* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine Vol XL No. 3 March 1852

Date of first publication: 1852

Author: George R. Graham (1813-1894)

Date first posted: May 22, 2019

Date last updated: May 22, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190535

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. March, 1852. No. 3.

Contents

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| Granny’s Fairy Story | |

| Spectral Illusions | |

| Campaigning Stories (continued) | |

| Law and Lawyers | |

| A Life of Vicissitudes (continued) | |

| Milton | |

| The Miser and His Daughter | |

| The Lost Deed (continued) | |

| Beauty’s Retreat | |

| Death | |

| The Philadelphia Art-Union | |

| Review of New Books | |

| Graham’s Small-Talk | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

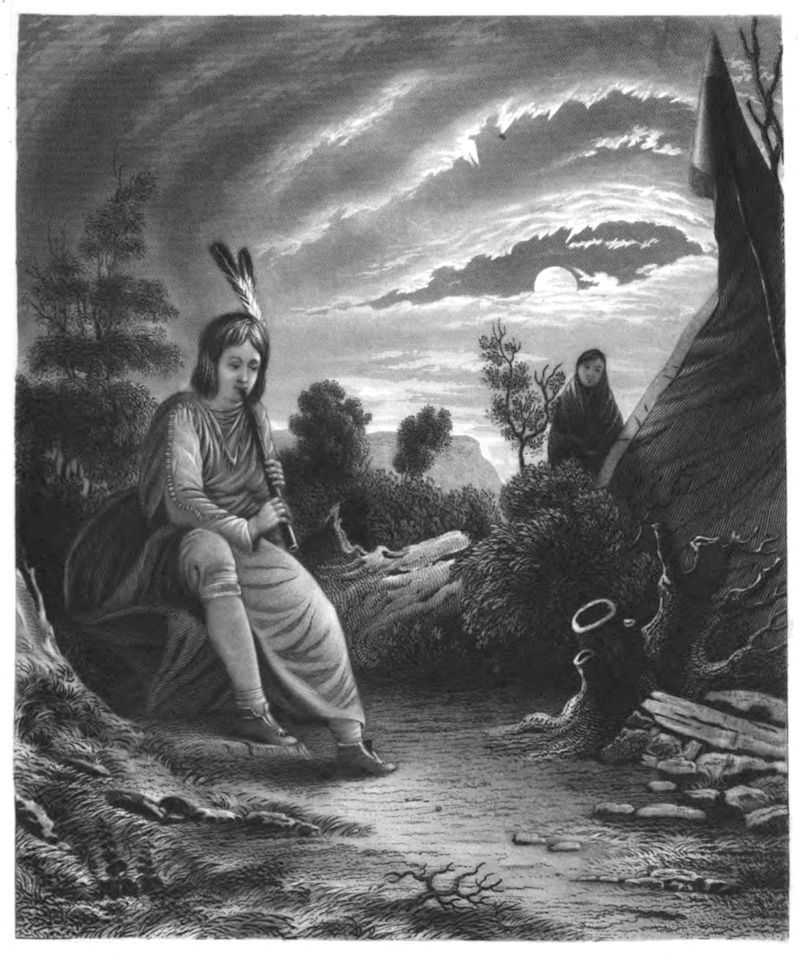

A DACOTAH INDIAN COURTING.

Drawn by S. Eastman U.S.A. and Engraved expressly for Graham’s Magazine by F. Humphry.

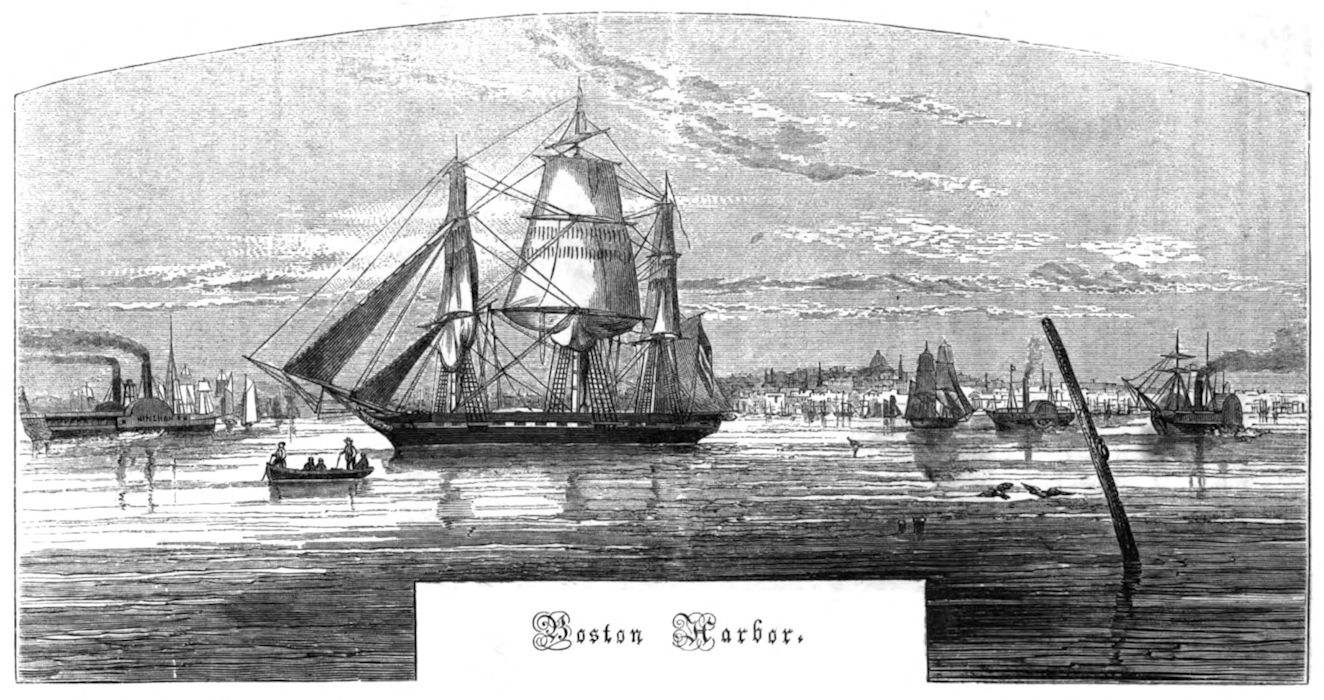

Boston Harbor.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. PHILADELPHIA, MARCH, 1852. No. 3.

(FOR THE YOUNG FOLKS.)

There was a young woman so kind and sweet-tempered that every person loved her. Among the rest, there was an old witch who lived near where she dwelt, and with whom she was a great favorite. One day this old witch told her she had a nice present to give her. “See,” she said, “here is a barley-corn, which, however, is by no means of the same sort as those which grow in the farmer’s field, or those we give to the fowls. Now you must plant this in a flower-pot, and then take care and see what happens.”

“Thank you a thousand times,” said the young woman. And, thereupon, she went straight home, and planted the barley-corn the witch had given her in a flower-pot. Immediately there grew out of it a large, handsome flower, but its leaves were all shut close as if they were buds.

“That is a most beautiful flower!” said the woman, while she bent down to kiss its red and yellow leaves; but scarcely had her lips pressed the flower, than it gave forth a loud sound and opened its cup. And now the woman was able to see that it was a regular tulip, and in the midst of the cup, down at the bottom, there sat a small and most lovely little maiden; her height was about one inch, and on that account the woman named her Ellise.

She made the little thing a cradle out of a walnut-shell, gave her a blue violet-leaf for a mattress, and a rose-leaf for a coverlet. In this cradle Ellise slept at night time, and during the day she played upon the table. The woman had set a plate filled with water upon the table, which she surrounded with flowers, and the flower-stalks all rested on the edge of the water; on the water floated a large tulip-leaf, and upon the tulip-leaf sat the little Ellise, and sailed from one side of the plate to the other; and for this she used two white horse-hairs for oars. The whole effect was very charming, and Ellise could sing too, but with such a delicate little voice as we have never heard here.

One night as she lay in her bed, an ugly toad hopped into her through the broken window pane. It was a large and very hideous toad; and it sprang at once upon the table, where Ellise lay asleep under the rose-leaf.

“That would be, now, a nice little wife for my son,” said the toad, and seized, as she said it, the walnut-shell in her mouth, and hopped with it out through the window into the garden again.

Through the garden flowed a broad stream, but its banks were marshy, and among the marshes lived the toad and her son. Ha! how hideous the son was too; exactly like his mother he was, and all that he could say, when he saw the sweet little maiden in the walnut-shell, was “Koax! koax! breckke ke!”

“Don’t talk so loud,” said the old one to him, “else you’ll awake her, and then she might easily run away from us, for she is lighter than swans’-down. We will set her upon a large plant in the stream; that will be a whole island for her, and then she cannot run away from us; while we, down in the mud, will build the house for you two to live in.”

In the stream there were many large plants, which all seemed as if they floated on the water; the most distant one was, at the same time, the largest, and thither swam the old toad and set down the walnut-shell, with the little maiden upon it.

Early on the following morning the little Ellise awoke, and when she looked about her and saw where she was, that her new dwelling-place was surrounded on all sides by water, and that there remained no possible way for her to reach land again, she began to weep most bitterly.

Meanwhile the old toad sat in the mud and adorned the building with reeds and yellow flowers, that it might be quite grand for her future daughter-in-law, and then, in company with her hideous son, swam to the little leaf-island where Ellise lay.

She now wanted to fetch her pretty little bed, that it might at once be placed in the new chamber, before Ellise herself was brought there. The old toad bent herself courteously before her in the water, while she presented her son in these words—“You see here my son, who is to be your husband, and you two shall live together charmingly down in the mud.”

“Koax! koax! breckke-ke!” was all that the bridegroom could find to say.

