Produced by Al Haines

* A Distributed Proofreaders US Ebook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Gun-Brand

Author: Hendryx, James B.

Date of first publication: 1917

Date first posted: July 1, 2005

Date last updated: January 3, 2019

Faded Page ebook#20190117

| CHAPTER | |

| I | THE CALL OF THE RAW |

| II | VERMILION SHOWS HIS HAND |

| III | PIERRE LAPIERRE |

| IV | CHLOE SECURES AN ALLY |

| V | PLANS AND SPECIFICATIONS |

| VI | BRUTE MACNAIR |

| VII | THE MASTER MIND |

| VIII | A SHOT IN THE NIGHT |

| IX | ON SNARE LAKE |

| X | AN INTERVIEW |

| XI | BACK ON THE YELLOW KNIFE |

| XII | A FIGHT IN THE NIGHT |

| XIII | LAPIERRE RETURNS FROM THE SOUTH |

| XIV | THE WHISKEY RUNNERS |

| XV | "ARREST THAT MAN!" |

| XVI | MACNAIR GOES TO JAIL |

| XVII | A FRAME-UP |

| XVIII | WHAT HAPPENED AT BROWN'S |

| XIX | THE LOUCHOUX GIRL |

| XX | ON THE TRAIL OF PIERRE LAPIERRE |

| XXI | LAPIERRE PAYS A VISIT |

| XXII | CHLOE WRITES A LETTER |

| XXIII | THE WOLF-CRY! |

| XXIV | THE BATTLE |

| XXV | THE GUN-BRAND |

Seated upon a thick, burlap-covered bale of freight—a "piece," in the parlance of the North—Chloe Elliston idly watched the loading of the scows. The operation was not new to her; a dozen times within the month since the outfit had swung out from Athabasca Landing she had watched from the muddy bank while the half-breeds and Indians unloaded the big scows, ran them light through whirling rock-ribbed rapids, carried the innumerable pieces of freight upon their shoulders across portages made all but impassable by scrub timber, oozy muskeg, and low sand-mountains, loaded the scows again at the foot of the rapid and steered them through devious and dangerous miles of swift-moving white-water, to the head of the next rapid.

They are patient men—these water freighters of the far North. For more than two centuries and a quarter they have sweated the wilderness freight across these same portages. And they are sober men—when civilization is behind them—far behind.

Close beside Chloe Elliston, upon the same piece, Harriet Penny, of vague age, and vaguer purpose, also watched the loading of the scows. Harriet Penny was Chloe Elliston's one concession to convention—excess baggage, beyond the outposts, being a creature of fear. Upon another piece, Big Lena, the gigantic Swedish Amazon who, in the capacity of general factotum, had accompanied Chloe Elliston over half the world, stared stolidly at the river.

Having arrived at Athabasca Landing four days after the departure of the Hudson Bay Company's annual brigade, Chloe had engaged transportation into the North in the scows of an independent. And, when he heard of this, the old factor at the post shook his head dubiously, but when the girl pressed him for the reason, he shrugged and remained silent. Only when the outfit was loaded did the old man whisper one sentence:

"Beware o' Pierre Lapierre."

Again Chloe questioned him, and again he remained silent. So, as the days passed upon the river trail, the name of Pierre Lapierre was all but forgotten in the menace of rapids and the monotony of portages. And now the last of the great rapids had been run—the rapid of the Slave—and the scows were almost loaded.

Vermilion, the boss scowman, stood upon the running-board of the leading scow and directed the stowing of the freight. He was a picturesque figure—Vermilion. A squat, thick half-breed, with eyes set wide apart beneath a low forehead bound tightly around with a handkerchief of flaming silk.

A heavy-eyed Indian, moving ponderously up the rough plank with a piece balanced upon his shoulders, missed his footing and fell with a loud splash into the water. The Indian scrambled clumsily ashore, and the piece was rescued, but not before a perfect torrent of French-English-Indian profanity had poured from the lips of the ever-versatile Vermilion. Harriet Penny shrank against the younger woman and shuddered.

"Oh!" she gasped, "he's swearing!"

"No!" exclaimed Chloe, in feigned surprise. "Why, I believe he is!"

Miss Penny flushed. "But, it is terrible! Just listen!"

"For Heaven's sake, Hat! If you don't like it, why do you listen?"

"But he ought to be stopped. I am sure the poor Indian did not try to fall in the river."

Chloe made a gesture of impatience. "Very well, Hat; just look up the ordinance against swearing on Slave River, and report him to Ottawa."

"But I'm afraid! He—the Hudson Bay Company's man—told us not to come."

Chloe straightened up with a jerk. "See here, Hat Penny! Stop your snivelling! What do you expect from rivermen? Haven't the seven hundred miles of water trail taught you anything? And, as for being afraid—I don't care who told us not to come! I'm an Elliston, and I'll go whereever I want to go! This isn't a pleasure trip. I came up here for a purpose. Do you think I'm going to be scared out by the first old man that wags his head and shrugs his shoulders? Or by any other man! Or by any swearing that I can't understand, or any that I can, either, for that matter! Come on, they're waiting for this bale."

Chloe Elliston's presence in the far outlands was the culmination of an ideal, spurred by dissuasion and antagonism into a determination, and developed by longing into an obsession. Since infancy the girl had been left much to her own devices. Environment, and the prescribed course at an expensive school, should have made her pretty much what other girls are, and an able satellite to her mother, who managed to remain one of the busiest women of the Western metropolis—doing absolutely nothing—but, doing it with éclat.

The girl's father, Blair Elliston, from his desk in a luxurious office suite, presided over the destiny of the Elliston fleet of yellow-stack tramps that poked their noses into queer ports and put to sea with queer cargoes—cargoes that smelled sweet and spicy, with the spice of the far South Seas. Office sailor though he was, Blair Elliston commanded the respect of even the roughest of his polyglot crews—a respect not wholly uncommingled with fear.

For this man was the son of old "Tiger" Elliston, founder of the fleet. The man who, shoulder to shoulder with Brooke, the elder, put the fear of God in the hearts of the pirates, and swept wide trade-lanes among the islands of terror-infested Malaysia. And through Chloe Elliston's veins coursed the blood of her world-roving ancestor. Her most treasured possession was a blackened and scarred oil portrait of the old sea-trader and adventurer, which always lay swathed in many wrappings in the bottom of her favourite trunk.

In her heart she loved and admired this grandfather, with a love and admiration that bordered upon idolatry. She loved the lean, hard features, and the cold, rapier-blade eyes. She loved the name men called him; Tiger Elliston, an earned name—that. The name of a man who, by his might and the strength and mastery of him, had won his place in the world of the men who dare.

Since babyhood she had listened with awe to tales of him; and the red-letter days of her childhood's calendar were the days upon which her father would take her down to the docks, past great windowless warehouses of concrete and sheet-iron, where big glossy horses stood harnessed to high-piled trucks—past great tiers of bales and boxes between which trotted hurrying, sweating men—past the clang and clash of iron truck wheels, the rattle of chains, the shriek of pulleys, and the loud-bawled orders in strange tongues. Until, at last, they would come to the great dingy hulk of the ship and walk up the gangway and onto the deck, where funny yellow and brown men, with their hair braided into curious pigtails, worked with ropes and tackles and called to other funny men with bright-coloured ribbons braided into their beards.

Almost as she learned to walk she learned to pick out the yellow stacks of "papa's boats," learned their names, and the names of their captains, the bronzed, bearded men who would take her in their laps, holding her very awkwardly and very, very carefully, as if she were something that would break, and tell her stories in deep, rumbly voices. And nearly always they were stories of the Tiger—"yer gran'pap, leetle missey," they would say. And then, by palms, and pearls, and the fires of blazing mountains, they would swear "He wor a man!"

To the helpless horror of her mother, the genuine wonder of her many friends, and the ill-veiled amusement and approval of her father, a month after the doors of her alma mater closed behind her, she took passage on the Cora Blair, the oldest and most disreputable-looking yellow stack of them all, and hied her for a year's sojourn among the spicy lotus-ports of the dreamy Southern Ocean—there to hear at first hand from the men who knew him, further deeds of Tiger Elliston.

To her, on board the battered tramp, came gladly the men of power—the men whose spoken word in their polyglot domains was more feared and heeded than decrees of emperors or edicts of kings. And there, in the time-blackened cabin that had once been his cabin, these men talked and the girl listened while her eyes glowed with pride as they recounted the exploits of Tiger Elliston. And, as they talked, the hearts of these men warmed, and the years rolled backward, and they swore weird oaths, and hammered the thick planks of the chart-table with bangs of approving fists, and invoked the blessings of strange gods upon the soul of the Tiger—and their curses upon the souls of his enemies.

