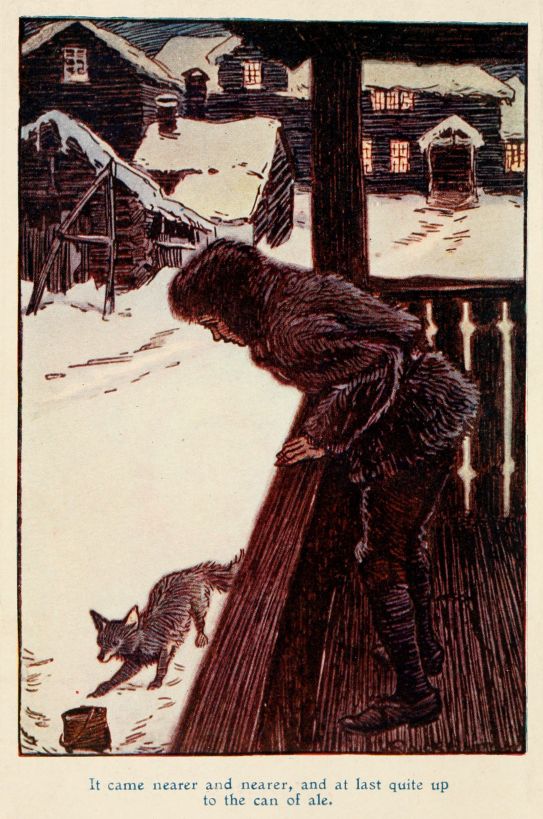

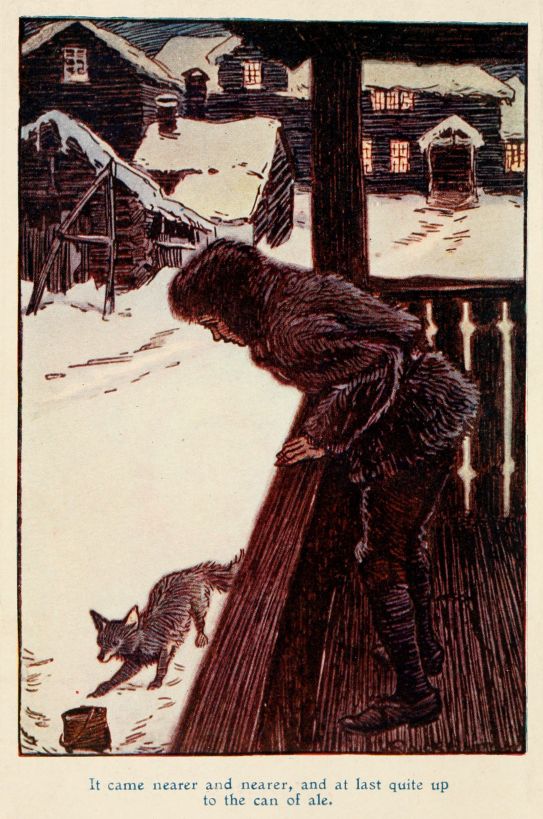

It came nearer and nearer, and at last quite up to the can of ale.

Produced by Al Haines

* A Distributed Proofreaders US Ebook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Feats on the Fiord

Author: Martineau, Harriet

Date of first publication: 1914

Date first posted: May 13, 2011

Date last updated: January 4, 2019

Faded Page ebook#20190128

It came nearer and nearer, and at last quite up to the can of ale.

FEATS ON THE FIORD

BY

HARRIET MARTINEAU

WITH COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS

BY ARTHUR RACKHAM

LONDON: J. M. DENT & SONS LIMITED

NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

1914

INTRODUCTION

Miss Martineau's Norwegian romance won its way long since into the hearts of children in this country. The unhackneyed setting to the incidents of the tale distinguish it from thousands of more ordinary children's stories; nor is there any other tale so well-known having its scenes laid in the land of the fiords. It is quite safe to add that perhaps no other author has felt so strongly and communicated so convincingly the mystic charm of these northern lagoons with their still depths and reflections, their inaccessible walls of rock and their teeming wild-fowl life.

This mystic charm is deepened in the book by the thread of popular superstition which runs throughout the episodes and, in fact, gives rise to them. Miss Martineau's dénouements were calculated to shatter the follies of belief in Nipen and other supernatural agents; but her own crusading traffic in them rather endears them to the imagination of the reader and certainly supplies a fascination which the most sceptical of young readers would be sorry to miss.

The author also brings home to the youthful mind the wonder of the physiographical peculiarities of northern latitudes. The book opens with the long nights and ends with the long days. The midnight sun and the northern lights play their parts, whilst the beautiful simplicity of farm-life in the Arctic circle is unfolded with authoritative interest.

As for the hero, young Oddo, he is a prince among dauntless boys, yet he never oversteps the bounds of true boyishness. He would be a hero anywhere; but as a leading character in this romance, combined with all the charm of natural effect in which he moves, he makes Feats on the Fiord a book to be classed among the few best of its kind.

F. C. TILNEY.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

It came nearer and nearer, and at last quite up to the can of ale . . . . . . . . . . . Frontispiece

