* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine Vol XL No. 6 June 1852

Date of first publication: 1852

Author: George R. Graham (1813-1894)

Date first posted: Aug. 13, 2019

Date last updated: Aug. 13, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190827

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. June, 1852. No. 6.

Contents

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| New York Printing Machine, Press, and Saw Works | |

| Edith Morton | |

| Ferdinand De Candolles | |

| The Ghost-Raiser | |

| Tom Moore—The Poet of Erin | |

| A Life of Vicissitudes (continued) | |

| Two Ways to Manage | |

| The Master’s Mate’s Yarn (concluded) | |

| The First Age (concluded) | |

| Titus Quinctius Flamininus | |

| Nelly Nowlan’s Experience | |

| Review of New Books | |

| Literary Gossip | |

| Graham’s Small-Talk | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

J. Hayter W. H. Mote

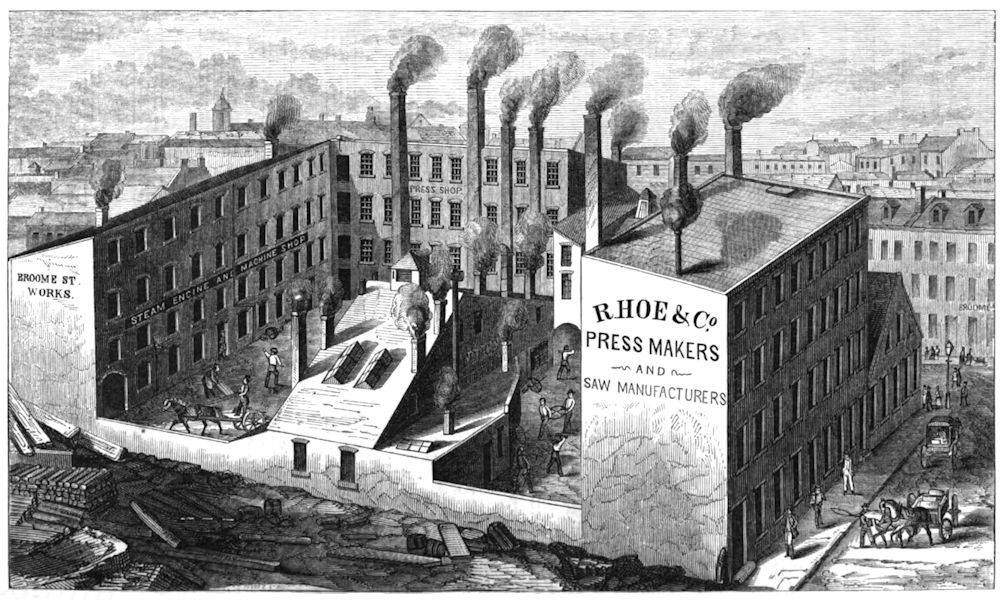

THE BROOME STREET MANUFACTORIES.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. PHILADELPHIA, JUNE, 1852. No. 6.

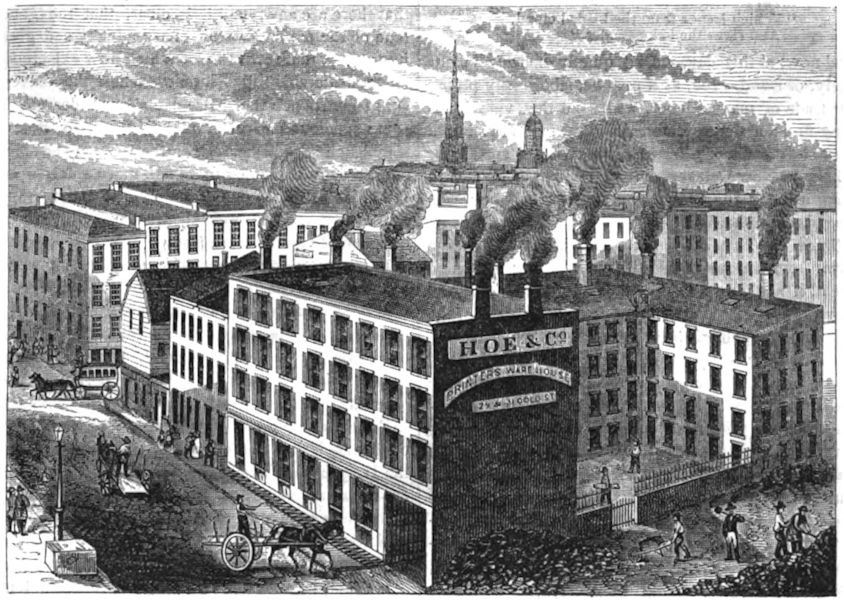

R. HOE & CO.

GOLD STREET WAREHOUSES.

Had it been possible for any human intellect, at the close of the eighteenth century, or the commencement of this its nineteenth successor, so to grasp and comprehend the development of science, its expansion and diffusion, and, above all, its application to the every-day wants and conveniences of ordinary human life, as to predict, only fifty years beforehand, any one of the almost incredible marvels which have long ceased to move especial wonder, as being now established facts, witnessed by all eyes, and of occurrence at all hours, the owner of that intellect would not have been merely laughed at as a crazy, crack-brained enthusiast, but would have run a very reasonable chance of being consigned to the cell of a madhouse, as an incorrigible and incurable monomaniac.

The writer of these lines, lacking several years yet of the completion of his tenth lustre, clearly remembers how, within thirty years at furthest, to assert an opinion of the feasibility of lighting streets by gas was to be sneered at for a visionary, or regarded with suspicion as a probable speculator in the fancy, even by the best informed, and most enlightened classes.

To the youngest of his readers the dictum of the then infallible Doctor Dionysius Lardner against the possibility of Ocean Steam Navigation—for, deny it now as he may, he can be clearly convicted of its utterance—is familiar as a household word.

And now, what insignificant town, to say nothing of innumerable private dwellings, innumerable factories and workshops, prison houses, as it were, and ergasteria, would it were otherwise! of plebeian labor, innumerable theatres, assembly-halls, and banquet-rooms, abodes of patrician pleasure, are not ablaze through the murkiest midnight, and light as the broadest day, with the released and radiant spirit, that lay so long enthralled and unsuspected in the hard heart of the swart coal mine?

And now, with what quarter of the world are we not in daily, if not hourly, communication by the united agencies of those two most irreconcilable powers, fire and water?

Hardly one century has elapsed since the American Franklin revealed to the admiring world the scarcely suspected fact, that the subtle spark elicited from the electrifying magazine, or from the hairs of a cat, rubbed contrariwise to their direction, is identical with the sovereign, all-pervading flash,

“Which issues from the loaded cloud,

And rives the oak asunder.”

And now, at this day, we sit quietly engaged in our study, or stand, even, as it may be, laboriously plying our trade of manual labor, and send that very lightning-flash, a tamed domestic influence, nay, but a very slave and pack-horse to our will, to speed our tidings to New Orleans, or to Newfoundland, and to bring us back the answer, before a second hour has lagged round the dial.

Time was, nor very long ago, when to receive news from Europe within thirty days, was esteemed a feat, if not a miracle, on the part of the carriers. Now, or ere a second summer shall have passed, the electric telegraph will be in operation to Cape Race, the south-easternmost point of Newfoundland, and mail steamers will be cleaving the Atlantic far to the northward, to and fro, from the green shores of Galway. Then, within seven days at the utmost, the news of farthest Europe, news from the Vistula, the Danube, and the Don; news from the Tartar and the Turk, shall be sped, more swiftly than though they “had taken the wings of the morning,” to the uttermost parts of America, shall be read almost simultaneously on the shores of the Atlantic and Pacific, and sent far aloof among the oceanic isles of the southern hemisphere, even to drowsy China and remote Taprobane, by the almost unearthly powers of steam and electricity, and last, not least, the press.

The word is out—we have said it—the press—a kindred, not antagonistic, scarcely even rival, power to the two mighty elements we have named—since it has pressed both into its service; and itself, purely human in its origin, its influence, and its importance, purely material in “its age and body, form and pressure,” derives most of its incalculable puissance from the coöperation and subservience of the two mightiest, most unearthly, most immaterial, and most spiritual of essences, existing, or which have existed, in the universe.

But we are not about to write an essay on the power, the influence, the utility of the press. These are too generally appreciated and acknowledged, to render a single paragraph necessary. In the two first particulars of power and influence, the press is incomparable—not to be equaled by any instrument or agency of humanity that ever has existed. The extent of its utility—although still unquestionable—is limited and diminished, “cribbed, coffined,” and curtailed by the weakness, the willfulness, and the wickedness of the very many men, unfit and evil-minded, who have thrust themselves forward, assuming to conduct it, and through it the public mind, with no ulterior object nobler or higher than the misapplication of the weight and moral power with which it invests them, to all sorts of immorality and wrong, to which avarice, rapacity, ambition, and the insane desire of demagogueism may impel them.

This is, however, only to admit that the press is an agency of time and mortality; and as such liable, of a necessity, to be perverted. Perhaps it is rather to be wondered, that there are few base, dishonest, licentious, and self-seeking journals in circulation, than that there are any; and it is clear, that the general tone of the reading world is so gradually and greatly improving, that few of those which now exist receive any considerable support, unless where they have the skill to introduce their false doctrines under cover of some specious sophistry, making them to wear the semblance of reforms. Even these, it may be observed, are daily becoming more and more transparent to the broad and keen eye of the public; and, in proportion as they are comprehended, lose their ill-acquired and abused popularity and power.

In one word, the utility of the press, its beneficial influences, its charities, its diffusion of knowledge and true light, and its general maintenance of the right, out-balance, as by ten thousand fold, the occasional obliquities, injustice, falsehood, and advocacy of devil’s doings here on earth, which periodically disgrace its columns.

For these the press is no more to be censured or condemned, than is the Book of Common Prayer, or the Holy Bible; because—in the middle ages—men, mad with too much, or too little learning—it matters not whether—applied their most hallowed texts, read backward, to the evocation of departed souls from Hades, or of evil spirits from the abyss of very Hell.

