PLATE I.—HEAD OF A YOUNG GIRL

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Vermeer

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Herbert Granville Fell (1872-1951)

Date first posted: July 3, 2019

Date last updated: July 3, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190702

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

(Mauritshuis, The Hague)

This enchanting little work, one of the most highly prized treasures of the Mauritshuis, measuring barely 18½ inches by 16, is unquestionably one of the most popular pictures in the world to-day. Yet as recently as the late nineteenth century it was sold at auction at The Hague for the sum of two and a half florins. Apart from its other fine qualities, its sculptural feeling is particularly noteworthy.

BY H. GRANVILLE FELL

ILLUSTRATED WITH SIX

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

LONDON AND EDINBURGH

T. NELSON & SONS, Ltd. | T. C. & E. C. JACK, Ltd.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Plate

I. Head of a Young Girl ... Frontispiece

(Mauritshuis, The Hague)

II. The Lace Maker

(Louvre, Paris)

III. The Guitar Player

(Iveagh Collection, Ken Wood)

IV. A Lady at the Virginals (Standing)

(National Gallery, London)

V. View of Delft

(Mauritshuis, The Hague)

VI. The Little Street

(Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

VERMEER OF DELFT

1632-1675

The seventeenth century was Holland's golden age. When Vermeer was born, Dutch culture was approaching its zenith. In that narrow land, scarce able to keep its head above water—that skeleton of a country, stretching its dislocated bones beyond the Zuider Zee in an ineffectual effort against the invasion of the Northern Ocean—were born some of the master-minds of the century. Never was a more sudden efflorescence of genius.

On January 30, 1648, after a war of liberation, that had lasted eighty years, by the Treaty of Münster the King of Spain had recognized the independence of the Seven United Provinces, and Holland had attained complete religious freedom. In the words of an eminent historian, "Holland had taken her place in the very front rank in the civilized world as the home of letters, science, and art, and was undoubtedly the most learned state in Europe."[1] Through the successful enterprising of her East India Company she had also become the foremost trading nation, and was reputed the wealthiest.

The challenge for naval supremacy with England had not yet been signalled. Peace and prosperity reigned throughout the land. Building was going on everywhere: town halls, churches, and fine houses were being erected in all the cities; the merchants and the burgher class were settling down to a life of homely comfort. It might be said that never was a time so propitious for the encouragement and development of the arts.

The painters of Holland were, during this century, overwhelmingly more numerous than those of any other country in Europe. "Every town," says Sir Robert Witt, "almost every village, produced its quota of gifted and highly skilled painters." There was no lack of patrons either at home or abroad. The traffic in pictures was enormous. Nothing can give a clearer idea of the new "picture-mindedness" of the Dutch than the entry John Evelyn made in his diary on August 13, 1641: "We arrived late at Roterdam, where was their annual marte or faire, so furnished with pictures (especially Landskips and Drolleries,[2] as they call those clownish representations) that I was amaz'd. Some I bought and sent into England. The reason of this store of pictures and their cheapness procedes from their want of land to employ their stock, so that it is an ordinary thing to find a common Farmer lay out two or £3,000 in this com'odity. Their houses are full of them, and they vend them at their faires to very great gaines."

Jan Vermeer, or Jan Van de Meer, one of the greatest of Holland's painters, and an innovator of artistic problems far in advance of his time—problems which he solved triumphantly—was born at Delft in 1632. He is a conspicuous example of the maxim that to genius it is unnecessary to travel beyond its own doorstep to find its complete fulfilment, since there is no record that he ever left his native city. Even in his lifetime he was accounted great, though it would seem that he met with little pecuniary encouragement.

Very scanty are the details of Vermeer's personal history. After his death, in 1675, he sank into all but complete oblivion. His output seems to have been small, and the works he left behind him were shared out in various attributions among artists with more popular reputations. As a better business proposition they have been marketed under the names of Pieter de Hooch, Vrel, Jan Van de Neer, C. de Man, Terborch, Metsu, Koedijck, and others, whilst in the case of his "Diana at her Toilet," now at The Hague, Vermeer's signature had been altered to that of Nicolaes Maes, and the Czernin picture, "The Painter and his Model," was brazenly signed P. de Hooch, in spite of the fact that Vermeer's signature was visible on the map on the wall.

For more than two centuries, then, Vermeer's fame was submerged, until Théophile Thoré, the art critic and collector, under the pseudonym W. Bürger, resuscitated him in his account of the Musées de la Hollands in 1858-60. This he followed up by a specific article on Vermeer in the Gazette des Beaux Arts in 1866. Bürger, with all the optimism and confidence of a discoverer, made out a list of some seventy-two pictures attributable to Vermeer, all of which he thought warrantable enough. At the time of the Exhibition of Dutch Art, held at Burlington House in 1929, only forty-one pictures had been assigned to him by general consent as indisputable.

It was Bürger's essay which formed the starting-point of Vermeer's present-day reputation. In this article he refers to the painter as the "Sphinx of Delft," and a later biographer, J. Chantavoine, adds, "He is indeed a mystery, a closed book that will reveal little to any interrogator." We may have a clue to his appearance, and that a back view only, in the above-mentioned Czernin picture at Vienna. It may well be that this portrait represents the artist and the interior of his studio at Delft, since the appurtenances therein reappear so constantly in his works. The picture itself is an enigma. "It may be," says Chantavoine in a fanciful speculation, "that the female figure is his wife or his daughter, dressed as Fame, as though to proclaim his renown—this oddity of a female, trumpet in hand, with her laurel crown and her book inscribed with the names of the illustrious dead. The artist is well, even foppishly, dressed. He has given us a picture of his fine clothes (he is wearing scarlet stockings, and has white tops to his boots), and, judged by the relative statures of the two figures, appears to be of giant height—or the lady to be extremely diminutive."[3]

Vermeer was baptized in the Oude Kerk of Delft on October 31, 1632. His father's name is given as Reynier-Janssoon (son of Jan) Vermeer, and his mother's as Dignum Balthasars. His godparents were Jan Heijndricz Bramer and Maertje Jan. There is presumptive evidence that he became a pupil of Carel Fabritius[4] (1624?-54), who himself had worked in the studio of Rembrandt. In any case, the influence of Fabritius is definitely seen in The Hague "Diana at her Toilet," and is still more marked in another work, "The Unmerciful Servant," accepted as genuine by Dr. Bode, and now in the possession of Lord Rothermere.

In his twenty-first year, on April 5, 1653, in the poorest circumstances, Vermeer married a townswoman, Catharina Bolenes. On 29th December of that same year he was admitted as a master-painter to the Guild of St. Luke. Membership involved payment of six gulden of which Vermeer was able to find only one gulden ten stuyvers. In 1654 he was forced to raise a loan, yet the balance remained unliquidated until July 24, 1656—two and a half years later. Apprenticeship to the Guild lasted six years, so that he must have been bound at the age of fifteen.

In 1656 Vermeer painted "The Courtesan," now at Dresden, the only work by him that bears a date. This picture, so rich in colour and so full in impasto, misled Bürger (who must have omitted to notice the date on the canvas) into supposing that Vermeer had received direct instruction from Rembrandt, professing to see in it a derivation from Rembrandt's "Syndics," which was not painted until 1661.

In 1661, 1663, 1670, and 1671 Vermeer was one of the Headmen of the Guild, serving on the Committee, and in 1670 he was elected President. Havard[5] has put forward a theory that Leonard Bramer, brother to his godfather, who had preceded him as President of the Guild, was his real master.[6]

Judging from Vermeer's limited production and from the facture of his pictures, he was clearly a fastidious and deliberate worker. This, doubtless, stood in the way of his worldly success. "Between 1656, the year of the Dresden picture, and 1675," says the excellent 1913 catalogue to the National Gallery, "Vermeer painted probably not more than thirty pictures." That he was a man capable of the last refinements of taste is evident, and undoubtedly he was extremely self-critical and difficult to please. It is hard to determine the exact amount of consideration Vermeer received during his lifetime. He was always in difficulties, and he may have been improvident. It is said that "he enjoyed a vogue and reputation" (National Gallery Catalogue, 1913), and Sir Robert Witt says "he was worshipped even in his lifetime." We must therefore assume that his works were readily bought. But his early marriage and his large family were a desperate handicap, and Vermeer was not given to "pot-boiling." Yet in no known work of his is the least sign of stress or mental strain. He only worked when the mood was on him.

