* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

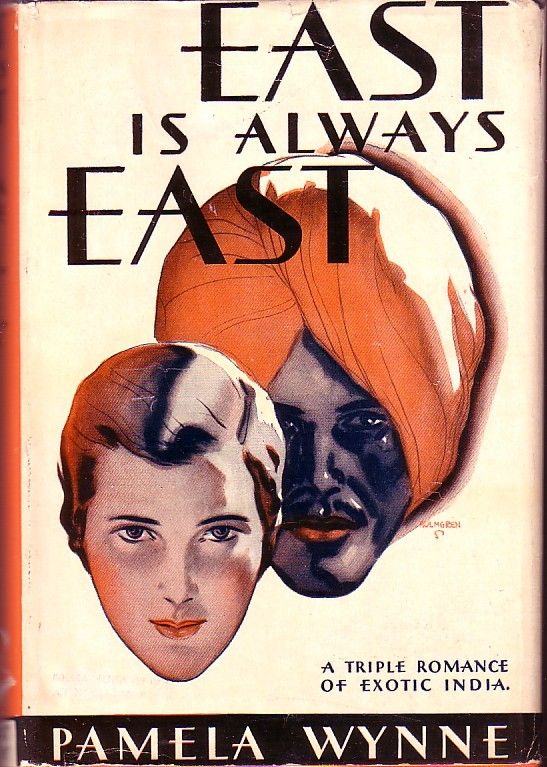

Title: East Is Always East

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Pamela Wynne (1879-1959)

Date first posted: Mar. 15, 2019

Date last updated: Mar. 15, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190335

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

EAST IS ALWAYS EAST

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ANN’S AN IDIOT

WARNING

THE DREAM MAN

ASHES OF DESIRE

PENELOPE FINDS OUT

CONCEALED TURNINGS

A PASSIONATE REBEL

MADEMOISELLE DAHLIA

UNDER THE MOSQUITO CURTAIN

RAINBOW IN THE SPRAY

AT THE END OF THE AVENUE

A LITTLE FLAT IN THE TEMPLE

EAST IS ALWAYS EAST

By

PAMELA WYNNE

(Winifred Mary Scott)

Author of “Ann’s an Idiot”

LONDON

PHILIP ALLAN & CO. LTD.

QUALITY HOUSE, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, W.1

First published 1930

Printed in Great Britain by

UNWIN BROTHERS LIMITED, LONDON AND WOKING

TO ALL THE NICE PEOPLE AT

THE GRAND CHALET, ESPECIALLY

MADAME HALDI

East Is Always East

Mrs. Metcalfe was tired. She was tired because she had been listening to her sister-in-law for more than half an hour. Over and over again she had repeated herself, saying in a hard metallic voice, “Yes, but think what a magnificent thing it would be for the girls. You can’t afford, at a time like this, to think only of yourself, Madeline. Pull yourself together!”

“Pull yourself together.” The drastic words waked Mrs. Metcalfe up. She had never cared for her sister-in-law and now she felt that she almost detested her. Paul, her late husband, had never cared for his sister either, and one of the last things he had said before he died was that she was not to let old Louisa try to run her. And now here she was running her and her affairs as hard as ever she could. She opened her round blue eyes and stared at her sister-in-law.

“Can’t you see what a magnificent thing it would be for the girls? India and cold weather in a military station. Both of them would marry at once. It’s a most generous offer. Your brother in such a good position, too!” Miss Metcalfe was angular and weather-beaten and had a face like a horse. She had never cared for her dead brother’s wife. The Metcalfes were County, and kept hosts of dogs, and always had all the windows open and hardly any fires, and even if there was a fire you couldn’t feel it because of the draught. Paul, Louisa’s brother, had been a dreamer and queer, and with his small income of eight hundred a year had pottered about the garden and done a little rough shooting and no work. And then on one disastrous day he had gone to a garden party and fallen in love with the daughter of a neighbouring vicar. For fifteen years this foolish couple had lived a limited but very peaceful life, buried in the country, as far away from the other Metcalfes as they could get, and then Paul had died from a severe attack of influenza, leaving his wife with twin daughters aged sixteen. That was two years ago.

“Yes, but I don’t know that I want to go out to India.” Mrs. Metcalfe, with her eyes now very wide open indeed, began to talk rather fast. Secretly she was afraid of Louisa. She was afraid of her calm assumption of always being in the right. Mrs. Metcalfe had the sense to know that she herself was very often in the wrong. Paul also had made her feel that sometimes, although he had tried not to. There was so much that she had not known: things like the date when pheasant shooting began and partridge shooting, and she had always thought that it was horribly cruel to hunt a fox to its death, although perhaps it was more cruel to allow it to live and be caught in a trap. But no one would ever think of catching a stag in a trap, and yet people, and well-bred people too, hunted a stag to its death, and what was the excuse for that? she had once asked her husband with blazing eyes.

But on the whole Paul had been kind and Mrs. Metcalfe had been very happy in the little cottage tucked away in a quiet Devonshire valley. And she would have been peacefully there now if it hadn’t been for Flavia, the elder of the twins and dazzlingly pretty. Both of them were dazzlingly pretty, although Mrs. Metcalfe, who secretly liked the younger one, April, much the best, thought she was the prettier. But other people said that the girls could not be distinguished apart. So Mrs. Metcalfe thought that it was perhaps only her great love for April that made her think her prettier, but she never confided to anyone that she did.

“Yes, but what should we do in India?” Mrs. Metcalfe fixed her eyes on the rather dingy wallpaper and prayed that she would be firm. If only her daughters had not gone out to a cinema. Louisa had arrived without giving any notice. She generally did that.

“What can you possibly do in a horrible boarding-house like this?” said Miss Metcalfe, staring round her and not caring a bit that the kindly careworn old waiter was clearing away the coffee-cups from the glass-topped tables in the lounge and must have heard.

“I don’t think it is horrible,” said Mrs. Metcalfe thinking of the excellent lunch that her sister-in-law had just eaten at her expense. Why, oh why had she ever told her about her brother’s invitation to India? It had only been from a low motive too. Arthur was in the I.C.S. and all the Metcalfes’ relations were in the Army, and Louisa always spoke as if anyone who wasn’t in the Army was hardly alive at all. Paul had been too delicate to go into the Army, and having an income of his own, he hardly had to do anything. But it was grander to be in the I.C.S., thought Mrs. Metcalfe childishly, setting her teeth and thinking that she would say so and not care what Louisa said or did, if the opportunity arose.

“That depends on what you are accustomed to,” said Miss Metcalfe crushingly, returning to her assault on the hotel. “Personally I can imagine no greater misfortune than to have to spend even a week in surroundings like these.”

“The girls love it. We have hardly ever moved from Pear Tree Cottage. This is their first real glimpse of London,” said Mrs. Metcalfe. “They love going to the cinema and looking in at shops. They think this boarding-house is nice. It is nice,” ended Mrs. Metcalfe fiercely. Her eyes filled with angry tears as she thought of the joyful excitement of the move from Devonshire to Ferndale Road. Pear Tree Cottage let for a year. The excited selection of a boarding-house from the tremulously flapping sheets of Bradshaw. An old Bradshaw certainly, but the prompt reply from the Private Hotel in Ferndale Road showed that the selected boarding-house still existed. It called itself a Private Hotel in Bradshaw. Mrs. Metcalfe suddenly remembered that and shot it out like a small bullet from an air pistol. “It isn’t a boarding-house at all; it’s a Private Hotel,” she said.

And somehow that last remark made Miss Metcalfe feel that this sister-in-law of hers was not worth bothering about at all. Anyone who could attempt to justify her present mode of living was surely beyond argument. She had come to look her up because she had heard that she was in town. And in course of conversation the news had leaked out that she had the chance of going to India for the cold weather and taking the two girls with her. Obviously the thing to do, because the girls, from photographs timidly shown, were apparently very good-looking. However, Madeline was not going to do this obvious thing; better to leave her alone to reap the results of her own stupidity. Miss Metcalfe got up to go, diving down the sides of the rather shabby easy chair to retrieve her workmanlike gloves.

“Oh, must you go?” Mrs. Metcalfe, showing herself to be still young and slim, also got up out of her chair. Was then this dread visit at an end? She could hardly believe it.

“Yes, I’ve got several things to fit in before dinner.” Miss Metcalfe was brief and businesslike. “I am sorry that I haven’t seen the girls. Give them my love, will you?”

