* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: In the Shadow of the Tower

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Carolyn Keene

Date first posted: June 23, 2019

Date last updated: June 23, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190643

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

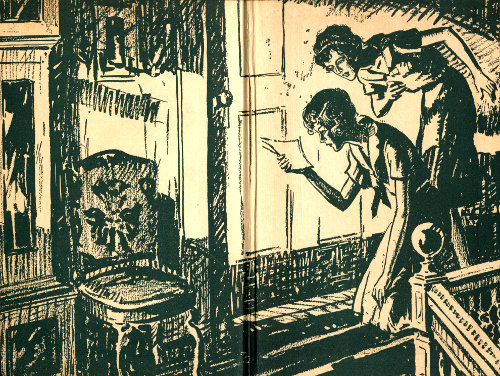

A FIGURE EMERGED FROM THE SHADOW OF THE TOWER. (Page 138)

THE DANA GIRLS MYSTERY STORIES

BY

CAROLYN KEENE

Author of

THE NANCY DREW MYSTERY STORIES,

THE DANA GIRLS MYSTERY STORIES

ILLUSTRATED BY

FERDINAND E. WARREN

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

BOOKS FOR GIRLS

By CAROLYN KEENE

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

THE DANA GIRLS MYSTERY STORIES

By the Light of the Study Lamp

The Secret at Lone Tree Cottage

In the Shadow of the Tower

THE NANCY DREW MYSTERY STORIES

The Secret of the Old Clock

The Hidden Staircase

The Bungalow Mystery

The Mystery at Lilac Inn

The Secret at Shadow Ranch

The Secret of Red Gate Farm

The Clue in the Diary

Nancy’s Mysterious Letter

The Sign of the Twisted Candles

The Password to Larkspur Lane

GROSSET & DUNLAP, PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK

Copyright, 1934, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

“Jean, I believe someone is following us!”

“Following us, Louise? What makes you think so?”

“Can’t you hear the whistling?”

Jean and Louise Dana, two pretty sophomores at the Starhurst School for Girls, halted on the trail which led through the woods. It was early winter, and the ground was covered with snow. The bare branches of the frost-laden trees glistened in the sunlight.

“Listen!” said Louise. “I can hear it again.”

On the still December air floated the notes of a plaintive whistling in a minor strain. It was not the warbling of a bird, nor did it seem like that of a human being. Puzzled, the girls looked behind them. There was no one in sight. The trail was deserted.

“It doesn’t sound human,” said Jean Dana, “yet it must be. There’s a sort of tune to it.”

Suddenly the whistling ceased. In the distance the girls could hear the snapping of twigs. It was late afternoon. Jean and Louise had been skating on Mohawk Lake in the hills not far from Starhurst, and had left before their companions. They were not disposed to be frightened, but the strange whistling really mystified them.

“There is someone coming,” insisted Louise. “Let’s hide.”

“Perhaps it’s some of the other girls trying to scare us.”

“Well, then, we’ll just fool them.”

The girls were near the outskirts of the woods where the trail dropped steeply down the hillside toward the meadows and the road below. They were familiar with the place, and knew that the path led past a natural cavern in the rocks not far ahead of them.

“Quick!” said Louise. “We’ll hide in the cave.”

The girls hurriedly descended the trail. The mournful and mysterious whistling was suddenly resumed, and they could still hear it when they reached the grotto. It continued as they scrambled into the gloomy hiding place among the rocks, where they crouched, watching the snow-covered path a few yards ahead of them.

In a short time they again heard the crackling of twigs, followed by the soft shuffling of footsteps in the snow. Jean clutched her sister’s arm in excitement as a strange-looking figure suddenly came into view.

It was that of a boy—a slender youth with a pinched, white face. The girls judged him to be about nineteen years of age. He was a furtive, odd-looking creature in ragged clothes that looked as if they had been made for someone else. As he shuffled along the trail, he looked fearfully from side to side.

“Why, he’s a hunchback,” whispered Jean.

The poor boy was, indeed, deformed by a hump that distorted his back, giving him a grotesque and dwarfed appearance. He walked in an ungainly manner, one hand thrust inside his tattered coat.

As the girls watched tensely, the hunchback came to a halt, looked back down the trail, and then nodded his head in satisfaction.

“I’m safe here,” he muttered. “There’s no one in sight.”

With that he sat down on a rock not far from the mouth of the cave. Rummaging in his pockets, he drew forth a long envelope, from which he extracted a letter.

The Dana girls regretted that they had concealed themselves in the cave. They knew they had nothing to fear from this pathetic cripple, and they had no intention of spying on him. However, not wishing to frighten the boy, they thought it best to remain where they were.

The letter, much-thumbed and frayed, appeared to be some kind of a legal document. The cripple read it carefully, muttering to himself in an undertone, while his thin face twitched strangely. Then, to the astonishment of the Dana girls, he began to cry.

It was evident that the letter had affected him deeply. The onlookers accordingly grew curious. They wondered what sort of message the document contained. Yet at the same time they were uncomfortable in the realization that they were peering at the secrets of a stranger.

“We ought to leave,” whispered Jean.

Louise, however, cautioned her to stay.

“We can’t go now. We’ll only frighten the poor fellow.”

Suddenly in the distance the girls could hear voices and shouts of laughter. The other students from Starhurst were sauntering down the trail from the lake.

The cripple scrambled hastily to his feet, and cast a frightened glance back up the snow-covered path.

“Someone coming!” gasped the hunchback. “I can’t let them find me.”

In evident terror he ran ahead a few paces, then paused in indecision and finally turned back. He saw the gloomy mouth of the cave, plunged through the snow toward it, and crouched down among the rocks at the entrance. He had not yet seen Jean and Louise, as they had withdrawn to the deeper shadows of the cave and had there hidden themselves, scarcely daring to breathe.

Suddenly nearby them the high, harsh laugh of a girl rang out.

“Oh, it will be the joke of the term! First of all we’ll leave a phone message for the Dana girls that their Uncle Ned is at the Continental House, and that they’re to go to see him at once. Then we’ll call up the clerk at the hotel and tell him that if two girls ask for their Uncle Ned Dana, they’re to be sent to the State Hotel. We’ll have them running all over Penfield looking for their precious relative, and when they get back to school they’ll surely be late. Won’t Mrs. Crandall give them a scolding?”

“Oh, Lettie,” came a shrill giggle, “that’s the best joke I’ve ever heard. We’ll get even with them for a few things they’ve done to us.”

Louise and Jean were very interested in the conversation which they had just overheard. The two persons sauntering down the trail were Lettie Briggs and Ina Mason, the only pupils at Starhurst with whom the Dana girls were not on good terms. Lettie Briggs, an angular, snobbish individual, fond of impressing upon everyone the fact that she was the wealthiest girl at Starhurst, was a very unpopular student because of her arrogance. Her one and only friend, Ina Mason, was a meek, toadying creature who seemed delighted to have the rich Miss Briggs deign to notice her.

The pair had clashed with the Dana girls on several occasions, for Lettie and Ina had a habit of playing mean practical jokes, and nothing delighted Jean and Louise more than to score a point against the unpopular chums.

Louise almost laughed aloud. She knew that she and Jean had overheard the details of an elaborate joke which was to be played upon them. Forewarned was to be forearmed. The sisters heard nothing further of Lettie’s plan, for Ina Mason said quickly:

“We’ll talk it over when we get back to school. The others are coming.”

In a few minutes a laughing, chattering group of girls came down the trail and passed the cave, unaware of the hidden watchers. Jean and Louise had a fleeting glimpse of gaily-colored sweaters and scarfs as their schoolmates passed by. Then the clamor of voices died away as the students descended the hillside.

The hunchback, who had been crouching near the mouth of the cave, rose to his feet. He groped in his pocket, withdrew the letter, and began to study it once more.

“We can’t stay here,” whispered Jean.

“And I’m cold. I’m going to speak to that poor boy.”

Louise advanced quietly toward the opening of the shallow cavern.

“We’re very sorry,” she said apologetically. “We aren’t spying on you, but——”

There was a cry of alarm as the cripple wheeled about and stared at them. Then he turned and fled as though terrified. Tripping and stumbling among the snow-covered rocks, he ran from the trail directly toward the edge of a steep cliff that dropped to the meadow below.

“Come back!” cried Jean. “You’ll fall!”

The lad paid no attention to her warning. In his mad flight he scrambled desperately to the very brink of the cliff. The girls gasped, as he suddenly slipped on the ice, staggered and fell. The letter flew from his hand.

