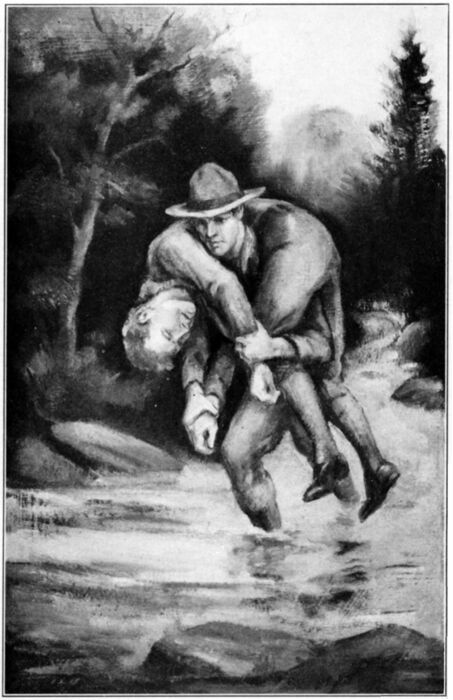

HE WAS REACHING FOR THE BIRD.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Mark Gilmore—Scout of the Air

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Nov. 10, 2019

Date last updated: Nov. 10, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20191117

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

MARK GILMORE—SCOUT OF THE AIR

HE WAS REACHING FOR THE BIRD.

MARK GILMORE

SCOUT OF THE AIR

BY

PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH

Author of

THE TOM SLADE BOOKS

THE ROY BLAKELEY BOOKS

THE PEE-WEE HARRIS BOOKS

THE WESTY MARTIN BOOKS

ILLUSTRATED BY

HOWARD L. HASTINGS

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1930, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Made in the United States of America

CONTENTS

| I | Waiting |

| II | A Decision |

| III | Mark and Edgar |

| IV | In the Storm |

| V | A Fiery Inspiration |

| VI | And Then |

| VII | A Matter of Miles |

| VIII | In the Forest |

| IX | So Near |

| X | On Time |

| XI | Headlines |

| XII | Escape |

| XIII | The Luck of Mark |

| XIV | Dawn |

| XV | A Wrong Step |

| XVI | Sunshine and Shadow |

| XVII | A Reunion |

| XVIII | Confession |

| XIX | Added Injury |

| XX | Fear |

| XXI | Eavesdropping |

| XXII | Good Intentions |

| XXIII | A Vigil |

| XXIV | Despair |

| XXV | A Shot |

| XXVI | Lefty Leighton |

| XXVII | Leatherstocking Again |

| XXVIII | Smoke |

| XXIX | A Live Ghost |

| XXX | Facing Things |

MARK GILMORE—SCOUT OF THE AIR

On a certain stormy night two events occurred in the town of Kent’s Falls in upper New York State, which were destined to have an important bearing on the life of Lefferts Leighton who participated in neither of these occurrences and was at the time many miles distant from this quiet town which he had never seen.

In the simple living room of a cottage along the main thoroughfare, a lady, highly nervous and trying to control her agitation, sat rocking in a chair by the marble-topped center table while her husband paced the floor, silent and preoccupied. The atmosphere in that rather homely room seemed tense.

For some minutes neither of these two had spoken. They were both clearly worried and anxious, but the man’s demeanor was one of anger, while that of the lady bespoke only suspense. They were the parents of Markle Gilmore.

“There’s one thing I will ask you,” said the boy’s mother, “and that is not to have a scene. There’s no use making matters worse by losing your temper; you’d simply make him stubborn and we’ll never get at the truth that way.”

Mr. Gilmore paced the floor, back and forth, and for a few moments said not a word. Clearly, he was not in the least influenced. “I think you may leave that to me,” he finally observed, tersely. “The best you can do is to withdraw altogether and leave the matter to me. I’m not going to brook any interference.” He looked at his watch, impatiently. “You don’t suppose he suspects anything, do you? It’s after ten o’clock.”

Mrs. Gilmore spoke as if her patience had already been subject to some strain. “I think, as I said before, that he stayed for supper at the Halburton’s. When he does that he never gets home before ten o’clock.” She uttered a long sigh, showing the effect of argument and suspense. “Here he comes now, I think.”

But he did not come, and the father continued pacing the floor back and forth, back and forth. The mother made no further effort to read her book, but inverted it in her lap and sat waiting, sighing occasionally. At every sound of footfalls in the street, she started anxiously. Her husband’s silence and steady pacing were portentous.

A tall boy of about nineteen lounged into the room, a cigarette dangling from his mouth. He wore a studied air of sophistication; he looked bored and cynical. It was not often that he graced the household with his presence in the evening.

“Edgar, why don’t you go to bed instead of wandering around?” his mother asked, in nervous annoyance. “Or else take a book and read.”

“I’m sticking around to see the circus,” said the boy, sprawling in a chair. “Didn’t he show up yet?”

Mr. Gilmore, still pacing the floor, darted a quick look of angry disapproval at his son, but said nothing.

“I thought you were going to take Grace Arnold to the movies, dear,” said the boy’s mother.

The son rubbed his thumb and finger tips together with that motion which is intended to convey the need of money, and by this pantomime informed his mother that the lack of it had been fatal to his gallant enterprise.

“Well then, why didn’t you just make a little call on her?” the simple lady asked, under the impression that this good old custom still survived.

“They got no use for you if you haven’t a car,” answered Edgar, sneeringly. “You can bet I’m going to have one by next year. Look at Collie Walters, she’s out with him every night.” There was a pause. “What’s the matter with the kid, anyway?” he asked. “Where’d he go—up to Halburton’s? I bet the little rascal knows he’s in Dutch. What are you going to do—chase him to Military School?”

His father wheeled about, angrily. “If you haven’t got anything to do with yourself, go to bed!” he snapped. “I should have sent you to Military School when you were Mark’s age. Perhaps you would have been capable of doing something worth while now. I want you to get out of the room when Mark comes in.”

The boy smiled, a singularly sneering smile, eloquent of disrespect and cheap sophistication, and slowly rousing himself, ambled out of the room. His mother rocked on silently in her chair, alert to every sound without. Her husband paced the floor with a kind of grim patience—back and forth, back and forth . . .

Back and forth, back and forth. The minutes dragged away; eleven o’clock arrived—half past eleven. The old-fashioned blinds began to rattle; it was blowing up outdoors. Then a patter of rain. A window shade flapped noisily. “I think the rain must be coming into the dining room,” said Mrs. Gilmore. It afforded some relief to her taut nerves to bestir herself to close the window where the rain was indeed blowing in.

At last a familiar footfall was heard on the pavement, and the still more familiar sound of hurrying feet on the steps and porch. Then a boy of about fifteen burst into the room, scaling his cap into a chair. “Oh, boy, but it’s starting to pour,” he said. “A big limb of a tree blew down up the street. The tin sign in front of Tony’s blew across the way and all the way down to the corner—I went chasing after it. If I hadn’t dragged it back to him, I’d have been here before the worst of it. Did I run!”

These were his specialties, doing favors and running. Whatever his shortcomings he was a cheery, good-hearted boy. He did not act as if he thought a serious charge was awaiting him. Be that as it might, there could be no question of his ability at running. He could make a home run where another boy would not get past second base. He had a medal for winning a running match. People said he was a little devil; whether they meant in his running or in his conduct, these pages must show. And he had that rare combination of brown eyes and blond hair.

“My dear, you shouldn’t throw your wet cap in the chair,” said his mother, picking it up. “Why, it’s simply saturated.”

“I’ll say it is.”

“Are your feet wet?”

The boy’s father put a sudden end to these considerations by a brisk onslaught. Thrusting his hands deep into his trousers pockets as if to encourage frankness and to issue a warning that he would stand no nonsense, he paused, then wheeled about, confronting the boy.

“Markle,” said he (usually he called the boy Mark, and his use of the full name was ominous), “Markle, where have you been these last five days?”

“Five—why, what’s the matter?” asked the boy. He had certainly been taken unawares and was obviously perturbed.

“Now Markle,” said his father tersely, “let’s get right down to facts. I want the plain truth and if you don’t tell it you’ll take the consequences. You haven’t been to school all this week. Yesterday afternoon, your mother came home and couldn’t get in the house; she never told me this until tonight. She ’phoned to the school to ask them to send you home with your key, and they told her you hadn’t been there all week—thought you were sick.”

