Produced by Al Haines

* A Distributed Proofreaders US Ebook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

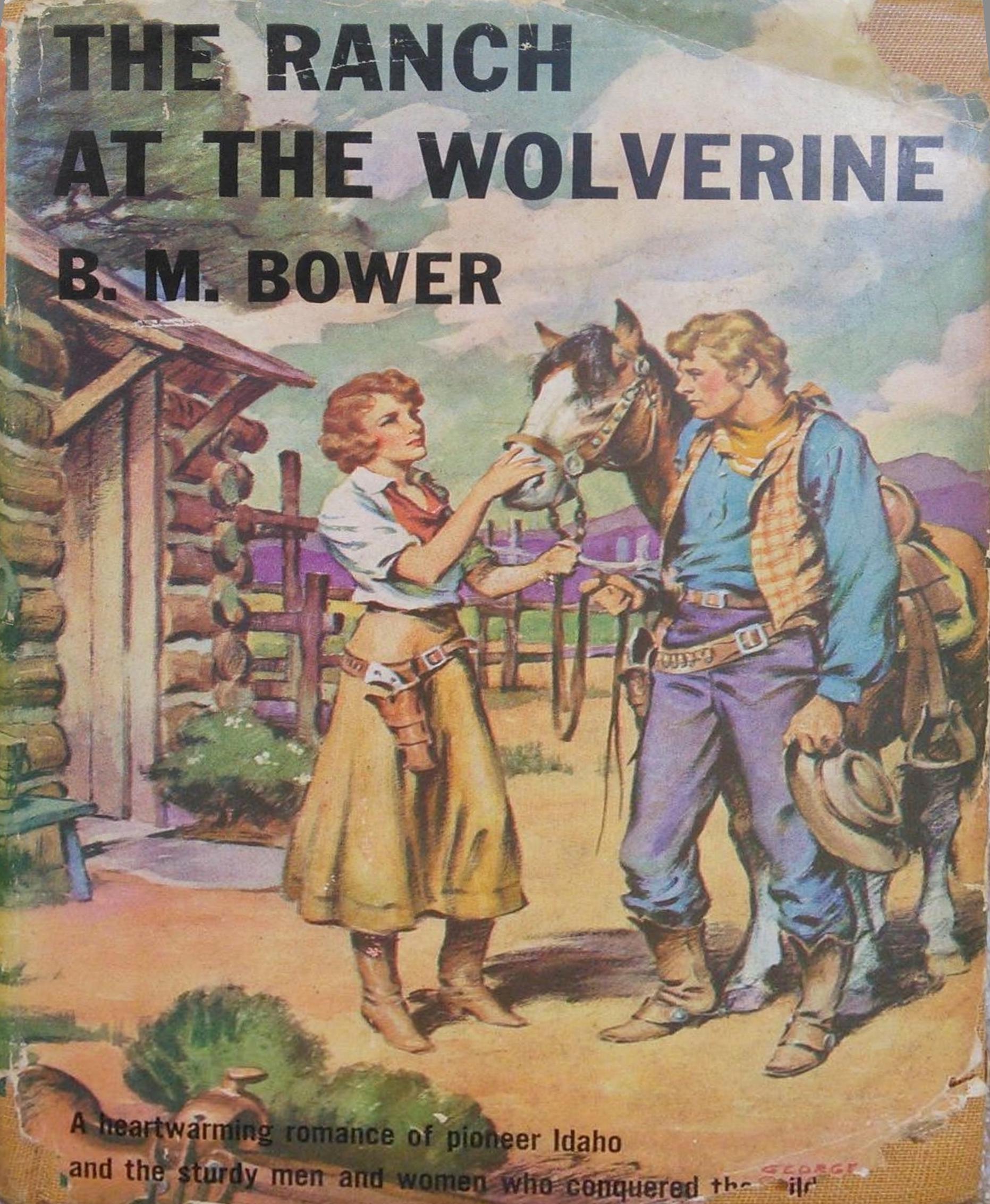

Title: The Ranch at the Wolverine

Author: Sinclair (Sinclair-Cowan), Bertha Muzzy

Date of first publication: 1914

Date first posted: March 19, 2009

Date last updated: July 31, 2018

Faded Page ebook#20180805

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | LET US START AT THE BEGINNING |

| II. | A STORM AND A STRANGER |

| III. | A BOOK, A BANNOCK, AND A BED |

| IV. | "OLD DAME FORTUNE'S USED ME FOR A FOOTBALL" |

| V. | MARTHY BURIES HER DEAD AND GREETS HER NEPHEW |

| VI. | A MATTER OF TWELVE MONTHS OR SO |

| VII. | WARD HUNTS WOLVES |

| VIII. | HELP FOR THE COW BUSINESS |

| IX. | WHEN EMOTIONS ARE BOTTLED |

| X. | THIS PAL BUSINESS |

| XI. | WAS IT THE DOG? |

| XII. | THE LITTLE DEVILS OF DOUBT |

| XIII. | THE CORRAL IN THE CANYON |

| XIV. | EACH IN HIS OWN TRAIL |

| XV. | "YOU WON'T GET ME AGAIN" |

| XVI. | "I'M GOING TO TAKE YOU OUT AND HANG YOU" |

| XVII. | "SO-LONG, BUCK!" |

| XVIII. | FORTUNE KICKS AGAIN |

| XIX. | THE BRAVE BUCKAROO |

| XX. | "WE BEEN SORRY FOR YOU" |

| XXI. | SEVEN LEAN KINE |

| XXII. | THE BILLY OF HER |

| XXIII. | BILLY LOUISE GETS A SURPRISE |

| XXIV. | THE HOOKIN'-COUGH MAN |

| XXV. | THE WOLF JOKE |

| XXVI. | "HM-MM!" |

| XXVII. | MARTHY |

| XXVIII. | ALL RIGHT AND COMFY |

Four trail-worn oxen, their necks bowed to the yoke of patient servitude, should really begin this story. But to follow the trail they made would take several chapters which you certainly would skip—unless you like to hear the tale of how the wilderness was tamed and can thrill at the stern history of those who did the taming while they fought to keep their stomachs fairly well filled with food and their hard-muscled bodies fit for the fray.

There was a woman, low-browed, uncombed, harsh of voice and speech and nature, who drove the four oxen forward over lava rock and rough prairie and the scanty sage. I might tell you a great deal about Marthy, who plodded stolidly across the desert and the low-lying hills along the Blackfoot; and of her weak-souled, shiftless husband whom she called Jase, when she did not call him worse.

They were the pioneers whose lurching wagon first forded the singing Wolverine stream just where it greens the tiny valley and then slips between huge lava-rock ledges to join the larger stream. Jase would have stopped there and called home the sheltered little green spot in the gray barrenness. But Marthy went on, up the farther hill and across the upland, another full day's journey with the sweating oxen.

They camped that night on another little, singing stream, in another little valley, which was not so level or so green or so wholly pleasing to the eye. And that night two of the oxen, impelled by a surer instinct than their human owners, strayed away down a narrow, winding gorge and so discovered the Cove and feasted upon its rich grasses. It was Marthy who went after them and who recognized the little, hidden Eden as the place of her dreams—supposing she ever had dreams. So Marthy and Jase and the four oxen took possession, and with much labor and many hard years for the woman, and with the same number of years and as little labor as he could manage on the man's part, they tamed the Cove and made it a beauty spot in that wild land. A beauty spot, though their lives held nothing but treadmill toil and harsh words and a mental horizon narrowed almost to the limits of the grim, gray, rock wall that surrounded them.

Another sturdy-souled couple came afterwards and saw the Wolverine and made for themselves a home upon its banks. And in the rough little log cabin was born the girl-child I want you to meet; a girl-child when she should have been a boy to meet her father's need and great desire; a girl-child whose very name was a compromise between the parents. For they called her Billy for sake of the boy her father wanted, and Louise for the girl her mother had longed for to lighten that terrible loneliness which the far frontier brings to the women who brave its stern emptiness.

Do you like children? In other words, are you human? Then I want you to meet Billy Louise when she was ten and had lived all her life among the rocks and the sage and the stunted cedars and huge, gray hills of Idaho. Meet her with her pink sunbonnet hanging down the back of her neck and her big eyes taking in the squalidness of Marthy's crude kitchen in the Cove, and her terrible directness of speech hitting squarely the things she saw that were different from her own immaculate home. Of course, if you don't care for children, you may skip a chapter and meet her later when she was eighteen—but I really wish you would consent to know her at ten.

