my teeth. “Ho’!—Ho’!—Ho’!—Hole on!—hole on, brother! Wait! Wait! Jest please to wait a second! Whoa! Whoa-up! Hoo-Haw! Gee! Back-a-leg! Doggone it!” I says. “If I jest knowed whether the thing was a human or a critter, I’d know how to talk to it! Hole on, Mister—Mister—Mister Man, or whatever you call yerself, please to put on the brakes,” I says jest as nice and polite as I knowed how. But the thing never checked up. “It don’t seem to understand human talk, so it must be some kinder critter,” I thinks. With that I commenced trying it with every kinder animal talk I could lay my tongue to. “Sukey! Suke! Suke! Suke! S-o-o-o, gal! Back a leg!” No, ’tain’t a cow, I says, seeing as it never took no heed of that cow talk. “Chickie! Chickee! Chickee! Duckie! Duck-ie!” (No, ’tain’t a fowl.) “Pig! Pig! Pig! Pig-ee!” (No, ’tain’t a hawg.) “Well, then—Here, Ponto! Here, Ponto! Here! Here! Here! He—re, Ponto! Good dog—ie! N—i—c—e ole feller!” I tries at it, and I would of patted its head if it had of had a head to pat, and I could of spared a hand from holding on to pat with. “No, ’taint a dawg,” I says, seeings as Ponto didn’t fetch it. “I guess, though, it’s lucky it ain’t,” I thinks, “for if it had a-been, it mought of wagged its tail, and wagged me right into Kingdom Come! My Soul! That was a narrer escape!” I thinks. “I better try it with some animal that don’t wag. Well, then—Sheep! Sheep! She-e-e-e-pie! Shee-pie! Sheep!” (No, ’tain’t a sheep.) “Mebbe it’s a horse then. Kope Kope! K—o—p—e! Whee-ooo! Whee-ooo! Whif—Whif—Whew! Whif—” I tries to whistle at it like you do to a horse, but we was going so fast the wind cut the whistle right off short in my throat, and nigh choked me to death. “Well doggone it, then it must be a mule!” I says, and I wouldn’t like to tell you the words I busts out with then—Aw well! You know how a person talks at a mule! But it jest kep’ right along skip-jumping from ridge to ridge, hop, hop, hop, and if it knowed mule talk it never let on like it did.

“Well, by the way it travels, it mought be a grasshopper,” I thinks. So I tries it with—

“Hoppy-grass, hoppy-grass,

Gimme some molasses!”

Which was the onliest thing I’d ever heard of a person saying to a hop-grass. But that never fetched it neither. “Well, dog my cats!” I says. “It don’t ’pear to be human, critter, ner insec’, and if it’s a veg-a-table, then Skat me! if I know a word to say to it!”

Well, there now! Looked like jest by chance I hit the right kinder talk, for the minute I said “Skat” the thing fa’rly split the wind wide open going. “Well, darn me, if it ain’t a cat!” I says. “Well, sirs! Puss! Puss! Puss! Kittie! Kittie! Kit! Nice little pussie-cat! Whoa-up, kitty! Wh-o-o-a-a, pussie! N-I-C-E little kitty!” I says, making out like I liked cats, though I don’t.

But if it was more a cat critter ’an any other kind, me saying “Skat,” and “dog my cats” like that had got it mad, and now it wouldn’t check up for nothing, but jest kept clipping right along from ridge to ridge, with me laid out on its back, and thinking mighty pale with every jump, “There sure will be a strange face in Heaven to-night—and it’ll be yours, Jerry Dan!”

But by now as I looked down and seen all below winking by, it seemed like the whole world was jest about to bust itself wide open laffing. The rocks and trees and bushes ’peared to be laffing, and every varmint that run out to look as we went by, was carrying on the same way. Rabbits, squirrels, and groundhogs, they’d all run out to look, r’ar back on they behind legs, p’int, and wave they paws up wide, hollering out somepen, and then jest fa’rly fall over on the ground, kicking, and rolling over, and laffing, “Ho! Ho! Ho! Haw! Haw!” fit to bust theyselves wide open.

I didn’t know what it was all about—and yit some way I did too—but d’rectly seeing the critters all so tickled, commenced to git me tickled, skeered though I was. “Well, there’s somepen powerful funny going on, Jerry Dan,” I says to myself, “but looks like I jest can’t reach it with my funny bone.”

But the more I didn’t know what the thing was, seemed like the more tickled I got—Aw well, you-all know how ’tis, sometimes a joke you don’t know’ll git you more tickled ’an one you do. “Well ’tis funny I know, but dogged if I know what ’tis!” I says.

“Hey now, what’s the big laf?” I hollers down at the varmints.

They waves they paws up wide, and hollers back, “Yer traveling from—from—traveling—” but going by so fast I couldn’t ketch what they said.

A ole black crow flopping along ’side of us let out a great “Caw! Caw! Haw—Haw—Haw!”

“You black raskil! Quit Caw-Hawing at me, and tell me what’s hit your funny bone!” I hollers at him.

“Haw! Haw! Haw! Don’t you know yer a-traveling from—from—Haw! Haw! From—traveling from—Haw! Haw! Haw!” He couldn’t git the words out for laffing, and d’rectly we was outer ear-shot.

“Well, I know it’s somepen funny if it’ll make a crow laf,” I says. But right that minute all the tickle was skeered outer me, and I tuck a fresh strangle holt on the path, for the thing scooted up the tallest ridge we’d hit yit, with the bresh and trees down below waving in the wind of it, the coons and squirrels, and varmints, rolling around all blowed about, still laffing and hollering, “Yer traveling from—from—Oh, Haw! Haw!” and jest at the top of the ridge the path flung itself out over a high cliff of rocks right into the air, and I never seen nothing no mo’, but the sky overhead and a twinkle of earth below, all going by in a kind of a daze.

“Good-bye Jerry Dan—pore young feller!” I thinks, wishing my stomick was more used to this kinder riding, and hanging on to the path with all four arms and legs, and toe nails.

Well, I stayed with my pig, as the saying is, and in another pair of seconds, the path landed down somewheres, give a final buck-jump, and a squirm, and lef’ me laying out flat on some kinder ground.

“Well, where in the thunder am I at now!” I thinks, setting up on the ground and looking about still in a kind of a maze. As I ketched my breath and looked, I seen log hands come a-running from every which way, all of ’em whooping and laffing, waving they arms out wide jest like the varmints, p’inting and hollering to one another, “Hey, look ayander! Look! Aw my soul, look what the path fetched in! Aw, Haw! Haw! Haw!”

I jined in too, whooping and laffing with the best of ’em, for I knowed it sure was comical, but still and all, I didn’t know what it was.

“Haw! Haw! Welcome, stranger!” they gits out.

“Welcome, yerself,” I says. “And—excuse me—Haw! Haw! Haw! Will you please to tell me what I’m a-laffing at, so’s I kin laf sure ’nough?”

“Why you big idgit!” one of ’em bellers back all in a breath, “you’re a-laffing ’cause you’ve traveled right from Somewheres to Nowheres, and now yer at it!”

“Well, dog my cats! Er course that’s it! Why—course—course I knowed that was what I was doing all the time! Aw, Haw! Haw! Haw! Traveled from Somewheres to Nowheres, and now yer at it! Well that is comical sure! Traveled—Somewheres—Nowheres—an’ now yer at it! Aw my jaws! My jaws!” I hollers out.

