Transcriber's note:

Page numbers in this book are indicated by numbers

enclosed in curly braces, e.g. {99} in the left margin.

They have been located where page

breaks occurred in the original book. For its

Index, a page number has been placed only at the start of that

section.

To re-create the shadowy figures of the heroic past, to clothe the dead once more in flesh and blood, to set the puppets of the play in life's great dramas again upon the stage of action,—frankly, this may not be formal history, but it is what makes the past most real to the present day. Pictures of men and women, of moving throngs and heroic episodes, stick faster in the mind than lists of governors and arguments on treaties. Such pictures may not be history, but they breathe life into the skeletons of the past.

Canada's past is more dramatic than any romance ever penned. The story of that past has been told many times and in many volumes, with far digressions on Louisiana and New England and the kingcraft of Europe. The trouble is, the story has not been told in one volume. Too much has been attempted. To include the story of New England wars and Louisiana's pioneer days, the story of Canada itself has been either cramped or crowded. To the eastern writer, Canada's history has been the record of French and English conflict. To him there has been practically no Canada west of the Great Lakes; and in order to tell the intrigue of European tricksters, very often the writer has been compelled to exclude the story of the Canadian people,—meaning by people the breadwinners, the toilers, rather than the governing classes. Similarly, to the western writer, Canada meant the Hudson's Bay Company. As for the Pacific coast, it has been almost ignored in any story of Canada.

Needless to say, a complete history of a country as vast as Canada, whose past in every section fairly teems with action, could not be crowded into one volume. To give even the story {iv} of Canada's most prominent episodes and actors is a matter of rigidly excluding the extraneous.

All that has been attempted here is such a story—story, not history—of the romance and adventure in Canada's nation building as will give the casual reader knowledge of the country's past, and how that past led along a trail of great heroism to the destiny of a Northern Empire. This volume is in no sense formal history. There will be found in it no such lists of governors with dates appended, of treaties with articles running to the fours and eights and tens, of battles grouped with dates, as have made Canadian history a nightmare to children.

It is only such a story as boys and girls may read, or the hurried business man on the train, who wants to know "what was doing" in the past; and it is mainly a story of men and women and things doing.

I have not given at the end of each chapter the list of authorities customary in formal history. At the same time it is hardly necessary to say I have dug most rigorously down to original sources for facts; and of secondary authorities, from Pierre Boucher, his Book, to modern reprints of Champlain and L'Escarbot, there are not any I have not consulted more or less. Especially am I indebted to the Documentary History of New York, sixteen volumes, bearing on early border wars; to Documents Relatifs à la Nouvelle France, Quebec; to the Canadian Archives since 1886; to the special historical issues of each of the eastern provinces; and to the monumental works of Dr. Kingsford. Nearly all the places described are from frequent visits or from living on the spot.

"The Twentieth century belongs to Canada."

The prediction of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Premier of the Dominion, seems likely to have bigger fulfillment than Canadians themselves realize. What does it mean?

Canada stands at the same place in the world's history as England stood in the Golden Age of Queen Elizabeth—on the threshold of her future as a great nation. Her population is the same, about seven million. Her mental attitude is similar, that of a great awakening, a consciousness of new strength, an exuberance of energy biting on the bit to run the race; mellowed memory of hard-won battles against tremendous odds in the past; for the future, a golden vision opening on vistas too far to follow. They dreamed pretty big in the days of Queen Elizabeth, but they did n't dream big enough for what was to come; and they are dreaming pretty big up in Canada to-day, but it is hard to forecast the future when a nation the size of all Europe is setting out on the career of her world history.

To put it differently: Canada's position is very much the same to-day as the United States' a century ago. Her population is about seven million. The population of the United States was seven million in 1810. One was a strip of isolated settlements north and south along the Atlantic seaboard; the other, a string of provinces east and west along the waterways that ramify from the St. Lawrence. Both possessed and were flanked by vast unexploited territory the size of Russia; the United States by a Louisiana, Canada by the Great Northwest. What the Civil War did for the United States, Confederation did for the Canadian provinces—welded them into a nation. The parallel need not be carried farther. If the same development {vi} follows Confederation in Canada as followed the Civil War in the United States, the twentieth century will witness the birth and growth of a world power.

To no one has the future opening before Canada come as a greater surprise than to Canadians themselves. A few years ago such a claim as the Premier's would have been regarded as the effusions of the after-dinner speaker. While Canadian politicians were hoping for the honor of being accorded colonial place in the English Parliament, they suddenly awakened to find themselves a nation. They suddenly realized that history, and big history, too, was in the making. Instead of Canada being dependent on the Empire, the Empire's most far-seeing statesmen were looking to Canada for the strength of the British Empire. No longer is there a desire among Canadians for place in the Parliament at Westminster. With a new empire of their own to develop, equal in size to the whole of Europe, Canadian public men realize they have enough to do without taking a hand in European affairs.

As the different Canadian provinces came into Confederation they were like beads on a string a thousand miles apart. First were the Maritime Provinces, with western bounds touching the eastern bounds of Quebec, but in reality with the settlements of New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island separated from the settlements of Quebec by a thousand miles of untracked forest. Only the Ottawa River separated Quebec from Ontario, but one province was French, the other English, aliens to each other in religion, language, and customs. A thousand miles of rock-bound, winter-bound wastes lay between Ontario and the scattered settlement of Red River in Manitoba. Not an interest was in common between the little province of the middle west and her sisters to the east. Then prairie land came for a thousand miles, and mountains for six hundred miles, before reaching the Pacific province of British Columbia, more completely cut off from other parts of Canada than from Mexico or Panama. In fact, it would have been easier for British Columbia to trade with Mexico and Panama than with the rest of Canada.

{vii} To bind these far-separated patches of settlement, oases in a desert of wilds, into a nation was the object of the union known as Confederation. But a nation can live only as it trades what it draws from the soil. Naturally, the isolated provinces looked for trade to the United States, just across an invisible boundary. It seemed absurd that the Canadian provinces should try to trade with each other, a thousand miles apart, rather than with the United States, a stone's throw from the door of each province. But the United States erected a tariff wall that Canada could not climb. The struggling Dominion was thrown solely on herself, and set about the giant task of linking the provinces together, building railroads from Atlantic to Pacific, canals from tide water to the Great Lakes. In actual cash this cost Canada four hundred million dollars, not counting land grants and private subscriptions for stock, which would bring up the cost of binding the provinces together to a billion. This was a staggering burden for a country with smaller population than Greater New York—a burden as big as Japan and Russia assumed for their war; but, like war, the expenditure was a fight for national existence. Without the railroads and canals, the provinces could not have been bound together into a nation.

These were Canada's pioneer days, when she was spending more than she was earning, when she bound herself down to grinding poverty and big risks and hard tasks. It was a long pull, and a hard pull; but it was a pull altogether. That was Canada's seed time; this is her harvest. That was her night work, when she toiled, while other nations slept; now is the awakening, when the world sees what she was doing. Railroad man, farmer, miner, manufacturer, all had the same struggle, the big outlay of labor and money at first, the big risk and no profit, the long period of waiting.

Canada was laying her foundations of yesterday for the superstructure of prosperity to-day and to-morrow—the New Empire.

When one surveys the country as a whole, the facts are so big they are bewildering.

{viii} In the first place, the area of the Dominion is within a few thousand miles of as large as all Europe. To be more specific, you could spread the surface of Italy and Spain and Turkey and Greece and Austria over eastern Canada, and you would still have an area uncovered in the east alone bigger than the German Empire. England spread flat on the surface of Eastern Canada would just serve to cover the Maritime Provinces nicely, leaving uncovered Quebec, which is a third bigger than Germany; Ontario, which is bigger than France; and Labrador (Ungava), which is about the size of Austria.

In the west you could spread the British Isles out flat, and you would not cover Manitoba—with her new boundaries extending to Hudson Bay. It would take a country the size of France to cover the province of Saskatchewan, a country larger than Germany to cover Alberta, two countries the size of Germany to cover British Columbia and the Yukon, and there would still be left uncovered the northern half of the West—an area the size of European Russia.

No Old World monarch from William the Conqueror to Napoleon could boast of such a realm. People are fond of tracing ancestry back to feudal barons of the Middle Ages. What feudal baron of the Middle Ages, or Lord of the Outer Marches, was heir to such heritage as Canada may claim? Think of it! Combine all the feudatory domains of the Rhine and the Danube, you have not so vast an estate as a single western province. Or gather up all the estates of England's midland counties and eastern shires and borderlands, you have not enough land to fill one of Canada's inland seas,—Lake Superior.

If there were a population in eastern Canada equal to France,—and Quebec alone would support a population equal to France,—and in Manitoba equal to the British Isles, and in Saskatchewan equal to France, and in Alberta equal to Germany, and in British Columbia equal to Germany,—ignoring Yukon, Mackenzie River, Keewatin, and Labrador, taking only those parts of Canada where climate has been tested and lands surveyed,—Canada would support two hundred million people.

{ix} The figures are staggering, but they are not half so improbable as the actual facts of what has taken place in the United States. America's population was acquired against hard odds. There were no railroads when the movement to America began. The only ocean goers were sailboats of slow progress and great discomfort. In Europe was profound ignorance regarding America; to-day all is changed. Canada begins where the United States left off. The whole world is gridironed with railroads. Fast Atlantic liners offer greater comfort to the emigrant than he has known at home. Ignorance of America has given place to almost romantic glamour. Just when the free lands of the United States are exhausted and the government is putting up bars to keep out the immigrant, Canada is in a position to open her doors wide. Less than a fortieth of the entire West is inhabited. Of the Great Clay Belt of North Ontario only a patch on the southern edge is populated. The same may be said of the Great Forest Belt of Quebec. These facts are the magnet that will attract the immigrant to Canada. The United States wants no more immigrants.

And the movement to Canada has begun. To her shores are thronging the hosts of the Old World's dispossessed, in multitudes greater than any army that ever marched to conquest under Napoleon. When the history of America comes to be written in a hundred years, it will not be the record of a slaughter field with contending nations battling for the mastery, or generals wading to glory knee-deep in blood. It will be an account of the most wonderful race movement, the most wonderful experiment in democracy the world has known.

The people thronging to Canada for homes, who are to be her nation builders, are people crowded out of their home lands, who had n't room for the shoulder swing manhood and womanhood need to carve out honorable careers. Look at them in the streets of London, or Glasgow, or Dublin, or Berlin, these émigrés, as the French called their royalists, whom revolution drove from home, and I think the word émigré is a truer description of the newcomer to Canada than the word "emigrant." They are {x} poor, they are desperately poor, so poor that a month's illness or a shut-down of the factory may push them from poverty to the abyss. They are thrifty, but can neither earn nor save enough to feel absolutely sure that the hollow-eyed specter of Want may not seize them by the throat. They are willing to work, so eager to work that at the docks and the factory gates they trample and jostle one another for the chance to work. They are the underpinnings, the underprops of an old system, these émigrés, by which the masses were expected to toil for the benefit of the classes.

"It's all the average man or woman is good for," says the Old Order, "just a day's wage representing bodily needs."

"Wait," says the New Order. "Give him room! Give him an opportunity! Give him a full stomach to pump blood to his muscles and life to his brain! Wait and see! If he fails then, let him drop to the bottom of the social pit without stop of poorhouse or help!"

A penniless immigrant boy arrives in New York. First he peddles peanuts, then he trades in a half-huckster way whatever comes to hand and earns profits. Presently he becomes a fur trader and invests his savings in real estate. Before that man dies, he has a monthly income equal to the yearly income of European kings. That man's name was John Jacob Astor.

Or a young Scotch boy comes out on a sailing vessel to Canada. For a score of years he is an obscure clerk at a distant trading post in Labrador. He comes out of the wilds to take a higher position as land commissioner. Presently he is backing railroad ventures of tremendous cost and tremendous risk. Within thirty years from the time he came out of the wilds penniless, that man possesses a fortune equal to the national income of European kingdoms. The man's name is Lord Strathcona.

Or a hard-working coal miner emigrates to Canada. The man has brains as well as hands. Other coal miners emigrate at the same time, but this man is as keen as a razor in foresight and care. From coal miner he becomes coal manager, from manager {xi} operator, from operator owner, and dies worth a fortune that the barons of the Middle Ages would have drenched their countries in blood to win. The man's name is James Dunsmuir.

Or it is a boy clerking in a departmental store. He emigrates. When he goes back to England it is to marry a lady in waiting to the Queen. He is now known as Lord Mount-Stephen.

What was the secret of the success? Ability in the first place, but in the second, opportunity; opportunity and room for shoulder swing to show what a man can do when keen ability and tireless energy have untrammeled freedom to do their best.

Examples of the émigrés' success could be multiplied. It is more than a mere material success; it is eternal proof that, given a fair chance and a square deal and shoulder swing, the boy born penniless can run the race and outstrip the boy born to power.

"Have you, then, no menial classes in Canada?" asked a member of the Old Order.

"No, I'm thankful to say," said I.

"Then who does the work?"

"The workers."

"But what's the difference?"

