Produced by Al Haines

* A Distributed Proofreaders US Ebook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

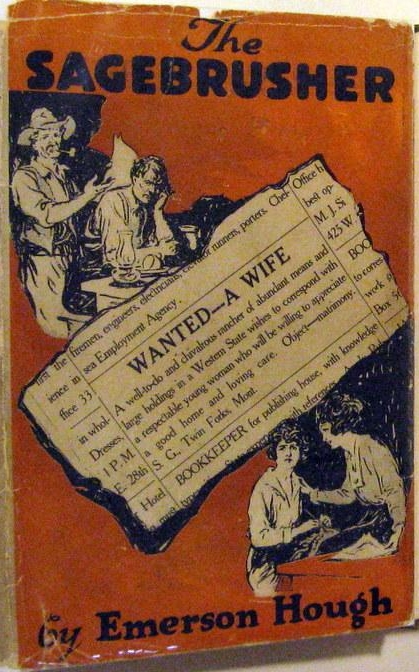

Title: The Sagebrusher: A Story of the West

Author: Hough, Emerson

Date of first publication: 1919

Date first posted: September 26, 2006

Date last updated: January 3, 2019

Faded Page ebook#20190115

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | SIM GAGE AT HOME |

| II. | WANTED: A WIFE |

| III. | FIFTY-FIFTY |

| IV. | HEARTS AFLAME |

| V. | BEGGAR MAN—THIEF |

| VI. | RICH MAN—POOR MAN |

| VII. | CHIVALROUS; AND OF ABUNDANT MEANS |

| VIII. | RIVAL CONSCIENCES |

| IX. | THE HALT AND THE BLIND |

| X. | NEIGHBORS |

| XI. | THE COMPANY DOCTOR |

| XII. | LEFT ALONE |

| XIII. | THE SABCAT CAMP |

| XIV. | THE MAN TRAIL |

| XV. | THE SPECIES |

| XVI. | THE REBIRTH OF SIM GAGE |

| XVII. | SAGEBRUSHERS |

| XVIII. | DONNA QUIXOTE |

| XIX. | THE PLEDGE |

| XX. | MAJOR ALLEN BARNES, M.D., PH.D.—AND SIM GAGE |

| XXI. | WITH THIS RING |

| XXII. | MRS. GAGE |

| XXIII. | THE OUTLOOK |

| XXIV. | ANNIE MOVES IN |

| XXV. | ANOTHER MAN'S WIFE |

| XXVI. | THE WAYS OF MR. GARDNER |

| XXVII. | DORENWALD, CHIEF |

| XXVIII. | A CHANGE OF BASE |

| XXIX. | MARTIAL LAW |

| XXX. | BEFORE DAWN |

| XXXI. | THE BLIND SEE |

| XXXII. | THE ENEMY |

| XXXIII. | THE DAM |

| XXXIV. | AFTER THE DELUGE |

| XXXV. | ANNIE ANSWERS |

| XXXVI. | MRS. DAVIDSON'S CONSCIENCE |

"Sim," said Wid Gardner, as he cast a frowning glance around him, "take it one way with another, and I expect this is a leetle the dirtiest place in the Two-Forks Valley."

The man accosted did no more than turn a mild blue eye toward the speaker and resume his whittling. He smiled faintly, with a sort of apology, as the other went on.

"I'll say more'n that, Sim. It's the blamedest, dirtiest hole in the whole state of Montany—yes, or in the whole wide world. Lookit!"

He swept a hand around, indicating the interior of the single-room log cabin in which they sat.

"Well," commented Sim Gage after a time, taking a meditative but wholly unagitated tobacco shot at the cook stove, "I ain't saying she is and I ain't saying she ain't. But I never did say I was a perfessional housekeeper, did I now?"

"Well, some folks has more sense of what's right, anyways," grumbled Wid Gardner, shifting his position on one of the two insecure cracker boxes which made the only chairs, and resting an elbow on the oil cloth table cover, where stood a few broken dishes, showing no signs of any ablution in all their hopeless lives. "My own self, I'm a bachelor man, too—been batching for twenty years, one place and another—but by God! Sim, this here is the human limit. Look at that bed."

He kicked a foot toward a heap of dirty fabrics which lay upon the floor, a bed which might once have been devised for a man, but long since had fallen below that rank. It had a breadth of dirty canvas thrown across it, from under which the occupant had crawled out. Beneath might be seen the edges of two or three worn and dirty cotton quilts and a pair of blankets of like dinginess. Below this lay a worn elk hide, and under all a lower-breadth of the over-lapping canvas. It was such a bed as primarily a cow-puncher might have had, but fallen into such condition that no cow camp would have tolerated it.

Sim Gage looked at the heap of bedding for a time gravely and carefully, as though trying to find some reason for his friend's dissatisfaction. His mouth began to work as it always did when he was engaged in some severe mental problem, but he frowned apologetically once more as he spoke.

"Well, Wid, I know, I know. It ain't maybe just the thing to sleep on the floor all the time, noways. You see, I got a bunk frame made for her over there, and it's all tight and strong—it was there when I took this cabin over from the Swede. But I ain't never just got around to moving my bed offen the floor onto the bedstead. I may do it some day. Fact is, I was just a-going to do it anyways."

"Just a-going to—like hell you was! You been a-going to move that bed for four years, to my certain knowledge, and I know that in that time you ain't shuk it out or aired it onct, or made it up."

"How do you know I ain't made her up?" demanded Sim Gage, his knife arrested in its labors.

"Well, I know you ain't. It's just the way you've throwed it ever' morning since I've knowed you here. Move it up on the bedstead?—First thing you know you can't."

"Well," said Sim, sighing, "some folks is always making other folks feel bad. I ain't never found fault with the way you keep house when I come over to your place, have I?"

"You ain't got the same reason for to," replied Wid Gardner. "I ain't no angel, but I sure try to make some sort of bluff like I was human. This place ain't human."

"Now you said something!" remarked Sim suddenly, after a time spent in solemn thought. "She ain't human! That's right."

He made no explanation for some time, and both men sat looking vaguely out of the open door across the wide and pleasant valley above which a blue and white-flecked sky bent amiably. A wide ridge of good grass lands lay held in the river's bent arm. The wind blew steadily, throwing up into a sheet of silver the leaves of the willows which followed the water courses. A few quaking asps standing near the cabin door likewise gave motion and brightness to the scene. The air was brilliantly cool and keen. It was a pleasant spot, and at that season of the year not an uncomfortable one. Sim Gage had lived here for some years now, and his homestead, originally selected with the unconscious sense for beauty so often exercised by rude men in rude lands, was considered one of the best in the Two-Forks Valley.

"Feller, he loses hope after a while," began the owner of the place after a considerable silence. "Look at me, for instance. I come out here from Ioway more'n twenty-five years ago, when I was only a boy. When my pa died my ma, she moved back to Ioway. I stuck around here, like you and lots of other fellers, and done like you all, just the best I could. Some way the country sort of took a holt on me. It does, ain't it the truth?"

His friend nodded silently.

"Well, so I stuck around and done about what I could, same as you, ain't that so, Wid? I prospected some, but you know how hard it is to get any money into a mine, no matter what you've found fer a prospect. I got along somehow—seems like folks didn't use to pester so much, the way they do to-day. And you know onct I was just on the point of starting out fer Arizony with that old miner, Pop Haynes—do you suppose I'd struck anything if I'd of went down there?"

"Nobody can say if you would or you wouldn't," replied Wid. "Fact is, you never got more'n half started."

"Well, you see, this old feller, Pop Haynes, he'd been down in Arizony twenty years before, and he said there was lots of gold out there in the desert. Well, we got a team hooked up, and a little flour and bacon, and we did start—now, I'll leave it to you, Wid, if we didn't. We got as far as Big Springs, on the railroad. What did we hear then? Why, news comes up from down in Arizony that a railroad has went out into the desert, and that them mines has been discovered. What's the use then fer us to start fer Arizony with a wagon and team? Like enough all the good stakes would be took up before we could get there. Old Pop and me, we just turned back, allowing it was the sensiblest thing to do."

"And you been in around here ever since."

"Yes, sir; yes, sir, that's what I been. Been around here ever since. I told you the country kind of takes a holt on a feller. Ain't it the truth? Well, I trapped a little since then in the winters, and killed elk for the market some, like you know, and fished through the ice over on the lakes, like you know. Some days I'd make three or four dollars a day fishing. So at last when that Swede, Big Aleck, got run out of the county, I fell into his ranch. There ain't a better in the whole valley. Look at that hay land, Wid. You got to admit that this here is one of the best places in Montany."

