* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Riviera of the Corniche Road

Date of first publication: 1921

Author: Frederick Treves (1853-1923)

Date first posted: Apr. 22, 2019

Date last updated: Apr. 22, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190471

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE RIVIERA OF THE

CORNICHE ROAD

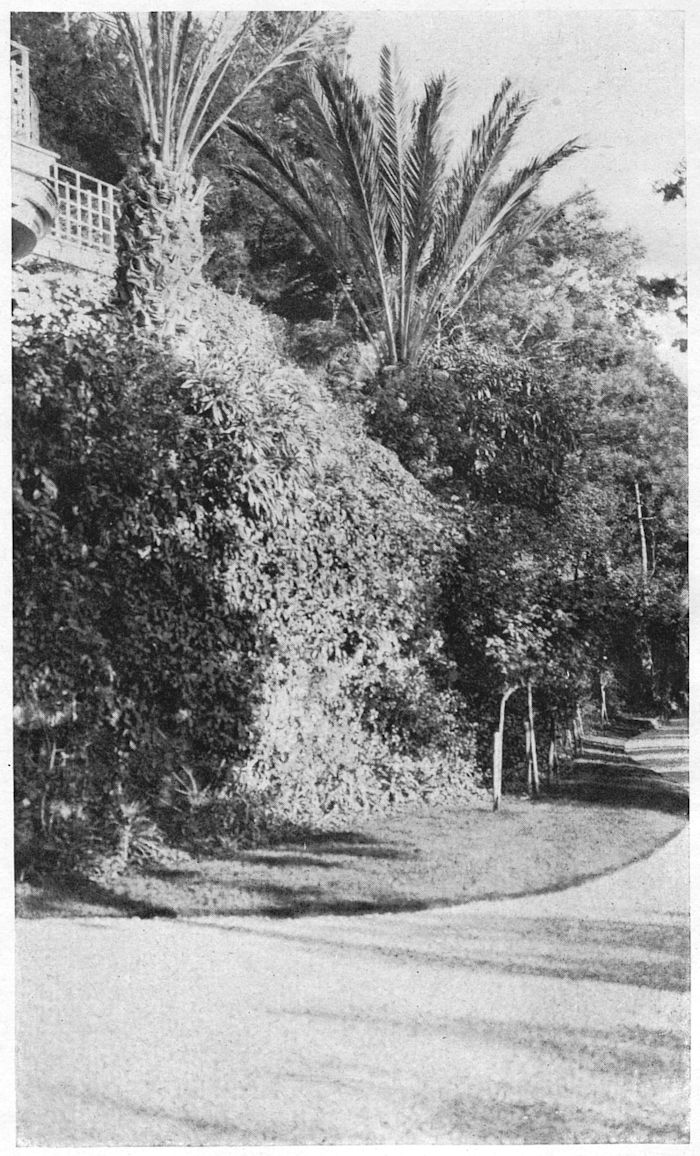

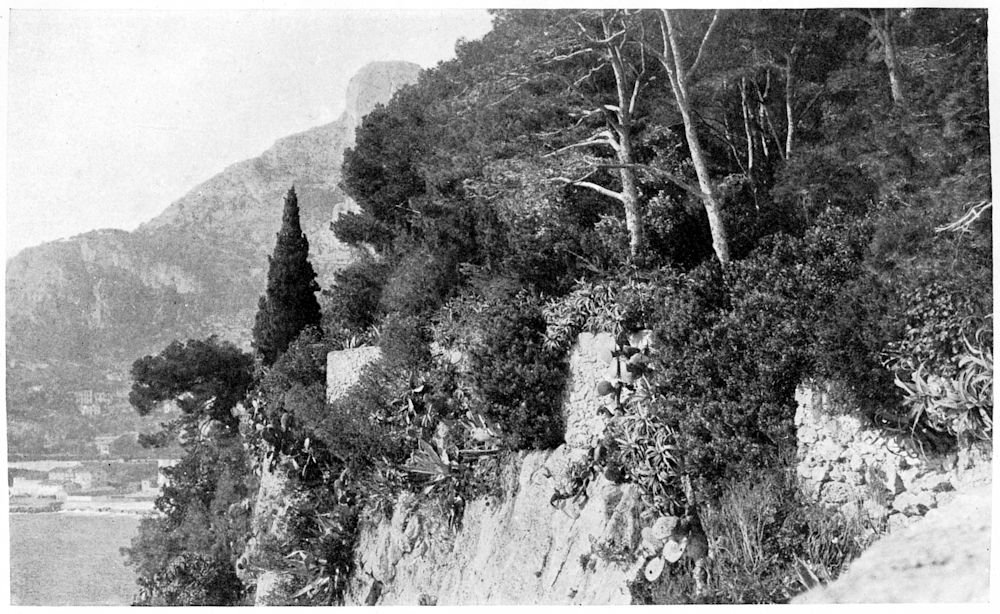

A RIVIERA GARDEN.

The Riviera of the

Corniche Road

BY

SIR FREDERICK TREVES, BART.

G.C.V.O., C.B., LL.D.

Serjeant-Surgeon to His Majesty the King; Author of “The

Other Side of the Lantern,” “The Cradle of the Deep,”

“The Country of the Ring and the Book,” “Highways

and By-ways of Dorset,” etc. etc.

Illustrated by 92 Photographs by the Author

CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1921

This book deals with that part of the French Riviera which is commanded by the Great Corniche Road—the part between Nice and Mentone—together with such places as are within easy reach of the Road.

I am obliged to the proprietors of the Times for permission to reprint an article of mine contributed to that journal in March, 1920. It appears as Chapter XXXVII.

I am much indebted to Dr. Hagberg Wright, of the London Library, for invaluable help in the collecting of certain historical data.

FREDERICK TREVES.