In the year 1663, when M. Balthasar de Monconys, a French amateur of the arts, visited Delft, he called upon the painter in the hope of seeing some of his works. As there was nothing whatever to show in the studio, Vermeer took him to the house of a baker in the neighbourhood. Here he was shown a single-figure subject valued at 600 livres, and probably taken in pledge for goods received. Vermeer must have been in the habit of paying this accommodating tradesman in pictures, for we are told that ten years later Madame Vermeer entered a lawsuit against a baker who held two of his works in pledge for a like amount. Vermeer's own pictures bear witness that money went to the acquisition of paintings and handsome furnishings for his studio.

Vermeer dwelt in a house on the Oude Landick (the Old Long Dyke), where he died in extreme poverty in 1675, at the age of forty-three, and was buried in the old church, leaving a widow and eight helpless children. Upon his death his widow was compelled to pawn three of his pictures to relieve their immediate necessities. One of these, which she pawned to her own mother, was the Czernin "Painter and his Model," to which we have referred (an additional reason for supposing it to be a family portrait), and the other two were pledged to the baker—which Madame Vermeer reserved the right to re-purchase. These two were the "Love Letter" of the Otto Beit Collection, and a "Guitar Player."

It would seem that certain pictures were in Vermeer's studio at the time of his death. The Encyclopædia Britannica says: "At his death he left twenty-six pictures undisposed of. His wife had to apply to the Court of Insolvency to be placed under a Curator. This was Leeuwenhoek, the naturalist." These pictures may have been pledged or gradually sold by the trustee to Jan Coelembier, a painter and picture dealer of Haarlem, since it is recorded that he had that exact number in 1676. "There were also the nineteen 'Schilderijen van Vermeer' in the possession of J. A. Dissius, the printer, of Delft, at his death in 1682, and of course some or all of these may have passed through Coelembier's hands. We have in the Catalogues of G. Hoet (Vol. I., p. 34) a list of twenty-one pictures by Vermeer which were sold by auction at Amsterdam on May 16, 1696, and of these all but six are known to us. The list, with the prices obtained for them, is as follows:

Gulden.

1. "Young Woman weighing Gold" . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

2. "The Cook pouring Milk" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175

3. "Vermeer in an Interior" (the Czernin picture?) . . . 45

4. "Young Woman playing the Guitar" . . . . . . . . . . 70

5. "A Gentleman in an Interior" . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

6. "Lady and Gentleman at a Clavichord" . . . . . . . . 30

7. "Young Woman receiving a Letter from her Servant" . . 70

8. "Drunken Servant asleep at a Table" . . . . . . . . . 62

9. "Merry Company in an Interior" . . . . . . . . . . . 73

10. "A Lady and Gentleman making Music" . . . . . . . . . 81

11. "Soldier and Laughing Girl" . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

12. "The Lace Maker" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

13. "View of Delft" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200

14. "House at Delft" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

15. "View of some Houses" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

16. "Young Woman Writing" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

17. "Young Woman at her Toilet" (Pearl Necklace) . . . . 30

18. "Lady at the Virginals" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

19. "Portrait in Antique Costume" . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

20 and 21. "Two Pendants" . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Various attempts at the chronology of Vermeer's pictures have been made; the most recent by Dr. Valentiner in The Pantheon of October 1932. Dr. W. Bode and Dr. C. Hofstede de Groot, the best accredited authorities on the subject, agree in thinking that the earlier works were induced by some Italian influence, possibly through Gerard Honthorst (familiarly known in Italy as Gerardo delle Notte). He it was who brought the Caravaggio tradition from Rome. Another possible source of influence was Terbruggen. The tradition of heavy shadow became lightened in transplantation to a northern climate where the shadows fall less abruptly; and in such a painter as Terbruggen, while the design remains Italianized, the whole key has become transposed and approximates more nearly to the plein-air vision we associate with Vermeer.

Amongst the earliest works, then, we place "Christ in the House of Mary and Martha," now in the Edinburgh National Gallery; the "Diana at her Toilet," in the Mauritshuis at The Hague; and, if genuine, the picture entitled "Lot and his Daughters," in the Hertz Collection at Hamburg. The last named is certified by Professor Willem Vogelsang, Director of the Kunstistor Institute, Utrecht. These are of unmistakably Italian origin. Following would come the more Fabritian works in which the transmission of the Rembrandt influence is evident. Amongst these we should mention first (unless it be a work by Fabritius himself) "The Parable of the Unmerciful Servant," in Lord Rothermere's collection, accepted by no less an authority than Dr. Bode. Next would come "The Procuress," known also as "The Courtesan," at Dresden; and then the "Portrait of a Young Woman," at Budapest. The middle period, in which the colours are dry, and fairly thickly applied, with a roughish surface, but less so than in the first period, contains such works as the "Woman pouring Milk" and the "Woman reading a Letter" of the Rijksmuseum, the "Soldier and Laughing Girl" (Frick Collection), the "View of Delft," at The Hague, and the "Little Street" of the Rijksmuseum, painted about, or soon after, 1656. Next would come "The Lace Maker" (Louvre), the technique becoming more closely knit, smoother, and more porcelain-surfaced, until we reach those works which we recognize as being in the most typical and personal manner of the master. These comprise the Windsor "Lady and Gentleman at a Clavichord," "Lady at the Virginals" (standing) in the National Gallery, London, Mr. Mellon's "Young Woman in a Red Hat," the "Lady writing a Letter" (Beit Collection), the "Young Lady with a Flute" (Widener Collection), "The Pearl Necklace" (Berlin), "Head of a Young Girl in a Turban" (Hague), "The Painter and his Model" (Czernin Collection), "The Love Letter" (Rijksmuseum), "The Lady at a Window with Ewer and Salver" (Metropolitan Museum, New York), and the curious allegorical subject, "The Faith," now in the Friedsam Collection in New York. Thus, although, as we have said, the exact chronological order of Vermeer's pictures is unknown, the stages of his development would seem to be clearly indicated.

If we speak first of Vermeer's so-called religious or Italianized works, they need not detain us long. Other painters have excelled him in this province as completely as he outdistanced them in the genre which he was to make peculiarly his own. Not here is the evidence of Vermeer's delight in his discovery and deep preoccupation with the problems of all-pervading daylight. But there is already some sensitiveness to it in his manner of illuminating his figures.

There is little or no religious mysticism in the painting of seventeenth-century Holland. The art of a free and Protestant state did not concern itself with religion in its spiritual aspects as did that of its opposite number, Spain. Instead of meditating upon salvation as attained only through intensity of suffering or of subduing the flesh by torture and cruelty, the Hollander looks out upon life with joy in his heart. All is physical well-being. The Dutchman has reconciled his faith with a joint of good beef and a flagon of ale, and it was no uncommon thing to paint these agreeable concomitants of existence in the forefront of his religious pictures. Save in the solitary instance of Rembrandt, there is no introspection in Dutch art. All trace of it was swept away with the religious wars.

"Christ in the House of Mary and Martha," now in the National Gallery of Scotland, is an unusually large canvas for Vermeer, but not, of course, for a subject of its kind. It measures 62½ inches by 55½. A furniture dealer came across it in Bristol and purchased it for the trifling sum of eight pounds. It passed into the Arthur-Leslie Collection, was sold to Mr. Paterson of Old Bond Street, and thence found its way to the W. A. Coats Collection at Skelmorlie Castle. The Royal Academy Catalogue of the Dutch Exhibition of 1929 describes it thus: "On the right Christ sits in an armchair at a table. He speaks to Martha, who stands behind the table holding a basket of bread. He points out Mary to her, who sits on a stool at His feet listening attentively to His words. Some repainting by the artist may be seen in the left hand of Christ. Signed on the stool: J. V. Meer." This work shows the unmistakable assimilation of Italian baroque influences, and from its similarity of handling has helped to establish the authenticity of the "Diana" at The Hague. The two pictures, in fact, corroborate one another.

As regards the "Diana," this "unlike" picture by Vermeer was purchased in Paris from the Neville D. Goldsmid (removed from The Hague) sale in 1876 as a work by Nicolaes Maes; and as we have said, falsely so signed. In the catalogue of The Hague Picture Gallery of 1895 it was ascribed to Vermeer of Utrecht, and only since the coming to light of the "Christ in the House of Mary and Martha" has it been definitely recognized as by Vermeer of Delft. In the picture the goddess is seated facing to the right, a crescent on her brow. About her are grouped her attendant nymphs, one of whom bathes her feet. To the left is a hound. The composition is rather huddled, and the light and shade patchy. The background is a thicket of dark trees. The canvas measures 38½ inches by 41½.

