* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 4, Issue 11

Date of first publication: 1868

Author: J. T. Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: July 12, 2019

Date last updated: July 12, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190725

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. IV. | NOVEMBER, 1868. | No. XI. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

HOW QUERCUS ALBA WENT TO EXPLORE THE UNDER-WORLD.

HALF-HOURS WITH FATHER BRIGHTHOPES.

uercus Alba lay on the ground, looking up

at the sky. He lay in a little, brown, rustic

cradle which would be pretty for any baby,

but was specially becoming to his shining,

bronzed complexion; for although his name,

Alba, is the Latin word for white, he did not

belong to the white race. He was trying to

play with his cousins, Coccinea and Rubra,

but they were two or three yards away from

him, and not one of the three dared to roll any

distance for fear of rolling out of his cradle;

so it wasn’t a lively play, as you may easily

imagine. Presently, Rubra, who was a sturdy

little fellow, hardly afraid of anything, summoned

courage to roll full half a yard, and, having

come within speaking distance, began to

tell how his elder brother had, that very morning,

started on the grand underground tour,

which to the Quercus family is what going to

Europe would be for you and me. Coccinea

thought the account very stupid, said his brothers

had all been, and he should go too sometime

he supposed, and, giving a little shrug of

his shoulders which set his cradle rocking, fell

asleep in the very face of his visitors. Not so

Alba; this was all news to him,—grand news. He was young and inexperienced,

and, moreover, full of roving fancies; so he lifted his head as far

as he dared, nodded delightedly as Rubra described the departure, and, when

his cousin ceased speaking, asked eagerly, “And what will he do there?”

uercus Alba lay on the ground, looking up

at the sky. He lay in a little, brown, rustic

cradle which would be pretty for any baby,

but was specially becoming to his shining,

bronzed complexion; for although his name,

Alba, is the Latin word for white, he did not

belong to the white race. He was trying to

play with his cousins, Coccinea and Rubra,

but they were two or three yards away from

him, and not one of the three dared to roll any

distance for fear of rolling out of his cradle;

so it wasn’t a lively play, as you may easily

imagine. Presently, Rubra, who was a sturdy

little fellow, hardly afraid of anything, summoned

courage to roll full half a yard, and, having

come within speaking distance, began to

tell how his elder brother had, that very morning,

started on the grand underground tour,

which to the Quercus family is what going to

Europe would be for you and me. Coccinea

thought the account very stupid, said his brothers

had all been, and he should go too sometime

he supposed, and, giving a little shrug of

his shoulders which set his cradle rocking, fell

asleep in the very face of his visitors. Not so

Alba; this was all news to him,—grand news. He was young and inexperienced,

and, moreover, full of roving fancies; so he lifted his head as far

as he dared, nodded delightedly as Rubra described the departure, and, when

his cousin ceased speaking, asked eagerly, “And what will he do there?”

“Do?” said Rubra,—“do? why, he will do just what everybody else does who goes on the grand tour. What a foolish fellow you are to ask such a question!”

Now this was no answer at all, as you see plainly, and yet little Alba was quite abashed by it, and dared not push the question further for fear of displaying his ignorance; never thinking that we children are not born with our heads full of information on all subjects, and that the only way to fill them is to push our questions until we are utterly satisfied with the answers; and that no one has reason to feel ashamed of ignorance which is not now his own fault, but will soon become so if he hushes his questions for fear of showing it.

Here Alba made his first mistake. There is only one way to correct a mistake of this kind, and it is so excellent a way that it even brings you out at the end wiser than the other course could have done. Alba, I am happy to say, resolved at once on this course. “If,” said he, “Rubra does not choose to tell me about the grand tour, I will go and see for myself.” It was a brave resolve for a little fellow like him. He lost no time in preparing to carry it out; but, on pushing against the gate that led to the underground road, he found that the frost had fastened it securely, and he must wait for a warmer day. In the mean time, afraid to ask any more questions, he yet kept his ears open to gather any scraps of information that might be useful for his journey.

Listening ears can always hear; and Alba very soon began to learn, from the old trees overhead, from the dry rustling leaves around him, and from the little chipping-birds that chatted together in the sunshine. Some said the only advantage of the grand tour was to make one a perfect and accomplished gentleman; others, that all the useful arts were taught abroad, and no one who wished to improve the world in which he lived would stay at home another year. Old grandfather Rubra, standing tall and grand, and stretching his knotty arms, as if to give force to his words, said, “Of all arts, the art of building is the noblest, and that can only be learned by those who take the grand tour; therefore all my boys have been sent long ago, and already many of my grandsons have followed them.”

Then there was a whisper among the leaves: “All very well, old Rubra, but did any of your sons or grandsons ever come back from the grand tour?”

There was no answer; indeed, the leaves hadn’t spoken loudly enough for the old gentleman to hear, for he was known to have a fiery temper, and it was scarcely safe to offend him; but the little brown chipping-birds said, one to another, “No, no, no, they never came back! they never came back!”

All this sent a chill through Alba’s heart, but he still held to his purpose; and in the night a warm and friendly rain melted the frozen gateway, and he boldly rolled out of his cradle forever, and, slipping through the portal, was lost to sight.

His mother looked for her baby; his brothers and cousins rolled over and about in search for him. Rubra began to feel sorry for the last scornful words he had said, and would have petted his little cousin with all his heart, if he could only have had him once again; but Alba was never again seen by his old friends and companions.

THE UNDER-WORLD.

“How dark it is here, and how difficult for one to make his way through the thick atmosphere!” so thought little Alba, as he pushed and pushed slowly into the soft mud. Presently, a busy hum sounded all about him, and, becoming accustomed to the darkness, he could see little forms moving swiftly and industriously to and fro.

You children who live above, and play about on the hillsides and in the woods, have no idea what is going on all the while under your feet; how the dwarfs and the fairies are working there, weaving moss carpets and grass-blades, forming and painting flowers and scarlet mushrooms, tending and nursing all manner of delicate things which have yet to grow strong enough to push up and see the outside life, and learn to bear its cold winds and rejoice in its sunshine.

While Alba was seeing all this, he was still struggling on, but very slowly; for first he ran against the strong root of an old tree, then knocked his head upon a sharp stone, and finally, bruised and sore, tired, and quite in despair, he sighed a great sigh, and declared he could go no further. At that two odd little beings sprang to his side,—the one brown as the earth itself, with eyes like diamonds for brightness, and deft little fingers, cunning in all works of skill. Pulling off his wisp of a cap, and making a grotesque little bow, he asked, “Will you take a guide for the under-world tour?” “That I will,” said Alba, “for I no longer find myself able to move a step.” “Ha, ha!” laughed the dwarf, “of course you can’t move in that great body, the ways are too narrow; you must come out of yourself before you can get on in this journey. Put out your foot now, and I will show you where to step.” “Out of myself!” cried Alba, “why that is to die! My foot, did you say? I haven’t any feet; I was born in a cradle, and always lived in it until now, and could never do anything but rock and roll.”

“Ha, ha ha!” again laughed the dwarf, “hear him talk! This is the way with all of them. No feet, does he say? Why, he has a thousand, if he only knew it; hands too, more than he can count. Ask him, sister, and see what he will say to you.”

With that a soft little voice said cheerfully, “Give me your hand, that I may lead you on the upward part of your journey; for, poor little fellow! it is indeed true that you do not know how to live out of your cradle, and we must show you the way.”

Encouraged by this kindly speech, Alba turned a little towards the speaker, and was about to say (as his mother had long ago taught him that he should in all difficulties) “I’ll try,” when a little cracking noise startled the whole company, and, hardly knowing what he did, Alba thrust out, through a slit in his shiny brown skin, a little foot reaching downward to follow the dwarf’s lead, and a little hand, extending upward, quickly clasped by that of the fairy, who stood smiling and lovely in her fair green garments, with a tender, tiny grass-blade binding back her golden hair. O, what a thrill went through Alba, as he felt this new possession! a hand and a foot,—a thousand such, had they not said? What it all meant he could only wonder; but the one real possession was at least certain, and in that he began to feel that all things were possible.

And now shall we see where the dwarf led him, and where the fairy? and what was actually done in the underground tour?