"Well, maybe it is," said his friend and neighbor. "Leastways, it's good enough to run like you mean to run it."

"I'm a-going to run her all right. She's all under wire—the Swede done that before I bought his quit claim. Can't no sheep get in on me here. I'll bet you all my clothes that I'll cut six hundred ton of hay this season—leastways I would if my horse hadn't hurt hisself in the wire the other day. Now, you figure up what six hundred ton of hay comes to in the stack, at prices hay is bringing now."

"Trouble is, your hay ain't in the stack, Sim. You'll just about cut hay enough to buy yourself flour and bacon for next winter, and that'll be about all. If you worked the place right you'd make plenty fer to——"

"Fer to be human?"

"Well, yes, that's about it, Sim."

"That's right hard—doing all your own work outside and doing all your own cooking and everything all the time in your own house. Just living along twenty years one day after another, all by your own self, and never—never——"

His voice trailed off faintly, and he left the sentence unfinished. Wid Gardner completed it for him.

"And never having a woman around?" said he.

"Ain't it the truth?" said Sim Gage suddenly. His eyes ran furtively around the room in which they sat, taking in, without noting or feeling, the unutterable squalor of the place.

"Well," said his friend after a time, rising, "it'd be a fine place to fetch a woman to, wouldn't it? But now I got to be going—I got my chores to do."

"What's your hurry, Wid?" complained the occupant of the cabin. "Cow'll wait."

"Yours might," said the other sententiously. As he spoke he was making his way to the door.

The sun was sinking now behind the range, and as he stood for a moment looking toward the west, he might himself have been seen to be a man of some stature, rugged and bronzed, with scores of wrinkles on his leathery cheeks. His garb was the rude one of the West, or rather of that remnant of the Old West which has been consigned to the dry farmers and hay ranchers in these modern polyglot days.

Sim Gage, the man who followed him out and stood for a time in the unsparing brilliance of the evening sunlight, did not compare too well with his friend. He was a man of absolutely no presence, utterly lacking attractiveness. Not so much pudgy as shapeless; he had been shapeless originally. His squat figure showed, to be sure, a certain hardiness and vigor gained in his outdoor life, but he had not even the rude grace of a stalwart manhood about him. He sank apologetically into a lax posture, even as he stood. His pale blue eyes lacked fire. His hair, uneven, ragged and hay-colored, seemed dry, as though hopeless, discouraged, done with life, fringing out as it did in gray locks under the edge of the battered hat he wore. He had been unshaven for days, perhaps weeks, and his beard, unreaped, showed divers colors, as of a field partially ripening here and there. In general he was undecided, unfinished—yes, surely nature must have been undecided as he himself was about himself.

His clothing was such as might have been predicted for the owner of the nondescript bed resting on the cabin floor. His neck, grimed, red and wrinkled as that of an ancient turtle, rose above his bare brown shoulders and his upper chest, likewise exposed. His only body covering was an undershirt, or two undershirts. Their flannel over-covering had left them apparently some time since, and as for the remnant, it had known such wear that his arms, brown as those of an Indian, were bare to the elbows. He was always thus, so far as any neighbor could have remembered him, save that in the winter time he cast a sheepskin coat over all. His short legs were clad in blue overalls, so far as their outside cover was concerned, or at least the overalls once had been blue, though now much faded. Under these, as might be seen by a glance at their bottoms, were two, three, or possibly even more, pairs of trousers, all borne up and suspended at the top by an intricate series of ropes and strings which crossed his half-bare shoulders. One might have searched all of Sim Gage's cabin and have found on the wall not one article of clothing—he wore all he had, summer and winter. And as he was now, so he had been ever since his nearest neighbor could remember. A picture of indifference, apathy and hopelessness, he stood, every rag and wrinkle of him sharply outlined in the clear air.

He stood uncertainly now, his foot turned over, as he always stood, there seeming never at any time any determination or even animation about him. And yet he longed, apparently, for some sort of human companionship, but still he argued with his friend and asked him not to hurry away.

None the less after a few moments Wid Gardner did turn away. He passed out at the rail bars which fenced off the front yard from the willow-covered banks of a creek which ran nearby. A half-dozen head of mixed cattle followed him up to the gate, seeking a wider world. A mule thrust out his long head from a window of the log stable where it was imprisoned, and brayed at him anxiously, also seeking outlet.

But Sim Gage, apathetic, one foot lopped over, showed no agitation and no ambition. The wisp of grass which hung now from the corner of his mouth seemed to suit him for the time. He stood chewing and looking at his departing visitor.

"Some folks is too damn dirty," said Wid Gardner to himself as he passed now along the edge of the willow bank toward the front gate of his own ranch, a half-mile up the stream. "And him talking about a woman!" He flung out his hand in disgust at the mere thought.

That is to say, he did at first. Then he began to walk more slowly. A touch of reflectiveness came upon his own face.

"Still," said he to himself after a time—speaking aloud as men of the wilderness sometimes learn to do—"I don't know!"

He turned into his own gate, approached his own cabin, its exterior much like that of the one which but now he had left. He paused for a moment at the door as he looked in, regarding its somewhat neater appearance.

"Well, and even so," said he. "I don't know. Still and after all, now, a woman——"

"I couldn't have ate at Sim's place if he would of asked me to," grumbled Wid Gardner aloud to himself as he busied himself about his own household duties in his bachelor cabin. "He's too damn dirty, like I said, and that's a fact."

Wid's cabin itself was in general appearance no better, if no worse, than the average in the Two Forks Valley. There was a bed on a rude pole frame—little more than a heap of blankets as they had been thrown aside that morning. The table still held the dishes which had been used, but at least these had been washed, and there was thrown across them what had served as a dish-towel, a washed and dried, fairly clean flour sack which had been ripped out and turned into a towel. There was a box nailed up behind the stove which served as a sort of store room for the scant supplies, and this had a flap at the top, so that it was partly curtained off. Another box nailed against the wall behind the table served as book case and paper rack, holding, among a scant array of ancient standard volumes, a few dog-eared paper-backed books of cheap and dreadful sort, some illustrated journals showing pictures of actresses and film celebrities—precisely the sort of literature which may be found in most wilderness bachelor homes.

At one end of the up-turned box which served as a sort of reading table lay a pile of similar magazines, not of abundant folios, but apparently valued, for they showed more care than any other of the owner's treasures. It was, curiously enough, to this little heap of literature that Wid Gardner presently turned.

Forgetful of the hour and of his waiting cows, he sat down, a copy in his hands, his face taking on a new sort of light as he read. At times, as lone men will, he broke out into audible soliloquy. Now and again his hand slapped his knee, his eye kindled, he grinned. The pages were ill-printed, showing many paragraphs, apparently of advertising nature, in fine type, sometimes marked with display lines.

Wid turned page after page, grunting as he did so, until at last he tossed the magazine upon the top of the box and so went about his evening chores. Thus the title of the publication was left showing to any observer. The headline was done in large black letters, advising all who might have read that this was a copy of the magazine known as Hearts Aflame.

Curiously enough, on the front page the headline of a certain advertisement showed plainly. It read, "Wanted: A Wife."

From this it may be divined that here was one of those periodicals printed no one knows where, circulated no one knows how, which none the less after some fashion of their own do find their way out in all the womanless regions of the world—Alaska, South Africa, the dry plains of Canada and our Western States, mining camps far out in the outlying districts beyond the edge of the homekeeping lands—it is in regions such as these that periodicals such as the foregoing may be found. Their circulation is among those who seek "acquaintance with a view to matrimony." They are the official organs of Cupid himself—or Cupid commercialized, or Cupid much misnamed and sailing his craft upon a wide and uncharted sea. In lands of the first pick or the first plow, these half-illicit pages find their way for their own reasons; and men and women both sometimes have read them.

Wid Gardner finished his own brief work about the corral, came in, washed his hands, and began to cook for himself his simple supper. Then he washed his dishes, threw the towel above them as before, and went to bed, since he had little else to do.

Early the next morning Wid had finished his breakfast, and was at the edge of the main valley road, which passed near to his own front gate. He lighted a pipe and sat down to smoke, now and again glancing down the road at a slowly approaching figure.