Whether "Lot and his Daughters" should ultimately prove to be by Vermeer, as attested by Professor W. Vogelsang, or not, there is no trace whatever of religious sentiment about it. It comes within the category described by Mr. R. H. Wilenski, in his Introduction to Dutch Art, as semi-lascivious subjects treated in a classical manner, for which there was always a demand. The Biblical derivation of the subject was merely a pretext. It was a subject quite frequently employed by a number of Italianized Dutch painters. In this example Lot is seen drinking from a cup which one of his daughters is handing to him. The other holds the wine-jug, beside which is an apple, grapes, and other fruits. The scene is set in a cave or place of high rocks, only a glimpse of sky being visible at the top left-hand corner. There is nothing intrinsically characteristic of Vermeer to interest us in the picture.

More exciting in every way is Lord Rothermere's "Parable of the Unmerciful Servant." This picture was discovered in England within recent years. As we have remarked, it has been accepted by Dr. Bode, but the supposition that it may be by Carel Fabritius is strong. It is solidly painted, full in colour with a Rembrandtian effect of light and shade. The light comes from a window to the left, falling upon a table covered with a Turkish rug, upon which are some manuscripts. The principal figure, that of the master, appears as a turbaned Turk. The three other figures have their heads bunched in a heap, a not too happy arrangement. The nearest figure is a dwarf in slashed and parti-coloured sleeves. A scarlet cloak is over his shoulders, and a short sword at his side. The picture is dramatic, but there is not much hint yet of the ultimate Vermeer.

Yet it does bring us closer to an unquestionable work by Vermeer, namely, "The Procuress" or "Courtesan" of the Dresden Gallery—a canvas both signed and dated, and the only date appearing on a picture by Vermeer accepted as valid, the year being 1656. The impasto is thick and solid. It contains four life-sized figures. A cavalier in a scarlet coat and plumed hat looks over the shoulder of a girl wearing a white lace-edged cap and canary yellow bodice. He has placed a large fat hand over her left bosom, and with his other hand offers her a piece of money. The girl is holding a glass half-filled with wine. The old procuress leers up at the man from behind his shoulder and offers him drink. The fourth figure is a smiling and enterprising looking cavalier in slashed sleeves and a large hat. A darkly patterned Turkey carpet of red and blue occupies the foreground. The marks of an alteration are clearly visible on the girl's bodice, from which a large collar of white lace has been removed. This, no doubt, Vermeer felt to be disturbing to the effect of the broad simplicity of the central mass of light. Yet it is still the least placid of all his pictures, the most restless in action, and the hottest in colour. Somehow the entire composition crowds too closely upon us. It stands apart in Vermeer's oeuvre by reason of its subject, and though one common enough in Dutch art, it is the only picture of bordel life we have from his hand, unless we so interpret the "Soldier and Laughing Girl."

Unless there is a break in the chain here, the missing links of which are yet to be found, we are now fairly launched upon the high tide of Vermeer's maturity, into which he seems to have swept with astonishing swiftness. The secret of his genius is that he united in his person no fewer than three distinct excellences, and these he possessed in supreme degree. The first of his qualifications is his faultless technique—at once the admiration and despair of all who practise the art of painting. Yet this is perhaps the least important of Vermeer's merits in considering his place in art history. Others have approached him in this respect. Nearly all the painters of consequence of his time, and especially those of Holland, had mastered their craft—and mastered it thoroughly—having received instruction through their Guilds as apprentices to some selected master. In the two other respects Vermeer was a great innovator. With Fabritius and Pieter de Hooch (1629-83) he was amongst the first to perceive that daylight was cool and permeating, and that all objects seen through it are bathed in and affected by it, and not projected in isolated roundnesses or reliefs of enforced light surrounded by shadow.

It is probably through Fabritius that Vermeer came to open his eyes so completely to the plein-air aspect of things. No one who has seen the marvellous little picture of a goldfinch[7] by Fabritius at The Hague (shown at the Royal Academy in 1929) can have failed to be delighted and astonished at its masterly breadth and its apprehension of out-of-door daylight. Trifling though the subject may be, it is one of the world's most perfect examples of pure painting. It is to our eternal regret that Fabritius died (it is said) in his thirty-first year, having been blown up in the explosion of the powder magazine at Delft, and presumably the bulk of his pictures went with him.

Lastly, Vermeer was the inventor of a system of pictorial geometry which he perfected and applied in a scientific manner. The result is that all his best pictures are distinguished for their rhythmic balance, cohesion, and orderly distribution of parts. So deliberately built up are his compositions that they would seem to have been arrived at by means of working diagrams. Whether this be so or not, and no working drawings are known to us, one and all bear evidence of most scrupulous care in planning, as though to leave no room for margin of error. He makes continual use of opposing squares—on the flat, diagonally arranged, and in perspective. These are frequently crossed by the long, sweeping lines of a partly drawn curtain, so that we get the illusion of looking into a room—at just so much of what is going on in the picture as can be seen satisfactorily at a glance. The accessories are few and well chosen, just so many as will complete the scheme, and these are placed with an almost uncanny rightness. Hence the extremely decorative effect of Vermeer's pictures, and the fascination they exercise upon all who are susceptible to the subtler elements of design. For the purely anecdotal side of painting Vermeer had little use. He realized that the most decorative effects in a picture are, after all, a question of mathematics—rigorously applied. It is quite as much by subtraction as by addition that perfection of harmony is reached. Indeed, without voids and spaces in their right occurrence there can be no harmony. Vermeer's eye for spacing, for proportion, and for rhythm was as faultless as his sensibility to tone and colour.

(Louvre, Paris)

A tiny canvas, measuring only 9½ inches by 8. So finely designed, and so broad in effect as to convey an impression of much larger scale. Observe the exquisite taste in the arrangement of the coloured silks, vivified by the brilliant vermilion note, and how, in spite of the crispness of touch and clearness of definition, everything keeps its place without conflict or confusion.

There is withal something mysterious about Jan Vermeer, some exceptional quality of austerity, some coolness of temper and aloofness that escapes every vestige of the claptrap and the commonplace, and which is very rare in art. This exclusiveness of mind and aristocratic temper in his work—the exact reverse of blatancy—may have accounted for his limited patronage in his lifetime and his long subsequent neglect. I have noted elsewhere, and repeat it here, that no art has ever been truly popular, and no artist has ever been materially successful, unless there has been an element of claptrap or touch of vulgarity in his work, and this especially applies in a democratic community. There is either a flattering verisimilitude, a false brilliancy, a sleek polish, or a theatrical effectiveness—all of them meretricious and superficial qualities—and it is the percentage of base metal in many of the greatest painters that accounts for their popularity. But there is no breath of vulgarity of any kind in Vermeer. His taste is fastidious to the point of impeccability. Is any proof needed? Miereveld, Van de Heist, Van de Werff, Pynacker, Wowermans, Gerard de Lairesse, lived and died rich men. Hals, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Ruysdael, died neglected, beggared, and forgotten.

The Dutch bourgeoisie liked to be amused with a homely story, and the wealthier classes loved to ape Italian culture. Hence the Italianized painters of the picturesque convention reaped a rich harvest, whilst Vermeer, the incomparable craftsman and artist of impeccable taste, was left in the cold. Such works as his could only have appealed to the intelligentsia, but amongst these there is seldom money to spare. The wealthier section of the community consisted almost entirely of the merchant class.[8]

It is only within the past half-century that Vermeer has received anything like his due meed of appreciation. But his reputation has grown so enormously that his market value has increased more rapidly and risen higher than that of any other painter. As recently as the late nineteenth century the enchanting little "Head of a Young Girl" at The Hague was bought at auction in that self-same city by M. A. A. des Tombe for the sum of two and a half florins, though in mitigation of the oversight on the part of the sellers it was said to have been in a state of deplorable obscurity. This little gem fascinates every beholder, and is assuredly the most coveted picture in the world to-day, as it is one of the most popular. It was painted at the peak of Vermeer's maturity, and on account of its popularity we give it pride of place here.

