* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 4, Issue 9

Date of first publication: 1868

Author: J. T. Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: June 1, 2019

Date last updated: June 1, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190604

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. IV. | SEPTEMBER, 1868. | No. IX. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

THE CRUISE OF THE LITTLE STARLIGHT.

SOLOMON JOHN GOES FOR APPLES AND CIDER.

OUR FIVE LITTLE KITTENS AND THEIR RELATIONS.

ne golden summer afternoon, three good friends

were sitting on the broad, flat top of a stone

wall, which rose from a river’s brink, all intent

upon a little ship. Their names were Harry,

Pinkie, and Major Brown.

ne golden summer afternoon, three good friends

were sitting on the broad, flat top of a stone

wall, which rose from a river’s brink, all intent

upon a little ship. Their names were Harry,

Pinkie, and Major Brown.

Of course you know that Harry was a boy; but I dare say you think Pinkie was a small gray cat, and Major Brown a big Newfoundland dog. Not a bit of it. They were Harry’s elder and younger brothers. Their father had given them these queer titles just because he loved them; for Major Brown’s real name was Ned, and as to Pinkie, I have either forgotten or never heard his other name, so we will just call him “Pinkie,” and that will be the long and the short of it.

Such a pretty little ship as they had, with her masts and sails all complete, and a long streamer of red, white, and blue floating from the tallest mast! She was Pinkie’s present on his last birthday; and this very afternoon she was to be christened and launched.

“Now, fellows!” shouted Pinkie, gleefully, “this splendid, clipper-built A No. 1 vessel is ready to sail on her first voyage. Hurrah for the Little Starlight! She’s the ship to go all the way to Panama and back before you can say ‘Jack Robinson’!”

“We must christen her first, of course,” said Harry. “I mean to ask mamma for a little bottle of real currant wine to break on her bows.”

“O Harry, I want to christen her! let me christen her!” cried Ned; and, in his delight at the thought, he got up on the flat stone and jumped round in a circle on one foot.

“But Marie is the one to do it,” answered Harry; “ladies always christen ships.”

“O-h!” said Ned, looking rather dismal for a moment, when Harry proposed that they should run to the house to get their little sister; whereupon Ned brightened up, and they raced off together at such a rate that they very nearly got ahead of themselves.

The town where these children live is in the State of Massachusetts. It is a very beautiful place, and there are a number of lovely country-seats all about it, but I think this place is the very nicest of all. It was also the most remarkable, for the house was built on a darling little island in the middle of a river. The whole island belonged to Mr. Ludlow, their father. Like Robinson Crusoe, he was monarch of all he surveyed, as far as the island went. It was entirely surrounded by a stone wall about two feet high, and was connected with the main-land by a very handsome stone bridge with one fair arch. A velvety lawn sloped gracefully before the house; grand old trees drooped their protecting boughs over the water’s edge, and waved their majestic heads above the gray walls of the fine old family mansion, while away to the south stretched garden, grapery, and orchard.

Presently Harry and Ned appeared on the front steps with their sister. She was a little darling, six years old. In her hand she carried very carefully a mite of a phial, such as is used for homœopathic medicine. It was filled with currant wine, of which it might hold about a thimbleful. Harry’s arms were laden with a dozen ginger snaps, three toy barrels, Shem, Ham, and Japhet out of Noah’s Ark, and a wooden horse with half a head and one leg. This was the cargo and crew. And dear little Major Brown, his eyes sparkling with delight and affection, lugged along his beloved cat Pepper, upside down, determined that he, too, should see the show, sucking his tongue (the Major, not the cat), as hard as he could the whole time.

The moment they appeared, Pinkie rushed towards them, stubbed his toe, went head over heels, never minded it an atom, got up again, and placed himself at the head of the procession; and they all marched to where the Little Starlight lay,—that is, her keel was run into a groove in a long, flat board.

“Now—let—me—see,” said Pinkie, when they were once more comfortably seated on the flat stone; “first of all, we must have some ballast.”

“Ballast? what’s that?” asked Marie.

“Why, stones to keep her steady,” said Pinkie.

“O, but, if you put stones in the dear little ship, she will drown,” said Marie.

“No, she won’t,” said Harry. “Real ships are always ballasted. Major, won’t you jump down and pick up some stones?”

“O, but if I let Pepper go he’ll run away,” objected the Major.

“Well, then, I’ll go myself,” said Harry, good-naturedly, and he jumped down from the wall to the narrow strip of sand that ran along the water’s edge, and soon filled his pockets with small round stones. Then he scrambled up again, and, taking off the cover of the hatchway,—which is a square hole in the deck of a ship where they put down the cargo,—he poured the stones into the hold, and smoothed them very even on all sides. The hatchway was just large enough for his hand to enter. Then some little chips of wood were laid over the stones, and next the poor old wooden horse was poked in. He gave them a good deal of trouble in consequence of his one leg having no joint at the knee; as it was, his tail broke short off; at seeing which, little tender Marie uttered a piteous “O-h!” and the boys burst out laughing, but the poor horse never said a word. Perhaps his having only half a head may account for this.

The barrels followed, and after these the ginger snaps were stuck round helter-skelter, wherever a place could be found, and then the Little Starlight was laden to her fullest capacity. As for Shem, Ham, and Japhet, they were set up on deck by way of a crew, and aired their round buttons of heads there with great dignity and grandeur.

With a merry cheer the boys leaped down upon the sand, and helped Marie after them. The darling ship with her sails all set, and the rudder tied fast to keep her in a straight course, was gently placed in the water, Harry holding her fast by the streamer. With flushing cheeks and eyes growing deeper and bigger, the little company were quite silent for half a moment, then Pinkie said, “Now, Marie.”

“Mustn’t she pray a prayer?” asked Major Brown, who had seen a christening in church.

“Why, no!” almost shouted Pinkie; “children can only pray prayers morning and night. Papa told her what to do”; and once more he said, “Now, Marie.”

Then the little girl raised the tiny bottle high above her head, and cried out in her sweet, singing voice, “Little Starlight, I christen you,” and dashed it on the deck. It shivered into a thousand fragments, greatly astonishing Shem, Ham, and Japhet, and the currant wine gushed over the bows. Harry let go the streamer; the gentle summer breeze swelled the tiny sails, and floated the little ship from the shore, and with a long, loud, ringing cheer the Little Starlight was fairly off on her first voyage.

Truly it was a lovely sight,—the four children watching with eager eyes their dainty craft, the long golden rays of the sun slanting over the velvet grass, on the white frock of little Marie, and touching into ruddy chestnut and gold the waving curls of her brothers. Harry’s great blue eyes were lit with the sweet inward smile that seems born of perfect happiness; and Marie curled her white arms round his neck, and whispered, “O Harry, isn’t our ship a real kitten darling?” As for Major Brown, he only hugged Pepper, right side up this time, and sucked his tongue without saying a word.

But you needn’t suppose they were going to be still very long on such a joyful occasion, for all of a sudden the Major gave his poor sucked tongue a holiday by opening his mouth and uttering a tremendous “Hoo-ray!” and in an instant all four were shouting, laughing, dancing, and clapping their hands. O what fun! “Hoo-ray!” they all cried; “three cheers for the Little Starlight!”

Away she sailed, making cunning little ripples in the water, and what Major Brown called soapsuds round her bows; her streamer flying out in gentle curves, and Shem, Ham, and Japhet standing up stiff and straight, gazing at the scenery with solemn faces. Then Pinkie all at once exclaimed: “Come, fellows, we must walk along the top of the wall, and watch the ship, or perhaps she will drive against the—the—what-u-call-’ems, and get wrecked and lost.”

“O dear, no! no! I don’t want the Little Starlight to get lost!” cried Marie; “please, Pinkie, don’t let her go against the—the—what did you say?”

“Well, but you know ships always have some dreadful adventures,” put in Harry; “and then it’s such fun to be lost on an uninhabited island, and catch oranges and eat monkeys,—no, I mean eat oranges, and catch monkeys; and then there’s guava jelly, you know, and poll parrots,—splendid! and caves and savages, and all sorts of jolly things.”

“Suppose we play that the Little Starlight is going on a voyage to New Orleans,” said Pinkie.

“Well,” answered Harry, “we will; where shall New Orleans be?”

“O, at the roots of the big willow-tree,” answered Pinkie.

“But how can you make her stop there?” asked Marie.

“Why, I shall pull her in with a long willow switch.”

“O-h!” said Marie.

While this conversation was going on, the children were walking along on the top of the wall in Indian file, Pepper following, with his tail bolt upright in the air. To be sure, they might just as well have walked on the grass, but that wouldn’t have been half the fun. Meanwhile the Little Starlight sailed away famously, dipping gracefully to the curling ripples; her streamer floating at the mast-head, and Shem, Ham, and Japhet still industriously admiring the prospect from the deck, as fine as you please.

