* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a Fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Canadian Horticulturist, Volume 7, Compendium and Index

Date of first publication: 1884

Author: D. W. (Delos White) Beadle (editor)

Date first posted: Dec. 14, 2018

Date last updated: Dec. 14, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20181221

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David Edwards, David T. Jones, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

CANADIAN

HORTICULTURIST.

PUBLISHED BY

THE FRUIT GROWERS’ ASSOCIATION

OF ONTARIO.

VOLUME VII.

D. W. BEADLE, EDITOR.

ST. CATHARINES, ONTARIO.

The Canadian Horticulturist.

VOLUME VII, COMPENDIUM & INDEX

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

[Added for the reader’s convenience--Transcriber.]

| INDEX |

ATLANTIC

THE

| VOL. VII.] | JANUARY, 1884. | [No. 1. |

With a New Year’s greeting to you, gentle reader, and all the usual compliments of the holiday season, the Canadian Horticulturist presents you with this New Year number a nicely executed colored picture of a new strawberry that is being brought prominently forward. It is the duty of a magazine like this, devoted to the interests of horticultural progress, to keep its patrons fully informed of what is going on in the fruit-growing world, and as far as possible to present the facts with regard to each new fruit or plant that is offered to the public. While recognizing this to be the duty of this monthly, and endeavoring in all fidelity to give you the truth in regard to these new things, it is nevertheless no easy matter satisfactorily to discharge this duty. To say nothing of those who, for the sake of some pecuniary gain, will intentionally magnify the good qualities and conceal the defects of their bantling, there are many, whose opportunities of observation and comparison have been limited, who think that they have something wonderfully nice, merely because they do not know that there are already in cultivation fruits of the same season far superior in every respect. These at once raise a shout of ecstasy over their new-found treasure. Again, it is so natural for most of us to think highly of that which is our own, to regard our own geese with such a partial eye that to us they have become changed into swans, so having in this way convinced ourselves, we try to impart to others the same high opinion that we ourselves entertain. Besides this, there remains yet this other fact, that soil and climate and cultivation do so modify results, that changes in these respects frequently bring about most unexpected consequences.

However, to the best of our ability, the Canadian Horticulturist will endeavor to give you the fullest information possible, both for and against, so that you may be able to form your own opinions intelligently. It requires time to test fully the qualities and value of new fruits, so that by the time their real value has been ascertained the charm of novelty is gone, and public attention is directed to recent comers. It is well to hold firmly to tried friendships, and by no means discard the old until the new has been well tested. True, novelty has its attractions, and it is well that it has. To this we owe much of our enjoyment, and much of our progress, and likewise many disappointments. Could we prevent the introduction and dissemination of new things until their superiority in some essential particular over varieties already in cultivation has been fully established, much of the disappointment now experienced would be avoided. No means of doing this has yet been devised. Hence, there is nothing left us but to seek the fullest and most impartial information within reach, and select from the numerous novelties, that seem to be showered upon us thicker and faster than snow flakes in the winter’s storm, those that we think most worthy of attention.

The Atlantic strawberry, of which our colored frontispiece is said to be an excellent illustration, is brought forward as having especial claims on the attention of the grower for market. These claims are based upon the alleged superior firmness of the berry which enables it to travel long distances without injury; upon its beauty, which is said to be such as to make it tempting to purchasers; upon its productiveness, and its late season of ripening, coming after the great rush of strawberries is over, and therefore commanding better prices. It is said to have perfect blossoms, which should mean that the stamens are fully developed so that sufficient pollen is produced to perfectly fertilize the seed germs, thereby insuring full development of the fruit. It is also said in its behalf that the fruit does not deteriorate as rapidly after being picked as that of most varieties, but that the keeping qualities are something remarkable. Having had its origin, like the Manchester, in a soil of sea sand, it is thought it will thrive well in sandy soil. It is not claimed for it that the flavor is of a high grade, hence those who are seeking for exquisite quality have no need to plant it. Purchasers of fruit in our markets are influenced more by appearance than quality.

The writer has not yet seen the fruit of this new strawberry. He has not even been able to arrive at a very definite opinion concerning the Bidwell, Manchester, James Vick, Old Iron Clad, Big Bob, and the like, which were new a few weeks ago, the fruit of which he has seen. The experience of you who have tried any of these in this Ontario will be gladly published in the Canadian Horticulturist as a valuable contribution to our knowledge, and a help in forming a just estimate of their respective values. If our readers would contribute freely of the results of their trials, whether favorable or unfavorable, they would confer a favor upon each other and help to settle definitely the value of new fruits for cultivation in this Province.

—————

Holds its next annual meeting in Kansas City, beginning on Tuesday, the 22nd January, and continuing until the 30th. There will be a voluntary exhibition of fruits and other horticultural products. The railways from Chicago to Kansas City will return those who paid full fare going, at one cent per mile for the return trip. Valuable papers are announced upon various horticultural subjects by some of the leading men in the science and practice of horticulture of our time. Members pay an annual fee of two dollars, and receive a copy of the transactions by mail without further expense.

—————

Water-Lily

(Nymphea odorata).

We desire to call the attention of our readers to the fact that this beautiful, sweet-scented flower, which is to be found in so many of our ponds and sluggish streams, can be very easily grown in a tub or half barrel. It is only necessary to have a water-tight tub, place a little rich soil from the bottom of any shallow pond or ditch in it, say to the depth of a foot or fifteen inches, in this set a plant of the water-lily, and then fill the tub to the brim with soft water. For convenience the tub may be set in the ground with the top just about even with the surface. It will only be necessary to add a little water occasionally to supply the waste by evaporation. There is a variety of this lily that is tinged with red. If not convenient to obtain plants from the ponds, they can be procured through any of our seedsmen or nurserymen.

If we can not ornament our grounds with the showy Victoria Regia, we can plant our own native species, which belongs to the same order, and in its leaf structure bears a miniature resemblance to its majestic South American relative.

Indeed we are quite too prone to think that beautiful things must come from some far-off land, and that plants which can be found growing in our own woodlands, or lakes, or streams can not be worthy of attention. There are very few things more beautiful or more deliciously scented than our native white water-lily.

—————

An association of the fruit-growers of Renfrew County has been formed for the purpose of collecting the information on the subject of fruit-growing that lies scattered about in the experience of those who have been experimenting in fruit-growing in different parts of the county. It is expected that when these persons meet together they will be able to prepare a list of the varieties of fruit suitable for cultivation in that county which will be reliable. It is intended that this association shall be affiliated with the Ontario Fruit Growers’ Association, who will publish in their Annual Report the proceedings of the Renfrew County society. To this end they have made the membership fee to the Renfrew Association twenty-five cents per annum, and to both the Renfrew and Ontario Associations one dollar and twenty cents per annum. Those who pay the latter sum will be entitled to full privileges of membership in the Ontario Association, and receive the Annual Report, the monthly Canadian Horticulturist and their choice of the four premiums.

This example is worthy of imitation by the fruit-growers and horticulturists of every county. There is in each county such difference in soil, in amount of rain fall, in degrees of summer heat and winter’s cold from every other county that the experience of those residing within the county can alone be a sure guide in horticultural matters. The Ontario Association would willingly publish the proceedings of each county association whose members were subscribers to its publications, and thus preserve and disseminate the information derived from the county meetings in the best possible manner.

—————

Professor Budd states that when in Russia he saw in the Provinces of Orel and Voronesh, bushy, low trees of the Morus tartarica, perhaps twenty feet high and eight inches in diameter, and in the Botanic garden at Kiev he found old specimens not over twenty-five feet high and not to exceed one foot in diameter. That if the Nebraska men have found a mulberry growing “fifty feet high, and from three to five feet in diameter,” they have found something wholly unknown to the Russian foresters, or to the Botanic gardens of Northern Europe.

He says it is in truth a rapid growing small tree that bears bountiful crops of fruit, which he advises may be planted on account of its hardiness for ornament, or as a windbreak, or for fruit, but not for timber.

