* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

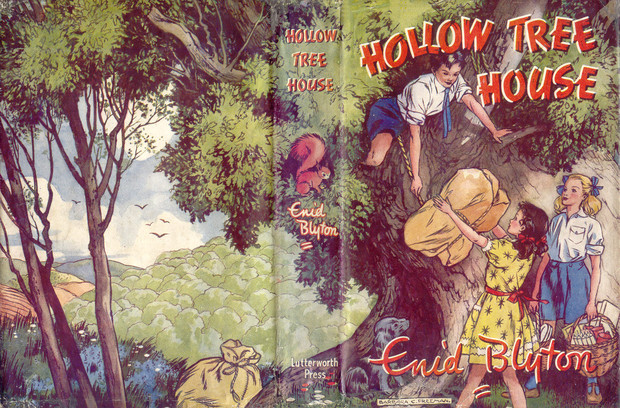

Title: Hollow Tree House

Date of first publication: 1945

Author: Enid Blyton (1897-1968)

Date first posted: June 19, 2019

Date last updated: June 19, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190636

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

HOLLOW

TREE

HOUSE

Enid Blyton

First published in 1945 by Lutterworth Press.

Text from the 1987 Beaver edition.

| 1 | Cross Aunt Margaret | 7 |

| 2 | Two Pounds for the Treat | 14 |

| 3 | A Day by the Sea | 22 |

| 4 | Three Children—and Barker | 29 |

| 5 | In the Heart of the Wood | 36 |

| 6 | The Old Hollow Tree | 43 |

| 7 | Exciting Plans | 51 |

| 8 | Moving-in Day | 58 |

| 9 | A Lovely Tree-House | 66 |

| 10 | Trouble with Aunt Margaret | 73 |

| 11 | In Disgrace | 79 |

| 12 | A Peculiar Sunday | 86 |

| 13 | A Dreadful Shock | 93 |

| 14 | In the Middle of the Night | 101 |

| 15 | An Exciting Home | 108 |

| 16 | Where is Angela? | 116 |

| 17 | Barker Changes Hands | 123 |

| 18 | A Narrow Escape | 130 |

| 19 | An Anxious Time | 137 |

| 20 | Barker is Good Medicine | 144 |

| 21 | Angela Tells a Story | 151 |

Two children stood outside the kitchen door of their home, and listened. From inside came the sound of a scolding voice.

‘You’ve sat in that chair and slept for two whole hours, you lazy thing! You go out and bring me in some wood!’

‘She’s in a bad temper again,’ said Peter to his sister Susan. ‘It’s no good asking her today.’

The children went away from the kitchen door and sat down on a pile of logs in a corner of the garden. Susan looked at Peter.

‘Well, if we don’t ask soon, we shan’t be able to go,’ she said. ‘We’ve got to take the money tomorrow.’

Peter and Susan lived with their Aunt Margaret and their Uncle Charlie. They dimly remembered a time when they had lived with someone pretty and merry—their mother, who had died when they were very small. Then they had gone to live with their aunt and uncle.

They were afraid of Aunt Margaret. She was bad-tempered and spiteful, with a scolding tongue. Uncle Charlie was afraid of her, too. He was a lazy, good-tempered man, who could never keep a job for long, and that made Aunt Margaret crosser still.

Peter was eleven, and Susan was nine. It was easy to see that they were brother and sister, for they had the same deep blue eyes and black wavy hair—very like their uncle’s. They looked unhappy now. If only Aunt Margaret would let them, they could have a fine treat—but if she happened to feel extra bad-tempered, they would have to go without the treat.

‘Everyone else in the school is going, simply everyone,’ said Susan. ‘A whole day by the sea! Think of it! And all for a pound.’

‘I know. I wish we had a pound each, then we could go without asking Aunt Margaret,’ said Peter. ‘We never have even ten pence pocket money, as other children do. It’s only when Uncle gives us ten pence on the sly that we ever have anything to spend. And then, if Aunt Margaret finds it, she takes it away!’

‘Well, Peter, we simply must ask about the school treat tonight,’ said Susan. ‘If we don’t take the money tomorrow, our teacher won’t buy a ticket for us—and we shan’t be able to go. We’re the only ones who haven’t taken the money yet.’

Still the scolding voice came out from the open kitchen door.

‘Sitting there with the newspaper in front of you all day long! Lost your job again—and no wonder! The only thing you’re ever on time for is your meals. What with you to look after, and your tiresome nephew and niece, I’m just about fed up!’

There was the bang of an iron on the table as Aunt Margaret spoke. She was ironing, and the children could tell by the bangs of the iron what a bad temper she was in.

They waited for a while. Then their uncle came out with a sulky look on his face. He caught sight of the two children.

‘One of these days I shall walk right out of this house and never come back!’ he said to them. ‘There’s no peace in this place at all! Nag—nag—nag, all day long.’

‘Uncle—I suppose you couldn’t possibly let us have a pound each, could you?’ said Peter, rather hopelessly, for when his uncle had no job, he usually had no money either.

‘A pound each! Whatever for?’ asked Uncle Charlie.

‘To go to the school treat,’ said Susan eagerly. ‘It’s a whole day by the sea!’

‘I haven’t a pound for myself, let alone for you!’ said her uncle, dipping his hands into his pocket. He brought up a few pence, and that was all. ‘Your aunt takes all she can get. Better ask her!’

He went off down the lane, and the children watched him. They liked him, but they did not admire him. He was so lazy and weak, and even when he got a good job, he lost it through being late in the mornings, or being careless. Perhaps Aunt Margaret might have been a bit better-tempered if Uncle Charlie had been a finer man.

Suddenly their aunt came to the door and saw them. ‘Now what are you idling out there for?’ she called out, in her usual sharp voice. ‘Susan, come on in and help me with the ironing. Peter, get me some wood. If you think I’m going to let you grow up lazy and good-for-nothing like your uncle, you’re wrong.’

That wasn’t a fair thing to say, because neither Peter nor Susan was lazy. They worked well at school and were top of their classes. At home they did plenty of odd jobs for their aunt, and did them well.

Susan went indoors with a sigh. It was hot and ironing would make her feel much hotter. Peter went to get the wood that his uncle had forgotten to take in. He was always doing things that his uncle had forgotten to do, or was too lazy to do.

Bang, bang, bang, went the iron. Aunt Margaret was still in a bad temper. Susan said nothing. She began to iron the handkerchiefs and fold them neatly. Then she took the towels to iron. She was a good little worker. She did her best hoping that Aunt Margaret would feel pleased with her. Then perhaps she might ask her aunt if they could go to the school treat.

Peter made up the fire, and filled the wood-box. Then he stood near the two ironers, wondering if he dared to ask for the two pounds now.

‘What are you standing there for, doing nothing?’ said his aunt, sharply. ‘Want to get something out of me, I suppose! Well, what is it?’

Aunt Margaret was clever at reading people’s thoughts. Peter knew he would have to ask her now.

‘Well, Aunt—you see, it’s the school treat tomorrow and our teacher is taking us all to the sea for a day,’ he began. ‘Our tickets are only a pound, and that pays for our tea as well. We have to take our own dinner. Everybody’s going, every boy and girl in the school. So Susan and I wondered if we could go too.’

Bang, bang, went the iron angrily, and Peter’s heart sank. ‘And where are you going to get the two pounds from?’ said his aunt.

‘Well—we thought perhaps you could spare them just this once,’ said Peter. ‘Or perhaps you could spare one pound, Aunt Margaret—for Susan to go. She has never seen the sea, and I have.’

‘Oh no, Peter—I couldn’t bear you to be the only one in all the school left behind!’ cried Susan.

BANG, went the iron. And then Aunt Margaret began one of her tiresome scoldings.

‘Two pounds! With your lazy uncle out of work again! And me working and slaving hard to make money to keep all four of us! You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Peter Frost, and you too, Susan!’

Peter opened his mouth to speak, but his aunt swept on, banging the iron down at the end of each sentence.

‘It was a bad day for me when I married that lazy uncle of yours! And what does he do when his silly little sister dies, but bring you along here and tell me it’s our duty to look after you! Says he to me, “Their father’s dead, and now their mother’s gone, poor little orphans! We’ve no children of our own, Margaret,” he says, “so we’ll do our best by these!” And he too lazy to earn a penny to keep you!’

‘Aunt Margaret!’ began Peter, ‘it was kind of you to take us in—and we’ll both do our best when we’re grown-up to pay you back the money you’ve spent on us.’

Bang, bang, bang! Aunt Margaret snorted as she ironed.

‘Yes, I’ve heard tales like that before, from your uncle. You’ll be like him, when you grow up—there’s no good in your family. I don’t know why he brought you here, when you could have gone into some good children’s home. I didn’t want you. But I’ve put up with you for a good many years now, and paid out good money for you—and now you have no better sense than to ask me for pounds to go off on a treat!’