“I know a piece of poetry about a ship sailing on her first voyage.”

“Tell it,” cried Harry, catching at the drooping bough of a willow, and swinging himself along.

So Pinkie began, “ ‘The Sailing of the Princess,’—but I mean to call it the ‘Starlight,’ wouldn’t you?”

“Of course,” said the others, and Pinkie, looking straight up in the air, as if the poetry was written in the sky, went on:—

“We watched her fondly day by day,

As slowly from the stocks she rose,

Till at the water’s edge she lay,

Perfect in her serene repose!

The soft waves crept up dutiful

To greet our Starlight beautiful!

The fairy ship in the harbor.

Hurrah! hurrah! our labor’s o’er!

Hurrah! hurrah! hip, hip, Hurrah!

For the good ship in the harbor!

“The anchor’s weighed, the sails are taut,

We strain our eyes o’er distant blue,

And hearts grow heavy with the thought,

‘The sea is wider than we knew,’

And perils many may she have,

From sunken rock and beating wave,—

The strong ship in the harbor!

Yet still—Hurrah! one loud cheer more!

Hurrah! Hurrah! hip, hip, Hurrah!

For the good ship in the harbor.

“The sea is calm, the wind is fair,

Our flag floats proudly at her stern;

Our friends on board; we breathe a prayer

‘God keep them till her safe return!’

Then loud we cheer her o’er and o’er,

As, gently gliding from the shore,

The brave ship leaves the harbor!

Hurrah! hurrah! ay, three times more!

Hurrah! hurrah! hip, hip, Hurrah!

And the good ship clears the harbor!”*

The children listened with deep interest to these beautiful lines, and at the end of the last verse Harry and the Major chimed in with three tremendous cheers and a “tiger!” The “tiger” scared Pepper so that he jumped off the wall, and scampered with might and main back to the house, crying, “Meou! meou! ffts! ffts! m-e-a-o-u!” at the top of his voice.

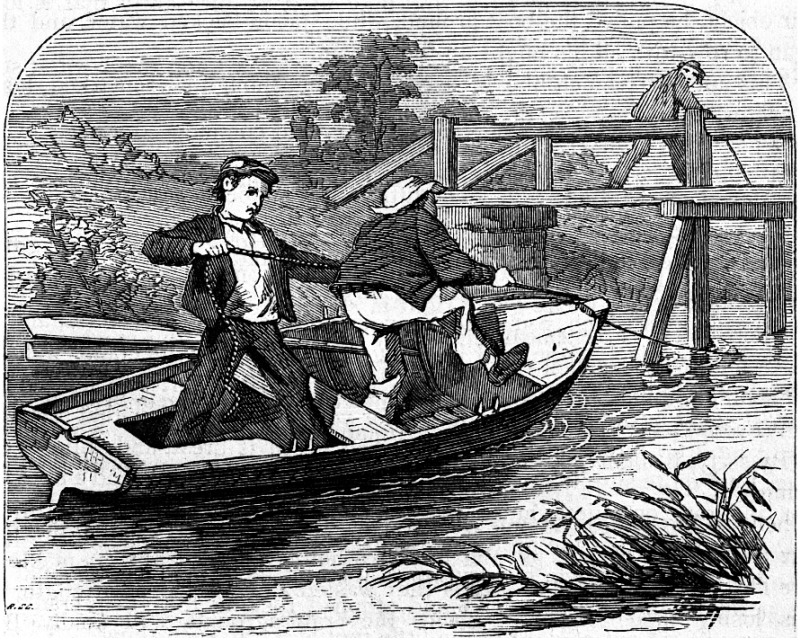

But, oh! ah! dear me! while they were listening to Pinkie, they forgot to watch the Little Starlight, and, dreadful to tell, she was just entering the roughest part of the river. Several quite large stones lay there, and the stream brawled and scolded around them at a great rate. Such rapids were as dreadful and dangerous for the Little Starlight as the rapids of Niagara would be to a real ship.

The poor little ship seemed to be a live thing and to know her terrible danger. She struggled and turned, trembling, quivering,—then, as if giving up all hope, in her despair rushed headlong among the stones. A huge wave—huge to her—curled up, and dashed down on the doomed ship, and crash! she was driven over on her side, and wedged fast between two great stones. Ham, Shem, and Japhet went instantly heels up in the air, and swam off like three great cowards. Perhaps, being made of wood, they couldn’t help swimming, or at least floating, when they were so unexpectedly upset into the water,—anyhow we’ll be good-hearted enough to think so; but the poor Little Starlight was left without a crew, and in great danger of becoming a total wreck, sure enough.

“Oh! oh! oh! what shall we do?” cried all the children, with clasped hands, and eyes nearly starting out of their heads. Then Marie pinched Harry’s arm nearly black and blue in her terror and distress, while Major Brown threw himself flat on his stomach, on the stone wall, and began to cry.

“I tell you! One of us must wade out and save her,” exclaimed Harry; “and I’ve a great mind to do it this very minute.”

“O Harry, you mustn’t!” cried Marie, clinging to him. “You will be drowned!”

“Boo!” retorted Harry; “that river isn’t deep enough to drown a mouse!”

“But the current is very rapid there, Harry,” said Pinkie. “You had better look out, old fellow. Papa won’t like it if you get a ducking.”

No frightening Master Harry, however! His balmorals and stockings were already off; his knickerbockers were rolled up as high as he could get them. The delight of paddling about in the stream, added to the desire of rescuing the little ship, were too much for mortal boy to resist. But the adventurous young monkey had undertaken a feat rather more dangerous than he imagined. Such a wide, shallow river, with a rough, pebbly bed, and swirling mid-rapids, does not offer the most secure footing in the world; and so Harry found as he floundered along, and presently was neatly capsized and tumbled down on all fours; but he dug his fingers in the sand, and scrambled up like a cat on a wall, only to go down head-first again, as the current dashed against his legs. Once more he clawed himself up, and this time stood hard and fast for a moment,—just long enough to make a grab at the Little Starlight, and stagger breathless out of the rapids, holding the ship triumphantly in the air.

“Is she hurt?” shouted Pinkie, dancing up and down in violent agitation.

“Not the least speck,” hailed back Harry; “only Shem, Ham, and Japhet must be drowned, for I don’t see them anywhere.”

“Fiddle! never mind them,” answered Pinkie.

“But it’s my Nooer’s Ork,” whimpered Major Brown.

The dear little fellow meant his “Noah’s Ark,” and it was dreadful to think that the beasts and birds would have nobody to take care of them; the spider would insist on marching in procession side by side with the elephant, instead of bringing up the rear, as it ought.

It couldn’t be helped, however, and Ned consoled himself as well as he could, and soon forgot to grieve for the luckless navigators, especially as Harry threw his arm round his brother’s neck with a kind, “Never mind, Major, you shall have my new peg-top to make up,”—which was such an enchanting promise that the little fellow had to hug and kiss Harry, and say, “Thank you, you good old boy! I love you bester than any one!”

Then Harry put on his stockings and boots, and said his clothes would dry first-rate in the sun, and the children concluded to carry the Little Starlight farther on to a smoother part of the river. They were soon past the rapids, and Harry once more started the precious vessel on her course. When she was fairly under way, he scrambled up on top of the wall like a grasshopper, and they all rushed like the wind down to the big willow-tree, which was quite at the end of the lawn. The great gnarled roots spread out high above the ground, and made comfortable seats from which to watch the Little Starlight floating smoothly down the stream.

While they waited, they chattered away about various things, when all at once Harry exclaimed, “There now! did I ever tell you what a dreadful fright I had last winter, when mother and I were down at Aunt Sally’s?”

“Why, no,” said Pinkie; “let’s hear about it, old fellow.”

“Well,” began Harry, twitching up his knickerbockers, which were still quite wet,—“well, you know mother thought I had better go to school while we stayed, for fear Aunt Sally would go crazy with my noise; and so to school I went,—mad enough, I can tell you. Of course you know I couldn’t have learned a single thing without chewing india-rubber,—of course not. Well, one day I was munching away at the india-rubber as hard as ever I could, and studying that plaguy eight times in the multiplication table, when, all at once, bang! went the master’s ruler on his desk. I gave such a jump! and down went the india-rubber like a flash of lightning! That wasn’t the worst, either; for Cousin Will told me if I swallowed india-rubber it was certain death; so just fancy how I felt!” Here Harry opened his blue eyes very wide, and stared solemnly at the company.

“O, but you didn’t die,—did you, Harry?” cried Marie, looking quite frightened.

“He seems to have come to life again as good as new,” laughed Pinkie. “Go on, old chap.”