The canvas is barely 18½ inches high by 16, showing the head and shoulders only. It is of a cool grey scheme, the colour resembling the soft tints of those choice Delft wares that had recently been created in the city[9] and were coming into fashion everywhere. The little girl turns her head towards us archly with a bewitching appeal in her dark eyes. Her lips are slightly parted—full, red, and moist. She wears a turban head-dress of Delft blue and pale crocus yellow; a grey gold cape or jacket is over her shoulders; a large pearl decorates her left ear. The accentuation is perfect; so adjusted in its relation to the dark background as to give the utmost relief to the rounded contours of the head. Though enveloped in air, it yet preserves a sculptural solidity. Every brush mark is concealed except the positive accents—softened into the flesh, and leaving it undisturbed by any chance roughness of pigment that may lessen the illusion of reality. Mr. E. V. Lucas refers (if my memory serves me) to the curve of the cheek as the subtlest and most beautiful line in the whole of painting. It is a triumph of the painter's craft. The canvas is signed in the upper left-hand corner, J. V. Meer, the initials interwoven. It was bequeathed to The Hague Picture Gallery by M. A. A. des Tombe in 1903, and was graciously lent by the Gallery to the Royal Academy Exhibition of Dutch Art in 1929.

A small canvas measuring 15¾ inches by 12¼ of a "Head of a Young Girl," showing somewhat similar characteristics was lent by the Hon. Andrew W. Mellon, late United States Ambassador, to the Royal Academy at the same time as the above. It was described in the catalogue as "Bust portrait, turned left, showing a part of the back with the head turned over the left shoulder. Her eyes are directed towards the spectator; a smile illuminates the face." It was acquired from Herr Walther Kurt Rohde of Berlin in 1926. Besides this was a diminutive canvas of 8½ inches by 7½, belonging to Mr. E. W. Edwards, showing a bust "Portrait of a Lady," also turned to the left and looking towards the spectator. It is accepted as genuine by Dr. W. Bode, Dr. Hofstede de Groot, and Dr. Max Friedlander.

For evidence of the claim made for Vermeer as the most scientific of designers, we must turn to his more elaborate compositions. Simple as they look, each is based upon a geometrically conceived plan, into which all the parts interlock and are dovetailed together with the deliberation of a Chinese puzzle. Yet even so simple a design as the little girl's head in The Hague has been conditioned by Vermeer's researches and cast of thought. This is seen in its perfect poise and relation of parts, its strong sense of rhythm in unity, the hall-mark of style, and the distinguishing sign of masterhood.

Vermeer's single figures—such a figure, for example, as the "Girl in a Red Hat," belonging to Mr. Mellon—exhibit an incredible largeness of design and amplitude of form when the small scale of the work is considered. To say that this merely depends upon due recognition of proportion between parts and the suppression of all petty inessentials is to state a self-evident truth, but as artists know, of all qualities it is the most rare and the most difficult of attainment.

One of the simplest in construction of the figure compositions, and perhaps one of the earliest, since it has some affinities with the Dresden "Courtesan," is the "Soldier and Laughing Girl." It was formerly in the collection of Mrs. Joseph of London, who was, however, tempted to part with it to Mr. Frick of New York. "Painted about 1656," says Sir Robert Witt, "time was when it masqueraded gaily under the forged signature of Pieter de Hooch." The design is boldly conceived, the large hat and red coat of the cavalier in the foreground massed in broad silhouette and nearly filling a quarter of the picture. Beyond this is seen, isolated in clear light drawn from the window opposite her, the smiling face of his female companion. The black roller of the map which hangs from the wall cuts just below the top of the lady's head, so that map and wall, down which the light pours, take their place definitely in the same plane behind her. The girl's head is focused in this space with the rarest skill. The upper parts of two lion-headed chairs and the glass in the lady's hands, together with a fraction of the table top, are the remaining furnishings of the picture. The pitch of the open window against which the cavalier's hat is projected has also been carefully considered. The field of vision is as usual limited by the back wall, but the "shut-in" feeling is relieved by the partly opened window. The whole of the picture beyond the dark red mass of the man's figure is bathed in cool, clear light in which tones of blue, grey, green, and yellow interfuse. The pointillist spotting of the table-cloth cannot fail to be noticed. It is an early example of this method of treatment, and no doubt was an independent discovery of Vermeer's. It occurs on several occasions in his work: in the speckled brown loaves in the "Milk Woman" in the Rijksmuseum, in the "Gold Weighing Woman," and in the Delft views.

(Iveagh Collection, Ken Wood)

When Vermeer died, this picture, together with "The Love Letter" (collection of the late Sir Otto Beit), was given as security by the painter's widow for a debt of 617 florins. The composition is particularly interesting, as the great void in the background, to the right—nearly half the space of the canvas—is satisfactorily occupied solely by the introduction of the book with red edges. An exquisitely painted landscape hangs upon the wall.

Vermeer's taste for decorative accessories expresses itself in a marked form in his use of maps. There is a map of Holland in the "Soldier and Laughing Girl," and another, with views in the border, in "The Artist and his Model." The skill with which this latter map is painted, especially the light breaking across its cracks and irregularities of surface, is almost incredible. Tapestries had been employed for the enrichment of backgrounds before, but as Mr. E. V. Lucas says, "Vermeer was the first to perceive the decorative possibilities that lie in cartography." Gabriel Metsu, who borrowed frequently from Vermeer, has a map on the walls of his "Sick Child" at The Hague.

Holland was at that time a centre of mapmakers. Perhaps Vermeer's maps were the work of Willem Jansz Blaeu, the most advanced cartographer of his age.[10]

The figure of "The Geographer" or "Cartographer," a wonderful picture by Vermeer at Frankfort, in the Rembrandt-Fabritius tradition, may represent, as Mr. Lucas suggests, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, who was born in the same year as Vermeer, and became his executor.[11] There are three versions of this "Cartographer," two of them fine and unquestionably authentic, the third (in the collection of Mr. Edouard Jonas of New York) suspect. The first and incomparably the finest version, that of the Frankfort Museum—its noble composition alone would make it memorable—shows the geographer leaning forward over his table, compasses in hand. The light from the window (which, with Vermeer, is nearly always to the left of the observer) travels downwards across his maps and the crumpled carpet-cloth on the table, and falls sharply upon the rolled-up scrolls on the floor, where it is checked abruptly by a stool placed at an angle to the picture plane. In the background is a tall cabinet upon which stands a globe—telling as a solitary circle, in diminished tone. The picture is very finely built up of square forms traversed by a broad diagonal of light, and gives an impression of simple grandeur. The date upon it, 1668, is not accepted as genuine. The same youngish, long-haired model sat for the second "Geographer" in the Edouard de Rothschild Collection in Paris. Here the figure is seated—in the same room—and is turning the globe with his fingers. Both, in their subject-matter and their broad chiaroscuro, remind us of Rembrandt's "Philosophers."

An important number of Vermeer's canvases have for their subject-matter a single female figure, seen either at half-length or three-quarter length. In all probability the sitters for several of these were his wife and members of his family. Especially do we like to believe that the Amsterdam "Young Woman reading a Letter," one of the finest of them all, is a portrayal of Madame Vermeer. But we must first speak of the rather puzzling and far less attractive half-length portrait in the Budapest Gallery, which we suspect to be a comparative early work. It is that of a rather unprepossessing-looking woman in middle age. This picture is in the Van de Heist, or the still earlier Mireveld, convention in the matter of design, though smaller in scale. The lady faces the spectator, her figure turned slightly to the right. Her hands are clasped, the one gloved, the other glove and the fan suspended from them rather in the manner of the Franz Hals portrait (No. 2529), "Lady with a Fan," in our National Gallery. She wears a broad white collar and a coiffed hood, which looks like the dress of an earlier date. Can this be No. 19 of the Amsterdam Catalogue, the lost "Portrait in Antique Costume"?