The dwarf had need of his bright eyes and his skilful hands; for the soft, tiny foot intrusted to him was a mere baby that had to find its way through a strange dark world, and, what was more, it must not only be guided, but also fed and tended carefully; so the bright eyes go before, and the brown fingers dig out a road-way, and the foot that has learned to trust its guide utterly follows on. There is no longer any danger; he runs against no rocks, he loses his way among no tangled roots; and the hard earth seems to open gently before him, leading him to the fields where his own best food lies, and to hidden springs of sweet fresh water.

Do you wonder when I say the foot must be fed? Aren’t your feet fed? To be sure, your feet have no mouths of their own; but doesn’t the mouth in your face eat for your whole body, hands and feet, ears and eyes, and all the rest? else how do they grow? The only difference here between you and Alba is that his foot has mouths of its own, and as it wanders on through the earth, and finds anything good for food, eats both for itself and for the rest of the body; for I must tell you that, as the little foot progresses, it does not take the body with it, but only grows longer and longer and longer, until, while one end remains at home, fastened to the body, the other end has travelled a distance such as would be counted miles by the atoms of people who live in the under-world. And, moreover, the foot no longer goes on alone; others have come, by tens, even by hundreds, to join it, and Alba begins to understand what the dwarf meant by thousands. Thus the feet travel on, running some to this side, some to that; here digging through a bed of clay, and there burying themselves in a soft sand-hill; taking a mouthful of carbon here and of nitrogen there. But what are these two strange articles of food? Nothing at all like bread and butter, you think. Different, indeed, they seem; but you will one day learn that bread and butter are made in part of these very same things, and they are just as useful to Alba as your breakfast, dinner, and supper are to you; for just as bread and butter, and other food, build your body, so carbon and nitrogen are going to build his; and you will presently see what a fine, large, strong body they can make; then, perhaps, you will be better able to understand what they are.

Shall we leave the feet to travel their own way for a while, and see where the fairy has led the little hand?

QUERCUS ALBA’S NEW SIGHT OF THE UPPER-WORLD.

It was a soft, helpless, little baby hand. Its folded fingers lay listlessly in the fairy’s gentle grasp. “Now we will go up,” she said. He had thought he was going down, and he had heard the chipping-birds say he would never come back again; but he had no will to resist the gentle motion, which seemed, after all, to be exactly what he wanted; so he presently found himself lifted out of the dark earth, feeling the sunshine again, and stirred by the breeze that rustled the dry leaves that lay all about him. Here again were all his old companions,—the chipping-birds, his cousins, old grandfather Rubra, and, best of all, his dear mother; but the odd thing about it all was that nobody seemed to know him; even his mother, although she stretched her arms towards him, turned her head away, looking here and there for her lost baby, and never seeing how he stood gazing up into her face. Now he began to understand why the chipping-birds said, “They never came back! they never came back!” for they truly came in so new a form that none of their old friends recognized them.

Everything that has hands wants to work,—that is, hands are such excellent tools that no one who is the happy possessor of a pair is quite happy until he uses them; so Alba began to have a longing desire to build a stem and lift himself up among his neighbors. But what should he build with? Here the little feet answered promptly, “You want to build,—do you? Well, here is carbon, the very best material; there is nothing like it for walls; it makes the most beautiful, firm wood; wait a minute, and we will send up some that we have been storing for your use.”

And the busy hands go to work, and the child grows day by day. His body and limbs are brown now, but his hands of a fine shining green. And, having learned the use of carbon, these busy hands undertake to gather it for themselves out of the air about them, which is a great storehouse full of many materials that our eyes cannot see. And he has also learned that to grow and to build are indeed the same thing; for his body is taking the form of a strong young tree; his branches are spreading for a roof over the heads of a hundred delicate flowers, making a home for many a bushy-tailed squirrel and pleasant-voiced wood-bird; for, you see, whoever builds cannot build for himself alone; all his neighbors have the benefit of his work, and all enjoy it together.

What at the first was so hard to attempt became grand and beautiful in the doing; and little Alba, instead of serving merely for a squirrel’s breakfast, as he might have done had he not bravely ventured on his journey, stands before us a noble tree, which is to live a hundred years or more.

Do you want to know what kind of a tree?

Well, Lillie, who studies Latin, will tell you that Quercus means oak. And now can you tell me what Alba’s rustic cradle was, and who were his cousins Rubra and Coccinea?

Author of “The Seven Little Sisters.”

In fact, there is so much more about him that I hardly know where to begin; but, after having devoted just about a year’s study to the subject, I am inclined to take the Ginger-snap Story.

If it had not been ironing-day, there never would have been such a story to tell.

But then it was ironing-day, so it is of no use to say anything about that.

Trotty was sitting on the ironing-table too.

Trotty felt the responsibilities of ironing-day. Nobody knows how he felt them. The labors of his mother and Biddy were nothing in comparison. In the first place, there were his “pocky-hankychers” to be ironed. O those poor little pocky-hankychers! He used to crawl up behind the clothes-basket, and pull them out of his pockets (Trotty had two pockets) one by one till he came to the end, and there were always at least three or four. Such a sight as they were! All rolled up, and twisted up, and tied up, and squeezed up,—and as for the color! Well, Trotty picked all his dandelions, and all his fox-berries, and all his flagroot in them; watered his flowers, fed his chickens, brushed his shoes, and made his mud-pies with them, so perhaps you can have some idea of the color. I don’t believe you can, though. Nothing would do but that Biddy must heat his little iron,—it wasn’t much larger than a table-spoon, nor hotter than fresh milk,—and let him iron every one of those handkerchiefs to his entire satisfaction. A washed one, fresh from the pile on the window-sill, did not answer the purpose at all.

Then he must always have his shoe-strings pressed out.

Then there was Jerusalem. Jerusalem must, I think, have been remotely connected with the Flat-head Indians, though he was in skin an Ethiopian, and in temper quite harmless. Compounded from one of grandmother’s ravelled stockings, Lill’s old black silk apron, and the cotton-wool bag, Jerusalem possessed, in the beginning, an ample supply of brains; but Trotty bored a gimlet-hole in the top of his head one day, and pulled them out. Jerusalem, however, did not appear to suffer seriously from this treatment; and the little black silk bag which was left answered the purpose of a head to him quite as well as some fuller ones have done in the course of this world’s history. The only inconvenience about it was the slight one of having your face lop down on your neck whenever anybody shook you a little. Jerusalem felt it quite a comfort to be flattened out.

So Trotty ironed him every Tuesday afternoon.

On this afternoon, he had finished the handkerchiefs and the shoe-strings, and was ready to devote all his energies to Jerusalem, when Biddy dropped her flat-iron and jumped.

“Ow!” said Trotty; for the iron fell plump upon Jerusalem’s face, and scorched it to a delicate, smoky brown from forehead to chin. Jerusalem bore it manfully, and did not so much as wink. Trotty compassionately stuck him head-first into the sprinkling-bowl, and left him there to cool.

“Shure an’ it’s the baker goin’ by on me up the street,” said Biddy running to the window; “there’s not a crumb of cake in the house for supper the night, an’ it’s your mother as told me to stop him, bless my soul! Rin out now, Trotty, and holler afther him, there’s a good boy!”

Trotty, never loath to “rin out and holler” for any cause, prepared to obey; but the baker’s cart had turned the corner, and the jingling of his bells was growing faint. Biddy went to report to her mistress, and Trotty, having hung Jerusalem on the door-latch by his head, trotted along after her, to find out what was going to happen.

“Well,” said his mother, “there is no way now but to send to the Deacon’s for some ginger-snaps.”

Trotty beat a soft retreat. But his shoes squeaked,—Trotty’s shoes always did squeak,—so everybody heard him.

“Come, Trotty!”

“O, I don’t want to,” said Trotty, briskly, backing off.

“But mother wants you to. Come! see how quick you can be. You wouldn’t want to go without any cake for supper, you know.”

“Biddy can bake me some cake. I should like to know if that isn’t what God made her for!” said Trotty, with decision.

“No; Biddy can’t bake cake on ironing-days; she has too much else to do. Now, which would you rather do,—go without the ginger-snaps, or go to the Deacon’s?”

“Have Lill go,” said Trotty, looking bright.