“Well, I was in the most awful fix. I didn’t want to die away from mother, and it did seem as if school never would be out. I was so scared, I couldn’t learn ‘eight times’ at all, and the master boxed my ears with the arithmetic because I didn’t know it. I thought it was the most cruel thing that ever was heard of, to box a fellow’s ears when he was dying; and the instant school was out I put for home double-quick, rushed into mother’s room, threw myself into her arms, burst into tears, and sobbed out, ‘O mother, mother! kiss me quick, and bid me good by. I am dying, I know I am!’ ”

At this most affecting climax, Major Brown couldn’t stand it any longer, and, pulling out a very small pocket-handkerchief, he indulged in a series of doleful sniffs, carefully keeping one eye and both ears open so as not to lose an atom of the story.

“Well,” went on Harry, quite affected himself at his own eloquence, “mother asked me what in the world was the matter; and, when I told her, what do you think she did?”

“W-h-a-t?” asked all the rest, staring at Harry, and listening as if they had three pairs of ears apiece.

“Why, she burst out laughing, she almost screamed laughing! and then she hugged me, and kissed me, and told me that india-rubber wasn’t deadly poison, and wouldn’t do me any very tremendous harm; but she advised me not to chew any more. So I wiped my eyes, and ran off to play, and that’s the last I’ve heard of it from that day to this.”

Just as Harry finished his interesting experience with india-rubber, the Little Starlight swept gracefully past the willow, so close that Pinkie could draw her in with his hand.

She was lifted out tenderly, and set again in her groove in the plank. Then the Major unfastened her hatchway, and all four commenced to unload her cargo. They ate up her cargo,—that is, the ginger snaps,—taking out only one at a time to prolong the pleasure, and nodding and grinning at each other to signify how very enchanting it all was, and what a glorious time they were having. Such fun! don’t you wish you had been one of the party? I do, and that’s a fact; and what’s more, every word of this story is true, and that very Harry, with his curly wig and china-blue eyes, is one of my particular favorites.

I told you they took out one ginger snap at a time, but I forgot to mention that they broke each one into four pieces, dividing them around. Each piece made one good-sized mouthful; so, if you love me, do this sum in arithmetic,—how many mouthfuls did each of them have? I told you in the beginning of the story how many snaps Harry brought out.

Just as the fun was at its height, somebody came softly up behind them, and cried out in a funny, rough voice, “Odds bobbs and buttercups! what are you all at?”

The children started and looked round, and there was Mr. Ludlow, laughing softly to himself at their chatter. Every one of them jumped up to kiss him; and every one of them told him all together about the wonderful cruise of the darling Little Starlight.

The sun was just setting midst purple and rosy clouds. The tiny ripples of the river were crested with gold, while the waveless eddies near the shore were of the color of a rose unutterably delicate and lovely. The beautiful light touched into warmer color the bright faces of the children, as they clung fondly round their stately, handsome father.

And now a silvery-toned bell rang out in the still sunset air. Spite of all the ginger snaps, this must have been an enchanting sound, for the little ones “skipped and tripped and danced and dipped” into the house,—Pinkie carrying the precious Little Starlight in triumph before them. She was laid safely up in dry dock on top of Mr. Ludlow’s desk, while, as for poor Shem, Ham, and Japhet, like Harry’s india-rubber, no one has heard the first grain about them from that day to this. I haven’t,—have you?

Aunt Fanny.

|

Tennyson. |

A butterfly, roving, with nothing to do,

Over the wall of a clover-field flew.

Fine scented clover,—white clover and red,—

Up from the mowing-grass lifting its head.

There but a moment he dared to alight,

Timorous Butterfly! off in a fright,—

Off, when the Grasshopper, leaping too near,

Scraped his small violin piercing and clear,—

Little old Grasshopper! Grasshopper green,

With legs doubled under him crooked and lean!

Over the garden fast flitted the rover,

Caring no more for the tall, sweet clover.

What though its blossoms be fragrant and gay?

Richer and redder the Rose is than they;

Under the sunny south window it grows,

Sweet-breathing, bright-blooming, elegant Rose!

Here, then, he settles with wings upright,

Closing them gracefully, closing them tight,

Just as if never again to unfold

All the rich tinting of purple and gold.

Ah! But, approaching the same sweet cup,

Slowly the Rose-Bug came travelling up,

Down by the Butterfly soberly sat,

Horny and crawly and ugly and flat!

Soon as this ill-favored neighbor he knew,

Here away, there away, Butterfly flew,

Upward and downward, around and around;

Down where the buttercups gladden the ground,—

Buttercups nodding, all golden and gay,

Glancing and dancing the summer away.

Lured by their charms, here he fluttered about,

Till midst the glad party a Snail crept out.

Toilsomely dragging his shell-house along,

Doing no mischief, and thinking no wrong.

“Now,” cries the Butterfly, “comes a new foe!

Dangers are with us wherever we go.”

Off then he speeds; and each flower, as he springs,

Looks after and laughs at his quivering wings.

Over the cornfield and over the wheat

There lies an orchard, old, shady, and sweet.

“This is the spot for me!” cries he, at last,

“Here all is tranquil, and danger is past!”

O coward Butterfly! Butterfly silly!

See where, with cap in hand, runs roguish Willie,

Under the apple-tree, where he was lying,

Think you he saw you not, resting and flying?

Soar away, Butterfly,—off at full speed;

Now there is danger,—great danger, indeed;

Snail, Bug, nor Grasshopper, they have not sought you,—

Bareheaded, curly-locked Willie has caught you!

Mrs. A. M. Wells.

Solomon John agreed to ride to Farmer Jones’s for a basket of apples, and he decided to go on horseback. The horse was brought round to the door. Now he had not ridden for a great while; and, though the little boys were there to help him, he had great trouble in getting on the horse.

He tried a great many times, but always found himself facing the wrong way, looking at the horse’s tail. They turned the horse’s head, first up the street, then down the street; it made no difference; he always made some mistake, and found himself sitting the wrong way.

“Well,” said he, at last, “I don’t know as I care. If the horse has his head in the right direction, that is the main thing. Sometimes I ride this way in the cars, because I like it better. I can turn my head easily enough, to see where we are going.” So off he went, and the little boys said he looked like a circus-rider, and they were much pleased.

He rode along out of the village, under the elms, very quietly. Pretty soon he came to a bridge, where the road went across a little stream. There was a road at the side, leading down into the stream, because sometimes wagoners watered their horses there. Solomon John’s horse turned off too, to drink of the water.

“Very well,” said Solomon John, “I don’t blame him for wanting to wet his feet, and to take a drink, this hot day.”

When they reached the middle of the stream, the horse bent over his head.

“How far his neck comes into his back!” exclaimed Solomon John; and at that very moment he found he had slid down over the horse’s head, and was sitting on a stone, looking into the horse’s face. There were two frogs, one on each side of him, sitting just as he was, which pleased Solomon John, so he began to laugh instead of to cry.

But the two frogs jumped into the water.

“It is time for me to go on,” said Solomon John.

So he gave a jump, as he had seen the frogs do; and this time he came all right on the horse’s back, facing the way he was going.

“It is a little pleasanter,” said he.

The horse wanted to nibble a little of the grass by the side of the way; but Solomon John remembered what a long neck he had, and would not let him stop.

At last he reached Farmer Jones’s, who gave him his basket of apples.

Next he was to go on to a cider-mill, up a little lane by Farmer Jones’s house, to get a jug of cider. But as soon as the horse was turned into the lane, he began to walk very slowly,—so slowly that Solomon John thought he would not get there before night. He whistled, and shouted, and thrust his knees into the horse, but still he would not go.

“Perhaps the apples are too heavy for him,” said he. So he began by throwing one of the apples out of the basket. It hit the fence by the side of the road, and that started up the horse, and he went on merrily.

“That was the trouble,” said Solomon John; “that apple was too heavy for him.”

But very soon the horse began to go slower and slower.

So Solomon John thought he would try another apple. This hit a large rock, and bounded back under the horse’s feet, and sent him off at a great pace. But very soon he fell again into a slow walk.

Solomon John had to try another apple. This time it fell into a pool of water, and made a great splash, and set the horse out again for a little while; but he soon returned to a slow walk,—so slow that Solomon John thought it would be to-morrow morning before he got to the cider-mill.

“It is rather a waste of apples,” thought he; “but I can pick them up as I come back, because the horse will be going home at a quick pace.”

So he flung out another apple; that fell among a party of ducks, and they began to make such a quacking and a waddling, that it frightened the horse into a quick trot.

So the only way Solomon John could make his horse go was by flinging his apples, now on one side, now on the other. One time he frightened a cow, that ran along by the side of the road, while the horse raced with her. Another time he started up a brood of turkeys, that gobbled and strutted enough to startle twenty horses. In another place he came near hitting a boy, who gave such a scream that it sent the horse off at a furious rate.