"Mommie makes cookies with a raising in the middle. She gives me two sometimes when the Bill of me has been workin' like the deuce with dad; one for Billy and one for Louise. When I'm twelve, Mommie's goin' to let the Louise of me make cookies all myself and put a raising on top. I'll put two on top of one and bring it over for you, Marthy. And—" Billy Louise was terribly outspoken at times—"I'll put four raisings on another one for Jase, 'cause he don't have any nice times with you. Don't you ever make cookies with raisings on 'em, Marthy? I'm hungry as a coyote—and I ain't used to eating just bread and the kinda butter you have. Mom says you don't work it enough. She says you are too scared of water, and the buttermilk ain't all worked out, so that's why it tastes so funny. Does Jase like that kind of butter, Marthy?"

"If your mother had to do the outside work as well as the inside, mebbe she wouldn't work her butter so awful much, either. I dunno whether Jase likes it or not. He eats it," Marthy stated grimly.

Billy Louise sighed. "Well, of course he's awful lazy. Daddy says so. I guess I won't put but one raising on Jase's cookie when I'm twelve. Has Jase gone fishing again, Marthy?"

A gleam of satisfaction brightened Marthy's hard, blue eyes. "No, he ain't. He's in the root suller. You want some bread and some nice, new honey, Billy Louise? I jest took it outa the hive this morning. When you go home, I'll send some to your maw if you can carry it."

"Sure! I can carry anything that's good. If you put it on thick, so I can't taste the bread, I'll eat it. Say, you like me, don't you, Marthy?"

"Yes," said Marthy, turning her back on the slim, wide-eyed girl, "I like yuh, Billy Louise."

"You sound like you wish you didn't," Billy Louise remarked. Even at ten Billy Louise was keenly sensitive to tones and glances and that intangible thing we call atmosphere. "Are you sorry you like me?"

"No-o, I ain't sorry. A person's got to like something that's alive and human, or—" Marthy was clumsy with words, and she was always coming to the barrier between her powers of expression and the thoughts that were prisoned and dumb. "Here's your bread 'n' honey."

"What makes you sound that way, Marthy? You sound like you had tears inside, and they couldn't get out your eyes. Are you sad? Did you ever have a little girl, Marthy?"

"What makes you ask that?" Marthy sat heavily down upon a box beside the rough kitchen table and looked at Billy Louise queerly, as if she were half afraid of her.

"I dunno—but that's the way mommie sounds when she says something about angel-brother. Did you ever—"

"Billy Louise, I'm going to tell you this oncet, and then I don't want you to ast me any more questions, nor talk about it. You're the queerest young one I ever seen, but you don't hurt folks on purpose—I've learnt that much about yuh." Marthy half rose from the box, and with her dingy, patched apron shooed an investigative hen out of the doorway. She knew that Billy Louise was regarding her fixedly over the huge, uneven slice of bread and honey, and she felt vaguely that a child's grave, inquiring eyes may be the hardest of all eyes to meet.

"I never meant—"

"I know yuh never, Billy Louise. Now don't tell your maw this. Long ago—long before your maw ever found you, or your paw ever found your ranch on the Wolverine, I had a little girl, 'bout like you. She was a purty child—her hair was like silk, and her eyes was blue, and—we was Mormons, and we lived down clost to Salt Lake. And I seen so much misery amongst the women-folks—you can't understand that, but mebby you will when you grow up. Anyway, when little Minervy kep' growin' purtyer and sweeter, I couldn't stand it to think of her growin' up and bein' a Mormon's wife. I seen so many purty girls... So I made up my mind we'd move away off somewheres, where Minervy could grow up jest as sweet and purty as she was a mind to, and not have to suffer fer her sweetness and her purtyness. When you grow up, Billy Louise, you'll know what I mean. So me and Jase packed up—we kinda had to do it on the sly, on account uh the bishops—and we struck out with a four-ox team.

"We kep' a-goin' and kep' a-goin', fer I was scared to settle too clost. I seen how they keep spreadin' out all the time, and I wanted to git so fur away they wouldn't ketch up. And we got into bad country, where there wasn't no water skurcely. We swung too fur north, and got into the desert back there. And over next them three buttes little Minervy took sick. We tried to git outa the desert—we headed over this way. But before we got to Snake river she—died, and I had to leave 'er buried back there. We come on. I hated the church worse than ever, and I wanted to git clear away from 'em. Why, Billy Louise, we camped one night by the Wolverine, right about where your paw's got his big corral! We didn't stay there, because it was an Injun camping-ground then, and they wasn't no use getting mixed up in no fuss, first thing. In them days the Injuns wasn't so peaceable as they be now. So we come on here and settled in the Cove.

"And so—I like yuh," said Marthy, in a tone that was half defiance, "because I can't help likin' yuh. You're growin' up sweet and purty, jest like I wanted my little Minervy to grow up. In some ways you remind me of her, only she was quieter and didn't take so much notice of things a young one ain't s'posed to notice. Now I don't want you askin' no more questions about her, 'cause I ain't going to talk about it ag'in; and if yuh pester me, I'll send yuh home and tell your maw to keep yuh there. If you're the nice girl I think yuh be, you'll be good to Marthy and not talk about—"

Billy Louise opened her eyes still wider, and licked the honey off one whole corner of the slice without really tasting anything. Marthy's square, uncompromising chin was actually quivering. Billy Louise was stricken dumb by the spectacle. She wanted to go and put her arms around Marthy's neck and kiss her; only Marthy's neck had a hairy mole, and there was no part of her face which looked in the least degree kissable. Still, Billy Louise felt herself all hot inside with remorse and sympathy and affection. Physical contact being impossible because of her fastidious instincts, and speech upon the subject being so sternly forbidden, Billy Louise continued to lick honey and stare in fascinated silence.

"I'll wash the dishes for you, Marthy," she offered irrelevantly at last, as a supreme sacrifice upon the altar of sympathy. When that failed to stop the slow procession of tears that was traveling down the furrows of Marthy's cheeks, she added ingratiatingly: "I'll put six raisings on the cookie I'm going to make for you."

Whereupon Marthy did an unprecedented, an utterly amazing thing. She got up and gathered Billy Louise into her arms so unexpectedly that Billy Louise inadvertently buried her nose in the honey she had not yet licked off the bread. Marthy held her close pressed to her big, flabby bosom and wept into her hair in a queer, whimpering way that somehow made Billy Louise think of a hurt dog. It was only for a minute that Marthy did this; she stopped almost as suddenly as she began and went outside, wiping her eyes and her nose impartially upon her dirty apron.

Billy Louise sat paralyzed with the mixture of unusual emotions that assailed her. She was exceedingly sticky and uncomfortable from honey and tears, and she shivered with repugnance at the odor of Marthy's unbathed person. She was astonished at the outburst from phlegmatic Marthy Meilke, and her pity was now alloyed with her promise to wash all those dirty dishes. Billy Louise felt that she had been a trifle hasty in making promises. There was not a drop of water in the house nor a bit of wood, and Billy Louise knew perfectly well that the dishpan would have a greasy, unpleasant feeling under her fastidious little fingers.

She sighed heavily. "Well, I s'pose I might just as well get to work at 'em," she said aloud, as was her habit—being a child who had no playmates. "I hate to dread a thing I hate."

She looked at the messy slice of sour bread and threw it out to the speckled hen that had returned and was standing with one foot lifted tentatively—ready for a forward step if the fates seemed kind—and was regarding Billy Louise fixedly with one yellow eye. "Take it and go!" cried the donor, impatient of the scrutiny. She picked up the wooden pail and went down to the creek behind the house, by a pathway bordered thickly with budding rosebushes and tall lilacs.

Billy Louise first of all washed her face slowly and with a methodic thoroughness which characterized her—having lived for ten full years with no realization of hours and minutes as a measure for her actions. She dried her face quite as deliberately upon her starched calico apron. Then she spent a few minutes trying to catch a baby trout in her cupped palms. Never had Billy Louise succeeded in catching a baby trout in her hands; therefore she never tired of trying. Now, however, that rash promise nagged at her and would not let her enjoy the game as completely as usual. She took the wooden pail, and squatting on her heels in the wet sand, waited until a small school swam incautiously close to the bank, and scooped suddenly, with a great splash. She caught three tiny, speckled fish the length of her little finger, and she let the half-full pail rest in the shallow stream while she watched the fry swimming excitedly round and round within.

There was no great fun in that. Billy Louise could catch baby trout in a pail at home, from the waters of the Wolverine, whenever she liked. Many a time she had kept them in a big bottle until she tired of watching them, or they died because she forgot to change the water often enough. She could not get even a languid enjoyment out of them now, because she could not for a minute forget that she had promised to wash Marthy's dishes—and Marthy always had so many dirty dishes! And Marthy's dishpan was so greasy! Billy Louise gave a little shudder when she thought of it.