"Just this: your menial of the Old Country is the child of a menial, whose father before him was a menial, whose ancestors were in servile positions to other people back as far as you like to go,—to the time when men were serfs wearing an iron collar with the brand of the lord who owned them. With us no stigma is attached to work. Your menial expects to be a menial all his life. With our worker, just as sure as the sun rises and sets, if he continues to work and is no fool, he will rise to earn a competency, to improve himself, to own his own labor, to own his own home, to hire the labor of other men who are beginners as he once was himself."

"Then you have no social classes?"

"Lots. The ups, who have succeeded; and the half-way ups, who are succeeding; and the beginners, who are going to succeed; and the downs, who never try. And as success doesn't necessarily mean money, but doing the best at whatever one tries, {xii} you can see that the ups and the halfway ups, and the beginners and the downs have each their own classes of special workers."

"That," she answered, "is not democracy; it is revolution." She was thinking of those Old World hard-and-fast divisions of society into royalty, aristocracy, commons, peasantry.

"It is not revolution," I explained. "It is rebirth! When you send your émigré out to us, he is a made-over man."

But it is not given to all émigré's to become great capitalists or great leaders. Some who have the opportunity have not the ability, and the majority would not, for all the rewards that greatness offers, choose careers that entail long years of nerve-wracking, unflagging labor. But on a minor scale the same process of making over takes place. One case will illustrate.

Some years before immigration to Canada had become general, two or three hundred Icelanders were landed in Winnipeg destitute. From some reason, which I have forgotten,—probably the quarantine of an immigrant,—the Icelanders could not be housed in the government immigration hall. They were absolutely without money, household goods, property of any sort except clothing, and that was scant, the men having but one suit of the poorest clothes, the women thin homespun dresses so worn one could see many of them had no underwear. The people represented the very dregs of poverty. Withdrawing to the vacant lots in the west end of Winnipeg,—at that time a mere town,—the newcomers slept for the first nights, herded in the rooms of an Icelander opulent enough to have rented a house. Those who could not gain admittance to this house slept under the high board sidewalks, then a feature of the new town. I remember as a child watching them sit on the high sidewalk till it was dark, then roll under. Fortunately it was summer, but it was useless for people in this condition to go bare to the prairie farm. To make land yield, you must have house and barns and stock and implements, and I doubt if these people had as much as a jackknife. I remember how two or three of the older women used to sit crying each night in despair till they disappeared in the crowded house, fourteen or {xiii} twenty of them to a room. Within a week, the men were all at work sawing wood from door to door at a dollar and a half a cord the women out by the day washing at a dollar a day. Within a month they had earned enough to buy lumber and tar paper. Tar-papered shanties went up like mushrooms on the vacant lots. Before winter each family had bought a cow and chickens. I shall not betray confidence by telling where the cow and chickens slept. Those immigrants were not desirable neighbors. Other people moved hastily away from the region. Such a condition would not be tolerated now, when there are spacious immigration halls and sanitary inspectors to see that cows and people do not house under the same roof. What with work and peddling milk, by spring the people were able to move out on the free prairie farms. To-day those Icelanders own farms clear of debt, own stock that would be considered the possession of a capitalist in Iceland, and have money in the savings banks. Their sons and daughters have had university educations and have entered every avenue of life, farming, trading, practicing medicine, actually teaching English in English schools. Some are members of Parliament. It was a hard beginning, but it was a rebirth to a new life. They are now among the nation builders of the West.

But it would be a mistake to conclude that Canada's nation builders consisted entirely of poor people. The race movement has not been a leaderless mob. Princes, nobles, adventurers, soldiers of fortune, were the pathfinders who blazed the trail to Canada. Glory, pure and simple, was the aim that lured the first comers across the trackless seas. Adventurous young aristocrats, members of the Old Order, led the first nation builders to America, and, all unconscious of destiny, laid the foundations of the New Order. The story of their adventures and work is the history of Canada.

It is a new experience in the world's history, this race movement that has built up the United States and is now building up Canada. Other great race movements have been a tearing down of high places, the upward scramble of one class on the {xiv} backs of the deposed class. Instead of leveling down, Canada's nation building is leveling up.

This, then, is the empire—the size of all the nations in Europe, bigger than Napoleon's wildest dreams of conquest—to which Canada has awakened.[1]

Canada . . 3,750,000 square miles Europe . . 3,797,410 square miles

Maritime Provinces Square Miles Square Miles

Nova Scotia . . . . . 20,600 England . . . . . 50,867

Prince Edward Island 2,000 Germany . . . . . 208,830

New Brunswick . . . . 28,200 France . . . . . 204,000

------ Italy . . . . . . 110,000

50,800 Spain . . . . . . 197,000

Quebec . . . . . . . . 347,350 Austria and Hungary 241,000

Ontario . . . . . . . . 222,000 Russia in Europe 2,000,000

Manitoba

Saskatchewan 204,000

Alberta . . . . . . . . 350,000

British Columbia . . . 383,000

Unorganized Territory of

Keewatin . . . . . . 756,000

Yukon . . . . . . . . 200,000

MacKenzie River and

Ungava . . . . . . 1,000,000

| United States | Canada | |||

| In 1800 | 5,000,000 | In 1881 | 4,300,000 | |

| " 1810 | 7,000,000 | " 1891 | 5,000,000 | |

| " 1820 | 9,600,000 | " 1901 | 5,500,000 | |

| " 1830 | 12,800,000 | " 1906 | 6,500,000 | |

It will be noticed that for twenty years Canada's population becomes almost stagnant. The reason for this will be found as the story of Canada is related. If she keeps up the increase at the pace she has now set, or at the rate the United States' population went ahead during the same period of industrial development, the results can be forecast from the following table:

| United States in 1840 | 17,000,000 |

| " " " 1850 | 23,000,000 |

| " " " 1860 | 31,000,000 |

| " " " 1870 | 38,000,000 |

| " " " 1880 | 50,000,000 |

| " " " 1890 | 63,000,000 |

| " " " 1900 | 85,000,000 |

{xv} A few years ago, when talking to a leading editor of Canada, I chanced to say that I did not think Canadians had at that time awakened to their future. The editor answered that he was afraid I had contracted the American disease of "bounce" through living in the United States; to which I retorted that if Canadians could catch the same disease and accomplish as much by it in the twentieth century as Americans had in the nineteenth, it would be a good thing for the country. It is wonderful to have witnessed the complete face-about of Canadian public opinion in the short space of six years, this editor shouting as loud as any of his exuberant brethren. Still, as the outlook in Canadian affairs may be regarded as flamboyant, it is worth while quoting the comment of the most critical and conservative newspaper in the world,—the London Times. The Times says: "Without doubt the expansion of Canada is the greatest political event in the British Empire to-day. The empire is face to face with development which makes it impossible for indefinite maintenance of the present constitutional arrangements."

Regarding the Iceland immigrants, to whom reference is made, I recently met in London a famed traveler, who was in Iceland when the people were setting out for Canada, Mrs. Alec. Tweedie. She explains in her book how these people were absolutely poverty-stricken when they left Iceland. In fact, the sufferings endured the first year in Winnipeg were mild compared to their privations in Iceland before they sailed.

The explanations of Canada's hard times from Confederation to 1898—say from 1871, when all the provinces had really gone into Confederation, to 1897, when the Yukon boom poured gold into the country—can be figured out. Of a population of 3,000,000, four fifths need not be counted as taxpayers, as they include women, children, clerks, farmers' help, domestic help,—classes who pay no taxes but the indirect duty on clothes they wear and food they eat. This practically means that the billion-dollar burden of making the ideal of Confederation into a reality by building railroads and canals was borne by 600,000 people, which means again a large quota per man to the public treasury. People forget that you can't take more out of the public treasury than you put into it, that it is n't like an artesian well, self-supplied, and the truth is, at this period Canadians were paying more into the public treasury than they could afford,—more than the investment was bringing them in.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | FROM 1000 TO 1600 | 1 |