Nor were these men slow to return hospitality, and Chloe Elliston was entertained royally in halls of lavish splendour, and plied with costly gifts and rare. And honoured by the men, and the sons and daughters of men who had fought side by side with the Tiger in the days when the yellow sands ran red, and tall masts and white sails rose like clouds from the blue fog of the cannon-crashing powder-smoke.

So, from the lips of governors and potentates, native princes and rajahs, the girl learned of the deeds of her grandsire, and in their eyes she read approval, and respect, and reverence even greater than her own—for these were the men who knew him. But, not alone from the mighty did she learn. For, over rice-cakes and poi, in the thatched hovels of Malays, Kayans, and savage Dyaks, she heard the tale from the lips of the vanquished men—men who still hated, yet always respected, the reddened sword of the Tiger.

The year Chloe Elliston spent among the copra-ports of the South Seas was the shaping year of her destiny. Never again were the standards of her compeers to be her standards—never again the measure of the world of convention to be her measure. For, in her heart the awakened spirit of Tiger Elliston burned and seared like a living flame, calling for other wilds to conquer, other savages to subdue—to crush down, if need be, that it might build up into the very civilization of which the unconquerable spirit is the forerunner, yet which, in realization, palls and deadens it to extinction.

For social triumphs the girl cared nothing. The heart of her felt the irresistible call of the raw. She returned to the land of her birth and deliberately, determinedly, in the face of opposition, ridicule, advice, and command—as Tiger Elliston, himself, would have done—she cast about until she found the raw, upon the rim of the Arctic. And, with the avowed purpose of carrying education and civilization to the Indians of the far North, turned her back upon the world-fashionable, and without fanfare or trumpetry, headed into the land of primal things.

When the three women had taken their places in the head scow, Vermilion gave the order to shove off, and with the swarthy crew straining at the rude sweeps, the heavy scows threaded their way into the North.

Once through the swift water at the tail of Slave Rapids, the four scows drifted lazily down the river. The scowmen distributed themselves among the pieces in more or less comfortable attitudes and slept. In the head scow only the boss and the three women remained awake.

"Who is Pierre Lapierre?" Chloe asked suddenly.

The man darted her a searching glance and shrugged. "Pierre Lapierre, she free-trader," he answered. "Dees scow, she Pierre Lapierre scow."

If Chloe was surprised at this bit of information, she succeeded admirably in disguising her feelings. Not so Harriet Penny, who sank back among the freight pieces to stare fearfully into the face of the younger woman.

"Then you are Pierre Lapierre's man? You work for him?"

The man nodded. "On de reevaire I'm run de scow—me—Vermilion! I'm tak' de reesk. Lapierre, she tak' de money." The man's eyes glinted wickedly.

"Risk? What risk?" asked the girl.

Again the man eyed her shrewdly and laughed. "Das plent' reesk—on de reevaire. De scow—me'be so, she heet de rock in de rapids—bre'k all to hell—Voilà!" Somehow the words did not ring true.

"You hate Lapierre!" The words flashed swift, taking the man by surprise.

"Non! Non!" he cried, and Chloe noticed that his glance flashed swiftly over the sprawling forms of the five sleeping scowmen.

"And you are afraid of him," the girl added before he could frame a reply.

A sudden gleam of anger leaped into the eyes of the half-breed. He seemed on the point of speaking, but with an unintelligible muttered imprecation he relapsed into sullen silence. Chloe had purposely baited the man, hoping in his anger he would blurt out some bit of information concerning the mysterious Pierre Lapierre. Instead, the man crouched silent, scowling, with his gaze fixed upon the forms of the scowmen.

Had the girl been more familiar with the French half-breeds of the outlands she would have been suspicious of the man's sudden taciturnity under stress of anger—suspicious, also, of the gradual shifting that had been going on for days among the crews of the scows. A shifting that indicated Vermilion was selecting the crew of his own scow with an eye to a purpose—a purpose that had not altogether to do with the scow's safe conduct through white-water. But Chloe had taken no note of the personnel of the scowmen, nor of the fact that the freight of the head scow consisted only of pieces that obviously contained provisions, together with her own tent and sleeping outfit, and several burlapped pieces marked with the name "MacNair." Idly she wondered who MacNair was, but refrained from asking.

The long-gathering twilight deepened as the scows floated northward. Vermilion's face lost its scowl, and he smoked in silence—a sinister figure, thought the girl, as he crouched in the bow, his dark features set off to advantage by his flaming head-band.

Into the stillness crept a sound—the far-off roar of a rapid. Sullen, and dull, it scarce broke the monotony of the silence—low, yet ever increasing in volume.

"Another portage?" wearily asked the girl.

Vermilion shook his head. "Non, eet ees de Chute. Ten miles of de wild, fast wataire, but safe—eef you know de way. Me—Vermilion—I'm tak' de scow t'rough a hondre tam—bien!"

"But, you can't make it in the dark!"

Vermilion laughed. "We mak' de camp to-night. To-mor', we run de Chute." He reached for the light pole with which he indicated the channel to the steersman, and beat sharply upon the running-board that formed the gunwale of the scow. Sleepily the five sprawling forms stirred, and awoke to consciousness. Vermilion spoke a guttural jargon of words and the men fumbled the rude sweeps against the tholes. The other three scows drifted lazily in the rear and, standing upon the running-board, Vermilion roared his orders. Figures in the scows stirred, and sweeps thudded against thole-pins. The roar of the Chute was loud, now—hoarse, and portentous of evil.

The high banks on either side of the river drew closer together, the speed of the drifting scows increased, and upon the dark surface of the water tiny whirlpools appeared. Vermilion raised the pole above his head and pointed toward a narrow strip of beach that showed dimly at the foot of the high bank, at a point only a few hundred yards above the dark gap where the river plunged between the upstanding rocks of the Chute.

Looking backward, Chloe watched the three scows with their swarthy crews straining at the great sweeps. Here was action—life! Primitive man battling against the unbending forces of an iron wilderness. The red blood leaped through the girl's veins as she realized that this life was to be her life—this wilderness to be her wilderness. Hers to bring under the book, and its primitive children, hers—to govern by a rule of thumb!

Suddenly she noticed that the following scows were much nearer shore than her own, and also, that they were being rapidly out-distanced. She glanced quickly toward shore. The scow was opposite the strip of beach toward which the others were slowly but surely drawing. The scow seemed motionless, as upon the surface of a mill-pond, but the beach, and the high bank beyond, raced past to disappear in the deepening gloom. The figures in the following scows—the scows themselves—blurred into the shore-line. The beach was gone. Rocks appeared, jagged, and high—close upon either hand.

In a sudden panic, Chloe glanced wildly toward Vermilion, who crouched in the bow, pole in hand, and with set face, stared into the gloom ahead. Swiftly her glance travelled over the crew—their faces, also, were set, and they stood at the sweeps, motionless, but with their eyes fixed upon the pole of the pilot. Beyond Vermilion, in the forefront, appeared wave after wave of wildly tossing water. For just an instant the scow hesitated, trembled through its length, and with the leaping waves battering against its bottom and sides, plunged straight into the maw of the Chute!

Down, down through the Chute raced the heavily loaded scow, seeming fairly to leap from wave to wave in a series of tremendous shocks, as the flat bottom rose high in the fore and crashed onto the crest of the next wave, sending a spume of stinging spray high into the air. White-water curled over the gunwale and sloshed about in the bottom. The air was chill, and wet—like the dead air of a rock-cavern.

Chloe Elliston knew one moment of swift fear. And then, the mighty roar of the waters; the mad plunging of the scow between the towering walls of rock; the set, tense face of Vermilion as he stared into the gloom; the laboured breathing of the scowmen as they strained at the sweeps, veering the scow to the right, or to the left, as the rod of the pilot indicated; the splendid battle of it; the wild exhilaration of fighting death on death's own stamping ground flung all thought of fear aside, and in the girl's heart surged the wild, fierce joy of living, with life itself at stake.

For just an instant Chloe's glance rested upon her companions; Big Lena sat scowling murderously at Vermilion's broad back. Harriet Penny had fainted and lay with the back of her head awash in the shallow bilge water. A strange alter ego—elemental—primordial—had taken possession of Chloe. Her eyes glowed, and her heart thrilled at the sight of the tense, vigilant figure of Vermilion, and the sweating, straining scowmen. For the helpless form of Harriet Penny she felt only contempt—the savage, intolerant contempt of the strong for the weak among firstlings.

