* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: In the Secret Sea

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: William Edward Cule (1870-1944)

Date first posted: June 19, 2019

Date last updated: June 19, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190637

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

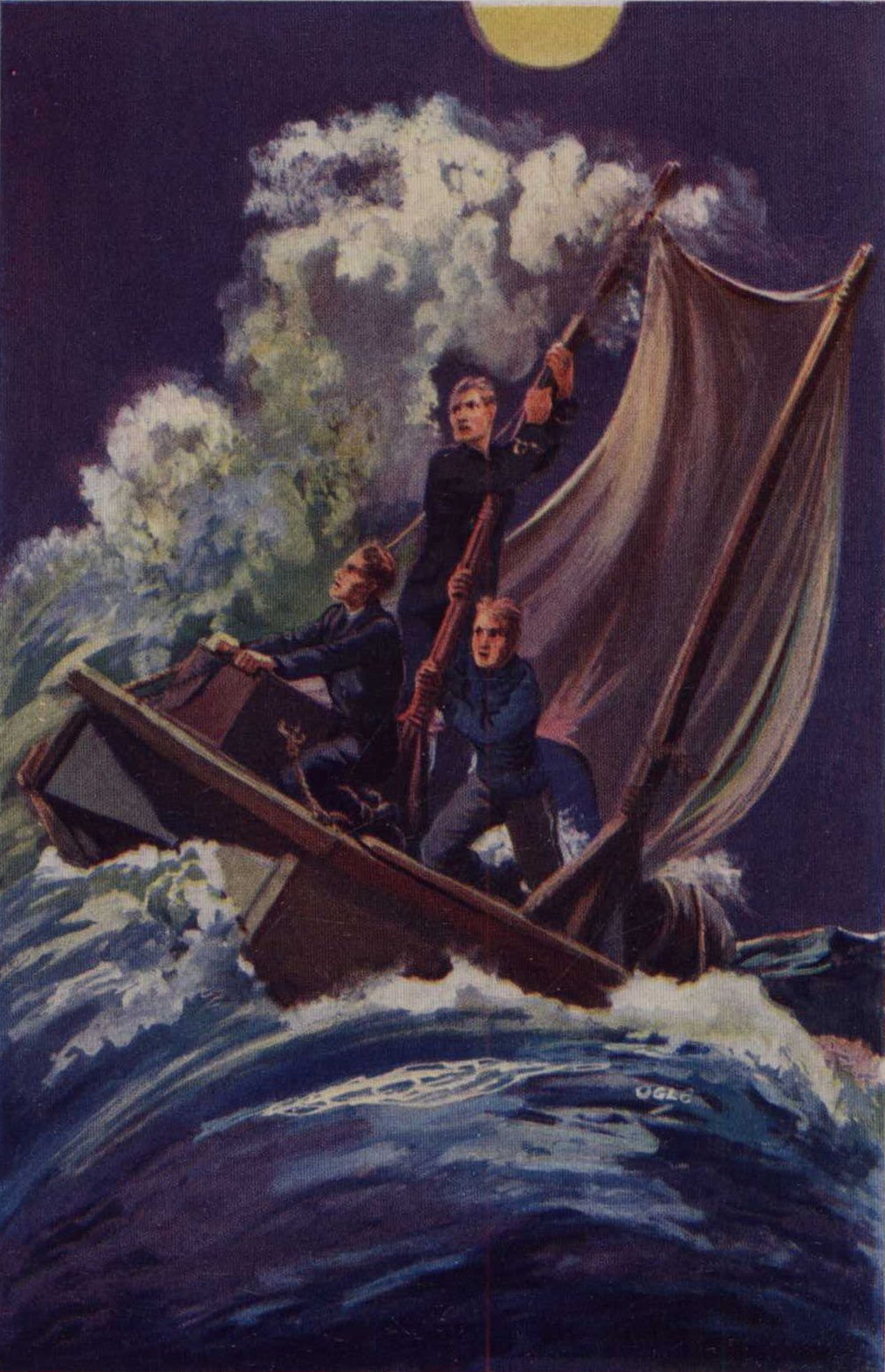

In the Secret Sea. See p. 164.

“IT’S A WAVE! HOLD FAST FOR YOUR LIFE.”

IN THE SECRET SEA

BY

W. E. CULE

AUTHOR OF “ROLLINSON AND I,” “THE BLACK FIFTEEN,”

“RODBOROUGH SCHOOL,” ETC.

LONDON

THE SHELDON PRESS

NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C.2

MADE IN GREAT BRITAIN

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE SEA GIVES ME A SURPRISE | 7 |

| II. | TWO STEAMERS IN SANDY BAY | 14 |

| III. | THE BOTTOM OF THE GREAT PIT | 21 |

| IV. | THE MAN OF THE BUNGALOW | 28 |

| V. | THE STORY OF RICHARD LEWIS OF BARMOUTH | 36 |

| VI. | THE INSIDE OF A PRISON | 45 |

| VII. | THE STATEMENT OF CAPTAIN VAYNOR POWELL | 55 |

| VIII. | THE GIANT BUBBLE | 63 |

| IX. | THE THREADING OF THE MAZE | 72 |

| X. | THE CAVE OF DEAD MEN | 79 |

| XI. | THE GHOST OF CHARLIE CORNWALL | 91 |

| XII. | THE DEVIL’S EYE | 102 |

| XIII. | THE SHADOW OF EVIL | 110 |

| XIV. | WHAT I HEARD AND SAW AT THE BUNGALOW | 119 |

| XV. | THE END OF THE “PLYNLIMMON” | 128 |

| XVI. | OUR SOLEMN LEAGUE AND COVENANT | 136 |

| XVII. | THE BUILDING OF “THE GOOD HOPE” | 145 |

| XVIII. | WE PUT OUT TO SEA | 153 |

| XIX. | THE WALL OF WATER | 160 |

| XX. | AN EXPERT ON THE EYE | 169 |

| XXI. | BALANCING UP | 182 |

On the night before we sighted Honeycomb Island, my uncle, Captain James, held fast to his post on the bridge almost from dark till dawn. He took rest for an hour between three and four, and it was during this time, while the first mate occupied his place, that a singular incident occurred. One of the watch, a man named Jenkins, gave a false alarm by reporting a light on the starboard bow. No one else saw it, and under cross-examination Jenkins admitted that he might have made a mistake; so the Captain was not disturbed, and the matter became something of a sea-joke.

“When a man has been staring into darkness for two hours he is quite likely to see stars,” said Ralph Oliver next day, when I was with him in the charthouse. “He said he had seen a kind of glare in the sky. It came and went in about half a second, or perhaps less; so there wasn’t much time for making notes.”

“Perhaps he was a little bit tipsy?” I suggested.

“Well, he’s not one of our total abstainers,” said the third officer, with a bit of a smile, “and he’d just had his special storm ration.”

At this time the John Duncan was creeping steadily down the eastern side of the island, to seek her refuge on the southern coast. The towering heights of the Honeycomb were wreathed in great banks of mist, and though we were all glad to see land, there was a grim loneliness about this desolate place that seemed to chill every heart on board. Above, heavy banks of mist and cloud upon a stark line of uneven rocks a thousand feet high; below, a troubled sea that beat unceasingly upon an iron rampart with a dull, monotonous roar and a broad white bar of foam and spray.

“For cheerlessness this is hard to beat,” said Ralph Oliver grimly. “But it’s a case of any port in a storm. Gibbon says that he’ll get the engines right if he can have twelve hours at a quiet anchorage. Just see for yourself what the Navigator says.”

The Atlantic Navigator was lying open on the table, as Captain James had left it. One paragraph had been marked in pencil, and I read it aloud:

“The Honeycomb (Lat. 35 S., Long. 25.42 W.) is apparently so called from the curious appearance of some of the cliffs. The coast is precipitous, rising everywhere to a height of 1,000-2,000 feet. The only practicable landing is on the S.W., where there is a sheltered cove and a good supply of fresh water from a cascade. The island measures some five miles by four. The cliffs are often enveloped in cloud. There is no vegetation, and there is a complete absence of animal life. Even the sea-birds appear to avoid the spot. The British gunboat Lizard was cast away here in 1899 and every soul lost.”

“No,” said Oliver, “it isn’t a cheerful prospect. But no doubt the place will serve our turn.”