The white sheet of paper, together with a green object that had been concealed in its folds, was whisked up by the breeze. The two articles fluttered over the rocks and went sailing out toward a distant field.

Jean and Louise hastily ran to the assistance of the hunchback, who lay panting and gasping in the snow.

“Are you hurt?” asked Louise. “We didn’t mean to frighten you.”

The cripple thrust the proffered hand aside.

“My money! My letter!”

The girls knew then that the green object had been a bill.

“We’ll help you get your money again,” said Jean. “Look! It has blown down into the field.”

The letter and the greenback had come to rest in the branches of a clump of bushes not far from the base of the cliff. But even as she spoke, the wind suddenly dislodged the letter and the bill from the trees and sent them both skimming across the snow.

“I must have it back,” declared the hunchback fearfully. “It’s all the money I have in the world——”

Then Jean uttered a cry of dismay. From among the rocks there emerged a lean black animal with a bushy tail—a fox. The little beast leaped playfully at the fluttering papers, snapped up the greenback, then sprang lightly toward the letter. A gust of wind sent it flying out of reach. The little beast whirled in pursuit, jumped into the air, and deftly caught the swirling bit of paper.

Then, like a fleeting black shadow against the white snow, the fox raced away across the meadow.

The Dana girls were overcome with concern. They felt that they were somewhat to blame for the loss of the letter and the money.

Sobbing with grief, the cripple was already hastening down the trail, wailing:

“Oh, the fox is gone. Gone with my letter.”

As the animal scurried off across the meadow, Jean and Louise scrambled down the hillside.

“We’ll never catch it!” gasped the younger Dana girl.

“But we may find its den,” replied Louise.

When they reached the foot of the trail, the cripple was already following the tracks across the snow. The sly fox, however, had disappeared. The girls traced the footprints as far as the meadow fence, but soon saw that the chase was futile.

It was growing dark, and the wind was rising. The breeze sent the snow shifting over the surface of the field, and the tracks were being blotted out swiftly.

The boy sank down beside the fence and burst into tears. Something about that heartbroken sobbing caught Jean’s attention. She looked significantly at her sister. Louise uttered an exclamation of surprise.

“Why, he isn’t a boy at all!” she cried.

“No boy ever cried like that,” declared Jean.

The hunchback looked up, eyes filled with tears.

“No,” the cripple sobbed, “I’m n-not a boy. I’m a g-girl. Oh, why didn’t you leave me alone? I’ve lost my letter and my money, and now I don’t know what to do.”

Jean sat down and slipped an arm around the shoulders of the weeping girl.

“We’re dreadfully sorry,” she said, “but you mustn’t blame us. We didn’t intend to frighten you. We’ll do everything we can to help you find your letter again.”

“Indeed we will,” Louise assured her. “Was it important? Was there very much money?”

It was in her mind that she and Jean might make good the loss if the amount were small.

“It was all the money I had,” confessed the girl in the snow. She was a little calmer now. “It was a thousand-dollar bill!”

The Dana girls were stunned by this unlooked for statement.

“A thousand dollars?” exclaimed Jean incredulously. “In one bill?”

The two sisters at once scented a mystery. Those of our readers who have made the acquaintance of Louise and Jean in previous volumes of this series can readily understand that a problem of this kind would appeal to them. They possessed marked talent as amateur detectives, and had already been successful in solving two strange cases that had created a great deal of excitement and bewilderment at Starhurst.

In the first book which introduced the Dana girls, By the Light of the Study Lamp, they encountered many thrilling adventures in getting to the bottom of the mystery surrounding the theft of a study lamp given to them by their Uncle Ned. Their clever work in this affair had brought about the recovery of a fortune in jewels.

Jean and Louise were orphans. Louise, a pretty, dark-haired girl of sixteen, was rather quiet, and the more serious of the two. Jean, a year her junior, was fair-haired, boyish, and impetuous. They made their home with their uncle, Captain Ned Dana, who lived at Oak Falls, which was not far from Starhurst. He was skipper of the Balaska, one of the great trans-Atlantic liners. Aunt Harriet, his maiden sister, was housekeeper of the picturesque old residence on the outskirts of the town.

In the second volume of the series, The Secret at Lone Tree Cottage, the Dana girls again proved their abilities as detectives when they solved the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Miss Tisdale, their young and beloved English instructress at Starhurst. In clearing up the case they also succeeded in restoring to a fine family a long-lost relative.

The success of the two sisters in these cases had given a decided impetus to their interest in detective work. It was only natural, therefore, that they should be excited by the mystery presented by the girl in boys’ clothing, who had lost a thousand-dollar bill.

“I’m afraid we’ll never find the money tonight,” said Louise kindly. “It’s getting dark.”

The cripple agreed that further search was useless at the time.

“I’m going to stay in Penfield tonight,” she said, “but I’ll come back here early tomorrow and look for my money.”

“We’ll help you,” Jean offered. “If we can find the den of that fox, we ought to be able to locate the money and the letter, too.”

“Why,” asked Louise, “are you dressed as a boy?”

A shadow crossed the thin face of the hunchback as she started to walk across the meadow.

“It’s because I have run away.”

At first she was not inclined to explain anything further, but as they went back toward the main road that led to Penfield the Dana girls were so kind and sympathetic toward her that she soon realized they were sincerely eager to help her. At last, won over by their tact and understanding, the hunchback told them more of her story.

“My name is Josephine Sykes,” she said. “Everyone calls me Josy. I ran away from the Home for Crippled Children at Bonny Lake.”

“Didn’t they treat you well?” asked Jean.

“Well enough,” replied Josy Sykes, with a pathetic smile, “compared to the other places.”

“What other places?”

“The farmhouses. Ever since I was fifteen I have done housework on farms. Being a cripple, I was never sent to any of the better places. You see, I was left at the Home when I was a baby.”

“Oh!” exclaimed Louise. “Your father and mother——”

“Dead,” replied the girl shortly. “I don’t know anything about my folks. My uncle left me at the Home. That’s how I got my name. He was Joseph Sykes and I was named after him. I was brought up at the Home as a sort of charity girl, because my uncle just seemed to drop out of sight after he left me there. I didn’t mind going out to work at the farmhouses, because I wanted to repay the people at the institution in some way, and it was time I was earning my own living anyway—but—oh, some of the places were awful! I ran away from the last one.”

Although Josy Sykes told her story in a matter-of-fact tone, the Dana girls sensed the tragedy of loneliness that had shadowed the life of the crippled girl. Yet they were still puzzled by her present disguise.

“Where did you go when you ran away from the farm?” asked Louise.

“I went back to the Home. They were very kind to me—they have always been kind—and gave me a job in the office. I thought my bad luck was over, but it wasn’t. I hadn’t worked there two days before a big sum of money disappeared from the safe. There had been a benefit for the Home and the cash proceeds had come to nearly a thousand dollars. Every cent of it was stolen.”

“They surely didn’t accuse you, did they?” asked Jean indignantly.

The hunchback nodded.

“They thought I took it. You see, while I was away from the institution, an important letter came to the Home addressed to me. The secretary put it in the safe. She was on a vacation when I came back, and I suppose the superintendent forgot to tell me about my mail. At any rate, I found the letter when I was putting some papers into the safe and naturally I took it. That was the one I was reading a little while ago. It was from my uncle, Joseph Sykes. He had enclosed a thousand-dollar bill. So you see, when I was accused of taking the benefit money from the safe, I was afraid they would find my thousand dollars——”

“So you ran away!” exclaimed Louise.

“I borrowed an old suit of clothes from a boy at the Home and climbed out of the dormitory window last night. I’ve been wandering about ever since.”

The girls were deeply concerned over the plight of the unfortunate girl.

“What are you going to do?” asked Jean.

“I don’t know,” confessed Josy, her lips trembling. “I felt safe enough when I had the money—but now that it’s gone—I haven’t any money—I haven’t any friends——”

Her voice faltered. With a cuff of her ragged sleeve she brushed away tears from her eyes.

“You have friends,” Louise assured her. “We’re your friends. You’re coming to Starhurst with us, and we’ll get some proper clothes for you. Then we’ll talk to Mrs. Crandall. She is the headmistress at the school and perhaps she’ll be able to help you.”

Josy Sykes looked at the Dana girls gratefully.

“You’re the very first strangers,” she said, “who ever paid any attention to me or tried to do anything for me.”

By this time they had reached the Penfield road. When they came within sight of Starhurst School, the Dana girls realized that their new acquaintance presented a grotesque appearance. Josy Sykes, who was evidently sensitive about her deformity, was conscious of her shabby clothes and bedraggled appearance.