The intoxication of a new existence was upon her, or, better, a world-old existence—an existence that was new when the world was new. In that moment, she was a throw-back of a million years, and through her veins fumed the ferine blood of her paleolithic forebears. What is life but proof of the fitness to live? Death, but defeat.

On rushed the scow, leaping, crashing from wave to wave, into the Northern night. And, as it rushed and leaped and crashed, it bore two women, their garments touching, but between whom interposed a whole world of creeds and fabrics.

Suddenly, Chloe sensed a change. The scow no longer leaped and crashed, and the roar of the rapids grew faint. No longer the form of Vermilion appeared couchant, tense; and, among the scowmen, one laughed. Chloe drew a deep breath, and a slight shudder shook her frame. She glanced about her in bewilderment, and, reaching swiftly down, raised the inert form of Harriet Penny and rested it gently against her knees.

The darkness of night had settled upon the river. Stars twinkled overhead. The high, scrub-timbered shore loomed formless and black, and the flat bottom of the scow rasped harshly on gravel. Vermilion leaped ashore, followed by the scowmen, and Chloe assisted Big Lena with the still unconscious form of Harriet Penny. As if by magic, fires flared out upon the shingle, and in an incredibly short time the girl found herself seated upon her bed-roll inside her mosquito-barred tent of balloon silk. The older woman had revived and lay, a dejected heap, upon her blankets, and out in front Big Lena was stooping over a fire. Beyond, upon the gravel, the fires of the scowmen flamed red, and threw wavering reflections upon the black water of the river.

Chloe was seized with a strange unrest. The sight of Harriet Penny irritated her. She stepped from the tent and filled her lungs with great drafts of the spruce-laden night-breeze that wafted gently out of the mysterious dark, and rippled the surface of the river until little waves slapped softly against the shore in tiny whisperings of the unknown—whisperings that called, and were understood by the new awakened self within her.

She glanced toward the fires of the rivermen where the dark-skinned, long-haired sons of the wild squatted close about the flames over which pots boiled, grease fried, and chunks of red meat browned upon the ends of long toasting-sticks. The girl's heart leaped with the wild freedom of it. A sense of might and of power surged through her veins. These men were her men—hers to command. Savages and half-savages whose work it was to do her bidding—and who performed their work well. The night was calling her—the vague, portentous night of the land beyond outposts. Slowly she passed the fires, and on along the margin of the river whose waters, black and forbidding, reached into the North.

"The unconquered North," she breathed, as she stood upon a water-lapped boulder and gazed into the impenetrable dark. And, as she gazed, before her mind's eye rose a vision. The scattered teepees of the Northland, smoke-blackened, filthy, stinking with the reek of ill-tanned skins, resolved themselves into a village beside a broad, smooth-flowing river.

The teepees faded, and in their place appeared rows of substantial log cabins, each with its door-yard of neatly trimmed grass, and its beds of gay flowers. Broad streets separated the rows. The white spire of a church loomed proudly at the end of a street. From the doorways dark, full-bodied women smiled happily—their faces clean, and their long, black hair caught back with artistic bands of quill embroidery, as they called to the clean brown children who played light-heartedly in the grassed dooryards. Tall, lean-shouldered men, whose swarthy faces glowed with the love of their labour, toiled gladly in fields of yellow grain, or sang and called to one another in the forest where the ring of their axes was drowned in the crash of falling trees.

Her vision of the North—the conquered North—her North!

As Sir James Brooke and Tiger Elliston overthrew barbarism and established in its place an island empire of civilization, so would she supersede savagery with culture. But, her empire of the North should be an empire founded not upon blood, but upon humanity and brotherly love.

The girl started nervously. Her brain-picture resolved into the formless dark. From the black waters, almost at her feet, sounded, raucous and loud, the voice of the great loon. Frenzied, maniacal, hideous, rang the night-shattering laughter. The uncouth mockery of the raw—the defiance of the unconquerable North!

With a shudder, Chloe turned and fled toward the red-flaring fires. In that moment a feeling of defeat surged over her—of heart-sickening hopelessness. The figures at the fires were unkempt, dirty, revolting, as they gouged and tore at the half-cooked meat into which their yellow fangs drove deep, as the red blood squirted and trickled from the corners of their mouths to drip unheeded upon the sweat-stiffened cotton of their shirts. Savages! And she, Chloe Elliston, at the very gateway of her empire, fled incontinently to the protection of their fires!

Wide awake upon her blankets, in the smudge-pungent tent where her two companions slept heavily, Chloe sat late into the night staring through the mosquito-barred entrance toward the narrow strip of beach where the dying fires of the scowmen glowed sullenly in the darkness, pierced now and again by the fitful flare of a wind-whipped brand. Two still forms wrapped in ragged blankets, lay like logs where sleep had overcome them.

A short distance removed from the others, the fire of Vermilion burned brightly. Between this fire and a heavily smoking smudge, four men played cards upon a blanket spread upon the ground. Silently, save for an occasional grunt or mumbled word, they played—dealing, tossing into the centre the amount of their bets, leaning forward to rake in a pot, or throwing down their cards in disgust, to await the next deal.

The scene was intrinsically savage. At the end of the day's work, primitive man followed primitive instinct. Gorged to repletion, they slept, or wasted their substance with the improvidence of jungle-beasts. And these were the men Chloe Elliston had pictured labouring joyously in the upbuilding of homes! Once more the feeling of hopelessness came over her—seemed smothering, stifling her. And a great wave of longing carried her back to the land of her own people—the land of convention and sophistry.

Could it be that they were right? They who had scoffed, and ridiculed, and forbade her? What could she do in the refashioning of a world-old wild—one woman against the established creeds of an iron wilderness? Where, now, were her dreams of empire, her ideals, and her castles in Spain? Was she to return, broken on the wheel? Crushed between the adamantine millstones of things as they ought not to be?

The resolute lips drooped, a hot salt tear blurred Vermilion's camp-fire and distorted the figures of the gambling scowmen. She closed her eyes tightly. The writhing green shadow-shapes lost form, dimmed, and resolved themselves into an image—a lean, lined face with rapier-blade eyes gazed upon her from the blackness—the face of Tiger Elliston!

Instantly, the full force and determination of her surged through the girl's veins anew. The drooping lips stiffened. Her heart sang with the joy of conquest. The tight-pressed lids flew open, and for a long time she watched the shadow-dance of the flames on her tent wall. Dim, and elusive, and far away faded the dancing shadow-shapes—and she slept.

Not so Vermilion, who, when his companions tired of their game and sought their blankets, sat and stared into the embers of his dying fire. The half-breed was troubled. As boss of Pierre Lapierre's scowmen, a tool of a master mind, a unit of a system, he had prospered. But, no longer was he a unit of a system. From the moment Chloe Elliston had bargained with him for the transportation of her outfit into the wilderness, the man's brain had been active in formulating a plan.

This woman was rich. One who is not rich cannot afford to transport thirty-odd tons of outfit into the heart of the wilderness, at the tariff of fifteen cents the pound. So, throughout the days of the journey, the man gazed with avarice upon the piles of burlapped pieces, while his brain devised the scheme. Thereafter, in the dead of night occurred many whispered consultations, as Vermilion won over his men. He chose shrewdly, for these men knew Pierre Lapierre, and well they knew what portion would be theirs should the scheme of Vermilion miscarry.

At last, the selection had been made, and five of the most desperate and daring of all the rivermen had, by the lure of much gold, consented to cast loose from the system and "go it alone." The first daring move in the undertaking had succeeded—a move that, in itself, bespoke the desperate character of its perpetrators, for it was no accident that sent the head scow plunging down through the Chute in the darkness.

But, in the breast of Vermilion, as he sat alone beside his camp-fire, was no sense of elation—and in the heart of him was a great fear. For, despite the utmost secrecy among the conspirators, the half-breed knew that even at that moment, somewhere to the northward, Pierre Lapierre had learned of his plot.

Eight days had elapsed since the mysterious disappearance of Chenoine—and Chenoine, it was whispered, was half-brother to Pierre Lapierre. Therefore, Vermilion crouched beside his camp-fire and cursed the slowness of the coming of the day. For well he knew that when a man double-crossed Pierre Lapierre, he must get away with it—or die. Many had died. The black eyes flashed dangerously. He—Vermilion—would get away with it! He glanced toward the sleeping forms of the five scowmen and shuddered. He, Vermilion, knew that he was afraid to sleep!

For an instant he thought of abandoning the plan. It was not too late. The other scows could be run through in the morning, and, if Pierre Lapierre came, would it not be plain that Chenoine had lied? But, even with the thought, the avaricious gleam leaped into the man's eyes, and with a muttered imprecation, he greeted the first faint light of dawn.