It is not, however, of the moral influences, but of the mere material powers of the press, as now existing in its wonderfully improved condition, with all appliances of marvelous time-saving machinery, that we would now speak—machinery born itself of machinery, self-developed from the swart, unplastic ore, with, comparatively speaking, small expense of human labor, though under the control of the all-contriving human brain, into engines of strange and mysterious potency.

It is little to say that the efficiency, and of course the utility, of the printing-press has been increased a thousand fold, that the facility and consequent cheapness, of the reproduction of books has been improved to such an extent that thousands and tens of thousands of volumes are now printed, published, and put into circulation, where there was one thirty years ago; and that too at prices, which bring it easily within the means of all—but the very idlest and poorest—to become familiar with the best thoughts of the brightest geniuses of all ages—That the whole system of journalism, and journal publishing, has passed through a complete revolution, reducing individual prices to a mere nominal fraction, and referring the question of profits, and remuneration of labor, to gross sales of tens of thousands of daily copies—the consequence of which revolution is to place the whole news of the world, including all discoveries of art or science, all arguments and disputations of the first statesmen and orators, all lectures of the most prominent literateurs and philosophers of the day, within the hand’s reach of every farmer and farm-laborer, every artisan, mechanic, clerk and shop-boy of the land, from the Aroostook to the Sacramento and Columbia.

It is little to say this—yet this is something; for it is the first step toward making those who do govern the land, fit to govern it—namely, the people—toward enabling them to judge, unlike the constituents of best European representative governments, not of men only, but, mediately, of measures; toward giving them to judge and learn for themselves, from the actual progress of recorded events, daily occuring, something of the policy of foreign nations, something of the interest of their own country; lastly, toward rendering the permanent establishment of a falsehood, or the long suppression of the truth, an impossibility.

And yet all this is to say little, as compared with what may be said—namely, that the difference between the efficiency of the modern printing-press and that of Guttenberg, Faustus and Schoffer, is almost greater than the difference between that and the manuscript system, which it superseded.

And all this is to be ascribed to the perfection of mechanics and machinery, brought by the aid of every branch of science to what we might well deem perfection, did not every coming day awake to perfectionate what was last night deemed perfect.

In all branches of human labor, in all phases of human ingenuity, for above half a century, this vast increase—both of the application and the power of machinery—has been in progress; constantly awakening the fears and jealousies, sometimes inducing the overt opposition and illegal violence of the working classes, as cheapening their labor, and about ultimately to subvert their trade and destroy their means of subsistence.

Than these fears and jealousies, nothing can be more erroneous, not to say absurd. For it is no longer a theory, but an established fact, that consumption of, and demand for, any article grows almost in arithmetical progression from the reduction of its price, to such a degree, as to render it available to all classes.

Two examples, alone, will be sufficient to make this clear:—

Some twenty years ago, the renewal of the English East India Company’s charter was refused by Parliament, and the tea-trade of Great Britain opened to all British bottoms[1]. The price of tea was reduced by above one-half, and the company exclaimed loudly, as companies ever do, against the unjust legislation, which must needs ruin them.

Mark the result, however. The price of tea fell one-half; the consumption of tea increased—we speak generally—almost ten-fold. The company never were more prosperous than now.

Again—within the same period, inland postage in Great Britain was reduced to a uniform rate of one penny sterling, not without much opposition and strenuous contest, the opponents insisting that the department must become a burden on the state, from sheer inability to do the work of transportation at prices merely nominal. The results are before the public, and not a boy but knows that they precisely reverse the prediction.

The same thing is true of the growth of the cotton trade; of the growth of agricultural productions: and last, not least, and most of all to the purpose, of the growth of the so-called penny-press of New York, and the United States in general. We use the term so-called, because though nominally penny, most, if not all, of the very paying papers of this class are really two-penny papers.

While we were considering these matters, to which consideration we were led by a visit to the extraordinary machine works of Messrs. Hoe & Co., the inventors and manufacturers of the great fast power-presses, which have effected the revolution of which we have spoken, we accidentally stumbled upon the following article from the columns of the New York Tribune; and it is so entirely germane to the matter, that we have no hesitation in quoting the former portion of it, without alteration or comment.

The latter portion we omit, because we entirely disagree with Mr. Greely in the deduction which he draws from the admitted facts, as we do with most of his socialistic and communistic notions.

It is to the increase of demand, growing out of the increase and cheapness of production, that he must look for employment and profit, not to the catching at the empty bubble of ownership, or to the ambition of governing, with none to serve under him.

A thoughtful laborer—for wages—sends us an account he finds current in the journals of the rapid progress of Printing by Machinery, as illustrated by a single cheap daily newspaper. That paper now prints 48,475 sheets—or 101 reams—per day, which it is enabled by rapid machinery to do from one set of types, whereas, if obliged to use the Hand-Press of former days, it would be obliged to set up its type twenty-nine times over for each daily edition, employing 812 compositors instead of barely 28, and 116 pressmen instead of some ten or twelve only. Hereupon our correspondent comments as follows:—

Mr. Greely:—It will be seen by the above, which I quote merely as a convenient text to illustrate the matter in hand, that in one establishment a difference is made of nearly or quite nine hundred men, in consequence of the invention or improvement of machinery, which has taken place within a less time than the last 25 years, from the number it would have been necessary to have employed to prosecute the same amount of business had no such progress been made. The same is true, I suppose, to an equal extent, of The Tribune and other journals of large circulation. The same—i. e., the alarming encroachment which machinery is every day making on what has heretofore been performed by human muscles alone—is not peculiar to any one branch of employment. The restless inquiry and invention of the present is rapidly and surely intruding iron muscles, which do not become hungry, or experience the depression of low wages and consequent low fare, into every department of human industry, crowding out and setting adrift thousands of the industrious, to seek new and untried means of subsistence, from which soon again to be driven, by—what many of them have come to look upon as their greatest, most persevering and relentless enemy—machinery.

Whither, I would thoughtfully and anxiously ask, do these facts, which stare us in the face from every quarter, tend? What is their mighty significancy? The unprecedented increase of the most cunningly adapted, durable, and economical machinery—on the one hand—to perform, in great part, the work heretofore done by us—the laborers; and—on the other hand—the sure and certain increase of that most reliable portion of humanity which we represent, and whose only capital is their muscles, and whose hope of bread for themselves and children is in the performance, to a large extent, of that same labor thus snatched from us by the offspring of invention. What wonder that the honest laborer, who knows no cunning but the use of the physical force which God has given him, or the mechanic who plies his trade, should stand aghast, and feel his heart sink within him, as he is forced from his legitimate occupation, to another and still another, and at last finds his employment altogether fitful and uncertain, from the number of his fellows driven to the same condition as himself. His labor is truly “a drug in the market,” and stern necessity is fast putting him, if it has not already, wholly at the mercy of capital. I could not but sadly ponder, as one—while watching the nicely adjusted movements of a cheap engine, which had ejected him and his fellow, in like condition, from the place whence, for years, they had obtained a livelihood for themselves and families—significantly observed to me that, “the best thing that could be done with that thing would be to break it to pieces, and pitch it out of the window.” They saw wood about town now, when they can get it to do, as the machinery, which they have in such successful operation in Chicago and some other cities for that purpose, has not yet been introduced here. Their daughters, too, who have, till within a six month back, had work at $2 50 per week, in the factories, are now out of employ. This, you know, is but one of countless similar illustrations which take place every day in poor families.

H.

We have thus allowed our friend to state his whole case—though he only submitted it that we might comment on its substance—and we now solicit his attention to some thoughts by it suggested.

Why does our friend go back only to the Hand-Press to exhibit the disastrous effects of Machinery on the interests of Labor? The hand-press itself is a labor-saving machine of immense capacity—far more so in its day than the power-press which is now extensively superseding it. It threw wholly out of employment and reduced to absolute destitution thousands upon thousands of skillful, accurate, admirable penmen, who had given the best years of their lives to acquire skill in a profession, or pursuit, which the press almost extirpated. To be at all consistent, “H.” must demand, not the destruction of the power-press only, but of all printing or copying presses whatever.

“Ah! but then there could be no newspapers?”—Nay; that does not follow. Kossuth’s first gazette was not printed, but a carefully prepared abstract of the sayings and doings of the Hungarian Diet, whereof copies were made by scribes for general diffusion. There have been many such instances of unprinted journals.

“Well; there could be no such journals as we now have.” No, nor could there be without the power-press. We could not afford such a paper as The Tribune now is for four times its present price, if we were obliged to print it on hand-presses; in fact, no such paper could be supported at all.

The subsisting truth, then, must be accepted and looked fairly in the face. The mountain will not come to Mahomet; he must go to the mountain. The existence and rapid progress of Machinery is a fact which cannot be set aside; the world will not, cannot go backward: Machinery cannot be destroyed; it cannot even be held where it is, but must move onward to further and vaster triumphs. We may deplore this, but cannot prevent it.”

The perusal of this article would have determined us, had we not been resolved beforehand, to lay before our readers an account of the very remarkable works to which we have before alluded, by the proprietors of which the machinery mentioned in the letter of “the thoughtful laborer” was of course manufactured, as by them it was invented; being no other than the great eight-cylinder, type-revolving, fast-printing press. Similar machines, though varying in the number of cylinders, are employed by the New York Herald and Tribune, the eight-cylinder being used by the Sun, the Philadelphia Ledger, and other journals in the United States, as also by the Parisian La Patrie, the quasi organ of the present Prince President, and, according to present appearances, future Emperor of the French.

These works are in truth one of the most remarkable sights, if not the most worthy of remark, of all that are shown to strangers in New York—and yet to how few are they shown. The changes to which they have already given birth are great enough, even now,

“To overcome us like a summer cloud,”

but the end of those changes is not yet, nor shall be, while we are. What they shall be, we may not even conjecture—perhaps the civilization, the christianizing of the world entire, and the reduction of all tongues and dialects to one universal English language.

To waste no more words, however, in mere speculation, but to come to facts, the history of the origin and progression of these truly wonderful works, of which more anon, is in itself by no means void of interest—even of something of romance.

