* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a Fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

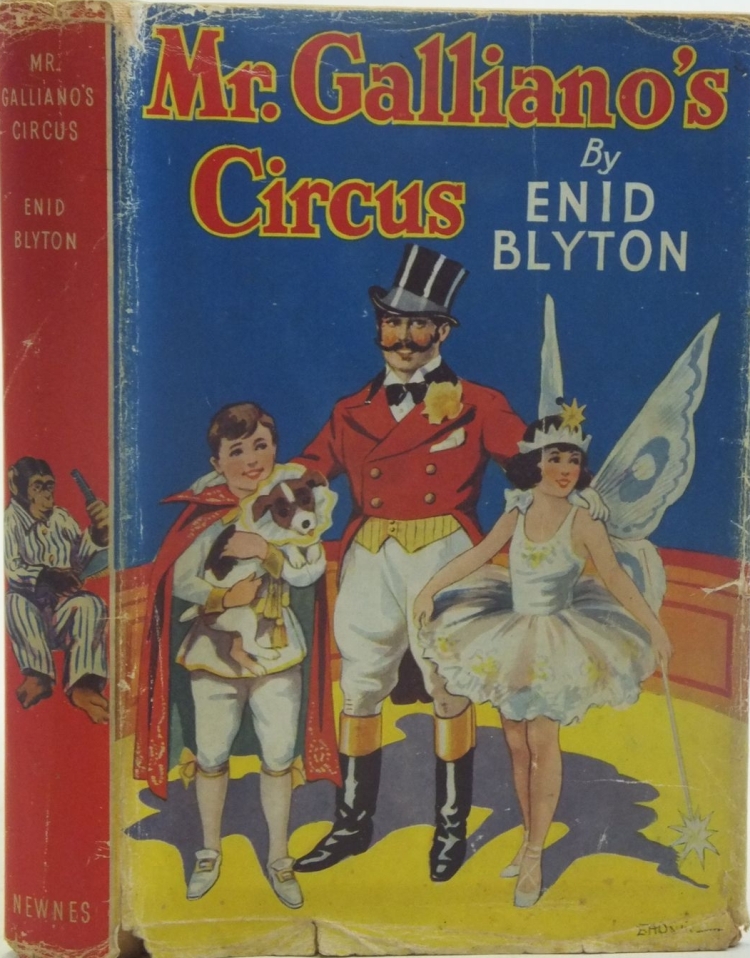

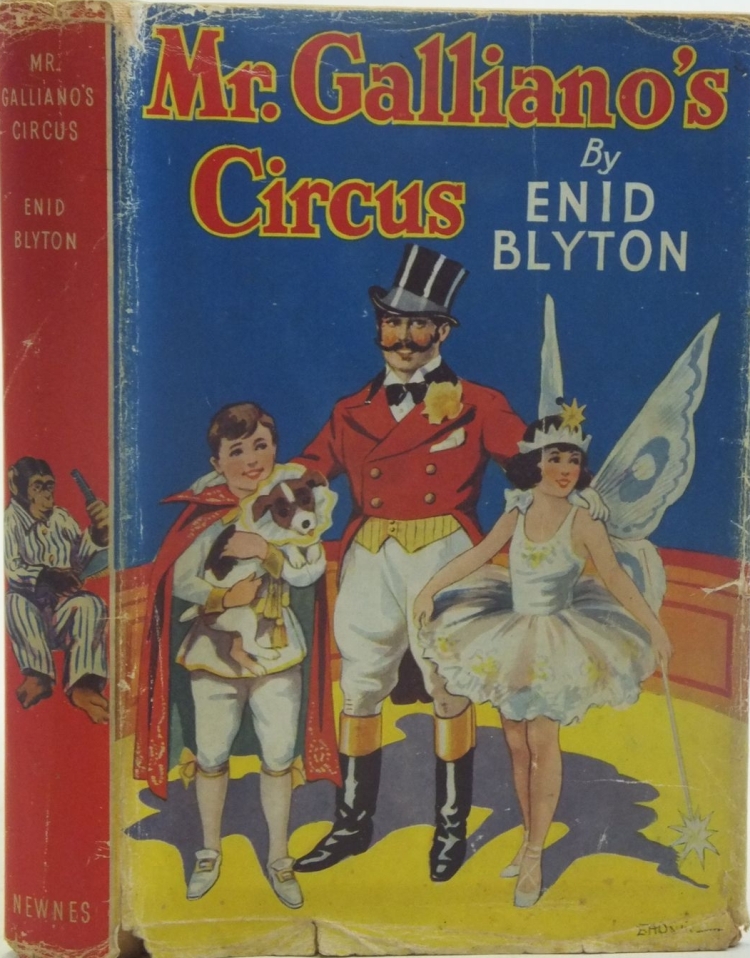

Title: Mr. Galliano's Circus

Date of first publication: 1938

Author: Enid Blyton (1897-1968)

Date first posted: Jan. 11, 2019

Date last updated: Jan. 11, 2019

Faded Page eBook #20190155

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Other titles by Enid Blyton in Armada

Hurrah for the Circus!

Circus Days Again

Come to the Circus

The Naughtiest Girl in the School

The Naughtiest Girl Again

The Naughtiest Girl is a Monitor

The Adventurous Four

The Adventurous Four Again

The Rockingdown Mystery

The Rubadub Mystery

The Ring O’Bells Mystery

The Rilloby Fair Mystery

The Rat-a-tat Mystery

The Secret Island

The Secret of Killimooin

The Secret Mountain

The Secret of Spiggy Holes

The Secret of Moon Castle

Happy Day Stories

Rainy Day Stories

The Six Bad Boys

The Children of Cherry Tree Farm

The Children at Green Meadows

The Children of Willow Farm

Adventures on Willow Farm

The Put-Em-Rights

Six Cousins at Mistletoe Farm

Six Cousins Again

Those Dreadful Children

The Family at Red-Roofs

Holiday House

Picnic Party

Storytime Book

MR. GALLIANO’S

CIRCUS

Enid Blyton

First published in the U.K. by

George Newnes Ltd. First published in this

edition in 1972 by Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd.,

14 St. James’s Place, London S.W.1.

© Enid Blyton

Printed in Great Britain by

Love & Malcomson Ltd., Brighton Road,

Redhill, Surrey.

CONDITIONS OF SALE:

This book is sold subject to the condition

that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise,

be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated

without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is

published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed

on the subsequent purchaser.

One morning, just as Jimmy Brown was putting away his books at the end of school, he heard a shout from outside:

“Here comes the circus!”

All the children looked up from their desks in excitement. They knew that a circus was coming to their town and they hoped that the circus procession of caravans, cages, and horses would go through the streets when they were out of school.

“Come on!” yelled Jimmy. “I can hear the horses’ hoofs! Goodbye, Miss White!”

All the children yelled good morning to their teacher and scampered out to see the circus procession. They were just in time. First of all came a very fine row of black horses, and on the front one rode a man dressed all in red, blowing a horn. He did look grand!

Then came a carriage that looked as if it were made of gold, and in it sat a handsome man, rather fat, and a plump woman dressed all in pink satin.

“That’s the man who owns the circus!” said somebody. “That’s Mr. Galliano—and that’s his wife! My, don’t they look fine!”

Mr. Galliano kept taking off his hat and bowing to all the people and the children round about. Really, he acted just like a king. He had a very fine moustache with sharp-pointed ends that turned upwards. His top-hat was shiny and black. Jimmy thought he was simply grand.

Then came some white horses, and on the first one, leading the rest, was a pretty little girl in a white, shiny frock. She had dark-brown curls, and eyes as blue as the cornflowers in the cottage gardens near by. She made a face at Jimmy, and tried to flick him with her little whip. She hit his wrist and made him jump.

“You’re a naughty girl!” shouted Jimmy. But the little girl only laughed and made another face. Jimmy forgot about her when he saw the next bit of the procession. This was a clown, dressed in red and black, with a high, pointed hat; and he didn’t walk along the road—no, he got along by turning himself over and over on his hands and feet, first on his hands and then on his feet, and then on his hands again.

“That’s called turning cart-wheels,” said Tommy, who was standing next to Jimmy. “Isn’t he clever at it? See, there he goes, like a cart-wheel, over and over and round and round!”

Suddenly the clown jumped upright and took off his hat. He turned over on to his hands again, and popped his hat on his feet, which were now up in the air. Then the clown walked quickly along on his hands so that his feet looked like his head with a hat on. All the children laughed and laughed.

Next came a long string of gaily-coloured caravans. How Jimmy loved these! There was a red one with neat little windows at which curtains blew in the wind. There was a blue one and a green one. They all had small chimneys, and the smoke came out of them and streamed away backwards.

“Oh, I wish I lived in a caravan!” said Jimmy longingly. “How lovely it must be to live in a house that has wheels and can go away down the lanes and through the towns, and stand still in fields at night!”

The horses that drew the caravans were not so fine-looking as the black and white ones that had gone in front. Jimmy hardly had time to look at them before there came a tremendous shout down the street:

“There’s an elephant!”

And, dear me, so there was! He came along grandly, pulling three cages behind him. He didn’t feel the weight at all, for he was as strong as twenty horses. He was a great big creature, with a long swinging trunk, and as he reached Jimmy he put out his trunk to the little boy as if he wanted to shake hands with him! Jimmy was pleased. He wished he had a biscuit or a bun to give the elephant.