—————

During the past summer we received a few specimens of a new gooseberry from Stone & Wellington, of Toronto. The fruit received was of good size, oblong in form, and of a golden yellow color, and of good flavor. In a letter received from them they state that the original plant was found in the State of New York, growing wild in a decayed hickory stump, by a person who was hunting. Being pleased with the appearance of the fruit he took the trouble to return at the proper season and take up the plant. He removed it successfully, and it has been in bearing ever since.

Messrs. Stone & Wellington have now fruited this gooseberry for four years and find that it is perfectly hardy, never having shewn any sign of mildew, and each year bearing immense crops. They describe it as a remarkably strong, vigorous, upright grower, with dark green glaucous leaves which resist mildew perfectly, and remain on the plant until the end of the season; while good samples of the fruit measure an inch and three-quarters in length.

The accompanying cut, which will give a more perfect idea of its appearance than any verbal description, has been kindly furnished by Messrs. Stone & Wellington, who have given to this new berry the name of Large Golden Prolific.

LARGE GOLDEN PROLIFIC.

—————

The morning session of the fourth and last day was opened at ten o’clock. The invitation given by the Louisville and Nashville railway, to make an excursion as the guests of the railway to Mobile, was accepted by about one hundred of the members, and Tuesday, 27th February, was designated as the day for the excursion. After reports from several of the committees, Capt. E. Hollister, of Illinois, read a paper on markets and marketing. His advice was to study the peculiarities of the particular market as to the kinds that were popular in it, and the style of package most acceptable, then send only such fruit as you would put upon your own table, dividing it into two grades, the best, and that of fair size and quality. That which is below this should not be sent to market. Mark each package so that consignee may at once see the grade of fruit it contains. For berries he advises the use of the square quart box, for peaches and tomatoes, the one-third of a bushel box. The remainder of the session was taken up with discussions on this subject, but nothing different of importance was elicited. In the afternoon, a paper was read by Mrs. H. M. Lewis, of Wisconsin, on “Birds in horticulture.” The first point made in her paper was that natural history should be taught in our schools, so that the children might at least know the correct name and the family to which each common bird belonged. The blue-bird, robin, blackbird, song sparrow, oriole, bobolink, &c., were kindly mentioned, but the English sparrow was evidently not a favorite with the lady, nor the butcherbird, nor bluejay. The next paper was by Mrs. D. Huntley, also of Wisconsin on “Adorning rural homes,” full of excellent suggestions and valuable thoughts. “It matters little,” she said, “whether the dwelling be a mansion or a cottage; it is the taste displayed in the adornment of the grounds, the planting of trees, the care of the lawn, which indicate the culture and refinement of the owner.” And again, “the educating influence of pleasant surroundings upon the minds of the young cannot be over-estimated.” What shall be said of very many, yea of most of our Canadian rural homes, if these expressions are correct? What is their educational effect upon the children brought up in them, and may we not find just here the reason why so many farmers’ sons and daughters are disgusted with life on the farm? And if she truly remarked, that “the outward surroundings of the homes of any people are the truest indications of the prosperity of the country and the intelligence of its inhabitants,” what shall we say of ourselves when measured by this standard? How many of our rural homes have no lawn at all, hardly a tree about the house, the way to the front door through the barn yard, and if there be any garden at all, not a fruit or flower in it, but plenty of tall weeds growing in unsightly tangle. What are the attractions to the children of such a home? What must be the intelligence of the people who live in such homes? And shall such be the homes of our beautiful land? We answer in the words of this lady’s paper, “hundreds of new homes are constantly springing up all over our land, and it is a question for the owner to decide whether these shall be all bleak, and bare, and desolate, with nothing to shelter or shade them, or shall they be adorned with the beauties of nature till they become ornaments to the landscape, a second Eden wherein to dwell.” Yes, the owners must decide it, and gentle reader, countryman, Canadians, what shall your home be?

It would be difficult to express the pleasure with which we listened to this paper, so sensible, so earnest, and so full of hints for making home beautiful, which any one who has any love of nature in his soul can put into practice.

Mr. W. H. Ragan followed with a short paper on the insect enemies of the orchard, in which he showed that they could be mastered if orchardists, large and small, would act in concert with the object of winning the day in view, otherwise he feared they would never be overcome. The discussion elicited by this paper was to the effect that orchardists can secure good crops of fruit despite the negligence of the careless by keeping up a constant and vigilant war upon the injurious insects of every kind.

The evening session was opened with the reading of a paper on raspberry management and the new raspberries, by Mr. J. C. Evans, of Missouri, in which he stated that land having a gentle inclination in any direction, except south or south-west, and that would produce a good crop of corn, was suitable for raspberry culture. He would plant in rows seven feet apart, and three feet apart in the row, and devote the ground solely to raspberries, doubting the economy of planting any other crop between the rows at any time. On the new varieties he did not throw much light, merely stating that some were planting Hopkins and Gregg as the more profitable black-caps, and that Turner and Thwack were the popular red raspberries. Mr. D. B. Wier, of Arkansas, read a paper on the persimmon in his state, but the conditions are so unlike those of our climate that we took no notes of it, nor of the paper by Mr. W. M. Samuels, of Kentucky, on the new apples of value for market, which treated almost exclusively of southern varieties. Mr. T. T. Lyon, of Michigan, submitted the report of the committee on fruits exhibited, stating that there were 145 plates of apples exhibited by the Missouri Valley Horticultural Society, and sixty varieties of apples and three of pears exhibited by Mr. Geo. P. Peffer, of Wisconsin. Of the Salome apple, which has been attracting considerable notice of late, the report says that it is a fine looking, medium sized fruit, in perfect condition, and of fair sprightly flavor, fine grained, juicy and agreeable; said to be in good eating condition from autumn until late spring with only ordinary care, and expresses the opinion that if valuable, it will probably be so on account of some quality of the tree or fruit that peculiarly fits it for the climate of Illinois.

Thus was closed the sessions of the Mississippi Valley Horticultural Society. Many papers of great value were not read at the meeting for want of time, but they are all published in the Volume of Transactions, which may be had for the sum of one dollar on application to Mr. W. H. Ragan, Secretary, Lafayette, Indiana.

—————

In the cold parts of the province it is the safer way to lay the grape vines down at the approach of winter in order to secure crops of fruit. By laying the vines down the evaporation is lessened, and when the snow falls they are covered by it, and thus protected until it is melted. It is the frosty drying winter winds sweeping through the vine branches if left on the trellis that injure the buds, seemingly lowering the vital force so that they push feebly, if at all, on the return of warm weather. The writer has seen vines through which the sap ran freely, unable to burst a bud; the buds were killed, though the wood was seemingly uninjured. It is usually better merely to throw the vine upon the ground and trust to the snow for a covering, than to place strawy manure in which mice may harbor upon them, or to cover them with much earth, which in wet weather will rot the buds.

—————

The World’s Industrial Exposition is to be held in New Orleans, commencing on Monday, December 1st, 1884, and continuing for six months. It is intended that in many important features this Exposition shall surpass any that has ever been held. The Main Building is now being erected; it will cover thirty-two acres of ground, giving far more exhibition space than any that has ever been built. The Art building, the Agricultural and Horticultural buildings, and other structures for special purposes, will be on the same liberal scale.

The winter season being the one of greatest leisure to those who till the ground, it is anticipated that this exhibition will be more generally visited by agricultural and horticultural people than any previous one. There is also the great charm to those whose homes are in the north of leaving the frost, and the snow and the biting winter blasts, and spending a few weeks among the roses, and yuccas, and orange blossoms of the south. The city, where the exhibition is to be held, is itself full of attractions to a stranger. There is a novelty even in the ways of the people that makes a visit always interesting to a northerner.