And, therewith, they both seized upon the beautiful little bed, and swam away with it; while Ellise sat alone upon the leaf and cried very much, for she did not like at all to live with the frightful toad, much less have her odious son for her husband. Now the little fishes which swam about under the water, had seen the toad, and heard, moreover, perfectly well all that she said; they, therefore, raised their heads above water, that they might have a look at the beautiful little creature. No sooner had they seen her than they were, one and all, quite moved by her beauty; and it seemed to them very hard that such a sweet maiden should become the prey of an ugly toad. They assembled themselves, therefore, round about the green stalk from which grew the leaf whereon Ellise sat, and gnawed it with their teeth until it came in two, and then away floated Ellise and the leaf far, far away, where the toad could come no more.

And so sailed the little maiden by towns and villages, and when the birds upon the trees beheld her, they sang out—“Oh, what a lovely young girl.” But away, away floated the leaf always further and further. Ellise made quite a foreign journey upon it.

For some time a small white butterfly had hovered over her, and at last he sat himself down on her leaf, because he was very much pleased with Ellise, and she, too, was very glad of the visit, for now the toad could not come near her, and the country through which she traveled was so beautiful. The sun shone so bright upon the water that it glittered like gold. And now the idea occurred to her to loosen her girdle, bind one end of it to the butterfly, the other on to the leaf; she did this and then she flew on much faster, and saw much more of the world than she would have done.

But, at last, there came by a cock-chafer, who seized her with his long claws round her slender waist, and flew away with her to a tree, while on swam the leaf, and the butterfly was obliged to follow, for he could not come loose, so fast and firm had Ellise bound him.

Ah! how terrified was poor Ellise when the cock-chafer carried her off to the tree. But her sorrow over the little butterfly was quite as great, for she knew he must certainly perish, unless by some good accident he should chance to free himself from the green leaf. But all this made no impression upon the cock-chafer, who set her upon a large leaf, gave her some honey to eat, and told her she was very charming, although not a bit like a chafer. And now appeared all the other cock-chafers who dwelt upon this tree, who waited upon Ellise, and examined her from top to toe; while the young lady-chafers turned up their feelers and said, “She has only two legs! how very wretched that looks!” and added they, “she has no feelers whatever, and is as thin in the body as a human being! Ah! it’s really hideous!” and all the young lady-cock-chafers cried out, “Ah! it’s perfectly hideous!” And yet Ellise was so charming! and so felt the cock-chafer; but at last, because all the lady-chafers thought her ugly he began to think so too, and resolved he would have nothing more to do with her; “she might go,” he said, “wherever she liked;” and with these words he flew with her to the ground, and set her upon a daisy. And now the poor little thing wept bitterly, to find herself so hideous that not even a cock-chafer would have any thing to do with her. But, notwithstanding this decisive opinion of the young lady-cock-chafers, Ellise was the loveliest, most elegant little creature in the world, as delicate and beautiful as a young rose-leaf.

The whole summer through the poor little maiden lived alone in the great forest; and she wove herself a bed out of fine grass, and hung it up to rock beneath a creeper, that it might not be blown away by the wind and rain; she plucked herself sweets out of the flowers, for food, and drank of the fresh dew, that fell every morning upon the grass. And so the summer and the autumn passed away. All the birds which had sung so sweetly to Ellise, left her and went away, the trees lost all their green, the flowers withered, and the great creeper which, until now, had been her shelter, shriveled away to a bare yellow stalk. The poor little thing shivered with cold, for her clothes were now worn out, and her form was so tender and delicate that she certainly would perish with cold. It began also to snow, and every flake which touched her, was to her what a great heapfull would be to us, for her whole body was only one inch long.

Close beside the forest in which Ellise lay, there was a corn-field, but the corn had long since been reaped, and now, only the dry stubble rose above the earth; yet, for Ellise was this a great forest, and hither she came. So she reached the house of a field-mouse, which was formed of a little hole under the stubble. Here dwelt the field-mouse warm and comfortable, with her store-room full of food for the winter, and near at hand a pretty kitchen and eating-room. Poor Ellise stepped up to the door and begged for a little grain of barley, for she had tasted nothing for the whole day.

“You poor little wretch!” said the field-mouse, who was very kind-hearted, “come in to my warm room and eat something.” And when now she was much pleased with Ellise, she added, “you may if you like, spend the winter here with me; but you must keep my house clean and neat, and tell me stories, for I am very fond of hearing stories.”

Ellise did as the field-mouse wished, and, as a reward for her trouble, was made comfortable with her.

“Now we shall have a visit,” said the field-mouse to her one day. “My neighbor is accustomed to pay me a visit every week. He is much richer than I am, for he has several beautiful rooms, and wears the most costly velvet coat. Now if you could only have him for your husband, you would be nicely provided for, but he does not see very sharply, that’s one thing. Only you must tell him all the best stories you can think of.”

But Ellise would hear nothing of it, for she could not endure the neighbor, for he was nothing more nor less than a mole. He came, as was expected, to pay his respects to the field-mouse, and wore his handsome velvet coat as usual. The field-mouse said he was very rich, and very well informed, and that his house was twenty times larger than hers. Well informed he might be, but he could not endure the sunshine or the flowers, and spoke contemptuously of both one and the other, although he had never seen either. Ellise was obliged to sing before him, and she sang the two songs—“Chafers fly! the sun is shining!” and “The priest goes to the field!” Then the mole became very much in love with her because of her beautiful voice, but he took good care not to show it, for he was a cautious, sensible fellow.

Very lately he had made a long passage from his dwelling to that of his neighbor, and he gave permission to Ellise and the field-mouse to go in it as often as they pleased; yet he begged of them not to be startled at the dead bird which lay at the entrance. It was certainly a bird lately dead, for all the feathers were still upon him, it seemed to have been frozen exactly there where the mole had made the entrance of his passage.

Mr. Neighbor now took a piece of tinder in his mouth, and stepped on before the ladies, that he might lighten the way for them, and as he came to the place where the dead bird lay, he struck with his snout on the ground, so that the earth rolled away, and a large opening appeared through which the daylight shone in. And now, Ellise could see the dead bird quite well—it was a swallow. The pretty wings were pressed against the body, and the feet and head covered over by the feathers. “The poor bird has died of cold,” said Ellise, and it grieved her very much for the dear little animal, for she was very fond of birds, for they sang to her all through the summer. But the mole kicked him with his foot and said, “The fine fellow has done with his twittering now! It must indeed be dreadful to be born a bird! Heaven be praised that none of my children have turned out birds! Stupid things! they have nothing in the wide world but their quivit, and when the winter comes, die they must!”

“Yes,” returned the field-mouse, “you, a thoughtful and reflecting man, may well say that! What indeed has a bird beyond its twitter when the winter comes? he must perforce hunger and freeze!”

Ellise was silent; but when the others had turned their backs upon the bird, she raised up its feathers gently, and kissed its closed eyes.

“Perhaps it was you,” she said softly, “who sang me such beautiful songs! How often you have made me happy and merry, you dear bird!”

And now the mole stopped up the opening again through which the daylight fell, and then accompanied the young ladies home. But Ellise could not sleep the whole night long. She got up, therefore, wove a covering of hay, carried it away to the dead bird, and covered him with it on all sides, in order that he might rest warmer upon the cold ground. “Farewell, you sweet, pretty little bird!” said she. “Farewell! and let me thank you a thousand times for your friendly song this summer, when the trees were all green, and the sun shone down so warm upon us all!” And therewith she laid her little head on the bird’s breast, but started back, for it seemed to her as if something moved within. It was the bird’s heart; he was not dead, but benumbed, and now he came again to life as the warmth penetrated to him.

In the autumn, the swallows fly away to warmer countries; and when a weak one is among them, and the cold freezes him, he falls upon the ground, and lies there as if dead, until the cold snow covers him.

Ellise was frightened at first, when the bird raised itself, for to her he was a great big giant, but she soon collected herself again, pressed the hay covering close round the exhausted little animal, and then went to fetch the curled mint-leaves which served for her own covering, that she might lay it over his head.

The following night she slipped away to the bird again, whom she found now quite revived, but yet so very weak, that he could only open his eyes now and then, to look at Ellise, who lighted up his face with a little piece of tinder.

“I thank you a thousand times, you lovely little child,” said the sick swallow, “I am now so thoroughly warmed through, that I shall soon gain my strength again, and shall be able to fly out in the warm sunshine.”

“Oh! it is a great deal too cold out there,” returned Ellise, “it snows and freezes so hard! only just stay now in your warm bed, and I will take such care of you!”

She brought the bird some water to drink out of a leaf, and then he related to her how he had so hurt his wing against a thorny bush that he could not fly away to the warm countries with his comrades, and at last had fallen exhausted to the ground, where all consciousness left him.

The little swallow remained here the whole winter, and Ellise attended to him, and became every day more and more fond of him; yet she said nothing at all about it to the mole or the field-mouse, for she knew well enough already that neither of them could bear the poor bird.

As soon, however, as the summer came, and the warm sunbeams penetrated the earth, the swallow said good-bye to Ellise, who had now opened the hole in the ground, through which the mole let the light fall in. The sun shone so kindly, that the swallow turned and asked Ellise, his dear little nurse, whether she would not fly away with him. She could sit very nicely upon the swallow’s back, and then they would go away together to the green forest. But Ellise thought it would grieve the good field-mouse if she went away secretly, and therefore she was obliged to refuse the bird’s kind offer.

“Then, once more farewell, you kind, good maiden,” said the swallow, and therewith he flew out into the sunshine. Ellise looked sorrowfully after him, and the tears rushed into her eyes, for she was very fond of the good bird.

“Quivit! quivit!” sang the swallow, and away he flew to the forest.

And now Ellise was very mournful, for she hardly ever left her dark hole. The corn grew up far above her head, and formed quite a thick wood round the house of the field-mouse.