As Trotty’s mother had a habit of meaning what she said, Lill did not go, and Trotty did. He jammed his little straw hat over his curls in a melancholy manner, back side in front, with the blue ribbons hanging down into his eyes, took Jerusalem down from the door-latch, looked unutterable things at Biddy, slammed the door severely, and trudged away through the dust to call for Nat, talking impressively to himself: “Now I don’t care! She needn’t have went and made me get her old ginger—”

“One pound, remember!” called his mother from the house; “and you and Nat may have one apiece.”

Trotty’s spirits rose. He called Nat out, and told him about that; and Nat said that it was “bully,” and Trotty thought so too. On the whole he began to be very glad that he was not at home ironing Jerusalem. Jerusalem himself seemed to be quite of the opinion that he had had ironing enough for one week; what with the scorching, and the drowning, and the hanging, he was in rather a depressed state of mind. Thinking to encourage him, Trotty carried him by the head awhile.

It took Trotty and Nat a long time to go to the Deacon’s. It never took Trotty and Nat anything but a long time to go anywhere. They dug wells in every sand-bank, and sailed chips on every mud-puddle, and knocked the stones off from every wall, and covered themselves with pitch on every wood-pile, and made friends with every kitty, and ran away from every puppy, and picked every dandelion that they came across,—to say nothing of Jerusalem; for Jerusalem could be an elephant, and Jerusalem could be a mouse, and Jerusalem excelled in the character of a horse-car or a steamboat. Jerusalem was unequalled as a telegraph-wire and a fish-hook; he could be buried, could be married, could be a minister and an apple-pie; made such a Daniel in the den of lions that the lions never would have known the difference; and in the capacity of Jeff Davis on a sour-apple tree has never been thought, by more impartial minds than Trotty’s, to have a rival.

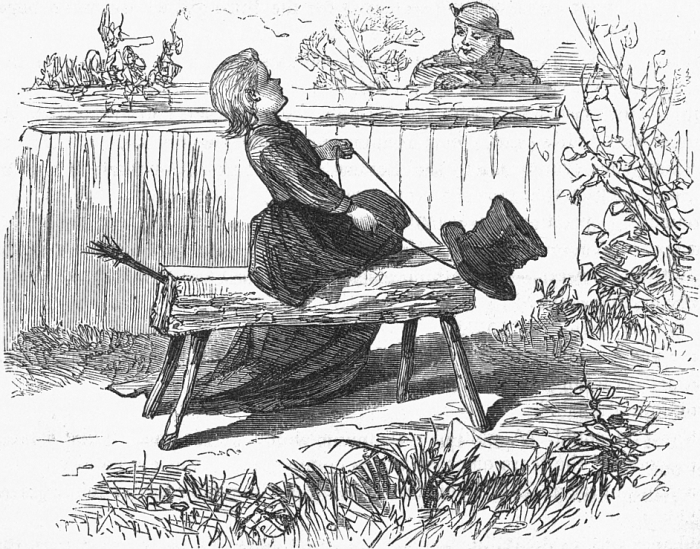

Much to Jerusalem’s relief, they came to the Deacon’s at last, and Trotty climbed the high wooden steps, and stood on tiptoe, so that the end of his nose and the top of his curls just showed above the counter, and hammered away for a while with his little brown fists, till the Deacon heard him. How he opened his eyes and mouth, while the Deacon’s boy weighed out a pound of brown, round, crisp, fresh, sweet ginger-snaps!

“O my!” said Nat.

“Wait a minute,” said Trotty; “mother told me to sharge ’em.”

So Trotty took the ginger-snaps, and waited about; and the Deacon’s boy was busy, and did not notice him.

“What does it mean to have ’em charged?” asked Nat, in a hungry whisper, after they had walked drearily about the store for five minutes. Trotty shook his head. He had an idea of his own,—I’m sure I do not know how he came by it,—that he was to carry home a paper with something written on it, and that the Deacon was to write it for him, but he did not feel quite sure, and did not dare to ask. So he and Nat walked back and forth, and began to feel very hungry and very homesick.

“Hulloa!” said the Deacon, presently, “why, what’s the matter?”

“Mother wants ’em sharged,” said Trotty, half ready to cry, but looking as important as he knew how.

“O,” said the Deacon, “they’re all ‘sharged’ long ago. Run along!”

Trotty ran along in some perplexity. He had a vague impression that either he or the Deacon had made a mistake, but I doubt if he knows which, to this day.

Out again in the sunlight and the yellow dust, among the stone walls and the dandelions, he and Nat opened the paper.

Think of it,—a pound of ginger-snaps, and nobody to be seen among the stone walls and dandelions but Trotty and Nat! Nobody to look on, all the way home, and nothing but ginger-snaps away down to the bottom of that big paper bag! O you great grown-up people who talk about “temptations,” think of it!

“J-j-j-est look a there!” stammered excited Nat, hardly able to put one word straight after the other; for Nat did not have a ginger-snap very often.

“Mother said I might have one, and you might have one, an’ we might bof two of us have one,” said Trotty, graciously. So he put in his dainty, dimpled fingers, and felt all about till he found the largest two ginger-snaps in the brown bag.

O, well, to think how they tasted! Trotty nibbled his up in little bites about as big as a canary’s, and felt the sunshine all about, and heard a bluebird singing as she hopped along on the wall, and wondered in his secret heart—though this he did not say to Nat—whether there would be any Deacon’s, up in heaven; if he would keep ginger-snaps; if you could go down there some afternoon, and just eat all you wanted.

By and by the ginger-snap was all nibbled away.

“O, see here!” said Trotty, abstractly; “don’t you wish peoples hadn’t any mammas, Nat?”

“Let’s look in and see if they’re all safe, you know,” suggested Nat, after some thought.

Trotty opened the paper in a vague way, and peeped in.

“I’d like to look and see how safe they are,” said Nat. So Nat looked to see how safe they were.

“Wonder if there’s a hundred of ’em,” observed Nat, putting just the tips of his fingers over just the edge of the paper.

“O, I guess there’s more’n that; there’s as many as fifteen, I shouldn’t wonder,” said Trotty.

Presently he opened the bag again, and took out two ginger-snaps again.

“I don’t b’lieve she’d care if we had two ones, Nat.”

“That must ’a’ been what she meant,” explained Nat.

But something was the matter with that ginger-snap; Trotty thought that it did not taste as good as the other.

“I guess this one’ll taste better, you see. Free isn’t a great many more’n one, is it, Nat?”

Nat felt positive on that point. He didn’t think that four were a great many more, either.

“Look here,” said Trotty, after a while, “I’m glad mamma isn’t God.”

“Why?” asked Nat.

“ ’Cause then she’d just have to be round everywhere looking on.”

The bluebird had stopped singing, and the sunshine ran away, as fast as it could, to hide behind a cloud.

“Where’s Trotty?” asked everybody, when supper-time came; for nobody ever knew Trotty to fail of being on hand at supper-time.

“Trotty, Trotty! Trotty Tyrrol! Kitty Clover! Little pink Dai-sy! Trotty Teaser!”

Lill went up stairs and down, shouting a few dozen of Trotty’s names; to tell you all the names that Trotty had would take a separate number of Our Young Folks.

Lill looked in the attic; she looked in the cellar; she searched the woodshed; she peered into the refrigerator.

“Why, what has become of the child?”

“I’ll look myself,” said his mother, coming up. “Trotty!”

“Yes ’um!” said Trotty, faintly, from somewhere. And where do you suppose it was? His mother came into the entry by the linen-closet, and went up to the tall clothes-basket that stood in the corner, and peeped in. There sat Trotty, all curled up in a little heap at the bottom, with his elbows on his knees and his chin in his hands.

“Couldn’t get out,” said Trotty, meekly, looking up from the depths.

“But what did you get in for?”

“O, I was a fish, and fell down the well, I guess,” said Trotty, stopping to think; “don’t want any supper. I think you must be hungry, mamma; you’d better go down, you know.”

But mamma did not know. She fished him out somewhat gravely, and put him down upon the floor.

“We are all at supper now, and waiting for Trotty. Where are the ginger-snaps? Did you forget them?”

“No ’um.”

“Well, show me where they are. Come, dear.”

But Trotty hung back. They were “in the shina-closet,” he said, on the lowest shelf.

