* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Land of the Spotted Eagle

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Luther Standing Bear (1868-1939)

Date first posted: Jan. 24, 2018

Date last updated: Jan. 24, 2018

Faded Page eBook #20180142

This ebook was produced by: Al Haines, Jen Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

LAND OF THE SPOTTED EAGLE

BY

LUTHER STANDING BEAR

University of Nebraska Press

Lincoln and London

Copyright, 1933, by Luther Standing Bear

Renewal copyright, 1960, by May Jones

Foreword Copyright © 1978 by the University of Nebraska Press

All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or any

part thereof in any form

First Bison Book printing: 1978

Most recent printing indicated by first digit below:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Standing Bear, Luther, Dakota chief, 1868—

Land of the spotted eagle.

1. Teton Indians. 2. Teton Indians—Government relations. 3.

Indians of North America—Government relations. I. Title.

E99.T34S7 1978 970’.004’97 77-14062

ISBN 0-8032-0964-9

ISBN 0-8032-5890-9 pbk.

Bison Book edition published by arrangement with Albert L. Cole

Manufactured in the United States of America

DEDICATED TO

My Indian mother, Pretty Face, who, in her humble way, helped to make the history of her race. For it is the mothers, not the warriors, who create a people and guide their destiny.

It is this loss of faith that has left a void in Indian life—a void that civilization cannot fill. The old life was attuned to nature’s rhythm—bound in mystical ties to the sun, moon and stars; to the waving grasses, flowing streams and whispering winds. It is not a question (as so many white writers like to state it) of the white man “bringing the Indian up to his plane of thought and action.” It is rather a case where the white man had better grasp some of the Indian’s spiritual strength. I protest against calling my people savages. How can the Indian, sharing all the virtues of the white man, be justly called a savage? The white race today is but half civilized and unable to order his life into ways of peace and righteousness.

Luther Standing Bear, “The Tragedy of the Sioux,”

American Mercury 24, no. 95 (November 1931): 277.

In this book I attempt to tell my readers just how we lived as Lakotans—our customs, manners, experiences, and traditions—the things that make all men what they are. There are reasons why men live as they do, think as they do, and practice as they do; hence, there were forces that made the Lakota the man he was.

White men seem to have difficulty in realizing that people who live differently from themselves still might be traveling the upward and progressive road of life.

After nearly four hundred years’ living upon this continent, it is still popular conception, on the part of the Caucasian mind, to regard the native American as a savage, meaning that he is low in thought and feeling, and cruel in acts; that he is a heathen, meaning that he is incapable, therefore void, of high philosophical thought concerning life and life’s relations. For this ‘savage’ the white man has little brotherly love and little understanding. From the Indian the white man stands off and aloof, scarcely deigning to speak or to touch his hand in human fellowship.

To the white man many things done by the Indian are inexplicable, though he continues to write much of the visible and exterior life with explanations that are more often than not erroneous. The inner life of the Indian is, of course, a closed book to the white man.

So from the pages of this book I speak for the Lakota—the tribe of my birth. I have told of his outward life and tried to tell something of his inner life—ideals, religion, concepts of kindness and brotherhood; of laws of conduct and how we strove to arrive at arrangements of equity and justice.

The Lakotas are now a sad, silent, and unprogressive people suffering the fate of all oppressed. Today you see but a shattered specimen, a caricature, if you please, of the man that once was. Did a kind, wise, helpful, and benevolent conqueror bring this situation about? Can a real, true, genuinely superior social order work such havoc? Did not the native American possess human qualities of worth had the Caucasian but been able to discern and accept them; and did not an overweening sense of superiority bring about this blindness?

These questions may be answered in the light of the reader’s sense of justice and quality of imagination. As for myself I risk this indulgence and say: Of my old life I have much to remember with pride. There were among us men of vision and humane ideals; there were great honesty and loyalty; beautiful faith and humility; noble sacrifice and lofty concepts. We were unselfish and devout. In some instances we attained notable success, and we were on the way. On the whole, we succeeded as well in being good and creditable members of our society as do many of the dominant world in being good members of their citizenry.

Nevertheless, Indian life has been enriched with fine and understanding white friends, and one such, a man of true nobility, has been of inestimable value to me in reading my manuscript and offering suggestions—Professor Melvin Gilmore, Curator of Ethnology for the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, himself an author. As a botanist of recognized standing he made valuable suggestions, and his keen technical knowledge refreshed my memory that had become somewhat dimmed through a broken contact with the land of my birth. To Professor Gilmore I express my sincerest appreciation, not only for his assistance in this particular work, but for his fidelity in portraying the Sioux people in his published works.

My last word is to give credit to my niece and secretary, Wahcaziwin, who now assists me in writing and editing. All former difficulty has been eliminated, since my hardest work came in making myself understood in all the details and intricacies of Indian thought and life. But Wahcaziwin has a broad and complete understanding of her own, and when I speak she fully understands.

Chief Standing Bear

Lakota is the tribal name of the western bands of Plains people now known as the Sioux, the eastern bands calling themselves Dakotas. The word Sioux is not an Indian but a French word, and since the author is dealing with the tribal customs of his people, he chooses to use the ancient tribal name of the band to which he belongs.

| CONTENTS | ||

| Preface | xv | |

| Explanatory Note | xix | |

| Introduction | xxv | |

| I. | Cradle Days | 1 |

| II. | Boyhood | 13 |

| III. | Hunter, Scout, Warrior | 39 |

| IV. | Home and Family: Courtship, Marriage, Parenthood | 83 |

| V. | Civil Arrangements: Bands, Chiefs, Lodges | 120 |

| VI. | Social Customs: Manners, Morals, Dress | 148 |

| VII. | Indian Wisdom: Nature, Religion, Ceremony | 192 |

| VIII. | Later Days | 226 |

| IX. | What the Indian Means to America | 247 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | |

