* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

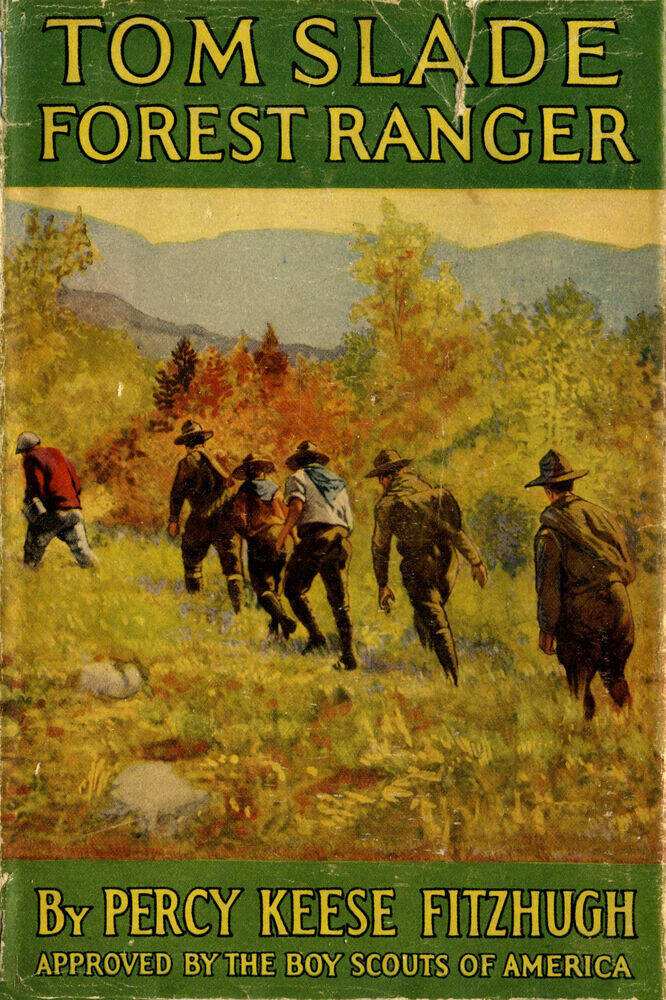

Title: Tom Slade: Forest Ranger

Date of first publication: 1926

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Oct. 18, 2019

Date last updated: Oct. 18, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20191043

This eBook was produced by: Roger Frank and Sue Clark

TOM SLADE: FOREST RANGER

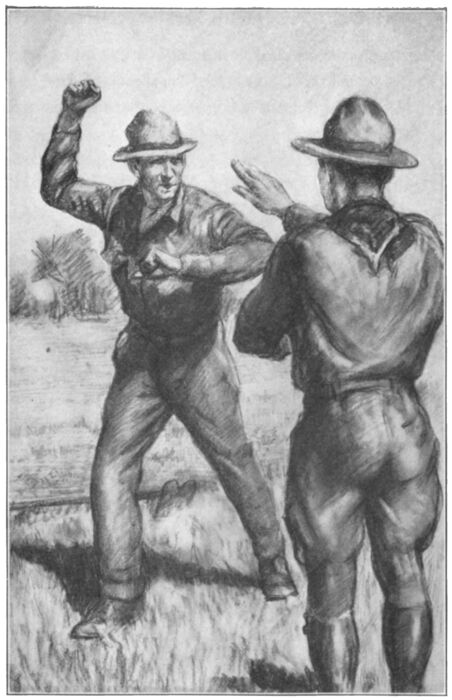

“WELL—I’LL BE—BRENT GAYLONG!”

TOM SLADE:

FOREST RANGER

BY

PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH

Author of

THE TOM SLADE BOOKS

THE ROY BLAKELEY BOOKS

THE PEE-WEE HARRIS BOOKS

THE WESTY MARTIN BOOKS

ILLUSTRATED BY

HOWARD L. HASTINGS

PUBLISHED WITH THE APPROVAL OF

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1926, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| I. | Voices of the Night |

| II. | As Luck Would Have It |

| III. | Watson’s Bend |

| IV. | The Schoolmaster |

| V. | The New Job |

| VI. | The Wind in the East |

| VII. | The Monster |

| VIII. | Tempest Peak |

| IX. | The Face |

| X. | The Fugitive |

| XI. | Dawn of a Great Day |

| XII. | The Blind Trail |

| XIII. | The Black Sheep |

| XIV. | Flight |

| XV. | Trailer Bentley |

| XVI. | The Voice of the Village |

| XVII. | Baffled |

| XVIII. | Seen in the Storm |

| XIX. | Who? |

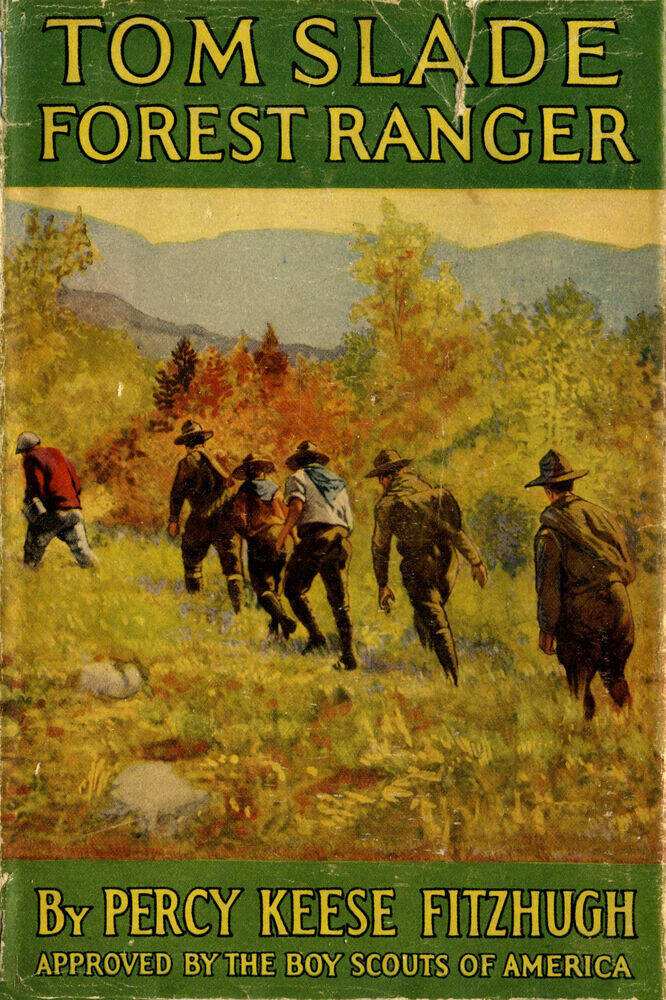

| XX. | Three’s a Company |

| XXI. | Down in Black and White |

| XXII. | Straight Talk |

| XXIII. | Tom in Action |

| XXIV. | The Fire Warden |

| XXV. | Brent in Action |

| XXVI. | On the Window Sill |

| XXVII. | Reading, Writing and Spelling |

| XXVIII. | News of Henny |

| XXIX. | Henny’s Cross |

| XXX. | Lizzie |

| XXXI. | The Hearing |

| XXXII. | The Scout Handbook |

| XXXIII. | The Bird has Flown |

| XXXIV. | Brent the Philosopher |

| XXXV. | An Answer to “Why?” |

| XXXVI. | The Biggest Good Turn |

| XXXVII. | Moonlight |

TOM SLADE: FOREST RANGER

In a momentary lull of the storm the baying of a dog could be heard in the heavy darkness at the base of the lonely lookout station—a weird, long moan seeming like one of the many voices of the raging wind. It lasted for only a few seconds, then was drowned in the furious tempest. The structure trembled as the frenzied gale swept through the steel framework.

Up in the little surmounting enclosure Tom Slade stood aghast. Could it have been the voice of the spectral dog that he had heard? What nonsense! The very thought aroused all Tom’s common sense and he laughed to think that the wild elements could play such a trick on him. If it had not been for the weird stories he had heard, the moaning would never have sounded like the voice of a dog at all. He laughed good-humoredly, as he had laughed when the people of the distant village had edified him with those ghostly yarns.

“It’s blamed funny the different noises the wind can make,” he reflected aloud. It was so lonesome in that high, storm-swept wilderness that almost unconsciously he spoke aloud to keep himself company.

Yet the sound of his own cheery voice, bespeaking his common sense, did not quite reassure him. And in spite of himself he listened again for that moaning voice amid the storm. He waited; he was almost ashamed of himself for his credulity, but yet he waited for another lull in the black hurricane.

Then in a brief subsidence of the gale he heard again the baying in the darkness below him. To be sure, it seemed unreal, intangible, a part of the furious storm. Yet he could distinguish it as something different. If it was not the robust voice of a dog heard clearly above the clamorous elements, that only bore out the stories told by the people down in Watson’s Bend. For was it not the whining of a spectral dog of which they had spoken? Was it not this that had caused the place to be deserted and shunned? The whining of a spectral dog and the terrifying presence of a ghostly master.

