* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Farewell Victoria

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: T. H. (Terence Hanbury) White (1906-1964)

Date first posted: Aug. 20, 2019

Date last updated: Aug. 20, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190849

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

By the same author

THE GODSTONE AND THE BLACKYMOR

THE ONCE AND FUTURE KING

THE MASTER

THE ELEPHANT AND THE KANGAROO

MISTRESS MASHAM’S REPOSE

THE GOSHAWK

ENGLAND HAVE MY BONES

THE BOOK OF BEASTS

A Translation of a Latin Bestiary

of the twelfth century

Farewell Victoria

by

T. H. WHITE

JONATHAN CAPE

THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON

FIRST PUBLISHED BY COLLINS 1933

REPRINTED 1933

PUBLISHED BY PENGUIN BOOKS 1943

REPRINTED 1945

NEW ILLUSTRATED EDITION, TYPE RESET

PUBLISHED BY JONATHAN CAPE 1960

TYPE SET IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE ALDEN PRESS, OXFORD

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BOUND BY BURN, ROYAL MILLS, ESHER, SURREY

‘. . . and yet time hath his revolution, there must be a period and an end of all temporal things, finis rerum, an end of names and dignities, and whatsoever is terrene; . . . For where is Bohun? where’s Mowbray? where’s Mortimer? nay, which is more, and most of all, where is Plantagenet?’

FAREWELL VICTORIA

October 2nd, 1858, was to be a fine Saturday. The yews in front of Ambleden stood up out of a ground mist; looming and, if one might say so, luminous with darkness, in the silver light before dawn. It was cold. A rabbit hunched on the wet grass. It extended like a concertina, bounded a few paces, and shut up again into its browsing hump. The furry atomy seemed shaken from inside with a spasmodic pleasure. Either it was enjoying its breakfast or trembling from the cold. A shy woodland creature of the mist, it looked surprisingly solid at the same time. It was a landmark in the haze; once one had come near enough to distinguish it as a rabbit, rather than as a croquet ball left over from last night.

The rabbit’s movements became more brisk. It extended itself more often, sat up and listened in the traditional pose. Somebody was moving half a mile away, in the second keeper’s cottage. It was the keeper himself. He had come down the narrow stairs in his stockinged feet, had begun to put on his boots. He stirred over the embers which had been covered to keep them in the night before, and set a kettle on the hob with slow fingers. He lit no candle, but moved in the darkness with assurance. It was cold, he thought; but it would be a warm day. No rain with that dew, certainly. He put all four fingers of each hand in his mouth, one hand at a time, and breathed on them. Then, sitting down and leaning forward in the chair, he began to do up his gaiters. They were of stiff leather, buttoning on the ordinary hole and button system. It was a harsh job for those strong, cold, patient fingers.

The sun prepared to rise. Its pale pre-light began to filter into the keeper’s kitchen; informing it, translating it into fact. The keeper himself became visible, a grizzled figure, bearded, in a velvet coat. His hard cut-down hat stood on the table by his side. The kettle began to steam, grey also. Everything was grey or silver. The light ran along the barrels of the two guns. One was a muzzle-loader; the other fired pin-fire cartridges. Like all keepers’ guns, they were a little out of date.

As the light strengthened, the two great yew trees—they had been called Adam and Eve for centuries—began to have premonitions of shade. Their embryo shadows faintly, intermittently, hinted at the possibility of their existence. The rabbit nibbled on.

One realized suddenly that he was nibbling in daylight. Glancing quickly towards the yew tree, one realized that the shadows were really there. In two broad feelers they reached across the greensward, now pearly, far and away under the horizontal rays. One stripe fell below across the façade of the house, at the corner. Cold, but distinct and lambent, the sun was in the east. The day had dawned. October 2nd, 1858.

How impossible and extraordinary it now seems that a real day, an integral and definite day existing individually by itself, should have dawned so long ago. It seems beyond natural probability that a day in so many respects quite like the present one should have taken place a hundred years ago. There was a Today, a hundred years before Today. That bright mystery of the present leaps before us without the least pathos, but curious, but provocative and strange.

Meanwhile, they were stirring in the house. From the other side, at the back, came footsteps; the rattle of a pail. A spry voice cried to a horse, whose metal shoe rang again in answer on the stone, as the shutter of a loose-box banged the wall. They would be cubbing today. The stable was alive.

And then the house was alive also.

All these reincarnations were imperceptible. It was not possible to say: Now the house is coming back to life again. It was only possible to notice that it had come, and to wonder when the miracle had happened.

Little Augusta, waking in the night nursery, listened to the noise of stair-rods outside the door. Pleasant and comfortable noises on morning stairs, pledges of security, laborious antitheses of snug sheets, music for idle revivals, symbols of a passing age; Augusta listened to them with vexation. Soon there would be the bath. It was indeed cruel, was it not? Papa had decreed that they were both to have cold baths every morning. He considered that it was good for their health.

Standing together in the low tin circle, so that to modern eyes the ablution would seem impossibly top-heavy, the two pink frogs would pour the water in thin trickles over each other’s shoulders. These little cold bodies, which were to grow through girlhood into the splendid maturity of a Victorian chatelaine and then down into the common grave, would hop and squeal and argue. There was a pact between them, to pour the water down the front side only, where it was less cold. But Priscilla, who was the elder, insisted on the privilege of pouring last; and was inclined to allow a small rivulet, lacing like crystal on the skin, to run down Augusta’s back. It was impossible to retaliate, on account of the precedence, even in a tin tub, of primogeniture. If only Augusta could have been the last to pour! How she would have made her wriggle! But Priscilla always apologized and pretended it had been a mistake.

Meanwhile the woods had woken. There were four keepers for the birds, and three more for the river. The former were on their day-long circles already. They thanked the Almighty that it was not the breeding season; when, what with the rearing of pheasants and the killing of vermin, sleep became occasional and eating a matter of chance. Yet they had enough to do. Sir William would be shooting the pheasants this afternoon, and there were the dispositions to make. He liked to line a hedge or a ridge in the new way, to have the birds driven for him; and this meant getting them where they were needed. Then there were the traps to see to (it meant a six-mile walk for each of them) and there were the rides to be cut if only the time could be found.

So they circled through the early woods, disturbing the late-staying rabbits, which sat up at the edge of the fields and skipped undecidedly and thumped and scuttered; starting the silly pheasants, which ran for safety in undignified straight sprints.

The stable was getting forward too. The saddles and leathers had been soaped and the stirrups scoured the night before: only the horses remained. The men, who had taken nothing so far but a hot drink, hissed and smacked vigorously, feeling faint on their empty stomachs, but at the same time hardy and joyful of the morning. They cried out to each other, and to the horses. Water ran from a cold pump and buckets clashed on the pebbles. As each horse was finished, with the faintest illicit gloss of paraffin, the saddles were put on and the girths loosely fastened. Then a blanket, mustard coloured in the acute light, came over the saddle. The horses that had been finished differed from those that were yet to come by this sweet bulge of the saddle under the blanket.

The house was alive. In the lower parts, whose noises were inaudible to Augusta upstairs, the maids had lighted the fires and finished the essential dusting for the day. Smoke came out of the chimneys. Sir William had his own valet, but the footmen had been looking after the guests; so they were in their coats already. Jarvis issued from the housekeeper’s room, where he had his own breakfast with the upper servants, and went into the pantry to change his brown coat for the full fig. He made a critical inspection of the breakfast table and ordered the fish forks to be changed. The footmen were silent and deferential beneath the butler’s eye.

Upstairs, the children were fed in the nursery. There were three nurses. The whole place was a layer of hierarchies, in which all the gradations were nicely calculated. The head nurse, for instance (who had been born well in the eighteenth century), would eat with the housekeeper. So would the head cook and the valet, either because he was the only one of his kind, like the mate of the Nancy Brig, and, therefore, might be considered as a head valet—the captain as well as the crew—or because his propinquity to Sir William in the private levée lent him an aura. The gradations of service formed a regular social service, which was of the greatest importance to the servants, giving them dignity and ambition. They possessed hopes of feasible advancement and relished their ranks to the full. Each lieutenant lorded it over his inferiors and exacted the respect which he gave willingly to those above. The caste-ladder was polite and gentlemanly. It gave pleasure to all, for even the boot-boy could snub the cowman, and he, presumably, could kick the cows. Not that there were any kicks; only a superiority, abetted by both parties. It was a system of manners, which had been the discovery of the preceding century.