And Solomon John got quite excited himself, and he did not stop till he had thrown away all his apples, and had reached the corner by the cider-mill.

“Very well,” said he, “if the horse is so lazy, he won’t mind my stopping to pick up the apples on the way home. And I am not sure but I shall prefer walking a little to riding the beast.”

The man came out to meet him from the cider-mill, and reached him the jug. He was just going to take it, when he turned his horse’s head round, and, delighted at the idea of going home, the horse set off at a full run, without waiting for the jug. Solomon John clung to the reins, and his knees held fast to the horse. He called out “Whoa! whoa!” but the horse would not stop.

He went galloping on past the boy, who stopped, and flung an apple at him; past the turkeys, that came and gobbled at him; by the cow, that turned and ran back in a race with them until her breath gave out; by the ducks, that came and quacked at him; by an old donkey, that brayed over the wall at him; by some hens, that ran into the road under the horse’s feet, and clucked at him; by a great rooster, that stood up on a fence, and crowed at him; by Farmer Jones, who looked out to see what had become of him; down the village street, and he never stopped till he had reached the door of the house.

Out came Mr. and Mrs. Peterkin, Agamemnon, Elizabeth Eliza, and the little boys.

Solomon John got off his horse all out of breath.

“Where is the jug of cider?” asked Mrs. Peterkin.

“It is at the cider-mill,” said Solomon John.

“At the mill!” exclaimed Mr. Peterkin.

“Yes,” said Solomon John; “the little boys had better walk out for it; they will quite enjoy it; and they had better take a basket; for on the way they will find plenty of apples, scattered all along either side of the lane, and hens, and ducks, and turkeys, and a donkey.”

The little boys looked at each other, and went; but they stopped first, and put on their india-rubber boots.

Lucretia P. Hale.

As on through life’s journey we go day by day,

There are two whom we meet, at each turn of the way,

To help or to hinder, to bless or to ban,—

And the names of these two are “I Can’t” and “I Can.”

“I Can’t” is a dwarf, a poor, pale, puny imp,

His eyes are half blind, and his walk is a limp;

He stumbles and falls, or lies writhing with fear,

Though dangers are distant and succor is near.

“I Can” is a giant; unbending he stands;

There is strength in his arms and skill in his hands;

He asks for no favors; he wants but a share

Where labor is honest and wages are fair.

“I Can’t” is a sluggard, too lazy to work;

From duty he shrinks, every task he will shirk;

No bread on his board and no meal in his bag;

His house is a ruin, his coat is a rag.

“I Can” is a worker; he tills the broad fields,

And digs from the earth all the wealth which it yields;

The hum of his spindles begins with the light,

And the fires of his forges are blazing all night.

“I Can’t” is a coward, half fainting with fright;

At the first thought of peril he slinks out of sight;

Skulks and hides till the noise of the battle is past,

Or sells his best friends, and turns traitor at last.

“I Can” is a hero, the first in the field;

Though others may falter, he never will yield;

He makes the long marches, he deals the last blow,

His charge is the whirlwind that scatters the foe.

How grandly and nobly he stands to his trust,

When, roused at the call of a cause that is just,

He weds his strong will to the valor of youth,

And writes on his banner the watchword of Truth!

Then up and be doing! the day is not long;

Throw fear to the winds, be patient and strong!

Stand fast in your place, act your part like a man,

And, when duty calls, answer promptly, “I Can!”

William Allen Butler.

Away up in the northern part of Michigan, in a little village, there lived a baby,—her parents’ only one, and therefore the dearest, sweetest, cunningest little creature in all the world. Never before had there been seen such a baby as this. She was the queen, as well as the pet and plaything, of the house. Her wants were anticipated, her wishes obeyed, and she had everything that the heart of a baby could desire. Her little frocks were tucked and embroidered to the very last extreme. She had a beautiful crib to sleep in, a baby-jumper to jump in, a silver cup to drink from, and playthings innumerable to amuse herself with. But there was one thing that she didn’t have, which money was not able to buy, and that was a name. To be sure there were a dozen pet names that she was called by, such as Precious, and Birdie, and Brighty, and Flutterbudget, and Susquehanna, and Troublehouse; but she had no “real truly name,” as her cousin Charley used to say, and which he thought was altogether too bad; and so, in the generosity of his heart, he bestowed upon her the one belonging to his black, curly-tailed dog, Whisk. Little three-years-old Nell was bent upon calling her Jimmy, but her sister Kate, older and wiser by a year, though still innocent of grammar, exclaimed contemptuously, “Why, don’t you know, Nell, Jimmy is a boy’s name, and he’s a girl?”

The uncles, aunts, and friends generally, all brought their favorite names, and laid them, willing offerings, at her feet. One would have her called Beatrice, another Zoraida, another Ethelind, and so on; so that, if they could all have had their will, the little creature would have been fairly smothered under so many. But her father and mother had some objection to them all. Not a single one could be found quite dainty enough for the little lady, so that the probabilities were very strong that one would have to be manufactured expressly for her, or else that she would live all her life and go down to her grave nameless. Meanwhile she smiled on, and if she could only have the usual amount of kisses, and tossings, and rides to Banbury Cross, cared not a straw whether she ever had a name or not.

One day her mother and a friend took her out for a ride in her little carriage. As they were going through the beautiful winding paths of the forest, they came suddenly upon the half-dozen tents of an Indian encampment. These Indians, who are scattered all through the northern part of the State in settlements of their own, often come down to the villages and pitch their tents for a few days, and sell baskets, and berries, and maple sugar, and such things. The encampment was deserted just now, except by one woman, who sat under a pine-tree, embroidering a pair of moccasons with gay-colored beads, and at the same time keeping guard over the empty tents.

“Bushoo,” said the ladies, going up to her.

“Bushoo,” she replied. This was simply the polite way of saying, “How do you do?” in the Pottawatamie dialect. When she saw the baby in her carriage, she smiled, and pointed up towards the tree above her head. Her visitors looked up too, and what do you think they saw? They saw a board, very prettily carved, and with something fastened to the upper side, hanging from one of the branches and swinging about in the wind.

“Oh!” they cried, “there’s a baby! Do take it down and let us see it.” She understood, and laughed, and took it down; and there, sure enough, was a little brown baby, bound firmly to the board, all except its arms, and with its feet resting upon a kind of little shelf. It had been having a fine time up in the tree, with the wind to rock its cradle, and the birds to sing its lullaby, and the leaves to dance and flutter for its amusement. The squirrels came and peeped at it with grave eyes, and wondered what manner of creature it was, and chattered together about what business it had to intrude itself into their busy home, and then went away to their work of gathering nuts. And the baby swung, listening to the birds and the squirrels, and trying to catch the sunbeams that flickered through the leaves.

She had a pair of small, shining, black eyes, which opened as wide as ever they could in wonder at the other pair of big blue ones in the carriage. Little Flutterbudget was for making acquaintance directly. She laughed, and crowed, and held out her little arms; but the brown baby looked gravely back, not understanding such demonstrations at all.

“Suppose you swap babies,” said the friend.

“No, no, my pappoose best”; and the Indian mother hugged the pappoose, board and all, closer to her, as if she was afraid they really meant to carry off her treasure.

“How old is she?”

“Ten moons.”

“Why, that’s just as old as Birdie! What is her name?”

“Winogene.”

“Winogene. That’s a pretty name. What does it mean?” for Indian names always have some meaning. The Indian woman understood English much better than she could speak it, so she looked around for something to help her. A knife was lying on the ground; she took it up and held it in the sunshine, giving it a quivering motion, so that the dazzling rays glanced off in every direction. They caught something of the idea, and, after a few more words, went home, and left the mother to her work and the baby to its swinging.

Arrived at home, Birdie’s mother flew up stairs to the library, where was an old Indian dictionary, and, opening it, she found, “Winogene,—a quivering ray of light.” All that day she kept saying over to herself, “Winogene,—a quivering ray of light”; and at last she exclaimed aloud:—

“That is just what my baby is, and her name shall be Winogene.” And Winogene it was.

There were some wry faces when this decision became known. Some of the aunties and friends thought it was an outrage to hang such a barbarous name upon an innocent little baby that couldn’t help itself at all. If she must have a foreign name, better call her Gretchen, or Hedwig, or even Bridget, than to go to the wild Indians for one. Meanwhile she thrived under it beautifully. She grew out of her babyhood into a healthy, happy, romping child, and her name was prophetic of her sunny spirit. She was, indeed, a ray of light all through the house. Every room seemed brighter when she was in it, and she trailed the sunshine after her wherever she went. It was the delight of her parents and friends to make her happy. Everything that love and wealth could procure for their darling she had. And it did not spoil her. She was growing up in all good and lovely ways,—an affectionate, obedient, happy child.