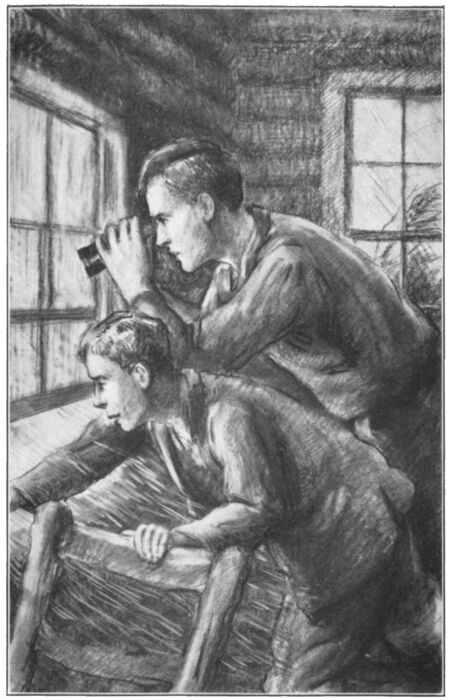

Tom stood motionless, gazing at the candle which cast its faint glow over the large, round map that covered the table in the center of the little, lofty shelter. The electric wires had gone down in the storm and this candle was all that stood between Tom and utter darkness. And the little box of a shelter standing high upon its trestled pedestal was all that stood between him and the tempestuous night.

Now and again, as the shrieking, furious demon shook the tower, the tin candlestick joggled and the light flickered on the glass which covered the map. And the field-glass, which stood there too, ready for scanning those rugged mountain slopes and distant hills in the daytime, danced a little jig with its two stout legs with every fresh gust of the hurricane. There was something uncanny in the way those two connected cylinders would start and cease to joggle on the sounding glass to the uproarious accompaniment without. It was odd and disturbing how, whenever they ceased their ghoulish dancing, that ominous baying could be heard below.

“And then the ghost of his dead master comes out up there in the tower and tries to call the dog, only he can’t make out to speak, so the ghost of the dog never knows he’s up there.” That was what they had told Tom off in the village. “No, siree, you couldn’t get none of us ter go up and mind that tower—not us.” And Tom had tried to laugh them to shame.

But he did not laugh now, for just then he saw the face.

If any one in Watson’s Bend had been willing to take charge of the fire lookout station on Tempest Peak, that lonely job would never have fallen to Tom Slade.

Even Tom, with all his adventurous spirit, would have balked at the isolation of the tower far up in the mountain wilderness, had it not been that his companion in former adventures, Brent Gaylong, had agreed to spend the summer with him in his wild retreat. But Brent could not join his friend until the summer was well on and, meanwhile, the job must be filled.

“Look for me around the first of July,” Brent had said. “Keep scanning the horizon with your trusty field-glass and you’ll espy me in the distance approaching up the rugged slopes with my knitting. I’ll spend the summer doing crossword puzzles while you’re fire-lookouting. I only hope we have some good conflagrations. Keep the forest fires burning. If we don’t I’m going in for floods on the Mississippi next summer. My soul craves adventure. How about the ghost?”

“Oh, he pokes his head out now and then, so I’m told,” Tom had answered laughingly.

“That’s great,” Brent had answered with a kind of drawling relish, “but I’m afraid he’ll be away on his vacation while I’m there. I kind of like the idea of a spectral dog, don’t you? Don’t know as I ever heard of one.”

“You’ll hear enough about one if you go to Watson’s Bend,” Tom had laughed.

“I hope he’s not a spectral mut,” Brent had answered. “Anyway, we won’t have to feed him.”

“I’m not worrying about the ghost and his ghostly dog,” Tom had said, “but if you don’t show up I’ll kill you.”

“Never fear, Tommy,” Brent had laughed. “It’s always been the dream of my young life to meet a ghost. I feel like Hamlet already.”

That conversation had occurred a couple of months prior to the tempestuous night when Tom’s adventures on Tempest Peak began. During April he had driven up to Temple Camp in his outlandish flivver. As assistant manager of the big Scout community in the Catskills, it was his custom to run up from Bridgeboro each spring to look about and help old Uncle Jeb Rushmore open up the cabins and pavilions and get ready for the rush to camp which would begin as soon as school closed.

During the winters Tom was in the Temple Camp office, which was maintained in Bridgeboro under the supervising eye of Mr. John Temple, Bridgeboro’s most public-spirited citizen as well as founder of the famous Scout camp. The Temple Camp office was in the fine building which Mr. Temple owned and in which his bank was housed.

Tom was particularly anxious to make an early flying trip to camp this spring, for he was to have the summer off, and he wished to see Uncle Jeb and find out how that old hickory nut of a scout had enjoyed his own summer off in his old familiar Rockies. Old Uncle Jeb had returned to the closed-up camp in March, and Tom was to have his turn in the summer now approaching. Mr. Temple had insisted on Tom’s taking a summer off, as his old superior had done. “Get out among grown-ups for a while and then you’ll appreciate the kids when you get back,” Mr. Temple had said.

We need not concern ourselves with Tom’s visit with Uncle Jeb. He stayed there two days, then bade a regretful good-by to the beloved camp and to the old man who was its very spirit. As he drove home in his dilapidated nineteen-ten flivver, he had not the slightest idea how he was going to spend the summer. He was a little sorry that he had not insisted on staying at camp, his camp, where the thunderous voice of Pee-wee Harris could be heard to the bantering accompaniment of Roy Blakeley.

As he drove down the state road, one loose fender waving like some martial emblem in the breeze, he thought that perhaps he would go out and surprise his sister in Missouri. He had not seen her since he was a little boy in Barrel Alley. She had renounced the alley and had married and gone west. Then it occurred to him that he would take a flyer over the water and see the old battlefields where he had fought. He would hunt up Frenchy (you remember Frenchy?) and they would have an old-time hike in the Black Forest. Then he thought he would like to go up to Overlook Mountain, just for memory’s sake, and see——

Whoa! That was a narrow escape. His daydreaming had almost brought him plunk into a big red sign which stood across the road. And upon that sign perched Tom’s good little angel of adventure. ROAD CLOSED. TAKE DETOUR TO LEFT. FOLLOW ARROW, he read. Around went the rickety little Ford down into a sequestered country road, over bumps and into puddles, and into a country where it seemed to Tom that no automobile had ever gone before. Soon he was in a wilderness. And his own particular little angel of adventure perched upon the leaky radiator of his car. But of course Tom could not see her. Lickety-split, he went, down into the loneliest and wildest region he had ever seen, cursing the autocratic signs and bone-racking detours.

And that is how Tom Slade came to Watson’s Bend.

Whoever Watson was, about the only thing he seemed to have was his Bend. But it was a terrible bend. From whichever direction the motorist approached it, it was a place to cause a shudder. At night, thought Tom, it would be the worst kind of a death-trap. He paid his respects to it by jamming on his brakes and going around the horrible corner at a decorous speed. That was more respect than he had shown the remote little village itself which lay just westward of the bend. The turn formed almost a right angle. The narrow, grass-grown road ran west and east, then turning as if some giant had pulled it across his knee and broken it, it ran north and south.

After Tom had made the turn, he paused to look about him. He was so interested that he drove his long-suffering car into a thicket of brambles and sauntered out into the road. He saw that the road, such as it was, bordered the lower reaches of a mountain which towered in the southwest. It was because the road followed so closely the base of that frowning height that it made so abrupt and perilous a turn. Off to the north and east the land lay in low, undulating fields as far as the eye could see.

The road was not exactly cut into the mountainside like many scenic highways—it followed a natural course around the base of the heights. It cut a sharp corner because the base of the mountain did. In other words, this sequestered road enclosed a mountain or jumble of mountains. Off to the other side of the road was low country. If you plunged off the road at the bend you would go down twenty or thirty feet, and that would be enough.

“Some place, I’ll say!” mused Tom.

He shaded his eyes and looked away off up into that mountain wilderness. “What the—dickens——” he said, somewhat puzzled. Then he concentrated his gaze on something which he saw or thought he saw. The trees upon those distant slopes were still bare, though here and there a patch of green could be seen in the bleak landscape.

“That’s some blamed kind of a thing away up there,” said Tom. “I’ll be hanged if it——”

He changed his position and gazed again, long, intently. Then, as if resolved to settle some matter in his mind, he strode back along the road, around the bend, and to the little village. He paused to gaze again far off into that rising wilderness. But from this new point of view he could see nothing.

Beside its perilous corner, Watson’s Bend possessed about twenty houses, a village store, a tiny schoolhouse and some chickens perched in a row on a wayside watering trough. Watson’s Bend was absolutely harmless save for its sharp turn in the road.

On the platform of the village store sat three men who had not yet recovered from their astonishment at seeing the stranger go rattling by.

“That turn in the road is the sharpest thing I ever saw outside of a razor,” said Tom. “But I don’t suppose there’s much traffic through here ordinarily.”

“Don’t drive like yer hadn’t oughter do ’n’ ye’ll be all right, I reckon,” said one of the men.

“’T’wan’t fer that there bend this town wouldn’ hev no name at all,” said another, evidently the local wit. “Yer in the army?” he asked, alluding to the khaki which Tom almost invariably wore.

“No, I’m mixed up with the Scouts,” Tom said. And he could not deny himself the pleasure of adding, “Ever hear of them?”

“We got one on ’em.”

“No, we hain’t, they go in gangs, sort o’ regiments like,” said another of the trio.

“Sterrett’s youngster, he’s one on ’em.”

“No, he hain’t nuther.”

“Yere, he is,” said the first speaker, “he’s one them all ’lone scouts.”

“He hain’t got no togs,” said another of the three. “’N’f I wuz Sterretts I wouldn’ git ’im none. He’s a dirty little devil of a Heinie, that’s what he is. All ’lone scout, huh? If I wuz ter give ’im anything, I’d give ’im a taste er harness strap.”