| II. | FROM 1600 TO 1607 | 23 |

| III. | FROM 1607 TO 1635 | 41 |

| IV. | FROM 1635 TO 1666 | 61 |

| V. | FROM 1635 TO 1650 | 71 |

| VI. | FROM 1650 TO 1672 | 94 |

| VII. | FROM 1672 TO 1688 | 117 |

| VIII. | FROM 1679 TO 1713 | 143 |

| IX. | FROM 1686 TO 1698 | 161 |

| X. | FROM 1698 TO 1713 | 189 |

| XI. | FROM 1713 TO 1755 | 205 |

| XII. | FROM 1756 TO 1763 | 241 |

| XIII. | FROM 1763 TO 1812 | 276 |

| XIV. | FROM 1812 TO 1820 | 318 |

| XV. | FROM 1812 TO 1846 | 380 |

| XVI. | FROM 1820 TO 1867 | 410 |

| INDEX | 439 |

| Page | |

| MAP OF WESTERN CANADA | Frontispiece |

|

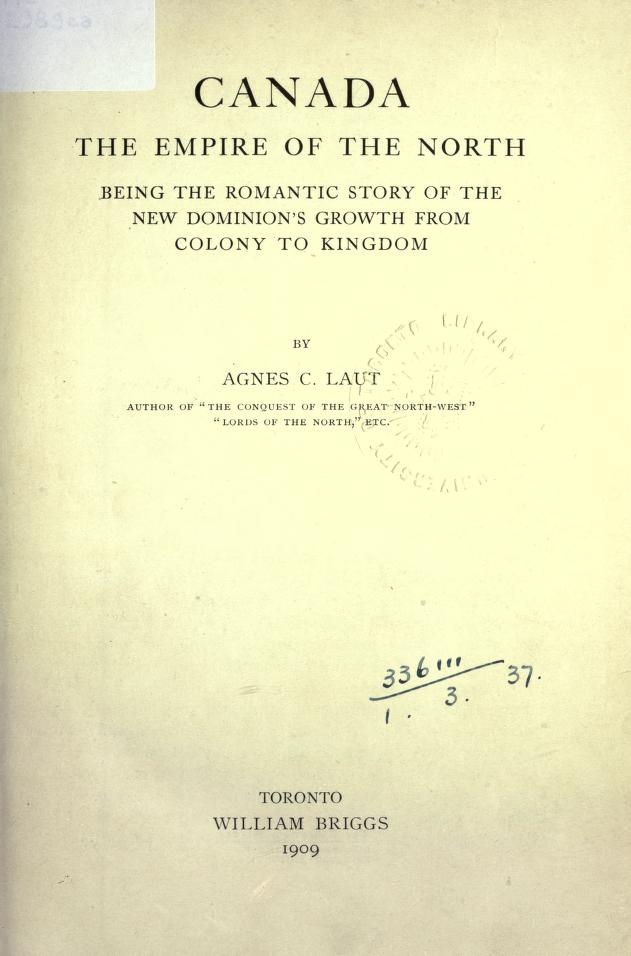

VIKING SHIP RECENTLY DISCOVERED

After a photograph of the Viking Ship at Sandefjord, Norway. |

2 |

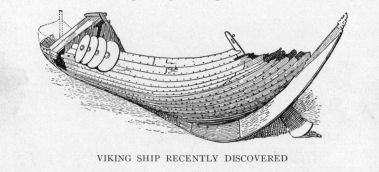

| MAP SHOWING DIVISION OF THE NEW WORLD BETWEEN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL | 3 |

|

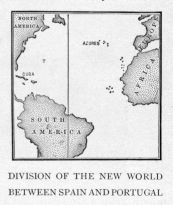

A TYPICAL "HOLE IN THE WALL" AT "KITTY VIDDY," NEAR

ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND

From a photograph. |

4 |

|

SEBASTIAN CABOT

After the portrait attributed to Holbein. |

5 |

|

JACQUES CARTIER

After the portrait at St. Malo, France, with signature. |

8 |

|

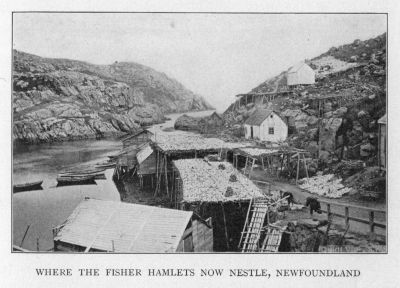

WHERE THE FISHER HAMLETS NOW NESTLE, NEWFOUNDLAND

From a photograph. |

9 |

|

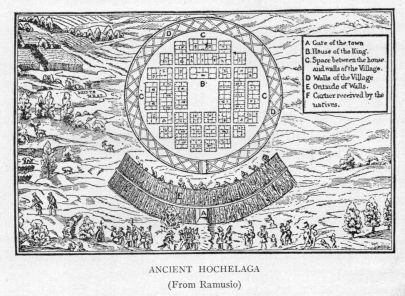

ANCIENT HOCHELAGA

After a cut in the third volume of Ramusio's Raccolta, Venice, 1565. |

15 |

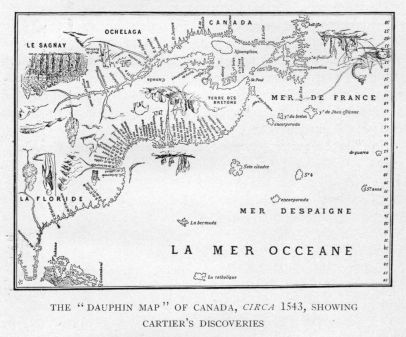

| THE "DAUPHIN MAP" OF CANADA, CIRCA 1543, SHOWING CARTIER'S DISCOVERIES | 21 |

|

QUEEN ELIZABETH

After the ermine portrait in Hatfield House, with signature. |

25 |

|

THE BOYHOOD OF GILBERT AND RALEIGH

From the painting by Sir John Millais. |

26 |

|

SIR HUMPHREY GILBERT

After the print in Holland's Herwologia-Anglica, 1620. |

27 |

|

SIR WALTER RALEIGH

After the portrait in the possession of the Duchess of Dorset. |

29 |

|

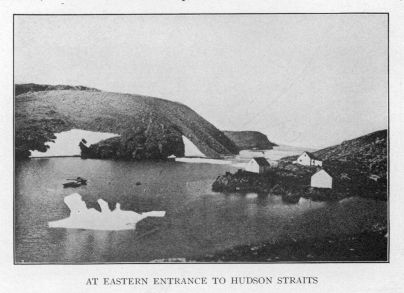

AT EASTERN ENTRANCE TO HUDSON STRAITS

From a photograph by Dominion Geological Survey. |

31 |

|

HUDSON COAT OF ARMS

From Lenox Collection, New York City. |

32 |

|

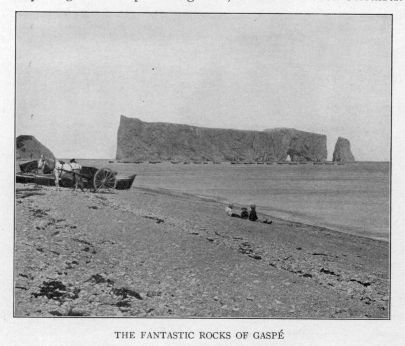

THE FANTASTIC ROCKS OF GASPÉ

From a photograph. |

33 |

|

SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN

After the Moncornet portrait, with signature. |

34 |

|

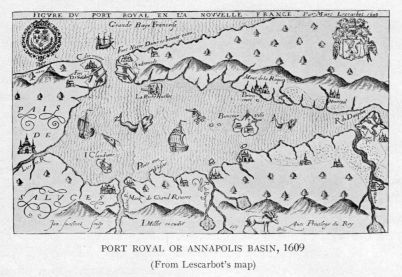

PORT ROYAL OR ANNAPOLIS BASIN, 1609

From Lescarbot's map. |

36 |

|

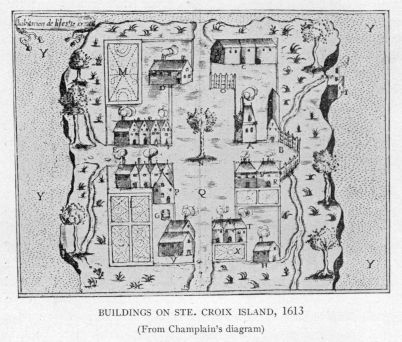

BUILDINGS ON STE. CROIX ISLAND

From Les Voyages du Sieur de Champlain, Paris, 1613. |

38 |

|

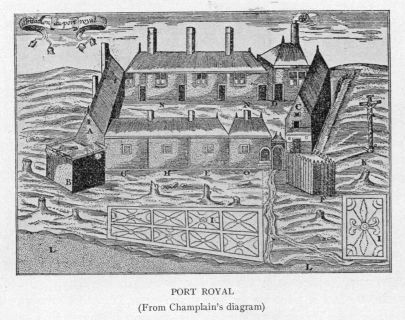

PORT ROYAL

From the same. |

43 |

|

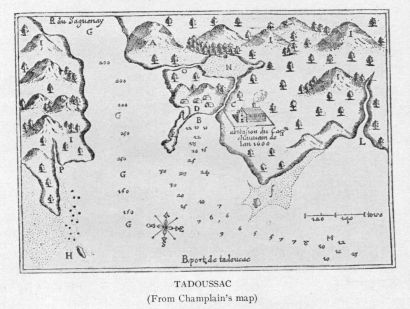

TADOUSSAC

From the same. |

45 |

|

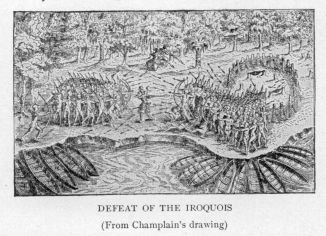

DEFEAT OF THE IROQUOIS

From the same. |

47 |

|

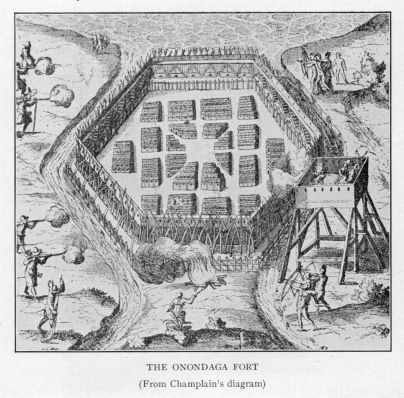

THE ONONDAGA FORT

From the same. |

55 |

|

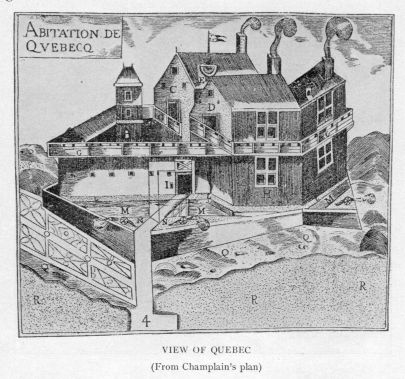

VIEW OF QUEBEC

From the same. |

56 |

|

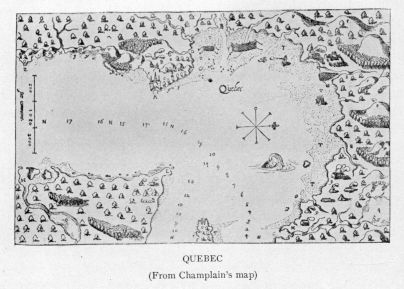

QUEBEC

From the same. |

59 |

|

SIR WILLIAM ALEXANDER

After an engraved portrait by Marshall. |

62 |

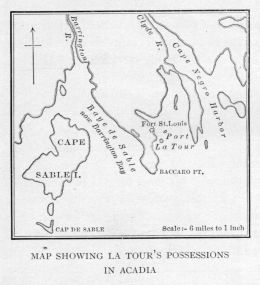

| MAP SHOWING LA TOUR'S POSSESSIONS IN ACADIA | 64 |

|

CARDINAL RICHELIEU

After the portrait by Philippe de Champaigne |

66 |

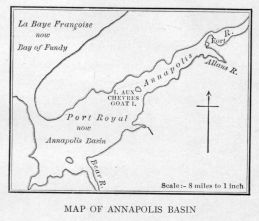

| MAP OF ANNAPOLIS BASIN | 69 |

|

MADAME DE LA PELTRIE

After a picture in the Ursuline Convent, Quebec. |

73 |

|

PIERRE LE JEUNE

From an engraving in Winsor's America, after an old print. |

80 |

|

GEORGIAN BAY

From a photograph by A. G. Alexander. |

84 |

|

BRÉBEUF

From a bust in silver at Quebec. |

89 |

|

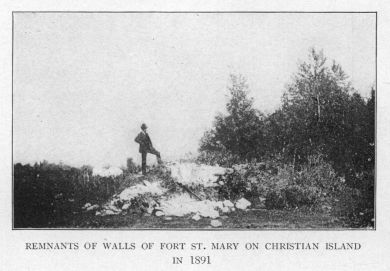

REMNANTS OF WALLS OF FORT ST. MARY ON CHRISTIAN ISLAND

IN 1891

After a photograph reproduced in Ontario Historical Society Papers and Records. |

91 |

|

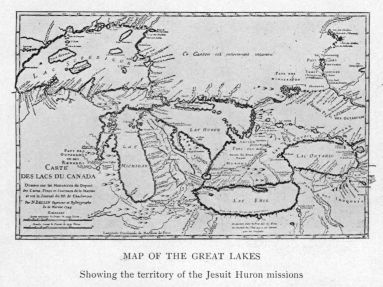

MAP OF THE GREAT LAKES, SHOWING THE TERRITORY OF THE

JESUIT HURON MISSIONS

Bellin's map, 1744. |

92 |

|

A CANADIAN ON SNOWSHOES

From La Potherie's Histoire de l'Amerique Septentrionale, Paris, 1753. |

96 |

|

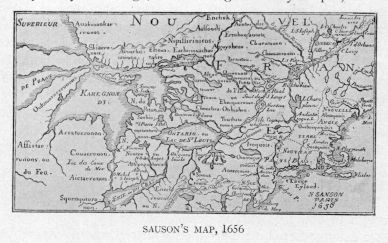

SAUSON'S MAP, 1656

|

99 |

|

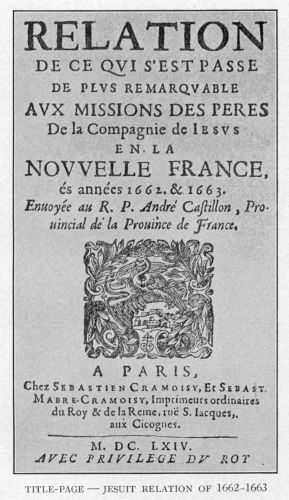

TITLE-PAGE—JESUIT RELATION OF 1662-1663

|

111 |

|

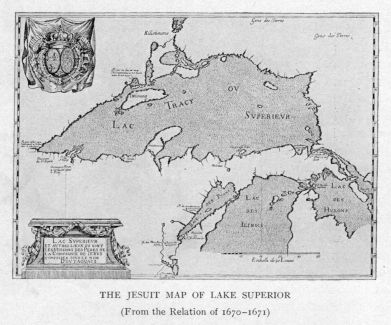

THE JESUIT MAP OF LAKE SUPERIOR

From the Relation, of 1670-1671. |

112 |

|

CHARLES II

After the miniature portrait by Cooper, with signature. |

114 |

|

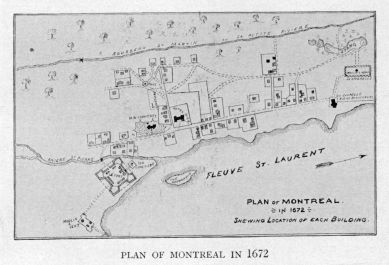

PLAN OF MONTREAL IN 1672

From Quebec Historical Society Papers and Records. |

119 |

|

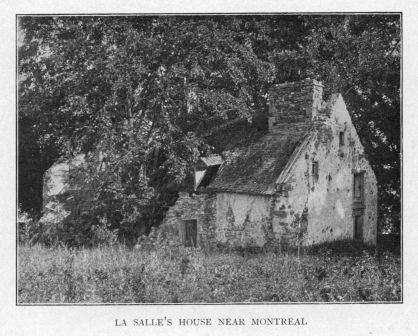

LA SALLE'S HOUSE NEAR MONTREAL

From a photograph. |

120 |

|

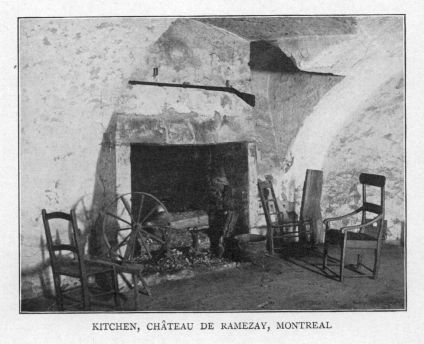

KITCHEN, CHÂTEAU DE RAMEZAY, MONTREAL

From a photograph. |

120 |

|

LAVAL

After the portrait in Laval University, Quebec. |

122 |

|

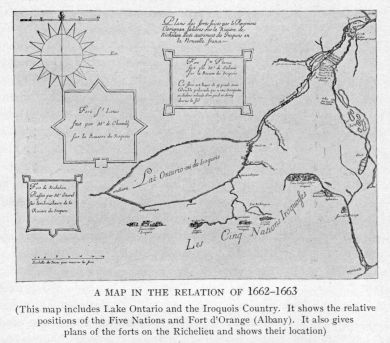

A MAP IN THE RELATION OF 1662-1663

|

126 |

|

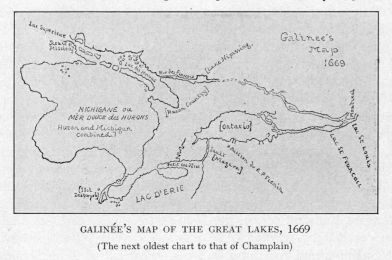

GALINÉE'S MAP OF THE GREAT LAKES, 1669

|

129 |

|

ROBERT DE LA SALLE

After an engraved portrait said to be preserved in the Bibliothèque de Rouen, with signature. |