Well, sirs! That thing come nigh killing me, for I reckon I don’t have to tell none of you-all that’s reading this tale, that to travel from Somewheres to Nowheres is jest about the beatenest thing a person kin do. And if you don’t b’lieve me, you jest travel that way onced yerself, and see if it don’t come nigh putting your funny bone outer place. There’s jest one thing funnier than traveling from Somewheres to Nowheres, and that’s to git there—and now I’d done both, and the joke of it come nigh ruining my jaws. It’s the truth they had a kind of a crick in ’em till a right smart time afterwards when we-all up Eel River hit the world’s funny bone, and the big laf that time kinder put ’em back into place ergin—but I don’t aim to tell you-all about that now.

“Well, well!” I says at last, sitting up on the ground, all wore out. “If I’m Nowheres, where am I?”

“Why, yer up Eel River——”

“Yer in Tony Beaver’s log camp——”

“Tony’s path fetched you in——”

“Tony Beaver——”

“Eel River——”

“Ain’t that so!”

“Eerrr—erk! Errr—erk! Errrr—ROOOO!” They all bellers out in a jumble together.

“Eel River!” Well sure enough, there I was! I mighter knowed all the time I was heading for it, and I would’ve liked to laf some more, only that trip from Somewheres to Nowheres had jest laffed me dry. I looks around and yonder was all the hands from Tony Beaver’s log camp I’d been hearing sech tales about, and never b’lieving they was true. There was Preacher Moses Mutters as solemn as a billy goat, and his ole buddy Ain’t-That-So; there was the little fiddler, mighty wide looking betwixt the eyes, and kinder laffing to hisself like he knowed somepen funnier ’an he could lay his tongue to; and there was Big Henry and Jack Sullivan, what’s the biggest kinder buddies, ’cept when they’s fighting one another—which they ’most generally air: yes, sure ’nough! There they all was, and a heap more besides.

“Well, sirs!” I says looking all about with my mouth gapping open. “Here you all air sure ’nough, when all the time, I jest thought you was nothing in this world but a whole parcel of lies!”

“You thought we was what?——”

“What’s that you say, stranger?” Big Henry and the Sullivan feller bawls out, dancing up to me and looking powerful dangerous.

“Excuse me! Excuse me, partners!” I says all in a hurry. “I was jest aiming to say I never thought none of you was so.”

“Aw yes, we’re so—leastways we’re so-so,” says Jack Sullivan, unrolling his fists.

“Hey now! Here’s Tony Beaver hisself! He’ll tell you whether we’re so or not!” Big Henry hollers.

Well, sirs! Believe me or not! There was the great Tony Beaver hisself coming moseying along with that little boy buddy of hisn sitting up on his shoulder mighty proud, his arm round Tony’s neck, looking like he owned the whole world, and then some.

Well now, I ain’t aiming to tell you-all jest what Tony Beaver looks like. He’s sech a great hero that mebbe it’s best jest to think in yer own heads what he looks like—thataway every feller kin think him up to suit hisself.

Well, he come swinging along with that kinder limber tread he’s got, more like some kinder wild varmint than a human, and “Hey! What’s all this about?” he hollers.

“Look a-here, Tony! Here’s a stranger what the path fetched in, saying as how he never knowed we was so,” Big Henry says, all worried up. “Stranger, shake hands with Mister Beaver,” he says.

“Welcome to Eel River, stranger!” Tony says mighty nice and friendly, and “Welcome, stranger!” the little boy up on his shoulder says right after him.

“Pleased to meet you, Mister Beaver! Pleased to meet you, sonny!” I says fetching out the best manners I had.

“I got your word all right, and sent the path out for you,” says Tony.

“Why, I didn’t send no word to you, Mister Beaver,” I says.

“Didn’t you send word by a blue jay you was wanting to see me?” he says, and “Yes, sure you did! Sure you sent word by the jay bird!” his little buddy says.

“Why, come to think of it, sure I did! Ain’t that so! But I never thought nothing in this world of it!” I says.

“Yes! Never-thought-nothing-of-it gits a heap of keerless young fellers like you into trouble!” Brother Moses Mutters, the preacher, bawls at me, clawing his fingers through his whiskers, and looking turrible scan’alized, and “Ain’t—that—so!” another ole feller sing-songs, dragging out his words jest thataway, mighty solemn and heavy, like he was dropping rocks down a well. I never did know what that ole brother’s name was. All the fellers jest called him “Ain’t-That-So,” ’count of him allus backing up the preacher with jest them words, no more, and no less.

“Errrr—erk! Errrr—erk! Errrr—ROOOOOO!” Another hand comes out all at onced, flopping his arms, and making out to crow like he’s a rooster. That sure did give me a great jump, but come to find out that was pretty nigh allus what that feller done. Ole Brother Mutters ’ud say somepen mighty solemn; “Ain’t——that——so!” his old partner’d back him up, and, “Errrrr-erk! Errrrr—erk! Errrr—ROOOOOOO!” the joky hand ’ud flop his arms and crow right after them solemn old buddies. Aw, I dunno why the feller done it! It was jest a kind of a way he had—but seemed like it allus made them two ole fellers mad.

“Tell the stranger we’re so, Tony—’fore I tell him with my fist!” Big Henry hollers, all fired up.

“Yes, sure we’re so, all right! But if the feller don’t know it, he’ll jest have to stay in camp a spell to find out how so we air,” says Tony. “Looks like that path tore you up some, stranger,” he says looking me all over, and seeing how all tousled to pieces I was. “But the hands’ll rig you out all right ergin.”

“Yes, sure! We fellers’ll fix you fine!” says the little buddy.

Well, sir! That there path what had fetched me in at sech a clip, had been laying off in the bresh, kinder dozing along, resting up after the trip, but the minute it heared Tony say “path,” it give a bound, and come a-romping and a-wriggling up to him, rolling over on the ground at his feet, humping itself up and rubbing round his legs, precisely like some kinder cat critter.

That was the first time I’d had a right good sight of the thing, for when I come in, I was too busy holding on and too skeered to look—and believe me! now I jest looked and looked at it with all the looks I had. It looked like a—Well, it looked like—like—Aw, you know! Like a—a—a—Well, now I come to study on it, be darned if I kin tell you-all jest what the thing did look like! But anyhow, it sure did make my eyes bulge to see it.

“Look out! Look out, stranger!” the little fiddler yells at me all of a sudden.

“Hey, what!” I says, giving a big jump.

“Hol’ yer eyes in place, or they’ll pop right outer yer head with looking!” he hollers back.

The little feller warned me jest in time, for it’s the truth, in another pair of seconds my eyes would’ve busted right outer my head.

That’s one thing I’ll jest take time right now to warn you strangers of—I mean you-all that’s reading this book. If you ever happen to go up Eel River, do pray mind and hole onto yer eyes, or you sure will lose ’em looking at what you’ll see up there. One time there was a right pitiful happening jest on account of that very thing. Whilst I was still up yonder in Tony’s camp, there was a young feller—but that’s some piece off yit, so I’ll come on back now to the beginning.

“Well, now you air here, what was you wanting to know?” Tony asks me, after I’d got my eyes settled back safe in my head again.

Well, what was it? Traveling so fast, being so skeered, and laffing so hard, had kinder jolted the sense outer me. But in a second it all come back.

“Why, it’s the truth I’m after, Mister Beaver,” I says. “They’s a whole heaper tales going around in the woods about you and all your doings, and I’m aiming to git at what’s so, and what ain’t. For you know as well as I do, even the finest brand of gen-u-ine truth kin very easy be stretched into the tother thing—ain’t that so?”