“The war’s over,” said the one member of the trio who was hatless. Tom thought he was the presiding genius of the store.

“How’d yer find that out?” the village wit shot at him.

Tom laughed too and, looking casually about him, wondered how they had found it out.

“Nice day,” the hatless man said.

“You bet,” said Tom. “I was going to ask you if that’s a fire lookout station away off up the mountain. I saw it from around the Bend, I don’t seem to be able to see it from here. Kind of a box up on—I guess it’s on a framework? I could only see the top part.”

“’Tain’t, but uster be,” said one of the trio. “They ain’t nobody up there now—’less yer call a spook somebody.”

“There seem to be plenty of woods all around to get on fire,” Tom said.

“Oh, there’s woods enough,” said the other loiterer. “I’d take my chances with a fire any time before I’d get inter a mess with a spook, I would. I seed fires sence I wuz a kid, ’n’ I ain’t seed nobody killed by one yet, I hain’t.”

“Lizey Henk’s man wuz killed by a wood fire,” the other visitor said. “Comin’ through from Skunk Holler.”

“That wuz thirty year ago,” said the other.

“Killed then or killed now, it’s no matter,” his companion retorted. “All Derry Conner’s woods wuz burned down. Nobody never knowed what started ’em.”

“’Twas the ole feud started it, that’s what ’twas. Derry’s wife’s folks wuz agin her hookin’ up with Irish. Skunk Holler ’n’ Irish Pond wuz alluz hittin’ back one way or another.”

The proprietor of the store leisurely pulled a corncob pipe out of his ticking overalls and, disregarding the conversation, proceeded to fill and light it. It seemed to Tom that this comfortable, white-haired man was not altogether of a mind with the others.

“Lizey Henk’s man wuz tipsy,” the old man finally drawled.

Tom was rather amused at these village reminiscences with all their quibblings and ignorant prejudices. But he thought that the store owner was rather more intelligent, or at least more mellowed than the others, and so to him he addressed his next question. There was something breezy and offhand and broad-minded about Tom which set him off in strange contrast with these citizens of Watson’s Bend.

“Well, anyway,” he said cheerily, “tell me about the ghost. I don’t know as I’m specially interested in ghosts, but I’m blamed interested in saving the forests, and you can bet there ought to be somebody up there for what’s the use of having it if they don’t use it? Why, you’ve got miles and miles of unbroken forests around here. That’s a nice state of things.”

“’N’ I s’pose you’d like to go up here?” the old man asked.

“Well, I sure wouldn’t let a spook keep me out,” laughed Tom.

“If you went up there ye’d come back lickety-split, hop, skip and a jump, quick enough,” said the humorist of the party.

“No, he wouldn’ come back nuther,” said the other loitering historian. “Did Chevy Ward come back? Yere, I reckon! But not hop, skip and jump. He come back ’cause we carried him back, me an’ George Terris an’ Denny.”

“What happened to him?” Tom asked.

“Murdered.”

“Murdered? Did they get the one who did it?”

“A spook done it, him ’n’ his spook dog. Why, sonny, if yer wuz to offer one thousand dollars ter any one round these parts ter go ’n’ look after that hell spot, they’d on’y laugh in yer face. The State wardens they ain’t even tryin’ ter git anybody, not this season, as I heered. Let the ole woods blaze away, I don’t want ter go near no place that’s haunted.”

“Reckon the ole thing’s ’bout fallin’ ter pieces anyway,” said the store proprietor.

Tom gazed at him. That, at least, seemed a sensible observation.

The thought which was uppermost in Tom’s mind was not that of ghosts. It was that the safety of the forest was being jeopardized in deference to ignorant superstition.

“Can’t they get some one from another village?” he asked.

“They’d hev ter git th’ other village fust, I’m thinkin’,” said the local wag. “Chevy, he come here from over the mountain yonder in Todd’s Crossroads. He was the fust one ter live up on the peak.”

“Vollmer, he stayed up there some nights,” said the storekeeper.

“He was welcome,” said the other, “a heap sight more welcome ’n he wuz down here.”

“Dead rebels is worser’n live ones, I says,” his companion observed.

“Oh, I don’t know about that,” Tom laughed. “You can’t do much harm after you’re dead.”

“Looks if poor Chevy had some harm done him by somebody ’t was dead,” the storekeeper remarked.

“Well,” said Tom conclusively, “if I can get that job I’m going to take it. So maybe you’ll have me for a neighbor. My name is Slade and I live in Bridgeboro, New Jersey, and I’m not afraid of spooks, but I am afraid of fires. Who should I apply to, I wonder; the head warden, State warden, or whatever you call him?”

The three men simply gaped at him. What the climax of their amazement might have been it would be hard to say; for the tableau of incredulity was cut short by an anticlimax. The storekeeper turned lazily around and addressed a young man who had just come unobtrusively among them and was leaning back against one of the supports of the platform roof. How long he had been standing there listening Tom did not know. His age might have been thirty and he was attired in city fashion; that is, he wore a suit of clothes. His face was pale and intelligent, and it was evident from his appearance that he was not a tried and true native of Watson’s Bend.

He seemed so far above the level of the conversation that Tom was a little perplexed at his not laughing as he himself was doing. He would have supposed that such an apparently enlightened young man would give him at least a sly wink to denote his amusement. Yet the young man gave no sign of being his ally in this absurd talk.

“Wotcher after, Horry?” the storekeeper asked.

“Cigarettes,” said the young man; “no hurry.”

The storekeeper lazily arose and went within, which had the effect of ending the talk. The young man, having received his purchase, strolled along toward the Bend with Tom.

“I didn’t know there were any houses down this way,” Tom said, by way of making talk. “I left my machine around the corner. You live here, I suppose.”

“Yes, I board here,” the young man answered. “Watson’s Bend isn’t quite so small as it looks. There are a few houses scattered around in the woods. You can’t see them all. My name is Dennison, I’m school teacher here.”

“Oh,” said Tom.

“Yes, I came here just after the war when jobs were hard to get and I’ve been stalled here ever since.” He seemed to apologize for his rustic position. “It isn’t so bad though,” he added; “nice and quiet. You’re on your way down through to Jersey, I suppose? We’ve seen more traffic in the last six days than we’ve seen in the last six years, I guess.”

“Yes, the road’s closed from High Falls down,” Tom said. “What do you think about those ghost stories? Some spook fans, hey, these rubes?”

They had passed around the treacherous Bend and were standing by Tom’s car. Far up on the distant mountain could be seen a gray speck, the little surmounting shelter of the lookout tower. The supporting structure was concealed among the trees and the tiny house looked like a large nest in the new foliage. At such a distance not one among a hundred strangers would have distinguished it for what it was. Dennison commented upon this.

“Oh, I suppose I happened to notice it because I’m interested in forest conservation,” Tom said. “But I never saw one so far up before. Boy, it must be pretty lonely up there! Well, I’m going to see if I can get the job; I’ll try anything once. Did you ever hear such nonsense as those men talked? Spooks!”

“There are lots of things that we don’t know anything about,” Dennison said. “It’s easy to say you don’t believe a thing just because you don’t understand it. You never saw anything supernatural, so you say there isn’t any such thing. I don’t say there is, either, but just the same I wouldn’t go up there. And I wouldn’t advise you to either. It’s an uncanny place.”

Tom stared at his chance acquaintance in blank amazement. “Well—I’ll—be—jiggered!” he laughed. “You don’t mean to tell me that you believe those stories?”

“Where there’s a lot of smoke there’s apt to be a little fire,” Dennison commented. “I wouldn’t just exactly advise any one to go up there.” Tom laughed. “Well, there’ll be some smoke and some fire too if somebody doesn’t go up there,” he said. “Why, this little berg is just surrounded by woods. There’ll be some pretty little bonfire in this country first thing you know.”

By way of showing his resolve and his impatience with the silly rumors, he jumped into his car as if this were a first decisive step toward carrying out his plan. “Well, I’ll see you later,” he said.

“I guess you’ll never be back,” laughed the school teacher. Then after a pause he added, “You don’t really mean that, do you?”

It seemed to Tom that Dennison was just a trifle anxious, too anxious for one who had no interest in the matter.

“I’ll say I do,” said Tom, leaning on the steering wheel.

“Did they tell you what happened up there?” Dennison asked.

“No, what happened up there?” Tom laughed derisively.

The young schoolmaster of Watson’s Bend climbed into the car and sat beside Tom. “I don’t meet many people from the great world,” he said. He seemed to offer this as an excuse for causing Tom to linger. “It’s like a circus come to town.”

“Oh, I’m in no hurry,” Tom said. “Half the time I can’t get the blamed old thing started anyway,” he added, in his happy-go-lucky way. “Go ahead, shoot. We often tell ghost stories around the camp-fire. I’m connected with the Scouts.”

“Oh, I thought maybe you were in the service,” Dennison said. It seemed to Tom that he was just a trifle reassured by this intelligence.

“Scouts, eh,” Dennison said. “We boast of one of those youngsters here; sort of near scout, I guess he is. It was his father who used to be up at the lookout station; Vollmer, his name was. That was before my time. You know there are always feuds in a little place like this. Folks think all is peace and quiet in these simple, little rustic hamlets, but believe me it’s just in little places like this that quarrels become feuds. I suppose that’s because there isn’t any social life to feed on. So they feed on quarrels. Why, the war isn’t over here yet.”