His face bore that strained look which marked every face on board, from the Captain’s to that of the cabin boy. Nor was it anything to wonder at. On the fourteenth of the month the John Duncan, churning her way laboriously from Monte Video towards Table Bay, had found the North-West trade wind rise to a gale of unusual violence for those latitudes at this season. The wide waste of grey sea had darkened with wind and rain into a vast, murky battlefield, where mountains of water raced incessantly after us. On the second day there was no sun, only that grim battlefield in a twilight of rain and sleet and howling wind; and on the third day it was the same scene, only darker and still more hopeless. But through it all the sturdy old John Duncan had held on her way, labouring heavily but gallantly, rolling and slobbering indeed, but still shaking her grimy old hull free from the wash of those hostile seas. No man came on deck without oilskins, no man left it without being soaked, chilled to the marrow, and sore in every fibre; but this was in the seaman’s day’s work, and all was well as long as the fires could be kept going. My uncle, Captain James, was a hard man, but there was no better seaman in the Seven Seas.

It was on the third day that disaster came—the shock of a mighty sea on our port quarter, the shudder and struggle of the old boat as she strove to recover, the sound of grinding iron, and then the failure of her pulse. The propeller had jammed, and the steam steering gear had been thrown out of use. For some minutes the John Duncan had rolled helplessly, with giant billows climbing over her; then she had turned her head from the fight and was driving straight before the storm.

That wild flight had lasted for two days and nights, but she had come through without the loss of a man; and now the winds had gone down, and a strange sun, pale and shamefaced, had for a time looked down upon us through the clouds. Moreover, the engineers had never ceased their efforts to repair the damage, and some part had been made good. The engines were working again, though only feebly, and the damaged propeller had once more begun to churn the waters. The confident strength was gone, but the old ship was alive once more and could turn her head eastwards. Battered from stem to stern, she waddled along at something like four knots.

It was then that the officers had come to a decision as to their course of action. The nearest inhabited land was Tristan d’Acunha, but even if the John Duncan could fight the wind for two hundred and fifty miles, it would be impossible to find harbourage there. The Honeycomb was not inhabited, and it was a bit out of our course; but it was a hundred miles nearer by the Captain’s reckoning, and it had a sheltered harbour. So the ship’s course had been set due south, and now we were nearing our destination.

We skirted the eastern coast at a distance of two miles, going very slowly; and all the way ran that gaunt wall of sheer rock and that foaming fringe of breakers. But when we had turned the south-eastern point the rock took us into its shelter, and the moan gave place to comparative quiet. So, still keeping at a respectful distance, our old ship felt her way along the great wall towards the breach which marked the entrance to Sandy Bay; and it was when we were within half a mile of our anchorage, full in view of that grim, stony gateway to rest and safety, that the John Duncan came to a pause.

Then our little motor launch was lowered, and the first officer, with three men, went off to explore. The coast was clear for all that anyone knew to the contrary, but Captain James was not the man to take unnecessary risks. Since so much time had been lost already, an extra hour could well be spared.

From the starboard rail we watched the progress of the boat over that half mile of grey water to the gloomy shadow of the rock. Johnny Tawell, my fellow-apprentice, had no hesitation about expressing his opinion.

“What a sickening view!” he said. “Did you ever see anything like it? ‘Honeycomb,’ indeed! Is there anything sweet about it? What do you say to ‘The Isle of Ghosts,’ or ‘Dead Man’s Isle’? Of course, it doesn’t matter about ghosts or dead men being there. We just want to suit the look of the rotten place.”

“Then they’ll do,” I said. “But, anyhow, I’ll be precious glad to get ashore.”

“Yes,” agreed Johnny, in his melancholy drawl. “I never thought, when I came to sea, that I should be so glad to get off it.”

“All the same, when we’ve been on that shore a little while we’ll be jolly glad to get to sea again, I guess,” was my cheerless reply; and Johnny sighed.

“It’s always the same,” he said. “I wanted a desert island—I’ve always wanted one. Now I’ve got it—and it’s like this!”

“You wanted a coral island,” I said. “Golden sand, green grass, turtles—and wild fruit growing everywhere.”

“Yes,” said Johnny sadly, “and some nice, kind, simple savages who would make me their king.”

Then I laughed; and Johnny gave me a jaundiced look sideways as he went on:

“And this is the kind of luck I get—the shore as bad as this old tub of a ship. If there’s any luck going, it’s other chaps that get it. The Captain is their uncle, and the third mate plays the part of big brother—and so on. And if there’s any sort of luck to be got on this old rock, I’ll bet it’ll be the Little Favourite that gets it all. There won’t be a streak left for anybody else.”

It was difficult to talk to Johnny Tawell for five minutes without discovering the jealous vein in him, but I never troubled to quarrel with him now. Once he had provoked me to a fight, and I had licked him thoroughly to the satisfaction of everybody but myself; for when I had come to think of it, the fellow couldn’t help the jaundice in his disposition any more than I could help my freckled skin and celestial nose. So from the hour of that first fight I had managed to bear with his weakness, leaving him to sulk alone when I could bear him no longer. I followed the same course now.

“Well, don’t cry,” I said comfortingly. “Perhaps you’ll be king some day after all.” And with that I moved away to continue my watch from another part of the rail. The boat had just disappeared through the great rocky gateway, and I wanted to get the first glimpse of it when it should come out again.

But while I waited I was full of thoughts, for Johnny’s melancholy moan had touched a chord of memory. I had had the same dreams myself in earlier days, and had seen myself the hero of scores of pirate cruises, sea battles, and adventures on mysterious islands. In our more peaceful moments Johnny and I had exchanged confidences, and had found that common bond between us. Indeed, it was just the influence of such thoughts and dreams that had determined me to go to sea, much to the sorrow of my sister Ruth, whom I had left to fight her battle alone after she had almost worn her heart out in “bringing me up.” But since that time I had learnt the truth about the sea, and knew, or thought I knew, that the days of romance were gone for ever. The reality was just as Johnny had said—grey, grim, and disheartening, like the prospect around us now. No, there was no romance; the sea had nothing to give but hard work, and hard knocks, and hard tack, even if you were the nephew of the Captain! And I sighed wearily as I stared away at that mighty rock whose shelter we were about to seek. Certainly, there was no romance about that!

Presently I was roused by someone remarking that the first officer was taking his time about his job. He had nothing to do but cast an eye around Sandy Bay and then come back, and there wasn’t likely to be any house of call on that shore, anyway! Then I saw that there was a little surprise even on my uncle’s bronzed and patient face, as he stood on the bridge with the second officer. Five minutes later, however, there was a general stir of relief, for the boat came slowly out from the rocky passage; and, as had been arranged, the first officer was showing a white handkerchief as a signal that all was well.

A minute later the John Duncan was once more under way. At her slowest pace, with jealous care, she crept inshorewards, while the boat came speeding out to meet her. Five minutes later the first officer ran smartly up the ladder. When he reached the deck the Captain spoke to him from the bridge:

“All right, Mr. Smerdon?”

“Yes, sir, all right. Plenty of room and still water. We couldn’t want a better place. . . . But that’s not all. We are not the first callers. There’s another boat in the bay.”

Every ear was attentive. “Another boat in the bay”—hundreds of miles from anywhere!

“It’s a small American steamer, sir—the Maud Muller of New Orleans. It was this discovery that delayed us. But wait one minute, sir, and I’ll tell you all about it.”

He turned to give necessary instructions to his boat’s crew, and then ran up the ladder to the bridge. A moment more and the officers were talking busily, and the first shock of surprise had passed. But the whole ship was discussing the news in subdued but very natural excitement. It was the touch of the unexpected.

And I was excited, too. As if in answer to my musings of disenchantment, the sea had suddenly given me a bit of a surprise. Little could I guess how much more she was going to do before she had finished with me!

The John Duncan lay at rest in Sandy Bay, to the right of the narrow entrance and only some thirty yards from the shore. She was big in the little bay, for it was only about three hundred yards across, but she was small indeed under the shadow of the mighty cliffs that rose a thousand feet behind her. And right across the bay lay the Maud Muller of New Orleans.

She was an object of interest of course, but there was nothing in her looks to excite remark. She was smaller than our old tub, but there was a neatness about her that spoke very favourably of her owners and officers. No one could have mistaken her for an ocean tramp, anyway. Half an hour after we had anchored, her Captain came over to call, bringing a friend with him; and as I was with my uncle on the afterdeck at this time I was able to make a few mental notes of the meeting.

Captain Stuart Jackson was a lithe little man of the Captain Kettle build, but much milder in air and in countenance than that famous mariner, and notably spruce and neat in his clothing. He was hearty and full of goodwill, but his keen blue eyes took proper stock of everything that came before them, and also of some things that another person might easily have missed. His companion offered a much more remarkable figure, but it was plain that he was no sailor. He was an older man, something near sixty, perhaps, and he wore a rough tweed suit with a thick, dark, shoregoing overcoat and a soft felt hat. He was big, clean-shaven, with iron-grey hair, a heavy-jawed, rather forbidding face, and sharp, peering eyes sheltered by heavy brows and gold-rimmed spectacles. But from the first that ordinary-looking landsman caught my attention. There was something about him that gave a curious impression of power.

