* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Mystery Lady

Date of first publication: 1925

Author: Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933)

Date first posted: July 23, 2018

Date last updated: July 23, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180793

This ebook was produced by: Al Haines, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

MYSTERY LADY

By

ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

Author of

THE COMMON LAW, AMERICA, IN SECRET, ETC.

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1925 By

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Printed in the United States of America

| Page | |||

| No. | 1. | The Adventure of the Girl’s Brother | 1 |

| No. | 2. | The Adventure of the Museum | 21 |

| No. | 3. | The Adventure of the Forty Club | 50 |

| No. | 4. | The Adventure of Drawing-Room A | 77 |

| No. | 5. | The Adventure of Stede’s Landing | 107 |

| No. | 6. | The Adventure at Place-of-Swans | 138 |

| No. | 7. | The Adventure on Tiger Island | 168 |

| No. | 8. | The Adventure at the Gay-Cat | 204 |

| No. | 9. | The Adventure on False Cape | 232 |

| No. | 10. | The Adventure in Crescent Blind | 256 |

| No. | 11. | The Adventure of the Little Death | 283 |

| No. | 12. | The Adventure in Loveless Land | 312 |

The Mystery Lady

A STORY IN TWELVE ADVENTURES

That was the trouble with the boy when he came into his own money—a headstrong desire to prove himself a grown man—reaction, probably, from twenty years of apron-strings, from which the death of his widowed mother and the advent of his majority set him free.

Now he was through with advice. He was through with having anybody tell him anything. He was now ready to tell the world. . . . At twenty-one.

His sister could do nothing with him. He was sensitive, stubborn, cocksure of himself. He flared up at any hint of admonition, of authority, of pressure.

He was neither vicious nor weak; he was a healthy cub suddenly unleashed in the world’s very large back yard. It went to his head, and he raced all over the place, intoxicated by a freedom with which he did not know what to do.

There’s always some dog-catcher watching for crazy pups.

A Mr. Barney Welper made the boy’s acquaintance one evening in the Club at Palm Beach. At West Palm Beach there was a religious revival and prohibition rally, whither, it appeared, Mr. Welper was bound. That he could not induce the boy to go, saddened Mr. Welper.

So, as the boy did not take readily to the spiritual, Mr. Welper tried him with the material.

Like the Red Fisherman who has such a varied assortment of bait in his bait-box, Mr. Welper therefore changed the lure and put on a gang-hook garnished with cruder bait.

So several enormously wealthy friends of Mr. Welper’s sauntered onto the stage, taking their several and familiar cues in turn.

The first of these was a very pretty brunette woman of thirty—a Mrs. Helen Wyvern. She had been “misunderstood,” it appeared.

After half an hour on the beach with her the boy discovered that Mrs. Wyvern was the first woman who ever had “understood” him.

Still all a-quiver with wonder, pride, and gratitude, he met another friend of Mr. Welper’s—a Mr. Eugene Renton.

Mrs. Wyvern whispered to the boy that, like Mr. Welper and herself, Mr. Renton was making millions out of Orizava Oil.

The rest is redundant.

When the boy’s money went into Orizava Oil they fed him “dividends” until his last penny was up.

He was proudly a part of Orizava Oil. On a salary he travelled on “confidential” missions for the corporation. All the glamour of a King’s Messenger was his, only he didn’t carry the Silver Greyhound: he was enough of a pup without other insignia.

And now the boy prepared to show the world,—and his incredulous sister. Already the inevitable astonishment and admiration of Wall Street entranced him in advance. He was a sad dog. He gazed into the brown eyes of Mrs. Wyvern and knew he was as sad a dog as ever had been whelped on earth.

Now it happened, when travelling on one of his “confidential” missions—which were devised to keep him out of the way because he bored Mrs. Wyvern——the boy found himself in Charleston, South Carolina, where Mr. Welper awaited him.

What Mr. Welper ever was about few people on earth knew; but he inhabited Charleston at that time, and the boy found him at the St. Charles Hotel and delivered a heavily sealed packet proudly. No doubt there were millions in securities in that envelope. It thrilled the boy to see Welper lock it in his satchel. It thrilled the boy still more to fish out a heavy automatic from the holster under his left arm-pit and lay it carelessly upon Mr. Welper’s bureau.

“They’d be up against hell itself if they tried to pull anything on you, wouldn’t they?” remarked Mr. Welper solemnly.

The boy attempted to look modest.

“Possibly,” suggested Welper, “while I’m busy here you might like to stroll about town—m—m, yes—or see a moving picture—” He handed the boy a local newspaper.

With the weary and patronising air of extremest sophistication the boy condescended to glance over the newspaper. He remarked that theatres bored him.

“There are some amusing auctions in the older part of town—if you are psychologically inclined,” suggested Mr. Welper. “Man is, m—m, the proper study of man.”

Psychology was the cant word of the hour.

“I’ll stroll around that way,” said the boy. In the back of his blond head his thoughts were fixed upon a movie.

In the crowd in which the boy was standing a friendly neighbour drawled gratuitous information to the effect that the house,—the contents of which were being sold preparatory to demolition,—was “one of the oldest houses in Charleston, Suh.”

Also the boy learned that here Governor Eden of evil fame, and of North Carolina, died of fright several hundred years previously.

“What frightened him?” the boy inquired.

He was informed that Governor Eden had been in secret partnership with Stede Bonnet, the pirate; and that when Bonnet was finally caught the guilty Royal Governor, in terror of Bonnet’s confession, fled to Charleston and died of sheer fright in this very house.

“The coward!” commented the boy, who had never known a guilty fear.

The auctioneer, in his soft, pleasant, Southern voice, continued to describe the contents of this ancient house as it was sold under the hammer, lot by lot.

A small but heavy leather box, garnished with strap hinges and nails of copper, was offered.

According to the auctioneer it bulged family papers; he urged it as a fine speculation for any collector of antique documents.

As there appeared to be no such collectors present, the boy bid a dollar. A negro wanted the box for some unknown purpose and bid a dollar and a quarter.

At two dollars the boy got the box.

Why he bought it he did not quite understand,—except that like all boys he was interested in pirates; and the mention of Stede Bonnet revived the deathless appetite.

“Send it to me at the St. Charles Hotel,” he said carelessly, and paid for the cartage also.

Then, having had enough of romantic antiquity, he started for reality and the nearest movie.

That evening after dinner Mr. Welper wrote letters, and the boy went to the theatre.

Mr. Welper was still writing letters when the boy returned. Tired, ready for bed, he went into his room, which adjoined Mr. Welper’s. But a boy, no matter how sleepy, welcomes any diversion that postpones that outrageous waste of time called sleep.

As he stood yawning and undecided, his eye fell on the box which he had purchased at auction.

A large, wrought-iron key was tied to one handle. With his penknife he cut it loose, unlocked the box, and gazed at the stacks of ancient documents within.

All were tied with pink tape. A musty odour filled the room. The boy seated himself on the carpet, still yawning, picked up a packet of ancient deeds, tossed them aside, glanced over a sheaf of letters, petitions, invoices, legal documents with waning interest. Then, of a sudden, his eye fell upon the signature of Stede Bonnet. Interest freshened; he read the letter with the conscious thrill that invades all boys even when in vaguest contact with great malefactors.

He looked with awe upon the signature of Stede Bonnet, touched his finger to the faded ink, strove to realise that the hand which had penned this screed had been imbrued in human blood; shivered agreeably.

The letter was written by Bonnet on board the sloop Revenge off the Virginia Capes, to one Edward Teach, Esq., on board a ship called the Man-o’-War.

It requested a rendezvous for the two ships off False Cape.

Further, Bonnet informed Teach, he had obtained documents in the Barbadoes which, if deciphered, might clear up the mystery of the ship Red Moon. But, he added, it would require the crew of the Man-o’-War as well as his own crew to salvage the cargo if, indeed, the location of the sunken ship could be discovered.

Eden believed it lay in five fathoms somewhere off Tiger Island. The crews of the two ships could camp on Tiger Island, or, more comfortably, on the group of three islands west of False Cape and known as “The Place-of-Swans.”

The boy was wide awake now. Letter after letter he examined, untying and re-tying the faded yellowish packets.

These letters and documents offered all sorts of information concerning events on the high seas two hundred years ago. Among other things the boy learned that Bonnet had hoisted the black flag and had taken the Anne of Glasgow; that the other name for Edward Teach, Esq., was “Blackbeard the Pirate;” and that Blackbeard had as ally a bloody scoundrel named “Dick Hands,” commanding a sister ship near Ocracoke Inlet, North Carolina.

And now the thrills that had swept the boy when he first read Treasure Island so long ago again stirred his blond and curly hair. He read of abominable cruelties, of treachery unspeakable, of savage reprisal, of robbery, of torture, of murder, of heartless mirth, of horrible excesses, carouses, mutiny, of pursuit, of escapes by sea and land.

