* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Canada and its Provinces Vol 3 of 23

Date of first publication: 1914

Author: Adam Shortt (1859-1931) and Arthur G. Doughty (1860-1936)

Date first posted: Aug. 15, 2018

Date last updated: Aug. 15, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180866

This eBook was produced by: Iona Vaughan, Marcia Brooks, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Archives Edition

CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES

IN TWENTY-TWO VOLUMES AND INDEX

| (Vols. 1 and 2) | (Vols. 13 and 14) |

| SECTION I | SECTION VII |

| NEW FRANCE, 1534-1760 | THE ATLANTIC PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 3 and 4) | (Vols. 15 and 16) |

| SECTION II | SECTION VIII |

| BRITISH DOMINION, 1760-1840 | THE PROVINCE OF QUEBEC |

| (Vol. 5) | (Vols. 17 and 18) |

| SECTION III | SECTION IX |

| UNITED CANADA, 1840-1867 | THE PROVINCE OF ONTARIO |

| (Vols. 6, 7, and 8) | (Vols. 19 and 20) |

| SECTION IV | SECTION X |

| THE DOMINION: POLITICAL EVOLUTION | THE PRAIRIE PROVINCES |

| (Vols. 9 and 10) | (Vols. 21 and 22) |

| SECTION V | SECTION XI |

| THE DOMINION: INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION | THE PACIFIC PROVINCE |

| (Vols. 11 and 12) | (Vol. 23) |

| SECTION VI | SECTION XII |

| THE DOMINION: MISSIONS; ARTS AND LETTERS | DOCUMENTARY NOTES GENERAL INDEX |

GENERAL EDITORS

ADAM SHORTT

ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

| Thomas Chapais | Alfred D. DeCelles | |

| F. P. Walton | George M. Wrong | |

| William L. Grant | Andrew Macphail | |

| James Bonar | A. H. U. Colquhoun | |

| D. M. Duncan | Robert Kilpatrick | |

| Thomas Guthrie Marquis | ||

VOL. 3

SECTION II

BRITISH DOMINION

PART I

Photogravure-Annan. Glasgow

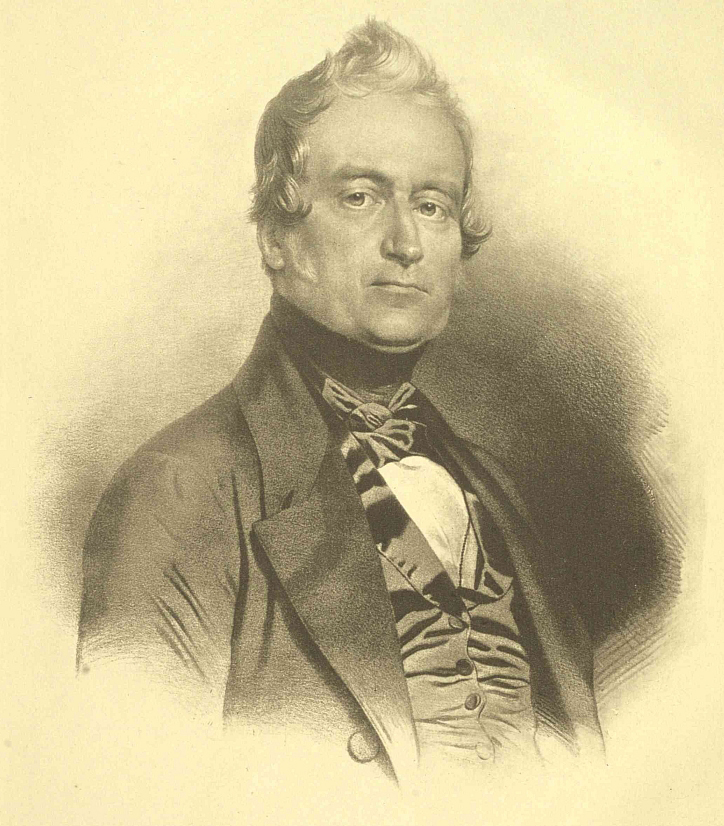

LOUIS JOSEPH PAPINEAU

From a lithograph by Maurin, Paris

Copyright in all countries subscribing to

the Berne Convention

| PAGE | |||

| BRITISH RULE TO THE UNION: GENERAL OUTLINES. By F. P. Walton | 3 | ||

| THE NEW RÉGIME. By Duncan McArthur | |||

| THE CAPITULATION | 21 | ||

| MILITARY GOVERNMENT | 23 | ||

| THE TREATY OF PARIS | 25 | ||

| THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CIVIL GOVERNMENT | 27 | ||

| GOVERNOR MURRAY | 29 | ||

| CIVIL versus MILITARY AUTHORITY | 32 | ||

| RETIREMENT OF MURRAY | 34 | ||

| GUY CARLETON | 35 | ||

| THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE | 36 | ||

| THE QUEBEC ACT | 42 | ||

| PONTIAC'S WAR. By T. G. Marquis | |||

| CAUSES OF THE INDIAN RISING | 53 | ||

| TAKING OVER THE WESTERN POSTS | 57 | ||

| PONTIAC | 59 | ||

| DESIGNS AGAINST DETROIT | 60 | ||

| CAPTURE OF THE WESTERN POSTS | 63 | ||

| BLOODY RUN AND BUSHY RUN | 65 | ||

| THE TRAGEDY OF DEVIL'S HOLE | 67 | ||

| CLOSING EVENTS OF THE WAR | 68 | ||

| CANADA AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION. By William Wood | |||

| I. | THE CONTENDING FORCES | 73 | |

| A Widespread War—The Defences of Canada | |||

| II. | THE INVASION | 79 | |

| American Victories—Carleton's Escape from Montreal | |||

| III. | ARNOLD AND MONTGOMERY BEFORE QUEBEC | 83 | |

| The Continental Army—The Assault of the Fortress—Defeat and Retreat—A Humane Victor—Congress and the Savages | |||