Susan was crying. ‘Don’t keep saying you don’t want us,’ she sobbed. ‘It’s awful not be wanted. I’m glad you didn’t let us go to a home for children. We really and truly will pay you back some day for all you’ve spent on us.’

‘Oh, go on out of doors if you’re going to cry all over the ironing,’ said her aunt, impatiently, but she looked a little ashamed of herself. Susan slipped out at once, and Peter followed her.

They went out of the gate and crossed to the wood that stretched for some miles over the countryside. They sat down on a bank of grass and Peter put his arm round Susan.

‘Don’t cry, kid,’ he said. ‘What’s the use? We know Aunt Margaret doesn’t want us and never did. But at any rate she gives us a home.’

‘It’s not a proper home,’ said Susan, wiping her eyes. ‘Proper homes aren’t like ours. Think of Angela’s home Peter—or Hilda’s—or Tom’s.’

Peter thought of them. Yes, they were homes, proper homes, no doubt about that. But then, there was a mother in each home, who loved the children there, and did not mind how much trouble and money she spent on them.

There was love in those homes, too. The children loved their parents, and the parents loved their children. Susan thought of how Hilda always ran to kiss her mother when she got back from school. She remembered how Joan’s father picked her up and put her on his shoulder when he came home from work. She thought of how Tom always rushed home to tell his mother about school.

‘I wish our mother hadn’t died,’ she said. ‘Oh, Peter, I do want a proper home and a mother.’

‘Well—we’re just unlucky about that,’ said Peter, and he put his arm round Susan again and gave her a squeeze. ‘But anyway, we’ve got each other, and that’s something. One day I’ll make a fine home for you, Susan.’

‘I know you will,’ said Susan. ‘You’re a darling. But I want a proper home now, while I’m little, with a mother in it. Somebody who will welcome me when I come home from school, and somebody who will come and see me when I’m in bed and say good night.’

‘Oh, Susan, you know that’s impossible,’ said Peter.

‘Well, when I say my prayers at night, I always put that in,’ said Susan, in an obstinate little voice.

‘What do you put in?’ said Peter, puzzled.

‘I ask for a proper home and a mother,’ said Susan. ‘I keep on and on asking God for those. He can do everything, can’t He?’

‘Well—He might think He has given you a proper home, with Uncle Charlie, and He has given you Aunt Margaret instead of a mother,’ said Peter.

Susan looked scornfully at her brother. ‘God knows quite well what I mean,’ she said. ‘I’m sure He wouldn’t make a mistake like that. One day you’ll see. He’ll give me what I ask.’

‘You’re still a baby,’ said Peter, with a sigh. ‘It’s no good asking and wishing for what’s impossible, Susan. We must make the best of what we’ve got.’

The sound of someone singing in a little high voice came through the wood. Susan wiped her eyes for the last time and sat up straight.

‘It must be Angela,’ she said. ‘It sounds like her.’

A girl of about Susan’s age came down a little path towards them. She was very pretty, and her blue, flowery frock suited her beautifully. She had a mop of silky gold hair and blue eyes, though not such a deep blue as those of the other two children.

‘Hallo, Sue, hallo, Peter!’ she said. ‘I wondered if I should see you today.’

Angela was lucky. She had all the things that Susan hadn’t got and wanted so badly. She had a pretty, loving mother, a strong, clever father, a lovely house and garden, and a family of the loveliest dolls Susan had ever seen.

But Angela was not spoilt. Her mother was too sensible and too kind-hearted to spoil Angela and make her think she was wonderful. She tried to make Angela share her things with others who hadn’t so many, and she tried to teach her to be as kind as she herself was.

And Angela was kind. Everyone liked her, not because she was pretty and dainty, or because she had plenty of toys, but because she was merry and kindly, always friendly to everyone. Susan adored her, and her most precious possession was a little doll from Angela’s dolls’ house, that Angela had given her for her birthday.

Angela did not go to the village school. She had a governess, Miss Blair, who taught her each morning. Susan and Peter had met Angela at the Sunday School they all went to. She was in their class.

One afternoon the story had been about the boy with the loaves and fishes, and how pleased he had been when Jesus had, by a miracle, made his simple meal into enough food for thousands of people.

When it was finished Angela had beamed at the teacher. ‘That’s my favourite Bible story,’ she said. ‘My very favourite. I often imagine what that boy must have felt like when Jesus took his picnic basket and fed all the crowd from it! I expect he rushed home to tell his mother all about it.’

Susan had joined in at once. ‘Oh, it’s my favourite story, too. And my next favourite is about the little boy who had sunstroke, and the old man cured him and gave him back to his mother.’

‘I don’t know that one,’ Angela had said. ‘Will you walk home with me and tell me?’

So the three children had walked home together, and Susan had told the story of the little boy who had sunstroke and died. She had found the story for Angela in her Bible, so that she could read it herself. All the children liked the miracle stories, and thought they were full of magic.

‘We could act some of those stories, couldn’t we?’ said Angela, when they stood outside the gate of her home. ‘I love acting and pretending. Oh, do let’s act some of them. We could easily act the boy with sunstroke. You could be the boy, Peter, and I could be Elisha, and Susan could be the poor mother.’

And so a friendship had been begun between the three children, and many a time had they met in the wood and acted all the stories they loved, out of any book they happened to be reading.

Angela had no brothers or sisters, and was a lonely little girl. She had a great imagination and loved pretending. Susan and Peter were great pretenders, too. Angela made their pretence games very real, because her mother let her borrow old curtains or rugs to dress up in.

‘I like you and Peter best of all the village children,’ Angela said to them. ‘You like to play the same games as I do. The others laugh at me if I want them to dress up and act. Let’s be friends, shall we? Real friends, I mean. I haven’t any brothers or sisters, and I’d love to pretend you are my sister and brother. You’re lucky to have each other.’

‘And you’re lucky to have a mother,’ said Susan, at once. ‘Your mother is lovely. She hardly ever scolds, does she? And she’s always so kind. You must love her a lot!’

‘I do,’ said Angela. ‘Well, if you will pretend to be my brother and sister, you will have to share my mother. She likes you, and she says you can come and play with me when you like.’

The children had told Angela about their Aunt Margaret, and had warned her of her bad temper. But Angela, used to being loved and made much of, hadn’t believed that their aunt would be anything but nice to her.

However, after one or two undeserved scoldings Angela had decided to keep away from the bad-tempered woman, and now the children only met in the wood, or at Angela’s own home.

They were pleased to see her that afternoon, as she came through the trees to find them. She saw Susan’s red eyes at once.

‘What’s the matter?’ she asked, sitting down beside her. ‘Been getting into trouble with your aunt again? I do think she’s horrid.’

Peter told her what their aunt had said—that she hadn’t wanted them, and grudged every penny spent on them. Then he told her about the two pounds they had to take to school the next day, if they wanted to go to the seaside.

‘Well, that’s easy,’ said Angela, jumping up. ‘I’m sure I’ve got more than that in my money-box at home. I’ll go and get it for you.’

‘No, Angela,’ said Peter. ‘We can’t take your money. Thank you all the same—you’re always so generous. But we just can’t take it.’

‘Why not?’ said Angela. ‘Aren’t I your friend? You’re being silly.’

‘I would take it if I thought I could pay you back,’ said Peter. ‘But I know I can’t.’

‘No, we couldn’t take your money, Angela,’ said Susan, who, badly as she wanted the pound, thought the same as Peter. ‘We could never, never pay it back.’

‘I don’t want you to, silly,’ said Angela, beginning to look indignant. ‘What’s two pounds, anyway?’

‘An awful lot, to us,’ said Peter. ‘It’s just that we don’t like taking money for nothing, Angela. If we could do something in return for it, we would take it.’

‘Well—I know what you could do!’ said Angela, cheering up. ‘You know those lovely little baskets you make from the rushes that grow by the stream? Well, will you make me some of those for Mummy’s sale of work next week? I can fill them with raspberries from the garden and she can sell them. The money is to go towards building a new hospital in the next town so it’s a good cause, isn’t it? You would help Mummy to make a lot of money if you let me buy the baskets and fill them with raspberries.’

Susan’s eyes shone. This did seem a very good way out. She turned to Peter, who still looked a bit doubtful. ‘Peter! Let’s make the baskets, and fill them with wild raspberries ourselves. We know where plenty grow. We’ll charge Angela ten pence a basket, and her mother can sell them for fifty pence each. So we would help her to make a lot of money.’

‘All right,’ said Peter. ‘We would really be earning the two pounds then, and I don’t mind that.’

‘Good,’ said Angela. ‘I’ll get the money now, and you can make the baskets in time for the sale of work, and fill them with wild raspberries the day before.’

She sped off. Susan took Peter’s arm and gave it a tight squeeze. She was overjoyed. She had so few treats, and a day by the sea seemed marvellous to her.

‘Angela’s a sport,’ said Peter. ‘We’ll make our very, very best baskets for her, Sue. We might as well make one or two now while we are waiting for her. Come on down to the stream.’