Hour after hour he sat there cross-legged on the carpet devouring the ancient records of wickedness; but, not until he came to the very last packet in the box, did he discover any further mention of the “Red Moon, galley.”

“She has been missing,” Bonnet wrote, “since the month of July in 1568, which is now more than a hundred and fifty years ago. But it is known that she sailed loaded from bilge to gunwales with pure, soft, Indian gold. . . . Which knowledge, when imparted to me by Eden,” added poor Bonnet, “so inflamed me that, although I was an English gentleman with vast estates in the West Indies, and indeed was rich and everywhere respected, I could think of naught but this Spanish shipful of soft, Indian gold.

“My God, Mr. Teach, I think my mind is crazed with the fierce flame of desire that devours me night and day. For such a man as I must be mad indeed to abandon estates, riches, and the approbation of honest men to take the sea for gold he hath no need of.

“Yes this, God help me, is what I have done in my sloop, Revenge; and I am committed, for I have taken the Anne of Glasgow; and the black flag flies at my fore.”

The other documents in the last packet were a paper and a parchment tied together.

The paper was grimly significant. In Governor Eden’s hand was written:

“This parchment, if properly translated, should indicate the precise spot where the Red Moon, galley, sank in 1568.”

Under this Stede Bonnet had written his name and: “Property of Governor Eden, who had it of the late Captain William Kidd.”

Under this was written:

“Kidd is in hell and Eden may go thither at his convenience. This document now belongs to Wm. Teach. Let him who hath a gamecock’s gizzard come and take it!”

The boy sat with mouth open staring at a specimen of that kind of Truth which makes fiction tasteless.

Here between his own fingers he had the terrible story as told by those who once enacted it; he actually was touching a paper which had been touched by the reeking hands of Blackbeard!

Legendary pirates suddenly had become living creatures of to-day, leering at him out of the lamplight, telling their frightful tales for his ears alone,—tales of blood and gold!

Again and again as in a trance he read the tragedy,—strove to read between the brief, grim lines, to visualise, to comprehend.

And now, trembling, the boy unfolded the parchment which, these bloody men informed one another, contained the key to a sunken ship loaded to the gunwales with “pure, soft, Indian gold!”

It was the strangest document he ever had gazed upon. Half of the parchment was covered with outlandish signs and symbols. Then there was a space; then some writing in Spanish, done with ink, perhaps; perhaps with blood.

The boy could neither decipher the strange and rather ghastly symbols, nor could he read Spanish.

For a long while he pored over the parchment, his eyes heavy now with sleep; and at last he placed it on his dresser and laid him down to dreams of blood and gold.

When Mr. Welper came in the morning to awake the boy he found him still sleeping.

It was a habit of Mr. Welper’s to satisfy a perennial curiosity concerning other people’s private business when opportunity offered.

He was a soft-handed, soft-footed, short, stout gentleman with a sanctimonious face and voice. His hands and feet were so disproportionately small that they seemed almost dwarfed; but they were endlessly busy implements in Mr. Welper’s service; and now his little feet trotted him soundlessly to the open box with its contents of yellow papers; and his little hands touched and pried and meddled and shuffled the documents, while at intervals his sly eyes fluttered toward the sleeping boy.

Presently Mr. Welper discovered the documents on the boy’s dresser; he approached, and had been cautiously studying them for a minute or so when suddenly the boy sat up in bed.

Caught in the act, Mr. Welper was, as always, efficient in any crisis.

“The wind,” he explained, “blew these papers into the bathroom. Supposing that, m—m, they belong to you, I entered your room to return them.”

Some latent instinct stirred the boy to get out of bed and take the papers which Welper laid upon the dresser. He got back into bed still clutching them.

“Where,” inquired Mr. Welper with gently jocose but paternal interest, “did you collect this ancient box of junk?”

“Oh, it’s just worthless stuff,” said the boy, reddening at the lie.

Mr. Welper stood motionless, a remote expression on his countenance.

“You had better dress and come to breakfast,” he said absently. “We start back to New York this morning, and our train leaves at ten.”

It was evident to the boy that Mr. Welper attached no importance to the documents.

All the way to New York, Barney Welper was occupied in contriving a safe and sane way to possess himself of the documents which he had read sufficiently to realise that he wanted them.

But some blind, odd instinct led the boy to keep them upon his person night and day—not that it occurred to him to suspect Mr. Welper—

But, if he had anything at all of tangible value in those papers, he had a fortune! And so vast a fortune that it made him almost uncomfortable and slightly giddy to try to calculate what a ship loaded to the gunwales with “soft, pure, Indian gold” might be worth.

One thing in these pirate papers had instantly engaged the boy’s attention—the mention of False Cape, Tiger Island, and Place-of-Swans.

Because, westward from False Cape and across the sea-dunes, lay those vast inland fresh-water sounds and bays spreading through Virginia and North Carolina which he had known from earliest childhood.

And Place-of-Swans was the valuable island property inherited by his sister and himself from a sportsman father; and which, for two months every year, had been the family’s home in early winter.

Tiger Island was farther away—a place of no value for shooting, because for some reason neither duck, geese nor swan haunted the adjacent waters, nor ever had within the memory of living men.

To see False Cape and Place-of-Swans and Tiger Island mentioned by a bloody pirate in his own handwriting had thrilled the boy as he never before had been thrilled.

Suppose—but it would be sheer madness to suppose that the Red Moon, galley—And yet the boy understood that the first thing he meant to do on reaching New York was to sell enough stock in Orizava Oil to buy Tiger Island.

And now he began to recollect that in earliest childhood he had heard mention of the region as an ancient haunt of pirates. . . . There was the almost forgotten nursery legend of False Cape, and of the aged horse wandering all alone over the wintry dunes with a lighted lantern tied around his sagging neck. . . . And the boy now remembered to have heard his father speak of an ocean inlet which once existed somewhere to the eastward, and which now had filled up with a solid mile-wide barrier of snow-white sand, barring the salt sea water from the fresh.

So the long hours in the train wore away for the boy in the endless glamour of other days; for Mr. Welper in mousy cogitation.

When the boy, to his stupefaction, discovered that his shares in Orizava Oil were neither regarded as attractive collateral by any financial institution, nor as salable at any except ruinous figures, he went in terror to Mr. Welper, and was calmed and reassured at a “confidential” interview in the private office of that pious financier.

In about six months, it transpired, the “inner interests” would be ready to start Orizava Oil sky-high. Until then, mum!—not a word, not the wink of an eyelash!

The boy, tremulous but comforted, resigned himself to await the millions which, within six months, were certain to be his.

Yet, meanwhile there was Tiger Island. The state owned it, but offered it for sale. A few hogs pastured in the reeds and the gloomy pines of Tiger Island. There was no habitation on the snake-ridden place; for centuries it had been ownerless and common property for any who cared to pasture hogs or cut logs and float them to the mainland. Which latter enterprise was more of an effort than anybody ever had undertaken; and the pine woods were still primeval.

Finally the state took title to Tiger Island; set, arbitrarily, a ridiculously high figure on it, and offered it for sale, claiming that the purchaser could cut a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of timber from the untouched woods.

The boy now suffered deadly fears that either some lumber interests would buy Tiger Island, or that somebody’s anchor might accidentally foul the wreck of the Red Moon and drag up golden relics which would start a gold craze and set the entire region wild.

Somehow or other the boy had to raise enough money to secure Tiger Island and the adjacent waters, worthless as far as wild fowl were concerned.

The boy’s sister was still in Europe. He cabled her that he needed a hundred thousand dollars—without any other result than worrying his sister and starting a flight of sisterly and admonitory letters.

Then he wrote her and explained the matter in full; and his sister, thoroughly alarmed at what he had done in Orizava Oil, made preparations to terminate her delightful sojourn on the Riviera and return to New York where, it was very evident, her younger brother was attempting to make ducks and drakes of his inheritance.

And now the boy was becoming nervous and desperate, and he tried to borrow the money from Mr. Welper personally, without explaining why he wanted it, and was severely and piously chastened by that austere gentleman, who pointed out the enormity of anybody in the secret being treacherous enough to move a finger or stir an eyelash until the time set for starting an eruption of Orizava Oil as high as the volcano after which the corporation had been named.

The next week the boy’s apartment was broken into and ransacked by burglars who, oddly enough, burgled only the documents which the boy had bought at auction in Charleston.

The packet containing the parchment, however, was in the boy’s safe-deposit box,—or rather in two separate boxes in different banks. For the boy, supposing that the Spanish inscription was a translation of the hieroglyphics, had torn the parchment in two, thinking it safer to separate the duplicate inscriptions in case of any accident to either.

