A LITTLE DOG SCOOTED BETWEEN PEE-WEE’S LEGS.

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Roy Blakeley’s Camp on Wheels

Date of first publication: 1920

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh (1876-1950)

Date first posted: Sep. 19, 2019

Date last updated: Sep. 19, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190951

This eBook was produced by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

ROY BLAKELEY’S CAMP ON WHEELS

A LITTLE DOG SCOOTED BETWEEN PEE-WEE’S LEGS.

ROY BLAKELEY’S

CAMP ON WHEELS

By

PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH

Author of

TOM SLADE, BOY SCOUT, TOM SLADE WITH THE COLORS,

TOM SLADE WITH THE FLYING CORPS

ROY BLAKELEY, ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

HOWARD L. HASTINGS

Published with the approval of

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1920, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| I | Brewster’s Center |

| II | The Housing Problem |

| III | “A Wide-Awake Lot” |

| IV | A Wild Night |

| V | Somewhere in America |

| VI | The Big B |

| VII | On to Skiddyunk |

| VIII | Labor Troubles |

| IX | Sandwiches |

| X | Scout Harris |

| XI | We Meet the Cheerful Idiot |

| XII | On the Screen |

| XIII | An Invitation |

| XIV | Pee-wee on Scouting |

| XV | To the Rescue |

| XVI | Unconditional Surrender |

| XVII | A Wild-Cat Ride |

| XVIII | The Middle of the Road |

| XIX | Westy |

| XX | Taking It Easy |

| XXI | The Sheriff Arrives |

| XXII | Railroading |

| XXIII | Crazy Stuff |

| XXIV | Up in the Air |

| XXV | In the Dark |

| XXVI | Walter Harris, Scout |

| XXVII | “Pots” |

| XXVIII | “Seen in the Movies” |

| XXIX | “Foiled” |

| XXX | Our Patrol “Sing” |

| XXXI | Flimdunk Siding |

| XXXII | Exploring |

| XXXIII | Our Young Hero |

| XXXIV | The Train |

| XXXV | The Profiteers |

| XXXVI | A Friend in Need |

| XXXVII | Tenderflops and Other Flops |

| XXXVIII | All Aboard |

ROY BLAKELEY’S CAMP ON WHEELS

Maybe you think just because scouts go camping in the summer time, and take hikes and all that, that there’s nothing to do in the winter. But I’m always going to stick up for winter, that’s one sure thing.

Anyway, this story isn’t exactly a winter story, it’s a kind of a fall story—lightweight. Maybe after this I’ll write a heavyweight winter story. Dorry Benton (he’s in my patrol) says that if this story should run into the winter, I can use heavier paper for the last part of it. That fellow’s crazy.

Believe me, there’s plenty happening in the fall and in the winter; look at nutting and skating and ice-boating. Only last winter there were two big fires here in Bridgeboro and one of them was the High School. Gee whiz, what more could you want?

But the best fire I ever went to was when the Brewster’s Centre railroad station burned down. That was three or four years ago, and the railroad decided that as long as there was going to be a big war in Europe, they wouldn’t build a new station.

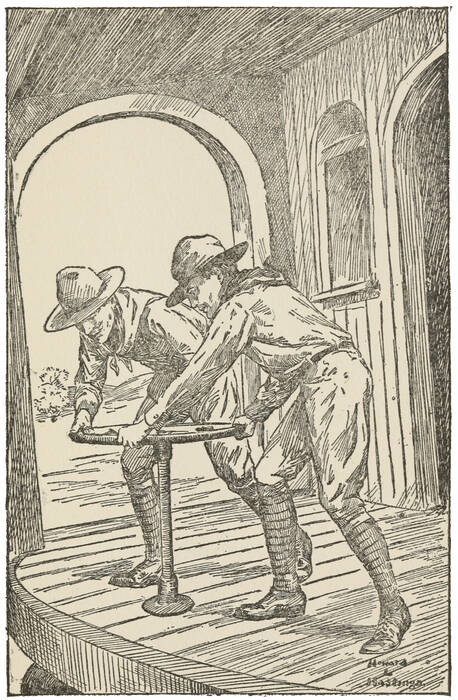

It won’t do you any good to look on the map for Brewster’s Centre, because you won’t find it. Even with a microscope you couldn’t find it. The reason you can’t find it is, because it isn’t there. I guess the men who made the map couldn’t make a small enough dot. That’s one thing I’m crazy about—maps. But I hate geography—geography and cough mixture. But I’m crazy about apple dumplings.

Anyway, you’ll have to take my word for it that Brewster’s Centre is four or five stations above Bridgeboro. There isn’t any man named Brewster. He went out West about fifty years ago. I guess he forgot to take his centre with him. Anyway, it’s up there. I guess nobody wants it.

There are about a dozen people up in Brewster’s Centre who go to the city; gee, you can’t blame them. So the railroad put an old passenger car on a side track up there and boarded up the under part so you couldn’t see the wheels, just the same as on a lunch wagon. They partitioned off part of the inside of it for a ticket office and made a window in the boards, and the rest of the car was a waiting-room. There was a stove in the corner. It was like the Pennsylvania Station in New York, only different. They used the same old sign that used to be on the regular station and it looked funny sprawling all over the side of that car. It said:

Buffalo 398 Mls.—BREWSTER’S CENTER—N. Y. 30 Mls.

You’d think that Brewster’s Centre was the centre of the whole earth. Anyhow it showed two different ways of getting away from there. It’s a wonder it didn’t tell how far it is from Brewster’s Centre to Paris. I guess the moon is about ’steen billion miles from Brewster’s Centre. But one thing, there’s a place where you get dandy ice-cream cones up there.

That’s all there is to this chapter. It isn’t much of a chapter, hey? But it’s big enough for Brewster’s Centre. It’s a kind of a prologue chapter. It’s like Brewster’s Centre, because nothing happens in it. The only thing that ever happened up there was the fire, and that happened three or four years ago. You can’t even smell the smoke in this chapter. But just you wait and see what happens.

Now comes a lapse of three years—I got that out of the movies. Maybe if you’ve read all about our adventures you’ll remember how my patrol, the Silver Foxes, hiked home from Temple Camp last summer. Believe me, that was some hike. The other two patrols came home later by boat. They said they had more fun without us. I should worry about them.

The second night after we were all home I started around to the church to troop meeting and I met Pee-wee Harris coming scout pace down through Terrace Street. He’s one of the raving Ravens. He was all dolled up like a Christmas tree, with his belt axe hanging to his belt and his scout knife dangling around his neck and his compass on his wrist like a wrist watch.

I said, “You look like a hardware store. Where are you going? To chop down the North Pole?”

He said, “There’s bad news waiting for us at troop meeting.”

“Well, it’ll have to wait till we get there,” I told him; “I wouldn’t go scout pace hunting for bad news.” Cracky, if that kid was on his way to the electric chair he’d go scout pace.

“We’ve got to give up the troop room,” he said; “Doctor Warren told my mother to-day. The men are going to use it for a club.”

“Good night!” I told him; “why should they use a club? We’ll get out without any trouble; peace at any price.”

“It’s a sociable club,” he said.

“Well,” I told him, “I wouldn’t want to get hit with a club no matter how sociable it is.”

“It’s going to be called the forearm club,” he said.

Gee, I had to laugh. “You mean forum,” I said. “What are you trying to do? Scare the life out of me with clubs and forearms?”

When we got to the troop room all the fellows were standing around and Mr. Ellsworth, our scoutmaster, was there to tell us the worst.

He said, “Scouts, you’ll all remember that this pleasant meeting place was put at our disposal by Doctor Warren to be used by us until it should be needed for other purposes.” (This is just what he said, because I asked him to write it out in my troop book afterwards.) “Doctor Warren now informs me that the plans for building a new church being postponed on account of the cost of labor and materials, the use of this room practically every night in the week is imperative. Since we are not actually a part of the church, I think we should insist on relinquishing it in favor of the many church activities for which this old building is all too small. We shall presently find another home. I am sure that every scout in this troop will join me in expressing our gratitude to Doctor Warren and his good people for their interest in us and their hospitality. I am in hopes that the room in the Public Library where the Red Cross ladies worked may be available to us. Meanwhile, we have the great scout roof over our heads—the blue heaven.”

“Believe me,” I said, “that great scout roof is all right, only it leaks like the dickens. Anyway, we should worry; we’ll find a place.”

So that night we spent taking down our pictures and all our birch bark ornaments, and packing our books and getting ready to move. We were up against the housing problem, that’s what Westy Martin said.

The next day was Saturday. That’s the thing I like best about school—Saturday. So I went into the city to get a new scout suit on account of my other one being all torn from our long hike from camp. I came home on the Woolworth Special, that’s the 5.10 train. On the train I met Mr. John Temple. He’s the man that started Temple Camp. He lives in Bridgeboro and he owns a lot of railroads and things. Anyway, he did, only the government took them. He should worry, he’s going to get them back. He’s head of the bank, too. Gee, I hope nobody takes that away from him. I’ve got fifty-seven dollars in that bank. He used to be mad at the scouts, but then he found out that he was mistaken and he went off and built Temple Camp just out of spite to himself, kind of. Whenever he sees me he’s awful nice.

