* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Canadian Horticulturist, Volume 8, Compendium and Index

Date of first publication: 1885

Author: D. W. (Delos White) Beadle (editor)

Date first posted: June 27, 2019

Date last updated: June 27, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190649

This eBook was produced by: David Edwards, David T. Jones, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

CANADIAN

HORTICULTURIST.

PUBLISHED BY

THE FRUIT GROWERS’ ASSOCIATION

OF ONTARIO.

VOLUME VIII.

D. W. BEADLE, Editor.

ST. CATHARINES, ONTARIO.

COPP, CLARK & CO.

GENERAL PRINTERS, 67 & 69 COLBORNE STREET, TORONTO

1885

The Canadian Horticulturist.

VOLUME VIII, COMPENDIUM & INDEX

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

[Added for the reader’s convenience—Transcriber.]

| INDEX |

Bignonia Radicans

THE

| VOL. VIII.] | JANUARY, 1885. | [No.1. |

We call the attention of our readers to this beautiful climbing plant, not only for the purpose of assisting those who may be seeking for attractive plants to train over screens and lattice, but also to request those who have grown it to give our readers the results of their experience. More especially do we desire the experience of those who live in the colder parts of the Province, that we may be able to ascertain, if possible, the northern limits of its successful cultivation.

It will be noticed that the name given to it on the colored plate is Bignonia radicans. This was the name originally assigned to it, and by which it is yet very generally known. Later botanists have placed it in the genus Tecoma, and it is by them called Tecoma radicans. The plant belongs to the natural order of Bignoniads which furnishes probably the most gorgeous climbers in the world. By far the most of these are natives of tropical regions, and consequently cannot endure the rigors of our climate. Indeed, we believe that the species shown in the plate is the only one that has been grown successfully in Canada. It is a native of North America, and is found growing wild from Pennsylvania to Illinois and southward. It is said to bear the climate perfectly as far northward as the Lake Superior region. We trust that our readers will enable us to verify this statement, for if this be so, it will be gratifying to know that a climber as showy and desirable as this, can be confidently planted over the greater part of this Province.

This species was introduced into England in the year 1640, where it is very generally cultivated. It continues in bloom for several weeks, is a very healthy and vigorous grower, requires no special care, being fully able when once established to take care of itself. It throws out rootlets from every joint, whereby it fastens itself to any support provided for it, and will soon cover any desired object. If it is preferred to train it in bush form, it can be allowed to fasten itself to a stake, and the shoots pinched in when they reach the top. This will cause it to throw out numerous branches, which will hang gracefully from the centre in every direction, and give in the flowering season a profusion of bloom.

—————

Of the Fruit Growers’ Association of Ontario will be held in the City of London, on Wednesday and Thursday, the 28th and 29th of January, 1885, in Victoria Hall, Clarence Street. The opening Session will begin at 10 o’clock, a.m., on Wednesday.

Favorable arrangements have been made with the hotels. The Tecumseth House will accommodate any members attending the meeting at $2 per day. The Grigg House at $1 50 per day.

Delegates from the Michigan and New York State Horticultural Societies have signified their intention to be present.

The evening Session of Thursday will be devoted to short addresses on different subjects by delegates from abroad and members of the Association. Good music will be interspersed with good speeches.

Arrangements have been made with the leading Railways for the usual reduction of a fare and a third for the round trip.

Members will receive certificates entitling them to reduced fare on application to D. W. Beadle, Secretary, St. Catharines. The certificates must be presented to the railway agent when purchasing the ticket on going to the meeting.

Specimens of fruit in season at that time will be exhibited in connection with the meeting. Members are particularly requested to send samples of any new fruits they may have, and especially of any seedling fruits of value.

—————

This new raspberry has been highly recommended as very valuable on account of the great vigor and fruitfulness of the plant, and the large size, bright color, firm texture, and very early ripening of the fruit. Its qualities are fully stated at page 196, vol. vii., of the Canadian Horticulturist. The plants are now offered for sale by those nurserymen who are so fortunate as to have them at one dollar each. We have made an arrangement with the Rural New-Yorker to present to all subscribers to both publications who prefer to pay three dollars instead of two dollars and sixty-five cents, as mentioned in the advertisement on the second page of the cover, four plants of the Marlboro’ raspberry free of cost to the subscriber. Hence we announce that any person sending us three dollars will receive both the Canadian Horticulturist and the Rural New-Yorker during the year 1885, and all the free seed and plant distributions mentioned on the second page of cover, and four plants of the new Marlboro’ raspberry, that could not be otherwise procured for less than four dollars. Those of our subscribers who have already sent us two dollars and sixty-five cents can avail themselves of this unparalleled offer by remitting to us the further sum of thirty-five cents. Were ever such advantages offered before? Two of the leading rural publications of the day, the Report of the Fruit-Growers’ Association for the year 1884, the free seed and plant distribution of both, and four plants of the Marlboro’ raspberry that alone would cost four dollars; all this for only three dollars! Only think what this is really worth.

—————

The Fruit Growers’ Association will send by mail, post-paid, to every subscriber to the Canadian Horticulturist for the year 1885, your choice of any one of the five following articles, namely:—

A yearling tree of a Russian apple; or,

A yearling tree of the hardy Catalpa; or,

A yearling plant of Fay’s Prolific Currant; or,

A tuber of a choice double Dahlia; or,

Three papers of Flower seeds, one each of the Diadem Pink, Salpiglossis and Striped Petunia.

These will be securely packed and sent by mail in the spring to each subscriber, if he states which is desired. When no choice is indicated, none will be sent, it being understood that none is wanted.

—————

For every new subscriber to the Canadian Horticulturist, accompanied with one dollar and thirty-seven cents, we will send not only the Canadian Horticulturist for 1885 and the Report of the Fruit Growers’ Association of Ontario for 1884, now in press, and the premium chosen from among those offered by the Horticulturist, but also the “Floral World” for 1885, and sixteen packets of choice flower seeds. Remember that this offer is made only for new subscribers. The ladies have here an opportunity of securing a collection of seeds of beautiful flowers, and a monthly magazine devoted to floriculture for the present year.

—————

| The Canadian Horticulturist and American Agriculturist for 1885 | $2 00 |

| The Canadian Horticulturist and American Agriculturist for 1885 and American Agriculturist “Family Cyclopedia” of 700 pages and over 1,000 illustrations, for | 2 40 |

| The Canadian Horticulturist and Floral Cabinet, with premiums of both magazines, for | 1 80 |

| Canadian Horticulturist and Rural New Yorker for 1885 | 2 65 |

| Canadian Horticulturist and Grip for 1885 (without premium) | 2 00 |

—————

Messrs. Keeling and Hunt, of Pudding Lane, London, England, report that on the 12th and 13th of November, 1884, they sold 873 barrels of Canadian apples at public auction, with the following result: Greenings brought 14s. to 15s. 6d. sterling per barrel. Northern Spy, 14s. 6d. to 15s. Baldwin’s, 15s. to 17s. Fameuse, 13s. 6d. Golden Russet, 14s. to 21s. Roxbury Russet, 14s. 6d. to 16s. Ben Davis, 12s. 6d. Pomme Grise, 17s. 6d. King of Tompkins, 18s. 6d. Ribston Pippin, 22s. to 22s. 6d. Montreal Fameuse, 16s. 6d.

They had for sale on 18th November, 1,516 barrels of Nova Scotia apples. These brought good prices. Greenings selling at 12s. 6d. King of Tompkins at 19s. 6d. Baldwin’s at 14s. 6d. Ribston’s at 22s. to 25s. 6d. Blenheim Orange at 24s. and Gravenstein at 14s. sterling. Some No. 1 Extra Ribston Pippins, went as high as 28s. They report 2,052 more barrels of Nova Scotia apples to be sold on 25th November.

—————

The Editor acknowledges, with many thanks, the gracious gift of a Scotch Dictionary from Mr. John Croil. It is an old saw, that it is hard for old dogs to learn new tricks. He will study the dictionary with care, but fears that it is too late for him to acquire such a familiarity with this most beautiful language as to enable him to pass for a Scotchman. Thanks too, a thousand thanks, for the poems. Many of them are rich in beauty of thought and expression. We copy one for the benefit of our readers, who, though not Sons of Scotia, will not need the dictionary to appreciate its touching tenderness.

THE ROWAN TREE.[A]

Oh Rowan tree; oh Rowan tree, thou’lt aye be dear to me,

Intwined thou art wi’ mony ties o’ hame and infancy.

Thy leaves were aye the first o’ spring, thy flow’rs the simmer’s pride;

There was nae sic a bonnie tree in a’ the countrie side.

How fair wert thou in simmer time, wi’ a’ thy clusters white,

How rich and gay thy autumn dress, wi’ berries red and bright;

On thy fair stem were mony names, which now nae mair I see,

But they’re engraven on my heart, forgot they ne’er can be.