Captain Jackson was cordial enough. “I won’t exactly say I’m glad to see you, sir,” he said cheerily. “It would almost seem to be like chuckling over your ill-fortune. But I do say that I shall be glad to do anything I can to help you.”

The two Captains shook hands warmly. “I don’t know that we shall want help,” said my uncle. “We have everything we need, and my chief engineer says he can do it all in twelve hours. But I shan’t hesitate to draw upon you, Captain Jackson, if I see the need; and anyway it is good to find friends in this God-forsaken spot. My first officer tells me that you have been here some time.”

“Near a month,” said the other, “and mean to stay another if we see the call. But that reminds me—let me introduce Professor Delling, of the Rio University. He is the head of our party.”

Professor Delling bowed and shook hands, but he was evidently a man of silence. “We’re out on a geological survey,” went on Captain Jackson pleasantly. “The University has given the Professor six months to do some of the islands in the South Atlantic, and has chartered the Maud Muller and your obedient servant to take him about, under exploration licences from the Governments of Argentina and Brazil. Do you know anything of geology, Captain James?”

My uncle smiled as he shook his head.

“Nor do I,” said Captain Jackson. “But I’m sure it’s very interesting. Get the Professor to talk about it—if you can. And I need hardly say, sir, that Stuart Jackson is honoured by being employed in the Sacred Cause of Science. I guess we’ll have a big book about these islands some day, and my boat and I will be in it. Isn’t that so, Professor?”

For the first time the Professor spoke, and he spoke with a dry little smile. His voice was deep but pleasant.

“I have promised it, Captain Jackson,” he said. “I will give you all the immortality I can give. You certainly deserve it.”

They all laughed, and directly afterwards went down to my uncle’s cabin to celebrate the meeting in a little refreshment. Ten minutes later, however, the visitors departed, Captain Jackson declaring that he had no intention of delaying our repairs by any neighbourly attentions. He would feel honoured, however, if Captain James or any of his officers could find time to visit the Maud Muller before they left the island. And with that invitation, to which my uncle made a cordial response, the visitors went down the ladder and were rowed back to their ship. A very interesting pair they had proved, and obviously full of kindness and goodwill.

Repairs had begun on the John Duncan, however, before they left, and nobody had time or inclination to think further of our chance neighbours. “Give me twelve hours,” the chief engineer had said, but those hours must be crowded with work. There were other things wrong besides the engine gear, and soon the ship rang with the voice of the saw and the hammer.

While all this was going forward the Captain saw to it that a supply of fresh water was taken on board, Tawell and myself being told off to help, under the eye of the third officer. The cascade mentioned in the Navigator came down the face of the cliff not a hundred yards from the beach, and I had heard it through my dreams all night.

It was hardly possible to imagine a more dreary prospect. That narrow strip of beach was not common sea sand, but a minute dust mixed with dark, smooth pebbles. At the back of this the cliffs rose in a sheer wall some fifty feet to a broad ledge, with another stretch of cliff wall above. And so it rose for something like a thousand feet to a top that stood against the sky like the teeth of a gigantic saw. Over all brooded a silence unbroken even by the cry of a sea-bird.

“All the other islands in this region are smothered with sea-fowl,” said Oliver. “Here we haven’t a single feather. The place is uncanny.”

“They wouldn’t find much to eat here,” grumbled Johnny, under his breath.

“No,” said the third officer, “and that’s curious, too. The place is as bare as a billiard-ball. I only hope the water’s all right.”

The water, however, seemed to be very good, and long before noon our task had been ended. It was just before we finished that Johnny made a suggestion.

“I say, Frank, how would you like a run ashore? It would be a change to get up those cliffs. Anyway, anything’s better than work.”

“Good,” I said. “Go and ask Smerdon.”

Tawell grinned, for the first officer was poison to him. “You ask Big Brother,” he said mockingly. “Do, now—and I’ll give you something—some day.”

I gave him something on the spot, but I spoke to Oliver all the same. And, as it turned out, Oliver had had his mind working in the same direction.

“I should like a turn myself,” he said. “I’ll see if we can be spared. But I shouldn’t let you two young rapscallions go alone.”

The Captain raised no objection, but gave a word of warning. “If you go up there,” he growled, “keep a sharp eye for holes and crevices. The Honeycomb didn’t get its name without a reason. And see that you come back by sunset. If you get astray you mustn’t expect us to wait for you. We’ve lost too much time already. We leave at dawn.”

Ten minutes later, after a quick lunch in the cook’s galley, we went ashore in the water boat; and I, for one, found it good to be free, even on such a bleak and barren strand as that. It was like an unexpected half-holiday in the lost days of school, when Charlie Cornwall and I would slip off together to the beach at Leigh and hunt around for some kind of craft in which we might get out upon the water. Indeed, for a moment I could almost have fancied that the footsteps coming close behind me on that slippery beach were those of my old chum, and that if I turned suddenly I should see the brown face I knew so well. But when I did turn, it was Johnny Tawell that stood at my elbow.

“What were you grinning over?” he asked suspiciously.

“I was thinking of something.”

“What was it?”

“An old chum of mine.”

“Oh! And I suppose you were wishing him here instead of me?”

“Rather!” I said flatly; for when I thought of Charlie Cornwall it was impossible to be civil to the melancholy Johnny. But he took it in good part.

“All right,” he said, with a grin. “But as he isn’t here you’ll have to put up with me.”

Oliver’s idea was to ascend the cliff, ledge by ledge, until we reached the summit and got a view of the prospect beyond; but it was some little time before we found a track to carry us even to the first ledge. We found one at last at the extreme western end of the bay, and from the first ledge a similar track led us to the second. So we proceeded, with very little conversation, until we came to a halt for rest, some six hundred feet up. There we looked down upon a dwarfed John Duncan and Maud Muller lying in a fountain basin, with small men creeping busily about the former, and tapping here and there with tinkling hammers. Above us still rose the gaunt wall of cliff, and out beyond the rocky entrance to the bay we could see the unending dreariness of the immense Atlantic, stretching away, league after league, to the ice regions of the Pole.

So we moved on, slowly climbing higher. The mountain walls were as hard and black as iron, but I noticed at last that the ledges were caked with some substance that was neither rock nor sand.

“Why, this is guano,” I said. “There must have been millions of sea-birds here at one time. And now there isn’t one!”

“They got sick of it,” said Johnny. “But if you want to know why, ask a policeman. Look, now, here’s a new path for a change. Are we going to take it?”

That question put the guano mystery out of our minds for the time. We were now about eight hundred feet up the cliff, and this was the first break we had found in that immense barrier. It was just a narrow entrance which from the bay below would have been quite invisible; but it widened as it went inwards and upwards.

“It seems to be a way,” said Oliver, half doubtfully. “It’s not quite so steep, and it’s bound to get to the top somewhere. We’ll try it. But I wish we had got a word with that Professor person before we started. No doubt he’s explored this part and could give us a few hints. Perhaps we’ll compare notes with him afterwards.”

Accordingly we entered the cleft and began to follow its uneven course round and round, but moving gently upward all the while. Presently we were wandering about in a maze of rocky pathways running between the peaks and crags whose outline gave the island that sawlike, jagged effect which we had noticed from the sea. But there was no hope of climbing these, for in most cases they rose sheer from their base without foothold for man or beast. We could only follow the most promising tracks between, taking care that they always tended upwards. It seemed that they must bring us presently to the base of a great cliff some quarter of a mile away over the rocks—a cliff which rose so steeply and towered so high that it seemed to say “No farther!” And we calculated that by the time we reached it we should just have to turn and get back again.

It was in that way that we arrived at disaster. We had not forgotten the Captain’s warning, and had kept a good lookout for holes and pitfalls. Had we not done this, we should never have noticed the place at all, but have passed it unhurt. As it was, a sudden fall in the ground to the right of the track caught my eye, and we turned to examine it more closely; and presently we were all standing on the brink of the Great Pit.

For a pit it seemed to be—a pit which giants might have drilled through the solid rock before mankind had come upon the scene. It was roughly oval, the edge darkened by a few coarse bushes; but we had no sooner looked at the place than we fell silent.

“My word!” said Johnny at last. “That’s the most awful hole I’ve ever seen.”

He found a large fragment of rock, and hurled it over. We stood in breathless silence; and at last there came up to us, faintly, a sound. It was a hollow, ominous reverberation, with the faint splash of water in it.