They picked the long narrow leaves they needed for weaving the little baskets, and then sat down to work. Both children were clever with their fingers, and soon two neat little baskets began to take shape.

Angela soon appeared again, rather out of breath. ‘Here you are,’ she said, and held out two pounds. ‘One for each of you. I hope you will have a good day tomorrow. Oh, you’ve begun on the baskets already—aren’t they sweet?’

‘Thank you,’ said Peter, putting the money carefully into his pocket. He wondered whether or not to tell his aunt they were going to the school treat after all. He decided that he wouldn’t. She might make him give up the two pounds to her!

‘We’ll just go, and say nothing to Aunt Margaret about it,’ he said to Susan. ‘Save up your supper tonight, Susan, if you get any, and we’ll have it for our dinner tomorrow. I daren’t ask Aunt Margaret for sandwiches in case she guesses we’ve got the money to go tomorrow.’

‘I’ve got to go now,’ said Angela. ‘Miss Blair wants me to do something with her. See you at Sunday School, if I don’t see you before! Goodbye and have a lovely time!’

‘Goodbye, and thanks very much,’ said Peter. Susan walked with her a little way, then ran back to Peter, who was finishing off his basket very neatly with a strong little handle.

‘What fun! We’re really going tomorrow!’ said Susan, her blue eyes shining with joy. ‘Oh, Peter—what is the sea really like?’

‘You’ll soon find out,’ said Peter. There—that basket is finished. I’ll hide it somewhere, and put yours away too. Look—under this thick bush would be a good place.’

He hid the two little baskets, and then they went back to their aunt’s cottage. Aunt Margaret was now sitting outside in the garden, mending. She did everything very fast, even darning, and her needle seemed to fly in and out. She looked up as the children came along.

‘There’s some weeding to be done,’ she began, as soon as she saw them. ‘You’ll just have time to do it before you go to bed. Do it well, or there’ll be no supper for you.’

‘Yes, Aunt Margaret,’ said Susan, meekly, feeling that she didn’t mind how much weeding she did, now that she was sure of having a treat the next day. They set to work with a will, and not even their aunt could find fault with the way they weeded that onion bed!

‘You’ll find your supper in the larder, on the blue plate,’ said Aunt Margaret, when they had finished. ‘Eat it, and go to bed.’

Their uncle had not come back. He sometimes stayed away for hours, to be out of reach of his wife’s sharp tongue. Peter and Susan went indoors and opened the larder door. On a plate were two thick sandwiches of bread and cheese.

They were hungry, but they knew they must save the bread and cheese for the next day’s dinner. Keeping an eye on their aunt through the window, they quickly took a newspaper and wrapped up the two sandwiches. Peter stuffed them into his school bag.

‘We’ll take a bottle of water too,’ he said, and filled an old lemonade bottle at the tap. That went into his bag with the sandwiches.

‘Now let’s go up to bed before Aunt begins to ask awkward questions!’ said Peter. ‘Mind you don’t say one single word about the treat at breakfast, Susan!’

Up to bed they went. Peter hid his two pounds under his pillow. It was too precious even to leave in his shorts pocket! It meant a whole day by the sea for both of them.

Susan awoke feeling very excited. It was early, but she couldn’t go to sleep again. She wished she had a nice clean frock to wear. All the other children would be sent off looking nice by their mothers.

‘That’s just it,’ thought Susan. ‘Mothers do anything for their children. It’s awful if you haven’t got a mother. If I had a mother I’d love her every minute of the day, and she’d love me and be proud of me, the way Angela’s mother is of her. I do want a mother and proper home. I’ll have to keep on and on praying about it. Our Sunday School teacher said last time that God does answer prayers, and He does do miracles even now. I wish He would do one for me. Perhaps I don’t deserve one, though. Perhaps you have to be awfully good to have a miracle done for you.’

Aunt Margaret’s voice came in through the door. ‘It’s time to get up, Susan. Go down and lay the breakfast-table, and tell Peter to light the fire.’

The children certainly earned their keep at their aunt’s for they did a great many jobs for her. She would have kept Susan home all day long to work for her, if she hadn’t known that the school teacher would ask Peter where she was. Susan dressed quickly, and ran downstairs to lay the breakfast.

Peter lighted the fire, and both children looked in delight at the sunny day outside. ‘It’s going to be fine,’ said Peter. ‘Isn’t that good? The sea will be as blue as forget-me-nots.’

‘Sh! Here comes Aunt Margaret,’ whispered Susan.

They had breakfast. Their uncle was lost in his newspaper, and looked sulky. He glanced at the children, and wished he had two pounds to give to them. He was fond of them—but not fond enough to go out and work hard and keep his jobs.

Aunt Margaret made a few remarks to him about going off to look for work as soon as breakfast was finished. He scowled at her.

‘Nagging for breakfast, nagging for dinner, nagging for tea,’ he said. ‘I tell you, one of these days I’ll walk out and never come back!’

‘It’s a pity you don’t,’ said Aunt Margaret. ‘There’d be one mouth less for me to feed.’

The children said nothing. It was always safer to keep quite quiet when Aunt Margaret was cross. They were longing to get away to school. Peter could feel the precious two pounds almost burning a hole in his pocket. Aunt Margaret didn’t know about them, so she couldn’t take them away and stop them going to the sea for the day!

But Susan, who dreaded her aunt’s sharp, piercing eyes, almost felt as if she might be able to see through Peter’s shorts into his pockets, and spy the money there. She fidgeted to get up from the table and go.

‘For goodness’ sake, Susan, what’s the matter with you this morning?’ said Aunt Margaret at last. ‘Stop fidgeting. Be off to school before I slap you!’

Susan shot off at once, and pretended not to hear when her aunt shouted to her to come back and put her chair away. Peter came out soon after, his school bag on his back and a broad grin on his face.

‘Aunt can’t make out why we’re not moaning and groaning because we can’t go to the school treat!’ he said. ‘We ought to have looked sad and sorrowful. You nearly gave the game away, you looked so excited, Sue.’

‘I can’t help it,’ said Susan, and skipped off beside Peter. ‘I feel so happy. A whole day’s holiday by the sea! A train-ride first—and then the sea—and paddling. And we’ll find some shells and seaweed.’

Then a thought struck her, and she turned to Peter, looking scared.

‘What will Aunt Margaret say when we don’t go home to dinner?’

‘She’ll guess where we are all right,’ said Peter. ‘She’ll think our school teacher paid for us to go to the sea, I expect. We mustn’t tell her we got the money from Angela.’

‘It’s horrid not be able to be honest with Aunt Margaret,’ said Susan. ‘Oh, Peter, I wish we needn’t deceive her. But we can’t help it, can we?’

‘We’re not doing any harm,’ said Peter. ‘We shall be earning money by ourselves by making the baskets. We are not robbing Aunt Margaret of it. Still, it would be nice if we could trust her and tell her everything.’

The whole school was excited. Every child was going. They marched off to the station with the three teachers. Susan went with her class, and Peter went with his.

As they waited on the platform, who should come along but their Aunt Margaret with her shopping-basket! Susan saw her first and stared in horror. She pulled at Peter’s arm.

‘Quick! Hide somewhere! Aunt may see us as she passes the station.’

‘The train is just coming in—there’s no time to hide,’ said Peter. ‘Come on, get in before she sees us.’

Just as they were climbing into a carriage their aunt saw them. She stared in surprise, and then looked most annoyed. Who had paid for them? Where had they got the money? She hurried round to get to the platform and the children sat back in the carriage with beating hearts.

‘Oh, train, do go, oh, train, do go!’ cried Susan to herself. ‘Quick, before Aunt Margaret comes!’

Her aunt came on to the platform, and called loudly. ‘Peter! Susan!’

The train gave a jolt, and began to move. Aunt Margaret ran alongside, trying to find the carriage with the children in it. But the train went too fast for her. Before she came to their carriage the children were well beyond the platform, and were safe!

‘We’re really off!’ said Peter, thankfully. ‘She can’t catch us now, Sue.’

It was a lovely day. The sea was far far bigger than Susan had thought it could be, and was as blue as the sky. She loved the little white-edged waves that seemed to spill foamy white lace round her feet. Everything was lovely.

The two children were so hungry at dinner-time that their two cheese sandwiches disappeared in a trice. Their teacher saw what a poor lunch they had brought, and asked them to help with hers.

‘I seem to have brought too much,’ she said, and the children believed her, gobbling up more sandwiches and cake in delight. Then off they wandered again to paddle and hunt for shells and seaweed.

Peter found some lovely shells, and Susan pulled a long frond of brown, shiny seaweed from a rock. ‘It’s like a brown ribbon,’ she said. ‘I shall take it home and hang it up. I shall feel it every morning. If it’s wet, I shall know we shall have wet weather. If it’s dry, then the weather will be fine.’