| CANADA UNDER THE QUEBEC ACT. By Duncan McArthur | |||

| THE AMERICAN WAR | 107 | ||

| CARLETON AND THE COLONIAL OFFICE | 110 | ||

| CARLETON RETIRES | 111 | ||

| FREDERICK HALDIMAND | 112 | ||

| UNITED EMPIRE LOYALISTS | 115 | ||

| HALDIMAND RESIGNS | 118 | ||

| HAMILTON AND HOPE | 120 | ||

| A HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY | 121 | ||

| LORD DORCHESTER | 123 | ||

| ADMINISTRATIVE REFORM | 125 | ||

| ADAM LYMBURNER | 127 | ||

| THE CANADA BILL | 129 | ||

| THE CONSTITUTIONAL ACT | 132 | ||

| LOWER CANADA, 1791-1812. By Duncan McArthur | |||

| INAUGURATION OF REPRESENTATIVE GOVERNMENT | 141 | ||

| LORD DORCHESTER'S RETURN | 143 | ||

| RELATIONS WITH THE UNITED STATES | 146 | ||

| DORCHESTER'S RESIGNATION | 150 | ||

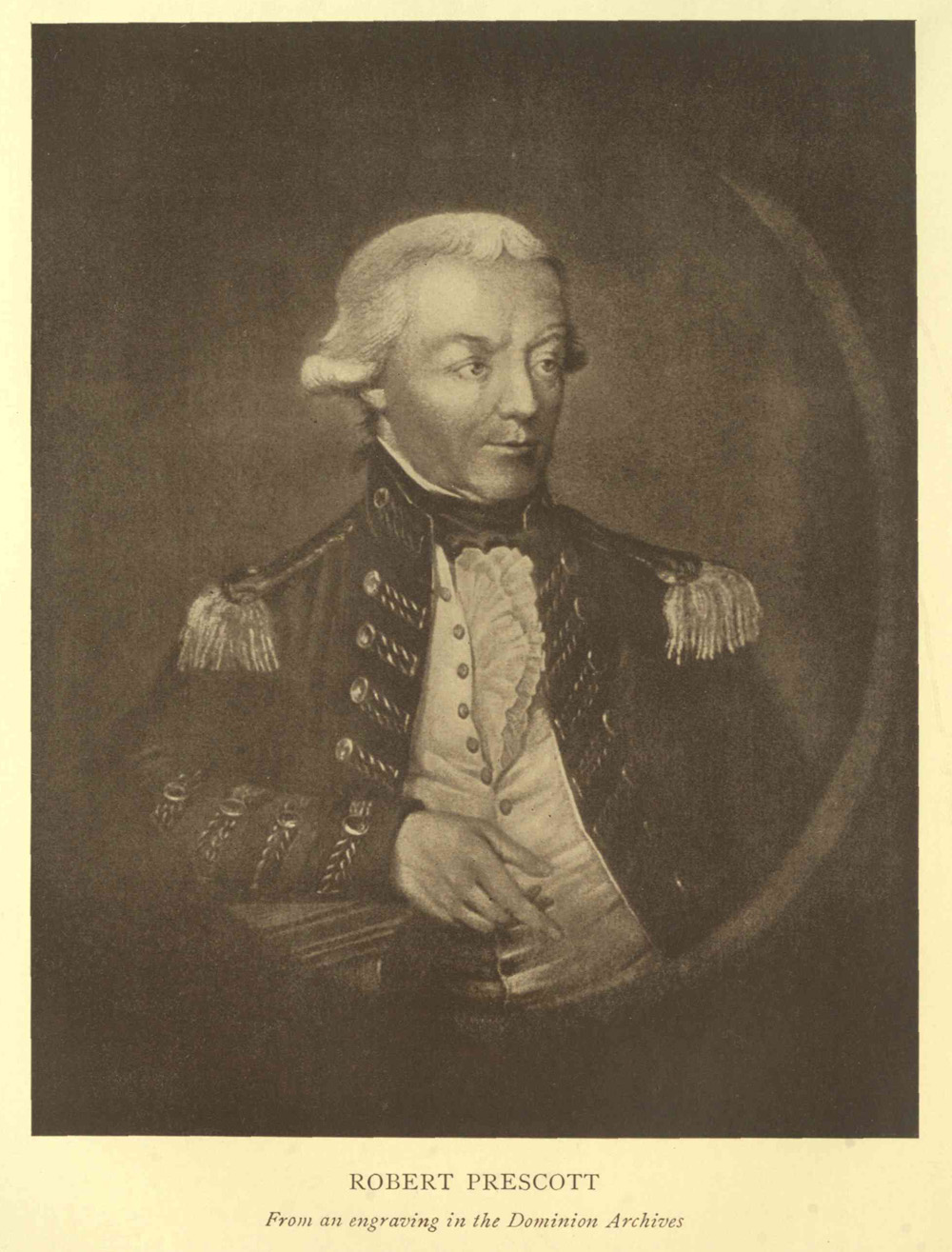

| GENERAL ROBERT PRESCOTT | 153 | ||

| THE LAND-GRANTING SYSTEM | 154 | ||

| ROBERT SHORE MILNES | 156 | ||

| RETIREMENT OF MILNES | 158 | ||

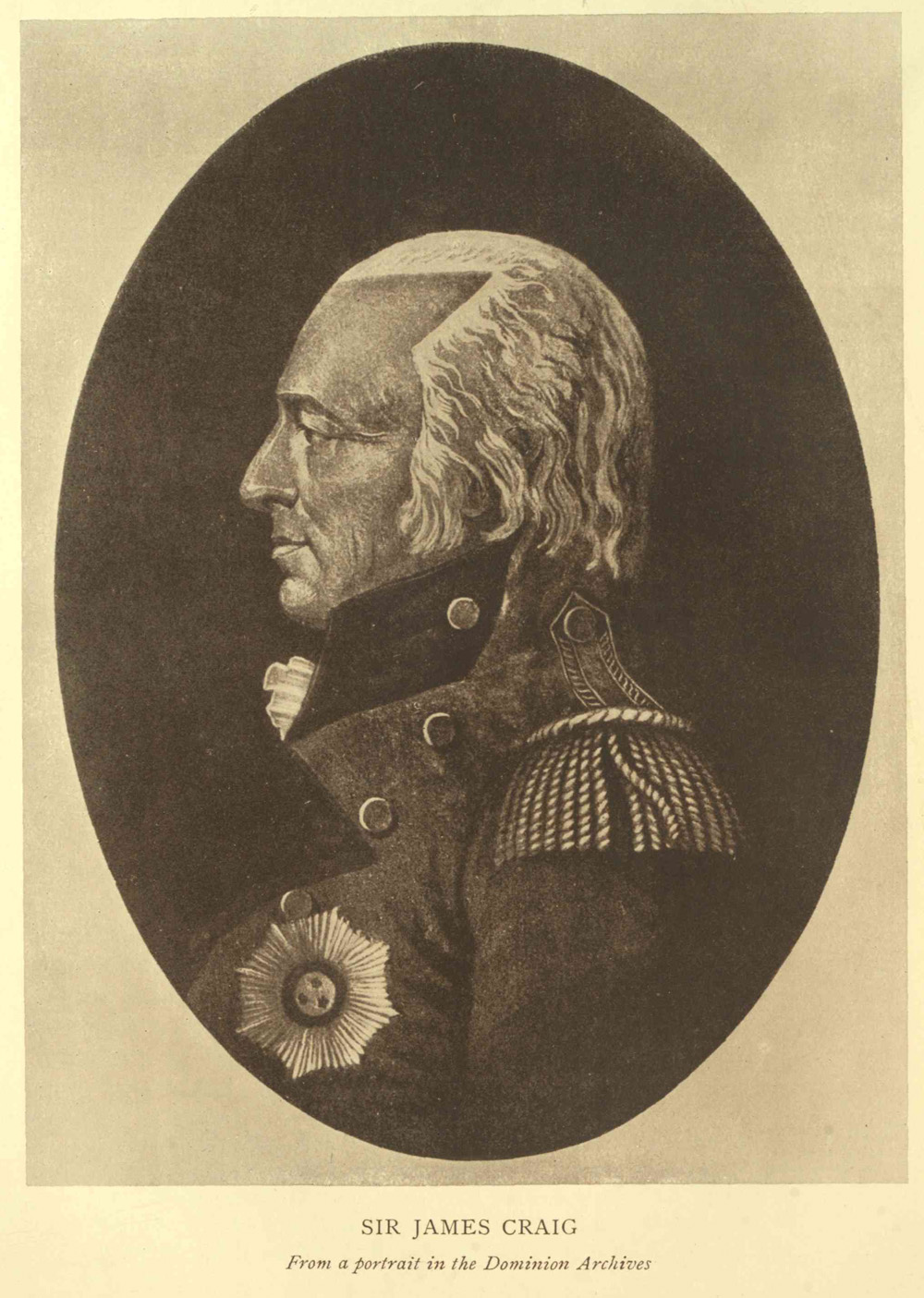

| SIR JAMES CRAIG | 159 | ||

| CRAIG versus FRENCH-CANADIAN NATIONALISM | 161 | ||

| CRAIG'S POLICY | 165 | ||

| UPPER CANADA, 1791-1812. By Duncan McArthur | |||

| EARLY SETTLEMENT | 171 | ||

| JOHN GRAVES SIMCOE | 172 | ||

| SIMCOE'S IMPERIALISM: DEFENCE | 175 | ||

| SIMCOE'S IMPERIALISM: SETTLEMENT | 176 | ||

| SIMCOE'S IMPERIALISM: GOVERNMENT | 177 | ||

| SIMCOE AND DORCHESTER | 180 | ||

| SIMCOE'S RETIREMENT | 181 | ||

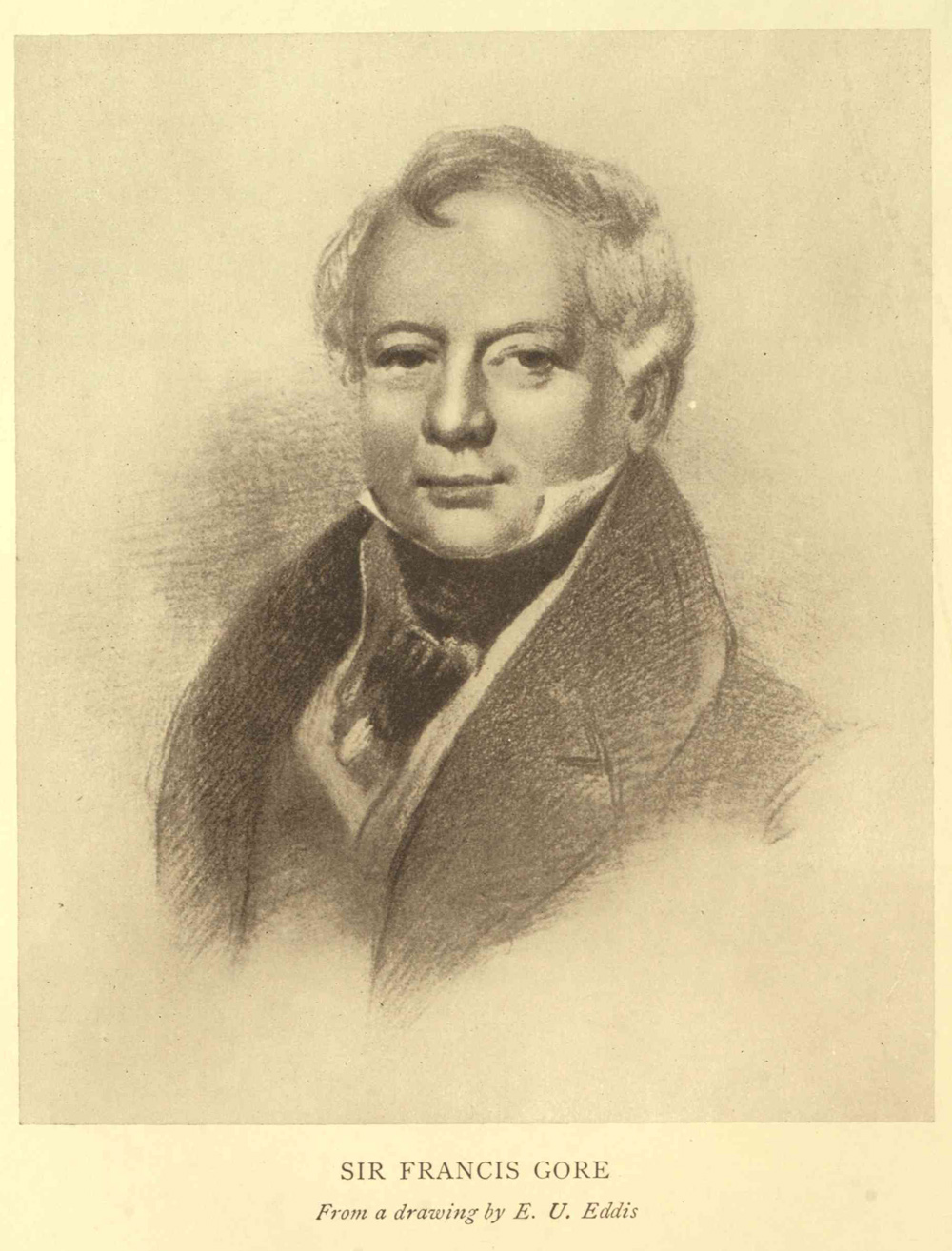

| FRANCIS GORE: POLITICAL DISSENSION | 184 | ||

| CANADA IN THE WAR OF 1812. By William Wood | |||

| I. | CAUSES OF THE CONFLICT | 189 | |

| Trade Rivalry—The Navigation Act—Anti-British Feeling—The Desire to conquer Canada | |||

| II. | ELEMENTS OF AMERICAN WEAKNESS | 196 | |

| Cleavage between North and South—An Insignificant Navy—An Undisciplined Army | |||

| III. | THE CANADIAN MILITARY SITUATION | 203 | |

| An Unwelcome War—The Defences of Canada—The Canadian Militia—A Fusion of National Forces | |||

| IV. | THE OPENING YEAR OF THE WAR | 216 | |

| First Fights by Sea and Land—Brock's Military Genius—The Fall of Detroit—On the Niagara Frontier—The Battle of Queenston Heights | |||

| V. | THE CAMPAIGN OF 1813 | 236 | |

| A Year of Complex Operations—Varied Fortunes on the Lakes—Stoney Creek and Beaver Dam—The Battle of Lake Erie—Châteauguay and Chrystler's Farm—Operations along the Niagara River | |||

| VI. | THE FINAL CAMPAIGN | 252 | |

| Minor Engagements—American Attack on Niagara—The Battle of Lundy's Lane—The British Counter-Invasion—Prevost's Incompetence—Plattsburg and New Orleans—Decisive Influence of Sea-Power | |||

