* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Canada and its Provinces Vol 6 of 23

Date of first publication: 1914

Author: Adam Shortt (1859-1931) and Arthur G. Doughty (1860-1936)

Date first posted: Oct. 7, 2018

Date last updated: Oct. 7, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20181011

This ebook was produced by: Iona Vaughn, Marcia Brooks, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Archives Edition

CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES

IN TWENTY-TWO VOLUMES AND INDEX

| (Vols. 1 and 2) | (Vols. 13 and 14) |

| SECTION I | SECTION VII |

| NEW FRANCE, 1534-1760 | THE ATLANTIC PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 3 and 4) | (Vols. 15 and 16) |

| SECTION II | SECTION VIII |

| BRITISH DOMINION, 1760-1840 | THE PROVINCE OF QUEBEC |

| (Vol. 5) | (Vols. 17 and 18) |

| SECTION III | SECTION IX |

| UNITED CANADA, 1840-1867 | THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO |

| (Vols. 6, 7, and 8) | (Vols. 19 and 20) |

| SECTION IV | SECTION X |

| THE DOMINION: POLITICAL EVOLUTION | THE PRAIRIE PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 9 and 10) | (Vols. 21 and 22) |

| SECTION V | SECTION XI |

| THE DOMINION: INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION | THE PACIFIC PROVINCE |

| (Vols. 11 and 12) | (Vol. 23) |

| SECTION VI | SECTION XII |

| THE DOMINION: MISSIONS; ARTS AND LETTERS | DOCUMENTARY NOTES GENERAL INDEX |

GENERAL EDITORS

ADAM SHORTT

ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

| Thomas Chapais | Alfred D. DeCelles | |

| F. P. Walton | George M. Wrong | |

| William L. Grant | Andrew Macphail | |

| James Bonar | A. H. U. Colquhoun | |

| D. M. Duncan | Robert Kilpatrick | |

| Thomas Guthrie Marquis | ||

VOL. 6

SECTION IV

THE DOMINION

POLITICAL EVOLUTION

PART I

Photogravure. Annan. Glasgow

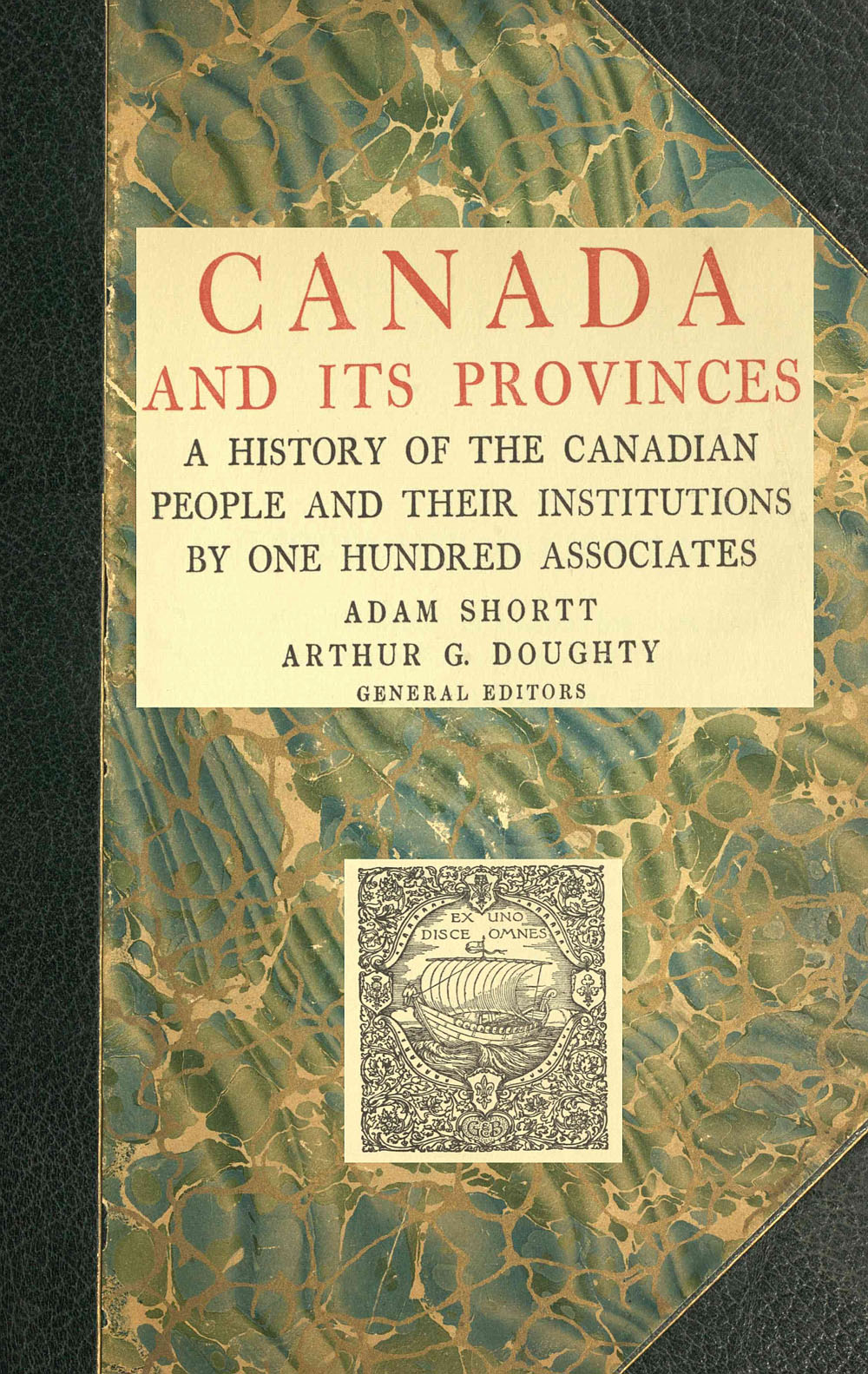

| Alexander Mackenzie | Sir John Abbott | Sir John Thompson | ||

| 1873-78 | 1891-92 | 1892-94 | ||

| Sir Wilfrid Laurier | Sir John A. Macdonald | |||

| 1896-1911 | 1867-73, 1878-91 | |||

| Sir Mackenzie Bowell | Sir Charles Tupper | Robert Laird Borden | ||

| 1894-96 | 1896 | 1911- |

PRIME MINISTERS, 1867-1912

From photographs by Topley, Ottawa, and Notman, Montreal

Copyright in all countries subscribing to

the Berne Convention

| PAGE | |||

| THE FEDERATION: GENERAL OUTLINES, 1867-1912. By George M. Wrong | 3 | ||

| THE NEW DOMINION, 1867-1873. By John Lewis | |||

| I. | CHIEF ARCHITECTS OF CONFEDERATION | 15 | |

| II. | THE COALITION GOVERNMENT | 20 | |

| III. | THE INTERCOLONIAL RAILWAY | 29 | |

| IV. | EXPANSION WESTWARD | 31 | |

| Annexing the Great West–Red River Insurrection–Donald Smith's Mission–The Scott Tragedy–Bishop Taché as Peacemaker–The Wolseley Expedition–The Amnesty | |||

| V. | THE WASHINGTON TREATY | 45 | |

| VI. | FALL OF THE MACDONALD GOVERNMENT | 52 | |

| THE MACKENZIE ADMINISTRATION, 1873-1878. By John Lewis | |||

| I. | THE LIBERALS IN POWER | 63 | |

| Protests from British Columbia–Reciprocity–Canada First–The Supreme Court–The Clergy and Politics–Temperance Legislation–The Letellier Case | |||

| II. | THE NATIONAL POLICY | 78 | |

| Defeat of Mackenzie | |||

| CANADA UNDER MACDONALD, 1878-1891. By John Lewis | |||

| THE NEW TARIFF | 87 | ||

| THE CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY | 88 | ||

| THE REDISTRIBUTION OF 1882 | 91 | ||

| THE ONTARIO BOUNDARY | 93 | ||

| THE STREAMS BILL | 96 | ||

| THE LICENCE LAW | 97 | ||

| THE FRANCHISE | 98 | ||

| THE NORTH-WEST REBELLION | 99 | ||

| JESUIT ESTATES CASE | 106 | ||

| RECIPROCITY | 108 | ||

| FOUR PREMIERS, 1891-1896. By John Lewis | |||

| I. | SIR JOHN ABBOTT | 119 | |

| II. | SIR JOHN THOMPSON | 120 | |

| III. | SIR MACKENZIE BOWELL | 125 | |

| IV. | SIR CHARLES TUPPER | 126 | |

| THE LAURIER RÉGIME, 1896-1911. By John Lewis | |||

| THE MANITOBA SCHOOL QUESTION | 131 | ||

| THE NEW TARIFF | 132 | ||

| THE JOINT HIGH COMMISSION | 134 | ||

| THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR | 137 | ||

| PREFERENTIAL TRADE | 144 | ||

| THE ALASKAN BOUNDARY | 145 | ||

| A NEW TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILWAY | 148 | ||

| LORD DUNDONALD | 151 | ||

| THE GENERAL ELECTION OF 1904 | 152 | ||

| NEW WESTERN PROVINCES | 153 | ||

| A SALARY BILL | 157 | ||

| THE LORD'S DAY ACT | 159 | ||

| THE DEPARTMENT OF LABOUR | 160 | ||

| OLD AGE ANNUITIES | 161 | ||

| CHARGES OF MALADMINISTRATION | 162 | ||

| CIVIL SERVICE REFORM | 163 | ||

| THE HALIFAX PLATFORM | 165 | ||

| THE ELECTION OF 1908 | 165 | ||

| THE CANADIAN NAVY | 167 | ||

| THE FISHERIES QUESTION | 172 | ||

| RECIPROCITY | 176 | ||

| THE NATIONALISTS | 186 | ||

| IMPERIAL CONFERENCES | 188 | ||

| GROWTH OF POPULATION | 199 | ||

| CANADIAN EXPANSION | 203 | ||

| THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION. By A. H. F. Lefroy | |||

| I. | CONSTITUENT PARTS AND FUNDAMENTAL ARRANGEMENTS | 209 | |

| II. | STATUTORY FOUNDATION OF THE CONSTITUTION | 215 | |

| The Crown in Canada–Dominion Veto of Provincial Acts | |||

| III. | LAW-MAKING BODIES | 221 | |

| Imperial Legislation affecting Canada–Canadian Legislative Powers–Observations on the Federation Act–Contrasts with the United States–General Scheme of Dominion Powers–The Provincial Residuary Power–Predominance of Dominion Laws–Limitation of Provincial Powers–The Federation Act as a Whole–Plenary Powers of Canadian Legislatures–Dominion Interference with Provincial Legislation–Provincial Interference with Dominion Legislation–Provincial Independence and Autonomy–Legislative Power distributed by Subject, not by Area–Aspects of Legislation–The True Nature and Character of Legislation–Proprietary Rights under the Federation Act | |||

| IV. | SPECIFIC POWERS OF LEGISLATION | 253 | |

| Dominion Powers under Section 91–Provincial Powers | |||

| V. | A CONSTRUCTIVE FEAT OF STATESMANSHIP | 264 | |

| THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. By Sir Joseph Pope | 271 | ||

| THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL | 272 | ||

| THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL'S SECRETARY | 277 | ||

| THE PRIVY COUNCIL | 278 | ||

| THE PARLIAMENT | 279 | ||

| THE SENATE | 280 | ||

| THE HOUSE OF COMMONS | 286 | ||

| THE CABINET | 300 | ||

| THE PRIME MINISTER | 304 | ||

| THE PRESIDENT OF THE PRIVY COUNCIL | 308 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF FINANCE | 311 | ||

| THE TREASURY BOARD | 314 | ||

| THE AUDITOR-GENERAL | 315 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE | 316 | ||

| THE SOLICITOR-GENERAL | 320 | ||

| THE SECRETARY OF STATE | 320 | ||

| THE DEPARTMENT OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS | 322 | ||

| THE KING'S PRINTER | 324 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF PUBLIC WORKS | 325 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF RAILWAYS AND CANALS | 327 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR | 328 | ||

| THE DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN AFFAIRS | 331 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE | 333 | ||

| THE DOMINION ARCHIVES | 334 | ||

| THE POSTMASTER-GENERAL | 336 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF MARINE AND FISHERIES | 337 | ||

| THE DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVAL SERVICE | 339 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF CUSTOMS | 339 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF TRADE AND COMMERCE | 341 | ||

| THE DEPARTMENT OF MINES | 343 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF MILITIA AND DEFENCE | 345 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF INLAND REVENUE | 348 | ||