“Yes, sure that’s so!” he says, and “Sure is so!” the little feller follows him up. “Well now,” says Tony. “If it’s the truth yer after I kin give it to you—Here, run up to camp and fetch me some of that lie-paper!” he hollers to one of the hands. “Mebbe you’ve seen this here sticky fly-paper what ketches flies?” he asks me. “Well, I’ve invented me some sticky lie-paper, what’ll ketch lies as fast as the fly-paper ketches flies—sure is a handy trick!” he says.

And it sure is! When the hand come running back with the paper, there, jest like he said, was three or four great, round, black, ole lies hanging on to it, jest for all the world like flies on fly-paper.

“If there’s one thing I hate worse’n a fresh lie, it’s a ole one! But I’ll fix you all right!” Tony says, picking off them ole lies and stomping ’em into the ground.

“How in the world did you ever come to think of it, Mister Beaver?” I says, jest looking at the paper, and all carried away.

“Aw, it was jest a matter of using yer brains!” he says, shrugging up his shoulders, making out like he didn’t think nothing of it—but I could easy see the feller was tickled to death over his own smartness. “It come to me all of a sudden one day when I was looking at some flies on a fly-paper,” he says. “ ‘Lor’ me! I wished I had somepen that would ketch lies as good as that paper ketches flies,’ I thinks. Then I commenced saying over to myself, ‘Fly-paper, lie-paper, flies, lies, lies, flies, flies, lies,’ jest thataway, and bang! in one second it come to me that lies wa’n’t a thing in this world but flies with the ‘f’ left off! So then I seen all I had to do was jest to invent some sticky paper with the ‘f’ left outer it—that’s exactly what I done, and that’s why this here paper ketches lies ’stead of flies—it’s jest a matter of using yer brains. But I’m still kinder bothered,” he says, looking worried, “for the paper only ketches flies when they’s more’n one of ’em around, for course it takes more’n leaving the ‘f’ off to make a single lie match up to a fly—but it don’t really make no difference,” he says cheering up, “for lies never do come single, they allus travels in droves.”

Well, I looked and I looked at the thing, and says, “Fly-paper, lie-paper, flies, lies, lies, lies, flies,” over and over, and back’ards and for’ards jest like Tony said he’d done, but for the life of me I couldn’t git it figgered out why jest leaving the “f” off would make flies into lies. “Excuse me, Mister Beaver,” I says. “Excuse me, sir, but—but, some way, that don’t ’pear to me to have no sense to it.”

“ ’Tain’t got no sense—that’s why it works so well!” says Tony. “Look a-here!”

With that he swishes the paper round in the air and ketches a whole slew of lies didn’t nobody know was there till the paper fetches ’em into sight.

“Well, it sure is a handy trick!” I says. “And now I see why it’s having no sense makes it work so good! But I never would’ve knowed it, if I hadn’t traveled all the way from Somewheres to Nowheres!”

“Now yer talking, young feller! You’ve ketched right on to the hang of things in this camp,” says Tony. “And seeing as yer sech a great hand for the truth, I’ll ast you to stay with us a spell and be the—the—the—Well doggone it!” says the feller, scratching his ear, “you know what I mean—the—the—Aw! The feller what writes up the doings of a place.”

“Historian, is the word yer aiming at,” says ole Brother Mutters, rolling his tongue ’round, mighty proud of his smartness.

“Ain’t—that—so!” says his ole buddy.

“Errrr—erk! Errrr—erk! Errrr—ROOOOOOOOO!” says the joky feller.

“Yes, historian—I’ll thank you not to take the words outer my mouth, Preacher Mutties!” says Tony. “Now then!” he says to me, “since you’ve traveled all the way from Somewheres to Nowheres, jest to git the truth, I’m a-going to make you the Eel River historian, and hand this here lie-paper over to you, so’s you kin try out things with it, and sort out what’s so, from what ain’t. The tales you tell about Eel River’ll be the truth—and the tales the tother fellers tells, why they’ll jest be the tother thing,” he says. “What mought yer name be, young feller?”

“It mought be Christopher Columbus, or it mought be George Washington, but it is Jeremire Daniel Doolittle—Jerry Dan, for short,” I says.

“Well, Jerry Dan, I’m a-going to give you a new name,” says Tony. “Fellers!” he bawls out, “meet the Truth-Teller, what’s going to tell the truth about this camp!”

At that all hands busts out with a great hullabaloo, stomping they feets, slapping they pants legs, cheering, and hollering out, “Pleased to meet you, Truth-Teller!” “Welcome to Eel River!” “Howdy, Mister Truth-Teller!” and all like that, mighty nice and friendly.

So there you see, strangers—you-all that’s reading this book—how it was I happened to go up Eel River, and to write this tale of Tony and his camp—it all jest come outer me being sech a hog for the truth!

Well now, strangers—you-all what’s reading this book—I sure did hit Tony’s camp at a mighty lucky time! I hadn’t been up Eel River more’n about a week or so, and was jest gitting used to holding my eyes in place, swishing the lie-paper round to find out what was the truth, and what was the tother thing, and coming to understand why things worked so good when they didn’t have no sense to ’em, when Tony pulled off one of the most my’rac’lous jobs even he ever put through. Dogged if the feller didn’t go and hitch them powerful steers of hisn on to the wheels of time, and had time running all up and down the days, back’ards and for’ards, being yesterday and to-morrer, and last week, just whichsoever way he said for it to go. That sure was a terrible sight to see, and dangerous too, when you come to study on it, yit Tony done the whole thing for nothing in this world but to satisfy that little boy buddy of hisn, what I been telling you-all about. That little feller ain’t more’n about four, going-on five years old; he runs away from his mammy to play around the log camp every chance he gits. He’s got a crippled foot, and can’t walk so very good, so all hands totes him, but his fav’rite riding place is Tony Beaver’s shoulder, and I b’lieve he thinks Tony pulls the sun up with a string in the morning, and lets her run down ergin at night. It’s a sight what he thinks o’ Tony! Seems like Tony he takes a dee-light in doing all sorter outer the way stunts jest to please that kid.

Mebbe you’ve seen fellers take a bucket of water and swing it around so fast never a drop’ll drap? Well, Tony he went ’em one better’n that. When he got his bucket going good, he stopped it right spang upside down over his head, and never a drop spilled. I dunno how the feller done it, and all hands was jest carried away by the sight too, but that young-un, he never batted a eye.

“I knowed you could do it, Tony,” he says. “Yes, sir, fellers!” he says, telling ’em all, “Tony Beaver, he kin do it all right!”

That little feller’s faith in him tickles Tony right much. It’s a kind of a off-set to ole Preacher Moses Mutters, what’s allus a-hanging round camp, and sing-songing out, “Yer can’t do it, Tony—it’s ergin reason!” With the tother solemn ole partner backing him up, “Ain’t—that—so!”

Them two ole customers, they sets a great store by reason, and they’s mightily outdone by all the onreasonable things Tony pulls off.

“Mutters” ain’t that ole preacher’s right name, that’s jest a way the hands all has of calling him, ’count of him allus muttering round, and so gloomy-like.

So there Tony is sorter betwixt him and the little feller; the ole preacher allus tuning up, “Yer can’t do it, Tony—it’s ergin reason!” and the little feller jest looking at him so trustful, and saying, “I knowed you could do it, Tony!”