“Your teacher said that Larry Vreeland told her you were ill, dear,” said Mrs. Gilmore. “I do think you might have . . .”

“Well,” Mr. Gilmore snapped, “a boy who stays away from school a week wouldn’t scruple to ask another boy to lie for him. Now what I want to know is, where were you and what were you doing?”

“I—can’t—I——,” the boy began.

His father cut him short. “I didn’t say much when you played truant one afternoon,” he stormed, “and I’m not going to go into the past. But I want to know . . .”

“You don’t give him the chance to tell you,” Mrs. Gilmore interposed, gently.

“Well, now he has his chance. One—whole—week—you’ve been away from school, deceiving your parents, misleading the school authorities, loafing around, I suppose. Now what have you got to say for yourself?” Mr. Gilmore snapped, angrily.

“We just don’t understand it, dear,” said Mrs. Gilmore. “Tell us frankly, what have you been doing?”

“Going off with your books every morning,” said Mr. Gilmore, contemptuously; “and I understand you haven’t been coming in until pretty near supper time every night. Doesn’t it mean anything to you that you’ve been living a lie? Well, I’m not going to have you utter any lies now. Where have you been, and what have you been doing?”

This was a crucial moment in the boy’s life. The momentary diversion afforded by his elder brother’s sauntering into the room gave him time to think. There was that in the elder boy’s cynical smile which bespoke pleasant anticipations; he was going to enjoy the rumpus. Not that he was glad that Mark’s delinquency had been discovered; his smile seemed to express contempt of the boy’s inability to “get away with it.” If he could be said to have any sympathy at all, it was for his younger brother rather than for his parents. But he had little sympathy. This was a sporting event and he was going to enjoy it. He lounged into a chair, lighted a cigarette, and appeared not to be listening. He looked bored.

“I didn’t tell you any lies and I’m not going to,” Mark said, finally. “I told Larry Vreeland that I couldn’t come to school until . . .”

“You couldn’t!” stormed his father. “Well, why couldn’t you? Ball playing——fishing?”

“There wouldn’t be anybody to play with in school hours,” Edgar suggested.

“Well, what was it then?” Mr. Gilmore fairly roared. “One—whole—week, lost at school! Now what have you got to say for yourself?”

“I admit I haven’t been to school and I’m not going to tell why,” the boy answered, nervously, but with a certain fine resolve.

His father seemed staggered.

“You admit! Well, well! And you’re not going to tell! Now see here, young man, I want no nonsense. I want to know what you’ve been doing this last week. Come now, out with it!”

“I don’t want to tell and I’m not going to,” said the boy, firmly.

“You had better tell your father the truth, dear,” Mrs. Gilmore encouraged.

“I didn’t say I wouldn’t tell the truth; I said I’m not going to tell at all.” He probably thought that by this nice distinction he was saving his self esteem.

But his father was in no mood for quibbling. For just a moment he paused, perplexed how to handle this situation. Then he clapped his hands suddenly and vigorously, with an ominous air of finality. “All right, sir, that ends it. Off you go to Military School. If you won’t tell what you do, you’ll go where they can see what you do. So I guess that’s about all and you can march upstairs to bed. I’ll have news for you by tomorrow night. Don’t want to and are not going to, eh? Well, we’ll see about that. Now you march upstairs to bed.”

The boy stepped forward and kissed his mother goodnight; his eyes were brimming. “Dearie,” she said, as she drew him toward her, “please tell your father why you stayed away from school so long. Please do, before you make matters worse.”

“Sure, spill it,” said Edgar. “I bet it had something to do with exams. So long as you’re caught with the goods, kid, you might as well tell why.”

Mark turned to his brother and gave him a look that was at once wistful and pleading. He then hurried from the room and as he plodded up the stairs, they heard him gulp once or twice.

The wind was blowing a hurricane and driving the rain through the opened window of Mark’s room as he entered. It caught the door which he had opened and blew it shut with such a resounding clamor that the brother downstairs thought that Mark had slammed it in angry defiance.

“Little devil,” he laughed. Then he drew himself together and lounged out of the room and upstairs to his own apartment, whose walls were gaily decorated with photographs of girls.

He was almost ready for bed, indeed he had but one thing to lay aside, and that was his cigarette, when he was astonished to see the door softly open and his younger brother enter, closing it as silently behind him.

Mark was still fully dressed, his eyes tear stained, his blond hair disheveled and tumbling down over his forehead. A more sympathetic observer than the gallant Edgar might have discerned that he had tossed upon the bed in the silence of his room and indulged in his little bit of tearful shame. Edgar was observant of only one thing and that was that Mark very softly turned the key in the door.

“What’s the big idea, kid?” asked Edgar, speaking softly. “A week! Holy Smoke, I used to go on the hook for an afternoon once in a while when there was a ball game. But a week! You might have known you’d get nailed. Where were you all the time; down at the carnival? I’ll tell you one thing, kiddo, the old man means business. He’s going to chase you up to Military School; you’ll be marching in line and saluting a lot of tin soldiers and turning out for a bugle. That’s what you’ll be doing, you stubborn little dumbbell. You must have been goofy to think you could get by with that.”

“And how do you think you’re going to get by with what you did and what you’ve been doing,” Mark said, with a kind of hopelessness in his voice. “Do you think you’ll always have me to cover you up—lying for you—yes, and working for you so’s Father and Mother won’t know what kind of a guy you really are!” Edgar’s face grew livid and he tiptoed over to his brother. “You mean you’re going to tell about . . .”

“Did I ever tell anything, Ed?” Mark asked. “It’s a week since you took that money out of Sis ’ drawer—the money Father gave her toward her vacation money. Maybe you didn’t hear Mother say it but Sis phoned this morning before school time and said that she’d he back home tomorrow. Alice Leslie’s mother will get back from Pennsylvania tonight and they won’t have need of Sis’ company. It’s a good thing I thought about Carlin’s truck farm—they pay pretty good money for just pulling weeds. Twenty dollars for a week’s work isn’t bad for a kid my age.”

Edgar’s face remained a pasty white except for two tiny points of color at his cheekbones. “And is that what you’ve been doing all week—at Carlin’s pulling weeds!” he exclaimed in utter amazement.

“Where else did you think the money would come from, huh?” Mark asked, curiously without so much as a hint of anger or disgust at this weak brother of his. “I knew when I caught you taking that out of Sis’ drawer that you’d never be able to replace it—never in the world. Someone had to get the money, so it might as well have been me.” A sardonic chuckle broke the stillness in the room.

“Sh!” warned Edgar as he tiptoed cautiously over to the door, opened it and listened. There was not a sound downstairs; evidently their parents had retired to their ground-floor room. All of the lights were out, and there was no sound but the incessant lashing of the storm, as it rattled the loose windows and streamed down the panes, tumbling like a waterfall off the porch roof. Satisfied, he came back close to his brother. “You went to a lot of trouble it seems to me—how would Sis have known who took it—how would anyone have known for that matter! There could be ways of making it look as if someone came in from outside, couldn’t there? Rumple up the dresser drawers and things like that? Seems to me . . .”

“Never mind, Ed—never mind,” said Mark, as if his brother’s growing weaknesses caused him intolerable pain. “There’s only one way for a feller to act when he’s got a brother like you, and that’s to act decent so’s to make up for him, sort of. It’s bad enough to steal other people’s money but when it comes to your own sister——”

“Not so loud,” the cringing Edgar pleaded. “Anyway, how do you know what I needed that money for? It might have been something important, how do you know?”

Mark smiled wistfully. “Don’t I know what you mean by important!” he said, indifferently. “It’s that pool room, that’s what, and I’d like to know what takes so much money in a dump of a looking place like that is.”

“They’re my friends,” said Edgar, trying to be at least manly in the role of loyalty to his friends, but making a pathetic failure of it. “They like me and treat me swell.”

“Yes?” said Mark, going over and sitting down on the edge of his brother’s bed. “Tell me all about it—for instance: if they think so much of you, why they can’t trust you for twenty dollars or whatever amount it was that you owed them?”

“They’re business people and you can’t owe them money,” Edgar protested. “They make their living that way.” He stopped short as if he was aware that he had said a little bit more than he had originally intended.

Mark shrugged his shoulders as if he were tired of the whole affair. He dug his hands deep down into his trousers pocket and brought out the twenty dollars—a crackling, shiny new bill.

