* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Dominion of Canada

Date of first publication: 1868

Author: Henry Youle Hind, 1823-1908

Date first posted: Mar. 24, 2018

Date last updated: Mar. 24, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180320

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David T. Jones, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE

DOMINION

OF

CANADA;

CONTAINING

A HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE PRELIMINARIES AND ORGANIZATION OF CONFEDERATION;

ALSO,

THE VAST IMPROVEMENTS MADE IN AGRICULTURE, COMMERCE AND TRADE, MODES OF TRAVEL AND TRANSPORTATION, MINING, AND EDUCATIONAL INTERESTS, ETC., ETC.

FOR THE PAST EIGHTY YEARS UNDER THE PROVINCIAL NAMES.

WITH A LARGE AMOUNT OF STATISTICAL INFORMATION,

FROM THE BEST AND LATEST AUTHORITIES.

BY

H. Y. HIND, M. A., F. R. G. S.

T. C. KEEFER, CIVIL ENGINEER.

J. G. HODGINS, LL. B., F. R. G. S.

CHARLES ROBB, MINING ENGINEER.

M. H. PERLEY, ESQ.

REV. WM. MURRAY.

FULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH STEEL AND ELECTROTYPE PLATE ENGRAVINGS,

SHOWING THE PROGRESS IN THE VARIOUS BRANCHES TREATED OF.

(FURNISHED TO SUBSCRIBERS ONLY.)

TORONTO:

PUBLISHED BY L. STEBBINS.

1868.

| Transcriber's Notes and Errata are placed at the end of this file. |

| Part I. | Introductory, (2 sections.) |

| Part II. | Period of English and French Discovery and Settlement, (10 sections.) |

| Part III. | Political and Military History—French Period, (26 sections.) |

| Part IV. | Political History of Canada—British Period, (18 sections.) |

| Part V. | The Maritime Provinces, (8 sections.) |

| Part VI. | Confederation of the Provinces—with Statistical Tables, (16 sections.) |

HISTORICAL SKETCH

OF THE NEW

CONFEDERATED DOMINION OF CANADA.

The prosperous provinces of British North America, which now constitute the "Dominion of Canada," were, with the islands of Prince Edward and Newfoundland and the outlying territory of the Hudson Bay company, (and even portions of the United States,)—once known as Nouvelle France. This vast area was two centuries ago held by one people, and ruled by one viceroy—with his subordinates as governors of districts. It will be curious and interesting briefly to trace the successive steps which led not only to the rapid expansion of French power and influence on the continent, but also to note the causes which led to the no less certain decay and extinction of that power as a political entity in America. Equally instructive will it be to take a glance at the successive steps which led to the establishment of that other rival power in the very seat of French dominion on this continent, and caused to be transferred to Great Britain these fine provinces, which afterwards under her beneficial rule grew and prospered as single communities, and at length confederated together as one Dominion—a Dominion with a population and territory equal to that which formed the United States at the close of its successful revolution of 1776.

2. Growth of British North America.—Long after the discovery of America, Great Britain had no permanent foothold in any part of the continent. For many years she maintained but a nominal claim, for fishing purposes, upon the outlying island of Newfoundland—her sovereignty over which was chiefly based upon Cabot's discovery in 1497, and Sir Humphrey Gilbert's act of possession in 1583. Gradually, however, she advanced her power and increased her influence, until she absorbed nearly the whole of the North American continent. But very soon after the absorption of this vast territory, there arose that restless spirit among her own children, which at length issued in rebellion against her authority, and in the end bereft her of more than half of her possessions. Since that event there has again grown up in what was once New France, a prosperous cluster of colonies, which stretch across the continent from the island of Newfoundland to that of Vancouver.

1. Cabot's Discovery of Newfoundland.—Soon after the news of the discovery by Columbus had reached England, John Cabot, a Venetian merchant, resident at Bristol, obtained a commission from Henry VII., in 1496, to make a voyage to the New World. In June 1497, he left Bristol with his son Sebastian. On the 24th of that month, he reached a point on the Trinity Bay coast, Newfoundland, which he named Prima Vista. On St. John's day he came to an island which he named St. Jean, (afterwards Prince Edward.) By virtue of these discoveries, the English first laid claim to sovereignty over these islands.

2. Cortereal's Voyages.—In 1500 Gaspard Cortereal, a Portuguese, made a voyage to Labrador, Newfoundland, and New England. He made a second voyage in 1501, and, having reached Hudson Strait, was never heard of afterwards.

3. Verazzani's Voyage.—In 1524, John Verazzani made a voyage to America, under the patronage of Francis I. In 1525 he made a second voyage, and explored more than 2,000 miles of coast. In consequence of his discoveries the French claimed jurisdiction of all places visited by him.

4. Cartier's Discovery of Canada.—In 1534 Philip Cabot, admiral of France, urged King Francis I. to establish a colony in the new world. He recommended Jacques Cartier, a noted navigator of St. Malo, to command an expedition of discovery to the New World. In April 1534 Cartier left St. Malo, and twenty days after reached a cape on the Newfoundland coast which he named Bona Vista. On the 9th of July he entered a bay (of New Brunswick) in which he experienced such intense heat that he called it the "Baie des Chaleurs." Passing northwards out of this bay he rounded the peninsula, and on the 24th of July landed on the coast since known as "Gaspé,"—an Indian name for Land's end. There he erected a cross, on which he placed a shield bearing the fleur-de-lis, as emblematical of the new sovereignty of France in America. He then returned to France. In July, 1535, after a tempestuous voyage, he again reached Newfoundland. On the 10th of July he anchored in a bay to which he gave the name of St. Lawrence,—having entered it on the festival of that saint. The name thus given to the little bay has since been applied to the vast gulf and noble river which Cartier was the first European to discover and afterwards explore.

5. Name of Canada.—When Cartier reached Stadacona (Quebec) the Algonquin Indians intimated to him that Kanata,—a collection of wigwams at the native Huron village of Hochelaga (Montreal)—was farther up the river. He probably understood them to apply that word to the whole country lying beyond him. In this way, it is supposed the name Kanata, or Canada, was given to the entire country which Cartier was then engaged in exploring.

6. Other Futile Expeditions—Feudal System introduced.—During the next fifty years little more was accomplished. But in 1598 the Marquis de la Roche was constituted lieutenant-general of the king, and was invested by him with power to "grant leases of land in New France, in form of fiefs, to men of gentle blood." Thus was the feudal system introduced into Canada. It was modified by Richelieu into a seigniorial tenure, and was not finally abolished until 1854.

7. Commercial Efforts.—Not only did the French fishermen continue to frequent the coast of Newfoundland, but, under the patronage of Henry IV., Dupont Gravé, a merchant of St Malo, and Chauvin, a master-marine of Rouen, made several voyages up the St Lawrence to Tadoussac, and brought home cargoes of the rich furs which had been collected from the north at that place. De Chattes, the governor of Dieppe, formed a company of Rouen and other merchants, to prosecute the work more vigorously.

8. Champlain's Discoveries.—The first expedition to Canada projected by this Company was placed under the command of Samuel de Champlain. In company with Dupont Gravé, he, in 1603-7, explored the St Lawrence from Tadoussac to Three Rivers. On the 3d of July, 1608, he founded the city of Quebec. In 1609 he ascended the river Richelieu, and discovered the beautiful lake since called Champlain. In 1615 he ascended the Ottawa to Lake Nipissing, descended French River to Georgian Bay, and from Lake Simcoe he passed by a long portage to the head-waters of the river Trent, and thence to Lake Ontario.

9. Reverses—Further Explorations.—The Prince de Condé having been appointed viceroy, a new and enlarged company was incorporated under his auspices, and an effort was made to introduce Christianity among the Indians. For this purpose Champlain brought the first missionaries to Canada. These were four Recollet fathers, who accompanied him in 1615.

10. Montreal Founded.—Huron War.—M. De Montmagny followed Champlain. During his administration in 1642, Montreal was founded with religious ceremonies under the name of Villa Maria, (Town of Mary,) and soon after, the long threatened war of extermination against the Huron Indians was commenced by the Iroquois. It was to this governor that the Indians first applied the term Onontio, the great mountain—a literal translation of M. de Montmagny's name. The term was afterwards applied to each of the French governors of Canada. On-ti-go-a was the Indian name of the king of France.

1. Proposed Union of the English, French, and Dutch Colonies.—The four New England colonies had, in 1643, formed a union or alliance. It was then proposed that this union should include all the European colonies in America—English, French, and Dutch—whose existence should not be imperilled by the politics or wars of Europe. Each colony was to retain its own laws, customs, religion, and language.