"I wish her little girl hadn't died," she said, her mind swinging from effect back to cause. "I could play with her. And she'd wash the dishes herself. I'm going to name my new little pig Minervy. I wish she hadn't died. I'd show her my little pig, if Marthy'd let her come over to our place. We could both ride on old Badger; Minervy could ride behind me, and we'd go places together." Billy Louise meditatively stirred up the baby trout with a forefinger. "We'd go up the canyon and have the caves for our play-houses. Minervy could have the secret cave away up the hill, and I'd have the other one across from it; and we'd have flags and wigwag messages like daddy tells about in the war. And we'd play the rabbits are Injuns, and the coyotes are big-Injun-chiefs sneaking down to see if the forts are watching. And whichever seen a coyote first would wigwag to the other one..." A baby trout, taking advantage of the pail tipping in the current, gave a flip over the edge and interrupted Billy Louise's fancies. She gave the pail a tilt and spilled out the other two fish. Then she filled it as full as she could carry and started back to pay the price of her sympathy.

"I don't see what Minervy had to go and die for!" she complained, dodging a low-hanging branch of bloom-laden lilac. "She could wash the dishes and I'd wipe 'em—and I s'pose there ain't a clean dish-towel in the house, either! Marthy's an awful slack housekeeper."

Billy Louise, being a young person with a conscience—of a sort—washed the dishes, since she had given her word to do it. The dishpan was even more unpleasant than experience had foretold for her; and of Marthy's somewhat meager supply there seemed not one clean dish in the house. The sympathy of Billy Louise therefore waned rapidly; rather, it turned in upon itself. So that by the time she felt morally free to spend the rest of the afternoon as she pleased, she was not at all sorry for Marthy for having lost Minervy; instead, she was sorry for herself for having been betrayed into rashness and for being deprived of a playmate.

"I don't s'pose Marthy doctored her right, at all," she considered pitilessly, as she returned down the lilac-bordered path. "If she had, I guess she wouldn't have died. I'll bet she never gave her a speck of sage tea, like mommie always does when I'm sick—only I ain't ever, thank goodness. I'm just going to ask Jase if Marthy did."

On the way to the root cellar, which was dug into the creek-bank well above high-water mark, Billy Louise debated within herself the ethics of speaking to Jase upon a forbidden subject. Jase had been Minervy's father, and therefore knew of her existence, so that mentioning Minervy to him could not in any sense be betraying a secret. She wondered if Jase felt badly about it, as Marthy seemed to do. On the heels of that came the determination to test his emotional capacity.

At the root cellar her attention was diverted. The cellar door was fastened on the outside, with the iron hasp used to protect the store of vegetables from the weather. Jase must be gone. She was turning away when she heard him clear his throat with that peculiar little hacking, rasping noise which sounded exactly as one would expect a Jase to sound. Billy Louise puckered her eyebrows, pressed her lips together understandingly—and disapprovingly—and opened the door.

Jase, humped over a heap of sprouting potatoes, blinked up apathetically into the sudden flood of sweet, spring air and sunshine. "Why, hello, Billy Louise," he mumbled, his eyes brightening a bit.

"Say, you was locked in here!" Billy Louise faced him puzzled. "Did you know you was locked in?"

"Yes-s, I knowed it. Marthy, she locked the door." Jase reached out a bony hand covered with carrot-colored hairs and picked up a shriveling potato with long, sickly sprouts proclaiming life's persistence in perpetuating itself under adverse circumstances. He broke off the sprouts with a wipe of his dirty palm and threw the potato into a heap in the corner.

"What for?" Billy Louise demanded, watching Jase reach languidly out for another potato.

"She seen me diggin' bait," Jase said tonelessly. "I did think some of ketchin' a mess of fish before I went to sproutin' p'tatoes, but Marthy she don't take no int'rest in nothin' but work."

"Are the fish biting good?" Billy Louise glanced toward the wider stream, where it showed through a gap in the alders.

"Yes-s, purty good now. I caught a nice mess the other day; but Marthy, she don't favor my goin' fishin'." The lean hands of Jase moved slowly at his task. Billy Louise, watching him, wondered why he did not hurry a little and finish sooner. Still, she could not remember ever seeing Jase hurry at anything, and the Cove with its occupants was one of her very earliest memories.

"Say, I'll dig some more bait, and then we'll go fishing; shall we?"

"I—dunno as I better—" Jase's hand hovered aimlessly over the potato pile. "I got quite a lot sprouted, though—and mebby—"

"I'll lock you in till I get the bait dug," suggested Billy Louise craftily. "And you work fast; and then I'll let you out, and we'll lock the door agin, so Marthy'll think you're in there yet."

"You're sure smart to think up things," Jase admired, smiling loose-lipped behind his scraggly beard, that was fading with the years. "I dunno but what it'd serve Marthy right. She ain't got no call to lock the door on me. She hates like sin t' see me with a fish-pole in m' hand—but she's always et her share uh the messes I ketch. She ain't a reasonable woman, Marthy ain't. You git the bait. I'll show Marthy who's boss in this Cove!"

He might have encouraged himself into defying Marthy to her face, in another five minutes of complaining. But the cellar door closed upon him with a slam. Billy Louise was not interested in his opinion of Marthy; with her, opinions were valueless if not accompanied by action.

"I never thought to ask him about Minervy," occurred to her while she was relentlessly dragging pale, fleshly fishworms from the loose black soil of Marthy's onion bed. "But I know she was mean to Minervy. She's awful mean to Jase—locking him up in the root cellar just 'cause he wanted to go fishing. If I was Jase I wouldn't sprout a single old potato for her. My goodness, but she'll be mad when she opens the cellar door and Jase ain't in there; I—guess I'll go home early, before Marthy finds it out."

She really meant to do that, but the fish were hungry fish that day, and the joy of having a companion to exclaim with her over every hard tug—even though that companion was only Jase—enticed her to stay on and on, until a whiff of frying pork on the breeze that swept down the Cove warned Billy Louise of the near approach of supper-time.

"I guess mebby I might as well go back to the suller," Jase remarked, his defiance weakening as he climbed the bank. "You come and lock the door agin, Billy Louise, and Marthy won't know I ain't been there all the time. She'll think you caught the fish." He looked at her with a weak leer of conscious cunning.

Billy Louise, groping vaguely for the sunbonnet that was dangling between her straight shoulder-blades, stared at him with wide eyes that held disillusionment and with it a contempt all the keener because it was the contempt of a child, whose judgment is merciless.

"I should thing you'd be ashamed!" she said at last, forgetting that the idea had been born in her own brain. "Cowards do things and then sneak about it. Daddy says so. I don't care if Marthy is mad 'cause I let you out, and I don't care if she knows we went fishing. I thought you wanted Marthy to see she ain't so smart, locking you up in the cellar. I ain't going to bake you a single cookie with raisings on it, like I was going to."

"Marthy's got a sharp tongue in 'er head," Jase wavered, his eyes shifting from Billy Louise's uncompromising stare.

"Daddy says when you do a thing that's mean, do it and take your medicine," Billy Louise retorted. "The boy of me that belongs to dad ain't a sneak, Jase Meilke. And," she added loftily, "the girl of me that belongs to mommie is a perfeck lady. Good day, Mr. Meilke. Thank you for a pleasant time fishing."

Whereupon the perfect lady part switched short skirts up the path and held a tousled head high with disdain.

Jase, thus deserted, went shambling back to the cellar and fell to sprouting potatoes with what might almost be termed industry.

It pained Jase later to discover that Marthy was not interested in the open door, but in the very small heap of potatoes which he had "sprouted" that afternoon. There was other work to be done in the Cove, and there were but two pairs of hands to do it; that one pair was slow and shiftless and inefficient was bitterly accepted by Marthy, who worked from sunrise until dark to make up for the shirking of those other hands.

It was the trail experience over again, and it was an experience that dragged through the years without change or betterment. Marthy wanted to "get ahead." Jase wanted to sit in the sun with his knees drawn up, just—I don't know what, but I suppose he called it thinking. When he felt unusually energetic, he liked to dangle an impaled worm over a trout pool. Theoretically he also wanted to get ahead and to have a fine ranch and lots of cattle and a comfortable home. He would plan these things sometimes in an expansive mood, whereupon Marthy would stare at him with her hard, contemptuous look until Jase trailed off into mumbling complaints into his beard. He was not as able-bodied as she thought he was, he would say, with vague solemnity. Some uh these days Marthy'd see how she had driven him beyond his strength.

When one is a Marthy, however, with ambitions and a tireless energy and the persistence of a beaver, and when one listens to vague mutterings for many hard laboring years, one grows accustomed to the complainings and fails to see certain warning symptoms of which even the complainer is only vaguely aware.