“Yes, I will,” said Mrs. Metcalfe eagerly.

“What do they think about this visit to India?” enquired Miss Metcalfe, walking with long, leisurely strides to the tall, black painted door of the lounge.

“They don’t know anything about it,” replied Mrs. Metcalfe guiltily. “They went off very early, before the second post came.”

“They don’t know anything about it! But then of course they’ll insist on going,” exclaimed Miss Metcalfe, stopping dead in the middle of the floor.

“Yes, I know. I expect we’re sure to go,” said Mrs. Metcalfe placidly. For a moment or two she looked quite young. Louisa was a donkey, she thought complacently.

“But you gave me to understand——” Miss Metcalfe was really angry now. She stood still and glared at her sister-in-law and her weather-beaten face flushed.

“Yes, I know. But you always take it for granted that I’m such an idiot,” said Mrs. Metcalfe unexpectedly. “Just because I don’t understand things like hunting and dogs and wasn’t presented: all the things that you think matter, and I don’t think matter a bit. You think I’m hopeless. And now Paul is dead and I am left with the twins, and you immediately think that I’m not going to do the best I can for them. But I am. Perhaps you can’t imagine girls like mine that like just pottering about and being with their mother,” said Mrs. Metcalfe, thinking of April with a warm flame round her heart, and shivering a little because she knew that Flavia wasn’t in the least like that really.

“Well!” and then, as there was obviously nothing else to say, Miss Metcalfe shook hands with her sister-in-law and walked down the short flight of steps to the pavement. And the last sight of her that Madeline had was of Louisa signalling to a bus to stop, and the driver of it not taking the faintest notice and careering triumphantly to a stopping-place quite a hundred yards ahead.

The Metcalfe girls certainly were astonishingly good-looking. The few callow youths in the hotel could not keep their eyes off them. Flavia was delighted. She held herself rather more erect and made little jerky movements of her pencilled eyebrows. April felt uncomfortable when she did it and hated it. She was afraid of Flavia or she would have refused to go out with her. People stared in buses and Tubes. April felt responsible, especially as they were dressed alike. In the Church and Commercial Stores, for instance, Flavia almost flirted with the assistants. And then went away to pay the bill at the desk, and the young man left behind the counter, too flustered to remember which sister was which, began feverishly to carry on the interrupted conversation with April. It was all degrading, thought April, miserable and shy, and returning bold glances with a fugitive fluttering of her eyelids that made the person who had levelled them feel dreadfully ashamed and instantly cease to do so. One tall elderly man at the hotel was soon able to distinguish the sisters apart. He watched them as they came into the lounge in the evening for their coffee. He watched their mother and thought that when she was a girl she must have been almost as good-looking. But he did not speak to them because he knew from long experience that as a rule it was a mistake to get to know people in London hotels. He only stayed in this quiet, shabby one himself because it was quiet, and very near the Natural History Museum, where he was engaged on important research work.

But the open admiration that Flavia received went to her head like a cocktail. It was too marvellous after existence in Devonshire. “Thank Heaven I made Mother give up that beastly cottage,” she said excitedly that night, as the girls undressed in their large comfortable bedroom on the second floor.

“How can you call it beastly?” April, in her silk princess petticoat, was sitting on the bed unfastening her suspenders. Her knees were young and round. She slipped her silk stockings down over her ankles and feet and then shuffled them over her feet and let them fall on the floor. Her down-bent face was melancholy as she solemnly squeezed her toes and then abruptly laughed. “Can you move your little toe away from the one next to it, Flavia?” she asked.

“No, and I’m not going to try,” said Flavia. She had her round chin very close to the mirror. “Look,” she said suddenly.

“What?” April turned round.

“Come closer; you can’t see from there.” Flavia spoke excitedly. Her face was triumphant. Yes, she was really most frightfully pretty, there was no doubt about it. And they might still have been stuck away in Devonshire if it hadn’t been for her. “See?” She swung round to face her sister.

“Oh, that horrible stuff on your lips! Don’t! Flavia, it’s hideous. Don’t. Your lips are so nice and pink anyhow.” April’s voice was eager. How could she explain to Flavia that it didn’t improve her at all?

“Everyone puts it on,” said Flavia calmly. “I’m not at all sure that I shan’t have my eyebrows plucked too,” she continued.

“If you do, you’ll get old much quicker than I shall,” said April excitedly. Terror filled her soul. She would have to go out with this dreadfully got-up sister of hers and people would stare more than ever. The staring was beginning to get on April’s nerves. Why had they ever come to London? It made their mother ill, too; she had gone to bed when they came back from the cinema because she was so tired after Aunt Louisa’s visit. Too tired even to talk, thought April, remembering with a clutch at her heart the lovely calm evenings by the fire in Pear Tree Cottage.

“Do you really think I don’t look nice with lipstick on?” Flavia was now not so cock-a-hoop as she had been. Inwardly she thought a good deal of what April said, although she would have died rather than confess it.

“I think you look ghastly; common,” said April decidedly. She watched her sister crumpling up her lips and sucking them. The soft delicate pink of them emerged again.

“There you are. Can’t you see that you look much nicer without it?” April, small and slender in her pale pink petticoat, was smiling. “It doesn’t go with your hair—the red,” she explained. “You don’t need those things—yet.”

“No, perhaps I don’t.” Flavia was complacent. “You get into bed: don’t wait for me,” she said after a pause. “I’m going to try on all my hats, and perhaps alter the felt one back to front.”

“All right.” April returned to her end of the room. That would mean that the light would be on for ages longer, she thought, but it wasn’t any good minding. But as she lay with her face turned to the high white ceiling she wondered why Flavia thought such a terrific amount about what she looked like. Who cared what you looked like if you were nice? pondered April, twisting herself so that her face was turned away from the bright electric light. For instance, that nice man in the lounge who never spoke to anyone, but who sat drinking his coffee as if he knew exactly what everyone else was doing although he never even looked up. He was old, thought April briefly, quite forty-five and not a bit good-looking. And yet there was something about his clean-shaven mouth that was frightfully attractive. Only kind words could come out of it, thought April, beginning to feel sleepy although Flavia’s shadow still danced aggravatingly over the ceiling. But perhaps she would soon be done. Although, no—April raised herself jerkily and rather uncertainly from her pillow.

“Would you have the paste thing where I’ve put it or rather further back?” Flavia’s voice was clear. “Good heavens, you don’t mean to say that you’ve gone to sleep already?”

“Oh no!” April’s voice was stammering and apologetic. She tried to see and could not. “I’ll get out of bed and come round to the glass,” she said anxiously. “I don’t know—I think it’s glary or something and that’s why I can’t see.”

“You can’t see because you’re half asleep,” said Flavia impatiently. “Come on; I want to sew it in before I get into bed.”

And as April stood yawning and shivering a little under the bright light Flavia still spoke impatiently. “I can’t think how we come to be twins at all,” she said, “we’re so frightfully different. Now is that right?”

“Perfectly,” said April, trying to be really interested and only able to think of the rapture it would be to be cosily back in bed again.

Mrs. Metcalfe had gone to bed directly after her sister-in-law’s visit for two reasons. One was that she was really tired. Mrs. Metcalfe was just forty-three, a tricky age for a highly-strung woman who has never really been satisfied emotionally. And the other was that she felt that she could not propound the idea of going to India to her children without a little more thought about it first. Flavia would want to go; Mrs. Metcalfe was quite certain about that. April might or might not want to go, but in any event she would be overruled by Flavia. As for what she wanted to do herself, Mrs. Metcalfe did not know. At the moment, she only felt that she wanted to be left alone. Letting Pear Tree Cottage had been an upheaval to her after the uneventful life she had led for so long. The packing up and leaving cupboards and drawers empty for the incoming tenants had been tiring. April had helped as much as she could, but Flavia had done nothing but make rather drastic suggestions. Certainly looking extremely pretty as she made them, but Mrs. Metcalfe had almost been ashamed of the unwelcome thought that one so soon got used to a person being pretty, but never used to him or her being selfish. Paul had been selfish in a way, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, feeling herself hideous and unnatural at even being able to think such a thing now that he was dead.

And now she lay and twisted about in her comfortable bed and reproached herself for having dismissed the girls with only a lazy murmur when they had come in keen to tell her all about what they had been doing since they had left the hotel that morning. But somehow she could not rouse herself. Louisa had tired her: tired and irritated her, and she could not undertake anything more until the next morning. She would sleep on her brother’s invitation and tell the girls about it in the morning.