Tom glanced sideways at this friendly and intelligent young man who seemed to understand the ignorant village life so thoroughly and was yet so respectful of the absurd local superstition.

“They feed on ghosts, too,” Tom said.

“The war has awakened many people to truths they never dreamed about,” Dennison said, lighting a cigarette. “Who are you and I to say that there is nothing in spirit manifestation? You’re not interested, that’s all.”

“I’m more interested in where you throw that lighted match,” Tom said. He jumped out of the car and trampled down a tiny area of dry grass which had become ignited.

“My fault,” said Dennison.

“As long as there’s no one up at the station we might as well be careful,” Tom laughed, as he climbed in again. “How about Vollberg or whatever his name was? Was he scared away?”

The young schoolmaster slid down on the seat and stuck his feet up on the frame of the broken windshield. He smoked and seemed friendly and at home. Tom did not wonder that an educated young man, marooned in such a place, should encourage a passer-by to pause and chat.

“Don’t mind my making myself at home?”

“Go to it,” Tom said. “As long as we’re going to know each other better we might as well start in now.”

“Oh, you won’t be back here,” Dennison laughed. “I guess you’re sort of adventurous, hey? Well, I’ll tell you about Vollmer. Did you notice a big white house around the Bend—opposite the store? Only decent house in the place. Well, old man Peck used to live there; Wolfson Peck, his name was. Place is closed up now, but I heard he’s coming back to fix it up or sell it or something. Well, there’s an old story about how—don’t you smoke?”

“Not now,” Tom said.

“Most troubles in little villages start on account of land disputes, do you know that? Somebody or other puts a fence a sixteenth of an inch beyond where he ought to put it, or something like that. Well, when old Peck built his place he put his fence so as to just bring Vollmer’s well on the Peck side of the fence. That’s what started it. I don’t know who was wrong or who was right. Only all of a sudden Vollmer couldn’t get any more water. Maybe he was wrong and maybe he was right, but anyway he went thirsty. Peck had a lot of money and he beat him in court. Then Vollmer carried it higher and I guess it must have looked as if he was going to win out. And then this country got into the war and Vollmer made a break——”

“He had charge of the lookout station, you say?” Tom interrupted.

“Oh, yes, he was up there. He said that in Germany a rich man couldn’t beat a poor man like that. That was old Peck’s cue. He came out and said that Vollmer had a wireless on the mountain and all sorts of stuff—no truth in it at all as far as I can make out. But that little break about the poor man’s chances in Germany queered him. Peck got him interned for disloyal utterances and poor Vollmer died in jail. War’s rotten anyway you look at it, isn’t it?”

“It’s no pink tea,” Tom said.

“I’ll say it isn’t. Well, after poor Vollmer died you can imagine how his folks felt. This kid, Henny, he swore he’d kill Peck if he ever came back to the Bend. You know how kids talk. But this little devil kept it up. He didn’t forget. Why, even after I came here I kept that little rascal in school one day for insolence. I told him to make a sentence and write it a hundred times—punishment. What do you think the little rascal wrote? I’ll kill Wolfson Peck. He wrote it one hundred times.

“Of course all these front-porch patriots here were against the Vollmers and they’re sore at the kid yet; he’s sixteen now. They cherish their grudges here and pass ’em down from father to son.”

“Is that the kid that’s a sort of a near scout as you say?” Tom asked.

“Yes, he got hold of some sort of a manual book, but I guess it isn’t doing him much good; keeping him from his lessons, that’s about all,” Dennison laughed. “He says he’s got to be loyal to his dead father; he says there’s a law about that. Which means he’ll kill old Peck if he ever sees him, I guess. I suppose that’s what you’d call the German mind, hey?”

Tom smiled, but he was thoughtful. “How about the ghost?” he finally encouraged.

“Well,” said Dennison, “they went up to the station one night after Vollmer had died to see if they could find any signs of a wireless. Of course the Secret Service men had visited the place and found nothing. But these woodland patriots had to go up and snook around just the same. They got a good scare for their pains.

“Vollmer’s face (he had a round face and blond hair all matted) appeared up in that little house and stared at them. They couldn’t get out of the place quick enough and they were crowding down the spiral stairs when they heard a dog baying at the foot of the tower. They had to do one thing or the other, so they went on down and there wasn’t any dog there. But still the baying kept up right close to them. There was the baying, but there wasn’t any dog. They recognized it for the baying of Vollmer’s dog.

“Nobody ever went up there again till Chevy Ward got the job. He laughed just as you’ve been laughing and went up there to take charge. They found him dead one day at the foot of the tower and there wasn’t any trace of another human presence to be found there. Stuck in his pocket was a piece of paper with a few words of writing on it. The paper had been wet and they could hardly make the words out. But the matter ran something like this: I jumped on account of his face—it’s horrible—the dog is yelping, but I can’t see him—he came close——

“Well, it ended like that,” Dennison said. “I don’t remember if those were just the exact words, but that was about the way we made it out. I was one of the party that went up to see what was the matter with Ward; he hadn’t been down for several days. We found him lying there with both his legs broken. He must have lived and been conscious for a while at that, or else he couldn’t have written the note. You listen down here any windy night and you’ll hear Vollmer’s dog baying up there. Nobody’s ever been up to the place since we brought Chevy down and as for me, well, you can laugh, but I’ve had enough of it.”

Tom sat whistling in an undertone.

“You couldn’t get anybody around these parts to go up there,” Dennison said.

“Well, I’m going up there,” said Tom; “that is, I am if I can get the job.” And by way of demonstrating his resolution he started at once, as it were, by pushing the starter button on his little Ford.

But the Ford did not start. Tom’s act was a hint to young Mr. Dennison to vacate the seat where he had been lolling and he stood beside the car waiting for it to depart. But Lizzie would not back out into the road.

“I’ll give her a shove,” said Dennison, pushing against the radiator. “Out she goes,” he added.

“Do you know who’s warded around these parts?” Tom asked, pausing while the engine rattled uproariously.

“Barrett, I think his name is,” Dennison said, “Harley Barrett; he’s in Chesterville. But I guess you’ll think better of it,” he laughed.

“Chesterville?” Tom queried.

“Yes; here, I’ll write it down for you.”

“Got a slip of paper?” Tom asked. “Here’s a card.”

“No, here’s a piece,” Dennison said, tearing a page from a notebook.

When Tom drove away he carried in his pocket the slip of paper on which was written the name of Harley Barrett, Forest Warden, Chesterville.

And it was through the influence of this man (to whom he wrote) that he was given the anything but desirable and far from lucrative position of fire lookout at the lonely station with all its dismal traditions, which stood in the dense wilderness on Tempest Peak.

It was several weeks after his first chance visit to Watson’s Bend that Tom drove there, bag and baggage, to begin his employment as fire lookout. The main road had been reopened, which fact had consigned Watson’s Bend to an even more remote obscurity than when Tom had first paused there. It was now completely buried with all its gossipy and ignorant superstitions, and the village store with its reminiscent trio seemed to Tom like a fragment of a dream.

There was something amusing in the thought of how Skunk Hollow and Irish Pond, Todd’s Crossroads and Derry Conner’s woods and Lizey Henk’s man, who was tipsy, and Chevy Ward and all the rest, were brought forth and given an airing, then put away again never more to be heard of by the world. There was a detour and presto, Watson’s Bend appeared, then suddenly withdrew again into its grave-like seclusion. As Tom thought of these things it seemed to him that his visit there had been like a sojourn to fairyland. He had a queer feeling that he would not find the place now, that the hamlet and its people were no more real than the white rabbit and the mock-turtle in Alice in Wonderland.

These apprehensions were perhaps somewhat encouraged by the dismal, wind-swept storm through which he drove. It was, as he observed to himself, an altogether fitting day on which to commit a murder. On this second descent upon the hamlet he left the main road, as he had been told to do, at Ferncliff Valley and so, of course, approached the scene of his adventures from the south. There was no reason to suspect that this road was ever serviceable to man except in role of detour. Detours, like excavations at the sites of ancient cities, are likely to unearth interesting relics. Do not scorn (much less swear at) the little arrow; it may point out the pathway to romance.

At somebody or other’s “Crossing” Tom’s fickle Lizzie lay down and it was nearly two hours (and then only after the most abusive treatment) before he could persuade her to start again. Hence it was evening before he drove along the foot of the spreading mountain which rose away to the left of him. It looked gloomy enough off there on the dense summit as he saw it through the rain and mist.

He could not see the top of the old lookout station at all as he drove along, and he almost steered off the road into the low land to the right as a consequence of trying to pick it out. The mountain looked different than before by reason of the thickening foliage. “I suppose there’s a trail up there,” Tom mused. “It will be a fine night for mountain climbing.”

In the springtime Nature is a lightning-change artist, donning her mantle of foliage suddenly. The whole scene had changed since Tom had been in the neighborhood before. If he had gone around the Bend and found that the village was not there, he would not have been greatly astonished. Even the sharp turn looked different; not quite so dangerous as when he had first seen it.

Watson’s Bend was not out to welcome the stranger. A more dismal scene than the hamlet presented could hardly be imagined. There was no sign of life now even at the village store. A waterfall poured off the platform roof and the steady sound, even of this, seemed companionable in the general gloom.

The big, white house standing well back on its extensive lawn across the road caught Tom’s notice now, as it had not before, for he knew it for the mansion of the absent Wolfson Peck. It seemed out of keeping with the rest of the village, pretentious and aloof. A white picket fence enclosed the grounds. Smoke was pouring out of a chimney of the house, but the wind and rain beat it down and it broke up like clabbered milk and dropped away below the roof level. Yet it seemed cheerful on such a day.