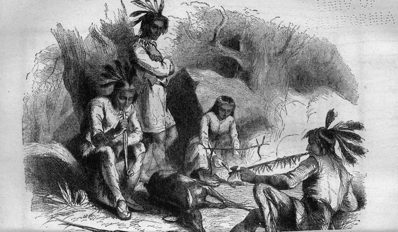

2. Projected Alliance with New England.—With a view to carry out this confederation, Governor Winthrop of Massachusetts wrote to the governors of New Netherlands and New France, or Canada, in 1647. The Dutch governor responded favorably at once, but the French governor delayed doing anything until 1650, when he dispatched Père Druilletes to Boston, to propose as an additional article of union, the stipulation that New England should join Canada against the Iroquois—the French having suffered so severely from the Iroquois in their prosecution of the peltry-traffic. This hostile stipulation on the part of the French, although skillfully presented as a righteous league in defense of Christianity against scoffing pagans, broke off the negotiations. When this proposed arrangement became known to the Iroquois, it exasperated them still more, and they redoubled their efforts to destroy the French colonists, so that for several years the French were virtually kept within their inclosures. Trade entirely languished, and the beavers were allowed to build their dams in peace, none of the colonists being able or willing to molest them.

3. Peace and Progress.—At length, however, a treaty was entered into with the five Iroquois tribes in 1654, and for a time war ceased its alarms. Trade revived, and the peltry-traffic was vigorously prosecuted by the French with such of the Iroquois as were near Canada. The others, however, preferred to trade with the English. During the intervals of war, explorations were made among the Sioux Indians beyond Lake Superior, and also among the Esquimaux. The year 1656 was noted for an overland expedition which was sent from Canada to Hudson Bay by way of Labrador, under Louis Jean Bourdon, attorney-general of New France, to take possession of that territory on behalf of the French King.

4. Royal Government Established.—In 1659, a royal edict was issued regulating the civil government of the colony. The resumption of Royal authority in Canada was made the occasion of introducing various reforms. A "Sovereign Council," invested with administrative and judicial functions, somewhat like the "Parlement de Paris," was instituted at Quebec. Legal tribunals were established, and municipal government in a modified form introduced. The right of taxation was, however, reserved to the king. The administration of government devolved upon a viceroy (who, as colonial minister, generally resided in France,) a governor, and an intendant, or chief of justice.

5. Police and Public Works.—West India Company.—With these modifications the king, in 1664, transferred the trading interests of Canada to the West India Company, by whom an ordinance was passed introducing into the colony "the law and customs of Paris," (la coutume de Paris.) With a view to insure harmony in this matter throughout Canada, all other French coutumes were declared illegal in it.

6. Vigorous Administration and Reform.—The new rulers sent out from France in 1665, were men of ability. M. de Tracy was selected by the king as lieutenant-general, M. de Courcelles as governor, and M. Talon as intendant. On their arrival with new emigrants and farming materials, the colony revived. Talon, by authority of the king, carried into effect various useful reforms in the system of government,—especially in regard to the finances, the punishment of peculators, and the reduction of the amount of tithes payable to the clergy. He further sought to encourage both agriculture and manufactures. During his administration the restrictions on trade in Canada, as imposed by the West India Company, were greatly relaxed.

7. Attempted Diversion of the Fur Trade.—The English, having, in 1663, superceded the Dutch in New Amsterdam, (afterwards New York,) pushed their trade northward through the agency of the Iroquois Indians. These allies, anxious to profit by the traffic, sought, in 1670, to obtain furs and skins for the English from the various tribes up the Ottawa, which was then the chief hunting ground of the French Indians.

8. Formation of the Hudson Bay Company.—In the meantime the English obtained a footing in the Hudson Bay territories, under the guidance of des Grosellières, a French pilot, aided by another Franco-Canadian, named Radisson. An English company was formed to trade for furs, under the patronage of Prince Rupert. Charles I., King of England, having claimed the Hudson Bay territories, by virtue of Hudson's discoveries in 1610, granted a charter in 1670 to this company, authorizing it to traffic for furs in that region.

9. Count de Frontenac.—In the year 1672 de Courcelles retired, and Count de Frontenac, a man of great energy and ability arrived. He remained ten years, and was recalled in 1682. In 1672 he built Fort Frontenac (Kingston.) It was rebuilt of stone by La Salle in 1678. Frontenac was re-appointed governor in 1689, and carried on a vigorous war against the English settlements in New York, and against their Indian allies, the Iroquois. The English retaliated, and the Iroquois made various successful inroads into Canada. In 1690 Frontenac defeated Sir William Phipps and the English fleet, before Quebec. He died greatly regretted in 1698, aged 78 years. Though naturally haughty, he was an able and enterprising man.

10. Spirit of Discovery and Adventure.—Nothing was so remarkable, during the early settlement of Canada, as the spirit of adventure and discovery which was then developed. Zeal for the conversion of the Indians seems to have inspired the Jesuit clergy with an unconquerable devotion to the work of exploration and discovery. Nor were they alone in this respect, for laymen exhibited the same adventurous spirit in encountering peril and hardship. From the first settlement of Quebec, in 1608, until its fall in 1759, this spirit of discovery and dominion was actively fostered by each succeeding governor, until there radiated from that city a series of French settlements which stretched from the St. Lawrence to the far West, and from the sources of the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico, and even to the shores of South America.

11. Summary of Discoveries.—After Champlain, other explorers extended their researches westward. In 1640 the southern shores of Lake Erie were visited by Pères Chaumonot and Breboeuf. In 1647, Père de Quesne went up the Saguenay and discovered Lake St. John. In 1651, 1661, and 1671, expeditions were sent northwards towards the Hudson Bay, with more or less success. In 1646, Père Druilletes ascended the Chaudière, and descended the Kennebec to the Atlantic. In 1659, the Sioux were visited by adventurous traders, and in 1660 Père Mesnard reached Lake Superior. In 1665, Père Alloüez coasted the same lake, and formed a mission at the Bay of Che-goi-megon. In 1668, Pères Dablon and Marquette formed a settlement of Sault Ste. Marie. In 1670 and 1672 Alloüez penetrated, with Dablon, to the Illinois region, where they first heard of the mysterious Mississippi,—the "great father of waters."

12. La Salle's Expeditions to the Mississippi.—Fired with the news of this notable discovery, Sieur de la Salle, a French knight, then at Quebec, determined to complete the discovery. He sought to reach China by the way of Canada. His design was frustrated by an accident at a place since called Lachine, or China. He explored the Mississippi from its source to its month in 1678-80; spent two years between Frontenac (Kingston) and Lake Erie, and constructed the first vessel on Lake Erie (near Cayuga Creek.) He sought to reach the Mississippi by sea, but, having failed, he sought to reach it overland. In doing so he was murdered by his jealous followers who, afterwards, justly suffered great hardships. Père Hennepin, a Recollet Franciscan friar emigrated to Canada in 1675. He accompanied La Salle in his exploration of the Mississippi in 1678, and visited the Falls of Niagara,—of which he wrote an interesting account.

13. Failure to restrict the Peltry Traffic to the Region of the St. Lawrence.—Great efforts were made by the French to restrict the traffic in beaver-skins and peltry within their own territories. They at one time interdicted trade with the Anglo-Iroquois—then they made them presents;—again they threatened them—made war upon them—invaded and desolated their villages;—they made treaties with them, and urged and entreated the Dutch and English to restrain them, and even sought to make the latter responsible for their acts;—but all in vain. As the tide rolled slowly in upon them, and the English, (who were always heralded by the Iroquois,) advanced northwards and westwards to the St. Lawrence and the great lakes, the French still gallantly holding possession of their old trading-forts, also pressed forward before them and occupied new ground.

14. Armed Trading Posts.—With sagacious foresight, the French, in addition to a regular fort at Quebec, erected, from time to time, palisaded inclosures round their trading posts at Tadoussac, at Sorel, and the Falls of Chambly (on the Iroquois, or Richelieu River) at Three Rivers, Montreal, and Cataraqui (Kingston.) Subsequently, and as a counterpoise to the encroachments of the English, they erected palisaded posts at Niagara, Toronto, Detroit, and at Sault Ste. Marie and Mich-il-i-mack-i-nac. Nor were the English idle. Creeping gradually up the Hudson river, they erected armed trading-posts at Albany, and at various points along the Mohawk valley, until, at length, in 1727, they fearlessly threw up a fort at Oswego, on Lake Ontario, midway between the French trading posts of Frontenac and Niagara.

15. The Cause of the Incessant Disputes and Wars must be looked for in the mutual determination of the French and English colonists to secure an exclusive right to carry on a traffic for furs with the Indian tribes. Territorial extension, no less than national resentment between the French and English colonists, gave intensity of feeling to the contest, and contributed to its duration. In their efforts to force the traffic into unnatural channels, the plans of the French were not only counteracted by the energy of the English traders, but they were even thwarted in them by separate classes among themselves—each having different interests to serve, but all united in their secret opposition to the government.