“Well, here you are, Ed,” he said, handing it to his brother. “Here it is. I even got it changed at the bank into a brand new bill—just the way that Father gave it to Sis.” He rose and stretched his arms way above his head, then suddenly stopped. “Maybe it won’t do any good for me to say so, but it wouldn’t hurt you to remember that Sis is a business person and so is Father. They both have to make a living the same as those rotten people . . .”

“Aw, all right,” Edgar interposed, and hiding his great relief under a cloak of boredom.

He yawned audibly and walked over to his bed. “You don’t need to rub it in. I know I’m not much good and that you’re a little brick for doing what you did.”

“You don’t need to thank me, Ed,” said Mark, wearily. “I honestly don’t know why I do these things for you and get myself in Dutch when you ought——”

Edgar wheeled around, cowardice showing in his every move. He came over to Mark and grabbed him by the shoulder, entreatingly. “You’re going to go and tell now, I can see it,” the wretched boy said. “Gee, you wouldn’t do that now, would you, Mark? Gosh, that isn’t being a good sport.”

Mark let the trembling hand remain on his shoulder. “It’s because you’re a punk sport that you think it of me, Ed,” he said, patiently. “You needn’t think I’ll ever tell. Not for anything.”

“How about Military School? You’ve always said you’d do anything rather than go away to one of those places. Suppose Father keeps his word and sends you—what then?”

“It won’t make a bit of difference,” answered Mark, loyally.

“How about Carlin’s—up at the farm?” Edgar asked with fear and trembling.

“Father doesn’t know—you ought to know that by now,” said Mark. “Goodnight, I’m going to bed now.”

But still the miserable brother detained him. He had at least the decency to reach for his brother’s hand and clasp it, gratefully. “All right, Mark,” he said, almost incoherently, “you’re all to the good, you are, but if you ever tell now, I’d . . .”

Mark paused and looked at his brother, thoughtfully. “You’d what?” he asked.

“I’d go throw myself in Lake George,” answered Edgar, with lowered eyes.

“Hmph,” said Mark, a pitying look in his eyes. “I didn’t think you were quite as bad as that, Ed. For one thing, I won’t tell and another thing is, that you’ve got the chance to quit that gang at the pool room and travel around with decent fellers. Wouldn’t Mother and Father be tickled to death if you said you’d get a job!”

“Maybe I will,” said Ed, not very convincingly. “I’ll pay you back for all this, Mark. Honest. Yes, I’ll pay you back.”

“Say, listen,” said Mark, pausing once more, “I don’t ask you to do anything but to work and be decent and quit doing things that I’ve got to cover up for you. Now, Father’ll send me away—away to one of those places, and you won’t have me to fall back on. You got to quit your monkey business then, Ed, or be found out yourself. I’m going to bed.”

The guilty Edgar was loath to let him go. Having no strength of character himself he could not comprehend his brother’s power to resist under pressure. “I’ll quit, Mark,” he said, “but how can I be sure you won’t squeal when it comes time to leave for the school?”

“You’re sure I won’t flunk now—at this minute, aren’t you?” Mark asked.

Edgar was sure.

“Well, you can be just as sure when it comes time for me to go,” said Mark, thoughtfully. Then: “I can promise you I won’t go if I can get out of it, so no matter where I go you can be sure I won’t flunk.” He released himself from his brother, unlocked the door and tiptoed softly into the hall and thence to his own room.

He did not go to bed. All unknown to him the gods had prepared an adventure that was worthy of him. The storm and lightning and thunder were ready to take him to their arms and bear him to his destiny. And that very night, amid the drenching and roaring tempest, he was to hear a voice—the voice of Fate.

Perhaps the gods had heard him say these words, “You can be sure I won’t flunk.” At all events they took him at his word.

As Mark passed to his room he looked down the stairs and saw through the front door that the porch light, which had been turned on before his arrival, was stil burning, and he descended the stairs very quietly to turn it out. But before his finger touched the switch in the lower hall, the light was extinguished, and he was aware of a sudden darkness outside where the street lights had also gone out. The storm must be worse than before, he thought.

He opened the front door and looked out into the pitch darkness. How strangely black the street seemed without those lights. Mutterings of thunder could be heard, and now and then a sudden flash of lightning illuminated the tall, gaunt electric poles standing at intervals along the deserted block. The rain was overflowing the roof gutters and pouring down with incessant splashing.

Mark stepped to the end of the porch where he could look up and see his own window; the light there was also extinguished. This abysmal darkness, relieved by not so much as one familiar light, intensified his feeling of loneliness. He had been somewhat buoyed up by his defiance of his father, and by the difficult scene with his brother. But these matters were past now and his fate was sealed—he was going to some Military School, some institution noted for its discipline, and he pictured it in its very worst light.

The more he thought of it the more he realized how unjust to be sent away from home, from everything. This was to be his reward for his week of labor performed to save his brother from certain exposure! But how could his father know that? His mother?

A streak of lightning flashed across the lawn and the flower beds. The thought came to him that he would defy this unjust sequel to his efforts and run away. But in this storm and without any funds? It was absurd, he told himself. How could he manage it; where would he go?

There was something about the storm and utter darkness that favored his mood, and he lingered in a recess of the porch, assailed by the driving rain. Suddenly amid the tumult of the elements he heard, or thought he heard, a sound which was not one of the voices of the storm. A whirring sound intermingled with the roaring of the wind and thunder.

Sometimes Mark could not hear it at all and when he did it sounded strangely inharmonious with the voices of the storm. Suddenly a dazzling streak of lightning lighted the sky, and there above him, thrown into a kind of ghastly relief, was an airplane. He saw it for only a few seconds, then the night closed about it, and a peal of thunder drowned its steady whirring. Soon he heard it again, but he saw it no more.

Mark was an extremely sensitive boy, and the momentary glimpse he got of that lone plane, struggling in the darkness, chilled him and set his nerves on edge. Such utter loneliness! Such an unequal struggle, it seemed to him! Just that momentary picture, revealed to him in the wild night, aroused in him somewhat the same feeling that he had had for Edgar when he saw him taking the twenty dollars out of their sister’s drawer. It was that very human instinct of the strong character desirous of carrying the weaker one’s burden upon his own shoulders.

He was too young, of course, to analyze his feelings in the matter of the plane. He was too young to realize that the airplane was a weak thing at best when buffeted about by the tremendous force of the elements, and that human nature can often outwit even those handicaps when there is strength of character behind the task. He only knew that he had an overpowering impulse to be of some service to that lonely airman up there in the black, tempestuous night and help him outwit the storm and wind so that he might make a safe landing.

Did that aviator know that Kent’s Falls boasted of a fair-sized landing field? Mark hoped that he did for the community had constituted itself a hospitable refuge for those who braved the perils of the air. It held its welcoming arms open, and those arms were two floodlights flanking the runway in a vast and level meadow.

HE SAW IT FOR ONLY A FEW SECONDS.

Seldom it was that any aviator made use of Kent’s Falls’ generous hospitality and yet the field was always kept mowed and ready, its two beacon lights shining ever aloft to tell the baffled wanderer who chanced in that region, that here between these glowing spots he might set his wheels down in safety.

And now Mark realized with a shudder of foreboding that these lights must also have gone out when the current failed throughout the little town. His own feeling of strangeness in the unfamiliar dark enabled him to form a picture of that baffled airman in a vain quest which meant safety or disaster for him. If it seemed strange and ghostly in the pitch dark of the porch, how must it seem up there in the pitch darkness of the angry night?

Mark had only to open the screen door and grope his way up to his room. But what of the struggling, bewildered airman? Now, in a lull of the storm he heard the whirring again. His nerves were on edge. In a minute, any second, those spreading wings might crash in a crumpled mass before him. What should he do?

Another zigzag streak of lightning brightened the sky, and there was the lonely, forlorn thing, thrown in bold relief for just a second. Then darkness. One of the blinds of a porch window blew loose and began to flap violently. He fastened it open, pushing it into place with difficulty. It relieved him a trifle to feel that he was doing something.

Well, at all events, he could not go upstairs to bed with impending tragedy above him. He forgot all about his own troubles now.