So somebody went to the “shina-closet.” There on the shelf lay a little, a very little, roll of brown paper. It had been a bag once; it was torn now, and twisted up.

They brought it to Trotty’s mother, and she opened it.

Just five ginger-snaps! Everybody looked at everybody else.

“They’ve eaten—why, did you ever in all your life?—they’ve eaten a pound!”

Lill laughed till the tears came; grandmother said that they would die before morning; mamma went sadly up stairs, and found her little fish sitting on the floor beside his well, head hanging, and dimple gone.

She took him up in her arms, and looked at him. Trotty lifted his great yellow eyelashes just enough to peep through and get an idea of the state of affairs; then dropped them down—down.

“Trotty, where are the rest of mother’s ginger-snaps?”

“The Deacon’s pounds ain’t—well, they ain’t so big as they used to be,” said Trotty, twisting his fingers into each other. “Sumfin’s the matter with his weighing-thing, I guess.”

“No, Trotty; the Deacon gave you a great many more than you have brought home, and somebody has eaten the rest. Was it Trotty and Nat?”

“Me and Nat, we eat free,” said Trotty, very low.

“Only three? But who ate the rest, Trotty?”

“Jerusalem!” said Trotty, after some consideration.

“Very well; whoever ate the ginger-snaps can’t go down stairs any more to-night, but must go to bed and stay alone. Shall I put Jerusalem to bed?”

Trotty opened his eyes rather wide, but said nothing. His mother put Jerusalem into Trotty’s bed, and covered him up, and tucked him in; Jerusalem folded his head quite over on the counterpane for shame and sorrow.

“O, see here!” said Trotty, with a little jump. “It—it wasn’t Jerusalem, either.”

Trotty cried himself to sleep that night. But, before he had cried himself to sleep, his mother came up with his mug of milk, and sat down on the bed. She looked very sober, and said nothing, nor did she kiss him.

“Mamma,” faltered Trotty, presently.

“What?”

“Trotty!”

Why, you would have thought his little heart was broken! He had never spent ten unnoticed, unpetted minutes in all his life before; and I suppose he had settled it in his wretched little thoughts that he never was going to be noticed or petted or kissed or forgiven.

“Too bad!” moaned Trotty. “O, it’s too bad!”

So he crept up into his mother’s arms,—he looked like a little tinted statue, with his nightgown, and bare feet, and wet curls, and grieving, red mouth,—and they talked it all over.

“Will I die?” asked he, by and by, very sorry and a little frightened.

O no, not now, his mother hoped; but she was afraid he would be sick to-morrow. Indeed, she had sent Lill to ask the doctor to stop in a moment on his way home; though that she did not tell Trotty.

Trotty called her back after she had started to go down stairs, and wanted to know “Which would be died first,—me or you or Jerusalem?”

“O, I presume I shall die first; I am the oldest. Come, Trotty, go to sleep now, it is very late.”

“Mamma—” when she had stepped on the very last stair: and up she must climb again, wearily.

“Look here, mamma. I should just like to know about it. If you go to heaven first, who’ll shoot me?”

You see, all the dead people that the poor little philosopher knew anything about, were two in number. One was his father, whose great, blue brave eyes looked down out of the picture up stairs, and who lay with a bullet in his heart among the solemn shadows of Gettysburg. The other was the Good President. Consequently, he had inferred that the only means of translation from this world to another was by pistol.

“And, O dear!” cried his mother, afterwards, “to think that I should have to be the one to do it!”

“A pound of ginger-snaps! A pound of ginger-snaps!” repeated grandmother at intervals throughout the evening. “He certainly will die before morning.”

Trotty did not, however, die before morning. And, what is more,—I do not expect to be believed, but it is true,—they never hurt him a bit.

The next Sunday he preached a sermon to Lill and Biddy. If you had only heard it! It began—

. . . . A telegram just received from the Editors, (who are not of a theologic turn of mind) mildly but decidedly hints that I may go on writing as long as I choose, if it is any comfort to me; but that young folks have sensibilities, and the Magazine has covers, and not another line will they print for me this time.

E. Stuart Phelps.

The old-wives sit on the heaving brine,

White-breasted in the sun,

Preening and smoothing their feathers fine,

And scolding, every one.

The snowy kittiwakes overhead,

With beautiful beaks of gold,

And wings of delicate gray outspread,

Float, listening while they scold.

And a foolish guillemot, swimming by,

Though heavy and clumsy and dull,

Joins in with a will when he hears their cry

’Gainst the Burgomaster Gull.

For every sea-bird, far and near,

With an atom of brains in its skull,

Knows plenty of reasons for hate and fear

Of the Burgomaster Gull.

The black ducks gather, with plumes so rich,

And the coots in twinkling lines;

And the swift and slender water-witch,

Whose neck like silver shines;

Big eider-ducks, with their caps pale green

And their salmon-colored vests;

And gay mergansers, sailing between,

With their long and glittering crests.

But the loon aloof on the outer edge

Of the noisy meeting keeps,

And laughs to watch them behind the ledge

Where the lazy breaker sweeps.

They scream and wheel, and dive and fret,

And flutter in the foam;

And fish and mussels blue they get

To feed their young at home:

Till, hurrying in, the little auk

Brings tidings that benumbs,

And stops at once their clamorous talk,—

“The Burgomaster comes!”

And up he sails! a splendid sight,

With “wings like banners” wide,

And eager eyes, both big and bright,

That peer on every side.

A lovely kittiwake flying past

With a slippery pollock fine,

Quoth the Burgomaster, “Not so fast,

My beauty! This is mine!”

His strong wing strikes with a dizzying shock;

Poor kittiwake, shrieking, flees;

His booty he takes to the nearest rock,

To devour it at his ease.

The scared birds scatter to left and right,

But the bold buccaneer, in his glee,

Cares little enough for their woe and their fright,—

“ ’Twill be your turn next!” cries he.

He sees not, hidden behind the rock,

In the sea-weed, a small boat’s hull,

Nor dreams he the gunners have spared the flock

For the Burgomaster Gull.

So proudly his dusky wings are spread,

And he launches out on the breeze,—

When lo! what thunder of wrath and dread!

What deadly pangs are these!

The red blood drips and the feathers fly,

Down drop the pinions wide;

The robber-chief, with a bitter cry,

Falls headlong in the tide!

They bear him off with laugh and shout;

The wary birds return,—

From the clove-brown feathers that float about

The glorious news they learn.

Then such a tumult fills the place

As never was sung or said;

And all cry, wild with joy, “The base,

Bad Burgomaster’s dead!”

And the old-wives sit with their caps so white,

And their pretty beaks so red,

And swing on the billows, and scream with delight,

For the Burgomaster’s dead!

Celia Thaxter.

The intolerable oppression of the patricians, to which was now added the tyranny of the Decemvirs, had excited a spirit of rancor in the breasts of the Roman commons, which was gradually extending itself to the entire army that now lay encamped in a strong position within sight of the enemy. But so sullen was their temper that the generals feared to lead them from their intrenchments, and the only barrier to open mutiny seemed to be the absence of special provocation, or the lack of a leader.

Upon the slopes of Crustumeria hung the dark masses of the Roman [their]* legions, while the watch-fires of their enemy, gleaming through heavy masses of foliage, lit up the vales below. But the haughty joy with which these stern warriors were wont to hail the hour of conflict no longer thrilled the soldiers’ breasts. By the dim light of stars, men spake in whispers; and murmurs, waxing louder as the night wore on, like the hollow moan of surf before the gathering tempest, rose on the midnight air.

Just as the red light, touching, tinged the mountain summits, a warrior, clad in a gory mantle from which the blood, slow dripping, had stained his armor and clotted upon his horse’s mane, rode down the sentry, and, bursting into the midst of the camp, shouted, “Soldiers, protect a tribune of the people!” Those pregnant words, associated with all of liberty the commons had ever known, were to the chafed spirits of the soldiery as fire to the flax. From every quarter of the camp trumpets sounded to arms, the clash of steel mingled with the tramp of hurrying feet, and, marshalled by self-elected commanders, the gleaming cohorts closed around him. But when the helmet, lifted, revealed a face of wondrous beauty, stained by the traces of recent grief, the eyes flashing with the light of incipient madness, tears trembled on the cheeks of that stern soldiery, and “Icilius!” ran in a low wail through their ranks.