16. The Three Classes of French Fur Traders were; 1, the Indians; 2, the trading officials; and 3, the coureurs de bois ("runners of the wood," or white trappers.) As to the first class, (the Indians of these vast territories,) they were ever proud of their unfettered forest life, and naturally disdained to be bound by the artificial trammels of the white man. The second class, (the officials of New France,) were secretly in league with the coureurs de bois against the king's revenue agents—their exaction and their exclusive privileges. The third or intermediary class of traders, or factors, (the coureurs de bois,) sought in every way to evade the jurisdiction of the farmers of the revenue at Quebec. Their own reckless and daring mode of life among the Indians in the woods, far from the seat of official influence and power, gave them peculiar facilities for doing so.

17. Various ameliorations.—During a peaceful interval, M. de Vaudreuil, the governor, set himself to develop the resources of the country, and to foster education among the people. He subdivided the three governments of Quebec, Three Rivers, and Montreal, into eighty-two parishes, and took a census of the people.

18. Maritime Defense of New France.—To provide for the maritime defense of Canada, (which, as yet, had no protection to the seaward,) France, in 1713, colonized the island of Cape Breton, and, in 1720, strongly fortified Louisbourg its capital, at great expense.

19. Pepperrell's Expedition from New England.—In 1745 war again broke out. From Crown Point, on Lake Champlain, the French and their Indian allies successfully attacked the English settlements; and from Louisbourg a host of French privateers sallied forth to harrass the commerce of Nova Scotia and New England. Governor Shirley, of Massachusetts, aided by the other colonies, at once sent an expedition under William Pepperrell for the reduction of this stronghold. It was highly successful, and Pepperrell was rewarded with a baronetcy. Nothing daunted, a fleet, under the Duke d' Anville, was dispatched from France to recapture Louisbourg. But having been dispersed by a tempest, it never reached its destination.

20. Proposed Federal Union of the Colonies, 1753-4.—With a view to concerted action against the French, the lords of trade suggested to the colonies the formation of a league with the Indians, which in its structure should be an enlargement of the Iroquois confederacy. Shirley, the indefatigable governor of Massachusetts, conceived the bolder project of an alliance among the colonies themselves, for the purposes of mutual defense. Neither schemes were, however, adopted, but the germ of such a colonial union was subsequently developed at the time of the American revolution.

21. Capture of Quebec.—The incessant trading disputes which had lasted for years between the English and the French ultimately culminated, in 1759, in that decisive contest between them on the Plains of Abraham. And thus, in the memorable fall of Quebec, fell also, in Canada, (although the after-struggle was protracted for a year,) that imperial power which, for more than one hundred and fifty years, had ruled the colonial destinies of New France.

22. Fall of French Power.—Thus, after years of heroic struggle—with scant means of defense against powerful rival colonists and a relentless Indian enemy,—the first promoters of European civilization and enterprise in Canada were compelled to give place to a more aggressive race. But they did so with honor. And little did those think who were then the victors over so brave an enemy in Canada, that, within twenty years from that event their own proud flag would be ignominiously lowered at the seat of their own power at New York, as well as at every other fort and military post within the thirteen American colonies.

23. The Treaty of Paris, 1763.—By this treaty France ceded to England the whole of her possessions in North America, with the exception of Louisiana and the small fishing islands of St. Pierre and Micquelon (off the coast of Newfoundland.)

24. The French and English Colonial Systems Contrasted.—The return to France of the French military officers and troops, as well as of many of the chief inhabitants, was encouraged by the English, who were anxious thus quietly to rid themselves of a powerful antagonistic element in their newly acquired possession. They well knew that the process of assimilation between the two races so long arrayed in hostility to each other, would be very slow indeed.

25. System of Government in the French Colony.—The French colony, in its relations to the Imperial government, was as a child of the State. Every thing in it was subject to political influence or official surveillance, while religious matters were subject to vigorous ecclesiastical control. Two principal objects engrossed the attention of the French colonists,—the extension of the peltry traffic, and the conversion of the Indian tribes. As a means of carrying out these two great projects, exploration and discovery formed a chief feature of French colonial life.

26. System of Government in the English Colony.—In the English colony, the government, on the contrary, partook rather of the nature of a civil and social bond between the governing and the governed. It interfered as little as possible in matters of trade. Hence exploration and discovery within the colony formed but a subordinate part of the objects and pursuits of the English colonist. When, therefore, the rival colonists came into contact, it was rather in a struggle for enlarged boundaries for trade, or for dominion over rival Indian tribes, and for the monopoly of the fur trade. That contest, although it was too often utterly selfish in its objects, nevertheless unconsciously developed in both colonies, in a wonderful degree, a spirit of enterprise and discovery, which has scarcely had a parallel in later times, when steam and electricity have added, as it were, wings to man's locomotive and physical power.

1. British Rule Inaugurated—In 1763 General Murray was appointed the first governor of the new British Province of Quebec,—the boundaries of which were contracted by the separation from it of New Brunswick, Labrador, &c. The old district divisions of Quebec, Montreal, and Three Rivers were, however, retained, and a subordinate governor appointed over the two outlying districts of Montreal and Three Rivers.

2. State of Canada at this Time.—The population of Canada at this time was about 80,000, including nearly 8,000 Indians. The country, however, had been exhausted by desolating wars, and agriculture and other peaceful arts languished. The failure of the French Government to pay its Canadian creditors the sums due to them, (chiefly through the fraud, rapacity, and extravagance of the Intendant Bigot,) involved many of these creditors in misery and ruin.

3. Ameliorations in the System of Government Discussed.—In 1766 Governor Murray was recalled, and General (Sir Guy) Carleton appointed Governor General. Sir Guy Carleton (afterwards Lord Dorchester) had taken a prominent part in the siege and capture of Quebec, under Wolfe, in 1759; and, during Governor Murray's absence in 1767 he administered the government. Being in England in 1770, he aided in the passage of the first Quebec Act. In 1774 he became Governor-General, and successfully resisted the attack of the Americans upon Quebec in 1776. In 1778 he returned to England and was knighted by the king. In 1782 he succeeded Sir Henry Clinton as commander-in chief of the royal forces in America. In 1786 he was created Lord Dorchester for his distinguished services; and from that time (with the exception of two years) he remained in Canada for the long period of thirty-six years. During that time he acquired great distinction as a colonial governor by his prudence, firmness, and sagacity.

4. The Quebec Act.—In 1774 the Quebec Act was passed as a conciliatory measure by the Imperial Parliament. It provided, among other things, for the "free exercise" of the Roman Catholic religion—for the establishment of a Legislative Council, and for the introduction of the criminal law of England into the province; but it declared "that in regard to property and civil rights, resort should be had to the laws of Canada as the rule for the decision of the same." Thus, the enjoyment of their religion, and protection under the civil laws of French Canada were confirmed to the inhabitants by Imperial statute, and a system of local self-government was introduced. The act gave satisfaction to the French Canadians; and, at a time when the old English colonies were wavering in their attachment to the British crown, it confirmed them in their allegiance to the king.

5. Efforts of the Disaffected colonists to Detach the Canadians from England.—In 1774, the assembly, from Massachusetts, requested a meeting of representatives from all the colonies to concert measures of resistance to England. Each of the thirteen old colonies, except Georgia, sent delegates. Canada declined to take any part in the revolt; and although one of the three addresses issued by the insurgent Congress was especially addressed to the Canadians, they declined to repudiate their formal allegiance to the British Crown. Strong efforts were also made by the Americans to detach the Iroquois (under Brant) from the British standard, but without effect.

6. Constitutional Changes—Clergy Reserves.—In 1789, the draft of a new constitution for Canada was prepared. It proposed to divide the province of Quebec into Upper and Lower Canada; to give to each section a Legislative Council and House of Assembly, with a local government of its own. This celebrated constitutional act was passed in 1791. By it representative government, in a modified form, was for the first time introduced into the two Canadas simultaneously, and gave very great satisfaction. In the same year the famous Clergy Reserve Act was passed in England. This act set apart one seventh of the unsurveyed lands of the Province, "for the support of a Protestant Clergy," and authorized the governor of either Province to establish rectories and endow them. This act became afterwards a fruitful source of agitation and discontent in Upper Canada.

7. Parliamentary Government Inaugurated.—In June, 1792, the first parliamentary elections were held in Lower Canada, fifty members were returned. The Legislative Council, appointed by the Crown, consisted of fifteen members. On the 17th of December the new Legislature was opened by General Alured Clarke, the Lieutenant-Governor. Eight acts were passed by both houses. During the second session five bills were passed. The revenue of Lower Canada this year was only $25,000. During the third session, of 1795, accounts of the revenue and expenditure, which had now reached $42,000, were first laid before the Legislature. Of the customs revenue, Upper Canada was only entitled to one eighth.

