* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 3, Issue 8

Date of first publication: 1867

Author: J. T. Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Aug. 13, 2018

Date last updated: Aug. 13, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180860

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Delphine Lettau, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. III. | AUGUST, 1867. | No. VIII. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

THE BIRD-CATCHERS.

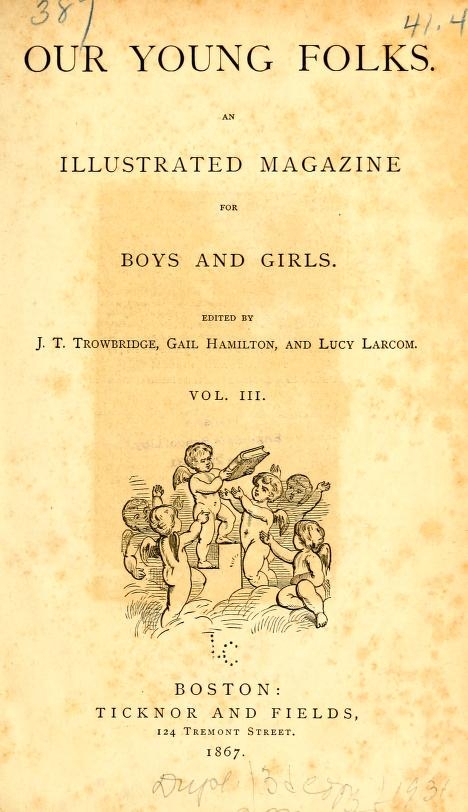

Drawn by Winslow Homer.] [See Bird-Catching, page 461.

bright sun shone on the little village

of Rockdale; a bright glare was on the

little bay close by, as on a silver mirror;

three bright children were descending

by a winding path towards the little village;

a bright old man was coming up

from the little village by the same winding

path.

bright sun shone on the little village

of Rockdale; a bright glare was on the

little bay close by, as on a silver mirror;

three bright children were descending

by a winding path towards the little village;

a bright old man was coming up

from the little village by the same winding

path.

The three children were named William Earnest, Fred Frazer, and Alice. Alice was William Earnest’s sister, while Fred Frazer was his cousin. William Earnest was the eldest, and he was something more than eleven and something less than twelve years old. His cousin Fred Frazer was nearly a year younger, while his sister Alice was a little more than two years younger still. Fred Frazer was on a holiday visit to his relatives, it being vacation time from school; and the three children were ready for any kind of adventure, and for every sort of fun.

The children saw the old man before the old man saw the children; for the children were looking down the hill, while the old man, coming up the hill, was looking at his footsteps. As soon as the children saw the old man, the eldest recognized him as a friend, and no sooner had his eyes lighted on him than, much excited, he shouted loudly, “Hurrah, there comes the ancient mariner!”

His cousin, much surprised, asked quickly, “Who’s the ancient mariner?” And his sister, more surprised, asked timidly, “What’s the ancient mariner?”

Then the eldest, much elated, asked derisively, “Why, don’t you know?” And then he said, instructively: “He’s been about here for ever so long a time; but he went away last year, and I haven’t seen him for a great while. He’s the most wonderful man you ever saw,—tells such splendid stories,—all about shipwrecks, pirates, savages, Chinamen, bear-hunts, bull-fights, and everything else that you can think of. I call him the ‘Ancient Mariner,’ but that isn’t his right name. He’s Captain Hardy; but he looks like an ancient mariner, as he is, and I got the name out of a book. Some of the fellows call him ‘Old Father Neptune.’ ”

“What a funny name!” cried Fred.

“What do they call him Father Neptune for?” inquired Alice.

“Because,” answered William, looking very wise,—“because, you know, Neptune, he’s god of the sea, and Captain Hardy looks just like the pictures of him in the story-books. That’s why they call him Old Father Neptune.”

By this time the subject of the colloquy had come quite near, and William, suddenly leaving his companions, darted forward to meet the object of his admiration.

“O Captain Hardy, I’m so glad to see you!” exclaimed the little fellow, as he rushed upon him. “Where did you come from? Where have you been so long? How are you? Quite well, I hope,”—and he grasped the old man’s hand with both of his own, and shook it heartily.

“Well, my lad,” replied the old man, kindly, “I’m right glad to see you, and will be right glad to answer all your questions, if you’ll let them off easy like, and not all in a broadside”;—and as they walked on up the path together, William’s questions were answered to his entire satisfaction.

Then they came presently to Fred and Alice, who were introduced by William, very much to the delight of Fred; but Alice was inclined to be a little frightened, until the strange old man spoke to her in such a gentle way that it banished all timidity; and then, taking the hand which he held out to her, she trudged on beside him, happy and pleased as she could be.

The party were not long in reaching the gate leading up to the house of William’s father. A large old-fashioned country-house it was, standing among great tall trees, a good way up from the high-road; and William asked his friend to come up with them and see his father, “he will be so delighted”; but the old man said he “would call and see Mr. Earnest some other time; now he must be hurrying home.”

“But this isn’t your way home, Captain Hardy, is it?” exclaimed William, much surprised. “Why, I thought you lived away down below the village.”

“So I did once,” replied the old man; “that is, when I lived anywhere at all; but you see I’ve got a new home now, and a snug one, too. See, down there where the smoke curls up among the trees,—that’s from my kitchen.”

“But,” said William, “that’s Mother Podger’s house where the smoke is.”

“So it was once, my lad,” answered the old man; “but it’s mine now; for I’ve bought it and paid for it, too; and now I mean to quit roaming about the world, and to settle down there for the remainder of my days. You must all come down and see me; and if you do, I’ll give you a sail in my boat.”

“O, won’t that be grand!” exclaimed William; and Fred and Alice both said it would be “grand”; and then they all put a bold front on, and asked the old man if he wouldn’t take them to see the boat now, they would like so much to see it.

“Certainly I will,” answered the old man. “Come along,”—and he led the way over the slope down to the little bay where the boat was lying.

“There she is!” exclaimed he, when the boat came in view. “Isn’t she a snug craft? She rides the water just like a duck,”—whereupon the children all declared that they had never, in all their lives, seen anything so pretty, and that “a duck could not ride the water half so well.”

It was, indeed, a very beautiful little boat, or rather yacht. It was half decked over, making a cosey little cabin in the centre, with space enough behind and outside of it for four persons to sit quite comfortably. The seat was a sort of semicircle. The yacht had but one mast, and was painted white, both inside and out, with only the faintest red streak running all the way around its sides, just a little way above the water-line.

Captain Hardy (for that was the old man’s proper name and title, and therefore we will give it to him) now drew his little yacht close in to a little wharf that he had made, and the children stepped into it and ran through the cosey cabin, which was but very little higher than their heads, and had crimson cushions all along its sides to sit down on. These crimson cushions were the lids of what the Captain called his “lockers,”—boxes where he kept his little “traps.” In this little cabin there was the daintiest little stove, on which the Captain said they might cook something when they went out sailing.

When they had finished looking at the yacht, they jumped ashore again, and then, after securing the craft of which he was so proud, the Captain took the children to his house. It was a cunning little house, this house of the Captain’s. It was only one story high, and had an odd bay-window at one end and two odd windows in the roof; and it was as white and clean as a new table-cloth, while the window-shutters were as green as the grass that grew around it. Tall trees surrounded it on every side, making shade for the Captain when the sun shone, and music for the Captain when the wind blew. In front there was a quaint porch, all covered over with honeysuckles, smelling sweet, and near by, in a cluster of trees, there was a rustic arbor, completely covered up with vines and flowers. Starting from the front of the house, a path wound among the trees down to the little bay where lay the yacht; and on the left-hand side of this path, as you went down, a spring of pure water gurgled up into the bright air, underneath a rich canopy of ferns and wild-flowers.

William was much surprised to find that this house, which everybody knew as “Mother Podger’s house,” should now really belong to Captain Hardy; and he said so.

“You’d hardly know it, would you, since I’ve fixed it up, and made it shipshape like?” said the Captain. “I’ve done it nearly all myself, too. And now what do you think I’ve called it?”

The children said they could never guess,—to save their lives, they never could.

“I call it ‘Mariner’s Rest,’ ” said the Captain.

“O, how beautiful! and so appropriate!” exclaimed William; and Fred and Alice chimed in and said the same.

“And now,” went on the Captain, “you must steer your course for the ‘Mariner’s Rest’ again,—right soon, too, and the old man will be glad to see you.”

“Thank you, Captain Hardy,” answered William, with a bow. “If we get our parents’ leave we’ll come to-morrow, if that will not too much trouble you.”

“It will not trouble me at all,” replied the Captain. “Let it be four o’clock, then,—come at four o’clock. That will suit me perfectly; and it may be that I’ll have,” continued he, “a bit of a story or two to tell you. Besides, I think I promised something of the kind before to William, when I came home this time twelvemonth ago. Do you remember it, my lad?”