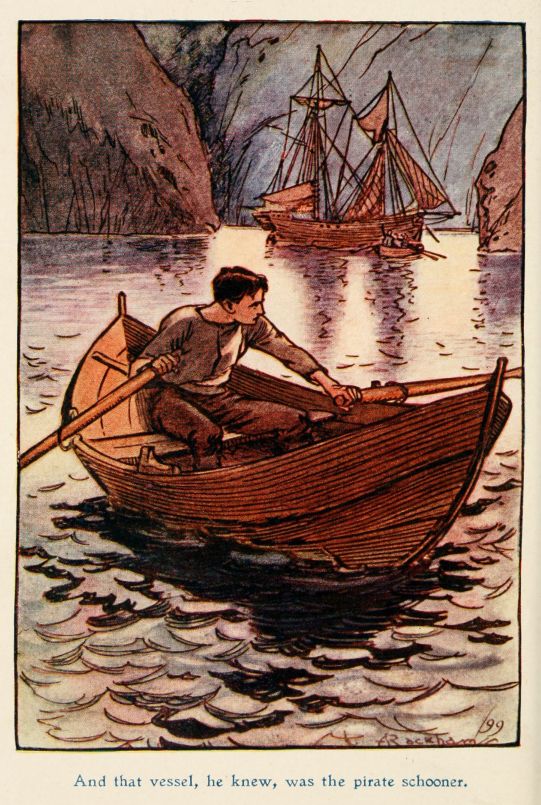

And that vessel, he knew, was the pirate schooner

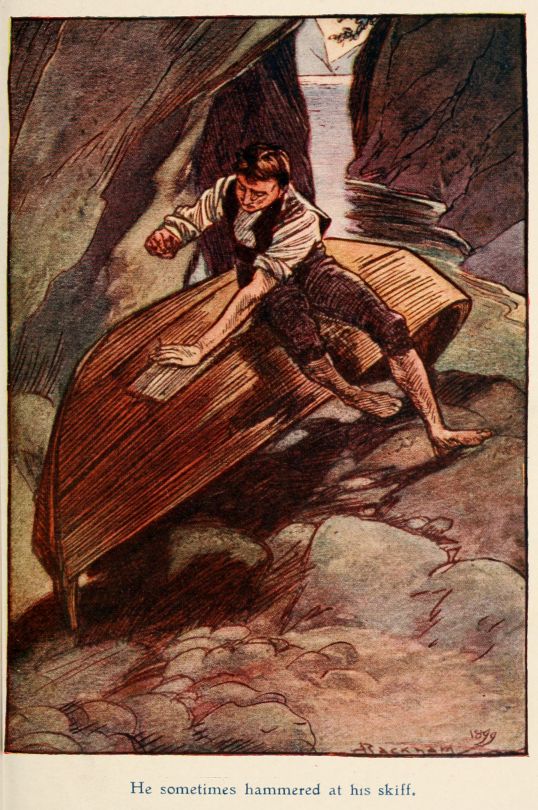

He sometimes hammered at his skiff

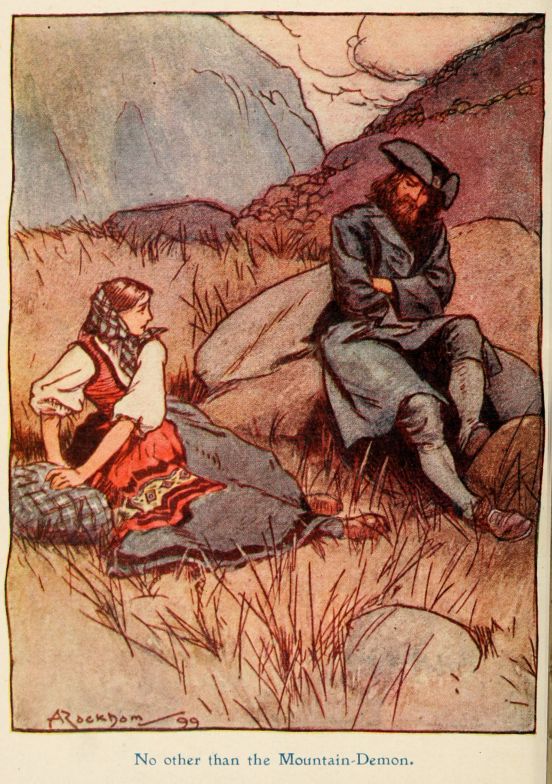

No other than the Mountain-Demon

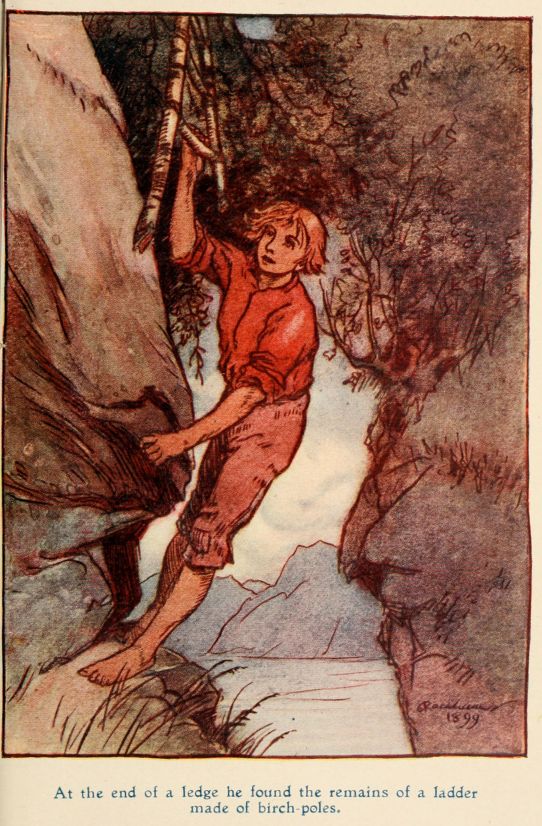

At the end of a ledge he found the remains of a ladder made of birch-poles

In desperation Hund, unarmed as he was, threw himself upon the pirate

It was Hund, with his feet tied under his horse, and the bridle held by a man on each side

Every one who has looked at the map of Norway must have been struck with the singular character of its coast. On the map it looks so jagged; a strange mixture of land and sea. On the spot, however, this coast is very sublime. The long straggling promontories are mountainous, towering ridges of rock, springing up in precipices from the water; while the bays between them, instead of being rounded with shelving sandy shores, on which the sea tumbles its waves, as in bays of our coast, are, in fact, long narrow valleys, filled with sea, instead of being laid out in fields and meadows. The high rocky banks shelter these deep bays (called fiords) from almost every wind; so that their waters are usually as still as those of a lake. For days and weeks together, they reflect each separate tree-top of the pine-forests which clothe the mountain sides, the mirror being broken only by the leap of some sportive fish, or the oars of the boatman as he goes to inspect the sea-fowl from islet to islet of the fiord, or carries out his nets or his rod to catch the sea-trout, or char, or cod, or herrings, which abound, in their seasons, on the coast of Norway.

It is difficult to say whether these fiords are the most beautiful in summer or in winter. In summer, they glitter with golden sunshine; and purple and green shadows from the mountain and forest lie on them; and these may be more lovely than the faint light of the winter noons of those latitudes, and the snowy pictures of frozen peaks which then show themselves on the surface: but before the day is half over, out come the stars—the glorious stars, which shine like nothing that we have ever seen. There the planets cast a faint shadow, as the young moon does with us; and these planets and the constellations of the sky, as they silently glide over from peak to peak of these rocky passes, are imaged on the waters so clearly that the fisherman, as he unmoors his boat for his evening task, feels as if he were about to shoot forth his vessel into another heaven, and to cleave his way among the stars.

Still as everything is to the eye, sometimes for a hundred miles together along these deep sea-valleys, there is rarely silence. The ear is kept awake by a thousand voices. In the summer, there are cataracts leaping from ledge to ledge of the rocks; and there is the bleating of the kids that browse there, and the flap of the great eagle's wings, as it dashes abroad from its eyrie, and the cries of whole clouds of sea-birds which inhabit the islets; and all these sounds are mingled and multiplied by the strong echoes, till they become a din as loud as that of a city. Even at night, when the flocks are in the fold, and the birds at roost, and the echoes themselves seem to be asleep, there is occasionally a sweet music heard, too soft for even the listening ear to catch by day. There is the rumble of some avalanche, as, after a drifting storm, a mass of snow too heavy to keep its place slides and tumbles from the mountain peak. Wherever there is a nook between the rocks on the shore, where a man may build a house, and clear a field or two;—wherever there is a platform beside the cataract where the sawyer may plant his mill, and make a path from it to join some great road, there is a human habitation, and the sounds that belong to it. Thence, in winter nights, come music and laughter, and the tread of dancers, and the hum of many voices. The Norwegians are a social and hospitable people, and they hold their gay meetings in defiance of their Arctic climate, through every season of the year.

On a January night, a hundred years ago, there was great merriment in the house of a farmer who had fixed his abode within the Arctic circle, in Nordland, not far from the foot of Sulitelma, the highest mountain in Norway. This dwelling, with its few fields about it, was in a recess between the rocks, on the shore of the fiord, about five miles from Saltdalen, and two miles from the junction of the Salten's Elv (river) with the fiord. The occasion, on the particular January day mentioned above, was the betrothment of one of the house-maidens to a young farm servant of the establishment. It was merely an engagement to be married; but this engagement is a much more formal and public affair in Norway (and indeed wherever the people belong to the Lutheran church) than with us. According to the rites of the Lutheran church, there are two ceremonies—one when a couple become engaged, and another when they are married.

As Madame Erlingsen had two daughters growing up, and they were no less active than the girls of a Norwegian household usually are, she had occasion for only two maidens to assist in the business of the dwelling and the dairy.

Of these two, the younger, Erica, was the maiden betrothed to-day. No one perhaps rejoiced so much at the event as her mistress, both for Erica's sake, and on account of her own two young daughters. Erica was not the best companion for them; and the servants of a Norwegian farmer are necessarily the companions of the daughters of the house. There was nothing wrong in Erica's conduct or temper towards the family. But she had sustained a shock which hurt her spirits, and increased a weakness which she owed to her mother. Her mother, a widow, had brought up her child in all the superstitions of the country, some of which remain in full strength even to this day, and were then very powerful; and the poor woman's death at last confirmed the lessons of her life. She had stayed too long, one autumn day, at the Erlingsen's and, being benighted on her return, and suddenly seized and bewildered by the cold, had wandered from the road, and was found frozen to death in a recess of the forest which it was surprising that she should have reached. Erica never believed that she did reach this spot of her own accord. Having had some fears before of the Wood-Demon having been offended by one of the family, Erica regarded this accident as a token of his vengeance. She said this when she first heard of her mother's death; and no reasonings from the zealous pastor of the district, no soothing from her mistress, could shake her persuasion. She listened with submission, wiping away her quiet tears as they discoursed; but no one could ever get her to say that she doubted whether there was a Wood-Demon, or that she was not afraid of what he would do if offended.

Erlingsen and his wife always treated her superstition as a weakness; and when she was not present, they ridiculed it. Yet they saw that it had its effect on their daughters. Erica most strictly obeyed their wish that she should not talk about the spirits of the region with Orga and Frolich; but the girls found plenty of people to tell them what they could not learn from Erica. Besides what everybody knows who lives in the rural districts of Norway—about Nipen, the spirit that is always so busy after everybody's affairs—about the Water-Sprite, an acquaintance of every one who lives beside a river or lake—and about the Mountain-Demon, familiar to all who lived so near Sulitelma; besides these common spirits, the girls used to hear of a multitude of others from old Peder, the blind houseman, and from all the farm-people, down to Oddo, the herd-boy. Their parents hoped that this taste of theirs might die away if once Erica, with her sad, serious face and subdued voice, were removed to a house of her own, where they would see her supported by her husband's unfearing mind, and occupied with domestic business more entirely than in her mistress's house. So Madame Erlingsen was well pleased that Erica was betrothed.

For this marrying, however, the young people must wait. There was no house, or houseman's place, vacant for them at present. The old houseman Peder, who had served Erlingsen's father and Erlingsen himself for fifty-eight years, could now no longer do the weekly work on the farm which was his rent for his house, field, and cow. He was blind and old. His aged wife Ulla could not leave the house; and it was the most she could do to keep the dwelling in order, with occasional help from one and another. Houseman who make this sort of contract with farmers in Norway are never turned out. They have their dwelling and field for their own life and that of their wives. What they do, when disabled, is to take in a deserving young man to do their work for the farmer, on the understanding that he succeeds to the houseman's place on the death of the old people. Peder and Ulla had made this agreement with Erica's lover, Rolf; and it was understood that his marriage with Erica should take place whenever the old people should die.