Well then, one day, right soon after I hit the Eel River camp, that little buddy, he tuck down sick. When Tony got the word of it, he jest fa’rly tore up Jack twill he got aholt of the finest doctor anywheres round. The doc’ he come up Eel River, went up Flint Holler and around Hare Hill, to where the little feller lives in a log cabin with his mammy. He looked the young-un all over, felt his pulse, had him to put out his tongue, and all like that, then he dosed him some and ’lowed he’d be all right to-morrer.

“I’ll be all right to-morrer,” the little feller says, saying it over after him, mighty trustful.

Well now, strangers, it was right then and there all the trouble commenced. The next morning when Tony went up Flint Holler and around Hare Hill, to the little feller’s cabin, he found the young-un all in a turrible fret.

Tony, he come right inside—though it’s the truth, he don’t like to go under a roof, or tromp on sawed boards—and steps over to the bed, where the little feller was laying all kivered up under a quilt of the Rising Sun pattern.

“Hey now! What’s the trouble, buddy?” Tony asks him.

“I can’t git better, Tony,” the little feller says kinder pitiful.

“Why, honey, the doc’ said you’d be better to-day,” Tony tells him.

“No, Tony! no!” the young-un says, all wrought up; “he said I’d be better to-morrer!”

Tony he burst out with a great Haw I Haw! at that. “Why, honey,” he says, “to-day is to-morrer!”

“No, it ain’t, Tony!” the little buddy answers him back. “This ain’t to-morrer—it’s jest to-day! An’—an’—” he says, all filling up to cry, “how kin to-day be to-morrer? We can’t find to-morrer, Tony. Mammy and me been a-looking and looking all night for it, but to-day jest kep’ right on and on being to-day and never did git to be to-morrer! I want to-morrer, Tony,” he says, crying, “I can’t git better till it comes.”

There you see how it was, stranger—the young-un had got all balled up in his mind, and jest couldn’t get it figgered out that to-day was to-morrer. And when you come to study it over, you’ll see there was some sense in what he said, for it cert’nly is so, stranger—to-day ain’t to-morrer—it jest natcherly can’t be! But if it ain’t, then where is to-morrer? Even watching it very close, a person can’t hardly say when to-day quits and to-morrer commences. And it’s the truth, I don’t know myself if to-day ever does git to be to-morrer—so it wa’n’t no wonder that sick child was kinder twisted up over it.

“No, Tony! No! To-day’s to-day—it ain’t to-morrer!” he kep’ on saying to everything Tony told him. “I can’t git better till it’s to-morrer—you git to-morrer for me,” he says putting his hand in Tony’s so trustful like; “you kin do it easy, Tony!”

Well now, I reckon that was jest about the biggest job Tony Beaver ever had handed out to him. But he ain’t never the feller to turn a job down ’count of its looking big, so he scratched his head a spell, and then he says, “Well, buddy, I’ll do the best I kin.” And then he come on back to camp to figger how he was to do it.

Ole Brother Mutters ’lowed the way was to set up all night with the little feller, and when the clock struck twelve to tell him now it was to-morrer. “That’s the reasonable way of doing it, Tony,” he says, and “Ain’t—that—so?” says his ole buddy. “Err—erk, Errrr—erk, Errr—ROOO!” sings out that joky hand, flopping his arms and making out he’s crowing at them solemn ole buddies.

“But the reasonable way ain’t my way,” Tony tells him. “And more’n that, you know I ain’t never a hand to go under a roof and tromp on sawed boards.”

Howsomever the hands all ’lowed Brother Mutters was right, and they got Tony pusuaded to try that way, though he done it ergin his better jedgment.

Well, that night Tony he went up Flint Holler to the little feller’s cabin, and fetched hisself in a big gray rock—what still had some moss hanging on it—to set on; for Tony he never will set in a cheer. And he told the little boy that to-morrer would be along late in the night, and he’d be there to ketch it.

So the little feller went on to sleep mighty trustful and satisfied; and Tony sets down on his gray rock by the fire, and dozes along till it come nigh midnight. Then he tiptoes over to the bed, and whispers that to-morrer would be there when the clock struck.

“When the clock strikes,” the little feller whispers back in a kind of a sacred voice, like he was at prayer-meeting. “O Tony!” he says, “let me set in your lap! I want to be setting there when to-morrer comes.”

So Tony he wraps the Rising Sun quilt round him, and sets down on his gray rock, with the little feller on his knee—and it was a funny sight to see Tony Beaver setting under a roof!

Well, after a little bit, the clock commenced to wheeze like it was cl’aring its throat for somepen big, and fetches out twelve strokes, and Tony hollers, “Here’s your to-morrer, honey!”

The little feller looks all about him, up at the joists, and down at the floor, and then back ergin at the clock, and seems like he was kinder blank, like he’d expected to-morrer to jump out from somewheres and be different

“Is it to-morrer, Tony?” he asks, sorter doubtful.

“Yes, sure it is!” Tony says. “And now to-day you’ll git better.”

Well, right there Tony slipped up. He sure oughter of knowed better’n to say that to-day word.

“You said to-day!” the little feller hollers out, ketching him right up. “And this is to-day, it ain’t to-morrer! Tony, you fooled me!” And with that he busts out crying like his very heart was broke. “Put me back in the bed,” he says. “You fooled me, Tony,I—I don’t want to set on your lap no more.”

Well, that pretty nigh killed Tony, and he come on back to camp fa’rly raging. He give one holler that fetched all us hands out of the bunk-house on the jump, and standing up there in the moonlight, looking powerful tall, he told us all what had happened.

“And that’s what comes of me going under a roof, and trying to be reasonable! And now,” he hollers out, “I’m done with reason! And by the sap of all the white oak trees running in spring, and by the breath of the gray rocks, I’ll fine me a onreasonable way of doing it!”

You better b’lieve all hands kep’ mighty still at that, for they knowed better’n to cheep when Tony busts loose with them cuss words. But course Brother Mutters had to tune up.

“Yer can’t do it, Tony! Yer can’t put back the wheels of time, and yer can’t put ’em for’ard neither!”

“I can’t, can’t I!” Tony hollers at him. And with that he let loose sech a blast of a look at that preacher, that I reckon it would of blowed him right off the bank, and down into Eel River itself, if Big Henry, what’s one of Tony’s stoutest hands, hadn’t of seen it coming, and ketched aholt of the ole feller jest in time.

“Yoke up them oxen of mine!” Tony hollers out, and all hands jumped like he’d cracked a pistol.

Well now, stranger, it’s jest like ole man Wiley tole me, them steers of Tony’s sure air jest about the most my’raclous critters a person ever did see! Mebbe you recollect a ole song that runs kinder this away—

“Tony Beaver had a ox,

I mind the day that he was born

It tuck a jay bird seven years

To fly from horn to horn.”

Well, that’s jest a doggoned lie, but you may know them beasts air all outer the common or folks wouldn’t make up no sech tales about ’em.

