* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Mates at Billabong

Date of first publication: 1911

Author: Mary Grant Bruce (1878-1958)

Date first posted: May 2, 2019

Date last updated: May 2, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190504

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

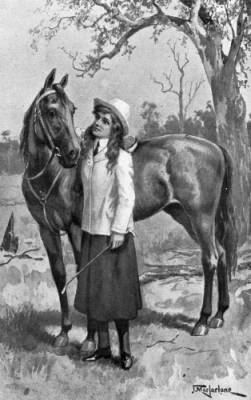

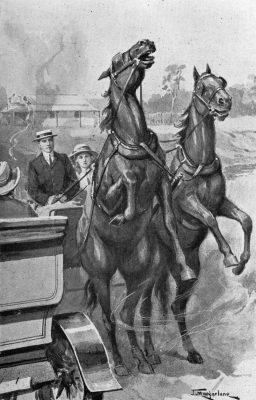

Norah and Bobs.

| Mates at Billabong] | [Frontispiece |

MATES

AT BILLABONG

By

MARY GRANT BRUCE

Author of “A Little Bush

Maid,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY J. MACFARLANE

WARD, LOCK & CO., LIMITED

LONDON, MELBOURNE AND TORONTO

| CONTENTS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER I | ||

| Norah’s Home | 9 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Together | 18 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| A Bath and an Introduction | 30 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Cutting-Out | 41 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| Two Points of View | 52 | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| Coming Home | 64 | |

| CHAPTER VII | ||

| Jim Unpacks | 77 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| A Thunderstorm | 88 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| The Billabong Dance | 100 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| Christmas | 119 | |

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| “Lo, the Poor Indian!” | 131 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| Of Poultry | 145 | |

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| Station Doings | 158 | |

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| Cunjee v. Mulgoa | 170 | |

| CHAPTER XV | ||

| The Ride Home | 183 | |

| CHAPTER XVI | ||

| A Child’s Pony | 198 | |

| CHAPTER XVII | ||

| On the Hillside | 210 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | ||

| Brother and Sister | 222 | |

| CHAPTER XIX | ||

| The Long Quest | 230 | |

| CHAPTER XX | ||

| Mates | 242 | |

The grey old dwelling, rambling and wide,

With the homestead paddocks on either side,

And the deep verandahs and porches tall

Where the vine climbs high on the trellised wall.

G. Essex Evans.

BILLABONG homestead lay calm and peaceful in the slanting rays of the sun that crept down the western sky. The red roofs were half hidden in the surrounding trees—pine and box and mighty blue gums towering above the tenderer green of the orchard, and the wide-flung tendrils of the Virginia creeper that was pushing slender fingers over the old walls. If you came nearer, you found how the garden rioted in colour under the touch of early summer, from the crimson rambler round the eastern bay window to the “Bonfire” salvia blazing in masses on the lawn; but from the paddocks all that could be seen was the mass of green, and the mellow red of the roof glimpsing through. Further back came a glance of rippled silver, where the breeze caught the surface of the lagoon—too lazy a breeze to do more than faintly stir the reed-fringed water. Towards it a flight of black swans winged slowly, with outstretched necks, across a sky of perfect blue. Their leader’s note floated down, as if in answer to the magpies that carolled in the pine trees by the stables. The sound seemed to hang in the still air.

Beyond the tennis-court, in the farther recesses of the garden, a hammock swung between two grevillea trees, whose orange flowers made a gay canopy overhead; and in the hammock Norah swayed gently, and knitted, and pondered. The shining needles flashed in and out of the dark blue silk sock. Outsiders—mothers of prim daughters, whom Norah pictured as finding their wildest excitement in “patting a doll”—were wont to deplore that the only daughter of David Linton of Billabong was brought up in an eccentric fashion, less girl than boy; but outsiders are apt to cherish delusions, and Norah was not without her share of gentle accomplishments. Knitting was one; the sock grew quickly in the capable brown fingers that could grip a stockwhip as easily as they handled the needles. All the while, she was listening.

About her the coo of invisible doves fell gently, mingling with the happy droning of bees in the overhead blossoms. Somewhere, not far off, a sheep bell tinkled monotonously, the only outside sound in the afternoon stillness. It was very peaceful. To Norah, who knew that the world held no place like Billabong, it only lacked one person for the final seal of perfection.

“ ’Wish Dad would come,” she said aloud, puckering her brow over a knot in the silk. “He’s late—and it is jolly dull without him.” The knot came free, and the needles raced as though making up for lost time.

Two dogs lay on the grass; a big sleepy collie that only moved occasionally to snap at a worrying fly; and an Irish terrier, plainly showing by his restlessness that he despised a lazy life, and longed for action. He caught his mistress’s eye at last, and jumped up with a little whine.

“If you had the heel of a sock to turn, Puck,” said Norah, “you’d be more steady. Lie down, old man.”

Puck lay down again discontentedly, put his nose on his paws, and feigned slumber, one restless eyelid betraying the hollowness of the pretence. Presently he rolled over—and chancing to roll on a spiky twig, rose with a wild yelp of annoyance. Across Norah’s laugh came a stockwhip crack; and the collie came to life suddenly, and sprang up, as impatient as the terrier. Norah slipped out of the hammock.

“There’s Dad!” she said. “Come along!”

She was tall for her fourteen years, and very slender—“scraggy,” Jim was wont to say, with the cheerful frankness of brothers. Norah bore the epithet meekly—she held the view that it was better to be dead than fat. There was something boyish in the straight, slim figure in the blue linen frock—perhaps the quality was also to be found in a frank manner that was the product of years of the Bush and open air life. The grey eyes were steady, and met those of others with a straight level glance; the mouth was a little firm-set for her years, but the child was revealed when it broke into smiles—and Norah was rarely grave. No human power had yet been discovered to keep in order the brown curls. Their distressed owner tied them back firmly with a wide ribbon each morning; but the ribbon generally was missing early in the day, and might be replaced with anything that came handy—possibly a fragment of red tape from the office, or a bit of a New Zealand flax leaf, or haply even a scrap of green hide. Anything, said Norah, decidedly, was better than your hair all over your face. For the rest, a nondescript nose, somewhat freckled, and a square chin, completed a face no one would have dreamed of calling pretty. In his own mind her father referred to it as something better. But then there was tremendous friendship between the master of Billabong and his small daughter.

The stockwhip cracked again, nearer home this time; and Norah crammed the blue silk sock hastily into a little work-bag, and raced away over the lawn, her slim black legs making great time across the buffalo grass. Beside her tore the collie and Puck, each a vision of embodied delight. They flashed round the corner of the house, scattered the gravel on the path leading to the back, and came out into the yard as a big black horse pulled up at the gate, and the tall man on his back swung himself lightly to the ground. From some unseen region a black boy appeared silently and led the horse away. Norah, her father, and the dogs arrived at the gate simultaneously.

“I thought you were never coming, Daddy,” said the mistress of Billabong, incoherently. “Did you have a good trip?—and how did Monarch go?—and did you buy the cattle?—and have you had any dinner?” She punctuated each query with a hug, and paused only for lack of breath.

“Steady!” said David Linton, laughing; “I’m not a ready reckoner! I’ve bought the bullocks, and Monarch went quite remarkably well, and yes, I’ve had dinner, thank you. And how have you been getting on, Norah?”

“Oh, all right,” said his daughter. “It was pretty slow, of course—it always is when you go away, Daddy. I worked, and pottered round with Brownie, and went out for rides. And oh, Dad! ever so many letters—and Jim’s coming home next week!” She executed an irrepressible pirouette. “And he’s got the cup for the best average at the sports—best all-round athlete that means, doesn’t it? Isn’t it lovely?”

“That’s splendid!” Mr. Linton said, looking as pleased as his daughter. “And any school prizes?”

“He didn’t mention,” Norah answered. “I don’t suppose so, bless him! But there’s one thing pretty sickening—the boys can’t come with him. Wally may come later, but Harry has to go to Tasmania with his father—isn’t it unreasonable?”

“I’m sorry he can’t come, but on the whole I’ve a fellow feeling for the father,” said Jim’s parent. “A man wants to see something of his son occasionally, I suppose. And any news from Mrs. Stephenson?”

“She’s better,” Norah answered, her face growing graver. “Dick wrote. And there’s a letter for you from Mrs. Stephenson, too. She says she’s brighter, and the sea-voyage was evidently the thing for her, ’cause she’s more like herself than at any time since—since my dear old Hermit died.” Norah’s voice shook a little. “They expect to be in Wellington all the summer, and perhaps longer.”