| THE ROYAL NORTH-WEST MOUNTED POLICE | 349 | ||

| THE MINISTER OF LABOUR | 351 | ||

| THE DEPUTY MINISTERS | 354 | ||

| PRIVATE SECRETARIES TO MINISTERS | 356 | ||

| THE LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT | 357 | ||

| THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION | 357 | ||

| THE COMMISSION OF CONSERVATION | 362 | ||

| THE INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION | 363 | ||

| THE HIGH COMMISSIONER | 369 | ||

| THE AGENT OF CANADA IN PARIS | 370 | ||

| THE SUPREME COURT | 371 | ||

| THE EXCHEQUER COURT | 372 | ||

| PRIME MINISTERS, 1867-1912 | Frontispiece | ||

| From photographs by Topley, Ottawa, and Notman, Montreal | |||

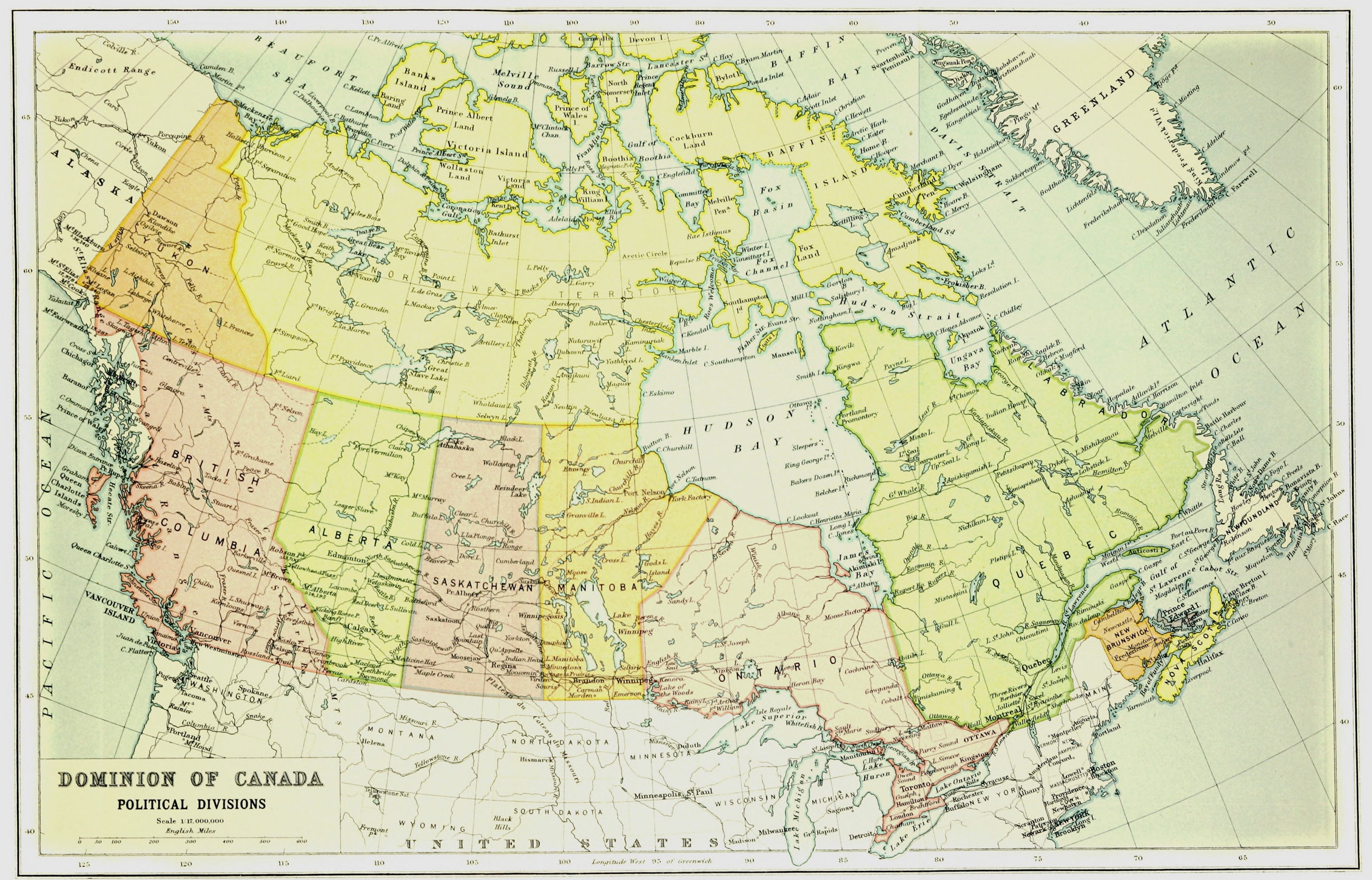

| POLITICAL DIVISIONS OF CANADA | Facing page | 1 | |

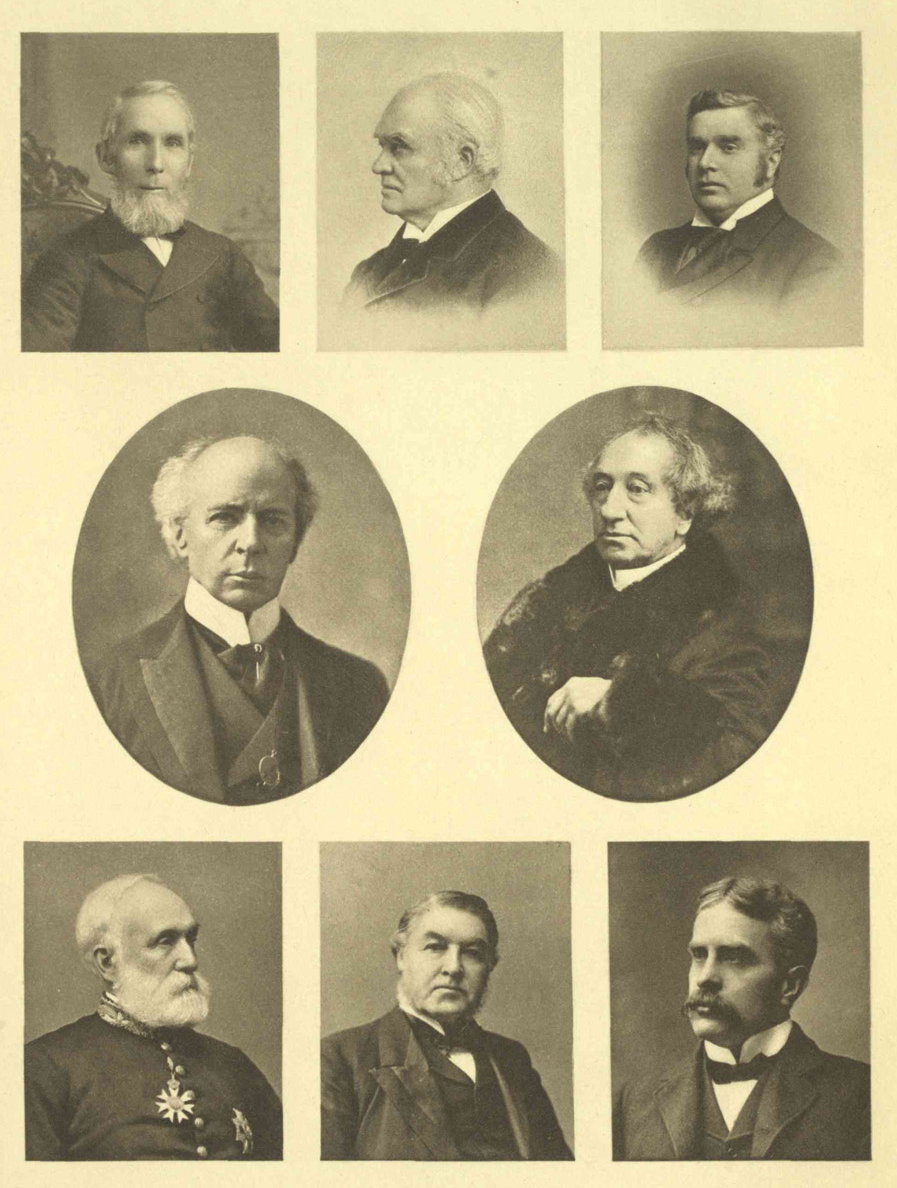

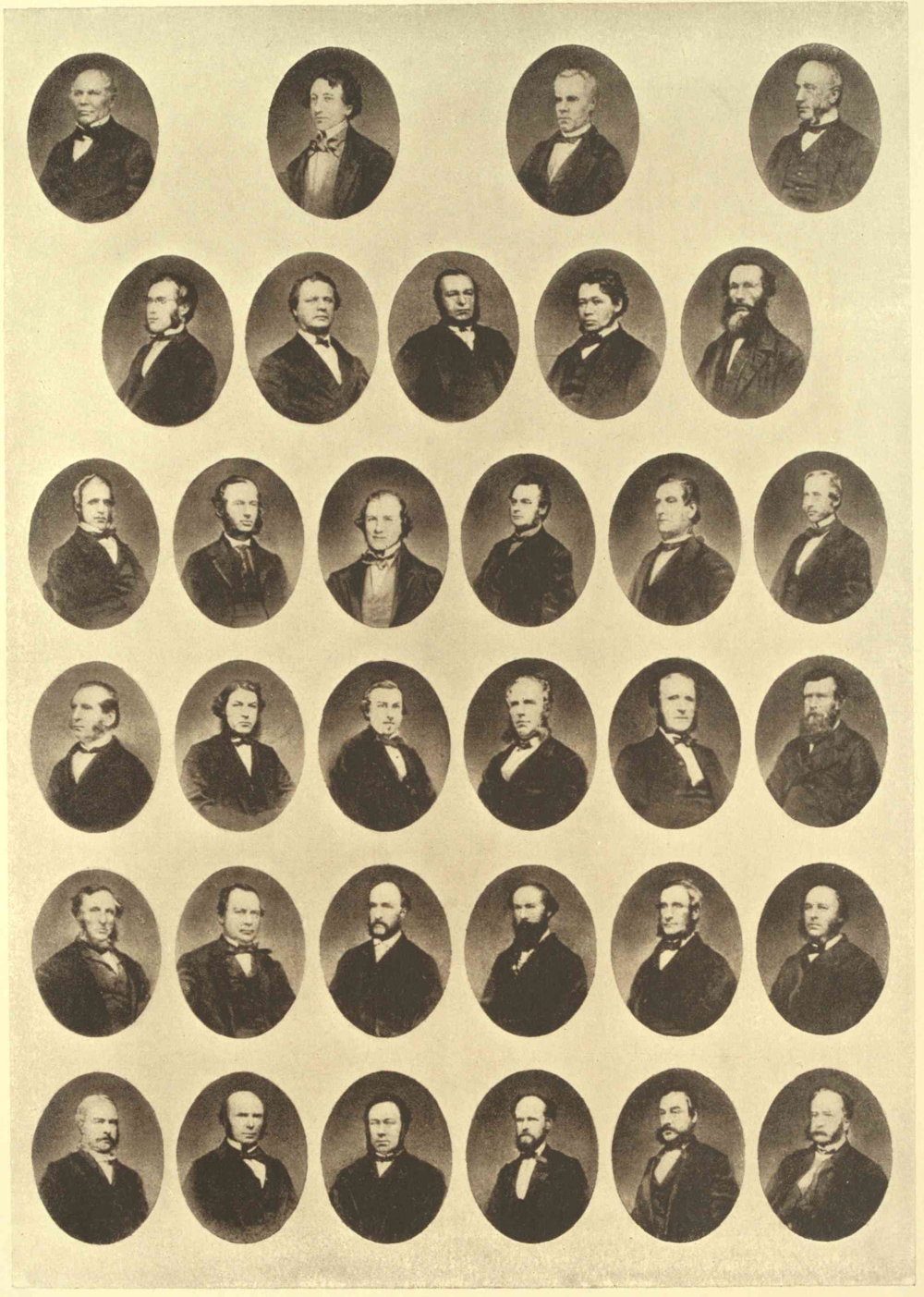

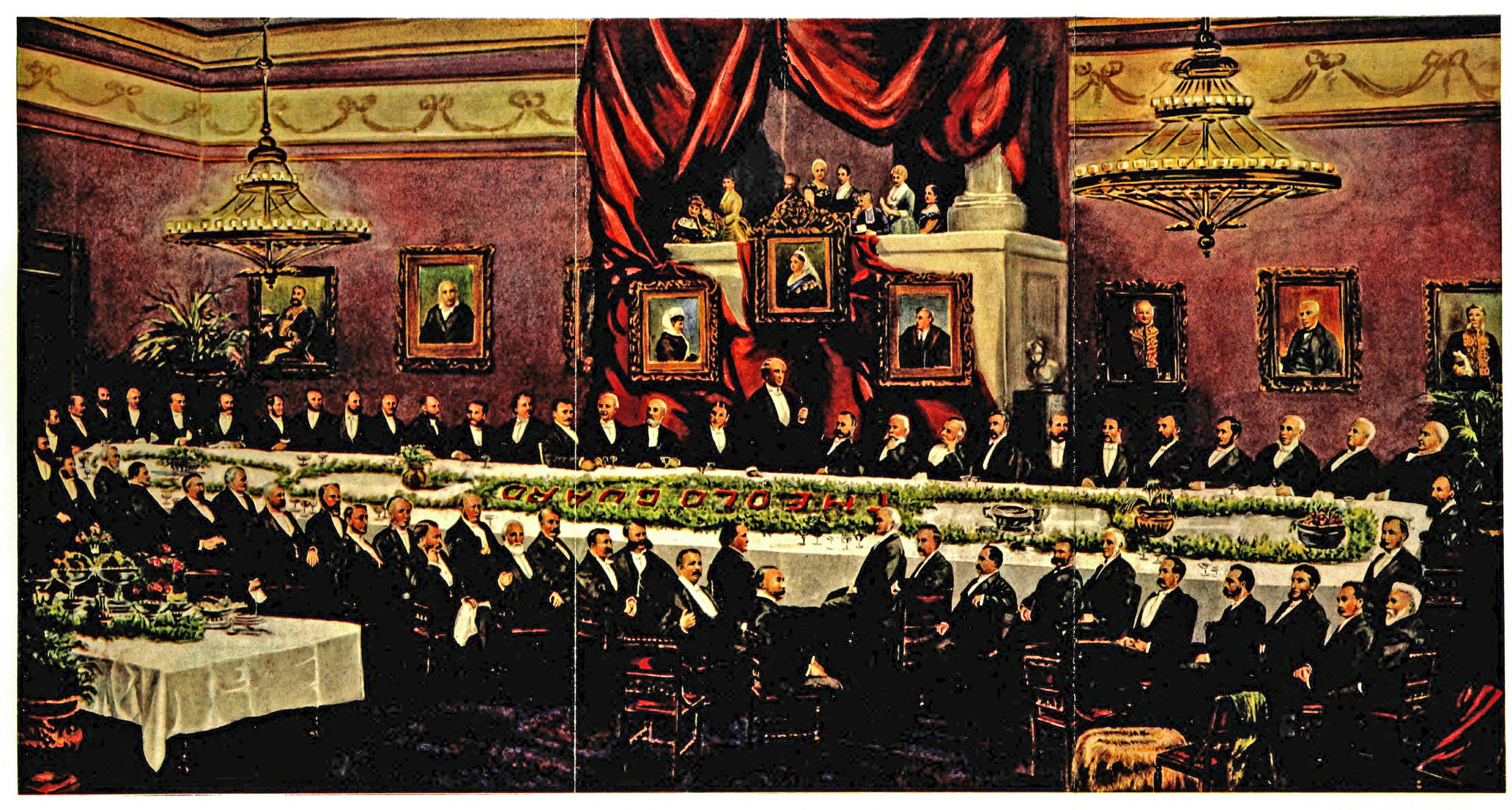

| THE FATHERS OF CONFEDERATION | " | 10 | |

| From a collection of portraits in the Dominion Archives | |||

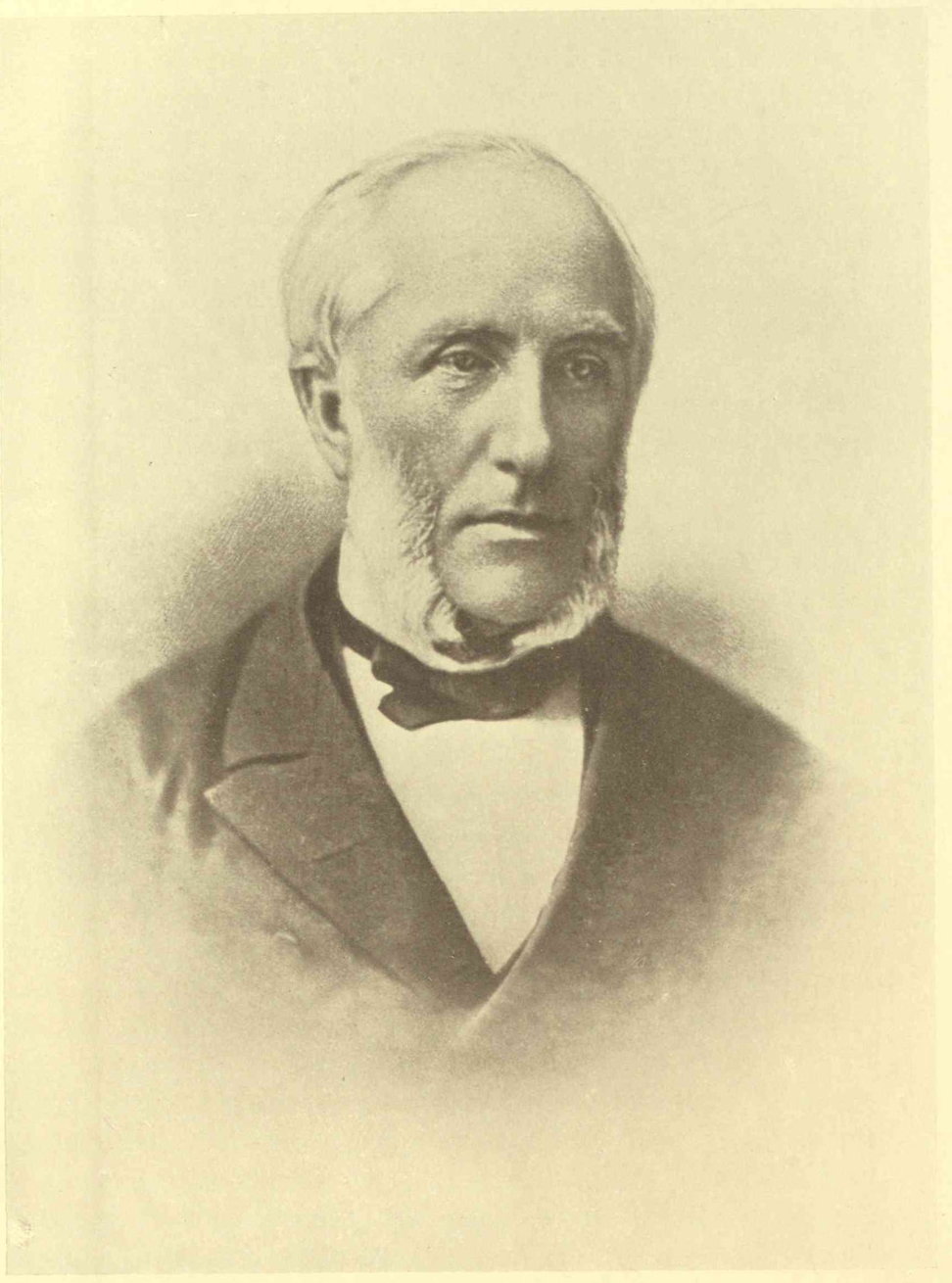

| GEORGE BROWN | " | 18 | |

| From a photograph in the possession of Mrs Freeland Barbour, Edinburgh | |||

| PROCLAMATION OF THE CONFEDERATION OF CANADA | " | 20 | |

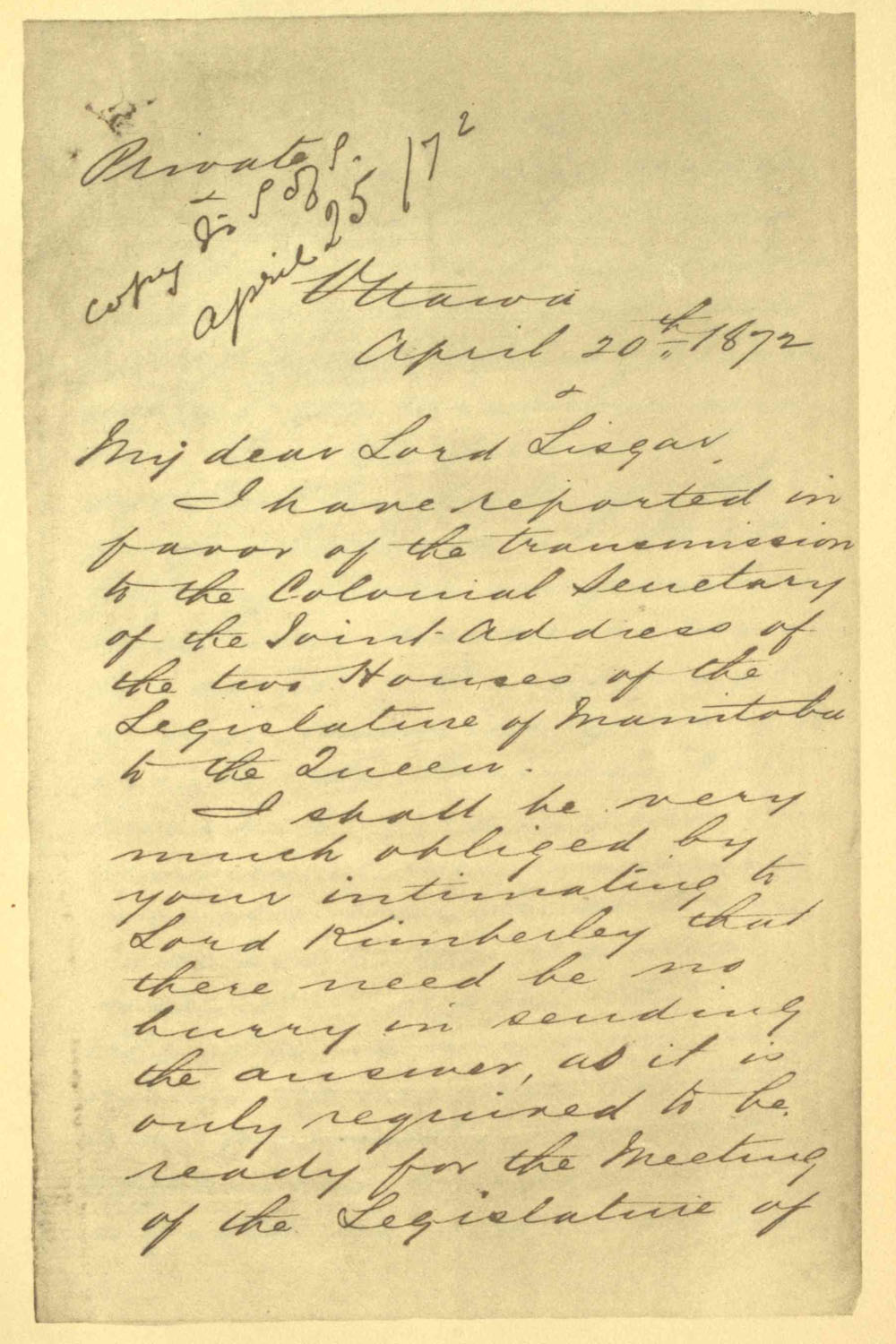

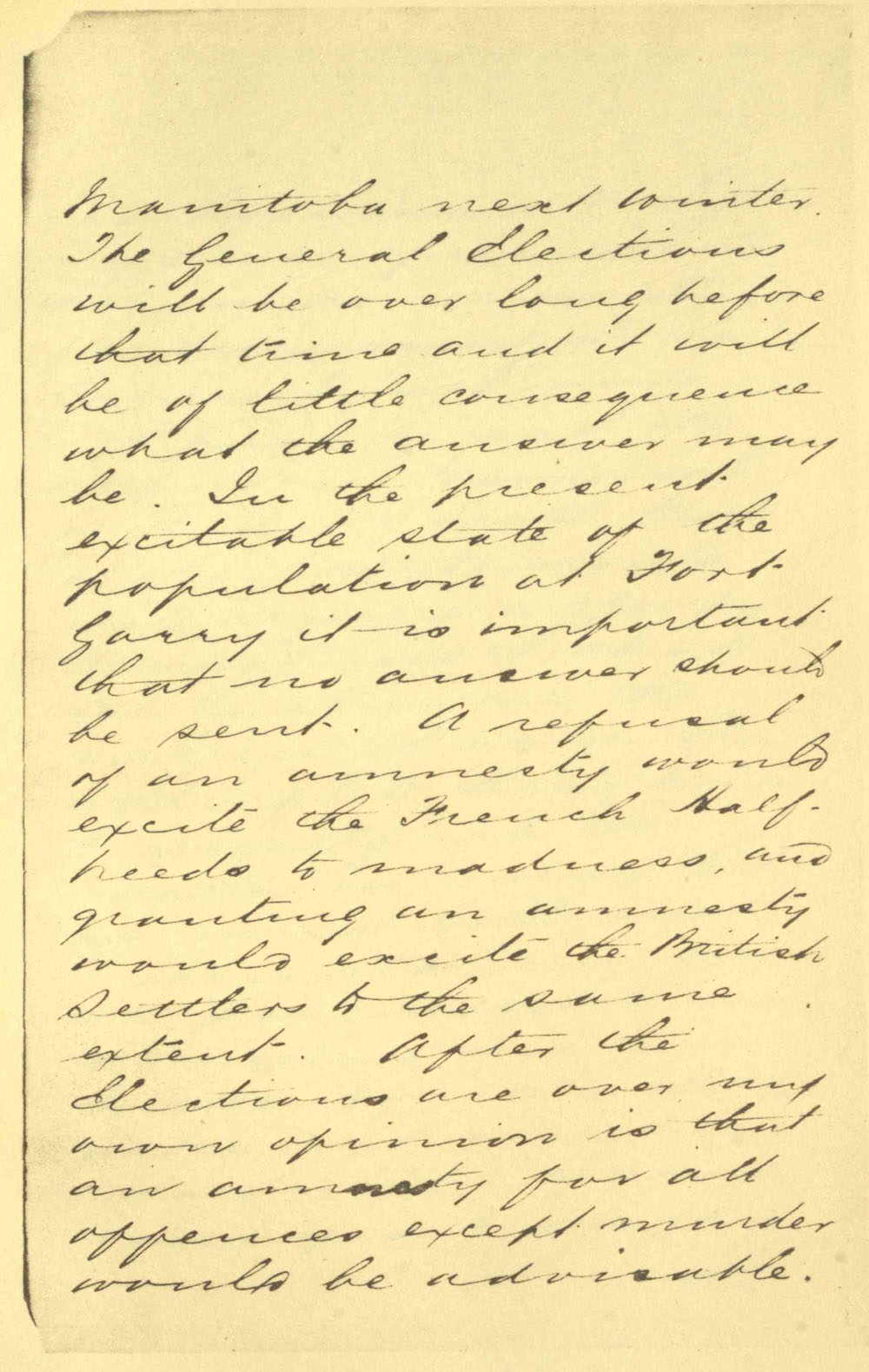

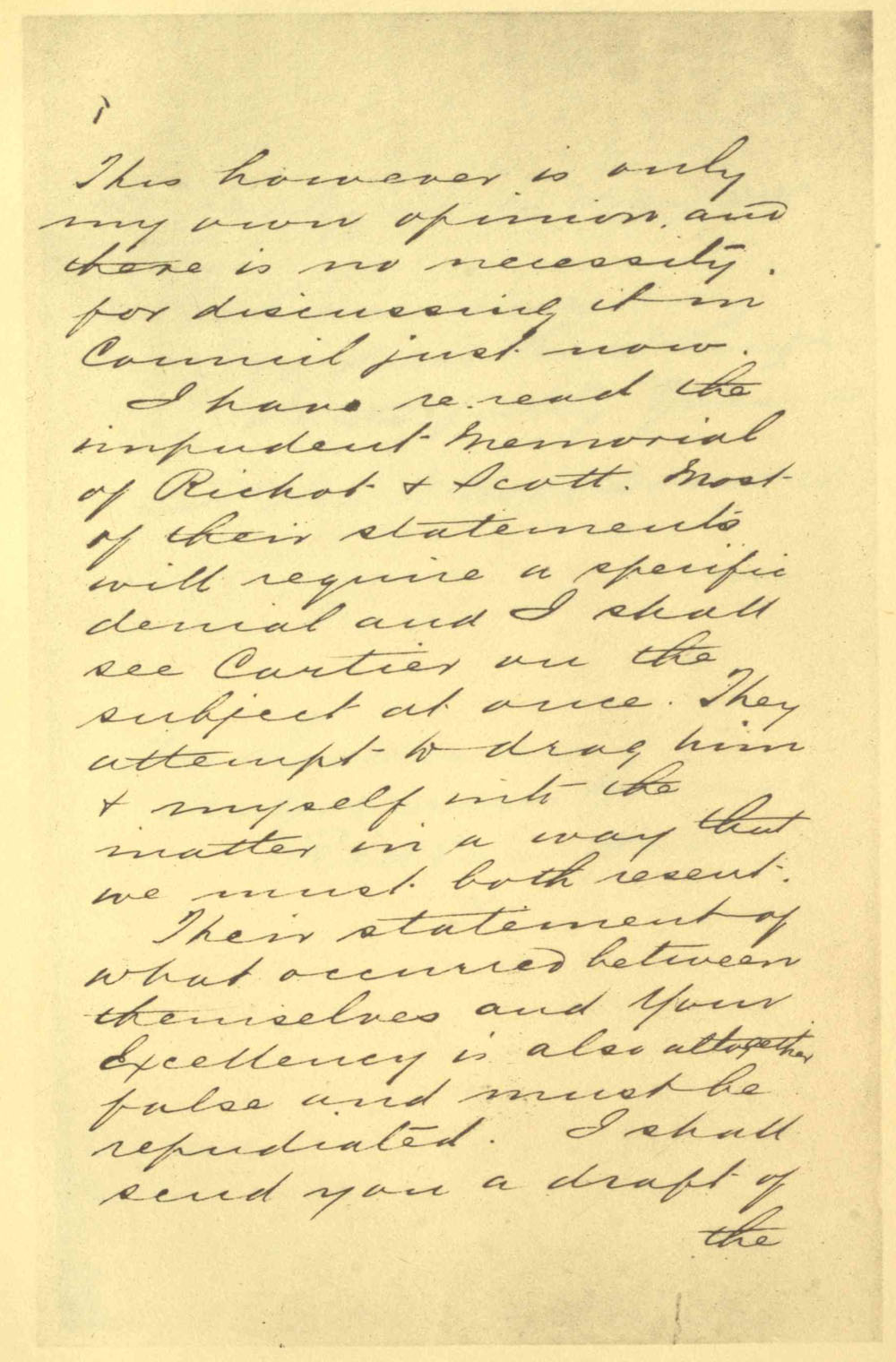

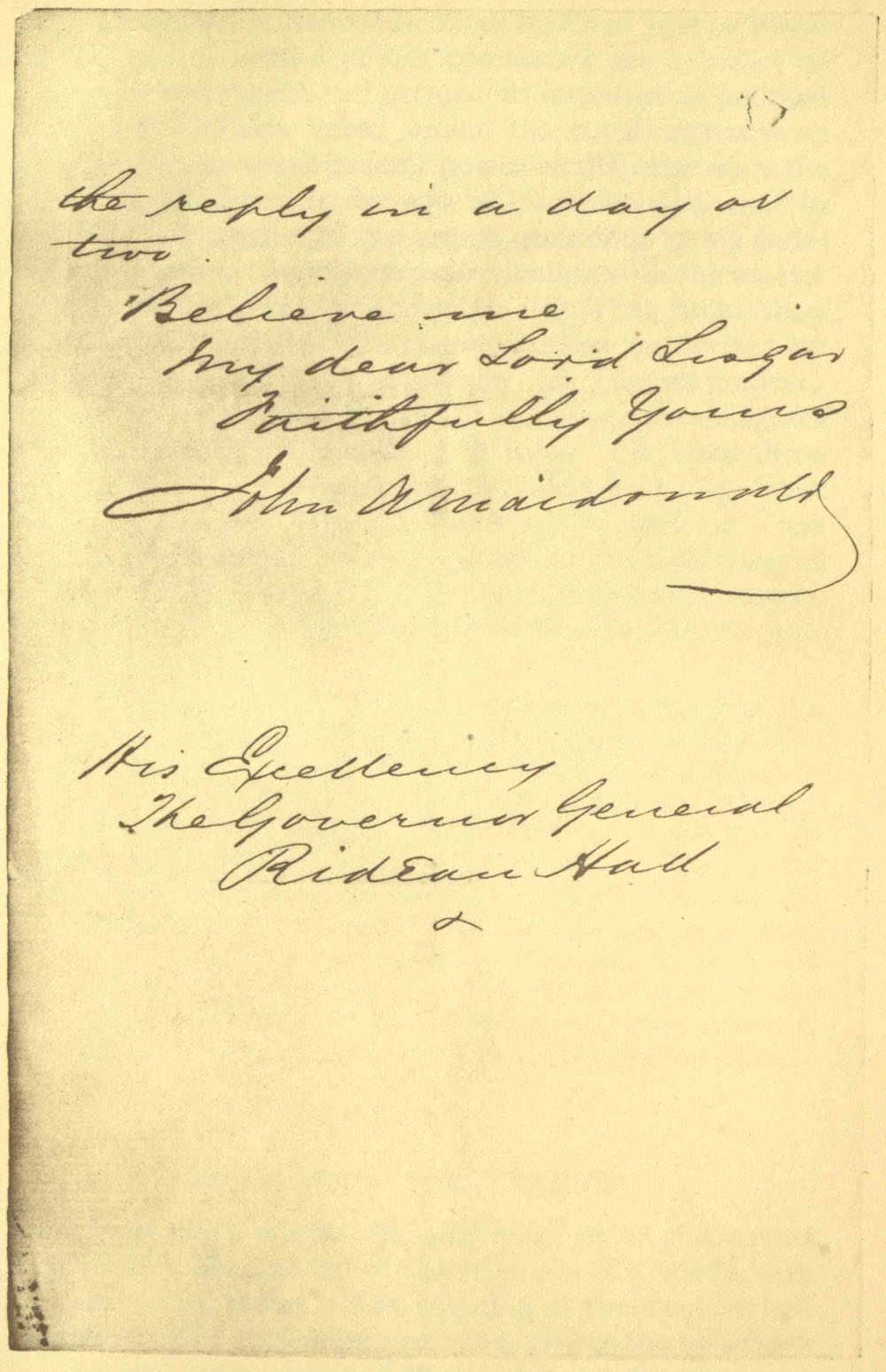

| LETTER FROM SIR JOHN A. MACDONALD TO LORD LISGAR | " | 44 | |

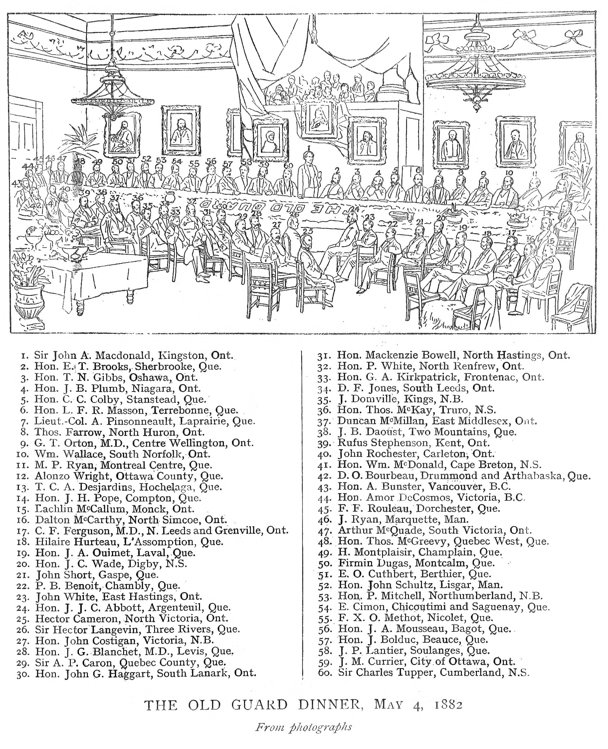

| THE OLD GUARD DINNER, May 4, 1882 | " | 90 | |

| From a photograph by Topley, Ottawa | |||

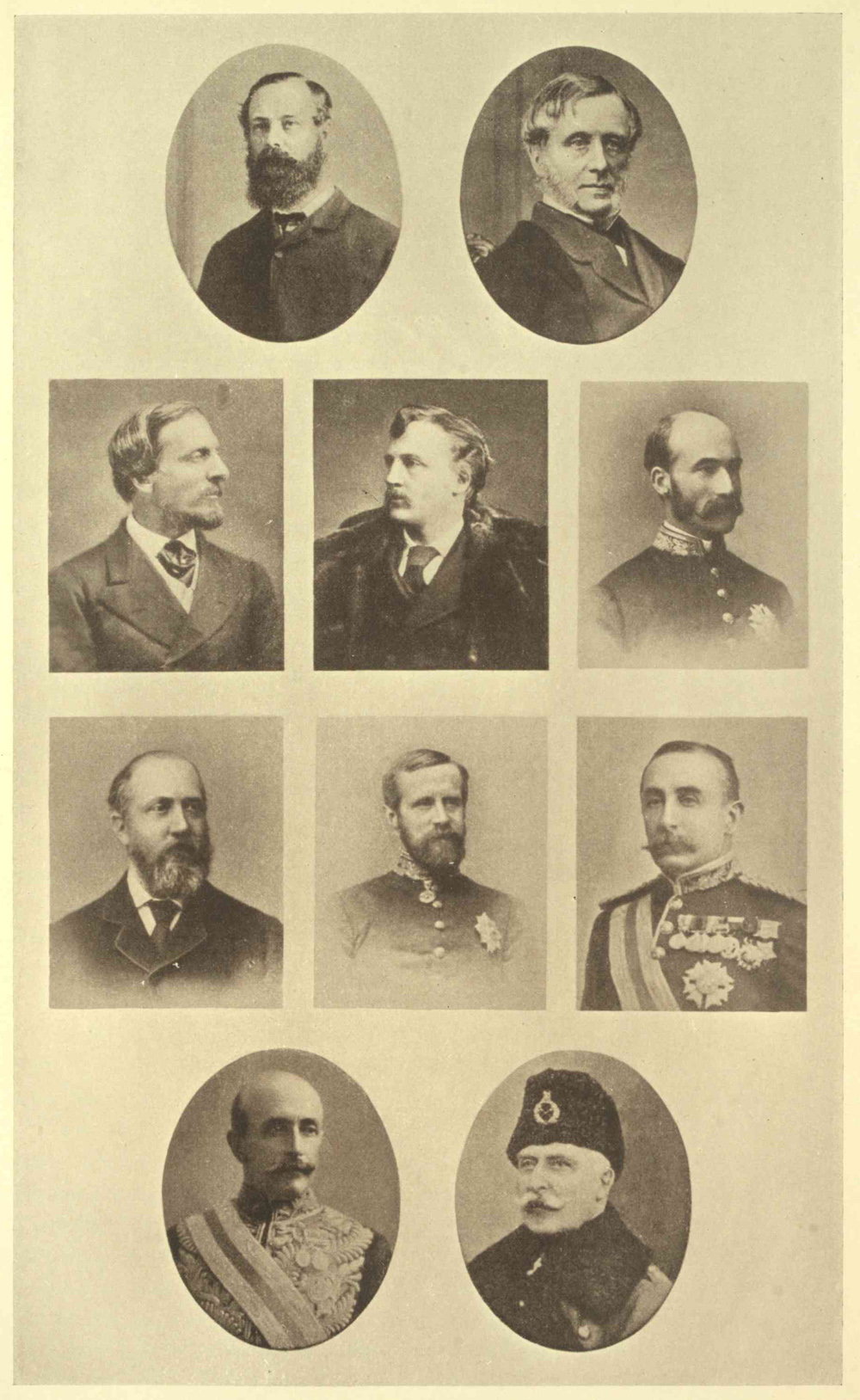

| GOVERNORS-GENERAL OF THE DOMINION | " | 272 | |

| From photographs by Topley, Ottawa | |||

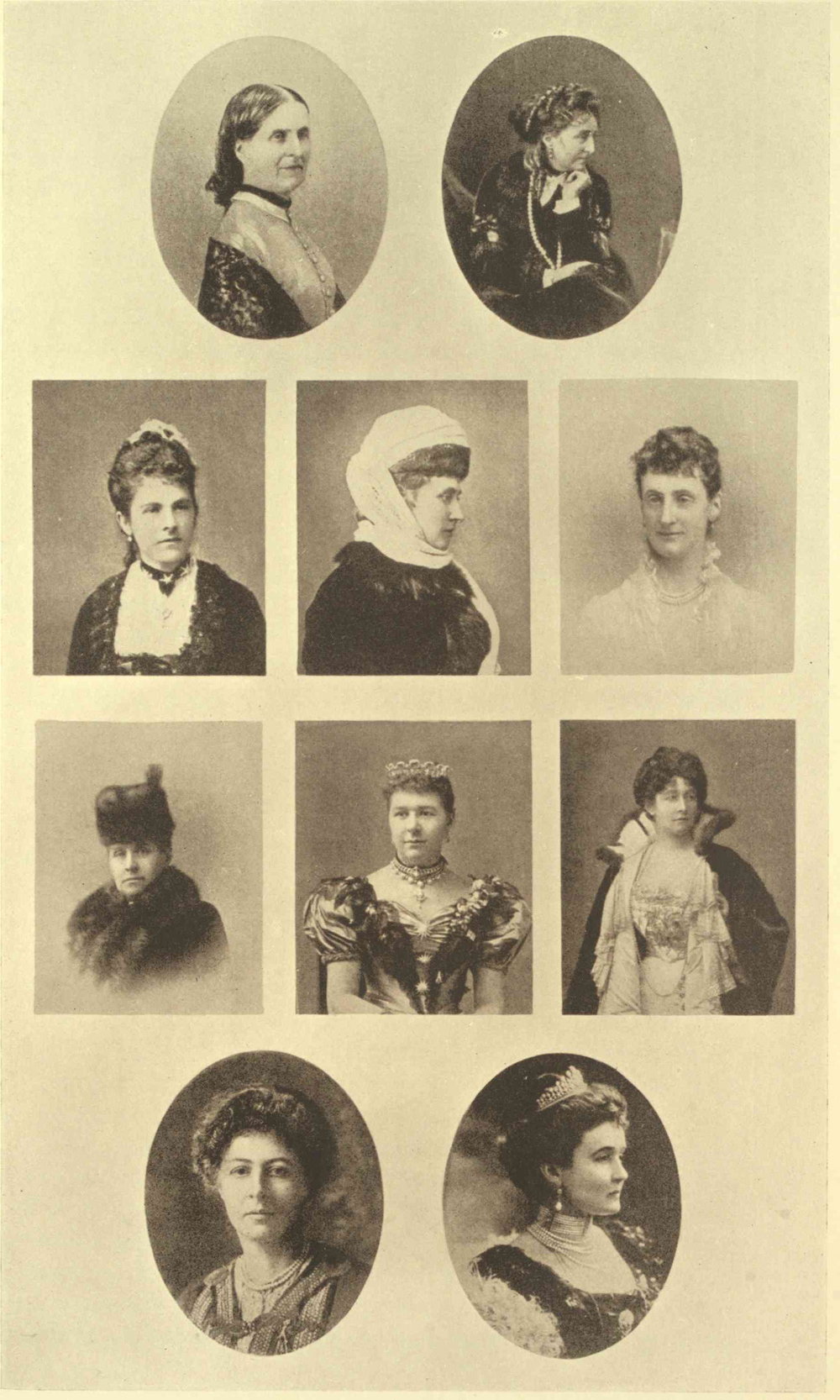

| VICE-REGAL CONSORTS | " | 274 | |

| From photographs by Topley, Ottawa | |||

| The Edinburgh Geographical Institute | John Bartholomew & Co. |

Prepared expressly for "Canada and Its Provinces."

THE FEDERATION: GENERAL

OUTLINES, 1867-1912

Time may show that the federation of Canada in 1867 is one of the important events in modern world history. It was separated by less than eighty years from the completion of the greatest of all federations–that of the United States. One parallel between the United States and Canada is striking. The American Union, like the Canadian, first consisted only of provinces on, or near, the Atlantic coast. Few dreamed, in 1789, that the United States would soon extend beyond the Mississippi to the Pacific. The Dominion of Canada, when first created, extended only to the western limits of the present Province of Ontario. The extension to the Pacific was more rapid than had been that of the United States: four years after the Dominion was first formed Canada had reached out across the continent.

The really vital task in the history of Canada, since 1867, has been the creating of a great state from the divers elements which skilful statesmanship had brought together under a central parliament. So far is the task still from completion that it is only well begun. East and West, French and English, are not yet solidly one in Canada. In the older Canada sectionalism ran riot. When the Constitutional Act of 1791 established the two provinces, Upper Canada and Lower Canada, it was expected and even intended that they should remain different in type; one was to be English, the other French; one was to have English law in civil affairs, the other French law; one was to be prevailingly Protestant in character, the other Roman Catholic. For fifty years the two provinces grew, side by side, indeed, but almost wholly alien from each other. Their internal policies were petty and the strife between parties was singularly intense and bitter. When, in 1837, this strife reached the stage of an appeal to arms, it was time for a larger-minded statesmanship to take Canada in hand. The Earl of Durham was sent out from Britain. He probed the situation to the bottom, found that the chief enemy of peace was sectionalism, and proposed a remedy. Henceforth there should be but one parliament; all Canada should be under a single legislature.

Thus it came about that the Union Act of 1841 was passed by the imperial parliament. Canada had then but one legislature. In it sat French and English, and they could discuss their differences face to face. But the Union did not work well. The two Canadas were united by act of parliament, but they were not united in any other sense. Each section treasured its old ideals. Each party had even its English and its French leader. The old sectional differences remained. Parties were almost evenly divided. In the end the machinery of the Union broke down, and then the new task of the political leaders in Canada was to evolve a real and workable union.