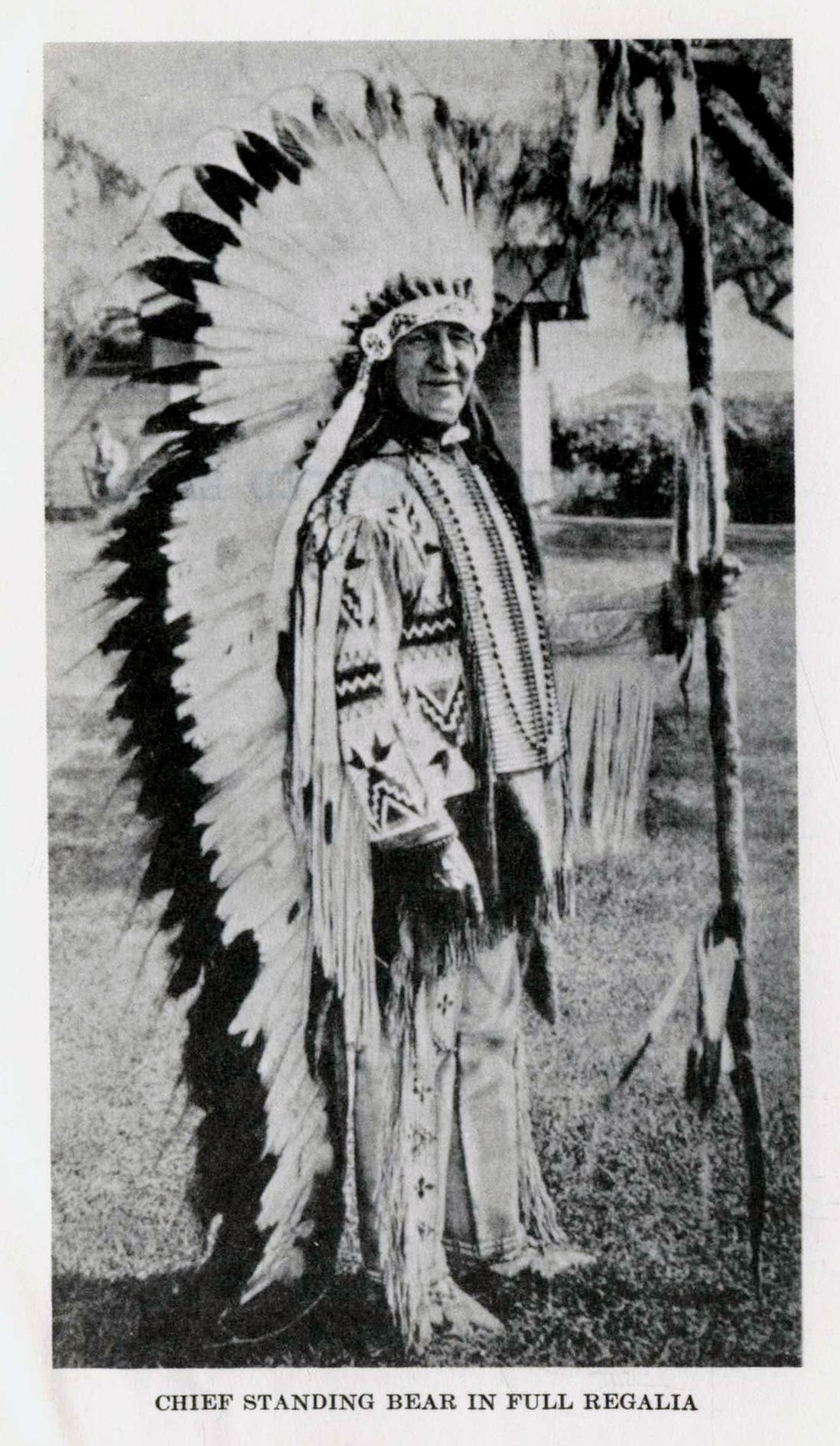

| Chief Standing Bear in Full Regalia | Frontispiece |

| Sioux War Shields | 92 |

| From a drawing by the author | |

| The Hocoka, or Four Villages | 121 |

| From a drawing by the author | |

| Chief Standing Bear the Elder Visiting his Son at Carlisle | 234 |

I have often thought it a great pity that our people, the European race, should have burst in upon this land of America and spread ourselves over it as we did in the manner of unsympathetic aliens instead of introducing ourselves as prospective friends, desiring to become fully acquainted with the native features of beauty and of interest in the land, and with the admirable qualities of its people. The native people were able, willing, and ready to be our guides, and to put us at ease in the land which was their home, and to make us feel at home in it also. But we preferred to begin, and to carry on, so far as possible, the removal and destruction of all the belongings of this home and to substitute for them, whether fitting or not, the belongings of our former home in Europe. So we proceeded to destroy instead of adapting and enriching America. We began merely to try to build a New Spain, a New France, a New Netherlands, and a New England. Instead of accepting the good gifts of this new land and people, and adding to them desirable gifts from our own store, thus completely furnishing a really new and handsome home, we spurned them, and our endeavor has resulted in destroying untold native beauty and desirable character, in place of which we have succeeded in establishing a second-hand establishment, furnished out with many of the belongings of the old home to which we were accustomed, but lacking here their proper sense of fitness and independence. We have destroyed and driven out many delightful native birds and in their place have introduced such pests as the starling and the house sparrow. We have changed the landscape, and over extensive areas have destroyed all the native vegetation, and instead of exquisitely beautiful and richly varied native flowers appearing in continually successive waves of color throughout the round of the seasons, both in forest and prairie, we now have burdock, mullein, dandelion, and wild carrot and other boisterous intruders.

Meantime the native people of America could only look on at this devastation in inarticulate and sorrowful amazement. Whereas they had always lived on terms of friendliness and accord with nature, they saw our people ever set themselves in intentional antagonism with set purpose of ‘conquering nature,’ often simply for the sake of conquest.

It is strange that the people of European race coming into possession of this country never did make themselves acquainted with the native people of America. Instead of accepting them simply as one among the human races of the world, endowed with the powers of thought, with emotions and sentiments similarly as are all other races, they have preferred always to view them either in a hazy and spectral light or else in an equally unreal lurid light. Strangely enough, our people have refused to look upon the native people of America as people who had to adjust themselves to their natural environment and to reclaim their necessary food, clothing, and shelter, and to satisfy the demands of their æsthetic nature from among the natural gifts of this land.

Being so constantly misunderstood, the native people of America have been unable to give themselves true expression in the patterns of thought and feeling of the alien race, and hence have been for the most part mute or inarticulate. But now some representatives of the native American race are succeeding in some manner and degree in portraying the thought and feeling and the life of their people to the understanding of the alien race. In this undertaking The Land of the Spotted Eagle does fairly delineate the old native life in such manner as should be grasped with facility by the intelligence and the common human feeling of all persons. If the following paragraph from this book might be extensively and understandingly read by all our people it should go far to correct many false notions:

‘We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and winding streams with tangled growth, as “wild.” Only to the white man was nature a “wilderness” and only to him was the land “infested” with “wild” animals and “savage” people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery. Not until the hairy man from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families we loved was it “wild” for us. When the very animals of the forest began fleeing from his approach, then it was that for us the “Wild West” began.’

Melvin R. Gilmore

University of Michigan

∵

As a babe I was cared for and brought up in the same manner as all babes of the Lakota tribe. Wrapped in soft warm clothing made from buffalo calf skin I lay on a stiff rawhide board when not held in my mother’s arms. This board was slightly longer than my body, extending a few inches below my feet and above my head. It was without spring, hard and unbending, but it kept my tender back straight and allowed my neck to grow strong enough to hold up my head.

Special attention was given to the head of every Lakota babe, for a smooth round cranium was considered very pretty, and the Lakota mother, in common with all mothers, wished her child admired and praised. Accordingly, it was the custom to make for a newborn babe a strong but soft and pliable cap of deerskin or of buffalo calf skin. This garment fitted smoothly, but was made to let out as the child grew in size. For six or eight months, or as long as the bony structure was soft, the child wore this cap to keep the head from becoming misshapen.

When night came I was taken from my cradle and my body given further attention. I was stripped of my clothing and placed upon a soft bed by the fire where I was warm and comfortable. My entire body was thoroughly rubbed and cleansed with buffalo tallow. I was allowed to kick my legs, swing my arms, and exercise my muscles. My little brown body got the air and grew used to being without clothing. It was the aim of my mother gradually to get me used to all kinds of temperature, for she knew my health depended upon it. So, soon after birth and even in the coldest months, this training was carried on. It became a ritual that was regularly and religiously kept and I was never put to bed until I had been cleansed and massaged. After a time all Lakota babes became, as the Chinaman said, ‘All face.’

This thoughtful care was taken of me for the sake of keeping my growing body healthy and well formed just as it was at birth. It was intended that I should become an erect and a straight-limbed man without marks or blemishes. My muscles must be supple and I must use them with agility and grace. I must learn to run, climb, swim, ride, and leap with as much ease as most people walk.

Manhood was thus planned in babyhood. My mother was raising a future protector of the tribe. When the days of age and weakness came to the strong and active, there would have to be those to take their places. I was being fitted to take one of these places of responsibility in the tribe.

For the first six years of my life, mother’s thought was so largely centered on me that she sacrificed even companionship with my father in order to give me her full time. A weak or puny baby was a disgrace to a Lakota mother. It would be evidence to the tribe that she was not giving her child proper time and attention and not fulfilling her duty to the tribe. More than that, it was evidence that she had not used proper social discretion and defied an age-old tradition. It was a law with the Lakotas that for the first six years of a child’s life it should have the unrestricted care of the mother and that no other children should be born within the six-year period. To break this law was to lose the respect of the tribe and both father and mother suffered the penalty. A fine, healthy child was therefore a badge of pride and respect and healthy babies were the rule.

