* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a Fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

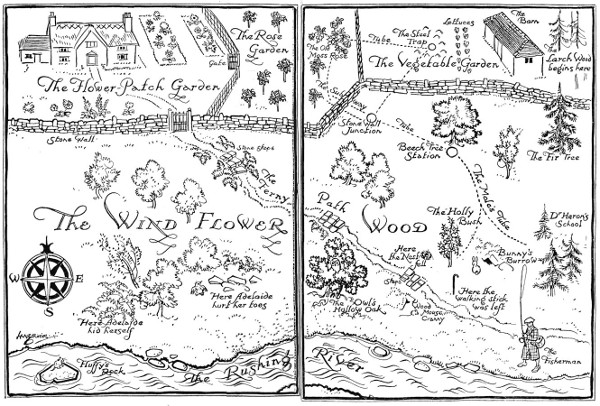

Title: Mystery in the Windflower Wood

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: Flora Klickmann (1867-1958)

Date first posted: Dec. 18, 2018

Date last updated: Dec. 26, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20181229

This ebook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Dianne Nolan & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

MYSTERY IN THE WIND-FLOWER WOOD

By the same Author:

DELICATE FUSS

Cr. 8vo. cloth. 7/6d. net.

THE CARILLON OF SCARPA

Cr. 8vo. cloth. 3/6d. net.

VISITORS TO THE FLOWER PATCH

Cheap Edition 3/6d. net.

THE FLOWER PATCH AMONG THE HILLS

(Twenty-ninth Edition)

Uniform with this volume

THE LADY-WITH-THE-CRUMBS

The Youngster’s Flower-Patch Book

F’cap 4to. 5/- net.

BETWEEN THE LARCH WOODS AND THE WEIR

THE TRAIL OF THE RAGGED ROBIN

FLOWER PATCH NEIGHBOURS

THE SHINING WAY

THE PATH TO FAME

MANY QUESTIONS

MENDING YOUR NERVES

THE LURE OF THE PEN

A Book for would-be Authors

First Published October 1932

Printed in England

The Shenval Press

CONTENTS

| Chap. i | The Disappearance | page 1 |

| ii | The Thrushes Move Again | 12 |

| iii | The Little White Dog Arrives | 18 |

| iv | The Carpenter is Consulted | 25 |

| v | The Lesson on Brunching | 31 |

| vi | Mac in His Younger Days | 39 |

| vii | About a Walking Stick | 57 |

| viii | That Adelaide! | 67 |

| ix | Trouble! More Trouble! | 74 |

| x | Mrs. Mole Tries to get in a Word | 79 |

| xi | The Rescue | 86 |

| xii | Mr. Pepperkin surprises Everybody | 96 |

| xiii | Mac appears before a Magistrate | 104 |

| xiv | Clearing up Mysteries | 111 |

Mystery in the Windflower Wood

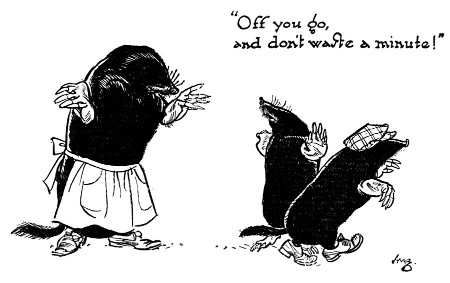

It began like this, and--as everyone in the Wind-Flower Wood agreed--it really was rather mysterious. Mrs. Song-Thrush put the children to bed at the usual time, in their nest in the holly bush, just as the sun was disappearing behind the opposite hill.

They had only moved into the holly bush that spring. The previous year they had lived in an old apple tree. But it had been a very cold season. The snow had come down on her as she sat on the nest, because the leaves had not yet opened on the apple tree, and there was nothing to shelter her but a very little bit of ivy trimming. Also, it had been rather too public up there at first, while the branches around her were bare. So, she had decided to move lower down, in the wood.

“The Hollies,” a most convenient place, was to let. It seemed exactly what the Thrushes needed, with its evergreen leaves making a splendid sort of umbrella over the nest. The only drawback was the fact that it was close to the Ferny Path that went down hill, right through the middle of the wood. But, as Mr. Song-Thrush pointed out, it was a very thick bush, with sharp prickles on every leaf; and these would not only keep inquisitive neighbours from poking their noses into the Thrushes’ affairs, but passers-by would not be anxious to scratch themselves by meddling with the bush.

So they decided to take it.

When they moved in, they found everything most cosy and convenient--plenty of leaves to hide them, and good stout branches to hold up the nest.

They felt they were very fortunate in having secured “The Hollies” before the Blackbirds had got it. They had seen Mrs. Blackbird hopping all about the premises, upstairs and down, evidently with a view to taking it. Therefore the Thrushes had hurriedly brought along a few twigs and moss, and some feathers from the farmyard, and started their nest; because they knew that the Blackbirds would then go further off and find another place to live in. They are like the Thrushes, very exclusive, and prefer to have a tree or bush to themselves.

This was how the Thrushes came to live at “The Hollies.”

Well--as I was saying--the young Thrushes went to bed one evening as usual. In a few minutes mother settled down, with her wings spread over them to keep them warm all night; while father perched on the branch of a beech tree close by. As soon as the sun had disappeared, and taken the golden sunset with it, the family went to sleep, with their heads tucked under their wings.

And everything seemed just as it always was.

But--it wasn’t!

For when the sun arrived back next morning and woke up Mr. Thrush--whose duty it was to arouse the birds and start their Dawn-Concert with his famous “Wake-up Song”--the poor bewildered father couldn’t find his wife and family!

He was positively certain he had left them in a beautiful nest, in a lovely holly bush, when he went to sleep over night. Whereas now--there wasn’t any holly bush!

At first he felt sure he must still be asleep and dreaming; but next minute he heard Mrs. Thrush calling him. She sounded as though she were down below him somewhere. Peering through the beech leaves, there he saw her--nest and children and all--flat on the ground! Quite close to the path, too! Such a dangerous spot to have chosen!

“How on earth did you get down there?” he asked, gazing in astonishment from his high-up perch, and wondering again if he were really awake.

“That’s what I want to know!” she said. “I thought the wind was very high last night. We seemed to sway about much more than usual, and once there was a big bump. But I didn’t worry about it, because I knew the children couldn’t fall out while I was there. And Eric had been so restless, I didn’t want to wake him up again to find out what had happened. But it’s plain enough now that we’re on the ground.”

“But what have you done with the holly bush?” he inquired anxiously.

“For goodness sake, don’t keep on asking ridiculous questions.” Mrs. Thrush was rather put out, as you can well believe. It isn’t a trifling matter to find your house has entirely vanished in the night. “Of course I’ve done nothing with it,” she continued. “And it would be more useful if you looked around for it. Better still, fetched the policeman. I can’t possibly leave the children alone down here on the ground.”

Mr. Thrush was so bewildered that he forgot all about the Wake-up Song. As the result, all the Little People in the Wind-Flower Wood overslept that morning. When at last they did wake up, they wondered what had happened to Mr. Thrush, and several came along kindly to inquire if he had caught a cold or had a sore throat, as he hadn’t sung a note that morning.

When they arrived at the place where “The Hollies” used to be and found Mrs. Thrush on the ground, loud were the squawks and whistles of surprise. Each caller was quite sure he or she knew exactly how it happened, and what had become of the holly bush. And everyone was in the midst of giving heaps of good advice and telling Mrs. Thrush what she ought to do--when Mr. Thrush returned with Police-Constable Crow. The neighbours immediately retired to the trees close by, taking care to be near enough to hear every single word.

The first thing P.C. Crow did was to question everybody. But though the neighbours seemed so wise before he came, they really knew nothing at all when he questioned them, and evidently had no more ideas than the Thrushes had as to how or why the bush had gone travelling in this unexpected manner.

Even Bunny, the rabbit with the silky ears, who had a very comfortable burrow under an adjoining rock, couldn’t give any information about the affair, because he had been out all night at a big supper-party one of his friends had given in the garden of the Flower-Patch House, which is higher up the hill, and just above the Wind-Flower Wood. He told Policeman Crow that the young carrots and lettuces up there were simply delicious. They had intended to nibble the carnation tops for dessert. But unfortunately the gardener had put netting all over them that very day, for which they were extremely sorry, of course. Still, they made up for it with young cabbages.

But Mr. Crow wasn’t interested either in carnations or cabbages just then, though he did inquire how the green peas were getting on, and he too seemed sorry when he heard that they also were netted now. He changed the subject, however, because of course his business at the moment was to discover what had become of Mr. Thrush’s desirable villa residence known as “The Hollies.” Therefore he insisted on searching “Bunny’s Burrow,” in case the rabbit had stolen the property. But no sign of the holly bush could he find.

