* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Canadian Horticulturist, Volume 6, Issue 5

Date of first publication: 1883

Author: D. W. (Delos White) Beadle (editor)

Date first posted: July 5, 2018

Date last updated: July 5, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180720

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David Edwards, David T. Jones, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

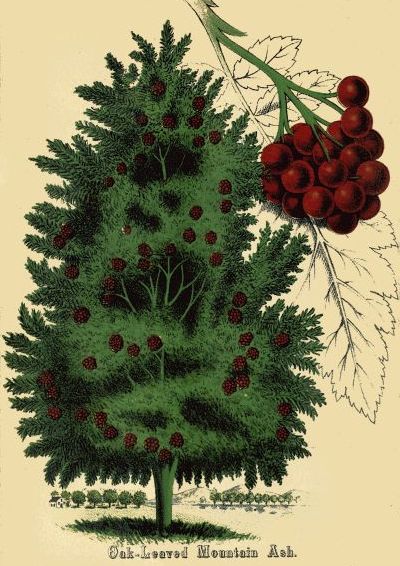

A handsome and hardy variety, with large and deeply lobed leaves, distinct and fine.

Covered in autumn with bright scarlet berries.

THE

| VOL. VI.] | MAY, 1883. | [NO. 5. |

When the term ornamental trees is used, it is intended thereby to designate trees that have been planted, not for the sake of their fruit, but for the sake of shade and adornment. Every man of taste and refinement wishes to make his home surroundings neat and attractive, as well as to have that home bountifully supplied with all the comforts and luxuries which the soil and climate can be made to produce. For the latter purpose he plants a fruit garden, and sets in it those trees and vines that will yield the finest fruits; but when his object is to shelter the house from the heat of the mid-summer sun or the chill blasts of mid-winter winds, or make an attractive picture to delight the eye and gratify the sense of the beautiful, he plants the trees and shrubs that will best secure these ends, irrespective of any consideration of what fruit they will yield to the table.

Every one who takes an honest pride in having a pretty home, or in living in a pretty country, rejoices in seeing our rural residences nicely ornamented with groups of pretty trees and flowering shrubs, and the country road sides planted with trees, whose grateful shade is so refreshing, and whose sylvan beauty adds so much to the value of every homestead. And it is a most favorable sign when the legislature of a country so appreciates the value of road side planting as to grant a pecuniary reward to the people who will thus plant and care for ornamental trees.

Fortunately we have not far to seek for trees that are suitable for street planting, home adornment, and winter protection. Our native forests abound with them, and if these are not enough, our nurserymen have collected the most hardy and beautiful of other climes, which, when judiciously mingled with our native trees, give a most pleasing effect to the rural picture. And yet with all this wealth of comfort and beauty at command, with the certain fact also before us that this sort of planting is more than doubly repaid in the enhanced value of our lands, and ten-fold repaid in shelter from the noon-day heat of summer and the frosty blasts of winter, notwithstanding all this, the fact remains that ornamental tree-planting is sadly neglected in this country, as a whole. However we are improving in this respect, and the enquiry for shade trees of beautiful forms and foliage, is in fact rapidly increasing.

Somehow, in what planting we have done, we have not given in this country the same prominence to the Oak as is given in England. The oak is slow, comparatively, of growth, and somewhat difficult to transplant, but it is a majestic tree, and where ample room can be given for its development makes a most beautiful feature in the landscape. With us the maple and the elm are the favorite trees. In the New England States the elm has been very generally planted as a village street tree. The author of “Norwood” says of our graceful American elm, “No town can fail of beauty, though its walks were gutters and its houses hovels, if venerable trees make magnificent colonnades along its streets. Of all trees, no other unites in the same degree majesty and beauty, grace and grandeur, as the American elm. Their towering trunks, whose massiveness well symbolizes Puritan inflexibility, their over-arching tops, facile, wind-borne and elastic, hint the endless plasticity and adaptableness of the people, and both united form a type of all true manhood, broad at the root, firm in the trunk, and yielding at the top, yet returning again after every impulse into position and symmetry. What if they were taken away from village and farm house? Who would know the land? Farm houses that now stay the tourist and the artist, would stand forth bare and homely; and villages that coquette with beauty through green leaves, would shine white and ghastly as sepulchres. Let any one imagine Conway or Lancaster without elms! or Hadley, Hatfield, Northampton or Springfield! New Haven without elms would be like Jupiter without a beard, or a lion shaved of his mane.”

The maples well deserve their popularity because of their beautiful symmetry, their abundant foliage, and great depth of shade. They are among the first to expand into full leaf in spring, and when autumn comes they glow with such rich colors and varied tints as only our sunset clouds can rival. The maples too are healthy trees, not very subject to insects, though by no means entirely exempt, and from their neat style of growth and moderate size, well suited to the dimensions of by far the greater number of our Canadian towns.

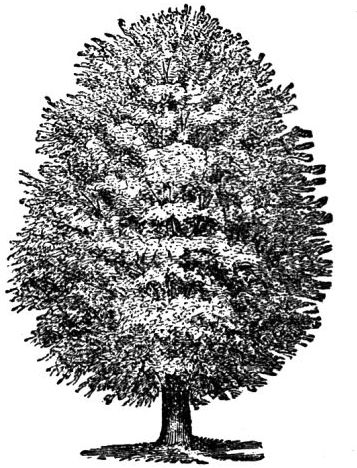

Sugar Maple.

The two varieties of maple that have been most generally planted with us are the Sugar Maple, Acer Saccharinum, and the Silver Maple, Acer Dasycarpum.

The difference in the style of growth of these two varieties will be seen at a glance by comparing the accompanying illustrations. The Sugar Maple forms a somewhat oval head, quite dense and compact, yet graceful in outline, and thickly covered with foliage. The lights and shadows are broken into many small masses, strongly defined, and yet melting softly into each other. But the lights so far exceed the shadows that the whole has a bright and cheerful expression. While lacking the grandeur, the broad bold shadows of the oak, and the chestnut and the hickory, it is on that very account more in harmony with cultivated grounds and our smaller suburban home-lots.

The Silver Maple, on account of its much more rapid growth, has been the more popular variety for street planting. It forms a loose, spreading head, with long, swaying branches, and slender leaf stems, so that when the wind blows, the ruffled leaves display a pleasing contrast of green and white, as the under surfaces are brought to view. It is not until the tree has attained to considerable age that it breaks into masses of light and shade, and at no time is its autumnal foliage so richly diversified with brilliant colors as that of the Sugar Maple. The length of its far out-spreading branches renders this tree more liable to be broken by high winds, or a heavy fall of snow or winter ice storms, yet this can be largely remedied by judicious shortening in of the growing branches, thus rendering the head more compact, and lessening the leverage of incumbent snow.

Silver Maple.

But there is neither time nor space to even mention the many trees we have that are suitable for home embellishment. The object of this article is to call attention to a tree that has not been much planted in Canada, but which possesses many excellencies which make it worthy of the attention of those who are selecting ornamental trees for small grounds. The colored illustration that accompanies this number will give our readers a very good idea of its general appearance. It is called the Oak-leaved Mountain Ash. It belongs to the great family of Rosaceæ, and to the genus Pyrus. By some botanists it is designated as the Pyrus pinnatifida. Although commonly called Oak-leaved Mountain Ash, it seems to the writer more nearly allied to the White Beam Tree, Pyrus aria, than to the Mountain Ash, Pyrus aucuparia. Its leaves are simple, not pinnate as the Mountain Ash, but with such deep indentations and irregular outline that it has received the name of oak-leaved, to which the term mountain ash has been added, doubtless because of its clusters of berries, which become bright red in the autumn, like those of the Mountain Ash. The leaves are bright green on the upper side, but covered with a white down beneath. Its mass of foliage is much more solid than that of the common Mountain Ash, and the play of light and shadow is more like that of the Sugar Maple. It is a perfectly hardy tree in our climate, and as it grows only to the height of from twenty to thirty feet, with proportionate breadth, it makes a very suitable ornamental tree for small lawns. Having regard to the neat, compact form of the tree, the contrasts of light and shade on its surface, the corymbs of white blossoms in early summer, and clusters of red berries in autumn, we think we do not err in regarding it as one of the finest of our lawn trees.