As for crippled or deformed babies, I have never known one to be born so. Occasionally, however, a child was born with a blue or red mark on the body, but this caused no concern having nothing to do with the health of the child. Among adults a cripple was so because of some accident of life or war. Now and then a man or woman would become afflicted with a crooked mouth or one that drooped at the corner. The explanation for this condition was that the person so troubled had at some time spoken unkindly or maliciously of another who had passed on to the land of the ghosts. The spirit of the injured one returning in the state of resentment would come close to the offending one and startle him with a quick whistle. The offender in his fright would turn quickly in the direction of the sound and the side of his face would be drawn down at the corner. No innocent person could hear the whistle of the ghost, but the guilty one hearing would be marked for life. Guilt was thus betrayed. So it became bad form for one Lakota to speak harshly of another, and the habit of speaking slowly and carefully with guarded words became the polite custom.

The stiff piece of rawhide on which I was kept most of the day was not at all uncomfortable with its soft padding of buffalo hide. Being so simple in construction, it enabled my mother to carry me about with her while busy with her household tasks. My head reclined on the board and could not bob backwards as she walked or moved about at her work or rode her pony. This cradle was not meant to be attractive, but was just an everyday utility article. For dress-up occasions I was carried about in a lovely cradle made of smooth rawhide boards covered with the softest of buckskin. The hood was also of buckskin decorated with porcupine quills dyed in the brightest of colors. To this gayly colored hood there were fastened tassels of eagle feathers also dyed in bright colors. It was kept perfumed with ‘wahpe waste mna’ or sweet leaves.

For six or eight months I spent a good deal of time in one of these cradles. When camp was moving, mother put me on her back and wrapped me to her with her blanket. Sometimes she placed me on the travois for a journey, but not often. If she rode her pony, she first mounted, then I was handed to her. With her blanket she fastened me securely to her. When I became old enough to sit up, she put me astride the horse in front of her. I cannot, of course, remember the first time I rode this way, but neither can I remember learning to ride by myself.

Most of mother’s work was performed while carrying me in my cradle on her back. She packed and unpacked her horses and even put up her tipi while carrying me in this fashion.

When working in the tipi she often leaned my cradle against something so that I stood in an upright position. In this way I could look around and, no doubt, I watched mother’s movements as she worked, listened to her as she talked or sang little songs to me. If I fell asleep she took me out of the cradle and I slept while she watched.

Most of the time a Lakota infant was lightly and simply dressed, but a great deal of time and care went into the making of the material for garments. Mothers preferred a light-weight buckskin or unborn buffalo calf skin for such purposes. When properly tanned, no manufactured material can equal these skins in richness of texture and quality. When the process of tanning is complete, these skins are exquisitely white, richer in sheen than fine broadcloth, and softer than velvet. The Lakota woman washed these garments in water and by rubbing brought them back to their original softness and whiteness. Garments for dress wear were trimmed with fringe, quillwork, and paintings.

For sanitary purposes the down from the cottonwood tree pods was used. Also in the fall of the year cattails furnished a soft airy down, but the cottonwood down was preferable. No like article manufactured in mills can equal this down in silky fineness, so light it floated in the air on a still day. Besides, the supply was plentiful and the women kept it stored in large deerskin bags. For sanitary purposes finely powdered buffalo chips were also stored away and was most effectual in its intended purpose.

As the Lakota child continued to develop, it had the constant companionship of an elder; if not father or mother, then aunt, uncle, or one of the numerous cousins of the band. Children were always welcome charges of all who were older. Every child not only belonged to a certain family, but also belonged to the band, and no matter where it strayed when it was able to walk, it was at home, for everyone in the band claimed relationship. Mother told me that I was often carried round the village from tipi to tipi and that sometimes she saw me only now and then during the day. I would be handed from relative to relative and someone was constantly amusing me.

A large portion of the care of a child fell to its grandmother, and in some respects she was as important in the child’s life as the mother. The interest of the older women became centered on the welfare of children, and, possessing both experience and wisdom, they were much depended upon. This wisdom concerning the lore of taking care of little ones gave grandmother a superior position, especially with the younger women and mothers. It made a place for her as teacher and adviser in her band. It was, too, lighter work than carrying wood and water and tanning skins, these tasks being taken care of by the younger and stronger women.

Grandmothers became skilled in preparing food for children, and most of them had a host of little ones running after them all the time. When children became hungry, they nearly always ran to grandmother first for food and she was never found lacking in a supply. Nor were children ever refused in their request for food. There was a special delicacy which took time and patience to prepare and of which all children were fond. This was wasna and it was grandmother’s job to make it. Wasna was made of dried meat and dried choke-cherries pounded together, seeds and all, until it was a fine meal. This meal was thoroughly mixed with and held together in loaves or cakes by the fat skimmed from the boiled bones of the buffalo. It was not only a delicious food, but a health food good for young children beginning to eat solid food. No one claimed grandmother’s official job as wasna-maker.

Grandmother took care of all our toys. Our winter toys she stored away in the summer. When winter came she stored away the summer toys. She made pretty bags in which she laid away our marbles, tops, and other toys.

Most grandmothers seemed to be happiest when caring for a number of little ones. And I especially remember one grandmother for her fondness for children. This grandmother—I have forgotten her name—belonged to the band of my grandfather, Chief One Horse. This old lady lived to a great age, but before her death became stricken with blindness. With all this handicap she could not give up caring for her charges. One day she called all the children together and began painting their faces. This was a daily task for someone and it was her way of helping. The children all grouped about her, each waiting his turn. Her bags of paint were near and soon all the children were fixed up. But pretty soon the children began to feel a queer drawing sensation of the face as if it was being all puckered up into one spot. They began to look at one another and found that each little brown face was speckled with white and withered in places. Then curious mothers began to look their children over. It was soon discovered that grandmother had got her bags of salt mixed up with her bags of paint and each child was generously salted instead of painted. This incident became a great joke in the village. Everybody laughed, including grandmother herself. The joke became history, for her band was thereafter called Mini skuya ki cun, or, ‘The band that paints their faces with salt.’ It is so called to this day.

When I became old enough to walk, I spent much time in the tipi of my grandmother. If mother and father were going out for the evening and I did not care to go, I went and slept in grandmother’s tipi and I was always welcome. I remember my grandmother as a patient and tireless worker. She went on long walks gathering fruits and plants, and sometimes she took me with her. When I grew old enough to understand, she told me many things about their nature and usefulness. Much of her simple knowledge would be of value today.

In learning to talk, Lakota children were encouraged and helped, beginning about the same time as children of the white race. But there was no ‘baby talk’ for them. All speech in their presence was full and complete.

And so the days of my infanthood and childhood were spent in surroundings of love and care. In manner, gentleness was my mother’s outstanding characteristic. Never did she, nor any of my caretakers, ever speak crossly to me or scold me for failures or shortcomings. For an elder person in the Lakota tribe to strike or punish a young person was an unthinkable brutality. Such an ugly thing as force with anger back of it was unknown to me, for it was never exhibited in my presence. For this nobility alone I sing the praises of the Lakotas—this thing alone denotes them a brave people.

Mother was a comely woman, not very large but plump and rounded in form. Her face was soft in outline and her features were good. Her skin was light in color and fine in texture. Her long black hair she wore in two braids which hung one on each side of her face after the fashion of the women of her tribe. When she was a child she was quite pretty and possessed a sweetness of disposition. She was called Wastewin, or Pretty Face, and since it turned out that she became a belle in her tribe she was well named. Her name signified grace and goodness as well as good looks, and my mother possessed both of these qualities.

As soon as I could walk steadily, my training in obedience began. I was asked to do little errands and my pride in doing them developed. Mother would say, ‘Son, bring in some wood.’ I would get what I was able to carry, and if it were but one stick mother would in some way show her pleasure. She had a way of saying ‘Son’ that expressed great affection for me. It was in doing this very errand for her that I met with my first childish mishap. I was a very small child, but I came into the tipi with some sticks for the fire and in my eagerness I stumbled and fell headlong. One of my hands went into the live coals and I have the scars to this day.