Master Harry was allowed downstairs to breakfast. He was at school already, but a frail child who had been too ill to go this term. Scorning the nursery, he had risen early and gone down to the stable. Now, since breakfast was approaching, he went into the dining-room to confer with Jarvis and the footmen. He begged permission to take the flasks out for the saddles. Cubbing was still early, but late enough for Sir William to take a quick breakfast before it. On such days as this he required no sandwiches, but would be in again at about twelve for a substantial luncheon. That gave him a good afternoon for the pheasants. Still, he liked to take his flask.

His foot was heard upon the stairs. He came down, rosy from cold water, pinkly shaved, cheerfully humming.

‘Such a gettin’ up stairs and playin’ on the fiddle,

Such a gettin’ up stairs I ne’er did see.

There was Mr Smith with his mackintosh

And his hair frizzled up like a pumpkin squash . . .’

He repeated the first two lines (perhaps the stairs had suggested them to him) and came into the dining-room, turning over in his mind the merits of Westphalian ham and kidneys. Seeing his son, who had come back from the stables, he spoke kindly to him, with a small pompous joke.

The second gong sounded with circumstance, and punctually the guests appeared. It would be easy to describe them by their plaids, their waistcoats, their Dundreary or other forms of whisker. But they were human like ourselves, and a great deal more admirable. Convention was not dead with them, but living; their formal quips, their durable clothes and standards, were of a justifiable complacency. They enjoyed being alive. Manners, etiquette, regulation; these were a recognition of the pleasures of life, which they respected enough to order it.

The servants came in after the guests, moving in a procession of precedence which was as regular as the precedence of a dinner party. They sat down demurely on the edges of the red leather chairs, whilst Sir William opened his Bible. They sat still, thinking about the day’s future, in a frame of red wallpaper, bright mahogany, sanguine portraits and dishes steaming on the sideboard. Sir William and his guests came hungry to this new fashion of family prayers. Their nostrils were titivated by the prospect of possible foods, still shrouded under covers, and by the expectation of a hardy day. So they prayed with pleasure, thanking God fervently upon sound occasion. They turned round and knelt, leaning their elbows upon the leather, with a decent movement. The maids presented their backsides to the Almighty rather shyly, for they were plump. But they knew that the heavenly birch would not be malevolent, that their lines would fall in pleasant places. They made their responses in low voices, deferential to Sir William and to God; perhaps, since they had broken their fasts and were already well launched upon the day’s work, with more deference to the former than the latter. They peeped between their fingers, conscious that they were sticking out behind.

When they had filed out, Mama began to dispense from the silver teapot. She was older than Sir William, more magnificent, more old-fashioned. He had married above his station and she was the daughter of an earl. As she sat in stately presidency among the cups, speaking seldom and with the faintest Georgian accent, one was reminded of the stories about her natural greatness. She was a woman for whom footmen carried prayer books to church, a potentate in spiritual as well as in temporal matters. She treated her Maker humbly, only because humility was the proper custom of the hierarchy. She stood in relation to her God in the same way as her upper servants stood towards herself. Her breakfast table was God’s housekeeper’s room, in which she conducted herself with dignity or subservience, according to the rules of precedence in earth or heaven. It was not with the least regret, or with the least doubt, or with the least lick-spittle ambition, that she recognized the natural priority enjoyed by an angel over the daughter of an earl. If there was a thunderstorm when she was staying in the London house, whither Sir William seldom accompanied her, she would ring a silver bell. Preceded by the butler and a footman carrying a chair, and followed by her ladies’ maid carrying a Bible, she would adjourn solemnly to the cellar; and there, upright in her chair, pale, composed, faintly nasal, she would read the psalms out loud until the danger had been passed. The butler, but not the footman, would reply ‘Amen.’

Now the horses were at the door. They stamped the gravel of the drive, in front of the yellow stone façade. It was a classical frontage, with steps, pillars and a pediment. The grooms, neat in their green uniforms, tested the girths and altered the stirrup leathers. One of them led a bay mare apart from the others, round and round in wide, uneasy circles. It was a crisp, bright morning. Nine o’clock.

Beautiful England! There was still something medieval about it, something feudal. ‘Sir William rides out today.’ The serfs were absent; the filth and horrible starvation of the normal beggars who should have thronged his outset had disappeared; the servile courtiers and dependent priests of the eighteenth century had faded, but still, as Sir William paused upon the steps among his guests, there was opulence and order and serviceable gear; there was colour and fine horseflesh; national property.

October 2nd was memorable for no reason, except that it occurred in 1858. The child Mundy, who was the son of a groom, was then eight years old. He passed it, like other holidays, in the placid pleasures which are not nowadays achieved.

Sir William’s hunt came by him and he saw it from the black-padding cub to the tootle of a horn in the vicarage spinney. He remembered afterwards, but without remembering when he remembered them, a pink coat and grey mare; also, a stout man and a stouter horse, rising at a low hedge, in juxtaposition, but not in contact. There was an admiral, dismounting upside down.

Other things contributed to October 2nd, as they contributed to his memory of Ambleden. There was Master Harry fishing in his special stream. He possessed no gum-boots or luxuries, but with his tight old-fashioned trousers rucked above a thin brown knee, he waded patiently upstream, casting a crucified worm before him. There was something lovely about the absorption of the small boy, which caught the other boy and made him feel it. Time was passing over without a touch. Patient like the stork whose red legs are said to fascinate and attract his luncheon, a leggy bird-fisher in attentive concentration, the toilsome angler seemed immobilized and remained so in memory. It would have been odd to think that this slender creature, with its Shelley features and untroubled heart, was to grow and set in bulk and opinions; was to be shot dead from a distance in the Boer War, a hidebound colonel of cavalry who had not thought or felt for thirty years.

Mundy remembered also the cattle in the park, yellow and hot-seeming, who browsed, straight-backed, and flicked their tails. He remembered rather oddly in the same picture the instrument with which Miss Augusta made holes for embroidery. It was an ivory spike, rather like a spillikin, with a glass eye at the thicker apex. If one held this to one’s own eye, as close as possible, and almost closed one’s eyelashes, one was rewarded with a dizzy view of the Taj Mahal, shimmering in a complicated mist of eye-film, eyelashes and refractions. It was a great treasure. He remembered Miss Augusta holding it up for him.

Then there was the noise of shooting in the woods, as Sir William discharged his piece upon the plethoric October pheasants. This noise made a background to the façade of Ambleden, and to a beech tree of which he was fond. The oaks were crocodiles, but this, the beech, was definitely an Indian elephant. Wise, old, trustworthy unlike the elm; its bulging muscular stems seemed fitted to carry logs of teak under the guidance of affectionate mahouts. With ancient elephantine might, to make them mirth, it wreathed its lithe proboscis. (Augusta once sketched it, with an incredible scrupulosity of detail, and the sketch survived to provoke the irreverent astonishment of her grandchildren. It survived along with an album full of flowers treated in the same way; of pansies and poppies defined with the histrionic exactitude of a virtuoso who draws pound notes on a sham blotting pad, so realistically that one tries to pick them off. The tendrils and pistils and little hairy stalks of her loving depictions were microscopically exact, so that one was provoked almost to dismember them; pollen, vein and petal.) Round the beech there was a circular seat; just such a seat as used to be successfully treated in pictures called ‘The Betrayal’ or ‘The Lovers’ Quarrel’. It was of six parallel green slats, nailed to eight supports octagonally disposed. He remembered Mylady sitting there with a tray, whilst her guests surrounded her in garden chairs. There were also two of those hooded wicker chairs, then fashionable at watering-places, which reminded one of beehives and of coracles, and of perambulators in the rain.