Tea was lovely, and there was plenty of it. Then, after one hour of wandering along the edge of the waves, it was time to take the train for home.

Then the lovely day began to be spoilt for Susan and Peter, because they couldn’t help wondering what their aunt would have to say to them.

‘Let’s say our teacher paid for us,’ said Susan.

‘That’s a lie,’ said Peter. ‘You know we shouldn’t tell lies, Susan. We can’t possibly say that. We’ll just say we earned the money ourselves. That’s quite true.’

They were very silent as the train sped homewards. It was horrid to be going home to someone they were so afraid of.

‘I’ll give Aunt Margaret some of my shells,’ said Peter. ‘Perhaps that will please her.’

‘Well—I can’t give her my seaweed,’ said Susan, who had tied it round her waist. ‘I want it too much myself. Anyway I’m sure she wouldn’t like it.’

There were many mothers at the station to meet their children. Susan looked round at them. There was Tom’s nice fat mother, smiling all over her face as usual. And Jack’s little mother, not much bigger than he was, waving to him as the train came in. And Ronnie’s mother, looking anxiously for her boy, hoping he hadn’t got lost.

There was no one to meet Susan and Peter. They thanked their teacher for a lovely day, and then walked slowly home. Their feet got slower and slower as they came near to their aunt’s cottage. They stood in the garden, hardly daring to go in.

Then door flew open and Aunt Margaret stood there, her eyes angry and sharp, and her thin-lipped mouth set in a straight line.

‘So you’ve come home at last! And where did you get the money from to go with, I should like to know? You got it out of your uncle, didn’t you? Ah, I’ve told him what I thought of him, giving you money that he keeps from me! You bad children, deceiving me, and making him deceive me too, and tell me lies!’

‘Uncle didn’t give us any money,’ said Peter, in surprise. ‘We did ask him, but he said he only had a few pence. Oh, I hope you didn’t nag at him, Aunt, because he really didn’t give us the money. He didn’t tell you a lie when he told you he hadn’t given us the money.’

‘Well, where did you get it from then?’ cried his aunt. ‘You just tell me, before I go to your teacher and find out!’

‘Please don’t go and make a fuss at school,’ begged Susan. ‘We earned the money, Aunt Margaret. We earned it ourselves, we really did.’

‘You earned two whole pounds and didn’t give it to me!’ said her aunt, speaking as if she was immensely astonished. ‘When you know your uncle is out of work and I’ve hardly any money left! You earn two pounds and don’t tell me a word about it! Ungrateful, mean children! I’ve a good mind to say I won’t keep you a week more! I’ve a good mind to pack you off to a children’s home somewhere and be rid of you. Go up to bed, before I whip you!’

The children ran upstairs, each getting a good slap as they passed their angry aunt. Susan whispered in fear to Peter.

‘She won’t really send us to a children’s home, will she? She won’t really get rid of us? Oh, Peter, it was such a lovely day we had—and now it’s all spoilt!’

‘No it isn’t. We’ll never forget the yellow sands and the blueness of the sea, and the feel of the water on our feet,’ said Peter. ‘Nothing can spoil that. Hurry up and wash and clean your teeth and say your prayers, Sue. You’re tired, and you look half asleep already!’

They were soon both in bed. Susan fell asleep almost at once, but Peter lay awake for some time. He heard his uncle come in. He heard his aunt’s complaining voice and guessed she was telling his uncle about their ingratitude in daring to keep for themselves money they had earned.

‘We must remember to finish making all those baskets for Angela,’ thought Peter, closing his eyes. I’ll make some tomorrow. Goodness, what a lovely day we’ve had!’

He fell asleep, while his aunt’s voice below went on and on and on. It seemed to change into the sound of the sea, and Peter dreamt peacefully of the waves breaking on the shore. What fun they had had, what fun!

Peter slipped into Susan’s room very early the next morning. ‘Susan! Listen! We’d both better give Aunt Margaret the shells and seaweed we brought back. If we don’t try to put her in a good temper she will scold all day long. It’s Saturday, so we shan’t be able to get away to school.’

‘All right,’ said Susan, sleepily. She looked at the seaweed hanging down from a knob on her chest of drawers. It was such an nice piece. She didn’t want to give it away at all.

Aunt Margaret was still in a bad temper. She was angry with the children for deceiving her, she was angry to think they had managed to get the two pounds and wouldn’t tell her where they had got it, and she was angry because she had accused Uncle Charlie of giving it to them when he hadn’t. It put her in the wrong, and she didn’t like that.

‘Now,’ said Uncle Charlie, setting the newspaper up in front of him at the breakfast table. ‘Now, Margaret, just you hold your tongue this morning. The children have told you I didn’t give them the money, so you wasted your breath yesterday telling me I did! Let’s have a little peace.’

‘Aunt Margaret, here are some shells I brought back for you,’ said Peter, and he put a handful of pretty little shells beside his aunt’s plate. Susan came up with the seaweed.

‘And here’s a lovely bit of seaweed,’ she said, trying to smile at her aunt.

‘Do you think that seaweed and shells can make up for being mean, deceitful children?’ said her aunt, in a scornful voice. She got up from the table, taking the shells and seaweed with her. To the children’s horror, she went to the kitchen range, lifted up the round lid from the top of the fire, and stuffed their seaweed and shells into the flames below!

‘Oh, Aunt Margaret! I did so like my seaweed!’ cried Susan, tears coming into her eyes as she heard it sizzling in the fire. ‘If you don’t want it, you might have let me keep it.’

‘Hold your tongue!’ said her aunt, in the kind of voice that meant a slap would soon be coming. ‘I don’t want to see either of you today. You can take your lunch and tea and get out. Don’t come back till bedtime.’

Nobody said anything more. Uncle Charlie read the paper, then folded it up and went out. The children washed up the breakfast things, and hung around wondering if their aunt was going to give them their picnic dinner and tea. She kept them waiting for a good while, and then cut sandwiches of bread and cheese and bread and jam.

She slapped them down on the table. ‘I hope you’re ashamed of yourselves,’ she said. ‘Here am I giving you a home and being a mother to you, when there’s little enough to feed you on—and the first time you earn a bit of money you keep it for yourselves.’

‘It’s not a home, and you aren’t being a mother!’ said Susan, before she could stop herself. Peter gave her a sharp nudge. It was silly to say things like that to Aunt Margaret.

‘One of these days I’ll turn you out!’ began Aunt Margaret, fiercely. But the children fled, taking their sandwiches with them. They felt that they could not bear to listen to another word.

They went to the wood and waited for Angela to come. If Miss Blair let her, she would come, they knew. And very soon she did. Susan cried out in delight when she saw her.

‘Oh, you’ve brought Barker! Oh, darling Barker, I’m so pleased to see you!’

Barker was a puppy of seven months, a black spaniel with melting brown eyes, drooping ears and a plumy black tail. He belonged to Angela and she loved him with all her heart.

‘I’ve brushed his silky coat well today. Doesn’t it shine beautifully?’ said Angela, proudly. ‘Barker, show how you can shake hands. Shake hands, now!’

Barker sat down, and put up his left paw, cocking his head on one side in a very knowing way.

‘Oh, no, Barker, no,’ said Angela. ‘The other paw, please!’

Barker obligingly put up the other paw and Angela shook it. ‘How do you do?’ she said.

‘Woof, woof,’ answered Barker, in a polite voice.

‘Isn’t he clever?’ said Susan. ‘Barker, shake hands with me now!’

Barker did so, first with one paw and then the other. The children thought he was wonderful. They all loved him and felt sure he was the nicest dog in the world. He often played with them and entered into their pretend games, being a horse, or a dragon, or a tiger, whatever it was they wanted.

‘Has he been naughty lately?’ asked Susan, holding one of Barker’s droopy ears in her hand.

‘Yes, awfully,’ said Angela, looking rather sad. ‘I wish he wasn’t. I know Mummy won’t keep him if he goes on being so awfully naughty.’

‘What has he done?’ asked Peter.

‘Well, he got on Mummy’s bed last night and chewed the top of her eiderdown to pieces,’ said Angela. ‘And this morning he went into the larder and somehow got a steak pie off the shelf and ate it all. Cook was so angry she said she would give notice and go.’

‘Oh, Barker, Barker, can’t you be good?’ said Susan, looking into the spaniel’s big brown eyes. ‘You look so very, very good—doesn’t he, Peter? Barker, do you want to lose your lovely home and darling mistress? Because you will, if you go on being naughty.’

‘It’s just mischief really,’ said Angela. ‘But he ought to be growing up a bit now, and be sensible. He can’t go on behaving badly. Barker, you made me sad the other day when you chewed Josephine’s arm off! That was very bad, wasn’t it?’

‘Woof,’ agreed Barker, putting a paw out, as if shaking hands would make things better.

‘And you chewed the chimneys off my dolls’ house,’ said Angela. ‘You are a very chewy dog. But no matter what you did to my things I’d never, never send you away. It’s only serious when you do mischief to other people. I’m sure if you steal things from the larder again you’ll get a whipping. And you won’t like that, you know.’