William said he remembered it well, and his eyes opened wide with pleasure and surprise.

“Now what was it?” inquired the Captain, thoughtfully. “Was it a story about the hot regions, or the cold regions? for you see things don’t stick in my memory now as they used to.”

“It was about the cold regions, that I’m sure,” replied William; “for you said you would tell me the story you told Bob Benton and Dick Savery,—something, you know, about your being ‘cast away in the cold,’ as Dick Savery said you called it.”

“Ah, yes, that’s it, that’s it,” exclaimed the old man, as if recalling the occasion when he had made the promise with much pleasure. “I remember it very well. I promised to tell you how I first came to go to sea, and what happened to me when I got there. Eh? That was it, I think.”

“That was exactly it, only you said you were ‘cast away in the cold,’ ” said William.

“No matter for that, my lad,” replied the Captain, with a knowing look,—“no matter for that. If you know how a story’s going to end, it spoils the telling of it, don’t you see? Consider that I didn’t get cast away, in short, that you know nothing of what happened to me, only that I went to sea, and leave the rest to turn up as we go along. And now, good day to all of you, my dears. Come down to-morrow, and we’ll have the story, and may be a sail, if the wind’s fair and weather fine,—at any rate, the story.”

And the children were probably the happiest children that were ever seen, as they turned about for home, showering thanks upon the Captain with such tremendous earnestness that he was forced in self-defence to cry, “Enough, enough! run home and say no more.”

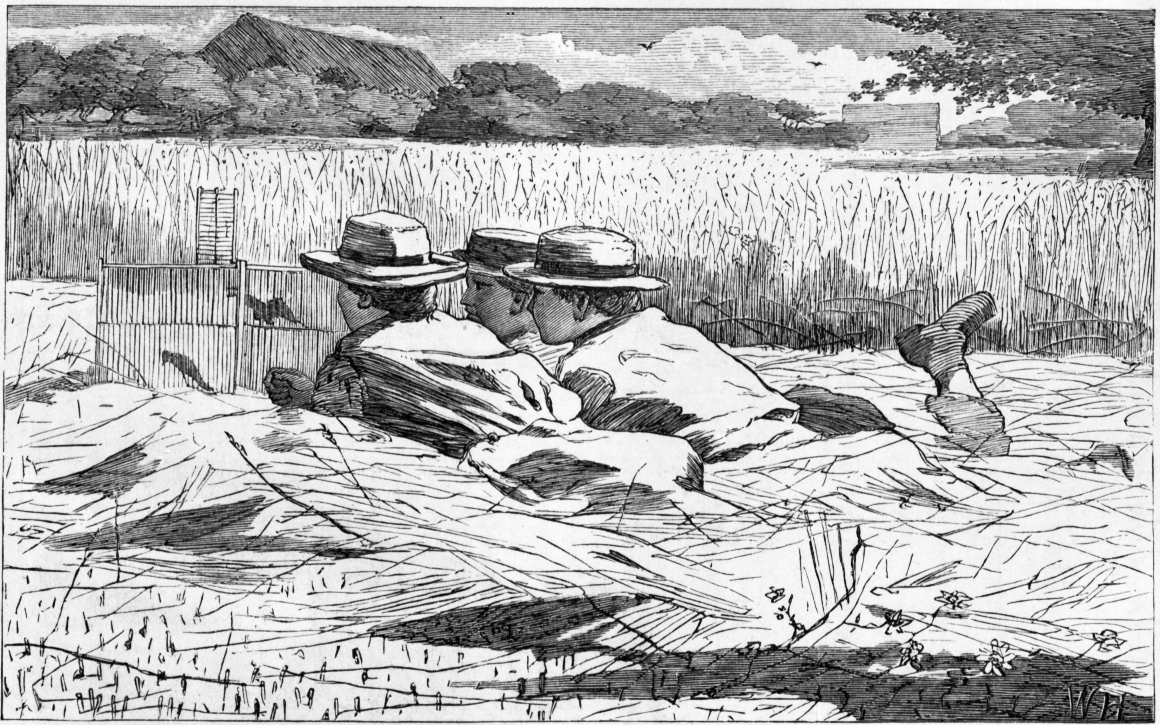

Captain Hardy, or Captain John Hardy, or Captain Jack Hardy, or plain Captain Jack, or simple Captain, as his neighbors pleased to name him, was a famous character in the village. Everybody knew the Captain, and everybody liked him. He was a mysterious sort of person,—here to-day and there to-morrow,—coming and going all the time, until he fairly tired out the public curiosity, so that even the greatest gossips in the town had to confess at length that there was no use trying to make anything of this strange man, and they gave up inquiring and bothering about him; but were glad to see him always, none the less.

The Captain was known as a great talker, and was always, in former years, brimful of stories of adventure to tell to any one he met, during his short stays in the village, who would listen to him; and, in truth, any one was glad to listen, he talked so well. Many and many a summer evening he spent seated on an old bench in front of the village inn, reciting tales of shipwrecks, and stories of the sea and land, to the wondering people. Of late years, however, he was not disposed to talk so much, and was not so often seen at his favorite haunt. “I’m getting too old,” he would say, “to tarry from home after nightfall.”

He had now grown to be fifty-nine years old, although he really looked much more aged, for he bore about him the marks of much hardship and privation. His hair was quite white, and fell in long silvery locks over his shoulders, while a heavy snow-white beard covered his breast. There was always something in his appearance denoting the sailor. Perhaps it was that he always wore loose pantaloons,—white in summer, and blue in winter,—and a sort of tarpaulin hat, with long blue ribbons tied round it, the ends flowing off behind like the pennant of a man-of-war.

Captain Hardy was known to everybody as a generous, warm-hearted, and harmless man; but he was thought to be equally improvident. The poor had a constant friend in him. No beggar ever asked the Captain for a shilling without getting it, if the Captain had it anywhere about him. Sometimes he had plenty of money, yet when at home he always lived in a frugal, homely way. Great was the rejoicing, therefore, among his friends (and they were many) when it was known that he had fallen in with a streak of good fortune. Having been chiefly instrumental in saving the British bark Dauntless from shipwreck, the insurance companies had awarded him a liberal salvage, and it was to secure this that he had gone away on his last voyage. As soon as he came home he went right off and bought the house which we have before described, with the money he brought back; and for once got the credit of doing a prudent thing.

The old man’s happiness seemed now complete. “Here,” exclaimed he, “Heaven willing, I will end my days in peace.” But after the excitement of fitting up his house and grounds, and getting his little yacht in order, had passed over, he began to feel a little lonely. He was so far away from the village that he could not see his old friends as often as he wished to. We have seen that he was a great talker; and he liked so much to talk, and thus to “fight his battles over again,” and had so much to talk about, that an audience was quite necessary to him. It is not improbable, therefore, that he looked upon his meeting with William and Fred and Alice as a fortunate event for him; and if the children were delighted, so was he. He was very fond of children, and these were children after his own heart. To them the coming story was a great event,—how great, the reader could scarcely understand, unless he knew how much every boy in Rockdale was envied by all the other boys, when he was known to have been specially picked out by Captain Hardy to be the listener to some tale of adventure on the sea.

As we may well suppose, the Captain’s little friends did not tarry at home next day beyond the appointed time; but, true as the hands of the clock to mark the hour and minute on the dial-plate, they set out for Captain Hardy’s house as fast as they could go,—as if their very lives depended on their speed. They found the Captain seated in the shady arbor, smoking a long clay pipe. “I’m glad to see you, children,” was his greeting to them; and glad enough he was too,—much more glad, may be, than he would care to own,—as glad, perhaps, as the children were themselves.

“And now, my dears,” continued he, “shall we have the story? There is no wind you see, so we cannot have a sail.”

“O, the story! yes, yes, the story,” cried the children, all at once.

“Then the story it shall be,” replied the old man; “but first you must sit down,”—and the children sat down upon the rustic seat, and closed their mouths, and opened wide their ears, prepared to listen; while the Captain knocked the ashes from his long clay pipe, and stuck it in the rafter overhead, and cleared his throat, prepared to talk.

“Now you must know,” began the Captain, “that I cannot finish the story I’m going to tell you all in one day,—indeed, I can only just begin it. It’s a very long one, so you must come down to-morrow, and next day, and every bright day after that until we’ve done. Does that please you?”

“Yes, yes,” was the ready answer, and little Alice fairly cried with joy.

“Will you be sure to remember the name of the place you come to? Will you remember that its name is ‘Mariner’s Rest’? Will you remember that?”

“Yes indeed we will.”

“And now for the boat we’re to have a sail in by and by; what do you think I’ve called that?”

“Sea-Gull?” guessed William.