“It was certainly a good prescription, that voyage,” Mr. Linton said. “I don’t think she would have been long in following her husband—poor old chap!—if they had remained here. But one misses them, Norah.”

“Horrid,” said Norah, with emphasis. “I miss her all the time—and it’s quite rum, Dad, but I do believe I miss lessons. Over five weeks since I had any! Are you going to get me another tutor?”

“We’ll see,” said her father. They were in the big dining-room by this time, and he was turning over the pile of letters that had come during his three days’ absence from the station. “Any chance of tea, Norah?”

“Well, rather!” said Norah. “You read your letters, and I’ll go and tell Sarah. And Brownie’ll be wanting to see you. I won’t be long, Daddy.” She vanished.

A few minutes later Mr. Linton looked up from a letter that had put a crease into his brow. A firm, flat step sounded in the hall, and Mrs. Brown came in—cook and housekeeper to the homestead, the guide, philosopher and friend of every one, and the special protector of the little motherless girl about whom David Linton’s life centred. “Brownie” was not a person lightly to be reckoned with, and her master was wont to turn to her whenever any question arose affecting Norah. He greeted her warmly now.

“We’re all glad to welkim you back, sirr,” said Brownie. “As for that blessed child, she’s not like the same ’uman bein’ when you’re off the place. Passed me jus’ now in the passige, goin’ full bat, an’ turned ’ead over ’eels, she did—I didn’t need to be told you’d got ’ome!” She hesitated: “You heard from Mrs. Stephenson, sir?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Linton, glancing at the letter in his hand. “As I thought—she confirms our opinion. I’m afraid there’s no help for it.”

“I knew she would,” said Mrs. Brown, heavily, a shadow falling on her broad, pleasant face. “Oh, I know there’s no ’elp, sir—it has to be. But—but——” She put her apron to her eyes.

“We’re really very lucky, I suppose,” Mr. Linton said, in tones distinctly unappreciative, at the moment, of any luck. “Mrs. Stephenson has been a second mother to Norah these two years—between you and her I can’t see that the child needed anything; and with Dick as tutor she has made remarkable progress. Personally, I’d have let the arrangement go on indefinitely. Now that they’ve had to leave us, however——” He paused, folding up the letter slowly.

“She couldn’t stay ’ere, poor lady,” Mrs. Brown said; “t’aint in reason she’d be able to after the old gentleman’s death, with the place full of memories an’ all. An’, of course, she’d want Mr. Dick along with her. Anyway, the precious lamb’s getting a big girl to be taught only by a young gentleman——” and Brownie pursed up her lips, looking such a model of all the proprieties that Mr. Linton smiled involuntarily.

“She’s all right,” he said, shortly. “Of course, her aunt has been at me for ever so long to send her to school.”

“Beggin’ your pardon, sir, Mrs. Geoffrey don’t know everythink,” said Mrs. Brown, bridling. “Her not havin’ any daughters of ’er own, ’ow can it be expected that she’d understand?—an’ town ladies can’t never compre’end country children, any’ow. Our little maid’s jus’ grown up like a bush flower, an’ all the better she is for it.”

“But the time comes for change, Brownie, old friend,” said Mr. Linton.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Brown; “it do. But what the station’ll do is more’n I can see just at present—an’ as for you, sir—an’ let alone me——” Her comfortable, fat voice died away, and the apron was at her eyes again. “What’ll Billabong be, with its little girl at school?”

“At—where?” asked Norah.

She had come in with the tea-tray in her hands—a little flushed from the fire, and her brown face alight with all the hundred-and-one things she had yet to tell Daddy. On the threshold she paused, struck motionless by that amazing speech. She looked a little helplessly from one face to the other; and the two who loved her felt the same helplessness as they looked back. It was not an easy thing to pass sentence of exile from Billabong on Norah.

“I——” said her father—“you see, dear—Dick having gone—you know, your aunt——” He stopped, his tongue tied by the look in Norah’s eyes.

Brownie slipped into the breach.

“You’re so big now, dearie,” she said—“so, big—and—and——” With this lucid effort at enlightenment she put her apron fairly over her head and turned away to the open window.

But Norah’s eyes were on her father. Just for a moment the sick sense of bewilderment and despair seemed to crush her altogether. She had realized her sentence in a flash—that the home that meant all the world to her, and from which Heaven only differed in that Mother was there, was to be changed for a new, strange world that would be empty of all that she knew and loved. Vaguely she had always known that the blow hung over her—now that it had fallen, for a moment there was no room for any other thought. Her look, wide with grief and appeal, met her father’s.

And then she realized slowly that he was suffering too—that he was looking to her for the response that had never failed him yet. His silence told her that this thing was unavoidable, and that he needed her help. Mates such as they must stand by one another—that was part of the creed that had grown up in Norah’s heart. Daddy had always said that no matter what happened he could rely upon her. She could not fail him now.

So, just as the silence in the room became oppressive, Norah smiled into her father’s eyes, and carefully put the tea-tray upon the table.

“If you say it’s got to be, well, that’s all about it, Daddy,” she said. The voice was low, but it did not quiver. “Don’t worry, darling; it’s all right. Sarah was out, and Mary goodness knows where, so I made tea myself; I hope it’s drinkable.” She brought her father’s cup to his side and smiled at him again.

“My blessed lamb!” said Mrs. Brown, hastily—and fled from the room.

David Linton did not take the cup; instead he slipped his arm round the childish body.

“You think we can stand it, then?” he asked. “It’s not you alone, little mate; your old Dad’s under sentence too.”

“I think that makes things a lot easier,” said Norah—“ ’cause you and I always do things together, don’t we, Daddy? And—and.” Just for a moment her lip trembled. “Must we, Dad?”

He tightened his arm.

“Yes, dear.”

There was a pause.

“After Christmas?”

“Yes—in February.”

“Then I’ve got nine weeks,” said Norah, practically. “We won’t talk about it more than we can help, I think, don’t you? Have your tea, Daddy, or it’ll be cold and horrid.” She brought her own cup and sat down on the arm of his chair. “How many bullocks did you buy?”

And you and I were faithful mates.

Henry Lawson.

AFTERWARDS—when the blow was a little less heavy as Norah grew accustomed to it—they talked it over thoroughly.

Norah’s education, in the strict sense of the term, had only been carried on for about two years. In reality it had gone on all her life, spent mostly at her father’s side; but that was the kind of education that does not live between the covers of books. Together, David Linton and his daughter had worked, and played and talked—much more of the former condition than of either of the latter. All that the bush could teach her Norah knew, and in most of the work of the station—Billabong was a noted cattle-run—she was as handy as any of the men. Her father’s constant mate, every day shared with him was a delight to her. They rode together, fished, camped and explored together; it was the rarest occurrence for Mr. Linton’s movements not to include Norah as a matter of course.

Yet there was something in the quiet man that had effectually prevented any development of roughness in Norah. Boyish and offhand to a certain extent, the solid foundation of womanliness in her nature was never far below the surface. She was perfectly aware that while Daddy wanted a mate he also wanted a daughter; and there was never any real danger of her losing that gentler attribute—there was too much in her of the little dead mother for that. Brownie, the ever watchful, had seen to it that she did not lack housewifely accomplishments, and Mr. Linton was wont to say proudly that Norah’s scones were as light as her hand on a horse’s mouth. There was no doubt that the irregular side of her education was highly practical.

Two years before Fate had taken a new interest in Norah’s development, bringing as inmates of the homestead an old friend of her father’s, with his wife and son. The latter acted as Norah’s tutor, and found his task an easy one, for the untrodden ground of the little girl’s brain yielded remarkable results. To Mrs. Stephenson fell the work of gently moulding her to womanly ways—less easy this, for while Norah had no desire to be a tomboy, she was firmly of the opinion that once lessons were over, she had simply no time to stay inside the house and be proper. Still, the gentle influence told, imperceptibly softening and toning her character, and giving her a standard by which to adapt herself; and Norah was nothing if not adaptable. Then, six months previously, the old man they all loved had quietly faded out of life; and after he had gone his widow could no longer remain in the place where he had died. She pined slowly, until Dick Stephenson, the son, had taken her almost forcibly away. The unspoken fear that the parting was not merely temporary had merged into certainty. Billabong would know them no more. The question remaining was what to do with Norah.