But with the "Milkmaid" of the Rijksmuseum, variously known as the "Maidservant pouring Milk" and "The Cook," we are again in the presence of the essential Vermeer. This picture is also believed to date from the artist's earlier period—though in so short a life the changes are necessarily small. It was catalogued as No. 2 in the Amsterdam sale, and its movements have been traced until it found a resting-place in the Six Collection at Amsterdam[12] early in the last century. In 1907 it found its present home, whence it was loaned to the unforgettable Dutch Exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1929. This purposeful-looking maidservant, brawny and capable, stands just beyond a table covered with a green cloth over which hangs another cloth of blue, flanked by a basket of bread and some fragments, a jug of blue Nassau earthenware with a pewter lid, and a stone pot into which she is pouring some milk from another jug. A basket and a brass container hang upon the wall near the window, which is placed rather high to the left of the canvas. Upon the floor is a square brazier or foot-warmer placed diagonally and cut by the line of Delft tiles which forms the skirting. The design is very compact, and the figure maps itself against the bare wall in a silhouette of great beauty and variety of line. The colour scheme is clear and cool, made up of blues, yellows, and pale browns: the woman's underskirt is of a dark, quiet red, and both figure and utensils are brought out into strong relief by the sunshine that streams over them, and, in a more tempered key, down the wall. The play of light over a bare wall in its infinite gradation had a particular fascination for Vermeer, and no painter, not even a Dutchman, has rendered it with such marvellous truth and felicity. The picture is of the usual small dimensions, measuring 18 inches high by 16¾, and yet how large it appears and how it fills the eye![13]

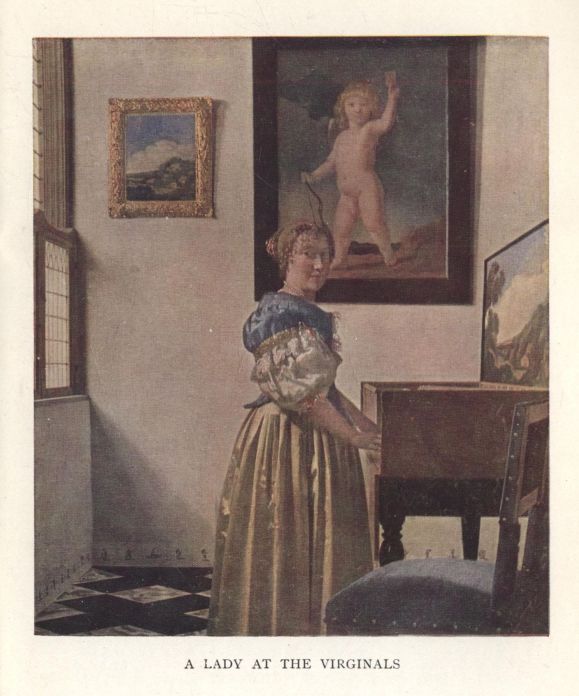

PLATE IV.—A LADY AT THE VIRGINALS (STANDING)

(National Gallery, London)

Acquired for the National Gallery in 1892. Its cool interior lighting is typical of Vermeer. Crisp sunny touches play about the edges of the lady's dress, and the scarlet bows enliven a colour scheme of extraordinary charm. There is an exquisite stillness about this picture.

About this period Vermeer is said to have painted the "Woman Asleep" (sometimes called "The Drunken Servant"), and the "Woman weighing Gold" in the Widener Collection, Philadelphia. The former is now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York, whither it came through the Altman Bequest. It is of undoubted quality, painted in Vermeer's characteristic colour scheme, a harmony mainly of blues and yellows. The young woman is depicted given up to her lassitude, her head resting on one hand, leaning over a table upon which are an Eastern rug, a dish of apples, chestnuts, and a beautifully painted white jug of Delft ware. A lion-headed chair occupies a space to the right. In the background is a mirror reflecting part of the room, with pictures on the wall and a covered table. The "Woman weighing Gold" wears a dark blue velvet jacket trimmed with ermine, and a white head covering. The composition is of squares, relieved by the contours of the figure and the crumpled dark blue rug on the table. There is a jewel chest with pearls. A Poelenburg-like picture hangs upon the wall behind her. This work is of undoubted pedigree, figuring as No. 1 in the Amsterdam Catalogue.

The same largeness of design that distinguishes "The Milkwoman" reappears in an enhanced degree in "A Young Woman reading a Letter," also in the Rijksmuseum. Its dimensions are almost identical, differing a bare half-inch each way. In his balancing of the shapes of light and shadow Vermeer has achieved here an effect of breadth and a simplicity of design that he never again reached. It is in this respect undoubtedly his high-water mark. Shorn of all but the barest accessories, there is not a disturbing note in the composition. As in the case of the Frankfort "Geographer," the light falls diagonally from the left-hand upper quarter (no window is seen), flows in luminous gradation down the wall, embracing the front part of the figure in an enhanced brilliance, to be broken by its shadowed back, and finally arrested by the chair leading out of the opposite side of the picture. The comely young woman, whom we have taken to be the painter's wife, stands in the centre of the picture at a table reading a letter. She is wearing a padded dressing-jacket of blue velvet, fastened down the front with ribbons, and is clearly enceinte. Upon the broadly shadowed table, covered with its usual cloth, is a desk, or deed box. A large map hangs upon the wall, and in the lion-headed chair-back the blue note is repeated, modified by the illumination. There are no perspectives thrust into the room to aid the recession. The composition is superbly reposeful and complete.

A variation of the letter-reading theme is seen in the far more elaborate but less satisfactory design in the Dresden Gallery's "Girl reading a Letter." She also is a prepossessing young woman. Her hair is treated à la "Dentellière,"[14] and the dress is the same as that worn by the young woman in the "Soldier and Laughing Girl." The figure is small in relation to the picture area, and is placed rather low on the canvas. The nearness to it of the window frame (in the panes of which the girl's head is reflected) seems rather to overpower it, and almost a third of the canvas, from top to bottom on the right, is occupied by a curtain hanging from a rail. It is a curious device, as though to convey the illusion that it is intended to be drawn across the picture to cover it from sight. The composition is, however, the result of very deliberate planning. The foreground, as in so many others, consists of a table covered by an Oriental rug in disarray. Upon it, tilted upwards towards the window, is a dish of Delft ware containing various fruits, and the corner below the window is filled by a chair-back. The painting is as exquisite as mortal hand can make it.

Another of these "Window" pictures is in the Metropolitan Museum of New York. It was formerly in the Marquand Collection, whence it passed to Mr. Jameson, who presented it a year or two ago. It represents a lady in a deep blue dress, relieved by a salmon-pink bow, and wearing a white hood and capelet, her right hand resting upon the casement, which projects into the room. This picture is especially noteworthy for the faultless painting of the silver ewer and salver in which the reflections are expressed with marvellous skill. Again great play has been made with rectangular forms, projected at different inclinations. In the background is the inevitable chair with the lion heads. The effect of permeating light which floods the picture is another of its great charms.

Still in the same category, and still more wonderful in its all-pervading radiance, is the exquisite "Pearl Necklace" in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum at Berlin. Here the lady is wearing a yellow satin jacket trimmed with ermine. She has a salmon-coloured bow in her hair. There is dark blue drapery on the table, a Chinese covered jar, a hand-brush, and to the right of and behind her is a chair. She is looking across the table into a small mirror whilst she adjusts her necklace. The window and the bare wall complete the scheme. Of this picture Mr. E. V. Lucas rhapsodizes in the following eloquent words: "After the 'Head of a Young Girl,' at the Mauritshuis, and the 'View of Delft,' it is, I think, Vermeer's most enchanting work. The white wall in the painting is beautiful beyond the power of words to express. It is so wonderful that if one were to cut out a few square inches of this wall alone and frame it, one would have a joy for ever.... The whole picture has radiance and light and delicacy; painters gasp before it. It has more, too; it is steeped in a kind of white magic, as the 'View of Delft' is steeped in the very radiance of the evening sun."[15]

We must now describe three tiny works, smallest of all in scale, but of most precious quality, so finely designed and broad in effect that the impression of size they create is not to be measured by inches. The best known of the three is the dainty "Lace Maker", the "Dentellière" of the Louvre, a canvas of only 9½ inches by 8. The sitter has brown hair and a blond complexion. Her dress is of yellow satin with a deep collar of lace. Intently she leans over her work, her fingers busy with her bobbins. The pillow and octagonal tambour upon which they are employed stand on a wooden frame. To the left (her right) is a pillow-covered case of blue velvet with three white stripes, a book, and various coloured silks in which white and scarlet skeins predominate. The light falls from the right-hand front. On the wall is the painter's signature, with the initials in monogram. The picture is wrought with the utmost precision in every detail, firm in drawing, and crisply accentuated, with a remarkable breadth of effect. In this last respect we cannot fail to remark the difference between the quality of Vermeer's finish and the excesses committed by Gerard Dow and his pupil Franz Mieris and—so facile is the descent—those still worse excesses of Willem van Mieris.

(Mauritshuis, The Hague)

Seen on a summer evening through the milky sunshine of Holland. In this work Vermeer proved himself a pioneer of modern landscape painters. It is perhaps the earliest known example of luminist painting; that is, of consciously striven-for atmosphere, illuminated by the permeation of the sun's rays, the perception of which slumbered until reawakened in John Constable, who was born a hundred years after Vermeer's death.