| PAPINEAU AND FRENCH-CANADIAN NATIONALISM. By Duncan McArthur | |||

| SIR GEORGE PREVOST | 275 | ||

| THE IMPEACHMENTS | 278 | ||

| SIR GORDON DRUMMOND | 280 | ||

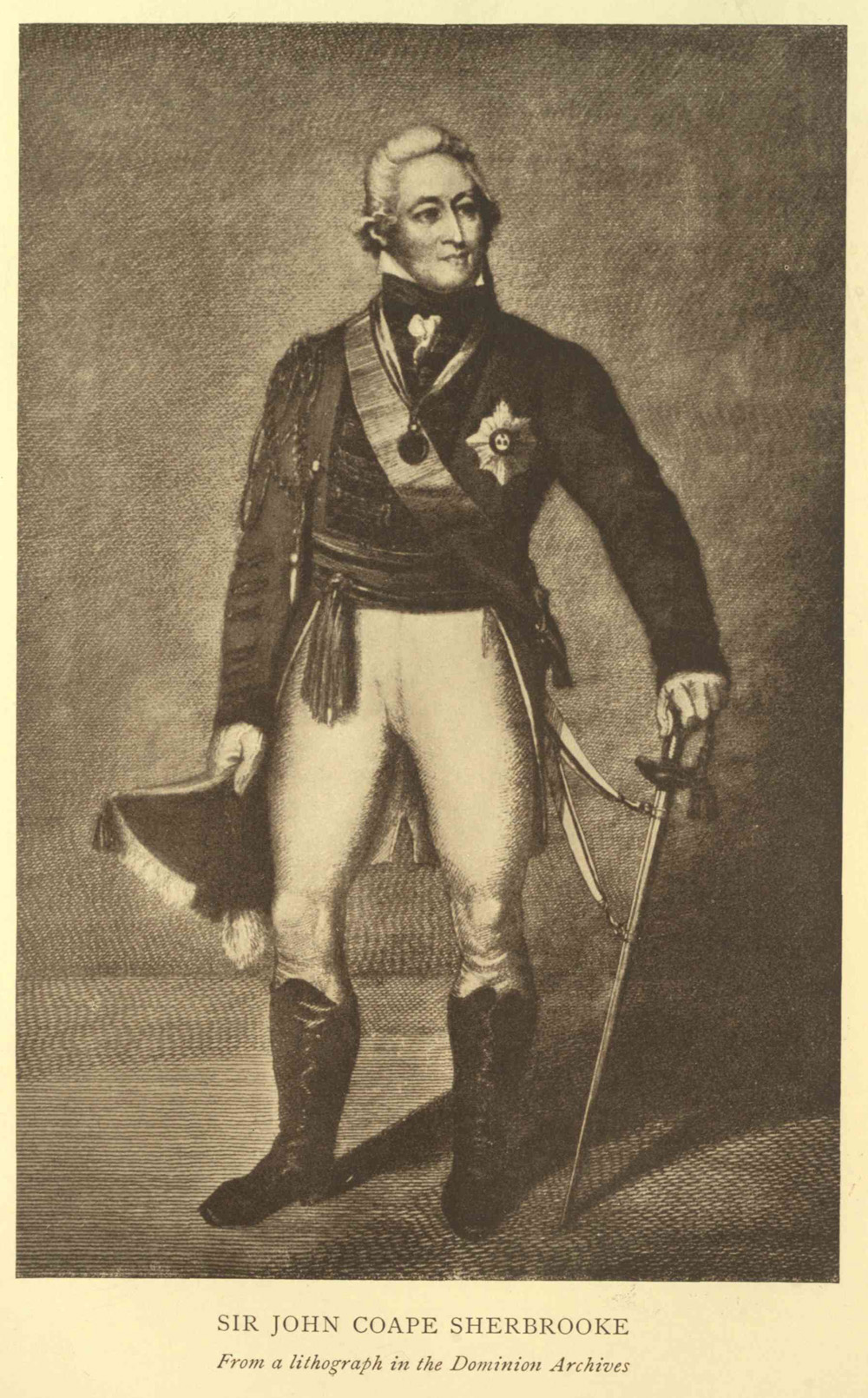

| SIR JOHN COAPE SHERBROOKE | 282 | ||

| STUART AND PAPINEAU | 286 | ||

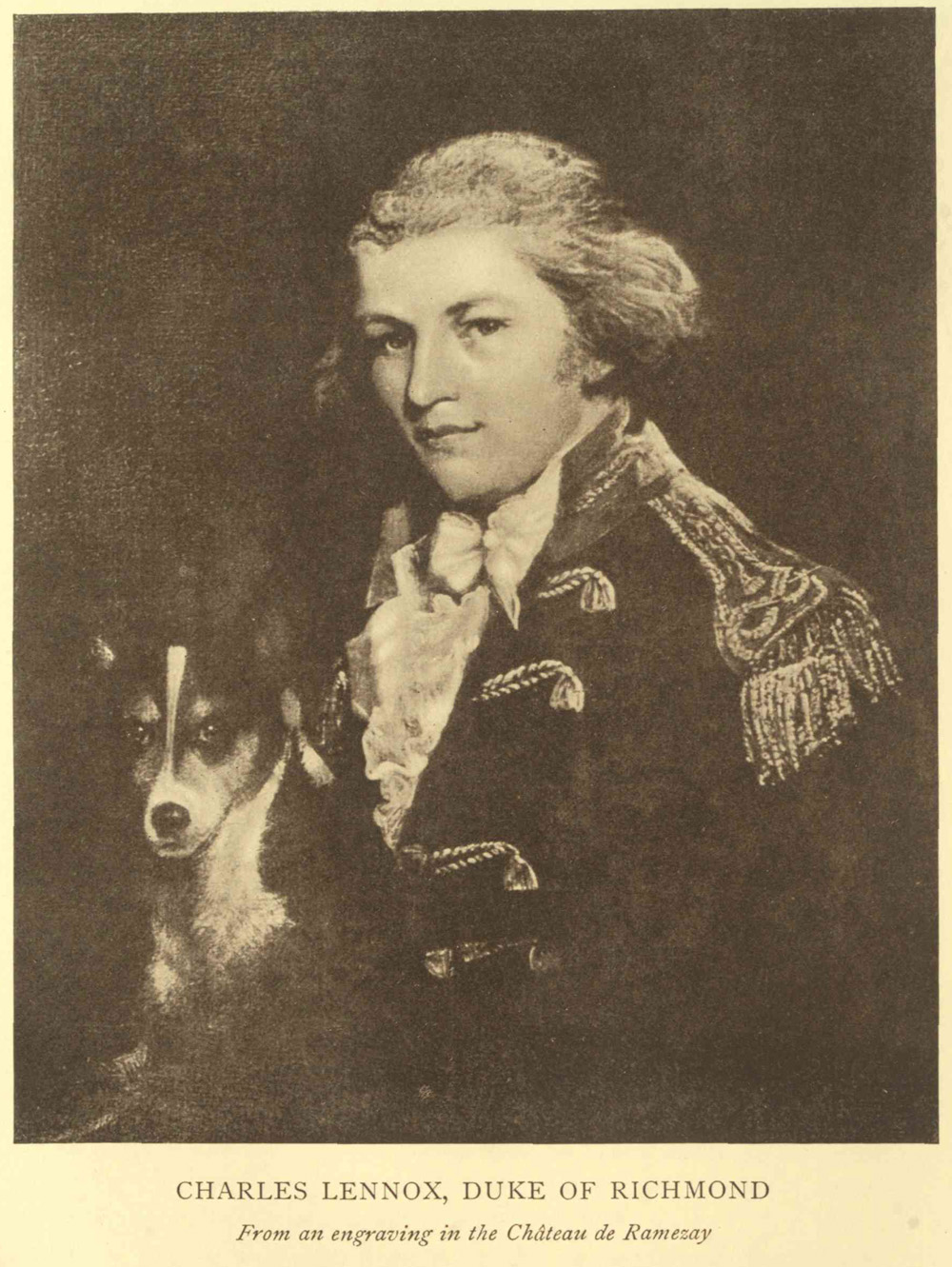

| THE DUKE OF RICHMOND | 289 | ||

| LORD DALHOUSIE | 293 | ||

| A SCHEME OF UNION | 295 | ||

| CONTROL OF SUPPLY | 299 | ||

| LORD DALHOUSIE AND PAPINEAU | 302 | ||

| THE CANADA COMMITTEE | 305 | ||

| SIR JAMES KEMPT | 307 | ||

| LORD AYLMER | 310 | ||

| THE PROGRAMME OF NATIONALISM | 312 | ||

| THE NINETY-TWO RESOLUTIONS | 316 | ||

| PAPINEAU AND NEILSON | 318 | ||

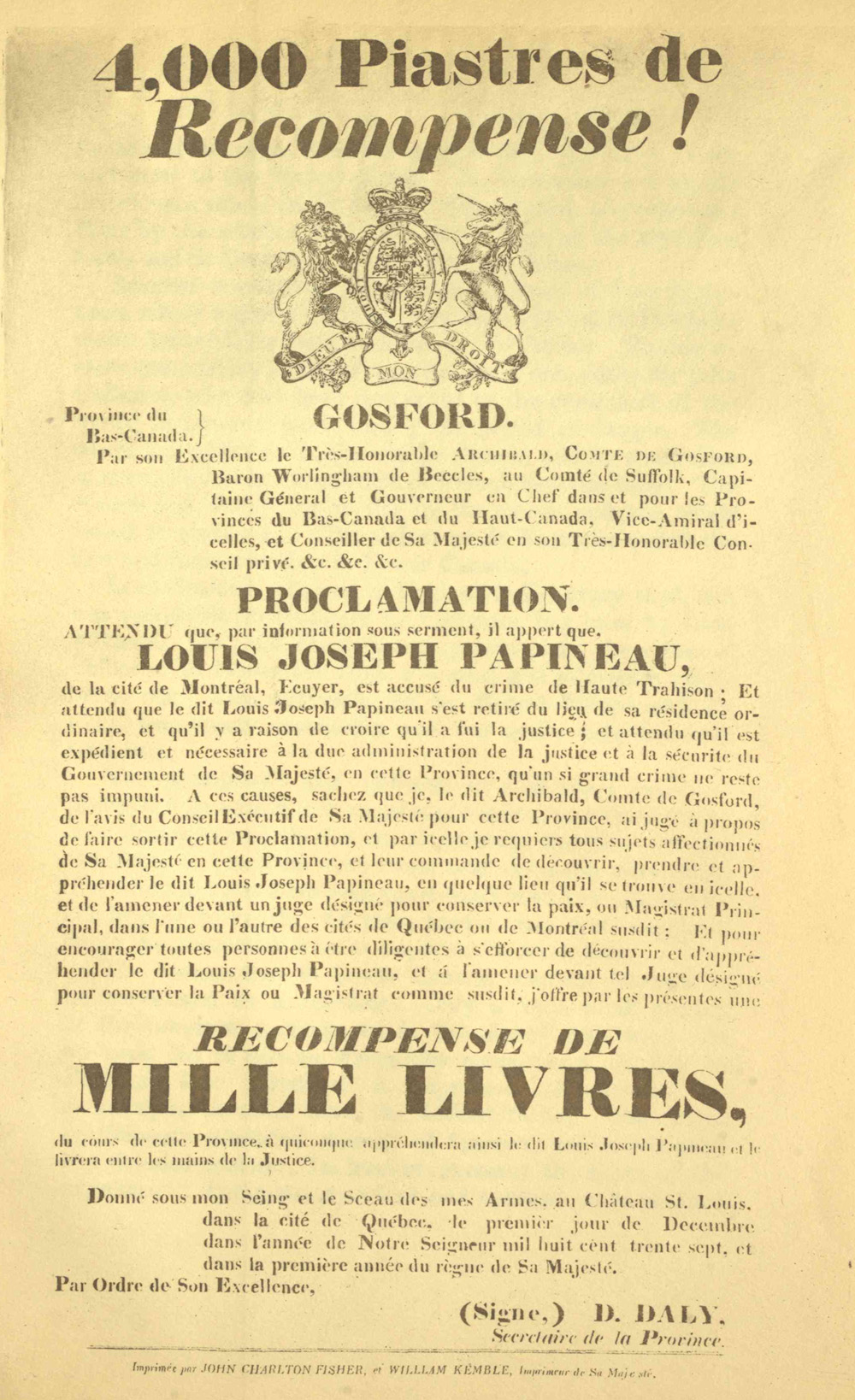

| LORD GOSFORD | 320 | ||

| THE REFORM MOVEMENT IN UPPER CANADA. By Duncan McArthur | |||

| THE WAR AND UPPER CANADIAN POLITICS | 327 | ||

| ROBERT GOURLAY | 329 | ||

| THE ALIEN QUESTION | 331 | ||

| THE CANADA COMPANY | 333 | ||

| EDUCATION AND THE CLERGY RESERVES | 335 | ||

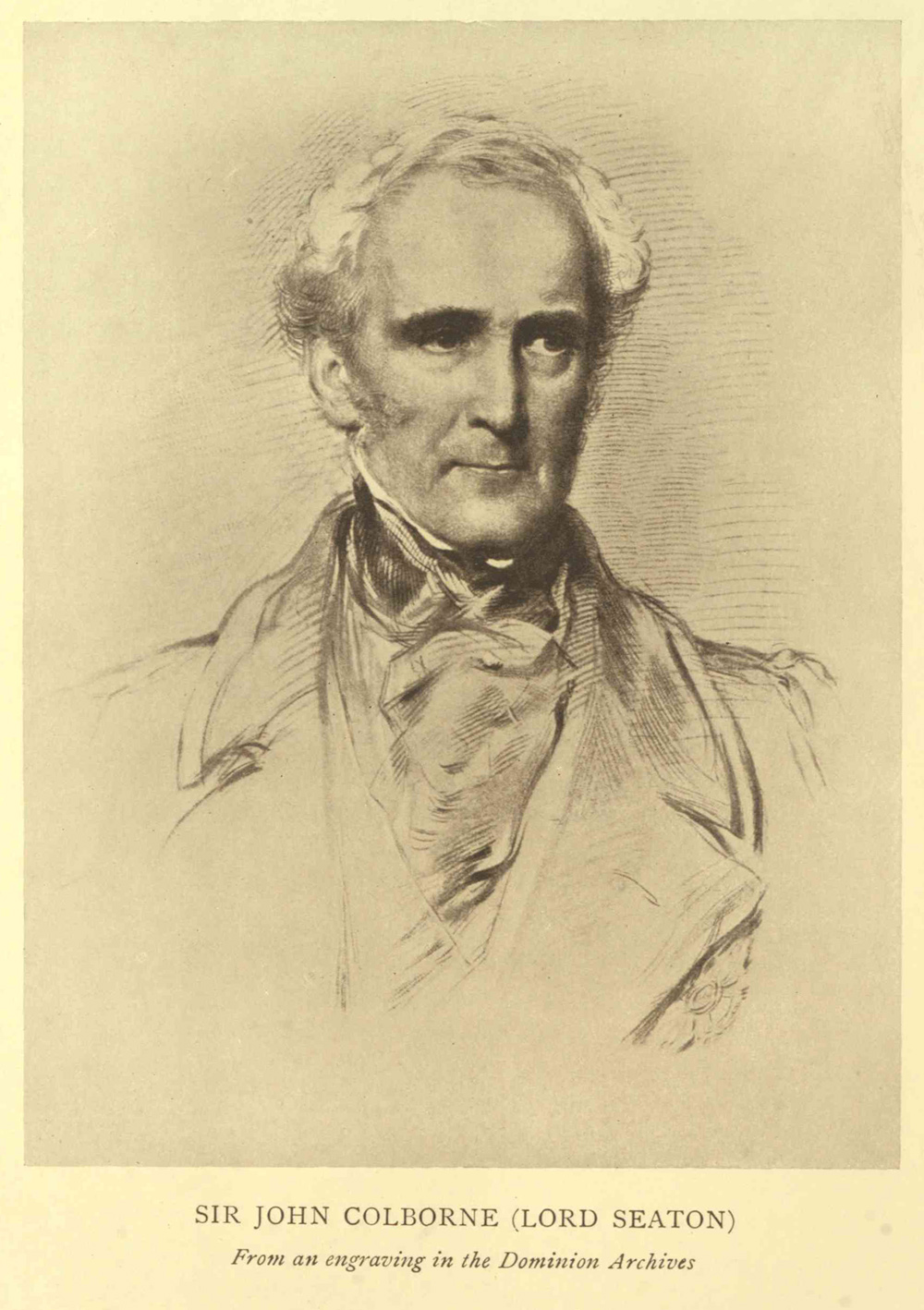

| SIR JOHN COLBORNE | 337 | ||

| FINANCIAL ADJUSTMENTS | 342 | ||

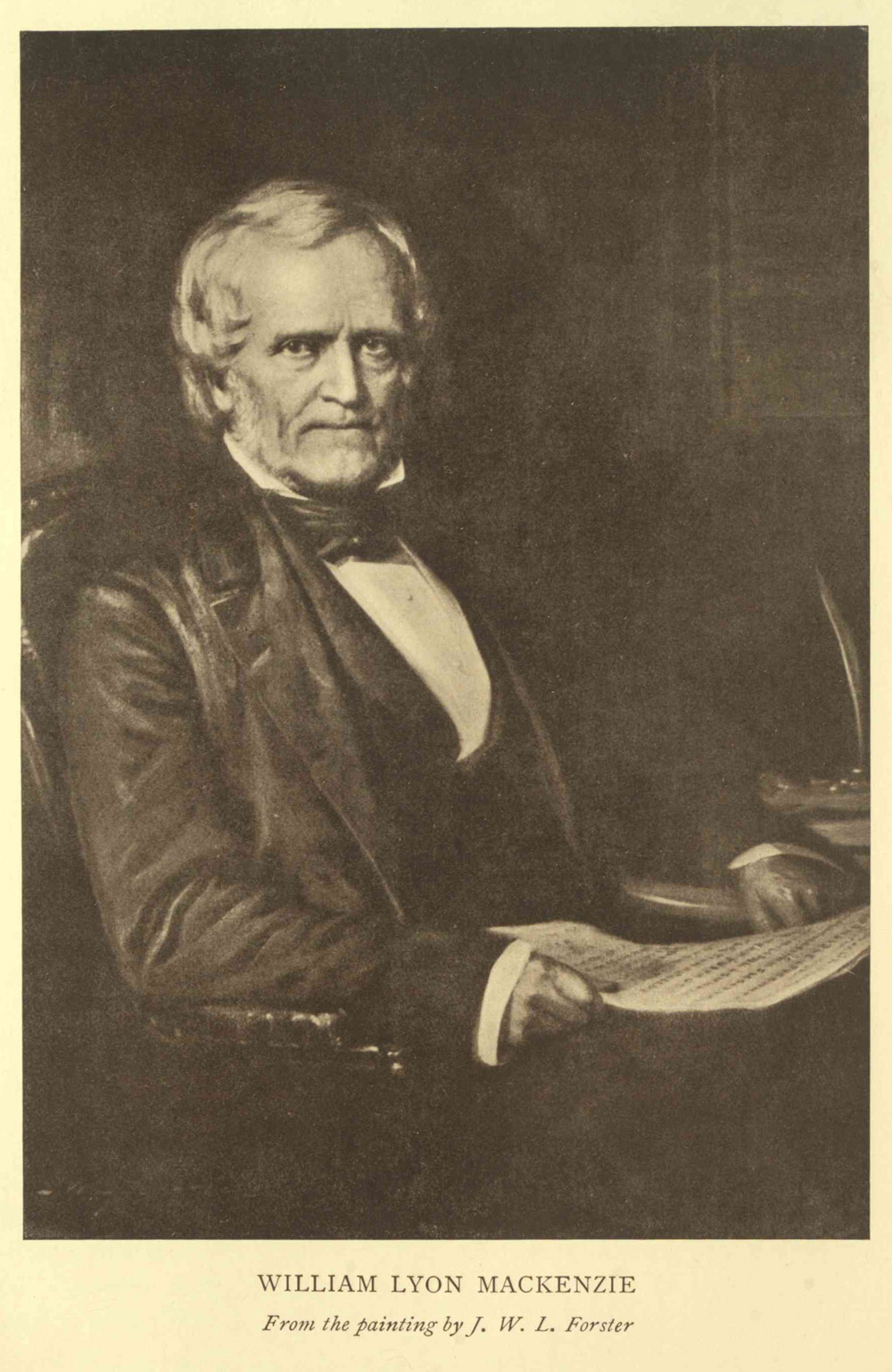

| WILLIAM LYON MACKENZIE | 343 | ||

| REPORT OF COMMITTEE ON GRIEVANCES | 349 | ||

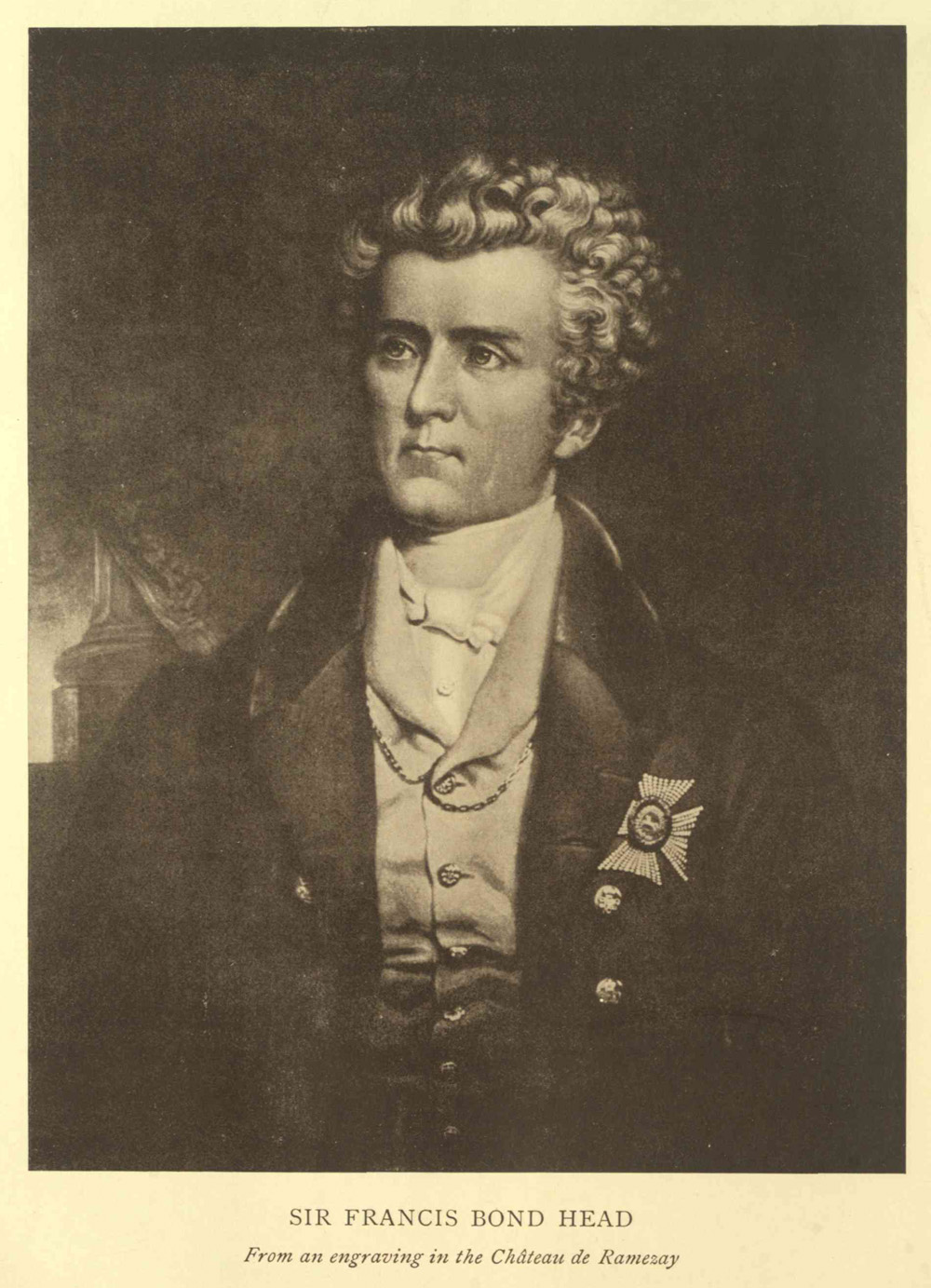

| SIR FRANCIS BOND HEAD | 352 | ||

| RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT | 354 | ||

| THE 'BREAD AND BUTTER' ASSEMBLY | 355 | ||

| THE CANADIAN REBELLIONS OF 1837. By Duncan McArthur | |||

| THE REBELLION IN LOWER CANADA | 361 | ||

| THE REBELLION IN UPPER CANADA | 364 | ||

| NATIONALISM AND THE REBELLION | 368 | ||

| BRITISH POLICY AND NATIONALISM | 369 | ||

| NATIONALISM AND GOVERNMENT | 371 | ||

| PAPINEAU AND NATIONALISM | 377 | ||

| CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM IN UPPER CANADA | 378 | ||

