* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Rembrandt Selected Paintings

Date of first publication: 1944

Author: Prof. T. (Tancred) Borenius

Date first posted: Aug. 17, 2018

Date last updated: Aug. 17, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180868

This eBook was produced by: Ron McBeth, David T. Jones, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

REMBRANDT

SELECTED PAINTINGS

PHAIDON EDITION

MAN WITH A GOLDEN HELMET. (COMPARE PLATE 53).

REMBRANDT

SELECTED PAINTINGS

WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY PROF. T. BORENIUS

LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD

NEW YORK: OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHED BY THE PHAIDON PRESS

MADE IN GREAT BRITAIN

SECOND IMPRESSION . 1944

PRINTED BY HARRISON & SONS, LTD., 44-47, ST. MARTIN’S LANE, LONDON, W.C.2

PRINTERS TO H.M. THE KING

Ever since the earliest times, art in the Northern and the Southern parts of the Netherlands never had quite the same character; and in the seventeenth century this difference became more pronounced than it had ever been before. This was due to several causes. For one thing, present-day Holland and Belgium now became politically divorced from one another: Belgium continued to acknowledge the sovereignty of the Kings of Spain while Holland achieved her complete political independence. In Belgium, Catholicism remained the predominant form of religion, and this meant that, for painting, there was open, in the decoration of the churches, a vast field for the cultivation of the style of monumental design—the style of which the greatest Flemish seventeenth century artist, Rubens, was such a supreme master. Holland, on the other hand, embraced a form of Protestantism which was particularly opposed to the decoration of the places of worship: and the Dutch painters thus came to be shut off from one of the principal opportunities of developing a style of monumental design. Then, another difference between Holland and Belgium in the seventeenth century is that Holland was by far the more democratic community of the two, and a country where—as an English observer noted in 1609—if the immensely rich people were very few, the number of quite poor people was also very small; in Belgium, on the other hand, we find a much more unequal division both of political power and of wealth. Consequently, in Belgium, the painters found plenty of work in the production of great decorative paintings of historical and mythological subjects, of hunting scenes and still-life pieces on a grand scale, for the palaces and châteaux of the aristocracy; while in Holland, the painters were principally engaged in producing pictures for the much less grand homes of the well-to-do burghers, pictures generally of quite moderate dimensions and distinctly homely character—portraits, scenes from passing life, landscapes, still-life pictures and the like. In the Flemish school there is no lack of painters, whose works are of a kindred character; but they do not predominate as they do in the Dutch school. Now, if we take a general view of Dutch painting of the seventeenth century, we shall find that while the painters are rarely lacking in feeling for colour, they show, on the other hand, generally speaking, a tendency towards trivial realism and commonplace anecdote, as well as neglect of the problems of design—facts which are easily to be explained from the conditions under which Dutch seventeenth century art developed. The greatest Dutch painter of the seventeenth century, Rembrandt, was, however, an artist of deeply poetic imagination, indeed with a definite inclination towards the fantastic, and keenly interested in problems of design; and although his pupils were fairly numerous and his influence was widely felt, he is, nevertheless, something of an exception among the contemporary artists of the Dutch school, which is not dominated by him anything like as effectively as the Flemish school is by Rubens.

In many other ways, Rembrandt also forms a contrast to Rubens, the manysided, much-travelled man, and, as a painter, the head of a regular picture factory. He quite probably never left Holland—there is no conclusive evidence to substantiate a story that he once visited England. He was certainly known outside Holland during his lifetime. Charles I, for example, at a time when the master was still comparatively young, owned no fewer than five pictures by him; but it is very seldom indeed that we hear of him definitely working for a patron abroad. He devoted all his energies to his art, working incessantly and only very occasionally availing himself of the assistance of pupils in executing a picture. Even now we possess by Rembrandt more than six hundred pictures, to which must be added well over two hundred etchings and not far short of two thousand drawings—figures which in themselves are sufficient to prove his untiring and undissipated industry.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was the son of a miller in Leyden, Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn, and was born in 1606, belonging thus to a much later generation than Rubens, who was born in 1577. His parents wished him to enter upon a career of learning, so he received a good education and actually matriculated at Leyden University. He left it, however, soon afterwards and was apprenticed to a local Leyden master, Jacob van Swanenburgh, a very indifferent painter, under whom, nevertheless, he studied for three years. He then went to Amsterdam where he became the pupil of Pieter Lastman, one of the most celebrated of the Dutch painters of his time, and certainly a much more distinguished artist than Jacob van Swanenburgh. Rembrandt stayed with Lastman for about six months, and then returned to Leyden. At some time during his student years, it should here be mentioned, he may also have received tuition from a third master, Jacob Pynas of Amsterdam. In Leyden, Rembrandt soon got busy on his own account; in the year 1632 he, however, left his native city for good and settled at Amsterdam where he rapidly rose to fame, acquiring considerable wealth. In 1634 he married, and we are familiar with the features of his pretty wife, Saskia van Uylenburch, from many portraits. [Plates 7, 8, 9, 37] Before many years had passed, he purchased a house of his own at Amsterdam, where he gradually accumulated a large collection of drawings, engravings and other works of art. By and by, things began, however, to go against him; his great picture, The Night Watch, finished in 1642 and representing a company of the Civic Guard of Amsterdam, did not give satisfaction; in the same year he lost his wife; and he got involved into financial difficulties which went on increasing. Finally, in 1656, he was publicly declared insolvent, and his house and the whole of its wonderful contents were sold by auction.

Fig. 1. LORENZO BERNINI: CONSTANTINE THE GREAT (1670).

Rome, Vatican, Scala Regia.

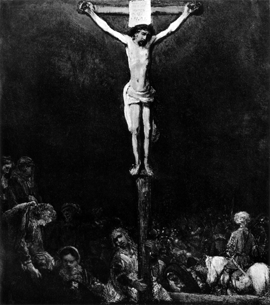

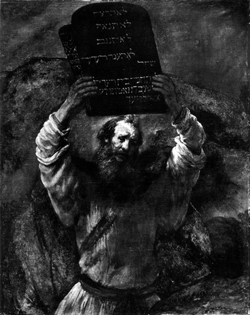

The remainder of Rembrandt's life was spent in poverty: he died in 1669, without having satisfied his creditors who had a right on a certain percentage of what he earned; and in order to evade this, Rembrandt's and Saskia's son Titus and his house-keeper Hendrickje Stoffels—both often depicted by the artist [Plates 49, 69, 72, 84, 85, 89]—established themselves as a firm of art-dealers, for which Rembrandt was to work, while all the profits were nominally to go to the firm. But his art was no longer a very valuable asset: for although to us the full greatness of Rembrandt as an artist is only revealed in the works of this last period of his activity, with their grandeur of conception, and boldness and freedom of handling, what contemporary taste in Holland was beginning to prize in art was affectation, a sham classicism of form and slippery smoothness of technique. Nevertheless, Rembrandt still received some important public commissions during these years [Plates 95, 96]—the Staalmeesters or Syndics of the Cloth Hall (1662), and two or three pictures of which now only fragments survive [Plates 76, 79, 82]—Dr. Deyman's Anatomy Lesson (1656), the Conspiracy of the Batavians (1661) and probably Moses showing the Tables of the Law to the People (1659).

Of Rembrandt as a man, the history of his life and the accounts of people who knew him allow us to form a pretty clear idea. There is ample evidence of his whole-hearted devotion to his art, and of his power of inspiring affection; also of a somewhat naive inclination towards extravagance and display and of a certain spirit of ostentation. Thus, one of his pupils tells us, that when attending art sales, as he often did, Rembrandt was wont, especially if pictures or drawings by famous artists were offered for sale, to bid so high at the outset that no further bidder came forward, and he would say that he did this to exalt the honour of his art. Also while we hear of his generosity in placing at the disposal of other artists such of his innumerable paraphernalia—draperies, arms, etc.—as they may have required, it must be admitted that in certain incidents of his personal life he cuts quite definitely a poor figure. Great as he was as an artist, he was by no means flawless as a character: but then it is very rarely that moralists can draw very comforting conclusions from the personal aspects of art history.

★

Appreciation of Rembrandt, not only spoken but also written, tends to be of a mainly descriptive nature, to be concerned, as it were, principally with the foreground of interest—the pictures, etchings and drawings by themselves, all of which is, of course, amply sufficient to hold our attention. But the art of Rembrandt also has a background in the general history of art, upon which as a rule less emphasis is laid: and if we see Rembrandt's art against that background, much becomes clear that otherwise would be difficult of explanation.

The seventeenth century, Rembrandt's century, is, in European art generally, pre-eminently the period of the Baroque. The Baroque is an artistic phenomenon, to which we can trace many counterparts in different periods of art: but for the purpose of our present enquiry we are only concerned with the European Baroque of the seventeenth century. And the important fact to bear in mind about it is that the Baroque, as here defined, was essentially a creation of Italy. Now what is it that Baroque art stands for? Speaking in very general terms, it stands for largeness and simplicity of rhythm and telling effect: also for a vital flow of movement and intensity of expression. In sculpture, Bernini is the typical Baroque artist—in none of his works more so than in his equestrian statue of Constantine the Great on the staircase of the Vatican, here reproduced (Fig. 1) for the purpose of indicating, by one typical example, the spirit and character of Baroque art. In Flanders, a splendid consummation of Baroque art is seen in the work of Rubens, who arrived at his style after years of study in Italy. In Holland, too, eyes were turned to Italy, though the national movement, going back to what we might call a Van Eyck-ian tradition of minute, matter-of-fact realism, during the greater part of the seventeenth century counted the larger number of followers. And it is amongst the artists of this type that Rembrandt stands out by contrast, as essentially a Baroque artist, influenced very decisively by Italian art. It is by bearing these facts in mind that we can arrive at a better understanding for one thing of Rembrandt's isolation in contemporary Dutch art; secondly of his relation to the main currents of European art of his time; and finally also of the features which go to make up the individual character of his art.