In view of all these considerations, the Board of Managers intend to give more attention to the great interest of Pomology than has ever been done before, and to carry out this intention has decided to have an International Show of fruits, a thing never before attempted. That this department of the exhibition may be made a great success, the management of it has been entrusted to the Mississippi Valley Horticultural Society, whose President, Mr. Parker Earle, is not only an able and enthusiastic pomologist, but also a gentleman of great executive ability, under whose directions the pomological department cannot fail to be most thoroughly equipped.

A building is to be erected specially for the display of plants and fruits, to be about six hundred feet long by one hundred wide, located in grounds handsomely laid out and embellished. The premiums for fruits in medals and money will aggregate from twelve to fifteen thousand dollars. Exhibits in fruits are expected from every State and Territory of the United States, from the British Provinces, Mexico, and the leading nations of the world. The Citrus fruits of the Gulf States, California, the Mediterranean, South America, India and the Islands of the Sea will form a display unparalleled in the history of the fruit exhibitions of the world. The fruit exhibit will be kept up during the whole time of the Exposition, shewing the fruits in their season, and many, by the help of cold storage, far beyond their season. The New Orleans Refrigeration Company has placed the most ample facilities for cold storage to be found on the continent at the command of the management.

It is matter for congratulation that the projectors of this Industrial Exhibition have been able to appreciate the importance of the great fruit interests of the world, and to form some adequate conception of the commercial value of fruit. In thus providing liberally for a display of the world’s fruit productions, as an important and attractive feature of their exposition, they have but assigned to fruit culture its true position among human industries. Doubtless their wisdom in this respect will also be seen in the magnificent display that will be made, and in the throng of interested spectators that will crowd the building devoted to these products.

The great railway lines leading to New Orleans, we are informed, have already made concessions in rates which are without parallel for cheapness. We are not yet informed what arrangements, if any, have been made for the accommodation of the vast throng of visitors that will crowd the city to its utmost capacity. The premium lists will shortly be issued, meanwhile those wishing to obtain fuller information will please apply to Mr. Parker Earle, Cobden, Illinois, U. S. A.

We shall endeavour to keep the Fruit Growers of Canada fully informed of everything of interest to them relating to this great exhibition of the fruits of the world, and feel confident that they will not let pass unimproved this grand opportunity of making the world acquainted with our truly splendid winter fruits, that for high flavor and long keeping are unexcelled.

—————

We are much pleased to notice that Mr. W. E. Smallfield, of the Renfrew Mercury, has offered a prize of FIVE DOLLARS to be awarded to the school making the best display of flowers at the annual exhibition of the South Renfrew Agricultural Society in 1884. He has also made arrangements through Mr. James Vick, seedsman, of Rochester, N. Y., to supply the five schools in that county which first apply, with twelve packages of flower seeds to each, FREE OF COST, the application to be made by the trustees or teachers. Mr. Vick himself offers as a SECOND PRIZE a beautiful floral chromo on cloth and stretcher ready for framing, worth a dollar and a half.

This has been done by Mr. Smallfield in order to stimulate a taste for the improvement and adornment of school grounds, of which in truth there is great need. Many, yes, so far as the writer’s observation extends, most of our school grounds in both town and country are a disgrace to our Canadian civilization. A barren, treeless waste, designates too many of our school sites, in some part of which stand a bare looking school house and, conspicuously planted in the rear, a couple of sentrybox outhouses, having about them a scanty growth of grass but luxuriant growth of weeds.

These prizes have not been offered by Mr. Smallfield as in any sense to be regarded as compensation for the labor of cultivation, but simply to draw public attention to that which in itself is recreation to the scholars, while at the same time it is refining in its tendency upon the school, and calls into exercise, if not into being, a taste for rural adornment that will be seen sooner or later about the homes of our people.

Can not this example be repeated in every county in our land? Are there not other gentlemen who sufficiently appreciate the value of a refined taste among our people, and the influence which the cultivation by the scholars of beds of flowers in their school ground must have for good upon the school itself, to offer like prizes in every county in Ontario? Surely an arrangement could be made with any of our Canadian seedsmen to supply the needed seeds for a beginning without cost to the schools.

But we must not stop even here. In some way we must offer in each county prizes for the best laid out and most appropriately planted school ground, and which is also most tastefully adorned with beds of flowers, and kept in the best order. The prize to be awarded by a committee who shall visit each school ground in the county not less than three times during the growing season, which times are not to be known beforehand by the schools. Would not the offering of such prizes, and the appointment of such visiting committee be an appropriate work for the Fruit Growers’ Association of Ontario, seeing that it now embraces tree planting and flower-gardening within the scope of its objects? We commend the subject to the consideration of the association at its next meeting on the thirtieth of the present month.

—————

This variety is taking a prominent position as a hardy tree and a desirable winter apple in Iowa. Mr. John Platt, of northern Iowa, writes to the Secretary of the Iowa Horticultural Society, that ten years ago in passing the orchard of a neighbor, he was surprised at the healthy condition of a number of the trees, which, on inquiry, proved to be Walbridge. They had then withstood the cold withering blasts, for which that part of Iowa is noted, for more than a quarter of a century, and shewed no sign of decay. On the contrary they were loaded with fruit almost to breaking, forming a striking contrast as compared with most of the original orchard which, save an occasional Haas, Golden Russet or Snow Apple, was either dead or dying. And now ten years later, the same old trees of the Walbridge are still standing, laden with a bountiful crop of apples, standing “as guiding posts to the solution of the problem of the successful cultivation of a hardy, good-keeping winter apple, adapted to the bleak climate of northern Iowa.”

With such a record in a climate so trying, surely this variety may be planted in Muskoka or Haliburton, or the Valley of the Ottawa, or in the Province of Quebec with every prospect of success. It is also known by the name of Edgar Red Streak, having originated in Edgar County, Illinois. The fruit is of medium size, of a pale light yellow color shaded with pale red in the sun, and striped and splashed with bright red over most of the exposed surface. The flesh is white, fine grained, juicy, with a mild sub-acid flavor. In use from January to May. The quality is not considered equal to that of Esopus Spitzenburg or Grime’s Golden Pippin, but the hardiness and productiveness of the tree and the late keeping character of the fruit make it valuable for a cold climate.

—————

Robert Douglas, of Illinois, states that in order to establish the fact that the very poorest lands can be profitably planted to certain kinds of forest trees, he purchased several hundred acres of sand ridges and blowing sands on the western shore of Lake Michigan. He succeeded with Scotch and Austrian pines on blowing sands, and with white pines and European larches on sand ridges sparsely covered with Bearberry, Potentilla and Trailing Juniper. These trees occupied about two years in extending their lower branches to cover the sand, and then threw up leaders almost as rapidly as if growing on good land. This experiment was not made by planting a few of the different kinds of trees on a few acres, but by hundreds of thousands of trees on three to four hundred acres.

The Russian foresters cut down their timber trees just after the spring growth is completed, and before the bark has tightened too much for peeling; they then strip off the bark, but allow the upper branches with their leaves to remain. These leaves will evaporate a large portion of the sap in the trunk of the tree before they dry up, and the bark being taken off, the trunk seasons rapidly, and makes more valuable timber for any purpose than that which has been cut in winter. Willow and oak bark taken from the trees in this way is valuable for tanning and has a market value. It is the willow bark that is used in the tanning of the soft leather for which Russia is so famous. The apple growers of central Russia pack their apples in boxes made of the bark of trees. As soon as the bark is taken from the tree it is flattened by pressure until dry. The boxes contain about three bushels of apples and the covers are fastened on with cords tied around the box both ways. Hundreds of thousands of these bark boxes are used every year. This we glean from the Report of the Iowa Horticultural Society for 1882.