In the well-known and ill-remembered yellow-fever summer of New York, an Englishman by birth, a carpenter by trade, landed in the city of the plague, a stranger, friendless, sick, and but scantily provided with what has been termed the root of all evil, which one-third of our people, however, regard as the sole object and aim of exertion and existence here and hereafter.

His good fortune, or rather—for we believe not in fortune—his good providence brought him in contact with that most singular of geniuses, Grant Thorburn. With him he boarded, with him struggled through the terrors of the prevailing pest, by him was tenderly nursed, and from his roof entered into business with Smith, the well-known machinist and inventor of the hand-press which still bears his name; nor is it yet superseded by more recent improvements. Their partnership terminated only with the decease of Mr. Smith; from which time, under the sole conduct of Mr. Hoe—for the stranger guest of Mr. Thorburn was no other than the father of the energetic, inventive and enterprising gentlemen, whose works we are about to describe—the business became permanently established, and yearly advanced in popularity and reputation, which constitute profits.

Still, greatly as he improved upon what had been before, at his death in 1834, the average annual sales of the concern did not exceed 50,000 dollars; they never now fall short of 400,000; and often amount to half a million. Such are, and will ever be, the consequences of energy, industry, probity and sobriety, joined to an earnest and sincere application of that talent, which each one of us in some sort possesses, to its true and legitimate increase and improvement—in other words, to quote a book so much out of fashion—find the more the pity!—in these piping times of progress, as the old church catechism, a quiet resolve to “do our duty in that state of life to which it hath pleased God to call us.”

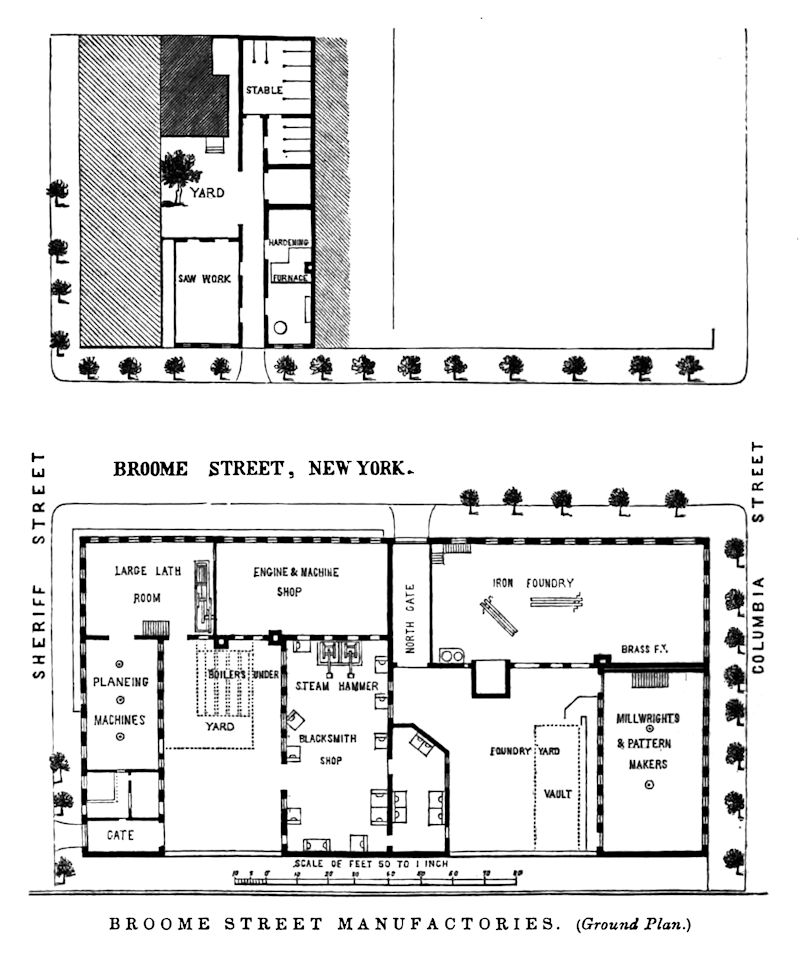

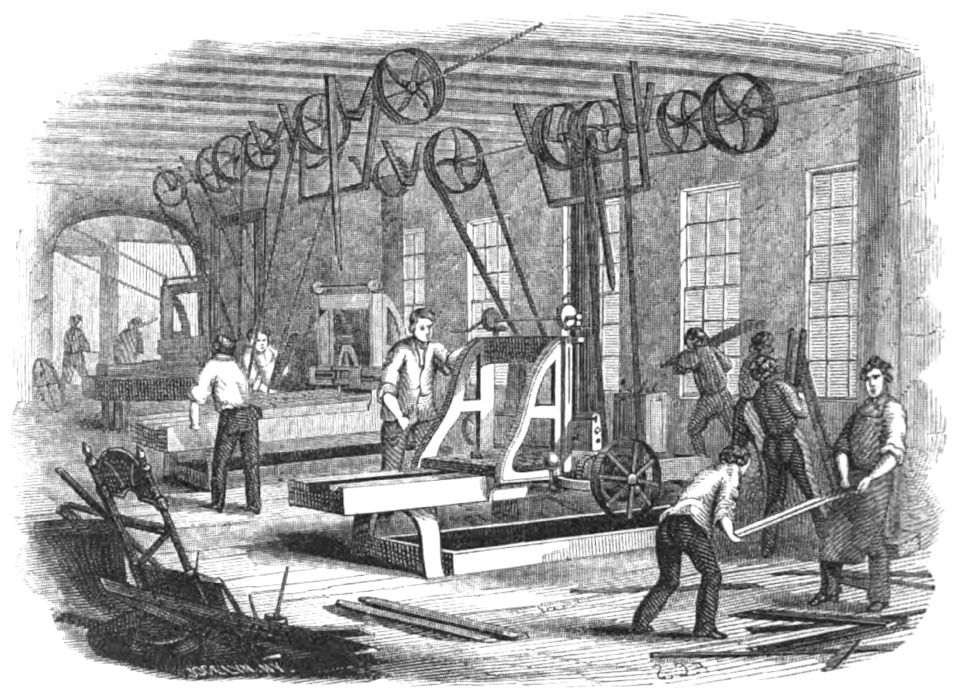

Shortly after the death of Mr. Hoe, sen., his sons and successors, finding the then premises insufficient, moved to the ground now occupied by their great manufactories, occupying a hollow block four stories in height, of two hundred feet front on Broome street, by one hundred in depth on Sheriff and Columbia streets, as also a second lot on the other side of Broome street, containing their saw works, hardening furnaces, stables, and other necessary buildings. In these works, a bird’s eye view of which is pre-fixed to this paper, and the ground plan of which we here present, the Messrs. Hoe continually employ three hundred men, some of them persons of great ability as draughtsmen, pattern-makers, mechanicians, and the like—men literally of every nation, as nearly as may be, under the sun; among whom are comprised several Armenians, said to be persons of great intelligence and excellent deportment.

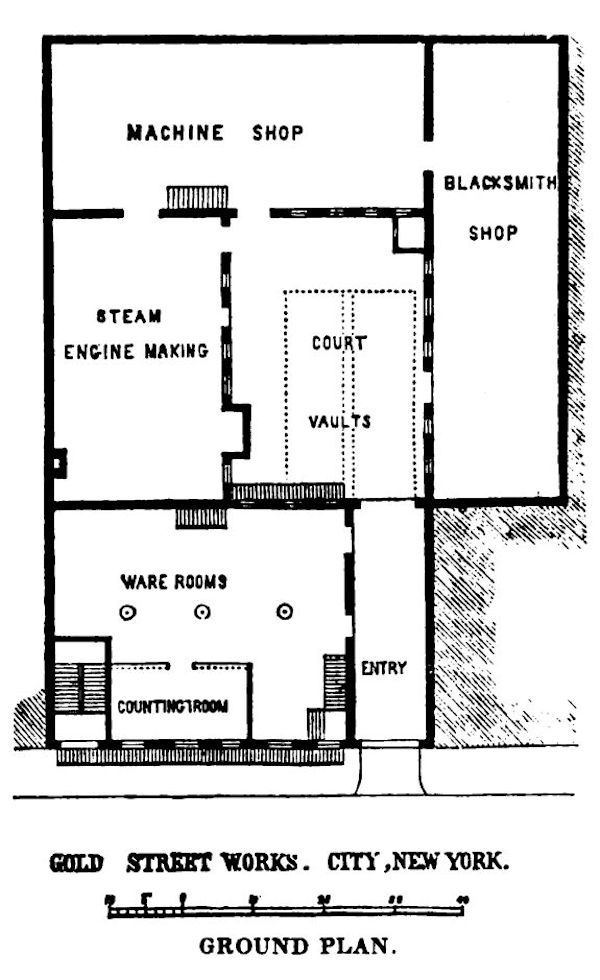

Besides this, their principal factory, they have another large and well built establishment, containing ware-rooms, counting-house, blacksmith’s shop, machine shop, and steam-engine room, in Gold street, nearly adjoining Fulton. This, though in fact headquarters, we shall pass over for the time being, premising only—in order to show the perfect method and system of time and labor-saving with which every thing belonging to this firm is conducted—that they have at their own expense, and for their own private use, erected an electric telegraph, carried by the permission of the proprietors over the roofs of houses, from the counting-room to the up-town factories, by which the smallest message or order is conveyed, and answered almost instantaneously. Nor are the proprietors dissatisfied with the result, having found by experience that the great original expense was very speedily compensated by the gain of time, and yet more of precision which it introduced.