His inspiration to save his brother, and all the events following it, were forgotten. He had another inspiration now. It carried him on its wings and he obeyed it with a reckless frenzy. Oh, if that airman up there in the black storm would only linger for just a few minutes—maybe only ten minutes! But an airplane, even in a storm, may go a long distance in ten minutes. How Mark wished he could call and ask that ghostly visitant to wait!

Rushing into the house he ran pell mell through to the back shed and lifted the five gallon kerosene can that stood there on a box. It was empty. Baffled, he paused. Then suddenly his big inspiration came to him. Running with all his might and main down the street he came, soaked and panting, to the back yard of the corner grocery. He had not the slightest scruple about what he intended to do, any more than he had harbored the slightest scruple about playing hookey from school for a week when it meant safety for his brother. It was this heroic theory of his that a noble end justified a dubious means, that was always getting him into trouble.

A strange figure of a very little demon he must have seemed as he climbed into the old delivery car, wiping his streaming hair and face with his soaked sleeve. His clothes were dripping from the driven rain, his shoes were saturated. But he was quite unconscious of these effects of his exposure. “If I can only get the blamed thing started,” he said.

More than once had the companionable Herman Schmitter, son of the proprietor, allowed Mark to drive this ramshackle car (despite the law) in byways unfrequented by the authorities. The boy knew that if he could only get it started he could drive it now. Fortunately, no one lived in the building behind which this antiquated Ford was housed under a protecting shed.

It started! Mark did not turn on the lights until he was well along the street, and only then because he was forced to by reason of the utter darkness. For a few moments he was apprehensive, but once on Edgetown Road he knew he was safe. No one would stop him or see him now.

The old flivver rattled along, sputtering and slowing down, then picking up again, for the rain was driving in through the radiator. Mark’s only fear was that it would stop. How strange and black the road seemed without the town lights! The lights of the car were reflected in huge puddles in the road through which the old Ford splashed.

Soon he passed the little cemetery and in a flash of lightning saw its gravestones standing white and stark and ghastly. Then, as quickly, they were lost again in the darkness. It seemed almost as if the spectral company housed there had struck a light to glimpse this drenched midnight apparition as he sped by.

Then he was at Kent’s Field. There were no sparks of light there. He drove the car lickety-split up over the hubbly border of the road and straight across to the center of the field. Here were the two flood lights atop their short posts, standing like twin ghosts.

He lost not a second. Driving the car close to one of these he threw open the hood and began to flood the carburetor. Soon his hand was wet with gasoline and he could feel it dripping off the frame. For just a few moments he continued this operation, then drove the car over to the other dead light some seventy-five or more feet distant. Then he ran back and threw a lighted match into the puddle of gasoline.

The effect was sensational. An imposing flame arose and spread which must have been quickly visible in the sky. But one blaze means nothing in a matter of this kind; two mean everything. A pair of lights separated by seventy-five or a hundred feet in surrounding darkness are eloquent to an airman. Mark ran back to the car, flooded the carburetor again, and soon had another blaze which, like its companion, defied the rain.

He had succeeded. Standing in the wind and rain, a forlorn and lonely figure in that vast, desolate, field, he contemplated the two flaming areas. What a strange sequel was all this to his secret labors of the week, his encounter with his father, his rescue of his brother from disgrace! And here he was in the tempestuous midnight, gazing anxiously into the sky—watching, listening . . .

And the next day (or very soon at all events) he was to go to a Military School. As he stood there this realization flashed into his mind, and he could not reason the thing out at all. That this should be the reward of a great, good turn! There was no sound in the sky—only the voice of the storm. He had spoken with his two masses of dazzling flame; he had sent his signal up into the night when all the fine equipment of the field had failed.

Still there was no response to his blazing welcome.

He could not stand there in the rain doing nothing. He kept as close as he could to one of the fires, but the rain, which helped to swell and prolong the flames of gasoline, soaked his clothing faster than the fire could dry it. He ran to the car and wrenching a floor board from the rickety affair, pushed up the soft earth into a little mound around each area of flame, for the fires were spreading as gasoline fires are sure to do. Thus confined, the flames mounted higher and brighter.

But spilled gasoline will not burn long and Mark was now well nigh frantic lest the fires die out and all his efforts go for naught. He could not drive the old Ford into the burning area, so he flooded the carburetor into a vegetable basket which he found in the car, having first pushed an old oil cloth side-curtain down into it. It dripped as he carried it and probably lost as much as he was able to add to the flames in all his frantic running back and forth.

Utterly exhausted at last, he took refuge in the old car, panting, drenched, his head swimming. From this shelter, he watched his precious beacons diminish. And now that his strenuous exertions were over he began to wonder what would happen the next morning when it became known that he had commandeered the Schmitter car. Of one thing he felt certain—his father would be in no mood to applaud his futile, if heroic, enterprise. The only thing that could save him now was success.

And there seemed no prospect of that. There was not a sound in the sky. The dying flames illuminated a considerable area above the field, but no sign was there of that lonely airman striving in darkness and storm. Had it been just a spectral airman that he had seen; something like a mirage?

One wistful thought did come to this soaked and lonely boy as he sat in the old car, a mere atom in that vast, storm-swept field. There was no doubt that he would have a cold and be ill in bed. And perhaps by this means could he checkmate his stern parent in the matter of the Military School.

He prayed fervently that he would be ill for at least one week.

The dramatic sequel of Mark’s heroism occurred suddenly. He had been gazing with a kind of forlorn hope up into the vacant sky and was beginning to realize how impracticable had been his plan to rescue an airman in the storm. The magnitude of such an achievement made the boyish, unscientific means seem silly. Subdued into hopelessness by his sorry plight his thoughts were dwelling on another and surer outcome of his mad endeavor and that was an encounter with his father.

Then, all in a flash, he heard the whirring of the plane. It came as a sort of challenge to the screeching of the wind and even as Mark listened it grew in intensity until it had drowned out the roar of the elements, nearer and nearer, and he saw with widened eyes, a dark bulk crawling along the field. A little short of the flames it swerved a trifle, then stopped.

Mark could not believe his eyes. He was thrilled to the very soul. There it stood, safe and sound, its graceful lines thrown into bold relief by the guiding fires which he, Mark Gilmore, had kindled. And he, he, had brought it safely down out of the jaws of the demon storm! The enterprise which had seemed so preposterous had been successful. He was staggered by his own glorious achievement. If he had thrown a stone at the moon and seen that mighty orb break and fall he could hardly have been more amazed.

He ran pell mell from the old Ford to encounter a weird-looking, helmeted figure that climbed out of the plane and limped over to the nearest fire. Mark approached him, breathlessly, and gazed at him in awe. He was well nigh frightened at this tangible result of his inspired efforts. But not for long. The figure soon proved to be a thoroughly modern person and did not speak the language of legendary heroes.

“What the heck is all this?” he demanded. “Is this Kent’s Falls? Who the dickens are you, anyway? Some night to be without rubbers, huh? I thought a couple of towns were on fire down here.”

“I lighted them—I did it!” exclaimed Mark, excitedly.

“Well, you did it good and plenty. Do you live around here?”

“Yes and the electric beacons went out—all the lights in town are out—and I heard you, even. I saw you once, and I got that car over there and I drove it here and flooded the carburetor and started those fires. They made dandy lights, I guess, huh? Gosh, I didn’t think you’d land because I didn’t hear you for a while. Now I’m glad I did all that.”

For answer, the airman laid both of his hands on Mark’s two shoulders, and holding him thus at arm’s length stared at him in the dying light. What that scrutiny meant, Mark did not know. But he was presently to learn that this stranger had by no means surrendered to the storm. And he was to learn, too, that the splendid service he had rendered to this visitor out of the night was only an incident in a still greater heroic enterprise. Here, indeed, was a young man who thought so nonchalantly of big things that little things troubled him not at all.

“Where’s the end of Lake George, do you know, kiddo?” he asked.

“It’s about seven miles straight north from here,” said Mark. “I know because I hiked it.”

“How far do you live from here?”

Mark hesitated a moment. Some small, inner voice was whispering to him. Why tell this strange aviator how far he lived or where? And in the wake of this small voice came the thought of a certain orphaned boy who had been a neighbor of the Gilmores. After the death of his parents he had been sent to a neighboring orphanage until he was sixteen and was then given work at Carlin’s truck farm. He had worked side by side with the truant schoolboy that whole memorable week and after they were paid off, he had announced that he was going to hike on down towards Albany and see something of the world.

