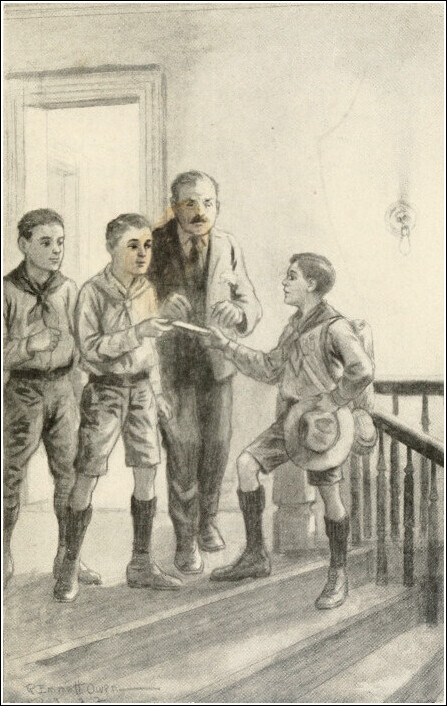

THE BOYS MINGLED SOME FUN WITH THEIR WORK.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Roy Blakeley in the Haunted Camp

Date of first publication: 1922

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Sep. 27, 2019

Date last updated: Sep. 27, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190965

This eBook was produced by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

ROY BLAKELEY IN THE HAUNTED CAMP

THE BOYS MINGLED SOME FUN WITH THEIR WORK.

ROY BLAKELEY

IN THE HAUNTED CAMP

BY

PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH

Author of

THE TOM SLADE BOOKS

THE ROY BLAKELEY BOOKS

THE PEE-WEE HARRIS BOOKS

ILLUSTRATED BY

R. EMMETT OWEN

PUBLISHED WITH THE APPROVAL OF

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1922, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| I | The House in the Lane |

| II | An Echo of the War |

| III | A New Acquaintance |

| IV | Pee-wee Fixes It |

| V | Pee-wee’s Discovery |

| VI | Sunday the Fourteenth |

| VII | Then and Now |

| VIII | Peace! |

| IX | Around the Fire |

| X | The Fall of Scout Harris |

| XI | Young Mr. Blythe |

| XII | Three’s a Company |

| XIII | Warde Is in Earnest |

| XIV | Baffled? |

| XV | Within Reach |

| XVI | Right Side Out |

| XVII | A Revelation |

| XVIII | The Test |

| XIX | The Dull Blaze |

| XX | The Voice |

| XXI | The Diagonal Mark |

| XXII | The Banshee |

| XXIII | After the Storm |

| XXIV | The Warning |

| XXV | The Good Turn |

| XXVI | Mr. Ferrett’s Triumph |

| XXVII | Scout Law Number Two |

| XXVIII | Home Sweet Home |

| XXIX | A Discovery |

| XXX | The Visit |

| XXXI | Hark, the Conquering Hero Comes |

| XXXII | Return of the Good Turn |

| XXXIII | The Mystery |

| XXXIV | Seein’ Things |

ROY BLAKELEY IN THE HAUNTED CAMP

One fine day in the merry month of August when the birds were singing in the trees and all the schools were closed and hikes and camping and ice cream cones were in season, and the chickens were congregated on the platform of the Hicksville, North Carolina, post office, something of far-reaching consequence happened.

On that day Joshua Hicks, postmaster-general of that thriving world centre, emerged from the post office, adjusted his octagon-shaped, steel-rimmed spectacles exactly half way down his long nose, held a certain large envelope at arm’s length and contemplating it with an air of rueful perplexity said,

“Well—by—gum!”

Then he cocked his head to one side, then to the other, squinted first his right eye, then his left, and at last inquired, of the chickens, apparently,

“What—in—all—cre-a-tion is this?”

The chickens did not answer him; on the contrary they departed from the platform, seeing, perhaps, that there was no mail for them. With the exception of two persons the chickens were the only creatures that ever waited for the mail in Hicksville.

In the peacefulness of the Hicksville solitude the train could be heard rattling over the bridge and into the woods beyond, going straight about its business as if Hicksville did not exist.

It was no wonder that Joshua Hicks was astonished, for things like this did not happen in Hicksville every day. The last previous event had been a circus but that was nothing compared to the large envelope. For the address on this was as follows:

To a lady in Hicksville, North Carolina, who lives in a white house with the end of the porch broken and with a dog that has a collar. Maybe there’s a window broken.

In the upper left hand corner was written:

If not delivered sometime or other return to W. Harris, scout, Raven Patrol 1st Bridgeboro New Jersey troop, Boy Scouts of America.

And at the lower right hand corner was the additional information:

P. S. There is a puddle outside the woodshed or a pail.

With such detailed information as this Uncle Sam, that world-renowned errand boy, could hardly do otherwise than deliver this formidable document. And thus it was that W. Harris, scout, had stopped a great train, which goes to show you what boy scouts can do.

Thinking no doubt that an envelope of such imposing dimensions containing such explicit descriptive matter was entitled to the honor of rural free delivery, the postmaster-general himself took off his spectacles, put on a large straw hat and started up the road.

He came presently to a small white house some distance up a lane, where a dog with a collar greeted him with a cordial wag of the tail.

That dog, in his humble abode, did not know that his fame had gone abroad and that his personal distinction of a collar was known in the sovereign commonwealth of New Jersey, not to mention the vast cosmopolitan centre of Bridgeboro, county seat so-called, because of the comfortable propensity of the people living there to spend their time sitting down. Perhaps it might more appropriately have been called the county couch, since the inhabitants were said to be forever in a kind of doze.

But if Bridgeboro, New Jersey, dozed, Hicksville, North Carolina, had the sleeping sickness. And it did not even walk in its sleep for not a soul was to be seen about the little white house nor anywhere else.

There was no doubt, however, of its being the house in question. A pillar at the end of the porch had rotted away and the roof over the little platform was tumbling down. A pane of glass was missing from the sitting room window.

But Joshua Hicks was not going to take any chances. So he playfully ruffled the dog’s hair to make sure that the collar was around the animal’s neck and having satisfied himself of this he strolled around in back of the house for an official inspection of the puddle or the pail. The United States government must be very thorough about these things; puddles especially....

There, sure enough, was the puddle, a perennial puddle, fed by a laughing, babbling, leaky drainpipe. Joshua Hicks dipped a finger in the mud and made sure of the puddle. He then looked for the pail, and not seeing it, put on his steel spectacles and glanced again at the envelope.

“A puddle or a pail,” he said. “I reckon that’s all right; it says or a pail.”

He was going to knock on the kitchen door, but he bethought him to make a supplementary inspection of the tumbled down porch roof. There could be no two opinions about that; even a profiteering landlord would have admitted the condition. And finally Postmaster Hicks satisfied himself in the best of all ways of the condition of the window, and that was by cutting his finger on a fragment of broken glass.

Staunch and true as he was, he was ready to shed his blood for his country.

Having satisfied himself beyond all doubt that this little white house was the proper destination of the letter, Joshua Hicks administered an authoritative knock on the front door. The response came in the form of a queer little old lady, who wore a very expectant look, a look almost pathetically expectant. She was slight and wizened, and stood straight. But her face was deeply wrinkled and her hair was snowy white.

There was something about her trim, erect little figure and white locks and furrowed cheeks which aroused sympathy; it would be hard to say why. Perhaps it was because her brisk little form suggested that she worked hard, and her thin heavily veined hands and wrinkled face reminded one that she ought not to work hard. There was a certain something about her which suggested that she was fighting a brave fight and keeping a good heart. At all events she wore a cheery smile.

“Joshua,” she said, “I was kinder hoping to see you over to-day. It’s good of you to bring it yourself. I wanted to put my name on it so’s you could get me the money in Centerville when you go.”

“’Tain’t your pension, Mis’ Haskell,” Joshua said. “Leastways, I never seen no pensions come like this before. It’s like as if it wuz a letter turned inside out; all the writin’ is on the outside.”

“Jes’ when I’m needing my pension most it don’t come,” she said, taking the big envelope. “When I saw you prowling around in back I thought you was the sheriff’s man, mebbe. It give me a shock because—what’s this?”

“Don’t ask me, Mis’ Haskell,” said the postmaster. “It’s for you, I’m certain sure of that, and that’s all I can say.”

With trembling hand and a look of pathetic fear and apprehension, the old lady started to tear open the envelope, saying the while, “You don’t reckon W. Harris is one of them smart lawyers up New York way, do you, Joshua? I’m ready to get out when I have to. I’ve—I’ve stuck it out alone, I always said I could fight, but I can’t fight the law, Joshua. They don’t need to set no lawyers on me—they don’t.”