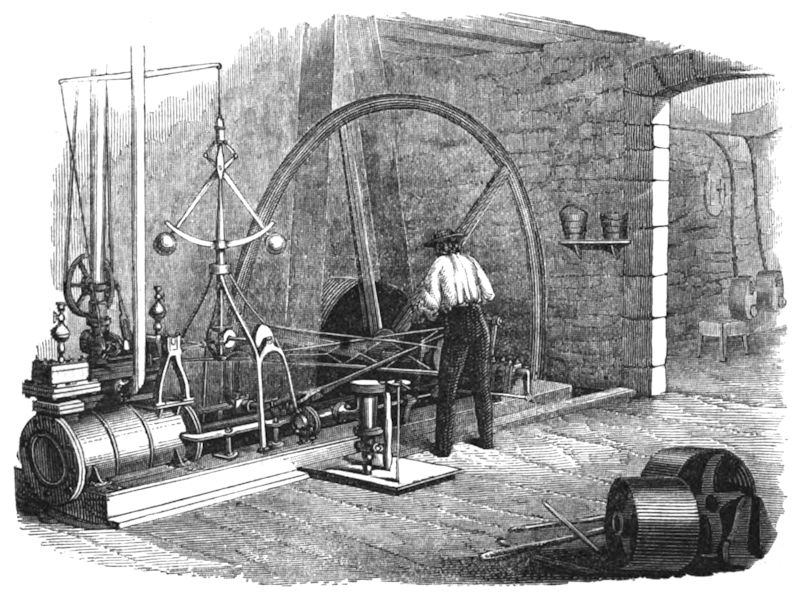

Returning up-town, therefore, we will descend into the vault under the first yard, in which we shall find the moving puissance of all the vast machinery of hammers, planes, lathes, drills, grindstones, tools and devices, almost without name or number, which are constantly laboring with their iron nerves, noiseless, tireless, indefatigable, through every story of the great building—in the shape of the boilers and steam-engine, which, beside furnishing all the motive power, supply every part of the building, by a very ingenious application, with a constant stream of evenly tempered, pure, heated air, at the same time maintaining a thorough ventilation, and all without the slightest danger of fire.

The spent steam is brought into a series of coiled pipes within a trunk, through which a continual stream of pure external air flows without intermission, and is carried by wooden tubes through every story and room of the building; as is likewise an ample provision of Croton water, as well a provision against fire, as for the cleanliness and comfort of the men.

Of the engine there is nothing very special to be observed, as it is of the old construction, and, though perfectly efficient, not now to be imitated or adopted. It is a horizontal high pressure engine of about forty horse power, under the head of steam usually employed, though capable of exerting considerably more force, if called upon. There has been recently attached to it a singularly ingenious little machine, in the shape of a hydraulic regulator, of which great expectations are entertained, and which, in the very short time it has been tested, works to admiration, one week only having elapsed since its application. To attempt to describe this, or in fact any other complicated machine, in an illustrative article such as this pretends only to be, were an absurdity; for the operations of the simplest engines can be rendered thoroughly comprehensible, only—if at all—by thorough diagrams with numerical references, and then comprehensible only to scientific readers, conversant at least with the principles and working of the motive power, and the forces to be exerted by it.

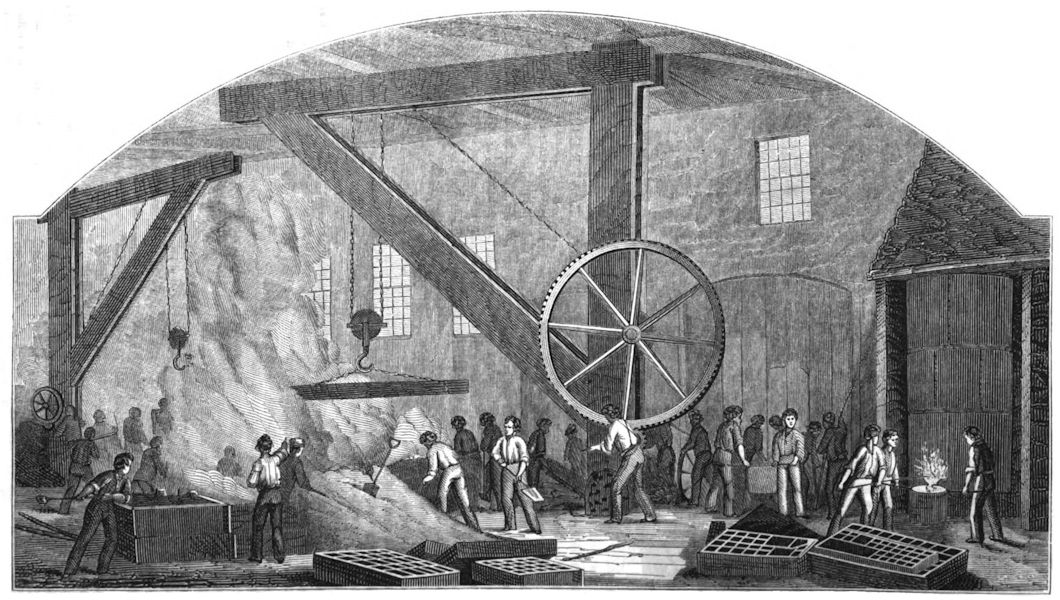

Ascending from the subterranean regions, which are, by the way, so constructed under an open and little occupied court-yard that even in case of any untoward accident the least possible damage would ensue, and certainly no upheaval of whole edifices, as by the explosion of a powder magazine, would be the consequence, we arrive next in the order of production at the great foundery, occupying nearly one half of the ground floor on the Broome street front.

OLD STEAM-ENGINE, BROOME STREET.

Of this, although it furnishes the rude material, the first degree we mean from the actual raw metal for the whole establishment, the saw manufactory alone excepted, there is little to be noted worthy of particular attention by those who are familiar with the operation of furnaces, founderies and casting on a large scale, as in fact there is nothing in it unusual or novel, unless it be what struck us as both novel and unusual, the general absence of noise, confusion, din and turmoil, not to mention ill sounds, ill savors, and oppressive heat, which seems to pervade the whole establishment. This, ministering as it does largely to the comfort and well-being of all concerned, detracts somewhat, it must be admitted from the picturesque effect of the scenery, and its adjuncts. Even the neatness and cleanliness of the orderly and well conducted moving about each his own business noiselessly, and obeying a sign or the wafture of a hand, diminished the effect which we almost expect to feel in an iron foundery, a furnace, or a machine shop.

We well remember the impression left on our mind years ago by a visit to some gigantic iron works in Sheffield, an impression which made itself felt for many a month in strange fantastic dreams and painful nightmares—such influence, not on the imagination only but on the nerves, had the dense murky gloom of the dim vaults, suddenly kindled, as by magic, into a fierce incandescent glare by the lava-like torrents of molten iron, the volumes of black smoke, the stifling heat of the oppressed and exhausted atmosphere, and then the roar of unseen waters, suggestive of those subterranean streams of Hades, Acheron and Cocytus, the whirr and hurtling of unnumbered wheels, the terrible and deafening clang of the huge trip-hammers, literally making the solid earth jar and tremble; and last and most appropriate to the scene, the swarthy, grim-visaged workmen, fit representatives of Vulcan and his Cyclops, now glancing into lurid light, now vanishing into darkness, as the fitful flashes rose and fell. Of a verity there can be no much more appropriate representation of Pandemonium than an old-fashioned English iron works on a large scale.

But there is no room for marveling or romancing after this fashion in the machine works of Messrs. Hoe & Co., for all the rooms are well aired, well lighted, and none the less adapted to their purpose for being suitable to the accommodation of men who neither are slaves, nor in anywise resemble devils.

GREAT FOUNDERY.

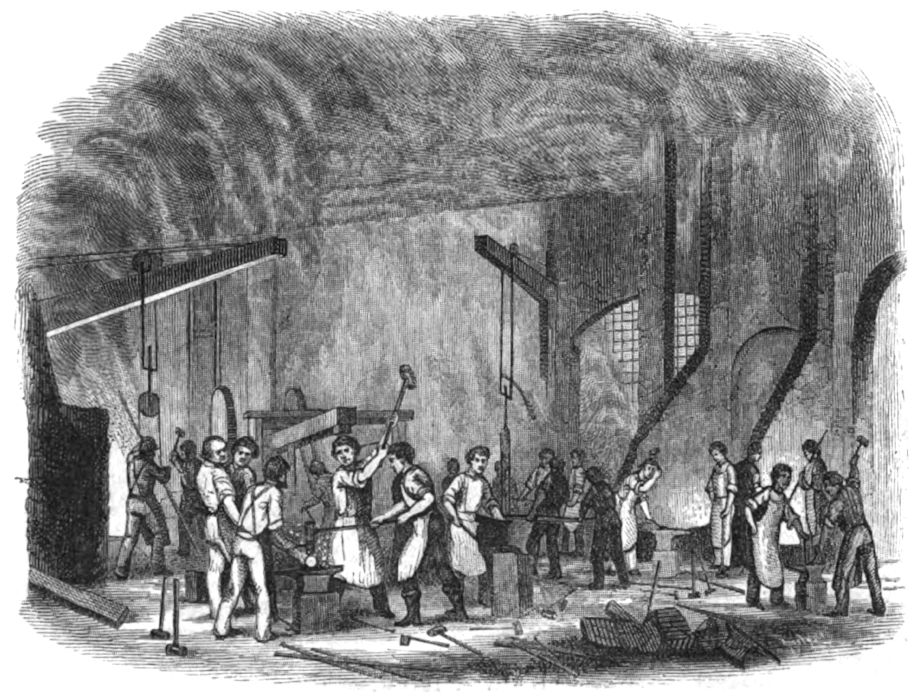

From the foundery we proceed, across the open yard, to the smithy, a large, lofty, well proportioned apartment, containing two enormous steam-hammers, the speed and consequent impetus of which can be modulated by a very easy application of manual force, at the pleasure of the operator, so that they can be made either to rise and fall as slowly as the maces of Gog and Magog on the great bell of Saint Dunstan’s, or to impinge upon whatever is objected to their descent with a velocity which almost mocks the eye. In this apartment and its adjunct forge there are no less than eighteen stithies, the bellows of all which are worked by the ubiquitous power of the engine, with anvils of all manners and sizes in due proportion, and sturdy operatives plying them with tranquil and regulated industry, worth five times the amount of human force exerted unequally and impulsively, by fits and starts. These men, for the most part, and, in fact, always when not called off by some casual and unexpected pressure of business in some one department, are kept constantly employed at that peculiar species of work with which each is the most familiar, such method and system in the subdivision of labor being found to insure not only the greatest excellence, but the greatest celerity of workmanship.