It was impossible for Erica herself to fear that Nipen was offended, at the outset of this festival day. If he had chosen to send a wind, the guests could not have come; for no human frame can endure travelling in a wind in Nordland on a January day. Happily, the air was so calm that a flake of snow, or a lock of eider-down, would have fallen straight to the ground. At two o'clock, when the short daylight was gone, the stars were shining so brightly, that the company who came by the fiord would be sure to have an easy voyage. Erlingsen and some of his servants went out to the porch, on hearing music from the water, and stood with lighted pine-torches to receive their guests when, approaching from behind, they heard the sound of the sleigh-bells, and found that company was arriving both by sea and land.

Glad had the visitors been, whether they came by land or water, to arrive in sight of the lighted dwelling, whose windows looked like rows of yellow stars, contrasting with the blue ones overhead; and more glad still were they to be ushered into the great room, where all was so light, so warm, so cheerful. Warm it was to the farthest corner; and too warm near the roaring and crackling fires, for the fires were of pine wood. Rows upon rows of candles were fastened against the walls above the heads of the company: the floor was strewn with juniper twigs, and the spinning-wheels, the carding-boards, every token of household labour was removed except a loom, which remained in one corner. In another corner was a welcome sight, a platform of rough boards two feet from the floor, and on it two stools. This was a token that there was to be dancing; and indeed, Oddo, the herd-boy, old Peder's grandson, was seen to have his clarionet in his belt, as he ran in and out on the arrival of fresh parties.

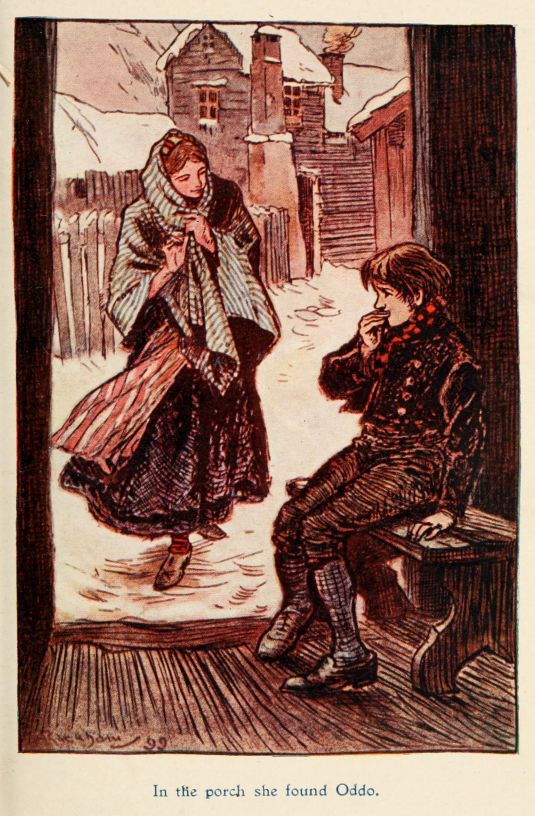

In the porch she found Oddo.

The whole company walked about the large room, sipping their strong coffee, and helping one another to the good things on the trays which were carried round. When these trays disappeared, Oddo was seen to reach the platform with a hop, skip, and jump, followed by a dull-looking young man with a violin. The oldest men lighted their pipes, and sat down to talk, two or three together. Others withdrew to a smaller room, where card-tables were sets out, while the younger men selected their partners. The dance was led by the blushing Erica, whose master was her partner. It had never occurred to her that she was not to take her usual place; and she was greatly embarrassed, not the less so that she knew that her mistress was immediately behind, with Rolf for her partner. All the women in Norway dance well, being practised in it from their infancy. Every woman present danced well; but none better than Erica.

"Very well! very pretty! very good!" observed the pastor, M. Kollsen, as he sat, with his pipe in his mouth, looking on. "There are many youths in Tronyem that would be glad of so pretty a partner as M. Erlingsen has, if she would not look so frightened."

"Did you say she looks frightened, sir?" asked Peder.

"Yes. When does she not? Some ghost from the grave has scared her, I suppose. It is her great fault that she has so little faith. I never met with such a case; I hardly know how to conduct it. I must begin with the people about her—abolish their superstitions—and then there may be a chance for her."

"Pray, sir, who plays the violin at this moment?" said Peder.

"A fellow who looks as if he did not like this business. He is frowning with his red brows, as if he would frown out the lights."

"His red brows! Oh, then it is Hund. I was thinking it would be hard upon him, poor fellow, if he had to play to-night. Yet not so hard as if he had to dance. It is weary work dancing with the heels when the heart is too heavy to move. You may have heard, sir, for every one knows it, that Hund wanted to have young Rolf's place; and, some say, Erica herself. Is she dancing, sir, if I may ask?"

"Yes, with Rolf. What sort of a man is Rolf—with regard to these superstitions, I mean? Is he as foolish as Erica—always frightened about something?"

"No, indeed. It is to be wished that Rolf was not so light as he is, so inconsiderate about these matters. Rolf has his troubles and his faults, but they are not of that kind."

"Enough," said M. Kollsen with a voice of authority. "I rejoice to hear that he is superior to the popular delusions. As to his troubles and his faults, they may be left for me to discover, all in good time."

"With all my heart, sir. They are nobody's business but his own; and, may be, Erica's."

"How goes it, Rolf?" said his master, who, having done his duty in the dancing-room, was now making his way to the card-tables, in another apartment, to see how his guests there were entertained. Thinking that Rolf looked very absent as he stood, in the pause of the dance, in silence by Erica's side, Erlingsen clapped him on the shoulder and said, "How goes it? Make your friends merry."

Rolf bowed and smiled, and his master passed on.

"How goes it?" repeated Rolf to Erica, as he looked earnestly into her face. "Is all going on well, Erica?"

"Certainly. I suppose so. Why not?" she replied. "If you see anything wrong—anything omitted, be sure and tell me. Madame Erlingsen would be very sorry. Is there anything forgotten, Rolf?"

"I think you have forgotten what to-day is, that is all. Nobody that looked at you, love, would fancy it to be your own day. You look anything but merry. O Erica! I wish you would trust me. I could take care of you, and make you quite happy, if you would only believe it. Nothing in the universe shall touch you to your hurt, while——"

"Oh, hush! hush!" said Erica, turning pale and red at the presumption of this speech. "See, they are waiting for us. One more round before supper."

And in the whirl of the waltz she tried to forget the last words Rolf had spoken; but they rang in her ears; and before her eyes were images of Nipen overhearing this defiance—and the Water-Sprite planning vengeance in its palace under the ice—and the Mountain-Demon laughing in scorn, till the echoes shouted again—and the Wood-Demon waiting only for summer to see how he could beguile the rash lover.

Long was the supper, and hearty was the mirth round the table. People in Norway have universally a hearty appetite—such an appetite as we English have no idea of.

At last appeared the final dish of the long feast, the sweet cake, with which dinner and supper in Norway usually conclude.

It is the custom in the country regions of Norway to give the spirit Nipen a share at festival times. His Christmas cake is richer than that prepared for the guests, and before the feast is finished it is laid in some place out of doors, where, as might be expected, it is never to be found in the morning. Everybody knew, therefore, why Rolf rose from his seat, though some were too far off to hear him say that he would carry out the treat for old Nipen.

"Now, pray do not speak so; do not call him those names," said Erica anxiously. "It is quite as easy to speak so as not to offend him. Pray, Rolf, to please me, do speak respectfully. And promise me to play no tricks, but just set the things down, and come straight in, and do not look behind you. Promise me, Rolf."

Rolf did promise, but he was stopped by two voices calling upon him. Oddo, the herd-boy, came running to claim the office of carrying out Nipen's cake. Erica eagerly put an ale-can into his hand, and the cake under his arm; and Oddo was going out, when his blind grandfather, hearing that he was to be the messenger, observed that he should be better pleased if it were somebody else; for Oddo, though a good boy, was inquisitive, and apt to get into mischief by looking too closely into everything, having never a thought of fear. Everybody knew this to be true; though Oddo himself declared that he was as frightened as anybody sometimes. Moreover, he asked what there was to pry into, on the present occasion, in the middle of the night; and appealed to the company whether Nipen was not best pleased to be served by the youngest of a party. This was allowed; and he was permitted to go, when Peder's consent was obtained.

The place where Nipen liked to find his offerings was at the end of the barn, below the gallery which ran round the outside of the building. There, in the summer, lay a plot of green grass; and, in the winter, a sheet of pure frozen snow. Thither Oddo shuffled on, over the slippery surface of the yard. He looked more like a prowling cub then a boy, wrapped as he was in his wolf-skin coat, and his fox-skin cap doubled down over his ears.