—————

The experiments made by the Director of the New York Experimental Station seem to indicate that manuring in the hill is of little benefit toward increasing the growth of the plant in its early stages, and that the same manure spread around the hill, instead of being placed in it, would probably have a larger influence on the growth. The roots of the corn plant extend widely, so that if a plant be dug up at any time during its later growth, the greater part of the feeding roots will be found away from the hill extending often to a distance of twelve feet. The inference is that broad cast fertilizing is better for corn than fertilizing in the hill.

The members of the Fruit Growers’ Association will learn with deep regret that a leader in pomology has fallen, one who was a Director of the Association at its organization in 1868, and has ever since been an active promoter of its interests. Those who have been privileged to attend the meetings will remember the venerable form and enthusiastic manner of Mr. Charles Arnold, of Paris, Ontario, and with what respectful considerations his experiences and opinions were always received. His remarks were founded upon his personal acquaintance with the subject in hand, and set forth for the guidance of others what had befallen him in his own cultivations, hence they had a value that could never attach to any mere conjectures or cunningly devised theories. But it is not to be our privilege to listen to him again. On the morning of the fifteenth of April, 1883, Mr. Charles Arnold passed away from earth. He was born at Ridgemount, Bedfordshire, Eng., December 18th, 1818, came with his parents to this country in 1833, and settled in Paris.

In early life Mr. Arnold enjoyed very few educational advantages; but even in boyhood he showed a taste for solid reading, and found time during his active and busy life to make himself thoroughly acquainted with several of the great masterpieces of English literature, and, although he never studied a grammar, he wrote clear, vigorous prose, and occasionally penned short poems, chiefly on horticultural topics. Throughout his life he displayed a fine literary taste, his favorite authors being Johnson, Goldsmith, Pope, Cowper, Longfellow and Tennyson. With the modesty and patient investigation of Charles Darwin he was particularly charmed. The writings of Lyell, especially the last edition of the “Elements,” were also a source of great pleasure to him. “The Origin of Species” appeared about the time Mr. Arnold had completed his first set of experiments in the hybridising of grapes, and the confirmation there given to some of his own private discoveries regarding the action of pollen and the fertilization of flowers, gave a new impulse to his efforts. In his youth he served his apprenticeship to the trade of a carpenter, and for some years of his early manhood followed the business of builder. But from a very early period of his life he showed a passionate fondness for flowers and fruits, and, coming into possession of a suitable piece of land in 1845, he determined to follow the bent of his inclination, which had been fostered and educated by the study of English books, American periodicals, &c. The Paris Nurseries were fully established by 1852, and have long been well known all over this continent, and to some extent in France, where Mr. Arnold’s new varieties of grapes attracted considerable attention. His success as a nurseryman is a fine example of the happy results which follow when a man of great enthusiasm tempered with good judgment finds himself free to pursue the kind of work he loves best.

In 1872 he gained the gold medal at the Hamilton, Ont., Exposition for a new and hardy white wheat; in 1876 he obtained the Philadelphia Centennial Medal for a very superior show of fruits, &c; and from the seed of a new cross-bred pea, “The American Wonder,” which he sold to Bliss & Sons, of New York, he lately realized a handsome sum. He originated several varieties of grapes which are now grown all over the continent, and was latterly engaged in hybridising wheat, strawberries, raspberries and peas. He was fifteen years in the town council of Paris, and was deputy reeve for some time.

For a year past he has been gradually failing in health, and after a few days of intense suffering from a disease of the heart, he ended his long and useful life.

A correspondent of the Fruit Recorder says that common tobacco stems placed on the ground round currant bushes in the spring, before frost is out, will keep off the currant-worm, and keep the bushes clean. The tobacco is distasteful to the worms, and they will not crawl over it to ascend the bushes.—Montreal Witness.

—————

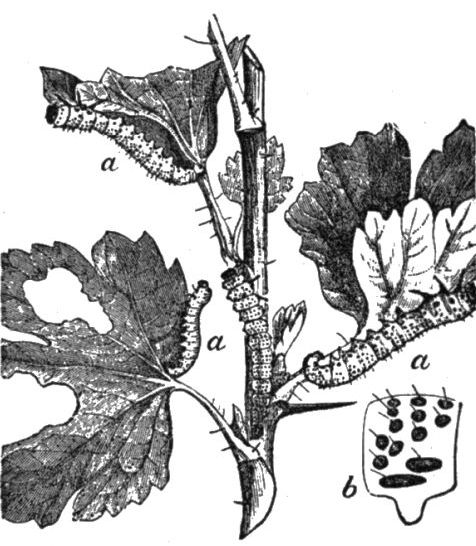

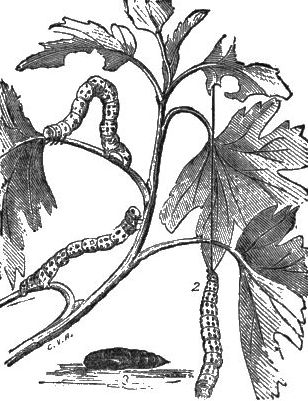

Larvae of the Gooseberry Saw-Fly.

We reprint the above to call attention to the arrant nonsense that sometimes goes the rounds of our newspapers, and even of agricultural papers. If tobacco stems placed on the ground under currant bushes in the spring will keep off the currant-worm, it is not because “they will not crawl over them to ascend the bushes.” Surely they will not crawl before they are hatched from the egg; and if the parent fly lays her eggs on the under side of the leaves, the little worms will have no occasion to crawl over tobacco stems in order to ascend the bushes. We wonder if “a correspondent of the Fruit Recorder” ever penned such trash, or if penned, that it escaped the sharp eyes of the intelligent Editor. Or is the crawling business the surmise of some astute scissors-man, who must needs give a reason to account for a fact, only to make his sublime ignorance manifest?

The most troublesome of the currant-worm is known as the Gooseberry Saw-fly, Nematus Ventricosus, an imported insect, which in the larva state is exceedingly destructive to both the gooseberry and currant.

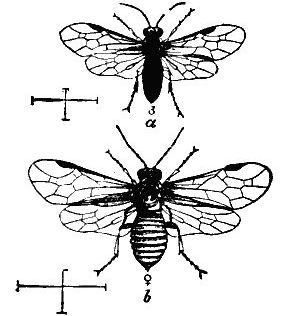

Perfect Insect of the Gooseberry Saw-Fly.

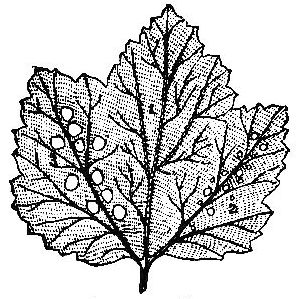

Leaf, with the Eggs.

The figures marked a in the accompanying illustration will be sufficiently familiar to those of our readers who have suffered from the depredations of these little pests; and if any have been so fortunate as to have escaped a visit from them, they will now have an opportunity of making their acquaintance. It is during this, the larva stage of their existence, that they are so injurious to our currants and gooseberries, being not only voracious, but usually numerous, so that they strip a plant of its leaves in a very short time. When two-thirds grown they are of a green color, thickly sprinkled with black dots. These dots are shown considerably magnified at b. When fully grown they are about three-quarters of an inch long, and at the last moult they lose their black spots and assume a plain green dress, tinged with yellow at the extremities. They now seek out a convenient place in which to pass the chrysalis state; sometimes they choose a place among the dry leaves on the surface of the ground, where they spin a cocoon over themselves, oval in form, of a paper like texture and brownish colour; and sometimes they fasten their cocoons to the stem of the bush. Sometimes they go into the ground and spin their cocoon there, and the later broods pass the winter in the pupa state on or under the surface of the ground. The Prest. of the Entomological Society of Ontario, who is excellent authority on these subjects, states at page 33 of the Entomological Report for 1875, that this insect passes the winter in the ground in the chrysalis state; and again in the Report for 1871, he says it usually passes the winter in the chrysalis state, enclosed in a small papery looking, silken cocoon, sometimes at, and sometimes under the surface of the ground. Occasionally they pass the winter in the caterpillar state. The pupa or chrysalis is about a quarter of an inch long, of a very pale and delicate whitish green color, becoming yellowish green at each extremity, remarkably transparent and delicate.