135 |

|

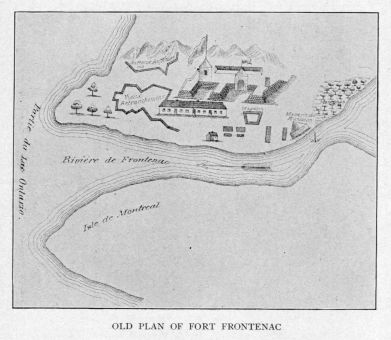

OLD PLAN OF FORT FRONTENAC

From Mémoirs sur le Canada, Quebec, 1873. |

136 |

|

THE BUILDING OF THE GRIFFON

From Father Hennepin's Nouvelle Découverte, Amsterdam, 1704. |

138 |

|

PRINCE RUPERT

After the painting by Sir P. Lely. |

145 |

|

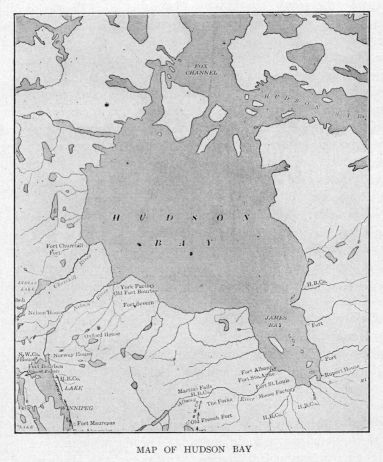

MAP OF HUDSON BAY

|

147 |

|

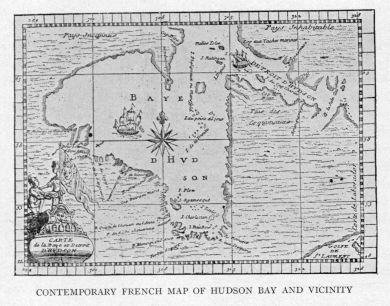

CONTEMPORARY FRENCH MAP OF HUDSON BAY AND VICINITY

From La Potherie's Histoire de l'Amerique Septentrionale. |

155 |

|

LE MOYNE D'IBERVILLE

After a portrait in Margry's Découvertes Établissemens. |

157 |

|

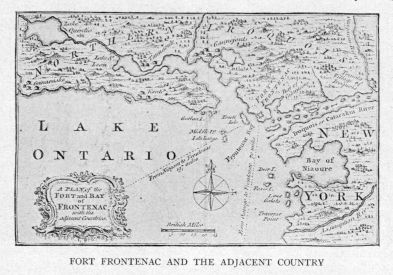

FORT FRONTENAC AND THE ADJACENT COUNTRY

From The London Magazine, 1758. |

164 |

|

WILLIAM OF ORANGE

After the portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller, with signature. |

166 |

|

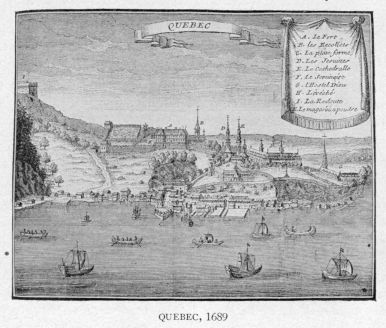

QUEBEC, 1689

From La Potherie's Histoire de l'Amérique Septentrionale. |

172 |

|

FRENCH SOLDIER OF THE PERIOD

After a cut in Massachusetts Archives, Documents collected in France, 111, 3. |

174 |

|

SIR WILLIAM PHIPS

After an accepted likeness reproduced in Winsor's America. |

176 |

|

COUNT FRONTENAC

From the statue by Hébert at Quebec. |

178 |

|

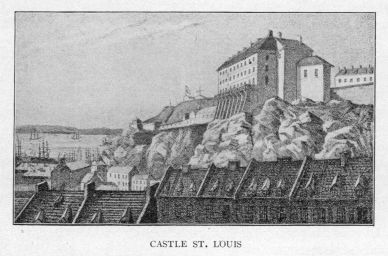

CASTLE ST. LOUIS

After a cut in Hawkins' Pictures of Quebec, Quebec, 1834. |

180 |

|

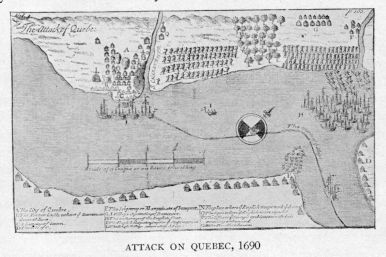

ATTACK ON QUEBEC, 1690

From La Hontan's Mémoires, 1709. |

181 |

|

CASTLE ST. LOUIS, QUEBEC

From Sulte's Canadiens Français, viii. |

183 |

|

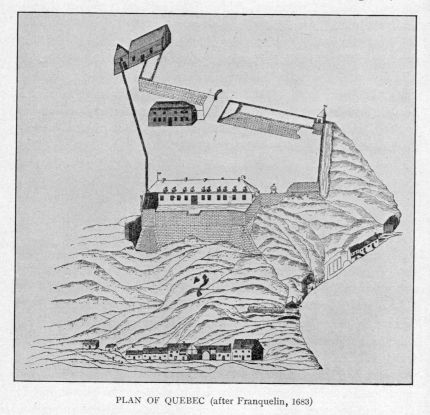

PLAN OF QUEBEC

From Franquelin, 1683. |

184 |

|

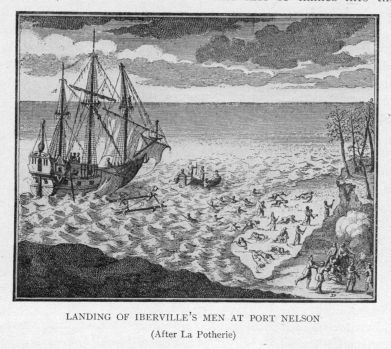

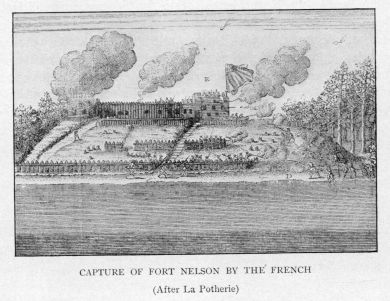

LANDING OF IBERVILLE'S MEN AT PORT NELSON

From La Potherie's Histoire de l'Amérique Septentrionale. |

186 |

|

CAPTURE OF FORT NELSON BY THE FRENCH

From the same. |

187 |

|

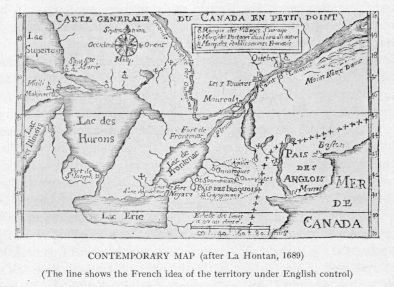

CONTEMPORARY MAP, 1689

From La Hontan. |

191 |

|

HERTEL DE ROUVILLE

After a portrait in Daniel's Nos Gloires Nationales. |

193 |

|

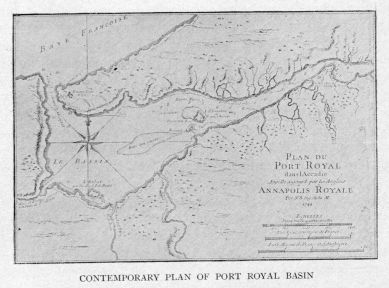

CONTEMPORARY PLAN OF PORT ROYAL BASIN

From Bellin's map, 1744. |

199 |

|

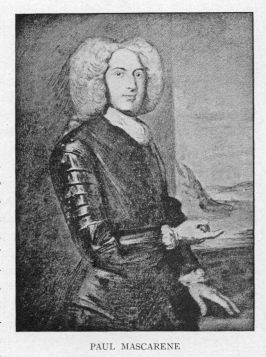

PAUL MASCARENE

After a portrait in Savary's edition of Calnek's Annapolis. |

201 |

|

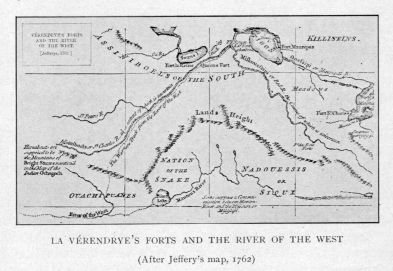

LA VÉRENDRYE'S FORTS AND THE RIVER OF THE WEST

After Jeffery's map, 1762. |

207 |

|

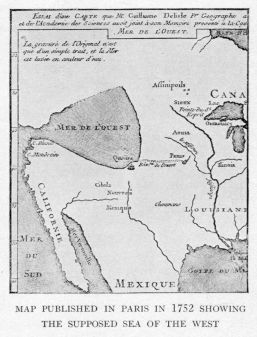

MAP PUBLISHED IN PARIS IN 1752 SHOWING THE SUPPOSED

SEA OF THE WEST

From the Mémoire presented to the Academy of Sciences at Paris by Buache, August, 1752. |

209 |

|

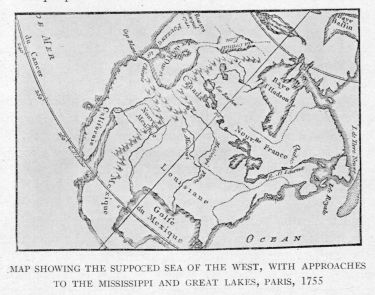

MAP SHOWING THE SUPPOSED SEA OF THE WEST, WITH APPROACHES

TO THE MISSISSIPPI AND GREAT LAKES, PARIS, 1755

From the same. |

211 |

|

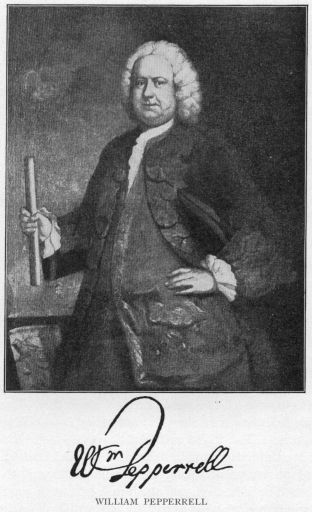

WILLIAM PEPPERRELL

After the portrait by Smibert. |

217 |

|

RUINS OF THE FORTIFICATIONS AT LOUISBURG

From a recent photograph. |

219 |

|

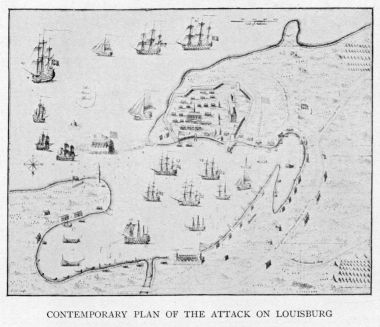

CONTEMPORARY PLAN OF THE ATTACK ON LOUISBURG

After a plan reproduced in Winsor's America. |

221 |

| FORT HALIFAX, 1755 (Restoration) | 222 |

|

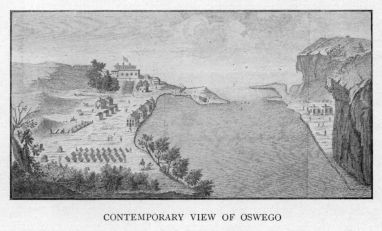

CONTEMPORARY VIEW OF OSWEGO

From Smith's History of the Province of New York. |

223 |

|

GOVERNOR DINWIDDIE OF VIRGINIA

After a portrait by Ramsay. |

225 |

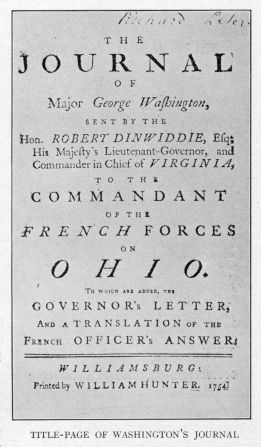

| TITLE-PAGE OF WASHINGTON'S JOURNAL | 227 |

|

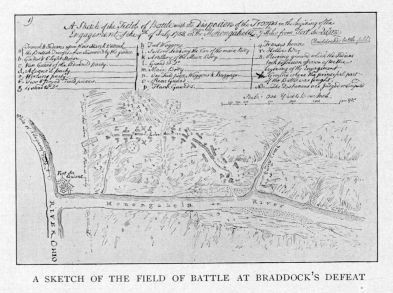

A SKETCH OF THE FIELD OF BATTLE AT BRADDOCK'S DEFEAT

From a contemporary manuscript in the Library of Harvard University. |

229 |

|

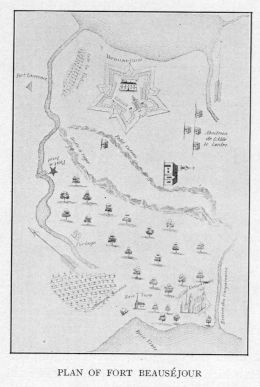

PLAN OF FORT BEAUSEJOUR

From Mante's History of the Late War in North America. |

230 |

|

GENERAL MONCKTON

After a mezzotint in the Library of the American Antiquarian Society. |

232 |

|

GENERAL JOHN WINSLOW

After the portrait in Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth, Massachusetts. |