It was the schoolma'am, Mrs. Davidson, who daily presided at the little log schoolhouse a mile further on up the road, where some twenty children found their way over varying distances from the surrounding ranches. This lady was of much dignity and of much avoirdupois as well. Her ruddy face was wrinkled up somewhat like an apple in the late fall. She walked slowly and ponderously, and her gait being somewhat restricted, it was needful that she make an early start each day to her place of labor, since the only possible boarding place lay almost a mile below Sim Gage's ranch. She had been the only applicant for this school, and perhaps was the only living being who could have contented herself in that capacity in this valley. Wid Gardner pulled at the edge of his broken hat as he stepped down the narrow road to meet her.

"'Morning, Mis' Davidson," said he.

"Good morning, Mr. Gar-r-r-dner," boomed out the great voice of Mrs. Davidson. "It is apparently promising us fair weather, sir-r-r."

Mrs. Davidson spoke with a certain singular rotund exactness, and hence was held much in awe in all these parts.

"Yes, ma'am," said Wid, "it looks like it would rain, but it won't."

"Your hay in that case would not flourish so well, Mr. Gar-r-r-dner?" said she.

"Without rain, not worth a damn, ma'am, so to speak. But I'll get by if any one can. This is one of the best locations in the valley. Me and Sim Gage; and Sim, he says——"

"Sim Gage!" The lady snorted her contempt of the very name. "That man! Altogether impossible!"

"He shore is. He certainly is," assented Wid Gardner. "He seems to be getting impossible-er almost every year, now, don't he?"

"I do not care to discuss Mr. Gage," replied the apostle of learning. "I was in his abode once. I should never care to go there again."

Already she was leaning partially forward, ponderously, as about to resume her journey toward the school house.

"Well, now, Sim Gage," began Wid, raising a restraining hand, "he ain't so bad as you might think, ma'am. He's just kind of fell into this way of living."

"Mr. Gar-r-r-dner," said the lady positively, "I doubt if he has made a bed or washed a dish in twenty years. His place is worse than an Indian camp. I have taught schools among the savages myself, in Government service, and therefore I may speak with authority."

"Well, now, ma'am, I reckon that's all true. But you see, if more women come out in here, now, things'd be different. I been thinking of Sim Gage, ma'am. I wanted you to do something fer me, or him, ma'am."

"Indeed?" demanded she. "And what may that be?"

"I don't mean nothing in the world that ain't perfectly all right," began Wid, hesitatingly. "I only wanted you to write something fer me. I'm this kind of a man, that when he wants anything to be fixed up, he wants it to be fixed up right. I kind of got out of practice writing. I want you to write a ad fer me."

"A what?" she demanded. "Oh, I see—you have something to sell?"

"No, ma'am, I ain't got nothing to sell—not unlessen—well, I'll tell you. I want to advertise fer a woman—fer a wife—that is to say, really fer him, Sim Gage—a feller's got to have something to sort of occupy his mind, hain't he?"

Mrs. Davidson was too much astonished to speak, and he blundered on.

"Folks has done such things," said he.

"You offer me a somewhat difficult problem," rejoined the other, "since I do not in the least understand what you desire to do."

"Well, it's this away, ma'am. There's papers that prints these ads—sometimes big dailies does, they tell me—where folks advertises for acquaintances just fer to get acquainted, you know—'acquaintance with a view to matrimony' is the way they usually say it—and that may be a tip fer you—I mean about this here ad I want you to write. Why, folks has got married that way, plenty of 'em—I'll bet there ain't more'n half the homesteaders in this state out here, leastways in the sagebrush country, that didn't get married just that way—it's the onliest way they can get married, ma'am, half the time.

"Once, up in Helleny, years ago, right after the old Alder Gulch placer mining days, there was eleven millionaires, each of 'em married to a Injun woman, and not one of them women could set on a chair without falling off. Now, there wasn't no papers then like this one here, or them millionaires might of done better."

She gasped, unable to speak, her lips rotund and pursed, and he went on with more assertiveness.

"They turn out just as good as any marriages there is," said he. "I've knowed plenty of 'em. There's three in this valley—although they don't say much about it now. I know how they got acquainted, all right."

"And you desire me to aid you in your endeavor to entr-r-r-ap some foolish woman?"

"They don't have to answer. They don't have to get married if they don't want to. You can't tell how things'll turn out."

"Indeed! Indeed!"

"Well, now, I was just hoping you would write the ad, that's all. Just you write me a ad like you was a sagebrusher out here in this country, and you was awful lonesome, and had a good ranch, and was kind-hearted—and not too good-looking—and that you'd be kind to a woman. Well, that's about as far as I can go. I was going to leave the rest to you."

Mrs. Davidson's lips still remained round, her forehead puckered. She leaned ponderously, fell forward into her weighty walk.

"I make no promise, sir-r-r!" said she, as she veered in passing.

But still, human psychology being what it is, and woman's curiosity what it also is, and Mrs. Davidson being after all woman, that evening when Wid Gardner passed out to his gate, he found pinned to the fastening stick an envelope which he opened curiously. He spelled out the words:

"Wanted: A Wife. A well-to-do and chivalrous rancher of abundant means and large holdings in a Western State wishes to correspond with a respectable young woman who will be willing to appreciate a good home and loving care. Object—matrimony."

Wid Gardner read this once, and he read it twice. "Good God A'mighty!" said he to himself. "Sim Gage!"

He turned back to his cabin, and managed to find a corroded pen and the part of a bottle of thickened ink. With much labor he signed to the text of his enclosure two initials, and added his own post office route box for forwarding of any possible replies. Then he addressed a dirty envelope to the street number of the eastern city which appeared on the page of his matrimonial journal. Even he managed to fish out a curled stamp from somewhere in the wall pocket. Then he sat down and looked out the door over the willow bushes shivering in the evening air.

"'Chivalerous!'" said he. "'Well-to-do! A good home—and loving care!' If that can be put acrosst with any woman in the whole wide world, I'll have faith again in prospectin'!"

It was late fall or early winter in the city of Cleveland. An icy wind, steel-tipped, came in from the frozen shores of Lake Erie, piercing the streets, dark with soot and fog commingled. It was evening, and the walks were covered with crowded and hurrying human beings seeking their own homes—men done with their office labors, young women from factories and shops. These bent against the bitter wind, some apathetically, some stoutly, some with the vigor of youth, yet others with the slow gait of approaching age.

Mary Warren and her room-mate, Annie Squires, met at a certain street corner, as was their daily wont; the former coming from her place in one of the great department stores, the other from her work in a factory six blocks up the street.

"'Lo, Mollie," said Annie; and her friend smiled, as she always did at their chill corner rendezvous. They found some sort of standing room together in a crowded car, swinging on the straps as it screeched its way around the curves, through the crowded portions of the city. It was long before they got seats, three-quarters of an hour, for they lived far out. Ten dollars a week does not give much in the way of quarters. It might have been guessed that these two were partners, room-mates.

"Gee! These cars is fierce," said Annie Squires, with a smile and a wide glance into the eyes of a young man against whom she had been flung, although she spoke to her companion.

Mary Warren made no complaint. Her face, calm and gentle, carried neither repining nor resignation, but a high and resolute courage. She shrank far as she might, like a gentlewoman, from personal contact with other human beings; the little droop beginning at the corners of her mouth gave proof of her weariness, but there was a thoroughbred vigor, a silken-strong fairness about her, which, with the self-respecting erectness in her carriage, rather belied the common garb she wore. Her frock was that of the sales-woman, her gloves were badly worn, her boots began to show signs of breaking, her hat was of nondescript sort, of small pretensions—yet Mary Warren's attitude, less of weariness than of resistance, had something of the ivory-fine gentlewoman about it, even here at the end of a rasping winter day.

Annie Squires was dressed with a trifle more of the pretension which ten dollars a week allows. She carried a sort of rude and frank vitality about her, a healthful color in her face, not wholly uncomely. She was a trifle younger than Mary Warren—the latter might have been perhaps five and twenty; perhaps a little older, perhaps not quite so old—but none the less seemed if not the more strong, at least the more self-confident of the two. A great-heart, Annie Squires; out of nothing, bound for nowhere. Two great-hearts, indeed, these two tired girls, going home.

"Well, the Dutch seems to be having their own troubles now," said Annie after a time, when at length the two were able to find seats, a trifle to themselves in a corner of the car. "Looks like they might learn how the war thing goes the other way 'round. Gee! I wish't I was a man! I'd show 'em peace!"

She went on, passing from one headline to the next of the evening paper which they took daily turns in buying. Mary Warren began to grow more grave of face as she heard the news from the lands where not long ago had swung and raged in their red grapple the great armies of the world.

Then a sudden remorse came to Annie. She put out a hand to Mary Warren's arm. "Don't mind, Sis," said she. "Plenty more besides your brother is gone. Lookit here."

