* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Isles of Adventure

Date of first publication: 1931

Author: Beatrice Grimshaw (1870-1953)

Date first posted: Feb. 20, 2018

Date last updated: Feb. 20, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180230

This ebook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

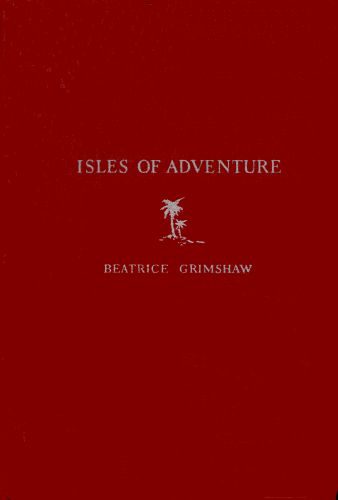

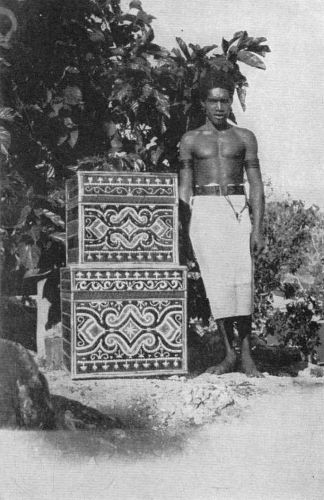

THE ART OF THE PAPUAN HEAD-HUNTERS

ISLES OF ADVENTURE

From Java to New Caledonia

but Principally Papua

BY

BEATRICE GRIMSHAW

With Illustrations

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1931

COPYRIGHT, 1931, BY BEATRICE ETHEL GRIMSHAW

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO REPRODUCE

THIS BOOK OR PARTS THEREOF IN ANY FORM

The Riverside Press

CAMBRIDGE • MASSACHUSETTS

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

CONTENTS

| I. | A Dream Come True | 1 |

| II. | The Head-Hunters of the Sepik | 27 |

| III. | Good Times in Torres Straits | 72 |

| IV. | Head-Hunters of Lake Murray | 98 |

| V. | Sorcery and Spiritism in Papua | 135 |

| VI. | The Sea Villages of Humboldt’s Bay | 146 |

| VII. | Treasures and Secrets of Papua | 161 |

| VIII. | Cannibalism | 187 |

| IX. | Dream Houses | 197 |

| X. | Strange Things in the Solomons | 208 |

| XI. | Boro Budur | 226 |

| XII. | New Caledonia, Land of the Lost | 237 |

| XIII. | The Island of Pines | 261 |

| XIV. | ‘Nightmare Island’ and ‘Island of My Own’ | 277 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| The Art of the Papuan Head-Hunters | Frontispiece |