He said, “Well, Roy, how are the scouts getting on?”

I said: “Believe me, they’re not getting on, they’re getting out. We can’t use the lecture room in the church any more. If we don’t get the room where the Cross Red Nurses were, I don’t know where we’ll meet We’ll meet in the sweet by and by, I guess.”

He just began to laugh and he said: “Property and real estate are hard to get just now. Rentals are pretty high.”

“Gee whiz,” I told him, “I wouldn’t care if it was real estate or imitation estate or any other kind if there was only a room on it.”

He said, laughing all the while, “Well now, I have an idea. How would this strike you? They’re finishing the new station up at the Centre. What do you think of that old car for a meeting place? Just for a while, you know, till you can find a regular place somewhere. It has a stove and seats and.... How would that strike you?”

Oh, boy!

“It strikes me so hard it makes a black and blue spot,” I said; “and that wouldn’t be so far to go for meetings.”

He said: “Oh, you wouldn’t have to go up there for meetings. If I can arrange to get it for you, I’ll have it brought down to Bridgeboro. I don’t know where you could put it or just how you would move it away from the tracks, but it could be done.”

Oh, bibbie, wasn’t I excited! “We could put it in the field down by the river,” I said; “oh, it would be simply great!”

Mr. Temple just laughed, and he said, “Well, don’t count too much upon it. Uncle Sam has a say in all these things nowadays. But I think perhaps I can arrange matters. The car is no use up there; it isn’t of much use anywhere. I’m afraid the difficult part would be in moving it away from the tracks when we got it to Bridgeboro. However, we’ll see.”

I was so excited that when we got to Bridgeboro I stayed on the train and went on up to Brewster’s Centre just to take a look at the car. As long as I was up there I thought I might as well get an ice-cream cone at that place I told you about. Then I hiked it home.

In a couple of days I got a letter from Mr. Temple. It came from his office in New York. This is what it said:

Dear Roy:

I have arranged with the railroad people to let you boys have the Brewster’s Centre Station car. You will please accept it as a gift to your troop from myself.

The freight which passes through Brewster’s Centre somewhere around 10 P.M. will take it on Friday night and leave it on the siding at Bridgeboro. I am going to talk with Mr. Ellsworth about the means of moving it from there to a suitable location.

I am informed that the new station will be opened Friday morning, so if you and your companions wish to take possession Friday afternoon, you may do so. But do not make any alterations or bother the local agent until he gives you permission to go ahead.

I hope the troop will find this makeshift meeting place suitable till conditions are more favorable for finding a permanent headquarters.

Best wishes to you.

John Temple.

Oh, boy, isn’t he a peach of a man? I bet we hiked up to Brewster’s Centre a dozen times before Friday. I guess Pee-wee thought the station would run away. He couldn’t even wait till it got down to Bridgeboro, but asked the girl ticket agent if it would be all right for him to bring some things up, and good night! he showed up Thursday afternoon with his moving picture outfit and a lot of other stuff.

On Friday morning the new station was opened. It had a nice little ticket office for the girl to read novels in. So on Friday afternoon we all went up and took the boarding away from under the car and piled it inside, because we thought we might use it again. The part that was boarded off for a ticket office was at one end, and in the other part the seats were left just the same as in a regular car. It was nice in there, especially for meetings where somebody had to talk to us, only in our troop most always everybody is talking at once, especially Pee-wee. He talks so fast that he interrupts himself.

After we got the windows washed and the boards from underneath piled inside and the little ticket office all cleaned out, it was about six o’clock. Westy Martin (he’s in my patrol) said it would be a lot of fun for some of us to stay and come down in the car.

“I’ll stay!” Pee-wee shouted.

“How about you?” Westy asked me.

I said: “We’re going to have apple turnovers for dessert to-night, but I should worry, I’ll stay.”

Most of the fellows had to go home on account of their lessons, but I didn’t have any lessons, because my teacher had to go to a lecture. That’s the only thing I like about lectures. Westy always does his lessons right after school, before he goes out. Then in case he gets killed his lessons are done. He’s a careful kid. Anyway, all of us hate to do lessons on Saturday, because that’s scouting day.

The fellows that said they’d stay were Pee-wee Harris and Wig-Wag Weigand (they’re both raving Ravens), and Connie Bennett of the Elks (he wears glasses), and Westy Martin, and dear little Roy Blakeley, that’s me. I use glasses, too—when I drink ice-cream sodas. The rest of the troop went home and they said they’d all be down at the siding near the Bridgeboro Station early in the morning.

Westy had his camp outfit along and we had a lot of fun that night cooking supper in that old car. Westy and Pee-wee went up to the store and got some eggs and stuff, and I made a dandy omelet. I flopped it over all right and Connie Bennett said it would do for a good turn, because I hadn’t done any good turn that day. Pee-wee just turned around a couple of times and said that was his—he should worry.

After supper we took a little hike in the woods but we didn’t stay very long, because we were afraid that freight might come along ahead of time. Safety first. When we got back we sat around on the plush seats waiting for the freight and jollying Pee-wee.

It got to be about half-past ten, but still the freight didn’t come. Every little while one of us would go out and hold an ear down to the track and listen. You can hear a train about ten miles off that way.

“If it’s coming at all it must be coming on tiptoe,” I said.

“Or else it’s wearing rubbers,” Wig answered back.

“Maybe it’s stalking a cow that’s on the track,” I said, “and has to sneak along quietly. We should worry.”

Pretty soon we began getting sleepy. Pee-wee said he wasn’t exactly sleepy, but he guessed he’d lie down a little while. That was the end of him. If there had been an earthquake it wouldn’t have stirred him. The only thing that could have awakened him would have been his own voice, only he doesn’t talk in his sleep.

Pretty soon Wig said it was funny how Pee-wee could fall asleep so easy and he guessed he’d just sprawl on one of the seats and think. Good night! but didn’t he snore while he was thinking. All of a sudden Westy went sliding down to the floor and I dragged him up on the seat again. He was dead to the world.

“Believe me,” I said to Connie; “what do you know about that? I’ll laugh if that freight comes along and gives us a good bunk. Look at that trio, will you?” He just didn’t answer me at all.

“G-o-o-d night!” I said to myself; “wake me early, mother dear.”

All of a sudden I happened to think of something that Mr. Temple said in a speech about the scouts being such a wide-awake lot. Gee whiz, I laughed so much that I just lay down on the seat and held my sides.

That’s the last that I remember. I guess I fainted from laughing so hard.

Now I’ll tell you just exactly what happened while I was lying on that seat. Charlie Chaplin came to me and he said, “General Pershing says for you to get off of that barrel.” I said, “I won’t get off of the barrel till I finish eating this apple.” Then he said, “If you don’t get off the barrel, we’ll shoot the barrel out from under you.”

So then General Pershing and Charlie Chaplin began wheeling a whole lot of cannons so as to make a big circle around me. And all the while Douglas Fairbanks was standing there laughing. Then they began shooting at the barrel, and every time a cannon ball hit the barrel it would joggle and almost shake me off. Sometimes the barrel stood up on edge and then a cannon ball would knock it back again and it would go dancing every which way with me on it. I had to hang on for dear life. Pretty soon I got mad (gee whiz, you couldn’t blame me) and I threw the core of the apple at General Pershing, and he began to laugh. He said, “Never hit me!”

Pretty soon the barrel got knocked over sideways and I was sprawling all over it trying to keep on top while it rolled down a hill. All the while Charlie Chaplin was running after me and trying to hook me with his cane and somebody shouted, “What does it say on the waybill? Look on the waybill!” And I could hear a sound like whistling. Then, good night! all of a sudden I went kerflop off the barrel. Just then a man shouted, “All on!” I guess he meant all off. Anyway, I didn’t care, because I was lying in an automobile and jogging along awful nice and easy.

In the morning I was lying on the floor of the car with my arm around Connie Bennett’s leg. Every one of those four fellows was dead to the world. I pushed up the shutter that had slipped down, like they always do, and looked out of the window. Right outside was a barrel. But I didn’t see General Pershing. There was a big field right near, and over farther was a lake. It was a dandy lake, with woods on the opposite shore. There were big high mountains, too, all bright on top, because the sun was coming up over them.

I went out on the platform and looked up the track. I could see way far off till the tracks went to a point. The car was on a siding. Not very far off I could see smoke curling up and I knew there must be a house there somewhere. On the other side from the lake was a store with a platform in front of it. It wasn’t open yet.

I went in and washed my hands and face at the water cooler, then went out and looked again. But there wasn’t anything to see, only the lake and the woods and the smoke curling up among the trees, and the store right near. I got out and looked at the side of the car. There was the big sign sprawling all over it.