Then he routed out the owl, who lived in the Hollow Oak across the way. But the owl, when questioned, said he had been away from home all night, hunting mice by the big barn. So he wasn’t any help. In any case he didn’t intend to be! for he much objected to being wakened in the daytime; and he said so in a very hooty manner.

But Policeman Crow didn’t let a little noise like that upset him; and he wasn’t going to stand any nonsense either. So he proceeded to search every nook and crannie of the “Owls Hollow” in the oak tree to make sure that the Thrushes’ happy home wasn’t hidden up there. In fact, he searched the place so thoroughly, and stirred up such heaps of dead leaves and twigs and pieces of bark and other bits of household furniture, that it was hours before Mr. Owl got his bedroom to rights again, and fit for a gentleman to sleep in.

Which only shows that it isn’t wise to hoot at a Policeman!

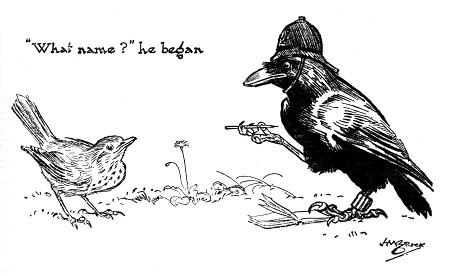

“As nobody seems able to give any information which will help me to arrest the stolen property, I must write down full particulars,” Mr. Policeman Crow said. Getting out his notebook, he started first to question Mr. Thrush.

I should explain that Mr. Crow and Mr. Thrush had never been very good friends. The Policeman had such a harsh voice, it quite got on Mr. Thrush’s nerves. Mr. Thrush was so extremely musical, and had such a highly cultured voice. Why, he could sing a dozen different songs at one recital, and all in the same breath, so to speak. And the worst of it was, the Crows thought they had magnificent voices too. And the more Mr. Thrush sang, the more noise did the Crow family make in the tree tops. Till at last Mr. Thrush offered to lend them a little hair-oil to see if it would improve their throats.

Mrs. Crow, too, had made some very personal remarks about Mrs. Thrush’s dress. Said she should be ashamed to go about like Mrs. Thrush did, in nothing better than that dowdy brown tweed coat and skirt. She (Mrs. Crow) always wore the richest black satin, even when getting breakfast in the morning.

Naturally, the two families hadn’t been over-friendly after this. But now Mr. Policeman Crow was the important person, and he meant Mr. Thrush to understand this.

“What name?” He began his questions in a loud voice, as though he had never seen or heard of these birds before.

“Thrush” was, of course, the reply he got.

“I see; Brush,” he said, and licked his pencil in order to get it to work properly.

“Not Brush. I said Thrush--it’s a T, not a B.”

“Who said you were a bee, may I ask?” said P.C. Crow severely. “Don’t try to be funny. I quite understand now that the name begins with a T, as I happen to be exceptionally intelligent. But in future kindly remember to be more accurate and perfectly clear in your statements, and say ’T for Treacle Tart, not B for Boiled Bacon; T for Toasted Tomatoes, not B for Braised Beef; T for Turnip Tops, not B for Baked Beans’--and then people may perhaps know what you are talking about. Always express yourself in simple, straightforward language when you are in the hands of the police, or, let me tell you, there may be trouble, my good man!”

He spelt it carefully to himself as he wrote it down--“T-H-R-U----” then he looked up: “Do you spell it with an S or a C, as you are so particular about the spelling?”

Mr. Thrush really wanted to smash the policeman’s helmet for him by this time, but he controlled his feelings, as he didn’t want to upset the children, and merely explained that they spelt it “T-H-R-U-S-H.”

“I see,” replied Mr. Crow, writing it down.

“No, it isn’t a C!” Mr. Thrush was nearly boiling over with annoyance. “I told you we spelt it with an S for Sauce, not C for Cheek; S for Singing, not C for Croaking. You’ve got C on the brain, man. We aren’t all crows you know.”

The listening neighbours were enjoying all this immensely, especially as none of them loved the policeman or his family. Indeed the blackbirds began to applaud.

Here Mrs. Thrush interrupted the conversation, because it looked as though they would be arguing all day, at this rate. And she wanted to find her house.

“Policeman Crow means that he knows exactly how to spell our name, dear. He’s written it quite correctly in his book.”

“Of course I write correctly,” the policeman replied. “And I must insist on SILENCE while I make my notes”--glaring round at the audience in the surrounding trees.

No one so much as twittered!

His pencil scratched away for a moment. Then he asked: “Any wife?”

“Yes, there’s me,” said Mrs. Thrush.

“I see”--writing down as he repeated it--“one wife named ‘ME’.”

“Oh, dear, that’s not my name,” said poor Mrs. Thrush, but he went on with his questions:

“How many children?”

“Three,” said Mrs. Thrush. “Eric, Adelaide and Ellen.” (She was determined he should get their names correctly.) “There used to be four; but unfortunately Gerald fell out of the nest. So there isn’t any Gerald now. Eric is rather delicate, takes cold easily. But I rub his chest each night with wild strawberry juice. That’s what makes him so red. It isn’t fever or anything infectious.”

“I see”--carefully writing again--“three children: Eric, Laid-an Egg, and Fell-in-Wild-Strawberry Juice. So there aren’t any children now.”

“Oh! That’s all wrong,” said Mrs. Thrush.

“Of course it’s all wrong!” said the policeman. “Children ought not to be allowed to fall into wild strawberry juice like that. It would be bad enough if they were tame strawberries. But WILD ones--why you never know what might happen. It’s such a dreadful waste of strawberries too! Now then, next question: What’s your address?”

“The Hollies,” Mr. Thrush told him, for poor Mrs. Thrush was nearly weeping.

“The Hollies? Whereabouts is it?”

“Unfortunately we don’t know! That’s all the trouble.”

“You don’t know where you live?” exclaimed P.C. Crow. “Then how can you live at ‘The Hollies’ if you don’t know where it is?”

“Yes, we do live there, only you see we’ve no idea where the holly bush is.”

“I don’t see!” said the policeman severely. “It’s puffeckly absurd to tell me that you live where you don’t, and you don’t know where you do live, and the house that you live in isn’t anywhere! I really can’t have my valuable time wasted in listening to such nonsense!”

“But everything you’ve written in your notebook is wrong,” said Mr. Thrush, who was fast getting into a temper. “In your notes you ought to have everything quite right.”

“Then if everything is quite right, why did you fetch me? I was told that there was something wrong here. Then, when I leave my early breakfast, which I was really enjoying in that newly-ploughed field, and hurry down here to inquire into it, you tell me that I must put down ‘Everything quite right’ in my notebook. Let me tell you this, Mr. Brush--no, I mean Thrush--I know someone who isn’t quite right, and that is the individual who says he lives in a home that isn’t anywhere, and he doesn’t know where it is when he does live there. I shall go back at once to the police station and report this case--after I’ve seen if those wretched rooks have left me any breakfast, and I don’t suppose they have.”

Mr. Thrush opened his beak to say something in reply, as Policeman Crow shut up his notebook with an important snap, but at that moment, someone among the neighbours who were perched on the trees all around, called out:

“Mrs. Thrush; Mrs. Thrush; your baby’s lost!”

Mrs. Thrush turned round to look at her nest, which was still on the ground, of course. Eric and Ellen were there, just as she had left them, with their little beaks open, waiting for father and mother to pop something in.

But Adelaide’s place was empty!

THE THRUSH’S WAKE-UP SONG

Wake up! Wake up! You sleepy heads,

For see! the daylight’s coming,

When everything should start to sing,

And bees begin their humming.

Wake up! Wake up! The sun is glad,

And warm, and bright, and cheery.

Without our songs, the world is sad;

Without the sun, it’s dreary.

So sing a song that’s sweet and strong,

And set the wood a-ringing;

For all too soon it’s afternoon--

And night-time needs no singing!

“Where’s Adelaide?” Mrs. Thrush asked in great concern, as she looked at the nest.

“She’s gone to find something to eat,” whimpered Eric, “but she says she isn’t going to bring us any, ’cos we’re lazy. We’re so hungry, Mother”--which reminded Mrs. Thrush that she had quite forgotten to get the breakfast, in her surprise at finding “The Hollies” had vanished.

She looked around to see if she could discover the missing Adelaide, but there was no sign of her. As the other two children were crying loudly for something to eat, she decided to get breakfast before she did anything else, in case they too should disappear.