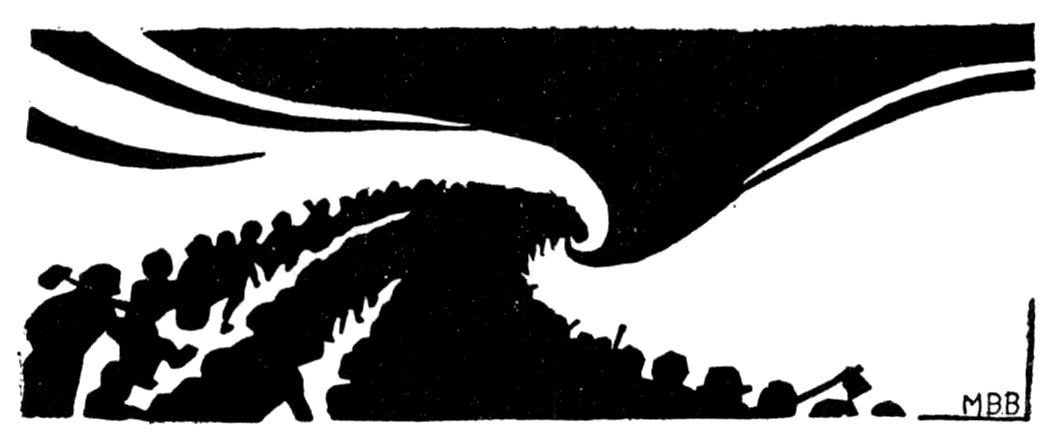

Well, when the hands fetched ’em around Tony he tuck a powerful stout log chain, and hitched one end of it to they yoke, and without saying nothing to none of us he went off into the woods with the tother end. The chain it onwound, and onwound, and went crawling away into the bresh after Tony Beaver, looking like the biggest, nastiest kind of a snake a person ever did see. After a right smart spell, the chain it quit enrolling and lay still, ’cept that every once in a while, it’d give a kind of a jerk, like Tony was fooling with it at the tother end.

But whoop-ee!—all to onced that chain it give a powerful jump and commenced to run back outer the woods like the dogs was after it! Then d’rectly there come the awfulest kind of a battle betwixt Tony Beaver and that log chain. Course we all couldn’t see nothing ’cept the chain’s end of it—but that was a plenty! The doggoned thing it wriggled and wrastled, and lashed itself up and down, hither and yon, like it was fighting for all it was wuth to bust loose and git on outer them woods. And every now and ergin it’d hump itself up in the middle, like you’ve seen a inch worm do, and strain and strain to pull free thataway. But in the end Tony he won, and after another tumble thrashing and lashing of itself that jest natcherly cut the bresh all to pieces anywheres near, and even felled a couple of white oak trees, the chain ’peared to give up and lay still—’cept that it was trembling like a person with the ague.

And you better b’lieve all hands stood back outer the way, looking on with all the looks they had, for you know, stranger, it must of been somepen mighty onnatural that would make cold iron carry on thataway.

Well, after a spell, Tony come on back outer the woods, with the sweat jest a-running off’n him.

“Thar now, that’s fixed!” he says, kinder panting like.

And not a one of the hands dast to ask him what was fixed, for they knowed doggoned well it must of been somepen turrible strange that would draw the sweat on Tony Beaver.

Tony looks around at us all, and he says, “One end of that chain’s hitched to the wheels of time, and the tother’s hitched to them beasts—and now I’ll have time going to suit me!”

And with that he spits on his hands and ketched aholt of his raw-hide whip, that’s got a lash to it pretty nigh half a mile long, and he swirls it out and cracks it, Pough! And them oxen, they bowed they heads and heaved into the yoke. And they heaved, and they heaved—but nothing didn’t happen.

“Yer can’t do it, Tony! It’s ergin reason!” ole Brother Mutters sings out.

“Man! I’m done with reason!” Tony hollers back at him. And this time Big Henry wa’n’t quick enough, and the blue-lightning look Tony lets loose at that preacher blowed him clean off’n the ground, and landed him down in a bresh pile a right smart piece away.

And Tony he cracks his whip ergin, and hollers “Yer-r—rup!” at the team. The crack of that whip was like a thunderclap in cl’ar weather, and that holler of Tony’s went bounding on down Eel River, chipping the rocks off from side to side, till it jest natcherly bounded out in the levels at the fur end. And Great Day in the Morning! Them beasts went for’ards, and the wheels of time commenced to turn!

Well, sirs! When that happened, stranger, it was like the whole world had busted loose from her brakes, and it made the stoutest hand there reel like he had the blind staggers—all, that is, ’cept Tony. It ketched ole Brother Mutters in the stomick, and he fell over acrost a stump, and commenced to give up his victuals.

“Whoop-ee! I got her going!” Tony sings out. “By the breath of the gray rocks! I got time going to suit me now!”

But hold and below! It wa’n’t more’n the shake of a lamb’s tail ’fore Tony and all of us seen he’d slipped up bad. Dogged if he hadn’t them beasts headed wrong, and what do you reckon! ’Stead of pulling down the to-morrer he was after he commenced fetching up yesterday, and the day before, and then d’rectly it was last week, and in a nother pair of seconds it was last month itself! Well, sirs! that was jest a little more’n the hands could stand, and they all busts out hollering at Tony to quit.

Stranger, did you ever see the past fetched back into the present?

Well, I kin tell you, you need never crave to. You see like it is—we looks down the past through a kind of a haze, like them pretty blue mists you’ll see hanging over the mountains in Indian summer weather, and everything looks mighty meller and nice through it. But when Tony set time to vomiting up them yesterdays thataway, they come up into the cold light of the present all mother-naked as you might say, and it was a turrible sight to see ’em. Big Henry seen hisself drunk last month, and while he’d looked back on it as a kinder glorious event, when the world was all lit up, and him the biggest Mister Man in it, it didn’t look thataway now. When he seen that past of hisn laid right out there in the present, he knowed that was one time he’d jest natcherly been a fool for want of sense. And the tother fellers seen things too that made ’em all swaller powerful hard. What I seen I don’t aim to tell.

Every feller seen his own past, but couldn’t see the tother feller’s; so didn’t nobody know what it was ole Brother Mutters seen, but whatsoever it was, it sunt him off in a long explanation to the Lord.

Well, Tony he seen right off he’d made a big mistake, so he drawed them beasts to a halt, and then he had ’em to back, back, and he run all them yesterdays and last weeks down into place ergin, very keerful like. All hands could hear them past days falling back down the skidways of time, Plup! Plup! Plup! to wait there for Jedgment Day. It sure was a mighty strange and awesome kind of a sound—and not a sound that any common person would crave to hear.

Well, Tony he seen the trouble was he had them beasts headed towards the east, and course thataway they was pulling up the west, which was where all them yesterdays had went. So he turned ’em round westward; and this time when he cracked his whip, and hollered at ’em, it wa’n’t but a minute ’fore they fetched into view jest the prettiest little to-morrer a person ever did see. But it was so all-fired skeery, it was nigh impossible to hold it. It wouldn’t more’n peep over the edge of to-day, when, whoop-ee! it’d run back ergin into its hole like a groundhog what had seen its shadder. Time and ergin them beasts fetched that to-morrer down, and time and ergin, strain as they would, it slipped erway from ’em. So in the end Tony seen he’d have to rigger out a nother way of ketching it. And he knowed, too, he’d have to hurry, for by now it was right late in the day, and it wouldn’t be so very long ’fore that to-morrer would be swinging into place at its natcheral time—and course that wouldn’t do that little feller no good at all.

So Tony he studied a spell, and then he had the hands to git to work and sew a whole parcel of feed-bags together. And when they had a big lot of ’em fixed, and all spread out on the ground, Tony smeared ’em over right thick with tar, and then he went on back to his team.