R. Douglas, the great arboriculturist of Illinois, writes to Professor Budd of Iowa, that this is one of the most profitable trees for forest culture; that it is a rapid grower, easy to transplant, healthy, and fit for the purposes of the cabinet maker when thirty years planted, while the black walnut requires fully double that time before the wood is suitable for such purposes. The tree grows well even on poor gravelly land, and can be planted where the black walnut and many other trees would not thrive. As to its being a breeding place for the tent caterpillar, it is only where the trees stand singly or very sparsely scattered that the caterpillar seems to be troublesome; growing in groves they do not suffer specially from this insect. If there be only half a dozen Austrian Pines in a township the sapsuckers will make sad havoc on them, but if there be thousands of the trees the work of the sapsucker will not be conspicuous. And so with the cherry tree, when grown in quantity the injury sustained from the depredations of insects will not be greater than might be inflicted by them on a like number of trees of the black walnut. The writer has seen fine trees of this cherry growing in the vicinity of Guelph, so that it will doubtless thrive over a large part of this Province. The wood is very valuable and much employed in cabinet work. The seed should be mixed with moist sand as soon as gathered and never allowed to become dry, for if once thoroughly dried it is very difficult if not quite impossible to make the seed germinate. It may be sown, if convenient to do so, as soon as gathered, thinly in drills, and transplanted into nursery rows when one year old, where they should be cultivated and kept free from weeds until of sufficient size to be set in permanent plantation.

The benefit derived from having my small fruit patch surrounded by evergreens has surprised me very much. It has at least doubled the amount of fruit and quality of plants over what it was when not thus protected. Evergreens do not rob and poison the ground like deciduous trees. All kinds of small fruit that I have experimented with do well in their immediate vicinity, which is not the case with deciduous trees. I have a row of Snyder blackberry planted on the north side of a red cedar hedge, running east and west; the way they thrive is a wonder to the neighborhood. The blackberry row is four feet from the hedge. I wish it were about six; it is now too close to allow room for picking.—C. H. Gardner, in Iowa Horticultural Report.

The annual meeting of the Province of Quebec Forestry Association was held in Forestry Hall, St. James street, Montreal. The President, Hon. H. G. Joly, M.P.P., occupied the chair, and after the usual routine business, addressed the meeting as follows:—

Gentlemen,—This Association was founded in October of last year. We have had no meeting since then, as it would have been difficult to collect our members, scattered as they are all over the province, but when we parted, we all knew what each one of us had to do, and we can show some work.

The first year of our existence has been a good year for us and one of unexpected success, but has been darkened by the loss of a dear and valued friend, our Honorary President, Mr. James Little. He died full of years, knowing that the seed sown by his hand so many years ago, in what appeared a hard and ungrateful soil, had sprung up at last and bid fair to ripen and bear fruit bountifully, seeing that his warnings had awakened the country at last and that the danger of total destruction to our forests, first pointed out by him, had been admitted by the thinking men of this continent.

I will now briefly sum up the work of the year, merely reminding you beforehand, that our association has no funds or next to it, and that it relies on the personal exertions of its members for doing the work that the association had in view, planting trees, as each member undertakes to plant or sow twenty-five forest trees every year.

We have been well supported by the Hon. W. W. Lynch, the Commissioner of Crown Lands; he has thrown himself, heart and soul, into the work, and we are deeply indebted to him, not only for the success of our first “Arbor Day,” but for the introduction, in our Legislature, of laws which have for their object the carrying out of the views expressed by the American Forestry Congress and by us, for the protection of forests against fire and waste, and for the classification of public lands in such a manner that settlement should be encouraged on the lands best fitted for agriculture, and that lands only fit for the growth of timber, and especially pine, should be reserved for that purpose, as long as it does not interfere with the colonization of the country.

Our first “Arbor Day” has been an unexpected success, not only in the large cities, like Montreal and Quebec, but especially in many of the country parishes, where it was much wanted, and where the clergy were most zealous in encouraging the people, in many cases setting the example by planting trees with their own hands.

The Council of Public Instruction are equally entitled to our gratitude for the way in which they have encouraged the observation of “Arbor Day” in all educational establishments under their control.

It will be a satisfaction for you to know that the news of the first “Arbor Day” in the Province of Quebec has reached such distant countries as Algeria, and that the example set by us is likely to be followed there.

In the absence of reports from all the different localities, it is impossible for me to say how many forest trees have been sown or planted in the province by the members of our association and by the people at large, on Arbor Day. I hope we shall be able to devise means for securing all those reports for another year, and for publishing a summary of them, if not the whole.

In the meantime I can take upon myself to state that many thousands of forest trees have been planted or sown since our meeting last autumn. There is one tree, however, upon which I can speak with a good deal of certainty; it is the ash-leaved maple (acer negundo, or box elder or érable à giguères). During the last twelve or thirteen months from four to five hundred thousand seeds of that tree must have been sown in the Province of Quebec. I come to that conclusion from the number of pounds of seed that have been sold during that time, as reported to me by those who most largely deal in that article.

The extraordinary rapidity of growth of the ash-leaved maple, the shortness of the time required before it can produce sugar (and thereby replace the old sugar orchards of the past) have acted as a wonderful stimulant on the minds of our people and done more for forestry than anything else could have done. In growing that tree people will learn how easy it is to grow forest trees; they will naturally take to the cultivation of more valuable trees, such as black walnut, butternut, elm, oak, ash, pine, spruce, tamarack, &c., according to the nature of the soil and other circumstances.

I think we can look, if not with pride, at least without shame, on the results of our first year’s work; we have certainly got something to show for our money, twelve dollars—total receipts up to date.

You have doubtless heard that it is proposed to hold next year, an International Forestry Exhibition at Edinburgh. I hope you will take this important matter into consideration, as it is one in which we, as a Forestry Association, and the whole Dominion, are deeply interested.

Mr. J. C. Chapais announced that he had brought out a book on forestry entitled “Illustrated Guide to Canadian Tree Culture,” which he hoped would be of benefit to the cause, and especially in the education of the young.

Mr. Wm. Little said that he had received a copy of the work, which was a very valuable one.

Mr. J. X. Perrault referred to the great importance of education in the matter of forestry, and expressed the hope that the association would encourage the distribution of forestry literature throughout the Province. He would like to know, from the Minister of Crown Lands, if his department intended taking any steps to assure a proper distribution of forests into districts, so that the cutting of the forests should be done systematically, and that when one portion was cut the lumbermen should not return to that district for say twenty years, when it would be restored. This was the system followed in Europe and he thought steps should be taken to procure the same here.

THE COMMISSIONER OF CROWN LANDS, Hon. Mr. Lynch, in reply, said that the progress that had been made in forestry matters since last year must prove a source of the greatest encouragement and satisfaction to the members of the society, and especially to the president, Hon. Mr. Joly, who had gone to much trouble. He did not think that persons generally realized the difficulties that attended the foundation of this society and the establishment of what was known as “Arbor Day.” When the idea of having such a day was inaugurated he himself had thought there was very little in it, that it was more of an idea that would never become a reality. Practical experience had, however, shown him that it was a reality which could not fail to be the source of much future good to the country. There had been not a few difficulties attending the inauguration of such a day, but he was glad to be able to say that from one end of the Province to the other a beginning had been made, and not only in the large cities and districts, but also in the smaller hamlets and villages, had the day been celebrated with much success. This, he was pleased to notice, was one of the results of that combined, associated effort that had led to the foundation of this Association, and to the adoption of legislation regarding the protection and separation of our timber and colonization lands. He firmly believed that the latter was one of those pieces of legislation that would be of great good to the country. The object of the legislation in question was in the direction to which Mr. Perrault had referred. He had only occupied, he might say, the position of Minister of Crown Lands for a few months, but in this short period he had learnt that it was a most responsible position and upon it depended very greatly the future prosperity of this province. He thought that they should protect their natural resources; about all that they had now was their forests, and they were a legacy handed down to us to preserve, not to destroy. He might add that there was no legislation of the nature spoken of by Mr. Perrault, and he did not know that he was in a position to bring such legislation before the approaching session of the Legislature, for the reason that it covered the whole ground and had to be most carefully considered. The aim of the Association, he thought, should be to encourage whatever Government was in power to preserve and protect their forests, and he was in hopes that before long the Association would depute one of its members to co-operate with the Minister of Crown Lands, and in this way such legislation might be effected as would assure the object spoken of by Mr. Perrault. He referred to the great need there was for education on this subject, as there existed, to a great extent, in the minds of the masses, an idea that this movement was one of no practical effect, and this idea would have to be dispelled. It had been said that conflict might arise between the Government and the lumbermen. He, however, believed that the great majority of the lumbermen would aid them, as it was to their interest to do so. The importance of the subject was great—so great, in fact, that when the meeting adjourned it would do so with the understanding that the members should meet again at an early date to discuss the question. Legislation was imperatively needed. He would like to see it well and carefully considered, but he would also wish to see it passed as speedily as possible. The future prosperity of the Province depended largely, he was convinced, upon the action they took now, and there should be no delay in the matter.