Back on the grounds, and just within the side fence was an ornamental well-house painted white, and beyond, some distance off, a wretched little unpainted house. As he drove past, Tom had a momentary fancy of that humble well suddenly brought within the exclusive area of pomp and circumstance and white paint and imbued with a haughty contempt for the lowly home which had unsuccessfully claimed it.

Was it in that poor little house beyond that Henny Vollmer lived? Tom laughed at the thought of the boy killing a man in order to obey the rules of scouting! Well, at all events, old Peck must have returned, and it would be cheerful with a fire going on such a day, with night coming on....

On the ornate well-house was a gilt weathervane showing that the wind was in the east. The bucket suspended blew in the impetuous gusts and banged against the sides of the trim enclosure. It was not a cheery sound and it bespoke a dismal night.

Tom had intended to look up Dennison and take shelter with him for the night. It was rather characteristic of him that at the last minute he decided not to seek hospitality at Watson’s Bend, even from the young schoolmaster. Since Watson’s Bend would view his coming as an act of bravado, he would make the bravado complete. The first they would know of his coming would be that he was on the job.

The State Warden who had sent Tom his appointment had told him that the trail up the mountain began alongside the schoolhouse; he had said that it was not hard to follow since the electric wire above would guide him in places where the disused trail might be overgrown. Watson’s Bend enjoyed no light from this wire; the power was relayed from Connington.

The schoolhouse was a little box of a building somewhat apart from the group of houses. Tom thought it could not possibly have housed more than a dozen of the Bend’s younger set. An unruly shutter was blowing back and forth, but the unruly children had long since gone home, if indeed there had been any school on that wretched day.

Tom drove his Ford across the open space adjacent to the schoolhouse and poked its nose into the very edge of the woods. Before alighting he donned his suit of oilskins and oilskin hat which had done duty on rough water during many a motor-boat trip. Then he selected a few provisions from the store which he had brought, put them in his duffel bag and wrapped this in a piece of balloon-silk tenting. With this slung over his back he looked equal to the weather and was ready for his journey. But he lingered long enough to throw a dilapidated old tent (souvenir of Temple Camp) over his Ford. His Lizzie was not unaccustomed to being parked for weeks at a time under the clinging shelter of this old tent. He then set out upon the trail into the woods behind the schoolhouse.

But this trail soon became overgrown and indistinguishable and it was fortunate for Tom that he found his way to the power line before dark. A mile or so up into the woods he saw that the storm had beaten down the wire and in one place it lay broken at his feet. But he was still able to follow it.

Soon, however, he realized that his adventurous spirit had brought him into a predicament. The darkness became so dense that he could not see the wire and even had to grope for the supporting poles which stood far apart. This sent him on many futile detours and he paused now and again in the rain and darkness, utterly baffled.

Once, in a prolonged flare of lightning, he saw where the poles were down for some distance and both poles and wire sunk in underbrush. He thought this wreckage must have dated from a former day. In any case the glare was too transitory to permit him to see beyond the point of wreckage and now he had lost his one fitful means of guidance altogether. He plunged into a yawning gully of soaking brush, descended on its drenched and yielding network, down, down, then scrambled up and out, he knew not how.

He stood in utter blackness with no better means of guidance than there is upon the ocean. It is all very well to talk about what to do if lost in the wilds, as if it were a choice of going one way or another. But Nature in her savage wastes is full of pitfalls and death-traps and with the frightful ally of darkness, fills every step of the wayfarer with peril.

She had Tom in her clutches, this demon Nature; she had buried his trail in rank luxuriance, she had cast his guiding wire to the ground, and she laughed at him with her raging wind and rolling thunder as he stood there, baffled, helpless; all but panic-stricken.

Such a small thing is scouting. Such a tremendous thing is Nature.

Tom never knew exactly how he did grope his way to the top of the mountain. He was a good scout, if ever there was one, and he used tactics in dealing with the monster. One fitful guide he had, the lightning. Whenever it flashed he quickly laid out his course for a few yards.

At last, after hours, a long flash showed him the lookout tower outlined against the black sky. There was something startling, uncanny, in the sudden and vivid appearance of this alien thing, the handiwork of man, there on the lonely mountaintop. He saw it first bathed in the luminous glare. It appeared before him, a sort of glowing specter, strange with a peculiar strangeness, thus lifted out of its black environment. Then it withdrew into the stormy darkness.

He ascended the zigzag stair wearily, holding fast to the rail, for the steps were slippery with running water and the wind blowing a gale through the open structure. At each little landing where the stairs turned he paused, fatigued to the point of dropping, and rested for a brief moment while the wind and rain lashed him. At the top landing he fumbled in his pockets for the key the warden had sent him and entered the musty little room.

The tiny place was suffocating: oppressive with the atmosphere of long disuse. Its shelter was welcome, but there was something strangely jarring in the beating of the rain against the windows which were on every side.

In his hours of almost hopeless groping through that mountain wilderness, he had thought fondly of the cozy little shelter which would shut out the wild night. But now that he was there, he felt a certain uneasiness in its small, dark confines. There had been nothing spooky about the boisterous storm while he was in it. But listening to it from within this tiny, aerial bunk was another matter. The place was full of creaks and uncanny noises and Tom felt that another minute without a light would well-nigh unnerve him.

He struck a match and had his first glimpse of the place. There was the round table covered with the map under glass. The dirty, misshapen candle in its tallow-covered, rusty holder. The field-glass. With difficulty he got the candle lighted. It illumined hardly more than the table, leaving the surrounding area in shadow. There was an old kitchen chair, a rough chest, and a little cupboard. On opposite sides of the room were two sleeping bunks, one entirely without coverings, the other containing a pillow and a smelly, mildewed quilt. An old magazine lay on this one; the picture on its cover showed a returning transport crowded with soldiers.

Outside the wind swept and moaned, and sometimes raised its voice in a sort of sudden, petulant complaint. The candlestick trembled audibly. The field-glass danced on the smooth glass. Tom laid it sideways and placed the magazine under the candlestick. Silence. He took down the telephone receiver and held it to his ear. He waited, ten seconds, half a minute, but no voice answered. He was shut off from the world. The storm raged and lashed the steel framework below him.

He threw off his oilskin coat and sank wearily down upon the locker. He was either almost asleep or almost fainting. He managed to raise the nearest window and in a second the gale cleansed the foul place. Then he sank down again, exhausted, his senses ebbing. The candle went out and the roaring wind blew the magazine open and drove it off the table. Its fluttering pages carried it against the field-glass and drove that also to the floor.

This aroused Tom and half-consciously he relit the candle and stood the field-glass upright on the table where it danced to the accompaniment of the driving wind. And then he heard, in an interval of the clamor, the baying of a dog far below him. The jolly little field-glass danced on its two stiff, stout legs. The tower shook. Then a lull. And the baying of dogs far below him in the tempestuous night.

And then he saw the face....

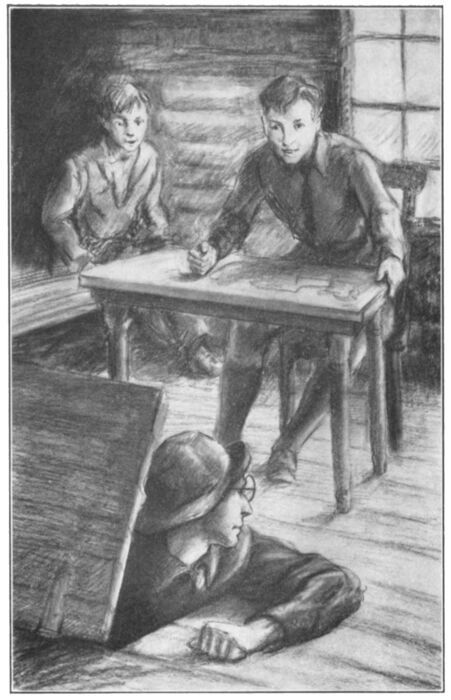

He saw it peering in through the open window as if it were hovering in space outside. A face with staring eyes and matted hair. The shrieking wind subsided momentarily, and in the interval the baying below could be clearly distinguished. The lull permitted the rain to pour straight down and Tom saw the face through the downpour as something unreal, intangible.

What was this horrible thing? Tom was no coward, but he shuddered. He did not speak for he thought that the apparition would not answer, that it had no power of human speech. If he spoke and it did not answer the effect would be unnerving. He stared at it, horrified, panic-stricken. And meanwhile the baying below could be faintly heard like a voice spent, as if coming from another world....

“They ain’t nobody up there now ’less you call a spook somebody.” Tom remembered those words, spoken on the porch of the village store. “A spook and his spook dog.” And the young schoolmaster’s words came back to him all in a flash. “Vollmer’s face—his hair was all matted—appeared up in that little house and stared at them. And they were crowding down the stairs when they heard a dog baying at the foot of the tower—but when they went down there wasn’t any dog there. But still the baying kept up....”

What was this ghastly business? Tom stood aghast, every nerve on edge. Fear thrives on uncertainty. Tom’s panic gave him an impulse which acted as a safety valve. Scarcely knowing what he did, he reached out suddenly as if to pass his hand through the spectral face. Then two arms clasped his and held fast.

“Let go!” Tom screamed.

“The dogs—they’re—they’re coming up,” said a voice.