The new system was the federal system established in 1867. Past failure had made wider vision necessary, and now the Canadian leaders reached out to form a state greater than the old Canada. In the East, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island came into the union, though Newfoundland stayed out. In the West, Canada secured the mighty heritage of prairie and mountain that stretches from the western borders of Ontario to the Pacific Ocean. A petty colony had become continental in extent. This vast territory might be made the home of a great nation, and to work towards this goal has been the task of the leaders in Canadian life since 1867. The history of Canada during this momentous period is not a tale of courts and camps, of the workings of diplomacy to avert or to lead to war, of the struggles between those who cherish what is old and what they think is good and those who dream of a new and better order. The pomp of a stately and well-ordered society, movements in art and literature, the menaces and friendships of other nations, have but little place in the narrative. The story is one of internal organization, of trade policy, of the occupation of land hitherto almost unpeopled, of the opening up of communication and the building of railways and canals, of the working of political institutions, of the disputes of the central government in its relations with the provincial governments and of the clear definition of their respective powers. In one sense it is not a dramatic tale; it has little of the glitter and ceremonial of old-world movements. But, none the less, it is a profoundly romantic story of the birth of a nation and of its passing from neglected obscurity into a conspicuous place. The Canadian statesmen of 1867, with one of their chief problems that of contriving, somehow, to build a railway from Quebec to Halifax, might well be staggered before Canada's problem of to-day as to how she can best discharge her duty in respect to world politics.

Two figures stand most conspicuous in this later history of Canada; they are Sir John Macdonald and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Since 1854 one or other of these leaders has been in the forefront of the political battle. During this time Sir John Macdonald was, in effect, if not always in name, prime minister for nearly thirty years, and Sir Wilfrid Laurier for half that period.

To hold the divergent elements in Canada together in one state, and to enlarge this state so as to include the whole of British North America, was the chief task which Macdonald faced as prime minister in 1867. He was well qualified for the work by his amazing skill and dexterity in managing men. He was aided too by the times. The federated colonies had just seen their mighty neighbour, the United States, fight through a bloody civil war on the question of national unity, and they had seen the forces of unity triumph. The lesson was not lost on them. Skilful leadership had brought them together, and the same skilful leadership now set to work to forge them into one people.

In the first instance, at least, it was to be actual links of steel that held the union together. A railway was soon built to bind the Maritime Provinces to the older Canada, and a greater railway was to stretch westward to link the far Pacific with the Atlantic, across Canadian territory. There were fewer than fifty thousand people, other than native Indians, west of Ontario, when Canada undertook to build a railway for thousands of miles across far-spreading plains and through towering mountains. No wonder many said that the thing could not be done; no wonder that governments rose and fell on this issue. But the thing was done, and the Canadian Pacific Railway stands to-day as the first great achieved material task of the new Canada.

To run these two parallel lines of steel from ocean to ocean may seem but a small thing for a people to achieve. It meant, however, things greater than itself. In the older Canada, the story of settlement is one of hewing step by step a painful path inland from river and lake, of laborious warfare with the enveloping forest, of a lifetime spent in winning green fields from this forest's encroaching strength. The rough wagon road was then the symbol of advance; the ox and the horse were the motive power by which the advance was achieved. In the newer Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway led to a different tale. The straight-driven line of steel, the long, swiftly moving train, the mysterious, the almost incalculable, power of steam