The big animal lumbered on, dragging behind it the cages. Two of them were closed cages and nothing could be seen of the animals inside. But one was open at one side and Jimmy could see three monkeys there. They sat in a row on a perch, all dressed in warm red coats, and they looked round at the children and grown-ups watching them, with bright, inquisitive eyes.

“Look! There’s another monkey—on that man’s shoulder!” said Tommy. Jimmy looked to where he pointed and, sure enough, riding on the step of the monkey’s cage was a funny little man, with a face almost as wrinkled as the monkey’s on his shoulder. The monkey he carried cuddled closely to the man and hugged him with its tiny arms. As they passed the children the monkey took off the man’s cap and waved it at the boys and girls!

“Did you see that?” shouted Jimmy in delight. “That monkey took off the man’s cap and waved it at us! Look! It’s putting it back on his head now. Isn’t it a dear little thing?”

At last the procession ended, and all the horses, cages, and caravans trundled into Farmer Giles’s field where the circus was to be held. The children went home to dinner, full of all they had seen, longing to go and see the circus when it opened on Wednesday.

Jimmy told his mother all about it, and his father too. Jimmy’s father was a carpenter, and he had been out of work for nearly a year. He was very unhappy about it, for he was a good workman, and he did not like to see Jimmy’s mother going out scrubbing and washing to bring in a few shillings.

“My!” said Jimmy, finishing up his dinner, and wishing there was some more, “how I’d like to go to that circus.”

“Well, you can’t, Jimmy,” said his mother. “So don’t think any more about it.”

“Oh, I know that, Mum,” said Jimmy cheerfully. “Don’t you worry. I’ll go and see the animals and the clown and everything in the field, even if I can’t go to the circus.”

So after school each day Jimmy slipped under the rope that went all round the ring of circus vans and cages, and wandered in and out by himself. At first he had been shouted at, and once Mr. Galliano himself had come along with his pointed moustaches bristling in anger, and told Jimmy to go away.

Jimmy was afraid then, and was just going when he heard a voice calling him from a caravan near by. He turned to see who it was, and saw the curly-haired little girl there.

“Hallo, boy!” she said. “I saw you watching our procession yesterday. Are you coming to the show to-morrow night?”

“No,” said Jimmy. “I’ve got no money. I say—can I just peep inside that caravan? It does look so nice!”

“Come up the ladder and have a peep if you want to,” said the little girl.

Jimmy went up the little ladder at the back of the caravan and peeped inside. There was a bed at the back, against the wooden wall of the caravan. There was a black stove, on which a kettle was boiling away. There was a tiny table, a stool, and a chair. There were shelves all round holding all sorts of things, and there was a gay carpet on the floor.

“It looks lovely!” said Jimmy. “I wonder why people live in houses when they can buy caravans instead.”

“Can’t think!” said the little girl. Jimmy stared at her—and she made a dreadful face at him.

“You’re rude,” said Jimmy. “One day the wind will change and your face will get stuck like that.”

“I suppose that’s how you got your own face,” said the little girl, with a giggle. “I wondered how it could be so queer.”

“It isn’t queer,” said Jimmy. “And look here—just you tell me why you hit me with your whip yesterday? You hurt me.”

“I didn’t mean to,” said the little girl. “What’s your name?”

“Jimmy,” said Jimmy.

“Mine’s Lotta,” said the girl. “And my father is called Laddo, and my mother is called Lal. They ride the horses in the circus and jump from one to another. I ride them too.”

“Oh,” said Jimmy, thinking Lotta was really very clever, “I do wish I could come and see you.”

“You come this time to-morrow and I’ll take you round the circus camp and show you everything,” said Lotta. “I must go now. I’ve got to cook the sausages for supper. Lal will be angry if she comes back and they’re not cooked.”

“Do you call your mother Lal?” said Jimmy, surprised.

“ ’Course I do,” said Lotta, smiling. “And I call my father Laddo. Everybody does. Good-bye till to-morrow.”

Jimmy ran home. He felt most excited. To think that the next day he would be taken all round the circus camp and would see everything closely! That was better than going to the circus.

The next day, as soon as afternoon school was over, Jimmy ran off to the circus field. A great tent had been put up. This was where the circus was to be held that night. The circus folk had been very busy all day long, getting everything ready.

Jimmy looked for Lotta. The little man who owned the monkeys came along and he glared at Jimmy.

“You go home just as quickly as ever you can,” he said. “Go along! No boys allowed here!”

“But . . .” began Jimmy.

“What! You dare to disobey me, the great Lilliput!” said the little man, and he ran at Jimmy. Jimmy didn’t know quite what was going to happen next, but a voice called out from the caravan near by:

“Lilliput! Lilliput! That’s my friend! Leave him alone!”

The little man turned round and bowed. “Your pardon,” he said. “Any friend of yours is welcome here, of course, dear Lotta.”

“Don’t be silly, Lilliput!” said Lotta, and the little girl jumped down from the caravan and ran over to Jimmy. “This is Jimmy. And this is Lilliput, Jimmy. He has the monkeys. Where’s Jemima, Lilliput?”

“Somewhere about,” said Lilliput. “Jemima love! Jemima love! Come along!”

A small, bright-eyed monkey came running out on all-fours from under a cart. She tore over to Lilliput, leapt up to his shoulder and put her arms round his neck.

“This is Jemima,” said Lotta. “She is the darlingest monkey in the world—isn’t she, Lilliput? And the cleverest.”

“That’s right,” said Lilliput. “I bought her from a black man when I was in foreign lands, and she’s just as cunning as can be. Look, Jemima—here’s Nobby! Go ride him, go ride him!”

The monkey made a little chattering noise, slipped down to the ground and ran quietly over to a large brown dog who was nosing about the field. She jumped on to his back, held on to his collar and jumped up and down to make him go. Jimmy laughed and laughed.

“Come along!” said Lotta, slipping her bare brown arm through his. “Come and see the clown.”

The clown lived in a rather dirty little caravan all by himself. He sat at the door of it, polishing some black shoes he meant to wear that night. He didn’t look a bit like a clown now. He had no paint on his face, and he wore a dirty old hat. But he was very funny.

“Hallo, hallo, hallo!” he said, when he saw Jimmy coming. “The Prince of Goodness Knows Where, as sure as I’m eating my breakfast!” He got up and bowed politely.

Jimmy laughed. “But you’re not eating your breakfast!” he said.

“Then you can’t be the Prince,” said the clown, “That just proves it—you can’t be the Prince.”

“Well, I’m not,” said Jimmy. “I’m Jimmy Brown. What’s your name?”

“I am Sticky Stanley, the world-famous clown,” said the clown proudly, and he gave his shoes an extra rub.

“What a funny name!” said Jimmy. “Why do you call yourself Sticky?”

“Because I stick to my job and my friends stick to me!” said Stanley. And he leapt down from his caravan, began to carol a loud song and juggle with his two shoes, his brush, and his tin of polish. He sent them all up into the air one by one and caught them very cleverly, sending them up into the air again, higher and higher.

Jimmy watched him, his eyes nearly falling out of his head. However could any one be so clever? The clown caught them all neatly in one hand, bowed to Jimmy, and turned two or three somersaults, landing with a thud right inside his caravan.

“Isn’t he funny?” said Lotta. “He’s always like that. Come and see the elephant. He’s a darling.”

The elephant was in a tall tent by himself, eating hay contentedly. His leg was made fast to a strong post.

“But he doesn’t really need to be tied up at all,” said Lotta. “He would never wander away. Would you, Jumbo?”

“Hrrrumph!” said Jumbo, and he lifted up his trunk and took hold of one of Lotta’s curls.

“Naughty Jumbo!” said Lotta, and she pushed his trunk down again. “Look, this is Jimmy. Say Jimmy, Jumbo.”

“Hrrrumph!” said Jumbo, and he said it so loudly that Jimmy’s cap flew off in the draught! Jumbo put down his trunk, picked up Jimmy’s cap and put it back on his head. Jimmy was so surprised.

“Hrrrumph!” said Jumbo again, and pulled out some more hay to eat.

“He’s very clever,” said Lotta. “He can play cricket just as well as you can. He holds a bat with his trunk, and hits the ball with it when his keeper, Mr. Tonks, bowls to him. Now come and see the dogs.”

Jimmy had heard the dogs long before he saw them. There were ten of them—all terriers. They were in a very big cage, running about and barking. They looked clean and silky and happy. They crowded up to Jimmy when he put his hand out to them.

“That’s Darky and that’s Nigger and that’s Boy and that’s Judy and that’s Punch and that’s . . .” began Lotta. But Jimmy couldn’t see which dog was which. He just stood there and let them all lick his hands as fast as they could.

“I take them all out once a day,” said Lotta. “They go out five at a time. I have one big lead and they each have a short lead off it, so I can keep them all together. They do pull though!”

“What do they do in the circus?” asked Jimmy.

“Oh, all kinds of things,” said Lotta. “They can all walk on their hind legs, and some of them can dance round and round in time to the music. This one, Judy, can jump through hoops held as high as my head. She is very clever.”

“I like Judy,” said Jimmy, letting the little sandy-headed terrier lick his fingers. “How do they teach the dogs their tricks, Lotta? Do they punish them if they don’t do them properly?”