And she did so. Sitting up in bed looking very young and nice with her shingled hair, Mrs. Metcalfe did not have breakfast: she contented herself with two slices of brown bread and butter with her early tea. The girls did have breakfast and they arrived from it gasping.

“The temperature of that dining-room! How the people stand it I can’t think!” Flavia had cast herself into the one easy chair and had begun to fan herself with the Morning Post.

“Yes, it’s astounding.” Mrs. Metcalfe had secretly taken hold of April’s hand, who had come up close to the bed. “I’ll take your tray away, Madeline,” April was smiling.

“You are not to call me by my Christian name, April!” Mrs. Metcalfe’s eyes were glinting with laughter as she spoke.

“Why? Mother’s so stiff.” April was walking to the door with the tray tucked under her arm. She came back and sat down on the end of the bed. “You’re desperately lazy,” she said slowly.

“I’m not in the least lazy,” said Mrs. Metcalfe. Even April, accustomed as she was to it, glowed inwardly at the love in her mother’s eyes. “I’ve got something to tell you both,” she said suddenly. “Something I can tell you better if I’m really warm and comfortable. It’s this. I’ve heard from Uncle Arthur—you know, the one in India. He wants us all to go out and stay with him for six months.”

“When?” Flavia spoke first, after a breathless silence.

“Soon. In two months’ time. To take our passages for the middle of October. The place where he is, Wandara, in the Punjab, is quite cold in the winter. Like a mild English winter, he says it is, only much nicer because it is dry.”

“Could we have fires out there?” April, from the end of the bed, spoke rapidly. Mrs. Metcalfe, looking at her child, felt a sensation of tears at her heart. The first thought for her! How could one ever be miserable about anything with a child like this, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, turning to fumble about under the pillow for her handkerchief.

“Yes, darling, of course we could. Uncle Arthur often talks about his lovely wood fires.” Mrs. Metcalfe’s eyes were tender. And then, conscience-stricken, she turned quickly to glance at her elder daughter. “What do you think about it, Flavia?” she asked.

“Think about it!” Flavia’s face was flushed and excited, “Why it’s the most gorgeous, the most heavenly thing in the world,” she gasped. “Mother! what a chance for us. Think of seeing it all: India, and the voyage and everything. Why I feel quite cracked already. Let’s go and get our tickets to-day. Can we?”

“Yes, I don’t see why not. The sooner we book them the better, and I believe you don’t have to pay at once.” Mrs. Metcalfe made a little movement of her feet.

April stirred and spoke. “Can we afford it, darling?” she asked. Her tender little brain was busy. How could she find out if her mother really wanted to go? she wondered. She herself did, desperately, and so of course did Flavia. But Madeline? The uprooting from Pear Tree Cottage had meant a great deal to her mother, April knew. And now another uprooting. Sometimes Madeline looked tired and as if she only wanted to be let alone. How could she find out what she really felt?

“I shall simply adore it,” said Mrs. Metcalfe suddenly. She disregarded April’s suggestion that it was going to cost a great deal of money. It was, but she would manage that somehow. She would sell something, and the six months’ visit would cost them very little because Arthur had made it very clear that they were to be his guests. Paul had left her with an income of eight hundred a year. Well, supposing she sold out enough to produce six hundred pounds she would still have lots of income left. Mrs. Metcalfe had thought all that out earlier that morning as she had lain and stared at the ceiling, waiting for her early tea.

“Would you really adore it?” April’s down-bent eyes had lost their look of tender anxiety. She turned them blazing on her mother. “Oh, I think I shall simply explode, I want to go so much,” she said, “Flavia, just think of it—the voyage and everything! Dances every night, perhaps! Mother, you will really have to get yourself some nice dresses for the evening,” said April.

“Yes, we shall want some clothes,” said Flavia emphatically. “We’ll go to Shaftesbury Avenue, they’ve got some heavenly things there. April and I were looking at them yesterday. Mother, when can we begin to get started about it all?”

“To-day,” said Mrs. Metcalfe. Her heart was singing in the most ridiculous way because again April had thought of her first. This was going to be the most wonderful adventure in the world for all of them, she thought. She laughed out loud.

“You are not to call me by my Christian name on the boat, April,” she said. “People will be simply scandalized if you do.”

“No, they won’t. They’ll know that it’s because you’re such a pet,” said April. She got off the end of the bed and walked up to her mother. “We are both always in blue and you’ve got to fit yourself out in the most entrancing mole colour,” she said. “Tiny little hats squashed down over your eyes with neat little paste ornaments in them, and dance dresses that fluff out. I don’t see why you shouldn’t have just as much fun as we do,” said April, suddenly looking thoughtful as it struck her that her mother did look astoundingly young. Not in the least like a stiff parent.

But Flavia was bored. It often bored her to see April and her mother together. They were so like sisters. April had got one sister, herself, thought Flavia decidedly, getting up out of her chair and suggesting that it was time they went.

April followed meekly. And Mrs. Metcalfe, left alone, tried not to think dreadful disloyal thoughts about how heavenly it would be if Flavia married very happily in India and left April and her free to travel about together and do exactly what they liked. But she couldn’t help thinking these thoughts, and so to stop it she got up. Louisa might scoff at the unpretentious little hotel in Ferndale Road, but at any rate they gave you awfully nice boiling-hot baths for nothing, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, collecting all her washing things in a flowered indiarubber sponge-bag and preparing to start off on her quest for the largest bathroom with the newest bath mat, already marked down during her few days’ stay at the slim hotel in the long terrace of slim houses.

Being a very understanding woman Mrs. Metcalfe knew exactly what would please her daughters most in the way of fitting themselves out for this great adventure. Flavia had excellent taste and was a very good shopper. Mrs. Metcalfe could trust her implicitly with any amount of money. So she went to see her nice broker in the City, took his advice, and sold out what he advised her to sell out. After the passages were paid for she had three hundred pounds left. She gave each of the girls sixty pounds; told them briefly the sort of clothes that they would want; said that she wished them to continue to dress alike and then left them to spend it as they chose. Both girls already had very nice moleskin coats, given them by an accommodating godmother. That they would want them in Wandara was certain, said Mrs. Metcalfe, and they would also want them for the first part of the voyage as they were going to start from Tilbury, and even the Mediterranean could be cold in late September and early October. They would also want quite four nice evening dresses, said their mother, who had found out all about everything from an old friend of hers who had married, gone out to India, and then come back and settled down in Eastbourne. But lots of the clothes that they had already would do. People who went East always got far too much, admonished the same friend from Eastbourne. “And for Heaven’s sake don’t buy topis till you get there,” she wrote excitedly. “If you go ashore at Port Said, take a sun umbrella and wear an ordinary hat. If you arrive in Wandara to stay with the Collector looking a fright in the wrong topis you’re finished for the whole of the cold weather,” wrote this same friend dramatically.

And fortunately the three women in the nice hotel in Ferndale Road were intelligent enough to listen to, and profit by, this intelligent advice. Both girls were wild with excitement at having so much money to spend. Every day was a delirium of shopping. They prowled up and down Shaftesbury Avenue staring in at windows. Flavia was brave enough to go into shops and come out again if she didn’t like the things they showed her. April was made nervous and self-conscious by this, but had to put up with it. And in the end she knew that Flavia had been right. Their outfit was beautiful. Their evening dresses, ridiculously inexpensive, were filmy and alluring. On one dramatic evening they called their mother into their bedroom and gave her a dress rehearsal. And then Mrs. Metcalfe was suddenly afraid. She was taking these two beautiful girls out to the East and she had no one to help her or advise her. Supposing anything happened to them? Supposing some unprincipled scoundrel got hold of her tender, helpless little April. Flavia was so much better able to take care of herself. But April! Her little snowdrop of a child, born when the snowdrops were just at their most beautiful after a late winter in the little Devonshire village. Married men were the danger in India, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, she had often heard it. Married men with their wives and families securely tucked away in England. You didn’t know that they were married until it was too late. Her precious little child’s heart, perhaps given innocently away, to be flung back at her after a dreadful agonizing interim. While the girls paraded up and down the room under the bright light Mrs. Metcalfe thought terrified thoughts. Her doing, all this! Supposing that any harm came of it?