Nevertheless, the affair alarmed the youngster fearfully, though he never dreamed of connecting Mr. Welper with such a thing—a gentleman he so frankly admired, revered, feared.

But the stupidity of burglars who made off with antique documents exasperated him. Such papers loose in the world might start clever minds in the direction of Tiger Island.

One day, almost beside himself with anxiety, the boy took from one of the safe-deposit boxes the cherished papers and went to the offices of Orizava Oil, determined to show Mr. Welper everything and offer him a partnership for money enough to start the enterprise.

Mr. Welper was not in his own private lair, but the boy walked in, all white and desperate. And saw the private safe of Mr. Welper wide open, yawning in his very face.

Like a little bird hypnotised by the wide jaws of a deadly snake, the boy moved irresistibly toward the open safe.

Good God!—here was plenty, and to spare,—packets of Treasury notes, securities instantly marketable, bonds better than bars of gold—

His half-swooning mind was trying to co-ordinate robbery with the fact that, in six months, he would be worth millions who to-day hadn’t a thousand dollars in the bank.

He took a hundred thousand dollars in Treasury notes and securities.

He placed the packets in his overcoat breast-pocket, turned, walked out, went very steadily to the corridor, out into the hall to the elevator.

The cars flashed up and down. He had not rung. He waited. But when at length a car stopped at the landing where he stood he let it go on without him. And, after a long while, the boy turned as though dazed and started unsteadily back toward the offices of Orizava Oil. And met Mr. Welper coming out.

The latter looked at him with sly, keen eyes veiled by heavy lashes.

“I’m just leaving—if you’ve come to see me. A very, m—m, very important matter.”

The boy now realised the private safe of Mr. Welper was closed. He turned deathly pale.

“Is anybody there?” he managed to ask.

“Nobody now—except Mrs. Wyvern. Why?”

A last straw!—the only woman who ever had understood him!

“I’ll come back if—m—m—if I can be of any service,” purred Welper. . . . “Are you sick?”

“N-no.”

“You look like a ghost, my son. Probably—ah—undoubtedly you are up late. M—m, yes; but youth!—ah, youth! Well, I must hasten. So—m—m, ah, good-day to you, my son.”

The boy went slowly back to the offices of Orizava Oil and straight into Mr. Welper’s lair. The safe was closed.

Now, more slowly still, he walked through the pretentious suite, noticing nobody until he came to the private retreat of the only woman who ever had understood him.

She was busy at her desk, looked up at him, annoyed, but smoothed her features instinctively. For even a fool of a boy might make mischief within the next few months if treated with too open contempt.

“Sit down, Jimmy,” she said sweetly. “What is the trouble?”

“Trouble—trouble—” he stammered, “I can’t tell you. . . . And I’ve got to—.” His face had become scarlet and there were tears in his eyes.

“Helen,” he whispered, “you won’t understand—you who are so chaste, so pure, so untempted—” he choked. And she looked at him tenderly, considering him a fool and an unmitigated nuisance.

“What is the trouble, Jim; a—” she smiled archly, “a love affair?—”

“Oh, my God!—when I am in love with the very ground you walk on!”

His voice had a little of the bleat about it—which perhaps was natural in a case of calf love—and it unutterably annoyed Mrs. Wyvern, who had no desire to be made ridiculous within hearing of the stenographers in the next office.

It was hard for her to play her part, but she was a thrifty and cautious woman, so she suppressed her temper and, rising, led the human calf to a sofa, where she retained his feverish hand.

For a while he sobbed on her shoulder. She set her even teeth and endured it.

“Helen,” he managed to say at last, “I’m disgraced. . . . I can’t tell you—looking into your pure eyes. . . . I—I’ll write it and you c-can read wh-what the man who loves you really is—”

He seized a scratch-pad and fountain pen, and, hunched up beside her on the sofa, began the hysterical scribble which was destined to put a quietus upon him and his asininity for a while. The screed was an explanation. He told her about the discovery of the parchment, of his dire necessity for money with which to buy Tiger Island, of his attempts to raise it.

He fished out the corroborative documents and laid them on her lap. Half of the parchment was missing—the Spanish part—because he had been in too much of a hurry to go to both banks.

Mrs. Wyvern’s brown eyes had now become magnificently brilliant. She examined the documents; read the statement he showed her.

“But,” she inquired, mystified, “where is the disgrace in all this, Jim?”

“Wait,” he said in a choking voice. Then, as she watched his clumsy boy’s fingers under her very and ornamental nose, this embryo ass wrote his valedictory:

“—Helen, try to be merciful and find it in your heart to forgive the man who loves you and who confesses his degradation at your feet.

“I have been weak enough to take from Mr. Welper’s safe notes and securities valued at a hundred thousand dollars.

“I am a common thief.”

And then he signed his full name, pulled the stolen securities and money from his pocket, and laid them in her lap.

Mrs. Wyvern really was dumb with amazement. This little whipper-snapper!—this sentimental little ass had had the courage to do that!

She looked at the packet, at the parchment covered with hieroglyphics, at the letter, at the boy’s confession, signed with his full name and the ink still wet—

In a flash she knew exactly what was to be done and how to do it. She drew the boy to her and gently kissed his forehead; sat patiently while the storm burst and swept his miserable young soul cleaner of vanity than it had been for many a month.

“You—you have the co-combination of Mr. Wel-el-per’s safe. Put them back and he will never know how low I sank. I—I thought I could be a thief, but it wasn’t in me—and I couldn’t do it—I couldn’t do it—”

Mrs. Wyvern could cheerfully have pushed a knife in him. She wore one in a satin sheath attached to her right garter.

“There, there,” she said soothingly, “there, there. Now go home and forget it. It’s all over, Jimmy—”

“B-but—”

“No, it hasn’t made any difference with me. Your behaviour was noble. There is no other word. You remember—there is more rejoicing in Heaven—you recollect?—something about the ninety and nine—”

“Oh, Helen!”

“Go home and leave it all to me.”

He went, at last, having bleated his fill.

Meanwhile Mr. Welper had returned. After the boy had left he came into Mrs. Wyvern’s office.

“What was the matter with that fool boy, Nell?” he inquired.

She told him exactly. She went over every incident with precision. She handed him the stolen securities; she showed him the documents concerning Tiger Island, letters, parchment, everything. Then she gave him the boy’s confession to read.

After a little while: “I think,” said Mr. Welper softly, “that this is going to be easy—very easy, and, m—m, remunerative. Yes, I think so.”

“I think so too,” smiled Mrs. Wyvern, delighted to be rid of the boy forever.

Then both of them, still smiling, put their heads together to sketch out the last act of the farce in which the boy had played the clown too long.

“Why not finish at once?” said Mrs. Wyvern. She rose, opened the safe, tossed in Mr. Welper’s securities, the boy’s documents and written confession. Then she closed and locked the safe.

“Very well, call him on the telephone. He’s home by this time, I suppose,” the man agreed.

Mrs. Wyvern called; the boy answered tearfully, and promised to return at once.

“I’ll have to go to the Forty Club and try to decipher these hieroglyphics,” said Mr. Welper.

“Do you think you can?”

“We are supposed to have every facility in our library for solving any cipher ever known,” remarked Mr. Welper. . . . “I ought to do it in a week.”

“Why not take it to the Museum of Inscriptions?”

“Why call in anybody unless I’m obliged to?” inquired Welper, slyly.

“Meanwhile you had better take a flyer and buy Tiger Island,” suggested pretty Mrs. Wyvern. “Fifty-fifty, you know. I might have kept it for myself, Barney.”

Welper hesitated, ventured a cautious glance, understood that he was at her mercy.

“Certainly, my dear,” he purred, “fifty-fifty was what I meant to offer.”

Both smiled again. But their expressions altered immediately as the boy entered and stood stock still at sight of Welper.

“Where are the Treasury notes and securities you stole from my safe?” asked Mr. Welper coldly.

The boy stared at him, horrified, then went white as death and turned to Mrs. Wyvern.

“I gave them to you,” he said in a ghastly voice.

“You did not,” she said calmly.

After a terrible silence: “God!” he gasped, “am I going crazy!”

“No,” said the woman, “you’ve always been a fool, and now you’re a thief.” And to Welper: “You tell him where he gets off, Barney. And if he pulls any gum about making restitution to me, tell him to get his witnesses or we’ll get his signed confession and turn it—and him—over to the police.”

Mrs. Wyvern rose leisurely, turned and left the office by another door, leaving the boy half fainting, leaning against the wall, and Mr. Welper slyly watching him.

The latter broke the frightful silence, harshly:

“Where’s that hundred thousand, you dirty thief!”

At the word the boy suddenly understood the entire and horrible duplicity. He made a movement toward his left arm, and Mr. Welper’s pistol muzzle dented his stomach.

Then the older man relieved the boy of his weapon.