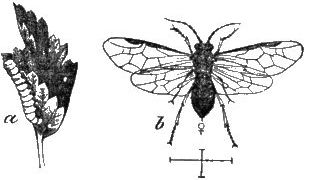

Native Gooseberry Saw-Fly.

From these pupæ the perfect insects are hatched, which are shown in the accompanying cut, the figure a represents the male, and figure b the female, both magnified; the cross lines indicating the length and wing-expansion of each. These appear very early in spring, usually sometimes before the leaves of the gooseberry and currant are expanded. The upper surface of the body of the male is black, with a yellow spot at the base and in front of the fore wings, the under side and tip of the abdomen are yellowish, and the legs are yellow. The female is larger than the male and mostly yellow. After the leaves of the gooseberry have expanded the female fly begins to lay her eggs on the under side of the leaf, in a row on the ribs or veins of the leaves. The eggs may be seen at figure 1 in the accompanying cut, arranged in a row along the central leaf-vein and its branches. In from eight to twelve days the caterpillars are hatched, and set to work at once to eat small holes in the leaf, which are shown at figures 2 and 3. They feed in company, with from twenty to forty on a leaf, and therefore soon completely consume all the soft parts of the leaf, so that only the veins are left remaining. Increasing in size they part company and spread over the plant, eating as they go.

Thus we have given briefly the life history of this insect, from which it will be seen that the caterpillars do not crawl up the stem of the plant but commence their existence on the under side of the leaves.

The Currant Geometer.

We have a native Saw-fly that feeds on the gooseberry, but which has not been such a pest as the imported. Figure b in the accompanying illustration represents the female fly magnified, the cross lines shewing the length of the body and the expansion of the wings. Figure a represents the larva. It is known by entomologists as the Pristiphora grossulariæ. The larva of this insect is always green, never having the black dots of its imported cousin, and always constructs its cocoon above ground among the leaves and twigs of the bush on which it feeds. This insect is said to be common and sometimes troublesome in New York and Illinois.

There is yet another insect that is often called the Currant Worm, known to entomologists as the Abraxis ribearia. It is a span or measuring worm, and is designated in the Reports of the Entomological Society of Ontario as the Currant Geometer or Measuring Worm.

The accompanying cut shews the worms in various positions. Figure 1 represents their mode of progression, and figure 2 their mode of suspending themselves by a thread when alarmed. When full grown the worm is about an inch long, whitish above, dotted with black dots on each segment, and a wide yellow stripe along the back and a similar stripe along each side. The under side is white, spotted with black and broadly striped with yellow along the middle.

Moth of the Currant Geometer.

About the end of June the larvæ attain their full size, descend to the ground, burrow a little way into it, and change to the chrysalis state. The chrysalis is shewn at figure 3 in the cut. From this chrysalis a moth hatches out in about twenty days, which is shewn in the annexed illustration.

The moth is of a pale yellowish color, with dusky spots of varying size and form. Shortly after the moths appear the female lays her eggs on the twigs and branches of the currant and gooseberry, where they remain uninjured by the heat of summer or frost of winter, until the following spring, when the young worms hatch out and commence their depredations upon the tender foliage.

If then by currant-worm it was intended to designate this insect, the paragraph above quoted is still erroneous, for neither does this worm crawl up the bushes from the ground to begin its work of destruction.

—————

At a recent meeting of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, Mr. Benj. P. Ware said he should speak only of varieties which, though new, have established a reputation. Of squashes he named the Butman as a beautiful variety, with fine colored flesh, and of excellent quality, also a good keeper, very desirable for amateurs but not sufficiently productive for a farm crop. The Marblehead, he said, generally commands a higher price than the Hubbard, but does not crop so well. The Essex hybrid is a cross between the Turban and Hubbard, uniting the form and fine quality of the Turban with the hard shell and keeping qualities of the Hubbard. It is a rapid grower and may be planted as late as the 1st of July, thus avoiding the maggot.

Of cabbages, Mr. Ware thought the Stone-Mason the best variety ever introduced, making solid heads of excellent quality; and said that the American Improved Savoy has a small stump and large head, while preserving the fine quality of the old variety, which had large stumps, and was very uncertain in heading.

Of sweet corn, he said that the Marblehead is earlier than any other, even the Minnesota and Narragansett. Next after comes the Crosby’s Early, then the Moore’s Early, and for a late variety either the Marblehead Mammoth, Burr’s Improved or Stowell’s Evergreen.

As to potatoes he said Early Ohio is earlier than Early Rose and has the requisites of a first-class variety, but that the Bell is probably the best new variety, several who had tested it in competition with twenty other sorts, claiming for it better qualities than are possessed by any other; it is very productive, remarkable for its uniform size, and of a pinkish color.

Mr. Ware thought the Acme and Paragon ahead of any other tomatoes for the table.

Among peas he considered the American Wonder to be rightly named, for the vines are very small, more peas than vines, the peas wrinkled, sweet, a great acquisition. For earliest he recommended Dan O’Rourke, then American Wonder, McLean’s Advancer, and for latest, the Champion of England.

Mr. Ware recommended White Egg Turnip as most reliable for a crop, and better than Purple Strap Leaf, though not quite as early. It is a flat variety.

—————

This society is to hold its next biennial session in Philadelphia, Penn., commencing on Wednesday, September, 12th, 1883, and continuing for three days. All kindred associations in the United States and Canada are invited to send delegations as large as they deem expedient. Arrangements have been made with hotels for reduced rates. The Hon. J. E. Mitchell, 310 York Avenue, Philadelphia, is chairman of the local committee of reception. There will be an exhibition of fruits; and a limited number of Wilder medals will be awarded to objects of special merit. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society will hold its annual exhibition at the same time in Horticultural Hall. We trust that Ontario will be fully represented on this occasion, not only by her horticulturists and fruit-growers, but also by a fine display of her excellent fruits.

—————

Seeing an inquiry in the March number of the Horticulturist on this subject, I will reply by giving our experience in the Province of Quebec, where from necessity we have to look for the earliest varieties for general culture, though some localities are highly favored, such as the Island of Montreal, the Valley of the Richelieu, some places on the Ottawa, and here in proximity to Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River. The variety in blacks most cultivated is the Champion, which has been re-named by some adventurers the “Beaconsfield.” At the time of ripening we can put up with its inferior qualities, welcome its advent, and despise its poor qualities as better varieties ripen. Moore’s Early, next in order of ripening, is some better, but thus far in this Province has not been found profitable, being a light bearer. Telegraph is better on some soils, and more productive. Early Victor gives great promise, and comes to us with very good endorsements; and its behaviour here is looked forward to with great interest, as supplying a very early black grape of excellent quality, and adapted for wine as well as table, which qualities the early Labrusca type of grapes thus far do not possess. Aruncia, Rogers’ No. 39, and Barry, No. 43, a little later, possess great vigor and good qualities and size. Mr. Rickett’s Backus, wine and table grape, is early, very vigorous, and an enormous bearer. Norwood, from Massachusetts, U. S., promises to give us a grape that will excel all others in keeping qualities, and is earlier than Concord, and its originator, of course, claims that it is better; not yet for sale.

Of white grapes Lady is the first to ripen, a slow grower, taking some years to bring it to its best; a shy bearer thus far; in size and other respects good; very fair in quality for an early grape; has a tendency to crack, which is of little moment for home use, except when bees are plenty; last year it showed no tendency to crack, probably from the cold season. Prentiss is our next earliest; a fine native seedling of much promise; quality very good. Mr. Dempsey’s No. 60, a cross with Allen’s Hybrid, fruited last year, and gave me much pleasure; if it does better, as grapes usually do, in subsequent years, we want no better early grape. All of Mr. Dempsey’s grapes have strong, healthy foliage—a point of great moment in these days of mildew and the thrip. Faith, an Elvira seedling, of Mr. Rommel’s, gives much promise; it is here a rampant grower; ripens its wood well; berry and bunch small; is of fine, sweet flavor. Duchess is late here; a vigorous grower, but does not ripen its wood well; we have not fruited it, but its quality, as raised south, is excellent. I have many other white varieties, but not sufficiently tested to speak favorably of.

