* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 4, Issue 2

Date of first publication: 1868

Author: J. T. Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Nov. 23, 2018

Date last updated: Nov. 23, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20181190

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. IV. | FEBRUARY, 1868. | No. II. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

THE DOWNFALL OF THE SAXON GODS.

WAKE UP!

e have now for some time followed the Ancient

Mariner through the recital of the wonderful

adventures which befell himself and the Dean

on the lonely little island in the Arctic Sea;

and we have watched the children going and

coming from day to day. And we have seen,

too, how happy the children were when listening

to the story, and how delighted they were

with every little scrap they got of it, and how

they remembered every word of it, and how

William wrote it down in black and white, and

had it safe and sound for future use,—little

dreaming, at the time of doing it, that the record

he was keeping would find its way at last

into “Our Young Folks,” and thus give other

than himself and Fred and Alice a

chance to make the acquaintance of the good

old Captain and the brave and handsome little

Dean.

e have now for some time followed the Ancient

Mariner through the recital of the wonderful

adventures which befell himself and the Dean

on the lonely little island in the Arctic Sea;

and we have watched the children going and

coming from day to day. And we have seen,

too, how happy the children were when listening

to the story, and how delighted they were

with every little scrap they got of it, and how

they remembered every word of it, and how

William wrote it down in black and white, and

had it safe and sound for future use,—little

dreaming, at the time of doing it, that the record

he was keeping would find its way at last

into “Our Young Folks,” and thus give other

than himself and Fred and Alice a

chance to make the acquaintance of the good

old Captain and the brave and handsome little

Dean.

And William Earnest kept his record regularly, and he kept it well, as we have seen before; and up to this point of time everything was set down with day and date. But now a change had clearly come over the habits of our little party. At first, as has been hitherto related, the old Captain was a little shy of the children, though he so much liked them,—afraid, as we have seen he was before, to say, “Come at any time you please”; but he rather said, “Come at such and such an hour to-morrow or the day after,” as the case might be. Now, however, all this formality was done away with, as the Captain learned that the children never interfered with him or troubled him in any way. So down they came to the Captain’s cottage whenever they had a mind, and the Captain was always glad to see them, be it morning, noon, or evening; and never were the children, in all their lives before, so happy as when romping through the Captain’s grounds, or cooling themselves upon the grass beneath the Captain’s trees, or looking at the Captain’s “hops,” or joking with that oddest boy that was ever seen, Main Brace, or playing with the Captain’s dogs,—the biggest dogs that ever bore the odd names of Port and Starboard.

The Captain now said, “Make yourselves at home, my dears,—quite at home”; and the children did it; and the Captain always went about whatever he had to do until he was ready once more to begin his story-telling; and then they would take themselves off to the yacht, or to the “Crow’s Nest,” or the “cabin,” or the “quarter-deck,” or some other cosey place; and as the Captain related something more and more extraordinary, as it seemed to them, each time,

“the wonder grew

That one small head should carry all he knew”;

while, as for the old man himself, he might well exclaim, with the lover in the play, “I were but little happy if I could say how much.”

Thus it came about, as we have good reason to suppose, that days and dates were lost in William’s journal; and thus it was that the young and truthful chronicler of this veritable history simply wrote down, from time to time, what the Captain said, without mentioning much about when it was that the Captain said it. Sometimes he wrote with lead pencil, sometimes with pen and ink, and often, as is plain to see from the manuscript itself, at considerable intervals of time; but always, as there is no doubt, with accuracy; for William’s mind, touching the Captain’s adventures, was like the susceptible heart of the Count in the Venetian story,—

“Wax to receive and marble to retain.”

So now, after this long explanation, the reader will perceive that we can do nothing else than report the Captain’s story, without saying where the little party were seated at the time the Captain told it. And, in truth, it matters little; at least so William thought, for he wrote one day upon the page,—

“Where’s the use, I’d like to know, putting in what Fred and me and Alice did, and where we went with the ‘Ancient Mariner’? I haven’t time to write so much, and I’ll only write what the Captain said”; and so right away he set down what follows.

“Now you see,” resumed the Captain, “when we had done all I told you of before,—having slept, you know, and got well rested,—we went about our work very hopefully. But as we were going along, meditating on our plans, the Dean stopped suddenly, and said he to me: ‘Hardy, do you know what day it is?’

“ ‘No,’ said I, ‘upon my word I don’t, and never once thought about it!’

“The Dean looked very sad all at once, and, not being able to see why that should be the case, I asked what difference it made to us what day it was.

“ ‘Why, a great deal of difference,’ said the Dean.

“ ‘How?’ said I.

“ ‘Why,’ said the Dean, ‘when shall we know when Sunday comes?’

“To be sure, how should we know when Sunday came! I had not thought of that before; but the Dean was differently brought up from me; for, while I had not been taught to care much what day it was, the Dean had been taught to look upon Sunday as a day when nobody should do any sort of work. I believe the Dean had an idea in his head that, if it was Sunday, and he was frozen half to death already, or starved about as badly, and should refuse to work to save himself from death outright, he would do a virtuous thing in sacrificing himself, and would go straight up to heaven for certain. So I became anxious too about the matter, and for the Dean’s sake, if not for my own, I tried hard to recall what day it was.”

“How very queer,” said William, “to forget what day it was! How did it happen? Won’t you tell us that, Captain Hardy?”

“To be sure,” said the obliging Captain,—“as well as I can, that is. Now, do you remember what I told you the other day about the sun shining all the time,—do you remember that?”

“Yes,” answered William, “that I do. Goes round and round, that way,” and he whirled his hat about his head.

“Just so,” went on the Captain,—“just so, exactly. Goes round and round, and never sets until the winter comes, and then it goes down, and there it stays all the winter through, and there is constant darkness where the daylight always was before.”

“What, all the time?” asked William.

“Yes,” replied the Captain; “dark all the time.”

“How dark?” asked Fred.

“Dark as dark can be. Dark at morning and at evening. Dark at noon, and dark at midnight. Dark all the time, as I have said before. Dark all the winter through. Dark for months and months.”

“How dreadful!” exclaimed Fred.

“Dreadful enough, as I can assure you, lad, with no light, all the whole winter-time, but the moon and stars,” said the Captain, as if it was not a pleasant thing for him to recollect. “A dreadful thing to live along for days and days, and weeks and weeks, and months and months, without the blessed light of day,—without once seeing the sun come up and brighten anything and make us glad, and the flowers unfold themselves, and all the living world praise the Lord for remembering it. That’s what you never see in all the Arctic winter,—no sunshine ever streaming up above the hills and making all the rainbow colors in the clouds. That’s what you never see at all, no more than if you were blind and couldn’t see. But never mind just now about the winter. We haven’t done with the summer yet, nor with Sunday either, for that matter.

“As I have said before, the loss of Sunday much grieved the Dean. So, you see, we had nothing else to do but make one on our own account.”

“What, make a Sunday!” exclaimed William. “I’ve heard of people making almost everything, even building castles in the air; but I never heard before of anybody putting up a Sunday.”

“Well, you see, we did the best we could. It is not at all surprising that we should have lost our reckoning in this way, seeing that the sun was shining, as I have told you, all the time; and we worked and slept without much regard to whether the hours of night or day were on us. So we had good reason for a little mixing up of dates. In fact we could neither of us very well recall the day of the month that we were cast away. It was somewhere near the end of June, that we knew; but the exact day we could not tell for certain. We remembered the day of the week well enough, and it was Tuesday; but more than this we could not get into our heads, and so it seemed that there was nothing for us but to sink all days into the one long continuous day of the Arctic summer, and nevermore know whether it was Sunday, or Monday, or Friday, or what day it was of any month; and if it should be Heaven’s will that we should live on upon the island until the New Year came round, and still other years should come and go, we should never know when the New Year was.

“But, as I was saying, about making a Sunday for ourselves. I did everything I could to refresh my memory about it. I counted up the number of times we had slept, and the number of times we had worked, and recalled the time when I first walked around the island; and I tried my best to connect all those events together in such a way as to prove how often the sun had passed behind the cliffs, and how often it had shone upon us; and thus I made out that the very day I am telling you about proved to be Sunday,—at least I so convinced the Dean, and he was satisfied. And that’s the way we made a Sunday for ourselves. So we resolved to do no work that day; and this was well, for we were very weary and needed rest.