Monte Carlo,

Christmas, 1920

| Contents | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

| 1. | Early Days in the Riviera | 1 |

| 2. | The Corniche Road | 8 |

| 3. | Nice: The Promenade des Anglais | 14 |

| 4. | Nice: The Old Town | 19 |

| 5. | The Siege of Nice | 29 |

| 6. | Cimiez and St. Pons | 36 |

| 7. | How the Convent of St. Pons came to an End | 41 |

| 8. | Vence, the Defender of the Faith | 49 |

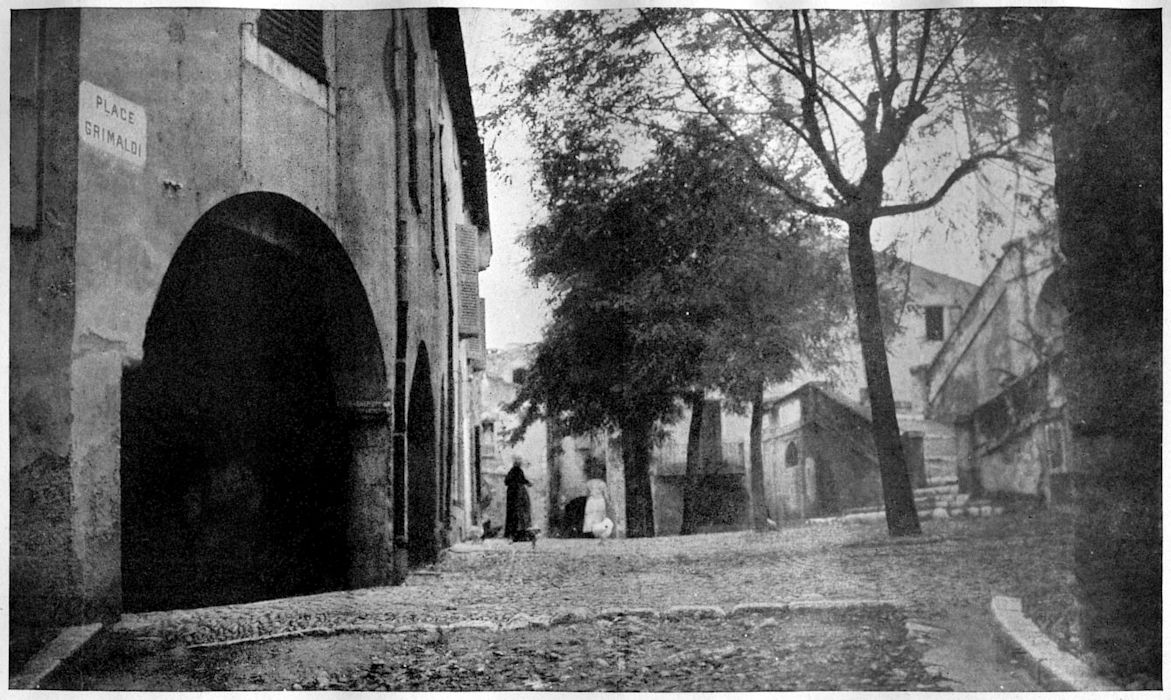

| 9. | Vence, the Town | 59 |

| 10. | Grasse | 67 |

| 11. | A Prime Minister and Two Ladies of Grasse | 80 |

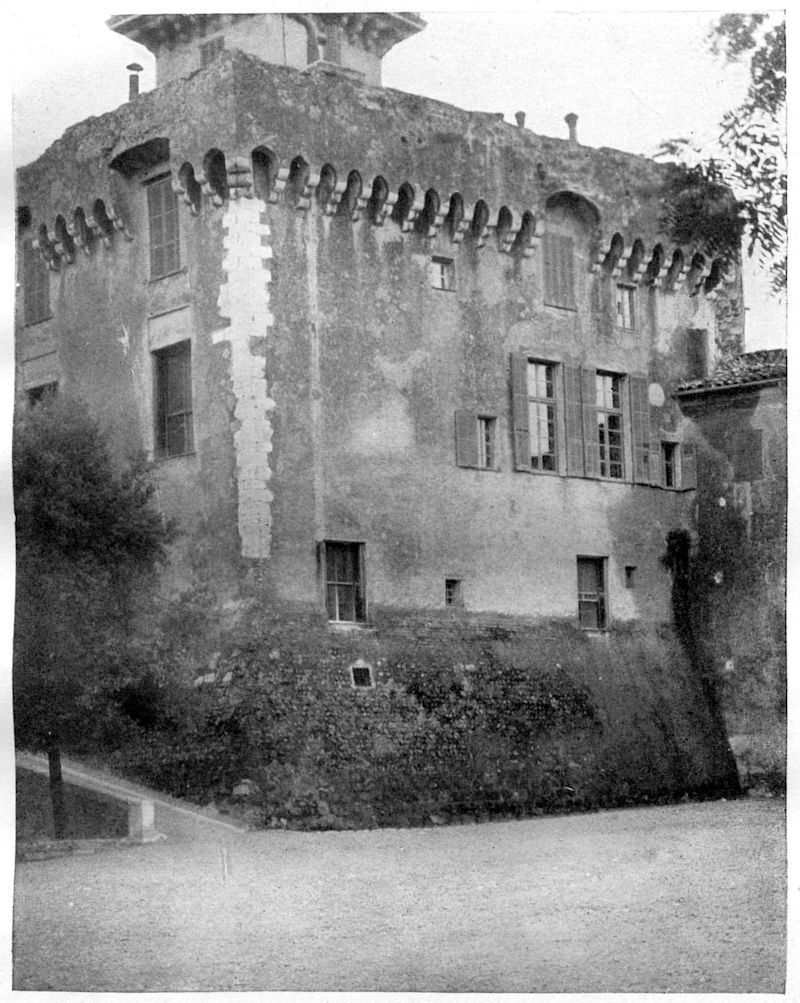

| 12. | Cagnes and St. Paul du Var | 97 |

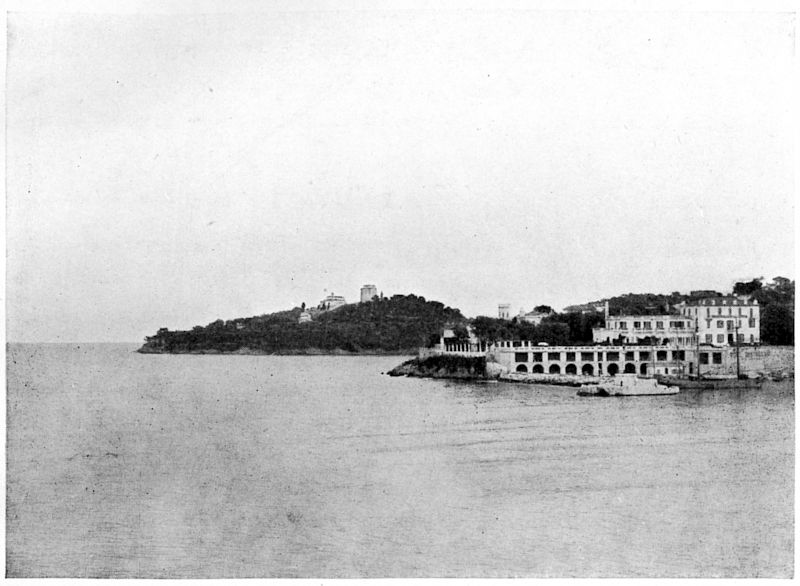

| 13. | Cap Ferrat and St. Hospice | 104 |

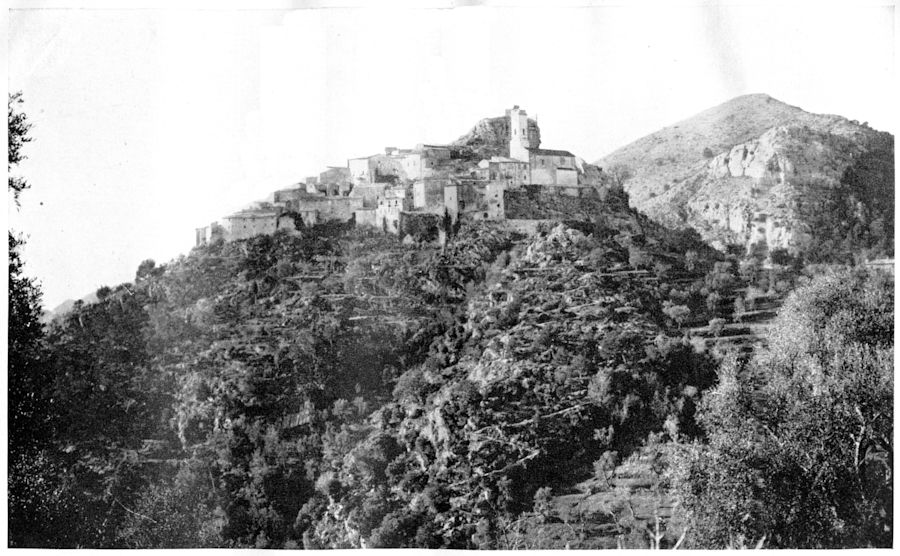

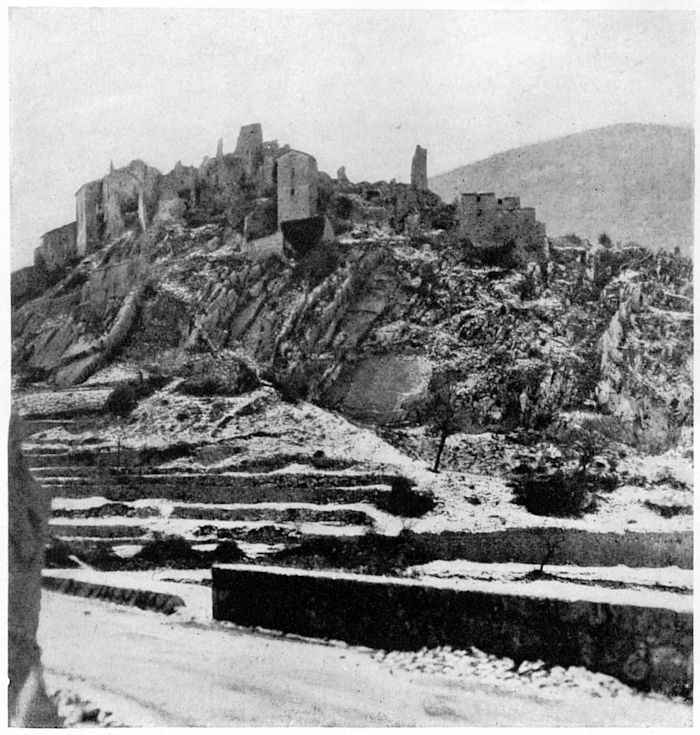

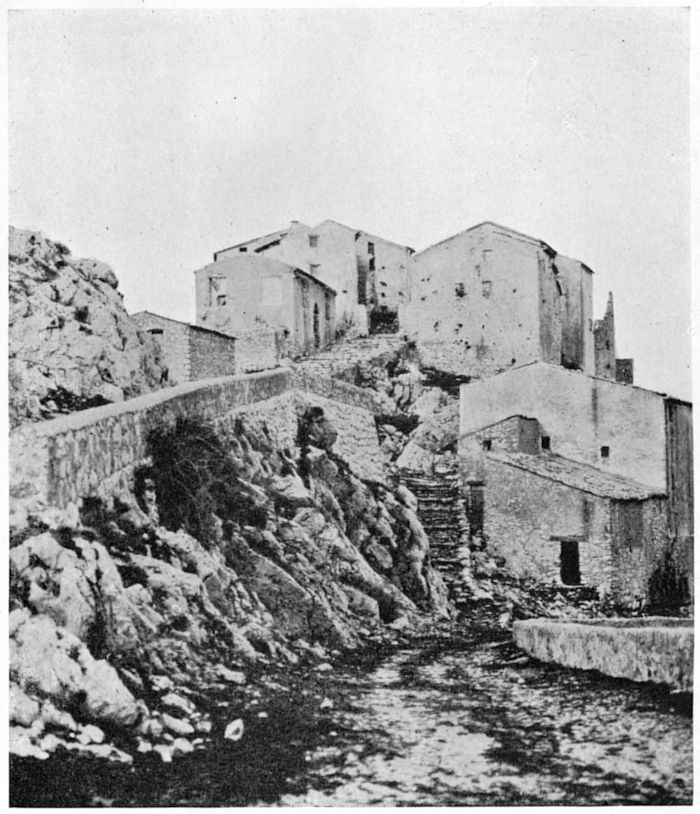

| 14. | The Story of Eze | 118 |

| 15. | The Troubadours of Eze | 123 |

| 16. | How Eze was Betrayed | 127 |

| 17. | The Town that Cannot Forget | 135 |

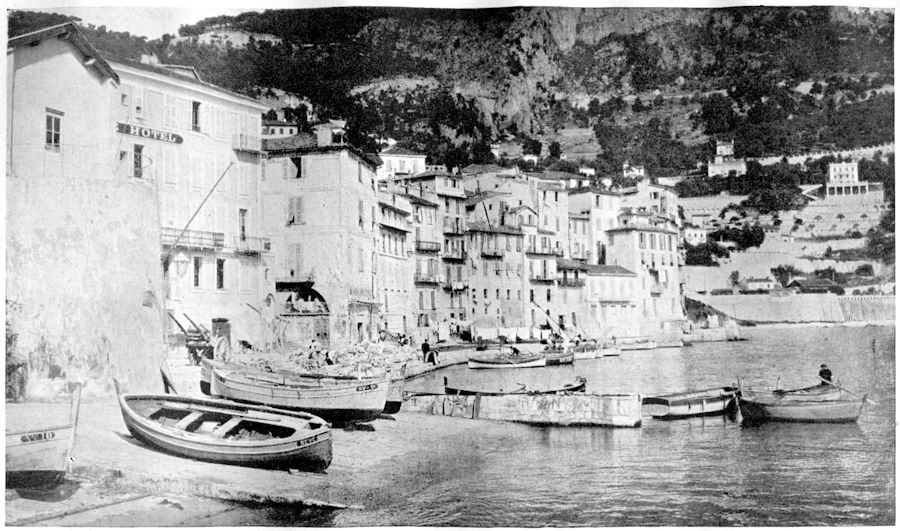

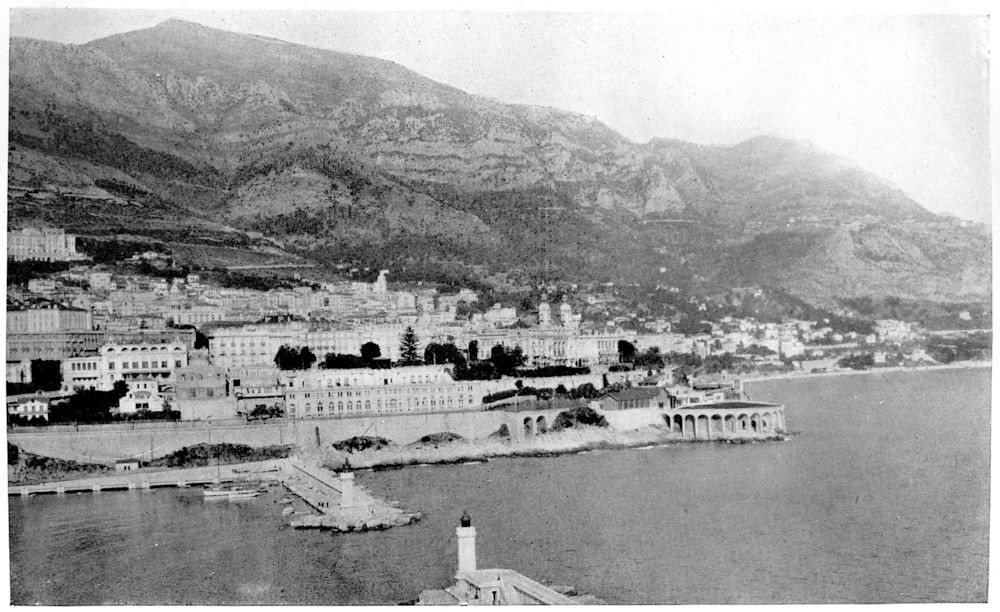

| 18. | The Harbour of Monaco | 143 |

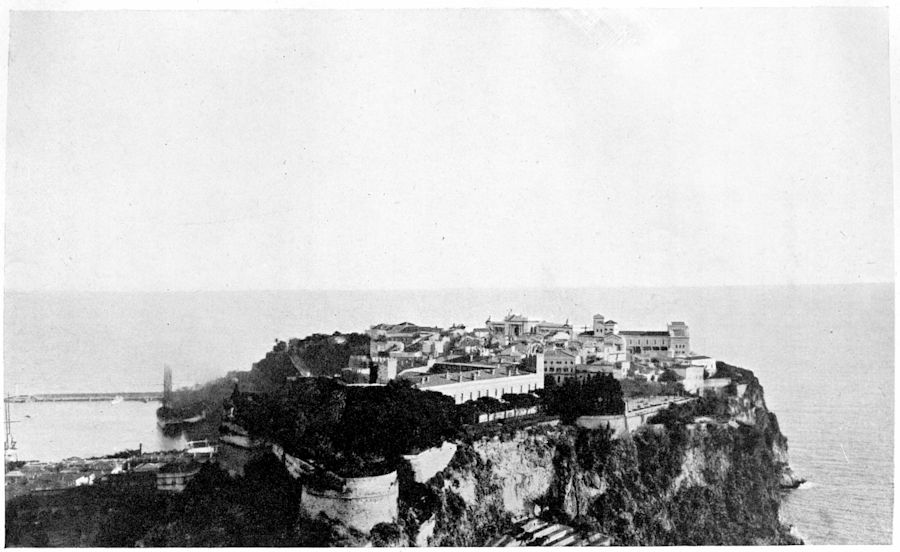

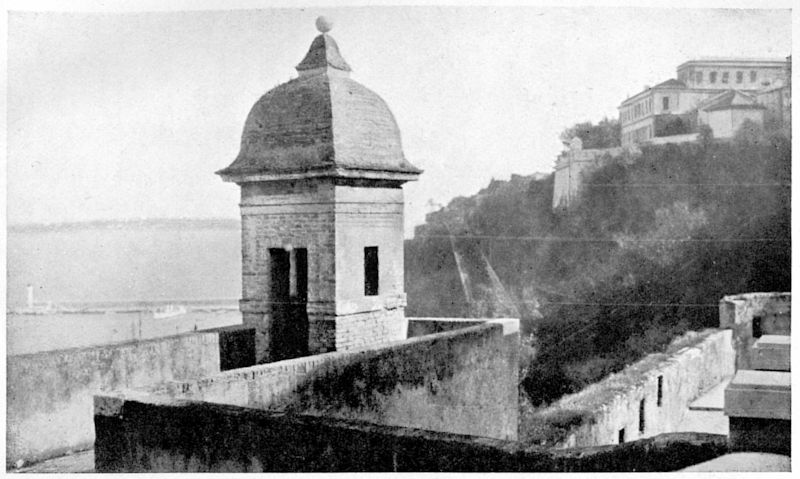

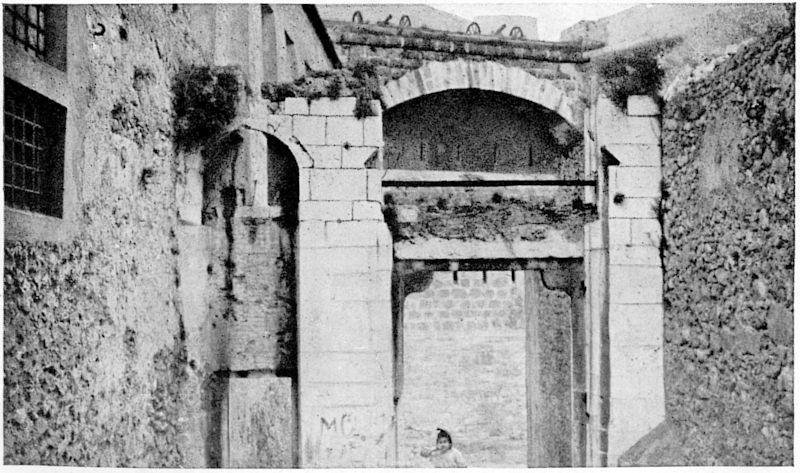

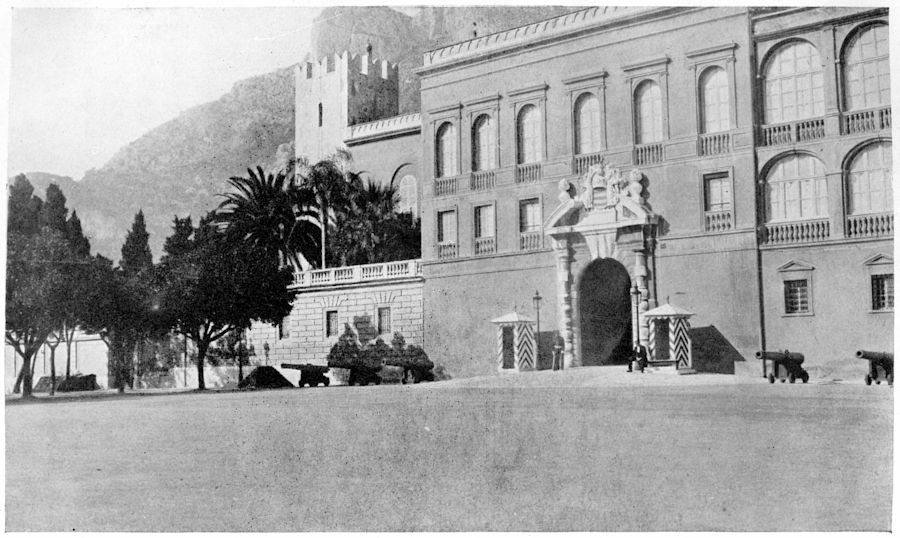

| 19. | The Rock of Monaco | 151 |

| 20. | A Fateful Christmas Eve | 161 |

| 21. | Charles the Seaman | 165 |

| 22. | The Lucien Murder | 170 |

| 23. | How the Spaniards were got rid of | 176 |

| 24. | A Matter of Etiquette | 181 |

| 25. | The Monte Carlo of the Novelist | 187 |

| 26. | Monte Carlo | 191 |

| 27. | Some Diversions of Monte Carlo | 195 |

| 28. | An Old Roman Posting Town | 206 |

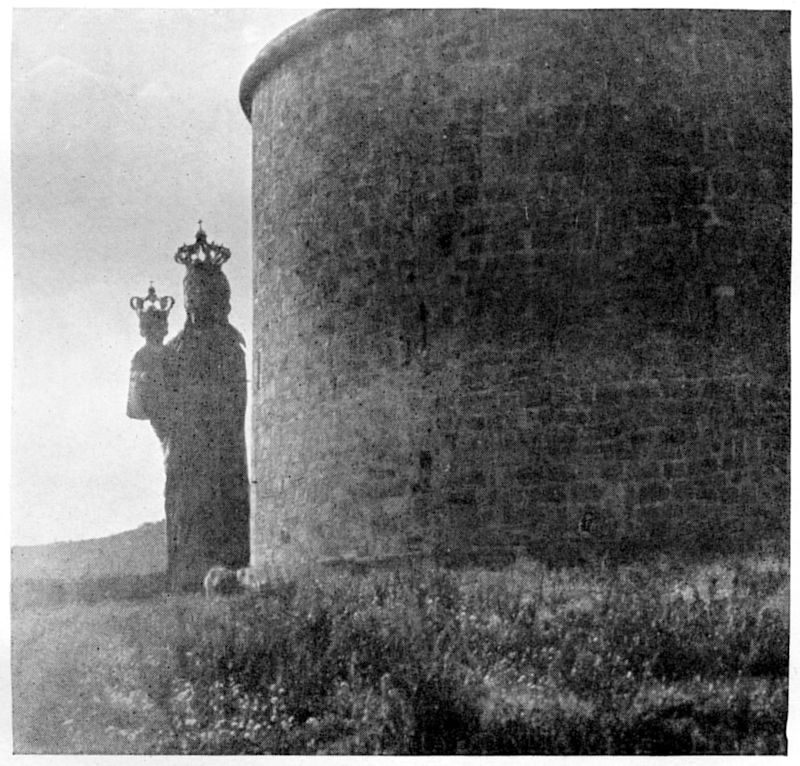

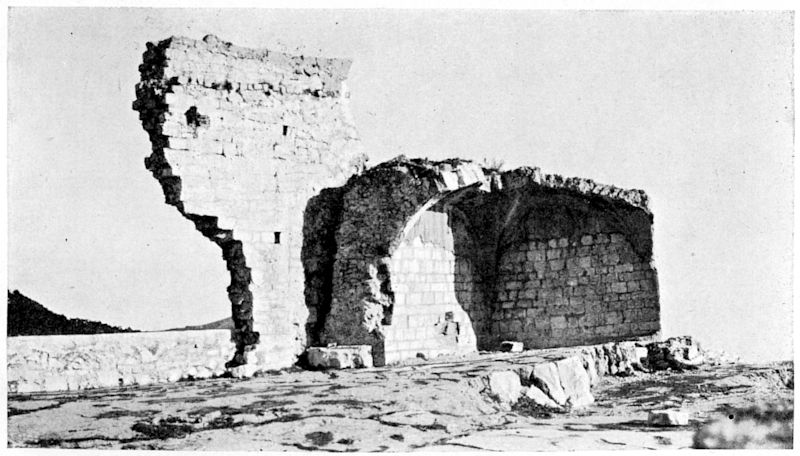

| 29. | The Tower of Victory | 214 |

| 30. | La Turbie of To-day | 224 |

| 31. | The Convent of Laghet | 231 |

| 32. | The City of Peter Pan | 239 |

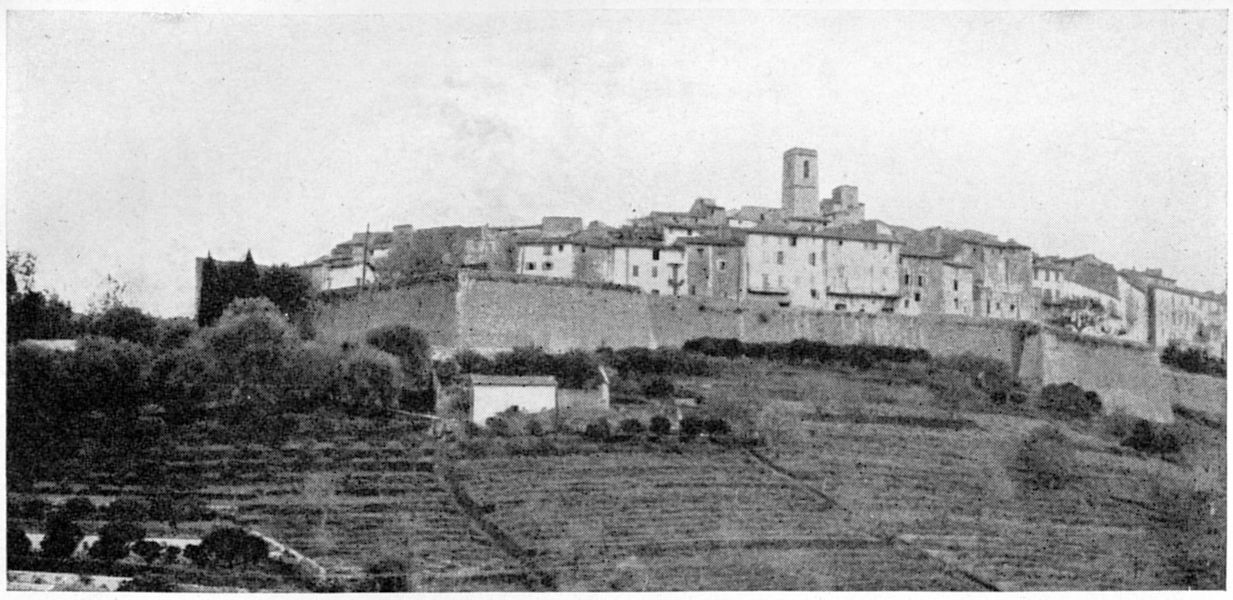

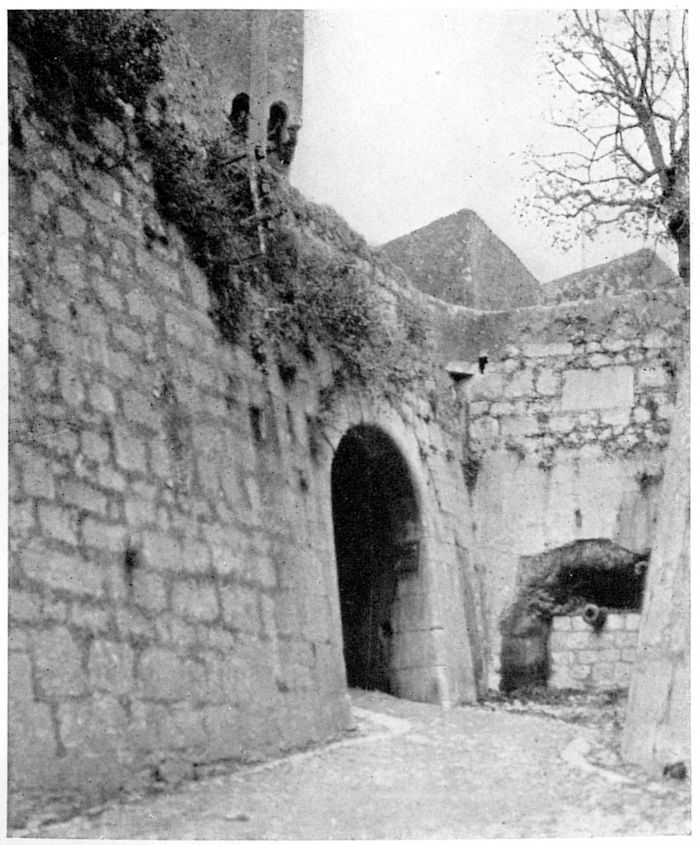

| 33. | The Legend of Roquebrune | 248 |

| 34. | Some Memories of Roquebrune | 252 |

| 35. | Gallows Hill | 259 |

| 36. | Mentone | 265 |

| 37. | The First Visitors to the Riviera | 273 |

| 38. | Castillon | 281 |

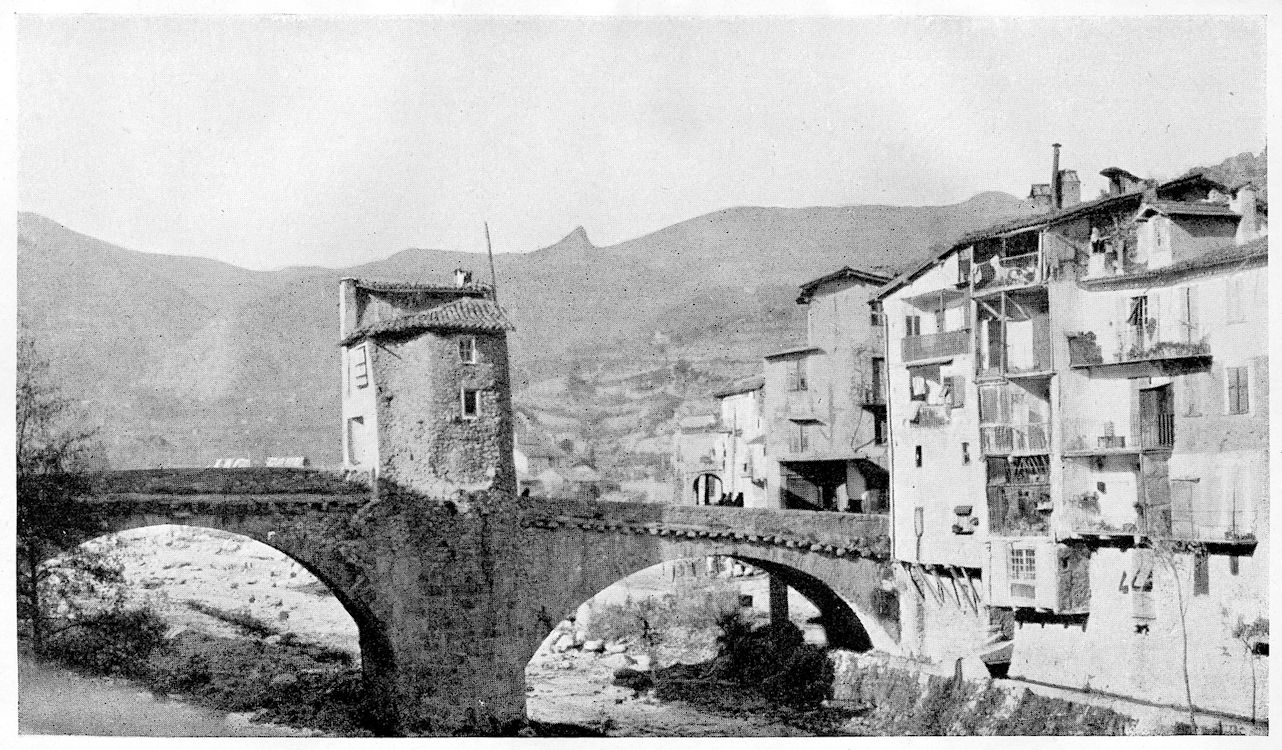

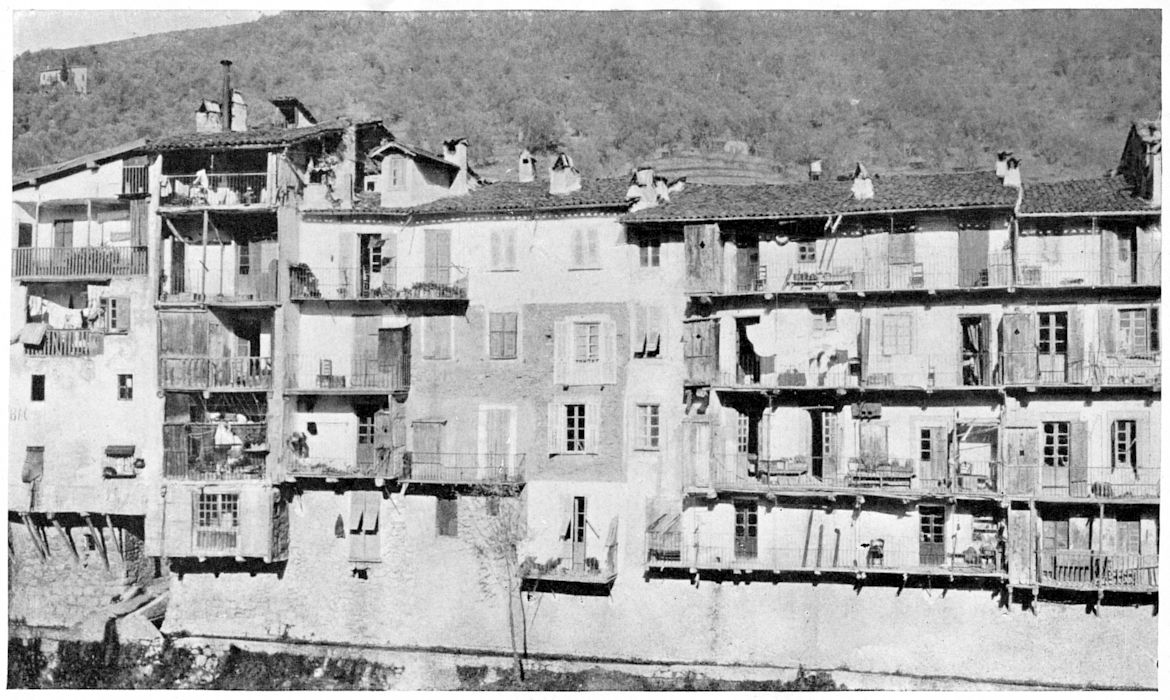

| 39. | Sospel | 286 |

| 40. | Sospel and the Wild Boar | 294 |

| 41. | Two Queer Old Towns | 297 |

| Index | 305 | |

THE RIVIERA OF THE

CORNICHE ROAD

THE early history of this brilliant country is very dim, as are its shores and uplands when viewed from an on-coming barque at the dawn of day. The historian-adventurer sailing into the past sees before him just such an indefinite country as opens up before the eye of the mariner. Hills and crags—alone unchangeable—rise against the faint light in the sky. The sound of breakers on the beach alone can tell where the ocean ends and where the land begins; while the slopes, the valleys and the woods are lost in one blank impenetrable shadow.

As the daylight grows, or as our knowledge grows, the forms of men come into view, wild creatures armed with clubs and stones. They will be named Ligurians, just as the earlier folk of Britain were named Britons. Later on less uncouth men, furnished with weapons of bronze or iron, can be seen to land from boats or to be plodding along the shore as if they had journeyed far. They will be called Phœnicians, Carthaginians or Phocæans according to the leaning of the writer who deals with them. There may be bartering on the beach, there may be fighting or pantomimic love-making; but in the end those who are better armed take the place of the old dwellers, and the rough woman in her apron of skins walks off into the wood by the side of the man with the bronze knife and the beads.

There is little more than this to be seen through the haze of far distant time. The written history, such as it is, is thus part fiction, part surmise, for the very small element of truth is based upon such fragments of evidence as a few dry bones, a few implements, a bracelet, a defence work, a piece of pottery.

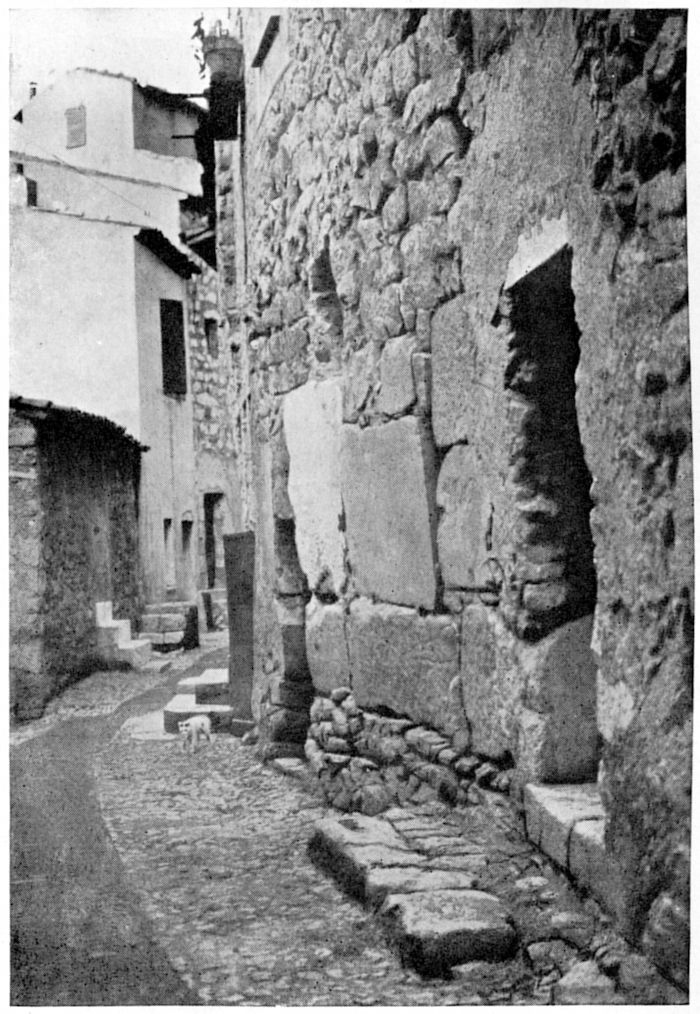

The Ligurians or aborigines formed themselves, for purposes of defence, into clans or tribes. They built fortified camps as places of refuge. Relics of these forts or castra remain, and very remarkable relics they are, for they show immense walls built of blocks of unworked stone that the modern wall builder may view with amazement. Nowhere are these camps found in better preservation than around Monte Carlo.

In the course of time into this savage country, marching in invincible columns, came the stolid, orderly legions of Rome. They subdued the hordes of hillmen, broke up their forts, and commemorated the victory by erecting a monument on the crest of La Turbie which stands there to this day. The Romans brought with them discipline and culture, and above all, peace. The natives, reassured, came down from their retreats among the heights and established themselves in the towns which were springing up by the edge of the sea. The Condamine of Monaco, for example, was inhabited during the first century of the present era, as is made manifest by the relics which have been found there.

With the fall of the Roman Empire peace vanished and the whole country lapsed again into barbarism. It was overrun from Marseilles to Genoa by gangs of hearty ruffians whose sole preoccupation was pillage, arson and murder. They uprooted all that the Romans had established, and left in their fetid trail little more than a waste of burning huts and dead men.

These pernicious folk were called sometimes Vandals, sometimes Goths, sometimes Burgundians, and sometimes Swabians. The gentry, however, who seem to have been the most persistent and the most diligent in evil were the Lombards. They are described as “ravishing the country” for the immoderate period of two hundred years, namely from 574 to 775. How it came about that any inhabitants were left after this exhausting treatment the historian does not explain.

At the end of the eighth century there may possibly have been a few years’ quiet along the Riviera, during which time the people would have recovered confidence and become hopeful of the future. Now the Lombards had always come down upon them by land, so they knew in which direction to look for their troubles, and, moreover, they knew the Lombards and had a quite practical experience of their habits. After a lull in alarms and in paroxysms of outrage, and after what may even be termed a few calm years, something still more dreadful happened to these dwellers in a fool’s paradise. Marauders began to come, not by the hill passes, but by sea and to land out of boats. They were marauders, too, of a peculiarly virulent type, compared with whom the Lombards were as babes and sucklings; for not only were their actions exceptionally violent and their weapons unusually noxious, but they themselves were terrifying to look at, for they were nearly black.

These alarming people were the Saracens, otherwise known as the Moors or Arabs. They belonged to a great race of Semitic origin which had peopled Syria, the borders of the Red Sea and the North of Africa. They invaded—in course of time—not only this tract of coast, but also Rhodes, Cyprus, France, Spain and Italy. They were by birth and inheritance wanderers, fighters and congenital pirates. They spread terror wherever they went, and their history may be soberly described as “awful.” They probably appeared at their worst in Provence and at their best in Spain, where they introduced ordered government, science, literature and commerce, and left behind them the memory of elegant manners and some of the most graceful buildings in the world.

As early as about 800 the Saracens had made themselves masters of Eze, La Turbie and Sant’ Agnese; while by 846 they seem to have terrorised the whole coast from the Rhone to the Genoese Gulf, and in the first half of the tenth century to have occupied nearly every sea-town from Arles to Mentone. Finally, in 980, a great united effort was made to drive the marauders out of France. It was successful. The leader of the Ligurian forces was William of Marseilles, first Count of Provence, and one of the most distinguished of his lieutenants was a noble Genoese soldier by name Gibellino Grimaldi. It is in the person of this knight that the Grimaldi name first figures in the history of the Ligurian coast.

As soon as the Saracens had departed the powers that had combined to drive them from the country began to fight among themselves. They fought in a vague, confused, spasmodic way, with infinite vicissitudes and in every available place, for over five hundred years. The siege of Nice by the French in 1543 may be conveniently taken as the end of this particular series of conflicts.

It was a period of petty fights in which the Counts of Provence were in conflict with the rulers of Northern Italy, with the Duke of Milan, it may be, or the Duke of Savoy or the Doge of Genoa. It was a time when town fought with town, when Pisa was at war with Genoa and Genoa with Nice, when the Count of Ventimiglia would make an onslaught on the Lord of Eze and the ruffian who held Gorbio would plan a descent upon little Roquebrune. This delectable part of the continent, moreover, came within the sphere of that almost interminable war which was waged between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. In the present area the Grimaldi were for the Guelphs and the Pope, and the Spinola for the Ghibellines and the Emperor. The feud began in the twelfth century and lasted until the French invasion in 1494.

This period of five hundred years was a time of interest that was dramatic rather than momentous. So far as the South of France was concerned one of the most beautiful tracts of country in Europe was the battle-ground for bands of mediæval soldiers, burly, dare-devil men carrying fantastic arms and dressed in the most picturesque costumes the world has seen.

It was a period of romance, and, indeed—from a scenic point of view—of romance in its most alluring aspect. Here were all the folk and the incidents made famous by the writers of a hundred tales—the longbowman in his leather jerkin, the man in the slashed doublet sloping a halberd, the gay musketeer, the knight in armour and plumes, as well as the little walled town, the parley before the gate, the fight for the drawbridge and the dash up the narrow street.

It was a period when there were cavalcades on the road, glittering with steel, with pennons and with banners, when there were ambushes and frenzied flights, carousing of the Falstaffian type at inns, and dreadful things done in dungeons. It was a time of noisy banquets in vaulted halls with dogs and straw on the floor; a time of desperate rescues, of tragic escapes, of fights on prison roofs, and of a general and brilliant disorder. It was a delusive epoch, too, with a pretty terminology, when the common hack was a palfrey, the footman a varlet, and the young woman a damosel.

The men in these brawling times were, in general terms, swashbucklers and thieves; but they had some of the traits of crude gentlemen, some rudiments of honour, some chivalry of an emotional type, and an unreliable reverence for the pretty woman.

It was a time to read about rather than to live in; a period that owes its chief charm to a safe distance and to the distortion of an artificial mirage. In any case one cannot fail to realise that these scenes took place in spots where tramcars are now running, where the char-à-banc rumbles along, and where the anæmic youth and the brazen damosel dance to the jazz music of an American band.

When the five hundred years had come to an end there were still, in this particular part of the earth, wars and rumours of wars that ceased not; but they were ordinary wars of small interest save to the student in a history class, for the day of the hand-to-hand combat and of the dramatic fighting in streets had passed away.

So far as our present purpose is concerned the fact need only be noted that the spoiled and petted Riviera has been the scene of almost continuous disturbance and bloodshed for the substantial period of some seventeen hundred years, and that it has now become a Garden of Peace, calmed by a kind of agreeable dream-haunted stupor such as may befall a convulsed man who has been put asleep by cocaine.

IT is hardly necessary to call to mind the fact that there are several Corniche roads along the Riviera. The term implies a fringing road, a road that runs along a cornice or ledge (French, Corniche; Italian, Cornice).

The term will, therefore, be often associated with a coast road that runs on the edge or border of the sea or on a shelf above it.

There are the Chemin de la Corniche at Marseilles which runs as far east as the Prado, the Corniche d’Or near Cannes, the three Corniche Roads beyond Nice, and—inland—the Corniche de Grasse.

The bare term “The Corniche Road” is, however, generally understood to refer to the greatest road of them all, La Grande Corniche.

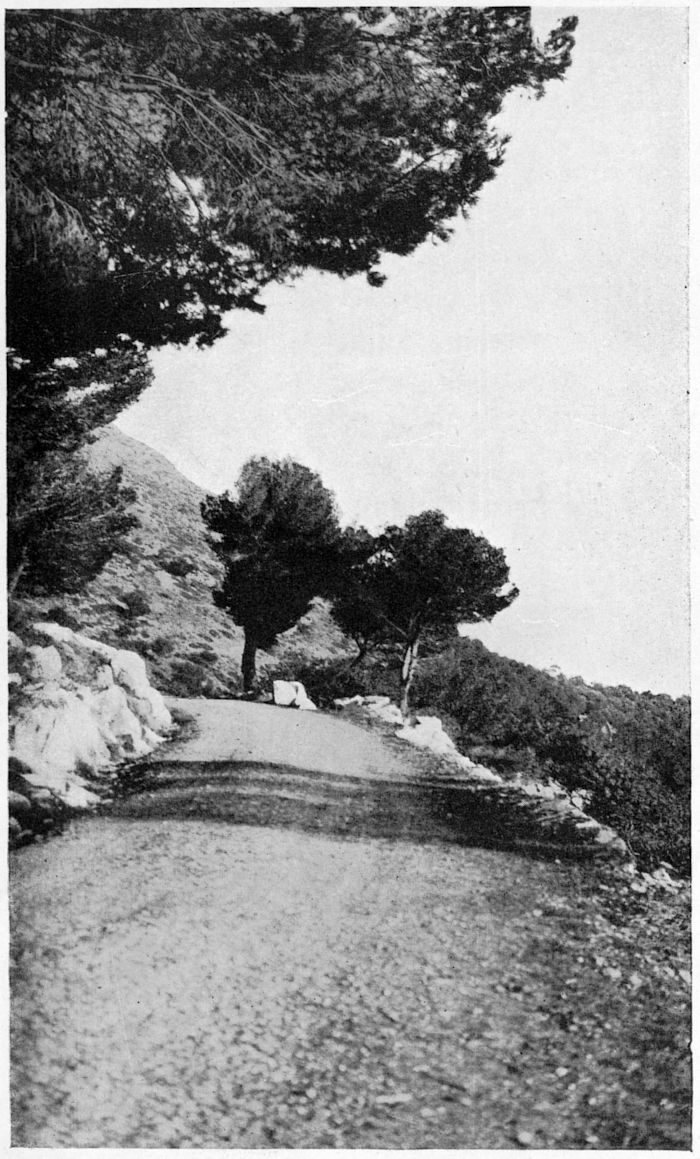

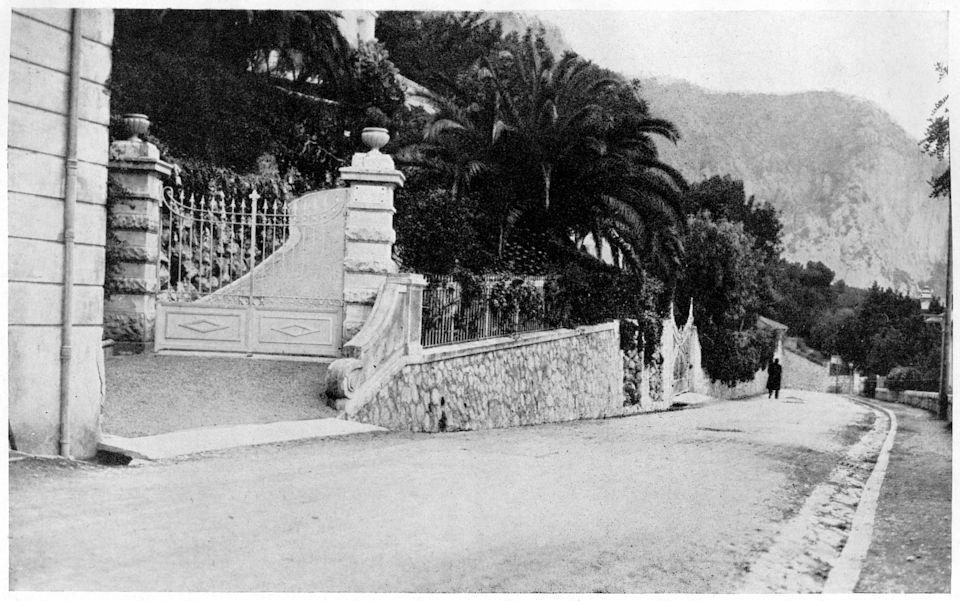

AT THE BEND OF THE ROAD.

Of all the great roads in Europe it is probable that La Grande Corniche—which runs from Nice eastwards towards Italy—is the best known and the most popular. Roads become famous in many ways, some by reason of historical associations, some on account of the heights they reach, and others by the engineering difficulties they have been able to surmount. La Grande Corniche can claim none of these distinctions. It is comparatively a modern road, it mounts to little more than 1,700 feet, and it cannot boast of any great achievement in its making. It passes by many towns but it avoids them all, all save one little forgotten village outside whose walls it sweeps with some disdain.

It starts certainly from Nice, but it goes practically nowhere, since long before Mentone is in view it drops into a quite common highway, and thus incontinently ends. It is not even the shortest way from point to point, being, on the contrary, the longest. It cannot pretend to be what the Italians call a “master way,” since no road of any note either enters it or leaves it.