Now one often hears Rembrandt referred to as an artist who owed but little to foreign influence. Of course, it is true that Rembrandt did not travel extensively—he certainly never visited Italy and, all things considered, the probability is that he never went beyond the frontiers of his native Holland—I have spoken before of the fairly old, but unsubstantiated story that, towards the end of his life, he visited England. It is also true that the intimacy of Rembrandt's feeling has a peculiarly northern note, and that he very rarely shows any approach to classicism of form; but it is equally certain that Rembrandt learnt very much through study of foreign art, and especially Italian art. A piece of evidence of some importance in this connection may be found in certain memoranda, written about 1630, or at a time when Rembrandt was still quite young, by a Dutch scholar and politician, Constantine Huygens, who speaks in terms of great admiration of Rembrandt and another young Leyden artist of kindred character, Jan Lievens, expressing, however, his regret at their not wishing to go to Italy. "But I must not omit to mention," says Huygens, "the excuse in which they fold themselves and explain their inactivity; for they say that, while in the flower of their years, of which they must make the most, they have not the time to spend in travel; and furthermore, that nowadays such is the love of Kings and Princes of the North for paintings, and so careful their choice, that the finest Italian pictures are here to be seen (i.e. in Holland) and that they are brought together here into collections, whereas in Italy they are scattered far apart." It is evident from this, that Rembrandt did not despise Italian art, and he was quite right in saying that he had ample opportunity for studying it without going south, for Holland was at this time becoming a very important centre of the art market.

Indeed, a near relative of Rembrandt—Gerrit van Uylenburch, the nephew of Rembrandt's wife Saskia, was concerned, among other things, with the importation into Holland of the bulk of the very fine collection of Italian, and more particularly Venetian, pictures formed by a Venetian nobleman Andrea Vendramin, and known to posterity mainly through an album of pen-and-ink drawings after the pictures composing it—an album now in the Library of the British Museum.

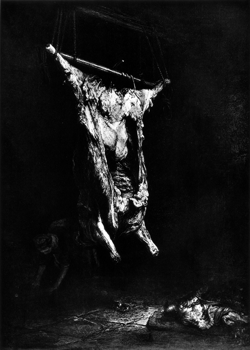

More than this—Rembrandt was an omnivorous collector himself. The inventory of Rembrandt's own collection, drawn up on the occasion of his bankruptcy, is simply astonishing as a revelation of what Rembrandt not only knew, but actually himself possessed in the way of examples of Italian and Classical art. To begin with, he owned a series of casts from the Antique, as well as a number of Classical sculptures; moreover, a few pieces of more recent sculpture, among which a statue of a child attributed to Michelangelo has been identified with the lost marble figure of the Sleeping Cupid which at one time was in the collection of Charles I. Then there were Italian pictures by artists who already ranked as Old Masters: we read of a picture of Christ and the Woman of Samaria, attributed to Giorgione (Fig. 2); of the Parable of Dives and Lazarus, held to be by Palma Vecchio; of A Camp on Fire by Old Bassano; and of no fewer than two pictures ascribed to Raphael, a Madonna and Child and a Portrait Head. Of prints by and after Italian Masters, Rembrandt possessed a very representative collection—beginning with the complete work of Mantegna, and continuing the representation of the school right down to the Bolognese Eclectics, including the Carracci and Guido Reni, as well as to one of the naturalists of the tenebroso school, Ribera. Finally, Rembrandt's collection of drawings by Italian Old Masters was a very extensive one, and was long remembered, setting an example, for instance, to his pupil, Govaert Flinck, another name famous in the annals of collecting.

Fig. 2. PALMA VECCHIO: CHRIST AND THE WOMAN OF SAMARIA (c. 1520).

England, privately ownership; destroyed by enemy action.

Probably a picture which belonged to Rembrandt, who ascribed it to Giorgione.

So much for Rembrandt's opportunities of getting to know about Italian art: and if we turn to Rembrandt's work, we shall find plentiful evidence of his acquaintance with it. Indeed, one might say that Rembrandt copied everything he could get hold of—Classical statues, Italian prints, pictures and drawings, Indian miniatures and what not, and of all great artists he is perhaps the one in whose work we can trace the largest number of definite borrowings from other artists—mainly Italian artists. Up to a point like Rubens, he does not, however, give us actual copies but free translations; and it is of great interest to compare these translations with the originals, as this brings out very clearly wherein the individual character of Rembrandt's art consists.

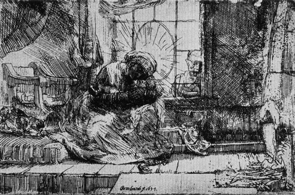

Fig. 3. REMBRANDT: THE VIRGIN AND CHILD WITH THE CAT: AND JOSEPH AT THE WINDOW (1654).

Etching (H.275).

Fig. 4. ANDREA MANTEGNA: THE VIRGIN AND CHILD.

(c. 1460). Engraving (B.8, T.B.1).

Let us take one of the most striking instances first. It is provided by Rembrandt's etching of 1654 The Virgin and Child with the cat: and Joseph at the Window (B. 63; H275), here reproduced (Fig.3) alongside Mantegna's engraving The Virgin and Child (B.8, T.B.1) (Fig. 4). A glance at the two compositions is sufficient to make us realize that Rembrandt has derived the whole of the idea of his group of the Madonna and Child from Mantegna—introducing a number of variations no doubt, and using his own language of form, but still upon many points—such as the placing of the Virgin's head and the disposition of the Child's feet—following his prototype with remarkable closeness. The analogy has, of course, no direct bearing on the question of Rembrandt's connection with the Baroque, as Mantegna belongs to a much earlier period of art: but this analogy does useful service as a piece of evidence that Rembrandt was alive to certain qualities of Italian art which remain fundamentally common to several of its successive stages. And here we may for a moment consider the question of how it is that Rembrandt will follow another artist so closely as he does in this instance, seeing that, if anyone, he was not deficient in inventive faculty. This, I am afraid, must remain a mystery, and all I can say is that similar remarks are suggested by the work of many other great artists. Nothing, I feel, can be urged against them for having acted as they did, and to the students of art history their borrowings often provide the most valuable clues as to how unexpectedly the currents of influence will run in the history of art. Raphael, for instance, in his frescoes in the Vatican, had to deal with the problem of representation of the crowd—a problem which half a century earlier Donatello had tackled in his bas reliefs of the Altar of the Santo at Padua. Now, though we have no written evidence, it is an indisputable fact, that Raphael was impressed by Donatello's performance: but what clinches the argument is that in the School of Athens three figures are bodily copied from Donatello—and again we may be sure that Raphael essentially was an artist who had no need of such expedients.

Fig. 5. LEONARDO DA VINCI: THE LAST SUPPER (1497).

From an engraving by Raphael Morghen.

Fig. 6. REMBRANDT AFTER LEONARDO DA VINCI: THE LAST SUPPER.

Drawing (1635) in the Berlin Print Room.

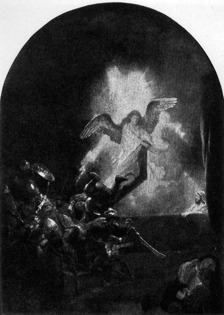

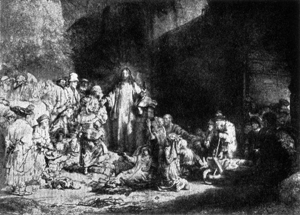

Another illuminating juxtaposition is that of Leonardo da Vinci's fresco of the Last Supper at Milan (Fig. 5) and a drawing (now in the Berlin Print Room) made by Rembrandt after some reproduction of that work—he never saw the original (Fig. 6). Now if we compare the two we shall find not only that Rembrandt has done away with the classical regularity of Leonardo's types, substituting for it a great coarseness; but also how his endeavour has been to produce as vigorous and striking an effect of movement as possible. With this end in view, he has introduced various modifications into Leonardo's design: the groups immediately to the left and right of Christ have been drawn much closer to Him, and at either end we have no longer the reposeful horizontals balancing one another, but quite irregular silhouettes which in no way correspond to one another, and new and very dramatic motifs. By his endeavour to produce this effect of intense movement and dramatic life, Rembrandt is following what we have found to be the main tendency of the Baroque: and one of the few authentic pronouncements of Rembrandt on his aims as an artist which are known to us deserves to be quoted in this connection. It occurs in a letter which he wrote in 1639 to the secretary of the Prince of Orange, for whom he had just finished two pictures; and Rembrandt now offers to deliver them "for the delectation of the Prince, as the utmost and most natural animation has been achieved in them" and it is for this reason that they have been so long in hand. One of the pictures in question represents the Resurrection of Christ and is now in the Gallery at Munich (Fig. 7); and while it certainly shows that "most natural animation" of which Rembrandt speaks, it also reveals the tendency towards grotesqueness and exaggeration which is by no means a rare feature in the earlier work of Rembrandt. But to return to the question of the relationship existing between Rembrandt and Italian art. Reproductions are here given of a picture of a Sibyl by Domenichino, an artist of the Bolognese school of the early seventeenth century (Fig. 8) and a picture by Rembrandt of the same subject, a very late work of the artist's, executed about 1667, and now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York (Fig. 9). It is evident from a comparison of these two pictures, that Rembrandt must have been acquainted with one of the many variations on this motif by Domenichino; and cases like this make one realize very vividly how deeply Rembrandt is indebted to his study of Italian art for his power of simple and imposing, as well as decoratively effective design; but because there is in Rembrandt concurrently a very pronounced tendency towards irregular rhythm of line and accidental picturesqueness of effect—qualities which are so radically opposed to the typically Italian qualities of regularity and balance—people are apt to lose sight of the fact that Rembrandt owes a great deal to the Italians.