Adelaide had always been an “up-and-doing” sort of a child, and much more forward than her brother and sister. And as she was nearly old enough to walk, she had struggled out of the nest, and toddled off on her own little legs, which seemed rather weak at first, but got stronger as she went on. She meant to find her own breakfast, as no one else seemed to be doing it. None of the neighbours noticed her go, they were all so intent on watching Policeman Crow. She was soon out of sight under a clump of big ferns, where, to her delight, she found several very nice morsels, that were just what she fancied.

She could hear her poor distracted father and mother flying from tree to tree, and calling her name. But not a scrap of notice did she take. She merely went on gobbling.

She was really enjoying herself immensely; and thought it was much more fun to be out in a huge world like the one she had found under the ferns, instead of being stuffed up in a nest, with Eric always kicking, and Ellen taking up more than her share of the room. Every day the nest had seemed to grow smaller, every day the children seemed to grow bigger, and every day there was less chance to turn round and have a good stretch than there was the day before. No! Adelaide decided that she wasn’t going to put up with that cramped nest any longer--and perhaps be starved to death into the bargain. Just look how they had left her this very morning, with not a morsel of food!

And Adelaide went on gobbling.

I daresay the other fathers and mothers would have helped to search for the missing child, but at the moment Mr. Crow was shutting up his notebook, and stalking off majestically, a big foxglove bell started to ring over the other side of the wood and everyone exclaimed:

“Good gracious! there’s the school bell! And the children haven’t had their breakfast yet!”

Each mother rushed home and hastily got her family ready for school, giving them some breakfast to eat on the way there.

By this time, Eric and Ellen were cheeping loudly for something to eat. And, what was also very worrying, they had both scrambled out of the nest, and were now actually on the path that ran through the wood, where they might easily be stepped on by anyone passing that way who didn’t happen to notice them.

Evidently something would have to be done, and done quickly too.

“We must get them to a safe spot,” said Mrs. Thrush. “Under that great fir tree wouldn’t be at all a bad place. Those big branches touching the ground are just like a tent and would hide them beautifully.”

“The very thing!” said Mr. Thrush, who was getting really exasperated with the collection of troubles which seemed to have rained down upon his head. “And while you are getting them there, I’ll go to the top of the tree and sing the song I composed yesterday. It will make that conceited Missel Thrush across the river simply pale-blue with envy.” (The Missel Thrushes--who love mistletoe berries--have rather harsh voices, not like the lovely Song Thrushes.) “And I’m sure you will enjoy this new song, my dear,” he added.

“I should enjoy a new caterpillar much more!” said Mrs. Thrush. She was getting exasperated too. “And so would the children. If you’ll just hunt about for a nice one, I’ll also get one, and then we’ll set about removing to ‘The Firs.’ Besides, I don’t feel a bit like listening to a concert this morning, with poor dear Adelaide” (here she began to weep) “perhaps dead with starvation by now.”

Mr. Thrush hadn’t thought of that! And of course he was very sorry too.

Little did they think that all the while that Adelaide was not so very far away, with so much food already inside her that she wouldn’t have died if she had had nothing more all day! And that naughty person was actually giggling to think how she had hidden herself. And still she went on gobbling! Creeping farther and farther away.

Shocking, wasn’t it!

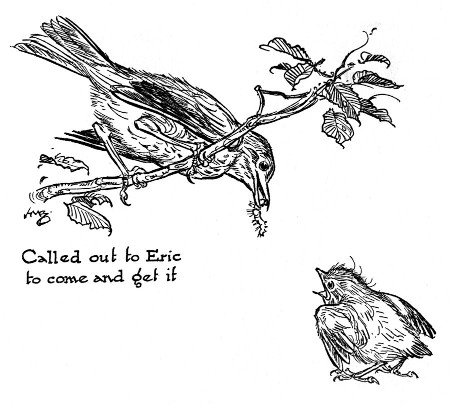

Father and Mother soon found something they knew the children would like. But--here is the curious part. Instead of flying down and feeding the youngsters, Mr. Thrush went to a low branch of a tree, near the spot where they were, and dangling the choice morsel in his beak, he called out to Eric to come and get it.

Of course Eric wailed that he couldn’t possibly fly so far.

But his father encouraged him; told him it was ever such a little way. And quite easy. And such a lovely breakfast treat when he got there. And “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try, try again!” which Eric did, because he was desperately hungry by this time, and willing at last to do anything, if only he could get some food.

Finally, after several floppity, feeble, half-afraid attempts, he made one mighty effort and flew across the few inches which separated him from his father. And wasn’t he proud of himself, too, when he was actually perched on the branch! Though his legs felt very wobbly, and he was sure he would topple off.

But when he saw his mother on another branch, dangling another tit-bit, and trying to get Ellen to come to her, he felt very superior indeed, and called out: “Hurry along Ellen. It’s quite simple. See how easily I hopped up here.”

This gave Ellen a little courage; she, too, made a hop and a jump and a sort of tumble, which landed her on a low branch beside Mother. And oh! how good it was to find something popped into her mouth!

The children were told to cling tightly to the branches, while father and mother got them something more to eat, that would be very nice. So they waited, hoping the food would come soon, as they felt top-heavy, and likely to tumble off! When they saw their parents coming, they opened their beaks so as to be quite ready.

Yet, instead of flying down and settling beside Ellen, Mrs. Thrush again stopped on a branch a little distance away, dangling the delicacy she had brought and telling Ellen to come and get it. While Father Thrush was doing exactly the same thing, in order to get Eric to come to him.

Well--the children hesitated for a minute; but it didn’t seem worth while to stay hungry, when there was such a beautiful morsel only a little way off. So, after another desperate effort, each child managed to land beside its parent once more.

In this way, by degrees, the thrushes got the children moved--a little way at a time, and then a little more--from branch to branch, until at last they reached the big fir tree which was to be their new home.

Wasn’t it clever of them?

It was really a long journey for the children, as they were so young. They were glad to nestle down among the warm, dry pine needles, which were like a thick bed under the sweeping dark-green branches. And soon they were asleep.

But what about that Adelaide?

Ah----!

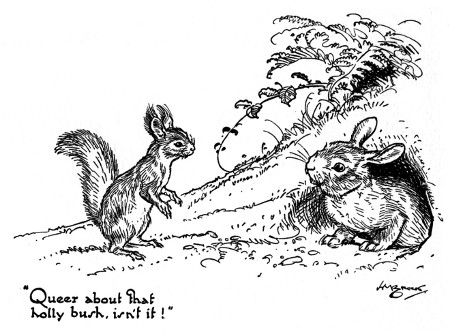

“Queer about that holly bush, isn’t it!” said the rabbit with the silky ears to Bushey Tail, the squirrel, who happened to come past “Bunny’s Burrow,” a little later on that morning. Bushey Tail was searching for some nuts he had buried nearby the previous autumn. Nuts become scarce in the summer time, before the new ones are ripe on the hazels. “I don’t like the look of it at all,” Bunny continued, rather anxiously. “And it’s quite spoilt the view from my front door. Everybody can see right into my living-room now that tree’s gone.”

“Any idea who took it?” asked Bushey Tail.

“Poachers, of course,” Bunny replied, “only I wasn’t going to say so this morning. Old Crow is so disagreeable.”

“How do you know it was the poachers?”

“Well, who else would it be if it wasn’t them? And you can easily see what for--they wanted to get me for certain; only, luckily, I wasn’t at home that night. I’m awfully nervous now about staying in the house alone.”

“Oh, keep your whiskers cheerful!” said the squirrel. “I don’t believe it was the poachers. They never carry off a bush. When they cut down anything that’s in their way, they always throw it down and leave it there. Dreadfully untidy they are. And what could they want with it if they did carry it off?”

“Why, they’d eat it, of course.”

“Eat it! They aren’t rabbits. People don’t eat green leaves like we do!”

“Don’t they? What about those lettuces and broccoli and radishes I saw the gardener taking into the kitchen, up at the Flower-Patch House? Who’s going to eat all that, let me ask you. The cat? I don’t think!” And the rabbit snorted.

“Taking them into the kitchen, was he?” Bushey Tail suddenly became excited. “That means that the Lady-with-the-Crumbs is coming soon. And I shall have plenty to eat. Hurrah!”

“Who is the Lady-with-the-Crumbs?” Bunny asked.