SMITHY.

In this shop all such portions of the engines, presses, large and small, printing and inking machines, and of the machinery by the agency of which the above machines themselves are created, as are composed of wrought metal, are forged, welded, made new from the commencement, or repaired in case of damage. For it is worthy of remark that, although many of the labor-saving machines and tools are of English make—not a few by the celebrated Whitworth, said to be the first tool-maker in the world—there is not one that cannot, on emergency, be made, mended, or altered, within the precincts of the establishment; while many of the most admirable contrivances are patents and inventions peculiar to this country and this firm.

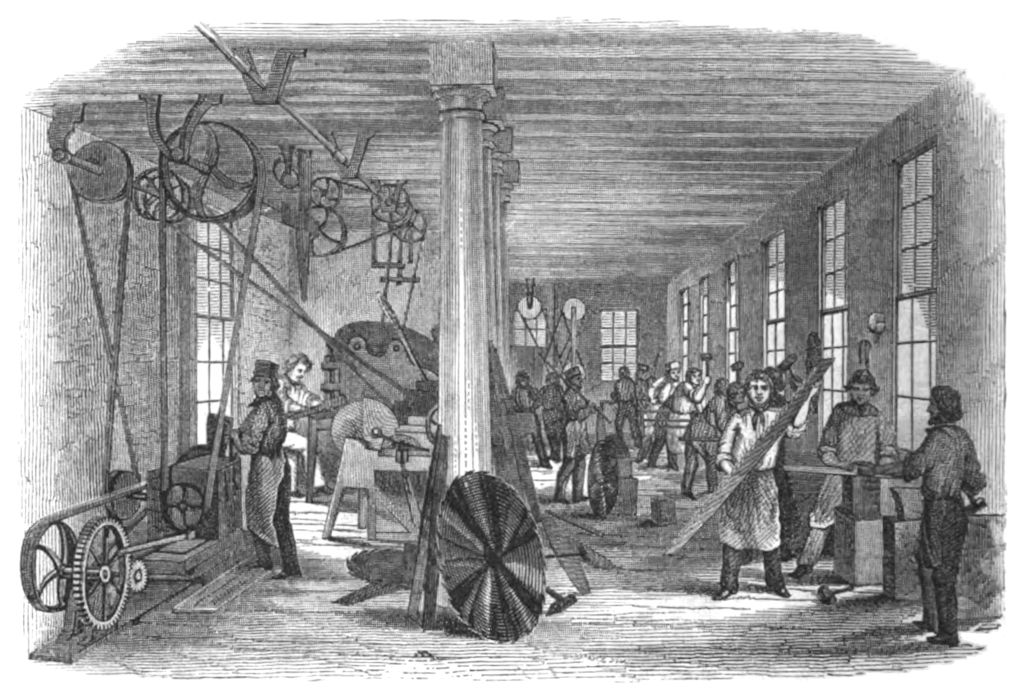

Immediately adjoining the smithy, is the engine and machine shop, and on the same floor the large lathe-room containing four enormous surface lathes and two turning lathes, for drilling, boring, turning, and finishing both circular and horizontal surfaces.

From this point, we shall proceed to the saw works, preferring to take each separate department of work by itself, from the commencement to the end, rather than to adhere to the precise order and position of the several rooms, as situated in the building.

The first room devoted to this branch of manufacture, which is a very considerable and important item in the business of Messrs. Hoe & Co., the annual sales amounting to not less than 140,000 dollars, in circular saws, mill-saws, pit-saws, and crosscut-saws, for all parts of the country, is known as the saw shop.

Herein is performed the business of smithing, teething, and blocking the great saws; hundreds of thousands of which are at work, driven by water or by steam-power in every portion of the boundless territories of the United States, to which the enterprising foot and adventurous axe of the white settler has found access—clearing with their restless and indomitable teeth the solid and tenacious fibres of the gnarled live-oaks in the pestilent swamps of Florida, and the dank “regions far away, by Pascagoula’s sunny bay,” into the crooked knees of mighty vessels, that shall set at naught the howling billows of the wild Atlantic, and the blasts of the mad storm-wind, Euroclydon, riving into planks and beams and timbers, that shall build up the palaces of commerce, and the happy homes of our lordly cities, the white and penetrable flesh of “those captive kings so straight and tall, those lordly pines, which fell long ago in the deer-haunted forests of Maine, when deep upon mountain and plain lay the snow.”

The machinery by which these various processes are accomplished is exceedingly fine and worthy of notice, and vastly superior to that used in England; in the dock-yards of which country the circular saws were first brought into service, if we do not err; especially that for cutting the teeth, which, worked by steam-power, does its duty with great rapidity and incomparable precision.

SAW SHOP.

This operation is performed by the vertical descent of a ponderous arm of iron, terminating in a cutter of the form of the notch to be made in the yet soft and smooth edge of the circular plate, which is made by the same power to revolve horizontally upon an axis placed at such distance from the impinging weight as the depth of the notch to be cut requires, and traversing at a rate so timed in unison with the descent of the cutters as to render the series of teeth perfectly continuous and equal; each blow of the cutter forming the interval between two teeth, and each full revolution of the plate completing a circular-saw. In the same way is effected the teething of the straight saws, the motion being a direct sliding action in a forward line, instead of a rotatory movement.

In the English saw works, owing to the influence of trade-unions, operative-unions, and the like, the application of steam-power to this machinery is prohibited, and the employer is restricted to the use of hand labor—the cutter being jerked down by man power, and the edge of the plate to be cut being subjected to the striker by hand, the formation of the teeth not being regulated by any absolute scale, but being executed by the calculation or guess-work of the artisan, and, of course, varying in accuracy, depth and precision of cutting according to the skillfulness or unskillfulness of the individual operator.

To the absence of these ingenious combinations, injurious alike to the true interest of operators and employers, the superiority in many respects of American to English machinery is in some degree due, and not less to the over stringency of the patent laws of Great Britain, which often prevent the application of really leading and most material improvements, of a radical nature, to principles secured for the benefit of the inventor.

We may here observe that the use of circular saws is very greatly on the increase in this country, more especially in the western portion of it. In the east, for some inexplicable reason, this admirable instrument is far less generally used; and the writer of this article, several years ago, when on a visit to the timber districts of Maine, on expressing his surprise at the non-adoption of this most excellent and labor-saving tool, could learn no adequate cause for the prejudice existing against it, unless it were some crude and absurd ideas concerning its vibration and consequent irregularity of cutting—objections not founded on facts, nor confirmed by experience.

From the saw shop the circular plates, now teethed and in the incipient stage of what Willis would call sawdom, are removed across Broome Street into the other building, and introduced to the saw hardening room, where they are converted into highly tempered steel.

SAW HARDENING ROOM.

This process is effected by heating the metal in charcoal furnaces to a white incandescent glow, and then cooling it by immersion in baths of oil and other drugs, the combination of which is, we believe, a secret. This done, the saws are ready for grinding which is effected in a special apartment of the main building—the flat, straight saws by hand application to a series of powerful grindstones, driven at a regular speed by gearings worked from the engine, and the circular saws by a very curious and effective patent machine, peculiar to this establishment, and invented by Mr. Hoe himself.

The old method of grinding circular saws, and that still practiced in all other works of this nature, is the application of them horizontally to the great vertically-moving grindstones by the hand; and, when it is considered that these great steel plates run up to six feet diameter and eighteen of circumference, and that they consequently entirely conceal the grindstone from the eyes of the operator who applies them, it will be evident that the process is mere guess-work, and that no certainty can be attained in regulating the thickness of the blades—in a word, that nothing was effected beyond the superficial brightening and abstersion of the surface.

GRINDING ROOM.

The new machine causes the great circular plate to revolve vertically on its access, while a “pad” to which is applied some sharp, detergent mineral-powder, is moved forcibly over its surface with a triple action.

In the first place, the pad itself is made to revolve with great velocity against the circular plane, in a direction perpendicular to its line of motion. In the second place, it is driven forward against it horizontally with a force increasing or diminishing, in proportion as it may be desirable to render the saw-blades thicker or thinner in any particular part of the circumference. It is usual to leave them thicker at the centre, and to grind them away gradually toward the circumference. Thirdly and lastly, the pad, while it revolves vertically in a direction perpendicular to the revolving plane, and is forced horizontally against it, is also driven laterally to and fro across its surface; and the result is a degree of equability, or graduation of thickness, as well as of superficial polish, scarcely otherwise attainable. This machine is one of the special wonders and ornaments of the establishment.

It will not be amiss here to add, that with the improvements of their manufacture the demand for circular saws is continually on the increase; and that a single house is in the habit of taking regularly six of these powerful tools weekly from the Messrs. Hoes’ establishment.

IRON PLANING, AND CUTTING ENGINE ROOMS.

Returning hence to the leading and principal feature of these works, the manufacture, namely, of all the various instruments and appliances for the art imprimatorial, we are next ushered into the iron planing and cutting engine rooms, for the cutting the cogs of engine wheels, and finishing the surfaces of whatever portions of the machinery must be brought to a smooth and polished face. This is done by the propulsion of the pieces of metal so to be planed, in a horizontal and longitudinal direction against cutting edges, which again move horizontally across the moving planes, and are pressed downward on them vertically, so as to bring the planing to the requisite depth. The abraded portions are thrown off from the surface, of cast iron in a sort of scaly dust, from wrought iron in long, curled shavings, and the planes can be wrought up to almost any desirable degree of finish and smoothness.

The cutting engine for the formation of cogged wheels, bears some relation to that for the teething of saws, the cutter impinging downward, with an action in some degree intermediate between that of sawing and filing, upon the exterior circumference of the circular wheels, which revolve on their axis under them in a rotation so regulated to the fall of the striker as to insure absolute equality in the width of the cogs or projections.

[Conclusion in our next

———

W. H. HOSMER.

———

Drifting on the darkened waters

Are Earth’s dying sons and daughters,

And, like ships that meet each other,

Brother gives a hail to brother:

Brief the pleasure of that meeting,

And forgotten oft the greeting.

Could I think that other faces

Would of me blot out all traces.