We sat aneath thy spreading shade, the bairnies round thee ran;

They pu’d thy bonnie berries red, and necklaces they strang;

My mither, oh, I see her still; she smil’d our sports to see,

Wi’ little Jeanie on her lap, an’ Jamie at her knee.

Oh, there arose my father’s prayer, in holy evening’s calm,

How sweet was then my mother’s voice, in the martyr’s psalm;

Now a’ are gane; we meet nae mair aneath the Rowan tree,

But hallowed thoughts around thee twine o’ hame and infancy.

|

Dictionary.—Rowan tree, the Mountain Ash. |

—————

The annual meeting of the Small-Fruit Growers’ Association of the Counties of Oxford and Brant will be held at Burford Village, County of Brant, on January 16th, 1885. All who are interested in fruit growing are invited to attend and take part in the discussion.

—————

Having used the meat chopper made by the Enterprise Manufacturing Company of Philadelphia, Penn., whose advertisement appeared in the December number, we take the liberty of calling the attention of those of our readers who have occasion to chop meat of any kind to this chopper. It is just complete in every respect, doing its work to perfection, simple in construction, easily kept clean, and a great saver of labor.

—————

It will interest all fruit, flower and vegetable growers to learn that the American Garden of New York has been sold to E. H. Libby, the well-known agricultural journalist. Established in 1872 as a quarterly, the American Garden has become a handsome monthly magazine, and a leader among horticultural publications. Under its new management it is an independent, illustrated, beautifully printed magazine, still ably edited by Dr. F. M. Hexamer and numbering as contributors many of the most successful fruit growers and gardeners in this and other countries. The coming volume will be greatly improved in many ways, and worthy of the earnest and hearty support of all who love fruits, flowers and nice gardens, and all who make a business of their culture. The price is only $1 a year, including some choice seed and plant premiums. Published in New York and Greenfield, Mass.

—————

I think the Horticulturist Report and Premium big value for the money.

Samuel H. Kerfoot.

Minesing, December, 1884.

—————

I like the Horticulturist, and a little more floral culture, as it would make it more interesting for the young people.

Thomas Gordon.

Bobcaygeon, Dec., 1884.

[Thanks for this suggestion. Will endeavor to meet the wishes of the young people. We are always very glad to receive suggestions from our readers that shall help us to make the Horticulturist more acceptable.]

—————

Most of the plants received from the Fruit Growers’ Association are doing well; and I think the paper improving all the time, and enjoy it very much.

Geo. E. Fisher.

Freeman, Dec., 1884.

—————

There is a great deal of useful information in the Canadian Horticulturist for any one who grows fruit for pleasure or for profit.

W. Brockie.

Pinkerton, Dec., 1884.

—————

Mr. Editor,—I am much pleased with the Horticulturist. It encourages us to grow an abundance of fruits, flowers, vegetables, ornamental trees and shrubs, tells us the varieties adapted to our locality, and shows us the modus operandi. All of us need the Horticulturist.

W. S. Forbes.

Ancaster, Dec. 15th, 1884.

—————

—————

Will you or some of your readers give us a plain article on the management of grape vines? It would be a great benefit to new beginners like myself. In summer pruning we cut within two buds of the fruit. What are we to do with the growth that has no fruit? Shall we cut these close to the old vine, or let them grow? Of all the articles that I have seen on grape culture, I have not yet seen one that my thick head could work from.

Also, could you give us an article on budding and grafting? My good friend, A. McD. Allan, was to come and bud for me last August; but unfortunately for me, and more so for him, he was taken ill about the time he was to come, so I got none done.

A. C. McDonald.

—————

Reply.—Perhaps the short article by Matthew Crawford in this number will help you. We advise you to read Beadle’s Canadian Fruit, Flower and Kitchen Gardener, which treats of budding, grafting and pruning the grape, with illustrations showing the whole process.

—————

At page 70 of the Canadian Fruit, Flower and Kitchen Gardener, I find, “Fameuse—Pomme de Neige—Snow Apple”—from which I inferred that it was three names for the same tree; but I have been informed by dealers in Ottawa that it is not so; that the Snow Apple can be grown in that vicinity, and that the Fameuse cannot.

W. P. T.

—————

Reply.—If you will look at the “Fruits and Fruit Trees of America,” by A. J. Downing, revised and corrected by Charles Downing, the acknowledged American authority, you will find that he also says that Fameuse, Snow and Pomme de Neige are three names for one and the same apple. Which will you believe, our leading pomologists or dealers in Ottawa?

—————

Mr. Editor,—I have before me a Liverpool wholesale fruit dealer’s price-list, 1882, and I find that the apples that fetch most money are Newton Pippins, quoted at 37s. per barrel, whereas finest New York Baldwins are down at 22s. per barrel. Will you kindly describe the former apple and its keeping qualities, and if fall or winter; and is the tree hardy and suitable to plant in our township?

I can only find a casual reference to it in “Beadle on Gardening,” etc.

I have heard and read a good deal about Wealthy and Walbridge apples. Are they in any way superior to the well tried Baldwins for this county?

Yours truly,

Bosanquet.

—————

Reply.—The Newton Pippin does not grow to perfection in Ontario, or even away from the Hudson River. It is a winter apple. The Wealthy and Walbridge are more hardy than Baldwin, and on that account better for cold sections where Baldwin falls.

—————

Sulphur Fumes for Curculio.—Johnston Eaton, of Pennsylvania, writes of his experience with plum trees:—For nearly twenty years I had plum trees on the farm, but not a plum to eat, when a lady told me to smoke the trees when the fruit was set, and continue for two months, once a week, with sulphur. This I did, and have had an abundance of fruit ever since. Sometimes put a little coal tar in a pan with the sulphur.—Fruit Recorder.

—————

—————

Mr. Editor,—At the fall meeting of the F. G. A., held in Barrie on the 1st and 2nd October, I suggested as a subject for discussion, “The most desirable new varieties of Strawberries, and their particular merits;” and my reason for doing so was because the past winter and summer have been so exceedingly trying to that plant, that a better opportunity is not likely to occur for testing their power of resisting both frost and drought. I know not how it may have been in other parts, but as regards this locality a more destructive winter, or rather spring, and a more disastrous drought than the one that visited us last June, have never occurred in my experience here or elsewhere; and should I live to attain the age of one hundred years I should never again expect to see the strawberry growers afflicted with two such calamities in one year. More than one-half of my previous spring’s plantation were killed as dead as a door-nail immediately after the snow melted in the spring, and those left living were so weakened that they did not set more than half a crop; and they had no sooner recovered from the effects of the frost as far as possible, and had prepared to ripen the few berries that had been formed, than the heat and drought of June wilted the plants and dried up the fruit, till the prospects of a profitable yield and the spirits of the cultivator went down to zero. Surely then such a season as this was favorable for testing the hardiness of any new varieties, and of such I had seven kinds that were at least new to me, viz., Bidwell, Finch’s Prolific, Mt. Vernon, Arnold’s Pride, James Vick, Manchester, and Jersey Queen. Of these, the Bidwell, Finch, Arnold and Vick were badly winter killed, the two last so badly that I only got two berries from the two lots, and those were Arnold. Vernon came through the winter all right, but I regard it as worthless, and I may say the same of Bidwell as far as I can judge from a first crop. One or two only of the Finch plants proved very prolific. The few of Arnold and James Vick that were left have been trying to make up their losses, and have sent out a splendid lot of new plants. Manchester and Jersey Queen came through the winter ahead of all other varieties, new or old. The Jersey Queen had sent out the most runners, and looked the brightest after the snow was gone. In regard to the yield of fruit, Manchester and Queen are the only ones that need be mentioned, and these I watched with considerable interest as the fruiting season approached. Manchester made a good show of fruit stalks and blossoms, which in due course developed into a fine show of fruit. Jersey Queen was later, and did not make as good a display. When Manchester was at its best it was a splendid sight to look at, every plant appearing to have five or six fine berries in different stages of ripeness, and it was at once pronounced an acquisition, and worthy of cultivation on a larger scale. Jersey Queen was later, and did not look so promising as to receive an immediate endorsement, but was voted worthy of further trial. When the Manchesters were nearly done the Jersey Queen began to show up a little better, and produced some splendid berries, but its habit is quite different to the other, in that you scarcely see the fruit till you look for it under the leaves, whereas the Manchester holds its berries up to the gaze of every passer-by. Comparison, therefore, of the two by appearances is very deceptive. As compared with the Wilson, the Manchester commences ripening later and is done earlier; therefore at a certain period it shows to better advantage, and gives rise to expectations that are not quite realized by the number of baskets picked. On the contrary, the Jersey Queen yields more baskets than its appearance would lead one to expect. It commences perhaps three days after Manchester, but it holds out a week after Wilson, and continues all the time slowly but surely bringing its berries to perfection—and such berries! They are as much ahead of the Manchester as the Manchester is of the Wilson, and neither of the two produce anything like the same proportion of small berries. The fine berries of the Jersey Queen soon fill up a basket; and although there did not appear to be so many of them as of the Manchester, they continued, in spite of the drought, in furnishing fine berries for repeated pickings, till from a row three yards shorter than that of its rival we had picked one basket the most. This was certainly unexpected. I am satisfied that I could not have selected in any part of my field a section of a row of Wilsons of the same length as the rows of those two kinds, and planted at the same time, that yielded as much fruit. But it must be recollected that the Wilsons had suffered very much the worst by the spring frosts, therefore the comparison another year might be quite different. As these two varieties escaped the frost better than the Wilson, so also they appeared to suffer less from the drought. All these new varieties were planted on sandy soil.