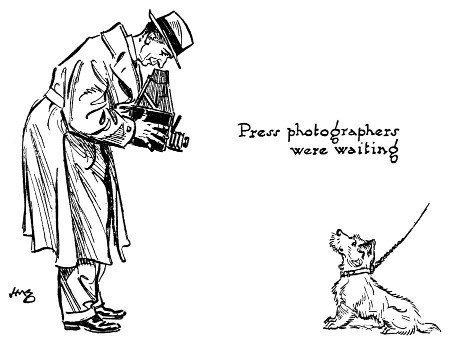

“I forgot; you don’t know about her, as you haven’t lived long in this wood. She and the Gentleman belong to the Flower-Patch House just above the wood--where you went to the party last night. Sometimes they live in London, and are only here for holidays. When they come, the Lady puts out miles of crumbs, and nice bits and rolled oats for the birds, and nuts for ME in the nut boxes. We have a gorgeous time. And you told old Crow that the peas were netted, I remember--then she’s certain to be here soon, and the gardener’s hurrying up and getting it all ready for them. That reminds me--Mac, their dog, is sure to come too. You’ll like him. He’s a bit umptious, but a real sport.”

“Oh, dear! I’m not at all keen on dogs,” said the rabbit, who was looking very upset--what with one thing and the other. “They’re as worse as poachers and even badder! He’ll be in my home before I have time to get out. What a life I do lead!”

“Don’t worry your whiskers about him. He’s a very good sort. He caught a poacher once and saved his master’s life. He doesn’t love poachers any more than you do. I’ll tell him you’re a friend of mine. It will be all right, you’ll see.”

Bunny was opening his mouth to say that he wasn’t so sure that it would be all right--when he espied something white trotting down the Ferny Path that ran through the middle of the wood. And there came the little dog, Mac, himself, looking as important as ever.

And before Bushey Tail could say: “Why there he is!” Bunny had disappeared, and a whisper came from far back in the burrow under the big rock, “Don’t let him know I’m here.”

Mac wagged his tail in a pleased manner as he caught sight of the squirrel. They used to be saucy to each other once upon a time; but they were very friendly now. Business matters, however, were always first with Mac. He knew it was his duty to see that each stone and bush and tree and gate was exactly where it ought to be, and where he left it last time.

When he came to the place where the holly bush had been, but wasn’t there now, he stopped! Looked! Sniffed! Ceased to wag his tail! He was just going to ask what had become of the bush, when he sniffed again a little nearer “Bunny’s Burrow,” and that time he caught a delicious scent--rabbit! Yes, as he sniffed still nearer, he was sure it was rabbit.

Now Mac, like all other dogs, loved to chase rabbits, to dig for rabbits, and to get as far into their burrow as he could. Once, indeed, when he was new to the game, he got stuck, head first of course, in a burrow, and couldn’t get out again. And if his master hadn’t chanced to see two white hind legs and a white tail waving frantically on a bank he might have been there now!

But since that day he had been taught that he must not chase anything that lived in the Wind-Flower Wood. And being a very intelligent dog, he soon learnt his lesson. But, all the same, he still thought that the most delicious scent on earth was rabbit!

“Won’t your friend come out and speak to me?” he said to the squirrel. “I hope I haven’t interrupted you?”

(“Tell him I’m awfully ill, dying, in fact; can’t possibly move!” said a hoarse whisper from the burrow.)

“I’m afraid he can’t come out,” the squirrel replied:

“His old head aches,

His small tail shakes;

He’s really very wonkey!

He stayed out late,

And ate and ate;

Of course he’s ill! the donkey!”

Naturally, Bunny wasn’t pleased at hearing himself called names. But he dared not say a word. There was that dog to be considered.

“What sort of a chap is he?” Mac asked.

The Squirrel replied:

“His ears are wrong,

His nose too long;

He’s like a bag of bones!

He has to stay

And hide all day

Under that heap of stones!”

This was still more annoying to Bunny. For everyone in the wood knew that he was the plumpest young rabbit--with the loveliest ears too--for miles around. Of course he could see that the squirrel was jealous of him; that was quite plain. He was so proud of his bushey tail, and for ever dangling it, for all the parish to see, from the branches. But Bunny was sure his own tail was quite correct--as rabbits’ tails go. In any case he usually sat on it; so what matter if it were not quite so large as the squirrel’s. In fact he much preferred short, stumpy tails. Far more artistic, and so much easier to sit upon. And as to his ears being wrong, his ears! Why----!

But the squirrel was continuing, in a loud voice:

“He’s such a fright,

The merest sight

Would give you quite a shock!

We’ve never had

An uglier lad

Living beneath that rock!”

Really, this was too much! Dog or no dog, he wasn’t going to stay quiet and listen to such horrid things being said about him--and he the handsomest rabbit in the district!

Out he bounced (which was exactly what Bushey Tail meant him to do). He was just going to fight the squirrel, when that young gentleman skipped up a tree and said, with the politest bow:

“Mr. Mac, will you allow me to introduce our new neighbour, Mr. Bunny?” Then to the rabbit: “This is Mr. Mac. You’ve heard me speak of him.”

Mac gave a dignified wag; Bunny sat up on his hind legs and waved a paw. That being that, the three then settled down in the sun for a friendly chat.

Of course they began with the holly bush, giving Mac all the details. He listened attentively, but didn’t talk a great deal. Dogs are too wise to say much when anything important is on hand. They listen, not only with their ears, as we do, but with their eyes and paws and tail. Watch your own dog when he is listening attentively, and you’ll see what I mean.

Mac intended to ask a few questions when they had finished; but at that moment he heard his master’s whistle. He was a wonderful dog, and a clever dog. And he knew that no one could possibly be wonderful or clever who disobeyed when he ought to be obedient. Instantly he jumped up, saying: “Ta! ta! till next time. I’ll keep my weather eye open for that holly bush.” And he bounded up the path and was soon out of sight.

“A nice sort of friend you are,” the rabbit began in an aggrieved tone, “to say such dreadful things about me, behind my back.”

But Bushey Tail, who was up a tree by this time, sang out:

“I said them to your face!

And I’m sure it’s no disgrace

To say things which I know that you can hear.

If you call that gratitood!

When I tried to do you good!--

I’ll merely say ‘Good afternoon, old dear!’ ”

“This bungalow will do very well while we’re rebuilding,” said Mr. Thrush, after breakfast, hopping about and inspecting the ins and outs of the place they had chosen under the fir tree. “But we must get the carpenter as quickly as possible, and find out how soon he can have the nest fixed in another tree. I’ll go round at once and see him about it.”

“Yes, do dear!” Mrs. Thrush urged him. “I should be so thankful to get up into a tree again. I know this is better than lying in the middle of the Ferny Path; but it’s unsafe for the children even here, being on the ground. The farm cat will be around the moment my back is turned. And as for that kitten of hers, Fluffy is the most inquisitive little baggage I ever came across. Wants to find out everybody’s business, and poke her nose into everything.”

“She’d better not poke it in here, or she’ll get a peck she won’t forget in a hurry,” valiant Mr. Thrush threatened.

“That’s all right if we are at home; but if we should be out when she comes snooping around----” Mrs. Thrush was very anxious.

“I’ll go and see about rebuilding at once!” and off he went.

Mr. Woodpecker, the carpenter, came back with Mr. Thrush.

He examined the stump of the holly. He examined the nest.

He measured the distance from the tree stump to the nest, and found it was exactly two feet three inches and a quarter.

Then he measured the distance from the nest to the tree stump, and found it was a little over two feet six inches and a half. After measuring several times and making it a different figure each time he said it was undoubtedly a serious matter.

Next he measured the height of the stump from the ground, and made it thirteen inches. And though he measured it twice over, it never came to more than fifteen inches. Therefore, he said, it looked to him as though the holly bush wasn’t there! Because holly bushes were always much higher than that when they grew up. And if the holly bush wasn’t there (and he was almost sure it wasn’t), he wasn’t quite certain if he could put the nest back in its branches! Though of course he would do his best.

Mr. Thrush explained that he didn’t expect him to put it back in the holly bush, under the sad circumstances. What they required him to do was to fix the nest very firmly in another tree--a steady sort of tree that wouldn’t be inclined to walk off all in a hurry; and with strong branches, not likely to break down easily, as their children were exceptionally fine children, and were growing finer every day.

Mr. Woodpecker said he quite understood, and thought the suggestion was a very good one.

“What you want is a commodious residence, at least three storeys high, guaranteed to last a whole summer if needed; not a jerry-built bungalow like that old hen-house over there,” said the Carpenter, pointing to the nest on the ground.

“Oh; but my wife wants the same nest used. She built it herself, you know, and doesn’t want to part with it. It’s made from a recipe her great-aunt gave her that has been in the family for ages.”

“H’m!” said Mr. Woodpecker. “H’m! To be sure!” And he looked at the old nest pityingly. “I can quite believe it! And we don’t want to upset any lady, of course. They are all very fond of quaint, old-fashioned things just now. But your family, Mr. Thrush, ought not to be living in a house with its wall plastered with mud like that. Really, sir, if you’ll excuse my saying so--it isn’t your style! However, I’ve no doubt but what I can work in a bit of the old place here and there, so that Mrs. Thrush won’t feel that she’s been turned out of house and home, so to speak. I could use that small bit of twig, very likely, and perhaps that feather. But you can safely leave it to me, now that I know exactly what you want.”