“I—I can’t go into that grand place with you,” she said. “They’ll all stare at me. People always do. Perhaps you had better leave me. I’ll get along somehow.”

“Nonsense!” said Jean warmly. “We’re not ashamed of you.”

As they approached the walk that led to the front entrance of Starhurst, they saw Lettie Briggs and Ina Mason standing on the pavement watching them in open-mouthed wonder. They heard a harsh cackle of laughter from Lettie, and then her high-pitched, disagreeable voice:

“Look what the Danas have picked up. They’ve been slumming.”

A deep flush suffused Josy Sykes’s pinched face.

“I don’t like those girls,” she whispered. “They’re laughing at me. I’m not going in with you.”

Before the Dana girls could prevent her, she left the sidewalk abruptly and stepped out into the road. Confused by the rude stares and contemptuous laughter of Lettie and Ina, she failed to see a roadster which at that moment swept around a bend. She stepped directly into the path of the speeding car.

Jean screamed.

“Come back!” cried Louise.

Josy Sykes turned, saw the approaching machine, and uttered a shriek of alarm. She seemed frozen with fear. The man at the wheel of the roadster applied his brakes, but it was evident that he would be unable to bring the car to a stop in time. Josy Sykes wavered, moved as if to run back toward the curb, and then to the horror of the Dana girls she slipped on the icy pavement and sprawled helplessly in front of the oncoming wheels.

Jean Dana did not hesitate. She sprang from the curb and grabbed Josy Sykes by the arm. Even as the driver of the car swung desperately to one side, Jean dragged the helpless girl out of danger.

The roadster flashed past, brakes screeching, and skidded to a stop. It had missed the cripple by a couple of inches.

The Dana girls helped Josy to her feet.

“Are you hurt?” demanded Jean anxiously.

Josy’s face was white as she realized the narrowness of her escape.

“No,” she panted. “And you saved my life!” she declared gratefully. “I should have been run down if you hadn’t caught my arm in time.”

The driver of the car, a stout, red-faced man, was stepping from his machine.

“Close call!” he said. “A mighty narrow squeak. Young lady,” he remarked to Jean, “if you had been half a second slower, I’d be reporting a serious accident to the police.”

Some of the Starhurst girls were already running toward the scene. Jean took Josy Sykes by the arm.

“Come!” she said. “Let’s hurry into the school.”

The little hunchback was embarrassed with the thought of being the central figure of any excitement, so before the gathering crowd could learn what had happened, the Dana girls and Josy were hustling up the school steps. They reached the study unobserved, and there Jean and Louise quickly found a complete outfit of clothing for their new acquaintance. Within half an hour the ungainly crippled boy of the hillside had vanished, being transformed into a shy, wide-eyed girl in a neat blue woolen dress. Josy’s gratitude was pathetic.

“It’s a long time since I’ve worn silk stockings,” she sighed luxuriously, looking at her slender ankles. “You are too good to me.”

Josy was a little more cheerful as they went down the stairs, although she was still painfully conscious of her deformity and shrank from the curious glances of the students whom they encountered in the hall. When she reached Mrs. Crandall’s office, however, she was immediately put at her ease by the kindly manner of the headmistress. The Dana girls told their story, and the mentor of Starhurst School was at once sympathetic.

“If you are looking for work, Josy,” she told the hunchback, “I can offer you a temporary position in the linen room. It will give you time to look around and make plans for the future.”

There were tears of happiness in the cripple’s eyes.

“It’s wonderful of you to give me this chance,” she said. “I promise to work hard and try to please you.”

“I’m sure you will,” said Mrs. Crandall. “And I sincerely hope you will find your money. If you wish, you may take time off tomorrow afternoon to go back and look for it.”

“Exactly what we were going to ask, Mrs. Crandall,” said Jean promptly.

The headmistress smiled.

“I thought so.” She turned to Josy. “Was the letter very important?”

The cripple hesitated.

“Yes,” she said simply. “It was important.”

Josy said nothing more about the missive. When she returned to the study with the Dana girls, they noticed that she was evasive and silent whenever the letter or the robbery at the Home for Crippled Children was mentioned.

After dinner the girls left Josy in the room in the servants’ wing to which she had been assigned by Mrs. Crandall. Louise was puzzled by the girl’s reticence about her private affairs.

“Do you think she could have stolen that money?” she said to Jean.

“I don’t believe Josy Sykes would take a nickel that didn’t belong to her.”

“It would be dreadful if the police were to come here and take her away. After all, Jean, her story is very strange. She tells us she received a thousand-dollar bill in a letter, but she hasn’t said anything more than that. Who sent her that much money? And why?”

“Suspicious?” asked Jean.

“Well, after all, we don’t know anything about Josy.”

“I know what we’ll do. We’ll call up the Home for Crippled Children and ask about her,” Jean decided promptly.

Over the telephone the superintendent of the institution was gruff.

“We once had a girl here by that name,” he said, “but she isn’t here any more. Are you a friend of hers?”

“Well—yes,” admitted Louise.

“If you hear from her,” said the superintendent, “I wish you would let us know. We’re very eager to find Josy. Something very unpleasant happened here just before she left. A big sum of money was taken from the office safe, and we’d like to question her about it.”

“Do you think Josy stole it?”

“I can’t think anything else.”

“But I’m sure she wouldn’t do such a thing.”

“That was my opinion, too. But Josy is gone, and so is the money. By the way, who is speaking?”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Louise, and replaced the receiver. She turned to Jean. “Her story is true to that extent, anyway.”

They went back to the study and discussed the affair but decided to withhold judgment for the time being.

“She isn’t a thief,” declared Jean warmly. “I’m sure of that. It’s odd that she wouldn’t tell us why the money was sent to her, but it’s her own business after all and we have no right to be inquisitive.”

The door opened and they looked up to see the homely face of Lettie Briggs in the opening.

“Telephone call for you,” said the visitor, trying to appear unconcerned. “You’re to call at the Continental House for your Uncle Ned.”

“Really?” said Jean, without apparent interest.

“How strange!” murmured Louise.

They did not move from their chairs, but merely smiled at Lettie. They could see Ina Mason hovering in the background.

“I should think you’d be excited,” said Lettie. “Your uncle hasn’t been in town since Thanksgiving.”

“That’s so,” observed Jean.

“Very true,” agreed Louise.

Lettie looked puzzled.

“You’re to go down to the Continental House now and ask for him.”

Louise smiled.

“Are we?”

“At once?” asked Jean.

“Yes. Right away,” declared Lettie, who was beginning to have an uncomfortable suspicion that the practical joke was not working out as she had expected.

“I think I shan’t go out tonight,” remarked Louise. “It’s too cold. And I’m too comfortable here.”

“Uncle Ned,” said Jean, “can easily wait until tomorrow.”

“You’re not going down to see him!” exclaimed Lettie Briggs, astounded.

The Dana girls shook their heads solemnly.

“But—but—I thought—do you mean to say you won’t go to see your uncle when he comes all the way from Oak Falls?” stammered Lettie.

“Oh, if he did that,” said Jean, “we’d rush right down to the Continental House. But you see, our Uncle Ned——”

“Is on the Atlantic Ocean just now,” said Louise.

“Bringing the Balaska back to New York.”

The face of Lettie Briggs was a study in chagrin. The maddening indifference of the Dana girls was explained. They had seen through her deceitful joke from the beginning. Deliberately they had sat there and let her make a fool of herself.

“Then there must be a mistake,” she muttered.

“You made it,” said Jean, “when you thought you could send us on a senseless chase down to the Continental House. After that I suppose we’d have been sent to the State Hotel.”

With a wrathful exclamation Lettie Briggs turned, slammed the door, and fled. How the Dana girls had seen through her silly trick she did not know, but of one thing she was certain: they were now enjoying a hearty laugh at her expense, and Lettie Briggs did not like to be laughed at by anyone.

“They knew it was a joke,” she stormed, as Ina meekly followed her down the corridor.

“But how could they have known?” inquired Ina in a puzzled voice.

“You must have told someone what we were going to do.”

“Why, Lettie, I did not.”

“You did. How else could they have known? I suppose they’ll tell this all over school.” Lettie was furious. “I never felt so humiliated before in all my life. But I’ll get back at them. I’ll get even yet. I’ll make trouble for that homely little witch they pal around with——”

Lettie’s voice died away in a startled gasp.

On the wall of the corridor there suddenly loomed a huge, misshapen shadow. Hunchbacked and weird, it hovered mysteriously before them, making a strange and terrifying picture. Lettie stared in fright, and her screams of fear were echoed by Ina as the two girls wheeled about and fled down the hall.