8. Settlement of Upper Canada.—As Upper Canada was chiefly settled by United Empire Loyalists (to whom the British Government had liberally granted land and subsistence for two years,) it was deemed advisable to confer upon these settlers a form of government, similar to that which they had formerly enjoyed. In 1788 Lord Dorchester divided Upper Canada into four districts, viz.: Lunenburg, Mecklenburg, Nassau, and Hesse. In 1792, the Legislature changed these names into Eastern, Midland, Home and Western. These districts were afterwards divided, and their number increased; but they were abolished in 1849.

9. The First Upper Canada Parliament was opened at Newark (Niagara) on the 17th of September, 1792, by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe. The House of Assembly consisted of only sixteen members, and the Legislative Council of seven. Eight bills were passed—one of which provided for the introduction of the English Civil Law. Trial by jury was also specially introduced, by statute, in that year. The English Criminal Law was also (as it stood in 1792) made the law of the land in Upper Canada.

10. Slavery Abolished.—In 1793, Slavery was abolished in Upper Canada; and in 1803, Chief Justice Osgoode decided that it was incompatible with the laws of Lower Canada.

11. The Seat of Government in Upper Canada was, in 1796, removed from Newark (Niagara,) to York (Toronto) by Governor Simcoe.

12. Progress of Affairs.—From 1796 to 1810 little of public or historical interest occurred in Canada. The local discussions related chiefly to abuses in land-granting by the government, the application of the forfeited Jesuit estates to the founding of a Royal Institution for the promotion of public education in Lower Canada, and the establishment of Grammar Schools in Upper Canada. Efforts were also made to improve the navigation of the lower St. Lawrence, to regulate the currency, extend the postal communication, ameliorate the prison system, promote shipping and commerce. Soon after, the war of 1812 took place.

13. Conditions of the Provinces at the Close of the War.—Although the war of 1812 lasted only three years, it left Upper and Lower Canada very much exhausted. It, however, developed the patriotism and loyalty of the people in the two provinces in a very high degree.

14. Political Discussions in Upper and Lower Canada.—The distracting influences of the war having gradually ceased, political discussions soon occupied public attention. In Lower Canada, a protracted contest arose between the Legislative assembly and the Executive Government, chiefly on the subject of the finances and political rights. In Upper Canada an almost similar contest arose between the same parties in the state; while the abuses arising out of an irresponsible system of government were warmly discussed and denounced. Nevertheless, progress was made in many important directions. Emigration was encouraged; wild lands surveyed; commercial intercourse with other colonies facilitated; banking privileges extended; the system of public improvements (canals, roads, &c.) inaugurated. Steamboats were employed to navigate the inland waters; primary and higher education encouraged, and religious liberty asserted as the inherent right of all religious persuasions.

15. Political Crisis.—Remedy.—The political discussions culminated, at length, in 1837, into armed resistance. This however was soon put down; and Lord Durham was sent out from England to inquire into the grievances complained of. His mission resulted in their removal, and in 1840 the two provinces were reunited under one government.

16. Political Progress.—Lord Sydenham was sent out as Governor General to inaugurate and carry the union into effect. Under his administration the foundation of many of the most important civil institutions were laid, especially those relating to the municipal system, popular education, the customs, currency, &c.

17. Lord Elgin.—From this period until 1847, when the distinguished Lord Elgin became Governor General, the political and material progress of the Province was marked and steady. In the discharge of the duties of his high office Lord Elgin exhibited a comprehensiveness of mind and a singleness of purpose which gave dignity to his administration, and divested the settlement of the various questions of much party bitterness and strife. Under his auspices, responsible government was fully carried out, and every reasonable cause of complaint removed. The consequence was that contentment, peace and prosperity became almost universal throughout Canada. During his period of office the Grand Trunk and Great Western Railways were projected, a free banking law was passed, a uniform letter postage rate of five cents was adopted, and the number of representatives in Parliament increased. He also procured the passage of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States, (since abrogated.) He fostered the systems of public instruction in Upper and Lower Canada, and greatly promoted their popularity and success by the aid of his graceful eloquence.

18. Sir Edmund Head succeeded Lord Elgin in 1854. His administration was noted for the final settlement of the Clergy Reserve question in Upper Canada, and of the Seigniorial Tenure question in Lower Canada; also for the completion of the Grand Trunk Railway to Rivière du Loup, and of its splendid Victoria Bridge over the St. Lawrence river at Montreal. In 1851, 1861, and 1863 Canada distinguished herself in the great International Exhibitions held in London, Paris and Dublin. In 1856, the Legislative Council was made elective; and the laws of the province consolidated. In the same year a Canadian line of ocean steamers was established; a decimal system of currency, with appropriate coins, was introduced; the handsome Parliament and Toronto University buildings were commenced; in 1860 the memorable visit of the Prince of Wales to British America took place; and in 1864 the project of Confederation was discussed.

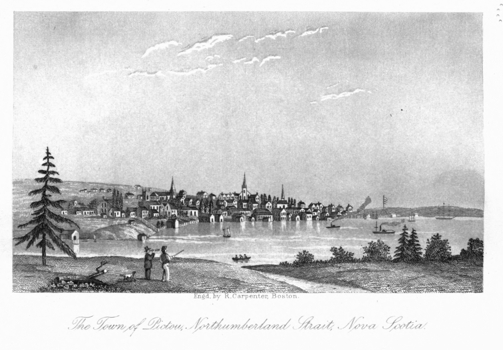

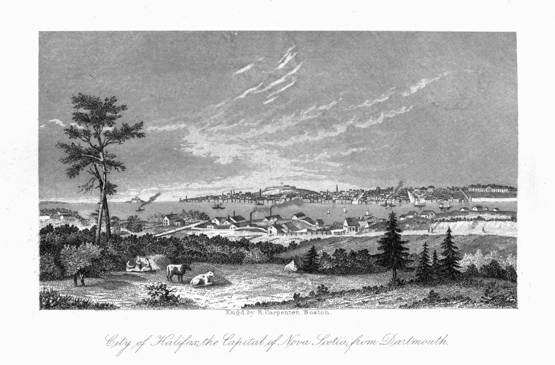

1. Nova Scotia, formerly called Acadie, was settled by the French under De Monts, in 1604; ceded to England in 1713; colonized in 1748-9; a constitution was granted in 1758; in 1784 it was modified. Cape Breton was taken from France by England in 1758; ceded formally to her in 1763; annexed to Nova Scotia in the same year; separated from it in 1784, and re-annexed again in 1819.

2. Political and Commercial Progress.—In 1820 efforts were first formally made to protect the English fisheries on the Nova Scotia coast. In 1823 the Roman Catholics were admitted to the full enjoyment of equal civil privileges with other denominations. In 1824-28 the Shubenacadie canal, designed to connect Halifax with Cobequid Bay, was commenced, and a line of stages between Halifax and Annapolis established.

3. Responsible Government.—In 1838 a deputation from Nova Scotia was sent to confer with Lord Durham, the Governor General at Quebec, on a proposed change in the constitution. In 1848 a system of government, responsible to the Legislature, as in Canada, was introduced. In 1851 further efforts were made to protect the fisheries; and, in 1852, a Provincial force, auxiliary to the Imperial, was placed under the direction of the British Admiral for that purpose. Afterwards a fishing and reciprocity treaty was made with the United States, but it was abrogated by that country in 1866.

4. Confederation in Nova Scotia.—In 1860 His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales, visited Nova Scotia. In addition to the other valuable minerals, gold was discovered in 1861. In 1864 Nova Scotia united with the other colonies in the consideration of a scheme for the confederation of all the provinces of British North America under one government. With that view a meeting of delegates from each province was held at Charlottetown, Halifax, and Quebec. Resolutions approving of confederation were passed by the Nova Scotia Legislature in 1866, and a feeling in favor of it exists in Nova Scotia, although the scheme is now strongly opposed by many of the people there, headed by the Hon. Joseph Howe, her leading statesman.

5. New Brunswick.—In 1713, this Province, being part of the French colony of Acadie, was, by treaty, ceded to the British Crown. This transfer was finally confirmed by another treaty in 1763. In 1785, New Brunswick, then the county of Sunbury, (Nova Scotia,) was, by an act of the Imperial Parliament, separated from Nova Scotia, and erected into a distinct Province. It was named New Brunswick, after Brunswick in Lower Saxony, in Germany, the place of residence, up to 1714, of the present royal family of England.

6. Ashburton Treaty, &c.—In 1842 a treaty was negotiated between Great Britain and the United States by Lord Ashburton. By it the disputed boundary between Maine and New Brunswick was settled. This territory contained 12,000 square miles, or 7,700,000 acres. Maine received 4,500,000 acres, and New Brunswick 3,200,000.

7. Responsible Government, similar to that in the other provinces, was introduced in 1848. Since then the Province has increased in wealth, population, and importance.

8. Confederation in New Brunswick.—During 1864-6 the project of confederating the Provinces of British America was discussed in New Brunswick, and in each province. The result was that in 1867 a basis of union was formally submitted to the British Parliament and passed into law.