“Yes, I think I’ve made it all clear.”

“Perfectly clear, sir; perfectly! And you would like to have one of the new Laurel Leaf roofs, I expect, to keep the rain off?”

“That sounds very useful.”

“It is. You would find it would keep the place beautifully dry. And, by the way, while we are going over details, what about a verandah just outside the nest? So handy for Mrs. Thrush to sit and nurse the baby there on sunny days.”

“That’s a splendid idea. The children could play there, too.”

“Exactly, sir. All the best birds are having verandahs now. And probably you’ll want me to put a handsome flight of stairs leading up to the nest. It’s so dangerous for the little ones to have to keep hopping up and down uneven, rough branches. You never find canaries, or budgerigars, or any of the really aristocratic birds using branches. They are so terribly common.”

“Ye-es; but I think I had better speak to my wife about the stairs. I’m not sure whether she would like them. You see the farm cat might easily----”

“I quite understand, sir. We’ll leave the stairs to be settled later. Though I’ll just take the measurements for them while I’m here. It will save going over the same sums again, won’t it. Let’s see, two and two makes--makes----”

“Four,” said Mr. Thrush.

“You’re absolutely correct, sir. Add two, that makes five, and three more makes----No, I’m wrong. Where was I? I’ll begin again. Two and three makes four, and then two more there, that will be five, no I mean seven----”

“That isn’t right,” said Mr. Thrush. “Now listen!” and he spoke very slowly. “If you have two steps there . . . and three next them . . . that will make--er--seven, won’t it? And then . . . if you have two more steps . . . that would make nine steps--or perhaps it’s eight--wouldn’t it?”

“Ah, yes, sir, I daresay you are correct. But you are counting steps; I was counting inches. That makes all the difference, you see. However, you needn’t worry a bit more about it, I can see your new country house in my eye. I’m going home to get my tools this very moment, and I’ll start the work straightaway. I had promised Mr. Nuthatch to make a hole in the bark of his larch tree, large enough for him to wedge a walnut in----”

(A nuthatch always fixes a nut firmly in a tree crevice, you know, and breaks the shell by striking it with his strong beak.)

“But walnuts won’t be ripe for several months yet. So there will be time to do that later on. And probably you won’t mind my leaving off your work for a little while in September, just to oblige another gentleman, while I make the walnut holder for Mr. Nuthatch?”

“But several months! That seems a long while to take over a job like this!” said Mr. Thrush. “Surely you’ll be finished before September?”

“Well--maybe I shall be, but on the other hand, maybe I shan’t. I’m like George Washington, when he cut down your holly bush--I can’t tell a wicked story. And if I tell the truth, which I very often do, I can’t say exactly how long it may take me. When you start on these pulling-down jobs, you never know what you’re going to find underneath.”

“Why, I could pull that nest to pieces in no time,” said Mr. Thrush, impatiently.

“Quite so, sir; I can believe it, for I makes it a rule always to believe a gentleman when I know he’s certain to pay my bill. But there’s one thing I would ask you, sir: After you’d pulled that nest to pieces, could you turn it into an imposing mansion suitable for a famous singer like yourself, with all modern conveniences--verandah, sun-parlour, breakfast room, day nursery, night nursery, staircase (if the lady approves), draughts, hot and cold, and an up-to-date roof?”

“Perhaps not. But I want to get the youngsters moved from the ground as soon as possible.”

“I understand that. And I daresay you could get it done quicker by some people. That fellow Rook, for instance, would only use about three sticks, and simply fling ’em up into the branches, call it a nest, and charge you full price, same as if you were having high-class work done properly by a high-class bird. But that’s not my way. I take proper time to turn out a proper article. The work mayn’t be finished this year; it mayn’t be finished next year. But I can guarantee that it may be finished some time. What bird can say more? And in addition, I promise you this, and make no extra charge for it either--if it ever is finished, you and your good lady will have the surprise of your lives! And now, sir, as you are in a hurry, I’ll go back home at once and get my hammer.”

And for the rest of the day he hammered and hammered and hammered.

You will remember that the school bell was clanging away before the youngsters in the Wind-Flower Wood had started for school. Needless to say, when they arrived there, all breathless with hurrying, and still eating their breakfasts, the bell had stopped. Dr. Heron, the headmaster, looked at them over his spectacles with a displeased expression, and asked why so many were late for school when they knew how particular he was that all should be perched in their places on the hawthorn tree when the foxglove ceased ringing.

Bobbie Robin, who was very fond of putting himself forward, said: “Please, sir, Mr. Thrush didn’t sing the Wake-up Song ’cos he’d lost his house, and there wasn’t anything for breakfast, only the policeman, and we came as fast as ever we could.”

“I really don’t know what you are talking about, Robin,” Dr. Heron said. “It sounds a queer jumble. You had better go to your class now, and I’ll inquire into the matter later.”

Miss Blackbird, their teacher, was waiting for them. The birds from the Oak Wood across the river were already in their seats--had been there quite two minutes--and they were hoping that the Wind-Flower Gang (as they called them) would get a caning, or else be kept in for being late. For the Oak-Wood Gang and the Wind-Flower Gang were always at loggerheads. They were very disappointed when Miss Blackbird merely said: “Take your places quickly children, so that we can start lessons.”

Of course the birds don’t learn exactly the same things that you learn; but they have to be taught a number of very important subjects.

The girls learn weaving, and making feather beds, and things like that, because they must know how to make proper comfortable nests when they grow up.

Mrs. Gold-Crest is the Weaving Mistress. She can make a nest with a top to it, which covers it all up very snugly, leaving only a little hole at the side, just large enough for her to slip in and out. She can hang it by a bit of twig or woodbine or ivy, underneath the branch of a tree. When it swings in the summer breeze, it rocks the babies to sleep.

All the children have to learn how to feed themselves. Major Flycatcher takes this lesson. He sits on the branch of a tree, or on a post, waiting for some insect to come along; then he darts up into the air, catches the next piece of his dinner, and is back on the branch again all in a flash.

When you see a bird flitting out and back again like this, you’ll know it is a flycatcher--and perhaps he is giving a lesson!

Tobogganing is another subject many of the youngsters take--only they toboggan on air and without any sled! Mr. Tree Pippit is the teacher. This is the way he does it.

Going to the very top-most point of the tallest tree he can find, he suddenly flies right up into the air. Then--when he is up ever so high--he starts singing, and keeps on singing, as he slides down the air, just as though he had a toboggan under him, till he reaches the tree-top again. He has a most beautiful voice. And in May you can often see and hear him, in the country, and watch his wonderful performances.

I can’t stop now to tell you about the Gym. in the larch tree, where Sergeant Tit shows the children how to turn somersaults, and swing about on the end of the tiniest twig, and do all sorts of clever things, with heads downwards.

We must hurry back to Miss Blackbird, who was starting a lesson on Brunching; a most appetizing subject--all about food; what they may eat for breakfast, and what they may eat for lunch. But as it would be rather a mouthful to keep on saying “Breakfasting” and “Lunching,” they shorten it into “Brunching.” (The children, however, usually refer to it as Munching!)

Miss Blackbird began by telling them about the various eatables they would find growing in the woods and fields, and reminded them that some of it belonged to other Little People. This is how she put it:

“Heather-bells and clover

Belong to the bees,

And the scented blossoms

In the tall lime trees.

Fuchsias they are fond of;

Cowslips are their own;

And so the bees

Say—‘If you please

Just leave our flowers alone!’

“Birds may have the berries

On the mountain ash;

And the red wild cherries;

Or the ripe gooseberries

When they go to smash.

“Currants, too, are tasty

If the days are hot;

But do not be too hasty

And try to eat the lot!

Leave some for Big People

Who cannot live in trees;

Who cannot hang head downwards

When eating the green peas!

“A bird may take a morsel

From any fruit he sees.

But flowers belong

The whole day long

To the honey-making bees.”

Then Miss Blackbird told them that she had seen some birds--who should be nameless--nipping off the primroses to get the honey, and damaging crocuses. And she hoped this would not occur again!

(The sparrows hung their heads!)

She said she would be most ashamed if The Lady-with-the-Crumbs at the Flower-Patch House had to tie black cotton over her flowers, to keep the birds off, as she had seen done in some gardens.

Here Bobbie Robin (who wasn’t at all interested, as his family all prefer worms to flowers) moved ever so slightly along his perch, till he got close to young Chaffinch, an enemy of his; and he began, ever so gently, to push him off the branch!