are the symbols of its advance. It was long before the new meaning of these agencies for settlement was felt in Canada. The West grew but slowly, even after the Canadian Pacific Railway had been built. But the pause was only to gather strength for a greater effort. The line from the East to the West had been completed by 1885, and ten or twelve years later the movement westward was strong; in twenty years, that is by 1905, it had begun to attract world-wide attention, and soon it became one of the wonders of the world. With unprecedented rapidity towns and cities spring up in the new West. Not one, but three lines of railway are reaching out from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and a great population will soon dwell in the once empty region which Canada acquired after Confederation.

The commercial system under which the development should be regulated has from the first been the subject of acute controversy in Canada. Twelve years after Confederation was achieved, Canada turned its back definitely upon the policy of a tariff for revenue only and adopted that of a protective tariff. It was Sir John Macdonald who led in this policy, and it remains that of the conservative party. The liberal party, while not definitely committed to free trade, has aimed at preserving a low tariff. In pursuance of this aim, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, who came into power in 1896 and remained prime minister until 1911, took two steps towards freer trade. He gave a reduction of one-third of the tariff to British manufactures, and he agreed to a limited reciprocity in trade with the United States. The conservative party opposed both measures and drove the liberals from power in 1911 on the reciprocity issue. Thus one striking phase of the development of Canada since Confederation is represented by protection. The older Canada had a low tariff; the new Canada has a high tariff.

The federation of the Canadian provinces involved the working of a new and as yet untried system. An essential feature of federal government is the division of power between the central federal authority and the local authority in each province. The avowed aim of Sir John Macdonald was to make the provincial governments subordinate to the federal government at Ottawa. To carry out this policy he thought, while still prime minister, of becoming a member of the Ontario legislature at Toronto in order to keep the province in line with the policy of his administration. The liberals took strong ground on their policy of provincial rights, and claimed that the provinces, within their assigned spheres, were sovereign communities, in the same sense in which the federal government was sovereign. Keen disputes followed. The tribunal to which the ultimate appeal went was the Judicial Committee of the sovereign's Privy Council in London, and after Confederation this body was frequently called upon to interpret the meaning of the British North America Act. The ordinary reader of history cannot be expected to take a keen interest in the niceties of the constitutional points involved. Yet the history of Canada since Confederation is largely occupied with them. They are, too, of vital moment. To the people of each province the degree of authority which their legislature should have was of profound concern. Did their legislature or did the federal government control the liquor traffic? What were the rights of a province like Ontario to the natural resources, the minerals and timber, within its borders? What control might the provinces exert over fisheries? More important than all this perhaps was the question whether the provinces had complete control of education.

This last problem has proved disturbing in Canadian politics from the date of Confederation. Owing to certain factors in its being, Canada is the land of compromise in politics. Nearly two-fifths of its people adhere to the Roman Catholic faith, and more than one-half of these Roman Catholics are French in origin and speech. The Province of Quebec, the oldest and the most coherently organized of the provinces, is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic in faith and French in speech and race. Its neighbour Ontario, the most populous of the provinces, is overwhelmingly Protestant in faith and English in speech and race. The key to much of the history of Canada is to be found in the natural antagonism between these provinces, and in the appeals to religious and racial passions, which were made easy by their contrasts. In each province the minority had certain educational rights guaranteed under the constitution; the Roman Catholics of Ontario had the right to employ the taxes