Now as regards the keeping and shipping qualities of these two varieties, or I might say of the Jersey Queen only, for of the other I took no notice; but happening to put a basket of the former in a case I was sending to a friend, that had to travel on two lines of railroad and lie over for several hours at a station because trains did not connect, I was surprised to learn that when they reached their destination they appeared as fresh as though they had just been put in the case. I was surprised because they had not the appearance of a firm berry; in fact they are very easily bruised, and I should have called them rather soft; but I did not then know that the hardest or firmest berries are not always the best keepers; but I know it now. I know that the Wilson twenty-four hours after picking has lost both appearance and flavor, and that the Jersey Queen, in the same time, has suffered no perceptible change in either respect. I know that the latter can be kept three or four days without losing its gloss, although if left in a box that length of time the lower half of the berries will get mouldy; and it is quite remarkable that though it is not possible to handle them without in some cases breaking through the glossy varnish that covers them, the bruised spots do not appear to discolor, though they would of course more quickly get mouldy. This is certainly a remarkable quality for any berry to possess, and I shall look with considerable interest to its behavior another season. At present my Jerseys certainly are the finest row in the field.

Yours, &c.,

| Barrie, 15th Dec., 1884. | A. Hood. |

—————

Dear Sir,—You ask for the experience of subscribers. Mine is not worth much, as I am a novice at the business. I have only a small garden and orchard, probably about two hundred trees, and about one hundred and fifty gooseberries and currants together, and fifty-five grape vines. I have tried an experiment this summer: it may be of benefit to some of your readers, if it is beneficial to trees to have no grass growing around them. The experiment is this: I sawed a piece off from the end of a log twenty to twenty-four inches in diameter, and an inch and a half or two inches thick, then split it through the centre and made a hole to fit the trunk of the tree, and then closed the two pieces together, leaving them on the ground around the trunk of the tree. This will entirely kill all grass and weeds around the tree.

Yours truly,

A. C. McDonald.

Dunlop, Nov. 19th, 1884.

—————

Fruit growers are more interested in the climate of any given locality than are most other cultivators of the soil in that locality, as with the fruit growers, especially the growers of the more tender varieties, such as grapes, tomatoes, strawberries, &c., the lowering of the temperature two or three degrees below the freezing point at a time when such a decline is unusual, or at any unusual period, often makes all the difference between financial success and failure, while the ordinary farm crop might not be seriously affected. A case of this kind occurred in this locality on the 30th of May last, when we had our last spring frost (two weeks later than it has occurred for many years previously). It did not seriously injure farm crops, but very materially injured the fruit crop generally, and caused nearly a total failure of the grape, pear and strawberry crop.

Believing that a record of some of the leading features of the climatic conditions prevalent in this locality during the past five years may be of interest to your readers in this neighborhood, and also be of service to such other persons who may desire to compare the peculiarities of the climate in their several localities with that of this place, I subjoin the following table. All the data given refer only to the seasons from the 1st May to 31st October for the last five years, viz., from 1880 to 1884, inclusive:—

| More | Highest | More | Lowest | More | ||||||

| Mean | or | temper- | or | Date. | temper- | or | Date. | |||

| temp- | less | ature | less | ——— | ——— | ature | less | ——— | ——— | |

| era- | than | of each | than | of each | than | |||||

| Summer | ture | average | summer | average | Month | Day | summer | average | Month | Day |

| 1880 | 58.97 | +.63 | 91.7 | -1.06 | July | 24 | 17.4 | -1.2 | Oct. | 24 |

| 1881 | 60.80 | +2.46 | 100.7 | +7.94 | Aug. | 30 | 20.3 | +1.7 | Oct. | 27 |

| 1882 | 58.26 | -.08 | 91.3 | -1.46 | July | 26 | 20.1 | +1.5 | Oct. | 20 |

| 1883 | 54.81 | -3.53 | 85.2 | -7.56 | Aug. | 22 | 18.4 | -.2 | Oct. | 17 |

| 1884 | 58.85 | +.51 | 94.9 | +2.14 | Aug. | 18 | 16.8 | -1.8 | Oct. | 26 |

| Average | 58.34 | .. | 92.76 | .. | .. | .. | 18.6 | .. | .. | .. |

| Mean | ||||||||||

| temp- | ||||||||||

| era- | Date of | |||||||||

| ture. | More | Date. | More | last | Low- | |||||

| Warmest | or | Mean | or | spring | est | |||||

| day | less | ——— | ——— | Warm- | temp- | less | frost. | temp- | ||

| each | than | est | era- | than | ——— | ——— | era- | |||

| Summer | month | average | Month | Day | month | ture | average | Month | Day | ture |

| 1880 | 79.63 | +.13 | July | 9 | July | 66.58 | +.16 | May | 15 | 31.4 |

| 1881 | 85.20 | +5.70 | Sept. | 6 | July | 69.03 | +2.61 | May | 5 | 30.2 |

| 1882 | 75.30 | -4.20 | Aug. | 6 | Aug. | 67.06 | +.64 | May | 16 | 27.3 |

| 1883 | 74.90 | -4.60 | June | 18 | July | 63.32 | -3.1 | May | 17 | 26.5 |

| 1884 | 82.45 | +2.95 | Aug. | 20 | June | 66.13 | -.29 | May | 30 | 27.4 |

| Average | 79.50 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 66.42 | .. | .. | .. | .. |

From the foregoing it may be seen that the summer of 1881, judging from the temperature throughout, should have been the most favorable fruit season of the period referred to, and that 1883 should have been the least favorable. It will also be noticed that the summer of 1884 was in every important feature a little above the average, excepting the last spring frost, which was very severe, and about two weeks later than usual. This frost was pretty general, and was undoubtedly the principal cause of the partial failure of the fruit crop in so many localities.

The summer seasons of 1881 and 1883 were dissimilar in almost every respect. The highest temperature recorded during the whole period was on the 30th August, 1881. The summer having the highest mean temperature was 1881. The lowest temperature recorded for the summer of 1881 was above that of either of the others. The warmest day of the whole period, September 6th, and the warmest month, July, were both in 1881, while the temperatures of all the corresponding data and events for the year 1883 were lower than for either of the other summers.

It is also on record that the average summer rain-fall for the five seasons referred to was 17.34 inches. In 1881 only 16.44 inches fell, or .90 inches less than the average. In 1883 there fell 22.35 inches, or an excess of 5.01 inches. The average number of days on which rain fell for each season was 69.6. In 1881 rain fell on 70 days, and in 1883 on 85 days. Neither the extra number of days on which rain falls, nor the extra quantity deposited during the season, seems of itself to have much influence in providing a fruitful season. In the summer of 1882 rain fell on only 57 days, and the total deposit was only 14.81 inches, or 2.53 inches less than the average, and yet, although noted for having fewer rainy days and a considerably less rain-fall than either of the other seasons, it was a fairly good season for fruit in this neighborhood.

J. B.

Lindsay, December, 1884.

—————

Dear Sir,—The arrival of the December number of the Canadian Horticulturist reminds me that it is about time to renew my subscription, and also to report to you about the premiums you have sent me, and a little of my experience in fruit culture.

And first let me say that I prize the magazine very much, and always look for it with interest, and would be glad if it were larger. I think it would be well if the members of the Association would write more for it.

The Niagara Raspberry sent me in the spring of ’83 grew nicely; but in the winter it froze nearly to the ground, so there was but one small branch that had a few berries on. The fruit appeared very well. Last spring I set out the young plants growing from the roots, about thirty of them, and they, with the first bush, have grown well through the summer, and I hope, if they do not freeze down again, to have some more fruit next season.

The Worden Grape, sent at the same time, grew middling, but was frozen to the ground, as were most other young grapes, in the early fall. This spring it started to grow again, and when the growth was about two inches long it was killed off again by frost. It grew a second time, and made about 18 inches of vine.

The Prentiss Grape, sent last spring, grew, making about one foot of vine. I have my doubts whether grapes will succeed in this part. I have several, and the best growing one has only made about four feet of vine in two summers.

I had two kinds of Black Cap Raspberry fruit this season, the Mammoth Cluster and Gregg. They fruited fairly well. The Mammoth Cluster stood the winter best, it not being hurt much. The canes of the Gregg were hurt considerably by the winter frost.