I went nearer to the edge of the well to peer downwards. I wondered whether I should see anything.

To this day I cannot tell how it happened. Perhaps I was unduly confident, or perhaps I had miscalculated my distance. Then the ground, instead of being solid rock, was probably just a thick layer of guano, and the great fragment on which I tried to stand, at the very brink of the well, was simply embedded in this, instead of being part of the immovable mountain. So when my foothold really began to move I did not realise it, refused to credit my senses, and stayed there just one second too long; and before I understood my danger, that fragment was slipping over the brink.

I gave a gasping cry and threw out my hands. Oliver instinctively moved to grip me, and could not recover his balance. Then my gasp became a brief, strangled shriek as I caught a last glimpse of Johnny Tawell’s long face, with the blue eyes bulging from their sockets in sheer terror. And he, poor fellow, could only answer my shriek with one of his own as both Oliver and I vanished from his sight.

Now and again the sensation comes back to me in my sleep, and I wake up with a start, my whole body bathed in a cold dew of dread. To me, the Great Pit has been a nightmare ever since.

I went hurtling down, with Johnny’s cry echoing in my ears; and I knew that the great fragment of rock was still at my feet, falling, falling with me. It was then that the terror came, in a swift rushing wave that seemed to still my heart and blind my eyes.

All this could only have taken one brief, breathless moment, for then sensation—bodily sensation—came back with a rush. There must have been a screen of some kind of shrub growing round the sides of the pit in the crevices of the rock, stretching up weak, hopeless shoots to the glimpses of light above. These brushed me as I hurtled down, calling me back to life with a rustling of leaves and a faint rending of twigs. With desperate instinct, rather than thought, I closed my hands upon them once, twice, thrice. Once I held them, and they held me. Then I felt them give way, relinquished my hold to get another, tried, and failed: tried again desperately, hung for one brief instant, my eyes full of dust and grime, my arms almost wrenched from their sockets; then went down, down like a plummet, till the waters of silence closed over me.

Those shrubs had saved my life and my reason, and they did the same service for Oliver. We had fallen a hundred and fifty feet, but had done it, as it were, in three stages. There was a brief agony of cold and fear and suffocation, but after that I was on the surface again, still alive, dashing the water from my eyes. Then, in the clinging cold and silence and darkness, I looked up and saw light. It was the faint light at the mouth of the pit, oval-shaped, like an egg, and seemingly not much larger. At the same instant a gasping voice came out of the darkness behind me.

“Frank!”

Oh, the joy of it that I was not alone! I could have wept for the relief it gave me. Instead, I gave a little cry, and instantly Oliver was at my side, breathless, but as real and ready as ever.

“Hurt?” he asked.

“N-no,” I spluttered. “Are you?”

“Not much——”

There was a long pause, while we recovered our breath. Oliver was touching me now, and he never left me till the danger had passed. It was then that I ceased to think, for I knew that he was thinking for both of us, and I knew, too, that his thinking could be trusted. Since I had come to know him I had trusted it often, and never in vain. He was only twenty-three, and I was over seventeen myself; but those six years had been for him full of hard fighting.

“We must get ashore,” he said at last. “I will lead and you will keep close. Good thing the water’s not very cold; but it’s much too cold to stay long in. Now, Frank.”

Without waiting for a reply, he struck out; and with a great fear of being left behind, I followed his lead. No, the water was not cold, but I had little time to wonder why, for another mystery was upon us. I knew that the pit was wider at the bottom than the top, but after a dozen long, steady strokes which sent a thousand strange, sibilant echoes from side to side of the great shaft, there was still water before me. Even when we had swum some twenty yards, and the egg-shaped fragment of light had disappeared, we had not reached the side.

If Oliver had not been there, I think I should have failed then; but he was there, striking into the darkness without a pause. Because I must keep near him, I struggled on against the chilling flood, the colder darkness, the growing terror. What else could I do?

I cannot tell how long it lasted, that ordeal of terror. Oliver said afterwards that it was ten minutes, but it seemed thousands. Once I almost shrieked as something touched me, some floating fragment of the vegetation I had torn down in my fall; but it might have been some giant devil-fish searching for me in the dark. And as my shriek was choked back, I struck out again with mad haste.

Then the voice spoke again before me. “Keep up, Frank. We’re going right.” At the same moment a current of cold air began to play upon my face. Cold air—just that, coming over the black water, out of the black nowhere. But there must be some passage here, to earth and light and life. Hurrah!

“Steady!” growled Oliver. “I touched bottom.”

A moment more and I touched it also; a minute after that and I was out of the water, prostrate upon a shelving verge of what seemed to be rough-edged stones and clinkers. Oliver had his hands upon me, feeling my face, my limbs, and at last holding my hands. He was breathing hard, like a spent man—just as I was.

“Thank God!” he said. “Thank God!” And, thus reminded, I repeated, like a child of six, the words of the Lord’s Prayer. Then for a time we simply rested, panting, not daring to move except to feel our bruised limbs and to wring the water from our hair and clothes; and when we moved at last it was by the result of Oliver’s silent thinking.

“This current of air,” he said. “If it ceases we shall be lost. Can you start?”

“I’m with you,” I replied promptly. “Is it stand or crawl?”

“Crawl, till we can see where we are. It’s safer. You keep close to me.”

Our eyes were beginning to distinguish outlines, and it seemed that we were in a cave. In front, where the breeze came from, was black darkness, to right and left rugged walls of rock, and above a rocky and uneven roof. Our first task was to crawl up the rough bank on which we had fallen, and try to take our bearings; our next to follow the course of that blessed breeze until we should find the outlet of our prison.

Very cautiously we moved upwards, until we were on almost level ground. I was glad to get away from that dark subterranean water. Then we moved forward, foot by foot, in the direction the breeze seemed to come from. And as we rose from the sheltering basin to the level ground, it blew still stronger and colder. There must be a free entrance somewhere.

The ground was very rough, and it required great care to move over it. I fancied it must be the bed of a stream—perhaps in the rainy season the subterranean pond into which we had fallen would overflow and rush away to another outlet by the road we were now taking. Somehow, somewhere, it would find its way to the sea. In this lay our hope. It was the sea we wanted, and the faces of our friends. Why, just think of it—if we were lucky, we might reach the bay and the John Duncan as soon as Johnny Tawell—or, perhaps, even before him!

As you see, I was beginning to think on my own account—and most of it was wrong!

We stumbled on for fifty yards, on a course that was slightly downwards. That, I thought, was right—water could not flow upwards, and we had climbed so high that we must be considerably above sea level still. It was awful to keep struggling on in the dark on such a path, but it was better than the water of the Great Pit, and we had the cool breeze for company. So we held steadily on—or unsteadily, rather—for that fifty yards; and then—then we reached a corner!

Yes, a corner. Not a sharp, right-handed corner, but a curve in the wall of rock leading round to another long cavern something like the first. But ah, it was utterly different after all. Oliver stood upright and pointed. There was a queer, strained note in his voice.

“The light!” he cried. “The light!”

Yes, the light. For that long cavern went down—sharply down—its course paved with great boulders and fragments of stone; and it was a long course, nearly a quarter of a mile long, as rugged and trying a journey as anyone might see in a lifetime. But we could see to the end; and the end of it was light—the welcome light of day! The long, long cave before us was like a great telescope, and there, at the end of it, cut sharply in a rugged circle, was the lost daylight. When I saw it I gasped with joy. I had to sit down on a boulder and rest a while before I could begin what seemed to be the last stage of our adventurous journey. And Oliver sat with me, still holding my hand.

Is there any need to describe it—that eager, headlong rush to the light, so slow in spite of its headlong eagerness? Heavens! what a mad course it was—that panting escape from the Pit of Darkness! We tore our hands on the sharp rock-edges, stumbled and fell again and again, bruised knees and shins and ankles and thighs till we were scratched and bleeding in a score of places. In a few minutes I was in a bath of perspiration, in spite of the clinging cold of my wet clothes; but, heedless of everything, I pounded on towards the light. I had lost my reason for the time, and was in a wild panic of hope and longing. Oliver, now the follower instead of the leader, had to keep close or lose me. He kept close, steadying me now and again with a word.

Before we reached the end I was thoroughly exhausted, but my efforts were not relaxed. Again and again I brushed away from my eyes the mist of sweat and steam, angry that anything should come for an instant between me and the light. And steadily the light-circle grew larger, until I could distinguish objects without; and we saw at last that there were cliffs there—cliffs with the steep, wall-like faces which we had seen everywhere on the island.