She opened the envelope, and unfolded a sheet of paper. It was old and faded and wrinkled. She glanced at it, then grasped the door jam with her thin, trembling hand, as if she feared she might fall.

“’Tain’t the law, is it?” Joshua Hicks inquired.

“You better be gone, Joshua,” she said. “No, it ain’t the law—it’s—it’s something else. It ain’t the law, Joshua.”

“Is it any trouble?” he asked.

She answered, strangely agitated, “No, ’tain’t no trouble, Joshua.”

“They ain’t a goin’ to stop sendin’ you your pension?”

“Not as I know of, Joshua, but jes’ I want to be alone. It ain’t no trouble of money, Joshua, not this time....”

If it were no matter of money, then Joshua Hicks could not conjecture what in the world it was, for there were only two things in old Mrs. Haskell’s life, and these were both concerned with money. One was the monthly receipt of her pension, for in her small way she had helped to make the world safe for democracy and all that sort of thing. The other was the mortgage and interest on her little home which the pension could not begin to take care of. Mrs. Haskell did not understand about this mortgage at all, but the most important part of it she did understand, and that was that pretty soon she was going to be put out. She did not have to be a financier or a lawyer to understand that. She had tried to beat this mortgage back by sewing and gardening and selling eggs, but the interest had grown faster than the potatoes, the pen was mightier than the needle and the mortgage had kept right on working while the chickens had taken a vacation.

The mortgage had beaten poor old Mrs. Haskell at every turn. It had bombarded her with notices and writs and summonses and things and she had lost the fight. She had a sort of armistice with this mortgage, but she knew there could be but one end to that armistice. The little war, a very heroic little war, was as good as over. The little white house had been made safe for the Liberty Realty Company.

For one brief, terrible moment, before the postmaster had departed, Mrs. Haskell had feared that perhaps she had done something lawless in connection with her little pension, signed her name in the wrong place perhaps, and that W. Harris with all his high sounding names, was some doughty governmental minion coming to apprehend her in true military fashion. But if the paper contained in the envelope dispelled that fear, at least it did not cheer her.

She returned into the house, her eyes brimming, the paper shaking in her poor old hand. She groped her way to an old haircloth armchair in her sitting room, and put on her spectacles. The moisture from her eyes dimmed the glasses and she had to take them off and wipe them before beginning to read.

She was quite alone in her little castle, or rather the Liberty Realty Company’s little castle. She wanted to be alone. It was very quiet. Outside the birds could be heard twittering in the vine on the ramshackle little porch. The kettle sang cheerily in the kitchen. There was that musty indoor odor of the country homestead, the odor which soldier boys remembered and longed for in trenches and dugouts. And mingling with this was the fragrance of flowers coming in through the open window. The dog with a collar strolled in, laid his head in the old lady’s lap, looked up into her eyes and listened. There were only those two there, so she read the contents of the paper aloud.

Dear Old Mother:

I was hoping I might get down to Hicksville before we sail, but guess I can’t. They don’t tell us much here but it seems to be in the air that we’ll sail in a day or two. Feeling pretty disappointed because I wanted to see you again and say good-bye and have just one good home-cooked meal. I’m sick of beans and black coffee. Don’t worry, you’ll hear from me in France. I don’t suppose you’ll be able to get the end of the porch fixed up, but try to get the window put in before winter. I meant to do that myself. Put a pail under the drain so the water won’t flood under the woodshed. Tell Don to be a good watch dog and be sure to tie him outside at night.

I don’t suppose you’ll hear from me again till we get across. Don’t worry, pretty soon it will all be over and I’ll come marching home and you’ll be telling people it was me that won the war and I’ll be glad to get a good squint at my old N. C. hills. It will be over before you know it. Now you have to be brave, see? Just like you were when dad died. Remember what you said then? Now don’t think this is good-bye just because I’m sailing but remember the Atlantic Ocean isn’t a one way street. Just chalk that up on the wall, and speaking about oceans don’t forget about the water by the woodshed and do what I told you. So now good-bye dear old Mum and don’t worry, and I won’t go near Paris like you said. Hicksville is good enough for me.

Your loving son.

Old Mrs. Haskell read this letter twice. She had to clean her glasses several times while doing so. Whatever of comfort the letter gave her was expressed in tears. She arose, a straight, wizened little figure. She went over to an old-fashioned whatnot which stood in the corner, opened a plush album which lay there and turned the pages till she came to a certain photograph. This she gazed at for fully five minutes, the dog standing patiently at her side. Then she took a postal card which had been laid between the two stiff cardboard leaves. This also she gazed at though it contained but few words. It bore a date of more than two years before. The printing, with its blank spaces filled, stated that the War Department regretted to inform her that her son Joseph Haskell had been killed in action on some date or other in the “operations” west of some place or other.

She stooped down and patted the dog and he held up his head against the almost threadbare material of her poor gown.

“He did write after—all—he did—Don,” she sobbed. “He did—he wrote before he went—away. I don’t know who—W. Harris—I don’t understand it—but he did write. See?” The dog seemed to understand.

Mrs. Haskell dried her eyes with her kitchen apron, folded the letter, laid it with the post card, took a final pensive look at the photograph and clasped the heavy plush covers over all three. Then she sat down by the window and patted the dog with one thin hand while with the other she lifted the kitchen apron again to those poor old eyes. Thus they sat silently.

It was just an echo, a faint, belated echo of the great war....

To know something of the circumstances which caused this letter to reach Mrs. Haskell like a ghost out of the past, we shall have to betake ourselves to Bennett’s Fresh Confectionery and Ice Cream Parlor on Main Street in Bridgeboro, New Jersey. And that is by no means a bad sort of place to begin, for Bennett had the genial habit of filling an ice cream cone so that the cream stood up on top like the dome on the court house in Bridgeboro, and extended down into the apex, packed tight and hard.

It was long before the great sensation in Hicksville, and on a certain pleasant day early in vacation, that Roy Blakeley, leader of the Silver Fox Patrol, and several scouts of the First Bridgeboro Troop were lined up along Bennett’s counter partaking of refreshment. To be exact, they had finished and were waiting for Walter, alias Pee-wee Harris to finish, for Pee-wee had the true scout thoroughness and went down to the very bottom of things.

“How is it you boys aren’t off camping this summer?” Mr. Bennett asked sociably, as he leaned against the fixtures behind the counter.

“We should worry about camp this year,” Roy said. “We’ve been fixing up our old railroad car for a meeting-place down by the river and we’re going to stay home and earn some money to buy a rowboat and a canoe and start a kind of a camp of our own down there.”

“We’re going to build a float,” Pee-wee said, digging with his spoon.

“Sure, and a sink,” Roy said, “so we can wash our hands of Bridgeboro. We’ll be dead to the world down there. We’re going to lead the simple life like a lot of simps. We’re going to catch salt fish in the salt marshes and everything. All we need is a treasury; you didn’t happen to see one around anywhere, did you?”

“If I should happen to see a treasury I’ll let you know,” Mr. Bennett laughed.

“We need a standing capital,” said Artie Van Arlen, leader of the Ravens.

“We wouldn’t care if it was lying down as long as we had it,” Roy said.

“We’d like some assessments,” Pee-wee said.

“You mean assets,” Doc Carson laughed.

“It’s the same only different,” said Roy.

“What we want is a few standing capitals, and some small letters and a couple of surpluses.”

“Deficits are good; did you ever hear of those?” Pee-wee asked.

“We need about eighty-five cents and fifty dollars,” Roy said. “I guess we’ll start a drive only we haven’t got any horse. Maybe we can catch some goldfish down there and sell them for old gold. We should worry.”

Mr. Bennett said, “Well now, you scouts ought to be able to raise some funds. You seem to raise pretty nearly everything else.”

“We raise the dickens,” Grove Bronson said.

“We ought to be able to sell some stock,” Roy said. “We’ve got some rolling stock down there—one car. Only it doesn’t roll. Who wants to buy some stock in the Riverside Scout Camp? Watered stock, we dip it in the river.”

“You don’t know what watered stock is; you’re so smart,” Pee-wee sneered.

“Sure, it’s milk,” Roy said. “Right the first time, no sooner said than stung.”

“Never laugh at poverty,” Westy said, as all the party began to shout. “We’re poor but dishonest.”

“Sure,” Roy ejaculated, “we wouldn’t even steal a cent, that’s why we haven’t any sense; deny it if you dare.”

“We can sell papers at the station,” Westy said.