And then she suddenly reflected that after all scores of girls went out to India every year. And that Arthur, being a widower, was very sensible. He would know beforehand whether people were married or not and tell her, so that she could warn the girls if she saw them becoming involved. That it was all going to be all right, as things always were all right if you did not worry. And that with two such lovely daughters she ought never to have a moment’s unhappiness about anything. Mrs. Metcalfe sat still with closed eyes as the girls had told her to do, while they changed into something else. And then as she sat there like that, she got a perfectly illogical thought that she too would like to dress up in some of her nice new evening clothes and parade up and down in front of somebody who would be interested and pleased. But who was there who would be? And then Mrs. Metcalfe flushed guiltily as she knew who there was. The tall middle-aged man who sat in the lounge and read his paper and spoke to nobody. Once or twice she had seen him watching her and then he had looked down at his paper again. There was something in his glance that had made her think that he thought she was nice. Nothing stupid, of course, she was far too old for that. But just nice. And thinking this, it was time for her to open her eyes again. Yes, certainly, her children had chosen their outfit beautifully: Mrs. Metcalfe was smiling with genuine pleasure and approval. Flavia was a very clever girl. Everything was just right, and the lovely starry blue suited them both to perfection.

“I’m so glad you’re pleased. Now what about your clothes?” April had taken off the last lovely filmy dance dress and was standing in her silk princess petticoat. Flavia was busy with many cardboard boxes and lots of tissue paper.

“Would you like to see one of my dinner dresses? Really, would you?” Mrs. Metcalfe suddenly felt excited.

“Of course we would!” Even Flavia was enthusiastic. “Go and put it on. You’ve heaps of time before we need change. Don’t wear it for dinner, though, or you’ll crush it so. Those velvet chairs in the lounge stick.”

“All right,” and Mrs. Metcalfe had gone. She ran downstairs. Because even she had been pleased when she had seen herself in the long glass in the palely upholstered fitting room in the big shop. It had not been dear, either. She got into the soft velvet folds of it eagerly. What a mercy she had kept her figure, she thought, tipping the mirror on her dressing-table at an angle so that it caught the reflection of the long glass in the wardrobe. And the three-fold necklace of pearls from Ciro’s was lovely too. The paste clasp made them look so much more as if they were real. Mrs. Metcalfe showed her still excellent teeth in a little happy smile as she switched off the electric light and ran out on to the landing. She felt like a girl again in her beautiful new dress. Happier than a girl really, because, from her own recollection youth was not the desperately happy time that it was supposed to be. One was too self-distrustful: too apprehensive of the unknown future that yawned ahead of one, to be really happy, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, not looking where she was going because she was so absorbed in her sudden thought of the two young things upstairs whom she had brought into the world and whom she had not the least idea really how to bring up.

This was the opportunity that John Maxwell had been waiting for and that he knew would come his way if he waited long enough. He burst out laughing.

“Not a bit,” he smiled as Mrs. Metcalfe gasped a hurried apology.

“Oh, but I must have hurt you!”

“No, you didn’t.”

“I wasn’t looking where I was going. I’m going upstairs to my daughters to show them my new dress. We’re all going out to India,” said Mrs. Metcalfe in a sudden burst of confidence. “We’ve all bought new clothes and I suddenly felt that I wanted to show them to my girls.”

“I don’t wonder.” John Maxwell stood looking down on to Mrs. Metcalfe’s dark hair, in which white threads were beginning to sparkle. “Show it to me first though. I love nice clothes.”

“Do you really?”

“Yes, of course I do. What man doesn’t? Yes, it suits you well.” John Maxwell’s deep grey eyes were appreciative. Mrs. Metcalfe was a very pretty woman, he decided briefly. Where was her husband? Unless she was a widow, why was she alone like this?

“You must think I’m funny to talk to you like this,” said Mrs. Metcalfe, speaking rather breathlessly. “But have you ever had the feeling that you want someone of your own age to think you look nice? I’ve got it awfully just now. I suppose I’m not quite old enough to absolutely find all my happiness in thinking that other people look nice.”

“Yes, I know the feeling very well indeed,” said John Maxwell. “Most people of our age get it sooner or later. Walk along as far as that wardrobe and back again, and then I’ll give you a considered opinion on the great garment.”

Mrs. Metcalfe walked. And as she walked she felt a thrill of excitement at this sudden adventure. She thought of her two girls upstairs waiting for her and felt that she didn’t mind. This tall man looked so awfully nice in his tails and white tie. He must be going out to a dinner party. A swift disappointment ran over her at the thought that he would therefore not be in the lounge when they went in to have their coffee there.

“Yes, it’s charming,” John Maxwell spoke after a little pause. Mrs. Metcalfe had come back and was standing looking up at him. “Black suits you,” he said. “When are you going out to India?”

“At the end of the month. My brother is out there in the I.C.S. I am a widow,” Mrs. Metcalfe suddenly got a strong feeling that she wanted this nice man to know all about her.

“I see. You have two very beautiful daughters,” said John Maxwell warmly. “And it is amazing how alike they are. At first I could not tell them apart. Now I can.”

“Yes?”

“One of them has a slightly different expression on her mouth,” said John Maxwell.

“Ah, that must be April,” exclaimed Mrs. Metcalfe. And then she suddenly remembered April, upstairs waiting for her. “I must go,” she hesitated.

“Yes, and so must I,” John Maxwell drew a flat gold watch on a watered ribbon out of his pocket. “Well, thank you for letting me share in the dress rehearsal,” he smiled.

“Yes,” and then shyly and like a child Mrs. Metcalfe bolted away up the staircase without saying any more. But when she got to the top she unwisely turned round. And there he was still standing and looking up after her. Mrs. Metcalfe hesitated, and then very reprehensibly ran all the way down the stairs again.

“I hope you’ll enjoy yourself to-night wherever you’re going,” she stammered.

“I’m sure I shall. But it was nice of you to think of it. That’s what one misses too, someone really to mind whether one enjoys oneself or not,” said John Maxwell, and the look in his eyes was very delightful.

“Oh, my daughters do mind,” Mrs. Metcalfe was suddenly frightened at what she had done. She turned to bolt up the stairs again.

“I am sure they do.” John Maxwell said the words to Mrs. Metcalfe’s frightened and retreating back. He laughed a little quietly to himself as without looking back again she fled round the corner of the landing. And then he went on down the stairs into the narrow hall to collect a taxi.

April was the first to notice that her mother looked more spry. But she kept her discovery to herself. By now both the girls had got to know Mr. Maxwell too. He had quietly taken for granted that as he knew their mother he would of course get to know them as well. They now very often sat together in the lounge after dinner to drink their coffee, although during the day they very rarely saw him. But that was because Flavia and April were nearly always out shopping. April sometimes felt conscience-stricken about it.

“We do leave mother most frightfully alone,” she said one day, as in a 79 bus they went careering off up the Brompton Road.

“She doesn’t mind. Besides, we must get our shopping done. We’ve only got three weeks now until we start. And mother gets so tired if we go in and out of shops all the time. It’s the only way to get what one wants, though,” said Flavia, frowning down her delicate nose to try to locate a smut that had impertinently lodged on it.

“Yes, I know, but still——” and then April fell silent. Certainly Madeline didn’t seem to mind, she reflected. Only that morning, for instance, she had asked her if she wouldn’t like to come with them. And she had said no, that she was busy. And when April had asked her how she was busy, she had turned a delicate pink and said vaguely that she had something to do at Harrods’. April had not questioned further, but for some reason a dreadful stab had seemed to penetrate her heart. What was there to do that Madeline could prefer to do that did not include her, she wondered? What was there that she herself would prefer rather than be with her mother? Her mother filled her horizon. She was only living for the moment when this dreadful ceaseless drive of shopping would be over and they could sit quietly on the deck of a big comfortable steamer. They had all three got lovely deck-chairs. Flavia would not be much in hers, reflected April with a little wry smile. But that would be all the better, because she and her mother could sit quietly together, talking if they wanted to talk and not if they didn’t. Just the same old lovely serene companionship of Pear Tree Cottage. How desperately April longed for it only she knew. But it would be here in three weeks, she thought, looking out on to the brown dried-up grass of Hyde Park and the ceaseless flow of traffic sweeping in at the big Connaught Gate.