Buffalo 398 Mls.—BREWSTER’S CENTER—N. Y. 30 Mls.

That place wasn’t Bridgeboro, that was one sure thing. Because, gee whiz, I know Bridgeboro when I see it. And it wasn’t Brewster’s Centre, either.

I went in and began shaking Pee-wee, but it wasn’t any use. Then I gave Westy a good shove and I shouted at him, “Wake up, the plot grows thicker. We’re somewhere, but I don’t know where. We’re lost, strayed or stolen. Wake up, your country needs you.”

He sat up in the seat, rubbing his eyes and yawning. Then he said, kind of half asleep, “I—s—s—s—a—t—day? Wha’—we—doin’—a—a—a—here?”

I said, “It’s Saturday, and we’re here because we’re here. But I don’t know where. There’s a lake and a lot of woods and some mountains.”

“Le’s see ’em,” he said.

“Look out of the window,” I told him.

He just yawned, “Where are they? Outside?”

“They’re on the landscape,” I told him; “come on, we’ll go and stalk them before they sneak away. Get up, you lazy....”

Just then Connie Bennett rolled over and sat up and tried to keep his eyes open while he looked out of the window.

“Wass become Bridgeboro?” he said.

“It just went out to get some rolls for breakfast,” I said; “it’ll be right back.”

“Where are we at?” he wanted to know.

“Search me,” I told him; “all I know is I was rolling down a hill on a barrel and Charlie Chaplin was running after me. There’s the barrel out there now.”

As soon as I mentioned Charlie Chaplin’s name, Pee-wee woke up. Charlie Chaplin is one of his favorite heroes; George Washington, Napoleon, and Charlie Chaplin—and Tyler’s milk chocolate.

“Where are we?” he began shouting. “There’s a lake! Look at the lake! What’s that lake doing here?”

“That lake has got as much right here as you have,” I told him.

Of course, as soon as Pee-wee began shouting Wig Weigand woke up, and after the whole four of them were through stretching and gaping, we had a meeting of the General Staff.

I said, “Something happened in the night. The first thing for us to do is to find out where we are. We can’t go home till we know where we have to go from.”

“I don’t care where we are,” Pee-wee shouted; “the first thing is to have breakfast.” Cracky, he’s like all the Ravens; always thinking about eats.

“We can’t eat breakfast till we know where we’re eating it,” I told him; “we’ve got to find out where we’re at.”

“You make me tired,” he shouted; “will you answer me one question?”

“Sure, ask me an answer and I’ll question you,” I said.

“Are we in the Brewster’s Centre Railroad Station or not?” he yelled.

“Sure we are,” Westy said.

“Then we know where we are, don’t we?” Pee-wee came back. “A location is a place, isn’t it?”

“Yes, but where’s the station?” Connie piped up.

“Pee-wee’s right,” I said; “we should worry about where the Brewster’s Centre Station is. We’re on the earth, aren’t we?”

“Sure we are,” Wig said.

“All right,” I told him; “we don’t know where the earth is, do we?”

“It’s right here,” Westy said.

“Yes, but where is here?” I shot back at him.

“Search me,” Westy said.

“Just the same as if you say a place is up,” I told him; “how high is up? Suppose the lights go out, where do they go? How do we know? But anyway, we know they go out.”

“Sure, that’s rhetoric,” Pee-wee shouted.

“You mean logic,” I told him. “Nobody really knows where he’s at. Even the smartest man in the world doesn’t know where he’s at. What do we care? Just because the earth is in the Solar System, that doesn’t say we have to tell where the Solar System is, does it? We’re in the Brewster’s Centre Railroad Station and the Brewster’s Centre Railroad Station is somewhere in France—I mean somewhere in the Solar System. Secretary Hines has charge of the railroads—he should worry. Come on, let’s get breakfast.”

We only had enough stuff to last for about one meal, so we put all our money together and counted it up. We had forty-two cents, and an eraser, and a subway ticket, and a little hunk of icing from a piece of cake, and a trolley zone ticket, and two animal crackers. I dumped the money and the hunk of icing and the two animal crackers into Connie’s hand (because he’s our troop treasurer anyway). “Here,” I told him; “food will win the war, don’t waste it.”

I made some coffee and then we fixed two of the seats facing each other and two of the fellows sat on one seat and two on the other with a piece of board between them.

There was a red flag on that car and I used it for an apron. Some chef, hey? The heating stove was in the little ticket office and I just passed the tin cups out through the window, and each time I called “one coffee” and slapped it down on the counter. I guess I’ll be a waiter in Child’s after I’m not a child any more—that’s a joke. Anyway, it was lucky we had some Uneeda crackers; we needed them enough, believe me.

After breakfast, Westy said, “There ought to be a town somewhere around here.”

“Look around and see if you can see it,” I told him; “maybe it ran away when it saw us coming.”

He and Connie were just going to start out looking for the town, when a man came along and went up the steps of the platform in front of the store. I guess he kept the store. He had a big straw hat on and one suspender over his left shoulder. He had a little beard like a billy goat. When he got up on the platform he stood there staring at us. Pretty soon a couple more men came and they all stood there in front of the store, staring.

“I think we’re pinched,” Westy said.

“I wonder how much we can buy for forty-two cents in that store,” Pee-wee wanted to know.

“About forty-two cents’ worth,” I told him.

“That won’t keep us alive for one day,” he said.

“Are you thinking about lunch already?” I asked him. “You should worry about lunch. All we have to do is to send a telegram to Bridgeboro and Mr. Temple will have another freight pick us up. We can be back there by to-night. I don’t know where we are, but if we got here in one night, we can get back in one day, can’t we? Anybody that knows anything about geometry can tell that. You should worry, we won’t starve.”

“What’ll you say in the telegram?” he wanted to know.

“Lost, strayed or stolen. Tag, you’re it. Come and find us. How would that do?” I asked him. “We’ll send it in your handwriting, then they’ll know who it’s from.”

Good night, you should have seen that kid. He jumped up on one of the seats and began shouting, “Do you think I’m a quitter? Do you think I’m going to send and ask anybody to take me home?”

“You’re a raving Raven,” Westy began, laughing.

“Do you think a raving Raven—I’m not a raving Raven,” Pee-wee just yelled, he was so excited; “you think you’re funny, don’t you? Do you think I’m a big baby?”

“Not so very big,” Connie said.

Pee-wee just stood there, yelling at us, “If you want to send word home, go ahead. You admit yourself you’re somewhere—don’t you?”

“Shout a little louder and they’ll hear you in Bridgeboro,” Wig said; “and then we won’t have to wire them.”

“It isn’t up to us, is it?” Pee-wee yelled. “Some train or other brought us here. When they find out they made a mistake, let them take us away again. What do we care? It’s none of our business. It’s up to the colonel, I mean the general or whatever you call him, of railroads. We can get along all right; we’re scouts, aren’t we?”

“How about school?” Westy said.

“How are they going to get the school here, all the way from Bridgeboro?” Pee-wee shouted.

“That settles it,” Connie said.

“Sure it settles it,” Pee-wee shouted; “and besides, Monday is Columbus Day—and Monday night, too. That’s a holiday.”

“There are a lot of Knights of Columbus, but there’s only one Columbus Day,” Westy shouted at him.

“They’ll find out where we are in three days, won’t they?” Pee-wee screamed. “I say let’s stay here. I say let’s be too proud to send for help.”

“Sure, we should worry,” I said.

“That’s what I say,” Connie shouted.

“Scouts don’t ask for help, do they?” Pee-wee yelled at the top of his voice.

I said, “No, but believe me, scouts like to eat. I know one scout that does, anyway. What are we going to eat between now and next Monday or Tuesday or Wednesday?”

“We’ll find a way,” Pee-wee shouted. “Maybe they’ll pick us up to-night, you can’t tell. Anyway, I’m not going to be a quitter. Whenever I have to do anything I can always find a way. We can have a movie show, can’t we? We can charge ten cents. We can have it to-night. You needn’t sign my name to any telegrams.”

“How can we have a movie show when there isn’t any town here?” Westy wanted to know.

“We’ll find the town,” Pee-wee shouted; “it must be somewhere.”

Connie said, “Oh, it’s probably somewhere.”

“Sure it is,” Pee-wee hollered; “and I’ve got that Temple Camp film in the machine. Remember about those scouts that were lost for a week in the Maine woods? We’re not as bad off as they were, are we?”

“Sure we’re not,” I said; “this is only the main line. Maybe it’s only a branch line.”

“Do you mean to tell me that scouts can’t get along when they’re lost on a branch line?” he wanted to know. “Scouts can do anything, can’t they? If I have to do something, I just do it. If I can’t do it, I do it anyway. I can find a way, all right.”

“Bully for you! Hurrah for P. Harris!” we began shouting.