“Now you can spend the summer in working at your wedding-clothes,” said the field-mouse, for the neighbor, the wearisome mole, had at last really proposed for Ellise. “I will give you every thing you want, that you may have all things comfortable about you, when you are the mole’s wife.”

And now Ellise was obliged to sit all day long busy at her clothes, and the field-mouse took four clever spiders into her service, and kept them weaving day and night. Every evening came the mole to pay his visit, and every evening he expressed his wish that the summer would soon come to an end, and the heat cease, for then, when the winter was here, his wedding should take place. But Ellise was not at all happy to hear this, for she could hardly bear even to look upon the ugly mole, for all his expensive velvet coat. Every evening and every morning she went out at the door, and when the wind blew the ears of corn apart, and she could look upon the blue heaven, she saw it was so beautiful out in the open air, that she wished she could only see the dear swallow once more; but the swallow never came; he preferred rejoicing himself in the warm sunbeams in the green woods.

By the time autumn came, Ellise had prepared all her wedding-garments.

“In four weeks your wedding will take place,” said the field-mouse to her; but Ellise wept, and said she did not want to have the stupid mole for a husband.

“Fiddle-de-dee,” answered the field-mouse—“Come, don’t be obstinate, or I shall be obliged to bite you with my sharp teeth. Isn’t he a good husband that you’re going to have? Why, even the queen hasn’t such a fine velvet coat to show as he has! His kitchen and his cellar are well-stocked, and you ought rather to thank Providence for providing so well for you!”

So the wedding was to be! Already was the mole come to fetch away Ellise, who, from henceforth, was to live always with him. Deep under the earth, where no sunbeam could ever come! The little maiden was very unhappy, that she must take her farewell of the friendly sun, which at all events she saw at the door of the field-mouse’s house.

“Farewell, thou beloved sun!” said she, and raised her hands toward heaven, while she advanced a few steps from the door; for already was the corn again reaped, and she stood once more among the stubble in the field. “Adieu, adieu!” she repeated, and threw her arms round a flower that stood near her, “Greet the little swallow for me, when you see him again,” added she.

“Quivit! quivit!” echoed near her in the same moment, and, as Ellise raised her eyes, she saw her well-known little swallow fly past. As soon as the swallow perceived Ellise, he too, became quite joyful, and hastened at once to his kind nurse; and she told him how unwilling she was to have the ugly mole for her husband, and that she must go down deep into the earth, where neither sun nor moon could ever look upon her, and with these words she burst into tears.

“See now,” said the swallow, “the cold winter is coming again, and I am flying away to the warm countries, will you come and travel with me? I will carry you gladly on my back. You need only to bind yourself fast with your girdle, so we can fly away far from the disagreeable mole, and his dark house, far over mountains and valleys, to the beautiful countries, where the sun shines much warmer than it does here; where there is summer always, and always beautiful flowers blooming. Come, be comforted, and fly away with me, dear, kind Ellise, who saved my life when I lay frozen in the earth.”

“Yes, I will go with you,” cried Ellise joyfully. She mounted on the back of the swallow, set her feet upon his out-spread wings, bound herself with her girdle to a strong feather, and flew off with the swallow through the air, over woods and lakes, valleys and mountains. Very often Ellise suffered from the cold when they went over icy glaciers and snowy rocks; but then she concealed herself under the wings and among the feathers of the bird, and merely put out her head to gaze and wonder at all the glorious things around her.

At last, too, they came into the warm countries. The sun shines there clearer than with us; the heavens were a great deal higher, and on the walls and in the hedges grew the most beautiful blue and green grapes. In the woods hung ripe citrons and oranges, and the air was full of the scent of thyme and myrtle, while beautiful children ran in the roads playing with the gayest colored butterflies. But farther and farther flew the swallow, and below them it became more and more beautiful. By the side of a lake, beneath graceful acacias, there rose an ancient marble palace, the vines clung around the pillars, while above them, on their summits, hung many a swallow’s nest. Into one of these nests the bird carried Ellise.

“Here is my house,” said he, “but look you for one of the loveliest flowers, which grow down there, for your home, and I will carry you there, and you shall have every thing you can possibly want.”

“That would be glorious indeed!” said Ellise, and she clapped her hands together for very joy.

Upon the earth there lay a large white marble pillar, which had been thrown down, and was broken into three pieces, but between its ruins there grew the very fairest flowers, all white, the loveliest you would ever wish to see.

The swallow flew with Ellise to one of these flowers, and set her down upon a broad leaf; but how astonished was Ellise when she saw that a wee little man sat in this flower, who was as fine and transparent as glass. He wore a graceful little crown upon his head, and had beautiful wings on his shoulders; and withal he was not a bit bigger than Ellise herself. He was the angel of this flower. In every flower dwell a pair of such like little men and women, but this was the king of all the flower angels.

“Heavens! how handsome this king is,” whispered Ellise into the ear of the swallow. The little prince was somewhat startled by the arrival of the large bird; but when he saw Ellise, he became instantly in love with her; for she was the most charming little maiden that he had ever seen. So he took off his golden crown, set it upon Ellise, and asked what was her name, and whether she would be his wife; if so, she should be queen over all the other flowers—ah! this was a very different husband to the son of the hideous toad, and the heavy, stupid mole, with his velvet coat! So Ellise said yes, to the beautiful prince; and now, from all the other flowers, appeared either a gentleman or a lady, all wonderfully elegant and beautiful, to bring presents to Ellise. The best presents offered to her was a pair of exquisite white wings, which were immediately fastened on her; and now she could fly from flower to flower.

And now the joy was universal. The little swallow sat above in his nest, and sang as well as he possibly could, though at the same time he was sorely grieved, for he was so fond of Ellise that he wanted never to part from her again.

“You shall not be called Ellise any more,” said the flower-angel, “for it is not at all a pretty name, and you are so pretty! But from this moment you shall be called Maja.”

“Farewell! Farewell!” cried the little swallow, and away he flew again, out of the warm land, far, far away, to the little Denmark, where he had his summer nest over the window of the good man, who knows how to tell stories, that he might sing his Quivit! Quivit! before him. And it is from him, the little swallow, that Granny learnt all this wonderful history.

Those eyes, they are so bright and blue,

They seem as if just bathed in dew,

And if they but reflect aright,

Thy heart must joyous be and bright,

Where cherished images must dwell,

Oh! number mine with thine, ma Belle.

Come listen, ladies! listen, knights!

Ye men of arms and glory!

Ye who have done right noble deeds,

Aye love the poet’s story.

As minstrels love the warriors bold,

And joyfully sing their fame,

O’er warriors’ hearts the poet’s tale

Shall peaceful triumphs claim.

From distant lands Arion came,

From wandering far and long,

With gifts and gold—for princely hearts

Denied no gift to song.

The song that cheered the saddest wo,

The tale that sings of youth,

Flowing sweetly, flowing on,

Through labyrinths of truth.

Rich tributes had been poured on him,

Arion far renowned,

And fair and gentle loved the rule,

Of one by nature crowned.

But what can gifts and what can gold,

Or Fame’s loud peal avail,

Wandering from his childhood’s home,

His own Corinthian vale?

WRITTEN ON ST. VALENTINE’S DAY.

———

BY GEO. D. PRENTICE.

———

Fair lady, on this day of love,

My spirit, like a timid dove,

Exulting flies to thee for rest,

And nestles on thy gentle breast.

Thou seemest of my life a part,

A haunting presence in my heart,

A glory in my day-dreams bright,

An angel in my dreams at night,

Like yon pure bow of airy birth

A vision more of heaven than earth.

Soft, lovely, beautiful, divine—

But wilt thou be my Valentine?

I’ve looked into thy deep eyes oft,

Where heaven seemed sleeping blue and soft.

I’ve gazed on all thy beauty long,

I’ve heard thy witching voice of song,

I’ve listened when thy deep words came

As if thy lips were touched with flame,

I’ve marked thee smile, I’ve marked thee weep.

I’ve blest thee in the hour of sleep,

I’ve felt thy heart beat wild to hear

Love’s cadence stealing on thine ear,

And I have been supremely blest

When thou wast folded to my breast,

And thy dear lips were pressed to mine—

But wilt thou be my Valentine?

Dove of my spirit! gentle dove,

That bring’st the olive-bough of love

To me when waters vast and dark

Are tossing wild beneath my bark,

Sweet queller of my bosom’s strife,

Blest haunter of each thought of life.

Dear brightner of my soul’s eclipse,

Sultana of my longing lips,

Queen-fairy of my fairy dreams,

Young Naiad of my soul’s deep streams,

Bright rainbow of life’s stormy day,

Lone palm-tree of my desert way,

Soft dew-drop of my heart’s one flower,

Young song-bird of my spirit’s bower,

My star when all beside is dim,

My morning prayer, my evening hymn,

My hope, my bliss, my life, my love,

My all of earth, my heaven above,

On lightning pinions wild and free,

My panting spirit flies to thee,

And worships at thy burning shrine—

But wilt thou be my Valentine?

Do you ask what the birds say? The sparrow, the dove,

The linnet, and thrush say, “I love, and I love!”

In the winter they’re silent—the wind is so strong;

What it says I don’t know, but it sings a loud song.

But green leaves and blossoms and sunny warm weather,

And singing and loving, all come back together.

But the lark is so brimful of gladness and love,

The green-fields below him, the blue sky above,

That he sings, and he sings, and forever sings he,

“I love my love, and my love loves me!”

A BALLAD OF SPAIN.

At her lattice sits Leora,

In the long and mellow June,

What time when whitely westward

Shines the round and pendent moon.

Sits she silent, sits she sadly,

With her head upon her hand,

Looking outward where the Ebro

Throws its ripples on the sand.

Never lighter blew the breezes

In the vales of Aragon,

Never smiled Hesperia’s heavens

With more lovely glories on.