And meanwhile Mrs. Metcalfe, having seen her children safely off for their day’s shopping, went up to her bedroom and sat down on the bed and stared straight in front of her. She, too, was going out to lunch, but not yet. She had some letters to write first. Also she had to decide which hat to wear. At the moment the hat was the more important of the two. Mrs. Metcalfe went to the shelf in her wardrobe and got all the hats out. She would wear the one that April had helped her choose. And the neat coat and skirt that went with it. Also the silver fox fur that she had bought in the July Sales. Mrs. Metcalfe dressed herself all up and stood in front of the glass and made silly little movements with her hands and feet. And then she suddenly tore off the close-fitting hat and flung it into a chair. She was a complete fool, she told herself passionately. As if he meant anything at all except just a delightful friendship. Men always had women friends nowadays; it was part of the new way of going on.

However, she was at Harrods’ dreadfully before the time he had said. But to conceal it she went and wandered about through the different departments. She was to meet him in the long gallery lounge on the top floor. “And if I am a few minutes late don’t be angry with me and go away,” he had said, smiling delightfully. “My time is not altogether my own, although very nearly so, thank Heaven.”

However, he was punctual. Before her, Mrs. Metcalfe diplomatically arranged. John Maxwell, smiling his quiet smile, wondered what this charming woman would do if she knew that he had seen her arrive half an hour too soon and take the non-stop lift to the top floor where they had arranged to meet! He himself at the moment had been doing some business in the banking section and had seen her come in through the big swing doors, hurrying like a child. She had stopped dead and stared at the clock, but all the same had made for the non-stop lift and gone up in it. He had laughed to himself as he turned to speak pleasantly to the clerk. That was what he loved about her, her childish spontaneity. And yet, did he love her? That was the bother, how was he to know? Love between two well-bred unattached people of opposite sexes should mean marriage. But did one undertake marriage with a widow with two grown up and beautiful daughters? Would it not be better to wait until the two beautiful daughters were married, which they certainly would be after a cold weather in India. Although, again, there was always the chance that the sweet mother of the beautiful daughters would be snapped up in marriage too. John Maxwell felt thoroughly unsettled as he glanced amiably through the brass grille to the young man behind it. As a rule he knew his own mind instantly. That was why, ten years before, he had ruthlessly broken off his engagement with a girl to whom he was devotedly attached. Her fault really: she had sent him by mistake a letter intended for another man. There might or might not have been anything at the back of it. But his trust and confidence in the girl were gone for ever. Her tears and protestations of innocence were utterly useless. He only gazed at her and asked her to keep the ring as the sight of it would only remind him of what he was anxious to forget.

After that John Maxwell steered clear of women. But Madeline Metcalfe attracted him deeply. Was it because he obviously attracted her? She was blushing delightfully as she came towards him.

“I’m afraid I’ve kept you waiting,” she said nervously.

“No, you haven’t. You’re deliciously punctual. If only women always were,” said John, smiling down at her.

“I was early really. Half an hour too soon,” said Mrs. Metcalfe in a sudden burst of confidence. “I was so afraid of being late because I was looking forward to it so.”

“Were you really? How sweet of you to say so,” said John slowly. He suddenly made up his mind. “Don’t let’s have lunch here,” he said, “it’s dull. I mean, there’s no adventure about it. Let’s go somewhere else. Come along to the lift and we’ll think of a nice place while we go down.”

“Yes, but have you time?” Mrs. Metcalfe was hurrying along to keep pace with the tall man by her side.

“Loads of time. I’m fed to the teeth with research. We’ll get a taxi and go off somewhere. That is to say, if you have time, too,” said John, suddenly stopping short.

“Oh, yes, I’ve got nothing to do at all,” said Mrs. Metcalfe simply. She smiled with pleasure as they shot downwards in the lift, and crossed the wide hall to stand outside the big swing doors waiting for a taxi.

“Where would you like to go? Have you any pet place?” They were safely in the taxi now and John was looking at her.

“Well. . . .” Mrs. Metcalfe hesitated. “It might not be grand enough for you: I mean, not the sort of place that you would like,” she explained. “But I have always wanted to go to one of those restaurants in Soho. Not a very expensive one,” she stammered.

“They are none of them expensive,” smiled John. “But the food is uncommonly good and one always feels rather out on the spree when one is lunching or dining in Soho,” he said. “Come along then, we’ll go to the Chantecler, in Frith Street. It’s unconventional but absolutely true to type. I’ve had many an excellent meal there.”

“Oh, how heavenly!” and then Mrs. Metcalfe sat silent. If only she did not feel suddenly so guilty, she thought. She had told the girls that she was going to Harrods’. Soho was not Harrods’, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, as the taxi buzzed along and then suddenly came to a standstill in a solid block of traffic.

“Well, still enjoying yourself?” John Maxwell was an intensely perceptive man. He glanced down at the woman by his side. Something was wrong. What? he wondered simply.

“I’ve just remembered that I told the girls that I was going to Harrods’. I didn’t say anything about lunch or you or anything,” faltered Mrs. Metcalfe, her eyes filling with stupid tears. “Fancy if they found out, they would think that I had deceived them.”

“Would you rather go back to Harrods’ then?” John’s eyes were clear and reflective. Marry this woman! Supposing he didn’t get the chance; how was he going to endure life any more?

“Do you think that I ought to?” said Mrs. Metcalfe miserably.

“No, I don’t,” said John frankly. “Take for example the ten to one chance that anything happened to the girls and they went to look for you there. They wouldn’t find you; the place is a rabbit warren. They would go to the hotel. And you will be back at the hotel very nearly as quickly from Soho as you would be from Harrods’. It’s further away, I admit, but only about ten minutes in a taxi.”

“Oh!”

“Satisfied?”

“Yes,” said Mrs. Metcalfe simply. Not only satisfied but blissfully and completely happy, she thought wildly, wrenching her eyes away from his steady gaze and looking out of the window.

And John sat silent. Largely because there was nothing to say. He also sat and stared out of the window on his side. His thoughts also were in a whirl. Until about a week ago he had not dreamed of falling in love for a second time. Until an hour before that he had not thought of ever being in love sufficiently to risk the dreadful and irrevocable adventure of marriage. And now it abruptly seemed to him that anything else would be simply stupid. The delicious fun that he could have with this slender, well-bred woman for ever by his side. The gorgeous adventure, for instance, of a holiday spent abroad together. And then his thoughts suddenly fell rather flat. Abroad—of course, she was going abroad. And soon too: in three weeks. He would have to say something in a day or two. But not yet; it was too soon.

“Well, we’re nearly there. Too slummy for you?” The taxi was picking its way carefully through the narrow streets of Soho.

“Oh no, I love it. I’ve always wanted to come to one of these restaurants. There’s something so exciting about it.” Mrs. Metcalfe’s lips were parted a little. Her eyes were smiling and excited. She forgot that she was forty-three and a parent. “You see, I’ve always lived in the depth of the country,” she explained. “Both before I was married and after. This is almost the first time I’ve ever really been able to wander about London and enjoy myself.”

“I see.” John’s keen eyes were on the shop windows sliding past. “Here we are,” he said. He helped Mrs. Metcalfe out of the taxi and stood and paid the man, giving him obviously a good deal too much. Everyone was pleased and smiling, including the maître d’hôtel who welcomed them into the friendly low-ceilinged restaurant and showed them to a nice table in the corner. A fatherly old waiter came padding up and showed them the menu with an air of friendly anticipation. John glanced at it and then across the table at Mrs. Metcalfe. She had taken off her gloves and her delicate hands were folded together in her lap. She was looking about her with an air of expectancy.

“What would you like?” asked John.

“What is there?” inquired Mrs. Metcalfe, trying not to beam with pleasure, and failing.

“A great deal,” said John laughing up at the old waiter.

“You choose,” said Mrs. Metcalfe, also smiling at the waiter and wondering with a little leap of excitement in her veins if he thought that they were husband and wife.

“All right.” John ran his eyes down the gaily decorated card and made a careful choice. The waiter lingered.

“What will you drink?” asked John.

“Water,” said Mrs. Metcalfe promptly.

The waiter and John exchanged amused glances. John ordered a light lager for himself, and the waiter vanished.

“Ought I to have said that I would drink something?” asked Mrs. Metcalfe, feeling a little uncomfortable.

“No. Apparently they don’t scowl at you here if you drink what you like,” said John. “In some places they do. But I’ve soothed his wounded feelings by ordering some lager and we’ll have coffee at the end.”

“If I drink anything it always goes to my head,” said Mrs. Metcalfe apologetically.

“Then you are wise to avoid it,” said John, and he laughed across the table. When he laughed his eyes took on a very kind and friendly look. Mrs. Metcalfe saw the look and thought with a little pang that in three weeks’ time she would not see it any more. India suddenly looked menacing and unfriendly. Fancy if she had not had that letter from her brother they could have stayed on at the hotel almost indefinitely. She sighed and began to fumble with her bread.