And how fared it with the other Winogene? Her home was a little, filthy, smoky wigwam. Her clothes were poor and scanty enough, and she often went to sleep at night very hungry; but when the pleasant summer days came she forgot all about that, and was as happy as a bird. Then she lived out of doors. She could climb a tree as nimbly as a squirrel. She knew just where the first flowers would blossom and the first berries ripen. She knew the name of every tree and shrub, of every bird and animal, in the forest. Her father made her a bow and arrows, and taught her how to shoot with them; and her mother taught her to hoe corn and embroider moccasons and leggins. And the little dark Winogene was a happy child too, but in a very different way.

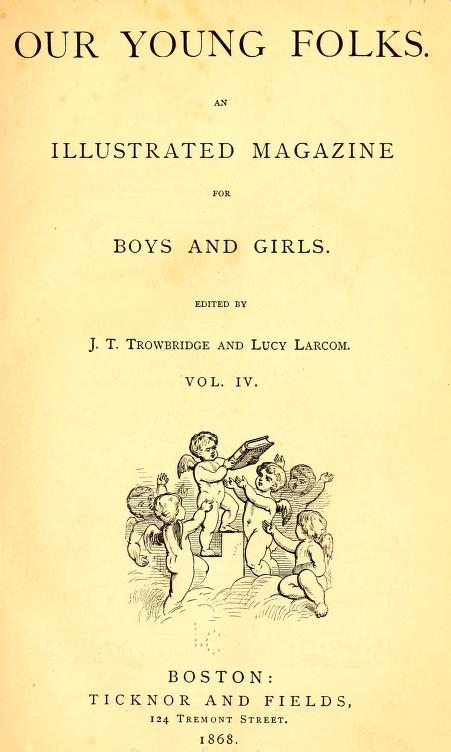

One day as Winny was trundling her hoop in the yard, she saw a company of Indian women and children coming down the street. They were walking solemnly, one behind another, at just such a distance apart, and looking right ahead. Their stiff, straight black hair was flying loosely in their necks. They wore blankets over their heads instead of bonnets, and moccasons upon their feet instead of shoes; and, strapped upon their backs, the women each carried a huge pile of baskets, and occasionally from some basket there peeped out a little, sober, brown face, belonging to a baby whose mother found this the most convenient way of carrying it. This strange-looking cavalcade was by no means an unfamiliar sight to the child; still, when a woman and a little girl left the procession, and came through her father’s gate, she stopped her play and ran in, for she always liked to hear them talk. They had some very pretty open-work baskets to sell, made of splints, and stained with all sorts of bright colors.

“Winogene,” said her mother, “shall I buy you a basket?”

The woman and child both started at the name, and looked at the little girl in surprise.

“Her name Winogene?” she inquired, pointing to Winny.

“Yes.”

“Her name Winogene too,” pointing to her own little girl. The two mothers looked at each other a moment. Each recognized the other, and remembered the meeting under the pine-tree six years before.

“Yes, and I named my baby for yours.” Both laughed, and brought forward their little girls for exhibition. A greater contrast than they presented could scarcely be imagined. The one with her clear complexion, sunny curls, and blue eyes, dressed in a blue muslin frock and white apron, and jaunty little hat,—the other with her dusky skin, and small black eyes shining out from under the straight hair that fell over them, wearing a faded frock, below which were seen a pair of leggins gayly embroidered with beads, and a multitude of strings of gaudy beads, of which she was very proud, around her neck. But each mother still firmly believed her own to be the prettier. The children were shy, and only looked curiously at each other. Their mothers tried to talk, but it was slow work when they had so few words in common. However, Winny’s mother gave them a bundle of clothes, and a bountiful dinner, and bought twice as many baskets as she had any use for; and, just as they were going, Winny brought one of her dolls, the one that could open and shut its eyes, and cry, and gave it to Winogene. I suppose she intended it as part payment for her name. The little wild girl had never seen such a thing before, and did not know what to make of it. She thought it was alive, and was afraid, and clung to her mother. It was a long time before she could be made to comprehend anything about it; but when at last she did, and realized that it was her own, her black eyes danced for joy. She keeps it yet. She has a special corner for it in her mother’s wigwam, and she ties it to the same carved board which was her own cradle, and sets it swinging among the branches, as her mother used to her. She is a heroine in the eyes of her playfellows. They look with wonder and admiration and envy upon her and her treasure, and I suppose there never lived a prouder little pappoose than she.

A few weeks after, as Winny was playing in the yard, she looked up and saw another company of Indians coming. As they came opposite her father’s house, a grotesque little figure left the procession and came towards her. She recognized Winogene at once, but she laughed aloud as she recognized also one of her own muslin frocks, which, without hoops, almost dragged upon the ground, and her own old doll, which the little girl was carrying perched upon her back. She was leading a beautiful fawn by a cord, and, running up to Winny, she put the cord into her hand.

“This for you,” was all she said; and before Winny had time to recover from her surprise enough to thank her she was back, walking solemnly along in file with the rest. I don’t know which is the happier of the two girls,—the one with her doll, or the other with her fawn, which is as tame and loving as a kitten, and her constant companion everywhere.

And so occasionally the pathways of the two Winogenes cross each other, and perhaps will long continue to, for they live not very many miles apart; but how different will be their lives! One will grow up amidst all the refinements of civilization. No pains will be spared to make her an educated, useful, and Christian woman. The other will be perfectly content to hoe the corn, and cook the meat, and do cunning embroidery, with no thought of any higher life. She may learn to read, for the government provides schools and teachers for them; but it will do her very little good, for she likes to climb trees and pick berries so much better, and her father and mother do not care whether she learns or not. Ah! the two Winogenes will have very little in common but their names.

H. A. F.

Our five little cats one day decided to have a dinner-party,—a real Thanksgiving dinner; and they all sat round in a circle on their tails to consult about it.

Little Pickey spoke first: “We must have old Watch; he would look grand, and shake paws so politely with all our friends. Perhaps he would bring a bone or two from his underground pantry in the garden, and that would help, if the mice and rats should be scarce.”

“Then the poor little white cat must come,” said Maltie, “for her back is broken, and her kittens, they say, have gone on a long voyage. It may cheer her up a bit, poor thing!”

By this time all the kittens were speaking at once. To us it would have sounded only “Mew, mew”; but to them it was “Blackey,” and “Mouser,” and “Tiptoe,” and “Dumbey,” and “Cry-baby,” and “Scratcher” must come, “and—and—” but here Tiger, the little striped cat, will make herself heard; so, giving Maltie a bite, and Spotty a scratch, and boxing Whitey’s ears, she lets them know that all must be still and listen to her. This is a very foolish way for little Tiger to behave; for now, instead of smiling-faced brothers and sisters, she has only snarling and fierce little cats, all around her, and I fear that whatever she says won’t sound pleasant. Poor little foolish puss! she don’t seem to know that, but begins to speak,—“Mew, mew, mew, meau-au-au-au-au, meau-au-au.” If you don’t understand cat language, I will tell you that this means, “We must invite Fanny and Willie, who so kindly washed us in the street mud-puddle to keep us from having the cholera.” Then Tiger stopped, showing all her white teeth, and whisking her tail wildly, in excitement at this bright idea.

Each kitten had opened her mouth for a mew or a growl, when the old mother cat commanded silence with a look, and began to speak. “Long before you were born, children, I lived far away in what is called Yankee Land. In the great house where I was born, only the relations of the family were invited to the Thanksgiving dinner, and my mother and grandmother said it had always been so, and always should be among those who had any family pride and aristocracy. Now, our family is a large and highly respectable one,—very aristocratic; but, I grieve to say, in the course of years it has become scattered all over the earth, and many of its members are so changed that we should not know them. Indeed, I have heard that some are without tails, and some are so large and strong that they can carry away calves as easily as I do mice. They live so many miles away that we cannot go to invite them; but I am sure our friend, the wind, who plays such nice games with us among the leaves, will do us that service.

“As I hear that some of our relatives are very fierce, and may even eat us if we have not enough food on the table, I shall send them word to bring their own provisions; then they will surely have just what they like.”

All the kittens received these remarks with applause; and the wind, just then whistling round the corner, was called in and readily agreed to carry the invitations.