“I need not tell you that we passed the time in talking over our plans for the future, and in discussing the prospects ahead of us, and arranging in a general way what we should do. You see we had settled about Sunday, so that was off our minds; and after recalling many things which had happened to us, and things which had been done on the Blackbird, we finally concluded that we had found out the day of the month, and so we called the day ‘Sunday, the second of July,’ and this we marked, as I will show you, thus: On the top of a large flat rock near by I placed a small white stone, and this we called our ‘Sunday stone’; and then, in a row with this stone, we placed six other stones, which we called by the other days of the week. Then I moved the white stone out of line a little, which was to show that Sunday had passed, and afterwards, when the next day had passed, we did the same with the Monday stone, and so on until the stones were all on a line again, when we knew that it was once more Sunday. Of course we knew when the day was gone, by the sun going around on the north side of the island, throwing the shadow of the cliffs upon us. For noting the days of the month we made a similar arrangement to that which we had made for the days of the week; and thus you see we had now got an almanac among our other things. ‘And now,’ said the Dean, ‘let us put all this down for fear we forget it.’ So away the little fellow ran and gathered a great quantity of small pebbles, and these we arranged on the top of the rock so as to form letters; and the letters that we thus made spelled out ‘John Hardy and Richard Dean, cast away in the cold, Tuesday, June 27, 1824.’

“Now, when we came to look ahead, and to speculate upon what was likely to befall us, we saw that we had two months of summer still remaining; and, as midsummer had hardly come yet, we knew that we were likely to have it warmer than before, and we had now no further fears about being able to live through that period. In these two months it was plain that one of two things must happen,—that is, a ship must come along and take us off, or we must be prepared for the dark time that must follow, after the sun should go down for the winter.

“I said one of two things must happen; but then there was a third thing that might happen besides,—we might both die; and that seemed likely enough, so we pledged ourselves to stand by each other through every fortune, each helping the other all he could. At any rate, we would not lose hope, and never despair of being saved through the mercy of Providence, somehow or other.

“Having reached this resigned state of mind, we were ready to consider rationally what we had to do. It was clear enough that if we only looked out for a ship to save us, and that chance should in the end fail us, we should be ill prepared for the winter if we were left on the island to encounter its perils. Therefore it was necessary to be ready for the worst, and accordingly, after a little deliberation, we concluded to proceed as follows:—

“Firstly, we must construct a place to shelter ourselves from the cold and storms. In this we had made some satisfactory progress already.

“Secondly, we must collect all the food we can while there is opportunity.

“Thirdly, we must gather fuel, of which, as had been already proved, there was Andromeda (or fire-plant) and moss and blubber to depend upon. Of this latter the dead narwhal and seal would furnish us a moderate supply; but for the rest we must rely upon our own skill to capture some other animals from the sea; though, as to how this was to be done, we had to own ourselves completely at fault.

“Fourthly, we must in some manner secure for ourselves warmer clothing, otherwise we should certainly freeze; and here we were completely at fault too.

“Fifthly, we must contrive in some way to make for ourselves a lamp, as we could never live in our cave in darkness; and here was a difficulty apparently even more insurmountable than the others,—as much so as appeared the making of a fire in the first instance,—for while we had a general idea that we might capture some seals, and get thus a good supply of oil, and that we might also get plenty of fox-skins for clothing, yet neither of us could think of any way to make a lamp.

“When we came thus to bring ourselves to a practical view of the situation, the prospect might have made stouter hearts than ours quake a little; but, as we had seen before, nothing was to be gained by lamentation, so we put a bold front on, firmly resolved to make the best fight we could for life.”

“A poor chance for you, I should think,” said Fred, “and I don’t see how you ever lived through so many troubles,”—while little Alice declared her conviction that “the poor Dean must have died anyway.”

“A very bad prospect, indeed, my dears,” continued the Captain,—“very bad, as I can assure you; but as it is a poor rule to read the last page of a book before you read the rest of it, so we will go right on to the end with our story, and then you will find out what became of the Dean, as well as what happened to myself.

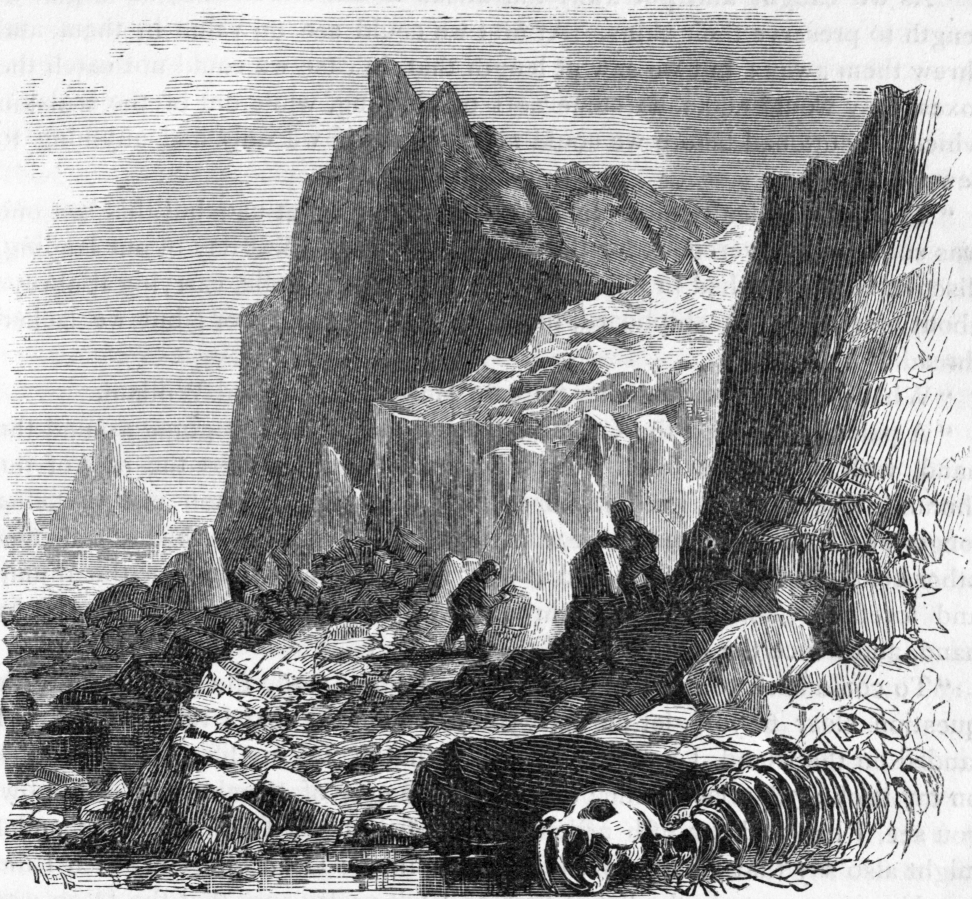

“Well, as I was going to say, when Monday came, we set about our work, not exactly in the order which I have named, but as we found most convenient; and as day after day followed each other through the week, and as one week followed after another week, we found ourselves at one time building up the wall in front of the cave, then catching ducks and gathering eggs, then collecting the fire-plant, and then turning moss up on the rocks to dry, and then cutting off the blubber and skins of the dead seal and narwhal. All of these things were carefully secured; and in a sort of cave, much like the one we were preparing for our abode, only larger, we stowed away all the fire-plant and dried moss that we could get. Then we looked about us to see what we should do for a place to put our blubber in,—that is, you know, the fat we got off the dead narwhal and the seal, and also any other blubber that we might get afterwards. When we had cut all the blubber off the seal and narwhal, we found that we had an enormous heap of it,—as much, at least, as five good barrels,—and, since the sun was very warm, there was great danger, not only that it would spoil, but that much of it would melt and run away. Fortunately, very near our hut there was a small glacier hanging on the hillside, coming down a narrow valley from a greater mass of ice which lay above. From the face of this glacier a great many lumps of ice had broken off, and there were also deep banks of snow which the summer’s sun had not melted. In the midst of this accumulation of ice and snow we had little difficulty in making, partly by excavating and partly by building up, a sort of cave, large enough to hold twice as much blubber as we had to put into it. Here we deposited our treasure, which was our only reliance for light in case we invented a lamp, and our chief reliance for fire if the winter should come and find us still upon the island.

“After we had thus secured, in this snow-and-ice cave, our stock of blubber, we constructed another much like it near by for our food, and into this we had soon gathered a pretty large stock of ducks and eggs. And now, when we contemplated all that we had done in this particular, you may be sure our spirits rose very considerably.”

“Odd, wasn’t it?” said Fred, “having a storehouse made of ice and snow. But, Captain Hardy, if you’ll excuse me for interrupting you, what did this glacier that you spoke about look like? and what was it, anyway?”

“A glacier is nothing more,” replied the Captain, “than a stream of ice made out of snow partly melted and then frozen again, and which, forming, as I have said before, high up on the tops of the hills, runs down a valley and breaks off at its end and melts away. Sometimes it is very large,—miles across,—and goes all the way down to the sea; and the pieces that break off from it are sometimes very large, and are called icebergs. Sometimes the glaciers are very small, especially on small islands such as ours was. This little glacier I tell you of lay in a narrow valley, as I said before; and, as the cliffs were very high on either side, it was almost always in shadow, and the air was very cold there; so you see how fortunate it was that we thought of fixing upon that place for our storehouses. Then another great advantage to us was, that it was so near our hut,—being within sight, and only a few steps across some very rough rocks; but among these rocks we contrived to make, by filling in with small stones, a tolerably smooth walk.