Fig. 7. REMBRANDT: THE RESURRECTION (1639).

Munich, Aeltere Pinakothek.

Fig. 8. DOMENICHINO: THE CUMAEAN SIBYL (c. 1625).

Rome, Galleria Borghese.

Fig. 9. REMBRANDT: A SIBYL (c. 1667).

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A very essential difference between these two pictures may, of course, be found in the treatment of light and shade, Rembrandt's method of chiaroscuro being a most powerful means of conveying to us an intensely mysterious and fantastic mood, of which there is no trace in Domenichino. Now Rembrandt's method of chiaroscuro, though independent of Domenichino, has undoubtedly its origin elsewhere in Italian art.

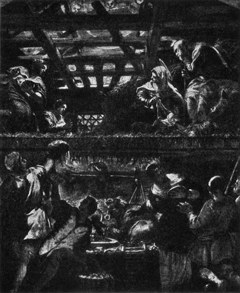

Figs. 10 and 11. TINTORETTO: ADORATION OF THE SHEPHERDS—BAPTISM OF CHRIST (1577-81).

Venice, Scuola di San Rocco.

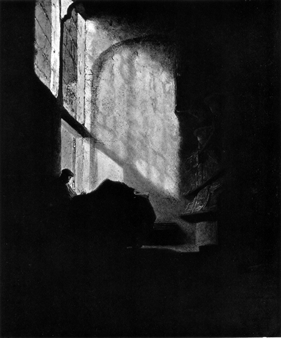

In Italy, the ancestry of Rembrandt's method of treating light and shade can, in its full development, ultimately be traced back as far as Tintoretto. I am here mentioning a master who is perhaps the most influential single artistic force in the whole of the history of painting, from the end of the sixteenth century down to our own times: and Tintoretto's great gift to art, above all others, was, I think, his method of using light and dark masses, one standing out against the other, in alternating succession of silhouettes. The magnificent sweep of line or tornado-like rush of movement, the superb rhythmic harmony of his designs; his consummate mastery of colour, atmosphere and brushwork—to all this Tintoretto's method of contrasting light and shade is ultimately the life-giving touch. He subordinates everything else to this obsession of his. Ruskin, in noticing that some of the dark heads in Tintoretto's pictures appear relieved against a halo of light, vouchsafes the information that "the daguerrotype has proved this to be quite a realistic effect." But how little Tintoretto really cared for verisimilitude in this respect! For the purpose of articulating his compositions effectively, his resources of lighting contrivances were as unlimited and as arbitrary in their application as those of any stage-electrician of to-day. We can see that with particular clearness from such a classic example of Tintoretto's style of chiaroscuro as his Baptism of Christ in the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice (Fig. 11) where the whole of the composition is built up on a most elaborate system of contrasted silhouettes, light upon dark and dark upon light, and where his completely arbitrary use of reflected light, whenever the design demands it, is most strikingly evidenced in the figure in the extreme foreground, stripping himself. And how extraordinarily Rembrandtesque is not all this, by anticipation!

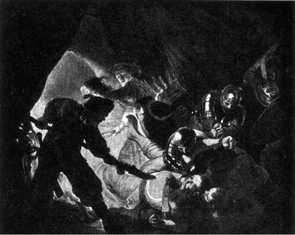

Fig. 12. REMBRANDT: THE BLINDING OF SAMSON (1636).

Frankfort, Staedel Museum.

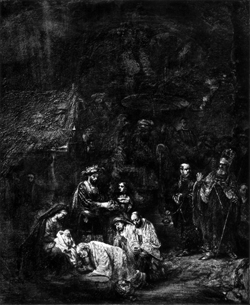

Take another instance from the work of Tintoretro, the Adoration of the Shepherds, also in the Scuola di San Rocco (Fig. 10), a scene of an indescribably magic and haunting effect of chiaroscuro, the light penetrating the stable through the open timber of the roof, and the design being again built on contrasting silhouettes, though this is not carried through in the almost mechanical fashion noticeable in the Baptism. Added to the treatment of light and shade, the homely realism of the figures, and the setting, make us feel that we are here getting very near indeed to Rembrandt.

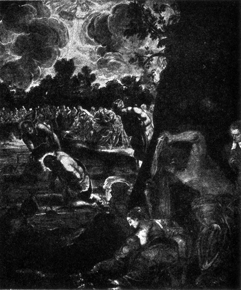

Fig. 13. REMBRANDT: THE SUPPER AT EMMAUS (c. 1629).

Paris, Musée Jacquemart-André.

And, if we turn to the work of Rembrandt, there is no lack of examples in which, conversely, the distance from Tintoretto strikes us as being very small. Take a work such as his Blinding of Samson of 1636 (Fig. 12) known to many generations of students in the possession of Count Schönborn-Buchheim of Vienna, but now in the Staedel Museum at Frankfort. This simply could not have come about but for Tintoretto, so extraordinarily close is the approach to him, in the turbulent rhythm of line, in the composition, and above all in the use of light and shade with a view to getting as strikingly contrasted silhouettes as possible. I will quote yet another instance, quite an early work by the master, The Supper at Emmaus in the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris (Fig. 13) dating from about 1629: it bears out all I have said of Rembrandt's adoption of Tintoretto's methods of chiaroscuro. And, incidentally, how close do we not get in this scene of exaggerated dramatic agitation to some of Tintoretto's rowdy Last Suppers and other Biblical banqueting scenes, in which chairs are upset and people fling themselves about, throwing all self-control to the winds.

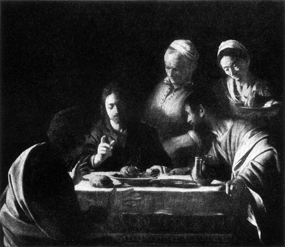

Fig. 14. CARAVAGGIO: THE SUPPER AT EMMAUS (c. 1595).

Milan, Brera Gallery.

In the history of Italian art, it was upon the shoulders of Caravaggio that the mantle of Tintoretto in a sense descended. I think there can be no doubt that Caravaggio's forceful naturalism is derived from Tintoretto and the same is true of his treatment of light and shade, though there is this important difference—that Caravaggio favours what has been called a cellar-lighting with the most unmitigated and violent oppositions of tone, glaring patches of light next to large masses of unbroken shadow (Fig. 14), whereas Tintoretto—and after him Rembrandt—very largely depends upon the effect of reflected light, playing across the shadows. Still, I think there can be no question but that Rembrandt owes Caravaggio a considerable debt: and if we look at such a picture by Caravaggio as his Penitent Magdalen in the Palazzo Doria-Pamphili in Rome (Fig. 15) we shall find in this uncompromisingly naturalistic study of a plain girl asleep an astonishingly complete anticipation of many of Rembrandt's methods. To what extent Rembrandt had first-hand acquaintance with Caravaggio's work is difficult to say: on the whole it may be doubted whether by then many examples of Caravaggio's art had found their way to Holland; but close at hand there was the whole of that interesting school of Caravaggio-imitators at Utrecht, the principal one of whom was Gerard van Honthorst, of whose peculiar effects of illumination by candle-light there are some very palpable imitations in the work of Rembrandt.

Fig. 15. CARAVAGGIO: THE PENITENT MAGDALEN (c. 1595).

Rome, Palazzo Doria-Pamphili.

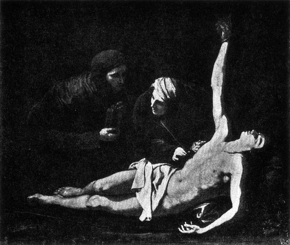

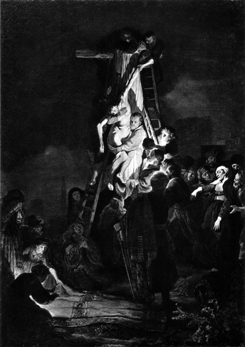

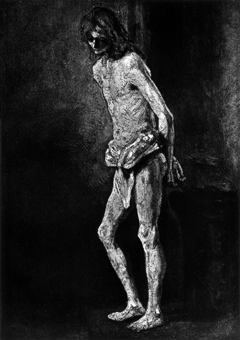

Then there is the case of Ribera—an artist whose etchings we know that Rembrandt did possess and whose pictures too we may be certain were known to him. A picture which offers valuable evidence in this connection is the Descent from the Cross in the John and Mabel Ringling Art Museum at Sarasota (Fig. 16). Although bearing a Rembrandt signature (and the date 1650) the authenticity of the picture was for a while doubted; but opinion has lately again veered round in favour of Rembrandt's authorship. However, the actual question of attribution matters comparatively little for the purpose of our present enquiry: it is enough that the picture should reflect the tendencies of Rembrandt's immediate circle. Here not only are the oppositions of tone more forced than is usual with Rembrandt, and singularly reminiscent of Ribera, but even the character of the forms and the arrangement of the composition make one think of him (compare Fig. 17).