| A Corner of the Lounge in the Author’s House at Port Moresby | 10 |

| Wild Sugar-Cane, Sepik River | 30 |

| Wild Natives Looking out of the Bush as the Boat Passes | 30 |

| Skulls with Clay Portrait Masks Attached, Sepik River | 42 |

| Carvings, Sepik River | 42 |

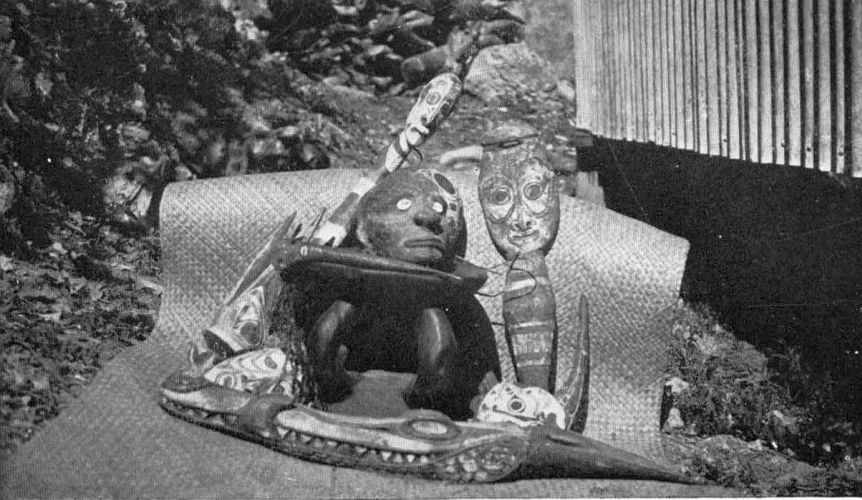

| Scar Tattooing, Sepik River | 50 |

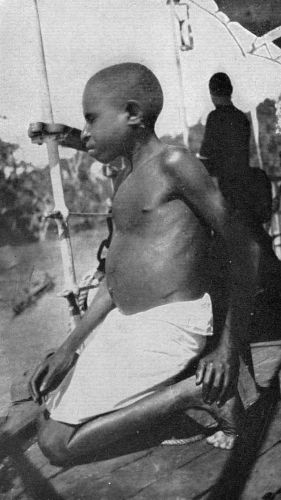

| Rescued Boy on the Launch | 50 |

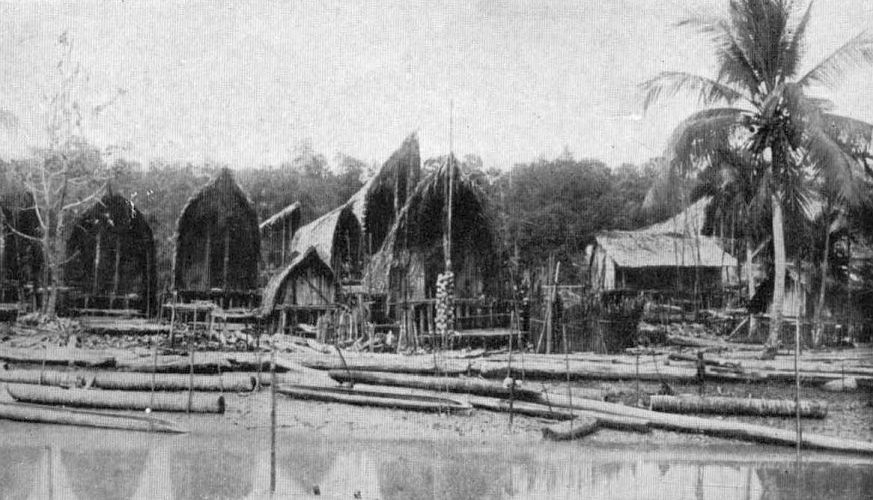

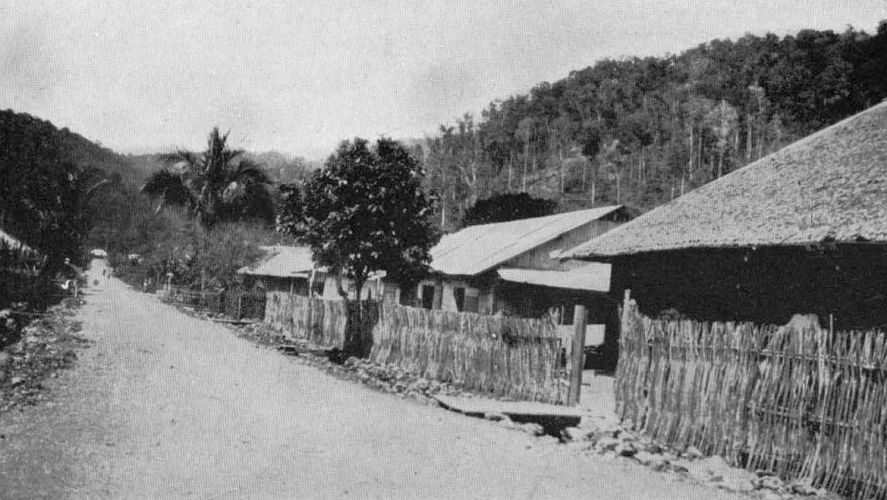

| Native Village, Western River, Papua | 72 |

| Men’s House, Western Papua | 72 |

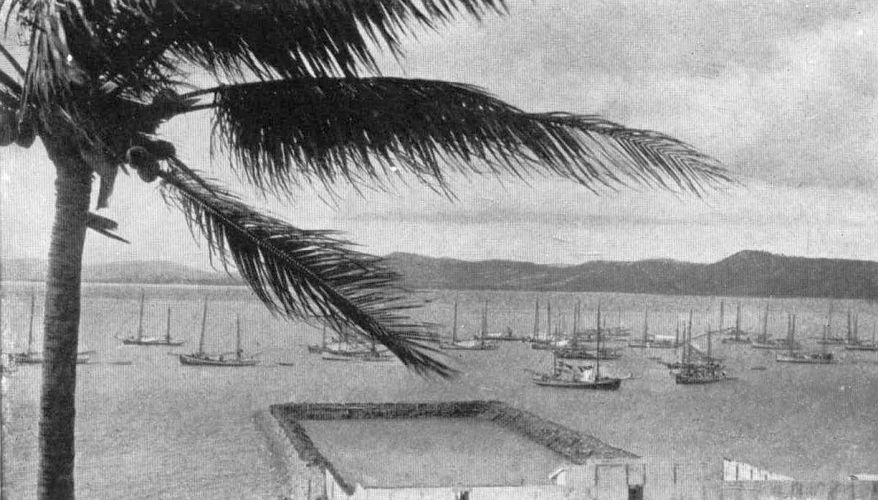

| Thursday Island | 82 |

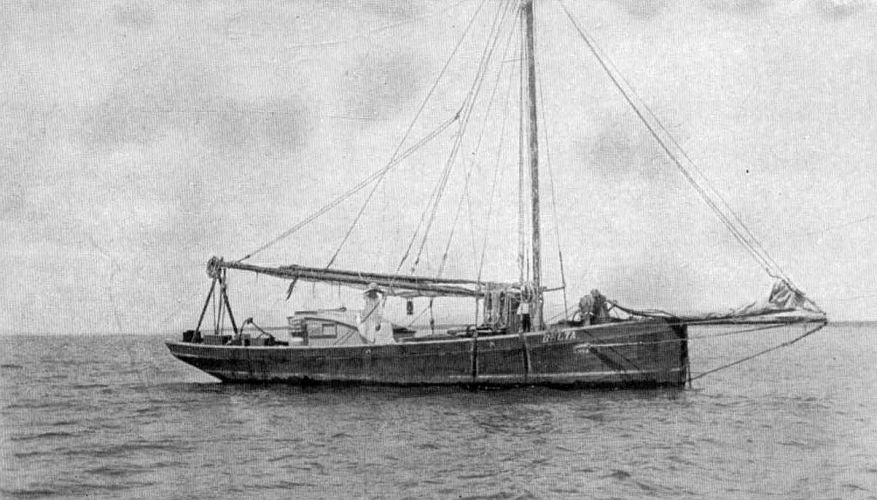

| Author Returning to Papua from Australia | 82 |

| Scarlet-Flowering Poinciana, Daru | 92 |

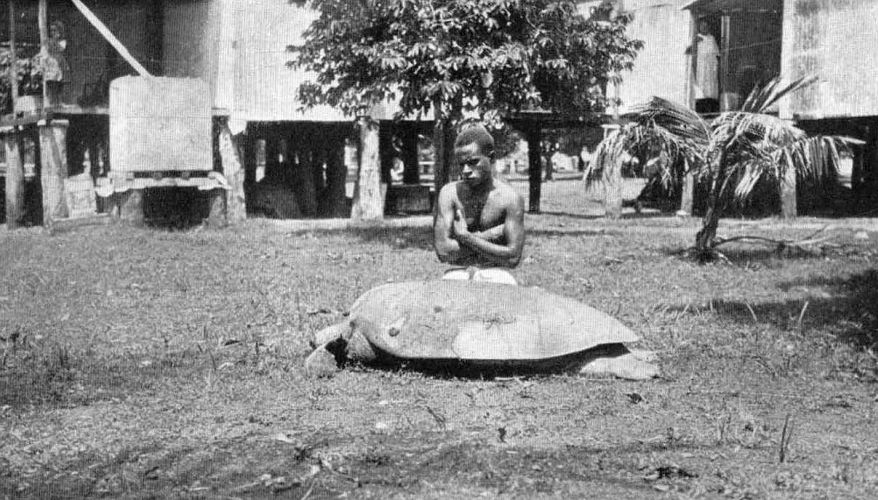

| Turtle For The Feast, Daru | 92 |

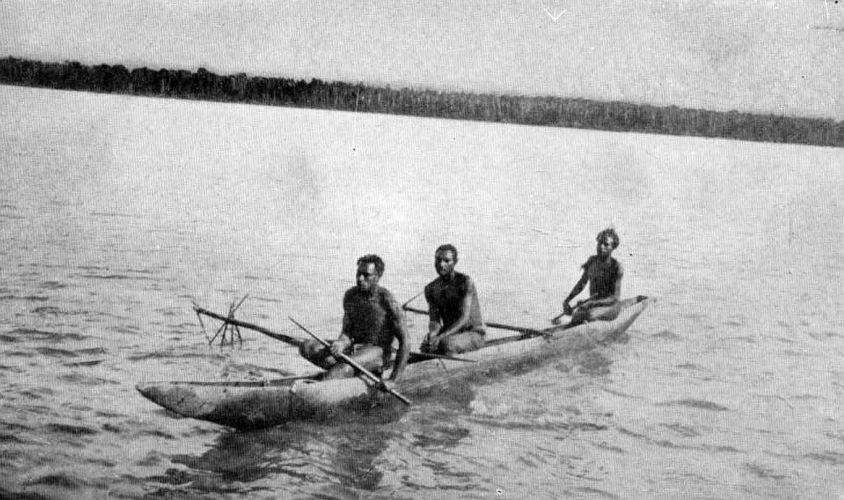

| Natives of the Lower Fly River | 114 |

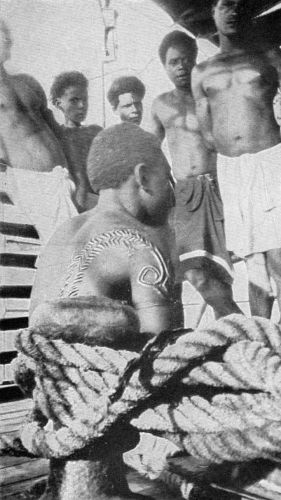

| A Fine Type of Head-Hunter, Lake Murray | 114 |

| Women Coming in from Refuge Island, Lake Murray | 122 |

| Leaving a Village, Lake Murray | 122 |

| Native Chief, Humboldt’s Bay | 148 |

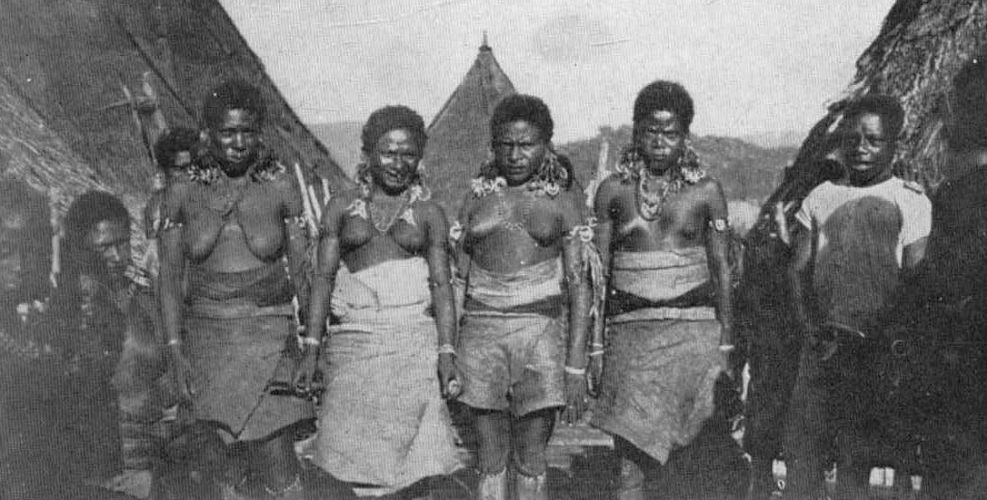

| Girls, Humboldt’s Bay | 148 |

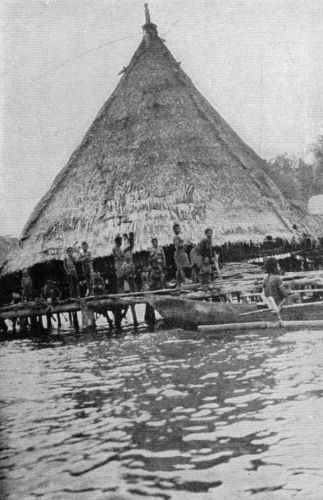

| Pyramidal Sea House, Humboldt’s Bay | 152 |

| Shellwork by Dutch New Guinea Natives | 152 |

| Settlement of Humboldt’s Bay | 158 |

| Natives of Humboldt’s Bay Staging a Friendly Symbolical Reception | 158 |

| The Author’s Former Home on Sariba Island | 206 |

| Rona Falls, Port Moresby, from the Author’s Cottage | 206 |

| Old Gaols, Bourail, New Caledonia | 248 |

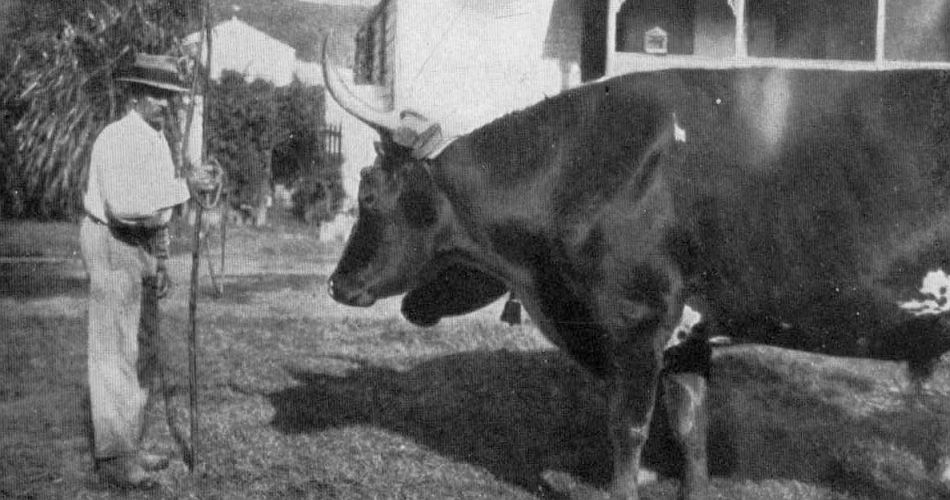

| Old Libéré with Bullock-Team | 248 |

| Sea-Wall, Isle of Pines, New Caledonia | 262 |

| Ruined Gardens, Isle of Pines | 262 |

ISLES OF ADVENTURE

ISLES OF ADVENTURE

∵

It was the dining-room of a set of rooms in Number 6, Fitzgibbon Street, Dublin. It was in the nineties, and a summer day.

From the back window you could see (perhaps you still can) a bit of high white wall, outlined against a sky that occasionally was blue. On that summer day a dream, from the white wall and the blue sky, took birth; a dream of things longed for, never seen. One could almost see those things. One could almost fancy, behind that un-European-looking scrap of shining wall, against the blue that might have been Mediterranean, or Pacific, the trembling of tall palms. . . .

That was the beginning.