“As we caught and put away the ducks in our storehouse, we began at length to preserve their skins. At first we could see no value in them, and threw them away; but we saw at length that, in case we could not catch the foxes, they would make us some sort of clothing, while out of the sealskin which I mentioned before we could make boots, if we only had anything to sew with.

“Thus one difficulty after another continually beset us; but this last one was soon partly overcome, for the Dean, on the very first day of our landing, discovered that he had in his pocket his palm and needle, carrying it always about him when on shipboard, like any other good sailor; but we lacked thread.”

“What is a palm and needle, Captain Hardy?” inquired William.

“A palm,” answered the Captain, “is a band of leather going around the hand, with a thimble fitted into it where it comes across the root of the thumb. The sailor’s needle differs only from the common one in being longer and three-cornered, instead of round. It is used for sewing sails and other coarse work on shipboard. The needle is held between the thumb and forefinger, and is pushed through with the thimble in the palm of the hand, and hence the name.

“To come back to our story (having, as I hope, made the palm and needle question clear to you), let me ask you to remember that I told you, when I landed on the island, I had four things,—that is, 1st, my life; 2d, the clothes on my back; 3d, a jack-knife; and 4th, the mercy of Providence. But now, you see, I had added a fifth article to that list, in the Dean’s needle; and I might also say that I had a sixth one, too, in the Dean himself, which I did not dare enumerate in the list at first, as I felt pretty sure that the Dean was going to die, or at least wake up crazy, which would be just as bad for me.

“But you see a sailor’s palm and needle could be of very little use unless we had some thread, of which we did not possess a single particle, except the small piece that was in the needle, and by which it was tied to the palm. It was a good while before we obtained anything to make thread of, so we will pass that subject by for the present, and come back to what we had more immediately in hand. This was the preparation of our cave, or rather, as we had better say, hut,—that being more nearly what it was.

“The building of our hut, then, was indeed a very difficult task, as the solid wall we had to construct in front was much higher than our heads, and in this wall we had, of course, to leave a door-way and a window, besides a sort of chimney, or outlet, for the smoke from the fireplace, which was opposite to the door.

“We must have been at least two weeks making this wall, for we had not only to construct the wall itself, but when it got so high that we could no longer reach up to the top, we had, in addition, to build steps. We left a window above the door-way, not thinking, of course, to find any glass to put in it, but leaving it rather as a ventilator than a window. It was very small, not more than a foot square, and was easily shut up at any time, if we should not need it. For a door, we used a piece of the narwhal skin, when it became necessary to close up the orifice. This skin was fastened above the door-way with pegs, which we made of bones, driving them into the cracks between the stones, thus letting the skin fall down over the door-way like a curtain.

“In making the wall we were greatly helped by the bones which I had found down on the beach, as they were much lighter than the stones, and aided in holding the moss in its place, so that we were able to use much more of that material than we otherwise could. When the wall was completed, we were gratified to see how tight it was, and how perfectly we had made it fit the rocks by means of the moss.

“Having completed the wall, our next concern was to arrange the interior; but about this we had no need to be in so great a hurry as with the wall, for we had now a place to shelter us from any storm that might come, and we could hope to make ourselves somewhat comfortable there, even although the inside was not well fitted up; for we had a fireplace, and could do our cooking without going outside. And when we found how perfect was the draft through the outlet, or chimney (such as it was), you may be very sure we were greatly delighted.

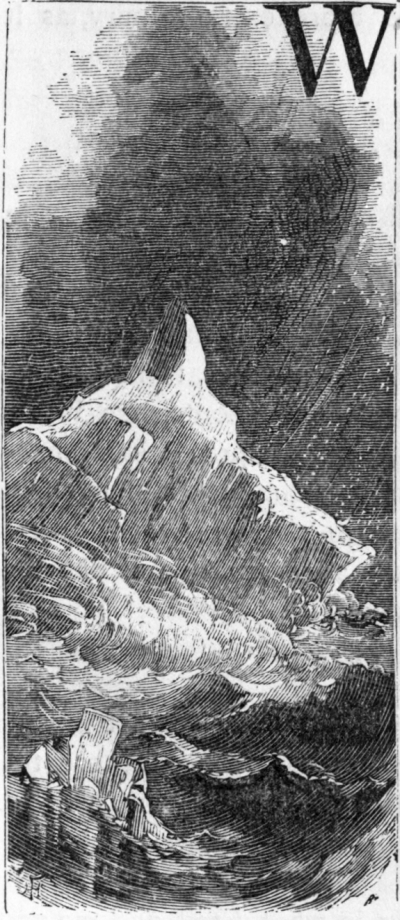

“As it fell out, we had secured this shelter in the very nick of time, for in two days afterwards a violent storm arose,—a heavy wind with hail and occasional gusts of snow,—a strange kind of weather, you will think, for the middle of July. This storm made havoc with the ice on the east side of the island, breaking it up, and driving it out over the sea to the westward, filling the sea up so much in that direction that there was no use, for the present at least, in looking for ships, as none could come anyway near us. The storm made a very wild and fearful spectacle of the sea, as the waves went dashing over the pieces of ice and against the icebergs. When I looked out upon this scene, and listened to the noises made by the waves and the crushing ice, and heard the roaring wind, I wondered more than ever what could possess anybody to go to such a sea in a ship, for it seemed to me that the largest possible gains would not be a sufficient reward for the dangers to be encountered.

“But so it always was and always will be, I suppose. Wherever there is a little money to be made, men will encounter any kind of hazard in order to get it. Thus the risks in going after whales and seals for their blubber, which is very valuable, are great; but then, if the ship makes a good voyage, the profits are very large, and when the sailors receive their ‘lay,’ that is, their share of the profits on the oil and whalebone which have been taken, it sometimes amounts to quite a handsome sum of money to each, and they consider themselves well rewarded for all their privations and hardships. And it must be owned that the whalers and sealers are a very brave sort of men, especially the whalers who go among the ice; for besides the dangers to the vessel, and the danger always encountered in approaching a whale to harpoon him (for, as you must know, he sometimes knocks the boat to pieces with his monstrous tail, and spills all the crew out in the water), he may, while swimming away with the harpoon in him, and the boat fast to it dragging after,—he may, I say, take it into his head to rush beneath the ice, and thus destroy the boat and endanger the lives of the people in it.

“But this is too long a falling to ‘leeward’ of our story, as the sailors would call it; so we will come right back into the wind again.

“When the weather cleared off after the storm, we went to work again as before. But everything about looked gloomy enough. The cliffs were besprinkled with snow, and about the rocks the snow had drifted, and it lay in streaks where it had been carried by the wind. The sea was still very rough, and, as there were many pieces of ice upon the water, when the waves rose and fell, the pounding of the ice against the rocks and the breaking of the surf made a most fearful sound.

“The sun coming out warm soon, however, melted the snow, and, getting heated up with work, we got on bravely. Indeed, we soon became not less surprised at the rapid progress we were making than at the facility with which we accommodated ourselves to our strange condition of life, and even grew cheerful under what would seem a state of the greatest possible distress. Thus you observe how perfectly we may reconcile ourselves to any fate, if one has but a resolute will, and the fear of God before his mind. I do not mean to boast about the Dean and myself; but I think it must be owned that we kept up our courage pretty well, all things considered,—now, don’t you think so, my dears?”

“To be sure we do,” replied William. “And if anybody dares to doubt it, I will go, like Count Robert, to the cross-road, and give battle for a week to all comers, just as he did.”

“Poking fun at the Ancient Mariner again,—are you?” said the Captain, trying hard to look serious. “And so I’ll punish you, my boy, by knocking off just where we are, and saying not another word this blessed day.”

Isaac I. Hayes.

O dear! little mother, I’m falling!

And what can a poor Dolly do?

I can’t even hear myself calling;

And nobody’s near me but you.

You sang me a lullaby sweetly;

But dolls’ eyes wide open will keep;

And so you were tired out completely,

And sang yourself soundly to sleep.

I love you; I wish you would fold me

Close up to your cheek rosy-red.

’Tis a dangerous way that you hold me;

The sawdust will rush to my head.

I’m sliding, I’m tumbling, I’m bumping;

I’m sure I shall fracture my skull;

Against your hard boot it is thumping,—

O save me! do give me one pull!

If you down a steep chasm were slipping,

On terrible rocks almost dashed,

To your aid there’d be somebody tripping:

Wake up, or you’ll find Dolly smashed!

Good morning, Dolly, my dear.

And how did you sleep last night?

Not soundly, I very much fear;

But have you forgiven me quite?

The sun is out warm to-day;

Can you trust my motherly care?

In-doors it is hard to stay,

And you certainly need the air.

We will make the Doctor a call;

And if he and I can agree

That you are not hurt by your fall,

What a glad mamma I shall be!

I shall watch you tenderly hence.

But you never were over-bright;

And if you are bumped into sense,

You will be, dear, my heart’s delight.

Lucy Larcom.