“Comrades,” he cried, “you behold no more that young Icilius who, foot to foot and shield to shield with you, has borne the brunt of many a bloody day, and whose life was like a summer’s morning, rich with the fragrance of the opening buds, while every morn gave promise of new joys, and twilight hours were in their lingering glories dressed,—but a man sore broken, made ruthless by oppression, and so beset with horrors that this reeling brain, just tottering on the verge of madness, is steadied only by the purpose of revenge.

“Yesterday, Virginia, my betrothed, was by her father slain, to thwart the lust of Appius Claudius, a guardian of the public virtue and a ruler of the State.

“As she crosses the forum, on her way to school, that she may take leave of her mates and invite them to her bridal, some ruffians set on by Appius Claudius lay hold upon her, averring that she is not the daughter of Virginius, but of a slave-woman, the property of Marcus, his client. The matter is brought to public trial; Appius, failing to obtain in this manner the custody of her, that he may gratify his evil passions, commands his soldiers to take her by force. Her friends, apprehending no violence at a legal tribunal, are without arms. Soldiers are tearing her from her father’s embrace, when the stern parent, preferring death to dishonor, catches a knife from the butcher’s stall, and crying, ‘Thus only can I restore thee untainted to thy ancestors,’ stabs her to the heart.

“The purple torrent gushing from her breast, she falls upon my neck,—her arms embrace me,—her lips close pressed to mine, murmuring in death my name, she dies.

“In childhood we were lovers; from her father’s door to mine was but a javelin’s cast. We sought the nests of birds,—played in the brooks,—chased butterflies,—we clapped our hands in childish wonder when the great eagle from the Apennines plunged headlong to the vale, or skimmed with level wing along the flood,—and I, adventurous boy, risked life and limb upon the jutting crag, to pluck some wild-flower that her fancy pleased.

“As generous wine by age becomes more potent, thus fared it with our loves. For her I kept myself unstained, rushed to the battle’s front, and honors gained, that I might lay them at her feet, and, by her love inspired, press on to worthier deeds. Like flowers whose kindred roots intwine, whose perfume mingles on the morning air, did our affections blend. ’Twas but three nights ago that we sat hand in hand beside the Tiber, and listened to the song of nightingales among the elms. The purple twilight quivering through the leaves streamed o’er her brow, and bathed in heavenly hues her lovely form.

“There we talked of our approaching nuptials. Love ripened into rapture. I kissed her lips, and chid the slow-paced hours that kept us from our bliss. The marriage day was fixed. With curtains richly wrought, and coverings of finest linen, spun by her own hands and by her maidens, my mother had adorned the couch.

“To that sweet home where I had hoped through happy years to cherish her a wife, I bore her mangled corpse, gashed by a father’s hand. Her blood bedewed the bed decked with those nuptial gifts.

“To you, mates of my boyhood, brethren in battle tried, I stretch my hands; not in the petty interest of a private wrong, but in the sacred right of Roman liberty, of virgin purity, sweet household joys, and in the name of those whose fair forms mingle with your dreams, in the fierce shock of battle nerve your arms, the fragrance of whose parting kiss yet lingers on your lips.

“The blood of age creeps slowly, and in its timid counsels interest and fear bear sway. Shall youthful swords lie rusting in the scabbard, and young men count the odds, when slaughtered beauty from its bloody grave clamors for vengeance?

“Behold this mantle, drenched in the blood of her whose fingers wove it as a gift of love,—each precious drop a tongue to shame your lingering courage. Led by the father with his bloody knife, your comrades thunder at the gates of Rome, while you, unworthy sons of sires who banished Tarquin and expelled the kings, sit here deliberating whether the virgin’s sanctity, the wife’s fair virtue, and all that men and gods hold sacred, are worth the striking for. Consume your youth in hunger, cold, and vigils, with spoils of conquered realms to pamper tyrants, till, waxing wanton on your bounty, they desolate your homes; and ye, hedged in by mercenary spears, revile your misery.”

His words were drowned in the clash of steel and the cries of multitudes calling to arms. Tearing the bloody garment in pieces, he flung them among the thronging battalions. “Be these your eagles! Bind them to your helmets; and, in the spirit they inspire, strike down the oppressor, that sweet Virginia’s unquiet ghost no more may wander shrieking for vengeance on the midnight air, but to the silent shades appeased return.”

Elijah Kellogg.

Note.—The Publishers of “Our Young Folks” are obliged, by their arrangement with the author of the foregoing declamation, positively to prohibit its republication.

|

If the first paragraph be spoken, the speaker will here use the reading in brackets, instead of “the Roman.” |

Small events and trials in the life of a young child have more effect upon after life than we always know.

The following, which among other family and nursery records I remember, is a true story.

Little Mary sat alone in the parlor, “sewing a weary seam”; and she sighed once or twice as the breeze came soft and sweet through the open window, and she thought how very, very pleasant it was out there, where the lilacs were in bloom and the trees in full blossom.

Presently a door opened, and her mother came from the adjoining bedroom. Mary’s mother—a grave, stately-looking lady—was dressed for going out. We should smile to meet any one in our streets apparelled in like manner, but it was the fashion of that time. Her dress was a bright-patterned chintz sack, long, and open in front; the corners drawn back and fastened up behind, so displaying a flower-quilted petticoat beneath. Fifty years ago a young girl took that dress from the bottom of an old trunk, where it had lain for nearly thirty, and appropriated it to private theatricals. Over the lady’s shoulders lay a black mantle, and on her arms she wore long black mits, reaching to the bare elbows. A black silk hat was set low over the forehead, and raised behind so as not to crumple the starched high crown, clear and delicate, of her muslin cap; and she carried an open green fan, larger than some of the sunshades now in use. The pointed toes and high heels of her prunella, paste-buckled slippers clicked daintily as she walked, and left slight trace upon the sanded floor.

At the opposite door she paused, with her hand upon the lock, and looked back at the child, who, prim and silent, sat upon a low stool near the window. There was a flush of excitement on the pale little face, for she had hoped to be the companion of her mother’s walk; but the strict discipline of those days forbade much freedom of speech in children, so Mary could not dream of asking excuse from a task unaccomplished, however industrious she might have been; but her dark eyes looked so wistful there was no mistaking their language.

“Go fetch your hat, Mary,” said the lady, at length; and with pleased smiles the little maiden folded her work, replaced the square, oaken stool in exact angle with the lion-clawed table, and obeyed the welcome summons.

With careful steps the mother and daughter walked along the unpaved streets of Glostown,—I give it that name, though the four first letters alone belong to it. They stopped at a square wooden house, which was approached by two very low flat steps, and entered through a pair of red folding-doors, having a brass knocker on the one and a brass handle on the other. Blinds had not yet come into general use; but the windows of this house were hung with curtains, and four thickly leafed poplars shaded them outwardly. Here lived the parish clergyman, Parson Fordes.

The town of Glostown has now its six or eight places of public worship, perhaps more; but at that time the one old meeting-house—which, if it had ever been painted, retained no trace of it—stood solitary, with its belfry and pointed steeple, overlooking the whole parish.

The little fishing-town has since become a thickly settled place. Hotels and rows of stores have displaced all the pretty gardens; and railroad tracks stretch along where Mary and her mother walked that afternoon so quietly.

The two visitors were received in the parlor of Madam Fordes, the wife of the clergyman. This lady, well advanced in years, sat in a white dimity-covered easy-chair, dressed all in white herself; her Bible and spectacles lying on a three-footed light-stand beside her, and her favorite cat on a cushion near by. The floor was carpeted,—a rare thing in those days. This carpet was home-made; industry and ingenuity had slowly accomplished it. Bits of woollen cloth—black, red, gray, green, and yellow—cut to the width of common tape, and sewed together in long variegated strips, braided and interwoven, had produced a durable fabric, a carpet, giving to this room a look of cheerful comfort.

Between the windows stood a small table with raised edges, bow-legged and curiously carved, supporting a tea-service of china with cups almost toy-like in size. If a lady has only one such now she holds it precious, and gives it place among curiosities.

On the opposite side of the room was a high chest of drawers, kept in shining nicety; and beside it—close beside it—there stood, unfortunately as it proved, a child’s arm-chair,—the only chair among the high, stiff-backed ones that stood round the room on which the little girl could have seated herself in comfort.