“Now,” he said, “you listen. You go to prison. Understand? I’ve got it on you, and your fist at the bottom; and I’ve got my witness, and your finger prints on my safe and on the packets. And I’m going to see that they railroad you, my young buck, and you’ll do your stretch and disgrace your family forever.

“Now get out. You’re just one jump ahead of the cops. And if ever you show that boob mug anywhere you can kiss yourself good-bye—one way or another. . . . Beat it!”

After a night of such agony as he never dreamed could be, even in hell, the boy was terrified by a ring at his door-bell. But it was only a messenger boy with a wireless dispatch from his sister in mid-ocean, whose steamer, she warned him, would dock in four days.

Haggard, half dead from the shock of it all, almost crazed by his ruin and threatened disgrace, he packed a suit-case and sat down to write a letter to his sister. He was shaking all over. Had Welper not taken his pistol away he probably would have committed the supreme fool act.

Very shakily and painfully the boy wrote out the circumstances of his connection with Orizava Oil from the beginning. He ended with the fear expressed that it was a gigantic swindle and that his money was gone forever.

Then, forcing his flagging hand, he wrote out the history of his love for Mrs. Wyvern and how it had ended.

And last of all he told her about the Bonnet-Eden-Teach documents, the parchment covered with South American symbols, his attempt to raise money to buy Tiger Island, his temptation, disgrace, the restitution, and how utterly he had put himself into the hands of this woman and this man who now were about to hand him over to the police.

“Sis,” he continued, “I’ve been a fool. I can’t face the disgrace. I can’t disgrace you. I’m ruined utterly. They mean to send me to prison. They have sufficient evidence.

“There’s only one way out of it to save the family name. I’m going to Place-of-Swans. You will get a telegram by Thursday from old Jake saying I’ve had a bad accident with a shotgun. I’ll be dead, Sis darling. It’s the only way. You’ll find this letter at your bank waiting for you. I enclose our safe-deposit key. The half of the parchment which Welper did not steal is in the box at the Imperial Trust Company, which you and I rent together. If the paper is of value, turn it over to your lawyer and try to get hold of Tiger Island before Welper buys it. I firmly believe it is worth millions. Good-bye, dear Sister. Forgive me for being a fool. I wasn’t a thief; I did give back everything, no matter what they say.

“Your unhappy brother.”

Three days later, when the boy’s sister landed, a telegram awaited her to say that her only brother had been drowned off Tiger Island by the capsizing of his sailboat.

That morning the Curator of the Division of Inscriptions arrived at the Museum at about ten o’clock, as usual.

In the anteroom his secretary rose from her typewriter, and handed him a visiting card. And at the same time be became aware of a slender girl in mourning seated on a sofa in the corner.

He read the visiting card: Miss Maddaleen Dirck; turned toward the motionless figure in black:

“Miss Dirck?” he inquired.

The girl stood up: “Yes; could I speak to you for a moment in private?”

He opened the door to his private office: “Come in,” he said.

Except for a cast of the Rosetta Stone, a model of some Argive ruins, and one or two photographs on glass, showing Egyptian excavations, and hung against the window-panes, the private office of the Curator of Inscriptions resembled that of any ordinary business man.

Dr. Walton laid off his hat and coat, adjusted his spectacles, regarded his visitor absently, and suggested that she be seated. But the girl remained standing, her dark blue eyes fixed on him with intensity almost disturbing.

“Well,” inquired the Curator of Inscriptions, “what can I do for you?”

After a moment’s silence: “Dr. Walton, please help me,” she said.

The Curator looked surprised: “My dear young lady, what is it you wish?”

“Please give me permission to come here every day and sit in your office. I beg you will not refuse.”

“Come every day and sit in my office?” he repeated in mild astonishment. “Why?”

“Please let me,” she pleaded. “I promise to remain very silent and still. I shall not disturb you—”

“But, my dear child—”

“I know shorthand and typewriting—”

“But I already have what assistance I require—”

“It isn’t for money; I don’t care to be paid for helping you. . . . I know how to clean your desk, sweep and dust, wash the woodwork and floors—I’ll do anything, anything, for you if only you will let me come here every day.”

He was frowning a trifle; his large, mild eyes seemed larger, rounder, and more owlish through his spectacles.

“Miss Dirck,” he said, “your request is most extraordinary.”

“I know it is—”

“Why do you desire to come here?”

The girl stood silent, twisting a black-edged handkerchief between black-gloved fingers, her distressed gaze fixed on the Curator.

“Come,” he said kindly, “there must be some reason for your rather unusual request. Are you interested in ancient inscriptions?”

“Yes.” Her gaze fell to the carpet.

“Do you know anything about the subject?”

She shook her head.

“Did you suppose that merely by coming here you might pick up information?”

She lifted her dark eyes from the handkerchief which she had been twisting. The transparent honesty in them, and the tragedy, too, were plain enough.

“Please do not refuse,” she said. “I promise I won’t disturb you. I will work for you without pay. Just let me come here—for a while. . . .”

“For how long, Miss Dirck?”

“I don’t know. . . . A day—a month—”

“You seem to be in trouble,” he said solemnly.

“No. . . . Yes, I am in—in some distress of mind.”

“Could I aid you?”

“Only by letting me come here.”

“Why do you select this place? Can you not tell me that much?”

“Because I am informed that ancient inscriptions are studied and deciphered here.”

The Curator, thoroughly perplexed, gazed at her through his glasses, owlishly but not unkindly.

“Is there any particular kind of ancient inscription that interests you?” he asked. “You’ll have to tell me something, you know.”

She hesitated, moistened her lips: “Inscriptions which—which come from Central and South America interest me.”

“Maya or Aztec?”

“Both, I think.”

“But, my dear young lady, how are you ever going to learn anything about Aztec and Maya hieroglyphics,—ideographs, phonetics,—by coming into my private office every day and remaining in a corner still as a mouse?”

He smiled owlishly in his kindly way; but on the girl’s pale features there was no smile in response.

“Do not people come here sometimes to have inscriptions deciphered?” she asked tremulously.

“Sometimes. Have you any ancient inscriptions which you desire us to solve for you?”

“We—I had one—”

“Your family had one?”

“My brother. . . . He is dead. . . . I have nobody, now.”

Dr. Walton looked at her intently for a moment; then he walked up to her, took both her black-gloved hands between his own.

“Sometime,” he said, “you may care to tell me a little more about yourself. . . . I don’t mean that I’m vulgarly inquisitive.”

“You are good and kind,” she murmured.

He smiled and patted her hands:

“Now what do you wish me to do for you, Miss Dirck?”

“Let me sit quietly in your office while you are here. . . . And if people—come in—and talk about Central American inscriptions—I’d like to listen, if I may.”

He smiled: “You may; unless others object. I shan’t. But, my child, there is no deciphering work of that description done in my private office.”

“Oh,” she said, blankly, “where is it done?”

“Let me arrange matters for you,” he said, still smiling. He went to his desk and asked through the telephone for the division of Maya and Aztec Inscriptions.

“Mr. Whelan, please. . . . Is this you, Scott? Would you mind coming over to my office for a moment? Thanks.”

He hung up the instrument and nodded to the girl in black:

“Scott Whelan, one of our assistant curators, will be here presently. The Aztec and Maya division is his—”

The door opened and a lively young man entered.

“Miss Dirck,” said Dr. Walton, “this is Mr. Whelan.” And, to the latter: “Scott, Miss Dirck desires to have the privileges of your division. She wishes to see how it’s all done. In return she offers her services gratis. Anything of a clerical and useful nature that you may desire of her she volunteers to do,—copying, stenography, typing, cleaning, scrubbing—”

Under Mr. Whelan’s astonished gaze Miss Dirck reddened brightly. Dr. Walton laughed; and then Whelan laughed too; and, for the first time, a pale trace of a smile touched the girl’s lips.

When they all had laughed a little over the situation, Dr. Walton pleasantly explained it. Whelan, still perplexed but courteous, conducted Miss Dirck to his own private office.

Through an open door the girl saw another office where, at long tables, two or three men and as many women were seated poring over plaster models of inscriptions engraved on stone, studying, comparing, taking notes, making sketches, using magnifying glasses and even microscopes.

All around the room were ranged great plaster casts of massive, vermiculated blocks of stone covered with elaborate carvings and with hieroglyphics. Charts set thickly with symbols hung on the wall above rows of shelves filled with books.

“In there,” said Whelan, “my assistants are helping me to decipher the hieroglyphic inscriptions of a very ancient and wonderful civilisation,—the Maya.

“A thousand years before Christ a civilised people lived in Central America, Miss Dirck. They had priests, they had astronomers, mathematicians, politicians, architects, sculptors, painters,—they had a system of writing such as was developed in China and in Egypt—”

He checked himself with a smile: “Doubtless you already know all this, Miss Dirck?”