Chloe Elliston opened her eyes sleepily in answer to a gruff call from without her tent. A few minutes later she stepped out into the grey of the morning, followed by her two companions. Vermilion was waiting for her as he watched the scowmen breaking open the freight pieces and making up hurried trail-packs of provisions.

"Tam to mush!" sad the man tersely.

"But where are the other scows?" asked Chloe, glancing toward the bank where the scow was being rapidly unloaded. "And what is the meaning of this? Here, you!" she cried, as a half-breed ripped the burlap from a bale. "Stop that! That's mine!" By her side, Vermilion laughed, a short, harsh laugh, and the girl turned.

"De scow, she not com'. We leave de rivaire. We tak' 'long de grub, eh?" The man's tone was truculent—insulting.

Chloe flushed with anger. "I am not going to leave the river! Why should I leave the river?"

Again the man laughed; there was no need for concealment now. "Me, Vermilion, I'm know de good plac' back in de hills. We go for stay dere till you pay de money."

"Money? What money?"

"Un hondre t'ousan' dollaire—cash! You pay, Vermilion—he tak' you back. You no pay—" The man shrugged significantly.

The girl stared, dumbfounded. "What do you mean? One hundred thousand dollars! Are you crazy?"

The man stepped close, his eyes gleaming wickedly. "You reech. You pay un hondre t'ousan' dollaire, or, ba gar, you nevaire com' out de bush!"

Chloe laughed in derision. "Oh! I am kidnapped! Is that it? How romantic!" The man scowled. "Don't be a fool, Vermilion! Do you suppose I came into this country with a hundred thousand dollars in cash—or even a tenth of that amount?"

The man shrugged indifferently. "Non, but you mak' de write on de papaire, an' Menard, he tak' heem to de bank—Edmonton—Preence Albert. He git de money. By-m-by, two mont', me'be, he com' back. Den, Vermilion, he tak' you close to de H.B. post—bien! You kin go hom', an' Vermilion, he go ver' far away."

Chloe suddenly realized that the man was in earnest. Her eyes flashed over the swarthy, villainous faces of the scowmen, and the seriousness of the situation dawned upon her. She knew, now, that the separating of the scows was the first move in a deep-laid scheme. Her brain worked rapidly. It was evident that the men on the other scows were not party to the plot, or Vermilion would not have risked running the Chute in the darkness. She glanced up the river. Would the other scows come on? It was her one hope. She must play for time. Harriet Penny sobbed aloud, and Big Lena glowered. Again Chloe laughed into the scowling face of the half-breed. "What about the Mounted? When they find I am missing there will be an investigation."

For answer, Vermilion pointed toward the river-bank, where the men were working with long poles in the overturning of the scow. "We shove heem out in de rivaire. Wen dey fin', dey t'ink she mak' for teep ovaire in de Chute. Voilà! Dey say: 'Een de dark she run on de rock'—pouf!" he signified eloquently the instantaneous snuffing out of lives. Even as he spoke the scow overturned with a splash, and the scowmen pushed it out into the river, where it floated bottom upward, turning lazily in the grip of an eddy. The girl's heart sank as her eyes rested upon the overturned scow. Vermilion had plotted cunningly. He drew closer now—leering horribly.

"You mak' write on de papaire—non?"

A swift anger surged in the girl's heart. "No!" she cried. "I will not write! I have no such amount in any bank this side of San Francisco! But if I had a million dollars, you would not get a cent! You can't bluff me!"

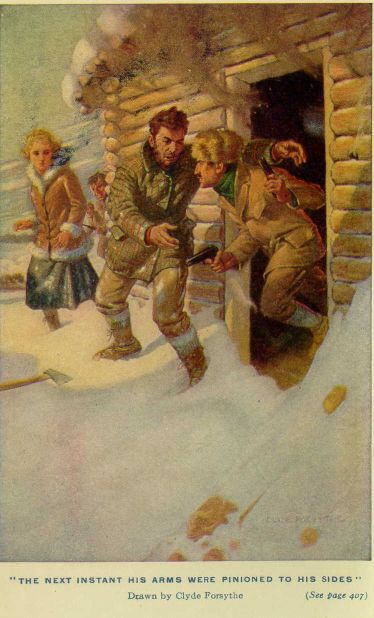

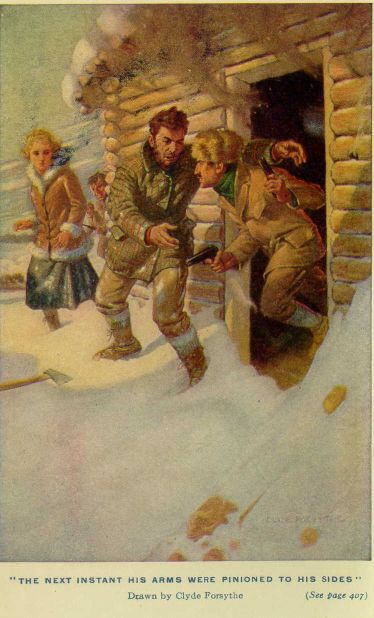

Vermilion sprang toward her with a snarl; but before he could lay hands upon her Big Lena, with a roar of rage, leaped past the girl and drove a heavy stick of firewood straight at the half-breed's head. The man ducked swiftly, and the billet thudded against his shoulder, staggering him. Instantly two of the scowmen threw themselves upon the woman and bore her to the ground, where she fought, tooth and nail, while they pinioned her arms. Vermilion, his face livid, seized Chloe roughly. The girl shrank in terror from the grip of the thick, grimy fingers and the glare of the envenomed eyes that blazed from the distorted, brutish features.

"Stand back!"

The command came sharp and quick in a low, hard voice—the voice of authority. Vermilion whirled with a snarl. Uttering a loud cry of fear, one of the scowmen dashed into the bush, closely followed by two of his companions. Two men advanced swiftly and noiselessly from the cover of the scrub. Like a flash, the half-breed jerked a revolver from his belt and fired. Chenoine fell dead. Before Vermilion could fire again the other man, with the slightest perceptible movement of his right hand, fired from the hip. The revolver dropped from the half-breed's hand. He swayed unsteadily for a few seconds, his eyes widening into a foolish, surprised stare. He half-turned and opened his lips to speak. Pink foam reddened the corners of his mouth and spattered in tiny drops upon his chin. He gasped for breath with a spasmodic heave of the shoulders. A wheezing, gurgling sound issued from his throat, and a torrent of blood burst from his lips and splashed upon the ground. With eyes wildly rolling, he clutched frantically at the breast of his cotton shirt and pitched heavily into the smouldering ashes of the fire at the feet of the stranger.

But few seconds had elapsed since Chloe felt the hand of Vermilion close about her wrist—tense, frenzied seconds, to the mind of the girl, who gazed in bewilderment upon the bodies of the two dead men which lay almost touching each other.

The man who had ordered Vermilion to release her, and who had fired the shot that had killed him, stood calmly watching four lithe-bodied canoemen securely bind the arms of the two scowmen who had attacked Big Lena.

So sudden had been the transition from terror to relief in her heart that the scene held nothing of repugnance to the girl, who was conscious only of a feeling of peace and security. She even smiled into the eyes of her deliverer, who had turned his attention from his canoemen and stood before her, his soft-brimmed Stetson in his hand.

"Oh! I—I thank you!" exclaimed the girl, at a loss for words.

The man bowed low. "It is nothing. I am glad to have been of some slight service." Something in the tone of the well-modulated voice, the correct speech, the courtly manner, thrilled the girl strangely. It was all so unexpected—so out of place, here in the wild. She felt the warm colour mount to her face.

"Who are you?" she asked abruptly.

"I am Pierre Lapierre," answered the man in the same low voice.

In spite of herself, Chloe started slightly, and instantly she knew that the man had noticed. He smiled, with just an appreciable tightening at the corners of the mouth, and his eyes narrowed almost imperceptibly. He continued:

"And now, Miss Elliston, if you will retire to your tent for a few moments, I will have these removed." He indicated the bodies. "You see, I know your name. The good Chenoine told me. He it was who warned me of Vermilion's plot in time for me to frustrate it. Of course, I should have rescued you later. I hold myself responsible for the safe conduct of all who travel in my scows. But it would have been at the expense of much time and labour, and, very possibly, of human life as well—an incident regrettable always, but not always avoidable."

Chloe nodded, and, with her thoughts in a whirl of confusion, turned and entered her tent, where Harriet Penny lay sobbing hysterically, with her blankets drawn over her head.