Secondly comes Mr. Andrew Mellon's "Young Woman in a Red Hat," which to my mind is unsurpassed in brilliancy of handling and largeness of design by any work of its scale, although smaller by a fraction even than "The Lace Maker." About a century ago (1822) it was one of the gems of the Lafontaine Collection in Paris, and I think it afterwards came into possession of W. Bürger, who referred to it as a "Portrait of a Young Man." The sitter has turned her head to face the spectator, her lips parted like those of the "Young Girl in a Turban" at The Hague. Her broad hat is of a fine rose colour, of a tint and quality extremely rare in Dutch painting, and her cloak of a boldly contrasting blue. Her right arm rests along the back of one of the painter's well-known lion-headed chairs. The background consists of some tapestry fabric of pale brownish-green with bold blue markings. Some believe the sitter to be Vermeer's wife. The expression is startlingly life-like, and the features illuminated by crisp and brilliant accents placed with impeccable taste and judgment. The quality of the paint is indeed something to gloat over. Mr. Mellon acquired the picture from Messrs. Knoedler, who exhibited it in London about eight years ago.[16]

The last of this group, and the tiniest of them all, is the 7 by 7½ inch picture known alternatively as "Young Woman with a Flute" or "The Chinese Hat." It was in the Goudstikker Collection as lately as 1919, but now belongs to Mr. Widener of Philadelphia. It, too, bears the unmistakable stamp of authority: the sharp, crisp touch denoting the master hand. The picture is rather a Watteau-ish conception, anticipating by a curious hap one of the shepherdess chinoiseries of the eighteenth century. The sitter is seen at half-length, wearing a striped hat of conical form, something like a coolie's. In one hand is held a flageolet; she wears earrings, and has a thin gold chain about her neck. The colour scheme is a characteristic one of blue and golden ochre.

We now proceed to another group, of which Music is the delightful theme, and in which musical instruments play an important part. These extremely decorative objects, often works of art in their own right, were as much loved by the Dutchmen as by the Italians, and occur with great frequency in their pictures. Can anything be more charming in a picture, or anything more appropriate with Music as a theme? Their beautiful lines, their enchanting decorations, apart from their harmonious attributes, have inspired painters in all times. The square forms of the harpsichord and the virginals, the luscious curves of the viol and viola da gamba, must have appealed strongly to Vermeer, and to have been of great assistance to him in planning his more elaborate compositions, whilst the details of their decorations have put to the test the utmost skill of his brush.

Prominent amongst these is His Majesty the King's magnificent example at Windsor, "A Lady at the Virginals and a Gentleman." It is of large dimensions as Vermeers go, measuring 29 inches by 25½. This also was in the Amsterdam sale of 1696—No. 6 in the catalogue. It was purchased on the Continent for George III. by Richard Dalton, under the surprising attribution to Franz van Mieris. Here we have a scientifically worked-out composition of a most unusual kind. The figures are placed far back, at the very end of the room, and the lady has her back turned to the spectator.[17] The virginals, which stand against the back wall, are so minutely painted as to detail that the following inscription on the opened lid can clearly be read, "Musica lætitiæ C(ome)s Medicina Doloris." The lady's face and part of the tessellated pavement of the floor are reflected in a mirror above the instrument. By her side, to the right, stands a gentleman whose violoncello lies nearer to us, on the floor. The pavement, a prominent feature in the design, is of black and white tiles, seen in sharp perspective. In the foreground is a table covered with a Turkish rug upon which stands a tray and a jug of Delft ware.

A "Music Party," sometimes called "The Concert," is one of the prizes of Mrs. Gardner's collection at Boston, U.S.A. There are three figures in it: a man whose back is turned, a lady playing upon a harpsichord, and another singing. An interesting fact here is that one of the pictures hanging upon the wall is "The Procuress," by Dirck van Baburen, now in the Rijksmuseum. It must have been the personal property of Vermeer, since he introduced it also in his "Young Lady seated at the Virginals" in our National Gallery. The other picture upon the wall is a landscape. The National Gallery example just mentioned was at one time in the Bürger Collection. Later it belonged to Mr. Humphry Ward, who lent it to the Royal Academy Winter Exhibition of 1894. It then became the property of Mr. George Salting, who bequeathed it to the National Gallery in 1910. Probably the sitter is one of Vermeer's daughters. It is assumed to be a late work. There is the series of box-like forms, relieved by the curves and the sharply accentuated folds in the lady's blue skirt and the yellow-varnished viola da gamba—the same instrument as that seen in His Majesty's picture at Windsor. The blue and gold tapestry curtain reappears, more prominently, in "The Allegory of the Faith," formerly at The Hague. Our own second Vermeer, the "Lady standing at the Virginals," is an older favourite. It was also in the Bürger Collection, but has delighted us from the walls of the National Gallery since 1892. Its colour scheme is cooler, there is less golden ochre spread about it. A crystalline quality of surface distinguishes it, but it seems to have suffered in the lapse of time, since the flesh tints have sadly deteriorated and the terra vert underpainting is visible. Here again is an ingenious plan of rectangular shapes in variation, some on the flat plane, some in perspective, but resolved to a perfect harmony and sense of repose. The cumbrous Cupid in the large picture on the wall seems to be Vermeer's single lapse of taste, disturbing in the slightest degree the exquisite stillness of the scene, but the adorable little landscape framed in gold on the same wall is perfection itself. Crisp, sunny touches of light play about the edges of the gold-grey satin skirt. The pale blue bodice, repeating with more animation the tint of the velvet chair covering, and the touches of scarlet, placed with extreme reticence and perfect taste, complete a harmony of extraordinary charm. There is another "Lady playing the Virginals" in the late Sir Otto Beit's collection, attributed with some plausibility to Vermeer, which, judging from a photograph, seems to bear the characteristics of the master.

"The Music Lesson," in the Frick Collection, New York, which companions, not unworthily, the "Soldier and Laughing Girl," is another work of characteristic charm. A gentleman offers a lady a sheet of music, leaning towards her. She is seated in profile towards the window, but turns to look at us. The well-known properties reappear, among which are a covered Delft wine flagon, and a guitar or mandola. The dimensions are given as 17¾ inches by 15¾.

(Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

A small canvas of precious quality. The velvety red of the brickwork and the sheer dexterity and obvious enjoyment with which the paint has been manipulated in every part has always been the delight and despair of artists. The pale blue-green of the painted woodwork and the sprightly little tree in its spring dress make a perfect foil to the red brickwork. Sir Henry Deterding bought this little picture from the Six family at Amsterdam for £80,000 sterling, and presented it to the Rijksmuseum.

A slightly larger canvas belonging to Mr. H. E. Huntington of New York, which also appears to be authentic, shows us a young lady tuning a guitar at a window. She wears a yellow jacket trimmed with ermine. A lion-headed chair, with deep blue drapery thrown over it, darkly occupies the foreground. The table-cloth has blue stripes, and music books lie upon it. A map of Europe hangs on the wall. The Ken Wood (Iveagh Collection) "Lute Player" is a variant with many points of similarity. The costumes are alike in style and colour. The lady in the Iveagh picture is playing upon a guitar inlaid with ivory. The face is painted broadly, with fine effect, being partly in cleverly managed shadow. A book with red edges is a small but important factor in heightening the colour scheme. In the background hangs a large landscape in a gold frame, the lower line of which passes behind the lady's head. It is a highly typical work, well worth a visit to Ken Wood for its sake alone. A poor copy is in the Johnson Collection, Philadelphia.

Closing the group of Vermeer's music pictures, and at the same time initiating a fresh series of "Letter" themes, aptly comes another picture from the "Rijks," known as "The Love Letter." The composition is certainly unusual, and indeed somewhat puzzling at first sight. Here Vermeer has pushed the box-like interior or peep-show conception of a picture further than any picture yet mentioned.[18] We seem to be standing outside a room in a sort of darkened vestibule, along with some dimly seen objects (placed there presumably to relieve the emptiness). Over one corner of the opening, partly lifted to reveal the scene, hangs Vermeer's favourite bronze and blue tapestry. This forms the framework or setting for the piece itself. The interior, brilliantly illuminated in cool, clear sunshine, which the black picture frames serve to heighten, is a ravishing scheme of blue, yellow, and silver, peopled by a lady of obvious quality and a housemaid. It must be early morning—the room is en deshabille, broom and pattens are left about—the housemaid is clearly in the midst of her duties. Yet the lady upon whom the sun shines so brilliantly is seated in the middle of the room with her guitar. Her playing has been interrupted by the arrival of the love letter which the maid has just handed her. The maid, who has rolled-up sleeves and apron, smiles sympathetically. The mistress looks up inquiringly, apprehensive. For the first time we have a little drama hinted at. Yet all this is to divert our attention from the real purport of the picture. The cunning Vermeer has played this game of surprising his sitters in their unreadiness as a pretext for the most baffling and complicated of all his structural experiments. Every line and every shape in this picture is fitted into the scheme as precisely as the flat pieces of wood in a tangram puzzle. For the whole of the picture lies in that room beyond; the attention is riveted there the moment the spectator sets his eyes upon it. And what a delightful little glimpse it gives us of a well-to-do Hollander's house! I have thought I could spare the broom and the pattens, but upon covering them up, I saw at once that the framework detached itself abruptly from the picture and the design fell apart.