She shook her head.

“You are interested?” he asked.

“Yes. May I stay here in your office?”

“Certainly.”

She removed her hat; he took it and her fur coat and hung them beside his own.

When the girl had seated herself, Whelan sat down at his desk. She slowly stripped off her gloves.

“If,” he said, “it is Maya hieroglyphs that interest you, I must warn you that as yet we know very little about them. But about Aztec hieroglyphic writing we know pretty nearly all there is to know.”

“What is the difference between the two?” asked the girl, plainly interested.

“The Maya writing is a combination of the ideographic and phonetic,—symbols representing ideas, and symbols representing sounds. The Aztec is largely phonetic. It is simpler than the Maya, which is the older. Generally, the ancient Maya gentleman made a picture of what he wanted to say in writing; the Aztec drew a symbol representing a sound—as we do in our own alphabet. Their writing was homophonetic. Their basic symbols number about two hundred. We know most of them.

“But in the Maya hieroglyphics there are many more,—we don’t know yet how many. Almost all are ideographs,—that is, picture of ideas—”

He hesitated, realising that the girl was not able to follow him, although she listened with an intensity almost painful.

“Is there any beginner’s book, any primer, I might study?” she asked anxiously as a perplexed child.

He said: “There are a number of pamphlets, monographs, and reports published by our Museum. There are only three original Maya manuscripts known in the world. We have copies. All other Maya inscriptions are engraved on stone. We have many originals of these, and many casts.

“On the bookshelves over there you’ll find all the writings on Maya and Aztec civilisations that ever have been published. They are at your disposal, Miss Dirck.”

“Mr. Whelan, do people come to you with Maya and Aztec inscriptions which they wish to have you decipher for them?”

“Sometimes. Very few people are interested. Fewer still possess any such inscriptions. Now and then an amateur explorer or a hunter or a naturalist comes to us with a fragment of stone which he has picked up in some Mexican or Guatemalan jungle.”

“And you decipher for him what is written?”

“If we can—” He spoke absently but politely as he glanced over the morning mail laid upon his deck for his inspection.

Now, as the girl fell silent, he pleasantly asked her indulgence, and occupied himself with the pile of letters.

For half an hour he remained so occupied. Then laying aside his mail, he caught her dark eyes watching him.

“By chance,” he said with a smile, “I have a letter this morning from a man who says he has a parchment covered with Central American hieroglyphics, and who desires us to decipher it. If this is literally true it is important. Probably it is not true.”

“Is he coming here?” asked the girl quickly.

Whelan glanced at the clock. “Yes, and he is due now.”

“May I remain?”

“Certainly.”

“May I listen?”

“Yes, unless he objects.”

She drew a swift, nervous breath, sat up rigidly on her chair with a tense expression on her white face and her ungloved hands tightly clasped in her lap.

Minutes passed; the office clock ticked loudly. Whelan re-read his letters, made marginal notes on some of them, called his secretary from the anteroom, and dictated one or two replies; talked to several people on the telephone, conferred with two or three assistants who came to him for aid.

As the last of these retired, a museum guard opened the door and announced, “Mr. Barney Welper, sir. He says you expect him.”

“Show him in, Mike.”

Mr. Welper came in.

He was a man of sixty, perhaps, under middle height, rather fat, smoothly shaven, carefully but very simply dressed.

His grey hair was closely clipped; his features pasty but regular and almost expressionless—except the eyes. These were a hazel hue, shaded by remarkable lashes which, on a woman, would have been beautiful,—long, curling black lashes partly veiling the slyest pair of eyes that Whelan had ever encountered.

Urbane, softly moving, soft of voice, and with small, soft, pallid hands—these and the long lashes shadowing two sly eyes were the salient features which checked up the surface personality of Mr. Welper.

He bowed cautiously to Miss Dirck; he bowed very cautiously to Mr. Whelan.

The latter said: “I received your letter, Mr. Welper. Have you brought the inscription?”

Mr. Welper bowed again and Whelan indicated a chair beside his desk and asked his visitor to be seated.

Out of his breast-pocket Mr. Welper produced a folded paper, opened it, and laid it politely upon Whelan’s desk.

“Oh,” remarked Whelan, “a photograph?”

“There were reasons why I could not bring the original document.”

Whelan gave him rather a sharp glance.

“On what substance were these symbols written?” he asked bluntly. “It makes some difference, you see.”

“The original is written on parchment,” said Mr. Welper softly.

“Skin, fibre, wood, stone,—genuine Maya records are written on these. Unless I can examine the parchment I cannot tell you whether or not your records are genuine.”

He continued to study the photograph before him for a moment:

“However,” he added, “genuine or not, these Maya and Aztec characters are not difficult to decipher. I think I can translate this into English for you without much difficulty—”

He spoke into the transmitter of his desk telephone: “Please bring me the Maya and Aztec keys, Mr. Francis.”

In a few moments a thin young man with bulging forehead and scant hair came in, laid the two working documents on his desk, and retired.

Whelan spread out the photograph; Mr. Welper looked over his shoulder; Miss Dirck, deadly pale, got up and came toward the other side of the desk.

Mr. Welper rose noiselessly as though to intercept her.

“Pardon,” he said, politely,—and impolitely covered the photograph with one pasty little hand—“the matter is confidential, and I am not at liberty to show this document to anybody except Mr. Whelan.”

The girl flushed as though she had been struck. She had halted half-way across the room.

Whelan looked at Mr. Welper in surprise, then with a smile and the slightest of shrugs he asked the girl to step into the inner office where his assistants were at work.

As she passed the desk where Whelan sat he noticed that she had lost all her colour.

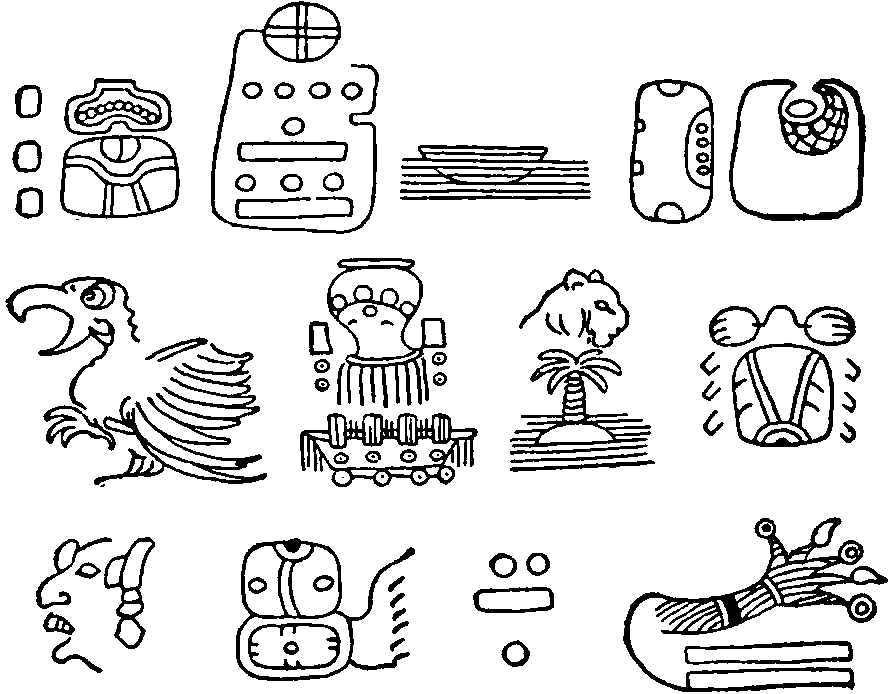

When she had gone, and the door was closed behind her, Whelan and his visitor bent over the sheet of hieroglyphs. And this is what they saw:

For a few minutes the two men neither spoke nor moved. Finally Whelan half-reached out for the working list of Maya hieroglyphics, hesitated, reconsidered, pushed away the volume.

“This document of yours isn’t genuine,” he said bluntly.

“I beg your pardon?” said Mr. Welper very gently.

“I say it isn’t genuine. No Maya ever wrote this jargon.”

“Jargon?”

“Certainly. It’s nonsense. It has been written by some European.”

“Doesn’t this inscription mean anything, Mr. Whelan?” demanded his visitor, visibly worried.

“It’s not an ancient Maya inscription.”

“Are these not Maya symbols?”

“Yes—some of them.”

“Have these symbols no meaning?” insisted Welper.

“Yes—but this is not the way the Mayas wrote their chronicles. . . . They didn’t do it this way. They didn’t employ their ideographs in this manner. . . . And there are symbols here with which I am not familiar. . . . I don’t believe they are Maya ideographs or Aztec phonetics. . . . I don’t know what they are—what they stand for. . . . The whole thing looks to me as though some European, with a smattering of Maya and Aztec, and a vague general idea of hieroglyphics, had attempted to write something using symbols.”