There are white walls about me. White cool pillars, grey cool floor. On all four sides of the forty-foot room, palms, pawpaws, sea look in, for the shutters and windows are only closed in storm. There is a sky of dry pale blue beyond the palms. This is my home at the end of the world, and the end of the dream, thirty years after.

Has it been good? It has been very good.

In the nineties, one had a Career. Careers have died; they need explaining. One began, as a rule, by leaving a perfectly good home, where the manners and the food were better than one found anywhere else, but where life was infested by givers and takers of loathsome parties, and nobody was really Serious.

Some careerists learned typing and shorthand, and wrote letters in men’s offices; a daring thing to do, but when the daring began to pall, not very profitable. Some became lecturers in ladies’ colleges; upon these, about the thirties, a strange blight seemed to fall, so that they became desiccated, nervous, and inclined to giggle miserably in the presence of pupils’ fathers. Afterwards they got religion, or became cultured atheists.

Some took up journalism, and told the listening world, with variations, that a pretty BUT quiet wedding had taken place, and that Mrs. Willibald received her guests in a chaudron velvet double skirt. . . . One pictured her doing it—fielding, as it were. . . .

As for me, being very young and rather brazen and full of the ‘beans’ that go with a good muscular system, I started to teach other and older people their jobs. Life being so short (one argued), why waste it in learning? One had had enough of that at the ‘London.’ One would carefully refrain from ever learning again. But as for teaching—teaching that had nothing to do with colleges and universities—that was fun.

I don’t know how one got away with it; but somehow one did. A sporting paper kindly endured me as sub-editor; there were reporters whom, with awful impudence, I instructed in their duties. There was afterwards a society journal, which I edited mostly by main force, once locking the door against rivals. Over the way they were dynamiting each other on daily-paper staffs, so locking the door seemed an absolute gesture of courtesy, by comparison. The staff of the society paper did not tear me in pieces, but that was not for want of good will towards the task. The proprietors sat back, saw their bank account fatten, and laughed.

Sometimes I edited both papers, taking both editorial rooms, and feeling quite seven feet high. The absent editor of the sporting journal, a fine athlete and fighter (he needed to be), had once left the paper to me just after the appearance of a stinging article about football amateur-professionals, written by himself. I was sitting at his desk, full of glory, with my Sunday frock on (we had Sunday frocks then), and my hair painstakingly done in the latest fashion, when a noise as of some one, strangely, throwing sacks of coal upstairs instead of down, finally resolved itself into a scuffle in the outer office, and the violent entrance of a huge young man armed with a blackthorn club. The back of the desk was high, and he did not see me.

‘I want,’ he shouted, ‘to see the villain who edits this paper! I want to talk to him!’ He gave the blackthorn a whirl. ‘Where is the hound?’ he added.

I came out, spreading my six yards of skirt. ‘I am the editor,’ I told him proudly. ‘What can I have the pleasure of doing for you?’

‘I—I——’ he answered helplessly. ‘You—you—please—I——’

He backed himself out. Female editors! Was the sky going to fall? Who had ever heard——

I thought the outer office would never stop laughing.

Journalism in Dublin, in those days, was a gay scramble, with little of the seriousness that informed the papers across the Irish Sea. One knew plenty of celebrities, and found them, as a rule, less interesting than the irresponsible folk who were not celebrated, and never would be. One dipped into society and, lest it should stick to one’s skirts and hold one fast, fled quickly. The bicycle had not long been discovered; every careerist had one, and some few even ventured to ride in bloomers, more or less camouflaged as skirts.

‘No wonder the decent poor is wanting for bread,’ said a beggarwoman, strangely, as she saw me pass thus daringly dressed. I have wondered ever since just what she meant. It may have been merely a way of saying with more or less politeness that I was enough, in my audacity and wickedness, to call down a curse on the whole country.

The careerist of that day, in Dublin, was daring—but within iron limits. Much was made and much said of latchkeys. But one lived with respectable widows, and the chaperon was never absent, even from the bicycle clubs famous for hard riding. Sometimes a racing husband mounted his wife on a tandem bicycle, to run down offenders more certainly. ‘Fast’ was a word at which every one trembled, unless it applied to the speed of your wheels.

‘You should not belong to that dreadful club,’ fumed one of the old ladies who took a single paying guest. ‘I hear they have a clubhouse miles out in the country, and come home from it in the middle of the night.’

‘That’s quite true,’ I told her eagerly, ‘but you haven’t heard it all——’

‘No?’ she said, licking her lips.

‘Certainly not. You don’t understand. It’s true about the club, and the fourteen miles out, but we never come home alone—never!’

‘So I——’

‘When the evening’s over, and we’ve all danced enough, it’s often quite late, perhaps nearly eleven. The captain of the club calls us all out onto the avenue, and starts us, and he sees that EVERY girl has a man to see her ALL the way home, no matter how out of the way it may be. And the men are dears, they NEVER leave you till they see you right to your door, and they just love to do it. They couldn’t leave you because we all go different ways, and the roads are very lonely at that time of night, and very, very dark. So each stays with his girl all the time, and so we are perfectly safe.’

The old lady looked at me. I thought she stared oddly; once or twice she opened and shut her mouth like a frog. She seemed to be about to say something. But all that came out was, ‘Well, well, my dear! Well, well!’—which was at least not unsatisfactory. And she never remonstrated again.

Dear Irish boys, so elderly now, so young and hot-blooded then—how few of us, your girl companions, realized your true fineness and chivalry! Could it all have happened in any other land in the world, one wonders? Could it ever happen anywhere now? Thirty or forty youths and girls, many of them more or less in love with one another—black-dark and deserted roads, and fourteen miles to cover late at night, in widely separated twos and twos—and ‘they never left us, so we were quite safe. . .’

The wanderer’s ‘Salue’ to you—those of you who live. Some elderly doctor, some tired Indian Civilian, some parson growing old, some engineer getting a little past his bridge-making at the back of beyond, may read, and remember. I will wager that your sons are different, in this different day.

There never was a scandal in that club. There certainly were some miracles, not labelled as such.

Propriety took strange forms. Being more than ever ‘full of beans,’ and wanting to enjoy what the present day would call a real thrill, I went out after a world’s cycling record, the women’s twenty-four hours road, and got it, by five miles. But before that came about, a difficulty arose. The previous holder had been a married woman; her husband, naturally, ‘paced’ and accompanied her throughout, which gave her a considerable advantage. But I was single. It was seven times impossible for me to ride through the proper twelve hours and the improper twelve hours alike, of a twenty-four, accompanied by any man. Every one knew that, of course. I had to try, unpaced.

I left my rooms at eleven o’clock at night; rode through the dark alone, with provisions packed on the bicycle, and an ankle-length skirt encumbering my limbs. Checks were necessary for world records. I got my first on leaving; my next, far out on the central plains of Ireland, at 5 A.M., from a police barracks. From eight o’clock on through the ‘proper’ hours I was paced from time to time by various enthusiastic friends. The newspapers of the day ‘featured’ the performance, and maintained discreet silence as to pacers, except where they ventured to say that I had been paced ‘through the latter part.’

The old ladies, who suffered much in those days, were pained by the idea of the solitary ride from eleven till five, but not shocked. It was considered that a difficult question had been ingeniously solved. . . .

‘Instead of which, they go about,’ to-day, from England to America, Australia and India, in flying-machines, with what would once have been called ‘male escort.’. . . The old ladies would have died, in congealed heaps!

In the midst of wild journalism, varied by wanderings through most parts of Ireland, and punctuated, for the good of one’s manners and soul, by excursions back into the ordered world one had left, the dream persisted. I wanted to go to the South Sea Islands.

Many people have, and have had, the same desire. Not many, one thinks, have been able to realize it so fully, and enjoy the realization so completely, as I have.

This is why I am telling the tale, including details that (for some reason hard to understand) seem always to be omitted from other accounts.

To be a traveller, an ‘explorer,’ either in the old or the modern sense, is the vague ambition of quite a number of youths and girls. It is not until one is confronted with the towering cost of long-distance steamer fares, the big incidental expenses, that the question arises—how is it to be paid for?

I was in the plight of a good many others, whose people were just discovering in that nineteenth-century-end, that the ‘top drawers’ would not, and did not, hold them any longer, and that it mattered not the least bit in the world during how many or how few centuries they had inhabited those top drawers, now that harder conditions and a changing world had shaken them out. It was no question of wish and have any longer. What you wanted, beyond the ordinary necessaries of life, you must get for yourself.

I was in London by this time, having rather a good time on the whole among the newspapers, though I do not know, and I am sure they did not know, any particular reason why I should, except natural greed allied to North of Ireland persistence. But no newspaper offered, or consented, to pay my passage round the world. When I inquired about prices on my own account, the companies’ answers were staggering.

I thought for a while, and then had some neat cards engraved—not printed—with my name, and the intriguing (at that time) addition ‘Advertising Expert.’ (Incidentally, I have never respected the word ‘expert’ since.) With these and my very best frock, quite unsuitable to business, but very suitable for bluff, I penetrated the shipping offices, and suggested that my way round the world should be paid, provided I guaranteed plenty of newspaper advertisement. I did not adopt shock tactics, but tried to remember that the heads of big businesses were gentlemen, and should be approached as such.

It seems impossible, but it is true that the very biggest and proudest shipping companies agreeably consented to frank a totally unknown young woman all over the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, with the Mediterranean and the Channel thrown in, if I could assure them of certain newspaper commissions.

I procured the latter by the simple expedient of showing work, not very different from any one else’s work, and offering to pay my own way round the world if they could come to terms. They did, and, provided with their letters, I collected my free passes, took as many introductions as I could get, and started, the newspaper payments furnishing expense money.

A CORNER OF THE LOUNGE IN THE AUTHOR’S HOUSE AT PORT MORESBY

I do not think for a minute that this sort of thing could be done in 1929; the world, before the War—long before—was simpler. But I hope that none of the newspapers had reason to regret their kindness.