I not only obeyed mother, but I just as readily obeyed father, grandmother, and grandfather. This, no doubt, helped in keeping peaceful relations in the family group.

But lessons in obedience were not the only ones to begin at an early age. I was taught kindness to grandmother and to all old people. I saw my mother give frequently to them and I was allowed to give at the same time. I learned truthfulness, respect for the rights of all people, order, and like virtues. So each day, with a brightening mind, I learned by examples of kind action. Just as the tiny roots of a plant silently absorbed the earth food, so my childish consciousness absorbed the influences which surrounded me, especially the silent, subtle influence of my mother.

Lakota babies cried very little, as has often been noted and commented on by white writers. This habit of being quiet was not due to punishment but to training. It was, no doubt, dangerous in olden days to allow a child to cry, especially at night or when the camp was on the march. Children were told, ‘Be quiet, a witch might hear you.’ This is the only way in which Lakota children were frightened, so far as I know, until the white man came among us, and then mothers often said, ‘Be quiet, child, a white man may be near.’ So the white man was used to frighten little Indian children into silence. Indian women, and as might be expected, Indian children, were much frightened at the first white man they saw. Many times a white mother has said to her child, ‘Be good or a terrible Indian will get you.’ But just as many Indian mothers have quieted their children with the dread thought that a white man might be near. We with mature minds might ponder on this and see what we have really done to children with these foolish statements. We can see, if we are fair with ourselves, that much unnatural fear and hatred may have been bred in this way.

Now and then twins were born to a Lakota woman, but not often. In our tribe they were regarded as very mysterious beings. Twins were people, it was believed, who had lived with the tribe at some past time and had come back again to live life over. They were therefore regarded as old people and not young people. I have seen twins with ear-holes for earrings and this was proof that they had lived before with us. The spirits of little twins would hover about a tipi, lifting up the curtains and peeking in. They were then looking for a place in which to be reborn. They were visible only to certain people and when the person who saw them shouted or called for some one else to look, the twins disappeared. These little twin spirits always appeared about the tipi tied together with a rope.

The twins who were born among us had habits and characteristics that boys and girls born singly did not have. They were always doing things that ordinary boys and girls did not do. Though it was forbidden for Lakota brothers and sisters to speak and joke freely with one another, twin brothers and sisters were the closest of companions and often stood apart from the others, holding whispered conversations; and it would never be known what the whispered talk was all about. There were ties between twins that did not exist for the rest of us and they broke social laws that we were not permitted to break. Another strange thing was that if one of the twins died the other scarcely ever lived. Marriage sometimes brought about a break in companionship if the twins were brother and sister. However, if the twins were of the same sex the companionship usually continued. From the mother’s standpoint, twins were as well liked as other children and there was never any difference in the treatment of them.

As a child I was of just as great importance to my warrior father as I was to my attentive mother. He found it a great pleasure to provide for us both and much of the time he was away on the hunt procuring food and clothing. Whenever he was about the tipi we spent much time together. Indian fathers seem to enjoy their sons, and mine played often with me. It was a pastime with him to lie on the ground on his back and with his legs crossed toss me up and down on one foot. It was his delight and mine also to ‘play horse’ this way. Father sang to me, too, but not the childish songs and the lullabys that mother sang. He sang the brave or warrior songs, so I grew up loving the songs of my people and learning them as soon as I could speak.

Since father was training me also, the lessons that mother began were kept up by him. When I became sturdy enough to run he would tell me to bring his pony close to the tipi door so it could be bridled. One thing that I ran after more than anything else was the village whetstone. Usually there were but one or two of these useful articles in a village, so it was much in demand. Whenever father wanted to sharpen his arrows he sent me for the ‘izuza’ or rubbing-stone. I went from tipi to tipi until I had found the much-used article.

Father gave me my first pony and also my first lesson in riding. The pony was a very gentle one and I was so small that he tied me in place on the pony’s back. Not that I would suffer fright, but so that father could lead the pony about slowly while I got used to the sway of the animal’s motion. In time I sat my horse by myself and then I rode by father’s side. When I could keep pace with him and my pony stayed side by side with him, that was real achievement, for I was still very small indeed.

Such expressions as ‘I can’t,’ and ‘I don’t want to,’ found no place in my mind. I did not have to listen to long speeches on ‘how to be like father.’ A lesson, in fact, did not imply much conversation on either side. But since I was to learn to do the things that he did, I watched my father closely.

Certain ceremonies are considered very important in the life of a Lakota child and to these father attended. Of course, the morning of my birth, father had a man cry the news to the village and gave away a horse. But my first real ceremony took place a few days later. This was my naming ceremony. There are two other important ceremonies in the life of a Lakota child, and I, being the son of a chief, received them all.

The morning of my naming ceremony the singing of praise songs announced to the village that the ceremony was to take place. The singers stood by our tipi door and sang songs of praise for my father. When the people of the village had assembled, a praise singer called out, ‘Hear All! Hear all! The son of Standing Bear will be named. Hear all! Hear all! His name will be Plenty Kill.’ Mother came out of the tipi holding me in her arms. In the meantime father had selected an old man who was to receive the horse to be given away in honor of the event. Some one led the horse up and the end of the rope about its neck was placed in my tiny hands. He took the rope from my hands and extending his arms toward me said, ‘Ha-ye-e-e, Ha-ye-e-e,’ which meant both thanks and blessings for me. He led the horse away while the singers still sang songs of praise.

About nine months after my birth the second ceremony took place. At this time my ears were pierced and it was a much more impressive ceremony than the first. It was held during the sun dance when many bands were gathered together. It was customary to hold many minor ceremonies of various sorts before the actual Sun Dance began. There was much singing and much dancing by groups of performers. Also there was a great deal of giving and receiving of presents.

The ceremony began, as usual, with the singers announcing the ceremony. Then mother walked to the center of the large circular enclosure carrying me in her arms and leading two splendid spotted horses. They were lively and spirited and pranced about a good deal while different groups took up the singing. An old man, considered an expert in piercing ears, came and stood beside mother. He carried instruments of bone, sharp and fine as needles. Father then came, and last of all the needy man who was to have the two spotted horses. There was more singing while the old man thrust my ears with the sharp instrument and father placed something in them which he had prepared for the purpose. For several days mother watched my ears carefully and soon they were ready for rings. The two holes in my ears cost father two valuable spotted horses.

With the coming of boyhood, life became more lively and exciting and gradually my activities took me further away from the care and influence of the tipi. I still continued to learn, however, in the same manner in which I had learned as a babe—by watching, listening, and imitating. Only I watched my mother less and began to observe the ways of my father more. In time too, I took to watching the older boys and whatever they did I tried to do.

In Lakota society it was the duty of every parent to give the knowledge they possessed to their children. Each and every parent was a teacher and, as a matter of fact, all elders were instructors of those younger than themselves. And the instruction they gave was mostly through their actions—that is, they interpreted to us through actions what we should try to do. We learned by watching and imitating examples placed before us. Slowly and naturally the faculties of observation and memory became highly trained and the Lakota child became educated in the manners, lore, and customs of his people without a strained and conscious effort. I have known children to become very apt in learning the songs they heard. One singing would sometimes suffice and the child would have the words and tune so well in mind that he could never forget it.

This process of learning went on all the time. There was no period in the life of the Lakota child such as that referred to by some as the ‘playtime’ of life, when the child is growing only in body size and not in mind. Body and mind grew together. No one would be able to say how much can be learned through great keenness of sight and hearing unless, having possessed them, they were suddenly deprived of them.

But very early in life the child began to realize that wisdom was all about and everywhere and that there were many things to know. There was no such thing as emptiness in the world. Even in the sky there were no vacant places. Everywhere there was life, visible and invisible, and every object possessed something that would be good for us to have also—even to the very stones. This gave a great interest to life. Even without human companionship one was never alone. The world teemed with life and wisdom; there was no complete solitude for the Lakota.