She kept on working through the years, and as far as was humanly possible she kept Jase working. She did not soften, except toward Billy Louise, who rode sometimes over from her father's ranch on the Wolverine to the flowery delights of the Cove. The place was a perfect jungle of sweetness, seven months of each year; for Marthy owned and indulged a love of beauty, even if she could not realize her dream of prosperity. Wherever was space in the house-yard for a flower or a fruit tree or a berry bush, Marthy planted one or the other. You could not see the cabin from April until the leaves fell in late October, except in a fragmentary way as you walked around it. You went in at a gate of pickets which Marthy herself had split and nailed in place; you followed a narrow, winding path through the sweet jungle—and if you were tall, you stooped now and then to pass under an apple branch. And unless you looked up at the black, lava-rock rim of the bluff which cupped this Eden incongruously, you would forget that just over the brim lay parched plain and barren mountain.

When Billy Louise was twelve, she had other ambitions than the making of cookies with "raisings" on them. She wanted to do something big, though she was hazy as to the particular nature of that big something. She tried to talk it over with Marthy, but Marthy could not seem to think beyond the Cove, except that now and then Billy Louise would suspect that her mind did travel to the desert and Minervy's grave. Marthy's hair was growing streaked with yellowish gray, though it never grew less unkempt and dusty looking. Her eyes were harder, if anything, except when they rested on Billy Louise.

When she was thirteen, Billy Louise rode over with a loaf of bread she had baked all by herself, and she put this problem to Marthy:

"I've been thinking I'd go ahead and write poetry, Marthy—a whole book of it with pictures. But I do love to make bread—and people have to eat bread. Which would you be, Marthy; a poet, or a cook?"

Marthy looked at her a minute, lent her attention briefly to the question, and gave what she considered good advice.

"You learn how to cook, Billy Louise. Yuh don't want to go and get notions. Your maw ain't healthy, and your paw likes good grub. Po'try is all foolishness; there ain't any money in it."

"Walter Scott paid his debts writing poetry," said Billy Louise argumentatively. She had just read all about Walter Scott in a magazine which a passing cowboy had given her; perhaps that had something to do with her new ambition.

"Mebby he did and mebby he didn't. I'd like to see our debts paid off with po'try. It'd have to be worth a hull lot more 'n what I'd give for it."

"Oh. Have you got debts too, Marthy?" Billy Louise at thirteen was still ready with sympathy. "Daddy's got lots and piles of 'em. He bought some cattle and now he talks to mommie all the time about debts. Mommie wants me to go to Boise to school, next winter, to Aunt Sarah's. And daddy says there's debts to pay. I didn't know you had any, Marthy."

"Well, I have got. We bought some cattle, too—and they ain't done 's well 's they might. If I had a man that was any good on earth, I could put up more hay. But I can't git nothing outa Jase but whines. Your paw oughta send you to school, Billy Louise, even if he has got debts. I'd 'a' sent—"

She stopped there, but Billy Louise knew how she finished the sentence mentally. She would have sent Minervy to school.

"Your paw ain't got any right to keep you outa school," Marthy went on aggressively. "Debts er no debts, he'd see 't you got schoolin'—if he was the right kinda man."

"Daddy is the right kinda man. He ain't like Jase. He says he wishes he could, but he don't know where the money's coming from."

"How much's it goin' to take?" asked Marthy heavily.

"Oh, piles." Billy Louise spoke airily to hide her pride in the importance of the subject. "Fifty dollars, I guess. I've got to have some new clothes, mommie says. I'd like a blue dress."

"And your paw can't raise fifty dollars?" Marthy's tone was plainly belligerent.

"Got to pay interest," said Billy Louise importantly.

Marthy said not another word about debts or the duties of parents. What she did was more to the point, however, for she hitched the mules to a rattly old buckboard next day and drove over to the MacDonald ranch on the Wolverine. She carried fifty dollars in her pocket—and that was practically all the money Marthy possessed, and had been saved for the debts that harassed her. She gave the money to Billy Louise's mother and said that it was a present for Billy Louise, and meant for "school money." She said that she hadn't any girl of her own to spend the money on, and that Billy Louise was a good girl and a smart girl, and she wanted to do a little something toward her schooling.

A woman will sacrifice more pride than you would believe, if she sees a way toward helping her children to an education. Mrs. MacDonald took the money, and she promised secrecy—with a feeling of relief that Marthy wished it. She was astonished to find that Marthy had any feelings not directly connected with work or the shortcomings of Jase, but she never suspected that Marthy had made any sacrifice for Billy Louise.

So Billy Louise went away to school and never knew whose money had made it possible to go, and Marthy worked harder and drove Jase more relentlessly to make up that fifty dollars. She never mentioned the matter to anyone. The next year it was the same; when, in August, she questioned Billy Louise clumsily upon the subject of finances, and learned that "daddy" still talked about debts and interest and didn't know where the money was coming from, she drove over again with money for the "schooling." And again she extracted a promise of silence.

She did this for four years, and not a soul knew that it cost her anything in the way of extra work and extra harassment of mind. She bought more cattle and cut more hay and went deeper into debt; for as Billy Louise grew older and prettier and more accustomed to the ways of town, she needed more money, and the August gift grew proportionately larger. The mother was thankful beyond the point of questioning. An August without Marthy and Marthy's gift of money would have been a tragedy; and so selfish is mother-love sometimes that she would have accepted the gift even if she had known what it cost the giver.

At eighteen, then, Billy Louise knew some things not taught by the wide plains and the wild hills around her. She was not spoiled by her little learning, which was a good thing. And when her father died tragically beneath an overturned load of poles from the mountain at the head of the canyon, Billy Louise came home. The Billy of her tried to take his place, and the Louise of her attempted to take care of her mother, who was unfitted both by nature and habit to take care of herself. Which was, after all, a rather big thing for anyone to attempt.

Jase began to complain of having "all-gone" feelings during the winter after Billy Louise came home and took up the whole burden of the Wolverine ranch. He complained to Billy Louise, when she rode over one clear, sunny day in January; he said that he was getting old—which was perfectly true—and that he was not as able-bodied as he might be, and didn't expect to last much longer. Billy Louise spoke of it to Marthy, and Marthy snorted.

"He's able-bodied enough at mealtimes, I notice," she retorted. "I've heard that tune ever since I knowed him; he can't fool me!"

"Not about the all-goneness, have you?" Billy Louise was preparing to wipe the dishes for Marthy. "I know he always had 'cricks' in different parts of his anatomy, but I never heard about his feeling all-gone, before. That sounds mysterious, don't you think?"

"No; and he never had nothin' the matter with his anatomy, neither; his anatomy's just as sound as mine. Jase was born lazy, is all ails him."

"But, Marthy, haven't you noticed he doesn't look as well as he used to? He has a sort of gray look, don't you think? And his eyes are so puffy underneath, lately."

"No, I ain't noticed nothing wrong with him that ain't always been wrong." Marthy spoke grudgingly, as if she resented even the possibility of Jase's having a real ailment. "He's feelin' his years, mebby. But he ain't no call to; Jase ain't but three years older 'n I be, and I ain't but fifty-nine last birthday. And I've worked and slaved here in this Cove fer twenty-seven years, now; what it is I've made it. Jase ain't ever done a hand's turn that he wasn't obliged to do. I've chopped wood, and I've built corrals and dug ditches, and Jase has puttered around and whined that he wasn't able-bodied enough to do no heavy lifting. That there orchard out there I planted and packed water in buckets to it till I got the ditch through. Them corrals down next the river I built. I dug the post-holes, and Jase set the posts in and held 'em steady while I tamped the dirt! In winter I've hauled hay and fed the cattle; and Jase, he packed a bucket uh slop, mebby, to the pigs! If he ain't as able-bodied as I be, it's because he ain't done nothing to git strong on. He can't come around me now with that all-gone feeling uh his; I know Jase Meilke like a book."

There was more that she said about Jase. Standing there, a squat, unkempt woman with a seamed, leathery face and hard eyes now quite faded to gray, she told Billy Louise a good deal of the bitterness of the years behind; years of hardship and of slavish toil and no love to lighten it. She spoke again of Minervy, and the name brought back to Billy Louise poignant memories of her own lonely childhood and of her "pretend" playmate.

Half shyly, because she was still sometimes touched with the inarticulateness of youth, Billy Louise told Marthy a little of that playmate. "Why, do you know, every time I rode old Badger anywhere, after that day you told me about Minervy, I used to pretend that Minervy rode behind me. I used to talk to her by the hour and take her places. And up our canyon is a cave that I used to play was Minervy's cave. I had another one, and I used to go over and visit Minervy. And I had another pretend playmate—a boy—and we used to have adventures. It's a queer place; I just found that cave by accident. I don't believe there's another person in the country who knows it's there at all. Well, that's Minervy's cave to me yet. And, Marthy—" Billy Louise giggled a little and eyed the old woman with a sidelong look that would have set a young man's blood a-jump—"I hope you won't be mad; I was just a kid, and I didn't know any better. But just to show you how much I thought: I had a little pig, and I named it Minervy, after you told me about her. And mommie told me that was no name for it; it was—it wasn't a girl pig, mommie said. So I called it Man-ervy, as the next best thing." She gave Marthy another wasted glance from the corners of her eyes. "Oh, Marthy!" she cried remorsefully, setting down the gravy bowl that she might pat Marthy on her fat, age-rounded shoulder. "What a little beast I am! I shouldn't have told that; but honest, I thought it was an honor. I—I just worshiped that pig!"