Such an evening ’tis as gladdens

Cavaliers of sunny Spain—

Such an evening ’tis when maidens

Recount their loves again.

Now more restless grows Leora,

Fair Leora, gentle maid,

With sweet eyes so dark and fervent,

And each tress of nightly shade.

Heaves her bosom fast and wildly

Like a billow snowed with foam,

For there’s something boding tells her

That Almagro will not come.

Clouds are passing swiftly o’er her,

On her heart their shadows rest,

And the tear-drops from their fountains

Fall embittered to her breast.

Listens now she to the gallop

Of a steed adown the vale;

Now with hope her face is radiant,

Now with fear her cheek is pale.

But no lover rideth swiftly,

Swiftly to the trysting bower,

And Leora still is waiting

Through the long and dreary hour.

And the tears cease not to gather,

And the tears cease not to flow,

And she feels like one abandoned

On the haunted paths of wo.

Where a mountain streamlet gurgles,

From that watcher leagues away—

Where the hours amid the valleys

Listen to the waters’ play—

Faithless Almagro is breathing

Vows of deeply passioned love,

To a maiden on his bosom

In the sweetness of a dove.

And he tells her how he never

To another gave his heart,

Till her innocence is fallen

In the meshes of his art.

Till another than the midnight

Throws a darkness o’er her soul,

Leaving there a troubled fountain,

Leaving there a broken bowl.

Softly sigh the sleeping branches

On the bosom of the breeze,

Sweetly stars are gazing downward

To earth’s blue, unclouded seas:

And in fragrance dream the blossoms

Pure and taintless as before—

But heart-flowers have been gathered

That shall blossom nevermore.

Lowly westward walketh Dian,

On her watches with the night,

And the hours far have stolen

To the gateways of the light.

But, ah! wo is thee, Leora,

Though hopeless, hoping on,

Till Aurora up the Orient,

Rosy-fingered, leads the dawn.

But less wo is thee, Leora,

By thy lattice weary worn—

More’s the wo for thee, Estella,

When thou wakest at the morn.

———

BY THOMAS MILNER, M. A.

———

A series of curious and interesting phenomena, involving the apparent elevation and approach of distant objects, the production of aerial images of terrestrial forms, of double images, their inversion, and distortion into an endless variety of grotesque shapes, together with the deceptive aspect given to the desert-landscape, are comprehended in the class of optical illusions. Different varieties of this singular visual effect constitute the mirage of the French, the fata morgana of the Italians, the looming of our seamen, and the glamur of the Highlanders. It is not peculiar to any particular country, though more common in some than others, and most frequently observed near the margin of lakes and rivers, by the sea-shore, in mountain districts and on level plains. These phantoms are perfectly explicable upon optical principles, and though influenced by local combinations, they are mainly referable to one common cause, the refractive and reflective properties of the atmosphere, and inequalities of refraction arising from the intermixture of strata of air of different temperatures and densities. But such appearances in former times were really converted by the imagination of the vulgar into supernatural realities; and hence many of the goblin stories with which the world has been rife, not yet banished from the discipline to which childhood is subject,—

“As when a shepherd of the Hebrid Isles

Placed far amid the melancholy main,

(Whether it be lone fancy him beguiles,

Or that aerial beings sometimes deign

To stand, embodied, to our senses plain)

Sees on the naked hill, or valley low,

The whilst in ocean Phœbus dips his wain,

A vast assembly moving to and fro,

Then all at once in air dissolves the wondrous show.”

Pliny mentions the Scythian regions within Mount Imaus, and Pomponius Mela those of Mauritania, behind Mount Atlas, as peculiarly subject to these spectral appearances. Diodorus Siculus likewise refers to the regions of Africa, situated in the neighborhood of Cyrene, as another chosen site:—“Even,” says he, “in the severest weather, there are sometimes seen in the air certain condensed exhalations that represent the figures of all kinds of animals; occasionally they seem to be motionless, and in perfect quietude; and occasionally to be flying; while immediately afterward they themselves appear to be the pursuers, and to make other objects fly before them.” Milton might have had this passage in his eye when he penned the allusion to the same apparitions:—

“As when, to warn proud cities, war appears

Waged in the troubled sky, and armies rush

To battle in the clouds; before each van

Prick forth the airy knights, and couch their spears,

Till thickest legions close, with feats of arms

From either side of heaven the welkin rings.”

The Mirage of the Desert.

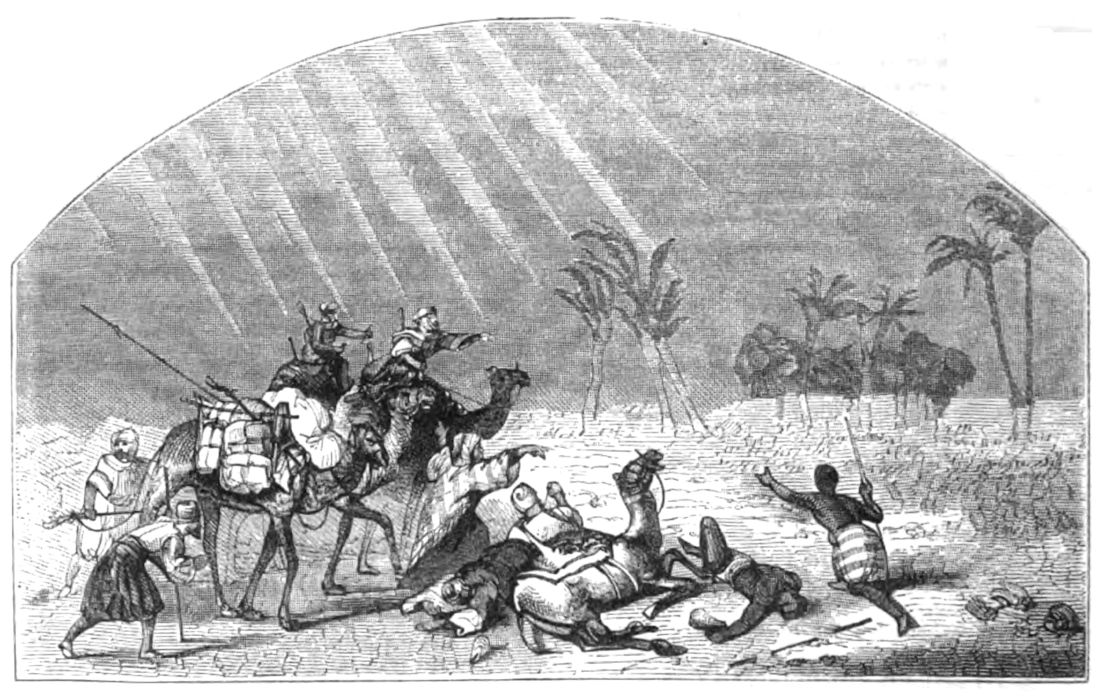

The mirage is the most familiar form of optical illusion. M. Monge, one of the French savans, who accompanied Buonaparte in his expedition to Egypt, witnessed a remarkable example. In the desert between Alexandria and Cairo, in all directions green islands appeared, surrounded by extensive lakes of pure, transparent water. Nothing could be conceived more lovely or picturesque than the landscape. In the tranquil surface of the lakes, the trees and houses with which the islands were covered were strongly reflected with vivid and varied hues, and the party hastened forward to enjoy the refreshments apparently proffered them. But when they arrived, the lake on whose bosom they floated, the trees among whose foliage they arose, and the people who stood on the shore inviting their approach, had all vanished; and nothing remained but the uniform and irksome desert of sand and sky, with a few naked huts and ragged Arabs. But for being undeceived by an actual progress to the spot, one and all would have remained firm in the conviction that these visionary trees and lakes had a real existence in the desert. M. Monge attributed the liquid expanse, tantalizing the eye with an unfaithful representation of what was earnestly desired, to an inverted image of the cerulean sky, intermixed with the ground scenery. This kind of mirage is known in Persia and Arabia by the name of Serab or miraculous water, and in the western deserts of India by that of Tehittram, a picture. It occurs as a common emblem of disappointment in the poetry of the orientals.

Atmospheric Illusion.

In the Philosophical Transactions for the year 1798, an account is given by W. Latham, Esq., F.R.S., of an instance of lateral refraction observed by him, by which the coast of Picardy, with its more prominent objects, was brought apparently close to that of Hastings. On July the 26th, about five in the afternoon, while sitting in his dining-room, near the sea-shore, attention was excited by a crowd of people running down to the beach. Upon inquiring the reason, it appeared that the coast of France was plainly to be distinguished with the naked eye. Upon proceeding to the shore, he found, that without the assistance of a telescope, he could distinctly see the cliffs across the Channel, which, at the nearest points, are from forty to fifty miles distant, and are not to be discovered, from that low situation, by the aid of the best glasses. They appeared to be only a few miles off, and seemed to extend for some leagues along the coast. At first the sailors and fishermen could not be persuaded of the reality of the appearance, but they soon became thoroughly convinced, by the cliffs gradually appearing more elevated, and seeming to approach nearer, that they were able to point out the different places they had been accustomed to visit, such as the Bay, the Old Head, and the Windmill at Boulogne, St. Vallery, and several other spots. Their remark was that these places appeared as near as if they were sailing at a small distance into the harbor. The apparition of the opposite cliffs varied in distinctness and apparent contiguity for nearly an hour, but it was never out of sight, and upon leaving the beach for a hill of some considerable height, Mr. Latham could at once see Dungeness and Dover cliffs on each side, and before him the French coast from Calais to near Dieppe. By the telescope the French fishing-boats were clearly seen at anchor, and the different colors of the land on the heights, with the buildings, were perfectly discernible. The spectacle continued in the highest splendor until past eight o’clock, though a black cloud obscured the face of the sun for some time, when it gradually faded away. This was the first time within the memory of the oldest inhabitants, that they had ever caught sight of the opposite shore. The day had been extremely hot, and not a breath of wind had stirred since the morning, when the small pennons at the mast-heads of the fishing-boats in the harbor had been at all points of the compass. Professor Vince witnessed a similar apparent approximation of the coast of France to that of Ramsgate, for at the very edge of the water he discerned the Calais cliffs a very considerable height above the horizon, whereas they are frequently not to be seen in clear weather from the high lands above the town. A much greater breadth of coast also appeared than is usually observed under the most favorable circumstances. The ordinary refractive power of the atmosphere is thus liable to be strikingly altered by a change of temperature and humidity, so that a hill which at one time appears low, may at another be seen towering aloft; and a city in a neighboring valley, may from a certain station be entirely invisible, or it may show the tops of its buildings, just as if its foundations had been raised, according to the condition of the aerial medium between it and the spectator.