“Water-Witch?” guessed Fred.

“White Dove?” guessed Alice.

“All wrong,” said the Captain, smiling a smile of satisfaction. “I’ve painted the name on her in bright golden letters, and when you go down again to look at her, you’ll see ‘Alice’ there, and the letters are just the color of some little girl’s hair I know of.”

“Is that really her name?” shouted both the boys at once, glad as they could be; “how jolly!” But little Alice said never a word, but crept close to the old man’s side, and the old man put his great, big arm around the child’s small body, and as the soft sunlight came stealing in through the openings in the foliage of the trees, flinging patches of brightness over the green grass around, the Captain began his story. And thus it was:—

“Now, my little listeners,” spoke the Captain, “you must know that what I am going to tell you occurred to me at a very early period of my life, when I was a mere boy; in fact, the adventures which I shall relate to you were the first I ever had.

“To begin, then, at the very beginning, I must tell you that I was born very near this place. So you see I have good reason for always liking to come back to the neighborhood. It is like coming home, you know. The place of my birth is only eleven miles from Rockdale by the public road, which runs off there in a west-nor’westerly direction.

“My mother died when I was six years old, but I remember her as a good and gentle woman. She was taken away, however, too early to have left any distinct impression upon my mind or character. I was thus left to grow up with three brothers and two sisters, all but one of whom were older than myself, without a mother’s kindly care and instruction; and I must here own, that I grew to be a self-willed and obstinate boy; and this disposition led me into a course of disobedience which, but for the protecting care of a merciful Providence, would have brought my life to a speedy end.

“My father being poor, neither myself nor my brothers and sisters received any other education than what was afforded by the common country school. It was, indeed, as much as my father could do at any time to support so large a family and at the end of the year make both ends meet.

“As for myself, I was altogether a very ungrateful fellow, and appreciated neither the goodness of my father nor any of the other blessings which I had. Of the advantages of a moderate education which were offered to me I did not avail myself,—preferring mischief and idleness to my studies; and I manifested so little desire to learn, and was so troublesome to the master, that I was at length sent home, and forbidden to come back any more. Whereupon my father, very naturally, grew angry with me, and, no doubt thinking it hopeless to try further to make anything of me, he regularly bound me over, or hired me out, for a period of years, to a neighboring farmer, who compelled me to work very hard; so I thought myself ill used, whereas, in truth, I did not receive half my deserts.

“With this farmer I lived three years and a half before he made the discovery that I was wholly useless to him, and that I did not do work enough to pay for the food I ate; so the farmer complained to my father, and threatened to send me home. This made me very indignant, as I foolishly thought myself a greatly abused and injured person, and, in an evil hour, I resolved to stand it no longer. I would spite the old farmer, and punish my father for listening to him, by running away.

“I was now in my eighteenth year,—old enough, as one would have thought, to have more manliness and self-respect; but about this I had not reflected much.

“I set out on my ridiculous journey without one pang of regret,—so hardened was I in heart and conscience,—carrying with me only a change of clothing, and having in my pocket only one small piece of bread, and two small pieces of silver. It was rather a bold adventure, but I thought I should have no difficulty in reaching New Bedford, where I was fully resolved to take ship and go to sea.

“The journey to New Bedford was a much more difficult undertaking than I had counted upon, and I believe, but for the wound which it would have caused to my pride, I should have gone back at the end of the first five miles. I held on, however, and reached my destination on the second day, having stopped overnight at a public house or inn, where my two pieces of silver disappeared in paying for my supper and lodging and breakfast.

“I arrived at New Bedford near the middle of the afternoon of the second day, very hot and dusty, for I had walked all the way through the broiling sun along the high-road; and I was very tired and hungry, too, for I had tasted no food since morning, having no more money to buy any with, and not liking to beg. So I wandered on through the town towards the place where the masts of ships were to be seen as I looked down the street,—feeling miserable enough, I can assure you.

“Up to this period of my life, I had never been ten miles from home, and had never seen a city, so of course everything was new to me. By this time, however, I had come to reflect seriously on my folly, and this, coupled with hunger and fatigue, so far banished curiosity from my mind that I was not in the least impressed by what I saw. In truth, I very heartily wished myself back on the farm; for if the labor there was not to my liking, it was at least not so hard as that which I had performed these past two days, in walking along the dusty road,—and then I was, when on the farm, never without the means to satisfy my hunger.

“What I should have done at this critical stage, had not some one come to my assistance, I cannot imagine. I was afraid to ask any questions of the passers-by, for I did not really know what to ask them, or how to explain my situation; and, seeing that everybody was gaping at me with wonder and curiosity, (and, indeed, many of them were clearly laughing at my absurd appearance,) I hurried on, not having the least idea of where I should go or what I should do.

“At length I saw a man with a very red face approaching on the opposite side of the street, and from his general appearance I guessed him to be a sailor; so, driven almost to desperation, I crossed the street, looking, I am sure, the very picture of despair, and I thus accosted him: ‘If you please, sir, can you tell me where I can go and ship for a voyage?’

“ ‘A voyage!’ shouted he, in reply, ‘a voyage! A pretty-looking fellow you for a voyage!’—which observation very much confused me. Then he asked me a great many questions, using a great many hard names, the meaning of which I did not at all understand, and the necessity for which I could not exactly see. I noticed that he called me ‘land-lubber’ very frequently, but I had no idea whether he meant it as a compliment or an abusive epithet, though it seemed more likely to me that it was the latter. After a while, however, he seemed to have grown tired of talking, or had exhausted his collection of strange words, for he turned short round and bade me follow him, which I did, with very much the feelings a culprit must have when he is going to prison.

“We soon arrived at a low, dingy place, the only noticeable feature of which was that it smelled of tar and had a great many people lounging about in it. It was, as I soon found out, a ‘shipping office,’—that is, a place where sailors engage themselves for a voyage. No sooner had we entered than my conductor led me up to a tall desk, and then, addressing himself to a hatchet-faced man on the other side of it, he said something which I did not clearly comprehend. Then I was told to sign a paper, which I did without even reading a word of it, and then the red-faced man cried out in a very loud and startling tone of voice, ‘Bill!’ when somebody at once rolled off a bench, and scrambled to his feet. This was evidently the ‘Bill’ alluded to.

“When Bill had got upon his feet, he surveyed me for an instant, as I thought, with a very needlessly firm expression of countenance, and then started towards the door, saying to me as he set off, ‘This way, you lubber.’ I followed after him with much the same feelings which I had had before when I followed the man with the red face, until we came down to where the ships were, and then we descended a sort of ladder, or stairs, at the foot of which I stumbled into a boat, and had like to have gone bodily into the water. At this, the people in the boat set up a great laugh at my clumsiness,—just as if I had ever been in a boat before, and could help being clumsy. To make the matter worse, I sat down in the wrong place, where one of the men was to pull an oar; and when, after being told to ‘get out of that,’ with no end of hard names, I asked what bench I should sit on, they all laughed louder than before, which still further overwhelmed me with confusion. I did not then know that what I called a ‘bench,’ they called a ‘thwart,’ or more commonly ‘thawt.’

“At length, after much abuse and more laughter, I managed to get into the forward part of the boat, which was called, as I found out, ‘the bows,’ where there was barely room to coil myself up, and, the boat being soon pushed off from the wharf, the oars were put out, and then I heard an order to ‘give way,’ and then the oars splashed in the water, and I felt the boat moving; and now, as I realized that I was in truth leaving my home and native land, perhaps to see them no more forever, my heart sank heavy in my breast.

“It was as much as I could do to keep the tears from pouring out of my eyes, as we glided on over the harbor. Indeed, my eyes were so bedimmed that I scarcely saw anything at all until we came around under the stern of a ship, when I heard the men ordered to ‘lay in their oars.’ Then one of them caught hold of the end of a rope, which was thrown from the ship; and, the boat being made fast, we all scrambled up the ship’s side; and then I was hustled along to a hole in the forward part of the deck, (having what looked like a box turned upside down over it,) through which, now utterly bewildered, I descended, by means of a ladder, to a dark, damp, mouldy place, which was filled with the foul smells of tar and bilge-water, and thick with tobacco-smoke. This, they told me, was the ‘fo’castle,’ where lived the ‘crew,’ of which, I became now painfully conscious, I was one. If there had been the slightest chance, I should have run away; but running away from a ship is a very different thing from running away from a farm.

“If I had wished myself back on the farm before, how much more did I wish it now! But too late, too late, for we were all ordered up out of the forecastle even before I had tasted a mouthful of food. In truth, however, it is very likely that I was too sick with the foul odors, tobacco-smoke, and heart-burnings to have eaten anything, even had it been set before me.