| PRIVILEGE IN CHURCH AND STATE | 380 | ||

| MACKENZIE AND THE REBELLION | 382 | ||

| COMPARISON | 383 | ||

| LOUIS JOSEPH PAPINEAU | Frontispiece | ||

| From a lithograph by Maurin, Paris | |||

| BRITISH SOLDIERS DRAWING WOOD FROM STE FOY TO QUEBEC, 1760 | Facing page | 22 | |

| From a painting by J. H. Macnaughton in the Château de Ramezay | |||

| JAMES MURRAY | " | 30 | |

| From a painting in the Dominion Archives | |||

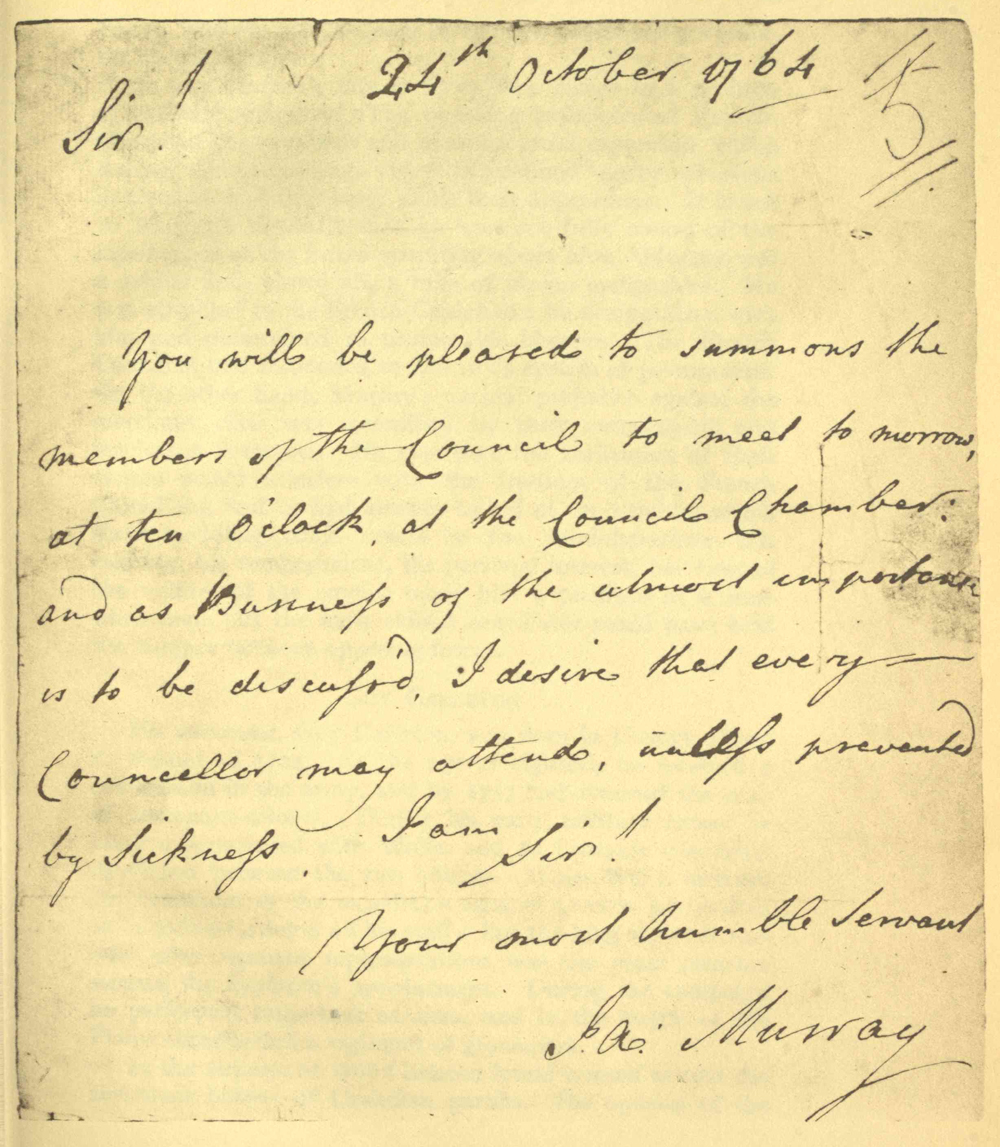

| FACSIMILE OF A DOCUMENT SIGNED BY MURRAY | " | 34 | |

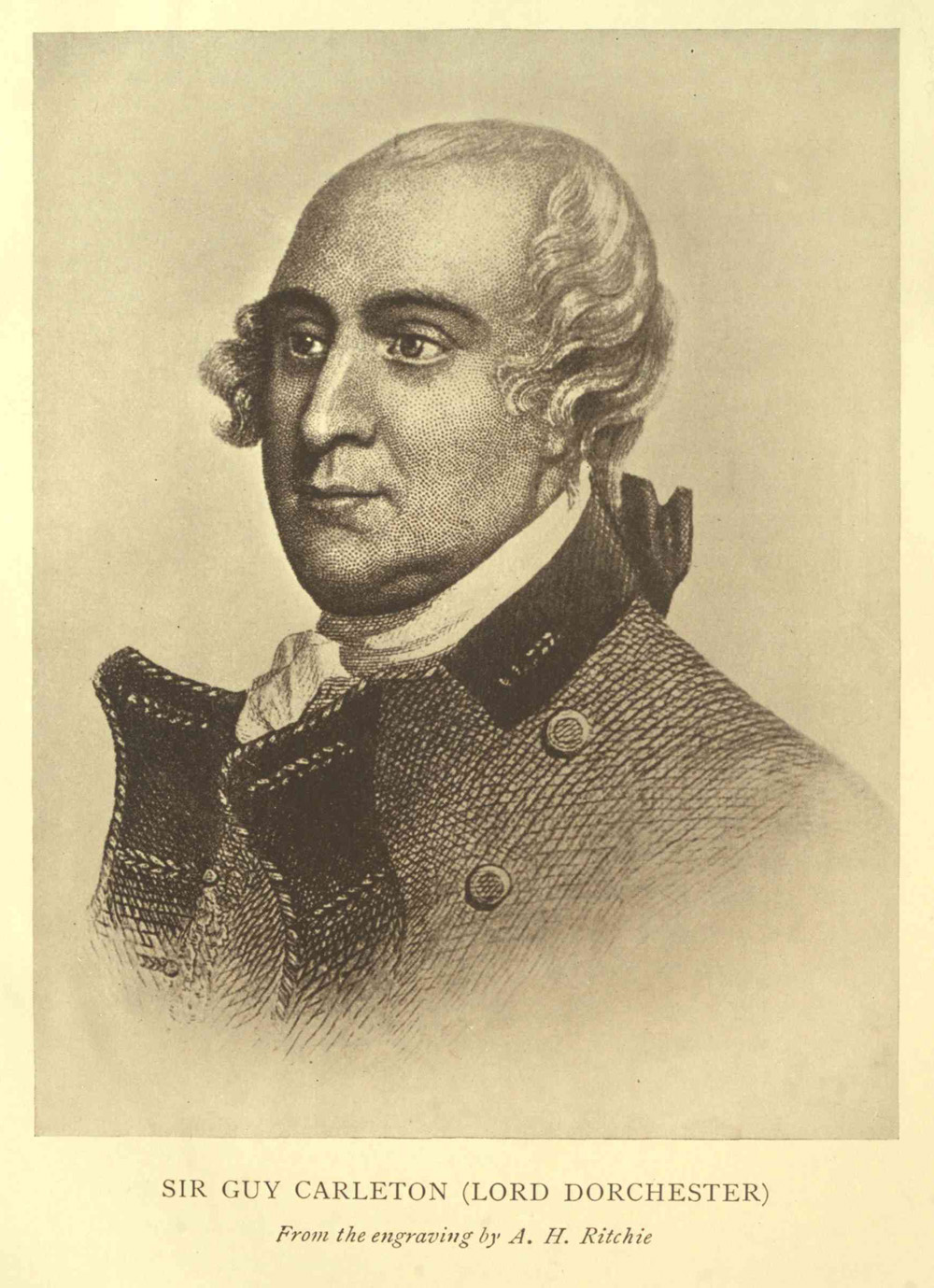

| SIR GUY CARLETON (LORD DORCHESTER) | " | 36 | |

| From the engraving by A. H. Ritchie | |||

| ROBERT PRESCOTT | " | 154 | |

| From an engraving in the Dominion Archives | |||

| SIR JAMES CRAIG | " | 160 | |

| From a portrait in the Dominion Archives | |||

| JOHN GRAVES SIMCOE | " | 172 | |

| From the bust in Exeter Cathedral | |||

| SIR FRANCIS GORE | " | 184 | |

| From a drawing by E. U. Eddis | |||

| SIR GEORGE PREVOST | " | 204 | |

| From the painting in the Dominion Archives | |||

| SIR ISAAC BROCK | " | 218 | |

| From a miniature in the possession of Miss Sara Mickle, Toronto | |||

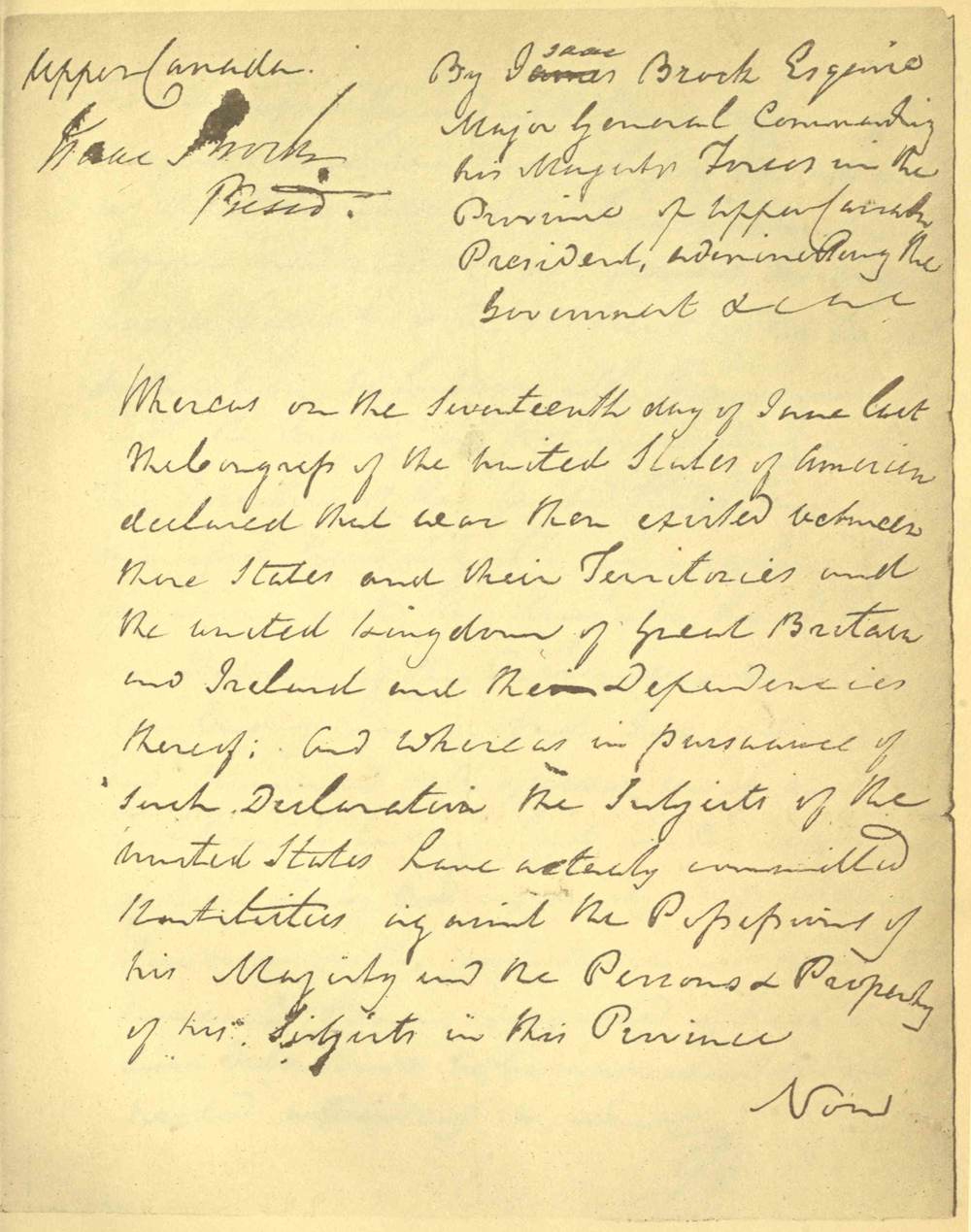

| FACSIMILE OF BROCK'S PROCLAMATION, 1812 | " | 220 | |

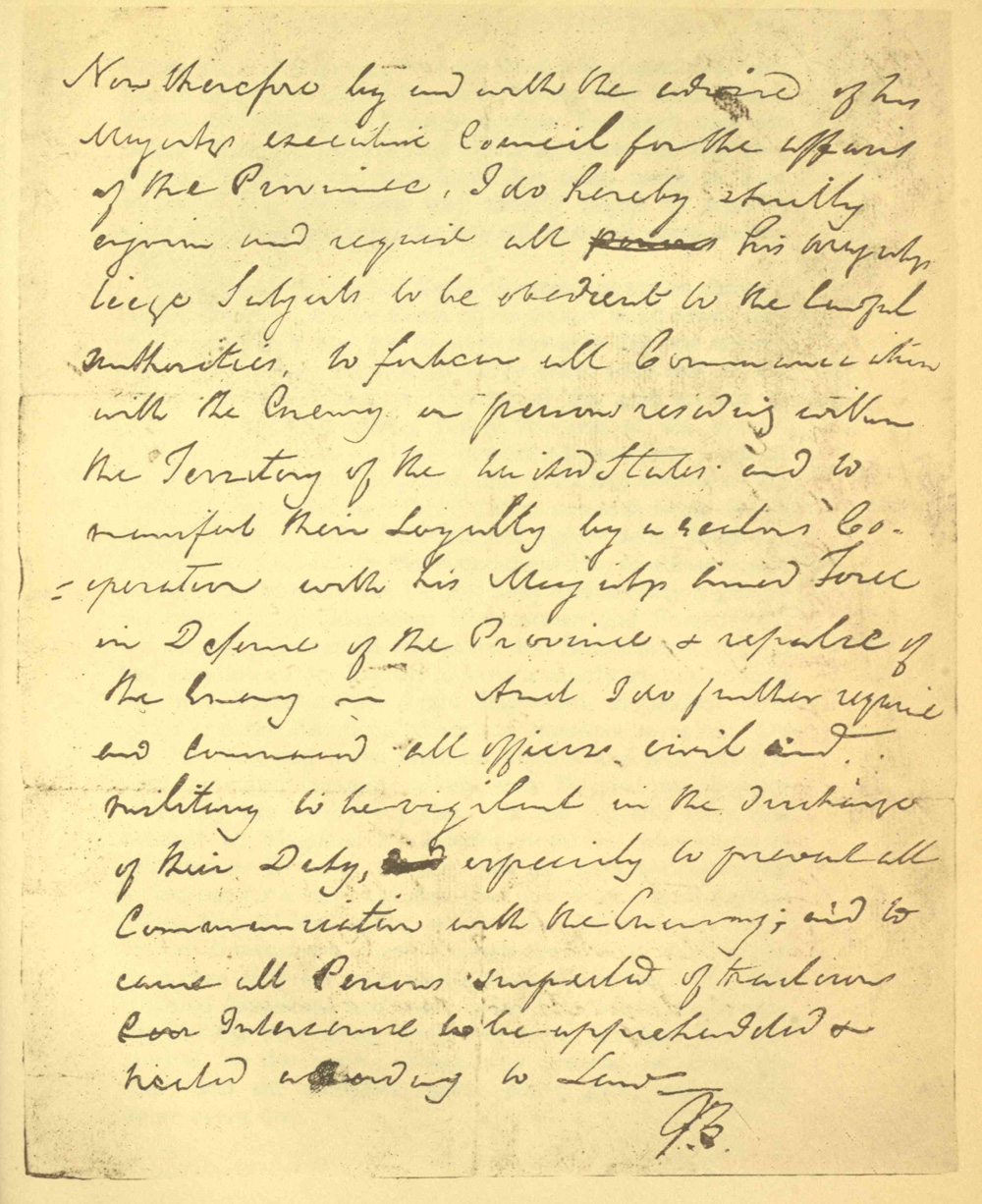

| THE 'SHANNON' AND THE 'CHESAPEAKE' IN ACTION | " | 236 | |

| Painted by G. Webster under the direction of Lieut. Falkner of the 'Shannon' | |||