I have also several kinds of strawberries. The Sharpless does very well. The Bidwell is a good grower, and forms a good plant, but I am disappointed in the fruit, there being not much of it and very imperfect.

I am trying several kinds of currants and gooseberries. The trees are young, not much fruit yet, but it is good.

I am but beginning small fruit raising, but am finding a growing interest in it, and purpose, if spared, to report as I find interesting and profits able matter.

Yours truly,

Samuel Fear.

Brussels, Dec. 10th, 1884.

—————

To the Editor of the Canadian Horticulturist.

Dear Sir,—How fast the months go by, so say you, and so, methinks, do all of your readers who, like you and me, have passed the sixtieth mile stone.

Your retrospect of the past in connection with our journal is a pleasant one. Many a compliment you have been paid, many an encouragement given, to persevere in a good work, though at times with wearisomeness and worry.

Surely the Horticulturist has been a good investment to many a one. It seems to me scarcely can that reader be a man ava who has not profited by its perusal. But I find myself wandering into my mother tongue, and think I hear you saying, “There goes Croil again in his broad Scotch; he has never yet sent me his promised Scotch Dictionary.”

But I am in earnest to-day, and send you herewith a nice volume of Scottish songs, at the end of which you will find a miniature Scottish Dictionary. Small though it is, well studied there is enough in it to pass you for a fair sample of a Scotchman. But what of songs, you say? I’ll tell you about that too. A new feature promised at our next meeting is good music. I go for that, and so well have you reminded us of passing years you must be just in mood to give us in all its beauty,

“John Anderson, my Jo.”

Friend Goldie will surely enliven us with “The Dusty Miller.” I only give you the concluding verse:

“In winter when the wind and rain

Blaws o’er the hoose and byre,

He sits beside a clean hearth stane,

Before a rousing fire;

With nut-brown ale he tells his tale,

Which rows him o’er fu’ nappy.

Who’d be a king—a petty thing,

When a miller lives so happy?”

Mrs. Saunders, I hope, will favor us with the song, the most beautiful in the Scottish or any other language:

“There’s nae luck aboot the hoose.”

And before she gets through with it, her worthy husband, I know he’s full of music, will be so worked up with the music of the good old land as to lead off in lively style in

“Auld lang syne,”

Scott Act notwithstanding.

Wishing you and your readers a happy New Year, and many returning ones,

Dear Sir, yours truly,

John Croil.

—————

The Niagara Raspberry (received from the Fruit Growers’ Association) did very well this summer. It had quite a lot of berries, and very large. I think it will do well.

Edward Ryerse.

Port Dover, Dec., 1884.

—————

The Flemish Beauty Pear sent out by the Fruit Growers’ Association some years ago has blighted badly this summer, but had a heavy crop of fruit, bearing about four or five bushels. The Glass’ Seedling plum, also sent out, is about the only plum tree which stood the blight last year out of three hundred, and had a very fair crop this season. The Swayzie Pomme Grise apple has fruited the last two years, but not very well. The Ontario apple had twenty-five large apples the next season after planting, which proved to be good keepers for so young a tree. My raspberries and grapes proved a total failure.

Wm. Ross.

Owen Sound, December, 1884.

—————

In reading your article on the Niagara Grape, I notice that you are under the impression that the vines of that variety planted in Canada are mainly in the neighborhood of Grimsby. I doubt if that is the case, as I think Oakville comes to the front in the Niagara Grape as well as in strawberries. I think there are about four thousand vines of Niagara planted in this vicinity. I have two thousand five hundred of them, and if you want to see some thrifty vines, come during the growing season and take a look at them.

Yours truly,

R. Postano.

Oakville, Dec., 1884.

—————

Isham Sweet is a Wisconsin apple of decided value. My own trees have given me a barrel this year, and it has been the first winter sweet that has proved hardy enough for this climate. It is of medium size, nearly round, dark red, yellow flesh, and a very rich sweet,—a very good dessert fruit of its class. It keeps quite well.—Dr. Hoskins, in Home Farm.

—————

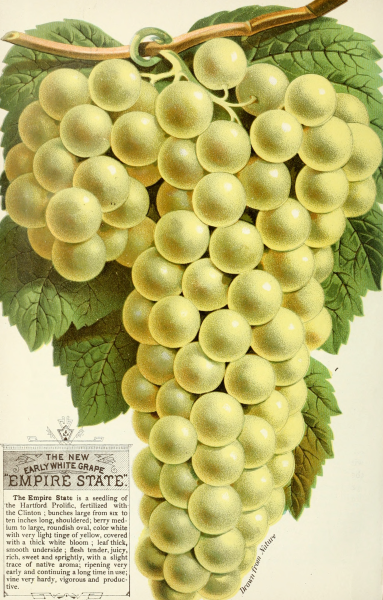

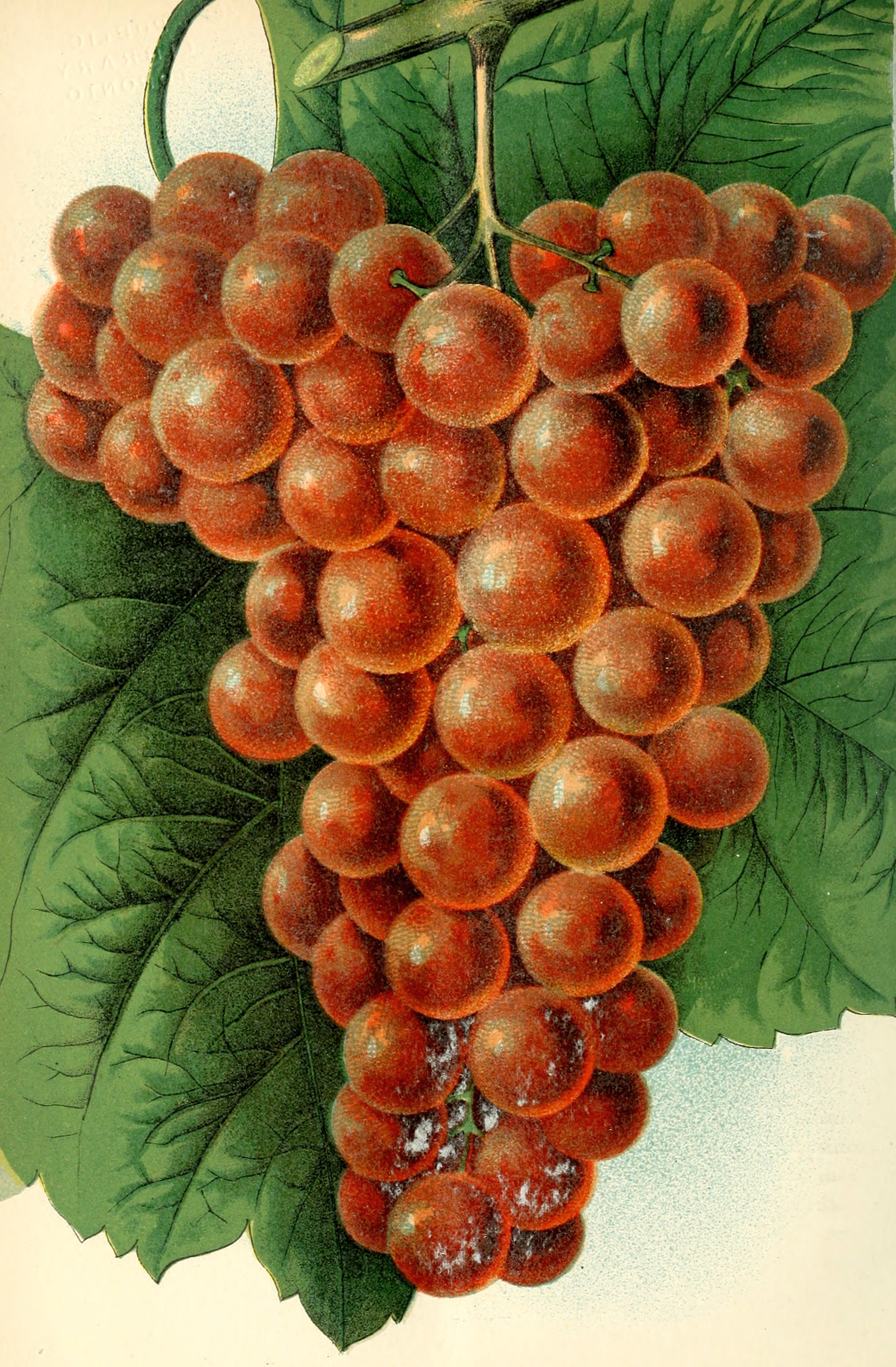

[A paper read before the Summit County Horticultural Society, by M. Crawford, of Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio]

There is a pressing need of more light on grape culture, for the reason that such knowledge can be turned to good account by nearly all classes. We can not all have an orchard, or even a single fruit tree. Some have not room for a row of currant bushes or a strawberry bed; but who has not room for a grape vine? Its branches may be trained on a building or fence. Its roots will run under the sidewalk, along the foundation, beneath the buildings—anywhere and everywhere—in search of plant food, which, dissolved in water, is carried to the leaves and boiled down, as it were, and converted into grapes. What an opportunity this is for every man and woman to add to the comfort, health and happiness of those dependent on them! Horticulture gives to working men almost the only opportunity of adding to their income outside of working hours, and this branch of it is especially inviting. I once knew of a large vine in a city lot that produced over a hundred dollars’ worth of grapes each season for several consecutive years. How much is it worth to have all the grapes one wants for himself, his family and his friends for even three months in the year? And this is within the reach of nearly all, without making any effort to keep them beyond the season. The vine, besides furnishing such delicious fruit, adds greatly to the attractiveness of home. Even the name, “vine-covered cottage” or “vine-clad hills,” suggests that which, once possessed, can never be forgotten.