This time he didn’t crack his whip or holler at ’em; he jest whispered somepen right easy in the year of one of ’em. What that word was I don’t know, stranger. All I know is that the minute he’d said it, and jumped back outer the way, them powerful beasts give sech a heave ergin the yoke, that they jest fa’rly fetched that to-morrer down with sech a run and a jump, that it bounded out head over heels, and landed down right spang in the middle of all them tarred bags—and thar it stuck! The tar it helt it, and when the team was drawed back by the turrible pull of time at the tother end, that to-morrer it busted loose from the string of tother days, and was left laying out there flat in broad daylight.

Well, sirs! it was the furst time in all of our lives that any of us hands had ever seen a to-morrer laid out along side of a to-day, and we sure was carried away by the sight. It was one time we jest natcherly had to hold our eyes in place, or they’d of popped right outer our heads and down into all that tar like a row of buttons. We looked, and we looked, and it’s the truth we couldn’t find nothing ’cept cuss words to say erbout it.

Don’t ask me what the doggoned thing looked like, for I jest ain’t got the words to tell you and you kin easy see I ain’t no hand to make a tale up and pass it off for truth.

Well, after all hands had jest erbout cussed theyselves dry over it, Tony had ’em to ketch aholt of them bags and tote the to-morrer up Flint Holler. There they spread it out in front of the little boy’s cabin. Tony he went inside and fetched the young-un out in his arms, and the minute he laid eyes on it, his face all broke into a laugh. “It’s to-morrer!” he says.

It beats me how that kid knowed right off it was to-morrer, for it’s the truth, stranger, I wouldn’t know to-morrer from last week—no, sir, I wouldn’t, not even if you was to lay ’em out right side by side! But course you know children is different.

“It’s to-morrer!” the little feller says, “and now I’ll be all right!” And with that he reaches his arm round Tony’s neck right tight, and snuggles his head erginst him. “I knowed you could do it, buddy!” he says.

So Tony he knowed he’d been right in picking the onreasonable way.

Well now, stranger, you mought think after all that big to-do, we could of had some rest up Eel River; but you got to recollect that when any feller’s so high-handed as to pull a to-morrer outer place like that, they’s mighty apt to see trouble ’fore all’s over; and I tell you, it wa’n’t but jest a little bit ’fore all us fellers run up erginst jest about the worst piece of trouble a person ever did see.

But not knowing what we was heading for, all hands lef that to-morrer laying up there in the holler for the little feller to git well on, and made for camp as onconsarned as you please.

Tony he went off in the woods ergin, and d’rectly that thar log chain commenced to squirm and jump erbout mighty oneasy like. And then all to onced from ’way off somewheres, we heard Tony holler, “Look out! Look out!” And Great Day! That chain come a-lashing, and a-t’aring outer the woods like a black-snake racer—and you hear me, all hands side-stepped outer its way in a hurry.

Well then, Tony come on back, and he says, “Now we’ll knock off and call it a day.”

So all hands tumbled into the bunk-house early, and was snoring along jest as pretty and nice as you please, when late in the night, ole Brother Moses Mutters sets up a tumble lamentation, groaning and moaning.

“What in the Heaven’s the matter with you? Air you tuck in the stumick ergin?” Big Henry hollers at him, mighty mad at being waked up. Only it wa’n’t Heavens Big Henry said, and he didn’t use no sech genteel word as stumick neither, for he’s a kind of a rough hand ’at’ll lay his tongue to any word he pleases, and be jest as apt as not to come right out and call a bull a bull, ’stead of a “gentleman cow,” like any person what’s been raised right knows it ought to be called.

“Big Henry,” says ole Brother Mutters, looking mighty wild and solemn with his hair all tousled up on end, and nothing but his shirt on, “Big Henry, git up from there, and make ready to die—for the end of the world is coming at sunup!” And with that the ole feller busts out with a turrible howl, and flops down on his knees. “Lord, I never done it,” he says. “It was all Tony Beaver’s doing! Lord, this is me—Moses Mutters speaking. Do pray take notice I didn’t have no hand in it, it was that crazy Tony Beaver——”

“Quit that!” Big Henry hollers at him, jumping outer his bunk, and jerking the preacher up standing. “You quit telling the Lord tales on Tony Beaver or I’ll jest nacherly bust your head off,” he says. “Now then stand up on your two hoofs, and tell the fellers what’s the trouble.”

All hands was awake by now, sitting up in the bunks, kinder blinking in the lantern light.

Brother Mutters had to ketch his breath, and swaller some, ’fore he could git his words out, Big Henry’d jerked him up so sudden; but he layed it all out plain enough onced he got his wind.

“Don’t you all know we’re a-heading for to-morrer jest as fast as the world kin travel—and there ain’t no to-morrer thar,” he says.

“Ain’t—that—so!” says his ole Buddy.

The fellers all stiffened up mighty pale at that, and commenced to cuss to theyselves.

“Well, I reckon there’s a plenty more to-morrers—Tony he only tuck one,” Big Henry says.

“Yes! He only tuck one!” the preacher hollers out. “But he tuck the one we got to have! O my Lord! Tony Beaver’s made a hole in the roadbed of time, and we’re a-heading straight for it!”

Jack Sullivan rips out a powerful cuss word at that. “What’ll happen when we hit the hole?” he says.

“She’ll drap—the world’ll drap right through it,” Brother Mutters hollers. “She’ll either drap away from the sun, and all flesh will be froze to death; or she’ll drap spang into it, and all be burnt alive, like a Juney bug in a light.”

Well, sirs! At that all hands bust outer the bunk-house, like logs busting over a dam, and made for where Tony was laying out in the moonlight, with his head on a gray rock.

“Git up from there, Tony Beaver!” we hollers at him. “Git up ’fore the world draps!”

And then, turrible skeered, and all clammering at onced, we layed out to him what we was heading for.

“Aw, it’ll be all right,” Tony says, gitting up and shaking hisself more like some kind of a wild varmint than a human.

But us hands kinder sensed that for all his bluff he was right oneasy hisself, and that skeered us worse’n ever. Some of the fellers was all for rustling round, and trying to run that there to-morrer back into place ergin ’fore it was too late. But Tony he wouldn’t hear to that.

“Any hand that wants kin take that there log chain back in the bresh, and hitch it to what I had it hitched to,” he says, “but you hear my horn, I’d as soon have the world drap, as to fool with that place ergin!”

And recollecting how that chain had carried on, there wa’n’t a hand that craved to take the job.

“More’n that,” Tony says, “that there to-morrer’s jest natcherly ruined anyhow, and you couldn’t run it back into place ergin, all stuck up with tar like it is.”

That ’peared to be sense, too, and it looked like there wa’n’t a thing to do but jest set and wait for the world to drap.

Well, while we was all standing round waiting—and a plenty of us was shaking like they had the buck ague, and mebbe I was one of ’em—the question come up, if the world was to drap, when would she do it? Some fellers ’lowed it’d be at midnight, and some ergin said it wouldn’t be till daybreak. So there they had it back and forth, and all got so hot, that Big Henry, and Jack Sullivan, that’s Irish stock off’n Piney Ridge, even squared theyselves off to settle it with they fists. But the tother fellers made ’em quit, for they said it’d look kinder ornery, and mebbe give the Eel River crew a bad name, if they was to go into Kingdom Come fighting. That ca’med the Sullivan feller, but Big Henry said he’d as leave go there fighting, as to go any other way. But erbout then the little fiddler had the sense to look at the time.

“Here!” he sings out, “it’s after midnight now, and she ain’t drapped yit!”