I had no time to be disappointed—no time to consider that I had expected to find the open sea and the great waste of the Atlantic. I was on the threshold of success, too eager and exultant to think. I scrambled wildly on at a breakneck pace, and in a moment more was standing at the mouth of the cave.

Then I rubbed my eyes.

We were on the brow of a steep hill, at the top of a rude ravine which led by an easy course—an old water-course, no doubt—to the beach below. And at the first glance we saw, or seemed to see, the bay in which we had left the John Duncan, its water as smooth as a millpond, and with the familiar steep beach of dark-coloured dust and pebbles. And it seemed to me, in that first glance, that I saw the old John Duncan too, lying just as I had left her. But I rubbed my eyes, because even at the first glance some things were different.

The bay seemed larger—considerably larger. It was at least twice as far to the opposite side. But the curious part of it was that the John Duncan was smaller—considerably smaller; more curious still, she was utterly changed in appearance! And there was no Maud Muller!

It was then that I rubbed my eyes. And after that I looked again, and laughed weakly. Had a miracle happened? What else could have changed our one old black funnel with the grey bars into two dingy white ones? Then I rubbed my eyes again—and immediately saw something else.

Just below me and a little to the right, well up from the beach, was a house. Yes, a house. Only a small one, it is true, but still a house! It had a roof of corrugated zinc. That was the first thing I saw; and then I saw that it was built of wood, very neatly and trimly, built with doors and windows all complete.

I felt dazed and silly. The bay and the ship and the bungalow—were they a dream? I turned to look at Oliver, and when I saw his face I saw that I must be awake—or else he was dreaming too. It is impossible to describe the astonishment of his look.

He stared at me blankly. I gave another glance at the ship, and my head began to swim. Could it be possible that I was dreaming—that the ship and the bay and the little house were not real life at all, but a bit of scenery out of dreamland? I tried to pull myself together, tried to be sane and sensible.

And in that pause something happened. The door of the house—the bungalow—just below us, opened, and a man came out.

A man came out of the house and stood near the open door. He had not seen us—we knew that from his movements, which were slow and unconcerned; and at the moment we could not see his face, for he was looking down towards the water and the ship. He was a seaman of some kind, and wore a closely buttoned reefer coat, something after the style of a naval petty officer; but instead of the peaked cap which usually goes with the uniform, he had the round cap of the ordinary sailor.

We were not surprised to see him, for the presence of the house and the ship must mean the presence of men; but even then it struck me that there was something curious about the matter. All was so quiet and still; and here stood one solitary man in the stillness, looking out upon it all. My excitement somehow died down, and I had nothing to say. My bewilderment died also, to be replaced by another feeling still less pleasant. I was glad, yet afraid, when Oliver spoke.

“Let’s hail him!” he whispered.

I had no voice, so he did it himself; but it was a rather hoarse and feeble “Ahoy!” that floated down the hill to the solitary man below. But it reached him, and he turned to see where it came from.

There was still the same unconcern in his movements—no suggestion of haste or wonder; and when he had seen us he made no sign but simply stood and gazed. Yes, it was certainly curious and a trifle chilling. Oliver felt it too, for he said suddenly:

“Let’s go down.”

Of course! It was so obviously the thing to do that I gave a little laugh. Then we ran and slid down the slippery hill together, and over the stretch of clinkers and stones beyond; and we did not stop until we were face to face with the stranger.

As we came nearer we saw that he was an old man, sixty years of age at least. Yes, quite a veteran of a sailor, with grizzled beard, and grey hair beneath the cap, and a grey, weather-beaten face. But it was the eyes that were noteworthy, for they looked upon us entirely without surprise. Neither our sudden appearance, nor our queer and draggled condition, seemed to be anything to be wondered at. He simply stood and looked at us, just as if he waited to hear why we had hailed him. It was an extraordinary attitude, and even Oliver was taken aback.

“Hullo!” he said lamely.

The old man looked him up and down; and as he looked I felt that I could read the spirit of his glance. Surely, there was doubt, suspicion, even resentment and hostility in those faded grey eyes and that knitted brow. And when the old man spoke, his words were almost as mysterious as his manner.

“An’ how did you come?” he asked.

Oliver pulled himself together—indeed, he seemed to try to shake himself free from some unpleasant influence.

“We fell into a pit,” he said; “on the top of the cliffs. But we fell into water, and when we got out of it we found our way here along an old water-course.”

The old man’s eyes left us for a moment to glance at the road by which we had come. He seemed to weigh the story critically.

“I know the water,” he said slowly. “It’s the end of that underground tunnel. I’ve been there. But I never saw any pit.”

“We had to swim a good way,” said Oliver. “Quite ten minutes.”

Again the old man seemed to weigh the statement.

“You’re wet, anyway,” he said. “The thing’s a bit of a change, too. I’ve had many people here, but they’ve never come through that tunnel before. I never knew there was a way through.”

His words were as puzzling as his manner. Oliver became a little impatient.

“Our ship is the John Duncan of Cardiff,” he said crisply. “She is lying in Sandy Bay for repairs. What is your vessel called?”

“She is called the Plynlimmon,” answered the old man quite simply. “You will see her name on her bows.”

We glanced from the man to his ship. He was mysterious, and the ship was uncannily silent and still. Uncanny, too, was the whole atmosphere of the place, shut in on every side by those enormous cliffs. Oliver became irritated, and frowned.

“Well,” he said bluntly, “isn’t there anyone else about? Could we get a loan of some clothes, and have something to eat?”

The old man seemed to rouse himself to the duties of the moment and the situation. “There’s plenty of clothes on board,” he said. “You’re just about the build of our chief engineer, and this young fellow is about the same weight and height as our second engineer. Their quarters are on the lower deck, amidships—cabins ten and eleven. Go you aboard and fit yourself up with anything you want.”

That was distinctly better. “But what will they say?” cried Oliver, bewildered. “Aren’t they on board?”

The old man shook his head. “No,” he said, “they’re not on board. They’re gone on an expedition across the island. They’re all gone—that’s why it’s so quiet here. I’m left in charge. But what I’ve told you is just what the Master would tell you if he was here. So it’s all right.”

Now we began to see light, and it made an enormous difference; but why couldn’t the old fellow have said all that before, instead of keeping us there in suspense and bewilderment? Oliver looked at me, and I smiled back at him; and at once the face of affairs was entirely altered. The atmosphere of the place was explained away, and even the curious conduct of the old man began to seem a bit reasonable. He was a cranky old seaman, left behind, no doubt, because he was too old to go with the rest; and at first he had been presuming a little upon his office.

“You’re sure they won’t mind?” asked Oliver cheerfully.

And he answered simply but positively: “Quite sure.” Then he pointed down to the beach to show us a tiny landing-stage built firmly of planks. And at the stage lay a small dinghy.

“You won’t want me to take you,” he said. “I’m a bit tired to-day, and there’s no need, either. You take the dinghy. She’s quite sound. And don’t be afraid to pick anything you may need. It will be all right. I’ll answer for that.”

There was evidently nothing more to be said, and, with a murmur of thanks, Oliver led the way down to the boat. She was indeed in excellent order, and the old man stood watching as we stepped in and took our seats. Oliver took the oar to scull her over the fifty feet or so that separated the ship from the beach; but even as we started our hospitable old gentleman did a rather curious thing. He marched slowly up the beach without once looking back, and when he reached the bungalow he went inside and closed the door behind him. No, he did more than close the door—he locked it, for the distance was so little and the air was so still that I heard the key turn. Oliver heard it also and gave a queer little smile.

“Well, he’s a cranky old chap, and no mistake!” he said; and then we both forgot the old fellow and turned our attention to the things before us.

These were very interesting matters. There was a handsome accommodation ladder on the ship’s side, some four feet wide and beautifully carpeted. That was something to start with, and it gave a fair indication of the rest; for in the next ten minutes, feeling that the old man’s attitude as well as his words had given us the right, we took a rapid survey of the Plynlimmon from stem to stern—of course without entering any closed doors, and even when doors were open before us, without laying a finger upon anything that could be called private. From the first, however, we saw what the accommodation ladder had suggested—namely, that the Plynlimmon was not and never had been a cargo-boat. She was a well-appointed steam yacht of some two thousand tons, fitted with every requisite for comfort and efficiency, every appliance and invention that could make a voyage pleasant and enjoyable. Even the crew’s quarters—well, I thought of the old John Duncan and smiled.

“This becomes more and more interesting,” said Oliver in a hushed voice, as we looked into a large saloon which seemed to be partly a gentleman’s study and library, partly a sitting and smoking room. “There are quite a thousand books on those shelves. I think we might have a look at them.”