The two ladies conversed of their dairies, their gardens, their spinning and knitting, their quiltings and weavings, and in more serious tones of the Dark Day which had very recently occurred, filling people’s hearts with terror while it lasted, and leaving them impressed with awe and solemnity; for the Dark Day of the year 1780 was not an eclipse, and many looked upon it as a forewarning that the world was coming to an end. Up to the present time it has not been satisfactorily accounted for. It lasted from early forenoon to near sunset; candles were lighted, for it was like night; the fowls went to roost, the birds to their nests, and when the sun reappeared, just before its setting, they awoke as to a new day.

Engaged upon so serious a subject, they thought not of little Mary, sitting unnoticed and silent in her low chair apart; but although she had studied the blue tiles round the fireplace several times over, and gazed, till her fancy was more than satisfied, upon the picture of Queen Anne with a string of beads round her throat, she was neither weary nor inactive. Her curiosity and her admiration had become strongly excited by an object that fixed her gaze with a magical charm.

One of the drawers of the great shining chest was a little—a very little—way open, and from it peeped forth a bit of pink sarcenet; it was but a small bit,—not much larger than the pink surface of Mary’s own little hand; but it was triangular, just the shape and size for a doll’s shawl; so suitable to supply the scant wardrobe of that beloved, wooden-faced Mehitable at home. Mary longed to examine it more nearly; after a while she ventured just to touch the end of it. It was hanging so that a slight movement would cause it to fall.

Mary sighed; she sat up a little straighter in her chair; she turned away her head; she stared again at the staring Queen Anne; she looked this way and that; but there was nothing in the whole room so interesting, so altogether lovely, as that bit of sarcenet, and her eye reverted still, in sidelong glances, to its first allurement. Again her soul was fascinated. Eve’s temptation was not stronger. Suddenly, she scarcely knew how or when, she had withdrawn the silken treasure; it was in her hand, but ah, its charm was gone! She hardly dared to look at it; she trembled, and felt flushed as with fever. Now could she but replace it in the drawer,—but no; it was the narrowest crack through which the fatal silk had escaped, and it could not be put back.

She sat behind her mother, and was thus screened also from the observation of Madam Fordes; but her mother would rise; she would turn towards her daughter; the eyes of both would be upon her, and then,—where could she hide her shame? At length the dreaded moment came; the conversation had closed, the ladies were exchanging the ceremonies of taking leave; from an impulse of terror, Mary hastily crushed the silk into her pocket, made her courtesy with downcast eyes, and, sick at heart, returned home.

A sleepless night had the child, and morning brought no relief. She knew nothing about moral courage; she had that yet to learn. She dared not go to her mother for counsel or comfort, as you, dear young friends, would do, not because love was lacking between them, but because in those old days it was thought right to check all familiarity in children, and to inculcate fear quite as much as love,—so different was home education then from now; so Mary kept her secret, and was miserable.

A week had passed when, one night, as she repeated her Lord’s Prayer, and asked to be delivered from evil, a good angel whispered to her—so she believed, for the thought came suddenly to her, like the sun breaking through a cloud—that the detested bit of sarcenet might be carried back.

Next day was the Sabbath, and Mary’s mother was glad to see her little one repairing to church with her usual cheerful step. After morning service the children stayed for catechism; after this, too, Mary still lingered. The good clergyman observed her, and, thinking she might wish to speak to him, came and took her hand.

“What, Mary, left behind? Well, so am I. Shall we walk along together?”

Mary could not reply, but she unclasped her fingers, and Mr. Fordes felt that something was slipped from them, and left in his hand.

“What is this?” he asked, smiling, and looked inquiringly at the sarcenet and at Mary.

“It is yours, sir,—I mean—it is Madam’s. I—I took it away, sir.”

“Took it?”

“Yes, sir, from your house when I was there. Oh! oh! I stole it, sir,” and the child burst into tears.

“Did your mother tell you to bring it to me, Mary, dear?”

“No, sir, I think it was an angel.”

The effort was made,—the first great effort, which makes all after effort easier. Mary’s heart unburdened itself to her kind friend, whose gentle admonitions sent her home strengthened and comforted.

It was a lesson that she never forgot; and I believe that the eloquence with which my dear, long-since-departed mother—for she it was—used to picture to us children the happiness of the good, and the misery of doing wrong, may be traced back to this trial of her childhood.

“Listen, children,” she would say,—“listen always for the angel voices.”

Mrs. A. M. Wells.

In the glow of the rosy western light

I met two children walking;

Each clasped the waist of the other tight,

And the faces that touched were fond and bright,

But no sound was there of talking.

Four pretty bare feet in the quiet street

Rang a faint, sweet chime in perfect time;

Two forms lithe and round were gracefully crowned

By pretty heads bare save of sunny hair;

Crossed behind two arms, clasped in front two palms;

On the setting light so ruddy bright

Gazed four full eyes, clear as June’s calm skies.

And as lilies blooming in lowly grace,

Dashed by the soil in showers,

Despite every stain reveal Beauty’s trace,

So these, low in circumstance of place,

Were lovely, though sullied flowers,—

Lovely, through many a marring trace

Of human apathy;

While fragrance stole out of that holy grace

Which draws two hearts in one embrace,

Sweet human sympathy.

Charlotte F. Bates.

When the little Traveller again came before the court and the Lord High Fiddlestick, it was with a face of wicked glee; and before my lord could open his mouth, he took a tall wax taper and a candlestick out of his pocket, and, lighting it, set it on the table, saying,—

“My Lord High Fiddlestick, here is a flame, and of course your friend Heat; but will you show me where is the force, or motion, in this candle?”

“Why, it is all in motion,” answered my Lord High Fiddlestick. “This candle is simply a stick of wax, with a cotton wick drawn through it. You light the wick. It melts the wax just below it. The cotton wick is full of tiny tubes, called capillary tubes, because they are as fine as a hair. The heat which has pulled apart the stiff wax atoms, so that we call them melted, drives and pulls them up through these hair-like tubes, and makes them into vapor, as it turns water into steam. This vapor is made of two gases, one called carbon, and the other hydrogen; and the air around the vapor is full of another substance, that we call oxygen. Now, sir, atoms of oxygen, and atoms of hydrogen and carbon, are fond of each other; so fond, though I can’t tell why, that, wherever they find each other, they are sure to rush together. They are too much in earnest to come gently and quietly, and Heat gives them so much more motion, and brings them together with such a clash, that they burst into flame. It is the swiftness and violence with which these atoms meet and struggle that makes the flame. So, you see, there is a prodigious force and motion, to strike out a white heat by their violence; and now, your Majesty, I should like to explain what I have here,” pointing to something that looked like a large wash-bowl of iron, mounted on a tall iron stick. “Doubtless your Highness remembers a miserable little country called Iceland, in which are horrible ice-mountains, and great caves, from which steam rushes roaring and hissing; and pools of mud which send up bubbles of slime; and ice-fields from which streams of water spread out over the country in dreadful swamps, so that your Majesty declined to consider Iceland as part of your kingdom, because it was too sloppy. Probably you must remember also that wonderful boiling spring called the Geyser. This spring has a tube more than seventy feet deep, and a beautiful wide basin lined with something like hard, smooth plaster. Regularly the ground shakes with a noise like thunder, the water struggles in the basin, and at last it is lifted, and, mixed with clouds of steam, is thrown high in the air.”

“I remember all about it,” exclaimed the little Prince Imperial. “That is the boiling spring where the water doesn’t boil. Our wise man said so.”

“He! he! he!” tittered the little Traveller.

“His Highness is quite right,” answered the Lord High Fiddlestick. “Water and steam burst out, and yet our wisest man discovered that the water in the tube was nowhere at what we call the boiling-point.”

“See here!” observed the King, looking with great round eyes at the Lord High Fiddlestick. “What is the Great Geyser’s receipt for that? Here we can never get our tea till the water boils.”