“Do you think I’m going to starve?” he screamed.

“Gee whiz, it never looked that way to me,” I said.

“Why should we go home while we’re waiting?” he yelled at us.

“Look out, you’ll fall off the seat,” Connie said.

“We’re here because we’re here, you can’t deny that!” the kid fairly screeched, all the while hanging onto one of those cage things they put bundles in, so he wouldn’t fall off. “And I say we just stay here until they take us back in what-do-you-call-it—triumph—and put us where we belong. This is our station. No matter where it is, it’s our station. We’re good at tracking. If there’s a town we’ll trail it.”

“If it’s hiding we’ll find it,” I shouted; “hip, hip and a couple of hurrahs for P. Harris, scout!”

So we decided that we wouldn’t send any telegrams or anything, and that we’d stay right there in Brewster’s Centre Station till the railroad took us away and put us where we belonged. We said it was up to them. Westy’s mother knew he had his “eats” outfit along, and I guess all our families knew about there being a stove and coal in the car. Anyway, you can bet that scouts’ mothers don’t worry about them when they’re away. Gee whiz, my mother worries more about me when I’m home, because I always eat a lot of pie and cake when I’m home. And I’m always using the ’phone.

We all said it would be a lot of fun to camp out in that car and to just not pay any attention to what had happened. When we got home, we’d be home. We decided on some poetry that we’d send to the Bridgeboro News when we got back. It isn’t much good, but anyway, this is it:

We started out to wander,

We didn’t mean to roam.

We’re here because we’re here,

And when we’re home we’re home.

We hope they’ll come and get us,

But we’re not in a hurry.

We’ve got forty-two cents and a movie outfit,

We should worry.

That isn’t much good, is it? Anyway, we decided that the next thing to do was to find out if there was a town anywhere around. There wasn’t any railroad station, that was sure. Now all the time that we were having that rumpus in the car, those men stood over there on the platform in front of that store, staring and staring and staring.

Pretty soon they all came over and the man with one suspender said, “Thar be’nt no growed-up man along o’ you youngsters, be there?”

Westy told him no.

Then he looked us all over, very easy like, and he said, “Yer chorin’ on the railroad?”

I said, “We’re boy sprouts and this is Brewster’s Centre.”

He said, “Brewster’s Centre? Whar?”

I said, “Right here in this car.”

He just looked all around and then he said, “They haint cal’latin’ on changin’ the name of this here taown ter Brewster’s Centre, be they?”

“’Cause that won’t go here,” another one of the men said. “We wuz promised a station, but we haint goin’ ter have no changin’ of names. The railroad folks tried that down ter Skunk Hollow, settin’ up a jim-crack station, all red shingles and fancy roof, and callin’ it Ozone Valley. But they can’t come any of that business up here.”

“After Eb Brewster, too,” the other man said; “and him crazier’n a loon.”

“Hadn’t ought ter be thirty mile nuther,” the man with one suspender said; “that three oughter be an eight. Noow York is eighty mile on the rail.”

They all stood there squinting up at the Brewster’s Centre sign, and all of a sudden I had a thought and I whispered to the fellows, “Don’t spoil the plot, it’s growing thicker. Let me do the talking.”

One of the men said to the others, “I alluz allowed Eb was jest talkin’ crazy when he said haow he had friends amongst them big railroad maganates. But the taown haint never goin’ to stand fer this, it haint.”

Then I spoke up and said very sober-like, “What used to be the name of this town?”

The man said, “’Taint youster; ’tis. This here taown is Ridgeboro, Noow York, and so it’ll stay, by thunder!”

“Good night!” I said, and all the fellows started to laugh.

Because then I knew how it was. We must have been picked up by the wrong train—a train going the other way. And the conductor must have had Ridgeboro instead of Bridgeboro on his paper. Oh, boy, that was some bull. And just as luck would have it, the people of that place were expecting the railroad to give them a new station. I didn’t know where the old station was; I guessed there wasn’t any.

Connie whispered to me, “Who do you suppose Eb Brewster is?”

“Search me,” I told him; “but I bet he’ll be tickled to death to find that the town is named after him.”

I didn’t want him to ask us any more questions, so I said I guessed we’d go and look for the town if he would tell us where we could find it. He got kind of mad at that, because that was the town right there, and all the while we didn’t know it. Gee whiz, how could we tell? He said some day that town would be as big as Skiddyunk and that once upon a time New York had only one store, too.

“It has one store three or four now,” I said.

Then he told us that Skiddyunk was about one mile along the track and that we’d see it as soon as we got around the bend. I guess Ridgeboro was just kind of on the edge of Skiddyunk. Gee whiz, if the railroad was going to give it a station, that station ought not to be a car. A wheelbarrow would be good enough.

“I wish we had some money, I know that,” Connie said, as we were walking along the ties. “That’s the only thing that’s worrying me.”

“Same here,” I told him, “but we’re going to have a lot of fun here, believe me; I can see it coming.”

“Keep your eyes peeled and see if you see a train coming,” Westy said. Can you beat that fellow? Oh, but he’s a reckless boy—not.

“Careful Carl,” I said.

“What do you do with all the money you spend?” Connie wanted to know.

“Oh, I save it,” I told him; “ask me another one.”

“Who do you think Eb Brewster is?” Pee-wee piped up.

“He’s the man the town is named after,” I said; “good night, there’s going to be some fun around this way. I’m glad I’m not the railroad.”

“I bet those men will take that sign down,” Wig said.

“I bet they’ll put it up again, then,” I told him.

“Are you going to tell them the station is for them?” Pee-wee asked me.

“A scout is truthful,” I said; “why should I tell them that? I’m just going to keep still and see what happens. I may decide to name the car after Eb Brewster. I should worry. We can name it after anybody we want to name it after, can’t we? Jiminetty, I’m glad we’re here; we dropped in at the right place.”

“One thing, I’m glad Monday’s Columbus Day,” Pee-wee said.

“Believe me” I told him, “Columbus never discovered anything like this. I could kind of read in that man’s face, the one with the suspender——”

“He didn’t have the suspender on his face,” Pee-wee shouted.

“Take a demerit for that, and stay after school,” I told him. “I could kind of read in that man’s face, that there is going to be some fun in Ridgeboro.”

“A tempest in a teapot, hey?” Westy said.

“You ought to apologize to the next teapot you meet,” I shot back at him. “Teapots aren’t so small.”

Pretty soon we got around the bend and then we could see the Skiddyunk Station. It was a regular station with a platform and everything, all fancy kind of.

“It makes the poor little Brewster’s Centre Station look like a dollar and a quarter,” Connie said.

I said, “I haven’t seen a dollar and a quarter for so long that I can’t tell, but the Brewster’s Centre Station has traveled; that’s what counts.”

Before we got to the station we saw where tracks branched off from the tracks we were following, so we knew that all the trains that passed Skiddyunk didn’t pass Ridgeboro. I guess they didn’t bother with that place much. At the Skiddyunk Station we got a time table and found that only one train a day passed Ridgeboro. It didn’t go much further than Ridgeboro. I guess it got sick, hey? It only went as far as Slopson. Then we asked the express agent about freight trains and he said that a freight train went along that branch line every three days. He said there wouldn’t be another one going east till Tuesday morning.

Oh, boy, weren’t we glad!

“I’ll miss French and civil government,” Westy said.

Connie said he’d only miss history.

“I’ll lose English and geography,” I said; “but I won’t miss them. Come on up the main street and let’s see if we can find an ice-cream store.”

Skiddyunk was a nice town only, one thing, there were industrial disturbances there. Maybe you know what those are, hey? The boy that delivered the newspapers was on a strike. He was on a sympathy strike, that’s what the man in the candy store told us. He was on a sympathy strike on account of the steel strikers. He read in a book that car wheels are made out of compressed paper sometimes, and as long as some of them were made out of steel, too, he decided he wouldn’t deliver the papers that Saturday, on account of the newspaper being printed on paper. Gee whiz, I don’t see how a paper could be printed on anything else except paper. That paper only came out twice a week, because there wasn’t much news in Skiddyunk.

As long as we only had forty-two cents we decided it was best to buy five ice-cream cones, because then we’d have only seventeen cents left and we couldn’t send a telegram. Pee-wee said it was best not to have any temptation to send a telegram.

We asked the man in the candy store if he thought the people who lived in Skiddyunk would come to a movie show in Ridgeboro that night. He said they would if they knew about it, only he didn’t see where we could have it there. So then we told him about our car.

He said, “Is it a movie theatre?”

“You said it,” I told him; “it moves all over. Even the Strand Theatre in New York doesn’t move so much. And anyway,” I said, “are there any fish in that lake?”

He said if there were only as many people up there in Ridgeboro as there were fish in the lake that Ridgeboro would be as big as New York.

“Good night!” I said.

He said they just stood in a row up there waiting to be caught. He said nobody had to starve around that way, if he had a fish-hook.