A half-hour later, when Chloe again ventured from the tent, all evidence of the struggle had disappeared. The bodies of the two dead men had been removed, and the canoemen were busily engaged in gathering together and restoring the freight pieces that had been ripped open by the scowmen.

Lapierre advanced to meet her, his carefully creased Stetson in hand.

"I have sent word for the other scows to come on at once, and in the meantime, while my men attend to the freight, may we not talk?"

Chloe assented, and the two seated themselves upon a log. It was then, for the first time that the girl noticed that one side of Lapierre's face—the side he had managed to keep turned from her—was battered and disfigured by some recent misadventure. Noticed, too, the really fine features of him—the dark, deep-set eyes that seemed to smoulder in their depths, the thin, aquiline nose, the shapely lips, the clean-cut lines of cheek and jaw.

"You have been hurt!" she cried. "You have met with an accident!"

The man smiled, a smile in which cynicism blended with amusement.

"Hardly an accident, I think, Miss Elliston, and, in any event, of small consequence." He shrugged a dismissal of the subject, and his voice assumed a light gaiety of tone.

"May we not become better acquainted, we two, who meet in this far place, where travellers are few and worth the knowing?" There was no cynicism in his smile now, and without waiting for a reply he continued: "My name you already know. I have only to add that I am an adventurer in the wilds—explorer of hinterlands, free-trader, freighter, sometime prospector—casual cavalier." He rose, swept the Stetson from his head, and bowed with mock solemnity.

"And now, fair lady, may I presume to inquire your mission in this land of magnificent wastes?" Chloe's laughter was genuine as it was spontaneous.

Lapierre's light banter acted as a tonic to the girl's nerves, harassed as they were by a month's travel through the fly-bitten wilderness. More—he interested her. He was different. As different from the half-breeds and Indian canoemen with whom she had been thrown as his speech was from the throaty guttural by means of which they exchanged their primitive ideas.

"Pray pause, Sir Cavalier," she smiled, falling easily into the gaiety of the man's mood. "I have ventured into your wilderness upon a most unpoetic mission. Merely the establishment of a school for the education and betterment of the Indians of the North."

A moment of silence followed the girl's words—a moment in which she was sure a hard, hostile gleam leaped into the man's eyes. A trick of fancy doubtless, she thought, for the next instant it had vanished. When he spoke, his air of light raillery was gone, but his lips smiled—a smile that seemed to the girl a trifle forced.

"Ah, yes, Miss Elliston. May I ask at whose instigation this school is to be established—and where?" He was not looking at her now, his eyes sought the river, and his face showed only a rather finely moulded chin, smooth-shaven—and the lips, with their smile that almost sneered.

Instantly Chloe felt that a barrier had sprung up between herself and this mysterious stranger who had appeared so opportunely out of the Northern bush. Who was he? What was the meaning of the old factor's whispered warning? And why should the mention of her school awake disapproval, or arouse his antagonism? Vaguely she realized that the sudden change in this man's attitude hurt. The displeasure, and opposition, and ridicule of her own people, and the surly indifference of the rivermen, she had overridden or ignored. This man she could not ignore. Like herself, he was an adventurer of untrodden ways. A man of fancy, of education and light-hearted raillery, and yet, a strong man, withal—a man of moment, evidently.

She remembered the sharp, quick words of authority—the words that caused the villainous Vermilion to whirl with a snarl of fear. Remembered also, the swift sure shot that had ended Vermilion's career, his absolute mastery of the situation, his lack of excitement or braggadocio, and the expressed regret over the necessity for killing the man. Remembered the abject terror in the eyes of those who fled into the bush at his appearance, and the servility of the canoemen.

As she glanced into the half-turned face of the man, Chloe saw that the sneering smile had faded from the thin lips as he waited her answer.

"At my own instigation." There was an underlying hardness of defiance in her words, and the firm, sun-reddened chin unconsciously thrust forward beneath the encircling mosquito net. She paused, but the man, expressionless, continued to gaze out over the surface of the river.

"I do not know exactly where," she continued, "but it will be somewhere. Wherever it will do the most good. Upon the bank of some river, or lake, perhaps, where the people of the wilderness may come and receive that which is theirs of right——"

"Theirs of right?" The man looked into her face, and Chloe saw that the thin lips again smiled—this time with a quizzical smile that hinted at tolerant amusement. The smile stung.

"Yes, theirs of right!" she flashed. "The education that was freely offered to me, and to you—and of which we availed ourselves."

For a long time the man continued to gaze in silence, and, when at length he spoke, it was to ask an entirely irrelevant question.

"Miss Elliston, you have heard my name before?"

The question came as a surprise, and for a moment Chloe hesitated. Then frankly, and looking straight into his eyes she answered:

"Yes, I have."

The man nodded, "I knew you had." He turned his injured eye quickly from the dazzle of the sunlight that flashed from the surface of the river, and Chloe saw that it was discoloured and bloodshot. She arose, and stepping to his side laid her hand upon his arm.

"You are hurt," she said earnestly, "your eye gives you pain."

Beneath her fingers the girl felt the play of strong muscles as the arm pressed against her hand. Their eyes met, and her heart quickened with a strange new thrill. Hastily she averted her glance and then—— The man's arm suddenly was withdrawn and Chloe saw that his fist had clinched. With a rush the words brought back to him the scene in the trading-room of the post at Fort Rae. The low, log-room, piled high with the goods of barter. The great cannon stove. The two groups of dark-visaged Indians—his own Chippewayans, and MacNair's Yellow Knives, who stared in stolid indifference. The trembling, excited clerk. The grim chief trader, and the stern-faced factor who watched with approving eyes while two men fought in the wide cleared space between the rough counter and the high-piled bales of woollens and strouds.

Chloe Elliston drew back aghast. The thin lips of the man had twisted into a snarl of rage, and a living, bestial hate seemed fairly to blaze from the smouldering eyes, as Lapierre's thoughts dwelt upon the closing moments of that fight, when he felt himself giving ground before the hammering, smashing blows of Bob MacNair's big fists. Felt the tightening of the huge arms like steel bands about his body when he rushed to a clinch—bands that crushed and burned so that each sobbing breath seemed a blade, white-hot from the furnace, stabbing and searing into his tortured lungs. Felt the vital force and strength of him ebb and weaken so that the lean, slender fingers that groped for MacNair's throat closed feebly and dropped limp to dangle impotently from his nerveless arms. Felt the sudden release of the torturing bands of steel, the life-giving inrush of cool air, the dull pain as his dizzy body rocked to the shock of a crashing blow upon the jaw, the blazing flash of the blow that closed his eye, and, then—more soul-searing, and of deeper hurt than the blows that battered and marred—the feel of thick fingers twisted into the collar of his soft shirt. Felt himself shaken with an incredible ferocity that whipped his ankles against floor and counter edge. And, the crowning indignity of all—felt himself dragged like a flayed carcass the full length of the room, out of the door, and jerked to his feet upon the verge of the steep descent to the lake. Felt the propelling impact of the heavy boot that sent him crashing headlong into the underbrush through which he rolled and tumbled like a mealbag, to bring up suddenly in the cold water.

The whole scene passed through his brain as dreams flash—almost within the batting of an eye. Half-consciously, he saw the girl's sudden start, and the look of alarm upon her face as she drew back from the glare of his hate-flashing eyes and the bestial snarl of his lips. With an effort he composed himself:

"Pardon, Miss Elliston, I have frightened you with an uncouth show of savagery. It is a rough, hard country—this land of the wolf and the caribou. Primal instincts and brutish passions here are unrestrained—a fact responsible for my present battered appearance. For, as I said, it was no accident that marred me thus, unless, perchance, the prowling of the brute across my path may be attributed to accident—rather, I believe it was timed."

"The brute! Who, or what is the brute? And why should he harm you?"

"MacNair is his name—Bob MacNair." There was a certain tense hardness in the man's tone, and Chloe was conscious that the smouldering eyes were regarding her searchingly.

"MacNair," said the girl, "why, that is the name on those bales!"

"What bales?"

"The bales in the scow—they are on the river-bank now."

"My scows carrying MacNair's freight!" cried the man, and motioning her to accompany him he walked rapidly to the bank where lay the four or five pieces, upon which Chloe had read the name. Lapierre dropped to his knees and regarded the pieces intently, suddenly he leaped to his feet with a laugh and called in the Indian tongue to one of his canoemen. The man brought him an ax, and raising it high, Lapierre brought it crashing upon the innocent-looking freight piece. There was a sound of smashing staves, a gurgle of liquid, and the strong odour of whiskey assailed their nostrils.