In the late Sir Otto Beit's version of the "Love Letter" theme, mistress and maid are in the same room with us. This picture is more of the nature of a "close-up," though the figures are shown at full length. The lady is seated, writing at a table covered with the usual Oriental rug. The maid stands behind her with folded arms, waiting to take the letter. Her face takes the light from the window. That of her mistress is doubly illuminated, the light being largely reflected from the paper upon which she is writing. The lady wears a white lace cap and pearl ear-rings. Her head is one of the most superb passages of painting in reflected light in the whole of art. In the window—to the left, as usual—is a coat of arms, no longer legible. On the wall beyond is a large picture of "The Finding of Moses." Part of the left foreground is occupied by a shadowed curtain. Vermeer's signature appears upon a sheet of paper hanging forward from the table, with the initials intertwined. This canvas measures 28 inches by 23. Together with the Iveagh "Lute Player" at Ken Wood it was in Vermeer's studio at the time of his death. The two pictures were given as security by his widow, Catharina Bolnes, for a debt of 617 florins. This "Love Letter" has passed through several hands, all well attested, and was in the Secretan sale in Paris in 1889. The picture hanging on the wall in the background of this work appears also in the de Rothschild "Geographer" in Paris.

A "Lady writing at a Table" is in Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan's possession, but though I have only seen a photograph, it has impressed itself on my memory. The lady here is in the ermine-lined jacket, seated in one of the lion-headed chairs. The design is ample, the attitude easy, and the handling broad and characteristic in touch, so far as can be seen.

The Kaiser Friedrich Museum at Berlin contains one of two pictures of which "Wine Drinking" is the theme. There are no new problems. It is possible that these two pictures were as near to a concession to popular taste as Vermeer ever condescended. The lighting comes from the window as usual. The man in the Berlin version is standing, the lady drinking from a glass. She is in a rose-coloured dress. The lion-headed chairs appear again, and on the table is an exquisitely painted white jug. In the second version the gentleman is seen offering a glass of wine to the lady with an ingratiating bow. She is seated, and indicates her acceptance by a smile. There is a third figure, that of a disgruntled male, seated, unwanted, at the far side of the table, his head resting upon his hand. The napkin, white Delft jug, and fruit on the dish are painted as only Vermeer can paint them. Again there is a picture upon the wall. In both these "Wine" subjects the opened casement of the window is a stained-glass panel bearing the same coat of arms. The latter version is in the Brunswick Museum.

Of attributions to Vermeer there are enough and to spare. It is difficult to believe that only a very few years ago the picture of a "Family Group," by Michael Sweertz (1615-20—after 1656), in our National Gallery, was accredited to Vermeer. This immense canvas of nearly eight feet wide by six feet high bears no likeness whatever to any Vermeer we know, except that the floor has a black-and-white pavement. It came to the Gallery in halves at two separate dates, and was joined together in 1915. A conversation piece discovered by Dr. Abraham Bredius is supported by Dr. W. Martin, director of the Mauritshuis, and is now in a private collection. From a photograph I have seen, it seems to me both disappointing and unconvincing.

We now come to the little masterpiece of the Czernin Gallery at Vienna, known alternatively as "The Painter and his Model" or "The Artist in his Studio." The principal figure has been supposed to be a self-portrait of Vermeer as seen from the back, and painted with the aid of two mirrors. This does not necessarily imply that the whole picture was painted in the same way. Indeed the figure has a somewhat detached silhouette. But it is quite as likely to be a sitter dressed in the artist's holiday clothes. The costume, as already remarked, borders on the fantastic, and is certainly not a painter's ordinary studio garb. The quaint little creature who is posing as Fame with her trumpet, and said to be one of the artist's daughters, is also something outside Vermeer's usual conception of a female figure. The curiosity this picture stimulates in us adds much to its peculiar fascination. It is "Vermeerish" in the highest degree. Its decorative luxuriance, yet in perfect taste, the supreme skill in workmanship, the cunning artifice of the composition, the high luminous key of colour—brilliant as an early illumination—make this a picture of especial interest to artists. We feel very strongly that this must be the veritable workshop of the "Phoenix" himself, and regret poignantly that he has not vouchsafed us a glimpse of his features.

A still more enigmatic work is the picture known as the "Allegory of the Faith," which was at one time deposited on loan to the Mauritshuis by Dr. Bredius. The subject is a complete departure in spirit from Vermeer's usual healthy mundanity. It has rather an atmosphere of Jesuitry about it, and the entire conception is in a distinctly alien vein. It may possibly have been painted to the order of a foreign patron, and in any case was not included in the Amsterdam sale of 1696. Doubtless Vermeer followed the description of the subject from some book. The figure is that of a well-dressed woman of the period. Perhaps she is intended to suggest an impending renunciation. She is leaning to the right on a sort of altar, raised from the floor and partly covered with a thick rug. Her right hand is pressed to her breast, like the Magdalens in Italian pictures; her bare feet are sandalled, one of them resting on a globe. Her expression is rapt, the eyes looking into space. Before her are an open book, a chalice, and a crucifix. A serpent wriggling from under a stone is in the foreground,[19] and near it is an apple. A crystal globe is suspended above her head. On the shadowed wall in the background is a large picture of the Crucifixion, much in the manner of Vandyck. The oft-used Brussels tapestry hangs to the left, drawn apart as if to reveal the scene, a chair being pushed against it to keep it in position. Here are all the arcana of Romanism in the heart of Holland. What is the solution of the mystery?

We cannot take leave of Vermeer's box-like pictures without some reference to Mr. R. H. Wilenski's ingenious theory as to Vermeer's use of mirrors.[20] It is certain that mirrors have always been used by painters as aids in various ways, and indeed they are to-day almost a necessary part of an artist's studio equipment. But I cannot see any reason why, with the reality available before his eyes, the artist should deliberately turn his back and paint its reflection. There can be no possible advantage in it. Sometimes mirrors are used to give distance, but Vermeer's pictures are nearly all "close-ups." Sitting between mirrors, especially small ones, involves an inconvenient angle of vision, and the optical effect of Vermeer's pictures is invariably, as Mr. Wilenski has noted, that of a scene bounded by a flat wall parallel to the picture plane. Nor do I think mirrors of any great size were procurable in those days. Further, there would inevitably be a serious diminution of clarity (especially in the re-reflection seen in the dim mirrors of Vermeer's day), and the painting of such elaborate detail as we see on the harpsichord in the King's picture would be impossible. And those amazingly luminous white walls were assuredly not painted from any reflection. It is impossible to accept such a theory without practical demonstration.

The lacquer-like surface of Vermeer's supposedly later pictures, which was to become an obsession with later painters like Adriaen van de Werff, was also in the approved fashion of the time, and such works were most in demand and most highly paid. All rugosities were made to disappear under a liberal application of the badger "softener," and the brighter accents touched in afterwards. Hence, I think, came the "vitreous" effect Mr. Wilenski has remarked. The crystalline Dutch varnishes, moreover, which have had a marvellously preservative effect, have played an important part. The loveliness of the newly invented Delft ware, and the copious importation of Chinese porcelain and other Oriental work, which had a new and potent fascination for connoisseurs, also exercised an influence on the taste of the time, and affected the style of Dutch art irrevocably.

I have a suspicion that Vermeer had a movable screen in his studio with a door cut in it, with which he was able to frame and focus any part of it, and that he used it in painting "The Love Letter." With this screen he could arrange his lights and cut off any portion of the room necessary. The Brussels tapestry that appears in so many of his pictures would seem to have hung across the middle of his studio on a rod, dividing it into two parts, and this he could loop up over the edge of the screen, as seen in "The Love Letter." The arrangement of the curtain and his method of using it may also be clearly seen in "The Artist and his Model" and the "Allegory of the Faith," and in both these pictures the beams across the ceiling identify the two opposite sides of the room.