It would, of course, have been possible to travel, somehow or other, third-class, working one’s way as stewardess, or taking the most thankless and tiresome job in the world, that of companion. That, however, would not have been fun, and what is a trip round the world if it cannot be fun all through?—especially when you are young, and hungry for all the delights of all the earth.

As things were, I travelled like what I certainly was not, a millionaire, in the best cabins of the best liners, with kindness and consideration everywhere. And I enjoyed every minute of it from beginning to end. And that six months round the world expanded, like the magic tent in the Arabian Nights, until in the end it covered all my life.

So the dream came true. Incidentally, I wrote eighteen books about it.

I wonder now sometimes who inhabits the ground floor at 6, Fitzgibbon Street, and if he, or she, ever looks out at the bit of white wall against the bit of blue sky that changed a life for some one else—thirty years ago.

There are people—an increasing number in these days—whom the tropics call; to whom life within sight of palm trees, among blue seas, is the only life worth living. It used to be supposed, quite as a matter of course, that these were born wastrels. The natural place for all industrious, sensible, and consequently successful, people was at home. Certain exceptions were allowed. You might, without loss of character, go ‘ranching’ in various colonies. You might follow the mode of the year that prescribed from time to time such adventures as orange-growing in Florida, lemon-growing in California, gentleman-farming in Calgary or thereabouts. There is always a fashion in these things, and it has seldom much relation to solid facts. The orange-growers of Rhodesia, in recent years, could dot those i’s and cross those t’s.

You might, of course, enter the Indian Civil, with glory and approval. But you were not expected to like it too much. It was correct to rule the ‘natives’ from a height, treat them justly but firmly, do the right things socially, and go Home as much and as often as you could. To say that you liked India because it was India, and would prefer to spend your entire life there instead of a grudged few years, was to start instant speculation as to how many ‘annas in the rupee’ you had, and set your neighbours at a dinner party furtively scrutinizing your nails. . .

As for the Pacific Islands, they were, and still are, to most people, a section of the world inhabited by beachcombers, blackbirders, bad lots, missionaries who are equally sanctimonious and depraved, and native beauties invariably and delightfully immoral.

That there is, in the South Seas, a big world of perfectly respectable residents—officials, planters, business folk, much like their counterparts elsewhere, missionaries who are no more hypocritical and depraved than your own homely parson—seems incredible to stay-at-home people. It is, however, true, and it is also true that a great many of these live in the Islands, even the groups subject to fever and not innocent of cannibals—because they like the life.

It is not—a hundred times not—only the waster who appreciates the South Seas. He does not appreciate them as a rule. He is there because his people have thrown him out, and he drinks too much ever to have a chance of making his way home again or keeping a decent job. He has little eye for the beauty and wonder of earth’s loveliest region—he is, in himself, the worst blot upon it; and, if it please you, we will now forget all about him, since he has already had much more than his share of literary notice.

What is the fascination of the South Seas, which all men know and most long to taste?

It is a heady brew compounded of different ingredients. One is the vivid and striking scenery, coloured like the gems on the gates of the Heavenly City, never touched by winter or by cold, seldom dimmed by storm. Forever it is warm, green, flowery in the Islands; almost forever seas and skies are blue. There is an illusion of eternity about this age-long summer; in a world of death and change it seems to offer one thing at least that does not change and does not die.

Another ingredient is the exquisite remoteness of it all, even in these days of swift steamers and swiftest flying-machines. Without doubt, the aeroplane, one day, will rob it of this charm. But that day has not yet come; the plane means little to the Island world, which is still far removed from ‘the fever and the fret,’ from the places where ‘men sit and hear each other moan.’ There is leisure in the Islands; time, between hours of work, to think and dream. There, as almost nowhere else in the world, the lost art of conversation survives. Friends, as their ancestors did, can spend long evenings or afternoons happily talking, and satisfied with the entertainment of their own tongues. . . .

I know an island where the trading community, when it feels the need of rest, agrees to shut up shop and holiday together for days at a time. Nobody loses and every one is the gainer by a little bit more enjoyment, another slice of happiness, filched from the grudging hands of Time.

From Tahiti to the Dampiers, and from the Kermadecs to Diamond Head, the natives of the Pacific interest and charm all those who know them. Enough has been written, over and over, about the men and women of Fiji, Samoa, Tahiti, Tonga, and other Eastern and Mid-Pacific groups. But the Solomons, New Hebrides, above all New Guinea, have their own fierce attractions, and not the least of these are the natives—stronger, ruder, more primitive than the Eastern folk; far more mysterious, deeply more intriguing. I shall have more to say of that later on.

Above and beyond all, there is a certain holiday feeling in the world of the Islands; a spirit of light-heartedness, that has died out from the harsher and more crowded lands. This is not to say that we are a world of idlers. As much sheer hard work is done in the Pacific as anywhere else. But hours are more elastic, pressure of time less unyielding. Our world moves to the slow beat of the monthly, weekly, or six-weekly steamer, rather than to the unbroken rush of a speeded-up, motorized day. There are curious discrepancies. The cook in my own home comes from a district so recently cannibal that one may be quite sure he has, at all events, roasted human flesh in his time; the ‘parlour-maid,’ a huge Western warrior, firmly believes that ‘God bites him’ when he sleeps (i.e., he is attacked by unfriendly spirits). Both handle electric house-fittings with the utmost nonchalance, and another, of much the same type, drives and can repair a motor car.

Even though the Stone Age and the Aeroplane Age jostle each other after this fashion, leisure and peace, those precious things, remain. And there is always the open door into ‘outback,’ that wonderland of which I have written much, and have yet more to write.

Last, and perhaps most important, is the chance that the Island world gives to individuality, and to the man or woman who enjoys handling the primitive things of life. There is room to spare in the vast Pacific world for those who find the civilized places too narrow, who like to blaze their own trails, make their own roads, find their own way, both literally and metaphorically. The outdoor life is the typical life; to use an Irishism, it extends to indoor life as well, since houses are built with the view of admitting as much air as possible, rather than excluding it.

This statement must not go without its due word of warning. The Islands are not for the weakling, for the lazy, the intemperate, the sensual. They are not for the man who dislikes civilization because it asks too much of him. The Islands will ask more; they will demand that he stand on his own feet, keep himself up without leaning on the shoulders of his neighbours, make his own code and stick to it without being forced to do so by any one else. A man who cannot get on well in cities or settled countries will not get on in the Pacific world, unless his failure was due to his being too big, not too small for his surroundings.

There are plenty of weaklings in the Island world. They go where they belong, and that is to the devil, rather quicker than they would anywhere else.

Of the influence exerted by the Island women, black, brown, or merely coloured, this is perhaps the best place to speak, briefly and plainly.

All that can be said has been said already about the woman of the Eastern Pacific, the more or less beautiful, more or less mixed blood, Tahitian, Samoan, Tongan, or Fijian. In the Western Pacific, things are somewhat different. Melanesian and Papuasian girls are sometimes pretty in early youth; more often they are plain, according to white ideas. They have their own attraction, however, and it would be absurd to say that white men in the Solomons, New Hebrides, New Guinea, do not live with, occasionally marry, native women. But the general feeling towards native women is different from that which obtains farther east. The wandering sensualist, on the lookout for new amusements, who influences public ideas in other islands, is absent from the wilder and more dangerous Western groups. While human nature is human nature, and men dependent on the society of women, the single man (whether married or not) will turn, more or less, to coloured women, in the absence of white.

But—it is a large but, and should obtain full emphasis—in Papua, at all events, the coloured housekeeper is by no means the rule; she is an exception; as time goes on, more and more of an exception. Single men in Papua, as ‘in barricks,’ ‘don’t grow into plaster saints.’ Nevertheless, the white inhabitant here would rather be decently married than not; does his best to find and keep a wife as soon as possible, treats her well when found.

One of the troubles of life in the Pacific—a trouble that is diminishing but not dead—is the semi-detached marriage. All over the Island world are men whose part in marriage is chiefly confined to paying for it; who live, anyhow, on the disgusting meals provided by unsupervised native cooks, who enjoy no home comforts, and suffer constantly from the dreariness of life that besets the married bachelor. Withal, they have none of the luxuries they enjoyed as real bachelors; drinks, smokes, and cards are cut down, newspapers have to be borrowed, trips ‘South’ are not to be heard of.

In the mean time, the wives, fortified by the advice of complaisant doctors, or by their own simple opinion that ‘the Islands are no place for a lady,’ make themselves into happy colonies in Sydney or Melbourne, enjoy life, have good food, live in cool houses and in the midst of pleasant weather. They go to theatres and picture shows. They have the society of their friends. Once in a year or two, for the sake of appearances, they come up to spend a Southeast season at home. The sword of criticism is readily turned aside by one of two well-tried parries—health and the children. Children must be educated, and they ought to have the care of their mothers. No boarding-school can—etc., etc. As for health——

Well, there are hard cases, and sad cases. But, apart from these, one cannot but realize, after more than twenty years of Island life, that there is only one thing that keeps husband and wife together in the far-off places; only one lack that separates them—love, and the want of it.

After a year or two it becomes plain as day, in an Island community, which marriages were made for the best of reasons and which for the poorest. One sees the woman who ‘sticks it out,’ through fever and bad food, loneliness, heat, mosquitoes, and all the other drawbacks of tropical life, contrasted glaringly with the other who is a living complaint, who cannot bear a crumpled roseleaf. One knows, with certainty, which of them married because her man was more to her, and remains more to her, than all the world; which, to use an expressive piece of slang, merely wanted, and got, a ‘meal-ticket for life.’