The piece was a keg, cunningly disguised as to shape, and covered with burlap. One by one the man attacked the other pieces marked with the name of MacNair, and as each cask was smashed, the whiskey gurgled and splashed and seeped into the ground. Chloe watched breathlessly until Lapierre finished, and with a smile of grim satisfaction, tossed the ax upon the ground.

"There is one consignment of firewater that will never be delivered," he said.

"What does it mean?" asked Chloe, and Lapierre noticed that her eyes were alight with interest. "Who is this MacNair, and——"

For answer Lapierre took her gently by the arm and led her back to the log.

"MacNair," he began, "is the most atrocious tyrant that ever breathed. Like myself, he is a free-trader—that is, he is not in the employ of the Hudson Bay Company. He is rich, and owns a permanent post of his own, to the northward, on Snare Lake, while I vend my wares under God's own canopy, here and there upon the banks of lakes and rivers."

"But why should he attack you?"

The man shrugged. "Why? Because he hates me. He hates any one who deals fairly with the Indians. His own Indians, a band of the Yellow Knives, together with an onscouring of Tantsawhoots, Beavers, Dog-ribs, Strongbows, Hares, Brushwoods, Sheep, and Huskies, he holds in abject peonage. Year in and year out he forces them to dig in his mines for their bare existence. Over on the Athabasca they call him Brute MacNair, and among the Loucheaux and Huskies he is known as The-Bad-Man-of-the-North.

"He pays no cash for labour, nor for fur, and he sees to it that his Indians are always hopelessly in his debt. He trades them whiskey. They are his. His to work, and to cheat, and to debauch, and to vent his rage upon—for his passions are the wild, unbridled passions of the fighting wolf. He kills! He maims! Or he allows to live! The Indians are his, body and soul. Their wives and their children are his. He owns them. He is the law!

"He warned me out of the North. I ignored that warning. The land is broad and free. There is room for all, therefore I brought in my goods and traded. And, because I refused to grind the poor savages under the iron heel of oppression, because I offer a meagre trifle over and above what is necessary for their bare existence, the brute hates me. He came upon me at Fort Rae, and there, in the presence of the factor, his clerk, and his chief trader, he fell upon me and beat me so that for three days I lay unable to travel."

"But the others!" interrupted the girl, "the factor and his men! Why did they allow it?"

Again the gleam of hate flashed in the man's eyes. "They allowed it because they are in league with him. They fear him. They fear his hold upon the Indians. So long as he maintains a permanent post a hundred and seventy-five miles to the northward—more than two hundred and fifty by the water trail—they know that he will not seriously injure the trade at Fort Rae. With me it is different. I trade here, and there, wherever the children of the wilderness are to be found. Therefore I am hated by the men of the Hudson Bay Company who would have been only too glad had MacNair killed me."

Chloe, who had listened eagerly to every word, leaped to her feet and looked at Lapierre with shining eyes. "Oh! I think it is splendid! You are brave, and you stand for the right of things! For the welfare of the Indians! I see now why the factor warned me against you! He wanted to discredit you."

Lapierre smiled. "The factor? What factor? And what did he tell you?"

"The factor at the Landing. 'Beware of Pierre Lapierre,' he said; and when I asked him who Pierre Lapierre was, and why I should beware of him, he shrugged his shoulders and would say nothing."

Lapierre nodded. "Ah yes—the company men—the factors and traders have no love for the free-trader. We cannot blame them. It is tradition. For nearly two and one-half centuries the company has stood for power and authority in the outlands—and has reaped the profits of the wild places. Let us be generous. It is an old and respectable institution. It deals fairly enough with the Indians—by its own measure of fairness, it is true—but fairly enough. With the company I have no quarrel.

"But with MacNair—" he stopped abruptly and shrugged. The gleam of hate that flashed in his eyes always at the mention of the name faded. "But why speak of him—surely there are more pleasant subjects," he smiled, "for instance your school—it interests me greatly."

"Interests you! I thought it displeased you! Surely a look of annoyance or suspicion leaped from your eyes when I mentioned my mission."

The man laughed lightly. "Yes? And can you blame me—when I thought you were in league with Brute MacNair? For, since his post was established, no independent save myself has dared to encroach upon even the borders of his empire."

Chloe Elliston flushed deeply. "And you thought I would league myself with a man like that?"

"Only for a moment. Stop and think. All my life I have lived in the North, and, except for a few scattered priests and missionaries, no one has pushed beyond the outposts for any purpose other than for gain. And the trader's gain is the Indian's loss—for, few deal fairly. Therefore, when I came upon your big outfit upon the very threshold of MacNair's domain, I thought, of course, this was some new machination of the brute. Even now I do not understand—the expense, and all. The Indians cannot afford to pay for education."

It was the girl's turn to laugh. A rippling, light-hearted laugh—the laughter of courage and youth. The barrier that had suddenly loomed between herself and this man of the North vanished in a breath. He had shown her her work, had pointed out to her a foeman worthy of her steel. She darted a swift glance toward Lapierre who sat staring into the fire. Would not this man prove an invaluable ally in her war of deliverance?

"Do not trouble yourself about the expense," she smiled. "I have money—'oodles of it,' as we used to say in school—millions, if I need them! And I'm going to fight this Brute MacNair until I drive him out of the North! And you? Will you help me to rid the country of this scourge and free the people from his tyranny? Together we could work wonders. For your heart is with the Indians, as mine is."

Again the girl glanced into the man's face and saw that the deep-set black eyes fairly glittered with enthusiasm and eagerness—an eagerness and enthusiasm that a keener observer than Chloe Elliston might have noticed, sprang into being suspiciously coincident with her mention of the millions. Lapierre did not answer at once, but deftly rolled a cigarette. The end of the cigarette glowed brightly as he filled his lungs and blew a plume of grey smoke into the air.

"Allow me a little time to think. For this is a move of importance, and to be undertaken not lightly. It is no easy task you have set yourself. It is possible you will not win—highly probable, in fact, for——"

"But I shall win! I am right—and upon my winning depends the future of a people! Think it over until tomorrow, if you will, but—" She paused abruptly, and her soft, hazel eyes peered searchingly into the depths of the restless black ones. "Your sympathies are with the Indians, aren't they?"

Lapierre tossed the half-smoked cigarette onto the ground. "Can you doubt it?" The man's eyes were not gleaming now, and into their depths had crept a look of ineffable sadness.

"They are my people," he said softly. "Miss Elliston, I am an Indian!"

A shout from the bank heralded the appearance of the first scow, which was closely followed by the two others. When they had landed, Lapierre issued a few terse orders, and the scowmen leaped to his bidding. The overturned scow was righted and loaded, and the remains of the demolished whiskey-kegs burned. Lapierre himself assisted the three women to their places, and as Chloe seated herself near the bow, he smiled into her eyes.

"Vermilion was a good riverman, but so am I. Do you think you can trust your new pilot?"

Somehow, the words seemed to imply more than the mere steering of a scow. Chloe flushed slightly, hesitated a moment, and then returned the man's smile frankly.

"Yes," she answered gravely, "I know I can."

Their eyes met in a long look. Lapierre gave the command to shove off, and when the scows were well in the grip of the current, he turned again to the girl at his side. Their hands touched, and again Chloe was conscious of the strange, new thrill that quickened her heart-beats. She did not withdraw her hand, and the fingers of Lapierre closed about her palm. He leaned toward her. "Only quarter Indian," he said softly. "My grandmother was the daughter of a great chief."

The girl felt the hot blood mount to her face and gently withdrew her hand. Somehow, she could not tell why, the words seemed good to hear. She smiled, and Lapierre, who was watching her intently, smiled in return.

"We are approaching quick water; we will cover many miles today, and tonight beside the camp-fire we will talk further."

Chloe's eyes searched the scows. "Where are the two who attacked Lena? Your men captured them."

Lapierre's smile hardened. "Those who deserted me for Vermilion? Oh, I—dismissed them from my service."

Hour after hour, as the scows rushed northward, Chloe watched the shores glide past; watched the swirling, boiling water of the river; watched the solemn-faced scowmen, and the silent, vigilant pilot; but most of all she watched the pilot, whose quick eye picked out the devious channel, and whose clear, alert brain directed, with a movement of the lancelike pole, the labours of the men at the sweeps.

She contrasted his manner—quiet, graceful, sure—with that of Vermilion, the very swing of whose pole proclaimed the vaunting, arrogant braggart. And she noted the difference in the attitude of the scowmen toward these two leaders. Their obedience to Vermilion's orders had been a surly, protesting obedience; while their obedience to Lapierre's slightest motion was the quiet, alert obedience that proclaimed him master of men, as his own silent vigilance proclaimed him master of the roaring waters.