Mark thought of it all in a flashing moment—how he had envied him his freedom. Didn’t he, Mark Gilmore, now have that same chance of freedom as that orphaned boy? Did he not look at least sixteen years of age? He was sure he did and he resolved to obey the warnings of that small, inner voice. He would lie—perhaps this strange airman would then help him on the road to this coveted freedom.

“I—I just—I don’t exactly live anywhere now, mister,” said Mark, falteringly. “I just got through working at a truck farm—I boarded there.” Then quickly: “I was just thinking about beating it down to Albany or somewheres when the storm came on. Then I saw you. I was thinking about getting work somewheres down . . .”

“Hmph—pretty young to be a free lance, aren’t you?” asked the aviator.

“A—a what?” asked Mark.

“Free lance. Beating it around on your own hook, that’s what it means.”

“I—I’m sixteen, mister. Don’t I look it?”

“Yeh, I guess so. You’re pretty big. Anyway, this isn’t any time to be wasting words. And I can’t go hunting around this burg when time’s so precious. I need help and you seem to be the answer to the problem whether you were going to Albany or China. I’m on my way from Mercy Hospital in Duluth with a supply of rattlesnake serum for a kid that got too close to a rattler. He’s in a camp northwest of Harkness. Know where Harkness is?”

“Yep,” Mark answered. “I went there once with a feller in his delivery car—that car over there,” he added, nodding toward the Ford.

“Good,” said the young man, briskly. “I don’t know much about that country ’round there. Pretty mountainous, I hear. The hospital people told me that the doctor who has charge of the case phoned that I could make a landing right back of the camp—Leatherstocking’s the name. I’m not taking any chances though—not on a night like this. They’re to have a couple beacons, but from what I could understand this landing field is surrounded by mountains and forests and a lake. Phew! Suppose I don’t see those beacons with all this mist and rain, huh? I’m not anxious to land on a precipice or in a tree or in any lake. I made one forced landing just before I got here and I sprained my ankle good and proper and that means I can’t navigate very well on it. So if I can’t find those beacons and have to land a mile or two from the camp I’d like to have someone to chase the rest of the way to that camp with the serum—see?”

Mark nodded. “And what do you want, mister?” he asked, anxiously.

“I want someone to come along with me—right now,” answered the airman, briskly. “Maybe I won’t land anywheres near that place—how do I know on a night like this? It’s better to be safe than sorry and that doc told the hospital people that the stuff’s got to be delivered to him by three o’clock or the kid’ll die. They could just get enough of that stuff in Harkness to keep him going until three—that’s the time limit. If I start on right now I can allow two hours for trouble.”

“You mean if you don’t see those beacons?” queried Mark, eagerly.

“Right,” answered the aviator, smilingly. “Maybe you can help me find them, huh? Two heads are better than one so if you’re a free lance I guess it doesn’t make much difference whether you go north or south or east or west, huh?”

Mark’s heart palpitated furiously. His chance had come after all! “I should worry where I go,” he said, excitedly. “Not only that, I’d like to help you find those beacons, mister, I really would! And I’d like to help that poor feller too. Gee, it must be awful to have those things bite you, huh?”

“No pink tea, I guess,” the airman answered, and turned his attention to the plane. Then: “You sure did a stunt with that carburetor, kid. Heaven must have sent you—now I’ll hang on to you until this job is finished. What do you say?”

“I say yes,” Mark laughed, nervously.

“That’s settled. Keep your hand away from that fan!”

“Is it idling?”

“Yep, for about five seconds more. Climb up, and if you put your foot on that wing, I’ll bust you in the eye,” the young man laughed. “Don’t step on the fabric—step on the brass there. Wait a second—will anyone worry about you at the farm?”

“Nope,” Mark answered in a small voice, “there’s no one there to worry about me—nobody.”

“Hmph. And what about your clothes—want me to drop you back here so you can get ’em!”

“Er—er, I can send for them sometime,” Mark answered. “Don’t bother about them. There’s not many anyhow.”

The aviator shook his helmeted head rather pityingly and murmured something about “an orphan of the storm.” Mark turned his head away. The deception he had practiced upon the unsuspecting aviator had worked! The thought of the lies just uttered was distasteful to him but anything was better than Military School—anything! His father’s stern face flashed vividly before his mind’s eye and those grim, tight lips seemed to be warning him. “Well, we’ll see about that!” Would he be such a fool as to want to come back and face the inevitable punishment? No, never.

With a decisive air he stepped in and sat down in the little enclosure. But he was trembling—trembling with the knowledge of his recklessness and as his brusque companion strapped him in he recalled a ride far less ambitious in a gaudy, circling car at an amusement park. His mind was like a whirlpool now.

“Maybe we won’t get back here until morning,” the aviator was saying. “It’s not safe to say.”

Mark sat up straight. “Morning?” he repeated, mechanically. “No, I don’t want to come back here—you don’t have to bring me back at all. I’ll—I’ll stay up there—up there in the mountains if it’s just the same to you.”

“Hmph! I thought you wanted to go to Albany?”

“Er—er—I changed my mind. I should worry about Albany. Since you’ve been talking I thought how maybe I’d have a better chance up Harkness way. Don’t you think so?”

“Suit yourself, kid. You’re your own boss. Where’s the Delaware and Hudson tracks around here?”

“They’re at Fort Edward—that’s east,” answered Mark.

“And you say Lake George is straight north?”

“Yep, and Fort Edward is only about three miles east.”

“All right, we’ll keep our eagle eyes on the rails—that’s surest a night like this. Now we’ll forget about the earth for a little while, eh?” Mark agreed with a nervous shake of his head and sat tense as he watched the aviator climb into the cockpit and busy himself at the controls. Now indeed the whirring of the propeller proved that it had been only idling before and in a flash they sped across the field and up into the drenching night. It was like a fairy tale to Mark. Yet venturesome and reckless as he was he could not help asking himself just once whether the dread uncertainty of the future was not going to be worse than the dead certainty of his future at Military School had he remained at Kent’s Falls.

In the next second, however, he was laughing away the troublesome thought. He even dared laughing aloud for his voice sounded no more than a mere whisper in the roaring of the elements and the beating of the plane through the vast, black heavens. The aviator’s head and shoulders swayed with the motion of it and Mark suddenly recalled those carelessly spoken words of his, “Now, we’ll forget about the earth for a little while, eh?”

He looked down in the black, abysmal pit that was the earth and wondered how one could ever forget about it. It was where homes were and parents lived—parents that threatened one with the punishment of Military School as a reward for one’s great, good turn—a week at Carlin’s truck farm pulling weeds. No, he could not forget about the earth—ever.

And also down on that same earth was the boy that was dying of rattlesnake poison. Could one forget about that?

From that moment on, Mark completely forgot about himself and thought only of that unknown boy to whom they were racing with the life-giving serum. After they had left Fort Edward they flew low, carefully following the gleaming rails of the Delaware and Hudson. There was a fascination in watching those miles of radium-like rails shining up at them through the darkness and storm.

Thunder boomed around them and the lightning zigzagged threateningly first at the nose of the plane and then at the tail. It seemed to be playing a sort of game with them and after each onslaught of this kind the driving rain pelted them fiercely. Mark huddled himself up inside the enclosure and shivered.

Soon afterward lights appeared below and twinkled very faintly through the mist that seemed to cover the earth. Mark craned his neck and guessed that they must be passing over Ausable Chasm for it seemed as if there was no more than just that gleam before they had plunged into utter darkness again.

It seemed an interminable time before more lights twinkled faintly up through the mists. It must be Harkness. Mark relaxed his cramped muscles and watched the dim outline of the airman’s helmeted head and shoulders swaying with the motion of the plane. They swerved slightly and the twinkling lights began to fade away.

Darkness—wind, rain and darkness. There was not a light except an occasional vivid flash of forked lightning, if one could call that light. But still the plane bounded on with a sure purpose and suddenly they soared upward, then circled over the shadowy rim of a mountain.

Several times they circled about in that same area until Mark guessed that the aviator was looking for the promised beacons. But they could see nothing but an impenetrable mist that hid the valley completely. If there was a camp down there they could not find it except by flying low and to do that was dangerous for the mountain wall jutted out here and there in the most unexpected places.