This without disparagement of the many splendid women who, in Papua and elsewhere, make of themselves civilization’s very foundation stones. All the more credit is theirs, in that the relative positions of men and women are, to some extent, reversed. In the Islands it is the man who is tied, and the woman who is free. The bread-winner must stick to his task; the house-mistress may leave hers. There are far more of the plucky, stick-to-it kind than of the complainers who revert to city life, but, in the nature of things, the latter are more conspicuous.

There are two other aspects of social life in the Western Pacific that must be touched on—the ‘Black Peril,’ and the ‘Eternal Triangle.’

It may be said at once that the Black Peril, in Papua, is not serious. Twenty years ago it scarcely existed. Civilization, however, generally brings some trouble of this kind in its train. Brown men, violent and unrestrained of feeling, like all savages, are separated, sometimes for years, from their homes and families, and go to work in the houses of white people, where the women are constantly left alone for the greater part of the day, sometimes for weeks, in the absence of husbands and fathers. Tropical houses lack privacy; the heat makes people who would otherwise be careful somewhat careless in dress and demeanour. There is gunpowder here, and at times it has been known to explode.

Carelessness and contempt on the part of white women are answerable for a good deal. In very rare cases, there may have been direct encouragement. But it may be said on the whole that the white woman in the Western Pacific is about as likely to be attracted by a native man as to commit murder. There are women who murder, and there are women who insult their race in the deepest possible manner. Neither need be reckoned with in considering ordinary, decent folk who make up the world.

All allowance made, however, it would be idle to deny that the Papuan has been known, though rarely, to assault white women. The remedy is simple. If white women made a habit of learning how to use firearms and kept them in the house, nothing more would be heard of these troubles. Everything is known among the native servants, and the fact that a certain ‘sinabada’ (lady) keeps a revolver in her bedroom is sufficient to secure her from annoyance at any and all times.

A quarter of a century of Island life teaches one many things about the native that hysterical scaremongers do not seem to suspect. One is that he is extremely susceptible to the claims of etiquette, good manners, conventions of all sorts. A wild head-hunter from the main range will learn in a very few days what is and is not ‘done,’ in the way of entering people’s rooms at odd hours, knocking or not knocking on doors, keeping out of the way when he is supposed to be out of it—all matters that must be considered in houses open to every breath of air. His own village has imposed upon him elaborate social codes of all kinds, to which he has unquestioningly submitted, no matter what inconvenience or even suffering may result. Our conventions, if utterly different, are conventions still, and, as such, he is ready enough to learn them.

To dot the i’s and cross the t’s, the brown man is decent and modest enough, given a fair chance.

That is not to say that he is to be regarded as a firework that cannot possibly go off. The old motto of trusting God and keeping your powder dry may very fairly be applied in respect to him.

If one judged by the work of certain brilliant and able writers, as well as that of a good many who have no claim to brilliance or ability, one would naturally suppose that the Eternal Triangle of fiction and films is a constant part of Island life. It is, on the contrary, a rarer feature than in the life of cities. Divorce figures are extraordinarily low, which fact is as good a proof as any. Apart from divorce, however, there are in most communities a number of more or less doubtful cases, about which scandal clings like slime; regarding which interested neighbours are continually and excitedly ‘kept guessing.’

Of these there are no doubt a few in Papua, which is to say that the inhabitants, like the inhabitants of Clapham, Paris, and Timbuctoo, are not made of stained glass. Life would certainly be duller than it is, between steamers, if this substitute for the theatre were not provided by a handful of public benefactors. But the Triangle, as such, shows up poorly among the many unbroken circles; which is to say that, semi-detached couples and triangular troubles fully allowed for, Western Pacific folk, with Papua fairly in the lead, are conventionally and generally happy. It is the strange habit of Port Moresby married couples to go out walking frequently in each other’s company, to sit pleasantly and lazily talking with one another, through many unoccupied hours, to be absurdly proud of one another, and inclined to one another, and to think each other’s faces, somewhat yellowed and fever-worn, just as handsome as they were on the day when the confetti was thrown.

This is horribly uninteresting. If one could have said that the people of the Western groups, especially Papua, live in a sort of amazing community of husbands and wives; that they murder each other now and then, keep brown partners ‘on the side,’ and generally, like the monkey people in Ann Veronica’s dream, ‘go on quite dreadfully,’ there would be something to interest the most casual reader, something for the most bored and inattentive reviewer to quote. I have to apologize, and to hope that any appetite for sensations and horrors will be more fully appeased later on, when I come to the ‘bluggy’ parts of Papuan life.

To us who live in the Territory of Papua (constantly and hopelessly confounded with that part which was once German New Guinea, and is now the Mandated Territory of New Guinea) things are exciting and interesting which would bore the outsider to tears; things are dull and ten-times-told that set the visitor screaming.

Our electric service, light and power, our telephones, motor cars (we have only a twenty-four-mile stretch of road to run them on, but who would not be in the mode?); our steamship service, four-weekly, poor in quality and high in price, our tea-parties and bridge-parties and dances and launch picnics, interest us passionately, in the little capital of some four hundred white souls. Outside, a step or two away, the Stone Age walls us round. Most of us forget it. When somebody comes in from outback with a tale of hairbreadth adventures, not imagined—like the tales of the passing journalist, who is usually the prince or princess of liars—but true, we, like Queen Victoria, ‘are not amused.’ We have heard it all before. . . . Who cares if the men of a village at the back of back of beyond asked the men of another to a dinner-party, and made the guests the chief dishes? What if a couple of explorers, scarcely more than boys, sent out by the Government to map new districts and discover things unheard of, have come back with all their carriers safe and all their work done? Tell us something about the price of rubber. . . .

That is how it looks to some of us. Others—quite a good many on the whole—love the outback better than the towns, are far more interested in it; visit it as often as we can. It is not easy to visit. The nature of the country is such that roads are almost impossible to make, except at prohibitive expense, which the numbers of the white population, scarce twelve hundred, do not justify. It follows that, unless you want to fit out and conduct a serious exploring expedition (and that will take months of time, and thousands of money), the rivers are your only road. Here again, difficulty is met with. Distances are big; the Territory of Papua has over two thousand miles of coastline, and some hundreds of miles may lie between you and the river you wish to visit. There may be a little local boat going that way, and there may not. If there is such a boat, it will almost certainly not run beyond the river-mouth; no Papuan river is settled, and, in consequence, the only people who ascend the rivers are Government officials and, once in a long while, a recruiter or so.

You can charter if a boat is available, and you can wait and hope for luck if it is not. I have been lucky several times. The Sepik and the Fly, both unvisited by any white woman before myself, and by few white men at any time, are among the most interesting rivers in New Guinea. The first I saw in the beginning of 1923, the latter three years later. A somewhat rough and hurried account of these visits, written for the most part right upon the spot, makes the next chapter. There is little to be gained by touching up one’s first impressions, so I have altered nothing and added little.

I have written as a traveller, a wanderer, to whom new and strange things are the chief happiness of life; a dreamer who has had near twenty-five years of realized dream, and is not yet satisfied. As I said elsewhere, at the beginning of that quarter-century, I say again to-day—my writings, such as they are, are dedicated to the Man-who-could-not-go. I know that he (and she) finds pleasure in them.

It is needless to apologize for the absence of any scientific observations. No country in the world has been more constantly written about and discussed, from an anthropological point of view, than New Guinea, and that, too, by thoroughly qualified people. As for statistics, those who want them, can easily find them in their appropriate place, which is not, one thinks, the pages of a gipsy tale. But there are other grave deficiencies in the tale which must not pass unnoticed.

I have never been captured by cannibals. I have never been present at a cannibal orgy. Feasts in my honour have been unaccountably neglected by the chiefs of the country; perhaps because there are practically no chiefs. Worst of all, nobody has ever attempted to make me queen of any place whatever, or worshipped me as a goddess, or tried to sacrifice me to idols.

This certainly suggests stupidity on my part, and negligence on that of the Papuan in general, because such things seem to happen to every one else. A film-acting party cannot land upon a coral beach without experiencing most, or all, of the adventures above set down, within forty-eight hours. A press photographer on holiday, or a traveller tired of sheiks on their native sands, and looking for new thrills, will be captured, rescued, made sovereign of wild tribes, carried about in triumph, tied up for slaughter—all in a week, and all between the Sogeri plantations and Tim Ryan’s corner pub. An explorer will discover some spot ‘on which the white man’s foot has never trod’ within a mile of the automatic selenium beacons of Port Moresby Harbour, photograph it in triumph, and become a hero on the strength of it. The queen of a cannibal tribe will be found smoking a pipe among the palms at the back of Government House, and interviewed for publication, with sensational results. . . .

These things do not happen to the people who live in the country. If they go outback, they do have adventures, but the adventures run on different lines. Only to the round-trip tourist, and to the newspaper man qualifying for the title of explorer by a run in a coastal boat, do these strangely standardized adventures happen. . . .

Something in the monotony of the tales, the vague megalomania that produces them, reminds one irresistibly of what is said about a certain temple wall in Egypt. It seems that this piece of masonry is in danger of serious damage at the hands of an unceasing stream of women tourists, who have all come to see the authentic portrait of Cleopatra carved upon it, and are all determined to secure a souvenir, because every last one of them knows that she WAS Cleopatra—in a ‘former life.’ . . .

Remembering the magnificent exploring work done recently by those amazing youths, Champion, Healy, and Karius, and somewhat earlier, by Humphreys (all young Government officers, travelling in the course of their ordinary duties), one is almost ashamed to mention ordinary travels. Still, the business of these young men is to map new districts and pacify wild, strange peoples, while mine is to observe, enjoy, and describe for those who are less fortunate. Seeing and doing much less, one may, therefore, have more to say.

The sum of recent serious explorations in Papua and the Mandated Territory will be found in the last chapter. The tale of a few of my own pleasure journeys follows this.

There is not a more wonderful river in the world than the Sepik, the largest river of the island-continent of New Guinea.