‘Woof,’ said Barker, looking solemn.

‘He understands every word,’ said Peter, tickling Barker’s sides. ‘Angela, we’ve got our dinner and tea with us. We haven’t got to go back home at all today. Can’t you get Miss Blair to let you bring your dinner and tea out, too, and we could really do a bit of exploring in the wood? We could go quite a long way into it.’

‘We might get lost,’ said Susan, opening her eyes wide in fright at the thought.

The children looked back into the wood. It was a very big one, and the trees seemed very thick and dark behind them. People had been lost in the wood. Once even Peter had been lost when he had gone in just a little way, and it was by luck that he had found the right path again.

Angela’s eyes lighted up in the way they always did when she got a good idea.

‘I know! We’ll go right into the heart of the woods today, for miles and miles! But we won’t lose our way because we’ll use the idea we read of in that story the other day! You know—where they tied silver string to a tree, and then unravelled the ball as they walked to the middle of the wood. Then, when they wanted to find their way out, they only had to follow the string back again!’

‘I say! That would be a good idea!’ said Peter, sitting up. ‘We could act that story. We could act that we were escaping through the wood, and had gone to hide from our enemies—and used the string to get out of the wood when our enemies had gone! Shall we?’

‘Oh yes!’ said the girls, and Angela jumped up. ‘I’ll go and ask Miss Blair if I can have my dinner and tea in the woods with you—and I’ll get the very biggest ball of string I can find. I know Daddy keeps some big ones in a cupboard off the hall. I’ll ask him if I can have one.’

‘That will be fun,’ said Susan. ‘While you are gone we’ll make one or two baskets, Angela. We mustn’t forget we have twenty to make altogether.’

‘Leave Barker with us,’ said Peter. ‘He can look for rabbits.’

But Barker wouldn’t stay. Where Angela went he had to go too. He loved her as much as she loved him. So off the two went together, Barker close to Angela’s flying heels.

‘We’ll get the rushes from the stream,’ said Peter, getting up. ‘Angela won’t be back for an hour, I should think. We can make a few baskets in that time. You’ve still got to make a handle for your first one, too, haven’t you?’

Peter brought back some rushes, and the two set to work on more baskets. They were glad to think they need not go back to their aunt till bedtime. They knew how their uncle felt, too, when he went out of the house and didn’t come back for hours. What a pity Aunt Margaret had such a bad temper and such a sharp tongue!

They worked hard, and soon three or four pretty little baskets, light yet strong, lay on the grass beside them.

‘When they are filled with wild raspberries they will look lovely,’ said Peter. ‘It was a good idea of Angela’s. There are plenty of raspberries deeper in the wood.’

‘Won’t it be thrilling to go right into the heart of the wood?’ said Susan. ‘We’ve never done that before. It’s a very, very big wood, isn’t it, Peter?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Peter. ‘Maybe no one has ever gone right into the middle of it, Susan. Perhaps we shall be the very first ones!’

Susan felt a delicious shiver creep down her back. Woods were mysterious. You didn’t know what you might find in the very heart of them.

‘I suppose there aren’t any witches nowadays, are there?’ said Susan.

Peter shook his head. ‘No. We shan’t find any witches’ cottages in this wood, so don’t expect that, Susan! We might find an old woodcutter’s cottage, but that’s about all. There won’t be any paths either, further in—only little rabbit paths. But we shall have old Barker with us, so you needn’t be afraid.’

‘I’m not afraid!’ said Susan, indignantly. ‘I’m never afraid when I’m with you. I wouldn’t be afraid of a witch either.’

‘Well, I don’t expect we shall find anything very thrilling really,’ said Peter, finishing off a basket. ‘Just more and more trees, thicker and thicker together, and the sunlight peeping here and there, lying like golden freckles on the ground. That’s all.’

Almost an hour went by, and then they heard Angela’s excited voice.

‘Where are you? Here I am! I’ve got my dinner and tea, and I’ve got the most enormous ball of string you ever saw! I’ve remembered to bring a bone for Barker, too. And I’ve got some ginger beer for everyone!’

‘Oh good!’ said Peter, pleased. ‘Mind my baskets, Barker! Take your big paws off that one! Well, are we ready to explore? Come on, then!’

Angela had an enormous packet of food, and three bottles of ginger beer.

‘What have you brought?’ said Peter, looking in astonishment at the package in the school-bag on Angela’s shoulder.

‘Oh—egg sandwiches, tomatoes and a bit of salt, jam tarts and cherry cake!’ said Angela. ‘Enough for all of us. I know what your mean old aunt is like—she’s probably given you stale bread and left-over cheese!’

This was quite true. Peter and Susan looked at Angela gratefully. She always thought of sharing everything with them. Now they really would have a fine picnic. Peter took the bag from Angela.

‘I’ll carry everything,’ he said. ‘My goodness, what’s that smell?’

‘Only Barker’s bone,’ said Angela. ‘Wrapped up in that bit of paper. He likes them smelly. If they aren’t smelly enough he buries them till they are. He nearly got shut up in his kennel just before I came back. He was naughty again.’

‘What did he do?’ asked Susan.

‘He found Miss Blair’s bedroom slippers and chewed the heel off one,’ said Angela. ‘Miss Blair was awfully cross, because they were new ones.’

Susan looked anxiously at Barker. ‘You really will have to turn over a new leaf,’ she said. ‘You’ll be given away to the milkman or the postman or someone, if you don’t. You wouldn’t like to be given away, would you?’

‘Woof,’ said Barker, and wagged his tail. He offered Susan a paw.

‘He keeps wanting to shake hands with everyone now,’ said Angela. ‘He put his paw out to the cat, too, and she hissed at him.’

They all laughed. Barker was very funny, and very lovable. Even his naughty ways seemed lovable to the children, though grown-ups thought differently.

‘Well, we’d better make a start,’ said Peter. ‘My goodness, that certainly is an enormous ball of string. Angela! There must be miles of string on it, it’s so thin and yet so strong. Just what we want.’

‘Now we tie the beginning of it to a tree, don’t we,’ said Angela. ‘And we hold the ball as we walk into the wood—and let the string unwind behind us. It will be fun. We’ll take turns at it.’

They set off into the wood. They purposely left the path and wandered into the wilder parts, knowing that with the string to guide them safely back, they could not get lost. It was exciting.

‘I don’t expect anyone but rabbits has been here before,’ said Susan, looking round at the whispering trees. ‘Let me have the ball of string now, Angela. I’d like to have a turn.’

Angela gave it to Susan. Susan marched along, letting the thin string unravel from the ball behind her. She looked back and saw the strand running waist-high around tree-trunks and bushes.

‘I feel as if I’m really in a story now,’ she said. ‘Peter, Angela—we’re escaping from our enemies. Talk quietly, in case they are just behind us. Crouch down if you hear anything.’

‘Barker, keep to heel,’ whispered Angela. ‘Our enemies are upon us!’

A green woodpecker suddenly flew through the trees, laughing loudly as he always did. At once the children dived below a bush and lay there quietly.

‘The call of the enemy!’ said Peter, peering round the bush. ‘I hear him! Come on, into the heart of the wood before he appears again!’

It was fun, pretending like that. They went on and on. The trees grew closer together. Not so much sunlight came through. Sometimes the ground was bare beneath the trees, sometimes there was thin green grass. There was a whispering noise all round when a breeze blew.

‘It’s getting mysterious,’ whispered Susan. ‘Here, Peter, you take the string now. It’s your turn. We must have left miles of it behind us.’

They walked for an hour or two, and then came to a little clearing. There was a patch of grass where no trees grew. The sun shone down and made it golden. The children ran to it gladly, happy to feel the warm sun again.

‘This is where we’ll have our picnic,’ said Peter, lying in the warm sun. ‘I’m hungry now. Oh, Barker, don’t lick my nose away! Sue, this must be almost the heart of the wood! What a nice little place to find.’

‘It feels kind of magic,’ said Susan, and she sat down in the middle. Angela flopped down beside her. Barker went to the bag and sniffed at it. He tried to paw out his bone.

‘Wait, Barker,’ said Peter. ‘Let us have a little rest before we have our dinner. Lie down and keep still for a minute.’

But that was impossible for Barker. He wandered round, sniffing here and there, and then barked loudly.

‘Sh! You’ll tell our enemies where we are!’ said Susan. ‘Be quiet!’

Barker barked again. He wanted his bone. Peter groaned and reached for the bag. ‘You are a most impatient dog,’ he said. ‘Well, here you are. Wait till I take the paper off! Barker, WAIT!’

The sight of the things in the bag made Peter want his own dinner. So he handed out the packets to Angela and they all began to eat their dinner. It certainly was a nice one. Tomatoes dipped in salt were delicious, Susan thought. The cherry cake was lovely, too. Miss Blair had cut three very big slices. There was chocolate as well, in three bars.