In so far as it evades all towns it is unlike the usual great highway. It passes through no cobbled, wondering street; breaks into no quiet, fountained square; crosses no market-place alive with chattering folk; receives no blessing from the shadow of a church. Nowhere is its coming heralded by an avenue of obsequious trees, it forces its way through no vaulted gateway, it lingers by no village green, it knows not the scent of a garden nor the luscious green of a cultivated field. Neither the farmer’s cart nor the lumbering diligence will be met with on this unamiable road, nor will its quiet be disturbed by the patter of a flock of sheep nor by a company of merry villagers on their way to the fair.

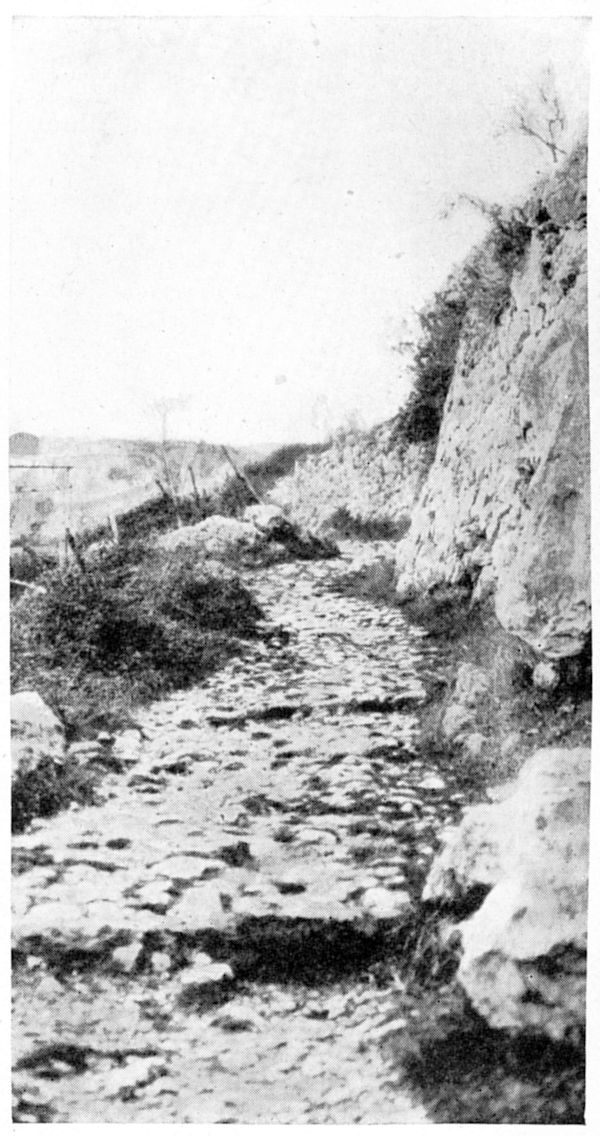

La Grande Corniche is, in fact, a modern military road built by the French under Napoleon I in 1806. It was made with murderous intent. It was constructed to carry arms and men, guns and munitions and the implements of war. It was a road of destruction designed to convey bloodshed and desolation into Italy and beyond. He who conceived it had in his mind the picture of a road alive, from end to end, with columns of fighting men marching eastwards under a cloud of angry dust with the banner of France in the van; had in his ears the merciless tramp of ten thousand feet, the clatter of sweating cavalry, the rumble of unending cannon wheels. It was a picture, he thought, worthy of the heart-racking labour that the making of the road involved.

But yet, in spite of all this, the popularity of the road is readily to be understood. It is cut out, as a mere thread, upon the side of a mountain range which is thrown into as many drooping folds as is a vast curtain gathered up into a fraction of its width. It is never monotonous, never, indeed, even straight. It winds in and out of many a valley, it skirts many a fearful gorge, it clings to the flank of many a treacherous slope. Here it creeps beneath a jutting crag, there it mounts in the sunlight over a radiant hill or dips into the silence of a rocky glen.

It has followed in its making any level ledge that gave a foothold to man or beast. It has used the goat track; it has used the path of the mountaineer; while at one point it has taken to itself a stretch of the ancient Roman road. It is a daring, determined highway, headstrong and self-confident, hesitating before no difficulty and daunted by no alarms, heeding nothing, respecting nothing, and obedient only to the call “onwards to Italy at any cost!”

From its eyrie it looks down upon a scene of amazing enchantment, upon the foundations of the everlasting hills, upon a sea glistening like opal, upon a coast with every fantastic variation of crag and cliff, of rounded bay and sparkling beach, of wooded glen and fern-decked, murmuring chine. Here are bright villas by the water’s edge, a white road that wanders as aimlessly along as a dreaming child, a town or two, and a broad harbour lined with trees. Far away are daring capes, two little islands, and a line of hills so faint as to be almost unreal. It is true, indeed, as the writer of a well known guide book has said, that “the Corniche Road is one of the most beautiful roads in Europe.”

Moreover, it passes through a land which is a Vanity Fair to the frivolous, a paradise to the philanderer, and a garden of peace to all who would escape the turmoil of the world. It is a lazy, careless country, free from obtrusive evidence of toil and labour, for there are neither works nor factories within its confines. Here the voice of the agitator is not heard, while the roar of political dispute falls upon the contented ear as the sound of a distant sea.

The Grand Corniche is now a road devoted to the seeker after pleasure. People traverse it, not with the object of arriving at any particular destination, but for the delight of the road itself, of the joy it gives to the eye and to the imagination. Its only traffic is what the transport agent would call “holiday traffic”; for when the idle season ends the highway is deserted. In earlier days there would rumble along the road the carriage and four of the traveller of great means; then came the humbler vehicle hired from the town; then the sleek motor; and finally, as a sign of democratic progress, the char-à-banc, the omnibus, and the motor-brake.

No visitor to the Riviera of any self-respect can leave without traversing the Corniche Road. Mark Twain says that “there are many sights in the Bermudas, but they are easily avoided.” This particular road cannot be avoided. The traveller who returns to his home without having “done” La Grande Corniche may as well leave Rome without seeing the Forum.

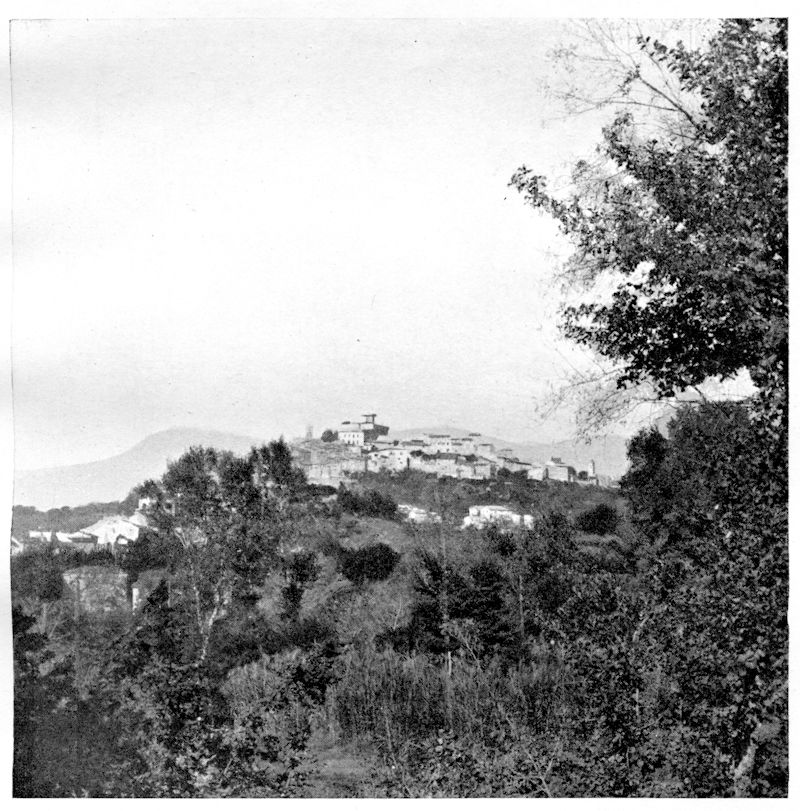

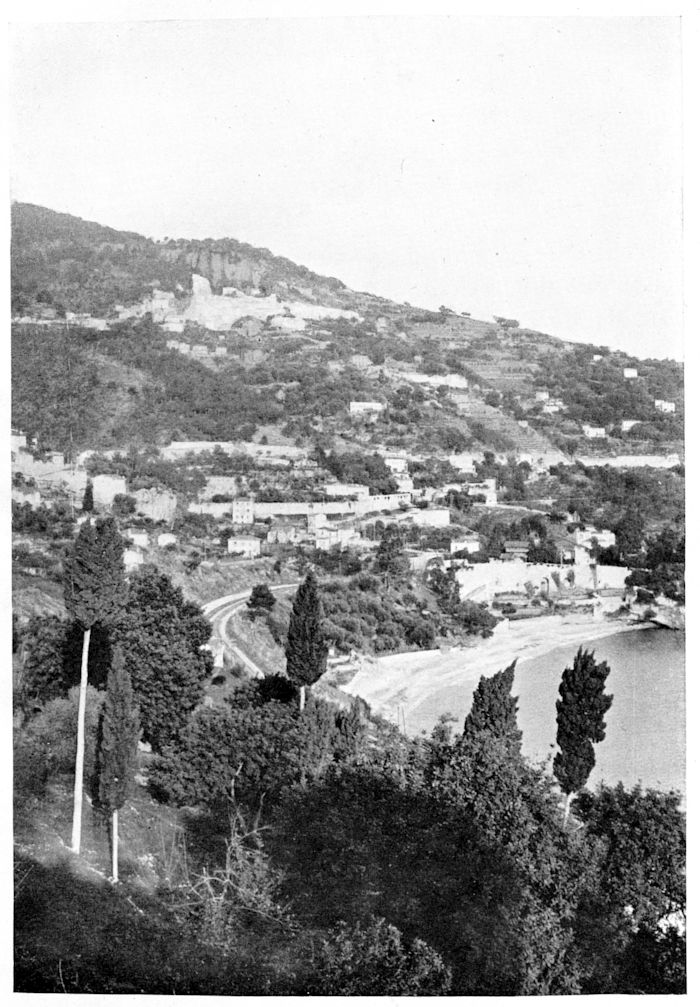

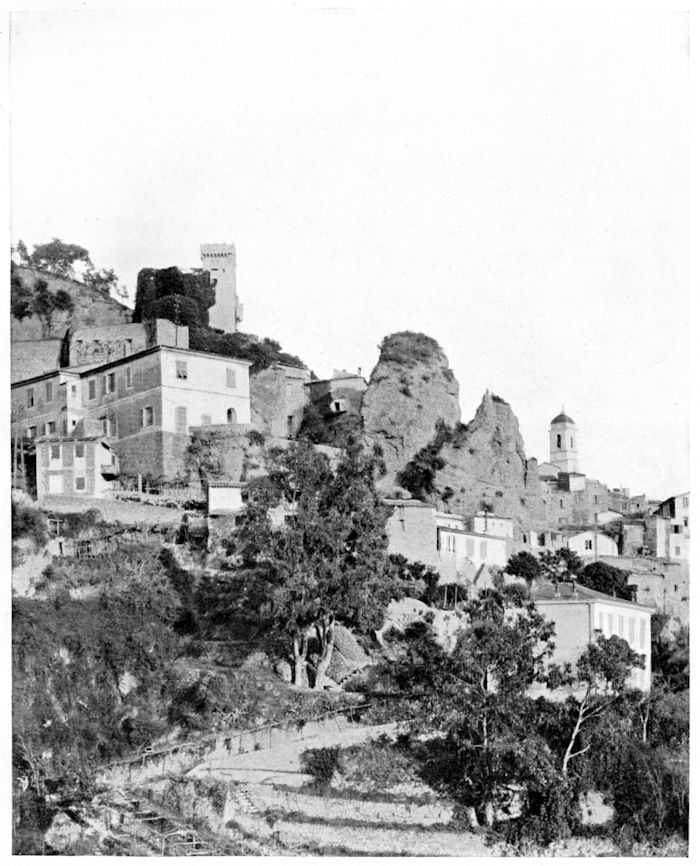

The most picturesque section of the road is that between Nice and Eze. Starting from Nice it winds up along the sides of Mont Vinaigrier and Mont Gros which here form the eastern bank of the Paillon valley. The hills are covered with pine and olive trees, vines and oaks. There is soon attained a perfect view over the whole town of Nice, when it will be seen how commanding is the position occupied by the Castle Hill. Across the valley are Cimiez and St. Pons. At the first bend, as the height is climbed, is a tablet to mark the spot where two racing motorists were killed. When the road turns round the northern end of Mont Gros a fine view of the Paillon valley is displayed. This valley is much more attractive at a distance than near at hand. By the river’s bank on one side is St. André with its seventeenth-century château; while on the other side is the Roman station of La Trinité-Victor, a little place of a few houses and a church, where the old Roman road comes down from Laghet. High up above St. André, at the height of nearly 1,000 feet, is the curious village of Falicon. Far away, at a distance of some seven miles, is Peille, a patch of grey in a cup among the mountains. Northwards the Paillon river is lost to view at Drap.

When the road has skirted the eastern side of Mont Vinaigrier the Col des Quatre Chemins is reached (1,131 feet). Here are an inn and a ridiculous monument to General Massena. The hills that border on the road are now bleak and bare. Just beyond the col is a fascinating view of Cap Ferrat and Cap de St. Hospice. The peninsula is spread out upon the sea like a model in dark green wax on a sheet of blue. The road now skirts the bare Monts Pacanaglia and Fourche and reaches the Col d’Eze (1,694 feet), where is unfolded the grandest panorama that the Corniche can provide. The coast can be followed from the Tête de Chien to St. Tropez. The wizened town of Eze comes into sight, and below it is the beautiful Bay of Eze, with the Pointe de Cabuel stretched out at the foot of Le Sueil.

The view inland over the Alps and far away to the snows is superb. To the left are Vence and Les Gorges du Loup, together with the town of St. Jeannet placed at the foot of that mighty precipice, the Baou de St. Jeannet, which attaining, as it does, a height of 2,736 feet is the great landmark of the country round. Almost facing the spectator are Mont Chauve de Tourette (2,365 feet) and Mont Macaron. The former is to be recognised by the fort on its summit. They are distant about five miles. To the right is Mont Agel with its familiar scar of bare stones. Some two kilometres beyond Eze the Capitaine is reached, the point at which the Corniche Road attains its greatest height, that of 1,777 feet.

The track now very slowly descends. When La Turbie (1,574 feet) is passed a splendid view is opened up of Monaco and Monte Carlo, of the Pointe de la Vieille, of Cap Martin, and of the coast of Italy as far as Bordighera. Roquebrune—which can be seen at its best from the Corniche—is passed below the town, and almost at once the road joins the sober highway that leads to Mentone and ends its romantic career on a tramline.

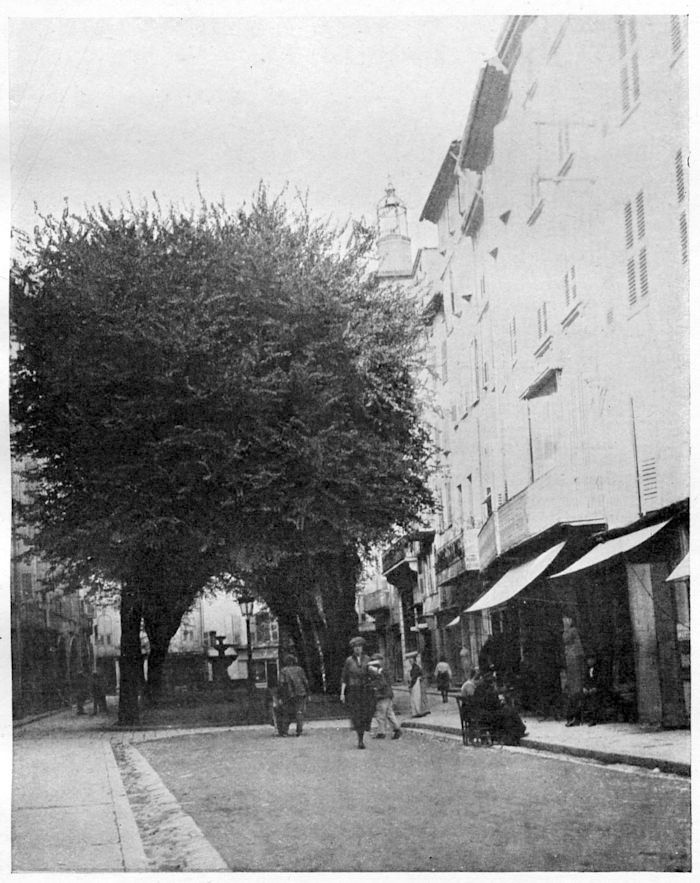

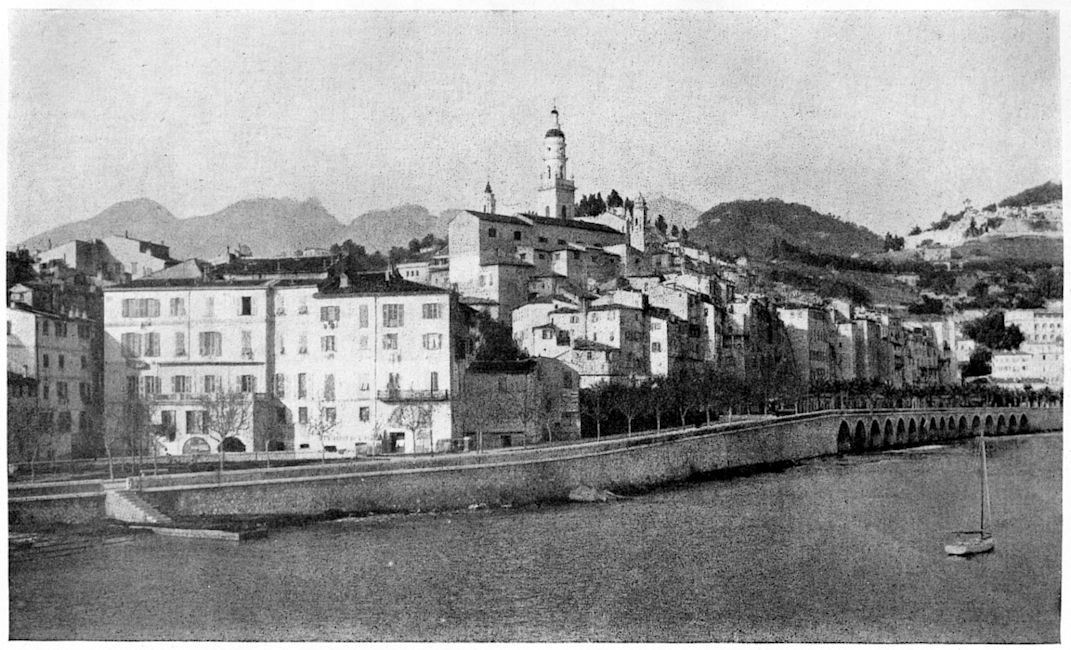

NICE is a somewhat gross, modern seaside town which is beautiful in its situation but in little else. It lies at the mouth of a majestic valley and on the shores of a generous bay, open to the sun, but exposed at the same time to every villainous wind that blows. It is an unimaginative town with most excellent shops and a complete, if noisy, tramway system. It is crowded, and apparently for that reason popular. It is proud of its fine sea front and of the bright and ambitious buildings which are ranged there, as if for inspection and to show Nice at its best.

The body of the town is made up of a vast collection of houses and streets of a standard French pattern and little individuality. Viewed from any one of the heights that rise above it, Nice is picturesque and makes a glorious, widely diffused display of colour; but as it is approached the charm diminishes, the dull suburbs damp enthusiasm, and the bustling, noisy, central streets complete the disillusion. On its outskirts is a crescent of pretty villas and luxuriant gardens which encircle it as a garland may surround a plain, prosaic face. The country in the neighbourhood of this capital of the Alpes Maritimes is singularly charming, and, therefore, the abiding desire of the visitor to Nice is to get out of it.

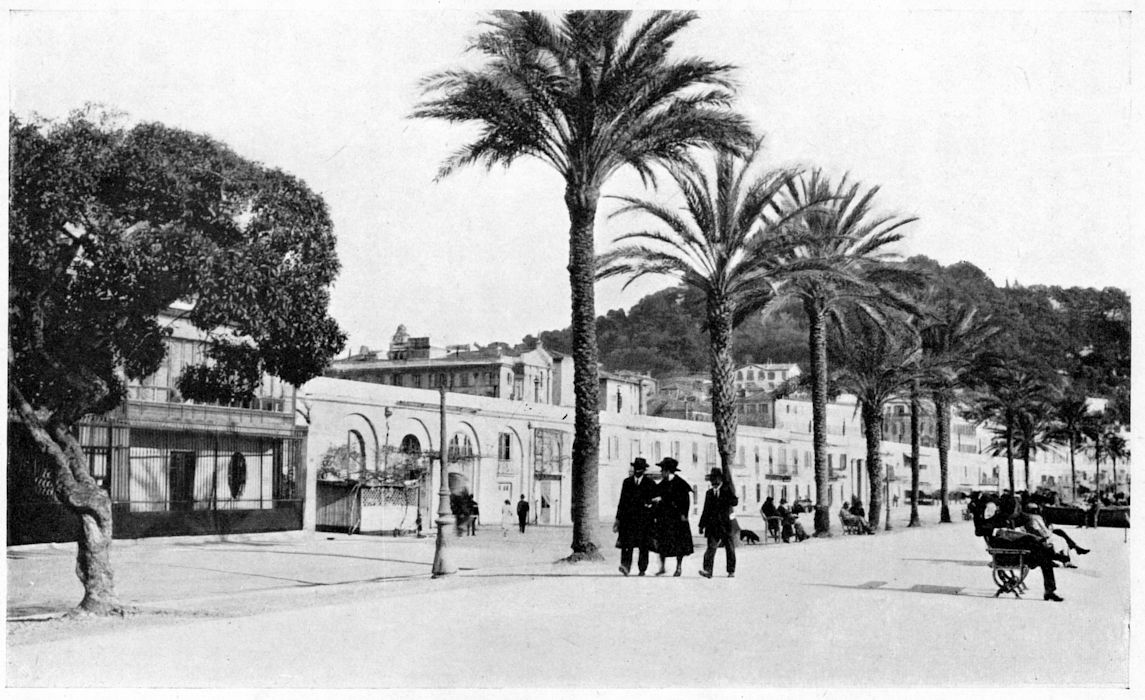

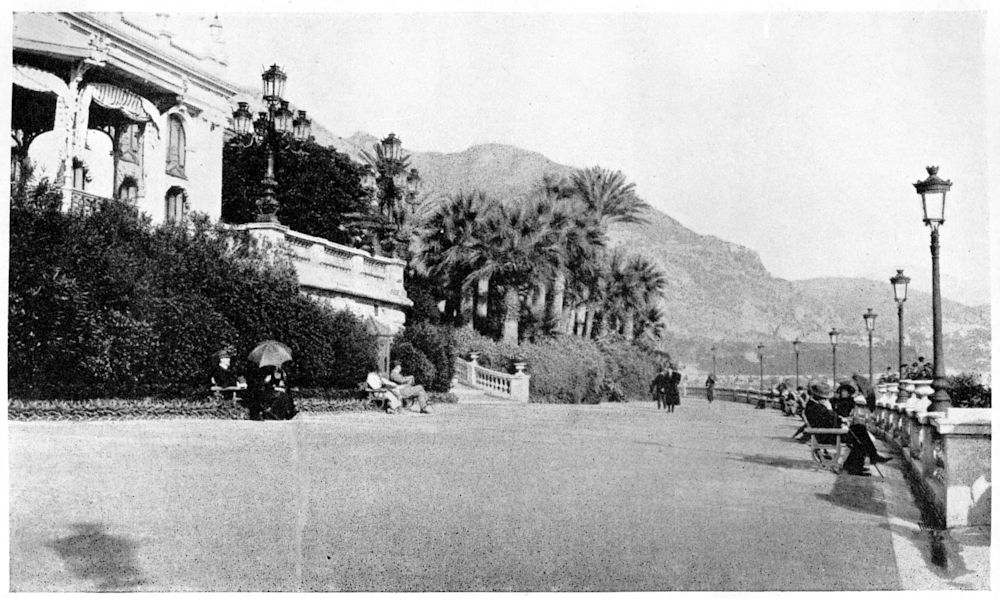

Along the sea front is the much-photographed Promenade des Anglais with its line of palm trees. It is marked with a star and with capital letters in the guide books and it is quite worthy of this distinction. It appears to have been founded just one hundred years ago to provide work for the unemployed. To judge from the crowd that frequents it, it is still the Promenade of the Unemployed.

The Promenade has great dignity. It is spacious and, above all, it is simple. As a promenade it is indeed ideal. It is free from the robust vulgarity, the intrusions, and the restlessness of the parade in an English popular seaside resort. There are no penny-in-the-slot machines, no bathing-houses daubed over with advertisements, no minstrels, no entertainments on the beach, no importunate boatmen, no persistent photographers. If it gives the French the idea that it is a model of a promenade of the English, it will lead to an awakening when the Frenchman visits certain much-frequented seaside towns in England.

A little pier—the Jetée-Promenade—steps off from the main parade. On it is a casino which provides varied and excellent attractions. The building belongs to the Bank Holiday Period of architecture and is accepted without demur as exactly the type of structure that a joy-dispensing pier should produce. It is, however, rather disturbing to learn that this fragile casino, with its music-hall and its refreshment bars, is a copy of St. Sophia in Constantinople. That mosque is one of the most impressive and most inspiring ecclesiastical edifices in the world, as well as one of the most stupendous. Those who know Constantinople and have been struck by the lordly magnificence of its great religious fane will turn from this dreadful travesty with horror. It is a burlesque that hurts, as would the “Hallelujah Chorus” played on a penny whistle.

It is along the Promenade des Anglais—the Promenade of the Unemployed—that the great event of the Carnival of Nice, the Battle of Flowers, is held every year. The Carnival began probably as the modest festa of a village community, a picturesque expression of the religion of the time, a reverent homage to the country and to the flowers that made it beautiful. It seems to have been always associated with flowers and one can imagine the passing by of a procession of boys and girls with their elders, all decked with flowers, as a spectacle both gracious and beautiful.

It has developed now with the advancing ugliness of the times. The simple maiden, clad in white, with her garland of wild flowers, has grown into a coarse, unseemly monster, blatant and indecorous, surrounded by a raucous mob carrying along with it the dust of a cyclone. The humble village fête has become a means of making money and an opportunity for clamour, licence and display. Reverence of any kind or for anything is not a notable attribute of the modern mind; while with the advance of a pushing democracy gentle manners inevitably fade away.

It is pitiable that the Carnival has to do with flowers and that it is through them that it seeks to give expression to its loud and flamboyant taste. It is sad to see flowers put to base and meretricious uses, treated as mere dabs of paint, forced into unwonted forms, made up as anchors or crowns and mangled in millions. The festival is not so much a battle of flowers as a Massacre of Flowers, a veritable St. Bartholomew’s Day for buds and blossoms.