Of reds, Northern Muscadine is the first to ripen; healthy and vigorous grower; drops no more than Hartford, and eatable before fully ripe; thought highly of in its season. None of the early varieties possess the high qualities of Delaware, Burnet, Wilder and Lindley, later varieties. Wyoming Red, though small in bunch and berry, is about the first to ripen. Massasoit, Rogers’ No. 3, follows in ripening, is much better in flavor and a good bearer. Vergennes, for a new grape, has at once taken a high position in public favor, maturing and ripening its wood quick; fruit red and delicious; is valuable alone for its extraordinary keeping qualities. Salem, an old favorite, is eclipsed by the former in keeping qualities; like most of Rogers’ Hybrids, it is a rampant grower, requiring ample space to succeed well, and prevent mildew, to which it is subject in some seasons. Brighton, though I am getting down into the later varieties, I must mention, possesses the fine qualities of one of its parents, Diana Hamburg, without its defects; it is growing in favor, though a shy bearer; like Champion, it requires to be eaten as soon as ripe.

Your inquirer, with the help of an ardent enthusiast, I trust, can select from the above enough to make him happy in the season. I see that I have omitted Worden, a great favorite and early black grape; and he will by all means try the Jessica.

Wm. Mead Pattison.

Clarenceville, Quebec.

—————

I am still greatly delighted with the varied contents of the Canadian Horticulturist, and long for the monthly supply of general horticultural information which it never fails to impart.

Have you been informed of any experiments made during the past year which have been successful in checking or destroying that detested Codlin Moth, which works such havoc in the orchards of Ontario? In the Canadian Horticulturist of March or April of last year, tar water sprinkled on the fruit blossoms was recommended by some one. Printer’s ink smeared on paper or cloth, tied round the trunks of the trees by another. Are you aware of any experiments made with these materials, successful or not? The announcement of such in the May number of C. H. will, I am sure, confer a favour on the fruit-growing public.

Yours truly,

G. W. Strauchon.

Woodstock, April 11, 1883.

—————

[If any of our readers have tried these or any other methods of destroying the Codlin Moth, will they please give their experience through the Can. Horticulturist.—Ed.]

—————

Could you mention sometime in the Can. Horticulturist whether grape growing could be made successful in this county (Huron), and if so, what varieties of grapes would you advise growing?

D. C. C.

—————

Ans.—Mr. A. McD. Allan, of Goderich, says that all the usually cultivated out-door varieties do succeed in the County of Huron, except the very late ripening sorts, such as the Catawba. We can see no reason why a large number of varieties should not be very successfully grown, particularly the early ripening sorts. It is of the first importance that the soil be suitable, thoroughly drained and friable. Grape vines will not thrive in cold, wet soil. Of the early ripening sorts we feel confident that Early Victor, Moore’s Early and Worden among the black grapes, Massasoit, Brighton and Vergennes of the red grapes, and Lady, Martha and Jessica among the white sorts will be found to do well.

—————

I have two fine oleanders that I put out into my garden the latter part of May. They blossom freely, but the blossoms always fade and fall off after two or three days. Can you tell me the reason, and the remedy?

When should pear scions be cut off for budding? May they be taken off immediately before budding?

R.

Toronto, April 9th, 1883.

—————

It may be want of sufficient moisture at the root, or exposure to burning rays of the sun that makes the oleander flowers fade. Dark colored roses fade quickly under our burning sun. Cut pear scions just before budding. See p. 77.

—————

The dahlia is one of the choicest of the tuberous rooted perennials, which have been greatly improved on the last few years, and now consist of every shade of red, white, yellow, as well as an endless variety of mixtures of these colors. To have success with the dahlia, in the first place the soil must be well drained, which must be neither light nor of a strong sticky nature. Any good fresh soil will do exceedingly well. If it is naturally poor some fresh soil should be added along with some well decomposed cow manure or old hot bed mould, which should be well mixed into the soil at the time of planting. Much strong manure is as bad if not worse than too little, as it is apt to cause canker in the tubers, as well as inducing over luxuriance of growth, and in a great measure prevent the producing of bloom. An open situation is necessary, not shaded by trees. The tall varieties suit admirably in shrubbery borders. They also form most brilliant appearance when planted in masses, or in centres of large beds. About the latter end of May, as soon as all danger of frost is over, the plants may be planted out in the open border, holes are made, two feet apart, according to the height of the variety. The tubers or plants are carefully placed in, and some fine soil put in around, shaking the plant slightly so as to admit the soil freely around the tubers. As the plants advance in height, they should be tied to stakes with bass matting strings, and any superfluous shoots removed. When the buds have formed, liquid manure made of one part of cow dung, hen dung and horse dung, may be given with great advantage, once or twice a week. In taking up the tubers in the fall it is necessary that as soon as the stems are injured by frost, they should be cut down to within six inches of the ground, and the tubers taken up with a potato fork, labeled with the name of the variety, and turned stem downwards for a few days to permit the moisture to drain off, when dry they may be placed in hay, straw or dry sand, the crown being left uncovered in a cool place, which is secure from frost and from dampness. There they may remain with no other attention and care than examining them from time to time, and remove any that is rotten, as well as cutting off parts which are beginning to decay.

Thos. E. Davies.

Ottawa, Ont.

—————

A correspondent residing at Clarenceville, Province of Quebec, writes that “Early Victor is likely to be an acquisition with us. I will have it in bearing this season.”

—————

Some people are down on anything but facts about fruit, because so many new and highly praised varieties have proved unworthy of cultivation, and anything approaching a guess is sufficient to draw forth their indignation or contempt. Yet we want to have some idea of the value of new sorts, and what are we to do about it at first, unless we compare one fact with another given by those who have had a little experience, and draw inferences and conclusions? Perhaps this is not guessing: so much the better then. Now I will tell what I know and what I infer about some new sorts, and I hope other readers of the Horticulturist will do the same; for it is a matter of exceeding interest to me (and no doubt to others) to know as soon as possible what kinds will do best throughout the province.

Several new kinds make their appearance every year, but of the different rivals, usually two or three stand out, close together in importance, beyond the crowd. Two or three years ago the Sharpless and Crescent were the favored ones, with Marvin, Miner’s Prolific, Forest Rose and a host of nonentities in the rear. Now we look eagerly to Bidwell, Manchester, and James Vick for success, with a vague impression that among the Big Bobs, Jersey Queens, Old Iron-clads, and Pipers, that figure on the lists, there may yet spring forward something as good as these, or better. Beside these we find the old historic name of “Daniel Boone” casting its shadows before, and in prospect to share the honors, Mrs. Garfield; and yet others in the realms of rumor, so that the man who loves to test new varieties can anticipate a pleasant time in future seasons.

Does the man who grows “only one kind” rise here to explain that it is all nonsense to fuss with these new varieties, because there has never been anything better than Wilson’s Albany, and never will be? “My dear sir, the Wilson is a grand old berry, and be you sure to stick to it, for it is money in the pockets of those who cultivate the improved varieties to have you peg away at the public with the Wilson and sour their teeth so they will want our sweeter berries, instead of bringing our prices down by going into the big fruit yourself. And just remember too that Wilson’s Albany Seedling was “quite new” once, and was no doubt objected to then, in favor of others.” The fact is there is a feeling abroad just now, that whether new or old, the best berry is good enough for us all, and hence the many enquiries about Bidwell, Manchester and James Vick, which are to the front at the present time. Bidwell is the oldest, and its remarkable claims, productiveness to exceed Wilson and Crescent, size to equal the average Sharpless, unusual firmness, and superior quality, will probably be decided for the average strawberry grower by this year’s crop. My carelessness in allowing all my plants to form runners during ’81, instead of saving a few to bear a full crop last season, is a source to me of no little vexation, for I do not like to plant it largely, or recommend it without reserve, until I have seen it in full fruiting. There is no doubt in my mind that it is good, but how good is what I want to know more about.

The good points that I have established on my place are its vigor and hardiness of plant, persistent and very abundant setting of young fruit, and the fine size, firmness and color of the berries. The points that I want to be assured of are its glossiness and size towards the last; and if these are decided as I hope, I shall cheer for it as the best market berry yet tested. On my young potted plants, without mulching, the fruit got splashed so badly as to spoil its appearance, and the berries were small towards the last, hence my hesitation on these points. If I may guess about it I will say that on rich loamy land I think that it will prove an enormous bearer of first-class handsome market berries that will ship about as well as Wilson; but that on light poor soil, and especially without runners cut, it will run down in size towards the last. I consider the quality better than Wilson, but not as good as Seneca Queen and some others.