1. History of Confederation.—The germ of confederation, (as we have seen in the rapid glance which we have taken,) may be traced in the efforts which were made from time to time, by the colonies themselves, to overcome the weakness of their isolated position, and to concentrate their energies and resources for the purpose of mutual defense. (1) The first step in this direction was the union of the New England colonies in 1643, and (2) in the projected league between the Dutch, English, and French Colonies in 1647-50. (3) The celebrated confederated league which existed among the Iroquois until 1780 was a remarkable instance of the sagacious instinct of this brave and noble people to maintain their power, and to perpetuate their existence. (4) The project of an extension of this league so as to include in it the English Colonies (with the Iroquois) was urged by the Lords of Trade in 1753; (5) Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, however, conceived the bolder plan of a federal union between all the British Colonists themselves for the purpose of mutual defense. (6) Neither scheme succeeded at that time; but it was afterwards fully developed in the memorable union of the thirteen insurgent colonies in 1776. (7) In 1784 it was mooted, when New Brunswick was separated from Nova Scotia. (8) In 1800, Hon. R. J. Uniacke of Nova Scotia brought the matter under the notice of the Imperial authorities. (9) In 1814, Chief Justice Sewell of Quebec wrote a letter to the Duke of Kent, while in Nova Scotia, advocating a union of the provinces. (10) In 1822, Sir J. B. Robinson, of Toronto, while in England, submitted to the colonial office, by request, a scheme of union. (11) In 1825 the noted Robert Gourley, of Canada, in a letter from London, recommended a scheme of confederation. (12) In 1838 a deputation from Nova Scotia brought the matter before the Earl of Durham, Lord High Commissioner, in a conference with them on the political state of that province. (13) In the same year, Bishop Strachan of Toronto also urged the expediency "of consolidating the provinces into one territory or kingdom," on Lord Durham's attention. (14) Lord Durham himself also favored the plan of a single "ruled government" over that of a "federal union." (15) In 1840 the union of the Canadas too, (16) and in 1843 Elliot Warburton in his "Hochelaga," advocated an extension of the principle to other colonies. (17) In 1849 the British American Conservative League advocated "colonial union." (18) In 1851 Col. Rankin, of the Canadian Parliament, in an address to his constituents, and in 1856 in a speech before the House, urged a "union of colonies." (19) In 1858 the Hon. A. T. Galt, finance minister of Canada, renewed the project; (20) and in the same year the governor-general recommended it in a speech from the throne. (21) In 1864-6 the present confederate scheme was discussed at meetings of delegates from all the provinces, at Charlottetown, Prince Edward's Island, and at Halifax and Quebec, and finally assented to by the British Parliament in 1867.

2. Principle of Confederation.—This act of confederation provides for the union of the four provinces of Ontario, (Upper Canada) Quebec, (Lower Canada) Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, into one Dominion, with the seat of government at Ottawa. The Executive Government consists of a Governor-general, and a Privy Council of 13 members. The Legislature consists of three branches, viz., the Governor-general, 72 senators, and 181 members of the House of Commons. Each Province retains its own Local Government, viz., Lieutenant-governor, Legislative Council, and House of Assembly. (Ontario alone has no legislative council.)

3. To the Central Legislature belongs the right to deal with all matters relating to the Public Debt and Property; the regulation of trade and commerce; the raising of money by any mode or system of taxation; the borrowing of money on public credit; postal service; the census and statistics; militia, military and naval service, and defense; the fixing of and providing for the salaries and allowances of civil and other officers of the Government of Canada; construction of beacons, buoys, lighthouses, navigation and shipping, quarantine, and the establishment and maintenance of marine hospitals; sea-coast and inland fisheries; ferries between a Province and a British or foreign country, or between two provinces; currency and coinage, banking, incorporation of banks, and the issue of paper money, savings banks, bills of exchange and promissory notes, interest, legal tender, bankruptcy and insolvency; weights and measures; patents of invention and discovery; copyrights; Indians, and lands reserved for the Indians; naturalization and aliens; marriage and divorce; the criminal law, except the constitution of courts of criminal jurisdiction, but including the procedure in criminal matters; the establishment, maintenance, and management of penitentiaries; and such classes of subjects as are expressly excepted in the enumeration of the classes of subjects by the act assigned exclusively to the legislatures of the provinces.

4. To the Local Legislatures belong matters relating to the provincial government and revenue; public lands; education; reformatories and prisons; municipal institutions; trading licenses; local public works; agriculture; property and civil rights in the province; marriage; and the administration of justice; and "generally all matters of a merely local or private nature in the province."

5. Financial Arrangements.—The Dominion is made liable for the debts of all the provinces; and these provinces are held liable to the Dominion in the following ratio—interest payable at the rate of five per cent, per annum.

| Ontario and Quebec | for any debt over | $62,500,000 |

| Nova Scotia, | ditto, | 8,000,000 |

| New Brunswick, | ditto, | 7,000,000 |

The payments to these provinces from the Dominion government are as follows:—

| Province of Ontario | $80,000 | per annum. |

| Province of Quebec | 70,000 | do. |

| Province of Nova Scotia | 60,000 | do. |

| Province of New Brunswick | 50,000 | —and $63,000 ... |

... for ten years, (on account of her small debt.) Each province is also entitled to 80 cents per head of the population as per census of 1861.

6. Intercolonial Trade and Customs.—All articles of the growth, produce or manufacture of any one of the provinces are admitted free into each of the other provinces. Only one tariff of customs and excise shall prevail in all the provinces.

7. Intercolonial Railway.—The interest on a loan of £3,000,000 is guaranteed by the British Government. This loan is to be expended in the construction of a railway to connect Nova Scotia and New Brunswick with Quebec and Ontario.

8. Progress of Population in the Dominion.—The following table exhibits the progress of population in the four provinces of the Dominion.

| 1775 | 1800 | 1820 | 1861 | 1861 | 1861 | 1867 | |

| Males. | Females. | Total. | Estimate. | ||||

| Ontario | 8,000 | 50,000 | 158,000 | 725,575 | 670,516 | 1,396,091 | 1,802,000 |

| Quebec | 96,000 | 225,000 | 450,000 | 567,864 | 543,702 | 1,111,566 | 1,300,000 |

| Nova Scotia | {20,000 | 57,000 | 150,000 | 165,584 | 165,273 | 330,857 | 370,000 |

| New Brunswick | 10,000 | 75,000 | 129,948 | 123,099 | 252,017 | 296,000 | |

| Totals | 196,000 | 342,000 | 833,000 | 1,588,97 | 1,502,59 | 3,090,561 | 3,768,000 |

9. The present Political Divisions of the whole of British North America are as follows:—

| Name of Province. | Discoverer and Date. | Mode of Acquisition and Date. | Government Established. |

| Quebec. | Jacques Cartier, 1535 | Capitulation, 1759 | French, 1608; English, 1764; separ. gov'mt, 1792; united, 1840 |

| Ontario | Champlain, 1615 | Cession, 1763 | Separ. gov't, 1748; |

| Nova Scotia | {Sebastian Cabot, 1498 | Cabot's visit and treaty of 1713 | {Sep. gov't, 1784; united, 1819 |

| Cape Breton | Capitulation, 1758 | ||

| New Brunswick. | Jacques Cartier, 1535 | Treaty, 1763 | Separ. governm't, 1784 |

| Name of Province. | Discoverer and Date. | Mode of Acquisition and Date. | Government Established. |

| Prince Edward Island | Sebastian Cabot, 1498 | Treaty, 1763 | Separate gov't, 1771 |

| Newfoundland | Sir John Cabot, 1497 | Sir H. Gilbert, 1583 Utrecht treaty, 1713 | By Charles I., 1663; separate gov't, 1728 |

| Hudson Bay Territory | H. Hudson, 1619 & 1794 | Treaty, 1713 & 1763 | Charter, 1670 and license, 1821 & 1842 |

| Red River | Canada Explorers | Lord Selkirk's settlement, 1811 | Crown Colony, 186- |

| British Columbia | Sir A. Mackenzie, 1793 | Treaty, 1793 | Act of Parliament, |

| Vancouver Island | Sir F. Drake, 1759 | V'couver's visit, 1799 settled, 1848 | Charter to Hudson Bay Co. 1849 |

10. The extent, population, and capitals of these divisions of British North America are as follows:—

| Name of Provinces. | Area in Eng. sq. Miles. | Population. | Capital. | Where Situated. | Population. | |