The aviator was plainly puzzled, Mark readily understood, for they flew back and forth, back and forth. Evidently they were in the neighborhood of the camp for the bewildered pilot would strain his neck each time they skimmed the mountain rim for some little twinkle of light, then shake his head hopelessly to the watching boy.

Mark wondered if anyone down there could hear the roar of the plane as he had done back at Kent’s Falls. It seemed to him that they must hear for the noise of the motors sounded equally as loud as the wind and rain through which they were passing.

After a good deal of circling the aviator shrugged his shoulders and turned the plane due east leaving the mountain frowning behind them. They began to fly lower and lower until the mist was about them and soon a little speck of light appeared out of the darkness.

Mark watched it happily, and hoped that the airman would now be able to land. But that person was not taking any chances at any time, it seemed, for he circled cautiously above the light, bringing the plane nearer to earth with each turn.

Suddenly the light grew brighter. Or perhaps it was another light. Mark watched intently and saw that his surmise was correct. It was another light—bigger and brighter than the first and it seemed to be moving to and fro, to and fro. A lantern! The other light came from a low, rambling farmhouse, for presently they swooped clear of its roof and in an instant the boy felt the wheels of the plane grip the ground, wobble along violently for a little stretch, then gradually come to a stop.

“Well, we’re here because we’re here,” the airman’s voice called in the wake of a gust of wind. “I don’t know where we are, kiddo, but we’ve landed safe and sound, eh?”

“You’ve landed on Seth Tomkins’ farm, young feller,” said a man’s squeaky voice. Its owner, clad in oilskins, appeared out of the shadow, bearing the lantern, whose gleaming rays seemed to swing wide with each vigorous step that the man took. “I heerd you up in that storm’n I reckoned you wuz lookin’ fer a place to land without breakin’ yer bones so I lighted up the house an’ the lantern an’ here you are like you says—‘safe and sound’!”

“Yep,” said the airman, climbing out of the cockpit with much difficulty in order to favor his lame ankle, “I’m much obliged to you, Mr. Tomkins—but, where are we?”

“Wa’al, yer jest five miles frum Harkness, young feller,” the farmer answered. “What place are ye aimin’ ter be?”

“At Leatherstocking Camp,” the aviator answered. “I couldn’t see their beacons because of the heavy mist in the valley and I’m not taking any chances in busting up this outfit of mine on any mountain ledge. This was the first place I spied that’s fairly clear of the mist.”

“We seem ter ’scape it every time, thank goodness,” the farmer returned. “But, bye the bye, young feller, you ain’t happenin’ ter be the aviator what they’re expectin’ frum the hospital in Duluth, are ye?”

“I’m he, all right,” answered the aviator, “and I’ve got the stuff.” He pulled a square package from out his jacket pocket and held it up to the light. Then he scrutinized his wrist watch. “How near are we to the Camp?”

“Six miles as the crow flies, young feller,” the farmer answered, pursing his lips, thoughtfully. “I take it yore in a predicament to git there an’ it jest happens that my son’s gone ter Keeseville on business fer me ’till tomorrer. He’s got th’ car an’ the telephone’s out o’ commission frum this here pesky storm. Otherwise we could call th’ camp an’ git one o’ them ter come an’ fetch it. An’ the next farm ter me is five miles east o’ here. Yer cud be all the way ter the camp by that time if yuh can hike it.”

“That’s just what we’re prepared for,” said the aviator. “That’s why I brought this kid along—in case something went wrong. He can run six miles in a jiffy, eh, kiddo?”

Mark smiled and nodded. “Just show me the way and I’ll do the rest,” he said.

“Thet’s easy,” said the farmer. “The trail to th’camp runs right west o’ my land, but it’s mostly woods all th’ way. Thar’s a small bridge what takes yer over the creek—it’s an inlet of Weir Lake. Then yuh’ll come ter a fork in th’ trail thar an’ take th’ one to th’ right. It’s only a few minutes after that fer yer to strike into th’camp. Come ’long, son, ’n I’ll set yer straight on the’way.”

The aviator stuffed the package into Mark’s coat pocket, then thrust a searchlight into his hand. “You’ll need it, kiddo,” he said. “Run as if the devil was after you, too, because the sooner you get there, the better.”

“Sure,” said Mark, proudly. “That’s the way I always run.”

“Good,” the aviator laughed. “You have just an hour and a half so don’t waste another minute. I’ll park here tonight and I’ll see you in the morning. S’long!”

Mark hurried away and followed the farmer. The cheery light from the farmhouse suddenly became a mere speck for they had turned away from the field and into a lane that ran through an apple orchard. They made not a sound for the ground was soft with rain and only a tiny creak from the lantern was audible as it swung to and fro in the farmer’s hand.

Mark felt all a-tingle for some unknown reason. There was so much he wanted to say to the farmer and yet he said nothing but silently followed him out of the orchard and onto a wide, dirt road. Just beyond, in the lantern’s light, the tall gaunt trees of the forest loomed up before him, grim and forbidding looking.

“Wa’al now, here ye are,” said Farmer Tomkins, holding his lantern high. It revealed the narrow trail starting almost at their feet and gaping out of the darkness like the entrance to some gigantic tunnel. “This’ll take yer plunk in ter th’ camp ’ceptin’ fer thet fork what I told yer about. Remember?”

“I remember everything,” said Mark.

“That’s a good thing. And now I reckon yer better git along fer I guess th’ folks at th’ camp an’ the doctor too will be gittin’ anxious for that there serum. Good luck to ye, good luck!” The farmer nodded, swung around and was soon swallowed up in the gloom of the apple orchard. Only the swinging yellow rays from the lantern lingered a short moment there on the wide dirt road.

But Mark had not waited to see this. He had immediately plunged into the trail and the clear white rays from his searchlight penetrated the eerie darkness around him and spurred him onward. He smiled at the thought of the farmer’s wishes of good luck. As if he needed them! Why it was a simple matter of six miles along this trail. He had only to be careful in watching out for that fork . . .

Mark soon settled down into a steady pace and told himself that he could make it in no time. His hopes ran high and he minded not his wet clothes nor soggy shoes—he had escaped, for a time at least, a dreaded punishment. And in this self-congratulatory mood he suddenly became aware that it was really because of this unknown, dying boy that escape had been made possible.

Mark had not given much thought to the suffering boy before. He had been moved, of course, when the airman first told him that “a kid got too close to a rattler.” That kid had seemed rather vague to the running boy; he had not seemed a definite sort of person until now.

He patted his coat pocket and felt the bulge of the serum package. There was something of a miracle in it, he thought. To think that it contained the power to sustain life and drive out of one’s body a poisonous death! And it was he, he who was bringing that power to the boy’s bedside.

The thought gave him impetus and his long slim legs rose and fell over the soft trail with deer-like precision. When he would slow down, the silence of the dark forest outside the area of the flashlight’s rays overwhelmed him. The tall, gaunt trees looked like spectral sentinels back there in the gloom and when a slight breeze stirred the new, green leaves Mark fancied that they sounded very much like human beings sighing plaintively. For this reason he did not once come to a full stop.

After a time the trees seemed to be thinning out, and here and there he would see a great patch of bare, brown earth where some tree had recently been felled. He felt that it was a good sign and that he must be not so very far from the camp now.

“I bet I’ve gone four miles at least,” he thought. “My legs feel that way, anyhow.”

In point of fact, he had not gone quite three miles. Ordinarily he would not have felt fatigued at that distance but his long, hard week of weed-pulling at Carlin’s truck farm was beginning to have its effect upon him. Also the hour was late and that last day at the farm had been the most strenuous of all; he had not had time to rest since a hastily eaten lunch.

He hurried on nevertheless, keeping his mind occupied with various thoughts so that he would not think too much of the weariness that was beginning to creep into his limbs. He dwelt on the scene that he had had with his father and the thought of his escape from a like scene on the morrow gave him an exaggerated sense of exhilaration, for a little while spurring him on like wildfire.

A reaction set in, however, when a thought crossed his mind as to what the Schmitters would have to say about their abandoned delivery truck. He doubted whether they would ever be able to see the heroic intention that had fathered his deed. It made his stomach feel queer and his limbs felt weighted down as if by lead.

A fresh downpour of rain retarded his progress still more, slashing right and left through the wide spaces where the trees had been thinned out and making a bubbling rivulet of the narrow trail. There were times when he sank in rain-filled holes and had to fairly pull his feet out of the sucking mud.