The carriages arrived for the Pic-Nic; the grooms held the horses’ heads and lowered the steps; the butler appeared processionally with the refreshments, followed by the flunkeys.

The October sun shone on the tree, whose turning leaves, secretly rustling, threw a dappled shade upon the tinkle of the cups. Voices were moderated by the open air, so that they fitted the natural noises of the afternoon: of leaves, bees, birds, and growing autumn. The full skirts rustled with the branches, soft and laundered. It was a congeries of plumy birds almost, in that arboreal setting.

Mundy knew that children were not allowed at such parties. (They were, indeed, very reasonably excluded from all polite activities. Augusta, for instance, was never allowed to enter a room which harboured her elders without first curtseying at the door. ‘And as,’ she remarked sixty-eight years later, ‘to going to the fire to warm myself on a cold winter’s day, the thing was unheard of. The hearth-rug was named “puppy-dog’s corner” and we were not allowed to stand upon it.’) He remembered, however, a game of Blindman’s Buff with the gardener’s son Teddy, and a strange game in the stables with Master Albert. Then there was Miss Augusta pretending to be a butterfly, and the youngest Miss Louisa imitating her. The smaller figure fell, cutting her knee; and was taken indoors, with her screams muffled in an apron. (That was also to remain for Miss Louisa her earliest recollection, of sitting still in the nursery with wet bandages over her cuts. Augusta relished the position of consoler at a sick-bed, and read to her out of Mangnall’s Queries. There was the position of important immobility, and the cold bandages trickling down her legs, and the sunlight on the unvarnished rocking-horse; all mixed up inextricably with the profound mystery of Mangnall’s—what was Mangnall? Queries—what were Queries?)

Mundy remembered Albert leading them round a corner of the house, and a white lady sitting beautifully among the cushions of a carriage. She was about to leave the Pic-Nic. He remembered that he had never seen a strange lady so close before, and that she, summing the situation and the children’s dirty faces at a glance, had prodded her coachman in the back. The two women (the other was Mylady) smiled and waved their little handkerchiefs. The carriage with its vision grumbled on the crisp gravel, and Mylady glanced at the urchins in perplexity. They looked filthy and ought not to have been there. ‘Well,’ she said at last, speaking between them, ‘what are you doing here?’ And then her distance melted, she began to laugh. The small respectful face of little Mundy was so surprised, was so attentive; his eyes followed the carriage with such a look of wonder. ‘Well, Mundy,’ he remembered, ‘take a good look.’ She touched his yellow mop with her white fingers. ‘That was Lady Catherine de Bourgh, and mind you don’t forget her.’

They were at dinner. The grand, endless, Victorian celebration was proceeding through its score of courses. The décolleté busts and shoulders of the ladies shone under the chandelier with a pearly lustre, rising from the foamy tulle and fichus like Aphrodites born among the waves. The champagne bottles yielded their corks with a discreet pop; Sir William took a glass with the Marquis of Bute; the servants moved silently over the carpet, threading upon their prudent errands of mercy between the shoulders and the whiskers. The épergnes and the silver plate flashed with a magnificent and lordly gleam.

Augusta was in bed. Priscilla and Albert would be called to the superior mysteries of dessert, but Augusta was too young. She lay upon her back, thinking of everything in particular.

Dessert and the great world, she would very much like to be a part of them. She would wear a gown like Mama’s, and take a sip of champagne, and play billiards with the Marquis of Bute, dressed in tartans and Dundrearies. They would go to London together and have a ball. The great advantage of going to London with the marquis would be that one would escape from the nursery.

Augusta moved her head restlessly on the hard pillow, and ran over a few subjects for speculation, which would relieve the tedium of her aching curls. They were in papers.

Tomorrow would be Sunday. When one said ‘Tomorrow is Sunday,’ Miss Bown pounced at once. ‘Tomorrow will be Sunday.’ Evidently it was an important point.

Tomorrow would be Sunday, and no doubt poor Mr Newcome would have a bothering time as usual. Papa very much objected to the Lord’s Prayer being read so often during the church service, and he constantly made a practice of telling the vicar so. The vicar was Mr Newcome. Papa would count over the number of times on his fingers, and hold them up in church. One would see Mr Newcome looking anxiously towards him as the prayer became due, and one would hear his sigh of relief if it passed off without a demonstration.

One day the poor fellow had broken the fact to Papa that the bishop had ordered him to wear a white surplice in the pulpit, while he was preaching the sermon. He had always worn a black gown before. Papa had exploded in wrath, saying that the white surplice was a sign that the clergyman was reading the word of God. The black gown made the people understand that all the words which they were hearing had only been composed by the clergyman, and might be believed or not as they thought fit.

Yes, Augusta was afraid that the poor vicar had rather a troublesome congregation. Papa would not open his mouth during the Athanasian creed, and forbade the family to do so; whilst Mr Cobb, who lived at Arrick, would only read the responses to a certain distance in it. Then the vicar, after waiting vainly for the voices which never came, would have to finish it by himself. His tone was low and trembling.

Something in that monotonous voice recalled the sea to Augusta. Broadstairs, the donkey rides . . . the gallop . . . At Margate they had bathed, had seen the Great Eastern pass—the largest ship in the world! They had gazed at her in awe. There also, brother Albert had been promoted to trousers, a fact which had equalled in importance the apparition of Leviathan. On the great occasion of his wearing them for the first time he had walked ahead with Priscilla and the governess, the others all following discreetly in the rear, their eyes glued upon him, hardly able to breathe from excitement. ‘I wish,’ the poor child had said to Miss Bown, ‘they all would not look at me so.’ He imagined, dear boy, that all the passers-by knew about the great event. His face was red!

And then the bathing. Men and women bathed separately, and men wore only a short pair of drawers—big boys were as Nature made them. So it was considered most immodest to go anywhere near the gentlemen’s bathing place, and Augusta had been told to keep her eyes away.

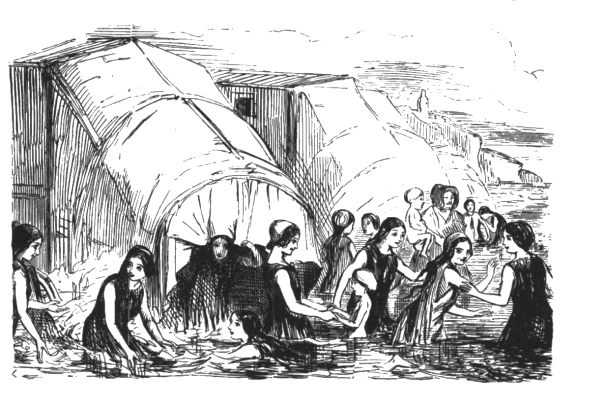

After one had entered the bathing machine and closed the door, a man would ride up on a horse and attach it to the machine by two ropes with hooks at the ends. Then he would gaily trot the structure into the sea. Sometimes the shore was very uneven and one had to hang on for all one was worth; sometimes the waves would bang against the floor, often wetting one’s clothes if the planks were at all defective. Then one heard the man unfasten the ropes, and was left to the mercy of the swirling sea. Augusta had always hoped that they had not been taken very far in. She had felt she could be brave, if the water did not come above her knees.

The ladies’ machines differed from the men’s. A huge hood was let down seawards from each machine so that no naughty man would be able to see the women and girls as they disported themselves in the water. It would have been a difficult matter for them to see anything, even if there had not been the canvas hood, for all the women wore long serge bathing gowns which reached to the ankles. They had long sleeves, and were tied round the waist.

Augusta remembered how Miss Bown and Nurse had robed her for the first dip, how presently a loud knock had been heard on the seaward door; which Nurse had immediately opened. There, up to her waist in water inside the hood, had stood a stout figure with a weather-beaten face. It was the bathing woman, clad in a serge costume, a shawl over her shoulders, a dark sun-bonnet upon her head. She had stretched out her arms towards Augusta (how they had all hastily backed!) and in a harsh voice had exclaimed: ‘Now my little dear, come along. Betsy will take care of you. Don’t make me wait!’