Lotta looked at Jimmy in horror. “Punish them!” she said. “That shows how little you know about a real good circus, Jimmy. Why, we all know that no animals will play or work properly for us unless we love them and are kind to them. If Mr. Galliano saw any one hitting a dog or a monkey he would send him off at once. We love our animals and feed them well, and look after them. Then they are so full of love and good spirits that they think it is fun to play and work with us.”

“I like animals too,” said Jimmy. “I would never hurt one, Lotta, so don’t look at me like that. One thing I’d like better than any other is a dog of my own—but Dad couldn’t possibly buy a licence for him, so I’ll never have one! How I wish I belonged to a circus!”

“I wish you belonged too,” said Lotta. “Usually in a circus there are lots of children—but I’m the only one here and it’s often lonely for me.”

“Oh, I say! Look! Who’s that over there?” said Jimmy suddenly, pointing to a man who was doing the most extraordinary things on a large mat outside a caravan.

“Oh, that’s Oona the acrobat,” said Lotta. “He is just practising for to-night. Oona! Here’s a friend of mine! Where’s your ladder? Do go up it upside down on your hands and stand on your head on the top of it, just to show Jimmy!”

Oona was at that moment looking between his legs at them in a very peculiar manner. He grinned and stood the right way up. “Hallo, youngster!” he said. “So you want to see me do my tricks before you come to the circus!”

“He’s not coming,” said Lotta. “So do your best trick for him, Oona, do!”

Oona, who was a fine strong-looking young man with a mop of curly golden hair, fetched a step-ladder from his caravan. It was painted gold and looked very grand. Oona stood it firmly on the ground, turned a few somersaults on his mat first, and then walked up the ladder to the very top on his hands, waving his legs above him as he did so. When he got to the top he stood there on his head alone, and Jimmy stared as if he couldn’t believe his eyes. Oona lightly twisted himself over and came down beside Jimmy on his feet.

“There!” he said; “easy as winking! Try it yourself, young man.”

“Oh, I couldn’t possibly!” said Jimmy. “I can’t even walk on my hands.”

“That’s easy, if you like!” said Lotta, and to Jimmy’s amazement the little girl flung herself lightly forward and walked a few steps on her hands.

“How I wish I could do that!” said Jimmy. “My goodness! The boys at school would stare!”

“Try it,” said Lotta. “I’ll hold your legs up for you till you get your balance.”

Somehow Jimmy got on to his hands and Lotta held his feet up. “Walk on them—walk on your hands!” she shouted. “Go on—I’ve got your legs all right!”

“I can’t!” gasped Jimmy. “I can’t make my hands go—my body is so heavy on them!”

Lotta began to laugh. She laughed so much that she dropped Jimmy’s legs, and there he was, lying sprawling in the grass, laughing too.

“You’d do for a clown, but not for an acrobat just yet,” said Oona, with a grin. “Now off you go—I want to practise!”

“I’ve got to go and help Lal get into her dress for to-night,” said Lotta, as the two children went away. “I must say good-bye, Jimmy. Come again to-morrow.”

Jimmy ran off home, his head full of elephants and monkeys and dogs and people standing on their heads and walking on their hands. If only he belonged to a circus too!

Every day Jimmy ran off to the circus field to see Lotta and to hear all her news. She was a lively little girl, kind-hearted but often naughty, and she really could make the most dreadful faces Jimmy had ever seen. She could pinch hard too, and Jimmy thought that was very unfair of her, because he didn’t like to pinch back.

The circus was doing well. Every night the big tent was crowded by people from the town, and, as it was a very good show, many people went three or four times. Mr. Galliano wore his big top-hat very much on one side of his head, so much so that Jimmy really wondered why it didn’t fall off.

“When Galliano wears his hat on one side the circus is taking lots of money,” said Lotta to him. “But when you see him wearing it straight up, then you know things are going badly. He gets into a bad temper then, and I hide under the caravan when I see him coming. I’ve never seen his hat so much on one side before!”

Jimmy thought that circus ways were very extraordinary. Even hats seemed to share in the excitement! He was afraid of Mr. Galliano, but he couldn’t help liking him too. He was such a big handsome man, and his face was so red and his moustache so fierce-looking. He usually carried a whip about with him, and he cracked this very often. It made a noise like a pistol-shot, and Jimmy jumped whenever he heard it. Jimmy made himself a whip with a long string like Mr. Galliano’s, but he couldn’t make it crack though he tried for a long time.

Jimmy soon knew everybody at the circus. He knew every single one of the dogs. He took them out with Lotta on Saturday morning when there was no school. Lotta had five and he had five. It was hard work keeping the dogs in order. His five kept getting tangled up, but Lotta’s never did. The dogs loved Jimmy. How they barked when they saw him!

He gave them their fresh water every day. He even cleaned out their big, airy cage, and put fresh sawdust down. He liked to feel the dogs running round his legs, licking him, and yapping to him.

Jumbo, the big elephant, was taken down to the nearby stream to drink twice a day. Mr. Tonks untied him and led him down. Jimmy asked if he could lead him back to his tent. Mr. Tonks looked at the little boy.

“What will you do if he runs away from you?” he asked. “Could you catch him by the tail and pull him back? Or would you pick him up and carry him?”

Jimmy laughed. “I guess if he ran away you couldn’t bring him back either, Mr. Tonks!” he said. “He won’t run away, will he? He’s the gentlest creature I ever saw, for all he is so big. Look how he’s putting his trunk into my hand now—just as of he wanted me to lead him back.”

“Jumbo wouldn’t do that if he didn’t like you,” said Mr. Tonks. “Come on—step on my hand and I’ll give you a leg-up, Jimmy. You shall ride on his neck!”

My word! That was a treat for Jimmy! In a trice the little boy was up on the elephant’s neck. He sat cross-legged, as Mr. Tonks told him to. The elephant’s neck was so broad that this was quite easy. Back went Jimmy and the elephant to the tent. Then, to Jimmy’s enormous surprise, the big creature put up his trunk, wound it firmly round his waist, and lifted the boy gently down to the ground himself.

“Oooh!” said Jimmy, astonished. “Thank you, Jumbo!”

“See that!” said Mr. Tonks in surprise. “Jumbo never does that to any one unless he really likes them. He’s your friend for good now, Jimmy. You’re lucky!”

After that Jimmy and Jumbo went down to the stream every day together, Jimmy always riding on the elephant’s head. Jimmy saved part of his bread and cheese for Jumbo, and the elephant always looked for it when the boy came to see him. He sometimes put his trunk round Jimmy’s neck, and it did feel funny. Like a big snake, Jimmy thought.

There was only one man that Jimmy didn’t like—and that was a little, crooked-eyed man called Harry. Harry never had a smile for any one. He snapped at Lotta, and pulled her hair whenever he passed her. Once Jimmy saw him try to hit Jemima the monkey, when she ran near him.

“I don’t like Harry,” he said to Lotta. “He has a horrid unkind face. What does he do in the circus, Lotta?”

“He doesn’t really belong to us,” said the little girl. “He’s what we call the odd-job man—he does all the odd-jobs—puts up the benches in the ring, mends anything that goes wrong, makes anything special we need. There’s always plenty for him to do. He’s very clever with his hands—that’s why Mr. Galliano keeps him on, because he can’t bear him really.”

“I saw him try to hit Jemima just now,” said Jimmy.

“I’ve seen him try too,” said Lotta. “But Jemima knows Harry all right. She hates him—do you know, she went to his box of nails one day and stuffed her cheeks with about fifty of his nails. He couldn’t find them anywhere—and there was Jemima running about with them in her mouth! I saw her taking them, and I had to hide under our caravan so that Harry shouldn’t see me laughing!”

Jimmy laughed. “Good for Jemima!” he said. “Well, it’s a pity you have to keep Harry, Lotta. If I were Mr. Galliano I’d send him away—always snapping and snarling like a bad-tempered dog! He threw his hammer at me yesterday.”

“Oh, he wouldn’t hit you,” said Lotta. “He’s too bad a shot for that. You keep out of his way, though, Jimmy. However much we dislike him we’ve got to have him—why, we couldn’t put up the circus tents and ring without him—and he’s so clever at making special ladders and things—and mending caravans.”

Just then Mr. Galliano came up, his hat more on one side than ever. He beamed at Jimmy. He had heard that the little boy was marvellous with the animals, and that always pleased Mr. Galliano. He loved every creature, down to white mice, and Lotta had told Jimmy that once, when one of his horses was ill, Mr. Galliano had sat up with her for four nights running and hadn’t gone to sleep at all.

“Hallo, boy,” he said. “So here you are again! You will be sorry when we move away? Yes?”

“Very sorry,” said Jimmy. “I think a circus life is fine!”

“You do not like to live in a house? No?” said Mr. Galliano, who had a very funny way of always putting yes or no at the end of his sentences.

“I’d rather live in a caravan,” said Jimmy.

“And you like my circus? Yes?” said Mr. Galliano, twisting his enormous moustache into even sharper points.

“I haven’t seen the real circus,” said Jimmy. “I haven’t the money to go into the big tent at night, Mr. Galliano. But I’ve seen all the animals and people here in the field.”

“What! This boy hasn’t seen our circus show, the best in the whole world?” cried Mr. Galliano, his big black eyebrows going right up under his curly hair. “He must come, Lotta, he must come to-night! Yes?”