Grapes may be grown in all parts of the United States and Canada, where ever a grape grower can be found; and the more unfavorable the locality, the better will be his success, for this reason: the greater the difficulties to be overcome, the greater effort is put forth. If he lives far north, he will cover his vines in winter; if too far south, he will grow them on the north side of a hill or building. If his ground be too wet, he will drain it, or grow his vines in a raised border. Michigan, cool and level, the last place one would expect this warm-blooded fruit to flourish, sends hundreds of tons to Chicago and other markets, and sends cuttings to France. Campbell, of Delaware, O., has the meanest place in the country to raise grapes, but he has splendid success, and long may he flourish!

Some parts of the country are so favorable to this industry that success comes almost without an effort, but people are slow to learn that it may be carried on successfully almost anywhere. Dr. Buckley, now travelling in Europe, writes of a noted vineyard where the vines are all planted in baskets and fastened to a bare rock, six or seven hundred feet high.

The vine may be planted after the leaves fall, and at any time before growth commences in the spring. A stronger growth will follow fall planting, provided the vines receive no injury during the winter.

If the vines be strong, it is only necessary that their roots be spread in a natural position, and a little deeper than they were before, and that fine, rich soil be brought in close contact with them, and the hole filled up. If weak, single-eye vines be used, greater care must be given. Fine roots that have grown in a mellow bed, and within an inch or two of the surface, should not be covered to a great depth at first. This is true even of asparagus. The roots of a plant must have air or die.

It is very important that the roots of no other plant occupy the soil near the newly planted vine. Its roots will stand a poor chance among those of an established tree or vine. Neither should strong growing varieties be planted near weak ones. Many a grape of real merit has been condemned as a poor grower because such gross feeders as the Concord have robbed it. I have an Isabella vine that has struggled between two Concords nine years, and has made but little headway, while they are increasing in strength. Few people have any idea of the distance a tree will send its roots. I read of a gardener who cut down a row of elms because their roots interfered with the flower beds three hundred feet distant.

That vines may be set three feet apart each way, and be kept in bearing condition, I have no doubt. Thirteen years ago I planted a lot of vines in a row thirty inches apart, and two in a place. The second year I allowed one in each place to bear a large crop, and then cut it away in the fall. These vines have remained in good condition ever since, although as much fruit might have been produced if they had been thinned first to five feet apart and then to ten.

The above cases are given to show what may be done—not what should be done. My experience leads me to believe that a vine is more likely to continue in health if it be allowed to increase in size—to have more room each year. In nearly every instance a thinning of the vines in a vineyard has been followed by satisfactory results. One grower who has thinned till his vines stand 15 feet apart each way, claims to have found the best distance. For a vineyard I prefer about eight feet each way, and for a town lot I would stick them wherever I could find room. It is well, when vines are worth but a few cents apiece, to plant two or three times as many as are wanted, and the extra ones may be allowed to bear heavily—one-half the second year, and the other the third, and then be cut away. This gives the permanent vines a fine chance to get strong before they bear. A vine may be extended to any distance along a trellis or support, but it requires time. It should not be lengthened more than two or three feet in any direction in a single season.

What to plant is an important question and should be carefully considered. Very much will depend on the grower. If he understand the wants of the vine, and can supply them, he can raise any variety, and should choose only such as are desirable. It is very unsatisfactory to spend money, time and skill in raising an inferior article—especially if it be for one’s own. It is always well for beginners to plant some Concord and Worden vines, for they are very reliable and quite good.

To prepare the soil for grapes is to make it dry and rich. If you want to do more than this, make it drier and richer. It is not sufficient that it be well under-drained, so that water will not lie, but the surface water should be allowed to get off before the ground becomes saturated. Then plow and harrow thoroughly, as for any other crop.

Thoroughly decomposed barn-yard manure is sufficient for the grape or any other crop we cultivate. In its absence, bone dust and ashes answer all purposes. Nitrogenous manures cause a rapid growth, but they should never be used where the highest flavored fruit is desired. The choicest wine is made from grapes grown on poor, rocky hillsides, and when it becomes necessary to use a fertilizer the next crop is made up and sold under an assumed name, lest the brand be brought into disrepute.

Manure should be applied in the fall after the grapes are gathered, so that it may leach into the soil during the winter. Grape roots have a special liking for bones, and seem almost to know where to go to find them. A Delaware vine sent a root some distance to a hole in which bones had been buried, and then it branched, and nearly surrounded every bone with roots. The owner prized the vine, and would not have injured it willingly, but in spading he accidentally cut the root leading to the hole. The vine died, and he ascertained that it had drawn nearly all its food through that one root.

Eight or nine years ago, when the Lady grape was introduced, I obtained one and planted it as follows: I dug a hole four feet in diameter and two feet deep, and nearly filled it with cows’ heads from the slaughter-house. I then filled in among the bones some good soil and planted the vine, and then sodded it over. The turf has never been removed since, and the vine has done well from the first, although I have no doubt but that the roots of the Concord and Worden near by are trying to get the bones away from the Lady.

Is it not encouraging to think that on ten feet square of ordinary land, a boy may dig in a wheelbarrow load of bones, and a bushel of ashes, plant a vine worth 10 cents, and then cover the space with grass, and that vine will go on changing those bones into fruit, producing bushels every year until the boy becomes an old man. All the vine will need is a little trimming and a place to hang out its leaves.

The majority of vines are grown in the open air from cuttings. If they have ripened at least a foot of wood, and their roots have received no injury, they are safe to plant. Layers of the best quality, from bearing vines that have not been weakened in any way, are still better, while those made from green wood, late in the season, are almost worthless.

Vines made from single eyes, started under glass early in the season, and grown with skill and care, are superior to those grown in the open air. New, high-priced varieties are usually grown in this manner. * * *

A vine needs some summer pruning—enough to regulate its growth. No matter what care and skill may have been exercised in pruning and tying up before the growing season, some buds will start with greater vigor than others, and unless they be stopped early in the summer, they will appropriate to themselves more than their share of sap, leaving other parts of the vine in a starving condition. It is the vine grower’s place to see that all have an equal chance, and he should be on the lookout and nip the ends of these would-be-monopolists, and while they are recovering the weaker shoots will catch up, and perhaps hold their own. This much seems necessary to equalize the growth. Besides this, we must see that the fruit has a fair chance to ripen, and that good bearing wood be provided for the next season; for without such provision, fine fruit can not be produced. A vine in vigorous growth sends out a lateral at every joint, and these should be nipped off beyond the first leaf when the best results are desired. This should be done early. By this means the main cane with its leaves and fruit will receive the sap instead of its being wasted in the production of useless laterals. This will greatly enlarge and strengthen the leaves, and give more chance for light and air among them.

Some varieties keep on growing until quite late without ripening their wood. This can be remedied by stopping the shoots when they have grown far enough. Unripe wood accompanies unripe roots, and neither are desirable. The above, if faithfully carried out, is the perfection of summer pruning, and is really nothing but the prevention of useless growth. The removal of any considerable amount of foliage in the growing season is weakening to the vine.

Constitute the important part of grape culture, and without them there can be no permanent success. A vine on trees, with plenty of room, will flourish with little or no pruning; and a young vine on a trellis will endure bad pruning for a time; but a poor method, or a good method poorly carried out, will ultimately result in failure. We prune to enable the vine to mature the greatest amount of fruit, with a satisfactory amount of wood for the following year. To do this intelligently, one must know something of the habits of the vine, the treatment to which it has been subjected, and the fertility of the soil in which it grows. There is enough in the subject for an entire essay, and I can do no more here than to give a few suggestions.

Before a vine can produce fruit, it must have bearing wood; i. e., well matured canes of the previous year’s growth; and as the sap tends towards the extremities, especially the top, this bearing wood must be left on a level as far as possible. Otherwise, the sap will flow past the lower buds and force the top ones into a rampant growth. For this reason it is entirely useless to attempt to cover any considerable amount of vertical space with a single vine, and expect it to bear above and below at the same time. With a majority of people it requires but a few years to get all the bearing wood to the top of the trellis. Where a cane of even two or three feet is left to bear, it must be bent to impede the flow of sap, in order that all the buds may start alike. If this be properly attended to, each bud will get its full share, the growth will be uniform, and but little summer pruning will be needed.