I suppose I would favor the Bidwell more if it were not for the smack I had of the Manchester. How those little Manchesters—after coming in a mail bag in October from near New York City, standing on an exposed sandy knoll all winter, with only the protection of a little soil around the crowns, and then choking up so badly with drifting sand in April as to need frequent handling to prevent smothering—finally stood up in early July and produced the handsomest berries on my place, is something I can’t understand. I know that such behavior does not prove that their claims are sure to be fully established when they are full grown; but I guess that I know enough about Manchester to put it out as fast as I can get the plants, and I wish I had “a good square acre” to bear this year. The point I regard as doubtful with this berry is firmness. The fruit seems behind Bidwell in this respect; and it is pistillate too, which is a positive objection in the eyes of many. I liked the quality better than Bidwell, but quality, on such young plants, cannot always be taken as a fair sample. It is later than Bidwell, and different growers are likely to fancy it more or less than Bidwell, on account of its success on sandy land, while the former flourishes on moister soils.

But now for the James Vick. Last fall I took a notion to turn a good old stable into a poor apology for a greenhouse. Out came a four foot wide strip for glass along the whole south side, and a second siding of plank comprising and compressing a warm lining of tramped pea straw around the rest of the building, with a small box stove inside, and complement of common stove pipes, furnished me, at a total cost of about $15 with a climate that plants could live in. Much and hearty was my inward chuckling at the thought of the multitudes of Vicks, Souhegans and Hansells that should issue in spring from this sorry looking greenhouse, in which I now write. But the worst west winds howled in derision through my pea straw, and the occasional frosts they managed to insinuate, combined with my inexperienced treatment as to watering, reduced my precious Vicks from over fifty to a bare dozen, and at this writing—April 10th—not a runner has started on them, or on the Manchester, Big Bob, Ray’s Prolific and Shirts, that kept them company. How I wished that sawdust had been put in the place of the straw. But if my spring plantings must come from open ground, and if my results in this line are mostly in the way of experience, I have one bit of experience that I think will prove uncommonly useful. Of all these kinds the Vick is making the greatest promise of fruit. Those mean little plants that just managed to live through January are loaded down with blossoms, and the abundant supply of pollen is shewn by the fine and perfect shape of the berries already formed. Manchester near by is growing more and larger leaves, but is evidently later, as a blossom bud is only showing here and there. But the Vick is fairly revelling in blossoms. “What is the fruit like?” That is just what I hope to know about the time that this number of the Horticulturist reaches its readers. But while I must have my little guess about the James Vick too, I must only go so far as to prophecy that its great superiority to the other kinds thus far, must indicate at least a great tendency to set fruit in open ground; the handsome shape of those already formed would seem to speak well for its appearance where circumstances are more favorable to development. I am glad that the peculiarities of foliage and fruit lead me to discredit the report of its similarity to Captain Jack, one of the meanest, sourest deceptions that ever in the guise of strawberry set my teeth on edge, and my temper over the edge. But just how the berries will taste, how the sunshine will glance on their blushing cheeks, and how a single plant will pile them around in stacks so that a bug cannot reach the centre without climbing, all such fascinating points I must leave to the decision of open ground culture, or accept on the word of the good men and true who have been there already. Now who next will tell what he knows, or help us to a better guessing?

—————

To the Editor of the Canadian Horticulturist:

I have much pleasure in adding testimony to the use of tobacco stems as indited by H. Primrose in your March number of the Horticulturist. I have used most successfully for years the siftings from the tobacco stems on cabbages and cauliflowers. In spring, when planted out, they are attacked by the Black Beetle, especially in bright sunny days. Having procured in a box a supply of the tobacco, I drop a small quantity on each plant. Mr. Beetle skedadles forthwith, the plants are invigorated by its use. I repeat the dose in a few days if there happens to be much rain-fall, which washes the nicotine too soon away. Growers, try it faithfully.

Yours truly,

Geo. Vair.

Chestnut Park, March 19, 1883.

P. S.—Anti-tobacco men may yet laud the name of Sir Walter Raleigh for the introduction of the weed.

G. V.

—————

(Discussion on various hardy border plants at the meeting of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, held in Boston, February, 1883.)

Edward L. Beard said that the narcissus is among the most neglected plants. They will repay all the care that can be given them. The double Narcissus poeticus has a tendency to blight its buds when the soil becomes exhausted, but generous feeding will cause an astonishing improvement, and the same is the case with the long-tubed species, such as the Emperor and Empress, two very fine new varieties. The same may be said of the Lily of the valley, which is so generally left to take care of itself; and indeed the mistake is made with many herbaceous plants. The double Pyrethrums are among the most desirable plants; they require division and good culture. Some herbaceous plants will live along without much care, but the finer kinds require as much as a bed of roses. The Anemone Japonica, especially the white variety, may be placed in the foreground of useful plants.

Hon. Marshall P. Wilder spoke of the old double candytuft as having been so neglected that ten or fifteen years ago it was introduced as a new plant. It is very desirable.

Mrs. H. L. T. Wolcott said that her narcissus buds failed so that she gave up in despair, but she took them up and reset them, and every bud gave a flower.

Dr. Wolcott said there is one plant, the Fraxinella, which will flourish year after year without removal; he knows a plant seventy-five years old, which blooms just as well as ever. It is the typical hardy perennial.

Mr. Wilder spoke of spiræa sinensis (known also as Spiræa astilbe or Hoteia Japonica) as one of the most beautiful herbaceous plants. It forces finely. Nothing is more gorgeous than the pæonies, either tree or herbaceous, but they are much neglected. If the old dark crimson pæony were introduced now as new, it would be highly esteemed.

Mrs. Wolcott thought it should be the aim of the society to encourage the cultivation of plants which are within the reach of people generally. The tree pæony is virtually out of their reach. She had tried the fraxinella over and over again without success.

Mr. Beard thought the fraxinella likes a clay soil; a plant which he set in such a soil five years ago had done well.

C. M. Hovey said that the fraxinella should be grown from seed where it is wanted; it makes strong woody roots, with no fibres, and is very difficult to transplant. The same is the case with the Asclepias tuberosa, which he esteems the most beautiful of all our native plants. The herbaceous pæony is everybody’s flower; it is easily grown and makes an unsurpassed show in the garden. The delphinium has been much improved; some of the new kinds are apt to die off, but the old ones are very stately. The dahlia is again coming up in the single form.

Mr. Beard spoke of the Everlasting Pea, either the rose-colored or white variety, as one of the most beautiful of garden flowers, scrambling over rocks or a low trellis. If the seed pods are removed, it will bloom continuously. Like the fraxinella, it forms immense roots, and must be raised from seed where it is wanted. He saw the Gloxinia cultivated successfully in a cold frame last summer, and forming a most beautiful sight. When grown in this way the roots can be easily wintered by storing them in a temperature of forty-five degrees. In the spring they must be started in the house.

E. H. Hitchings mentioned as desirable native climbing plants, the Clematis Virginiana, Mikania scandens and Apios tuberosa.

Mr. Manning said that the Apios tuberosa must be grown in sandy soil, as the tubers decay in rich soil, and when it thrives it is apt to become a weed. The Iris Kæmpferi does better after dividing.

Mr. Hovey recommended the tuberous rooted begonia for planting in the open air. Some of the varieties are too delicate, but others grow freely and blossom up to frost when treated like gladioli.

Mr. Beard said that the light-colored varieties stand the sun better than the dark, and all are benefited by partial shade, and in such a situation out doors they do better than under glass. The double ones are apt to drop their flowers.