| CHARLES DE SALABERRY | " | 248 | |

| From a portrait in the Dominion Archives | |||

| SIR JOHN COAPE SHERBROOKE | " | 282 | |

| From a lithograph in the Dominion Archives | |||

| CHARLES LENNOX, DUKE OF RICHMOND | " | 290 | |

| From an engraving in the Château de Ramezay | |||

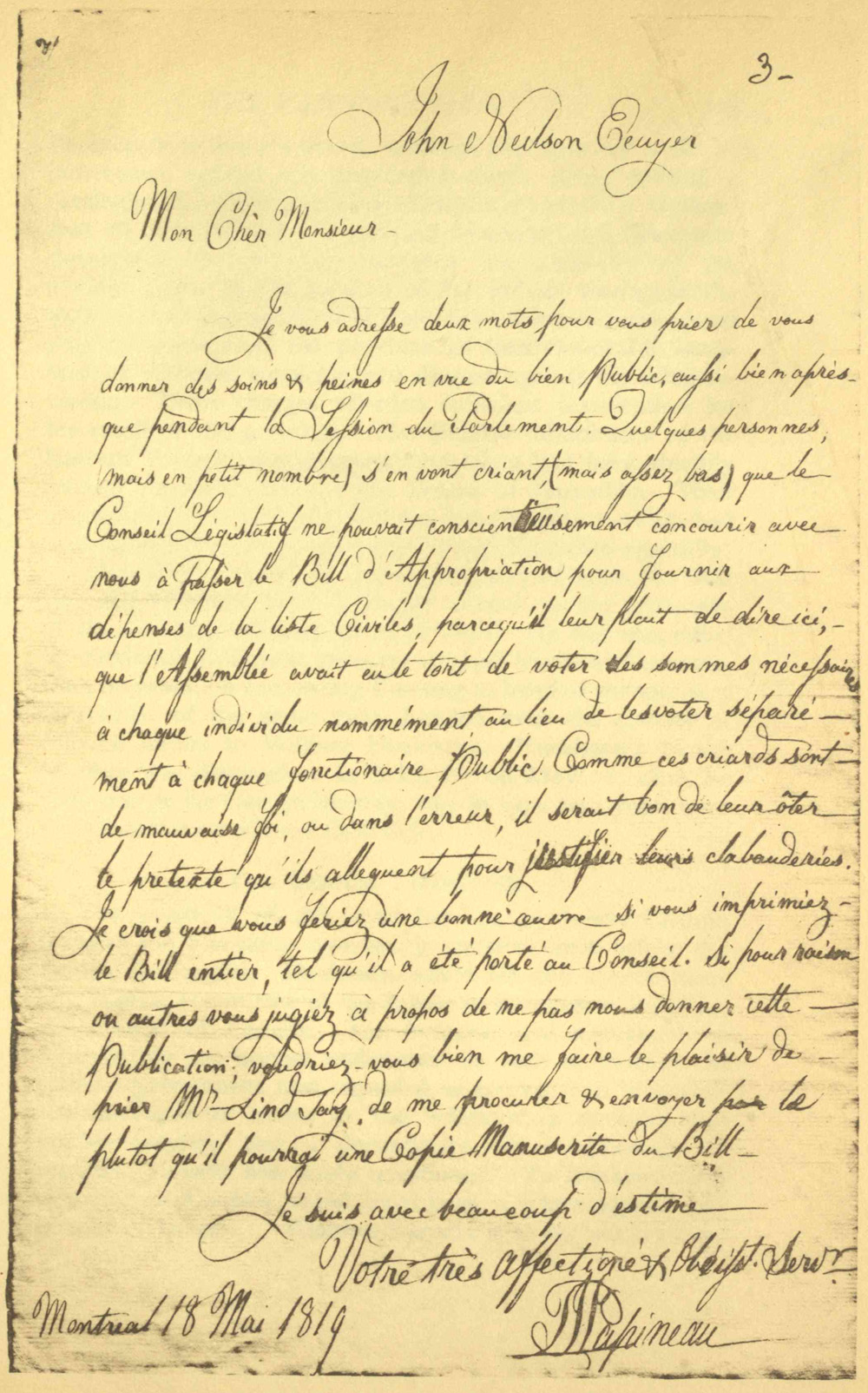

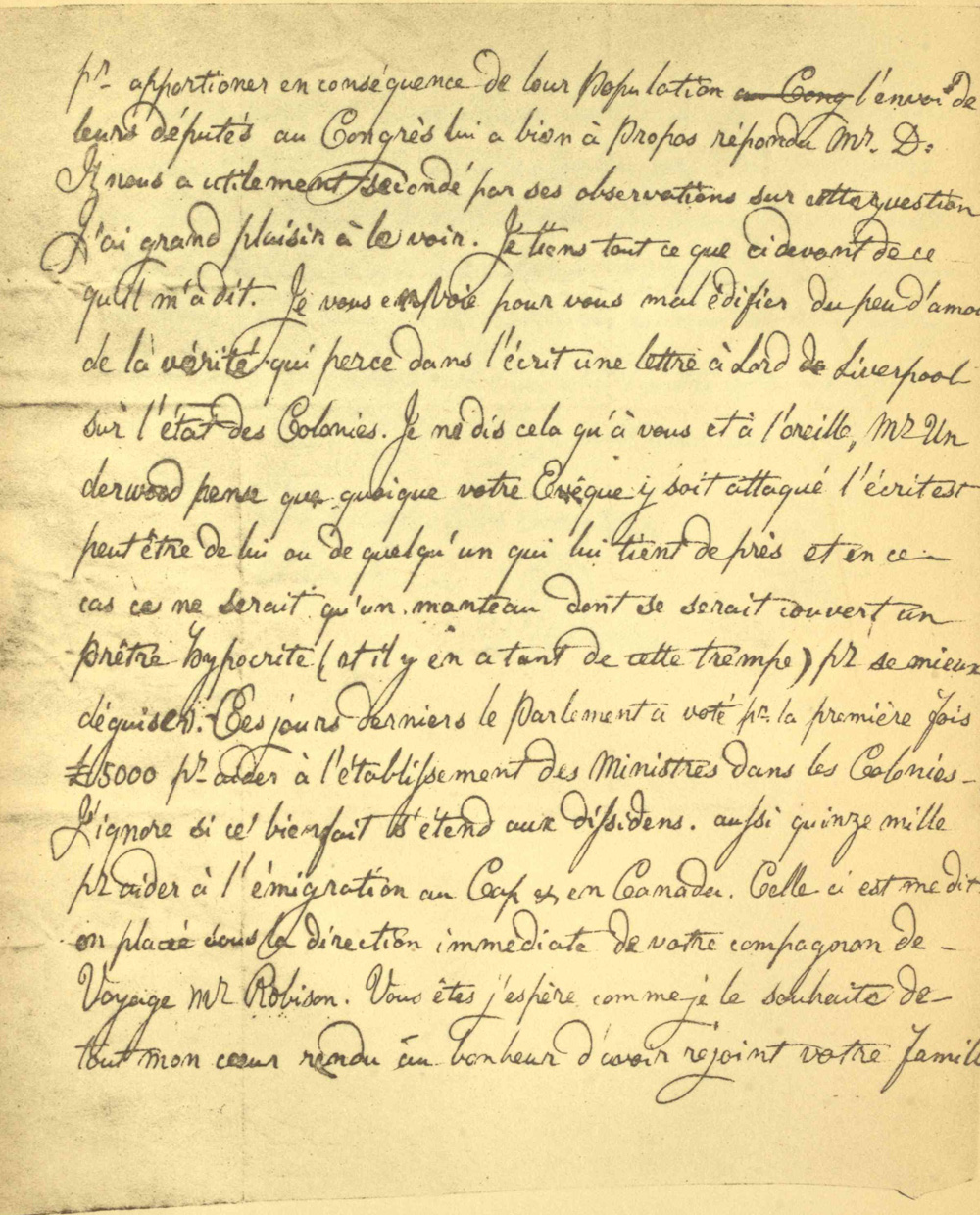

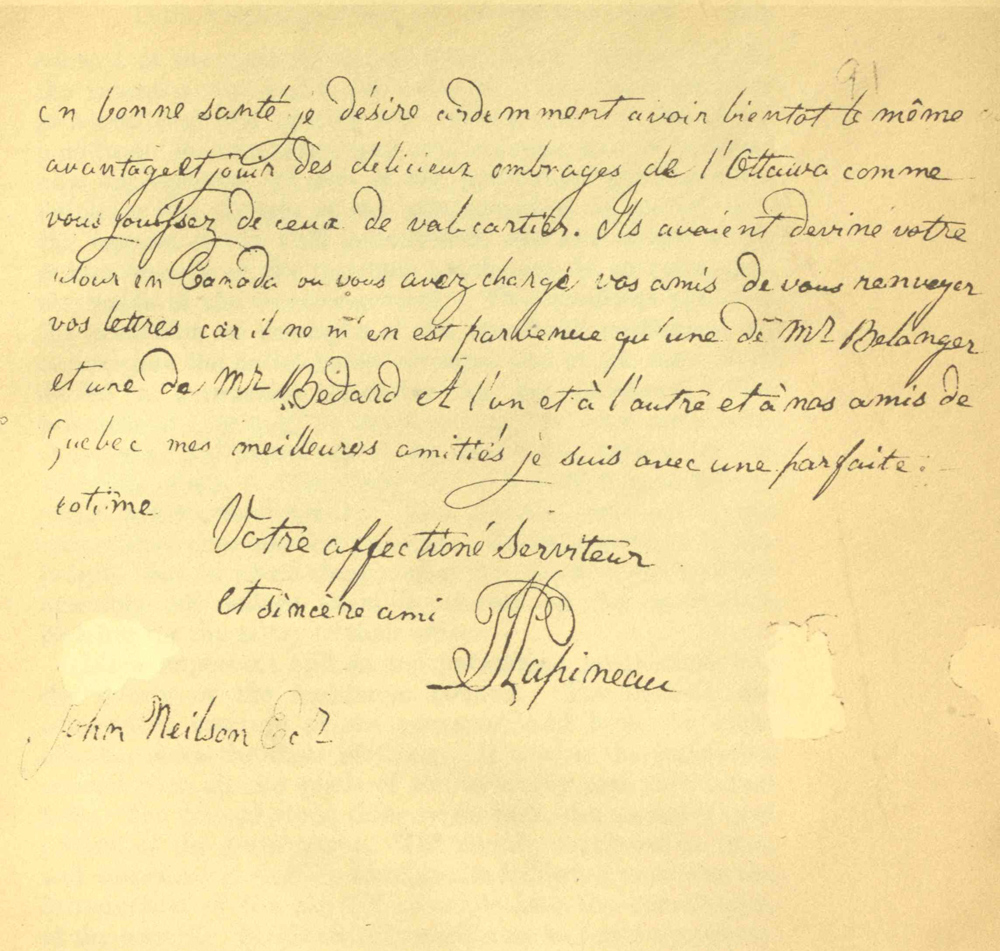

| FACSIMILE OF LETTER FROM LOUIS JOSEPH PAPINEAU TO JOHN NEILSON | " | 304 | |

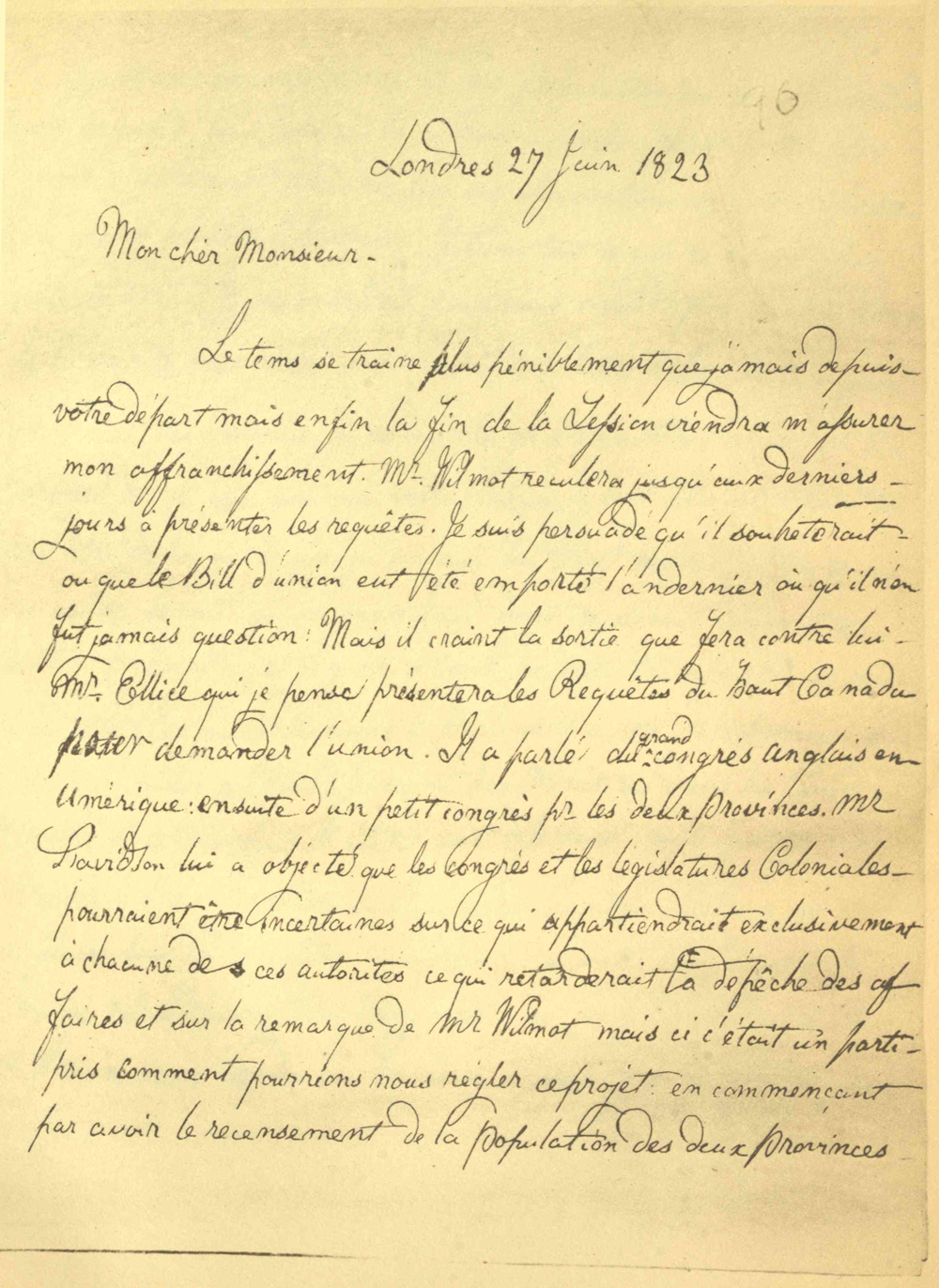

| FACSIMILE OF LETTER FROM LOUIS JOSEPH PAPINEAU TO JOHN NEILSON | " | 312 | |

| SIR JOHN COLBORNE (LORD SEATON) | " | 338 | |

| From an engraving in the Dominion Archives | |||

| WILLIAM LYON MACKENZIE | " | 344 | |

| From the painting by J. W. L. Forster | |||

| SIR FRANCIS BOND HEAD | " | 352 | |

| From an engraving in the Château de Ramezay | |||

| REWARD FOR THE ARREST OF LOUIS JOSEPH PAPINEAU | " | 362 | |

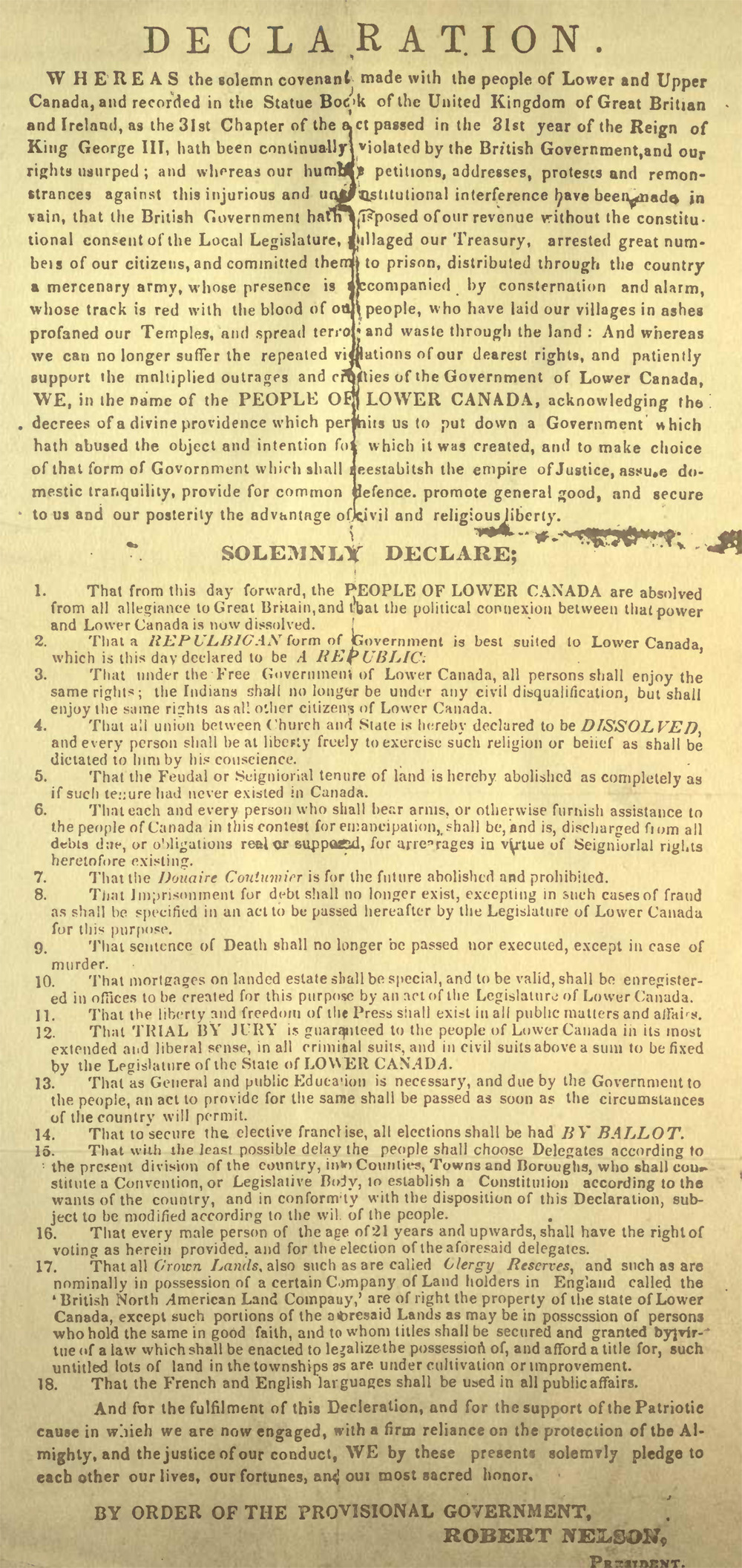

| PROCLAMATION BY ROBERT NELSON, 1838 | " | 364 | |

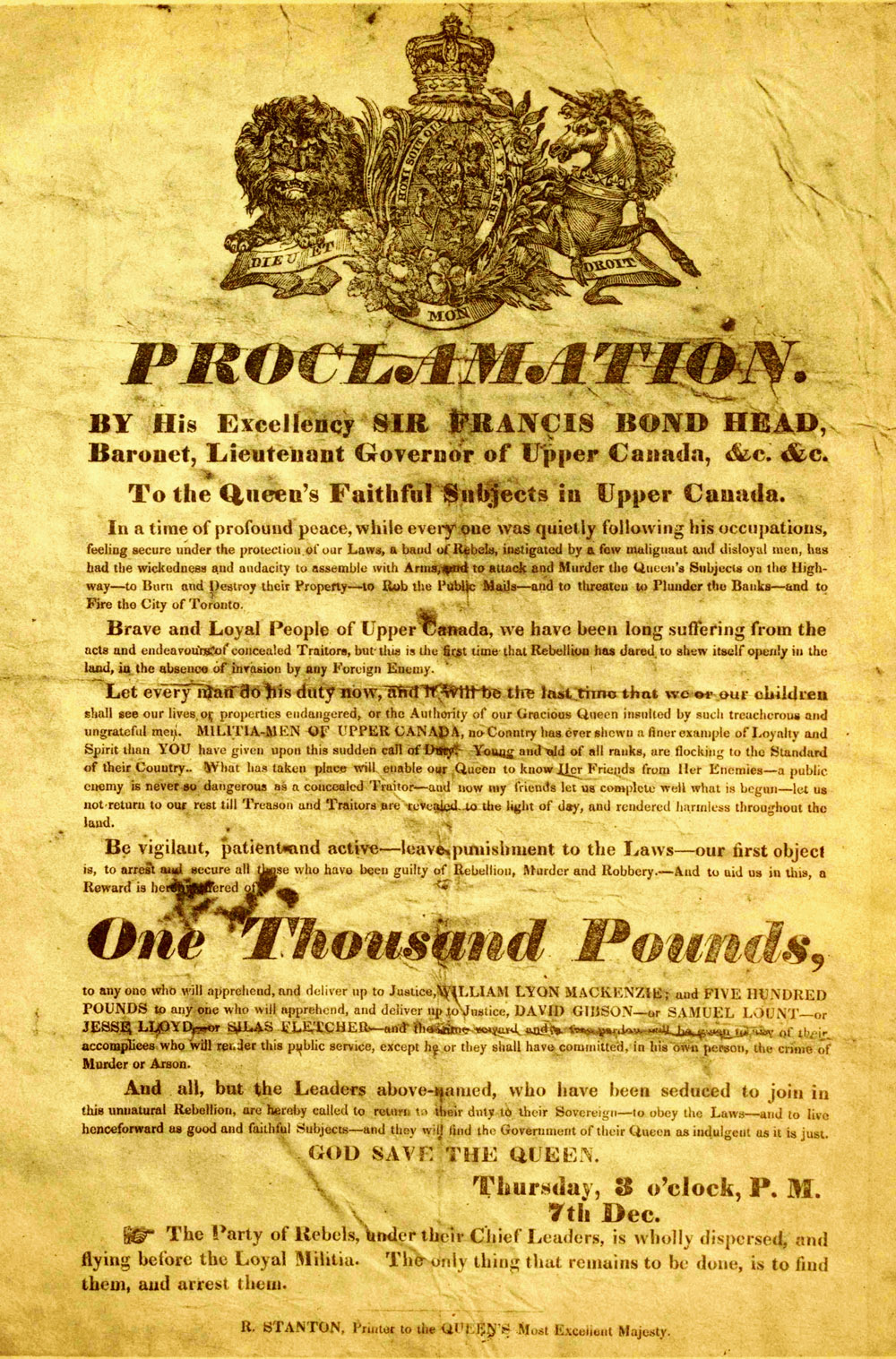

| REWARD OFFERED FOR THE ARREST OF WILLIAM LYON MACKENZIE AND OTHERS | " | 366 | |

The period of Canadian history terminating with the Union of the Canadas presents a vivid contrast to the preceding period which ended with the Cession.