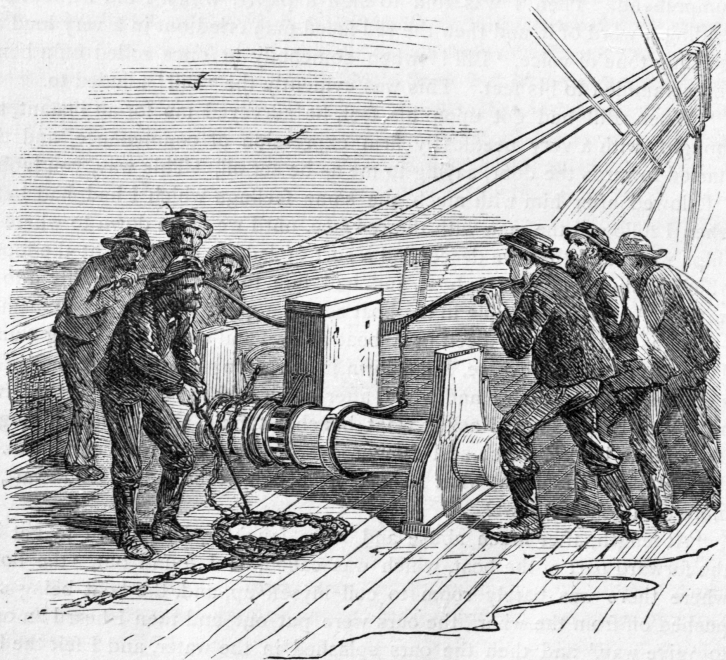

“Upon reaching the deck, I was immediately ordered to lay hold of a wooden shaft, about eight feet long, which ran through the end of an iron lever; and being joined by some more of the crew, we pushed down and lifted up this lever, just like firemen working an old fashioned fire-engine. Opposite to us was another party pushing down when we were lifting up, and lifting up when we were pushing down. I soon found out that by this operation we were turning over and over what seemed to be a great log of wood, with iron bands at the end of it, and having a great chain winding up around it. The chain came in through a round hole in the ship’s side, with a loud ‘click, click,’ and I learned that they called it a ‘cable,’ while the machine we were working was called a windlass. The cable was of course fast to the anchor, and it was very evident to me that we were going to put to sea immediately. The idea of it was now as dreadful to me as it had before been agreeable, when I had contemplated it from the stand-point of a quiet farm, a good many miles away from the sea. But I could not help myself: no matter what might happen, my fate was sealed, so far as concerned this ship.

“We had not been long engaged at this work of turning the windlass, before my companions set up a song, keeping time with the lever which we were pushing up and down, one of them leading off by reciting a single line, in which something was said about ‘Sallie coming,’ or ‘having come,’ or going to come to ‘New York town’; after which they all united in a dismal chorus, that had not a particle of sense in it, so far as I could see, from beginning to end. When they had finished off with the chorus, the leader set to screaming again about ‘Sallie’ and ‘New York town,’ and then as before came the chorus. Having completely exhausted himself on the subject of ‘Sallie,’ he began to invent, and his inventive genius was rewarded with a laugh which interfered with the chorus through two turns of the windlass. What he invented was this:—

‘We’ve picked up a lubber in New Bedford town.’

And now they drawled out the chorus as before, which I will recite that you may see how senseless it was. Here it is, following, as you will understand, directly after ‘New Bedford town’:—

‘Come away, away, sto-r-m along John,

Get a-long, storm a-long, stor-m’s g-one along.’

You see I drawl it out very slow to imitate them. As soon as they were through with this chorus, the leader put in his tongue again, inventing a sentiment to rhyme with the first, howling it out as if he would split his throat in the endeavor. This is what it was:—

‘Our lubber’s lugger-rigged, and we’ll do him brown,’—

which made them all laugh even more than the other sentiment, and caused an interruption of the chorus to the extent of four revolutions of the windlass; but when the laugh was over, they went at the dismal chorus again with double the energy they had previously shown, repeating all they had said before about ‘John’s getting along,’ and ‘storming along,’ after the same manner as before. And thus they went on without much variety, until I was sick and tired enough of it. The ‘lubber’ part of it was too clearly aimed at me to be mistaken; but I could not discover in it anything but nonsense all the way through to the end.

“After a while I heard some one cry out, ‘The anchor’s away,’ which, as I afterwards learned, meant the anchor had been lifted from the bottom; and then the sailors all scattered to obey an order to do something, which I had not the least idea of, with a sail, and with some ropes which appeared to me to be so mixed up that nobody could tell one from the other, nor make head nor tail of them. In the twinkling of an eye, however, in spite of the mixed-up ropes, there was a great flapping of white canvas, and a creaking and rattling of pulleys. Then the huge white sail was fully spread, the wind was bulging it out in the middle like a balloon, the ship’s head was turned away from the town, and we were moving off. Next came an order to ‘lay aloft and shake out the topsail’; but happily in this order I was not included, but was, instead, directed to ‘lend a hand to get the anchor aboard,’ which operation was quickly accomplished, and the heavy mass of crooked iron which had held the ship firmly in the harbor was soon fastened in its proper place on the bow, to what is called the ‘cat-head.’ By the time this was done, every sail was set, and we were flying before the wind out into the great ocean.

“And now you see my wish was gratified. I was in a ship and off on the ‘world of waters,’ with the career of a sailor before me,—a career to my imagination when on the farm full of romance, and presenting everything that was desirable in life. But was it so in reality, when I was brought face to face with it,—when I had exchanged the farm for the forecastle? By no means. Indeed, I was filled with nothing but disgust first, and terror afterwards. The first sight which I had of the ocean was much less impressive to me than would have been my father’s duck-pond. I soon got miserably sick; night came on, dark and fearful; the winds rose; the waves dashed with great force against the ship’s sides, often breaking over the deck, and wetting me to the skin. I was shivering with cold; I was afraid that I should be washed overboard; I was afraid that I should be killed by something tumbling on me from aloft, for there was such a great rattling up there in the darkness that I thought everything was broken loose. I could not stand on the deck without support, and was knocked about when I attempted to move; every time the ship went down into the trough of a sea I thought all my insides were coming up. So, altogether, you see I was in a very bad way. How, indeed, should it be otherwise? for can you imagine any ills so great as these?—1st, To have all your clothes wet; 2d, To have a sick stomach; and, 3d, To be in a dreadful fright. Now that was precisely my condition; and I was already reaping the fruits of my folly in running away from home and exchanging a farm for a forecastle.”

The Captain here paused and laughed heartily at the picture he had drawn of himself in his ridiculous rôle of “the young sailor-boy,” and, after clearing his throat, was about to proceed with the story, when he perceived that the shades of evening had already begun to fall upon the arbor. Looking out among the trees, he saw the leaves and branches standing sharply out against the golden sky, which showed him that the day was ended and the sun was set. So he told his little friends to hasten home before the dews began to fall upon the grass, and come again next day. This they promised thankfully, and told the Captain that they “never, never, never would forget it.”

But the head of William was filled with a bright idea, and he was bound to discharge it before he left the place. “O Captain Hardy,” cried the little fellow, “do you know what I was thinking of?”

“How should I, before you tell me?” was the Captain’s very natural answer.

“Why, I was thinking how nice it would be to write all this down on paper. It would read just like a printed book.”

The Captain said he “liked the idea,” but he doubted if William could remember it. But William thought he could remember every word of it, and declared that it was splendid; and Fred and Alice, following after, said that it was splendid too. But whether the story that the Captain told was splendid, or the idea of writing it down was splendid, or exactly what was splendid, was not then and there settled; yet it was fully settled that William was to write the story down the best he could, and ask his father to correct the worst mistakes. And now, when this was done, the happy children said “Good evening” to the Captain, and set out merrily for home, little Alice holding to her brother’s hand, as she tripped lightly over the green field, turning every dozen steps to throw back through the tender evening air, from her dainty little finger-tips, a laughing kiss to the ancient mariner, whose face beamed kindly on her from the arbor door.

I. I. H.

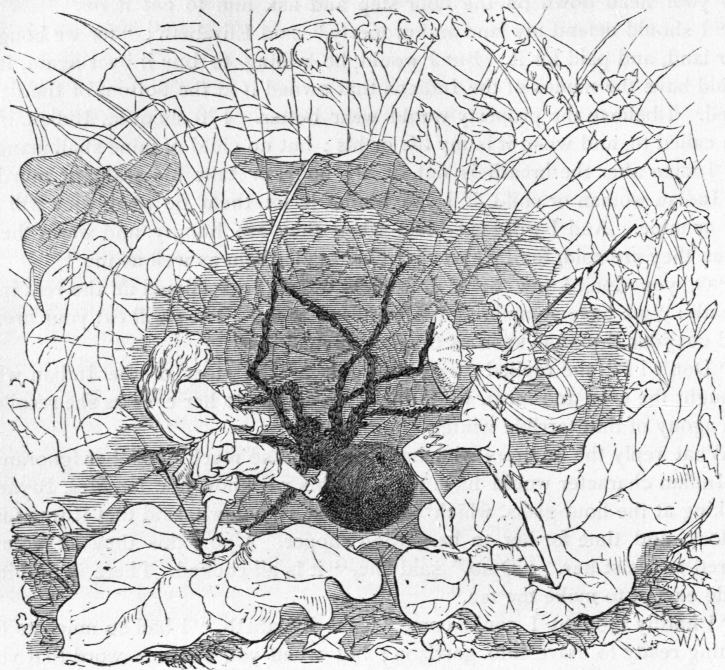

Down behind the grain together,

In the sunny summer weather,

It is pleasant, on my word,

Even if we lose the bird.