Such living filled one with a great desire to do, to be, and to grow. In my boyhood, and in actual childhood, I was filled with the desire to be a brave and this desire urged me to constant activity. I was overjoyed when at the age of ten years my father arranged for me to accompany him on a war party. I was not the least bit afraid and was only sorry when for some reason we were forced to come home without having met the enemy.

The way in which Lakota children were trained caused them to regard with admiration all those of wisdom and experience. All yearned for wisdom and looked for experience. For myself, I felt that if I grew wise, my people would honor me; if I became very brave, I should be like father, and if I could become a good hunter, it would please my mother. And so I thrived upon the thought of achievement and approval and I do not think that I was an unusual Indian boy. Dangers and responsibilities were bound to come, and I wanted to meet them like a man. I looked forward to the days of the warpath, not as a calling nor for the purpose of slaying my fellowman, but solely to prove my worth to myself and my people.

One lesson to learn was to be strong in will. Little children were taught to give and to give generously. A sparing giver was no giver at all. Possessions were given away until the giver was poor in this world’s goods and had nothing left but the delight and joy of pure strength. It was a bounden duty to give to the needy and helpless. When mothers gave food to the weak and old they gave portions to their children at the same time, so that the children could perform the service of giving with their own hands. Little Lakota children often ran out and brought into the tipi an old and feeble person who chanced to be passing. If a child did this the mother must at once prepare food. To ignore the child’s courtesy would be unpardonable. But it is easy to touch the heart of pity in a child, so the Lakota was taught to give at any and all times for the sake of becoming brave and strong. The greatest brave was he who could part with his most cherished belongings and at the same time sing songs of joy and praise. It was a custom to hold ‘Give-away-dances’ and to distribute presents that were costly and rare. To give is the delight of the Lakota.

Such an education could not be confined to a certain length of time nor could one be ‘finished’ in a certain term of years. The training was largely of character, beginning with birth and continued throughout life. True Indian education was based on the development of individual qualities and recognition of rights. There was no ‘system,’ no ‘rule or rote,’ as the white people say, in the way of Lakota learning. Not being under a system, children never had to ‘learn this today,’ or ‘finish this book this year’ or ‘take up’ some study just because ‘little Willie did.’ Native education was not a class education but one that strengthened and encouraged the individual to grow. When children are growing up to be individuals there is no need to keep them in a class or in line with one another.

Never were Lakota children offered rewards or medals for accomplishment. No child was ever bribed or given a prize for doing his best. No one ever said to a child, ‘Do this well and I will pay you for it.’ The achievement was the reward and to place anything above it was to put unhealthy ideas in the minds of children and make them weak. Neither were lessons forced upon a child by an attitude of threat or by punishment. There was no such thing as the ‘hickory stick,’ and any Lakota caught flogging a child would have been considered unspeakably low. I have never heard of a child in my tribe leaving home on account of discontent or to escape parental rule. There could be no greater freedom elsewhere. Neither have I ever heard of young people committing suicide over studies or duties imposed upon them. Lovers occasionally planned death for themselves, but never children.

In the course of learning, the strength of one small mind was never pitted against the strength of another in foolish examinations. There being no such thing as ‘grades,’ a child was never made conscious of any shortcomings. I never knew embarrassment or humiliation of this character until I went to Carlisle School and was there put under the system of competition. I can never forget the confusion and pain I one day underwent in a reading class. The teacher conceived the idea of trying or testing the strength of the pupils in the class. A paragraph in the reading book was selected for the experiment. A pupil was asked to rise and read the paragraph while the rest listened and corrected any mistakes. Even if no mistakes were made, the teacher, it seems, wanted the pupils to state that they were sure they had made no errors in reading. One after another the pupils read as called upon and each one in turn sat down bewildered and discouraged. My time came and I made no errors. However, upon the teacher’s question, ‘Are you sure that you have made no error?’ I, of course, tried again, reading just as I had the first time. But again she said, ‘Are you sure?’ So the third and fourth times I read, receiving no comment from her. For the fifth time I stood and read. Even for the sixth and seventh times I read. I began to tremble and I could not see my words plainly. I was terribly hurt and mystified. But for the eighth and ninth times I read. It was growing more terrible. Still the teacher gave no sign of approval, so I read for the tenth time! I started on the paragraph for the eleventh time, but before I was through, everything before me went black and I sat down thoroughly cowed and humiliated for the first time in my life and in front of the whole class! Never as long as I live shall I forget my futile attempts to fathom the reason of this teacher’s attitude. Out on the school grounds at recess I could not join in the games and play. I was full of foolish fears.

What would happen the following Saturday night at what we called, ‘Chapel meeting’? Every Saturday night the entire school gathered for a meeting in the chapel at which assembly various school matters were discussed. General Pratt, the superintendent of the school, usually gave a talk, urging us to be good pupils and instructing us in the ways of good behavior. Reports were given by the teachers and the roll-call held. Also any boy or girl who had broken any of the rules during the week were given the opportunity to report themselves and say they were sorry and would in the future attempt to do better. If they did not do this, they stood a chance of being reported by some other student or by the teacher. This was a splendid rule, but, of course, not pleasant, and I had never had a bad report handed in.

Saturday night came and the building was full of students and teachers. I was filled with anxiety and could not keep my mind from that reading lesson. I was, I thought, to be reprimanded before the entire school for having a poor lesson.

Soon General Pratt was on the platform, talking about the value of possessing confidence. He said he always wanted us to do our best and never to be afraid of failures. If we did not do well at first try over and over again, and as he said this he struck the table with his fist to emphasize his idea. Then he told the students that the class of Miss C. had received a reading test and that Luther Standing Bear had read his lesson eleven times in succession and correctly every time. My heart lightened. I truly liked General Pratt and words of praise from him meant a good deal to me. But in spite of the praise that I received that day and the satisfaction that I have had in all these years in knowing that I was a good student, I still have the memory of those hours of silent misery I endured in childish misgivings.

We were to learn that according to standards of the white man those not learned in books are not educated. Books were the symbol of learning, and people were continually asking others how many books they had read.

The Lakotas read and studied actions, movements, posture, intonation, expression, and gesture of both man and animal.

When the first white teachers came among us to take charge of the day schools, they were schooled and could read books. But they were unlearned in the ways of our country. Many things they did showed that they were not adjusted to the surroundings, and were amusing to us. I remember well one of the first men teachers sent out to take charge of the district schools. He was furnished a wagon and team but not being acquainted with teams, a driver was furnished also. For a while the driver took him from district to district until he felt able to handle the team himself. One day this teacher came to a place in the road that sloped down very abruptly. He neglected to put on the brakes and the horse began running down the hill. The driver, thoroughly frightened, thrust his leg out between the spokes, thinking to stop the wagon. Of course his leg was broken. Soon after he was again well, this man left his team to follow a flock of prairie chickens. When he returned to the road where he had left the wagon and horses, he found they had gone. Some time later he was picked up all fagged out and apparently lost in his sense of direction.

In teaching me, father used much the same method as mother. He never said, ‘You have to do this,’ or ‘You must do that,’ but when doing things himself he would often say something like, ‘Son, some day when you are a man you will do this.’ If he went into the woods to look for a limb for a bow, and forked branches for a saddle, I went too. When he began work I was sure to be close by, quietly observing with the keenest interest.

The most important thing for me to learn, father must have considered, was how to make and use the bow and arrow. For the making of these two articles was the first thing he taught me. There were trips to the woods which both of us enjoyed. I learned that ash was the preferred wood for a warrior’s bow. A hunter would use a cherry or cedar bow. The wood of the cedar made a very strong bow, but it cracked easily. As for myself, I started with willow wood. It was easy to work with and quite strong enough for me. Hickory does not grow in the country of the Lakotas, and so was not used until the white people brought it to the plains in their wooden yokes. If a discarded yoke was found, it furnished material for two good bows.