I said, “I wouldn’t eat a fish-hook no matter how hungry I was.”

He was a nice man, that fellow in the candy store. He started to laugh and he said he guessed we wouldn’t starve, because he could see we were a wide-awake lot.

“You ought to have seen us last night,” Wig said; “we reminded ourselves of Rip Van Winkle.”

So then he told us it would be good for us to see Mr. Tarkin who printed the Skiddyunk News. First we got some fish-hooks and a ball of cord and then we had five cents left—a cent each. Never laugh at poverty. Then we went to the place where the Skiddyunk News was printed and asked for Mr. Tarkin. He was in a little bit of an office with papers all over the floor.

I said, “We’re boy scouts and our railroad car that we’re going to use for a troop room is on a side track up at Ridgeboro, because it was brought there by mistake and we want to have a movie show in it to-night.” I told him all about the whole thing, just how it happened, and I asked him if he thought the people would come.

Pee-wee piped up and said, “We have pictures of Temple Camp where we go in the summer, and they show scouts doing all kinds of things—rowing and cooking and hiking and climbing trees and eating.”

Mr. Tarkin said, “And eating, eh?”

“Sure, and snoring,” Pee-wee said. Cracky, I could hardly keep a straight face.

“There’s a picture showing me peeling potatoes and another one where I’m stirring soup,” the kid told him, “and a lot of other peachy adventures.”

Mr. Tarkin said, “I should call the soup picture a stirring adventure. I’m afraid that potato peeling scene would be too thrilling for our simple people.”

“Anyway,” I said, “if we could help you on account of the strike maybe you’d be willing to help us let the people know—maybe.”

“If they don’t know they can’t come, can they?” Pee-wee said.

Mr. Tarkin just sat back and laughed and laughed and laughed. Jiminies, you wouldn’t think he had labor troubles, the way he laughed. Then he began asking us a lot of questions about the scouts and he asked us if most of them were like Pee-wee. He said they didn’t have any scouts in Skiddyunk.

After a while he kind of sobered up and he said, “I wonder if the boy scouts would make good strike-breakers?”

“Sure we would,” Pee-wee shouted; “breaking things is our middle name.”

“He even breaks the rules,” I said.

“When there isn’t anything to break, he makes breaks,” Westy said.

Then Mr. Tarkin told us how the boy that delivered the papers was on a strike. He said it wasn’t much of a sympathy strike, because nobody had any sympathy for him. He said that boy wanted a one-hour day and an hour and a half for lunch. I couldn’t tell whether that man was jollying us or not. Anyway, the papers weren’t delivered, that was one sure thing, and he told us that if we would deliver them for him, he’d boom our movie show, so that people would be standing up in that car.

“Believe me,” I told him; “they usually stand up in the cars down our way.”

Then he told us that the boy that was on a strike could deliver all the papers himself because he had a flivver, but that he’d let all five of us do it because we had to walk and because we didn’t know the streets in that town.

I said, “You leave it to us.”

So then he gave us a list of all the people that had papers delivered at their houses and we made five routes. I took all the papers for Main Street and Westy took all the papers for three other streets and Connie and Wig took the rest, all except a few scattered around in different parts of town, and Pee-wee took those, because he makes a specialty of scout pace. I thought that maybe we’d have trouble about finding some places, but what did we care? It was early.

While we were planning all about how we’d do, Mr. Tarkin called me into the room where they did the printing and showed me a handbill he had made up. He said, “As long as you’re a scout I guess you’d better write the copy for this yourself, and I’ll have it set up and run off while you’re getting ready to start out. Then you can slip one into every paper you deliver. How does that strike you?”

“Oh, it’ll be great!” I said.

Then he said I mustn’t write too much, because there wasn’t much time to set it up. This is what I made up and I could have made a better one only I was in such a hurry. First I was going to take it out into the office and ask the fellows about it, but I decided I wouldn’t because they were busy mapping out their routes. Anyway, I didn’t want Pee-wee to know what I said about him.

ATTENTION!

Big Movie Show in Boy Scout Traveling Theatre Opposite Store in Ridgeboro.

TO-NIGHT.

ADMISSION TEN CENTS.

See the Boy Scouts in Their Native Haunts.

Swimming, Tracking, Racing, Eating,

Diving, Stalking, Snoring!

See Scout Harris in His

Stirring Soup-Stirring Feat!

ONLY TEN CENTS!

TO-NIGHT.

When we got back from delivering the papers, Mr. Tarkin said he had a good idea but that he was afraid that maybe we wouldn’t like it. He said, “Do boy scouts believe in advertising? What is your opinion of sandwiches?”

I said, “We eat ’em alive. Do you want us to advertise some new kind of ham?”

“No, sir,” he said; “I’m going to suggest a plan for advertising your movie show. Something striking.”

Then he began laughing and he brought out a couple of big placards about as big as window-panes. They had fresh printing on them, all in great, big letters, and this is what they said:

TO-NIGHT!

Boy Scout Movie Show in Railroad Traveling

Movie Palace. One Night Only.

RIDGEBORO RIDGEBORO

TEN CENTS.

DON’T MISS IT!

He said, “Now this is a sandwich.”

Pee-wee just stood there gaping at it and I said to him, “What’s the matter? Do you want to eat it?”

The two big placards were tied together at the top with a rope and Mr. Tarkin slipped them over Pee-wee so that one covered the front of him and the other covered his back. You couldn’t see anything but his head and his feet. Mr. Tarkin began laughing and the fellows all screamed.

“Now you’re a sandwich man,” Mr. Tarkin said; “you’re the inside part.”

“You’re a hunk of cheese,” I said.

“You’re a sardine,” Connie shouted.

Oh, boy, you should have seen Pee-wee! He just stood there looking all around him, his head sticking up from between those two big placards, while the rest of us danced around him, just hooting. Crinkums! It was the funniest thing I ever saw. Even Mr. Tarkin was laughing so hard he could hardly speak.

“Walk over to the window and back again,” he said.

Honest, I can’t tell you about it. I just sat on the counter and screamed. Westy had his arms folded and he was just doubled up, laughing. Pee-wee strutted around and you couldn’t see any part of him, except just his head. It was as good as a circus.

“Smile and look pretty,” I said.

“Our young hero,” Connie giggled.

“Let’s see you go scout pace,” Wig said.

“Advancing stealthily,” I said; “our young hero charged upon the hooting multitude and——”

“Look at him turn around,” Wig laughed; “look at him try to read it. Oh, save me!”

Pee-wee was swinging around like a sailing ship in the wind and craning his neck and trying to read the printing. All of a sudden he lifted the whole thing off.

“Do you think I’d wear that thing?” he yelled. “What do you think I am?”

“If you’d just stroll up and down Main Street with that,” Mr. Tarkin said; “it would attract attention——”

“G—o—o—d night! You said it!” I just blurted out.

“I wouldn’t do it!” Pee-wee shouted “Do you think I’m a dunce? Do you think I’m going to march up and down Main Street with that thing on, like a—like a scarecrow—with all you fellows laughing at me?”

“You look too sweet for anything,” Westy told him.

“You think you’re so smart,” Pee-wee shot back; “why don’t you do it?”

“I’m too big,” Westy said; “Connie’s the best looking; let him do it.”

Connie said, “After you; sandwiches always disagreed with me.”

“You make me tired,” Pee-wee yelled; “I’ve seen you eat a dozen!”

“Let Roy do it,” Connie said.

“I’d be tickled to death,” I told him, “only I’m patrol leader and I have to be dignified.”

“Well, you won’t catch me doing it,” Pee-wee shouted.

“Same here,” Connie said.

“You all make me tired,” I told them; “afraid of being laughed at!”

Just then Mr. Tarkin asked me to carry a bundle of paper into the printing shop in the back of the office, and as soon as I got in there I saw about a dozen or so of those placards in a big waste paper box. I asked the printing man why he had printed so many, and he said they were only proofs or kind of samples that he made while he was trying to print a good one.

“Oh, boy,” I said to myself; “I’ll fix that bunch.”

So I went out into the office and I said, “I suppose all you crazy Indians claim to be good sports. Maybe some of you know how to be good losers. Suppose we draw lots and see who goes up and down Main Street as a sandwich man. I’ll make five slips of paper and the one who draws the one with number three on it will have to go out. What do you say?”

First nobody was willing, because each fellow said that if he went out, all the other fellows would laugh at him.

“You should worry,” I said; “I’ll fix it so nobody laughs at anybody else—positively guaranteed.”

“How can you be sure?” Pee-wee wanted to know.

“You leave it to me,” I told him; “nobody will have anything on anybody else. Absolutely, positively guaranteed. If not satisfied bring your sandwich in and get it exchanged for a hunk of pie.”

So then I tore five slips of paper and I put a three on every one of them. I knew how to handle that bunch.

“I’ll draw first,” Pee-wee shouted.