paid by them for education in the support of their own separate schools; the Protestants in Quebec had similar rights. Naturally the Roman Catholic minority wished for such rights in the other provinces. Under the terms of federation education was left in the control of the provincial legislatures; but, at the instance of the Roman Catholics, a clause was inserted in the bill giving the Dominion parliament the power under certain conditions to protect the educational rights of minorities and to pass legislation that might override provincial action. In 1890 the legislature of Manitoba abolished the Roman Catholic separate schools. At once an agitation began to force the Dominion government to intervene. Since the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church in Manitoba were chiefly French Canadians, their allies in the Province of Quebec took up their cause. Protestant Ontario ranged itself on the opposite side, and once again a question was raised which appealed to the old antagonism between the two chief provinces.

The question broke the long tenure of power by the conservatives. In 1891, while the dispute was still unsettled, Sir John Macdonald died, and the Manitoba School Question proved a deadly heritage to his successors. At last Sir Charles Tupper, the conservative leader, undertook to enact legislation which should re-establish separate schools in Manitoba. The liberal party united to oppose this overriding of the authority of the province in respect to education. It was the old liberal cry of provincial rights. The conservative government fell on the issue. Wilfrid Laurier (afterwards Sir Wilfrid) came into power and held office continuously for fifteen years. He fell when he advocated greater freedom of trade with the United States. It was destined that while he held power new issues should arise in Canadian politics, issues that mark the greater sense of independence and responsibility, and the broader outlook, of a growing nation.

Any one who surveys the history of the older Canada will find traces everywhere of what may be called the colonial habit of mind. The younger states of the British Empire grew up with a sense of dependence on the mother country. She had occupied or conquered the territory which they held; she retained final authority in their affairs, and it was her duty, they said, to protect them from danger; they were children in the arms of the strong mother. As late as 1861, when the Civil War broke out in the United States, this attitude was much in evidence in Canada. The Trent affair led to the possibility of war between Great Britain and the United States, and it was certain that if war broke out the chief aim of the United States would be to conquer Canada. In Britain there was acute concern and alarm over this prospect, and prompt steps were taken to throw a military force across the sea. It was striking that, at the same time, there was singular apathy in Canada at the prospect of war; the Canadians appeared to think that it was for Britain to look after them, and they concerned themselves but slightly over the affair. They had the colonial habit of mind.

A new outlook was bound to come in time, and it came during the ministry of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. In Canada a growing consciousness of national life made the people restless at being the mere wards of the parent state. The Canadians felt that they must learn to take care of themselves. As a result of this state of mind Canada undertook to provide for her own defence on land and the garrisons of imperial troops in Canada were withdrawn. The new problem to face was that of defence on the sea. This issue was forced on the minds of the Canadian people by a seeming menace to Britain's naval supremacy. Germany began to build a mighty fleet, and the rivalry between her and Britain attracted universal attention. Usually the Canadian farmer was little disposed to give thought to the larger issues involved in foreign policy. He had no conviction that Canada should play a part in naval defence. He could hardly believe that there was any danger to himself. But the constant discussion in the newspapers led him to conclude that there was danger to Britain, and, thoroughly British at heart, he felt that the time had come to aid instead of being merely aided. It may be said with truth that nothing has served more effectively to develop the sense of national life in Canada than the naval question. There is a long step between the days when Canada had to ask imperial aid to build the Intercolonial Railway and the days when she began to face the problem of becoming the partner of Great Britain in national defence.