“I must explain first what we mean by the boiling-point,” returned the Lord High Fiddlestick. “Your Majesty will observe the water boiling in this glass vessel. You see rising through the water thin bubbles of film. These are steam bubbles. On each of these thin films the air above it is pressing. The air presses very hard: though we can neither see nor feel it, there is as much air as would weigh fifteen pounds pressing on every square inch. Why does not such a weight of air break in through these films? Simply because the steam atoms are pushing out, just as strongly as the air atoms are pushing in: so when these steam atoms that are struggling up grow just as strong as the air atoms that are pressing them down, we see the steam bubbles; and the water boils, or it is at its boiling-point. Do I make it clear, your Majesty?”

“Perfectly,” mumbled the King, growing very red, for, to tell the truth, he was taking a sly bite at a ginger-snap.

“Then you see,” continued my Lord High Fiddlestick, “that all the world has not the same boiling-point. It takes more heat to make water boil in your Majesty’s palace than on the top of a mountain; because on the mountain the air, as it rises higher, stretches out, and grows lighter; so the air atoms do not press so hard, and the steam bubbles are not obliged to make so long a fight of it. Now we can come back to the Geyser. I have here a basin of iron, on top of a long tube of iron. I have filled the tube with water. Under it, as you see, is a fire. Just so the tube of the great Geyser is filled with hot water, that rushes in from a warm spring, down deep in the earth. The water is very warm towards the bottom of the tube, but it is not quite ready to boil; that is, the steam bubbles are not strong enough to push their way up against the water above and the air which presses heavily down there. More steam rushes in at the bottom; and being cooled, or made to draw together suddenly in water-drops by rushing into water cooler than itself, it makes the thundering noise of which I spoke. But before it is quite cooled, it pushes and presses for more room, as usual. You know how strong steam is. It pushes so hard, that it lifts the water that could not quite boil up higher, where the air does not press so heavily. The steam atoms are as strong as the new air atoms, and they burst out; and the water below has a lighter weight to lift. More steam comes in at the bottom of the tube, and lifts the water still higher, where the air is lighter yet, till the steam grows so strong that it throws the water above it high in the air. See! here goes our little Geyser, and sends the water almost to the ceiling. Is it clear, Mr. Traveller?”

“Clear as mud,” growled the Traveller.

“It is a beautiful experiment,” said the Lord High Fiddlestick, looking as pink as his slippers with pleasure; “but the credit of it belongs to our wisest man. We should never have found it out, but for him.”

“If he finds out anything like that again, I will have him hung,” growled the King; “that is, if I am obliged to hear about it.”

“Before concluding,” said my Lord High Fiddlestick, “I have something more to tell you about Heat. When air is heated, it grows larger and lighter. It gets more motion, and it rises. In this way, Heat makes the winds. The sun’s rays strike on the earth, and heat it. The air just above the earth is heated, and, as I have said, it rises. You know that the earth is round, and that it turns from west to east. Your Majesty remembers, also, that the middle of the earth is called the Tropics; for when we proposed to your Majesty to settle there, your Majesty answered, that you liked the bananas and oranges, but you objected to the lions and tarantulas. On this happy country of the tarantulas the sun shines straight down. Naturally there the earth and the air are most heated. Our earth is turning around, like a wheel, from west to east, and we keep up a good rate of speed. Where this warm air rises, the earth advances a thousand miles an hour. This warm air flows out, sideways, towards the ends of the earth, called the Poles, where they only have sun six months in the year, and where the rate of speed is nothing. Now if a man should jump out of a train that was moving, you know what would happen. He would be pitched forward, in the direction that the train was going. Just so this air is pitched forward with the earth, and makes what we call a westerly wind. The warm air leaves an empty place behind it, and into this place drops the cold heavy air from the Poles. This goes on continually, and we have the two great winds called the Trades, continually sliding over each other, one going out, and the other coming in. But this is not all.”

“Sorry to hear it,” muttered the King.

“With this warm air rises the vapor of water, which Heat has drawn up from the brooks, the rivers, and the oceans. It is not mist, or anything that you can see, but is as transparent as air. As the air and the vapor rise, they stretch out, and push on every side; but by this time you know what does the work. It is Heat. The vapor atoms use all their Heat. They find themselves high in what we call space. There is no air there, and space has no heat to give them back. Their nearest neighbors are the mountain-tops, but the mountain-tops are as poor as the vapor atoms. They have given all their Heat to space, too. The chilled atoms huddle together in water drops; the water drops cling together in clouds, and come down in rain. On the high mountain peaks it is so cold, that they get a second chill, and, drawing closer yet together, come down in snow. Much of this snow falls on the sides of the mountains, where it is so cold that snow can never melt. But if this snow always remained there, by and by Heat would have drawn up all the rivers and oceans, and we should have no water, and mountains of snow, greater than our earth mountains. The snow, however, does not remain there. It slips and slides, very slowly, but steadily, towards the earth; and it pushes and packs itself together. You know how hard you can make a snowball. If you could squeeze it hard enough, you could make it into ice. Well, we have here the mountain’s snowball, sliding and packing till it turns into ice, and makes those great ice-fields called the glaciers. The glaciers slip and slide also, like the snow above them, scratching the hard rock with deep lines, and dragging along under them earth and stones. After a time, they find Heat that is strong enough to set their atoms free, and melt them into water; and this water swells the brooks, and rushes down to swell the rivers, and carries with it some of that fresh mountain earth, that the glaciers dragged along, to the fields below, where it is needed. But there is more yet to be said about Heat. This world—”

The King groaned. To commence with the world, looks as if you might talk to the end of time.

“The world,” said my Lord High Fiddlestick, “is a great Heat-market. Every body and vapor gives Heat away, and gets back Heat from other bodies and vapors. But some bodies and vapors are wholesale dealers, and some are retail dealers. A tree is a retail dealer. Its wood gives away very little of the Heat that it gets from the ground, and its bark takes in very little Heat; so that it is not likely to be injured by sudden changes in the weather. The feathers and down of a bird are small dealers. They let in, and let out, very little Heat, so that birds can wear their winter coats all summer without suffering. Dry air, that is, air without the vapor of water, is only a sales-agent in the Heat-market. It takes in vast quantities of Heat, but it lets it all out again. For instance: In the Great Desert of Sahara, the sun beats down on miles of sand, where there is no water. The sand fairly burns, and the air is like flame; but when the sun sets, the sand, which never keeps Heat long on hand, makes over its Heat to the dry air; the dry air, as usual, lets all the Heat slip through it, and the consequence is, that the nights are often painfully cold, and ice is formed. Water, on the contrary, is a wholesale dealer. It drinks in all the Heat it can get. The ocean may be called the earth’s storehouse of Heat, for it takes in Heat all the summer, and gives it out through the winter; and the vapor of water, that clings about the earth, is the earth’s blanket. All day long, it takes Heat from everything that will give it. All night long, it gives Heat to whatever needs it; otherwise, after a burning summer day, we should give away all our Heat, like the sands of Sahara, and then, having none given back, would be pinched with frost and cold. Grass is also a dealer in Heat, and at night, like the vapor of water, it commences to give away its Heat; but as the grass has a smaller stock of Heat than the water vapor, it gets through first. Of course, when it has given all its Heat away, the grass is chilled. It chills the water vapor just above it. You know what vapor atoms do when they are chilled: they huddle together in water drops, and fall on the grass, in what we call dew.”

The little Traveller was noticed here nearly double in a fit of laughter.

“The world a great Heat-market!” he exclaimed, as soon as he could speak. “Ha! ha! he! he! So Heat runs the world, does it, my Lord High Fiddlestick? Hoo! hoo! hoo!”

“Precisely,” answered my Lord High Fiddlestick. “Heat is God’s magician. He comes down to earth, almost without shape or body that we can see. He enters the air, and comes out as our old friends, the north, south, east, and west winds. He packs his bag with water vapor, and sends us down clouds, rain, snow, and glaciers. He pulls the train, and turns the factory-wheels, and prints the papers—”

“And fries the cakes,” murmured the King.

My Lord High Fiddlestick stopped in astonishment. The King was talking in his sleep. The courtiers were all nodding, too. Not a soul was awake but the little Traveller.

Exit my Lord High Fiddlestick, his nose in the air, his green satin gown under one arm, and the iron basin under the other.

Louise E. Chollet.

“Dear Sir,—It becomes my painful duty to inform you of the death of your pet, left in my keeping. A lady very carelessly left him on the piano, and in his playfulness he jumped down and broke his neck.”