234 |

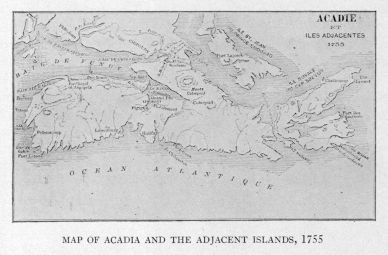

| MAP OF ACADIA AND THE ADJACENT ISLANDS, 1755 | 237 |

|

SIR WILLIAM JOHNSON

After the portrait by Adams. |

238 |

|

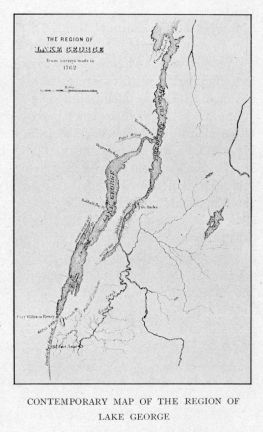

MAP OF THE REGION OF LAKE GEORGE

From Documentary History of New York. |

239 |

|

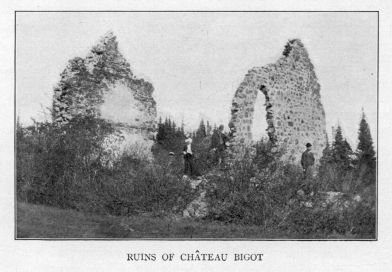

RUINS OF CHÂTEAU BIGOT

From a photograph by Captain Wurtelle. |

245 |

|

PARLIAMENT BUILDINGS, OTTAWA

From a photograph. |

246 |

|

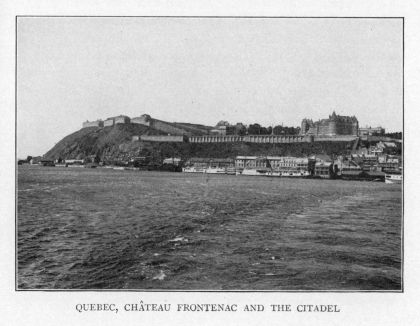

QUEBEC, CHÂTEAU FRONTENAC AND THE CITADEL

From a photograph. |

246 |

|

THE EARL OF LOUDON

After the portrait by Ramsay. |

249 |

|

BOSCAWEN

After the portrait by Reynolds. |

253 |

|

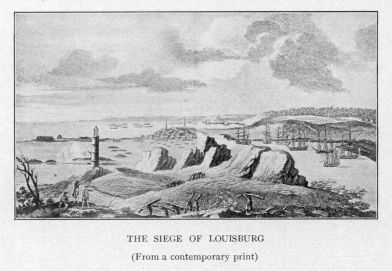

THE SIEGE OF LOUISBURG, 1758

From a picture in the Lenox Collection, New York Public Library. |

255 |

|

AMHERST

After the portrait by Reynolds. |

257 |

|

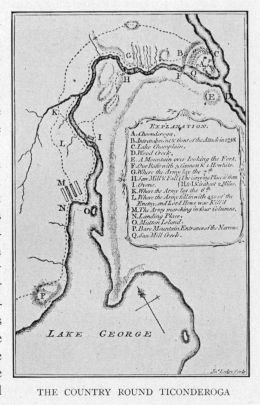

THE COUNTRY ROUND TICONDEROGA

From Documentary History of New York. |

259 |

|

GENERAL JAMES WOLFE

After the engraved portrait by Houstin. |

261 |

|

BOUGAINVILLE

After a cut in Bounechose's Montcalm. |

263 |

|

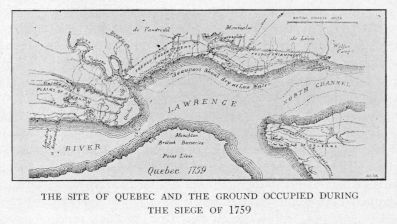

THE SITE OF QUEBEC AND THE GROUND OCCUPIED

DURING THE SIEGE OF 1759

After a plan in The Universal Magazine, London, December, 1859. |

265 |

|

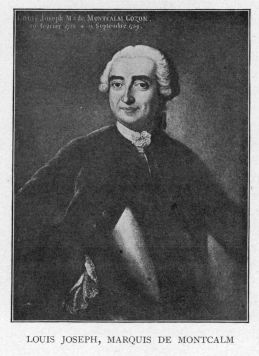

LOUIS JOSEPH, MARQUIS DE MONTCALM

After the portrait in the possession of his descendants. |

268 |

|

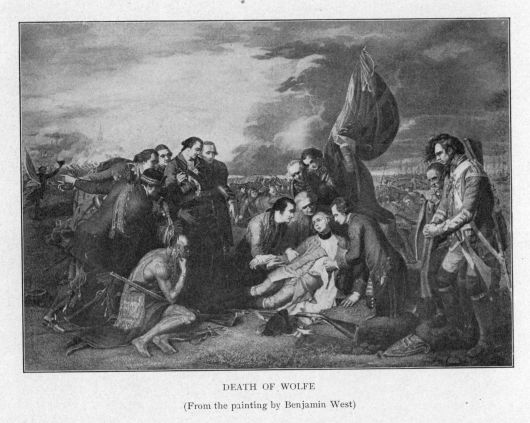

DEATH OF WOLFE

From the painting by West. |

272 |

|

MAJOR ROBERT ROGERS

After a mezzotint by an unknown engraver. Published in London, October 1, 1776 |

277 |

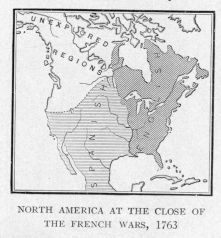

| NORTH AMERICA AT THE CLOSE OF THE FRENCH WARS, 1763 | 278 |

|

GENERAL MURRAY, FIRST GOVERNOR OF QUEBEC

After the portrait by Ramsay. |

280 |

|

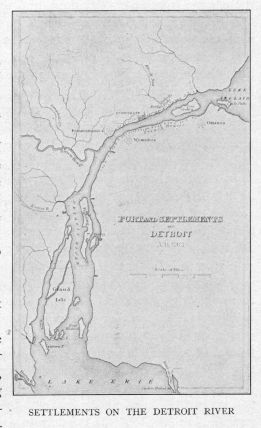

SETTLEMENTS ON THE DETROIT RIVER

From Parkman's Conspiracy of Pontiac. |

283 |

|

BOUQUET

After the portrait by West. |

289 |

|

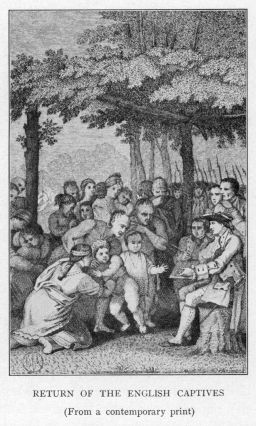

RETURN OF THE ENGLISH CAPTIVES

After the painting by West. |

291 |

|

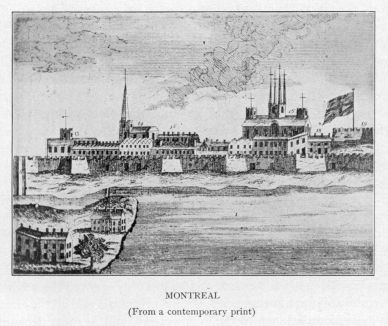

MONTREAL

After a print in the New York Public Library. |

293 |

|

SAMUEL HEARNE

After an engraving published in 1796. |

297 |

|

GENERAL RICHARD MONTGOMERY

After the painting by Chappel. |

301 |

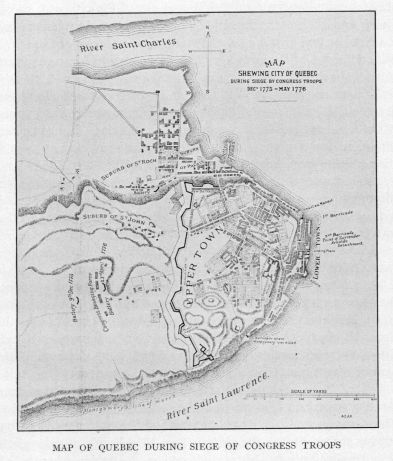

| MAP OF QUEBEC DURING THE SIEGE OF CONGRESS TROOPS | 303 |

|

SIR GUY CARLETON

After an engraving in The Political Magazine, June, 1782. |

307 |

|

BENEDICT ARNOLD

After the portrait by Tate. |

309 |

|

GENERAL HALDIMAND

After the portrait by Reynolds. |

311 |

|

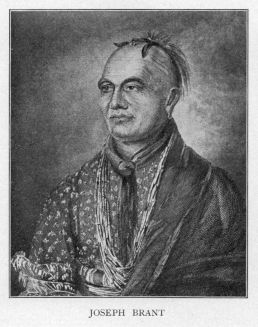

JOSEPH BRANT

After the portrait by Ames. |

315 |

|

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR SIMCOE

After an engraving in Scadding's Toronto of Old. |

316 |

|

CAPTAIN COOK

After the portrait by Dauce. |

320 |

|

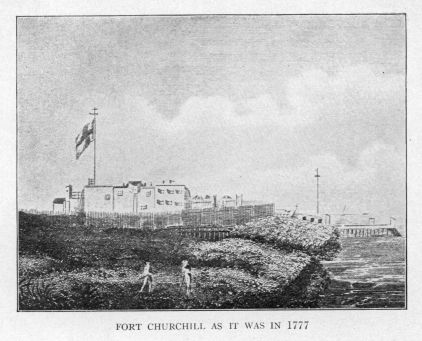

FORT CHURCHILL AS IT WAS IN 1777

After a print in the European Magazine, June, 1797. |

320 |

|

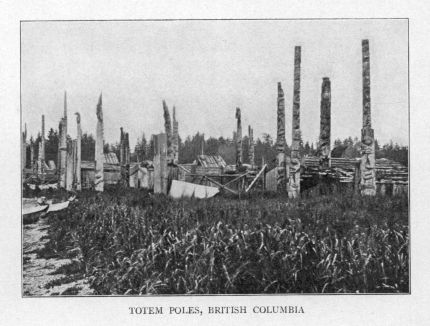

TOTEM POLES, BRITISH COLUMBIA

From a photograph. |

320 |

|

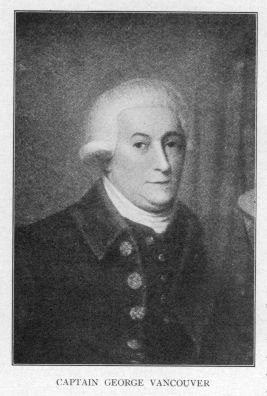

CAPTAIN GEORGE VANCOUVER

After the portrait by Abbott. |

322 |

|

NOOTKA SOUND

From an engraving in Vancouver's Journal. |

323 |

|

FORT CHIPPEWYAN, ATHABASCA LAKE

From a recent photograph. |

325 |

|

ALEXANDER MACKENZIE

After the portrait by Lawrence. |

327 |

|

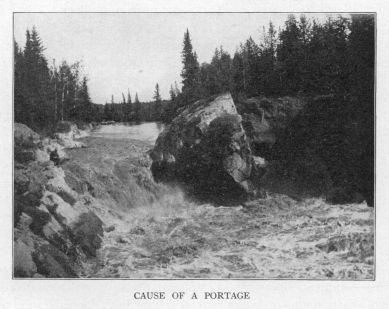

CAUSE OF A PORTAGE

From a photograph. |

329 |

|

SIMON FRASER

From a likeness in Morice's The History of the Northern Interior of British Columbia. |

331 |

|

ASTORIA IN 1813

From a cut in Franchere's Narrative of a Voyage. |

332 |

|

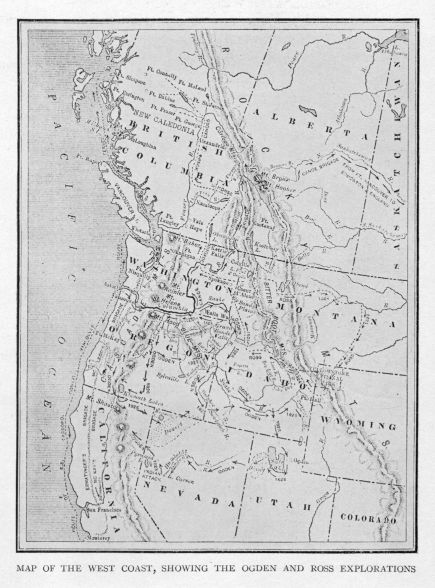

MAP OF WEST COAST, SHOWING THE OGDEN AND ROSS

EXPLORATIONS

From Laut's Conquest of the Great North West. |

332 |

|

GENERAL SIR JAMES HENRY CRAIG, GOVERNOR GENERAL OF CANADA,

1807-1811

After an engraving at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. |

336 |

|

WILLIAM HULL

After the portrait by Stuart, with autograph. |

338 |

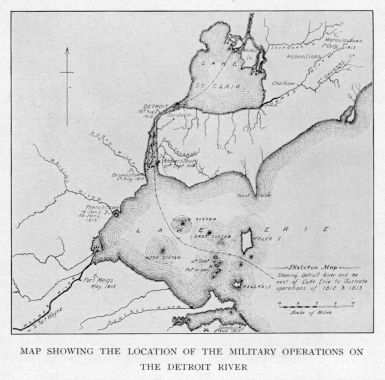

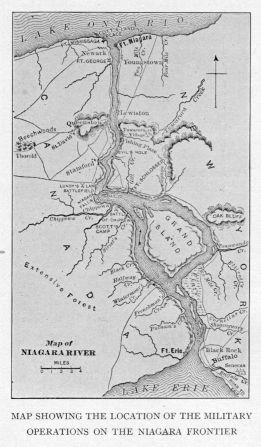

| MAP SHOWING THE LOCATION OF THE MILITARY OPERATIONS ON THE DETROIT RIVER | 340 |

| MAP SHOWING THE LOCATION OF THE MILITARY OPERATIONS ON THE NIAGARA FRONTIER | 342 |

|

GENERAL BROCK

After a portrait in the possession of J. A. Macdonell Esq., Alexandria, Ontario. |