Through the French period there breathes the spirit of romance. The voyageur exploring unknown rivers and untracked forests, the heroic missionary facing death in its most fearful forms, the sturdy Norman peasant fighting the wilderness and having at the same time to keep watch and ward against the treacherous and crafty Indian, the newness and strangeness of existence in a world so little known, give to the early history of Canada a perennial fascination.

Even the country life of the more peaceful and settled days has a colour and character entirely its own. We see transplanted to the new world the system of feudalism, an institution so venerable and so penetrated with historical associations that to find it on the virgin soil of Canada strikes us with a shock of surprise such as one might feel at meeting a knight in chain armour on the banks of the St Lawrence.

It is true that the feudalism of Canada was of a very benignant type, and it is by no means unlikely that its transplantation into that country by the French statesmen of the time was the wisest thing that could have been done. For there was, in fact, in this new world a reproduction of some of the conditions out of which European feudalism had sprung.

In the early days of that great system in Europe it was because the tillers of the soil had to be ready at any moment to take arms against savage invaders in the defence of their homes that it was of prime importance to have in every community a leader to organize the little fighting force. There was the same vital need for such a lord and leader in the seventeenth century in Canada as in the seventh century in Gaul. And when the daily peril from the redskins had passed away, the seigniory was still a most useful bond to hold together the simple, easily contented habitants. The seigneur and the curé—natural and traditional allies—were the leaders, advisers and friends of the peasants grouped round the manoir.

The Cession inevitably struck a deadly blow at this system, though it actually lingered on until after the Union. Many of the seigniories had passed into English hands, and a Protestant seigneur, who probably knew little or no French, fitted very ill into the old scheme. He might be well disposed towards his feudal tenants, but between him and them there could hardly exist that happy and patriarchal relation born of mutual sympathy and intimate knowledge, of which we have such pleasant pictures under the ancien régime in Canada. One of the marked features of British rule between the Cession and the Union is the decay of the feudal system and its growing unpopularity.

In this period also Canadian affairs become detached from European politics. For many years before the Cession the main interest centred on the struggle between France and England for the new world. It was a great drama played on a great stage. The eyes of Europe were fixed on Canada because it was there that European history was being made. But when France, worn out and beaten, had at length withdrawn from the contest, continental Europe had no longer much concern with a remote wilderness like Canada. Nor was it to be expected, or indeed to be desired, that England—the new sovereign power—should take any very acute interest in Canadian affairs. She could know but little of their true meaning and purport, and interference, however well meant, was likely to do more harm than good.

That the chief officials of the colony should be appointed by the governor, and that he should receive their advice without being by any means bound to follow it, were things which at that time were taken for granted. The plain commonsense which has never been wanting in England told her statesmen that the wisest plan was to leave Canada alone as far as possible to work out for herself her own destinies, which, as it seemed then, were not likely to be of special importance to the world in general. In the eighteenth century no one foresaw, or was in the least likely to foresee, that Canada was ever going to be of much consequence except to Canadians, nor were these expected to become very numerous.

The great difficulty which beset the English governors of the early period was to induce Downing Street to take any interest in the petty contentions which arose between the governor and the governed in these distant settlements. If things came to a head it was necessary on general principles to back up the governor, but the constant prayer of those at the Colonial Office was that such intervention should not be necessary. To some extent this was due, no doubt, to the deep-grained unwillingness of government officials at all times to interfere in matters which may lead them into difficulty, and out of which, in any event, no political capital can be made. But deeper down there was also the instinctive feeling that all interference from such a distance was dangerous.

At no time during the eighty years before the Union was there any approach to a good understanding between the two races in Canada, and about 1774, and again in 1837, the hostility between them was positively dangerous. In any judgment upon the disputes between them careful account must be taken of their respective numbers. According to such evidence as is available the French Canadians in 1760 were about 65,000, while the English were in all about 300. The population, except from 12,000 to 15,000, was all rural; Quebec had 6700 souls and Montreal 4000. After the Conquest the English population increased rather rapidly by the coming in of traders, but, although there has been some little dispute as to their numbers, it is safe to say that for many years the English formed less than five per cent of the population. In this state of matters, even if there had been no treaty obligations, the only sound policy was to conciliate the French population so far as was consistent with safety, and to make them feel that their customs and institutions would not be interfered with needlessly under British rule. But this was just the policy which the British settlers could not stomach. They demanded in season and out of season that the English laws and the English language ought to prevail in Canada, and that the government of the country should be entrusted to their hands. Forming not more than five per cent of the population, they clamoured for an assembly from which their Roman Catholic fellow-subjects—the vast majority of the people—would be excluded by their inability to take the oath renouncing the authority of the pope. General Murray, who had a low opinion of the English settlers which he expressed with remarkable freedom, described them as 'licentious fanatics,' and said, 'Nothing will satisfy them but the expulsion of the French Canadians.' Whether this absurd idea was ever seriously cherished may be doubted, but certainly the 'king's old subjects,' as they were fond of styling themselves, advanced claims which the home government was not at all disposed to recognize.

The Quebec Act of 1774 was the final answer to these extravagant pretensions. It was in a sense a formal disavowal by the British government of any desire to anglicize the Province of Quebec. It satisfied the reasonable demands of the French Canadians by declaring that all questions concerning property and civil rights should be decided by the French law, it left to the Roman Catholics the free exercise of their religion, gave the clergy the right to levy tithes on members of their communion, and amended the oath of allegiance so as to make it possible for a Roman Catholic to take it without doing violence to his conscience.

It is easy for people at the present day to say that all this was a fatal mistake and that the right course would have been to take measures to stamp out the French law and the French language. A careful study of the contemporary documents has convinced the writer, at any rate, that the result of such a policy would have been to drive the French Canadians into the arms of the American revolutionaries. Montreal would no doubt have spoken English, but if so, it would have been in the State instead of in the Province of Quebec. It was precisely because the French Canadians felt that they had been treated with justice and even with generosity by the British crown, that when the crisis came so soon afterwards they turned a deaf ear to the advances of the Americans. They were at that time almost entirely illiterate, and moved this way or that at the bidding of the priests and the seigneurs, who were their only leaders, and at this critical moment the whole influence of these leaders was exerted to restrain them, and they were threatened with excommunication if they joined the Americans. The priests and the seigneurs were strongly in favour of British connection because the Quebec Act had guaranteed to them the rights which they most valued. Any one who supposes that if the leaders had gone over to the side of the revolutionaries the people would have remained behind fails, in my judgment, to understand the conditions of society at that time in Canada.

The beginning of this first period of British rule saw Canada (omitting the Maritime Provinces) a colony of French habitants. Its close saw two flourishing provinces, which, in spite of civil dissensions and other adverse circumstances, had a number of large and prosperous cities, and more than the beginnings of great commercial interests. English, which in 1763 was spoken by a few hundreds of the people of Canada, was in 1837 the language of 550,000 out of the million inhabitants of the two provinces.

Adam Lymburner, who, as agent of the British part of the population, spoke at the bar of the Imperial House of Commons in 1791 against the formation of the new province of Upper Canada, said: 'What kind of a government must that upper part of the country form? It will be the very mockery of a province, three or four thousand families scattered over a country some hundred miles in length, not having a single town and scarcely a village in the whole extent; it is only making weakness more feeble and dividing the strength of the province to no purpose.' In 1837 Upper Canada had reached a population of 400,000, and to-day he would be a bold man who spoke of Ontario as the 'mockery of a province.'

Of the War of 1812 and the circumstances connected with it nothing need here be said except that it illustrated again the wisdom of the policy embodied in the Quebec Act. The Americans reckoned that the French Canadians, if they did not actually join forces with them, would at the worst remain neutral. This, to a considerable extent, explains their absolute confidence in the success of the invasion. Thomas Jefferson in the spring of 1812 wrote: 'The acquisition of Canada this year as far as the neighbourhood of Quebec will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us experience for the attack upon Halifax and the final expulsion of England from the American continent.' The defeat they sustained at Châteauguay from the little force of French Canadians contributed in no small measure to the dispelling of these illusions as to the easy conquest of Canada.

The history of Lower Canada between the Constitutional Act and the Union Act is little more than that of the struggle between the two races for supremacy. The position of each of them is perfectly intelligible and natural, and it is not necessary to impute blame to either for striving to attain its own ends. As the two parties drew farther and farther apart, and as the issues became more sharply defined, it was evident that no reconciliation between the policies of the two races was feasible, and that Lower Canada left to herself could never work out her own salvation.

The English-speaking part of the population was mainly gathered together in the cities of Quebec and Montreal, except for the Eastern Townships, where considerable sections of the country had been settled by people of British stock, many of whom were from the United States. Partly owing to insufficient representation in the assembly, and partly to the want of roads, this group of farmers sparsely scattered over a large territory could not keep in touch with each other or with the cities, and was able to render but little assistance to their compatriots. In the main, therefore, we have to regard the British party as townsfolk. They were, with few exceptions, merchants with their families and dependants. Their main desire was to improve the means of communication by land and water and to develop the exchange of commodities with the United States, with England and with foreign countries. The trade with the other provinces was inconsiderable. They felt that Canada even then had great commercial possibilities, and that they themselves had the capital and energy to enable them to profit by these opportunities if they could be assisted by simple and just laws and by a good administration. They looked upon the French Canadians as a conquered people whose tenacity in clinging to their national customs and to the French laws and language deserved the utmost reprobation. Their dream was to make Canada a new England beyond the seas. It was not enough that the English flag floated over it. A country won by force of arms could not be allowed to perpetuate the speech and institutions of England's hereditary enemy. The French laws, to which they were subject, they regarded with distrust and dislike. Nor can any honest student deny that in this respect they had real and important grievances. In principle the body of the civil law was the French law as it had been received in Canada before the Quebec Act of 1774. But to persons unacquainted with the French language that law was totally inaccessible, and even the French-Canadian lawyer had to work with very unsatisfactory materials. In France the obscurity and confusion of the old law had been to a great extent cleared away by the Code Napoléon and by the admirable writings of the early commentators on that great monument of the French genius for lucidity. But the Code Napoléon was a very unsafe guide to the law of Lower Canada because it was not specially based on the Custom of Paris, and in innumerable matters of detail it had broken away from the old law. As regards the law of land tenure and succession the lawyer in Canada knew pretty well where he was. But other branches of the law, and more particularly the commercial law, with which the trading class was most concerned, were in a state of the greatest obscurity. Moreover the jury system, whether in criminal or in commercial matters, was singularly ill adapted to a country divided, as Lower Canada was, into two hostile camps. In criminal cases the juries were apt to show a strong bias in favour of the accused if he belonged to their race, and in commercial cases the British trader felt that the view of the facts which would be taken by the French members of the jury would inevitably be coloured by race prejudice.

In the neighbouring states roads and canals were being constructed, and the local governments were lending every aid to the commercial class in its efforts to develop the trade and resources of the country. In Lower Canada any proposal made by the British merchants for the expenditure of public money on schemes of this kind was sure to be blocked by the sullen opposition of a majority composed of little farmers incapable of any broad view. The English party hoped against hope that there would be such an immigration as would convert their minority into a majority, but as time went on the futility of these hopes became apparent. The separation of Upper Canada in 1791 was a severe blow, because it weakened the English party by taking away from them some ten thousand settlers whom they could ill spare, but the effect of the separation at the time was trifling compared with its consequences in the years which followed. The English in Lower Canada saw with something like dismay the tide of immigration flowing steadily past them. Settlers of English speech, whether coming from Great Britain or from the United States, were not likely to be attracted by the prospect of living in a French country whose backward condition and internal dissensions were notorious. With pardonable envy they saw Upper Canada growing and prospering with just the kind of population which they desired for their own province, the English speech spoken, the English law followed, the English Church honoured and favoured. The English mark was being set very deeply upon Upper Canada, and a naturalist in search of the typical John Bull would have been as likely to find a perfect specimen at York, Upper Canada, as at York in England.

Is it any wonder that the English in Lower Canada felt the iron entering into their souls? Swamped by a hostile majority of foreigners (for by a somewhat humorous exercise of imagination they regarded themselves and not the French Canadians as the true children of the soil), to whom could they turn for comfort and support but to England and to the governors who represented the crown? In their eyes the mission of the governor was to be their shield and buckler against their hereditary enemies, and, as a matter of fact, this was precisely the rôle that most of the governors were destined to play whether they liked it or not. They came out anxious to hold the balance true, to find a just mean between the two extremes, to try to reconcile conflicting views and to avoid committing themselves definitely to either side in this bitter and long-protracted struggle. The circumstances were too strong for them. Joseph Howe went so far as to say that most governors came out so ignorant of the colony that for the first six or twelve months they were like overgrown boys at school. The irresponsible executive councillors, the chief justice, the attorney-general and the rest were the schoolmasters. Howe says:

It is mere mockery to tell us that the Governor himself is responsible. He must carry on the government by and with the few officials whom he finds in possession when he arrives. He may flutter and struggle in the net, as some well-meaning Governors have done, but he must at last resign himself to his fate and like a snared bird be content with the narrow limits assigned him by his keepers. I have known a Governor bullied, sneered at, and almost shut out of society while his obstinate resistance to the system created a suspicion that he might not become its victim; but I never knew one who, even with the best intentions and the full concurrence and support of the representative branch, backed by the confidence of his Sovereign, was able to contend on anything like fair terms with the small knot of functionaries who form the Councils, fill the offices and wield the powers of the government.

The political creed of the English party, with a comparatively few striking exceptions, was simple enough. In its eyes the French were at bottom traitors, waiting for an opportunity to shake off their allegiance; generosity would be thrown away upon them, and any power which was placed in their hands would be used to further their nefarious designs. The governor may have doubted sometimes whether the French were as black as they were painted, but he ended by feeling that as the king's representative it was his duty to support those who, whatever their prejudices might be, were undeniably devoted heart and soul to the British connection.

To the English party the proposal for a reunion of the two Canadas was as welcome as the sight of a sail to a shipwrecked crew. It was true that, although a minority, it had always governed Lower Canada, but with what infinite pains had the machinery of government been made to work. Hampered and worried at every turn by the permanent opposition of the assembly, supported as it was by the vast majority of the voters, the mere work of carrying on the administration from day to day had absorbed the energies of the governing class. It had been hopeless to think of undertaking the public works, the legal reforms, and, in short, the many problems, executive and legislative, on the happy solution of which the progress of the country depended.

Now the English in Lower Canada would no longer be isolated. Their brethren in Upper Canada might be depended on to support those progressive measures which had fared so badly in the past, and in the new house they would have a majority. For though Upper Canada had only 465,000 persons against 691,000 in Lower Canada, each of the old provinces was to have an equal number of members in the new assembly. Lord Durham had made no secret of the fact that the main motive of the union which he recommended was to bring about the gradual anglicization of the whole country. This made the whole scheme, and Durham as its father, abhorrent to the French Canadians.

It is now time to turn for a moment to the other side of the medal. The French had been in Quebec for a century and a half before the English came. The lives of countless brave men and women had been spent in laying the foundations of civilized life in this vast wilderness. Hardly was there a settlement the name of which was not associated with some story of heroic deeds, or whose soil was not hallowed by the blood of the saints. The Roman Catholic Church had watched over Canada from its early days with anxious solicitude, and nowhere in the world was there a people which clung more closely to the faith of their fathers. The French Canadians moreover had become truly Canadian. Even before the Conquest, in spite of the political tie which bound them to Old France, the mass of the people had lost all vital connection with the country from which they sprang. The peasants and fishermen of Normandy, transplanted to the woods of Canada, were little likely to keep up any correspondence with relations in France even if they had had time and ability to do so. But hardly any of them could write, and of those who possessed that capacity few could afford the expense of getting letters conveyed by such means as then existed. The French officers and gentlemen of family, who to a slight extent had kept in touch with their old home, had, with few exceptions, gone back to France after the Conquest. The priests and nuns who from time to time came over described France after the Revolution as a country smitten by Heaven for its offences and given over to destruction. For a brief space during the Napoleonic age, when it seemed as if the Corsican was to be the master of the world, it was natural that some Canadians should cherish vague hopes of being restored to their old allegiance. But the battle of Waterloo put an end to all dreams of this kind, and the French Canadians ceased to feel any keen interest in the politics of Europe.