Fata Morgana at Reggio.

Of all instances of spectral illusion, the fata morgana, familiar to the inhabitants of Sicily, is the most curious and striking. It occurs off the Pharo of Messina, in the strait which separates Sicily from Calabria, and had been variously described by different observers, owing, doubtless, to the different conditions of the atmosphere at the respective times of observation. The spectacle consists in the images of men, cattle, houses, rocks, and trees, pictured upon the surface of the water, and in the air immediately over the water, as if called into existence by an enchanter’s wand, the same object having frequently two images, one in the natural and the other in an inverted position. A combination of circumstances must concur to produce this novel panorama. The spectator, standing with his back to the east on an elevated place, commands a view of the strait. No wind must be abroad to ruffle the surface of the sea; and the waters must be pressed up by currents, which is occasionally the case, to a considerable height, in the middle of the strait, so that they may present a slight convex surface. When these conditions are fulfilled, and the sun has risen over the Calabrian heights so as to make an angle of 45° with the horizon, the various objects on the shore at Reggio, opposite to Messina, are transferred to the middle of the strait, forming an immovable landscape of rocks, trees, and houses, and a movable one of men, horses, and cattle, upon the surface of the water. If the atmosphere, at the same time, is highly charged with vapor, the phenomena apparent on the water will also be visible in the air, occupying a space which extends from the surface to the height of about twenty-five feet. Two kinds of morgana may therefore be discriminated; the first, at the surface of the sea, or the marine morgana; the second, in the air, or the aerial. The term applied to this strange exhibition of uncertain derivation, but supposed by some to refer to the vulgar presumption of the spectacle being produced by a fairy or magician. The populace are said to hail the vision with great exultation, calling every one abroad to partake of the sight, with the cry of “Morgana, morgana!”

Father Angelucci, an eye-witness, describes the scene in the following terms:—“On the 15th of August, 1643, as I stood at my window, I was surprised with a most wonderful, delectable vision. The sea that washes the Sicilian shore swelled up, and became, for ten miles in length, like a chain of dark mountains; while the waters near our Calabrian coast grew quite smooth, and in an instant appeared as one clear polished mirror, reclining against the aforesaid ridge. On this glass was depicted, in chiaro scuro, a string of several thousands of pilasters, all equal in altitude, distance, and degree of light and shade. In a moment they lost half their height, and bent into arcades, like Roman aqueducts. A long cornice was next formed on the top, and above it rose castles innumerable, all perfectly alike. These soon split into towers, which were shortly after lost in colonnades, then windows, and at last ended in pines, cypresses, and other trees, even and similar. This was the Fata Morgana, which, for twenty-six years, I had thought a mere fable.”

Brydone, writing from Messina, evidently in a dubious vein, states:—“Do you know, the most extraordinary phenomenon in the world is often observed near to this place? I laughed at it at first, as you will do, but I am now convinced of its reality, and am persuaded, too, that if ever it had been thoroughly examined by a philosophical eye, the natural cause must long ago have been assigned. It has often been remarked, both by the ancients and moderns, that in the heat of summer, after the sea and air have been much agitated by winds, and a perfect calm succeeds, there appears, about the time of dawn, in that part of the heavens over the straits, a great variety of singular forms, some at rest, and some moving about with great velocity. These forms, in proportion as the light increases, seem to become more aerial, till at last some time before sunrise they entirely disappear. The Sicilians represent this as the most beautiful sight in nature. Leanti, one of their latest and best writers, came here on purpose to see it. He says the heavens appeared crowded with a variety of objects: he mentions palaces, woods, gardens, etc., besides the figures of men and other animals, that appear in motion amongst them. No doubt the imagination must be greatly aiding in forming this aerial creation; but as so many of their authors, both ancient and modern, agree in the fact, and give an account of it from their own observation, there certainly must be some foundation for the story. There is one Giardini, a Jesuit, who has lately written a treatise upon this phenomenon, but I have not been able to find it. The celebrated Messinese Gallo has likewise published something on this singular subject. The common people, according to custom, give the whole merit to the devil; and, indeed, it is by much the shortest and easiest way of accounting for it. Those who pretend to be philosophers, and refuse him this honor, are greatly puzzled what to make of it. They think it may be owing to some uncommon refraction or reflection of the rays, from the water of the straits, which, as it is at that time carried about in a variety of eddies and vortices, must consequently, say they, make a variety of appearances on any medium where it is reflected. This, I think, is nonsense, or at least very near it. I suspect it is something of the nature of our aurora borealis, and, like many of the great phenomena of nature, depends upon electrical cause; which, in future ages, I have little doubt, will be found to be as powerful an agent in regulating the universe as gravity is in this age, or as the subtle fluid was in the last. The electrical fluid in this country of volcanoes, is probably produced in a much greater quantity than in any other. The air, strongly impregnated with this matter, and confined betwixt two ridges of mountains—at the same time exceedingly agitated from below by the violence of the current, and the impetuous whirling of the waters—may it not be supposed to produce a variety of appearances? And may not the lively Sicilian imaginations, animated by a belief in demons, and all the wild offspring of superstition, give these appearances as great a variety of forms? Remember, I do not say it is so; and hope yet to have it in my power to give you a better account of this matter.”

Ingenious as Brydone was, he here indulges a most unfortunate speculation, which, had he enjoyed the good fortune of personally observing the phenomenon, most likely, he would not have proposed. It is to be accounted for upon optical principles, which M. Biot, in his Astronomie Physique, thus applies, from Minasi’s dissertation upon the subject:—“When the rising sun shines from that point whence its incident ray forms an angle of forty-five degrees, on the sea of Reggio, and the bright surface of the water in the bay is not disturbed either by wind or current—when the tide is at its height, and the waters are pressed up by the currents to a great elevation in the middle of the channel; the spectator being placed on an eminence, with his back to the sun, and his face to the sea, the mountains of Messina rising like a wall behind it, and forming the back-ground of the picture—on a sudden there appear in the water, as in a catoptric theatre, various multiplied objects—numberless series of pilasters, arches, castles, well-delineated regular columns, lofty towers, superb palaces, with balconies and windows, extended alleys of trees, delightful plains, with herds and flocks, armies of men on foot, on horseback, and many other things, in their natural colors and proper actions, passing rapidly in succession along the surface of the sea, during the whole of the short period of time while the above-mentioned causes remain. The objects are proved, by accurate observations of the coast of Reggio, to be derived from objects on shore. If, in addition to the circumstances already described, the atmosphere be highly impregnated with vapor and dense exhalations, not previously dispersed by the action of the wind and waves, or rarified by the sun, it then happens that, in this vapor, as in a curtain extended along the channel to the height of above forty palms, and nearly down to the sea, the observer will behold the scene of the same objects not only reflected on the surface of the sea, but likewise in the air, though not so distinctly or well-defined. Lastly, if the air be slightly hazy and opaque, and at the same time dewy, and adapted to form the iris, then the above-mentioned objects will appear only at the surface of the sea, as in the first case, but all vividly colored or fringed with red, green, blue, or other prismatic colors.”

Aerial images of terrestrial objects are frequently produced as the simple effect of reflection. Dr. Buchan mentions the following occurrence:—“Walking on the cliff about a mile to the east of Brighton, on the morning of the 18th of November, 1804, while watching the rising of the sun, I turned my eyes directly to the sea, just as the solar disc emerged from the surface of the water, and saw the face of the cliff on which I was standing represented precisely opposite to me, at some distance from the ocean. Calling the attention of my companion to this appearance, we soon also discovered our own figures standing on the summit of the opposite apparent cliff, as well as the representation of a windmill near at hand. The reflected images were most distinct precisely opposite to where we stood; and the false cliff seemed to fade away, and to draw near to the real one, in proportion as it receded toward the west. This phenomenon lasted about ten minutes, till the sun had risen nearly his own diameter above the sea. The whole then seemed to be elevated into the air, and successively disappeared. The surface of the sea was covered with a dense fog of many yards in height, and which gradually receded before the rays of the sun.” In December, 1826, a similar circumstance excited some consternation among the parishioners of Miqué, in the neighborhood of Poitiers, in France. They were engaged in the exercises of the jubilee which preceded the festival of Christmas, and about three thousand persons from the surrounding parishes were assembled. At five o’clock in the evening, when one of the clergy was addressing the multitude, and reminding them of the cross which appeared in the sky to Constantine and his army, suddenly a similar cross appeared in the heavens, just before the porch of the church, about two hundred feet above the horizon, and a hundred and forty feet in length, of a bright silver color tinged with red, and perfectly well-defined. Such was the effect of this vision, that the people immediately threw themselves upon their knees, and united together in one of their canticles. The fact was, that a large wooden cross, twenty-five feet high, had been erected beside the church as a part of the ceremony, the figure of which was formed in the air, and reflected back to the eyes of the spectators, retaining exactly the same shape and proportions, but changed in position and dilated in size. Its red tinge was also the color of the object of which it was the reflected image. When the rays of the sun were withdrawn the figure vanished.