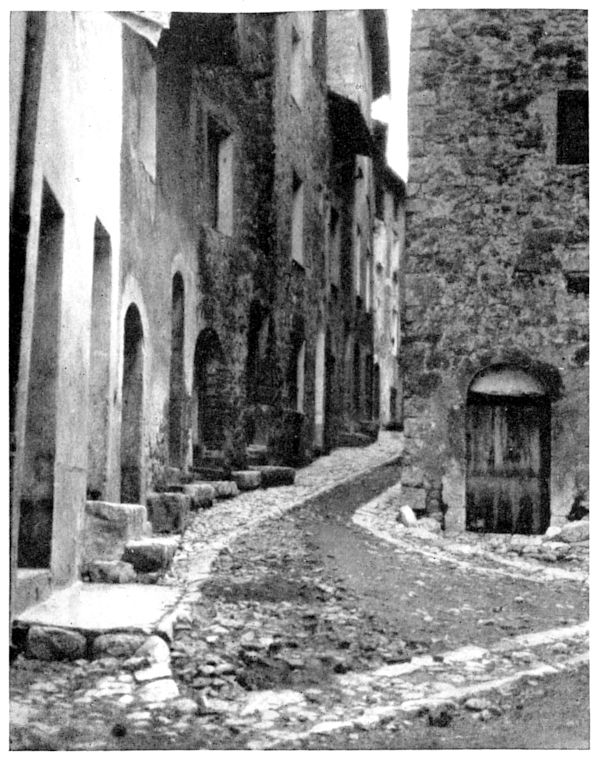

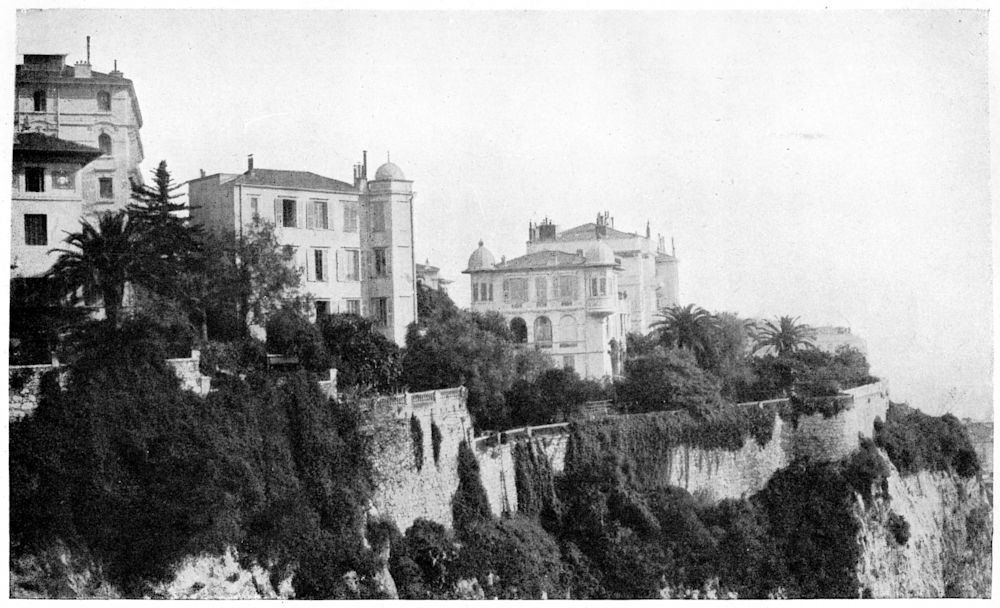

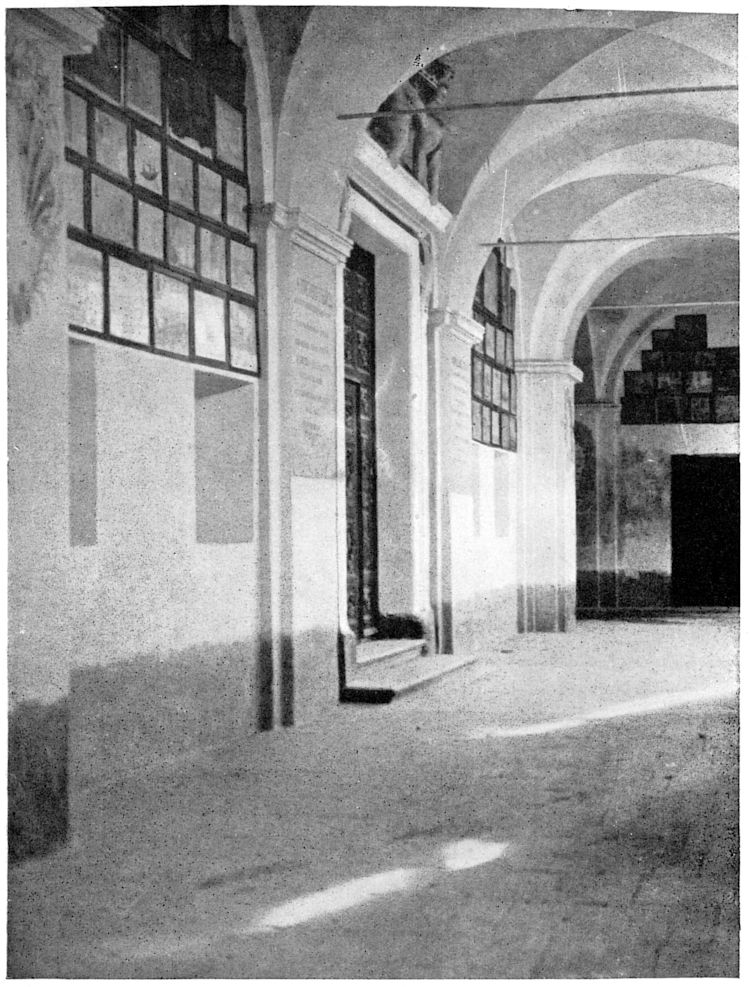

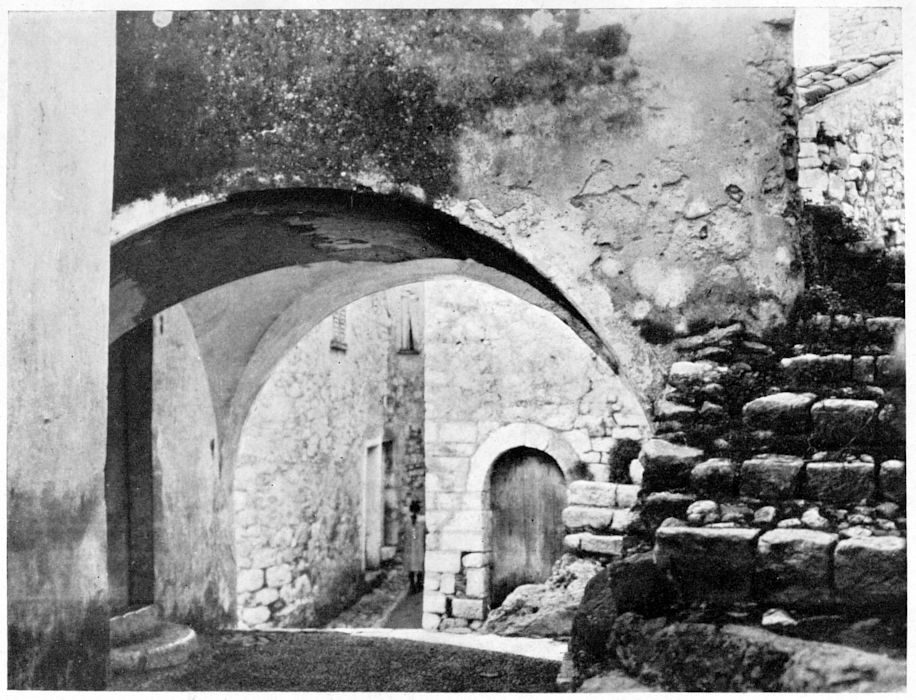

NICE: THE OLD TERRACES.

The author of a French guide book suggests that the visitor should attend the Carnival “at least once.” He makes this proposal with evident diffidence. He owns that the affair is one of animation incroyable, that the streets are occupied by une cohue de gens en délire and recommends the pleasure seeker to carry no valuables, to wear no clothes that are capable of being spoiled, no hat that would suffer from being bashed in, and to remember always that the dust is énorme.

Those who like a rollicking crowd, hustling through streets a-flutter with a thousand flags and hung with festoons by the kilometre, and those who have a passion for throwing things at other people might go even more than once. They will see in the procession much that is ludicrous, grotesque and puerile, an exaggerated combination of a circus car parade and a native war dance, as well as a display of misapplied decoration of extreme ingenuity.

On the other hand, the flower lover should escape to the mountains and hide until the days of the Carnival are over, and with him might go any who would prefer a chaplet of violets on the head of a girl to a laundry basket full of peonies on the bonnet of a motor.

On that side of the old town which borders upon the sea are relics which illustrate the more frivolous mood of Nice as it was expressed before the building of the Promenade des Anglais. These relics show in what manner the visitor to Nice in those far days sought joy in life. Parallel to the beach is the Cours Saleya, a long, narrow, open space shaded by trees. It was at one time a fashionable promenade, comparable to the Pantiles at Tunbridge Wells. It is now a flower and vegetable market. On the ocean side of this Cours are two lines of shops, very humble and very low. The roofs of these squat houses are level and continuous and so form two terraces running side by side and extending for a distance of 800 feet.

These are the famous Terrasses where the beaus and the beauties of Nice promenaded, simpered, curtsied or bowed, and when this walk by the shore was vowed to be “monstrous fine, egad.”[1] The terraces are now deserted, are paved with vulgar asphalt and edged by a disorderly row of tin chimneys. On one side, however, of this once crowded and fashionable walk are a number of stone benches, on which the ladies sat, received their friends, and displayed their Paris frocks. The terrace is as uninviting as a laundry drying ground and these grey, melancholy benches alone recall the fact that the place once rippled with colour and sparkled with life as if it were the enclosure at Ascot.

|

The first of these terraces was completed in 1780 and the second one in 1844. |

LOOKING down upon the city from Mont Boron it is easy to distinguish Nice the Illustrious from Nice the Parvenu. There is by the sea an isolated green hill with precipitous flanks. This is the height upon which once stood the ancient citadel. On one side is a natural harbour—the old port—while on the other side is a jumble of weather-stained roofs and narrow lanes which represent the old town. The port, the castle hill, with the little cluster of houses at its foot, form the real Nice, the Nice of history.

Radiating from this modest centre, like the petals of a sunflower spreading from its small brown disc, are the long, straight streets, the yellow and white houses and the red roofs of modern Nice. This new town appears from afar as an immense expanse of bright biscuit-yellow spread between the blue of the bay and the deep green of the uplands. It presents certain abrupt excrescences on its surface, like isolated warts on a pale face. These are the famous hotels. This city of to-day is of little interest. It commends itself merely as a very modern and very prosperous seaside resort. Within the narrow circuit of the old town, on the other hand, there is much that is worthy to be seen and to be pondered over.

It is said that Nice was founded by the Phocæans about the year 350 B.C., and that the name of the place, Nicæa, the city of victory, records the victory of these very obscure people over the still more obscure Ligurians. The Romans paid little heed to Nice. They passed it by and founded their own city, Cemenelum (now Cimiez), on higher ground away from the sea. Nice was then merely the port, the poor suburb, the fishers’ town. After Cimiez came to an end Nice began to grow and flourish. It was, in the natural course of events, duly sacked or burned by barbarous hordes and by Saracens, and was besieged as soon as it had walls and was besiegable. It took part in the local wars, now on this side, now on that. It had, in common with nearly every town in Europe, its periods of pestilence and its years of famine.

In the thirteenth century it fell into the hands of the Counts of Provence, and at the end of the fourteenth century it came under the protection of the Dukes of Savoy. Like many a worthier place it was shifted to and fro like a pawn on a chess-board. It had for years a strong navy and the reputation of being a terror to the Barbary pirates. These tiresome men from Barbary interfered with the pursuits of Nice, which consisted largely of robbery on the high seas. Nice did not object to the Barbary men as pirates but as poachers on the Nice grounds. The picture drawn by one writer who represents Nice in the guise of an indignant moralist repressing piracy because of its wickedness, may be compared with the conception of Satan rebuking sin. In 1250 Charles of Anjou, Prince of Provence, built a naval arsenal at Nice. It occupied the area now covered by the Cours Saleya but was entirely swept away by a storm in 1516.

In 1548 Nice—then a town of Savoy—was attacked by the French and sustained a very memorable siege, which is dealt with in the chapter which follows. After this it became quite a habit with the French to besiege Nice; for they set upon it, with varying success, in 1600, again in 1691, in 1706, and again in 1744. Finally, after changes of ownership too complex to mention, Nice was annexed to France, together with Savoy, in the year 1860.

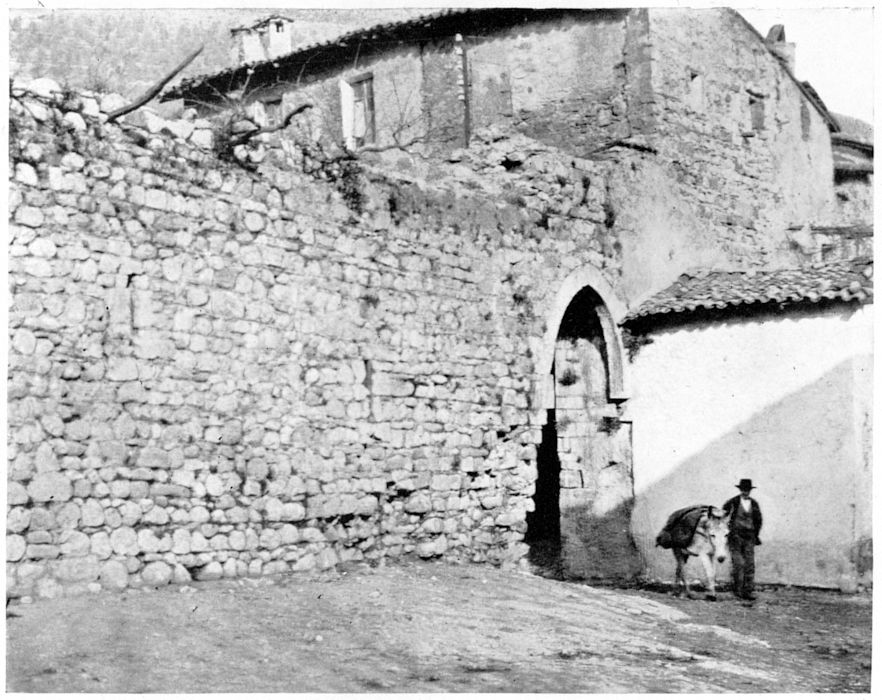

In Bosio’s interesting work[2] there is a plan of the city of Nice published in 1610. Although bearing the date named it represents the disposition of the city as it existed at a much earlier period. It shows that the town was situated on the left or east bank of the Paillon and that it was divided into two parts, the High Town and the Low Town. The former occupied the summit of the Castle Hill, was strongly fortified and surrounded by substantial walls. On this plateau were the castle of the governor, the cathedral, the bishop’s palace, the Hôtel de Ville, and the residences of certain nobles. The Low Town, at the foot of the hill, was occupied by the houses and shops of merchants, by private residences, and the humbler dwellings of sailors, artisans and poor folk. In the earliest days the High Town, or Haute Ville, alone existed; for Nice was then a settlement on an isolated hill as difficult of access as Monaco. In the fifteenth century the castle was represented only by the old keep or donjon, a structure, no doubt, massive enough but not adapted for other than a small garrison. It was Nicode de Menthon who enlarged the fortress of Nice and greatly increased the defences of the town during the century named.

As years progressed the military needs of the time caused the High Town, as a place of habitation, to cease to exist; for the whole of the top of the hill was given up to fortifications, bastions, gun emplacements, magazines, armouries and barracks. It is said by Bosio that the private houses and public buildings within the walls of the High Town were abandoned in 1518 to be replaced by the military works just named. The whole of these works were finally levelled to the ground in the year 1706 by order of Louis XIV.

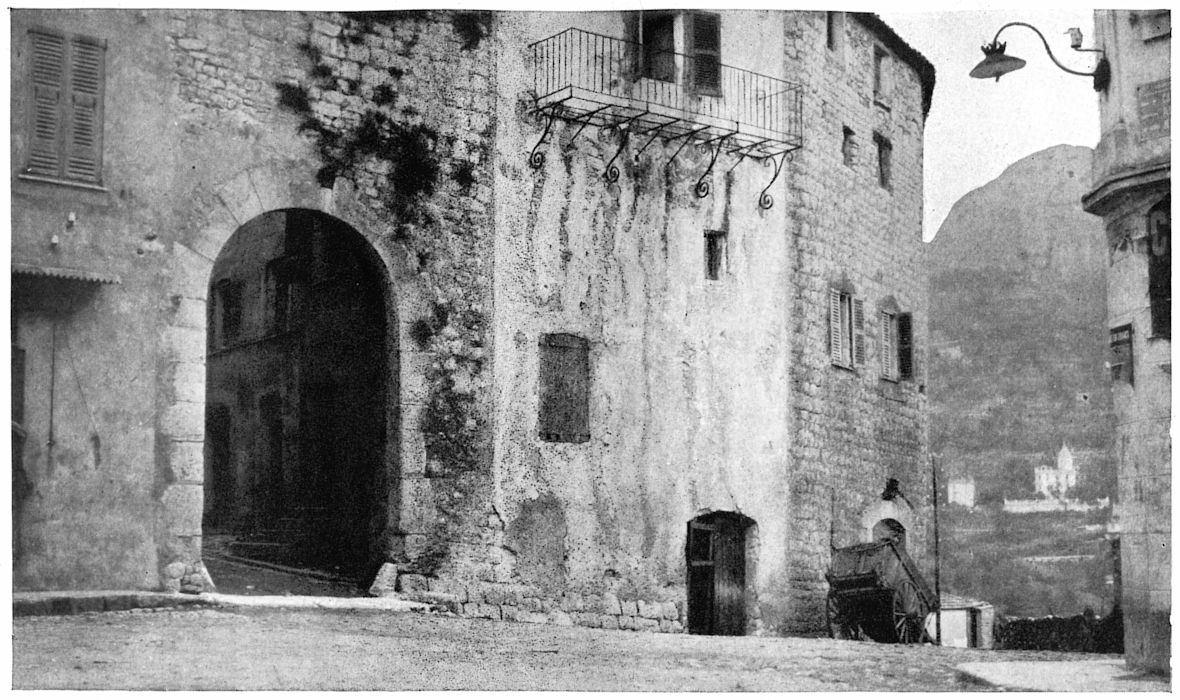

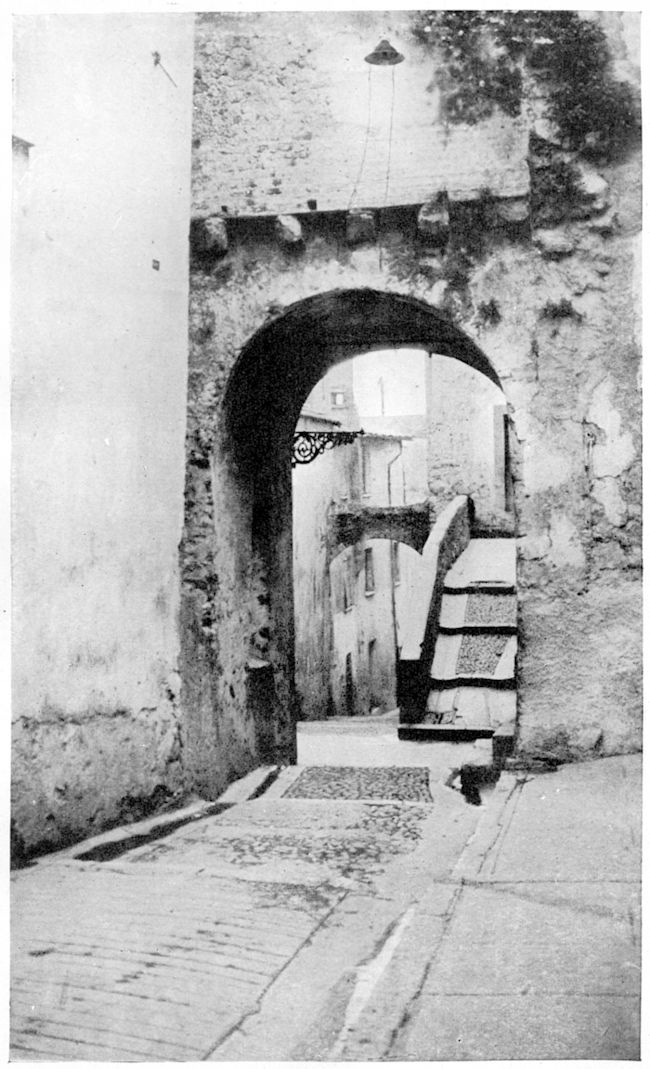

The Low Town, la Ville Basse, was bounded on the south by the sea, on the east by the Castle Hill, and on the west by a line running from the shore to the Paillon and roughly represented in position and direction by the present Rue de la Terrasse. To the north the town extended as far as the Boulevard du Pont Vieux. The town was surrounded by ramparts and bastions. On the ruins of the bastions Sincaire and Païroliera the Place Victor[3] (now the Place Garibaldi) was constructed in 1780. The position of the two bastions on the north is indicated roughly by the present Rue Sincaire and Rue Pairollière. On one side of the Rue Sincaire there still stands, against the flank of the hill, a solid and lofty mass of masonry which is a relic of the defences of old days.

There were four gates to the old town, Porte de la Marine, Porte St. Eloi, Porte St. Antoine, and the Païroliera Gate. The St. Eloi and the Païroliera gates were broken down during the great siege of 1543, and the others have since been cleared away. Of these various gates that of St. Antoine was the most important. It was at this gate that criminals were pilloried. A faint trace of the old walls is still to be seen near the end of the Fish Market.

The Bellanda Tower was built in 1517 by de Bellegarde, the then Governor of Nice. It served to protect the city from the sea. The tower now exists as a low round work which has been incorporated in the grounds of an hotel and converted into a “belvedere.” It might, however, be readily mistaken for a stone water-tank. There was another tower, called the Malavicina, which was constructed to defend the town upon the land side; but of this erection no trace remains. A little suburb, or small borough, existed just outside the old town and on the other side of the river. It was called St. Jean Baptiste, and was connected with the town by a bridge in front of the St. Antoine Gate. Its position is indicated by the present Quai St. Jean Baptiste.