For many years after the Conquest the French thought and cared little about political rights. They had been used to autocracy, and hardly understood the pother which the Americans made about the principle that taxation and representation must go together. The creation of the representative assembly under the Constitutional Act they regarded with suspicion, and the act as an instrument for laying upon them heavier burdens. They were determined, however, to maintain inviolate the rights guaranteed to them by the Quebec Act, namely, the free exercise of their religion and the French civil law. Nothing had been said at the Cession about the French language, for the idea of imposing on sixty-five thousand people the language of a minority of a few hundreds was too absurd to occur to any one. As time went on, and as the English population increased around them, the French Canadians came to regard the official recognition of the French language as a matter in which they were vitally interested. So long as their religion, their laws and their language were left undisturbed they were not much troubled by the fact that the governor and his little council of English officials managed the public business of the country. Nothing could have been more fortunate for England than this indifference in regard to politics, for it was out of the question at first to give political power into the hands of a people who had no historic reason for loving British connection and might be disposed to seek support in other quarters. But in the years which followed the War of 1812 the desire to get political power proportionate to their numbers gradually became stronger. Although the mass of the people was still largely illiterate, their leaders had not been blind to what was going on in other countries and even in the Maritime Provinces. The long struggle in England for parliamentary reform turned men's minds even in Canada to a consideration of the basis of government. The French Canadians felt keenly that though they had been conquered they were entitled to the same political rights as other British subjects. That they who had been in Canada a hundred and fifty years before the English should be characterized as foreigners and treated as an inferior race was not to be endured.

The final years of this period are memorable, not only in the history of Canada but in the history of liberty, as those in which the great struggle for responsible government took place. Unhappily in Lower Canada passion ran so high as to make the contest rather a smouldering war between the two races than a political fight between conservatives and reformers. The violence of Papineau and his inveterate hatred of English institutions prevented him drawing to his side those honest and loyal citizens who otherwise would gladly have helped in the cause of reform. Those who were fighting that battle in the other provinces were unwilling to associate themselves with men who made hardly any pretence of loyalty to the British crown. Joseph Howe, the most brilliant of them all, in his speech at Halifax in 1837 said: 'I wish to live and die a British subject, but not a Briton only in the name. Give me—give to my country the blessed privilege of her constitution and her laws; and as our earliest thoughts are trained to reverence the great principles of freedom and responsibility which have made her the wonder of the world, let us be contented with nothing less. Englishmen at home will despise us if we forget the lessons our common ancestors have bequeathed.' And in another speech in the same debate Howe referred to the possibility of his paying a visit to England, and said: 'I trust in God that when that day comes I shall not be compelled to look back with sorrow and degradation to the country I have left behind; that I shall not be forced to confess that, though the British name exists and her language is preserved, we have but a mockery of British institutions; that, when I clasp the hand of an Englishman on the shores of my fatherland he shall not thrill with the conviction that his descendant is little better than a slave.'

But when Howe was invited to lend his moral support to Papineau and his party and to send a consignment of Nova Scotia grievances to be tacked on to the ninety-two which they had enumerated, he stated his misgivings as to the attitude of the French party in Lower Canada with the most perfect frankness, saying indeed that he was convinced 'that an independent existence or a place in the American Confederation is the great object which at least some of the most able and influential of the Papineau party have in view.' And of the ninety-two resolutions, an incredibly verbose and weak composition, Howe says: 'I have rarely seen a more unstatesmanlike and discreditable paper from any legislative body than were the famous ninety-two resolutions. I do not speak so much of their substance as of their style and of there being ninety-two of them.'

Durham was too clear-sighted not to see that much of the strong language of Papineau and his friends was mere claptrap and not to be taken too seriously. Having no chance of getting into power, when promises, even political promises, are said to come home to roost, the members of the assembly were not in the habit of weighing their words very carefully. As Durham put it, 'the colonial demagogue bids high for popularity without the fear of future exposure.' Durham's policy, so amply justified by its success, was to remove the real grievances, and in this way deprive the hot-headed malcontents of any colour of right.

It is the fashion to belittle the Whig statesmen in England for their want of faith in the permanence of the tie between Canada and England, and for supposing that the grant of colonial self-government was but a half-way house to the complete independence of the colonies. This criticism is, on the whole, hardly deserved. Why should we expect them to be wiser on this matter than the Canadians themselves? No Canadian could be more loyal than Howe and no part of Canada more devoted to the British connection than Nova Scotia, yet Howe in various places speaks of the possibility of independence, though he hopes it will not be in his time. And the legislative council of Upper Canada, adopting the report of the Select Committee to which Durham's Report had been referred, expressed the clear opinion that the adoption of 'his lordship's great panacea for all political disorders, "Responsible Government" . . . must lead to the overthrow of the great colonial empire of England.' Is it surprising that with such a warning British statesmen should be in no hurry to take a step so hazardous? The men who had fought the battle of reform in England were not the men to suppose that Canada could be kept in the Empire by main force, and when, largely through the dogged pertinacity of Baldwin, it became necessary to grant self-government, they realized how serious an experiment they were making. It would not be possible to produce more weighty testimony for the Whig view of the colonial question in the forties than that of the third Lord Grey, and it would be hard to find a clearer exposition of sane and moderate imperialism than that which is given in the preliminary remarks to his essay on the 'Colonial Policy of Lord John Russell's Administration':

I consider then that the British Colonial Empire ought to be maintained principally because I do not consider that the nation would be justified in throwing off the responsibility it has incurred by the acquisition of this dominion, and because I believe that much of the power and influence of this Country depends upon its having large colonial possessions in different parts of the world. The possession of a number of steady and faithful allies, in various quarters of the globe, will surely be admitted to add greatly to the strength of any nation; while no alliance between independent states can be so close and intimate as the connection which unites the Colonies to the United Kingdom as parts of the Great British Empire . . . the tie which binds together all the different and distant portions of the British Empire so that their united strength may be wielded for their common protection must be regarded as an object of extreme importance to the interests of the Mother country and her dependencies. To the latter it is no doubt of far greater importance than to the former, because, while still forming comparatively small and weak communities, they enjoy, in return for their allegiance to the British Crown, all the security and consideration which belong to them as members of one of the most powerful States in the world.

It is round the theory of responsible government, so new and daring an experiment, that the great interest of this period of Canadian history must always centre. The actual application of the theory was, it is true, postponed for a few years beyond the Union. It was left for Robert Baldwin and for Lord Elgin to complete the work of Joseph Howe and of Lord Durham. But the battle had really been won. No one can read Durham's Report or Howe's Letters without feeling that the policy they laid down was in the long run as inevitable as it was just.

Home Rule has long converted the French of Lower Canada into peaceable and law-abiding British subjects, and we have recently seen in South Africa that Lord Durham's 'panacea for all political disorders,' as it was contemptuously styled by the Legislative Council of Upper Canada, has not lost its efficacy.

After the Seven Years' War, with its bold strokes of genius, its daring strategies and thrilling actions, the record of the puny and impoverished remnant of the colonists of New France may seem to have little to commend it. But a new epoch had dawned in the history of the British Empire and of the North American continent: the din of the battle of the Plains still resounds in world history.

Even in Canada a mighty problem of empire challenged solution. Although the citadel of Quebec had fallen, the conquest of Canada had just begun. The welding into one nation of two peoples, whom tradition had declared to be inveterate foes, whom language and religion had kept asunder, was a problem which a century and a half of effort has not solved.

On the death of General Wolfe the command of the British troops devolved on General Monckton, but the condition of his health prevented his remaining at Quebec. Accordingly the responsibility of preserving Quebec and extending the Conquest descended to General James Murray. Murray, who had just reached his fortieth year, was the son of the fourth Lord Elibank, and had served in the West Indies, in Flanders and in Brittany. When Pitt determined on the policy of reducing the power of France by cutting off her colonies, Murray was sent to assist at the siege of Louisbourg. His service there won the special commendation of Wolfe, and in the final attack on Quebec he was entrusted with the command of the left wing of the army. Murray was an officer of tireless energy and activity. He had not escaped the prevalent prejudices of a soldier, yet his varied military experience in no way blinded him to the needs of the unique situation with which he was compelled to deal.

The military genius of Murray was soon put to a severe test. The long-continued siege had left the city of Quebec and its defences in ruins, and the advanced season of the year made it impossible to restore them at once to a state of security. Murray's first months at Quebec were not lacking in stirring incident. The troops on whom the safety of the city depended were themselves restrained from mutiny only by the tact and wisdom of Murray. The scurvy, which during many previous winters had levied its heavy toll on Quebec, returned to add to his distress. In the spring he was compelled to defend his shattered walls against a vastly superior army. The Marquis de Lévis, after the defeat of Montcalm, made preparations for a vigorous campaign, and in April 1760 advanced with ten thousand men and laid siege to the city. Murray paid Montcalm the compliment of adopting his tactics of defence, and in the second battle of the Plains the British army was compelled to retire. So serious, however, was the damage which Murray inflicted that Lévis could not follow up his victory and capture Quebec, and when British reinforcements arrived with the opening of navigation he found it expedient to retreat hurriedly to Montreal.

The capitulation of Montreal, September 8, 1760, completed the military conquest of Canada, and the terms of agreement reached by the Marquis de Vaudreuil and General Amherst defined the conditions under which the French Canadians became subjects of the British crown. After the necessary provisions had been made respecting the occupation of the city, the protection of the property of the conquered, and the return to France of the officers of the late government, the questions of religious and political rights were discussed. The demand was made and granted that the free exercise of the Roman Catholic religion 'shall subsist entire, in such manner that all the states and the people of the Towns and countries, places and distant posts, shall continue to assemble in the churches, and to frequent the sacraments as heretofore.'[1] The right of the priests to collect tithes was made to depend on the pleasure of His Majesty, while the request that the king of France should continue to nominate the bishop of the colony was pointedly refused. The request that the Canadians who remained in the colony should continue to be governed by their ancient laws and usages and, in case of war with France, should be permitted to observe a neutrality received the significant reply: 'They become subjects of the King.' It was the policy of Amherst to settle the issues on which depended the peaceful and speedy occupation of the country, and to reserve for the determination of the king the larger questions of general policy affecting the future of the colony.

|

Article XXVII of the Capitulation. See Canadian Constitutional Documents, 1759-91, Shortt and Doughty, 1907, p. 25. |

For purposes of government the administrative divisions which formerly existed in the colony were preserved, and each of the three districts of Quebec, Three Rivers and Montreal was placed in charge of a lieutenant-governor. General Murray remained in command at Quebec; Colonel Burton was appointed to Three Rivers, and General Gage to Montreal.

The population of Canada at the time of the capitulation scarcely exceeded sixty-five thousand, of whom less than fifteen thousand occupied the cities of Quebec and Montreal. Four separate classes existed, distinguished by occupation, social standing and education. The gentry, descended from the ancient seigneurs or from the military or civil officers of former governments, constituted what remained of the aristocracy of New France. The gentry of the district of Quebec were described by Murray—and the description applies equally to those of the other districts—as vain and extravagant in their pretences, though in general poor and professing an utter contempt for trade and industry. The clergy was composed both of native Canadians and of priests from France. The Canadian clergy were descended in general from the humbler classes, and, though including men of undisputed ability and integrity, lacked something of the scholarship and refinement of their European brethren. The merchants, though not numerous, formed a distinct class in the community. The wholesale trade of the colony was largely confined to the French merchants, while the French Canadians remained content with the smaller retail business. The redemption of the French paper money was the issue of absorbing interest to the merchants. Most important of all were the habitants, whom Murray described as 'a strong, healthy race, plain in their dress, virtuous in their morals, and temperate in their living.' Murray could not but reflect on the extreme ignorance of the peasantry, which was attributed to the absence of newspapers and an apparent unwillingness on the part of the clergy to popularize education.

Now that the conflict was over, the colony directed its enfeebled efforts to repairing the breaches which the ravages of warfare had created. Agriculture, which during the campaigns prior to the Conquest was all but entirely suspended, was now gradually resumed. The trade which the war had so seriously disturbed was directed into new channels. Until the destiny of the colony had been determined the activity of government was confined to maintaining peace and order in the community. The lieutenant-governors received instructions that in the administration of justice the laws and customs of the Canadians should be respected and that, wherever possible, the former French magistrates should be retained. The inhabitants were protected in the exercise of their religion, and the prejudices against the heretic conqueror were gradually removed.

The system of military government as administered by Murray and his associates was well adapted to give the Canadians a favourable impression of British government. It singularly resembled the system to which they were accustomed, in exalting the authority of the governor and making few demands on the political intelligence of the governed. It was simple and, above all, it was administered by officers in sympathy with the needs of the new subjects. Yet the colony was not without those who were dissatisfied and who secretly longed for its restoration to France.

The disposition of the prizes of the Seven Years' War was causing serious agitation in England. Many forces were operating to determine the destiny of Canada. Pitt's reign ended with the death of George II in October 1760. With the accession of a king in George III Bute and the other personal favourites assumed the direction of British policy. To King George and his party Pitt and his 'bloody and expensive war' were alike distasteful, and it was their hope that by concluding the war the foundation of Pitt's popularity and influence would be shattered. Pitt's policy of pursuing to the full the advantages of his more recent conquests would most probably have placed Britain in a position to dictate terms of peace. But now the war policy was discontinued and the negotiation of the peace was entrusted to the advocates of compromise.

Yet another and more potent factor was forming the character of the settlement. The mercantile theory of empire still received the homage of ardent devotees and very largely determined the attitude of Britain towards colonial possessions. The Empire was economically self-sufficient, and the colonies existed for the express purpose of contributing to the welfare of the motherland. The division of labour in the empire was simple, yet it produced an exceedingly well-balanced process: the motherland provided articles of manufactures; the West Indies produced sugar; Africa supplied slave labour; while America contributed farm products for both the motherland and the West Indies. This theory of empire had already fixed the main channels of trade; vested interests had been created which in any readjustment of empire would permit no destruction of the perfect scheme of commerce. The problem which British statesmen had to solve was to decide which of the conquered territories it were best to retain and which should be restored to the French king. The economic principle of selection placed Canada in the balance against Guadeloupe, one of the West India sugar islands wrested from France. In favour of Guadeloupe were its rich sugar trade and the extensive shipping which its acquisition would secure. Canada's shipping was insignificant, and its great possibilities had not yet been unfolded. On the other hand, in favour of Canada it was argued that its market would give to British manufactures a rich monopoly; its natural resources would in time be discovered; while its climate rendered it more suitable for colonization than the southern islands. In any event the demand for sugar was already being supplied, and it was urged with calm assurance that with North America British the acquisition of Guadeloupe would be a mere incident.

The effect on the American colonies of the proposed addition to the Empire became, if not an actual determining factor, at least a most interesting phase of the peace discussions. Arguments advanced from that angle in general favoured retaining Guadeloupe rather than Canada. The production of sugar in the West India Islands would encourage agriculture in the American colonies, and, in consequence, would reduce the inclination to establish manufactories which would decrease the export trade of Britain. The safety of the Empire seemed to depend on maintaining in the American colonies a population of farmers. A still more subtle argument was evolved for the restoration of Canada. The power of France in the northern half of the continent would operate as a most effective check on insubordination in the American colonies. This clever freak of political sophistry had not yet been fully developed, and was compelled to wait for several years in order to receive serious consideration. In fact, the advocacy of such a policy would much more probably have hastened rebellion. After the American colonies had aided substantially in the reduction of French dominion in the north, what greater treachery could Britain have perpetrated than the conversion of Canada into a shackle for the restraint of those very colonies?

In the end Canada won, and time has justified the wisdom of the choice. By the Treaty of Paris, concluded February 10, 1763, France renounced all claim to Nova Scotia and ceded to Britain Canada, Cape Breton, and everything which depended upon them. The king of England agreed 'to grant the liberty of the Catholic religion to the inhabitants of Canada' and, to that end, undertook to order that 'his new Roman Catholic subjects may profess the worship of their religion according to the rites of the Romish church, as far as the laws of Great Britain permit.' Such of the inhabitants of the colony as wished to return to France were given liberty to do so, and were granted eighteen months in which to dispose of their estates.

Now that the destiny of the colony had been determined, the subjects, both new and old, were able to enter on definite plans for the future. To many of the ancient inhabitants the Treaty of Paris was a distinct disappointment. What emigration to France took place affected the cities and towns alone, and was confined to the officials of the former government, the professional men and the wealthier merchants. Not a few of these faithful subjects entered the service of their fatherland, where they attained positions of honour and distinction.