Augusta had been chosen to go first. Terror-stricken, she had clambered down the ladder towards the Ogress, to be promptly seized. Augusta had clung to her, frantically entreating that she should not be dipped. But it was of no avail; Betsy was too strong. With her mouth open in a last petition she had been plunged backwards into the horrible and tugging medium. The green sea had closed over her face, cold, swirling and filmy above the smarting eyes, rushing with a salty gurgle into the protesting mouth. The Last Trump had been repeated three times. A stout rope which hung from the top of the awning had then been put into her hand, and she had been left to look after herself.

Behind all this reminiscence and speculation a cross-current was troubling Augusta. Something about society, something analogous to Priscilla’s dessert and billiards with the marquis . . . Could it have been old Miss Lydekker, driving up in her coach, with four postilions riding on the horses? She thought that when it reached the lodge a horn must have been blown, for the gates flew open at once. Or was that an exaggeration of childhood? It must have been quite two years ago that Miss Lydekker arrived with the postilions. In any case, they had looked so gay, coming up the drive. Augusta wished that she would come more often.

But no, it was not Miss Lydekker. It was Lady Catherine de Bourgh, who had been seen by Albert. Now why was one expected to remember having seen her? Was it because she was a fast lady, or so very great, or so very good? Why, like Donati’s comet, had she streamed across the firmament with such portentous signs?

There was another small head in Ambleden which was troubled with the same matter. Mundy was awake, though without curl papers to keep him so. He was awake, without knowing it, because he was hungry; an infant craving, an appeal for funds to build the little body, kept him sleepless with a vague disorder.

He lacked Augusta’s poetical acumen, her fancy and wide interest in living. He was not bothered by any reason for the importance of the person. For him it was a simple though a vital matter. Mylady had told him to remember the encounter; a tip straight from the horse’s mouth. He had seen Lady Catherine de Bourgh (as one might see the Great Pyramid, or the aloe’s centenarian bloom, or a man whose grandfather had met Ben Jonson; and with as little comprehension of the phenomenon); he had been told to remember her; he must prove himself worthy of the trust.

The small creature lay in bed with his three brothers; his credulous kind face staring up into the darkness, with something of the wisdom of the monkey’s.

It was dark. Adam and Eve, solemnly in darkness shrouding themselves, had slowly vanished. The timid rabbit was nibbling on the bowling green, betrayed now only by the crisp plucking of his teeth. The keeper in his cottage had taken off his boots, was warm beside his wife, satisfied with a good bag; the first pheasants of the season.

The men drank their port round the log fire, whilst the clear shoulders of the women hung over the albums in the drawing-room, or poised their ringlets over needlework.

Inside the bright room the lamplight shone on red tablecloth, on sociables, on the grand piano which would soon be played. Outside, in the darkness of Ambleden, the beech tree waited faithfully for its mahout. Upstairs Augusta herself had gone to sleep, to dream of bathing machines, and in the room above the horse-boxes little Mundy was sleeping too. He slept with a rag doll clutched tightly to his bosom. It was called the Duke of Wellington.

The Deutschland was wrecked at night on December 7th, 1875, while Gerard Hopkins slept at St Beuno’s. He was under a roof there, he was at rest, and they the prey of the gales.

That stormy day, which ended with five Franciscan nuns drowned on the Kentish Knock, and with a poet dreaming who would never know the smallest recognition till he had long been dead, died also with a few pale beams upon a tired party hacking home at intervals to Ambleden.

Sir William turned into the stableyard. The hoofs on the cobbles made a sudden clatter, a sound tied up with welcome. A young groom ran out into the rainy darkness and took the horse’s head. Sir William lifted his spurred heel over the withers with a voluptuous groan, slid down on the near side and landed awkwardly. His knees gave a little, stiff and unaccustomed to the terra firma; the spurred heels turned on the cobbles, so that he lurched a pace to regain his balance.

‘Ah,’ he said, with a long breath. And then: ‘Thank you, Mundy.’

He appeared to unknit his muscles, transforming himself with painful pleasure into a land animal. He moved to the horse’s side and slapped its neck affectionately. ‘He’s tired,’ he said. ‘I’ll send some ale. But try him with the gruel first.’ He made off clumsily towards the house door, his spurs biting his ankles, aching for his bath. At the door he called back: ‘I shall see him after dinner.’ He disappeared. That was the end of his day’s hunting.

The groom’s day would not end for two hours. He had dressed three horses before half-past nine, had been out in the same rain as Sir William in the part of second horseman, had enjoyed the same hack home with the first horses, and had dressed two of them. Now he would have the business of nursing an exhausted horse.

Mundy led the tired creature into a wide loose-box, lighted with the kind modern beams of gas. As they came into the light they materialized, shedding the dusky skins which they had worn outside and becoming translated into visible identities; the horse streaked, muddy and with drooping ears, the man golden and vigorous. Young Mundy had a skin of amber. The shock of yellow hair, which had tumbled at Blindman’s Buff in the same yard seventeen years ago, had sobered to a brown, soft and consistent like the mole’s. The monkey face was full and hardy, informed by clear and gentle eyes—eyes which were like a terrier’s, faithful and weak.

The boy looked at the horse with an instinctive attention. Silvertail was soaked but not sweating, was tired out. He drew the bridle over his head, loosed the buckles of the girths and lifted off the saddle, throwing it over the ridge of the box. He threw the clothing lightly over the withers and drew it down. The gruel he had prepared already, but he hesitated to present it, temporizing with a little hay. Whilst the horse played with the sweet wisps, remembrances of the summer, he bent to dress the legs.

Standing thus, with his head below his shoulders, he was faced with a perspective of gnarled hocks; shaggy with their passage through undergrowth, caking a little at the top, but below purely muddy, with wet mud. The mud stood on them in little islands, like blisters. They were so wet that he thought he might as well wash them, and he did, with warm water. He looked for thorns and scratches. Then he swathed the flannel bandages, neatly and not too tight; carefully dried the heels.

It was a miracle to see the understanding between him and the beast, whilst his mind was absent and suffering.

His mind was on Ellen entirely, stupefied by her, so that he compared even the movements of the animal with her movements, and matched the smoothness of its flanks with her body’s sweet complexion. Five years of marriage had done nothing to dispel her beauty, nothing to overlay the rapture of his first possession. He could remember her as movements, as times of day, as kinds of weather; so that she was inextricably bound up with every corner of his life and left nothing which he could call his own.

They had been brought up together. He remembered Ellen as a child of ten, slovenly in her country clothes, leggy and gawkish. But she had always possessed a grace, a quietness in boys’ company; she would sit on a stile attractively, silently, but with an unspoken appeal. It was her passivity which lent her grace. She had never flounced and flirted, never sniggered in the lanes with the other troops of interlaced and giggling girls. When she was ten he had been thirteen. He had taken no notice of her, except to be grateful that she did not shame him. She had been the only girl in Ambleden he did not fear. The forward maturity of the others had confused his secret manhood; he had been frightened of the freemasonry and difference which they possessed. When errands had taken him to the village, and going there he had heard their cruel laughter on the roads, he had been accustomed to turn aside, taking a path across the fields, or hiding in the hedges. Ellen had been the only one that he could meet.

The other boys had solved the problem early. Their wars of French and English round the haystacks had merged imperceptibly into wars of love, until the boy’s misogyny had crept in and they had become retiring bachelors, but bachelors who had taken a measure of the other sex, and knew with what they had to deal. Mundy had lacked experience. Adaptable and ready to be led, he had played when others played. But he had wanted the initiative to transform the game.

But still he could remember Ellen. She had never leered at him, mocking him for something which he did not understand. Even when she was only twelve he had been almost friendly with her, ready to trust her company when it came his way.

They had first been drawn together by a frog. It had been a dead one. An errant from its native pond, lost, wandering in the parching heat of summer, it had dragged its shrivelling body to the middle of the road. There, surrounded on all sides by a stony desert, like an early explorer stranded in Sahara, it had given up the ghost. Baked almost to a mummy in that arid heat, it had yet preserved the spirit of those early explorers; planting itself foursquare in the trackway, its head up, its webs apart—it had retained even in death a minatory and pugnacious appearance. Ellen had been afraid to pass it. It had seemed about to spit at her.