Such has been the evolution of Canada since Confederation. Canadian politics have in some respects close parallels with the politics of Britain. The struggle for Home Rule in Ireland becomes in Canada the struggle for provincial rights. The same principles which cause sharp strife in Britain over the place of religion in education are expressed in Canada in the struggle over separate schools in Manitoba. The problem of tariff reform in Britain is in Canada this same issue between free trade and protection. The problems of federal government in Canada steadily attract more attention in Britain as suggesting possible solutions of some of the difficulties of the homeland. Britain, with its long history, naturally has questions in regard to landholding and taxation from which Canada is free. Yet is it true that the two peoples are dealing with questions steadily becoming more similar in character, and herein is to be found one key to their growing unity.

| Étienne Paschal Taché | John A. Macdonald | Georges Étienne Cartier | Georges Brown | ||

| 1795-1865 | 1815-1891 | 1814-1873 | 1818-1880 | ||

| Can. | Can. | Can. | Can. | ||

| Oliver Mowat | J. C. Chapais | J. Cockburn | Thomas D'Arcy McGee | Col. John Hamilton Gray | |

| 1820-1903 | 1812-1885 | 1819-1883 | 1825-1868 | 1811-1887 | |

| Can. | Can. | Can. | Can. | P.E.I. | |

| William McDougall | Alexander Campbell | Alexander T. Galt | Samuel Leonard Tilley | W. H. Steeves | E. B. Chandler |

| 1822-1905 | 1821-1892 | 1817-1893 | 1818-1896 | 1814-1873 | 1800-1880 |

| Can. | Can. | Can. | N.B. | N.B. | N.B. |

| Charles Fisher | Charles Tupper | Hector Langevin | J. McCully | Ambrose Shea | W. H. Pope |

| 1808-1880 | 1821- | 1826-1906 | 1809-1877 | 1818-1905 | 1825-1879 |

| N.B. | N.S. | Can. | N.S. | N'f'd. | P.E.I. |

| George Coles | Edward Whalen | Thomas H. Haviland | A. A. Macdonald | E. Palmer | Adams G. Archibald |

| 1810-1875 | 1824-1867 | 1822-1895 | 1829-1912 | 1809-1889 | 1814-1892 |

| P.E.I. | P.E.I. | P.E.I. | P.E.I. | P.E.I | N.S. |

| R. B. Dickie | F. B. T. Carter | W. A. Henry | Peter Mitchell | J. M. Johnson | J. H. Gray |

| 1811-1903 | 1819-1900 | 1816-1888 | 1824-1899 | 1818-1868 | 1814-1889 |

| N.S. | N'f'd. | N.S. | N.B. | N.B. | N.B. |

THE FATHERS OF CONFEDERATION

From a collection of portraits in the Dominion Archives

THE FATHERS OF CONFEDERATION

From a collection of portraits in the Dominion Archives

The real history of a people is not fully told in the political struggles. History dwells upon politics because they touch the most obvious and general interests of a state. Apart from politics lies a great world of thought and life in regard to which history is for the most part silent. Strife, tumult, the heat of debate, the exciting incident, the stately ceremonial, these have a lesser part in the real life of a nation than has the quiet thing we call growth. Education and religion play their silent part in this process, and of this inner life history writes few annals. In Canada a young people has, since 1867, been slowly finding itself. In warehouses and factories, on railways, ships and farms, busy men have been growing into larger manhood, and this is the vital thing in their life. 'Happy the nation which has no history,' says the old proverb. The story of the development of Canada cannot be told on the written page. It is to be read in the character of her people, the thoughts they cherish, the insight into the meaning of life which they possess. Poets, men of letters, religious leaders, great teachers, have as yet but little place in the annals of Canada. On them, however, the real life of the nation depends, and in the growth of their influence lies the best hope of the future.

THE NEW DOMINION

1867-1873

On July 1, 1867, the new Dominion of Canada began its career. 'The Act of Union,' said Lord Monck in his speech on opening the first Confederation parliament, 'has laid the foundations of a new nationality that I trust and believe will ere long extend its bounds from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean.' But the work was only begun. The Confederation Act contained the plans and specifications of a structure yet to be reared.

The legislative union of Upper and Lower Canada had been dissolved. In its place stood a federal union comprising old Canada–henceforth to be known as Ontario and Quebec–Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. It was necessary at once to organize a government for the Dominion and for each province and to make provision for the election of a central parliament and of four provincial legislatures. A railway was to be built connecting old Canada with the Atlantic provinces. A new and vast region, extending from the Great Lakes to the Pacific Ocean, was to be brought within the scope of the 'new nationality,' and eventually to be connected with old Canada by railway. Above all, the whole was yet to be vitalized, to be converted from a mere legal entity into a living organism.

The public career of the first head of the new government, Sir John A. Macdonald, covered almost the whole period from the Union to Confederation and nearly a quarter of a century beyond this; and he played a large part in moulding, and a still larger part in working, the institutions of Canada. He was a native of Glasgow, but had spent little more than his infancy in Scotland. When he arrived in Upper Canada in 1820 the country was in the pioneer stage, and there was but a fringe of population along the St Lawrence. Macdonald's father was poor, and when the lad left school at fifteen and entered upon the study of the law, it was under an arrangement which enabled him to earn his living, and perhaps to help his family. He carried a musket against the rebels of 1837. One of his first briefs was for Von Shoultz, a Polish gentleman, who was hanged for his part in the rebellion.

Macdonald first entered public life as conservative candidate in Kingston in 1844, 'to fill a gap,' as he afterwards said. The legislature had been dissolved by Sir Charles Metcalfe, Governor of Canada, as a result of his rupture with the Baldwin-La Fontaine ministry. Broadly speaking, the issue was self-government. This at least was what the reformers contended for, while Sir Charles Metcalfe believed that in resisting them he was fighting against forces that tended to disintegrate the Empire. His attitude made him virtually the leader of the conservative or tory party in Canada during the election of 1844, and Macdonald in his election address accepted his view.

But Macdonald's demeanour in his early parliamentary career showed that he was watching events and preparing to take his own course. He spoke seldom, and observed and studied much. One of his contemporaries says that he often looked 'half careless and half contemptuous, sometimes in the library while the assembly was in a tumult, often buried in a study of constitutional history.' He took office in 1847 under William Henry Draper, who was Metcalfe's chief friend and adviser. He shared in the fate of the ministry in 1848. The triumph of the reformers marked the end of the old order; henceforth Macdonald was to take his part in the new era of self-government.

The first signal evidence of his skill as a political architect was given in the formation of the coalition government of 1854. His policy at this time, as described by his biographer, Sir Joseph Pope, was to draw into the conservative ranks all men of moderate political views, no matter under what name they had previously been known, and to bring the French Canadians to a realization of the fact that their natural alliance was with the conservative party. At this time the party took the name of 'Liberal Conservative.' Robert Baldwin, the distinguished leader of the reformers, who no longer took an active interest in public affairs, in a letter to Francis Hincks gave his benediction to the new combination, and those who agreed with him were called 'Baldwin Reformers.' Macdonald was also successful in winning over to his side the dominant party in Quebec, an alliance which remained firm up to the time of Confederation and for some years afterwards.

Until Confederation John A. Macdonald had not a strong and sure hold upon Upper Canada. Power alternated between him and the reformers, of whom George Brown was the real, though not always the titular, leader. Finally, in the early sixties, came deadlock, which was broken only by Brown's offer of co-operation with Macdonald for the purpose of federating the provinces. Macdonald and Brown entered a coalition administration under Sir Étienne P. Taché, whose venerable and benign personality made him acceptable to both. Soon after the death of Taché, Brown left the coalition, and the undisputed leadership fell to Macdonald, whose humour and urbanity gave him great personal charm, enabled him to turn enemies into friends, and won him an immense following. He was, however, much more than a clever politician and a gay companion. He rose to his opportunities, and he made a greater and more dignified figure in confederated Canada than in the smaller Union. He was a typical conservative, disliking constitutional change and holding aloof from popular agitation. Nearly all the great movements with which he was associated were begun by others, and in some cases opposed by him at the outset.

He was never attracted by the idea of federalizing the existing union of Upper and Lower Canada. Ultimately Confederation appealed to him as a means of enlarging the territory and increasing the strength of Canada. His imperial sympathies were strong and genuine; his hope, as he said in a speech on Confederation, was that Canada should become not a mere dependent colony of England, but 'a friendly nation–a subordinate but still a powerful people–to stand by her in North America, in peace or war.'

Although George Brown was not a member of the government or of the first parliament, he occupies a large place in the history of the time. It did not fall to his lot to administer the government of the new Confederation, but he was one of its architects, if not the chief architect. He had filled a great place in Upper Canada, as tribune, journalist, agitator, advocate of causes. Born near Edinburgh in 1818, he came to New York with his father as a young man, had some experience in journalism there, moved to Toronto in 1843, founded first the Banner as a champion of Free Church Presbyterianism, and then the Globe as the advocate of responsible government, taking sides with Robert Baldwin and the reformers against the governor, Sir Charles Metcalfe. This struggle over, and responsible government apparently safe, he worked for the secularization of the clergy reserves and generally for religious equality. He became a powerful opponent of the influence of French Canada and of the Roman Catholic Church in politics, and a champion of Upper, as against Lower, Canada. At length he decided that justice could be obtained for Upper Canada by giving it representation according to population, instead of continuing the arrangement by which the two sections were equally represented. As Lower Canada resisted this change, it was suggested that a solution might be found in federalizing the Union, thus leaving to each section the enjoyment of its own liberties and local laws. In order to carry out this arrangement, Brown consented to join forces temporarily with Macdonald, and was persuaded to enter a coalition government with his political rival and personal enemy. Various reasons were assigned for his leaving the coalition, but the strongest real reason was that the two leaders were not personally congenial, and neither would yield to the other. Some of Brown's most intimate friends had opposed his entering the coalition. It was in the nature of things temporary, and the first opportunity for ending it was eagerly seized.

GEORGE BROWN

From a photograph in the possession of Mrs Freeland Barbour, Edinburgh

William McDougall first became prominent in public life as one of the leading spirits of the 'Clear Grit' party, a radical organization which, in the time of Baldwin and La Fontaine, advocated the election of officials, universal suffrage, vote by ballot, fixed dates for elections and for the assembling of the legislature, free trade and direct taxation, the reduction of lawyers' fees and the abolition of the Court of Chancery. As a 'Clear Grit' and editor of the North American he came into violent conflict with George Brown and the Globe, but his paper was subsequently amalgamated with the Globe, of which he became chief editorial writer. He played a prominent part in the Reform Convention of 1859, which advocated the federation of Canada, and he was one of the earliest advocates of the union of the North-West Territories with Canada. He was a lawyer as well as a journalist, and in the later years of his life gave most of his time to his law practice. McDougall was a man of commanding presence, with a concise, impressive delivery. His mind was at once radical and constructive, and there can be little doubt that his adherence to the coalition of 1864 was due to his desire to be connected with two great constructive works, Confederation and the acquisition of the West. When he was appointed lieutenant-governor of the North-West Territories and was prevented by Riel from entering on his duties, his political prospects were seriously impaired; but his fault on this occasion was merely failure to execute an impossible task.

For some years there was an attempt to carry on government by means of a coalition. Confederation had been brought about by a truce between George Brown with his Upper Canada followers, and Sir John Macdonald with the conservatives. Brown's party friends in Lower Canada had held aloof, and many of the Upper Canadian reformers were distrustful of the alliance and glad when Brown withdrew from the coalition government.

As the first election under the new system drew near, it was necessary to settle definitely the attitude of the reformers of Upper Canada towards the coalition. On June 27, 1867, a convention of the reformers of Upper Canada was held. There were present at this gathering William McDougall and William P. Howland, who had entered the ministry as liberals. They upheld their right to remain in that position. McDougall argued that the old party issues were dead and buried, and that the Dominion of Canada was beginning with a clean slate: that the work designed by the framers of Confederation was not finished, but only begun. He and Howland defended their positions with skill and force, but they were overwhelmed by George Brown, Alexander Mackenzie, and the other opponents of the coalition. The convention resolved that the coalition of 1864 could be justified only on the ground of imperious necessity, as a means of obtaining just representation for the people of Upper Canada, and should end as soon as this measure was attained; that the temporary alliance between the reform and conservative parties should cease; and that there should be an end to government maintained by a coalition of public men holding opposite principles.

Sir John Macdonald persevered in his attempt at governing by coalition, and it may be convenient at this point to show how the experiment worked out. The coalition government won the election of 1867. The people practically identified support of the government with support of Confederation. Hence the vote of Nova Scotia was hostile to Confederation as well as to the government, while in Ontario, formerly a stronghold of reform, the government was sustained by a large majority, and George Brown himself was defeated in the riding of South Ontario.

Evidently, therefore, a considerable number of Ontario reformers were willing to go a little farther in support of the coalition than the reform convention had resolved. They stood midway between Brown and McDougall. Once the new system of government had been firmly established they returned to their old party allegiance. The reformers would not accept as leader any of the liberals with whom Macdonald allied himself. Some of these leaders retired from public life; some, like Sir Leonard Tilley, went over to the conservative party. Before the first parliament had expired all trace of the composite character of the ministry had disappeared. It had become conservative. During the same time the coalition government established by the influence of Sir John Macdonald in Ontario under the leadership of John Sandfield Macdonald was defeated and its place taken by a liberal ministry.