“If,” suggested Mr. Welper softly, “some European did this, how long ago did he do it?”

“I don’t know. Yesterday, perhaps; perhaps three hundred years ago. Maybe I can tell you if you show me the original manuscript.”

“It is on parchment and seems very old,” breathed Welper.

“It may seem old and be no older than a forgery furnished yesterday,” remarked Whelan, examining the photograph through a lens.

Presently he shrugged his shoulders: “This,” he said, “is not a Maya inscription; it is a fraud.”

“Yet you say that the symbols have a meaning,” urged Mr. Welper. “Can you read these symbols, Mr. Whelan? Here is your key—”

“I don’t need it, thank you. I can decipher these symbols without a key—I mean the Maya ideographs and numerals—”

“Would it be too much trouble for you to write in pencil under each symbol what it stands for?” pursued Mr. Welper.

“Not at all,” said Whelan, picking up a pencil.

This is what Whelan wrote:

When he finished he said: “You see? That’s not Maya work. Some white man has composed this jargon, using these hieroglyphs—or rather misusing them.” . . . He handed the paper to Mr. Welper: “Probably I could tell you how old your original parchment is if you care to bring it around. . . . Did you buy it in some antique shop?”

Mr. Welper did not seem to hear the question.

“Mr. Whelan, I thank you,” he said. “I shall not further encroach upon your valuable time.”

He offered his remarkably small, soft hand:

“Once more, thank you, and good-bye.”

“Good-bye,” said Whelan, looking after him with the slightest scowl as he disappeared through the door.

Something about the touch of that small, pudgy hand annoyed him, too. Scarcely conscious of what he did he went to the wash-basin, rinsed his hand, dried it, came back and picked up the desk telephone.

“Please say to Miss Dirck that she may return,” he said.

Miss Dirck, with pencil and tablets, had been noting the titles of certain translated volumes on the shelves: The Letters of Cortes to Charles the Fifth, printed in Seville in 1522; Castillo’s Conquest of New Spain, printed in Madrid in 1632; volumes by Alonzo de Mata; Ojeda; Herrera; Juan Torquemada; Lopez de Gomara; Toribio de Benavente, the Franciscan; the Jesuit, Juan de Tobar; Padillo, a Dominican; Arrias Villalobos; Abbé Raynal; and the Abbé D. Francesco Saverio Claverigo, who wrote in Italian, and whose works were translated by Charles Cullen.

This is as far as she had written on her tablets when Whelan’s message came.

Instantly and swiftly she moved toward Whelan’s office. He rose to receive her.

“Where is that man?” she asked excitedly.

“He has just left,” replied Whelan, surprised by her tone and manner.

“May I see that paper he brought?”

“He took it away with him—”

The girl ran for hat and coat.

“Please,” she said breathlessly, “forgive my rudeness. I’ll come back—”

She had her hat and coat on and was out of the door before Whelan could stir or utter a word.

He was sufficiently astonished to remain immobile in his chair for several minutes. Presently, however, being a busy man, he turned to the papers on his desk again. Then, too late, he noticed her reticule of black leather and black silver lying beside her black-edged handkerchief. The handkerchief was faintly fragrant.

As he picked it up, with the idea of tucking it into the hand-bag, an automatic pistol fell from the reticule to the carpet.

Whelan picked it up, replaced the weapon in the little black hand-bag, went swiftly into the outer office.

“Which way did that young lady go?” he asked his secretary.

The secretary, naturally, didn’t know, and Whelan hurried to the corridor and called to the museum guard on duty: “Which way did that girl go, Mike?”

“Th’ wan in black, Sorr?”

“Yes! Did she take the lift?”

“Faith, I seen her go skippin’ an’ bucketin’ down the stair, Sorr. Sure she’s the light-footed wan, Misther Whelan,—she is that, Sorr!”

Whelan hastened through the corridor into the gallery.

It was too early for many visitors in the museum. He scanned the few people there with a single glance. The girl in black was not among them.

However, he took the lift and descended to the ground floor. No sign of her in any gallery, or in the lobby where a few early school-children, personally conducted, lingered around the big metallic mass which had fallen to the earth from interstellar space.

No guard on duty had happened to notice her; but a small, freckled, cloak-room boy remembered a very pretty lady in black who sped out into the sunshine of Central Park, West, as though the devil were at her heels.

“How long ago?” demanded Whelan.

“I dunno. Half’n hour, I guess.”

Whelan surveyed the lad in silent disgust, forgetting, perhaps, that time drags very slowly with a small, freckled boy who has to work for a living.

“She’ll miss her reticule and come back for it,” he reflected as he returned to the lift and was hoisted toward his own domain.

Seated at his desk once more he gazed curiously at the reticule.

“Probably,” he thought, “she’ll be back within half an hour. . . . It was rather a queer proceeding. . . . I didn’t care for that man, Welper. . . . But she was—unusually—ornamental. . . .”

He shrugged his well-set shoulders and opened a volume on the Archæology of Guatemala. But he was aware of a faint perfume in the air. It came from her handkerchief in the satchel, and he found it difficult to concentrate his thoughts upon Guatemala.

The girl who disturbed the archæological reflections of Scott Whelan had caught sight of the object of her impulsive pursuit as she emerged from the entrance to the Museum.

Mr. Welper was in the act of entering a taxicab in front of the porte cochère; and the next moment the taxi and Mr. Welper started for parts unknown to her.

Outside the Museum grounds on the street curb stood several taxicabs. Miss Dirck ran along the paved way past beds of winter-blighted flowers, hailed the chauffeur of the foremost vehicle, and pointed at the distant taxi containing Mr. Welper.

“It’s absolutely necessary that I keep that taxi in sight!” she said breathlessly. “Please follow it wherever it goes!”

“I getcha, Lady!” said the chauffeur briskly. And the chase began.

Central Park, West, is a southbound avenue. Welper’s taxi swung south and the taxi containing Maddaleen Dirck did the same.

“Don’t get too near, but don’t lose that taxi!” she called to her driver.

“Getcha, Miss,” he nodded.

Half way to Columbus Circle the girl missed her reticule. In a panic she rummaged her fur coat and the seat and floor of the cab, then seemed to recollect that she had left it in Mr. Whelan’s office. A desperate expression came into her pallid face; she leaned close to the window and gazed at the taxi ahead. Her purse was in her reticule and she hadn’t a penny.

At Columbus Circle the traffic police stopped both vehicles; beyond, Mr. Welper’s cab swung into Broadway, and hers followed.

Now her driver drew closer to the pursued taxi, because there were chances that some traffic policeman might arbitrarily separate goat from sheep.

However, Mr. Welper never turned around to peer back through the oval window behind his head. Probably he would not have remembered her or recognised her if he did. It was quite evident, also, that he had no fear of pursuit by anybody.

She could see the sleek, grey back of his head under a grey felt hat, and his plump shoulders.

Down town they drove close together, swerved into Seventh Avenue, continuing south, were halted at Forty-Second Street, again at Thirty-Fourth Street; turned east on that thoroughfare.

Welper’s cab stopped at the Waldorf; Miss Dirck’s halted behind. She said quietly to her driver; “Wait here, please.”

No suspicions concerning her insolvency occurred to her driver. Her appearance, manner, voice placed her beyond any doubt.

Mr. Welper was just entering the Waldorf. Miss Dirck followed without a cent in her possession.

On the Thirty-Third Street side, near the news stand, a maid gave Welper a check for hat and coat.

He dropped the check in the side pocket of his coat and turned to enter the breakfast room. As he passed close to Miss Dirck in the crowd she slipped her left hand into his side pocket and drew out the coat check.

It was done in a flash. She never before had done such a thing—wouldn’t have known how, had she hesitated. Scarcely realising what she had done, she passed on through the little throng gathering before the maid, who was rapidly exchanging checks for hats and coats.

Had anybody seen her? She halted near the news stand, suddenly terrified. Not even daring to look around, she stood motionless, enduring all the agony of reaction, listening, trembling lest a hand fall upon her shoulder from behind.

With an effort she mastered her fright, strove to reflect, to consider.

Calm again. Somehow or other she must present that check to the maid, invent an excuse for claiming a man’s overcoat, face the crisis coolly, plausibly. Because she had to have that paper if it were in his overcoat. . . . And, if he carried it on his person, then she must continue to follow him and, somehow, to rob him. . . . God only knew how she was to accomplish this—how the affair might end. . . .

And suddenly the end came, like a stroke of lightning, as a man stepped to her side, looked into her eyes, stood so in utter silence, looking at her.

She seemed paralysed with fear; she could not stir, could not command her quivering mouth or the scarlet flush that scorched her dreadful pallor.