The cake steamed up in the frosty air under his nose, so warm and spicy and rich, that Oddo began to wonder what so very superior a cake could be like. He had never tasted any cake so rich as this; nor had any one in the house tasted such, for Nipen would be offended if his cake was not richer than anybody's else. He broke a piece off and ate it, and then wondered whether Nipen would mind his cake being just a little smaller than usual. After a few steps more the wonder was how far Nipen's charity would go for the cake was now a great deal smaller; and Oddo next wondered whether anybody could stop eating such a cake when it was once tasted. He was surprised to see when he came out into the starlight, at the end of the barn, how small a piece was left. He stood listening whether Nipen was coming in a gust of wind; and when he heard no breeze stirring, he looked about for a cloud where Nipen might be. There was no cloud, as far as he could see. The moon had set; but the stars were so bright as to throw a faint shadow from Oddo's form upon the snow. There was no sign of any spirit being angry at present; but Oddo thought Nipen would certainly be angry at finding so very small a piece of cake. It might be better to let the ale stand by itself, and Nipen would perhaps suppose that Madame Erlingsen's stock of groceries had fallen short, at least that it was in some way inconvenient to make the cake on the present occasion. So putting down his can upon the snow, and holding the last fragment of the cake between his teeth, he seized a birch pole which hung down from the gallery, and by its help climbed one of the posts and got over the rails into the gallery, whence he could watch what would happen. To remain on the very spot where Nipen was expected was a little more than he was equal to; but he thought he could stand in the gallery, in the shadow of the broad eaves of the barn, and wait for a little while. He was so very curious to see Nipen, and to learn how it liked its ale!

There he stood in the shadow, growing more and more impatient as the minutes passed on, and he was aware that he was wanted in the house. Once or twice he walked slowly away, looking behind him, and then turned again, unwilling to miss this opportunity of seeing Nipen. Then he called the spirit—actually begged it to appear. His first call was almost a whisper; but he called louder and louder till he was suddenly stopped by hearing an answer.

The call he heard was soft and sweet. There was nothing terrible in the sound itself; yet Oddo grasped the rail of the gallery with all his strength as he heard it. The strangest thing was, it was not a single cry: others followed it, all soft and sweet; but Oddo thought that Nipen must have many companions, and he had not prepared himself to see more spirits than one. As usual, however, his curiosity grew more intense from the little he had heard, and he presently called again. Again he was answered by four or five voices in succession.

"Was ever anybody so stupid!" cried the boy, now stamping with vexation. "It is the echo, after all. As if there was not always an echo here opposite the rock. It is not Nipen at all. I will just wait another minute, however."

He leaned in silence on his folded arms, and had not so waited for many seconds before he saw something moving on the snow at a little distance. It came nearer and nearer, and at last quite up to the can of ale.

"I am glad I stayed," thought Oddo. "Now I can say I have seen Nipen. It is much less terrible then I expected. Grandfather told me that it sometimes came like an enormous elephant or hippopotamus, and never smaller than a large bear. But this is no bigger then—let me see—I think it is most like a fox. I should like to make it speak to me. They would think so much of me at home if I had talked with Nipen."

So he began gently—"Is that Nipen?"

The thing moved its bushy tail, but did not answer.

"There is no cake for you to-night, Nipen. I hope the ale will do. Is the ale good, Nipen?"

Off went the dark creature without a word, as quick as it could go.

"It is offended?" thought Oddo; "or is it really what it looks like, a fox? If it does not come back, I will go down presently and see whether it is only a fox."

He presently let himself down to the ground by the way he had come up, and eagerly laid hold of the ale can. It would not stir. It was as fast on the ground as if it was enchanted, which Oddo did not doubt was the case; and he started back with more fear than he had yet had. The cold he felt on this exposed spot soon reminded him, however, that the can was probably frozen to the snow, which it might well be, after being brought warm from the fireside. It was so. The vessel had sunk an inch into the snow, and was there fixed by the frost.

None of the ale seemed to have been drunk; and so cold was Oddo by this time, that he longed for a sup of it. He took first a sup and then a draught; and then he remembered that the rest would be entirely spoiled by the frost if it stood another hour. This would be a pity, he thought; so he finished it, saying to himself that he did not believe Nipen would come that night.

At that very moment he heard a cry so dreadful that it shot, like sudden pain, through every nerve of his body. It was not a shout of anger: it was something between a shriek and a wail—like what he fancied would be the cry of a person in the act of being murdered. That Nipen was here now, he could not doubt; and, at length, Oddo fled. He fled the faster, at first, for hearing the rustle of wings; but the curiosity of the boy even now got the better of his terror, and he looked up at the barn where the wings were rustling. There he saw in the starlight the glitter of two enormous round eyes, shining down upon him from the ridge of the roof. But it struck him at once that he had seen those eyes before. He checked his speed, stopped, went back a little, sprang up once more into the gallery, hissed, waved his cap, and clapped his hands, till the echoes were all awake again; and, as he had hoped, the great white owl spread its wings, sprang off from the ridge, and sailed away over the fiord.

Oddo tossed up his cap, cold as the night was, so delighted was he to have scared away the bird which had, for a moment, scared him. He hushed his mirth, however, when he perceived that lights were wandering in the yard, and that there were voices approaching. He saw that the household were alarmed about him, and were coming forth to search for him. Curious to see what they would do, Oddo crouched down in the darkest corner of the gallery to watch and listen.

First came Rolf and his master, carrying torches, with which they lighted up the whole expanse of snow as they came. They looked round them without any fear, and Oddo heard Rolf say—

"If it were not for that cry, sir, I should think nothing of it. But my fear is that some beast has got him."

"Search first the place where the cake and ale ought to be," said Erlingsen. "Till I see blood, I shall hope the best."

"You will not see that," said Hund, who followed; his gloomy countenance, now distorted by fear, looking ghastly in the yellow light of the torch he carried. "You will see no blood. Nipen does not draw blood."

"Never tell me that any one that was not wounded and torn could send out such a cry as that," said Rolf. "Some wild brute seized him, no doubt, at the very moment that Erica and I were standing at the door listening."

Oddo repented of his prank when he saw, in the flickering light behind the crowd of guests, who seemed to hang together like a bunch of grapes, the figures of his grandfather and Erica. The old man had come out in the cold for his sake; and Erica, who looked as white as the snow, had no doubt come forth because the old man wanted a guide. Oddo now wished himself out of the scrape. Sorry as he was, he could not help being amused, and keeping himself hidden a little longer, when he saw Rolf discover the round hole in the snow where the can had sunk, and heard the different opinions of the company as to what this portended. Most were convinced that his curiosity had been his destruction, as they had always prophesied. What could be clearer, by this hole, than that the ale had stood there, and been carried off with the cake; and Oddo with it, because he chose to stay and witness what is forbidden to mortals?

"I wonder where he is now," said a shivering youth, the gayest dancer of the evening.

"Oh, there is no doubt about that; any one can tell you that," replied the elderly and experienced M. Holberg. "He is chained upon a wind, poor fellow, like all Nipen's victims. He will have to be shut up in a cave all the hot summer through, when it is pleasantest to be abroad; and when the frost and snow come again, he will be driven out, with a lash of Nipen's whip, and he must go flying wherever the wind flies, without resting, or stopping to warm himself at any fire in the country."

Oddo had thus far kept his laughter to himself; but now he could contain himself no longer. He laughed aloud—and then louder and louder as he heard the echoes all laughing with him. The faces below, too, were so very ridiculous—some of the people staring up in the air; and others at the rock where the echo came from; some having their mouths wide open, others their eyes starting, and all looking unlike themselves in the torchlight. His mirth was stopped by his master.

"Come down, sir," cried Erlingsen, looking up at the gallery. "Come down this moment. We shall make you remember this night, as well perhaps as Nipen could do. Come down, and bring my can, and the ale and the cake. The more pranks you play the more you will repent it."

Most of the company thought Erlingsen very bold to talk in this way; but he was presently justified by Oddo's appearance on the balustrade. His master seized him as he touched the ground, while the others stood aloof.

"Where is my ale can?" said Erlingsen.

"Here, sir;" and Oddo held it up dangling by the handle.

"And the cake—I bade you bring it down with you."

"So I did, sir."

And to his master's look of inquiry, the boy answered by pointing down his throat with one finger, and laying the other hand upon his stomach. "It is all here, sir."

"And the ale in the same place?"

Oddo bowed, and Erlingsen turned away without speaking. He could not have spoken without laughing.

"Bring this gentleman home," said Erlingsen presently to Rolf; "and do not let him out of your hands. Let no one ask him any questions till he is in the house." Rolf grasped the boy's arm, and Erlingsen went forward to relieve Peder, though it was not very clear to him at the moment whether such a grandchild was better safe or missing. The old man made no such question, but hastened back with many expressions of thanksgiving.

As the search-party crowded in among the women, and pushed all before them into the large warm room, M. Kollsen was seen standing on the stair-head, wrapped in the bear-skin coverlid.

"Is the boy there?" he inquired.

Oddo showed himself.

"How much have you seen of Nipen, hey?"

"Nobody ever had a better sight of it, sir. It was as plain as I see you now, and no farther off."

"Nonsense—it is a lie," said M. Kollsen. "Do not believe a word he says," advised the pastor.

Oddo bowed, and proceeded to the great room, where he took up his clarionet, as if it was a matter of course that the dancing was to begin again immediately. He blew upon his fingers, however, observing that they were too stiff with cold to do their duty well. And when he turned towards the fire, every one made way for him, in a very different manner from what they would have dreamed of three hours before. Oddo had his curiosity gratified as to how they would regard one who was believed to have seen something supernatural.