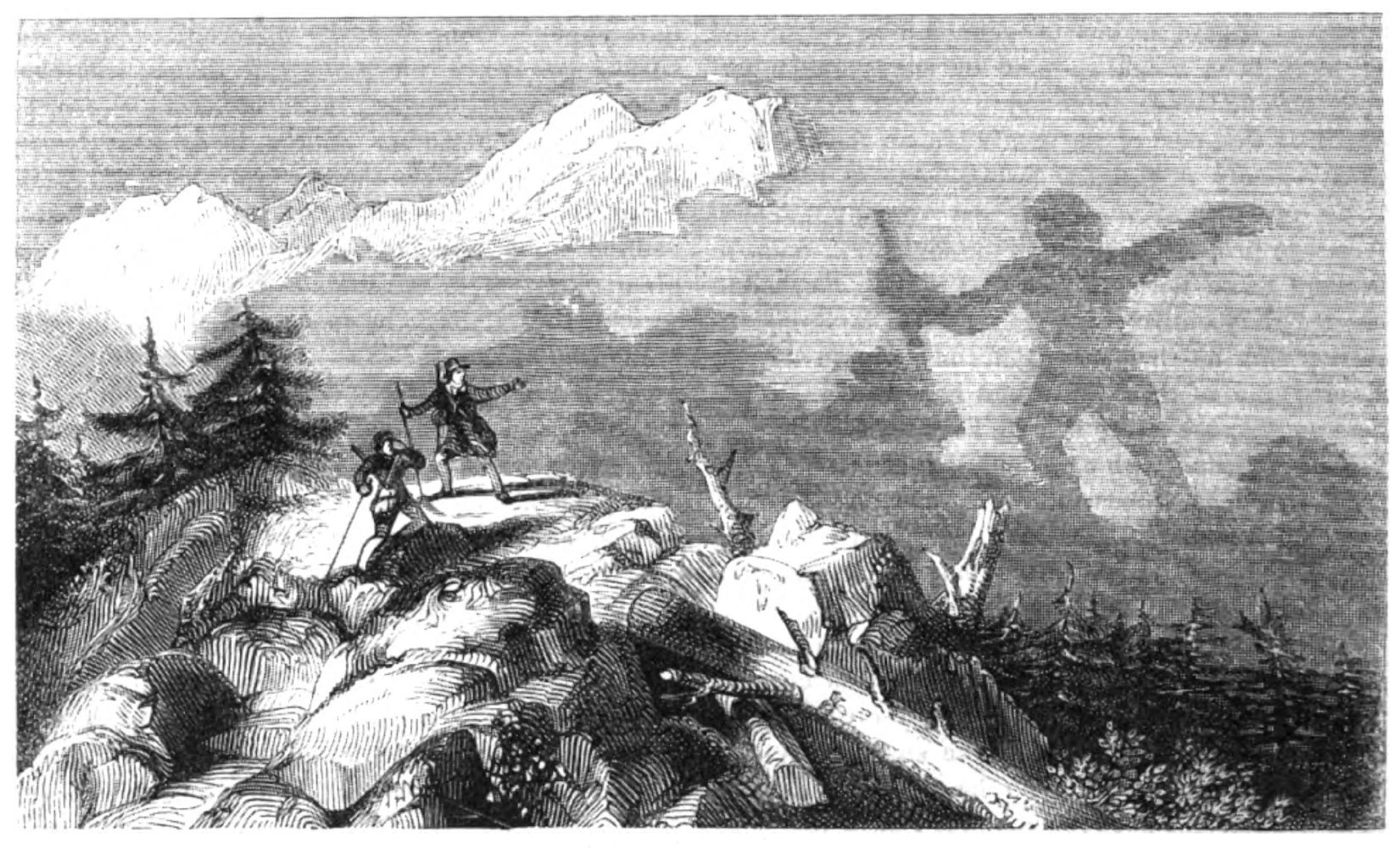

Spectre of the Brocken.

The peasantry in the neighborhood of the Harz Mountains formerly stood in no little awe of the gigantic spectre of the Brocken—the figure of a man observed to walk the clouds over the ridge at sunrise. This apparition has long been resolved into an exaggerated reflection, which makes the traveler’s shadow, pictured upon the clouds, appear a colossal figure of immense dimensions. A French savan, attended by a friend, went to watch this spectral shape, but for many mornings they traversed an opposite ridge in vain. At length, however, it was discovered, having also a companion, and both figures were found imitating all the motions of the philosopher and his friend. The ancient classical fable of Niobe on Mount Sipylus belongs to the same category of atmospheric deceptions; and the tales, common in mountainous countries, of troops of horse and armies marching and counter-marching in the air, have been only the reflection of horses pasturing upon an opposite height, or of the forms of travelers pursuing their journey. On the 19th of August, 1820, Mr. Menzies, a surgeon of Glasgow, and Mr. Macgregor began to ascend the mountain of Ben Lomond, about five o’clock in the afternoon. They had not proceeded far before they were overtaken by a smart shower; but as it appeared only to be partial, they continued their journey, and by the time they were half way up, the cloud passed away, and most delightful weather succeeded. Thin, transparent vapors, which appeared to have risen from Loch Lomond beneath, were occasionally seen floating before a gentle and refreshing breeze; in other respects, as far as the eye could trace, the sky was clear, and the atmosphere serene. They reached the summit about half-past seven o’clock, in time to see the sun sinking beneath the western hills. Its parting beams had gilded the mountain-tops with a warm glowing color; and the surface of the lake, gently rippling with the breeze, was tinged with a yellow lustre. While admiring the adjacent mountains, hills, and valleys, and the expanse of water beneath, interspersed with numerous wooded islands, the attention of one of the party was attracted by a cloud in the east, partly of a dark red color, apparently at the distance of two miles and a half, in which he distinctly observed two gigantic figures, standing, as it were, on a majestic pedestal. He immediately pointed out the phenomenon to his companion; and they distinctly perceived one of the gigantic figures, in imitation, strike the other on the shoulder, and point toward them. They then made their obeisance to the airy phantoms, which was instantly returned. They waved their hats and umbrellas, and the shadowy figures did the same. Like other travelers, they had carried with them a bottle of usquebaugh, and amused themselves in drinking to the figures, which was of course duly returned. In short, every movement which they made, they could observe distinctly repeated by the figures in the cloud. The appearance continued about a quarter of an hour. A gentle breeze from the north carried the cloud slowly away; the figures became less and less distinct, and at last vanished. North of the village of Comrie, in Perthshire, there is a bold hill called Dunmore, with a pillar of seventy or eighty feet in height built on its summit in memory of the late Lord Melville. At about eight o’clock of the evening of the 21st of August, of the year 1845, a perfect image of this well-known hill and obelisk, as exact as the shadow usually represents the substance, was distinctly observed projecting on the northern sky, at least two miles beyond the original, which, owing to an intervening eminence, was not itself at all in view from the station where the aerial picture was observed. The figure continued visible for about ten minutes after it was first seen, and was minutely examined by three individuals. One of these fancied that there was a projection at the base of the monument, as represented in the air, which was not in the original; but, upon examining the latter the next morning, the image was found to have been more faithful than his memory; for there stood the prototype of the projection, in the shape of a clump of trees, at the base of the real obelisk.

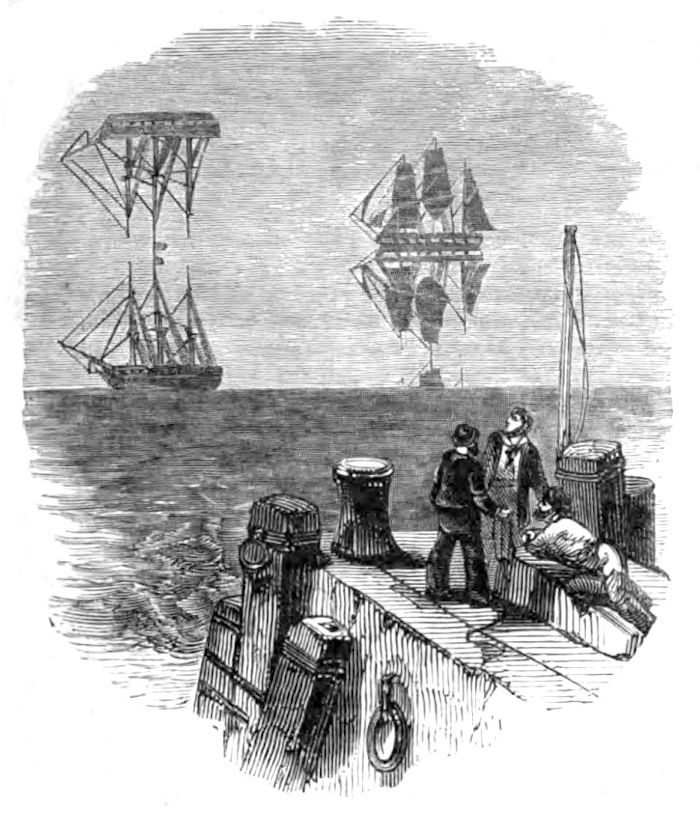

In northern latitudes the effects of atmospheric reflection and refraction are very familiar to the natives. By the term of uphillanger the Icelanders denote the elevation of distant objects, which is regarded as a presage of fine weather. Not only is there an increase in the vertical dimensions of the objects affected, so that low coasts frequently assume a bold and precipitous outline, the objects sunk below the horizon are brought into view, with their natural position changed and distorted. In 1818, Captain Scoresby relates that, when in the polar sea, his ship had been separated for some time from that of his father, which he had been looking out for with great anxiety. At length, one evening, to his astonishment, he beheld the vessel suspended in the air in an inverted position, with the most distinct and perfect representation. Sailing in the direction of this visionary appearance, he met with the real ship by this indication. It was found that the vessel had been thirty miles distant, and seventeen beyond the horizon, when her spectrum was thus elevated into the air by this extraordinary refraction. Sometimes two images of a vessel are seen, the one erect and the other inverted, with their topmasts or their hulls meeting, according as the inverted image is above or below the other. Dr. Wollaston has shown that the production of these images is owing to the refraction of the rays through media of different densities. Looking along a red-hot poker at a distant object, two images of it were seen, one erect and the other inverted, arising from the change produced by the heat in the density of the air. A singular instance of lateral mirage was noticed upon the Lake of Geneva by MM. Jurine and Soret, in the year 1818. A bark near Bellerire was seen approaching to the city by the left bank of the lake; and at the same time an image of the sails was observed above the water, which, instead of following the direction of the bark, separated from it, and appeared approaching by the right bank—the image moving from east to west, and the bark from north to south. When the image separated from the vessel, it was of the same dimensions as the bark; but it diminished as it receded from it, so as to be reduced to one-half when the appearance ceased. This was a striking example of refraction, operating in a lateral as well as a vertical direction.