"He was all I had," said Mary simply, her lips trembling.

"Yes, I know. But what's up to-night, Mollie? You're still. Anything gone wrong at the store?" She was looking at her room-mate keenly. This was their regular time for mutual review and for the restoring gossip of the day.

"Well, you see, Annie, they told me that times were hard now after the war, and more girls ready to work." Mary Warren only answered after a long time. A passenger, sitting near, was just rising to leave the car.

Annie also said nothing for a time. "It looks bad, Mollie," said she, sagely.

Mary Warren made no answer beyond nodding bravely, high-headed. Ten dollars a week may be an enormous sum, even when countries but now have been juggling billions carelessly.

They were now near the end of their daily journey. Presently they descended from the car and, bent against the icy wind, made their way certain blocks toward the door which meant home for them. They clumped up the stairs of the wooden building to the third floor, and opened the door to their room.

It was cold. There was no fire burning in the stove—they never left one burning, for they furnished their own fuel; and in the morning, even in the winter time, they rose and dressed in the cold.

"Never mind, dear," said Annie again, and pushed Mary down into the rocking chair as she would have busied herself with the kindling. "Let me, now. I wish't coal wasn't so high. There's times I almost lose my nerve."

A blue and yellow flame at last began back of the mica-doored stove which furnished heat for the room. The girls, too tired and cold to take off their wraps, sat for a time, their hands against the slowly heating door. Now and again they peered in to see how the fire was doing.

Mary Warren rose and laid aside her street garb. When she turned back again she still had in her hands the long knitting needles, the ball of yellowish yarn, the partially knitted garment, which of late had been so common in America.

"Aw, Sis, cut it out!" grumbled Annie, and reached to take the knitting away from her friend. "The war's over, thank God! Give yourself a chanct. Get warm first, anyways. You'll ruin your eyes—didn't the doctor tell you so? You got one bum lamp right now."

"Worse things than having trouble with your eyes, Annie."

"Huh! It'll help you a lot to have your eyes go worse, won't it?"

"But I can't forget. I—I can't seem to forget Dan, my brother." Mary's voice trailed off vaguely. "He's the last kin I had. Well, I was all he had, his next of kin, so they sent me his decoration. And I'm the last of our family—and a woman—and—and not seeing very well. Annie, he was my reliance—and I was his, poor boy, because of his trouble, that made him a half-cripple, though he got into the flying corps at last. I'm alone. And, Annie—that was what was the trouble at the store. I'm—it's my eyes."

They both sat for a long time in silence. Her room-mate fidgeted about, walked away, fiddled with her hair before the dull little mirror at the dresser. At length she turned.

"Sis," said she, "it ain't no news. I know, and I've knew it. I got to talk some sense to you."

The dark glasses turned her way, unwaveringly, bravely.

"You're going to lose your job, Sis, as soon as the Christmas rush is over," Annie finished. She saw the sudden shudder which passed through the straight figure beside the stove.

"Oh, I know it's hard, but it's the truth. Now, listen. Your folks are all dead. Your last one, Dan, your brother, is dead, and you got no one else. It's just as well to face things. What I've got is yours, of course, but how much have we got, together? What chanct has a girl got? And a blind woman's a beggar, Sis. It's tough. But what are you going to do? Girls is flocking back out of Washington. The war factories is closing. There's thousands on the streets."

"Annie, what do you mean?"

"Oh, now, hush, Sis! Don't look at me that way, even through your glasses. It hurts. We've just got to face things. You've got to live. How?"

"Well, then," said Mary Warren, suddenly rising, her hands to her hot cheeks, "well, then—and what then? I can't be a burden on you—you've done more than your half ever since I first had to go to the doctor about my eyes."

"Cut all that out, now," said Annie, her eyes ominous. "I done what you'd a-done. But one girl can't earn enough for two, at ten per, and be decent. Go out on the streets and see the boys still in their uniforms. Every one's got a girl on his arm, and the best lookers, too. What then? As for the love and marriage stuff—well——"

"As though you didn't know better yourself than to talk the way you do!" said Mary Warren.

"I'm different from you, Mollie. I—I ain't so fine. You know why I liked you? Because you was different; and I didn't come from much or have much schooling. I've been to school to you—and you never knew it. I owe you plenty, and you won't understand even that."

Mary only kissed her, but Annie broke free and went on.

"When they come to talk about the world going on, and folks marrying, and raising children, after this war is over—you've got to hand it to them that this duty stuff has got a strong punch behind it. Besides, the kid idea makes a hit with me. But even if I did marry, I don't know what a man would say, these times, about my bringing some one else into his house. Men is funny."

"Annie—Annie!" exclaimed Mary Warren once more. "Don't—oh, don't! I'd die before I'd go into your own real home! Of course, I'll not be a burden on you. I'm too proud for that, I hope."

"Well, dope it out your own way, Sis," said her room-mate, sighing. "It ain't true that I want to shake you. I don't. But I'm not talking about Mary Warren when she had money her aunt left her—before she lost it in Oil. I'm not talking about Mary Warren when she was eighteen, and pretty as a picture. I ain't even talking about Mary a year ago, wearing dark glasses, but still having a good chanct in the store. What I'm talking about now is Mary Warren down and out, with not even eyes to see with, and no money back of her, and no place to go. What are you going to do, Sis? that's all. In my case—believe me, if I lose my chanct at this man, Charlie Dorenwald, I'm going to find another some time.

"It's fifty-fifty if either of us, or any girl, would get along all right with a husband if we could get one—it's no cinch. And now, women getting plentier and plentier, and men still scarcer and scarcer, it's sure tough times for a girl that hasn't eyes nor anything to get work with, or get married with."

"Annie!" said her companion. "I wish you wouldn't!"

"Well, I wasn't thinking how I talked, Sis," said Annie, reaching out a hand to pat the white one on the chair arm. "But fifty-fifty, my dear—that's all the bet ever was or will be for a woman, and now her odds is a lot worse, they say, even for the well and strong ones. Maybe part of the trouble with us women was we never looked on this business of getting married with any kind of halfway business sense. Along comes a man, and we get foolish. Lord! Oughtn't both of us to know about bargain counters and basement sales?"

"Well, let's eat, Mary," she concluded, seeing she had no answer. And Mary Warren, broken-hearted, high-headed, silent, turned to the remaining routine of the day.

Annie busied herself at the little box behind the stove—a box with a flap of white cloth, which served as cupboard. Here she found a coffee pot, a half loaf of bread, some tinned goods, a pair of apples. She put the coffee pot to boil upon the little stove, pushing back the ornamental acorn which covered the lid at its top. Meantime Mary drew out the little table which served them, spread upon it its white cloth, and laid the knives and forks, scanty enough in their number.

They ate as was their custom every evening. Not two girls in all Cleveland led more frugal lives than these, nor cleaner, in every way.

"Let me wash the dishes, Sis," said Annie Squires. "You needn't wipe them—no, that's all right to-night. Let me, now."

"You're fine, Annie, you're fine, that's what you are!" said Mary Warren. "You're the best girl in the world. But we'll make it fifty-fifty while we can. I'm going to do my share."

"I suppose we'd better do the laundry, too, don't you think?" she added. "We don't want the fire to get too low."

They had used their single wash basin for their dish pan as well, and now it was impressed to yet another use. Each girl found in her pocket a cheap handkerchief or so. Annie now plunged these in the wash basin's scanty suds, washed them, and, going to the mirror, pasted them against the glass, flattening them out so that in the morning they might be "ironed," as she called it. This done, each girl deliberately sat down and removed her shoes and stockings. The stockings themselves now came in for washing—an alternate daily practice with them both since Mary had come hither. They hung the stockings over the back of the solitary spare chair, just close enough to the stove to get some warmth, and not close enough to burn—long experience had taught them the exact distance.

They huddled bare-footed closer to the stove, until Annie rose and tiptoed across to get a pair each of cheap straw slippers which rested below the bed.

"Here's yours, Sis," said she. "You just sit still and get warm as you can before we turn in—it's an awful night, and the fire's beginning to peter out already. I wish't Mr. McAdoo, or whoever it is, 'd see about this coal business. Gee, I hope these things'll get dry before morning—there ain't anything in the world any colder than a pair of wet stockings in the morning! Let's turn in—it'll be warmer, I believe."

The wind, steel-pointed, bored at the window casings all that night. Degree after degree of frost would have registered in that room had means of registration been present. The two young women huddled closer under the scanty covering that they might find warmth. Ten dollars a week. Two great-hearts, neither of them more than a helpless girl.