It was after such a task and in the wake of a particularly loud crash of thunder that the brush to his left moved suddenly. Presently, there was a flash of fur and bushy tail across the trail and it moved with such lightning-like rapidity that the startled boy could not discern whether it was a skunk or a squirrel.

Hardly had he recovered from this surprise when he heard a sound like the splitting of twigs or the falling of a young limb from a tree. He stopped a moment, looked around and saw the leaves on the lower limb of a drooping willow moving slightly as if someone were behind it.

He felt strangely cold and fearful for a moment. All was so still in that grim, silent place and his flashlight now seemed to add to the ghostliness. But he stilled his fears by flashing the light all around, then caused it to gleam steadily upon the limb where the leaves were moving and waked two robins and their young ones who had a nest in the crotch of the tree.

The tiny, slumber-blinking eyes and the sharp beaks poking up out of the nest made him laugh aloud. In the midst of his mirth, a loud swish sounded and suddenly a young deer leaped out from behind the tree and into the trail, blinked her beautiful, big brown eyes in the glare of the light, then trotted a few steps and leaped away into the luxuriant growth of the forest.

Mark was intensely relieved, felt of his pocket, patted the bulging package, then ran on. Those few seconds had rested his legs a little and he was certain that he could run the rest of the way in a few short moments. It seemed to him that he must certainly have covered more than three-quarters of the distance.

It was just about that time when an elfin breeze brought to his nostrils the pungent odor of burning wood.

“That sure must be the camp,” be said happily, and visualized the relief he would have when he ran swiftly into its midst. It seemed that there could not be any greater joy than just being able to sit down anywhere.

Mark could not rid himself of that thought and he realized that it was an admission of utter physical fatigue. His feet dragged now and then, he even stumbled, but still he went doggedly on. The rain pelted him furiously and thunder and lightning dogged his every footfall but he seemed not to be aware of it at all for there was fear in his mind—a fear that he would not be able to make his leaden legs carry him on.

“It can’t be much farther,” he would say as each breeze brought the odor of wood smoke nearer. But still the trail loomed ahead, interminably.

Again and again he thought of Farmer Tomkins’ directions—the small bridge over the creek and then that fork in the trail. It had sounded so simple and yet he seemed not to have gained very much headway after all. He was certain that hours had passed since he had said goodnight to the airman and yet an hour and a half was the time limit that he had been given.

He became cold with fear. That boy must not die—not while he could run! And once again he was spurred on, once again he was certain that his goal was merely a matter of minutes. He dashed away the rain that was dripping down his face and gritted his teeth resolutely. He would think of nothing except reaching that bridge!

He brought his foot down with firm resolve—brought it down so hard that it sank deeper in the soft, wet earth than he had intended. There was no stepping out of it; he had to pull at his foot with all his strength and with a terrific jerk of his body he managed to release it.

In anger, he jumped clear of the treacherous spot only to stumble headlong over a fallen limb that had stretched itself across the trail. His flashlight fell out of his hand with a thud, rolled a few feet and after striking against a sharp rock, went out. Mark cried out in dismay and lay where he fell.

After a few seconds his eyes became used to the darkness and he managed to crawl over the log and get up on his feet. But the trail he could not see more than a few feet ahead and that indistinctly. He might have been groping his way through so much pitch as to try and find the elusive light in all that darkness.

He felt around with his hands but the only solid object he came in contact with was a rock, perhaps the one that the light had struck. Finally he gave it up. Time was precious. He had that bridge to find and he would have to find it in the dark.

It was almost impossible to run after that. He had to go ever so much more slowly for the trail seemed suddenly to have become impervious with the shadowy shapes of trees and bushes stretching their great leafy arms across it and sweeping his face in stinging blows. He had not encountered such obstacles before, he told himself. But then perhaps it was because he had had the light and could dodge them.

After he had gone a little way the fearful thought occurred to him that perhaps he would lose the trail. It was so easy to lose one’s sense of direction in the dark. And yet he had seen no other trail so far—Farmer Tomkins had mentioned none except after he came to the fork. Only then would he have to be careful.

He stumbled on, ankle deep in water. A sharp twig on a low-hanging branch struck him in the face and presently he felt a warm pricking sensation on his cheek and knew that he had been cut. But then he got the whiff of wood smoke full in the face and he forgot all else save the fact that he must be not far from the camp.

Suddenly he realized that the ground was not so soft and that he stood on a slight elevation. And just ahead the shadows seemed devoid of trees and brush. Something else loomed up bulkily—a post was it? He stepped up cautiously and felt of it.

A little murmur of joy escaped his lips—he was on the bridge! “I’m in luck,” he breathed. “I should worry about the old flashlight anyway.”

With a bound he stepped onward, his hand gratefully clasping the cool, iron rail. A loose board rattled welcomely underfoot and echoed above the hissing rain. Another board rattled and still another. “Some rickety old bridge, I bet,” Mark observed, and into his step came something of a spring. He was almost at the camp!

He felt of his bulging pocket with his left hand and patted it pridefully. Fatigue seemed to have left his body entirely—he fairly leaped over another shaking board and before his right foot could be brought up with the left one he had the fearful, sickening sensation of having stepped into space.

Instinctively, his right hand struck out and he caught hold of the rail, but his body had slipped down—his legs were dangling in space. He dared not move—hardly dared even put up his left hand to insure more support for the rail was vibrating even then under the strain.

He rubbed his forefinger along the cold metal and found it to be rough. His frightened eyes gradually made out the awful situation—the lower rail which he was holding had partly broken away and was merely hanging out over the space in which he was dangling. The rest of the rail above seemed twisted and bent, but of the bridge floor, he could see nothing.

Where had it gone to? Into the creek below? Had it just collapsed during the storm? Before the unfortunate boy had time to solve these difficult questions the answer came in the form of a breeze heavily laden with wood smoke.

Part of the bridge had burned.

He clasped the bit of rail with strong fingers and put all his strength into it. Though his heart did not cease palpitating, he could think more clearly. The rain had almost ceased and he could hear the steady lapping of the creek below him. How great a drop it was he did not know—did not dare to guess. The knowledge that he was a poor swimmer was bad enough.

He thought of the package of serum. What if he should not be able to hold on there for very long and should drop into the creek—would the serum become affected by water? The thought of such a possibility gave him a chill. So near the camp and yet so far.

The rain ceased and up in the black heavens appeared a small streak of light. It was a cloud moving swiftly and behind it, Mark was sure, hid the moon. He was inspired with hope and sent a call resounding through the woodland.

“H-e-l-p!”

If the camp was near enough they ought to hear it. He roared his appeal twice more to make sure. Then he waited and listened, while the muscles in his hand began to rebel. His fingers had a queer, tingling sensation that soon developed into an unbearable ache.

A company of bullfrogs broke the silence with a steady chant. Mark was grateful for it though. It took his mind off of his own troubles for a fleeting second. But then the thought of his mission came racing back just as the moon came bursting through the black clouds.

It shone and glittered with a radiance that Mark had never beheld before, lighting up the broken bridge and bent, twisted railings, vividly. He let his eyes wander below, then over his shoulder and gave vent to a loud, mocking laugh.

“Well, if this isn’t April fool!” he cried in self-derision. “It’s a joke and a pretty mean one.”

He had been a victim of that joker, Night. Just when time was so precious, when a life was at stake, the forces of darkness had been laughing at him and working against him, and had kept him ignorant of the fact that the creek was but a seven foot jump with no more than six inches of water rippling over its white, sandy bed. And although he had not been deceived about the bridge being burned (for bits of timber still lay smoking against the bank below), there had been no more than three feet of that quaint little rustic structure destroyed.

It was obvious that lightning had played one of her freakish pranks on the bridge that night.

It had twisted the stout railings, had torn away that bit of flooring and had probably gone on her way rejoicing, setting a trap for poor, hapless Mark. But the moon, praise be to her, had befriended him.

Mark never forgot that moon.

The boy had the feeling of one defeated when he emerged from the trail and into the vast grounds of Leatherstocking Camp, for just ahead a dim light twinkled from a picturesque rubblestone lodge. All the other log-cabins surrounding it stood in utter darkness and he told himself that this somberness could mean only one thing—death! If life still flickered in that unknown boy would they not keep the camp bright with light?