Mr. Wm. Little moved, seconded by Mr. G. L. Marler,

That a committee be appointed to memorialize His Excellency the Governor-General on the subjects of the forests of the country, with a view of having a Parliamentary enquiry made into their condition, especially with reference to the white pine, respecting which it is said there is now a growing scarcity of the merchantable or first quality pine, a description of wood on which the prosperity of the country has greatly depended. That the chairman be requested to name the committee, who shall be authorized to make what representations, enquiries or suggestions to them may seem requisite in the premises.

The motion was carried.

On motion of the Chairman it was resolved:—That in view of the proposed International Exhibition, to be held in Edinburgh in 1884, respecting which full particulars have been received by this association from the executive committee of this exhibition, and the success thereof fully assured, this association would respectfully urge upon the Government of Canada the great importance of having the Dominion represented at this International Forestry Exhibition by as full and complete an exhibit as possible of our Canadian woods, forest products, and the articles referred to in the circulars of the exhibition committee, and would further urge that such assistance be given to all contributors from Canada, having articles of merit to exhibit who desire to compete for prizes, as to enable them to do so.

Considering how much the forests and the industries connected therewith have contributed to the prosperity of the country, it is to be hoped that such action may be taken by the Government as will make the Canadian exhibit worthy of the prominent position Canada occupies as a producer of forest products.

—————

To the Editor of the Canadian Horticulturist.

I see in the November number of your valuable paper a copied article on the Niagara grape, which you say you copy for the benefit of your readers, and to contribute your mite towards keeping the grape before the public, and I also have decided to give my experience of the Niagara grape through the Horticulturist as often as I think it will be of any service to the growers of vineyards. I should take it, that the writer of the Wine and Fruit Grower had only seen the grape for once, and based his opinion on that exhibition alone, which would hardly be a fair test. As I have had some experience in grape culture for the last fifteen years, I may venture to give my opinion of the Niagara. I visited the vineyards of the Niagara Grape Co., at Lockport, N. Y., in the fall of 1882, and saw three acres of this grape in bearing, and from its extra productiveness, healthy foliage, and apparent good qualities, I decided at once to plant 700 of the vines, and did so last spring. Although I was disappointed when I got them, they being so small, yet I was determined to give them a fair trial, and I must say that I have never seen vines make a more vigorous growth. I again visited the Niagara vineyards in the fall of 1883, which is well known to have been a very poor year for grapes, and I again found an abundant crop of grapes well ripened and of fine quality. Desiring to test their shipping qualities, I procured some and sent them to Winnipeg, and they were received there in perfect order. So firmly am I impressed with the market value of this grape as a keeper and shipper, that I have given my order for 1,000 more vines to plant next spring, and I have no fears of getting left either.

If the Niagara grape proves to be a failure, I think the sooner that people know it the better; but if it proves to be a profitable grape for our country, give it its just due. As a wine grape I do not profess to be a judge, but I do think it would only be fair to give it a thorough test as a wine grape, and then give the results to the people, and do away with any question or doubt as to whether the wine made was the production of the Niagara or not.

Aaron Cole.

St. Catharines, Ont.

—————

Note by the Editor.—The experience of cultivators is just what we desire to have sent for publication. It is worth more as a guide to others than any mere opinion not based upon experience possibly can be. And that not only in regard to one fruit, but with regard to everything. Our Canadian cultivators are especially requested to send the results of their experience for publication in the Canadian Horticulturist.

—————

To the Editor of this Canadian Horticulturist.

Dear Sir,—In the June number of your paper I saw an enquiry from Mr. Geo. Strauchan, for a good, efficient orchard force pump, for spraying poisonous liquids on fruit trees for the purpose of destroying the aphis, codlin moth, canker worm, and other insects so fatal to our fruit. Last year I used one of Field’s orchard force pumps, manufactured in this city. I used one-fourth pound of London purple in forty gallons of water; kept it well mixed by pumping through the hose back into the cask; threw it above the tree allowing it to fall back in a spray. I had nicer fruit than I ever had before from this orchard; in fact, my pears were entirely free from worms, while my neighbor’s were wormy and most of their fruit dropped off. I can recommend Field’s pumps for this purpose, and I believe it absolutely necessary to spray trees with poisons to counteract the ravages of these fruit pests.

Yours truly,

H. S. Chapman.

Lockport, Dec. 15, 1883.

—————

To the Editor of the Canadian Horticulturist.

Dear Sir,—When it was decided at our last winter meeting that the English sparrow is an evil-doer and as such should be banished from our shores, I remember friend Gott, of Arkona, pleaded earnestly to spare the little emigrant. Mr. Brooks, of Milton, in an able letter in your March number, did the same. I came across a third advocate in a Scotch piece, so Scotch I doubt if our Editor can understand it, but so beautiful I would have him give it for the benefit of his Scotch readers of whom among these three thousand there are doubtless many. It is from the pen of a Montrealer.

Yours truly,

John Croil.

THE SPARROW.

When the cauld wind blaws snell wi’ snow and wi’ sleet,

An’ the immigrant sparrows hae naething to eat,

Open your winnocks, an’ throw out your crumbs,

An’ they’ll chirp their blythe thanks round your cozie auld lums.

Come here, bonnie birdie, I’ll do ye nae harm.

Your chirpin’ to me has sic a hame charm;

Whar cam ye frae, and whar hae ye been?

Ken ye “auld Reekie,” or ken ye “the Dean?”

Aiblins ye’ve chirp’t on my dear mother’s grave,

So for you, puir wee birdie, my moolins I’ll save,

Gin you come every day, your gebbie I’ll fill,

An’ I’ll shelter ye weel frae the frost an’ the chill.

But tho’ I show pity, I maun tell ye the truth,

I ne’er lo’ed ye, birdie, in the days of my youth;

Na, na, your bold deeds brought the tears frae my ’ee,

For ye killed puir Cock Robin “as he sat on a tree.”

Yet I’ll no let ye starve, tho’ a bird o’ ill name,

Tho’ may be ’twar better ye had bidden at hame,

It’s weel kent ye hae cam o’ a murderous race,

An’ I never could see ony guid in your face.

But gif ye tak tent, an’ earn a guid name,

We’ll let byganes be byganes, we’re baith far frae hame;

Ah! ye care na for counsel, I see at a whup,

As ye chirp i’ my face, dight ye’r neb, an’ flee up.

Gae wa’ ye prood birdie, sin advice ye’ll hae nane,

All birdies like you are safest at hame,

Ye thrawart auld carlin! what maks ye sae prood,

I’ll get twa for a farthing, the best o’ your brood.

Oh, come back, puir wee birdie, an’ peck up your fill,

An’ mak a guid breakfast, on my window sill;

I forgot when I scolded, and bade ye gae wa’,

That our Heavenly Father taks tent gin ye fa’,

An’ tenderly cares for baith you an’

Grandma.