‘Don’t undo the sandwiches marked “T”,’ said Angela ‘We must keep those for this afternoon. They’re for our tea. There’s some more cherry cake, I think.’

‘We’ll have one and a half bottles of ginger beer now,’ said Peter. ‘And keep the rest for teatime. Barker, take your bone right away, please. It smells awful!’

Barker was enjoying his smelly bone. He chewed it and gnawed it, he sucked out bits of marrow and he licked every scrap of meat on it. It was a good bone. Barker made a fine meal off it and then wondered what to do with the rest.

‘He’s going to save up some for his tea,’ said Susan, watching Barker wander off with his bone. ‘He’s going to find some safe place to bury it. Isn’t he funny?’

Peter poured out the ginger beer into a cardboard cup. It was lovely.

‘It gets up my nose somehow,’ said Susan. ‘Not the ginger beer—the fizzy part. It prickles my nose.’

‘That’s what I like,’ said Angela. She collected the bits of paper, and put them neatly into the bag. Neither she nor the others ever left bits about. They couldn’t bear to spoil the woods or the fields by leaving orange peel or paper or tins behind them. They even collected other people’s left-behind rubbish and buried it, rather than have it lying about the places they loved.

They lay down on their backs, and let the warm sun play on their faces and bare legs. They felt sleepy.

‘Let’s have a nap,’ said Peter. ‘I don’t expect our enemies would ever find us here!’

‘We’ll go into a magic sleep,’ said Susan, shutting her eyes tightly. She yawned. ‘The magic is working in me. I’m full of sleep.’

‘Where’s Barker?’ said Angela, sitting up and looking round. ‘Barker! Barker!’

A bark came from somewhere near. Angela lay down again. ‘He’ll come when he’s finished burying that bone, I suppose. I only hope he won’t wake us all up by licking our faces like he sometimes does.’

It wasn’t long before the children were asleep. They slept for about half an hour, then Angela woke up with a jump. What had woken her?

She sat up. The others were still asleep. Angela was about to lie down again when a doleful sound came to her ears.

It was Barker howling dismally! ‘Wooooh! Woooo-ooooh!’

‘Barker! What’s the matter?’ shouted Angela. The others woke up suddenly. Peter sat up at once.

‘What’s up?’ he said to Angela, seeing her startled face.

‘It’s Barker. Listen,’ said Angela. The whining and yelping began again, and Peter stood up.

‘Hope he hasn’t got caught in a trap,’ he said. ‘Come on—we must find him.’

‘The string, the string,’ said Susan, as they ran to the edge of the clearing. ‘Let’s get that, or we may get lost. We might not be able to find our way back to this clearing!’

‘Quite right,’ said Peter and ran to pick up the ball of string, which was now very small indeed. They set off in the direction of Barker’s whines.

‘Woooo-ooooh! Woooo-ooooh!’ went on Barker, sounding curiously muffled.

‘Has he gone down a rabbit-hole and got stuck, do you think?’ said Angela, anxiously.

‘Shouldn’t think so,’ said Peter. ‘All I hope is he hasn’t got his poor paw into a trap. Those traps are such cruel things. They cause the most dreadful pain.’

They set off in the direction of the howls. They went between the thick-set trees, and then stood still and listened.

‘Over there,’ said Peter, as the howling began again. ‘Round this clump of trees.’

They ran round the trees, and then all three stopped in amazement. In front of them was one of the biggest trees they had ever seen!

‘It’s an oak tree,’ said Peter. ‘An enormous old oak tree—hundreds of years old, I should think. Look at its great trunk—twenty people could stand inside it, easily!’

It certainly was a strange old tree. Its trunk was enormous, and the tree itself rose tall and sturdy. But some of its branches were dead. The tree was so old that it was dying bit by bit.

‘The howling comes from that tree, surely,’ said Peter, and he stepped towards it. As soon as he spoke, Barker set up a terrific whining again, and there came the noise of scratching and jumping.

‘He’s in the tree! That’s where he is!’ cried Susan. ‘Barker, Barker, are you in this old tree?’

‘Woof, woof!’ came a joyful bark. Now that he knew the children were near at hand, Barker felt sure he would soon be rescued. ‘Wooooof!’

The children looked at the enormous trunk. ‘It must be hollow inside,’ said Peter. ‘It sounds as if Barker is in the middle of it. No wonder his barks and yelps sounded so muffled. Barker, how did you get in?’

‘Woof,’ said Barker, and scratched hard somewhere.

‘Get out where you got in, silly,’ said Angela. But Barker didn’t know where he had got in.

‘We’ll have to get him out somehow,’ said Peter. ‘But goodness knows how!’

‘Let’s walk all round the tree,’ said Susan. ‘I expect Barker must have crept in at a hole somewhere with his bone. He may have thought that it would be a fine hiding-place, inside this tree!’

They began to walk round the vast trunk. They found a small hole at last, at the bottom of the trunk. Peter poked a stick inside.

‘Barker! Barker! See this stick! You must have got in at this hole, so you can get out by it. Come on, Barker!’

But evidently Barker had some reason for not getting out of the hole. He sat inside the tree and howled dismally again.

‘Isn’t he silly?’ said Angela. ‘Why can’t he come out when we show him the way? Barker, don’t be an idiot! Here, Barker, come along! Good dog, Barker!’

Another long howl came from the tree. An idea struck Peter.

‘Perhaps he has hurt himself—or got stuck. Maybe we had better climb up the tree and see if there is any way of getting down to rescue him.’

They all looked up into the big oak tree. It would not be very difficult to climb. ‘I’ll go up,’ said Peter. ‘Give me a shove, Sue.’

He was soon up on the big lowest branch. He climbed up a little higher, and then looked down, trying to find out if there was any way into the middle of the tree. It must surely be hollow, if Barker had managed to get there!

But he could see no way in, so he climbed higher still. When he next looked down he gave a cry of surprise. He could see right down into the hollow trunk of the great tree! It had rotted away through many long years, and now the old tree was really nothing but a dying shell, still putting out leaves on its many great boughs—but fewer and fewer each year.

‘Susan! Angela! The whole of the tree is hollow! It’s as big as a room. And the branches up here are so big and broad that I can lie on them easily without falling off! We could almost have a house in this tree!’

A howl came up to him. Barker wanted to be rescued and couldn’t imagine why the children were so long about it.

‘All right, Barker. I can see how to get to you now,’ said Peter.

‘You be careful you don’t find yourself a prisoner inside the tree too!’ called Angela’s voice, anxiously. ‘I once read a story about someone who got inside a hollow tree and couldn’t get out again. They almost starved to death before anyone found them. Be careful, Peter.’

‘You bet,’ answered Peter, cheerfully. ‘Well, here I go—sliding down and down—right into the old hollow tree!’

The girls heard a thud and knew that Peter had landed right in the middle of the tree. Then there came a loud collection of delighted barks from Barker, who was evidently flinging himself on Peter in joy.

‘What is it like in there?’ called Susan, who was longing to explore the tree herself.

‘Weird!’ shouted back Peter, his voice sounding muffled. ‘I tell you it’s as big as a room inside here. We could play house here easily. It’s the most wonderful hiding-place in the world! Get down, Barker, you idiot. Let me look round.’

‘Is it dark in there?’ yelled Angela.

‘Very,’ said Peter. ‘But as far as I can make out, it’s quite dry—and really awfully big. Can you hear me knocking against the trunk?’

A sound like a woodpecker tapping on dead wood came to the ears of the listening girls. ‘Yes! Of course we can hear you!’ cried Angela. ‘We’re coming up the tree, Peter, and we’ll jump down too.’

‘Wait till I make sure I can get out all right,’ said Peter. He looked up, seeing the daylight above him, filtering through the branches of the great tree. He tried to swing himself up, but it was difficult.

‘I think I can just manage it,’ he said, ‘but we’ll have to bring a rope if we are going to play inside the tree. Then we can fasten it to a branch above and haul ourselves up.’

‘Peter, can you see where Barker got in?’ called Angela. ‘You’ll never be able to get him out if you have to climb up yourself. You’ll want both your hands.’

‘Yes, I shall,’ said Peter. ‘All right, I’ll hunt around a bit, on my hands and knees. Oh, Barker, get off my back, I’m not playing tigers! Hallo, here’s some sort of hole. He must have got in by that. But a dead bough has fallen across it, so he couldn’t squeeze out. I’ll move it.’

Peter dragged away the dead bough. He pushed Barker’s nose to the hole. ‘Now you can get out, Barker. Go on, go to the girls, quickly!’

Barker sniffed round the hole, then decided it was possible to squeeze through. To the girls’ delight they saw his black nose appear, then his drooping ears, and finally his whole body, complete with wagging tail.

They patted him. ‘Were you playing a game of hide-and-seek, silly?’ asked Susan. ‘No, I don’t want to keep on shaking hands with you. You should only do that when you meet people or say goodbye to them.’