“Then it’ll be at sunup!” ole Brother Mutters busts out. “She’ll drap at daybreak! O Lord! I never done it! Lord, this is Moses Mutters speaking. It was all Tony’s——”

“Didn’t I tell you to quit that?” Big Henry hollers at him, dancing up to the preacher, and looking powerful dangerous. “You shet up now and forever!” he says, “and more’n that, when we git across into the next world, if I ketch you up at the Golden Gate tattling out tales on Tony Beaver to Saint Peter, I’ll jest natcherly bust you down to the tother place,” he says. Only Big Henry laid his tongue to a stronger word than “the tother place.”

Well, that dried up Brother Mutters on that head; for skeered as he was of what was coming, he was more skeered of what was right beside him. So he went off on another trail, and commenced telling the Lord how it looked like a shame to have the world come to a end in sech nice fall weather. And that was kinder funny too, for heretofore, the ole feller was allus preaching erbout the world being a desert drear. But he tuned up different now.

“O Lord,” he blubbers, “don’t let the world drap in fall weather when the ground smells so good, and the trees is all colored up nice. If she’s bound to drap, let it come in a cold spell in the winter, or along late in March, when the traveling’s bad, and the mud up to the hubs of the wheels; but do pray don’t let her drap now!”

That set all the hands off sniffling, and wiping they sleeves acrost they noses. For if ole Brother Mutters had to tell the Lord how pretty it was in fall weather, he didn’t have to tell none of them. They jest natcherly knowed for theyselves how the ridges looked, all colored up red and yeller, with the sun shining over ’em, and the squirrels barking up every holler on frosty mornings. “Now jest look what Tony Beaver’s done!” they says sniffling and using they sleeves; “gone and ruined the world on a pretty day in October!”

Tony he told ’em to shet up all that foolishness, and he jest kep’ a-standing up there on his gray rock with his arms folded, and trying to make out like he didn’t keer nothing for nobody. But Big Henry noticed he was staring mighty hard at a pint off erginst the sky. “What’s that you’re a-looking at, Tony?” he asks him.

“Well,” Tony says, “I been noticing these last mornings, that the sun strikes right betwixt them two big pines jest as it tops the ridge. If she don’t strike there this morning, then we’ll know the world is kinder out of plumb.”

Well, sirs! That sunt all hands limp, for it looked like Tony hisself wa’n’t so sure how things was going to be. And when Tony Beaver’s oneasy, you better b’lieve it’s time for any common person to be skeered outer his very gizzards. All the fellers bust loose into a turrible cussing and praying and clammering, like a gang of wild geese what had lost they leader.

By now it was drawing on towards dawn, there was a pale glimmer in the east, and them two pine trees stood up powerful black and strange-looking erginst the sky and every last one of us could feel the goose flesh walking up his back. All to onced Tony Beaver raised up his hand and says, “Listen!” mighty solemn.

Every feller quit cussing, and ketched his breath at that, and over in the woods we heard a little bird cheep, and another answered it back, and then another and another. Not singing yit, jest cl’aring they throats to tune up. And that was a turrible awesome sound, for every hand knowed it was the forerunner of dawn.

And Great Day in the Morning! Jest that minute a strange kind of a dampness come out all over the ground, like the earth itself had broke into a cold sweat. And while we was all a-staring down at that, and listening to the birds cheep, and knowing we was right on the edge of to-morrer, and no to-morrer there—jest that minute the whole world commenced to tremble and to quiver, and to kind of squat down like a skittish horse what sees somepen turrible on in front.

“She’s drapping! She’s drapping!” ole Brother Mutters screeches out, and fell over like he was dead.

The world give another kind of a long tremble, and then, whoop-ee! it give sech a powerful leap and a bound, that it knocked every feller there right off’n his feet head over heels down on the ground—all, that is, ’cept Tony. For a pair of seconds it seemed like we kind of hung on the edge of somepen, and then there was another kick and a scramble, and after that the world settled down like it was over all right.

“She made it! She made it!” Tony busts loose. “By the breath of the gray rocks, she made it all right!”

Jest that minute the sun come up over the ridge, and hung right spang betwixt them two pines, and all the little birds tuck a big mouthful of song, and commenced to pour it out. All hands set up on the ground looking round kinder dazed; and there was jest about the prettiest fall day a person ever did see, with the long blue shadders laying over the frost, and the mists smoking off’n the mountains that was all red and yeller and joyful.

“Tony,” Big Henry says, gitting onto his feet kinder weak like, “what happened?”

“Why, you big idgit,” Tony says looking him squar’ in the eyes, “don’t you know this is a Leap Year? Do you reckon,” he says, “I’d be sech a fool for want of sense, as to pull a to-morrer outer a year what couldn’t leap the hole, and what had a extry day to spare anyhow?”

Big Henry looks at him for quite a spell, and then he says, “Well, I will be dogged!” kinder awestruck.

Well, stranger, you jest can’t make me b’lieve Tony had it all figgered out as fine as that, for he ain’t no kind of a forelooker, and if he wanted a to-morrer, he’d help hisself to it and never stop to think; and I b’lieve him happening to hit a leap year wa’n’t nothing in this world but his doggoned luck.

But it was all too much for ole Brother Mutters, and they laid him out for dead till nigh sundown.

Well now, I jest have to tell you-all that they’s some things a person can’t never git the rights of lessen he’s been up Eel River and met Tony Beaver right face to face. That was what that missionary woman from ’way up North somewheres—Maine or Spain, I fergits which State it was—come to find out.

I was still a-hanging round Tony’s camp, taking notes as you mought say, and sorting out the truth with the lie-paper, when that there woman come up Eel River with her mouth all made up to save the soul of Tony Beaver.

It was a right funny thing how the woman ever got word of Tony ’way up North yonder, and it was all on account of Tony’s hitching them steers of hisn onto the wheels of time and pulling down that there to-morrer for the little feller. That was somepen to talk about sure ’nough, and I reckon some of the hands muster blabbed, for the tale leaked out through the woods ’fore I could git all the lies sifted outer it, and commenced to run wild from mouth to mouth, gitting bigger every second—though I reckon it was big enough when it commenced.

Well, traveling thataway it wa’n’t hardly no time ’fore the tale got up North to Maine or Spain, whichsoever place it was that woman lived at, and the minute the woman heared it, she laid her years back and fa’rly come a-loping down to West Virginia, burning up the trail, for she ’lowed any sech doings as that was jest a pure scandal, and the feller what done ’em must think he owned the earth, and if he thought that, he was a-heading right straight for—for—Aw well! You know the place I mean ’thout me saying it—and it was her business for to save him.

Well, when she come down from the North and hit these parts and commenced inquiring round for Tony Beaver, she run up erginst the same snag I’d hit, for seemed like nobody couldn’t locate him for her. Everybody she ast tole her he had his camp up Eel River, but seemed like nobody couldn’t say where that river was. She was a right smart woman, and had been a school teacher back up North, ’fore she tuck to saving souls, so she hollers for a map, and asts ’em to pint out Eel River to her. Well, there was some Eel Rivers here and yonder out through the country, but didn’t none of ’em ’pear to be Tony’s. Everybody knowed it was up Eel River he lived, but couldn’t nobody pint to the place on the map.