Jase maundered in at that moment, and Marthy, catching up a corner of her dirty apron—Billy Louise could not remember ever seeing Marthy in a perfectly clean dress or apron—wiped away what traces of emotion her weathered face could reveal. Also, she turned and glared at Jase with what Billy Louise considered a perfectly uncalled-for animosity. In reality, Marthy was covertly looking for visible symptoms of the all-goneness. She shut her harsh lips together tightly at what she saw; Jase certainly was puffy under his watery, pink-rimmed eyes, and the withered cheeks above his thin graying beard really did have a pasty, gray look.

"D' you turn them calves out into the corral?" she demanded, her voice harder because of her secret uneasiness.

"I was goin' to, but the wind's changed into the north, 'n' I thought mebby you wouldn't want 'em out." Jase turned back aimlessly to the door. His voice was getting cracked and husky, and the deprecating note dominated pathetically all that he said. "You'll have to face the wind goin' home," he said to Billy Louise. "More 'n likely you'll be facin' snow, too. Looks bad, off that way."

"You go on and turn them calves out!" Marthy commanded him harshly. "Billy Louise ain't goin' home if it storms; I sh'd think you'd know enough to know that."

"Oh, but I'll have to go, anyway," the girl interrupted. "Mommie can't be there alone; she'd worry herself to death if I didn't show up by dark. She worries about every little thing since daddy died. I ought to have gone before—or I oughtn't to have come. But she was worrying about you, Marthy; she hadn't seen or heard of you for a month, and she was afraid you might be sick or something. Why don't you get someone to stay with you? I think you ought to."

She looked toward the door, which Jase had closed upon his departure. "If Jase should—get sick, or anything—"

"Jase ain't goin' to git sick," Marthy retorted glumly. "Yuh don't want to let him worry yuh, Billy Louise. If I'd worried every time he yowled around about being sick, I'd be dead or crazy by now. I dunno but maybe I'll have somebody to help with the work, though," she added, after a pause during which she had swiped the dish-rag around the sides of the pan once or twice, and had opened the door and thrown the water out beyond the doorstep like the sloven she was. "I got a nephew that wants to come out. He's been in a bank, but he's quit and wants to git on to a ranch. I dunno but I'll have him come, in the spring."

"Do," urged Billy Louise, perfectly unconscious of the potentialities of the future. "I hate to think of you two down here alone. I don't suppose anyone ever comes down here, except me—and that isn't often."

"Nobody's got any call to come down," said Marthy stolidly. "They sure ain't going to come for our comp'ny and there ain't nothing else to bring 'em."

"Well, there aren't many to come, you know," laughed Billy Louise, shaking out the dish towel and spreading it over two nails, as she did at home. "I'm your nearest neighbor, and I've got six miles to ride—against the wind, at that. I think I'd better start. We've got a halfbreed doing chores for us, but he has to be looked after or he neglects things. I'll not get another chance to come very soon, I'm afraid; mommie hates to have me ride around much in the winter. You send for that nephew right away, why don't you, Marthy?" It was like Billy Louise to mix command and entreaty together. "Really, I don't think Jase looks a bit well."

"A good strong steepin' of sage'll fix him all right, only he ain't sick, as I see. You take this shawl."

Billy Louise refused the shawl and ran down the twisted path fringed with long, reaching fingers of the hare berry bushes. At the stable she stopped for an aimless dialogue with Jase and then rode away, past the orchard whose leafless branches gave glimpses of the low, sod-roofed cabin, with Marthy standing rather disconsolately on the rough doorstep watching her go.

Absently she let down the bars in the narrowest place in the gorge and lifted them into their rude sockets after she had led her horse through. All through the years since Marthy had gone down that rocky gash in search of Buck and Bawley, no human being had entered or left the Cove save through that narrow opening. The tingle of romance which swept always the nerves of the girl when she rode that way fastened upon her now. She wished the Cove belonged to her; she thought she would like to live in a place like that, with warlike Indians all around and that gorge to guard day and night. She wished she had been Marthy, discovering that place and taming it, little by little, in solitary achievement the sweeter because it had been hard.

"It's a bigger thing," said Billy Louise aloud to her horse, "to make a home here in this wilderness, than to write the greatest poem in the world or paint the greatest picture or—anything. I wish..."

Blue was climbing steadily out of the gorge, twitching an ear backward with flattering attention when his lady spoke. He held it so for a minute, waiting for that sentence to be finished, perhaps; for he was wise beyond his kind—was Blue. But his lady was staring at the rock wall they were passing then, where the winds and the cold and heat had carved jutting ledges into the crude form of cabbages; though Billy Louise preferred to call them roses. Always they struck her with a new wonder, as if she saw them for the first time. Blue went on, calmly stepping over this rock and, around that as if it were the simplest thing in the world to find sure footing and carry his lady smoothly up that trail. He threw up his head so suddenly that Billy Louise was startled out of her aimless dreamings, and pointed nose and ears toward the little creek-bottom above, where Marthy had lighted her camp-fire long and long ago.

A few steps farther, and Blue stopped short in the trail to look and listen. Billy Louise could see the nervous twitchings of his muscles under the skin of neck and shoulders, and she smiled to herself. Nothing could ever come upon her unaware when she rode alone, so long as she rode Blue. A hunting dog was not more keenly alive to his surroundings.

"Go on, Blue," she commanded after a minute. "If it's a bear or anything like that, you can make a run for it; if it's a wolf, I'll shoot it. You needn't stand here all night, anyway."

Blue went on, out from behind the willow growth that hid the open. He returned to his calm, picking a smooth trail through the scattered rocks and tiny washouts. It was the girl's turn to stare and speculate. She did not know this horseman who sat negligently in the saddle and looked up at the cedar-grown bluff beyond, while his horse stood knee-deep in the little stream. She did not know him; and there were not so many travelers in the land that strangers were a matter of indifference.

Blue welcomed the horse with a democratic nicker and went forward briskly. And the rider turned his head, eyed the girl sharply as she came up, and nodded a cursory greeting. His horse lifted its head to look, decided that it wanted another swallow or two, and lowered its muzzle again to the water.

Billy Louise could not form any opinion of the man's age or personality, for he was encased in a wolfskin coat which covered him completely from hatbrim to ankles. She got an impression of a thin, dark face, and a sharp glance from eyes that seemed dark also. There was a thin, high nose, and beyond that Billy Louise did not look. If she had, the mouth must certainly have reassured her somewhat.

Blue stepped nonchalantly down into the stream beside the strange horse and went across without stopping to drink. The strange horse moved on also, as if that were the natural thing to do—which it was, since chance sent them traveling the same trail. Billy Louise set her teeth together with the queer little vicious click that had always been her habit when she felt thwarted and constrained to yield to circumstances, and straightened herself in the saddle.

"Looks like a storm," the fur-coated one observed, with a perfectly transparent attempt to lighten the awkwardness.

Billy Louise tilted her chin upward and gazed at the gray sweep of clouds moving sullenly toward the mountains at her back. She glanced at the man and caught him looking intently at her face.

He did not look away immediately, as he should have done, and Billy Louise felt a little heat-wave of embarrassment, emphasized by resentment.

"Are you going far?" he queried in the same tone he had employed before.

"Six miles," she answered shortly, though she tried to be decently civil.

"I've about eighteen," he said. "Looks like we'll both get caught out in a blizzard."

Certainly, he had a pleasant enough voice—and after all it was not his fault that he happened to be at the crossing when she rode out of the gorge. Billy Louise, in common justice, laid aside her resentment and looked at him with a hint of a smile at the corners of her lips.

"That's what we have to expect when we travel in this country in the winter," she replied. "Eighteen miles will take you long after dark."

"Well, I was sort of figuring on putting up at some ranch, if it got too bad. There's a ranch somewhere ahead, on the Wolverine, isn't there?"

"Yes." Billy Louise bit her lip; but hospitality is an unwritten law of the West—a law not to be lightly broken. "That's where I live. We'll be glad to have you stop there, of course."

The stranger must have felt and admired the unconscious dignity of her tone and words, for he thanked her simply and refrained from looking too intently at her face.

Fine siftings of snow, like meal flung down from a gigantic sieve, swept into their faces as they rode on. The man turned his face toward her after a long silence. She was riding with bowed head and face half turned from him and the wind alike.