“I’d love to,” said Jimmy, red with excitement. “Thanks awfully.”

“Give this to the man at the gate,” said Mr. Galliano, and he gave Jimmy a card on which was printed Mr. Galliano’s own name. “I shall see you in the big tent to-night then? Yes?”

“Yes sir,” said Jimmy, and stuffed the card into his pocket very carefully. Lotta was pleased. She squeezed Jimmy’s arm. “Now you’ll see us all in the ring!” she said. “I shall be riding too, to-night, as it’s Saturday. I don’t always—but Saturday is a special night. Come early!”

The little boy raced home to dinner. He was tremendously excited. All his school-friends had seen the circus—but he, Jimmy, had a special ticket, one of Mr. Galliano’s own cards—and he knew every one there! He knew all the dogs—he had ridden Jumbo! He had cuddled Jemima the clever little monkey! Ah! He would have a glorious time to-night!

The circus began at eight o’clock and lasted for two hours. Jimmy was at the gate at a quarter-past seven. He gave his card to the man there. He was one of the men who looked after Mr. Galliano’s many beautiful horses. He grinned at Jimmy. “You can sit anywhere you like with that card!” he said. “My word! Old Galliano was feeling generous this morning, wasn’t he—giving free tickets to shrimps like you!”

“I’m not a shrimp,” said Jimmy, offended, for he was quite big for his age.

“Well, maybe you’re a prawn then,” said the ticketman. That was just like circus-folk, Jimmy thought—they always had an answer for everything. Perhaps one day he too would be quick enough to think of funny answers—but, oh dear, by that time the circus would have gone!

The little boy went into the big tent. It was lighted by huge flares. Not many people were there yet. There were a great many benches set all round a big red ring in the middle. Mr. Tonks was spreading sawdust in the middle of the ring, whistling loudly.

Jimmy chose a seat right in the very front. He whistled to Mr. Tonks. Mr. Tonks looked up and pretended to be most surprised to see Jimmy there.

“Hallo, hallo!” he said, “has somebody left you a fortune or what! Fancy seeing you here—in the best seats too—my word, you are throwing your money about!”

“No, I’m not,” said Jimmy. “Mr. Galliano gave me a ticket.”

The tent filled up with people. By the time eight o’clock came there wasn’t an empty seat. Jimmy thought that Mr. Galliano must have taken a lot of money to-night, and he wondered if his hat would keep on, he would wear it so much to one side!

There was a doorway at one end of the tent, hung with red curtains. Suddenly these were drawn aside and two trumpets blew loudly.

“Tan-tan-tara! Tan-tan-tara! Tan-tan-tara!”

The circus was going to begin! What fun!

“Tan-tan-tara!” went the trumpets again, and into the ring cantered six beautiful black horses. They ran gracefully round the ring, noses to tail. Mr. Galliano came striding into the ring, dressed in a magnificent black suit, his top-hat well on one side, his long stiff moustaches turned up like wire.

He cracked his whip. The horses went a bit faster. Galliano cracked his whip twice. The horses all stopped, turned round quickly—and went cantering round the other way. It was marvellous to watch them. How every one clapped!

Three of the horses went out. The three that were left went on cantering round the ring. They were thoroughly enjoying themselves. Mr. Galliano shouted out something and a barrel-organ began to play a dance tune.

The three horses were delighted. They all loved music. Mr. Galliano cracked his whip sharply. At once all three horses rose up on their hind legs and began to sway in time to the music. Their coats shone like silk. The whip cracked again. Down they went on all-fours and began to gallop round the ring. Every time the music came to a certain chord the horses turned round and galloped the other way.

Every one clapped till they could clap no more when the horses went out, and they hadn’t finished clapping when Sticky Stanley the clown came in. He did look funny. His face was painted white, but his nose and lips were red, and he had big false eyebrows that jerked up and down.

He had a broom in his hand and he began to sweep the ring—and he fell over the broom. He picked himself up, and found that his legs had got twisted round themselves, so he carefully untwisted them and then found that the broom was twisted up with them. So of course he fell over the broom again, and every one laughed and laughed.

Stanley turned somersaults, walked on his hands, carried a sunshade with one of his feet, went round the ring walking on a great round ball, and made so many jokes that Jimmy had a pain in his side with laughing.

Then came Lal, Lotta’s mother, with the ten terrier dogs. How lovely they looked, all running into the ring in excitement, their tails wagging, their barks sounding loudly in the big tent.

There were ten little stools set out in the ring, and Lal patted a nearby stool.

“Up! Up!” she said to a dog, and he neatly jumped up and sat down on his stool. Then each dog jumped up on a stool and there they all sat, their mouths open, their tongues hanging out, their tails wagging.

Lal looked grand. She was dressed in a short, fluffy frock of bright pink, and it sparkled and shone as if it were on fire. She had a bright wreath of flowers in her hair and these shone too. Jimmy thought she looked wonderful. He had only seen her before dressed in an old jersey and skirt—but now she looked like something out of Fairyland!

How clever those dogs were! They played follow-my-leader in a long line, and the leader wound them in and out and in. Not a single dog made a mistake! Then they all sat up and begged, and when Lal threw them a biscuit each, they caught their biscuits one after another and barked sharply once. “That’s their thank-you!” thought Jimmy.

Lal ran to the side of the ring and fetched the big round ball that Sticky Stanley the clown had walked on so cleverly.

“Up! Up!” she cried to a dog, and it leapt up on the ball and did just as the clown had done—walked swiftly on the top of it as the ball went round! Lal threw him a biscuit for doing it so well.

Then Judy, the little brown-headed terrier, impatient to do her special trick, jumped down from her stool and ran behind Lal. Lal turned in surprise—for it was not like Judy to leave her stool before the right time.

But Judy had seen the hoops of paper that Lal had ready for her, and she wanted to do her trick and get her share of clapping. So she took hold of a hoop and ran to Lal with it. She put it down at Lal’s feet and stood there wagging her tail so fast that it couldn’t be seen.

Lal laughed. She picked up the hoop and held it shoulder high. “Jump, Judy, jump then!” she cried.

Light as a feather Judy jumped through the hoop, breaking the thin paper as she did so. Then Lal picked up two paper hoops and held them high up, about two feet apart.

“Jump, Judy, jump!” she cried. And Judy, taking a short run, jumped clean through both hoops. How every one clapped the clever little dog!

Jimmy’s face was red with excitement and happiness. How wonderful the circus folk were in the things they could do, and in their love for their animals! Jimmy watched the ten dogs go happily out with Lal, a forest of wagging tails, and he knew that Lal would see that they all got a good hot meal at once. She loved them and they loved her.

The horses came in again—white ones this time—and who do you suppose came in with them? Why, Lotta! Yes, little Lotta, no longer dressed in her ragged old frock, but in a fairy’s dress with long silvery wings on her back! Her dark curls were fluffed out round her head and her long legs had on silvery stockings. She wore a little silver crown on her head and carried a silver wand in her hand.

“It can’t be Lotta!” said Jimmy to himself, staring hard. But it was. She waved her wand at him as she passed his seat, and—what else do you suppose she did? She made one of her dreadful faces at him!

Lotta jumped lightly up on to the back of one of the white horses. She sat there without holding on at all with her hands, blowing kisses and waving. The horses had no saddles and no bridles. Lotta couldn’t have held on to anything if she had wanted to.

Jimmy watched her, his heart thumping in excitement. Whatever would she do next? She suddenly stood up on a horse’s back, and there she stayed, balancing perfectly, whilst the horse cantered round and round the ring.

Jimmy was afraid the little girl would fall off—but Lotta knew she wouldn’t! She had ridden horses since she was a baby. Down she went again, sitting, and then up again, this time standing backwards, looking towards the tail of the horse. Every one thought she was very brave and very clever.

Then in came Laddo, her father, dressed in a tight blue shining suit, with glittering stars sewn all over it. He was much cleverer than Lotta. The little girl jumped down when her father came in, and ran to the middle of the ring. Laddo jumped up in her place. He leapt from one horse to another as the three of them cantered round the ring. He stood on his hands as they went, he swung himself from side to side underneath a horse’s body—really, the things he did you would hardly believe!

Then Lotta jumped up behind him and the two of them galloped out of the ring together, followed by a thunderstorm of clapping and shouting. Jimmy’s hands were quite sore with clapping Lotta. He felt very proud of her.

Jumbo came next, and he was very clever, for he certainly could play cricket extremely well. Mr. Tonks bowled a tennis-ball to him and he hit it every time. Once, to Jimmy’s great delight, Jumbo hit the ball straight at him, and by jumping up from his seat Jimmy just managed to catch the ball. And then everybody clapped him, and Jumbo said, “Hrrrumph, hrrrumph!” very loudly indeed. Jimmy threw the ball to him and he caught it with his trunk.

The circus went on through the evening. Sticky Stanley the clown came in a great many times and always made every one laugh, because he seemed to fall over everything, even things that were not there. Lilliput and his monkeys were very clever. They helped Lilliput to set a table with cups and saucers and plates. They got chairs. They sat down at the table. They had feeders tied round their necks, and they passed one another a plate of fruit.

Jemima was the best. She peeled a banana for Lilliput and fed him with it! But then she stuffed the peel down his neck and he pretended to chase her all round the ring, and everyone laughed till they cried.