“I want you to have the school training,” Mr. Linton said, when they talked the matter over. “You must mix with other girls—learn to see things from their point of view, and realize how many points of view there are outside Billabong. Oh, I don’t want you to think there are any better”—he laughed at the vigorous shake of the brown curls—“but the world has wider boundaries, and you must find them out. There are other things, too”—vaguely—“dancing and deportment, and—er—the use of the globes, and I think there’s a thing called a blackboard, but I’m not sure. Dick didn’t know. In fact, there’s a regulation mill, and I suppose you must go through it—I don’t feel afraid that they’ll spoil my little girl’s individuality in the process.”

“Is it a big school, Daddy?”

“Yes, I believe so. Several people I know send their girls there. And it’s a great place for sports, Norah. You’ll like that. They’re keen on hockey and cricket and all sorts of things girls never dreamed about when I was young. Possibly I may live to see you a slow bowler yet, and playing in a match! Honestly, Norah, I believe you’ll be very happy at school.”

“And what’ll you do, Daddy?”

“I don’t know,” he said, heavily. “I told you I was under sentence.”

They sat awhile in silence. It was evening, and they were on the verandah; Mr. Linton in a big basket chair, and Norah curled up at his feet in the way she loved. She could not see his face—just then she did not want to. She said nothing. The moon climbed up slowly, and the frogs were merry in the lagoon. Far off the cry of a bittern boomed across the flats.

“Well, at least we’ve got nine weeks,” Norah said at length. “Nine weeks to be mates—and Jim’ll be home next week, and he’ll be mates, too. Don’t let’s get blue about it, Daddy. It’ll be so horrid when the time comes, that it’s no good letting it spoil these nine weeks. Can’t we try to forget it?”

“We can try,” said David Linton.

“Course, we won’t do it,” Norah said. “But don’t let’s talk about it. I’m going to put it out of my head as much as ever I can, and have this time for just Billabong and us. Will you, Daddy?”

“I’ll do all I can, my girlie,” said her father. “You mustn’t start off with any bad memories; we’ll have the most crowded nine weeks of our lives, and make a solemn resolve to ‘buck up.’ I’d like to plan something for this week, but, upon my word, I’m too busy to play, Norah. There’s any amount to be done.”

“But I don’t want to play,” Norah said. “Work’s good enough for me, Daddy, if I can work with you. Can’t I come, too?”

“I’ll be exceedingly glad of your help,” said her father—which was exactly what Norah wanted him to say, and went far to cheer her. She put the dismal future resolutely from her, and set out upon the present with a heart as light as possible.

It was never dull at Billabong. Always there were pets of all kinds to be seen to. Mr. Linton laid no restriction on pets if they were properly tended, and Norah had a collection as wide as it was beloved. Household duties there were, too; but these could be left if necessary—two adoring housemaids were always ready to step into the breach if “business on the run” claimed Norah’s attention. And beyond the range of the homestead altogether, there lay an enchanted region that only she and Daddy shared—the wide and stretching plains of Billabong dotted with cattle, seamed with creeks and the river, and merging at the boundary into a long low line of hills. Norah used to gaze at them from her windows—sometimes purple, sometimes blue, and sometimes misty grey, but always beautiful to the child who loved them. Others might know Billabong—visit it, ride over it, exclaim at its beauties; but Norah always felt that there were only two who really understood and cared—Daddy and herself.

Of course there was Jim—the big brother who was seventeen now, and just about to leave school. Norah was immensely proud of him, and the affection between them was a thing that never wavered. Jim loved Billabong, too; but it was only to be expected that six years of school in Melbourne would make something of a difference. He knew, in the words of the old Roman, “There is a world elsewhere.” But Norah knew no world beyond Billabong.

For all that, Jim was distinctly desirable as a brother. He had always made a tremendous chum of Norah, and the friends he brought home found they were expected to do the same. This might cause them surprise at first, but they very soon found that “the kiddie” was quite excellent as a mate, and could put them up to a good deal more than they usually knew about the Bush. Norah was invariably Jim’s first thought. He was a big, quiet fellow, very like his father; not over brilliant at books, but a first-rate sport, and without a trace of meanness in his generous nature. At school he was worshipped by the boys—was not he captain of the football team, stroke of the eight, and best all-round athlete?—and liked by the masters, who found him inclined to be careless over work but absolutely reliable in every other way. Such a fellow does not win scholarships, but he is a tower of strength to his school.

For the week preceding Jim’s return Norah and her father worked hard, clearing up various odd jobs so that their time might be free when the boy arrived. There was a quaint side to this, in that Jim would without doubt have been delighted to help in any station work, which always presented itself to him as “no end of a lark” after the strenuous life at school. But it was a point of honour with those at home to leave none of their work until the holidays and the last week was invariably the scene of many labours.

Not that there were not plenty of hands on the station. It was a big run, and gave employment in one way or another to quite a band of men. But Mr. Linton preferred to keep a very close watch over everything, and he had long realized that the best way of seeing that your business is done is to take a hand yourself. The men said, “The boss was everywhere,” and they respected him the more in that he was no kid glove employer, but was willing to share in any work that was going forward. Especially he insisted on working among the cattle, and—Norah was nearly always with him on his rides—they had a more or less accurate knowledge of every beast on the place. Outside the boundary fences they went very seldom; the nearest township, seventeen miles away, Norah regarded as merely a place where you called for the mail, and save that it meant a ride or drive with her father, she had never the slightest desire to go there.

Summer was very late that year, and “burning-off” operations on the rougher parts of the run had been carried on much longer than was generally possible. Norah always regarded “burning-off” as an immense picnic, and used to beg her father to take her out. Night after night found them down on the flats, getting rid of old dead trees, which up to the present had refused obstinately to burn. It was picturesque work, and Norah loved it, though she would have been somewhat embarrassed had you hinted that the picturesqueness had anything to do with its attractions.

One after another, they would light the stumps, some squat and solid, other rising thirty or forty feet into the air. Once the fires were lit, it was necessary to keep them going; moving backwards and forward among the trees, stoking, picking up fallen bits of burning timber and adding them to the fires, coaxing sullen embers into a blaze, edging the fire round a tree, so that the wind might do its utmost in helping the work—there were no idle moments for the “burners-off”. Sometimes it would be necessary to enlarge a crack or hole in a tough stump, to gain a hold for the fire. Norah always carried a light iron bar, specially made for her at the station forge, which she called her poker, and which answered half a dozen purposes equally well, and though not an ideal weapon for killing a snake, being too stiff and straight, had been known to act in that capacity also. Every scrap of loose timber on the ground would be picked up and added to the flames. Some stumps were very obstinate and resisted all blandishments to burn; but careful handling generally ensured the fate of the majority.

There are few sights more weird, or more typically Australian, than a paddock at night with burning-off in process. Low and high, the red columns of fire stand in a darkness made blacker by their lurid glow. Where the fire has taken hold fairly the flames are fierce, and showers of sparks fall like streams of gold. Sometimes a dull crack gives warning of the fall of a long dead giant; and the burning mass leans slowly over, and then comes down with a crash, while the curious bullocks, which have poked as near as they dare to the strange scene, fling round and lumber off in a heavy gallop, heads down and tails up. From stump to stump flit the little black figures of the workers, standing out clearly sometimes, by the light of a blaze so fierce that to face it is scarcely possible; or half seen in the dull glow of a smouldering tree poking vigorously—seeming as ants attacking living monsters infinitely beyond their strength. Perhaps it is there that the fascination of the work comes in—the triumph of conquering tons of inanimate matter by efforts so small. At any rate it is always hard to leave the scene of action, and certainly the first glance next morning is to see “which are down.”

Then there were days spent among the cattle—days that always meant the high-water mark of bliss to Norah. She rode astride, and her special pony, Bobs, to whom years but added perfection, loved the work as much as she did. They understood each other perfectly; if Norah carried a hunting-crop, it was merely for assistance in opening gates, for Bobs never felt its touch. A hint from her heel, or a quick word, conveyed all the big bay pony ever needed to supplement his own common sense, of which Mr. Linton used to say he possessed more than most men. The new bullocks arrived, and had to be drafted and branded—during which latter operation Norah retired dismally to the house and the socks that had to be finished in time to be Jim’s Christmas present. Then, after the branding, came a most cheerful time, putting the cattle into their various paddocks.

One day was spent in mustering sheep, an employment not at all to Norah’s taste. She was frankly glad that Billabong devoted most of its energies to cattle, and only put up with the sheep work because, since Daddy was there, it never occurred to her to do anything else but go. But she hated the slow, dusty ride, and hailed with delight a gallop that came in their way towards the end of the day, when a hare jumped up under Bob’s nose as they rode homewards from the yards. The dogs promptly gave chase; and, almost without knowing it, Norah and Bobs were in hot pursuit, with Monarch shaking the earth behind them. The average sheep dog is no match for a hare, and the quarry easily escaped into the next paddock, after a merry run. Norah pulled up, her eyes dancing.