It is wider, longer, deeper than most of the great European rivers. Large ocean liners can—or could, since they have never done so—travel up the first sixty miles; and steamers drawing ten to fifteen feet would find plenty of water for three hundred. Above that there are rapids; but the Sepik still remains a big river for another three hundred miles, back towards the mountains of Dutch New Guinea. Above this point, nearing its source, it dwindles to a tiny stream.

There is oil somewhere along its course—not yet located; there is gold; there is a seventy-mile stretch of sago, and hundreds of miles of wild sugar-cane. Tobacco is grown by the head-hunters of the middle river in such quantities that stray traders buy it by the ton, the quality of the leaf being good enough for white men to make into cigars. There is much swamp country, but there is also flat land suitable for cotton, tobacco, or sugar; and even the swamp lands are naturally rich, for they grow sago and nipa, the latter now known to be one of the best sources of commercial alcohol.

This mighty river runs through a great part of the Mandated Territory of New Guinea (formerly known as Kaiser Wilhelm’s Land) and back through Dutch New Guinea, but the best stretches of the stream are all in our own new colony. Not until 1914 was any serious exploration done, and then a German traveller, just before the War, ascended the river and traced out its course as far as its source. Until 1927-28, little more exploring was done. Even now the tributaries are not much known, and the resources of the Sepik country are scarcely guessed at. No steamers run along the coast to the river-mouth; no regular communication of any kind is kept up. Recruiting schooners have gone up the river a few times; a German man-of-war once visited the lower reaches; the tiny steam pinnace of the Catholic mission travels the middle reaches from the mission station forty miles up. As for Government officials, they visit the river, at the time of writing, in native canoes. Unless one is prepared to charter a ship and bring it hundreds of miles up the coast, or unless some extraordinary chance favours you, the Sepik cannot be visited.

Extraordinary chance did favour myself. The Catholic mission launch, a ninety-ton boat, happened to be making a trip up the river (her only trip in six years) and I was fortunate in being able to accompany her. We went two hundred miles from the mouth, stayed a week in the head-hunting country, had some adventures, and saw many sights that hardly any white person—certainly no white woman—had ever seen before. The heat, with every mile, grew worse and worse—it was already bad at the very mouth of the river—and the mosquitoes increased in a sort of geometrical progression, till one began to wonder how human life continued to exist any farther up. All the same, the journey was worth any and every discomfort; from the estuary to the two-hundred-mile point and back again, every mile had a new interest.

It was nipa and nipa at first—thirty-foot green ostrich plumes standing up in the dishwater-coloured stream; then sago, sago, sago for scores of miles; endless forests massed upon the banks; trees flowering and ready to cut, trees young and spreading, all beautiful beyond words. A sago palm cut down at eight years old (when it would naturally die) contains enough starchy food to keep a man and his wife and family for half a year. In the place of the cut-down palm, another springs up, so there is no risk of exhausting the supply. The pith is chopped out and washed in bark troughs; the resulting starch is collected and made into cakes. On the Sepik, sago is boiled into a pale jelly, and sometimes cooked into thin flexible cakes, rather like oatcakes in appearance. This fine nourishing starch is entirely different from the grained stuff—mostly made from potatoes—which is sold in shops under the name of sago.

All over New Guinea the biggest and most vigorous people are those who live upon the produce of the sago forests, supplemented by coconut and fish. On the Sepik they have yams as well, the best I have seen; the women catch prawns by basketfuls; and there are bananas of every kind. The flesh of pigs, dogs, and human beings is kept for feast days only.

Towards the end of the first day’s run we came upon marvellous creepers, dripping, flowing from top to bottom of tall trees in waterfalls and curtains of close leaf. They draped themselves over half a mile of forest in solemn folds like giant funeral palls; they dropped in unbroken walls; they opened into arches, windows, and green, mysterious corridors. The river was half a mile wide, but one could see on the far side the same wonderful and beautiful display, concealing altogether the forest that supported it. In June, the D’Alberti creeper, with geranium-scarlet flowers, would have added its own special loveliness, but this was not the time, and no flower less robust than the splendid D’Alberti can live in such a torrent of leaf.

It was here, or a little after, that the sago began to lessen; to appear only in clumps, while beyond the regions of the smothering creeper, wild sugar-cane began.

WILD SUGAR-CANE, SEPIK RIVER

This wild sugar-cane is worthy of note. There are hundreds of miles of it bordering the Sepik and the Sepik’s tributaries; it runs as high as fifteen and twenty feet, and its young shoots are quite as good as cultivated cane, though the older stems are too hard for natives to chew. There has been talk of using it commercially, but the Sepik is very far from anywhere, and nothing, so far, has come of any plans.

At forty miles the launch stopped for the night at a little mission station managed by one father and one brother—both Germans. And here is the place to say that the German ‘Mission of the Divine Word,’ left in possession of its different stations on sufferance, and under many conditions, has been behaving, since the end of the War, with a loyalty, an honourable acceptance of conditions and promises, that could not be surpassed. Many of the new residents in our Territory, and not a few of the Government officials, would fare badly without the help and kindness freely given by these missionaries. They even go so far as to report native murders to the proper authorities for the good of the country, though they know, as any resident knows, that such a course puts their own lives in serious danger.

WILD NATIVES LOOKING OUT OF BUSH AS THE BOAT PASSES

The people who inhabit the many villages about this part of the Sepik are cannibals. Some of them have been Christianized, but a great number remain completely savage. Although cannibal, they are not particularly aggressive compared with the head-hunting tribes of the middle river. Nevertheless, a few years ago some of them plotted to wipe out the mission, and they would have done so had not others who were friendly come by night and warned the missionaries.

The touch of humour that is never absent in New Guinea appeared when the friendly natives explained that they would protect the missionaries even if there was a fight; but should there be a dead body or two as a result, they hoped the Fathers would permit them to eat it!

A couple of days later, the launch had made her way up nearly two hundred miles of the great river, which was still half a mile wide and deep enough for large ships, and we were in the country of that most interesting of tribes, the Sepik head-hunters.

These people are not supposed to belong to the same race as the common, unenterprising cannibals of the upper and lower river, who merely enjoy an occasional fight, and devour an enemy once in a way. It is thought that they came across country to the Sepik from the sea countless generations ago, armed with a little more knowledge, a trifle more of civilization than the other tribes, and immediately proceeded to make themselves unquestioned masters. ‘Romans of the Sepik’ they might well be called. They are better, bigger, stronger than any one else on the river; they hold the others in subjection, make them grow tobacco for the conquerors’ needs, and exact tribute of yams and sago as they please. They are much cleaner than the other natives; they have not a bad idea of art; their houses are well built, and their towns—some of which number nearly two thousand people—are kept in good order. What they know of white people is not much. One or two explorers; a few recruiting schooners; the tiny mission pinnace creeping up and down the river; a Government canoe once in a long while—that is all the head-hunters see of the white people who own the land. A white woman they had never seen until I came among them.

The immense distance of the Sepik from all settlements and the neglect that it has experienced until recent years have encouraged lawlessness. Head-hunting, at the time of my visit, flourished openly in the middle-river districts. If it did not reach the point attained during the War years—when one tribe is said to have taken about seven hundred heads in two years—it was still a menace to safety and a defiance to authority.

Heads, heads, heads—there was no getting away from them on the middle Sepik, that March and April of 1923. Every village had a display of heads in its men’s communal house; every canoe that came about the launch offered a head or so for sale; every native who could speak pidgin English—and there were a good many, since Sepik folk have often been taken away to work on the plantations—had a tale of gossip about the head-hunting raids of yesterday and last week. On the deck of the launch, natives, given a lift up the stream, with their canoes towing happily behind, talked to each other in pidgin English with the most perfect candour about the inescapable subject. The ‘cooky’ of the boat—an alleged-to-be-civilized native—when he ought to be getting dinner was hanging entranced on the lips of a local chief, who was telling him all about the last raid.

‘I go along that fellow village night-time, altogether I make finish that man, woman, monkey (child)—I take altogether head belong him,’ he boasted.

‘How many fellow head you taken?’ asked the cook eagerly, tin-opener in hand and kettles boiling over unheeded.

The chief counted on his fingers and toes. ‘Nine fellow head I gettem,’ he answered.

‘You strong man!’ declared the cooky admiringly, and returned reluctantly back to his galley-pots.

We went on and on up the river; and now the local colour began to show itself thickly. Some of the returned labourers whom we were carrying as passengers seemed very reluctant, as their village drew near, to disembark. It was three years since they left; they could not be sure, they said, that their tribesmen would receive them well. Why not? . . . Over the dark faces dropped the darker veil that white men in these mysterious lands know well. The returned labourers could not—would not—say. But they were uneasy; one could see it.

Their village was reached next day. Like most Sepik towns, it was partly on the river-bank and partly far back in the bush. The houses—brown sago thatch, brown sago walls, set on high piles under the shade of palms—seemed few, but that was delusive; there were scores more behind.

The village folk assembled on the bank. We landed the boys, who were not now unwilling, only anxious, and we stood by for a while to see that they were well received. There was much talking, weight seemed to be lifted from their minds, and off they went into the gloom of the forests with their friends, chattering eagerly about matters that seemed of the first importance.

Later, we stopped at a village renowned for its friendliness. Here, it was said, the white man was in no danger at all of losing his head; here every one had always been civil and well-behaved. Crowds met the launch; men clad in a handful of fur and an armful of shell beads—their hair trained into long wiry curls, their eyes painted horribly with black, their noses and cheeks reddened. They jumped about, wild with excitement, as the two missionaries and myself came ashore. They had never seen a white woman; they expressed their astonishment, somewhat unflatteringly, by yelping like dogs. No doubt they were friendly, but they had not brought their women out, and every one who knows New Guinea knows that that suggests distrust. One of them, who spoke pidgin English, proposed a sort of confidence trick; they had their women away back in the bush, he said, and if I would leave the white men on the bank and go with the natives, they would take me to their women—and then, apparently, every one would trust every one else. . . . The offer was accepted.