“I saw what you did,” he said in a low tone.

She stared at the man until his features blurred a little and she felt faint.

Her evident distress under the sudden shock seemed to disconcert the man beside her.

“You seem to be a novice in this work,” he said. “I don’t wish to frighten you. But I have a word or two to say to you. Perhaps we had better find a seat—”

He turned, waited; she found strength to move forward beside him. Down the corridor they moved until he found two gilded chairs together at some distance from any group. She sank down on one of them; he seated himself beside her.

“Why did you pick that man’s pocket?” he asked pleasantly.

The girl remained mute.

“What did you take?”

Her black-gloved hand lay in her lap. She opened it, showing him the coat-check.

“That,” remarked the man beside her, “is a new one on me. Do you think you can get away with it?”

“I—” She could not utter another sound.

“I suppose you meant to pass as his wife—say he’d gone to his room and wanted you to bring his coat?”

It was what Miss Dirck had thought of attempting and her terrified eyes filled with tears.

“What is it you want out of that man’s overcoat?” demanded her inquisitor.

“A—a paper.”

“Oh. You’re not a dip?”

“A—a what?”

There was a silence during which the man beside her studied her intently.

“You’re no crook,” he said, slowly.

“N-no.”

“What is the paper you wish to find? Don’t be afraid of me. Maybe I might help you.”

“Are you the—the hotel detective?”

“Come,” he said, “don’t ask questions. Answer me. . . . And give me that coat check.”

She handed it to him.

“What paper do you want out of that coat?—or shall I bring you everything in it?”

“D-do you mean—”

“Yes, I do. I can get away with it; you couldn’t. Now describe the paper you are after.”

“It—has figures—not numbers—but strange signs on it—I think—”

“You don’t mean hieroglyphics, do you?”

“Yes. . . . Central American hieroglyphs.”

“Oh. . . . All right. Wait here for me—”

He rose, sauntered down the corridor to the distant cloak-room; presented his check.

“I want to get something out of my overcoat,” he said to the maid.

She glanced at the number, brought the coat, and the young man ransacked it thoroughly but found only a pair of grey suede gloves and a neatly folded handkerchief.

“Thank you,” he said, returning the coat; and he walked back to where Miss Dirck was seated.

“Nothing in the coat,” he said. “Now what are you going to do?”

The girl made no reply but her eyes now met his with less fear than perplexity in their dark depths.

He smiled at her in friendly fashion: “You’re in trouble of some kind.”

“Yes.”

“Do you know who that man is whose pocket you picked so neatly?”

“No,” she said, flushing painfully, “—that is, I know his name only.”

“So do I,” smiled the man beside her. “What do you suppose his name to be?”

“Mr. Welper.”

“That’s it. And what do you want of Mr. Welper?”

“That—paper.”

“Oh, the Central American hieroglyphs! Well—how do you mean to get that paper?”

The girl’s mouth quivered: “If you will—will let me go—if you don’t mind—I must try to follow him—”

“Why?”

“I have got to know where he lives.”

“I can tell you where he lives.”

“Where?”

“He lives at his club.”

“What club, please—”

The young man beside her laughed:

“It’s called The Forty Thieves.”

Miss Dirck stared.

“If you were a crook,” said the young man, “you’d know the name of that club.”

“What—what kind of club is it?”

“I’ll tell you. It’s a very quiet club. There are forty members, never more. Only when a member gets bumped can another be elected—”

“B-bumped?” she repeated in perplexity.

“Well—when a member—dies. . . . That man, Welper, is President. A Mr. Potter is Secretary. There are no other officers. The dues are five thousand dollars a year and five thousand dollars initiation fee. . . . When any member becomes worth a million dollars he must resign. . . . It’s an odd sort of club, isn’t it?”

“Y-yes.”

“Unique. Only forty members. And every member a crook. . . . How do you expect to follow Mr. Welper into the Forty Club and pick his pockets?”

“I—don’t know—”

“You don’t mean you contemplate trying such a thing?”

“I—I must.”

“But it can’t be done.”

“Somehow—”

“Utterly impossible.”

“I must have that paper—”

The man beside her looked at her intently, then spoke to a passing page:

“Here, boy, take this check to the coat-room. Somebody has lost it.” And he handed the check to the boy, who went smartly on his way.

To Miss Dirck the man said: “Welper might as well have his coat. No use to us, that check.”

He had said “to us,” with a smile, and he saw that the girl noticed it.

“I don’t know why you want that paper,” he said, “but I suppose Barney Welper has done you some crooked trick. . . . Why don’t you call in the police?”

“I can’t!”

“Oh.” The young man’s brown eyes fairly bored into hers.

“You don’t care to ask for a warrant?”

“No.”

“Couldn’t you prove your charge?”

“Even if I could—”

“All right. I’m not inquisitive. Every family has its skeleton.”

The girl turned crimson and gazed at him out of distressed eyes.

“You’re not a good actress,” he said bluntly.

She was silent.

“If you were,” he said, “I’d take you to the Forty Club. I’m a member,” he added blandly.

He saw pain turn to incredulity in her eyes.

“Yes,” he said, “you mistook me for a dick, didn’t you? Well, I’m a crook! You ain’t. But if you’re after Barney Welper I wouldn’t stop you. Not me.”

From a cultivated vocabulary he was steadily slipping into vulgarisms, yet still spoke with the accent and manner of a man well born.

“Do you understand?” he went on with his pleasant smile; “I could get you into the Forty Club if you were a crooked little girl with that face and shape—and if you had the jack to stake yourself. But—you’re good.”

He sat very still, watching her; and she was stiller yet, listening, her eyes bent on the floor at her feet; and, in her brain, lightning!—flash after flash of wild and desperate intuition. . . . Only she must control the crisis, dominate it, take swift, instant command of her fate—

“That’s the trouble,” he repeated; “you’re good. You look it. And—” he shrugged, “you’re no actress.”

She looked up, laughing.

“That’s where you get off, old dear,” she said with the devil glimmering in her blue eyes.

His astonishment was so genuine that the girl laughed again.

“Did it get over?” she inquired merrily.

“It—did,” he said. She could scarcely sustain his intent gaze.

“See here,” he said, “you’re good, aren’t you?”

“Not very.”

“Oh. . . . What’s your line?”

“Oh, I—don’t know—”

“All right. . . . You made a monk of me, didn’t you? . . . Is that straight—your being a professional?”

“Professional?”

He was completely taken aback and puzzled.

“I admit you’re an actress,” he said. “You’ve done two turns. Which is you?”

She looked at him for a little while, her cheeks flushed with the terrific excitement of it all, her eyes lovely and brilliant.

“Are you really a—crook?” she asked gaily.

“I told you.”

“All right,” she said. “I’ve come a thousand miles to get that paper. I want to know what’s written on it. An hour ago I thought I was going to find out. I didn’t.” She turned and looked toward the breakfast-room: “The man’s in there,” she said. “That paper is in his pocket. I want it. Will you help me get it?”

He smiled: “How?”

“You’ve just told me. Take me to that club.”

“I told you only forty could belong.”

“But you said you’d take me if I were an actress.”

“Yes. I said so. I can. Because the bulls bumped a member last night. There are only thirty-nine. . . . Have you ten thousand dollars, little lady?”

“Yes.”

“What do you mean to do; stick up your man? Vamp and creep? Dope and frisk? . . . What are you staging?”

She regarded him with contemplative eyes, almost absently. Under her waist her heart was racing, almost suffocating her.

“I don’t know how it’s to be done,” she said. “But it’s got to be done.”

He remained silent.

“You’ll want to be paid, of course,” she added.

He nodded.

“How much?” she asked.

“Do we work together, little lady?”

“Yes, I’d be very glad.”

“Pals?”

“Yes. . . . You mean like sister and brother?”

“All right: that way—if you don’t fall for my map. . . . I flop for yours.”

“M-map?”

“Face,” he said coolly, watching her vivid blush deepen from hair to throat.

After a moment: “I asked you,” he said, “which is you—a troubled young girl in mourning, who seemed scared out of her wits, or the cleverest actress I’ve ever met?”

“Which do you think?”

“If you’re an actress you’re new to the crooked game.”

“Why?”

“You don’t talk the patter. You don’t seem to understand it. . . . You’ve got me guessing anyway. I admit it. What are you? Which? You can tell me; I’ll work with you anyway.”

“Keep guessing,” she said with a little smile, tremulous from the strain of excitement.

His thoughtful eyes never left hers. He nodded after a moment.

“You promise to take me to the Forty Club?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“When?”

“Whenever you are ready.”

She reflected and decided not to leave him even for an instant.

“I’ve got to go up town. I left my money. You must come,” she said.

He rose; they went out by the Thirty-Fourth Street side.

Her taxi-driver, who had become anxious, welcomed her; she directed him to drive to the Museum.