“Don’t you know it’s useless to try to get a hare with those fellows?” asked Mr. Linton, checking the reeking Monarch, and indicating with a nod the dogs, which were highly aggrieved at their defeat.

“But I never wanted to get it,” said his daughter, in surprise. “It’s perfectly awful to get a hare; they cry just like a baby, and it makes you feel horrid.”

“Then why did you go after it?”

“Why?” asked Norah, opening her eyes. “Well, I knew the dogs couldn’t catch it—and I believe you wanted a gallop nearly as much as I did, Daddy!” They laughed at each other, and let the impatient horses have their heads across the cleared paddock to the homestead.

There a letter awaited them.

Norah coming in to dinner in a white frock, with her curls unusually tidy, found her father looking anything but pleased over a closely covered sheet of thin notepaper.

“I wish to goodness women would write legibly,” he said, with some heat. “No one on earth has any right to write on both sides of paper as thin as this—and then across it! No one but your Aunt Eva would do it—she always had a passion for small economies, together with one for large extravagances. Amazing woman! Well, I can’t read half of it, but what she wants is unhappily clear.”

“She isn’t coming here, Daddy?”

“Saints forbid!” ejaculated Mr. Linton, who had a lively dread of his sister—a lady of much social eminence, who disapproved strongly of his upbringing of Norah. “No, she doesn’t mention such an extreme course, but there’s something almost as alarming. She wants to send Cecil here for Christmas.”

“Cecil! Oh, Daddy!” Norah’s tone was eloquent.

“Says he’s been ill,” said her father, glancing at the letter in a vain effort to decipher a message written along one edge. “He’s better, but needs change, and she seems to think Billabong will prove a sanatorium.” He looked at Norah with an expression of dismay that was comical. “I shouldn’t have thought we’d agree with that young man a bit, Norah!”

“I’ve never seen him, of course,” Norah said, unhappily, “but Jim says he’s pretty awful. And you didn’t like him yourself, did you, Daddy?”

“On the rare occasions that I’ve had the pleasure of meeting my nephew I’ve always thought him an unlicked cub,” Mr. Linton answered. “Of course it’s eighteen months since I saw him; possibly he may have changed for the better, but at that time his bumptiousness certainly appeared to be on the increase. He had just left school then—he must be nearly twenty now.”

“Oh—quite old,” said Norah, “What is he like?”

“Pretty!” said Mr. Linton, wrinkling his nose. “As pretty as his name—Cecil—great Scott! I wonder if he’d let me call him Bill for short! Bit of a whipper-snapper, he seemed; but I didn’t take very much notice of him—saw he was plainly bored by his uncle from the Bush, so I didn’t worry him. Well, now he’s ours for a time your aunt doesn’t limit—more than that, if I can make a guess at these hieroglyphics, I’ve got to send a telegram to say we’ll have him on Saturday.”

“And this is Wednesday—oh, Dad!” expostulated Norah.

“Can’t be helped,” her father said. “We’ve got to go through with it; if the boy has been ill he must certainly have all the change we can give him. But I’m doubtful. Eva says he’s had a ‘nervous breakdown,’ and I rather think it’s a complaint I don’t believe in for boys of twenty.”

The dinner gong sounded. Amid its echoes Norah might have been heard murmuring something about “nervous grandmother.”

“H’m,” said her father, laughing; “I don’t think he’ll find much sympathy with his more fragile symptoms in Billabong—we must try to brace him up, Norah. But whatever will Jim say I wonder!”

“He’ll be too disgusted for words,” Norah answered. “Poor old Jimmy! I wonder how they’ll get on. D’you suppose Cecil ever played football?”

“From Cecil’s appearance I should say he devoted his time to wool-work,” said Mr. Linton. “However, it may not turn out as badly as we think, and it’s no use meeting trouble halfway, is it? Also, we’ve to remember that he’ll be our guest.”

“But that’s the trouble,” said Norah, laughing. “It wouldn’t be half so bad if you could laugh at him. I’ll have to be so hugely polite!”

“You’ll probably shock him considerably, in any case,” said her father. “Cecil’s accustomed to very prim young ladies, and it’s not at all unlikely that he’ll try to reform you!”

“I wish him luck!” said Norah. But there was a glint in her eyes which boded ill for Cecil’s reformatory efforts.

Quiet and shy, as the Bush girls are,

But ready-witted and plucky too.

A. B. Paterson.

THE telegram assuring a welcome to Cecil Linton was duly dispatched, and the fact of his impending arrival broken to Mrs. Brown, who sniffed portentously, and gave without enthusiasm directions for the preparation of his room. “Mrs. Geoffrey” was rather a bugbear to Brownie, who had unpleasant recollections of a visit in the past from that majestic lady. During her stay of a week, she had attempted to alter every existing arrangement at Billabong—and when she finally departed, in a state of profound disapproval, the relief of the homestead was immense. Brownie was unable to feel any delight at the idea of entertaining her son.

Norah and her father made the utmost of their remaining time together. Thursday was devoted to a great muster of calves, which meant unlimited galloping and any amount of excitement; for the sturdy youngsters were running with their mothers in one of the bush paddocks, and it was no easy matter to cut them out and work them away from the friendly shelter and refuge of the trees. A bush-reared calf is an irresponsible being, with a great fund of energy and spirits—and, while Norah loved her day, she was thoroughly tired as they rode home in the late evening, the last straggler yarded in readiness for the branding next day. Mr. Linton sent her to bed early, and she did not wake in the morning until the dressing gong boomed its cheerful summons through the house.

Mr. Linton was already at breakfast when swift footsteps were heard in the hall above, a momentary silence indicated that his daughter was coming downstairs by way of the banisters, and the next moment she arrived hastily.

“I’m so sorry, Dad,” Norah said, greeting him. “But I did sleep! Let me pour out your coffee.”

She brought the cup to him, investigated a dish of bacon, and slipped into her place behind the tall silver coffee pot.

“What are we going to do to-day, Dad?”

“I really don’t quite know,” Mr. Linton said, smiling at her. “There aren’t any very pressing jobs on hand—we must cut out cattle to-morrow for trucking, but to-day seems fairly free. Have you any ideas on the subject of how you’d like to spend it? I’ve letters to write for a couple of hours, but after that I’m at your disposal.”

Norah wrinkled her brows.

“There are about fifty things I want to do,” she said. “But most of them ought to wait until Jim comes home.” She thought for a moment. “I don’t want to miss any more time with Bobs than I have to—could we ride over to the backwater, Dad, and muster up the cattle there? You know you said you were going to do so, pretty soon.”

“I’d nearly forgotten that I had to see them,” Mr. Linton said, hastily. “Glad you reminded me, Norah. We’ll have lunch early, and go across.”

Norah’s morning was spent in helping Mrs. Brown to compound Christmas cakes—large quantities of which were always made and stored well before Christmas, with due reference to the appetites of Jim and his friends. Then a somewhat heated and floury damsel donned a neat divided riding skirt of dark blue drill, with a white linen coat, and the collar and tie which Norah regarded as the only reasonable neck gear, and joined her father in the office.

“Ready?—that’s right,” said he, casting an approving glance at the trim figure. “I’ve just finished writing, and the horses are in.”

“So’s lunch,” Norah responded. “It’s a perfectly beautiful day for a ride, Daddy—hurry up!”

The day merited Norah’s epithet, as they rode over the paddocks in the afternoon. As yet the grass had not dried up, thanks to the late rains, and everywhere a green sea rippled to the fences. Soon it would be dull and yellow; but this day there was nothing to mar the perfection of the carpet that gave softly under the horses’ hoofs. The dogs raced wildly before them, chasing swallows and ground-larks in the cheerfully idiotic manner of dogs, with always a wary ear for Mr. Linton’s whistle: but as yet they were not on duty, and were allowed to run riot.

An old log fence stretched before them. It was the only one on Billabong, where all station details were strictly up-to-date. This one had been left, partly because it was picturesque, and partly at the request of Jim and Norah, because it gave such splendid opportunities for jumping. There were not many places on that old fence that Bobs did not know, and he began to reef and pull as they came nearer to it.

“I don’t believe I’ll be able to hold him in, Daddy!” said Norah, with mock anxiety.

“Not afraid, I hope?” asked her father, laughing.

“Very—that you won’t want to jump! I’d hate to disappoint him, Daddy—may I?”