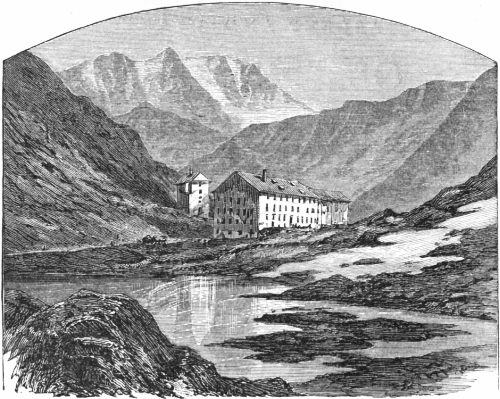

Most of the readers of the “Young Folks,” are doubtless familiar with the name of the Grand St. Bernard,—that celebrated pass among the Alps, where the good monks live all the year and provide food and shelter for the poor travellers. Every school-boy can repeat the words of Longfellow’s poem, “Excelsior,” and it is the spot where this scene is laid of which we purpose giving a short account. In the warm and bright days of early October, a year or two ago, a party of Americans started from the little Swiss village of Martigny, in the valley of the Rhone, to cross the pass of the St. Bernard. Two large carriages, drawn by mules, rattled along through the valley. Behind us was the “blue Rhone, in deepest flow,” rushing on towards the beautiful Lake of Geneva, winding around the foot of lofty mountains, now falling in beautiful cascades, and then again rushing onward, swollen by mountain torrents. The lofty peaks of the snow-covered Dent du Midi rise up in the distance on the right; and on the left is the little village of Sion, with its two curious old towers standing like sentinels to guard the entrance. The beautiful snow-peak of the Jungfrau is plainly visible, and beyond that the high mountains of the Simplon pass sparkle like diamonds in the sunlight. As we drive on through the valley, we see on all sides of us the peasants busy in the vineyards gathering in the harvest. Old and young are at work, for the labor must be performed within a given time, and to many a poor family this is the only source of income. It is a picturesque sight to see the women and girls, in their cantonal costume,—the tall straw hat, or the silk turban-like covering for the head, the short skirt of colored woollen fabric, and the heavy wooden shoes,—at work among the green vines, and the men with large wooden panniers on their backs, filled with the purple and white fruit, as they carry it away to be pressed. Beside us, but down deep in the valley, is a foaming mountain-torrent, dashing over rocks, and the débris of the mountain-slides. High above us are the cattle, feeding upon the remnants of green pastures,—the sheep, smooth and white after the shearing, and the black and white cows each with a bell around her neck; for here there are very few red cows, such as we see in our pastures in America. The children here are never idle. As soon as a child can take care of herself she must help take care of the household. The boys are generally seen in the fields, watching the cattle, and the little girls must learn to mind the baby. I have seen plenty of girls not ten years old lugging about babies in their arms, or carrying great heavy loads on their backs. For this reason we see very few bright, healthy-looking children. They live in miserable little homes, dark and dreary, with scarcely any sunlight; they sleep in poorly ventilated rooms, and all day long carry heavy burdens, or do hard work in the fields. No wonder, then, they become old-looking and wrinkled before they are at the age when our girls become the brightest. As we rode along, we drove through little villages, with streets so narrow that the passers-by had to scamper along ahead of us, or make wall-flowers of themselves to let us pass. On both sides of us were low Swiss cottages, which look far better in the white wooden models, and in the pictures, than they are in reality. They are never painted, and the dirt that accumulates on the outside is only in keeping with the smoky and filthy appearance within. But if we find the houses and inhabitants so very uninviting in appearance, we have, on all sides of us, the beautiful mountains, the deep gorges, the green valleys, and the little mountain-torrents, to admire. Nature’s handiwork is always lovely, and, as we looked at these things, we wondered if the people living among such beautiful objects ever gave them one thought. After resting for two hours for dinner we resumed our ride. And now the road became more difficult, winding around the mountains, and going close to the edge of precipices. Far on ahead of us we could see the tall peak of Mount Velan, rising, like an obelisk of frosted silver, against the clear blue sky. Two hours brought us to the last of the Swiss towns, and here we left our carriages, and, putting saddles on the mules, mounted them for the last ascent. The road here is very narrow and stony, as the mountains rise on either side more precipitously. Here is the great danger of this pass, in stormy weather; and there is no month that snow-storms do not come to this place. We are here eight thousand feet above the lake; and at such a height it is too cold for rain. The cold here is intense all the year. Even when we have the hottest summer weather in the valley, it is very cold at the summit of the pass. As we reached the top, the sun was just setting, and then occurred one of those phenomena which are so common among the Alps. The rays of the sun were not seen, but the sky assumed a deep orange color, and the tops of the mountains covered with snow wore a beautiful rose-colored tint, which lasted for several minutes. This is the Alpengild. Slowly the twilight faded, and then it became cold and dark. But before this our little party were at the Hospice, and had been cordially welcomed by one of the brethren who met us at the door. The Hospice is a large stone building, four stories high, and capable of accommodating a great number of people. It was founded, nine hundred years ago, by a good monk called Bernard de Menthon. Then it was a little building erected for the purpose of sheltering poor travellers who crossed from Italy into Switzerland. When Napoleon Bonaparte made his celebrated passage of the Alps, in May, 1800, he rested and refreshed himself at this little house of the good monk St. Bernard. The room in which he rested is still preserved, and is over the front door. Additions have been made to both ends of the house, but the original foundation and rooms are preserved. Bonaparte’s army of thirty thousand men carried over all their artillery, by placing it on trees, which they cut down in the valley near St. Pierre. Three weeks after accomplishing this wonderful feat, the same soldiers were engaged in the battle of Marengo. During the war of 1798-1801 both the French and Austrian soldiers used this passage continually. The Hospice was captured by the Austrians in 1799, and afterwards retaken by the French, who placed a garrison in it. This same pass has been used for ages, even longer than since the Christian era.