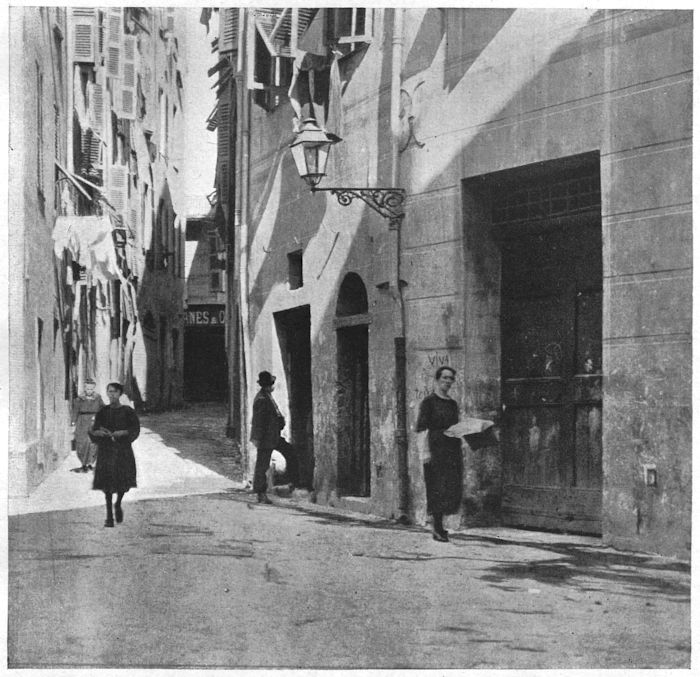

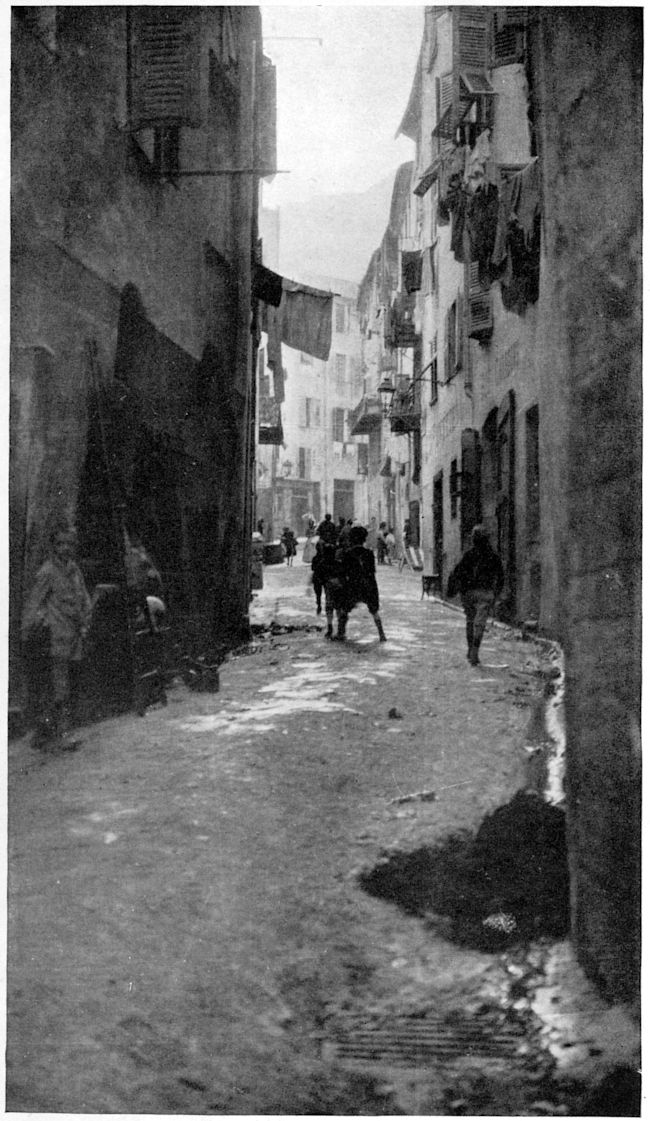

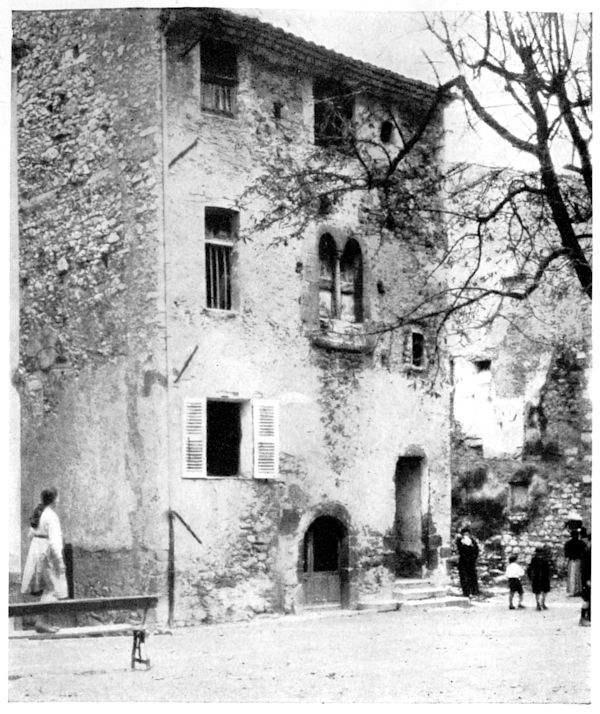

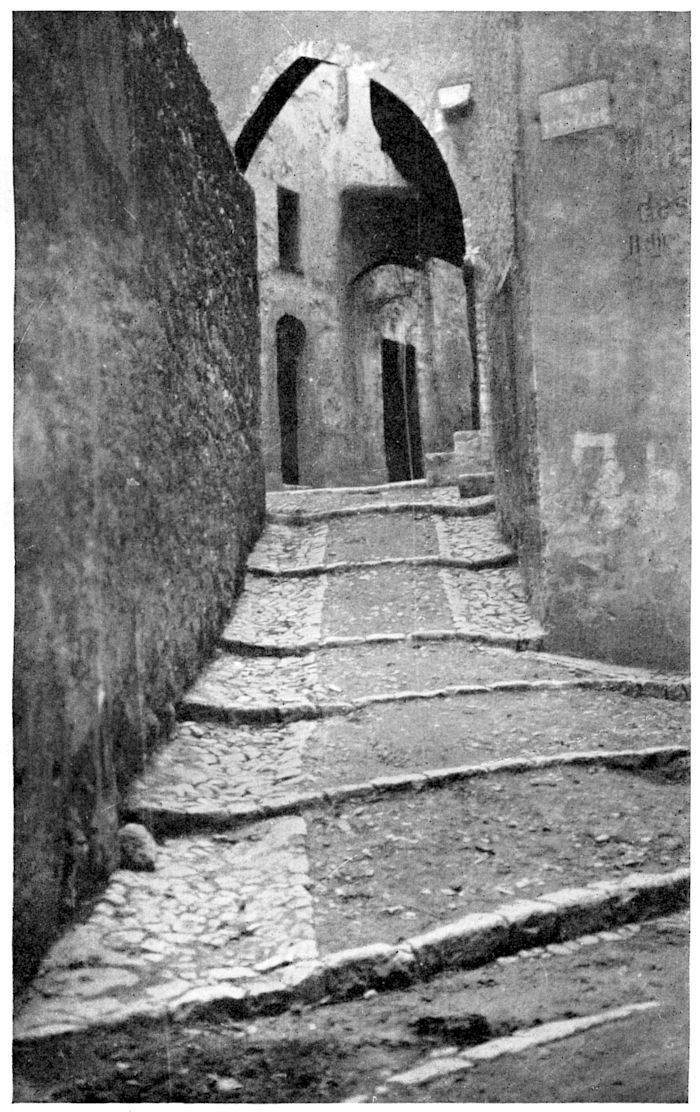

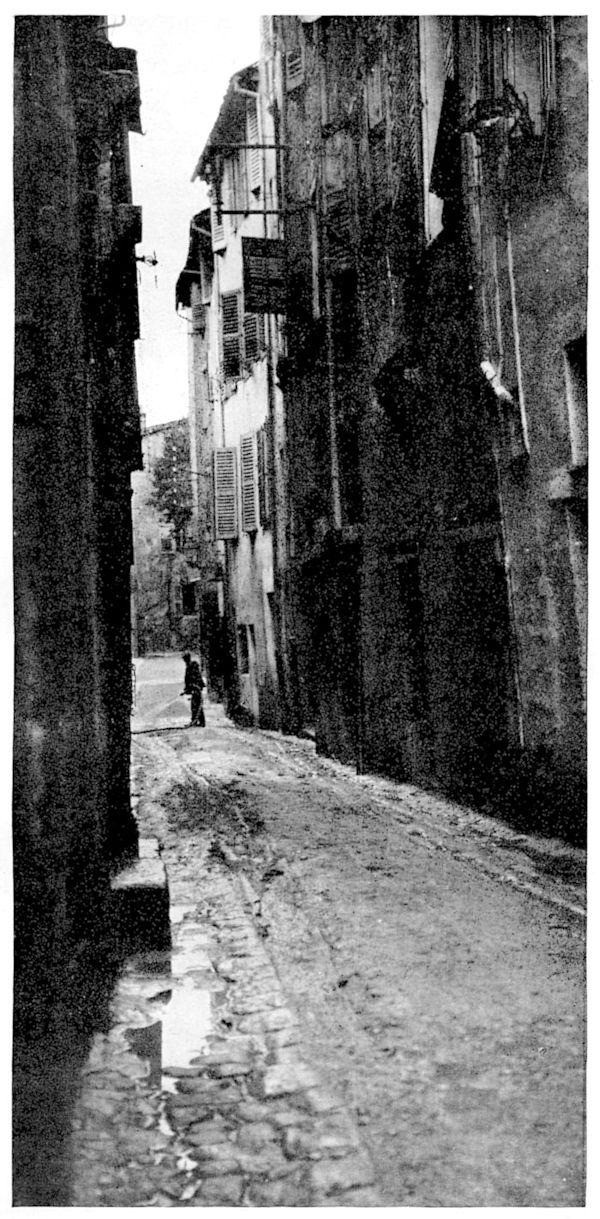

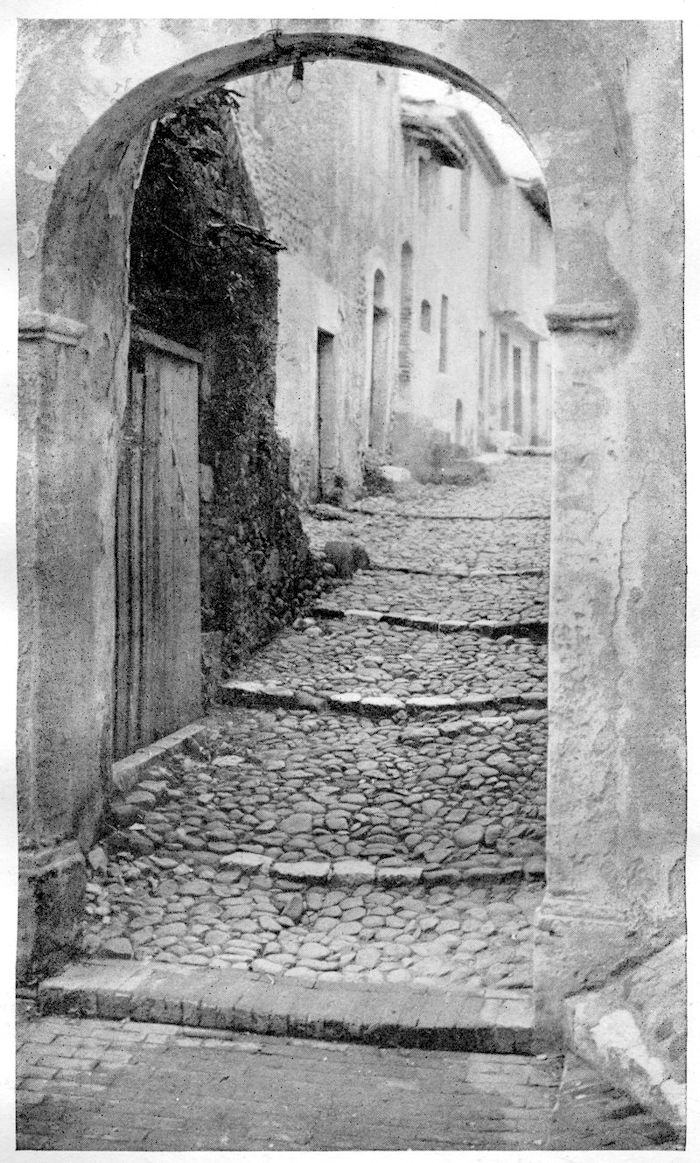

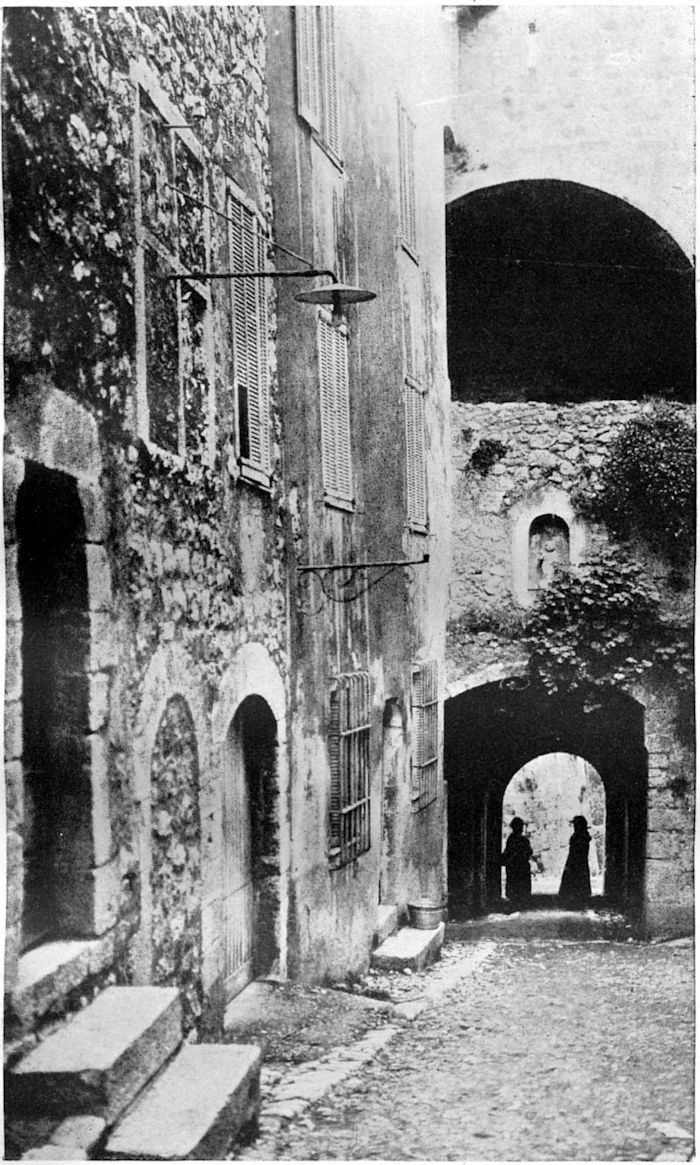

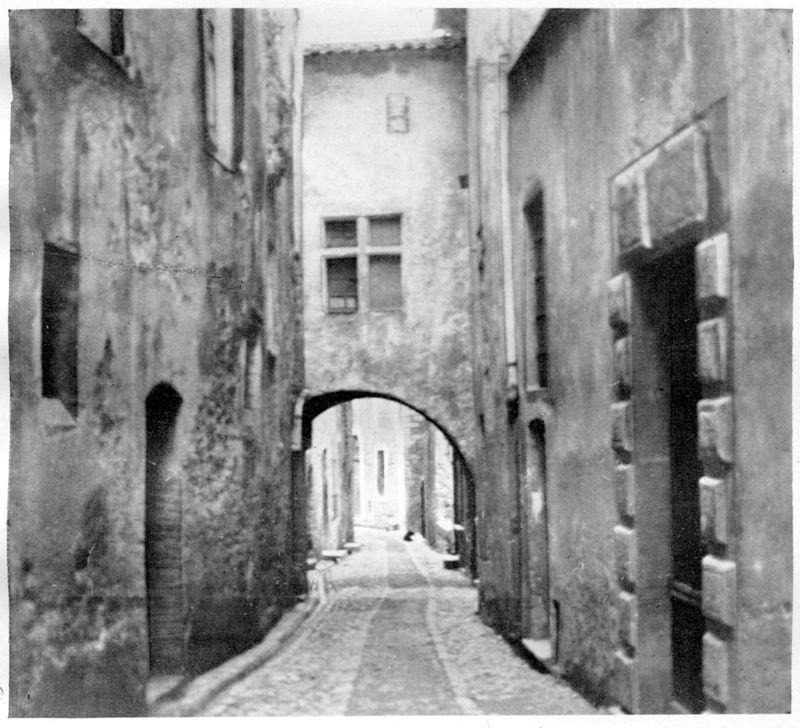

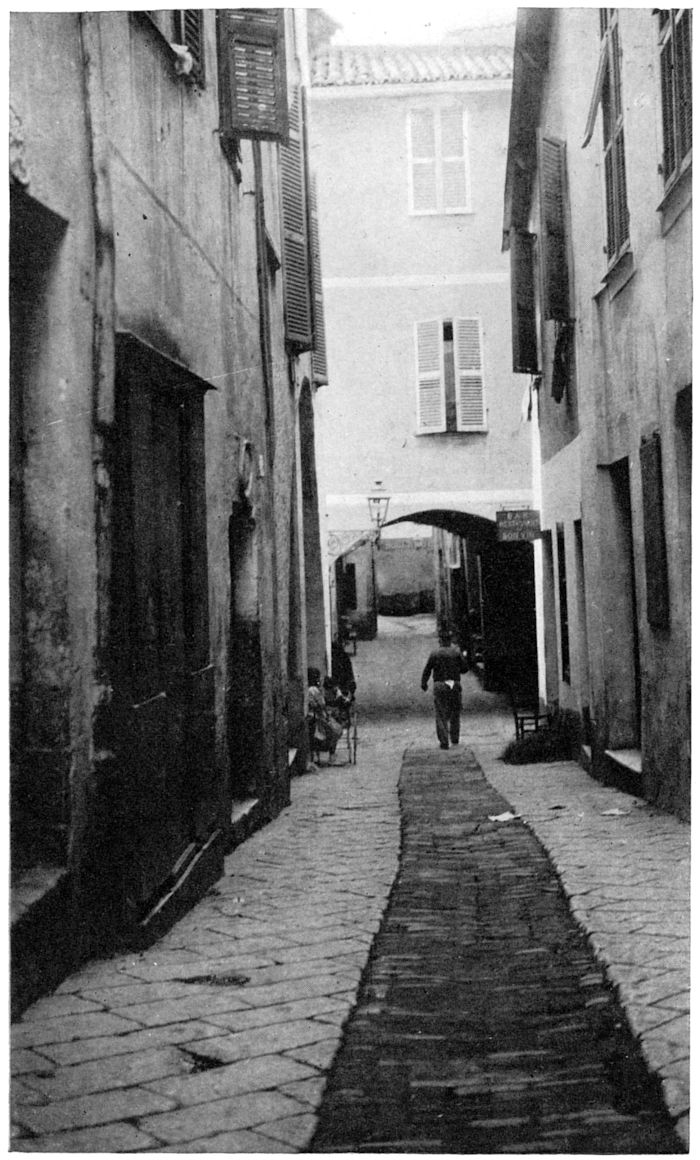

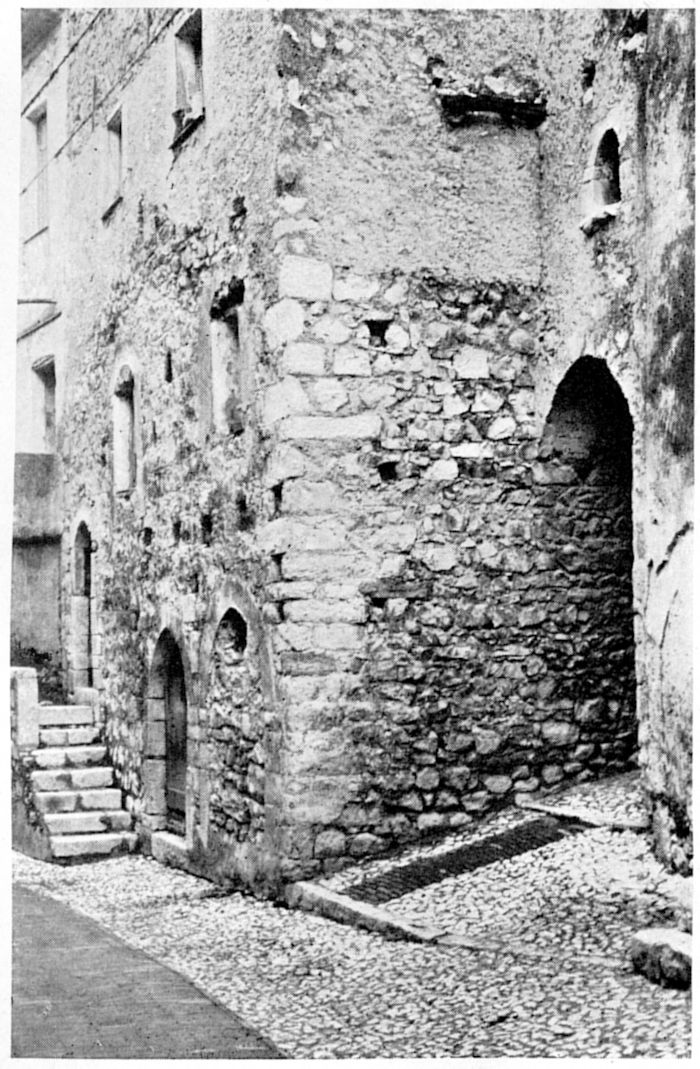

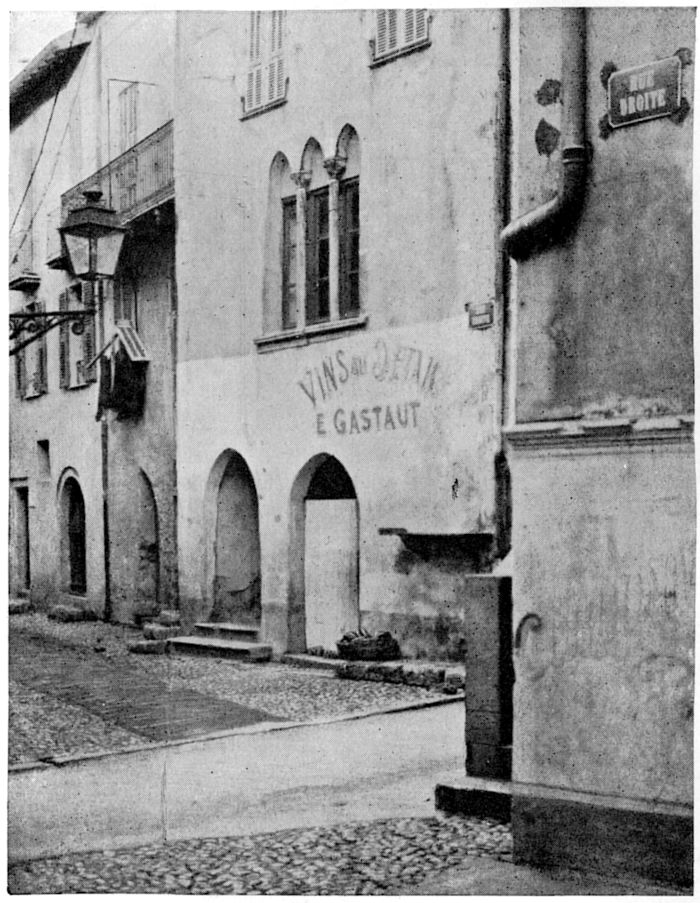

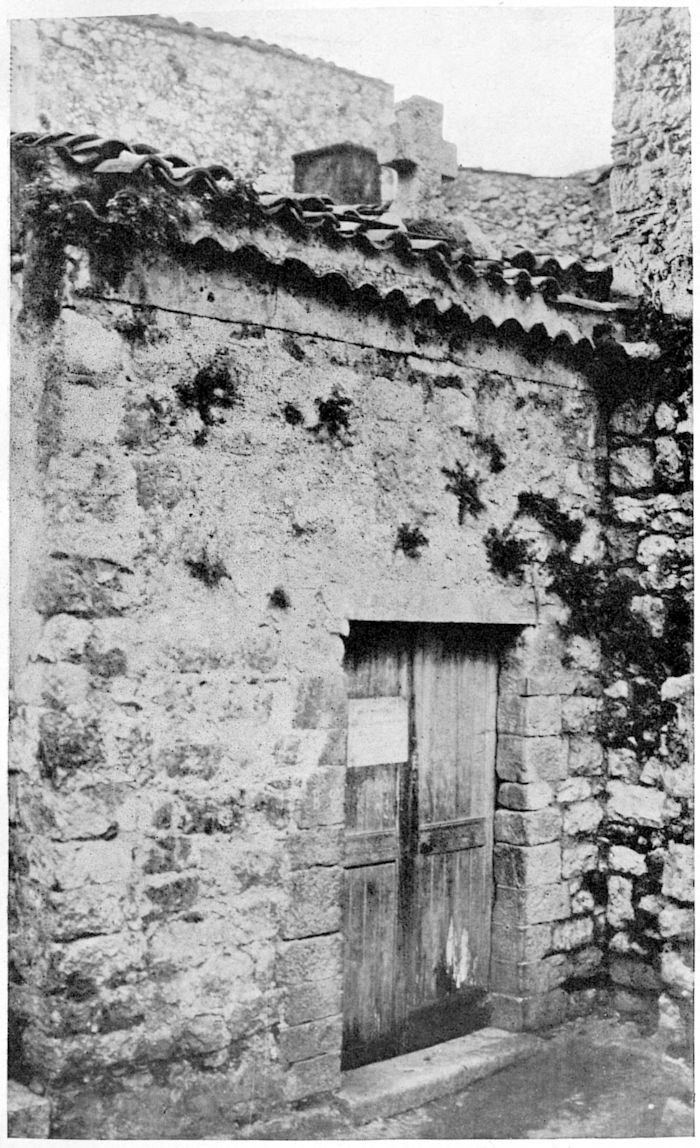

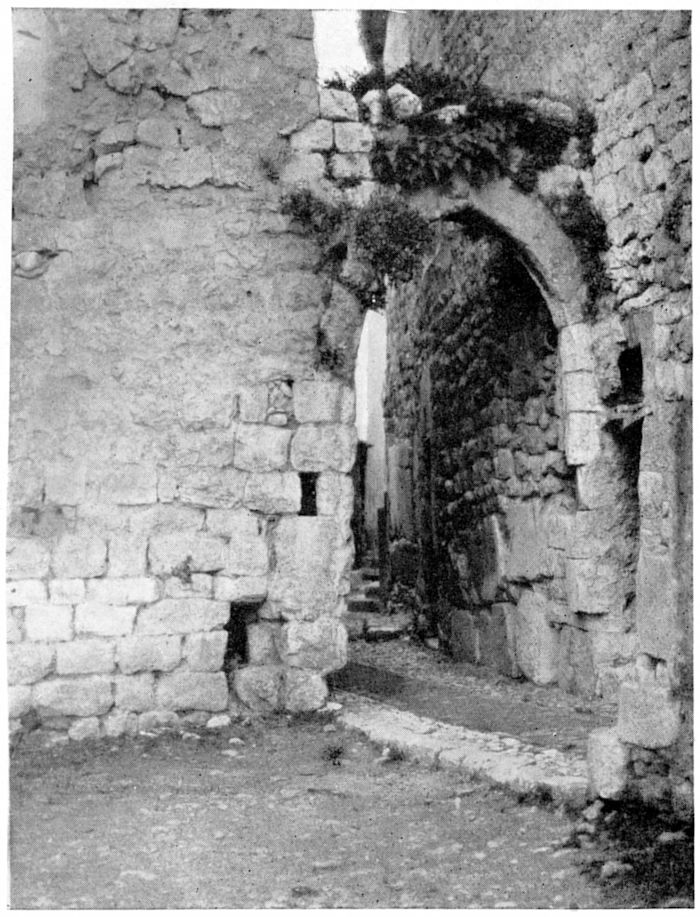

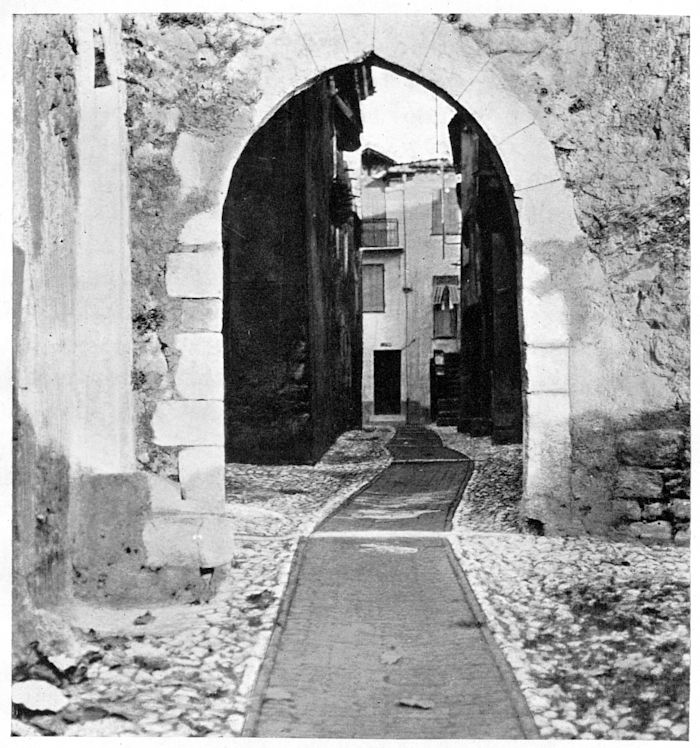

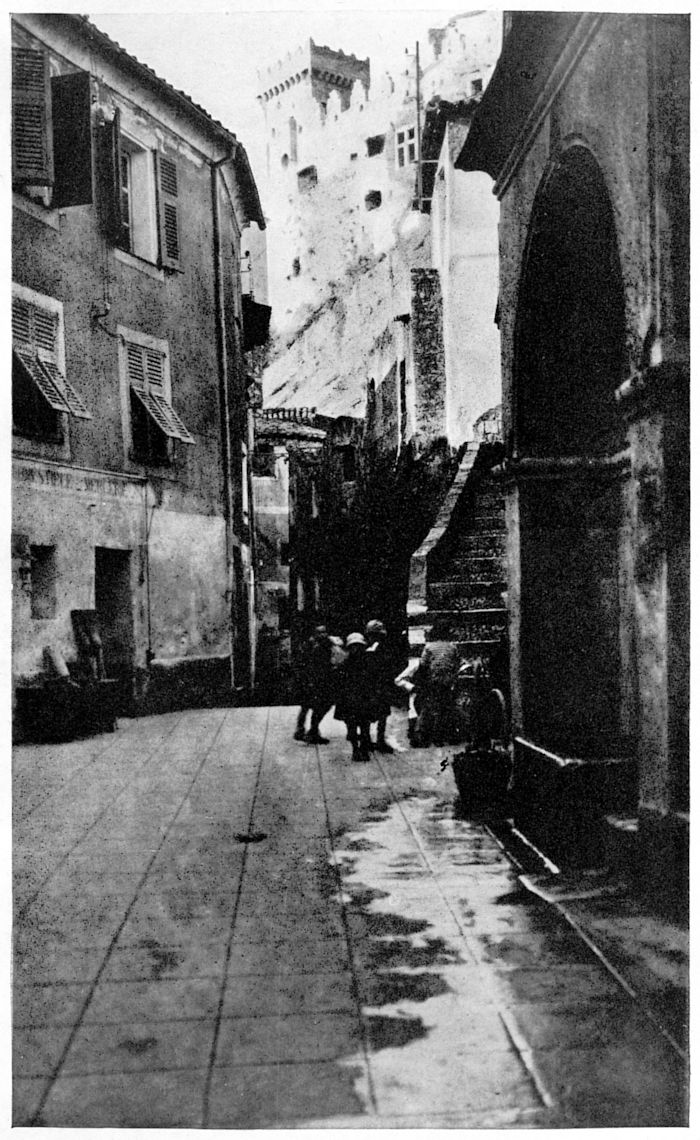

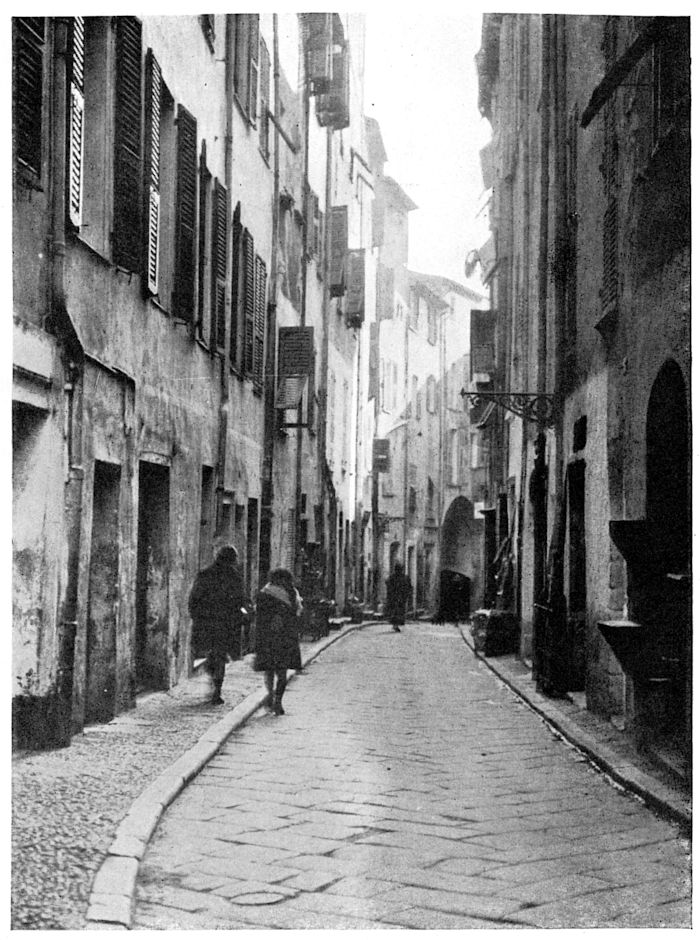

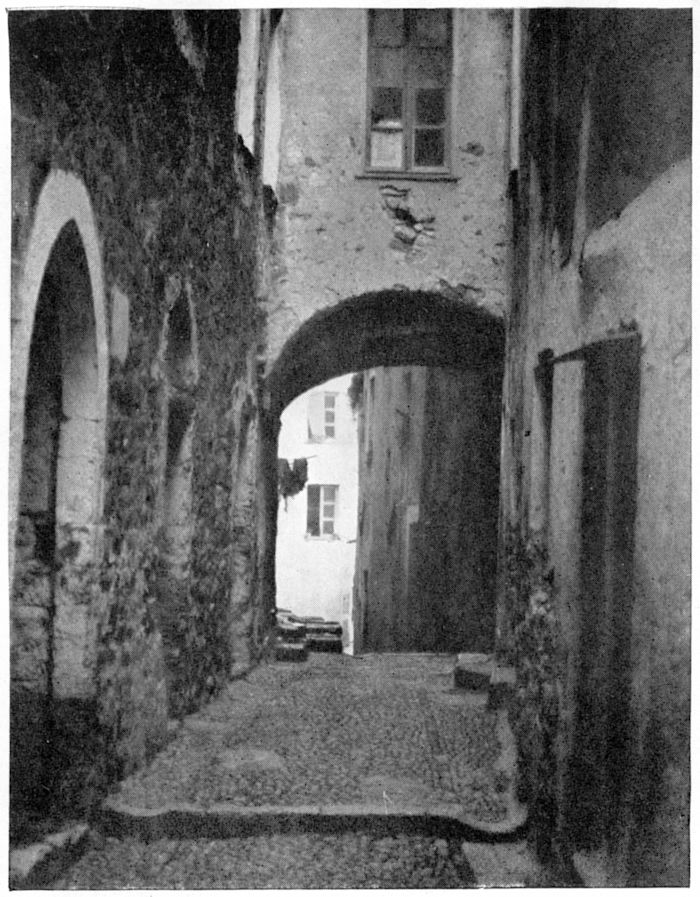

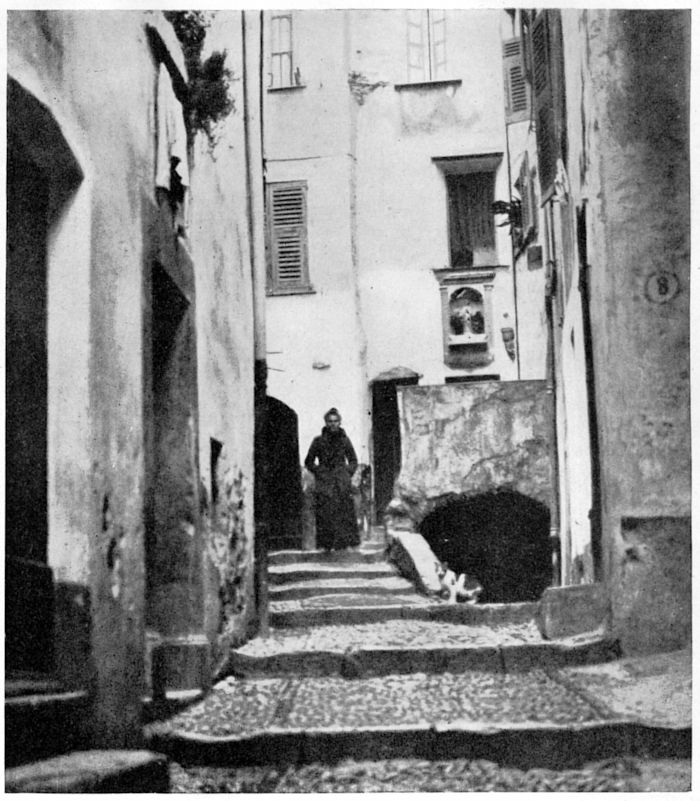

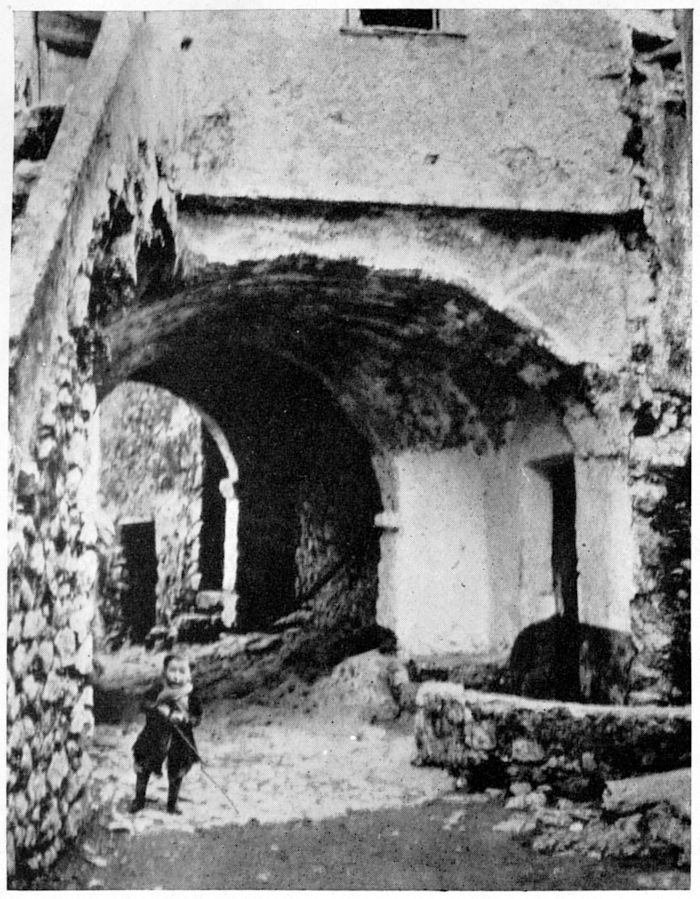

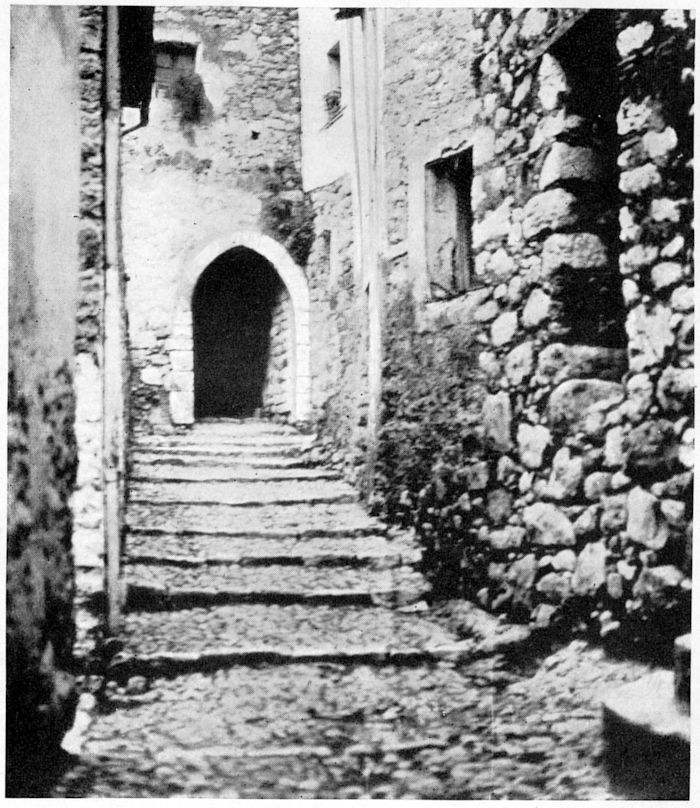

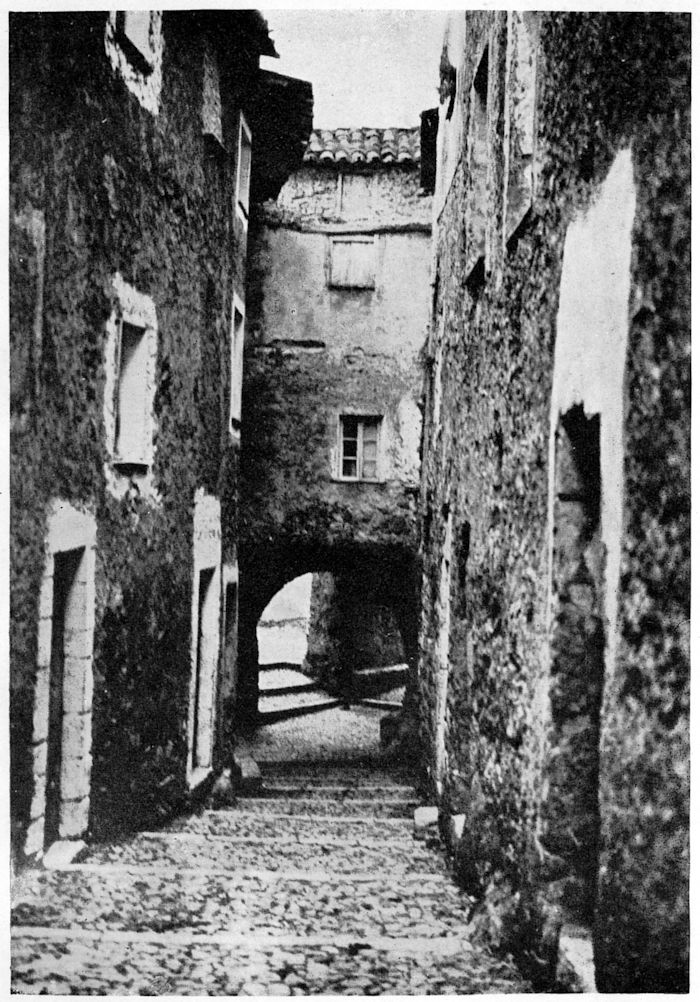

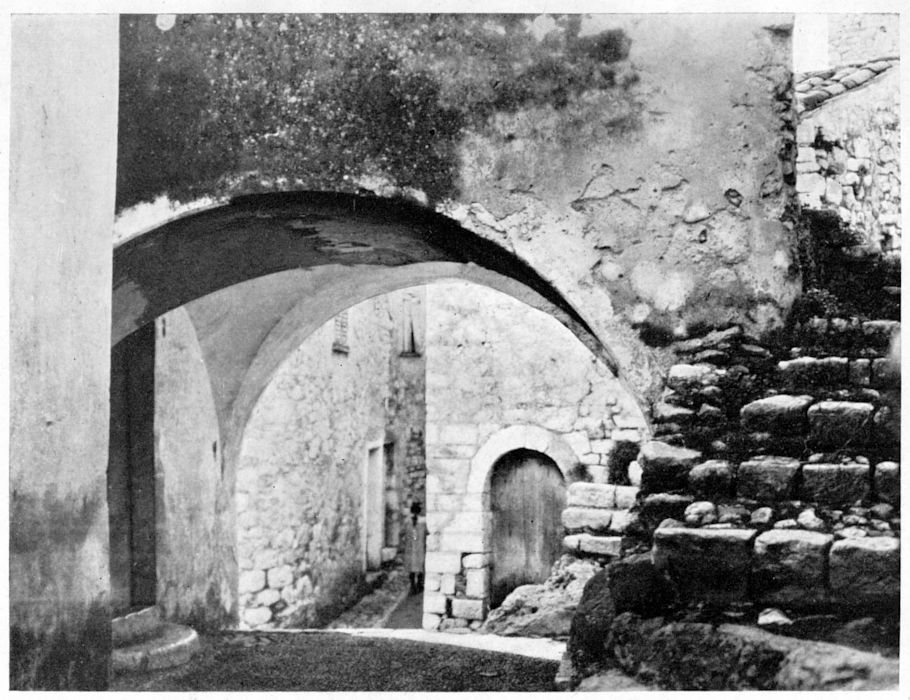

The old town of Nice is small and well circumscribed. It occupies a damp and dingy corner at the foot of the Castle Hill. It seems as if it had been pushed into this corner by the over-assertive new town. Its lanes are so compressed and its houses, by comparison, so tall that it gives the idea of having been squeezed and one may imagine that with a little more force the houses on the two sides of a street would touch. It is traversed from end to end by an alley called the Rue Droite. This was the Oxford Street of the ancient city. A series of narrower lanes cross the Rue Droite; those on one side mount uphill towards the castle rock, those on the other incline towards the river.

The lanes are dark, dirty and dissolute-looking. The town is such a one as Gustave Doré loved to depict or such as would be fitting to the tales of Rabelais. One hardly expects to find it peopled by modern mechanics, tram conductors, newspaper boys and honest housewives; nor do electric lights seem to be in keeping with the place. Its furtive ways would be better suited to men in cloaks and slouched hats carrying rapiers, and at night to muffled folk groping about with lanterns. One expects rather to see quaint signboards swinging over shops and women with strange headgear looking out of lattice windows. In the place of all this is modern respectability—the bowler hat, the stiff collar and the gramophone.

The only thing that has not changed is the smell. It may be fainter than it was, but it must be centuries old. It is a complex smell—a mingling of cheese and stale wine, of salt fish and bad health, a mouldy and melancholy smell that is hard to bear even though it be so very old. The ancient practice of throwing all refuse into the street has drawbacks, but it at least lacks the insincere delicacy of the modern dustbin.

Strange and interesting industries are carried on in doorways and on the footpath. Intimate affairs of domestic life are pursued with unblushing frankness in the open and with a singular absence of restraint. Each street, besides being a public way, is also a laundry, a play-room for children and a fowl run.

The houses are of no particular interest, for, with a few exceptions, they have been monotonously modernised. The lanes are so pinched that the dwellings are hard to see as a whole. If the visitor throws back his head and looks in the direction in which he believes the sky to be, he will be aware of dingy walls in blurred tints of pink or yellow, grey or blue with green sun-shutters which are swinging open at all angles. From any one of the windows may protrude a mattress—like a white or red tongue—or a pole may appear from which hang clothes to dry, or, more commonly still, a female head will project. Women talk to one another from windows all day long. Indeed, social intercourse in old Nice is largely conducted from windows. If one looks along a lane, these dark heads projecting at various levels from the houses are like hobnails on the sole of a boot. The sun-shutters, it may be explained, are not for the purpose of keeping out the sun, but serve as a protection from the far more piercing ray of the neighbour’s eye.