345 |

|

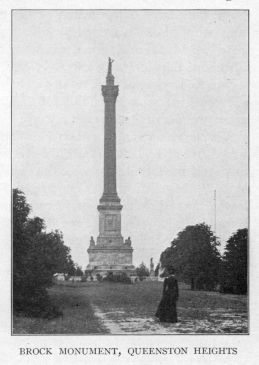

BROCK MONUMENT, QUEENSTON HEIGHTS

From a photograph. |

347 |

|

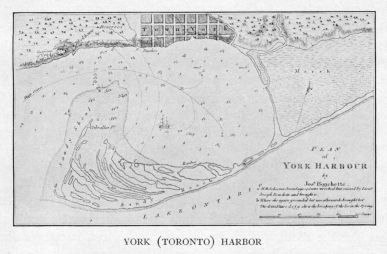

YORK (TORONTO) HARBOR

From Bouchette's British Dominions in North America. |

351 |

|

FITZGIBBONS

After a photograph reproduced in Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, 1900. |

357 |

|

LAURA SECORD

From Ontario Historical Society Papers and Records. |

361 |

|

TWO VIEWS OF THE BATTLE OF LAKE ERIE

From prints published in 1815 |

364 |

|

TECUMSEH

After the drawing by Pierre Le Drie. |

366 |

|

DE SALABERRY

After a portrait in Fannings Taylor's Portraits of British Americans. |

368 |

|

SIR GORDON DRUMMOND

After an engraving at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. |

371 |

|

MONUMENT AT LUNDY'S LANE

From a photograph. |

375 |

|

SELKIRK

From Ontario Archives Collection. |

381 |

|

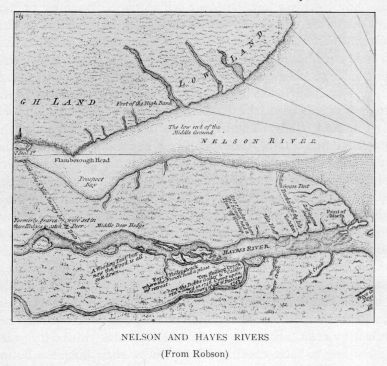

NELSON AND HAYES RIVERS

From a map in Robson's Hudson Bay. |

384 |

|

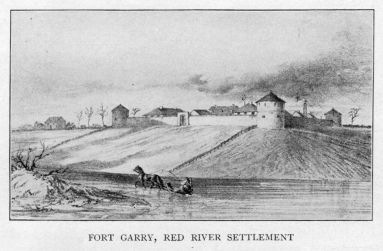

FORT GARRY, RED RIVER SETTLEMENT

From Ross' Red River Settlement. |

387 |

|

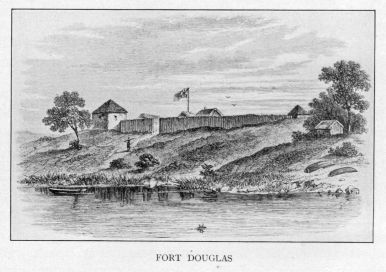

FORT DOUGLAS

After an old engraving. |

388 |

|

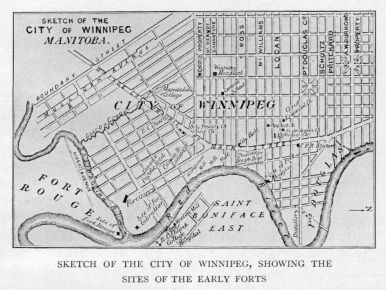

SKETCH OF THE CITY OF WINNIPEG, SHOWING THE SITES

OF THE EARLY FORTS

From Manitoba Historical Society |

391 |

|

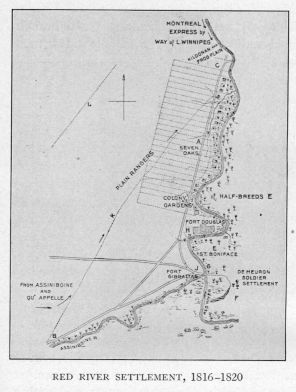

RED RIVER SETTLEMENT, 1816-1820

After a map in Amos' Report of the Trials Relative to the Destruction of the Earl of Selkirk's Settlement. |

392 |

|

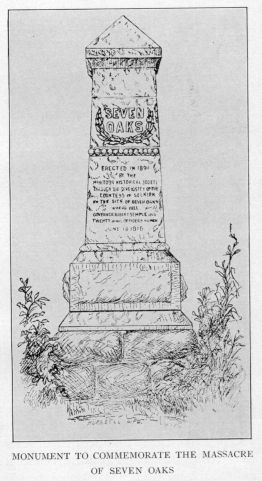

MONUMENT TO COMMEMORATE THE MASSACRE OF SEVEN OAKS

After a sketch. |

397 |

|

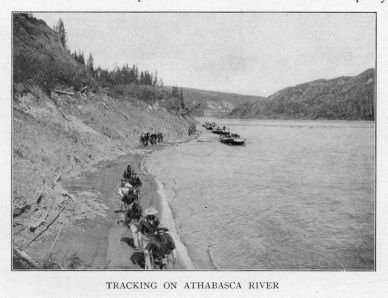

TRACKING ON ATHABASCA RIVER

From a photograph. |

401 |

|

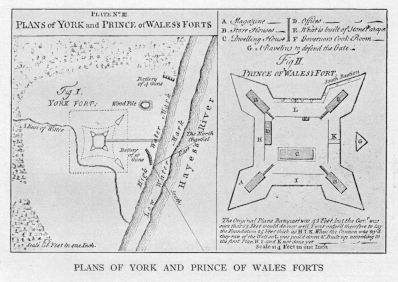

PLANS OF YORK AND PRINCE OF WALES FORTS

From a plate in Robson's Hudson Bay. |

405 |

| SIR GEORGE SIMPSON, GOVERNOR OF HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY, 1820 | 406 |

|

JOHN MCLOUGHLIN

After a likeness in Laut's Conquest of the Great Northwest. |

408 |

|

SIR JOHN SHERBROOKE, GOVERNOR GENERAL OF CANADA, 1816-1818

After an engraving at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. |

413 |

|

THE FOURTH DUKE OF RICHMOND, GOVERNOR GENERAL OF CANADA,

1818-1819

After an engraving at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. |

419 |

|

WILLIAM LYON MACKENZIE

After a likeness in Lindsey's Life and Times of Mackenzie. |

421 |

|

ALLAN McNAB

After the portrait in the Speaker's Chambers, Ottawa. |

423 |

|

LOUIS J. PAPINEAU

After a likeness in Fannings Taylor's British Americans. |

428 |

|

SIR JOHN COLBORNE, GOVERNOR GENERAL OF CANADA, 1838-1841

After an engraving at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. |

430 |

|

LORD DURHAM, SPECIAL COMMISSIONER TO CANADA, 1838

After an engraving at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. |

432 |

|

JOHN A. MACDONALD

From a photograph. |

435 |

|

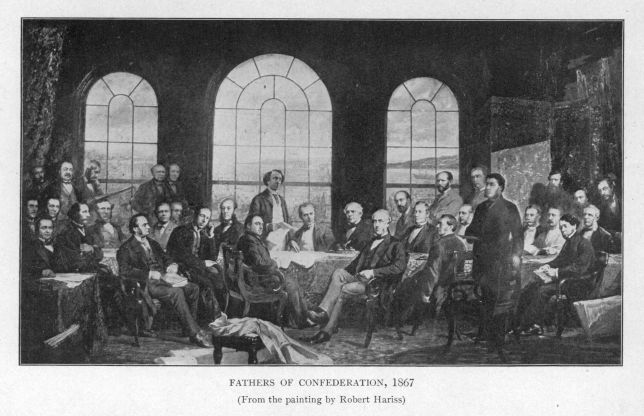

FATHERS OF CONFEDERATION, 1867

From the painting by Hariss. |

436 |

Early voyages to America—Voyages of the Cabots—The French fisher folk—Cartier's first voyage—Cartier's second voyage—Cartier's third voyage—Marguerite Roberval

Who first found Canada? As many legends surround the beginnings of empire in the North as cling to the story of early Rome.

When Leif, son of Earl Eric, the Red, came down from Greenland with his Viking crew, which of his bearded seamen in Arctic furs leaned over the dragon prow for sight of the lone new land, fresh as if washed by the dews of earth's first morning? Was it Thorwald, Leif's brother, or the mother of Snorri, first white child born in America, who caught first glimpse through the flying spray of Labrador's domed hills,—"Helluland, place of slaty rocks"; and of Nova Scotia's wooded meadows,—"Markland"; and Rhode Island's broken vine-clad shore,—"Vinland"? The question cannot be answered. All is as misty concerning that Viking voyage as the legends of old Norse gods.

Leif, the Lucky, son of Earl Eric, the outlaw, coasts back to Greenland with his bold sea-rovers. This was in the year 1000.

For ten years they came riding southward in their rude-planked ships of the dragon prow, those Norse adventurers; and Thorwald, Leif's brother, is first of the pathfinders in America to lose his life in battle with the "Skraelings" or Indians. Thornstein, another brother, sails south in 1005 with Gudrid, his wife; but a roaring nor'easter tears the piping {2} sails to tatters, and Thornstein dies as his frail craft scuds before the blast. Back comes Gudrid the very next year, with a new husband and a new ship and two hundred colonists to found a kingdom in the "Land of the Vine." At one place they come to rocky islands, where birds flock in such myriads it is impossible to land without trampling nests. Were these the rocky islands famous for birds in the St. Lawrence? On another coast are fields of maize and forests entangled with grapevines. Was this part of modern New England? On Vinland—wherever it was—Gudrid, the Norse woman, disembarks her colonists. All goes well for three years. Fish and fowl are in plenty. Cattle roam knee-deep in pasturage. Indians trade furs for scarlet cloth and the Norsemen dole out their barter in strips narrow as a little finger; but all beasts that roam the wilds are free game to Indian hunters. The cattle begin to disappear, the Indians to lurk armed along the paths to the water springs. The woods are full of danger. Any bush may conceal painted foe. Men as well as cattle lie dead with telltale arrow sticking from a wound. The Norsemen begin to hate these shadowy, lonely, mournful forests. They long for wild winds and trackless seas and open world. Fur-clad, what do they care for the cold? Greenland with its rolling drifts is safer hunting than this forest world. What glory, doomed prisoners between the woods and the sea within the shadow of the great forests and a great fear? The smell of wildwood things, of flower banks, of fern mold, came dank and unwholesome to these men. Their {3} nostrils were for the whiff of the sea; and every sunset tipped the waves with fire where they longed to sail. And the shadow of the fear fell on Gudrid. Ordering the vessels loaded with timber good for masts and with wealth of furs, she gathered up her people and led them from the "Land of the Vine" back to Greenland.

Where was Vinland? Was it Canada? The answer is unknown. It was south of Labrador. It is thought to have been Rhode Island; but certainly, passing north and south, the Norse were the first white men to see Canada.

Did some legend, dim as a forgotten dream, come down to Columbus in 1492 of the Norsemen's western land? All sailors of Europe yearly fished in Iceland. Had one of Columbus's crew heard sailor yarns of the new land? If so, Columbus must have thought the new land part of Asia; for ever since Marco Polo had come from China, Europe had dreamed of a way to Asia by the sea. What with Portugal and Spain dividing the New World, all the nations of Europe suddenly awakened to a passion for discovery.

There were still lands to the north, which Portugal and Spain had not found,—lands where pearls and gold might abound. At Bristol in England dwelt with his sons John Cabot, the Genoese master mariner, well acquainted with Eastern-trade. Henry VII commissions him on a voyage of discovery—an empty honor, the King to have one fifth of all profit, Cabot to bear all expense. The Matthew ships from Bristol with a crew of eighteen in May of 1497. North and west sails the tumbling craft two thousand miles. Colder grows the air, stiffer the breeze in the bellying sails, till the Matthew's crew are shivering on decks amid fleets of icebergs that drift from Greenland in May and June. This is no realm of spices and gold. Land looms through the mist the last week in June, {4} rocky, surf-beaten, lonely as earth's ends, with never a sound but the scream of the gulls and the moan of the restless water-fret along endless white reefs. Not a living soul did the English sailors see. Weak in numbers, disappointed in the rocky land, they did not wait to hunt for natives. An English flag was hastily unfurled and possession taken of this Empire of the North for England. The woods of America for the first time rang to the chopper. Wood and water were taken on, and the Matthew had anchored in Bristol by the first week of August. Neither gold nor a way to China had Cabot found; but he had accomplished three things: he had found that the New World was not a part of Asia, as Spain thought; he had found the continent itself; and he had given England the right to claim new dominion.