—————

We do not “live up to our privileges” in the matter of beans. Custom has established the arrangement that certain varieties of beans, as the “Early Valentine,” “Golden Wax,” and others, are good for “snaps” or “string beans;” that the “London Horticultural,” the “Lima,” and others are good when shelled green; and that the “Blue Rod,” “Medium,” “Navy,” and several others are proper for winter, or as ripe beans. All of this is very well, so far as it goes. But it restricts the usefulness of some beans. As the best of all green beans are the Lima, so are they the best of all ripe beans. In the localities where the season allows of their ripening, they should be collected. If frost threatens, pull up the poles, with the vines attached, place them under cover, and allow what will, to ripen in this manner, and when the pods are dry, shell the beans. If any one likes the Yankee dish of “pork and beans,” let him try the Limas, treated in the same manner as the ordinary white bean, and he will have a new experience as to the utility and excellence of this bean. The ripe Lima beans, soaked or parboiled until quite tender, and then fried in butter, make a pleasing variety in winter.—American Agriculturist.

—————

EARLY HARVEST BLACKBERRY.

Of this new early ripening blackberry, Mr. J. T. Lovett, of New Jersey, says, It is a chance seedling. It was found growing in the proverbial fence corner, nearly ten years ago, in Illinois, where it was so hardy, productive, luscious and extremely early as to attract the attention of the unobserving farmer—in no wise interested in fruit culture—on whose land it sprang into existence. A neighboring horticulturist, being informed of it, went in after years to see it in fruit, but owing to its very remarkable earliness was for two seasons frustrated in his endeavors, as he did not reach the spot until the fruit had ripened and disappeared. At last finding the bushes laden with such excellent fruit he made arrangements at once for its propagation, and succeeded in getting enough in fruit to make a shipment to the Chicago market in 1881, which sold for twenty-one cents per quart, wholesale. From that date the propagation of the variety has steadily gone forward, but there being only a small stock at the beginning, the supply of plants is as yet limited. As the berry was found ripening with Winter wheat in an adjoining field when discovered, the appellation of Early Harvest was chosen as an appropriate name for it. From its general appearance in leaf and cane, or other causes, the Early Harvest has become much confused with Brunton’s Early, from which, however, it is not only quite distinct in fruit, but its blossoms are entirely perfect or self-fertilizing, having an abundance of stamens, while those of Brunton’s are pistillate or imperfect, requiring the presence of some other variety to fructify it. It is also exceptionally hardy while Brunton’s is not.

The peculiar form and size of it, under good culture, are well portrayed by the accompanying engraving. The berries are very uniform in size and shape, shiny black, with exceptionally small drupes or grains, compactly and evenly arranged, rendering it most attractive in appearance and its shipping qualities unexcelled. Quality sweet and excellent; without the sour disagreeable core present in most varieties. In New Jersey it commences to ripen from the first to the fourth of July, or about with the Turner Raspberry, and fully ten days in advance of the first ripening berries of Wilson’s Early—ripening its entire crop in a short period, enabling the fruit-grower to gather the whole of it in a few pickings and have it out of the way while prices are high and by the time of making the first picking of the old popular Wilson. Canes are of rather dwarf, rugged, upright growth, with numerous side branches, enormously productive and very hardy. In hardiness it nearly or quite equals the iron clad Snyder, having stood twenty degrees below zero in Illinois, without being harmed. Owing to its dwarf habit it should be planted in rows but five feet apart and three feet apart in the rows, while it is so excessively prolific it needs to be pruned severely to check this tendency and thus add size to the fruit. Blossoms altogether perfect or self fertilizing. It is decidedly distinct from all the standard varieties, descending apparently from a different species, and from its remarkable earliness and other merits is of untold value to all growers of fruit, whether for market or for family use only. Having fruited it for two seasons I speak from experience, and am confident that those with whom the Wilson and other early varieties have proved profitable in the past, will find in Early Harvest a berry yielding even greater returns in the future.

BRUNTON’S EARLY.

Parker Earle, Pres. Mississippi Valley Horticultural Society, before the American Pomological Society, September, 1883, says:—“I have fruited the Early Harvest three seasons, and I find it a berry with many merits. It is the earliest to ripen of all the blackberries. With us it ripens a week or more before the Wilson; others report even more difference. It ripens with the red raspberries. This one quality gives it unrivalled advantages for market growing wherever early ripening is desirable, and for all growers for home use. The fruit is only medium in size, but it is a very symmetrical and uniform berry, making a handsome dish on the table, and a fine appearance in the market. It carries three hundred miles to market with us in excellent condition and pleases buyers. The plant is healthy, of sturdy but not rampant growth. It is so far perfectly hardy in South and South Central Illinois, and has with us endured fifteen below zero, and further north twenty below, without material harm. It is exceedingly prolific, and in all respects, so far as I have yet seen, excepting its rather inferior size, it is a perfect blackberry. But though it is no bigger than Snyder, and possibly not so large, yet it is so early, and it bears so well, and eats so well, and ships so well, and SELLS so well, that it has very notable value for a large portion of our country.

We give also an engraving of Brunton’s Early, that our readers may be able to compare the general appearance of the two fruits.

—————

In former addresses, I have spoken to you of the importance of the establishment of short, plain, and proper rules, to govern the nomenclature and description of our fruits, and of our duty in regard to it; and I desire once more to enforce these opinions on a subject which I deem of imperative importance. Our Society has been foremost in the field of reform in this work, but there is much yet to be done. We should have a system of rules consistent with our science, regulated by common sense, and which shall avoid ostentatious, indecorous, inappropriate and superfluous names. Such a code your Committee have in hand, and I commend its adoption. Let us have no more Generals, Colonels, or Captains attached to the names of our fruits; no more Presidents, Governors, or titled dignitaries; no more Monarchs, Kings, or Princes; no more Mammoths, Giants, or Tom Thumbs; no more Nonsuches, Seek-no-furthers, Ne plus ultra, Hog-pens, Sheep-noses, Big Bobs, Iron Clads, Legal Tenders, Sucker States, or Stump-the-World. Let us have no more long, unpronounceable, irrelevant, high-flown, bombastic names to our fruits, and, if possible, let us dispense with the now confused terms of Belle, Beurre, Calebasse, Doyenne, Pearmain, Pippin, Seedling, Beauty, Favorite, and other like useless and improper titles to our fruits. The cases are very few where a single word will not form a better name for a fruit than two or more. Thus shall we establish a standard worthy of imitation by other nations, and I suggest that we ask the co-operation of all pomological and horticultural societies, in this and foreign countries, in carrying out this important reform.

As the first great national Pomological Society in origin, the representative of the most extensive and promising territory for fruit culture, of which we have any knowledge, it became our duty to lead in this good work. Let us continue it, and give to the world a system of nomenclature for our fruits which shall be worthy of the Society and the country,—a system pure and plain in its diction, pertinent and proper in its application, and which shall be an example, not only for fruits, but for other products of the earth, and save our Society and the nation from the disgrace of unmeaning, pretentious, and nonsensical names to the most perfect, useful, and beautiful productions of the soil the world has ever known.

—————

These rules are recommended to the attention of all horticultural and pomological societies, in the hope that by concert of action some much needed reforms may be secured, especially as indicated in that portion of President Wilder’s address which we copy in this number:

Naming and Describing New Fruits.

Rule 1.—The originator or introducer (in the order named) has the prior right to bestow a name upon a new or unnamed fruit.

Rule 2.—The Society reserves the right, in case of long, inappropriate, or otherwise objectionable names, to shorten, modify, or wholly change the same, when they shall occur in its discussions or reports; and also to recommend such changes for general adoption.

Rule 3.—The names of fruit should, preferably, express, as far as practicable by a single word, the characteristics of the variety, the name of the originator, or the place of its origin. Under no ordinary circumstances should more than a single word be employed.

Rule 4.—Should the question of priority arise between different names for the same variety of fruit, other circumstances being equal, the name first publicly bestowed will be given precedence.