Then Jemima got into a corner and pretended to cry. When Lilliput came up she took his handkerchief out of his pocket and wiped her eyes with it. Then she leapt on to Lilliput’s shoulder and spread the handkerchief over the top of his head. Jimmy laughed just as much at Jemima as he did at the clown.

Of course Oona the acrobat had a lot of clapping too, especially when he walked up his step-ladder on his hands and stood on the top on just his head! Stanley the clown came running in to try and do it, but of course he couldn’t, and he fell all the way down the ladder, bumpity-bumpity-bump! Jimmy was afraid he might hurt himself, but he saw Stanley grinning all the time, so he knew he was all right.

Oona did another clever thing too—he had a wire rope put up from one post to another, and he walked on the rope, which was about as high as Mr. Galliano’s top-hat from the ground. Jimmy hadn’t known he could do that—and he wondered how Oona did it. Surely it must be very difficult to walk on a rope without falling off at all!

The circus came to an end all too soon. All the circus folk came running into the ring, shouting, bowing, jumping, and every one clapped them and shouted too.

“Best circus that’s ever come to this town!” said a big man next to Jimmy. “Fine show. I shall come and see it next week too. That little girl on horseback was very good—one of the best!”

Jimmy saved that up to tell Lotta. He would see her to-morrow. There was no circus on Sunday. The circus folk had a rest that day, and Lotta had said that Jimmy could spend the day with her.

“I must run straight home now,” thought Jimmy to himself. “Mother will be waiting for me. What a lot I shall have to tell her!”

So he ran home, though he would dearly have loved to find the fairy-like Lotta with her silvery wings and talked to her.

It was Sunday. Jimmy remembered that he was to spend the whole day with Lotta. What fun it would be to wander about among the circus folk and see old Jumbo, and pet Jemima the clever little monkey, and have his hands licked by all the jolly little terrier dogs! Jimmy sang loudly as he got up.

He was soon in the circus field. The sun shone down. It was going to be a lovely day. But as he made his way between the caravans and the tents Jimmy was surprised to see that everyone looked gloomy.

“I wonder what the matter is?” thought Jimmy to himself. He passed the clown’s caravan, and saw Sticky Stanley eating a breakfast of bacon and eggs. Stanley looked miserable. It was strange to see the clown looking like that.

He was usually full of jokes and nonsense.

He saw Jimmy and called out to him: “Hey, Jimmy, don’t you let Mr. Galliano see you this morning! He’s forbidden any outsiders to come into the circus field.”

“Why?” asked Jimmy, in astonishment. “He was very nice to me yesterday. He gave me a ticket for the show. What’s the matter?”

“Listen to that, then!” said the clown, pointing with his fork towards the big blue caravan in which Mr. Galliano lived with his wife. “Just listen to that!”

Jimmy listened. It sounded as if about six cows were bellowing in Galliano’s caravan—but it was only Mr. Galliano being very angry indeed, and shouting at the top of his very big voice. Jimmy stared in the direction of the blue caravan—and as he stared, Mr. Galliano came down the steps at the back.

“He’s got his hat on quite straight up,” said Jimmy, at once. “He’s always had it on one side before.”

“Yes, that means bad news, all right,” said the clown. “Hop off. Jimmy. Don’t let him see you.”

Jimmy hopped off. He ran round the clown’s caravan and came to the red-and-white one in which Lotta lived with Lal and Laddo, her father and mother. Lotta was sitting on the steps outside, polishing her circus shoes.

“Hallo, Jimmy,” she said. “Come up here.”

“Lotta, what’s the matter with every one this morning?” asked Jimmy. “You all look so gloomy, and I just heard Mr. Galliano in a bad temper.”

“There’s matter enough,” said Lotta, dropping her voice. “You know Harry, our odd-job man—the carpenter who puts up the benches, does most of the packing and unpacking and all the little mending and making jobs a circus always has? Well—he ran away last night, taking nearly all the money with him that the circus took last week!”

“Oh, I say, how dreadful!” said Jimmy, shocked. “Won’t you get any money, then?”

“Not a penny,” said Lotta. “And that’s very hard, you know, because we none of us save anything. The worst of it is, Harry was so useful—we don’t really know how we are going to do without him.”

“Perhaps he will be caught,” said Jimmy.

“I don’t think so,” said Lotta. “He had a good start, because he took the money when we were all asleep last night and went off about two o’clock in the morning. He may be anywhere now. I do hope we have a good week now, Jimmy—if we don’t, it will be very bad for us all.”

“I hope you do too,” said Jimmy. “I do wish I could help a bit, Lotta.”

“I suppose you don’t know a good handy carpenter in your town who could come along for a week and help us, do you?” said Lal, Lotta’s mother, coming to the door of the caravan. “There are a lot of jobs that must be done before to-morrow night. Oona’s ladder must be made stronger, he says. And there’s a bar loose in the dogs’ big cage.”

“What about my father?” said Jimmy eagerly. “He’s a carpenter, you know! He could do anything you wanted!”

“Yes, but what about his work?” said Lal. “He can’t leave that to come to us.”

“He’s out of work,” said Jimmy. “He would be glad to come. Oh, Lotta—will you come to tea with me at home this afternoon and we could find out if my father will come? I do, do hope he can.”

“We’d better tell Mr. Galliano first,” said Lal. She called to her husband at the back of the caravan: “Laddo, will you go with Jimmy and tell Galliano about his father being a carpenter?”

“Right,” said Laddo. He put down his newspaper and ran down the caravan steps with Jimmy. “Come on, son,” he said.

Mr. Galliano was with his horses, patting them and speaking gently to them. No matter how bad a temper he sometimes flew into he was never anything but gentle with his beloved horses. No one had ever seen him sharp or unkind with any animal. All his horses loved him and would do anything in the world for him.

He heard Jimmy and Laddo coming and he turned to meet them.

“What do you want?” he said, not seeming at all pleased to see Jimmy.

“Mr. Galliano, sir, this boy says his father is a carpenter and could take Harry’s place for the week,” said Laddo.

“Tell him to come and see me this evening, yes,” said Mr. Galliano shortly, and he turned back to his horses. Laddo and Jimmy went out. Jimmy felt excited. Just suppose his father got the job to help the circus—and just suppose they kept him on! Oh, wouldn’t that be wonderful!

He ran back to Lotta. “Let’s go for a walk with the dogs,” said Jimmy. “It’s such a lovely day—and every one is so gloomy here this morning. We can get back here to dinner.”

“All right,” said Lotta, and the two ran to get the excited terriers. Soon Lotta had five of the dogs on her big lead, and Jimmy had the other five. Lotta was a little bit jealous because all the dogs seemed to want to go with Jimmy.

“I never saw any one so good with animals as you, Jimmy,” she said. “At least, that’s not counting Mr. Galliano—he can tame a wild tiger and make it purr like a cat in two days!”

The two children set off over the countryside. In a little while Lotta forgot about Harry and how he had run off with every one’s money. Soon the two were having great fun, racing with their dogs and joining in the barking with laughs and shrieks.

“Shall we let them loose for a real good run?” asked Jimmy, when they were well out in the country. “They would love it so!”

So they let all the dogs loose, and with excited yaps the neat little terriers tore off to go rabbiting. Jimmy and Lotta sat under a tree.

“I did love the circus last night, Lotta,” said Jimmy. “And I did think you were clever—riding on a horse standing up and never falling off!”

“Pooh,” said Lotta, making a face at him. “That’s easy. You could do it yourself.”

“I couldn’t,” said Jimmy. “I can’t even walk on my hands yet, and it does look so easy when you all do it! I wish you’d teach me, Lotta.”

“All right,” said Lotta. “But not now. I’m too hot. I wish you belonged to the circus, Jimmy. I shall be dull without you. It’s nice to have some one to make faces at when I feel like it.”

“I can’t think why you want to do that,” said Jimmy, surprised. “All the same—I’d like to go with you when you go off again. But I wouldn’t like to leave my mother and father behind.”

“Where are those dogs?” said Lotta suddenly. “We mustn’t lose any, you know, Jimmy. My word, we should get into trouble if we did! Hie, Judy, Judy, Nigger, Spot!”

Some of the dogs came running up and flung themselves on the two children. Jimmy counted them. “Eight,” he said. “Where are the others?”

They quickly put the eight dogs on the leads. Lotta looked worried. “Whistle, Jimmy,” she said. So Jimmy whistled.

“There comes Punch!” said Lotta, and sure enough one of the missing dogs came loping over the field towards them. Jimmy whistled again and again—but the tenth dog was nowhere to be seen!

“We shall have to go,” said Lotta, looking scared. “Whatever will Lal and Laddo say when we turn up without Darky? Come on—it’s getting late. Perhaps Darky will come after us when he’s finished hunting.”

They went back to the circus. No Darky came after them. Lotta was very silent. Jimmy was miserable too. What a horrid day this was after all!

“We’ll put the dogs into the cage, and then we’ll go and tell Lal we’ve lost Darky,” said Lotta. She was crying now. Lotta loved all the dogs and she couldn’t help wondering if Darky had been caught in a trap. Also she knew that her mother would be very angry with her.

Jimmy opened the door of the great cage. As he did so a little dark dog crept out from under the cage itself. Jimmy gave a yell.

“Lotta! Darky’s here! He must have run all the way home before us and hidden under his cage. Look!”