When the sun finally dipped behind the barren scrub-topped hills, the scows were beached at the mouth of a deep ravine, from whose depths sounded the trickle of a tiny cascade. Lapierre assisted the women from the scow, issued a few short commands, and, as if by magic, a dozen fires flashed upon the beach, and in an incredibly short space of time Chloe found herself seated upon her blankets inside her mosquito-barred tent.

Supper over, Harriet Penny immediately sought her bed, and Lapierre led Chloe to a brightly burning camp-fire.

Nearby other fires burned, surrounded by dark, savage figures that showed indistinct in the half-light. The girl's eyes rested for a moment upon Lapierre, whose thin, handsome features, richly tanned by long exposure to the Northern winds and sun, presented a pleasing contrast to the swart flat faces of the rivermen, who sat in groups about their fires, or lay wrapped in their blankets upon the gravel.

"You have decided?" abruptly asked Chloe, in a voice of ill-concealed eagerness. Lapierre's face became at once grave, and he gazed sombrely into the fire.

"I have pondered deeply. Through the long hours, while the scow rushed into the North, there came to me a vision of my people. In the rocks, in the bush, and the ragged hills I saw it; and in the swirl of the mighty river. And the vision was good!"

The voice of the man's Indian grandmother spoke from his lips, and the soul of her glowed in his deep-set eyes.

"Even now Sakhalee Tyee speaks from the stars of the night sky. My people shall learn the wisdom of the white man. The power of the oppressor shall be broken, and the children of the far places shall come into their own."

The man's voice had dropped into the rhythmic intonation of the Indian orator, and his eyes were fixed upon the names that curled, lean and red, among the dry sticks of the camp-fire. Chloe gazed in fascination into the rapt face of this man of many moods. The soul of the girl caught the enthusiasm of his words, and she, too, saw the vision—saw it as she had seen it upon the wave-lapped rock of the river-bank.

"You will help me?" she cried; "will join forces with me in a war against the ruthless exploitation of a people who should be as free and unfettered as the air they breathe?"

Lapierre bent his gaze upon her face slowly, like one emerging from a trance.

"Yes," he answered deliberately; "it is of that I wish to speak. Let us consider the obstacles in our path—the matter of official interference. The government will soon learn of your activities, and the government is prone to look askance at any tampering with the Indians by an institution not connected with the Church or the State."

"I have my permit," Chloe answered, "and many commendatory letters from Ottawa. The men who rule were inclined to think I would accomplish nothing; but they were willing to let me try."

"That, then, disposes of our most serious difficulty. Will you tell me now where you intended to locate?"

"There is too much traffic upon the river," answered the girl. "The scow brigades pass and repass; and, at least until my little colony is fairly established, it must be located in some place uncontaminated by the presence of so rough, lawless, and drunken an element. As I told you before, I do not know where my ideal site is to be found. I had intended to talk the matter over with the factor at Fort Rae."

"What! That devil of a Haldane? The man who is hand-in-glove with Brute MacNair!"

"You forget," smiled the girl, "that until this day I never even heard of Brute MacNair."

The man smiled. "Very true. I had forgotten. But it is fortunate indeed that chance threw us together. I tremble to think what would have been your fate should you have acted upon the advice of Colin Haldane."

"But surely you know the country. You will advise me."

"Yes, I will advise you. I am with you in this venture; with you to the last gasp; with you heart and soul, until that devil MacNair is dead or driven out of the North, and his Indians scattered to the four winds."

"Scattered! Why scattered? Why not held together for their education and betterment? And you say you will be with me until MacNair is either dead or driven out of the North. What then—will you desert me then? This MacNair is only an obstacle in our path—an obstacle to be brushed aside that the real work may begin. Yet you spoke as though he were the main issue."

Lapierre interrupted her, speaking rapidly: "Yes, of course. Bear with me, I pray you. I spoke hastily, and without thinking. My feelings for the moment carried me away. As you see, the marks of the Brute's hands are still too fresh upon me to regard him impersonally—an obstacle, as it were. To me he is a brute! A fiend! A demon! I hate him!"

Lapierre shook a clenched fist toward the North, and the words fairly snarled between his lips. With an effort he controlled himself. "I have in mind the very place for your school, a spot accessible from all directions—the mouth of the Yellow Knife River, upon the north arm of Great Slave Lake. There you will be unmolested by the debauching rivermen, and yet within easy reach of any who may desire to take advantage of your school. The very place above all places! In the whole North you could not have chosen a better! And I shall accompany you, and direct the building of your houses and stockade.

"MacNair will learn shortly of your fort—everything is a 'fort' up here—and he will descend upon you like a ramping lion. When he finds you are a woman, he will do you no violence. He will scent at once a rival trading-post and will hurt your cause in every way possible; will use every means to discredit you among the Indians, and to discourage you. But even he will do a woman no physical harm.

"And right here let me caution you—do not temporize with him. He stands in the North for oppression; gain at any cost; for debauchery—everything that you do not. Between you and Brute MacNair there can be no truce. He is powerful. Do not for a moment underrate either his strength or his sagacity. He is a man of wealth, and his hold upon the Indians is absolute. I cannot remain with you, but through my Indians I shall keep in touch with you, work with you; and together we will accomplish the downfall of this brute of the North."

For a long time the two figures sat by the fire while the camp slept, and talked of many things. And when, well toward midnight, Chloe Elliston retired to her tent, she felt that she had known this man always. For it is the way of life that stress of events, and not duration of time, marks the measure of acquaintance and intimacy. Pierre Lapierre, Chloe Elliston had known but one day, and yet she believed that among all her acquaintances this man she knew best.

By the fire Lapierre's eyes followed the girl until she disappeared within the tent, and as he looked a huge figure arose from the deep shadows of the scrub, and with a hand grasping the flap of the tent, turned and stared, silent and grim and forbidding, straight into Lapierre's eyes.

The man turned away with a frown. The figure was Big Lena.

At the mouth of the Slave River the outfit was transferred to twelve large freight canoes, each carrying three tons, and manned by six lean-shouldered canoemen, in charge of one Louis LeFroy, Lapierre's boss canoeman. Straight across the vast expanse of Great Slave Lake they headed, and skirting the shore of the north arm, upon the evening of the second day, entered the Yellow Knife River.

The site selected by Pierre Lapierre for Chloe Elliston's school was, in point of location, as the quarter-breed had said, an excellent one. Upon a level plateau at the top of the high bank that slants steeply to the water of the Yellow Knife River, a short distance above its mouth, Lapierre set the canoemen to cutting the timber and brush from a wide area. The girl had come into the North fully prepared for a long sojourn, and in her thirty-odd tons of outfit were found all tools necessary for the clearing of land and the erection of buildings. Brushwood and trees fell before the axes of the half-breeds and Indians, who worked in a sort of frenzy under the lashing drive of Lapierre's tongue; and the night skies glowed red in the flare of the flames where the brush and tree-tops burned in the clearing.

Two days later a rectangular clearing, three hundred by five hundred feet, was completed, and early in the morning of the third day Chloe stood beside Lapierre and looked over the cleared oblong with its piles of smoking grey ashes, and its groups of logs that lay ready to be rolled into place to form the walls of her buildings.

Lapierre seemed ill at ease. Immediately upon the arrival of the outfit he had dispatched two of his own Indians northward to spy upon the movements of MacNair, for the man made no secret of his desire to be well upon his way before the trader should learn of the building of the fort on the river.

It had been Chloe's idea to lay out her "village," as she called it, upon a rather elaborate scheme, the plans for which had been drawn by an architect whose clients' tastes ran to million-dollar "summer cottages" at Seashore-by-the-Sea.

First, there was to be the school itself, an ornate building of crossed rafters and overhanging eaves. Then the dormitories, two long, parallel buildings with halls, individual rooms, and baths—one for the women and one for men—the two to be connected by a common dining-hall in such a manner as to form three sides of a hollow square. Connected to the dining-hall was to be a commodious kitchen, and back of that a fully equipped carpenter-shop and a laundry.

There were also to be a trading-post, where the Indians could purchase supplies at cost; a six-room cottage for the accommodation of Big Lena, Miss Penny, and Chloe; and numerous three-room cabins for the housing of whole families of Indians, which the girl fondly pictured as flocking in from the wilderness to have the errors of their heathenish religion pointed out to them upon a brand-new blackboard, and the discomforts of their nomadic lives assuaged by an introduction to collapsible bath-tubs and the multiplication table. For hers was to be a mission as well as a school. Truly the souls north of sixty were destined to owe her much. For they borrow cheerfully, and repay—never.