The attention of the British government was now definitely directed to the question of the form of government to be established in the newly acquired colonies. A reference was made to the Lords Commissioners for Trade, and they, in an exhaustive report of June 8, 1763, discussed the situation in each of the colonies. They observed:

It is obvious that the new Government of Canada, thus bounded, will, according to the Reports of Generals Gage, Murray and Burton, contain within it a very great number of French Inhabitants and Settlements, and that the Number of such Inhabitants must greatly exceed, for a very long period of time, that of Your Majesty's British and other Subjects who may attempt Settlements, even supposing the utmost Efforts of Industry on their part either in making new Settlements, by clearing of Lands, or purchasing old ones from the ancient Inhabitants, From which Circumstances, it appears to Us that the Chief Objects of any new Form of Government to be erected in that Country ought to be to secure the ancient Inhabitants in all the Titles, Rights and Privileges granted to them by Treaty, and to increase as much as possible the Number of British and other new Protestant Settlers, which Objects We apprehend will be best obtain'd by the Appointment of a Governor and Council under Your Majesty's immediate Commission & Instructions.

In a later report the Lords of Trade urged that, in the interests of emigration, there should be a public statement of His Majesty's intentions regarding the government of the colonies. With this object in view the commissioners revised their former report by adding the recommendation that the first commissions should authorize the governors to call popular assemblies. Accordingly a proclamation was issued October 7, 1763, declaring that Canada, East and West Florida and Grenada had been erected into separate governments, and outlining the form of government with which each was to be endowed. The boundaries of the Province of Quebec were fixed as: on the north, the River St John; on the west, a line from the head of the River St John through Lake St John to the south end of Lake Nipissing; on the south, a line from the southern extremity of Lake Nipissing to the point where the forty-fifth parallel of latitude intersected the St Lawrence and thence along the forty-fifth parallel to the height of land; on the east, the height of land between the St Lawrence and the Atlantic. Notification was then given that the various governors had been authorized, with the consent of the council, and as soon as circumstances would permit, to call general assemblies 'in such Manner and Form as is used and directed in those Colonies and Provinces in America which are under our immediate Government.' The governors, with the advice of the council and assembly so constituted, were empowered to make laws for the good government of their respective colonies.

What principles shaped Britain's attitude towards Canada? Canada had been acquired because by its conquest a death-blow would be struck at the empire of France. Canada was retained in 1763 because it afforded an excellent field for settlement, and because it was capable of affording a valuable market for British produce. So far as trade was concerned Canada belonged to the same category as the American colonies and received the same treatment. But the differences of race and religion placed Canada in a unique position. The treaty rights of the Canadian subjects demanded recognition. Two principles, then, entered into the settlement of the form of government—the preservation of the rights of the French Canadians, and the establishment of British settlement. To what extent these principles were contradictory was not then evident, nor could this well have been so. The ideal which determined the settlement of the government in 1763 was that of a colony on the banks of the St Lawrence in which ultimately the Protestant religion and British ideas should predominate.

The commissions to the governors were framed in accordance with the principles stated in the proclamation of October 7, 1763, and, after Pitt had graciously declined free transportation to political obscurity via Canada,[1] General Murray was entrusted with the civil government of the Province of Quebec. In the administration of the government Murray was assisted by a council composed of the leading officers of government together with eight persons chosen by the governor from the inhabitants of the province.

Murray's real difficulties now began. Such were the divisions in the character of the people, and so great were the diversities of their interests, that a clash was inevitable. The seigneurs had been the special object of Murray's attention. Though no longer able to support the dignity of an aristocracy, they still preserved their patrician character. Trade and commerce they despised, and by natural affinity they were attracted to the military class. Social intercourse welded a firm union between them and the British officers. The French-Canadian inhabitants composed the great mass of the people. They were tillers of the soil, taught by religion and social custom to respect and obey their superiors. Their horizon seldom extended beyond their parish, and their interests were confined to the cultivation of their fields and the strict performance of their religious duties. Of the old subjects of the king none were more interesting than the actual conquerors of the colony. These soldiers and officers of the army were a distinct factor in its early political history. They had been associated with Murray during the period of military rule, and had formed a lively sympathy for the ancient French inhabitants. Justly proud of their profession, they entertained nothing but contempt for the vulgar commercial classes.

It was in such a soil as this that British trade was to be established. The proclamation of 1763 had expressly encouraged British emigration and had promised the old subjects in Canada the benefit of the laws of England. Nothing was more natural than that the London merchants should seize this splendid opportunity to extend their trade. But the creation of commerce with Canada required the development of production and industry in the province. It introduced a spirit alien to the life of the colony and clashed with the prejudices of the French Canadians. Not only so, but it aroused their fears and created a suspicion that these alien interlopers were cherishing designs on their homes and properties. The interests of trade and commerce were thus brought into conflict with those with which Murray was most intimately associated. Although there were doubtless among the traders men of character and ability, there was also another more clamorous element which gave to the trading community its unhappy reputation. Murray, who had no occasion to love them, at one time characterized them as the most immoral collection of men he had ever known. Again, writing to the Lords of Trade, he refers to them as 'chiefly adventurers of mean education, either young beginners, or, if old Traders, such as have failed in other countrys. All have their fortunes to make and are little solicitous about the means, provided the end is obtained.'[2]

Civil government was not formally established until August 1764. The first problem which required Murray's attention was the establishment of courts of justice. Accordingly, in the September following, an ordinance was passed constituting a Court of King's Bench, for the trial of criminal and civil causes, agreeable to the laws of England; a Court of Common Pleas for the trial of civil causes alone; and a Court of Appeals.[3] The Court of Common Pleas was designed particularly for the benefit of the French Canadians, and the ancient customs of the colony were admitted in cases which arose prior to 1764. If demanded by either party, trial by jury was granted, and, much to the displeasure of the incoming English, French Canadians were admitted as jurors.

The constitution of a Grand Jury in connection with the sitting of the court at Quebec in October 1764 afforded the representatives of the traders an unequalled opportunity to state their grievances. The difficulty of Murray's task in conducting the administration may be better appreciated in the light of their demands.[4] They were greatly concerned with the observance of the Sabbath and found that 'a Learned Clergyman of a moral and exemplary life, qualified to preach the Gospel in its primitive Purity in both Languages, would be absolutely necessary.' Further, they represented that 'as the Grand Jury must be considered at present as the only Body representative of the Colony, they, as British subjects, have a right to be consulted, before any Ordinance that may affect the Body that they represent, be pass'd into a Law, and as it must happen that Taxes levy'd for the necessary Expences or Improvement of the Colony in Order to prevent all abuses & embezzlements or wrong application of the publick money.' To prevent the abuses and confusions too common in such matters they proposed that 'the publick accounts be laid before the Grand Jury at least twice a year to be examined and check'd by them and that they may be regularly settled every six months before them.' They graciously informed His Excellency that they apprehended that certain clauses of the ordinance establishing courts were unconstitutional and ought forthwith to be amended. The French-Canadian members of the jury signed the presentment, but that it was in ignorance of its contents and spirit can well be understood when it is seen that the Protestant jurors added a supplemental article protesting against the admission of the French Canadians to juries as 'an open violation of our Most Sacred Laws and Liberties, and tending to the utter subversion of the protestant Religion and his Majesty's power, authority, right and possession of the province to which we belong.' Is it any wonder that Murray should have characterized these men as 'little calculated to make the new subjects enamoured with our Laws, Religion and Customs, far less adapted to enforce these Laws and to Govern'?[5]

|

Frederic Harrison in his Chatham, in the 'Twelve English Statesmen' series, says of Pitt that 'Bute pressed him to accept the governorship of Canada, with a salary of five thousand pounds, or the chancellorship of the Duchy with its large salary' (p. 130). |

|

The Canadian Archives, Q 2, p. 377. |

|

For a description of the judicial system of Quebec see p. 436. |

|

The Presentments of the Grand Jury are given in full in Canadian Constitutional Documents, 1759-91, Shortt and Doughty, 1907, p. 153. |

|

Murray to Shelburne, August 20, 1760: the Canadian Archives, B 8, p. 1. |

The British government was not particularly happy in its selection of civil officers for the colony. Murray complained bitterly that 'the judge pitched upon to conciliate the minds of seventy-five thousand Foreigners to the Laws and Government of Great Britain was taken from a Gaol, entirely ignorant of the Civil Law, and of the Language of the people.' The administrative offices were given to friends of the government in England, who had no interest in the successful government of the colony. The appointments were delegated to deputies ignorant of the language and customs of the people, whose sole interest was to exploit the inhabitants to the full limit of their capacity or endurance.

The relation between the civil and military authority, particularly in Montreal, was the cause of much trouble to the government. Unfortunately the situation was complicated by the lack of cordiality between Murray and Burton. On the promotion of General Gage to the post of commander-in-chief at New York, Colonel Burton was transferred from Three Rivers to Montreal, and was credited with having aspired to the government of the colony. On Murray's appointment as governor, Burton refused the office of lieutenant-governor, but was appointed a brigadier on the American staff with command of the troops at Montreal.

The natural antipathy existing between the soldiers and merchants was aggravated by certain unfortunate incidents connected with the change from military to civil government. It had, at this time, been found necessary to billet the troops in private houses, but the regulations regarding billeting had exempted the homes of magistrates. A captain of the 28th regiment was billeted with a French family with whom one of the magistrates lodged. The magistrates, conceiving this a violation of the ordinance, committed the captain to gaol. The reply of the soldiers assumed a most barbarous form. On the night of November 6, 1764, a group of masked men forcibly entered the home of Thomas Walker, one of the magistrates of the town, and, after violently beating him, cut off his ear. Despite offers of reward and the utmost endeavours of Murray and the council, no reliable evidence could be secured to lead to a conviction of the persons implicated in the outrage. The condition of Montreal at this time was well described by Murray when he said that he 'found everything in confusion and the greatest Enmity raging between the Troops and the Inhabitants . . . and a stranger entering the Town from what he heard and saw might reasonably have concluded that two armies were within the Walls ready to fight on the first occasion.'[1] The hostility between the soldiers and the inhabitants was restrained only by the fear on both sides that any outbreak would result in serious bloodshed.

The Walker incident was the symptom of a grave disorder in the life of the colony. The situation was one which presented peculiar difficulties. It had been created by deep-seated prejudices which no action of government could have prevented or removed. But the broader question of the administration of justice was involved. From the small group of Protestant settlers the magistracy of the colony required to be selected. Of their qualifications Murray speaks in terms of contempt, and, after the proper discount has been made, there is no doubt that the magistrates, as a whole, were not such as to command the respect and confidence of the community. Their conduct was frequently such as to aggravate the prejudice and bitterness which already divided the inhabitants of the towns.

|

Murray to the Lords of Trade, March 3, 1765: the Canadian Archives, Q 2, p. 386. |

The opposition to Murray was becoming more persistent. The presentment of the Grand Jury in October 1764 was followed by a statement of grievances and a request from the merchants for Murray's recall. They complained of the restraint of their trade, of vexatious and oppressive ordinances; they complained of the discourtesy of the governor and of his interference with the administration of justice, and lamented his total neglect of attendance on the service of the church. Their grievances, they urged, could be remedied by the removal of the governor and the appointment of a man of less pronounced military inclinations. Finally, they requested His Majesty 'to order a House of Representatives to be chosen in this as in other your Majesty's Provinces; there being a number more than sufficient of Loyal and well affected Protestants, exclusive of military officers, to form a competent and respectable House of Assembly; and your Majesty's new Subjects, if your Majesty shall think fit, may be allowed to elect Protestants without burdening them with such Oaths as in their present mode of thinking they cannot conscientiously take.'[1]

In order that the Lords of Trade should have full information on the subject of Canadian affairs, Murray sent to England Hector Theophilus Cramahé, formerly his civil secretary when lieutenant-governor of the district of Quebec, and now one of the leading members of the council. But the course of events in the colony favoured the opponents of Murray, and on April 1, 1766, he was asked to return to Britain to give an account of the affairs of his government. Murray was succeeded immediately by Lieutenant-Colonel Irving, who was soon relieved by the new lieutenant-governor, Sir Guy Carleton.

FACSIMILE OF A DOCUMENT SIGNED BY MURRAY

It was Murray's fate to have been placed in a position of extreme difficulty. The opposing principles of French-Canadian conservatism and of commercial expansion, which during the succeeding years determined party divisions in Canada, had thus early made their appearance. It is not to Murray's discredit that he was not fully aware of the significance of the forces operating about him. Murray was a soldier and, above all, a man of strong sympathies. He was attracted to the French Canadian; he sympathized with him and determined to protect his liberties. The French Canadian had responded to Murray's system of government. On the other hand, Murray's natural prejudice against the merchant class was intensified by their extravagant and intolerant pretences. He saw that the realization of their claims would interfere with the freedom of the French Canadians, and he had already tasted of the troubles which their meddling could create in the administration. His training, his temperament, his personal interest, his view of the welfare of the empire made him a partisan at a time when none but the most skilled conciliator could have held the balance between opposing forces.

|

See Canadian Constitutional Documents, 1759-91, Shortt and Doughty, 1907, p. 168. |

His successor, Guy Carleton, was born in County Down in Ireland in 1724. At the age of eighteen he received a commission in the army, and by 1757 had attained the rank of lieutenant-colonel. During his early military career he became acquainted with Wolfe, and an intimate friendship developed between the two officers. When Wolfe received the command of the expedition against Quebec he insisted on including Carleton on his staff; but the king objected, and only after repeated representations was the royal pleasure secured for Carleton's appointment. During the campaign he performed important services, and in the battle of the Plains commanded a regiment of grenadiers.

In the autumn of 1766 Carleton found himself amidst the turbulent billows of Canadian parties. His opinion of the situation was soon formed, for within two months after his arrival he published a proclamation designed to relieve the burden of taxation on the French-Canadian subjects. The scale of fees and perquisites which Murray had introduced, acting under instructions, was not adapted to the circumstances of the colony. The frauds of Bigot, the general destruction of property caused by the war, the retirement of the wealthier families, leaving the colony in an impoverished state, had rendered the fees a burdensome tax on the people. Carleton now relinquished all the fees connected with the governor's office, excepting those for the granting of liquor licences, which he converted into a source of revenue for charitable relief within the province.

Carleton's troubles now began in earnest. The Walker affair came up again and roused renewed bitterness and rancour. One McGovock, a discharged soldier from the 28th regiment, laid information against Saint Luc de la Corne, Captain Campbell of the 27th, Lieutenant Evans of the 28th, Captain Disney of the 44th, Joseph Howard and Captain Fraser, the officer who had charge of the billeting. These gentlemen were arrested and arraigned for trial before the chief justice at Quebec. The Grand Jury, which was composed of both Protestants and French-Canadian noblesse, found a true bill against Captain Disney alone. Captain Disney's trial took place in March 1767, but he was declared 'most honourably acquitted.' The evidence against the accused officers was of such a contradictory character that McGovock was indicted for perjury and spent a term in gaol. Such unhappy incidents as this kept the community continually in a ferment and effectively prevented any permanent reconciliation between the magistracy and the military.

An unfortunate abuse in the administration of justice was the cause of much oppression to the French Canadians. Murray's ordinance of September 1764 gave to the justices of the peace jurisdiction in property cases not exceeding £10, but this power had been degraded by the magistrates into an instrument of extortion. As Carleton explained it, the magistrates who prospered in business could not afford to act as judges:

When several from Accidents and ill judged Undertakings, became Bankrupts, they naturally sought to repair their broken Fortunes at the expence of the People, Hence a variety of Schemes to increase the Business and their own Emoluments, Bailiffs of their own Creation, mostly French soldiers, either disbanded or Deserters, dispersed through the Parishes with blank Citations, catching at every little Feud or Dissension among the People, exciting them on to their Ruin, . . . putting them to extravagant Costs for the Recovery of very small Sums, their Lands, at a Time there is the greatest Scarcity of Money, and consequently but few Purchasers, exposed to hasty Sales for Payment of the most trifling Debts, and the Money arising from these sales consumed in exorbitant Fees, while the Creditors reap little Benefit from the Destruction of their unfortunate Debtors.[1]

The abuses perpetrated on an ignorant and submissive people under the pretext of the administration of justice were a disgrace to British citizenship. In French Canada after the Conquest, as elsewhere and at other times, the greatest hindrance to the anglicizing of the community was the Englishman. Murray and Carleton, in their endeavours to establish the loyalty of French Canada to the British crown on a firm and natural basis, were compelled to be constantly on their guard against the rapacity of their fellow-countrymen. In spite of the bitter opposition of the British element, Carleton succeeded in securing an ordinance which defeated the designs of these unscrupulous self-seekers. The jurisdiction of the justices of the peace in matters of private property was withdrawn except in case of a special commission, and certain of the necessary possessions of the habitants were exempted from seizure.