We examined one or two, but they did not greatly appeal to us. The volumes were in a special binding, with a coat-of-arms on the side, but the series I got hold of was called Transactions of the Geological Society, while Oliver hit on several volumes of Notes and Queries. “Quite old ones, too,” he said. “I fancy the owner must be a student of science, to say the least of it. But here are some magazines.”

The magazines were lying in a rack, and he picked up two or three and turned them over. For a moment after that he was silent, but as I was still examining the library I did not notice the expression upon his face. He was about to say something, but checked himself abruptly; and directly afterwards he laid the magazines down and led the way into the next room.

That was evidently the Captain’s cabin. It was handsomely furnished in mahogany and velvet, and as sumptuous an abode as any man might desire. Oliver glanced quickly round, and then went over to a large writing-table which had three shelves of books behind it. Stooping over the table he examined some of the titles of the books, which were mostly works of reference. He took down several of them and opened them, still in silence; and then he took from the lowest shelf a black, leather-covered volume of foolscap size which had the single word “Log,” in gold, on the back.

I was greatly interested but a little surprised; for though his action was natural in one way, seeing that he was himself a ship’s officer, it seemed a little intrusive also. After all, a Captain’s log is the Captain’s private record. But Oliver opened the book and examined several pages; then he called me.

“Just look at this, Frank,” he said.

I looked. It was apparently the last written page of the log, and I could not see it all because his finger covered one of the entries; but the items he pointed to were certainly interesting; they formed the heading to the page.

Log of the Steam Yacht Plynlimmon of Cardigan.

Owner: The Right Honourable the Earl of Barmouth.

Captain: Thomas Vaynor Powell, R.N.R.

First Officer: James Williams.

Voyage:

I did not read more—indeed, the position of Oliver’s hand obscured the other details. Suddenly he closed the book and replaced it.

“Now we know a little,” he said. “The Plynlimmon came here for some scientific purpose, the Earl of Barmouth being the owner of that learned library next door. For the rest, I think we will interview the caretaker again—after we have got into our new clothes. Frank, my boy, we have almost forgotten the purpose of our visit. First, then, numbers ten and eleven on the lower deck; then, I suggest, a bath in those elegant enamelled baths. You can have the Earl’s, and I will take the Captain’s. I want to wash away all taste and trace of the Great Pit. What do you say?”

“I say ‘Yes,’ ” I replied at once. “I’m with you—or at least I’ll be next door! A bath will be just the thing.”

Accordingly we sought and found the engineers’ cabins, which were quite as hospitable to our needs as the old sailor had promised. Everything about us was in apple-pie order, and it did not take us long to find in those well-stocked lockers the very things we wanted. I selected a woollen shirt and socks, a strong pair of blue serge trousers, a knitted jersey and a reefer coat, bearing everything in triumph to the Earl’s bathroom. While I enjoyed a thorough cleansing, I heard Oliver undergoing the same process three or four yards away, and did my best to get finished first. In this I was successful, and was awaiting him in the corridor when he came out, all fresh and new, but with a gravity of countenance that gave me quite a shock.

“Why, what’s the matter?” I cried. “You’re as solemn as an owl.”

He smiled. “It doesn’t hurt,” he said. “Now I think we’ll go back for that interview. There’s a lot of things I want to know yet. And we’ll take our wet clothes with us in the hope of getting them dried.”

We descended that splendid ladder and made our way back to the beach. By this time dusk was creeping over the tremendous cliffs which surrounded that inland sea. It was so eerie and solemn, so gloomy and so majestic, that I was impressed against my will and gave a little shudder. That stillness was so great, so intense, that every slightest sound seemed to be a crime. Oliver’s tones were hushed and low as he spoke.

“That is the big cliff face,” he said, pointing. “From the distance of two miles it would be hard to see the cavern-like opening by which the Plynlimmon entered. You can see the entrance from this side—that great archway. I imagine that the Earl of Barmouth found it by accident, perhaps when he was examining the coast in a small boat. He found the passage navigable, and so came in. If all’s well, we’ll get out that way in the morning, before the John Duncan sails—it’s too late to try any adventures to-night. Besides, there’s that interview.”

He fell silent again. “Well,” I said, in the same hushed tones, as we touched the little landing-stage and tied the dinghy up. “Well, I said the other day that there were no adventures to be had nowadays by going to sea—nothing but hard tack and hard work. But it strikes me that we’ve found a very remarkable adventure on this island.”

“Yes,” said Oliver grimly. “And it’s going to turn out more remarkable still. But that’s to be seen. But there’s one peculiar coincidence, Frank. You remember the bound volumes you looked at in the Earl’s library?”

“Yes—you mean the Geological Magazine?”

“Just so. The Earl was, I guess, a learned man with a special interest in geology. That’s all right. But the American ship in Sandy Bay has come to this island for scientific purposes; and the learned Professor on board is also a geologist.”

“That’s so,” I said, puzzled. “But what about it?”

“I don’t quite know—in fact, I haven’t the slightest idea yet. We’ll just have to wait and see.”

The bungalow was a small one, built entirely of wood. As we discovered later, the Earl of Barmouth, on finding reasons for a prolonged stay upon the Honeycomb, had made a special voyage to Monte Video for timber and other materials, so that he might remain ashore with some comfort and convenience. Thus his little house would have shamed many a country cottage in Old England.

We had very curious sensations as we knocked at the door. It was so strange to find a civilised wooden door in such a place as this! But the first knock brought no answer; and the second, though much more decided, was equally fruitless. At last Oliver positively thumped the wood with his fist, ending up by seizing the latch and shaking it impatiently. Then we heard footsteps, the lock was turned, and once more we were face to face with the old man of the beach.

His glance was noticeably vacant, and without his cap, with his thin grey hair all awry, he looked older and feebler than when we had met him earlier. From the first Oliver was very gentle and considerate with him, as you shall see.

“Well, we’re back,” he said cheerfully. “And we’ve borrowed lots of things. We’ve seen your ship, too, and a very fine ship she is.”

The old man stood aside to let us pass, and closed the door behind us. Then, still without speaking, he led the way up a short passage which had one door on each side of it. He chose the door on the right, and we followed him into the room.

It was a room measuring about fourteen feet square, with its window looking out upon the sea and the ship. It contained a comfortable-looking bed, a small table, and several chairs, while warmth was furnished by a very neat, open-fronted coal stove, whose chimney found an outlet in the back wall of the room. At our coming the occupant had been about to light a lamp, and he completed this task before he paid any further attention to his guests. It was a good lamp, and as the light shot up he turned to look us over. Then we both noticed that he had been about to partake of a meal, for there was a dish of biscuits on the table and a plate of some kind of tinned meat; but it was very obvious that he had made preparations for only one person!

“I expect you had forgotten all about us, hadn’t you?” asked Oliver, as we threw our caps down upon the bed.

“No,” said the old man simply. “It wasn’t that. I wasn’t quite sure that you were real. I have so many visitors, but never real ones.”

“How would you tell if they were real or not?” asked Oliver, showing no surprise whatever; and the old man’s reply was of a pathetic and startling nature. For a long minute he looked at us, and then he drew slowly nearer. He laid his hands upon my sleeve, and gripped the arm beneath. He looked into my eyes and touched my cheeks. Then he turned to Oliver.

“Take my hand,” said my friend suddenly.

They clasped hands. I knew Oliver’s hand-clasp, how warm and vital it was, and now the old man realised it too. He was past the age of agitation or excitement, but he showed that he was satisfied. Going to a small cupboard, he produced a couple of plates, cups, saucers, and knives and forks, and laid them upon the table. Then, still in silence, but visibly shaken, he made coffee on the little stove.

Everything he needed was at hand, and though he moved slowly he worked with the sure touch of the sailor. Five minutes later we were seated at the queerest meal we had ever taken, and I was listening to the most remarkable conversation I had ever heard.

“What kind of people have your visitors been?” asked Oliver, in a friendly, sympathetic way. “Mostly folks you knew, I suppose?”

“Always,” said the old man, in the same simple, unemotional fashion. “Old friends and shipmates. All the men I have ever sailed with have come in from the sea, sometimes very friendly, but never real. And almost every day the Master comes along the beach from the way he went, with the Captain at his side and all the others marching behind. More than once they were so real that I have gone running out to meet them; and he has always said: ‘Well, Lewis, how are things going? Is all well?’ But when I got close enough to touch his hand, there was nobody there.”