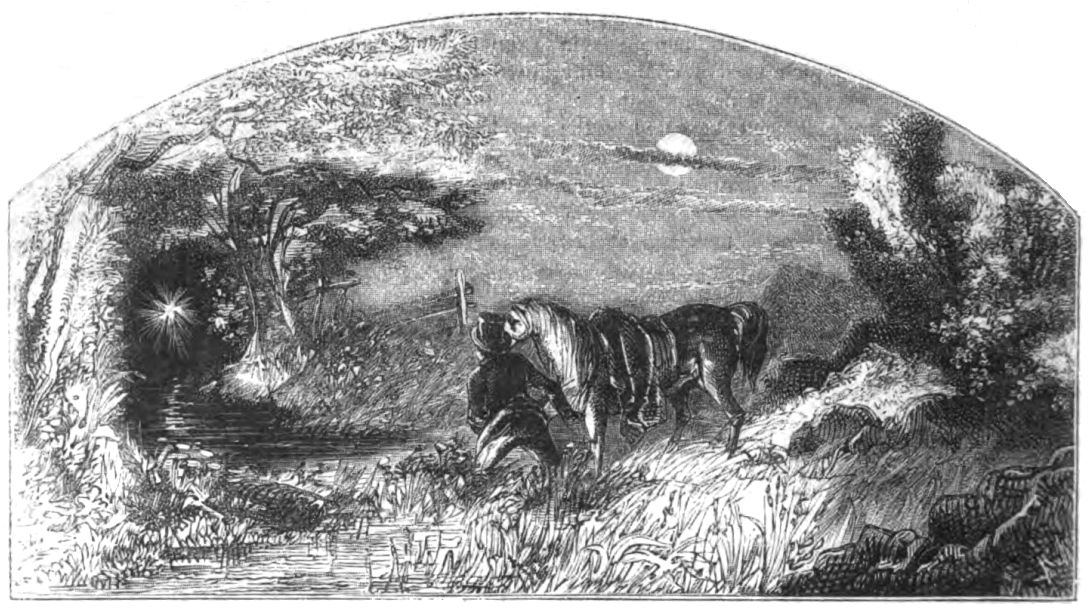

Ignis Fatuus. This wandering meteor known to the vulgar as the Will-o’-the-Wisp, has given rise to considerable speculation and controversy. Burying-grounds, fields of battle, low meadows, valleys, and marshes, are its ordinary haunts. By some eminent naturalists, particularly Willoughby and Ray, it has been maintained to be only the shining of a great number of the male glow-worms in England, and the pyraustæ in Italy, flying together—an opinion to which Mr. Kirby, the entomologist, inclines. The luminosities observed in several cases may have been due to this cause, but the true meteor of the marshes cannot thus be explained. The following instance is abridged from the Entomological Magazine:—“Two travelers proceeding across the moors between Hexham and Alston, were startled, about ten o’clock at night, by the sudden appearance of a light close to the road-side, about the size of the hand, and of a well-defined oval form. The place was very wet, and the peat-moss had been dug out, leaving what are locally termed ‘peat-pots,’ which soon fill with water, nourishing a number of confervæ, and the various species of sphagnum, which are converted into peat. During the process of decomposition these places give out large quantities of gas. The light was about three feet from the ground, hovering over the peat-pots, and it moved nearly parallel with the road for about fifty yards, when it vanished, probably from the failure of the gas. The manner in which it disappeared was similar to that of a candle being blown out.” We have the best account of it from Mr. Blesson, who examined it abroad with great care and diligence.

Ignis Fatuus.

“The first time,” he states, “I saw the ignis fatuus was in a valley in the forest of Gorbitz, in the New Mark. This valley cuts deeply in compact loam, and is marshy on its lower part. The water of the marsh is ferruginous, and covered with an iridescent crust. During the day bubbles of air were seen rising from it, and in the night blue flames were observed shooting from and playing over its surface. As I suspected that there was some connection between these flames and the bubbles of air, I marked during the day-time the place where the latter rose up most abundantly, and repaired thither during the night; to my great joy I actually observed bluish-purple flames, and did not hesitate to approach them. On reaching the spot they retired, and I pursued them in vain; all attempts to examine them closely were ineffectual. Some days of very rainy weather prevented further investigation, but afforded leisure for reflecting on their nature. I conjectured that the motion of the air, on my approaching the spot, forced forward the burning gas, and remarked that the flame burned darker when it was blown aside; hence I concluded that a continuous thin stream of inflammable air was formed by these bubbles, which, once inflamed, continued to burn, but which, owing to the paleness of the light of the flame, could not be observed during the day.”

The ignis fatuus of the church-yard and the battle-field arise from the phosphuretted hydrogen emitted by animal matter in a state of putrefaction, which always inflames upon contact with the oxygen of the atmosphere; and the flickering meteor of the marsh may be referred to the carburetted hydrogen, formed by the decomposition of vegetable matter in stagnant water, ignited by a discharge of the electric fluid.

NO. II.—THE CAPTIVE RIVALS.[1]

———

BY THE AUTHOR OF “TALBOT AND VERNON.”

———

(Concluded from page 212, Vol. XXXIX.)

I have not seen

So likely an embassador of love.

Merchant of Venice.

It gives me wonder, great is my content,

To see you here before me.

Othello.

The sun had not yet climbed the hills on the east of the valley, when Harding set forth on his uncertain mission; and not one of the indolent people of the country was any where to be seen. The houses were all closed—no smoke issued from their rude chimneys—no sound or motion broke the stillness. Apart from its solitude, however, it was a beautiful scene. The haziness of the evening before was now gone—the valley was refreshed by the dew of the night; and the reviving influence of the cool morning seemed to have had its effect upon the inanimate as well as the animate. The slope of the hills on the north, where the first rays of the sun rested for hours before they touched the southern plateau, was dotted here and there by straggling goats, browsing listlessly upon the scanty vegetation; while lower down the valley and along the banks of the little river, numbers of cattle were either standing patiently around the inclosures or wandering slowly away toward the hills. The river, silvered by the morning light, wound thread-like down the valley toward the west, and was visible even to the turn of the mountain miles away, where it enters the labyrinth of ridges in the neighborhood of Parras. There were no waving fields of grain; but the hedges were all green and fresh; verdure was springing even at that season, where the ground had been cleared of its products; and the evergreen trees, and groves of oranges which dotted the land imparted an aspect of fertile beauty. The shadows of the rugged hills were traceable along the ground, so clearly that the line of separation could be followed through the fields—one-half in sunlight, half in shade—the former gradually encroaching on the latter. There were no birds to cheer the solitude with matin songs; but so peaceful was the scene that even their presence might have seemed unwelcome.

Harding gazed about him as he crossed the bridge as if in search of the road. There were two paths; one leading along the front of several ranchos, and apparently taking him directly to the point he wished to reach. The other led away to the left, sweeping round the fields and avoiding the houses, with the danger of meeting their inmates. It was the latter that the count directed him to take; but for some reason best known to himself he followed the first, without heeding De Marsiac’s hail, and soon found himself riding slowly between two straggling rows of neat cottages. There was no one astir, however, and he had ridden nearly the whole length of the avenue without seeing any signs of life—when, judging himself to be out of view of Embocadura, he turned his horse in among the elms, and sprang to the ground.

Throwing his bridle-rein over a limb, he first carefully examined his pistols, and then loosening his sword in the scabbard, stepped out from the cover and approached the nearest cottage. It was not until he had knocked several times that any answer was returned. Then, however, the door was suddenly swung open, and he was confronted by one of those specimens of Mexican youth, whose faces combine in so remarkable a degree, great beauty with an expression of wicked cunning. He was a boy—perhaps eighteen years of age, with a slender figure, but evidently very active, and unless an exception to his race, capable of enduring great fatigue and privation. His eyes were dark as night, small, and keen; his nose thin and straight, his lips rather pinched, but red and clearly cut. The rest of his features were appropriate to these, and his complexion was rather lighter than the general hue of his people. He held a lareat coiled in his hand, and his goat-skin shoes were armed at the heel with enormous spurs.

“Buenas dias, Señor,” said he, in a clear, sharp voice, stepping back at the same time, in mute invitation to Harding to enter.

The latter returned the salutation and asked—

“On whose lands are these ranchos?”

“On those of La Señora Eltorena,” answered the boy, promptly.

“How far is it to Anelo?” he inquired.

“Twelve leagues, sir.”

Harding reflected for a moment, and then beckoned the boy aside. The latter gazed at him inquiringly; but drawing the door to, followed him to the place where his horse was standing.

“You see that horse?” said he.

“I do,” answered the boy “and a very fine one he is, too.”

“Could you ride him to Anelo and back,[2] to-day?”

“How much money could I get to do it?” asked the youth, eyeing the officer as if to measure his liberality.

“Twenty dollars,” Harding answered; “or, if you do not find me on your return, you may keep the horse.”