“Oh, go on!” said Mr. Linton. “If I said ‘no’ the savage animal would probably bolt!” He held Monarch back as Norah gave the bay pony his head, and they raced for the fence; watching with a smile in his eyes the straight little form in the white coat, the firm seat in the saddle, the steady hand on the rein. Bobs flew the big log like a bird, and Norah twisted in her saddle to watch the black horse follow. Her eyes were glowing as her father came up.

“I do think he loves it as much as I do!” she said, patting the pony’s neck.

“He’s certainly as keen a pony as I ever saw,” Mr. Linton said. “How are you going to manage without him, Norah?”

Norah looked up, her eyes wide with astonishment.

“Do without Bobs!” she exclaimed. “But I simply couldn’t—he’s one of the family.” Then her face fell suddenly, and the life died out of her voice. “Oh—school,” she said.

The change was rather pitiful, and Mr. Linton mentally abused himself for his question.

“He’ll always be waiting for you when you come home, dear,” he said. “Plenty of holidays—and think how fit he’ll be! We’ll have great rides, Norah.”

“I guess I’ll want them,” she said. There fell silence between them.

The scrub at the backwater was fairly thick, and the cattle had sought its shade when the noonday sun struck hot. Well fed and sleek, they lay about under the trees or on the little grassy flats formed by the bends of the stream. Norah and her father separated, each taking a dog, and beat through the bush, routing out stragglers as they went. The echoes of the stockwhips rang along the water. Norah’s was only a light whip, half the length and weight of the one her father carried. It was beautifully plaited—a special piece of work, out of a special hide; while the handle was a triumph of the stockman’s art. It had been a gift to Norah from an old boundary rider whose whips were famous, and she valued it more than most of her possessions, while long practice and expert tuition had given her no little skill in its use.

She worked through the scrub, keeping her eyes in every direction, for the cattle were lazy and did not stir readily, and it was easy to miss a motionless beast hidden behind a clump of dogwood or Christmas bush—the scrub tree that greets December with its exquisite white blossoms. When at length she came to the end of her division, and drove her cattle out of the shelter she had quite a respectable little mob to add to those with which her father was already waiting.

It was only to be a rough muster; rather, a general inspection to see how the bullocks were doing, for the nearest stockyards were at the homestead, and Mr. Linton did not desire to drive them far. He managed to get a rough count along a fence—Norah in the rear, bringing the bullocks along slowly, so that they strung out under their owner’s eye. Occasionally one would break out and try to race past him on the wrong side. Bobs was as quick as his rider to watch for these vagrants, and at the first hint of a break away he would be off in pursuit. It was work the pair loved.

“Hundred and thirty,” said Mr. Linton, as the last lumbering beast trotted past him, and, finding the way clear, with no harrowing creatures to annoy him, and head him back to his mates, kicked up his heels and made off across the paddock.

“Did any get behind me, Norah?”

“No, Daddy.”

“That’s a good girl. They look well, don’t they?”

Norah assented. “Did you notice how that big poley bullock had come on, Dad?”

“Yes, he’s three parts fat,” said Mr. Linton. “All very satisfactory, and the count is only two short—not bad for a rough muster.”

They turned homewards, cantering quickly over the paddocks; the going was too good, Norah said, to waste on walking; and it was a delight to feel the long, even stride under one, and the gentle wind blowing upon one’s cheeks. As he rode, Mr. Linton watched the eager, vivid little face, alight with the joy of motion. If Bobs were keen, there was no doubt that his mistress was even keener.

They crossed the log fence again by what Norah termed “the direct route,” traversed the home paddock, and drew up with a clatter of hoofs at the stable yard. Billy, a black youth of some fame concerning horses, came forward as they dismounted and took the bridles. But Norah preferred to unsaddle Bobs herself and let him go; she held it only civil after he had carried her well. She was leading him off when the dusky retainer muttered something to her father.

“Oh, all right, Billy,” said Mr. Linton. “Norah, those fellows from Cunjee have come to see me about buying sheep. I expect I shall have to take them out to the paddock. I don’t think you’d better come.”

“All right, Dad.” Sheep did not interest Norah very much. “I think I’ll go down to the lagoon.”

“Very well, don’t distinguish yourself by falling in,” said her father, with a laugh over his shoulder as he hurried away towards the house.

Left to herself, Norah paid a visit to Brownie in the kitchen, which resulted in afternoon tea—there was never a bush home where tea did not make its appearance on the smallest possible pretext. Then she slipped off her linen jacket and brown leather leggings, and, having beguiled black Billy into digging her some worms, found some fishing tackle and strolled down to the lagoon.

It was a broad sheet of water, at one end thickly fringed with trees, while in the shallower parts a forest of green, feathery reeds bordered it, swaying and rustling all day, no matter how soft the breeze. The deeper end had been artificially hollowed out, and a bathing box had been built, with a spring board jutting out over the water. Under the raised floor of the bathing box a boat was moored. Norah pulled it out and dropped down into it, stowing her tin of worms carefully in the stern. Then she paddled slowly into the deepest part of the lagoon, baited her line scientifically, and began to fish.

Only eels rewarded her efforts; and while eels are not bad fun to pull out, Norah regarded them as great waste of time, since no one at Billabong cared to eat them, and in any case she would not let them come into the boat—for a good-sized eel can make a boat unpleasantly slimy in a very short time. So each capture had to be carefully released at the stern—not a very easy task. Before long Norah’s white blouse showed various marks of conflict; and being by nature a clean person, she was rather disgusted with things in general. When at length a large silver eel, on being pulled up, was found to have swallowed the hook altogether, she fairly lost patience.

“Well, you’ll have to keep it,” she said, cutting her line; whereupon the eel dropped back into the water thankfully, and made off as though he had formed a habit of dining on hooks, and, in fact, preferred them as an article of diet. “I’m sure you’ll have shocking indigestion,” Norah said, watching the swirl of bubbles.

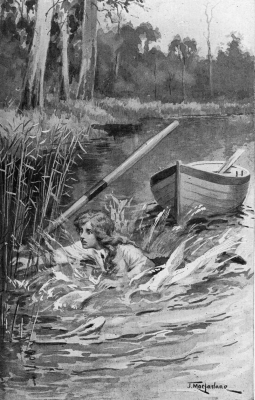

The boat had drifted some way down the lagoon, and a rustle told Norah that they were near one of the reedy islands dotted here and there in the shallows. There was very little foothold on them, but they made excellent nesting places for the ducks that came to the station each year. The boat grounded its nose in the soft mud, and Norah jumped up to push it off. Planting the blade of the oar among the reeds, she leant her weight upon it and shoved steadily.

The next events happened swiftly. The mud gave way suddenly with a suck, and the oar promptly slithered, burying itself for half its length; and Norah, taken altogether by surprise, executed a graceful header over the bow of the boat. The mud received her softly, and clung to her with affection; and for a moment, face downward among the reeds, Norah clawed for support, like a crab suddenly beached. Then, somehow, she scrambled to a sitting position, up to her waist in mud and water—and rocked with laughter. A little way off, the boat swayed gently on the ruffled surface of the water.

“Well—of all the duffers!” Norah said. She tried to stand, and forthwith, went up to one knee in the mud. Then, seeing that there was no help for it, she managed to slip into deeper water—not very easy, for the mud showed a deep attachment to her—and swam to the boat. To get into it proved beyond her, but, fortunately, the bank was not far off, and, though her clothes hampered her badly—a riding skirt is the most inconvenient of swimming suits—she was as much at home as a duck in the water, and soon got ashore.

Then she inspected herself, standing on the grass, while a pool of water rapidly widened round her. Alas, for the trim maiden of the morning! soaked to the skin, her lank hair clinging round her face, her collar a limp rag, the dye from her red silk tie spreading in artistic patches on her white blouse! Over all was the rich black mud of the lagoon, from brow to boot soles. Her hat, once white felt, was a sodden black-streaked mass; even her hands and face were stiff with mud.

“Thank goodness, Daddy’s out!” said the soaked one, returning knee-deep in the water to try and cleanse herself as much as might be—which was no great amount, for lagoon mud defies ordinary efforts. She waded out, still laughing; cast an apprehensive glance at the quarter from which her father might be expected to return, and set out on her journey to the house, the water squelching dismally in her boots at every step.

In the garden at Billabong walked a slim youth in most correct attire. His exquisitely tailored suit of palest grey flannel was set off by a lavender striped shirt, with a tie that matched the stripe. Patent leather shoes with wide ribbon bows shod him; above them, and below the turned-up trousers, lavender silk socks with purple circles made a very glory of his ankles. On his sleek head he balanced a straw hat with an infinitesimal brim, a crown tall enough to resemble a monument, and a very wide hat band. His pale, well-featured face betrayed unuttered depths of boredom.