When seriously questioned, Oddo had no wish to say anything but the truth; and he admitted the whole—that he had eaten the entire cake, drunk all the ale, seen a fox and an owl, and heard the echoes, in answer to himself. As he finished his story, Hund, who was perhaps the most eager listener of all, leaped thrice upon the floor, snapping his fingers, as if in a passion of delight. He met Erlingsen's eye, full of severity, and was quiet; but his countenance still glowed with exultation.

The rest of the company were greatly shocked at these daring insults to Nipen: and none more so than Peder. The old man's features worked with emotion, as he said in a low voice that he should be very thankful if all the mischief that might follow upon this adventure might be borne by the kin of him who had provoked it. If it should fall upon those who were innocent, never surely had boy been so miserable as his poor lad would then be. Oddo's eyes filled with tears as he heard this; and he looked up at his master and mistress, as if to ask whether they had no word of comfort to say.

"Neighbour," said Madame Erlingsen to Peder, "is there any one here who does not believe that God is over all, and that He protects the innocent?"

"Is there any one who does not feel," added Erlingsen, "that the innocent should be gay, safe as they are in the goodwill of God and man? Come, neighbours—to your dancing again! You have lost too much time already. Now, Oddo, play your best—and you, Hund."

"I hope," said Oddo, "that, if any mischief is to come, it will fall upon me. We'll see how I shall bear it."

When M. Kollsen appeared the next morning, the household had so much of its usual air that no stranger would have imagined how it had been occupied the day before. The large room was fresh strewn with evergreen sprigs; the breakfast-table stood at one end, where each took breakfast, standing, immediately on coming downstairs. At the bottom of the room was a busy group. Peder was twisting strips of leather, thin and narrow, into whips. Rolf and Hund were silently intent upon a sort of work which the Norwegian peasant delights in—carving wood. They spoke only to answer Peder's questions about the progress of the work. Peder loved to hear about their carving, and to feel it; for he had been remarkable for his skill in the art, as long as his sight lasted.

The whole party rose when M. Kollsen entered the room. He talked politics a little with his host, by the fireside; in the midst of which conversation Erlingsen managed to intimate that nothing would be heard of Nipen to-day, if the subject was let alone by themselves: a hint which the clergyman was willing to take, as he supposed it meant in deference to his views.

Erica heard M. Kollsen inquiring of Peder about his old wife, so she started up from her work, and said she must run and prepare Ulla for the pastor's visit. Poor Ulla would think herself forgotten this morning, it was growing so late, and nobody had been over to see her.

Ulla, however, was far from having any such thoughts. There sat the old woman, propped up in bed, knitting as fast as fingers could move, and singing, with her soul in her song, though her voice was weak and unsteady.

"I thought you would come," said Ulla. "I knew you would come, and take my blessing on your betrothment. I must not say that I hope to see you crowned; for we all know—and nobody so well as I—that it is I that stand between you and your crown. I often think of it, my dear——"

"Then I wish you would not, Ulla—you know that."

"I do know it, my dear; and I would not be for hastening God's appointments. Let all be in His own time."

"There was news this morning," said Erica, "of a lodgment of logs at the top of the foss;[1] and they were all going, except Peder, to slide them down the gully to the fiord. The gully is frozen so slippery, that the work will not take long. They will make a raft of the logs in the fiord; and either Rolf or Hund will carry them out to the islands when the tide ebbs."

[1] Waterfall. Pine-trunks felled in the forest are drawn over the frozen snow to the banks of a river, or to the top of a waterfall, whence they may be either slid down over the ice, or left to be carried down by the floods, at the melting of the snows in the spring.

"Will it be Rolf, do you think, or Hund, dear?"

"I wish it may be Hund. If it be Rolf, I shall go with him. O Ulla! I cannot lose sight of him, after what happened last night. Did you hear? I do wish Oddo would grow wiser."

Ulla shook her head. "How did Hund conduct himself yesterday? Did you mark his countenance, dear?"

"Indeed there was no helping it, any more than one can help watching a storm-cloud as it comes up."

"So it was dark and wrathful, was it, that ugly face of his?" There was a knock, and before Erica could reach the door, Frolich burst in.

"Such news!" she cried—"You never heard such news."

"Good or bad?" inquired Ulla.

"Oh, bad—very bad," declared Frolich; "there is a pirate vessel among the islands. She was seen off Soroe some time ago, but she is much nearer to us now. There was a farmhouse seen burning on Alten fiord last week, and as the family are all gone and nothing but ruins left, there is little doubt the pirates lit the torch that did it. And the cod has been carried off from the beach in the few places where any has been caught yet."

"They have not found out our fiord yet?" inquired Ulla.

"Oh dear! I hope not. But they may, any day. And father says the coast must be raised, from Hammerfest to Tronyem, and a watch set till this wicked vessel can be taken or driven away. He was going to send a running message both ways, but there is something else to be done first."

"Another misfortune?" asked Erica faintly.

"No; they say it is a piece of very good fortune—at least for those who like bears' feet for dinner. Somebody or other has lighted upon the great bear that got away in the summer, and poked her out of her den on the fjelde. She is certainly abroad with her two last year's cubs, and their traces have been found just above, near the foss. Oddo has come running home to tell us, and father says he must get up a hunt before more snow falls and we lose the tracks, or the family may establish themselves among us and make away with our first calves."

"Does he expect to kill them all?"

"I tell you we are all to grow stout on bears' feet. For my part I like bears' feet best on the other side of Tronyem."

"You will change your mind, Miss Frolich, when you see them on the table," observed Ulla.

"That is just what father said. And he asked how I thought Erica and Stiorna would like to have a den in their neighbourhood when they got up to the mountain for the summer."

Erica with a sigh rose to return to the house. In the porch she found Oddo.

Wooden dwellings resound so much as to be inconvenient for those who have secrets to tell. In the porch of Peder's house Oddo had heard all that passed within.

"Dear Erica," said he, "I want you to do a very kind thing for me. Do get leave for me to go with Rolf after the bears. If I get one stroke at them—if I can but wound one of them, I shall have a paw for my share, and I will lay it out for Nipen. You will, will not you?"

"It must be as Erlingsen chooses, Oddo, but I fancy you will not be allowed to go just now."

The establishment was now in a great hurry and bustle for an hour, after which time it promised to be unusually quiet.

M. Kollsen began to be anxious to be on the other side of the fiord. It was rather inconvenient, as the two men were wanted to go in different directions, while their master took a third, to rouse the farmers for the bear-hunt. The hunters were all to arrive before night within a certain distance of the thickets where the bears were now believed to be. On calm nights it was no great hardship to spend the dark hours in the bivouac of the country. Each party was to shelter itself under a bank of snow, or in a pit dug out of it, an enormous fire blazing in the midst, and brandy and tobacco being plentifully distributed on such occasions. Early in the morning the director of the hunt was to go his rounds, and arrange the hunters in a ring enclosing the hiding-place of the bears, so that all might be prepared, and no waste made of the few hours of daylight which the season afforded. As soon as it was light enough to see distinctly among the trees, or bushes, or holes of the rocks where the bears might be couched, they were to be driven from their retreat and disposed of as quickly as possible. Such was the plan, well understood in such cases throughout the country. On the present occasion it might be expected that the peasantry would be ready at the first summons. Yet the more messengers and helpers the better, and Erlingsen was rather vexed to see Hund go with alacrity to unmoor the boat and offer officiously to row the pastor across the fiord. His daughters knew what he was thinking about, and, after a moment's consultation, Frolich asked whether she and the maid Stiorna might not be the rowers.

Nobody would have objected if Hund had not. The girls could row, though they could not hunt bears, and the weather was fair enough; but Hund shook his head, and went on preparing the boat. His master spoke to him, but Hund was not remarkable for giving up his own way. He would only say that there would be plenty of time for both affairs, and that he could follow the hunt when he returned, and across the lake he went.

Erlingsen and Rolf presently departed. The women and Peder were left behind.

They occupied themselves, to keep away anxious thoughts. Old Peder sang to them, too. Hour after hour they looked for Hund. His news of his voyage, and the sending him after his master, would be something to do and to think of; but Hund did not come. Stiorna at last let fall that she did not think he would come yet, for that he meant to catch some cod before his return. He had taken tackle with him for that purpose, she knew, and she should not wonder if he did not appear till the morning.

Every one was surprised and Madame Erlingsen highly displeased. At the time when her husband would be wanting every strong arm that could be mustered, his servant chose to be out fishing, instead of obeying orders. The girls pronounced him a coward, and Peder observed that to a coward, as well as a sluggard, there was ever a lion in the path. Erica doubted whether this act of disobedience arose from cowardice, for there were dangers in the fiord for such as went out as far as the cod. She supposed Hund had heard——

She stopped short, as a sudden flash of suspicion crossed her mind. She had seen Hund inquiring of Olaf about the pirates, and his strange obstinacy about this day's boating looked much as if he meant to learn more.

"Danger in the fiord!" repeated Orga; "oh, you mean the pirates. They are far enough from our fiord, I suppose. If ever they do come, I wish they would catch Hund and carry him off, I am sure we could spare them nothing they would be so welcome to."

"Did not you see M. Kollsen in the boat with Hund?" Madame Erlingsen inquired of Oddo when he came in.