They went to the other side of the tree to watch Peter. He had managed to get out of the hollow trunk now, and was climbing up high.

‘There’s a simply marvellous view over the wood!’ he called to the girls. ‘Come on up and see!’

So up they both went, for they were good tree-climbers. Poor Barker was left whining below. He couldn’t climb trees.

They sat about three quarters of the way up the tree and looked out. The wind blew and the tree shook. The children liked it.

‘It’s like being on a ship,’ said Susan. ‘When the tree shakes in the wind, it’s like a ship rolling on the waters. It’s a lovely feeling.’

‘We must be exactly in the heart of the wood,’ Angela said. ‘You can see the tops of trees wherever you look. This great old oak tree stands up high above all the others, I wonder how old it is.’

‘Look,’ said Susan, suddenly. ‘There’s a hole in this branch, here—and a bigger hole still over there. Like little cupboards. We could hide things here.’

‘We could play here, and make ourselves a tree-house,’ said Angela, her eyes gleaming. ‘It’s big enough to live in. The summer holidays will begin next week, and Miss Blair will go home. We shall be able to play together all day, and pretend heaps of things. We could come here every day and make it our own secret tree-house.’

‘Oh yes. It would be a simply wonderful secret!’ said Susan, who loved secrets. ‘We wouldn’t tell anyone. It would be our own house. Couldn’t we bring things here? I’ve got an old rug I could bring. And Peter’s got a stool he made himself. And we could have a box for a table.’

‘Well, I’ve got lots of things I could bring!’ cried Angela. ‘You know that little play-house in our garden that Daddy had built for me? Well, I could bring some of the furniture here! We could put it inside the tree and make a proper house there. It would be lovely!’

‘We could put a rug down for a carpet. And Susan, you’ve got a dolls’ teaset, haven’t you?’ said Peter, getting excited too. ‘We could have that for meals.’

‘No, that would be too small,’ said Angela, who knew the little tin teaset quite well. ‘I’ll bring some of the old nursery china. Miss Blair put it away when Mummy gave me some new things for Christmas. It’s got a teapot and everything.’

‘We could keep some of the things in these holes in the branches,’ said Susan, putting her hand into one. ‘I suppose the owls have used them for nests. They shall be our cupboards.’

‘That branch down there, the very broad one, would make a fine couch where it forks from the trunk,’ said Peter. ‘We could put a rug over it and call it our couch.’

It was all very thrilling. To have a house of their own for the holidays, a house in a tree! What could be more fun? They could hardly wait to furnish it.

‘The front door can be where we drop down into the middle of the tree,’ said Susan. ‘The back door is the hole that Barker uses.’

Everyone laughed. Barker, down below, gave a whine. He didn’t like being left out of things like this.

‘What about a lamp? It’s dark down there,’ said Peter.

‘Candles, of course!’ said the two girls, together. And Angela added, ‘Oh, think of sitting down in our tree-house by the light of candles! It would be like a dream—sitting in the middle of a tree in the heart of a wood, all by ourselves. Nobody would guess where we were. It’s the most exciting thing we’ve ever thought of. We’ve often pretended to play house but this time it will be real!’

The girls climbed lower down and peered into the hollow heart of the tree. It looked dark and mysterious. The wind blew and the leaves whispered.

‘They are saying “A house for you, a house for you!” ’ said Susan. And it really did almost sound like that!

‘Let’s have our tea up here in the tree, shall we?’ said Peter. ‘It’s fine up here. We can pretend we are in a rolling ship, looking out for pirates. The tops of the green trees we can see can be the green ocean! I’ll go down and get the food.’

‘Tell Barker to find his bone and have his tea, too,’ called Angela. ‘It’s a pity he can’t come up here, but even if we could carry him, which we can’t, he’d probably fall down and hurt himself.’

Barker was most indignant when Peter fetched the tea, addressed a few loving words to him, and then disappeared up the tree once more, leaving poor Barker behind. He whined loudly and scratched on the tree-trunk vigorously with his front paws. But it was impossible to take him up the tree.

The children divided the jam sandwiches and cake. They stood the ginger-beer bottles in one of the ‘cupboards’. It was nice to see them there.

‘We shall be able to make lovely plans all this week and next, till holidays begin,’ said Peter. ‘We’ll collect everything we can for our tree-house. I’ve thought of lots of things already. My old clock, for instance. It would make it seem awfully like a house if we hear it ticking away down there.’

‘Oooh yes,’ said Susan. ‘And I could bring one of my dolls and leave her here to caretake for us when we’re not here. And we could bring a few books too.’

‘And I’ll bring some biscuits in a tin and some sweets in a jar,’ said Angela. ‘We shall always be glad of something to eat, I expect.’

They talked until it was time to go back. Then down the tree they went to find the string that would lead them safely back again. Barker was overjoyed to have them down on the ground with him once more.

‘Down, Barker, down!’ said Angela. ‘Home we go! Where’s the string? Here it is. I’d never find my way home without it!’

Before they set off home Peter tied the string firmly to a small tree at the edge of the little clearing. Then it could not slip about, and they would find the way back to the hollow tree whenever they wanted to. Taking hold of the thin brown string that ran twisting through the trees, Peter led the way home.

It was true that they would never have found the way back without help of this kind. There was no path to follow, nothing to guide them at all. It was evening time now, and the sun hardly came through the trees at all, for it lay low in the west. Peter ran his hand along the string and followed it the way it went.

The girls did not bother to touch the string. They followed Peter, and Barker ran here and there, sniffing at rabbit-holes, but never getting very far behind.

‘I’m a bit tired of running my hand along the string,’ said Peter at last. ‘Susan, you have a turn.’

So Susan let herself be guided by the string and on they all went. Once Susan saw a flower she didn’t know and left the string to pick it—and then, when she looked for the string again to guide her on her way, she couldn’t find it!

‘Oh dear—where is it?’ she cried. ‘I’m sure it went round this tree!’

But it didn’t. In a panic the other two searched for the string too, but it was very difficult to find it in the fading light. They looked at one another in fright.

‘I say! Now what are we going to do?’ said Peter.

‘Susan, you are an idiot, really! You might have had more sense than to let go the string. It’s an awfully difficult thing to see once you’ve let go.’

‘I know. I’m awfully sorry,’ said poor Susan, almost in tears. ‘I just didn’t think.’

They hunted about a little more—but it was Barker who really found it after all! He was sniffing about for rabbits and suddenly got one leg caught in the string, which, just there, had fallen rather low. He tugged, and set the whole bush in motion, as the string pulled against it.

‘There it is—round Barker’s leg! Look!’ yelled Angela. ‘Oh, Barker, what a clever dog you are!’

‘Woof,’ said Barker, modestly, and held out a paw. Everyone shook hands with him. They thought he deserved it.

Peter took the string himself. He felt that it was safest with him! Off they went again, and at last came into the part of the wood they knew. They said goodbye there.

‘It’s been a simply lovely day,’ said Angela. ‘I shall look forward to our house in the tree, won’t you? I shall think about it in bed tonight. It will be a lovely thing to go to sleep on!’

‘Goodbye, Barker. Be good,’ said Susan, patting him. ‘Look, Angela, he knows he must shake hands when he says goodbye. He’s putting out his paw so politely—only it’s the wrong one again!’

Angela ran home, and Peter and Susan made their way back to their aunt’s cottage. They wished they were Angela, going back to a mother and father who would welcome her, and love to hear all she had to tell them—though she would not talk about their secret house, they knew. That was a very special secret, shared by the three of them and Barker.

‘You’re late enough!’ said their Aunt Margaret when they got in. ‘There’s no supper for you tonight, unless you want bread and margarine.’

But the two children had feasted well on Angela’s food and were not hungry. They said good night and went up to bed, secretly glad that they were late and did not need to sit up and be with their bad-tempered aunt.

Susan tried to keep awake to think about the tree-house. She imagined she was there, cosily inside, with a little candle flickering beside her. She imagined the trees in the wood outside, whispering together, while she sat in the oak tree, listening. Nobody would know where she was. How lovely it would be to have a place like that for themselves!

Peter thought about it too, and so did Angela. Barker remembered his bone, which he had unfortunately left there! He whined, and Angela patted him.

Never mind! He could always get the bone when he wanted it. He knew the way. He didn’t need to follow the string like the children. He could follow his nose.

The next day was Sunday. The church bells rang and people walked across the fields to the little stone church. Aunt Margaret didn’t go. Nor did Uncle Charlie. Peter often thought that perhaps if they did go, Uncle Charlie might get some strength in him to find work and keep it, and Aunt Margaret might be ashamed of her unkindness and her sharp tongue.

The school teacher always went, and any child who wanted to could go with her and sit in her pew. Angela went with her father and mother, and, if Peter and Susan were in good time, they were allowed to go in with them, and sit with Angela. If not, they saw her at Sunday School.