The proper amount of wood to leave for bearing depends on the age and strength of the vine, the fertility of the soil and the trellis accommodations, and can be best learned by experience. If allowed to over-bear, the wood and fruit will fail to ripen and the vine will be weakened, if not permanently injured. If pruned too close, a vigorous growth will follow, but little fruit will be produced, and, unless well summer-pruned, the usefulness of the vine will be injured for the following year, and the evil tends to perpetuate itself. The bearing wood should be evenly distributed over the vine and about the same amount on each arm.

The grape, like all other fruits, is subject to disease, especially if its vitality be lowered by any means. Mildew and rot are most to be feared.

Mildew is caused mainly by too much moisture in the soil, and is augmented by a lack of air and sunshine on the foliage. Rapid and perfect drainage is the remedy.

The rot is caused by the spores of a fungus, which, though invisible to the naked eye, are carried by the wind and deposited on the fruit, where they germinate and grow, causing the rot. These rotten grapes lie on the ground all winter, and when the warm weather comes the spores are again sent out, like “smoke” from a puffball, and are deposited on green grapes, where the same process is repeated. Now, to prevent this, we must either destroy the spores before they reach the grapes, prevent their germinating on the grapes, or prevent their growth after they germinate. If the rotten grapes could be swept up and burned in the fall, the number of spores would be greatly diminished, especially if our neighbors do the same. No matter how many spores there may be, they cannot germinate without moisture. This is why grapes never rot when grown on a building under a cornice. A wide board nailed over the trellis answers very well, and paper bags put over the clusters, when the berries are small, and fastened with a pin or tied on, are effective. It has been known for years that no fungus growth can take place in the presence of carbolic acid. One ounce of carbolic acid, dissolved in five gallons of water, and sprayed over the fruit when the rot appears, will stop its farther progress. This discovery, like all others in horticulture, is given free as air, although no man can estimate its value.

People should exercise some common sense in buying new varieties of grapes or other fruits. If one can afford the outlay—which of necessity must be considerable—it is a pleasure to test the new varieties as they come into the market. He is then qualified to report for the benefit of those who may profit by his experience. Until a variety has had a fair trial no man has any right to speak against it. The fact of its being new argues nothing; all were new once.

If one can not afford to buy high-priced varieties, he should in all fairness withhold his testimony in regard to them. It is worthless to others and damaging to himself. It is very unfortunate that in this matter—and most others—those who know the least make the most noise.

The originators of new fruits have done more to advance the cause of horticulture than any other class, and they are clearly entitled to a reward for their labors; and this they can not get without charging a seemingly high price. With the introducer the case is the same. He must publish lengthy descriptions and testimonials, and this is costly and must be met by high prices.

A few years ago I planted fifty very small Concord vines four feet apart. They received no extra care, and the third year, while yet on stakes, they produced over 400 pounds. I have often known vines to yield over 60 pounds the third year. I once planted an Iona vine four years old, that had been three times transplanted and root-pruned. It was cut back to three eyes, each of which sent out a shoot bearing three clusters. One-third of the fruit was removed, and quite early in the summer the shoots reached the top of an eight-foot stake. They were then allowed to grow seven feet further on twine stretched horizontally, at which point the ends were nipped. The vine ripened the 45 feet of wood and six fine clusters of fruit. The next season two of the canes were shortened to three feet, and the other to two buds. The three-foot canes were laid down horizontally and allowed to bear over 25 pounds of fruit.

—————

The “Working” Report of the Forestry Division at Washington (revised in the Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture) fixes the estimated value of the United States forest products at $700,000,000, which is more than the value of the corn crop, nearly twice that of the wheat product, ten times the output of the silver and gold mines or the value of the wool product, and three times the value of the output from all the mines of the United States put together.

—————

A rubber hose is generally the most available means for watering gardens in towns and villages in which there are public water-works. But this is so expensive that people of moderate means do not use it extensively. As a substitute for rubber hose I have employed half-inch iron pipe, with very satisfactory results. From the water-pipe in the street to the rear end of my garden, the distance is over three hundred feet. Last year there was not a day, during the entire growing season, when any portion of the garden needed water; but the season previous we had no rain for more than six weeks. During such dry and hot weather the garden needed water almost every day.

As a substitute for hose, I purchased two hundred feet of half-inch iron pipe, in lengths of about sixteen feet each, at $3.75 per hundred feet. Galvanized pipe usually costs twice as much as the plain iron. To keep the pipe from rusting, a heavy coat of paint was applied to the outside; but pitch or coal-tar, applied boiling hot, will be cheaper and more durable than paint.

Now, instead of burying the pipe in the ground, I laid it on the surface and screwed the lengths together, thus forming a line of pipe from a faucet in the kitchen to the rear end of the garden. About every fifty feet, there is a Ꭲ coupling, provided with a short piece of pipe, say six inches long, the ends of which are closed by an iron cap screwed on the end of each short piece where there is a Ꭲ. By opening the faucet in the kitchen, water will rush in a minute to the farther end of the garden. Now we attach a hose, ten feet long, to any part of the pipe where there is a Ꭲ, and with that an abundant supply of water can be directed to any part of the grounds. As soon as one part of the garden has been watered sufficiently, unscrew the short hose from the Ꭲ, screw on the iron cap, and carry the hose to the next Ꭲ, remove the cap and screw on the hose, and throw water fifty feet or more on both sides of the line of iron pipe. At the close of the growing season, unscrew the lengths of iron pipe and store them under the floor of a veranda or in the garret until wanted another season.—Am. Garden.

—————

The editor of the Rural Home recently visited some of the farms in Western New York belonging to the Wayne County Evaporated Fruit Company, and says as follows:

Mr. Van Dusen has taken a great fancy to the Shaffer raspberry, and is planting them as fast as he can make plants. As we saw it bearing on the Lyons farm we are not surprised at his enthusiasm in its favor. It was bearing an immense crop. The Shaffer was, evidently, a chance hybrid of the red and black found on the farm of a Mr. Shaffer, of Wheatland (we think), Monroe County. Was introduced by Chas. A. Green, of Clifton, in the same county. When we first saw it on Mr. Green’s grounds, about four years since, we said that it was the largest raspberry we ever saw, but thought its color a dark purple—would prove an obstacle to its ready sale in market. But that objection has been avoided by not offering for sale in its fresh state, but by canning or evaporating. Mr. Van Dusen evaporated his crop last year, and disposed of the dried fruit at 50 cents per pound, 20 cents more than he received for black caps dried. He was offered, this year, 10 cents a quart for his Shaffer’s for canning. So it would appear that no difficulty need be feared in disposing of the fruit. It loses considerable more in drying than Ohio or the juiciest black cap.

We believe that it will yield as much or more than any other variety and as it is perfectly hardy and a wonderful grower, it will readily be seen that it has strong claims. We have seen no other red raspberry which equals it for canning purposes.

—————

A correspondent of the Country Gentleman thinks that coal ashes are in some as yet unexplained way beneficial to garden vegetables. This is what he says:

It has been long known that coal ashes have the effect of mellowing the soil, particularly clay. A rigid clay may thus be greatly improved in its texture. It has been held that the fertilizing properties of coal ashes are small; repeated analyses have shown this. Yet, used as they have been here in gardens, without other manure, the effect has been such as to lead irresistibly to the conclusion that they develop in some way a considerable amount of fertility. All cannot be accounted for by the mechanical improvement, as in cases where this is not lacking the effect is still present, and apparently undiminished, if not sometimes increased—in this case acting seemingly as wood ashes do, requiring other (organic) fertility to aid, if full results would be obtained.

I was surprised, early in the spring, on seeing unusually thrifty tomatoes and beans, to learn that the only manure used was coal ashes, scattered in the garden to get them out of the way. This was practiced for several years, and no manure other than this had been used. I was shown another garden to-day which was treated exactly in the same way the only dressing being coal ashes. Here the growth seemed all that it could be. I was shown a potato grown here that weighed one pound eleven ounces and a half. It was the early Vermont, a variety not noted, I believe, for its large specimens. But they were all large, averaging from half a pound to a pound; no small ones among them, and many exceeding a pound. They were planted fifteen inches apart in the rows, a small potato dropped in each hill. The owner of this garden lays the success to the coal ashes, and says there can hardly be any mistake about it. This is the opinion of others also. My own experience is confirmatory. But the effect I find is not immediate. It is more tardy than with wood ashes, whose potash and soda act promptly.