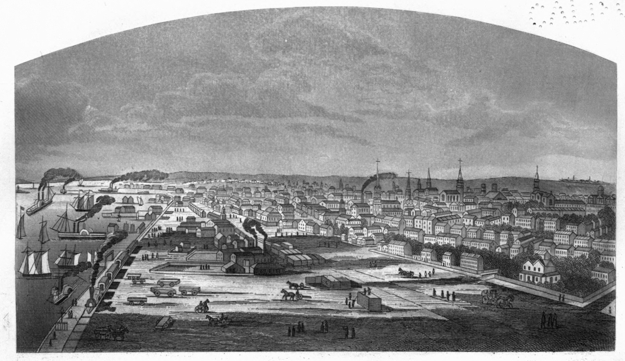

| Quebec | 210,000 | 1,111,566 | Quebec. | }Ottawa. | St Lawrence | 62,140 |

| Ontario | 150,000 | 1,396,091 | Toronto. | Lake Ontario | 44,425 | |

| Nova Scotia & C. B. | 19,650 | 330,857 | Halifax. | S. E. Coast | 26,000 | |

| New Brunswick | 27,710 | 252,047 | Fredericton. | River St. John | 7,000 | |

| Name of Provinces. | Area in Eng. sq. Miles. | Population. | Capital. | Where Situated. | Population. |

| Prince Edward Island | 2,134 | 80,857 | Charlottetown | Near centre of island | 6,700 |

| Newfoundland | 57,000 | 124,288 | St. Johns | S. E. Peninsula | 25,000 |

| Hudson Bay Territory | 2,200,000 | 175,000 | York Factory | Hayes' River | 500 |

| Red River | ... | 10,000 | Fort Garry | Assiniboine, Red River | ... |

| British Columbia | 210,500 | 8,000 | } Victoria | S. of island | 3,500 |

| Vancouver Island | 18,000 | 11,463 |

11. The general area of these divisions of British North America is as follows:—

key = A Average length in miles; B Average width in miles; C Miles of Sea-coast lines; D Area in Acres E Acres in Cultivation; F Surveyed Acres uncultivated; G Value of Farms.

| Name. | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Quebec. | }1,200 | 300 | 1,000 | 160,500,000{ | 4,804,235 | 5,575,000 | 172,000,000 |

| Ontario. | 6,051,620 | 7,304,000 | 296,000,000 | ||||

| Nova Scotia. | }330 | 100 | 1,150 | 13,534,200 | 1,028,032 | 1,000,000 | 40,000,000 |

| Cape Breton. | |||||||

| New Brunswick. | 190 | 150 | 500 | 17,600,000 | 835,108 | 2,905,000 | 32,000,000 |

key = A Average length in miles; B Average width in miles; C Miles of Sea-coast lines; D Area in Acres E Acres in Cultivation; F Surveyed Acres uncultivated; G Value of Farms.

| Name. | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Prince Edward Island. | 130 | 40 | 350 | 1,370,000 | 268,127 | 260,000 | 8,000,000 |

| Newfoundland. | 320 | 130 | 1,100 | 2,304,000 | 41,108 | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 |

| Hudson Bay Ter. | } ... | ... | 1,500 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Red River. | |||||||

| British Columbia. | 450 | 250 | 900 | 136,640,000 | 26,500 | 73,000 | 500,000 |

| Vancouver Island. | 278 | 55 | 850 | 8,320,000 | 17,000 | 63,000 | 300,000 |

12. Value of Products.—The estimated quantity and value of the products of the four provinces in the Dominion is as follows:—[A]

| Grain, viz. | Wheat, | 30,000,000 | bushels. | ||||

| " | Barley, | 8,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Oats, | 50,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Buckwheat, | 4,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Indian Corn, | 3,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Rye, | 2,000,000 | " | 97,000,000 | bushels, | valued at | $60,000,000 |

| Peas, &c., | 15,000,000 | ditto | ditto | 12,000,000 | |||

| Roots, viz. | Potatoes, | 50,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Turnips, &c. | 25,000,000 | " | 75,000,000 | ditto | ditto | 25,000,000 |

| Hay, | 2,500,000 | tons | ditto | 25,000,000 | |||

| Butter and Cheese, | 75,000,000 | lbs | ditto | 10,000,000 | |||

| Meats, viz. | Mutton, | 250,000,000 | lbs. | ||||

| " | Beef, | 200,000,000 | do. | ||||

| " | Pork, | 150,000,000 | do. | 600,000,000 | lbs. | ditto | 35,000,000 |

| Fish, | 80,000,000 | do. | ditto | 3,500,000 | |||

| Lumber, viz. | Oak, | 1,500,000 | cubic feet. | ||||

| " | Elm, | 1,500,000 | " | ||||

| " | White Pine | 25,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Red Pine, | 4,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Tamarack & Spruce, | 2,000,000 | " | ||||

| " | Miscellaneous, | 1,000,000 | " | 35,000,000 | cubic feet, | 30,000,000 | |

| Wool, | 10,000,000 | lbs. | 5,000,000 | ||||

| Miscellaneous, | 5,000,000 | ||||||

| Grand Total, | $210,500,000 |

|

Year Book of Canada for 1868, page 40. |

13. The Income, Expenditure &c., of each province in the Dominion, during the last year of their separate existence, was about as follows:—

| Items. | Quebec and Ontario. | Nova Scotia. | New Brunswick. |

| Income | $16,419,000 | 1,800,000 | 1,450,000 |

| Expenditure | 14,727,000 | 1,900,000 | 1,350,000 |

| Debt | 62,734,000 | 5,000,000 | 5,000,000 |

| Assets | 69,500,000 | 5,700,000 | 5,054,000 |

| Imports | 59,100,000 | 14,400,000 | 10,000,000 |

| Exports | 48,500,000 | 8,050,000 | 8,200,000 |

15. Recent Example of Confederation of States.—It is a striking fact that during the last few years a more general and rapid confederation of States has taken place, than had occurred during the whole of the preceding century. Not to mention the absorption of the native states in India under British rule, we have seen how rapid has been the consolidation of Italy into one kingdom. Later, there took place in the United States a memorable contest against a principle of separation of States. Within the last year or two, the fate of one noted battle led to the absorption by Prussia of a number of petty States in Germany; and now guided by an unerring instinct four large provinces of British America have confederated themselves together into one Dominion.

16. The Objects and Advantages of such a confederation may be stated in a few words: It has long been the desire of the sagacious statesmen of the Dominion to concentrate the resources and energies of the isolated provinces into a powerful and prosperous State, and thus to give free scope, on a wider and broader field, for the enterprise and talent of a young and growing people; to enable them to present a bold and united front against aggression or absorption, by an active and powerful rival; to develop internal trade and commerce; to bring into settlement and productive life large tracts of outlying territory, now a vast uninhabited forest, in the various provinces; and, as was fitting, at this period in the history of the provinces, to lay broad and deep the foundation of a new nationality, whose heritage and birthright are the priceless blessings of civil and religious freedom, as long felt and enjoyed in England and in these provinces.—A nationality whose future should witness the consolidation and growth, on this continent, of those principles of British colonial freedom which are so eminently calculated to promote internal peace and prosperity, and, under God's blessing, the enjoyment also of "life and liberty," as well as "the pursuit of happiness," among all classes of people.

PREFACE.

The business of the historian of the earlier ages of the world was to record changes in forms of government, to give accounts of long and bloody wars, and to narrate the rise or fall of dynasties and empires. From the days of Herodotus, to the middle of the last century, the world made little progress. It is true, that great empires rose one after another upon the ruins of their predecessors; but so far from there being any thing like real progress, the reverse seems to have been the case. It has remained for the present age to witness a rapid succession of important inventions and improvements, by means of which the power of man over nature has been incalculably increased, and resulting in an unparalleled progress of the human race.

But great as has been the movement in the world at large, it is on the North American continent that this has been most remarkable. The rise of the United States, from a few feeble colonies to a high rank among nations, has never ceased to attract the attention of the world; and their career has been indeed so wonderful, that the quiet but equally rapid growth and development of the British North American provinces has received comparatively little notice. It will be seen from the following pages that they have at least kept pace with their powerful southern neighbors, and that, though laboring under some disadvantages, they have in eighty years increased tenfold, not only in population but in wealth; they have attained to a point of power that more than equals that of the united colonies when they separated from the mother country. They have, by means of canals, made their great rivers and remote inland seas accessible to the shipping of Europe; they have constructed a system of railroads far surpassing those of some of the European powers; they have established an educational system which is behind none in the old or the new world; they have developed vast agricultural and inexhaustible mineral resources; they have done enough, in short, to indicate a magnificent future—enough to point to a progress which shall place the provinces, within the days of many now living, on a level with Great Britain herself, in population, in wealth, and in power. If in the next eighty years the provinces should prosper as they have in the eighty years that are past, which there seems no reason to doubt, a nation of forty millions will have arisen in the North.

To exhibit this progress is the object of the present volume. It will be seen, from the well-known names of the gentlemen who have contributed to its pages, that a high order of talent has been secured to carry out the design of the work.