The above is an extract from a letter I received during a little visit to Washington, last winter. It came in a black-edged envelope, was written on black-edged paper, and was handed to me at the breakfast-table; so, taken all in all, it might have been said to be the mourning news.

It was an announcement of the death of “Toodles.”

You do not know who “Toodles” is, perhaps? Ah, well, “Toodles” is a dog, one of the prettiest little dogs that ever were seen, with white curly hair, soft as silk, and eyes bright and black as beads,—black beads of course. He got his name from a funny trick he has of pawing at the bow of his ribbon when it slips round to one side of his neck, just as Toodles does at the ends of his cravat in the play. You have never seen the play, of course, but perhaps your papa has, and, if you ask him, it may be that he’ll show you what Toodles does, and then you will understand how funny it must be when done by a little dog.

To explain how “Toodles” came into my possession would be to tell a long story, and in this busy world of ours long stories are out of place. But I may say that he was a philopena from a little girl with whom I was eating almonds one evening. “Give and take” was agreed on. You will readily imagine the various stratagems we practised on each other; how queer things, that under other circumstances would have been seized with eagerness, were offered for examination and refused; how my curiously contrived pencil-case, that could be transformed at pleasure into a pen, a knife, a pair of scissors,—almost anything, in fact, but a boot-jack,—suddenly lost its charms for my little friend, while a wonderful doll, that would open its eyes, and cry “mamma,” and attempt to kick the clothes off on being laid in its cradle, extended its arms to me in vain, though I had long been anxious for a closer acquaintance with the flaxen-haired young lady than Miss Carrie, in her jealous care, would allow me. At last I won the day with a silkworm’s cocoon. An opportunity to see “how silk aprons growed” was not to be neglected, and Miss Carrie fell a victim to her curiosity. The next morning a little basket came to me half filled with cotton-wool. At first I thought it contained nothing but cotton-wool, and that the whole thing was one of Carrie’s famous jokes; but closer examination revealed a black nose and a pair of pink ears peeping out, and I knew what the present was. What to do with it was the next question. I was really afraid to take it out of the basket for fear of breaking it. Such a little dog I do believe was never before seen; it might almost have been sent to me in an envelope like a letter. You could take it up in your thumb and finger, as you may have seen an old lady take a pinch of snuff. I called it a watch-dog, because I could carry it around in my pocket like a watch. Indeed,—this is no exaggeration,—I often took it out, to make calls on little ladies of my acquaintance, comfortably tucked away in the inner breast-pocket of my coat.

“Toodles” was very funny in those infant days,—the days when he was an “it.” His bark was but a loud breath. You could scarcely believe that it was a real dog,—he seemed a toy-dog, or at least a burlesque on dogs generally. When he reared up on his hind legs, in real or pretended anger, we almost rolled out of our chairs with laughter. On these terrible occasions he would go over to the other side of the room, and crouch down like a lion, to suddenly spring up and rush at us, with mouth so wide open, that one could almost thrust a peanut into it, trying to utter a ferocious roar, but only accomplishing a faint whistle. Indeed, you could not believe that he was a dog,—he seemed to be something else, only playing dog. Now Toodles is larger. I have to carry him in an overcoat-pocket when I take him out of evenings, and Katy, the chambermaid, tells me that yesterday he got out two real barks. Rolling around on the floor, you would formerly have mistaken him for a ball of white wool; now, in his caperings, he looks like an animated muff, and we warn visitors against teasing him or making him angry, lest he should tear them in pieces.

To return to the beginning of my story, and proceed in regular order. When “Toodles” first arrived at my domicile, I wrote a note to the donor (if my little friends find any words here they do not understand, they must look them up in the dictionary, for they’ll have to read Carlyle and Miss Evans some day), thanking her for the gift, but asking what she expected me to do with it, and how and where I could keep it. She replied that she expected me to feed the little baby regularly, wash and comb him every day, and see that he always had a nice ribbon round his neck; and as for keeping him, if I had no other place, I must do with him what “Peter, Peter, Pumpkin-Eater,” did with his wife.

By diligent inquiry, I learned that the said Peter put his wife “in a pumpkin-shell,” and the rhyme went on to say that “there he kept her very well.” But unfortunately I had no pumpkin-shell; and a nut-shell not seeming likely to answer the purpose, I had to bargain for a box. So “Toodles” had his private box, and enjoyed himself in it quite as much as he could have done at the opera.

Just as things got comfortably settled, and working well in their grooves, business called me to Washington. The period of my absence was indefinite; it might be ten days, or ten weeks, or ten months. What to do with “Toodles” became a matter of serious consideration. I couldn’t take him with me, for he didn’t know any more about reconstruction than members of Congress do, and he couldn’t make noise enough to be a successful politician. In the midst of my trouble, a woman who lived in the same house with “Toodles” and me suddenly appeared and said she would take care of him while I was gone.

I did not then know that the woman was a witch, or I should not have accepted so readily what seemed a kind offer. She said he should be fed on rose-leaves and chicken-bones,—an excellent diet for little dogs,—that his hair should be combed and curled every day, that he should have his ears pierced and gold rings put in them, that he should have a velvet collar, too, with a gold buckle, and that she would take him out in her carriage every day to ride in Central Park.

Not knowing that she was a witch, I of course didn’t know that her only carriage was a broomstick, and that she only wanted “Toodles” to keep her company and bark at the moon when she went careering through the sky. So I innocently accepted her offer, and thanked her for the kindness,—and went to Washington.

I’m wiser now, and know witches when I see them. They have black hair, and bold features, and wear a good many rings on their fingers, and talk loudly, and find fault with everything on the table, and scold the servants, and are always finding out things about others that none but a witch could find out, and telling things about others that none but a witch or a wicked woman would tell. “Toodles” knows witches too, now, and tries to bark and bite and tear their dresses, when they come into the room. Some day he’ll eat one of them up, perhaps, and then she’ll be rather sorry, I guess, that she was a witch.

As I was saying, I went to Washington. Some two or three days after my arrival there, before I had got the national difficulties half settled, or determined what it would be best to do with the President, the letter from which the extract which begins this story is taken was brought to me at the breakfast-table. It didn’t take away my appetite, because I was already through; but it made me feel very bad indeed, and a little provoked.

“Jumped from the piano,” did he? How came he to be playing on the piano? He was not musically educated, he had no bad habits of that kind, he was not a young lady! Nor could I exactly see how, in jumping off a piano, he could break his neck,—unless he jumped from an extraordinarily high note. Had he even fallen, so much was he like a bag of wool, that beyond bounding two or three times, and bumping a little against the ceiling, no harm could have happened to him. Altogether the affair was so mysterious that I determined to investigate it on my return.

On my return, I found that the witch had flown. One morning she got on her broomstick and whisked away to Boston. But before going she told others in the house a story similar to the one she wrote to me. She sent the little dog down to her daughter’s, she said, to see something of society, and a lady left him on the piano, and he jumped off and broke his neck, and was buried in Washington Park. There was great mourning in our house; and one of the young ladies wanted to put crape on the door, and muffle the knocker, for “Toodles” was a favorite.

Some way my suspicions were excited; the piano story seemed scarcely in tune,—there was a false note somewhere, and it occurred to me that the letter I received in Washington was the one. So one day, in passing Washington Park, I stopped and asked the keeper if there had been any dog-funerals there lately. No. I then discussed the subject in all its bearings, and learned that dogs were sometimes buried there in summer; for a small consideration he dug green little graves under the trees, and planted poodles and other pets. If I examined the trees carefully, he thought I could easily discover the ones under which dogs had been buried,—by their bark. But there had been no burials since last August; that was the funeral of a fat old lady dog, a black and tan, that had been in some family for a long while, and was followed to the grave by her mistress and several descendants. The coffin was of oak, with a little silver plate inscribed “Lady Jane”; and in compliment to the greatness of the occasion and the race to which the deceased dog belonged,—he called it “breed,” I think,—the sexton-keeper filled in the grave with tan-bark instead of common earth. He would have used black and tan bark, he said, but it could not be procured. He was sure that since that illustrious interment none other had taken place; it was impossible, in fact, that one could come off without his knowledge, especially when the ground was so hard frozen that digging the grave would be the work not of a moment, but of hours.