—————

These minute insects are the larvæ (maggots) of the clover seed midge, known as Cecidomyia leguminicola, and also as C. trifolii. It belongs to the same class of insects as the Hessian fly, and is about half as large in all its stages as that insect. The larvæ are of an orange color, looking like any other minute maggot. It attacks the seed heads, and when ready to transform into the perfect insect, drops to the ground, hiding under any shelter, and spins itself an oval, compressed, rather tough cocoon, to which particles of earth adhere, thus rendering it difficult to distinguish. Transformed to the perfect insect, it issues forth as a long-limbed, slender, two-winged fly of the general appearance of the Hessian fly to the unscientific observer. The eggs are deposited in the young heads of clover, and the maggot lives on the juices, and when numerous, destroys the crop. It has one or two minute species parasitic on it, but when the fly becomes abundant the only remedy is to quit raising clover for seed until the insect disappears; and to be successful, this abandonment of the crops must be general in a locality.—Prairie Farmer.

—————

This prominent and distinct member of the oak family is not so widely distributed as the gray, red, scarlet, yellow, swamp, white and pin oaks; the last is found mostly from Connecticut south; all the others are common in New England forests.

The leaf of the chestnut oak resembles that of the American sweet chestnut more than any other tree; it also has more of the upright habit of the chestnut when growing in the forest than any other oak.

The texture of the wood is sufficiently tough and durable to make it most desirable for wheelwright work, ship timber and planking; it splits, as I well remember, when cutting it, into cordwood more readily than any other oak, and in this respect it also resembles the American chestnut.

The best transplanted chestnuts of this oak that we have seen are at Ben. Perley Poore’s Indian Hill Farm, in West Newbury; they were planted and still owned by him, and are in the plantation that took the first prize of $1,000 offered by the State for the best forest produced by tree planting.

Here the tree is nearly forty feet high, and is of tall, upright habit, but has not yet shown the deep-furrowed bark that is to be seen on older trees; it has a peculiar glassy smoothness when young.

We have seen trees of this oak in Bedford, N. H., seventy-five feet high; trees that make the best timber for pile driving, for the support of buildings and bridge piers. In open ground it makes a strong, robust trunk, with more upright branches than any other oak named; the acorn is large, sweet-flavored, and is produced by quite young trees; they sprout freely when planted fresh from the trees; like all species of nuts, they germinate best when not allowed to dry.

It transplants as safely as any of the oak family, and as a lawn tree it is not excelled when a tree of upright habit and expanding, regular outline is desired.

—————

The garden pays well, even with hand labor. It would pay much better if the main burden of the cultivation were put upon the muscles of the horse. But the saving of cost in cultivation is only a small part of the benefit of the long-row arrangement. It would lead to a much more frequent and thorough cultivation of our garden crops. Most farmers neglect the garden for their field crops. The advantage of a frequent stirring of the surface soil to growing crops is greatly under-estimated. It is said that it pays to hoe cabbage every morning before breakfast during the early part of the season. We can testify to the great advantage of cultivation every week. This frequent breaking of the crust admits of a freer circulation of the air among the roots below, and makes the most of the dews and rains that fall. The manufacture of plant food goes on more rapidly, and to a certain extent, cultivation is a substitute for manure. Another benefit of the long-row system would be the almost certain enlargement of the fruit and vegetable garden, and a better supply of these fruits for the table. This, we believe, would have an important sanitary influence in every household.—American Agriculturist.

—————

The Florida Dispatch thinks the time is at hand when we shall be supplied with fresh figs that are fresh, not dried, and ventures to prophesy as follows:

As a shipping fruit, we predict for the Fig an immense sale in the near future. We have, already, many sorts which may be picked a short time before full maturity, and, like the strawberry, carefully packed in quart boxes and shipped in Bowen’s refrigerators to any of the northern cities. If not fully mature when packed, they will ripen in transitu, reaching the epicurean tables of New York and Boston as fresh and inviting as when plucked here from the trees. There cannot be the slightest doubt that, if fine, sweet, ripe Figs can be thus safely transported and properly presented to the people of the North, they will speedily become immensely popular as a dessert fruit; and that, to come anywhere near supplying the coming demand, we shall need a hundred trees where we now have one.

The possibility of safe transportation in refrigerators is no untried experiment. It was successfully accomplished by Col. D. H. Elliott, of The Dispatch, a year or more ago, and the Figs were sold in New York, (if our recollection is correct,) at forty cents per quart. We would ask no more profitable or remunerative business than to produce Figs by the car-load at half or even one-quarter of that price; and we confidently advise all our fruit-growers who live within reach of transportation lines to plant Figs largely and at once.

—————

EARLY HARVEST BLACKBERRY.

The following remarks concerning this new Blackberry are from the pen of Mr. Parker Earle, one of the most extensive small fruit growers of Illinois:

This new Illinois seedling, or, if you please, “wilding,” is attracting a good deal of attention among blackberry cultivators. Having tested it in a small way, and written some words in its favor to the introductor, I am the recipient of a multitude of inquiries concerning its merits. If you will permit me, I will say all I know about it in the Country Gentleman, and so possibly save the fraternity of inquirers, and myself too, some trouble. First of all, the Early Harvest is not the same as Brunton’s Seedling, another Illinois production, as has been stated in some horticultural papers. The two are much alike as to size of fruit and season of ripening, and also in appearance of the plants, but they are distinctly unlike in their blossoms, the Harvest having perfect flowers, while the Brunton is entirely pistillate, and will not bear a berry without having some good staminate variety planted with it. Both these sorts are very early, but which is first I cannot say, as my experience with the Brunton was terminated some years before the Harvest was sent out.

I think the Early Harvest will prove valuable for those growers with whom very early ripening is an important quality. It seems to be a few days earlier than the Wilson, and has some other points of advantage over that sometimes excellent kind. It cannot be ranked with it in size, as the Harvest is only small to medium, while the Wilson is among the largest. But the former is far more hardy than the latter, being equal, and possibly superior to the Lawton in this important respect. The Wilson is safest as to the rust, as it is rarely affected, while the Harvest shows some weakness in that direction. But every blossom of the Harvest makes a berry, and there is an abundance of them, while the Wilson has some radical weakness in its flowers, which sometimes in the best situation, and always in many localities, produce more abortions than perfect berries. The Harvest has not yet been marketed in any considerable quantity, and it is not safe to say how well it may please the trade. But as a berry for home use, it has unquestionable value, because of its earliness and reliable productiveness.—Country Gentleman.

In the Farm and Garden we find the following:—

Early Harvest is very distinct in growth and foliage from any other cultivated variety, and its name, aside from its pretty sound, is singularly appropriate, ripening as it does just as the earliest winter wheat is in condition to harvest. The canes are of strong, upright growth and branching and immensely productive. Berries of excellent quality; and although not large are of good size, averaging larger than Snyder. What adds much value to the variety, especially for the fruit-grower, it ripens its entire crop in a few days, and is all gone when the Wilson and other of the early kinds begin to turn black. While the Early Harvest is a good blackberry in other respects, its distinctive value, is its earliness, ripening as it does far in advance of all other varieties, which, together with its good size, large yield, and hardy, healthy canes, render it of almost inestimable value, either for the amateur or professional fruit-grower.

—————

Twenty-eight varieties of cabbage, early and late, were tested under garden culture. The seeds—thirty of each sort—were planted in the cold-frame April 7th and 8th, and the plants transplanted to the garden April 27th, in rows three feet apart, plants two feet apart in rows, the soil made moderately rich and the plants kept cultivated throughout the season with a hoe.

One of the first troubles which we met was in the varieties not coming true to name, although the seeds were procured of one of our most reliable seedsmen. Thus, Henderson’s Early Summer gave but thirteen genuine plants, Schweinfurt Quintal twenty-five, Sugar Loaf fifteen, American Savoy thirteen, etc. But little difference was perceived in the time required for vegetation, varying only from 9 to 10 days in the varieties. There was, however, quite a large difference between the germinative powers of the different varieties of seed. In no case, however, did all thirty seeds vegetate. In two cases twenty-nine seeds; in four cases twenty-eight; in two cases twenty-seven; in two cases twenty-five; in one case twenty-four; in two cases twenty-three; in six cases twenty-two, etc. The first to arrive at edible maturity was the Early Oxheart and the Nonpareil on July 26th. Vilmorin’s Early Flat Dutch and Newark Early Flat Dutch came two days later, then followed, on August 1st, the Early Ulm Savoy, the Early Jersey Wakefield, and the Early Winningstad; on August 4th, Cannon-ball and Little Pixie; on August 11th, Henderson’s Early Summer, Crane’s Early, Schweinfurt Quintal, Early Blood Red Erfurt; on August 15th, Sugar Loaf, Fottler’s Improved Early Brunswick, Large York and Danish Drumhead; on August 22, Premium Flat Dutch, Improved American Savoy, Early Bleicheld, Early York, Stone-Mason, Red Drumhead, Drumhead Savoy and Red Dutch; on September 1st, St. Dennis Drumhead, and on October 17th, Bergen Drumhead.