Fig. 16. REMBRANDT: DESCENT FROM THE CROSS (1650).

Sarasota, John and Mabel Ringling Art Museum.

Fig. 17. RIBERA: ST. SEBASTIAN AFTER HIS MARTYRDOM (1628).

Leningrad, Hermitage.

Yet another artist who, although a German by birth, ranks in the history of art as a member of that Roman school of the seventeenth century which is of such vital importance for the development of European art, and who must be considered in any discussion of Rembrandt's treatment of chiaroscuro is Adam Elsheimer. This painter, a native of Frankfurt, who settled in Italy about 1598, and died at Rome while still quite young in 1610, painted practically only landscapes, of very small size and distinguished by an extraordinary softness and tenderness of illumination and richness of atmosphere; and it is quite clear that the art of Elsheimer made a most powerful impression on Rembrandt, directly as well as indirectly through Lastman. Take such a picture by Elsheimer as his Flight into Egypt in the Munich Gallery (Fig. 19), revealing an interest which comes to the fore in several of Elsheimer's works, the study of complicated effects of light. The darkness of night is here broken by the emanation of light from several different sources: the torch carried by St. Joseph, the fire round which the shepherds have gathered and the moon which is just rising on the starlit sky over the dark masses of foliage and is reflected in the calm waters of a lake. Now let us turn to a picture of the same subject by Rembrandt, painted in 1647 and belonging to the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin (Fig. 18). Here we see, in the foreground, the Holy Family resting by the fire, lighted by some shepherds and reflected in a little pond: the moon is just breaking through the clouds and the masses of foliage and the castle with lights in its windows tell as a dark silhouette against the sky. The picture is so similar in composition and effect, to the one by Elsheimer just shown, that judging merely from reproductions one might almost be tempted to think that they are by the same artist: there is, however, undoubtedly a far greater freedom of handling and richness of tone in the picture by Rembrandt.

Fig. 18. REMBRANDT: THE FLIGHT INTO EGYPT (1647).

Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland.

Fig. 19. ADAM ELSHEIMER: THE FLIGHT INTO EGYPT (1609).

Munich Gallery.

Many more examples, bearing upon the points I have been endeavouring to make could easily be accumulated: but from what I have said I hope it is abundantly clear to what an extent Rembrandt, although all the time giving evidence of his individual bent, yet was influenced by Italian art; to what an extent his art is an exponent of tendencies which are characteristic of the Baroque generally. And while, as I have said, this differentiates him from the bulk of artistic endeavour in the Dutch school of the seventeenth century, I am anxious not to be misunderstood as if wanting to convey that Rembrandt was absolutely unique in this assimilation on his part of qualities in the art of Italy. We can trace a whole group of kindred phenomena in Dutch seventeenth century painting, and another of the very greatest artists of the school, Jan Vermeer of Delft, offers a case in point, although with Vermeer the working of the Italian influence is for the most part of a much more mysterious nature, much more difficult to analyse and demonstrate than is the case with Rembrandt. Now as regards Rembrandt and Italian art, an enquiry such as I am here sketching can be rounded off in a most interesting fashion by going into the question as to how contemporary Italy reacted to Rembrandt's art. Concerning this question we possess some extremely remarkable information which has come to light not so very long ago, and which deserves to be much more widely known than it is.

Fig. 20. GUERCINO: THE ANGEL APPEARING TO ST. JOSEPH (c. 1625).

Naples, Palazzo Reale.

By the middle of the seventeenth century it is clear that the fame of Rembrandt had penetrated into Italy. So far as the available evidence goes, the person who must be mentioned by preference to anyone else, among the contemporary admirers of Rembrandt in Italy, was a member of a great Sicilian noble house, Don Antonio Ruffo, who lived at Messina. Don Antonio, who was a great art collector, ordered of Rembrandt direct three pictures for his gallery: the first of these painted in 1653, being the picture of Aristotle, now belonging to Messrs. Duveen of New York [Plate 60]; and the two others, dating from about ten years later, being a Homer [Plate 98]—doubtless the picture of which a fragment is in the Mauritshuis at the Hague—and an Alexander which has been identified with the Mars now at Glasgow [Plate 73], though the latter for various reasons, I think, is most unlikely to be the Ruffo picture—for one thing the Glasgow picture is dated 1655 and secondly it does not show the figure seated as the Ruffo inventory describes it. Now when Rembrandt's picture of Aristotle arrived at Messina, in 1654, Don Antonio thought he would have a companion picture painted for it. He commissioned this of an Italian painter and his selection of an artist for this task is a most interesting one: for he chose Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, better known as il Guercino, one of the most celebrated of Italian Baroque painters whose art combines features of style derived both from the Bolognese Eclectics and from the tenebroso painters of the Naturalist group, headed by Caravaggio (Fig. 20). We possess the letter which Guercino in 1660 wrote to Don Antonio Ruffo in response to his invitation that he should paint a pendant to Rembrandt's picture: and it is one of the most interesting documents imaginable, imparting a character of extraordinary actuality and vividness to the whole of this curious episode. Guercino begins by saying that the picture by Rembrandt is sure to be a work of great perfection, as he has seen several etchings by the Dutch artist, which are very beautiful, engraved in good taste and executed in a good manner, allowing the inference that Rembrandt's colouring must be of equal exquisiteness and perfection: indeed, says Guercino, I sincerely hold him to be a great virtuoso. Guercino goes on to declare his readiness to paint the companion picture, adopting, as Ruffo wishes, the manner of his own early period in which light and shade are boldly contrasted—a very notable point this, since it proves for one thing that Ruffo quite rightly felt the affinity between Rembrandt's style of chiaroscuro, and that of the Naturalist school of Caravaggio; and secondly this conveys a very useful warning to art historians, not to be too sure as regards their chronologies, if based solely on the evidence of style, seeing that here Guercino, quite late in life, calmly declares: "Very well, I will paint a picture in my early manner." Guercino then asks for the size of Rembrandt's picture and that a sketch of it be sent to him so that he can design his companion figure accordingly. The picture by Guercino—representing a Cosmographer—was eventually carried out by him, but most unfortunately cannot be traced at present: it would undoubtedly be of the most absorbing interest to know what a picture looked like if painted by Guercino for the avowed purpose of harmonizing with a picture by Rembrandt. But even so, the letter from Guercino gives us all the evidence we can possibly demand as to the extent to which a leading Italian Baroque painter looked upon Rembrandt as an artist sharing his own outlook: there is not a vestige of criticism or dissent in Guercino's pronouncements, nothing but admiration and praise. Inevitably we come to wonder in this connection whether Rembrandt knew Guercino and what he thought of the Italian artist. There is every probability on general grounds that Rembrandt was acquainted with the art of Guercino: and there exist one or two pictures by Rembrandt which to me suggest something of an exercise in the manner of Guercino. I am particularly referring to the great picture of Mordecai before Esther and Ahasuerus (Fig. 21), a very late work, dating from about 1665, belonging to the King of Roumania. Though I cannot give chapter and verse as in many previous instances, I feel in the types and forms, in the colouring, chiaroscuro and character of design a very distinct echo here of Guercino's dramatic compositions of scriptural and historical subjects.

Fig. 21. REMBRANDT: MORDECAI BEFORE ESTHER AND AHASUERUS (c. 1666).

H.M. The King of Roumania.

★

In making the above general remarks on the art of Rembrandt I have referred indiscriminately to works from different stages of his career; but Rembrandt is emphatically one of those artists whose evolution takes them very far indeed from where they began; and I must now pass on to illustrate with a few examples the principal stages of that evolution into which even those of our selection of plates, not mentioned especially, will be found to fit naturally.

Fig. 22. JACOB VAN SWANENBURGH: SQUARE OF ST. PETER

Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst.

By way of introduction, a word or two may here be said about Rembrandt's teachers. They were all of them—a point of importance—artists who had studied in Italy, where Jacob van Swanenburgh (c. 1571-1638) lived for several years in Naples and Rome. Of his scarce, and far from distinguished work, a Square of St. Peter's, Rome in the Copenhagen Gallery, offers a characteristic example (Fig. 22); it is signed and dated 1628 and thus almost belongs to the period when Rembrandt was studying under him. Jacob Pynas (c. 1585?-after 1650)—who may have been one of Rembrandt's teachers—was an artist of quite different calibre: the drawing by him here reproduced (Fig. 23) is a late production, dated 1646, curiously Rembrandtesque in character. Pieter Lastman (1583-1633) was in Rome from 1604 to 1607—years which witnessed the brief, but all-important activity of Adam Elsheimer in that city; and the example of the latter artist undoubtedly meant a great deal to Lastman. The picture by him chosen for illustration—Orestes and Pylades in the Rijksmuseum at Amsterdam, dated 1614 (Fig. 24)—shows well his adoption of the Italian manner; but one cannot help feeling the clash between the exaggerated rhetoric of the style and the tendency to a trivial and even gross realism which is characteristically Dutch and comes out notably in certain of the heads. All things considered, Pieter Lastman is little more than a tiresome and dull academic. His influence on Rembrandt was, however, far from negligible at the beginning of Rembrandt's career; and reminiscences of Lastman occur even in comparatively late works of Rembrandt; while it is of great interest to observe how Rembrandt, in making drawings after Lastman—as it almost goes without saying that he did—improves upon the composition of his teacher. Of Rembrandt's method of chiaroscuro, we find but a very slight anticipation in the art of Lastman.