Good night, you should have seen that kid when he drew number three! All the fellows began kidding him and saying he was unlucky. Then came Connie, and he drew three, and then Wig and, oh, boy, I just can’t tell you about it. Each fellow stood there staring at his little slip and I drew the last one.

“There you are,” I said; “we’re all stung and everybody’s got the laugh on everybody else. So what’s the use of laughing at all? That’s logic.”

“Sure it is,” Pee-wee yelled; “how can anybody laugh at anybody when everybody is laughing at everybody else?”

“It can’t be did,” Connie said. “We’re all stung, Roy too.”

“You can’t laugh at anybody,” Pee-wee piped up, all the while hoisting those big placards up over his head, “unless the person you laugh at has got something about him that you can laugh at that nobody else has about him that anybody else can laugh at——”

“You’re talking in chunks,” Westy said.

“If everybody gets a prize then it isn’t a prize, is it?” Pee-wee screamed.

“Sure, you can do that by long division,” I told him. “Come on and let’s start the parade.”

That was some parade! The whole five of us marched up and down Main Street looking as sober as we could, Pee-wee strutting along at the head of the line and every now and then getting his feet tangled up with the edge of the big frames, and stumbling all over himself.

“Don’t laugh,” I said; “every one of us is as bad as another, if not worse; keep a straight face and march in step; the public is with us.”

Oh, boy, you ought to have seen the people laugh. I guess mostly they laughed because we kept such straight faces, except when Pee-wee stumbled all over himself; then we had to howl. Everybody stopped and stared at us and read the signs and laughed.

Pretty soon we passed an automobile full of girls that was standing in front of a store. They were camp-fire girls, because they had on khaki middies or whatever you call them with kind of, you know, braid things like snakes around their necks. One of them had a banner that said Camp Smile Awhile.

Pee-wee turned around and whispered, “Did you see that girl smile when she looked at me?”

“Smile!” I said, “that’s nothing; the first time I ever saw you I laughed out loud. Keep your eyes straight ahead and look pretty—as if you were posing for animal crackers.”

When we got to the corner, Pee-wee turned around and marched back, just because he wanted to pass those girls again. He made himself as tall as he could, so as he wouldn’t trip over the placards. Honest, he looked just like a turtle standing up on its hind legs and waddling along and poking its head around this way and that.

“Don’t laugh,” he said, just as we passed the girls.

“Oh, isn’t he just too cute for anything!” one of them said.

“Isn’t he just a little dear!” another one said.

“Oh, me, oh, my,” I whispered to Westy who was just in front of me. “Pee-wee’s got them started. Isn’t he the little heart-breaker?”

He marched back again when we got to the other corner, standing up as high as he could, so as to lift the placards and looking straight ahead of him with a sober face.

“Oh, I think he’s just as cute as he can be,” one of the girls in the auto said.

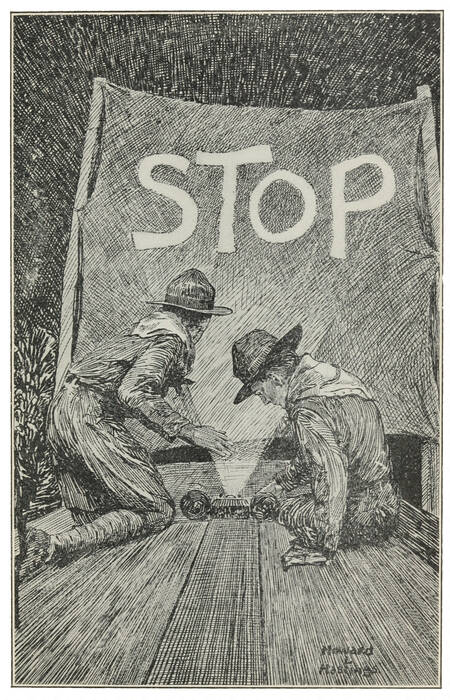

Just then a little dog came running out of one of the stores and scooted between Pee-wee’s legs and good night, down he went, sprawling on the ground with one leg kicking through one of the big placards and his arms all mixed up in the rope.

“Watch your step,” I said. I just couldn’t help it.

“Where’s that dog?” Pee-wee yelled, all the while trying to straighten things out and get up. “I’ll—I’ll——”

“A scout is always kind to animals,” Wig said; “the poor little dog was in a hurry, that was all.”

“That dog was going scout pace,” I said; “you should worry.”

By now, Pee-wee was all tangled up with the two big placards and the rope that had held them together, and the whole business, Pee-wee, placards, rope and all, looked like a double sailor’s knot having an epileptic fit. Laugh! We simply screamed.

“Get up, you’re blocking the traffic,” I said.

“It’s got around my leg,” he shouted.

“That’s what you get for trying to show off,” Westy told him. “Talk about your soup-stirring scene! It can’t be mentioned alongside of this.”

By now, Pee-wee had managed to scramble to his feet, and he stood there staring around as if he didn’t know what had struck him. One of the placards was all torn and muddy and hanging by one rope and the other piece of rope was wound around his leg. Honest, I never knew that one little dog could make such a wreck.

“You look as if you’d been torpedoed,” Wig said; “stand still till we brush you off. Turn around and smile and look pretty.”

By that time all the girls had gotten out of the auto and were crowding around Pee-wee, brushing him off and asking him if he was hurt.

“Oh, it’s just too bad,” one of them said; “his nice khaki jacket is torn. I’m going to fix it. We’ve got needles and thread and everything right in the machine, because we’re on our way to camp.”

“I don’t need to have it fixed,” Pee-wee said; “I can fix it myself. Scouts can do everything like that.”

“Yes, but they can’t sew,” the girl said.

“Sure, they can do everything,” Pee-wee told her. “Maybe you think,” he said, all the while pounding the dust out of his clothes, “maybe you think that just because I fell down—gee, that could happen to the smartest man—even—even—Edison——”

“Sure,” I said, “lots of times Edison fell down.”

“Scouts can do anything,” Pee-wee said. I guess after what had happened he wanted to let those girls know that just because a scout fell down, it didn’t prove he wasn’t smart.

“Hurrah for P. Harris,” I said.

“Oh, is he P. Harris?” one of the girls said; “Oh, isn’t that glorious! Is he the one that stirs soup?”

By that I knew they must have seen one of the handbills.

“Oh, we’re all coming to-night to see him stir it,” she said; “our camp is just across the lake from Ridgeboro. Don’t you think Ridgeboro is a poky old place? We’ll canoe over. We’re camping over the holiday and we call our camp, Camp Smile Awhile. Isn’t that just a peachy name?”

Connie said, “I should think a girls’ camp ought to be named Camp Giggle a Lot.”

“Oh, aren’t you perfectly terrible!” one of them said; “the idea! Is it ten cents to get in? Have you really got a railroad car of your very own? Oh, I think that’s just simply scrumptious. I wish I were a boy.”

“That’s nothing,” Pee-wee said; “we hike hundreds of miles. Once we got lost on a mountain—we didn’t care. We were lost two days. We could have been lost three if we’d wanted to.”

“Only what’s the use of being extravagant?” I said.

“Once I fell down a cliff forty feet high,” Pee-wee said; “that’s nothing.”

“Oh, and didn’t you kill yourself?” one of the girls wanted to know.

“Sure he did,” Westy said; “but he’s all right now.”

“It’s fine being a boy,” Pee-wee said; “gee, I feel sorry for girls.”

“Oh, and you can sew, too?” one of them asked him. “And cook?”

“Cook!” I said. “He used to be the chef in the Waldorf Castoria.”

“Scouts have to know how to do everything,” Pee-wee told her; “because suppose a scout is alone in the woods; he has to cook his dinner, doesn’t he? He has to know how to do everything for himself, see? That’s why I’ll sew this jacket myself. That’s what you call resourcefulness. A scout has to be full of that, see?”

“Oh, I think it’s just wonderful!” the girl said.

“That’s nothing,” Pee-wee told her; “you can even cook moss and eat it if you’re lost and hungry. Once I went two days without food.”

“You mean two hours,” Connie said.

“Anyway, it was two something or other,” Pee-wee shouted.

“Most likely it was two minutes,” I told the girl.

“And you came all the way out here alone? Oh, isn’t that perfectly adorable! And you’re going to give a show to earn money——”

“So we won’t perish,” Pee-wee said.

“Which?” Westy asked him.

“Perish,” he said; “don’t you know what perish means?”

“And will the pictures show you doing all those things?” one of the girls wanted to know.

“Sure,” Pee-wee said; “maybe you’ll get some good ideas from them, only you mustn’t scream when you see one of the fellows fall out of a tree into the water, because that’s nothing. That’s one thing scouts don’t do—scream.”

But believe me, that was one thing scouts did do the very next day. I did, anyway; I screamed till I had a headache.