The click of the gate made him turn. Coming up the path was a figure that might have been plaintive but that Norah was so immensely amused at herself; and the stranger opened his pale eyes widely, for such apparitions had not come his way. She did not see him for a moment. When she did, he was directly in her path, and Norah pulled up short.

“Oh!” she said, weakly; and then—“I didn’t know any one was here.”

The strange youth looked somewhat disgusted.

“I should think you’d—ah—better go round to the back,” he said, condescendingly. “You’ll find the housekeeper there.”

This time it was Norah’s turn to be open-eyed.

“Thanks,” she said a little shortly, “Were you waiting to see any one?”

The boy’s eyebrows went up. “I am—ah—staying here.”

“Oh, are you?” Norah said. “I didn’t know. I’m Norah Linton.”

“You!” said the stranger. There was such a world of expression in his tone that Norah flushed scarlet, suddenly painfully conscious of her extraordinary appearance. Then—it was unusual for her—she became angry.

“Did you never see any one wet?” she asked, in trenchant tones. “And, didn’t you ever learn to take your hat off?”

“By Jove!” said the boy, looking at the truculent and mud-streaked figure. Then he did an unwise thing, for he burst out laughing.

“I don’t know who you are,” Norah said, looking at him steadily. “But I think you’re the rudest, worst-mannered boy that ever came here!”

She flashed past him with her head in the air. Cecil Linton, staring after her with amazement, saw her cross the red-tiled verandah hurriedly and disappear within a side door, a trail of wet marks behind her.

“By Jove!” he said again. “The bush cousin!”

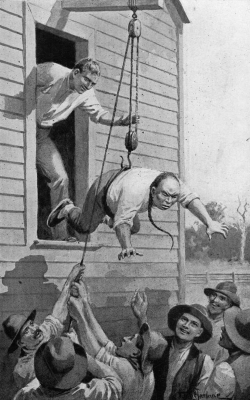

“The mud received her softly, and clung to her with affection.”

| Mates at Billabong] | [Page 37 |

And the loony bullock snorted when you first came into view,

Well, you know, it’s not so often that he sees a swell like you.

A. B. Paterson.

NORAH did not encounter the newcomer again until dinner time.

She was in the drawing-room, waiting for the gong to sound, when Cecil came in with her father. For a moment he did not recognize the soaked waif of the garden whom he had recommended “to go round to the back.”

A hot bath and a change of raiment had restored Norah to her usual self; had helped her also to laugh at her meeting with her cousin, although she was still ruffled at the memory of the sneer in his laugh. Perhaps because of that she had dressed more carefully than usual. Cecil might have been excused for failing to recognize the grave-faced maiden, very dainty in her simple frock of soft white silk, with her still moist curls tied back with a broad white ribbon.

“As you two have already met, there’s no need to introduce you,” said Mr. Linton, a twinkle in his eye. “Sorry your reception was so informal, Cecil—you took us by surprise.”

“I suppose the mater mixed things up, as usual,” Cecil said, in a bored way. “I certainly intended all along to get here to-day, but she’s fearfully vague, don’t you know. I was lucky in getting a lift out.”

“You certainly were,” his uncle said, drily. “However, I’m glad you didn’t have to wait in the township. You’d have found it slow.”

“I’d probably have gone back,” said Cecil.

“Ah—would you?” Mr. Linton looked for a moment very much as though he wished he had done so. There was an uncomfortable pause, to which the summons to dinner formed a welcome break.

Dinner was very different to the usual cheery meal. Cecil was not shy, and supplied most of the conversation as a matter of course; and his conversation was of a kind new to Norah. She remained unusually silent, being, indeed, fully occupied in taking stock of this novel variety of boy. She wondered were all city boys different to those she knew. Jim was not like this; neither were the friends he was accustomed to bring home with him. They were not a bit grown up, and they talked of ordinary, wholesome things like cricket and football, and horses, and dormitory “larks,” and were altogether sensible and companionable. But Cecil’s talk was of theatres and bridge parties, and—actually—clothes! Horses he only mentioned in connexion with racing, and when Mr. Linton inquired mildly if he were fond of dances, he was met by raised eyebrows and a bored disclaimer of caring to do anything so energetic. Altogether this product of city culture was an eye-opener to the simple folks of Billabong.

Of Norah, Cecil took very little notice. She was evidently a being quite beneath his attention—he was secretly amused at the way in which she presided at her end of the table, and decided in his own mind that his mother’s views had been correct, and that this small girl would be all the better for a little judicious snubbing. So he ignored her in his conversation, and if she made a remark contrived to infuse a faint shade of patronage into his reply. It is possible that his amazement would have been great had he known how profoundly his uncle longed to kick him.

Dinner over, Norah fled to Brownie, and to that sympathetic soul unburdened her woes. Mr. Linton and his nephew retired to the verandah, where the former preferred to smoke in summer. He smiled a little at the elaborate cigarette case Cecil drew out, but lit his pipe without comment, reflecting inwardly that although cigarettes were scarcely the treatment, though they might be the cause, of a pasty face and a “nervous breakdown,” it was none of his business to interfere with a young gentleman who evidently considered himself a man of the world. So they smoked and talked, and when, after a little while, Cecil confessed himself tired, and went off to bed, he left behind him a completely bored and rather annoyed squatter.

“Well, Norah, what do you think of him?”

Norah, sitting meekly knitting in the drawing-room, looked up and laughed as her father came in.

“Think? Why, I don’t think much, Daddy.”

“No more do I,” said Mr. Linton, casting his long form into an arm chair. “Of all the spoilt young cubs!—and that’s all it is, I should say: clearly a case of spoiling. The boy isn’t bad at heart, but he’s never been checked in his life. Well, I’m told it’s risky for a father to bring up his daughter unaided, but I’m positive the result is worse when an adoring mother rears a fatherless boy! Possibly I’ve made rather a boy of you—but Cecil’s neither one thing nor the other. Why didn’t you come out, my lass?”

“Felt too bad tempered!” said Norah; “he makes me mad when he speaks to you in that condescending way of his, Daddy. I’ll be calmer to-morrow.” She smiled up at her father. “Have a game of chess?”

“It would be soothing, I think,” Mr. Linton answered. He laughed. “It’s really pathetic—our Darby and Joan existence to be ruffled like this! Thank goodness, he’s in bed, for to-night, at any rate!” They got out the chessmen, and played very happily until Norah’s bedtime.

“Do you ride, Cecil?” Mr. Linton asked next morning at breakfast.

“Ride? Oh, certainly,” Cecil answered. “I suppose you’re all very keen on that sort of thing up here?”

“Well, that’s how we earn our living,” his uncle remarked. “Norah is my right-hand man on the run.”

“Ah, how nice! Do you find it hard to get labour here?”

“Oh, we get them,” said Mr. Linton, his eyes twinkling. “But I prefer to catch ’em young. We’re cutting-out cattle for trucking to-day. Would you care to come out?”

“Delighted,” said the nephew, glancing without enthusiasm at his flannels. “But I didn’t dress for riding.”

“Oh, we’re not absolute sticklers for costume here,” Mr. Linton said, laughing outright. “Wear what you like—in any case, we shan’t start for an hour.”

It was more than that before they finally got away. The delay was due to waiting for the visitor, whose toilet was a lengthy proceeding. When at length he sauntered out, in blissful ignorance of the fact that he had been keeping them waiting, no one could have found fault with his clothes—a riding suit of very English cut, with immensely baggy breeches, topped by an immaculately folded stock, and a smart tweed cap.

“That feller plenty new,” said black Billy, gazing at him with astonishment.

Mr. Linton chuckled as he swung Norah to her saddle.

“Let’s hope his horsemanship is equal to his attire!”

Norah smiled in answer. Bobs was dancing with impatience, and she walked him round and round, keeping an eye on her cousin.

A steady brown mare had been saddled for Cecil—one of the “general utility” horses to be found on every station. He cast a critical eye over her as he approached, glancing from her to the horses of his uncle and cousin. Brown Betty was a thoroughly good stamp of a stock horse, with plenty of quality; while not, perhaps, of the class of Monarch and Bobs, she was by no means a mount to be despised. That Cecil disapproved of her, however, was evident. There was a distinct curl on his lip as he gathered up the reins. However, he mounted without a word, and they set off in pursuit of Murty O’Toole, the head stockman, who was already halfway to the cutting-out paddock.