Rule 5.—To entitle a new fruit to the award or commendation of the Society, it must possess (at least for the locality for which it is recommended) some valuable or desirable quality or combination of qualities, in a higher degree than any previously known variety of its class and season.

Rule 6.—A variety of fruit, having been once exhibited, examined, and reported upon, as a new fruit, by a committee of the Society, will not, thereafter, be recognized as such, so far as subsequent reports are concerned.

Competitive Exhibits of Fruits.

Rule 1.—A plate of fruit must contain six specimens, no more, no less, except in the case of single varieties, not included in collections.

Rule 2.—To insure examination by the proper committees, all fruits must be correctly and distinctly labeled, and placed upon the tables during the first day of the exhibition.

Rule 3.—The duplication of varieties in a collection will not be permitted.

Rule 4.—In all cases of fruits intended to be examined and reported by committees, the name of the exhibitor, together with a complete list of the varieties exhibited by him, must be delivered to the Secretary of the Society on or before the first day of the exhibition.

Rule 5.—The exhibitor will receive from the Secretary an entry card which must be placed with the exhibit, when arranged for exhibition, for the guidance of committees.

Rule 6.—All articles placed upon the tables for exhibition must remain in charge of the Society till the close of the exhibition, to be removed sooner only upon express permission of the person or persons in charge.

Rule 7.—Fruits or other articles intended for testing, or to be given away to visitors, spectators, or others, will be assigned a separate hall, room, or tent, in which they may be dispensed at the pleasure of the exhibitor, who will not, however, be permitted to sell and deliver articles therein, nor to call attention to them in a boisterous or disorderly manner.

Committee on Nomenclature.

Rule 1.—It shall be the duty of the President, at the first session of the Society, on the first day of an exhibition of fruits, to appoint a committee of five expert pomologists, whose duty it shall be to supervise the nomenclature of the fruits on exhibition, and in case of error to correct the same.

Rule 2.—In making the necessary corrections they shall, for the convenience of examining and awarding committees, do the same at as early a period as practicable, and in making such corrections they shall use cards readily distinguishable from those used as labels by exhibitors, appending a mark of doubtfulness in case of uncertainty.

Examining and Awarding Committees.

Rule 1.—In estimating the comparative values of collections of fruits, committees are instructed to base such estimates strictly upon the varieties in such collections which shall have been correctly named by the exhibitor, prior to action thereon by the committee on nomenclature.

Rule 2.—In instituting such comparison of values, committees are instructed to consider:—1st, the values of the varieties for the purposes to which they may be adapted; 2nd, the color, size, and evenness of the specimens; 3rd, their freedom from the marks of insects and other blemishes; 4th, the apparent carefulness in handling, and the taste displayed in the arrangement of the exhibit.

—————

CUTHBERT.

Among the red raspberries we have found nothing better for marketing than the Cuthbert, and for drying or canning we think very much of Shaffer’s Colossal. Its berry is very large; it is a wonderful grower, and as far as we have tried a great bearer. We know of nothing equal to it when cooked; colour too dark for general market purposes. We intend to put out about ten acres the coming spring. We have had an opportunity to contract all we can raise on twenty acres at ten cents for canning, which we did not accept, as we have no doubt they will sell for more. Canners are using them largely, and offer good paying prices. We last year sold 25,000 quarts at ten cents for our whole crop. We have usually found that they pay better to evaporate, which can be done with much less cost and trouble; and notwithstanding that the acreage has increased largely during the last few years the demand grows stronger, and we do not anticipate seeing the prices fall below a profitable point for years to come.

In evaporating, the temperature should never be over 190°, and it is better not to raise it above 160° or 170°. To make the best fruit they should not be dried hard, but should be taken from the evaporators while much of the fruit is yet more or less soft.—H. P. Van Dusen in Country Gentleman.

—————

Landreth’s Rural Register and Almanac for 1884 is full of information concerning seed growing, garden vegetables, and flower seeds, and marks the one hundredth year of the business career of D. Landreth & Sons, as seedsmen, in Philadelphia.

Calendar of Queen’s College and University, Kingston, Canada, for the year 1883-84, contains the usual announcements, subjects of study, scholarships, and examination papers in arts, theology and medicine, with list of graduates and alumni.

The American Angler is a weekly journal devoted to fish and fishing, published by the Angler’s Publishing Company, 252 Broadway, New York, at $3 a year, W. C. Harris, editor. Judging from the specimen copy received it is well filled with reliable information on the subjects to which it is devoted.

Catalogue of Books on Agriculture, Horticulture, and Botany, including the best works on Floriculture, Gardening, Domestic Animals, Rural Architecture, and kindred subjects, for sale by Robert Clarke & Co., 61, 65, West Fourth Street, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1884.

Our Little Ones and the Nursery is published monthly by the Russell Publishing Company, Boston, Massachusetts, at $1.50 a year. It is illustrated with engravings in the best style of the art on every page, and the reading matter is printed in clear type of good size that will not weary the eyes of the little readers.

The Weather, by S. S. Bassler, in a pamphlet of fifty-four pages, published by Robert Clarke & Co., Cincinnati, Ohio, price 25 cents, which aims to be a help to the better understanding of the weather reports and predictions daily issued by the signal service. It treats of the dew-point, high and low barometer, storms, &c., and is fully illustrated with diagrams shewing the progress of storms.

Vennor’s Almanac for 1884, printed by the Gazette Printing Company, Montreal, contains papers on Lunar Influence on Vegetation, Sun-spots and Aurora, the Solar System, Earthquakes, and others of general interest even to those who place no confidence in his weather forecasts.

The Agricultural Review and Journal of the American Agricultural Association for December contains, among other valuable papers, a very interesting account of stock-raising in the North-West by Gen. Brisbin, of the U. S. Army. Does our own North-West offer the same facilities for stock-raising as does Montana? If so, those who undertake that business there will find it very profitable. The Review will be published monthly during 1884 at $3 a year by Jos. H. Reall, 32 Park Row, New York.

Godey’s Lady’s Book for January is illustrated with two amusing steel engravings, entitled the “First Call in the Country,” and the “First Call in the City.” A little red-breasted robin is the country visitor, while a telephone call is the trouble-saving substitute for personal attendance in the city. The Fashion illustrations are full and abundant. Of the literary excellencies we are not, perhaps, qualified to speak. Those who are fond of light reading, very light reading, will be pleased. Published monthly by J. H. Haulenbeck & Co., Box H. H., Philadelphia, at $2 a year.

Vick’s Illustrated Magazine.—The Christmas number of this welcome monthly is more than usually attractive in its holiday dress. The papers on Fruit Raising, on Flowers in School Grounds, and the one entitled a Wild-Flower Talk are all deeply interesting, and contain much valuable information. This number is profusely illustrated, and adorned, as all the numbers are, with an exquisitely executed coloured lithograph in the very best style of the art. The chapter describing Harrisburg, the capital of Pennsylvania, will be especially attractive to those who are interested in ornamental tree planting. Published by James Vick, Rochester, N. Y., at $1.25 per year.

Southern Cultivator for December.—We cordially welcome the Southern Cultivator for December. It is replete with articles of interest and value on every subject which is allied in any manner to the pursuit of agriculture. It is a charming number, a fit conclusion to the year, and an encouraging harbinger for the future. As we turn page after page we are delighted with its varied contents, and feel sure that the man or the woman who applies $1.50 in payment for a year’s subscription thereto, makes a wise and profitable investment. The “Departments of the Household,” “Children’s Corner” and “Fashions,” constitute most interesting features of this journal.

American Agriculturist, published in English or German, by the Orange Judd Co., New York, at $1.50 a year, contains nearly one hundred columns of original reading matter by the leading rural writers of the United States, and as many engravings executed by the best artists. The editorial matter is from the pens of such men as Joseph Harris, Geo. Thurber, Byron D. Halsted, all well known to the agricultural world. During the coming year special attention will be given to house plans for farmers, the exposure of humbugs, &c. The January number, already on our table, has a very suggestive picture, entitled “Talking over the crop prospects,” and illustrations of two new varieties of blackberry, with many other pictures, and an excellent variety of reading matter.