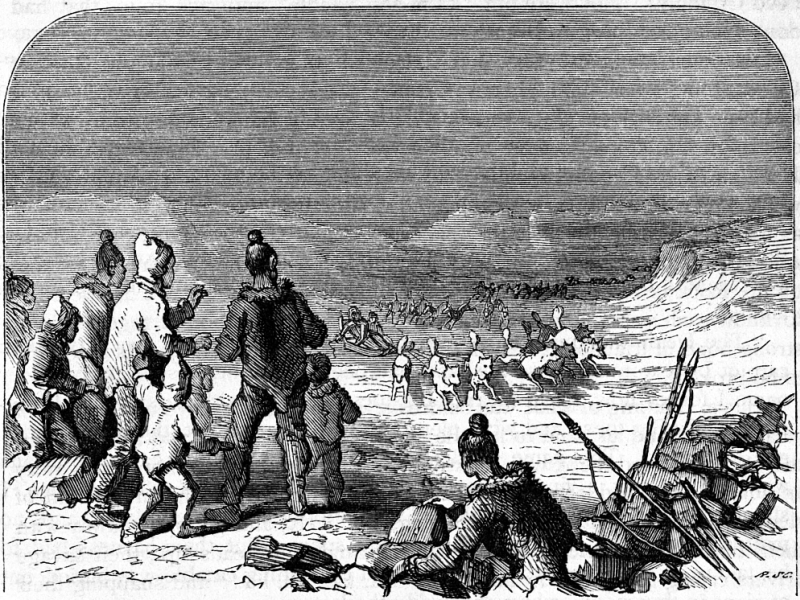

The wind, as we all know, is one of the swiftest travellers in the world. He needs no horses, nor cars, nor boats, but whistles merrily along over mountain, valley, and sea, as much as to say, “How foolish men are to make so much work out of what is only play!” It is well that he thinks it play; for to carry the pussy-cat’s invitations he must take a very long journey,—all over the great world on which we live.

Off he starts on his errand, over the wide, blue sea, pausing now and then at some pleasant island, and even at that one where live the poor little cats without tails. On, on he hurries to great deserts, where he whirls the sand in clouds before him; then down deep in dark woods where men have never been; but even there live some of our pussy’s relations. He creeps along the swamps, where we should sink neck-deep in thick mud, and rushes over the prairies, waving the tall grass and flowers; and in every one of these places the wind has found some of the cat’s family to invite to the dinner.

Poor little pussies! I’m afraid they will want to run away from their strange relatives when the day comes. But we shall see. Thanksgiving is almost here, and old puss and her friends have worked hard and collected a large store of rats and mice, and the little ones have stolen many a nice bit of meat from the kitchen. These treasures are all hidden under the barn, and will be brought out into the grove, where the table is to be laid; for they have no room large enough to accommodate such a party.

The morning has arrived, and the little cats, with paws and faces carefully washed, are impatiently waiting for the company. They would climb the trees to look out in the distance for their guests; but mamma says it would soil their paws, and besides it wouldn’t be proper; so they only eye the dishes wistfully, and now and then growl at each other, they are so tired waiting.

Suddenly two great, glaring eyes look in at them between the trees. Each little cat scampers to a hiding-place, while the air is filled with a strange roar. What can this roar mean? Hark! it is their own language, though fearfully loud. Each little cat pricks up her poor, trembling ears to catch the words: “Is this where I am invited to dinner?” So it is only their first guest that has caused them such fright. Immediately mother puss steps politely forward, bowing, and the stranger introduces himself as Mr. Lion, from Africa, and leads in his wife and their son Whelp, who, though but six months old, is larger than puss and all her family taken together. “We have brought but a small addition to your dinner,” roars the Lion, throwing down four antelopes.

“Small, did he say?” whispers Pickey to Mouser. “Why, they are the biggest rats I ever saw, and with horns too! Where can he have caught them?”

But now Mouser is called up to talk with her cousin, Whelp Lion; and they are soon on the most friendly terms, and Mouser has asked him where his father got those “big rats.”

Little Whelp is very polite, so he doesn’t laugh at her mistake, but tells her how all night long his father and mother lay under the tangled bushes by the dark stream near their home, until they heard the soft tread of these same little antelopes coming down to drink. “But the rest of the story father didn’t tell me,” said Whelp; “I think he must have caught them as you do the rats, for the next morning I saw them lying close to my bed, when mother waked me to get ready to come here.”

While all this talking is going on, other guests have arrived; so we must leave Whelp and Mouser to entertain each other, and look around us.

Why, really, the grove is quite full! The table is loaded with monkeys and birds and rabbits and squirrels and calves and sheep, and even one great scaly alligator. I wonder who brought that; and don’t you wonder who can bite through its tough skin,—tougher even than your thickest shoes?

But the dinner-bell—a long “Meau-au-au-au”—has sounded, and we must content ourselves with observing the company after they are seated at table. They are arranged by families. First are the brown and yellow Lions that have come from far over the sea. Their home is in the deep, dark forests, where the light of the sun is almost shut out by the thick leaves, and where men have never been. They are the lords of that country, and all the other beasts bow before them, and call them kings; so little Whelp, you see, belongs to the royal family.

Next is seated the Panther, or, as he prefers to be called, the Silvery Lion of America, with his two younger brothers, Dusky and Tawney. They dropped down from the trees only a minute ago, right into the midst of the party; and it is old Silvery who brought the alligator which he is now tearing in pieces with his sharp teeth and claws, giving, now and then, some more tender parts to his brothers who haven’t yet the strength to bite through the hard skin. This family have long, slender bodies, though short and stout legs; and we may hear Tawney remarking to his neighbor, Mr. Lynx, that he has often been through a whole grove by leaping from tree to tree, and not touching the ground. “You should have seen Silvery drop down on that alligator yesterday, as he lay asleep in the swamp. Why, he hadn’t even time to wake up, before we had dragged him up on the tree, dead as you see him now.”

Mr. Lynx puts on a very fierce look, saying, “Nothing new to me, sir; you can’t tell me or my family anything new about leaping. You should have seen us yesterday, when the hunters were after us! Why, my wife and I went ten feet at every bound, and—”

“Hunting,—did you speak of hunting?” growls the next neighbor, before Mr. Lynx can say another word. “I have the best way of hunting. I do it all myself. When a man tries to hunt me, I turn and tear him in pieces; and as for the deer and monkeys, why, I make short work with them.”

The poor little Manx cat, who sits near by, shakes herself almost under the table with fright.

Then a fierce, growling voice from the other end of the table breaks in with, “I do better than that! I don’t wait for men to come to me, I go to them. You should see me in their villages. They do not try to fight, they only run and hide; but I find them out! I find them out!” and he shows all his fierce white teeth, and grins horribly.

At this the poor kittens can control themselves no longer, and up go their tails over their backs as big as any squirrel’s. They had been sitting on them ever since their cousin Manx came in, so that she might not feel bad at having none; but now their terror has overcome their politeness.

“O, they are so thin!” whispers Maltie to little Manx. “I know they will eat us up before they go. If they do have such pretty stripes and spots, I don’t like them.”

But Mr. Lion has noticed their fright, and has already cautioned their savage visitors, Mr. Leopard and Mr. Tiger, to be more gentle, or all their smaller relations will run away.

So there is no cause for fear, little pussies; they are only trying to show off, as we have seen many persons do who should be wiser.

Still Mr. Leopard is carrying on a low conversation with his next neighbor, little Miss Jaguar, while Mr. Tiger sits sullen and silent, and we hear now and then,—“We hid in the bushes,—sprang—tore—killed,—how good monkeys’ tails are with antelopes’ legs,” &c., &c. They must be telling about their hunts; but we won’t attend to them now, for before us are the young beauties among cats,—Misses Tortoise, Angola, Maltese, Egyptian, and dear little Miss Manx, whose pretty head and gentle manner fully make up for her lack of tail. There are the famous “Cheshire cats,” grinning from ear to ear; and perhaps “Puss in Boots” is round that corner, but I can’t see. Their talk is of rats and mice and milk, and even of ribbons for the neck, and I think I hear old Mrs. Tabby speaking of a scarlet collar with a bell; but there is so much talking now, I may mistake her. Still of one thing I am sure,—little Blackey is telling Mouser, that, if she will just slip under the table with her where it is dark, she will show the little fires which she keeps in her fur, and which don’t burn her at all. They are sliding quietly down, when old mother puss rises to speak.

After some hesitation, being unused to public speaking, she tells the company that matters of a strictly private nature, family matters, will now be brought before them for discussion; among others the question, “Why cats, when giving fine concerts at night, have old shoes and such worthless articles thrown to them, instead of nice meat, as a reward? How this great mistake of mankind is to be remedied.”

As these questions are best discussed in private, it is requested that all who do not belong to the family will leave the grove.

Since we have been so decidedly requested, I suppose we must go, and therefore cannot report the discussion of these important family matters. We can only hope that they won’t eat each other up before the dinner is ended, and that all may return safely to their homes.