The woman ’lowed she never had struck sech a ignorant parcel of folks afore in all of her life. She said it was very distressing to run up against sech ignorance—an’ I reckon it was. I reckon, too, the woman never would of got up Eel River, if Tony hisself hadn’t got the word that she was wanting to see him, and sunt for her. He sunt his path out for her, but ’course Tony wouldn’t never let that there path travel with a lady like it traveled with me, for he’s allus mighty nice and polite to the ladies. So he had two hands to go with the thing, to hole it down, and make it pace along like it ought with a lady.

It was Big Henry he sunt ’cause he’s sech a powerful stout hand, he could hold the path down, and he had that little Eyetalian feller to go along with him to give style to things. Eyetalians now, strangers, if you’ll notice, they ain’t much force in the woods, but jest put ’em at any kind of a digging job, and you’ll find ’em nigh perfect in dirt. I reckon that’s why Tony allus has a few of ’em in camp—and ’count of they nice manners too.

Big Henry now, he ain’t got no style at all to him. He’s jest one of these here great big two-fisted Jim-bruisers of a feller, what’s a boss hand at his vittles, and at felling trees, spudding tanbark, and skidding logs, but no good at all with the ladies, and handles his table fork like it’s a cant hook. That was why Tony had the little Eyetalian to go along, ’cause he has all kinds of manners, and knows when to take off his hat, when to stand up and set down, and all like that. The missionary woman tuck quite a shine to him ’count of him being so genteel, and on the way out back ergin she tole him ’most everything that had happened to her in Tony’s camp, and that’s how I come to know so well jest what the woman thought.

You would of thought that ole Brother Moses Mutters would of wanted to go out and meet the woman and give her the glad hand, seeing as they was both on the same job, but no, sir! Him and his ole partner Ain’t-That-So went off up a holler and kinder sulked to theyselves all the time the woman was in camp, for Brother Mutters has got him a mighty special brand of religion, and he jest natcherly despises any other feller’s brand.

Well, Big Henry and the little Eyetalian, they tied a right stout rope around that there path’s neck and led the thing out to where the woman from Maine or Spain was a-waiting for ’em, having got the word that they was coming. The woman was right much tuck back when she seen the way she was to travel, for she hadn’t never run acrost nothing like that afore. But she had spunk all right—I will say that for her!

“You stepa on heem, lady,” says the little Eyetalian, taking off his hat and making a grand bow.

The woman balked for a spell, but in the end she says, “Well, I come right down from the Pilgrim fathers—and mothers—and I’ll not go back on my stock,” she says. “One of my feets is Pilgrim, and the tother is Puritan, an’ I’ll trample on that heathenish thing with both of ’em,” she says, gritting her jaws.

I dunno what the woman meant by that, lessen Pilgrim and Puritan is some kinder brand of shoes they got up North. I know they’s got mighty good stout shoes up yonder.

“Stepa on heem, lady, you stepa on heem, and I holda da hand,” says the little Eyetalian, jest as nice and polite as could be. And I’ll be dogged if that ain’t jest what he done! I got to hand it to that little feller. For all he’s a foreigner, he’s got nerve all right, and it’s the truth, he helt the woman’s hand all the way to camp.

So that was the way they traveled. The little Eyetalian walking along ’side the path, holding the woman’s hand, and talking to her mighty nice and genteel all the time, and Big Henry not saying nothing, walking along behind, hanging on to the rope and bracing his muscles to hole the path down. And it tuck some holding too, for seemed like having Pilgrim and Puritan—whatever they was—tromp on it that away made the thing powerful skittish. The sweat was jest a-running offer Big Henry when he got to camp, and he tole Jack Sullivan he’d liefer hole down a four-horse team of mules ’an that path when it wanted to go. And knowing how that thing kin travel when it gits ready, I don’t blame the feller.

Well, they got to camp all safe, but right then and there the woman got another shock, for it’s the truth, strangers, if a person ever sees that lumber camp of Tony’s he ain’t ever liable to fergit it ergin. I ain’t never reely tole you-all jest what the place looks like, jest for fear you might think I wa’n’t telling you the truth, and ever since they commenced to call me “Truth-Teller,” I’ve felt like I had what you might call a reputation to hole up, and I’ve jest come to hate a lie worse ’an anything in this world. I may be a fool but that’s the way I feel about it. One time I rec-lect hearing ole Brother Mutters preaching, and he says, refuting some statement, “My breth’en, that’s a lie! And why is it a lie?” he hollers out, thumping down hard on the desk in front of him. “I’ll tell you why—it’s a lie because it hain’t so!” That sure was one time the ole feller hit the nail right on the head, for it’s a fact, the onliest thing in this world the matter with a lie is that it ain’t so. That’s the very reason why I don’t aim to tell you nothing about Tony’s camp for fear you might think it was a lie because it wa’n’t so.

Well, to double back on the trail to where we was—that there missionary woman was right smartly set back when she got a good look at the place she’d struck. It wasn’t like nothing she’d ever seen afore, and I reckon she wished she was back home ergin and had a-lef’ Eel River alone. Howsomedever, now she had come she knowed it was neck or no duck, as the saying is, and she’d have to stay with her pig and see the job through.

But Tony, he’s allus mighty genteel with the ladies, and he come for’ard jest as nice and common as you please. “Welcome, stranger,” he says.

Well, the woman she wa’n’t used to things too free and easy, and she draws back, and says kinder short, “My name’s Miss Preserved Green.”

“You say you was preserved green,” says Tony mightily s’prised, for the woman cert’nly didn’t look it.

“I said my name was Preserved Green,” says the woman like she’s mad, and buttoning up her mouth right tight ergin.

“Aw-oh! Ex—cuse me!” says Tony, seeing he’d slipped up bad. “Miss Preserves, pleased to meet you,” he says making a fresh start, and holding out his hand.

I reckon that woman kinder sensed she’d better not shake hands with Tony Beaver; but it would of looked awk’ard not to, with him so friendly and all, so she done it. But she told the little Eyetalian afterwards that right then and there she knowed she’d made a big mistake, for the minute she give her hand to hisn, and looked up in his face, somepen kinder slided away inside of her, and it seemed like she could look right through Tony’s eyes, and at the back of ’em was forest trees waving, and the sky with clouds trailing over it; and in the shake of a lamb’s tail, she jest didn’t know nothing ’cept mountains, and mountains, stretching away pretty nigh to the end of the world, and a sky over ev’ything that was bigger’n the world itself; with the wind blowing down the hollers from ’w—a—y off yonder somewheres, and going on by to ’w—a—y off somewheres else and all around the good hot smell of the ground warm in the sun. And seemed like all them things she’d been raised on, and set store by, like sin and jedgment, went blowing a—w—a—y off yonder with the wind inter never, and it come to her all at onced that mebbe the Lord wa’n’t setting up there in the sky watching to see sin trip the world up, but was out there in the mountains enjoying creation.

Right the minute she thought that, she seen Tony Beaver had aholt of her soul and was a-dragging it to deestruction a-long with hisn. At that all the blood of her anchestors riz up inside of her, she tuck a great brace and dug in with both feet. An’ it’s like I said, one foot was Pilgrim and the tother was Puritan, and them good shoes saved her onced she got ’em planted stiff and straight. She snatched her hand outer Tony’s, and the minute she was free she was right back in her ev’yday self, and knowed she had a never dying soul to save, and fit it for the skies. She recollected too what she’d come for.

“Mister Beaver,” she says mighty solemn, and like she was looking acrost the fence into the next world, “I have come for to save your soul.”

Tony he looks kinder dub’us at that, but he ain’t never one to disappint a lady, so he says, “Well anyhow, let’s set a spell and talk it over.”