The children had been walking together, had been talking volubly without knowing that they were talking, and without an interchange of ideas. Up to that moment they had been distinct—no thought had passed across to link their minds—they had been unconscious of any mutual feelings in each other. She had been frightened of the frog, and so had he. It had been an introduction.

When he had kicked the leathery corpse aside they confided their revulsion. Thereafter, it had been a common world for both of them, a world with which they surprised each other, finding that they had used the same thoughts about it. It was an impetus to find that Ellen thought about cows as he did. The world for the first time achieved an exterior existence. If Ellen felt in a certain way about cows, when he felt in the same way, it meant that the creatures themselves possessed an attribute. This sudden, two-dimensional view of the created universe, like beam wireless, brought objectivity into perspective. The two children set out to map the world which they had discovered together.

Cows, for instance, were attractive. Their soft and glossless coats were comfortable and melting. They moved so slowly, chewed with such placid absorption, and yet with a remote eye of interest. Ellen was not afraid of them. She liked to stand in front with an equal, polite attention, returning their milky gaze from eye to eye. Young Mundy would stand so too; finally, stretching out a gentle hand, to stroke the cool slobber of their wet, ungreasy snouts.

It was not difficult to understand that they should have fallen in love, nor improper that it should have been in June. They had gone fishing together in Master Harry’s stream, with bent pins tied without gut to garden string. Their rods were boughs of trees, their method to abandon them to fortune. It was the firm and perhaps reasonable belief of their countryside that fish could best be caught by leaving them to their own devices.

It was a hot afternoon, airless and presaging the next day’s thunder. Two fish were rising intermittently, with a kind of lazy caution, in the stretch they chose. The mayfly were not out, or only in small hatches, and these two fish were not taking them. They would have risen to a black gnat.

The stream was woody on the one side, on the other clear. They chose the woody side, where the straight young chestnuts struck up in unthinned profusion, a glade of mottled light among the nettles. Here they sat, in the bird silence of the wood; looking, across the deep-cut banks which edged the stream, at a wide hayfield. It was a deserted valley, edged by a slight rise which cut off every human house from view. The bowing tops of the green hayfield were secret, peopled by the flies. A dragonfly flew, with the action of those aeroplanes which were still within the womb of time. Two mayflies curled their soft tubular bodies. The fish rose with startling effort, out of another world.

The green wood was so beautiful and so private. They were so much alone together in a world of sanctuary and soft couches. It was difficult to be unnatural in the heart of nature.

Silvertail had his gruel, but without enthusiasm for it. He leaned his head against Mundy’s chest, confident and with returning pleasure, whilst the boy rubbed his ears. The ale was carried out, already warmed, and he grated in the ginger. He would have liked to drink it himself. But he gave it conscientiously, and turned to scraping the wet coat.

The other horses had come in, and he could hear the busy sounds, the kind rough voices in the boxes on either side of him. ‘Git over,’ they said, and ‘Kerm-up,’ slapping the wide flanks to make them move. In the old days, with the keen perception of a young man, he had sometimes stopped to listen. The gaslight and the shoulders; the familiar noises of attendance; the companionship of the stables, between men with each other in jocular cries, and with their beasts in angry gentleness; the pleasant exhaustion of a day’s work done; these had filled him with a rapture, so that he had hugged himself, saying: ‘I am among friends.’

But tonight he was out of reach of friendship. Even his soft spot for Silvertail, whom he had helped to school, was in abeyance to the confusion of his mind. It was all he could do to subordinate this confusion to his duties, reminding himself what he would have to do next, planning the tasks so that they fitted with each other. Sir William made it a rule that his horses should be groomed, even after hunting. He did not believe that a tired horse ought not to be worried with dressing, that it could be ‘made-do’ and cleaned up properly the following morning. He argued along the lines of his own experience, saying that as he himself would sleep the better after a bath, after a good dinner in the fresh costume of propriety, so would a horse be more comfortable that had been properly dressed. Mundy, therefore, had to occupy his mind with a number of coincident needs. The horse had to be dried, had to be warmed, had to be made anxious for his food, had to be groomed when dry. All these essentials had to be worked in with each other, in the best sequence. Throughout the whole process the question of temperature had to be considered. He was dealing with an unnatural mechanism which must not catch cold.

Mundy looked about for a curry-comb. Among the many essentials which he had remembered to prepare, this was the one that he had forgotten. He covered the horse and went off to inquire in the saddle-room.

Here, on the other side of the cobbled yard, was a flight of wooden steps; a wooden door at the top, hermetically sealed. He opened it, pulling a hemp latch, and let in the December night.

There was a cracked lamp smoking horribly, a stove on which a pail of water boiled with a grey scum. The saddles hung high up among the brown shadows, like banners in a chapel. The walls were invisible from the dark festoons of hanging bridles; the spare bits shone in a bright line on rusty nails.

The senior stablemen preferred the unhygienic atmosphere of tradition. It was a sweet atmosphere. They looked so warm and cosy, the old men sitting round the walls on horsecloths and three-legged chairs. They were in their shirtsleeves, cleaning slowly but with the celerity of experience. Sometimes they would watch the busy waste of effort as a younger man tried their craft. And ‘Come you here,’ they would say, ‘that’s no way to set about it.’ Then, without speed, patiently, without apparent thoroughness, they would clean three saddles whilst the boy was cleaning two, and theirs would be the cleaner. They spat upon the floor, joking with a kind tortoise humour, protesting, grumbling, passing the grey cloths and sponges from hand to hand. The air was humid from the water, welcoming with the smell of saddle soap. The stirrup irons stood in a straight line.

Now they were grumbling about the railways. Ah, they said, that would be the death of hunting. Hounds killed, good lines of country spoiled, gentlemen who did not reside in the country coming flibberty-gibbeting from London! Niminy-piminy young men with no responsibilities, riding over seeds, kicking at the gates and thrusting in front of everyone. They did not know what the country was coming to.

Mundy escaped with his curry-comb. His heart was beating. The railways had suggested Ellen too unbearably, Ellen as she must be at this moment, sitting in a third-class carriage. As he stumbled across the yard he felt the letter crackling in his pocket, and withdrew his hand.

He loved her still, more even than he had loved her by the stream that summer day. They had walked back in the evening, with a grey mist running along the valley after a sunset of strontium. The dew had dropped from the leaves of their protecting trees, pattering on the undergrowth or plopping on the water to simulate the rise of tiny fishes. They had caught nothing, but carried away with them the recollection of their private bodies; of a green bower in the silence of the wood; of the two mayflies rising and falling in an endless vertical dance; of rapture and unremorseful sleep.

They had been married three months later, and a child had been born after another six. They had called him Robin, from an obscure recollection of the greenwood tree. He had died in his first year, from the effects of whooping cough.

Mundy rubbed the horse’s ears, waiting for the moment when it would be propitious to begin the dressing. He thought about his first son. If he had lived he would now have been more than four years old. Ellen had been seventeen when he married her, and he had been twenty. They had been pleased to have the baby, miserable when he died. But the tiny grave in the churchyard had been almost forgotten until this moment, except by Ellen. The second son, who was now two years old, had made up to Mundy for the loss of the first; he had no childbirth wasted, to make any such loss always irreparable. But he now remembered the mite with sorrow. If only he had lived there would have been another bond, at least a memento. Ellen would not have taken both the children.

As if prompt to his thought, as if with forethinking malice his brother called out to him from the next box: ‘How’s the missus, Johnnie? Ain’t you going to hurry home?’