When our pussy disappears next Thanksgiving day, we shall know where she has gone. We won’t tell her that we have found out her secret, for it might trouble her, poor little puss!

M. L. A.

“His name is Force,” squeaked the little traveller, “but for the sort of person that he is, I cannot exactly say, your Royal Highness, seeing that he is sometimes as great as a giant, and at others as fine as a thread; only that he is the worst used and best-natured individual in your Majesty’s dominions; for there is not a ship or a house, a road or a garden, made, or a dinner got, or so much as a cup of water drawn, without his help. He is wanted to do everything, every minute of the day, all over the earth; and he does it without grumbling; and now mark how he is paid! Every time that he gives anybody a neighborly lift, from sawing a stick of wood to dragging a train, he disappears. He is destroyed. All day long he is smashed, blown up, choked, your Royal Highness, under your Royal Highness’s very nose,—under everybody’s nose,—made away with, done for, murdered, used up, in a hundred thousand places all at once, by Christians and heathens all alike,—which your Majesty will see is quite improper. For, if it is so very bad to choke, blow up, and murder a man once, how much worse to do all these things to a person all the time! and if your Highness would protect even a thief from such abuse, how is it that there is nobody to say a word for poor Force, who wags your very heads for you? and whose blame is it?”

When the little traveller said, “Whose blame is it?” he looked hard at the King. The King was quite thrown out of countenance,—for here was a very bad case, you see, made out against somebody,—and he looked severely at the Lord High Fiddlestick, because it was understood that, when anything happened to be right, the credit was due to the King; but when anything was wrong, the blame fell to my Lord High Fiddlestick. As the King looked severe, the courtiers looked severe also, and as if—come now, this was really too bad, and a little the worst thing they had heard yet about my Lord High Fiddlestick. But my Lord High Fiddlestick only crossed his pink slippers comfortably one over the other, and said:—

“Your Majesty, there is no one to blame here. The gentleman is quite right and entirely wrong.”

The little traveller jumped up. He was wrapped from head to heels in a long overcoat, full of pockets. Out of one pocket he took a bit of iron and a hammer. He laid the iron on a table, and pounded it with the hammer. “There!” he said, “Force did that; but now where has he gone, my Lord High Fiddlestick?” Then he pulled at his mustache, and stamped his foot, and got out a saw and a piece of wood, and had off an end of the wood before you could wink. “Force did that, too,” said the little traveller; “but, if he did not die in the doing of it, can you tell me where he is now, my Lord High Fiddlestick?” Then he drew out a pistol, and, aiming at the third leg of the King’s extension table, sent a bullet at it as savagely as if it had been the Lord High Fiddlestick himself.

“Force did that, too,” screamed the queer, angry little man, “and now where is he? I am not to be put off with a riddle about being quite right and entirely wrong. If he is dead, as you are to blame for whatever happens in this country, you ought to be hung at once; and if he is not dead, I will trouble you to show him to me.”

“Good Mr. Traveller,” answered my Lord High Fiddlestick, picking up the saw, “will you feel of that? It is cold,—is it not? and the wood,—that is cold, too. Well, now suppose you saw us off another bit of wood. Thank you. Feel now of the wood. Is it cold, just as it was before? No? You mean to say that it is warmer? Touch the saw. That is warmer, too. Very good. Here are your iron and your hammer. Will your Majesty touch them? You see they are cold enough. Now, my friend, favor us with a little more of that lively pounding which you say your friend Force died to do. How are your iron and hammer? I declare!—feel, your Majesty,—they are both warm. Now for the pistol. Here is a target,—but stop! feel the bullet. It is cold, of course. Fire away! Very good. You, or your friend Force, hit the target fairly; but the bullet! feel it, Mr. Traveller. Your Majesty perceives that it is quite hot,—this bullet which was cold a moment ago!”

“What if it is?” growled the traveller.

My Lord High Fiddlestick put his hands in the pockets of his green satin gown, and laughed.

“Ah, Mr. Traveller, you have not learned yet all the tricks of your friend Force. Just now he pounded a cold bit of iron with a cold hammer. Then he was gone, nowhere to be seen,—dead, you said! but you found Heat in the iron and the hammer. You sawed a cold piece of wood with a cold saw. That done, whisk! Force was lost; but there was Heat in the wood and saw. You fired your cold bullet at a cold target. Off went Force, but there was Heat again in the bullet. Whenever you lose Force you find Heat. What does that mean? You say that Force is sometimes a giant. Did it ever occur to you that he may be a giant with two heads under his hood? Let us follow this giant a little farther. He is pulling a train at the rate of thirty miles an hour. You put on the brakes, the train stops. Force is gone from the engine, but what do you find at the wheels, where the brake rubbed on them? Why, so much heat that you see fire and sparks; and the engine-driver sends a man to rub grease on the wheels of the train. Why? Because, if the wheels turn around with difficulty, the engine cannot pull the train so fast; Force, who should give all his attention to urge the engine, must give a part of his strength to the wheels; and just as much as he gives to the wheels, just so much is lost to the engine.”

“As if every school-boy did not know that!” growled the little traveller.

“Wait a minute,” said my Lord High Fiddlestick. “You say every school-boy knows that; but, when Force goes to the wheels, what shape does he take? He is there, turning the wheels in spite of themselves, and the engine is missing him, and these ungreased wheels show that he is there. How? By their heat. You miss Force from the engine. The last time he was seen, he was going to the ungreased wheels. You go to the wheels. You see no Force there, but a stranger; but if it is the giant Force that you have lost from the engine, this stranger will be a giant; if Force is at his pygmy tricks, the stranger will be a dwarf; and in either case he will tell you his name is Heat. While you are staring at him, you observe something familiar about him, and you say, ‘Pray, Mr. Heat, have I not seen you before, somewhere about the engine? You are the fireman, perhaps!’ ‘Exactly,’ answers Heat, ‘I was in the fire under the boiler.’ Under the boiler! Why, that is where our lost Force came from. Put it all together. You put Heat under the boiler, and Force comes out, and pulls the train. You miss Force, and, when you go to look for him, you find Heat in his place. Is it not reasonable, good Mr. Traveller, to think that, as Heat can turn into Force, Force can turn back into Heat again?”

“Your Royal Highness,” cried the little traveller, jumping up in a great rage, “I hope your Royal Highness won’t listen to such stuff as this. Heat a person, indeed! Heat is a fluid, and it is called caloric. I see my Lord High Fiddlestick is laughing, but he won’t laugh long. Here is the dictionary, and the word in it to prove what I say; and the ungreased wheels were hot because they turned so hard that some of their caloric was squeezed out of them; and when the hammer came down hard on the iron, some of the caloric was squeezed out of that, and all the old philosophers say so; and if you want us to believe that Force is not burned in the fire, and blown off from the engine, and crushed under the wheels, but is turned into Heat, you must make us swallow the dictionary and the old philosophers first.”

“I see I must tell you a little story,” answered my Lord High Fiddlestick, gently. “As my friend Count Rumford and your friend Force were one day boring a cannon, Count Rumford tried to pick up some of the brass chips that Force had just cut off, and discovered that they were hotter than boiling water. Brass is not generally hotter than boiling water. Before we go farther, perhaps you will tell us, Mr. Traveller, what had happened to these chips.”

“Why, the boring had squeezed so much caloric fluid into these chips,” answered the traveller.

“Then, of course,” said my Lord High Fiddlestick, “if the brass chips held so much more heat-fluid than they ever held before, they must be altered in some way. If you are going to put, say, a quart of heat-fluid in chips that only held a pint before, you must alter your chips. But Count Rumford found, that the chips were not altered; that is, if you are right, Mr. Traveller, a pint could hold a quart; and he thought that was tougher to swallow than the old philosophers. So he took a hollow tube of brass, called a cylinder. In it he put a flat piece of hard steel. The steel was almost as large as the cylinder, so that it could just turn around the steel. He put the cylinder in a box filled with water. A horse was made to turn the cylinder round and round. The piece of steel rubbed hard all the time on the bottom of the brass cylinder. The brass grew warm, and the water grew warm. Count Rumford and a great many people stood watching it curiously. The cylinder turned and turned, all the time growing hotter. The water all the time grew hotter, too; and, at the end of two hours and a half, the water was so hot that it boiled. Now, Mr. Traveller, what makes water boil?”

“Heat,” answered the little man, sulkily.

“Well, there was no Heat here,” cried my Lord High Fiddlestick,—“only Force; and Force made the water boil. Own up, Mr. Traveller. It begins to look as if Heat and Force were the same person.”

“I shall not own anything of the sort,” answered the little man. “Pray, my Lord High Fiddlestick,” catching up the hammer and bringing it down hard on the iron, “how did Force turn into Heat then?”

“This iron,” said my Lord, “is made of what we call atoms,—tiny particles, too small to be seen separately.”