“I know you,” Tom panted, trying to wrench his arm free while with the other he tried frantically to pull down the window. “Vol—you let go—you’re Vollmer—let me get out of this place—you—are you—Vollmer?”

“Yes, help me in,” the voice answered, “the hounds are coming up.”

The two hands clutched Tom’s trembling arm—they were very real. And a drenched form clambered over the window ledge. A round face with blond hair and staring eyes was before him in that little lofty shelter. “They’re—they’re down—they’re down there,” the voice panted. “You—got to—I didn’t do anything—save me.”

THEN TWO HANDS CLASPED HIS ARM.

Tom was ashamed that for the first time in his life he had fallen victim to fear and credulity. Here was an amazing apparition indeed, but it was no specter. It was a boy of perhaps fifteen years, drenched to the skin and in a state of panic fright. By way of proving his restored composure, Tom nonchalantly threw the field-glass on the covered sleeping shelf and closed the window. He seemed quite cynical in his attitude toward ghostly sights and noises. One might have thought that he would have tossed a ghost aside in the same way.

“Well, I’ll be hanged!” he said. “Who the dickens are you and what are you doing here?”

“I—I climbed up,” cried the boy, brushing aside his streaming hair. “They set dogs—I didn’t do it—I didn’t mean to——”

“How did you cut your hand?” Tom asked.

“Climbing up and hanging on,” the boy cried. His terror was shocking. “I—I wouldn’t—I didn’t—I don’t care what they say—I didn’t, I didn’t, I didn’t!”

“Shh, take it easy,” said Tom. “How am I going to help you if I don’t know what’s the matter?”

“They’ll tear me all to pieces, they will,” the boy wailed. “They got to prove—haven’t they? I didn’t, I didn’t, I cross my heart I didn’t!”

Amid the gusts of the storm the baying could be heard far below in the darkness.

“I’m—I’m a scout—do you think they kill people?” the boy cried. “They’ll tear me all to pieces—and they’ll let them know where I am, they will.”

“Vollmer, is that your name?” Tom asked.

“Yes, and they’ll kill me,” the boy cried, clutching Tom’s arm. “I’m a real one—a real scout—don’t you believe me——”

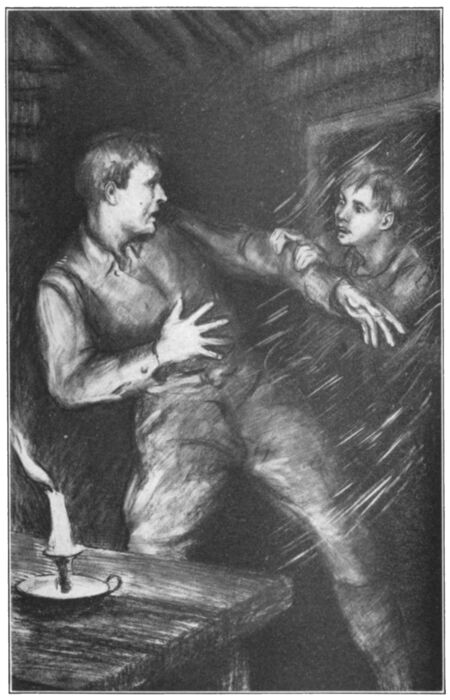

Tom Slade, who knew what a scout was if any one did, slowly drew a pistol out of his pocket. “They won’t kill you, Henny,” he said.

“Why—they—why won’t they?”

“Why, just because they won’t,” said Tom. “I’m a scout too, so you can believe me just as I believe you. Give us your hand, Henny—shake. Sit down now and let’s see what’s what.”

But Tom did not sit down. He picked up the pistol and, opening the little door, descended down the steps into the black night. The gale careered among the girders of the tower, whistling and shrieking, then swept off to moan and wail in the lonely forest.

At the foot of the structure two sparkling eyes looked at Tom, and a dark form sprang at his throat. A pistol shot sounded, almost drowned in the tempestuous gale, and the great bloodhound that had leaped up at him lay dead at his feet.

“Now, now they’ll kill you,” the boy said as Tom reëntered the little room.

“I don’t think they will,” said Tom grimly. “Nobody will ever try twice to kill me whether it’s a dog or a man. So it’s a real boy and a real dog—or it was! Sit down over there and tell me what it’s all about, Henny. I don’t think anybody will bother us up here, not for a while anyway. Let’s blow out the candle, hey? Now they won’t have any light or any sound to help them, whoever they are.”

And so these two were alone in the darkness in that little shelter in the mountain wilderness while the raging storm beat furiously outside.

He was the image of his poor father, that boy. Round face, blond hair and a certain glare in his eyes. In the old man this stern look had suggested a relentless, uncompromising habit; it had something of the war lord in it. In the boy this aspect of severity, which he had inherited, gave him a funny rather than a forbidding look. It had something to do with making him unpopular in the little school. And his blundering habit of autocratic declaration had not helped him in the village. Nor had the sorry fate of his honest father helped him in that hotbed of gossip and bigotry. It was not strange that Tom, fed up with the old superstitious yarn, had mistaken the boy for the shade of his dead father.

“So you’re the fellow that was kept in after school to write a sentence a hundred times, hey?” Tom said.

Now, indeed, Henny Vollmer stared.

“Yes, and you wrote you were going to kill Wolfson Peck too, you little rascal, didn’t you? You could have thought of a shorter sentence if you’d only had sense enough, and got out earlier,” Tom laughingly ran his hand through the boy’s wet, tousled hair. “Well, what are you doing up here on such a night? Why didn’t you come up the stairs? You gave me a scare, you little rascal! What was that dog doing, howling down there?”

The boy stared at Tom as if the new lookout were the specter. His unconsciously heroic glare consorted ill with his drenched appearance and evident predicament. If that glare had always been so humorously construed down at Watson’s Bend as it was by Tom, much of poor Henny’s trial and trouble would have been averted.

“You don’t intend to kill me, I hope,” Tom said.

“They set him on my trail,” the boy answered, “because I—because on account of Mr. Peck getting killed——”

“What?” Tom asked incredulously.

“I climbed up the framework so as to baffle him away.”

“Baffle him away?” Tom repeated. He would have been inclined to laugh at the quaint phrase but for the appalling information in the boy’s previous sentence. Such oddities of speech were peculiar to Henny. They were the one remnant of his Teutonic lineage.

“So you thought to baffle him away!” Tom repeated again, scrutinizing the boy. “Well, I see you’re a kind of a scout——”

“I’m a pioneer scout,” the boy asserted proudly. You would have thought he was declaring himself to be emperor of the universe. “I do a good turn and I don’t forget neither—every day I do. I don’t care how many lies they tell, I wouldn’t kill Mr. Peck. He killed himself because he didn’t look.”

“Yes?” Tom pulled off his soaking shoes, then settled down to listen, the while watching the boy closely. “Mr. Peck is dead? Isn’t that big white house his? I saw smoke coming out of it this evening when I started up the mountain.”

“He got killed,” the boy said in that tone which made all his declarations sound assertive, as if there could be no contradiction to anything he said. “But I wouldn’t kill him because I am a pioneer scout. So then I changed my mind and I wouldn’t kill him.”

“That was very kind of you,” Tom said. “How did he get killed?”

“Everybody knows what I wrote, but that don’t say I killed him, does it?”

“No.”

“Dumb-bell Denny, he has to tell all that happens in school so he can get his board and the people will like him in their homes——”

“You mean Mr. Dennison?” Tom asked, watching the boy shrewdly and smiling a little.

“He’s teacher,” the boy said, “but a lot he don’t know about scouts, else he’d teach us like that; he’s a dumb-bell. I got to be one all alone. Are you a detective maybe?” he asked suddenly.

Tom shook his head. “No, I’m a scout, a kind of a head scout, and I’m going to be lookout here for a while. Go on, how did Mr. Peck get killed?”

The boy stared at Tom as if to tell him not to dare to lie. “You know about good turns?” he asked.

“I’ll hope to tell you,” Tom said.

“That man—he was the one sent my father to jail with a lot of lies. He stole our well, that man did. Wouldn’t you want to kill him?”

Tom was silent, interested, keenly observant. “The war’s over, Henny,” he said.

“Not here, it ain’t yet,” the boy said. “I got a red lantern to-night out of the barn. In school yesterday Sally Kane told me Mr. Peck is coming back to-day to sell his house—he wouldn’t live here any more. In New York, near there, he lives now. So——”

“Just a minute, don’t get excited,” said Tom. “You live with your mother in that little house near Mr. Peck’s—beyond the white fence?”

“My mother is dead,” said the boy. “I work on Mr. Sterrett’s farm.”

“Oh,” said Tom; “yes, go on.”

“I thought of a good turn and I got the lantern they hang under the wagon when they take the milk to Connington station——”

“A red one?”

“Yes, and I went to the Bend with it—you saw that Bend maybe?”

“I’ll say I did.”

“I was going to stay there on account of Mr. Peck coming home. I guess that’s all right for a good turn, hey? Because it was good and dark and raining hard and blowing and everything. I was going to wave the red lantern whenever I’d see a car come. Not many come up that road. But, anyway, I’d know Mr. Peck’s car if it should come because the lights are far apart—it’s a Pierce-Arrow. He’s some rich—I mean he was—that man. You wouldn’t know a Pierce-Arrow coming in the dark like that,” Henny added with an air of triumph. “The lights are out far apart on the fenders. But I would know it.”