Those plants which produced as many heads as there were plants, were Schweinfurt Quintal and Early Winningstadt. Green Glazed produced no heads, and among those which produced but few may be mentioned, the Early Ulm Savoy, seven heads from twenty-nine plants; Henderson’s Early Summer, ten heads from twenty-eight plants; Sugar Loaf, nine heads from twenty-two plants; Fottler’s Improved Early Brunswick, twelve heads from twenty-eight plants; Improved American Savoy, eight heads from twenty-seven plants; Early York, five heads from twenty-two plants; Drumhead Savoy seven heads from nineteen plants; Bergen Drumhead, five heads from twelve plants; St. Dennis Drumhead, six heads from twenty-three plants. Selecting the few varieties which commend themselves to us, we can name the Vilmorin’s Early Flat Dutch, at edible maturity July 28th, nineteen seeds germinating, giving seventeen heads, and the trimmed heads weighing about four pounds apiece; the Newark Early Flat Dutch, at edible maturity July 28th, furnishing nineteen heads from the twenty-two seeds which vegetated, and the trimmed heads weighing about 5½ lbs.; the Early Winningstadt, which was edible August 1st, furnished twenty-three heads from twenty-three plants which vegetated, the trimmed heads weighing about three and half lbs.; the Schweinfurt Quintal, which was ready for the table August 11th, which gave twenty-four heads from twenty-nine plants, the trimmed heads weighing about seven lbs., and very solid.

—————

We were troubled considerably by the ravages of the cabbage butterfly, pieris rapæ, or rather by its larvæ. The Butterfly was seen flying about the plants early in summer, and in the latter part of June the first brood of caterpillars appeared. These did less destruction, however, than the second brood, which came about the middle of August. In order to test the efficacy of a few of the so-called remedies for the cabbage worm, we confined some of the caterpillars in a bottle and noted their behavior under various treatments. One specimen confined for three hours in a bottle partly filled with black pepper crawled away discolored by the powder, but apparently unharmed. The second repeatedly immersed in a solution of saltpetre, and a third in one of Boracic acid exhibited little indications of inconvenience. Bi-sulphide of carbon produced instant death when applied to the worm, though its fumes were not effectual. The fumes of benzine as well as the liquid, caused almost instant death, but when applied to the cabbages, small whitish excrescences appeared on the leaves. Hot water applied to the cabbage destroyed a portion of the worms, causing also the leaves to turn yellow. One ounce of saltpetre and two pounds common salt dissolved in three gallons of water, formed an application which was partly efficient. The most satisfactory remedy tested, however, consisted of a mixture of ½ lb. each of hard soap and kerosene oil in three gallons of water. This was applied August 26th, and examination the following day showed many, if not all, of the worms destroyed.

The growing cabbage presents such a mass of leaves in which the caterpillars may be concealed that it is hardly possible to reach all the worms at one application. It is of importance, therefore, to repeat the use of any remedy at frequent intervals.—E. Lewis Sturtevant, M. D., Director.

—————

The extent to which our supplies of fruit, for all purposes, are now furnished by the market is most suggestive and instructive, especially when we reflect how much of it comes from foreign sources.

At this season, the most prominent features of the fruiter’s store are the apples and pears and pine apples. Writers may say what they like about the comparative excellence of English apples and pears, but so long as Newtown Pippins are in the market, and French pears, both seem to be preferred. And look at the prices good samples of the latter have been fetching in the retail fruiterers’ shops! Taking it altogether, there are few or no apples which surpass the Newtown Pippin. It is an excellent keeper in the barrel, turning out in the soundest condition months after it has been stored. We have frequently unpacked in January barrels that were filled when the fruit was gathered, in which there was hardly one decayed fruit, and very few bruised ones; but in the barrel the bruised fruits do not decay as they rapidly do on exposure, so that the fruit is best kept in the barrel, stored in a dry, cool cellar or some such place. The reason the fruit does not rot when bruised is no doubt because of the air being excluded, as the apples, being firmly packed together, do not shift on the journey; and where they squeeze each other so closely the air cannot reach them. The wonder is, however, that there are so few damaged fruits in the barrels, the quantity not being worth mentioning. No doubt the excellence of these apples hinders home culture very much, for numbers, knowing they can supply their wants at this season at little cost and trouble, do not think of growing their own fruit—the market is their orchard. When a large quantity is wanted, the best way is to buy in the barrel at the seaport, and keep them in the barrels. A fruit room is not needed in this case. The best brand should also be secured. Other varieties of American apples are also sold very extensively, and at a cheaper rate than the Newtown.

In selecting good sorts for general cultivation the Americans have entirely beaten the English growers, and this, more than anything else, has tended to promote the American apple trade, the origin of which may be said to date from yesterday. It is now beginning to be realized where our mistake has been, and there is an earnest desire exhibited to imitate American cultivators in the matter of selection; but, while the latter have long since settled the main problem for themselves, we are still only groping in the dark, so to speak, as regards the best sorts to grow. The American horticultural societies have no doubt greatly promoted the apple trade, for they have been far more practical and nationally useful than similar societies in this country. Their objects have been of greater national importance, and they have done much to foster the cultivation of useful fruits and vegetables all over the States. In presence of the American societies for the promotion of horticulture, British enterprise in the same direction dwindles into the most insignificant proportions; for, although the Royal Horticultural Society is one of the oldest in existence, and has had great opportunities, it has a poor record to show. Its aims have been paltry and frivolous in most instances, and instead of leading it has been led; for it would be difficult to mention any important service to horticulture which it has conferred. The vine, pine, peach, apple, and pear, &c., have been objects of improvement and culture but in none of these has the Horticultural Society ever rendered any signal service. If, when it had the chance, it had set to work to find out what sorts of fruits were best for English gardens, and what kinds of hardy fruits succeeded best in different parts of the country, or attempted some useful task of that description among the many open to it, what might not have been accomplished by this time? There have been, and always are, important problems interesting and engaging the attention of horticulturists, which might often suggest work for a society which professes to be national in its aims; but the Royal Society has usually set about demonstrating such problems, when it did try, long after other people were satisfied of their utility.—Gardeners’ Chronicle.

—————

Franklin Davis, the veteran fruit grower of Richmond, Va., gives an account, in his report to the American Pomological Society, of the pear orchard of the Old Dominion Fruit-growing Company. The ground which it occupies is on the south bank of the James river, 75 miles below Richmond. The farm belonging to the company contains 500 acres, mostly sandy loam, underlaid with shell-marl from 5 to 15 feet below the surface, with a natural drainage. About 18,000 peach trees were planted from 1860 to 1867, but the fruit rotted badly, and the orchard was neglected. At the same time a few pear trees were set out. About 1871 the pear trees gave handsome fruit, which sold well in market. The owner then saw that it was the place for pears, and next year set out 1,000 Bartletts. The following spring 400 more Bartletts were added, and 600 Clapp’s favorite. In 1873 the above named company was incorporated, and the farm passed into its hands, with a capital stock of $20,000, in 200 shares of $100 each. Nine thousand more trees were set out the following spring, and the same number a year later. The orchard now numbers over 20,000 trees, or over 19,000 Bartletts. When planted they were 1 and 2 year trees, were cut back to a foot of the ground, and were thus made quite low headed, which form was thought to be best suited to that climate. Twenty or thirty acres are annually planted with corn, as much more with peanuts, and the remainder with black peas, plowed under in autumn. This, with the marl, constitutes nearly the only fertilizing.

Clapp’s Favorite ripens about the first of July, and the Bartletts from the 10th to the 25th. The fruit is carefully assorted and graded, and packed in boxes holding a bushel each, made of 5/8-inch dressed lumber, and nearly water-tight. It carries better and ripens better in tight boxes. Being gathered ten days before ripe, time is allowed for conveyance to New York and Boston, and for the arrangements of the commission merchant and the retailer.