Fig. 23. JACOB PYNAS: LANDSCAPE (1646).

Red chalk.

Fig. 24. PIETER LASTMAN: ORESTES AND PYLADES (1614).

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

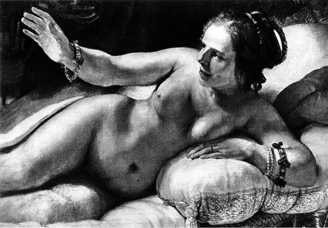

Among the early works by Rembrandt—who may be assumed to have begun working on his own in 1625—two groups immediately define themselves. We have for one thing pictures showing considerable breadth of treatment, such as is particularly well shown by his Supper at Emmaus already reproduced (Fig. 13) in which the false pathos, over-emphatic action and the tendency to grotesque realism remind one of Lastman, while there is much in it too—as hinted before—to recall Tintoretto. In other early works by Rembrandt we then find great delicacy of execution, as for instance in his Rape of Proserpine (painted about 1632) in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum at Berlin (Fig. 26) which also still has many features of style in common with the art of Lastman, while as regards the colouring, it shows the lovely harmonies of green and old gold which are so characteristic of Rembrandt.

Fig. 25. REMBRANDT: THE MONEY CHANGER (1627).

Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum.

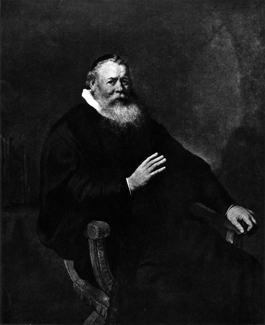

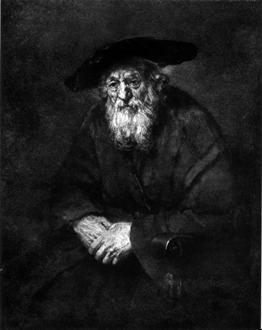

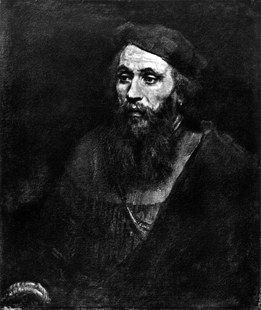

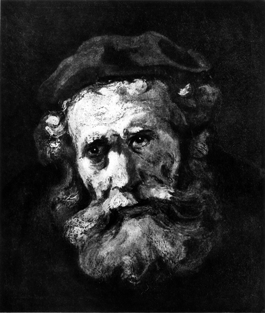

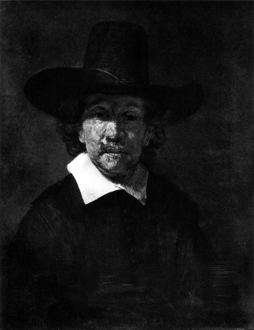

Alongside sacred or mythological subjects, we then find among the early works of Rembrandt subjects from everyday life and notably a great number of portraits of Rembrandt's relatives as well as of the artist himself—he remained indeed partial to these classes of subjects all through his life—no painter ever painted his own portrait as often as Rembrandt [Plates 1, 6-9, 23, 37, 49, 58, 59, 64, 67, 72, 81, 84, 87, 91, 99]. In these portraits of Rembrandt and his relatives the sitters are frequently shown dressed up in gorgeous costumes, helmets, steel gorgets, turbans, all the trappings in short which we know Rembrandt collected with perfect passion, but which, it must be confessed, tend to produce, in certain cases, a somewhat obviously picturesque and fantastic effect.

Fig. 26. REMBRANDT: THE RAPE OF PROSERPINE (c. 1632).

Berlin, Kaiser Friedrich Museum.

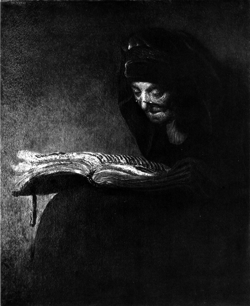

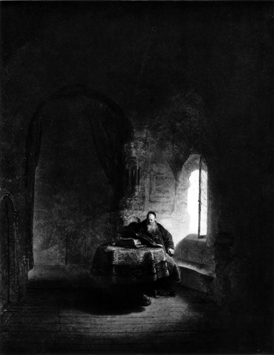

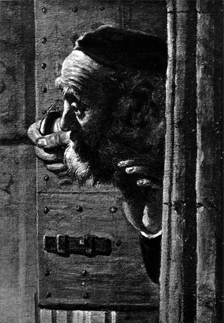

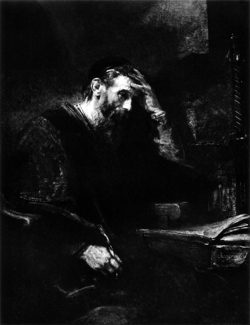

A different note is struck in his early pictures of scholars and old recluses, among which we will here specially instance the one in the Gallery at Turin, dated 1629 (Fig. 27). This interior of a room with an old man asleep—quite a small picture of the most delicate execution—shows Rembrandt pointing the way to a very numerous group of Dutch seventeenth century painters of homely subjects. And to mention yet another early work by Rembrandt, in his picture of a Money Changer in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum at Berlin, dated 1627 (Fig. 25) we see Rembrandt returning to the subject which one hundred years earlier had been such a favourite one with Quentin Massys and his school. The scene is lit by the candle, held by the old man, the flame being hidden by his hand—it is indeed a frequent device of Rembrandt (as of his older contemporary of the Italianizing Utrecht school, Gerard van Honthorst) to make the light emanate from the centre of the composition, the actual source being concealed; whereas Caravaggio uses strong side light coming from above.

Fig. 27. REMBRANDT: OLD MAN ASLEEP (1629).

Turin Gallery. The sitter probably Rembrandt's father.

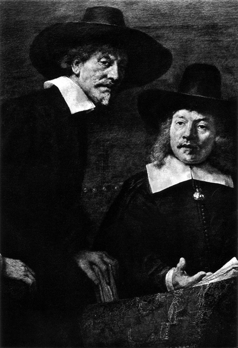

If the Dutch seventeenth century painters received but little patronage from the church, they were on the other hand frequently employed by other public bodies, on commissions which are quite peculiar to Holland. I have referred previously to the very democratic constitution of the Dutch community: the army was a volunteer force composed by all able-bodied men, the large and powerful guilds, to which the members of the various professions belonged, were administered by executives elected from amongst their number, and altogether, elected committees formed a very important part of the administrative machinery of Holland. Now it was customary for the members of these committees and bodies or burgher companies to have their portraits painted grouped together in life-size pictures, which were then hung in the assembly rooms of the respective public bodies; and to this day Holland contains an immense number of portrait groups of this kind. Among the most famous of them is a series of pictures by Rembrandt's older contemporary Frans Hals, now in the Museum at Haarlem, representing the officers of the Civic Guard of Haarlem celebrating the anniversary days of their companies. Rembrandt only painted very few pictures of this type, but three of them are among his most celebrated works and illustrate well three successive stages of his career.

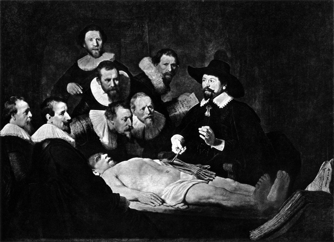

The earliest of them is the picture, known as The Anatomy Lesson of Professor Tulp [Plate 5], painted in 1632 for the guild of the surgeons at Amsterdam; it represents a famous Dutch surgeon and anatomist, Nicolaes Tulp, demonstrating on the dissected body in front of him, his hearers being the members of the committee of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons. It is a somewhat stiff and formal composition: Rembrandt has evidently been determined to give every figure in this group of portraits an equal chance, and the light is, for him, very evenly diffused; the handling is very smooth, the whole strikes one as a piece of somewhat prosaic and literal realism. This is one of the first pictures Rembrandt executed after he had settled at Amsterdam, and to the same period belong also a number of other works, mainly portraits, exhibiting a similar style; but although Rembrandt no doubt owed something of his initial success at Amsterdam to these works [Plates 10, 11], he soon abandoned this style of relatively cold and literal realism, giving fresh emphasis to his characteristic method of chiaroscuro and developing gradually an ever greater freedom of handling.

Fig. 28. REMBRANDT: THE HOLY FAMILY (1646).

Cassel Gallery.