“Why the heavy sigh?”

“I don’t know. I begin to feel that India won’t be so much fun as I thought it would,” said Mrs. Metcalfe.

“Really? And what makes you feel that?”

“I don’t know,” faltered Mrs. Metcalfe stupidly.

“Don’t you? I do,” thought John, and he felt inclined to laugh aloud from sheer delight and pleasure. The waiter padding up broke the rather difficult moment. The soup was delicious and just the right temperature. Mrs. Metcalfe found that she was more hungry than she had thought she was. He ate so nicely too: although she did not look at John she knew that he was eating nicely.

“Tell me what gave you the idea of going out to India?” The fish had come and gone and John sat back in his chair and folded his arms. Mrs. Metcalfe was a pleasant person to take out to lunch. She did not talk all the time.

“I just had the letter from my brother and the girls wanted to go,” said Mrs. Metcalfe simply.

“And what about you?”

“I don’t think I thought about it. Of course, if they want to go I do too,” said Mrs. Metcalfe.

“Exemplary mother.”

“No, don’t say that; I’m not in the least. You know I’m not,” said Mrs. Metcalfe, flushing. “I told you a long time ago that I did sometimes feel that I wanted someone of my own age to want to do just exactly the same things that I do. But I can’t have it. People of my age can’t. April does, almost entirely though. I adore April,” said Mrs. Metcalfe simply.

“Do you?” and somehow this little simple remark gave John Maxwell a feeling of discomfort. Mothers were sometimes like that about a child, especially if they were widows. Generally it was a son who sent them off the deep end, but of course a charming and sympathetic daughter might have the same effect. Everything made subject to the beloved child. And then the beloved child married, and either its wife or husband didn’t like you and your last state was worse than your first.

“April will marry and so will Flavia,” said John. “Both will probably get engaged on the voyage out and then where will you be?”

“Alone,” said Mrs. Metcalfe simply. “And you know, although it sounds a funny thing to say, I don’t think it will be very different to what it always has been with me. Human beings always are alone. No one really understands what one feels and thinks and longs for. Do they?”

“They might,” said John, and heaved a sigh of relief as the old waiter came triumphantly out of the spotless little kitchen at the back of the restaurant. That had been a near thing, he thought, as he shook some salt out of the queer little glass pot on to his chicken. Fancy if he had proposed then! At half-past one across a little table in a Soho restaurant. She would have refused him, of course, and quite rightly. He would have to be more circumspect until he had safely deposited her at Harrods’ again.

And he was. John Maxwell was a man of the world and had plenty of things to talk about. Mrs. Metcalfe listened and tried to be really interested and could not be. She had hoped that he was going to be personal and help her with advice and talk about the girls. But he would not talk about anything except plays she hadn’t seen, and things like the decadence of our modern art; the paganism, for instance, of that unpleasant Epstein idea of Night. Mercifully not the idea of anyone else, at least, no one that he had ever met, said John sardonically.

So lunch was, on the whole, not altogether a success. Mrs. Metcalfe felt depressed when at last she found herself in her bedroom again. And the hat had made her head ache. Too tight. She took it off and threw it angrily on the bed. She was old enough to know better, she thought, leaning forward so that she could see herself more clearly in the dressing-table mirror, and noticing with a pang how dreadfully grey her hair was getting over her ears.

Soon there was only a week left before it was time for them to start for India. The heavy luggage was all packed and labelled and ready to go. One morning John Maxwell saw it all standing in the hall. Nine packages in all, he counted. And as he stood staring at it April came down the stairs and stood by his side. More and more she had begun to like this tall, distinguished-looking man who gazed so often and so long at her mother. Why didn’t Madeline say something to her about it, thought April rather resentfully. She would understand so absolutely. This nice man could see what a dear Madeline really was. Like a nice understanding brother. And yet Madeline never mentioned him. It was odd. Very odd, thought April, who, however, kept her own counsel about it, never mentioning it to Flavia.

“Well, this looks like business.” From his greater height John Maxwell looked down into April’s beautiful little face. How odd that he had ever found it difficult to distinguish the sisters apart. They were not in the least alike really. At least not in spirit, which was the only thing that mattered, thought John, knowing that he ought to start off for the South Kensington Museum and yet hating the thought of it. Life was meant to be happy and alive in. All this grubbing about in the past. . . . Useless!

“Yes, we shall soon be gone now,” said April, returning John’s gaze with a look of complete confidence.

“Glad?”

“Madly, for some things. Not for others,” returned April.

“Such as . . . ?” John smiled.

“I don’t believe Mother wants to go,” said April slowly.

“What makes you think that?”

“Well, I can’t quite explain it,” said April.

“Try. Come in here, it’s empty.” John glanced through the glass door of the lounge. He put his hand on April’s shoulder, pushing her in ahead of him. He had absolutely forgotten about the South Kensington Museum: if someone had suddenly rushed in and told him that it was on fire he felt that he would have been rather glad. He certainly would not have left the girl who stood beside him now, to go and help to put it out.

“Now then, tell me why you don’t think your mother wants to go to India,” said John. They were both sitting in low chairs close to the fire. It was beginning to get chilly, being nearly the end of September, and a fire was nice. That was why 129 Ferndale Road was nearly always full. Mrs. Rixon, who ran it, never grudged fires.

“Well, she hasn’t got that sort of joyous look about her any more,” said April confidentially. “I know Mother so well, you see. When we first got here she was just ordinarily cheerful. Then after about a week she got most frightfully cheerful, sort of shining through—I don’t know if you understand what I mean. And now for the last ten days she has got as if something inside her had gone out. As if a lamp that had been keeping her alive had gone out,” said April, struggling to make herself intelligible to this kind man who sat listening to her so intently.

“I see.” John sat back in his chair and then leant forward again. “I haven’t really seen your mother to speak to for about ten days,” he said; “she seems suddenly to be so busy.”

“Oh, well then, perhaps that’s it,” said April brightly. “She misses you, I expect. That quite accounts for it. I noticed that you stared at her a good deal as if you wanted to say something and couldn’t get the opportunity.”

“Did you?” With difficulty John controlled his face. But in spite of himself the corners of his clean-shaven mouth twitched. This child was delicious; no wonder her mother thought so much of her.

“Make an opportunity to say it,” said April soberly.

“Well, will you help me?” said John suddenly. “What does your mother like, for instance? Does she like pictures? I could take her to Burlington House to see the Italian Art. Or does she like the theatre? Milestones is on. She might enjoy that.”

“She simply adores the theatre,” said April eagerly. “Oh, do take her to Milestones, Mr. Maxwell. I know she would love that. Take her on Friday, because that is the day that Flavia and I have been invited down into the country for the night. We are going to stay with one of Flavia’s friends and go to a dance. Do ask her for that night,” said April, her delicate face flushing.

“Well, I think I will,” said John slowly. “Is she in the hotel now?—because I might ask her if she is. I ought to book seats at once if I am to get good ones.”

“Shall I go and find out? I am sure she is,” said April excitedly.

“Do, will you?” said John, and as April bolted out of the lounge he got up and walked to the window. So his carefully-thought-out scheme of action had been a success after all. She did like him and had missed his society. And now his mind was made up. He would ask her on Friday evening to marry him, because they would have loads of time as the girls were going away for the night. She would accept him. He would make her accept him, thought John, clenching his hands in his pockets and then wheeling round because he heard the door of the lounge open and shut.

“April said that you wanted me,” Mrs. Metcalfe’s mouth was a little tremulous. How the light from the two huge windows must be showing up her wrinkles, she thought, trying to meet his eyes and not being able to because the look from them was so intent.

“Yes, I do.” What an opportunity, thought John, staring at the lounge door and wondering what fool had conceived the idea of making it of glass. “I want you to come to the theatre one night,” he said. “I was talking to April, and she tells me that she and her sister are going down into the country on Friday. How would Friday do for you?”

“Oh, I’ve packed all my nicest clothes!” The words escaped Mrs. Metcalfe in spite of herself.

“Never mind. I expect you’ve got something that will do,” smiled John. “I’ll only wear a short coat to keep you in countenance.”

“Oh, I should love to come,” faltered Mrs. Metcalfe.

“Good. What would you like to see?”

“Milestones,” said Mrs. Metcalfe promptly.