“Sure, the Saturday Evening Post,” Roy said. “We can do golden deeds and get gold that way. We should bother our young lives. What care us, quoth we? We’ll think of a way. All we need is fifty dollars to put tar-paper on the roof and a new cook stove in the car.”

“Money talks,” the kid shouted.

“Good night!” said Roy, “then we don’t want any of it. You do enough talking in this troop.”

“Are you fellows all one outfit?” asked a young man who had been leaning against the opposite counter, amused at their talk.

“United we stand, divided we sprawl,” Roy said. “There are more of us, too, only they’re not here. They’re by the river.”

“I can give you a chance to earn some money if you really want to,” the young man said. “Do you think you could stick?”

“Our middle name is fly-paper,” Roy informed him.

“Like camping?”

“Camping is named after us,” Connie Bennett of the Elk Patrol said. “We’d rather camp than eat.”

“No we wouldn’t,” vociferated Pee-wee Harris.

“What kind of hours?” Doc Carson of the Ravens inquired.

“The usual kind,” Roy volunteered, and put it up to their new friend if this were not so. “The same kind we use in school, hey?” he added.

“Give him a chance to tell us what it is,” said Westy Martin of Roy’s patrol. “We all started saying we’d like to earn some money; talk is cheap.”

“Sure, that’s why we use so much of it,” said Roy. “If it cost anything we couldn’t afford it.”

“Well,” said the young man, “I’ve got a job and I need help. It’s outdoors and it means camping and living rough. It means cooking our own meals. You could get a little money out of it; not much, but a little.”

Perhaps it was what the stranger said, perhaps the way he said it, but something caused them all to turn and stare at him.

He was a young fellow of about twenty-three or four and of very shabby appearance. The threadbare suit which he wore must have seen long service and either it had never been a very trim fit or he had lost flesh. His face, indeed, seemed to imply this, being thin and pale, and there was a kind of haunting look in his eyes.

But his demeanor was creditable, he seemed quite free of any taint of the shiftlessness which his appearance might have suggested, and his amusement at the scouts’ bantering nonsense was open and pleasant. Mr. Bennett contemplated him with just a tinge of dubiousness in his look. But the scouts liked him.

“What’s the nature of the work?” Mr. Bennett asked.

The young man seemed a trifle uneasy at being directly questioned but no one would have said it was more than the diffidence which any sensitive young fellow might show towards strangers.

“It’s taking down two or three buildings,” he said; “just shacks. My name is Blythe.”

“Here in town?”

“No, up at the old camp.”

“Oh, you mean Camp Merritt? I heard the government sold the whole shebang. What are they doing? Putting gangs to work up there?”

“I’ll help you tear down Camp Merritt!” Pee-wee shouted.

“No, they’re just giving the jobs out piecemeal,” the young man said amid the general laughter. “Anybody that wants to tear a building down can get permission. They give so much a building. I undertook three. If I could get some help and do it in a month or so I’d have a little money. I haven’t got anybody so far. I suppose that’s because it’s out of the way.”

“Oh, then you don’t work for the wrecking concern?” Mr. Bennett queried.

“Only that way,” the stranger said.

“You belong hereabouts?”

“N—no.”

“Anybody else working up there?”

“Not now.”

“I suppose these youngsters could get a commission to haul down several buildings themselves if they wanted to?” Mr. Bennett inquired. “Cut out the middle man, huh?”

The young fellow seemed a trifle worried. “I—I didn’t think of that,” he said; “I guess they could. But I don’t want much out of it myself,” he added, in a voice that had almost a note of pleading in it; “and I picked out the easiest shacks. They’d—I’d be willing—they’d get most of the money. Beggars can’t be choosers. I’m out of work—I——”

“And it’s best for youngsters to have a boss, eh?” Mr. Bennett added, genially. “Well, I guess you’re right. Somebody to keep them out of mischief.”

The scouts and their new friend strolled out onto Main Street and, pausing there in a little group, continued talking.

“If you think we’re the kind to get an idea from you and then go and use it and leave you out, you’re mistaken,” said Connie Bennett.

“The camp isn’t mine,” their new friend said, hesitatingly.

“No, but that particular job is yours,” Westy Martin insisted, “and we’re on that job, if we go there at all.”

“That’s a good argument,” Pee-wee ejaculated.

“Are you staying up there?” Connie asked.

The stranger seemed pleased, even relieved. That uncertain, diffident smile hovered for a moment about his mouth. “I’d treat you right, that’s sure,” he said. “It’s pretty hard for a fellow to get work. I just sort of stumbled into this——”

“Well, I’m glad you stumbled into us, too,” said Roy, a note of sympathy and sincerity in his voice that there was no mistaking. “We’ll have to speak to our mothers and fathers, but don’t you worry, we have them trained all right. We have cooking outfits and everything, too. We’ll take a hike up there to-morrow. We’d like to make some money, but gee whiz, that isn’t the only thing we care about. Camping and all that—that’s what we like. Don’t we, Westy?”

“Where can we find you up there?” Westy asked.

“You go up the Knickerbocker Road and right in through the old entrance,” Blythe said. “The second shack you come to on your left is where I’m bunking. You’ll see me around somewhere.”

“You do your own cooking?” Artie Van Arlen asked him.

“Yes, but I’m not much of a cook,” Blythe said. “I—I don’t—I won’t get anything till the work’s finished——”

“You should worry about that,” Roy said.

“I guess I can eat most anything,” Blythe laughed.

“Can you eat as many as eleven?” Pee-wee demanded.

That same elusive, half-bashful, pleasant smile lingered on the stranger’s lips again as he said, “—I guess—not——”

“Then I can beat you,” Pee-wee announced conclusively.

“Here comes the bus,” Westy said. “Do you go up in that?”

“I guess I’ll walk,” Blythe said.

“Well, we’ll be up there to-morrow, sure,” Doc Carson reassured him; “some of us anyway. Even if we don’t come to stay we’ll be up there, so you look for us.”

“I’m fair and square,” Blythe said. “When you come you can look the place over and then say——”

“You should worry about that,” Roy interrupted him.

“Maybe your people——”

“You leave our people to us,” Roy said. “My father believes in camping and fun—he inherits that from me. Scouts know how to pick out fathers all right.”

Their new friend smiled again, with a kind of simple pleasure at Roy’s nonsense. “I’ll look for you,” he said. Then they parted.

“He’s got some walk all the way up to Camp Merritt,” Doc Carson said. “Do you suppose he hasn’t any money?”

“Looks that way,” said Westy.

“I kind of like him,” Doc said. “I guess he’s in hard luck all right. I’m glad we met him.”

“I’m the one that did it,” Pee-wee shouted. “Didn’t I say for us all to go into Bennett’s? Now you see!”

“All we have to do is to follow you,” Roy said, “and adventures come around wanting to eat out of our hands.”

“And I—I’m the one to show you where there’s money too,” Pee-wee said. “I’m a capital or whatever you call it.”

“You’re the smallest capital I ever saw,” Roy said.

The concerted assault which the scouts made upon their parents for permission to proceed with their plan ended in a compromise. Late that same afternoon Mr. Ellsworth, scoutmaster of the troop, drove up to the old camp in his auto and looked over the situation. He talked with Blythe also and was evidently not unfavorably impressed, for he returned to Bridgeboro quite converted to the enterprise.

“He’s a queer kind of a duck,” he said to Mr. Blakeley, referring to Blythe. “I think he’s out of luck and rather discouraged. He doesn’t say much. I think he took this job in desperation not knowing exactly how he was going to go ahead with it. He expects to get three hundred dollars for what he’s undertaken. He means to divide evenly, he said, but of course that will leave him with only twelve dollars, if the whole troop goes up. He doesn’t seem to have any grasp of things at all.

“I proposed to him that he keep one hundred dollars for himself and give the boys the other two hundred. This fellow has lost his grip and I doubt if he’ll do much work, but of course it’s his job. It’s as much to help him as anything else that I’d like to see the troop go up there. It ought to be fun camping in the ramshackle old place; I’d rather like it myself.”

“This Blythe, he doesn’t belong around these parts, does he?” Mr. Blakeley asked.

“No, I believe not, but I think he’s all right. I size him up for a disheartened member of the big army of unemployed who stumbled on this opportunity. He has a look in his eyes that goes to my heart. He needs to be out-of-doors, that’s sure. If the troop doesn’t give him a hand he’ll have to pass it up. The boys want a little money and here’s a good chance to earn it and do a good turn at the same time.”

“You liked him, eh?” Mr. Blakeley asked.

“Yes, on the whole I did. He’s an odd case and I can’t altogether make him out, but I liked him. I don’t think he’s very well, for one thing.”