So much for Chloe Elliston's plan. Lapierre, however, had his own eminently more practical, if less Utopian, ideas concerning the erection of a trading-post; for in the quarter-breed's mind the planting of an independent trading-post upon the very threshold of MacNair's wilderness empire was of far greater importance than the establishment of a school, or mission, or any other institution—especially when the post was one which he himself had set about to control. The man's eyes gleamed and the thin lips smiled as his glance rested momentarily upon the figure of the girl—the unwitting, and therefore the more powerful, weapon that chance had placed in his hands in his battle against MacNair.

His idea of a post was simplicity itself: One long, log trading-room with an ell for a storehouse, and a room—two at the most—in the rear for the accommodation of the three women. The whole to be erected in the centre of the clearing, and surrounded by a fifteen-foot log stockade.

Boldly he broached his plan.

"But this is not a trading-post!" objected the girl. "The store is a side issue and is to be conducted merely to permit those who take advantage of my school to obtain the necessities of life at a fair and reasonable price."

"Your words were well chosen, Miss Elliston. For if you begin to undersell the H.B.C., and more especially the independents, every Indian in the North will proceed to 'take advantage' of your school and of you also."

"But they are being robbed!"

Lapierre smiled. "They do not know it; they are used to it. Let me warn you that to tamper with existing trade schedules, except by one experienced in the commerce of the North, is to invite disaster. You will lose money!"

"But you told me that you yourself gave the Indians better bargains than either the Hudson Bay Company or MacNair."

"I know the North! And you may be assured the concessions are more nominal than real."

"Very well, then," flashed the girl. "My concessions will be more real than nominal, and of that you may be assured. If my store pays expenses, well and good!" And by the tone of the girl's voice, and the slight, unconscious out-thrust of her chin, Pierre Lapierre knew that the time was unpropitious for a further discussion of trade principles.

Chloe was speaking again: "But to return to the buildings——"

Lapierre interrupted her, speaking earnestly: "My dear Miss Elliston, consider the circumstances, the limitations." He tapped lightly the roll of blue-prints the girl held in her hand. "Those plans were made by a man who had not the slightest knowledge of conditions as they exist here."

"The buildings are to be very simple."

"Undoubtedly. But simplicity is relative. A building that would be considered simplicity itself in the States, might well be intricate beyond the possibility of construction here in the wilderness. Do you realize that among our men is not one who can read a blue-print, or has ever seen one? Do you realize that to erect buildings in accordance with these plans would require a force of skilled mechanics under the supervision of a master builder? And do you realize that time is a most important factor in our present undertaking? Who can tell at what moment Brute MacNair may swoop down, upon us like Attila of old, and strike a fatal blow to our little outpost of civilization? And if he finds me here—" His voice trailed into silence and his eyes swept gloomily the northern reach of the river.

Chloe appeared unimpressed. "I hardly think he will resort to violence. There is the law—even here in the wilderness. Slow to act, perhaps, because of the inaccessibility of the wild country; but once its machinery is in motion, as unbending and as indomitable as justice itself. You see, I have read of your Mounted Police."

"The Mounted!" Lapierre laughed. "Yes—I see you have read of them! Had you derived your information in a more direct manner—had you lived among them—if you knew them—your childlike trust in them would seem as absurd, perhaps, as it does to me!"

"What do you mean?" cried the girl, regarding the quarter-breed with a searching glance. "That the men of the Mounted are—that they may be—influenced?"

Again Lapierre laughed—harshly. "Just that, Miss Elliston! They are—crooked. They may be influenced!"

"I cannot believe that!"

"You will—later."

"You mean that MacNair has——"

The man interrupted with a wave of his hand. "What I have told you of MacNair is the truth. I shall prove this to your own satisfaction, at the proper time. Until then, I ask you to believe me. Admitting, then, that I have spoken the truth, do you suppose for an instant that these facts are not known to the Mounted? If not, then the officers are inefficient fools. If they are known, why don't the Mounted remedy matters? Because MacNair is rich! Because he buys them, body and soul! Because he owns them, like he owns the Indians! That's why!

"Just stop and consider what is ahead of a dollar-a-day policeman. When his five-year term of enlistment has expired, he has his choice of enlisting for another term, or making his living some other way. At the end of the five years he has learned to hate the service with a hatred that is soul-searing. It is the hardest, strictest, most exacting, and most ill-paid service in the world; and the five years of the man's enlistment have practically rendered him unfit for earning a living.

"He has lived in the wild country. He knows the wild country. And civilization, with its rapid advance, has left him five years behind the times. Our ex-man of the Mounted is fit for only the commonest labour. And, because there are almost no employers in the North, he cannot turn his knowledge of the wilds to profitable account, unless he turns smuggler, whiskey-runner, or fur-poisoner. The men know this. Therefore, when an officer whose patrol takes him into the far 'back blocks' is approached by a man like MacNair, with his pockets bulging with gold, what report goes down to Regina, and on to Ottawa?

"Yes, Miss Elliston, in the Northland there is law. But the law is a fundamental law—the primitive law of savage might. The strong devour the weak. Only the fit survive—survive to be ruled, to be trampled, to be owned by the strongest. And the law is the measure of might! Primal instincts—pristine passions—primordial brutishness permeate the whole North—rule it.

"The wolf and savage carcajo drag down the hunger-weakened caribou and the deer, and rip the warm, red flesh from their bones before their eyes have glazed. And, in turn, the wolf and the carcajo, the unoffending beaver and musquash, the mink, the fisher, the fox, and the otter are trapped by savage man and the pelts ripped from their twitching bodies while life and sensibility remain. They are harder to skin when cold. And with the thermometer at forty or sixty below zero, the little bodies chill almost instantly if mercifully killed—therefore, they are not killed, but flayed alive and their bleeding bodies tossed upon the snow. They die quickly—then. But—they have lived through the skinning! And that is the North!"

Chloe Elliston shuddered and drew away in horror. "Is—is this possible?" she faltered. "Do they——"

"They do. The fur business is not a pretty business, Miss Elliston. But neither is the North pretty—nor are its inhabitants. But the traffic in fur is inherently the business of the North—and its history is written in blood—the blood and the suffering of thousands of men and millions of animals. But the profits are great. Fashion has decreed that My Lady shall be swathed in fur—therefore, men go mad and die in the barrens, and the quivering red bodies of small animals bleed, and curl up, and stiffen upon the hard crust of the snow! No, the North is not gentle, Miss Elliston——"

"Don't! Don't!" faltered the girl. "It is all too—too horrible—too sickeningly brutal—too—too unbelievable!" She covered her eyes with her hand.

Lapierre answered, dryly. "Yes. The North is that way. It has always been so—and it always will——"

Chloe's hand dropped from her eyes and, she faced him in a sudden burst of passion. Her sensitive lips quivered and her eyes narrowed to the rapier-blade eyes that were the eyes of Tiger Elliston. She tore the roll of blue-prints to bits and ground them into the mould with the heel of her boot.

"It will not!" Her voice cut sharply, and hard. "What do you know of what the North will be? You know it only as it has been—as it is, perhaps. But, of its future you know nothing. I tell you the North will change! It is a hard land—cruel—elemental—raw! But it is big! And, when it awakens, its very bigness, the virile force and strength of it, will turn against its savagery, its cruelty, its brutishness; and above all other lands it will stand for the protection of the weak and for the right of things to live!"

The quarter-breed gazed into her face with a look of undisguised admiration. "Ah, Miss Elliston, you are beautiful, now—beautiful always—but, at this moment—radiant—divine—" Chloe seemed not to hear him.

"And that is to be my work—to awaken the North! To bring to its people the comforts—the advantages of civilization!"

"The North is too big for you, Miss Elliston. It is too big for men. Pardon, but it is not a woman's land."

The girl's eyes flashed. "Suppose we leave sex out of it, Mr. Lapierre. They said of my grandfather that 'the harder they fought him, the better he liked 'em,' and that 'he never knew when he was licked.' Maybe that is the reason he never was licked, but lived to carry civilization into a land that was a thousand years deeper in savagery than this land is. And today civilization—education—Christianity exist where seventy-five years ago the chance visitor was tortured first and eaten afterward."

Lapierre shrugged. "It is useless to argue. I am in sympathy with your undertaking. I admire your courage, and the high ideals of your mission. But, permit me to remind you that your grandfather, whoever he was, was not a woman. Also, that here, in the North, Christianity and education have failed to civilize—the educated ones and the converts are worse than the others."