Lotta gave a shriek of delight and hugged Darky. “You silly animal!” she said. “You did give me a fright! Oh, Jimmy—I’m so happy now!”

Jimmy was glad. He squeezed Lotta’s hand as they ran to the caravan for dinner. Lotta squeezed his hand back—but she was so strong that she made Jimmy yell out in pain. You never knew what that little monkey of a Lotta was going to do next! Jimmy dropped her hand in a hurry and felt half-cross with her. But when he smelt the smell of frying sausages he forgot everything except that he was dreadfully hungry.

They all had their dinner sitting outside the caravan. The sausages were lovely and so were the potatoes cooked in their jackets and eaten with butter and salt. Jimmy thought he had never had such a lovely dinner in his life. Afterwards there were oranges and chocolate to eat.

Jimmy took Lotta home to tea with him. He ran indoors with the little girl and found his mother making toast for tea. They always had toast on Sundays. It smelt good.

“Mother, this is Lotta. I’ve brought her home to tea because I want to ask Dad something. Where is he?”

“Out in the garden, mending the old shed,” said Mother. “Hallo, Lotta! How’s the circus going?”

“All right, thank you,” said Lotta shyly. She looked at Jimmy’s mother and thought she was lovely. She was so neat and her face was so kind. Lotta had not often been inside a house, and she looked round curiously. It seemed just as strange to her to be inside a house as it was to Jimmy to be inside a caravan.

“Dad! Dad!” shouted Jimmy, running into the back garden, “Harry, the odd-job man at the circus, has run off with the circus money—and Mr. Galliano wants a new carpenter. He says will you go and see him tonight.”

“That’s the first bit of luck I’ve had for a long time,” said Jimmy’s father, delighted. “Yes, I’ll go up and see if I can get the work after tea. A week’s work is better than nothing. Well, that’s given me an appetite for my tea! Is the toast ready, Mother?”

Soon Lotta, Jimmy, and the two grown-ups-were sitting round the tea-table. Lotta was on her very best behaviour. She didn’t make a single face. She liked Jimmy’s mother much too much to shock her!

After tea, Jimmy, Lotta, and Jimmy’s father set off to the circus field. “If only I can get that job!” said Jimmy’s father.

“I do hope you do, Dad!” said Jimmy.

Jimmy, Lotta, and Jimmy’s father soon got to the circus field. “There’s Mr. Galliano, over there,” said Lotta, as they went through the gate.

“Right,” said Mr. Brown. “I’ll go over and see him now.” He left the two children and walked over to where Mr. Galliano was talking to Oona the acrobat.

“What do you want?” said Mr. Galliano, seeing that Mr. Brown was a stranger.

“I’m Jimmy Brown’s father,” said Mr. Brown. “I’m a carpenter, sir, and I can turn my hand to anything. I’d like you to give me a chance, if you will. I’d work well for you.”

Mr. Galliano looked Mr. Brown up and down. He liked what he saw—a strong, kindly-faced man, with bright eager eyes just like Jimmy’s.

“Come to-morrow morning,” said Mr. Galliano. “There will be plenty for you to do, yes!”

“Thank you, sir,” said Mr. Brown, and he walked off, pleased. It would be fine to work at last! The two children ran to meet him. How glad Jimmy was to know that his father would belong to the circus for at least a week! What would the boys at school say when they knew that his father was with the circus all day? They would think that was fine!

Jimmy’s father worked well. Mr. Galliano was delighted with him. He could, as he said, turn his hand to anything. He mended five of the circus benches. He put a new wheel on to Mr. Galliano’s caravan. He made Oona’s ladder stronger than it had ever been before. He put in two new bars where the dogs had pushed them loose in their cage. And he won Lilliput’s heart by making him a proper little house for Jemima the monkey to live in—it even had a little door!

Jimmy was delighted to hear every one praising his father. He had always loved his father and thought him the finest man in the world—and it was nice to hear people saying he was ten times better than Harry!

“His laugh is worth ten shillings a week!” said Lal. “My, when old Brownie starts laughing, you’ve got to hold your sides! He’s as merry as a cricket!”

Jimmy thought it was funny to hear his father called Brownie. But the circus folk hardly ever called anyone by their right name. Brownie was the name they gave to Mr. Brown, and Brownie he always was, after that!

The circus did well again that week. Mr. Galliano began to wear his hat on the side of his head once more. Every one cheered up. If Galliano was merry and bright then the circus folk were happy.

Jimmy was happy too that week. He had to go to school, but every spare minute he had he was in the circus field, helping. He was always ready to give a hand to any one. When the circus show began each night, Jimmy stood near the curtains through which the performers had to pass, and pulled or shut the curtains properly each time. He got Oona’s ladder and tightrope ready for him. He took care of the dogs whilst they were waiting for their turn. He got Jumbo out of his tent too, for Mr. Tonks, and took him back again when the show was over. Jumbo loved Jimmy. He blew gently down the little boy’s neck to show him how much he liked him. Jimmy thought that was very funny!

When Saturday came, Mr. Galliano whistled to Mr. Brown—or Brownie, as he was now called—and Brownie went over to him.

“Here’s your week’s money,” said Mr. Galliano, paying him. “Now look here—you’ve done well—what about you coming along with us, yes? We can do with a man like you—always cheerful, and able to do anything that turns up.”

Mr. Brown went red with pleasure. It was a long time since any one had praised him.

“Thank you, sir,” he said. “I’ll have to talk it over with my wife. You see—I think she would be upset if I left her and Jimmy. I might not see them again for a long time.”

“Well, think over it,” said Mr. Galliano. “If you come, you can live with Stanley, the clown. He’s got room in his caravan for another fellow. We go off tomorrow—so let me know quickly, yes?”

Mr. Brown hurried home to dinner. He told Jimmy and Jimmy’s mother all that Mr. Galliano had said.

“I think I’ll have to take the job,” he said. “It’s hard to leave you both, though.”

Jimmy’s mother didn’t know what to say. She couldn’t help the tears coming into her eyes. Jimmy gave her his handkerchief.

“Oh, Tom,” said his mother, “I shall miss you so. Don’t go. I can’t bear to be without you—and Jimmy will miss you so much too. We shall never know where you are, travelling about the country—and goodness knows when we shall see you again!”

“Well, we needn’t tell Mr. Galliano till to-morrow,” said Mr. Brown. “We’ll talk about it to-night.”

Jimmy thought and thought about it. He badly wanted his father to belong to the circus—but not if he and his mother had to be left behind! No—that would never do at all! And yet they couldn’t go with him. There wasn’t room for them. And if his father said no to Mr. Galliano, then he might be out of work again for a long long time—just as he had found a job that he could do so well.

It was a puzzle to know what to do. Jimmy felt that he really, really, couldn’t bear it if his father had to leave home. His mother would be so sad.

The circus gave its last show that night. It did very well, and once again there was not an empty seat in the big tent, for people came from all the towns round to see it. Somebody gave Lotta a big box of chocolates and she was very pleased. She showed them to Jimmy. “We’ll share them,” she said, emptying out half the box into a bag. “They’re lovely.”

That was just like Lotta. She was the most generous little girl that Jimmy had ever known. But Jimmy could not smile very much at her. The circus was going off the next day to a far away town. He would have to say good-bye to every one. He felt as if he had known the circus folk all his life, and he was sad to part with them.

“I’ll come and see you to-morrow morning, Lotta,” he said.

“Come early,” said Lotta. “We’ll be packing up to go, and that is a busy time. We shall start off about twelve o’clock. We’ve got to get to Edgingham by night.”

“Good-night then,” said Jimmy, looking at Lotta hard, so as to remember for always just how she looked—she had on her fluffy circus frock, her long silver wings, her little silver crown and her silvery stockings. As he looked at her she made one of her dreadful faces!

“Don’t!” said Jimmy. “I was just thinking how nice you looked.”

“You’d better hurry home,” said Lotta. “It looks as if a storm is coming up. Hark! That’s thunder!”

Jimmy ran off. Certainly there was a storm coming. Great drops of rain fell on him as he ran through the town, and stung his face. The thunder rolled nearer. A flash of lightning lit up the sky, and Jimmy saw that it was full of enormous black clouds, hanging very low.

Jimmy’s mother was glad to see him, for she had been afraid he would be caught in the storm. She bundled him into bed and he fell asleep almost at once, for he was tired.

The storm crashed on. Jimmy slept peacefully and didn’t hear it. Away up in the circus field the folk there listened to the pouring rain pattering down on their caravans.

Crash! The thunder rolled again. The horses whinnied, half-frightened. The dogs awoke and barked. Jemima, the monkey, who always slept with Lilliput, crept nearer to him and began to cry like a child. Lilliput petted her gently.

Jumbo, the big elephant, raised his great head. What was this fearful noise that was going on around him? Jumbo was angry with it. He threw back his head and trumpeted loudly to frighten it away.

Crash! Crash! The thunder still rolled on, and one crash sounded just overhead. Jumbo, half-angry half-frightened, pulled at his post. His leg was tied to it, but in a trice the big elephant had snapped the thick rope. He blundered out of the tent, looking for the one man he trusted above everything—his keeper, Mr. Tonks.

But Mr. Tonks was fast asleep in his caravan. Not even a storm could keep Mr. Tonks awake. He snored in his caravan as if he were trying to beat the loudness of the thunder!