The Clover Paddock of Billabong was famous—a splendid stretch of perfect green, where the cattle moved knee-deep in fragrant blossoming clovers, with pink and white flowers starring the wide expanse. At one end it was gently undulating plain, towards the other it came down in a gradual slope to the river, where tall gums gave an evergreen shelter from winter gales or summer heat. The cattle were under them as the riders came up—great splendid Shorthorns, the aristocracy of their kind, their roan sides sleek, their coats in perfect condition, and a sprinkling of smaller bullocks whose inferiority in size was compensated by their amazing fatness. It was evident that this week there would be no difficulty in making up the draft for the Melbourne market.

The cattle were mustered into one herd; no racing or hastening now, but with the gentle consideration one should extend to the dignified and portly. They moved lazily, as if conscious of their own value. Cecil hurrying a red-and-white bullock across a little flat, was met by a glare from Murty O’Toole, and a muttered injunction to “go aisy wid ’em,” followed by a remark that “clo’es like thim was only fit to go mustherin’ turkeykins in!” Luckily the latter part of the outbreak was unheard by Cecil, who was quite sufficiently injured at the first, and favoured Murty with a lofty stare that had the effect of throwing the Irishman and black Billy into secret convulsions of mirth.

Norah rode not far from her father as they brought the cattle out into the open and to the cutting-out camp—a spot where the beaten ground showed that very often before such scenes had been enacted. The bullocks knew it, and huddled there contentedly enough in a compact body, while slowly Mr. Linton and Murty rode about them, singling out the primest. Once marked down, O’Toole would slip between the bullock and his mates and edge him away, where Billy took charge of him, preventing his returning to the mob. With the first two or three this was not quite easy: but once a few were together they gave little trouble, feeding about calmly: and generally a bullock cut out from the main body would trot quite readily across to the others.

Privately, Cecil Linton thought it remarkably dull work. All that he had read of station life was unlike this. He had had visions of far more exciting doings—mad gallops and wild cattle, thoroughbred horses, kangaroo hunts and a score of other delights. Instead, all he had to do was to tail after a lot of sleepy bullocks and then watch them sorted out by some men whose easy-going ways were unlike anything he had imagined. He had no small opinion of his riding, and he yearned for distinction. The very sight of Norah, leaning a little forward, keenness on every line of her face, was an offence to him. He could see nothing whatever to be keen about. Yawning, he lit a cigarette.

Just then a bullock was cut out and pointed in the way he should go. He lumbered easily past black Billy, apparently quite contented with his fate; and Billy, seeing another following gave a crack of his whip to speed him on his way, and turned to deal with the new comer. The first bullock became immediately seized with a spirit of mischief. He flourished his heels in the air, turned at right angles and made off towards the river at a gallop.

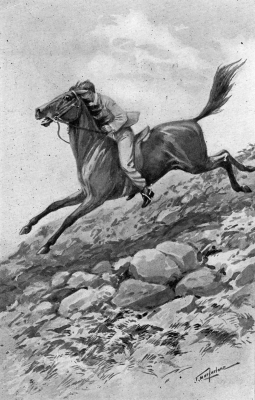

Cecil, busy with his cigarette, saw Norah sit up suddenly and tighten her hand on the bridle. Simultaneously Bobs was off like a shot—tearing over the paddock a little wide of the fugitive. The race was a short one. Passing the bullock, the bay pony and his rider swung in sharply and the lash of Norah’s whip shot out. The bullock stopped short, shaking his head; then, as the whip spoke again, he wheeled and trotted back meekly to the smaller mob. Behind him Norah cantered slowly. The work of cutting-out had not paused and no one seemed to notice the incident. But Cecil saw his uncle smile across at the little girl, and caught the look in Norah’s eyes as she smiled back. She and Bobs took up their station again, silently watchful.

Cecil was fired with ambition. Norah’s small service had seemed to him ridiculously easy; still, insignificant though everyone appeared to regard it, it was better than doing nothing. He had not the faintest doubt of his own ability, and the idea that riding in a decorous suburb might not fit him for all equine emergencies he would have scouted. He gathered up his reins, and waited anxiously for another beast to break away.

One obliged him presently; a big shorthorn that decided he had stayed long enough in the mob, and suddenly made up his mind to seek another scene. Norah had already started in pursuit when she saw her cousin send his spurs home in Betty, and charge forward. So she pulled up the indignant Bobs, who danced; and left the field to Cecil.

Betty took charge of affairs from the outset. There was no move in all the cattle-game that she did not understand. Moreover, she was justly indignant at the spur-thrust, which attention only came her way in great emergencies; and the heavy hand on her mouth was gall and wormwood to her. But ahead was a flying bullock, and she was a stock horse, which was sufficient for Betty.

“That feller brown mare got it all her own way!” said Billy, in delight.

She had. Cecil, bumping a little in the saddle, had no very clear idea of how things were going. He had a moment of amazement that the quiet mare he had despised could make such a pace. Once he tried to steady her, but at that instant Betty was not to be steadied. She galloped on, and Cecil, recovering some of his self-possession, began to think that this was the thing whereof he had dreamed.

The bullock was fat and scant of breath. It did not take him very long to conclude that he had had enough, especially when he heard the hoofs behind him. It was sad, for close before him was the shade of the trees and the murmur of the river; but discretion is ever the better part of valour, particularly if one be not only valorous but fat. He pulled up short. Betty propped without a second’s hesitation, and swung round.

To Cecil it seemed that the world had dropped from under him—and then risen to meet him. The brown mare turned, in the bush idiom, “on a sixpence,” but Cecil did not turn. He went on. The onlookers had a vision of the mare chopping round, as duty bade her, to head off the bullock, while at right angles a graceful form in correct English garments hurtled through the air in an elegant curve. When he came down, which seemed to be not for some time, it was into a handy clump of wild raspberries—and only those who know the Victorian wild raspberry know how clinging and intrusive are its hooked thorns. Two legs kicked wildly. There was no sound.

When the rescuing party extricated Cecil from his involuntary botanical researches he was a sorry sight. His clothes were torn in many places, and his face and hands badly scratched, while the red stains of the raspberries had turned his light tweeds into something resembling an impressionist sketch. It was perhaps excusable that he had altogether lost his temper. He burst out in angry abuse of the mare, the bullock, the raspberry clump, and the expedition in general—anger which the scarcely concealed grins of the stockmen only served to intensify. Norah, who had choked with laughter at first, but had become sympathetic as soon as she saw the boy’s face, extracted numerous thorns from his person and clothing, and murmured words of regret, which fell on unheeding ears. Finally his uncle lost patience.

“That’ll do, Cecil,” he said. “Everyone comes to grief occasionally—take your gruel like a man. Come on, Norah. Murty’s waiting.” Saying which he put Norah up, and they rode off, while Billy held the brown mare’s rein for Cecil, who mounted sulkily. Something in his uncle’s face forbade his replying. But in his heart came the beginning of a grudge against the Bush, Billabong in general, and Norah in particular. Later on, he promised himself, there might come a chance to work it off.

For the present, however, there was nothing to be done but nurse his scratches and his grievance; so he sat sulkily on Betty, and took no further active part in the morning’s work, the consciousness of acting like a spoilt child not tending to improve his temper. Nobody took any notice of him. One by one the bullocks were cut out, until between twenty and thirty were ready, and then the main mob was left to wander slowly back to the river, while O’Toole and Billy started with the others to the paddock at the end of the run, which was their first stage in the seventeen-mile journey to the trucking yards at Cunjee. They moved off peacefully through the blossoming clover.

“Lucky they don’t be afther knowin’ what’s ahead av thim!” said Murty. He lifted his battered felt hat to Norah, as he rode away.

“We’ll go down and see how high the river is before we go home,” said Mr. Linton.

So they rode down to the river, commented on the unusual amount of water for so late in the year, inspected the drinking places, paid a visit to a beast in another paddock, which had been sick, but was now apparently in rude health, and finally cantered home to lunch. Brownie prudently refrained from comment on Cecil’s scratched countenance, further than to supply him with large quantities of hot water in his room, together with a small pair of pliers, which she remarked were ’andy things for prickles. Under this varied treatment Cecil became more like himself, and recovered his spirits, though a soreness yet remained at the thought of the little girl who had done so easily what he had failed so ignominiously in trying to do. He decided definitely in his own mind that he did not like Norah.

You found the Bush was dismal, and a land of no delight—

Did you chance to hear a chorus in the shearer’s hut at night?