It was not very far, only a few hundred yards, till we came to the bush part of the village, pretty and pleasant and cool, deeply shaded by thick trees and boasting a number of houses built with considerable skill. We were not yet in the region of the biggest villages, built by the ‘strong men’ of the Sepik, but this was a pleasant dwelling-place enough. There was a fine assembly hall, open on all sides to the cool river breezes, and roofed with heavy thatch; it had long tables (more used, one must confess, for sitting on than for meals), and it had a number of very cleverly made high stools, each carved from a large tree-trunk, with four outward-curving legs.

And now, out of the high-up door of the women’s house, small brown faces began peeping. The men roared to their wives to come down; and very timidly they came, pattering down the high ladder, staring and laughing nervously. Most of them would not even approach till the men, shouting with laughter, dragged them up to me. They were rather superior to the usual type of savage women, not nearly so hideous, nor so crushed-looking. One inferred that the wives of the head-hunters were not ill-treated, and enjoyed some position in the community.

Whether they, or the men, were responsible for the creepers prettily trained over some of the houses, the neat, tidy walks, and the occasional bunches of flowering orchids, I cannot say. There was no interpreter, and if there had been, every one was far too excited to keep up a conversation. Then and thereafter, every visit which I made to the villages resembled nothing so much as a combination of a dog-show and a bazaar; yelping and howling, crowding and pushing, offering of weapons, feathers, carvings, heads for sale. Knives were in keen demand as ‘trade’; a good way after came fish-hooks, beads, and salt. But whatever the transaction was, the shouting and chattering that accompanied it, the excited dancing about, the laughing and pointing and general bedevilment were the same.

I went back to the river by and by, escorted by all the men of the place, but none of the women; the latter retired at once to their houses. The Fathers had concluded their own business, which, as mission work, seemed rather hopeless, and we went on board the launch.

It was a typical Sepik River afternoon; over huge open lagoons, steely and livid, under a sky that was black with terrible heat, the launch panted on her way; through narrower reaches, less than half a mile in width, where the silent dark green trees on either bank stirred not a leaf, but stood like gloomy soldiers, stiff at attention. The boat was full of mosquitoes now; whenever we approached the bank, they came on board in thousands, and if one walked about in the villages, one had to fight them off ceaselessly with branches of trees. All the natives carried long brooms made of cassowary feather or coconut fibre, and used them continually. And with every mile of our advance up the river, the mosquitoes and the heat increased.

Every one was streaming from every pore; clothes remained saturated night and day. Sleep within airless, close mosquito-nets became almost impossible; rest at any time of the day was hopeless. Two thoughts dominated the mind above all others—mosquitoes and heat, heat and mosquitoes.

And yet—how lovely the waterways that we passed; the tributaries running far back into lagoons set with silvery sugar-cane and gemmed with secret, exquisite islands! Sometimes the tops of coconuts, rising above apparently untouched brakes of cane, told of the existence of hidden towns in the centre of natural island fortresses. The Sepik has many villages that are thus half-hidden, and many more entirely concealed, kept jealously guarded from any white who may stray into the wild interior of the Forgotten Land.

The tale of one of these places is tantalizing to the last degree. All middle-river villages are well supplied with pottery—large ornamented clay pots (used for cooking food and also for boiling heads taken in a raid) and tall, bottle-shaped vessels in which the invaluable sago is stored. No village makes its own—they all come from one source, a hidden town, some miles back from the river-bank, into which no white of the few who know the Sepik has ever been able to make his way. Even Father Kirschbaum, who knows more about the river and its people than any living man, and who is in the confidence of the head-hunting tribes if any one is, acknowledges that he has been defeated in all his attempts to find the mysterious village. He has hunted for it in and out of the huge marshes, the tangles of little artificial canals made for canoes, the tributaries of the river, the unknown islets. He knows within a few miles where it is—but at the time of writing he has not found it. Instead, he came across cleverly devised trap roads, well-trodden, and ending suddenly in a swampy lagoon; trick pathways through forests leading to spear-pits—but no village.

The people of this secret village, whoever and whatever they may be, will hold no commerce with whites; and every head-hunter on the Sepik swears—in the teeth of the fact that his house is full of pottery from the Unknown Town—that he doesn’t know where it is, and that no one else does. Head-hunters, like thieves, hang together. By the time these lines are in print, the secret may be a secret no longer. And yet the New Guinea native is a past-master in the art of hiding his dwelling-place. I think he will keep his secret on the Sepik a little longer.

Some of the cooking-pots are enormous, as large as hip-baths; others are graduated down to the size of saucepans. All are cleverly decorated in various patterns of raised waving lines and chains; most have odd, fanciful representations of human faces. The sago jars are also fancifully decorated and excellently shaped—one and all the work of no mean craftsman.

Going on up the river, I had reason to be glad that in the old days of Papua it had been my chance, far to the south, to see much of the uncivilized and hostile tribes; for no one who knew New Guinea could travel the Sepik in March of this year and not see that care was necessary when visiting towns or going inland. Old New Guinea travellers will know what it was that one saw, or rather felt—a something, a nothing; a fierce look in native faces, an uneasiness in native manners. They are always fierce, always uneasy, these wild tribes, but sometimes it is with a difference—and now the difference was there. Even the missionary Fathers, who are, in their quiet way, the most complete dare-devils in the Territory, took some precautions. The little pinnace used for travelling up and down side streams carried loaded guns, hung in a handy place, and cautious questions were asked as to the state of the towns ahead, though I do not know that the answers made any difference to any one’s plans. At night we did not tie up to the bank, but anchored some way out in the stream. And always, as we went on, it grew hotter and hotter, and the mosquitoes, incredible to relate, grew worse. . . .

Then we came to a town with an absurd name that sounded like ‘Come-on-a-bit’—and this town, represented on the bank by one house and one ruin (though there were many more buildings behind), we passed without visiting. Come-on-a-bit is a place that knows its own mind and always greets strangers with showers of spears. That would not (I am sure) have prevented the Fathers from making a call, but it happened that they had no errand there, so we passed. One could just see in the distance the warriors of the village collecting outside the big house, ready to start spear-throwing as soon as we got within range. They must have felt disappointed when we went on.

By and by—on a Tuesday forenoon it was—we came to a town where the men’s big house stood on the very bank of the river—an unusual circumstance. The warriors of the place were sitting and loafing about, chewing the eternal betelnut, eating cakes of sago—and staring. We had seen many fierce and wicked faces in other villages, but here one knew instantly that something different had been touched. There was a black horror that one felt like an evil mist; one saw something in the faces of the men for which civilized language has no words.

A young man, a comely fellow, came forward. He was oiled and painted; there were jet-black circles round his eyes; his nose was scarlet; he had black and scarlet patches on his cheeks. He had huge muscles, accentuated by the oily clay that had been streaked about his naked body. Sidelong he watched the party, and once or twice he smiled. Hell might have sickened at that smile, at the hideous knowledge, the horrible lusts late-satisfied that looked out of it. An old man strutted about, uneasy, nervy, on wires. He had a venerable grey beard and a wrinkled body. His face was full of strange furies. Unlike the youth, he knew it, and looked down at the ground when the white folk came too near. One was blood-intoxicated, full-fed; the other was still thirsty. And whether the happiness of the one or the uneasy restlessness of the other was the more appalling, it was impossible to say.

SKULLS WITH CLAY PORTRAIT MASKS ATTACHED, SEPIK RIVER

Quietly enough, however, they stood about and watched the white people examining the treasures of the men’s houses, which, in this village, held rather less than usual. Heads were plenty—a woman’s head among them, with short black curls on the dried scalp; a child’s head or two; men’s heads cleverly worked up, with modelled and painted clay faces and eyes of shell or mother-of-pearl. I asked if any were to be bought. No, none of the dried and completed heads could be parted with, but a knife would buy a skull, and one of the young men would put a face on it in no time. The young man—a harmless, amiable creature to all appearances—sat down at once and began his work. Then the warrior, who had been staring at me and walking round me in somewhat unusual silence, made the inevitable request. Would I come into the bush with them and let the women see me?

Through heat that seemed to burn the very ground beneath one’s feet, I followed the men for a quarter-mile or so. The way led past good vegetable gardens of yam, banana, and cultivated sugar-cane; under great clumps of betelnut and coconut palm that stood dark and motionless against the iron sky. Houses appeared soon, stringing out at long intervals into the forest behind. Still there were no women. The awful heat, the black sky, the stillness, and the silence of the evil-faced folk who accompanied me were almost hypnotizing in their effect. I wondered why I was here; I reflected, so far as reflection was possible, that curiosity led one into strange places and predicaments; wondered whether I should ever get away again, and told myself that the mosquitoes were impossible—there could not be so many mosquitoes anywhere.

Then at last a woman came in sight, peering round the corner of a banana tree. The men dragged her forth and talked to her loudly, and she consented to come up and stare. She tried to run away, but they called her back sharply. Two old and frightfully ugly women looked down from a house—the women’s house. I went in. There was nothing out of the ordinary to see, and the heat was growing worse and worse, so I climbed down and said I was going back. At this they became talkative. One of the men who had accompanied me along the road told me that the women had not all come back, and invited me to follow him into the depths of the forest where they remained concealed.

CARVINGS, SEPIK RIVER

The inward monitor known to travellers in New Guinea shook its head. I refused. Then the men begged me to return to the women’s house. I had not been five minutes away, but in that brief time a temporary door had been put into the previously open doorway, and a number of men, armed with spears and knives, had joined the two women inside. This time I declined their invitation to come in, but sat on the top step of the ladder looking through the door. There were two women outside. While the men were persuading me to come into the house again, these two slipped off into the bush so quietly that I should not have noticed had not old experience jogged my elbow. Then I saw the other women taking a place near the back door of the house, inside. This might have been for coolness, but it might also have meant that they were getting ready to run away.