He threw back the quarter piece from the shoulders. He began brushing the horse vigorously, making as much noise as possible, pretending that he had not heard. He was in confusion and could not answer. That Ellen should leave him had seemed a matter purely between themselves: an agony for him, but not a social question. Now he realized that he was overtaken, that she had put a shame upon him. Some reaction would be expected by the outside world. He would have to be angry and bitter against her, or to pretend that she had gone by his own wish. Or he would have to be indifferent, behaving as though nothing had happened, presenting a purely supercilious front to the prurient eye of inquisition. He did not know what to do, how to be brave in public. All that he truly felt was that he wanted Ellen to come back to him, a poor dog-like feeling of a dog begging. He felt that he could never get a stomach to brave it out; failing to realize that all this hunting day, since he found the letter in the kitchen when he got his breakfast, he had been putting a face upon it adequately.

His brother’s question threw him into a new state of feeling. He saw the whole of Ambleden, and the village too, meddling with his concerns. The relationship with Ellen was to be thumbed by gossip, made poor and beastly in talk. Sir William would look at him with pity, would be less exacting, would be pleased to commend him for small things. The stablemen would do their best to cheer him up, but would speak of him in the Crown. The absolute oblivion which would have been his only medicine would be denied. He imagined fearfully, with the fear of a mind essentially humble, the knowing glances which would be exchanged.

Nobody must know. Nothing must ever be said. He saw in a flash the whole of Ambleden knowing; Mister Harry smoking a cigar and talking to him, but knowing; Miss Augusta giving him a pitiful look; Sir William and Mylady talking about it after dinner; knowledge at the vicarage, at the Hall, at the pub. Directly Silvertail was finished he would go to the pub, quell all possibilities of discussion by his presence merely. The widening circles of publicity, of ineffectual and shaming pity, coloured his face with a flush of blood. He brushed vigorously at the little valleys where the ears jointed to the skull.

The pain of the present situation was that the past had been sincere. It is only in sincerity that one can be natural, and their relationship had been so. Their conduct had been native to humanity, not to an epoch. Whether she had worn a bonnet of Victorian make, had ornamented their kitchen with antimacassars, or slept in a flannel nightdress which it was improper to discard, their love had been true to its own nature. The bonnet had been stripped off passionately and the hair thrown down; the antimacassar had been pressed with instinctive embraces; the impropriety of no nightgown had scarcely lent a happy naughtiness to its eviction from the country bed. They had been children together. Seen without the informing eye of love they had been absurd. Such sincerity in the past now laid him open to ridicule, to a pain greater than would have been consequent upon a formal relation. Perhaps he could have borne to have the village discussing their marriage if it had been a civil or religious convention. But they would be discussing a matter which entailed Ellen in the wood, Ellen enjoyed under the sky, Ellen against the leap of his heart. They would be thumbing two hearts and bodies, naked; a joy of two children whose added ages would have scarcely made them middle-aged. He could not bear that his relations with Ellen should be public property, as they appeared to become by being mentioned by other lips. His recollections of her were private to themselves; could not bear the eye of an external world.

He had been left to face the music. She would not suffer it because she was gone. Gone. Sir William had found nothing improper in an early marriage; young wives were more native to those days than they are to ours. He had given them a cottage of their own, left vacant by the death of an old cowman. They had added to its furniture on a tiny pittance, revelling in their joint childish possession, merry-making and admiring over the least addition. So now nothing in the house existed by itself. Everything was in a place as they had put it there together. Mundy could remember the scene of every installation, almost the exact words with which the innovation had been acclaimed. Everything was a monument to themselves, and she was gone.

He could not bear to think of the cottage as it would await him when Silvertail was finished. It would be empty, like heaven to the philosopher. The prodigious emptiness of the accustomed rooms, fireless, untidied, bachelor and alone, made him determine not to go back there; not now, not yet, not till he had sucked a small companionship from the Crown.

He busied himself with Silvertail, hissing mechanically to keep the dust out of his lungs. The horse had got his name by the albinism of a few hairs in his tail. He was standing up now, with his head higher, his ears attentive to the dressing. He curved his lovely neck and nibbled at the boy’s shoulder with his lips; seeming to thank him, or tell him that he was fond, or perhaps to attract his attention and remind him about his dinner; or else merely in order to annoy him with a sly nip, using a dim sense of humour.

Mundy changed his curry-comb to the other hand and cleaned the brush on it. He went round to the other side, turned the mane over, and began again at the ears.

He could not blame Ellen for going. He had been weak with her, must have grown stupid and insipid. He thought to himself: it is living always the same life that has done it. If I could have been a bit different she would have stayed with me. I was dull for her, always being at Ambleden and never being anything but a groom.

He had been with horses since he could remember. The ponies for Miss Augusta and the other children had been tried out by him first, even when he was quite tiny. He had sat upon them like a small ape, born to it, with an air. He had been inclined to show off and to despise the children of his master, so far as horsemanship was concerned. He had been conscious of his business-like appearance, of his close seat on the animal. He would speak to it in a grown-up voice, imitating what he had heard his father say. Sir William had been amused by the little chap, by the reserved dog-face, superior and correct. He had laughed secretly to see him riding the larger animals, bareback, or unable to hold a puller, crying out anxiously to his father and complaining of the reins, but anxious for his reputation, not for his skin.

He had started at the age of nine, an unpaid handyman, helping his father. He had always been in the yard during that summer, holding horses for somebody, fetching things, or, which was his pleasure, washing the long tails with soap and water. A big mare would be standing in the sunlight, rope haltered to a ring, enjoying the warm brickwork and the swallows dipping at the water-butt. Behind this placid and beautiful creature would be the little boy, happy, soapy, talking to her familiarly about her bottom. He would cry out to anybody within hearing. Is that good? Shall I put on some more soap? No, they would tell him. You leave the soap alone. Get it parted out and don’t leave the poor creature standing there like a drowned rat. But always in kindly voices, always playing up to the young limb. They were fond of him, and thought he was a good rider, though they would not say so before him.

He had been an elf, freckled and quick in the grooms’ repartee. His large family and sensible parents had kept ‘the nonsense’ out of him. His father was a coarse, easygoing man, but with a strong sense of rectitude in his children. He beat them with a strap for a catholic selection of errors which did not vary. They were not afraid of him because they knew what he would beat them for. He was fond of them, and they were proud of him. They thought that nobody in the world could ride so well as he did.

Their mother had been a managing woman; always washing, and cleaning the rooms, and cooking their small meals. She turned her children loose, but kept them clean with a rough tenderness. The agony which she felt when she saw her tiny hostages mounted, proud and responding to their father’s trade (she never trusted horses) was not apparent. She seemed to take very little notice of their pursuits. But she had seen to it that they went to church every Sunday, and that they learned to read and write after a fashion at the nearest church school. There had even been a little arithmetic. Their father loved her in a curious way, tinged strongly with admiration and much with fear. His loose nature responded to the principles of hers, so that he thought how good she must be, to be always busy, and upright, and clear between right and wrong. His own strong sense of what was proper, which dictated his children’s penal code, might have been innate, a curious contradiction in his nature, but it might more probably have followed upon his affection for his wife, upon the pliability and hero-worship which was peculiar to him, and would be inherited by his son.

Between the mother’s discipline, the father’s horses, and the three Rs of the village school, Mundy had enjoyed a happy childhood. It was not the training, he now reflected, trying to find excuses for her, to make him an interesting husband for such as Ellen. He had been too happy, too careless and contented with a tiny world.

The whole complexion of his childhood was unconscious pleasure, or at least pleasure that was not self-conscious. It had been a self-sufficient rapture to throw himself down in long grass, panting at hide-and-seek. The smell of hay, the tickle of small bugs down his dirty neck, the habits of ants and woodlice and eels (that was what they fished for with their brown string and bent pins; his father was partial to eels) had made his childish summers. Puddles and conkers, snowballs and the ethereal groundless slide on ice, had been the sum of other seasons.

The horses had run through it all, ever since he could remember. Plump ponies, gentle geldings, temperamental mares, they had melted through the texture in an unbroken string of idiosyncrasies and colours. Winsomely pig-eyed and cunning, devils whom it was triumph to subdue; pullers with large hearts; wallers with a fiend inside them; touchy and nervous thoroughbreds, whose great eyes, whose silky mouths, left the riding to the knees, to the voice, to a hinting constantly upon the reins; horses of all the glowing shades, skewbald like shining autumn, bay, chestnut, black, or steadfast flea-bitten, like the thaw; their white socks, three or four, superstitiously counted, had moved his heart.