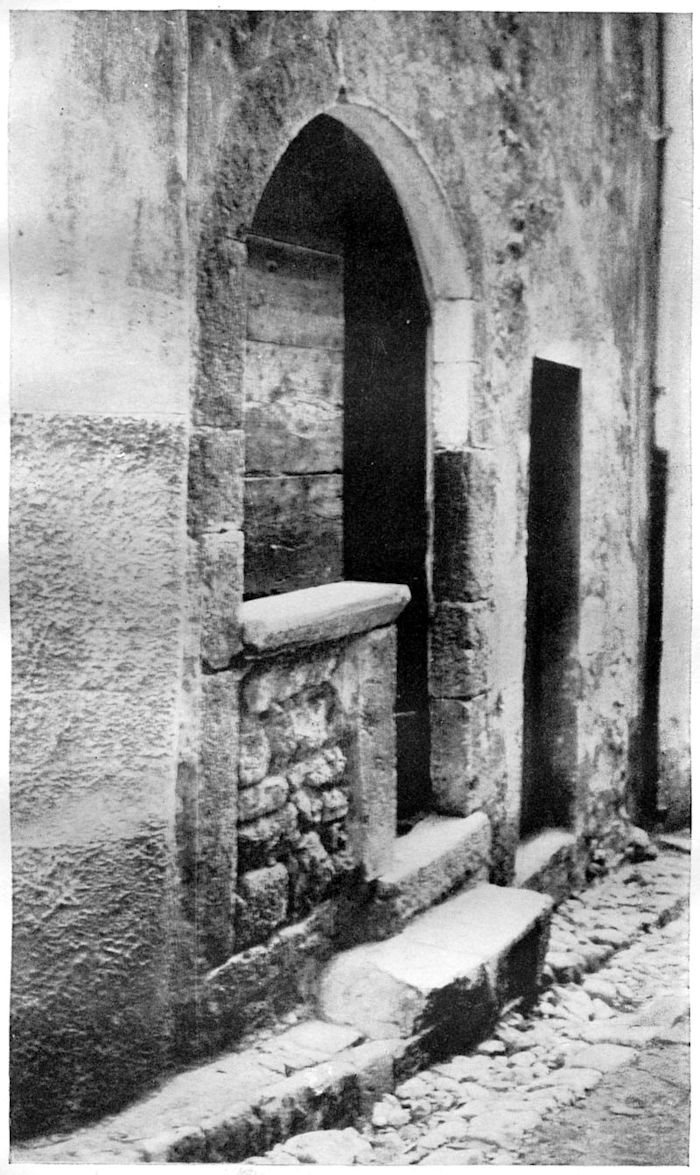

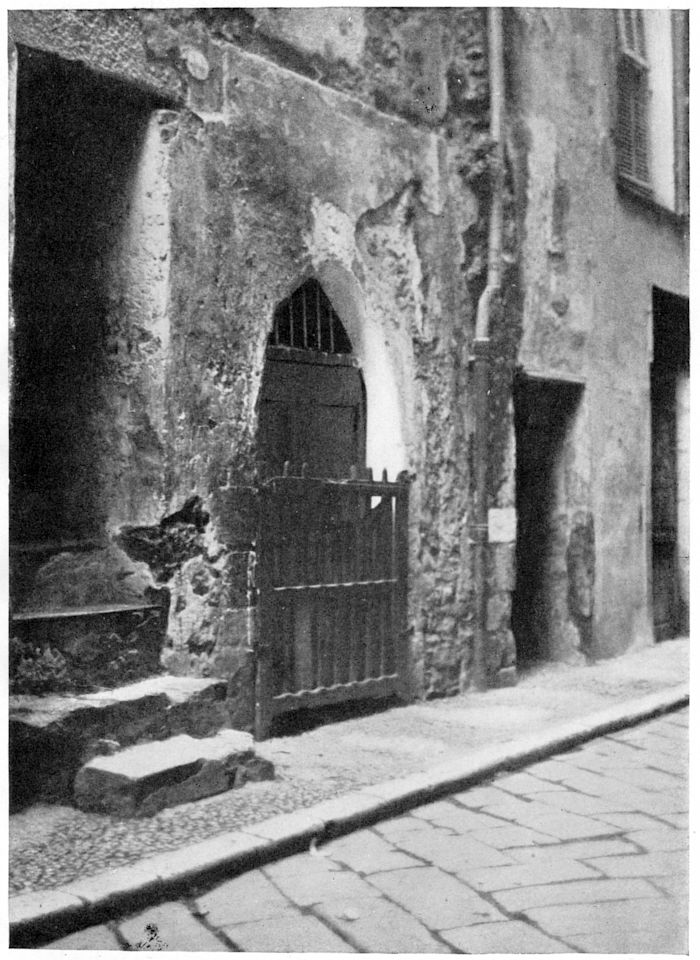

A picturesque street is the Rue du Malonat. It mounts up to the foot of the Castle Hill by wide, low steps like those on a mule-path. Poor as the street may be, there is in it an old stone doorway, finely carved, which is of no little dignity. At the bottom of the lane is a corner house with three windows furnished with grilles. This is said to have been at one time the residence of the Governor of Nice. The house in the Rue de la Préfecture (No. 20) where Paganini died is featureless but for its old stone entry, and its ground floor has become a shop where knitted goods are sold.[4]

In the Rue Droite (No. 15) is an amazing house which one would never expect to find in a mean street. It is the palace of the great Lascaris family. Theodore Lascaris, the founder of the family, is said to have been driven from his Byzantine throne in 1261 and to have taken refuge in Nice. There he built himself a palace. It could not have been erected in the Rue Droite, as so many writers repeat, since the Lower Town as a retreat for ex-emperors, had no existence at this period. The descendants of the exile, however, continued to live in Nice for some centuries, and the present building dates, with little doubt, from the early part of the seventeenth century.

The street is so narrow that it is difficult to appreciate the fine façade of this palace; but by assuming the attitude of a star-gazer it is possible to see that the great house of four stories would look illustrious even in Piccadilly. It has a very finely carved stone doorway which leads into a vaulted hall. In the road outside the door are heaps of vegetable refuse, a pyramid of mouldy lemons and a pile of pea husks. From the upper windows hang bedding and clothes to dry. It is quite evident that the exposed garments do not belong to the family of an ex-emperor. On the main floor, or piano nobile, are seven large and ornate windows, each provided with a balcony.

From the hall a stone staircase ascends in many flights. It has a vaulted ceiling, supported by large stone columns. On the wall are niches containing busts of indefinite men and some elaborate work in plaster. The staircase on one side is open to a well all the way and so the lights and shadows that cross it are very fascinating. Still more fascinating is it to recall for a moment the people who have passed up and down the stair and upon whom these lights and shadows have fallen during the last three hundred years. Among them would be the old count on his way to the justice room, the faltering bride whose hand has rested on this very balustrade, the tired child crawling up to bed with a frightened glance at the fearsome busts upon the wall.[5]

The rooms on the piano nobile have domed ceilings, which are either covered with frescoes or are richly ornamented by plaster work. There is a great display on the walls of gilt panelling and bold mouldings. The rooms are dark and empty and so dirty that they have apparently not been cleaned since the Lascaris family took their departure. Apart from the filth and the neglect the place provides a vivid realisation of the town house of a nobleman of Nice in the olden days.

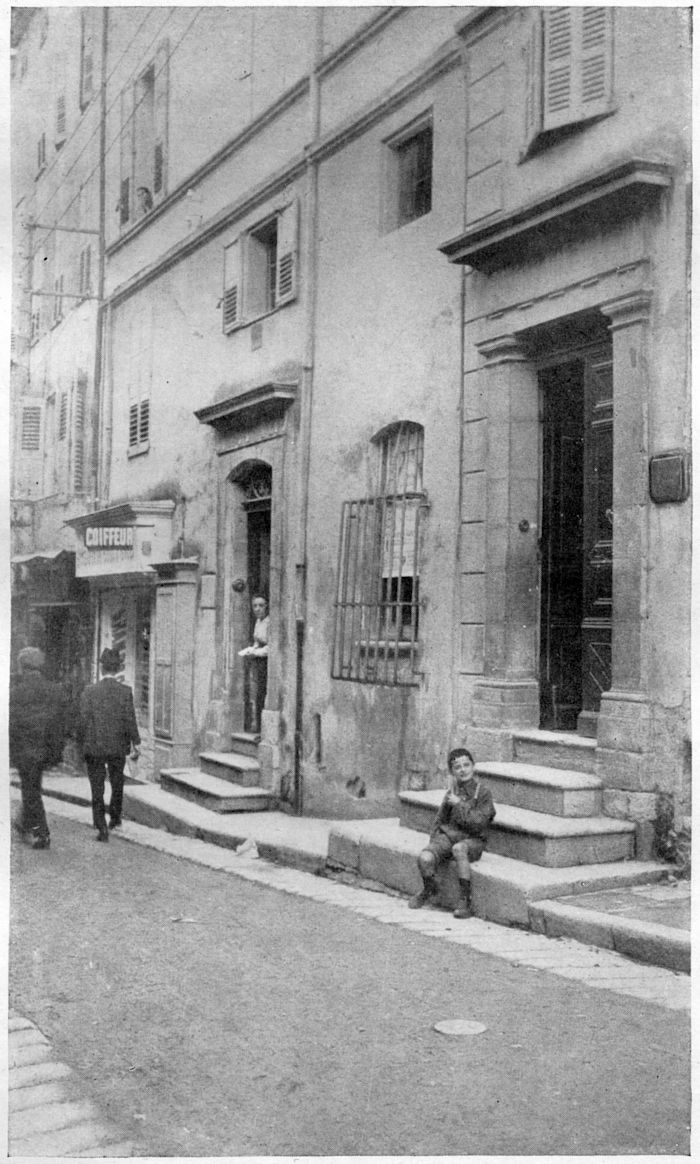

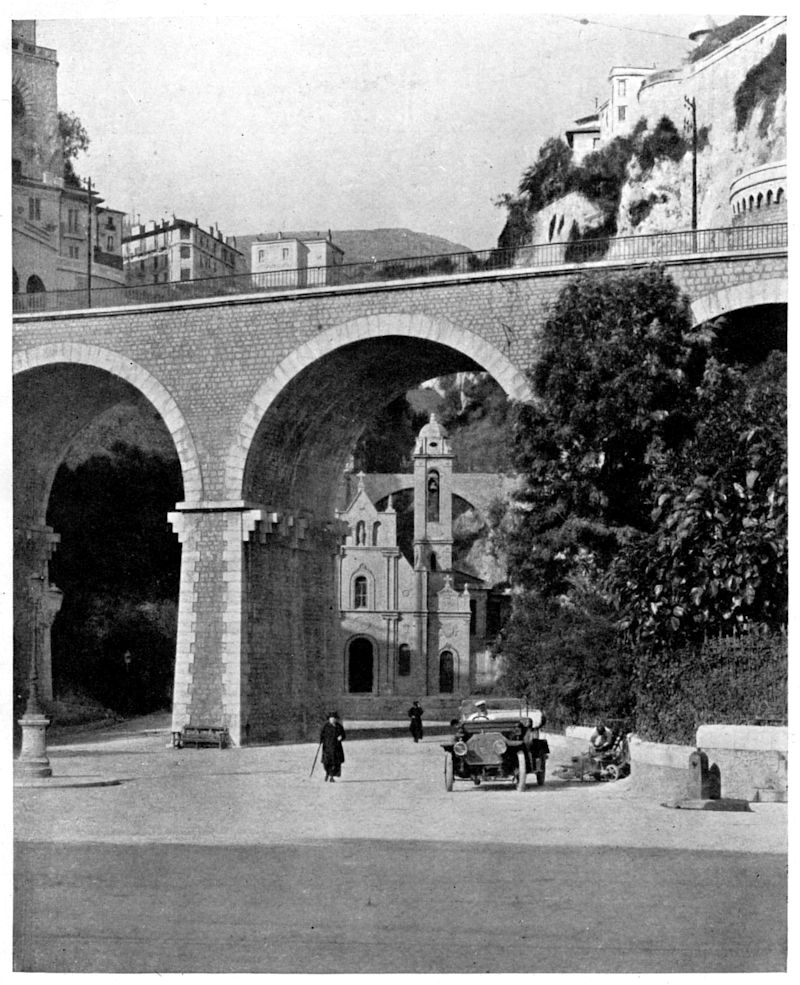

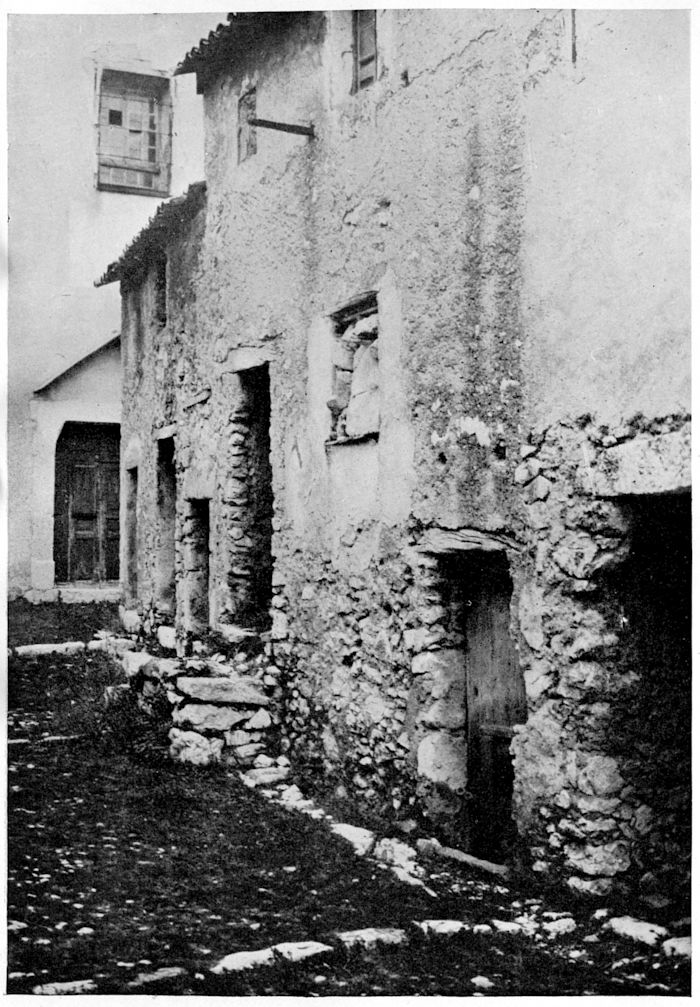

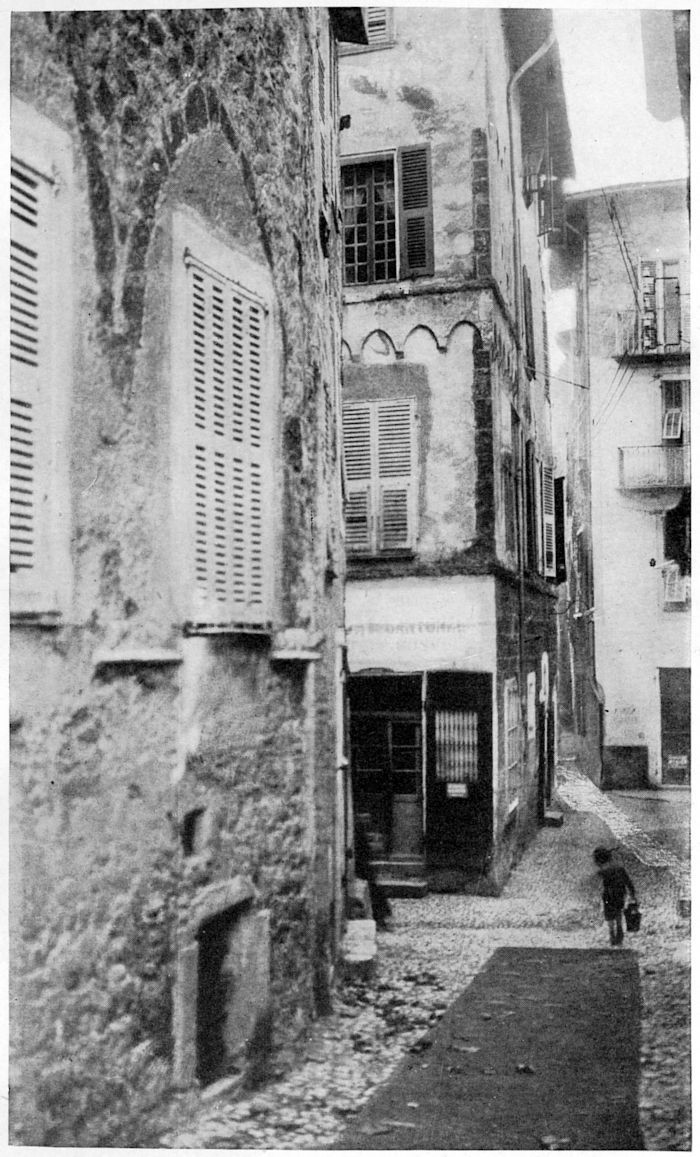

NICE: RUE DU SENAT.