A bow looks to be a very simple weapon, but sometimes a great amount of skill is used in its making. A bow in the rough does not look like much, but when it has been smoothed on a rough surfaced rock, heated and bent to shape over a fire, and polished, it looks very little like the limb of a tree. The Lakota bows were short and strengthened with sinew, the man behind the bow deciding the strength. When the bow was shaped, small flattened strings of wet sinew were pasted lengthwise on the back until it was covered. The ends of the strings did not meet flush, but each extended, wedge-shaped, past the other, thus adding strength. The tips of the bow were then covered with sinew and the weapon placed in the shade to dry slowly. When thoroughly dry, the hard edges of sinew were rubbed smooth and tassels of dyed horse hair added as decoration. A bow of this description was good for many years’ use, and a warrior armed with such a weapon and plenty of arrows in his quiver felt pretty safe. The bow was strictly a man’s weapon, and I have never known a woman of my tribe to even try to use one.

For arrows we used the slender limbs of a shrub which we called the ‘early berry,’ but which the white people called the wild currant. In the spring, masses of pink, red, and almost black berries appeared so it was aptly named wica-kanaska or early-berry bush. The limbs of this shrub grew straight up from the ground and had very small hearts or cores. Arrows made from them were heavy and could not be wind-swept. Feathering correctly was quite important too. The best specimen of Lakota hunting arrow had three feathers finished with a fluff of down that came from under the tail feathers of the bird. Two red wavering lines, the symbol of lightning, were painted from the feathered end halfway to the arrow tip, but grooved the rest of the way to the tip so as to allow the blood to flow freely from the body of the animal, thereby hastening death.

Every warrior wore his quiver as he wore his clothes—it was a part of his attire. Ordinarily the quiver was worn at the back, but in case of quick action it was thrust under the belt of the warrior or hunter in front where his right hand reached the head of the arrows with scarcely a movement. A skilled man shot with great rapidity when necessary, doing so automatically. At night the warrior’s bow and quiver hung on the tripod at the head of the bed, so that it was close at hand.

A boy’s first bow was not a weapon; it was a toy made of a twig so small it could be used in the tipi. The arrow was of slough grass. Shooting was a game called cunksila wahinkpi. As I grew larger and older I always had a bow to suit my age and size. Unconsciously my bow became a part of my body, as it were, and I used it as I did my feet, hands, or arms.

At the age of eight I was considered expert enough to be included in a party of youths who went on a hunting trip. A deer was killed, and though I was in no way responsible for it I brought home my first piece of meat. Father at once gave away a horse. I was a very proud boy and my longing to become a good hunter increased. I wanted to bring my family more meat.

Just as unconscious skill came to me in the use of my bow and arrow, so it came to me in riding. When I was on my horse I might have been a part of him, for nothing but force could unseat me. When too small to leap to his back, I ran and climbed up his foreleg like a squirrel and was on the go while climbing; for small chance a slow horseman would have getting away from a rapid firing arrow expert. Always we kept in mind the skill of the enemy. But being a rider did not mean being a complete horseman. Father taught me how to make saddles of cottonwood and elm, ropes of rawhide or twisted buffalo hair, blankets, and halters. I learned to look after my horse when he was troubled with sore feet, and how to make horse-shoes of buffalo hide; and, too, how to recognize horse sense and intuition. The horse is continually giving signs of what he sees, hears or smells. In the daytime the Lakota horseman watched his horse’s tail and ears. With these he indicated the presence and direction of animals or people. At night he snorted at any unusual smell or sound. My father once had a horse which was as good as any watchdog. At the slightest cause he would snort his distrust or displeasure, then run straight to father. For this reason father used him in his journeys, as he could lie down at night feeling sure that nothing would get near without a warning from his friendly sentinel.

Father had a great sense of the rights of animals and was a true humanitarian. His ideas along this line would meet with the approval of any humane society in the land and I am sure it would be hard for him to tolerate some of the brutalities one sees on a city street. Father inculcated in me a feeling of interdependence toward my horse something like one would feel towards a companion. The dog had been the age-long companion of the Lakota woman, assisting her in household duties and the care of children, but the horse was the Lakota man’s most trusted friend in the animal kingdom.

In order to see that my ponies were well fed and kindly treated, father once said to me, when presenting me with a fine pony, ‘Son, it is cowardly to be cruel. Be good to your pony.’ So in the winter I never turned him out to forage as best he might. I placed him in the cottonwood groves for protection. There was a grass that grew in damp places or bordering streams and that stayed green all winter. Our horses were very fond of it and father had me cut bundles of it to carry to my pony. In the summertime when I went to the stream, it was suggested that I should take my pony and throw water on him; and if we found deep water we swam together, my hand grasping his mane.

When I grew to be a young man I possessed a great pride, just as had my father in his youth, in riding a fine horse. When, as a young brave, I went out on parade, I brushed my horse until he shone, wove wreathes of sweet grass for his neck, and tied eagle feathers to his tail and mane.

All this was in accordance with the Lakota belief that man did not occupy a special place in the eyes of Wakan Tanka, the Grandfather of us all. I was only a part of everything that was called the world. I can now see that humaneness is not a thing which can be ordered by law. It is an ideal to be lived.

It was at councils, feasts of the lodges, and ceremonies that children learned a great deal concerning social conduct and manners. Social custom was closely observed and many ceremonies, both social and religious, were performed according to strict form. The men, especially the warriors and councilors, were quiet and dignified in manner. The women were quiet too, and very retiring. Loud talking and exaggerated or boisterous actions were considered very unseemly for either man or woman. The speeches were short and spoken without affectation. The dancing was done mostly by the warriors, and the singing by groups who were trained for such occasions. The women, dressed in their best, sat around the circle watching the scene with interest. When food was served everybody joined.

These gatherings were for all members of the band, so whenever my parents attended I was allowed to go. Children were never put to bed to be got out of the way, never given some work to do, nor pushed off to play. My father and mother enjoyed my presence; of that I am sure.

There was much dressing for these festivities and whenever my parents dressed up I was dressed in my finery too. It seems to me that father must have considered me a very valuable boy, or else his pride in me was more than ordinary, for he was always dressing me up. Of course, it may be that I, like all small boys, found it very disagreeable to be dressed in fine clothes. Anyway, I well remember that father made for me a very long, heavy ornament for my hair. I disliked very much to wear this headpiece, for it was made of six or eight silver disks, graduated in size, and strung on buckskin. It was a very wonderful ornament to be sure, but its weight was something to be appreciated and furthermore it was tied to what white people are pleased to call the ‘scalp lock.’ Now when father dressed for some festivity he would paint my face, smooth my hair and tie my confirmation plume at the left side of my head at the top, and tie the silver ornament so that it hung down the back of my head. I always went as father dressed me and never told him how uncomfortable I felt. But I would wait my chance, and when he was occupied and could not see me, I slipped over to mother, told her of my discomfort and that I could not play well. Like all mothers she knew well how little boys like to play, so, saying nothing, she would slyly remove the ornament from my head. Mothers have a way of doing things for little boys and girls without disturbing father’s feelings about them.

There was another ornament that father made for me and which no boy could wear with comfort. This was a breastplate made of imitation bone beads some three or four inches in length and put together with small brass beads. It covered my small chest and extended beyond my shoulders in such a way that I could not lift anything from the ground, nor could I shoot my bow. Such an ornament was considered very elegant and I may have looked very imposing in the eyes of my father, but how could any boy get joy out of life if he could only carry his bow in his hand?