And when, Rembrandt, ten years later, painted his second corporation picture he took up a very different attitude. The picture in question, now in the Rijksmuseum at Amsterdam, is world-famous under the title of 'The Night Watch' which came to be given to it in the eighteenth century, when it was supposed to represent a Night Watch turning out on its rounds by artificial light [Plate 33]. At the time, the picture was considerably darker than it is now that the old varnish has been removed from it; and there can be no question but that the light which strikes the figures as they emerge from the gloom of the hall or passage in the background is that of the sun, though it must be admitted that the contrasts of tone are, and always have been, somewhat unnaturally forced. As for the subject, the picture represents a company of the Civic Guard of Amsterdam leaving its Assembly Hall for a shooting competition: at the head of the men walk the captain and lieutenant of the company, and we can see that the sun is still quite high by the shadow, cast by the hand of the captain on the coat of the lieutenant. The animation of the whole is extraordinary and we do not stop to question the naturalness of the method of lighting, so magic is it in effect: but it is on record that the people who had ordered the picture were far from pleased with it, as it decidedly did not correspond to the accepted notion of a portrait group, which was that attention should not in the first place be attracted by the main action and the general effect, but by the individual portraits; and it evidently made no difference to the objectors that, although Rembrandt saw the whole picture first, yet all the individual heads are full of life and character. It must be owned, however, that admirable though it is, this picture does not as yet show Rembrandt at his greatest, producing as it does an effect of too great virtuosity: he had yet to learn a greater economy of expression, to acquire a greater intensity of feeling as well as simplicity, boldness and effectiveness.

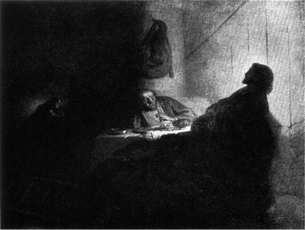

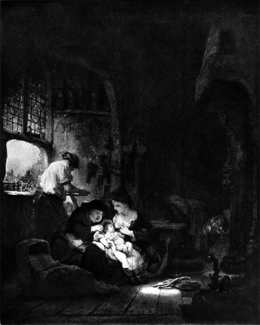

Fig. 29. REMBRANDT: THE HOLY FAMILY (c. 1644).

Formerly Downton Castle, Boughton-Knight Collection.

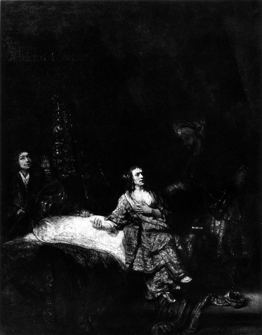

His development in the direction indicated took place by degrees during the remaining years of the 1640's. The character of his art is noticeably changed already in a specially remarkable picture painted four years after The Night Watch, or in 1646, and now in the Gallery at Cassel (Fig. 28). It represents the Holy Family in their humble home: the Virgin with the Infant Christ in her arms, seated in the foreground, and in the background, vaguely seen, the figure of St. Joseph cutting wood. No better instance could be chosen of the way in which Rembrandt infuses an altogether new life into the old and well-worn scriptural subjects, through the nobly and intensely human spirit in which he approaches them and the touching intimacy and simplicity of his conception. If there is anything to be criticized in this picture, it is perhaps the somewhat sophisticated device of imagining the whole as an altarpiece, the hanging in front of which is not quite pushed aside. Equally beautiful is a picture, formerly in the Boughton-Knight Collection at Downton Castle (Fig. 29) and of about the same date, in which a similar scene is treated in a similar spirit of typically Northern intimacy—again a humble interior, with the Virgin and St. Anne quietly seated by the cot in which the Infant Child is asleep, the candle, hidden by the figure of the Virgin, causing a large and phantastic shadow of St. Anne to be thrown on the wall at the back.

Fig. 30. REMBRANDT: WINTER LANDSCAPE (1646).

Cassel Gallery.

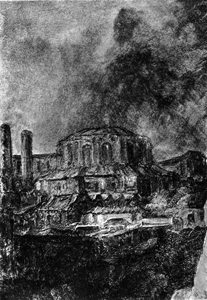

Fig. 31. REMBRANDT: LANDSCAPE WITH A RUIN (c. 1650).

Cassel Gallery.

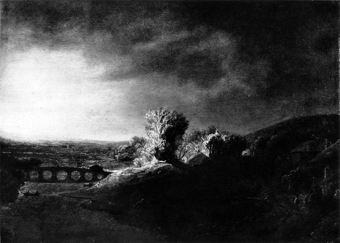

A work which also belongs to this phase of Rembrandt's career is a tiny landscape, dated 1646, now in the Cassel Gallery (Fig. 30). Among the paintings by Rembrandt, the landscapes form a very small group, contrary to what is the case in his etchings and drawings; and here, as generally in his landscape drawings and etchings, Rembrandt has given a frankly realistic rendering of a simple and characteristic bit of Dutch scenery—a frozen canal on which some figures are moving about, and in the distance a cottage and a bridge, the whole in the clear cool light of a winter morning. This little picture is most crisply and vigorously touched, and is besides, for all its apparent simplicity, a most consummately beautiful design. In several of Rembrandt's landscape paintings he introduces, by contrast, motifs from scenery of which he had no first-hand knowledge: as he has done in a noble landscape, now also in the Gallery at Cassel (Fig. 31), and painted a little later than the one just mentioned. The hill in the distance with the lonely ruin standing out against the glowing sky of evening, is quite Italian, and this very ruin suggests one which occurs over and over again in the landscapes of Rembrandt's contemporary Gaspard Poussin—the little temple of the Sybil at Tivoli near Rome—and there can be no question but that Rembrandt had received his inspiration for this picture from the heroic landscapes of Gaspard Poussin. But just as Rembrandt loves to draw figures of the most common and pronouncedly Dutch type in the most gorgeous and exotic costumes, so he has introduced into this heroic landscape a typically Dutch windmill such as one never associates with Italian scenery. A Dutch painter who strongly influenced Rembrandt in his landscapes was Hercules Seghers (1590-c. 1640): his etchings and pictures often give quite an astonishing anticipation of Rembrandt.

★

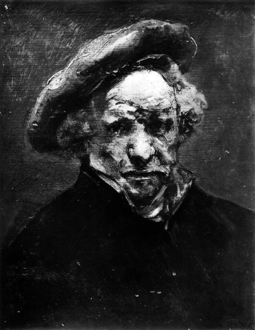

About 1650 one may say that the characteristics of Rembrandt's final manner have become clearly pronounced, and aesthetically speaking his career represents one great crescendo, so that one may claim that the latest Rembrandts are the finest of all. His characters now get increasingly heroic, and his design acquires a quality of reposeful and monumental majesty—there is but little endeavour on his part at this stage to achieve the "greatest and most natural animation" that had been his ideal previously. Again, as regards his technique, he achieves a boldness of brushwork and fatness of impasto far surpassing anything in his previous works—purely pictorial qualities which have made Rembrandt one of the artists to whom modern painters have turned most frequently for study. In such a work as his Portrait of an Old Man, painted about 1658, and now in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence (Fig. 32), with its marvellous patriarchal dignity and vigour and freedom of execution, we are removed far indeed from the idyllic quality of conception and the daintiness and delicacy of execution in that full-length picture of an Old Man asleep at Turin, painted by Rembrandt some thirty years earlier and reproduced upon a previous page (Fig. 27).

Fig. 32. REMBRANDT: AN OLD MAN (c. 1658).

Florence, Pallazzo Pitti.

Later still is one of Rembrandt's most famous works [Plates 95, 96], the last of the corporation pictures painted by him and representing the Syndics of the cloth workers' guild at Amsterdam, presiding over an ideal assembly. Rembrandt has here returned to the formal method of composition, exemplified in the first of his corporation pictures, the Anatomy Lesson; and it is indeed impossible to imagine that any of the objections raised against the Night Watch can have been heard from any of the persons here portrayed: but there is nothing here of the timid and primitive stiffness of the early composition, the grasp of character is much more subtle and sympathetic and as regards the warmth and richness of tone, the magic of chiaroscuro and the breadth of handling, a wide gulf separates the two pictures.

Fig. 33. REMBRANDT: PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST (c. 1663).

London, Ken Wood, Iveagh Collection.

Among the greatest of the last works of Rembrandt's are some portraits of the artist by himself, of which one, in the Iveagh Collection at Ken Wood (Fig. 33), shows the aged master in his rough and shabby clothes, with the bare wall of his studio in the background, quite otherwise heroic than in many of the dashing self-portraits of his earlier time. And when the works of Rembrandt's last years do not have this character of majestic and self-contained repose, the expression has nevertheless a perfectly elemental power: as witness the amazing portrait of the old Rembrandt laughing [Plate 99], a very late work, dating from about 1665, and now in the Cologne Museum.

Fig. 34. REMBRANDT: FAMILY GROUP (c. 1668).

Brunswick Gallery.

A very important example among the latest works of Rembrandt is also his Family Group in the Brunswick Gallery (Fig. 34). Though not dated, considerations of style allow us to assign this work to the very end of Rembrandt's life—recent criticism favours as its date 1668, the year before the master's death—and it is indeed astonishing to find Rembrandt at this stage breaking into a colour scheme of utter novelty and boldness, based in the main on a triple chord of different shades of red. The subtlety with which the whole is harmonized goes hand in hand with a freedom, and brilliance of brush work which are unsurpassed in Rembrandt's production and make the picture into a never-ending marvel and delight to the eye.