Jumbo grew frightened in the dark. He stood in the rain, waving his big ears to and fro and swinging his trunk backwards and forwards. Another peal of thunder broke through the night, and a flash of lightning showed the field-gate to Jumbo. It was open.

The elephant, remembering that he had come in through that gate, made his way towards it. No one heard him, for the rolling of the thunder and the pattering of the rain made such a noise. Jumbo slipped through the gate like a great black shadow, and set off alone up the lane that led to the town.

No one was about except Mr. Harris, the town policeman. He was sheltering from the rain in a doorway. He got a dreadful shock when he saw Jumbo lit up in a flash of lightning, coming up the street towards him. He didn’t know it was only Jumbo. He fled away as fast as he could back to the police-station. He was the only person who met Jumbo running away.

The storm passed. The rain stopped. The night became peaceful and every one slept. The circus dogs lay down and Jemima the monkey stopped crying.

The morning broke peaceful and bright, though the circus field was soaking wet. Still, the May sunshine would soon dry that up.

Mr. Tonks dressed himself and went straight out to see his beloved Jumbo. When he looked into the tall tent and saw no elephant there, he went white.

“Jumbo! Where’s my elephant!” he shouted, and he tore all round the field, waking every one up. Heads peeped out of caravans and scared faces looked up and down.

“Jumbo’s gone! My elephant’s gone!” cried Mr. Tonks, tears pouring down his cheeks. “Where is he, where is he?”

“Well, he’s not in anybody’s caravan, that’s certain,” said Stanley, the clown. “Can’t you see his big tracks anywhere, Tonky?”

“Yes—they lead out of the gate!” said Mr. Tonks, almost off his head with shock and grief. “What’s happened to him? I’ll let the police know. He must be found before anything happens to him.”

“Well, he’s too big to lose for long,” said Mr. Galliano, coming out of his caravan with his hat on the side of his head. “Don’t worry, Tonks. We’ll soon find him.”

But somebody already knew where Jumbo had gone—and who do you suppose that was? It was Jimmy!

In the middle of the storm Jimmy awoke suddenly. He sat up in bed, looking puzzled. He had heard a funny noise outside his house. It sounded like “Hrrrumph! Hrrumph!” Who made a noise like that? Jumbo, of course!

“But it can’t be Jumbo,” said Jimmy, in the greatest astonishment. He hopped out of bed and ran to the window. A flash of lightning lit up the little street—and quite clearly Jimmy saw Jumbo, plodding heavily up the street towards the heart of the town!

“It is Jumbo—and he’s frightened of the storm—and has run away!” thought Jimmy. “I must go after him!”

He dragged on his coat, put his feet into his shoes at the same time, and slipped downstairs. In a trice he was out of the house and running up the street after Jumbo. He must get him, he must! Poor old Jumbo, running away all alone, frightened of the storm!

“Jumbo, Jumbo!” called Jimmy—but Jumbo padded on and on!

Jimmy rushed up the street, calling Jumbo. The thunder rolled round and every now and again a flash of lightning showed him the big elephant padding through the streets. Jumbo could go very fast indeed when he liked and Jimmy couldn’t catch up with him. “If only I can keep him in sight,” panted Jimmy to himself. “Jumbo! Can’t you hear me shouting to you? Jumbo! Come to Jimmy!”

Jumbo took no notice at all. He went round the corner. He lumbered up the next street and the next. He came to the market-square and crossed it. Jimmy panted and puffed a good way behind him, pleased when the lightning lighted the night and showed him where Jumbo was.

Jumbo came to the better part of the town where the roads were wider, and where the houses were large, with big gardens. He padded along, his great feet making very little sound. Pad-pad-pad he went through the night, his big ears twitching and his little tail swinging. His trunk was curled up safely, for Jumbo was afraid that the thunder and lightning might harm it. Sometimes he gave a loud “hrrumph!” and then the people sleeping in the houses near by sat up in alarm and wondered whatever the strange noise was!

The elephant left the town behind. Beyond lay the woods, sloping up a big hill. Jumbo was pleased to come to trees and grass. He plodded on right into the wood and climbed half-way up the hill. Jimmy still followed him—and then he lost him!

It happened like this—the storm suddenly died down, and the lightning stopped. Jimmy could no longer see the elephant in the flashes, and as the wood was thick it was difficult to know which way Jumbo went now that he was not going down a road. Jimmy stopped and listened. Far away he could hear something crashing through the bushes—he knew it was Jumbo, but he could not tell which way to go to find him.

“Oh dear,” said the little boy, terribly disappointed. “I’ve come all this way—and I’m wet through—and I haven’t found Jumbo after all!”

He stood there by himself in the dark woods, wondering what to do. And then he suddenly saw a little light shining through the trees! He stared at it in surprise.

“What can that light be from?” he wondered. He made his way towards it, feeling before him as he went, for he did not want to walk into trees. It was dark and everywhere was wet. Jimmy shivered. He wished he were back in his own warm bed!

Stumbling over bushes and roots he came at last to the light. It shone from a cottage window. The blind was not drawn and Jimmy could see inside the room. He peeped in at the window.

A man was in the room, dressed in a gamekeeper’s coat and leggings. He was bending over a dog that lay in a basket. The dog was ill, and one of its legs was bandaged. The man was stroking it and saying something to it, though Jimmy could not hear a word.

“He looks a kind man,” thought the little boy. “Perhaps he will let me come in and dry my clothes.” So Jimmy knocked gently at the window.

The gamekeeper looked up at once, in the greatest astonishment, for it was the middle of the night. He walked to the window and opened it.

“Who’s there?” he said.

“It’s me, Jimmy Brown,” said Jimmy, the light shining on his face. “I came to look for Jumbo, the elephant, but I’ve lost him, and I’m so wet I thought perhaps you’d let me come in and dry my clothes.”

The gamekeeper stared as if he couldn’t believe his ears.

“What nonsense are you talking?” he said. “Looking for an elephant—an elephant! Whatever do you mean?”

“It’s Jumbo, the circus elephant,” said Jimmy, and he was going on to explain everything when the keeper told him to go to the door and come inside.

The little boy was glad to get into the cottage. The gamekeeper listened to his story in surprise. Then he felt Jimmy’s coat, which he had thrown on over his pyjamas.

“I’ll make a fire here,” said the man. “You’ll get a terrible chill if you keep those wet clothes on any longer. It’s a mercy you found me up. My dear old dog, Flossie, got knocked down by a car this morning and I’m sitting up with her to-night to make sure she’s all right. Else I should have been in bed.”

He made Jimmy take off his wet things and put on a coat and dressing-gown of his. They were much too big for Jimmy, but they were dry. The man lighted a fire on the hearth and soon there was a cheerful crackling of wood. Jimmy was pleased. The gamekeeper made a big jug of cocoa too, and the little boy sat drowsily by the fire, drinking hot cocoa and feeling suddenly very sleepy.

“I do wish I could have found Jumbo,” he said. “I don’t know how I can find him now. Mr. Tonks, his keeper, will be so upset.”

“Don’t you worry about finding elephants,” said the man. “I can track a baby rabbit if I want to—and you may be sure that Jumbo will leave tracks quite plain to see! We’ll go hunting for him in the morning!”

“But I must go home to-night,” began Jimmy—and then somehow his eyes closed, his head nodded, and he was fast asleep in the keeper’s chair by the blazing fire!

He didn’t wake up till morning. He heard the gamekeeper moving about and opened his eyes. Breakfast was on the table! There was porridge, bread and marmalade, and hot cocoa. It looked good to Jimmy.

The man had put him on a sofa in the corner, still wearing his large coat and dressing-gown. But now Jimmy’s own clothes were dry and he put them on, chattering to the kind keeper all the time, and really feeling most excited. They were going to find Jumbo after breakfast!

“How is your dog Flossie?” asked Jimmy, patting the sleek head of the big spaniel in the basket.

“Better,” said the keeper. “I think her leg will heal all right. I’ll leave her in her basket this morning with some milk near by, and she’ll sleep and be all right. If it hadn’t been for Flossie you wouldn’t have seen a light shining in my cottage last night, young man!”

“I know,” said Jimmy, stroking the dog, who lifted her pretty head and gave Jimmy a feeble lick with her tongue. “Good dog, Flossie! Get better soon! Good dog, then!”

“You’re good with animals,” said the keeper watching Jimmy. “Flossie hates strangers—you’re the first one she has ever licked.”

Soon the breakfast things were cleared away and the two of them slipped out-of-doors into the wet woods. The sun was shining, the birds were singing, and everywhere was golden. It was a beautiful May day.

“Look! That’s where Jumbo passed last night,” said Jimmy, pointing to where some bushes were trampled down. “We can follow his track from there.”

“Come along, then,” said the keeper. So the two of them followed Jumbo’s track. It was not at all difficult, for the elephant had made a real pathway for himself through the wood.

“Look! Jumbo pulled up a whole tree there!” said Jimmy in surprise. He pointed to where a birch tree lay uprooted. Yes—Jumbo had pulled it up. How strong he was!

“Elephants can easily pull up trees,” said the keeper. “Come on—the track goes over to the right just here.”

They went on and on through the wood, up the side of the hill—and quite suddenly they came upon Jumbo! He was lying down beneath a thick oak tree, his ears flapping to and fro, and his little eyes watching to see who was coming.