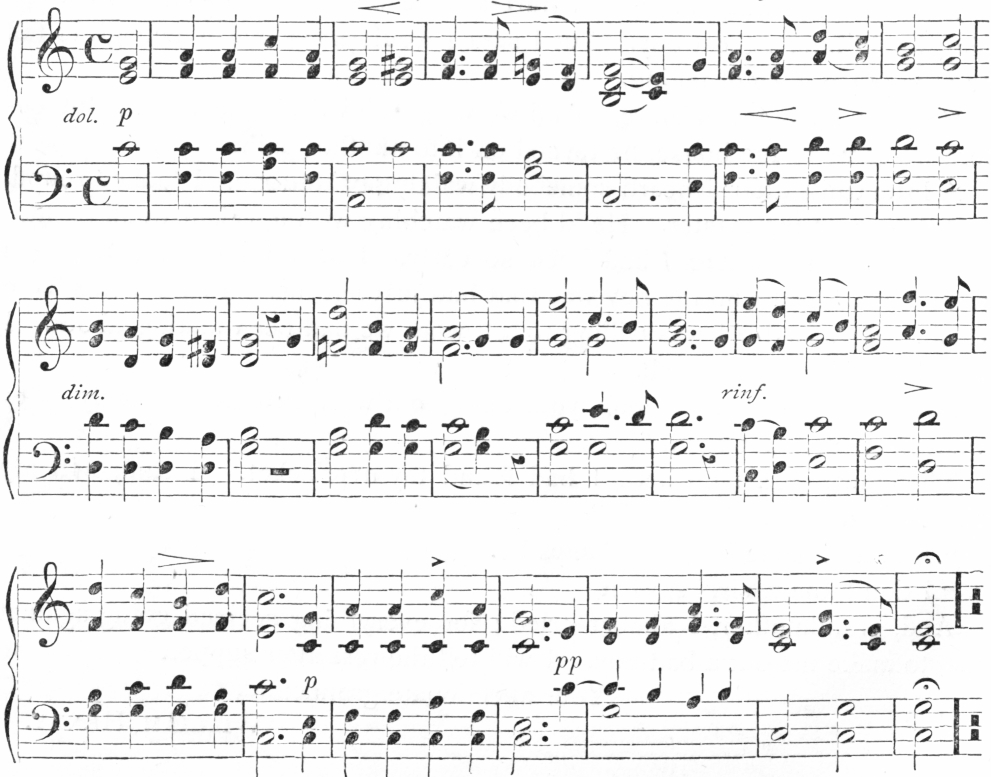

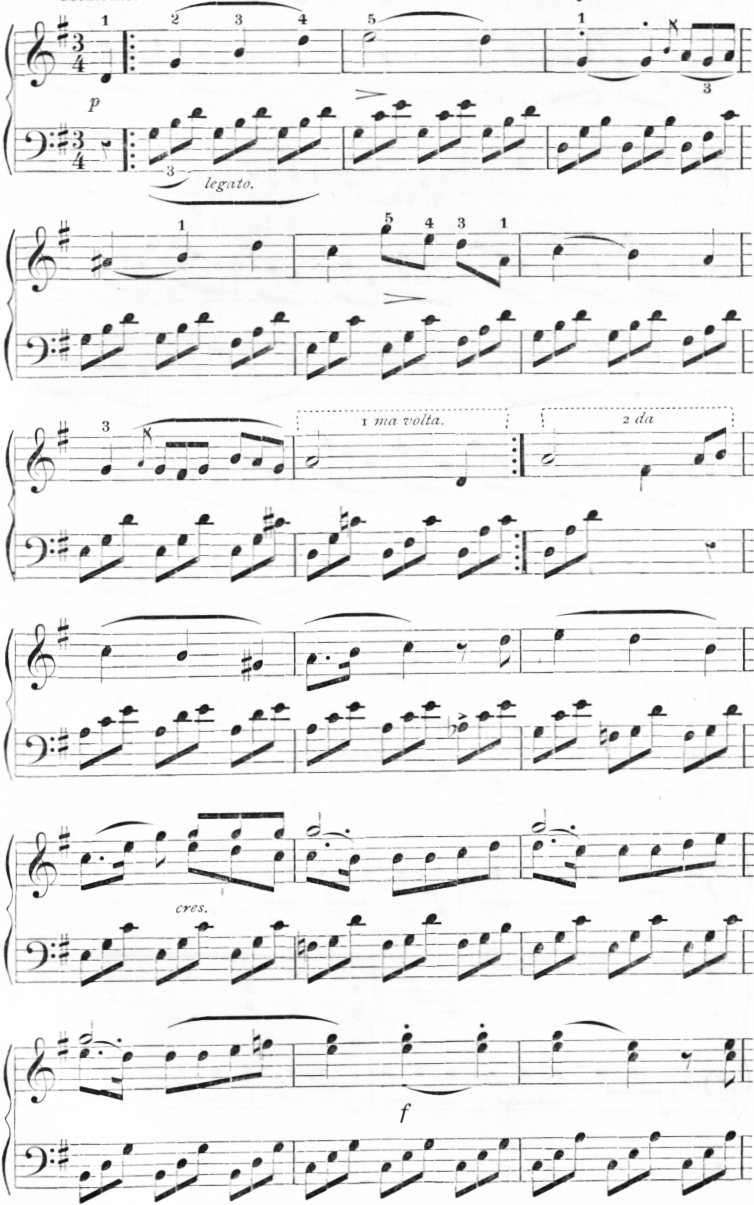

The town of Augusta, which was founded twenty-six years B. C., is at the foot of the pass on the Italian side; and the Romans doubtless used this route in passing to and from Cisalpine Gaul. At this Hospice we were each provided with comfortable rooms for the night. Everything about it was very clean, and every possible provision is made for the comfort of travellers. A plain, well-cooked supper was given us, at half past six, at which one of the brethren presided. The reception-room, which is also the dining-room, is well furnished, the walls being hung with engravings and pictures presented by travellers in return for the hospitality extended to them. A very fine piano, the gift of the Prince of Wales, stands in one corner, and by it a harmonium, the gift of a friend of the Hospice. A wood fire was burning on the hearth, gathered around which we spent the evening. Some of our party played upon the piano, and sang, after which, two of the brethren sang a few songs for us. Thus the evening passed away, the monks entertaining us with their conversation, and asking questions about our country and its institutions. Hundreds of Americans during the past summer have been the guests of these good brethren, and all leave some testimonial of their goodwill by placing a donation of money in the box appropriated to the expenses of the Hospice. There is no charge for the hospitality; all are guests and are treated alike; but we hope none are so thoughtless as to go away without depositing something in the box. Let us consider a little the use to which this money is put. In the first place the expense of living at the Hospice. There is not a tree nor a shrub within five miles on either side. All the wood, as well as provisions of every kind, must be brought up the mountain on mules; and there are only three months in the year when this can be done, on account of snow-storms. The air at this height is so rarefied that water will not boil, nor fire burn, as soon as in the valley. Nearly double the time is required to prepare the meals, and of course double the amount of fuel is consumed. The monks are bound by their vows to give shelter and food to all travellers who seek it. During the past year twenty-three thousand persons were thus accommodated. The majority of these were poor, seeking work, and using this as the shortest route between Italy and Switzerland. From such people very little, if anything, is received; and, while they diminish the store of provisions, they leave nothing with which to replenish it. The monks are a noble class of men, who give their lives to the good cause of aiding their fellows. It is so cold at the Hospice, that they cannot remain longer in the service than fifteen years, and these years are the best part of their lives. Between the ages of twenty and thirty-five, they are generally engaged in this Christian work. After that they descend to the valley to pass the remaining years of their lives. They are all well-educated, gentlemanly men, loving their work, and devoting all their time and energies to it. The pass of the St. Bernard is one peculiarly liable to storms and avalanches. It is not that it is higher than other Alpine passes, but, from the position of the mountains, it is more exposed. The snow frequently lies in drifts, near the Hospice, from thirty to forty feet deep. The wind is very severe here, and blows the snow directly down the path. Travellers overtaken by a storm are very glad to seek shelter in the dark little stone houses of refuge which are built in the dangerous parts of the road. Every morning, in the winter, the good brethren set out with servants and dogs, and descend to the foot of the pass on both sides of the mountains. The dogs carry baskets of provisions strapped to their necks, in case any poor traveller is met with, that they may give him food and wine, and bring him up to the Hospice. Many a poor wayfarer has thus been saved from perishing in the snow. It frequently happens that some traveller is completely hidden by the snow, and would be passed over by the monks but for the dogs. These noble animals have a very strong faculty for scenting human beings, and have been the means of saving many lives. One fine and noble-looking dog, by the name of Barry, saved eighteen peoples’ lives during his lifetime of nine years. When he died, it was thought too cruel to bury him, and, instead, his skin was stuffed, and you can see him, as natural almost as when living, in the museum at Berne. He well deserved to be preserved for his noble deeds during his lifetime, and not forgotten like other dogs. We saw about a dozen of these fine animals. They are large, like a Newfoundland dog, some with shaggy hair, some quite small, only two months old, and others of various sizes and colors. They are named Juno, Castor, Pluto, Jupiter, &c. Castor is the oldest fellow, being now in his ninth year. He is large and shaggy, and has the privilege of the house. They all sleep together in a little room under the kitchen, and require considerable care. There are two keepers, whose duty it is to provide their food, keep them clean and see that the sick, if any, are properly taken care of. Imagine what joy it must be to any poor and fatigued traveller, who has lost his way, is blinded by the driving snow, and is nearly frozen and famished, to be found by these hospitable men, provided with food and shelter till he is able to go on again, on his journey. Those who make excursions there for pleasure, and are pleased with all they see in pleasant weather, know very little of the hardships these men endure during nine months of the year. And for all their life-long devotion to this noble cause they receive no recompense save the approbation of their own consciences for having done a good work, and the hope of a reward hereafter from the hands of Him who has said, “Forasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” In the Hospice is a very good library for the use of the monks, and a good collection of minerals and coins. There is a good collection of American money, which has been donated at different times, ranging from our new three-cent pieces to the little gold dollars we used to see. Everything has been donated to them by persons visiting there, and among the pictures are some very good portraits of distinguished people, as well as choice sketches of different subjects. One could amuse himself very well for a whole day in their cabinet of minerals and natural history. The chapel, too, is very pretty. It contains a well-executed marble monument, placed there by Napoleon I. to the memory of General Desaix, who was killed at the battle of Marengo, in 1800. The ceiling and walls are frescoed, and on one side is a full-length picture of St. Bernard with his dog by his side, and opposite this is a copy of one of Raphael’s Madonnas. The altar-piece is of colored marble, with white facings, and contains a fine large painting of the Ascension of our Lord. The stalls, or places inside the railing, occupied by the monks, during service, are of carved wood, quite well executed. Over one of the doors is a large wooden figure, representing St. Michael overcoming the dragon. Here, in this little chapel, far away from human habitation, our little party assembled at sunrise for the usual service, which is always performed morning and evening by the good brethren. Near by the Hospice is another building, which is used as a store-house, but, in case of fire to the Hospice, can be made to accommodate travellers. A small building stands by itself, called the morgue, and this is the saddest thing connected with this noble institution. At this great height no graves can be made for those who die, for there are rocks all around, and the bodies are all placed in this little house called the morgue, which you know is derived from the Latin word mors, signifying death. The bodies of all who are found who have perished in the snow are brought here, and placed in the same position in which they were discovered. The air is so rarefied here that no decay can take place, and the bodies dry up. Those found are mostly men, but there is one young boy there, and one poor mother with a little infant in her arms. How sad it is to think of that poor woman, with her little baby, wandering about in the terrible snow-storm, with the cold wind blowing, and drifting the snow in her path and blinding her eyes. How vainly she called for help! How eagerly she must have listened for every sound, hoping that assistance would yet come! And then as it grew dark and she sank down in the snow to rest, and shield her child from the cold wind, how she must have suffered from hunger! And when at last death came to her, and relieved her of her sufferings, think of the poor little baby, all alone in the snow-drift, and at last growing cold and stiff and perishing of hunger. Doubtless many a poor person has been thus exposed, and just when life was expiring, has been found by the good brethren, and carried to the Hospice. Is not this a noble, Christian work, dear children? and, should we not all be very thankful to these good monks, who live away from friends, and the pleasures of the world, that they may assist their suffering brethren? God bless and prosper the “pious monks of St. Bernard,” in their present labor of love, as we are sure he will reward them hereafter.