They said they would surely canoe across that night and take in the show and so we told them we’d see them later. Westy gave Pee-wee one of his sign placards and we marched up and down Main Street for about an hour, till we got hungry. Then we decided that as long as everybody in Skiddyunk knew about our show, we’d go back to Ridgeboro and catch some fish. Mr. Tarkin told us that as long as everybody had laughed so much and had seemed to take so much interest, he guessed our show was a safe investment and that if we needed a couple of dollars or so to carry us through, he’d let us have it. But we didn’t take it, because scouts like to rely on themselves, and we knew there were lots of fish in that lake.

When we got back to Ridgeboro, the man that owned the store came and gave us a telegram. He said a boy on horseback had brought it from the office in Skiddyunk. This is what it said:

“Just learned of unfortunate error of freight conductor. Don’t be afraid or worried. Have wired money to Skiddyunk. You can get eastern train there at three. Parents informed. Keep cool.

“John Temple.”

“Just our luck,” Westy said; “we’ve got to go home.”

“What!” Pee-wee shouted.

“Keep cool,” I said; “that means you.”

“Are you going to answer it?” he wanted to know.

“Absolutely, positively,” I told him; “and I’m going to send it collect.”

“If you think I’m going home,” Pee-wee yelled, “you’ve got another think. A scout is not a quitter. We’ve got things coming our way now—do you think I’m going to admit——”

“Come on in the car and we’ll make up an answer,” I said, “and I’ll sign it, because I’m patrol leader.”

So this was the answer we made up and Westy and Connie went back to Skiddyunk with it, while the rest of us were fishing.

“Cannot make afternoon train. Are giving big movie show in car to-night. Great excitement. Expect to clear thirty dollars. Will not desert car. Expect us when you see us. Good fishing. Love to all. We should worry.

“Roy (S. F.)”

When Westy and Connie got back, they had fifty dollars that Mr. Temple had sent, but we decided we wouldn’t use a single cent of it, just so as to show him that we could look after ourselves. Anyway, we should bother about fifty dollars, because we had a big string of perch and some catfish.

It was about the middle of the afternoon when we got the fish cooked and, believe me, we were good and hungry. After the meal was over, we were sprawling around in the car before starting to get ready for the show, when all of a sudden we heard somebody speaking outside, and then in came a little man with an awful funny face and a funny little cap on. He wore spectacles way down near the end of his nose and he was smiling and seemed awful happy, but there was something funny about his eyes. I guess he wasn’t more than about thirty years old, but he looked awful funny and his eyes were bright and queer like.

He said, “How do you do.” And then he started to shake hands with all of us. He said, “I called twice this morning, but you weren’t here. And now I have found you and I’m delighted, and I suppose you wonder who I am, eh?” Then he looked all around and put his finger to his lips and said, very secret like, “My name is Ebenezer Brewster and I’m a poet. I have written a little poem to thank you boys for the great honor you have done me, in naming the village after me. Shh! There is opposition. The public is scandalized. There is likely to be a riot. I am not appreciated—shh.”

“Six or seven people wouldn’t make much of a riot,” I told him. “If they start any riot here, we’ll put the village in the car and take it away with us.”

“That’s a very good idea,” he said, “a very good idea. Did you graduate from a public school?”

I said, “No, I have my ideas made to order; they last longer.”

He said, “Much longer, that’s my idea exactly. And they fit better. Would you like to hear the poem?”

“Go ahead, shoot,” Westy said.

So then he took a paper out of his pocket and read what was on it, and this was it:

“There are eleven people here,

Nine chickens and a rooster;

The village it is named for me,

I’m Ebenezer Brewster.”

Connie came over and whispered to me, “Where are we, anyway? I feel like Alice in Wonderland. He’s a cheerful idiot. He thinks we named this town after him. This is some comedy.”

That fellow didn’t stay long and he went away very sudden like, just the same as the way he came. We told him to come to the movie show and he said he would. We decided that he was kind of crazy, but anyway, he was awful nice about it, and gee whiz, if you’re happy, what’s the difference whether you’re crazy or not? He was happy all right, and he seemed to be mighty proud, because he thought the town was named after him. So we let him think so.

By six o’clock we had everything ready for the big show. We fixed the apparatus so that the lens cylinder stuck through the ticket window, and that way the operator (that was Pee-wee, because the machine belonged to him) could be all by himself in the ticket agent’s room. We hung the screen at the other end of the car, and turned all the seats facing that way.

The man over in the store came and watched us and got friendly. I guess he knew how it was by that time, and he wasn’t afraid that the name of the village was really changed. He gave us some cakes and we had cakes and fried perch for supper. They were dandy cakes, with jam in them. There were seven of them and only five fellows, but anyway, Pee-wee hadn’t done any good turn that day, so he ate three. That was so none of the rest of us would get a stomachache. That’s the way with Pee-wee, he’s always thinking about some one else.

All the while we were eating supper, we could see smoke curling up out of the woods across the lake, and we guessed that was where the girls had their camp.

“I bet they’re getting supper now,” Connie said.

Pee-wee said, “Maybe some of us ought to borrow that store man’s boat and row over after them, because girls can’t row or paddle very well. It would be a good turn.”

“Good night,” I said; “didn’t you just eat three peach cakes and call that a good turn? You should worry about the girls. Probably they know how to row and paddle better than you do.”

“You make me tired,” he yelled; “scouts are supposed to do things for them, and show them how to do things.”

“Well, they’ll see you doing enough things on the screen,” I told him; “girls aren’t as helpless as you think they are. Come on, help get ready.”

At about half-past seven, people began coming and I could see that we were going to have a big house, I mean a big car. First an automobile full of people arrived and then a lot more who had walked from Skiddyunk. Then a couple more automobiles came and pretty soon there were a half a dozen of them parked around the car, and the seats inside the car were full. Westy stood on the platform collecting ten cents from each one and letting them through, past the screen. Oh, boy, there was some crowd.

Pretty soon the store man came over and said that as long as the weather was so warm, it would be a good idea to open the car windows and have standing room outside. So he gave us some boxes and barrels and things to put outside the windows for people to stand on. All the people out there paid their ten cents just the same and they laughed and said it was a lot of fun. Some of them were summer people, I guess; holdovers. The girls from Camp Smile Awhile came over in two canoes and a rowboat.

When there wasn’t space for another head to stick through a window, I got up in front of the screen and made a speech. This is what I said:

“Ladies and gentlemen, we thank you for coming to see our show, and we hope you’ll like it. I guess maybe I ought to tell you about Temple Camp, then you’ll understand the pictures better.

“Temple Camp is where lots of scouts go in the summer. It’s near the Hudson. Maybe you’ve heard about all the different things that scouts learn how to do. So these pictures will show you some of those things.

“Some of the things are hard, but some of them are easy, like eating and things like that. Especially desserts. So now the show will begin.”

First we flashed the sentence that is in the handbook:

A SCOUT IS HANDY AND USEFUL

and then came the picture of Pee-wee with a big white apron on, standing in front of the stove in the cooking shack, stirring a big boiler full of soup. I heard one of the girls say, “Oh, isn’t he simply too cute for anything!” Then we flashed another sentence that said:

A SCOUT IS SKILFUL

and then came the picture of Pee-wee standing at the kitchen table, rolling dough. Everybody applauded and the girls said it was wonderful, but that anyway, the Boy Scouts was started before the Camp-Fire Girls was, and so they had had more time to learn things. I heard one lady say it was splendid how scouts got to be self-reliant, on account of learning the domestic arts.

Oh, bibbie, I just had to laugh, because that was the one thing that Pee-wee didn’t know anything about at all—cooking. The only thing that kid knew about domestic arts, was eating. He was a good ice-box inspector and pantry-shelf sleuth. He could track a jar of jam to its dim retreat, but when it came to cooking—good night! The only reason we had him in those pictures was because he was so small and looked so funny.

The next sentence we flashed said:

A SCOUT IS QUICK

and the picture showed Pee-wee flopping a wheat cake and catching it in the frying pan again. Honest, when we were trying to get that picture up at Temple Camp, the whole floor was covered with wheat cakes and there was one on Pee-wee’s head like a Happy Hooligan cap. But the audience didn’t know that. There are lots of things you don’t see in the movies. It takes about twenty wheat cakes to get a good picture of Scout Harris flopping one.

The regular cook wasn’t there the day we got that picture.

That was the comedy sketch and Pee-wee was so puffed up over his screen success that he could hardly work the machine. I guess he felt as if he were a regular Douglas Fairbanks.

“Did you hear what those girls were saying?” he whispered to me behind the screen. “Did you hear what the one with the red sweater was saying? About a scout being so resourceful? Did you hear her?”

“Oh, you’ve got the town eating out of your hand,” I told him; “you’re a regular Mary Picklefoot. You’re such a swell cook you ought to cook for Cook’s Tours.”

“Did you hear what one of them said about how I rolled the rolling pin?” he whispered.

“She said you were the finest roller she ever saw,” I said, in an undertone; “shh, you’ve got them going. There’s no use trying to stand up against the Boy Scouts of America.”