“Well I guess it’s a good chance for the boys,” Mr. Blakeley said.

That, indeed, was the consensus of opinion of the men higher up and there was another demonstration of the remarkable power which the scouts had over their parents.

“We know how to manage them all right,” said Pee-wee to Roy. “I told your father I’d see that you got back all safe; I told him to leave it to me.”

Pee-wee’s responsibilities, according to his own account, were many and various. He promised Doc Carson’s mother that he would personally see to it that Doc wore his sweater at night. He gave his word to Mr. Hollister that Warde would not over-eat—Pee-wee was an authority on that subject. He distributed his promises and undertook obligation with a generosity that only a boy scout can show. He advised Mrs. Benton, Dorry’s mother, not to worry, that her son should be the subject of his especial care.

He magnanimously volunteered to be responsible for the safety of the whole troop. And he announced that Mr. Ellsworth’s judgment was the same as his own precisely.

With such assurances the troops’ parents could not do otherwise than surrender unconditionally, and Pee-wee of the Ravens was the hero, the George Washington, of the expedition.

At all events he carried his little hatchet with him, and it pulled on his belt so that he had to be continually hoisting it up and tightening his belt so that before the expeditionary forces had gone far he looked not unlike a bolster tied in the middle.

The next morning the troop started on their hike to the old camp. Excepting their tents they carried full camping equipment, blankets, cooking utensils, first aid kit, lanterns, changes of clothing, and plenty of those materials which Roy’s magic could conjure into luscious edibles. The raw material for the delectable flipflop was there, cans groaning with egg-powder, raisins for plum-duff, savory bacon, rice enough for twenty weddings and chocolate enough to corner the market in chocolate sundaes. Cans of exasperated milk, as Pee-wee called it, swelled his duffel bag, and salt and pepper he also carried because, as Roy said, he was both fresh and full of pep. Carrots for hunter’s stew were carried by the Elks because red was their patrol color. A can of lard dangled from the end of Dorry Benton’s scout staff. Beans were the especial charge of Warde Hollister because he had come from Boston.

Most of the scouts had visited Camp Merritt during the war when it was seething with activity, and when watchful sentinels stood on every road of approach, challenging the visitor and demanding to see his pass. They had been familiar with the boys in khaki, strangers in New Jersey mostly, who filled the streets of Bridgeboro. But they had not visited the old camp since it had become a deserted village.

It seemed strange to them that the place which had so lately swarmed with life, and had a sort of flaunting air of martial energy and preparation, should have become the lonely biding place of one poor soul and that its only service now was to stand between that poor stricken derelict and starvation.

If they had taken their way up the Knickerbocker Road along which auto parties and pedestrians had once thronged to see the soldiers, they would have found the going easy, but instead they followed the river northward, for five or six miles, then cut through the country eastward which would bring them to the western extremity of the old camp.

In this last part of their journey they fell into an indistinct trail, much overgrown, running through an area of comparatively wild country. This, indeed, had been a beaten path between the camp and the villages to the west. It had known the tread of many an A. W. O. L.[1] soldier, yet it had not been altogether a secret path, but rather one of convenience. At all events it had been well clear of the main entrance on the Knickerbocker Road, and this conspicuous advantage had given it a certain popularity.

At the time of the boys’ journey this path would probably have been indistinguishable to any but scouts. It brought them soon to an old tumbled-down building which had never been more than a mere shack, and was now so utterly dilapidated that living in it would be quite out of the question. Some remnants of a roof remained in a few shreds of curled, rotten shingles, the foundation was intact, and the sides though bulging and full of gaping crevices were still standing.

“Oh look at the house, it’s all ruined like Reims Cathedral,” Pee-wee shouted. This, indeed, was its only point of resemblance to Reims Cathedral. “Come on inside,” he continued, leading the way, “it’s a dandy place, it’s all caving in.”

“I suppose they want about a thousand dollars a month rent for this place,” said Westy Martin.

“Sure,” said Roy, “it has all modern improvements, free shower-baths when it rains and everything.”

Within, the place was dank and musty and cobwebs spread across the openings where the windows had been. Much broken glass and a couple of sash weights fastened to ends of rotten sash cord lay upon the floor. In the corner was a makeshift bed of straw, matted from age, damp and unwholesome. The place was in possession of spiders. Whole boards of the flooring had rotted, yielding like mud under the feet of the scouts.

“Some place,” said Connie Bennett.

“Oh, here’s a dime,” Pee-wee shouted reaching under an open space in the flooring. “I can get a soda with that.”

“Here’s another,” said Westy.

It seemed likely that some of the heroes who had made the world safe for democracy had beguiled their time playing craps before going forth to glory.

Suddenly Pee-wee shouted, “Oh look at this! I bet it has something to do with a spy! I bet it has secret papers in it! Look what I found!”

From under the edge of the rotten straw our observant young hero had pulled out an oilskin wallet. There were not many such places as this old ruin that did not yield up their treasures to Pee-wee. The veriest ash heap became a place of romance under his prying hand and inquisitive eye. This find was just one of those ordinary oilskin wallets which had held and protected many letters from mothers and sweethearts and which had been shot through and through in the trenches in France. Black spots of mildew were upon it and it had an oily, unpleasant odor.

“I found it! I found it!” Pee-wee vociferated, as the scouts all clustered about him eager to see.

“You’re the greatest discoverer next to Christopher Columbus,” Roy said. “Let’s see what’s inside it.”

“Didn’t I say to stop here?” Pee-wee demanded.

“You never thought you’d find an ice cream soda here,” Roy said.

“You never know where you’ll find one,” Pee-wee said in high excitement. “Didn’t I find a dime in a sewer-pipe?”

“That’s a nice place to find a soda,” Roy laughed. “Open the wallet and let’s see what’s in it.”

[1] A. W. O. L.—Absent without leave.

Pressing about Pee-wee, the scouts read eagerly the contents of that old musty oilskin memento of the days when Camp Merritt was a seething community of boys in khaki. The big spiders lurked in their webs; the repulsive little slugs, made homeless by the lifting of a damp, rotten board, hurried frantically about on the floor; a single ray of sunlight penetrated through a crevice, a slanting, dusty line, and lit up a little area of the dim, musty place. But there was no sound, not even from the scouts, save only the voice of Westy Martin as he read that old, creased, damp, all but undecipherable letter:

Dear Old Mother:

I was hoping I might get down to Hicksville before we sail, but I guess I can’t. They don’t tell us much here but it seems to be in the air that we’ll sail in a day or two. Feeling pretty disappointed because I wanted to see you again and say good-bye and have just one good home-cooked meal. I’m sick of beans and black coffee. Don’t worry, you’ll hear from me in France. I don’t suppose you’ll be able to get the end of the porch fixed up, but try to get the window put in before winter. I meant to do that myself. Put a pail under the drain so the water won’t flood under the woodshed. Tell Don to be a good watch dog and be sure to tie him outside at night.

I don’t suppose you’ll hear from me again till we get across. Don’t worry, pretty soon it will all be over and I’ll come marching home and you’ll be telling people it was me that won the war and I’ll be glad to get a good squint at my old N. C. hills. It will be over before you know it. Now you have to be brave, see? Just like you were when dad died. Remember what you said then? Now don’t think this is good-bye because I’m sailing but remember the Atlantic Ocean isn’t a one way street. Just chalk that up on the wall, and speaking about oceans don’t forget about the water by the woodshed and do what I told you. So now good-bye dear old Mum and don’t worry, and I won’t go near Paris like you said. Hicksville is good enough for me.

Your loving son.

There was something about this old missive which sobered the bantering troop of scouts and made even Pee-wee quiet and thoughtful.

“It’s a letter he was going to send,” Artie Van Arlen finally said.

“Who?” Doc Carson asked.

Artie shrugged his shoulders. “Somebody or other, that’s all we know,” he said. “We don’t even know who he was going to send it to; there are a whole lot of dear old mothers.”

“You said it,” commented Roy.

“Let’s see the other papers,” one of the scouts said.

The only other contents of the wallet were a small paper with blanks filled in, and an engraved calling card. The paper with the blanks filled in was so smeared from long moisture that the written parts were undecipherable. The paper was evidently a leave of absence from camp. The name was utterly blurred out, but by studying the smeared writing in the space where the date had been written the scouts thought they could determine the date, or at least part of it. Sun—1918 was all they could be sure of.

But fortunately the calling card appeared to confirm this date. It was a card of fine quality and beautifully engraved with the name of Helen Shirley Bates. In the lower left hand corner was engraved Woodcliff, New Jersey. On the back of the card was written in a free feminine hand For dinner Sunday April 14th, 1918. One o’clock.