The Dana girls rushed out of their study, alarmed by the screeching and tumultuous disappearance of the pair. They saw Lettie and Ina rushing pell-mell down the stairs at the end of the corridor. At the foot of a flight of steps leading from the upper floor stood Josy Sykes.

The poor cripple gazed at them with stunned, pathetic eyes. She realized that it was her shadow, cast upon the wall by a light at the head of the landing, that had created such panic. Overwhelmed by the knowledge that her deformity had such power to repel and frighten others, she broke into a fit of sobbing.

“They’re afraid of me!” she wept. “I knew I shouldn’t have come here. Everyone is afraid of me. They don’t like me. I’m going to run away again.”

The Dana girls did their best to comfort the stricken cripple. They brought her into the study and tried to convince her that she was foolish to allow her affliction to prey upon her mind. It was a long time, however, before Josy Sykes finally dried her eyes and became somewhat cheerful again.

“And you mustn’t think of running off,” Louise declared. “Don’t let a pair of foolish girls like Lettie and Ina frighten you away from Starhurst. It isn’t your fault that you are crippled.”

“Besides,” said Jean, “we want to help you find that money.”

“Tomorrow,” said Louise.

“I’m cold!” declared Jean Dana, shivering.

“So am I,” said Louise, thrusting her hands deep into the pockets of her coat. “And it’s going to snow.”

“We’ll never find that money,” said Josy disconsolately. “We can’t even find any trace of the fox.”

It was mid-afternoon and the white hillside was swept by a bitter north wind. The three girls stood beneath the rocky ledge that had been the scene of the previous afternoon’s misadventure and looked at one another in disappointment.

As soon as classes had been dismissed that day, they had hurried out toward the Mohawk Lake trail. For an hour they had searched in vain for the missing thousand-dollar bill and Josy’s letter. They had explored the rocks in hopes of finding the den of the black fox, but their search had proven fruitless.

“I don’t like to admit that we’re beaten,” said Louise, “but I’m afraid——”

“We may as well go back to Starhurst,” remarked Josy quietly. “I really didn’t have much hope. You have done all you can, but the money is lost, so I’ll just have to get along without it the best way possible.”

The Dana girls were reluctant to give up the search, but they realized that it was futile. Josy Sykes accepted the loss of her money philosophically. Jean and Louise were surprised to learn that she was more concerned about the missing letter.

“It was very important,” she told them as they retraced their steps toward the road, “the most important letter I have ever received in my life.”

“But you had read it,” said Jean.

“It was very long and there was so much to it that I can’t recall all it contained. If I could only remember the address that was written in it, I shouldn’t feel so bad. I was just reading the letter for the second time when—when I lost it.”

“Our fault, too,” declared Louise.

“It wasn’t your fault,” returned Josy indignantly. “The wind was to blame. And so was the fox. You have done everything anyone could do to help me.”

When the girls reached the road, they trudged back in the direction of Penfield. They had not gone very far before they encountered a lanky old gentleman who strode briskly down the highway with the air of one who walks for the pure joy of it.

“Why, it’s Mr. Tisdale!” exclaimed Louise.

The gentleman in question beamed with delight when he recognized them.

“The Dana girls!” he cried. “Well, this is a surprise.”

Mr. Tisdale may have been surprised to see them, but the Dana girls were nothing short of astonished at his appearance. Mr. Tisdale was the father of their English teacher, Miss Amy Tisdale, whose mysterious disappearance had inaugurated the many adventures surrounding The Secret at Lone Tree Cottage. When the girls first made his acquaintance, he was a querulous, ill-tempered old man who constantly complained about his health. To find him as he now was, striding along a country road in the face of an incipient snowstorm, seemed beyond their comprehension.

He immediately launched into an enthusiastic account of his latest health fad, and indorsed at great length the virtues of long-distance walking. At the first opportunity Louise managed to change the subject.

“Do you know anything about the habits of foxes, Mr. Tisdale?”

“Foxes? Were we talking about foxes? No, I don’t know anything about them. And I don’t want to know anything about them, either. Nasty animals. They steal hens, I believe. Why don’t you go to the fox farm if you want information about them?”

“Fox farm!” exclaimed Jean. “Where is it?”

“A fellow named Brodsky runs a fox farm about fifteen miles away. Catch the next bus. It will take you right to the front door. Brodsky will tell you all about foxes.”

Mr. Tisdale suddenly looked at his watch.

“Bless my soul! I’m behind schedule. Goodbye. Goodbye.” And he went away, his coat tails flapping in the breeze.

“He gave us a clue,” Louise cried. “Let’s go to this fox farm.”

“Perhaps that animal escaped from there,” said Jean. “I’ve never heard of any wild foxes near Starhurst. If it were a tame one, perhaps it ran home.”

Around the curve in the road there rolled a heavy passenger bus. The Dana girls made their decision without delay.

“We’re going,” announced Jean, as she signaled to the driver.

Great was their surprise when they climbed on board to find Lettie Briggs and Ina Mason perched in one of the front seats. Lettie sniffed contemptuously when she saw Josy Sykes.

“Some people are hard up for company when they have to pal around with the hired help,” she remarked in an audible tone.

Josy flushed, but Jean soon put the snobbish Miss Briggs in her place.

“Just had a wireless from Uncle Ned,” she murmured as she passed Lettie’s seat. “He sends his love.”

Lettie greeted that reminder with haughty silence.

The Dana girls and Josy made their way to the rear seats. They assumed that Lettie and Ina were merely bound for the next town, which was about five miles distant, but it soon became evident that the pair were on a longer journey. Ten miles passed, then twelve, then fifteen, and Lettie and Ina were still on board. Finally the girls saw long lines of high wire fences and whitewashed buildings, and heard the driver call out:

“Brodsky’s Fox Farm.”

To their unlimited astonishment Lettie Briggs leaned over and pressed the button as a signal to stop.

“Why, they’re getting off here, too!” said Josy.

Louise nudged Jean.

“Not a word about the money,” she cautioned. “If Lettie and Ina know why we’re here, they’ll want to take a hand in the search themselves.”

“More detective work, I suppose,” snapped Lettie when she saw the others alighting from the bus. “Not shadowing me, I hope.”

She was obviously annoyed by the presence of the Dana girls. The truth of the matter was that Lettie, who had unlimited pocket money, was mean and grasping at heart and seldom neglected an opportunity to save a dollar. She had set her mind upon having a fox fur piece and had already driven several Penfield store-keepers to the point of exasperation by her haggling over prices. She refused to pay the lowest compensation asked, and seemed to feel that because she was Lettie Briggs she should receive special concessions. Now the economical young woman was out to teach the store-keepers a lesson. She would buy her fur direct from the fox farm.

“You go in, Louise,” suggested Jean. “Josy and I will look around outside while you speak to the owner.”

The elder Dana did as her sister suggested and followed Lettie and Ina into the office. The Briggs girl was already talking to Ivan Brodsky, owner of the farm. He was a fat, swarthy foreigner of the peasant type. He bowed politely to Louise.

“Ve haf some nice furs,” he was saying to Lettie. “You come vit me.”

He ushered the haughty girl and her chum into the showroom next to the office, where the furs were laid out upon a table. “You do not mind vaiting?” he inquired of Louise Dana.

“Not at all,” the girl assured him.

She listened in amusement as Lettie priced one fur piece after another, invariably declaring that the amount asked was outrageous. Brodsky’s prices were quite fair, and it was soon evident that he was not in the least impressed by Lettie and her overbearing manner. She tried to browbeat him when he refused to lower his price on a seventy-five dollar fur, but Brodsky merely shrugged.

“I’ll give you sixty dollars and not a cent more,” offered Lettie.

“I should give it away first,” said Brodsky. “I do you a favor at seventy-five.”

“Oh, very well,” snapped Lettie. “I’ll take it. Here’s the money.”

She opened her purse and Brodsky went back to the office for change. As he opened the till, he winked solemnly at Louise. A moment later Lettie came out of the showroom with a parcel under her arm.

“I wrapped it up myself,” she said. “My change, please.”

“Oh, Lady,” said Ivan Brodsky, “should I let my customers wrap their own packages? A fur must be wrapped so——”

Then, without handing Lettie her change, he reached over the counter and took the parcel from under her arm.

“It really doesn’t matter,” said Lettie.

Ivan Brodsky was already removing the paper, however. When a magnificent black fox fur was revealed, Lettie uttered a cry of feigned astonishment.

“Why, I must have picked up the wrong one by mistake!”

“Hundred dollar mistake,” grunted Brodsky.