They rose the next morning and dressed in the room without fire, shivering now as they drew on their stockings, frozen stiff. They had their morning coffee in a chilly room downstairs, where sometimes their slatternly landlady appeared, lugubriously voluble. This morning they ate alone, in silence, and none too happily. Even Annie's buoyant spirits seemed inadequate. A trace of bitterness was in her tone when she spoke.

"I'm sick of it."

"Yes, Annie," said Mary Warren. "And it's cold this morning, awfully."

"Cotton vests, marked down—to what wool used to be. Huh! Call this America?"

"What's wrong, Annie?" suddenly asked Mary Warren, drawing her wrap closer as she sat.

"I'd go to the lake before I'd go to the streets, though you mightn't think it. But how about it with only the discards in Derby hats and false teeth left? If we two are going to get married, Mollie, we got to look around among the remnants and bargains—we can't be too particular when we're hunting bargains. Whether it's all off for you at the store or not ain't for me to say, but you might do worse than listen to me."

Mary Warren looked at her in a sort of horror. "Annie, what do you mean?" she demanded.

The real reply came in the hard little laugh with which Annie Squires drew from the pocket of her coat—in which she also was muffled at the breakfast table—a meager little newspaper, close-folded. She spread it out before she passed it to her companion.

"Hearts Aflame!" said she. "While you have to dry your own socks, while you break the ice in your coffee! Can't you feel your heart flame? Anyway, here you are—bargains in husbands and wives! Take 'em for the asking. Here's a lot of them advertised. Slightly damaged, but serviceable—and marked down within the reach of all.

"Why, us girls over at the shop, we read these things regular," she rattled on in explanation, her mouth full. "Some of the girls answer these ads—it's lots of fun. You ought to see what some of the men write back. Look at this one, Sis!" said she, chuckling. "Some class to it, eh?" She pointed to an advertisement a trifle larger than its fellows, a trifle more boldly displayed in its black type.

"Wanted: A Wife. A well-to-do and chivalrous rancher of abundant means and large holdings in a Western State wishes to correspond with a respectable young woman who will appreciate a good home and loving care. Object—Matrimony."

"How ridiculous," said Mary Warren simply.

"Uh huh! Is it, though? I don't know. I put this thing to my ear, and it sort of sounded as if there was something behind it. That fellow wants a woman of his own to keep house for him. Out there women are scarce. It's supply and demand, Sis, same as in your store. Well, here's a man looking for goods. So'm I. I've been looking him over for myself, because I ain't as strong for Charlie Dorenwald as I might be, even if he's foreman. He talks so damn much Bolshevik, somehow. Of course, the country's rotten, but it's ours! Still and all, I'll tell you what I'll do, Sis, with you!"

She pulled her chair up to the side of her companion, fumbling in her little purse as she did so; drew out a copper coin and held it balanced between her fingers.

"'The one shall be taken and the other left,' Sis," said she. "Two women, grinding at the mill, the same little old mill, as the Bible said; and 'The one shall be taken and the other left.' Which one? One throw, Mary. Heads or tails. It's got to hit the ceiling before it falls."

"Why, nonsense, Annie—— No, no!"

"Heads or tails!" insisted Annie Squires; and as she spoke she flipped the coin against the ceiling. It rolled toward the street window, where neither of them at first could see it.

"Tails!" called Mary Warren faintly, suddenly. It seemed to her she heard some other voice, speaking for her, without her real volition.

"You're on!" said Annie. They both rose and walked toward the darker side of the room.

"I can't see," said Mary. "Strike a match."

Annie did so, and they both bent over the coin.

"Tails—you win!" said Annie Squires. "Well, what do you know about that?"

She was half in earnest about her chagrin—half in earnest as she spoke. "I'd saved him for myself. Sometimes, I say, I don't know about this Charlie Dorenwald, even if he is crazy over me—I'm mostly being beware of foremen, me. And here's a chivalrous and well-to-do ranchman—out West! Gee! Congratulations, Sis!"

They laughed like girls, each with slightly heightened color in spite of all the make-believe. Then Annie ran to a vase of artificial flowers which stood upon the mantel, and pulled out a draggled daisy.

"What's he going to be, Kid—your man? Is he rich or poor? Listen! 'Lawyer—doctor—merchant—chief—rich man—poor man—beggar man—thief——'" She stopped in a certain consternation, the last petal in her hand—"A thief?——"

"Why, Annie, you surely don't believe in such things," said Mary Warren reprovingly. "And of course we oughtn't to have done anything foolish as this. It's—it's awful."

Annie, her mood suddenly changing, drew apart and sat down moodily.

"You couldn't blame a fellow for trying to forget things, Sis," said she. "Look at me. I'm on the street, you might say—they canned me yesterday! Yes! that's the truth. I wasn't going to tell you—you looked so cold last night, and you with your eyes what they are. It—it looks like Charlie had a chance, eh?"

Mary Warren looked at her for a time in silence. "You'll never have to toss a copper for a husband, I'm sure of that. If I were handsome as you——"

"Oh, am I?" said her companion. "Men hang around—what does it get me? Time passes. Where are we pretty soon? Men ain't all husbands that make love."

"How much money you got saved up, Mary?" she asked suddenly.

"Just one hundred thirty-five dollars and eighty cents," said Mary, not needing to consult her pass book. "I can pay for my bond now."

"Got me beat. Best I can do for my life savings is fifty-eight dollars and seventy-five cents. How long will that last you and me?"

"You're despondent, Annie—you mustn't feel blue—why, to-morrow we'll both go out and see what we can do."

"About me? I like that! It's you we got to bother about. My Lord! It ain't so far off, this ad in Hearts Aflame! What you really do need is a man who'll be kind and chivalrous with you."

"I haven't got to that yet," said Mary Warren, stoutly. Her color rose.

"No? Funnier things have happened. You might do worse."

"I'm not bred that way, Annie," said Mary Warren slowly; but her color rising yet more as she realized that perhaps she had been cruel.

"You needn't explain anything to me," replied Annie. "I'm not sore. You came of a better family, and so it'll be harder for you to get through life than it is for me."

As she spoke she had risen, and was buttoning her street wraps. Mary Warren sat silent, the dark lenses of her glasses turned toward her companion.

"Beggar man—thief!" she said at last. "I'd be robbing him, even then!" She smiled bitterly. "Who'd take me?"

When spring came above the icy shores of the inland seas, Mary Warren had been out of work for more than three months. She was ill; ill of body, ill of mind, ill of heart. Her splendid, resilient courage had at last begun to break. She was facing the thought that she could not carry her own weight in the world.

She sat alone once more one evening in the little room which after all thus far she and Annie had been able to retain. Her oculist had taken much from her scanty store of money. She held in her hand his last bill—unpaid; and though she had paid a score of his bills, yet her eyesight now was nearly gone. Her doctor called it "retinal failure"; and it had steadily advanced, whatever it was. Now she knew that there was no hope.

She greeted the homecoming of her room-mate each nightfall with eagerness. Annie by this time had found harder and worse paid work in another factory. She came in with her hands scarred and torn, her nails broken and stained. She had grown more reticent of late.

"Well, how are things coming along, Sis?" said she this evening on her return, after she had thrown her wrap across a chair back. "How much money have you got left? You look to me like you was counting it."

"Not very much, Annie—not very much. The doctor—you see, I can't take his time and not pay him."

"You're too thin-skinned. What are doctors for?"

"But, Annie, I don't know what to do. I'm scared. That's the truth about it—I'm scared!"

Her companion smiled, with her new slow and cynical smile. "Some of us go to the lake—or to a man—or to men," said she, succinctly. "Look over the stock of goods that's within your means. Bargains. Odds and Ends."

"What could I do?"

"Suppose you got married to your gentle and chivalrous rancher out West. Maybe you'd be able to stand it after a while, even if he dyed his hair, or had his neck shaved round. Mostly they have false teeth—before they'll advertise. Probably he's a widower. Object: matrimony; that mostly is a widower's main object in life; and you can't show 'em nothing except when you bury 'em."

"I'd die before I'd answer that sort of a thing!" said Mary Warren hotly.

"You would," replied Annie. "I know that. I knew it all along. That's why I had to take it into my own hands." Again the cynical smile of Annie Squires, twenty-two.

"Your own hands—what do you mean by that?"

"I might as well tell you. I've been writing to him in your name! I've sent him a picture of you—I got it in the bureau drawer. And he's crazy over you!"

Mary Warren looked at her with wrath, humiliation and offended dignity showing in her reddened cheeks.