“So would I,” said John. “I saw it years ago, but I believe it’s better than ever now because of that. Nineteen-twelve fashions make us laugh just as much as the 1860 ones do. I’ll get tickets, then, and we’ll dine somewhere first, if you will.”

“How heavenly,” exclaimed Mrs. Metcalfe, forgetting instantly her misery and depression of the last week. She had thought that he had got tired of her and he hadn’t. She had waked up so dreadfully early that morning and thought it all over, about how disgustingly selfish she was becoming and that the happiness of her children used to be enough, and it wasn’t now. About how she had developed a dreadful clutching feeling that she wanted happiness of her very, very own. And now here it was! She stood and gazed up into the kind face that she knew by heart. One of his dark eyebrows was just an atom higher than the other. His mouth had a whimsical, amused look on it even when it wasn’t smiling.

“Well, then we’ll consider it settled,” said John. Again he cursed the transparent door because if it hadn’t been there he would have taken Mrs. Metcalfe in his arms and kissed her then. Kissed her, and then got her faltering confession that she loved him, and then rushed out and bought a special license and married her without telling those two pretty girls. And then chucked his work at the South Kensington Museum and gone out for a jolly cold weather in India, which he already knew fairly well. And then he came down to earth again. He was a man of forty-five. When you are forty-five you stop to think, he reflected, taking hold of Mrs. Metcalfe’s hand for no reason at all except that it looked soft and that he wanted to take hold of it.

“Good-bye then,” he said and he gave it a little shake as an excuse for having taken hold of it, and walked out of the room. And like any stupid girl of twenty Mrs. Metcalfe rushed to the window directly he had disappeared and watched him after a second or two appear again and go down the steep stone steps. How tall he was and how enchantingly he put on his hat, she thought wildly. Oh, supposing he was run over! she thought breathlessly, watching him sauntering across the road and stopping and standing very still as a bus charged by him on both sides.

Ah! but he was still alive! Mrs. Metcalfe dodged back from the window as he reached the opposite kerb and stood for a moment glancing back at the house he had just left. Ah, there she was, watching him! John turned his steps and his face towards the South Kensington Museum and his heart sang foolishly.

John Maxwell belonged to two clubs. One where you could take women and one where you couldn’t. In the one where you could, the dining-rooms were soft with little tables with shaded rose-coloured lights on them. The tables were not too close together either. John had been in earlier that morning to choose one well away in a corner. Close, although not too close, to a gay little sparkling fire. He was also going to have a special dinner. He stood and chatted to the head steward, consulting him as to what he should have.

The head steward was helpful and delighted inwardly to think that Mr. Maxwell was at last bringing a lady to dine there. More than a couple of female relatives with this fine-looking gentleman had never been seen, meditated the head steward. And the ordinary dinner had been good enough for them, although Mr. Maxwell was always very particular about his wines. But to-night he was going to have champagne and a special dinner. “Being a lady, I doubt if she will appreciate anything too dry, Morton,” he had said. “And a pint bottle I am afraid will be enough. But mind it’s cold,” and then John Maxwell had gone away.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Metcalfe, after seeing her two girls off at Waterloo, had rushed straight to Shaftesbury Avenue. So ashamed of herself that she dared hardly think what she was doing, she had decided to buy herself a new dress. Up to the very last minute she had determined to wear the black one that she wore every night at the hotel. It was nice, and very becoming, but now that evening frocks were long it was not really long enough. Mrs. Metcalfe suffered tortures of indecision before she decided to buy herself a new one. The girls would wonder so dreadfully where she had got it from, and why. But Mrs. Metcalfe at last did not care. This was to be her evening and the evening of the man that she adored. She was going to look nice if she never again spent another penny on herself. The shop in Shaftesbury Avenue rose nobly to the occasion. Mrs. Metcalfe was always a success in shops because she was so humble and anxious to be helped. The beautifully-got-up lady who ran the shop scented romance and became very interested indeed. The result was charming and very inexpensive considering how nice it was. A little frock in panné ring velvet that clung where it ought to cling and flowed out where it ought to flow out. Patterned all over with little soft pale flowers. No sleeves, and that frightened Mrs. Metcalfe dreadfully until a darling little coat to match was produced. A little coat with a soft upstanding fur collar. Mrs. Metcalfe’s eager little face peeped out of the collar like a soft little owl’s face out of a hollow in a tree. The lady in the shop stood back a little way and was delighted. Women of forty were much more interesting to dress than girls of twenty, she decided. Especially when they had kept their figures as this one had done.

So that was all very delightful and Mrs. Metcalfe, clutching the dainty flowered box that contained the garment, got on to a bus and went home again. She left it in her bedroom and then went out again to have a cheap lunch somewhere. Lunch in the hotel, and a very nice one at that, was three shillings.

After her extravagant morning one and sixpence for lunch, including a tip, was all that she could allow, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, wishing that she had decided to go into a Corner House while she was near one, and now knowing that she must content herself with an ordinary Lyons.

However, the lunch was very nice. Anything would have been nice with the glow of joys to come that was stowed away at the back of Mrs. Metcalfe’s mind. Only the afternoon to get through, and then after a very early tea she could have a bath and begin to get ready. They were going to start from the hotel at half-past six, so as to have loads of time for dinner. “Don’t have anything to eat for tea or you won’t be able to manage dinner at seven,” said John laughingly as he happened to meet Mrs. Metcalfe on the stairs that morning on his way to the Museum.

“No, I won’t,” said Mrs. Metcalfe solemnly. As she went on up the stairs to her room she wondered if all women at her age had the capacity for such extreme joy as she had. Surely those two lovely girls of hers whom she was just going to see off at Waterloo couldn’t know this rapture of anticipation, this tingling excitement of something heavenly in store, that she had at the moment.

Although perhaps they could. Half an hour later both came into her room carrying their neat little suitcases with their faces all excitement and anticipation. Although April looked the happier, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, stopping to give a second glance at herself in the glass because Flavia had told her that her hat was just a little too far down over her eyes.

“It’s made it just perfect for me, knowing that you are going to have a happy evening too,” said April tenderly, waiting, however, until Flavia had gone on down the stairs, to say the words.

“Precious child,” said Mrs. Metcalfe. And as she felt April’s soft kiss on her face she wondered whether anything could quite equal the love that a mother felt for a child who really understood her. Yes it could, only in a different way, decided Mrs. Metcalfe, back in her bedroom again after seeing the girls off and buying the dress in Shaftesbury Avenue and having lunch at Lyons’, and now preparing to have a lie down until four o’clock. The dress and little coat to match it hung triumphantly on a hanger in the pale September sunshine. Heavenly, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, getting on to the bed and eyeing it rapturously from there. The sun would take out the few creases that remained from its hasty journey in the flowered box. Now she must try to go to sleep, she thought, rolling resolutely on to her side and closing her eyes, and knowing that there was not the remotest chance of going to sleep because she was far too excited.

John Maxwell had taken many more women out to dinner than the head steward at his Club thought he had. Only that they had not been the sort of women that he would take to his Club. He knew exactly how to make a woman feel happy and at her very best when she was taken out. When at last, at about three minutes before half-past six, Mrs. Metcalfe stood in the hall of 129 Ferndale Road he was also there ready and waiting for her.

“I’m early, I know,” Mrs. Metcalfe began to speak before she had finished coming down the stairs. “But I was so dreadfully afraid that my clock might be wrong.”

“You’re not in the least early. This clock is always wrong,” said John promptly and untruthfully. The large round clock that had kept perfect time for at least twenty years stared spikily at John as though it would gladly have stabbed him with the long hand that was pointing towards him and that registered exactly three minutes to the half hour.

“The car is here and waiting,” he went on. For one ridiculous moment John had been so terribly afraid that it might not have been. He loved Mrs. Metcalfe’s youthful eagerness and had a ridiculous longing that nothing should happen to distress it.

“A car! how lovely!” Mrs. Metcalfe really did look very nice. Her small face was sheltered and softened by the high enveloping collar of her fur coat. She had darkened her eyebrows a little and also her eyelashes. Both looked softer and more luxuriant because of it. She had added a little rouge to her rather pale face. This anxious making-up had taken more than half an hour. Mrs. Metcalfe had stared into her looking-glass until she felt as if her face belonged to somebody else. Too much make-up was so ghastly. But a little made you look nicer, especially if you were dining somewhere where the lights were not shaded. Men sometimes did not think about that. But she would not touch her lips. She had always hated that. Besides. . . . And then Mrs. Metcalfe crushed down the thought that would come, however much she tried not to let it. Of course, though, he never would. He wouldn’t want to, to begin with.