The company paid $12,000 for the farm, leaving $8,000 for planting trees, and various other expenses. The first dividend was paid in 1880. The pear crop brought $4,000, which, with the balance in the treasury from the previous year, gave a cash dividend of 20 per cent. on the capital. In 1881, four thousand boxes of pears were sold, with net returns of $13,684, out of which 50 per cent. was paid to the stockholders, besides 10 per cent. set aside for current expenses. Most of the trees were set out within the last eight years, and are still comparatively small.

The two valuable facts taught by this successful experiment are—1. Choosing a site which previous experience had proved well adapted to pear-growing; and 2. Planting the orchard where the fruit would ripen four to six weeks before that of the multitude of orchards at the North, but easy of access to northern cities, to which the boxes could be conveyed for less than 25 cents each. Another important point was in securing the last named advantage before other southern orchards were under way, to dispute the profits of the early market.—Country Gentleman.

—————

Kieffer’s Hybrid.—This new and unique pear was raised by Peter Kieffer, Roxbury, near Philadelphia, from seed of the Chinese Sand pear, accidentally crossed with Beurre d’Anjou or some other kind grown near it. Tree remarkably vigorous, having large, dark green, glossy leaves, and is an early and very prolific bearer. The fruit is of good size, good color, good quality, and is a promising variety for the table or market. Fruit medium, roundish oval, narrowing at both ends, with the largest diameter near the centre. Some specimens roundish, inclining to oblong obtuse pyriform; skin deep yellow, orange yellow in the sun—a few patches and nettings of russet, and many brown russet dots; stalk short to medium, moderately stout; cavity medium; calyx open; basin medium, a little uneven; flesh whitish, a little coarse, juicy, half melting, sweet; quality very good, partaking slightly of the Chinese Sand pears. Ripens all of October and a part of November. To have it in perfection, it should be gathered when fully grown, and ripened in the house.

—————

The evaporating process is working a revolution in the dried fruit industry, especially with the product of the apple. It renders the dried article so far superior in appearance and quality to that produced by the old methods, that the latter have been nearly driven from the market. Evaporated apples become a staple wherever they are known, and the scope of their market is constantly growing wider.

An increased demand for dried fruit tends to create an increased demand for green fruit, and operates favorably to the business of fruit production. By utilizing the surplus of apples in seasons of over-production, the evaporating process helps to equalize and ensure the apple market. Large evaporators, located in extensive apple-producing regions, by appropriating a vast amount of fruit that would otherwise be forced upon the market, make room for the product of thousands of orchards.

The tendency of this revolution in apple drying is to make the production of apples a reliable business. We think that farmers who have come to the conclusion that apple growing is unprofitable need no longer fear to set out apple trees. In average seasons the fruit will always be in demand; and in years of over-production, which have heretofore been a dread, it will command a price that will well repay harvesting.—The Husbandman.

—————

Probably never before in the history of Grape-culture have so many new varieties of promise been offered in competition for preference. Considering the vigor, productiveness, quality, and beauty of many of these new candidates, I am led to predict something of a revolution in Grape-growing. It would seem inevitable that many old favorites will be supplanted. That the interest is reviving there can be no doubt, and there are several reasons for it: First, Grape-growing in this country has never received the attention it deserves. Second, the failure of many of the large vineyards of France calls attention to this country. Third, Grape-growing, intelligently pursued, without extravagant expectations, is a profitable occupation over a large tract of our country. Fourth, the successful attempt to originate improved varieties is in harmony with the advance in other branches of pomology, but somewhat in advance, as may be seen by a glance at a few of the new white Grapes. Lady Washington, Niagara, Prentiss, Duchess, and Pocklington are the leading new white Grapes, that have originated in New York; there are numerous others that have not yet attracted much attention. From Missouri we have seven new white Grapes that are exceedingly promising in that State. In summing up the record of the other States it will be seen that the supply is ample, yet the new colored Grapes are still more numerous. It is a pleasure to test these novelties in the garden, and we have no reason for apprehending danger from the avalanche of white clusters impending.—Charles A. Green.

—————

THE OLD FARM GATE.

The old farm-gate hangs sagging down,

On rusty hinges, bent and brown,

Its latch is gone, and, here and there

It shows rude traces of repair.

The old farm-gate has seen each year,

The blossoms bloom and disappear;

The bright green leaves of spring unfold,

And turn to Autumn’s red and gold.

The children have upon it clung,

And in and out with rapture swung,

When their young hearts were good and pure,

When hope was fair and faith was sure.

Beside that gate have lovers true,

Told the old story, always new;

Have made their vows, have dreamed of bliss,

And sealed each promise with a kiss.

The old farm-gate has opened wide

To welcome home the new-made bride,

When lilacs bloomed, and locusts fair,

With their sweet fragrance filled the air.

That gate with rusty weight and chain

Has closed upon the solemn train,

That bore her lifeless form away,

Upon a dreary Autumn day.

The lichens gray and mosses green,

Upon its rotting posts are seen,

Initials, carved with youthful skill,

Long years ago, are on it still.

Yet dear to me above all things.

By reason of the thoughts it brings,

Is that old gate, now sagging down,

On rusty hinges, bent and brown.

Eugene J. Hall.

—————

Forcing Rhubarb.—Outside of places where there are professional gardeners, the forcing of vegetables is very little known in this country. People in general are content with “things in their season,” and do not trouble themselves to force or retard. Perhaps the easiest vegetable to force is rhubarb; and by taking a little trouble, material for pies and sauce may be had some weeks in advance of the supply from the open ground. The things needed are clumps of rhubarb roots, soil, and a dark warm place. The roots should be dug before the ground freezes, but in most places there is usually an “open spell” when it may be done. As fine rhubarb as we ever saw was forced in a barrel or cask; the roots packed in on a layer of soil and surrounded by it, the cask covered tight, and set near the furnace in the cellar. A box to hold the roots, and set in a cupboard or closet in the kitchen will answer; or a box or barrel may be placed in the kitchen. Keep moderately warm, and see that the roots are sufficiently moist. A few roots will give an astonishingly abundant supply, much more tender and crisp and less violently sour than the out-door crop.—American Agriculturist.

—————

The following is the result of the Rural New Yorker’s experiment with paper bags:—

In order to ascertain what effect paper bags have in preserving grapes, we have left a number of bunches bagged until the present time (Oct. 20). To-day we removed them from several bunches of Wilder and Highland to find the berries plump and perfect in every way. Goethe (Rogers No. 1) were mildewed, though less than those uncovered. Nothing remained of bunches of El Dorado (Rickett’s) except traces of the stems. This bagging of grapes, though it will not keep many of Rickett’s squeamish hybrids and other ne’er-do-wells of the same sort, is a splendid success upon most kinds, and the person who first suggested it is entitled to the thanks of all who love to cultivate the queen of fruits, as we think the grape is richly entitled to be considered. Nothing in fruit culture has ever given us greater pleasure than, upon removing the paper bags, to find the clusters as perfect as if made of wax. Everybody will bag his grapes, or some of them, at any rate, another year, and the grape displays at fairs will show the results.

At the October meeting of the Montgomery County (Ohio) Horticultural Society, Mrs. Longstreth stated that she had tried paper bags, and with results so satisfactory that she wished to impress upon all, whether they had a few or many vines, the efficiency of this rather novel and to many, new way of protecting grapes. She had noted the difference in vines so protected, growing by the side of those not protected. The difference in favor of those thus protected was so marked that she knows she does not err in commending the method in the highest terms. The labor of doing it is but slight. A woman can put on one hundred per hour. By this method the bloom is preserved and the mildew and rot guarded against.—Rural New Yorker.

PRINTED AT THE STEAM PRESS ESTABLISHMENT OF COPP, CLARK & CO., COLBORNE STREET, TORONTO.

TRANSCRIBER NOTES

Misspelled words and printer errors have been corrected. Where multiple spellings occur, majority use has been employed.

Punctuation has been maintained except where obvious printer errors occur.

Some illustrations were moved to facilitate page layout.

A Table of Contents was created with links to the articles for easier use.

[The end of The Canadian Horticulturist, Volume 6, Issue 5 edited by D. W. (Delos White) Beadle]