“Didn’t I tell them scouts have to be resourceful?” he whispered. “Did they notice how I flopped it?”

“They said you were the floppiest flopper they ever saw,” I told him. “Go ahead and give them some deep stuff.”

So then we reeled off some pictures of good stunts at Temple Camp. One showed scouts doing fancy diving from the springboard, and there were a couple showing the races on the lake. The people seemed to like them a lot. Some of the pictures had Pee-wee in them and then there was a lot of applause. There was one showing the forest fire near camp; it was the best of all and everybody said so.

After the show, when the people were going, they all said it was fine and asked us a lot of questions about Temple Camp and scouting. Pee-wee got down off the car and stood around with his sleeves still rolled up and his jacket off, and everybody talked to him. Believe me, he was a walking advertisement for the scouts. I heard him telling one man that scouts had to have plenty of initials.

The man said, “What?”

“Initials,” Pee-wee told him; “it means starting to do things of your own accord, see?”

The man laughed and he said, “Oh, you mean initiative.” He said Pee-wee was worth ten cents not counting the movie show.

After most everyone else had gone, the girls all crowded around Pee-wee before they went back to their canoes. Oh, you should have seen that kid! The girl in the red sweater said, “My name is Grace Bentley and my friends want me to tell you what a perfectly lovely time we’ve had. And we think it’s just wonderful how boy scouts are so, you know, what you may call it——”

“Sure,” Pee-wee said; “resourceful, that’s what you mean.”

She said, “But you must remember that the Camp-fire Girls are new and we’ll catch up to you yet.”

“Oh, sure,” Pee-wee said; “you’ll catch up with us. All you have to do is try. First I couldn’t learn scout pace. Gee, don’t get discouraged. If you want to do a thing just make up your mind that you’ll do it. And if you can’t do it, do it anyway.”

Gee, the rest of us just stood there trying to keep from screaming, while Pee-wee stood in the center of that crowd of girls, looking about as big as a toadstool, and giving them a scout lecture.

“All you have to do is try,” he said; “did you notice where I was diving from the springboard?”

“Oh, I thought it was just dandy,” a girl said.

“That was nothing,” Pee-wee told her; “it looks hard, but that’s nothing. There’s no such word as fail; that’s a what d’ye call it, a maxwell.”

“You mean a Ford,” Connie said.

“He means a Pierce-Arrow,” Westy shouted.

“He means a maxim, don’t you?” the girl named Grace said. “And I think it’s a perfectly splendid maxim.”

“That’s nothing,” Pee-wee piped up; “I know a lot of maxims. I’ve got a collection of them.”

“He catches them in the woods,” I said.

“Don’t you get discouraged,” Pee-wee shouted.

“No, we won’t,” Grace said; “and don’t you mind them, either. They’re just teasing you. And we want to ask you if you’ll do us a favor—a good turn. Will you?”

“Sure I will,” he said, very manly; “what is it?”

“We want you to promise to come over to Camp Smile Awhile to-morrow and cook dinner for us. And we want to ask all the rest of you boys to come, too. We’re just a lot of greenhorns about cooking; isn’t it shameful to have to admit it? But we’ve got everything over there, food and utensils, and you can make us up a feast and we’ll spend the afternoon visiting. Say you will. Will you?”

G—o—o—d night! I laughed so hard I nearly fell off my feet. Oh, boy, you should have seen Pee-wee’s face. You just ought to have seen it.

“Absolutely, positively,” I said; “he’ll be there at ten-thirty. Do you want him to bring references?”

“We should say not,” Grace Bentley said; “the idea! What we saw in the pictures was reference enough.”

Good night, you should have seen Pee-wee’s face. He just stood there, gazing about as if he were in a trance.

One of the girls said, “Won’t it be adorable! We’re going to have chicken.”

“Cooking chicken is his favorite indoor sport,” Westy said. “How do you like your roast chicken; fried or stewed? It’s all the same to him.”

I took out my scout note-book and made believe to write things down. “We’ll just make up the menu,” I said.

All of a sudden Pee-wee came out of his trance and shouted, “You mean me?”

“Menu,” I said; “yes, they mean you.” Then I said, “Would you like to have the fried potatoes stewed, or would you prefer to have them mashed with the skins on?”

One of the girls said to Pee-wee, “Don’t you mind him, he’s just too silly.”

“Do you prefer your fried eggs in the shells, or would you like them roasted in ice-water? It doesn’t make any difference to him,” Connie said.

“Don’t you pay any attention to them,” Grace Bentley said to Pee-wee; “some of us will come over in the boat for you to-morrow morning, and when the dinner is ready, we want all of you to come, won’t you?”

“Sure, we’ll hike around the shore,” I said, “and get up good appetites. We’ll be there at about twelve-sixty. We’ll come around the longest way, so we’ll get good and hungry.”

“Oh, that will be just lovely,” they said, “and we’ll have a perfectly scrumptious time. Do you like pie? We’ve got a whole big jar full of mince meat.”

“You have to be careful about mince pie,” Pee-wee said; “it’s better, maybe, not to eat mince pie.”

“Who’s a coward?” Westy piped up. “Do you think a scout is afraid of a piece of mince pie?”

“Oh, it will be just dear,” another one of the girls said, and then they all crowded around Pee-wee and began saying, “You’ll surely be ready, won’t you? We’ll come over for you at ten o’clock. And we’ll have everything ready for you. We’ve got lots of flour and seasoning——”

I said, “What kind of seasoning; summer or winter?”

They told Pee-wee not to mind us, and that we probably wouldn’t stop talking till our mouths were busy doing something else.

“What—what—time did you say you’d come?” he began stammering.

“At ten o’clock, and you’ll be ready, won’t you?”

“I—ye—yes,” he stammered out.

“Positively?” Grace Bentley said.

“You—you can—you know, you never—kind of—maybe—you never can be sure of anything,” he blurted out.

“But say you’ll surely come,” she hammered at him. “Will you?”

He said, “I guess—sure—yop.” And he looked all around as if he was going to start to run.

“Absolutely, positively guaranteed,” I told them; “a scout can be trusted.”

So then we helped them off with their boat and their canoes, and they started across the lake in the dark. We said we’d paddle them over and then hike back through the woods, but they wouldn’t let us, because there wasn’t room enough and anyway, they said they wanted to show us that there were some things girls could do. They rowed and paddled pretty good, too; I have to admit it.

Pee-wee didn’t go down to the shore with the rest of us, but just stood where he was, like a statue. He was in a kind of a trance, I guess.

As we came near him, Westy said, “Of course, they don’t row very well, or paddle either, but they’re trying. All they have to do is to try.”

“Oh, sure,” I said; “if you can’t do a thing, just go ahead and do it anyway. You have to be resourceful. You have to have plenty of initials.”

“Now you take making dressing for roast chicken, for instance,” Connie said; “all you have to do is to know how. It’s a cinch.”

“And if you don’t know how,” I said; “do it anyway. It’s as easy as pie.”

“Oh, pie’s a cinch,” Wig said.

“Those girls will learn,” I said; “they shouldn’t get discouraged.”

“They should be pitied, not blamed,” Westy said.

All of a sudden Pee-wee exploded. He sounded like a munition factory going up. “You think you’re smart, all of you, don’t you!” he hollered.

“A scout is smart,” Westy said.

“A scout can do anything,” I said.

“He is resourceful—it’s in the handbook,” Wig said, very sober like.

“It’s in the handbook—it’s in the handbook—it’s in the handbook,” Pee-wee fairly yelled, “that a scout has to be——”

“Helpful,” I said; “he has to be helpful to women.”

“You make me sick!” he fairly shrieked.

“You’ll be the one to make us sick,” Westy put in.

“Do you think I’m going to do that?” he fairly screamed; “do you think—do you think—do you think——”

“Three strikes out,” Connie shouted.

“Do you think I’m a fool?” Pee-wee finished.

“A scout’s honor is to be trusted,” I said; (that’s scout law number one) “if he were to violate his honor——”

“You make me tired,” Pee-wee yelled; “a scout has got to be cautious—it says so—he’s got to leap—I mean look—he’s, he’s got to consider others—just because somebody that ought to know how to do a thing that he doesn’t know how to do asks somebody to do something that the other person won’t learn to do if the other person does it for him, because that isn’t being resourceful, if somebody else does that thing for you, and so the other person doesn’t learn how to do it himself—do you mean—do you mean to tell me—that that’s being a good scout?”

“Sure it is,” I told him; “it’s just the same as if a person that wants to do something, doesn’t do it because if he does, he won’t. Why then, how could the other person do something that somebody else wanted another person not to do——”

“You’d have to have a crowbar,” Westy said.

“Pee-wee’s right and we’re wrong, as he usually is,” Connie shouted.

We made the plush seats up into beds that night and, oh, didn’t we sleep, with the breeze blowing in through the windows! It was dandy.