The genius of Vermeer manifests itself in no more astonishing fashion than in his treatment of landscape. His pre-eminence in this field is even more remarkable than in that of genre. The especial cause of wonder is the fact that Vermeer seems to have attained complete mastery at a bound. Only two landscapes from his hand are known that can be accepted without question. A third, now lost, was mentioned in the old Amsterdam Catalogue. Yet in these two canvases Vermeer asserts himself a pioneer—the first of landscape plein-airists, anticipating exactly by a century the re-awakening to God Almighty's style by John Constable.[21]

The prodigious "View of Delft" from the Rotterdam Canal is like a view from a window—seen through the milky air of Holland. This milky luminosity is an inseparable feature of the Dutch atmosphere and its most characteristic quality. The light is reflected back into the skies from the North Sea, surcharged with myriads of particles of water, enveloping the fields and polders and market gardens, and penetrating the interior of the houses. If the reader looks at one of Emmanuel de Witte's (1617-92) wonderful church interiors with their white walls, he will have further evidence of the Dutch painters' growing awareness of this fact, and feel their response to it. When the dusk is falling I have watched these walls grow positively phosphorescent in their luminosity. Vermeer's "View of Delft" is seen on a summer evening, through this milky sunshine, the brickwork and the trees and the spires of the old city sparkling with the pointillist touches which this painter was the first to apply. A shadow passes over the city walls and gateways, the reflections of which are broken by the rippling of the tide. The Rotterdam Gate with its two flanking towers is separated from the Schiedam Gate by a bridge under which the water flows up into the city. Beyond, the church tower and the roofs are bathed in sunlight. The picture has a "tall" sky in which cumulus clouds float. On the hither bank are two groups of figures, and a barge moored to the shore. Nearer to us can be seen the traces of a man's figure walking towards the left, which has been painted out by the artist. On the barge is Vermeer's monogram. The picture is on canvas, and measures 38¾ inches high by 46¼ wide, and is one of the most cherished treasures of the Mauritshuis.

The "Little Street" of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, is no less precious in quality. The red bricks are positively velvety in their richness, and the dexterity with which the mortar which binds them has been trickled over the canvas is the delight and despair of painters. Indeed the handling of this picture, the colour of the pale blue-green woodwork, the painting of the stone setts, the shimmering little tree, and the little figures interested in their trifling business, make this little picture one of the most enjoyable "bits of paint" in existence. This canvas (measuring 21¼ inches by 17¼) was, with the "View of Delft," in the Amsterdam sale of 1696, when it fetched the sum of 48 gulden. It came into possession of the Six family at Amsterdam, from whom it was purchased by Sir Henry Deterding and presented to the Rijksmuseum in 1921. The price he had to give for it was £80,000 sterling!

There are versions and variants of these two landscapes extant, but none approach them in quality, and are unlikely to be other than school or gallery copies. There is a "View of Delft" at Rohoncz Castle, Hungary, which, judging from a photograph, seems worth closer examination, and a "possible" landscape in the collection of General de Villestreux of Paris.

Of drawings attributed to Vermeer there is a fine pen and bistre study of a Delft street or courtyard in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin, and a charcoal study on blue paper of the larger "Delft" view at Frankfort. Another fine drawing which carries conviction is a bistre study of the Westenkerk, Amsterdam (presuming he went there), in the Albertina. It is brimful of sunshine: a road bordering a canal, with a windmill, lies to the right; on the left are some old barns or boathouses, with a moored boat. The church with its tall spire rises to the left centre. There is also a spirited drawing in reed pen and wash, somewhat in the Rembrandtian vein, at Dresden, for or after the "Geographer" with the globes. No sketches or studies revealing his methods of working out his composed pictures are known to us. The only remaining work by Vermeer known to the writer is a small study of a "Boy's Head," on yellowish-brown paper, in the Staatliches Kupferstichkabinet at Berlin which was shown in London at the Royal Academy Dutch Exhibition in 1929.

Jan Vermeer is one of the supreme exponents of the art of facture in painting. His quality of surface and faultless manipulation of paint, in which he retains his colour, crystalline and unsullied through all its modulations, is without a rival. In his earlier and more heavily impasted canvases, Chardin perhaps approaches him most nearly, though there have been other miraculous handlers of paint in the Netherlands. Both possessed that elusive but satisfying quality that makes us think of their pigment as compounded of the crushed fragments of the actual material it represents—it is so nearly the real thing—but by art made transcendently precious. Barely forty works of the "Phoenix" have been accounted for. Strange that such perfection should have flowered for so short a time to die with him!

THE END

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT

THE PRESS OF THE PUBLISHERS

[1] History of Holland, by George Edmundson, D.Litt., F.R.G.S., F.R.Hist.S., some time Fellow of Brasenose College, Oxford, Hon. Member of the Dutch Historical Society of Utrecht, Foreign Member of the Netherland Society of Literature, Leyden. (Cambridge University Press.)

[2] For example, such pictures as Pieter Van Laer's "Bambochades": Bamboche, or Bamboccio, being the nickname the painter had earned in Rome.

[3] Curiously enough, this extraordinary variation in the relative proportions of figures in the same picture appears frequently in Dutch art—for example in De Hooch, Palamedes, Jan Steen, and even in Rembrandt himself.

[4] In a contemporary poem on the death of Carel Fabritius, by Arnold Bon, is a stanza describing Vermeer as a Phoenix arising from the ashes of Carel, who perished in the Delft explosion of 1654. The verse is as follows:

"So doov'dan disen Phoenix t'onser schade

In't midden, en in't beste van zyn swier

Maar weer gelukkig rees 'er uyt zyn vier

VERMEER, die meesterlyck betrat zyn pade."

The catalogue of the Burlington House Exhibition of 1929 gives the date of Fabritius's birth as 1614.

[5] Henri Havard, a French traveller and author, and a former owner of Vermeer's "Pearl Necklace" and "Young Lady at the Virginals."

[6] Leonard Bramer had studied in Rome with Adam Elsheimer (1578-1610).

[7] This picture is signed and dated 1654, and at one time belonged to Bürger-Thoré. It was included in the sale of his pictures at Paris in 1892.

[8] Judging by a Flemish picture painted by Hans Jordaens III. of Antwerp, 1595-1643 ("Interior of an Art Gallery," No. 1,289 in the National Gallery), it would seem to have been the taste of connoisseurs of the time to crowd their rooms with pictures to the roofs. In this painting the class of picture favoured is clearly indicated. Several such "interiors" are extant.

[9] Delft ware was first manufactured about 1600.

[10] John Evelyn writes in his Diary, 1641: "I went to Hundius's shop to buy some mapps, greatly pleased with the designs of that indefatigable person, Mr. Bleauw, the setter forth of the Atlas's and other works of that kind worth seeing." (This was at Amsterdam.)

[11] Antoni van Leeuwenhoek died in 1723, a pioneer in microscopic research; discoverer of the infusoria and of facts connected with the circulation of the blood, and the structure of the eye and brain. His portrait, by Nicolaes Maes, is in our National Gallery, No. 2581.

[12] Here also, in the old house of Burgomaster Six, No. 511 Heerengracht, situated on a peaceful backwater, was housed Vermeer's "Little Street in Delft."

[13] Sir Joshua Reynolds, in A Journey to Flanders and Holland, made the bald statement concerning this work: "A woman pouring milk from one vessel to another, by O. Vandermeere." It was in the cabinet of M. J. J. de Bruyn, and at his death, in 1798, realized the sum of 2,125 florins. Thence it passed to Mr. H. Muilman, and was transferred to the Six Collection as stated.

[14] The "Dentellière," the picture by Vermeer in the Louvre.

[15] Vermeer of Delft, by E. V. Lucas. (Methuen and Co., Ltd.)

[16] There is another "Lace Maker," attributed to Vermeer, in Mr. Mellon's collection, which, judging from a photograph, seems to be in an unsatisfactory condition, the hands especially looking as though they had been overcleaned. Also a third picture of a young girl laughing, in a yellow dress and blue cap, which Mr. Mellon acquired from Messrs. Duveen.

[17] Back views, even in single-figure pictures, are frequent in Dutch art.

[18] In this connection see Hoogstraten's remarkable peep-show at the National Gallery. The Dutch were fond of peep-shows.

[19] Probably symbolizing Temptation rendered powerless by Faith.

[20] An Introduction to Dutch Art, by R. H. Wilenski. (Faber and Gwyer.)