Without another word he went back into the showroom, put the costly fur back on the table, and returned with the cheaper piece Lettie had purchased. Silently he wrapped it up, handed it to her with her change, and opened the door.

Followed by the frightened Ina, the vanquished Lettie flounced out of the building.

“People got to get up early if they cheat Ivan Brodsky,” observed the fur dealer as he closed the door. “Now, young lady, what can I do for you?”

“Have you lost a fox?” demanded Louise.

Brodsky looked startled. He glanced around, as if fearing someone might have overheard.

“Haf you found one?”

“I have seen one,” said Louise. “I thought it might have wandered away from this farm.”

The dealer sat down heavily.

“I suppose it is mine,” he groaned. “Yes, a fox has run away. And what will happen to me when the farmers find out? If their chickens are stolen? Not a living soul have I told about that fox. Bring him back to me, dead or alive, and I give you five dollars.”

“We thought the animal might have returned,” said Louise.

Then, without mentioning the thousand-dollar bill, she explained how the fox had snatched up an important letter in the meadow near Mohawk Lake. Ivan Brodsky excitedly assured her that the fugitive had not returned to the farm, though in all probability it was one of his foxes. He begged her to keep his secret, as he feared the wrath of the farmers in the vicinity if they knew the animal was at large.

“I shall leave my address,” said Louise, “and if the fox returns, will you please notify me at once?”

The man promised, and Louise left the office. She located her sister and the crippled girl at the back of the farm, looking at some handsome furry specimens.

“Any news?” asked Jean.

Louise shook her head, and told of the conversation with Brodsky. Although the girls were disappointed, they were not discouraged. Nevertheless, they had little hope that the animal would make its way back with the thousand-dollar bill in its mouth.

They found that they would have to wait half an hour for a bus back to Penfield, so decided to cut across the fields back of the farm and make their way to the railroad station where a train would soon arrive, bound for Penfield. They had walked only a short distance when Josy suddenly cried out:

“Look! What’s that thing over there by the fence?”

About two hundred yards away, beyond a clump of trees, the crippled girl had caught sight of a black object against the snow.

“It’s our fox!” exclaimed Louise in excitement.

The animal was bounding toward a heap of rocks piled up against the fence. It carried a dead rabbit in its mouth. Swiftly the little beast sped toward a dark opening among the rocks and then vanished.

“Quick!” urged Jean to her sister. “Run back and tell Mr. Brodsky. We’ve found the fox, all right, and its den, too.”

Louise lost no time in hastening back to the fur dealer. In the meantime, Jean and Josy hurried through the snow until they reached the heap of boulders at the fence. Fearing that the animal might escape, they pushed a heavy rock in front of the entrance and sealed the creature in its lair.

“I’ll stand on guard,” offered Josy, and leaned over to listen for sounds from the imprisoned animal.

As Jean moved off toward the path to await the coming of the farmhands, she was startled at the really grotesque picture which Josy made. The girl hardly seemed like a human being; rather like a huddled gnome.

The same idea must have sprung into the mind of Brodsky, who had rushed up and caught sight of the deformed figure. Without hesitation the superstitious man slung to his shoulder a rifle which he was carrying and aimed it directly at Josy Sykes!

Jean screamed. Louise shouted.

Josy turned, stood up, and Ivan Brodsky lowered his rifle.

“A girl!” he gasped, sitting down weakly on the ground. “Oh, Ivan, you are a foolish man. But I cannot help it. When I was a little boy, I was frightened in the woods one day by a strange creature, and ever since——”

Meanwhile, the Dana girls had rushed to Josy’s side and were assuring her everything was all right. She did not fully understand that the excited foreigner had really intended to shoot her, and they did not enlighten her.

Presently the humiliated man was once more on his feet, giving directions to his helpers.

“Get dat net ready,” he ordered.

The men rolled the rocks aside to expose the frightened animal in its den, and its owner swept the large net over it, just as it leaped forward to escape. The quivering captive was carried back to the farm in triumph. Brodsky was so grateful that he paid more than the promised reward of five dollars.

“You haf saved me much trouble, young ladies,” he assured them.

“Give the money to Josy,” said Louise.

Meanwhile, Josy Sykes was exploring the rocky lair. She searched in every corner of the animal’s refuge, and finally shook her head in disappointment.

“There isn’t even a scrap of paper here,” she said, her voice trembling. “I never really thought we would be lucky enough to find the bill.”

It was a bitter blow, but Josy was courageous. She even tried to smile as the Dana girls sympathized with her.

“It was too much to expect. I’m going to make the best of things even though I’ve lost my money. I’ve been poor all my life, so it doesn’t make much difference now.”

However, they all felt the setback keenly. Having unexpectedly located the fox, it was doubly difficult to bear the disappointment at having lost the money. They were glum and crestfallen when they returned to Starhurst that night.

In their study Jean and Louise discussed the problem of Josy Sykes. The Christmas vacation was only a few days off, and they were already packing for their return to Oak Falls where they were to spend the holidays with Uncle Ned and Aunt Harriet. They knew that there was but little likelihood of Mrs. Crandall’s giving the crippled girl a permanent position at Starhurst. Now that Josy had lost all hope of recovering her thousand dollars, the girl had a very uncertain future.

“She won’t go back to the Home. And I’m sure Mrs. Crandall won’t be able to keep her,” said Louise. “I do wish we could do something for her.”

Nothing that would further the fortunes of Josy Sykes developed within the next two days, and when Starhurst School finally closed for the Christmas vacation, Jean and Louise bade goodbye to a lonely and pathetic little figure.

“You’ve been wonderfully good to me,” said Josy. “I’ll never be able to thank you.”

“Please don’t try,” said Jean. “And we are not going to forget you.”

The plight of the Danas’ unfortunate little friend was temporarily put out of their minds in the excitement surrounding their return to Oak Falls. Uncle Ned, red-faced and smiling, was at the station to meet them. Aunt Harriet had decorated the big rambling house in their honor, with holly wreaths and cedar branches at every window and a prodigious Christmas tree in the living room. Cora Appel, otherwise known as “Applecore,” the clumsy but good-natured servant girl, alternately laughed and cried with delight.

For two days Jean and Louise were engrossed in the joyous flurry of Christmas preparations. The wrapping of presents, the addressing of cards and parcels, the various parties and outings to which they were invited by their friends in Oak Falls sent the hours flying.

“I declare,” said Aunt Harriet on Christmas Eve, “I don’t know how you keep it up. You’ll be all tired out when you go back to school. I’m glad you’re staying at home with us this one evening at any rate.”

Louise hugged her.

“It wouldn’t seem like Christmas Eve unless we spent it with you and Uncle Ned.”

Captain Dana lit his pipe and stretched out his legs before the fire.

“We won’t be seeing much of you, I’ll be bound. You’re going to Barnwold Farm tomorrow afternoon, and you’ll be staying there, I suppose, for the rest of the week.”

Barnwold Farm, near Mount Pleasant, was the home of Miss Bessie Marsh, a cousin of the girls. She was a handsome, practical woman of thirty, who had inherited the property from her parents, and managed it with an efficiency that any man might envy. She was a great favorite with Jean and Louise, and they always looked forward to their visit at her home on Christmas Day.

The Dana household rang with laughter next morning. Uncle Ned, officiating as Santa Claus, distributed the gifts piled at the foot of the shimmering tree. The room was littered with gaily colored wrapping paper. Jean and Louise had been well remembered by their aunt and uncle, while in their turn they had come from Starhurst with numerous pretty gifts for each member of the household.

Jean and Louise had each sent a little gift to Josy Sykes at Starhurst, and were touched and surprised to find that the crippled girl had not forgotten them. Josy had evidently spent a part of the reward she had received from Ivan Brodsky, for there were two neatly wrapped packages for the Dana girls, which had arrived in the mail the day before. There was also a letter which read:

“My dear, dear Friends: I hope you are having a happy Christmas. This little note is to send my best wishes and to say goodbye. I shall not be here when you return to school. Mrs. Crandall has been very kind, but she does not need me any more, and I am to leave at the end of the week. With many thanks for all the kindness you have shown me, I am,

Gratefully, Josy Sykes.”

“But she can’t go away like that!” exclaimed Louise. “Where will she go? How can we ever find her again?”

“I have it!” said Jean impulsively. “Perhaps Cousin Bessie will let us invite her to Barnwold Farm.”

When they talked to their relative over the phone a few minutes later, they found her to be instantly sympathetic.

“The poor child!” she exclaimed. “Spending Christmas in a lonely school! By all means bring her with you. I’m expecting you by dinner time tonight, of course.”