It was at these councils that we listened to wisdom and learned to regard it with esteem. Parents instructed the young to be quiet and respectful and soon they felt the importance of their tribal gatherings. The old warriors retold stories that had become tribal history. Some of these stories had been told many times, but yet were never old. There were always the young to tell them to, and, besides, the people lived over their lives through the memory of great events. The young warriors, some of them just back from their first big hunt or war-party, told their stories in song and dance. Some may have come home badly wounded, while some may have been fortunate and killed many of the enemy without meeting with mishap. A mark of special bravery was to rescue from danger a friend who had either been wounded or lost his horse. Every young brave who was entitled to do so, wore his decoration indicating his deed. If he had been wounded, he painted his wounds with red, and likewise his horse if it had been wounded. One young man—I forget his name—told a thrilling story of his attack on a buffalo. He was returning home from a war-party. He carried his gun, for it was after the coming of the white man, but he was out of ammunition. His only weapon was a knife. He became very hungry, for he had been without food for several days, and game on the plains had been very scarce. At last he came upon a small herd of buffalo and seeing one lying on the ground and apart from the others conceived the idea of killing it with his knife. Getting on the leeward side of the animal, the young warrior crept close enough to spring upon its back. Grasping the long hair upon the neck, the brave plunged his knife into the infuriated animal. The charging buffalo was unable to throw him off and finally the kill was made. The young man had his meal and continued his journey homeward.

At these ceremonies, praises were sung for all our braves and it was there that the boys determined to be braves themselves some day. They wanted to be men of courage and to merit praise and honor. Within me, I can still feel the force of those stirring songs.

The Victory ceremonies centered about the young warriors and everyone was very proud of them. This was because the young hunters and warriors were the protectors of the tribe. To them everyone, young and old, looked for protection. Lives, food, property, and fireside were in their keeping and the cost was theirs even to giving up their lives. For this reason, mothers and sisters joined happily in honoring the braves at these big celebrations.

Mother further interested me by sometimes talking about the braves. She would tell me what they had done and why they were honored. Men in council were there because of merit. A man might be poor in goods, own few horses, and live in a small tipi, but he would sit with the council. Riches brought no man power and though he might have many horses he could not buy a seat with the wise ones. Mother tried, I believe, to develop in me a spirit of fair dealing and also the wish to appraise people justly.

Father liked the company of braves very much and he sometimes invited a number of them to come to his tipi for a good time. He arranged for these parties beforehand by asking mother to prepare a nice meal. When the friends arrived, there would be plenty of food to serve. While the feast was being enjoyed, the braves related experiences of the hunt, of war, of their vigils and of wico oyake, which is the only word in Lakota denoting the history of the tribe. These talk fests usually ended with the braves telling jokes on one another and there was much merriment. I was sure to be about somewhere sitting very quiet and where I would not be easily observed but seeing and hearing everything. So brave in their hearts were these warriors that they sat and told the most thrilling and hair-raising experiences as if they were everyday happenings. It was a great sight and I am glad that I have this picture of my Lakota forbears.

Lakota children, like all others, asked questions and were answered to the best ability of our elders. We wondered, as do all young, inquisitive minds, about the stars, moon, sky, rainbow, darkness, and all other phenomena of nature. I can recall lying on the earth and wondering what it was all about. The stars were a beautiful mystery and so was the place where the eagle went when he soared out of sight. Many of these questions were answered in story form by the older people. How we got our pipestone, where corn came from, and why lightning flashed in the sky, were all answered in stories. The springs were wiwila or living things. But all things lived and were good for the Lakota. Even the spider came to the brave on the mountain top with a message of friendship.

A Lakota brave was once holding his vigil and fasting. In his vision there came to him a human figure all in black. The person in black handed to the brave a plant and said, ‘Wrap this plant in a piece of buckskin and hang it in your tipi. It will keep you in good health.’ When the brave asked who was speaking to him, the figure answered, ‘I can walk on the water and I can go beneath the water. I can walk on the earth, and I can go into the earth. Also I can fly in the air. I am smaller than you, but I could kill you in a moment. I can do more work than any other creature, and my handiwork is everywhere, yet no one knows how I work. I am Spider. Go home and tell your people that the Spider has spoken to you.’ This happened long ago, but the Lakotas still use the Spider’s medicine.

These stories were the libraries of our people. In each story there was recorded some event of interest or importance, some happening that affected the lives of the people. There were calamities, discoveries, achievements, and victories to be kept. The seasons and the years were named for principal events that took place. There was the year of the ‘moving stars’ when these bright bodies left their places in the sky and seemed to fall to earth or vanished altogether; the year of the great prairie fire when the buffalo became scarce; and the year that Long Hair (Custer) was killed. But not all our stories were historical. Some taught the virtues—kindness, obedience, thrift, and the rewards of right living. Then there were stories of pure fancy in which I can see no meaning. Maybe they are so old that their meaning has been lost in the countless years, for our people are old. But even so, a people enrich their minds who keep their history on the leaves of memory. Countless leaves in countless books have robbed a people of both history and memory.

When I was about nine years of age I had the third and last ceremony of childhood—the Confirmation ceremony. This event is the most important one in the life of a Lakota child. In it the confirmed one accepts trusts and obligations that are forever kept and vows are taken that are never broken. In exchange for consecrating one’s life to service the tribe places the one who takes the ceremony in the highest social position and bestows upon him the right to wear the white eagle plume. Those who wear this feather sit at the feasts and take part in ceremonies at which others may only look on.

The Confirmation ceremony is deep and serious in meaning. In nature it is social, religious, and ethical. It is social, for the life of the child will be devoted as much as possible, or as much as wealth will allow, to the service and welfare of other members of his band. Throughout life the confirmed one must stand ready at all times to help the needy and distressed. It is a great honor to be asked by those in want to share your food, clothing, horses, or any comfort of life. By the same rule it is considered a breach of etiquette for one in need to go to another band for help when there are those in his own band consecrated to the work.

The ceremony is ethical in nature, for the practice of all virtues—kindness, generosity, truthfulness and service—are placed above gain and personal profit. The saying, ‘It is more blessed to give than to receive,’ is literally and practically observed. One really becomes his ‘brother’s keeper’ and selfishness is utterly destroyed. For one to shrink from meeting the duties implied in the Confirmation ceremony is to lose face and standing.

The religious import of the ceremony is profound, for the child is given into the guardianship of the invisible powers of goodness. With solemn ceremony and before the sacred altar of earth, the Spirit of the Great Mystery is felt and acknowledged. Through song and prayer His power is begged to remain and guide the child throughout life, that it may walk only in righteous ways. When at last the pipe has been smoked, the pact with the Great Mystery is made.

My two sisters and myself were confirmed at the same time. We wore the finest clothing we had ever worn and enjoyed the richest feast ever prepared for us. Our godfather provided the feast and furnished the clothing for me and my sisters. As for father, it cost him as many of his best horses as he could spare from his herd. When all was over, father and godfather were poor men, but it was worth the sacrifice to enjoy the honor for the rest of our lives.

The father wishing to give his child the benefit of the Confirmation, first takes stock of his wealth. He counts his horses and decides the least number that he can possibly get along with. The rest of the herd he will contribute as presents the day of the ceremony. The father then chooses a man whom he knows to be trustworthy and most fitted to be the godfather of his children. A friend is asked to carry the information to the man chosen to be godfather. It is considered a great honor to be asked to be a godfather and I have never known a man to refuse such a request. To be able to stand the sacrifice willingly and gladly is a mark of strength and quality.

The godfather at once begins preparations. He selects the singer of the sacred songs and two dancers to perform the Confirmation or Corn dance. These songs and dances are given on no other occasion. Godfather makes the rattles, drums, and wands which are sometimes highly decorated. Sometimes the small children are carried in buffalo robes. Godfather gets the robe and selects four women to carry the four corners. All the women relatives are called together and asked to help in making the garments for the children. Everything worn by the child must be new, and no effort is spared to make each one look its best. All the art and skill of the maker is applied, and sometimes there is much vying in having one set of garments outdo the garments of another ceremony. Some of the articles of dress made for Confirmation are very valuable when decorated with painting, porcupine-quill work, and elk’s teeth. A tipi is set up in some convenient place in the village to house the beautiful garments until they are to be worn. Then there is the feast to think of, and godfather furnishes the food for this and selects the cooks, helpers, and waiters. Last of all, godfather builds the sacred altar of earth. It is square and at each corner there stands a stick at the top of which is tied a little bag of tobacco. In the center of the altar is placed a buffalo skull and around are spread fresh boughs of sagebrush. Close to the altar the pipe is placed, leaning upright against a small rack of boughs or limbs.