“What do you make out of it? What does it mean? Who was he anyway?” the scouts, interrupting each other, asked, as these memorials of an unknown soldier boy were passed around from hand to hand and eagerly read.

Of all the scouts Westy Martin, of Roy’s Patrol, was the soberest and most thoughtful. He had the most balance. Not that Roy did not have balance, but he never had much on hand because he was continually losing it.

“Whoever he was,” Westy said, “it looks as if he got a leave of absence to go to the girl’s house for dinner. Going this way would be a shortcut to Woodcliff. Maybe he was going to take the train up from New Milford.”

“I guess he was going to mail the letter to his mother in New Milford, hey?” Hunt Ward of the Elks suggested.

“Yes, but why didn’t he?” Doc Carson asked.

“It’s a mystery,” said Pee-wee. “Do you know what I’m going to do?”

“Break it to us gently,” Roy said.

“Some day soon I’m going to hike to Woodcliff and see that girl and find out what that soldier’s name is and I’m going to send the letter to his mother.”

“What’s the use of doing that?” Vic Norris asked. “The soldier has probably been home two years by now.”

“I don’t care,” Pee-wee insisted; “the letter is to his mother and I’m going to see that she gets it.”

“Are you going to get a soda while you’re up at Woodcliff?” Roy asked him.

“That’s all right,” Pee-wee said with great vehemence; “if you got a letter that went astray you’d want it, wouldn’t you?”

“You’re talking in chunks,” Roy said. “Go ahead and see the girl if you want to. I bet she’ll think you’re sweet. Only come ahead and let’s get to camp.”

“Unanimously carried by a large majority,” Dorry Benton said. “Mysteries aren’t going to buy tar-paper for our old car.”

“There might have been a thousand dollars in this wallet,” Pee-wee reminded them.

“Except for one thing,” Roy said.

“And what’s that?” Pee-wee asked.

“That there wasn’t,” Roy said. “Put it in your pocket and come on.”

Though they treated Pee-wee’s find as something of a joke and attached no significance to it, still the discovery of these old papers which had now no meaning for anybody kept recurring to them as they made their way to the old camp. But the consensus of opinion was that these old mildewed remnants of another time were unimportant.

“What good is a letter when the fellow who sent it is already home?” Doc Carson asked.

“What use is a leave of absence that expired two or three years ago?” Connie Bennett added.

“If that fellow’s away yet, he’s overstaying his leave, that’s sure,” said Roy.

“What good is a Sunday dinner that somebody ate a couple of years ago?” Doc queried.

“Maybe he’s up there eating it yet,” Will Dawson suggested.

“That’s the way our young hero would do,” said Roy.

“Do you mean to say it isn’t important—that dinner?” Pee-wee demanded.

“Sure, all dinners are important,” Roy said. “But one two years old isn’t much good. If it was only six months old I wouldn’t say anything, but two years——”

“You’re crazy!” vociferated Pee-wee.

“Sure,” said Roy, “one dinner is as important as another if not more so. Deny it if you can.”

“Anyway I’m going to see that girl,” Pee-wee said.

“At dinnertime?” Roy asked slyly.

“I’m going to find out who that fellow is, I’ve got his finger prints here, too, on this card——”

“G-o-o-d night,” laughed Roy. “The boy scout Sherlock Home Sweet Holmes. I suppose you’ll have that poor girl in Atlanta Penitentiary before you get through.”

“Let’s see the finger prints?” Westy asked.

Pee-wee showed him the card and there, sure enough, was a finger print on the face of it and two on the back. It looked as if someone with greasy hands had taken the card up as one usually holds a card....

Within ten or fifteen minutes more they were in the old camp. They entered the reservation territory at its western edge and cutting across soon came to the concrete road which runs north and south through the middle of the camp. This is the Knickerbocker Road which traversed the reservation territory before ever Camp Merritt was heard of, and bears its scanty traffic now through that pathetic scene of ruin and desolation. It is the one feature of the camp that was not of its temporary character.

Up this road through Dumont to the south, there once passed a never ceasing procession of autos, encountering guards and sentinels for a mile south of the camp. The atmosphere of military officialdom permeated the public approaches for miles in both directions.

If one were so fortunate as to have a pass, he could by dint of many stops and absurd inquiries and parleys, succeed in reaching the large gate posts on which was printed UNITED STATES RESERVATION. Through this the Knickerbocker Road, being especially privileged, passed without challenge, straight through the middle of the camp and out of its northern extremity, then through the pleasant little town of Haworth.

On either side of this road, within the confines of the camp, were board shacks of every size and variety. They were for every purpose conceivable and, large and small, they were all alike in this, that they had a makeshift, temporary look, and were a delight to the eye of the tried and true camper. They were all alike in this, too, that civilian patriots had charged twenty dollars a day to put them up. This was in odd contrast to the one poor, hapless soul who was to receive three hundred dollars for the work of tearing several of them down.

As the scouts, his one hope now, came up onto the central road and hiked southward toward the main entrance, they scrutinized the weather-beaten and windowless structures on either side for a sign of their friend. But no hint of any human presence was there, no suggestion of life of any kind, save a companionable windmill nearby, the moving wheel of which creaked cheerfully as if to assure these scout pilgrims that the scene of their destination was not altogether deserted. It seemed a kind of living, friendly thing, in that forlorn surrounding. What surging life it had witnessed, what hearty, reckless, resolute departures! One might fancy it saying as it revolved, “I have seen all, seen the boys come and go, and I alone am left in all this hollow desolation.”

The boys paused a moment to watch this lonely sentinel and listen to its creaking.

“That sound would give me the shudders at night, if I didn’t know what caused it,” one of them said.

“Shut your eyes, then listen,” said Westy. “It sounds kind of spooky, huh?”

“Gee whiz, but this is a lonely place,” Roy said. “It reminds you of Broadway, it’s so different. It’s a peach of a place to camp.”

“I bet there are ghosts up here,” Pee-wee said darkly.

“Sure, you’d better look around for finger prints,” Roy said.

“Maybe that old windmill is haunted, hey?” our young hero suggested.

“It needs oil anyway,” Roy said.

“You make me tired,” said Pee-wee contemptuously. “A ghost can squeak, can’t it?”

“Sure,” said Roy, “if it’s rusty.”

But for all their banter the old windmill, perhaps because it was the only thing stirring, held them and sobered their thoughts as it would not have done elsewhere. Perhaps they felt a sort of consciousness of its lonely position and fancied it to be something human. It overlooked the obscure path along which they had come; how many forms in khaki had it seen stealing to or from the camp A. W. O. L.? How many truckloads of uproarious boys had it seen driven away? How many maimed and suffering brought back? Surely it had seen much that the most loyal citizens had not been permitted to see. A whimsical thought, perhaps, but what good fun it would be to climb up there and learn some dark and tragic secrets from this lonely old derelict, the only thing with any sign of life that Uncle Sam had left in that forlorn, deserted spot.

Had it any tragic secret? That seemed quite absurd. A creaky old windmill revolving to no purpose in that waste, because it had nothing else to do.

“Listen!” said Pee-wee. “Sh-h-h! I heard a noise—up there.”

Captivated for the moment by their own mood, they all paused, listening. Then, not far off, a friendly voice accosted them. It was young Mr. Blythe coming to greet them. His face wore that uncertain, hovering smile, which had the effect of arousing pity. His eyes had an eager, startled look, like those of a frightened animal. He seemed backward, almost bashful, but his joy at seeing them was unmistakable and sincere.

“Better late than never,” laughed Roy. “Here we are bag and baggage; we thought you were a spook or something....”

Blythe was bunking in one of the shacks which he had secured the privilege of tearing down and it was apparent to the scouts that his knowledge of camping was primitive. But Pee-wee, out of the greatness of his scout heart, volunteered to be his guide, philosopher, and friend in these matters.

“We’ll show you how to do,” he said. “If there’s anything you don’t understand you just come to me. I’ve got the camping badge and the pathfinder’s badge, and the astronomer’s badge——”

“He’s an astronomer,” interrupted Roy; “he knows all the movie stars.”

“He sees everything in the sky,” Hunt Ward added; “he’s the one that put the see in sea-scout.”

“Sure, and put the pie in pioneer scout too,” Roy said. “He studied first aid and last aid and lemonade and everything. He’s a scout in very high standing only he doesn’t stand very high. You stick to him and you can’t go wrong.”