England went mad over Cabot. He was granted the title of admiral and allowed to dress in silks as a nobleman. King Henry gave him 10 pounds, equal to $500 of modern money, and a pension of 20 pounds, equal to $1000 to-day. It is sometimes said that modern writers attribute an air of romance to these old pathfinders, {5} which they would have scorned; but "Zuan Cabot," as the people called him, wore the halo of glory with glee. To his barber he presented an island kingdom; to a poor monk he gave a bishopric. His son, Sebastian, sailed out the next year with a fleet of six ships and three hundred men, coasting north as far as Greenland, south as far as Carolina, so rendering doubly secure England's title to the North, and bringing back news of the great cod banks that were to lure French and Spanish and English fishermen to Newfoundland for hundreds of years.

Where was Cabot's landfall?

I chanced to be in Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland, shortly after the 400th anniversary of Cabot's voyage. King's Cove, landlocked as a hole in a wall, mountains meeting sky line, presented on one flat rock in letters the size of a house claim that it was here John Cabot sent his sailors ashore to plant the flag on cairn of bowlders; but when I came back from Newfoundland by way of Cape Breton, I found the same claim there. For generations the tradition has been handed down from father to son among Newfoundland fisher folk that as Cabot's vessel, pitching and rolling to the tidal bore, came scudding into King's Cove, rock girt as an inland lake, the sailors shouted "Bona Vista—Beautiful View"; but Cape Breton has her legend, too. It was Cabot's report of the cod banks that brought the Breton fishermen out, whose name Cape Breton bears.

{6} As Christopher Columbus spurred England to action, so Cabot now spurred Portugal and Spain and France.

Gaspar Cortereal comes in 1500 from Portugal on Cabot's tracks to that land of "slaty rocks" which the Norse saw long ago. The Gulf Stream beats the iron coast with a boom of thunder, and the tide swirl meets the ice drift; and it isn't a land to make a treasure hunter happy till there wander down to the shore Montaignais Indians, strapping fellows, a head taller than the tallest Portuguese. Cortereal lands, lures fifty savages on board, carries them home as slaves for Portugal's galley ships, and names the country—"land of laborers"—Labrador. He sailed again, the next year; but never returned to Portugal. The seas swallowed his vessel; or the tide beat it to pieces against Labrador's rocks; of those Indians slaked their vengeance by cutting the throats of master and crew.

And Spain was not idle. In 1513 Balboa leads his Spanish treasure seekers across the Isthmus of Panama, discovers the Pacific, and realizes what Cabot has already proved—that the New World is not a part of Asia. Thereupon, in swelling words, he takes possession of "earth, air, and water from the Pole Arctic to the Pole Antarctic" for Spain. A few years later Magellan finds his way to Asia round South America; but this path by sea is too long.

From France, Normans and Bretons are following Cabot's tracks to Newfoundland, to Labrador, to Cape Breton, "quhar men goeth a-fishing" in little cockleshell boats no bigger than three-masted schooner, with black-painted dories dragging in tow or roped on the rolling decks. Absurd it is, but with no blare of trumpets or royal commissions, with no guide but the wander spirit that lured the old Vikings over the rolling seas, these grizzled peasants flock from France, cross the Atlantic, and scatter over what were then chartless waters from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Grand Banks.

Just as they may be seen to-day bounding over the waves in their little black dories, hauling in… hauling in the endless line, or jigging for squid, or lying at ease at the noonday hour {7} singing some old land ballad while the kettle of cod and pork boils above a chip fire kindled on the stones used as ballast in their boats—so came the French fisher folk three years after Cabot had discovered the Grand Banks. Denys of Honfleur has led his fishing fleet all over the Gulf of St. Lawrence by 1506. So has Aubert of Dieppe. By 1517, fifty French vessels yearly fish off the coast of New-Found-Land. By 1518 one Baron de Lery has formed the project of colonizing this new domain; but the baron's ship unluckily came from the Grand Banks to port on that circular bank of sand known as Sable Island—from twenty to thirty miles as the tide shifts the sand, with grass waist high and a swampy lake in the middle. The Baron de Lery unloads his stock on Sable island and roves the sea for a better port.

The King of France, meanwhile, resents the Pope dividing the New World between Spain and Portugal. "I should like to see the clause in Father Adam's will that gives the whole earth to you," he sent word to his brother kings. Verrazano, sea rover of Florence, is commissioned to explore the New World seas; but Verrazano goes no farther north in 1524 than Newfoundland, and when he comes on a second voyage he is lost—some say hanged as a pirate by the Spaniards for intruding on their seas.

In spite of the loss of the King's sea rover, the fisher folk of France continue coming in their crazy little schooners, continue fishing in the fogs of the Grand Banks from their rocking black-planked dories, continue scudding for shelter from storm… here, there, everywhere; into the south shore of Newfoundland; into the long arms of the sea at Cape Breton, dyed at sundawn and sunset by such floods of golden light, these arms of the sea become known as Bras d'Or Lakes—Lakes of Gold; into the rock-girt lagoons of Gaspé; into the holes in the wall of Labrador…; till there presently springs up a secret trade in furs between the fishing fleet and the Indians. The King of France is not to be balked by one failure. "What," he asked, "are my royal brothers to have all America?" Among the Bank fishermen were many sailors of St. Malo. Jacques Cartier, master pilot, {8} now forty years of age, must have learned strange yarns of the New World from harbor folk. Indeed, he may have served as sailor on the Banks. Him the King chose, with one hundred and twenty men and two vessels, in 1534, to go on a voyage of discovery to the great sea where men fished. Cartier was to find if the sea led to China and to take possession of the countries for France. Captain, masters, men, march to the cathedral and swear fidelity to the King. The vessels sail on April 20, with the fishing fleet.

Piping winds carry them forward at a clipper pace. The sails scatter and disappear over the watery sky line. In twenty days Cartier is off that bold headland with the hole in the wall called Bona Vista. Ice is running as it always runs there in spring. What with wind and ice, Cartier deems it prudent to look for shelter. Sheering south among the scarps at Catalina, where the whales blow and the seals float in thousands {9} on the ice pans, Cartier anchors to take on wood and water. For ten days he watches the white whirl driving south. Then the water clears and his sails swing to the wind, and he is off to the north, along that steel-gray shore of rampart rock, between the white-slab islands and the reefy coast. Birds are in such flocks off Funk Island that the men go ashore to hunt, as the fisher folk anchor for bird shooting to-day.

Higher rises the rocky sky line; barer the shore wall, with never a break to the eye till you turn some jagged peak and come on one of those snug coves where the white fisher hamlets now nestle. Reefs white as lace fret line the coast. Lonely as death, bare as a block of marble, Gull Island is passed where another crew in later years perish as castaways. Gray finback whales flounder in schools. The lazy humpbacks lounge round and round the ships, eyeing the keels curiously. A polar bear is seen on an ice pan. Then the ships come to those lonely harbors north of Newfoundland—Griguet and Quirpon and Ha-Ha-Bay, rock girt, treeless, always windy, desolate, with an eternal moaning of the tide over the fretful reefs.

{10} To the north, off a little seaward, is Belle Isle. Here, storm or calm, the ocean tide beats with fury unceasing and weird reëchoing of baffled waters like the scream of lost souls. It was sunset when I was on a coastal ship once that anchored off Belle Isle, and I realized how natural it must have been for Cartier's superstitious sailors to mistake the moan of the sea for wild cries of distress, and the smoke of the spray for fires of the inferno. To French sailors Belle Isle became Isle of Demons. In the half light of fog or night, as the wave wash rises and falls, you can almost see white arms clutching the rock.

As usual, bad weather caught the ships in Belle Isle Straits. Till the 9th of June brown fog held Cartier. When it lifted the tide had borne his ships across the straits to Labrador at Castle Island, Château Bay. Labrador was a ruder region than Newfoundland. Far as eye could scan were only domed rocks like petrified billows, dank valleys moss-grown and scrubby, hillsides bare as slate; "This land should not be called earth," remarked Cartier. "It is flint! Faith, I think this is the region God gave Cain!" If this were Cain's realm, his descendants were "men of might"; for when the Montaignais, tall and straight as mast poles, came down to the straits, Cartier's little scrub sailors thought them giants. Promptly Cartier planted the cross and took possession of Labrador for France. As the boats coasted westward the shore rock turned to sand,—huge banks and drifts and hillocks of white sand,—so that the place where the ships struck across for the south shore became known as Blanc Sablon (White Sand). Squalls drove Cartier up the Bay of Islands on the west shore of Newfoundland, and he was amazed to find this arm of the sea cut the big island almost in two. Wooded mountains flanked each shore. A great river, amber with forest mold, came rolling down a deep gorge. But it was not Newfoundland Cartier had come to explore; it was the great inland sea to the west, and to the west he sailed.

July found him off another kind of coast—New Brunswick—forested and rolling with fertile meadows. Down a broad shallow stream—the Miramichi—paddled Indians waving furs {11} for trade; but wind threatened a stranding in the shallows. Cartier turned to follow the coast north. Denser grew the forests, broader the girths of the great oaks, heavier the vines, hotter the midsummer weather. This was no land of Cain. It was a new realm for France. While Cartier lay at anchor north of the Miramichi, Indian canoes swarmed round the boats at such close quarters the whites had to discharge a musket to keep the three hundred savages from scrambling on decks. Two seamen then landed to leave presents of knives and coats. The Indians shrieked delight, and, following back to the ships, threw fur garments to the decks till literally naked. On the 18th of July the heat was so intense that Cartier named the waters Bay of Chaleur. Here were more Indians. At first the women dashed to hiding in the woods, while the painted warriors paddled out; but when Cartier threw more presents into the canoes, women and children swarmed out singing a welcome. The Bay of Chaleur promised no passage west, so Cartier again spread his sails to the wind and coasted northward. The forests thinned. Towards Gaspé the shore became rocky and fantastic. The inland sea led westward, but the season was far advanced. It was decided to return and report to the King. Landing at Gaspé on July 24, Cartier erected a cross thirty feet high with the words emblazoned on a tablet, Vive le Roi de France. Standing about him were the painted natives of the wilderness, one old chief dressed in black bearskin gesticulating protest against the cross till Cartier explained by signs that the whites would come again. Two savages were invited on board. By accident or design, as they stepped on deck, their skiff was upset and set adrift. The astonished natives found themselves in the white men's power, but food and gay clothing allayed fear. They willingly consented to accompany Cartier to France. Somewhere north of Gaspé the smoke of the French fishing fleet was seen ascending from the sea, as the fishermen rocked in their dories cooking the midday meal.

August 9 prayers are held for safe return at Blanc Sablon,—port of the white, white sand,—and by September 5 Cartier is {12} home in St. Malo, a rabble of grizzled sailor folk chattering a welcome from the wharf front.

He had not found passage to China, but he had found a kingdom; and the two Indians told marvelous tales of the Great River to the West, where they lived, of mines, of vast unclaimed lands.

Cartier had been home only a month when the Admiral of France ordered him to prepare for another voyage. He himself was to command the Grand Hermine, Captain Jalobert the Little Hermine, and Captain Le Breton the Emerillon. Young gentlemen adventurers were to accompany the explorers. The ships were provisioned for two years; and on May 16, 1535, all hands gathered to the cathedral, where sins were confessed, the archbishop's blessing received, and Cartier given a Godspeed to the music of full choirs chanting invocation. Three days later anchors were hoisted. Cannon boomed. Sails swung out; and the vessels sheered away from the roadstead while cheers rent the air.

Head winds held the ship back. Furious tempests scattered the fleet. It was July 17 before Cartier sighted the gull islands of Newfoundland and swung up north with the tide through the brown fogs of Belle Isle Straits to the shining gravel of Blanc Sablon. Here he waited for the other vessels, which came on the 26th.

The two Indians taken from Gaspé now began to recognize the headlands of their native country, telling Cartier the first kingdom along the Great River was Saguenay, the second Canada, the third Hochelaga. Near Mingan, Cartier anchored to claim the land for France; and he named the great waters St. Lawrence because it was on that saint's day he had gone ashore. The north side of Anticosti was passed, and the first of September saw the three little ships drawn up within the shadow of that somber gorge cut through sheer rock where the Saguenay rolls sullenly out to the St. Lawrence. The mountains presented naked rock wall. Beyond, rolling back… rolling back to an impenetrable wilderness… were the primeval {13} forests. Through the canyon flowed the river, dark and ominous and hushed. The men rowed out in small boats to fish but were afraid to land.

As the ships advanced up the St. Lawrence the seamen could scarcely believe they were on a river. The current rolled seaward in a silver flood. In canoes paddling shyly out from the north shore Cartier's two Indians suddenly recognized old friends, and whoops of delight set the echoes ringing.