I remembered that savage races in New Guinea almost invariably send their women away before making any attack, and I began to think seriously.

On the whole it seemed best to be ‘a coward for half an hour,’ so I said I was tired and intended to return. I went back to the boat in the face of considerable, though not violent, opposition. One does not wish to traduce any one, even a village of head-hunters, but I could not forget that mine was the only long-haired head most of them had ever seen; certainly the only one they would ever have the chance of taking.

Next day the murder, most literally, was out, and the uneasy appearance of the villagers fully explained. Some friendly pidgin-English-speaking natives had been unable to restrain their tendency towards gossip and had told one of the missionaries that the village where we spent the morning, and where I had found the women so unfriendly, had just—to be accurate, three days earlier—invaded a neighbouring town, killed fifteen of its inhabitants, taken their heads, and captured a boy. What were they going to do with a boy? Undoubtedly make a ’sing-sing’ with him, kill him, and add his head to their collection.

It should be explained here that the Sepik River tribes torture prisoners, even though, on the middle river, they do not eat them. A ‘sing-sing’ is a tremendous festival, taking place by torchlight. Drums are beaten and dances go on hour after hour—savage dances designed to work up blood-lust and fury. The climax is the torturing and slaying of the victim and the cutting-off of his head.

The face of the young man rose up before me, blood-drunken and satisfied; and then I knew that the face of the old man—not yet sated, looking forward to a climax of red horror—was the worst.

It was natural and quite in order that the two Fathers, practically unarmed, should decide to stop the ‘fun’ before it went too far. It was also in order that they should be in no hurry about it; that they should lunch comfortably, unloose the pinnace calmly, and go off quite as if they were intending to hold a catechism class. It was also just like the mission folk not to stand in the way of my seeing whatever I wanted to see, to take me with them, and discourse on the habits of the egret heron and the way to catch fish, most of the way down to the village.

What followed is quite impossible, only, since it happened, it may as well be told.

The men were collected on the bank again. Among them was a boy, a mere child of about eleven years. He was not confined in any way, but it seemed as though a close watch were being kept over him. The cue of the hour seemed to be innocence—innocence, benevolence, and every Christian virtue. We landed. The Fathers talked to the old man, who explained that he had merely adopted the boy, and meant to treat him as his own son. The boy would say that was true.

The boy, dark, sullen, stunned, said it was true. He wouldn’t go away if he was asked—would he? (‘Answer properly, you young beggar!’)

The boy, through an interpreter, said he wouldn’t go away if he was asked. Once he looked up. I saw his eyes. I had seen that look once before—in the eyes of Michelangelo’s terrible head of ‘The Lost Soul.’

I have not the least doubt the Fathers saw it too. But they temporized tactfully, walked about, looked at the carvings in the men’s house. I asked if ‘my’ head was ready. It was ready. The man who had been working it brought it out—a fine piece of modelling—and was paid a knife for it. Afterwards questions were asked again, and then came a scene that could have been staged nowhere but on the Sepik.

The old man sprang forward, seized a handful of plaited fibre straps kept for the purpose, and began beating out his arguments and protestations upon a log that lay on the ground. As he beat, he yelled, and as he yelled, he cut demi-voltes in the air, coming down at one end or the other of the log with an agility worthy of the Russian Ballet. At the end of each argument or statement, he threw away a strap and took another until the bunch was nearly done, when a second man snatched it up, and repeated the yelling, the speech-making, the demi-volting round the log. It was an amazing sight, and would have been perfect if only the speakers had used the huge carved pulpit chair, with the grinning devil-face on its back, which is the ordinary vehicle of their emotion. But to-day they were so much in earnest that they simply took what came nearest, and that was the log. So do the ends of truth ravel out, whereas fiction is neat and trimmed.

In the middle of it all, the Fathers, seeing that argument was of no avail, took the boy by the arms and hustled him into the pinnace, where I had just settled myself to enjoy the old man’s speech. The pinnace was touching the shore. If it had not been. . .

It is hard to say how a fight begins. All one could see was a tangle of heads and legs, and all one heard was a noise just a little more like a dog-show than the noise that had been going on for the last hour. Only when I saw one of the Fathers’ boys jump for the gun and get forward with it, and the other—most commendably—leap into the engine-room to start the engine, did I realize there was trouble. I crawled over the engine-room roof; the other Father was sitting looking on, and the first had just detached himself and sprung back onto the pinnace with the boy. Nobody seemed to want my revolver. Nobody was the least bit in the world put out—except the head-hunters. They were making more noise than two dog-shows now, and as the engine and the extremely eager crew pushed us off into the river, the old man flung something down—it was a plane iron with which he had just tried to kill the Father—and frantically beat himself against a tree. At which (I do not expect any one to believe this) the other men left off dog-showing and burst into wild and frantic laughter, of the kind that arises at the ‘movies’ when the funny man on the screen bursts a custard pie on some one else’s head.

And the pinnace went off upstream carrying ourselves and the boy.

Nobody on the launch could speak his language. It was impossible to explain things to him. He only knew that he had been ‘blackbirded’ yet again, and that people in general were too strong for him. In a corner of the boat he crouched, clad only in his little scrap of breech-cloth, looking stunned and void of every feeling.

It was only a few hours before the launch was invaded by a whole villageful of savages in canoes.

I never saw a better dress—or rather undress—rehearsal of the cutting-off of a ship than that which these friends of innocence gave us. I think it was not altogether undesigned. The launch is a small steamer of ninety tons, standing very high out of the water. But the head-hunters charged her as soldiers charge a fort, and were all over her from keel to bridge before you could have laced your boots.

They were, however, friendly. They wanted to get the boy back by any means short of fighting, and even when they were met with plain refusal—besides some very plain talk from the missionaries—they kept up the same strained smile and appearance of kindliness. Being warned that the boat was leaving, they went off, still keeping up their smiles. Some of the natives on the boat explained the matter by suggesting that the visitors had been in the raid themselves and were to take part in the ‘sing-sing,’ though they wished to keep up an appearance of candid innocence in case inquiries were made later on.

But let me finish the tale of the boy. The interpreter having gone, no one could talk to him, for his village did not speak the common language of the river. In a corner of the upper deck he sat or lay, day and night, despair stamped on his small black face. His parents had been killed and beheaded before his eyes, his friends slaughtered. He had been carried off—once, twice. Was every one the same?

It was the gift of a blue loin-cloth that first woke him up.

With a gesture of scorn he flung his little strip of fur into the Sepik, and tied on the new magnificence, looking at himself in wonder. Much strange food was offered to him. His eyes narrowed and he tossed it away—poison, of course. The other boys howled with delight, and showed him, unmistakably, what should be done with such luxuries as bread and jam, wings of fowl from the cabin table, and secreted pancakes from the same rich source of good things. The boy, obediently answering by this time to the name of ‘Monkey,’ which is the pidgin English for child, was clearly no fool. Next time he was ready, and no one got in ahead of him. Any scraps remaining he placed in sanctuary beneath my deck-chair.

It was like taming a little wild beast. Confidence had to be won by feeding, and by pats and strokes. After a day or two Monkey understood that the white woman, at least, meant him well. He even consented, trembling and reluctant, to kneel down and be photographed. He used to creep to my chair and look up at me, still with the dead, stunned expression. But when I caressed him, tears suddenly flooded his frozen eyes. He spoke only in odd grunts. The Fathers he still feared; they were men. . . . But one day they took him ashore to see two or three of his own people who had escaped from the raid and gone down-river. The truth dawned upon Monkey: he was not going away to be killed or tortured in another place. He was going to live with good people. There must have been enlightening talk with his own race. At any rate, the child came back with the black despair gone from his eyes. After that he put on flesh visibly and cheered up every hour. When he was finally landed at the mission, where his lot will be of the happiest, I saw him following a crowd of newly recruited farm-boys up to the house, excited, curious, a real boy again. And so ends the tale of Monkey.

SCAR TATTOOING, SEPIK RIVER

The next happening of interest was a visit to a town of no less than two thousand people, a little farther up the river. In the upper middle Sepik there are a good many such towns—all given up heart and soul to head-hunting, and none possessed of any particular respect for the far-off, little-known Government on the island of New Britain, five hundred miles away. Still, this village was known to be friendly, and so far as we had heard, it had not lately been concerned in any special raid. Raids always make a village risky to visit; the people are ‘up,’ blood-drunk, and generally not disinclined to add a sheep or so to the lambs already on their conscience. I do not suppose the Mission Fathers would have let twenty raids interfere with their projected call. Still, it was well that the people of the big town were in an amiable mood, as one had so much the better chance of seeing everything that was of interest.

The approach lay along a narrow river widening into a great silver-green lagoon. Even on the lovely Sepik we had seen nothing more beautiful than this secluded, exquisite spot, with its parklike shores, wide stretches of deep grass, dotted with trees, its beds of rustling, bright green sugar-cane out in the water, its palms stooping, mirrored, over the lake surface, its fairy inlets bridged with leafy liana, its sharp, outrunning points where the stately egret—tall, white as sea-foam—stood or walked, and gazed at us with fearless eyes.

Into the loveliest inlet of all our pinnace went; and then took place the inevitable scene of shouting, dancing, crowding, pushing, the natives howling unanswerable questions in unknown native tongues, swarming all over the pinnace, all over us, all over everything.

This village was ‘all right’; one sensed that from the first. It was a little too vehement in its welcome; a trifle too violent in its attempts to make every one at home; but one could put up with that. It even—unprecedented act!—brought one or two of its older and uglier women down to the landing-place to show its utter good will; and then swept a missionary and myself off to the village proper, howling its delight.