“Do you mean to say I haven’t the badge for camping?” the diminutive Raven demanded as he unburdened himself of his various paraphernalia. “Do you mean to say I didn’t study the heavens when I was a tenderfoot?”

“No wonder the stars went out,” Roy said. “Here, take this bag of flour and put it over in the corner. You’re in Camp Merritt now, you have to obey your superior officer. Here, take the spools of thread out of this coffee-pot and kick that big can over here, the one marked dynamite. I’m going to put the sugar in that. Anyone who takes any sugar without permission will be blown up by his patrol leader. Look what you’re doing! Don’t set the pickles on the chocolate. Hand me that bottle of ink before you spill it in the egg powder.”

It was good to see Blythe laughing at Pee-wee’s heroic effort to dispose of the commissary stores which his companions loaded upon him. It was a laugh of simple, genuine pleasure, almost childlike.

“Don’t drop the fly-paper in the flour,” Roy shouted to Pee-wee in frantic warning, as Pee-wee wrestled valiantly under the load of boxes, packages and cans. “Put the cork back in the molasses jug before it spills into the Indian meal.”

“We’ll have home brew,” Westy said.

“You mean home glue,” Roy answered. “Look at him! He’s got the powdered cocoanut all over the bacon!”

“Keep those things off me!” the victim shouted as the boxes and cans piled up on him. “Do you think I’m a freight car?”

As he stooped to pick up a box a can went rolling under Blythe’s makeshift bed. As he reached for the can a bag of beans burst like a sky-rocket, pouring a shower down his neck and into his pockets and over the floor.

“Now you see!” he yelled. “The eggs are sliding down!”

“Help, help!” called several scouts.

Pee-wee picked up two cans of sardines and sacrificed a bag of rice. He gathered up rice and beans together, and a jar of jam went rolling on a career of foreign travel. All was confusion.

“Time!” he screamed.

“He asks for an armistice,” Roy shouted.

“You mean a couple of dozen arms,” Westy shrieked.

“If you put another thing on me I’ll drop the eggs,” Pee-wee screamed. “I’ll drop them so that they—they—bounce, too.”

This threat of frightfulness cowered his assailants.

“That’s against international law,” Roy shouted.

“I don’t care, I’ll do it!” Pee-wee yelled. “You pile one more thing on me and I’ll——”

“Start an eggmarine campaign,” Westy said.

“That’s the first time I ever knew food to get the best of Pee-wee,” Artie Van Arlen observed.

The diminutive mascot of the Raven Patrol having valiantly protected the eggs in one extended hand gradually divested himself of the mountain under which he had labored, and by a fine strategic move took a tactical position behind these defenses with the pasteboard box of eggs upraised in heroic and threatening defiance. The war had come to an end suddenly, like the World War.

“Unconditional surrender,” Roy shouted.

“Do I get three helpings of stew for supper?” demanded the victor, by way of imposing an indemnity before he proceeded with disarmament.

“Sure, eggs won the war,” Roy conceded.

As for Blythe, he was sitting on a grocery box in No Man’s Land, laughing so hard that his sides ached. Their banter seemed a kind of tonic to him. And it was when he laughed and seemed so simple and childlike and so much one of them, that they found him so likable.

After this decisive conflict the period of reconstruction or rather the period of demolition, began auspiciously. It began with a grand feast cooked out-of-doors in the brass kettle which was the pride of Roy’s life. That brass kettle stood upon a scout fireplace of stones, and from its interior a hunter’s stew diffused its luscious fragrance to those who sat about, feeding the companionable fire. The scouts were quite masters of the situation, their coming must have been like a freshening breeze to the lonely visitant at the old deserted camp, and their fun and brisk efficiency and readiness seemed to give him a new life and afford him amusement which was expressed in that silent, likeable, yet haunting smile. It was not often that he laughed aloud and he talked but little, and then with a kind of diffidence that seemed odd in one so much their senior.

“I’m going to leave that kettle to my ancestors when I die,” Roy said. “It’s been all over and I’ve cooked everything in it except Cook’s tours; it’s travelled more than they have, anyway. It’s been to Temple Camp and we fished it up from the bottom of the lake once and I guess as many as ten thousand wheat cakes have come out of that kettle. Hey, Pee-wee?”

“Nine thousand eight hundred is all Pee-wee can say for sure about,” Westy said.

“Are you used to camping?” Doc Carson asked Blythe. “I thought maybe you liked this kind of thing because you came here.”

“It was just that I was out of a job,” Blythe said frankly. “Anything’s better than nothing. I happened to wander in here and met a man with an auto. He works for the concern that’s going to tear the camp down; a salvage concern. He got me this job. I don’t suppose you’d call it a job, it’s an assignment. I picked out the three buildings and they sent me a paper with the numbers on. I’ve only been here a couple of days. Yesterday was the only time I was in Bridgeboro. I was going to give it up. I didn’t have any supplies and I didn’t know who to get to help me—I was mighty glad that friend of yours came up yesterday and said he’d tell you fellows it was all right.”

“He’s our scoutmaster,” said Pee-wee. “He’s all right, only you’ve got to know how to manage him. We’ll start in to-morrow morning and we’ll show that savage concern all right. We’ll show them what we can do.”

“Maybe they won’t be so savage,” Roy said.

“Pee-wee can manage them,” Westy observed.

“Oh sure, all you have to do is to know how to manage them,” commented Connie. “They can’t come too savage for our young hero.”

“He can even tame wild flowers,” Roy said; “lions—dandelions and tiger-lilies and everything. He eats them alive.”

“Speaking of eating, how about the stew?” Artie Van Arlen asked.

“It has to stew for an hour,” Roy said. “Somebody get out the tin plates; be prepared, that’s our motto. All the comforts of home. Where’s your home?” he asked Blythe in a sudden impulse.

“Oh I’m just a kind of a tramp,” Blythe said uneasily. “I guess I must have left home before I had my eyes open.”

“That was before you could walk,” Pee-wee reminded him.

“The last home I was in was in New York,” Blythe said. “It wasn’t mine.”

“I guess you’re like we are,” Westy said, noticing perhaps a little embarrassment in their friend’s manner, “our home is outdoors.”

“And believe me, the sky has all the tin roofs I ever saw beaten twenty ways,” observed Warde Hollister. That was pretty good for a new scout.

“Roofs are all right to slide down,” Pee-wee observed. “They’re all right as long as you’re not under them.”

“Believe me, we wouldn’t have the sky over us if we didn’t have to,” said Roy. “It’s a blamed nuisance when it rains. The trouble with the solar system is there are too many stars and planets and things in it. You can’t get out into the open.”

“What are you talking about?” Pee-wee retorted contemptuously.

“I’d get rid of all the stars, stationary stars, movie stars and all,” Roy said.

“Scouts are supposed to like the stars,” Pee-wee informed Blythe.

“Sure, if he had his own way he’d eat hunter’s stew out of the Big Dipper,” said Roy. “A lot he knows about the stars; he doesn’t even know that Mercury is named after a thermometer.”

“This bunch is crazy,” Pee-wee informed Blythe.

“That’s because we sleep under crazy quilts,” Roy said.

Blythe just sat there laughing, the silent, diffident pleasure in his countenance shown by the crackling, cheery blaze.

“What would you do if you didn’t have the North Star, I’d like to know?” Pee-wee demanded. “We’d be all roaming around lost in the woods, dead maybe.”

“I should worry about roaming around dead,” said Roy. “Do you think I’ve got the North Star?”

With a look of pitying contempt, Pee-wee turned from Roy to the more congenial bowl, now sizzling and bubbling on the fire. “It’s ready,” he said.

“Be prepared,” said Roy; “each one arm himself with a tin plate and after that every scout for himself. This is called a hunter’s stew because you have to hunt for the meat in it, but it’s got plenty of e-pluribus unions in it. The potatoes and dumplings go to the patrol leaders, carrots to first and second hand scouts; tenderfeet get nothing because the stew isn’t tender enough....”

It was pleasant sitting there in the bright area surrounded by darkness, chatting and planning the work for the morrow, and eating hunter’s stew, scout style, patent applied for. And notwithstanding the slurs which Roy had cast at the sky it was pleasant to see that vast bespangled blackness over head. In the solemn night the neighboring shacks were divested of their tawdry cheapness, the loose and flapping strips of tar-paper and the broken windows were not visible, and the buildings seemed clothed in a kind of sombre dignity—silent memorials of the boys who had made those old boards and rafters ring with their shouts and laughter. Not a sound was there now from all those barnlike remains of a life that was gone. Only the noise of the saw and the hammer would resound where once the stirring revelry echoed.

“You hear some funny sounds here at night, when the wind blows,” Blythe remarked.