Shall we catch him? None can tell us,

They are such suspicious fellows,—

Birds of every note and feather,

In the golden summer weather.

There,—you stirred, and scared him.—Who?

It was but the wind that blew,

Trampling through the rustling grain:

See! he lifts his head again.

Whether he will go or stay,

Neither he nor we can say,—

Of the same uncertain feather,

Creatures of the summer weather.

R. H. Stoddard.

I am Jack,—Jimmy-Jack,—My-Jimmy-Jack. Perhaps I shall never find a better time to tell my own story. I am beginning to be left a good deal by myself, so I can think it all over at my leisure. The only trouble is, that I am as likely to be left standing on my head in the waste-basket, or tied round the door-knob, or lying face downward in the bath-tub, as in any easier position, and this, of course, has a tendency to mix my wits sadly, and may make my story somewhat mixed; but I have a story of my own, and it is just as good to me as anybody’s story.

I was made something as Haydie Woodward said he was. How was that? Why, when he was about three years old, there came a visitor to the house who was very fond of him. She was sitting at the window with him one evening, when the great moon came creeping up over the mountains, with her wise old face turned full upon us to see if things were going any better than they were the last time she came round; and as the little boy turned as round and bright and almost as wise a face upward, the lady said, “It’s grand, isn’t it, Haydie? Do you know who made the moon?”

“No,” Haydie said, he was quite sure he didn’t know anything about it, and listened to the lady’s explanations as if he had never been told before.

When his mamma was putting him in bed that night, she said, “O Haydie! How could you tell the lady you didn’t know who made the moon? You mortified me; you knew that as well as you know who made you. Who did make you, Haydie?”

“Why, mamma! It was Dod—on the sewin’-machine!”

Now I was made by Miss Alice, on knitting-needles. Whether she began at the bottom of the blue tassel of my cap, or at the tip of one of my black stockings, I can’t say: there are several stitches dropped in my bump of memory. But one thing I do know: when I was once made, I was done, and didn’t have to be knit out longer in the legs and arms, every little while, as seems to be the uncomfortable way with boys and girls in general.

To be sure, a few stitches more would have made my left leg as long as my right, which it isn’t; and my right eyebrow as high as my left, which it also isn’t; and my two thumbs of the same size, which they are not by a good deal. But that is neither here nor there, when you think how nice it was to be born (as I was) as much of a man as I could ever be by living a hundred years, with a splendid (blue) black beard all ready grown and curled, and with all my clothes for a lifetime on my back. No sooner was I born and admired, than I was named Jack, and sent off, by rail, to my present home.

I may as well tell you first as last, that I was not “born free and equal,” (I don’t now refer to my legs, thumbs, and eyebrows,) like you “Young Folks,” but a slave! All my journey, I hardly drew a breath, I was so anxious about the hands I was to fall into at its end. When at last I arrived, and was unwrapped, (it was on Christmas day,) I nearly burst out laughing in spite of my good manners (Miss Alice took care to put that in, whatever other stitches she skipped), and my solemn old face (“old,” I say, for I looked fifty at least the day I was born), when I saw who the master I had been so dreading really was; for whom should it be but Queenie!

Don’t you know Queenie? Dear me! That’s a pity. I don’t know how I ever can describe her. She was a ten-months-old baby, as white, as pink, as sweet as any Mayflower, but given to much buzzing, like a honey-bee, and with very loose ideas as to the uses of things.

Accordingly, when I was presented to her, she buzzed and babbled and danced in her nurse’s arms, and finally pounced upon me as if she had been a humming-bird, and I so much trumpet-honeysuckle; and, first I knew, my red, white, blue, spick-span new cap (with my head inside it!) was in a fair way to be made into honey, on the inner side of her pretty little bill! Thanks to somebody, I was pulled out then; but many a time since I have been there,—some part of my body, I mean,—and the wonder is that I am alive to tell the tale.

Queenie was now staying at her grandpapa’s, because her own papa and mamma had been forced to leave her behind while they went over the seas in search of a blessing which they were not to find. The baby was too young to miss them, and indeed she was surrounded with such an atmosphere of love that I think she could hardly have wished for more had she been older. But how they missed her!

That very Christmas morning when I came to their darling, they were sitting on the great steps of St. Peter’s, in Rome, singing lullabies for her softly together, as they did every single day of their absence.

“Sleep, baby, sleep!

Thy father keeps the sheep;

Thy mother shakes the dream-land tree;

A little dream falls down for thee.

Sleep, baby, sleep!”

Since I began to write, I have happened to find two letters which were written to Queenie’s papa and mamma in honor of my arrival, which I think you ought to see. Here is

Grandpapa’s Letter.

“I think you would have been pleased to see the darling’s reception of a worked-up little Zouave”—(that’s just like a man!—no appreciation of the grand and beautiful!—“a worked-up little Zouave,” indeed! and I am one foot two, if I’m an inch)—“which the express brought from Aunt Alice for a Christmas present. I have never seen her act so. I laughed and I cried till the fountains were nearly dry, and so did mother. I can’t describe it.

“She scanned it at first at a distance, with her head on one side, rather soberly, but with now and then a smile, followed by a sort of whir. At length she flourished her feet imperatively, and stretched out her arms for it. Then followed the fun. She noticed each of the various colors, which seemed to please her greatly. She noticed every feature,—and Jack has a great many!—put her fingers into every fold, into his eyes and ears, pulled his whiskers, and was all the time crying, ‘Pitty! pitty! What’s dat? Who isht?’ interspersed with numerous whirs and spoutings and boisterous laughs, shaking Jack with one hand, and flirting the other crazily, with her legs flying like drumsticks.”

Next comes Nurse Susan’s letter,—“Hoosie,” as Queenie called her. She was a bright English girl, who had taken care of the little one ever since she was three weeks old. The moment she came into the nursery, Queenie had liked her. She took the wee baby right into her arms, and, seating herself in a chair without rockers, jounced backward and forward, singing at the top of her voice,—

“One, two, three, four, five;

Onct I caught a fish alive

Down by the river-side;

Back again at supper-time.

Why did ye let him go?

Cozz he bit my finger so!”—

till everybody in the house was distracted but the wee baby, who thought it was splendid, and to this day thinks the same!

Hoosie had been two years in this country, and had smoothed off her old English a good deal; still, if she were very much excited, she was apt to fall back on Staffordshire. “O, isn’t hurr too cunning!” she would say, when her little charge developed some new accomplishment.

The handwriting of this letter is so particularly nice that I wish I could show it to you, and all the more because the spelling isn’t quite what we are used to in New England. Still it may be all right in Staffordshire; and here is the letter precisely as she wrote it.

Nurse Hoosie’s Letter.

“i write to you hoping to find you quite well at this time and i wish you a happy new year and i hope you are beter and i hope you have got to your journey end now i must tell you a boute your little daughter for she is so cunning i wish you could see hear to night i lade hear on the bed and she lay on the bed and hid hear face on the bed i said whear is hear and then she would look up at me and laf and then would put it down again i wish you could see us in a morning in the bed whe have sum fun with Jack for that is the name of him it is the doll that miss alice sent it for hear christmas present granmother bout hear a doll so that she has got too and whe cal it name topsey for it is a darkey and last friday g mother went oute and when she came home she had got a picture for hear of three white kitties for hear and she will tell us whear they are and mris R Ball sent hear of a wisel for a christmas present i shall be veary glad when you come home a gain.”

Now if you think there was ever a letter written which gave much more pleasure to those who received it than this, I have the very best authority for telling you that you are mistaken.

From that Christmas day till now, I believe Queenie and I have never spent a day apart from each other.