“Good,” said Tom.

The boy glared at him with a fine look of challenge in his eyes. “You got to remember things like that,” he said.

“O.K.,” said Tom, “you’ll do.”

“I was going to wave that red lantern when I would see those lights come. Because he was away a long time and maybe he’d forget just where that place is, and if he didn’t slow down and turn he’d go straight ahead down into the swamp——”

“Yes, I know.”

“I knew a car went past before I got there, because there were fresh tracks. But I guess that was in the daylight.”

“Yes, that was my car,” said Tom.

“You got different kinds of tires right and left,” said Henny.

Tom studied the boy with increasing interest. “Right,” he said.

The boy looked frankly triumphant for a moment, then continued, “I stayed there most an hour in all the rain; it was blowing just like this, too. Then I went down off the road into the swamp because I knew there was a box there——”

“You had noticed that too, huh?”

“Sure, everything I notice. I went into the swamp, down away from the Bend, maybe I guess twenty feet. All of a sudden while my foot was stuck in the mud I could see two lights coming—far apart. Then in a minute the big car came kersmash down into the swamp. And it turned over and over and he was dead. Can you tell if a person is dead—where to feel?”

Tom did not answer. But there was a thrill in the steady scrutiny of his half-closed eyes.

“He thought the Bend was further off yet,” Henny said. “He thought it was way down as far as I was, hey? Where he saw the red light, hey?”

There was a wistful note of pathos in that little query, hey. The poor boy, victim of his own noble impulse, seemed pleading, begging, for Tom’s confidence. “Hey, that’s what he thought, I guess.”

“Yes, that’s what he thought, Henny,” Tom said. And he laid his hand gently on the frightened boy’s shoulder.

“I—I didn’t murder him? That isn’t murdering him?” the boy almost plead.

“No, that wasn’t murdering him,” Tom said quietly. “You’re all right, Henny.”

“They said I did it on purpose,” the boy cried. “They put Bentley’s bloodhound on the trail, I know. That was him you killed. I tried to shout to Mr. Peck while he was driving, but the wind made too much noise. So he came kersmash! But I started it for a good turn anyway ... Do you say I lie?” he suddenly demanded with that heroic glare.

Tom only looked at him.

Here, thought Tom, was a pitiful sequel indeed to one of the noblest instances of a scout good turn that had ever come to his notice. The boy’s desperate predicament went to his heart. To undertake to save his old enemy and in that very act to send him crashing to his death! And with that foolish boyish threat of his still cherished in the memories of those ignorant and bigoted villagers! Poor kid, thought Tom.

If he had known more of Henny Vollmer’s life in the village, he would have been even more fearful for the poor boy’s safety. The sympathy and kindness which goes out to an orphan found no place in the hearts of the unsentimental people of Watson’s Bend. Remoteness breeds narrowness, even hardness. You have read of the great, heartless, cold world. But it is not the great world that is flinty and heartless and unforgetting; it is the little village.

Carl Vollmer, the fire lookout, was an honest man of German birth who had taken out his first citizenship papers. He lived with his wife and son near the Peck mansion. He had an imperious manner (quite unconscious) and that fierce and proud glare which was inherited by his son. His case was as sad as the later predicament of his son seemed likely to be.

Wolfson Peck, the Bend’s one prosperous citizen, had wanted the well which was on the Vollmer land. It was a sorry tale of greed and sharp practice and the power of wealth against a man both poor and unenlightened. No one knew where the right lay. Peck could not strike water on his own land and laid claim to a strip of the Vollmer land which included the Vollmer well. It was a question whether the law would sustain him and if Vollmer had kept his mouth shut all might have gone well with him, notwithstanding his unpopularity after the war started.

But he had made that unhappy remark about the poor man’s rights in Germany. Here was Wolfson Peck’s chance. He made a fine gesture of having the lookout station searched for a wireless, he claimed that Vollmer’s first papers could not save his land from confiscation, and while these matters were in the air, Vollmer was subjected to summary action. He was taken away from the village and interned and died in a detention camp. His good wife died shortly afterward. Then Peck bought up the land and put up a handsome cupolaed affair over the old well and painted the structure white to match the fence and the house and the barn. And that was the end of the Vollmers.

Except for Henny. If Henny had been a wise boy he would have held his peace. But he was too much the son of his father to do that. He had not yet reached the minimum scout age when he swore that the first time he saw old Wolfson Peck he would kill him.

That was a pretty big threat for so small a boy. The trouble was that this boy had one scout virtue, he always kept his word. And people had learned to take him at his word. At the age of ten he had said that he would lick little Clyde Venner, a schoolmate, and he had done so with a vengeance. He had said he would smash every window in the schoolhouse if Dumb-bell Denny punished him, and he had indeed done that. He was the bad boy of the village and his being the son of Carl Vollmer did not help him any.

So when Henny proclaimed that he would surely kill old Peck, Watson’s Bend paid him the compliment of taking him at his word. But old Peck closed up his house at the Bend and moved away, so that tragedy was averted. Henny was then about fourteen years old, and he continually reiterated his threat. As he grew older and the Peck-Vollmer episode mellowed into village history, the boy’s oft-repeated declaration of vengeance came to be taken more and more seriously. “If he ever comes back once, I don’t care when it is, I will kill him,” the boy said. But the Pecks did not come back.

The monarch of the white house and the white fence and the fancy well-house had found Watson’s Bend too small and remote for his ideas and sumptuous living. But the threat lived on; it was more conspicuous in the village than the gorgeous well-house. The fine place was closed up tight and was not much thought about. But Henny’s threat of vengeance lived; he saw to that. So it befell that his contribution to the village was, in a sense, greater than that of Mr. Wolfson Peck....

Then, one fine day, Henny ran plunk into the Scout Handbook for Boys. He was walking home from Connington, where he had been on an errand for his guardian and employer, Mr. Sterrett, when he happened to see the book lying on a stone wall. He sat down to rest and began looking the book over.

Curiously enough he stumbled into some matter about the scouts’ need of being thorough; how scouts must remember all they see, must never forget anything. “He forgets his book a’ready,” said Henny. “He forgets to put his name and where he lives in it too.”

Here was Henny Vollmer’s uncanny, instinctive efficiency brought to bear upon scouting. He was a scout before he knew it. The orphan boy whom Watson’s Bend was quite ready to take at his word had certainly the makings of a scout. The boy who always did the things he said he would do would not remain long in the tenderfoot class. The only trouble was he was always saying he would do the wrong kind of things. But perhaps even that is better than being a false alarm.

The boy who instantly perceived the incongruity of a scout leaving his handbook on a stone wall had the makings of a winner. The boy who looked for the name and address of the sender, so that he might return the book, and was disgusted at the owner for not having written it on the flyleaf intended for that purpose, was certainly a scout in spirit. Why, here was a flyleaf dear to the heart of that little statistic-loving devil! All the traditions of Henny’s race and ancestry would have impelled him to fill in all the dotted line spaces on that enchanting page.

Name, town, state, age, height, weight, member of (blank) patrol, troop number (blank). Dotted line for name of scoutmaster. How the heart of Henny Vollmer longed to fill in those seductive spaces! And the spaces below, intended to be filled in with details of the scout’s history and progress in this wonderful strange field! What was all this delightful business, poor Henny wondered? Qualified as tenderfoot (space). Qualified as second-class scout (space). First-class, life scout, star and eagle scout, awarded honor medal—all with spaces to be filled in. What was this new country that poor Henny had discovered? “And he forgets it and don’t put his name in,” Henny said.

Then he settled himself on the stone wall and plunged into the book as a regular scout plunges into the woods or the water. That was a great day for Henny Vollmer. And it was a great day for the Boy Scouts of America....

Of course Henny knew that this enchanted land was not for him. He had his chores to do. And besides he had about as good a chance in Watson’s Bend of getting in with these adventurers as he would have had if he had resided at the North Pole. What he read about forest fires was a revelation to him. “We didn’t get nobody up there yet neither,” he said. He was especially interested in the matter on page one hundred and thirty-one about keeping records in a field observation book, records about the wind and the weather and about birds and their songs and their colors. Henny Vollmer felt like Columbus discovering a new world.

“That’s good too about good turns,” he said. “A lot of them you can make stunts.” And he would keep a record of them too, trust him for that....

Then Henny’s enraptured eye paused at something on page twenty-three. He read with the wildest interest. Could this actually be?

In case it is not possible for a boy to affiliate with a troop ... he may upon application be enrolled direct with the National Headquarters as a pioneer scout. He is entitled to all the benefits and privileges granted to regular scouts. Blanks may be secured upon request, etc.

That night, after his chores at the Sterrett farm were done, Henny concocted a weird letter to “Scout Nations Headmaster New York” in which he asked for “those blanks like you said in the book. This is good place for those good turns,” he added; “even one I made up my mind to a’ready, it’s a big one, it’s a fine kind because you can keep it up. So I hope to hear from you soon Henny Vollmer Watsons Bend it’s over the mountain from Connington that’s the nearest they have stores but none of those suits like you see. P.S. please hurry up.”

So Henry Vollmer was enrolled as a pioneer scout. He did not tell Farmer Sterrett because he was afraid scouting might be thought to interfere with his arduous chores. Likewise he did not tell young Mr. Dennison because he had an instinctive dislike for him. He did not tell anybody. Watson’s Bend was no longer a part of his world. He had a contempt for the people who were afraid of the old lookout station, especially Mr. Dennison, who encouraged the idea of the place being haunted. “If my father come back he would come to me and not stay up there,” the practical, sensible boy had said.