There was something of vacant wonder in the faded grey eyes that gazed at us in the light of the lamp; and as I met that gaze I suddenly began to understand the terror and the pity of it—no, not to understand fully, but to get some glimpse of understanding. Before Oliver could speak, he went on:

“Once the Ocean Pearl came sailing in, just in the evening, when it was getting dark; but I knew her, for she was my first ship. I went to Australia with Captain Williams. Yes, the Ocean Pearl came sailing in, and dropped anchor right astern of the Plynlimmon; and there was Williams on the poop, as big and red as ever. ‘You there, Dick Lewis?’ he calls out. ‘We’ve come to fetch you. You’ll come on board first thing in the morning, and we’ll take you home.’ ‘No, Captain Williams,’ says I. ‘I’m in charge here, and I can’t go till the Master comes back. It wouldn’t be like you to want me to desert, and it wouldn’t be like me to do it.’ Then I heard Captain Williams laugh out till the sound went all over the island. ‘It’s the same old Dick Lewis,’ he said. ‘He won’t budge an inch!’ And when I looked out in the morning the Ocean Pearl was gone. But of course, sir, she hadn’t really been there.”

There was a long pause—all the more terrible to me for the calm way in which Oliver took his food while he brought out this amazing story. Then:

“Tell us about the Master,” he said kindly. “How long has he been away?”

Lewis seemed to consider, and I perceived now what Oliver had seen earlier—that his mind was no longer capable of thought without a great effort.

“Well, it may be a month,” he said slowly. “Or, perhaps, a few days more. You see, the Master went first, taking the first officer with him, and the chief engineer, and the steward, and ten men besides. He would be away a week at most, he said; but he didn’t come back in a week, and there was no word of him. So then Captain Powell gets anxious, and sends another lot on the track of the party, to see what had become of them; but they didn’t come back either. So then Captain Powell, in ten days or so, made up another party, leaving three of us in charge of the house and the ship. And the other two with me were Charles Roper and Albert Perkins.”

At this point I almost forgot my food, for I perceived that a tragedy was being unrolled before me. But Oliver saw my face and gently kicked my foot under the table; so I looked as unconcerned as I could and went on eating. But my attention now was a taut and trembling cord.

“And what happened to them?” asked Oliver. Whereupon the old man raised his head to show a sudden angry gleam in those faded eyes.

“What happened to them? Just what they deserved. In a little while they got tired of waiting and said they would go. I would not go with them, so they went without me. They took the biggest boat and plenty of provisions, and went to get out through the water-cave, where we had come in; but next day some pieces of the boat were brought back here by the tide, and Albert Perkins was brought back too. I took him out of the water and buried him back in the shingle. The rocks in the water-cave had battered his poor body to death.”

“And then you were left alone?”

“Yes, sir. But I had plenty of everything on the ship, and I managed. It was very quiet, but then I was busy keeping things clean and neat for the Master when he should come. I had no time to be idle or to get rusty.”

We had seen the ship, and could imagine how her care had kept this one man employed; but Oliver had not yet finished.

“You said you had been into the water-course down which we came,” he said. “Have you made any other explorations? Which way did the Earl go? Have you tried to trace his party?”

“Oh yes, sir,” said Richard Lewis. “The Earl went to cross the island, thinking he might find his way to the northern coast. It is terrible rough going, for there is no road, only a jumble of rocks and boulders. But I gave two days to it—yes, that was last week—and came at last to the foot of the cliffs of the northern coast. Then there was no way, seemingly, except through a great cave, and I hadn’t taken enough candles with me to try it. So I had to come back; but I’m going again later, to make sure—if the Earl doesn’t come back before, which I expect he will. But this island is a wild place for caves and such like.”

“So it is,” said Oliver briefly.

“Yes, sir, so it is. And for my own part I like the open air and the open sea.”

For a while a silence fell. Oliver and I doubtless thought of the great pit, while old Dick Lewis thought of the great cave in the northern face of the island. But there was still a little more to know.

“Why did the Earl come to the island first?” asked Oliver. “What was he specially interested in?”

“Rocks and things,” said Richard Lewis.

“Geology?”

“That’s it, sir. It was his hobby, and he went right round the world for it. We came here as a last call on the way home, but as soon as he’d looked round he said he must stay a while. So we stayed, and his lordship gathered many bits of rock together here. Just come and look in the next room.”

By this time we had finished our meal and had pushed our plates aside. Lewis rose, took up the lamp, and led the way out across the passage to the next room.

It was similar in size to the first, but it was furnished and fitted differently. True, there was a bed in the middle here also, and a table and a couple of chairs; but the chief difference lay in the racks of wooden drawers which had been built up against the walls on every side but one. Lewis went to one of these and drew it out, to show it half filled with chippings of rock.

“There’s hundreds of these,” he said. “And no doubt the Master will bring back hundreds more. His lordship was a great one for having things done in order and neatly, as you see, though it was only for a little while. He would never have things lying about.”

“It couldn’t have been more thoroughly done if he had settled here for a couple of years,” I suggested.

“No, sir. That was just his way. And I’ve had to keep things in just his way.”

He turned to go back, but paused on the threshold.

“That’s my bed, sir,” he said. “I sleep in this room to look after the specimens. His lordship asked me to, and had the bed put there for me. The bed in the other room was his own, and that’s the one you shall use. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind . . . and I’ll take the risk.”

With slow, uncertain steps he led the way back, and put down the lamp. As he did so he looked up with just that touch of wistful pride which I had noticed more than once before.

“I’m a Barmouth man myself,” he said; “and I knew his lordship as a boy. My father was one of his shepherds. After he had bought the Plynlimmon he heard that I had been round the world, and asked me to join the crew. A good and easy place it was, too, and a kind and noble master he made. That’s why I wouldn’t join Albert Perkins and Charles Roper when they wanted to go. They were Bristol men, and of course it wasn’t the same to them.”

Oliver, I could see, was under strong emotion. But he did not glance at me. He looked around that cosy little room with its wooden walls, and for a moment he seemed to listen; but if he listened, it was only to the great silence without. The old man, however, concluded that the questions were finished.

“I always go to bed at dark, sir,” he said gently, “except sometimes when I read a while in the Book. I will now clear away the things, and after that, if you please, we will read together just one little passage.”

“Certainly,” said Oliver. “But we will help you to clear up. Come, Frank.”

Help him we certainly did, “washing up” in a little lean-to at the back of the bungalow, where the household utensils were stored. We did it by candle light, and when we came back Lewis carefully put out the candle. “Not that I’m mean, sir,” he explained. “But I cannot waste. And though there is plenty of everything on the ship, one cannot tell how long the Master may be.”

Oliver nodded, and then we drew round the table once more. The old man brought two books out of a cupboard.

“I am Welsh, sir,” he said. “And I like to read the Welsh. It seems better to me, being my native tongue. I will read the Welsh, if you please, and perhaps you will read the English of it after. It is the Twenty-third Psalm.”

So he read it in the strong, musical, and sonorous tongue of his homeland, very slowly, as if he liked the sound of it; and after he had finished, Oliver read the immortal passage in English. By that time the old man’s eyes were full of tears, and even I felt a tightness of the throat as I heard, on this bleak, forgotten, and inhospitable rock, of the green pastures and still waters of the Shepherd King.

Never shall I forget the passage as I heard it that night.

Then Richard Lewis, with a great composure, took up the books and lit the candle once more. “You have the lamp, sir,” he said. “Please put it out as soon as you have done with it. And I hope you will sleep well.”

“We shall sleep the better for that reading,” said Oliver earnestly; and then the old man, smiling, shook hands with both of us. For a few moments afterwards we heard him moving in the next room, but in a little while he became silent. Then Oliver turned to me:

“What do you think of it, Frank?” he asked, in a low tone.

“I think loads of things, but I can’t tell you them all at once. Anyway, that old chap is a gentleman.”

“Yes; and in a way God has been kind to him, too. He has let him forget. By this time, perhaps, he has forgotten that we are here.”

“Forgotten!” I cried, in hushed astonishment.

“Yes. Remember his story of Albert Perkins and Charles Roper. Do you think that they would have dared that voyage—the cavern passage and the South Atlantic beyond—in a small boat, after only a few weeks’ waiting here? They waited for months—perhaps years. They waited until they felt that they would lose their reason if they waited longer. Then they went—and died; but Lewis thinks it all happened a few days ago. He has lost all sense of the passage of time. He simply lives for the work of the moment, the day. He remembers things, but he can’t date them. For him they are all in the immediate past—the yesterday.”

I was bewildered and shocked, as much by Oliver’s expression as by his statements. He was in dead earnest plainly enough, but as I had not yet grasped his meaning, I could not understand his gravity. So he went on to explain:

“I did not tell you on the ship, because I wanted to make sure; but you may as well know the truth now. You noticed how old some of the books were, and the magazines; but I did not show you the date of the last entry in the Captain’s logbook. It was made in September, 1902. To-day is October the fifth, 1922. So I gather that Richard Lewis has been alone on this island, with the ship and the house and a crowd of ghosts, for twenty years!”