Adrian.

There was once a little boy, who lived at the very end of the world, far, far away toward the East, near the great and glorious gates through which the sun comes every morning. And this little boy said to himself, “I live so near the sunrise that I mean to go on just a little farther, and see where the sun sleeps at night.”

So one evening he set out to travel eastward, and presently was lost in the mountains, as he might have expected. However, he was not afraid, for he thought he had come so close to the sunrise, that, if he woke very early indeed, he should be sure to see the resting-place of the sun. So he lay down in a cave, and fell asleep. And it was the last night of the old year.

Presently some one called him, and he jumped up and ran to the mouth of the cave. Who was standing there? Was it a fairy man, or a giant, or an angel? He did not know; but he looked up at him and was not afraid; for, whoever it was, he was grand and beautiful and kind.

“Child,” he said, “you have strayed away from home. Come into my house. It is cold here in the cave. I am the New Year, and my house is larger and more splendid than anything you ever saw. Will you come?” And he stretched out his arms.

The boy looked up with trustful eyes into the beautiful face, and said “Yes”; and the New Year took him in his arms, laid the little head upon his strong shoulder, covered the blue eyes a moment with his large hand, and then removed it, and said, “Look!”

The boy looked. The mountains were all gone, and before him was a great palace, misty as cloud, and full of a pale, silvery light. They went in at the great doors, and the New Year sat down, and set the boy before him, holding the small hands in his.

“Child,” he said, “what shall I show you?”

“What is there?” asked the boy.

“What is there? Everything that shall be on earth for a whole year. All things beautiful and wonderful and terrible; all things good and evil; things to be feared, things to be desired, things to be marvelled at. So many! so many, my child! and the time is short.”

“Show me the beautiful things,” said the boy.

“You are right, my child; I will show you beautiful things”; and, holding him by the hand, he led him through corridors which seemed to have no end, for they reached to the horizon; and they passed great doors, on each of which was written the name of a nation; and all nations on earth were there. “A year’s destiny is in each of these halls,” said the New Year, as they passed them by. “But you are too young to understand.” Then he opened a door, and said, as if thinking aloud, “Shall I show him these?”

The boy looked in. There were pictures and statues and patterns and plans of all kinds of architecture and ornamental work.

“What are they?” he asked.

“These are the ideals which I shall show to poets and painters and artists of all kinds, that they may make these things upon the earth. Let us pass on; I have grander things than these”; and he closed the door and opened another. “Look,” he said. “Three hundred and sixty-five sunrises, and, yonder, three hundred and sixty-five sunsets. Glorious pictures,—are they not? I shall show them, one by one, to the world, to as many as care to look, and then hang them up again in my new house on the other side of the world.”

“O, sir,” said the boy, “are you going to move?”

“Yes,” he replied; “I have lived for ages without beginning in this house, and I am going to remove into another, to live there for ages without end.”

“I did not think,” said the child, “that there was room for so large a house in the whole world.”

“There is not,” he replied. “This house is not in the world, but in the realm of the Future, and my new house is to be in the land of the Past; and everything I have will be carried across the whole wide world and shown to it, before I am settled in my new home. But come into my garden.”

They stood on terraces which seemed made of silver cloud, and looked across spaces broader than the sea, all ablaze with blossoms.

“O the flowers! the million million flowers!” cried the boy, delighted.

“I need a million million,” said the New Year, “to supply the world for a spring and a summer and an autumn and a winter.

“You won’t want any for winter, shall you?” said the boy.

“Ah, my child, you have never been where there are flowers all the year round, and have forgotten, perhaps, that when it is winter in one place it is summer in another, to say nothing of the conservatories, which require some of the choicest. But come on; see this room, full of gifts for everybody.”

“For next Christmas?” asked the child.

“For every day,” he said.

There were more things than ever were in all the Crystal Palaces the world has seen; all the lovely things which all the brides of the year were to receive; all the gifts for gold and silver weddings; all birthday presents for children, rich and poor. There were real ponies, saddled and bridled, and penny jumping-jacks; there were miniature vessels and tiny steam-engines, pearls and diamonds and wax dolls. But I could not begin to tell them all, if I sat up all night to tell. The boy’s blue eyes opened wider and wider with wonder and delight. “O, how rich the world will be!” he exclaimed.

The New Year smiled. “I have better things than these,” he said, “holy treasures which I could not well show you,—peace, and hope, and patience, and gladness, and all goodness; and great sorrows, which are to be the best blessings of all to a great many people, only they will not think so when I bring them. You must tell them.”

“Shall I see you again?” the child said.

“Yes, I shall be your friend henceforth. I have things for you, too, but I shall not show them to you now; I will bring them to you, little by little, every day.”

“O, but please show me one thing, only one thing! I have two large rabbits at home, and I do so want two little ones,—cunning little white ones, you know; and mother said perhaps there would be some next year. O, do look and see if there are any little white rabbits!”

The New Year laughed, “See!” he said, opening a door into a wide park, where were playing thousands of young animals of all kinds,—baby lions and tigers, little lambs and kids, and more white rabbits than you could count in a week. “I should not wonder if two of them were for you.”

“O, thank you, thank you!” cried the boy. “And where are the birds?”

“In these eggs,” he answered, showing a vast number of beauties, such as no egg-gatherer on earth ever collected,—all sorts, from the ostrich’s to the humming-bird’s. “And see,” he added, “where the butterflies are hang-up in their little cases. You will see some of them when they come out of their chrysalides.”

“How funny they are!” said the child; and, as he spoke, silver trumpets began to sound. “What is that?” he asked.

“The call, the call!” he replied; “I have been waiting for it from the beginning. My time has come. The Old Year has passed into his new home. I must begin to remove.”

“What shall you send?”

“Starlight first, and rest, and sleep; till it is time to hang up in the east the first of my sunrise pictures. Now go, my child!” And he took him up in his arms again, and made the blue eyes close by kissing him on the eyelids.

When the boy opened them again, he found himself in his father’s arms. “My son, how did you come here? I followed you, with old Bruno’s help, till I found you.”

And he carried him home; and the boy never found where the sun slept at night; and people told him he had been dreaming, when he tried to describe to them the splendors of the New Year’s house.

Mary Ellen Atkinson.

“What an ugly old boat!” Fred said, and kicked it with his foot.

It was an ugly old boat, as it lay on the beach in the golden sunshine, patched all over, seamed, and battered; a great lumbering hulk of a thing, looking quite out of place, both Fred and Matty thought, amongst all the other bright, dapper little boats that surrounded it, or rode out on the blue sea. Fred felt as if he could not express sufficient contempt for it in any other way than by kicking it; so he kicked it once, and then he kicked it again, while Sister Matty stood by and looked at him quite approvingly.

“I never saw such an ugly old boat in all my life!” said Fred.

“I wonder they don’t break it up or burn it,” said Matty, contemptuously.

“Nay, I wonder how they could ever have built it at all!” cried Fred; and his feelings were so much roused now that he kicked it a third time.

“Fred!” suddenly called a sharp, clear voice across the sands; and Fred looked up, not quite easy in his mind, for he knew the voice very well, and he knew a certain warning tone in it, too, which, on many various occasions in the course of his career (he was just seven, and Matty was a year and a half older), had disturbed him at the moments when he was especially enjoying himself. So he looked up, and shouted out “Yes!” in answer; then (though, for his own part, he could not see a vestige of harm in what he was doing), reflecting that it was best to be prudent,—for Fred had learned by sad experience that you hardly ever can tell when you are not getting into mischief in this world,—he stood still, and abstained from kicking the old boat any more.

The lady who had called to him came quickly forward across the sands; and as soon as she was near enough to speak with ease, “Fred,” she said, “if you kick that old boat, and try to break in its sides, you will deserve that somebody should kick you.”

“But it’s so ugly!” said Fred, a little doggedly.

“Is that any reason for kicking it? You are no beauty yourself,” said the lady.

“I’m not as ugly as it is!” cried Fred, indignantly; and he felt so much hurt by the implied comparison that for a moment he instinctively raised his toes again; but luckily he recollected himself in time, and resumed his footing.

“If there were any chance, Fred, that you would do as much good in your day as this old boat has done,—that you would live as noble a life, and have as many lips to bless your name when you are old,—I for one would be content to have you, not only as ugly as it is now, but ten times uglier.”

“O mother, what do you mean?” cried Matty; and both the children stood and stared at her.

“Do you want to know what I mean? Well, sit down here, then, and I’ll tell you. Sit in the shadow of the old boat, if you like, and I’ll tell you one of the noble things—the first noble thing—that it ever did.”