“Yes, I always have a car when I go out for the evening like this. It makes it ever so much more comfortable,” said John. By now they were going down the steps. The page-boy ran on ahead of them and excitedly wrenched open the nice shiny door of the Daimler. He knew Mr. Maxwell very well indeed; he gave him foreign postage stamps whenever he happened to have them.

“The Arts and Services Club,” said John, standing on the pavement and speaking to the chauffeur. But he had taken quite a minute to settle Mrs. Metcalfe comfortably into her seat first. He knew exactly how to do it, too. Mrs. Metcalfe gave a little excited gasp as he drew himself out again backwards and spoke to the chauffeur, and then got in again.

“Comfortable?” John was smiling. He looked very nice in his evening dress with the white silk scarf tucked round his neck. His thin black overcoat was just right. “I hope you don’t mind me without a hat,” he said.

“Oh no, I like it,” said Mrs. Metcalfe. A child going to its first pantomime could not have been more excited than she was then. She stared out like a child as the car steered its smooth way along Ferndale Road and out into Queen’s Gate. . . . Along past Harrods’, Woolland’s and Hyde Park Corner. Crowds of people getting in and out of omnibuses. Poor things, thought Mrs. Metcalfe, snuggled in her corner and knowing that when she got out of the car her dress would be right and that she wouldn’t have to tug surreptitiously at it because it was too short somewhere, or anything like that.

“You know we really are rather early. I think we’ll go for a little drive first,” said John. He blew through the speaking-tube and the chauffeur slowed down and slanted his head a little to the left. He nodded twice at John’s briefly spoken order and did an elaborate manœuvre round the Royal Artillery Memorial outside St. George’s Hospital. Then he slid into the Park with a deep melodious blast from his horn.

“We’ll waste time by going round Regent’s Park,” said John. “At least, we won’t waste it, because I’ve got something to say to you.” During the ten minutes’ drive from Ferndale Road John had been thinking very hard. In a week from now Mrs. Metcalfe was sailing for India. In a little more than twelve hours from now her daughters would be back again. Conflicting claims were often very urgent with a woman of this type, especially when they clashed with her inclinations. He had better not waste any more time.

“Look here,” he said, and he cleared his throat a little as he spoke. “I want to tell you something. Give me your nice little hand. No, don’t give it to me, I can find it for myself,” said John, slipping his hand under the soft plush rug.

“What . . . ?” Mrs. Metcalfe’s voice failed in her throat.

“Why, I love you,” said John. “Yes, I know it sounds ridiculous when I have known you for so short a time. But I suppose it is one of those cases when time doesn’t matter. You’ve always belonged to me, I expect: at least, I feel as if you had. Well, what about it?” he ended tenderly, smiling at her look of alarm.

“I don’t feel as if I . . .” Mrs. Metcalfe, her hand quivering in the strong one that held it, gasped.

“I know. I know it must be a fearful shock to you,” said John suddenly. “How could it fail to be? You see, I’ve not led up to it at all: I thought it better not to, somehow.”

“The girls . . .” quavered Mrs. Metcalfe.

“I’m not talking about the girls, I’m talking about you and me,” said John quietly. “The girls will come presently: of course, they’ll have to, I know that. But at the moment you and I are the more important. Do you love me? If you don’t, of course it’s hopeless. But if you do. . . .”

“I do,” said Mrs. Metcalfe instantly.

“Thank God for that!” said John soberly. Then after a little pause: “I thought it got dark earlier in September,” he said discontentedly, and he turned from his quiet contemplation of Mrs. Metcalfe’s illumined face to stare impatiently out of the window.

“No, not till about seven,” said Mrs. Metcalfe tremulously.

“Bother!” said John. And then he turned to her. “Now we can,” he said. “It’s deserted here, thank goodness.”

“Oh no, wait!” gasped Mrs. Metcalfe. Her face was flushing and paling. “I’ve always felt there was something so desperate about a kiss,” she said. “I can’t—yet.”

“Sweetheart, I’m so sorry,” John could have kicked himself for his crude stupidity.

“No, I’m so frightfully stupid,” said Mrs. Metcalfe, her hand trembling in his.

“You’re not in the least stupid. I am,” said John. He blew through the speaking-tube again. The chauffeur turned round and nodded, then headed for the Club.

“We’ll have a lovely dinner,” he said. “And not speak of this again, if you’d rather not, until we’re on our way home. I brought you out to enjoy yourself, I’m not going to spoil it all for you by worrying you. Better?”

“I never was anything but quite well and blissfully happy,” said Mrs. Metcalfe frankly. “It’s because of that. It’s—it’s too much, somehow. It’s not that I don’t want you to kiss me,” stammered Mrs. Metcalfe. “It’s only that I feel when you do I shall . . .”

“I know, and thank God you do feel like that,” said John abruptly. “I understand absolutely. And now here we are.” He drew her hand out from under the rug. “If I kissed this you wouldn’t go absolutely off the deep end, would you?” he twinkled. He held her hand a little below his mouth.

“Someone in that omnibus will see,” said Mrs. Metcalfe tremulously.

“Let them: it will do them good,” said John mischievously. He lifted her prisoned hand to his mouth and turning it so that the soft palm curved upwards he buried his lips for a moment in it. And then he sighed and let it go again. “The Club,” he said. “Just in time.”

“Oh!” Mrs. Metcalfe had shrunk further back into her corner and was staring at him with eyes that were suddenly very bright indeed.

“I won’t promise to behave quite so well on my way back from the theatre,” said John briefly, as the car slid into the kerb and the minute page-boy came dashing down the Club steps.

“No?” and then Mrs. Metcalfe suddenly became speechless. She could not have said anything else if she had had to do so. And she hadn’t. John was already helping her out of the car and shepherding her up the steps with a careful hand on her arm. He showed her where to go and leave her coat, handing her over to another chubby page-boy for her final directions. And then he went off himself to hang up his own coat and brush his hair. It needed it, surely, thought John, passing a quick hand over the shining neatness of his head and then glancing at himself in the glass and seeing that it didn’t need it after all.

Mrs. Metcalfe had a delicate and sensitive conscience and she knew that stalls at the theatre nowadays were expensive things. She tried therefore to give her attention to what was going on on the stage. But she couldn’t. She was only conscious of the man sitting beside her. The white blur of his shirt-front. The thick white line that his collar drew against the darker texture of his neck. His hands: without moving her head at all she could see them clasped on his crossed knees. If only he would take hold of her hand with one of them. She tried to subdue her thoughts and could not. Everyone around her was staring at the stage and so would she. She gripped her hands on the velvet arm of her seat and tried to open her eyes wider, so that she could take it all in more. Hopeless: she could only think more acutely of the man sitting beside her. Sitting so still. What was he thinking about? Was he thinking about her? Was he perhaps thinking that he wished he had not said what he had so hurriedly in the car? wondered Mrs. Metcalfe, in a sudden agony of fear.

But John, sitting with one long leg crossed over the other, was wondering how he was going to keep up his attitude of calm middle-aged placidity when he had got Mrs. Metcalfe alone with him in the car going home. It had been difficult enough at dinner. One little incident had showed him how difficult. Everything had been just right. The dinner was excellent, and the table cosily close to the fire and daintily shaded. Mrs. Metcalfe had sipped at the champagne as if she was frightened of it, and had then liked it and smiled down into her brimming glass. And then after the entrée she had given a little gasp. “Oh, it’s hot,” she said.

“Oh! Now then what can we do?” John was instantly the attentive host. He glanced round to see if they could change their table, but the room had filled up and they couldn’t. After all he had put her close to the fire because he had thought she would like it. “I’m sorry.” He looked penitently across the table.

“No, no. I think . . .” and then Mrs. Metcalfe had hesitated.

“Doesn’t the saucy little coat come off?” said John, a sudden idea striking him. He suddenly noticed that Mrs. Metcalfe was rather wrapped up. She looked perfectly delicious, but still——

“It does. But I don’t know . . .” Mrs. Metcalfe looked hopelessly across the table.

“Take it off,” said John firmly. He got up and walked round the table. Mrs. Metcalfe yielded with shrugging shoulders, and the little velvet coat was in his hands. It left a very beautiful neck and arms uncovered. John’s eyes dwelt for one fleeting second on them and then he walked back to his place carrying the little coat.