CONTENTS.

| Page | |

| Physical Features of Canada | 13 |

| Agricultural History of Canada | 32 |

| Agricultural Societies in Upper Canada | 39 |

| Agricultural Productions of Canada | 52 |

| Forest Industry | 64 |

| The North-west Territory | 74 |

| The New Parliament Buildings at Ottawa | 94 |

By Henry Youle Hind, M. A., F. R. G. S., Professor of Chemistry and Geology in Trinity College, Toronto; Author of Narrative of the Canadian Exploring Expedition in North-west British America; Explorations in Labrador, and in the Country of the Montagnais and Nasquapee Indians; Editor of the British American Magazine, and of the Journal of the Board of Arts for Upper Canada.

| Travel and Transportation | 99 |

| Roads in Lower Canada | 104 |

| Roads in Upper Canada | 109 |

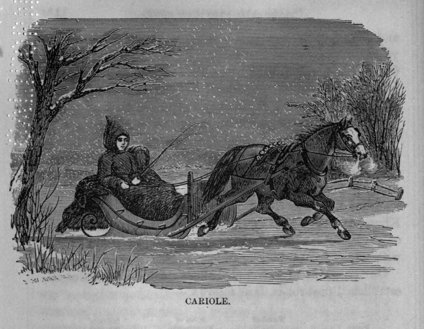

| Bridle and Winter Roads | 116 |

| Corduroy Roads | 119 |

| Common or Graded Roads | 120 |

| Turnpike and Plank Roads | 122 |

| Macadam Roads | 123 |

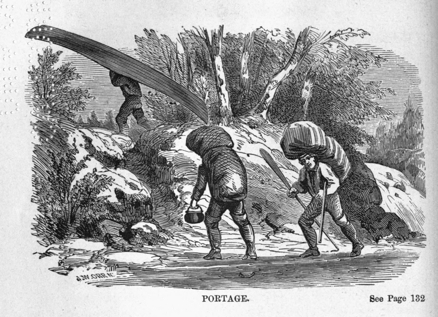

| Water Communications | 129 |

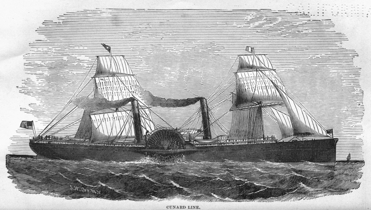

| Ocean Steamers | 141 |

| Early Navigation of the St. Lawrence | 146 |

| Railways in Canada | 187 |

| Grand Trunk Railway | 197 |

| Causes of Failure of the Grand Trunk Railway | 206 |

| Municipal Railways | 214 |

| Railway Morality | 221 |

| Great Western Railway | 229 |

| Buffalo, Brantford, and Goderich Railway | 234 |

| Grain Portage Railways | 236 |

| Intercolonial Railway | 238 |

| Railway Policy | 247 |

| Express Companies | 250 |

| Canadian Gauge | 253 |

| Horse Railways | 255 |

By Thos. C. Keefer, Civil Engineer, Author of "Philosophy of Railroads," Prize Essay on the Canals of Canada, &c.

| Victoria Bridge | 257 |

| The Electric Telegraph in Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick | 266 |

| Commerce and Trade | 268 |

| Early Trade of Canada | 268 |

| Fur Trade | 275 |

| Ship-Building and Lumber Trade | 284 |

| Produce Trade | 290 |

| Present Trade of Canada | 292 |

| The Reciprocity Treaty | 296 |

| Channels of Trade | 298 |

| Immigration | 301 |

| Free Grants of Land and Colonization | 303 |

By Henry Youle Hind, M. A., F. R. G. S., &c.

| Mineral Resources of British North America | 308 |

| Geological Structure of Canada | 310 |

| Catalogue of useful Minerals found in Canada | 313 |

| Mineral Resources of Nova Scotia | 350 |

| Mineral Resources of New Brunswick | 360 |

| Mineral Resources of Newfoundland | 363 |

| Mineral Resources of British Columbia and Vancouver Island | 365 |

| Mineral Resources of the North-west Territory | 371 |

By Charles Robb, Mining Engineer, Author of "The Metals in Canada," &c.

| Historical Sketch of Education in Upper Canada | 373 |

| Early Educational Efforts | 374 |

| Educational Legislation, 1806-1816 | 381 |

| First Establishment of Common Schools, 1816-1822 | 384 |

| Fitful Progress from 1822 to 1836 | 390 |

| Parliamentary Inquiry and its Results, 1836-1843 | 395 |

| Improvement, Change, and Progress, from 1844 to 1853 | 399 |

| Higher and Intermediate Education, &c., 1853-1861 | 401 |

| Summary of each Class of Educational Institutions | 407 |

| Public Elementary Schools receiving Legislative Aid | 409 |

| Elementary Schools not receiving Legislative Aid | 430 |

| Superior Schools receiving Legislative Aid | 431 |

| Superior Schools not receiving Public Aid | 433 |

| Professional Schools | 435 |

| Universities—Supplementary Elementary Educational Agencies | 467 |

| Other Supplementary Educational Agencies | 468 |

| Additional Supplementary Aids to Education | 476 |

| Educational Endowments for Upper Canada | 477 |

| Historical Sketch of Education in Lower Canada | 485 |

| Early Educational Efforts in Lower Canada, 1632-1759 | 485 |

| State of Education from the Conquest, 1759, until 1800 | 488 |

| Unfulfilled Promises and Failures, 1801-1818 | 491 |

| Common School Legislation, 1819-1835 | 495 |

| Final Educational Measures of the Lower Canada Legislature | 499 |

| A New Foundation Laid—First Steps onward, 1841-1855 | 503 |

| Normal Schools—Renewed Activity and Progress, 1856-1862 | 506 |

| Universities | 508 |

| Classical and Industrial Colleges | 523 |

| Academies for Boys and Girls | 530 |

| Normal Schools—Professional or Special Schools | 532 |

| Model, Elementary, and Private Schools, &c. | 533 |

| Educational Communities, Societies, and School Organizations | 534 |

| Supplementary Elementary Educational Agencies | 538, 539 |

| Educational Statistics and Parliamentary Grants | 540, 541 |

By J. George Hodgins LL. B., F. R. G. S., Author of the "Geography and History of British North America," "Lovell's General Geography," &c.

| The Progress of New Brunswick, with a Brief View of its Resources, Natural and Industrial | 542 |

| Sketch of the Early History of New Brunswick | 542 |

| Descriptive and Statistical Account | 552 |

| The Forest | 561 |

| The Fisheries | 574 |

| Geology of the Province | 585 |

| Mines, Minerals and Quarries | 590 |

| Ship-Building | 597 |

| Mills and Manufactures | 599 |

| Internal Communication | 600 |

| Railways | 604 |

| Electric Telegraph Lines | 605 |

| Commerce and Navigation | 606 |

| Form of Government | 609 |

| Judicial Institutions | 610 |

| Tenure of Land and Law of Inheritance | 612 |

| Religious Worship and Means of Education | 613 |

| Education | 614 |

| Civil List, Revenue, and Expenditures | 617 |

| Banks for Savings; Value of Coins; Rate of Interest | 618 |

| General Information for Immigrants | 619 |

| Fruits and Vegetables | 623 |

| Wild Beasts and Game—Aborigines | 624 |

| Natural Resources | 626 |

| Progress of Population—Description of Counties | 627 |

By M. H. Perley, Esq., British Commissioner for the North American Fisheries, under the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States.

| The Progress of Nova Scotia, with a Brief View of its Resources, Natural and Industrial | 654 |

| Discovery and Early Fortunes of Nova Scotia | 654 |

| Situation—Extent—Natural Features—Climate, &c. | 660 |

| Natural Resources | 666 |

| Population, Statistics, &c. | 677 |

| Industrial Resources | 684 |

| Commercial Industry | 690 |

| Public Works, Revenue, Crown Lands, &c. | 695 |

| Education and Educational Institutions | 704 |

| Ecclesiastical Condition of the Province | 711 |

| Political State of the Province | 714 |

| General Civilization, Social Progress, Literature, &c. | 719 |

| Sable Island | 726 |

| Prince Edward Island | 728 |

| Situation, Extent, General Features, Early History, &c. | 728 |

| Natural Resources, Climate, &c. | 734 |

| Industrial Resources | 736 |

| Population, Education, Civil Institutions, &c. | 738 |

| Newfoundland | 744 |

| Situation, Discovery, and Early History | 744 |

| Topography, Natural Resources, Climate, &c. | 747 |

| Industrial Resources | 751 |

| Population, Civil and Religious Institutions | 756 |

By Rev. William Murray.

THE PHYSICAL FEATURES OF CANADA.