And even there she insisted that the young man accompany her to the outer office of Mr. Whelan.

That young gentleman had just returned from luncheon and she was admitted.

“I expected you’d return,” he said. “And, by the way, when I put your handkerchief into your reticule, a rather large pistol fell out.”

“Thanks so much,” she said, reddening. “Please forgive my abrupt behaviour. I didn’t mean to be rude. But something so very important happened so very suddenly.”

Whelan looked at her: “Aren’t you coming back?” he inquired naïvely.

“I hope so. . . . Tell me, Mr. Whelan, did you read those hieroglyphics for the gentleman who came in while I was here?”

“I did. It was utter nonsense.”

“Would it be impertinent of me to ask you what was written on that paper?”

“No; but, as the matter was confidential, it would be unethical of me to tell you, even if I could recollect.”

“Please try to recollect the inscription!”

“The inscription was not Maya; it was a fraud perpetrated by somebody who—”

“That doesn’t matter. Can’t you remember it?”

“No; it was sheer nonsense; and I told Mr. what’s-his-name so. I can’t remember nonsense. I never could!—”

The girl came close to his desk where he was standing:

“Try to recollect,” she said in a low voice. “It may be a matter of life or death.”

“Good heavens!” he said. “All I recollect of it was something about a ship—a shipwreck—and an island—” He stood staring at her, both hands pressing his temples:

“A shipwreck near some island. . . . And some measurements. . . . That’s all I recall of that ridiculous trash—”

She gazed at him in tragic silence. Then her lips moved a silent “Thank you;” she turned and walked to the outer office, where the young man from the Waldorf awaited her.

They went together into the body of the great Museum, down the iron stairs, slowly, from floor to floor.

“Will a cheque be all right to pay for my initiation, and dues, at the Forty Club?” she asked in a low voice.

He smiled incredulously: “You’re too clever to do that, or to think Welper would cash it.”

She saw she mustn’t offer a cheque.

“Very well,” she said, “we’ll drive to my bank.”

On the way down town every few moments he looked at her, partly in admiration, partly in perplexity, and in swift moments of suspicion, too.

What was this girl? He hadn’t decided. All he understood was that, as an actress, she was matchless in his experience.

Never before had he seen any professional so exquisitely interpret unsullied youth—that delicate and virginal allure which to him had seemed inimitable, and never to be mistaken.

But, that suddenly lifted head; that laughter, charming, defiant, subtly sophisticated: and, to his query if she were not “good,” her demure “not very.” Well, that was art. . . . Yet, somehow, he seemed unable to divorce her art and herself.

They stopped at the Imperial Loan & Trust Company; he descended and offered his arm.

She remained in the bank about ten minutes. He paced the sidewalk by the taxi, smoking a cigarette.

When she reappeared she came to him and drew him a little aside.

“I want to be honest with you,” she said. “I don’t know that there will be anything to divide between us when I secure that paper from Mr. Welper. Suppose I pay you now what you think you should have for helping me?”

“No; I’ll take a chance.”

“Don’t you need some money?”

The young man reddened, and it seemed to annoy him.

“I’ll look out for myself,” he said bluntly. “Where do you want to go now?”

“I’ve had no lunch.”

“You can lunch at the Forty Club.”

The girl trembled slightly, then mastered herself and nodded with composure.

“Very well,” she said. “Please tell the driver where to go.”

They returned to the taxi; he aided her in, spoke to the driver, and followed her.

“Will I be in any—danger?” she asked calmly.

“None. . . . Unless you ever squeal.”

“I understand . . . They’ll take me for—for granted.”

“The Forty Club is like any other Club, except that wine and cards are forbidden. We don’t risk a row. There’s no betting, no drinking allowed. No quarrelling either. Any infraction of rules means expulsion. . . . And if you’re expelled you usually are found dead in a day or two.”

“Dead?”

“Yes, somewhere or other—in the river, in the Park, in a taxi—” he shrugged.

She sat silent, gazing out at the crowded traffic on Fifth Avenue.

He went on in his low, agreeable voice: “Only a genius in her or his own line ever cares, or dares, to join the Forty Club. The members are there for one purpose only—to make a million as quickly as possible, and resign.”

“What is the use of the club to them?”

“Its uses are infinite. Every facility is there to help you. Through the secret influences of the Forty Club you can go anywhere, meet anybody whom you need in your—ah—operations.

“All your operations are covered, too. It’s your own fault if you’re caught with the goods on or if you’re bumped.

“If you get into trouble there’s a bail, counsel, money for defence, influence for judge, jury, and pressure in legislative circles—pressure even in the Executive Mansion. You get the best of opportunities; you ought to make your million and get away with it in five years. Many do it in three, some in two, some in a year.”

She turned her pale face: “And you?”

“You are inquisitive,” he said, smiling.

She coloured: “I’m sorry. . . . You don’t look like—like—”

“A crook?”

“No.”

“You don’t either. And that’s the kind that does the business. It’s our kind you’ll find at the Forty Club. Not a mouth that would melt butter.”

He was laughing:

“Take Welper. He’s a sanctimonious guy to look at. . . . But—when you frisk him, for God’s sake make your getaway. He’s bad.”

“Yes, I thought so.”

“You take it coolly.”

“I have to.”

He smiled: “You are a sport, Miss—Miss—”

“Miss Dirck—Maddaleen.”

“That’s a good name,” he said gaily, “—Dirck or Dagger—a perfectly good name for the Forty Club. Some wear their hearts on their sleeves; some carry their names in their garters. . . . Maddaleen Dirck! That’s a first-rate name.”

“And yours?”

“Oh, nothing suggestive or subtle. My name is John Lanier.”

“John Lanier,” she repeated aloud to herself.

“You see,” he said, “what goes in the Underworld doesn’t go with us in the Forty Club. We look all right; we seem all right; we know how to behave, and we do it. None of us care to live in the Underworld. We’re merely out for a million and don’t care how we get it.

“And, when we get it, back to the fold for us—inside the law, Miss Dirck—that’s our aim and ambition,—the legit!”

She nodded.

“Interesting, isn’t it?”

“Very.”

“You expect to make your million?” he asked, smiling.

“All I want is that paper.”

“Sorry,” he said, flushing, “—none of my business, of course. Your line is your secret unless you care to mention it.”

“I have no other line, Mr. Lanier.”

“You are an actress, aren’t you?”

“I hope so.”

After a moment: “Suppose,” he said, “Barney Welper catches you at your little game. . . . Do you know he is quite certain to kill you?”

After a slight hesitation, Maddaleen Dirck leaned a little toward him and opened the reticule on her lap.

Her pistol lay there beside her handkerchief, purse, and vanity case.

“So—that’s your answer, Miss Dirck?” he asked, placing one finger on the pistol.

“Yes,” she said in a low voice, “that is my answer.”

She closed the reticule. The taxi stopped at the same moment.

Lanier said coolly: “You’ve lived in Paris?”

“Yes. Why?”

“So have I. Don’t blush when I tell them that we’ve lived there together.”

“Need you say that?”

“Yes. We lived very quietly in the rue d’Alencon, numero neuf. Y’êtes vous, mademoiselle?”

“Parfaitment, monsieur, si vous le trouvez necessaire—”

“Listen! We operated in the Opera quarter and sometimes in the Observatory and Luxembourg quarters. You know them?”

“I did—as a schoolgirl—”

“Then that’s all right.” He got out of the taxi, aided her.

She had her purse ready, but he insisted.

“You don’t realise how much I owe our driver,” she said with a nervous smile.

He looked at the metre, laughed, paid the fare. The taxi drove off.

“Now,” he said, “here’s the Forty Thieves. The moment I take you inside that door you’re on your own.”

She nodded.

“Have you ten thousand dollars in that reticule?”

“Yes, ten one thousand dollar bills.”

“Very well,” he said calmly, “come in.”

The girl turned and looked up at the house.

It* stood on the south side of the street just west of the shabby avenue—an ancient brick edifice in extreme dilapidation.

Broken blinds closed every window. Stoop, iron railing, deeply recessed door, fan-light, pilasters, all were sadly eloquent of generations forgotten.

For the age of this melancholy mansion could not have been less than a century; and it looked twice as old.

Maddaleen Dirck glanced at Lanier, and the smile he gave her was ironical and slightly sinister.

“You don’t have to come in,” he said.

“I do have to. . . . But goodness, how dismal! This house is not merely expiring; it’s already done for. It’s all in, Mr. Lanier.”

“Oh, a touch of lively paint would revive it—”

“No; only bedizen it. Like rouging a corpse. There’s no resurrection for this house. It’s dead.”

He seemed amused at her imagination: “Well,” he said, “shall we enter this melancholy morgue and make ourselves comfortable on a pair of slabs?”