Though I cannot be thy lover,

Clouds my path would gather over;

From remembrance, then, endeavor

Not to blot me out forever.

Fare thee well! must now be spoken,

And another tie be broken;

Though the hour hath come to sever,

Lady! I’ll forget thee never,

But thy warmth of soul remember

Till extinct life’s wasting ember.

———

BY MISS S. A. STUART.

———

Have you ever been, dear reader, in that sweet little village of A——, in Virginia? Well, if you have not, you certainly have yet to see, the most pleasant little Eden of this earth; where they have the purest air, the most beautiful sunsets, and the bluest skies imaginable—Italy not excepted—so I think. There lived my heroine; and such a heroine, at the time I have chosen to introduce her to you.

It was close upon sundown, on a lovely spring day, when a strikingly handsome, distingué looking young man, alighted from his buggy, at the residence of Mrs. Morton, in the above mentioned village. Charles Lennard—the young man spoken of—had been received as a boarder, for a few months, into Mrs. Morton’s quiet family, as his health was too delicate to allow him to trust to the precarious and uncertain kindness shown by the landladies, in general, of thriving village inns. Some moneyed affair had called him to A., and here he had arrived on this lovely spring evening; and the skies wore their rosiest blush to greet his coming.

“By all that’s pretty! ’tis a little Paradise,” was his muttered notice, as he passed through the flower-garden, whose clinging vines, creeping o’er the lattice supports, veiled the little bird-nest of white that peeped out amid the rich green foliage, varied in color by a thousand tinted flowers. “I hope Mrs. Morton has given me a room overlooking the garden; ’twill be delightful to read here whilst these perfumes are floating around one.”

The door was wide open, and a quiet, blue-eyed lady sat sewing in the back part of the wide hall, who raised her soft, kind eyes inquiringly to his face, as his shadow darkened the doorway.

“Mrs. Morton, I presume?” said he, as she approached him. “I am Mr. Lennard, whom you were so kind as to admit—”

“I am happy to see you, Mr. Lennard,” interrupted she, hospitably extending her hand to bid him welcome. “Walk into this room, sir. We are very plain folks here, Mr. Lennard—but you must endeavor to make yourself at home. Alec”—to a boy who entered—“take this gentleman’s buggy and horse and put them up.”

Turning to her guest, she conducted him into her cosy parlor, now filled with the golden moats of the glimmering sunbeams, that quivered through the foliage that draped the windows; whilst the atmosphere of the room itself breathed sweets unnumbered. They chatted of the weather, of his journey, of the village, etc., till Mrs. Morton, remembering her duty as hostess, begged her guest to excuse her, whilst she hurried off, “on hospitable thoughts intent.” Charles threw himself dreamily and indolently into the old-fashioned arm-chair, which stood invitingly in the shadow of the window.

A young, glad voice, a light, bounding step, broke on his reverie; and, as he glanced toward the door, whence the sound came—bang! almost in his face, fell a carpet-bag, half filled with books, and then an exclamation of surprise from a young fairy, who just stopped long enough to make him doubt whether she was mortal or angel—and then again bounded off like a young, startled fawn. ’Tis our heroine—Edith Morton—released from her duties at the village academy, wild with repressed play and mischief, who has done him this favor! She returned ere long with her mother, reluctant and blushing, to sanction by her presence the apology uttered for her.

“You will excuse Edith, Mr. Lennard, I hope, for her carelessness. She tells me that the light dazzled her eyes so much, that she was not aware of your presence; she has been in the habit of throwing her books into this room—the arm-chair which you now occupy being her morning study. Edith, speak to Mr. Lennard, and tell him how sorry you are for your rude greeting.”

“Do not trouble yourself, Miss Edith. Your apology is all-sufficient, my dear madam; I, too, must apologize, for having unknowingly taken possession of her study, which is indeed inviting. You must look upon me as belonging to the family, and act without restraint; for I assure you, the thought would be far from pleasant did I think I interfered in the slightest degree with your settled habits. Miss Edith, you did right to send me such a reminder at the outset, and I assure you I will be more careful in future.”

A gleam of light, like a lurking smile, might be detected in the arch eyes of Edith, as she received this apology from Lennard. And he thought, without, however, giving utterance to it, “What a bewitching little fairy.” Edith Morton, though she had not reached the age of sixteen, was an exquisite specimen of girlish beauty, as impossible to resist as to describe. Her charm did not lie in her regular features, golden ringlets, or beautifully moulded and sylph-like form; though each and every one of these adjuncts to female loveliness she possessed in a preëminent degree, but her expression—arch, spirituelle! ’Tis useless to endeavor to convey an idea of the impression she must have made on you with those divine eyes, lit up in their blue depths, with the sunlight of her merry heart, or the piquant expression of her rosy mouth, whose deeply-tinted portals, when wreathed with one of her infectious, heart-beaming smiles, disclosing white, even, little pearls, as Jonathan Slick says, shining like a mouthful of “chewed cocoa-nut.” Shy before strangers, from her secluded life, she was the life of the circle in which she was known, and loved. Full of mischief, and the ringleader in every school-girl frolick, her ringing, mellow laugh, often echoed through the play-ground of the village school, or singing merrily, as she was borne aloft in the swing, or dancing like a fairy on the green. Many were the boy-lovers who bowed at her shrine, with their simple, heartfull offerings; but none felt themselves signally favored—for, young as she was, she seemed to have erected a standard of excellence in her own mind, and her ideal hero was alone the loved.

Charles Lennard soon made himself perfectly at home with Mrs. Morton and Edith; and his first evening with them passed pleasantly enough to him. He felt himself much attracted by her exquisite beauty; and, as their acquaintanceship progressed, when her mother left the room on household duties, he was much amused by her piquant and original replies to his questions. He found her, too, not uneducated, and, young as she was, a reader and lover of many of his own favorite poets. At the close of the evening, Mrs. Morton requested Edith to sing, and, with a startled look toward Lennard, she left her seat to get the guitar from its case.

“Mother, ’tis dreadfully out of tune,” in a tone of entreaty.

“Well, Edith, that is soon remedied by your will. So, my daughter, do not make any further excuse, but sing to me as usual. Mr. Lennard will excuse the faults when he sees how willing you are to oblige.”

Edith bent low over the instrument as she tuned it, and looking up into her mother’s face, as if her shyness was not yet overcome, waited for that mother to tell her to commence.

“Are you ready? well, play then my favorite.”

And though the young voice was trembling, and not well drilled, yet she warbled her “wood notes wild” with marvelous sweetness; and she blushed with pleasure at Lennard’s seeming enjoyment of her simple music; and her “good-night” to him was as charming as to an acquaintance of longer date, accompanied as it was by such a sweet smile.

“What a nice little wife she will make for some one, in days to come,” thought he, as standing by the window overlooking the garden, he found himself musing on the singularly graceful and beautiful child whom he had left.

Charles Lennard had no idea at that moment of ever loving Edith Morton. She was too young, too unformed in mind to comprehend him, and to follow, as a kindred spirit, through the abstruse and almost transcendental range of thought, in which he often loved to engage. Delicate in health as in organization, he contented himself for the present to be a spectator in the world rather than actor, and in his day-dreams now weaving bright pictures for the future—pictures in which he was to play a most conspicuous part. We will not say but that a vision also of dazzling eyes, dancing ringlets, and woman’s light form, constituted a part of the reveries of the listless and dreamy student.

The neat breakfast-parlor of Mrs. Morton looked as fresh as herself as Charles descended, the next morning, to that meal. And there sat Edith in the old, deeply cushioned chair, book in hand, conning her morning task most zealously, but ever and anon pushing her little foot out to a kitten on the floor, as playful as herself, who, with its eyes distended to a perfect circle, sat watching it most sagely, and then jumping quickly to catch it, in retreat—so that the young girl would laugh most merrily, and then again resume her book. Charles watched her from the hall ere he entered, for on his entrance she drew herself up most demurely, and cut the kitten’s acquaintance instanter.

“May I assist you with your map-questions, Miss Edith?”

“No, I thank you. I have finished studying them. Mother always insists that if I rise early I will learn twice as fast, and also be prepared to say them when the bell rings.”

“I know,” said Mrs. Morton, “she will be obliged to stop for play every now and then. Yes, truly, Edith, you are a sad idler.”

“Ah, mother! but you should only see me in school. Here there is so much to take up my attention. I mean I am obliged to kiss you, to tend the flowers, and—and play with pussy;” and here, forgetting Mr. Lennard, she caught up her little pet, and began smoothing its soft fur with her white hand.

“For shame, Edith; will you always be a child? Come, Mr. Lennard, breakfast is ready.”

——

The holydays had come, and Edith was at home for the summer. How pleasant were her anticipations of her joyous freedom from dull books and the restraint of school routine for months to come. The next year she was to become a boarder in a fashionable school in Philadelphia, and her mother decided that the intervening time should be spent with her needle, in preparation for that event. Yes; how delightful! so Edith thought, to sit in that sociable room sewing, where the air was redolent with perfume, and the sunshine stole so coyly in through the vine-draped windows, making shimmering and fantastic figures on the highly polished and waxed floor of that peculiarly summer-room, as the sweet south wind waved them to and fro. Oh! for her, with her young heart of hope, the summer air was so delightful when it came through that window, where she loved to sit gazing dreamily of a lucid, still morning, coming, too, laden with sweets stolen from the dewy flowers; and then a glance at those fleecy, shifting clouds in the blue sky—why ’twas better to her than the fairy scenes of a magic lantern or gorgeous theatric spectacle.

And there, too, sat Lennard, quite domesticated by this time. Notwithstanding he thought it would be so very pleasant to study in his room overlooking the garden, he as regularly walked into the parlor every morning with his book, until quite a small library began to collect. Occasionally he would read favorite passages from them to Edith, as she sat sewing, and, child as she was, looking into her eyes for sympathy in his enthusiasm. But far oftener would he be wandering into the garden with her, selecting flowers; sometimes holding the tangled skein, and that, too, so intently, that often his dark brown locks were mingled with her golden ones. The peals of merry laughter! “How much amused they are,” repeated to herself Mrs. Morton; but on entering and inquiring what caused their merriment, ’twas too little to frame into an answer. Any thing—nothing—created a laugh or smile with them, they were so happy—so very happy. Nor was music’s soft strains neglected to gild the passing hours. There, in the witching, summer twilight, still, soundless, save the low melody gushing from Edith’s lips, as she sung to her simple accompaniment on the guitar, and with the fuller, deeper music of Charles’ voice, they sat wrapt in their happiness, unconscious—(at least one of them)—of the feelings rife within their hearts of what heightened their enjoyment.