Even when I first knew her she was a great talker; that is to say, she repeated the two or three words she knew over and over again a great many times, which makes the liveliest conversation in the world! When she was only five months old, she had said “Papa” and “Mamma,” and when her other grandpapa (for this little girl was so rich as to have two grandpapas, and really “grand” they were), who then lived with her, asked her, in his deep bass voice, to say “Grandpa,” what should the little mimic do, but drop her voice away down into the bottom of her throat and growl out “Papa,” as gruff as you please, which made everybody laugh; and so she did it over and over again, and thought, as sure as could be, that she was saying “Grandpa!” After that, she never failed to growl for “Grandpa,” while for “Papa” she used her natural tone: at least she did this until she learned to say “Gannapa,” two or three months later. But this happened before I knew her, as did her summer at the sea-shore at the same age, when she was the belle of the season, and promenaded the veranda on everybody’s arm; and every morning “received” a select company, who saw her come out of her bath, and take her “constitutional,” pacing up and down Nurse Susan from head to foot with as regular steps as if she had known how to walk; and where one day in the bowling-alley a gentleman kissed her, and said he should want to do it again sixteen years from that time, at which she buzzed and whirred very disdainfully, as she ought!

But to return to the things which I saw and part of which I was. Every day when the sun was bright, Queenie and Susan and I would go out on the green, where the gray squirrels keep house in grand style in the old elms, but come down very graciously (when they are hungry) to receive offerings of nuts, &c. from their admirers, little and big, or else we walked through the city streets, staring at all the pretty things in the shop windows, with nobody to say “Don’t!” to us.

But if I tell you all that was done and said, nobody would put me into print, which would be too dreadful for the world and me.

There came a sweet morning in May, when Queenie once more saw her papa and mamma. She was very shy at first. There she sat on Hoosie’s arm, holding me very tight, looking very stately in her short white frock and blue ribbons,—(“Deary me! what has become of our precious long baby whom we left behind us? Does this dainty little maiden really belong to us?”—this was one of the things they thought as they saw her,)—and looking at them solemnly from under her long lashes. But it wasn’t long before her papa had her seated on a big newspaper, spread upon the carpet, and was drawing her all about the parlors, bowing down his dear head, which was usually so high above us all, and almost breaking his back, for the sake of giving his baby one of his famous boat-rides, as he used to do before he went away. But although she sat up as straight as she did long before, when papa first invented the pretty paper boat, and wasn’t at all sea-sick, and was very much at home (she had me in her arms, you may be sure!) and delighted, yet we came to grief, for we “sat and sat and sat till we sat the bottom out” of our newspaper, and it was concluded that Queenie had grown quite too substantial for such a fairy craft.

But this return home brought me my first trial. We went back at once to Queenie’s birthplace to live again, and there, sitting in the biggest chair in the study, was a magnificent poupée as she called herself, nearly as tall as our Queenie! Her hair was crépé in the height of the fashion, and was also of the most modish shade,—a cream-white. Between you and me, it was nothing in the world but lamb’s wool! I think I ought to know, for I’ve worn that same wig (much against my will) a great many times since. But nobody would have imagined, when Mademoiselle Eugénie first arrived in this country, that graceful head to have been nothing but sheep-skin and Spalding’s glue! Her color was beautiful, and I think it must have been her own, for it was as bright as ever the last time I saw her, when she had been through everything and been scrubbed with everything imaginable.

When we first saw her—Queenie and I—she wasn’t in what we should call full dress. Queenie’s papa had done the best he could for her, for, as she had no clothes to speak of when she arrived, he had ransacked the house while mamma was gone, and found a baby nightgown, which fitted the pretty creature very nicely.

She was a beauty, I must confess, although later in our lives she cost me many a heart-burn. Her eyes were deep, and bright, and blue like Queenie’s, and her round limbs tapered into the plumpest little hands and feet, with real fingers and toes, as full of dimples as Queenie’s own.

Eugénie she was to have been named, because she was born under the very shadow of the Tuileries; but Queenie cried out “Minnie” when she first clasped the new playmate in her arms, and so “Minnie” she had to be forever, of course.

Minnie could sit down, and kneel down, and stand up, like any other lady, and she always gave you the impression that, if she didn’t walk, it was only because she didn’t think it worth her while. Her coquettish head could turn from side to side in the most fascinating manner, and indeed she tried this graceful art so often that the terrible consequence was that by and by she twisted it around so that the back was where her face should have been,—so look out, little folks, and not turn and twist too much!

But I am anticipating my story by a good many months.

At first, Minnie’s head was all right; but, alas for poor me! I was all wrong. At least, Queenie no sooner saw the new pet than she threw me behind the big Japan books on a lower shelf in the library, and there I lay for several hours, till little black Willy drew me out by one leg, and made much ado over me, comforting me.

Poor little soul! He knew how to sympathize with the neglected and lonely. He was the only child of black Nancy, who had been cook years and years ago at Queenie’s mamma’s mamma’s. She had heard great stories of what was to be seen in far countries from the sailor-boy of the family, and was wild to see for herself. So one day (when she was quite an old woman, as the young people thought) she set sail for the East Indies, where she saw many things which are not set down in the books. “I saw the Cave of the Elephants,” said she, in my hearing once. “White folks said it growed so, but I knowed, as quick as I see it, it was huged out of a rock.”

But after a time back she came from her wanderings, bringing with her a little black dot which she called a baby. By and by it grew till other people could see that it really was a baby, and after Queenie’s mamma had a house of her own in a strange city, who should come into its kitchen one day but black Nancy, looking no older than ever, (for she was like me in always being, and never growing, old,) and with her the black dot grown into a four-years-old morsel of a boy named Willy.

He was just as black as black could be; at least you thought so, until he snapped his eyes at you, which were so much blacker than his skin, that that began to seem “yaller” as Nancy called it, and which she thought was almost worse than being wicked; so it couldn’t have really been “yaller,” only a different shade of black. And as for his hair, that curled tighter to his head than French Minnie’s, although Nancy was so opposed to crooked hair that she once had her own head shaved as smooth as your hand, and Queenie’s mamma and uncle remember rushing out into the kitchen to see the operation, and how very queer her old pate looked when the barber had piled up the pure white “lather” all over it, and how brown and shiny it looked when the razor had done its work, and how odd she looked in a wig of straight brown hair, and how very cross she was when the new crop began to sprout, and was woollier and crookeder than ever, and how spitefully she would twitch it and say, “The black scorpion!”

But perhaps the new fashion had reconciled Nancy to frizzed hair; at any rate, Willy’s frizzed with a will; but his eyes shone with real fire, and he was as bright as if he had been snow-white and violet-eyed like our Queenie. But how he admired Queenie! He would sit on the floor at her feet, and show all his shining teeth as he laughed up at her, and once in a great while touch her little white hand with the tip of his black finger, or even his red lips.

As for Queenie, she just thought he was the funniest joke! She laughed as soon as she looked toward him; but when he ducked his queer little fleecy head at her, and said, “Moder’s little lamb! moder’s little lamb!” she laughed all over, and it seemed as if she could never stop.

But, as I said, Willy dragged me out from my Japan dungeon, and as soon as Queenie saw me again,—the darling!—she dropped Minnie, with all her roses, and dimples, and curls, and hugged me as if I had been gone a year. Then her papa picked her up with me in her arms, and gave Willy a whistle and a big bell, and marched all over the house, singing,

“Rub a dub dub,

Three men in a tub,

And how do you think they got there?”

while Willy squeaked the whistle and rang the bell before us, as solemnly as if he had been a Fourth-of-July celebration. And as for Minnie, she stayed in the drawer a good deal of the time after that, until Queenie grew bigger; for Mamma said Old Jack was best after all, for it made no difference whether he was wet or dry, or which side up or out he was, or how many ways he was doubled up.

Willy told Queenie and me a great many big stories. One of these was about a great gold woman who stood up night and day on the top of the court-house opposite us, holding a sword in one hand and a pair of scales in the other. Willy said his mother told him that this was the first woman who ever killed her husband in Massachusetts. But why she should be changed into pure gold for that reason, and set up on high, he didn’t tell us. Willy also tried to teach us to say, “Wiggle, waggle, little star,” (which Nancy used to repeat to Queenie’s mamma, instead of “Twinkle, twinkle,”) but we were dull learners and only laughed. Nancy had had a great deal of pains taken with her to teach her to read, but could never learn; and, indeed, said, “Colored folks haven’t any souls, and course dey can’t learn,”—because you must know she had been a slave once, and very badly treated, so that she had lost hope, and was sometimes very sour. But when she came to have a child of her own, though he was very “colored,” she was quite sure he had a soul, and wanted him to learn how to read and do everything like “white folks.”

So Queenie’s mamma, who had tried when a little girl to educate black Nancy, must needs try her hand now on Willy. But Willy liked to teach better than to learn. He never got beyond “round O,” which was where he began. But one day, when he was set to look for round O’s, he fixed upon a big C, and said “Dere’s a broken O”; which wasn’t so bad a mistake as might have been made.