"You had the audacity to do that, Annie! How dared you? How could you?"

"Well, I was afraid of the lake for you, and I knew that something had to be done, and you wouldn't do it. I've got quite a batch of letters from him. He's got three hundred and twenty acres of land, eight cows, a horse and a mule. He has a house which is all right except it lacks the loving care of a woman! Well, stack that up against this room. And we can't even keep this for very long.

"Listen, Mary," she said, coming over and putting both her broken hands on her friend's shoulders. "God knows, if I could keep us both going I would, but I don't make money enough for myself, hardly, let alone you. You don't belong where you've been—you wouldn't, even if you was well and fit, which you ain't. Mollie, Mollie, my dear, what is there ahead for you? We got to do some thinking. It's up to us right now. You're too good for the lake or the poor farm—or—why, you belong in a home. Keep house? I wish't I knew as much as you do about that."

"I'll tell you," she resumed suddenly. "I'll tell you what let's do! A stenographer down at our office does all these letters for me—she's a bear, come to correspondence like that. Now, I'll have her get out a letter from you to him that will sort of bring this thing to a head one way or the other. We'll say that you can't think of going out there to marry a man sight-unseen——"

"No," said Mary Warren. "The lake, first." She was wringing her hands, her cheeks hot.

"But now, as a housekeeper——" After a long and perturbed silence Annie spoke again. "That's the real live idea, Sis! That's the dope! You might think of going out there as a housekeeper, just to see how things looked—just so that you could look things over, couldn't you? You wouldn't marry any man in a hurry. You could say you'd only do your best as a sincere, honest woman—why, I have to tell that stenographer what to write, all the time. She's sloppy."

"But look at me, Annie—I wouldn't be worth anything as a housekeeper." Mary Warren was arguing! "As to marrying that way——"

—"Letter'll say you're not asking any pay at all. You don't promise anything. You don't ask him to promise anything. You don't want any wages. You don't let him pay your railroad fare out—not at all! You ain't taking any chances nor asking him to take any chances,—unless she falls in love with you for fair. Which I wouldn't wonder if he did. You're a sweet girl, Mollie. Put fifteen pounds on you, and you'd be a honey. You are anyway. Men always look at you—it's your figure, part, maybe. And you're so good—and you're a lady, Sis. And if I——"

"Tell him," said Mary Warren suddenly, pulling herself together with the extremest effort of will and in the suddenest and sharpest decision she had ever known in all her life, "tell him I'm square! Tell him I'll be honest all the time—all the time!"

"As though you could be anything else, you poor dear!" said Annie Squires, coming over and throwing a strong arm about Mary Warren's neck, as though they both had done nothing but agree about this after a dozen conversations. And then she wept, for she knew what Mary Warren's surrender had cost. "And game! Game and square both, you sweet thing," sobbed Annie Squires.

"Give me fifteen pounds on you," she wept, dabbing at her own eyes, "and I wouldn't risk Charlie near you,—not a minute!"

Around the Two Forks Valley the snow still lay white and clean upon the peaks, but the feet of the mountains were bathed in a rising flood of green. On the bottom lands the grasses began to start, the willows renewed their leafery. On the pools of the limpid stream the trout left wrinkles and circles at midday now, as they rose to feed upon the insects swarming in the warmth of the oncoming sun.

On this particular morning Wid Gardner turned down the practically untrod lane along Sim's wire fence. Now and again he glanced at something which he held in his hand.

When he entered Sim Gage's gate, the ancient mule, his head out of the stable window, welcomed him, braying his discontent. Here lay the ragged wood pile, showing the ax work of a winter. At the edge of a gnawed hay stack stood the remnant of Sim's scant cattle herd, not half of which had "wintered through."

No smoke was rising from Sim Gage's chimney. "Feller's hopeless, that's what," complained Wid Gardner to himself. "It gravels me plenty."

A muffled voice answered his knock, and he pushed open the door. Sim Gage was still in bed, and his bed was still on the floor.

"Come in," said he, thrusting a frowsy head out from under his blankets. He used practically the same amount of covering about him in winter and summer; and now, as usual, he had retired practically without removing his daily clothing. His face, stubbled and unshaven, swollen with sleep and surmounted by a tangled fringe of hair, might not by any flight of imagination have been called admirable or inviting, as he now looked out to greet his caller.

"Oh, dang it! Git up, Sim," said Wid, irritated beyond expression. "It's after ten o'clock."

His words cut through the somewhat pachydermatous sensibilities of Sim Gage, who frowned a trifle as, after a due pause, he crawled out and sat down and reached for his broken boots.

"Well, I dunno as it's anybody's damn business whether I git up a-tall or not, except my own," said he. "I'll git up when I please, and not afore."

"Well, you might git up this morning, anyhow," said Wid.

"Why?"

"I got a letter for you."

"Look-a-here," said Sim Gage, with sudden preciseness. "What you been doing? Letter? What letter? And how come you by my letters?"

"Well, I been talking with Mis' Davidson—she run the whole correspondence, Sim. We—now—we allowed we'd ought to take care of it fer you. And we done so, that's all."

"Huh!" said Sim Gage. "Fine business, ain't it?"

"Well, she's a-coming on out," said Wid Gardner, suddenly and comprehensively.

"What's that? Who's a-coming on out?"

The face of Sim Gage went pale even under the cold water to which at the moment he was treating his leathery skin in the basin on top the stove.

"Sim," said Wid Gardner, "it was understood that this thing was to run in your name. Now, Mis' Davidson—when it comes to fixing up a love correspondence, she's the ace! It all ain't my fault a-tall, Sim. We advertised—and we got a answer, and we follered it up. And this here letter is the re-sult. I allowed we'd ought to tell you too, by now."

"What you been doing—fooling with me, you two?" demanded Sim. "That whole thing was a joke."

"It's one hell of a fine joke now," rejoined Wid Gardner. "She's a-coming on out. Sim, it's up to you. I ain't been advertising fer no wife. This here letter is yours."

"That's a fine thing you done, ain't it?" said Sim Gage, turning on to his neighbor. "When you find the ford's too deep to git acrost, you begin to holler fer help."

"That's neither here nor there. That ain't the worst—I've got her picture here, and her letters too. She's been plumb honest all along. She says she's pretty much broke, and not too well. She says when she sees you she hopes you won't think she's deceived you. She says she knows you're everything you said you was—a gentle and chivalerous ranchman of the West, sure to be kind to a woman. She's scared—she's that honest. But she's a-coming. She's going to try housekeeping though—no more'n that. Rest's all up to you, not her. She balked from the jump on all marrying talk."

"Mis' Davidson ought to take care of this thing," said Sim Gage, his features now working, as usual, in his perplexity.

"Mis' Davidson is due to pull her freight. She's going down on her own homestead. I'm some scared too, Sim. You don't really know how you been making love to this woman. I didn't know Mis' Davidson had it in her. You got to come through now, Sim."

"Who says I got to come through?"

"You got to go to town to-morrow."

"So you're a-going to make me go in to town tomorrow and marry a woman I never seen, whether I want to or not?"

"No, it ain't right up to that—you needn't think she's coming out here to hunt up a preacher and git married to you right away. Not a-tall, Mr. Gage, not none a-tall! She never onct said she'd do any more'n come out here and keep house fer you one season—that's all. Said she wouldn't deceive you. God knows how you can keep from deceiving her. Look at this place. And you got to bring her here—to-morrow. She'll be at Two Forks station to-morrow morning at eight-thirty, on the Park train. This here thing is up to you right now. You made such a holler about needing a woman to make things human fer you. Well, here you are. There's the cards—play 'em the way they lay. You be human now if you can. You got the chance."

"I ain't got no wagon, Wid," said Sim, weakly. "You know I ain't got none."

"You'll have to take my buckboard."

"And you know I ain't got no team—my horse, he ain't right strong—didn't winter none too well—and I couldn't go there with just one mule, now could I?"

"You'll have to take my team of broncs," said Wid. "You can start out from my place."

"But one thing, Sim Gage," he continued, "when you've started, I'm a-coming down here with a pitch-fork and I'm a-going to clean out this place! It ain't human. We'll do the best we can. Since there ain't a-going to be no marrying right off, you'll have to sleep in your wall tent outside. You'll have to git some wood cut up. You'll have to git a clean bed here in the house,—this bed of yours is going to be burned out in the yard. You'll have to git new blankets when you go to town."

"As fer your clothes"—he turned a contemptuous glance upon Sim as he stood—"they ain't hardly fit fer a bridegroom! Go to the Golden Eagle, and git yourself a full outfit, top to bottom—new shirts, new underclothes, new pants, new hat, new socks, new gloves, new everything. This girl can't come out here and see you the way you are, and this place the way it's been. She'd start something."