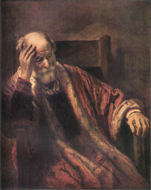

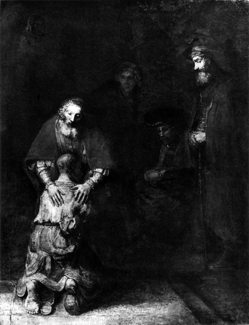

Finally, to give an example of Rembrandt's compositions of religious subjects dating from the closing stage of his career, in his great picture of the Return of the Prodigal Son [Plates 103, 104], in the Hermitage, painted perhaps in the year of Rembrandt's death, there is something strangely haunting in all these solemn and gigantic upright forms, related to one another, in defiance of every academic rule, in the surrounding twilight; while in the interpretation of the characters and the rendering of the drama, Rembrandt's power of appealing to our most intimate emotions is seen in an unsurpassed degree.

★

In conclusion, I should like to add one more remark of a general character suggested by the art of the great Dutch master. Rembrandt's powers of interpretative sympathy and of poetic imagination are such that it is perhaps no exaggeration to say that to some people a communion with Rembrandt's characters and conceptions has become a kind of religion. That, obviously, is one form of enjoyment: but it surely only takes us to "the point where art begins." And sight should not be lost of the fact that it is because of the way in which the work of Rembrandt can stand the test of strictly artistic form, without any consideration of subject and interpretation, that he can claim to rank as one of the world's greatest artists.

TANCRED BORENIUS

London, June 1942

As will inevitably happen in the case of a great artist, legend has busied itself a good deal about Rembrandt. It is, above all, the eighteenth century which gave currency to many of the fantastic notions about him—including his very name; for at one time he was quite gratuitously christened Paul Rembrandt van Ryn. The nineteenth century, which saw to the unearthing of many unimpeachable records concerning him, did away with numerous errors which had crept in and, moreover, brought to light a long series of neglected or misjudged works by Rembrandt; but it has, perhaps, to some extent ended by presenting rather an idealized picture of his personality. Despite some errors of fact, the earliest existing lives of Rembrandt contain a number of data, which anyone seriously interested in him will do well to bear in mind, just as the total picture which they give of him is of decided value.

None of the three principal early lives of Rembrandt has hitherto been available in English. It has therefore been thought that the translations of them, which follow, will be of some considerable interest. In chronological order, the lives in question are the one, in German, by Joachim von Sandrart, published in 1675, only six years after Rembrandt's death; the one in Italian, by Filippo Baldinucci, which appeared in 1686; and the one in Dutch by Arnold Houbraken, which dates from 1718. Apart from these, there exist references to Rembrandt of varying length in books by several early authors—notably the painters Samuel van Hoogstraten (1678) and Gerard de Lairesse (1714); but although the facts stated by these writers are of great interest—Samuel van Hoogstraten was indeed a pupil of Rembrandt's—they either did not produce an actual life of the master or the biography is too slight to warrant reproduction here.

It is a notable fact that each of the three lives with which we are concerned is either written by an artist or based on information supplied by an artist.

Joachim von Sandrart (1606-88), a native of Frankfort, was a painter who studied in Utrecht under that same Gerard van Honthorst, certain of whose tendencies Rembrandt's art so clearly reflects. Sandrart afterwards spent several years in Italy, before settling in Germany, whence he re-visited Holland. Born in the same year as Rembrandt and having been in personal touch with the latter at Amsterdam about 1637-42, his information about Rembrandt deserves every attention: unfortunately, his style of writing is so involved that his meaning at times is difficult to follow (if he knew it himself). In any case and whatever the prejudices which he absorbed in the course of his career, he does not by any means write of Rembrandt as a wholly unsympathetic observer.

Filippo Baldinucci (who died in 1696) was himself no artist. A Florentine ecclesiastic, of considerable taste and great learning, he compiled voluminous collections of artists' lives, to this day possessing great value; and his life of Rembrandt is, as he himself states, based on information supplied to him by the Danish painter Behardt Keil (1625-87), who for eight years (about 1648-87) had been a pupil of Rembrandt's at Amsterdam before settling in Italy. Attention has lately centred on the work of this artist, who was known in Italy as "Monsù Bernardo": his ultimate indebtedness to Rembrandt is clearly evident in the works of his Italian period, not a few of which have now been identified. Despite some egregious errors, Baldinucci's life possesses real importance through the vivid light which it throws on Rembrandt's personality, suggesting first-hand, if somewhat garbled, evidence.

Arnold Houbraken (1680-1719), finally, was quite a prolific painter and engraver, as an artist certainly not in the first rank, but at the same time unquestionably possessing skill and experience. His life of Rembrandt, though odd in its proportions, brings us, somehow, extremely close to the artist through handing on anecdotal tradition in Holland very freely: the number of actual mis-statements is very small, though amongst them is the erroneous indication of 1674 as the date of Rembrandt's death—a date which was not finally corrected until the nineteenth century.

(in Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-Bild- und Mahlerey-Kunste. Vol. I. Nuremberg, 1675).

It is almost to be wondered at that the excellent Rembrand von Ryn, springing as he did merely from the flat land and a miller, yet by nature was driven towards noble art in such a fashion that he reached so high a summit of art through great industry as well as native inclination and bent. He began at Amsterdam under the celebrated Lassman (sic), and, thanks to his natural gifts, unsparing industry and continuous practice, he lacked nothing but that he had not visited Italy and other places where the Antique and the Theory of Art may be studied: a defect all the more serious since he could but poorly read Netherlandish and hence profit but little from books.[1] In consequence, he remained ever faithful to the convention adopted by him, and did not hesitate to oppose and contradict our rules of art—such as anatomy and the proportions of the human body—perspective and the usefulness of classical statues, Raphael's drawing and judicious pictorial disposition, and the academies which are so particularly necessary for our profession. In doing so, he alleged that one should be guided only by Nature and by no other rules; and accordingly, as circumstances demanded, he approved in a picture light and shade and the outlines of objects, even if in contradiction with the simple fact of the horizon, as long as in his opinion they were successful and apposite. Hence, because the clean outlines had to be found in their true place, he, in order to avoid the danger, filled them in with pitch-black in such a fashion that he asked of them nothing but the keeping together of the universal harmony. As regards this latter, he was excellent and knew not only how to depict the simplicity of nature accurately, but also to adorn it with natural vigour in painting and powerful emphasis, notably in half-length pictures or in heads of old people—say, in little pieces, elegant dresses and other pleasant knick-knacks.

Alongside of this, he has etched on copper plates very many and various things, which are published by him in print. From all of which it may be seen that he was a very hard-working, indefatigable man; wherefore good fortune handed him large means in cash and filled his house in Amsterdam with almost innumerable young people of good families, who came there for instruction and tuition. Each of these paid him annually 100 florins; and to this we must add the profit which he made out of the pictures and engravings of these pupils of his—amounting to some 2,000 to 2,500 florins each[2]—and his earnings from his own handiwork. Certain it is that if he had been able to keep in with people, and look after his affairs properly, he would have increased his wealth considerably. For, although he was not a spendthrift, he did not know in the least how to keep his station, and always associated with the lower orders, whereby he also was hampered in his work.

This redounds to his praise, that he knew very intelligently and artistically how to break and imitate the colours in conformity with their individual character so that in the picture the true and vivid simplicity was depicted in the full harmony of life. In so doing he has opened the eyes of all those who, by following the common practice, are more dyers than painters, placing the hardness and coarseness of the colours quite brazenly and insensitively next to one another, so that they have absolutely nothing in common with nature, but resemble the colour boxes you see in shops or the cloths brought from the dyers. For the rest, he was also a great lover of art in its various forms, such as pictures, drawings, engravings and all sorts of foreign curiosities, of which he possessed a great number, displaying a great keenness about such matters. This was the reason why many people thought very highly of him and praised him.

In his works our artist introduced little light, except on the spot which he had chiefly in view; around this he kept light and shade together artistically. He also made well-considered use of reflections by which light penetrates shade very judiciously; his colour was powerfully glowing and in everything he showed consummate judgment. In depicting old people and their skin and hair he gave proof of great industry, patience and experience, so that he approached ordinary life very closely. He has, however, painted few subjects from classical poetry, allegories or striking historical scenes, but mostly subjects that are ordinary and without special significance, subjects that pleased him and were schilderachtig, as the people of the Low Countries say (paintable), and at the same time are full of charm, sought out in nature. He died in Amsterdam and is survived by a son who also is supposed to have good judgment of art.[3]

Fig. 35. JOACHIM VON SANDRART: CELEBRATION OF THE PEACE OF MUNSTER (1650).

Nuremberg, Germanisches Museum.

|

This is romantic exaggeration; Rembrandt was a man of considerable culture. |

|

Some notes which Rembrandt in 1635 made on the reverse of a drawing in the Berlin Print Room confirm that he sold his pupils' works, though the figures he mentions are very modest. |

|

This is a mistake: Titus predeceased Rembrandt, dying in 1668. |

(in Cominciamento e progresso dell 'arte d'intagliare in rame colla vita de' piu eccellenti maestri della stessa professione. Florence, 1686).