PROCLAMATION OF THE CONFEDERATION OF CANADA

BY THE QUEEN!

A PROCLAMATION

For Uniting the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, into one Dominion, under the name of CANADA.

VICTORIA R.

Whereas by an Act of Parliament, passed on the Twenty-ninth day of March, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty-seven, in the Thirtieth year of Our reign, intituled, "An Act for the Union of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, and the Government thereof, and for purposes connected therewith," after divers recitals it is enacted that "it shall be lawful for the Queen, by and with the advice of Her Majesty's Most Honorable Privy Council, to declare, by Proclamation, that on and after a day therein appointed not being more than six months after the passing of this Act, the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, shall form and be One Dominion under the name of Canada, and on and after that day those Three Provinces shall form and be One Dominion under that Name accordingly;" and it is thereby further enacted, that "Such Persons shall be first summoned to the Senate as the Queen by Warrant, under Her Majesty's Royal Sign Manual, thinks fit to approve, and their Names shall be inserted in the Queen's Proclamation of Union:"

We, therefore, by and with the advice of Our Privy Council, have thought fit to issue this Our Royal Proclamation, and We do ordain, declare, and command that on and after the First day of July, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty-seven, the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, shall form and be One Dominion, under the name of CANADA.

And we do further ordain and declare that the persons whose names are herein inserted and set forth are the persons of whom we have by Warrant under Our Royal Sign Manual thought fit to approve as the persons who shall be first summoned to the Senate of Canada.

| For the Province of Ontario. | |

| John Hamilton. | Elijah Leonard. |

| Roderick Matheson. | William MacMaster. |

| John Ross. | Asa Allworth Burnham. |

| Samuel Mills. | John Simpson. |

| Benjamin Seymour. | James Skead. |

| Walter Hamilton Dickson. | David Lewis Macpherson. |

| James Shaw. | George Crawford. |

| Adam Johnson Ferguson Blair. | Donald Macdonald. |

| Alexander Campbell. | Oliver Blake. |

| David Christie. | Billa Flint. |

| James Cox Aikins. | Walter McCrea. |

| David Reesor. | George William Allan. |

| For the Province of Quebec. | |

| James Leslie. | David Edward Price. |

| Asa Belknap Foster. | Elzear H. J. Duchesnay. |

| Joseph Nöel Bossé. | Leandre Dumouchel. |

| Louis A. Olivier. | Louis Lacoste. |

| Jacque Olivier Bureau. | Joseph F. Armand. |

| Charles Malhiot. | Charles Wilson. |

| Louis Renaud. | William Henry Chaffars. |

| Luc Lettellier de St. Just. | Jean Baptiste Guévremont. |

| Ulric Joseph Tessier. | James Ferrier. |

| John Hamilton. | Sir Narcisse Fortunat Belleau, Kt. |

| Charles Cormier. | Thomas Ryan. |

| Antoine Juchereau Duchesnay. | John Sewall Sanborn. |

| For the Province of Nova Scotia. | For the Province of New Brunswick. |

| Edward Kenny. | Amos Edwin Botsford. |

| Jonathan McCully. | Edward Barron Chandler. |

| Thomas D. Archibald. | John Robertson. |

| Robert B. Dickey. | Robert Leonard Hazen. |

| John H. Anderson. | William Hunter Odell. |

| John Holmes. | David Wark. |

| John W. Ritchie. | William Henry Steeves. |

| Benjamin Wier. | William Todd. |

| John Locke. | John Ferguson. |

| Caleb R. Bill. | Robert Duncan Wilmot. |

| John Bourinot. | Abner Reid McClelan. |

| William Miller. | Peter Mitchell. |

Given at our Court, at Windsor Castle, this Twenty-second day of May, in the year of our Lord One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty-seven, and in the Thirtieth year of our reign.

GOD SAVE THE QUEEN.

Curious questions arose as to the composition of the coalition government of Canada. At first there were three liberals and two conservatives from Ontario, but when the conservatives won a majority of the Ontario seats in the election of 1867, it was contended that the proportions should be reversed. Sir John Macdonald was attacked by both liberals and conservatives, each alleging that their opponents were favoured. He can hardly have deplored the change which eventually surrounded him with his own party friends, but there is no reason to suppose that this result was mainly due to his design. He loved power, but he cared more for its substance than for the name of the instrument by which it was wielded. By temperament he was conservative; but he moved in a different plane from many of his zealous partisans. He was capable of dissociating himself from party prejudice, if he deemed this necessary for the promotion either of personal ambition or of the public service. Hence his attempts at forming coalitions, which failed mainly because the people did not want them, because the energetic and aggressive men of the parties were too strong for them; and this was especially true of the reformers of Ontario.

The construction of the first ministry illustrates some of the political difficulties to be solved. Party politics, religion, race and locality had each to be considered. The ministry must be composed in almost equal proportions of liberals and conservatives. Each province was to be represented according to population. There must be so many French-Canadian representatives of Quebec, and also a special representative of the English minority in that province. There must be so many Protestants and so many Roman Catholics, and of the Roman Catholics one must be Irish. At length the delicate task was completed, and the ministry was formed as follows:

Conservatives

John A. Macdonald, minister of Justice and attorney-general.

Georges É. Cartier, minister of Militia and Defence.

Alexander T. Galt, minister of Finance.

Alexander Campbell, postmaster-general.

Jean Charles Chapais, minister of Agriculture.

Hector L. Langevin, secretary of state for Canada.

Edward Kenny, receiver-general.

Liberals

William McDougall, minister of Public Works.

William P. Howland, minister of Inland Revenue.

Adam J. F. Blair, president of the Privy Council.

Samuel L. Tilley, minister of Customs.

Peter Mitchell, minister of Marine and Fisheries.

Adams G. Archibald, secretary of state for the Provinces.

Writs were issued for the first general election in August 1867, and the elections were held during August and September. The government won a decisive victory in every province except Nova Scotia.

The first parliament assembled on November 6, 1867. The speech from the throne declared that the Act of Union conferred upon parliament the right of 'reducing to practice the system of government which it has called into existence, of consolidating its institutions, harmonizing its administrative details, and of making such legislative provisions as will secure to a constitution in some respects novel, a full, fair and unprejudiced trial.' Legislation was enacted for the management of the revenue and the establishment of various departments of government: public works, the post office, militia and defence, justice, customs, inland revenue, secretary of state, marine and fisheries, and for the organization of the civil service. A banking act and a railway act were passed. Provision was made for building the Intercolonial Railway, and resolutions were adopted for the admission of Rupert's Land and the North-West Territories into the Dominion. The indemnity of members was fixed at $600 for the session.

The first public accounts showed a revenue of $13,687,000, an expenditure of $13,486,000, and a net debt of $75,728,000. The exports of Canadian products were $45,543,177, of which $17,905,808 went to Great Britain, $22,387,846 to the United States, and $5,249,523 to other countries. Imports were $67,000,000, of which $37,600,000 came from the United States and $23,600,000 from Great Britain. It was the day of small things.

The session was held in two parts, one from November 7 to December 21, and the other from March 12 to May 22. The interval was for the purpose of allowing the provincial legislatures to be organized, and this necessity arose from the system of dual representation under which the same person might sit in the Dominion parliament and in a provincial legislature at the same time. John Sandfield Macdonald, the first prime minister of Ontario, was also a member of the Dominion parliament. Pierre Chauveau, the prime minister of Quebec, Blake, Cartier, Dunkin, Langevin and other members were in a similar dual position. The dual system was not abolished until several years after Confederation.

One of the leading members of this government and parliament was Georges Étienne Cartier. His public career began in storm. As a law student, twenty-three years of age, he took part in the Rebellion of 1837, and was compelled to flee to the United States and to remain there until an amnesty was proclaimed. In the struggle for responsible government from 1844 to 1848 he supported La Fontaine. He entered parliament in 1849, and in 1855 became a member of the Taché-Macdonald government. He was thus associated with Macdonald at about the time of the formation of the liberal-conservative coalition. In a few years he was the leader of the Lower Canada conservatives and Macdonald's chief ally. In 1855 Cartier was ranked as a liberal, and insisted that in joining hands with MacNab and Macdonald he was not giving up his liberal principles.

Cartier advocated with energy the construction of railways and the deepening of the St Lawrence, and used the expression, 'Our policy is a policy of railways.' He was one of the Fathers of Confederation, and to him was chiefly due the support which the Province of Quebec gave to that measure. While Macdonald's preference was for legislative union, Cartier was a strong federalist and insisted upon the constitution taking that form. He frankly championed the special interests of Quebec, and tried to organize a solid vote from that province. Energy, audacity, and boundless optimism were his leading characteristics.

Alexander Tilloch Galt was a son of John Galt, the distinguished novelist, and one of the chief promoters of settlement in Western Ontario. Galt entered public life in 1849, was an opponent of Baldwin and La Fontaine, voted against the Rebellion Losses Bill, and signed the annexation manifesto. He was not a tory of the type of Sir Allan MacNab, but belonged rather to the class of Canadians referred to by Lord Durham, who declared that 'in order to remain English they would cease to be British,' that is, they would take up annexation with the United States as a refuge from French domination. He was always a staunch champion of the Protestant minority in Quebec. His annexation ideas were short-lived, and in 1858 he appears as an advocate of Confederation. His scheme was remarkably well thought out, and closely resembled that which was adopted several years afterwards. He was also, as minister of Finance of old Canada, the author of a protective tariff, and he stoutly and ably vindicated Canada's right to impose duties on British imports. He was one of the authors of Confederation, and at the various conferences acted as the chief representative of the Protestant minority of Quebec, and did his best to have their rights protected in the British North America Act. Although he was chosen as the first minister of Finance after Confederation, he remained only a few months in the government. His independence made him little amenable to party discipline. When he was knighted in 1869 he stipulated that the acceptance of the honour should not be regarded as a disavowal of his opinion that Canada should be an independent nation.

Alexander Mackenzie, like Macdonald and Brown, was of Scottish birth. He learned his trade of stone-cutting in Scotland, and in 1842, when he was twenty years of age, emigrated to Canada. Here he worked first as a journeyman, afterwards as a builder and contractor, and in a few years he was one of the leading citizens of Sarnia, where his business was carried on. He was the typical religious Scotsman, grave rather than emotional in his religion, having a strong sense of responsibility for the spending of every hour of his life, occupying his leisure in study. Soon he began to take part in public life as a reformer and a devoted follower of George Brown. His platform style was effective. It was said that he built a speech as he built a wall; the sentences were compact, the points driven home with force, and often with sarcasm and dry humour. He carried into politics his habits of unflagging industry, and made himself master of every question with which he had to deal. His courage was unflinching.

Mackenzie had a deep distrust of coalitions. He advised Brown not to enter a government with Macdonald in 1864, and he was an uncompromising opponent of the combinations formed by Macdonald at Ottawa and at Toronto in 1867. Both were destroyed by his sledge-hammer blows and those of Edward Blake–a formidable combination. Mackenzie was for a short time Provincial Treasurer of Ontario, and in the early seventies he was an aggressive leader of the opposition at Ottawa. He had neither the diplomatic skill of Macdonald nor the intellectual subtlety of Edward Blake; simplicity, directness, force, courage, were the outstanding features of his character.

Edward Blake entered public life in 1867, when he was elected to the House of Commons for West Durham and to the Ontario legislature for South Bruce. In the legislature he became leader of the opposition against the Sandfield Macdonald government, was one of the chief instruments in its defeat, and was called upon to form a ministry. He held the premiership of Ontario for only about a year, and was succeeded by Oliver Mowat, who at Blake's suggestion resigned the vice-chancellorship of Ontario to re-enter public life. Blake then devoted his energy to federal politics and became one of the most powerful assailants of the government, taking a leading part in the debates which culminated in the defeat of the administration on the Pacific Scandal question. Blake was the leader of the Equity bar of Ontario and a brilliant advocate. In intellectual force and range of thought he ranks perhaps first among the public men of Canada. His political triumphs in the early seventies were almost sensational. With the accession of the liberals to power in 1873 he showed a tendency to break away from party ties, and he was for some time regarded with hope by the Canada First or National party. The bent of his mind was towards constitutional questions, and he gave powerful aid to the Ontario government in its fight for provincial rights.

From Nova Scotia the most notable figures were Joseph Howe and Dr Charles Tupper. Howe was of the type which in the United States is called a favourite son. He sprang into fame some thirty years before Confederation as the champion of self-government for Nova Scotia, and from that time his position as chief tribune of the people was unassailed. He had the temperament of the popular orator and idol; he was eloquent and not afraid to use impassioned language; he was warm-hearted, free and familiar in his intercourse with the people. Confederation, which brought fame to some public men, was full of unhappy results for Howe. He opposed the movement, but it was too strong for him. His acceptance of an office in the Macdonald government was an unfortunate step, weakening his prestige and his hold on the friendship of Nova Scotia. After his death the old love and admiration resumed their sway, and his place as one of the heroes of Nova Scotia is safe.

To Dr Tupper, on the other hand, Confederation was a great opportunity. He brought Nova Scotia into the federal union by sheer force of will. He quickly adapted himself to the wider field, and became Sir John Macdonald's most powerful ally. His party loyalty was unswerving, and his force and aggressiveness were greater than those of his chief. After Confederation and the settlement of the Nova Scotia difficulty we do not find him assigned to any part worthy of his courage and energy until he became minister of Railways and chief advocate of the bargain with the syndicate which built the Canadian Pacific Railway. With his stalwart frame, square jaw, deep, powerful voice, and strong rather than graceful oratory, he was the type of the fighter. He was of inestimable value to his party, ever ready to go anywhere and meet any opponent.