Young Chaffy didn’t want to tell tales, of course, and he tried his hardest not to budge. But every time Miss Blackbird chanced to look in another direction, Bobbie gave an extra hard shove. And just as she was saying:

“I’m sure you will all try to behave like little gentlemen, if only to please me----”

Bump! went young Chaffy, clean off the branch! While Bobbie looked most surprised, as though he knew nothing whatever about it, and couldn’t imagine what Chaffy was trying to do.

But their teacher saw more than they thought she did. And when they had picked up Chaffy, rubbed his sore place, brushed his coat with a bit of moss, and found him a seat on the other side of the class, Miss Blackbird said:

“Now we’ll have some mental arithmetic. Listen most carefully now”--as she began slowly, and in a clear voice:

“If one bird ate three blackberries in three minutes, how many blackberries on the same spray would two caterpillars eat? Bobbie Robin, what’s the answer?”

“Oh--oo--er--Miss Blackbird--er--do say it again, please. I--er----”

She repeated it. “Now think hard.”

“Er--er--oh, I expect they’d eat--er--er--er--a holly bush.”

“Bobbie Robin! What are you thinking about?”

All the class were grinning and giggling, of course; while Bobbie looked very foolish.

“He’s thinking about Mr. Thrush’s lost house,” one bird told her.

“Oh; then I’m afraid he’ll have to think about blackberries now instead of holly berries! I’ll repeat the sum, and the first one who gives me the right answer will go to the top of the class.”

All sorts of answers were given. Some said four blackberries; some thought half a berry would be enough. They were all wrong.

At last Jackie Wren put up his claw.

“Well, Wren, what do you say?”

“They wouldn’t eat any at all!”

“Why not?”

“ ‘Cos any bird would eat both of them before he began on the blackberries.”

“Quite right! And up to the top of the tree you go!”

Which naturally pleased Jackie Wren; but Bobbie scowled.

“And now Wind-Flower Wood children, you can tell me what is all this talk I’ve been hearing about a holly bush.”

Everyone started to tell her, but it was such a babel, she had to say: “Don’t all talk at once, or I shan’t be able to make any sense of it. Tommy Tit, you may begin.”

He quickly told her all he knew, the others joining in occasionally.

“And haven’t they found it yet?” she asked. “How unfortunate for poor Mrs. Thrush and the children.”

“Please Miss Blackbird”--it was Bobbie speaking--“Adelaide’s lost too. And please can we have anarf-holiday to-day, to go and look for all of the losts?”

“I’m afraid you can’t, Bobbie. You were all late for school. And you haven’t been the brightest bird on the branch this morning, have you?”

So that settled it.

“I say, you fellows,” said Bobbie, after morning school. “I’m getting sick of this old wood, and this old school. And I’m worse than sick of old Flypaper’s lessons. Let’s dodge him this afternoon, and slip across the river and have some fun.”

All the bad ones agreed with him, and I’m sorry to say most of them were bad that day.

But suddenly someone remembered that it would be useless to go over and pay a surprise visit to the Oak-Wood Gang if they weren’t at home, but were all safely in afternoon school. Whereas to-morrow, Saturday, would be a holiday; and they could get across the river early and have a fine what-you-may-call-it of a kick-up, while the mothers were out marketing and the fathers were having discussions.

Naturally they all saw the sense of this. So it was decided to start immediately after breakfast, when----

“Sh! Sh! Not another word,” Bobbie whispered, seeing some of the Oak-Wood Gang coming their way.

And they all looked the best of good children as they filed in to Major Flycatcher’s class.

Isn’t it strange, what a number of big things often happen, because of one little thing which someone says or does!

When Bobbie proposed that they should play truant from school in the afternoon, he was only thinking of the fun it would be to miss lessons, and have a jolly good row with the birds who lived across the river. The two gangs were constantly having riots. And didn’t they all enjoy them too! Little did Bobbie imagine what a number of other things would result from that jaunt of his.

But before I tell you of these adventures, I want you to know something about the history of Mac, the little white dog whom you met just now, because this will help to explain some of his later doings.

Did I hear someone asking about Mr. Woodpecker?

He is still hammering.

And about Adelaide?

She is still hopping about among the ferns, gobbling a bit here and a bit there. And all the time keeping out of the sight of her terribly worried father and mother; and never making the teeniest sound when she hears them calling and calling her. She has been there all the morning, while the children were at school. And she is still somewhere thereabouts, now that it is dinner-time.

(What happens to her later, we must wait and see!)

Meanwhile there is Mac to be considered--a far more important person than that naughty piece of goods--young Adelaide.

For the first few months of his life Mac lived with his mother and brothers and sisters in Scotland. Such a cosy kennel they had, with lots of straw inside; and though it was cold out of doors, he was ever so warm when they cuddled up together among the straw.

The master he had in those days owned a lot of sheep, and Mac’s mother was always out with the shepherd when she could spare time from looking after her family.

A very wise dog she was; and most careful to teach the children properly.

One day, Mac, who was beginning to notice things, said to his mother: “It’s very kind of that man to bring us those lovely things to eat, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” said his mother. “And you must always try to do everything you can for the Big People who belong to you. Because you can see how unfortunate they are--they have only two legs, poor things! whereas we have four. They really are very good to us, and will do anything they can for us. But of course they can’t do much beyond giving us nice food. I can’t imagine how they manage to walk at all. They don’t seem able to take care of themselves a bit; they can’t bark, and their teeth aren’t an atom of good, except for eating their dinner, so we have to protect them, and bark at anyone who is likely to hurt them.”

“And may I bite the other people?” Mac asked eagerly. He had some new teeth and was anxious to use them.

“Oh, no! A well-behaved dog doesn’t bite, unless the other person is ever so bad indeed, and going to hurt his master. In that case he may catch hold of the bad man’s leg.”

“Then what can I do besides barking? I do like that man who brings our dinner; he pats me and his voice is so kind. I wish I could do something for him. But it wouldn’t be right to bark at him, would it?”

“No, we don’t bark at kind people; we try to help them,” his mother explained. “For instance, when you are old enough to go out into the fields, you will see lots of animals, and especially sheep. Very well-meaning they are, though not as intelligent as dogs. But at least they have four legs, whereas the shepherd who looks after them is another of the two-legged Big People; so, of course, he can’t do very much running about. And I don’t know what in the world he would do if he hadn’t us dogs to look after his flocks. When he wants the sheep to go through a gate, into the next field, they never want to go; but prefer to stay where they are, and go on nibbling. If he tries to drive them, they simply run about wildly all over the place, going everywhere and anywhere excepting through the gate. They know he’s no good at catching them, without the other two legs. The poor man would be utterly helpless but for us!”

Mac was very interested. He felt he was getting old enough and fierce enough now to do anything, and he wanted to make a beginning.

“What do you do, Mother? Do you bite the sheep?”

“Certainly not! That is one of the most forbidden things! It would be absolutely dreadful if a dog were to bite a sheep. Never forget that. It’s tremendously important.”

“I’ll remember. Then what am I to do if I have to help the poor man who has lost his other legs?”

“As soon as you see that he wants his animals to go through a gate, run up quickly behind them, and tell them quietly what they have to do. If some of them start to scamper off in another direction, run after them and send them back. Keep behind them all the time, close to their tails; but don’t hurt them or frighten them; only make them go through the gate.”

“What are their tails, Mother?”

“Those tassels which hang on behind. You have one, you know.”

“Have I?”

“Yes, here it is.”

“Why, how funny! I never saw that before. I must examine it.” And he tried to catch it, running round and round after it. Only the more he went after it, the more it ran away from him! It was very strange.

“Now listen to me,” said his mother. “If you keep close to their tails, and send them along--in front of you, mind--it seems to help the animals to go on, when they know you are behind them. And if you keep them in a bunch, instead of letting them get all over the field, it saves you a lot of work and waste of time, in running around after the stray-aways.”

“It sounds great fun,” said Mac. “I’d love to send them along in front of me like that. Is there anything else I can do for kind Big People?”

“You must listen if you hear anyone coming; and bark, if it is a stranger, to let them know that you are there, protecting the house and the kind people. You must never let strangers come inside the door, if your master or mistress isn’t there, no matter how nice and friendly they pretend to be.”

“If I mustn’t bite them, may I show them that I have some teeth?”

“Yes, you may do that. But I think you had better go to sleep now. That’s enough for to-day. I’ll tell you some more to-morrow. Now I’ll sing you to sleepy-byes.”

And she began:

“Little Bo-Peep

She lost her sheep

Because she’d forgotten to mind them!

But little dog Mac

Ran all the way back

Up the hill-side, to help her to find them.

“Little Bo-Peep

Did nothing but weep--

Which wasn’t much help to the doggie!