Montreal, the commercial capital of Canada, is situated at an equal distance from the extreme western and eastern boundaries of the province. The source of Pigeon River, (long. 90° 50′,) one of the foaming tributaries of Lake Superior, forty-six miles in a straight line from its mouth, and 1,653 feet above the sea, is the point where its western limits touch the boundary between the United States and British America. Blanc Sablon harbor, (long. 57° 50′,) in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and close to the western extremity of the Straits of Belle Isle, marks the eastern limits of Canada, touching Labrador, a dreary waste under the jurisdiction of Newfoundland. Draw a line through the dividing ridge which separates the waters flowing into Hudson's Bay from those tributary to the St. Lawrence, and the ill-defined and almost wholly unknown northern limits of the Province are roughly represented. The boundary line between Canada and the United States follows the course of Pigeon River, runs north of Isle Royale, strikes through the center of Lake Superior, the St. Mary's River, Lake Huron, the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River, Lake Erie, the Niagara River, Lake Ontario, and the St. Lawrence as far down as the intersection of the 45th parallel of latitude. It follows this parallel to near the head waters of the Connecticut River, when, striking north-east, it pursues an undulating course roughly parallel to the St. Lawrence, and from thirty to one hundred miles distant from it, until it reaches the north entrance of the Bay of Chaleurs in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The States of the American Union which abut on this long and sinuous frontier, are Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and the British Province of New Brunswick.

The vast tract of country called the Province of Canada, has an area of about 340,000 square miles, 140,000 belonging to Upper Canada, and 200,000 to the lower division of the province. It lies wholly within the valley of the St. Lawrence, in which are included the most extensive and the grandest system of fresh water lakes in the world.

The bottom of Lake Superior is 600 feet below the level of the ocean, its mean surface is exactly 600 feet above it. With a length of 300 miles and a breadth of 140 miles, it comprises a water area of 32,000 square miles, and supposing its mean depth to be 600 feet, it contains 4,000 cubic miles of water. It is the grand head of the St. Lawrence, receiving the waters of many tributaries, and discharging them into Lake Huron by the St. Mary's River, with a fall of nearly 20 feet in half a mile, to overcome which, the most magnificent locks in the world have been constructed on the United States side, thus forming, with the Welland and the St. Lawrence canals, an uninterrupted communication with the sea, and enabling large vessels from any part of the world to penetrate one-third across the continent of America in its broadest part, or about 2,000 miles from its ocean boundary.

Lake Huron, the next fresh water sea in succession, has an area of 21,000 square miles, and, like its great feeder, Lake Superior, it is very deep, 1,000 feet in some places having been measured. The great Manitoulin Island, (1,500 square miles in area,) with others belonging to the same chain, divide the lake into two portions, the northern part being called Georgian Bay. It receives numerous important tributaries on the north side, among which French River is the most interesting, in consequence of its being on the line of a proposed canal communication between the Ottawa and Lake Huron. The distance between Montreal and the mouth of French River is 430 miles, and of this distance 352 are naturally a good navigation; of the remaining 78 miles it would be necessary to canal 29 miles in order to complete the communication for steam vessels. These data are the result of careful governmental surveys, and are calculated for vessels of one thousand tons burthen. The cost of establishing this important communication is estimated at $12,057,680. The distance between Chicago and Montreal by the St. Lawrence is 1,348 miles, by the Ottawa and Huron Canal route 1,005 miles.

Lake St. Clair forms the connecting link between Lake Huron and Lake Erie, another magnificent sea of fresh water, 265 miles long and 50 broad on the average, with a depth of 120 feet. Its shores, particularly on the United States side, are the seats of numerous populous cities; its waves on the north shore wash the garden of Canada—the fertile western peninsula. The last of this great and magnificent chain is Lake Ontario, separated from Lake Erie by the Niagara River, in whose short and tumultuous course occurs the most stupendous cataract on the face of the globe. Before reaching Niagara Falls the river descends about 50 feet in less than a mile, over limestone rocks, and then plunges 165 feet perpendicularly. For seven miles more the torrent rushes through a narrow gorge, varying from 200 to 400 yards in width and 300 feet deep. It then emerges into a flat, open country, at Queenstown, and after a further flow of about twelve miles, glides peacefully into Lake Ontario.

Lake Ontario is 180 miles long, 50 broad, 600 feet deep, and has an area of 6,300 square miles; it discharges its waters, together with those of the upper lakes, by the River St. Lawrence into the gulf of the same name. A few miles above Montreal, the Ottawa River comes in from the north, draining an area of 80,000 square miles. Below Montreal the St. Maurice debouches into the St. Lawrence at Three Rivers, drawing contributions from 22,000 square miles of timbered country. At Quebec the St. Lawrence is 1,314 yards wide, but the basin below the city is two miles across, and three and three-quarters long. From this point the vast river goes on increasing in size as it swells onward toward the gulf, receiving numerous large tributaries, among which is the famous Saguenay, 250 feet deep where it joins the St. Lawrence, and 1,000 feet deep some distance above the point of junction. Below Quebec the St. Lawrence is not frozen over, but the force of the tides incessantly detaches ice from the shores, and such immense masses are kept in continual agitation by the flux and reflux, that navigation is totally impracticable during part of the winter season. Vessels from Europe pass up the great system of canals which render the St. Lawrence navigable for 2,030 miles, and land their passengers at Chicago without transshipment.

THE HORSE SHOE FALL, NIAGARA.—WITH THE TOWER.

The table on the following page shows a profile of this ship route from Anticosti, in the Estuary of the St. Lawrence, to Superior City:

key = A Distance from Anticosti in miles; B Elevation above the Sea level; C Number of Locks; D Length of Locks in feet; E Breadth of Locks in feet; F Total Lockage in feet.

| Names. | A | B | C | D | E | F |

| Anticosti | ||||||

| Quebec | 410 | |||||

| Montreal | 590 | 14 | ||||

| Lachine Canal | 598½ | 14-58 | 5 | 200 | 45 | 44¾ |

| Beauharnois Canal | 614 | 58.5-141.3 | 9 | 200 | 45 | 82½ |

| Cornwall Canal | 662½ | 142.6-185.6 | 7 | 200 | 45 | 43 |

| Farren's Point Canal. | 673½ | 190.5-195 | 1 | 200 | 45 | 4 |

| Rapid Flat Canal | 688 | 195.3-207 | 2 | ... | ... | 12 |

| Pt. Iroquois Canal | 699½ | 207-213 | 1 | ... | ... | 6 |

| Galops Canal | 714½ | 213-225 | 2 | ... | ... | 8 |

| Lake Ontario | 766 | 234 | ||||

| Welland Canal | 1016 | 234-564 | 27 | 150 | 26½ | 330 |

| Lake Erie | 1041 | 564 | ||||

| Detroit River | 1280 | 564 | ||||

| Lake St. Clair | ||||||

| River St. Clair | ||||||

| Lake Huron | 1355 | 573 | ||||

| River Ste. Marie | 1580 | 573-582.5 | ||||

| Sault Ste. Marie Canal | 1650 | 582.5-600 | 2 | 550 | 75 | 17½ |

| Lake Superior | 1650 | 600 | ||||

| Fort William | 1910 | |||||

| Superior City | 2030 |

The entire area of the great lakes is about 91,000 square miles. They are remarkable for the purity of their waters, which do not contain more than eight grains of solid matter to the gallon of 70,000 grains. The variations to which their level is subjected are common to all, and may be generally stated to be as follows:

1. The mean minimum level is attained in January or February.

2. The mean maximum level is in June.

3. The mean annual variation is twenty-eight inches.

4. The maximum variation in twelve years has been four feet and six inches.

5. There is no periodicity observable in the variations of their levels, and there is no flux and reflux dependent upon lunar influence.

The St. Lawrence carries past the city of Montreal 50,000,000 cubic feet of water in a minute, and in the course of one year bears 143,000,000 tons of solid materials held in solution, to the sea. All the phenomena of a mighty river may here be witnessed on a stupendous scale, its irresistible ice masses, crushing and grinding one another in the depth of winter, its wide-spreading and devastating floods in spring, its swelling volume stealing on with irresistible power in summer, broken here and there by tumultuous and surging rapids or by swift and treacherous currents, or by vast and inexhaustible lakes. As it approaches the ocean it rolls on between iron-bound coasts, bearing the tributary waters of a region equal to half Europe in area, and subject to a climate which vainly endeavors to hold it frost-bound for fully one-third of the year. The whole valley of the St. Lawrence is a magnificent example of the power of water in motion, and the great lakes themselves are splendid illustrations of the "dependence of the geographical features of a country upon its geological structure."

The following table shows the relative magnitude of the great lakes of the St. Lawrence valley:

| Names of Lakes. | Area in Square Miles. | Elevation above the Sea | Mean Depth. |

| Lake Superior | 32,000 | 600 | 1,000 |

| Green Bay | 2,000 | 578 | 500 |

| Lake Michigan | 22,400 | 578 | 1,000 |

| Lake Huron | 19,200 | 578 | 1,000 |

| Lake St. Clair | 360 | 570 | 120 |

| Lake Erie | 9,600 | 565 | 84 |

| Lake Ontario | 6,300 | 232 | 600 |

| Total area, | 91,860 |

The greatest known depth of Lake Ontario is 780 feet; in Lake Superior, however, a line 1,200 feet long has, in some parts, failed in reaching the bottom.