"No, Hund was quite alone, pulling with all his might down the fiord. The tide was with him, so that he shot along like a fish."

"How do you know it was Hund that you saw?"

"Don't I know our boat? And don't I know his pull? It is no more like Rolf's then Rolf's is like master's."

"Perhaps he was making for the best fishing-ground as fast as he could."

"We shall see that by the fish he brings home."

"True. By supper-time we shall know."

"Hund will not be home by supper-time," said Oddo decidedly,

"Why not? Come, say out what you mean."

"Well, I will tell you what I saw, I watched him rowing as fast as his arm and the tide would carry him. It was so plain that there was a plan in his head, that I followed on from point to point, catching a sight now and then, till I had gone a good stretch beyond Salten heights. I was just going to turn back when I took one more look, and he was then pulling in for the land."

"On the north shore or south?" asked Peder.

"The north—just at the narrow part of the fiord, where one can see into the holes of the rocks opposite."

"The fiord takes a wide sweep below there," observed Peder.

"Yes; and that was why he landed," replied Oddo. "He was then but a little way from the fishing-ground, if he had wanted fish. But he drove up the boat into a little cove, a narrow dark creek, where it will lie safe enough, I have no doubt, till he comes back—if he means to come back."

And that vessel, he knew, was the pirate schooner.

"Why, where should he go? What should he do but come back?" asked Madame Erlingsen.

"He is now gone over the ridge to the north. I saw him moor the boat, and begin to climb; and I watched his dark figure on the white snow, higher and higher, till it was a speck, and I could not make it out."

"What do you think of this story, Peder?" asked his mistress.

"I think Hund has taken the short cut over the promontory, on business of his own at the islands. He is not on any business of yours, depend upon it, madame."

"And what business can he have among the islands?"

"I could say that with more certainty if I knew exactly where the pirate vessel is."

"That is your idea, Erica," said her mistress. "I saw what your thoughts were an hour ago, before we knew all this."

"I was thinking then, madame, that if Hund was gone to join the pirates, Nipen would be very ready to give them a wind just now. A baffling wind would be our only defence; and we cannot expect that much from Nipen to-day."

"I will do anything in the world," cried Oddo eagerly. "Send me anywhere. Do think of something that I can do."

"What must be done, Peder?" asked his mistress.

"There is quite enough to fear, Erica, without a word of Nipen. Pirates on the coast, and one farmhouse seen burning already."

"I will tell you what you must let me do, madame," said Erica. "Indeed you must not oppose me. My mind is quite set upon going for the boat—immediately—this very minute. That will give us time, it will give us safety for this night. Hund might bring seven or eight men upon us over the promontory; but if they find no boat, I think they can hardly work up the windings of the fiord in their own vessel to-night; unless, indeed," she added with a sigh, "they have a most favourable wind."

"All this is true enough," said her mistress; "but how will you go? Will you swim?"

"The raft, madame."

"And there is the old skiff on Thor islet," said Oddo. "It is a rickety little thing, hardly big enough for two; but it will carry down Erica and me, if we go before the tide turns."

"But how will you get to Thor islet?" inquired Madame Erlingsen. "I wish the scheme were not such a wild one."

"A wild one must serve at such a time, madame," replied Erica. "Rolf had lashed several logs before he went. I am sure we can get over to the islet. See, madame, the fiord is as smooth as a pond."

"Let her go," said Peder. "She will never repent."

"Then come back, I charge you, if you find the least danger," said her mistress. "No one is safer at the oar than you; but if there is a ripple in the water, or a gust on the heights, or a cloud in the sky, come back. Such is my command, Erica."

"Wife," said Peder, "give her your pelisse. That will save her seeing the girls before she goes. And she shall have my cap, and then there is not an eye along that fiord that can tell whether she is man or woman."

Ulla lent her deer-skin pelisse willingly enough; but she entreated that Oddo might be kept at home. She folded her arms about the boy with tears; but Peder decided the matter with the words—

"Let him go. It is the least he can do to make up for last night. Equip, Oddo."

Oddo equipped willingly enough. In two minutes he and his companion looked like two walking bundles of fur. Oddo carried a frail basket, containing rye-bread, salt fish, and a flask of corn-brandy; for in Norway no one goes on the shortest expedition without carrying provisions.

"Surely it must be dusk by this time," said Peder.

It was dusk; and this was well, as the pair could steal down to the shore without being perceived from the house. Madame Erlingsen gave them her blessing, saying that if the enterprise saved them from nothing worse than Hund's company this night, it would be a great good. There could be no more comfort in having Hund for an inmate; for some improper secret he certainly had. Her hope was that, finding the boat gone, he would never show himself again.

Erica now profited by her lover's industry in the morning. He had so far advanced with the raft that, though no one would have thought of taking it in its present state to the mouth of the fiord for shipment, it would serve as a conveyance in still water for a short distance safely enough.

And still indeed the waters were. As Erica and Oddo were busily and silently employed in tying moss round their oars to muffle their sound, the ripple of the tide upon the white sand could scarcely be heard; and it appeared to the eye as if the lingering remains of the daylight brooded on the fiord, unwilling to depart. The stars had, however, been showing themselves for some time; and they might now be seen twinkling below almost as clearly and steadily as overhead. As Erica and Oddo put their little raft off from the shore, and then waited with their oars suspended, to observe whether the tide carried them towards the islet they must reach, it seemed as if some invisible hand was pushing them forth, to shiver the bright pavement of constellations as it lay. Star after star was shivered, and its bright fragments danced in their wake; and those fragments reunited and became a star again, as the waters closed over the path of the raft, and subsided into perfect stillness.

The tide favoured Erica's object. A few strokes of the oar brought the raft to the right point for landing on the islet. They stepped ashore, and towed the raft along till they came to the skiff, and then they fastened the raft with the boat-hook, which had been fixed there for the skiff. This done, Oddo ran to turn over the little boat and examine its condition, but he found he could not move it. It was frozen fast to the ground. It was scarcely possible to get a firm hold of it, it was so slippery with ice; and all pulling and pushing of the two together was in vain, though the boat was so light that either of them could have lifted and carried it in a time of thaw.

This circumstance caused a great deal of delay; and what was worse, it obliged them to make some noise. They struck at the ice with sharp stones, but it was long before they could make any visible impression, and Erica proposed again and again that they should proceed on the raft. Oddo was unwilling. The skiff would go so incomparably faster, that it was worth spending some time upon it; and the fears he had had of its leaking were removed, now that he found what a sheet of ice it was covered with—ice which would not melt to admit a drop of water while they were in it. So he knocked and knocked away, wishing that the echoes would be quiet for once, and then laughing as he imagined the ghost stories that would spring up all round the fiord to-morrow, from the noise he was then making.

Erica worked hard too; and one advantage of their labour was that they were well warmed before they put off again. The boat's icy fastenings were all broken at last, and it was launched; but all was not yet ready. The skiff had lain in a direction east and west; and its north side had so much thicker a coating of ice than the other, that its balance was destroyed. It hung so low on one side as to promise to upset with a touch.

"We must clear off more of the ice," said Erica. "But how late it is growing!"

"No more knocking, I say," replied Oddo. "There is a quieter way of trimming the boat."

He fastened a few stones to the gunwale on the lighter side, and took in a few more for the purpose of shifting the weight if necessary, while they were on their way.

They did not leave quiet behind them when they departed. They had roused the multitude of eider ducks and other sea-fowl which thronged the islet, and which now, being roused, began their night-feeding and flying, though at an earlier hour than usual. When their discordant cries were left so far behind as to be softened by distance, the flapping of wings and swash of water, as the fowl plunged in, still made the air busy all around.

The rowers were so occupied with the management of their dangerous craft, that they had not spoken since they left the islet. The skiff would have been unmanageable by any maiden and boy in our country; but on the coast of Norway, it is as natural to persons of all ages and degrees to guide a boat as to walk. Swiftly but cautiously they shot through the water.

"Are you sure you know the cove?" asked Erica.

"Quite sure. I wish I was as sure that Hund would not find it again before me. Pull away."

"How much farther is it?"

"Farther than I like to think of. I doubt your arm holding out; I wish Rolf was here."

Erica did not wish the same thing. She thought that Rolf was, on the whole, safer waging war with bears than with pirates, especially if Hund was among them. She pulled her oar cheerfully, observing that there was no fatigue at present; and that when they were once afloat in the heavier boat, and had cleared the cove, there need be no hurry—unless indeed they should see something of the pirate schooner on the way; and of this she had no expectation, as the booty that might be had where the fishery was beginning was worth more than anything that could be found higher up the fiords, to say nothing of the danger of running up into the country so far as that getting away again depended upon one particular wind.

Yet Erica looked behind her after every few strokes of her oar; and once, when she saw something, her start was felt like a start of the skiff itself. There was a fire glancing and gleaming and quivering over the water, some way down the fiord.

"Some people night-fishing," observed Oddo. "What sport they will have! I wish I was with them. How fast we go! How you can row when you choose! I can see the man that is holding the torch. Cannot you see his black figure? And the spearman—see how he stands at the bow—now going to cast his spear! I wish I was there."