“Bosh!” snorted the traveller.

“These atoms,” said the Lord High Fiddlestick, “are held fast together by a liking they have for each other,—an attraction that we call cohesion. Force strikes this iron with the weight of the hammer. He jars the iron; he jars, he stirs, the atoms;—they can stir, although their band of cohesion holds them so close that they look as if they were stuck tight together. The hammer is down. You would say, Force is dead. I say, he has gone in among those atoms; he is carrying on the stir and jar from one atom to the other. “Stop!” says Cohesion, trying to hold them fast. “Go on!” cries Force. The atoms of iron cannot get away from one another, but they can move. Force makes them move and struggle. When you struggle, you get warm. When the atoms of iron struggle, they make what my friend, Lord Bacon, calls the fire and fury of Heat. They actually get farther away from each other; and this is why philosophers will tell you that heat makes a body larger. This hard, solid iron is actually a little larger than when it was cool, because the atoms have succeeded in getting farther from each other. Now, all the King’s horses, and all the King’s men, if you could set them to tug on each side of this little bit of iron, have not strength to do that. It required a great force, stronger than all the King’s horses and men. But who did pull the atoms? Heat. Then Heat is Force, or perhaps I should say motion; for, when we struck this iron with the hammer, and it became warmer, what had happened really? Why, the motion of the arm and hammer that struck it went in among the atoms of iron, and they moved and pulled a little away from each other. What we call Heat was really their motion; and so—”

“Stuff!” interrupted the traveller. “When a man comes down to atoms, he must be hard up for proofs.”

“Comes down to atoms!” exclaimed my Lord High Fiddlestick, opening a window. Outside, the sill was covered with fresh-fallen snow, which my Lord High Fiddlestick scraped up in his hands.

“Can anything be softer than this snow?” he asked. “Well, the pull and strain that brought the water-atoms together to make as much snow as I hold here would pitch a ton of stone over a precipice two thousand feet deep. Come down to atoms, indeed! Pray, let me show you a few of the things that atoms can do.”

“My Lord,” interrupted the King, in a hurry, “I observe that dinner is ready, and the beefsteak on the table. If the steak gets cold, according to your philosophy, it will grow smaller; and then, perhaps, there will not be enough to go round. Let us go to dinner, and hear what the atoms can do another time, my Lord High Fiddlestick!”

Louise E. Chollet.

Do you know Mother Nature? She it is to whom God has given the care of the earth, and all that grows in or upon it, just as he has given to your mother the care of her family of boys and girls.

You may think that Mother Nature, like the famous “old woman who lived in the shoe,” has so many children that she doesn’t know what to do; but you will know better when you become acquainted with her, and learn how strong she is, and how active; how she can really be in fifty places at once, taking care of a sick tree, or a baby flower just born; and, at the same time, building underground palaces, guiding the steps of little travellers setting out on long journeys, and sweeping, dusting, and arranging her great house, the earth. And all the while, in the midst of her patient and never-ending work, she will tell us the most charming and marvellous stories,—of ages ago when she was young, or of the treasures that lie hidden in the most distant and secret closets of her palace,—just such stories as you all like so well to hear your mother tell, when you gather round her in the twilight.

A few of these stories which she has told to me, I am about to tell you, beginning with that one whose title is printed at the beginning of this article.

I know a little Scotch girl, she lives among the Highlands. Her home is hardly more than a hut; her food, broth and bread. Her father keeps sheep on the hillsides, and, instead of wearing a coat, wraps himself in his plaid for protection from the cold winds that drive before them great clouds of mist and snow among the mountains.

As for Jeanie herself (you must be careful to spell her name with an ea, for that is Scotch fashion), her yellow hair is bound about with a little snood; her face is browned by exposure to the weather; and her hands are hardened by work,—for she helps her mother to cook and sew, to spin and weave.

One treasure little Jeanie has, which many a lady would be proud to wear. It is a necklace of amber beads,—“lamour beads,” old Elsie calls them; that is the name they went by when she was young.

You have perhaps seen amber, and know its rich, sunshiny color, and its fragrance when rubbed; and do you also know that rubbing will make amber attract things somewhat as a magnet does? Jeanie’s beads had all these properties, but some others besides, wonderful and lovely; and it is of those particularly that I wish to tell you. Each bead has inside of it some tiny thing, encased as if it had grown in the amber, and Jeanie is never tired of looking at and wondering about them. Here is one with a delicate bit of ferny moss shut up, as it were, in a globe of yellow light. In another is the tiniest fly, his little wings outspread and raised for flight. Again, she can show us a bee lodged in one bead that looks like solid honey, and a little bright-winged beetle in another. This one holds two slender pine needles lying across each other, and here we see a single scale of a pine cone, while yet another shows an atom of an acorn-cup, fit for a fairy’s use. I wish you could see the beads, for I cannot tell you the half of their beauty. Now, where do you suppose they came from; and how did little Scotch Jeanie come into possession of such a treasure?

All she knows about it is, that her grandfather, old Kenneth, who cowers now all day in the chimney-corner, once, years ago, when he was a young lad, went down upon the sea-shore, after a great storm, hoping to help save something from the wreck of the “Goshawk,” that had gone ashore during the night; and there, among the slippery sea-weeds, his foot had accidentally uncovered a clear, shining lump of amber, in which all these little creatures were embedded. Now, Kenneth loved a pretty Highland lass, and, when she promised to be his bride, he brought her a necklace of amber beads. He had carved them himself out of his lump of amber, working carefully to save in each bead the prettiest insect or moss; and thinking, while he toiled hour after hour, of the delight with which he should see his bride wear them. That bride was Jeanie’s grandmother; and when she died last year, she said, “Let little Jeanie have my lamour beads, and keep them as long as she lives.”

But what puzzled Jeanie was, how the amber came to be on the sea-shore; and, most of all, how the bees and mosses came inside of it. Should you like to know? If you would, that is one of Mother Nature’s stories, and she will gladly tell it. Hear what she answers to our questions:—

“I remember a time, long, long before you were born,—long, even, before any men were living upon the earth; then these Scotch Highlands, as you call them, where little Jeanie lives, were covered with forests,—there were oaks, poplars, beeches, and pines; and among them one kind of pine, tall and stately, from which a shining yellow gum flowed, just as you have seen little drops of sticky gum exude from our own pine-trees. This beautiful yellow gum was fragrant, and, as the thousands of little insects fluttered about it in the warm sunshine, they were attracted by its pleasant odor,—perhaps, too, by its taste,—and, once alighted upon it, they stuck fast, and could not get away, while the great yellow drops, oozing out, surrounded and at last covered them entirely. So, too, wind-blown bits of moss, leaves, acorns, cones, and little sticks, were soon securely embedded in the fast-flowing gum; and, as time went by, it hardened and hardened more and more. And this is amber.”

“That is well told, Mother Nature, but it does not explain how Kenneth’s lump of amber came to be on the sea-shore.”

“Wait, then, for the second part of the story.

“Did you ever hear that, in those very old times, the land sometimes sank down into the sea, even so deep that the water covered the very mountain-tops; and then, after ages, it was slowly lifted up again, to sink indeed, perhaps, yet again and again?

“You can hardly believe it, yet I myself was there to see, and I remember well when the great forests of the north of Scotland—the oaks, the poplars, and the amber-pines—were lowered into the deep sea. There, lying at the bottom of the ocean, the wood and the gum hardened like stone, and only the great storms can disturb them as they lie half buried in the sand. It was one of those great storms that brought Kenneth’s lump of amber to land.”

If we could only walk on the bottom of the sea, what treasures we might find!

Author of “The Seven Little Sisters.”

There was to be a picnic at the Grove, to which all the young folks in the Vale were going.

“There’ll be music by the band, and dancing on the green, and swinging in the swings under the trees; we’re to carry our own luncheons, and have such a nice time!” said Emma Reverdy. “And you must certainly go, Father Brighthopes! We can’t do without you. We are going over early in the morning, to be gone all day.”

“All day!” repeated the old clergyman, pleasantly. “You forget, my child, that I am no longer young. Much as I love the company of children, I fear I should become very weary before night.”

“I have thought of that too,” cried Emma; “and I’ll tell you what we can do. If you don’t like to go over when the teams go, we can go in the boat, and I am sure that will be a great deal pleasanter. The picnic is to be just across the river from Mr. Dobson’s farm; there is a good boat at the Grove, and some of the boys can bring it over to the bend for us. That will save you a long ride around the dusty roads and over the old bridge. That’s the way a lot of us went last year, and it was so nice!”

“Well, we will wait till the day comes, and then see what arrangements have been made, and what the weather is,” said Father Brighthopes, in a way that signified to the delighted Emma that he would go.