The children sat down, and she began to talk to them. She sat leaning against the old boat’s side. The sparkling yellow sands stretched out all round them, and beyond the sands was the blue, sunny sea, with just a delicate little changing line of foam at its edge as it broke in bright, tiny waves upon the shore. Those waves were dancing a little wilder and more quickly on one side, where the rough, strong pier stretched out amongst the rocks; and the children’s eyes turned oftenest to watch them here, leaping up with sudden, light, airy springs, and tumbling this way and that, as if they were half in play and half in anger.

“I wish there would come a real good storm, with waves like mountains,” Fred had said to Matty, only half an hour ago; and Matty had replied cheerily, that she hoped one would come before they went home again, and that it would be a shame, indeed, if it didn’t; for Fred and Matty did not live at this seaside town,—which, in fact, they had never seen, until two days before, though it had been their mother’s birthplace,—but had another home somewhere else, many miles away.

“You can’t imagine, children,” said the lady, “from what you see now, how wild this coast looks on many a winter day. If you were here then, you would often find that you could hardly keep your footing out on these open sands; and, far off as the sea looks, yet even at this distance the spray from it would come upon your faces, and, if you went near to it, it would almost blind you. Round there where the rocks are, if you once saw the great winter waves rolling, you would never forget them.”

“I wish it was winter now!” cried Fred, eagerly. “I should like to see them.”

“I have seen them often,” said the lady,—“oftener than I ever wish to see them again; for it is a terrible sight, though a grand one too, and sometimes a very, very sad one. Do you know how many a ship has struck out there on those rocks, Fred, and how many a life has been lost upon them?”

“No,” said Fred, a little awe-struck, and looking in her face.

“There have been more wrecks than you would like to think of; and if there are fewer now, and fewer lives lost, it is all owing to this noble old boat, and to the brave men who have manned her.”

“O mother, is she a life-boat, then?” Matty said, and her eyes brightened.

“Yes, she is a life-boat; and I remember long ago, when I was a little girl, sitting just as we are doing now by her side, and hearing my mother tell me of the first night that she put out to sea.

“It was a wild October night. All the town had long gone to bed, and the wind had been roaring and raving for many hours, when very early in the morning, a good while before the dawn, hundreds of people were awakened by the sudden booming of a gun at sea. It was a minute-gun,—a signal from a ship in distress, as almost everybody who heard it knew. Men, and women too, sprang out of their beds, dressed themselves, and hurried down to the beach through the great driving wind. They knew from the near sound of the gun that the vessel must be close in shore, and very soon through the darkness they saw the lights at her mast-head. She had struck on those rocks that you see out there, where the waves are dancing and playing so lightly. They were dancing in another kind of way that night.

“When a ship went on the rocks in a storm like this, there had till now been very little that any one could do for her. Brave men were always at hand (for in all the world, children, there are no braver men than you may find in almost every seaport town or fishing village), ready to go out, when it was possible, through the surf, and try to throw ropes to the poor perishing people, and so to save a few lives now and then. But sometimes, when the sea was very high, nothing of this kind was possible, and then there was nothing for it but to stand still with aching hearts, and watch the wrecked ship breaking up, as far as it was possible to watch it in the darkness, or through the blinding spray, and listen helplessly to the sad cries that sometimes reached the shore even above the wildest roaring of the storm. But to-night something was to be tried that had never been tried yet.

“Not long before, a few gentlemen of the town, headed by one whose name—Well, never mind his name just now,” the lady said, interrupting herself with a half-smile; “we will merely at present call him the Master; for at this time in everything that was done he was the master. These gentlemen had met together, and decided that they would subscribe amongst themselves for a life-boat. So the boat had been built, had been in its place for a month or two, and the fishermen had gravely shaken their heads over it. It was a queer, new-fangled-looking sort of thing, they said to one another. And they had looked very doubtfully at the Master when he talked to them, and tried to make them understand how a boat that was built like this life-boat of his, all cased and lined with cork to make it buoyant, might put out safely on a sea in which their ordinary small craft could never live. The Master talked very well, and had a shrewd tongue of his own, they said; but he was only a landsman; what could he know about the sea?

“Now, as they crowded down upon the beach, every man of them was wondering what the Master meant to do. He soon left them in no doubt as to that. Hardly ten minutes had passed since the first gun had been fired, when he was at the boat-house, unlocking the door.

“A little knot of men were gathered round him, some of whom had followed him out of curiosity, and a few of them, perhaps, because they were ready to trust him. He threw the doors wide open.

“ ‘She’s all ready. We’ll have her down in a couple of minutes,’ he cried.

“It was he who had taken care beforehand that she should be ready. He didn’t lose a moment.

“ ‘Here, lads! Throw these chains across your shoulders,’ he called aloud. ‘She’ll run as fast as you can go with her. Steady now! steady! All’s right!’

“They had only to draw her by her chains (you shall see, some day, children, the sort of bed on which she lies), and she ran forward on her two great wheels, like a carriage. In little more than the two minutes those wheels were crunching down the soft sand of the beach.

“A few of the people there set up a shout as the boat came in sight, but the greater number of them held their tongues, and only stood and shook their heads again, as they had been doing any time for the last six weeks.

“ ‘We’re none of us cowards, that I know of, but the Master’s like to find himself mistaken, if he thinks to get a crew for his fancy boat on such a night as this,’ one man said to a little knot of others that were standing with him; and there was not one of them but seemed to think as he did.

“ ‘I wouldn’t go out in her for ten pound,’ one said.

“ ‘She’ll be swamped before ever they can launch her,’ cried another.

“For it was indeed a fearful night, wild enough to make the bravest there grow grave at the thought of putting out to sea, even in the strongest boat that ever hands built. And yet, wild as it was, the Master went straight on with his work, as if he hardly knew that the wind was blowing, or the sea flinging its surf into his face.

“They brought the boat down almost to the water’s edge, and then the men who had been drawing her stood still. The Master stood still too, and looked about him. It was dark night yet, you know; he couldn’t see much; he stood with his back to the white boat, and with the light of a lantern that some one held falling full upon him. Everybody could see him, and he was worth seeing, children, for in all the town there was no nobler-looking man,—but he for his part could only see a dim mass of faces pressing near him,—eager and anxious faces, all curious to know what he would say or do.

“ ‘Now, my lads, who will go with her?’ he called out loud.

“Then he turned from one side to the other; but no one answered him. There was a little movement in the crowd, but that was all; no one seemed ready to be the first to speak.

“The Master looked sharp round him, and spoke again.

“ ‘I didn’t think you would have let me ask twice. What! is no one willing? You, John Martin,’—and he pointed suddenly at one man whose face he saw,—‘will you come?’

“In an instant the crowd made a clear way for the man who had been singled out to pass through it; but he merely came forward a step or two, and as though he only did it because he was ashamed.

“All at once a voice not far from the Master began to speak in a grumbling, discontented way.

“ ‘It’s easy for them as stay at home themselves to call on poor fellows like us to throw away our lives.’

“The Master flashed round with his quick, bright eyes. He could not see who had spoken, for it was all dark in the direction whence the voice had come; but he looked straight that way.

“ ‘Do you think I ask any of you to risk what I am not going to risk myself?’ he cried, in such a voice that everybody seemed to hear him through all the noise of the waves. ‘Whoever may be second, I’ll be the first man to step into her. Now, who will come next?’

“They gave him a cheer all at once, and two or three voices called out ‘Shame!’ to the man who had spoken in the dark. Then, the next instant, John Martin was at his side.

“‘I’ll be the next, Master,’ he said. And from that moment, one after another, they pressed forward,—they were such really brave men, though they had held back for a few seconds at the first. In two or three minutes the Master might have manned his boat twice over. It was not, probably, that they believed in what it could do a bit more than they had done for weeks past, but something had been roused in them by his words. The same feeling which has made all generous-hearted men who have ever lived or ever will live in this world ready for similar risk made them ready at his asking to face danger and death.

“So they launched the boat. That was no easy matter to do, but they did it safely; and in a few moments all that the crowd on shore could see was the little white spot she made, tossed up and down, and here and there, on the dark, wild waves.

“She had not far to go, but it must have been a hard voyage, children; and I think the Master had need indeed to be a brave man, sailing, as he did, with a crew that had no confidence in his power to lead them, but had followed him only because for the moment their hearts were fired by his own courage. Perhaps, when it was too late, some of them might have repented, and wished that they had their feet on dry land again. Perhaps, as they fought their wild way on, which must have seemed such a hopeless way to most of them, some might even have reproached him for having tempted them to leave their wives to become widows and their children fatherless. At any rate, some of those poor wives on shore spoke out like this, crying, and wringing their hands. For the most part the women had been slower to reach the beach than the men, and several who had husbands amongst those that had sailed in the life-boat only learned where they had gone when the boat had been out for half her time at sea. When they did learn it, they were wild with terror, and stood wailing and crying like broken-hearted creatures, for they thought that they should never look on their husbands’ faces any more.