He supposed that horses were a trade, were a narrow profession to those outside it. It must have been dull for Ellen to have a husband always stupidly happy and uncomprehending. She was a woodland creature, sportive, shy, direct as nature, requiring like nature to be ruled. His gauche gentleness, his selfish easiness, had failed to hold her. She had been slipping from him whilst he had been wrapped in dull content. He had been blind.

Mundy had finished the fore-quarters, the neck, shoulders, bosom and legs, with a wisp of damp hay. He turned the horse round in the box and stripped him completely, beginning again with the brush on the other end.

Ellen had been more beautiful even than a horse. It was astonishing that a country girl, without the arts of gentry, could have been so beautiful. Her skin had owned the texture of a child’s, burning with the summer to a rich peach, and even after the whole length of winter never completely colourless. The daughter of the vicar’s gardener, she had never given herself airs, never aspired to dress unsuitably. The fineries which she had consented to wear had been accepted to please him, worn happily, without a spurious enthusiasm. Yet she had looked beautiful. She had an animal’s consideration for her person so that Mundy would call her a kitten; though she was more a dove to him, more soft and wild and clawless.

He had, he loved her passionately. That she should go made a blank of life, a desolation which he could not face. His brother’s question had brought her before him vividly, more vividly than he could have managed by an effort of his own will. His visual recollections had been overworked. The oyster had overlaid the grit, and he could form no image of the precious face by voluntary strain. But at another’s mention, at the new angle of a third party, his heart plunged and fell aghast at the reviving features. This involuntary twist, this fresh turn provoked by circumstances external to him, raised Banquo in all his cerements to the life, so that his vitals turned about inside him.

Ellen! It was impossible that she should leave him. His whole life till now might have been calculated to unfit him for this crisis, so that he did not know what to do. If he could have expected it, it would have been less painful. But until he found the letter he had been as blind as death.

Yesterday had been a good day. He had been sent out hacking with Miss Louisa, now a young lady who, although she was past twenty, was too timid to enjoy a hunt. Perhaps Sir William’s powers of procreation had been failing with this last example, or perhaps it had been that early fall in the Italian garden, or the suggestive influence of Mangnall’s Queries; whatever the reason, Miss Louisa had grown up a frail and intellectual creature. She believed that she would die young.

Mundy had liked to go hacking with Miss Louisa, because it helped him to better himself. The pale girl, proud, fanciful and difficult, had taken a fancy to him. He believed in all her attitudes simply; accepting the facts of her mysterious lineage (she enjoyed the supposition that her mother was descended from King Alfred), of her genius, of her approaching untimely death, with a faithful assurance which was comforting after the dubiety of her own brothers and sisters. She persuaded herself that it was her last duty in life to educate this simple and affectionate rustic; a duty rendered doubly pleasant by the opportunity of airing her own education. At first, when they went hacking together, she had tried to teach him French; that fluent, Victorian French, unhampered by any but a conventional pronunciation, with which our grandmothers made their way abroad with such distinct diplomacy. The experiment had not been successful. It had never occurred to her that it was perhaps not a very practical one; and Mundy had enjoyed it very much. This mystery of ‘oui’ and ‘chat’ had seemed to him high, noble, profoundly valuable. He never forgot the French for cat, ruminated on it a good deal as he grew older, and produced it on more than one occasion with a marked success.

French was succeeded by poetry, in which he made little progress. He never retained any of that, except the stag at eve. It had been the sad want of sensibility which he displayed in this subject, listening respectfully whilst Louisa chanted her sing-song numbers from Tennyson (chanted in a ‘Tennyson’ voice, irrespective of the context), that caused her eventually to give up his higher education in despair. She came down to teaching him history, contemporary politics, and the rights of man.

Yesterday she had been explaining to him about Disraeli. The great Mr Gladstone’s first ministry had been defeated a year ago; which was a good thing, because he was a Liberal. But he had done much good. If it had not been for Mr Gladstone, Purchase in the Army would never have been abolished; Ireland would not have been pacified; it would not have been so easy for Mundy to educate his future children. Here Miss Louisa had given him a complex look, meaning that children were a joy which she would never live to share; meaning that he was in a sense her only child, a spiritual adoption, her small platonic sop in the happy realms of education. He had decoded the whole expression, risen to it with a look of gratitude, with determination to be worthy of the trust. His was a sympathetic nature, like the spaniel’s, to which the interpretation and gratification of such demanding looks came naturally.

So she had gone on about Disraeli; how it was a pity that he was a foreigner, a Jew, but that he was Conservative, which was the great thing. She spoke of those two great protagonists, of whom the one had bought the Suez shares that year, while the other hewed with a noble acerbity at Hawarden. She went on to talk of Mill and Darwin, of Liberty and Monkeys, of the wickedness of Trades Unions and the effects of Drink. Her opinions were correct and her delivery admirably studied. Mundy had enjoyed himself very much; had felt sure that he was getting much gain; but could not for the life of him have said what it was all about.

It had been a good day. They had cut through the usual labours early, started in the saddle-room before four o’clock. There, in the comfortable atmosphere of water, and stove, and smoking lamp, they had sat busy and garrulous. There had been the usual feuds, the usual grumbles and sly tormentors. They had got on with their work; preparation for hunting being always a happy preparation, even for the second horseman.

He had walked home in a December hush, presaging the ill weather which had been accomplished on the following day. Ellen had been kinder than was usual with her. There had been a fire to welcome him, a good stew of bacon and potatoes. They had been merry together. She had taken him in bed with something of the wild fervour of their earliest days. It must have been a fervour of remorse. She had been kind to him on this their last night, knowing that she nursed the dagger for his heart.

She had risen early whispering to him that he might sleep on. She had moved about; probably dressing the child. Her clothes she must have packed, even as she had written the letter, the day before.

He had woken late, grumbling and wondering. But she was a wild creature, who had often slipped out thus before. He had got his own breakfast, dratting her for a careless wife, had found and read the letter as he was fumbling with his clothes.

Perhaps a romantic character would have ridden after her and brought her back. But Mundy had gone out as Sir William’s second horseman, as he had been trained to do.

Tom Foxwell had come three years ago, a foreigner to Ambleden. He was a Berkshire man. The keeper who buttoned his leather gaiters in 1858 had died childless; and Foxwell had been given his place. He came of the old breed of keepers, men who were as much a class as policemen, and wore uniform.

Because he was a foreigner and, therefore, unwelcome to the older society of the estate, and because they were sorry for him with the sympathy of their own youth, Mundy and Ellen had taken pity on him, had done their best to make him feel at home. He had not needed sympathy, soon finding a place for himself. He had a nervous strength of character. But his first friends had remained friendly with him always, partly because, in spite of an overbearing or selfish way, he possessed the attraction of an animal. It was difficult to understand why he was attractive, or what sort of animal he might be said to represent. It was not a fox or a brock; perhaps it was an otter.

Foxwell was a quick man. Unlike most keepers, he was garrulous in company. He would apologize to Mundy for his wagging tongue, saying that his silent hours in the woods tied his thoughts inside him; that his daily hour of talk with friends liberated them, and eased his heart. He spoke the truth in this, for he was always silent when about his business, even when he was in the company of other keepers.

Mundy admired him. He always admired selfish people, and people who could think. Foxwell was a thinker in the true sense; not a country philosopher or politician, but one who thought about the inner mysteries of attributes. He would suddenly remark about the feelings of trees, saying that they were alive, like people, and wondering to what pangs and pleasures they were subject. They could die, evidently, but could not love. What delight, he would ask, redressed the balance of their asexual livelihood? Was it a slow and seasonal ecstasy; the feeling which in stretching men expressed itself before windows at dawn or sunset, the bone-crack and swell of sweet flesh which cried that it was good to be alive? Or he would remark that wood was a countryman, full of uses and protection, but a countryman with the rustic sense of humour, a savage joker suddenly sly and treacherous. Wet wood, he said, seems not to be slippery; but that is its subtlety. No surface, he maintained, was more deceitful than a tree trunk in a stream. When you fell, to break your leg, the wood chuckled; relapsed into honesty and usefulness; became straightforward again and blandly rustic; until the next practical joke.