But I must tell you something which happened one night after Queenie was fast asleep. Our cook had been sent away, and black Nancy came to fill her place for the time, and of course little Willy had to come with her. When bedtime came, Nancy found she had left his clothes in the little room, at the other side of the city, which these poor strays called home. So an old nightgown which had once belonged to a gentleman six feet high was brought out for her, as the best substitute that could be easily found, and Willy was tucked into it bodily, and put in bed in the fourth story, and left to his fate.

But when Nancy had been down in the kitchen some time, Willy waked up to the idea that he was in a strange place, and that a familiar face would be a pleasant sight. So, after shouting “Moder!” and “Nancy!” (he called his mother either name, as it happened) till he was tired, he decided to make a raid on the lower regions.

The young minister was sitting in his study on the second floor, writing away at his sermon, when he saw, through the open door, the oddest of ghosts sliding down the attic stairs. There was a little black knob on top, from which descended a dozen yards (more or less) of white drapery, which dragged and whisked and flopped from stair to stair as the little black knob came nearer. The sermon might have had some queer quavers in it by good rights, for it was a very funny sight. I was lying on the study-table under the concordance, and it almost killed me,—the ghost, and not the concordance.

It didn’t take the minister long to guess what was inside the bale of cotton, and he pitied the forlorn little fellow so much that, as soon as he could stop laughing, he told Willy he might come in and sit on the floor by him, and even gave him the chessmen to play with, which was a very rare treat to Queenie herself. And the little spectre never knew how it made the kind gentleman ache to keep the laugh in, as he talked so pleasantly with him.

One question Queenie’s papa asked Willy was, if Nancy had told him anything about Jesus Christ. “Yes sirr,” said Willy, sturdily. “What did she say about him?” “O, she said he was such a pooty man!” Now this made the minister feel as much like crying as he had felt before like laughing, for it touched him tenderly to see how the poor, ignorant woman had tried to teach her child, and had given to the Saviour of men the very choicest epithet she knew, “Pretty.”

But by and by Willy began to ask for “Moder” again, and the minister’s laugh came back as the little black knob with its trailing folds and floating streamers began to move off toward the door. So he bade Willy go down the staircase and knock at the door of the parlor below, and ask there for his “moder”! And so he did, and Queenie’s mamma (who, as the minister knew, was entertaining visitors there) opened the door, and there in the bright gas-light stood the long ghost with the little black knob to it! Then there was such a shout from the ladies and gentlemen below, echoed by the minister, leaning over the banisters above, that the little black knob spread all its wings—mighty pens and downy pin-feathers—and fluttered toward the basement, the most astonishing comet that ever appeared on anybody’s horizon. Another time, perhaps, I may tell you how I came to be surnamed “Jimmy”; and something of my thousands of miles of travel, and more about French Minnie.

Mrs. Edward A. Walker.

When I was a little maid,

I waited on myself;

I washed my mother’s teacups,

And set them on the shelf.

I had a little garden

Most beautiful to see;

I wished that I had somebody

To play in it with me.

Nurse was in mamma’s room;

I knew her by the cap;

She held a lovely baby boy

Asleep upon her lap.

As soon as he could learn to walk,

I led him by my side,—

My brother and my playfellow,—

Until the day he died!

Now I am an old maid,

I wait upon myself;

I only wipe one teacup,

And set it on the shelf.

Mrs. Anna M. Wells.

Little Pussy had now grown up to be quite a young woman. She was sixteen years old, tall of her age, and everybody said that, though she wasn’t handsome, she was a pretty girl. She looked so open-hearted and kind and obliging,—she was always so gay and chatty and full of good spirits,—so bright and active and busy,—that she was the very life and soul of all that was going on for miles around.

Little Emily Proudie was also sixteen, and everybody said she was one of the most perfectly elegant-looking girls that walked the streets of New York. Everybody spoke of the fine style of her dress; and all that she wore, and all she said and did, were considered to be the height of fashion and elegance. Nevertheless, this poor Emily was wretchedly unhappy,—was getting every day pale and thin, and her heart beat so fast every time she went up stairs that all the household were frightened about her, and she was frightened herself. She spent hours in crying, she suffered from a depression of spirits that no money could buy any relief from, and her mother and aunts and grandmothers were all alarmed, and called in the doctors far and near, and had solemn consultations, and in fact, according to the family view, the whole course of society seemed to turn on Emily’s health. They were willing to found a water-cure,—to hire a doctor on purpose,—to try homœopathy, or hydropathy, or allopathy, or any other pathy that ever was heard of,—if their dear, elegant Emily could only be restored.

“It is her sensitive nature that wears upon her,” said her mamma. “She was never made for this world; she has an exquisiteness of perception which makes her feel even the creases in a rose-leaf.”

“Stuff and folderol, my dear madam,” said old Doctor Hardhack, when the mamma had told him this with tears in her eyes.

Now Doctor Hardhack was the nineteenth physician that had been called in to dear Emily,—and just about this time it was quite the rage in the fashionable world to run after Doctor Hardhack,—principally because he was a plain, hard-spoken old man, with manners so very different from the smooth politeness of ordinary doctors that people thought he must have an uncommon deal of power about him to dare to be so very free and easy in his language to grand people.

So this Doctor Hardhack surveyed the elegant Emily through his large glasses, and said, “Hum!—a fashionable potato-sprout!—grown in a cellar!—not a drop of red blood in her veins!”

“What odd ways he has, to be sure!” said the grandmamma to the mamma; “but then it’s the way he talks to everybody.”

“My dear madam,” said the Doctor to her mother, “you have tried to make a girl out of loaf-sugar and almond paste, and now you are distressed that she has not red blood in her veins, that her lungs gasp and flutter when she goes up stairs. Turn her out to grass, my dear madam; send her to old Mother Nature to nurse; stop her parties and her dancing and her music, and take off the corsets and strings round her lungs, and send her somewhere to a good honest farm-house in the hills, and let her run barefoot in the morning dew, drink new milk from the cow, romp in a good wide barn, learn to hunt hens’ eggs,—I’ll warrant me you’ll see another pair of cheeks in a year. Medicine won’t do her any good; you may make an apothecary’s shop of her stomach, and matters will be only the worse. Why, there isn’t iron enough in her blood to make a cambric needle!”

“Iron in her blood!” said mamma; “I never heard the like.”

“Yes, iron,—red particles, globules, or whatever you please to call them. Her blood is all water and lymph, and that is why her cheeks and lips look so like a cambric handkerchief,—why she pants and puffs if she goes up stairs. Her heart is well enough, if there were only blood to work in it; but it sucks and wheezes like a dry pump for want of vital fluid. She must have more blood, madam, and nature must make it for her.”

“We were thinking of going to Newport, Doctor.”

“Yes, to Newport, to a ball every night, and a flurry of dressing and flirtation every morning. No such thing! Send her to a lonesome, unfashionable old farm-house, where there was never a more exciting party than a quilting-frolic heard of. Let her learn the difference between huckleberries and blackberries,—learn where checkerberries grow thickest, and dig up sweet-flag-root with her own hands, as country children do. It would do her good to plant a few hills of potatoes, and hoe them herself, as I once heard of a royal princess doing, because queens can afford to be sensible in bringing up their daughters.”

Now Emily’s mamma and grandmamma and aunts, and all the rest of them, concluded that Doctor Hardhack was a very funny, odd old fellow, and, as he was very despotic and arbitrary, they set about immediately inquiring for a nice, neat farm-house where the Doctor’s orders could be obeyed; and, curiously enough, they fixed on the very place where our Pussy lived; and so the two girls came together, and were introduced to each other, after having lived each sixteen years in this world of ours in such very different circumstances.

It was quite a circumstance, I assure you, at the simple little farm-house, when one day a handsome travelling-carriage drove up to the door, and a lady and gentleman alighted and inquired if they were willing to take summer boarders.

“Indeed,” said Pussy’s mother, “we have never done such a thing, or thought of it. I don’t know what to say till I ask my husband.”

“My daughter is a great invalid,” said the lady, “and the Doctor has recommended country air for her.”

“I’m afraid it would be too dull here to suit her,” said Pussy’s mother.

“That is the very thing the Doctor requires,” said Emily’s mother. “My daughter’s nerves are too excitable,—she requires perfect quiet and repose.”

“What is the matter with your daughter?” said Mary Primrose.

“Well, she is extremely delicate; she suffers from palpitations of the heart; she can’t go up stairs, even, or make the smallest exertion, without bringing on dreadful turns of fluttering and faintness.”

“I’m afraid,” said Mrs. Primrose, “we should not be able to wait on her as she would need. We keep no servants.”

“We would be willing to pay well for it,” said Emily’s mother. “Money is no object with us.”

“Mother, do let her come,” said Pussy, who had stolen in and stood at the back of her mother’s chair. “I want her to get well, and I’ll wait on her. I’m never tired, and could do twice as much as I do any day.”