“The boat was out for, perhaps, half an hour,—a long half-hour! Can you fancy how the crowd of people watched her from the shore? Again and again they lost sight of her, and thought that she had gone down; but again and again the white, bright spot gleamed upon the waves, like a star of hope to those who were watching her with strained eyes and beating hearts. They shouted when she rose, cheering her on with cries that she could not hear; and when she sank and disappeared they gasped for breath, and could not speak to one another. And then, presently, the pale gray dawn slowly began to break.

“It was half twilight when the life-boat came back to land, with her work done. They could see her more plainly then, coming slowly, tossed and beaten wildly, yet still battling her brave way on, minute after minute bringing her nearer home. They flocked down to the water’s edge—and beyond it—to meet her, some of them entering the very surf where they could scarcely stand, that they might be the first to lay their hands upon her, the noble boat! and drag her through to the safe sands. As they reached her, what a shout they gave! and as one by one her crew sprang out,—the men who had sailed in her, and the men whom she had saved,—how they caught and wrung them by the hands, as if they had all been friends alike! The wreck was a foreign fishing-smack, and they had brought off every man on board.

“The Master had been the first to set his foot within the boat, and he was the last to leave her. He stood up, waiting till his time came, in the pale half-light; and against the gray morning sky, they all saw him, and broke suddenly into a cheer that was like a blessing from many hundred lips. They gathered about him as he jumped on shore. He had been right, and they wrong, they said. Even the poor crying women, who had been saying such bitter things of him five minutes before, came round him now with their eyes wet with another kind of tears.

“The old boat has been out since that night, children, in many another wild sea. See how she has got patched all over, how worn and battered she is! But her scars are all noble, like a soldier’s wounds; for every one of them she can count a life that she has saved. Would you like her better now, Fred, do you think, if she were spruce and bright and new? Will you ever have the heart again to lay a rough touch on her worn old sides?”

Fred hung his head a little abashed, and the lady sat silent for a moment or two; then, looking up again, she went on speaking:—

“But, old as she is, she is not past work even yet; though all those who sailed in her that first night have finished their work long ago, and most of their names even are forgotten now. Amongst them all there is only one name that is remembered still, but that will be remembered as long as the old boat herself lives. When that night was over, in gratitude to the Master, and in memory of what he had done, they called her by his name. The old letters are there still where they were painted; go round and read them.”

The children found where the name was written in dim, dark letters; but the first word was a long one, and Fred knit his brows in deep perplexity over it. Matty, however, who could read better than Fred, began to spell it out.

“C-h-r-i-s, Chris,” spelt Matty, “t-o, to—” And then Matty’s face lighted up suddenly into a look of bright surprise. “ ‘Christopher Douglas’!” cried Matty. “Why, that’s grandpapa’s name!”

And then the lady looked round and laughed.

“Yes, it is grandpapa’s name, and it was grandpapa’s father’s name before him. And for my own part, children, I think the noblest record of his life that your great-grandfather has left behind him are those dim letters on the old life-boat.”

Georgiana M. Craik.

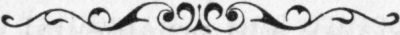

It was the year 627, more than twelve hundred and forty years ago. England was peopled by Anglo-Saxons, and divided into several kingdoms, frequently warring with one another. In some the Christian religion was taught and practised, and in others a cruel and bloody paganism was the faith of king and people. The fierce Northumbrians still clung to their idols, and worshipped huge images of Woden and Thor, Saturn and Freya; sometimes killing children, and the prisoners captured in war, as sacrifices to their false gods.

Edwin, the King of Northumbria, a year before had married Ethelberga, the daughter of a Christian king of a neighboring Anglo-Saxon people. At first her father objected to the marriage, for Edwin was a pagan. But the Northumbrian king promised that his wife should enjoy her own religion unmolested, so Ethelberga was married. She was accompanied to her new home by the venerable Bishop Paulinus and several priests, who hoped to convert the fierce Northumbrians to Christianity. Their efforts seemed to meet with little success. The people listened to their preaching in grim silence, and then turned to worship the gloomy idols their fathers had worshipped. Christianity, they said, might do for women, but not for Saxon men. It taught that people should love their enemies, whilst Thor, the god of war, said they should slay them, and their fathers, who were brave warriors, had always done so. Their Queen, who was good and gentle, was a Christian, but she was a woman. Their King, valiant and fearless in battle, sacrificed to Woden and Thor, and they would do as their King did.

For a year the good Bishop reasoned with Edwin, but to little purpose. For a year the gentle Ethelberga pleaded with him, but he did not yield. He became silent and thoughtful, sitting for hours in deep study after the preaching of Paulinus and the pleading of Ethelberga, but gave no other sign of conversion. Then a daughter was born, and the pagan priests came to bear her to the temple, to present her before the gods. But Edwin said: “She belongs to her mother. Let her become a Christian.” So the child was baptized Eanfled, and the hopes of the Queen and Bishop became stronger.

A short time afterwards, as the King sat thoughtfully listening to the arguments of the Bishop and the Queen, he declared that he was almost ready to become a Christian, and would do so if he were not a king; but he feared to change the faith of his people. Then, rising, he said he would summon his nobles, his chief priests, and his wise men, for consultation, and, if they thought it best, Northumbria should become Christian. Messengers were at once sent throughout the kingdom to summon the chiefs and men of rank to the Witan, or great council of the kingdom.

The council was to be held at the royal palace of Godmundingham, near the banks of the river Swale. A high wall of earth surrounded the palace and its ample court-yard, the entrance being through a single gateway. In the centre of the enclosure was a large wooden building, with pinnacles at the corners and on the points of the high pitched roof. The posts and beams were decorated with rude carvings. An open dome surmounted the centre of the building, through the windows of which the smoke found its way; for there were no chimneys in those days. This was the great hall where all the household took their meals, where guests were received and entertained, and where the councils were held. The heavy doors, iron-clasped and iron-bolted, remained open from morning to night, that all might come and go as they pleased. Only in time of war, or when attack was feared, were the great doors shut in the daytime.

Around the hall were smaller buildings, slightly built and with feeble doors. These were the sleeping-places of the King and Queen, and of the principal members of their household, the others sleeping in the hall, stretched on the floor. Each of the “bowers,” or chambers, had but one room, and all the buildings were detached from one another. The furniture was very simple, the beds of great nobles being oftentimes merely bags of straw on the bare floor, and that of the Queen but a simple crib. A stool or two, and sometimes a chest, completed the bedroom furniture. Besides the chambers, there were some small buildings for offices and out-houses. The palace of a Saxon king, in the seventh century, was a very simple affair,—the wind blowing through the loosely made wooden walls, and the sleeping-chambers being no better than a poor shanty of the present day.

It was a morning in early spring. The last snow had fallen and disappeared. Nestled amid the young grass, the modest, blush-tipped daisy sparsely sprinkled the turf. The pale primrose rested cosily among the matted and twisted roots of the trees, and the early violet peeped shyly from out fern-shaded nooks. The tree-buds were bursting into green, and amid their branches the birds twittered and fluttered, as they busily worked at nest-building. A butterfly that had come before its fellows flitted uncertainly about, basking in the early sunlight to strengthen its wings for more active flight. A sturdy little half-naked Saxon boy chased the winged visitor awhile, but soon gave up the pursuit to return and watch the proceedings around the king’s house.

There was no little stir and bustle in and around the palace. In the court-yard great fires were blazing under huge caldrons, in which whole oxen and swine were seething. In other caldrons meats and vegetables were boiling together, and were frequently stirred by the cooks with ladles and hooks. At smaller fires geese were roasting on spits turned by boys, who slyly pressed their fingers against the roast, and licked their greasy tips with an enjoyment heightened by the peril they ran of a hearty thwack from the stick of the master-cook. Stout men bent under loads of fagots for the fires in the court-yard, and others carried billets of wood for the fire on the raised hearth in the centre of the hall; for the spring was still young, and the air was chilly.

The hall itself was being made ready for the council and for the great feast that was to follow it. The place of honor was at the end of the apartment farthest from the main door. Here the floor was raised a few inches from the ground, this elevation being called the dais. On this was placed a high-backed chair for the King’s throne, and by its side a lower chair for the Queen when she came to the feast,—for she could take no part in the council. On either side of the throne was a cushioned bench for the principal men, and down the sides of the hall were other benches for the men of less rank and the servants of the household. The boards and cross-legged stands which served for tables were piled up at the lower end until the time for the feast. The unpainted and smoke-begrimed pillars and beams, and the warped and shrunken wall-boards, through whose cracks and crannies the wind whistled in storms, were screened behind and around the dais by tapestry hung on pegs, and brilliant with scarlet and purple dyes and with embroidery of gold and silver threads. On the pegs around the other parts of the room were hung shields and armor, bows and quivers. The fire in the middle of the floor crackled and blazed, sending its blue smoke up to play in wreaths and curls among the dark rafters overhead.