"Well, if you leave it to me," said Sim Gage mildly, "all this here seems kind of sudden. You come in afore I'm up, and tell me to burn my bed, and sleep in a tent, and borry a wagon and team and go to town fer to marry a girl I never seen. That don't look reason'ble to me, especial since I ain't had no hand in it."

"It's up to you now."

"How do I know whether I want that girl or not? I ain't read no letters—nor wrote none. I ain't seen no picture of her——"

"Well," said Wid, and reached a hand into his breast pocket, "here she is."

In a feeling more akin to awe than anything else, Sim Gage bent over, looking down at the clear oval face, the piled dark hair, the tender contour of cheek and chin of Mary Warren, as beautiful a young lady as any man is apt ever to see; so beautiful that this man's inexperienced heart stopped in his bosom. This picture once had been buttoned in the tunic of an aviator who flew for the three flags; her brother; and before his death and its return more than one of Dan Warren's army friends had looked at it reverently as Sim Gage did now.

"Wears glasses, don't she," said he, to conceal his confusion. "Reckon she's a school ma'am?"

"Ask me, and I'll say she's a lady. She says she's a working girl. Says she's had trouble. Says she's up against it now. Says she ain't well, and ain't happy, and—well, here she is."

"My good God A'mighty!" said Sim Gage, his voice awed as he looked at the high-bred, clear-featured face of Mary Warren.

The transcontinental train from the East rarely made its great climb up the Two Forks divide on time, and to-day it was more than usually late. A solitary figure long since had begun to pace the station platform, looking anxiously up and down the track.

It was Sim Gage; and this was the first time he ever had come to meet a train at Two Forks.

Sim Gage, but not the same. He now was in stiff, ill-fitting and exclaimingly new clothing. A new dark hat oppressed his perspiring brow, new and pointed shoes agonized his feet, a new white collar and a tie tortured his neck. He had been owner of these things no longer than overnight. He did not feel acquainted with himself.

He was to meet a woman! Her picture was in his pocket, in his brain, in his blood. A vast shyness, coming to consternation, seized him. He felt a sense of personal guilt; and yet a feeling of indignity and injustice claimed him. But all this and all his sullen anger was wiped out in this great shyness of a man not used to facing women. Sim Gage was product of a womanless land. This was the closest his orbit ever had come to that of the great mystery. And he had been alone so long. A sudden surging longing came to his heart. Sim Gage was shy always, and he was frightened now; but now he felt a longing—a longing to be human.

Sim Gage never in all his life had seen a young woman looking back at him over his shoulder. And now there came accession of all his ancient dread, joined with this growing sense of guilt. A few passengers from the resort hotel back in the town began to appear, lolling at the ticket window or engaged at the baggage room. Sim Gage found a certain comfort in the presence of other human beings. All the time he gazed furtively down the railway tracks.

A long-drawn scream of the laboring engines told of the approaching train at last. Horses and men pricked up their ears. The blood of Sim Gage's heart seemed to go to his brain. He was seized with a panic, but, fascinated by some agency he could not resist, he stood uncertainly until the train came in. He began to tremble in the unadulterated agony of a shy man about to meet the woman to whom he has made love only in his heart.

Sim Gage's team of young and wild horses across the street began to plunge now, and to entangle themselves dangerously, but he did not cross the street to care for them. She was coming! The woman from the States was on this very train. In two minutes——

But the crowd thinned and dissipated at length, and Sim Gage had not found her after all. He felt sudden relief that she had not come, mingled with resentment that he had been made foolish. She was not there—she had not come!

But his gaze, passing from one to another of the early tourists, rested at last upon a solitary figure which stood close to the burly train conductor near the station door. The conductor held the young woman's arm reassuringly, as they both looked questioningly from side to side. She was in dark clothing. A dark veil was across her face. As she pushed it back he saw her eyes protected by heavy black lenses.

Sim Gage hesitated. The conductor spoke to him so loudly that he jumped.

"Say, are you Mr. Gage?"

"That's me," said Sim. "I'm Mr. Gage." He could not recall that ever in his life he had been so accosted before; he had never thought of himself as being Mr. Gage, only Sim Gage.

One redeeming quality he had—a pleasant speaking voice. A sudden turn of the head of the young woman seemed to recognize this. She reached out, groping for the arm of the conductor. Consternation urged her also to seek protection. This was the man!

"Lady for you, Mr. Gage," said the conductor. "This young woman caught a cinder down the road. Better see a doctor soon as you can—bad eye. She said she was to meet you here."

"It's all right," said Sim Gage suddenly to him. "It's all right. You can go if you want to."

He saw that the young woman was looking at him, but she seemed to make no sign of recognition.

"I'm Mr. Gage, ma'am," said he, stepping up. "I'm sorry you got a cinder in your eye. We'll go up and see the doctor. Why, I had a cinder onct in my eye, time I was going down to Arizony, and it like to of ruined me. I couldn't see nothing for nearly four days."

He was lying now, rather fluently and beautifully. He had never been in Arizona, and so little did he know of railway travel that he had not noted that this young woman came not from a sleeping car, but from one of the day coaches. The dust upon her garments seemed to him there naturally enough.

She did not answer, stood so much aloof from him that a sudden sense of inferiority possessed him. He could not see that her throat was fluttering, did not know that tears were coming from back of the heavy glasses. He could not tell that Mary Warren had appraised him even now, blind though she was; that she herself suffered by reason of that wrong appraisal.

The throng thinned, the tumult and shouting of the hotel men died away. Sim Gage did not know what to do. A woman seemed to mean a sudden and strangely overwhelming accession of problems. What should he do? Where would he put her? What ought he to say?

"If you'll excuse me," he ventured at last, "I'll go acrosst and git my team. They're all tangled up, like you see."

She spoke, her voice agitated; reached out a hand. "I—I can't see at all, sir!"

"That's too bad, ma'am," said Sim Gage, "but don't you worry none at all. You set right down here on the aidge of the side walk, till I git the horses fixed. They're scared of the cars. Is this your satchel, ma'am?"

"Yes—that's mine."

"You got any trunk for me to git?" he asked, turning back, suddenly and by miracle, recalling that people who traveled usually had trunks.

He could not see the flush of her cheek as she replied, "No, I didn't bring one. I thought—what I had would do." He could not know that nearly all her worldly store was here in this battered cheap valise.

"You ain't a-going to leave us so soon like that, are you?"

She turned to him wistfully, a swift light upon her face. He had said, "leave us"—not "leave me." And his voice was gentle. Surely he was the kind-hearted and chivalrous rancher of his own simple letters. She began to feel a woman's sense of superiority. On the defensive, she replied: "I don't know yet. Suppose we—suppose——"

"Suppose that we wait awhile, eh?" said Sim Gage, himself wistful.

"Why—yes."

"All right, ma'am. We'll do anything you like. You don't need no trunk full of things out here—I hope you'll git along somehow."

Knowing that he ought to assist her, he put out a hand to touch her arm, withdrew it as though he had been stung, and then hastily stood as he felt her hand rest upon his arm. He led her slowly to the edge of the platform. Then she heard his footsteps passing, heard the voices of two men—for now a bystander had gone across to do something for the plunging horses, one of which had thrown itself under the buckboard tongue. She heard the two men as they worked on. "Git up!" said one voice. "Git around there!" Then came certain oaths on the part of both men, and conversation whose import she did not know.

Their voices were as though heard in a dream. There suddenly came an overwhelming sense of guilt to Mary Warren. She had been unfair to this man! He was a trifle crude, yes; but kind, gentle, unpresuming. She felt safer and safer—guilty and more guilty. How could she ever explain it all to him?

"I reckon they're all right now," said Sim Gage, after a considerable battle with his team. "Nothing busted much. Git up on the seat, won't you, Bill, and drive acrosst—I got to help that lady git in."

"Who is she?" demanded the other, who had not failed to note the waiting figure.

"It's none of your damn business," said Sim Gage. "That is, it's my housekeeper—she's going to cook for the hay hands."

"With a two months' start?" grinned the other.

"Drive on acrosst now," said Sim Gage, in grim reply, which closed the other's mouth at once.

Mary Warren heard the crunch of wheels, heard the thump of her valise as Sim Gage caught it up and threw it into the back of the buckboard. Then he spoke again. She felt him standing close at hand. Once more, trembling as in an ague, she placed a hand upon his arm.