A. B. Paterson.

‟DEAR MATER,—Arrived at Cunjee safely, and, thanks to the way you fixed up things found no one to meet me, as Uncle David thought I would not arrive until next day. However, a friendly yokel gave me a lift out to Billabong in a very dirty and springless buggy, so that the mistake was not a fatal one, though it gave me a very uncomfortable drive.

“The place is certainly very nice, and the house comfortable, though, of course, it is old-fashioned. I prefer more modern furniture; but Uncle David seems to think his queer old chairs and tables all that can be desired, and did not appear interested when I told him where we got our things. I have a large room, rather draughty, but otherwise pleasant, with plenty of space for clothes, which is a comfort. I do think it’s intensely annoying to be expected to keep your clothes in your trunk. The view is nice.

“Uncle David seemed quite prepared to treat me as a small boy, but I fancy I have demonstrated to him that I know my way about—in fact, as far as city life goes, I should say he knew exceedingly little. I can’t understand any man with money being content to live and die in a hole like this out-of-the-way place: but I suppose, as you say, Aunt Helen’s death made a difference. Actually, they have not even one motor! and when I spoke of it Uncle David seemed almost indignant, and said horses were good enough for him. That is a specimen of the way they are content to live. He seems quite idiotically devoted to the small child, and she lives in his pocket. If she weren’t so countrified in her ways she wouldn’t be bad looking; but, of course, she is quite the bush youngster, and, I should think, would find her level pretty quickly when she goes to school among a lot of smart Melbourne girls. I should hope so, at any rate, for she is quite spoilt here. It is exactly as you said—every one treats her like a sort of tin god, and she evidently thinks herself someone, and is inclined to regard those older than herself quite as equals. When I first saw her she had just fallen into some mud hole, and her appearance would have given you a fit. But what can you expect?

“The fat old cook is still here, and asked after you. It’s absolutely ridiculous to see the way she is treated—quite considers herself the mistress of the place, and when I told her one morning to let me have my shaving water she was almost rude. I think if there’s one thing sillier than another it’s the sort of superstition some people have about old servants.

“So far I find it exceedingly dull, and don’t feel very hopeful that things will be much better when Jim comes home. Of course, he may be improved, but he appeared to me a great overgrown animal when I last saw him, without an idea in his head beyond cricket and football. I don’t feel that he will be any companion to me. He will probably suffer badly from swelled head, too, as every one is making a fuss about his return. So quaint, to see the sort of mutual admiration that goes on here.

“I have had some riding, being given a horse much inferior to either Uncle David’s or Norah’s—the latter rides like a jockey, and, of course, astride, which I consider very ungraceful. She turns out well, however, and all her get-up is good—her habits come from a Melbourne tailor. I think I will get some clothes in Melbourne on my way back; they may not have newer ideas, but it may be useful for purposes of comparison with the Sydney cut. My riding clothes were evidently a source of much wonderment and admiration to the yokels. Unfortunately they have become badly stained with some confounded raspberry juice, and though I left them out for Mrs. Brown to clean, she has not done so yet.

“Well, there is no news to be got in a place like this; we never go out, except on the run, and there seems absolutely no society. The local doctor came out yesterday, in a prehistoric motor, but I found him very uninteresting. Of course, one has no ideas in common with these Bush people. Where the ‘Charm of the Bush’ comes in is more than I can see—I much prefer Town on a Saturday morning to all Billabong and its bullocks. They wanted me to go out one night and—fancy!—help to burn down dead trees; but, really, I jibbed on that. There is no billiard room. Uncle David intends building one when Jim comes home for good, but that certainly won’t be in my time here. I fancy a very few weeks will see me back in town.

“No bridge played here, of course! Have you had any luck that way?

Your affectionate son,

Cecil Aubrey Linton.”

Cecil blotted the final sheet of his letter home, and sat back with a sigh of satisfaction, as one who feels his duty nobly done. He stamped it, strolled across the hall to deposit it in the post box which stood on the great oak table, and then looked round for something to do.

It was afternoon, and all was very quiet. Mr. Linton had ridden off with a buyer to inspect cattle, Norah ruefully declining to accompany him.

“I’m awfully sorry, Dad,” she had said. “But I’m too busy.”

“Busy, are you? What at?”

“Oh, cooking and things,” Norah had answered. “Brownie’s not very well, and I said I’d help her—there’s a lot to do just now, you know.” She stood on tip-toe to kiss her father. “Good-bye, Dad—don’t be too long, will you? And take care of yourself!”

Cecil also had declined to go out, giving “letters to write” as a reason. The truth was that several rides had told on the town youth, whose seat in the saddle was not easy enough to prevent his becoming stiff and sore. Bush people are used to this peculiarity in city visitors, and, while regarding the sufferers with sympathy, generally prescribe a “hair of the dog that bit them”—more riding—as the quickest cure; which Cecil would certainly have thought hard-hearted in the extreme. However, nothing would have induced him to say that he had felt the riding, since Cecil belonged to that class of boy that hates to admit any inferiority to others. So he suffered in silence, creaked miserably at his uprising and down-sitting, and was happily unaware that every one on Billabong knew perfectly well what was the matter with him.

Cecil and his mother were very good friends in the cool, polite way that was distinctive of them. They “fitted” together admirably, and as a general rule held the same views, the one on which they were most in accord being the belief in Cecil’s own superior talents and characteristics. He wrote to her just as he would have talked, certain of her absolute agreement. When his letter was finished he felt much relieved at having, as Jim said, “got it off his chest.” Not that Cecil would ever have said anything so inelegant.

Sarah crossed the hall at the moment, carrying a tray of silver to be cleaned, and he called to her—

“Where is Norah?”

“Miss Norah’s in the kitchen,” said the girl, shortly. The Billabong maids were no less independent than modern maids generally are, but they had their views about the city gentleman’s manner to the daughter of the house. “On’y a bit of a kid himself,” Mary had said to Sarah, indignantly, “but any one’d think he owned the earth, an’ Miss Norah was a bit of it.” So they despised Cecil exceedingly, and refrained from shaking up his mattress when they made his bed.

“Er—you may tell her I want to speak to her.”

“Can’t I’m afraid,” Sarah said. “Miss Norah’s very busy, ’elpin’ Mrs. Brown. She don’t care to be disturbed.”

“Can’t she spare me a moment?”

“Wouldn’t ask her to.” Sarah lifted her tray—and her nose—and marched out. Cecil looked black.

“Gad! I wish the mater had to deal with those girls!” he said, viciously—Mrs. Geoffrey Linton was of the employers who “change their maids” with every new moon. “She’d make them sit up, I’ll wager. Abominable impertinence!” He strolled to the door, and looked out across the garden discontentedly. “What on earth is there for a man to do? Well, I’ll hunt up the important cousin.”

At the moment, Norah was quite of importance. Mrs. Brown had succumbed to a headache earlier in the day. Norah had found her, white-faced and miserable, bending over a preserving pan full of jam, waiting for the mystical moment when it should “jell.” Ordered to rest, poor Brownie had stoutly refused—was there not more baking to be done, impossible to put off, to say nothing of the jam? A brisk engagement had ensued, from which Norah had emerged victorious, the reins of government in her hands for the day. Brownie, still protesting, had been put on her bed with a handkerchief steeped in eau de Cologne on her throbbing forehead, and Norah had returned to the kitchen to varied occupations.

The jam had behaved beautifully; had “jelled” in the most satisfactory manner, just the right colour; now it stood in a neat array of jars on a side table, waiting to be sealed and labelled when cold. Then, after lunch, Norah had plunged into the mysteries of pastry, and was considerably relieved when her mince pies turned out very closely akin to those of Brownie, which were famous. Puddings for dinner had followed, and were now cooling in the dairy. Finally, the joint being in the oven, and vegetables prepared, the cook had compounded Jim’s favourite cake, which was now baking; during which delicate operation, with a large dab of flour on her nose, the cook sat at the table, and wrote a letter.

“Dear old Jim,—This must be in pencil, ’cause I’m watching a cake that’s in the oven, and I’m awfully scared of it burning, so I don’t dare to go for the ink. Dad said I was to write and tell you we would meet you on Wednesday, unless we heard from you again. We are all awfully glad and excited about you coming. I’m sure Tait and Puck understand, ’cause I told them to-day, and they barked like anything. Your room is all right, and we’ve put in another cupboard. We’re all so sorry about Wally not coming, but we hope he will come later on. Do make him.

“Dad and I aren’t talking about me going to school. It can’t be helped, and it only makes you jolly blue to talk about it.