“Shh, listen; I hear something now,” one of the scouts said.

“I heard that last night,” said Blythe uneasily; “or else I dreamed it.”

Westy, who had been poking up the fire, paused, his stick poised, listening. “It’s over there,” he said, pointing to the tall dark outline of the windmill.

“There isn’t breeze enough to turn the fan,” Doc Carson said.

“It sounds like someone groaning,” said another.

From the neighborhood of that old tower, though perhaps farther off, they could not tell, came a sound almost human, a kind of moaning intermingled with a plaintive wail, pitched in a higher key.

“Spooky,” Westy said.

“This is the kind of a place I like,” said Connie.

“Only it’s nice to have somebody here,” Blythe admitted.

“That’s all right, we’re here,” Pee-wee said.

They did not hear the sound again. If one were superstitious he might have conjured that sound into a crying of the ghost of some dead soldier haunting the old forsaken camp. But these scouts did not believe in ghosts.

They did, however, believe in hunter’s stew and they forgot all else as they sat around their camp-fire in the quiet darkness, telling yarns, and amusing their new friend by jollying....

As a camping place, perhaps the old reservation would not have proved a spot to the heart of the woods lover, but it was sequestered and had about it that romance which attaches to deserted habitations that are not tainted by the sordid environments of city life. The old buildings had never been beautiful and it was only the atmosphere of a place deserted which gave them a sort of romantic character.

But Nature had not been forced to evacuate the camp area; trees and tiny patches of woodland had remained, and the things which scouts love and seek had reasserted their supremacy there after the last of the soldiers, and later the army of clerical workers, had gone away.

The result was a kind of jumble of man’s hurried handiwork and Nature’s persistence, and the place, for a while, was a novel, nay even a delightful, spot in which to camp.

In conference with Blythe, who seemed cheerfully agreeable to any plan, the troop decided that each patrol should have the task of demolishing a building, and should work under the supervision of its leader, with Blythe as a sort of general overseer.

The whole troop, however, bunked in a small fourth building because this would not be in process of razing. From the appearance of this little building it had been a sort of club or meeting place. The window glass was quite gone, as indeed was all the window glass in the camp. Near by was a good place for their camp and cook fire. The little shack had shelves on which the scouts kept their stores. They made beds of balsam, scout fashion, and slept both in and out-of-doors, as the weather dictated.

Roy was cook, as he always was on their troop enterprises. In his forages against the stronghold of Chocolate Drop, the professional cook at Temple Camp, he had learned much of the beloved art in which that grinning negro excelled. The unruly flipflop tossed in air, fluttered down into his greasy pan like a tamed bird. In Pee-wee’s experiments it had a perverse habit of alighting on his head.

Roy’s spirit, indeed, seemed to pass into his cookery and give it a flavor all its own. His bacon sizzled with joy. His coffee bubbled over with mirth. His turnovers wore a scout smile. His baked potatoes had his own twinkle in their eyes. His dumplings were indented with merry dimples like those in his own cheeks.

The morning after their arrival they set to work in real earnest. They had not a complete equipment of axes and saws, excepting their belt-axes, but as much of the work consisted of gathering and piling the lumber, and removing nails from it, there were implements enough for all. Some of the scouts worked above, loosening the boards from the roofs, while others on the ground pulled the tar-paper and nails from these and made an orderly pile of them.

Such was the nature of their work during the first two or three days and they found it strenuous but neither too difficult nor heavy. And work was relieved somewhat by the comedy element furnished by Pee-wee who rolled off a roof on one occasion while eating a sandwich.

“Take the nails out of him, pull the sandwich out of his hands, and pile him up with the boards,” Roy called from a neighboring roof. “He’s docked thirty cents for the time lost in rolling down.”

“He ought to have an emergency brake,” Westy suggested, as the young Raven clambered up to his place again, sandwich and all, and proceeded working with the sandwich in one hand and a hammer in the other.

“Didn’t you say that’s all roofs are good for?” Pee-wee vociferously demanded. “To roll off of?”

“To roll down, I said,” Roy answered from his own perch among the beams of the next shack.

“Did you ever hear of anybody rolling up?” the young hero demanded.

“Sure,” said Roy; “didn’t you ever roll up and go to sleep? You never rolled down, and went to sleep, did you? That shows what you know about geometry.”

“That’s not geometry,” Pee-wee shouted. “I took geometry last year.”

“It’s about time you put it back,” Roy called.

“Look out or you’ll take another tumble,” Westy added.

“He didn’t put the last one back yet,” Roy observed.

“There goes your sandwich,” another one of the Silver Foxes called with glee, as that precious remnant of Pee-wee’s lunch went tumbling and separating down the slanting roof.

“Now you see what you made me do!” he fairly screamed.

“Food is coming down,” Roy laughed.

This is a fair sample of the fun and banter which accompanied their work and helped to make it easy and pleasant. Occasionally a harmless missile, perchance a luscious fragment of some honorably discharged tomato, would float gracefully from roof to roof bathing the face of some unsuspecting toiler with the crimson hue of twilight. And once again the weather-stained old shacks would seem alive with merriment and laughter.

As for Blythe he witnessed this merry progress with simple, grateful pleasure. He had expected to see the work done, but he had not expected to see it conjured by scout magic into a kind of play, nor the neighborhood of their joyous labor transformed into a scene of rustic comfort.

By the merest chance the scouts had come and seen and conquered, and presently the scene had that wholesome air of scout life about it. It seemed to poor Blythe as if he had awakened and found himself in fairyland, with a score or more of small brown gnomes climbing and scrambling about his domain, singing, jollying, planning, laughing, working, cooking, eating, kindling big camp-fires with odds and ends of wood, and telling such nonsensical yarns as he had never heard before. Pee-wee and Roy in particular amused him greatly. “Go on, make fun of him,” he would say to Roy. And then he would deliberately take sides with Pee-wee against the whole troop. But he was more prone to listen than to talk.

“Haven’t you got any adventures to tell?” Pee-wee asked him around camp-fire one night.

“Sure,” said Roy, “look in your pockets and see if you can’t find a couple.”

“I guess I’m not much of a hand for adventures,” Blythe laughed. “I like to hear about them though.”

“I’ll tell you some,” Pee-wee said. “I’ll tell you how I found a wallet——”

“And a dime,” Westy interrupted.

“Tell how you saved a fish from drowning at Temple Camp,” Roy said.

“Sure, that’s a fish story,” Connie piped up.

So Pee-wee launched forth recounting instances from his career of glory at Temple Camp, the boys prompting and jollying him, all to the simple delight of their new friend. His enjoyment seemed always an incentive to banter and nonsense....

It was soon apparent to the scouts that their coming had saved the enterprise for Blythe. He would not have been able to superintend the job with other helpers and even with the scouts he was rather their companion than their leader.

His attempts at sustained labor were pitiful. Yet he was never idle. But he moved from one unfinished task to another, never realizing apparently that each job he started was left undone. He was quite unequal to the harder part of the work, and the scouts, both kind and observant, could see that, and were content to let him gather and pile the fallen lumber and sometimes to rake up the smaller pieces for their evening fire, which he looked forward to with keen delight. What was the matter with him, they did not know. But this they did know, that he was their friend and that he took a kind of childish delight in their camping. He became excited easily and would sometimes seem almost at the point of crying. He would throw down his saw or hammer in a kind of despair.

But these traits were not noticeable except in the working hours and not always then. The boys kept up the fiction of his leadership, conferring with him and consulting him about everything. And with open hearts they took him into their scout life and liked him immensely.

The nearest they could get to a solution of his peculiarities was that he was not well and that a long course of unemployment and privation had resulted in his losing his grip. They took him as they found him, like the good scouts that they were, and their enterprise to earn a little money for improving their picturesque meeting-place at home seemed transformed into a collective, splendid good turn in which their scout loyalty shone like a light.

And so the days of strenuous, cheerful toil, and the nights around the companionable blaze, passed, and Blythe who seemed always fearful and apprehensive of something appeared to be haunted with a kind of dread that this remote and pleasant rustic life would come to an end.

“We won’t be finished next week?” he would say with a kind of simple air of wishing to put off that evil time. “You don’t think so, do you?” And Pee-wee would answer, “That’s all right, you leave it to me. I’ll fix it.”

And evidently he did succeed in fixing it, for it rained steadily for three days.

And now, since the sun had reappeared and they had decided to take things a little easier, Pee-wee announced his intentions of going on a pilgrimage to Woodcliff to hunt up the mysterious Helen Shirley Bates, and to ascertain from her the address of her soldier friend whom she had entertained at dinner during the war. For it was on Pee-wee’s conscience that the soldier who had lost his wallet had written a letter to his mother somewhere or other and that this had never reached its destination.