"You'd better ride on ahead and get in out of this," he said curtly. "Your horse is fresh. It's going to be worse and more of it, before long; this cayuse of mine has had thirty miles or so of rough going."

"I think I'd better wait for you," she said primly. "There are bad places where the trail goes close to the bluff, and the lava rock will be slippery with this snow. And it's getting dark so fast that a stranger might go over."

"If that's the case, the sooner you are past the bad places the better. I'm all right. You drift along."

Billy Louise speculated briefly upon the note of calm authority in his voice. He did not know, evidently, that she was more accustomed to giving commands than to obeying them; her lips gave a little quirk of amusement at his mistake.

"You go on. I don't want a guide." He tilted his head peremptorily toward the blurred trail ahead.

Billy Louise laughed a little. She did not feel in the least embarrassed now. "Do you never get what you don't want?" she asked him mildly. "I'd a lot rather lead you past those places than have you go over the edge," she said, "because nobody could get you up, or even go down and bury you decently. It wouldn't be a bit nice. It's much simpler to keep you on top."

He said something, but Billy Louise could not hear what it was; she suspected him of swearing. She rode on in silence.

"Blue's a dandy horse on bad trails and in the dark," she observed companionably at last. "He simply can't lose his footing or his way."

"Yes? That's nice."

Billy Louise felt like putting out her tongue at him, for the cool remoteness of his tone. It would serve him right to ride on and let him break his neck over the bluff if he wanted to. She shut her teeth together and turned her face away from him.

So, in silence and with no very good feeling between them, they went precariously down the steep hill (the hill up which Marthy and the oxen and Jase had toiled so laboriously, twenty-seven years before) and across the tiny flat to where the cabin window winked a welcome at them through the storm.

Blue led the way straight to the low, dirt-roofed stable of logs and stopped with his nose against the closed door. Billy Louise herself was deceived by the whirl of snow and would have missed the stable entirely if the leadership had been hers. She patted Blue gratefully on the shoulder when she unsaddled him. She groped with her fingers for the wooden peg in the wall where the saddle should hang, failed to find it, and so laid the saddle down against the logs and covered it with the blanket.

"Just turn your horse in loose," she directed the man shortly. "Blue won't fight, and I think the rest of the horses are in the other part. And come on to the house."

It pleased her a little to see that he obeyed her without protest; but she was not so pleased at his silence, and she led the way rather indignantly toward the winking eye which was the cabin's window.

At the sound of their feet on the wide doorstep, her mother pulled open the door and stood fair in the light, looking out with the anxious look which had lived so long in her face that it had lines of its own chiseled deep in her forehead and at the sides of her mouth.

"Is that you, Billy Louise? Oh, ain't Peter Howling Dog with you? What makes you so terrible late, Billy Louise? Come right in, stranger. I don't know your name, but I don't need to know it. A storm like this is all the interduction a fellow needs, I guess." She smiled, at that. She had a nice smile, with a little resemblance to Billy Louise, except that the worried, inquiring look never left her eyes; as if she had once waited long for bad news, and had met everyone with anxious, eager questioning, and her eyes had never changed afterwards. Billy Louise glanced at her with her calm, measuring look, making the contrast very sharp between the two.

"What about Peter?" she asked. "Isn't he here?"

"No, and he ain't been since an hour or so after you left. He saddled up and rode off down the river—to the reservation, I reckon."

"Then the chores aren't done, I suppose." Billy Louise went over and took a lantern down from its nail, turning up the wick so that she could light it with the candle. "Go up to the fire and thaw out," she invited the man. "We'll have supper in a few minutes."

Instead he reached out and took the lantern from her as soon as she had lighted it. "You go to the fire yourself," he said. "I'll do what's necessary outside."

"Why-y—" Billy Louise, her fingers still clinging to the lantern, looked up at him. He was staring down at her with that intent look she had objected to on the trail, but she saw his mouth, and the little smile that hid just back of his lips. She smiled back without knowing it. "I'll have to go along, anyway. There are cows to milk and you couldn't very well find the cow-stable alone."

"Think not?"

Billy Louise had been perfectly furious at that tone, out on the trail. Now that she could see his lips and their little twitching to keep back the smile, she did not mind the tone at all. She had turned away to get the milk pails, and now she gave him a sidelong look, of the kind that had been utterly wasted upon Marthy. The man met it and immediately turned his attention to the lantern wick, which needed nice adjustment before its blaze quite pleased him; he was not a Marthy to receive such a look unmoved.

Together they went out again into the storm they had left so eagerly. Billy Louise showed him where was the pitchfork and the hay, and then did the milking while he piled full the mangers. After that they went together and turned the shivering work horses into the stable from the corral where they huddled, rumps to the storm; and the man lifted great forkfuls of hay and carried it into their stalls, while Billy Louise held the lantern high over her head like a western Liberty. They did not talk much, except when there was need for speech; but they were beginning to feel a little glow of companionship by the time they were ready to fight their way against the blizzard to the house, Billy Louise going before with the lantern, while the man followed close behind, carrying the two pails of milk that was already freezing in little crystals to the tin.

"Did you get everything done? You must be half froze—and starved into the bargin." Mrs. MacDonald, as is the way of some women who know the weight of isolation, had a habit of talking with a nervous haste at times, and of relapsing into long, brooding silences afterwards. She talked now, while she pulled a pan of hot, brown biscuits from the oven, poured the tea, and turned crisp, browned potatoes out of a frying-pan into a deep, white bowl. She wondered, over and over, why Peter Howling Dog had left and why he did not return. She said that was the way, when you depended on Indians for anything. She did wish there was a white man to be had. She asked after Marthy and Jase and gave Billy Louise no opportunity to tell her anything.

Billy Louise glanced often at the man, who did not look in the least as she had fancied, except that he really did have a high nose and terribly keen eyes with something behind the keenness that baffled her. And his mouth was pleasant, especially when that smile hid just behind his lips; also, she liked his hair, which was thick and brown, with hints of red in it here and there, and a strong inclination to curl where it was longest. She had known he was tall when he stepped into the light of the door; now she saw that he was slim to the point of leanness, with square shoulders and a nervous quickness when he moved. His fingers were never idle; when he was not eating, he rolled bits of biscuit into tiny, soggy balls beside his plate, or played a soft tattoo with his fork.

"I didn't quite catch your name, mister," her mother said finally. "But take another biscuit, anyway."

"Warren is my name," returned the man, with that hidden smile because she had never before given him any opportunity to tell it. "Ward Warren. I've got a claim over on Mill Creek."

Billy Louise gave a little gasp and distractedly poured two spoons of sugar in her tea, although she hated it sweetened.

I've got to tell you why, even at the price of digression. Long ago, when Billy Louise was twelve or so, and lived largely in a dream world of her own with Minervy for her "pretend" playmate, she had one day chanced upon a paragraph in a paper that had come from town wrapped around a package of matches. It was all about Ward Warren. The name caught her fancy, and the text of the paragraph seized upon her imagination. Until school filled her mind with other things, she had built adventures without end in which Ward Warren was the central figure. Up the canyon at the caves, she sometimes pretended that Ward Warren had abducted Minervy and that she must lead the rescue. Sometimes, when she rode in the hills, Ward Warren abducted her and led her into strange places where she tried to shiver in honest dread. Often and often, however, Ward Warren was a fugitive who came to her for help; then she would take him to Minervy's cave and hide him, perhaps; or she would mount her horse and lead him, by devious ways, to safety, and upon some hilltop from which she could point out the route he must follow, she would bid him a touching adieu and beseech him, in the impossible language of some old romancer, to go and lead a blameless life. Sitting there at the table opposite him, stirring the sugar heedlessly into her tea, one favorite exhortation returned from her dream-world, clear as if she had just spoken it aloud. "Go, and sin no more; and if perchance you will in some distant far land send me a kind thought, that will be reward enough for what I have done this day. Farewell, Ward Warren—Kismet."

The lips of Billy Louise smiled and stopped just short of laughter, and she looked across at Ward Warren as if she expected him to laugh also at that frightfully virtuous though stilted adieu. She found him looking straight at her in that intent fashion that seemed as if he would see through and all around her and her thoughts. He was not smiling at all. His mouth was pulled into a certain bitter understanding; indeed, he looked exactly as if Billy Louise had dealt him a deliberate affront which he could neither parry nor fling back at her, but must endure with what stoicism he might.

Billy Louise blushed guiltily, took an unpremeditated swallow of tea, and grimaced over the sickish sweetness of it. She got up and emptied the tea into the slop bucket, and loitered over the refilling of the cup so that when she returned to the table she was at least outwardly calm. She felt another quick, keen glance from across the table, but she helped herself composedly to the cream and listened to her mother with flattering attention.