"We must get farther away—into the shadow somewhere, or wait," observed Erica. "I had rather not wait, it is growing so late. We might creep along under that promontory, in the shadow, if you would be quiet. I wonder whether you can be silent in the sight of night-fishing."

"To be sure," said Oddo, disposed to be angry, and only kept from it by the thought of last night. He helped to bring the skiff into the shadow of the overhanging rocks, and only spoke once more, to whisper that the fishing-boat was drifting down with the tide, and that he thought their cove lay between them and the fishing-party.

It was so. As the skiff rounded the point of the promontory, Oddo pointed out what appeared like a mere dark chasm in the high perpendicular wall of rock that bounded the waters. This chasm still looked so narrow on approaching it, that Erica hesitated to push her skiff into it, till certain that there was no one there. Oddo was so clear that she might safely do this, so noiseless was their rowing, and it was so plain that there was no footing on the rocks by which he might enter to explore, that in a sort of desperation, and seeing nothing else to be done, Erica agreed. She wished it had been summer, when either of them might have learned what they wanted by swimming. This was now out of the question; and stealthily therefore she pulled her little craft into the deepest shadow, and crept into the cove.

At a little distance from the entrance it widened, but it was a wonder to Erica that even Oddo's eyes should have seen Hund moor his boat here from the other side of the fiord; though the fiord was not more than a gunshot over in this part. Oddo himself wondered, till he recalled how the sun was shining down into the chasm at the time. By starlight, the outline of all that the cove contained might be seen, the outline of the boat among other things. There she lay! But there was something about her which was unpleasant enough. There were three men in her.

What was to be done now? Here was the very worst danger that Erica had feared—worse than finding the boat gone—worse than meeting it in the wide fiord. What was to be done?

There was nothing for it but to do nothing—to lie perfectly still in the shadow, ready, however, to push out on the first movement of the boat to leave the cove; for, though the canoe might remain unnoticed at present, it was impossible that anybody could pass out of the cove without seeing her. In such a case there would be nothing for it but a race—a race for which Erica and Oddo held themselves prepared without any mutual explanation, for they dared not speak. The faintest whisper would have crept over the smooth water to the ears in the larger boat.

One thing was certain—that something must happen presently. It is impossible for the hardiest men to sit inactive in a boat for any length of time in a January night in Norway. In the calmest nights the cold is only to be sustained by means of the glow from strong exercise. It was certain that these three men could not have been long in their places, and that they would not sit many moments more without some change in their arrangements.

They did not seem to be talking, for Oddo, who was the best listener in the world, could not discover that a sound issued from their boat. He fancied they were drowsy, and, being aware what were the consequences of yielding to drowsiness in severe cold, the boy began to entertain high hopes of taking these three men prisoners. The whole country would ring with such a feat performed by Erica and himself.

The men were too much awake to be made prisoners of at present. One was seen to drink from a flask, and the hoarse voice of another was heard grumbling, as far as the listeners could make out, at being kept waiting. The third then rose to look about him, and Erica trembled from head to foot. He only looked upon the land, however, declared he saw nothing of those he was expecting, and began to warm himself as he stood, by repeatedly clapping his arms across his breast. This was Hund. He could not have been known by his figure, for all persons look alike in wolf-skin pelisses, but the voice and the action were his. Oddo saw how Erica shuddered. He put his finger on his lips, but Erica needed no reminding of the necessity of quietness.

The other two men then rose, and after a consultation, the words of which could not be heard, all stepped ashore, one after another, and climbed a rocky pathway.

"Now, now!" whispered Erica. "Now we can get away."

"Not without the boat," said Oddo. "You would not leave them the boat?"

"No—not if—but they will be back in a moment. They are only gone to hasten their companions."

"I know it," said Oddo. "Now two strokes forward!"

While she gave these two strokes, which brought the skiff to the stern of the boat, Erica saw that Oddo had taken out a knife which gleamed in the starlight. It was for cutting the thong by which the boat was fastened to a birch-pole, the other end of which was hooked on shore. This was to save his going ashore to unhook the pole. It was well for him that boat chains were not in use, owing to the scarcity of metal in that region. The clink of a chain would certainly have been heard.

Quickly and silently he entered the boat and tied the skiff to its stern, and he and Erica took their places where the men had sat one minute before. They used their own muffled oars to turn the boat round, till Oddo observed that the boat oars were muffled too. Then voices were heard again. The men were returning. Strongly did the two companions draw their strokes till a good breadth of water lay between them and the shore, and then till they had again entered the deep shadow which shrouded the mouth of the cove. There they paused.

"In with you!" some loud voice said, as man after man was seen in outline coming down the pathway. "In with you! We have lost time enough already."

"Where is she? I can't see the boat," answered the foremost man.

"You can't miss her," said one behind, "unless the brandy has got into your eyes."

"So I should have said; but I do miss her."

Oddo shook with stifled laughter as he partly saw and partly overheard the perplexity of these men. At last one gave a deep groan, and another declared that the spirits of the fiord were against them, and there was no doubt that their boat was now lying twenty fathoms deep at the bottom of the creek, drawn down by the strong hand of an angry water-sprite. Oddo squeezed Erica's little hand as he heard this. If it had been light enough, he would have seen that even she was smiling.

One of the men mourned their having no other boat, so that they must give up their plan. Another said that if they had a dozen boats he would not set foot in one after what had happened. He should go straight back, the way he came, to their own vessel. Another said he would not go till he had looked abroad over the fiord for some chance of seeing the boat. This he persisted in, though told by the rest that it was absurd to suppose that the boat had loosed itself and gone out into the fiord in the course of the two minutes that they had been absent. He showed the fragment of the cut thong in proof of the boat not having loosed itself, and set off for a point on the heights which he said overlooked the fiord. One or two went with him, the rest returning up the narrow pathway at some speed—such speed that Erica thought they were afraid of the hindmost being caught by the same enemy that had taken their boat. Oddo observed this too, and he quickened their pace by setting up very loud the mournful cry with which he was accustomed to call out to the plovers on the mountain-side on sporting days. No sound can be more melancholy; and now, as it rang from the rocks, it was so unsuitable to the place, and so terrible to the already frightened men, that they ran on as fast as the slipperiness of the rocks would allow, till they were all out of sight over the ridge.

"Now for it, before the other two come out above us there!" said Oddo, and in another minute they were again in the fiord, keeping as much in the shadow as they could, however, till they must strike over to the islet.

"Thank God that we came!" exclaimed Erica. "We shall never forget what we owe you, Oddo. You shall see, by the care we take of your grandfather and Ulla, that we do not forget what you have done this night. If Nipen will only forgive, for the sake of this——"

"We were just in the nick of time," observed Oddo. "It was better than if we had been earlier."

"I do not know," said Erica. "Here are their brandy-bottles, and many things besides. I had rather not have had to bring these away."

"But if we had been earlier they would not have had their fright. That is the best part of it. Depend upon it, some that have not said their prayers for long will say them to-night."

"That will be good. But I do not like carrying home these things that are not ours. If they are seen at Erlingsen's they may bring the pirates down upon us. I would leave them on the islet but that the skiff has to be left there too, and that would explain our trick."

Erica would not consent to throw the property overboard. This would be robbing those who had not actually injured her, whatever their intentions might have been. She thought that if the goods were left upon some barren, uninhabited part of the shore, the pirates would probably be the first to find them; and that, if not, the rumour of such an extraordinary fact, spread by the simple country people, would be sure to reach them. So Oddo carried on shore, at the first stretch of white beach they came to, the brandy-flasks, the bear-skins, the tobacco-pouch, the muskets and powder-horns, and the tinder-box. He scattered these about, just above high-water mark, laughing to think how report would tell of the sprites' care in placing all these articles out of reach of injury from the water.

Oddo did not want for light while doing this. When he returned, he found Erica gazing up over the towering precipices at the Northern Lights, which had now unfurled their broad yellow blaze. She was glad that they had not appeared sooner to spoil the adventure of the night, but she was thankful to have the way home thus illumined now that the business was done. She answered with so much alacrity to Oddo's question whether she was not very weary, that he ventured to say two things which had before been upon his tongue without his having the courage to utter them.

"You will not be so afraid of Nipen any more," observed he, glancing at her face, of which he could see every feature by the quivering light. "You see how well everything has turned out."

"Oh, hush! It is too soon yet to speak so. It is never right to speak so. Pray do not speak any more, Oddo."

"Well, not about that. But what was it exactly that you thought Hund would do with this boat and those people? Did you think," he continued, after a short pause, "that they would come up to Erlingsen's to rob the place?"

"Not for the object of robbing the place, because there is very little that is worth their taking; far less than at the fishing-grounds. Not but they might have robbed us, if they took a fancy to anything we have. No; I thought, and I still think, that they would have carried off Rolf, led on by Hund——"

"Oh, ho! carried off Rolf! So here is the secret of your wonderful courage to-night, you who durst not look round at your own shadow last night! This is the secret of your not being tired, you who are out of breath with rowing a mile sometimes!"

"That is in summer," pleaded Erica. "However, you have my secret, as you say, a thing which is no secret at home. We all think that Hund bears such a grudge against Rolf, for having got the houseman's place——"

"And for nothing else?"