“Awake, Frank?”

“Yes.”

“Then I think we might talk a bit. It’s better than too much thinking.”

I had been thinking for an hour—the hour of day-dawn—and so had he, but each had kept quite still so that the other might sleep on. But we were young and strong, and a few hours’ sleep had been quite sufficient to restore the energies which had borne so severe a test yesterday. Indeed, we were both impatient for action and counsel, though we had talked a good deal before sleep had come.

Now Oliver turned, so that we might speak in whispers and not disturb the old man in the next room. “Great Scott!” he said. “What a nightmare it is! When I try to think it seems to grow more and more awful. Twenty years in a place like this! Why, a loss of the sense of time would be a blessing to pray for.”

“Perhaps he prayed for it,” I said.

“Yes. And then it was just routine, day after day, with two or three guiding principles. One was work, another was faith, and another was devotion. Another was care—and I think he must have got that before he lost the sense of time. He saw, then, that he must husband his resources, and so got into the habit of economy. No doubt the ship was well provisioned, but even one old man will consume a great deal in twenty years.”

Ralph Oliver had evidently been thinking to some effect, and we discovered afterwards that he was right in his surmise. There were provisions, coal, and lights on the Plynlimmon to last the three of us for about six months with care; but Richard Lewis had lived almost a hermit’s life and had wasted nothing. Day by day he drew his rations from the ship’s stores with pathetic care, but the incident of the candle was a faithful index to his methods.

“But,” proceeded Ralph earnestly, “that is not the point just now. I went to sleep feeling that it would be an easy thing to get back to our ship this morning. The thing is not so easy.”

“Not?” I said.

“Well, how is it to be done? We can’t go back the way we came, and there is only one other way—the way the Plynlimmon came in. But there is only one boat—the little dinghy—and that, for one thing, isn’t ours. It’s Lewis’s only way of getting to his ship, and, except as a last resource, we dare not risk it in an attempt to get through the cavern. Besides, I feel sure it would be madness. Perkins and Roper had a larger boat, and they failed. With a steam launch or electric motor it might be easy, but if there is any current through the cave the dinghy would be a mere cockle-shell.”

I was staggered—and convinced—and could find nothing to say. Oliver went on:

“Captain James will give us up for lost on Tawell’s report. How can he help it? Even if a man were lowered to the bottom of the Great Pit he wouldn’t find anything there but the water; so there could be no hope of our having survived. There would be nothing to suggest a search along the coast. As to letting them know that we are here, the only way possible to us would be by a rifle shot; but we are absolutely shut in by the cliffs on every hand, as, indeed, they are themselves at Sandy Bay. The sound would never reach them. As for climbing the cliff, why, I don’t suppose a goat could do it.”

“Not much. It’s mostly a bare wall. But what is to be done? If there is no hope, the John Duncan will go. Hadn’t we better go out and see?”

“I think so. But we must try not to disturb the old man.”

We did not disturb the old man. In complete silence, in the grey morning light, we dressed and slipped on our shoes. As we passed the door of the other room we listened to hear the breathing of the aged sleeper, but we did not look in to see him. The outer door was opened very quietly, and then we paused upon the threshold to survey the world in which we found ourselves. After one look, I slipped my arm through Ralph’s just for the comfort of the touch of him.

It was weird and grey, ghostly and terrible. Light was coming over the cliff from the east, but, below, the Secret Sea lay in shadow, with its ghostly grey ship and its lifeless waters, as silent as death. The very silence was appalling, for it was not broken even by a ripple against the beach. It was a dead and forgotten world on which we gazed, a dead and forgotten world into which we had been thrown by some heartless whim of fortune. I could not resist a shudder, and Oliver, feeling it, pressed my arm.

“Buck up, old chap,” he said, “we’ll make a do of it, never fear. Let’s walk along towards the sea cavern.”

So we shook off the spell of that eerie morning, and began to examine our situation and its surroundings; and though I had read some very remarkable tales of difficulties and adventures on desert islands, I soon discovered that it would puzzle any romancer to imagine such a problem as ours. I describe it here in some detail, though, of course, we did not discover everything on that first morning.

The island on which we stood was really the summit of an old and almost submerged volcano, a fact which explained the singular appearance of the place. Sandy Bay, where the John Duncan had found refuge, was undoubtedly an old crater, into which the sea had flowed during some convulsion long ago, or, perhaps, through the natural action of the water and weather upon the surrounding rocks. But this submerged mountain had had two craters, both of which were now mere basins for the sea. And the second of these was the one into which the Earl of Barmouth had found a way, and in which his deserted ship had lain so long.

The entrance to Sandy Bay was at the south-western extremity of the island, and was visible from a long distance away; but the opening to the Secret Sea was at the south-eastern end, and there were some three miles of dangerous rocks between. Moreover, all that could be seen from the sea, even at close quarters, was the grim mouth of a great cavern, dark and forbidding, with a swirling tide that seemed to speak of treacherous currents and eddies. The place offered no temptation to any mariner, but the Earl had entered the cavern one day in his launch, curious to examine the formation of its tremendous walls. He had found it apparently bottomless, a great channel through which three ships might pass abreast, and, on exploring it to the end, he had reached that quiet basin where the Secret Sea was securely sheltered by its belt of frowning cliffs, so securely sheltered that even the heaviest gale without would scarcely stir its sullen waters.

Ages ago, perhaps, that crater had spouted out a sea of boiling lava, before the masses of discharged rock had yet had time to harden. This molten flood had sought an outlet, and had found a weak place in the congealing ramparts that surrounded it. Through this it had poured in a mighty stream that swept away the rocks like straws, cleaving a vast chasm through the breast of the mountain to the outer air. When the flood had gone and the mountain had grown cold, the great outlet had remained, and the masses of molten rock had hardened all around and over it into a mighty grotto, a quarter of a mile from end to end; and after many changes and many ages, the sea had flowed into its mouth and had filled the empty basin that had once bubbled with fire and steam. Doubtless, too, the great pit into which we had fallen was another of the channels through which the now extinct volcanic forces had made their way. It was the existence of these caves and shafts that had gained the rock its peculiar name.

The Secret Sea, as we saw now, was about a mile long from north to south, and some three-quarters of a mile across. The beach was of a dark volcanic sand, and behind the beach stretched a wilderness of rocks and boulders, until you came to the almost sheer face of the cliff. But here and there we could see tracks that led into and over the rocky wilderness, and it was by these ways that the Earl had made his geological expeditions. Sometimes, as Lewis told us later, they were very brief, and he would return in an hour or two with his canvas bag well laden, spending the rest of the day in examining and selecting from the fragments he had brought. Sometimes they would last for many hours and yet be less fruitful in results.

The ship lay some distance from the entrance to the cavern, and about fifty feet from the beach above which the bungalow was built. It was marvellous that after her long idleness she should still look so spick and span, except that time had dulled the paint on her hull; but, as a matter of fact, her guardian had spent all his thought and care upon her to keep her ready for her master’s return. And there she had lain year after year, with that one old man about her, one living being in the midst of desolation and death. For there was no other life anywhere, no goats among the rocks, no rabbits, scarcely a stunted shrub, hardly a blade of grass. The tide, indeed, came up, raising the surface of the Secret Sea some four feet or so silently and stealthily, with a hollow murmur from the gloom of the great cavern; but even the tide brought a new and uncomforting mystery with it, for Lewis declared positively that not a single fish of any kind came in with the flow of the water.

But to come back to the tour of this first morning. We walked briskly down the beach to the southern end of the water till we could go no farther. The beach ended in a wilderness of rocks, beyond which rose the cliff face, absolutely unscalable. From this point, however, we could see the entrance to the great sea cavern which was the gateway to liberty, and it was for this purpose that we had come. But we saw nothing that could help us. It was simply a giant archway whose sides rose sheer from the water. Oliver’s fear that the passage would be too difficult for a small boat seemed to have every justification, for there seemed to be strong currents setting into the great arch and issuing from it.

“It is a very remarkable formation,” he said, as we stood there and gazed. “But it doesn’t stand alone. It occurs at Fernando de Noronha, far to the north of this; but that is a well-known case, while this is not. This coast is so dangerous that most people give it a wide berth even if they happen to come to the island itself.”

“Then you see no hope of our getting out?”

“Not in the dinghy. But it’s curious that there are no larger boats here. The ship must have had several, and we know that Perkins and Roper took one of them. But where are the others?”