“What a healthy-looking daughter you have!” said Emily’s mother, surveying her with a look of admiration.

“Well,” said Pussy’s mother, “if she thinks best, I think we will try to do it; for about everything on our place goes as she says, and she has the care of everything.”

And so it was arranged that the next week the new boarder was to come.

Harriet Beecher Stowe.

At the day of which we write, the intercourse between parents and children was much more formal than at present. The people were then living under a monarchy, and the spirit of the government was felt in the family. Deference to superiors in age or station was rigidly enacted. In many families children did not eat with their parents, but at a side-table in the same room. School-children were required to “make their manners” to their teachers, and to aged people or strangers whom they met in the road, going to or returning from school; the boys took off their hats and made a bow, the girls made a courtesy,—that is, they bent the knees, and depressed the body, very much as ladies do now when a person treads on their dress in the street. And this was a good custom: it taught children politeness, and made them easy in their manners, and so civility became habitual, because it had grown in them. They did not stand in the middle of the road, thumb in mouth, staring at a stranger, but made their manners and passed on.

Parents were not accustomed to take their children in their laps and kiss and caress them,—not after they were babes. I should have been frightened, if my father had kissed me when I was a child. But they loved just as well as parents love their children at this day, for all that, and were willing to endure the greatest hardships, death itself, in order that their children might have greater advantages than they themselves had enjoyed. Thus it was with Elizabeth and Hugh: they were not accustomed to caress their children, and their parental word or look was law, and neither to be questioned nor disobeyed. “Mother says so,” was reason enough.

His mother assisted William to put up the fence, after which they took their way in silence to the house. As they reached the door, Bose, having yarded the cows, was stealing around the corner of the pig-sty, and making for the woods. He could not get the Indian’s track out of his head, and, as William would not go with him, was determined to go “on his own hook.”

“Bose, you villain, you!” cried William, “come here, sir!” He had never spoken so to Bose before. The dog came slowly towards him, his ears drooping, his tail between his legs, his belly dragging on the ground, and with an astonished, supplicating look. William took him by the nape of the neck, and, dragging him into the house, tied him to the bedstead, exclaiming, “You shall stay there at any rate till the scent is washed out!”

He now shut the door, and fastened it to keep the other children out, and, sitting down before his mother, told her the whole story word by word. He told her what Beaver said, and how he answered him. “As long, mother, as he talked about his striking the war-post, and being a brave and killing folks, and swelled up so, and seemed so big, and to think he was so much better than I was, I didn’t care,—I should just as lief have fought with him as not. But you can’t tell how it made me feel when he came to talk so to me as he did at the last of it. I had half a mind to go off with him; but something held me back. I suspect it was because I thought how he looked when he said he liked to see blood run, and that he could drink it.”

“O William!” cried his mother, now thoroughly alarmed and distressed, “could you leave me and your father and your brothers and sisters and go to be an Indian and live with savages?” And, breaking through all the restraints and the customs of that day, she put her arms around his neck, and took his head upon her knees.

“No, mother,” he replied at length, “I could never leave you. But I did love Beaver so! You know I had nobody else to play with, as Uncle James’s boys have at Saco, and we agreed so well; and I’ve heard you yourself say, that, if he was an Indian, a better boy never stepped. When I saw how bad he felt, (though he kept it down,) and his voice sounded so, it did cut me deep. O mother, I don’t know what to do with myself!” Then the great boy, fairly getting into his mother’s lap, put his arms around her neck and sobbed like a little child.

It was the first sorrow and the first parting, and the “bitterness thereof drank up his spirit.” Elizabeth, who had endured so many bitter trials herself, was deeply touched; all the mother was aroused by the agony of her son. She pressed him to her bosom, ran her fingers through his hair, and kissed him as she had done when he was an infant. At length she persuaded him to lie down, and, sitting by him, soothed him till, worn out by his feelings, he was sleeping for sorrow.

The piety of Hugh and Elizabeth was not something put upon them, narrow and bounded by the Sabbath and the family altar, but the offspring of their affections. They prayed not only at stated times, but whenever they were moved to do so. They “walked with God,” and when they wished to say anything to Him, as to their father, they said it. If Hugh was building fence beside the woods on a pleasant spring morning, when the ground was steaming, and the fences smoking in the warm sun, the robins singing, and the wild geese honking overhead,—if the beauty of the scene, the promise of the year, or some blessing he had received, drew out his heart in gratitude to God,—the strong man who, if he feared God, feared nothing else, would drop his axe, and, retiring to the woods, pour out his soul in grateful prayer and praise.

Thus, when Elizabeth (after having spread the table for William when he should awake) sat down beside the bed, and thought over the circumstances he had related to her, considering the ripeness of judgment and sterling qualities both of mind and heart which he had manifested, and how fearlessly and nobly he had borne himself, she straightway knelt down and thanked her Maker for the boy, for his preservation from the bullet of the Indian, and that he had not been mastered by his feelings of attachment to his companion and his love for life in the woods, and gone off with the savage.

The history of those days proves abundantly that it is much easier to pass from civilized to savage life, than it is to emerge from the state of the savage to that of civilized man. And taking into consideration the boy’s attachment to his friend, and his passionate love for the free life of the woods, his mother had the best of reasons for anxiety. During that same year, a lad by the name of Samuel Allen was taken by the Indians at Deerfield. Though he had been with them but eighteen months, “yet, when his uncle went to redeem him, he refused to talk English, would not speak to his uncle, and pretended not to know him, and finally refused to go home, and had to be brought off by force. In his old age he always declared that the Indian’s life was the happiest.”

William, after an hour’s sleep, rose calm and refreshed. No slight cause could long disturb his well-balanced and healthy nature, and his emotions soon became subject again to his control. His mother placed food before him of which she knew he was fond, and, sitting down to the table with him, exerted herself to turn the conversation into a cheerful channel. While they were eating, Hugh came in and joined them at their meal.

When the children were put to bed, the three drew their stools around the fire, and entered into an anxious consultation in respect to their duty under the circumstances. It was probable that Beaver was only one of a body of savages on the war-path, who had committed the violence at Saco and Topsham and Purpooduck, and were watching for an opportunity to strike another blow. Ought they not instantly to give the alarm, in order that the settlers might be on their guard, and that they might, with the help of Bose, follow on the track of Beaver, and thus prevent the meditated blow, or capture him? Ought any feelings of good-will to him to influence them so far as to put in peril the lives of their neighbors? Perhaps before another morning they might hear the sound of the war-whoop.

It was their duty, perhaps, at that very moment, to alarm the nearest neighbors; under cover of night to get as silently as possible to the garrison, and fire the alarm gun, thus putting Mosier and the more distant inhabitants on their guard.

Thus reasoned Hugh and Elizabeth. On the other hand, William earnestly, though respectfully, opposed. He said that it was as clear as day to him that Beaver was neither a spy nor one of a party lying in ambush; for the Indians would never send so young a person on so dangerous and important an errand; that Beaver wouldn’t have dared to spare him if he had been a spy, when he could have taken his life without noise, because they would have asked him where he had been, and what he had done; and that Beaver had told him that his own people would never know where he had been.

“Why, father,” said William, “I had my back to him, putting up the fence; I turned round to look for a pole, and there he was, standing right behind me, and must have been standing there as much as fifteen minutes. He could have driven his tomahawk through my skull, or knocked me on the head with the breech of his gun, or shot me right through the back with an arrow, and I never should have known what hurt me. I believe that he came back on purpose to bid me good by, as he didn’t have time when they went away. I know Beaver wouldn’t lie,—he would think it mean for a warrior to lie,—and he said that was what he came for. I know that he had come a great way, and come fast too, for his moccasons and leggins were scratched and torn, he was spattered with clay, and the sweat had made the stripes of paint on his breast all mix together and run down on to his belt, and streak it all over, and he seemed beat out. There was but a little corn in his pouch; it wasn’t half full. He had a new French carbine, and his tomahawk and knife were new, and he had a breech-clout of broadcloth. I believe that they all went right from here to Canada to get their outfit, and that the rest of them are there to-night.”

Although Hugh was well aware that William’s judgment was far beyond his years, that a kind of instinct in respect to all matters of forest life, and a thorough knowledge of Indian habits, gave to his opinions a weight to which neither his age nor experience entitled them, yet he was astonished at the keen observation with which the lad had noted every part of the Indian’s equipment, and the maturity of mind evinced by the conclusions drawn from it.

“How mean it would be, mother, when he has just spared my life,” said William, in conclusion, “and we have agreed not to pick each other out, to go and set Bose and the Rangers on his trail! I’d rather be shot, any day.”

“Well, William,” replied his mother; “it is just as your father says. He knows what is best to be done.”