A stroll through the town will reveal many reminiscences of the past, which, although trivial enough, are still very pleasant to come upon amidst squalid surroundings. For instance over the doorway of a house in the Rue Centrale are carved, in a very boyish fashion, the letters I.H.S. with beneath them the sacred heart, the date 1648 and the initials of the owner of the building. Then again in the Rue Droite (No. 1), high up on the plain, deadly-modern wall of a wine-shop, is one very exquisite little window whose three arches are supported by two graceful columns. It is as unexpected as a plaque by Della Robbia on the outside of a gasometer.

There are several churches in the old town but they cannot claim to be notable. The cathedral of Sainte Réparate stands in an obscure and meagre square. It became a cathedral in 1531 but was reconstructed in 1737 and its interior “restored” in 1901. Outside it is quite mediocre, but within it is so ablaze with crude colours, so laden with extravagant and restless ornament, so profuse in its fussy and irritating decoration that it is not, in any sense, a sanctuary of peace. The old town hall of Nice in the Place St. François is a small, simple building in the Renaissance style which can claim to be worthy of the Nice that was.

There are two objects outside the old town which the visitor will assuredly see—the Pont Vieux and the Croix de Marbre. The former which dates from 1531 is a weary-looking old bridge of three arches, worn and patched. Any charm it may have possessed is destroyed by the uncouth structure of wood and iron which serves to widen its narrow mediæval way. The cross stands in the district once occupied by the convent of Sainte Croix which was destroyed during the siege of 1543. The monument serves to commemorate the meeting of peace held in 1538 by Pope Paul III, François I and the Emperor Charles V. The cross, which is very simple, rises under a canopy of old, grey stone, supported by pillars with very primitive capitals. The cross was hidden away during the Revolution but was replaced in 1806 by the then Countess de Villeneuve. The venerable monument, standing as it does in a busy street through which the tramcars rumble, looks singularly forlorn and out of place.

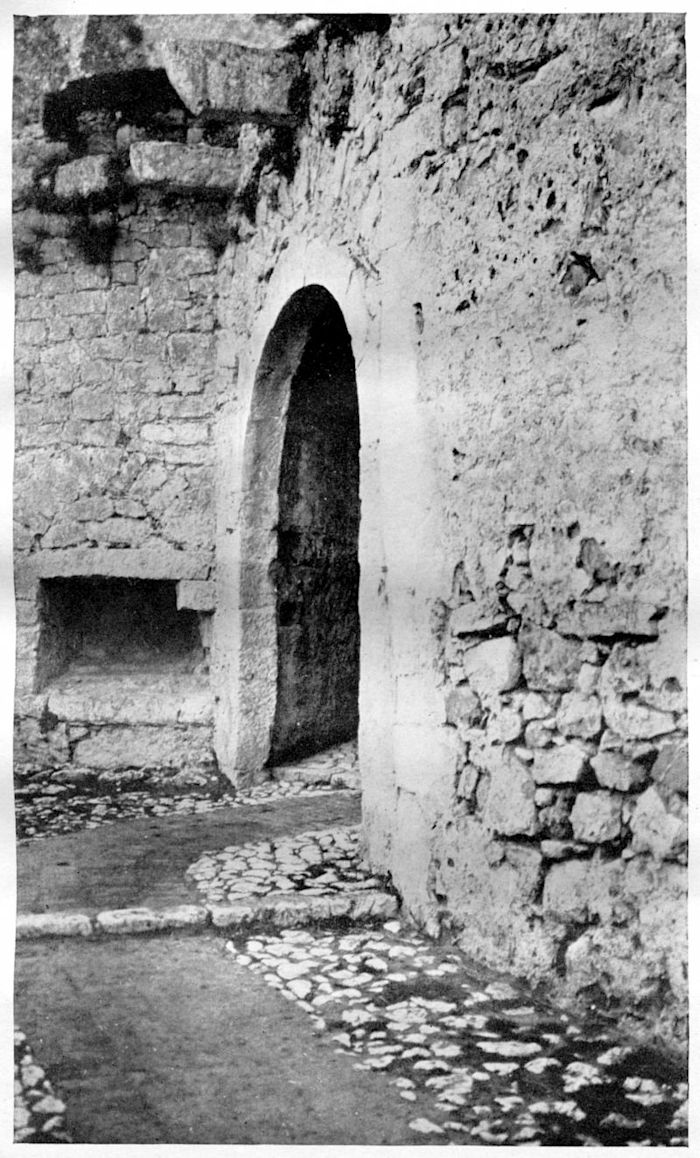

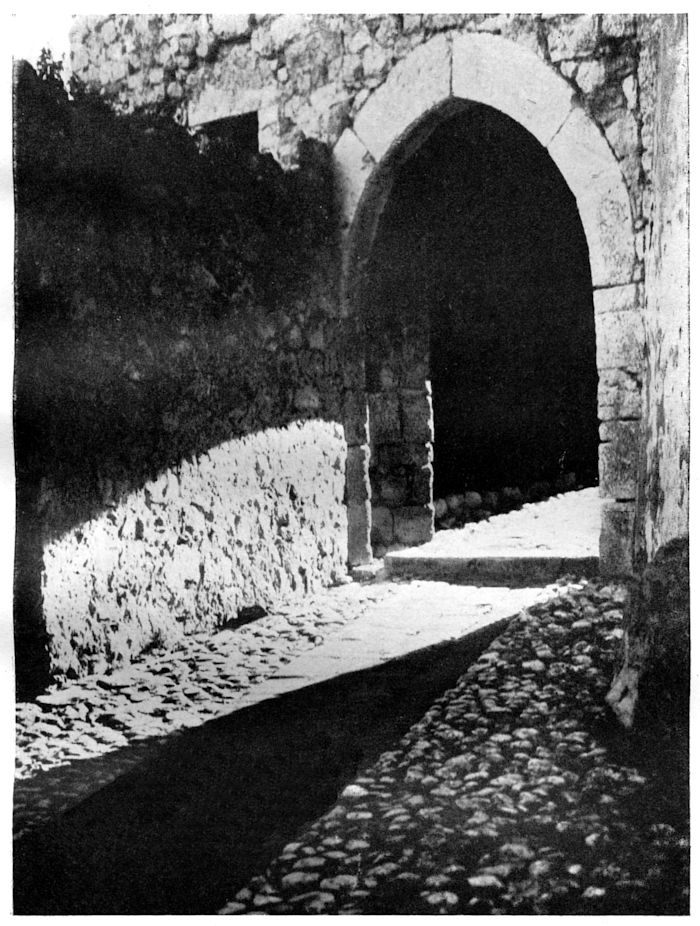

The Castle Hill is now merely a wooded height which has been converted into a quite delightful public park. Among the forest of trees are many remains of the ancient citadel, masses of tumbled masonry, a half-buried arch or a stone doorway. There are indications also of the foundations of the old cathedral. The view from the platform on the summit is very fine, while at the foot are the jumbled roofs of old Nice. It is easy to appreciate how strong a fortress it was and how it proved to be impregnable to the forces of Barbarossa in the siege of 1543. It is a hill with a great history, illumined with great memories, but these are not encouraged by the stall for postcards and the refreshment bar which now occupy the place of the old donjon.

|

“La Province des Alpes Maritimes,” 1902. |

|

So named after King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia. |

|

The strange wanderings of Paganini after death are dealt with in the account of Villefranche (page 114). |

|

A good photograph of this staircase will be found in Mr. Loveland’s “Romance of Nice,” page 146. |

NICE, as has been already stated, was many times besieged. If there be a condition among towns that may be called “the siege habit” then Nice had acquired it. The most memorable assault upon the place was in 1543. It was so gallant an affair that it is always referred to as the siege of Nice.

It was an incident of the war between Charles V and François I, King of France. A treaty had been entered into between these two sovereigns which is commemorated to this day by the Croix de Marbre in the Rue de France. Charles V thought fit to regard this obligation as “a scrap of paper” and declared war upon the French king. The French at once started to attack Nice which was conveniently near to the frontier and at the same time an important stronghold of the enemy.

Now in these days business entered largely into the practical affairs of warfare. A combatant must obviously have a fighting force. If he possessed an inadequate army he must take means to supplement it. He must hire an army on the best terms he could and in accord with the hire-system arrangement of the time. Professional warriors were numerous enough and were as eager for a temporary engagement as are “supers” at a pantomime. They could not be obtained through what would now be called a Registry Office; but there were contractors or war-employment agents who could supply the men en masse.

François I, when the war began, found himself very ill provided with fighting men and especially with seamen and ships, for Nice was a port. He naturally, therefore, applied to the nearest provider of war material and was able to secure no less a man than Barbarossa the pirate.

It is necessary to speak more fully about this talented man; for in all popular accounts of the great siege of Nice two persons alone are pre-eminent; two alone occupy the stage—a pirate and a laundress, Barbarossa and Segurana. Hariadan Barbarossa was a pirate by profession, or as some would style him who prefer the term, a corsair. His sphere of activity was the Mediterranean and especially the shores of Africa. He had done extremely well and, as the result of diligent robbery with violence pursued for many years, he had acquired territory in Tunis where he reigned as a kind of caliph. He was not a Moor nor was he black. He was a native of Mitylene. The name Barbarossa, or Redbeard, had been given him apparently in part on account of his hair and in part from the fact that his real name was unpronounceable. His exploits attracted the attention of the Sultan of Turkey who was so impressed with his ability that he took him into his service and made him Grand Admiral of the Ottoman fleet. It was, therefore, with Turkish ships and with Turkish men that Barbarossa came to the aid of the King of France.

The leader of the French troops was the Comte de Grignan. He seems, however, to have been a person of small importance. Barbarossa was the commanding figure, the leader and the hero of the drama.

The governor of Nice was a grey-headed warrior, one Andrea Odinet, Count of Montfort. Barbarossa commenced operations on August 9th but before his attack was delivered he sent a formal message to the governor demanding the surrender of the town. The governor replied enigmatically that his name was Montfort. Barbarossa probably perceived that the name was appropriate, for the hill held by the enemy was strong. He further informed the pirate that his family motto was “Bisogno tenere,” which may be rendered “I am bound to hold on.” Having furnished these biographical details he suggested that the Turkish admiral had a little more to do than he could manage.

The position of the town, with its walls, its bastions and its gates, has been already set forth in the preceding chapter. The main assault was made on the north side of Nice, the special object of attack being the Païroliera bastion which faced the spot now occupied by the Place Garibaldi. The batteries opened fire and poured no fewer than three hundred shots a day upon the unhappy city. This cannonade was supplemented by that of one hundred and twenty galleys which were anchored off the foot of Mont Boron.

By August 15th a breach was made in the Païroliera bastion, and the Turks and the French moved together to the assault. They were thrown back with fury. They renewed the attack, but were again repulsed and on the third violent onrush were once more hurled back. At last, wearied and disheartened, they retired, having lost heavily in men and having suffered the capture of three standards.

The poor, battered town of Nice, with its small garrison, could not however endure for long the incessant rain of cannon balls, the anxiety, the perpetual vigil and the bursts of fighting; so after eleven days of siege the lower town capitulated, leaving the haute ville, or Castle Hill, still untaken.

Barbarossa appears to have dealt with that part of the city which he had captured in quite the accepted pirate fashion and with great heartiness. He destroyed as much of it as his limited leisure would permit, let loose his shrieking Turks to run riot in the streets, set fire to the houses and took away three thousand inhabitants as slaves. Barbarossa—whatever his faults—was thorough.

There yet remained the problem of the upper town on the Castle Hill. It was unshaken, untouched and as defiant as the precipice on which it stood; while over the tower of the keep the banner of Nice floated lazily in the breeze as if it heralded an autumn fête day. The Turkish batteries thundered not against walls and bastions but against a solid and indifferent rock. To scale the side of the cliff was not within the power of man. The garrison on the height had little to do but wait and count the cannon balls which smashed against the stone with as little effect as eggshells against a block of iron.

NICE: A STREET IN THE OLD TOWN.

The view is generally accepted that little is to be gained by knocking one’s head against a stone wall. The general in command of the French was becoming impressed with this opinion and was driven to adopt another and more effective method of destroying Nice. In his camp were certain traitors, deserters and spies who had sold themselves, body and soul, to the attacking army. Conspicuous among these was Gaspard de Caïs (of whom more will be heard in the telling of the siege of Eze), Boniface Ceva and a scoundrel of particular baseness named Benoit Grimaldo, otherwise Oliva. These mean rogues assured the French general that Nice could be taken by treachery. They had co-conspirators in the town who were anxious to help in destroying the place of their birth and were masters of a plan which could not fail. Three Savoyard deserters offered their services as guides; and one day, as the twilight was gathering, Benoit Grimaldo, the three guides, and a party of armed men started out cheerfully for the Castle Hill. On gaining access to the town they were to make way for the body of the troops. The French to a man watched the hill for the signal that would tell that the impregnable fortress had been entered and, with arms in hand, were ready to spring forward to victory.

Unfortunately one of the deserters had a conscience. His conscience was so disturbed by qualms that the man was compelled to sneak to his colonel and “tell him all.” It thus came to pass that Benoit and his creeping company were met by a sudden fusillade which killed many of them. The survivors fled. Grimaldo jumped into the sea and saved himself by swimming. Later on—it may be mentioned—he was taken by some of his old comrades of the Castle Hill and was hanged within sight of his own home.

In this way did the siege of Nice come to an end, leaving the city untaken and the flag still floating over the gallant height; while the discomfited pirate sailed away for other fields of usefulness.[6]

It is necessary now to turn to the case of the laundress who shared with Barbarossa the more dramatic glories of the siege. She is said, in general terms, “to have fought valiantly and to have inspirited the defenders by her example.” As to her exact deeds of valour there is some obscurity in matters of detail and some conflict of evidence as to the scope and purpose of her military efforts. If her capacity for destroying Turks may be measured by the capacity of the modern laundress for destroying linen she must have been an exceedingly formidable personage. The story, as given by Baring-Gould, is as follows:[7]

“Catherine Segurane, a washerwoman, was carrying provisions on the wall to some of the defenders when she saw that the Turks had put up a scaling ladder and that a captain was leading the party and had reached the parapet. She rushed at him, beat him on the head with her washing bat and thrust him down the ladder which fell with all those on it. Then hastening to the nearest group of Nicois soldiers she told them what she had done, and they, electrified by her example, threw open a postern, made a sortie, and drove the Turks back to the shore.”

Apart from the fact that the picture of a washerwoman strolling about in the firing line with a laundry implement in her hand is hard to realise, it must be added that certain French accounts and the story of Ricotti differ materially from the narrative given. Ricotti speaks of Segurana as a poor lady of Nice, aged thirty-seven, who was so ill-looking that she went by the nickname of Donna Maufaccia or Malfatta which may be rendered as Madame Ugly Face. She is said to have been possessed of rare strength, to have been masculine in bearing and ingrate or unpleasing in her general aspect. She is described as having performed some feat of strength with a Turkish standard that she had seized with her own hands. According to one account she threw the standard into the moat and according to another she planted it upside down on the top of Castle Hill—a somewhat childish display of swagger.

From the rather ridiculous elements furnished by the various records a composite story comes together which is as full of charm as a beautiful allegory. It tells of no Joan of Arc with her youth, her handsome face, her graceful carriage, her shining armour and her powerful friends. It tells of a woman in a lowly position who was no longer young, who was ugly and, indeed, unpleasant to look upon, who was the butt of her neighbours and was branded with a cruel nickname by her own townfolk. When the city was attacked and in the travail of despair this despised woman, this creature to laugh at, came to the front, fought with noble courage by the side of the men, shared their dangers and displayed so fine and so daring a spirit that she put heart into a despairing garrison, put life into a drooping cause and made victorious what had been but a forlorn hope. It was the fire and patriotism and high resolve that she aroused that saved the city she loved and earned for her the name, for all time, of the Heroine of Nice. Poor Madame Ugly Face the butt of the town!

|

Nostredame, “History of Provence,” 1614. Durante’s “History of Nice,” 1823. Vol. ii. Ricotti, “Storia della monarchia piemontese,” 1861. Vol. i. |

|

“Riviera,” by S. Baring-Gould, 1905. |

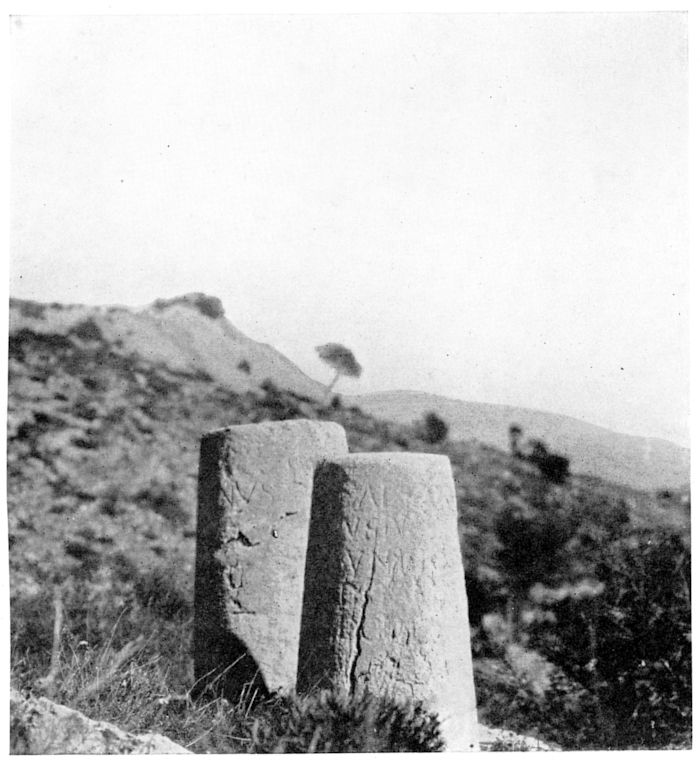

BEHIND the city of Nice rises the well known hill of Cimiez, on the gentle slope of which stand the great hotels. On the summit of the hill was the Roman town of Cemenelum, which is said to have numbered 30,000 inhabitants and which was at the height of its glory before Nice itself came into being. Through Cemenelum passed the great Roman road which ran from the Forum of Rome to Arles. It approached Cimiez from Laghet and La Trinité-Victor and traces of it are still indicated in this fashionable colony of gigantic hotels and resplendent villas.

Few remains of the Roman settlement are now to be seen; for the Lombards in the sixth century did their best to destroy it and after their cyclonic passage the town became little more than a quarry for stones. In the grounds of the Villa Garin is a structure of some size which is assumed by the learned to have been part of a temple of Apollo, together with minor fragments of walls which are claimed to have belonged to the Thermæ.