About the year 1640 there lived and worked in Amsterdam Reimbrond Vainrein, whom in our tongue we call Rembrante del Reno, born in Leyden: a painter, in truth, of much greater prestige than real greatness. He painted a large canvas, which was housed in the residence of the foreign Cavaliers and in which he portrayed a detachment of one of the Burgher Companies which existed over there [Plate 33]. This brought him such fame as was scarcely ever achieved by any other painter in those parts. The reason for this, more than any other, was that among the figures he had represented one with his foot raised in the act of marching and holding in his hand a halberd so well drawn in perspective that, though upon the picture surface it is no longer than half a yard, it yet appeared to every one to be seen in its full length. The remainder, however, turned out so jumbled and confused to such an extent, that the other figures could scarcely be distinguished from one another, in spite of their being all closely studied from life. For this picture, which luckily for him his contemporaries greatly admired, he was paid 4,000 scudi Dutch money, which corresponds to about 3,500 of our Tuscan currency.[4] In the house of a merchant who was a magistrate of Amsterdam he painted in oils on the wall many pictures of stories of Ovid.[5] In Italy, judging solely from what has come to our knowledge, there are two pictures by him: one, in Rome in the Gallery of Prince Pamfili, the head of a man with a slight beard and wearing a turban[6]; the other in Florence, in the Royal Gallery, in the room of the portraits of painters—his own portrait (Fig. 36).[7] This artist professed in those days the religion of the Menisti, which, though false too, is yet opposed to that of Calvin, inasmuch as they do not practise the rite of baptism before the age of thirty.[8] They do not elect educated preachers, but employ for such posts men of humble condition as long as they are esteemed by them honourable and just people, and for the rest they live following their caprice.

Fig. 36. REMBRANDT: PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST (c. 1664).

Florence, Uffizi.

One of the first pictures to acquaint Italy with Rembrandt's work as a painter.

This painter, different in his mental make-up from other people as regards self-control, was also most extravagant in his style of painting and evolved for himself a manner which may be called entirely his own, that is, without contour or limitation by means of inner and outer lines, but entirely consisting of violent and repeated strokes, with great strength of darks after his own fashion, but without any profound darks. And that which is almost impossible to understand is this: how ever he, painting by means of these strokes, worked so slowly, and completed his things with a tardiness and toil never equalled by anybody. He could have painted a great quantity of portraits, owing to the great prestige which in those parts had been gained by his colouring, to which his drawing did not, however, come up; but after it had become commonly known that whoever wanted to be portrayed by him had to sit to him for some two or three months, there were few who came forward.[9] The cause of this slowness was that, immediately after the first work had dried, he took it up again, repainting it with great and small strokes, so that at times the pigment in a given place was raised more than half the thickness of a finger. Hence it may be said of him that he always toiled without rest, painted much and completed very few pictures. Nevertheless, he always managed to retain such an esteem that a drawing by him, in which little or nothing could be seen, was sold by auction for 30 scudi, as is told by Bernardo Keillh of Denmark, the much-praised painter now working in Rome. This extravagance of manner was entirely on a par in Rembrandt with his mode of living, since he was a most temperamental man and despised everyone. The ugly and plebeian face by which he was ill-favoured, was accompanied by untidy and dirty clothes, since it was his custom, when working, to wipe his brushes on himself, and to do other things of a similar nature. When he worked he would not have granted an audience to the first monarch in the world, who would have had to return and return again until he had found him no longer engaged upon that work. He often went to public sales by auction; and here he acquired clothes that were old-fashioned and disused as long as they struck him as bizarre and picturesque, and those, even though at times they were downright dirty, he hung on the walls of his studio among the beautiful curiosities which he also took pleasure in possessing, such as every kind of old and modern arms—arrows, halberds, daggers, sabres, knives and so on—and innumerable quantities of exquisite drawings, engravings and medals, and every other thing which he thought a painter might ever need. He deserves great praise for a certain goodness of his, extravagant though it be, namely, that, for the sake of the great esteem in which he held his art, whenever things to do with it were offered for sale by auction, and notably paintings and drawings by great men of those parts, he bid so high at the outset that no one else came forward to bid; and he said that he did this in order to emphasize the prestige of his profession. He was also very generous in lending those paraphernalia of his to any other painter who might have needed them for some work of his.

Wherein this artist truly distinguished himself was in a certain most bizarre manner, which he invented for etching on copper plates. This manner too was entirely his own, neither used again by others nor seen again; with certain scratches of varying strength and irregular and isolated strokes, a deep chiaroscuro of great strength nevertheless springing forth out of the whole. And truth to tell, in this particular branch of engraving Rembrandt was much more highly esteemed by the professors of art than in painting, in which it seems he had exceptional luck rather than merit. In his engravings he used mostly to note, in badly formed, shapeless and tortuous letters, the word Rembrand.[10] Thanks to these engravings of his he achieved great riches, and proportionately with these there arose in him such pride and self-conceit that, since it seemed to him that his prints did not sell at the prices which they deserved, he imagined that he had found a method of increasing the desire for them universally. Hence at intolerable expense he had them bought back all over Europe, wherever he could find them, at any price. Among others he bought one for 50 scudi at a sale by auction in Amsterdam, which was a Raising of Lazarus and this he did while himself possessing the copperplate engraved by his own hand. Eventually, as a result of this wonderful idea, he spent his substance to such an extent that he was reduced to extremities; and something happened to him which is seldom told about other painters, namely, that he went bankrupt. Thereafter he left Amsterdam and entered the service of the King of Sweden, where he died miserably about the year 1670.[11] This is what we have been able to learn about this artist from someone who at that time knew him and saw a great deal of him.[12] Whether he persisted in that false religion of his we have not ascertained. There remained some who had been his pupils, that is to say, Bernardo Keillh of Denmark, mentioned above, and Guobert Flynk of Amsterdam[13]; and the latter in his colouring followed the manner of the master, but outlined his figures much better. Lastly, among his pupils there was the painter Gerardo Dou of Leyden.[14]

Fig. 37. BERNHARDT KEIL; SLEEPING GIRL (c. 1660).

Detroit Institute of Arts.

A typical work by the pupil of Rembrandt who supplied information about his master to Baldinucci.

|

The picture referred to is, of course, The Night Watch; and the figure singled out for praise is that of the lieutenant, Willem van Ruytenburg. The sum which Rembrandt was paid for the picture is greatly exaggerated; it was in reality 1,600 florins. |

|

These paintings no longer survive; cf. H. d. G. 216. They are sure not to have been painted in oil direct on the wall: here speaks the Italian accustomed to frescoes. |

|

This picture cannot now be traced. A bust of a shepherd in the Doria Gallery in Rome (No. 296), although bearing the signature of Rembrandt and the date 1645, cannot be accepted as genuine. It is doubtless a different picture from the one mentioned by Baldinucci. |

|

In the collection of self-portraits in Uffizi there are now two self-portraits by Rembrandt (H. d. G. 539, 540). It has been suggested that these were acquired as a result of the visit which Cosimo de' Medici (later the Grand Duke Cosimo III of Tuscany) paid to the studio of Rembrandt on December 29th, 1667. The pictures painted by Rembrandt for Antonio Ruffo of Messina (see above, p. 14) were unknown to Baldinucci. |

|

There is some documentary evidence in support of the statement that Rembrandt belonged to the sect of the "Menisti" (Mennonites). |

|

The large number of extant pictures by Rembrandt conflicts with the allegations here made to the effect that he might have painted much more. |

|

As regards Rembrandt's handwriting, it may be noted that as far back as the seventeenth century the misreading of one word—geretuckt, geretuckert, geretuck—i.e. retouched, upon certain etchings dated 1634 or produced about that time (H. 131, 132, 133) gave rise to the utterly groundless view that Rembrandt was in Venice in 1635, the word having been interpreted as "Venetiis." |

|

Nothing is known from any other source about a journey of Rembrandt's to Sweden, a country, for that matter, visited by several Dutch painters about this time. It is tempting to look for some connection between the story of Rembrandt's having gone to Sweden and the emergence of the great Conspiracy of the Batavians (Plate 94) in that country during the eighteenth century; but here we enter the field of pure and fanciful conjecture. Many records prove the presence of Rembrandt at Amsterdam towards the end of his life; the accurate date of his death was October 4th, 1669. |

|

The person referred to is Bernhardt Keil. |

|

Govaert Flinck (1615-60). |

|

Gerard Dou (1613-75). |

(in Groote Schouburgh der Nederlantsche Konstschilders en Schilderessen. Vol. I. Amsterdam, 1718).

The year 1606, so prolific in producing good artists, caused also, on July 15th, Rembrandt to be born on the Rhine near Leyden.

His father was called Herman Gerritzen van Ryn, and was a miller at the corn-mill between Leyendorp and Koukerk, on the Rhine.[15] His mother's name was Neeltje Willems van Zuitbroek, and both parents earned their livelihood honestly through their work.

Our Rembrandt was an only son,[16] and his parents were anxious that he should learn Latin and become a learned man, so they sent him to school at Leyden. But his particular inclination towards drawing caused them to alter their decision; and as a result they sent him, in order to acquire the elements of art, to Jakob Izakzen van Zwanenborg, with whom he spent some three years, in which time he made such progress that every one was amazed and thought that something important could be expected from him. For this reason his father, in order that he should lack no opportunity of laying a firm basis for his art, decided to bring him to P. Lastman at Amsterdam. He stayed with the latter six months, after which he spent some months with Jak. Pinas. Thereupon he determined to continue on his own, and from the very beginning he was marvellously successful in this. Others maintain that Pinas was his first teacher,[17] and Simon van Leeuwen says in his Short Description of Leyden that Joris van Schoten was the teacher of Rembrandt and Jan Lievensz.[18]