They sat beside her that afternoon, in their Sunday School class. The little ones had chosen the first hymn, which was the very short one that Angela said for her grace at mealtimes.

‘Thank you for the world so sweet,

Thank you for the food we eat.

Thank you for the birds that sing,

Thank you, God, for everything!’

Angela heard Susan whispering something under her breath at the end of the little hymn. She looked surprised. ‘What did you say, Susan?’ she whispered.

‘I said, “And thank you specially, God, for our tree-house!” ’ whispered back Susan. The teacher looked at her and she stopped talking. She had thought almost all the day of that lovely tree-house!

The children walked home together. Barker was not there, because he was very disturbing at Sunday School. He would go round the walls sniffing at the mouse holes, giving excited little barks when he smelt a particularly exciting smell. So now he was left at home; but he always came to meet them.

‘He won’t today, though,’ said Angela, sadly, ‘He got one of his naughty fits this morning, and dug up all the flowers in the front beds. Daddy was furious. He whipped him and put him in the kennel for the rest of the day. I expect he was really only looking for yesterday’s bone, but you’d think he would remember he left it in the wood, wouldn’t you?’

‘When can we next go to the woods together?’ asked Susan eagerly. ‘We break up on Thursday. When does Miss Blair go, Angela?’

‘She goes on Thursday too,’ said Angela. ‘But not till the evening. So I shan’t be free till Friday. We’ll go on Friday—and take lots of things with us! Won’t it be fun? Don’t you get into trouble with your Aunt Margaret, you two, because we simply must go to our tree-house the very first day we can!’

The days went swiftly by, and the end of the term came. Aunt Margaret hated the holidays. She said the children were always around the place, getting under her feet, and making themselves nuisances. As a matter of fact, they were really very good, amused themselves well, and always did anything she asked them to, cheerfully and willingly.

‘Holidays again!’ she said on Thursday, when they came home early, laden with their term’s books. ‘It always seems to be holidays. Now I suppose I’ll have you on top of me all day long! What with your uncle always at home too, I do have a time!’

‘Well, Aunt, we’ll try not be a nuisance,’ said Peter, cheerfully. ‘We’ll go off to the woods and play every day if you like, after we’ve done any jobs you want us to do.’

‘Yes, I’m the only one in this house that does any work!’ grumbled their aunt. ‘Your uncle doesn’t do more than two days’ work a month, and you play all day.’

The children said nothing. Aunt Margaret was never satisfied with anything, that was plain. If they were about the house she said they got under her feet. If they went off to the wood, she said they were like their uncle and left her to do all the work. There was no pleasing her!

The children looked about for things they could take to the tree-house; the old rug, a few sacks, very ragged and holey; the little stool Peter had once made, and his clock; an old saucepan with half the handle gone; the bit of old candle left on a shelf in the shed; a mug without a handle.

‘Nothing very much—but it will all help,’ said Peter.

‘Anyway, Angela will be able to bring a nice lot of things,’ said Susan. ‘She’s got plenty.’

‘Yes. But we must do our share too,’ said Peter. ‘We can’t bring much, but we must take what we can. I shan’t feel as if it’s our house, if we don’t take something towards it too.’

‘I’m going to take my picture,’ said Susan, suddenly. ‘The one that hangs over my mantelpiece.’

‘What—the one of Jesus in the manger, with the shepherds looking at him?’ said Peter. ‘You can’t. Aunt would miss it.’

‘It doesn’t matter. It’s mine, my very own,’ said Susan. ‘My own mother gave it to me when I was a baby. You know she did. You said you remembered her giving it to me, though I’ve forgotten.’

‘Well, she did,’ said Peter, ‘and of course it’s yours. But I don’t think you ought to take it.’

‘I’m going to,’ said Susan, obstinately. ‘I want it in our tree-house. It’s my favourite picture, and it would look lovely hanging on the trunk-wall of our house. I’ll take a nail too to hang it up by. I’ll use the heel of my shoe to hammer the nail in.’

The little girl was pleased when she thought of her picture hanging on the wall of the tree-house, shining in the light of a candle there. It would feel very cosy and homey and real. She felt that whatever else she took, she simply must take her own picture.

The children gathered together their few things and hid them at the back of the old shed. Aunt Margaret was always poking about, and they did not want her to find the things and ask questions. She must never know about the tree house!

‘I shan’t take my picture off the wall till tomorrow,’ said Susan. ‘Not that Aunt Margaret will see it’s gone! I do my own bedroom, and except for poking her nose in to see I’ve done it properly, she never comes in.’

‘I wonder what Angela will bring,’ said Peter. ‘She always has such good ideas. I hope she’ll bring some matches. I daren’t ask Aunt Margaret for any. We can’t light the candle without matches.’

They went off to bed feeling excited. They were to meet Angela at ten o’clock, in the usual place in the wood. They had not seen her the day before, because it was her mother’s sale of work and Angela had been helping. They had given her their twenty little rush baskets, filled with delicious wild raspberries. Angela had been very pleased.

‘Mummy will love them! You are clever! We shall make a lot of money out of these.’

Friday morning came at last. The children did everything their aunt set them to do, keeping their eyes on the clock. At last it was time to go. They rushed to the shed and got their things, and Susan ran upstairs to fetch her picture.

‘Now—off to the tree-house again!’ said Peter, stuffing everything into an old sack. ‘We’ll have a good time there today, Susan, won’t we!’

Angela was waiting for them in the place they usually met. She looked very excited. She was wearing blue shorts and a blouse, instead of a dress.

‘I told Mummy I was going tree-climbing, and she got me these shorts!’ she cried, as soon as she saw the others. She danced towards them. ‘I feel like a boy. Isn’t my mother a sport?’

Susan thought that she was indeed. She wondered what Aunt Margaret would say if she, Susan, asked her for shorts to wear, to go tree-climbing!

‘You look great,’ said Peter. ‘My word, Angela, what have you brought with you! And what’s Barker got on his back?’

Barker was not looking very happy. He did not come to greet the children as usual. He stood quite still with his tail drooping behind him. He had a package tied on his back.

‘I thought Barker ought to help as well, and carry his own luggage,’ said Angela. ‘I’ve packed up some biscuits for him, and a ball, and wrapped them in one of his own little rugs. I tied them on his back for him to carry. But you don’t like it, do you, Barker?’

Barker whined, and stood looking up at the three children pleadingly, from loving brown eyes.

‘It’s not at all heavy, really,’ said Angela, looking at the package, ‘but when he runs it sort of slips sideways and hangs under his tummy, and he doesn’t like that. Still, look what I had to carry!’

Peter and Susan looked. Angela had a great package tied on her back, and two baskets full of things. ‘You certainly have brought a lot!’ said Peter please. ‘What fun it will be arranging everything.’

‘I’ve brought my musical box—the one that plays six different tunes when you wind it up,’ said Angela. ‘I thought it would sound lovely when we are sitting inside the tree. I expect you think it’s a silly thing to bring, but I couldn’t help wanting it.’

The others didn’t think it was silly. They thought it was a lovely idea. ‘I brought my clock,’ said Peter. ‘And Sue brought her picture. I hope Aunt Margaret doesn’t miss them!’

‘Shan’t we have fun arranging everything?’ cried Angela, picking up her two baskets. ‘Peter, you’ll have to follow the string, because I haven’t a single hand to use!’

‘Give me one of the baskets,’ said Peter. ‘And if you like to untie the enormous package off your back, I’ll carry that, too. You can take my bundle. It’s not nearly so heavy.’

‘Oh no, thank you,’ said Angela. ‘I like carrying it. But you can take one of the baskets. That would be a help. Now, Barker, are you ready? Come on, then. Look a bit more cheerful, do! And remember, you’re still in disgrace!’

‘Why, what’s he done now?’ asked Susan.

‘He got into the hen-run and chased all the hens,’ said Angela. ‘He must have squeezed through a hole under the wire. The gardener was very angry, and told Daddy. I can’t think why Barker doesn’t get a bit of sense. He’s a darling, but he’s awfully stupid sometimes. He must know he’ll get into trouble if he chases the hens. I’ve told him so heaps of times.’

Barker trotted along sedately, cocking one eye up at Angela as she spoke his name. He knew he was still in disgrace. His package suddenly slipped off his back, slid down and hung under his tummy. He stopped and gave a howl.

‘Susan, put it right for him, will you?’ said Angela. ‘You can’t tie it too tightly because it hurts him.’

They went very slowly through the wood, for they were all heavily laden. But it didn’t matter. They were excited and happy. They had a tree house to go to. They were going to furnish it that very day and make it their own!

‘This is our moving-in day!’ said Susan, happily, and that made the others laugh. ‘Well, it is! We’re moving into our new home. Tree-House, Heart of the Wood. That’s our new address.’

‘It would be funny if a postman delivered a letter to us at that address,’ said Angela. ‘Barker, you can’t go down rabbit-holes with that parcel on your back!’