"Jase has got all-gone feelings now, mommie," she remarked irrelevantly during a brief pause and relapsed into silence again. She knew that was good for at least five minutes of straight monologue, with her mother in that talking mood. She finished her supper while Warren listened abstractedly to a complete biography of the Meilkes and learned all about Marthy's energy and Jase's shiftlessness.

"Ward Warren!" Billy Louise was saying to herself. "Did you ever in your life—it's exactly as if Minervy should come to life and walk in. Ward Warren! There couldn't possibly be two Ward Warrens; it's such an odd name. Well!"

Then she went mentally over that paragraph. She wished she did not remember every single word of it, but she did. And she was afraid to look at him after that. And she wanted to, dreadfully. She felt as though he belonged to her. Why, he was her old playmate! And she had saved his life hundreds of times, at immense risks to herself; and he had always been her devoted slave afterwards, and never failed to appear at the precise moment when she was beset by Indians or robbers or something, and in dire need. The blood he had shed in her behalf! At that point Billy Louise startled herself and the others by suddenly laughing out loud at the memory of one time when Ward Warren had killed enough Indians to fill a deep washout so that he might carry her across to the other side!

"Is there anything funny about Jase Meilke dying, Billy Louise?" her mother asked her in a perfectly shocked tone.

"No—I was thinking of something else." She glanced at the man eyeing her so distrustfully from across the table and gurgled again. It was terribly silly, but she simply could not help seeing Ward Warren calmly filling that washout with dead Indians so that he might carry her across it in his arms. The more she tried to forget that, the funnier it became. She ended by leaving the table and retiring precipitately to her own tiny room in the lean-to where she buried her face as deep as it would go in a puffy pillow of wild duck feathers.

He, poor devil, could not be expected to know just what had amused her so; he did know that it somehow concerned himself, however. He took up his position—mentally—behind the wall of aloofness which stood between himself and an unfriendly world, and when Billy Louise came out later to help with the dishes, he was sitting absorbed in a book.

Billy Louise got out her algebra and a slate and began to ponder the problem of a much-handicapped goat's feeding-ground. Ward Warren read and read and read and never looked up from the pages. Never in her life had she seen a man read as he read; hungrily, as a starved man eats; rapidly, his eyes traveling like a shuttle across the page; down, down—flip a leaf quickly and let the shuttle-glance go on. Billy Louise let her slate, with the goat problem unsolved, lie in her lap while she watched him. When she finally became curious enough to decipher the name of the book—she had three or four in that dull, brown binding—and saw that he was reading The Ring and the Book, she felt stunned. She read Browning just as she drank sage tea; it was supposed to be good for her. Her English teacher had given her that book. She never would have believed that any living human could read it as Ward Warren was reading it now; avidly, absorbedly, lost to his surroundings—to her own presence, if you please! Billy Louise glanced at her mother. That lady, having discovered that her guest's gloves needed mending, was working over them with pieces of Indian-tanned buckskin and beeswaxed thread, the picture of domestic content.

Billy Louise sighed. She shifted her chair. She got up and put a heavy chunk of wood on the fire and glanced over her shoulder at the man to see if he were going to take the hint and offer to help. She came back and stood close to him while she selected, with great deliberation, a book from the shelf beside his head. And Ward Warren, perfectly normal and not over twenty-five or so, pushed his chair out of her way with a purely mechanical movement, and read and read, and actually was too absorbed to feel her nearness. And he really was reading The Ring and the Book; Billy Louise was rude enough to look over his shoulder to make sure of that. She gave up, then, and though she picked a book at random from the shelf, she did not attempt to read it. She went to her room and made it ready for their guest, and after that she went to bed in her mother's room; and she thought and thought and did a lot of wondering about Life and about Ward Warren. She heard him go to bed, after a long while, and she wondered if he had finished the book first.

The next morning the blizzard raged so that he stayed as a matter of course. Peter Howling Dog had not returned, so Warren did the chores and would not let Billy Louise help with anything. He filled the wood-box, piled great chunks of wood by the fireplace, and saw that the water-pails were full to the icy brims. He talked a little, and Billy Louise discovered that he was quick to see a joke, and that he simply could not be caught napping, but had always a retort ready for her. That was true until after dinner, when he picked up a book again. When that happened, he was dead to the world bounded by the coulee walls, and he did not show any symptoms of consciousness until he had reached the last page, just when the light was growing dim and blurring the lines so that he must hold the pages within six inches of his eyes. He closed the book with a long breath, placed it accurately upon the shelf where it had stood since Billy Louise came home from school, and picked up his hat and gloves. It was time to wade out through the snow and feed the stock and bring in more wood.

"I wish we could get him to stay all winter, instead of that Peter Howling Dog," Mrs. MacDonald said anxiously, after he had gone out. "I just know Peter's off drinking. I don't think he's a safe man to have around, Billy Louise. I didn't when you hired him. I haven't felt easy a minute with him on the place. I wish you'd hire Mr. Warren, Billy Louise. He's nice and quiet—"

"And he's got a ranch of his own. He doesn't strike me as a man who wants a job milking two cows and carrying slop to the pigs, mommie."

"Well, I'd feel a lot easier if we had him instead of that breed; only we ain't even got the breed, half the time. This is the third time he's disappeared, in the two months we've had him. I really think you ought to speak to Mr. Warren, Billy Louise."

"Speak to him yourself. You're the one that wants him," Billy Louise answered somewhat sharply. She adored her mother; but if she had to run the ranch, she did wish her mother would not interfere and give advice just at the wrong time.

"Well, you needn't be cross about it; you know yourself that Peter can't be depended on a minute. There he went off yesterday and never fed the pigs their noon slop, and I had to carry it out myself. And my lumbago has bothered me ever since, just like it was going to give me another spell. You can't be here all the time, Billy Louise—leastways you ain't; and Peter—"

"Oh, good gracious, mommie! I told you to hire the man if you want him. Only Ward Warren isn't—"

Ward Warren pushed open the door and looked from one to the other, his eyes two question marks. "Isn't—what?" he asked and shut the door behind him with the air of one who is ready for anything.

"Isn't the kind of man who wants to hire out to do chores," Billy Louise finished and looked at him straight. "Are you? Mommie wants to hire you."

"Oh. Well, I was just about to ask for the job, anyway." He laughed, and the distrust left his eyes. "As a matter of fact, I was going over to Jim Larson's to hang out for the rest of the winter and get away from the lonesomeness of the hills. The old Turk's a pretty good friend of mine. But it looks to me as if you two needed something around that looks like a man a heap more than Jim does. I know Peter Howling Dog to a fare-you-well; you'll be all to the good if he forgets to come back. So if you'll stake me to a meal now and then, and a place to sleep, I'll be glad to see you through the winter—or until you get some white man to take my place." He took up the two water-pails and waited, glancing from one to the other with that repressed smile which Billy Louise was beginning to look for in his face.

Now that matters had approached the point of decision, her mother stood looking at her helplessly, waiting for her to speak. Billy Louise drew herself up primly and ended by contradicting the action. She gave him the sidelong glance which he was least prepared to withstand—though in justice to Billy Louise, she was absolutely unconscious of its general effectiveness—and twisted her lips whimsically.

"We'll stake you to a book, a bannock, and a bed if you want to stay, Mr. Warren," she said quite soberly. "Also to a pitchfork and an axe, if you like, and regular wages."

His eyes went to her and steadied there with the intent expression in them. "Thanks. Cut out the wages, and I'll take the offer just as it stands," he told her and pulled his hat farther down on his head. "She's going to be one stormy night, lay-dees," he added in quite another tone, on his way to the door. "Five o'clock by the town clock, and al-ll's well!" This last in still another tone, as he pushed out against the swooping wind and pulled the door shut with a slam. They heard him whistling a shrill, rollicking air on his way to the creek; at least, it sounded rollicking, the way he whistled it.

"That's The Old Chisholm Trail he's whistling," Billy Louise observed under her breath, smiling reminiscently. "The very song I used to pretend he always sang when he came down the canyon to rescue Minervy and me! But of course—I knew all the time he's a cowboy; it said so—"

The whistling broke and he began to sing at the top of a clear, strong-lunged voice, that old, old trail song beloved of punchers the West over:

"Oh, it's cloudy in the West and a-lookin' like rain,

And my damned old slicker's in the wagon again,

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy-a, youpy-a,

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy-a!"

"What did you say, Billy Louise? I'm sure it's a comfort to have him here, and you see he was glad and willing—"

But Billy Louise was holding the door open half an inch, listening and slipping back into the child-world wherein Ward Warren came singing down the canyon to rescue her and Minervy. The words came gustily from the creek down the slope:

"No chaps, no slicker, and a-pourin' down rain,

And I swear by the Lord I'll never night-herd again,

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy-a, youpy-a,

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy-a!