I would advise by all means, that coal ashes, instead of being thrown away, be used in our gardens, removing the coarser parts; also on potato ground, always mixing well with the soil, and as early as the ground will admit, and so be repeated yearly, giving thus time for effect upon the soil. I find the best success where the ashes have been applied for several years. The second year is sure to tell, even when thrown upon the ground and left to lie there undisturbed, as I have abundant evidence. But the place for full action is in the soil.

I should have stated that in the second garden mentioned, where the ashes were omitted, as was the case with a small space, there was a uniform lack in the growth, being seen in the size of the vines and tubers. About a quarter of the soil of this garden was composed of ashes. In places where the proportion of ashes was the greatest, the largest tubers were raised. There is no doubt of the general benefit of coal ashes in a garden, and their decided effect upon the tomato and potato family. They doubtless affect more or less favorably all plants, in the improved texture of the soil, which most of our old cultivated fields need. Add to this their well known manurial properties which science has pointed out, little though they be, and there is no reason why coal ashes should not be used on our land, to say nothing of what may seem an occult influence when they are put in union with the fertility of the soil, resulting thus, as appears to me, in an increased growth. I have faith in the discarded coal ashes, and I am using them to advantage.

—————

(By Hon. M. P. Wilder, in Green’s Fruit Grower.)

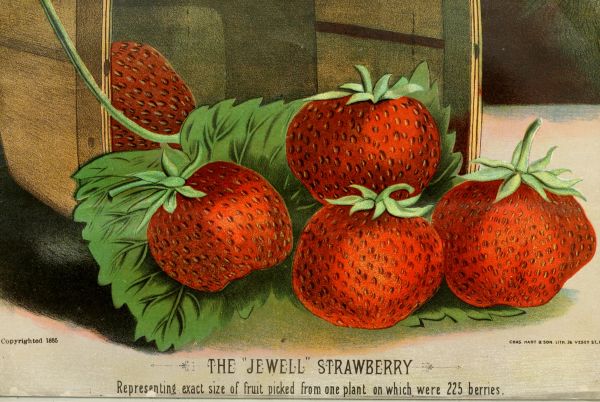

How has the James Vick done with you this season? It is a beautiful plant with noble trusses and a super-abundance of bloom, but cannot carry out the crop to perfection without high cultivation and plenty of water. It throws up too many fruit stalks. It is a pity that the fruit is not larger. We have had frequent rains and a good season to test a large number of the new varieties, some of which I think well of. Primo is a tine, large, uniform, bright, prolific, and late variety; very good. The Prince of strawberries planted last fall made large stools—some with four or more trusses and produced much handsomer and high-flavored fruit. Mrs. Garfield and Jewell make good plants and are promising, but Iron Clad has not been clad with much fruit. Bouquet (a new variety from the Hudson River) is rich and high-flavored. Crescent and Duncan (the former fertilized by the latter) are my most useful early sorts. Duncan is healthy, productive and aromatic; excellent for home use. I still hold on to many of the older sorts for a general crop, such as Charles Downing, Seth Boyden, Kentucky, Sharpless, Triomphe de Gand and Cumberland, nor would I omit the Hovey and Wilder, as grown by the originators, and as always shown at the annual strawberry exhibitions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. Strange indeed that these varieties are not more grown, but a neighbor of mine has an acre of the Wilder and finds a ready market previously engaged at twenty-five cents per quart. Mr. Hovey has some new plantations of his strawberry of great vigor, and I think he will be heard from next year. The Early harvest blackberry is two weeks earlier than any other I have.

—————

Eulalia Japonica variegata and E. J. zebrina are, in my opinion, two of the prettiest and most desirable ornamental grasses we have in cultivation, and both should be grown by all who possess the necessary facilities. They do best when grown in a rich, deep soil, and after they have become well established, so that it is well to avoid frequent removals. Propagation is effected by division of the plants early in the spring, just before they start into growth. I know that seeds of these Eulalias are often advertised; but as far as my experience has extended I have never been enabled to raise a plant of them with variegated foliage.

For the benefit of those who are not acquainted with the Eulalias, I would say that they are reed-like plants, attaining a height of from four to six feet. E. J. variegata has foliage that bears a striking resemblance to the old ribbon or striped grass of the gardens; while the foliage of E. J. zebrina has the striping or marking across the leaf instead of longitudinally. On this account, it is a plant that will always attract attention; but I will here say that I consider the former the prettier and more desirable of the two.

The Eulalia usually flowers about the middle of September, the flower panicles being produced from the summit of the stalks. At first they are brownish, and not at all showy; but as the flowers open the branches of the panicles curve over gracefully in a one-sided manner, thus presenting the appearance of ostrich plumes. If the flowers are cut when fully developed, and dried in a dry, airy situation, they will be found to be very desirable for decorative purposes during the winter season.—Rural New Yorker.

—————

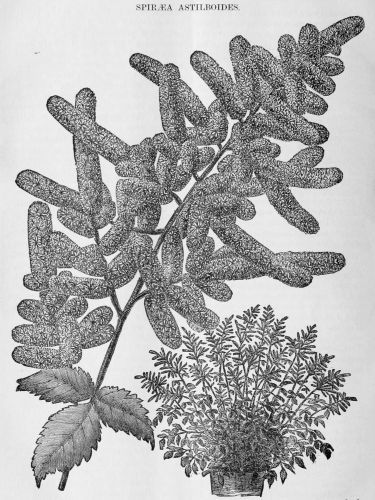

As some of the best spiræas found on Eastern lawns are not hardy on the prairies north of the 41st parallel, a few notes on the finest “ironclads” may be useful to propagators and planters.

Spiræa opulifolia: A large shrub with bold outlines. Its light green, lobed leaves give a pleasing expression through the season, and its abundant crop of white flowers in June is followed by showy seed capsules which in the latter part of the season are shaded with deep crimson. It is easily propagated by cuttings of the new wood.

S. trilobata: This is a special favorite in Michigan, Ohio, and the Eastern States, and seems still more beautiful on the prairie. Its branches spread out laterally, with recurved tips loaded in May with compact corymbs of pure white flowers. Its glaucous, lobed leaves are pretty through the season. It is propagated from cuttings with base of two-year-old wood.

S. Van Houtteii: Much like trilobata in leaf, expression, and flower, but the habit of the plant is more graceful, and the pure white flowers are larger. It is propagated the same as trilobata.

S. Douglasii: An erect, handsome shrub, with oblong lanceolate leaves with a white down beneath. The flowers appear in July and often continue to middle of August. The long, dense panicles of bright pink flowers form on the terminal points of the season’s growth of new wood. Where the wood of the preceding year’s growth is cut back in early spring or autumn, as practised with the roses, the exhibit of bloom exceeds even that on the spiræa callosa, which with us fails to endure the winters. Propagated from cuttings as above.

S. Nobleana: Much like Douglasii in habit and foliage, but with broader and looser racemes of purplish red flowers in July. In all respects a fine showy variety. It is propagated from cuttings.

S. hypericifolia: A larger growing shrub than the four preceding. It runs into many varieties varying in leaf and habit of flowering. The variety best known with us is acuta, sometimes grown as S. Sibirica. The flowers are white, in small terminal umbels on short spring growths from the new wood. Properly shaped and cut back it becomes a sheet of bloom in early May. It is propagated from cuttings of new wood, or from suckers or root cuttings.

S. chamædrifolia: This is a beautiful species running into a number of varieties, all hardy so far as tried. It has small, wiry branches covered in June with clusters of white flowers. In Northeast Europe it is much used for ornamental hedging. In this form it becomes literally a wall of pure white flowers and its foliage is pretty through the season.

The fine Japanese species are not noted, as my purpose is to direct attention to shrubs that will live and thrive in all parts of our interior prairies.

—————

For a neat flowering plant in the window, there is nothing which will repay so well for the space occupied as one or two of the Chinese Primroses. They are natives of China, and are not adapted to out-door culture. They bloom freely under glass, but unlike the other classes of primroses, require sun, and if properly managed, flower all the year round, although their most flourishing season is through the winter and early spring. All that is necessary for their cultivation is a moderately warm situation, close to the glass, medium moisture, and good drainage, which is secured by filling in the bottom of the crocks with pieces of broken crockery. It is not well to sprinkle the plants with water, as the leaves and flowers will be speckled easily and soon decay. The leaves and flower stalks seldom grow higher than about six inches, and if the plant grows top-heavy, it should be supported by a few little sticks placed near the collar of it. As the plants do not flower so well after the first year, it is therefore advisable to procure young plants every year, or to raise them from seed. This, however, is not easy; the seeds being very fine, if carelessly watered, or allowed to dry out, they will be lost.

In sowing the seed, care must be taken to cover them lightly with the soil, or what is better, not to cover them at all, but to press them gently into the surface of the soil with a smooth piece of wood. The watering should be done by saucers placed underneath the pots, or by very fine sprinklers, so as not to wash the soil; but even after the young plants have developed two or three leaves, they require careful watering; if the soil is permitted to get dry, the very tender roots may be dried up in a few hours. Our way of treating the seed is this: We water the lower body of earth in the pot by a saucer, and cover the surface from time to time with a wet cloth, so as to leave the seeds undisturbed.