"That," continued Erica, "he would be glad to—to——"

"To get rid of Rolf, and be a houseman, and get betrothed instead of him. Well; Hund is baulked for this time. Rolf must look to himself after to-day."

Erica sighed deeply. She did not believe that Rolf would attend to his own safety; and the future looked very dark, all shrouded by her fears.

By the time the skiff was deposited where it had been found, both the rowers were so weary that they gave up the idea of taking the raft in tow, as for full security they ought to do. They doubted whether they could get home, if they had more weight to draw than their own boat. It was well that they left this encumbrance behind, for there was quite peril and difficulty enough without it; and Erica's strength and spirits failed the more the farther the enemy was left behind.

A breath of wind seemed to bring a sudden darkening of the friendly lights which had blazed up higher and brighter, from their first appearance till now. Both rowers looked down the fiord, and uttered an exclamation at the same moment.

"See the fog!" cried Oddo, putting fresh strength into his oar.

"O Nippen! Nipen!" mournfully exclaimed Erica. "Here it is, Oddo, the west wind!"

The west wind is, in winter, the great foe of the fishermen of the fiords; it brings in the fog from the sea, and the fogs of the Arctic Circle are no trifling enemy. If Nipen really had the charge of the winds, he could not more emphatically show his displeasure towards any unhappy boatman than by overtaking him with the west wind and fog.

"The wind must have just changed," said Oddo, pulling exhausting strokes, as the fog marched towards them over the water, like a solid and immeasurably lofty wall. "The wind must have gone right round in a minute."

"To be sure, since you said what you did of Nipen," replied Erica bitterly.

Oddo made no answer; but he did what he could. Erica had to tell him not to wear himself out too quickly, as there was no saying now how long they should be on the water.

How long they had been on the water, how far they had deviated from their right course, they could not at all tell, when, at last more by accident than skill, they touched the shore near home, and heard friendly voices, and saw the light of torches-through the thick air. The fog had wrapped them round so that they could not even see the water, or each other. They had rowed mechanically, sometimes touching the rock, sometimes grazing upon the sand, but never knowing where they were till the ringing of a bell, which they recognised as the farm bell, roused hope in their hearts, and strengthened them to throw off the fatal drowsiness caused by cold and fatigue. They made towards the bell; and then heard Peder's shouts, and next saw the dull light of two torches which looked as if they could not burn in the fog. The old man lent a strong hand to pull up the boat upon the beach, and to lift out the benumbed rowers; and they were presently revived by having their limbs chafed, and by a strong dose of the universal medicine—corn-brandy and camphor—which, in Norway, neither man nor woman, young nor old, sick nor well, thinks of refusing upon occasion.

When Erica was in bed, warm beneath an eider-down coverlid, her mistress bent over her and whispered—

"You saw and heard Hund himself?"

"Hund himself, madame."

"What shall we do if he comes back before my husband is home from the bear-hunt?"

"If he comes, it will be in fear and penitence, thinking that all the powers are against him. But oh, madame, let him never know how it really was!"

"Leave that to me, and go to sleep now, Erica. You ought to rest well; for there is no saying what you and Oddo have saved us from. I could not have asked such a service. My husband and I must see how we can reward it." And her kind and grateful mistress kissed Erica's cheek, though Erica tried to explain that she was thinking most of some one else, when she undertook this expedition.

Great was Stiorna's consternation at Hund's non-appearance the next day, seeing us she did with her own eyes that the boat was safe in its proper place. She saw that no one wished him back. He was rarely spoken of, and then it was with dislike or fear; and when she wept over the idea of his being drowned, or carried off by hostile spirits, the only comfort offered her was that she need not fear his being dead, or that he could not come back if he chose. She was indeed obliged to suppose, at last, that it was his choice to keep away; for amidst the flying rumours that amused the inhabitants of the district for the rest of the winter—rumours of the movements of the pirate vessel, and of the pranks of the spirits of the region—there were some such clear notices of the appearance of Hund, so many eyes had seen him in one place or another, by land and water, by day and night, that Stiorna could not doubt of his being alive, and free to come home or stay away as he pleased. She could not conceal from herself that he had probably joined the pirates.

Erlingsen and Rolf came home sooner than might reasonably have been expected, and well laden with bears' flesh. The whole family of bears had been found and shot.

He sometimes hammered at his skiff.

Erlingsen kept a keen and constant look-out upon the fiord. His wife's account of the adventures of the day of his absence made him anxious; and he never went a mile out of sight of home, so vivid in his imagination was the vision of his house burning, and his family at the mercy of pirates.

So came on and passed away the spring of this year at Erlingsen's farm. It soon passed, for spring in Nordland lasts only a month. About the bridges which spanned the falls were little groups of the peasants gathered, mending such as had burst with the floods, or strengthening such as did not seem secure enough for the passage of the herds to the mountain.

During the one busy month of spring, a slight shade of sadness was thrown over the household within by the decline of old Ulla. It was hardly sadness, it was little more than gravity; for Ulla herself was glad to go. Peder knew that he should soon follow, and every one else was reconciled to one who had suffered so long going to her rest.

One day Rolf led Erica to the grave when they knew that no one was there.

"Now," he said, "you know what she who lies there would like us to be settling. She herself said her burial-day would soon be over, and then would come our wedding-day."

"When everything is ready," replied Erica, "we will fix; but not now. There is much to be done—there are many uncertainties."

"What uncertainties? It is often an uncertainty to me, Erica, after all that has happened, whether you mean to marry me at all. There are so many doubts, and so many considerations, and so many fears!"

Erica quietly observed that they had enemies—one deadly enemy not very far off, if nothing were to be said of any but human foes. Rolf declared that he had rather have Hund for a declared enemy than for a companion. Erica understood this very well, but she could not forget that Hund wanted to be houseman in Rolf's stead, and that he desired to prevent their marriage.

"That is the very reason," said Rolf, "why we should marry as soon as we can. Why not fix the day, and engage the pastor while he is here?"

"Because it would hurt Peder's feelings. There will be no difficulty in sending for the pastor when everything is ready. But now, Rolf, that all may go well, do promise not to run into needless danger."

"According to you," said Rolf, smiling, "one can never get out of danger. Where is the use of taking care, if all the powers of earth and air are against us?"

"I am not speaking of Nipen now—(not because I do not think of it)—I am speaking of Hund. Do promise me not to go more than four miles down the fiord. After that, there is a long stretch of precipices, without a single dwelling. There is not a boat that could put off, there is not an eye or an ear that could bear witness what had become of you if you and Hund should meet there."

"I will promise you not to go farther down, while alone, than Vogel islet, unless it is quite certain that Hund and the pirates are far enough off in another direction. I partly think as you do, and as Erlingsen does, that they meant to come for me the night you carried off their boat; so I will be on the watch, and go no farther than where they cannot hurt me."

"Then why say Vogel islet? It is out of all reasonable distance."

"Not to those who know the fiord as I do. I have my reasons, Erica, for fixing that distance and no other; and that far I intend to go, whether my friends think me able to take care of myself or not."

"At least," pleaded Erica, "let me go with you."

"Not for the world, my love." And Erica saw, by his look of horror at the idea of her going, that he felt anything but secure from the pirates. He took her hand, and kissed it again and again, as he said that there was plenty for that little hand to do at home, instead of pulling the oar in the hot sun. "I shall think of you all while I am fishing," he went on. "I shall fancy you making ready for the seater.[2] How happy we shall be, Erica, when we once get to the seater!"

[2] The mountain pasture belonging to a farm is called its seater.

Erica sighed, and pressed her lover's hand as he held hers.

Who was ever happier than Rolf, when abroad in his skiff, on one of the most glorious days of the year! He found his angling tolerably successful near home; but the farther he went the more the herrings abounded, and he therefore dropped down the fiord with the tide, fishing as he receded, till all home objects had disappeared. When he came to the narrow part of the fiord, near the creek which had been the scene of Erica's exploit, Rolf laid aside his rod, with the bright hook that herrings so much admire, to guide his canoe through the currents caused by the approach of the rocks and contraction of the passage; and he then wished he had brought Erica with him, so lovely was the scene. Here and there a clump of dark pines overhung some busy cataract, which, itself overshadowed, sent forth its little clouds of spray, dancing and glittering in the sunlight. A pair of fishing eagles were perched on a high ledge of rock, screaming to the echoes. On went Rolf, beyond the bounds of prudence, as many have done before him. He soon found himself in a still and somewhat dreary region, where there was no motion but of the sea-birds, and of the air which appeared to quiver before the eye, from the evaporation caused by the heat of the sun. Leisurely and softly did Rolf cast his net; and then steadily did he draw it in, so rich in fish, that when they lay in the bottom of the boat, they at once sank it deeper in the water, and checked its speed by their weight.

Rolf then rested awhile. There lay Vogel islet looming in the heated atmosphere. He was roused at length by a shout, and looked towards the point from which it came; and there, in a little harbour of the fiord, a recess which now actually lay behind him—between him and home—lay a vessel; and that vessel he knew, by a second glance, was the pirate-schooner.