Keeping close to the north coast, russet in the September sun, Cartier slipped up that long reach of shallows abreast a low-shored wooded island so laden with grapevines he called it Isle Bacchus. It was the Island of Orleans.

Then the ships rounded westward, and there burst to view against the high rocks of the north shore the white-plumed shimmering cataract of Montmorency leaping from precipice to river bed with roar of thunder.

Cartier had anchored near the west end of Orleans Island when there came paddling out with twelve canoes, Donnacona, great chief of Stadacona, whose friendship was won on the instant by the tales Cartier's Indians told of France and all the marvels of the white man's world.

Cartier embarked with several young officers to go back with the chief; and the three vessels were cautiously piloted up little St. Charles River, which joins the St. Lawrence below the modern city of Quebec. Women dashed to their knees in water to welcome ashore these gayly dressed newcomers with the gold-braided coats and clanking swords. Crossing the low swamp, now Lower Town, Quebec, the adventurers followed a path through the forest up a steep declivity of sliding stones to the clear high table-land above, and on up the rolling slopes to the airy heights of Cape Diamond overlooking the St. Lawrence like the turret of some castle above the sea. Did a French soldier, removing his helmet to wipe away the sweat of his arduous climb, cry out "Que bec" (What a peak!) as he viewed the magnificent panorama of river and valley and mountain rolling from his feet; or did their Indian guide point to the water of the river narrowing like {14} a strait below the peak, and mutter in native tongue, "Quebec" (The strait)? Legend gives both explanations of the name. To the east Cartier could see far down the silver flood of the St. Lawrence halfway to Saguenay; to the south, far as the dim mountains of modern New Hampshire. What would the King of France have thought if he could have realized that his adventurers had found a province three times the size of England, one third larger than France, one third larger than Germany? And they had as yet reached only one small edge of Canada, namely Quebec.

Heat haze of Indian summer trembled over the purple hills. Below, the river quivered like quicksilver. In the air was the nutty odor of dried grasses, the clear tang of coming frosts crystal to the taste as water; and if one listened, almost listened to the silence, one could hear above the lapping of the tide the far echo of the cataract. To Cartier the scene might have been the airy fabric of some dream world; but out of dreams of earth's high heroes are empires made.

But the Indians had told of that other kingdom, Hochelaga. Hither Cartier had determined to go, when three Indians dressed as devils—faces black as coals, heads in masks, brows adorned with elk horns—came gyrating and howling out of the woods on the mountain side, making wild signals to the white men encamped on the St. Charles. Cartier's interpreters told him this was warning from the Indian god not to ascend the river. The god said Hochelaga was a realm of snow, where all white men would perish. It was a trick to keep the white men's trade for themselves.

Cartier laughed.

"Tell them their god is an old fool," he said. "Christ is to be our guide."

The Indians wanted to know if Cartier had spoken to his God about it.

"No," answered Cartier. Then, not to be floored, he added, "but my priest has."

{15} With three cheers, fifty young gentlemen sheered out on September 19 from the St. Charles on the Emerillon to accompany Cartier to Hochelaga.

Beyond Quebec the St. Lawrence widened like a lake. September frosts had painted the maples in flame. Song birds, the glory of the St. Lawrence valley, were no longer to be heard, but the waters literally swarmed with duck and the forests were alive with partridge. Where to-day nestle church spires and whitewashed hamlets were the birch wigwams and night camp fires of Indian hunters. Wherever Cartier went ashore, Indians rushed knee-deep to carry him from the river; and one old chief at Richelieu signified his pleasure by presenting the whites with two Indian children. Zigzagging leisurely, now along the north shore, now along the south, pausing to hunt, pausing to explore, pausing to powwow with the Indians, the adventurers came, on September 28, to the reedy shallows and breeding grounds of wild fowl at Lake St. Peter. Here they were so close ashore the Emerillon caught her keel in the weeds, and the explorers left her aground under guard and went forward in rowboats.

{16} "Was this the way to Hochelaga?" the rowers asked Indians paddling past.

"Yes, three more sleeps," the Indians answered by the sign of putting the face with closed eyes three times against their hand; "three more nights would bring Cartier to Hochelaga"; and on the night of the 2d of October the rowboats, stopped by the rapids, pulled ashore at Hochelaga amid a concourse of a thousand amazed savages.

It was too late to follow the trail through the darkening forest to the Indian village. Cartier placed the soldiers in their burnished armor on guard and spent the night watching the council fires gleam from the mountain. And did some soldier standing sentry, watching the dark shadow of the hill creep longer as the sun went down, cry out, "Mont Royal," so that the place came to be known as Montreal?

At peep of dawn, while the mist is still smoking up from the river, Cartier marshals twenty seamen with officers in military line, and, to the call of trumpet, marches along the forest trail behind Indian guides for the tribal fort. Following the river, knee-deep in grass, the French ascend the hill now known as Notre Dame Street, disappear in the hollow where flows a stream,—modern Craig Street,—then climb steeply through the forests to the plain now known as the great thoroughfare of Sherbrooke Street. Halfway up they come on open fields of maize or Indian corn. Here messengers welcome them forward, women singing, tom-tom beating, urchins stealing fearful glances through the woods. The trail ends at a fort with triple palisades of high trees, walls separated by ditches and roofed for defense, with one carefully guarded narrow gate. Inside are fifty large wigwams, the oblong bark houses of the Huron-Iroquois, each fifty feet long, with the public square in the center, or what we would call the courtyard.

It needs no trick of fancy to call up the scene—the winding of the trumpet through the forest silence, the amazement of the Indian drummers, the arrested frenzy of the dancers, the sunrise turning burnished armor to fire, the clanking of swords, {17} the wheeling of the soldiers as they fall in place, helmets doffed, round the council fire! Women swarm from the long houses. Children come running with mats for seats. Bedridden, blind, maimed are carried on litters, if only they may touch the garments of these wonderful beings. One old chief with skin like crinkled leather and body gnarled with woes of a hundred years throws his most precious possession, a headdress, at Cartier's feet.

Poor Cartier is perplexed. He can but read aloud from the Gospel of St. John and pray Christ heal these supplicants. Then he showers presents on the Indians, gleeful as children—knives and hatchets and beads and tin mirrors and little images and a crucifix, which he teaches them to kiss. Again the silver trumpet peals through the aisled woods. Again the swords clank, and the adventurers take their way up the mountain—a Mont Royal, says Cartier.

The mountain is higher than the one at Quebec. Vaster the view—vaster the purple mountains, the painted forests, the valleys bounded by a sky line that recedes before the explorer as the rainbow runs from the grasp of a child. This is not Cathay; it is a New France. Before going back to Quebec the adventurers follow a trail up the St. Lawrence far enough to see that Lachine Rapids bar progress by boat; far enough, too, to see that the Gaspé Indians had spoken truth when they told of another grand river—the Ottawa—coming in from the north.

By the 11th of October Cartier is at Quebec. His men have built a palisaded fort on the banks of the St. Charles. The boats are beached. Indians scatter to their far hunting grounds. Winter sets in. Canadian cold is new to these Frenchmen. They huddle indoors instead of keeping vigorous with exercise. Ice hangs from the dismantled masts. Drifts heap almost to top of palisades. Fear of the future falls on the crew. Will they ever see France again? Then scurvy breaks out. The fort is prostrate. Cartier is afraid to ask aid of the wandering Indians lest they learn his weakness. To keep up show of strength he has his men fire off muskets, batter the fort walls, march and drill and {18} tramp and stamp, though twenty-five lie dead and only four are able to keep on their feet. The corpses are hidden in snowdrifts or crammed through ice holes in the river with shot weighted to their feet.

In desperation Cartier calls on all the saints in the Christian calendar. He erects a huge crucifix and orders all, well and ill, out in procession. Weak and hopeless, they move across the snows chanting psalms. That night one of the young noblemen died. Toward spring an Indian was seen apparently recovering from the same disease. Cartier asked him what had worked the cure and learned of the simple remedy of brewed spruce juice.

By the time the Indians came from the winter hunt Cartier's men were in full health. Up at Hochelaga a chief had seized Cartier's gold-handled dagger and pointed up the Ottawa whence came ore like the gold handle. Failing to carry any minerals home, Cartier felt he must have witnesses to his report. The boats are rigged to sail, Chief Donnacona and eleven others are lured on board, surrounded, forcibly seized, and treacherously carried off to France. May 6, 1536, the boats leave Quebec, stopping only for water at St. Pierre, where the Breton fishermen have huts. July 16 they anchor at St. Malo.

Did France realize that Cartier had found a new kingdom? Not in the least; but the home land gave heed to that story of minerals, and had the kidnapped Indians baptized. Donnacona and all his fellow-captives but the little girl of Richelieu die, and Sieur de Roberval is appointed lord paramount of Canada to equip Cartier with five vessels and scour the jails of France for colonists. Though the colonists are convicts, the convicts are not criminals. Some have been convicted for their religion, some for their politics. What with politics and war, it is May, 1541, before the ships sail, and then Roberval has to wait another year for his artillery, while Cartier goes ahead to build the forts.

From the first, things go wrong. Head winds prolong the passage for three months. The stock on board is reduced to a diet of cider, and half the cattle die. Then the Indians of Quebec {19} ask awkward questions about Donnacona. Cartier flounders midway between truth and lie. Donnacona had died, he said; as for the others, they have become as white men. Agona succeeds Donnacona as chief. Agona is so pleased at the news that he gives Cartier a suit of buckskin garnished with wampum, but the rest of the Indians draw off in such resentment that Cartier deems it wise to build his fort at a distance, and sails nine miles up to Cape Rouge, where he constructs Bourg Royal. Noel, his nephew, and Jalobert, his brother-in-law, take two ships back to France. While Cartier roams exploring, Beaupré commands Bourg Royal.

In his roamings, ever with his eyes to earth for minerals, he finds stones specked with mica, and false diamonds, whence the height above Quebec is called Cape Diamond. It is enough. The crews spend the year loading the ships with cargo of worthless stones, and set sail in May, high of hope for wealth great as Spaniard carried from Peru. June 8 the ships slip in to St. John's, Newfoundland, for water. Seventeen fishing vessels rock to the tide inside the landlocked lagoon, and who comes gliding up the Narrows of the harbor neck but Viceroy Roberval, mad with envy when he hears of the diamond cargoes! He breaks the head of a Portuguese or two among the fishing fleet and forthwith orders Cartier back to Quebec.

Cartier shifts anchor from too close range of Roberval's guns and says nothing. At dead of night he slips anchor altogether and steals away on the tide, with only one little noiseless sail up on each ship through the dark Narrows. Once outside, he spreads his wings to the wind and is off for France. The diamonds prove worthless, but Cartier receives a title and retires to a seigneurial mansion at St. Malo.

The episode did not improve Roberval's temper. The new Viceroy was a soldier and a martinet, and his authority had been defied. With his two hundred colonists, taken from the prisons of France, commanded by young French officers,—a Lament and a La Salle among others,—he proceeded up the coast of Newfoundland to enter the St. Lawrence by Belle Isle. {20} Among his people were women, and Roberval himself was accompanied by a niece, Marguerite, who had the reputation of being a bold horsewoman and prime favorite with the grandees who frequented her uncle's castle. Perhaps Roberval had brought her to New France to break up her attachment for a soldier. Or the Viceroy may have been entirely ignorant of the romance, but, anchored off Belle Isle,—Isle of Demons,—the angry governor made an astounding discovery. The girl had a lover on board, a common soldier, and the two openly defied his interdict. Coming after Cartier's defection, the incident was oil to fire with Roberval. Sailors were ordered to lower the rowboat. One would fain believe that the tyrannical Viceroy offered the high-spirited girl at least the choice of giving up her lover. She was thrust into the rowboat with a faithful old Norman nurse. Four guns and a small supply of provisions were tossed to the boat. The sailors were then commanded to row ashore and abandon her on Isle of Demons. The soldier lover leaped over decks and swam through the surf to share her fate.

Isle of Demons, with its wailing tides and surf-beaten reefs, is a desolate enough spot in modern days when superstitions do not add to its terrors. The wind pipes down from The Labrador in fairest weather with weird voices as of wailing ghosts, and in winter the shores of Belle Isle never cease to echo to the hollow booming of the pounding surf.

Out of driftwood the castaways constructed a hut. Fish were in plenty, wild fowl offered easy mark, and in springtime the ice floes brought down the seal herds. There was no lack of food, but rescue seemed forever impossible; for no fishing craft would approach the demon-haunted isle. A year passed, two years,—a child was born. The soldier lover died of heartbreak and despondency. The child wasted away. The old nurse, too, was buried. Marguerite was left alone to fend for herself and hope against hope that some of the passing sails would heed her signals. No wonder at the end of the third year she began to hear shrieking laughter in the lonely cries of tide and wind, and to imagine that she saw fiendish arms snatching through the spume of storm drift.

{21} Towards the fall of 1545, one calm day when spray for the once did not hide the island, some fishermen in the straits noticed the smoke of a huge bonfire ascending from Isle Demons. Was it a trick of the fiends to lure men to wreck, or some sailors like themselves signaling distress?