Of the Chinese Primroses, we have now some most beautiful varieties, double and single; the double white is certainly a beautiful plant, although it does not bloom so continuously as the other. The fringed flowers are considered the very best.—California Horticulturist.

—————

Gardening Illustrated, an English horticultural publication, thus speaks of the apple crop:—Messrs. J. W. Draper and Son, Covent Gardens, have kindly furnished us with the following particulars respecting the present appearance of the Apple crop in Europe and America: United Kingdom—Crop much below the average. France—An average yield of early kinds, especially in the Gironde; late and better descriptions somewhat short. Germany—Short crop generally. Belgium—Short crop. Holland—very light crop. Spain and Portugal—Crop short, description common. America—There are indications that the crop will not equal in bulk that of 1880, yet the yield in some of the best producing localities is likely to be very abundant, and superior in quality to the past two seasons. After mature consideration of the various reports there is little doubt that the crop of Europe is considerably under that of many years; thus it will be from America that the supply for the United Kingdom will be derived. The prospect of shipments being advantageously made to England were never more promising, particularly for better and later description of Apples.

—————

An industry which has steadily gained ground for some years is that of making unfermented wine. True, it is a sort of misnomer to speak of “wine” as unfermented, but in the absence of a better term it must pass at present. It is the pure expressed juice and “blood” of the grape, prepared in such a way that it can be used as a safe beverage in any season, with no danger of intoxication, nor any awakening of an old appetite for it. It first came into demand to supplant the use of intoxicating wine at the communion service, but it has found a demand outside of that field because it is agreeable and healthy. The steps regarding its manufacture are much the same as for ordinary wine, up to the point where fermentation begins; then various processes are used for “clarifying” it, so that it shall be free and clear from sediment. Any broken clusters of sound grapes will answer, and for that reason the manufacturer furnishes a market for many grapes that can not wisely be shipped to the great cities, though of course a rather low price is paid—two and three cents a pound.

The process used in finally closing the bottles or vessels in which it is to be kept, is like that of canning fruit, corked when at “a boil,” and then sealed. It must be treated much the same as canned fruit, and when opened for use in warm weather it must be speedily consumed or kept on ice to prevent fermentation. Old wine bibbers do not always take to it readily, but most other people like it amazingly, women particularly, after or during a fatiguing day’s work, as it warms and refreshes, and leaves no “bad feeling” as a penance. One of our manufacturers has shipped a good deal to England, and also has orders from long distances. Wine already fermented can be made into an unfermented brand of virtually the same quality, by placing it in open bottles in boilers filled with cold water, gradually heating it to the boiling point and then scalding; but it is troublesome and expensive, and attended with a good deal of breakage. This has been called “driving the devil out.” The cost of unfermented wine in bottles is usually about $6 a doz.—Rural World.

—————

Illustrated Catalogue of Trees, Plants and Vines for sale by Green’s Nursery Company, Rochester, N.Y., with hints on fruit culture; small fruits a specialty. Copy mailed free on application.

The Rural New Yorker is a weekly of sixteen pages, published at 34 Park Row, New York City, at $2 a year. The Editors are practical farmers, who write of that which they know from experience. Every new thing is tested on their experiment farm, and the results of the trial given to their readers without fear or favor.

The Fruit Recorder and Cottage Gardener, published monthly by A. M. Purdy, Palmyra, N.Y., at $1 a year. Mr. Purdy has devoted his life to horticultural pursuits, making a specialty of small fruits, which he grows on an extensive scale. His readers get the benefit of his large experience, besides the hints and suggestions of numerous correspondents.

Alden’s Literary Revolution.—John B. Alden’s Literary Revolution, though, possibly, not making so large a “noise” in the world as three or four years ago when its remarkable work was new to the public, is really making more substantial progress than ever before. A noticeable item is the improved quality of the books issued. Guizot’s famous “History of France,” not sold, till recently, for much less than $50, is put forth in eight small octavo volumes, ranking with the handsomest ever issued from American printing presses, including the 426 full page original illustrations, and is sold for $7. Rawlinson’s celebrated “Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World,” is produced in elegant form, with all the maps and illustrations, reduced in price from $18 to $2 75. These are but representative of an immense list of standard works, ranging in price from two cents to nearly $20, which are set forth in a descriptive catalogue of 100 pages, and which is sent free to every applicant. It certainly is worth the cost of a postal card to the publisher. John B. Alden, 393 Pearl Street, New York.

How the Farm Pays, by William Crozier and Peter Henderson. Published by Peter Henderson & Co., 35 and 37 Cortlandt Street, New York. We have very carefully perused this book, and unhesitatingly commend it to our readers as a most practical guide to successful farming. It is not a book of theories hatched in the brain of some agricultural quill driver, but the outcome of the actual experience of two men who have been successful tillers of the soil, and who herein give to others the methods and practice which have laid the foundations of their success. Mr. Crozier is widely known as a farmer who for the past twenty years has taken more prizes than any other working farmer in America for fine stock and farm products. Mr. Henderson is as widely known as a successful gardener, and is an acknowledged authority on all matters connected with the growing of vegetables and small fruits. The book is handsomely illustrated with engravings of implements found most desirable, and of animals of the most approved breeds. It is nicely printed on fine paper and strongly bound in cloth. Believing that many of our readers will desire to possess this valuable work, we will undertake to have a copy sent, post-paid, to any person who shall remit to us the price of the book, which is $2 50.

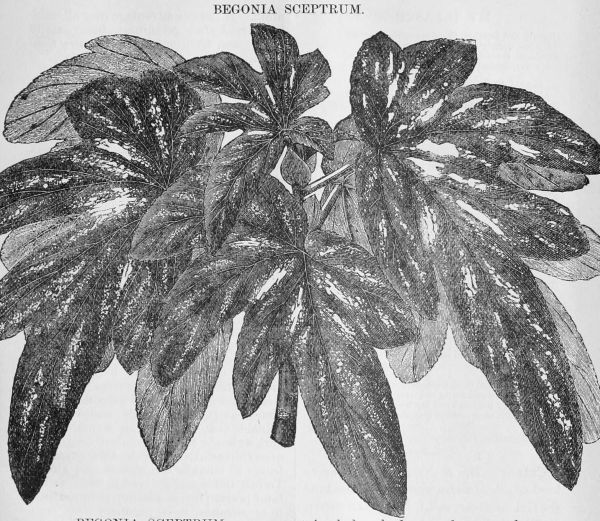

The December issue of the Floral Cabinet opens with a drawing made especially for it, entitled “Christmas Greetings,” and is followed by some pleasant words from the editors regarding their plans for the new year. Among other illustrations are two new and distinct varieties of well known plants, viz.: Begonia Sceptrum, a handsome species recently introduced from Brazil; its beautiful foliage will bring it at once into favor, and Spiræa Astilboides, which bears its flowers in plumy clusters, composed of myriads of white blossoms, which will be welcomed by all admirers of this hardy plant. “Comicalities of Plants,” “Some Christmas Greens” and “A Christmas Violet” are interesting contributions to the literary department, and the pages devoted to Home Decorations are filled with descriptions and illustrations of such fancy work as can be put to practical use. The managers hope to attain for 1885 a greater degree of perfection as a floral magazine, and to this end new names will appear among its contributors, and the number of illustrations will be increased.

The publishers of the Floral Cabinet supply to their subscribers each year premiums of a floral nature; and for 1885 they announce six different premiums from which subscribers may take their choice, embracing ten packets of flower seeds and some choice bulbs, details of which may be had on application to the publishers at 22 Vesey Street, New York. They will also send any of our readers a sample copy at half price (six cents), if this paper is mentioned.

We have arranged to furnish the Floral Cabinet for 1885 with choice of premiums together with our own publication at a combined price of $1.80.

—————

Will hold its annual meeting in the Town Hall, Renfrew, on Friday, the 16th of January, 1885, commencing at one o’clock p.m. At this meeting the officers for the ensuing year will be chosen, the President deliver his annual address, and other business affecting the welfare of the society will be transacted.

The County of Renfrew Fruit Growers’ Association is a live society, and doing a good work. It is the only one that sent a report of its transactions to be published with that of the Ontario Association.

—————

Corliss’ Matchless Potatoes.—The greatest yield of potatoes produced upon the R. N.-Y. experiment plot, up to and including 1883, was at the rate of 1,140.33 bushels per acre. The variety was Corliss’ Matchless.

The St. Hilaire Apple.—Dr. Hoskins writes to the Home Farm that this apple is larger than the Fameuse, more free from spots, more acid, and having perhaps slightly less flavor. It keeps five or six weeks longer, and is recommended by the Montreal Horticultural Society for those localities where the Fameuse spots badly. He adds that he regards it as preferable to the Fameuse as a market fruit.