This kind of poetry appealed to Mundy in a way that Miss Louisa’s had never done. But Foxwell’s boasting struck him more. The man talked like a genius; the smooth voice (it was a beautiful one) running on without artifice or check. Husband and wife would sit before him in a woven silence, listening and entranced. In this aspect he was perhaps more a serpent than an otter, and they the small toads that sat before him. But if he was a serpent at all, he was not the snake of fiction. The true serpent is clever but not cunning, wise but not treacherous, quick and egoistical, but capable of affection.

He would tell them his father’s stories about the old days—days which he pretended to remember, although he was only middle-aged. Till 1831 the game laws had been medieval. Only the squire and his eldest son had been allowed to kill game. Such licence had been forbidden even to their guests by invitation, except where law was evaded by a tiresome process. Foxwell told many stories of those times; of the savage punishment for carrying a net, of the gentlemen poachers who shot with impunity, bullying the keepers with lies and threats. Those had been the times of violence, of pitched battles between the poachers and the keepers. In these battles the squire and his friends had joined, for sport, if they were lively men.

He spoke of man-traps and spring-guns, engines which slew or maimed the guilty with the innocent; of poaching in its two forms, the poor man’s crime making him liable to transportation, and the gentry’s sport. Schoolboys in those days were not bound to the wheel of communist games, but found their pleasures for themselves. One of these pleasures was to poach, braving the excitements of the woods and their top-hatted guards, who would thrash them if they could. He made those small sportsmen live again for Mundy, with their short coats and tight buttocks, their stealthy creep and gleeful execution, their boasts of conquests, their distressful wails. It had been the age of bullying, of peers slaughtering each other in pitched battles at Eton, of birches and schoolboy tortures. But at the same time it had been an age in which robust delights were possible. They must have learned to understand the ways of nature, the little boys who scrambled in the undergrowth, dodging the keepers.

Many of Foxwell’s stories were of Berkshire; a country which for Mundy became Homeric. There, apparently, the great poachers still poached in a fearsome desperation, regardless of life and limb. Spring-guns had been abolished in 1827 and the death even of a bucolic trespasser had become a nasty matter. But the spirited squires and their retainers still lay in wait for them with sticks, still fought them in ambushed battles, with loud whacks, and oaths, and the noble art of self-defence. Foxwell himself claimed to have fought and vanquished in the ordinary course of affairs; to have trussed his victims, with broken crowns, for the magistrate next morning (and often the magistrate was the landlord whose pheasants had been poached); to have gathered the spoils of victory, the nets and ancient guns.

The navvies, called so because they dug the navigation canals, had been the main body of the enemy. They would poach in companies, according to an inspired plan of action. A dozen of them would stealthily patter through the midnight woods, moving among the autumn leaves, drained of all colour by night, a hardy band of desperadoes. They crept in single file, the last man stopping under a tree where he could see a pheasant in the moonlight roosting on a bough. As he stopped he would whisper to the man in front of him, who, in his turn, when he found a sleeping pheasant, would stop and whisper to the next. So they would wind along, until the leader, now alone, found his own bird. Then he would whistle shrilly; the whole band would fire a single volley; would snatch their dozen victims; would be gone before a single keeper came upon the scene.

Or he would teach them poaching tricks. The country butchers, he said, carried their brass weights with them in their vans. Returning from a late delivery at night, they would tie one of the smaller weights to the lash of their whips; would catch the roosting pheasants by swinging it, so that it wrapped about their necks. Pheasants were taken with a spot of bird lime in a brown-paper cone. The cone would be left where a trail of maize had been scattered, a trail which led into the cone, and which the birds would follow there. When they had put their heads inside the tunnel, the lime would catch the hackles of their necks; they would stand still, blinded and idiotic, until the trapper came to pick them up. Hares might be captured by mesmerism. If a poacher saw puss crouching in her form, he would come up in front of her, to within a few yards, and drive his stick into the ground. He would hang his hat on it, or perhaps his coat, and walk away, fetching a circumbendibus until he came upon her softly from the rear. She would be paralysed, with her faculties all bent upon the stick; so that he could often snatch her up by the ears, a startled captive. Then there were still the tumblers for the rabbits; poaching dogs which had been taught to somersault and tumble in a curious way. They would draw up to the rabbits in the performance of these antics, and the rabbits would watch them with a surprised and stupid interest, only waking to their treachery as the small teeth met behind the ears.

Mundy would listen to the stories with a respectful interest. Although he was a countryman, although he had been bred among the agriculturists, although he had been conscious of nothing but Ambleden for twenty years, yet this was his first introduction to the woods. He found it quite natural that Ellen should go with Foxwell to explore them. He wished indeed that he were not a groom, that he could go himself. She would air her new knowledge to him in the evenings, and he would listen with envy, as she described the snares.

Foxwell was a good-looking man. His dark hair, still raven at forty-five, his sharp, questing face; Mundy now saw that he must have been attractive. It was an attraction of maturity. The power of this woodland man, wise, quiet and effective about his duties, had been the antithesis of Mundy’s innocent stupidity. Ellen, wild, tameable Ellen, had leaned towards the security of his hands; just as the small pheasants nestled there quietly, just as even the old birds would come to his call. He had snared her with the same assuring strength.

Mundy wisped the horse in an agony. Now that the news was broken, he could see how affairs had tended. What was worse, he could imagine motives, secret assignations, springs behind small words, which had perhaps never existed. He suffered the extreme and wicked pang of physical jealousy.

Ellen had gone with Foxwell much, had sat with him in the twilight, waiting for the dim grey snout of an emerging badger. She had sat with him, sharing the silence of nature, till the vixen came out again and played with a maternal sternness among her frisking cubs. He had brought her the blue-brown silver trouts, still fresh in a nest of green grass, with their rosy spots unfaded.

These moments of companionship were now terrible to Mundy, so that he suspected every one of them. He could see her in the twilight, careless of any brock, wrapped in the strong secret arms. The grasses which their bodies pressed, the nests among the bracken, were an imagined torture.

She had been too natural to be true. His gauche assuming kindness had failed to hold her. She had gone with her wild heart to a quarter which held power over wild animals, to the natural forces with which she was naturally in keeping.

There had been no recriminations, no quarrel or hesitation. She had gone where her love willed her, sorry for her husband, remorseful for his suffering and without being flattered by it, instinctively intransigent and unflinching in going. Like nature she could take no account of stragglers and victims.

He could not feel that she had been deceitful. Their meetings had been secret to save him pain; they had gone secretly when it was impossible to stay. Perhaps Foxwell had been a traitor, but he could not call him so. He felt that the man was above him, a person governed by finer and to him incomprehensible laws. Even under this crushing blow he had not lost his admiration.

Mundy finished with the wisp and began the final stages with the rubber. He passed it, and then the leather, along the grain of the coat instinctively; smoothing unconsciously along the cunning sweeps, the economical hair-etching which covered with the minimum of cross-purpose, with the maximum accentuation of the solid curves. He took the whorls and conflicting tendencies with a careful arc, allowing each attempting wave its due.

Then, because the first was damp, he fetched a new blanket from the saddle-room, and threw it lightly, high on the withers, drawing it down with the grain of the coat, so that the hairs lay flat beneath it, warm and shining under cover. He sponged the nostrils and the dock. He cleaned away the traces of the gruel and offered the hard food for the night, oats with a few split beans.

He turned his attention to the bedding, taking a fork to lay it evenly and raise it against the travis. Unsatisfied with the morning’s litter, although Silvertail had been out all day and had not fouled it, he fetched the half of a new truss; sweet, stout, dry but not brittle. He spread it smoothly, as far as the drain.

He was putting on his coat when Sir William came out.

The master picked his way over the higher cobbles, between whose interstices the starlit puddles of rain and manure were trickling down; appeared suddenly in the gaslight on silent feet.