His eye lighted upon a small, wide field that lay between the frowning mountain and the murky looking lake. Two beacons were burning there, patiently—the beacons the aviator had missed. And now he had come too late to justify even those lights.

He had now approached the cabin on the outskirts of the camp, but all was still. It was only when he came within five feet of the rubblestone lodge that he could see a fair-sized, khaki-clad young man moving about within.

“Somebody’s got to stay up when there’s someone dead,” Mark whispered, mournfully. “Gosh, I bet they’ll feel like throwing me out when they see me. Two hours ago I’d have been welcome.”

A cool, damp mist blowing from the lake touched his burning cheeks and he stumbled up before the great door, trembling. Before he knocked he steeled himself for the rebuff he was sure they would give him. It was, therefore, something of a shock to him that his timid summons brought an immediate response and that in the form of a pleasant-faced young man who received him with a wide-mouthed grin of ineffable joy.

“Welcome kiddo, welcome!” he cried after a second, and pulled the bewildered Mark into the sumptuous lodge. He gave the boy’s wet coat collar a fraternal yank, then called joyfully, almost hysterically, up a rustic stair, “Oh, Doc! Oh, Doc!”

Two doors opened immediately and two men stepped out simultaneously onto the balcony, just under the heavy, polished rafters. In a sort of daze, Mark saw their two faces peering at him over the shining, balcony rail. They said something, then looked back at the boy as if he were a ghost. Both men then turned toward the stairs, and the man ahead was saying, “So, he’s here, eh Slade? He’s here!”

“He’s here, all right, Doc,” said the young man, and put his arm around Mark’s shoulder.

Mark came suddenly out of his surprised stupor and delved into his pocket for the serum. “I got it!” he said, breathlessly. “But is he really alive—is he really alive? Then it isn’t four o’clock and I’m not too late, huh?”

“No, you’re not too late and it isn’t four o’clock and he’s not dead, thank goodness!” answered Slade. “It’s only half past two and you’re just on time and you’re also a brick! Isn’t he, Doc?”

The doctor agreed that he was and with a preoccupied, professional air, he took the package of serum from Mark’s hands, examined it gravely and hurried up the stairs. The other man who had remained up on the balcony during this little scene, waited until the door had closed softly behind the doctor, then came on down the stairs.

Slade introduced him as Mr. Wainwright, a sort of chief administrant at Leatherstocking Camp. He grasped the boy’s hand heartily, looking at him meanwhile with a kindly, yet a studied scrutiny, then turned to Slade. “He looks pretty much the worse for wear, eh, Tom?”

Tom leaned over and tousled Mark’s straggling blond hair. “You’ve had quite a night of it, huh kiddo!” he said, jovially. “A night you’ll long remember, I bet.” He gave the boy a friendly push down into a nearby willow chair.

Mark twisted one foot over the other awkwardly. “My clothes are pretty wet,” he said in a small voice. “I even got worse than wet because I stumbled and fell and zip—my flashlight went out of my hand. I had to walk in the dark then and when I came to the bridge I got scared because I thought it was half-burned away. But it wasn’t—when the moon came out I saw I was April-fooled because I could have jumped over on the bank easy. There I wasted all that time when only a few feet of it had burned,” he added nervously.

“But you stuck to your guns and came on and that’s what we’re grateful to you for,” Mr. Wainwright said.

“I knew you’d be here,” Tom said, smiling. “I got a phone call from Tomkins’ farm just a few minutes before you came—the telephone wires had just been fixed, and the aviator told me the whole story. He said you were about due if nothing else had happened.”

“He told me to run like the devil and I did, except when I got stuck that time,” said Mark, naively. “Now I’m here and the feller’s saved, huh?”

Tom smiled. “You beat the devil at his own game,” he said.

“You mean—you mean that the rattlesnake was the devil, huh?” Mark asked, quickly.

“Exactly,” said Tom, “and I guess the kid won’t forget the chase you made to get here.”

“Lefferts is the kind of boy that doesn’t forget a thing like that,” said Mr. Wainwright, glancing up the rustic stairs in the direction of the sick room.

“Is that his name?” asked Mark, interested.

“Yes,” answered Mr. Wainwright. “You see he is just a guest here—a guest of Tom’s and we feel a double responsibility. If this thing had proved fatal we would have felt it keenly for Lefferts was the first scout to be our guest. This is a training camp for scoutmasters and it was founded by Mr. John Temple just the same as Temple Camp in the Catskills. Ever hear of Temple Camp?”

Mark’s brown eyes were full of light despite his weariness. “I know a feller—a scout that goes down there every summer,” he said.

“I bet you do,” Tom smiled. “But how is it that you’re not a scout so you can go down there too?”

Mark’s heart missed a beat. He was cornered into telling the hateful lie. But it had to be done. “I—I—didn’t that aviator tell you about me?” he asked, hesitatingly.

“Oh yes—yes, that’s so,” said Tom. “He said something about you being an orphan that was on the way to Albany to work. He told me all about the big stunt you did for him in Kent’s Falls—that was a stunt worthy of a scout!”

“So you’re an orphan and looking for work, eh?” Mr. Wainwright asked, with that studied air that frightened Mark.

“Yes sir,” answered the boy, timorously.

“You don’t look sixteen, my boy,” Mr. Wainwright said.

“Yes sir—I mean, no sir—I mean, I know I don’t,” Mark stuttered, with his mind in a whirl. “I mean, I’m big for my age. That’s what my—my friends all say. Everybody says it.”

“Hmph,” said Mr. Wainwright still studying him.

Mark was well nigh frantic and began to fear that the interview would have a disastrous result. Tom saved the day for him, however, by announcing that he was thoroughly tired and wanted to go to bed, and suggesting that the weary boy should sleep in his cabin so that he would not hear the disturbing noises of the lodge in the early morning.

Mark did not demur at further plans that were made for his comfort and when Tom talked about getting him a snack of a sandwich and milk from the eats shack, he smiled gratefully but said nothing. He had a fear that Mr. Wainwright would pounce upon him with another question should he utter only one word.

And so he was intensely relieved when he left the lodge and followed Tom across the flower-bordered gravel path to a small cabin. Somewhere a katydid was humming its insistent little ditty and the moon overhead was slipping under some clouds as they entered the cozy little place.

“That’s a sign you’re welcome,” Tom said, laughingly, referring to the katydid. “I’ll fix up the kid’s bunk for you and you can sleep as long as you like—you wouldn’t be able to do it at the lodge. There’s a contingent of aspiring scoutmasters coming in the morning and you’ll be out of the racket here.”

Mark felt awkward and shy alone with Tom but he had not the same fear of him that he had of Mr. Wainwright. He stood about fidgeting while the young camp assistant made up his bunk. After a few minutes he began to divest himself of his soggy clothes and the silence inside the little cabin continued.

Suddenly Tom turned from his task and looked squarely at him, smilingly. “Say, kiddo,” he said, pleasantly, “do you realize that you haven’t even told me your name?”

“Gosh!” said Mark, awkwardly. “I—I didn’t mean . . .”

“That’s all right,” said Tom, kindly. “I guess you just forgot. What is it?”

“Er—er,” Mark began and felt panicky—he couldn’t think of a single name save his own. In sheer desperation he got out of his trouser pocket his handkerchief—anything to kill time in order that he might think. But it did not do any good—he could not think. He was forced to say, “Mark Gilmore.”

“Mark Gilmore, eh?” Tom repeated, blissfully unaware of the turmoil that was seething in his young guest’s mind. “I like the name of Mark, kiddo. That’s a good snappy name for a scout.”

“But I’m not a scout,” Mark said, smiling at Tom’s breezy manner.

“You’d like to be one though, wouldn’t you?” Tom asked, insistently.

Mark nodded. “I’ve always wanted to be one,” he said, simply. In his heart he was thinking that it was because his father had never permitted it, giving as the sole excuse that, “Scouting is just another reason for you to get out of the house nights.”

Tom smiled, sympathetically it seemed, and flung the covers of the bunk in order. “There you are, Mark,” he said, briskly. “Now hop in and I’ll dash over to the eats shack and back before you get the chance to blink your eyes.” He gave the boy a friendly push toward the bunk and in a moment was gone.

Mark listened intently as the gravel crunched under his energetic footsteps and decided that he liked him very well. Into this deep contemplation of his came the sound of rain swishing against the cabin windows. It gave him pleasure to listen to it now for he was safe and sound and sheltered.