A tragic event of the first session was the murder of D'Arcy McGee. McGee was an Irishman who in early life had attached himself to the Young Ireland party, and had fled to America on account of his connection with Smith O'Brien's insurrection. After spending some years in the United States he went to Montreal, founded a newspaper there and entered the legislature in 1857. His opinions gradually underwent radical change, and from an enemy of Great Britain he became an ardent imperialist. He was attached first to the reform party, but afterwards formed a personal friendship and a political alliance with Sir John Macdonald. He was eloquent, witty and of a most kindly disposition. In 1865 he visited Ireland and spoke strongly against Fenianism, and to these speeches his assassination is attributed. On the morning of April 7, 1868, all Canada was horrified by the news that he had been assassinated at Ottawa while entering his lodgings after the adjournment of the House. His funeral at Montreal was attended by more than twenty thousand people. Patrick James Whelan was tried and found guilty of the murder and executed.[1]

In Nova Scotia a serious question was raised. The result of the general election of 1867 was an evidence of determined hostility to union with Canada. The same feeling was shown by the election for the legislature, in which only two out of thirty-eight members were for the union. The newly elected legislature passed an address to the queen, praying for the repeal of the union. The agitation was led by Joseph Howe, and he and three others were sent to England to press for repeal. The mission, however, was foredoomed to failure. The British government was determined that the federal union should be accomplished, and had done all in its power to promote the measure. The imperial parliament had passed the Confederation Act with a sigh of relief over the settlement of the troublesome Canadian question, and was resolved that it should not be reopened. John Bright's motion for a commission of inquiry was lost by two to one.

The decision of the imperial parliament did not end the agitation. Violent speeches against Confederation were made in the legislature of Nova Scotia. At length Macdonald resolved to win Howe over to the cause of union, hoping with his aid to quell the storm of opposition. Dr Tupper, the vigorous leader of the Confederation party in Nova Scotia, had accompanied Howe to England, holding a 'watching brief' for the government of Canada. Tupper sought out Howe, told him that he expected him to do all in his power to repeal the union, but that if he failed he would achieve nothing further by persistent antagonism. If Howe would go back to Nova Scotia and ask for a fair trial for the union, the government of Canada would make all reasonable concessions to Nova Scotia and would, as a guarantee of fair treatment, make Howe a minister. Howe showed a conciliatory spirit, and on his return to Canada entered into negotiations with Macdonald, and accepted the office of president of the Privy Council and afterwards of secretary of state for the Provinces.

Howe's position then became difficult and painful. He knew that after the decision of the British government, repeal was a lost cause. Nova Scotia could not fight the Empire, and annexation to the United States was an alternative abhorrent to a man of Howe's staunch British feeling. But it was hard for him to dissociate himself from his past as an advocate for repeal. Among the irreconcilables in Nova Scotia were many of his old admirers. His waning popularity, the cold, averted looks of old friends, were sources of keen pain to one who was intensely human and who loved to be loved by his fellow Nova Scotians. 'He might have yielded to destiny, but he should hardly have gone into the government,' is Goldwin Smith's summary. Keeping clear of this entangling alliance, he could have told his old friends frankly that further resistance was useless. The agitation would have died out. The federal members for Nova Scotia were becoming reconciled to the new conditions. The irreconcilable members of the legislature could not have gone on for ever fulminating against Confederation. Their combativeness would have found vent in fighting for provincial rights. As an independent member of parliament, protesting against the methods by which Nova Scotia had been forced into the union, yet accepting the situation, Howe would have occupied a dignified position. By accepting office he became a minor minister instead of an unrivalled tribune of the people. He not only lost friends in Nova Scotia, but he became a target for the opposition at Ottawa, who were bitterly opposed to the coalition, and regarded all men of reform antecedents in the ministry as traitors to the party.

In 1869 the 'better terms' intended to placate Nova Scotia were enacted. They increased the debt of Nova Scotia to be assumed by the Dominion from $8,000,000 to $9,186,756, and otherwise improved the financial position of the province. These terms were strongly opposed by the liberals. They contended that the British North America Act settled the financial relations of Canada and the provinces, that parliament had no right to change the basis of union; that if parliament could increase a provincial subsidy it could reduce one; that it might alter any other part of the Confederation Act and destroy Confederation itself. Macdonald justified the legislation simply on the ground of necessity, as the only means of saving Confederation.

Prince Edward Island still held aloof, and it was not until July 1, 1873, that the consolidation of Eastern Canada was completed by the entrance of the island province into the federal union.

|

Many hold that Whelan was not McGee's murderer. |

Between the more thickly settled parts of Quebec and of the Maritime Provinces there was a long stretch of sparsely settled country which had to be traversed by a railway if the union were to be complete.

The Intercolonial Railway was a project conceived long before Confederation. During the Rebellion of 1837 attention was drawn to the need of a military highway between Halifax and Quebec. In 1848 Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick had surveys made by Major Robinson and other imperial officers. Major Robinson reported on several possible lines from Halifax to Quebec giving preference on military grounds to the longest and most costly route farthest from the frontier of the United States. The colonies objected that this line would pass through a country little settled, and would not pay. The British government admitted the justice of this objection and offered a guarantee of the interest on the bonds on condition that the line was built wholly within British territory. This arrangement fell through on account of a disagreement as to the extension of the guarantee to a railway from New Brunswick to the United States. Military considerations and commercial necessities were continually coming into conflict. Portions of the railway, afterwards forming parts of the Intercolonial, were built between 1853 and 1867. In 1867 the success of the project was assured by making it a part of the scheme of Confederation. The resolutions adopted by the conference of provincial delegates in London in 1866 provided for the immediate construction of the railway by the government of Canada. The imperial government was to guarantee a loan of £3,000,000. The Confederation Act provided that the railway should be commenced six months after the union.

When, in the first session of the new parliament, the bill providing for the construction of the railway was introduced, the controversy as to the route was renewed. Antoine Aimé Dorion, a leading French-Canadian liberal, asked that the route should not be determined without the consent of parliament. The ministry objected that this would imperil the imperial guarantee, which was conditional on the approval of the route by the secretary of state for the Colonies.

The northern or Robinson route by the Chaleur Bay was preferred by the imperial government for military reasons, and it was also strongly supported by the Hon. Peter Mitchell of New Brunswick, and by Sir Georges Cartier and his Quebec following. The majority of the ministry were for the more direct line from Rivière du Loup to St John. Cartier, by absenting himself from cabinet meetings, practically threatened to resign unless his favourite route were accepted. Macdonald called in Sandford Fleming, an eminent engineer, who saved the situation by deciding for the northern route on both military and commercial grounds.

The union with Canada of the region lying between the Great Lakes and the Rocky Mountains had been advocated many years before Confederation. But a fresh impulse was given to the movement by the political reconstruction which freed Canada from political paralysis and endowed her with a more flexible instrument of government and with ampler resources. The British North America Act provided means for the admission into the union of Rupert's Land and the North-West Territory, and in the first session of the new parliament resolutions were adopted asking that the power should be exercised. In view of the difficulty which afterwards arose, it should be noted that these resolutions evinced an inclination to deal fairly with the people of the West. They were to have political institutions bearing analogy, as far as circumstances would admit, to those which existed in the provinces of the Dominion. Similar good intentions were shown in the agreement with the Hudson's Bay Company, which provided that the rights of Indians and half-breeds should be respected, and in the instructions given by Howe as secretary of state to William McDougall, when the latter was appointed lieutenant-governor of the new country. Unhappily these good intentions were not soon enough conveyed to the little community dwelling by the Red River. When Adams G. Archibald, afterwards lieutenant-governor of Manitoba, was a member of parliament, he described that community as secluded from the rest of the world, uninformed of what was happening around it, and alarmed by the sudden bursting of the barrier which separated it from the rest of the world and by the entrance of strangers. 'Is it any wonder,' he asked, 'that these fears should be raised, should be traded upon by demagogues ambitious of power and place?' By a series of misfortunes, blunders and accidents the inhabitants were kept in ignorance of the real intentions of Canada.

The extinction of the legal title of the Hudson's Bay Company to the western lands was comparatively simple and easy. By agreement between the company, the imperial government and the Canadian government, it was arranged that Canada should pay the company £300,000 for the transfer of the country, and the extinction of the company's exclusive trading, fishing and other privileges. At the same time the company retained the land immediately around the trading posts and two sections in every township. The land thus reserved amounted to about one-twentieth of the newly acquired territory.

The prime mistake was that while these negotiations were being carried on with the company in England, no one was treating with the inhabitants of the country. Their consent to the momentous change was taken for granted. Again, an act for the temporary government of the country, passed by the parliament of Canada in 1869, was criticized because it did not recognize the political rights of the people and their right to a voice in the formation of the government. That this charge was well founded was afterwards admitted by William McDougall, one of the chief actors in the drama.

On the banks of the Red River, in what is now the Province of Manitoba, dwelt some twelve thousand settlers, ten thousand of whom were half-breeds or Métis, partly of Indian and partly of Scottish or French blood. They had been living under the government of the Hudson's Bay Company. The governing body was called the Council of Assiniboia. Its head was the governor of the company–at this time William McTavish. The people subsisted by fishing, hunting and a little farming. Their farms ran back from the river in long strips, such as may now be seen in the Province of Quebec. Fort Garry, the site of the present city of Winnipeg, was the centre of government.

By a series of errors and misfortunes the settlement drifted into anarchy. The authority of the Hudson's Bay Company was passing away, that of Canada was not yet established. Canada had itself only recently emerged from the condition of a group of weak and distracted provinces. One of the sayings that touched the heart of the Red River Settlement was that it would not submit to be 'the colony of a colony.' Before attempting to take possession, there should have been a conference between representatives of Canada and representatives of the Red River Settlement. Unfortunately the inhabitants derived their first impressions of the new order from surveying parties and from newcomers spying out the land.

'A knowledge of the true state of the case and of the advantage they would derive from union with Canada had been carefully kept from them, and they were told to judge of Canada generally by the acts and bearing of some of the unreflective immigrants who had denounced them as cumberers of the ground, who must speedily make way for the superior race about to pour in upon them.' So wrote Donald A. Smith (afterwards Lord Strathcona) in reporting upon the mission to the Red River which he undertook in January 1870. He added that in various localities adventurers had marked off for themselves large and valuable tracts of land, impressing the existing inhabitants with the belief that they were about to be supplanted by the stranger. The settlers were fearful and perplexed, and, lacking other guidance and control, they fell under the influence of Louis Riel, a man of considerable ability and education, but vain, ambitious, and ill-balanced. He was the son of a half-breed miller who had some years before headed a successful revolt against the Hudson's Bay Company.

Several unfortunate circumstances tended to aid Riel's ascendancy. The local officers of the Hudson's Bay Company, who worked under a profit-sharing arrangement, were dissatisfied because they believed they would be defrauded out of their share of the £300,000 paid for the extinction of the company's rights, and would be turned adrift without compensation. Governor McTavish was ill and nearing his end. Bishop (afterwards Archbishop) Taché, who was a trusted spiritual leader of the people, was absent in Rome.

Joseph Howe, who was in the country in the early part of October 1869, when surveying operations were stopped by Riel, was in some ways qualified to act a conciliatory part. He was afterwards accused of disloyalty to Canada and of intriguing against McDougall. What seems more probable is that he failed to perceive the gravity of the situation. He thought he saw in the Red River Settlement a struggle for self-government, such as he had witnessed in Nova Scotia, and he naturally took the side of the inhabitants. He did not see the danger of anarchy, dictatorship and violence lurking in the situation; hence his failure to convey any warning of serious trouble to William McDougall, who had been appointed lieutenant-governor.

While Howe was in the settlement Riel called upon Colonel John Stoughton Dennis, who was in charge of the federal survey, and asked him to explain the meaning of his operations. He was assured that no injustice was intended, and he went away apparently satisfied. But a few days afterwards Riel forbade the surveyors to continue their work, organized the Métis and forced McDougall across the American border to Pembina. On November 1 he marched in through the open gates of Fort Garry, billeted his followers on the inhabitants, and armed them with the rifles stored in the fort. To the Hudson's Bay official who remonstrated somewhat feebly against this step, he explained that he had come to guard the fort against 'a danger.' Riel was now master of the situation.

Reports of hostile movements on the part of the Métis had been conveyed to McDougall at several points on his way from St Paul to Pembina. At Pembina, close to the Canadian border, he was met by a half-breed who served him with a formal notice not to enter the territory. McDougall pushed on to the Hudson's Bay post, two miles from Pembina, and within the Red River territory. There he learned of the stoppage of the surveys by Riel and of his determination to resist the entry of the federal officials into the territory. On November 2 a party of fourteen men approached the post and ordered McDougall to leave, and the following morning they became so menacing that he thought it prudent to return to Pembina. There he remained for several weeks.

When the news of the check received by McDougall reached Ottawa, Sir John Macdonald determined not to accept from the Hudson's Bay Company the territory in its disturbed state, held back the payment of the money due to the company, notified the British authorities of what he proposed, and warned McDougall not to try to force his way into the country, nor to assume the functions of government prematurely. Such an assumption, he said, would put an end to the authority of the Hudson's Bay Company. Then, if McDougall were not admitted, there would be no legal government, and anarchy must follow. In such a case, no matter how the anarchy was produced, it would be open by the law of nations for the inhabitants to form a government ex necessitate. The warning was given too late. The letter was written nearly a month after Riel was in possession of Fort Garry and only a few days before December 1, when McDougall supposed that the transfer would take effect. On that day, assuming that it had been made, he issued a proclamation in which he announced his appointment as lieutenant-governor, and he also issued a commission to Colonel Dennis as Conservator of the Peace, with power to raise armed forces and to attack those who resisted his authority. McDougall hopelessly failed to make his authority felt, and in despair returned to Canada. He has been harshly criticized, but while his proclamation of December 1 was hasty and ill-judged, it was not the cause of the difficulty. The mischief had already been done. The authority of the Hudson's Bay Company had been destroyed and the authority of Riel established, when Riel seized Fort Garry, a month before McDougall took action.