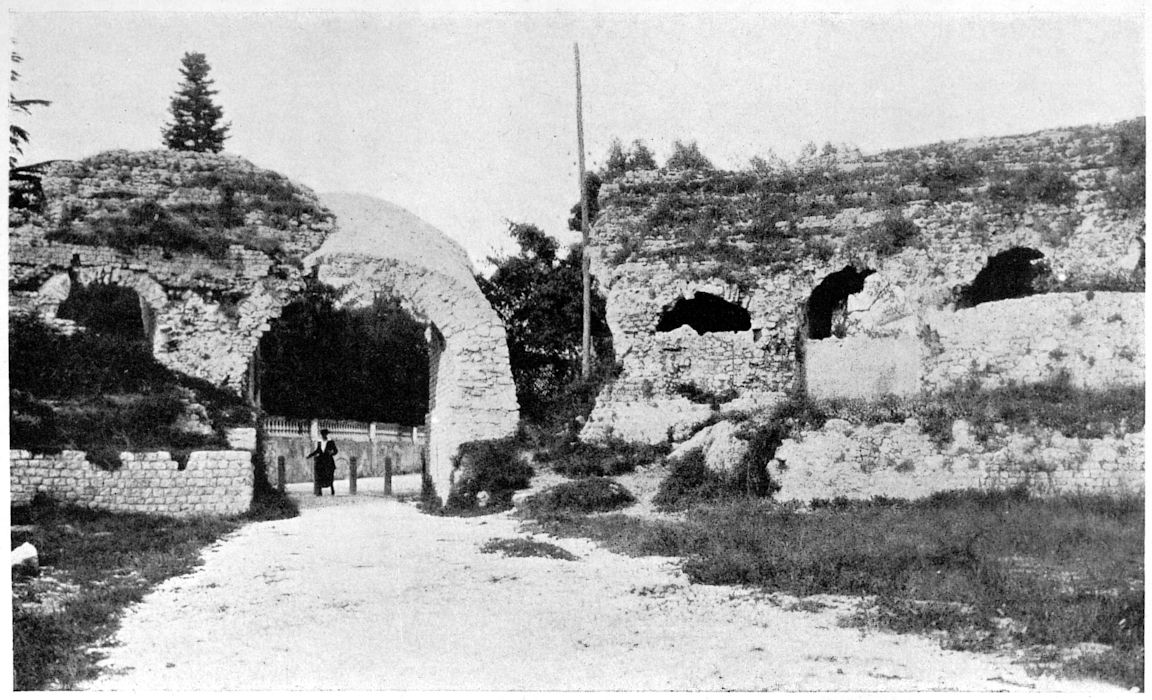

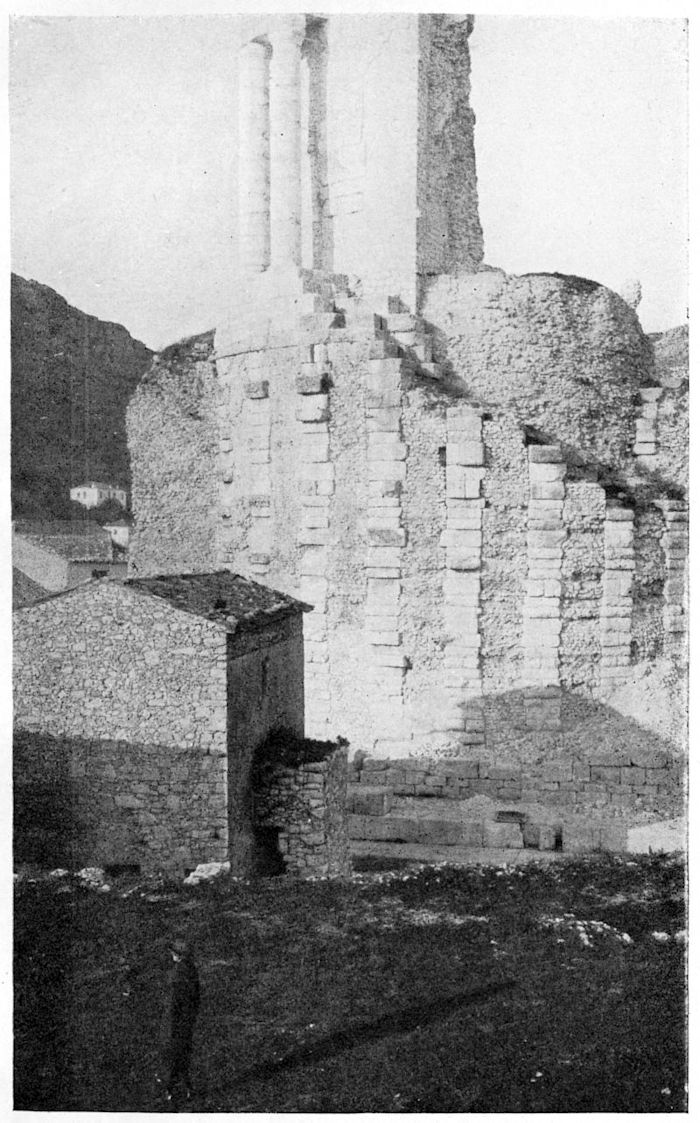

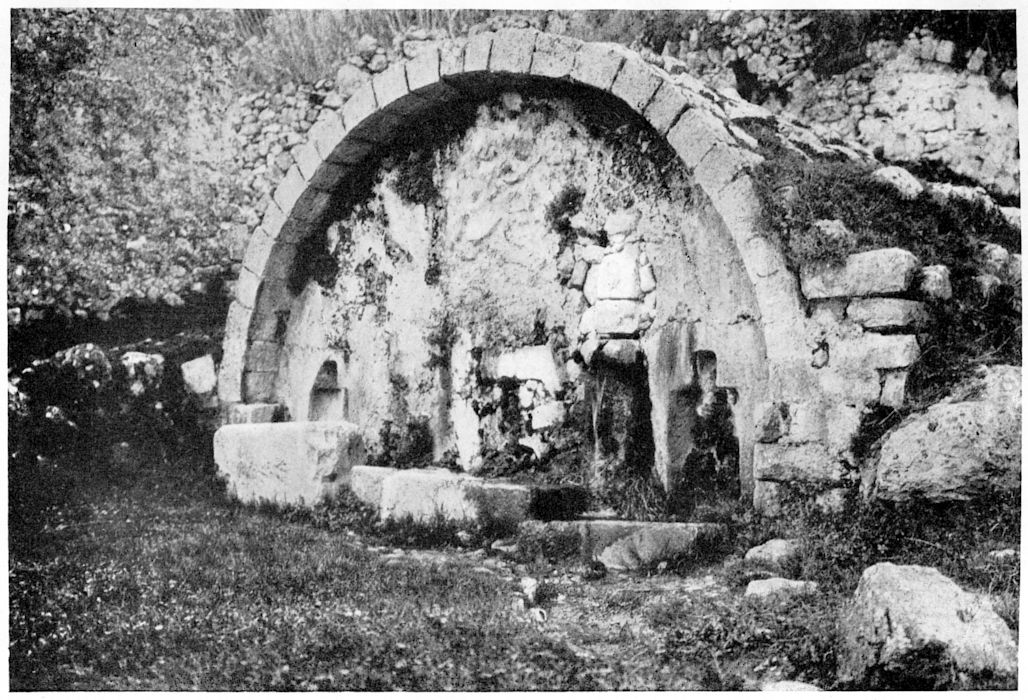

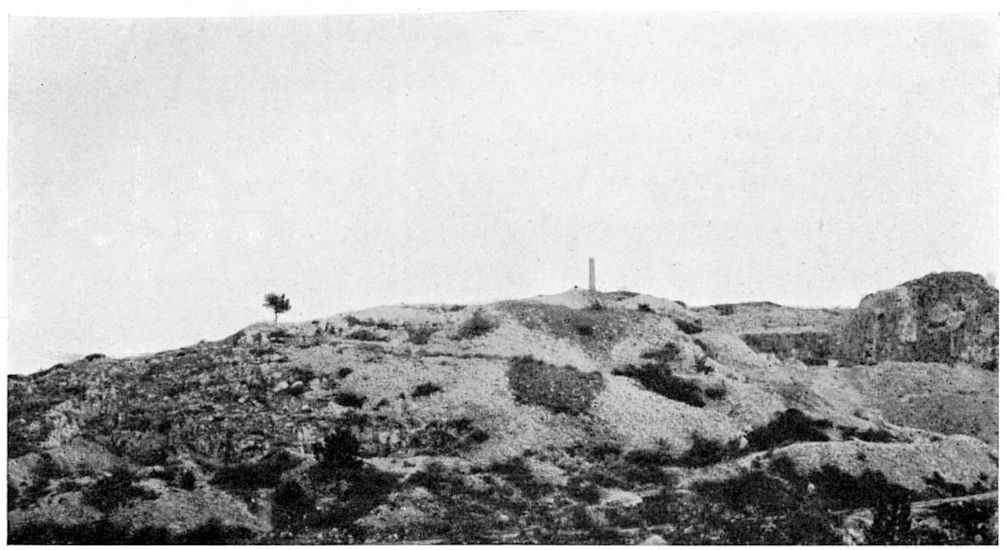

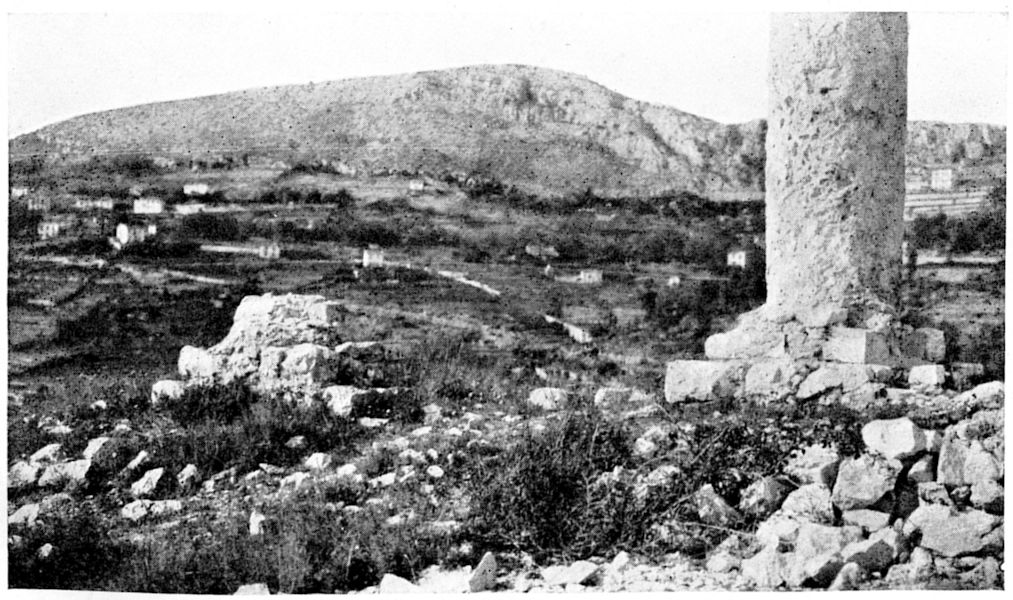

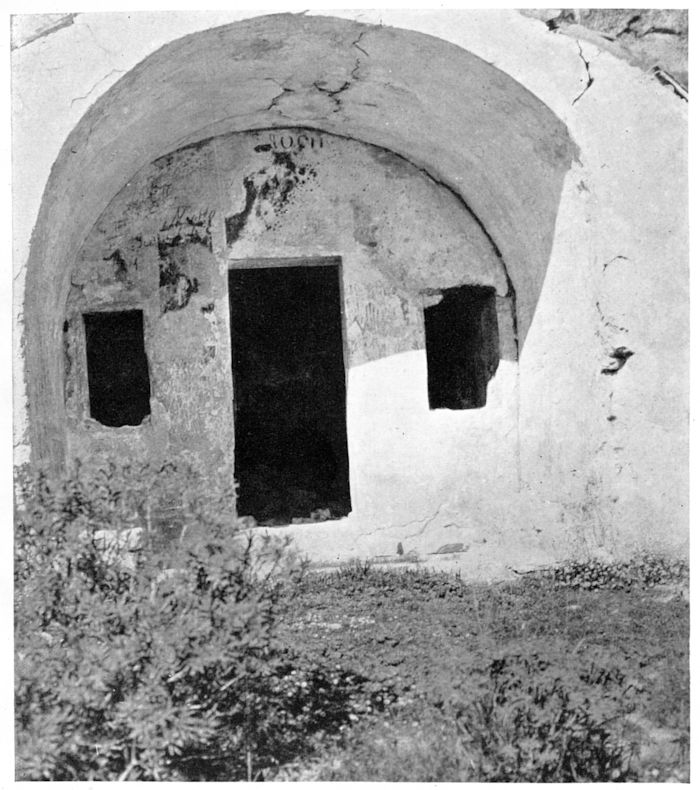

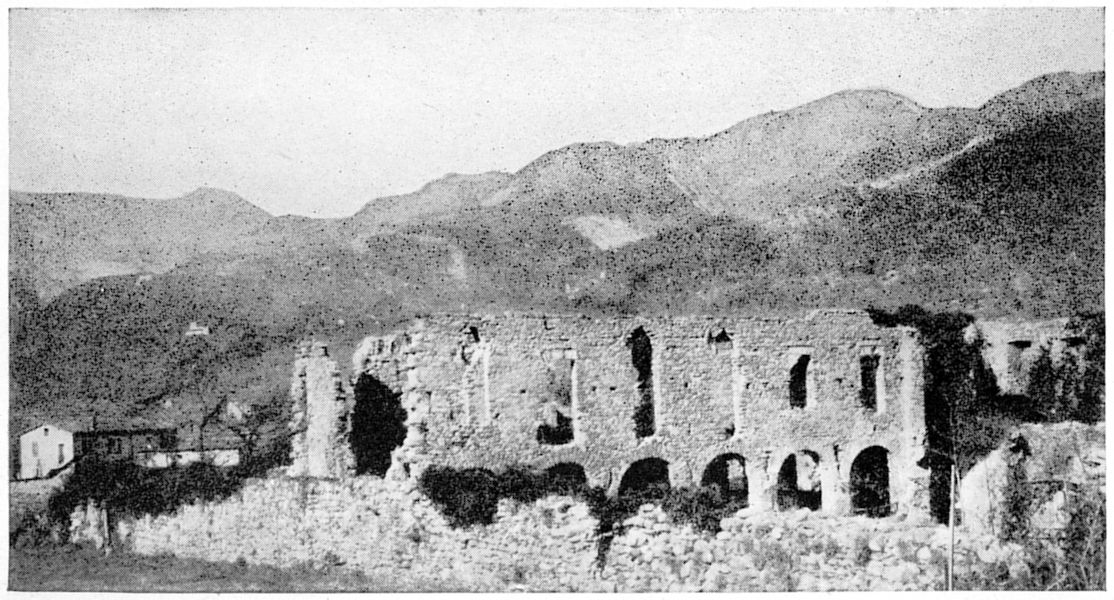

The most important ruin in Cimiez is that of the amphitheatre. It is a mere shell, but its general disposition is very clear. In addition to a lower tier of seats there are remains of the upper rows which are supported, as in the Coliseum, on arches. The vaulted porch at the main entrance is in singular preservation. The arena measures 150 feet in one axis and 115 feet in the other. It is, therefore, small and in the form of a broad oval. A great deal of the structure is buried in the ground, so that it is estimated that the original floor of the arena lies at least ten feet below the existing surface. The ruins, much overgrown with grass and brambles, have an aspect of utter desolation. It is said that the natives call the spot il tino delle fate, or the fairies’ bath. If this be so there is assuredly more sarcasm in the conceit than poetic merit, for the sorry parched-up ruin would better serve as a penitentiary for ghosts. Through the centre of the amphitheatre passed at one time the road from Cimiez to Nice. It is now closed and the present road, with its tramlines, runs outside the walls of the venerable building.

CIMIEZ: THE ROMAN AMPHITHEATRE

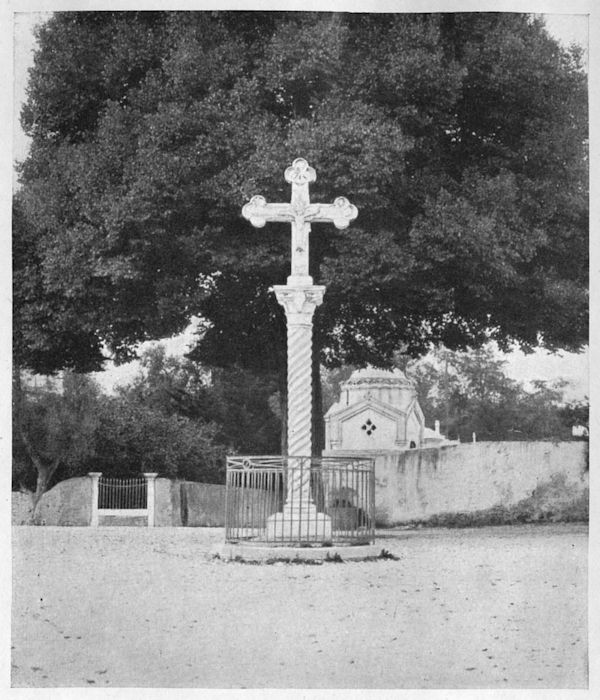

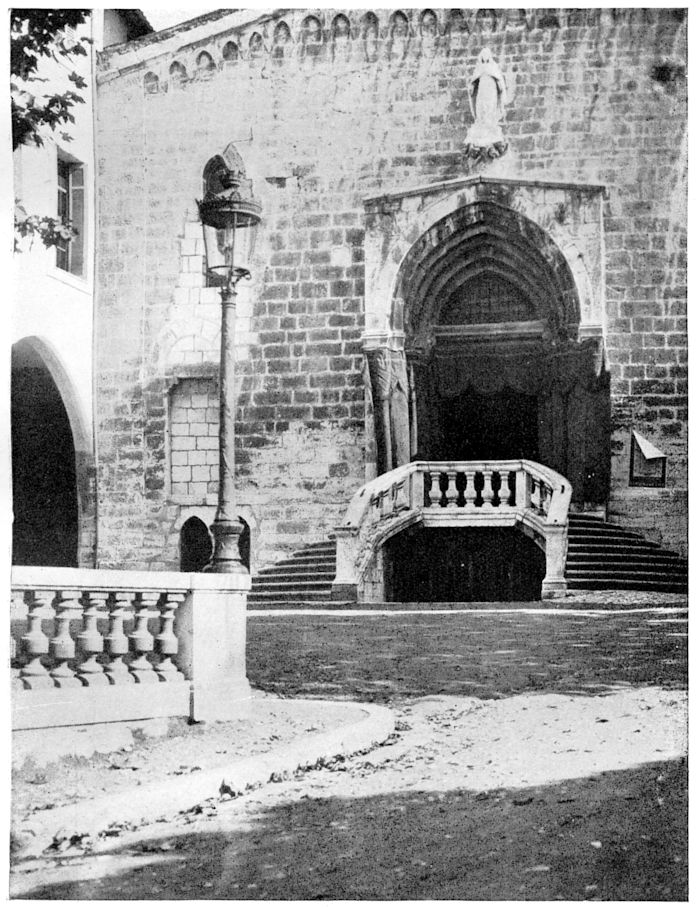

Near the amphitheatre and on the crest of the hill is the monastery of St. Francis of Assisi. It lies in a modest square, shaded by old ilex trees. At one end of the square is the cross of Cimiez. It stands aloft on a twisted column of marble. Upon the cross is carved the six-winged seraph which appeared to St. Francis in a vision. This marvellous work of art dates from the year 1477. The cross, like the column, is all white and, standing up as it does against the deep green background of a solemn elm, it forms an object of impressive beauty. Crosses in the open are to be found throughout the whole of France, but there is no cross that can compare with this.

The monastery was founded in 1543. The façade of the chapel, with its bell towers on either side and its central gable over a pointed window, is very simple. It is rather spoiled by a heavy arcade which, being recently restored is harsh and crude. The interior of the chapel is gracious and full of charm. It consists of a square nave flanked by narrow aisles. The roof, vaulted and groined, is decorated with frescoes and is supported by square columns of great size. At the far end, in a deep and dim recess, is the altar. This chancel is cut off from the church by a balustrade of white marble. Behind the altar is a high screen of daintily carved wood, gilded and relieved by three niches. It is a work of the sixteenth century.

Many churches offend by lavish and obtrusive ornament, by glaring colours, by reckless splashes of bright gold, by excessive detail, all of which give a sense of restlessness and discord. Such churches may not unfitly be spoken of as “loud.” If that term be appropriate, then this little shrine may be described as the chapel of a whisper. Its fascination lies in its exquisite and tender colouring which conveys a sense of supreme quietude and peace. It is difficult to say of what its colouring consists for it is so delicate and so subdued. There is a gentle impression of faint tints, of the lightest coral pink, of white, of grey, of a hazy blue. The general effect is that of a piece of old brocade, the colours of which are so faded and so soft that all details of the pattern have been lost. The light in the church is that of summer twilight. The altar is almost lost in the shadow. The screen behind it is merely such a background of old gold as that upon which the face of a saint was painted in the early days of art. The marble rail is a line of white and in the gloom of the chancel is the light of one tiny red lamp—a mere still spark.

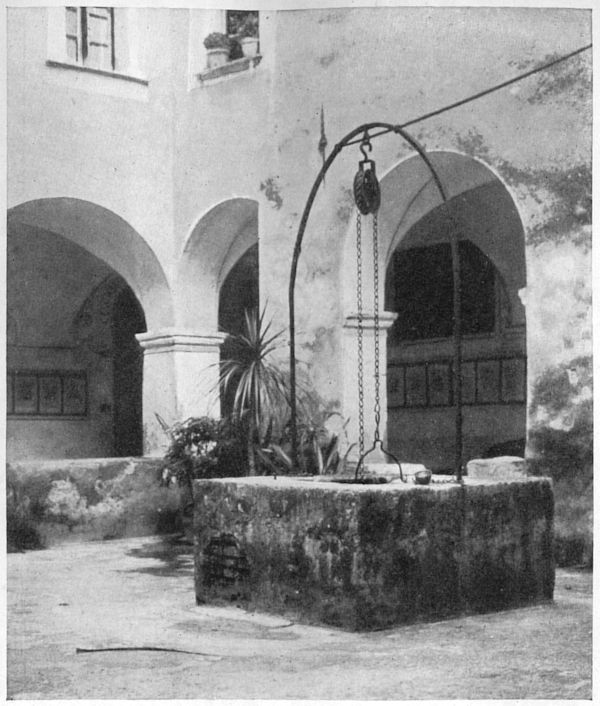

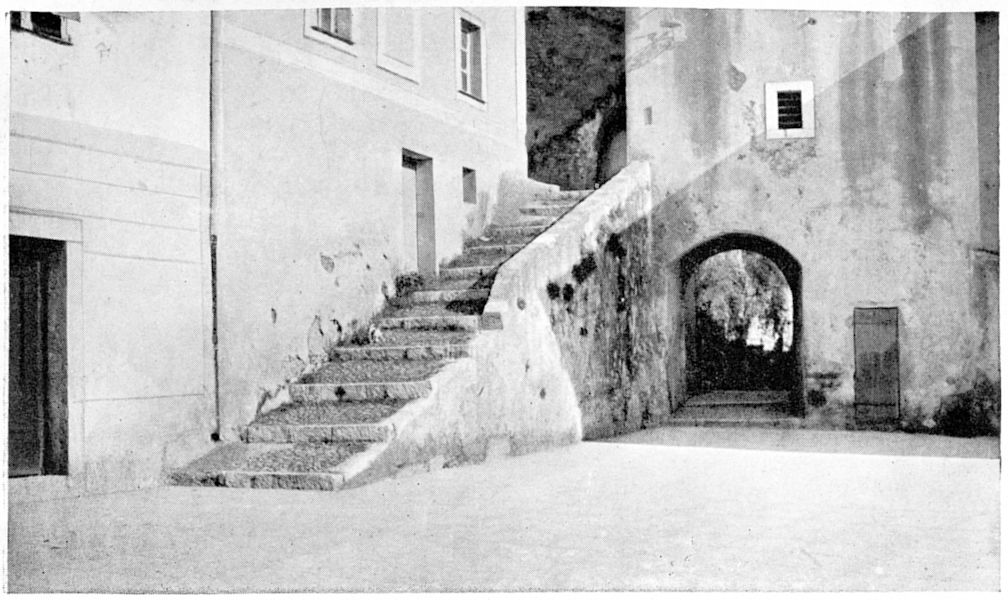

In two of the side chapels are paintings by Ludovici Bréa of Nice of about the year 1512. By the side of the church is the monastery which is now deserted. A corridor leads to a little courtyard, with a well in the centre, and around it a plain white-walled cloister. Beyond this is an enclosed garden shut in also by a cloister of pale arches in the shadows of which are the doors of the monastery cells. The garden is in a state of utter neglect; but in it still flourish palms and bamboos, orange trees and a few despondent flowers.

That side of the hill of Cimiez which looks towards the east is somewhat steep, and the zigzag road which traverses it leads down to the broad, open valley of the Paillon river. Near the foot of the hill and on a little promontory just above the level floor of the valley stands the Abbey of St. Pons. The name, St. Pons, is given to the district around which forms a scattered suburb of Nice. The place is still green, for it abounds with gardens and orange groves; but it is being “developed” and is becoming a semi-industrial quarter, very devoid of attraction. There are factories in St. Pons, together with workshops and depressing houses, a tramline and—across the river—a desert of railway sidings. It possesses many cafés which, on the strength of a few orange trees, a palm or two and an arbour, make a meretricious claim to be rural. From all these objects the abbey is happily removed; but its position is neither so romantic nor so picturesque as its past history would suggest.

The present abbey church is a drab, uninteresting building with a prominent tower. It was built about the end of the sixteenth century. The monastery is occupied by an asylum for the insane. The Abbey of St. Pons is of great antiquity, since it dates from the eighth century and it is claimed that Charlemagne sojourned there on two occasions. It stands on the site of ancient Roman buildings, for numerous remains of that period have been unearthed, among which are an altar to Apollo, many sarcophagi and some inscribed stones.

There was also a convent at St. Pons long centuries ago. Its precise position is a matter of doubt; for, so far as I can ascertain, no trace of the building can now be pointed out with assurance. In the history of St. Pons this convent plays a conspicuous, if momentary part. The episode is deplorable for it concerns the dramatic circumstances under which the convent came to an end.

CIMIEZ: THE MARBLE CROSS.

CIMIEZ: THE MONASTERY WELL.

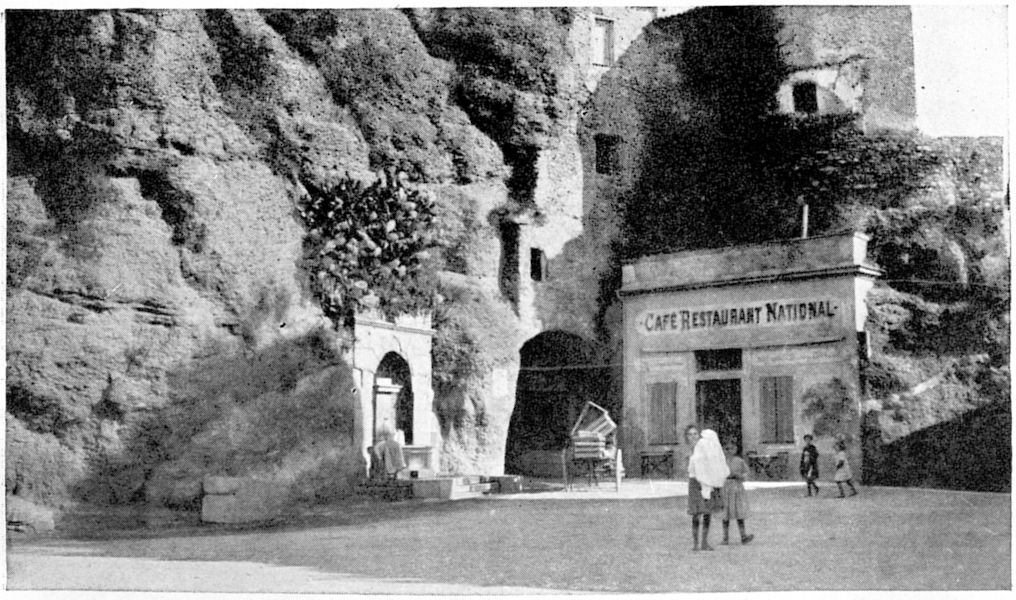

ON a kindly afternoon in St. Martin’s summer, when the shadows were lengthening and the beech woods were carpeted with copper and gold, a party of gallants were making their way back to Nice after a day’s ramble among the hills. It was in the year 1408, when this poor worried world was still young and thoughtless. They were strolling idly down the valley of St. Pons, loath to return to their cramped, dull palaces on the Castle Hill, when a storm began to rumble up from the south and the sky to become black and threatening. Slashed doublets and silken hose and caps of miniver are soon made mean by the rain; so the question arose as to a place of shelter.

At the moment when the first large ominous drops were falling the little party chanced to be near by the convent of St. Pons. It is a bold thing for a company of gay young men to approach a retreat of nuns; but the wind was already howling, the blast was chill and these youths were bold. The door was opened, not by an austere creature with a repellent frown, but by a comely serving sister of joyous countenance. The youths, adopting that abject humility which men assume when they find themselves where they ought not to be, begged meekly for shelter from the rain. Without demur and, indeed, with effusion the fair janitor bade them welcome and asked them to come in. The young men, whose faces until now were solemn, as was befitting to a sacred place, began to smile and to appear normal. The serving sister, with a winning curtsey, said she would call the abbess.

At this announcement the smile vanished from the lips of the refugees. An abbess was a terrible and awe-inspiring thing, something that was stout and red, imperious and chilling, inclined to wrath and very severe in all matters relating to young men. A few turned as if to make for the outer door; while one—who had held an outpost in a siege—whispered to his friend “Now we are in for it!” After a period of acute suspense an inner door opened and the abbess appeared. She was stout, it is true; but it was a very comfortable, embrace-inviting stoutness. She was red; but it was the ruddy glow of a ripe apple. Her face was sunny, her mouth smiling and her manner warm. In age she was just past the meridian. She was, indeed, the embodiment of St. Martin’s summer.

She greeted the new-comers with heartiness; laughed at their timidity; asked them what they were frightened at and told them, with no conventual restraint, that she was delighted to see them. When one mumbled something about being driven in by the rain she said, with a coy glance at her guests, that rain was much wanted just then about the convent. She put them at their ease. She chattered and warbled as one who loves to talk. Her voice rippled through the solemn hall like the song of a full-breasted thrush. She asked them their names and what they were doing. She wanted to hear the lighter gossip of Castle Hill and to be told of the scrapes in which they were involved and of the bearing of their lady loves. She twitted a handsome knight upon his good looks and caused a shy seigneur to stammer till he blushed.

It must not be supposed that she was an ordinary abbess or a type of the reverend lady who should control the lives and mould the conduct of quiet nuns. Indeed the recorder of this chronicle viewed her with disapproval and applied harsh terms to her; for in his description of this merry, fun-loving and comfortable person he uses such disagreeable expressions as mondaine and bonne viveuse.[8]

As the rain was still beating on the convent roofs and as the young men had travelled far the abbess invited them into the refectory, a white, hollow room with bare table and stiff chairs. Here wine was placed before them, of rare quality and in copious amount; while—sad as it may be to tell the truth—nuns began to sidle timidly into the room, one by one. Whatever might be the comment the fact cannot be concealed that the grim refectory was soon buzzing with as merry a company as ever came together and one very unusual within the walls of a convent.

The time was drawing near for the evening service. Whether the abbess invited the young men to join in the devotions proper to the house, or whether the young men, out of politeness, suggested that they should attend I am unable to state, for the historian is silent upon this point.

The service proceeded. The male members of the congregation were, I am afraid, inattentive. They were tired; they had passed through an emotional adventure and wine is soporific. They lolled in their seats; some rested their heads on the bench before them; some dozed; some even may have slept.

In a while the nuns began the singing of the “De Profundis” (Out of the Depths). As they sang one voice could be heard soaring above the rest, a voice clear and beautiful, vibrating with tenderness, with longing and with infinite pathos. The young men remained unmoved save one. This one, who had been lounging in a corner, suddenly awoke and was at once alert, startled and alarmed. He clutched the seat in front of him as if he would spring towards the spot whence the music came. His eyes, fixed on the choir, glared as the eyes of one who sees a ghost. His countenance bore the pallor of death. He trembled in every fibre of his body.

He knew the voice. It was to him the dearest in the world. It was a voice from “out of the depths,” for it belonged to one whom he believed to be dead. He could not see the singer; but he could see, as in a dream, the vision of a piteous face, a face with eyes as blue as a summer lake, with lips whimsical, tantalising and ineffable; could see the tender cheek, the chin, the white forehead, the waving hair. He knew that she who sang was no other than Blanche d’Entrevannes, whom he had loved and to whom he was still devoted.

But a few years past he had held her in his arms, had kissed those lips, and had thrilled to the magic of that voice. Her father had frowned upon their hopes and had forbidden their union. The lad had been called away to the wars. When he returned he had sought her out and was told that “she is dead.” He haunted every spot where they had wandered together, only to learn the truth that “no place is so forlorn as that where she has been,” and only to hear again that she was dead.

Blanche was not dead, but, believing their case to be hopeless, she had entered the convent of St. Pons and, in a few days’ time, would take the veil.

After the service the youth—whose name was Raimbaud de Trects—disappeared to find the singer at any cost. The search was difficult. At last he met a sympathetic maid who said that Blanche d’Entrevannes was indeed a novice in the convent and who, with little pressing, agreed to convey a message to her. The message was short. It told that he was there and begged her to fly with him that night. The answer that the maid brought back was briefer still, for it was a message of two words—“I come.”

The rain continued to pour, the harsh wind blew and the gallant knights were still in need of shelter. How they spent the night and how they were disposed of I do not know, for the strict narrative avoids all reference to that matter.

By the morning the storm had passed away and as the sun broke out the young men reluctantly prepared to take their leave. The abbess would not allow them to go without one final ceremony. They must all drink the stirrup cup together, “to speed the parting guest,” as was the custom of the time. It was an hilarious ceremony and one pleasant to look upon. In the road before the convent gate stood the cheery abbess in the light of the unflinching day. In her hand she raised a brimming goblet and her sleeve falling back revealed a white and comely arm. Around her was a smiling company of young men whose many-coloured costumes lit up the dull road and the old grey-tinted rocks. Behind her were the nuns in a semicircle of sober brown, giggling and chatting, nudging one another and a little anxious about their looks in the merciless morning light. It was a noisy gathering but very picturesque; for the scarlet and blue of the knights’ doublets and the glint of steel made a pretty contrast with the row of white faces in white coifs and the cluster of dark-coloured gowns. It was like a bunch of flowers in an earthenware bowl.

The abbess, beaming as the morning, was about to speak when something terrible came to pass. There appeared in the road the most dread-inspiring thing that the company of knights and nuns could have feared to see. It was not a lion nor was it a dragon. It was a bishop. It was not one of those fat, smiling bishops with flabby cheeks and ample girth, whose loose mouth breathes benevolence and whose hands love to pat curly heads and trifle with pretty chins. It was a thin bishop with a face like parchment and the visage of a hawk. He was frenzied with rage. He stamped and shrieked. He foamed at the mouth. His arm seemed raised to strike, his teeth to bite.

A word must here be said to explain how it was that the prelate had “dropped in” at this singularly unfortunate moment, since bishops are not usually wandering about in valleys at an early hour on November mornings. It came about in this way. The old almoner of the place, alarmed and horrified at the conduct of the abbess and the irreverent and indeed ribald “goings-on” at this religious house, had hurried during the night to the bishop and had given him an insight into convent life as lived at St. Pons. He begged the bishop to do something, and this the bishop did.

The arrival of the prelate at the convent gate had the effect of a sudden thunder-clap on a clear day. The abbess dropped her cup; the knights doffed their caps; the maids, peeping behind corners, fell out of sight; while the nuns stood petrified like a row of brown stones.

The great cleric screamed out his condemnation of the abbess, of the nuns, of the convent and of everything that was in it. He shrieked until he became inarticulate and until his voice had sunk to a venomous whisper like the hiss of a snake. He dismissed the young gallants with a speech that would have withered a worm. Turning to the women he said even more horrid things. He expelled the abbess and the nuns from St. Pons and ordered them to repair at once to the convent of St. Pierre d’Almanarre near Hyères, a convent notable for the severity of its rules. Here, as the historian says, they would be able “to expiate their sins with austerities to which they had long been strangers.”

It was in this way that the convent of St. Pons came to an end; for the desecrated building was never occupied from that day. No nun ever again paced its quiet courtyard; no pigeons came fluttering to the sister’s hand nor did the passer-by hear again the sound of women singing in the small grey chapel. In the course of centuries the building fell into ruin and, year by year, the scandalised walls crumbled away, while tender rosemary and chiding brambles crept over the place to cover its shame.

On this eventful morning the bishop’s efforts did not end when he had sentenced the lady abbess and had swept the convent from the earth. He proceeded, before he left, to pronounce over the assembly the anathema of the Church. He cursed them all from the abbess standing with bowed head to the scullion gaping from the kitchen door. He cursed the nuns, the novices, the lay helpers and the maids, and had there been a jackdaw in the building, as at Rheims, he would, no doubt, have included the bird in his anathema. So wide and so comprehensive a cursing, delivered before breakfast, had never before been known.

Two of the party—and two only—escaped the curse of the Church, Raimbaud de Trects and Blanche d’Entrevannes. It was not until the morning, when the whole of the company were assembled about the convent gate, that the two were missed.

The historian, in his mercy, adds this note at the end of his narrative: “In the parish register of the village of Entrevannes, in the year 1408, there stands the record of the marriage of the chevalier Raimbaud de Trects to the noble lady Blanche d’Entrevannes.”

|

“Legendes et Contes de Provence,” by Martrin-Donos. |