When all these details have been completed, godfather sets the day of the ceremony and so notifies the father of the children. The father gathers his horses in from the plain so as to have them handy to give away on the appointed day. Horses being very valuable property they, of course, form the greatest sacrifice on the part of the father.

On the day of the ceremony the procession begins at the tipi of the godfather and goes to the tipi of the father. It is led by a virgin carrying a lovely and perfect ear of white corn on a slender wand. From the tip of the ear of corn there waves a white eagle plume. Next come two dancers carrying rattles in their right hands and wands in their left hands. The wands are decorated with a fan-shaped ornamentation of eagle feathers, a fluff of green neck feathers of the duck, and some owl feathers, all symbolic. They are further decorated with paint, and tassels of dyed feathers. After the dancers follows a group of singers keeping time to the beat of the drum. They sing:

The entire thought of the first stanza is given in the first line, the only one that can be translated. This line says, ‘Where are the children whom we seek?’ The rest of the verse implies that the children are being sought, for something of importance is to take place.

The first line of the second verse says that the Hunka or Confirmation is to take place. The word Hunka means the whole ceremony—songs, dances, and speeches. The chorus of the song is merely an arrangement of syllables to carry the tune.

When the procession reaches the tipi of the father, there they find the child, or children. The women who carry the buffalo robe put the child in it, and each woman to a corner, join the procession. The singing continues, and in the same order of march, the child is taken to the tipi where the godfather has placed the new clothing and where he has built the altar. The child is taken in and the old clothing which it has been wearing, signifying the old life, is removed. New garments, signifying a new life, replace the old. The child is now ready for instruction from the wise man who has been brought there for that purpose. The old man offers thanks to the Great Holy before the sacred altar. He instructs the child in its duties to the tribe. The old, weak, or disabled must be looked after and the child must never refuse to help those who ask. He must live righteously, always speak truthfully, and fill his daily life with usefulness. When the wise man finishes, he paints a black line across the forehead and down the bridge of the nose of the child. He then ties a white-eagle fluff to the hair at the left side of the head. This fluffy plume, which symbolizes a prayer, completes the robing of the child. The wise man smokes the pipe while all is silent. When he puts the pipe once more upon the earth the tomtom beats are sounded in quick rhythm. The singers begin the song once more and the beautiful Confirmation dance is performed. When it is ended the ceremony is over and the solemnity of the occasion has passed. Feasting and fun begin and there is much giving away of presents.

The older boys as a rule had a group of younger ones following them and as I was now a good marksman with the bow and an expert horseman I joined this group of followers, too. In everything the little fellows were imitators, and no matter what the game or sport, they tried to meet the pace. The nice thing about it was that the older boys never seemed to regard the younger ones as nuisances. They took time to look after us and, in fact, all seemed proud to share in this responsibility.

There was a custom among the Lakotas often followed by young men whereby an older boy voluntarily adopted as a special charge some younger boy. The older one appointed himself as guardian and helpmate to the younger, the obligation to last throughout life; and through war or peace, in times good or ill, the brotherhood was to exist. If the two went with the same war-party, the older boy gave up his life if necessary to save that of the younger. The ties assumed could have been no stronger had they been actual blood ties. This trust we put in older companions was never questioned, not even by our parents, and my mother never worried when I was with my caretakers.

When the contests of the older boys became too much for us little fellows, then we watched them. It was natural for me, and I suppose it was the same with the other boys, to pick the best one to imitate, whether in work or in games. So strong with us was the idea of example that the boy who played ball better than all the rest was the one who became the example. If a boy in the group was outstanding as a rider, then I practiced riding, hoping that I might be as good. There was always one, or a few in every band, who swam the best, who shot the truest arrow, or who ran the fastest, and I at once set their accomplishment as the mark for me to attain. In spite of all this striving there was no sense of rivalry. We never disliked the boy who did better than the others. On the contrary, we praised him. All through our society, the individual who excelled was praised and honored.

On the hunts we younger boys carried the blankets and the extra arrows for the older boys. We made ourselves useful in exchange for our welcome. In following them we boys got our first hunting lessons. Woods hunting was easier than plains hunting, so we hunted first in the woods. When we had reached the haunts of the animal we sought, we began to look and listen. Animals are clever and we had to match their cleverness by reading their obscure signs. We not only watched the path ahead of us and the paths to the side, but kept watch of the path back of us. A good hunter watches all animals, for one often betrays the presence of another. Some of the signs we watched for were bits of hair, grass, broken sticks, the bark of trees, birds in the air, foot prints and overturned stones. Then, too, we depended much upon our sense of smell. Some of the animals that we could most readily scent were the porcupine, badger, bear, and skunk. A beaver-dam could also be smelled for some distance. Whenever signs grew scarce and our leaders stopped to survey the landscape and search for new signs, we did the same and tried to see the things they saw.

Rabbit-hunting was great fun even for the older boys, and we never refused to join one, for we little fellows got the tails. The fluffy tips were dyed in pretty colors and we wore them for hair ornaments. The skins we saved to make into winter hunting caps. Furs being usable, skinning was something else to be learned. When a porcupine was skinned, the quills, hair, and tails were saved—the quills to be dyed by the women for their decorative work, the hair for head roaches, and the tails for hair combs. The fur of the skunk was cut into strips and used for neck ornaments, while the entire hide was esteemed by the old men for tobacco pouches. The scent bag of this animal was carefully preserved, too, and the liquid kept for disinfectant purposes. A drop mixed with paint and smeared on the body kept away ailments. Skins of the raccoon made fine hunting caps and most hunters preferred a cap of fur to a bare head, for it helped in concealment. The tail of the raccoon we boys used to tie on the necks of our ponies. The furs of the otter and the beaver were most prized by the young braves, but these animals were wary and only the older boys hunted them. However, by the time we boys were ten or twelve years of age we were quite wise in trailing, stalking, covering, disguise, and all the arts of a good hunter. Some of the lads before their teens joined the men in their hunt for big game. At an early age physical strength was developed from long-distance walking, running, and climbing. Even long hours of crawling or walking in a stooped position had to be endured, for much of the hunting was on the low-shrubbed and grassy plains country.

Even the games which boys played put their strength to test, for most of them called for strenuous action. One of these games was called canhuyapi, meaning ‘wooden leg.’ White boys have this game, calling it stilts. Canhuyapi was a follow-the-leader game, the strongest boy being the leader. Through deep water, mud, snow-banks, brush thickets, and high grass, the leader took his followers, testing to the utmost their strength and courage. It was great fun, but when it came to going up and down steep banks or rocky places, the ones who tumbled were many, and, once down, one was out of the game.

Contests for strength were played in the water and the divers would search for a rock or root of a tree to hold, in order to see who could stay below the surface the longest. In winter the contestants plunged into the icy waters to see how much cold they could endure.

All boys did not have equal enthusiasm for all games, but one thing they all tried to do was to mount while their horses were running full speed. Running a few steps by the side of the horse, then grasping its mane and springing in the air, the rider was lifted by the motion of the animal. Another quite necessary thing to learn was to mount at the back of a rider who was going at full speed. In case of a battle, if a warrior were unhorsed, another could save him by riding swiftly by. The one on foot grasped the tail of the horse and leaped to the back of the rider and to safety. This was hard to do, but easily practiced with gentle ponies. Such training developed skillful horsemen.

A riding and shooting game was hanpa kute. A pole was planted in the earth and a moccasin placed on top of it for a target. Riding by as fast as possible, we shot an arrow at the moccasin. In order to be fair the rider must go by the target at full speed. If he slowed his pony down as he neared the pole he was ruled out of the game.