"Now, when I tell you," he said gently, "why, you put your foot up on the hub of the wheel here, and grab the iron on the side, and climb in quick—these horses is sort of uneasy."

"I can't see the wheel," said Mary Warren, groping.

She felt his hand steadying her—felt the rim of the wheel under her hand, felt him gently if clumsily try to help her up. Her foot missed the hub of the wheel, the horses started, and she almost fell—would have done so had not he caught her in his arms. It was almost the first time in his life, perhaps the only time, that he had felt the full weight of a woman in his arms. She disengaged herself, apologized for her clumsiness.

"You didn't hurt yourself, any?" said he anxiously.

"No," she said. "But I'm blind—I'm blind! Oh, don't you know?"

He said nothing. How could she know that her words brought to Sim Gage not regret, but—relief!

He steadied her foot so that it might find the hub of the wheel, steadied her arm, cared for her as she clambered into the seat.

"All right," she heard him say, not to her; and then he replaced the other man on the high seat. The horses plunged forward. She felt herself helpless, alone, swept away. And she was blind.

All the way across the Middle West, across the great plains, Mary Warren had been able to see somewhat. Perhaps it was the knitting—hour after hour of it, in spite of all, done in sheer self-defense. But at the western edge of the great Plains, it had come—what she had dreaded. Both eyes were gone! Since then she had not seen at all, and having in mind her long warning, accepted her blindness as a permanent thing.

She passed now through a world of blackness. She could not see the man who had written those letters to her. She could catch only the wine of a high, clean air, the breath of pine trees, the feeling of space, appreciable even by the blind.

Suddenly she began to sob. Sim Gage by now had somewhat quieted his wild team, and he looked at her, his face puckered into a perturbed frown.

"Now, now," he said, "don't you take on, little woman." He was abashed at his daring, but himself felt almost like tears, as things now were. "It'll all come right. Don't you worry none. Don't be scared of these horses a-tall, ma'am; I can handle 'em all right. We got to see that doctor."

But when presently they had driven the half mile to the village, he learned that the doctor was not in town.

"We can't do anything," said she. "Drive on—we'll go. I don't think the doctor could help me very much."

All the time she knew she had in part been lying to him. It was not merely a cinder in her eye—this was a helpless blindness, a permanent thing. The retina of each eye now was ruined, gone. So she had been warned. Again she reached out her hand in spite of all to touch his arm. He remained silent. She cruelly misunderstood him.

At last she turned fully towards him, and spoke suddenly. "Listen!" said she. "I believe you're a good man. I'll not deceive you."

"God knows I ain't no good man," said Sim Gage suddenly, "and God knows I'm sorry I deceived you like I have. But I'll take care of you until you can do something better, and until you want to go back home."

"Home?" she said. "I haven't any home. I tell you I've deceived you. I'm sorry—oh, it's all so terrible."

"It shore is," said Sim Gage. "I didn't really write them letters—but it's my fault you're here. You can blame me fer everything. Why, almost I was a notion never to come near this here place this morning. I felt guilty, like I'd shot somebody—I didn't know. I feel that way now."

"You're all your letters said you were," said Mary Warren, weeping now. "Any woman who would deceive such a man——"

"You ain't deceived me none," said Sim Gage. "But it's wrong of me to fool a woman such as you, and I'm sorry. Only, just don't you git scared too much. I'm a-going to take care of you the best I know how."

"But it wasn't true!" she broke out—"what the conductor said! It isn't just a cinder in my eye—it's worse. My eyes have been getting bad right along. I couldn't see anything to-day. You didn't know. I lost my place. I have no relatives—there wasn't any place in the world for me. I was afraid I was going blind—and yesterday I did go blind. I'll never see again. And you're kind to me. I wish—I wish—why, what shall I do?"

"Ma'am," said Sim Gage, "I didn't know, and you didn't know. Can you ever forgive me fer what I've done to you?"

"Forgive you—what do you mean?" she said. "Oh, my God, what shall I do!"

Sim Gage's face was frowning more than ever.

"Now, you mustn't take on, ma'am," said he. "I'm sorry as I can be fer you, but I got to drive these broncs. But fer as I'm concerned—it ain't just what I want to say, neither—I can't make it right plain to you, ma'am. It ain't right fer me to say I'm almost glad you can't see—but somehow, that's right the way I do feel! It's mercifuler to you that way, ma'am."

"What do you mean?" said Mary Warren. She caught emotion in this man's voice. "Whatever can you mean?"

"Well," said Sim Gage, "take me like I am, setting right here, I ain't fitten to be setting here. But I don't want you to see. I got that advantage of you, ma'am. I can see you, ma'am"; and he undertook a laugh which made a wretched failure.

"How far is it to your—our—the place where we're going?" she asked after a time.

"About twenty-three mile, ma'am," he answered cheerfully. "Road's pretty fair now. I wish't you could see how pretty the hills is—they're gitting green now some."

"And the sky is blue?" Her eyes turned up, sensible of no more than a feeling that light was somewhere.

"Right blue, ma'am, with leetle white clouds, not very big. I wish't you could see our sky."

"And trees?"

"Dark green, ma'am—pine trees always is."

She heard the rumble of the wheels on planks, caught the sound of rushing waters.

"This is the bridge over the West Fork, ma'am," said her companion. "It's right pretty here—the water runs over the rocks like."

"And what is the country like on ahead, where—where we're going?"

"It's in a valley like, ma'am," said Sim Gage.

"There's mountains on each side—they come closest down to the other fork, near in where I live. That fork's just as clean as glass, ma'am—you can see right down into it, twenty feet——" Then suddenly he caught himself. "That is, I wish't you could. Plenty of fish in it—trout and grayling—I'll catch you all you want, ma'am. They're fine to eat."

"And are there things about the place—chickens or something?"

"There's calves, ma'am," said Sim Gage. "Not many. I ain't got no hens, but I'll git some if you want 'em. We'd ought to have some eggs, oughtn't we? And I got several cattle—not many as I'd like, but some. This ain't my wagon. These ain't my horses; I got one horse and a mule."

"What sort is it—the house?"

Sim Gage spoke now like a man and a gentleman.

"I ain't got no house fitten to call one, ma'am," said he, "and that's the truth. I've got a log cabin with one room. I've slept there alone fer a good many years, holding down my land."

"But," he added quickly, "that's a-going to be your place. Me—I'm out a leetle ways off, in the flat, beyond the first row of willers between the house and the creek—I always sleep in a tent in the summer time. I allow you'd feel safer in a house."

"I've always read about western life," said she slowly, in her gentle voice. "If only—I wish——"

"So do I, ma'am," said Sim Gage.

But neither really knew what was the wish in the other's heart.

The sweet valley, surrounded by its mountains, was now a sight to quicken the pulse of any heart alive to beauty, as it lay in its long vistas before them; but neither of these two saw the mountains or the trees, or the green levels that lay between. Long silences fell, broken only by the crackling clatter of the horses' hoofs on the hard roadway.

It was Mary Warren who at last spoke, after a deep breath, as though summoning her resolution. "You're an honest man," said she. "I ought to be honest with you."

"I reckon that's so enough, ma'am," said Sim Gage. "But I just told you I ain't been honest with you. I never wrote one of them letters that you got—it was some one else."

"But you came to meet me—you're here——"

"Yes, but I didn't write them letters. That was all done by friends of mine."

"That's very strange. That's just the reason I wanted to tell you that I hadn't been honest—I never wrote the letters that you got! It was my room-mate, Annie Squires."

"So? That's funny, ain't it? Some folks has funny idees of jokes. I reckon they thought this was a joke. It ain't."

"Your letters seemed like you seem now," she broke in. "It seems to me you must have written every word."

"Ma'am——" said Sim Gage; and broke down.

"Yes, sir?"

"Them is the finest words I ever heard in my life! I ain't been much. If I could only live up to them words, now——

"Besides," he went on, a rising happiness in his tones, "seems like you and me was one just as honest as the other, and both meaning fair. That makes me feel a heap easier. If it does you, you're welcome."

Blind as she was, Mary Warren knew now the gulf between this man's life and hers. But his words were so kind. And she so much needed a friend.

"You're a forgiving man, Mr. Gage," said she.

"No, I ain't. I'm a awful man. When you learn more about me you'll think I'm the worst man you ever seen."

"We'll have to wait," was all that Mary Warren could think to say. But after a time she turned her face toward him once more.

"Do you know," said she, "I think you're a gentleman!"

"Oh, my Lord!" said Sim Gage, his eyes going every which way. "Oh, my good Lord!"