Edith was unconscious. She was fully aware, it is true, that life was gaining every day fresh charms. To her eye the blue vault had never looked “so deeply, darkly, so intensely blue.” The birds had surely never sung so sweetly, nor the very flowers borne so bright a hue; and yet, to all appearance, as time wore on, she was not so gleeful nor so wildly frolicksome as usual. No longer would her voice be detected in the ringing laugh, but smiles were rippling and dimpling o’er her face, in her quiet heart happiness. Yes, in her heart of hearts, what a spring of deep joy was bubbling up almost to overflowing, quietly unknown to others, but thrillingly alive to herself; so intense at times, that those sweet eyes would glisten with unshed tears at the very thought that death might come and bear her off from so bright, so joyous a world, where life itself was bliss. Her unusual quietness—her fitful and radiant blushes—the soul-full glances—the manner that was stealing so softly, yet so perceptibly o’er the young girl, toning down, as it were, her high spirits, was noticed by her mother; but her conclusion was simply “that Edith is growing into a woman, and will not be such a hoyden as I dreaded.”

Edith was unconscious! But not so the dreamy student. He, though albeit as much a child in the actual business of life as Edith, was much better skilled in the heart’s lore. He had seen the flash of joy which brightened her eye—had watched the cheek kindling at his approach, and the smile of womanly sweetness, wreathing her exquisite lip at his words or glance of approval.

He had become, with Mrs. Morton’s acquiescence—having nothing to occupy him, he had informed her—Edith’s instructor in French; and he saw how any thing but wearisome was the daily task; and, in the solitude of his chamber, stole welcomely into his mind the thought that he had taught her practically to conjugate through all its inflections the verb aimer. Mrs. Morton very often complained to Edith that she neglected her sewing for her book, her guitar, her evening rambles—but she was the widow’s only child, her bright gleam of sunshine; her idleness was overlooked, and she was allowed to have her own will, and continued to be the constant companion of Charles Lennard.

It was a moonlight evening in the latter end of October. Edith, Mrs. Morton, an elderly lady-visitor, and Charles, rambled about a quarter of a mile from the village, to a place called the Coolspring, to enjoy one of the nights which October had stolen from summer, and, delighted with the beauty of the lonely, sequestered spot, where the moonbeams rested so brightly and reflectingly on the rustic spring—now bubbling up from the rich green, velvetty sward—now hiding in the thick grass, and anon revealing itself by its glitter—that the old ladies seated themselves on the rude bench for a cozy chat of “auld lang syne,” and “when we were girls, you remember.” Charles and Edith were standing some distance from them, watching “the silver tops of moon-touched trees.” Very quietly had they thus stood drinking in the quiet loveliness of this enchanting scene, and no sound was heard but the mellowed hum of the village, borne but echoingly to their ear, and the rustling of the foliage, as it was kissed by the night-breeze.

“Edith!” and his voice was low, “is this not beautiful. I swear that I could be here content forever, were you but with me. But would you, dear Edith?”

A quick, eager, flashing gaze, as her eye was for the instant raised to his own, was her answer. ’Twas the look of some wondering and awakened child, as the consciousness of her feelings toward Charles stole upon her beautifully, though strangely; and something of gladness was in the melody of the child-like, trusting, and low-toned voice with which she breathed, rather than uttered, “Oh, yes!”

“Dearest Edith!” was all that Charles said for some moments, as he held the little trembling hand in his own, then placing it within his arm, he drew her to the shade of a large tree, under whose foliage lay the fallen trunk of an oak, upon which they sat.

“Dearest Edith,” he again said, as she, with downcast eyes, blushing even in that dim light at his impassioned tones and loving words, “promise me that you will love me and think fondly of me for the next two years I am doomed to wander, and then, when I have fulfilled my guardian’s wishes, that you will be my wife? My own Edith, say?”

You could almost hear the beating of that young heart, as she thus sat listening at his side, shrinking and trembling from the arm thrown around her waist, and turning in timid modesty from the eyes looking so ardently loving into the glistening depths of her own, striving to hide her feelings from those fondly searching eyes. And Charles—with the lightning’s rapidity came into his mind the words of the poet:

“She loves me much, because she hides it.

Love teaches cunning even to innocence;

And when he gets possession, his first work

Is to dig deep within the heart, and there

Lie hid, and like a miser, in the dark

To feast alone.”

“You will forget me long ere you come back,” was her answer to his reiterated appeal. “Why need I, then, to answer?” And there was a tear almost in the liquid voice, as a vision of what her life would be, should such prove the truth, arose before her mind’s eye.

“Forget you! Do you judge me from yourself, Edith, when you say that?”

“Oh, no!” was the impulsive reply of the young maiden, as she hastily and unthoughtedly now answered him. “Oh, no indeed! But you, Mr. Lennard, are going to Europe; and you will see there so many, very many things and persons to make you forget me—a school-girl—an ignorant child. I was ashamed of myself before you, to think I knew so little—so very little, and you—why you will blush for my ignorance, and then—how could you love me?”

How sweet were those tones, so full of heart-music that he, luxuriating in them, hesitated to answer, that he might catch even their echo; but at length came his reply.

“How could I love you! Rather ask, how can—how could I help it. You are to me, Edith, more perfect than any human being I ever dreamed of or imagined; so lovely, darling, that when you burst on me first, in your young, pure loveliness, I was almost in doubt if you, indeed, belonged to our dull earth. How could I love you!”

“What a simple question; yet, how deep in its very simplicity and artlessness. Yes, Edith, I almost ask myself the same question—how I could dare to love one so like an angel. I will not suffer myself to search into my right—lest I say with truth,

‘ ’Twere as well to love some bright particular star

And think to wed it.’

But, promise that you will love me—that you will think ever of me; and that when I return you will be my wife?”

“You must ask mother, Ch—Mr. Lennard I mean—Indeed, indeed I cannot answer you for—do not laugh when I tell you—I am almost frightened when you ask me such a question; though”—and here the young head, with its clustering, silken ringlets, bent low as she whispered—“though I do love you now better than any one in the world. But, let us go to mother, now, Mr. Lennard,” she quickly added, startled as it were, by her own confession; and, springing lightly from him, as he attempted still to detain her with his loving words, and almost nestling down by her mother’s side, like a truant dove returned, and yet, her heart beating with the fullness of joy at the sweet knowledge she had thus gained—her eye lit up with the lore conned from the new page of the book in her life which she had then learnt. And Charles stood by her, even more eloquent in his silence than when he wooed her beneath the shadowy, old tree.

“But they were young; oh! what without our youth

Would love be? What would youth be, without love?

Youth lends it joy and sweetness—vigor—truth,

Heart, soul, and all that seems as from above.”

——

Events mark time more than years, and this truth, so much known, serves me to tell the change wrought in Edith. A child in years, the beautiful fable of Psyche was realized; and the next morning found her soul awakened, and from her quiet, subdued manner, no longer the child but the woman—ay, and with a woman’s loving and devoted heart. Mrs. Morton had been informed—much to her surprise, of his proposal to her daughter—by Charles, and though prepossessed in his favor, yet she demurred giving her consent to their engagement on account of Edith’s extreme youth. Charles told her of his isolated condition—his fortune; and she at last, won by his earnest entreaties, and the bashful, asking look from Edith—whom she chanced to see whilst hesitating—consented to their correspondence and conditional engagement. And, now we must hurry over the subsequent time which intervened before Lennard’s departure, nor do I design to inflict the pangs of parting on any save the lovers themselves.

January found Edith at her new school, and her days glided on tranquilly and hopefully. She was assiduous at her studies, music, etc.; determined, in the depths of her loving yet ambitious little heart, to render herself worthy of her future husband.

Charles, carrying letters of introduction to persons of some consideration, and having good credit at his bankers, soon found himself admitted into circles of the élite in England, France and Italy. But every where did he carry about with him his vivid remembrance of Edith the young and the loving. Unlike most heroes, he met with no stirring adventures—no “accidents by flood or field”—no titled dames sued for his love. He traversed England—knew London and its lions—admired its gems; dwelt long enough in Paris to speak intelligently; sailed down the Rhine; crossed the Simplon, and spent some time at Florence, Naples, Venice, and at last settled down in Rome, to drag through the second winter of his probation in Europe. And most constant had he been all this time, thinking on Edith by day—dreaming of her by night, and repeatedly sending his missives of love o’er the broad Atlantic, laden with sighs sufficient to waft the bark of itself had not steam deigned to assist him.

It was in the month of March, when Lennard fell ill at Rome. Alone—recluse and dreamy still in his habits—he had made but few acquaintances, and would, I think, have fared but badly had it not been for the attention of an American family, like himself, sojourning in the “imperial city.”

Mr. Ashton, wife and daughter, were unremitting in their kindness to the invalid, the former watching him with a parent’s care, and the daughter cheering and amusing him during the listless and languid weeks of his slow convalescence. Isabel, or rather Bel Ashton, was not beautiful; but there was that nameless charm around her which often attaches more powerfully than mere beauty. Partly educated in Europe, she had passed much of her time in Paris and other cities of the continent, and possessed by des habitudes, and by nature, that

“Grace of motion and of look—the smooth

And swimming majesty of step and tread;

The symmetry of form, which set

The soul afloat, even like delicious airs

Of flute and harp.”