Though he ran very fast,

He gave up at last,

The hill was so dreadfully foggy!

“ ‘If you sit on this stone,

I’ll go on alone,’

Said Mac, ‘as they may be up higher.’

And when he got there

He found that the air

Was clear and decidedly drier!

“And there were the sheep

In the grass, fast asleep,

With never a notion of hurry!

‘Now why do you stay

Up here all the day,’

Asked Mac, ‘when you know how we worry?’

“ ‘It’s that silly Bo-Peep,’

Said Grandfather Sheep;

‘She always has lost us, you know;

For she wakes up and cries,

And it makes the damp rise,

Till it’s foggy wherever you go!’

“ ‘It’s so lazy to sleep,’

Said Grandmother Sheep,

‘And then never be able to find you!’

‘Now don’t stop to talk!’

Said Mac, ‘but just WALK--

And bring your long tails behind you!’ ”

When Mac woke up next morning, he found the shepherd looking at him. He hoped he was going to be taken out into the fields. But the shepherd said to him:

“You must say ‘good-bye’ to your mother, young man. You’re going a long journey to-day--all the way to London. And I hope you’ll turn out a credit to your family.”

This was a great surprise for Mac.

His mother licked him sorrowfully, for she knew she would never see him again. But she whispered:

“Always obey your master instantly, and try to help him all you can. That’s the way to make people love you. Remember that your father was a Champion, and I am a Champion too. You must never disgrace us.”

Then they put him in a box, with a hole at one end where he could see out. Quite comfortable it was, but decidedly close quarters. He was in the Guard’s van, and very frightened at first. The train made such an awful noise, so different from the quiet of the hills he had left behind. Sometimes he slept, sometimes the Guard talked to him. He didn’t seem to fancy any food, though he drank water, he was so thirsty.

After what seemed to him to be years and years and years in that small box--though it was only about eighteen hours--he found himself in a wonderful place with a lady and gentleman talking kindly to him. He didn’t understand the London language, but they seemed pleased to see him. It was strange, though, to see no straw. There wasn’t a bit on the floor, though it was soft and warm to walk on. But they were very friendly, and gave him milk. And then they sent for the gardener, and said: “You had better take him out for a little run now.”

He was so small that the gardener easily put him in his coat pocket. He took him into the kitchen and said:

“Here’s a little gentleman come to visit you, Cook!”

Cook only said: “For mercy’s sake, don’t bring a dog in here, when you know I can’t abide them. I won’t have him here at any price.”

The gardener let him peep out of his pocket, and then put him down on the floor. He certainly was a very small creature, and not particularly handsome, either, at that time.

He looked up at Cook, wondering whether she was one of the kind sort, or a stranger he ought to bark at. He was feeling dazed with so many new faces around him. Cook was cutting up meat at the table. She glanced down at him, and then said:

“If anyone thinks I’m going to have that miserable white rat rampaging over my kitchen, and getting under my feet, and upsetting my saucepans of boiling water, and stealing off the table--they’re mightily mistook!”

“Oh, have a heart, Cookie,” said the housemaid. “The poor little shrimp isn’t so bad.”

Mac looked at the housemaid. She certainly had a loving voice, though he was so confused with the noise and his long journey that he couldn’t remember whether he ought to drive her through a gate or bark and show his teeth.

“To call him the son of a Champion, indeed!” said Cook contemptuously, and chopping harder than ever at the meat. “I’ll say this much for him--when it comes to downright plainness, that puppy takes the biscuit!”

Mac pricked up his ears. “Biscuit!” He knew that word quite well. They used to say, in his old home: “He can have some soaked biscuit.” Perhaps they were going to give him some now. How lovely! He really was hungry. In his excitement he sat up on his hind legs, and waved his tiny front paws pathetically at Cook.

“Look at the darling,” said the housemaid, “asking you to excuse his being so plain. He’s explaining to you that he can’t help his looks any more than you can help yours.”

“None of your impertinence, Miss,” said Cook. “If you had any sense, you’d know that he’s asking for food. And though I don’t approve of dogs, I’m not one to see a dumb animal--or any other animal--starve!” And cutting up a nice tender bit of meat into small pieces, she gave it to him in a saucer.

How delicious it was! Mac had never tasted roast beef before. Evidently this was a very kind lady; he must certainly try to help her when he got a chance. At any rate, he could say “Thank you” now. And up he jumped, on to her lap, and gave her a little lick with his tiny pink tongue.

Poor little dog! It was the only way he could show that he was grateful!

Finding her lap extremely comfortable, he settled down at once on her apron, gave a sigh of contentment, wagged his absurdly small tail at the others, and then prepared to have a nap, for he was very tired.

You should have seen Cook’s face!

“Well! Of all things! Here’s a nice kettle of fish!” she exclaimed.

“Serves you right, Cook,” said the gardener. “He must be a most forgiving little thing to let bygones be bygones like that! Evidently you are going to be his pet!”

“If you had a little more sense,” said Cook to the gardener, “you’d know that the poor mite is dead tired with his rackety long journey. And although I don’t hold with dogs, excepting in their proper places--which is outside, digging up the flower-beds you ought to be digging, but aren’t!--I’m not one to turn a deaf ear when a mere baby like that asks to be put to bed. Here--just hold him a minute, and see that he doesn’t get on my table while I’m upstairs.”

She returned quickly with a nice soft cushion of her own. And in a few minutes she had rigged up a cosy bed for him in a box turned on its side, and placed in a warm corner of the kitchen.

When he woke up next day, he wondered why he was in such a funny kennel, with no mother and no straw. But he remembered there were some nice people here. So he tried to be useful, and carried off the black-lead brush, when the housemaid wasn’t looking, and ate as much of it as he could manage at one meal, in his box. Of course the black-lead didn’t improve his white coat.

But what pleased him very much was the discovery that if he went through the kitchen door, and along the hall, he came to the room he was in the night before, and found there the kind Gentleman and Lady who had given him milk. And then, if he walked out of that door, and back along the hall, he came to the room where Cook was, and his box. And if he kept on going to and fro, he kept on seeing these nice people. It was so funny the way the hall always led to one room or the other! At least these were the only doors he found open.

It amused him very much to keep on making these little journeys. Each time he appeared, he wagged his tail, and danced up to the persons in the room, as much as to say: “Well, I never did! Fancy seeing you again!”

After a while he discovered another part of the hall he hadn’t noticed before--a queer place that seemed to go up and up and up. He had never seen anything like it in his kennel. He decided he must investigate, in case there were some more kind people up there.

Before very long, however, a sad, sad wail startled everyone. And got louder until it became a big howl. The whole household rushed into the hall to find out what was the matter.

There, on the third step of the stairs, crouched poor little Mac, crying and shivering with fright. He had managed to get his fat little body up so far. Then he became afraid to go any higher. Also he hadn’t any idea how to get down those three steps again, and was evidently terrified lest he should fall down them. You can understand how nervous he was, because in the kennel and barn, where he had spent all his short life so far, he had never seen any stairs.

His master and mistress were out at the time, but Cook took command. “Poor little lamb,” she said, lifting him up tenderly, and carrying him to the kitchen, “of course I disapprove of dogs altogether, but I couldn’t bear to see a tiny mite so frightened. We must make a fuss of him so that he will forget it.”

And he got another saucer with roast beef cut up into little bits.

“We must teach him how to go upstairs,” said his mistress, later.

At first he didn’t want to go near those stairs again. They were dangerous! But she put his front paws on the first step, and holding him gently with her two hands, showed him how to jump on to the second one. Then she put his front paws on the next step, and he had another jump. And so on, step by step. Very soon he tried to do it by himself, and found it worked quite easily. He wasn’t afraid, with his mistress beside him. At last he got so courageous that he gave two or three jumps, and landed at the top of the first flight. And wasn’t he proud of himself!

“Now you must learn how to go down again,” said his mistress. That was a more difficult matter. It wasn’t so pleasant to find his head looking all down those stairs--miles and miles it seemed to be--and his hind legs no one knows where, up in the clouds somewhere behind him!

However, he realized that he must move on downwards, as he couldn’t stay like that. So down he went--at a terrific pace, too.

After a little rest at the bottom, he thought he would like to do it all over again. This time it was much easier, and he got to the top and down again, almost by himself.

He liked this new game. It was great fun; and he proceeded to race up and down, up and down, as fast as he could. Till at last they had to take him away lest he overdid it.

A few weeks later, Mac left London and was taken to the Flower-Patch House, when the family went there for a holiday. How he loved being in the country.

The first morning his master took him out to show him round the place, and introduce him to the cows. He was very fond of his master, and wanted to do something to help him. He remembered that his mother had told him that he must always help his master with the animals, and get them to go through the gates.