“We’ll be there,” Louise assured her. “And Josy will be with us.”

Happy at the prospect that they would be able to lend some brightness to Josy’s Christmas, the Dana girls dispatched a telegram to their friend at Starhurst, telling her of the invitation and asking her to meet them at Mount Pleasant station that afternoon. As they did so, they had no idea that their well-meant effort to brighten the unfortunate girl’s Christmas was to have such strange and far-reaching consequences as later events proved.

When they alighted from the train at four o’clock, Josy Sykes was waiting for them on the platform. Tears of gladness sprang to the eyes of the crippled girl as Jean and Louise greeted her.

“It really seems like Christmas now.”

When they arrived at Barnwold Farm, they were warmly greeted by Bessie Marsh, whose tact and good humor quickly put Josy at her ease.

“I’m so glad the girls told me about you,” said Cousin Bessie.

Josy’s natural shyness soon wore off. Curled up on a big sofa before the fireplace in the living room of the farmhouse, it was not long before the crippled girl began to beam with happiness.

Cousin Bessie, jolly and friendly, told anecdotes and teased the Dana girls about several little incidents which she recalled. The crippled girl joined in the laughter and merriment.

“A friend of mine,” said Cousin Bessie suddenly, “had an unusual experience the other day. He went hunting—and what do you think he brought-home?”

“A bear,” said Jean.

“A cold in the head,” laughed Louise.

“A frostbitten ear,” suggested Josy.

“You’d never guess,” declared Miss Marsh. “He went out hunting rabbits near Lake Mohawk, and brought home a thousand-dollar bill!”

Cousin Bessie was astonished at the effect of her words. She had created a sensation. The Dana girls gasped. As for Josy, she turned white and sprang up from the couch where she was seated.

“A thousand dollars!” she cried. “Oh, it’s mine. It’s mine.”

Then, with a low moan she fell to the floor in a faint.

Jean and Louise hastily knelt beside the insensible girl to render first aid. Cousin Bessie, puzzled and alarmed, ran from the room, but returned in a moment followed by her housekeeper, Mrs. Graves, carrying some cold water and smelling salts. The girls had lifted Josy back onto the divan and were rubbing her hands and wrists in an effort to revive her.

“What is the matter?” asked Cousin Bessie. “I can’t understand it. What did she mean by saying ‘It’s mine’! Just because Bart Wheeler found a thousand dollars——”

“But it’s Josy’s money,” cried Louise. “It must be. She lost a thousand-dollar bill and a letter in a field near Lake Mohawk a few days ago. No wonder she fainted.”

Bessie Marsh was immediately excited.

“I never heard of such a thing!” she declared. “Yes, this money was in one bill, and there was a strange letter with it, too. Mr. Wheeler is Constance Melbourne’s secretary. You’ve heard of her—the famous artist.”

Both girls nodded in the affirmative.

“It seems almost too good to be true,” said Jean. “I hope he hasn’t spent the money,” added Louise. “Josy had given up all hope of ever seeing it again.”

The housekeeper was busily and tenderly trying to bring the cripple back to consciousness. Her efforts were rewarded when the girl’s eyelids flickered and she moaned softly.

“She’ll be all right before long,” said Mrs. Graves.

“I’m going to telephone Bart Wheeler this very minute,” announced Bessie Marsh. “I’ll ask him to bring that money over here. It’s the oddest coincidence——”

Marvelling, she hurried from the room. Jean and Louise turned their attention to Josy, who opened her eyes and looked up at them appealingly.

“What has happened to me?” she asked in a weak voice. “I must have fainted.”

Suddenly she struggled in an effort to sit up.

“Oh, I remember now. My money. Someone found my thousand-dollar bill.”

“Cousin Bessie is telephoning to the man now,” said Louise in a soothing voice.

“She is going to ask him to come over and talk to you,” added Jean.

“Of course, it might not be your money after all,” Louise remarked cautiously.

It would be tragic, she felt, if Josy built her hopes high, only to suffer another disappointment.

“We’ll just have to wait until Mr. Wheeler tells us all about it.”

Mrs. Graves piled cushions under Josy’s head and drew a coverlet over her.

“Don’t excite yourself, my dear,” she advised kindly. “Just try to rest quietly.”

Josy closed her eyes and sighed.

“I hope there isn’t any mistake,” she murmured.

In less than half an hour a smart little roadster slid to a stop in the driveway of Barnwold Farm, and a handsome man in an ulster and rakish-looking hat stepped out and came hurriedly up the walk. The person in question was Bart Wheeler, a man in his early thirties, artistic and sensitive.

Cousin Bessie had already explained to the girls that he acted as secretary and business manager to Constance Fleurette Melbourne, the world-famous portrait painter and artist. Miss Melbourne, when she was not travelling, lived in a quaint, cobblestone towered studio home near Barnwold Farm.

Miss Marsh met him at the door.

“Hello, Bessie. What’s all the excitement?”

“Bart, we’ve found the owner of the thousand-dollar bill you picked up,” she replied.

“Well, that’s good,” rejoined Mr. Wheeler. “I’m sure I shouldn’t care to lose a thousand dollars if I had it. Where’s the lucky person?”

Cousin Bessie escorted him into the living room. He bowed politely when she introduced him to the Dana girls, but looked puzzled when Miss Marsh indicated Josy on the sofa.

“And this is Miss Sykes, the girl who lost the thousand dollars,” he said, musingly.

“Did you really find my money?” asked Josy eagerly. “Did you bring it with you?”

“Yes,” said Bart Wheeler slowly, looking steadfastly at the figure on the sofa. “I found a thousand-dollar bill and a letter.”

He was silent for a moment, and the Danas wondered what he was thinking about. Presently he spoke.

“But I think there must be a mistake somewhere.”

“A mistake?” gasped Josy.

“I’m afraid the letter and bill belong to someone else,” said Bart Wheeler, weighing each word.

“Oh, that isn’t so!” declared Louise indignantly. “Jean and I were with her when she lost it.”

“Perhaps so,” said Bart Wheeler. “But I still think there is a mistake.”

“How could there be?” came from Jean.

“How did you know she was the rightful owner in the first place?” the man asked.

The Dana girls were stunned by this accusation. There was no misunderstanding Bart Wheeler’s meaning. He was insinuating that Josy was either impersonating the owner of the money, or that she had come by it unlawfully in the beginning.

“Bart!” exclaimed Miss Marsh sharply. “You have no right to say such a thing.”

“I have every right in the world,” said the secretary. “I have proof.”

Louise and Jean looked at the girl on the sofa. She had drawn the coverlet up around her and was staring wild-eyed at the speaker, fear and anguish on her drawn face.

“The money doesn’t belong to her,” continued Wheeler, pointing toward Josy. “I’m sure of it. There was a letter with the bill. The money belonged to Miss Josephine Sykes, all right, but I think this is not Miss Sykes!”

Jean and Louise were speechless at Bart Wheeler’s announcement. Had they been befriending an impostor?

Bessie Marsh was the first to speak.

“What did the letter say?” she demanded.

“It stated,” answered the secretary, “that the owner of the money was a deformed and hopeless cripple. This girl is no cripple.”

With a sob of humiliation, Josy flung aside the coverlet and rose from the couch. When she stood up, revealing her deformed figure, Bart Wheeler uttered a startled gasp. An expression of amazement and horror crossed his face.

Josy could stand no more. Interpreting it as an expression of revulsion at her misshapen and ugly form, she burst into tears and hurried out of the room.

“Bart Wheeler!” stormed Bessie Marsh. “Of all the tactless, blundering people on the face of the earth——”

“But I tell you I didn’t know—I didn’t mean—oh, what have I done?” stammered Wheeler.

The room was in confusion. Louise and Jean ran after Josy to comfort her. They realized that Bart Wheeler’s expression was caused by his embarrassment when he learned that he had wrongly accused the girl of trying to claim the lost money.

The strain, however, had been too much for Josy. They found her weeping bitterly in the hall.

“I’m just a hopeless, unwanted girl, and cause trouble wherever I go,” she declared disconsolately.

Josy’s notion that she had caused trouble was unfortunately borne out by the fact that the incident had evidently precipitated a bitter quarrel between Cousin Bessie and Bart Wheeler. Always an outspoken woman, Miss Marsh could be heard warmly berating her friend for his tactless mistake. He in turn resentfully defended himself, and before long the argument was at its height. It ended when Bart Wheeler snapped:

“There’s the money and the letter. Give it to the girl.”

“I should think you would give it to her yourself and apologize at the same time!”

“Goodbye. I’m not coming back.”

“Don’t.”