Above all, her wit, sparkling and effervescing like champagne, and almost as intoxicating. How swiftly and agreeably speeded on his days. Every morning found Charles in the parlor of the suite of rooms occupied by the Ashtons, and as he gained strength, their escort in rides and sight-seeing promenades. Yet, though he admired Bel Ashton much, his betrothed Edith was not forgotten. He now, however, often caught himself contrasting them together—wondering had she changed from her spirituelle, radiant, girlish beauty, into any thing of more earthy, coarser mould. With something unpleasant pulling at his heart-strings, came the recollection that Edith’s mother had a great resemblance to her daughter, but was too much embonpoint to suit his ideas of matron comeliness, and then a haunting vision would cross his fastidious mind of his worshiped Edith becoming like her mother, a Turkish beauty as to her size. Bel, with her tact, her undulating, graceful motion, her mannerism, would come in comparison to this bug-bear—we may almost call it—of his imagination; and, though when he remembered her sweet, joyous temper; her appearance, as when standing by the moonlit spring, with her graceful, girlish embarrassment—her rare and dazzling beauty, her pure young love—Bel would yield instant precedence to Edith; yet was he constantly haunted by these ever recurring comparisons, until he began—the ingrate!—to feel his engagement as a binding chain.

“I am now strong enough,” sighed Charles Lennard, one morning, “to think of my preparations to return to America. ’Tis now May, and I must reach Virginia sometime in July, on account of my then having reached my twenty-first birthday, and am recalled by letters looking business-like, in every way. When do you think of returning, Mr. Ashton?”

“I have been debating that question very often of late with my wife, and we both have arrived at the conclusion that we have already been absentees too long, and must wend our way ‘westward-ho’ also. What say you, Mrs. Ashton, and you, ma Belle, to being traveling companions with our friend Lennard?”

“With all my heart,” said Mrs. Ashton; whilst Bel, who had been seated at the piano, ran over with taper and jeweled fingers a brilliant symphony, adding to its melody that of her own rich, mellow voice, in the words, “There is no home like my own.”

And thus ’twas decided; and Charles carried his unconscious tempter from his allegiance along with him. Their intimacy, the effect—where any agreeability exists at all—of being “alone on the wide, wide sea,” did much to render him still more dissatisfied with his engagement, and though he erred not in the letter, I fear the spirit suffered in his vows of fealty to his affianced Edith. Alas! for man’s love. It is indeed

“Of man’s life a thing apart.”

Yet, one who thinks should not wish it otherwise, for it would then be most unnatural. Man has a thousand and one things to call off his thoughts from his love to passing events, glowing and changing as rapidly as the evening clouds, tinging his thoughts and feelings, chameleon-like, with all the tints and varieties of change, and calling upon him to battle with the rough necessities of life. And all this prevents him from thinking constantly o’er his dream of love, and weakens, as a matter of course, the first passionate ardor which he felt when under the influence of the smiles, bright glances, and loving words. As Miss Landon most beautifully observes—“He may turn sometimes to the flowers on the way-side, but the great business of life is still before him. The heart which a woman could utterly fill were unworthy to be her shrine. His rule over her is despotic and unmodified, but her power over him must be shared with a thousand other influences.”

Whilst, on the other hand, woman goes steadily on with her domestic, monotonous duties, till they call for no exertion of thought, becoming purely mechanical, and the imagination having no healthy exercise, runs riot in its indulgence of day-dreams. Many and many is the maiden who sits sewing most industriously with bright smiles wreathing unconsciously her lips—ask her the subject of her thoughts—her blush will tell you better than my words. She is now feasting on her imagination till her love, by constant thought, constant association with her daily routine of duties and pleasures, becomes part and parcel of her very existence.

They have all landed in New York—the home of the Ashtons—and still Charles Lennard loiters. Day after day finds him among the groups who crowd Mrs. Ashton’s parlors to welcome their return. At length Bel and her parents decide to spend the summer at Old Point Comfort, and Charles immediately finds it necessary for his health to enjoy the sea air and bathing. And so he must answer Edith’s last letter, received whilst in Europe, and announce his arrival—excuse himself, also, for not flying at once to her presence!

——

And Edith? All this while of chances and changes how is the time passing with her? See for yourself reader! Follow me gently into that well-known parlor of her mother’s dwelling. There she sits, the beautiful one! as light, as graceful, and still more lovely than when we saw her last; for we now behold her a thinking, refined, intellectual woman, with all her youthful, beaming charms, heightened into exquisite and womanly perfection. She is leaning, rather pensively, on the arm of the chair, drawn to the opened and perfume draped window, with her soft, dimpled hand holding in its rose-colored palm the rounded chin; the neat, little foot patting unconsciously the floor—her eyes bent on the flowers of her garden, seeing them in all their floating hues, like the mingled colors of a kaleidoscope, before her musing gaze. Her guitar leans against her knee, and the other hand is straying across the strings, awaking its echoes like the notes of an Eolian harp.

“Mother, I will go with cousin Frank and Sallie to Old Point. They are so anxious I should do so.”

“And suppose, Edith, Mr. Lennard arrives in your absence, what shall I tell him?” said Mrs. Morton, with a smile.

“Mother, you must forgive my first breach of confidence, for I was too unhappy, too wounded in my pride and love to speak of what I am going to tell you,” said Edith, her listless attitude now abandoned for one of energy, and the usual musical tones were rapid and more harsh—“yes, mother, my very first. Mr. Lennard will be at Old Point soon after I reach there. Yesterday I received a letter from him, and such a letter!” Edith’s voice faltered, but indignantly driving back the tears which were filling her eyes, she drew from her pocket a letter, and handing it to her mother, told her to read it. Whilst Mrs. Morton arranged her glasses, Edith sunk back into the chair with a slight frown and heightened color, and one could see from the clenched hand how determined she was to overcome the agitation which was increasing by her disclosures.

“New York, June, 1847.

“Dear Edith,—You must pardon my seeming neglect in having left unanswered so long your last. I have been very ill, and had it not been for the unexampled kindness of an American family resident in Rome, should long ere this have slept my last sleep. And though barely recovered, I feel that my strength needs recruiting ere I can be considered aught but an invalid, and will therefore set out for Old Point Comfort the last of this month. I hope I need not assure you that I feel my exile from your presence most sensibly, and I anticipate the pleasure of visiting you in A—— as soon as I am better. I know, my dear Edith, that this is but a sorry return for your long and affectionate letter to me; but I never did excel in putting my thoughts and feelings upon paper, my weakness now, must excuse even this poor attempt. I know your kind heart will make every apology for me, and you will look upon this as only the announcement, from myself, of my return to my native land, and of course, to you. Believe me, dear Edith, as ever,

Truly yours,

Charles.”

Mrs. Morton folded the letter slowly, and gave it back to Edith.

“He may be as he says, Edith, too unwell and too weak to write as he wishes.”

“Unwell!” said Edith indignantly; “were I dying I would not have written such a letter to him. Yes, I will go to Old Point, and show Mr. Lennard that I can resign him, and still live: I am determined he shall never triumph in the thought, that I, a foolish girl, would weep, and pine away, because he has forgotten me,”—here the tears ran freely from her beautiful eyes; and, with her voice broken by sobs, she continued—as she knelt before her mother, burying her tear-stained face in her lap—“and then, dear mother, I will be all your own Edith again: no parting from you, for I will never, never love any one, or believe in their love as I have done.”

Mrs. Morton suffered her to weep, knowing it was the best for that poor, grieved heart thus to find vent from its bitterness; but she showed her sympathy in her child’s first grief by her loving words, and by softly smoothing the ringlets on her hot, throbbing brow, and by many a tender kiss. And Edith, with her head resting on her mother’s lap, sat on the floor as of old, when a little child she would listen to stories from her parent; and Mrs. Morton, very judiciously, sought to impress upon poor Edith, the instability of all things earthly, and begged her to lay her griefs, in prayer, at the feet of that kind Father, who is never tired of inviting the sorrowing and weary to lay their burthens upon him, exhorting her to pray for strength, and firm faith, so as to say from her heart—“Though thou slayest me, yet will I trust in Thee!”

Some days were passed in preparation for her trip; and, at the appointed time, she accompanied her cousin Frank and his wife. The Hygeia Hotel was crowded with fashionables and invalids from every section of the Union, and our party found they had arrived in excellent time for the fancy ball, to take place the ensuing week. Edith was only eighteen; and though really grieved at Charles’ cold letter, and supposed faithlessness, yet her indignation and wounded pride made her still bear up against her sorrow, at the thought of rupturing her engagement with Lennard—whom she really loved, with all the warmth of first and trusting love, notwithstanding this rude shock it had received. But she was hopeful and buoyant in disposition, and consoled herself with the thought—as she looked into the mirror, and saw there her loveliness—that she yet would win him back to love her still more deeply: and pleased was she, very naturally, at the universal admiration she excited among the gentlemen; looking forward, too, to her first ball—thinking Charles Lennard would then see her in a dress, on which she bent all her taste to render it bewitching—that he would feel proud to be the husband-elect of one to whom so many eyes turned in ecstasy at her exquisite beauty. All these, and many more thoughts of a like nature, kept her from becoming a prey to her heart sickness, and she was really as lively and gay as she intended appearing in his eyes. I hope no one will deem my heroine heartless, because she was not as unhappy is she first expected to have been. No, very far was Edith Morton from that: on the contrary, she possessed warm and ardent feelings, but—as I said before—she was hopeful and confident—as what really beautiful woman is not?—in the power of her attractions.

——

It was four o’clock, and the day of the expected fancy ball. The house, and its crowd of inmates, were in all the anxieties of preparation, and pleasing anticipation of the coming fête. The Baltimore boats have just arrived, bringing fresh accessions to the already thronged hotel; and the numerous waiters, and smartly-dressed chambermaids, might be seen hurrying here and there, busily preparing for the new comers. The long piazzas—that were in front and behind the central saloon—were full of gay groups: some sauntering to and fro, others in all the careless abandonnement of loose summer garb, were sitting with their cigars, and arguing about politics—lazily and prosily, as if even that was too much of an exertion for the warm weather. Groups of lovely women were promenading through the saloon, in tasteful dinner-dress—some laughing, flirting, some chess-playing with the officers of the garrison, in their uniforms. Nor was there wanting quite a number of sprightly “middies,” with their banded caps set jauntily on their heads, for Hampton Roads had two or three frigates, awaiting final orders, ere they put to sea.