Of course! There were the animals; and there was a gate at the top of the field. What could be easier?

It’s true the gate was shut, but Mac wasn’t to blame for that. At any rate he would do his best to get the animals through it, or over it--somehow! anyhow!

And off he started.

“Keep close behind their tails,” his mother had said.

“Certainly! That was quite easy, too.” The cows, after one glance at him, didn’t stop their eating. So it was quite a simple business to slip up behind them. And such lovely long tails they had; they were most inviting. He couldn’t resist the temptation to jump up and give a little nip to the tail of the first cow he came to.

Much surprised, she stopped eating, and turned round to see what sort of a fly had got on her tail this time. All she saw was a small dog scampering off in high glee. She scorned to take notice of such an insignificant creature--and continued her meal.

By this time Mac had discovered that all the cows had beautiful long dangling tails, and he was dancing round giving a nip to each in turn--not enough to hurt them, but distinctly irritating, when they desired to eat their breakfast in peace.

They tried to ignore him in a dignified fashion; but at last it got too much for one highly respectable cow, the Leading Lady of the herd, who had never been accustomed to such goings on, and didn’t intend to put up with them.

Lowering her horns, she suddenly made a dash for young impudence. But he was quicker than she was, and started up the field ahead of her. All the cows now gave chase. Some were much nearer to him than the Leading Lady had been. Then poor Mac realized that he must run for his life--which he did!

He was very glad to find that there was just room for him to squeeze under the gate, and truly thankful that the gate was shut with the cows inside.

“That will larn him!” said the cowman to his master, as they both stood watching the performance.

Later in the day, as Mac lay in front of the fire, going over all the high jinks of the morning, he said to himself: “It seems rather strange, but it was the animals who kept close to my tail, and got me to go through the gate. Now I come to think of it, I don’t believe that was exactly what Mother said.”

As the months went on, however, Mac quickly got to know his business, and how a dog should behave. I confess there were a few accidents occasionally, as, for example, when Cook couldn’t find the £1 note she had left on the table ready to pay the baker. As soon as she discovered that it wasn’t where she had left it, everyone said: “Where’s Mac?”

They found him very happy in his box, chewing away at the bank note! They collected the scraps that were left, and stuck them on a piece of paper. But it was like putting together a jig-saw puzzle, with a lot of the parts missing, because, of course, they couldn’t get back the portions he had swallowed.

When the baker was offered what remained of the note, he shook his head, and said he hadn’t any use for mincemeat at present, as Christmas wasn’t coming for months yet. And if he might give Cook some good advice, he thought she was feeding that puppy on food that was far too rich for one so young. Whereas if she had many £1 notes to spare, he himself could digest them quite easily. They never gave him a pain!

In the end, Mac’s master took what remained of the note to his banker, who thought at first that it was a piece of dog biscuit. But after examining it carefully with a magnifying glass and his best spectacles, he said it would be all right, as the dog had obligingly left the most important bits with the figures on--which was very thoughtful of him.

The master told Cook afterwards that he thought Mac ought to be punished; his dinners were getting too expensive.

But Cook said it was her fault entirely. It was true that she didn’t approve of dogs, and everybody was welcome to hear her say so. But, all the same, the trouble was because of her stupidity in leaving a bank note to be blown off the table with the first puff of wind. Naturally the poor innocent lamb thought he was only doing his blessed little duty by taking care of it for her in his inside pocket, as he hadn’t any other.

Another time some glass and china had come from the Stores. The gardener got his tools and undid the packing case, took off the lid, and then left the crate in the kitchen to be seen to later on.

No one else was in the kitchen at the time.

Mac watched the proceedings with his little head cocked on one side, as it invariably was when he was especially interested in what was going on.

As the lid came off, he espied straw, heaps of straw, stacks of straw! Why it was hundreds of years since he had seen any straw, he said to himself. How lovely it was! And didn’t it remind him of the games they used to have, playing at hide-and-seek in the kennel!

He pulled out a bit and took it under the table. Yes, it had just the same beautiful scent and flavour that he remembered in the past.

“You’d better not drag your fal-lals over the floor, young man, or you’ll get ‘what-for’ if you mess up the place,” the gardener said, as he hurried off to his outside work.

Mac sat and looked at the big case for a moment. Then it occurred to him that perhaps his brothers were inside.

In he jumped. He couldn’t find his relations, but there was a glorious lot of straw. He pulled it about; tossed it over and over, and out of the box; threw out packets containing glass, which got in his way; buried himself among it all; played hide-and-seek by losing his tail in the straw and then finding it again.

Altogether he was having a delightful time, and feeling quite young again, when the housemaid’s voice caused him to peep up above the box in which he was partially hidden. He hadn’t heard her come into the kitchen.

“Hurry up Cook; here’s a pleasant surprise for you.”

Cook appeared.

A great deal--a very great deal--was said.

Henry, the chauffeur, was invited in to have a look at the place, “strewn with straw and smashed glass from end to end,” they said.

The butcher, who called at that moment, inquired if Cook were starting a circus? Because, if so, he’d like a reserved seat ticket for the front row, please, if she was to be the Fairy Queen, and jump through a hoop!

The gardener was fetched from hoeing the potatoes. He called the dog some painfully uncomplimentary names, and offered to give him a good hiding there and then.

But Cook wouldn’t allow this. “As you know,” she said, “I consider all dogs a rare nuisance, and I don’t care who knows my views. But if you’ve got a poor little orphan in the house, who’s lost his father and mother, and is all alone in the world, at least you needn’t grudge him a bit of play. I expect he thought he was helping to unpack.”

By this time they had gathered up the wreckage, and found that nothing was broken but one wine glass; the other things, fortunately, had fallen on straw.

“Well, that’s cheaper than eating bank notes,” Cook went on, “and though I’m not fond of dogs--never was--at least the darling shall have a little bit of play if he wants it. See here, duckie, you can have that case of straw in the scullery, and do what you like there.”

And you should have seen that scullery when he had finished his “do-what-you-like.”

But Cook swept it up quite cheerfully.

After that, he soon grew up. And on one never-to-be-forgotten occasion, he saved his master’s life. But as I’ve told all about that in another book called: “The-Lady-With-The-Crumbs,” I need not repeat it here. He became a Truly Important Person after that brave deed, and all the Little People who lived in the Wind-Flower Wood looked upon him as their chief. Even the saucy squirrel wasn’t cheeky to him any more. Only one enemy remained--the cat! And she hated him and he disliked her, as much as ever.

And now that you know so much about Mac, we will get back to where we left him in Chapter III--racing uphill in answer to his master’s whistle, while Bushey Tail the squirrel, and Bunny the rabbit, each went about his own business.

“Come along, old man,” Mac’s master said to him, as he raced up the Ferny Path, in answer to the whistle. “We’ll take a short stroll around and see how things are getting on, and what has happened since we were here last.”

Mac was delighted, and trotted on ahead, to make sure that no dangerous enemy was waiting to attack his beloved master. All about the hillside they went, through woods; over brooks; across orchards; and around fields. Mac knew quite well that he must walk at the sides of a field when the grass was growing up for hay. But, all the same, he would have loved to nose in the tall grass, because he could smell that there were some new rabbits there, and he badly wanted to have a look at them.

When a pheasant rose from the grass, making a very loud whirring noise with its wings, Mac looked up inquiringly at his master, wishing he would give permission for him to rout around and see if there was another one there.

But his master shook his head. “Not this time. You must keep close to the hedges till the hay is cut.”

So the small dog pattered on, trying not to look at all the Little People he could see, playing about under the buttercups and moon daisies, though his master was too high up in the world to notice them. Sometimes Mac couldn’t help taking a peep at them out of the corner of his eye. He did so want to join in their games.

But then he remembered he was a Truly Important Dog, and his master must be protected. If any bad person should come along, his splendid teeth would soon settle them! So on he went, looking round every little while, to make sure that his master was safe, and each time giving a pleased wag, which was his way of saying: “Aren’t we having a jolly time here. Very different from being in London isn’t it? I do so enjoy having a walk like this with you.”

Presently they got back to the Wind-Flower Wood. This was exactly what Mac wanted. In the first place, he liked all his friends in the Wood to see how Important he was, and that his master couldn’t possibly be allowed to go out alone, without Mac to take care of him.

But also he felt that his master ought to know about the serious things that had happened to the Thrushes’ home. It was quite against the rules for a tree to walk itself off like that, without asking permission! Quite!

He quickly led the way to the vacant place, and stood still, looking at it, and then at his master, when he reached the spot.

“What is it, old chap? Is any friend of yours at home in that burrow?” But he suddenly stopped talking, and like Mac, he stared hard at the empty place.