Off with the old love, on with the new. Henny even forgot about his oft-repeated vow to wreak vengeance on the man who had caused his father’s downfall and death. Wolfson Peck’s long absence had much to do with this. Probably scouting had more to do with it. But Watson’s Bend did not forget the threat of the little “seeditious, bloodthirsty devil what if I had my way would of been packed off ter the deetention camp with ole Carl, the little rebel of a Hun. The only thing saves him is the war’s over.” And so forth and so forth. Meanwhile, Henny glared at them even more imperiously than before, for was he not of the tribe of Daniel Boone and Kit Carson and Buffalo Bill?

And so the day came when he started out to do one great thing and ended by doing another. Any one with sense in his head could have predicted that this boy would never do anything on a small scale. He would never make trails in the back yard and stalk grasshoppers. Nature set the scene for him on this fateful day of his young life. She stirred up a great storm that blew down haystacks and ripped the roof from Sterrett’s barn and smashed in the conservatory window in the Peck house, where old Aunt Carrie Holbrook was kindling a fire against the arrival of the master. He was expected that very day, and would depart again in a day or two.

The coming of Wolfson Peck was the subject of conversation at the village store and of whisperings in the little schoolhouse. Young Mr. Dennison cut out the afternoon session on account of the increasing storm and remarked to his little group of pupils that Squire Peck had a bad day for traveling.

On his way home he paused in the driving rain long enough to make the same remark to old Aunt Carrie, who was staggering against the wind and rain to the empty mansion. It was a big event in the life of Watson’s Bend. “I don’t want he should come afore I git a fire started,” Aunt Carrie said....

And all unnoticed by any one, Tom Slade’s little flivver came rattling merrily through the drenched village. All unknown to any one, Henny Vollmer, pioneer scout, stole out to the roofless barn of Darius Sterrett and got the red lantern that hung under the old buckboard. Poor boy, he could not see where the trail would lead. But he balked at neither storm nor gathering darkness. He was no parlor scout, this secretive, lonely young pioneer. So perhaps it was appropriate that the roaring demon of the storm should be with him as he went forth on his adventures.

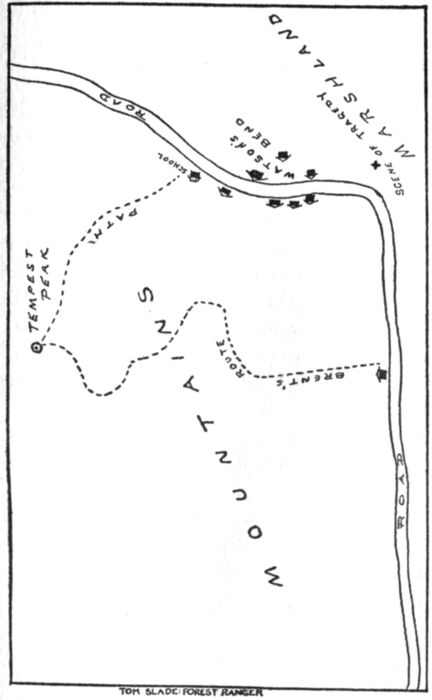

You know how the road turned, but it would be as well to glance at the crude map which Tom Slade later made of the neighborhood. In his anger and disgust I saw him crumple that map up and throw it on the floor. I picked it up and had it reproduced to make clearer the narrative of these events.

Tom’s flivver had already gone around the Bend, proceeding westward toward the village, and was parked behind the schoolhouse when Henny approached that outrageous turn. He was thinking mainly of Squire Peck, but he was thinking also of any one else who might be approaching in a car. At the spot marked with a cross on the map he managed to get the lantern lighted and there he stood where he could be seen from both directions. I think he must have made a pretty good picture of a scout, though it must be confessed that he did not look much like the picture of the natty youngster waving a flag, on the cover of the scout handbook.

Whenever Henny heard a noise which he thought might be a car in the distance he waved the lantern back and forth and sometimes over his head.

The storm raged, darkness was coming on fast, and he was soaked and weary. His face was sore from the force of the wind and the driving rain. Now and again he drew his wet sleeve across his eyes to clear away the water that was dripping from his hair. And he stood there. Scouts are not all alike; this was Henny’s idea of a good turn.

Then he bethought him of the old grocery box that he had once noticed lying down in the swampy land below. He thought he would get that and sit on it. He crawled down off the road into the oozy area which stretched away to the north. This was, perhaps, eight or ten feet below the level of the turn and the descent, though not precipitous, was steep. With his lantern Henny groped about for the box, found it and started up toward the road again.

He was still some twenty feet from the road when his foot sank in the swampy ground which was made worse by the rain. In trying to pull his foot out the other one sank too, and for a few moments he believed he was in a predicament perilous to himself. It was dark and he was trapped. The lantern stood on the box. By laying his body across the box he was able to obtain enough resistance to the marshy land to draw one foot, then the other, free. The box did not sink even with his weight upon it. He took a chance with one released foot and stepped again in the yielding ground. His foot went down.

He might now have feared for his own safety, but he gave no thought to that. For just in that moment he heard amid the storm the unmistakable sound of an approaching car. In a few seconds more two lights, wide apart, appeared. Half-sitting, half-lying on the box, he shouted and waved his lantern. But the wind carried his voice in the wrong direction. Then suddenly, as the lights loomed near, he realized the horrible issue which was imminent. He called again, he screamed, he swung the lantern frantically.

But it was too late. Of all the mistakes old Squire Peck had made in his willful and aggressive career this was the most horrible. He thought the red lantern marked the turn of the road and he held his course straight for it. In ten seconds more his Pierce-Arrow sedan plunged off the road, turned a complete somersault forward and with the appalling sound of breaking glass and splintering wood settled on its side in the marshy land below the road. The stern, hard, dominant man who had ruined Carl Vollmer, the lookout, and made his boy an orphan, lay dead and mangled in his sumptuous car.

The black sheep and pioneer scout had done his good turn.

Henny had never looked upon death save on the two occasions when he had seen his father, and later his mother, lying in the dim stillness of their little home under the shadow of the big white house. They had sent his father’s body home from a detention camp where he had died of the flu, and Henny had seen little in the figure which lay in peace to remind him of his father.

When his mother lay in that same musty little room later, he had thought she was smiling at him. Added to his tragic bewilderment at this sudden loss had been a fear about what would become of him. He had believed that old Wolfson Peck would somehow get hold of him as he had got hold of the well.

But his nervous bewilderment (which was the form in which his grief showed itself) was as nothing to the bewilderment which gripped him after that shocking catastrophe in the storm. He had, after all, brought old Wolfson Peck to his death. His threat had been carried out.

Henny was utterly bewildered and cold with fright. His usually stolid temperament was shaken. He was afraid to look in the car. He was afraid to return into the village. He tried to pull his foot out of the muck and was glad that he could not, for that kept him from doing anything.

But presently he found himself. Perhaps the victim was not dead and he could render service like a scout. He knew how to make a tourniquet; he had practiced that. With difficulty he drew his foot out of the marsh and for a few moments lay crosswise on the box like a seesaw. It was uncomfortable, even painful, but he did not sink. He listened, but could hear no call for help, no moaning even. Only the raging storm. It blew out the light in his lantern and he could not relight it, for the matches in his pocket were soaking wet. He could not remain as he was, that was sure.

Suddenly he heard a sound, as of a door closing on its latch. He craned his neck and looked at the dark bulk of the wrecked car which lay about fifteen feet from him. Had a deathly hand within it softly closed the door so that the prying eyes of life might not look upon the ghastly sight concealed there? Henny was not exactly conscious of such a thought, but he trembled at the sound. Such a sequel to a scout good turn!

Wind and rain. They beat in his face and glued his clothing to him and made him look thin and lithe in the sudden flashes of lightning. The elements, which had brought him into this frightful predicament, seemed to have furnished him with a disguise. He looked small and different, like a bird when its feathers are soaking wet.

The thought came to him that the sound which he had heard might after all mean that the victim was alive. He drew his legs up and stood upon the box, a statue of fright on a wabbling pedestal. His clothing was so wet and clung so tightly to his body that he looked indeed as if he might have been chiseled out of black, wet stone. He was just going to jump in the direction of the wrecked car, where he thought the saturated ground was more solid, when there was a sudden gust of wind. He paused. And in that pause the word STOP appeared before him in a little circle of red light.

Surely no suffering victim in need of help would present that forbidding sign. Only death. Ghastly death that wanted to be alone and unseen. Could it be that Squire Peck, in death, or near death, had recognized the diabolical triumph of his young enemy and was beseeching him not to approach and add to the horror of his deed? STOP. It appeared again, very faint, as if the hand that controlled the warning sign were weak.

Then Henny knew what it was. It was the stoplight of the car, lighting when the gale shook the wrecked machine and it settled in the mud. Some freakish contact in the wiring happening when the car was jarred. But it seemed dreadful in the stormy darkness to see that little red word of warning.

Henny jumped and landed on comparatively solid ground. The whole area below the road was not deeply marshy; he had only happened into a sort of hole. He now plowed through the mud to the car and sat upon it just a few seconds to rest and collect his nerves. If the car body had been shattered he would have been less fearful. But its form was not destroyed; only broken in places and the windows shattered. The rain pelting down on the metal side of the car made a loud, almost a metallic, sound. The car jarred and settled a little in a fresh gust of wind.