“Jumbo! Dear old Jumbo! I’ve found you at last!” cried Jimmy, and he ran up to the big animal and stroked his long trunk. Jumbo trumpeted loudly. He was pleased to see Jimmy. He was no longer frightened, for the storm had gone—but he felt strange and queer by himself in a quiet wood, instead of in the noisy circus field, with all his friends round him. He got to his feet and ran his trunk round Jimmy lovingly.

The gamekeeper stood a little way off, looking on in surprise. He was half afraid of the enormous elephant—but Jumbo took no notice of him at all. He had got his friend Jimmy and that was all he cared!

“Jumbo, you must come back to the circus field with me,” said Jimmy, stroking Jumbo’s trunk. “Mr. Tonks will be looking for you.”

“Hrrumph!” said Jumbo, when he heard Mr. Tonks’s name. He adored his keeper. He put his trunk round Jimmy’s waist and lifted him up on to his neck. But Jimmy cried out to him to take him down again.

“Jumbo, let me down! If you take me through the trees on your back the branches will sweep me off! You are so tall, you know. Let me walk beside you through the woods and when we come to the town I’ll ride.”

Jumbo understood. He lifted Jimmy down again, and then the two of them started off through the woods, down the hill towards the town. Jimmy called good-bye to the kind gamekeeper, who was staring at them in wonder, and very soon the two were out of sight.

After a while the woods came to an end and Jimmy walked beside Jumbo up a lane. Jumbo stopped and looked down at Jimmy. “Hrrumph?” he said gently.

Jimmy understood. “Yes, you can carry me now,” he said. “We can go more quickly then.”

Jumbo lifted him up on to his head. Jimmy crossed his legs and sat there. Jumbo set off at a good pace down the lane and into a big road. He knew the way back quite well, although he had only been there once, the night before.

People looked up when they heard the big elephant padding along—and how they stared when they saw Jimmy on the elephant! They ran after him, pointing and shouting in surprise and amazement.

“It’s the elephant that was lost! Look, it’s the circus elephant!” they cried.

Through the market-place went Jimmy, feeling tremendously proud, for really he was making a great disturbance and every one seemed most astonished. Jumbo padded on to the circus field—and there he and Jimmy were met by the whole of the circus folk, Mr. Galliano and Mr. Tonks at the front, Mr. Tonks yelling himself hoarse with delight to see his beloved elephant safely back again!

Jimmy had to tell his tale over and over again. Mr. Tonks flung his arms round him and hugged him till Jimmy felt as if his bones were breaking. The elephant’s keeper was quite mad with joy and delight. Tears poured down his cheeks as he stroked Jumbo’s trunk, and the big elephant stood trumpeting in joy to see his keeper again. Everyone was excited and pleased.

And in the middle of it all, Mr. Galliano, his hat well on one side, suddenly made a most surprising speech!

“Jimmy Brown!” he began. “You are a most remarkable boy—yes? You love animals and they love you—you should live with them and care for them. Yes? Very well. We will take you and your father with us, both of you, and if your mother will come too, then we will have your whole family, and it will not be too much for us. No? You shall belong to the circus—yes, no, yes?”

Mr. Galliano got quite muddled, he was so pleased and excited. As for Jimmy he was almost off his head with delight. Belong to the circus? Go off with them—and Lotta! Oh, what joy! The very thing he would like best in all the world.

“I must go and tell my mother!” he said, and he ran off home at top speed!

Jimmy tore home to tell his mother all the adventures of the night—and to ask her if she would go with the circus. Then Dad would have a job, and he, Jimmy, would be able to help with the animals, and Mother would be with them to care for them and love them. Nobody would have to be left behind.

His mother and father were looking very worried when he got home, for they had found his bed empty that morning and hadn’t known where he had gone. And what had puzzled them more than ever was to find that he had left his trousers behind! Wherever could he have gone in his pyjamas?

Jimmy soon told them all about how he had gone to find Jumbo in the middle of the night—and how he had spent the night at the gamekeeper’s cottage—and they had looked for Jumbo in the morning. His parents listened in amazement.

“But listen, Mum—listen, Dad,” said Jimmy, “I’ve got something much more wonderful to tell you! Mr. Galliano wants me to go off with the circus—to help with the animals! What do you think of that? And he says you can go too, Mother—and Dad will be the odd-job man and do everything that is needed in a travelling circus!”

His mother and father stared at Jimmy as if he had gone quite mad. Then his mother began to cry, quite suddenly. She wiped her eyes with her handkerchief and said, “I’m not really crying. I’m happy to think your father’s got a good job at last—and you’re quite a hero, Jimmy darling—and I can go with you both and look after you.”

“Mother, then you’ll come?” shouted Jimmy, jumping up and down in joy, and flinging his arms first round his father and then round his mother. “We’ll all be together. Oh, that will be glorious.”

“Yes—but what about a caravan?” said his father. “We can’t all share the clown’s caravan, you know. That would have been all right for me—but not for you two as well.”

“We’ll ask Mr. Galliano about that,” said Jimmy. “He’s a wonderful man. I’ll go right away now. Mother, can you pack to-day and come?”

“Jimmy! Of course not!” said his mother, looking round at her bits of furniture.

“Oh, Mother, you must!” said Jimmy. “You won’t want much in a caravan, really you won’t. I’ll get Lotta’s father and mother to come along and tell you what to take.”

The excited boy rushed off to the circus field. He was singing for joy. First he must find Lotta and tell her the great news. He saw her with five of the dogs.

“Lotta, Lotta!” he yelled. “I’ve got news for you! I’m going to join the circus too.”

Lotta was so surprised and delighted that she dropped the dogs’ lead and all the dogs scampered off in different directions. The two children spent ten minutes getting them back, and then Jimmy told Lotta everything. She listened joyfully, and then gave Jimmy a big pinch.

“I can’t help pinching you, I feel so glad!” she said.

“Well, it’s a funny way of showing you’re glad,” said poor Jimmy, rubbing his arm. “But you’re a funny girl altogether, Lotta—more like a boy—so I don’t mind much—I don’t mind anything to-day, because I’m joining the circus, the circus, the circus!”

“He’s joining our circus, circus, circus!” shouted Lotta, and she threw herself over on to her hands and turned cartwheel somersaults all round the field. That made Jimmy laugh. It always looked so easy and was so dreadfully difficult when he tried to do it!

He went to find Mr. Galliano. Mr. Galliano was so pleased that Jumbo had been found and brought back safely that his hat was almost falling off, it was so much on one side. He was glad to see Jimmy again.

“You are coming with us—yes?” he cried, and banged Jimmy on the back.

“Yes, Mr. Galliano,” said Jimmy, his brown eyes shining brightly. “But we haven’t a caravan, you know. How can we manage it?”

“Easy, easy!” said Mr. Galliano. “We have an old small caravan that is used for storing things in. We will take them out, and put them into an empty cage for now. Your mother can clean out the old caravan and you can all come in that! Yes? But we go to-day, Jimmy, we go to-day! Is that your father I see over there—yes?”

It was. “Good-day, sir,” said Mr. Brown, smiling at Jimmy, who was capering round in delight. “We’ll all come with you, sir.”

Mr. Galliano took Mr. Brown to the old caravan and told him he could have it, if he would store the things inside it into an empty cage they had. Mr. Brown listened. He turned to Jimmy.

“Go back to your mother and tell her all this,” he said. “Take Lotta with you. She may be able to help.”

“We will not start till two hours later than usual, yes?” said Mr. Galliano generously. “That will give you and your family time to get everything ready.”

My goodness, what a day that was! Jimmy, Lotta, and Lotta’s mother, Lal, went rushing off to Jimmy’s home to help his mother. Lal was a great help. She looked quickly round the bare little house and said at once what was to go and what was to be sold. She found a man who would buy the things that were not wanted. She helped to take down the curtains. She said that the frying-pans must certainly all be taken—and the big kettle—and the oil-stove for cooking—and the little stool—but only one chair. The big bed could go into the caravan, for it was not a very large size and Jimmy would have to sleep on a mattress at night, in a corner of the caravan.

It did sound exciting. Lotta said they must take their two candlesticks, and a little folding-table. The iron must be taken, for circus clothes must always be fresh and stiffly ironed. The wash-tub could hang under the caravan. Jimmy entered into everything, and was so thrilled to think he would sleep on a mattress only and not on a bed that he could hardly stop dancing around.

“Jimmy, you are more hindrance than help,” said his mother at last. “Go to your father and ask him if he can bring the caravan down to the house as soon as possible, for we can easily put the things into it here.”

Off went Jimmy and Lotta, rushing at top speed. Neither of them could walk that day, things were too exciting! They found Mr. Brown. He had stored all the things from the old caravan into an empty cage, and had given it a rough clean. It was a small and rather ugly old caravan, badly in need of paint—but to Jimmy’s eyes it was beautiful! It was a home on wheels, and what more could a little boy want?

He went to fetch one of the circus horses to take the caravan down to his house. Soon there was great excitement in Jimmy’s street when the neighbours learnt what was happening. “The Browns are going off with the circus!” people shouted to one another, and they came to help. Lal scrubbed the floor of the old caravan for Jimmy’s mother. Lotta cleaned the windows. There were four—two little ones at the front and one at each side. There was a door at the back and the usual little ladder hanging down.