—————

CODLIN MOTH.

A fruit was kindly given to me,

’Twas fair as that which had upon it,

“Da pulcharissima mihi,”

And perfumed like all Araby,

An apple worthy of a sonnet;

But faugh! all thought of song inditing

Was banished by the act of biting.

O fulsome worm! art thou some breed

Which was engendered at the eating

Of that first fruit of which we read?

Is thence thy treachery—thy greed?

Thy gift, to give repellent greeting

To sharp desire? and teach us mortals

Disgust will haunt e’en pleasure’s portals?

Alas! dear Eve, appearance caught her;

Had she but guessed a worm was in it,

She, like her wiser modern daughter,

Discreet, by what her nature taught her,

Had spurned that apple in a minute,

Or, eyed it with a dainty pout,

Then, deftly cut the traitor out.

How wonderful! that bite particular

Of that one typic, wormy apple,

Should make humanity vermicular—

Destroy man’s moral perpendicular—

And place a knob upon the “thrapple”

Of all his masculine posterity—

’Twould seem a very mythy verity.

But that the thesis is well backed—

“Man’s but a worm,” affirms the preacher,

If other evidence be lacked—

His inborn and fruit-fustive nack,

Corroborates the ortho-teacher;

Judged by his tricks, the human wriggler

Is but a true gigantic wiggler.

O turn-coat moth! alas, to wit,

What else is man! Both seek disguise;

Both in some seeming harmless flit

Can drop a mischief-working nit,

To hatch into an enterprise,

That shall despoil a brother-neighbour’s,

Appropriate his fruit and labor.

They name you in mellifluous Latin,

O carpo-capsa pomonella!

They say you sleep in finest satin,

As soft as millionaires grow fat in,

And yet you’re but a felon fellow,

That theft of fruit, that slimy train,

Decide you of the meanest strain.

This muddling kinship of a worm

I fain must leave to Willie Saunders,

Who, just by squinting at your squirm,

Can trace you back to proto-germ,

Unvail your transmutative wonders,

That scientist, when on his mettle,

Can ev’ry doubt about you settle.

S. P. Morse, Lowville, Ont.

—————

Pelargoniums Duke and Duchess of Albany.—These two new varieties belong to the regal class, distinguished by the crisped appearance of the petals, at first sight giving the flower the appearance of being semi-double, though in reality it is not so. Duke of Albany has large flowers of a deep crimson-maroon colour, with a narrow margin of rosy lake and a lighter coloured centre. Duchess of Albany has purplish violet coloured blooms, with the upper petals marked with maroon. Both are very fine sorts, and will no doubt become popular as they become better known.—The Garden.

Peaches in a Cold Climate.—A gentleman who has resided in Dakota, where the thermometer usually goes twenty below zero in winter, and last year sunk to thirty-eight below, informs us that he raises annually good crops of peaches. The trees are planted in a line at the foot of a steep sloping bank and inclined towards it. On the approach of winter, a slight bending brings them into contact with the ground, to which they are held by a weight, or by a forked stake driven into the ground. They then receive a thick covering of hay, straw or cornstalks, which enables them to obtain warmth from the ground. In the spring the covering is removed, and a few short stakes serve as props to raise the tree and its principal branches to its original position.—Country Gentleman.

The Lombard Plum.—Is more planted than any other plum, as it is supposed to be hardy and partly proof against the curculio. This is owing to its great bearing; as if the curculio took half, there would in general be more left than the tree could properly ripen. This habit of overbearing causes it to be a very short-lived tree, as it gets so weakened after bearing two or three large crops that the first severe winter kills it, or injures it so that it will die in a few years. The only remedy for this is heavy manuring and thinning out the fruit when small fully one-half or two-thirds. What is left, owing to increased size, will give a heavier yield and bring a higher price than if all were left on. The fruit is purple, of only medium size and quality, and will only bring about half as much per bushel as Bradshaw, Pond’s Seedling, white or yellow Egg, and other large varieties.—New York Witness.

Printed at the Steam Press Establishment of Copp, Clark & Co., Colborne Street, Toronto.

JESSICA.

THE

| VOL. VII.] | FEBRUARY, 1884. | [No. 2. |

The progress that has been made in the matter of grape growing within a few years is truly astonishing. It is not more than twenty-five years since all the varieties in cultivation in the open air did not exceed half a dozen in number. The principal of these were the Isabella, Catawba and Clinton. The Isabella is supposed to be a native of South Carolina, and to have been introduced to the notice of northern horticulturists about the year 1818 by the late Wm. Prince, who named it in honor of Mrs. Isabella Gibbs, of whom he obtained it. It does not mature its fruit well in Ontario generally, although until the advent of the Concord it was the variety most often to be found in our fruit gardens. The Catawba is said to have originated in North Carolina, to have been taken from there to Maryland, and was introduced by Major Adlum of the District of Columbia about the year 1820 to the horticultural public. This grape though unsurpassed in quality, unfortunately is later in ripening than even the Isabella. It is said that the original Clinton was planted in the grounds of Professor Noyes, of Hamilton College, N. Y. in 1821, by the Hon. Hugh White, where it still remains. This variety is very hardy, ripens its fruit over a large part of Ontario, but the flavor is too acid to admit of it ever becoming a favorite in this Province.

For a long time these continued to be about all the varieties we had. In 1853 Mr. E. W. Bull, of Concord, Massachusetts, first exhibited his now celebrated Concord grape, which has been widely disseminated, and more abundantly planted than any other, perhaps than all the others combined. From this time we date a new era in grape growing in America, and great improvements in the earliness, hardiness and general adaptation of the vines to our northern latitudes.

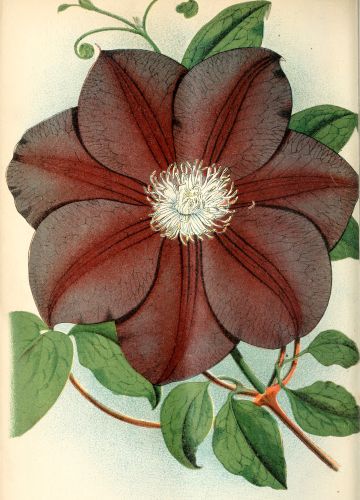

The variety called Jessica and now presented to the notice of our readers is of Canadian origin, having been grown from seed by Mr. W. H. Read, in the County of Lincoln and Province of Ontario. It has proved itself thus far to be perfectly hardy in our climate, free from disease and enormously productive. It ripens very early, among the earliest we have; it is very sweet, free from all foxiness, sprightly and aromatic. The colour is a yellowish green, in some berries a yellow amber. For general appearance of berry and bunch, and foliage, our readers are referred to the excellent colored illustration, executed by Canadian artists, Rolph, Smith & Co., of Toronto.

The venerable President of the American Pomological Society, the Hon. M. P. Wilder, in a letter to the writer says, “Its pulp is remarkably free from hardiness, and to my taste entirely free from the aroma of our native species. It resembles in appearance the Chasselas type, and affords another illustration of the progress which has been made in the improvement of the grape in our day.”

The late H. E. Hooker, of Rochester, N. Y., wrote of it, “the quality of the fruit and its fine flavor pleased me very much.”

John Hoskins, Esq., of Toronto, says of it, “I consider it an excellent grape, has not the slightest taint of ‘fox’, and is, I think, the earliest grape I have.”

Mr. John Blain, of Louth, Lincoln County, says, “having fruited the Jessica five or six years I can bear evidence that it is remarkably productive, very hardy, and without a rival in quality, of medium size, and a good keeper.”

Mr. James Taylor, of St. Catharines, says, “I have fruited the Jessica two years, have found it hardy, very prolific, and free from mildew or any other disease. I consider it superior to most of the new varieties, and know of no better white grape.”