"Feet in the stirrups and seat in the saddle,

I hung and rattled with them long-horn cattle,

Coma ti yi—"

"Do shut the door, Billy Louise! What you want to stand there like that for? And the wind freezing everything inside! I can feel a terrible draught on my feet and ankles, and you know what that leads to."

So Billy Louise closed the door and laid another alder root on the coals in the fireplace, the while her mind was given over to dreamy speculations, and the words of that old trail song ran on in her memory though she could no longer hear him singing. Her mother talked on about Peter and the storm and this man who had ridden straight from the land of daydreams to her door, but the girl was not listening.

"Now ain't you relieved, yourself, that he's going to stay?"

Billy Louise, kneeling on the hearth and staring abstractedly into the fire, came back with a jerk to reality. The little smile that had been in her eyes and on her lips fled back with the dreams that had brought it. She gave her shoulders an impatient twitch and got up.

"Oh—I guess he'll be more agreeable to have around than Peter," she admitted taciturnly; which was as close to her real opinion of the man as a mere mother might hope to come.

Ward Warren sat before the fireplace with a cigarette long gone cold in his fingers and stared into the blaze until the blaze died to bright-glowing coals, and the coals filmed and shrank down into the bed of ashes. Billy Louise had spoken to him twice, and he had not answered. She had swept all around him, and he had shifted his feet out of her way, and later his chair, like a man in his sleep who turns from an unaccustomed light or draws the covers over shoulders growing chilled, without any real consciousness of what he does. Billy Louise put away the broom, hung the dustpan on its nail behind the door, and stood looking at Ward curiously and with some resentment; this was not the first time he had gone into fits of abstraction as deep as his absorption in the books he read so hungrily. He had been at the Wolverine a month, and they were pretty well acquainted by now and inclined to friendliness when Ward threw off his moodiness and his air of holding himself ready for some affront which he seemed to expect. But for all that the distrust never quite left his eyes, and there were times like this when he was absolutely oblivious to her presence.

Billy Louise suddenly lost patience. She stooped and picked up a bit of bark the size of her thumb and threw it at Ward, with a little, vexed twist of her lips. She had a fine accuracy of aim—she hit him on the nape of the neck, just where his hair came down in a queer little curly "cow-lick" in the middle.

Ward jumped up and whirled, and when he faced Billy Louise he had a gun gripped in the fingers that had held the cigarette so loosely. In his eyes was the glare which a man turns upon his deadliest enemy, perhaps, but seldom indeed upon a girl. So they faced each other, while Billy Louise backed against the wall and took two sharp breaths.

Ward relaxed; a shamed flush reddened his whole face. He shoved the gun back inside the belt of his trousers—Billy Louise had never dreamed that he carried any weapon save his haughty aloofness of manner—and with a little snort of self-disgust dropped back into the chair. He did not stare again into the fire, however; he folded his arms upon the high chairback and laid his face down upon them, like a woman who is hurt to the point of tears and yet will not weep. His booted feet were thrust toward the dying coals, his whole attitude spoke of utter desolation—of a loneliness beyond words.

Billy Louise set her teeth hard together to keep back the tears of sympathy. Suffering of any sort always wrung the tender heart of her. But suffering like this—never in her life had she seen anything like it. She had seen her father angry, discouraged, morose. She had seen men fight. She had soothed her mother's grief, which expressed itself in tears and lamentations. But this hidden hurt, this stoical suffering that she had seen often and often in Ward's eyes and that sent his head down now upon his arms— She went to him and laid her two hands on his shoulders without even thinking that this was the first time she had ever touched him.

"Don't!" she said, half whispering so that she would not waken her mother, in bed with an attack of lumbago. "I—I didn't know. Ward, listen to me! Whatever it is, can't you tell me? You—I'm your friend. Don't look as if you—you hadn't a friend on earth!"

Still he did not move or give any sign that he heard. Billy Louise had no thought of coquetry. Her heart ached with pity and a longing to help him. She slid one hand up and pinched his ear, just as she would playfully tweak the ear of a child.

"Ward, you mustn't. I've seen you think and think and look as if you hadn't a friend on earth. You mustn't. I suppose you've got lots of friends who'd stand by you through anything. Anyway, you've got me, and—I understand all about it." She whispered those last words, and her heart thumped heavily with trepidation after she had spoken.

Ward raised his head, caught one of her hands and held it fast while he looked deep into her eyes. He was searching, questioning, measuring, and he was doing it without uttering a word. The plummet dropped straight into the clear, sweet depths of her soul. If it did not reach the bottom, he was satisfied with the soundings he took. He drew a deep breath and gave her hand a little squeeze and let it go.

"Did I scare you? I'm sorry," he said, speaking in a hushed tone because of the woman in the next room. "I was thinking about a man I may meet some day; and if I do meet him, the chances are I'll kill him. I—didn't—I forgot where I was—" He threw out a hand in a gesture that amply completed explanation and apology and fumbled in his pocket for tobacco and papers. Abstractedly he began the making of a cigarette.

Billy Louise put wood on the fire, pulled up a square, calico-padded stool, and sat down. She waited, and she had the wisdom to wait in complete silence.

Ward leaned forward with a twig in his hand, got it ablaze, and lighted his cigarette. He did not look at Billy Louise until he had taken a whiff or two. Then he stared at her for a full minute, and ended by flipping the charred twig playfully into her lap, and laughing a little because she jumped.

"What made you catch your breath when I told my name that night I came?" he asked quizzically, but with a tensity behind the lightness of his tone and behind the little smile in his eyes as well. "Where had you ever heard of me before?"

Billy Louise gasped again, sent a lightning-thought into the future, and answered more casually than she had hoped she could.

"When I was a kid I ran across the name—somewhere—and I used it to play with—"

"Yes?"

"You know—I was always making believe different things. I never had anyone to play with in my life, so I had a pretend-girl, named Minervy. And I had you. I used to have you rescue us from Indians and things, but mostly you were a road-agent or a robber, and when you weren't holding me or Minervy for ransom, I was generally leading you over some most ungodly trails, saving you from posses and things. I used," said Billy Louise, forcing a laugh, "to have some wild old times with you, believe me! So when you told your name, why—it was just like—you know; it was exactly like having a doll come to life!"

He eyed her fixedly until she tingled with nervousness.

"Yes—and what about—understanding all about it? Do you?" He drew in his under lip, let it go, and drew it again between his teeth, while he frowned at her thoughtfully. "Do you understand all about it?" he insisted, leaning toward her and never once taking that boring gaze from her face.

"I—well, I—do—some of it anyway." Billy Louise lifted a hand spasmodically to her throat. This was digging deeper into the agonies of life than she had ever gone before. "What was in the paper," she whispered later, as if his eyes were drawing it from her by force.

"What was that? What did it say?"

"I—I—what difference does it make, what it said?" Billy Louise turned imploring eyes upon him. Her breath was coming fast and uneven. "It doesn't matter—to me—in the least. It—didn't say much. I—can't tell exactly—" She was growing white around the mouth. The horror of being compelled to say, out loud—and to him!

"I didn't know there was a woman in the world like you," Ward said irrelevantly and looked into the fire. "I thought women were just soft things a man had to take care of and carry along through life, a dead weight when they weren't worse. I never knew a woman could be a friend—the kind of friend a man can be." He threw his cigarette into the fire and watched the paper shrivel swiftly and the tobacco turn into a thin, blue smoke-spiral.

"Life's a queer thing," he said, taking a different angle. "I started out with big notions about the things I'd do. Maybe I started wrong, but for a kid with nobody to point the trail for him, I don't think I did so worse—till old Dame Fortune spotted me in the crowd and proceeded to use me for a football." He leaned an elbow on one knee and stared hard at a burning brand that was getting ready to fall and send up a stream of sparks. Then he turned his head quite unexpectedly and looked at Billy Louise. "What was it you read?" he asked abruptly.

"I—don't like to—say it," she whispered unsteadily.

"Well, you needn't. I'll say it for you, when I come to it. There's a lot before that."

Ward Warren had never before opened his soul to any human; not completely. Perhaps, sitting that evening in the deepening dusk, with the firelight lighting swiftly the brooding face of the girl and afterward veiling it softly with shadows, perhaps even then there were desolate places in his life which his words did not touch. But so much as a man may put into words, Ward told her; more, a great deal more, than he would ever tell to any other woman as long as he lived. More perhaps than he would ever tell to any man. And in it all there was no word of love. It was of what lay behind him that he talked. The low, even murmur of his voice was broken by long, brooding silences, when the two stared into the shifting flames and saw there the things his words had conjured. Sometimes the eyes of Billy Louise were soft with sympathy. Sometimes they were wide and held the light of horror. Once, with a small sob that had no tears, she reached out and clutched his arm. "Oh, don't!" she gasped. "Don't go on telling—I—I can't bear to listen to that!"