Bart Wheeler, flushed and angry, strode out into the hall.

“I’m sorry, Miss Sykes,” he said curtly. Then he flung open the door and vanished.

Josy was trembling with embarrassment. She felt that she was directly responsible for this heated quarrel between Miss Marsh and her friend. Even when Cousin Bessie guided her back into the living room and gave her the letter and the thousand-dollar bill, she could muster up very little enthusiasm.

“Aren’t you glad?” asked Jean. “I think I’d be turning handsprings if I were to lose a thousand dollars and someone returned it to me like this.”

Josy’s face was sad.

“I’m glad to get the money, of course. But this letter——”

“Bad news?” asked Cousin Bessie.

“Disappointing news,” confessed Josy. “It’s from the only relative I have in the world.”

Josy Sykes was a moody, reticent girl. On several occasions she had seemed on the point of telling Jean and Louise more about her past life but had always hesitated when on the point of doing so. Beyond a sketchy account of her life at the Home, the Dana girls really knew very little about their friend. She told them now that the letter was from her uncle, Joseph Sykes. Further than that she volunteered little information.

“I wonder if I’ll ever see him again,” said Josy.

Then, fearing that she had been talking too much, she checked herself just when about to confide in her friends the reason for her mysterious uncle sending her the thousand-dollar bill.

In a short time other guests arrived, and soon the unpleasant incident of the money was forgotten.

The dinner party was a great success. Josy, evidently resolved that her hostess should not regret having invited her, had fought down her mood of despondency and was among the gayest at the table. After dinner, at Jean’s urging, she helped entertain the guests by whistling and singing.

The Dana girls were astonished at Josy’s talent. She had a good voice and her whistling was as finished as that of any stage performer. Nevertheless, she seemed to take neither pride nor pleasure in her accomplishment.

“It isn’t useful,” she said dolefully.

Josy went to bed early, and Jean and Louise accepted Cousin Bessie’s invitation to talk over the events of the afternoon. Jean and Louise had told their cousin the odd circumstances of their meeting with Josy.

“I do wish we could do something for her,” said Cousin Bessie. “Financially, she has no immediate worries—thanks to Bart Wheeler—but she should have some sort of work that will help her take her mind off her troubles.”

“Josy believes she is a failure,” observed Louise. “She thinks nothing can ever compensate for her being a cripple.”

“If some way could be found for her to make use of her talent,” said Cousin Bessie, “I think she would be much happier. As long as she feels that she is a burden to people, she will always be despondent.”

“She felt bad because you quarreled with Mr. Wheeler,” ventured Jean.

“It was Bart’s fault. He made her feel terrible. He might have known that I shouldn’t have asked him to bring the money and the letter here unless I was quite sure Josy was the rightful owner. I suppose I shouldn’t have lost my temper. Poor Bart. He threatened to go away forever.”

“He is a very handsome man,” said Louise.

“And an artist to his finger tips,” declared Bessie. “I think the world of Bart, really. Miss Melbourne says she couldn’t get along without him. She isn’t very practical, and he manages all her business affairs. I’m sorry she wasn’t here tonight, but she telephoned to say she was just recovering from a cold.”

At this moment the doorbell rang sharply and loudly. It was not the easy, casual ring of some chance caller, but an imperative, agitated trilling that sent Mrs. Graves bustling to answer it. Immediately a tall, commanding figure swept into the room.

“Why, Constance!” exclaimed Miss Marsh in surprise. “What brings you here?”

Constance Fleurette Melbourne’s appearance was in accord with her world-renowned reputation as being one of the greatest of American artists. She was very tall and slender, a woman of forty-five, with hair prematurely white. Just now she was excited and distressed.

“My dear!” she cried. “I’ve just had the most upsetting and nerve-wracking experience. What in the world has gone wrong with Bart Wheeler?”

“Bart?” exclaimed Bessie. “Why—well, we had a little quarrel——”

“A little quarrel?” said Miss Melbourne. “Why, the man has left me. The only capable secretary I ever had. I was listening to a mystery play on the radio tonight—the weirdest thing, all shouts and groans and screams and revolver shots—when he rushed into the studio tower. The man looked as if he had been wading in snowdrifts. His face was white as a sheet. His clothes were wet. He was ghastly. And he simply said, ‘I’m going away and I’m not coming back.’ Then he ran upstairs to his room and packed his things.”

Miss Marsh rose to her feet. Her face was pitiful to behold.

“He packed!”

“He crammed some clothes into a suitcase. I couldn’t get a word out of him. Then he snatched up the valise and ran down the tower stairs. He stumbled and fell on the steps, picked himself up, called out, ‘I’m not coming back,’ and away he went. Has the man gone crazy?”

“He told me he was going away!” cried Bessie despairingly. “I didn’t think he meant it though.”

“But that isn’t all,” continued Miss Melbourne. “Mammy Cleo, my cook, came running out of the kitchen a few minutes later, and when I told her that Bart had left, she became nearly hysterical and said an evil spirit had stolen him. Imagine that! She said she had seen a strange, supernatural figure in the snow in the shadow of the tower about fifteen minutes earlier. I declare I don’t know what to make of it.”

“A strange, supernatural figure!” said Louise in awe. She looked quickly at Jean.

“Mammy Cleo said it must have been an evil spirit, because it didn’t look like either man or woman. It was twisted and deformed——”

“Josy!” cried Jean.

She ran from the room, with Louise close at her heels. The two girls rushed up the stairs and rapped sharply at Josy’s room. There was no response. Jean thrust the door open and switched on the light.

The place was empty!

“Just as I thought,” Louise declared. “She has run away.”

“We’ll have to follow her,” gasped Jean.

In their haste and excitement the girls had no time to consider the strange features of the affair—Bart Wheeler’s disappearance, the story of the deformed figure in the shadow of the tower, and now the flight of Josy Sykes! What connection, if any, lay between these events they could not imagine.

As they hurried back downstairs, the doorbell rang frantically. Mrs. Graves was bustling into the hall as the Dana girls reached the foot of the stairway. When the housekeeper opened the door, the light fell on the rolling eyes and frightened face of an elderly negro.

“I’se got a hawss heah, Ma’am,” he stammered. “It belongs t’ Miss Mah’sh.”

Cousin Bessie, overhearing the man’s words, hurried from the living room.

“My mare?” she cried. “Where did you get it?”

The man rolled his eyes again. He stuttered and stammered so much that his words were scarcely intelligible. It was evident that he was badly frightened. Out of his terrified mumblings, however, they managed to learn that while he had been standing at the crossroads near Mount Pleasant, a weird, deformed figure had ridden up to him on horseback.

A hunchback had descended from the saddle and asked him to return the mare to Miss Marsh. A moment later the cripple had boarded a bus that had been approaching, and the negro had been left with the animal.

“Ma’am,” he said earnestly, “if it hadn’t been fo’ dat hawss, Ah would have thought Ah dreamed it.”

Cousin Bessie turned a startled face toward the Dana girls.

“A hunchback!” she exclaimed. “Why, it must have been Josy.”

Louise nodded gravely.

“It was Josy. She isn’t in her room.”

“But why—why should she run away?” Cousin Bessie was utterly bewildered. “She must have taken my mare from the stable so she could ride out to the bus line. And if what Mammy Cleo says is true, she must have been at the Studio Tower.”

“It’s too involved for me,” confessed Jean. “I think Louise and I had better bring the mare around to the stable. Then we’ll sit down and talk things over. Perhaps Josy will come back.”

In their hearts the Dana girls felt that the cripple would not return.

The colored man hurried off, still mumbling to himself about his encounter with the hunchback. It was obvious that his superstitious mind clung to the belief that there was an element of black magic about the whole business, and that the strange, dwarfed figure had not been entirely human after all.

Jean and Louise brought the mare around to the stable. When they came back to the house a few minutes later, Cousin Bessie was telling Miss Melbourne the story of the hunchback.

“There is a mystery about the girl,” contended Bessie. “The money and the letter that Bart Wheeler found belonged to her. But who would send a friendless orphan a thousand-dollar bill? And why? She claims that the money was dispatched by her only surviving relative, yet if he is wealthy enough to send her all that money, it seems odd that he should have left her in a Home.”

The Dana girls were surprised at the expression on Miss Melbourne’s face. She was very white. She looked ill. One slender hand was gripping the back of a chair tensely.

“Did she—did she ever tell you the name of this relative?” asked Miss Melbourne.

“His name was almost the same as her own,” said Louise. “Joseph Sykes.”

Miss Melbourne closed her eyes.