“Agreed,” said the boy, promptly. “I’ll set out now.”

Harding took a blank leaf from his pocket-book and wrote a note to the commandant of a detachment of Texan rangers, whom he knew to be then foraging at Anelo, and handed it to the boy.

“You must be back before midnight,” said he; “and you may ask for me at the hacienda. My name is Harding.”

“And mine is Eltorena,” said the youth. “I am six months older than Margarita, and entitled to the name by the same right.”

His eyes glistened as he spoke with an expression so devilish, that Harding was half inclined to take back the note and discharge him. But while reflecting upon the words of the boy, the latter, as if divining his half formed intention, suddenly put spurs to his horse’s flanks and bounded away. Harding watched him until he had crossed the river, and avoiding La Embocadura by a wide circuit, was fast disappearing among the groves to the east.

Concluding that if he had made a mistake it was now too late to amend it, he turned on his heel, and was about to pursue his way toward Piedritas on foot, when his attention was arrested by a voice pronouncing his name.

“Señor Harding, let me speak with you for a moment.”

He turned, and beheld a female in the very bloom of mature womanhood—tall, elegantly formed, and possessing a countenance of singular force and beauty. She was standing near the door at which he had knocked, and he had no difficulty in determining from the resemblance that she was the mother of his messenger. He advanced with the ordinary salutation, and followed her within the house.

“I am perfectly well acquainted,” she commenced abruptly, without offering him a seat, “with the object of your visit to the hacienda. You are here to wed the daughter of the woman who calls herself the Señora Eltorena—”

“Calls herself!” repeated Harding.

“And you are doubtless like other men,” she continued, without noticing the exclamation, “more attracted by the property than the bride. Now, I wish to warn you that this estate, with all that the late Colonel Eltorena owned, belongs to his son—and mine—the youth whom you have just sent away; and that I hold General Santa Anna’s pledge to see him righted as soon as the army marches this way. So, if you marry her, it is with your eyes open.”

“You are mistaken, madam,” said Harding, after a pause given to surprise; “I am here on no such errand: I am, on the contrary,” he added, with a smile, “only a humble ambassador, suing for the lady’s hand in the name of another, more potent individual.”

“In the name of the murdering thief, De Marsiac?” she exclaimed.

“Even so,” Harding replied, “the very same, without mistake.”

“You are a strange ambassador,” she said, with a laugh. “But,” she continued, resuming her somewhat wild manner, “I warn him through you, as I have done to his face, that the man who marries that woman’s daughter, must take her portionless!”

“In that case,” said Harding, with another smile, “I doubt whether the count will care to take her at all. But enlighten me about your son’s title—it may be important to my principal.”

Her story was not an uncommon one, though it took a long time in telling; for she dwelt with painful emphasis upon some parts, and talked so incoherently upon others, that Harding was confirmed in his suspicion that her mind was, upon that subject at least, quite unsettled. She had been induced by the late Colonel Eltorena to go to his house, as his wife, under a promise that the actual ceremony should be performed by the first priest who came from Monclova or Saltillo. It was a remote district in which they lived, and they might have to wait for months before the expected visit would be made; and knowing this, and at the earnest solicitation of her lover, she consented to an arrangement, which was not so uncommon as it should have been. Wherever the common law prevails as it does in the United States, this would have been a legal marriage; and she solemnly protested that she so considered it upon the representation of the colonel himself. Two or three priests had passed that way within a few months; but upon various pretexts the ceremony was postponed.

At last, after about six months, the Colonel went to the city of Mexico on a visit, and returned with a wife! “The woman,” said the narrator, “who now calls herself La Señora Eltorena!” She, the deceived and betrayed, was generously offered an asylum in the rancho, where she had lived ever since; and six months after her ejectment from the hacienda by “the proud English woman,” her son was born. For eighteen years she had been suing for her rights; but superior influence with the corrupt judges of that unhappy land had foiled all her efforts; and in the meantime, she had lived in plain view of the hacienda, determined never to lose sight of her object, until she saw her son in possession. She had never been inside of its walls: “but,” said she, “I will be there—and soon! May God give me revenge upon the sorceress, who stole away my rights!”

“It is a very hard case,” said Harding, when she had finished, “but I fear like many other wrongs, it has no remedy.”

“There is one remedy,” said she, significantly, “when all others fail.” And drawing aside the end of her mantilla, she disclosed the hilt of a long, keen dagger. She drew it forth, ran her finger along its edge, smiled faintly, and replaced it in its sheath.

“Well, well,” said Harding, turning away, “I am warned at all events, and will take care that the count is enlightened, also. I must speed upon my mission. Good morning.”

She made no reply, and he passed out, taking his way toward the hacienda, which lay in view, about a mile distant. Turning to the right, he soon reached the bank of the river, and followed its rapid but even current, which ran sparkling beneath the court-yard wall. It was yet quite early; and as he reached the front of the mansion, his fear, that as yet no one would be astir, was confirmed. Returning again to the margin of the stream, he commenced pacing up and down the sward under a row of elms, with the intention of awaiting the rising of the family. He had made but two or three turns, however, and had halted, gazing about upon the still morning scene, when he thought he observed something like drapery pass across the arches in the wall, through which the river entered the inclosure. He advanced somewhat closer, and could distinctly see a pair of small feet tripping across the river on a footway made by placing large stones a step apart from bank to bank. He could not doubt that it was Margarita; but without going again to the front of the house, he knew of no means of ingress.

Casting his glance up and down the stream, to his delight, he discovered a small boat moored to the bank, and slowly swinging in the current. A moment sufficed to untie the rope which bound it, and in another, he was seated on its light planks, rapidly floating toward the arched passage. The waters, raised by the rains of the preceding day, left but scanty room beneath the masonry; but lying down in the bottom of the boat, and guiding her with his hands, he soon had the satisfaction to emerge within the inclosure. On rising again, he found himself between an extensive garden on one side and the offices of the mansion on the other. The former seemed to be a neglected wilderness of trees, and flowering plants and vines, but on reaching the footway over which the feet had passed, he discovered an opening to the labyrinth, in a broad, graveled walk, which wound away between rows of shrubbery, sparkling in the morning sunlight, and lost itself in the distance.

Turning the boat broadside against the stones, to prevent its floating away, he sprang to the bank and walked rapidly down the avenue. He discovered neither form nor sign of life for several minutes; but as he turned from the main walk into a smaller, which led away to the left, he saw directly before him, walking slowly toward the place where he stood, a young girl whose exquisite beauty well justified his eagerness. She was slightly above the medium height, slender, but well-proportioned, with a carriage erect and graceful. Her rich, brown hair was braided in masses over a forehead of the purest white, and drawn back loosely so as almost to hang upon her round, snowy neck. Her eyes were of the same color with her hair—a rich, dark brown; and their expression, though somewhat pensive, was yet sparkling and clear. A nose of the true Grecian model, a round, though not full chin, a small mouth with thin, curling lips, and cheeks now tinged by exercise in the cool morning air, completed a face which might well have attracted a man of less taste than the Count De Marsiac. To complete the picture, she had small, beautiful feet, such as a sultana might have envied; and her perfect, white hands, which now lay folded together in front, might have been a model for a sculptor. She wore a thin morning dress of the purest white, and as she walked slowly and unconsciously, it waved like gossamer about her person—revealing, perhaps, too much of its contour to please our northern prejudices, but still adding to its exquisite attraction.

Harding’s circumstances were so peculiar, that he was embarrassed for a moment, and could not determine how to meet her. She had not yet seen him, and acting upon the impulse of perplexity, he stepped within the cover of the shrubbery, and allowed her to pass without speaking. She went but a few steps, however, before he called—

“Margarita!”

She started at his voice, but turned and at once advanced to meet him. Her eyes sparkled with pleasure, too, as she did so, and the hand she extended to him trembled from emotion. Harding could not know her feelings, and he had reason to doubt her truth; but, though he could not tell what it was, there was something in her look and manner as she met him which made him forget all suspicion. He took her hand in one of his, and placing the other about her waist, drew her to him, and—the love of a former time was renewed!

“We meet once more,” he whispered; it was all he could say.

“I feared we were parted forever,” she said, disengaging herself from his embrace, but still leaning on his arm.

“I thought you had forgotten me,” continued Harding.

“I am not sure but I ought to have done so,” she replied, with a smile which revealed how little she meant what she said. “But how is it that you are here?”

“I had forgotten,” answered he; “I am here as an envoy from another, to ask your hand in marriage!”

“You!” she exclaimed, drawing away from him. “From whom?”

“From his highness,” answered Harding, laughingly detaining her, “Eugene Raoul, Count De Marsiac!”

She gazed at him in surprise for a few moments; and then, catching the light of his smile, folded her hands upon his shoulder, looked archly into his eyes and said—

“If the envoy does not deem my hand a prize high enough to justify his preferring a claim on his own behalf. I must even listen to the overtures of his sovereign.”

“Then I must deliver my credentials,” said Harding, and drawing her to him, he kissed her upon both cheeks. “And now,” he continued, taking her hand, “my mission is ended; and in my own proper character I claim this hand as my own. Is it mine?”

“Forever,” she answered, and he was about to resume his “credentials,” when a rustling among the bushes attracted his attention; and before Margarita could disengage herself, Lieutenant Grant confronted them, and leveled a pistol at Harding’s breast!

“Traitor!” he shouted furiously; “you shall pay for this with your life!”

Margarita screamed loudly, and threw herself in front of her lover; but before Grant was aware of his intention, Harding drew his sword, and passing around her, threw himself upon him. He knocked the pistol into the air just as it exploded; and the next instant Grant was stretched upon the sward, bleeding profusely from a wound in the head given by the back of Harding’s sword! The latter drew the remaining pistol from the sash of the fallen lieutenant, and kneeling beside him raised him from the ground on his arm.

“Bring some water from the river,” he said to Margarita.