“Are you going to wear your Sunday uniform?” Roy asked. For Pee-wee kept a special suit of scout khaki for ceremonial occasions. Upon the sleeve of this were his merit badges.

On this notable pilgrimage, knowing the weakness of young ladies for official regalia, he wore also his canteen (empty), his scout axe—to hew his way into her presence perhaps—a coil of rope dangling from his belt, his scout scarf tied in the celebrated “raven knot” and his hat inside out as a reminder that he had not yet performed his daily good turn. Upon mailing the letter to its proper address, and not until then, would Scout Harris, R.P. F.B.T. B.S.A., put his hat on right side out. He also took some fudge which he had made as a tribute to his unknown Woodcliff friend. He was prepared to chop her to pieces or to give her candy, whichever the occasion required.

He was indeed a human quartermaster’s department and in addition to this equipment he carried also somewhere in the depths of one of his pockets a scout note book wherein the good scout rule of “jotting down things seen by the way” was scrupulously obeyed. There were few wayside trifles that escaped Scout Harris’ observant eye. A sample page from this record of his travels will give an idea of his thoroughness:

August 10th. From Temple Camp to Catskill. Passed a worm also a piece of a ginger snap. Passed a smell like a kitchen. Found a rubber heel in the road. A dead bug was upside down in a puddle. Met a fence. Saw something that looked like a snake but it was a shoe-lace. Had a soda in Catskill. Had another—raspberry. Saw a flat tire as flat as a pancake and it started me thinking about pancakes.

And so on, and so on.

It was Roy whom Pee-wee chose to accompany him on his important mission. They had reached a point about fifty yards from the shacks, two of which were well-nigh demolished, when they heard a voice and turning saw Warde Hollister drop from a rafter and come running toward them.

“How far is Woodcliff?” he asked, out of breath, and as if caught by a sudden idea.

“’Bout six or seven miles,” Roy said. “We don’t know just exactly where we’re going except that it’s somewhere around Woodcliff Lake.”

“I might make my last test,” Warde panted. “I just happened to think of it.” He looked rather appealingly at Roy who was his patrol leader.

“Come ahead,” said Roy, “I’m glad you thought of it.”

“Have you got your note book?” Pee-wee vociferously demanded. “You’ve got to jot down everything you see and write a satisfactory description of it.”

“Only the test says alone or with another scout.” Warde said doubtfully. “What do you think? It would be a peach of a chance and I’m crazy to get my first class badge.”

“The question is, are we to consider Pee-wee a scout?” Roy said, winking at Warde. “Is he a scout or a sprout?”

“It’s just as you say, you’re patrol leader,” Warde laughed.

“Sure, it’s all right,” laughed Roy, “come ahead. I’d have asked you only I never thought about it.”

“Have you got your note book?” Pee-wee again demanded.

“Yep,” Warde laughed.

“Then you’re all right,” Pee-wee assured him. “It doesn’t make any difference whether one scout goes with you or two.”

With such high legal authority as this, Warde’s mind was at rest. He was the newest scout in the troop and a member of Roy’s patrol, the Silver Foxes. He had made a great hit in the troop and was immensely liked.

He had not been long enough a member of the Silver Fox patrol to have imbibed the spirit of freedom with its sprightly leader which the others so hilariously exhibited. The Silver Fox patrol was an institution altogether unique in scouting. One had to be half crazy (as the Ravens and Elks said) before one became a tried and true Silverplated Fox—warranted. The Silver Foxes had a spirit all their own—and they were welcome to it.

Warde had shown his mettle by his tests, and also he had shown his fine breeding and spirit by not pushing too aggressively into troop familiarity. If he was not yet a full-fledged scout, he was at least a fine type for a scout, and the uproarious Silver Foxes and their irrepressible leader were proud of him.

He had now, as he had said, but one test to take before becoming a first class scout. This meant more to him than it might have meant to another for he had obtrusively prepared himself to claim several merit badges of the more easily won sort, as soon as his first class rank should enable him to properly lay claim to these.

He was ahead of the game in fact, and hence the anxiety of his tone and manner when he ran after Pee-wee and Roy, hoping that here might be the chance of fulfilling the final requirement before the coveted first class badge should be his. None fully knew how much he had dreamed of the first class badge. His fine loyalty had kept him at work among them, but he had not been able to see those two fare forth without jumping at the chance.

The test on which his achievement hung is on the same page of the handbook with the picture of the badge he longed for:

4.—Make a round trip alone (or with another scout) to a point at least seven miles away (fourteen miles in all) going on foot or rowing a boat, and write a satisfactory account of the trip, and things observed.

Warde Hollister was not the one to strain the meaning of this. To him it meant just exactly what it said. And so he had asked his patrol leader if it would be all right for three to go instead of two. It was a small matter and of course it was all right, as any scoutmaster or National Scout Somebody-or-other would have agreed. The point is that Warde’s thinking about it was very characteristic of him. In this instance he accepted his patrol leader’s decision....

It was not likely that Warde Hollister would forget his note book, for his habit of keen observation and a knack he had for full and truthful description had won him the post of troop scribe which Artie Van Arlen’s duties as Raven patrol leader had compelled him to relinquish.

“If it’s seven miles there,” said Warde, plainly elated at the thought of accompanying them, “all I’ll have to do is to write my little description when I get back and there you are.”

“A first class scout,” said Pee-wee, quite as delighted as his friend.

“It says fourteen miles there and back,” said Roy. “Maybe it’ll be seven miles there but we don’t know how far it will be back. Sometimes it’s longer one way than another. You never can tell.”

“You make me tired,” said Pee-wee.

“All right, you’re so clever,” said Roy; “how far is ten miles?”

“How far?”

“That’s what I said.”

“You’re crazy,” Pee-wee shouted.

“Answer in the affirmative,” said Roy. “There’s a grasshopper, get out your note book.... Do you know what he did once?” he asked, turning to Warde. “He wouldn’t jot down a fountain in Bronx Park because he didn’t have a fountain pen——”

“You’re crazy!” Pee-wee shouted.

“He went into a store and asked for the handbook and when they told him they didn’t have one he asked for the feetbook. He thinks the feetbook has got all the daring feats in it. He——”

“Don’t you believe him,” Pee-wee yelled.

“Before he was in the scouts he used to be a radiator ornament on an automobile,” Roy persisted. “There’s a caterpillar, enter him up, Kid,” he added.

“Up at Temple Camp,” Pee-wee yelled in merciless retaliation, “they—they told him he could play on the veranda and he said he could only play on the harmonica!”

“I admit it,” Roy said. “That was when I was a second-hand scout.”

“They ought to be called the Nickel Foxes, that’s what all the scouts up at Temple Camp say,” Pee-wee shouted. “Because none of them ever have more than five cents.”

“The Raving Ravens haven’t got any sense,” Roy came back. “Five is twice as good as nothing.”

“That shows how much you know about arithmetic,” Pee-wee retorted.

“It’s good the boss isn’t here,” Warde said, “or he’d laugh himself to death.” The boss was what they always called Blythe.

“Maybe you’ll say I didn’t discover him,” Pee-wee demanded.

“You’re the greatest discoverer next to Columbus, Ohio,” Roy said.

“Well anyway, whoever discovered him, I like him,” Warde said.

“Same here,” said Roy quite ready for any topic of conversation. “I can’t make him out but I like him.”

“He’s just down and out, sort of,” Warde said. “Maybe he’s been sick. That’s the way it seems to me. But he likes us and I like him. It’s fun to see him smile.”

“I wonder where he came from?” Roy asked, as they made their way across fields. “He never says anything about where he belongs or anything.”

“Maybe he doesn’t know,” Warde said.

“We shouldn’t worry about his history,” said Roy. “He’s all right and that’s enough. And he’s going up to Temple Camp with us if I can get him to.”

“I——” began Pee-wee.

“Sure, you discovered Temple Camp,” said Roy. “You discovered the North Pole and the South Pole and the clothes pole and the Atlantic Ocean and Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company and you’ve got them all down in your little book.”

“No joking,” said Warde. “I was——”

“I never joke,” said Roy, “except from Mondays to Saturdays, and on Sundays, morning, afternoon and evening.”

Warde tried again, “I was going to ask you about test four.”

“I’ll tell you about it,” said the irrepressible Pee-wee.

“How about writing the satisfactory account?”

“It doesn’t include worms and ginger snaps,” said Roy.

“But what’s the usual way?” Warde persisted.