“Joseph Sykes!” she murmured. Suddenly she swayed, and the girls thought she was about to faint, but she recovered with an effort and staggered toward the hall. “It is more than I can stand,” they heard her mutter. “Bessie—I’m going home.”

She stumbled to the door.

“But you can’t go alone, Constance,” cried Miss Marsh. “What is the matter?”

“We’ll go with her,” offered Louise. “I’m afraid she isn’t well.”

The Dana girls accompanied the artist through the snow to her quaint, picturesque towered home. It was not any great distance, but the artist seemed to find it extremely difficult to get there. She walked slowly and wearily, like one whose strength is utterly spent.

Although the girls were burning with curiosity as to why the story of Josy Sykes should have had such a peculiar effect upon the famous artist, Miss Melbourne explained nothing. She scarcely uttered a word on that strange, halting journey through the darkness and snow. Not until she reached her home with its studio tower looming black against the sky did she seem to be aware of their presence.

“It was good of you to come with me,” said Miss Melbourne mechanically. “I shouldn’t have gone out in the snow like this.”

She pressed her hand to her forehead. There was a wild, shining look in her eyes.

“Oh, find that child! Find that child!” she sobbed.

She swayed, tried to maintain her equilibrium, and then, in the shadow of the tower, fell unconscious.

As Jean and Louise Dana carried the unconscious woman into her home, they realized that they had stumbled upon one of the strangest mysteries in their experience.

“Find that child!”

They recalled the strange conduct of Miss Melbourne when she had heard the story of Josy Sykes. Now this heartbroken command puzzled them. It could have reference only to Josy. How the talented and wealthy artist could possibly be connected with the pathetic cripple they could not guess, yet it was obvious that some hidden thread existed among the lives of Josy, Miss Melbourne, and the missing Bart Wheeler.

Mammy Cleo, a huge colored woman, met them as they carried her mistress into the Tower.

“I’se gwine call de doctah,” she announced after one glance at the lady. “She’s sick, she is. Shouldn’t nebbah have gone outside dis doah tonight,” she went on, as she helped them carry Miss Melbourne upstairs to bed.

The lower part of the building consisted of one huge room, towered to the roof, which was used as the studio and living room, while the bedrooms were upstairs in the rear.

Miss Melbourne did not entirely recover consciousness. She stirred restlessly on the bed, moaning as she had done before her collapse:

“Find that child! Oh, you must find her——”

Although the house was warm, it failed to keep the artist from shivering. The girls realized that she was far from well. When Mammy Cleo bustled back into the bedroom after having telephoned to Mount Pleasant for the doctor, Jean and Louise gave what help they could. Miss Melbourne was undressed and put to bed. Mammy Cleo’s round, shiny face was grave.

“Black cat crossed mah path today,” she said portentously. “Allus means bad luck. Whaffor she keep talkin’ ’bout a chile? ‘Fin’ dat chile,’ she says. No chillen ’roun’ dis place.”

Although the Dana girls did not share Mammy Cleo’s superstition about the black cat, the doctor’s arrival brought them to a realization that bad luck had indeed befallen the Studio Tower. Miss Melbourne’s condition showed no improvement; in fact, she grew rapidly worse. She seemed to be in a sort of delirium, repeating Josy’s name over and over again, and time and again declaring that the crippled girl must be located at all cost.

The doctor, an elderly, soft-spoken man from Mount Pleasant, seated himself by the bedside.

“She was just recovering from a bad cold,” explained Louise, “and went out tonight. She wasn’t very warmly dressed.”

The doctor shook his head.

“Miss Melbourne is very ill,” he announced. “She has pneumonia.”

They were shocked into silence.

“She can’t be moved to the hospital now,” continued the doctor, “but if her life is to be saved, she must have the best of care. She will need a nurse with her, day and night.”

“If there is anything we can do,” volunteered Jean, “we’ll be glad to help.”

“Very little, I’m afraid. It was almost suicidal for her to go out in the snow on a night like this. She took a very bad chill and seems to have suffered a shock of some kind as well. I’ll call up Miss Robertson and ask her to come out right away. She is a very capable nurse.”

He left the room quickly, and a few moments later they heard him at the telephone. Mammy Cleo’s eyes were round with fear and she wrung her fat hands helplessly.

“I think we’d better go,” whispered Jean.

Louise nodded. They had done what they could, and they knew that if they were to remain, their presence might only add to the confusion of the household. Sadly they returned to Barnwold Farm. So much had happened since their arrival at Cousin Bessie’s home that they felt bewildered in the face of the mystery that seemed to deepen with every passing moment.

“I never went through such an evening in my life!” declared Louise. “First of all, Josy recovers her money. Then she runs away. Mr. Wheeler quarrels with Bessie and then he runs away.”

“And now Miss Melbourne comes down with pneumonia, and she can’t tell us what she knows about Josy. But she knows something—that’s plain enough.”

“What could it be? Josy didn’t give any inkling that she had ever heard of Miss Melbourne before.”

As they approached the house, they saw a light in Miss Marsh’s window. Against the drawn shade they could see the figure of their cousin silhouetted, pacing to and fro. When they hurried to her room to tell her about Miss Melbourne’s collapse and serious illness, they found that Bessie had been crying. In her hand she clutched a photograph.

“Pneumonia!” she cried. “Oh, this is terrible!” She sank into a chair. “Troubles never come singly. As if it wasn’t enough to have lost Bart——”

The photograph slipped from her hand. She began to cry softly. Jean knelt and recovered the picture, which was one of Bart Wheeler.

In a flash the girls realized why their cousin had been so distressed and upset by her quarrel that afternoon. Louise slipped an arm around Bessie’s shoulders.

“Do you care for him so very much?” she whispered.

“I—I’m engaged to him,” sobbed Bessie. “We’ve been engaged for three weeks. And—and now—I’ve sent him away—oh, what a fool I was to quarrel with him——”

The girls were stunned by this revelation. The flight of Bart Wheeler now assumed a new significance. What mystery lay behind his hasty departure they did not know, but they felt that there was something more than a mere lovers’ quarrel back of it all. Their hearts went out to their cousin in her distress, for Bessie blamed herself for the breach with her fiancé and upbraided herself constantly for her quick temper. She was taking Bart’s threat seriously, and firmly believed that he would never return.

Overwrought by excitement, Bessie had given way completely. She wept until she was exhausted. Jean and Louise comforted her as well as they could.

“I am sure he went away for some other reason than because he quarreled with you,” said Louise.

“I believe so too,” declared Jean. “If he did, you’re well rid of him. It’s too foolish. There was something else. He’ll be back again.”

“B-but he said he wouldn’t—ever,” sobbed Bessie.

She became a little less sad, however, when the girls insisted that Bart Wheeler’s departure had something to do with the disappearance of Josy Sykes. She was completely mystified when they told her of Miss Melbourne’s distraught pleas to “find that child,” but could throw no light on that part of the puzzle.

“I can’t understand why she should be interested in Josy’s case. As far as I know, she had never heard of the girl,” said Bessie. “She did act oddly when I told her Josy’s story, though. Perhaps it was because she was so ill.”

Bessie was in a more composed frame of mind when the Dana girls finally bade her good night and went on down the hall toward the guest room.

“One thing is certain,” declared Jean. “We’ve stumbled on a mystery that has my head in a whirl. This affair is a good deal more complicated than anything we’ve ever tackled before.”

“She seemed very upset when she heard about Josy. We must follow up every possible clue, Jean, if we are going to get Josy back for Miss Melbourne——”

“And Bart Wheeler for Bessie.”

“I do wish Josy had told us more about that letter. If we could find this man Joseph Sykes, he might be able to throw more light on the affair,” said Louise. “And if we could only find Bart Wheeler, he would be able to help us. He read Josy’s letter after he found it.”

As they approached their door, Jean suddenly spied a folded slip of paper.

“Why, what’s this?” she exclaimed, as she knelt and picked it up. “It was halfway beneath our door.”

“It’s a note!”

Jean unfolded it quickly. Her eyes swept over the few words written on the sheet, and then she turned to her sister in bewilderment.

“It’s from Josy Sykes,” said Jean. “But what a strange, strange note it is!”

“BUT WHAT A STRANGE, STRANGE NOTE IT IS!”

Josy’s farewell note was, indeed, a strange message. It consisted of only a few lines:

“My dear Friends: Please do not think unkindly of me, but I feel that I should go away. All the world hates me. I’m unwanted and I cause trouble wherever I go. Mr. Wheeler knows my secret sorrow. He can tell you, and then you will understand why I could not stay here any longer. I am everlastingly grateful to you for your kindness to me.”